로페라마이드

Loperamide | |

| |

| 임상자료 | |

|---|---|

| 발음 | /loʊˈpɛrrmaɪd/ |

| 상명 | 이모듐, 기타[1] |

| 기타 이름 | R-18553, 로페라마이드 염산염(USAN ) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| 메드라인플러스 | a682280 |

| 라이센스 데이터 | |

| 임신 범주 |

|

| 경로: 행정 | 입으로 |

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적현황 | |

| 법적현황 | |

| 약동학 데이터 | |

| 생체이용가능성 | 0.3% |

| 단백질 결합 | 97% |

| 신진대사 | 간(확장) |

| 제거 반감기 | 9-14시간[2] |

| 배설 | 소변(30~40%), 소변(1%) |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| 펍켐 CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드러그뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니 | |

| 케그 | |

| 체비 | |

| 켐벨 | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.053.088 |

| 화학 및 물리적 데이터 | |

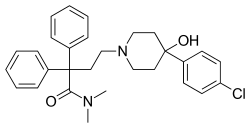

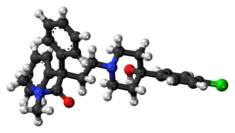

| 공식 | C29H33CLN2O2 |

| 어금질량 | 477.05 g·1998−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

로페라마이드(Loperamide)는 이모듐이라는 브랜드명으로 판매되는 것으로 설사의 빈도를 줄이기 위해 사용되는 약이다.[1][2] 염증성 장질환과 단장증후군에 이런 목적으로 자주 사용된다.[2] 대변에 피가 있거나 변에 점액이 있거나 열이 있는 사람에게는 권장하지 않는다.[2] 그 약은 입으로 복용한다.[2]

일반적인 부작용으로는 복통, 변비, 졸림, 구토, 입안이 건조하다.[2] 그것은 독성 메가콜론의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다.[2] 로페라마이드의 임신중 안전은 불분명하지만, 해로울 증거는 발견되지 않았다.[3] 모유 수유에 안전해 보인다.[4] 내장에서 크게 흡수되지 않는 오피오이드로 정상 용량에서 사용할 경우 혈액-뇌 장벽을 넘지 않는다.[5] 장의 수축 속도를 늦춤으로써 효과가 있다.[2]

로페라미드는 1969년에 처음 만들어졌고 1976년에 의학적으로 사용되었다.[6] 그것은 세계보건기구의 필수 의약품 목록에 올라 있다.[7] 로페라미드는 일반적인 약으로 이용할 수 있다.[2][8] 2017년에는 미국에서 가장 많이 처방된 351번째로 70만 개 이상의 처방전이 있었다.[9]

의학적 용법

로페라미드는 여러 종류의 설사를 치료하는데 효과적이다.[10] 여기에는 급성 비특이성 설사, 가벼운 여행자의 설사, 과민성 장 증후군, 장 절제술에 의한 만성 설사, 염증성 장 질환에 의한 만성 설사 등이 포함된다. 그것은 또한 장골절개 출력을 줄이는 데에도 유용하다. 로페라마이드의 오프라벨 용도는 화학요법에 의한 설사를 포함하며, 특히 이리노테칸 사용과 관련이 있다.

피비린내 나는 설사, 궤양성 대장염의 급성 악화 또는 세균성 장막염의 경우 로페라미드를 1차 치료제로 사용해서는 안 된다.[11]

로페아미드는 종종 디페녹실산염과 비교된다. 연구 결과 로페라미드가 더 효과적이고 신경학적 부작용이 낮다고 한다.[12][13][14]

부작용

로페라마이드와 가장 흔히 관련된 약물 부작용으로는 변비(사용자의 1.7~5.3%), 현기증(최대 1.4%), 메스꺼움(0.7~3.2%), 복통(0.5~3.0%)[15] 등이 있다. 드물지만 더 심각한 부작용으로는 독성 메가콜론, 마비성 일레우스, 혈관부종, 아나필락시스/알레르기 반응, 독성 표피 네크로리시스, 스티븐스–존슨 증후군, 홍반성 다형종, 비뇨기 보유, 열사병.[16] 로페라마이드 과다 복용의 가장 빈번한 증상은 졸음, 구토, 복통 또는 화형이다.[17] 많은 복용량은 비정상적인 심장 박동과 같은 심장 질환을 일으킬 수 있다.[18]

콘트라인커뮤니케이션

고열이 있거나 걸상이 피투성이가 된 경우에는 치료를 피해야 한다. 반발변비 등으로 부정적인 영향을 줄 수 있는 사람에게는 치료를 권하지 않는다. 대장균 O157과 같이 장벽을 투과할 수 있는 유기체와 관련된 설사가 의심될 경우:H7 또는 살모넬라균, 로페라마이드는 1차 치료제로 금지된다.[11] 로페라미드 치료는 독성 메가콜론의 독소 보유 및 침전 위험을 증가시키기 때문에 증상성 C. 디피실 감염에는 사용되지 않는다.

로페라미드는 1차 통과 신진대사가 감소해 간 장애가 있는 사람에게 주의해서 투여해야 한다.[19] 또한 바이러스성 및 박테리아성 독성 메가콜론의 사례가 보고되었기 때문에, HIV/AIDS가 발달한 사람들을 치료할 때는 주의를 기울여야 한다. 복부 팽창이 지적되면 로페라미드 치료는 중단해야 한다.[20]

아이들.

2세 미만 아동에서는 로페라마이드 사용을 권장하지 않는다. 복부팽창과 관련된 치명적인 마비성 장골에 대한 드문 보고가 있었다. 이러한 보고의 대부분은 급성 이질, 과다복용, 그리고 2살 미만의 매우 어린 아이들과 함께 일어난 것이다.[21] 12세 미만 어린이의 로페라미드를 검토한 결과 3세 미만 어린이에게만 심각한 부작용이 발생한 것으로 나타났다. 이 연구는 로페라마이드 사용이 3세 미만, 시스템적으로 병들거나 영양실조, 적당히 탈수되거나 피가 섞인 설사를 하는 어린이들에게 금지되어야 한다고 보고했다.[22] 1990년에, 파키스탄에서는 지사제 로페라마이드의 어린이들을 위한 모든 제형이 금지되었다.[23]

임신과 모유수유

로페라미드는 임신 중이나 수유 중인 산모에 의해 사용되도록 영국에서는 권장되지 않는다.[24] 미국에서 로페라마이드(loperamide)는 미국 식품의약국(fda)이 임신 범주 C로 분류하고 있다. 쥐 모델에 대한 연구는 기형성(teratogenity)이 없다는 것을 보여주었지만, 인간에 대한 충분한 연구는 수행되지 않았다.[25] 임신 첫 3개월 동안 로페라마이드에 노출된 89명의 여성에 대한 통제된 사전 연구는 기형의 위험성을 증가시키지 않았다. 그러나 이것은 표본 크기가 작은 하나의 연구일 뿐이었다.[26] 로페라미드는 모유에 들어 있을 수 있으며, 모유를 수유하는 산모에게는 권장되지 않는다.[20]

약물 상호작용

Loperamide는 P-glycoprotein의 기질이기 때문에 P-glycoprotein 억제제를 투여하면 Loperamide의 농도가 증가한다.[15] 일반적인 P-글리코프로테인 억제제로는 퀴니딘, 리토나비르, 케토코나졸 등이 있다.[27] 로페라미드는 다른 약물의 흡수를 줄일 수 있다. 예를 들어, 사퀴나비르 농도는 로페라마이드와 함께 주어졌을 때 절반으로 감소할 수 있다.[15]

로페라마이드(Loperamide)는 장 운동을 감소시키는 지사제다. 이처럼 다른 항독성 약물과 결합하면 변비 위험이 높아진다. 이 약물들은 다른 오피오이드, 항히스타민제, 항정신병 약물, 항콜리노르겐제 등을 포함한다.[28]

작용기전

로페라마이드(Loperamide)는 오피오이드 수용체 작용제로 대장의 근성 플렉서스에 있는 μ오피오이드 수용체에 작용한다. 모르핀처럼 작용하여 근막염의 활성을 감소시켜 장벽의 세로 및 원형 평활근의 톤을 감소시킨다.[29][30] 이것은 물질이 장에 머무르는 시간을 증가시켜 더 많은 물이 배설물로부터 흡수될 수 있게 한다. 또한 대장질량 운동을 감소시키고 위내반사를 억제한다.[31]

로페라마이드의 혈류 순환은 두 가지 방법으로 제한된다. 장벽에서 P-글리코프로틴에 의한 유출은 로페라마이드의 통과를 감소시키고, 이후 간에서 1차 통과대사를 통해 약물을 건너는 분율은 더욱 감소한다.[32][33] 로페라미드는 MPTP와 유사한 화합물로 대사되지만 신경독성을 발휘하지는 않을 것으로 보인다.[34]

혈액-뇌장벽

P-글리코프로틴에 의한 유출은 순환 로페라미드가 혈액-뇌 장벽을 효과적으로 넘지는 못하게 하므로 일반적으로 말초신경계 내 무스카린 수용체만 길항시킬 수 있으며,[35] 현재 항고체 인지부담 척도 1점이다.[36] 키니딘과 같은 P-glycoprotein 억제제를 동시에 투여하면 잠재적으로 로페라미드가 혈액-뇌 장벽을 넘고 중앙 모르핀과 같은 효과를 낼 수 있다. 키니딘과 함께 복용한 로페라미드는 중앙 오피오이드 작용을 나타내는 호흡기 우울증을 유발하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.[37]

로페라미드는 특히 쥐, 쥐, 붉은털원숭이에게 임상 전 연구를 하는 동안 가벼운 신체적 의존을 유발하는 것으로 나타났다. 로페라미드 동물에 대한 장기 치료가 갑자기 중단된 후 가벼운 아편모세포탈출 증상이 관찰되었다.[38][39]

원래 미국에서 의료용으로 승인되었을 때, 로페라미드는 마약류로 간주되어 1970년 통제 물질법의 부칙 2에 포함되었다. 1977년 7월 17일에 스케줄 V로 이관되었다가 1982년 11월 3일에 통제 해제되었다.[40]

역사

로페아미드 염산염은 벨기에 비에르세의 얀센 파마세우티카 출신의 폴 얀센에 의해 1969년에 처음으로 합성되었는데, 이전의 이페녹실산염(1956년)과 펜타닐 구연산(1960년)의 발견에 이은 것이다.[41]

로페라마이드에 대한 최초의 임상 보고서는 1973년 의학 저널에[42] 발표되었고, 발명가는 작가들 중 한 명이 되었다. 그것의 시험 이름은 "R-18553"[43]이었다. 로페라미드 산화물은 다른 연구 코드를 가지고 있다: R-58425.[44]

위약에 대한 재판은 1972년 12월부터 1974년 2월까지 진행되었으며, 그 결과는 1977년 영국 위약학회의 판인 구트에 발표되었다.[45]

1973년 얀센은 아이모듐이라는 브랜드명으로 로페라마이드 홍보를 시작했다. 1976년 12월, 이모디움은 미국 FDA 승인을 받았다.[46]

1980년대 동안, 이모디움은 미국에서 가장 잘 팔리는 처방전 지사제가 되었다.[47]

1988년 3월 맥닐제약은 로페라미드를 아이모듐A-D라는 상표명으로 장외 의약품으로 판매하기 시작했다.[48]

1980년대에는 로페라마이드도 드롭스(이모듐 드롭스)와 시럽의 형태로 존재하기도 했다. 당초 어린이용이었으나 1990년 파키스탄에서 18건의 마비성 일레우스(사망 6명)가 등록돼 세계보건기구(WHO)가 신고하자 존슨앤드존슨이 자발적으로 시장에서 철수했다.[49] 그 다음 해(1990-1991)에는 로페라미드가 함유된 제품이 여러 국가(만 2~5세)에서 어린이용으로 제한되어 있다.[50]

맥닐은 1990년 1월 30일 미국 특허가 만료되기 전인 1980년대 후반부터 설사와 가스를 동시에 치료하기 위해 로페라마이드와 시메티콘이 함유된 이모듐 어드밴스드 개발에 착수했다.[47] 1997년 3월 이 회사는 그러한 조합에 특허를 냈다.[51] 이 약은 1997년 6월 FDA에 의해 씹을 수 있는 알약 형태의 아이모듐 다식증 완화제로 승인되었다.[52] 캐플릿 제형은 2000년 11월에 승인되었다.[53]

1993년 11월, 로페라미드는 자이디스 기술을 기반으로 구강 분해 태블릿으로 출시되었다.[54][55]

2013년에는 세계보건기구(WHO)의 필수 의약품 모델 리스트에 2mg의 정제 형태의 로페라마이드(loperamide)가 추가됐다.[56]

2020년 괴테대 연구진에 의해 로페라마이드의 교모세포 제거에 효과가 있다는 사실이 밝혀졌다.[57]

사회와 문화

경제학

로페라미드는 일반 의약품으로 판매된다.[2][8] 2016년 아이모디움은 영국에서 판매된 장외 의약품 중 가장 많이 팔린 제품 중 하나로 3천 2백 7십만 파운드 판매됐다.[58]

브랜드명

로페라미드는 원래 이모디움으로 시판되었으며, 많은 제네릭 브랜드가 판매되고 있다.[1]

라벨이 부착되지 않은 사용/승인되지 않은 사용

로페라미드는 일반적으로 오용 위험이 상대적으로 낮은 것으로 간주되어 왔다.[59] 2012년에는 로페라마이드 남용에 대한 보고는 없었다.[60] 그러나 2015년에는 극도로 고선량 로페라미드 사용 사례 보고서가 발표되었다.[61][62] 사용자들의 주된 의도는 설사 등 오피오이드 철수의 증상을 관리하는 것이었지만, 비록 적은 부분이 이러한 높은 용량에서 정신 활성 효과를 도출한다.[63] 이러한 높은 용량에서 중추신경계 침투가 발생하며 장기간 사용하면 내성, 의존성 및 갑작스러운 중단에 대한 철수를 초래할 수 있다.[63] "가난한 남자의 메타돈"을 더빙하면서, 임상의들은 오피오이드 유행에 대응하여 통과된 처방전 오피오이드의 이용에 대한 제약이 증가하여 레크리에이션 사용자들이 금단 증상에 대한 처방전 없이 처방전 없이 살 수 있는 치료법으로 로페아마이드로 눈을 돌리게 되었다고 경고했다.[64] FDA는 이 같은 경고에 대해 의약품 제조업체에 공공 안전상의 이유로 로페라마이드의 포장 크기를 자율적으로 제한할 것을 요구해 대응했다.[65][66] 다만 구매가 가능한 패키지 수에 대한 수량 제한이 없고, 대부분의 약국이 판매를 제한할 수 있다고 느끼지 않아 이번 개입이 카운터 뒤에 로페아마이드(loperamide)를 두는 추가 규제 없이 별다른 영향을 미칠지는 불분명하다.[67] 2015년 이후 고선량 로페라미드 남용으로 인한 때로는 치명적인 카디오독성 보고서가 여러 차례 발표됐다.[68][69]

참고 항목

- 또 다른 말초 작용 오피오이드 길항제인 메틸날트렉손(Methylnaltrexone)은 진통증에 큰 영향을 주지 않고 오피오이드 유도 변비를 줄이기 위해 발명한 날록세골 로퍼스와 유사하다.

- 말초 작용 오피오이드 길항제인 날록세골은 진통증에 큰 영향을 주지 않고 오피오이드로 인한 변비를 줄여주는 효과가 있다. 이와 같이 말초 작용 아편작용제 로페아미드의 정반대라고 볼 수 있다.

- 오피오이드와 관계없는 실리콘인 시메티콘은 어떤 제형에서는 로페라마이드와 결합된다. 그것은 과도한 가스로 인한 팽창, 불편함 또는 고통을 줄이기 위해 사용되는 항균제다.

참조

- ^ a b c Drugs.com 2015년 9월 4일에 접속된 웨이백 머신 페이지에서 2015년 9월 23일 보관된 로페라마이드의 국제 브랜드

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Loperamide Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Loperamide use while Breastfeeding". Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "loperamide hydrochloride". NCI Drug Dictionary. 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ a b Patrick, Graham L. (2013). An introduction to medicinal chemistry (Fifth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 644. ISBN 9780199697397.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Richard J. (2013). Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia (14 ed.). [Sudbury, Mass.]: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 217. ISBN 9781449673611. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ "Loperamide Hydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Hanauer, S. B. (Winter 2008). "The Role of Loperamide in Gastrointestinal Disorders". Reviews in Gastroenterological Disorders. 8 (1): 15–20. PMID 18477966.

- ^ a b "Loperamide". Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Miftahof, Roustem (2009). Mathematical Modeling and Simulation in Enteric Neurobiology. World Scientific. p. 18. ISBN 9789812834812. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017.

- ^ Benson A, Chakravarthy A, Hamilton SR, Elin S, eds. (2013). Cancers of the Colon and Rectum: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Demos Medical Publishing. p. 225. ISBN 9781936287581. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Zuckerman JN (2012). Principles and Practice of Travel Medicine. John Wiley & Sons. p. 203. ISBN 9781118392089. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "Imodium label" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ "loperamide adverse reactions". Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Litovitz T, Clancy C, Korberly B, Temple AR, Mann KV (1997). "Surveillance of loperamide ingestions: an analysis of 216 poison center reports". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 35 (1): 11–9. doi:10.3109/15563659709001159. PMID 9022646.

- ^ "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Loperamide (Imodium): Drug Safety Communication - Serious Heart Problems With High Doses From Abuse and Misuse". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "rxlist.com". 2005. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Imodium (Loperamide Hydrochloride) Capsule". DailyMed. NIH. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010.

- ^ Li ST, Grossman DC, Cummings P (2007). "Loperamide therapy for acute diarrhea in children: systematic and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 4 (3): e98. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040098. PMC 1831735. PMID 17388664.

- ^ "E-DRUG: Chlormezanone". Essentialdrugs.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- ^ "Medicines information links - NHS Choices". Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Einarson A, Mastroiacovo P, Arnon J, Ornoy A, Addis A, Malm H, Koren G (March 2000). "Prospective, controlled, multicentre study of loperamide in pregnancy". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (3): 185–7. doi:10.1155/2000/957649. PMID 10758415.

- ^ "Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Loperamide Drug Interactions - Epocrates Online". online.epocrates.com. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ "DrugBank: Loperamide". Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Loperamide Hydrochloride Drug Information, Professional". Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Katzung BG (2004). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (9th ed.). ISBN 978-0-07-141092-2.[페이지 필요]

- ^ Lemke TL, Williams DA (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 675. ISBN 9780781768795. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Dufek MB, Knight BM, Bridges AS, Thakker DR (March 2013). "P-glycoprotein increases portal bioavailability of loperamide in mouse by reducing first-pass intestinal metabolism". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 41 (3): 642–50. doi:10.1124/dmd.112.049965. PMID 23288866. S2CID 11014783.

- ^ Kalgutkar AS, Nguyen HT (September 2004). "Identification of an N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-like metabolite of the antidiarrheal agent loperamide in human liver microsomes: underlying reason(s) for the lack of neurotoxicity despite the bioactivation event". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 32 (9): 943–52. PMID 15319335. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Upton RN (August 2007). "Cerebral uptake of drugs in humans". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 34 (8): 695–701. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04649.x. PMID 17600543. S2CID 41591261.

- ^ "Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Sadeque AJ, Wandel C, He H, Shah S, Wood AJ (September 2000). "Increased drug delivery to the brain by P-glycoprotein inhibition". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 68 (3): 231–7. doi:10.1067/mcp.2000.109156. PMID 11014404. S2CID 38467170.

- ^ Yanagita T, Miyasato K, Sato J (1979). "Dependence potential of loperamide studied in rhesus monkeys". NIDA Research Monograph. 27: 106–13. PMID 121326.

- ^ Nakamura H, Ishii K, Yokoyama Y, Motoyoshi S, Suzuki K, Sekine Y, et al. (November 1982). "[Physical dependence on loperamide hydrochloride in mice and rats]". Yakugaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 102 (11): 1074–85. doi:10.1248/yakushi1947.102.11_1074. PMID 6892112.

- ^ "DEA "Orange Book" Lists of Scheduling Actions" (PDF). DEA Office of Diversion Control. U.S. Department of Justice. February 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Florey, Klaus (1991). Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology, Volume 19. Academic Press. p. 342. ISBN 9780080861142.

- ^ Stokbroekx RA, Vandenberk J, Van Heertum AH, Van Laar GM, Van der Aa MJ, Van Bever WF, Janssen PA (1973). "Synthetic Antidiarrheal Agents. 2,2-Diphenyl-4-(4'-aryl-4'-hydroxypiperidino)butyramides". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (7): 782–786. doi:10.1021/jm00265a009. PMID 4725924.

- ^ Schuermans V, Van Lommel R, Dom J, Brugmans J (1974). "Loperamide (R 18 553), a novel type of antidiarrheal agent. Part 6: Clinical pharmacology. Placebo-controlled comparison of the constipating activity and safety of loperamide, diphenoxylate and codeine in normal volunteers". Arzneimittelforschung. 24 (10): 1653–7. PMID 4611432.

- ^ "Compound Report Card". Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Mainguet P, Fiasse R (July 1977). "Double-blind placebo-controlled study of loperamide (Imodium) in chronic diarrhoea caused by ileocolic disease or resection". Gut. 18 (7): 575–9. doi:10.1136/gut.18.7.575. PMC 1411573. PMID 326642.

- ^ "IMODIUM FDA Application No.(NDA) 017694". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1976. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-05.

- ^ a b McNeil-PPC, Inc., Plaintiff, v. L. Perrigo Company, and Perrigo Company, Defendants,F.207 Supp. 2d 356 (E.D. Pa. 2002년 6월 25일)

- ^ "IMODIUM A-D FDA Application No.(NDA) 019487". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1988. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-05.

- ^ "Loperamide: voluntary withdrawal of infant fomulations" (PDF). WHO Drug Information. 4 (2): 73–74. 1990. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-06.

The leading international supplier of this preparation, Johnson and Johnson, has since informed WHO that having regard to the dangers inherent in improper use and overdosing, this formulation (Imodium Drops), was voluntarily withdrawn from Pakistan in March 1990. The company has since decided not only to withdraw this preparation worldwide, but also to remove all syrup formulations from countries where WHO has a programme for control of diarrhoeal diseases.

- ^ Consolidated List of Products Whose Consumption And/or Sale Have Been Banned, Withdrawn, Severely Restricted Or Not Approved by Governments, 8th Issue. United Nations. 2003. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-92-1-130230-1. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ 미국 특허 5612054, 제프리 L. 가윈, "위장고통 치료를 위한 의약품 구성"은 McNeil-PPC, Inc.에 할당된 1997-03-18을 발행했다.

- ^ "IMODIUM MULTI-SYMPTOM RELIEF FDA Application No.(NDA) 020606". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1997. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-05.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Imodium Advanced (Loperamide HCI and Simethicone NDA #21-140". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 December 1999. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Scherer announces launch of another product utilizing its Zydis technology". PR Newswire Association LLC. 9 November 1993. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ Rathbone MJ, Hadgraft J, Roberts MS (2002). "The Zydis Oral Fast-Dissolving Dosage Form". Modified-Release Drug Delivery Technology. CRC Press. pp. 200. ISBN 9780824708696. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ World Health Organization (2014). The selection and use of essential medicines: report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2013 (including the 18th WHO model list of essential medicines and the 4th WHO model list of essential medicines for children). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/112729. ISBN 9789241209854. ISSN 0512-3054. WHO technical report series;985.

- ^ https://aktuelles.uni-frankfurt.de/englisch/anti-diarrhoea-drug-drives-cancer-cells-to-cell-death/

- ^ Connelly D (April 2017). "A breakdown of the over-the-counter medicines market in Britain in 2016". The Pharmaceutical Journal. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 298 (7900). doi:10.1211/pj.2017.20202662. ISSN 2053-6186.

- ^ Baker DE (2007). "Loperamide: a pharmacological review". Reviews in Gastroenterological Disorders. 7 Suppl 3 (Suppl 3): S11-8. PMID 18192961.

- ^ Mediators and Drugs in Gastrointestinal Motility II: Endogenous and Exogenous Agents. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-3-642-68474-6.

- ^ MacDonald R, Heiner J, Villarreal J, Strote J (May 2015). "Loperamide dependence and abuse". BMJ Case Reports. 2015: bcr2015209705. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-209705. PMC 4434293. PMID 25935922.

- ^ Dierksen J, Gonsoulin M, Walterscheid JP (December 2015). "Poor Man's Methadone: A Case Report of Loperamide Toxicity". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 36 (4): 268–70. doi:10.1097/PAF.0000000000000201. PMID 26355852. S2CID 19635919.

- ^ a b Stanciu CN, Gnanasegaram SA (2017). "Loperamide, the "Poor Man's Methadone": Brief Review". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 49 (1): 18–21. doi:10.1080/02791072.2016.1260188. PMID 27918873. S2CID 31713818.

- ^ Guarino, Ben (4 May 2016). "Abuse of diarrhea medicine you know well is alarming physicians". Washington Post. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ McGinley, Laurie (30 January 2018). "FDA wants to curb abuse of Imodium, 'the poor man's methadone'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Office of the Commissioner. "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Imodium (loperamide) for Over-the-Counter Use: Drug Safety Communication - FDA Limits Packaging To Encourage Safe Use". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ Feldman, Ryan; Everton, Erik (November 2020). "National assessment of pharmacist awareness of loperamide abuse and ability to restrict sale if abuse is suspected". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 60 (6): 868–873. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2020.05.021. ISSN 1544-3450. PMID 32641253. S2CID 220436708.

- ^ Eggleston W, Clark KH, Marraffa JM (January 2017). "Loperamide Abuse Associated With Cardiac Dysrhythmia and Death". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 69 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.03.047. PMID 27140747.

- ^ Mukarram O, Hindi Y, Catalasan G, Ward J (2016). "Loperamide Induced Torsades de Pointes: A Case Report and Review of the Literature". Case Reports in Medicine. 2016: 4061980. doi:10.1155/2016/4061980. PMC 4775784. PMID 26989420.

외부 링크

- "Loperamide". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Loperamide hydrochloride mixture with simethicone". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.