트라마돌

Tramadol | |

| |

| 임상 데이터 | |

|---|---|

| 발음 | 트라마 인형 |

| 상호 | Ultram, Zytram, Ralivia[1] 등 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| Medline Plus | a695011 |

| 라이선스 데이터 | |

| 임신 카테고리 |

|

| 의존성 책임 | 저중간[3] |

| 루트 행정부. | 구강별, 정맥주사(IV), 근육내(IM), 직장 |

| 약물 클래스 | 오피오이드 진통제[4] |

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 약동학 데이터 | |

| 바이오 어베이러빌리티 | 70 ~ 75 % (입에 의한), 77 % (직장), 100% (IM)[8] |

| 단백질 결합 | 20%[3] |

| 대사 | CYP2D6 및 CYP3A4를[8][9] 통한 간 매개 탈메틸화 및 글루쿠론화 |

| 대사물 | O-데스메틸트라마돌, N-데스메틸트라마돌 |

| 조치의 개시 | 1시간 이내(입으로)[3] |

| 반감기 제거 | 6.3 ± 1.4 시간[9] |

| 작업 기간 | 6시간[10] |

| 배설물 | 소변(95%)[11] |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| PubChem CID | |

| 드러그뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니 | |

| 케그 | |

| 체비 | |

| 첸블 | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA ) | |

| ECHA 정보 카드 | 100.043.912 |

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |

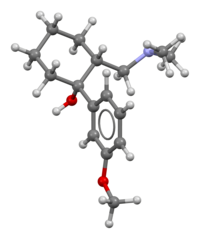

| 공식 | C16H25NO2 |

| 몰 질량 | 263.381 g/120−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| 녹는점 | 180~181°C(356~358°F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Tramadol은 [1]Ultram이라는 상표명으로 판매되며 중간에서 중간 정도의 심한 [3]통증을 치료하기 위해 사용되는 오피오이드 진통제이다.즉시 방출되는 제제로 입으로 복용할 경우, 통증 완화의 시작은 보통 [3]1시간 이내에 시작됩니다.주입으로도 [12]사용할 수 있습니다.파라세타몰(아세트아미노펜)과 함께 사용할 수 있습니다.

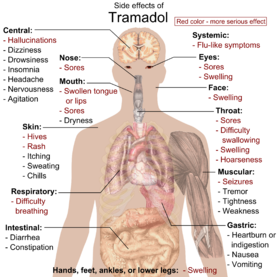

오피오이드와 마찬가지로 일반적인 부작용으로는 변비, 가려움증,[3] 메스꺼움 등이 있습니다.심각한 부작용으로는 환각, 발작, 세로토닌 증후군 위험 증가, 경각심 저하, 약물 [3]중독 등이 있을 수 있다.신장이나 간에 [3]문제가 있는 사람들에게는 복용량의 변화가 권장될 수 있다.자살 위험이 있는 사람이나 [3][12]임신한 사람에게는 권장되지 않습니다.모유 수유를 하는 여성에게는 권장되지 않지만, 한 번 복용하는 여성에게는 일반적으로 모유 [13]수유를 중단해서는 안 됩니다.트라마돌은 간에서 O-desmethyltramadol(desmetramadol)로 변환되며, O-desmethyltramadol은 μ-opioid [3][14]수용체에 대한 친화력이 강한 오피오이드이다.또한 트라마돌은 세로토닌-노레피네프린 재흡수 억제제(SNRI)[3][15]이다.

역사, 사회, 문화

Tramadol은 1963년 특허를 받았으며 1977년 서독 제약회사 Grünenthal GmbH에 [15][16]의해 "Tramal"이라는 이름으로 출시되었습니다.1990년대 중반, [15]그것은 영국과 미국에서 승인되었다.일반 의약품으로 판매되고 [1][3]있으며 전 세계적으로 많은 브랜드 이름으로 판매되고 있습니다.2019년 미국에서 가장 흔하게 처방되는 약으로 1,900만 건 이상의 [17][18]처방을 받았다.

의료 용도

Tramadol[19](미국의 스케줄 IV 약물)은 주로 급성 [20][21]및 만성적인 가벼운 통증부터 심각한 통증까지 치료하는데 사용된다.섬유근통의 2차 치료제로 사용할 수 있는 적당한 증거가 있지만,[22] FDA의 승인을 받은 것은 아니다. 그러나 섬유근통의 2차 진통제로서의 사용은 NHS에 [23]의해 승인되었다.

진통 효과는 약 1시간, 경구 투여 후 즉시 방출되는 [20][21]제제로 2~4시간 정도 소요됩니다.용량 기준에서 트라마돌은 모르핀의 약 10분의 1 효력을 가지며(따라서 100mg은 10mg 모르핀에 비례하지만 달라질 수 있음), 페티딘 및 [24]코데인과 비교했을 때 실질적으로 동등한 효력을 가진다.중간 정도의 통증의 경우, 그 효과는 저용량에서 코데인과 매우 높은 용량에서 하이드로코돈의 효과와 동일하며, 심한 통증의 [20]경우 모르핀보다 효과가 낮다.

이러한 진통 효과는 약 6시간 [21]동안 지속됩니다.진통제의 효능은 개인의 유전자에 따라 상당히 다르다.특정 변종의 CYP2D6 효소를 가진 사람은 효과적인 통증 [11][20]조절을 위해 적절한 양의 활성 대사물(데스메트라마돌)을 생성하지 못할 수 있다.

수면 내과 의사들은 때때로 난치성 안절부절 못하는 다리 증후군(RLS),[25][26] 즉 도파민 작용제(프라미펙솔과 같은)나 알파-2-델타(αands2) 리간드(가벤티노이드)와 같은 일선 약물의 치료에 적절하게 반응하지 않는 RLS를 처방하는데, 이는 종종 [27]증대에 기인한다.

금지 사항

트라마돌은 비활성 [11][20]분자로 트라마돌을 대사하기 때문에 특정 유전자 변종의 CYP2D6 효소를 가진 개인에게 적절한 통증 조절을 제공하지 못할 수 있다.이러한 유전적 다형성은 현재 임상 [28]실무에서 정기적으로 테스트되지 않는다.

임신 및 수유

임신 중 트라마돌의 사용은 [29]신생아에게 일부 가역적 금단 효과를 일으킬 수 있기 때문에 일반적으로 피한다.프랑스의 소규모 예비 연구는 유산 위험이 증가했지만 [29]신생아의 심각한 기형은 보고되지 않았다는 것을 발견했다.수유 중 수유 사용은 일반적으로 금지되어 있지만, 작은 실험 결과 트라마돌을 복용하는 산모가 모유를 먹인 영아는 산모가 복용하는 용량 중 약 2.88%에 노출되었다.이 선량이 신생아를 해친다는 증거는 [29]발견되지 않았다.

노동과 배달

진통 중 진통제로 사용하는 것은 작용 개시 시간(1시간)[29]이 길기 때문에 권장되지 않습니다.산모에게 진통제로 근육내 투여했을 때 태아의 평균 농도와 산모의 평균 농도의 비율은 1:[29]94로 추정되었다.

아이들.

어린이에게 사용하는 것은 일반적으로 금지되어 있지만 전문가의 [20]감독하에 실시될 수 있다.2015년 9월 21일 FDA는 17세 미만에서 사용되는 트라마돌의 안전성에 대한 조사를 시작했다.이 사람들 중 일부는 [30]호흡이 느려지거나 곤란을 겪었기 때문에 조사가 시작되었다.FDA는 12세 미만의 나이를 [31][32]금기 사항으로 명시하고 있다.

고령자

호흡기 우울증, 낙상, 인지장애, 진정제 등 오피오이드 관련 부작용의 위험이 증가한다.[20]트라마돌은 다른 약물과 상호작용하여 [28]부작용의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다.

간 및 신부전

이 약은 간(활성 분자 데스메트라마돌에 대한) 대사 및 [20]신장에 의한 제거로 인해 간 또는 신부전이 있는 사람에게 주의하여 사용해야 한다.

부작용

트라마돌의 가장 흔한 부작용은 메스꺼움, 어지럼증, 입마름, 소화불량, 복통, 현기증, 구토, 변비, 졸음, 그리고 [33][34]두통을 포함한다.다른 부작용은 다른 약과의 상호작용으로 인해 발생할 수 있다.트라마돌은 모르핀과 같은 용량 의존적 부작용(호흡기 [35]저하 등)을 가지고 있다.

의존과 탈퇴

트라마돌의 장기 복용은 신체적 의존과 금단 [36]증후군을 일으킨다.여기에는 전형적인 오피오이드 금단 증상과 세로토닌-노레피네프린 재흡입 억제제(SNRI) 금단 증세가 모두 포함된다. 증상에는 저림, 따끔거림, 예민함, 이명 [37]등이 포함된다.정신의학적 증상으로는 환각, 편집증, 극도의 불안, 공황 발작, [38]혼란 등이 있을 수 있다.대부분의 경우, 트라마돌 인출은 마지막 선량 이후 12-20시간 후에 설정되지만,[37] 이는 달라질 수 있다.트라마돌 금단 현상은 일반적으로 다른 오피오이드보다 오래 지속됩니다.다른 코데인 [37]유사체의 경우 일반적으로 3일 또는 4일이 아닌 7일 이상의 급성 금단 증상이 발생할 수 있습니다.

과다 복용

트라마돌 과다복용의 위험인자로는 호흡기 우울증, 중독, [39]발작 등이 있다.나록손은 트라마돌 과다 복용의 독성 효과를 부분적으로만 되돌리고 [20]발작의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다.

북아일랜드에서는 트라마돌 과다복용으로 인한 사망이 보고되고 있으며, 이러한 과다복용의 대부분은 [39]알코올을 포함한 다른 약물과 관련되어 있다.2013년 잉글랜드와 웨일스에서 254명, 2011년 [40][41]플로리다에서 379명이 사망했다.2011년 미국의 응급실 방문 건수는 21,649건이었다.[42]

상호 작용

트라마돌은 유사한 작용 메커니즘으로 다른 약물과 상호작용할 수 있다.

트라마돌은 세로토닌-노레피네프린 재흡수 억제제로 작용하여 다른 세로토닌 작동성 약물(선택적인 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제, 세로토닌-노레피네프린 재흡수 억제제, 세환성 항우울제, 트립탄, 기침, 덱스트로메토판을 포함하는 감기약)과 상호작용할 수 있다. John's wort 및 모노아민 산화효소 억제제와 같은 세로토닌의 대사를 억제하는 약물과 조합하여 세로토닌 증후군을 일으킬 수 있다.또한 일부 세로토닌 길항제([43]온단세트론)의 효과를 저하시킬 수 있습니다.

트라마돌은 또한 오피오이드 작용제로 작용하며, 따라서 다른 오피오이드 진통제(모핀, 페티딘, 타펜타돌, 옥시코돈, 펜타닐 [44]등)와 함께 사용될 때 부작용의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다.

트라마돌은 모든 약물의 약 25%의 신진대사에 기여하는 CYP2D6 효소에 의해 대사된다.이러한 효소를 억제하거나 유도할 수 있는 약물은 트라마돌과 [43]상호작용할 수 있다.

트라마돌은 발작 임계값을 낮추어 발작 위험을 높인다.발작 임계값을 낮추는 다른 약물(항정신병 약물 또는 암페타민 등)을 사용하면 이러한 [43]위험이 더욱 높아집니다.

약리학

작용 메커니즘

트라마돌은 노르아드레날린 시스템, 세로토닌 작동 시스템 및 오피오이드 수용체 [45]시스템의 다양한 다른 표적들을 통해 진통 효과를 유도한다.트라마돌은 라세미 혼합물로 존재하며, 양성 에난티오머는 세로토닌 재흡수를 억제하고, 음성 에난티오머는 노르아드레날린 재흡수를 억제하며, 트랜스포터에 [46][10]결합 및 차단한다.트라마돌은 또한 세로토닌 방출제로도 작용하는 것으로 나타났다.트라마돌의 두 에난티오머는 모두 μ-오피오이드 수용체의 작용제이며, 그 M1 대사물인 O-데스메트라마돌도 μ-오피오이드 수용체 작용제이지만 트라마돌 [47]자체보다 6배 강력하다.이 모든 효과는 진통을 유발하기 위해 상승작용을 한다.

| ★★★ | DSMT | species | ★ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | ,600~12,486 ,120-8,300 ≥1,000(EC50) | .4~18.6 17((+)) ≥240(EC50) | ★★★ rat ★★★ | [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] [56] [14] |

| DOR | 10,상 > ,600 ~100,000 | 2 2,900엔 690(+)) | ★★★ rat | [51] [52] [57] [55] [54] |

| KOR | 10,상 > ~,700 ~81,000 | 450450 1800(+)) | ★★★ rat | [51] [52] [57] [55] [54] |

| SERT | ~900(IC50) –1,196 | >2만(IC50) 2,980((−))(IC50) | ★★★ rat | [58] [55] [14] |

| NET | 14,600 785 | 1,080(−)(IC50) >860(IC50) | ★★★ rat | [14] [55] [14] |

| DAT | 100,000 상 | > 2회 | rat | [59] [57] |

| 5-HT1A | > 2회 | > 2회 | rat | [57] |

| 5-HT2A | ,000 † | ,000 † | rat | [57] |

| 5-HT2C | 1,000 (IC50) | 1,300 (IC50) | rat | [60] [61] |

| 5-HT3 | ,000 † | ,000 † | rat | [57] |

| NK1 | IA | rat | [62] [63] | |

| M1 | ,000 † 3,400 (IC50) | ,000 † 2,000 (IC50) | rat | [57] [64] [65] |

| M2 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M3 | 1,000 (IC50) | IA | ★★★ | [65] [66] |

| M4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M5 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| α7 | 7,400 | ND | . | [67] |

| σ1 | 10,상 > | ND | rat | [48] [68] |

| σ2 | 10,상 > | ND | rat | [48] |

| NMDAR | 16,400 (IC50) | 16,500 (IC50) | ★★★ | [69] |

| NMDAR MK-801 (MK-801) | ,000 † | ,000 † | rat | [57] |

| GABAA | 100,000 이상50 (IC) | 100,000 이상50 (IC) | ★★★ | [69] |

| GlyR | 100,000 이상50 (IC) | 100,000 이상50 (IC) | ★★★ | [69] |

| TRPA1 | 100 ~ 10,000()SI | 1, 1,000 ~ 10,000()SI | ★★★ | [70] |

| TRPV1 | 10,000 이상 (IC50) | 10,000 이상 (IC50) | ★★★ | [70]] [71 ] |

| 특별히 명기되어 있지 않는 한 값은 K(nMi)입니다.값이 작을수록 약물이 사이트에 강하게 결합됩니다. | ||||

| 치 | |

|---|---|

| 5-HT 재입수 | 1,820 |

| 5-HT 해방. | 10,> 10,상이 |

| NE 재입수 | 2,770 |

| NE 해방. | 10,> 10,상이 |

| DA 재입수 | 10,> 10,상이 |

| DA 해방. | 10,> 10,상이 |

| 재흡수 억제의 값은i K(nM), 방출 유도의 값은 EC(nM)이다50. | |

Tramadol은 다음과 같은 작용을 [49][50][46]하는 것으로 확인되었습니다.

- μ-오피오이드 수용체(MOR)의 작용제 및 γ-오피오이드 수용체(DOR) 및 γ-오피오이드 수용체(KOR)의 훨씬 적은 범위

- 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제(SRI) 및 노르에피네프린 재흡수 억제제(SNRI)

- 5-HT수용체2C

- M1 및3 M 무스카린성 아세틸콜린 수용체 길항제

- α7니코틴성 아세틸콜린수용체길항제

- NMDA 수용체 길항제(매우 약함)

- TRPA1

트라마돌은 주요 활성대사물인 데스메트라마돌을 통해 오피오이드 수용체에 작용하며, 이는 트라마돌에 [14]비해 MOR에 대한 친화력이 700배 이상 높다.또한 트라마돌 자체는 기능성 활성 측정에서 MOR 활성화에 효과가 없는 것으로 확인되었으며, 데스메트라마돌은 높은 내인성 활성(E는 [56][14][73]모르핀과 동일)으로max 수용체를 활성화한다.이와 같이 데스메트라마돌은 트라마돌의 [74]오피오이드 효과만을 담당한다.tramadol과 desmetramadol 모두 결합 [57][52][54]친화성 측면에서 DOR 및 KOR보다 MOR에 대한 선택성이 뚜렷하다.

Tramadol은 [49][50]SRI로서 확립되어 있다.또한 몇 가지 연구에 따르면, 펜플루라민과 [75][76][77][78]유사한 세로토닌 방출제(1~10μM) 역할을 하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.tramadol의 세로토닌을 영향 펜플루라민과 MDMA.[75][77][78] 하지만 같은 다른 세로토닌을 방출함 요원들에 의거하여 있는 세로토닌 재흡수 방해제 6-nitroquipazine의 충분히 높은 농도에 의해 차단될 수 있다면 두번 더 최근의 연구 각 사에서 tramadol의 해제 효과를 찾는 데 실패했습니다ncentration최대 10 μM과 30 μM입니다.[79][78][72]세로토닌 활성 외에 트라마돌은 노르에피네프린 재흡수 [49][50]억제제이다.그것은 노르에피네프린 방출제가 [80][81][82][72]아니다.트라마돌은 재흡수를 억제하거나 [80][72]도파민 분비를 유도하지 않는다.

양전자 방출 단층 촬영 영상 연구는 인간 지원자에 대한 단일 경구 50mg 및 100mg 용량 트라마돌을 통해 시상에서 세로토닌 운반체(SERT)[83]의 평균 점유율이 각각 34.7%, 50.2%로 나타났다는 것을 발견했다.따라서 SERT 점유에 대한 추정 중앙 유효 선량(ED50)은 98.1mg이었으며, 이는 약 330ng/ml(1,300nM)[83]의 혈장 트라마돌 수치와 관련이 있었다.400mg(100mg)의 트라마돌 추정 일일 최대 투여량은 (1,220ng/ml 또는 4,632nM의 [83]혈장 농도와 관련하여) 78.7%의 SERT 점유율을 가져올 것이다.이는 SERT를 80% [83]이상 점유하고 있는SSRI와 거의 비슷합니다.

트라마돌의 임상 용량으로 치료 중 최대 혈장 농도는 트라마돌의 경우 일반적으로 70 - 592ng/ml(266 - 2,250nM), 데스메트라마돌의 [21]경우 55 - 143ng/ml(221 - 573nM) 범위에 있는 것으로 밝혀졌다.1일 최대 경구 투여량인 400mg을 6시간마다 1회 100mg 용량으로 나눈 트라마돌(즉,[21][84] 100mg 용량 4회 균등 간격)에서 가장 높은 수치가 관찰되었다.트라마돌의 일부 축적은 만성 투여 시 발생한다. 최대 경구 일일 용량(100mg)의 피크 혈장 수치는 단일 경구 100mg [21]용량에 비해 약 16% 더 높고 곡선 아래 영역 수치는 36% 더 높다.보도에 따르면 양전자 방출 단층 촬영 연구는 트라마돌 수치가 [80][85]혈장보다 뇌에서 최소 4배 더 높다는 것을 발견했다.반대로, 데스메트라마돌의 뇌 수준은 "혈장 [80]내 뇌 수준에만 서서히 접근한다".트라마돌의 혈장 단백질 결합은 4~20%에 불과하며, 따라서 유통 중인 거의 모든 트라마돌은 자유롭기 때문에 생물 [86][87][88]활성이다.

와의

강력한 CYP2D6 효소 억제제인 키니딘과 데스메트라마돌의 수치를 현저하게 감소시키는 조합인 트라마돌의 동시 투여는 인간 [14][87]지원자의 트라마돌의 진통 효과에 유의미한 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 밝혀졌다.그러나 다른 연구들은 트라마돌의 진통 효과가 CYP2D6 불량 [14][74]대사제에서 유의미하게 감소하거나 심지어 없다는 것을 발견했다.tramadol의 진통제 효과 부분적으로만 낼럭손에 의해, 인간의 volunteers,[14]에 따라서는 오피오이드가 유일한 원인 가능성이 있는지 여부를 나타내는 값, tramadol의 진통제 효과도 부분적으로 yohimbine, 5-HT3 수용체 길항제 ondansetron고, 5-HT7 수용체는 같은α2-adrenergic 수용체 길항제에 의해 거꾸로 되었다 거꾸로 되었다.tagonists SB-269970 및 SB-258719.[21][89]약리학적으로 트라마돌은 MOR에 결합할 뿐만 아니라 비정형 오피오이드 [90]활성과 같은 노르아드레네르기 및 세로토닌 작동 시스템에 작용하기 때문에 세로토닌 및 노르에피네프린의[8] 재섭취를 억제한다는 점에서 타펜타돌 및 메타돈과 유사하다.

트라마돌은 5-HT2C 수용체에 억제 작용을 한다.5-HT2C의 대립 부분적으로 고통과co-morbid로 반영된는 신경학적 질병을 가진 환자들에서obsessive–compulsive 우울 증상에 tramadol의 감소 효과를 일으킬 수 있다.로 5-HT2C하는 쥐 디스플레이는 간질 seizu에 취약한 증가[60]5-HT2C 봉쇄도 발작 역치는 낮출 것을 고려할 수 있다.때로는 자연사를 일으키기도 합니다그러나 발작 임계값의 감소는 높은 용량에서 트라마돌의 GABAA 수용체 추정 억제(100μM에서 [69][46]유의미한 억제)에 기인할 수 있다.또한, 데스메트라마돌은 DOR의 고친화성 배위자이며, DOR 작용제가 [54]발작을 유발하는 것으로 잘 알려져 있기 때문에, 이 수용체의 활성화는 일부 개인에서 발작을 유발하는 트라마돌의 능력에 관여할 수 있다.

트라마돌에 의한 메스꺼움과 구토는 세로토닌 [58]수치 증가를 통한 5-HT3 수용체의 활성화에 기인하는 것으로 생각된다.따라서 5-HT3 수용체 길항제 온단셋론은 트라마돌 관련 메스꺼움 및 [58]구토 치료에 사용할 수 있다.트라마돌과 데스메트라마돌 자체는 5-HT3 [58][50]수용체에 결합하지 않는다.

트라마돌은 시토크롬 P450 이소자임 CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP3A4를 통해 5가지 다른 대사물로 O- 및 N-탈메틸화된다.이 중 데스메틸트라마돌(O-desmethyltramadol)은 트라마돌의 200배에 달하는 μ-친화도를 가지며, 트라마돌 자체의 6시간에 비해 9시간의 제거 반감기를 가지므로 가장 유의하다.코데인과 마찬가지로 CYP2D6 활성을 저하시킨 인구의 6%에서 감소된 진통제 효과가 나타난다.CYP2D6 활성이 감소된 사람은 CYP2D6 [91][92]활성이 정상 수준인 사람과 동일한 수준의 통증 완화를 달성하기 위해 30%의 선량 증가가 필요하다.

제2상 간대사는 신장에서 배출되는 대사물을 수용성으로 만든다.따라서 감소된 선량은 신장 [21]및 간 장애에 사용될 수 있다.

분포량은 경구 투여 후 306l, 비경구 [21]투여 후 203l이다.

★★★

트라마돌은 두 이성질체가 서로의 진통제 [8]활성을 보완하기 때문에 R 및 S-스테레오 [8]이성질체의 라세미 혼합물로 판매된다.(+)-이성체는 γ-opiate 수용체에 대한 친화력이 높은 아편제로서 주로 활성된다(-)-[93]이성체보다 친화력이 20배 높다).

및 입체

|  |

| (1R, 2R)-트라마돌 | (1S,2S)-트라마돌 |

|  |

| (1R,2S)-트라마돌 | (1S, 2R)-트라마돌 |

트라마돌의 화학적 합성은 [94]문헌에 설명되어 있다.트라마돌[2-(디메틸아미노메틸)-1-(3-메톡시페닐)시클로헥산올]은 시클로헥산 고리에 2개의 입체 중심을 가진다.따라서 2-(디메틸아미노메틸)-1-(3-메톡시페닐) 시클로헥산올은 4가지 다른 형태로 존재할 수 있다.

- (1R, 2R)-이성체

- (1S,2S)-이성체

- (1R,2S)-이성체

- (1S,2R)-이성체

합성 경로는 (1R,2R) 이성질체와 (1S,2S) 이성질체의 (1:1 혼합물) 레이스메이트로 이어진다.(1R,2S)-이성체와 (1S,2R)-이성체의 라세미 혼합물도 미량 형성된다.염산염의 재결정화에 의해 (1R,2R) 이성질체 및 (1S,2S) 이성질체와 (1S,2R) 이성질체와의 분리를 실현한다.약물 트라마돌은 (1R,2R)-(+)- 및 (1S,2S)-(-)-에난티오머의 염산염의 레이스메이트이다.레이스메이트 [(1R,2R)-(+)-이성체 / (1S,2S)-(-)-이성체]의 분해능은 (R)-(-)- 또는 (S)-(+)-만델산을 사용하여[95] 기술되었다.트라마돌은 (1R,2R) 이성질체와 (1S,[98]2S) 이성질체의 서로 다른 생리학적[96] 효과에도 불구하고 레이스메이트로[97] 사용되기 때문에 이 과정은 산업적 응용을 찾지 못한다.

트라마돌과 데스메트라마돌은 혈액, 혈장, 혈청 또는 타액으로 정량화할 수 있으며, 중독 진단을 확인하거나 돌연사의 법의학적 조사를 지원할 수 있다.대부분의 상용 아편 면역측정 검사는 트라마돌 또는 그 주요 대사물과 유의하게 교차 반응하지 않으므로 크로마토그래피 기술을 사용하여 이러한 물질을 검출하고 정량화해야 합니다.트라마돌을 복용한 사람의 혈액 또는 혈장 내 데스메트라마돌 농도는 일반적으로 모약의 [99][100][101]10-20%이다.

와

★★★

사용 가능한 용량 형태로는 액체, 시럽, 드롭, 엘릭시르, 발포성 정제 및 물과 혼합하기 위한 분말, 캡슐, 연장 방출 제제를 포함한 정제, 좌약, 배합 분말 및 [20]주사 등이 있다.

★★★★★

미국 식품의약국(FDA)은 1995년 3월에 트라마돌을 승인했으며 2005년 [102]9월에는 연장 방출(ER) 제제를 승인했다.ER Tramadol은 미국 특허 번호 6,254,887과[103] 7074,430에 [104][105]의해 보호되었다.FDA는 이 특허의 유효기간을 [104]2014년 5월 10일로 명시했다.그러나 2009년 8월 미국 델라웨어 지방법원은 이 특허가 무효라고 판결했으며, 이듬해 연방 순회 항소법원이 이 결정을 확정했습니다.따라서 Ultram ER의 미국 내 범용 제품 제조 및 유통은 특허 [106]만료 전에 허용되었습니다.

상태

2014년 8월 18일 발효된 트라마돌은 미국 [107][108]연방 통제 물질법 부칙 IV에 포함되었다.그 이전에 일부 미국 주에서는 이미 트라마돌을 해당 [109][110][111]주법에 따라 스케줄 IV 통제 물질로 분류했습니다.

Tramadol은 대부분의 다른 오피오이드와 [20]같이 스케줄 8 통제 약물(권한 없는 소유)이 아닌 스케줄 4(처방 전용)에 분류된다.

2008년 5월부터 스웨덴은 트라마돌을 코데인 및 덱스트로프옥시펜과 동일한 범주에 속하는 통제 물질로 분류했지만, 일반 처방을 사용할 [112]수 있도록 허용했다.

영국은 2014년 6월 10일 트라마돌을 C등급, 스케줄 3 통제 약물로 분류했지만 안전 보관 [citation needed]요건에서 제외했다.

★★★

불법 마약 사용은 보코하람 테러조직의 [113][114][115]성공에 주요 요인으로 생각되고 있다.더 많은 양을 복용할 때, 그 약은 [113]"헤로인과 비슷한 효과를 낼 수 있다."전직 멤버 중 한 명은 "트라마돌을 탈 때마다 우리를 매우 높고 대담하게 만들었기 때문에 우리가 무엇을 하도록 보내지는 것 외에는 아무 것도 우리에게 중요하지 않았다"[113]고 말했다.Tramadol은 또한 가자지구에서 [116]대처 메커니즘으로 사용된다.그것은 또한 영국에서도 남용되어 TV 쇼인 프랭키 보일의 트라마돌 나이트 (2010)[117][118]의 제목에 영감을 주었다.

속

2013년, 연구자들은 아프리카 핀 쿠션 나무(Naclea latifolia)[127] 뿌리에서 비교적 높은 농도(1% 이상)로 트라마돌이 발견되었다고 보고했다.그러나 2014년에는 이 [128]지역 농가에 의해 소에 투여된 트라마돌에 의해 나무 뿌리에 트라마돌의 존재가 보고되었으며, 트라마돌과 그 대사물이 동물의 배설물에 존재하여 나무 주변의 토양을 오염시켰다.따라서, 트라마돌과 그 포유류의 대사물은 카메룬 북쪽의 나무 뿌리에서 발견되었지만,[128] 동물을 사육하기 위해 투여되지 않는 남쪽에서는 발견되지 않았다.

Lab Times 온라인의 2014년 사설은 가축이 금지된 국립공원에서 자라는 나무에서 샘플을 채취했다고 언급하면서 나무 뿌리의 트라마돌은 인위적인 오염의 결과라는 개념에 이의를 제기했다. 또한 연구원 Michel de Waard는 "수천, 수천 마리의 트라마돌을 처리한 소 si.검출된 농도를 산출하기 위해서는 "나무 주위를 만지고 거기서 소변을 본다"[129]는 내용이 필요합니다.

2015년 방사성 탄소 분석 결과 N.latifolia 뿌리에서 발견된 트라마돌은 식물 유래가 아니며 합성 [130]유래임이 확인되었다.

수의학

트라마돌은 토끼, 코티, 쥐와 날다람쥐를 포함한 많은 작은 포유동물, 기니피그, 페레트, 너구리뿐만 아니라 개와 고양이의 [131]수술 후, 부상과 관련된 만성(예: 암 관련) 통증을 치료하는데 사용될 수 있다.

| 종. | 모약의 반감기(h) | 데스메트라마돌의 반감기(h) | 모약의 최대 혈장 농도(ng/mL) | 데스메트라마돌의 최대 혈장 농도(ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 낙타 | 3.2(IM), 1.3(IV) | – | 0.44 (IV) | – |

| 고양이 | 3.40(구강), 2.23(IV) | 4.82(구강), 4.35(IV) | 914(구강), 1323(IV) | 655(구강), 366(IV) |

| 개 | 1.71(구강), 1.80(IV), 2.24(수직) | 2.18(구강), 90-5000(IV) | 1402.75 (구강) | 449.13(구강), 90~350(IV) |

| 당나귀 | 4.2(구강), 1.5(IV) | – | 2817 (구강) | – |

| 염소 | 2.67(구강), 0.94(IV) | – | 542.9(구강) | – |

| 말들 | 1.29~1.53(IV), 10.1(오럴) | 4(구강) | 637(IV), 256(오럴) | 47(구강) |

| 라마 | 2.54(IM), 2.12(IV) | 7.73(IM), 10.4(IV) | 4036(IV), 1360(IM) | 158(IV), 158(IM) |

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ a b c "Tramadol". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ "Tramadol Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Tramadol Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Tramadol". MedlinePlus. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 1 September 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2009. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ "Ralivia Product information". Health Canada. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Ultram- tramadol hydrochloride tablet, coated". DailyMed. 7 June 2022. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "List of nationally authorized medicinal products" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 28 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Brayfield, A, ed. (13 December 2013). "Tramadol Hydrochloride". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Ultram, Ultram ER (tramadol) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b Dayer P, Desmeules J, Collart L (1997). "[Pharmacology of tramadol]". Drugs. 53 (Suppl 2): 18–24. doi:10.2165/00003495-199700532-00006. PMID 9190321. S2CID 46970093.

- ^ a b c "Australian Label: Tramadol Sandoz 50 mg capsules" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. 4 November 2011. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ a b British national formulary : BNF 74 (74 ed.). British Medical Association. 2017. pp. 447–448. ISBN 978-0857112989.

- ^ "Tramadol Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Raffa RB, Buschmann H, Christoph T, Eichenbaum G, Englberger W, Flores CM, et al. (July 2012). "Mechanistic and functional differentiation of tapentadol and tramadol". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 13 (10): 1437–1449. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.696097. PMID 22698264. S2CID 24226747.

- ^ a b c Leppert W (November–December 2009). "Tramadol as an analgesic for mild to moderate cancer pain". Pharmacological Reports. 61 (6): 978–992. doi:10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70159-8. PMID 20081232.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 528. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2019". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Tramadol – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Tramadol Hydrochloride Tablet Uses, Dosage, Benefits, Side Effects, Warnings, Free Advice About Tramadol 2021". 19 November 2021. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Grond S, Sablotzki A (2004). "Clinical pharmacology of tramadol". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 43 (13): 879–923. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443130-00004. PMID 15509185. S2CID 32347667.

- ^ MacLean AJ, Schwartz TL (May 2015). "Tramadol for the treatment of fibromyalgia". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 15 (5): 469–475. doi:10.1586/14737175.2015.1034693. PMID 25896486. S2CID 26613022.

- ^ "Treatment – Fibromyalgia (NHS)". NHS. 20 February 2019. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Lee CR, McTavish D, Sorkin EM (August 1993). "Tramadol. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in acute and chronic pain states". Drugs. 46 (2): 313–340. doi:10.2165/00003495-199346020-00008. PMID 7691519. S2CID 218465760.

- ^ Silber MH, Becker PM, Buchfuhrer MJ, Earley CJ, Ondo WG, Walters AS, Winkelman JW (January 2018). "The Appropriate Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Refractory Restless Legs Syndrome". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 93 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.11.007. PMID 29304922.

In summary, a number of opioid medications in low dose appear effective in refractory RLS. The risks of opioid use are relatively low, taking into account the much lower doses used for RLS compared with those in patients with pain syndromes. As long as reasonable precautions are taken, the risk-benefit ratio is acceptable and opioids should not be unreasonably withheld from such patients.

- ^ Winkelmann J, Allen RP, Högl B, Inoue Y, Oertel W, Salminen AV, et al. (July 2018). "Treatment of restless legs syndrome: Evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice (Revised 2017)§". Movement Disorders. 33 (7): 1077–1091. doi:10.1002/mds.27260. PMID 29756335. S2CID 21669996. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Lipford MC, Silber MH (December 2012). "Long-term use of pramipexole in the management of restless legs syndrome". Sleep Medicine. 13 (10): 1280–1285. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2012.08.004. PMID 23036265.

For the purposes of this study, augmentation was defined as earlier onset, increased severity, [increased] duration, or new anatomic distribution of RLS symptoms during treatment.

- ^ a b Miotto K, Cho AK, Khalil MA, Blanco K, Sasaki JD, Rawson R (January 2017). "Trends in Tramadol: Pharmacology, Metabolism, and Misuse". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 124 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001683. PMID 27861439. S2CID 24224625.

- ^ a b c d e Bloor M, Paech MJ, Kaye R (April 2012). "Tramadol in pregnancy and lactation". International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 21 (2): 163–167. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2011.10.008. PMID 22317891.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA evaluating the risks of using the pain medicine tramadol in children aged 17 and younger". FDA. FDA Drug Safety and Availability. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ Office of the Commissioner. "Press Announcements – FDA statement from Douglas Throckmorton, M.D., deputy center director for regulatory programs, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, on new warnings about the use of codeine and tramadol in children & nursing mothers". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA restricts use of prescription codeine pain and cough medicines and tramadol pain medicines in children; recommends against use in breastfeeding women". Food and Drug Administration. 9 February 2019. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Langley PC, Patkar AD, Boswell KA, Benson CJ, Schein JR (January 2010). "Adverse event profile of tramadol in recent clinical studies of chronic osteoarthritis pain". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 26 (1): 239–251. doi:10.1185/03007990903426787. PMID 19929615. S2CID 20703694.

- ^ Keating GM (2006). "Tramadol sustained-release capsules". Drugs. 66 (2): 223–230. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666020-00006. PMID 16451094. S2CID 22620947.

- ^ ""Weak" opioid analgesics. Codeine, dihydrocodeine and tramadol: no less risky than morphine". Prescrire International. 25 (168): 45–50. February 2016. PMID 27042732.

- ^ "Withdrawal syndrome and dependence: tramadol too". Prescrire International. 12 (65): 99–100. June 2003. PMID 12825576.

- ^ a b c Epstein DH, Preston KL, Jasinski DR (July 2006). "Abuse liability, behavioral pharmacology, and physical-dependence potential of opioids in humans and laboratory animals: lessons from tramadol". Biological Psychology. 73 (1): 90–99. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.01.010. PMC 2943845. PMID 16497429.

- ^ Senay EC, Adams EH, Geller A, Inciardi JA, Muñoz A, Schnoll SH, et al. (April 2003). "Physical dependence on Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride): both opioid-like and atypical withdrawal symptoms occur". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 69 (3): 233–241. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.524.5426. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00321-6. PMID 12633909.

- ^ a b Randall C, Crane J (March 2014). "Tramadol deaths in Northern Ireland: a review of cases from 1996 to 2012". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 23: 32–36. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2014.01.006. PMID 24661703.

- ^ White M. "Tramadol Deaths in the United Kingdom" (pdf_e). Public Health England. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Fauber J (22 December 2013). "Killing Pain: Tramadol the 'Safe' Drug of Abuse". Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Scheck J (19 October 2016). "Tramadol: The Opioid Crisis for the rest of the World". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Co. Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Miotto K, Cho AK, Khalil MA, Blanco K, Sasaki JD, Rawson R (January 2017). "Trends in Tramadol: Pharmacology, Metabolism, and Misuse". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 124 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001683. PMID 27861439. S2CID 24224625.

- ^ Pasternak GW (March 2012). "Preclinical pharmacology and opioid combinations". Pain Medicine. 13 (1): S4-11. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01335.x. PMC 3307386. PMID 22420604.

- ^ Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E (2015). Top 100 drugs : clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-0-7020-5516-4.

- ^ a b c Vazzana M, Andreani T, Fangueiro J, Faggio C, Silva C, Santini A, et al. (March 2015). "Tramadol hydrochloride: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, adverse side effects, co-administration of drugs and new drug delivery systems". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 70: 234–238. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2015.01.022. PMID 25776506.

- ^ "Tramadol". www.drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Minami K, Uezono Y, Ueta Y (March 2007). "Pharmacological aspects of the effects of tramadol on G-protein coupled receptors". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 103 (3): 253–260. doi:10.1254/jphs.cr0060032. PMID 17380034.

- ^ a b c d e Minami K, Ogata J, Uezono Y (October 2015). "What is the main mechanism of tramadol?". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 388 (10): 999–1007. doi:10.1007/s00210-015-1167-5. PMID 26292636. S2CID 9066672.

- ^ a b c Wentland MP, Lou R, Lu Q, Bu Y, VanAlstine MA, Cohen DJ, Bidlack JM (January 2009). "Syntheses and opioid receptor binding properties of carboxamido-substituted opioids". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 19 (1): 203–208. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.134. PMID 19027293.

- ^ a b c d Shen Q, Qian Y, Huang X, Xu X, Li W, Liu J, Fu W (April 2016). "Discovery of Potent and Selective Agonists of δ Opioid Receptor by Revisiting the "Message-Address" Concept". ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 7 (4): 391–396. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00423. PMC 4834657. PMID 27096047.

- ^ Volpe DA, McMahon Tobin GA, Mellon RD, Katki AG, Parker RJ, Colatsky T, et al. (April 2011). "Uniform assessment and ranking of opioid μ receptor binding constants for selected opioid drugs". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 59 (3): 385–390. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.12.007. PMID 21215785. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Potschka H, Friderichs E, Löscher W (September 2000). "Anticonvulsant and proconvulsant effects of tramadol, its enantiomers and its M1 metabolite in the rat kindling model of epilepsy". British Journal of Pharmacology. 131 (2): 203–212. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703562. PMC 1572317. PMID 10991912.

- ^ a b c d e Codd EE, Shank RP, Schupsky JJ, Raffa RB (September 1995). "Serotonin and norepinephrine uptake inhibiting activity of centrally acting analgesics: structural determinants and role in antinociception". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 274 (3): 1263–1270. PMID 7562497.

- ^ a b Gillen C, Haurand M, Kobelt DJ, Wnendt S (August 2000). "Affinity, potency and efficacy of tramadol and its metabolites at the cloned human mu-opioid receptor". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 362 (2): 116–121. doi:10.1007/s002100000266. PMID 10961373. S2CID 10459734.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Frink MC, Hennies HH, Englberger W, Haurand M, Wilffert B (November 1996). "Influence of tramadol on neurotransmitter systems of the rat brain". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 46 (11): 1029–1036. PMID 8955860.

- ^ a b c d Barann M, Urban B, Stamer U, Dorner Z, Bönisch H, Brüss M (February 2006). "Effects of tramadol and O-demethyl-tramadol on human 5-HT reuptake carriers and human 5-HT3A receptors: a possible mechanism for tramadol-induced early emesis". European Journal of Pharmacology. 531 (1–3): 54–58. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.11.054. PMID 16427041.

- ^ Raffa RB, Friderichs E, Reimann W, Shank RP, Codd EE, Vaught JL (January 1992). "Opioid and nonopioid components independently contribute to the mechanism of action of tramadol, an 'atypical' opioid analgesic". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 260 (1): 275–285. PMID 1309873.

- ^ a b Ogata J, Minami K, Uezono Y, Okamoto T, Shiraishi M, Shigematsu A, Ueta Y (May 2004). "The inhibitory effects of tramadol on 5-hydroxytryptamine type 2C receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 98 (5): 1401–6, table of contents. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000108963.77623.A4. PMID 15105221. S2CID 41718739.

- ^ Horishita T, Minami K, Uezono Y, Shiraishi M, Ogata J, Okamoto T, Shigematsu A (2006). "The tramadol metabolite, O-desmethyl tramadol, inhibits 5-hydroxytryptamine type 2C receptors expressed in Xenopus Oocytes". Pharmacology. 77 (2): 93–99. doi:10.1159/000093179. PMID 16679816. S2CID 23775035.

- ^ Okamoto T, Minami K, Uezono Y, Ogata J, Shiraishi M, Shigematsu A, Ueta Y (July 2003). "The inhibitory effects of ketamine and pentobarbital on substance p receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 97 (1): 104–10, table of contents. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000066260.99680.11. PMID 12818951. S2CID 35809206.

- ^ Minami K, Yokoyama T, Ogata J, Uezono Y (2011). "The tramadol metabolite O-desmethyl tramadol inhibits substance P-receptor functions expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 115 (3): 421–424. doi:10.1254/jphs.10313sc. PMID 21372504.

- ^ Shiraishi M, Minami K, Uezono Y, Yanagihara N, Shigematsu A (October 2001). "Inhibition by tramadol of muscarinic receptor-induced responses in cultured adrenal medullary cells and in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing cloned M1 receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 299 (1): 255–260. PMID 11561087.

- ^ a b Nakamura M, Minami K, Uezono Y, Horishita T, Ogata J, Shiraishi M, et al. (July 2005). "The effects of the tramadol metabolite O-desmethyl tramadol on muscarinic receptor-induced responses in Xenopus oocytes expressing cloned M1 or M3 receptors". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 101 (1): 180–6, table of contents. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000154303.93909.A3. PMID 15976229. S2CID 23861688.

- ^ Shiga Y, Minami K, Shiraishi M, Uezono Y, Murasaki O, Kaibara M, Shigematsu A (November 2002). "The inhibitory effects of tramadol on muscarinic receptor-induced responses in Xenopus oocytes expressing cloned M(3) receptors". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 95 (5): 1269–73, table of contents. doi:10.1097/00000539-200211000-00031. PMID 12401609. S2CID 39621215.

- ^ Shiraishi M, Minami K, Uezono Y, Yanagihara N, Shigematsu A, Shibuya I (May 2002). "Inhibitory effects of tramadol on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in adrenal chromaffin cells and in Xenopus oocytes expressing alpha 7 receptors". British Journal of Pharmacology. 136 (2): 207–216. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704703. PMC 1573343. PMID 12010769.

- ^ Sánchez-Fernández C, Montilla-García Á, González-Cano R, Nieto FR, Romero L, Artacho-Cordón A, et al. (January 2014). "Modulation of peripheral μ-opioid analgesia by σ1 receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 348 (1): 32–45. doi:10.1124/jpet.113.208272. PMID 24155346. S2CID 6884854.

- ^ a b c d Hara K, Minami K, Sata T (May 2005). "The effects of tramadol and its metabolite on glycine, gamma-aminobutyric acidA, and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 100 (5): 1400–1405. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000150961.24747.98. PMID 15845694. S2CID 35342038.

- ^ a b Miyano K, Minami K, Yokoyama T, Ohbuchi K, Yamaguchi T, Murakami S, et al. (April 2015). "Tramadol and its metabolite m1 selectively suppress transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 activity, but not transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 activity". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 120 (4): 790–798. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000000625. PMID 25642661. S2CID 8082654.

- ^ Marincsák R, Tóth BI, Czifra G, Szabó T, Kovács L, Bíró T (June 2008). "The analgesic drug, tramadol, acts as an agonist of the transient receptor potential vanilloid-1". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 106 (6): 1890–1896. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fefc. PMID 18499628. S2CID 45854233.

- ^ a b c d Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2006). "Therapeutic potential of monoamine transporter substrates". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (17): 1845–1859. doi:10.2174/156802606778249766. PMID 17017961. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Minami K, Sudo Y, Miyano K, Murphy RS, Uezono Y (June 2015). "µ-Opioid receptor activation by tramadol and O-desmethyltramadol (M1)". Journal of Anesthesia. 29 (3): 475–479. doi:10.1007/s00540-014-1946-z. PMID 25394761. S2CID 7091648.

- ^ a b Coller JK, Christrup LL, Somogyi AA (February 2009). "Role of active metabolites in the use of opioids". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 65 (2): 121–139. doi:10.1007/s00228-008-0570-y. PMID 18958460. S2CID 9977741.

- ^ a b Driessen B, Reimann W (January 1992). "Interaction of the central analgesic, tramadol, with the uptake and release of 5-hydroxytryptamine in the rat brain in vitro". British Journal of Pharmacology. 105 (1): 147–151. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14226.x. PMC 1908625. PMID 1596676.

- ^ Bamigbade TA, Davidson C, Langford RM, Stamford JA (September 1997). "Actions of tramadol, its enantiomers and principal metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol, on serotonin (5-HT) efflux and uptake in the rat dorsal raphe nucleus". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 79 (3): 352–356. doi:10.1093/bja/79.3.352. PMID 9389855. S2CID 15630689.

- ^ a b Reimann W, Schneider F (May 1998). "Induction of 5-hydroxytryptamine release by tramadol, fenfluramine and reserpine". European Journal of Pharmacology. 349 (2–3): 199–203. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00195-2. PMID 9671098.

- ^ a b c Gobbi M, Moia M, Pirona L, Ceglia I, Reyes-Parada M, Scorza C, Mennini T (September 2002). "p-Methylthioamphetamine and 1-(m-chlorophenyl)piperazine, two non-neurotoxic 5-HT releasers in vivo, differ from neurotoxic amphetamine derivatives in their mode of action at 5-HT nerve endings in vitro". Journal of Neurochemistry. 82 (6): 1435–1443. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01073.x. hdl:10533/173421. PMID 12354291. S2CID 13397864.

- ^ Gobbi M, Mennini T (April 1999). "Release studies with rat brain cortical synaptosomes indicate that tramadol is a 5-hydroxytryptamine uptake blocker and not a 5-hydroxytryptamine releaser". European Journal of Pharmacology. 370 (1): 23–26. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00123-5. PMID 10323276.

- ^ a b c d Driessen B, Reimann W, Giertz H (March 1993). "Effects of the central analgesic tramadol on the uptake and release of noradrenaline and dopamine in vitro". British Journal of Pharmacology. 108 (3): 806–811. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12882.x. PMC 1908052. PMID 8467366.

- ^ Reimann W, Hennies HH (June 1994). "Inhibition of spinal noradrenaline uptake in rats by the centrally acting analgesic tramadol". Biochemical Pharmacology. 47 (12): 2289–2293. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(94)90267-4. PMID 8031323.

- ^ Halfpenny DM, Callado LF, Hopwood SE, Bamigbade TA, Langford RM, Stamford JA (December 1999). "Effects of tramadol stereoisomers on norepinephrine efflux and uptake in the rat locus coeruleus measured by real time voltammetry". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 83 (6): 909–915. doi:10.1093/bja/83.6.909. PMID 10700792. S2CID 17830312.

- ^ a b c d Ogawa K, Tateno A, Arakawa R, Sakayori T, Ikeda Y, Suzuki H, Okubo Y (June 2014). "Occupancy of serotonin transporter by tramadol: a positron emission tomography study with [11C]DASB". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 17 (6): 845–850. doi:10.1017/S1461145713001764. PMID 24423243.

- ^ "Tramadol Dosage Guide with Precautions". Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ Tao Q, Stone DJ, Borenstein MR, Codd EE, Coogan TP, Desai-Krieger D, et al. (April 2002). "Differential tramadol and O-desmethyl metabolite levels in brain vs. plasma of mice and rats administered tramadol hydrochloride orally". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 27 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00384.x. PMID 11975693. S2CID 42370985.

- ^ Gibson TP (July 1996). "Pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of analgesia with a focus on tramadol HCl". The American Journal of Medicine. 101 (1A): 47S–53S. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(96)90035-2. PMID 8764760.

- ^ a b Dayer P, Collart L, Desmeules J (1994). "The pharmacology of tramadol". Drugs. 47 (Suppl 1): 3–7. doi:10.2165/00003495-199400471-00003. PMID 7517823. S2CID 33474225.

- ^ Nobilis M, Kopecký J, Kvetina J, Chládek J, Svoboda Z, Vorísek V, et al. (March 2002). "High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of tramadol and its O-desmethylated metabolite in blood plasma. Application to a bioequivalence study in humans". Journal of Chromatography A. 949 (1–2): 11–22. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(01)01567-9. PMID 11999728.

- ^ Yanarates O, Dogrul A, Yildirim V, Sahin A, Sizlan A, Seyrek M, et al. (March 2010). "Spinal 5-HT7 receptors play an important role in the antinociceptive and antihyperalgesic effects of tramadol and its metabolite, O-Desmethyltramadol, via activation of descending serotonergic pathways". Anesthesiology. 112 (3): 696–710. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181cd7920. PMID 20179508. S2CID 11913166.

- ^ Micó JA, Ardid D, Berrocoso E, Eschalier A (July 2006). "Antidepressants and pain". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 27 (7): 348–354. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2006.05.004. PMID 16762426.

- ^ Leppert W (2011). "CYP2D6 in the metabolism of opioids for mild to moderate pain". Pharmacology. 87 (5–6): 274–285. doi:10.1159/000326085. PMID 21494059.

- ^ Samer CF, Lorenzini KI, Rollason V, Daali Y, Desmeules JA (June 2013). "Applications of CYP450 testing in the clinical setting". Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 17 (3): 165–184. doi:10.1007/s40291-013-0028-5. PMC 3663206. PMID 23588782.

- ^ "Tramadol Hydrochloride 50mg Capsules". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. January 2016. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ 2003년부터 온라인상에서 2년마다 실현되고 있습니다Kleemann A, Engel J, Kutscher B, Reichert D, eds. (2000). Pharmaceutical Substances (4th ed.). Stuttgart (Germany): Thieme-Verlag. pp. 2085–2086. ISBN 978-1-58890-031-9..

- ^ Zynovy Z, Meckler H (2000). "A Practical Procedure for the Resolution of (+)- and (−)-Tramadol". Organic Process Research & Development. 4 (4): 291–294. doi:10.1021/op000281v.

- ^ Burke D, Henderson DJ (April 2002). "Chirality: a blueprint for the future". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 88 (4): 563–576. doi:10.1093/bja/88.4.563. PMID 12066734.

- ^ Raffa RB, Friderichs E, Reimann W, Shank RP, Codd EE, Vaught JL, et al. (October 1993). "Complementary and synergistic antinociceptive interaction between the enantiomers of tramadol". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 267 (1): 331–340. PMID 8229760.

- ^ Grond S, Meuser T, Zech D, Hennig U, Lehmann KA (September 1995). "Analgesic efficacy and safety of tramadol enantiomers in comparison with the racemate: a randomised, double-blind study with gynaecological patients using intravenous patient-controlled analgesia". Pain. 62 (3): 313–320. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(94)00274-I. PMID 8657431. S2CID 34150137.

- ^ Karhu D, El-Jammal A, Dupain T, Gaulin D, Bouchard S (September 2007). "Pharmacokinetics and dose proportionality of three Tramadol Contramid OAD tablet strengths". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 28 (6): 323–330. doi:10.1002/bdd.561. PMID 17575561. S2CID 22720069.

- ^ Tjäderborn M, Jönsson AK, Hägg S, Ahlner J (December 2007). "Fatal unintentional intoxications with tramadol during 1995-2005". Forensic Science International. 173 (2–3): 107–111. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.02.007. PMID 17350197.

- ^ Baselt R (2017). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (11th ed.). Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, CA. pp. 2185–2188. ISBN 978-0-692-77499-1.

- ^ McCarberg B (June 2007). "Tramadol extended-release in the management of chronic pain". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 3 (3): 401–410. PMC 2386353. PMID 18488071.

- ^ 미국 특허 6254887, Miller RB, Leslie ST, Malkowska ST, Smith KJ, Wimmer S, Winkler H, Han U, Prater DA, "Controlled Release Tramadol", 2001년 7월 3일 발행

- ^ a b 2016년 10월 25일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 염산트라마돌에 대한 FDA AccessData 입력.2009년 8월 17일 취득.

- ^ 미국 특허 7074430, Miller RB, Malkowska ST, Wimmer S, Han U, Leslie ST, Smith KJ, Winkler H, Prater DA, "Controlled Release Tramadol Tramadol 제제" 2006년 7월 11일 발행

- ^ Purdue Pharma Prods. L.P. v. Par Pharm., Inc., 377 Fed.부록 978 (Fed. Cir. 2010)

- ^ "DEA controls tramadol as a schedule IV controlled substance effective August 18, 2014". FDA Law Blog. 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ "Federal Registrar" (PDF). gpo.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ TRAMADOL(상표명: Ultram, Ultracet), Ultracet).의약품 집행국 (2011년 2월)

- ^ 테네시 뉴스: Tramadol과 Carisoprodol은 현재 기밀 스케줄 IV"입니다.전미약국위원회협회(2011년 6월 8일).2012년 12월 26일에 취득.

- ^ "State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy" (PDF). Pharmacy.ohio.gov. 18 August 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Substansen tramadol nu narkotikaklassad på samma sätt som kodein och dextropropoxifen" (in Swedish). Lakemedelsverket. 14 May 2008. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ a b c "If you take Tramadol away, you make Boko Haram weak". African Arguments. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ "Drugs for war: Opioid abuse in West Africa". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ "The Dangerous Opioid from India". www.csis.org. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ Berger M (7 January 2019). "Gaza's Opioid Problem". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ Winstock AR, Borschmann R, Bell J (September 2014). "The non-medical use of tramadol in the UK: findings from a large community sample". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 68 (9): 1147–1151. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12429. PMID 24734958. S2CID 21883884.

- ^ "Tramadol Abuse & Addiction Causes". UK Addiction Treatment Centres. 8 August 2018. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ Harati Y, Gooch C, Swenson M, Edelman S, Greene D, Raskin P, et al. (June 1998). "Double-blind randomized trial of tramadol for the treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy". Neurology. 50 (6): 1842–1846. doi:10.1212/WNL.50.6.1842. PMID 9633738. S2CID 45709223.

- ^ Harati Y, Gooch C, Swenson M, Edelman SV, Greene D, Raskin P, et al. (2000). "Maintenance of the long-term effectiveness of tramadol in treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy". Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 14 (2): 65–70. doi:10.1016/S1056-8727(00)00060-X. PMID 10959067.

- ^ Barber J (April 2011). "Examining the use of tramadol hydrochloride as an antidepressant". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 19 (2): 123–130. doi:10.1037/a0022721. PMID 21463069.

- ^ Göbel H, Stadler T (1997). "[Treatment of post-herpes zoster pain with tramadol. Results of an open pilot study versus clomipramine with or without levomepromazine]". Drugs (in French). 53 (Suppl 2): 34–39. doi:10.2165/00003495-199700532-00008. PMID 9190323. S2CID 46986791.

- ^ Boureau F, Legallicier P, Kabir-Ahmadi M (July 2003). "Tramadol in post-herpetic neuralgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Pain. 104 (1–2): 323–331. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00020-4. PMID 12855342. S2CID 42979548.

- ^ Wu T, Yue X, Duan X, Luo D, Cheng Y, Tian Y, Wang K (September 2012). "Efficacy and safety of tramadol for premature ejaculation: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Urology. 80 (3): 618–624. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2012.05.035. PMID 22840860.

- ^ Wong BL, Malde S (January 2013). "The use of tramadol "on-demand" for premature ejaculation: a systematic review". Urology. 81 (1): 98–103. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2012.08.037. PMID 23102445.

- ^ Ryan T, Hodge A, Holyoak R, Vlok R, Melhuish T, Binks M, et al. (July 2019). "Tramadol as an adjunct to intra-articular local anaesthetic infiltration in knee arthroscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 89 (7–8): 827–832. doi:10.1111/ans.14920. PMID 30684306. S2CID 59275648.

- ^ Boumendjel A, Sotoing Taïwe G, Ngo Bum E, Chabrol T, Beney C, Sinniger V, et al. (November 2013). "Occurrence of the synthetic analgesic tramadol in an African medicinal plant". Angewandte Chemie. 52 (45): 11780–11784. doi:10.1002/anie.201305697. PMID 24014188.

- ^ a b Kusari S, Tatsimo SJ, Zühlke S, Talontsi FM, Kouam SF, Spiteller M (November 2014). "Tramadol--a true natural product?". Angewandte Chemie. 53 (45): 12073–12076. doi:10.1002/anie.201406639. PMID 25219922.

- ^ 정말 누가 먼저 했습니까? 자연인가 약사인가?2015년 11월 22일 Wayback Machine, Lab Times 온라인 아카이브 완료, Nicola Hunt에 의해 2014년 9월 22일 발행, 2015년 11월 21일 취득

- ^ Kusari S, Tatsimo SJ, Zühlke S, Spiteller M (January 2016). "Synthetic Origin of Tramadol in the Environment". Angewandte Chemie. 55 (1): 240–243. doi:10.1002/anie.201508646. PMID 26473295.

- ^ a b Souza MJ, Cox SK (January 2011). "Tramadol use in zoologic medicine". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 14 (1): 117–130. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2010.09.005. PMID 21074707.

추가 정보

- Dean L (2015). "Tramadol Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520365. Bookshelf ID: NBK315950.

외부 링크

- "Tramadol". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Tramadol hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.