플루옥세틴

Fluoxetine | |

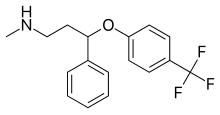

플루옥세틴(위), (R)-플루옥세틴(왼쪽), (S)-플루옥세틴(오른쪽) | |

| 임상 데이터 | |

|---|---|

| 발음 | /flucks(독일어)/ |

| 상호 | Prozac, Sarafem, Adofen, 기타 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| Medline Plus | a689006 |

| 라이선스 데이터 | |

| 임신 카테고리 |

|

| 중독 책임 | 없음[1] |

| 루트 행정부. | 입으로 |

| 약물 클래스 | 선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제(SSRI)[2] |

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 약동학 데이터 | |

| 바이오 어베이러빌리티 | 60~80%[2] |

| 단백질 결합 | 94~95%[3] |

| 대사 | 간(대부분 CYP2D6 매개)[4] |

| 대사물 | 노르플루옥세틴, 데스메틸플루옥세틴 |

| 반감기 제거 | 1 ~ 3 일 (표준) 4 ~ 6 일 (표준)[4][5] |

| 배설물 | 소변(80%), 대변(15%)[4][5] |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드러그뱅크 |

|

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니 |

|

| 케그 | |

| 체비 |

|

| 첸블 |

|

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA ) | |

| ECHA 정보 카드 | 100.125.370 |

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |

| 공식 | C17H18F3NO |

| 몰 질량 | 309.332 g/120−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| 키라리티 | 라세미 혼합물 |

| 녹는점 | 179~182°C(354~360°F) |

| 비등점 | 395°C(743°F) |

| 물에 녹는 정도 | 14 |

| |

| |

| (표준) | |

Prozac 및 Sarafem 상표명으로 판매되는 플루옥세틴은 선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제([2]SSRI) 클래스의 항우울제이다.그것은 주요 우울증, 강박장애, 폭식증, 공황장애,[2] 월경전 발작장애의 치료에 사용된다.또한 8세 [6]이상 청소년과 아동의 주요 우울증 질환 치료에도 적합합니다.그것은 또한 [2]조루증 치료에도 사용되어 왔다.플루옥세틴은 [2]입으로 섭취한다.

일반적인 부작용으로는 소화불량, 수면장애, 성기능장애, 식욕부진, 입마름, 발진 등이 있다.심각한 부작용으로는 세로토닌 증후군, 조증, 발작, 25세 미만의 사람들의 자살 행동 위험 증가, [2]출혈 위험 증가가 포함됩니다.항우울제 중단 증후군은 다른 항우울제보다 플루옥세틴에서 발생할 가능성은 낮지만 여전히 많은 경우에 발생합니다.임신 중에 섭취한 플루옥세틴은 [7][8]신생아의 선천성 심장 기형의 현저한 증가와 관련이 있다.임신 중 플루옥세틴 요법이 사용되거나 다른 항우울제가 효과가 [9]없는 경우 모유 수유 중에 플루옥세틴 요법을 지속할 수 있다고 제안되었다.

플루옥세틴은 1972년 일라이 릴리와 컴퍼니에 의해 발견돼 1986년 [10]의료용으로 사용됐다.그것은 세계보건기구의 필수 [11]의약품 목록에 있다.제네릭 [2]의약품으로 구입할 수 있습니다.2019년 미국에서 2700만 건 이상의 처방으로 [12][13]20번째로 많이 처방된 의약품이었다.릴리는 또한 플루옥세틴을 올란자핀/플루옥세틴(Symbyax)[14]으로 올란자핀과 고정 용량 조합으로 판매합니다.

도 ★★★★★★★★★★★★★.

플루옥세틴은 주요 우울증 장애, 강박-강박 장애, 외상 후 스트레스 장애, 폭식증,[15][16][17][18][19] 공황 장애, 월경 전 발화 장애, 트리코틸로마니아를 치료하기 위해 자주 사용된다.그것은 또한 폭식 [21]장애뿐만 아니라 강박증, 비만, 알코올 [20]의존증에도 사용되어 왔다.플루옥세틴은 사회 불안 [22]장애에 효과가 없는 것 같습니다.성인 [23][24][25][26]자폐증에 대한 잠정적인 증거가 있지만, 자폐증을 가진 어린이들의 이점을 뒷받침하는 연구는 없다.플루옥세틴은 플루옥사민과 함께 조기에 [27]투여될 경우 COVID-19 심각도를 감소시킬 수 있는 잠재적 치료제로서 일부 초기 가능성을 보였다.

성인뿐만 아니라 어린이와 청소년(8~18세)의 주요 우울증 질환 급성 및 유지 치료에 대한 플루옥세틴의 효능이 여러 임상 [28]시험에서 확인되었다.플루옥세틴은 6주 길이의 이중맹검 대조 시험에서 우울증에 효과적일 뿐만 아니라 원래 플루옥세틴에 반응했던 환자들이 38주 동안 더 치료받았을 때 우울증 재발 방지를 위해 플라시보보다 더 좋았다.소아 우울증뿐만 아니라 노인성 우울증에 대한 플루옥세틴의 효과도 위약 대조 [28]시험에서 입증되었다.

플루옥세틴은 삼환식 항우울제만큼 효과적이지만 내성이 더 좋다.임상시험의 네트워크 분석에 따르면 플루옥세틴은 효과가 낮은 항우울제 그룹에 속할 수 있지만 아고멜라틴을 [29]제외한 다른 항우울제보다 수용성이 높다.

강박증(OCD) 치료에서 플루옥세틴의 효과는 두 번의 무작위 다중 장상 III 임상 시험에서 입증되었다.이러한 시험의 종합 결과는 13주 치료 후 가장 높은 선량으로 치료한 보완체의 47%가 "훨씬 개선"되거나 "매우 개선"된 것으로 나타났으며,[3] 이는 실험의 플라시보 암의 11%에 비해 더 향상되었다.미국아동청소년정신과학회는 플루옥세틴을 포함한 SSRI가 중등도에서 중증 강박장애를 [30]치료하기 위해 인지행동치료(CBT)와 함께 어린이들의 첫 번째 치료제로 사용되어야 한다고 말한다.

공황장애 치료에서 플루옥세틴의 효과는 공황장애로 진단된 환자를 아고라포비아 유무에 관계없이 등록한 두 번의 12주 무작위 다중 장상 III 임상 시험에서 입증되었다.첫 번째 시도에서 플루옥세틴 치료 팔의 42%는 연구 종료 시 공황 발작이 없는 반면, 플라시보 팔의 28%는 공황 발작이 없었다.두 번째 시도에서 플루옥세틴 치료 환자의 62%는 연구 종료 시 공황 발작이 없는 반면, 플라시보 [3]팔은 44%였다.

폭식성 신경증

2011년 체계적 검토에서는 플루옥세틴을 폭식증 치료 시 위약에 비교한 7가지 실험을 논의했으며, 그 중 6개는 구토와 [31]폭식과 같은 증상의 통계적으로 유의한 감소를 발견했다.그러나 플루옥세틴과 심리치료를 심리치료와 단독 비교했을 때는 치료 팔 사이에 차이가 관찰되지 않았다.

월경 전 발화 장애

플루옥세틴은 월경 [32][33]전 발화장애를 치료하기 위해 사용되는데, 월경 전 발화장애는 개인이 황체기 동안 매달 감정적, 신체적 증상을 보이는 질환이다.플루옥세틴 20mg/d를 복용하는 것은 [34][35]PMDD 치료에 효과적일 수 있으나 용량 10mg/d도 효과적으로 [36][37]처방되었다.

충동적 공격성

플루옥세틴은 [38]저강도의 충동적 공격 치료를 위한 일선 약물로 여겨진다.플루옥세틴은 간헐적 공격적 장애와 경계선 인격 [38][39][40]장애 환자의 저강도 공격적 행동을 감소시켰다.플루옥세틴은 또한 알코올 [41]중독자의 가정 폭력 행위를 감소시켰다.

특수 모집단

어린이와 청소년에게 플루옥세틴은 그 효능과 [42][43]내성에 유리한 잠정적인 증거로 인해 항우울제로 선택된다.임신 중 플루옥세틴은 미국 식품의약국(FDA)에 의해 카테고리 C 약물로 간주된다.영국의 의약품 및 건강관리 제품 규제청(MHRA)은 처방자와 환자에게 플루옥세틴 노출의 가능성을 경고했지만 플루옥세틴 노출로 인한 주요 태아 기형의 위험을 뒷받침하는 증거는 제한적이다(장기형성, 태아 장기 형성 중).신생아에게 [44][45][46]선천성 심장 기형의 위험을 약간 증가시킨다.또한, 한 [45]연구에서 임신 초기 플루옥세틴 사용과 경미한 태아 기형의 위험 증가 사이의 연관성이 관찰되었다.

그러나 21개 연구의 체계적 검토와 메타분석(캐나다 산부인과 및 산부인과 저널에 발표됨)은 다음과 같이 결론지었다. "최근에 산모의 플루옥세틴 사용과 관련된 태아 심장 기형의 명백한 위험 증가는 임신 중 SSRI 치료를 연기한 우울증 여성에서도 나타났다. 따라서 대부분의 경우.명백하게 확인 편견을 반영한다.전반적으로 임신 초기 3개월 동안 플루옥세틴으로 치료를 받은 여성은 태아 [47]기형의 위험이 크게 높아지지 않는 것으로 보입니다."

FDA에 따르면 임신 후기에 SSRI에 노출된 영아는 신생아의 지속적인 폐고혈압에 걸릴 위험이 증가할 수 있다.제한된 데이터가 이러한 위험을 뒷받침하지만 FDA는 의사가 3개월 [3]동안 플루옥세틴과 같은 SSRI의 테이퍼를 고려할 것을 권고한다.2009년 리뷰에서는 "플루옥세틴은 모유 수유 산모, 특히 신생아의 산모 [48]및 임신 중 플루옥세틴을 섭취한 산모에게 덜 선호되는 SSRI로 간주해야 한다"고 언급하면서 플루옥세틴에 대해 권고했다.Sertraline은 비교적 최소한의 태아 노출과 모유 [49]수유 중 안전 프로파일 때문에 임신 중 선호되는 SSRI이다.

부작용

부작용은fluoxetine-treated명에서 발병률 을과 임상 실험에서 관찰되고, 5%, 적어도 두번으로fluoxetine-treated명 사람들의 플라시보 알약을 받았습니다에 비해 일반적인 비정상적인 꿈, 비정상적인 사정, 거식증, 불안, asthenia, 설사, 구강 건조, dyspepsia, 독감의 증후군, 발기 부전, 불면증, decrea을 포함한다.sed성욕, 메스꺼움, 신경과민, 인두염, 발진, 축농증, 졸음, 땀, 떨림, 혈관확장, 하품.[50]플루옥세틴은 SSRI 중 가장 자극적인 것으로 간주됩니다(즉, 불면증과 [51]동요를 일으키기 가장 쉽습니다).또한 피부과 반응(포진, 발진, 가려움 등)을 일으키는 SSRI 중 가장 잘 발생하는 것으로 보인다.[45]

성적 기능 장애

성욕 상실, 발기부전, 질 윤활 부족, 그리고 무지외반증을 포함한 성기능 장애는 플루옥세틴과 다른 SSRI로 치료했을 때 가장 일반적으로 발생하는 부작용 중 일부입니다.초기 임상시험은 상대적으로 낮은 성기능장애 비율을 나타냈지만, 연구자가 성문제에 대해 적극적으로 질문하는 최근의 연구는 발병률이 70% [52]이상임을 시사한다.

6월 11일 2019년에는, Pharmacovigilance 위험 평가 위원회 유럽 의약품 청의의 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제 사용과 지속적인 성 기능 장애 사이의 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제의 fluoxetine 등 중단에도 불구하고,가 가능한 인과 유대'이며 이 약품의 라벨을 경고 포함하도록 개정해야 한다. 하다고 결론지었다.[53][54]

항우울제 중단 증후군

플루옥세틴의 긴 반감기는 치료 중단 후 항우울제 중단 증후군이 발생하는 것을 덜 흔하게 만들며, 특히 파록세틴과 [55][56]같이 반감기가 짧은 항우울제에 비해 더욱 그러하다.반감기가 짧은 항우울제에는 점진적인 용량 감소가 권장되지만 플루옥세틴에는 [57]테이퍼링이 필요하지 않을 수 있습니다.

임신

항우울제 피폭(플루옥세틴 포함)은 임신 평균 기간 단축(3일), 조산 위험 증가(55%), 출산 체중 감소(75g), 압가르 점수 감소(0.4점 [58][59]미만)와 관련이 있다.임신 [7][8]중 엄마가 플루옥세틴을 처방받은 어린이들 사이에서 선천성 심장 기형이 30-36% 증가했으며, 임신 초기 3개월 동안 플루옥세틴을 복용하면 중격성 심장 [60][7]기형이 38-65% 증가했다.

자살

이 섹션은 업데이트해야 합니다.할 수 , 이.(2022년 3월) |

2004년 10월 FDA는 모든 [61]항우울제에 어린이 사용에 관한 블랙박스 경고를 추가했다.2006년에 FDA는 25세 [62]이하의 성인들을 포함시켰다.FDA 전문가로 구성된 두 독립적인 그룹이 수행한 통계 분석 결과, 아동과 청소년에서 자살에 대한 관념과 행동이 2배 증가하고 18-24세 그룹에서 자살이 1.5배 증가했다.24세 이상에서는 동일성이 약간 감소했고, 65세 [63][64][65]이상에서는 통계적으로 유의하게 낮았다.이 분석은 자살의 관념과 행동인 자살이 반드시 자살의 좋은 대용물이 아니라고 지적한 도널드 클라인에 의해 비판되었고, 항우울제가 자살이 [66]증가하는 동안 실제 자살을 막을 수 있다는 것은 증명되지 않았지만 여전히 가능하다.2018년 2월 FDA는 위약 시험에 [67]비해 그러한 사건의 위험이 2%에서 4%로 증가한 24개 시험의 통계적 증거에 기초한 경고 업데이트를 명령했다.

1989년 9월 14일, 조셉 T. 웨스베커는 [68]자살하기 전에 8명을 죽이고 12명을 다치게 했다.그의 친척들과 피해자들은 그가 한 달 전에 복용하기 시작한 프로작 약물 때문이라고 비난했다.그 사건은 일련의 소송과 대중의 [69]항의를 불러일으켰다.변호사들은 [70]의뢰인의 비정상적인 행동을 정당화하기 위해 프로잭을 사용하기 시작했다.일라이 릴리는 사건 [71]발생 몇 년 전에 환자들과 의사들에게 "활성화"라고 표현했던 부작용에 대해 충분히 경고하지 않았다는 비난을 받았다.

전체적으로 항우울제보다 플루옥세틴에 대한 데이터가 적다.2004년 FDA는 통계적으로 유의한 결과를 얻기 위해 11개 항우울제의 295개 시험 결과를 정신의학적 징후에 대해 결합해야 했다.별도로 고려했을 때, 어린이에서 플루옥세틴을 사용하면 당수의 확률이 50% [72]증가했고, 성인의 경우 당수의 확률이 약 30%[64][65] 감소하였다.2009년 5월에 발표된 연구에 따르면 플루옥세틴이 전반적인 자살 행동을 증가시킬 가능성이 더 높은 것으로 나타났다. 플루옥세틴을 복용한 환자의 14.7%(n = 44명)가 자살 사건을 겪은 반면, 정신 치료 그룹은 6.3%, 복합 치료 [73]그룹은 8.4%였다.마찬가지로, 영국 MHRA가 실시한 분석에서는 플루옥세틴을 복용한 어린이와 청소년에서 위약과 비교하여 통계적 유의성에 도달하지 못한 자살 관련 사건이 50% 증가했다.MHRA 데이터에 따르면, 플루옥세틴은 성인의 자해 비율을 바꾸지 않았고 통계적으로 자살 생각을 50%나 [74][75]줄였다.

QT 연장

플루옥세틴은 심장 근육 세포가 수축하는 것을 조정하기 위해 사용하는 전류, 특히 심장 활동 [76]전위를 다시 분극시키는 칼륨 전류to I과Ks I에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.특정한 상황에서, 이것은 각 심장 박동 후에 심장이 전기적으로 충전되는 데 걸리는 시간을 반영하는 심전도 측정인 QT 간격의 연장으로 이어질 수 있습니다.플루옥세틴을 QT 간격을 연장하는 다른 약물과 함께 복용하거나 긴 QT 증후군에 걸리기 쉬운 약물에 의해 복용할 경우,[77] 비틀림과 같은 잠재적으로 치명적인 비정상적인 심장 리듬의 위험이 작습니다.2019년 현재, 약물 참조 사이트인 CrustibleMeds는 부정맥의 조건부 [78]위험을 유발하는 플루옥세틴을 열거하고 있다.여러 SSRI 약물에 대한 추가 연구는 시탈로프람과 에스시탈로프람에서 QT 연장 위험이 가장 높다는 것을 지적했다.플루옥세틴은 QT 간격을 변경하지 않았으며 심장 활동 [79]전위에 임상적으로 유의미한 영향을 미치지 않았다.

과다 복용

과다 복용 시 가장 빈번한 부작용은 다음과 같습니다.[80]

| 신경계의 영향 | 위장 효과 | 기타 효과

|

상호 작용

세로토닌 [4]증후군의 잠재성으로 인해 페넬진 및 트라닐시프로민과 같은 MAOI를 사용한 사전 치료(선량에 [81][82]따라 지난 5~6주 이내)가 금지된다.플루옥세틴 또는 사용된 [4]제제의 다른 성분에 대한 과민성이 알려진 경우에는 사용을 피해야 한다.피모지드 또는 티오리다진을 동시에 투여하는 경우에도 사용을 [4]권장한다.

경우에 따라서는 플루옥세틴이 세로토닌 수치를 증가시키는 플루옥세틴과 함께 덱스트로메토르판이 정상 속도로 대사되지 않도록 하는 시토크롬 P450 2D6 억제제인 점뿐만 아니라 플루옥세틴이 세로토닌을 포함한 덱스트로메토르판을 함유한 감기 및 기침 약물의 사용이 권장되며, 따라서 세로토닌의 위험이 증가한다.그리고 덱스트로메토르판의 [83]다른 잠재적 부작용들.

항응고제나 NSAIDS를 복용하는 환자는 플루옥세틴이나 다른 SSRI를 복용할 때 이러한 [84]약물의 혈액 희석 효과를 증가시킬 수 있으므로 주의해야 합니다.

플루옥세틴과 노르플루옥세틴은 약물 대사에 관여하는 시토크롬 P450 시스템의 많은 동질효소를 억제한다.둘 다 CYP2D6 및 CYP2C19의 잠재적 억제제이며, CYP2B6 및 CYP2C9의 [85][86]경미하고 중간 정도의 억제제이다.생체 내 플루옥세틴과 노르플루옥세틴은 CYP1A2와 CYP3A4의 [85]활성에 유의미한 영향을 미치지 않는다.또한 약물의 운반과 대사에 중요한 역할을 하는 막수송단백질의 일종인 P당단백질의 활성을 억제하므로 로페라미드와 같은 P당단백질 기질이 중심 효과를 증강할 [87]수 있다.약물 대사를 위한 신체의 경로에 대한 이러한 광범위한 영향은 일반적으로 사용되는 많은 [87][88]약물과의 상호작용 가능성을 창출한다.

또한 모노아민 산화효소 억제제, 삼환식 항우울제, 필로폰, 암페타민, MDMA, 트립탄, 버스피론, 세로토닌-노레피네프린 재흡수 억제제 및 [4]그 결과로 발생하는 세로토닌의 잠재성으로 인해 기타 SSRI와 같은 세로토닌 작동성 약물에는 사용을 피해야 한다.

플루옥세틴은 또한 부분적으로는 시토크롬 P-450에 [89][90]대한 억제 효과 때문에 오피오이드 과다 복용의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다.플루옥세틴이 덱스트로메토르판의 신진대사에 영향을 미치는 방법과 유사하게, 옥시코돈과 같은 약물이 정상적인 속도로 대사되지 않도록 할 수 있으며, 따라서 세로토닌 신드롬의 위험을 증가시킬 뿐만 아니라 우발적인 과다 복용으로 이어질 수 있다.2000년에서 2020년 사이에 SSRI를 사용하는 동안 옥시코돈을 복용하기 시작한 200만 명 이상의 미국인의 건강보험 청구를 조사한 2022년 연구에서는 파록세틴 또는 플루옥세틴을 복용하는 환자가 다른 SSRI를 [89]사용하는 환자보다 옥시코돈을 과다 복용할 위험이 23% 높았다.

또한 플루옥세틴이 해당 약물을 혈장 또는 그 반대로 치환함으로써 플루옥세틴 또는 유해물질의 [4]혈청 농도를 높일 수 있기 때문에 고단백 결합 약물과 상호작용할 가능성이 있다.

약리학

| 분자의 대상 | 플루옥세틴 | 노르플루옥세틴 |

|---|---|---|

| 서비스 | 1 | 19 |

| 그물 | 660 | 2700 |

| 디에이티 | 4180 | 420 |

| 5-HT2A | 200 | 300 |

| 5-HT2B | 5000 | 5100 |

| 5-HT2C | 72.6 | 91.2 |

| α1 | 3000 | 3900 |

| M1 | 870 | 1200 |

| M2 | 2700 | 4600 |

| M3 | 1000 | 760 |

| M4 | 2900 | 2600 |

| M5 | 2700 | 2200 |

| H1 | 3250 | 10000 |

| 이 색상의 엔트리는 K 값의i 하한을 나타냅니다. | ||

약역학

플루옥세틴은 선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제(SSRI)이며 치료용량에서 노르에피네프린과 도파민 재흡수를 현저하게 억제하지 않는다.그러나 그것은 세로토닌의 재섭취를 지연시켜 세로토닌이 방출될 때 더 오래 지속되도록 한다.랫드의 다용량은 시냅스 노르에피네프린과 [93][94][95][96]도파민의 유의미한 증가를 유도하는 것으로 나타났다.따라서 도파민과 노르에피네프린은 초치료 용량(60~80mg)[95][97]에서 플루옥세틴의 항우울 작용에 기여할 수 있다.이 효과는 플루옥세틴의 [98]고농도에 의해 억제되는 5HT2C 수용체에 의해 매개될 수 있다.

플루옥세틴은 [96][99]뇌에서 잠재적A GABA 수용체 양성 알로스테릭 변조제인 순환 알로프레나놀론의 농도를 증가시킨다.플루옥세틴의 일차 활성 대사물인 노르플루옥세틴은 생쥐의 [96]뇌에서 알로프린산올론 수치에 비슷한 효과를 낸다.또한 플루옥세틴과 노르플루옥세틴은 모두 그러한 조절제이며 임상적으로 [100]관련이 있을 수 있다.

또한 플루옥세틴은 시탈로프람보다 효력은 크지만 플루옥사민보다 낮은 γ수용체의1 작용제로서 작용한다는 것이 확인되었다.그러나 이 속성의 중요성은 완전히 [101][102]명확하지 않다.플루옥세틴은 칼슘 활성 염화물 [103][104]통로인 아녹타민 1의 채널 차단제로서도 기능한다.니코틴성 아세틸콜린 수용체와 5-HT3 수용체를 포함한 많은 다른 이온 채널도 유사한 [100]농도로 억제되는 것으로 알려져 있다.

플루옥세틴은 스핑고미엘린에서 [105][106]세라마이드를 추출하는 세라마이드 수치의 핵심 조절제인 산 스핑고미엘라아제를 억제하는 것으로 나타났다.

작용 메커니즘

플루옥세틴은 신경막의[107] 재흡수 펌프에 결합함으로써 시냅스 내 세로토닌 재흡수를 억제하여 세로토닌 가용성을 높이고 신경 [108]전달을 촉진함으로써 항우울제 효과를 유도한다.노르플루옥세틴과 데스메틸플루옥세틴은 플루옥세틴의 대사물이며 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제로 작용하여 약물의 작용 [109][107]기간을 증가시킨다.

약동학

플루옥세틴의 생체 가용성은 비교적 높고(72%) 혈장 농도는 6~8시간 내에 최고치에 도달한다.그것은 주로 알부민과 [4]α-글리코프로틴인1 혈장 단백질과 매우 결합되어 있다.플루옥세틴은 CYP2D6를 [110]포함한 시토크롬 P450계의 이소효소에 의해 간에서 대사된다.플루옥세틴의 대사에서 CYP2D6의 역할은 임상적으로 중요할 수 있는데, 이는 사람들 사이에서 플루옥세틴의 기능에 큰 유전적 변화가 있기 때문이다.CYP2D6는 플루옥세틴을 유일한 활성 대사물인 노르플루옥세틴으로 [111]변환하는 역할을 합니다.두 약물 모두 CYP2D6의 [112]잠재적 억제제이다.

플루옥세틴과 그 활성대사물 노르플루옥세틴의 체내 제거가 매우 느리기 때문에 다른 항우울제와 구별된다.시간이 지남에 따라 플루옥세틴과 노르옥세틴은 자체 대사를 억제하므로 플루옥세틴 제거 반감기는 1회 복용 후 1~3일에서 장기 [4]복용 후 4~6일로 증가한다.마찬가지로 노르플루옥세틴의 반감기는 장기 [110][113][114]사용 후(16일) 길다.따라서 치료 후 처음 몇 주 동안 약물과 그 활성대사물의 혈중 농도는 계속 증가하며, 4 [115][116]주 후에야 혈중 농도가 안정적으로 달성된다.게다가 플루옥세틴과 그 대사물의 뇌 농도는 적어도 치료 [117]첫 5주 동안 계속 증가한다.환자가 현재 복용하는 선량의 완전한 편익은 섭취 후 최소 한 달 동안 실현되지 않는다.예를 들어, 한 6주간의 연구에서 일관된 반응을 얻기 위한 중앙값은 [115]29일이었습니다.마찬가지로, 그 약의 완전한 배설에는 몇 주가 걸릴 수 있다.치료 중단 후 첫 주 중에 오직 50%로서 플루옥세틴의 두뇌 집중력 감소 ,[117]치료 중단 후norfluoxetine 4주 정도의 수준 첫 치료를 주 말까지 등록된 약 80%, 그리고, 중단 7주 후에,norfluoxetine에 아직은 감지하기의 피 수준이다.그피를 [113]흘리다.

체액 측정

플루옥세틴과 노르플루옥세틴은 혈액, 혈장 또는 혈청에서 정량화되어 치료를 감시하거나 입원한 사람의 중독 진단을 확인하거나 법적 사망 조사를 지원할 수 있다.혈액 또는 혈장 플루옥세틴 농도는 일반적으로 항우울제 효과로 약을 복용하는 사람의 경우 50–500μg/L, 급성 과다 복용 생존자의 경우 900–3000μg/L, 치명적 과다 복용의 경우 1000–7000μg/L의 범위에 있다.노르플루옥세틴 농도는 만성 치료 중 모약의 농도와 거의 동일하지만, 대사물이 [118][119][120]평형을 이루는 데 최소 1~2주가 필요하기 때문에 급성 과다 복용 후에는 상당히 적을 수 있다.

사용.

2010년 미국에서는 [121]2,440만 건 이상의 일반 플루옥세틴이 처방되어 세르트랄린과 시탈로프람에 [121]이어 세 번째로 많이 처방된 항우울제가 되었다.2011년,[122] 영국에서 플루옥세틴에 대한 6백만 개의 처방전이 작성되었습니다.

역사

플루옥세틴의 발견을 이끈 작업은 브라이언 몰로이와 로버트 래스번의 공동작업으로 1970년 일라이 릴리와 컴퍼니에서 시작되었다.당시 항히스타민 디펜히드라민은 항우울제와 유사한 성질을 보이는 것으로 알려졌으며 디펜히드라민과 구조적으로 유사한 화합물인 3-페녹시-3-페닐프로필아민을 기점으로 하여 몰로이가 수십 개의 [123]유도체를 합성하였다.세로토닌 재흡수를 억제하는 유도체를 찾고자 하는 일라이 릴리의 과학자 데이비드 T. 웡은 세로토닌, 노르에피네프린, 도파민의 체외 재흡입에 대한 시리즈를 재검사할 것을 제안했다.1972년 [123]5월 Jong-Sir Horng에 의해 수행된 이 테스트는 나중에 플루옥세틴이라고 명명된 화합물이 세로토닌 [124]재흡수의 가장 강력하고 선택적인 억제제라는 것을 보여주었다.Wong은 [124]플루옥세틴에 대한 첫 번째 기사를 1974년에 발표했다.1년 후, 그것은 공식 화학명 플루옥세틴으로 명명되었고, 일라이 릴리와 회사는 프로작이라는 상표명을 붙였다.1977년 2월, Eli Lilly & Company의 부문인 Dista Products Company는 미국 식품의약국(FDA)에 플루옥세틴에 [125]대한 조사적 신약 신청서를 제출했다.

플루옥세틴은 [126]1986년 벨기에 시장에 등장했다.미국에서는 1987년 [127]12월 FDA가 최종 승인을 내렸고 한 달 뒤 엘리 릴리가 프로작 마케팅을 시작했다. 미국 내 연간 매출은 1년 [125]만에 3억5000만 달러에 달했다.전 세계 매출은 결국 연간 [128]26억 달러에 달했다.

Lilly는 월경 전 발작 장애에서 플루옥세틴의 효능과 안전성을 테스트하기 위한 임상시험 비용 지불을 포함한 여러 제품 라인 확장 전략을 시도했으며, 2000년 FDA에 의해 승인된 후 플루옥세틴을 "사라펨"으로 재브랜딩했다.1999년 [129][130][131]위원회.PMDD를 치료하기 위해 플루옥세틴을 사용하는 발명은 MIT의 리처드 워트먼에 의해 이루어졌습니다.특허는 그의 스타트업인 인터뉴론에게 라이선스를 받았고, 인터뉴론은 이를 [132]릴리에게 팔았습니다.

제네릭 경쟁에서 프로 작은 수익을 방어하는 것, 릴리도 법정에서 제네릭 회사 바 제약 회사와의 플루옥세틴에 대한 특허권을 보호하며, 제네릭 제조 업체들 2001년부터 fluoxetine 개방 line-extension 특허, 그 Sarafem보다 다른을 위해 잃어버린 5년 수백만 싸웠다.[133]2001년 [134]8월 Lilly의 특허가 만료되었을 때, 제네릭 의약품 경쟁은 Lilly의 플루옥세틴 판매를 두 [129]달 만에 70% 감소시켰다.

2000년에 한 투자은행은 사라펨의 연간 매출이 [135]연간 2억 5천만 달러에 달할 것으로 예측했습니다.2002년 사라펨의 매출은 연간 약 8500만달러에 달했고, 그 해 릴리는 약과 관련된 자산을 산부인과 의사 사무실을 담당하는 소규모 아일랜드 제약회사 갤런 홀딩스에 2억9500만달러에 매각했다.분석가는 사라펨의 연간 매출 이후 이 거래가 합리적이라고 판단했다.게일런에게는 금전적인 차이가 있었지만 [136][137]릴리에게는 그렇지 않았어요

사라펨을 시장에 내놓는 것은 릴리의 평판을 손상시켰다.PMDD의 진단 카테고리는 1987년 처음 제안된 이후 논란이 됐으며 1998년 논의가 시작된 DSM-IV-TR 부록에서 이를 유지하는 릴리의 역할도 [135]비판받아 왔다.릴리는 돈을 [135]벌기 위해 병을 발명했고 혁신은 하지 않고 기존 [138]약으로 돈을 계속 벌 수 있는 방법을 모색했다는 비난을 받았다.그것은 또한 사라펨이 처음 출시되었을 때 너무 공격적인 마케팅으로 인해 FDA와 여성 건강에 관심이 있는 단체들에 의해 비판을 받았다. 이 캠페인에는 식료품점에서 자신에게 [139]PMDD가 있는지 물어보는 괴로워하는 여성이 나오는 텔레비전 광고가 포함되어 있었다.

사회와 문화

미국의 항공기 조종사

2010년 4월 5일부터, 플루옥세틴은 FAA가 항공 검시관의 허가를 받아 조종사에게 허가한 4가지 항우울제 중 하나가 되었다.다른 허용되는 항우울제는 Sertraline(Zoloft), citalopram(Cellexa), escitalopram(lexapro)[140]이다.이 4가지 항우울제는 2016년 [ref][141]12월 2일 현재 FAA가 허용하는 유일한 항우울제이다.

2019년 [142][143]1월 현재 EASA 의료 인증에 허용된 항우울제는 Sertraline, citalopram 및 escitalopram뿐이다.

환경에 미치는 영향

플루옥세틴은 특히 북미의 [144]수생 생태계에서 검출되었다.비표적 수생종에 대한 플루옥세틴 노출의 영향을 다루는 연구가 증가하고 [145][146][147][148]있다.

2003년 첫 번째 연구 중 하나는 수생 야생동물에 대한 플루옥세틴의 잠재적 영향을 상세하게 다루었다. 이 연구는 위험성 평가에 [147]위해성 지수 접근법을 적용할 경우 환경 농도에서의 노출은 수생 시스템에 거의 위험이 없다는 결론을 내렸다.그러나, 그들은 플루옥세틴의 치사 이하 결과를 다루는 추가 연구의 필요성도 언급했으며, 특히 세로토닌 시스템에 [147]의해 조절된 연구 종의 민감성, 행동 반응 및 끝점에 초점을 맞췄다.

2003년 이후, 다수의 연구에서 플루옥세틴 유도 영향이 다수의 행동 및 생리학적 종말점에 대해 보고되었으며, 이는 현장 검출 농도 이하에서 항산화제 행동,[149][150][151] 번식 [152][153]및 먹이[154][155] 찾기를 유발한다.그러나 2014년 플루옥세틴의 생태독성학 리뷰에서는 당시 야생동물의 행동에 영향을 미치는 환경적 현실적 용량에 대한 공감대가 [146]형성되지 않았다고 결론지었다.환경 친화적인 농도로 플루옥세틴은 곤충 출현 시기를 [156]변화시킨다.Richmond et al., 2019년 저농도에서는 Diptera의 출현을 가속화하지만 비정상적으로 고농도에서는 식별 가능한 [156]효과가 없다는 것을 발견했다.

몇몇 흔한 식물들은 플루옥세틴을 [157]흡수하는 것으로 알려져 있다.몇 가지 작물이 시험되었고, 레드쇼 외 연구진은 콜리플라워가 줄기와 잎에 많은 양을 흡수하지만 머리나 [157]뿌리는 흡수하지 않는다는 것을 발견했다.2012년 Wu 등에서는 상추와 시금치가 검출 가능한 양을 흡수하는 반면, Carter 등은 2014년 무(Raphanus sativus), 라이그래스(Lolium perenne), 2010년 Wu 등에서는 콩(Glycine max)이 거의 [157]흡수하지 않는다는 것을 발견했다.우 교수는 콩의 모든 조직을 검사했고 모두 낮은 [157]농도만 보였다.이와는 대조적으로 다양한 Reinhold et al. 2010에서 오리풀은 플루옥세틴을 많이 흡수하고 오염된 물, 특히 Lemna minor와 Landoltia pentata의 [157]생물적 개선 가능성을 보여준다.양식업과 관련된 유기체의 생태독성은 잘 [158]: 275–276 입증되어 있다.플루옥세틴은 수생 무척추동물과 척추동물 모두에 영향을 미쳐 토양 미생물을 억제하고 항균 효과가 [158]크다.이것의 적용에 대해서는, 「기타 용도」를 참조해 주세요.

정치

1990년 플로리다 주지사 선거 운동 중 후보 중 한 명인 로튼 칠레스가 우울증을 앓아 플루옥세틴 복용을 재개한 사실이 알려지면서 그의 정적들이 주지사로서의 [159]적합성에 의문을 제기하게 되었다.

기타 용도

상기의 항균효과( environ 환경효과)는 작물세균질환 및 세균양식질환의 [158]다저항 생물형에 적용할 수 있다.

레퍼런스

- ^ Hubbard JR, Martin PR (2001). Substance Abuse in the Mentally and Physically Disabled. CRC Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0824744977.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Fluoxetine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Prozac Label" (PDF). FDA. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "PROZAC® Fluoxetine Hydrochloride" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Eli Lilly Australia Pty. Limited. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ a b Altamura AC, Moro AR, Percudani M (March 1994). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 26 (3): 201–14. doi:10.2165/00003088-199426030-00004. PMID 8194283. S2CID 1406955.

- ^ "Depressive Disorders in Children and Adolescents – Pediatrics". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Gao SY, Wu QJ, Sun C, Zhang TN, Shen ZQ, Liu CX, et al. (November 2018). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during early pregnancy and congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies of more than 9 million births". BMC Medicine. 16 (1): 205. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1193-5. PMC 6231277. PMID 30415641.

- ^ a b De Vries C, Gadzhanova S, Sykes MJ, Ward M, Roughead E (March 2021). "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Considering the Risk for Congenital Heart Defects of Antidepressant Classes and Individual Antidepressants". Drug Safety. 44 (3): 291–312. doi:10.1007/s40264-020-01027-x. PMID 33354752. S2CID 229357583.

- ^ "Fluoxetine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ Myers RL (2007). The 100 most important chemical compounds: a reference guide (1st ed.). Westport, CN: Greenwood Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2019". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Fluoxetine – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "FDA Approves Symbyax as First Medication for Treatment-Resistant Depression". Eli Lilly. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Hagerman RJ (16 September 1999). Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512314-2.

Dech and Budow (1991) were among the first to report the anecdotal use of fluoxetine in a case of PWS to control behavior problems, appetite, and trichotillomania.

- ^ Truven Health Analytics, Inc.DrugPoint® 시스템(인터넷) [2013년 10월 4일 갱신]그린우드 빌리지, CO: 톰슨 헬스케어, 2013년.

- ^ 호주 의약품 핸드북 2013.호주 의약품 핸드북 유닛 트러스트; 2013.

- ^ BNF(British National Formulaary) 65.제약학 박사, 2013년

- ^ Husted DS, Shapira NA, Murphy TK, Mann GD, Ward HE, Goodman WK (2007). "Effect of comorbid tics on a clinically meaningful response to 8-week open-label trial of fluoxetine in obsessive compulsive disorder". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 41 (3–4): 332–337. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.007. PMID 16860338.

- ^ "Fluoxetine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "NIMH•Eating Disorders". The National Institute of Mental Health. National Institute of Health. 2011. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ "Treating social anxiety disorder". Harvard Health Publishing. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Williams K, Brignell A, Randall M, Silove N, Hazell P (August 2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD004677. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004677.pub3. PMID 23959778.

- ^ Myers SM (August 2007). "The status of pharmacotherapy for autism spectrum disorders". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 8 (11): 1579–1603. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.11.1579. PMID 17685878. S2CID 24674542.

- ^ Doyle CA, McDougle CJ (August 2012). "Pharmacotherapy to control behavioral symptoms in children with autism". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 13 (11): 1615–1629. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.674110. PMID 22550944. S2CID 32144885.

- ^ Benvenuto A, Battan B, Porfirio MC, Curatolo P (February 2013). "Pharmacotherapy of autism spectrum disorders". Brain & Development. 35 (2): 119–127. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2012.03.015. PMID 22541665. S2CID 19614718.

- ^ Mahdi M, Hermán L, Réthelyi JM, Bálint BL (March 2022). "Potential Role of the Antidepressants Fluoxetine and Fluvoxamine in the Treatment of COVID-19". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (7): 3812. doi:10.3390/ijms23073812. PMC 8998734. PMID 35409171.

- ^ a b "DailyMed - PROZAC- fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule".

- ^ Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- ^ Geller DA, March J, et al. (The AACAP Committee on Quality Issues (CQI)) (January 2012). "Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 51 (1): 98–113. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019. PMID 22176943.

- ^ Aigner M, Treasure J, Kaye W, Kasper S (September 2011). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of eating disorders" (PDF). The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 12 (6): 400–43. doi:10.3109/15622975.2011.602720. PMID 21961502. S2CID 16733060. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2014.

- ^ Sarafem 라벨 2016년 5월 8일 Wayback Machine 최종 갱신 2014년 10월

- ^ Rapkin AJ, Lewis EI (November 2013). "Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Women's Health. 9 (6): 537–56. doi:10.2217/whe.13.62. PMID 24161307.

- ^ Carr RR, Ensom MH (April 2002). "Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (4): 713–7. doi:10.1345/aph.1A265. PMID 11918525. S2CID 37088388.

- ^ Romano S, Judge R, Dillon J, Shuler C, Sundell K (April 1999). "The role of fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Clinical Therapeutics. 21 (4): 615–33, discussion 613. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88315-0. PMID 10363729.

- ^ Pearlstein T, Yonkers KA (July 2002). "Review of fluoxetine and its clinical applications in premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 3 (7): 979–91. doi:10.1517/14656566.3.7.979. PMID 12083997. S2CID 9455962.

- ^ Cohen LS, Miner C, Brown EW, Freeman E, Halbreich U, Sundell K, McCray S (September 2002). "Premenstrual daily fluoxetine for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a placebo-controlled, clinical trial using computerized diaries". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 100 (3): 435–44. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02166-X. PMID 12220761. S2CID 753100.

- ^ a b Felthous A, Stanford M (2021). "34.The Pharmacotherapy of Impulsive Aggression in Psychopathic Disorders". In Felthous A, Sass H (eds.). The Wiley International Handbook on Psychopathic Disorders and the Law (2nd ed.). Wiley. pp. 810–13. ISBN 978-1119159322.

- ^ Coccaro EF, Lee RJ, Kavoussi RJ (April 2009). "A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in patients with intermittent explosive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 70 (5): 653–62. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04150. PMID 19389333.

- ^ Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ (December 1997). "Fluoxetine and impulsive aggressive behavior in personality-disordered subjects". Archives of General Psychiatry. 54 (12): 1081–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240035005. PMID 9400343.

- ^ George DT, Phillips MJ, Lifshitz M, Lionetti TA, Spero DE, Ghassemzedeh N, et al. (January 2011). "Fluoxetine treatment of alcoholic perpetrators of domestic violence: a 12-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled intervention study". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 72 (1): 60–5. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05256gry. PMC 3026856. PMID 20673556.

- ^ Taurines R, Gerlach M, Warnke A, Thome J, Wewetzer C (September 2011). "Pharmacotherapy in depressed children and adolescents". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 12 (Suppl 1): 11–5. doi:10.3109/15622975.2011.600295. PMID 21905988. S2CID 18186328.

- ^ Cohen D (2007). "Should the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in child and adolescent depression be banned?". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 76 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1159/000096360. PMID 17170559. S2CID 1112192.

- ^ Morrison JL, Riggs KW, Rurak DW (March 2005). "Fluoxetine during pregnancy: impact on fetal development". Reproduction, Fertility, and Development. 17 (6): 641–50. doi:10.1071/RD05030. PMID 16263070.

- ^ a b c Brayfield, A, ed. (13 August 2013). Fluoxetine Hydrochloride. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 24 November 2013.(설명 필요)

- ^ "Fluoxetine in pregnancy: slight risk of heart defects in unborn child" (PDF). MHRA. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 10 September 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ Rowe T (June 2015). "Drugs in Pregnancy". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 37 (6): 489–92. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30222-X. PMID 26334601.

- ^ Kendall-Tackett K, Hale TW (May 2010). "The use of antidepressants in pregnant and breastfeeding women: a review of recent studies". Journal of Human Lactation. 26 (2): 187–95. doi:10.1177/0890334409342071. PMID 19652194. S2CID 29112093.

- ^ Taylor D, Paton C, Shitij K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ^ Bland RD, Clarke TL, Harden LB (February 1976). "Rapid infusion of sodium bicarbonate and albumin into high-risk premature infants soon after birth: a controlled, prospective trial". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 124 (3): 263–7. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(76)90154-x. PMID 2013.

- ^ Koda-Kimble MA, Alldredge BK (2012). Applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs (10th ed.). Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1609137137.

- ^ Clark MS, Jansen K, Bresnahan M (November 2013). "Clinical inquiry: How do antidepressants affect sexual function?". The Journal of Family Practice. 62 (11): 660–1. PMID 24288712.

- ^ Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) (11 June 2019). "New product information wording – Extracts from PRAC recommendations on signals" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. EMA/PRAC/265221/2019.

- ^ "Minutes of PRAC meeting of 13–16 May 2019" (PDF).

- ^ Bhat V, Kennedy SH (June 2017). "Recognition and management of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 42 (4): E7–E8. doi:10.1503/jpn.170022. PMC 5487275. PMID 28639936.

- ^ Warner CH, Bobo W, Warner C, Reid S, Rachal J (August 2006). "Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome". American Family Physician. 74 (3): 449–56. PMID 16913164.

- ^ Gabriel M, Sharma V (May 2017). "Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome". CMAJ. 189 (21): E747. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160991. PMC 5449237. PMID 28554948.

- ^ Ross LE, Grigoriadis S, Mamisashvili L, Vonderporten EH, Roerecke M, Rehm J, et al. (April 2013). "Selected pregnancy and delivery outcomes after exposure to antidepressant medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (4): 436–43. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.684. PMID 23446732.

- ^ Lattimore KA, Donn SM, Kaciroti N, Kemper AR, Neal CR, Vazquez DM (September 2005). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and effects on the fetus and newborn: a meta-analysis". Journal of Perinatology. 25 (9): 595–604. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211352. PMID 16015372.

- ^ Gao SY, Wu QJ, Zhang TN, Shen ZQ, Liu CX, Xu X, et al. (October 2017). "Fluoxetine and congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 83 (10): 2134–2147. doi:10.1111/bcp.13321. PMC 5595931. PMID 28513059.

- ^ Leslie LK, Newman TB, Chesney PJ, Perrin JM (July 2005). "The Food and Drug Administration's deliberations on antidepressant use in pediatric patients". Pediatrics. 116 (1): 195–204. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0074. PMC 1550709. PMID 15995053.

- ^ Fornaro M, Anastasia A, Valchera A, Carano A, Orsolini L, Vellante F, et al. (3 May 2019). "The FDA "Black Box" Warning on Antidepressant Suicide Risk in Young Adults: More Harm Than Benefits?". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 10: 294. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00294. PMC 6510161. PMID 31130881.

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C. "Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ^ a b Stone MB, Jones ML (17 November 2006). "Clinical Review: Relationship Between Antidepressant Drugs and Suicidality in Adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 11–74. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ a b Levenson M, Holland C (17 November 2006). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 75–140. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ Klein DF (April 2006). "The flawed basis for FDA post-marketing safety decisions: the example of anti-depressants and children". Neuropsychopharmacology. 31 (4): 689–699. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300996. PMID 16395296. S2CID 12599251.

- ^ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (3 November 2018). "Suicidality in Children and Adolescents Being Treated With Antidepressant Medications". FDA.

- ^ Wolfson A. "Prozac maker paid millions to secure favorable verdict in mass shooting lawsuit, victims say". USA TODAY. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "Prozac Litigation - Link to Suicide, Birth Defects & Class Action". Drugwatch.com. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Angier N (16 August 1990). "HEALTH; Eli Lilly Facing Million-Dollar Suits On Its Antidepressant Drug Prozac". The New York Times.

- ^ "Eli Lilly in storm over Prozac evidence". Financial Times. 30 December 2004. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Hammad TA (13 September 2004). "Results of the Analysis of Suicidality in Pediatric Trials of Newer Antidepressants" (PDF). Presentation at the Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Pediatric Advisory Committee on September 13, 2004. FDA. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. 페이지 25, 282008년 1월 6일 취득.

- ^ Vitiello B, Silva SG, Rohde P, Kratochvil CJ, Kennard BD, Reinecke MA, et al. (April 2009). "Suicidal events in the Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS)". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 70 (5): 741–747. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04607. PMC 2702701. PMID 19552869.

- ^ Committee on Safety of Medicines Expert Working Group (December 2004). "Report on The Safety of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants" (PDF). MHRA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D (February 2005). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA's safety review". BMJ. 330 (7488): 385. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.385. PMC 549105. PMID 15718537.

- ^ Cubeddu LX (2016). "Drug-induced Inhibition and Trafficking Disruption of ion Channels: Pathogenesis of QT Abnormalities and Drug-induced Fatal Arrhythmias". Current Cardiology Reviews. 12 (2): 141–54. doi:10.2174/1573403X12666160301120217. PMC 4861943. PMID 26926294.

- ^ Tisdale JE (May 2016). "Drug-induced QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes: Role of the pharmacist in risk assessment, prevention and management". Canadian Pharmacists Journal. 149 (3): 139–52. doi:10.1177/1715163516641136. PMC 4860751. PMID 27212965.

- ^ "CredibleMeds :: Quicksearch". crediblemeds.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "Certain antidepressants may prolong QT interval". www.healio.com. Healio Cardiology. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ "Toxicity". Fluoxetine. PubChem. NCBI. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ Gury C, Cousin F (September 1999). "[Pharmacokinetics of SSRI antidepressants: half-life and clinical applicability]". L'Encéphale. 25 (5): 470–6. PMID 10598311.

- ^ Janicak PG, Marder SR, Pavuluri MN (26 December 2011). Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4511-7877-7.

A 2-week interval is adequate for all of these drugs, with the exception of fluoxetine. Because of the extended half-life of norfluoxetine, a minimum of 5 weeks should lapse between stopping fluoxetine (20mg/day) and starting an MAOI. With higher daily doses, the interval should be longer.

- ^ "Dextromethorphan and fluoxetine Drug Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Fluoxetine and ibuprofen Drug Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ a b Sager JE, Lutz JD, Foti RS, Davis C, Kunze KL, Isoherranen N (June 2014). "Fluoxetine- and norfluoxetine-mediated complex drug-drug interactions: in vitro to in vivo correlation of effects on CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 95 (6): 653–62. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.50. PMC 4029899. PMID 24569517.

- ^ Ciraulo DA, Shader RI, eds. (2011). Pharmacotherapy of Depression. SpringerLink (2nd ed.). New York: Humana Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-435-7. ISBN 978-1-60327-434-0.

- ^ a b Sandson NB, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL (2005). "An overview of psychotropic drug-drug interactions" (PDF). Psychosomatics. 46 (5): 464–94. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.464. PMID 16145193. S2CID 21838792. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2019.

- ^ 생각할 수 있는 상호작용의 광범위한 목록은 다음 URL에서 이용할 수 있습니다.

- ^ a b "Combining certain opioids and commonly prescribed prescribed antidepressants may increase the risk of overdose". www.Popsci.com. 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ 헤머릭 알렉스와 벨페어 M.Frans, 선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제 및 시토크롬 P-450 매개 약물-약물 상호작용: 업데이트.벤담 과학 출판사2002; 3(1).ISSN:1875-5453https://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1389200023338017

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Owens MJ, Knight DL, Nemeroff CB (September 2001). "Second-generation SSRIs: human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetine". Biological Psychiatry. 50 (5): 345–50. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01145-3. PMID 11543737. S2CID 11247427.

- ^ Perry KW, Fuller RW (1997). "Fluoxetine increases norepinephrine release in rat hypothalamus as measured by tissue levels of MHPG-SO4 and microdialysis in conscious rats". Journal of Neural Transmission. 104 (8–9): 953–66. doi:10.1007/BF01285563. PMID 9451727. S2CID 2679296.

- ^ Bymaster FP, Zhang W, Carter PA, Shaw J, Chernet E, Phebus L, et al. (April 2002). "Fluoxetine, but not other selective serotonin uptake inhibitors, increases norepinephrine and dopamine extracellular levels in prefrontal cortex". Psychopharmacology. 160 (4): 353–61. doi:10.1007/s00213-001-0986-x. PMID 11919662. S2CID 27296534.

- ^ a b Koch S, Perry KW, Nelson DL, Conway RG, Threlkeld PG, Bymaster FP (December 2002). "R-fluoxetine increases extracellular DA, NE, as well as 5-HT in rat prefrontal cortex and hypothalamus: an in vivo microdialysis and receptor binding study". Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (6): 949–59. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00377-9. PMID 12464452.

- ^ a b c Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A (February 2009). "SSRIs act as selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs) at low doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 9 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.006. PMC 2670606. PMID 19157982.

- ^ Miguelez C, Fernandez-Aedo I, Torrecilla M, Grandoso L, Ugedo L (2009). "alpha(2)-Adrenoceptors mediate the acute inhibitory effect of fluoxetine on locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons". Neuropharmacology. 56 (6–7): 1068–73. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.03.004. PMID 19298831. S2CID 7485264.

- ^ Pälvimäki EP, Roth BL, Majasuo H, Laakso A, Kuoppamäki M, Syvälahti E, Hietala J (August 1996). "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor". Psychopharmacology. 126 (3): 234–40. doi:10.1007/BF02246453. PMID 8876023. S2CID 24889381.

- ^ Brunton PJ (June 2016). "Neuroactive steroids and stress axis regulation: Pregnancy and beyond". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 160: 160–8. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.08.003. PMID 26259885. S2CID 43499796.

- ^ a b Robinson RT, Drafts BC, Fisher JL (March 2003). "Fluoxetine increases GABA(A) receptor activity through a novel modulatory site". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 304 (3): 978–84. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.044834. PMID 12604672. S2CID 16061756.

- ^ Narita N, Hashimoto K, Tomitaka S, Minabe Y (June 1996). "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with subtypes of sigma receptors in rat brain". European Journal of Pharmacology. 307 (1): 117–9. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(96)00254-3. PMID 8831113.

- ^ Hashimoto K (September 2009). "Sigma-1 receptors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: clinical implications of their relationship". Central Nervous System Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (3): 197–204. doi:10.2174/1871524910909030197. PMID 20021354.

- ^ "Fluoxetine". IUPHAR Guide to Pharmacology. IUPHAR. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ "Calcium activated chloride channel". IUPHAR Guide to Pharmacology. IUPHAR. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ Gulbins E, Palmada M, Reichel M, Lüth A, Böhmer C, Amato D, et al. (July 2013). "Acid sphingomyelinase-ceramide system mediates effects of antidepressant drugs" (PDF). Nature Medicine. 19 (7): 934–8. doi:10.1038/nm.3214. PMID 23770692. S2CID 205391407.

- ^ Brunkhorst R, Friedlaender F, Ferreirós N, Schwalm S, Koch A, Grammatikos G, et al. (October 2015). "Alterations of the Ceramide Metabolism in the Peri-Infarct Cortex Are Independent of the Sphingomyelinase Pathway and Not Influenced by the Acid Sphingomyelinase Inhibitor Fluoxetine". Neural Plasticity. 2015: 503079. doi:10.1155/2015/503079. PMC 4641186. PMID 26605090.

- ^ a b "Fluoxetine". www.drugbank.ca. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E (2015). Top 100 drugs : clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. ISBN 978-0-7020-55-16-4.

- ^ Benfield P, Heel RC, Lewis SP (December 1986). "Fluoxetine. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in depressive illness". Drugs. 32 (6): 481–508. doi:10.2165/00003495-198632060-00002. PMID 2878798.

- ^ a b "Prozac Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, Studies, Metabolism". RxList.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 10 April 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ Mandrioli R, Forti GC, Raggi MA (February 2006). "Fluoxetine metabolism and pharmacological interactions: the role of cytochrome p450". Current Drug Metabolism. 7 (2): 127–33. doi:10.2174/138920006775541561. PMID 16472103.

- ^ Hiemke C, Härtter S (January 2000). "Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 85 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(99)00048-0. PMID 10674711.

- ^ a b Burke WJ, Hendricks SE, McArthur-Miller D, Jacques D, Bessette D, McKillup T, et al. (August 2000). "Weekly dosing of fluoxetine for the continuation phase of treatment of major depression: results of a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 20 (4): 423–7. doi:10.1097/00004714-200008000-00006. PMID 10917403.

- ^ "Drug Treatments in Psychiatry: Antidepressants". Newcastle University School of Neurology, Neurobiology and Psychiatry. 2005. Archived from the original on 17 April 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ a b Pérez V, Puiigdemont D, Gilaberte I, Alvarez E, Artigas F, et al. (Grup de Recerca en Trastorns Afectius) (February 2001). "Augmentation of fluoxetine's antidepressant action by pindolol: analysis of clinical, pharmacokinetic, and methodologic factors". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 21 (1): 36–45. doi:10.1097/00004714-200102000-00008. hdl:10261/34714. PMID 11199945. S2CID 13542714.

- ^ Brunswick DJ, Amsterdam JD, Fawcett J, Quitkin FM, Reimherr FW, Rosenbaum JF, Beasley CM (April 2002). "Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine plasma concentrations during relapse-prevention treatment". Journal of Affective Disorders. 68 (2–3): 243–9. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00333-5. PMID 12063152.

- ^ a b Henry ME, Schmidt ME, Hennen J, Villafuerte RA, Butman ML, Tran P, et al. (August 2005). "A comparison of brain and serum pharmacokinetics of R-fluoxetine and racemic fluoxetine: A 19-F MRS study". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (8): 1576–83. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300749. PMID 15886723.

- ^ Lemberger L, Bergstrom RF, Wolen RL, Farid NA, Enas GG, Aronoff GR (March 1985). "Fluoxetine: clinical pharmacology and physiologic disposition". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 46 (3 Pt 2): 14–9. PMID 3871765.

- ^ Pato MT, Murphy DL, DeVane CL (June 1991). "Sustained plasma concentrations of fluoxetine and/or norfluoxetine four and eight weeks after fluoxetine discontinuation". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 11 (3): 224–5. doi:10.1097/00004714-199106000-00024. PMID 1741813.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 645–48.

- ^ a b "Top 200 Generic Drugs by Units in 2010" (PDF). Drug Topics: Voice of the Pharmacist. June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2012.

- ^ Macnair P (September 2012). "BBC – Health: Prozac". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 December 2012.

In 2011 over 43 million prescriptions for antidepressants were handed out in the UK and about 14 per cent (or nearly 6 million prescriptions) of these were for a drug called fluoxetine, better known as Prozac.

- ^ a b Wong DT, Bymaster FP, Engleman EA (1995). "Prozac (fluoxetine, Lilly 110140), the first selective serotonin uptake inhibitor and an antidepressant drug: twenty years since its first publication". Life Sciences. 57 (5): 411–41. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(95)00209-O. PMID 7623609.

- ^ a b Wong DT, Horng JS, Bymaster FP, Hauser KL, Molloy BB (August 1974). "A selective inhibitor of serotonin uptake: Lilly 110140, 3-(p-trifluoromethylphenoxy)-N-methyl-3-phenylpropylamine". Life Sciences. 15 (3): 471–9. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(74)90345-2. PMID 4549929.

- ^ a b Breggin PR, Breggin GR (1995). Talking Back to Prozac. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-312-95606-6.

- ^ Swiatek J (2 August 2001). "Prozac's profitable run coming to an end for Lilly". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on 18 August 2007.

- ^ "Electronic Orange Book". Food and Drug Administration. April 2007. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- ^ Simons J (28 June 2004). "Lilly Goes Off Prozac The drugmaker bounced back from the loss of its blockbuster, but the recovery had costs". Fortune Magazine.

- ^ a b Class S (2 December 2002). "Pharma Overview". Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Lilly Menstrual drug OK'd – Jul. 6, 2000". Money.cnn.com. 6 July 2000. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Mechatie E (1 December 1999). "FDA Panel Agrees Fluoxetine Effective For PMDD". International Medical News Group.

- ^ Herper H (25 September 2002). "A Biotech Phoenix Could Be Rising". Forbes.

- ^ Petersen M (2 August 2001). "Drug Maker Is Set to Ship Generic Prozac". The New York Times.

- ^ "Patent Expiration Dates for Common Brand-Name Drugs". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ a b c Spartos C (5 December 2000). "Sarafem Nation". Village Voice. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Galen to Pay $295 Million For U.S. Rights to Lilly Drug". Dow Jones Newswires in the Wall Street Journal. 9 December 2002.

- ^ Murray-West R (10 December 2002). "Galen takes Lilly's reinvented Prozac". Telegraph.

- ^ Petersen M (29 May 2002). "New Medicines Seldom Contain Anything New, Study Finds". The New York Times.

- ^ Vedantam S (29 April 2001). "Renamed Prozac Fuels Women's Health Debate". The Washington Post.

- ^ Duquette A, Dorr L (2 April 2010). "FAA Proposes New Policy on Antidepressants for Pilots" (Press release). Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Office of Aerospace Medicine; Federal Aviation Administration (2 December 2016). "Decision Considerations – Aerospace Medical Dispositions: Item 47. Psychiatric Conditions – Use of Antidepressant Medications". Guide for Aviation Medical Examiners. Washington, DC: United States Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017.

- ^ "Mental Health GM - Centrally Acting Medication". Civil Aviation Authority. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint :url-status (링크) - ^ "Class 1/2 Certification – Depression" (PDF). Civil Aviation Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Hughes SR, Kay P, Brown LE (January 2013). "Global synthesis and critical evaluation of pharmaceutical data sets collected from river systems". Environmental Science & Technology. 47 (2): 661–77. Bibcode:2013EnST...47..661H. doi:10.1021/es3030148. PMC 3636779. PMID 23227929.

- ^ Stewart AM, Grossman L, Nguyen M, Maximino C, Rosemberg DB, Echevarria DJ, Kalueff AV (November 2014). "Aquatic toxicology of fluoxetine: understanding the knowns and the unknowns". Aquatic Toxicology. 156: 269–73. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.08.014. PMID 25245382.

- ^ a b Sumpter JP, Donnachie RL, Johnson AC (June 2014). "The apparently very variable potency of the anti-depressant fluoxetine". Aquatic Toxicology. 151: 57–60. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.12.010. PMID 24411166.

- ^ a b c Brooks BW, Foran CM, Richards SM, Weston J, Turner PK, Stanley JK, et al. (May 2003). "Aquatic ecotoxicology of fluoxetine". Toxicology Letters. Hot Spot Pollutants: Pharmaceuticals in the Environment. 142 (3): 169–83. doi:10.1016/S0378-4274(03)00066-3. PMID 12691711.

- ^ Mennigen JA, Stroud P, Zamora JM, Moon TW, Trudeau VL (1 July 2011). "Pharmaceuticals as neuroendocrine disruptors: lessons learned from fish on Prozac". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B: Critical Reviews. 14 (5–7): 387–412. doi:10.1080/10937404.2011.578559. PMID 21790318. S2CID 43341257.

- ^ Martin JM, Saaristo M, Bertram MG, Lewis PJ, Coggan TL, Clarke BO, Wong BB (March 2017). "The psychoactive pollutant fluoxetine compromises antipredator behaviour in fish". Environmental Pollution. 222: 592–599. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.010. PMID 28063712.

- ^ Barry MJ (21 April 2014). "Fluoxetine inhibits predator avoidance behavior in tadpoles". Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry. 96 (4): 641–49. doi:10.1080/02772248.2014.966713. S2CID 85340761.

- ^ Painter MM, Buerkley MA, Julius ML, Vajda AM, Norris DO, Barber LB, et al. (December 2009). "Antidepressants at environmentally relevant concentrations affect predator avoidance behavior of larval fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas)" (PDF). Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 28 (12): 2677–84. doi:10.1897/08-556.1. PMID 19405782. S2CID 25189716. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2019.

- ^ Mennigen JA, Lado WE, Zamora JM, Duarte-Guterman P, Langlois VS, Metcalfe CD, et al. (November 2010). "Waterborne fluoxetine disrupts the reproductive axis in sexually mature male goldfish, Carassius auratus". Aquatic Toxicology. 100 (4): 354–64. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.08.016. PMID 20864192.

- ^ Schultz MM, Painter MM, Bartell SE, Logue A, Furlong ET, Werner SL, Schoenfuss HL (July 2011). "Selective uptake and biological consequences of environmentally relevant antidepressant pharmaceutical exposures on male fathead minnows". Aquatic Toxicology. 104 (1–2): 38–47. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.03.011. PMID 21536011.

- ^ Mennigen JA, Sassine J, Trudeau VL, Moon TW (October 2010). "Waterborne fluoxetine disrupts feeding and energy metabolism in the goldfish Carassius auratus". Aquatic Toxicology. 100 (1): 128–37. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.07.022. PMID 20692053.

- ^ Gaworecki KM, Klaine SJ (July 2008). "Behavioral and biochemical responses of hybrid striped bass during and after fluoxetine exposure". Aquatic Toxicology. 88 (4): 207–13. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.04.011. PMID 18547660.

- ^ a b

- Richmond EK, Rosi EJ, Reisinger AJ, Hanrahan BR, Thompson RM, Grace MR (1 January 2019). "Influences of the antidepressant fluoxetine on stream ecosystem function and aquatic insect emergence at environmentally realistic concentrations". Journal of Freshwater Ecology. Taylor & Francis. 34 (1): 513–531. doi:10.1080/02705060.2019.1629546. ISSN 0270-5060. S2CID 196679455.

- Bundschuh M, Pietz S, Roodt AP, Kraus JM (April 2022). "Contaminant fluxes across ecosystems mediated by aquatic insects". Current Opinion in Insect Science. Elsevier. 50: 100885. doi:10.1016/j.cois.2022.100885. PMID 35144033. S2CID 246673478.

- ^ a b c d e

- Qin Q, Chen X, Zhuang J (9 September 2014). "The Fate and Impact of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Agricultural Soils Irrigated With Reclaimed Water". Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. Taylor & Francis. 45 (13): 1379–1408. doi:10.1080/10643389.2014.955628. ISSN 1064-3389. S2CID 94839032.

- Carvalho PN, Basto MC, Almeida CM, Brix H (October 2014). "A review of plant-pharmaceutical interactions: from uptake and effects in crop plants to phytoremediation in constructed wetlands". Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. Springer. 21 (20): 11729–11763. doi:10.1007/s11356-014-2550-3. PMID 24481515. S2CID 25786586.

- Christou A, Papadavid G, Dalias P, Fotopoulos V, Michael C, Bayona JM, et al. (March 2019). "Ranking of crop plants according to their potential to uptake and accumulate contaminants of emerging concern". Environmental Research. Elsevier. 170: 422–432. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2018.12.048. hdl:10261/202657. PMID 30623890. S2CID 58564142.

- Wu C, Spongberg AL, Witter JD, Fang M, Czajkowski KP (August 2010). "Uptake of pharmaceutical and personal care products by soybean plants from soils applied with biosolids and irrigated with contaminated water". Environmental Science & Technology. American Chemical Society (ACS). 44 (16): 6157–6161. doi:10.1021/es1011115. PMID 20704212. S2CID 20021866.

- ^ a b c Solsona SP, Montemurro N, Chiron S, Barceló D, eds. (2021). Interaction and Fate of Pharmaceuticals in Soil-Crop Systems. Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. Vol. 103. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. x+530. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-61290-0. ISBN 978-3-030-61289-4. ISSN 1867-979X. S2CID 231746862.

- ^ MacPherson M (2 September 1990). "Prozac, Prejudice and the Politics of Depression". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

추가 정보

- Shorter E (2014). "The 25th anniversary of the launch of Prozac gives pause for thought: where did we go wrong?". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 204 (5): 331–2. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.129916. PMID 24785765.

- Haberman C (21 September 2014). "Selling Prozac as the Life-Enhancing Cure for Mental Woes". The New York Times.

외부 링크

- "Fluoxetine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Fluoxetine hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.