아미트리푸틸린

Amitriptyline | |

| |

| 임상 데이터 | |

|---|---|

| 발음 | /tr-pt-li-n/[1] |

| 상호 | 엘라빌, 기타 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| Medline Plus | a682388 |

| 라이선스 데이터 | |

| 임신 카테고리 |

|

| 루트 행정부. | 경구주사 |

| 약물 클래스 | 삼환식 항우울제(TCA) |

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 약동학 데이터 | |

| 바이오 어베이러빌리티 | 45%[3]-53%[4] |

| 단백질 결합 | 96 %[5] |

| 대사 | 간(CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP3A4)[7][4][8] |

| 대사물 | 노르티프틸린, (E)-10-히드록시 노르티프틸린 |

| 반감기 제거 | 21시간[3] |

| 배설물 | 소변: 48시간 [6]후 12~80%, 대변: 연구하지 않음 |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드러그뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니 | |

| 케그 | |

| 체비 | |

| 첸블 | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA ) | |

| ECHA 정보 카드 | 100.000.038 |

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |

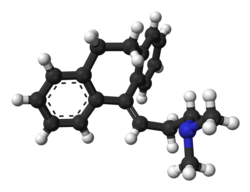

| 공식 | C20H23N |

| 몰 질량 | 277.411 g/120−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| 녹는점 | 197.5°C(387.5°F) |

| |

| |

| (표준) | |

Elavil이라는 브랜드명으로 판매되는 아미트리프틸린은 주로 순환구토증후군(CVS), 주요 우울증 질환 및 신경성 통증, 섬유근통, 편두통, 긴장성 [10]두통 등의 다양한 통증 증후군을 치료하는데 사용되는 삼환계 항우울제이다.부작용의 빈도와 현저성 때문에 아미트리푸틸린은 일반적으로 이러한 징후들에 [11][12][13][14]대한 2차 치료법으로 간주된다.

가장 흔한 부작용은 입 안이 마르고 졸음, 어지럼증, 변비, 체중 증가이다.주목할 만한 것은 주로 남성들에게서 관찰되는 성적 기능 장애이다.녹내장, 간 독성, 비정상적인 심장 박동은 드물지만 심각한 부작용이다.아미트리프틸린의 혈중 수치는 사람에 [15]따라 크게 다르며 아미트리프틸린은 부작용을 악화시킬 수 있는 많은 다른 약물들과 상호작용한다.

아미트리푸틸린은 1950년대 후반 머크의 과학자들에 의해 발견되었고 1961년 [16]미국 식품의약국(FDA)에 의해 승인되었다.그것은 세계보건기구의 필수 [17]의약품 목록에 있다.제네릭 [18]의약품으로 구입할 수 있습니다.2019년에는 미국에서 94번째로 많이 처방된 의약품으로 800만 건 이상의 [19][20]처방을 받았다.

의료 용도

아미트리프틸린은 주요 우울증 질환 및 신경성 통증의 치료와 편두통 및 만성 긴장성 두통 예방에 사용된다.다른 치료가 [10]실패한 후 6세 이상 어린이의 야뇨증 치료에 사용할 수 있습니다.

우울증.

아미트리프틸린은 [21]우울증에 효과적이지만 과다복용 시 독성이 높고 일반적으로 [22]내성이 떨어지기 때문에 1선 항우울제로 거의 사용되지 않는다.다른 [11]치료법이 실패한 후 2차 치료법으로 우울증 치료를 시도할 수 있다.치료내성 청소년 우울증이나[23] 암 관련 우울증[24] 아미트리프틸린은 플라시보보다 나을 것이 없다.파킨슨병의 [25]우울증 치료에 사용되기도 하지만, 그에 대한 근거가 부족하다.[26]

고통

아미트리푸틸린은 당뇨병성 신경장애를 완화시켜준다.다양한 가이드라인에서 1차 또는 2차 [12]시술로 권장하고 있습니다.그것은 가바펜틴이나 프레가발린만큼 이 적응증에 효과적이지만 [27]잘 견디지 못한다.

저용량의 아미트리프틸린은 수면 장애를 적당히 개선하고 섬유근육통과 [28]관련된 통증과 피로를 감소시킨다.독일 과학[28] 의학 협회 협회의 우울증을 동반하는 섬유근육통 및 유럽 [13]류머티즘 방지 연맹의 첫 번째 선택 사항인 섬유근육통의 두 번째 선택 사항으로 권장된다.아미트리프틸린과 플루옥세틴 또는 멜라토닌의 조합은 어느 [29]약품만 사용하는 것보다 섬유근육통을 더 잘 줄일 수 있다.

아미트리푸틸린이 암 환자의 통증을 줄일 수 있다는 (저품질) 증거가 있습니다.오피오이드가 원하는 [30]효과를 제공하지 않는 경우 비화학요법 유발 신경병증 또는 혼합 신경병증에 대한 2차 치료제로만 권장된다.

비정형 안면통증에 [31]아미트리푸틸린 사용을 지지하는 적당한 증거가 존재한다.아미트리푸틸린은 HIV관련 [27]신경장애에 효과가 없다.

두통.

아미트리프틸린은 성인의 주기성 편두통 예방에 효과적일 것이다.아미트리프틸린은 벤라팍신 및 토피라메이트와 효능이 유사하지만 [14]토피라메이트보다 부작용에 대한 부담이 크다.많은 환자에게는 아주 적은 양의 아미트리푸틸린도 도움이 되며,[32] 이는 부작용을 최소화할 수 있다.아미트리프틸린은 어린이 [33]편두통 예방을 위해 사용될 때 위약과 크게 다르지 않다.

아미트리프틸린은 만성 긴장성 두통의 빈도와 지속 시간을 줄일 수 있지만, 미르타자핀보다 더 나쁜 부작용과 관련이 있다.전반적으로, 아미트리푸틸린은 긴장성 두통 예방에 권장되며, 진통증과 [34]카페인의 회피가 포함되어야 하는 생활 습관 조언과 함께 권고된다.

기타 표시

아미트리프틸린은 과민성 대장증후군 치료에 효과적이지만 부작용 때문에 다른 약물이 [35]작용하지 않는 선별된 환자들에게만 사용해야 한다.기능성 위장 [36]장애를 가진 아이들의 복통 사용을 뒷받침하는 증거는 불충분하다.

삼환식 항우울제는 주기성 구토 증후군의 발생 빈도, 심각도 및 지속 시간을 감소시킨다.이들 중 가장 일반적으로 사용되는 아미트리푸틸린은 치료의 [37]첫 번째 약제로 권장된다.

아미트리프틸린은 방광통 증후군과 관련된 통증과 긴급도를 개선시킬 수 있으며 이 [38][39]증후군의 관리에 사용될 수 있다.아미트리푸틸린은 아동의 야뇨증 치료에 사용될 수 있다.그러나 치료 종료 후에는 효과가 지속되지 않습니다.경보 치료는 더 나은 장단기적인 결과를 [40]낳는다.

미국에서 아미트리프틸린은 ADHD를 앓고 있는 어린이에게 이러한 [41]관행을 뒷받침하는 어떠한 증거나 지침 없이 자극제 약물의 보조제로 흔히 사용된다.영국의 많은 의사들(그리고 미국도 마찬가지)은 일반적으로 [42]불면증에 대해 아미트리프틸린을 처방한다. 그러나 Cochrane 리뷰어는 이러한 [43]관행을 지지하거나 반박할 무작위 대조 연구를 찾을 수 없었다.

금기사항 및 주의사항

아미트리프틸린의 기존 금기는 다음과 같습니다.[10]

아미트리프틸린은 간질, 간기능 저하, 색소세포종, 소변 보유, 전립선 비대, 갑상선 기능 항진증, 유문 협착증 [10]환자에게 주의하여 사용해야 한다. 뇌전증

드물게 안구의 전실이 얕고 전실 각도가 좁은 환자에서 아미트리프틸린은 동공의 확장에 의한 급성 녹내장의 발작을 일으킬 수 있다.정신분열증 우울증에 사용하면 정신병을 악화시키거나 조울증 [10]환자의 조증 전환을 촉진할 수 있다.

CYP2D6의 저조한 신진대사는 증가하는 부작용으로 인해 아미트리푸틸린을 피해야 한다.사용할 필요가 있는 경우는, 반회 복용을 추천합니다.[44]SSRI가 작동하지 않는 경우 임신 및 [45]수유 중에 아미트리프틸린을 사용할 수 있습니다.

부작용

20% 이상에서 발생하는 가장 흔한 부작용은 입 안 건조, 졸음, 어지럼증, 변비, 체중 증가(평균 1.8kg[46])[21]이다.다른 일반적인 부작용으로는 시력 문제 (10% 이상), 빈맥, 식욕 증가, 떨림, 피로감/운동저하감, 소화불량 [21]등이 있다.

비정상적인 움직임과 아미트리프틸린에 대한 문헌 리뷰는 이 약물이 다양한 운동 장애, 특히 운동 장애, 디스토니아, 미오클로누스 등과 관련이 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.말더듬이와 안절부절못하는 다리증후군은 덜 흔한 [47]연관성 중 하나이다.

아미트리푸틸린의 덜 흔한 부작용은 배뇨 문제(8.7%)[48]이다.

아미트리푸틸린 관련 성기능장애(6.9%)는 대부분 우울증이 있는 남성에게만 국한된 것으로 보이며, 주로 사정과 오르가즘 문제의 빈도가 낮은 발기부전 및 저성욕장애로 표현된다.우울증 이외의 징후로 치료된 남성과 여성의 성적 기능 장애 비율은 [49]위약과 유의하게 다르지 않다.

간 검사 이상은 아미트리푸틸린 환자의 10-12%에서 발생하지만, 일반적으로 경미하고, 증상이 없으며,[50] 일시적인 것으로 전체 [51][52]환자의 3%에서 알라닌 트랜스아미나아제가 지속적으로 증가한다.간독성의 3배 역치를 초과하는 효소의 증가는 드물며 임상적으로 간독성이 명백한 경우는 드물다.[50] 그럼에도 불구하고 아미트리프틸린은 간독성의 위험이 [51]큰 항우울제 그룹에 포함된다.

아미트리프타일린은 QT [53]간격을 연장합니다.이러한 연장은 치료용량에서는[54] 상대적으로 적지만 과다 [55]복용 시에는 심각해진다.

과다 복용

과다 복용의 증상 및 치료는 세로토닌 증후군의 증상 및 심장 부작용 등 다른 TCA와 대체로 동일하다.영국 국립 조제법은 아미트리프틸린이 [56]과다복용으로 특히 위험할 수 있으므로, 아미트리프틸린과 다른 TCA는 더 이상 우울증에 대한 일선 치료제로 권장되지 않는다고 지적한다.아미트리프틸린 과다 복용에 대한 특별한 해독제가 없기 때문에 과다 복용의 치료는 대부분 도움이 된다.활성탄은 섭취 후 1~2시간 이내에 투여할 경우 흡수를 저하시킬 수 있다.환자가 의식이 없거나 재갈반사 장애가 있는 경우 활성화탄을 위장으로 전달하기 위해 비위관을 사용할 수 있다.심전도 이상에 대한 심전도 모니터링이 필수적이며 심전도 이상이 발견되면 심장 기능을 면밀히 모니터링하는 것이 좋습니다.필요한 경우 담요 난방 등의 방법으로 체온을 조절해야 합니다.약물 과다복용 후 최소 5일간 심장 감시를 권고한다.벤조디아제핀은 발작을 억제하기 위해 권장된다.투석은 아미트리푸틸린과의 [5]단백질 결합도가 높아 아무 소용이 없습니다.

상호 작용

아미트리프틸린과 그 활성대사물 노르티프틸린은 주로 시토크롬 CYP2D6 및 CYP2C19에 의해 대사되기 때문이다(아미트리프틸린# 참조).약리학) 이러한 효소의 억제제는 아미트리푸틸린과 약동학적 상호작용을 보일 것으로 예상된다.이 처방 정보에 따르면 CYP2D6 억제제와의 상호작용에 의해 아미트리푸틸린의 [10]혈장 레벨이 상승할 수 있다.그러나, 다른 문학에서 그 결과:를 입력하고 주요 활성 대사 물질 노르트 립틸린 1.5-fold,[57]지만 덜 강력한 CYP2D6 방지제나 levomepromazine 티오 리다 진와 함께 아미 트리 프탈린는 건 두가지 요소의 혈장 수준을 증가시킨다는 amitriptyline의 강력한 CYP2D6 억제제 paroxetine과 co-administration[7]도 일관성이 없다. 하n적당한 CYP2D6 억제제 플루옥세틴은 아미트리프틸린 또는 노르트리프틸린의 [59][60]수준에 [58]유의한 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 보인다.잠재적 CYP2D6 억제제 Terbinafine과 임상적으로 유의한 상호작용 사례가 [61]보고되었다.

CYP2C19 및 기타 시토크롬 플루복사민의 강력한 억제제는 노르티프틸린의 [59]농도를 약간 낮추면서 아미트리프틸린의 농도를 2배로 증가시킨다.CYP2C19 및 기타 시토크롬 시메티딘의 중간 억제제에서도 유사한 변화가 발생한다. 아미트리프틸린 수치는 약 70% 증가하지만 노르티프틸린은 50%[62] 감소한다.CYP3A4 억제제 케토코나졸은 아미트리프틸린 수치를 약 [8]4분의 1 상승시킨다.한편 카르바마제핀, St 등의 시토크롬 P450 유도제. John's Wort는 아미트리푸틸린과 노르트리푸틸린의[58][63] 수준을 낮춥니다.

경구 피임약은 아미트리푸틸린의 혈중 농도를 [64]90%까지 높일 수 있다.발프로산염은 불분명한 [65]메커니즘을 통해 아미트리푸틸린과 노르티푸틸린의 수치를 적당히 증가시킨다.

처방 정보는 아미노산 산화효소 억제제와 아미트리프틸린의 조합이 잠재적으로 치명적인 세로토닌 [10]증후군을 일으킬 수 있다고 경고하지만,[66] 이는 논란이 되고 있다.처방 정보에 따르면 일부 환자에게 토피라마이트가 [67]있을 경우 아미트리프틸린 농도가 크게 증가할 수 있습니다.그러나, 다른 문헌에서는 상호작용이 거의 없거나 전혀 없다고 기술하고 있다. 약동학 연구에서 토피라마이트는 아미트리프틸린의 수준을 20%, 노르티프틸린은 33%[68]만 증가시켰다.

아미트리푸틸린은 구아네티딘의 [5][69]강압작용을 중화시킨다.아미트리프틸린과 함께 투여될 경우 다른 항콜린제들은 과열증 또는 마비성 [67]장뇌증을 일으킬 수 있다.아미트리프틸린과 디술피람을 함께 투여하는 것은 독성 [5][70]섬망의 발생 가능성 때문에 권장되지 않는다.아미트리프틸린은 프로트롬빈 시간의 큰 변동이 [71]관찰되는 동안 항응고제 펜프로쿠몬과 비정상적인 형태의 상호작용을 일으킨다.

약리학

약역학

| 위치 | AMI | NTI | 종. | 참조 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 2.8–36 | 15–279 | 인간 | [73][74] |

| NET | 19–102 | 1.8–21 | 인간 | [73][74] |

| DAT | 3,250 | 1,140 | 인간 | [73] |

| 5-HT1A | 450–1,800 | 294 | 인간 | [75][76] |

| 5-HT1B | 840 | ND | 쥐. | [77] |

| 5-HT2A | 18–23 | 41 | 인간 | [75][76] |

| 5-HT2B | 174 | ND | 인간 | [78] |

| 5-HT2C | 4-8 | 8.5 | 쥐. | [79][80] |

| 5-HT3 | 430 | 1,400 | 쥐. | [81] |

| 5-HT6 | 65–141 | 148 | 인간/쥐 | [82][83][84] |

| 5-HT7 | 92.8–123 | ND | 쥐. | [85] |

| α1A | 6.5–25 | 18–37 | 인간 | [86][87] |

| α1B | 600–1700 | 850–1300 | 인간 | [86][87] |

| α1D | 560 | 1500 | 인간 | [87] |

| α2 | 114–690 | 2,030 | 인간 | [74][75] |

| α2A | 88 | ND | 인간 | [88] |

| α2B | 1000을 넘다 | ND | 인간 | [88] |

| α2C | 120 | ND | 인간 | [88] |

| β | 10,000 이상 | 10,000 이상 | 쥐. | [89][80] |

| D1. | 89 | 210 (랫) | 인간/쥐 | [90][80] |

| D2. | 196–1,460 | 2,570 | 인간 | [75][90] |

| D3. | 206 | ND | 인간 | [90] |

| D4. | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| D5. | 170 | ND | 인간 | [90] |

| H1 | 0.5–1.1 | 3.0–15 | 인간 | [90][91][92] |

| H2 | 66 | 646 | 인간 | [91] |

| H3 | 75,900;>1000 | 45,700 | 인간 | [90][91] |

| H4 | 34–26,300 | 6,920 | 인간 | [91][93] |

| M1 | 11.0–14.7 | 40 | 인간 | [94][95] |

| M2 | 11.8 | 110 | 인간 | [94] |

| M3 | 12.8–39 | 50 | 인간 | [94][95] |

| M4 | 7.2 | 84 | 인간 | [94] |

| M5 | 15.7–24 | 97 | 인간 | [94][95] |

| σ1 | 287-300 | 2,000 | 기니피그/쥐 | [96][97] |

| hERG | 3,260 | 31,600 | 인간 | [98][99] |

| PARP1 | 1650 | ND | 인간 | [100] |

| TrkA | 3,000 (아고니스트) | ND | 인간 | [101] |

| TrkB | 14,000 (아고니스트) | ND | 인간 | [101] |

| 특별히 명기되어 있지 않는 한 값은 K(nMi)입니다.값이 작을수록 약물이 사이트에 강하게 결합됩니다. | ||||

아미트리프틸린은 세로토닌 트랜스포터(SERT)와 노르에피네프린 트랜스포터(NET)를 억제한다.더 강력한 노르에피네프린 재흡수 억제제인 노르티프틸린으로 대사되어 노르에피네프린 재흡수에 대한 아미트리프틸린의 영향을 더욱 증가시킨다(오른쪽 표 참조).

아미트리프틸린은 추가로 세로토닌 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, α-아드레날린1A, 히스타민1 H 및 M-M15 무스카린 아세틸콜린 수용체의 잠재적 억제제 역할을 한다(오른쪽 표 참조).

아미트리프틸린은 여러 이온 채널, 특히 전압 게이트 나트륨 채널v Na1.3, Na1v.5, Na1v.6, Na1v.7 및 Na1v.8,[102][103][104] 전압 게이트 칼륨 채널v K7.2/K7v.3,[105] K7v.1, K7v.1/[106]Kerg 및 Herg의 비선택적 차단제이다.

작용 메커니즘

아미트리프틸린에 의한 세로토닌 및 노르에피네프린 트랜스포터의 억제는 세로토닌 및 노르에피네프린의 신경 재흡입에 간섭을 일으킨다.재흡수 과정은 생리적으로 전달 활성을 종료하는 데 중요하기 때문에 이 작용은 세로토닌 및 아드레날린 신경세포의 활성을 강화하거나 연장할 수 있으며 아미트리푸틸린의 [67]항우울제 활성을 밑바탕으로 하는 것으로 여겨진다.

노르에피네프린의 재흡수를 억제하여 척수 후회색 컬럼에서 노르에피네프린의 농도를 증가시키는 것이 아미트리푸틸린의 진통작용에 주로 관여하는 것으로 보인다.노르에피네프린의 수치가 증가하면 척추간 신경세포 사이에서 감마-아미노락산 전달을 증가시킴으로써 진통 효과를 매개하는 알파-2 아드레날린 수용체의 기초 활성이 증가한다.나트륨 채널에 대한 아미트리푸틸린의 차단 효과 또한 통증 [4]조건에서 효과의 기여가 될 수 있다.

약동학

아미트리푸틸린은 소화관에서 쉽게 흡수된다(90~[4]95%).흡수는 [3]약 4시간 후에 혈장의 최고 농도에 도달하여 점진적으로 이루어집니다.간을 통과하는 첫 번째 경로에서의 광범위한 신진대사는 약 50%(45%-[3]53%)[4]의 평균 생체 가용성으로 이어진다.아미트리프틸린은 주로 CYP2C19에 의해 노르토리프틸린으로, CYP2D6에 의해 다양한 히드록실화 대사물로 대사되며, 그 중 주요 대사물은 (E)-10-히드록시[7] 노르트리프틸린(대사 스킴 [4]참조)이며, CYP3A4에 의해 [8]낮은 수준으로 대사된다.

아미트리푸틸린의 주요 활성 대사물인 노르토리푸틸린은 그 자체로 항우울제이다.노르티프틸린은 혈장 중 모약 아미트리프틸린보다 10% 높고 곡선 아래 면적이 40% 더 크며, 그 작용은 아미트리프틸린의 [3][7]전체 작용에서 중요한 부분이다.

(E)-10-히드록시노르티프릴린 혈중 농도는 노르티프릴린보다 4배 약하지만 뇌척수액 수치는 노르티프릴린보다 2배 이상 높다.이를 바탕으로 (E)-10-hydroxynortriptyline은 아미트리프틸린의 [107]항우울 효과에 크게 기여하는 것으로 제안되었다.

아미트리프틸린과 노르티프틸린의 혈중 농도와 아미트리프틸린의 약물 동태는 개인마다 [108]최대 10배까지 차이가 난다.정상상태에서 곡선하부의 변동성도 높기 때문에 선량의 느린 상향적정이 필요하다.[15]

혈액에서 아미트리프틸린은 혈장 단백질에 96% 결합되어 있고, 노르토리프틸린은 93~95% 결합되어 있으며, (E)-10-히드록시노티프틸린은 약 60% [5][109][107]결합되어 있다.아미트리프틸린은 21시간,[3] 노르티프틸린 - 23~31시간,[110] (E)-10-히드록시노티프틸린 - 8~[107]10시간의 제거 반감기를 가진다.48시간 이내에, 12-80%의 아미트리프틸린이 소변에서, 주로 대사물로 [6]제거된다.변하지 않은 약물의 2%가 [111]소변으로 배출된다.대변의 제거는 연구되지 않은 것으로 보인다.

아미트리푸틸린의 치료 수준은 75~175ng/mL(270~631nM)[112] 또는 아미트리푸틸린과 대사물 노르티푸틸린의 [113]80~250ng/mL에 이른다.

약제유전학

아미트리프틸린은 주로 CYP2D6와 CYP2C19에 의해 대사되기 때문에 이들 효소를 코드하는 유전자 내의 유전자 변이가 대사 작용에 영향을 미쳐 [114]체내 약물의 농도 변화를 초래할 수 있다.아미트리프틸린의 농도가 증가하면 항콜린제 및 신경계 부작용을 포함한 부작용 위험이 증가하고 농도가 감소하면 약의 효과가 [115][116][117][118]감소할 수 있습니다.

개인은 어떤 유전적 변이를 가지고 있는지에 따라 다양한 유형의 CYP2D6 또는 CYP2C19 대사제로 분류될 수 있다.이러한 대사제 유형에는 불량, 중간, 광범위 및 초산성 대사제가 포함됩니다.대부분의 개인(약 77~92%)은 광범위한 [44]대사제이며 아미트리푸틸린의 "정상적인" 신진대사를 가지고 있다.신진대사가 불충분하고 중간인 경우 광범위한 신진대사에 비해 약물의 신진대사가 감소합니다. 이러한 유형의 신진대사가 있는 환자는 부작용을 경험할 확률이 높아질 수 있습니다.초아라피드 대사제는 광범위한 대사제보다 훨씬 더 빨리 아미트리프틸린을 사용한다; 이 대사제의 유형을 가진 환자들은 약리학적 [115][116][44][118]실패를 경험할 가능성이 더 높을 수 있다.

임상약리유전학실현컨소시엄은 CYP2D6 초산성 또는 저대사물인 환자에게 아미트리푸틸린을 사용하지 말 것을 권고하고 있다. 이는 각각 효능과 부작용의 위험이 있기 때문이다.컨소시엄은 또한 CYP2C19 초기압 대사제인 환자들에게 CYP2C19에 의해 대사되지 않는 대체 약물을 고려할 것을 권고한다.CYP2D6 중간 대사물 및 CYP2C19 불량 대사물인 환자에게는 시작 용량을 줄이는 것이 좋습니다.아미트리프틸린의 사용이 보장되는 경우, 치료 [44]약물 모니터링을 통해 선량 조정을 안내할 것을 권고한다.네덜란드 약리유전학 워킹 그룹은 또한 CYP2D6 불량 또는 초기파 대사제 환자의 혈장 아미트리프틸린 농도를 모니터링하거나 CYP2D6 중간 [119]대사제인 환자의 초기 투여량을 줄일 것을 권고한다.

화학

아미트리프틸린은 옥탄올-수분할계수(pH 7.4)가 3.[120]0인 고친유성 분자이며, 유리염기의 로그 P는 4.[121]92로 보고되었다.유리염기 아미트리프틸린의 물 중 용해도는 14 mg/L이다.[122]디벤조스베론과 3-(디메틸아미노)프로필마그네슘염화물을 반응시킨 후 염산과 가열하여 [4]수분을 제거하는 아미트리프틸린.

역사

아미트리프타일린은 1950년대 후반에 미국 제약회사 Merck에 의해 처음 개발되었다.1958년, Merck는 정신분열증에 대한 아미트리프틸린의 임상시험을 실시할 것을 제안하는 많은 임상 연구자들에게 접근했다.대신에, 이 연구원들 중 한 명인 프랭크 에이드는 우울증에 아미트리푸틸린을 사용할 것을 제안했다.Ayd는 130명의 환자를 치료했고 1960년에 아미트리푸틸린이 [123]다른 것과 유사한 항우울제 특성을 가지고 있다고 보고했으며, 그 당시에 알려진 것은 삼환식 항우울제 이미프라민뿐이었다.이에 따라 미국 식품의약국은 1961년 [16]우울증에 대한 아미트리푸틸린을 승인했다.

유럽에서는 화학합성 특허만 허용하고 의약품 자체는 허용하지 않는 당시 특허법의 변칙으로 인해 [124]1960년대 초 로체와 룬드벡은 독자적으로 아미트리푸틸린을 개발하고 판매할 수 있었다.

정신약리학자 데이비드 힐리의 연구에 따르면 아미트리푸틸린은 두 가지 요인 때문에 이미프라민보다 훨씬 더 많이 팔리는 약이 되었다.우선 아미트리푸틸린은 훨씬 더 강한 항불안 효과가 있습니다.둘째, Merck는 임상 주체로 [124][123]우울증에 대한 임상의들의 인식을 높이는 마케팅 캠페인을 실시했습니다.

사회와 문화

영국의 포크 가수 닉 드레이크는 1974년 [125]트립티졸 과다복용으로 사망했다.

스와질란드 국왕 음스와티의 부인 센테니 마상고는 2018년 4월 6일 아밀트리프틸린 [126]캡슐 과다복용으로 자살한 후 사망했다.

2021년 영화 뉴어크의 많은 성인에서 아미트리프틸린(브랜드명 엘라빌)은 영화의 [127]줄거리의 일부이다.

일반명

아미트리프틸린은 약의 영어와 프랑스어 총칭이며, 염산아미트리프틸린은 , , , ,[128][129][130][131] 그리고 입니다.총칭은 스페인어와 이탈리아어로 아미트리푸틸리나, 독일어로는 아미트리푸틸린, 라틴어로는 아미트리푸틸리눔이다.[129][131]엠보네이트 소금은 아미트리프틸린 엠보네이트 또는 [129]아미트리프틸린 파모네이트로 비공식적으로 알려져 있습니다.

조사.

섭식 장애에서 아미트리푸틸린의 효능을 조사하는 몇 가지 무작위 대조 실험들은 [132]실망스러웠다.

레퍼런스

- ^ "Amitriptyline Definition of Amitriptyline by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Amitriptyline". Lexico Dictionaries English. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "Amitriptyline Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 2 September 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Schulz P, Dick P, Blaschke TF, Hollister L (1985). "Discrepancies between pharmacokinetic studies of amitriptyline". Clin Pharmacokinet. 10 (3): 257–68. doi:10.2165/00003088-198510030-00005. PMID 3893842. S2CID 41881790.

- ^ a b c d e f g McClure EW, Daniels RN (February 2021). "Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Amitriptyline". ACS Chem Neurosci. 12 (3): 354–362. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00467. PMID 33438398. S2CID 231596860.

- ^ a b c d e "Endep Amitriptyline hydrochloride" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ a b Schulz P, Balant-Gorgia AE, Kubli A, Gertsch-Genet C, Garrone G (1983). "Elimination and pharmacological effects following single oral doses of 50 and 75 mg of amitriptyline in man". Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr (1970). 233 (6): 449–55. doi:10.1007/BF00342785. PMID 6667101. S2CID 20844722.

- ^ a b c d Breyer-Pfaff U (October 2004). "The metabolic fate of amitriptyline, nortriptyline and amitriptylinoxide in man". Drug Metab Rev. 36 (3–4): 723–46. doi:10.1081/dmr-200033482. PMID 15554244. S2CID 25565048.

- ^ a b c Venkatakrishnan K, Schmider J, Harmatz JS, Ehrenberg BL, von Moltke LL, Graf JA, Mertzanis P, Corbett KE, Rodriguez MC, Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ (October 2001). "Relative contribution of CYP3A to amitriptyline clearance in humans: in vitro and in vivo studies". J Clin Pharmacol. 41 (10): 1043–54. doi:10.1177/00912700122012634. PMID 11583471. S2CID 27146286.

- ^ Blessel KW, Rudy BC, Senkowski BZ (1974). "Amitriptyline Hydrochloride". Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances. 3: 127–148. doi:10.1016/S0099-5428(08)60066-0. ISBN 9780122608032.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Amitriptyline Tablets BP 50mg – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Actavis UK Ltd. 24 March 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ a b Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E (2015). Top 100 drugs : clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7020-5516-4.

- ^ a b Alam U, Sloan G, Tesfaye S (March 2020). "Treating Pain in Diabetic Neuropathy: Current and Developmental Drugs". Drugs. 80 (4): 363–384. doi:10.1007/s40265-020-01259-2. PMID 32040849. S2CID 211074023.

- ^ a b Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, Atzeni F, Häuser W, Fluß E, Choy E, Kosek E, Amris K, Branco J, Dincer F, Leino-Arjas P, Longley K, McCarthy GM, Makri S, Perrot S, Sarzi-Puttini P, Taylor A, Jones GT (February 2017). "EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia". Ann Rheum Dis. 76 (2): 318–328. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724. PMID 27377815.

- ^ a b Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E (April 2012). "Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 78 (17): 1337–45. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d20. PMC 3335452. PMID 22529202.

- ^ a b Tfelt-Hansen P, Ågesen FN, Pavbro A, Tfelt-Hansen J (May 2017). "Pharmacokinetic Variability of Drugs Used for Prophylactic Treatment of Migraine". CNS Drugs. 31 (5): 389–403. doi:10.1007/s40263-017-0430-3. PMID 28405886. S2CID 23560743.

- ^ a b Fangmann P, Assion HJ, Juckel G, González CA, López-Muñoz F (February 2008). "Half a century of antidepressant drugs: on the clinical introduction of monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclics, and tetracyclics. Part II: tricyclics and tetracyclics". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 28 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e3181627b60. PMID 18204333. S2CID 31018835.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "Amitriptyline Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2019". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Amitriptyline - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Leucht C, Huhn M, Leucht S (December 2012). "Amitriptyline versus placebo for major depressive disorder". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: CD009138. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009138.pub2. PMID 23235671.

- ^ Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ Zhou X, Michael KD, Liu Y, Del Giovane C, Qin B, Cohen D, Gentile S, Xie P (November 2014). "Systematic review of management for treatment-resistant depression in adolescents". BMC Psychiatry. 14: 340. doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0340-6. PMC 4254264. PMID 25433401.

- ^ Riblet N, Larson R, Watts BV, Holtzheimer P (2014). "Reevaluating the role of antidepressants in cancer-related depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 36 (5): 466–73. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.010. PMID 24950919.

- ^ 2013년 11월 18일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 파킨슨병.Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.2007년 8월2013년 12월 22일 취득.

- ^ Seppi K, Weintraub D, Coelho M, Perez-Lloret S, Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Hametner EM, Poewe W, Rascol O, Goetz CG, Sampaio C (October 2011). "The Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Review Update: Treatments for the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease". Mov Disord. 26 (Suppl 3): S42–80. doi:10.1002/mds.23884. PMC 4020145. PMID 22021174.

- ^ a b Liampas A, Rekatsina M, Vadalouca A, Paladini A, Varrassi G, Zis P (November 2020). "Pharmacological Management of Painful Peripheral Neuropathies: A Systematic Review". Pain Ther. 10 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00210-3. ISSN 2193-8237. PMC 8119529. PMID 33145709.

- ^ a b Sommer C, Alten R, Bär KJ, Bernateck M, Brückle W, Friedel E, Henningsen P, Petzke F, Tölle T, Üçeyler N, Winkelmann A, Häuser W (June 2017). "[Drug therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome : Updated guidelines 2017 and overview of systematic review articles]". Schmerz (in German). 31 (3): 274–284. doi:10.1007/s00482-017-0207-0. PMID 28493231.

- ^ Thorpe J, Shum B, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Gilron I (February 2018). "Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD010585. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010585.pub2. PMC 6491103. PMID 29457627.

- ^ van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Graeff A, Jongen JL, Dijkstra D, Mostovaya I, Vissers KC (March 2017). "Pharmacological Treatment of Pain in Cancer Patients: The Role of Adjuvant Analgesics, a Systematic Review". Pain Pract. 17 (3): 409–419. doi:10.1111/papr.12459. PMID 27207115. S2CID 37418010.

- ^ Do TM, Unis GD, Kattar N, Ananth A, McCoul ED (October 2020). "Neuromodulators for Atypical Facial Pain and Neuralgias: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Laryngoscope. 131 (6): 1235–1253. doi:10.1002/lary.29162. PMID 33037835. S2CID 222256076.

- ^ Loder E, Rizzoli P (November 2018). "Pharmacologic Prevention of Migraine: A Narrative Review of the State of the Art in 2018". Headache. 58 (Suppl 3): 218–229. doi:10.1111/head.13375. PMID 30137671. S2CID 52071815.

- ^ Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Billinghurst L, Potrebic S, Gersz EM, Gloss D, Holler-Managan Y, Leininger E, Licking N, Mack K, Powers SW, Sowell M, Victorio MC, Yonker M, Zanitsch H, Hershey AD (September 2019). "Practice guideline update summary: Pharmacologic treatment for pediatric migraine prevention: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 93 (11): 500–509. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105. PMC 6746206. PMID 31413170.

- ^ Ghadiri-Sani M, Silver N (February 2016). "Headache (chronic tension-type)". BMJ Clin Evid. 2016. PMC 4747324. PMID 26859719.

- ^ Trinkley KE, Nahata MC (2014). "Medication management of irritable bowel syndrome". Digestion. 89 (4): 253–67. doi:10.1159/000362405. PMID 24992947.

- ^ de Bruijn CM, Rexwinkel R, Gordon M, Benninga M, Tabbers MM (February 2021). "Antidepressants for functional abdominal pain disorders in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (3): CD008013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008013.pub3. PMC 8094232. PMID 33560523.

- ^ Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Tarbell SE, Jaradeh SS, Hasler WL, Issenman RM, Adams KA, Sarosiek I, Stave CD, Sharaf RN, Sultan S, Li BU (June 2019). "Guidelines on management of cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Association". Neurogastroenterol Motil. 31 (Suppl 2): e13604. doi:10.1111/nmo.13604. PMC 6899751. PMID 31241819.

- ^ Giusto LL, Zahner PM, Shoskes DA (July 2018). "An evaluation of the pharmacotherapy for interstitial cystitis". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 19 (10): 1097–1108. doi:10.1080/14656566.2018.1491968. PMID 29972328. S2CID 49674883.

- ^ Colemeadow J, Sahai A, Malde S (2020). "Clinical Management of Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis: A Review on Current Recommendations and Emerging Treatment Options". Res Rep Urol. 12: 331–343. doi:10.2147/RRU.S238746. PMC 7455607. PMID 32904438.

- ^ Caldwell PH, Sureshkumar P, Wong WC (January 2016). "Tricyclic and related drugs for nocturnal enuresis in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 (1): CD002117. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002117.pub2. PMC 8741207. PMID 26789925.

- ^ Klein T, Woo TM, Panther S, Odom-Maryon T, Daratha K (2019). "Somnolence-Producing Agents: A 5-Year Study of Prescribing for Medicaid-Insured Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". J Pediatr Health Care. 33 (3): e1–e8. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.10.002. PMID 30630642. S2CID 58577978.

- ^ Everitt H, McDermott L, Leydon G, Yules H, Baldwin D, Little P (February 2014). "GPs' management strategies for patients with insomnia: a survey and qualitative interview study". Br J Gen Pract. 64 (619): e112–9. doi:10.3399/bjgp14X677176. PMC 3905408. PMID 24567616.

- ^ Everitt H, Baldwin DS, Stuart B, Lipinska G, Mayers A, Malizia AL, Manson CC, Wilson S (May 2018). "Antidepressants for insomnia in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 (5): CD010753. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010753.pub2. PMC 6494576. PMID 29761479.

- ^ a b c d Hicks JK, Swen JJ, Thorn CF, Sangkuhl K, Kharasch ED, Ellingrod VL, Skaar TC, Müller DJ, Gaedigk A, Stingl JC (May 2013). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of tricyclic antidepressants". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 93 (5): 402–8. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.2. PMC 3689226. PMID 23486447.

- ^ Nielsen RE, Damkier P (June 2012). "Pharmacological treatment of unipolar depression during pregnancy and breast-feeding--a clinical overview". Nord J Psychiatry. 66 (3): 159–66. doi:10.3109/08039488.2011.650198. PMID 22283766. S2CID 11327135.

- ^ Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Leppin A, Sonbol MB, Altayar O, Undavalli C, Wang Z, Elraiyah T, Brito JP, Mauck KF, Lababidi MH, Prokop LJ, Asi N, Wei J, Fidahussein S, Montori VM, Murad MH (February 2015). "Clinical review: Drugs commonly associated with weight change: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 100 (2): 363–70. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3421. PMC 5393509. PMID 25590213.

- ^ Rissardo JP, Caprara AL (April 2020). "The Link Between Amitriptyline and Movement Disorders: Clinical Profile and Outcome". Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 49 (4): 236–251. doi:10.47102/annals-acadmed.sg.202023. PMID 32419008. S2CID 218679271.

- ^ Leucht C, Huhn M, Leucht S (December 2012). "Amitriptyline versus placebo for major depressive disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Wiley. 12: CD009138. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009138.pub2. PMID 23235671.

- ^ Chen LW, Chen MY, Lian ZP, Lin HS, Chien CC, Yin HL, Chu YH, Chen KY (March 2018). "Amitriptyline and Sexual Function: A Systematic Review Updated for Sexual Health Practice". Am J Mens Health. 12 (2): 370–379. doi:10.1177/1557988317734519. PMC 5818113. PMID 29019272.

- ^ a b Amitriptyline. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 6 January 2012. PMID 31643729. Retrieved 6 January 2021 – via PubMed.

- ^ a b Voican CS, Corruble E, Naveau S, Perlemuter G (April 2014). "Antidepressant-induced liver injury: a review for clinicians". Am J Psychiatry. 171 (4): 404–15. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13050709. PMID 24362450.

- ^ HOLMBERG MB, JANSSON (1962). "A study of blood count and serum transaminase in prolonged treatment with amitriptyline". J New Drugs. 2 (6): 361–5. doi:10.1177/009127006200200606. PMID 13961401.

- ^ Zemrak WR, Kenna GA (June 2008). "Association of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs with Q-T interval prolongation". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 65 (11): 1029–38. doi:10.2146/ajhp070279. PMID 18499875. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016.

- ^ Hefner G, Hahn M, Hohner M, Roll SC, Klimke A, Hiemke C (January 2019). "QTc Time Correlates with Amitriptyline and Venlafaxine Serum Levels in Elderly Psychiatric Inpatients". Pharmacopsychiatry. 52 (1): 38–43. doi:10.1055/s-0044-102009. PMID 29466824.

- ^ Campleman SL, Brent J, Pizon AF, Shulman J, Wax P, Manini AF (December 2020). "Drug-specific risk of severe QT prolongation following acute drug overdose". Clin Toxicol (Phila). 58 (12): 1326–1334. doi:10.1080/15563650.2020.1746330. PMC 7541562. PMID 32252558.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65th ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ Leucht S, Hackl HJ, Steimer W, Angersbach D, Zimmer R (January 2000). "Effect of adjunctive paroxetine on serum levels and side-effects of tricyclic antidepressants in depressive inpatients". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 147 (4): 378–83. doi:10.1007/s002130050006. PMID 10672631. S2CID 22476829.

- ^ a b Jerling M, Bertilsson L, Sjöqvist F (February 1994). "The use of therapeutic drug monitoring data to document kinetic drug interactions: an example with amitriptyline and nortriptyline". Ther Drug Monit. 16 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1097/00007691-199402000-00001. PMID 7909176. S2CID 1428027.

- ^ a b Vandel S, Bertschy G, Baumann P, Bouquet S, Bonin B, Francois T, Sechter D, Bizouard P (June 1995). "Fluvoxamine and fluoxetine: interaction studies with amitriptyline, clomipramine and neuroleptics in phenotyped patients". Pharmacol Res. 31 (6): 347–53. doi:10.1016/1043-6618(95)80088-3. PMID 8685072.

- ^ Vandel S, Bertschy G, Bonin B, Nezelof S, François TH, Vandel B, Sechter D, Bizouard P (1992). "Tricyclic antidepressant plasma levels after fluoxetine addition". Neuropsychobiology. 25 (4): 202–7. doi:10.1159/000118838. PMID 1454161.

- ^ Castberg I, Helle J, Aamo TO (October 2005). "Prolonged pharmacokinetic drug interaction between terbinafine and amitriptyline". Ther Drug Monit. 27 (5): 680–2. doi:10.1097/01.ftd.0000175910.68539.33. PMID 16175144.

- ^ Curry SH, DeVane CL, Wolfe MM (1985). "Cimetidine interaction with amitriptyline". Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 29 (4): 429–33. doi:10.1007/BF00613457. PMID 3912187. S2CID 25430195.

- ^ Johne A, Schmider J, Brockmöller J, Stadelmann AM, Störmer E, Bauer S, Scholler G, Langheinrich M, Roots I (February 2002). "Decreased plasma levels of amitriptyline and its metabolites on comedication with an extract from St. John's wort ( Hypericum perforatum )". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 22 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1097/00004714-200202000-00008. PMID 11799342. S2CID 25670895.

- ^ Berry-Bibee EN, Kim MJ, Simmons KB, Tepper NK, Riley HE, Pagano HP, Curtis KM (December 2016). "Drug interactions between hormonal contraceptives and psychotropic drugs: a systematic review". Contraception. 94 (6): 650–667. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.07.011. PMID 27444984.

- ^ Wong SL, Cavanaugh J, Shi H, Awni WM, Granneman GR (July 1996). "Effects of divalproex sodium on amitriptyline and nortriptyline pharmacokinetics". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 60 (1): 48–53. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90166-6. PMID 8689811. S2CID 37720622.

- ^ Gillman PK (June 2006). "A review of serotonin toxicity data: implications for the mechanisms of antidepressant drug action". Biol Psychiatry. 59 (11): 1046–51. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.016. PMID 16460699. S2CID 12179122.

- ^ a b c "DailyMed - AMITRIPTYLINE HYDROCHLORIDE tablet, film coated".

- ^ Bialer M, Doose DR, Murthy B, Curtin C, Wang SS, Twyman RE, Schwabe S (2004). "Pharmacokinetic interactions of topiramate". Clin Pharmacokinet. 43 (12): 763–80. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443120-00001. PMID 15355124. S2CID 10427097.

- ^ Meyer JF, McAllister CK, Goldberg LI (August 1970). "Insidious and prolonged antagonism of guanethidine by amitriptyline". JAMA. 213 (9): 1487–8. doi:10.1001/jama.1970.03170350053016. PMID 5468457.

- ^ Maany I, Hayashida M, Pfeffer SL, Kron RE (June 1982). "Possible toxic interaction between disulfiram and amitriptyline". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 39 (6): 743–4. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290060083018. PMID 7092508.

- ^ "CHAPTER 132 ORAL ANTICOAGULATION Free Medical Textbook". 9 February 2012.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ^ a b c Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB (1997). "Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolites". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 283 (3): 1305–22. PMID 9400006.

- ^ a b c d Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology. 114 (4): 559–65. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217. S2CID 21236268.

- ^ a b Peroutka SJ (1988). "Antimigraine drug interactions with serotonin receptor subtypes in human brain". Ann. Neurol. 23 (5): 500–4. doi:10.1002/ana.410230512. PMID 2898916. S2CID 41570165.

- ^ Peroutka SJ (1986). "Pharmacological differentiation and characterization of 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1C binding sites in rat frontal cortex". J. Neurochem. 47 (2): 529–40. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb04532.x. PMID 2942638. S2CID 25108290.

- ^ Schmuck K, Ullmer C, Kalkman HO, Probst A, Lubbert H (1996). "Activation of meningeal 5-HT2B receptors: an early step in the generation of migraine headache?". Eur. J. Neurosci. 8 (5): 959–67. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01583.x. PMID 8743744. S2CID 19578349.

- ^ Pälvimäki EP, Roth BL, Majasuo H, Laakso A, Kuoppamäki M, Syvälahti E, Hietala J (1996). "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor". Psychopharmacology. 126 (3): 234–40. doi:10.1007/bf02246453. PMID 8876023. S2CID 24889381.

- ^ a b c Sánchez C, Hyttel J (August 1999). "Comparison of the effects of antidepressants and their metabolites on reuptake of biogenic amines and on receptor binding". Cell Mol Neurobiol. 19 (4): 467–89. doi:10.1023/a:1006986824213. PMID 10379421. S2CID 19490821.

- ^ Schmidt AW, Hurt SD, Peroutka SJ (1989). "'[3H]quipazine' degradation products label 5-HT uptake sites". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 171 (1): 141–3. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90439-1. PMID 2533080.

- ^ Kohen R, Metcalf MA, Khan N, Druck T, Huebner K, Lachowicz JE, Meltzer HY, Sibley DR, Roth BL, Hamblin MW (1996). "Cloning, characterization, and chromosomal localization of a human 5-HT6 serotonin receptor". J. Neurochem. 66 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010047.x. PMID 8522988. S2CID 35874409.

- ^ Hirst WD, Abrahamsen B, Blaney FE, Calver AR, Aloj L, Price GW, Medhurst AD (2003). "Differences in the central nervous system distribution and pharmacology of the mouse 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 receptor compared with rat and human receptors investigated by radioligand binding, site-directed mutagenesis, and molecular modeling". Mol. Pharmacol. 64 (6): 1295–308. doi:10.1124/mol.64.6.1295. PMID 14645659. S2CID 33743899.

- ^ Monsma FJ, Shen Y, Ward RP, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR (1993). "Cloning and expression of a novel serotonin receptor with high affinity for tricyclic psychotropic drugs". Mol. Pharmacol. 43 (3): 320–7. PMID 7680751.

- ^ Shen Y, Monsma FJ, Metcalf MA, Jose PA, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR (1993). "Molecular cloning and expression of a 5-hydroxytryptamine7 serotonin receptor subtype". J. Biol. Chem. 268 (24): 18200–4. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)46830-X. PMID 8394362.

- ^ a b Nojimoto FD, Mueller A, Hebeler-Barbosa F, Akinaga J, Lima V, Kiguti LR, Pupo AS (2010). "The tricyclic antidepressants amitriptyline, nortriptyline and imipramine are weak antagonists of human and rat alpha1B-adrenoceptors". Neuropharmacology. 59 (1–2): 49–57. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.03.015. PMID 20363235. S2CID 207225294.

- ^ a b c Proudman RG, Pupo AS, Baker JG (August 2020). "The affinity and selectivity of α-adrenoceptor antagonists, antidepressants, and antipsychotics for the human α1A, α1B, and α1D-adrenoceptors". Pharmacol Res Perspect. 8 (4): e00602. doi:10.1002/prp2.602. PMC 7327383. PMID 32608144.

- ^ a b c Fallarero A, Pohjanoksa K, Wissel G, Parkkisenniemi-Kinnunen UM, Xhaard H, Scheinin M, Vuorela P (December 2012). "High-throughput screening with a miniaturized radioligand competition assay identifies new modulators of human α2-adrenoceptors". Eur J Pharm Sci. 47 (5): 941–51. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2012.08.021. PMID 22982401.

- ^ Bylund DB, Snyder SH (1976). "Beta adrenergic receptor binding in membrane preparations from mammalian brain". Mol. Pharmacol. 12 (4): 568–80. PMID 8699.

- ^ a b c d e f von Coburg Y, Kottke T, Weizel L, Ligneau X, Stark H (2009). "Potential utility of histamine H3 receptor antagonist pharmacophore in antipsychotics". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19 (2): 538–42. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.012. PMID 19091563.

- ^ a b c d Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (February 2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H1, H2, H3, and H4 receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 385 (2): 145–70. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803. S2CID 14274150.

- ^ Ghoneim OM, Legere JA, Golbraikh A, Tropsha A, Booth RG (2006). "Novel ligands for the human histamine H1 receptor: synthesis, pharmacology, and comparative molecular field analysis studies of 2-dimethylamino-5-(6)-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalenes". Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14 (19): 6640–58. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.05.077. PMID 16782354.

- ^ Nguyen T, Shapiro DA, George SR, Setola V, Lee DK, Cheng R, Rauser L, Lee SP, Lynch KR, Roth BL, O'Dowd BF (2001). "Discovery of a novel member of the histamine receptor family". Mol. Pharmacol. 59 (3): 427–33. doi:10.1124/mol.59.3.427. PMID 11179435.

- ^ a b c d e Stanton T, Bolden-Watson C, Cusack B, Richelson E (1993). "Antagonism of the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in CHO-K1 cells by antidepressants and antihistaminics". Biochem. Pharmacol. 45 (11): 2352–4. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90211-e. PMID 8100134.

- ^ a b c Bymaster FP, Nelson DL, DeLapp NW, Falcone JF, Eckols K, Truex LL, Foreman MM, Lucaites VL, Calligaro DO (1999). "Antagonism by olanzapine of dopamine D1, serotonin2, muscarinic, histamine H1 and alpha 1-adrenergic receptors in vitro". Schizophr. Res. 37 (1): 107–22. doi:10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00146-7. PMID 10227113. S2CID 19891653.

- ^ Weber E, Sonders M, Quarum M, McLean S, Pou S, Keana JF (1986). "1,3-Di(2-[5-3H]tolyl)guanidine: a selective ligand that labels sigma-type receptors for psychotomimetic opiates and antipsychotic drugs". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83 (22): 8784–8. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.8784W. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.22.8784. PMC 387016. PMID 2877462.

- ^ Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, Nuwayhid SJ (October 2007). "A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder". Exp Neurol. 207 (2): 248–57. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.013. PMID 17689532. S2CID 38476281.

- ^ a b Jo SH, Youm JB, Lee CO, Earm YE, Ho WK (April 2000). "Blockade of the HERG human cardiac K(+) channel by the antidepressant drug amitriptyline". Br J Pharmacol. 129 (7): 1474–80. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703222. PMC 1571977. PMID 10742304.

- ^ Yamakawa Y, Furutani K, Inanobe A, Ohno Y, Kurachi Y (February 2012). "Pharmacophore modeling for hERG channel facilitation". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 418 (1): 161–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.153. PMID 22244872.

- ^ Fu L, Wang S, Wang X, Wang P, Zheng Y, Yao D, et al. (December 2016). "Crystal structure-based discovery of a novel synthesized PARP1 inhibitor (OL-1) with apoptosis-inducing mechanisms in triple-negative breast cancer". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 3. doi:10.1038/s41598-016-0007-2. PMC 5431371. PMID 28442756.

- ^ a b Jang SW, Liu X, Chan CB, Weinshenker D, Hall RA, Xiao G, Ye K (June 2009). "Amitriptyline is a TrkA and TrkB receptor agonist that promotes TrkA/TrkB heterodimerization and has potent neurotrophic activity". Chemistry & Biology. 16 (6): 644–56. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.05.010. PMC 2844702. PMID 19549602.

- ^ Horishita T, Yanagihara N, Ueno S, Okura D, Horishita R, Minami T, Ogata Y, Sudo Y, Uezono Y, Sata T, Kawasaki T (December 2017). "Antidepressants inhibit Nav1.3, Nav1.7, and Nav1.8 neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels more potently than Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 390 (12): 1255–1270. doi:10.1007/s00210-017-1424-x. PMID 28905186. S2CID 23385313.

- ^ Atkin TA, Maher CM, Gerlach AC, Gay BC, Antonio BM, Santos SC, Padilla KM, Rader J, Krafte DS, Fox MA, Stewart GR, Petrovski S, Devinsky O, Might M, Petrou S, Goldstein DB (April 2018). "A comprehensive approach to identifying repurposed drugs to treat SCN8A epilepsy". Epilepsia. 59 (4): 802–813. doi:10.1111/epi.14037. PMID 29574705. S2CID 4478321.

- ^ Nau C, Seaver M, Wang SY, Wang GK (March 2000). "Block of human heart hH1 sodium channels by amitriptyline". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 292 (3): 1015–23. PMID 10688618.

- ^ Punke MA, Friederich P (May 2007). "Amitriptyline is a potent blocker of human Kv1.1 and Kv7.2/7.3 channels". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 104 (5): 1256–1264. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000260310.63117.a2. PMID 17456683. S2CID 21924741.

- ^ Villatoro-Gómez K, Pacheco-Rojas DO, Moreno-Galindo EG, Navarro-Polanco RA, Tristani-Firouzi M, Gazgalis D, Cui M, Sánchez-Chapula JA, Ferrer T (June 2018). "Molecular determinants of Kv7.1/KCNE1 channel inhibition by amitriptyline". Biochem Pharmacol. 152: 264–271. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2018.03.016. PMID 29621539. S2CID 4929937.

- ^ a b c Nordin C, Bertilsson L (January 1995). "Active hydroxymetabolites of antidepressants. Emphasis on E-10-hydroxy-nortriptyline". Clin Pharmacokinet. 28 (1): 26–40. doi:10.2165/00003088-199528010-00004. PMID 7712660. S2CID 38046048.

- ^ Bryson HM, Wilde MI (June 1996). "Amitriptyline. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in chronic pain states". Drugs Aging. 8 (6): 459–76. doi:10.2165/00002512-199608060-00008. PMID 8736630.

- ^ "Pamelor, Aventyl (nortriptyline) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ Dawlilng S, Lynn K, Rosser R, Braithwaite R (July 1981). "The pharmacokinetics of nortriptyline in patients with chronic renal failure". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 12 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01852.x. PMC 1401753. PMID 7248140.

- ^ "Amitriptyline". drugbank.ca. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (2008). Kaplan & Sadock's Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-7817-8746-8. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017.

- ^ Orsulak PJ (September 1989). "Therapeutic monitoring of antidepressant drugs: guidelines updated". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 11 (5): 497–507. doi:10.1097/00007691-198909000-00002. PMID 2683251.

- ^ Rudorfer MV, Potter WZ (1999). "Metabolism of tricyclic antidepressants". Cell Mol Neurobiol. 19 (3): 373–409. doi:10.1023/A:1006949816036. PMID 10319193. S2CID 7940406.

- ^ a b Stingl JC, Brockmoller J, Viviani R (2013). "Genetic variability of drug-metabolizing enzymes: the dual impact on psychiatric therapy and regulation of brain function". Mol Psychiatry. 18 (3): 273–87. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.42. PMID 22565785. S2CID 20888081.

- ^ a b Kirchheiner J, Seeringer A (2007). "Clinical implications of pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450 drug metabolizing enzymes". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1770 (3): 489–94. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.09.019. PMID 17113714.

- ^ Hicks JK, Swen JJ, Thorn CF, Sangkuhl K, Kharasch ED, Ellingrod VL, Skaar TC, Muller DJ, Gaedigk A, Stingl JC (2013). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotypes and Dosing of Tricyclic Antidepressants" (PDF). Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 93 (5): 402–8. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.2. PMC 3689226. PMID 23486447.

- ^ a b Dean L (2017). "Amitriptyline Therapy and CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520380. Bookshelf ID: NBK425165.

- ^ Swen JJ, Nijenhuis M, de Boer A, Grandia L, Maitland-van der Zee AH, Mulder H, Rongen GA, van Schaik RH, Schalekamp T, Touw DJ, van der Weide J, Wilffert B, Deneer VH, Guchelaar HJ (2011). "Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte—an update of guidelines". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 89 (5): 662–73. doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.34. PMID 21412232. S2CID 2475005.

- ^ 의약 고문서, 1994년12학번, 약학의 원칙과 실천제약 출판사

- ^ Hansch C, Leo A, Hoekman D. 1995.QSAR의 조사소수성, 전자성 및 입체성 상수.워싱턴 DC: 미국 화학 협회.

- ^ Box KJ, Völgyi G, Baka E, Stuart M, Takács-Novák K, Comer JE (June 2006). "Equilibrium versus kinetic measurements of aqueous solubility, and the ability of compounds to supersaturate in solution--a validation study". J Pharm Sci. 95 (6): 1298–307. doi:10.1002/jps.20613. PMID 16552741.

- ^ a b Healy D (1997). The Antidepressant Era. Harvard University Press. pp. 74–76. ISBN 0674039572.

- ^ a b Healy D (1999). The Psychopharmacologists II. Arnold. pp. 565–566. ISBN 1860360106.

- ^ 브라운, M., "닉 드레이크: 연약한 천재", 데일리 텔레그래프, 2014년 11월 25일.

- ^ "Swaziland King Mswati's Eighth Wife, Senteni Masango Commits Suicide". Parents Magazine. 8 April 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Press J (10 January 2021). "The Sopranos Fan's Guide to The Many Saints of Newark". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

Livia is already troubled enough in the yesteryear of Many Saints that her doctor wants to prescribe her the antidepressant Elavil, but she rejects it. "I'm not a drug addict!" she sneers. Tony pores over the Elavil pamphlet with great interest and even schemes with Dickie Moltisanti to get his suffering mother to take it: "It could make her happy."

- ^ Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 889–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Amitriptyline". Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ Flament MF, Bissada H, Spettigue W (March 2012). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of eating disorders". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000381. PMID 21414249.

추가 정보

- Dean L (March 2017). "Amitriptyline Therapy and CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520380.

외부 링크

- "Amitriptyline". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.