날록손

Naloxone |

| |

| |

| 임상자료 | |

|---|---|

| 상호 | 나르칸, 에브지오, 닉소이드 등 |

| 기타이름 | EN-1530; N-알릴노록시모르폰; 17-알릴-4,5α-에폭시-3,14-디하이드록시모르피난-6-원, 날록손 염산염 (USAN) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| 메드라인 플러스 | a612022 |

| 라이센스 데이터 | |

| 임신 카테고리 |

|

| 경로 행정부. | 비강, 정맥내, 근육내 |

| 드럭 클래스 | 오피오이드 길항제 |

| ATC코드 | |

| 법적지위 | |

| 법적지위 | |

| 약동학적 자료 | |

| 생체이용률 | 2% (입으로 90% 흡수하지만 1차 통과 대사량이 높음) 43~54% (비강내) 98% (근육내, 피하)[12][13] |

| 신진대사 | 간 |

| 동작개시 | 2분(IV툴팁 정맥주사), 5분(IM근육 주사 도구 팁)[13] |

| 제거 반감기 | 1-1.5시간 |

| 조치기간 | 30-60분[13] |

| 배설 | 소변,담즙 |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| 펍켐 CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드럭뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니아이 | |

| 케그 | |

| ChEBI | |

| 쳄블 | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA) | |

| ECHA 인포카드 | 100.006.697 |

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |

| 공식 | C19H21NO4 |

| 어금니 질량 | 327.380g·mol−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSMO) | |

| |

| |

| | |

나록손은 오피오이드의 효과를 되돌리거나 줄이기 위해 사용되는 약입니다.[13]오피오이드 과다복용 시 호흡 감소를 억제하는 데 사용됩니다.[13]효과는 정맥 주사로 2분, 근육 주사로 5분,[13] 비강 스프레이로 10분 이내에 시작됩니다.[14]나록손은 30분에서 90분 동안 오피오이드의 효과를 차단합니다.[15]

오피오이드 의존성 개인에게 투여하면 불안, 동요, 메스꺼움, 구토, 빠른 심박수 및 땀 흘림을 포함한 오피오이드 금단 증상을 유발할 수 있습니다.[13]이를 방지하기 위해 원하는 효과에 도달할 때까지 몇 분마다 소량씩 투여할 수 있습니다.[13]이전에 심장병을 앓았거나 심장에 부정적인 영향을 미치는 약을 복용한 사람들에게서는 더 많은 심장 문제가 발생했습니다.[13]제한된 수의 여성에게 투여된 후 임신 중에는 안전한 것으로 보입니다.[16]날록손은 비선택적이고 경쟁적인 오피오이드 수용체 길항제입니다.[6][17]오피오이드로 인한 중추신경계와 호흡기계의 우울증을 반전시켜 작용합니다.[13]

Naloxone은 1961년에 특허를 받았고 1971년에 미국에서 오피오이드 과다복용으로 승인되었습니다.[18][19]그것은 세계보건기구의 필수 의약품 목록에 올라있습니다.[20]나록손은 일반의약품으로 판매되고 있습니다.[13][21]

의료용

오피오이드 과다 복용

나록손은 급성 오피오이드 과다 복용과 오피오이드로 인한 호흡기 우울증 또는 정신적 우울증 치료에 유용합니다.[13]오피오이드 과다 복용으로 인해 심정지 상태에 있는 사람들에게 유용한지는 불분명합니다.[22]

헤로인 및 기타 오피오이드 약물 사용자 및 응급 대응자에게 배포되는 긴급 과다복용 대응 키트의 일부로 포함됩니다.이것은 과다복용으로 인한 사망률을 감소시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[23]많은 용량의 오피오이드(100 mg 이상의 모르핀 당량/일)를 복용하고 있거나, 벤조디아제핀을 동반한 오피오이드를 처방받거나, 오피오이드를 비의료적으로 사용하는 것으로 의심되거나 알려진 경우 날록손 처방이 권장됩니다.[24]날록손을 처방하는 것은 과다복용의 예방, 확인 및 대응, 호흡 구조, 응급 서비스 호출을 포함하는 표준 교육이 수반되어야 합니다.[25]

약물 과다 복용자와 마주칠 가능성이 있는 사람들에게 날록손을 투여하는 것은 피해 감소의 일부입니다.[26]

그러나 반감기가 더 긴 오피오이드의 경우 날록손이 마모된 후 호흡 저하가 돌아오므로 적절한 투약과 지속적인 모니터링이 필요할 수 있습니다.[27]

클로니딘 과다 복용

날록손은 또한 혈압을 낮추는 약인 클로니딘의 과다 복용에서 해독제로 사용될 수 있습니다.[28]클로니딘 과다복용은 작은 용량이라도 심각한 해를 끼칠 수 있는 어린이들에게 특별한 관련이 있습니다.[29]그러나, 클로니딘 과다복용의 증상, 즉 느린 심박수, 저혈압, 그리고 혼동/졸음의 치료에 있어서 날록손의 효능에 대해서는 논란이 있습니다.[29]0.1 mg/kg (최대 2 mg/dose)의 사용 용량이 1-2분 간격으로 반복(총 10 mg 용량)되었다는 사례 보고서에서 일관되지 않은 이점이 나타났습니다.[29]문헌 전반에 걸쳐 사용되는 투여량이 다양하기 때문에, 이 설정에서 날록손의 이점에 관한 결론을 내리기는 어렵습니다.[30]클로니딘 과다복용에서 날록손의 제안된 이점에 대한 메커니즘은 명확하지 않지만, 내인성 오피오이드 수용체가 뇌와 신체의 다른 곳에서 교감 신경계를 중재한다고 제안되었습니다.[30]

오락용 오피오이드 사용 방지

날록손은 경구 복용 시 흡수가 잘 되지 않아 부프레노핀, 펜타조신 등 여러 경구용 오피오이드 제제와 결합해 경구 복용 시 오피오이드만 효과를 발휘합니다.[13][31]그러나 오피오이드와 날록손 조합을 주사하면, 날록손은 오피오이드의 효과를 차단합니다.[13][31]이 조합은 의약외품 사용을 방지하기 위한 목적으로 사용됩니다.[31]

기타용도

2003년 기존 연구의 메타 분석은 패혈증, 심장원성, 출혈성 또는 척추성 쇼크를 포함한 쇼크 환자의 혈류를 개선하는 날록손을 보여주었지만, 이것이 환자의 사망을 감소시키는지는 결정할 수 없었습니다.[32]

특수집단

임신 및 모유수유

그러나 모유에서 날록손이 배설되는지 여부는 알려지지 않았지만, 이는 경구적으로 생체이용이 가능하지 않기 때문에 모유 수유를 하는 유아에게 영향을 미칠 가능성은 낮습니다.[33]

아이들.

날록손은 분만 중 산모에게 투여된 자궁 내 아편에 노출된 유아에게 사용할 수 있습니다.그러나, 이러한 유아들의 심장 호흡기 및 신경학적 우울증을 낮추기 위한 날록손의 사용에 대한 증거는 충분하지 않습니다.[34]임신 중 고농도 아편에 노출된 유아는 주산기 질식사 환경에서 CNS 손상이 있을 수 있습니다.Naloxone은 이 집단의 결과를 개선하기 위해 연구되어 왔지만, 현재 증거는 약합니다.[35][34]

날록손의 정맥내, 근육내 또는 피하 투여는 아편 효과를 역전시키기 위해 소아와 신생아에게 투여될 수 있습니다.미국 소아과 학회는 다른 두 가지 형태가 예측할 수 없는 흡수를 일으킬 수 있기 때문에 정맥 주사 투여만 권장합니다.용량이 투여된 후에는 최소 24시간 동안 어린이를 감시해야 합니다.패혈성 쇼크로 인한 저혈압 어린이의 경우 날록손의 안전성과 효과가 확립되어 있지 않습니다.[36]

노인성 용법

65세 이상 환자의 경우 반응에 차이가 있는지 여부가 불분명합니다.그러나 노인들은 종종 간과 신장 기능이 감소하여 몸 안에 날록손의 수치를 증가시킬지도 모릅니다.[6]

사용가능양식

정맥주사

병원 환경에서 날록손은 정맥 주사되며, 시작 시간은 1-2분, 지속 시간은 최대 45분입니다.[37]

근육내 또는 피하

나록손은 근육 주사나 피하 주사를 통해서도 투여될 수 있습니다.이 경로를 통해 제공되는 날록손의 시작 시간은 2분에서 5분이며 약 30분에서 120분 정도입니다.[38]근육 내에 투여되는 날록손은 미리 채워진 주사기, 바이알 및 자동 주입기를 통해 제공됩니다.휴대용 자동 주입기는 포켓 사이즈로 가정과 같은 의료 외 환경에서 사용할 수 있습니다.[22]이 제품은 가족을 포함한 일반인과 오피오이드 사용자의 간병인이 오피오이드 과다 복용과 같은 오피오이드 응급 상황에 위험이 있는 사용자를 위해 설계되었습니다.[39]FDA의 국가 약물 코드 디렉토리(National Drug Code Directory)에 따르면, 자동 주사기의 일반 버전은 2019년 말에 시판되기 시작했습니다.[40]

비강내

Narcan 비강 스프레이는 2015년 미국에서 승인되었으며, 긴급 치료 또는 과다 복용 의심에 대한 최초의 FDA 승인 비강 스프레이입니다.[41][42]라이트레이크 테라퓨틱스와 국립 약물 남용 연구소의 협력으로 개발되었습니다.[43]승인 절차는 신속하게 진행되었습니다.[44]2019년 미국에서 일반 버전의 비강 스프레이가 승인되었지만 2021년까지 시판되지 않았습니다.[41][45]

FDA는 2021년 히크마제약이 개발한 8mg 용량의 인트라나살날록손인 클로사도를 승인했습니다.[46]Kloxxado Nasic Spray의 팩은 Narcan의 여러 4mg 용량이 약물 과다 복용을 성공적으로 되돌려야 하는 빈번한 필요성을 언급하며, 각각 8mg의 naloxone을 포함하는 2개의 사전 포장된 비강 스프레이 장치를 포함합니다.[47][9]

그러나, 웨지 디바이스(nasal atomizer)는 또한 주사기에 부착될 수 있고, 이는 약물을 코 점막으로 전달하기 위한 미스트를 생성하는데 사용될 수도 있습니다.[48]이 기능은 이미 주입기를 비축하고 있는 과잉 투여가 많이 발생하는 시설 근처에서 유용합니다.[49]

부작용

오피오이드를 사용한 사람에게 날록손을 투여하면 오피오이드의 급속한 방출이 일어날 수 있습니다.[50]

나록손은 오피오이드가 존재하지 않으면 거의 효과가 없습니다.아편계를 가지고 있는 사람들에게, 그것은 땀을 증가시키고, 메스꺼움, 불안함, 떨림, 구토, 홍조, 두통을 유발할 수 있고, 드물게 심장 리듬 변화, 발작, 폐부종과 관련이 있습니다.[51][52]

날록손은 신체가 자연적으로 생성하는 통증을 낮추는 엔도르핀의 작용을 차단하는 것으로 나타났습니다.이 엔돌핀들은 날록손이 차단하는 것과 같은 오피오이드 수용체에서 작동할 가능성이 있습니다.날록손의 숨겨진 주사나 맹목적인 주사와 함께 플라시보를 투여한다면, 그것은 플라시보 통증을 감소시키는 반응을 차단할 수 있습니다.[53]다른 연구들은 위약만으로도 신체의 μ-opioid endorphin 시스템을 활성화시켜 모르핀과 같은 수용체 메커니즘에 의해 통증 완화를 전달할 수 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.[54][55]

나록손은 현재 심혈관계에 악영향을 미칠 수 있는 약물을 복용 중인 사람뿐만 아니라 저혈압, 폐액 축적(폐부종), 심장리듬 이상 등을 유발할 수 있는 사람에게는 주의해서 사용해야 합니다.오피오이드 길항제로 갑자기 역전되어 폐부종과 심실세동을 일으킨다는 보고가 있습니다.[56]

오락적으로 오피오이드를 사용해온 사람들을 치료하기 위해 날록손을 사용하는 것은 오피오이드의 급성 금단현상을 유발할 수 있으며, 오피오이드는 떨림, 빈맥, 메스꺼움과 같은 고통스러운 생리적 증상을 일으킬 수 있습니다.[57]

약리학

약력학

| 컴파운드 | 친화도()Ki툴팁 억제 상수) | 비율 | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOR툴팁 μ-Opioid 수용체 | DOR툴팁 δ-Opioid 수용체 | KOR툴팁 κ-Opioid 수용체 | MOR:DOR:KOR | ||

| 날록손 | 1.1 nM 1.4 nM | 16nM 67.5 nM | 12nM 2.5 nM | 1:15:11 1:48:1.8 | [58] [59][60] |

| (-)-날록손 | 0.559nM 0.93nM | 36.5 nM 17nM | 4.91nM 2.3 nM | 1:65:9 1:18:2 | [61] [62] |

| (+)-날록손 | 3,550 nM >1,000 nM | 122,000 nM >1,000 nM | 8,950nM >1,000 nM | 1:34:3 ND | [61] [62] |

날록손은 비선택적이고 경쟁적인 오피오이드 수용체 길항제로 작용하는 친유성 화합물입니다.[17][6]날록손의 약리활성 이성질체는 (-)-날록손입니다.[61][63]날록손의 결합 친화도는 μ-오피오이드 수용체(MOR), δ-오피오이드 수용체(DOR)에서 가장 높고, κ-오피오이드 수용체(KOR)에서 가장 낮습니다. 날록손은 노시셉틴 수용체에 대해 무시할만한 친화도를 가지고 있습니다.

오피오이드를 함께 사용하지 않을 때 날록손을 투여하면 신체가 자연스럽게 통증과 싸울 수 없는 것을 제외하고는 기능적인 약리 작용이 일어나지 않습니다.[citation needed]아편 내성이 있는 사람들에게 중단되었을 때 아편 금단 증상을 이끌어내는 직접적인 아편 작용제와는 대조적으로, 날록손에 대한 내성이나 의존성의 발달을 나타내는 증거는 없습니다.작용기전이 완전히 이해된 것은 아니지만, 뇌 내에서 오피오이드 수용체(직접적인 작용제가 아닌 경쟁적인 길항제)와 경쟁함으로써 금단증상을 일으키는 기능을 한다는 연구결과가 있습니다.따라서 직접적으로 어떠한 효과도 생성하지 않으면서 이러한 수용체에 대한 내인성 및 이종 생물학적 오피오이드의 작용을 방지합니다.[65]

정맥 주사에 의한 2 mg의 비교적 고용량의 날록손을 한 번 투여하면 5분에 80%, 2시간에 47%, 4시간에 44%, 8시간에 8%의 뇌 MOR 차단이 발생하는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[66]저용량(2μg/kg)은 5분에 42%, 2시간에 36%, 4시간에 33%, 8시간에 10%의 뇌 MOR 차단을 나타냈습니다.[66]비강 분무를 통한 날록손의 비강 내 투여도 마찬가지로 뇌 MOR을 빠르게 차지하는 것으로 확인되었으며, 최대 점유율은 20분에 발생하고, 최대 점유율은 2mg에서 67%, 최대 점유율은 4mg에서 85%이며, 점유율 소멸의 추정 반감기는 약 100분(1.67시간)입니다.[67][68]

약동학

가장 일반적인 것처럼, 날록손은 비경구적으로 (예를 들어, 정맥내 또는 주사에 의해) 투여될 때, 전신에 빠른 분포를 갖습니다.평균 혈청 반감기는 30분에서 81분으로 일부 아편제의 평균 반감기보다 짧은 것으로 나타났습니다. 오피오이드 수용체가 장시간 동안 유발되는 것을 중단해야 한다면 반복 투여가 필요합니다.날록손은 주로 간에 의해 대사됩니다.주요 대사산물은 소변으로 배출되는 날록손-3-글루쿠로니드입니다.[65]알코올성 간질환이나 간염과 같은 간질환이 있는 사람들의 경우, 날록손 사용이 혈청 간효소 수치를 증가시키지 않는 것으로 나타났습니다.[69]

나록손은 간의 퍼스트패스 대사로 인해 경구 복용 시 전신 생체이용률이 낮지만 장에 위치한 오피오이드 수용체를 차단합니다.[70]

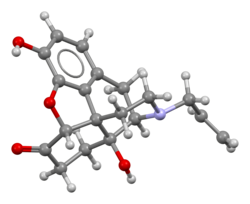

화학

N-알릴노록시모르폰 또는 17-알릴-4,5α-에폭시-3,14-디하이드록시모르피난-6-원으로도 알려진 날록손은 합성 모피난 유도체이며, 오피오이드 진통제인 옥시모르폰(14-히드록시디히드로모르피논)으로부터 유래되었습니다.[71][72][73]옥시모르폰은 아편 양귀비의 자연적으로 발생하는 오피오이드 진통제인 모르핀에서 유래되었습니다.[74]날록손은 두 개의 거울상이성질체, (–)-날록손 (레보날록손) 및 (+)-날록손 (덱스트론알록손)의 라세믹 혼합물이며, 전자만이 오피오이드 수용체에서 활성입니다.[75][76]그 약은 매우 친유성이어서, 그것이 빠르게 뇌에 침투할 수 있게 하고, 모르핀보다 훨씬 더 큰 뇌 대 혈청 비율을 달성할 수 있게 해줍니다.[71]날록손과 관련된 오피오이드 길항제로는 시프로다임, 날메펜, 날로데인, 날록솔, 날트렉손 등이 있습니다.[77]

역사

날록손은 1961년 모제스 J. 르웬슈타인, 잭 피시맨 그리고 산쿄 회사에 의해 특허를 받았습니다.[18]1971년 미국에서 오피오이드 사용 장애 치료 승인을 받았습니다.[78]

사회와 문화

오보

Naloxone은 부정확한 언론 보도의 대상이 되었고 그것에 대한 많은 도시 전설들이 널리 퍼졌습니다.[79]

그러한 신화 중 하나는 나록손이 받는 사람을 폭력적으로 만든다는 것입니다.[80]다른 하나는 "라자루스 파티"라고 불리는 사건들이 일어났다는 것인데, 사람들이 날록손 치료를 받을 것을 예상하고 치명적인 과다복용을 한 것으로 알려졌습니다. 사실 이것은 경찰에 의해 퍼진 허구였습니다.[79]또 다른 하나는 사람들이 극단적인 "높은" 상태와 그 이후의 부활을 즐기기 위해 날록손과 오피오이드를 동시에 복용하는 "요요잉"에 탐닉했다는 주장입니다. 과학적으로 터무니없는 생각입니다.[79]

이름들

나록소네는 국제적으로 독점적이지 않은 이름, 영국 승인된 이름, 데노미네이션 코뮌 프랑세즈, 데노미네이션 코뮌 이탈리아나, 일본 승인된 이름이며, 나록소네 하이드로클로라이드는 미국 승인된 이름과 영국 승인된 이름(수정됨)입니다.[81][82][83][84]

특허가 만료되어 일반의약품으로 사용할 수 있습니다.여러 제형이 특허 받은 분사기(분무기구 또는 자동분무기)를 사용하는데, 2016년부터 2020년 사이 판사가 일반 제조업체인 테바의 손을 들어주면서 비강분무기의 일반 형태 대신 특허 분쟁이 소송으로 이어졌습니다.[85]2021년 12월, 테바는 최초의 일반적인 비강 스프레이 제형의 출시를 발표했습니다.[45]날록손의 브랜드명은 나르칸, 클로사도, 날론, 에브지오, 프레녹사드 인젝션, 나르산티, 나르코탄, 지미 등이 있습니다.

법적 상태 및 법 집행 및 응급 인력에 대한 가용성

이 섹션의 예와 관점은 주로 미국과 캐나다를 다루며 주제에 대한 전 세계적인 관점을 나타내지 않습니다.(2022년 9월)(본 방법 및 |

Naloxone(Nyxoid)은 2017년 9월 유럽 연합에서 사용이 승인되었습니다.[86]

2023년 3월, 미국 FDA는 처방전 없이 사용할 수 있도록 승인된 최초의 날록손 제품인 장외(OTC)용 날록손 염산염 비강 스프레이(Narcan)를 승인했습니다.[87]날록손의 다른 제형과 투여량은 처방전에 따라 사용할 수 있습니다.[87]2023년 7월 FDA는 OTC 사용에 대해 리비브 비강 스프레이를 승인했습니다.[88][89]

미국에서는 처방전 없이 날록손을 구입할 수 있습니다.[87][88][90][91]나록손은 일부 약국에서 구입할 수 없을 수도 있습니다.[92][93]

2019년 현재, 29개 주의 관리들은 개인이 먼저 처방사를 방문하지 않고도 허가받은 약사들이 환자들에게 날록손을 제공할 수 있도록 대기 명령을 내렸습니다.[94]위해 감소 또는 저임계값 치료 프로그램을 진행하는 처방사들은 이들 기관이 고객에게 날록손을 배포할 수 있도록 대기 명령을 내리기도 했습니다.[95]"비환자 특정 처방전"이라고도 불리는 스탠딩 명령은 의사, 간호사 또는 기타 처방사에 의해 의사-환자 관계 밖에서 의약품 배포를 허가하기 위해 작성됩니다.[96]날록손의 경우, 이러한 주문은 오피오이드를 사용하는 사람들과 그들의 가족 및 친구들에게 날록손을 쉽게 배포하기 위한 것입니다.[94]200개 이상의 날록손 유통 프로그램은 허가된 처방사를 활용하여 그러한 명령을 통해 또는 약사의 권한을 통해 의약품을 유통합니다(캘리포니아의 법 조항 AB1535와 같이).[97][98]

많은 미국 사법권의 법률과 정책이 날록손의 더 넓은 유통을 허용하도록 변경되었습니다.[99][100]위험에 처한 개인과 가족에게 의약품을 배포하는 것을 허용하는 법 또는 규정 외에도, 약 36개 주에서 날록손 처방자에게 민형사상 책임에 대한 면책권을 제공하는 법을 통과시켰습니다.[101]미국의 구급대원들이 수십 년 동안 날록손을 가지고 다니는 동안, 전국의 많은 주에서 법 집행관들은 구급대원들보다 먼저 그 장소에 도착할 때 헤로인 과다복용의 효과를 뒤집기 위해 날록손을 가지고 갑니다.2015년 7월 12일 현재, 미국 28개 주의 법 집행부는 오피오이드 과다복용에 신속하게 대응하기 위해 날록손을 소지할 수 있거나 소지할 것을 요구하고 있습니다.[102]나록손을 이용한 오피오이드 과다복용 대응에 소방인력을 양성하는 프로그램도 미국에서 가능성을 보여주었고, 미국의 과다복용 사태로 인해 오피오이드 치명 예방을 응급대응에 통합하려는 노력이 커지고 있습니다.[103][104][105][106]

뉴욕 스태튼 아일랜드에서 경찰관들이 비강 분무 장치를 사용한 데 이어, 2014년 중반에 추가로 2만 명의 경찰관들이 날록손을 운반하기 시작할 예정입니다.주 검찰총장실은 약 20,000개의 키트를 공급하기 위해 미화 120만 달러를 제공할 예정입니다.윌리엄 브래튼 경찰국장은 "날록손은 개인들에게 두 번째 도움을 받을 수 있는 기회를 줍니다."[107]라고 말했습니다.EMS(Emergency Medical Service Providers)는 기본적인 응급 의료 기술자가 정책 또는 주법에 의해 금지된 경우를 제외하고 naloxone을 정기적으로 관리합니다.[108]시민들이 오피오이드 과다복용 가능성에 대한 도움을 구하도록 장려하기 위해, 많은 주들은 선의로 자신이나 오피오이드 과다복용을 경험하고 있을 수 있는 주변의 누군가를 위해 응급의료를 추구하는 모든 사람들에게 특정 범죄 책임에 대한 면책을 제공하는 착한 사마리아인 법을 채택했습니다.[109]

버몬트 주와 버지니아 주를 포함한 주들은 과다복용에 대한 예방책으로 처방이 하루에 일정 수준 이상의 모르핀 밀리 당량을 초과할 경우 날록손 처방을 의무화하는 프로그램을 개발했습니다.[110]의료 기관에 기반을 둔 날록손 처방 프로그램은 노스 캐롤라이나에서 오피오이드 과다 복용 비율을 줄이는 데 도움이 되었으며, 미군에서도 복제되었습니다.[97][111]

캐나다에서는 날록손 1회용 주사기 키트가 배포되어 여러 의원과 응급실에서 구입할 수 있습니다.앨버타 보건국은 모든 응급실과 지방 전역의 다양한 약국과 클리닉에서 날록손 키트의 유통점을 늘리고 있습니다.에드먼턴 경찰국과 캘거리 경찰국 순찰차는 모두 1회용 알록손 주사기 키트를 휴대하고 있습니다.일부 캐나다 왕립 기마 경찰 순찰 차량은 사용자와 관련 가족/친구들에게 날록손을 배포하는 데 도움을 주기 위해 과도하게 약물을 운반하기도 합니다.간호사, 구급대원, 의료기사, 응급의료대응요원 등도 약을 처방하고 배포할 수 있습니다.2016년 2월 현재 앨버타 주와 다른 일부 캐나다 지역의 약국에서는 일회용 테이크홈 날록손 키트를 배포하거나 오피오이드를 사용하는 사람들에게 약을 처방할 수 있습니다.[112]

앨버타 보건 서비스에 이어 캐나다 보건부는 날록손의 처방전 전용 상태를 검토하여 2016년에 제거할 계획을 세웠고, 날록손을 더 쉽게 접근할 수 있게 만들었습니다.[113][114]전국적으로 마약 사망자 수가 증가함에 따라 캐나다 보건부는 증가하는 오피오이드 과다복용을 해결하기 위한 노력을 지지하기 위해 캐나다 사람들이 날록손을 더 널리 사용할 수 있도록 하는 변화를 제안했습니다.[115]2016년 3월, 캐나다 보건부는 "약국들은 이제 오피오이드 과다 복용을 경험하거나 목격할 수 있는 사람들에게 사전에 날록손을 나누어 줄 수 있습니다."라고 말하며 날록손의 처방 상태를 변경했습니다.[116]

커뮤니티 액세스

2021년 12월 미국 일반인을 대상으로 한 설문조사에서 대부분의 사람들은 훈련된 방관자들이 날록손으로 과다복용을 역전시킬 수 있다는 과학적으로 뒷받침된 아이디어를 믿었습니다.[117]

2010년 미국의 naloxone 처방 프로그램을 조사한 결과 48개 프로그램 중 21개 프로그램에서 naloxone을 구입하는 데 어려움을 겪었다고 보고했는데, 이는 주로 할당된 자금을 초과하는 비용 증가 또는 공급업체가 주문을 채우지 못하기 때문인 것으로 나타났습니다.[118]미국의 naloxone 1ml 앰플의 대략적인 가격은 대부분의 다른 나라들보다 상당히 높을 것으로 추정됩니다.[97]

오피오이드를 사용하는 사람들을 위한 테이크-홈 날록손 프로그램이 많은 북미 도시에서 진행되고 있습니다.[118][119]CDC는 마약 사용자들과 그들의 간병인들을 위한 미국의 프로그램이 집에서 나록손을 처방하고 그 사용에 대한 교육을 통해 2014년까지 10,000명의 오피오이드 과다 복용 사망자를 예방했다고 추정하고 있습니다.[118]

호주에서는 2016년 2월 현재 처방전 없이 약국에서 일부 형태의 날록손을 구입할 수 있습니다.[2][120][121]그것은 법 집행 키트와 유사한 1회용 충전 주사기로 제공됩니다.1회 투여량은 20 호주 달러이며, 처방전이 있는 경우 5회 투여량을 40 호주 달러에 구입할 수 있으며, 이는 1회 투여량(2019년)당 8달러의 비율에 달합니다.[122]

앨버타 주에서는 약국 유통 외에도 테이크홈 날록손 키트를 구입할 수 있으며 대부분의 약물 치료 또는 재활 센터에서 유통됩니다.[112]

유럽연합에서는 1990년대 후반 채널 제도와 베를린에서 Take home naloxone 조종사들이 발사되었습니다.[123]2008년 웨일스 의회 정부는 테이크홈 날록손을 위한 시범 장소를 설립할 의도를 발표했고,[124] 2010년 스코틀랜드는 전국적인 날록손 프로그램을 도입했습니다.[125]북미와 유럽의 노력에 고무되어 약물 사용자들을 약물 과다 복용 반응자로 훈련시키고 날록손을 공급하는 프로그램을 운영하는 비정부기구는 현재 러시아, 우크라이나, 조지아, 카자흐스탄, 타지키스탄, 아프가니스탄, 중국, 베트남, 태국에서 운영되고 있습니다.[126]

2018년, 날록손의 한 제조업체는 미국의 16,568개의 공공 도서관과 2,700개의 YMCA에 각각 교육 자료뿐만 아니라 2회 투여분의 비강 스프레이가 포함된 무료 키트를 제공할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[127]

비평

2022년 연구에서는 날록손의 증식이 오피오이드 관련 절도를 증가시켰다고 보고했습니다.[128]

2010년대에 몇몇 정치 평론가들, 법 집행 직원들, 그리고 중독 전문가들은 날록손이 오피오이드 중독을 가능하게 하고 위기를 악화시킨다고 주장했습니다.보건당국은 이런 인식에 반발하고 나섰습니다.[129][130]

Narcan의 제조사는 또한 비강 스프레이에 대해 150달러를 청구하고 더 저렴한 허가받지 않은 복제약을 시판하려는 경쟁사들을 공격적으로 고소했습니다.[131]나록손에 대한 인지도를 높이고 경찰청의 대량 구매 등의 정책을 추진하는 홍보 노력은[132] 분명히 매출을 증가시킵니다.

참고문헌

- ^ "Naloxone Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 2 September 2019. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ a b Lenton SR, Dietze PM, Jauncey M (March 2016). "Australia reschedules naloxone for opioid overdose". The Medical Journal of Australia. 204 (4): 146–147. doi:10.5694/mja15.01181. PMID 26937664. S2CID 9320372. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: Access to naloxone in Canada (including Narcan Nasal Spray)". Health Canada. 6 July 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ "Naloxone 400 micrograms/ml solution for Injection/Infusion – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 6 February 2019. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Narcan- naloxone hydrochloride spray Narcan- naloxone hydrochloride spray". DailyMed. 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "Evzio- naloxone hydrochloride injection, solution". DailyMed. 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Zimhi- naloxone hydrochloride injection, solution". DailyMed. 29 September 2022. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Kloxxado- naloxone hcl spray". DailyMed. 10 May 2022. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "NDA 208411/S-006 Supplemental Approval letter" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "RiVive: Naloxone HCl Nasal Spray 3 mg Emergency Treatment of Opioid Overdose" (PDF). Front Actuator (nasal spray device) Label. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ Ryan SA, Dunne RB (May 2018). "Pharmacokinetic properties of intranasal and injectable formulations of naloxone for community use: a systematic review". Pain Management. 8 (3): 231–245. doi:10.2217/pmt-2017-0060. PMID 29683378.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Naloxone Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ McDonald R, Lorch U, Woodward J, Bosse B, Dooner H, Mundin G, et al. (March 2018). "Pharmacokinetics of concentrated naloxone nasal spray for opioid overdose reversal: Phase I healthy volunteer study". Addiction. 113 (3): 484–493. doi:10.1111/add.14033. PMC 5836974. PMID 29143400.

- ^ "Naloxone DrugFacts". National Institute on Drug Abuse. 1 June 2021. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 190–191, 287. ISBN 9780071481274.

Products of this research include the discovery of lipophilic, small-molecule opioid receptor antagonists, such as naloxone and naltrexone, which have been critical tools for investigating the physiology and behavioral actions of opiates. ... A competitive antagonist of opiate action (naloxone) had been identified in early studies. ... Opiate antagonists have clinical utility as well. Naloxone, a nonselective antagonist with a relative affinity of μ > δ > κ, is used to treat heroin and other opiate overdoses.

- ^ a b Yardley W (14 December 2013). "Jack Fishman Dies at 83; Saved Many From Overdose". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ 미국 특허 3493657, Jack Fishman & Mozes Juda Lewenstein, "n-allyl-14-hydroxy-dihydronormorphinane 및 morphine의 치료 조성물", 1970-02-03 공개, 1970-02-03 발행, Mozes Juda Lewenstein Archived at the Wayback Machine 2022 12월 7일

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Competitive Generic Therapy Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 June 2023. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ a b Lavonas EJ, Drennan IR, Gabrielli A, Heffner AC, Hoyte CO, Orkin AM, et al. (November 2015). "Part 10: Special Circumstances of Resuscitation: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S501–S518. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000264. PMID 26472998.

- ^ Maxwell S, Bigg D, Stanczykiewicz K, Carlberg-Racich S (2006). "Prescribing naloxone to actively injecting heroin users: a program to reduce heroin overdose deaths". Journal of Addictive Diseases. 25 (3): 89–96. doi:10.1300/J069v25n03_11. PMID 16956873. S2CID 17246459.

- ^ "Project Lazarus, Wilkes County, North Carolina" (PDF). Policy Briefing Document Prepared for the North Carolina Medical Board in Advance of the Public Hearing Regarding Prescription Naloxone. Raleigh, NC. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.[페이지 필요][검증 필요]

- ^ Bowman S, Eiserman J, Beletsky L, Stancliff S, Bruce RD (July 2013). "Reducing the health consequences of opioid addiction in primary care". The American Journal of Medicine. 126 (7): 565–571. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.11.031. PMID 23664112.

- ^ Marlatt GA, Larimer ME, Witkiewitz K, eds. (2011). Harm reduction: Pragmatic strategies for managing high-risk behaviors (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-4625-0256-1.

- ^ van Dorp E, Yassen A, Dahan A (March 2007). "Naloxone treatment in opioid addiction: the risks and benefits". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 6 (2): 125–132. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.2.125. PMID 17367258. S2CID 11650530.

- ^ Niemann JT, Getzug T, Murphy W (October 1986). "Reversal of clonidine toxicity by naloxone". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 15 (10): 1229–1231. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80874-5. PMID 3752658.

- ^ a b c Ahmad SA, Scolnik D, Snehal V, Glatstein M (2015). "Use of naloxone for clonidine intoxication in the pediatric age group: case report and review of the literature". American Journal of Therapeutics. 22 (1): e14–e16. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e318293b0e8. PMID 23782760.

- ^ a b Seger DL (2002). "Clonidine toxicity revisited". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 40 (2): 145–155. doi:10.1081/CLT-120004402. PMID 12126186. S2CID 2730597.

- ^ a b c Orman JS, Keating GM (2009). "Buprenorphine/naloxone: a review of its use in the treatment of opioid dependence". Drugs. 69 (5): 577–607. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969050-00006. PMID 19368419. S2CID 209147406.

- ^ Boeuf B, Poirier V, Gauvin F, Guerguerian AM, Roy C, Farrell CA, Lacroix J (2003). "Naloxone for shock". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (4): CD004443. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004443. PMC 9036847. PMID 14584016.

- ^ "Naloxone use while Breastfeeding". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ a b Moe-Byrne T, Brown JV, McGuire W (October 2018). "Naloxone for opioid-exposed newborn infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD003483. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003483.pub3. PMC 6517169. PMID 30311212.

- ^ McGuire W, Fowlie PW, Evans DJ (26 January 2004). "Naloxone for preventing morbidity and mortality in newborn infants of greater than 34 weeks' gestation with suspected perinatal asphyxia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2010 (1): CD003955. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003955.pub2. PMC 6485479. PMID 14974047.

- ^ "Narcan (Naloxone Hydrochloride Injection): Side Effects, Interactions, Warning, Dosage & Uses". RxList. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ Drug information handbook for advanced practice nursing: a comprehensive resource for nurse practitioners, nurse midwives and clinical specialists, including selected disease management guidelines. Lexicomp. 2013. ISBN 978-1591953234. OCLC 827841946.

- ^ 2016년 10월 오피오이드 과다 복용 치료를 위한 날록손

- ^ "FDA approves new hand-held auto-injector to reverse opioid overdose" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ "NDC 72853-051-02 Naloxone Hydrochloride Auto-injector". NDClist.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b "FDA approves first generic naloxone nasal spray to treat opioid overdose" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 11 September 2019. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ "FDA Approves Narcan Nasal Spray". www.jems.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Volkow N (18 November 2015). "Narcan Nasal Spray: Life Saving Science at NIDA". National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Archived from the original on 26 February 2017.

- ^ Dennis B (3 April 2014). "FDA approves device to combat opioid drug overdose". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Teva Announces Launch of First-to-Market Generic Version of Narcan (Naloxone Hydrochloride Nasal Spray), in the U.S." (Press release). Teva Pharmaceuticals. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2023 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "FDA Approves Higher Dosage of Naloxone Nasal Spray to Treat Opioid Overdose" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 11 May 2021. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ Abdelal R, Raja Banerjee A, Carlberg-Racich S, Darwaza N, Ito D, Shoaff J, Epstein J (May 2022). "Real-world study of multiple naloxone administration for opioid overdose reversal among bystanders". Harm Reduction Journal. 19 (1): 49. doi:10.1186/s12954-022-00627-3. PMC 9122081. PMID 35596213.

- ^ Wolfe TR, Bernstone T (April 2004). "Intranasal drug delivery: an alternative to intravenous administration in selected emergency cases". Journal of Emergency Nursing. 30 (2): 141–147. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2004.01.006. PMID 15039670.

- ^ Fiore K (13 June 2015). "On-Label Nasal Naloxone in the Works". MedPage Today. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Britch SC, Walsh SL (July 2022). "Treatment of opioid overdose: current approaches and recent advances". Psychopharmacology (Berl) (Review). 239 (7): 2063–2081. doi:10.1007/s00213-022-06125-5. PMC 8986509. PMID 35385972.

- ^ "Naloxone Side Effects in Detail". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Schwartz JA, Koenigsberg MD (November 1987). "Naloxone-induced pulmonary edema". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 16 (11): 1294–1296. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(87)80244-5. PMID 3662194.

- ^ Sauro MD, Greenberg RP (February 2005). "Endogenous opiates and the placebo effect: a meta-analytic review". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 58 (2): 115–120. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.07.001. PMID 15820838.

- ^ "More Than Just a Sugar Pill: Why the placebo effect is real - Science in the News". Science in the News. 14 September 2016. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Carvalho C, Caetano JM, Cunha L, Rebouta P, Kaptchuk TJ, Kirsch I (December 2016). "Open-label placebo treatment in chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial". Pain. 157 (12): 2766–2772. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000700. PMC 5113234. PMID 27755279.

- ^ "Naloxone: Contraindications". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ "Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management" (PDF) (Practice guideline). Public Health England. November 2017. p. 181.

- ^ Tam SW (February 1985). "(+)-[3H]SKF 10,047, (+)-[3H]ethylketocyclazocine, mu, kappa, delta and phencyclidine binding sites in guinea pig brain membranes". European Journal of Pharmacology. 109 (1): 33–41. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(85)90536-9. PMID 2986989.

- ^ Toll L, Berzetei-Gurske IP, Polgar WE, Brandt SR, Adapa ID, Rodriguez L, et al. (March 1998). "Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications". NIDA Research Monograph. 178: 440–466. PMID 9686407.

- ^ Clark SD, Abi-Dargham A (October 2019). "The Role of Dynorphin and the Kappa Opioid Receptor in the Symptomatology of Schizophrenia: A Review of the Evidence". Biological Psychiatry. 86 (7): 502–511. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.05.012. PMID 31376930. S2CID 162168648.

- ^ a b c Codd EE, Shank RP, Schupsky JJ, Raffa RB (September 1995). "Serotonin and norepinephrine uptake inhibiting activity of centrally acting analgesics: structural determinants and role in antinociception". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 274 (3): 1263–1270. PMID 7562497. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ a b Raynor K, Kong H, Chen Y, Yasuda K, Yu L, Bell GI, Reisine T (February 1994). "Pharmacological characterization of the cloned kappa-, delta-, and mu-opioid receptors". Molecular Pharmacology. 45 (2): 330–334. PMID 8114680. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Naloxone: Summary". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

The approved drug naloxone INN-assigned preparation is the (-)-enantiomer. ... The (+) isomer is inactive at the opioid receptors. Marketed formulations may contain naloxone hydrochloride

- ^ "Opioid receptors: Introduction". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

The opioid antagonist, naloxone, which binds to μ, δ and κ receptors (with differing affinities), does not have significant affinity for the ORL1/LC132 receptor. These studies indicate that, from a pharmacological perspective, there are two major branches in the opioid peptide-N/OFQ receptor family: the main branch comprising the μ, δ and κ receptors, where naloxone acts as an antagonist; and a second branch with the receptor for N/OFQ, which has negligible affinity for naloxone.

- ^ a b "Naloxone Hydrochloride injection, solution". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ a b Colasanti A, Lingford-Hughes A, Nutt D (2013). "Opioids Neuroimaging". In Miller PM (ed.). Biological Research on Addiction. Comprehensive Addictive Behaviors and Disorders. Vol. 2. Elsevier. pp. 675–687. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-398335-0.00066-2. ISBN 9780123983350.

- ^ Waarde AV, Absalom AR, Visser AK, Dierckx RA (30 September 2020). "Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Imaging of Opioid Receptors". In Dierckx RA, Otte A, De Vries EF, Van Waarde A, Luiten PG (eds.). PET and SPECT of Neurobiological Systems. Springer International Publishing. pp. 749–807. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-53176-8_21. ISBN 978-3-030-53175-1. S2CID 241535315. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Johansson J, Hirvonen J, Lovró Z, Ekblad L, Kaasinen V, Rajasilta O, et al. (August 2019). "Intranasal naloxone rapidly occupies brain mu-opioid receptors in human subjects". Neuropsychopharmacology. 44 (9): 1667–1673. doi:10.1038/s41386-019-0368-x. PMC 6785104. PMID 30867551.

- ^ "Naloxone", LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2012, PMID 31643568, archived from the original on 28 August 2021, retrieved 30 October 2019

- ^ Meissner W, Schmidt U, Hartmann M, Kath R, Reinhart K (January 2000). "Oral naloxone reverses opioid-associated constipation". Pain. 84 (1): 105–109. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00185-2. PMID 10601678. S2CID 42230143.

- ^ a b Dean R, Bilsky EJ, Negus SS (12 March 2009). Opiate Receptors and Antagonists: From Bench to Clinic. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 514–. ISBN 978-1-59745-197-0.

- ^ Nagase H (21 January 2011). Chemistry of Opioids. Springer. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-3-642-18107-8.

- ^ "Morphinan-6-one, 4,5-epoxy-3,14-dihydroxy-17-(2-propenyl)-, (5α)-". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Seppala MD, Rose ME (25 January 2011). Prescription Painkillers: History, Pharmacology, and Treatment. Hazelden Publishing. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-1-59285-993-1. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Bennett LA (2006). New Topics in Substance Abuse Treatment. Nova Publishers. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-1-59454-831-4. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Wang JQ (2003). Drugs of Abuse: Neurological Reviews and Protocols. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-1-59259-358-3. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B (20 December 2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, Twelfth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 510. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "Naloxone: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Crabtree A, Masuda JR (May 2019). "Naloxone urban legends and the opioid crisis: what is the role of public health?". BMC Public Health. 19 (1): 670. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7033-5. PMC 6543555. PMID 31146721.

- ^ "Naloxone myths debunked" (PDF) (pdf). Indiana State Department of Health. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 851–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 715–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 189–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- ^ "Naloxone". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "Teva Invalidates Opiant Patents In Narcan Suit - Law360". www.law360.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "Nyxoid EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "FDA Approves First Over-the-Counter Naloxone Nasal Spray" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

이 기사는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

이 기사는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다. - ^ a b "FDA Approves Second Over-the-Counter Naloxone Nasal Spray Product". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 28 July 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "FDA Approves Harm Reduction Therapeutics' Over-the-Counter Opioid Overdose Reversal Medication" (Press release). Purdue Pharma. 1 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "Naloxone Opioid Overdose Reversal Medication". CVS Health. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Suttles C. "Wyoming's Albertsons, Safeway pharmacies to offer Narcan over the counter". Wyoming Tribune Eagle. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Meyerson BE, Agley JD, Davis A, Jayawardene W, Hoss A, Shannon DJ, et al. (July 2018). "Predicting pharmacy naloxone stocking and dispensing following a statewide standing order, Indiana 2016". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 188: 187–192. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.032. PMC 6375076. PMID 29778772.

- ^ Meyerson BE, Agley JD, Jayawardene W, Eldridge LA, Arora P, Smith C, et al. (May 2020). "Feasibility and acceptability of a proposed pharmacy-based harm reduction intervention to reduce opioid overdose, HIV and hepatitis C". Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy. 16 (5): 699–709. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.08.026. PMID 31611071.

- ^ a b "Addressing Opioid Overdose through Statewide Standing Orders for Naloxone Distribution". Network for Public Health Law. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ (June 2015). "Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons - United States, 2014". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 64 (23): 631–635. PMC 4584734. PMID 26086633.

- ^ "Guide: Treating Heroin and Opioid Use Disorder". PA.Gov. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Beletsky L, Burris SC, Kral AH (2009). "Closing Death's Door: Action Steps to Facilitate Emergency Opioid Drug Overdose Reversal in the United States" (PDF). doi:10.2139/ssrn.1437163. SSRN 1437163. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2023 – via Boonshoft School of Medicine.

{{cite journal}}:저널 요구사항 인용journal=(도움말) - ^ Burris SC, Beletsky L, Castagna CA, Coyle C, Crowe C, McLaughlin JM (2009). "Stopping an Invisible Epidemic: Legal Issues in the Provision of Naloxone to Prevent Opioid Overdose". SSRN 1434381.

- ^ Davis C. "Legal interventions to reduce overdose mortality: Naloxone access and overdose good samaritan laws" (PDF). Network for Public Health Law. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2014.

- ^ Davis C, Webb D, Burris S (March 2013). "Changing law from barrier to facilitator of opioid overdose prevention". The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 41 (Suppl 1): 33–36. doi:10.1111/jlme.12035. PMID 23590737. S2CID 22127036.

- ^ Cutcliff A, Stringberg A, Atkins C. "As Naloxone Accessibility Increases, Pharmacist's Role Expands". Pharmacy Times. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "US Law Enforcement Who Carry Naloxone". North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Beletsky L, Rich JD, Walley AY (November 2012). "Prevention of fatal opioid overdose". JAMA. 308 (18): 1863–1864. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14205. PMC 3551246. PMID 23150005.

- ^ Lavoie D (April 2012). "Naloxone: Drug-Overdose Antidote Is Put In Addicts' Hands". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012.

- ^ Davis CS, Beletsky L (July 2009). "Bundling occupational safety with harm reduction information as a feasible method for improving police receptiveness to syringe access programs: evidence from three U.S. cities". Harm Reduction Journal. 6 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-6-16. PMC 2716314. PMID 19602236.

- ^ "2013 National drug control strategy" (PDF). Office of National Drug Control Policy. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2017 – via National Archives.

- ^ Durando J (27 May 2014). "NYPD officers to carry heroin antidote". USA Today. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Faul M, Dailey MW, Sugerman DE, Sasser SM, Levy B, Paulozzi LJ (July 2015). "Disparity in naloxone administration by emergency medical service providers and the burden of drug overdose in US rural communities". American Journal of Public Health. 105 (Suppl 3): e26–e32. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302520. PMC 4455515. PMID 25905856.

- ^ "Drug Overdose Immunity and Good Samaritan Laws". www.ncsl.org. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Jones CM, Compton W, Vythilingam M, Giroir B (August 2019). "Naloxone Co-prescribing to Patients Receiving Prescription Opioids in the Medicare Part D Program, United States, 2016-2017". JAMA. 322 (5): 462–464. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.7988. PMC 6686765. PMID 31386124.

- ^ Albert S, Brason FW, Sanford CK, Dasgupta N, Graham J, Lovette B (June 2011). "Project Lazarus: community-based overdose prevention in rural North Carolina". Pain Medicine. 12 (Suppl 2): S77–S85. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01128.x. PMID 21668761.

- ^ a b "Naloxone kits now available at drug stores as province battles fentanyl crisis". CBC News. 17 February 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ "Naloxone's prescription-only status to get Health Canada review". CBC News. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ "Fentanyl and the take-home naloxone program Alberta Health". Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ "Health Canada Statement on Change in Federal Prescription Status of Naloxone". news.gc.ca. 14 January 2016. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 29 February 2016 – via Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Questions and Answers - Naloxone". Health Canada. 22 March 2017. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Agley J, Xiao Y, Eldridge L, Meyerson B, Golzarri-Arroyo L (May 2022). "Beliefs and misperceptions about naloxone and overdose among U.S. laypersons: a cross-sectional study". BMC Public Health. 22 (1): 924. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13298-3. PMC 9086153. PMID 35538566.

- ^ a b c Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (February 2012). "Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone - United States, 2010". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 61 (6): 101–105. PMC 4378715. PMID 22337174. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012.

- ^ Donkin K (9 September 2012). "Toronto naloxone program reduces drug overdoses among addicts". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Davey M (29 January 2016). "Selling opioid overdose antidote Naloxone over counter 'will save lives'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Why the 'heroin antidote' naloxone is now available in pharmacies". ABC. 1 February 2016. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Coulter E (27 August 2019). "This drug can temporarily reverse an opioid overdose. So why aren't people using it?". ABC News. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Dettmer K, Saunders B, Strang J (April 2001). "Take home naloxone and the prevention of deaths from opiate overdose: two pilot schemes". BMJ. 322 (7291): 895–896. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7291.895. PMC 30585. PMID 11302902.

- ^ "IHRA 21st International Conference Liverpool, 26th April 2010 - Introducing 'take home' Naloxone in Wales" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ McAuley A, Best D, Taylor A, Hunter C, Robertson R (1 August 2012). "From evidence to policy: The Scottish national naloxone programme". Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 19 (4): 309–319. doi:10.3109/09687637.2012.682232. ISSN 0968-7637. S2CID 73263293. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Stopping Overdose". Open Society Foundations. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Every U.S. Public Library and YMCA Will Soon Get Narcan for Free". Time. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Doleac JL, Mukherjee A (May 2022). "The Effects of Naloxone Access Laws on Opioid Abuse, Mortality, and Crime". The Journal of Law and Economics. 65 (2): 211–238. doi:10.1086/719588. ISSN 0022-2186. S2CID 214717309.; Doleac J, Mukherjee A. "Preprint: The Effects of Naloxone Access Laws on Opioid Abuse, Mortality, and Crime" (PDF).

- ^ "Naloxone: Frequently Asked Questions". Anne Arundel County Department of Health. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Ungar L. "Surgeon General's advisory: You can stop an overdose death by carrying this simple kit". Courier Journal. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Gilgore S. "Emergent BioSolutions defends opioid overdose drug against generic competitor". Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Ducharme J (24 October 2018). "Every U.S. Public Library and YMCA Will Soon Get Narcan for Free". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

추가열람

- Naloxone, Flumazenil and Dantrolene as Antidotes. IPCS/CEC Evaluation of Antidotes Series. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. 1993. ISBN 0-521-45459-X. EUR 14797 EN. Archived from the original on 15 December 2003. Retrieved 15 February 2004.

외부 링크

- "Naloxone Nasal Spray". MedlinePlus.

- "Naloxone". U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 16 June 2015.