니코틴

Nicotine 상단: 니코틴 농축액 왼쪽 하단: 니코틴 분자의 골격 표현 오른쪽 하단: 니코틴 분자의 볼 앤 스틱 모델 | |||

| |||

| 임상자료 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 상호 | 니코레트, 니코트롤 | ||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 | ||

| 임신 카테고리 |

| ||

| 의존성 책임 | 물리적: 저-중등도[1] 심리학: 중등도-하이[2][3] | ||

| 중독 책임 | 매우 높음[4] | ||

| 경로: 행정부. | 흡입, 인플레이션, 경구 - 협측, 설하 및 섭취, 경피, 직장 | ||

| ATC코드 | |||

| 법적 지위 | |||

| 법적 지위 | |||

| 약동학적 데이터 | |||

| 단백질 결합 | <5% | ||

| 대사 | 주로 간: CYP2A6, CYP2B6, FMO3, 기타 | ||

| 대사산물 | 코티닌 | ||

| 탈락 반감기 | 1-2시간, 활성 대사산물 20시간 | ||

| 배설 | 신장, 소변 pH 의존성;[8] 10~20%(껌), 30%(inhaled), 10~30%(비강내) | ||

| 식별자 | |||

| |||

| CAS 번호 | |||

| 펍켐 CID | |||

| IUPHAR/BPS | |||

| 드럭뱅크 | |||

| 켐스파이더 | |||

| 유니 | |||

| 케그 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| CHEMBL | |||

| PDB 리간드 | |||

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA) | |||

| ECHA 인포카드 | 100.000.177 | ||

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |||

| 공식 | C10H14N2 | ||

| 어금니 질량 | 162.236 g·mol−1 | ||

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |||

| 키랄리티 | 카이랄 | ||

| 밀도 | 1.01g/cm3 | ||

| 융점 | −79 °C (−110 °F) | ||

| 끓는점 | 247 °C (477 °F) | ||

| |||

| |||

| 에 관한 시리즈의 일부 |

| 담배 |

|---|

|

니코틴은 나이트쉐이드 식물군(주로 담배와 두부아 홉우디이)[9]에서 자연적으로 생성되는 알칼로이드이며, 흥분제 및 불안제로 레크리에이션에 널리 사용됩니다. 의약품으로 금단 증상 완화를 위한 금연에 사용됩니다.[10][7][11][12] 니코틴은 수용체 길항제로 작용하는 2개의 니코틴 수용체 소단위(nAChRα9 및 nAChRα10)를 제외한 대부분의 니코틴 아세틸콜린 수용체(nAChR)에서 수용체 작용제로 작용합니다.[13][14][15][13]

니코틴은 담배 건조 중량의 약 0.6~3.0%를 차지합니다.[16] 니코틴은 감자, 토마토, 가지를 포함한 솔라나과의 식용 식물에도 ppb-농도로 존재하지만,[17] 이것이 인간 소비자에게 생물학적으로 중요한 의미가 있는지에 대해서는 소식통이 동의하지 않습니다.[17] 이것은 항초식 독소로서 기능합니다; 결과적으로 니코틴은 과거에 살충제로서 널리 사용되었고,[18][19] 이미다클로프리드와 같은 네오니코티노이드(구조적으로 니코틴과 유사함)는 가장 효과적이고 널리 사용되는 살충제 중 일부입니다.

니코틴은 중독성이 강합니다.[20][21][22] 느린 릴리스 양식(검 및 패치, 올바르게 사용할 경우)은 중독성이 약하고 그만두는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[23][24][25][26] 담배 연기에 존재하는 모노아민 산화효소 억제제가 니코틴의 중독성을 강화할 수 있다는 동물 연구 결과가 나왔습니다.[27][28] 평균적인 담배 한 개비는 약 2mg의 흡수된 니코틴을 산출합니다.[29] 치명적인 결과에 대한 추정 하한선은 성인의 경우 섭취한 니코틴 500–1,000 mg (6.5–13 mg/kg)입니다.[27][29] 니코틴 중독에는 약물 강화 행동, 강박적 사용, 금욕 후 재발 등이 포함됩니다.[30] 니코틴 의존성은 내성, 감작,[31] 신체적 의존성,[32] 심리적 의존성을 포함하며 고통을 유발할 수 있습니다.[33][34] 니코틴 금단 증상으로는 우울한 기분, 스트레스, 불안, 짜증, 집중력 저하, 수면 장애 등이 있습니다.[2] 가벼운 니코틴 금단 증상은 담배마다 혈중 니코틴 수치가 최고조에 달했을 때만 정상적인 기분을 경험하는 제한 없는 흡연자에게서 측정할 수 있습니다.[35] 그만두면 금단 증상이 급격히 악화되다가 점차 정상적인 상태로 호전됩니다.[35]

금연 도구로 사용되는 니코틴은 안전 이력이 좋습니다.[36] 동물 연구에 따르면 니코틴이 청소년기의 인지 발달에 악영향을 미칠 수 있지만 이러한 결과가 인간의 뇌 발달과 관련이 있는지는 논쟁의 여지가 있습니다.[37][27] 적은 양으로 가벼운 진통 효과가 있습니다.[38] 국제 암 연구 기관에 따르면, "니코틴은 일반적으로 발암 물질로 간주되지 않습니다."[39][40] 미국의 외과의사는 니코틴 노출과 암 위험 사이의 인과관계의 유무를 추론하기에 증거가 불충분하다고 지적합니다.[41] 니코틴은 인간의 선천적 결함을 유발하는 것으로 나타났으며 테라토겐으로 간주됩니다.[42][43] 인간의 니코틴 치사량의 중앙값은 알려져 있지 않습니다.[44] 고용량은 심각하거나 치명적인 과다복용은 [41][45]드물지만 호흡근육 마비를 통해 니코틴 중독, 장기부전, 사망을 유발하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[46]

사용하다

의료의

니코틴의 주요 치료 용도는 니코틴 의존성을 치료하여 흡연과 건강에 미치는 피해를 제거하는 것입니다. 통제된 수준의 니코틴은 잇몸, 진피 패치, 로젠, 흡입기 또는 비강 스프레이를 통해 환자에게 제공되어 환자의 의존을 완화합니다. 2018년 코크란 콜라보레이션 리뷰에 따르면 모든 현재 형태의 니코틴 대체 요법(껌, 패치, 로젠, 흡입기 및 비강 스프레이)은 설정에 관계없이 금연에 성공할 가능성이 50~60% 증가한다는 고품질 증거를 발견했습니다.[47]

니코틴 패치 사용과 껌 또는 스프레이와 같은 더 빠른 작용 니코틴 대체물을 결합하면 치료 성공 확률이 향상됩니다.[48] 니코틴 껌 2mg 대비 4mg 또한 성공 가능성을 높입니다.[48]

니코틴은 파킨슨병, 치매, ADHD, 우울증 및 육종 치료에 가능한 이점을 위해 임상 시험에서 연구되고 있습니다.[49]

중독 가능성을 최대화하도록 설계된 오락용 니코틴 제품과 대조적으로 니코틴 대체 제품(NRT)은 중독성을 최소화하도록 설계되었습니다.[41]: 112 니코틴이 빠르게 전달되고 흡수될수록 중독 위험이 높아집니다.[33]

살충제

니코틴은 적어도 1690년부터 담배 추출물의[19][50][51] 형태로 살충제로 사용되었습니다(비록 담배의 다른 성분들도 살충제 효과가 있는 것처럼 보이지만).[52] 니코틴 살충제는 2014년부터 미국에서 시판되지 [53]않고 있으며 유기농 작물에[54] 대해서는 집에서 만든 살충제를 금지하고 소규모 정원사에게는 주의를 권고하고 있습니다.[55] 니코틴 살충제는 2009년부터 EU에서 금지되어 왔습니다.[56] 식품은 중국과 같이 니코틴 살충제가 허용되는 국가에서 수입되지만 식품은 최대 니코틴 수치를 초과하지 않을 수 있습니다.[56][57] 니코틴에서 유래하고 구조적으로 유사한 이미다클로프리드와 같은 네오니코티노이드는 2016년 현재 농업용 및 수의용 살충제로 널리 사용되고 있습니다.[58][50]

성능

니코틴 함유 제품은 인지에 대한 니코틴의 성능 향상 효과에 사용되기도 합니다.[59] 41개의 이중 맹검, 위약 대조 연구에 대한 2010년 메타 분석은 니코틴 또는 흡연이 미세 운동 능력, 주의 환기 및 지향, 에피소드 및 작업 기억의 측면에 상당한 긍정적인 영향을 미친다고 결론지었습니다.[60] 2015년 리뷰에서는 α4β2 니코틴 수용체의 자극이 주의력 성능의 특정 개선에 책임이 있다고 언급했습니다; 니코틴 수용체 아형 중 니코틴은 α4β2 수용체(k=1)에서 가장 높은 결합 친화력을 가지며, 이는 니코틴의 중독성을 매개하는 생물학적 표적이기도 합니다. 니코틴은 잠재적으로 유익한 효과가 있지만 역설적인 효과도 있는데, 이는 용량-반응 곡선의 역 U자 모양이나 약동학적 특징 때문일 수 있습니다.[63]

오락의

니코틴은 오락용 약물로 사용됩니다.[64] 널리 사용되고 중독성이 높으며 단종이 어렵습니다.[22] 니코틴은 종종 강박적으로 사용되며 [65]의존성은 수일 내에 발생할 수 있습니다.[65][66] 오락용 약물 사용자는 일반적으로 기분 전환 효과를 위해 니코틴을 사용합니다.[33] 기호용 니코틴 제품에는 씹는 담배, 시가,[67] 담배,[67] 전자담배,[68] 스너프, 파이프 담배,[67] 스너프 및 니코틴 파우치가 포함됩니다.

금지사항

금연을 위한 니코틴 사용은 금기 사항이 거의 없습니다.[69]

니코틴 대체요법이 청소년의 금연에 효과가 있는지는 2014년 기준으로 알 수 없습니다.[70] 따라서 청소년에게는 권장하지 않습니다.[71] 니코틴은 흡연보다 안전하지만 임신 중이나 모유 수유 중에 사용하는 것은 안전하지 않습니다. 따라서 임신 중 NRT 사용의 바람직성이 논란이 되고 있습니다.[72][73][74]

심혈관 환자의 니코틴 대체 요법에 대한 무작위 시험 및 관찰 연구는 위약으로 치료한 것과 비교하여 심혈관 부작용의 증가를 보여주지 않습니다.[75] 니코틴이 종양 성장을 촉진할 수 있기 때문에 암 치료 중에 니코틴 제품을 사용하는 것은 금지될 수 있지만, 흡연을 줄이기 위해 일시적으로 NRT를 사용하는 것이 좋습니다.[76]

니코틴 껌은 턱관절 질환이 있는 사람에게는 금기입니다.[77] 만성비강장애와 심한 반응성 기도질환이 있는 사람은 니코틴 코 스프레이를 사용할 때 추가적인 주의가 필요합니다.[71] 어떤 형태로든 니코틴은 니코틴에 대한 과민성이 알려진 개인에게는 금지됩니다.[77][71]

부작용

니코틴은 독극물로 분류됩니다.[79][80] 그러나 소비자가 사용하는 용량에서는 사용자에게 위험이 있는 경우 거의 나타나지 않습니다.[81][82][83] 2018 Cochrane Collaboration 리뷰에는 니코틴 대체 요법과 관련된 9가지 주요 부작용(두통, 어지럼증/광두통, 메스꺼움/토기, 위장 증상, 수면/꿈 문제, 비허혈성 두근거림 및 흉통, 피부 반응, 구강/비강 반응 및 딸꾹질)이 나열되어 있습니다.[84] 이들 중 상당수는 니코틴이 없는 위약군에서도 흔했습니다.[84] 두근거림과 가슴 통증은 "희귀한" 것으로 간주되었으며 확립된 심장 질환이 있는 사람에서도 위약 그룹에 비해 심각한 심장 문제가 증가했다는 증거는 없었습니다.[47] 니코틴 노출로 인한 일반적인 부작용은 아래 표에 나열되어 있습니다. 니코틴 대체 요법 사용으로 인한 심각한 부작용은 극히 드물습니다.[47] 적은 양으로 가벼운 진통 효과가 있습니다.[38] 충분히 높은 용량에서 니코틴은 메스꺼움, 구토, 설사, 타액, 서맥 부정맥을 유발할 수 있으며 발작, 저환기 및 사망 가능성이 있습니다.[85]

| 투여경로 | 복용량식 | 니코틴의 관련 부작용 | 원천 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 부칼 | 니코틴 껌 | 소화불량, 메스꺼움, 딸꾹질, 구강 점막 또는 치아의 외상성 손상, 입과 목의 자극이나 따끔거림, 구강 점막 궤양, 턱 근육통, 트림, 잇몸이 치아에 달라붙는 불쾌한 맛, 어지러움, 현기증, 명치, 두통, 불면증 등이 있습니다. | [47][77] |

| 로젠지 | 메스꺼움, 소화불량, 팽만감, 두통, 상기도 감염, 자극(즉, 작열감), 딸꾹질, 인후통, 기침, 마른 입술, 구강 점막 궤양 등이 있습니다. | [47][77] | |

| 경피 | 경피 패치를 붙이다 | 적용 부위 반응(예: 소양증, 화상 또는 홍반), 설사, 소화불량, 복통, 구강건조증, 메스꺼움, 어지럼증, 신경성 또는 불안, 두통, 생생한 꿈 또는 기타 수면 장애 및 과민성. | [47][77][86] |

| 비강내 | 비강분무 | 콧물, 비인두 및 안구 자극, 눈에 물기가 있는 눈, 재채기, 기침 등이 나타납니다. | [47][77][87] |

| 구강흡입 | 흡입기 | 소화불량, 구강인두 자극(예: 기침, 입과 목의 자극), 비염, 두통. | [47][77][88] |

| 모두(비특정) | 말초혈관 수축, 빈맥(즉, 빠른 심박수), 혈압 상승, 경계 및 인지 수행력 증가. | [77][87] | |

수면.

니코틴은 경피 패치를 통해 니코틴이 투여된 건강한 비흡연자의 급속 안구 운동(REM) 수면, 서파 수면(SWS) 및 총 수면 시간을 감소시키며, 그 감소는 용량 의존적입니다.[89] 급성 니코틴 중독은 총 수면 시간을 크게 줄이고 REM 지연, 수면 시작 지연 및 NREM(non-rapid eye movement) 2단계 수면 시간을 증가시키는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[89][90] 우울한 비흡연자들은 니코틴 투여 하에서 기분과 수면 개선을 경험하지만, 이후 니코틴 금단은 기분과 수면 모두에 부정적인 영향을 미칩니다.[91]

심혈관계

이 섹션은 다음과 같이 확장이 필요합니다."Cardiac adverse effects of nicotine replacement therapy". Prescrire International. 24 (166): 292–3. December 2015. PMID 26788573.추가해서 "Cardiac adverse effects of nicotine replacement therapy". Prescrire International. 24 (166): 292–3. December 2015. PMID 26788573.도와주시면 됩니다. (2019년 1월) |

2018년 Cochrane 리뷰에 따르면 드물게 니코틴 대체 요법은 비허혈성 흉통(즉, 심장마비와 무관한 흉통)과 심장 두근거림을 유발할 수 있지만 대조군에 비해 심각한 심장 부작용(즉, 심근경색, 뇌졸중 및 심장 사망)의 발생을 증가시키지 않는 것으로 나타났습니다.[47]

2016년 니코틴의 심혈관 독성에 대한 검토는 "현재 지식에 기초하여, 우리는 심혈관 질환이 없는 사람들의 전자 담배 사용으로 인한 니코틴의 심혈관 위험이 상당히 낮다고 믿습니다. 우리는 전자담배의 니코틴이 심혈관 질환을 가진 사용자들에게 약간의 위험을 줄 수 있다는 우려가 있습니다."[92]

혈압

단기적으로는 니코틴이 일시적인 혈압 상승을 일으키지만, 장기적으로는 일반적으로 니코틴 사용자의 혈압 상승이나 고혈압이 나타나지 않습니다.[92]

강화장애

니코틴은 중독성이 강하지만 역설적으로 다양한 동물의 다른 학대 약물에 비해 상당히 약한 강화 특성을 가지고 있습니다.[21][22][95][96] 그것의 중독성은 그것이 투여되는 방법에 따라 다르고 또한 니코틴이 사용되는 형태에 따라 다릅니다.[25] 동물 연구에 따르면 모노아민 산화효소 억제제, 아세트알데히드[96][97] 및 담배 연기의 기타 성분이 중독성을 강화할 수 있다고 합니다.[27][28] 니코틴 의존성은 심리적 의존성과 물리적 의존성의 측면을 모두 포함하는데, 이는 연장 사용의 중단이 정의적(예: 불안, 짜증, 갈망, 무긴장증) 금단 증상과 신체적(떨림과 같은 가벼운 운동 기능 장애) 증상을 모두 생성하는 것으로 나타났기 때문입니다.[2] 금단 증상은 1~3일[98] 후에 최고조에 달하고 몇 주 동안 지속될 수 있습니다.[99] 증상이 6개월 이상 지속되는 경우도 있습니다.[100]

제한 없는 흡연자에서 정상적인 담배 간 중단은 경미하지만 측정 가능한 니코틴 금단 증상을 유발합니다.[35] 여기에는 약간 더 나쁜 기분, 스트레스, 불안, 인지 및 수면이 포함되며, 이 모든 것은 다음 담배와 함께 잠시 정상으로 돌아옵니다.[35] 흡연자들은 니코틴에 의존하지 않는다면 일반적으로 가지고 있는 것보다 더 나쁜 기분을 가지고 있습니다; 그들은 흡연 직후에만 정상적인 기분을 경험합니다.[35] 니코틴 의존성은 흡연자들의 낮은 수면의 질과 짧은 수면 시간과 관련이 있습니다.[101][102]

독립 흡연자인 금단은 기억력과 주의력에 장애를 일으키며 금단 중 흡연은 이러한 인지 능력을 금단 이전 수준으로 되돌립니다.[103] 흡연자들이 담배를 흡입한 후 일시적으로 증가하는 인지 수준은 니코틴 금단 기간 동안 인지가 감소하는 기간으로 상쇄됩니다.[35] 따라서 흡연자와 비흡연자의 전반적인 일일 인지 수준은 거의 비슷합니다.[35]

니코틴은 중림프 경로를 활성화하고, 자주 흡입하거나 고용량으로 주입할 때 핵 내에서 장기간의 δ FosB 발현(즉, 인산화된 δ FosB 동형체 생성)을 유도하지만, 반드시 섭취할 때는 그렇지 않습니다. 결과적으로, 니코틴에 대한 높은 일일 노출(구강 경로 제외)은 핵에서 δ FosB 과발현을 유발하여 니코틴 중독을 유발할 수 있습니다.

암

|

니코틴 자체가 사람에게 암을 유발하지는 않지만,[40] 2012년[update] 기준으로 종양 촉진제로 기능하는지는 불분명합니다.[107] 미국 국립 과학, 공학 및 의학 아카데미의 2018년 보고서는 "니코틴이 종양 촉진제 역할을 할 수 있다는 것이 생물학적으로 그럴듯하지만, 기존의 증거는 이것이 인간 암의 위험 증가로 이어질 가능성이 낮다는 것을 나타냅니다"라고 결론을 내렸습니다.[108]

낮은 수준의 니코틴은 세포 증식을 자극하는 [109]반면 높은 수준은 세포 독성이 있습니다.[76] 니코틴은 대장암 세포에서 콜린성 신호전달과 아드레날린성 신호전달을 [110]증가시켜 세포자멸사(programmed cell death)를 저해하고 종양성장을 촉진하며 5-리폭시게나제(5-LOX), 표피성장인자(EGF)와 같은 성장인자와 세포 유사분열인자를 활성화합니다. 니코틴은 또한 혈관신생과 신생혈관을 자극하여 암 성장을 촉진합니다.[111][112] 니코틴은 폐암 세포에서 존재가 확인된 nAChR 수용체에 대한 영향을 통해 폐암 발생을 촉진하고 증식, 혈관신생, 이동, 침입 및 상피-중간엽 전이(EMT)를 가속화합니다.[113] 암세포에서 니코틴은 상피-중간엽 전이를 촉진하여 암세포가 암을 치료하는 약물에 더 저항력을 갖게 합니다.[114]

담배 속 니코틴은 질화 반응을 통해 발암성 담배 특이 니트로사민을 형성할 수 있습니다. 이것은 대부분 담배의 경화 및 가공에서 발생합니다. 그러나 입과 위의 니코틴은 반응하여 알려진 1형 발암물질인 [115]N-니트로소노르니코틴을 형성할 수 있으며,[116] 이는 비담배 형태의 니코틴 섭취가 여전히 발암에 역할을 할 수 있음을 시사합니다.[117]

유전독성

니코틴은 혜성 분석, 사이토키네시스-블록 소핵 검사 및 염색체 이상 검사와 같은 유전독성에 대한 분석으로 판단되는 여러 유형의 인간 세포에서 DNA 손상을 일으킵니다. 사람의 경우 원발성 부갑상선 세포,[118] 림프구 [119]및 호흡기 세포에서 이러한 손상이 발생할 수 있습니다.[120]

임신 및 모유수유

니코틴은 일부 동물 종에서는 선천적 결함을 생성하는 것으로 나타났지만 다른 동물 종에서는 생성되지 않았습니다.[43] 결과적으로, 니코틴은 인간에게 가능한 테라토겐으로 여겨집니다.[43] 선천적 결함을 초래한 동물 연구에서 연구원들은 니코틴이 태아의 뇌 발달과 임신 결과에 부정적인 영향을 미친다는 것을 발견했습니다;[43][41] 초기 뇌 발달에 대한 부정적인 영향은 뇌 대사 및 신경 전달 물질 시스템 기능의 이상과 관련이 있습니다.[121] 니코틴은 태반을 가로질러 담배를 피우는 엄마는 물론 수동 연기를 흡입하는 엄마의 모유에서도 발견됩니다.[122]

자궁 내 니코틴 노출은 임신과 출산의 여러 합병증에 책임이 있습니다: 담배를 피우는 임신부는 유산과 사산 모두에 더 큰 위험이 있고 자궁 내 니코틴에 노출된 유아는 출생 체중이 더 낮은 경향이 있습니다.[123] 맥마스터 대학의 한 연구 그룹은 2010년에 자궁에서 니코틴에 노출된 쥐들이 말년에 2형 당뇨병, 비만, 고혈압, 신경 행동 결함, 호흡기 기능 장애, 불임을 포함한 질병을 가지고 있다는 것을 관찰했습니다.[124]

과다 복용

흡연만으로 니코틴을 과다 복용할 가능성은 거의 없습니다. 2013년 미국 식품의약국(FDA)은 담배와 같은 다른 니코틴 함유 제품과 동시에 하나 이상의 형태의 장외 니코틴 대체 요법을 사용하거나 OTC NRT를 동시에 사용하는 것과 관련된 중대한 안전 문제가 없다고 밝혔습니다.[125] 인간의 니코틴 치사량의 중앙값은 알려져 있지 않습니다.[44][29] 그럼에도 불구하고 니코틴은 생쥐에게 투여했을 때 LD가50 127mg/kg인 카페인과 같은 다른 많은 알칼로이드에 비해 상대적으로 높은 독성을 가지고 있습니다.[126] 충분히 높은 용량에서 니코틴 중독과 관련이 있으며,[41] 어린이들에게 흔히 발생하지만(몸무게[38] 1kg당 낮은 용량에서 독성 및 치사 수준이 발생함) 심각한 질병이나 사망을 초래하는 경우는 거의 없습니다.[43] 치명적인 결과에 대한 추정 하한선은 성인의 경우 섭취한 니코틴 500–1,000 mg (6.5–13 mg/kg)입니다.[27][29]

니코틴 과다복용의 초기 증상은 일반적으로 메스꺼움, 구토, 설사, 과호흡, 복통, 빈맥(빠른 심박수), 고혈압(고혈압), 빈호흡(빠른 호흡), 두통, 어지럼증, 창백함( 창백한 피부), 청각 또는 시각 장애, 땀을 포함합니다. 곧이어 현저한 서맥(심박수가 느림), 서맥(호흡이 느림), 저혈압(저혈압)이 뒤따릅니다.[43] 호흡수 증가(즉, 빈호흡)는 니코틴 중독의 주요 징후 중 하나입니다.[43] 충분한 고용량에서는 졸음(졸음 또는 졸음), 혼란, 실신(실신으로 인한 의식 상실), 호흡 곤란, 현저한 쇠약, 발작, 혼수 상태 등이 발생할 수 있습니다.[8][43] 치명적인 니코틴 중독은 발작을 빠르게 일으키고, 몇 분 안에 발생할지도 모르는 사망은 호흡 마비로 인한 것으로 여겨집니다.[43]

독성

오늘날 니코틴은 중독의 주요 원인이었던 농업용 살충제에 덜 일반적으로 사용됩니다. 보다 최근의 중독 사례는 일반적으로 GTS(Green Tobacco Sickness),[43] 담배 또는 담배 제품의 우발적 섭취 또는 니코틴 함유 식물 섭취의 형태로 나타납니다.[127][128][129] 담배를 수확하거나 재배하는 사람들은 젖은 담배 잎에 피부가 노출되어 발생하는 니코틴 중독의 일종인 GTS를 경험할 수 있습니다. 이것은 담배를 소비하지 않는 젊고 경험이 부족한 담배 수확자에게 가장 흔하게 발생합니다.[127][130] 사람들은 니코틴을 들이마시거나, 피부를 흡수하거나, 삼키거나, 눈을 마주치면 작업장에서 니코틴에 노출될 수 있습니다. 산업안전보건청(OSHA)은 직장 내 니코틴 노출에 대한 법적 허용 한도(허용 노출 한도)를 8시간 근무시간 동안 0.5mg/m3 피부 노출로 설정했습니다. 미국 국립 산업 안전 보건 연구소(NIOSH)는 8시간 근무에 걸친 피부 노출 권장 한도(REL)를 0.5mg/m로3 설정했습니다. 5mg/m의3 환경 수준에서 니코틴은 즉시 생명과 건강에 위험합니다.[131]

약물 상호작용

약력학

약동학

니코틴과 담배 연기는 모두 약물을 대사하는 간 효소(예: 특정 시토크롬 P450 단백질)의 발현을 유도하여 약물 대사의 변화 가능성을 유도합니다.[77]

- 금연은 아세트아미노펜, 베타차단제, 카페인, 옥사제팜, 펜타조신, 프로폭시펜, 테오필린 및 삼환계 항우울제의 대사를 감소시켜 이러한 약물의 혈장 농도를 높일 수 있습니다.[77]

- 혈관 확장 또는 혈관 수축을 유발하는 약물에 의한 경피 니코틴 패치로부터의 피부를 통한 니코틴 흡수의 변경 가능성.[77]

- 비강 혈관 수축기(예: 자일로메타졸린)에 의한 니코틴 비강 분무로부터 비강을 통한 니코틴 흡수의 변경 가능성.[77]

- 타액 pH를 수정하는 음식과 음료에 의한 니코틴 껌과 로젠으로부터 구강 점막을 통한 니코틴 흡수의 변화 가능성.[77]

약리학

약동학

니코틴은 수용체 길항제로 작용하는 2개의 니코틴 수용체 소단위(nAChRα9 및 nAChRα10)를 제외한 대부분의 니코틴 아세틸콜린 수용체(nAChR)에서 수용체 작용제로 작용합니다.[13][14][13] 이러한 길항작용은 가벼운 진통을 초래합니다.

중추신경계

니코틴은 뇌의 니코틴성 아세틸콜린 수용체에 결합함으로써 정신 활동 효과를 이끌어내고 다양한 뇌 구조에서 여러 신경 전달 물질의 수준을 증가시켜 일종의 "볼륨 조절" 역할을 합니다.[132][133] 니코틴은 골격근의 니코틴 수용체보다 뇌의 니코틴 수용체에 대한 친화력이 높지만 독성 용량에서는 수축과 호흡 마비를 유발할 수 있습니다.[134] 니코틴의 선택성은 이러한 수용체 아형의 특정 아미노산 차이에 기인하는 것으로 생각됩니다.[135] 니코틴은 대부분의 약물과 비교할 때 특이한데, 니코틴은 용량이 증가함에 따라 자극제에서 진정제로 변화하는데, 이는 1969년 처음 니코틴을 기술한 의사의 이름을 따서 "네스빗의 역설"로 알려진 현상입니다.[136][137] 매우 높은 용량에서는 신경 활동을 약화시킵니다.[138] 니코틴은 동물의 행동 자극과 불안감을 동시에 유발합니다.[8] 니코틴의 가장 주요한 대사산물인 코티닌에 대한 연구는 니코틴의 정신 활동적 효과 중 일부가 코티닌에 의해 매개된다는 것을 시사합니다.[139]

니코틴은 도파민의 방출을 유발하는 것으로 보이는 중배엽 경로 및 복측 분절 영역을 내재화하는 뉴런에서 니코틴 수용체(특히 α4β2 니코틴 수용체, 또한 α5 nAChRs)를 활성화합니다.[140][141] 이 니코틴에 의한 도파민 방출은 적어도 부분적으로 복부 분절 부위에서 콜린성-도파민성 보상 연결의 활성화를 통해 발생합니다.[141][142] 니코틴은 복부 분절 부위 뉴런의 발화 속도를 조절할 수 있습니다.[142] 이러한 행동은 행복감이 없을 때 종종 발생하는 니코틴의 강력한 강화 효과에 큰 책임이 있습니다.[140] 그러나 니코틴 사용으로 인한 가벼운 행복감은 일부 개인에서 발생할 수 있습니다.[140] 만성 니코틴 사용은 이 효과가 니코틴 중독에 역할을 하는 선조체에서 클래스 I 및 클래스 II 히스톤 탈아세틸화효소를 억제합니다.[143][144]

교감신경계

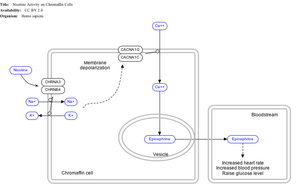

니코틴은 또한 교감신경을 활성화시켜 [145]부신수질에 대한 부엽신경을 통해 작용하여 에피네프린의 방출을 자극합니다. 이러한 신경의 전강생 교감 섬유에 의해 방출되는 아세틸콜린은 니코틴성 아세틸콜린 수용체에 작용하여 에피네프린(및 노르에피네프린)을 혈류로 방출합니다.

부신수질

니코틴은 부신수질에 있는 신경절형 니코틴 수용체와 결합함으로써 자극 호르몬이자 신경전달물질인 아드레날린(에피네프린)의 흐름을 증가시킵니다. 수용체에 결합함으로써 세포의 탈분극과 전압 게이트 칼슘 채널을 통한 칼슘 유입을 유발합니다. 칼슘은 크로마핀 과립의 엑소사이토시스를 유발하여 혈류로 에피네프린(및 노르에피네프린)의 방출을 유발합니다. 에피네프린(아드레날린)의 방출은 심박수, 혈압 및 호흡을 증가시키고 혈당 수치를 높입니다.[146]

약동학

니코틴은 체내로 유입되면서 혈류를 통해 빠르게 분포되어 흡입 후 10~20초 이내에 혈액-뇌 장벽을 넘어 뇌에 도달합니다.[148] 체내 니코틴 제거 반감기는 약 2시간입니다.[149] 니코틴은 주로 소변으로 배출되며 소변의 유속과 소변의 pH에 따라 소변 농도가 달라집니다.[8]

흡연으로 인한 니코틴 흡수량은 담배의 종류, 연기 흡입 여부, 필터 사용 여부 등 많은 요인에 따라 달라질 수 있습니다. 그러나 개별 제품의 니코틴 수율은 니코틴의 혈중 농도에 작은 영향(4.4%)을 미치는 것으로 [150]밝혀져 "저타르 및 저니코틴 담배로 전환할 때 가정되는 건강상 이점은 흡연자들이 흡입량을 증가시켜 보상하는 경향에 의해 크게 상쇄될 수 있다"고 제안했습니다.

니코틴의 반감기는 1~2시간입니다. 코티닌은 혈액 속에 남아 있는 니코틴의 활성 대사산물로 반감기가 18~20시간으로 분석이 용이합니다.[151]

니코틴은 사이토크롬 P450 효소(대부분 CYP2A6, 그리고 또한 CYP2B6에 의해)와 선택적으로 (S)-니코틴을 대사하는 FMO3에 의해 간에서 대사됩니다. 주요 대사산물은 코티닌입니다. 다른 주요 대사 생성물에는 니코틴 N'-옥사이드, 노르니코틴, 니코틴 이소메토니움 이온, 2-하이드록시니코틴 및 니코틴 글루쿠로니드가 포함됩니다.[152] 어떤 조건에서는 미오스민과 같은 다른 물질이 형성될 수 있습니다.[153][154]

니코틴의 코티닌으로의 글루쿠론화 및 산화 대사는 모두 멘톨화된 담배의 첨가제인 멘톨에 의해 억제되어 생체 내에서 니코틴의 반감기를 증가시킵니다.[155]

대사

니코틴은 배고픔과 결과적으로 음식 소비를 줄이고 에너지 소비를 증가시킵니다.[156][157] 대부분의 연구는 니코틴이 체중을 감소시킨다는 것을 보여주지만, 일부 연구자들은 니코틴이 동물 모델에서 특정 유형의 식습관 아래에서 체중 증가를 초래할 수 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.[157] 체중에 대한 니코틴 효과는 니코틴이 궁상핵의 POMC 뉴런에 위치한 α3β4 nAChR 수용체와 그 후 멜라노코르틴 시스템, 특히 시상하부의 방실핵의 2차 뉴런에 위치한 멜라노코르틴-4 수용체를 자극하여 섭식 억제를 조절하는 것으로 보입니다.[142][157] POMC 뉴런은 체중 및 피부 및 모발과 같은 말초 조직의 중요한 조절자인 멜라노코르틴 시스템의 전구체입니다.[157]

화학

| NFPA 704 불을 지피다 | |

|---|---|

니코틴에[158] 대한 화재 다이아몬드 위험 표시 |

니코틴은 흡습성, 무색에서 황갈색의 유성 액체로 알코올, 에테르 또는 경질 석유에 쉽게 용해됩니다. 60°C에서 210°C 사이의 중성 아민 염기 형태의 물과 섞입니다. K=1×10, K=1×10의 이염기성 질소염기입니다. 일반적으로 고체 및 수용성인 산과 쉽게 암모늄 염을 형성합니다. 인화점은 95°C, 자동점화 온도는 244°C입니다.[160] 니코틴은 휘발하기 쉽습니다(25°C에서 증기압 5.5Pa)[159] 자외선이나 각종 산화제에 노출되면 니코틴은 산화니코틴산(니아신, 비타민 B3), 메틸아민으로 전환됩니다.[161]

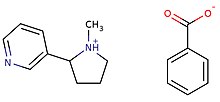

니코틴은 카이랄이고 따라서 광학적으로 활성이며 두 가지 거울상이성질체 형태를 갖습니다. 니코틴의 자연적으로 발생하는 형태는 [α]=–166.4°((-)-nicotine)의 특정 회전을 갖는 승강성(levorotary)입니다. 덱스트로로터리 형태인 (+)니코틴은 생리학적으로 (-)니코틴보다 덜 활성입니다. (-)니코틴은 (+)니코틴보다 독성이 더 강합니다.[162] (-)-니코틴의 염은 일반적으로 dextrootary이며, 양성자화 시 levorotary와 dextrootary 사이의 전환은 알칼로이드에서 일반적입니다.[161] 염산염과 황산염은 180°C 이상의 밀폐 용기에서 가열하면 광학적으로 비활성화됩니다.[161]아나바신은 니코틴의 구조 이성질체입니다. 두 화합물 모두 분자식을 가지고 있기 때문입니다. C10H14N2.

천연 담배에서 발견되는 니코틴은 주로 (99%) S- 거울상이성질체입니다.[163] 반대로, 니코틴을 생성하기 위한 가장 일반적인 화학 합성 방법은 S- 및 R- 거울상이성질체의 거의 동일한 비율의 생성물을 생성합니다.[164] 이것은 담배 유래 니코틴과 합성 니코틴이 서로 다른 두 거울상이성질체의 비율을 측정함으로써 결정될 수 있음을 시사하지만, 거울상이성질체의 상대적인 수준을 조정하거나 S- 거울상이성질체로만 이어지는 합성을 수행하기 위한 수단이 존재합니다. 이 두 거울상이성질체의 상대적인 생리학적 영향, 특히 사람에게서 나타나는 영향에 대한 데이터는 제한적입니다. 그러나 현재까지의 연구에 따르면 (S)-니코틴이 (R)-니코틴보다 더 강력하고 (S)-니코틴이 (R)-니코틴보다 더 강한 감각이나 자극을 유발한다고 합니다. 현재까지 연구는 사람들에게 두 거울상이성질체의 상대적 중독성을 결정하는 데 적합하지 않습니다.

포드 모드 전자 담배는 이전 세대에서 발견된 유리 염기 니코틴이 아닌 양성자화 니코틴 형태로 니코틴을 사용합니다.[165]

준비

니코틴의 최초의 실험 준비는 1904년에 기술되었습니다.[166]

출발 물질은 N-치환된 피롤 유도체로서, 피롤과 피리딘 고리 사이에 탄소 결합을 갖는 이성질체로의 [1,5] 시그마트로픽 이동에 의해 이를 전환시키기 위해 가열된 후, 주석과 염산을 사용하여 메틸화 및 피롤 고리의 선택적 환원.[166][167] 그 이후로 라세미 형태와 카이랄 형태의 니코틴의 많은 다른 합성이 발표되었습니다.[168]

생합성

니코틴의 생합성 경로는 니코틴을 구성하는 두 고리 구조 사이의 커플링 반응을 포함합니다. 대사 연구에 따르면 니코틴의 피리딘 고리는 니아신(니코틴산)에서 유래하는 반면 피롤리딘은 N-메틸-δ-피롤리듐 양이온에서 유래하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 두 성분 구조의 생합성은 나이아신에 대한 NAD 경로와 N-메틸-δ-피롤리듐 양이온에 대한 트로판 경로의 두 가지 독립적인 합성을 통해 진행됩니다.

니코티아나 속의 NAD 경로는 아스파르트산이 아스파르트산 산화효소(AO)에 의해 α-아미노 숙시네이트로 산화되는 것으로 시작됩니다. 그 다음 글리세르알데히드-3-인산염으로 축합하고 퀴놀린산을 만들기 위해 퀴놀린산 합성효소(QS)에 의해 촉매되는 고리화가 뒤따릅니다. 퀴놀린산은 퀴놀린산 포스포리보실 전이효소(QPT)에 의해 촉매되는 포스포리보실 피로인산염과 반응하여 나이아신 모노뉴클레오티드(NaMN)를 형성합니다. 반응은 이제 NAD 회수 주기를 통해 진행되어 효소 니코틴아미드에 의한 니코틴아미드의 전환을 통해 나이아신을 생성합니다.[citation needed]

니코틴 합성에 사용되는 N-메틸-δ-피롤리듐 양이온은 트로판 유래 알칼로이드 합성의 중간체입니다. 생합성은 푸트레신을 생산하기 위해 오르니틴 탈카복실화효소(ODC)에 의한 오르니틴의 탈카복실화로 시작됩니다. 그런 다음 푸트레신은 푸트레신 N-메틸트랜스퍼라제(PMT)에 의해 촉매되는 SAM에 의해 메틸화를 통해 N-메틸 푸트레신으로 전환됩니다. 그런 다음 N-메틸 푸트레신은 N-메틸 푸트레신 산화효소(MPO)에 의해 4-메틸아미노부타날로 탈아미노화된 다음 자발적으로 N-메틸-δ-피롤리듐 양이온으로 고리화됩니다.

니코틴 합성의 마지막 단계는 N-메틸-δ-피롤리듐 양이온과 나이아신 사이의 결합입니다. 비록 연구들이 두 구성 요소 구조 사이의 어떤 형태의 결합을 결론짓고 있지만, 확실한 과정과 메커니즘은 아직 밝혀지지 않았습니다. 현재 합의된 이론은 나이아신을 3,6-디히드로노틴산을 통해 2,5-디히드로피리딘으로 전환하는 것을 포함합니다. 2,5-디히드로피리딘 중간체는 N-메틸-δ-피롤리듐 양이온과 반응하여 거울상이성질체로 순수한(-)-니코틴을 형성합니다.

체액에서의 검출

니코틴은 혈액, 혈장 또는 소변에서 정량화하여 중독 진단을 확인하거나 약물 합법적인 사망 조사를 용이하게 할 수 있습니다. 요중 또는 타액 코티닌 농도는 사전 취업 및 건강보험 의료검진 프로그램을 목적으로 자주 측정됩니다. 담배 연기에 수동적으로 노출되면 니코틴이 상당히 축적되고 이어서 다양한 체액에 니코틴 대사산물이 나타날 수 있기 때문에 결과에 대한 신중한 해석이 중요합니다.[172][173] 니코틴 사용은 경쟁 스포츠 프로그램에서 규제되지 않습니다.[174]

거울상이성질체 분석방법

두 거울상이성질체를 측정하는 방법은 간단하며 정상상 액체 크로마토그래피,[163] 카이랄 컬럼을 사용한 액체 크로마토그래피가 있습니다.[175] 그러나 두 거울상이성질체를 변경하는 방법을 사용할 수 있기 때문에 단순히 두 거울상이성질체의 수준을 측정하는 것만으로는 담배 유래 니코틴과 합성 니코틴을 구별할 수 없을 수 있습니다. 새로운 접근법은 수소와 중수소 핵자기 공명을 사용하여 담배 공장에서 수행되는 천연 합성 경로에 사용되는 기질과 합성에 가장 많이 사용되는 기질의 차이를 기반으로 담배 유래 니코틴과 합성 니코틴을 구별합니다.[176] 또 다른 접근 방식은 천연 담배와 실험실 기반 담배 간의 차이인 탄소-14 함량을 측정합니다.[177] 이러한 방법은 광범위한 샘플을 사용하여 완전히 평가되고 검증되어야 합니다.

자연발생

니코틴은 솔라나과의 다양한 식물에서 생성되는 2차 대사산물이며, 특히 담배 니코티아나 타바쿰에서 0.5~7.5%[178]의 고농도로 발견될 수 있습니다. 니코틴은 니코티아나 루스티카(Nicotiana rustica)와 같은 다른 담배 종의 잎에서도 발견됩니다(2-14%). 니코틴 생성은 자스모네이트 의존성 반응의 일부로 상처에 대한 반응으로 강력하게 유도됩니다.[179] 담배뿔벌레(Manduca sexta)와 같은 담배 전문 곤충은 니코틴의 해독과 심지어 적응적인 재사용에 많은 적응을 합니다.[180] 니코틴은 또한 담배 식물의 과즙에서 낮은 농도로 발견되며, 벌새 꽃가루 매개자의 행동에 영향을 주어 교차를 촉진할 수 있습니다.[181]

니코틴은 감자, 토마토, 가지, 고추와 같은 일부 작물 종과 [17][182]두부아이아 홉우디와 같은 비 작물 종을 포함하여 다른 솔라나과 식물에서 더 적은 양(2-7μg/kg 또는 습윤 중량의[17] 2-7천만 분의 2-7천만 분의 1)으로 발생합니다.[159] 토마토의 니코틴 양은 과일이 익을수록 상당히 낮아집니다.[17] 1999년의 한 보고서는 "식이 니코틴 섭취의 기여가 ETS[환경 담배 연기]에 노출되거나 적은 수의 담배를 적극적으로 피우는 것과 비교할 때 상당하다고 제안합니다. 다른 사람들은 지나치게 많은 양의 특정 채소를 섭취하지 않는 한 식이 섭취를 무시할 수 있다고 생각합니다."[17] 니코틴 섭취량은 약 1.4, 2.25μg/day 정도로 95백분위에 속합니다.[17] 이러한 수치는 음식 섭취 데이터가 충분하지 않기 때문에 낮을 수 있습니다.[17] 야채의 니코틴 농도는 매우 낮기 때문에 정확하게 측정하기가 어렵습니다(10억분의 1 범위).[183]

역사, 사회, 문화

니코틴은 원래 1828년 독일의 화학자 빌헬름 하인리히 포셀트와 카를 루트비히 라이만에 의해 담배 공장에서 분리되었습니다.[184][185] 화학적 경험식은 1843년 멜센스에 의해 기술되었고,[186] 그 구조는 1893년 아돌프 피너와 리처드 볼펜슈타인에 의해 발견되었으며,[187][188][189][clarification needed] 아메 픽테와 A에 의해 처음으로 합성되었습니다. 1904년 롯치.[166][190]

니코틴은 담배 식물 니코티아나 타바쿰의 이름을 따서 명명되었으며, 이는 포르투갈 주재 프랑스 대사인 장 니코 드 빌랭(Jean Nicot de Villeman)이 1560년에 담배와 씨앗을 파리로 보내 프랑스 왕에게 선물하고 [191]약용을 홍보한 사람의 이름을 따서 명명되었습니다. 흡연은 질병, 특히 전염병을 예방하는 것으로 여겨졌습니다.[191]

담배는 1559년에 유럽에 소개되었고, 17세기 후반에는 흡연뿐만 아니라 살충제로도 사용되었습니다. 제2차 세계대전 이후 전 세계적으로 2,500톤 이상의 니코틴 살충제가 사용되었지만 1980년대에 이르러 니코틴 살충제의 사용은 200톤 이하로 감소했습니다. 이것은 포유류에게 더 저렴하고 덜 해로운 다른 살충제를 구할 수 있기 때문입니다.[19]

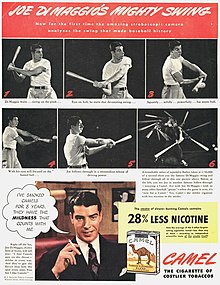

인기 있는 미국 브랜드 담배의 니코틴 함량은 시간이 지남에 따라 증가했으며, 한 연구에 따르면 1998년과 2005년 사이에 연평균 1.78% 증가한 것으로 나타났습니다.[192]

합성 니코틴의 생산 방법은 수십 년 동안 존재해 왔지만,[193] 실험실 합성에 의한 니코틴 제조 비용은 담배에서 니코틴을 추출하는 것에 비해 엄청난 비용이 든다고 믿었습니다.[194] 그러나 최근 합성 니코틴은 다양한 브랜드의 전자 담배와 구강 파우치에서 발견되기 시작했고 "담배가 없는" 것으로 시판되었습니다.[195]

미국 FDA는 전자담배와 같은 담배 제품을 검토하고 판매 허가를 받을 수 있는 제품을 결정하는 임무를 맡고 있습니다. FDA가 많은 전자담배의 시판을 허가하지 않을 가능성에 대응하여, 전자담배 회사들은 담배에서 제조되거나 파생되지 않은 니코틴을 함유하고 있다고 주장하는 제품을 마케팅하기 시작했고, 따라서 대신 합성 니코틴을 함유하고 있으므로 FDA의 담배 규제 권한 밖에 있게 됩니다.[196] 마찬가지로 비담배(합성) 니코틴을 함유하고 있다고 주장한 니코틴 파우치도 소개됐습니다. 합성 니코틴의 가격은 제품의 시장이 증가함에 따라 감소했습니다. 2022년 3월, 미국 의회는 FDA의 담배 규제 권한을 모든 출처의 니코틴이 포함된 담배 제품을 포함하도록 확장하여 합성 니코틴으로 만든 제품을 포함하는 법(Consolidated Adopment Act, 2022)을 통과시켰습니다.

법적 지위

니코틴 제품 및 니코틴 대체 요법 제품은 미국에서 18세 이상에게만 제공되며, 나이 증명은 필수이며, 나이 증명이 확인되지 않는 자판기 또는 출처에서 판매되지 않습니다. 2019년 기준 미국에서 담배를 사용할 수 있는 최소 연령은 연방 차원에서 21세입니다.[197]

유럽연합에서 니코틴 제품을 구매할 수 있는 최소 연령은 18세입니다. 그러나 담배나 니코틴 제품을 사용하기 위한 최소 연령 요건은 없습니다.[198]

영국에서는 2016년 담배 및 관련 제품 규정(Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016)이 2019년 담배 제품 및 니코틴 흡입 제품(Amendment 등)(EU Exit) 규정(2019) 및 2020년 담배 제품 및 니코틴 흡입 제품(Amendment)(EU Exit) 규정(2020)에 의해 개정된 유럽 지침(2014/40/EU)을 구현했습니다. 또한 기타 규정은 담배 제품 및 니코틴을 함유한 기타 제품의 광고, 판매 및 표시를 인간이 소비할 수 있도록 제한합니다. 수낙 정부는 아이들을 위한 일회용 베이프를 금지하고, 매력과 경제성을 제한할 것을 제안했습니다.

미디어에서

| 외부이미지 | |

|---|---|

일부 금연 문헌에서 담배 흡연과 니코틴 중독이 하는 해악은 닉 오틴으로 의인화되며, 담배나 담배꽁초의 일부 측면이 그 또는 그의 옷과 모자에 있는 휴머노이드(humanoid)로 표현됩니다.[199] 닉 오틴(Nick O'Teen)은 보건 교육 위원회(Health Education Council)를 위해 만들어진 악당이었습니다. 이 캐릭터는 DC 코믹스 캐릭터 슈퍼맨에 의해 좌절되기 전에 아이들을 담배에 중독되게 만드는 세 개의 애니메이션 금연 공익 광고에 등장했습니다.[199]

니코틴은 니코틴 사용과 관련된 위험에 대한 오명과 대중의 인식을 줄이기 위한 노력으로 1980년대 담배 산업과 2010년대 전자 담배 산업의 광고에서 종종 카페인과 비교되었습니다.[200]

조사.

중추신경계

급성/초기 니코틴 섭취는 신경 니코틴 수용체의 활성화를 유발하지만, 만성적인 저용량 니코틴 사용은 (내성 발달로 인한) 수용체의 탈감작을 초래하고 항우울 효과를 초래합니다. 저용량 니코틴 패치가 비 smokers의 주요 우울 장애의 효과적인 치료가 될 수 있다는 초기 연구 결과가 있습니다.

비록 담배 흡연이 알츠하이머병의 위험 증가와 관련이 있지만,[202] 니코틴 자체가 알츠하이머병을 예방하고 치료할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다는 증거가 있습니다.[203]

흡연은 파킨슨병의 위험 감소와 관련이 있습니다. 그러나 이것이 더 건강한 뇌 도파민 보상 센터(파킨슨병에 의해 영향을 받는 뇌의 영역)를 가진 사람들이 흡연을 즐길 가능성이 높기 때문에 그 습관을 습득하기 때문인지는 알 수 없습니다. 니코틴은 직접적으로 신경 보호제 역할을 합니다. 또는 신경 보호제 역할을 하는 담배 연기의 다른 화합물.[204]

면역계

선천성 면역계와 적응성 면역계의 면역세포는 니코틴성 아세틸콜린 수용체의2 α, α, α56, α, α710, α9 소단위를 발현하는 경우가 많습니다.[205] 증거는 이러한 소단위체를 포함하는 니코틴 수용체가 면역 기능의 조절에 관여한다는 것을 시사합니다.[205]

광약리학

특정 조건의 자외선에 노출되면 니코틴을 방출하는 광활성 형태의 니코틴은 뇌 조직에서 니코틴 아세틸콜린 수용체를 연구하기 위해 개발되었습니다.[206]

구강건강

여러 시험관 내 연구에서 니코틴이 다양한 구강 세포에 미치는 잠재적 영향을 조사했습니다. 최근 체계적인 검토에 따르면 니코틴은 대부분의 생리학적 조건에서 시험관 내 구강 세포에 세포독성이 없을 것으로 보이지만 추가 연구가 필요합니다.[207] 최근 새로운 니코틴 제품의 도입과 흡연자의 금연을 돕는 잠재적인 역할을 고려할 때 구강 건강에서 니코틴의 잠재적인 역할을 이해하는 것이 점점 더 중요해지고 있습니다.[208]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ McLaughlin I, Dani JA, De Biasi M (2015). "Nicotine Withdrawal". The Neuropharmacology of Nicotine Dependence. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 24. pp. 99–123. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-13482-6_4. ISBN 978-3-319-13481-9. PMC 4542051. PMID 25638335.

- ^ a b c D'Souza MS, Markou A (July 2011). "Neuronal mechanisms underlying development of nicotine dependence: implications for novel smoking-cessation treatments". Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 6 (1): 4–16. PMC 3188825. PMID 22003417.

Withdrawal symptoms upon cessation of nicotine intake: Chronic nicotine use induces neuroadaptations in the brain's reward system that result in the development of nicotine dependence. Thus, nicotine-dependent smokers must continue nicotine intake to avoid distressing somatic and affective withdrawal symptoms. Newly abstinent smokers experience symptoms such as depressed mood, anxiety, irritability, difficulty concentrating, craving, bradycardia, insomnia, gastrointestinal discomfort, and weight gain (Shiffman and Jarvik, 1976; Hughes et al., 1991). Experimental animals, such as rats and mice, exhibit a nicotine withdrawal syndrome that, like the human syndrome, includes both somatic signs and a negative affective state (Watkins et al., 2000; Malin et al., 2006). The somatic signs of nicotine withdrawal include rearing, jumping, shakes, abdominal constrictions, chewing, scratching, and facial tremors. The negative affective state of nicotine withdrawal is characterized by decreased responsiveness to previously rewarding stimuli, a state called anhedonia.

- ^ Cosci F, Pistelli F, Lazzarini N, Carrozzi L (2011). "Nicotine dependence and psychological distress: outcomes and clinical implications in smoking cessation". Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 4: 119–28. doi:10.2147/prbm.s14243. PMC 3218785. PMID 22114542.

- ^ Hollinger MA (19 October 2007). Introduction to Pharmacology (Third ed.). Abingdon: CRC Press. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-1-4200-4742-4.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "The Medicines (Products Other Than Veterinary Drugs) (General Sale List) Amendment Order 2001". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b Nicotine. PubChem Compound Database. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. 16 February 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d Landoni JH. "Nicotine (PIM)". INCHEM. International Programme on Chemical Safety. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Fagerström K (December 2014). "Nicotine: Pharmacology, Toxicity and Therapeutic use". Journal of Smoking Cessation. 9 (2): 53–59. doi:10.1017/jsc.2014.27.

- ^ Sajja RK, Rahman S, Cucullo L (March 2016). "Drugs of abuse and blood-brain barrier endothelial dysfunction: A focus on the role of oxidative stress". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 36 (3): 539–54. doi:10.1177/0271678X15616978. PMC 4794105. PMID 26661236.

- ^ "Nicotine: Clinical data". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

Used as an aid to smoking cessation and for the relief of nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

- ^ Abou-Donia M (5 February 2015). Mammalian Toxicology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 587–. ISBN 978-1-118-68285-2.

- ^ a b c d "Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Introduction". IUPHAR Database. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ a b Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 9: Autonomic Nervous System". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 234. ISBN 9780071481274.

Nicotine ... is a natural alkaloid of the tobacco plant. Lobeline is a natural alkaloid of Indian tobacco. Both drugs are agonists are nicotinic cholinergic receptors ...

- ^ Kishioka S, Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Saika F (2014). "Nicotine effects and the endogenous opioid system". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 125 (2): 117–24. doi:10.1254/jphs.14R03CP. PMID 24882143.

- ^ "Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Siegmund B, Leitner E, Pfannhauser W (August 1999). "Determination of the nicotine content of various edible nightshades (Solanaceae) and their products and estimation of the associated dietary nicotine intake". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 47 (8): 3113–20. doi:10.1021/jf990089w. PMID 10552617.

- ^ Rodgman A, Perfetti TA (2009). The chemical components of tobacco and tobacco smoke. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-7883-1. LCCN 2008018913.[페이지 필요]

- ^ a b c Ujváry I (1999). "Nicotine and Other Insecticidal Alkaloids". In Yamamoto I, Casida J (eds.). Nicotinoid Insecticides and the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag. pp. 29–69.

- ^ Perkins KA, Karelitz JL (August 2013). "Reinforcement enhancing effects of nicotine via smoking". Psychopharmacology. 228 (3): 479–86. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3054-4. PMC 3707934. PMID 23494236.

- ^ a b Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA (May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826.

- ^ a b c Siqueira LM (January 2017). "Nicotine and Tobacco as Substances of Abuse in Children and Adolescents". Pediatrics. 139 (1): e20163436. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3436. PMID 27994114.

- ^ Etter JF (July 2007). "Addiction to the nicotine gum in never smokers". BMC Public Health. 7: 159. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-159. PMC 1939993. PMID 17640334.

- ^ Olausson P, Jentsch JD, Taylor JR (January 2004). "Nicotine enhances responding with conditioned reinforcement". Psychopharmacology. 171 (2): 173–178. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1575-y. PMID 13680077. S2CID 11855403.

- ^ a b "Evidence Review of E-Cigarettes and Heated Tobacco Products" (PDF). Public Health England. 2018.

- ^ "Tobacco more addictive than Nicotine". Archived from the original on 20 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Royal College of Physicians (28 April 2016). "Nicotine without smoke: Tobacco harm reduction". Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ a b Smith TT, Rupprecht LE, Cwalina SN, Onimus MJ, Murphy SE, Donny EC, et al. (August 2016). "Effects of Monoamine Oxidase Inhibition on the Reinforcing Properties of Low-Dose Nicotine". Neuropsychopharmacology. 41 (9): 2335–2343. doi:10.1038/npp.2016.36. PMC 4946064. PMID 26955970.

- ^ a b c d Mayer B (January 2014). "How much nicotine kills a human? Tracing back the generally accepted lethal dose to dubious self-experiments in the nineteenth century". Archives of Toxicology. 88 (1): 5–7. doi:10.1007/s00204-013-1127-0. PMC 3880486. PMID 24091634.

- ^ Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Papale G, Russo C, Polosa R (February 2012). "The emerging phenomenon of electronic cigarettes". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 6 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1586/ers.11.92. PMID 22283580. S2CID 207223131.

- ^ Jain R, Mukherjee K, Balhara YP (April 2008). "The role of NMDA receptor antagonists in nicotine tolerance, sensitization, and physical dependence: a preclinical review". Yonsei Medical Journal. 49 (2): 175–88. doi:10.3349/ymj.2008.49.2.175. PMC 2615322. PMID 18452252.

- ^ Miyasato K (March 2013). "[Psychiatric and psychological features of nicotine dependence]". Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine. 71 (3): 477–81. PMID 23631239.

- ^ a b c Parrott AC (July 2015). "Why all stimulant drugs are damaging to recreational users: an empirical overview and psychobiological explanation". Human Psychopharmacology. 30 (4): 213–24. doi:10.1002/hup.2468. PMID 26216554. S2CID 7408200.

- ^ Parrott AC (March 2006). "Nicotine psychobiology: how chronic-dose prospective studies can illuminate some of the theoretical issues from acute-dose research" (PDF). Psychopharmacology. 184 (3–4): 567–76. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0294-y. PMID 16463194. S2CID 11356233.

- ^ a b c d e f g Parrott AC (April 2003). "Cigarette-derived nicotine is not a medicine". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 4 (2): 49–55. doi:10.3109/15622970309167951. PMID 12692774. S2CID 26903942.

- ^ Schraufnagel DE, Blasi F, Drummond MB, Lam DC, Latif E, Rosen MJ, et al. (September 2014). "Electronic cigarettes. A position statement of the forum of international respiratory societies". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 190 (6): 611–8. doi:10.1164/rccm.201407-1198PP. PMID 25006874. S2CID 43763340.

- ^ "E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. 2016 Surgeon General's report.lts" (PDF). surgeongeneral.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Schraufnagel DE (March 2015). "Electronic Cigarettes: Vulnerability of Youth". Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology. 28 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1089/ped.2015.0490. PMC 4359356. PMID 25830075.

- ^ IARC 인체 발암 위험 평가 워킹 그룹 개인의 습관과 실내 연소. Lyon (FR): 국제 암 연구 기관; 2012. (IARC Monographs, No. 100E) 담배를 피웁니다. 제공처: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304395/

- ^ a b "Does nicotine cause cancer?". European Code Against Cancer. World Health Organization – International Agency for Research on Cancer. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking Health (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, Chapter 5 - Nicotine. Surgeon General of the United States. pp. 107–138. PMID 24455788.

- ^ Kohlmeier KA (June 2015). "Nicotine during pregnancy: changes induced in neurotransmission, which could heighten proclivity to addict and induce maladaptive control of attention". Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 6 (3): 169–81. doi:10.1017/S2040174414000531. PMID 25385318. S2CID 29298949.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Nicotine". United States National Library of Medicine – Toxicology Data Network. Hazardous Substances Data Bank. 20 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Nicotine". European Chemicals Agency: Committee for Risk Assessment. September 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ Effah F, Taiwo B, Baines D, Bailey A, Marczylo T (October 2022). "Pulmonary effects of e-liquid flavors: a systematic review". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B: Critical Reviews. 25 (7): 343–371. Bibcode:2022JTEHB..25..343E. doi:10.1080/10937404.2022.2124563. PMC 9590402. PMID 36154615.

- ^ Lavoie FW, Harris TM (1991). "Fatal nicotine ingestion". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (3): 133–136. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(91)90318-a. PMID 2050970.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T (May 2018). "Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD000146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5. PMC 6353172. PMID 29852054.

There is high-quality evidence that all of the licensed forms of NRT (gum, transdermal patch, nasal spray, inhalator and sublingual tablets/lozenges) can help people who make a quit attempt to increase their chances of successfully stopping smoking. NRTs increase the rate of quitting by 50% to 60%, regardless of setting, and further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of the effect. The relative effectiveness of NRT appears to be largely independent of the intensity of additional support provided to the individual.

A meta-analysis of adverse events associated with NRT included 92 RCTs and 28 observational studies, and addressed a possible excess of chest pains and heart palpitations among users of NRT compared with placebo groups (Mills 2010). The authors report an OR of 2.06 (95% CI 1.51 to 2.82) across 12 studies. We replicated this data collection exercise and analysis where data were available (included and excluded) in this review, and detected a similar but slightly lower estimate, OR 1.88 (95% CI 1.37 to 2.57; 15 studies; 11,074 participants; OR rather than RR calculated for comparison; Analysis 6.1). Chest pains and heart palpitations were an extremely rare event, occurring at a rate of 2.5% in the NRT groups compared with 1.4% in the control groups in the 15 trials in which they were reported at all. A recent network meta-analysis of cardiovascular events associated with smoking cessation pharmacotherapies (Mills 2014), including 21 RCTs comparing NRT with placebo, found statistically significant evidence that the rate of cardiovascular events with NRT was higher (RR 2.29 95% CI 1.39 to 3.82). However, when only serious adverse cardiac events (myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death) were considered, the finding was not statistically significant (RR 1.95 95% CI 0.26 to 4.30). - ^ a b Theodoulou A, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Fanshawe TR, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. (June 2023). "Different doses, durations and modes of delivery of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (6): CD013308. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013308.pub2. PMC 10278922. PMID 37335995.

- ^ The MIND Study. "Why Nicotine?". MIND. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b Tomizawa M, Casida JE (2005). "Neonicotinoid insecticide toxicology: mechanisms of selective action". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 45: 247–68. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095930. PMID 15822177.

- ^ Rodgman A, Perfetti TA (2009). The chemical components of tobacco and tobacco smoke. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-7883-1. LCCN 2008018913.[페이지 필요]

- ^ "Tobacco and its evil cousin nicotine are good as a pesticide – American Chemical Society". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ USEPA (3 June 2009). "Nicotine; Product Cancellation Order". Federal Register: 26695–26696. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ 미국 연방 규정. 7 CFR 205.602 – 유기농 작물 생산에 사용 금지된 비합성 물질

- ^ Tharp C (5 September 2014). "Safety for Homemade Remedies for Pest Control" (PDF). Montana Pesticide Bulletin. Montana State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ a b Michalski B, Herrmann M, Solecki R (July 2017). "[How does a pesticide residue turn into a contaminant?]". Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (in German). 60 (7): 768–773. doi:10.1007/s00103-017-2556-3. PMID 28508955. S2CID 22662492.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (7 May 2009). "Potential risks for public health due to the presence of nicotine in wild mushrooms". EFSA Journal. 7 (5): 286r. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2009.286r.

- ^ Abreu-Villaça Y, Levin ED (February 2017). "Developmental neurotoxicity of succeeding generations of insecticides". Environment International. 99: 55–77. Bibcode:2017EnInt..99...55A. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.019. PMC 5285268. PMID 27908457.

- ^ Valentine G, Sofuoglu M (May 2018). "Cognitive Effects of Nicotine: Recent Progress". Current Neuropharmacology. 16 (4). Bentham Science Publishers: 403–414. doi:10.2174/1570159X15666171103152136. PMC 6018192. PMID 29110618.

- ^ Heishman SJ, Kleykamp BA, Singleton EG (July 2010). "Meta-analysis of the acute effects of nicotine and smoking on human performance". Psychopharmacology. 210 (4): 453–69. doi:10.1007/s00213-010-1848-1. PMC 3151730. PMID 20414766.

- ^ Sarter M (August 2015). "Behavioral-Cognitive Targets for Cholinergic Enhancement". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 4: 22–26. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.01.004. PMC 5466806. PMID 28607947.

- ^ "Nicotine: Biological activity". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

Kis as follows; α2β4=9900nM [5], α3β2=14nM [1], α3β4=187nM [1], α4β2=1nM [4,6]. Due to the heterogeneity of nACh channels we have not tagged a primary drug target for nicotine, although the α4β2 is reported to be the predominant high affinity subtype in the brain which mediates nicotine addiction

- ^ Majdi A, Kamari F, Vafaee MS, Sadigh-Eteghad S (October 2017). "Revisiting nicotine's role in the ageing brain and cognitive impairment" (PDF). Reviews in the Neurosciences. 28 (7): 767–781. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2017-0008. PMID 28586306. S2CID 3758298.

- ^ Uban KA, Horton MK, Jacobus J, Heyser C, Thompson WK, Tapert SF, et al. (August 2018). "Biospecimens and the ABCD study: Rationale, methods of collection, measurement and early data". Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 32: 97–106. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.005. PMC 6487488. PMID 29606560.

- ^ a b Stolerman IP, Jarvis MJ (January 1995). "The scientific case that nicotine is addictive". Psychopharmacology. 117 (1): 2–10, discussion 14–20. doi:10.1007/BF02245088. PMID 7724697. S2CID 8731555.

- ^ Wilder N, Daley C, Sugarman J, Partridge J (April 2016). "Nicotine without smoke: Tobacco harm reduction". UK: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 58, 125.

- ^ a b c El Sayed KA, Sylvester PW (June 2007). "Biocatalytic and semisynthetic studies of the anticancer tobacco cembranoids". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 16 (6): 877–87. doi:10.1517/13543784.16.6.877. PMID 17501699. S2CID 21302112.

- ^ Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A, Worrall-Carter L (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: patterns of use, health effects, use in smoking cessation and regulatory issues". Tobacco Induced Diseases. 12 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/1617-9625-12-21. PMC 4350653. PMID 25745382.

- ^ Little MA, Ebbert JO (2016). "The safety of treatments for tobacco use disorder". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 15 (3): 333–41. doi:10.1517/14740338.2016.1131817. PMID 26715118. S2CID 12064318.

- ^ Aubin HJ, Luquiens A, Berlin I (February 2014). "Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation: pharmacological principles and clinical practice". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 77 (2): 324–36. doi:10.1111/bcp.12116. PMC 4014023. PMID 23488726.

- ^ a b c Bailey SR, Crew EE, Riske EC, Ammerman S, Robinson TN, Killen JD (April 2012). "Efficacy and tolerability of pharmacotherapies to aid smoking cessation in adolescents". Paediatric Drugs. 14 (2): 91–108. doi:10.2165/11594370-000000000-00000. PMC 3319092. PMID 22248234.

- ^ "Electronic Cigarettes – What are the health effects of using e-cigarettes?" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 February 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

Nicotine is a health danger for pregnant women and their developing babies.

- ^ Bruin JE, Gerstein HC, Holloway AC (August 2010). "Long-term consequences of fetal and neonatal nicotine exposure: a critical review". Toxicological Sciences. 116 (2): 364–74. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq103. PMC 2905398. PMID 20363831.

there is no safe dose of nicotine during pregnancy... The general consensus among clinicians is that more information is needed about the risks of NRT use during pregnancy before well-informed definitive recommendations can be made to pregnant women... Overall, the evidence provided in this review overwhelmingly indicates that nicotine should no longer be considered the safe component of cigarette smoke. In fact, many of the adverse postnatal health outcomes associated with maternal smoking during pregnancy may be attributable, at least in part, to nicotine alone.

- ^ Forest S (1 March 2010). "Controversy and evidence about nicotine replacement therapy in pregnancy". MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 35 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e3181cafba4. PMID 20215949. S2CID 27085986.

- ^ Barua RS, Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, Cummings KM, Jazayeri MA, Morris PB, et al. (December 2018). "2018 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Tobacco Cessation Treatment: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 72 (25): 3332–3365. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.027. PMID 30527452.

- ^ a b Sanner T, Grimsrud TK (2015). "Nicotine: Carcinogenicity and Effects on Response to Cancer Treatment - A Review". Frontiers in Oncology. 5: 196. doi:10.3389/fonc.2015.00196. PMC 4553893. PMID 26380225.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Nicotine". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ 자세한 참조 목록은 별도의 이미지 페이지에 있습니다.

- ^ Vij K (2014). Textbook of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology: Principles & Practice (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 525. ISBN 978-81-312-3623-9. 525페이지 발췌

- ^ "NICOTINE : Systemic Agent". 8 July 2021.

- ^ Royal College of Physicians. "Nicotine Without Smoke -- Tobacco Harm Reduction". p. 125. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

Use of nicotine alone, in the doses used by smokers, represents little if any hazard to the user.

- ^ Douglas CE, Henson R, Drope J, Wender RC (July 2018). "The American Cancer Society public health statement on eliminating combustible tobacco use in the United States". CA. 68 (4): 240–245. doi:10.3322/caac.21455. PMID 29889305. S2CID 47016482.

It is the smoke from combustible tobacco products—not nicotine—that injures and kills millions of smokers.

- ^ Dinakar C, O'Connor GT (October 2016). "The Health Effects of Electronic Cigarettes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (14): 1372–1381. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1502466. PMID 27705269.

Beyond its addictive properties, short-term or long-term exposure to nicotine in adults has not been established as dangerous

- ^ a b Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T (May 2018). "Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD000146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5. PMC 6353172. PMID 29852054.

- ^ England LJ, Bunnell RE, Pechacek TF, Tong VT, McAfee TA (August 2015). "Nicotine and the Developing Human: A Neglected Element in the Electronic Cigarette Debate". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 49 (2): 286–293. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015. PMC 4594223. PMID 25794473.

- ^ "Nicotine Transdermal Patch" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Nicotrol NS" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ "Nicotrol" (PDF). Pfizer. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ a b Garcia AN, Salloum IM (October 2015). "Polysomnographic sleep disturbances in nicotine, caffeine, alcohol, cocaine, opioid, and cannabis use: A focused review". The American Journal on Addictions. 24 (7): 590–8. doi:10.1111/ajad.12291. PMID 26346395. S2CID 22703103.

- ^ Boutrel B, Koob GF (September 2004). "What keeps us awake: the neuropharmacology of stimulants and wakefulness-promoting medications". Sleep. 27 (6): 1181–94. doi:10.1093/sleep/27.6.1181. PMID 15532213.

- ^ Jaehne A, Loessl B, Bárkai Z, Riemann D, Hornyak M (October 2009). "Effects of nicotine on sleep during consumption, withdrawal and replacement therapy". Sleep Medicine Reviews (Review). 13 (5): 363–77. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2008.12.003. PMID 19345124.

- ^ a b Benowitz NL, Burbank AD (August 2016). "Cardiovascular toxicity of nicotine: Implications for electronic cigarette use". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 26 (6): 515–23. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2016.03.001. PMC 4958544. PMID 27079891.

- ^ Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW (September 2001). "DeltaFosB: a sustained molecular switch for addiction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (20): 11042–6. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9811042N. doi:10.1073/pnas.191352698. PMC 58680. PMID 11572966.

Although the ΔFosB signal is relatively long-lived, it is not permanent. ΔFosB degrades gradually and can no longer be detected in brain after 1–2 months of drug withdrawal ... Indeed, ΔFosB is the longest-lived adaptation known to occur in adult brain, not only in response to drugs of abuse, but to any other perturbation (that doesn't involve lesions) as well.

- ^ Nestler EJ (December 2012). "Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction". Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. 10 (3): 136–43. doi:10.9758/cpn.2012.10.3.136. PMC 3569166. PMID 23430970.

The 35–37 kD ΔFosB isoforms accumulate with chronic drug exposure due to their extraordinarily long half-lives. ... As a result of its stability, the ΔFosB protein persists in neurons for at least several weeks after cessation of drug exposure. ... ΔFosB overexpression in nucleus accumbens induces NFκB

- ^ Dougherty J, Miller D, Todd G, Kostenbauder HB (December 1981). "Reinforcing and other behavioral effects of nicotine". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 5 (4): 487–495. doi:10.1016/0149-7634(81)90019-1. PMID 7322454. S2CID 10076758.

- ^ a b Belluzzi JD, Wang R, Leslie FM (April 2005). "Acetaldehyde enhances acquisition of nicotine self-administration in adolescent rats". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (4): 705–712. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300586. PMID 15496937.

- ^ "Acetaldehyde RIVM".

- ^ Das S, Prochaska JJ (October 2017). "Innovative approaches to support smoking cessation for individuals with mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 11 (10): 841–850. doi:10.1080/17476348.2017.1361823. PMC 5790168. PMID 28756728.

- ^ Heishman SJ, Kleykamp BA, Singleton EG (July 2010). "Meta-analysis of the acute effects of nicotine and smoking on human performance". Psychopharmacology. 210 (4): 453–69. doi:10.1007/s00213-010-1848-1. PMC 3151730. PMID 20414766.

The significant effects of nicotine on motor abilities, attention, and memory likely represent true performance enhancement because they are not confounded by withdrawal relief. The beneficial cognitive effects of nicotine have implications for initiation of smoking and maintenance of tobacco dependence.

- ^ Baraona LK, Lovelace D, Daniels JL, McDaniel L (May 2017). "Tobacco Harms, Nicotine Pharmacology, and Pharmacologic Tobacco Cessation Interventions for Women". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 62 (3): 253–269. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12616. PMID 28556464. S2CID 1267977.

- ^ Dugas EN, Sylvestre MP, O'Loughlin EK, Brunet J, Kakinami L, Constantin E, et al. (February 2017). "Nicotine dependence and sleep quality in young adults". Addictive Behaviors. 65: 154–160. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.020. PMID 27816041.

- ^ Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Riemann D, Szagun B, Jaehne A, Brinkmeyer J, et al. (May 2014). "Impaired sleep quality and sleep duration in smokers-results from the German Multicenter Study on Nicotine Dependence". Addiction Biology. 19 (3): 486–96. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00487.x. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0025-BD0C-B. PMID 22913370. S2CID 1066283.

- ^ Bruijnzeel AW (May 2012). "Tobacco addiction and the dysregulation of brain stress systems". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 36 (5): 1418–41. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.015. PMC 3340450. PMID 22405889.

Discontinuation of smoking leads to negative affective symptoms such as depressed mood, increased anxiety, and impaired memory and attention...Smoking cessation leads to a relatively mild somatic withdrawal syndrome and a severe affective withdrawal syndrome that is characterized by a decrease in positive affect, an increase in negative affect, craving for tobacco, irritability, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, hyperphagia, restlessness, and a disruption of sleep. Smoking during the acute withdrawal phase reduces craving for cigarettes and returns cognitive abilities to pre-smoking cessation level

- ^ a b Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–43. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

- ^ a b Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–37. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. S2CID 19157711.

The knowledge of ΔFosB induction in chronic drug exposure provides a novel method for the evaluation of substance addiction profiles (i.e. how addictive they are). Xiong et al. used this premise to evaluate the potential addictive profile of propofol (119). Propofol is a general anaesthetic, however its abuse for recreational purpose has been documented (120). Using control drugs implicated in both ΔFosB induction and addiction (ethanol and nicotine), ...

Conclusions

ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure. The formation of ΔFosB in multiple brain regions, and the molecular pathway leading to the formation of AP-1 complexes is well understood. The establishment of a functional purpose for ΔFosB has allowed further determination as to some of the key aspects of its molecular cascades, involving effectors such as GluR2 (87,88), Cdk5 (93) and NFkB (100). Moreover, many of these molecular changes identified are now directly linked to the structural, physiological and behavioral changes observed following chronic drug exposure (60,95,97,102). New frontiers of research investigating the molecular roles of ΔFosB have been opened by epigenetic studies, and recent advances have illustrated the role of ΔFosB acting on DNA and histones, truly as a molecular switch (34). As a consequence of our improved understanding of ΔFosB in addiction, it is possible to evaluate the addictive potential of current medications (119), as well as use it as a biomarker for assessing the efficacy of therapeutic interventions (121,122,124). - ^ Marttila K, Raattamaa H, Ahtee L (July 2006). "Effects of chronic nicotine administration and its withdrawal on striatal FosB/DeltaFosB and c-Fos expression in rats and mice". Neuropharmacology. 51 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.02.014. PMID 16631212. S2CID 8551216.

- ^ Cardinale A, Nastrucci C, Cesario A, Russo P (January 2012). "Nicotine: specific role in angiogenesis, proliferation and apoptosis". Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 42 (1): 68–89. doi:10.3109/10408444.2011.623150. PMID 22050423. S2CID 11372110.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (2018). "Chapter 4: Nicotine". In Eaton DL, Kwan LY, Stratton K (eds.). Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. National Academies Press. ISBN 9780309468343.

- ^ Dasgupta P, Rizwani W, Pillai S, Kinkade R, Kovacs M, Rastogi S, et al. (January 2009). "Nicotine induces cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in a variety of human cancer cell lines". International Journal of Cancer. 124 (1). The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism: 36–45. doi:10.1002/ijc.23894. PMC 2826200. PMID 18844224.

- ^ Wong HP, Yu L, Lam EK, Tai EK, Wu WK, Cho CH (June 2007). "Nicotine promotes colon tumor growth and angiogenesis through beta-adrenergic activation". Toxicological Sciences. 97 (2): 279–287. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfm060. PMID 17369603.

- ^ Natori T, Sata M, Washida M, Hirata Y, Nagai R, Makuuchi M (October 2003). "Nicotine enhances neovascularization and promotes tumor growth". Molecules and Cells. 16 (2): 143–146. doi:10.1016/S1016-8478(23)13780-0. PMID 14651253.

- ^ Ye YN, Liu ES, Shin VY, Wu WK, Luo JC, Cho CH (January 2004). "Nicotine promoted colon cancer growth via epidermal growth factor receptor, c-Src, and 5-lipoxygenase-mediated signal pathway". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 308 (1): 66–72. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.058321. PMID 14569062. S2CID 9774853.

- ^ Merecz-Sadowska A, Sitarek P, Zielinska-Blizniewska H, Malinowska K, Zajdel K, Zakonnik L, et al. (January 2020). "A Summary of In Vitro and In Vivo Studies Evaluating the Impact of E-Cigarette Exposure on Living Organisms and the Environment". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (2): 652. doi:10.3390/ijms21020652. PMC 7013895. PMID 31963832.

이 기사에는 CC BY 4.0 라이센스로 제공되는 Merecz-Sadowska A, Sitarek P, Zielinska-Blizniewska H, Malinowska K, Zajdel K, Zakonnik L, Zajdel R의 텍스트가 포함되어 있습니다.

이 기사에는 CC BY 4.0 라이센스로 제공되는 Merecz-Sadowska A, Sitarek P, Zielinska-Blizniewska H, Malinowska K, Zajdel K, Zakonnik L, Zajdel R의 텍스트가 포함되어 있습니다. - ^ Kothari AN, Mi Z, Zapf M, Kuo PC (2014). "Novel clinical therapeutics targeting the epithelial to mesenchymal transition". Clinical and Translational Medicine. 3: 35. doi:10.1186/s40169-014-0035-0. PMC 4198571. PMID 25343018.

- ^ Knezevich A, Muzic J, Hatsukami DK, Hecht SS, Stepanov I (February 2013). "Nornicotine nitrosation in saliva and its relation to endogenous synthesis of N'-nitrosonornicotine in humans". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 15 (2): 591–5. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts172. PMC 3611998. PMID 22923602.

- ^ "List of Classifications – IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans". monographs.iarc.fr. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Sanner T, Grimsrud TK (31 August 2015). "Nicotine: Carcinogenicity and Effects on Response to Cancer Treatment - A Review". Frontiers in Oncology. 5: 196. doi:10.3389/fonc.2015.00196. PMC 4553893. PMID 26380225.

- ^ Ginzkey C, Steussloff G, Koehler C, Burghartz M, Scherzed A, Hackenberg S, et al. (August 2014). "Nicotine derived genotoxic effects in human primary parotid gland cells as assessed in vitro by comet assay, cytokinesis-block micronucleus test and chromosome aberrations test". Toxicology in Vitro. 28 (5): 838–846. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2014.03.012. PMID 24698733.

- ^ Ginzkey C, Friehs G, Koehler C, Hackenberg S, Hagen R, Kleinsasser NH (February 2013). "Assessment of nicotine-induced DNA damage in a genotoxicological test battery". Mutation Research. 751 (1): 34–39. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2012.11.004. PMID 23200805.

- ^ Ginzkey C, Stueber T, Friehs G, Koehler C, Hackenberg S, Richter E, et al. (January 2012). "Analysis of nicotine-induced DNA damage in cells of the human respiratory tract". Toxicology Letters. 208 (1): 23–29. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.09.029. PMID 22001448.

- ^ Behnke M, Smith VC (March 2013). "Prenatal substance abuse: short- and long-term effects on the exposed fetus". Pediatrics. 131 (3): e1009-24. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3931. PMC 8194464. PMID 23439891.

- ^ "State Health Officer's Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat" (PDF). California Department of Public Health. January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Holbrook BD (June 2016). "The effects of nicotine on human fetal development". Birth Defects Research. Part C, Embryo Today. 108 (2): 181–192. doi:10.1002/bdrc.21128. PMID 27297020.

- ^ Bruin JE, Gerstein HC, Holloway AC (August 2010). "Long-term consequences of fetal and neonatal nicotine exposure: a critical review". Toxicological Sciences. 116 (2): 364–374. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq103. PMC 2905398. PMID 20363831.

- ^ "Consumer Updates: Nicotine Replacement Therapy Labels May Change". FDA. 1 April 2013.

- ^ 독성학 및 응용 약리학. Vol. 44, Pg. 1, 1978.

- ^ a b Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM (September 2009). "Nicotinic plant poisoning". Clinical Toxicology. 47 (8): 771–81. doi:10.1080/15563650903252186. PMID 19778187. S2CID 28312730.

- ^ Smolinske SC, Spoerke DG, Spiller SK, Wruk KM, Kulig K, Rumack BH (January 1988). "Cigarette and nicotine chewing gum toxicity in children". Human Toxicology. 7 (1): 27–31. doi:10.1177/096032718800700105. PMID 3346035. S2CID 27707333.

- ^ Furer V, Hersch M, Silvetzki N, Breuer GS, Zevin S (March 2011). "Nicotiana glauca (tree tobacco) intoxication--two cases in one family". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 7 (1): 47–51. doi:10.1007/s13181-010-0102-x. PMC 3614112. PMID 20652661.

- ^ Gehlbach SH, Williams WA, Perry LD, Woodall JS (September 1974). "Green-tobacco sickness. An illness of tobacco harvesters". JAMA. 229 (14): 1880–3. doi:10.1001/jama.1974.03230520022024. PMID 4479133.

- ^ "CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Nicotine". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS (1984). "Neuroregulators and the reinforcement of smoking: towards a biobehavioral explanation". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 8 (4): 503–13. doi:10.1016/0149-7634(84)90007-1. PMID 6151160. S2CID 23847303.

- ^ Pomerleau OF, Rosecrans J (1989). "Neuroregulatory effects of nicotine". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 14 (6): 407–23. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(89)90040-1. hdl:2027.42/28190. PMID 2560221. S2CID 12080532.

- ^ Katzung BG (2006). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 99–105.

- ^ Xiu X, Puskar NL, Shanata JA, Lester HA, Dougherty DA (March 2009). "Nicotine binding to brain receptors requires a strong cation-pi interaction". Nature. 458 (7237): 534–7. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..534X. doi:10.1038/nature07768. PMC 2755585. PMID 19252481.

- ^ Nesbitt P (1969). 흡연, 생리적 각성, 정서적 반응. 미발표 박사학위 논문, 컬럼비아 대학교.

- ^ Parrott AC (January 1998). "Nesbitt's Paradox resolved? Stress and arousal modulation during cigarette smoking". Addiction. 93 (1): 27–39. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.465.2496. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931274.x. PMID 9624709.

- ^ Wadgave U, Nagesh L (July 2016). "Nicotine Replacement Therapy: An Overview". International Journal of Health Sciences. 10 (3): 425–35. doi:10.12816/0048737. PMC 5003586. PMID 27610066.

- ^ Grizzell JA, Echeverria V (October 2015). "New Insights into the Mechanisms of Action of Cotinine and its Distinctive Effects from Nicotine". Neurochemical Research. 40 (10): 2032–46. doi:10.1007/s11064-014-1359-2. PMID 24970109. S2CID 9393548.

- ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 369, 372–373. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ a b Dickson SL, Egecioglu E, Landgren S, Skibicka KP, Engel JA, Jerlhag E (June 2011). "The role of the central ghrelin system in reward from food and chemical drugs" (PDF). Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 340 (1): 80–7. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2011.02.017. hdl:2077/26318. PMID 21354264. S2CID 206815322. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

This reward link comprises a dopamine projection from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens together with a cholinergic input, arising primarily from the laterodorsal tegmental area.

- ^ a b c Picciotto MR, Mineur YS (January 2014). "Molecules and circuits involved in nicotine addiction: The many faces of smoking". Neuropharmacology (Review). 76 (Pt B): 545–53. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.028. PMC 3772953. PMID 23632083.

Rat studies have shown that nicotine administration can decrease food intake and body weight, with greater effects in female animals (Grunberg et al., 1987). A similar nicotine regimen also decreases body weight and fat mass in mice as a result of β4* nAChR-mediated activation of POMC neurons and subsequent activation of MC4 receptors on second order neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Mineur et al., 2011).

- ^ Levine A, Huang Y, Drisaldi B, Griffin EA, Pollak DD, Xu S, et al. (November 2011). "Molecular mechanism for a gateway drug: epigenetic changes initiated by nicotine prime gene expression by cocaine". Science Translational Medicine. 3 (107): 107ra109. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003062. PMC 4042673. PMID 22049069.

- ^ Volkow ND (November 2011). "Epigenetics of nicotine: another nail in the coughing". Science Translational Medicine. 3 (107): 107ps43. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003278. PMC 3492949. PMID 22049068.

- ^ Yoshida T, Sakane N, Umekawa T, Kondo M (January 1994). "Effect of nicotine on sympathetic nervous system activity of mice subjected to immobilization stress". Physiology & Behavior. 55 (1): 53–7. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(94)90009-4. PMID 8140174. S2CID 37754794.

- ^ Marieb EN, Hoehn K (2007). Human Anatomy & Physiology (7th Ed.). Pearson. pp. ?. ISBN 978-0-8053-5909-1.[페이지 필요]

- ^ Henningfield JE, Calvento E, Pogun S (2009). Nicotine Psychopharmacology. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 192. Springer. pp. 35, 37. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5. ISBN 978-3-540-69248-5.

- ^ Le Houezec J (September 2003). "Role of nicotine pharmacokinetics in nicotine addiction and nicotine replacement therapy: a review". The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 7 (9): 811–9. PMID 12971663.

- ^ Benowitz NL, Jacob P, Jones RT, Rosenberg J (May 1982). "Interindividual variability in the metabolism and cardiovascular effects of nicotine in man". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 221 (2): 368–72. PMID 7077531.

- ^ Russell MA, Jarvis M, Iyer R, Feyerabend C (April 1980). "Relation of nicotine yield of cigarettes to blood nicotine concentrations in smokers". British Medical Journal. 280 (6219): 972–976. doi:10.1136/bmj.280.6219.972. PMC 1601132. PMID 7417765.

- ^ Bhalala O (Spring 2003). "Detection of Cotinine in Blood Plasma by HPLC MS/MS". MIT Undergraduate Research Journal. 8: 45–50. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013.

- ^ Hukkanen J, Jacob P, Benowitz NL (March 2005). "Metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine". Pharmacological Reviews. 57 (1): 79–115. doi:10.1124/pr.57.1.3. PMID 15734728. S2CID 14374018.

- ^ Petrick LM, Svidovsky A, Dubowski Y (January 2011). "Thirdhand smoke: heterogeneous oxidation of nicotine and secondary aerosol formation in the indoor environment". Environmental Science & Technology. 45 (1): 328–33. Bibcode:2011EnST...45..328P. doi:10.1021/es102060v. PMID 21141815. S2CID 206939025.

- ^ "The danger of third-hand smoke: Plain language summary – Petrick et al., "Thirdhand smoke: heterogeneous oxidation of nicotine and secondary aerosol formation in the indoor environment" in Environmental Science & Technology". The Column. Vol. 7, no. 3. Chromatography Online. 22 February 2011.

- ^ Benowitz NL, Herrera B, Jacob P (September 2004). "Mentholated cigarette smoking inhibits nicotine metabolism". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 310 (3): 1208–15. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.066902. PMID 15084646. S2CID 16044557.

- ^ "Nicotine' actions on energy balance: Friend or foe?". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 219. March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Hu T, Yang Z, Li MD (December 2018). "Pharmacological Effects and Regulatory Mechanisms of Tobacco Smoking Effects on Food Intake and Weight Control". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 13 (4): 453–466. doi:10.1007/s11481-018-9800-y. PMID 30054897. S2CID 51727199.

Nicotine's weight effects appear to result especially from the drug's stimulation of α3β4 nicotine acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which are located on pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the arcuate nucleus (ARC), leading to activation of the melanocortin circuit, which is associated with body weight. Further, α7- and α4β2-containing nAChRs have been implicated in weight control by nicotine.

- ^ "NFPA Hazard Rating Information for Common Chemicals". Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Metcalf RL (2007), "Insect Control", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, p. 9

- ^ "L-Nicotine Material Safety Data Sheet". Sciencelab.com, Inc.

- ^ a b c Henry TA (1949). The Plant Alkaloids (PDF) (4th ed.). Philadelphia, Toronto: The Blakiston Company. pp. 36–43.

- ^ Gause GF (1941). "Chapter V: Analysis of various biological processes by the study of the differential action of optical isomers". In Luyet BJ (ed.). Optical Activity and Living Matter. A series of monographs on general physiology. Vol. 2. Normandy, Missouri: Biodynamica.

- ^ a b Zhang H, Pang Y, Luo Y, Li X, Chen H, Han S, et al. (July 2018). "Enantiomeric composition of nicotine in tobacco leaf, cigarette, smokeless tobacco, and e-liquid by normal phase high-performance liquid chromatography". Chirality. 30 (7): 923–931. doi:10.1002/chir.22866. PMID 29722457.

- ^ Hellinghausen G, Lee JT, Weatherly CA, Lopez DA, Armstrong DW (June 2017). "Evaluation of nicotine in tobacco-free-nicotine commercial products". Drug Testing and Analysis. 9 (6): 944–948. doi:10.1002/dta.2145. PMID 27943582.

- ^ Jenssen BP, Boykan R (February 2019). "Electronic Cigarettes and Youth in the United States: A Call to Action (at the Local, National and Global Levels)". Children. 6 (2): 30. doi:10.3390/children6020030. PMC 6406299. PMID 30791645.

이 문서에는 CC BY 4.0 라이센스로 제공되는 Jensen BP, Boykan R의 텍스트가 포함되어 있습니다.

이 문서에는 CC BY 4.0 라이센스로 제공되는 Jensen BP, Boykan R의 텍스트가 포함되어 있습니다. - ^ a b c Pictet A, Rotschy A (1904). "Synthese des Nicotins" [Synthesis of nicotine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 37 (2): 1225–1235. doi:10.1002/cber.19040370206.

- ^ Ho TL, Kuzakov EV (2004). "A New Approach to Nicotine: Symmetry Consideration for Synthesis Design". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 87 (10): 2712–2716. doi:10.1002/hlca.200490241.

- ^ Ye X, Zhang Y, Song X, Liu Q (2022). "Research Progress in the Pharmacological Effects and Synthesis of Nicotine". ChemistrySelect. 7 (12). doi:10.1002/slct.202104425. S2CID 247687372.

- ^ Lamberts BL, Dewey LJ, Byerrum RU (May 1959). "Ornithine as a precursor for the pyrrolidine ring of nicotine". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 33 (1): 22–6. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(59)90492-5. PMID 13651178.

- ^ Dawson RF, Christman DR, d'Adamo A, Solt ML, Wolf AP (1960). "The Biosynthesis of Nicotine from Isotopically Labeled Nicotinic Acids". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 82 (10): 2628–2633. doi:10.1021/ja01495a059.

- ^ Ashihara H, Crozier A, Komamine A, eds. (7 June 2011). Plant metabolism and biotechnology. Cambridge: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-74703-2.[페이지 필요]

- ^ Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob P (1 January 2009). "Nicotine Chemistry, Metabolism, Kinetics and Biomarkers". Nicotine Psychopharmacology. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 192. pp. 29–60. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_2. ISBN 978-3-540-69246-1. PMC 2953858. PMID 19184645.

- ^ Baselt RC (2014). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (10th ed.). Biomedical Publications. pp. 1452–6. ISBN 978-0-9626523-9-4.

- ^ Mündel T, Jones DA (July 2006). "Effect of transdermal nicotine administration on exercise endurance in men". Experimental Physiology. 91 (4): 705–13. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.2006.033373. PMID 16627574. S2CID 41954065.

- ^ Hellinghausen G, Roy D, Wang Y, Lee JT, Lopez DA, Weatherly CA, et al. (May 2018). "A comprehensive methodology for the chiral separation of 40 tobacco alkaloids and their carcinogenic E/Z-(R,S)-tobacco-specific nitrosamine metabolites". Talanta. 181: 132–141. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2017.12.060. PMID 29426492.

- ^ Liu B, Chen Y, Ma X, Hu K (September 2019). "Site-specific peak intensity ratio (SPIR) from 1D 2H/1H NMR spectra for rapid distinction between natural and synthetic nicotine and detection of possible adulteration". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 411 (24): 6427–6434. doi:10.1007/s00216-019-02023-6. PMID 31321470. S2CID 197593505.

- ^ Cheetham AG, Plunkett S, Campbell P, Hilldrup J, Coffa BG, Gilliland S, et al. (14 April 2022). Greenlief CM (ed.). "Analysis and differentiation of tobacco-derived and synthetic nicotine products: Addressing an urgent regulatory issue". PLOS ONE. 17 (4): e0267049. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1767049C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267049. PMC 9009602. PMID 35421170.

- ^ "Tobacco (leaf tobacco)". Transportation Information Service.

- ^ Baldwin IT (December 2001). "An ecologically motivated analysis of plant-herbivore interactions in native tobacco". Plant Physiology. 127 (4): 1449–1458. doi:10.1104/pp.010762. JSTOR 4280212. PMC 1540177. PMID 11743088.

- ^ N.d. 자연사 기반 식물 매개 RNAi 기반 연구는 니코틴 매개 항포식자 초식동물 방어 PNAS에서 CYP6B46의 역할을 밝혀냅니다.

- ^ Kessler D, Bhattacharya S, Diezel C, Rothe E, Gase K, Schöttner M, et al. (August 2012). "Unpredictability of nectar nicotine promotes outcrossing by hummingbirds in Nicotiana attenuata". The Plant Journal. 71 (4): 529–538. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05008.x. PMID 22448647.

- ^ Domino EF, Hornbach E, Demana T (August 1993). "The nicotine content of common vegetables". The New England Journal of Medicine. 329 (6): 437. doi:10.1056/NEJM199308053290619. PMID 8326992.

- ^ Moldoveanu SC, Scott WA, Lawson DM (April 2016). "Nicotine Analysis in Several Non-Tobacco Plant Materials". Beiträge zur Tabakforschung International/Contributions to Tobacco Research. 27 (2): 54–59. doi:10.1515/cttr-2016-0008.

- ^ Henningfield JE, Zeller M (March 2006). "Nicotine psychopharmacology research contributions to United States and global tobacco regulation: a look back and a look forward". Psychopharmacology. 184 (3–4): 286–91. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0308-4. PMID 16463054. S2CID 38290573.

- ^ Posselt W, Reimann L (1828). "Chemische Untersuchung des Tabaks und Darstellung eines eigenthümlich wirksamen Prinzips dieser Pflanze" [Chemical investigation of tobacco and preparation of a characteristically active constituent of this plant]. Magazin für Pharmacie (in German). 6 (24): 138–161.

- ^ Melsens LH (1843). "Note sur la nicotine" [Note on nicotine]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique. third series (in French). 9: 465–479, see especially page 470. [참고: 당시 화학자들이 탄소에 대해 원자량을 잘못 사용했기 때문에 멜센스가 제공하는 실험 공식은 올바르지 않습니다(12가 아닌 6).]

- ^ Pinner A, Wolffenstein R (1891). "Ueber Nicotin" [About nicotine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 24: 1373–1377. doi:10.1002/cber.189102401242.

- ^ Pinner A (1893). "Ueber Nicotin. Die Constitution des Alkaloïds" [About nicotine: The Constitution of the Alkaloids]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 26: 292–305. doi:10.1002/cber.18930260165.

- ^ Pinner A (1893). "Ueber Nicotin. I. Mitteilung". Archiv der Pharmazie. 231 (5–6): 378–448. doi:10.1002/ardp.18932310508. S2CID 83703998.

- ^ Zhang S. "E-Cigs Are Going Tobacco-Free With Synthetic Nicotine". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ a b Dale MM, Ritter JM, Fowler RJ, Rang HP. Rang & Dale's Pharmacology (6th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. p. 598. ISBN 978-0-8089-2354-1.

- ^ Connolly GN, Alpert HR, Wayne GF, Koh H (October 2007). "Trends in nicotine yield in smoke and its relationship with design characteristics among popular US cigarette brands, 1997-2005". Tobacco Control. 16 (5): e5. doi:10.1136/tc.2006.019695. PMC 2598548. PMID 17897974.

- ^ "Industry Documents Library". www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Jewett C (8 March 2022). "The Loophole That's Fueling a Return to Teenage Vaping". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Jewett C (8 March 2022). "The Loophole That's Fueling a Return to Teenage Vaping". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Jordt SE (September 2021). "Synthetic nicotine has arrived". Tobacco Control. 32 (e1): tobaccocontrol–2021–056626. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056626. PMC 8898991. PMID 34493630.

- ^ Center for Tobacco Products (26 September 2022). "Tobacco 21". FDA.

- ^ "21, 18, or 14: A look at the legal age for smoking around the world". Straits Times. 3 October 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ a b Jacob M (1 March 1985). "Superman versus Nick O'Teen — a children's anti-smoking campaign". Health Education Journal. 44 (1): 15–18. doi:10.1177/001789698504400104. S2CID 71246970.

- ^ Becker R (26 April 2019). "Why Big Tobacco and Big Vape love comparing nicotine to caffeine". The Verge.

- ^ Mineur YS, Picciotto MR (December 2010). "Nicotine receptors and depression: revisiting and revising the cholinergic hypothesis". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 31 (12): 580–6. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2010.09.004. PMC 2991594. PMID 20965579.

- ^ Peters R, Poulter R, Warner J, Beckett N, Burch L, Bulpitt C (December 2008). "Smoking, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly, a systematic review". BMC Geriatrics. 8: 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-8-36. PMC 2642819. PMID 19105840.

- ^ Henningfield JE, Zeller M (2009). "Nicotine Psychopharmacology: Policy and Regulatory". Nicotine Psychopharmacology. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 192. pp. 511–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_18. ISBN 978-3-540-69246-1. PMID 19184661.

- ^ Quik M, O'Leary K, Tanner CM (September 2008). "Nicotine and Parkinson's disease: implications for therapy". Movement Disorders. 23 (12): 1641–52. doi:10.1002/mds.21900. PMC 4430096. PMID 18683238.

- ^ a b Fujii T, Mashimo M, Moriwaki Y, Misawa H, Ono S, Horiguchi K, et al. (2017). "Expression and Function of the Cholinergic System in Immune Cells". Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 1085. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01085. PMC 5592202. PMID 28932225.

- ^ Banala S, Arvin MC, Bannon NM, Jin XT, Macklin JJ, Wang Y, et al. (May 2018). "Photoactivatable drugs for nicotinic optopharmacology". Nature Methods. 15 (5): 347–350. doi:10.1038/nmeth.4637. PMC 5923430. PMID 29578537.

- ^ Holliday RS, Campbell J, Preshaw PM (July 2019). "Effect of nicotine on human gingival, periodontal ligament and oral epithelial cells. A systematic review of the literature". Journal of Dentistry. 86: 81–88. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2019.05.030. PMID 31136818. S2CID 169035502.

- ^ Holliday R, Preshaw PM, Ryan V, Sniehotta FF, McDonald S, Bauld L, et al. (4 June 2019). "A feasibility study with embedded pilot randomised controlled trial and process evaluation of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation in patients with periodontitis". Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 5 (1): 74. doi:10.1186/s40814-019-0451-4. PMC 6547559. PMID 31171977.