미페프리스톤

Mifepristone | |

| |

| 임상 데이터 | |

|---|---|

| 상호 | 미페긴, 미페렉스, 기타 |

| 기타 이름 | RU-486; RU-38486; ZK-98296; 11β-[p-(디메틸아미노)페닐]-17α-(1-프로피닐)에스트라-4,9-디엔-17β-ol-3-온 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| Medline Plus | 42파운드 |

| 라이선스 데이터 | |

| 임신 카테고리 | |

| 루트 행정부. | 입으로 |

| 약물 클래스 | 항프로게스토겐(Antiglucocorticoid) |

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 법적 상태 |

|

| 약동학 데이터 | |

| 바이오 어베이러빌리티 | 69% |

| 단백질 결합 | 98% |

| 대사 | 간 |

| 배설물 | 대변: 83% 소변: 9 % |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드러그뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니 | |

| 케그 | |

| 체비 | |

| 첸블 | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA ) | |

| ECHA 정보 카드 | 100.127.911 |

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |

| 공식 | C29H35NO2 |

| 몰 질량 | 429.604 g/120−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| 밀도 | 1.120g/cm3 |

| 녹는점 | 194°C(381°F) |

| 비등점 | 629°C(1,164°F) |

| |

| |

| (표준) | |

RU-486으로도 알려진 미페프리스톤은 임신 중 낙태를 초래하고 조기 [1]유산을 관리하기 위해 일반적으로 미스프로스톨과 함께 사용되는 약물이다.이 조합은 임신 [2]첫 63일 동안 97% 효과적이다.임신 [3][4]후기에도 효과가 있습니다.사용 [1]후 2주 후에 유효성을 검증해야 한다.입으로 [1]먹는 거예요.

일반적인 부작용으로는 복통, 피로감, 질 [1]출혈 등이 있다.심각한 부작용은 심한 질 출혈, 세균 감염, 그리고 임신이 [1]끝나지 않으면 선천적인 기형을 포함할 수 있다.사용할 경우 적절한 사후 관리를 [1][5]이용할 수 있어야 합니다.미페프리스톤은 항프로게스토겐이다.[1]프로게스테론의 영향을 차단하여 자궁과 자궁 혈관을 확장시켜 자궁 수축을 [1]일으키는 효과가 있습니다.

미페프리스톤은 1980년에 개발되어 [6]1987년에 프랑스에서 사용되었다.그것은 [3]2000년에 미국에서 이용 가능하게 되었다.그것은 세계보건기구의 필수 [7][8]의약품 목록에 있다.미페프리스톤은 2015년 캐나다 보건부의 승인을 받았으며 2017년 [9]1월 캐나다에서 사용할 수 있게 되었다.비용과 가용성으로 인해 개발도상국의 [10][11]많은 지역에서 접근이 제한됩니다.

의료 용도

낙태

미페프리스톤에 이어 프로스타글란딘 유사체(미소프로스트롤 또는 제메프로스트)가 낙태를 [12][13]위해 사용된다.의료기관들은 이 조합이 안전하고 효과적이라는 것을 발견했다.왕립산부인과대학과 산부인과 전문의들의 가이드라인은 미페프리스톤과 미소프로스톨을 사용한 약물 낙태가 임신 연령에 [14]상관없이 효과적이고 적절하다고 설명한다.세계보건기구(WHO)와 미국 산부인과 의사회의(American Congress of 산부인과 의사회의)는 임신 중절 1, 2기 의료 [15][16][17][18]낙태에 대해 미페프리스톤에 이어 미스프로스톨을 권고하고 있다.13개 [19]연구의 검토에 따르면, 미페프리스톤만으로는 효과가 낮으며, 임신의 54%에서 92% 사이의 범위에서 1~2주 이내에 낙태가 발생한다.

쿠싱 증후군

미페프리스톤은 내인성 쿠싱증후군 성인의 혈중 코르티솔 수치가 높아 발생하는 고혈당(고콜티솔증) 치료에도 사용되며, 이 역시 2형 당뇨병이나 포도당 과민증이 있어 수술에 실패했거나 [20][21]수술을 할 수 없다.

다른.

응급피임에는 저용량의 미페프리스톤이 사용되고 있다.[22][23][24]또한 초기 임신손실을 [25]위해 미소프로스톨과 함께 사용될 수 있다.미페프리스톤은 또한 증상성 평활근종과 자궁내막증 [26]치료에 사용되어 왔다.

부작용

미페프리스톤과의 심각한 합병증은 드물며, 약 0.04~0.9%는 입원이 필요하고 0.05%는 [27]수혈이 필요하다.

미페프리스톤/미소프로스톨 요법을 사용하는 거의 모든 여성들은 평균 9-16일 동안 복통, 자궁경련, 질 출혈 또는 반점을 경험했다.대부분의 여성의 경우, 미소프로스톨 사용 후 가장 심한 경련은 6시간 미만으로 지속되며 일반적으로 이부프로펜으로 [28]관리할 수 있습니다.최대 8%의 여성들이 30일 이상 어떤 종류의 출혈을 경험했다.다른 덜 흔한 부작용으로는 메스꺼움, 구토, 설사, 어지럼증, 피로, [29]열이 있었다.골반염증은 매우 드물지만 심각한 [30]합병증이다.과도한 출혈과 임신의 불완전한 중절에는 의사의 추가 개입이 필요합니다(예: 미조프로스트롤의 반복 용량 또는 진공 흡입).미페프리스톤은 부신 기능 부전, 장기 경구 코르티코스테로이드 치료(흡입 및 국소 스테로이드제는 괜찮지만), 출혈성 질환, 유전성 포르피린증, 혈우병 또는 항응고제 [29]사용으로 금지된다.자궁에 자궁 내 장치가 있는 여성들은 불필요한 경련을 피하기 위해 약물 낙태 전에 IUD를 제거해야 한다.미페프리스톤은 자궁외 임신 치료에 효과가 없다.

시판 후 요약본에 따르면 미국에서 2011년 4월까지 미페프리스톤을 투여받은 약 152만 명의 여성 중 14명이 투여 후 사망한 것으로 보고됐다.이 사건들 중 8건은 패혈증과 관련되었고, 나머지 6건은 약물 남용과 살인 혐의와 같은 다양한 원인이 있었다.FDA에 보고된 다른 사건으로는 612건의 비살상 입원, 339건의 수혈, 48건의 중증 감염, 그리고 모두 2,[31]207건의 부작용 등이 있었다.

암

미페프리스톤의 발암 가능성을 평가하기 위한 장기 연구는 수행되지 않았다.이는 ICH 지침에 따른 것으로, 6개월 [32]미만의 투여를 목적으로 하는 비독성 약물에 대한 발암성 검사를 요구하지 않는다.

임신

미페프리스톤만으로도 [19][33]임신의 54%에서 92%에서 1~2주 이내에 낙태를 한다.미페프리스톤 [34]후에 misoprostol을 투여하면 효과가 90% 이상으로 증가한다.일부 낙태 반대 단체들은 프로게스테론을 [36][37]투여함으로써 되돌릴 수 있다고 주장하지만,[19][35] 미페프리스톤의 효과가 되돌릴 수 있다는 증거는 없다.미국 연구진은 2019년 이른바 '역방향' 요법의 시험을 시작했지만 후속 미스프로스톨 [38][39]없이 미페프리스톤을 사용하는 것에 대한 심각한 안전상의 우려로 조기 중단했다.프로게스테론을 투여하는 것이 약물 낙태를 멈추는 것으로 보여지지 않았고, 미페프리스톤과 미소프로스톨의 조합 요법을 완료하지 않으면 심각한 [39]출혈을 일으킬 수 있다.

미페프리스톤과 미소프로스톨을 함께 사용한 후 임신을 계속하는 경우에는 선천성 기형이 [5]발생할 수 있습니다.신생 쥐의 미페프리스톤에 대한 만성 저선량 피폭은 구조적 및 기능적 생식 [29]이상과 관련이 있었지만, 신생 쥐의 단일 대용량 미페프리스톤 피폭은 생식 문제와 관련이 없었다.쥐, 쥐, 토끼를 대상으로 한 연구에서 토끼의 발달 이상은 밝혀졌지만 쥐나 [29]쥐는 밝혀내지 못했다.

약리학

약역학

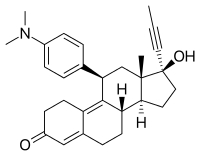

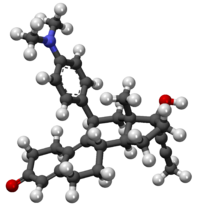

미페프리스톤은 스테로이드계 항프로게스토겐(PR의50 경우 IC = 0.025nM), 항루코코르티코이드(GR의50 경우 IC = 2.2nM), 항안드로겐(AR의50 경우 IC = 10nM)[40]이다.그것은 [41]수용체 수준에서 경쟁적으로 코티솔 작용에 대항한다.

프로게스테론의 존재 하에서 미페프리스톤은 경쟁적인 프로게스테론 수용체 길항제로서 작용한다(프로게스테론이 없는 경우, 미페프리스톤은 부분작용제로서 작용한다).미페프리스톤은 불활성 수용체 구조를 유도 또는 안정시키는 역할을 하는 11β 위치에서 분자 평면 위에 부피가 큰 p-(디메틸아미노) 페닐 치환기를 가진 19-nor 스테로이드이며 프로게스테론 수용체 바인딘을 증가시키는 17α 위치에서 분자 평면 아래에 있는 소수성 1-프로피닐 치환기를 가진 스테로이드이다.g [42][43][44]어피니티

미페프리스톤은 항프로게스토겐일 뿐만 아니라 항루코코르티코이드, 약한 항안드로겐이기도 하다.프로게스테론 수용체에서의 미페프리스톤의 상대적 결합 친화력은 프로게스테론의 2배 이상, 글루코콜티코이드 수용체에서의 상대적 결합 친화력은 덱사메타손의 3배 이상, 코르티솔의 [45]10배 이상이다.안드로겐 수용체에서의 상대적 결합 친화력은 테스토스테론의 3분의 1 미만이며 에스트로겐 수용체 또는 미네랄콜티코이드 [46]수용체와 결합하지 않는다.

매일 2mg의 정기적인 피임약인 미페프리스톤은 배란을 예방한다(매일 1mg은 예방하지 않는다).단일 사전배란성 10mg 용량 미페프리스톤은 배란을 3~4일 지연시키고 프로게스틴 [47]레보노르제스트렐의 단일 1.5mg 용량만큼 효과적인 응급피임약이다.

여성의 경우 1mg/kg 이상의 용량에서 미페프리스톤은 프로게스테론의 자궁내막 및 근막효과에 대항한다.사람에서는 ACTH 및 코르티솔의 보상적 증가에 의해 4.5mg/kg 이상의 용량으로 미페프리스톤의 항루코코르티코이드 효과가 나타난다.동물에서는 10~100mg/[48][49]kg의 매우 높은 용량을 장기간 투여하면 약한 항안드로겐 효과가 나타난다.

약물 낙태 요법에서 프로게스테론 수용체의 미페프리스톤 차단은 자궁내막 퇴화, 자궁경부 연화 및 확장, 내인성 프로스타글란딘의 방출 및 프로스타글란딘의 수축 효과에 대한 근막 민감도의 증가를 직접적으로 일으킨다.미페프리스톤 유도 십이지장 분해는 간접적으로 영양아세포 분리를 유도하여 hCG의 합성영양아세포 생성을 감소시키고, 이는 황체에 의한 프로게스테론의 생산을 감소시킨다(임신은 임신 첫 9주 동안 황체에 의한 프로게스테론 생산에 의존함).엔탈 프로게스테론 생산량이 루테움 프로게스테론 생산량을 대체할 수 있을 정도로 증가했다.프로스타글란딘을 순차적으로 따를 경우, 미페프리스톤 200mg은 의료 [42][44]낙태를 생성하는 데 600mg만큼 효과적이다.

'콘트라게스티온'은 아티엔-에밀 바울리에가 미페프리스톤을 옹호하는 맥락에서 추진하는 용어이며,[50] 일부 피임약과 낙태를 유도하는 미페프리스톤의 가설된 작용 메커니즘을 포함하는 것으로 정의한다.Baulieu의 '반란성'에 대한 정의는 수정 후 그리고 임신 [50]9주 이전에 행동할 수 있는 모든 피임 방법을 포함했다.

약동학

제거 반감기는 복잡한데, 라벨에 따르면 "분포 단계 후 제거는 처음에는 느리고, 약 12~72시간 사이에 농도가 반감한 후 더 빠르게 감소하여 18시간의 제거 반감기를 제공한다.방사성 수용체 분석 기술을 사용하면 프로게스테론 [12]수용체에 결합할 수 있는 미페프리스톤의 모든 대사물을 포함하여 말기 반감기는 최대 90시간입니다."메타프리스톤은 미페프리스톤의 [51][45][52]주요 대사물이다.

화학

11β-(4-(디메틸아미노)-17α-(1-프로피닐)에스트라-4,9-디엔-17β-ol-3-one이라고도 하는 미페프리스톤은 합성 에스트란 스테로이드이며 프로게스테론,[41] 코르티솔, 테스토스테론 등의 스테로이드 호르몬 유도체이다.C11β 및 C17α 위치에 치환되고 C4(5) [41]및 C9(10) 위치에 이중 결합이 있습니다.

역사

1980–1987

1980년 4월에서 프랑스 제약 회사 Roussel-Uclaf에 공식적인 연구 프로젝트의 글루코 코르티코이드 수용체 길항제의 개발의 일부로써,Étienne-Émile Baulieu[53][54]과 화학자, 조르주 Teutsch을 합성했다 mifepristone(RU-38486,38,486th 화합물 Roussel-Uclaf에 의해 1949년 1980년까지 합성, shorten endocrinologist.RU기 위해(-486) 또한 프로게스테론 수용체 [55][56]길항제인 것으로 밝혀졌다.1981년 10월, 루셀-우클라프의 컨설턴트인 에티엔-에밀 바울리외는 스위스 제네바 대학 광둥병원의 산부인과 의사 발터 헤르만에 의해 11명의 여성을 대상으로 낙태에 대한 테스트를 주선하여 1982년 [55][57]4월 19일 성공적인 결과를 발표했다.1987년 10월 9일, 프로스타글란딘 유사체(처음에는 설프로스톤 또는 제메프로스트롤, 나중에는 미스프로스트롤)를 가진 미페프리스톤 여성 20,000명을 대상으로 의료 낙태를 위한 임상실험을 한 후, Rousel-Uclaf는 1988년 [55][58]9월 23일 승인과 함께 프랑스에서 의료 낙태에 대한 승인을 요청했다.

1988–1990

1988년 10월 21일 낙태 반대 시위와 다수 소유주(54.5%)의 우려에 대응하여, Rousel-Uclaf의 경영진과 이사회는 [55][59]1988년 10월 26일 미페프리스톤의 배포를 중단하는 투표를 16 대 4로 실시했다.이틀 후 프랑스 정부는 공중보건을 위해 [55][60]루셀-우클라프에게 미페프리스톤을 배포하라고 명령했다.프랑스 보건부 장관 클로드 에빈은 "여성들에게서 의학적인 발전을 나타내는 제품을 빼앗는 낙태 논쟁은 용납할 수 없다"고 설명했다.RU-486은 정부로부터 약물에 대한 승인을 받은 순간부터 제약회사의 [55]재산뿐만 아니라 여성의 도덕적 재산이 되었습니다."1988년 4월부터 1990년 2월까지 34,000명의 프랑스 여성들이 무료로 배포한 미페프리스톤을 사용한 후, Rousel-Uclaf는 1990년 2월부터 프랑스의 병원에 미페진(미페프리스톤)을 [55]미화 48달러(프랑스 정부와 협의하여 2021년 6천956달러에 상당)의 가격으로 판매하기 시작했다.

미국의 "낙태에 대한 전국적인 싸움의 한가운데에 끼기를 원하지 않았다"는 것 외에, "2차 세계대전 동안, Hoechst는 강제 수용소에서 그렇게 많은 [61]사람을 죽인 독가스를 제조한 회사인 I.G. Farben"이라고 뉴욕 포스트가 인용한 또 다른 이유가 있었다.

1991–1996

이후 [62]1991년 7월 1일 영국에서, 1992년 [63]9월 스웨덴에서 각각 승인받았지만 1994년 4월 말 은퇴할 때까지 독실한 로마 [61]가톨릭 신자인 Hoechst AG의 회장 볼프강 힐거는 [55][64]더 이상의 가용성 확대를 막았다.5월 16일 1994년 Roussel-Uclaf이 보수를 받지 않고 인구 Council,[65]는 그 Danco 연구소, 28명을 9월에 Mifeprex로 FDA승인을 획득 새로운single-product 회사 임신 중절에 반대하는 보이콧에 면역에 mifepristone 허가에 mifepristone의 미국에서 의학적 이용에 대한 모든 권리를 기증했는지 발표했다. 2000.[66]

1997–1999

4월 8일 1997년 일찍 1997,[67]회흐스트 AG(미화 30(달러 51.83에 해당하는 2021년에)억 연간 매출액에서 Roussel-Uclaf 주식의 남아 있는 43.5%구입한 후에)Mifegyne(미화 3.44(달러 5.94에 해당하는 2021년에)만 연간 수입금을 제조 판매)의 종식과 모든 권한을 mifepristone의 의료 이용을 위한 전달 발표했다. 아웃미국의 ide는 낙태 반대 보이콧에 면역이 된 새로운 단일 제품 회사인 Exelgyn S.A.의 CEO는 전 Rousel-Uclaf CEO 에두아르 사키즈였습니다.[68]1999년 Exelgyn은 11개국의 Mifegyne의 승인을 획득했으며, 이후 [69]10년간 28개국의 승인을 받았습니다.

사회와 문화

미페프리스톤은 세계보건기구(WHO)[7]의 필수 의약품 목록에 올라 있다.2019년 이후, misoprostol과 함께 핵심 목록에 포함되었으며, "국법에 따라 허용되고 문화적으로 허용되는 경우"[7]라는 특별한 문구가 첨부되어 있다.

사용 빈도

미국

투약은 낙태를 자발적으로 미국 질병 통제 예방(CDC)에 33미국 states[70]으로 보고된 총 낙태 가운데 mifepristone의 승인 이후 백분율 매년:2000년 1.0%, 2001년에는 2.9%, 2002년 5.2%, 2003년 7.9%, 2004년 9.3%, 2005년 9.9%, 2006년 10.6%, 2007년에 13.1%그 중(20.3%로 증가했다. 나는에임신 [71]9주 이상).

Guttmacher Institute의 낙태 제공자 조사는 2008년 미국에서 임신 9주 전에 약물 낙태가 전체 낙태의 17%와 낙태의 25%를 약간 넘는 비중을 차지했다고 추정했다(병원 외 약물 낙태의 94%는 미페프리스톤과 미소프로스톨,[72] 6%는 메토렉세이트와 미소프로스톨을 사용했다).2008년 [73]미국의 계획적 부모 클리닉에서 임신 초기 낙태의 32%를 약물 낙태가 차지했다.비병원 시설에서 이뤄지는 낙태를 고려하면 약물 낙태는 2011년 24%, 2014년 31%를 차지했다.2014년에는 비교적 적은 수의 낙태(연간 400건 미만의 시술)를 제공하는 시설들이 [74]약물로 낙태를 시행할 가능성이 더 높았다.약물 낙태는 2017년 [75]미국 전체 낙태의 39%를 차지했고 [76]2020년에는 54%를 차지했다.

유럽

프랑스에서는 2003년 38%, 2004년 42%, 2005년 44%, 2006년 46%, 2007년 49%(1996년 [77]18% 대비)의 낙태율이 계속 증가하고 있다.잉글랜드와 웨일즈에서는 2009년 조기 낙태의 52%(임신 9주 미만)가 약물 기반이었다. 모든 낙태의 비율은 지난 14년 동안 매년 증가했고(1995년 5%에서 2009년 40%로) 지난 5년 [78]동안 두 배 이상 증가했다.스코틀랜드에서는 2009년 조기 낙태의 81.2%가 약물 기반이었다(약물 낙태가 도입된 1992년의 55.8%에서 증가). 모든 낙태의 비율은 지난 17년간 매년 증가했다(1992년 16.4%에서 2009년 [79]69.9%로).스웨덴에서는 2009년 임신 12주째가 끝나기 전 조기 낙태의 85.6%, 낙태의 73.2%가 약물 기반이었다. 2009년 전체 낙태의 68.2%는 약물 [80]기반이었다.영국과 스웨덴에서는 미페프리스톤이 질 제메프로스트 또는 경구 미소프로스트롤과 함께 사용하도록 허가되었다.2000년 현재 유럽에서 62만 명 이상의 여성들이 미페프리스톤 요법을 [81]사용하여 약물 낙태를 했다.덴마크에서 [82]미페프리스톤은 2005년 15,000건이 조금 넘는 낙태 중 3,000건에서 4,000건 사이에서 사용되었습니다.

법적 상태

미국

미페프리스톤은 2000년 [83]9월 FDA에 의해 미국에서 낙태를 승인받았다.그것은 합법적이며 워싱턴, D.C., 괌, 푸에르토리코 [84]등 50개 주에서 이용 가능하다.이 약은 처방전 약이지만 처음에는 약국을 통해 일반인에게 제공되지 않았습니다. 유통은 주로 Danco Laboratory가 Mifeprex라는 상표명으로 판매하는 특수 자격을 갖춘 의사로 제한됩니다.2021년 9월 현재 32개 주에서는 허가받은 의사만 약을 제공할 수 있었고, 19개 주에서는 처방하는 임상의가 환자가 [85]약을 복용하는 동안 물리적으로 병실에 있어야 했다.

Rousel Uclaf는 미국의 승인을 구하지 않았기 때문에 미국에서는 초기에 법적 이용이 불가능했다.[86]미국은 1989년 [87]개인 용도로 미페프리스톤의 수입을 금지했는데, 이는 Rousel Uclaf가 지지한 결정이다.1994년 Roussel Uclaf는 모든 제품 책임 [65][88]클레임에 대한 면책특권의 대가로 인구위원회에 미국 의약품의 권리를 주었다.인구위원회는 미국에서 [89]임상실험을 후원했다.그 약은 1996년부터 허용 가능한 상태가 되었다.생산은 1996년 단코그룹을 통해 시작될 예정이었으나 1997년 사업 파트너의 부패로 잠시 철수하면서 다시 [90][91]출시가 지연됐다.

2016년 미국 식품의약국은 미페프리스톤이 임신 70일(여성 마지막 생리 첫날부터 70일 이내)에 걸쳐 임신을 끝내는 것을 승인했다.승인된 투약 요법은 200mg의 미페프리스톤을 구강(흡입)으로 섭취하는 것이다.미페프리스톤 복용 후 24~48시간 후 800mcg(마이크로그램)의 미소프로스톨을 환자에게 [13][92][93][94]적합한 위치에서 볼 파우치 내(볼 파우치 내)

미페프리스톤 정제는 2형 당뇨병이나 포도당 과민증을 앓고 수술에 실패했거나 [20]수술을 할 수 없는 내인성 쿠싱 증후군을 가진 성인의 혈중 코르티솔 수치(고콜티솔증)로 인한 고혈당 치료에 대해 미국에서 시판 허가를 받았다.

2019년에는 GenBioPro가 [95]제조한 미국 최초의 범용 미페프리스톤이 출시되었습니다.

COVID-19 대유행으로 인해, 미페프리스톤에 대한 안전한 접근이 우려되었고, 미국 산부인과 학회와 다른 단체들은 통신 판매와 소매 약국에서 미페프리스톤을 획득할 수 있도록 허용하는 FDA의 규정을 완화하기 위한 소송을 제기했다.제4서킷이 이 분배를 허용하는 예비 가처분 명령을 내린 반면, 미국 대법원은 2021년 1월 진행 중인 [96]소송 결과가 나올 때까지 FDA의 판결을 유지하는 정지 명령을 내렸다.

2021년 12월 16일 FDA는 자발적으로 알약을 직접 구해야 하는 요건을 영구적으로 완화하는 새로운 규칙을 채택하여 알약을 우편으로 보낼 수 있도록 했다.의사가 [97]산모에게 약을 복용하는 것을 안전하지 않게 만드는 위험 요소를 검사할 수 있도록 처방전이 여전히 필요합니다.

H관

일부 약물은 두 개의 하위 부분으로 구성된 H항에 따라 FDA에 의해 승인된다.첫 번째는 HIV와 암 치료와 같은 실험용 약물을 가능한 환자의 건강에 빠른 승인이 필수적이라고 생각될 때 서둘러 시장에 내놓는 방법을 제시한다.H항의 두 번째 부분은 안전성 요구사항으로 인한 사용 제한을 충족해야 할 뿐만 아니라 임상시험에 나타난 안전성 결과가 훨씬 더 광범위한 모집단에서 사용됨으로써 입증될 수 있도록 시판 후 감시를 충족해야 하는 의약품에 적용된다.2021년 12월까지 Mifepristone은 H항 제2부에 따라 승인되었다.그 결과 여성들은 약국에서 약을 받을 수 없었지만 의사로부터 직접 약을 받아야 했다.수혈이 필요할 수 있는 과도한 출혈과 외과적 개입이 필요할 수 있는 불완전한 낙태와 같은 부작용의 가능성 때문에, 그 약은 그러한 경우에 환자에게 수혈이나 외과적 낙태를 할 수 있는 의사가 있을 경우에만 안전하다고 여겨졌다.긴급 [98]상황H항에 따른 미페프리스톤의 승인에는 블랙박스 경고가 포함되었다.

유럽

미페프리스톤은 Exelgyn Laboratories에서 Mifegyne라는 상표명으로 판매 및 유통되고 있습니다.1988년 프랑스(1989년 최초 판매), 1991년 영국, 1992년 스웨덴, 이후 오스트리아, 벨기에, 덴마크, 핀란드, 독일, 그리스, 룩셈부르크, 네덜란드, 스페인 및 스위스에서 사용이 승인되었습니다.[99]2000년에는 노르웨이, 러시아, 우크라이나에서 승인되었다.세르비아 몬테네그로는 2001년,[100] 벨라루스와 라트비아, 2003년 에스토니아, 2004년 몰도바, 2005년 알바니아와 헝가리, 2007년 포르투갈, [69]2008년 루마니아, 2013년 [101]불가리아, 체코, 슬로베니아를 승인했다.이탈리아에서 임상시험은 여성의 입원을 요구하는 프로토콜에 의해 3일간 제약되어 왔지만, 바티칸의 강력한 반대에도 불구하고 2009년 7월 30일(올해 말 공식화)에 최종적으로 승인되었다.이탈리아에서는 이 알약이 처방되어 임상 구조에서 사용되어야 하며 [102]약국에서 판매되지 않습니다.2005년 헝가리에서 승인됐지만 2005년 현재 시중에 출시되지 않아 [103]항의의 대상이 되고 있다.미페프리스톤은 2018년 [104]합법화된 이후 현재 아일랜드에서 낙태 사용허가를 받고 있다.미페프리스톤은 낙태가 매우 [105]제한적인 폴란드에서는 구할 수 없다.

Mifepristone 200mg 정제(Mifegyne, Mifepristone Linepharma, Medabon)는 유럽 의약청(EMA)으로부터 유럽 경제 영역에서 다음 제품에 대한 [12][106][107]시판 허가를 받았다.

- 임신 63일까지 프로스타글란딘 유사체(미소프로스트롤 또는 제메프로스트)에 이어 임신 초기 임신 중절

- 프로스타글란딘 유사체 이후 임신 중절 중절

- 임신 중절 전 자궁경부 연화 및 확장

- 프로스타글란딘 유사체와 옥시토신이 금기시 자궁 내 태아 사망 후 분만 유도

기타 국가

미페프리스톤은 1996년 호주에서 금지되었다.2005년 말, 호주 상원에 한 민간 의원의 법안이 제출되어 금지를 해제하고 치료용품국에 승인권을 이양했다.이러한 움직임은 호주 언론과 정치인들 사이에서 많은 논쟁을 불러일으켰다.이 법안은 2006년 2월 10일 상원을 통과했으며 현재 호주에서는 미페프리스톤이 합법적이다.주당 [108][109]몇 개의 전문 낙태 클리닉에서 정기적으로 제공된다.Mifepristone 200mg 정제는 임신 63일[110] 동안 프로스타글란딘 아날로그 미소프로스톨 및 프로스타글란딘 [111]아날로그 임신 63일 동안 중절 후 TGA로부터 TGA로부터 시판 허가를 받았다.

뉴질랜드에서는 낙태를 찬성하는 의사들이 수입업체 아이스타를 설립하고 뉴질랜드 제약 규제 기관인 메드세이프에 승인 신청서를 제출했다.Right to Life New Zealand가 제기한 소송이 기각된 후, 미페프리스톤의 사용이 [112]허용되었다.

미페프리스톤은 [113]1999년 이스라엘에서 승인되었다.

중국에서 미페프리스톤의 임상시험은 1985년에 시작되었다.1988년 10월 중국은 세계 최초로 미페프리스톤을 승인했다.중국 기관들은 루셀 우클라프로부터 미페프리스톤을 구입하려 했으나 판매를 거부하자 1992년부터 미페프리스톤 국내 생산을 시작했다.2000년에는 미페프리스톤에 의한 약물 낙태 비용이 외과적 낙태보다 높았고 약물 낙태 비율은 도시에서 30%에서 70%까지 다양했으며 농촌에서는 [114][115]거의 존재하지 않았다.2000년 베이징 주재 미국 대사관의 보고에 따르면 미페프리스톤은 약 2년 전부터 중국 도시에서 널리 사용되고 있으며 언론 보도에 따르면 많은 여성들이 처방전 없이 개인 클리닉과 드러그스토어에서 불법으로 미페프리스톤을 약 15달러(약 236달러 상당)에 구입하기 시작하면서 암시장이 발달했다고 한다.2021년)는 중국 당국이 의사의 [116]감독 없이 사용하는 것으로 인한 의료 합병증에 대해 우려하게 한다.

2001년 대만에서 [117]미페프리스톤이 승인되었다.베트남은 2002년 [118]국가 생식 건강 프로그램에 미페프리스톤을 포함시켰다.

미페프리스톤은 사하라 사막 이남의 아프리카 국가인 남아프리카에서만 2001년에 [119]승인되었습니다.그것은 또한 북아프리카의 한 국가에서도 승인되었다.:[120] 2001년에도 Tunisia.

미페프리스톤은 2002년 인도에서 사용이 승인되었으며, 약물 낙태는 "임신의 의학적 종료"로 언급된다.과다출혈 등 부작용으로 처방전이 아닌 의료감독 하에만 살 수 있으며 암시장과 [121]약국에서 판매하면 형사처벌을 받는다.

약물 낙태는 캐나다에서 사용 가능했지만 메토트렉세이트와 미소프로스톨을 사용하는 제한적인 기준이었다.2000년 캐나다 여러 도시에서 연방정부의 승인을 거쳐 메토트렉세이트와 미페프리스톤을 비교하는 임상시험이 실시되었다.두 약물 모두 전반적으로 유사한 결과를 보였지만, 미페프리스톤은 더 [122]빨리 작용하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.캐나다 보건부는 2015년 [123]7월에 미페프리스톤을 승인했다.처음에는 임신 후 7주로 사용이 제한되었지만, 2017년에 9주로 변경되었습니다.여성의 기존 서면동의 요건도 동시에 종료됐다.약사 또는 처방된 건강 전문가가 환자에게 직접 투여할 수 있습니다.여성들은 임신이 [124]이소성되지 않도록 하기 위해 초음파 검사를 받아야 한다.

Mifepristone은 2002년 아제르바이잔, 조지아, 우즈베키스탄, 2004년 가이아나, 몰도바, 2005년 몽골, 2007년 아르메니아에서 [69][125]사용되도록 등록되었습니다.

응급피임용 저용량 미페프리스톤정(비윤, 푸나이얼, 후딩누오, 화뎬, 시미안)은 처방전 없이 중국에서 [22][23][24]약사로부터 직접 구할 수 있다.

응급피임용 저용량 미페프리스톤 정제는 아르메니아(Gynepriston), 러시아(Agesta, Gynepriston, 72, Negelle), 우크라이나(Gynepriston), 베트남(Mifestad 10, Ciel EC)[22][23][24]에서 처방으로 구할 수 있다.

논란

미국의 낙태 반대 단체들은 미페프리스톤[126][127][128] 승인 반대 운동을 활발히 벌이며 탈퇴 [129]운동을 계속하고 있다.그들은 낙태에 관한 윤리적 문제나 약물에 관한 안전상의 문제, 그리고 그것과 [130]관련된 부작용들을 언급하고 있다.2022년 3월, 켄터키 하원에서 낙태금지법에 대한 토론에서, 공화당 대표 대니 벤틀리는 미페프리스톤이 원래 자이클론 B로 불렸고 2차 세계대전 때 나치에 의해 개발되었다는 주장을 포함한 몇 가지 잘못된 주장을 했다.벤틀리의 발언에 대해 미국 유대인 위원회를 포함한 몇몇 유대인 옹호 단체들이 불만을 제기하자, 그는 나중에 "분명히 그의 발언에 더 민감했어야 했다"며 그가 야기한 모든 피해에 대해 사과했지만,[131][132] 마약 개발에 관한 잘못된 진술을 바로잡지는 못했다.

미국 밖의 종교 단체와 낙태 반대 단체들 또한 미페프리스톤, 특히 독일과 [134][135]호주에서 시위를[133] 벌였다.

조사.

연구 그룹의 원래 목표는 항루코콜티코이드 [136]성질을 가진 화합물의 발견과 개발이었다.이러한 항루코코르티코이드 성질은 비록 발표된 기사의 검토가 그 효능에 대한 결론을 내리지 못했지만, 심각한 기분 장애와 정신병의 치료에 큰 관심을 가지고 있으며, '개념 증명'[137] 단계에서 기분 장애에서 이러한 약물의 사용을 고려했다.

자궁경부 숙성제로서 미페프리스톤의 사용이 [138]설명되었다.그 약은 전립선암 [139][140]치료에서 항안드로겐으로 연구되어 왔다.미페프리스톤은 임상시험에서 [43][47][141][142]검출 가능한 항HIV 활성을 보이지 않았다.

미페프리스톤은 치료하기 어려운 [143][144]형태의 우울증인 정신대우울증에서 초기 가능성을 보였지만 [145]효능이 떨어져 임상시험 3상이 조기 종료됐다.그것은 조울증, 외상 후 스트레스 장애,[146][144] 신경성 거식증으로 [147]연구되어 왔다.

레퍼런스

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Mifepristone". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Chen MJ, Creinin MD (July 2015). "Mifepristone With Buccal Misoprostol for Medical Abortion: A Systematic Review". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 126 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000897. PMID 26241251. S2CID 20800109. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ a b Goldman MB, Troisi R, Rexrode KM, eds. (2012). Women and Health (2nd ed.). Oxford: Academic Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-12-384979-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ Wildschut H, Both MI, Medema S, Thomee E, Wildhagen MF, Kapp N (January 2011). "Medical methods for mid-trimester termination of pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (1): CD005216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005216.pub2. PMC 8557267. PMID 21249669.

- ^ a b "Mifepristone Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Corey EJ (2012). "Mifepristone". Molecules and Medicine. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-36173-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ Kingston A (5 February 2017). "How the arrival of the abortion pill reveals a double standard". Maclean's. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Hussein J, McCaw-Binns A, Webber R, eds. (2012). Maternal and perinatal health in developing countries. Wallingford, Oxfordshire: CABI. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-84593-746-1. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Winikoff B, Sheldon W (September 2012). "Use of medicines changing the face of abortion". International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 38 (3): 164–6. doi:10.1363/3816412. PMID 23018138.

- ^ a b c Exelgyn (25 March 2015). "Mifegyne Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)" (PDF). London: Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b U.S. Food and Drug Administration (30 March 2016). "Mifeprex (mifepristone) Information". Silver Spring, Md.: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (23 November 2011). "The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion. Evidence-based Clinical Guideline No. 7, 3rd revised edition" (PDF). London: RCOG Press. pp. 68–75. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (21 June 2012). Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems, 2nd edition. Geneva: WHO. pp. 113–116. hdl:10665/70914. ISBN 978-92-4-154843-4.

- ^ World Health Organization (10 January 2014). Clinical practice handbook for safe abortion. Geneva: WHO. hdl:10665/97415. ISBN 978-92-4-154871-7.

- ^ "Practice Bulletin No. 135: Second-Trimester Abortion". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (6): 1394–1406. June 2013. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000431056.79334.cc. PMID 23812485. S2CID 205384119.

- ^ "Practice Bulletin No. 143: Medical Management of First-Trimester Abortion". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 123 (3): 676–692. March 2014. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000444454.67279.7d. PMID 24553166. S2CID 23951273.

- ^ a b c Grossman D, White K, Harris L, Reeves M, Blumenthal PD, Winikoff B, Grimes DA (September 2015). "Continuing pregnancy after mifepristone and "reversal" of first-trimester medical abortion: a systematic review". Contraception. 92 (3): 206–11. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.06.001. PMID 26057457.

- ^ a b Corcept Therapeutics (June 2013). "Korlym prescribing information" (PDF). Menlo Park, Calif.: Corcept Therapeutics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Ciato D, Mumbach AG, Paez-Pereda M, Stalla GK (January 2017). "Currently used and investigational drugs for Cushing´s disease". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 26 (1): 75–84. doi:10.1080/13543784.2017.1266338. PMID 27894193.

- ^ a b c Trussell J, Cleland K (13 February 2013). "Dedicated emergency contraceptive pills worldwide" (PDF). Princeton: Office of Population Research, Princeton University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b c ICEC (2016). "EC pill types and countries of availability, by brand". New York: International Consortium for Emergency Contraception. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Trussell J, Raymond EG, Cleland K (March 2016). "Emergency Contraception: A Last Chance to Prevent Unintended Pregnancy" (PDF). Princeton: Office of Population Research, Princeton University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Henkel A, Shaw KA (December 2018). "Advances in the management of early pregnancy loss". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (6): 419–424. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000501. PMID 30299321. S2CID 52939637.

- ^ Murji A, Whitaker L, Chow TL, Sobel ML, et al. (Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group) (April 2017). "Selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) for uterine fibroids". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (4): CD010770. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010770.pub2. PMC 6478099. PMID 28444736.

- ^ Cleland K, Creinin MD, Nucatola D, Nshom M, Trussell J (January 2013). "Significant adverse events and outcomes after medical abortion". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 121 (1): 166–71. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182755763. PMC 3711556. PMID 23262942.

- ^ Friedlander EB, Soon R, Salcedo J, Davis J, Tschann M, Kaneshiro B (September 2018). "Prophylactic Pregabalin to Decrease Pain During Medication Abortion: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 132 (3): 612–618. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002787. PMC 6105469. PMID 30095762.

- ^ a b c d "Mifeprex label" (PDF). FDA. 19 July 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2006.

- ^ Lawton BA, Rose SB, Shepherd J (April 2006). "Atypical presentation of serious pelvic inflammatory disease following mifepristone-induced medical abortion". Contraception. 73 (4): 431–2. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2005.09.003. PMID 16531180.

- ^ "Mifepristone U.S. Postmarketing Adverse Events Summary through 04/30/2011" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Guideline IH. Guideline on the Need for Carcinogenicity Studies of Pharmaceuticals S1A (PDF). International Conference on Harmonization. 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2013.

- ^ Paul M, Lichtenberg S, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD, eds. (24 August 2011). Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy: Comprehensive Abortion Care. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5847-6. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ CADTH Canadian Drug Expert Committee Final Recommendation Mifepristone and Misoprostol. CADTH Common Drug Reviews. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 18 April 2017. PMID 30512906. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ Bhatti KZ, Nguyen AT, Stuart GS (March 2018). "Medical abortion reversal: science and politics meet". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 218 (3): 315.e1–315.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.555. PMID 29141197. S2CID 205373684.

- ^ "As controversial 'abortion reversal' laws increase, researcher says new data shows protocol can work". Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ "California Board of Nursing Sanctions Unproven Abortion 'Reversal' (Updated) - Rewire". Rewire. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ Gordon M (22 March 2019). "Controversial 'Abortion Reversal' Regimen Is Put To The Test". NPR. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ a b Gordon M (5 December 2019). "Safety Problems Lead To Early End For Study Of 'Abortion Pill Reversal'". NPR. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Nuclear Receptors as Drug Targets: Design and Biological Evaluation of Small Molecule Modulators of Nuclear Receptor Action. 2006. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-0-549-70288-7.

- ^ a b c Gallagher P, Young AH (March 2006). "Mifepristone (RU-486) treatment for depression and psychosis: a review of the therapeutic implications". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2 (1): 33–42. PMC 2671735. PMID 19412444.

- ^ a b Loose DS, Stancel GM (2006). "Estrogens and Progestins". In Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1541–1571. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.

- ^ a b Schimmer BP, Parker KL (2006). "Adrenocorticotropic Hormone; Adrenocortical Steroids and Their Synthetic Analogs; Inhibitors of the Synthesis and Actions of Adrenocortical Hormones". In Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1587–1612. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.

- ^ a b Fiala C, Gemzel-Danielsson K (July 2006). "Review of medical abortion using mifepristone in combination with a prostaglandin analogue". Contraception. 74 (1): 66–86. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.018. PMID 16781264.

- ^ a b Heikinheimo O, Kekkonen R, Lähteenmäki P (December 2003). "The pharmacokinetics of mifepristone in humans reveal insights into differential mechanisms of antiprogestin action". Contraception. 68 (6): 421–6. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(03)00077-5. PMID 14698071.

- ^ Brogden RN, Goa KL, Faulds D (March 1993). "Mifepristone. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential". Drugs. 45 (3): 384–409. doi:10.2165/00003495-199345030-00007. PMID 7682909.

- ^ a b Chabbert-Buffet N, Meduri G, Bouchard P, Spitz IM (2005). "Selective progesterone receptor modulators and progesterone antagonists: mechanisms of action and clinical applications". Hum Reprod Update. 11 (3): 293–307. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmi002. PMID 15790602.

- ^ Exelgyn Laboratories (February 2006). "Mifegyne UK Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- ^ Danco Laboratories (19 July 2005). "Mifeprex U.S. prescribing information" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2005. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- ^ a b Baulieu ÉÉ (1985). "RU 486: An antiprogestin steroid with contragestive activity in women". In Baulieu ÉÉ, Segal SJ (eds.). The antiprogesin steroid RU 486 and human fertility control (Proceedings of a conference on the antiprogestational compound RU 486, held October 23–25, 1984, in Bellagio, Italy). New York: Plenum Press. pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-0-306-42103-7.

Baulieu ÉÉ (1985). "Contragestion by antiprogestin: a new approach to human fertility control". Abortion: medical progress and social implications (Symposium held at the Ciba Foundation, London, 27–29 November 1984). Ciba Foundation Symposium. Vol. 115. London: Pitman. pp. 192–210. doi:10.1002/9780470720967.ch15. ISBN 978-0-272-79815-7. PMID 3849413.

Baulieu EE (January 1989). "Contragestion with RU 486: a new approach to postovulatory fertility control". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica Supplement. 149 (S149): 5–8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.1989.tb08041.x. PMID 2694738. S2CID 723825.

Greenhouse S (12 February 1989). "A new pill, a fierce battle". The New York Times Magazine. p. SM22. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017.

Palca J (September 1989). "The pill of choice?". Science. 245 (4924): 1319–23. Bibcode:1989Sci...245.1319P. doi:10.1126/science.2781280. JSTOR 1704254. PMID 2781280.

Baulieu EE (September 1989). "Contragestion and other clinical applications of RU 486, an antiprogesterone at the receptor". Science. 245 (4924): 1351–7. Bibcode:1989Sci...245.1351B. doi:10.1126/science.2781282. JSTOR 1704267. PMID 2781282.

Baulieu EE (October 1989). "The Albert Lasker Medical Awards. RU-486 as an antiprogesterone steroid. From receptor to contragestion and beyond". JAMA. 262 (13): 1808–14. doi:10.1001/jama.262.13.1808. PMID 2674487. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013.

Bonner S (July 1991). "Drug of choice". SPIN. 7 (4): 55–56, 88. ISSN 0886-3032. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016.

Baulieu EE, Rosenblum M (15 November 1991). The "abortion pill": RU-486: a woman's choice (translation of: 'Génération pilule). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 18, 26–28. ISBN 978-0-671-73816-7. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016.

Beck J (2 January 1992). "RU-486 pill adds a new dimension to the abortion debate". Chicago Tribune. p. 25. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

Chesler E (31 July 1992). "RU-486: we need prudence, not politics". The New York Times. p. A27. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

Baulieu ÉÉ (13 April 1993). "1993: RU 486—a decade on today and tomorrow". In Benet LZ, Brown SS, Dorflinger L, Donaldson MS (eds.). Clinical applications of mifepristone (RU 486) and other antiprogestins; assessing the science and recommending a research agenda; (Committee on Anti-progestins: Assessing the Science; Division of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention; Institute of Medicine). Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. pp. 71–119. doi:10.17226/2203. ISBN 978-0-309-04949-8. PMID 25144090. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013.

Baulieu ÉÉ (June 1994). "RU486: a compound that gets itself talked about". Hum. Reprod. 9 (Suppl 1): 1–6. doi:10.1093/humrep/9.suppl_1.1. PMID 7962455.

Baulieu ÉÉ (1997). "Innovative procedures in family planning". In Johannisson E, Kovács L, Resch BA, Bruyniks NP (eds.). Assessment of research and service needs in reproductive health in Eastern Europe — concerns and commitments. Proceedings of a workshop organized by the ICRR and the WHO Collaborating Centre on Research in Human Reproduction in Szeged, Hungary, 25–27 October 1993. New York: Parthenon Publishing. pp. 51–60. ISBN 978-1-85070-696-0. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016.

"contragestive". The American Heritage medical dictionary. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2008. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-618-94725-6. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

Ammer C (2009). "contragestive". The encyclopedia of women's health (6th ed.). New York: Facts On File. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-8160-7407-5. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2020.임플란트를 방지하거나 임플란트를 한 후 자궁 내벽이 벗겨짐으로써 임신을 예방할 수 있다.:n. 파괴약 또는 약제.

낙태약도 있어요미페프리스톤(RU-486)이라고 불리는 물질로 박사님이 개발했습니다.에티엔 바울리외와 루셀-우클라프 회사입니다.역파괴는 자궁내막(자궁내막)의 프로게스테론 수용체를 차단하여 프로게스테론에 의한 프로게스테론 축적을 방지하므로 자궁은 임신을 지속할 수 없습니다.수정이나 착상을 막는 것은 아니기 때문에 엄밀히 말하면 피임약이라기보다는 ABROGIFACIENT입니다.

- ^ Heikinheimo O (July 1997). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of mifepristone". Clin Pharmacokinet. 33 (1): 7–17. doi:10.2165/00003088-199733010-00002. PMID 9250420. S2CID 25101911.

- ^ Wang J, Chen J, Wan L, Shao J, Lu Y, Zhu Y, Ou M, Yu S, Chen H, Jia L (March 2014). "Synthesis, spectral characterization, and in vitro cellular activities of metapristone, a potential cancer metastatic chemopreventive agent derived from mifepristone (RU486)". AAPS J. 16 (2): 289–98. doi:10.1208/s12248-013-9559-2. PMC 3933578. PMID 24442753.

- ^ Baulieu EE, Rosenblum M (1991). The "abortion Pill": RU-486, a Woman's Choice. ISBN 9780671738167. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Schenker JG, Sciarra JJ, Mettler L, Genazzani AR, Birkhaeuser M (29 September 2018). Reproductive Medicine for Clinical Practice: Medical and Surgical Aspects. ISBN 9783319780092. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Baulieu ÉÉ, Rosenblum M (1991). The "abortion pill": RU-486, a woman's choice. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-73816-7.

Lader L (1991). RU 486: the pill that could end the abortion wars and why American women don't have it. Reading: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-57069-4.

Villaran G (1998). "RU 486". In Schlegelmilch, Bodo B (eds.). Marketing ethics: an international perspective. London: Thomson Learning. pp. 155–190. ISBN 978-1-86152-191-0.

Ulmann A (2000). "The development of mifepristone: a pharmaceutical drama in three acts". Journal of the American Medical Women's Association. 55 (3 Suppl): 117–20. PMID 10846319. - ^ Teutsch G (November 1989). "RU 486 development". Science. 246 (4933): 985. doi:10.1126/science.2587990. PMID 2587990. S2CID 41144964.

Cherfas J (November 1989). "Dispute surfaces over paternity of RU 486". Science. 246 (4933): 994. Bibcode:1989Sci...246..994C. doi:10.1126/science.2587988. PMID 2587988.

Philibert D, Teutsch G (February 1990). "RU 486 development". Science. 247 (4943): 622. Bibcode:1990Sci...247..622P. doi:10.1126/science.2300819. PMID 2300819.

Ulmann A, Teutsch G, Philibert D (June 1990). "RU 486". Scientific American. Vol. 262, no. 6. pp. 42–8. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0690-42. PMID 2343294.

Teutsch G, Deraedt R, Philibert D (1993). "Mifepristone". In Lednicer D (ed.). Chronicles of drug discovery, Vol. 3. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. pp. 1–43. ISBN 978-0-8412-2523-7.

Teutsch G, Philibert D (June 1994). "History and perspectives of antiprogestins from the chemist's point of view". Human Reproduction. 9 (Suppl 1): 12–31. doi:10.1093/humrep/9.suppl_1.12. PMID 7962457.

Sittig M, ed. (2007). "Mifepristone". Pharmaceutical manufacturing encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Norwich, NY: William Andrew Publishing. pp. 2307–2310. ISBN 978-1-60119-339-1.

US 4386085, Teutsch JG, Costerouse G, Philibert D D Deraedt R, "Novel 스테로이드"는 1983년 5월 31일 발행되어 Rousel Uclaf에게 할당되었다. - ^ Eder R (20 April 1982). "Birth control: 4-day pill is promising in early test". The New York Times. p. C1. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016.

Herrmann W, Wyss R, Riondel A, Philibert D, Teutsch G, Sakiz E, Baulieu EE (May 1982). "[The effects of an antiprogesterone steroid in women: interruption of the menstrual cycle and of early pregnancy]". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série III. 294 (18): 933–8. PMID 6814714. - ^ Kolata G (24 September 1988). "France and China allow sale of a drug for early abortion". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017.

- ^ Greenhouse S (27 October 1988). "Drug maker stops all distribution of abortion pill". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Greenhouse S (29 October 1988). "France ordering company to sell its abortion drug". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b Peyser A (2 July 1992). "Nazi link may keep RU-486 out". The New York Post. pp. 5, 18.

- ^ Smith W (September 1991). "Great Britain second country to allow use of RU-486". Plan Parent Eur. 20 (2): 20. PMID 12284548.

- ^ "RU 486 licensed in Sweden". IPPF Med Bull. 26 (6): 6. December 1992. PMID 12346922.

- ^ Newman B (22 February 1993). "Drug dilemma: among those wary of abortion pill is maker's parent firm; Germany's Hoechst is facing pressure from Clinton to sell RU-486 in U.S.". The Wall Street Journal. p. A1.

"F.D.A. says company delays abortion pill". The New York Times. Associated Press. 16 April 1993. p. A14. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016.

Jouzaitis C (17 October 1994). "Abortion pill battle surprises French firm". Chicago Tribune. p. 1 (Business). Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. - ^ a b Seelye KQ (17 May 1994). "Accord opens way for abortion pill in U.S. in 2 years". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016.

- ^ Kolata G (29 September 2000). "U.S. approves abortion pill; drug offers more privacy and could reshape debate". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017.

- ^ Moore SD, Kamm T, Fleming C (11 December 1996). "Hoechst to seek rest of Roussel-Uclaf; expected $3.04 billion offer would add to the wave of drug-sector linkups". The Wall Street Journal. p. A3.

Marshall M (11 December 1996). "Hoechst offers to pay $3.6 billion for rest of Roussel". The Wall Street Journal. p. A8.

Bloomberg Business News (11 December 1996). "Hoechst to buy rest of Roussel". The New York Times. p. D4. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. - ^ Bloomberg News (9 April 1997). "Pill for abortion ends production". The New York Times. p. D2. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016.

Jouzaitis C (9 April 1997). "Abortion pill maker bows to boycott heat; German firm gives up RU-486 patent; little impact likely in U.S." Chicago Tribune. p. 4. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

Lavin D (9 April 1997). "Hoechst will stop making abortion pill". The Wall Street Journal. p. A3.

"Roussel-Uclaf to transfer RU 486 rights". Reprod Freedom News. 6 (7): 8. 18 April 1997. PMID 12292550.

Dorozynski A (19 April 1997). "Boycott threat forces French company to abandon RU486". BMJ. 314 (7088): 1150. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7088.1145m. PMC 2126515. PMID 9146386. - ^ a b c "List of mifepristone approval" (PDF). New York: Gynuity Health Projects. 4 November 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

"Map of mifepristone approval" (PDF). New York: Gynuity Health Projects. 4 November 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2010. - ^ 앨라배마, 캘리포니아, 코네티컷, 워싱턴, DC, 플로리다, 조지아, 하와이, 일리노이, 켄터키, 루이지애나, 매사추세츠, 메릴랜드, 네브래스카, 네바다, 뉴햄프셔, 로드아일랜드, 테네시, 위스콘신 제외

- ^ Berg C, Cook DA, Gamble SB, Hall LR, Hamdan S, Parker WY, Pazol K, Zane SB, et al. (Division of Reproductive Health) (25 February 2011). "Abortion surveillance — United States, 2007" (PDF). MMWR Surveill Summ. 60 (1): 1–44. PMID 21346710. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2011.

- ^ Jones RK, Kooistra K (March 2011). "Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008" (PDF). Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 43 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1363/4304111. PMID 21388504. S2CID 2045184. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2011.

Stein R (11 January 2011). "Decline in U.S. abortion rate stalls". The Washington Post. p. A3. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. - ^ Fjerstad M, Trussell J, Sivin I, Lichtenberg ES, Cullins V (July 2009). "Rates of serious infection after changes in regimens for medical abortion". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (2): 145–51. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0809146. PMC 3568698. PMID 19587339.

Allday E (9 July 2009). "Change cuts infections linked to abortion pill". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A1. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2022. - ^ Jones RK, Jerman J (March 2017). "Abortion Incidence and Service Availability In the United States 2014". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 49–1 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1363/psrh.12015. PMC 5487028. PMID 28094905. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "Medication Abortion". Guttmacher Institute. 26 April 2017. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ Jones RK (24 February 2022). "Medication Abortion Now Accounts for More Than Half of All US Abortions". Guttmacher Institute. Archived from the original on 10 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Vilain A (December 2009). "Voluntary terminations of pregnancies in 2007" (PDF). DREES, Ministry of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ Department of Health (25 May 2010). "Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2009". Department of Health (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ ISD Scotland (25 May 2010). "Abortion Statistics, year ending December 2009". Information Services Division (ISD), NHS National Services Scotland. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden (12 May 2010). "Induced Abortions 2010" (PDF). National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ "FDA Approves Mifepristone for the Termination of Early Pregnancy". FDA press release/U.S. Gov. 2000. Archived from the original on 10 September 2006. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ "The abortion pill Mifegyne tested for adverse reactions". Danish Medicines Agency. 27 July 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2006.[데드링크]

- ^ "FDA approval letter for Mifepristone". FDA. 28 September 2000. Archived from the original on 16 November 2001. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ "Medication Abortion in the United States: Mifepristone Fact Sheet" (PDF). Gynuity Health Projects. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2007.

- ^ Jones RK, Jerman J (March 2017). "Abortion Incidence and Service Availability In the United States, 2014". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 49 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1363/2019.30760. PMC 5487028. PMID 28094905. S2CID 203813573.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint :url-status (링크) - ^ Klitsch M (November–December 1991). "Antiprogestins and the abortion controversy: a progress report". Fam Plann Perspect. 23 (6): 275–82. doi:10.2307/2135779. JSTOR 2135779. PMID 1786809.

- ^ Garcilazo M (2 July 1992). "U.S. Grabs Banned Abort Pill From an Activist here". The New York Post. p. 5.

- ^ Gibbs N (2 October 2000). "The Pill Arrives". Cnn.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ Lewin T (30 January 1995). "Clinical Trials Giving Glimpse of Abortion Pill". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ Lewin T (13 November 1997). "Lawsuits' Settlement Brings New Hope for Abortion Pill". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ Lerner S (August 2000). "RU Pissed Off Yet?". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 7 November 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ Danco Laboratories (29 March 2016). "Mifeprex prescribing information" (PDF). Silver Spring, Md.: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 March 2016.

- ^ American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (30 March 2016). "ACOG Statement on Medication Abortion". Washington, D.C.: ACOG. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers". US Food & Drug Administration. 30 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ North A (20 August 2019). "The first generic abortion pill just hit the US market. Here's what that means". Vox. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Millhauser I (13 January 2021). "The Supreme Court hands down its first anti-abortion decision of the Amy Coney Barrett era". Vox. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ "FDA relaxes restrictions on abortion pill". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Woodcock J (12 May 2006). "Testimony on RU-486". Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives. FDA. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2006.

- ^ Christin-Maitre S, Bouchard P, Spitz IM (March 2000). "Medical termination of pregnancy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 342 (13): 946–56. doi:10.1056/NEJM200003303421307. PMID 10738054.

- ^ Stojnić J, Ljubić A, Jeremić K, Radunović N, Tulić I, Bosković V, Dukanac J (June 2006). "[Medicamentous abortion with mifepristone and misoprostol in Serbia and Montenegro]". Vojnosanitetski Pregled. 63 (6): 558–63. doi:10.2298/VSP0606558S. PMID 16796021.

- ^ "List of Mifepristone Approvals". Gynuity Health Projects. March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ "Abortion pill approved in Italy". BBC News. 31 July 2009. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ^ "Abortion pill sparks bitter protest". The Budapest Times. 19 September 2005. Archived from the original on 11 January 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: 제목으로 아카이브된 복사(링크) - ^ Green PS (24 June 2003). "A Rocky Landfall for a Dutch Abortion Boat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ Linepharma (7 November 2014). "Mifepristone Linepharma Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)" (PDF). London: Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Sun Pharmaceuticals (4 March 2015). "Medabon Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)" (PDF). London: Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ "Marie Stopes International Australia – Medical Abortion". 2010. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ "Abortion pill – RU486 (mifepristone)". Better Health Channel Victoria. July 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ MS Health (24 December 2014). "Mifepristone Linepharma (MS-2 Step) 200 mg tablet product information". Symonston, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Therapeutic Goods Administration. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ MS Health (12 May 2015). "Mifepristone Linepharma 200 mg tablet product information". Symonston, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Therapeutic Goods Administration. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Sparrow MJ (April 2004). "A woman's choice". The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 44 (2): 88–92. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2004.00190.x. PMID 15089829. S2CID 27365359.

- ^ Baulieu EE, Seidman DS, Hajri S (October 2001). "Mifepristone (RU486) and voluntary termination of pregnancy: enigmatic variations or anecdotal religion-based attitudes?". Human Reproduction. 16 (10): 2243–4. doi:10.1093/humrep/16.10.2243. PMID 11574524.

- ^ Ulmann A (2000). "The development of mifepristone: a pharmaceutical drama in three acts". J Am Med Women's Assoc. 55 (3 Suppl): 117–20. PMID 10846319.

- ^ Wu S (2000). "Medical abortion in China". J Am Med Women's Assoc. 55 (3 Suppl): 197–9, 204. PMID 10846339.

- ^ "Family planning in China: RU-486, abortion, and population trends". U.S. Embassy Beijing. 2000. Archived from the original on 11 March 2002. Retrieved 14 September 2006.

- ^ Tsai EM, Yang CH, Lee JN (2002). "Medical abortion with mifepristone and misoprostol: a clinical trial in Taiwanese women". J Formos Med Assoc. 101 (4): 277–82. PMID 12101864.

- ^ Ganatra B, Bygdeman M, Nguyen DV, Vu ML, Phan BT (2004). "From research to reality: the challenges of introducing medical abortion into service delivery in Vietnam". Reprod Health Matters. 12 (24): 105–13. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24022-8. PMID 15938163. S2CID 23303852.

- ^ "Medical Abortion-Implications for Africa". Ipas. 2003. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ Hajri S (2004). "Medication abortion: the Tunisian experience". Afr J Reprod Health. 8 (1): 63–9. doi:10.2307/3583307. hdl:1807/3883. JSTOR 3583307. PMID 15487615.

- ^ "Mifepristone can be sold only to approved MTP Centres: Rajasthan State HRC". Indian Express Health Care Management. 2000. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012.

- ^ "Results of the Canadian trials of RU486, the 'Abortion Pill". Archived from the original on 21 June 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ^ "RU-486 abortion pill approved by Health Canada". Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Health Canada eases restrictions on abortion pill Mifegymiso". CBC News. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "Medication Abortion". Ibis. 2002. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ Cunningham PC, McCoy L, Ferguson CD (28 February 1995). "Citizen Petition to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration". Americans United for Life. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ Talbot M (11 July 1999). "The Little White Bombshell". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ "Abortion Foes to Boycott Drugs (Altace) Made By RU-486 Manufacturer". The Virginia Pilot. 8 July 1994. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ^ Guthrie S (11 June 2001). "Counteroffensive Launched on RU-486". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on 20 September 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ Kolata G (24 September 2003). "Death at 18 Spurs Debate Over a Pill For Abortion". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ Watkins M, Sonka J (2 March 2022). "Kentucky lawmaker apologizes for referencing Jewish women's sex life amid abortion debate". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Grasiosi G (4 March 2022). "Kentucky politician sparks outrage with comments on Jewish women's sex in error-laden argument against abortion". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Allen JL (12 February 1999). "Abortion debates rock Germany: introduction of abortion pill exacerbates controversy". National Catholic Reporter. Archived from the original on 28 May 2005. Retrieved 14 September 2006.

- ^ "Catholic and Evangelical students join Muslims in RU-486 fight". Catholic News. 9 February 2006. Archived from the original on 27 October 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2006.

- ^ "Death Toll Rises to 11 Women". Australians Against RU-486. 2006. Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ Hazra BG, Pore VS (2001). "Mifepristone (RU-486), the recently developed antiprogesterone drug and its analogues". J Indian Inst Sci. 81: 287–98.

- ^ Gallagher P, Malik N, Newham J, Young AH, Ferrier IN, Mackin P (January 2008). MacKin P (ed.). "Antiglucocorticoid treatments for mood disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005168. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005168.pub2. PMID 18254070. (retracted, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005168.pub3, PMID 26098594를 참조해 주세요.용지에 로

- ^ Clark K, Ji H, Feltovich H, Janowski J, Carroll C, Chien EK (May 2006). "Mifepristone-induced cervical ripening: structural, biomechanical, and molecular events". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194 (5): 1391–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.026. PMID 16647925.

- ^ Taplin ME, Manola J, Oh WK, Kantoff PW, Bubley GJ, Smith M, Barb D, Mantzoros C, Gelmann EP, Balk SP (2008). "A phase II study of mifepristone (RU-486) in castration-resistant prostate cancer, with a correlative assessment of androgen-related hormones". BJU Int. 101 (9): 1084–9. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07509.x. PMID 18399827. S2CID 205538600.

- ^ "Mifepristone - Corcept Therapeutics - AdisInsight". Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Flexner C (December 2007). "HIV drug development: the next 25 years". Nat Rev Drug Discov. 6 (12): 959–66. doi:10.1038/nrd2336. PMID 17932493. S2CID 31261997.

- ^ Tang OS, Ho PC (2006). "Clinical applications of mifepristone". Gynecol Endocrinol. 22 (12): 655–9. doi:10.1080/09513590601005946. PMID 17162706. S2CID 23295715.

- ^ Belanoff JK, Flores BH, Kalezhan M, Sund B, Schatzberg AF (October 2001). "Rapid reversal of psychotic depression using mifepristone". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 21 (5): 516–21. doi:10.1097/00004714-200110000-00009. PMID 11593077. S2CID 3067889.

- ^ a b Howland RH (June 2013). "Mifepristone as a therapeutic agent in psychiatry". Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 51 (6): 11–4. doi:10.3928/02793695-20130513-01. PMID 23814820.

- ^ Gard D (7 May 2014). "Corcept tanks as depression drug comes up short in Phase III". Fierce Biotech. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016.

- ^ Soria V, González-Rodríguez A, Huerta-Ramos E, Usall J, Cobo J, Bioque M, et al. (July 2018). "Targeting hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hormones and sex steroids for improving cognition in major mood disorders and schizophrenia: a systematic review and narrative synthesis". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 93: 8–19. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.012. PMID 29680774. S2CID 5041081.

- ^ Bou Khalil R, Souaiby L, Farès N (March 2017). "The importance of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis as a therapeutic target in anorexia nervosa". Physiology & Behavior. 171: 13–20. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.12.035. PMID 28043861. S2CID 6329552.

외부 링크

- "Mifepristone". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.