낙타

Camel| 낙타 시간 범위: | |

|---|---|

| |

| 단봉자리 (카멜루스 드로메다리우스) | |

| |

| 쌍봉낙타 (박테리아누스) | |

| 과학적 분류 | |

| 왕국: | 애니멀리아 |

| 문: | 챠다타 |

| 클래스: | 젖꼭지 |

| 주문: | 아티오닥틸라속 |

| 패밀리: | 낙타과 |

| 부족: | 카멜리니 |

| 속: | 카멜루스 린네, 1758년 |

| 모식종 | |

| 카멜루스드롬다리우스 [6] 린네, 1758년 | |

| 종. | |

| |

| 전 세계 낙타 분포 | |

| 동의어 | |

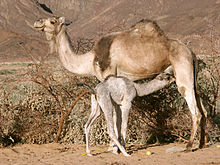

카멜(라틴어: camelus, 그리스어: άμμμμμμομμμο(카멜로스)에서 유래)은 등에 혹으로 알려진 독특한 지방 침전물을 가진 카멜루스속 유제 동물이다.[7][8]낙타는 오랫동안 길들여져 왔고 가축으로서 음식과 섬유질을 제공한다.낙타는 사막 서식지에 특히 적합한 일하는 동물이며 승객과 화물을 위한 중요한 운송 수단이다.낙타에는 3종류가 생존해 있다.혹이 하나뿐인 단봉낙타는 세계 낙타 개체수의 94%를 차지하고 있으며, 혹이 두 개인 박트리아 낙타는 6%를 차지하고 있습니다.야생 박트리아 낙타는 별도의 종으로 현재 심각한 멸종 위기에 처해 있다.

그 말 낙타는 또한 비공식적으로가 더 정확한 용어"camelid"은 더 넓은 어떤 의미에서, 가족의 Lamini[9]Camelids 유래된 별도의 부족에 속하는 모든 7종 낙타과:진정한 낙타,"신세계"camelids과 함께(위의 세 종족):라마, 알파카, guanaco고, vicuña, 포함시키는 데 사용됩니다. 에서현대 낙타의 조상인 파라카멜루스가 약 6백만 년 전 마이오세 말기에 베링 육교를 건너 아시아로 이주한 에오세 동안의 북미.

분류법

현존종

| 이미지 | 통칭 | 학명 | 분배 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 쌍봉낙타 | 카멜루스박트리아누스 | 길들여진, 박트리아의 역사적 지역을 포함한 중앙아시아. |

| 단봉낙타 | 카멜루스드롬다리우스 | 현지화; 중동, 사하라 사막, 남아시아; 호주에 도입 |

| 야생 쌍봉낙타 | 카멜루스페루스 | 중국 북서부 및 몽골의 외딴 지역 |

생물학

낙타의 평균 수명은 40년에서 50년이다.[12]다 자란 단봉낙타는 어깨가 1.85m이고 혹이 [13]2.15m입니다.쌍봉낙타는 키가 1피트 더 클 수 있다.낙타는 단시간에 최대 65km/h로 달릴 수 있고 최대 40km/[14]h의 속도를 유지할 수 있습니다.쌍봉낙타는 무게가 300에서 1,000kg이고 단봉낙타는 300에서 600kg입니다.낙타 발굽의 넓어진 발가락은 다양한 토양 [15]퇴적물에 보조적인 그립을 제공합니다.

수컷 단봉낙타는 목에 덜라라고 불리는 기관을 가지고 있는데, 이것은 발정기에 암컷을 유혹하기 위해 그의 입에서 나오는 크고 부풀려진 주머니입니다.그것은 그의 [16]입가에서 길게 부풀어 오른 분홍색 혀를 닮았다.낙타는 수컷과 암컷을 모두 땅에 앉히고 수컷은 [17]뒤에서 올라타면서 짝짓기를 한다.수컷은 보통 한 번의 짝짓기 [18]기간 동안 서너 번 사정한다.낙타류는 [19]앉은 자세에서 짝짓기를 하는 유일한 유제동물이다.

생태적 및 행동적 적응

낙타는 혹에 직접 물을 저장하지 않는다; 낙타는 지방 조직의 저장고이다.이 조직이 대사될 때, 그것은 처리된 지방 1그램 당 1그램 이상의 물을 생산한다.에너지를 방출하는 동안, 이 지방 대사는 호흡 중에 물을 증발시킵니다: 전반적으로,[20][21] 물의 순 감소가 있습니다.

낙타는 외부의 [23]물 공급원 없이 오랜 시간 동안 견딜 수 있게 해주는 일련의 생리적인 적응을 가지고 있다.단봉낙타는 매우 더운 환경에서도 10일에 한 번 정도 술을 거의 마시지 않고 [24]탈수로 인해 체질량의 최대 30%를 잃을 수 있다.다른 포유동물들과 달리 낙타의 적혈구는 원형이라기 보다는 타원형이다.이것은 탈수 중에[25] 적혈구의 흐름을 촉진하고 많은 양의 물을 마실 때 파열되지 않고 높은 삼투압 변화를 견딜 수 있게 합니다. 낙타 600kg(1,300파운드)은 [26][27]3분 만에 200L(53미국 갤)의 물을 마실 수 있습니다.

낙타는 대부분의 다른 포유동물을 죽일 수 있는 체온과 수분 소비의 변화를 견딜 수 있다.새벽에는 온도가 34°C(93°F)까지 다양하며, 해질 무렵에는 40°C(104°F)까지 꾸준히 상승한 후 밤에 [23]다시 냉각됩니다.일반적으로 낙타와 다른 가축을 비교해보면, 낙타는 매일 1.3리터의 액체 섭취량을 잃는 반면, 다른 가축들은 하루에 [28]20에서 40리터를 잃는다.뇌 온도를 일정한 한계 이내로 유지하는 것은 동물들에게 매우 중요하다; 이것을 돕기 위해, 낙타는 동맥과 정맥이 서로 매우 가까이 놓여 있는 리테 기적을 가지고 있는데, 이것은 [29]뇌로 흐르는 피를 식히기 위해 역류 혈류를 이용한다.낙타는 주변 온도가 49°C(120°F)[30]에 달할 때에도 땀을 거의 흘리지 않습니다.발생하는 땀은 피부 표면보다는 피부 수준에서 증발합니다. 따라서 기화열은 주변 열보다는 체열에서 발생합니다.낙타는 물에서 체중의 25%를 감량하는 것을 견딜 수 있는 반면, 대부분의 다른 포유류는 순환 [27]장애로 인한 심부전이 발생하기 전에 12-14%의 탈수만을 견딜 수 있습니다.

낙타가 숨을 내쉴 때, 수증기는 그들의 콧구멍에 갇히게 [31]되고 물을 보존하기 위한 수단으로 체내에 재흡수된다.녹색 목초를 먹는 낙타는 물을 [32]마시지 않고도 몸의 수분 상태를 유지하기 위해 온화한 조건에서 충분한 수분을 섭취할 수 있습니다.

낙타의 두꺼운 털은 사막 모래에서 방출되는 강렬한 열로부터 낙타를 보호하며, 껍질을 깎은 낙타는 [33]과열을 피하기 위해 50% 더 땀을 흘려야 합니다.여름 동안 코트는 햇빛을 피할 뿐만 아니라 빛을 반사하면서 색이 더 [27]옅어집니다.낙타의 긴 다리는 70°C (158°[34][35]F)까지 가열할 수 있는 땅에서 몸을 더 멀리 유지함으로써 도움을 줍니다.단봉대에는 흉골 위에 대좌라고 불리는 두꺼운 조직 패드가 있다.동물이 흉골에 누운 자세에서 눕으면 받침대가 뜨거운 표면에서 몸을 일으켜 차가운 공기가 [29]몸 아래로 흐를 수 있도록 한다.

낙타의 입에는 두꺼운 가죽 같은 안감이 있어서 가시가 있는 사막 식물을 씹을 수 있게 해줍니다.긴 속눈썹과 귀털은 닫힐 수 있는 콧구멍과 함께 모래에 대한 장벽을 형성합니다.모래가 눈에 쌓이면 투명한 세 번째 눈꺼풀을 이용해 모래를 제거할 수 있다.낙타의 걸음걸이와 넓어진 발은 [34][36][37]낙타가 모래 속으로 가라앉지 않고 움직일 수 있도록 도와준다.

낙타의 신장과 장은 물을 재흡수하는데 매우 효과적이다.낙타의 신장은 1:4의 피질 [38]대 수질을 가지고 있다.따라서 낙타의 신장은 소의 신장보다 두 배나 많은 면적을 차지한다.둘째, 신장소체는 직경이 작기 때문에 여과용 표면적을 줄일 수 있다.이 두 가지 주요 해부학적 특성은 낙타가 물을 보존하고 극단적인 [39]사막 조건에서 소변의 양을 제한할 수 있게 해준다.낙타의 소변은 걸쭉한 시럽으로 나오고 낙타 배설물은 매우 건조해서 베두인이 불을 [40][41][42][43]지피기 위해 사용할 때 건조할 필요가 없다.

낙타 면역 체계는 다른 포유동물과 다르다.일반적으로 Y자형 항체 분자는 Y자 길이에 따라 두 개의 무거운(또는 긴) 사슬과 Y자 끝의 두 개의 가벼운(또는 짧은) 사슬로 구성됩니다.이것들 외에도 낙타는 단지 두 개의 무거운 쇠사슬로 만들어진 항체를 가지고 있는데, 이것은 낙타를 더 작고 더 오래도록 만드는 특성이다.1993년에 발견된 이 "중쇄 전용" 항체는 반추동물과 [44]돼지에서 낙타류가 갈라진 후 5천만 년 전에 발달한 것으로 생각됩니다.낙타는 [45]세계 어디에서나 트리파노소마 에반시에 의한 수라를 앓고 있으며, 그 결과 낙타는 많은 포유동물과 마찬가지로 트리파노소마 항체를 진화시켰다.앞으로 나노바디/단일 도메인 항체 치료는 천연 항체의 크기가 커 현재 도달하기 어려운 위치에 도달함으로써 천연 낙타 항체를 능가할 것이다.그러한 치료법은 다른 [46]포유동물들에게도 적합할 수 있다.

유전학

다른 낙타과 종들의 핵형은 많은 그룹들에 [47][48][49][50][51][52]의해 이전에 연구되어 왔지만, 낙타과 종들의 염색체 명명법에 대한 합의는 아직 이루어지지 않았다.2007년 연구 흐름은 낙타가 37쌍의 염색체를 가지고 있다는 사실에 기초해 낙타 염색체를 분류했고, 핵형은 1개의 메타센터, 3개의 서브메타센터, 32개의 아크로센트릭 자동차로 구성되었다는 것을 발견했다.Y는 작은 메타센터 염색체이고 X는 큰 메타센터 [53]염색체이다.

박트리아 낙타와 단봉낙타 사이의 잡종인 이 잡종 낙타는 앞과 뒤를 나누는 4-12cm 깊이의 움푹 패인 곳이 있지만 하나의 혹을 가지고 있다.이 잡종은 어깨가 2.15m(7피트 1인치)이고 험프 높이가 2.32m(7피트 7인치)입니다.무게는 평균 650kg (1,430파운드) 이며, 약 400~450kg (880~990파운드)을 운반할 수 있는데, 이는 단봉대나 [54]박트리아보다 더 많은 양이다.

분자 자료에 따르면 야생 박트리아 낙타(C. ferus)는 약 100만년 [55][56]전 국내 박트리아 낙타(C. bactrianus)와 분리됐다.신세계와 구세계 낙타류는 약 1100만년 [57]전에 갈라졌다.그럼에도 불구하고, 이 종들은 교배하여 생존 가능한 [58]자손을 낳을 수 있다.카마는 과학자들이 부모 [59]종이 얼마나 밀접하게 관련되어 있는지 보기 위해 번식한 낙타와 라마의 잡종이다.과학자들은 인공 질을 통해 낙타에게서 정액을 채취한 뒤 고나도트로핀 [60]주사로 배란을 자극한 뒤 라마를 수정했다.카마는 낙타와 라마의 절반 크기이고 혹이 없다.낙타와 라마 사이의 중간 귀, 라마보다 긴 다리, 부분적으로 갈라진 [61][62]발굽을 가지고 있다.노새처럼 카마는 양쪽 부모가 같은 수의 [60]염색체를 가지고 있음에도 불구하고 불임상태이다.

진화

프로틸로푸스라고 불리는 최초의 낙타는 4천만 년에서 5천만 년 전 (에오세 [18]동안) 북아메리카에 살았다.그것은 토끼만한 크기였고 지금의 사우스다코타 주의 [63][64]탁 트인 삼림지대에 살았다.3천 5백만 년 전에 포브러더리움은 염소 크기였고 낙타와 [65][66]라마와 비슷한 특징을 더 많이 가지고 있었다.발끝으로 걷는 발굽이 달린 스테노밀루스도 이 무렵 존재했고 목이 긴 아이피카멜루스는 마이오세에 [67]진화했다.

현대 낙타의 조상인 파라카멜루스는 750만 년에서 650만 년 전 [68][69][70]사이 마이오세 말기에 베링기아를 통해 북미에서 유라시아로 이주했다.약 3백만 년 전, 플레이스토세 동안, 북미 낙타과는 새롭게 형성된 파나마 지협을 통해 대미 교류의 일부로 남아메리카로 퍼져 나갔고, 그곳에서 구아나코와 그와 관련된 동물들을 [18][63][64]낳았다.파라카멜루스 개체군은 플레이스토세 초기까지 [71][72]북미 북극에 계속 존재했다.이 생물의 키는 약 2.7미터로 추정된다.화석 기록에 따르면,[73] 박트리아 낙타는 약 100만 년 전에 단봉대에서 갈라졌다.

북아메리카에서 태어난 마지막 낙타는 카멜롭스 헤스테누스로, 말, 짧은 얼굴을 가진 곰, 매머드, 마스토돈, 땅 나무늘보, 사베르트투스 고양이, 그리고 많은 다른 거대 동물군과 함께 사라졌는데, 이는 약 1511,000년 전,[74][75] 플라이스토세 말기에 아시아에서 인류가 이주한 것과 일치한다.

가축화

말처럼, 낙타는 북미에서 시작되었고 결국 베링기아를 가로질러 아시아로 퍼져나갔다.그들은 구세계에서 살아남았고, 결국 인간들은 그들을 길들여서 전세계에 퍼뜨렸다.북미의 많은 다른 거대 낙타들과 함께, 원래의 야생 낙타들은 10,000년에서 12,000년 전 아시아에서 북미로 아메리카 원주민들이 확산되는 동안 전멸했습니다; 비록 화석이 [74][75]사냥의 결정적인 증거와 관련이 있는 것은 결코 아닙니다.

오늘날 살아남은 낙타는 대부분 [43][76]길들여진 것이다.야생 낙타는 호주, 인도, 카자흐스탄에 존재하지만 고비 [12]사막의 야생 박트리아 낙타 개체군에서만 생존한다.

역사

인간이 처음 낙타를 길들였을 때 논란이 되었다.단봉대들은 기원전 3,000년경 소말리아와 남부 아라비아에서 인간들에 의해 처음 길들여졌을 수도 있고,[80] 이란의 샤리 소크타에서처럼 기원전 2,[18][77][78][79]500년경 중앙아시아의 박트리아인에 의해 길들여졌을 수도 있다.

마틴 하이데의 2010년 낙타 길들이기 연구는 인간이 적어도 3천 년 중반쯤 자그로스 산맥 동쪽 어딘가에서 박트리아 낙타를 길들였다는 잠정적인 결론을 내렸고, 그 후 메소포타미아로 옮겨갔다.하이데는 낙타가 [81]가나안과의 관계에서 언급되지 않는 반면, "가부장적 서술에서 적어도 어떤 곳에서는 박트리아 낙타를 언급할 수 있다"고 주장한다.

Lidar Sapir-Hen과 Erez Ben-Yosef에 의한 최근 팀나 계곡에서 발굴된 것은 기원전 930년 경으로 거슬러 올라가는 이스라엘이나 심지어 아라비아 반도 밖에서 발견된 최초의 국내 낙타 뼈일 수 있는 것을 발견했다.이는 아브라함, 야곱, 에서, 그리고 요셉의 이야기가 이 [82][83]시기 이후에 쓰여졌다는 강력한 증거이기 때문에 상당한 언론의 주목을 받았다.

동부 지중해에는 아니지만 메소포타미아에 낙타가 존재한다는 것은 새로운 생각이 아니다.역사학자 리처드 불리에트는 성경에 가끔 낙타에 대해 언급하는 것이 그 당시 [84]성지에서 집 낙타가 흔했다는 것을 의미한다고 생각하지 않았다.고고학자 윌리엄 F. 올브라이트는 성경에 나오는 낙타를 시대착오적인 [85]것으로 보았다.

Sapir-Hen과 Ben-Joseph의 공식 보고서에는 다음과 같이 기술되어 있다.

단봉낙타(카멜루스 드로메다리우스)가 남부 레반트에 무리지어 유입되면서 아라비아의 광활한 사막을 가로지르는 무역이 크게 촉진됐다(예: 콜러 1984; 보로스키 1998: 112–116; 자스민 2005).이거...남부 레반트(및 그 이후)에서 가장 이른 국내 낙타의 날짜(예: Albright 1949: 207; Epstein: 558–584; Bulliet 1975; Zarins 1989; Zarins 1989; Köhler-Rolefson 1993; Uerpmann 및 Uerpmann 2002; 2006; Rosen 2005; 2010)에 대한 광범위한 논의를 불러일으켰다.오늘날 대부분의 학자들은 단봉이 초기 철기시대(12세기 이전이 아님)에 무리지어 사는 동물로 착취되었다는 데 동의한다.

그리고 결론:

아라바 계곡의 구리 제련 현장의 현재 데이터는 광범위한 방사성 탄소 대추와 관련된 층서학적 맥락에 기초하여 남부 레반트에 국내 낙타의 유입을 보다 정확하게 파악할 수 있게 해준다.데이터에 따르면 이 사건은 10세기 마지막 3분의 1 이전부터 일어났으며 아마도 이 시기에 일어났을 것이다.파라오 쇼셴크 1세의 캠페인의 결과로 이 지역의 구리 산업의 큰 재편성과 우연이 일치함에 따라 두 사람이 연결되어 무역을 [83]촉진함으로써 효율성을 높이기 위한 노력의 일환으로 낙타가 도입되었을 가능성이 제기되고 있다.

조셉은 바르톨로메우스 브린버그(1655)의 곡물을 팔고, 왼쪽에 기수가 있는 낙타를 보여준다.

텍스타일

사막 부족과 몽골 유목민들은 낙타 털을 텐트, 유르트, 의류, 침구, 액세서리로 사용한다.낙타는 겉의 보호모와 부드러운 속살을 가지고 있으며, 섬유는 동물의 색깔과 나이에 따라 분류되어[by whom?] 있다.보호모는 목동용 방수 코트로 사용할 수 있으며, 부드러운 털은 프리미엄 [86]상품으로 사용할 수 있습니다.섬유는 직물에 사용하기 위해 방적되거나 손뜨개나 코바늘을 위한 실로 만들어질 수 있습니다.순낙타 털은 17세기부터 서양 의복에 사용된 것으로 기록되고 있으며, 19세기부터는 양털과 낙타 털의 [87]혼합물이 사용되었다.

군사용

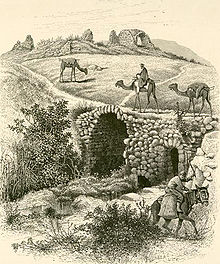

적어도 기원전 1200년경에는 최초의 낙타 안장이 나타났고, 쌍봉낙타는 탈 수 있었다.첫 번째 안장은 낙타 뒤에 놓였고, 박트리아 낙타의 제어는 막대기로 행해졌다.그러나 기원전 500년에서 100년 사이에 쌍봉낙타가 군사적으로 사용되기 시작했다.신축성이 없고 구부러진 새 안장을 혹 위에 얹고 기수의 무게를 동물 위에 분산시켰다.기원전 7세기에 아라비아 군용 안장이 진화하여 안장 디자인이 [88][89]약간 개선되었다.

군부대는 아프리카, 중동 및 현대의 인도 국경경비대(BSF)에 낙타 기병을 투입했다. (2012년 7월 현재 BSF는 낙타를 ATV로 대체할 계획을 세웠다.낙타 기병의 최초의 사용은 기원전 [90][91][92]853년 카르카르 전투에서 일어났다.군인들은 또한 말과 [93][94]노새 대신 낙타를 화물 동물로 사용해 왔다.

동로마 제국은 로마인들이 [95][96]사막 지방에서 모집한 드로메다리라고 알려진 보조군을 사용했다.낙타는 가까운 거리에서 말을 [19]쫓는 능력 때문에 주로 전투에 사용되었는데, 이는 아케메네스 페르시아인들이 티브라 전투에서 리디아와 싸울 때 사용했던 것으로 잘 알려져 있다.[54][97][98]

19세기와 20세기

미 육군은 19세기에 [19]캘리포니아에 주둔하는 미국 낙타 부대를 창설했다.캘리포니아 베니시아의 베니시아 아스널에서 마굿간을 볼 수 있는데, 이 마굿간은 오늘날 베니시아 역사 [99]박물관으로 사용되고 있다.비록 낙타의 실험적인 사용은 성공으로 보였다. 1858년 육군 장관 플로이드는 낙타 천 마리를 더 얻기 위해 자금을 배분할 것을 권고했다.) 1861년 남북전쟁의 발발은 낙타 군단의 종식을 가져왔다: 텍사스는 남군의 일부가 되었고 대부분의 낙타들은 사막으로 [94]떠돌아다니도록 남겨졌다.

프랑스는 1912년 사하라 사막에[100] 있는 Armée d'Afrique의 일부로 낙타를 타고 다니는 투아레그와 아랍 반군들을 도보로 물리치려는 이전 노력이 [101]실패하자 이들을 통제하기 위해 메하리스테 낙타 부대를 창설했다.자유 프랑스 낙타단은 제2차 세계 대전 동안 싸웠고 낙타를 탄 부대는 [102]1962년 프랑스의 알제리 통치가 끝날 때까지 계속 복무했다.

1916년에 영국은 제국 낙타단을 창설했다.그것은 원래 세누시족과 싸우기 위해 사용되었지만, 후에 제1차 세계대전의 시나이와 팔레스타인 캠페인에 사용되었다.황실낙타단은 낙타를 타고 사막을 건너 이동하는 보병들로 구성되었지만, 그들은 전쟁터에서 말에서 내려 걸어서 싸웠다.1918년 7월 이후, 군단은 새로운 증원군을 받지 못하면서 쇠약해지기 시작했고 [103]1919년에 정식으로 해산되었다.

세계 1차 대전 때, 영국 육군은 또한 이집트 낙타 운전자들과 낙타들로 구성된 이집트 낙타 수송대를 창설했다.그 군단은 군대에 [104][105][106]보급품을 수송함으로써 시나이, 팔레스타인, 그리고 시리아에서의 영국의 전쟁 작전을 지원했다.

소말릴란드 낙타단은 1912년 영국령 소말릴란드 식민지 당국에 의해 창설됐다가 [107]1944년 해체됐다.

쌍봉낙타는 제2차 세계대전 당시 백인 [108]지역에서 루마니아군에 의해 사용되었다.같은 시기 1942년 아스트라한 일대에서 활동하던 소련군은 트럭과 말이 부족해 현지 낙타를 징병동물로 입양해 이 지역을 떠난 뒤에도 기르고 있었다.심각한 손실에도 불구하고, 이 낙타들 중 일부는 서쪽으로 베를린까지 갔다.[109]

영국령 인도의 비카너 카멜 부대는 1차,[110] 2차 세계대전에서 영국령 인도 군대와 함께 싸웠다.

트로파스 노마다스(노마드 부대)는 스페인 사하라(오늘날 서사하라)의 식민지 군대에서 복무하던 사하라 부족의 보조 연대였다.1930년대부터 1975년 스페인 주둔이 끝날 때까지 활동한 트로파스 노마다 호는 소형 무기를 갖추고 스페인 장교들이 이끌었다.그 부대는 전초기지를 지키고 때로는 [111][112]낙타를 타고 순찰을 하기도 했다.

21세기 경쟁

사우디 아라비아의 킹 압둘아지즈 낙타 축제에서, 수천 마리의 낙타가 행진하고 입술과 혹으로 심판을 받는다.이 축제는 또한 낙타 레이싱과 낙타 우유 시음회가 특징이며 총 상금 5천700만 달러(약 4천만 파운드)가 지급된다.2018년, 12마리의 낙타 주인들이 낙타의 입술, 코, [113]턱에 보톡스 주사를 놓아 낙타의 미모를 개선하려 한 사실이 밝혀져 미인대회에서 자격을 박탈당했다.2021년에 40마리 이상의 낙타가 [114]낙타 미화 조작과 기만행위로 실격 처리되었다.

식품 사용

유제품

낙타 우유는 사막 유목민 부족의 주식이고 때때로 식사 그 자체로도 여겨집니다; 유목민은 낙타 우유만으로 거의 한 [19][40][115][116]달 동안 살 수 있습니다.

낙타 우유는 쉽게 요구르트로 만들 수 있지만, 먼저 시어서 휘저은 후 정화제를 [19]첨가해야만 버터가 될 수 있다.최근까지, 낙타 우유는 레넷이 우유 단백질을 응고시켜 응고를 할 [117]수 없었기 때문에 낙타 치즈로 만들 수 없었다.우유의 낭비가 적은 사용을 개발하기 위해 FAO는 [118]1990년대에 인산칼슘과 야채 렌넷을 첨가하여 응고를 생산할 수 있었던 에콜 국립수페리에르 데 아그로노미에 데 산업 알리멘테르의 J.P. 라메트 교수에게 의뢰했다.이 과정에서 생산된 치즈는 콜레스테롤 수치가 낮고 심지어 [119][120]유당불내증에도 소화되기 쉽습니다.

낙타 우유는 아이스크림으로도 [121][122]만들 수 있다.

고기

그들은 고기와 [123]우유의 형태로 음식을 제공한다.전세계적으로 [124]매년 약 330만 마리의 낙타와 낙타가 고기를 얻기 위해 도살된다.낙타 사체는 상당한 양의 고기를 제공할 수 있다.수컷 단봉데리의 사체는 300-400kg (661-882파운드)이 될 수 있는 반면, 수컷 단봉데리의 사체는 650kg (1,433파운드)까지 무게가 나갈 수 있다.암컷 단봉낙타의 사체는 수컷보다 무게가 적게 나가며 250~350kg(550~770파운드)[18]에 이른다.양지머리, 갈비, 등뼈는 선호 부위 중 하나이며, 혹은 [125]별미로 여겨진다.혹에는 "하얗고 병든 지방"이 들어 있는데, 이것은 양고기, 쇠고기 또는 [126]낙타의 클리를 만드는 데 사용될 수 있다.반면에, 낙타 우유와 고기는 단백질, 비타민, 글리코겐, 그리고 다른 영양소가 풍부해서 많은 사람들의 식단에 필수적입니다.화학 성분에서 육질까지, 단봉낙타는 고기 생산에 선호되는 품종이다.극단적인 기온에 대한 내성, 태양으로부터의 방사선, 단수, 험준한 풍경, 낮은 [127]초목 등 특이한 생리학적 행동과 특성으로 인해 건조한 지역에서도 잘 나타난다.낙타 고기는 거친 소고기 맛이 나는 것으로 알려져 있지만, 더 나이든 낙타들은 더 많이 [128]익힐수록 낙타 고기가 더 단단해 지지만 매우 [13][18]질긴 것으로 증명될 수 있다.아부다비 오피서스 클럽은 식감과 [129]맛을 향상시키기 위해 소고기 또는 양지방을 섞은 카멜 버거를 제공합니다.파키스탄 카라치에서는 낙타 [130]고기로 니하리를 만드는 식당도 있다.전문 낙타 정육점에서는 가장 [131]인기 있는 혹으로 여겨지는 전문가용 칼집을 제공합니다.

낙타 고기는 수세기 동안 먹어왔다.그것은 고대 그리스 작가들에 의해 고대 페르시아의 연회에서 이용 가능한 음식으로 기록되었으며, 보통 [132]통째로 구워졌다.로마 황제 헬리오가발루스는 낙타의 [40]발뒤꿈치를 즐겼다.낙타 고기는 주로 에리트레아, 소말리아, 지부티, 사우디아라비아, 이집트, 시리아, 리비아, 수단, 에티오피아, 카자흐스탄과 같은 특정 지역에서 먹는데 대체 단백질의 형태가 제한되거나 낙타 고기가 오랜 문화적 [18][40][125]역사를 가지고 있는 다른 건조한 지역입니다.낙타의 피 또한 소비할 수 있는데, 케냐 북부의 목축민들이 낙타의 피를 우유와 함께 마시고 철분, 비타민 D, 소금과 [18][125][133]미네랄의 주요 공급원으로 작용한다.

사우디 보건부와 미국 질병통제예방센터가 공동으로 발표한 2005년 보고서에는 생낙타 [134]간 섭취로 인한 인간선종성 페스트의 4가지 사례가 자세히 나와 있다.

호주.

낙타 고기는 호주 요리에서도 가끔 볼 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 낙타 라자냐가 앨리스 [132][133]스프링스에서 제공됩니다.호주는 수년 동안 [135]낙타 고기를 주로 중동 지역뿐만 아니라 유럽과 미국에도 수출해왔다.이 고기는 소말리아와 같은 동아프리카 호주인들 사이에서 매우 인기가 있고 다른 호주인들 또한 그것을 구입하고 있다.그 동물의 야생성은 그들이 [136]세계의 다른 지역에서 사육되는 낙타와 다른 종류의 고기를 생산한다는 것을 의미하며, 그것은 질병이 없고 독특한 유전자 집단이기 때문에 인기가 있다.수요가 공급을 앞지르고 있고, 각국 정부는 낙타를 도살하지 말고 도살 비용을 시장 개발로 돌려야 한다고 촉구하고 있다.호주에는 고기 [137]외에 우유, 치즈, 스킨케어 제품도 생산하는 7개의 낙타 유흥업소가 있다.

종교

이슬람

무슬림들은 낙타 고기 할랄을 생각한다.하지만, 일부 이슬람 학파에 따르면, 불순물 상태는 그것의 소비로 인해 야기된다.따라서, 이 학교들은 이슬람교도들이 낙타 [138]고기를 먹은 후 다음 기도를 하기 전에 반드시 우두(우두)를 행해야 한다고 주장한다.Also, some Islamic schools of thought consider it haram (Arabic: حرام, 'forbidden') for a Muslim to perform Salat in places where camels lie, as it is said to be a dwelling place of the Shaytan (Arabic: شيطان, 'Devil').[138]Abu Yusuf(d.798)에 따르면, 필요하다면 낙타의 소변을 치료에 사용할 수 있지만, Abu Yusufha에 따르면 낙타의 소변을 마시는 것은 권장되지 [139]않는다.

이슬람 교서에는 낙타가 등장하는 몇 가지 이야기가 포함되어 있다.In the story of the people of Thamud, the Prophet Salih miraculously brings forth a naqat (Arabic: ناقة, 'milch-camel') out of a rock.예언자 무함마드가 메카에서 메디나로 이주한 후, 그는 그의 암낙타가 그곳에서 돌아다닐 수 있도록 허락했다; 낙타가 쉬기 위해 멈춘 장소는 [140]메디나에서 그의 집을 지을 장소를 결정했다.

유대교

유대인의 전통에 따르면 낙타 고기와 우유는 [141]순결하지 않다.낙타는 두 가지 기준 중 하나만 가지고 있다. 비록 바느질을 하고 있지만, 바느질을 하는 사람과 굽이 있는 사람 사이에선 먹을 수 없다. 낙타는 바느질을 하는 사람이지만, 바느질을 하는 사람은 먹을 수 없다. 낙타는 바느질을 하는 사람은 바느질을 하지만 굽이 완전히 나 있지 않기 때문이다. [142]낙타는 너에게 부정하다.

문화 묘사

2018년 사우디아라비아에서 가장 오래된 낙타 조각이 발견되었다.그것들은 여러 과학 분야의 연구자들에 의해 분석되었고 2021년에는 7,000년에서 8,000년 [143]된 것으로 추정되었다.암각화의 연대는 시험할 수 있는 조각품에 유기물질이 부족하기 때문에 어렵게 되었다. 그래서 그 연대를 측정하려는 연구원들은 조각과 관련된 동물의 뼈를 테스트하고, 침식 패턴을 평가했으며, 조각의 정확한 제작 날짜를 결정하기 위해 도구 자국을 분석했다.이 신석기 시대의 연대는 스톤헨지와 기자의 이집트 피라미드(4500년)보다 훨씬 오래되었고 낙타의 가축화에 대한 추정보다 앞선다.

마루 라기니 (낙타를 타는 도라와 마루), c. 1750 브루클린 박물관

마지쥬르닝(Les Rois Marges in Navigaing)-James Tissot, 1886년 경, 브루클린 박물관

분포 및 수

2010년 현재[update] 약 1,400만 마리의 낙타가 살고 있으며 90%가 [144]단봉낙타입니다.오늘날 살아있는 단봉다리는 길들여진 동물입니다(대부분 아프리카 북동부, 사헬, 마그레브, 중동, 남아시아에 살고 있습니다).혼 지역만 해도 세계에서 [22]낙타가 가장 많이 밀집해 있어 단봉대가 지역 유목민 생활의 중요한 부분을 차지하고 있다.그들은 소말리아와 에티오피아의[18] 유목민들에게 우유, 음식,[116][145][146][147] 교통수단을 제공한다.

호주에서 100만 마리 이상의 단봉낙타가 야생으로 추정되는데, 이는 19세기와 20세기 [148]초에 운송 수단으로 도입된 낙타의 후손이다.이 인구는 매년 [149]약 8%씩 증가하고 있으며,[133][144][150] 2008년에는 약 700,000명으로 추정되었습니다.호주 정부 대표들은 낙타들이 [151]양치기들이 필요로 하는 제한된 자원을 너무 많이 사용하기 때문에 부분적으로 10만 마리 이상의 동물들을 도살했다.

19세기에 미국 낙타단 실험의 일부로 수입된 후 소개된 소수의 낙타들, 단봉낙타들과 박트리아인들이 미국 남서부를 돌아다녔다.프로젝트가 끝났을 때, 그들은 광산에서 징병 동물로 사용되었고 탈출하거나 풀려났다.카리브 골드 [94]러시 기간 동안 25마리의 미국 낙타가 구입되어 캐나다로 수출되었다.

2010년 현재[update], 박트리아 낙타는 140만 마리로 감소했으며, 대부분은 [43][144][152]가축으로 사육되고 있다.야생 박트리아 낙타는 별개의 종으로 세계에서 유일하게 진짜 야생 낙타입니다.야생 낙타는 중국과 [12][153]몽골의 고비 사막과 타클라마칸 사막에 서식하며 멸종 위기에 처해 있으며 개체수는 약 1400마리이다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

인용문

- ^ "Fossilworks: Camelus". fossilworks.org.

- ^ Geraads, D.; Barr, W. A.; Reed, D.; Laurin, M.; Alemseged, Z. (2019). "New Remains of Camelus grattardi (Mammalia, Camelidae) from the Plio-Pleistocene of Ethiopia and the Phylogeny of the Genus" (PDF). Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 28 (2): 359–370. doi:10.1007/s10914-019-09489-2. S2CID 209331892.

- ^ Titov, V. V. (2008). "Habitat conditions for Camelus knoblochi and factors in its extinction". Quaternary International. 179 (1): 120–125. Bibcode:2008QuInt.179..120T. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.10.022.

- ^ Falconer, Hugh (1868). Palæontological Memoirs and Notes of the Late Hugh Falconer: Fauna antiqua sivalensis. R. Hardwicke. p. 231.

- ^ Martini, P.; Geraads, D. (2019). "Camelus thomasi Pomel, 1893 from the Pleistocene type-locality Tighennif (Algeria). Comparisons with modern Camelus". Geodiversitas. 40 (1): 115–134. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2018v40a5.

- ^ Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "camel". The New Oxford American Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, Inc. 2005.

- ^ Herper, Douglas. "camel". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Bornstein, Set (2010). "Important ectoparasites of Alpaca (Vicugna pacos)". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 52 (Suppl 1): S17. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-52-S1-S17. ISSN 1751-0147. PMC 2994293.

- ^ Burger, P. A.; Ciani, E.; Faye, B. (2019-09-18). "Old World camels in a modern world – a balancing act between conservation and genetic improvement". Animal Genetics. 50 (6): 598–612. doi:10.1111/age.12858. PMC 6899786. PMID 31532019.

- ^ Chuluunbat, B.; Charruau, P.; Silbermayr, K.; Khorloojav, T.; Burger, P. A. (2014). "Genetic diversity and population structure of Mongolian domestic Bactrian camels (Camelus bactrianus)". Anim Genet. 45 (4): 550–558. doi:10.1111/age.12158. PMC 4171754. PMID 24749721.

- ^ a b c "Bactrian Camel: Camelus bactrianus". National Geographic. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ a b "The amazing characteristics of the camels". Camello Safari. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ "How Fast Can Camels Run and How Long Can They Run For?". Big Site of Amazing Facts. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ 페이드, R. H. "낙타의 사막 환경 적응"제11회 ESARF 연차총회 의사록.< http://esarf2[permanent dead link] . tripod . com / conf2001proc :::: 。htm>, (2010년 11월 18일에 액세스)2001.

- ^ Abu-Zidana, Fikri M.; Eida, Hani O.; Hefnya, Ashraf F.; Bashira, Masoud O.; Branickia, Frank (18 December 2011). "Camel bite injuries in United Arab Emirates: A 6 year prospective study". Injury. 43 (9): 1617–1620. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.039. PMID 22186231.

The male mature camel has a specialized inflatable diverticulum of the soft palate called the "Dulla". and During rutting the Dulla enlarges on filling with air from the trachea until it hangs out of the mouth of the camel and comes to resemble a pink ball. This occurs in only the one-humped camel. Copious saliva turns to foam covering the mouth as the male gurgles and makes metallic sounds. [6 cites to 5 references omitted]

- ^ Two Male Camels Fighting Over One Female. Youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-19. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mukasa-Mugerwa, E. (1981). The Camel (Camelus Dromedarius): A Bibliographical Review. International Livestock Centre for Africa Monograph. Vol. 5. Ethiopia: International Livestock Centre for Africa. pp. 1, 3, 20–21, 65, 67–68.

- ^ a b c d e "Bactrian & Dromedary Camels". Factsheets. San Diego Zoo Global Library. March 2009. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ Vann Jones, Kerstin. "What secrets lie within the camel's hump?". Sweden: Lund University. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ Rastogi, S. C. (1971). Essentials Of Animal Physiology. New Age International. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9788122412796.

- ^ a b Bernstein, William J. (2009). A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. Grove Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780802144164.

- ^ a b Roberts, Michael Bliss Vaughan (1986). Biology: A Functional Approach. Nelson Thornes. pp. 234–235, 241. ISBN 9780174480198.

- ^ "The Camel from Tradition To Modern Times" (PDF).

- ^ Eitan, A; Aloni, B; Livne, A (1976). "Unique properties of the camel erythrocyte membraneII. Organization of membrane proteins". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 426 (4): 647–58. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(76)90129-2. PMID 816376.

- ^ "Dromedary". Hannover Zoo. Archived from the original on 25 October 2005. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b c Halpern, E. Anette (1999). "Camel". In Mares; Michael A. (eds.). Deserts. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 9780806131467. Archived from the original on 2016-04-29.

- ^ Breulmann, M., Böer, B., Wernery, U., Wernery, R., El Shaer, H., Alhadrami, G. 등Norton, J. (2007)'전통에서 현대로의 낙타'(PDF).유네스코 도하 사무소.

- ^ a b '자연의 거인' 속.채널 4(영국) 다큐멘터리2011년 8월 30일 송신

- ^ "Arabian (Dromedary) Camel". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Paul (12 July 1981). "A Pilgrimage To A Mystic's Hermitage In Algeria". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ "Camels, llamas and alpacas". A manual for primary animal health care worker. FAO Animal Health Manual. FAO Agriculture and Consumer Protection. 1994. ISSN 1020-5187. Archived from the original on 2008-07-27.

- ^ Schmidt-Nielsen, K. (1964). Desert Animals: Physiological Problems of Heat and Water. New York: Oxford University Press. 에 인용되다

- ^ a b Bronx Zoo. "Camel Adaptations". Wildlife Conservation Society. Archived from the original (Flash) on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Rundel, Philip Wilson; Gibson, Arthur C. (30 September 2005). "Adaptations of Mojave Desert Animals". Ecological Communities And Processes in a Mojave Desert Ecosystem: Rock Valley, Nevada. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780521021418.

- ^ "Camels — Old World Camels". Science Encyclopedia. Net Industries. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Silverstein, Alvin; Silverstein, Virginia B; Silverstein, Virginia; Silverstein Nunn, Laura (2008). Adaptation. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9780822534341.

- ^ "Morphometric analysis of heart, kidneys and adrenal glands in dromedary camel calves (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 2017-03-04. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ^ Rehan S and AS Quershi, 2006.반자동 이미지 분석 시스템을 사용하여 혹이 하나뿐인 낙타 송아지(Camelus dromedarius)의 심장, 신장 및 부신을 현미경으로 평가합니다.J 카멜 연습 규정 13(2): 123

- ^ a b c d Davidson, Alan; Davidson, Jane (15 October 2006). Jaine, Tom (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 68, 129, 266, 762. ISBN 978-0192806819.

- ^ "Kidneys and Concentrated Urine". Temperature and Water Relations in Dromedary Camels (Camelus dromedarius). Davidson College. Archived from the original on February 25, 2003.

- ^ "Fun facts about the Camel". The Jungle Store. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Fedewa, Jennifer L. (2000). "Camelus bactrianus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ Koenig, R. (2007). "VETERINARY MEDICINE: 'Camelized' Antibodies Make Waves". Science. 318 (5855): 1373. doi:10.1126/science.318.5855.1373. PMID 18048665. S2CID 71028674.

- ^ Sazmand, Alireza; Joachim, Anja (2017). "Parasitic diseases of camels in Iran (1931–2017) – a literature review". Parasite. EDP Sciences. 24: 1–15. doi:10.1051/parasite/2017024. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 5479402. PMID 28617666. S2CID 13783061. 기사 번호 21. 페이지 2

- ^ Muyldermans, Serge (2013-06-02). "Nanobodies: Natural Single-Domain Antibodies". Annual Review of Biochemistry. Annual Reviews. 82 (1): 775–797. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-063011-092449. ISSN 0066-4154. PMID 23495938. 페이지 788

- ^ Taylor, K.M.; Hungerford, D.A.; Snyder, R.L.; Ulmer Jr., F.A. (1968). "Uniformity of karyotypes in the Camelidae". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 7 (1): 8–15. doi:10.1159/000129967. PMID 5659175.

- ^ Koulischer, L; Tijskens, J; Mortelmans, J (1971). "Mammalian cytogenetics. IV. The chromosomes of two male Camelidae: Camelus bactrianus and Lama vicugna". Acta Zoologica et Pathologica Antverpiensia. 52: 89–92. PMID 5163286.

- ^ Bianchi, N. O.; Larramendy, M. L.; Bianchi, M. S.; Cortés, L. (1986). "Karyological conservatism in South American camelids". Experientia. 42 (6): 622–4. doi:10.1007/BF01955563. S2CID 23440910.

- ^ Bunch, Thomas D.; Foote, Warren C.; Maciulis, Alma (1985). "Chromosome banding pattern homologies and NORs for the Bactrian camel, guanaco, and llama". Journal of Heredity. 76 (2): 115–8. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a110034.

- ^ O'Brien, Stephen J.; Menninger, Joan C.; Nash, William G., eds. (2006). Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes. New York: Wiley-Liss. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-471-35015-6.

- ^ Di Berardino, D.; Nicodemo, D.; Coppola, G.; King, A.W.; Ramunno, L.; Cosenza, G.F.; Iannuzzi, L.; Di Meo, G.P.; et al. (2006). "Cytogenetic characterization of alpaca (Lama pacos, fam. Camelidae) prometaphase chromosomes". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 115 (2): 138–44. doi:10.1159/000095234. PMID 17065795. S2CID 21378633.

- ^ Balmus, Gabriel; Trifonov, Vladimir A.; Biltueva, Larisa S.; O’Brien, Patricia C.M.; Alkalaeva, Elena S.; Fu, Beiyuan; Skidmore, Julian A.; Allen, Twink; et al. (2007). "Cross-species chromosome painting among camel, cattle, pig and human: further insights into the putative Cetartiodactyla ancestral karyotype". Chromosome Research. 15 (4): 499–515. doi:10.1007/s10577-007-1154-x. PMID 17671843. S2CID 23226488.

- ^ a b Potts, Danel. "Bactrian Camels and Bactrian-Dromedary Hybrids". Silkroad. 3 (1). Archived from the original on 2016-06-23. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ Mohandesan, Elmira; Fitak, Robert R.; Corander, Jukka; Yadamsuren, Adiya; Chuluunbat, Battsetseg; Abdelhadi, Omer; Raziq, Abdul; Nagy, Peter; Stalder, Gabrielle (30 August 2017). "Mitogenome Sequencing in the Genus Camelus Reveals Evidence for Purifying Selection and Long-term Divergence between Wild and Domestic Bactrian Camels". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 9970. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.9970M. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08995-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5577142. PMID 28855525.

- ^ Ji, R; Cui, P; Ding, F; Geng, J; Gao, H; Zhang, H; Yu, J; Hu, S; Meng, H (August 2009). "Monophyletic origin of domestic bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) and its evolutionary relationship with the extant wild camel (Camelus bactrianus ferus)". Animal Genetics. 40 (4): 377–382. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2008.01848.x. ISSN 0268-9146. PMC 2721964. PMID 19292708.

- ^ Stanley, H. F.; Kadwell, M.; Wheeler, J. C. (1994). "Molecular Evolution of the Family Camelidae: A Mitochondrial DNA Study". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 256 (1345): 1–6. Bibcode:1994RSPSB.256....1S. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0041. PMID 8008753. S2CID 40857282.

- ^ Skidmore, J. A.; Billah, M.; Binns, M.; Short, R. V.; Allen, W. R. (1999). "Hybridizing Old and New World camelids: Camelus dromedarius x Lama guanicoe". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 266 (1420): 649–56. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0685. PMC 1689826. PMID 10331286.

- ^ "Meet Rama the cama ..." BBC. 21 January 1998. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b Fahmy, Miral (21 March 2002). "'Cama' camel/llama hybrids born in UAE research centre". Science in the News. The Royal Society of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (15 July 2002). "Bad karma for cross llama without a hump". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "Joy for world's first camel and llama cross". Metro UK. 6 April 2008. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b Harington, C. R. (June 1997). "Ice Age Yukon and Alaskan Camels". Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. Government of Yukon, Department of Tourism and Culture, Museums Unit. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ a b Bernstein, William J. (6 May 2009). A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. Grove Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9780802144164.

- ^ North Dakota Industrial Commission Department of Mineral Resources. "Poebrotherium" (PDF). North Dakota State Government. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ "Fossil camel skull (Poebrotherium sp.)". Science Buzz. Science Museum of Minnesota. January 2004. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ Kindersley, Dorling (2 June 2008). "Camels". Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Life. Penguin. pp. 266–7. ISBN 9780756682415.

- ^ Heintzman, Peter D.; Zazula, Grant D.; Cahill, James A.; Reyes, Alberto V.; MacPhee, Ross D.E.; Shapiro, Beth (September 2015). "Genomic Data from Extinct North American Camelops Revise Camel Evolutionary History". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 32 (9): 2433–2440. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv128. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 26037535.

- ^ Rybczynski, Natalia; Gosse, John C.; Richard Harington, C.; Wogelius, Roy A.; Hidy, Alan J.; Buckley, Mike (June 2013). "Mid-Pliocene warm-period deposits in the High Arctic yield insight into camel evolution". Nature Communications. 4 (1): 1550. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1550R. doi:10.1038/ncomms2516. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 3615376. PMID 23462993.

- ^ Singh; Tomar. Evolutionary Biology (8th revised ed.). New Delhi: Rastogi Publications. p. 334. ISBN 9788171336395.

- ^ Rybczynski, Natalia; Gosse, John C.; Harington, C. Richard; Wogelius, Roy A.; Hidy, Alan J.; Buckley, Mike (March 5, 2013). "Mid-Pliocene warm-period deposits in the High Arctic yield insight into camel evolution". Nature Communications. 4 (3): 1550. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1550R. doi:10.1038/ncomms2516. PMC 3615376. PMID 23462993.

- ^ Buckley, Michael; Lawless, Craig; Rybczynski, Natalia (March 2019). "Collagen sequence analysis of fossil camels, Camelops and c.f. Paracamelus, from the Arctic and sub-Arctic of Plio-Pleistocene North America". Journal of Proteomics. 194: 218–225. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2018.11.014. PMID 30468917. S2CID 53713960.

- ^ Geraads, Denis; Didier, Gilles; Barr, Andrew; Reed, Denne; Laurin, Michel (April 2020). "The fossil record of camelids demonstrates a late divergence between Bactrian camel and dromedary=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 65 (2): 251–260. doi:10.4202/app.00727.2020. eISSN 1732-2421. ISSN 0567-7920.

- ^ a b Worboys, Graeme L.; Francis, Wendy L.; Lockwood, Michael (30 March 2010). Connectivity Conservation Management: A Global Guide. Earthscan. p. 142. ISBN 9781844076048.

- ^ a b MacPhee, Ross D. E.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (30 June 1999). Extinctions in Near Time: Causes, Contexts, and Consequences. Springer. pp. 18, 20, 26. ISBN 9780306460920.

- ^ Walker, Matt (22 July 2009). "Wild camels 'genetically unique'". Earth News. BBC. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ Scarre, Chris (15 September 1993). Smithsonian Timelines of the Ancient World. London: D. Kindersley. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-56458-305-5.

Both the dromedary (the seven-humped camel of Arabia) and the Bactrian camel (the two-humped camel of Central Asia) had been domesticated since before 2000 BC.

- ^ Bulliet, 리처드(5월 20일 1990년)[1975년].그 카멜과 휠.모닝 사이드 북 시리즈이다.콜럼비아 대학 프레스. p. 183. 아이 에스비엔 978-0-231-07235-9.이미 언급되었다, 활용[낙타 수레를 끌고]이런 종류의 다시two-humped 낙타는 길들이기의 세번째 천년의 가장 오래된 것으로 알려진 기간에 간다.—Note이 Bulliet 낙타의 조기 사용에 더 많은 추천서를 갖고 있다.

- ^ Richard, Suzanne (2003). Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader. ISBN 9781575060835. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ^ Hirst, K. Kris. "Camels". About.com Archaeology. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Heide, Martin (2011). "The Domestication of the Camel: Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible". Ugarit-Forschungen. 42: 367–68. doi:10.13140/2.1.2090.8161.

- ^ Hasson, Nir (Jan 17, 2014). "Hump stump solved: Camels arrived in region much later than biblical reference". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ a b Sapir-Hen, Lidar; Erez Ben-Yosef (2013). "The Introduction of Domestic Camels to the Southern Levant: Evidence from the Aravah Valley" (PDF). Tel Aviv. 40 (2): 277–285. doi:10.1179/033443513x13753505864089. S2CID 44282748. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ Dias, Elizabeth (Feb 11, 2014). "The Mystery of the Bible's Phantom Camels". Time. Archived from the original on 15 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Heide, Martin (2011). "The Domestication of the Camel: Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible". Ugarit-Forschungen. 42: 368.

- ^ Petrie, OJ (1995). Harvesting of textile animal fibres. FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin No. 122. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-103759-1. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Cumming, Cunnington, Cunnington, Valerie, CW and PE (2010). The Dictionary of Fashion History. Oxford: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781847887382.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Fagan, Brian M, ed. (2004). "Transportation". The Seventy Great Inventions of the Ancient World. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-0-500-05130-6.[페이지 필요]

- ^ Baum, Doug (1 November 2018). "The Art of Saddling a Camel". Saudi Aramco World. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (2007). Soldiers' Lives Through History: The Ancient World. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. xvi. ISBN 9780313333484.

- ^ Bhatia, Vimal (23 July 2012). "BSF to ditch camels to ride sand scooters". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ Gann, Lewis Henry; Duignan, Peter (1972). Africa and the World: An Introduction to the History of Sub-Saharan Africa from Antiquity to 1840. University Press of America. p. 156. ISBN 9780761815204.

The camel was acclimatized in Egypt long before the time of Christ and was subsequently adopted by the Berbers of the desert, who used camel cavalry to fight the Romans. The Berbers spread the use of the camel across the Sahara.

- ^ Fleming, Walter L. (February 1909). "Jefferson Davis's Camel Experiment". The Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 74, no. 8. Bonnier Corporation. p. 150. ISSN 0161-7370. Archived from the original on 2016-05-04.

Other trials of the camel were made in 1859 by Major D. H. Vinton, who used twenty-four of them in carrying burdens for a surveying party...All in all, he concluded, the camel was much superior to the mule.

- ^ a b c Mantz, John (20 April 2006). "Camels in the Cariboo". In Basque, Garnet (ed.). Frontier Days in British Columbia. Heritage House Publishing Co. pp. 51–54. ISBN 9781894384018. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016.

- ^ Southern, Pat (1 October 2007). The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History. Oxford University Press. p. 123. ISBN 9780195328783.

- ^ Nicolle, David (26 March 1991). The Desert Frontier. Rome's Enemies. Vol. 5 (illustrated, reprint ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 9781855321663.

Nevertheless the military prowess of desert peoples impressed the Romans, who recruited large numbers as auxiliary cavalry and archers. In addition to providing the Roman Army with its best archers, the Easterners (largely Arabs but generally known as 'Syrians') served as Rome's most effective dromedarii or camel-mounted troops.

- ^ Herodotus (440 BC). The History of Herodotus. Rawlinson, George (trans.). Archived from the original on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

He collected together all the camels that had come in the train of his army to carry the provisions and the baggage, and taking off their loads, he mounted riders upon them accoutred as horsemen. These he commanded to advance in front of his other troops against the Lydian horse; behind them were to follow the foot soldiers, and last of all the cavalry. When his arrangements were complete, he gave his troops orders to slay all the other Lydians who came in their way without mercy, but to spare Croesus and not kill him, even if he should be seized and offer resistance. The reason why Cyrus opposed his camels to the enemy's horse was because the horse has a natural dread of the camel, and cannot abide either the sight or the smell of that animal. By this stratagem he hoped to make Croesus's horse useless to him, the horse being what he chiefly depended on for victory. The two armies then joined battle, and immediately the Lydian war-horses, seeing and smelling the camels, turned round and galloped off; and so it came to pass that all Croesus's hopes withered away.

- ^ "Cameliers and camels at war". New Zealand History online. History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 30 August 2009. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ "The Posts at Benicia". The California State Military Museum. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ "Vitrine N° 108 (partie droite): LES PELOTONS MEHARISTES" (in French). Musée de l'infanterie. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Hall, Bruce S. (6 June 2011). A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960. Cambridge University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9781107002876.

- ^ Guillaume, Philippe (16 June 2012). "L'incroyable épopée des méharistes français" [The incredible epic of the French méharistes]. BDSphère (in French). Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ "Cameliers and camels at war". New Zealand History online. History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 30 August 2009. pp. 1, 2, 4, 5. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Woodward, David R. (2006). Hell in the Holy Land: World War I in the Middle East. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 36, 39, 43, 56, 133. ISBN 9780813123837.

- ^ Murray, Archibald James (1920). Sir Archibald Murray's despatches (June 1916 – June 1917). J.M. Dent. p. 123.

A great deal of the work of supplying the troops on both fronts has been done by the Camel Transport Corps

- ^ McGregor, Andrew James (30 May 2006). A Military History of Modern Egypt: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 215. ISBN 9780275986018.

- ^ Federal Research Division (30 June 2004). Somalia a Country Study. Area handbook series (3rd ed.). Kessinger Publishing. pp. 230–231. ISBN 9781419147999.

- ^ "Romanian troops using camels". WWII in Color. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21.

- ^ "Наш советский верблюд покарает!". WARHEAD.SU. March 2, 2020.

- ^ Jupiter Infomedia Ltd (28 November 2012). "Bikaner Camel Corps, Presidency Armies in British India". IndiaNetzone.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ Shelley, Toby (December 2007). "Sons of the Clouds". Red Pepper. Location. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Hermandad de Veteranos Tropas Nómadas del Sáhara. "Los Medios" [The Means]. Historia: Agrupación de Tropas Nómadas (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Camels banned from Saudi beauty contest over Botox". BBC News. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Adams, Abigail (9 December 2021). "Over 40 Camels Disqualified From Beauty Contest in Saudi Arabia For Receiving Botox Injections". PEOPLE.com.

- ^ Bulliet, Richard W. (1975). The Camel and the Wheel. Columbia University Press. pp. 23, 25, 28, 35–36, 38–40. ISBN 9780231072359.

- ^ a b "Camel Milk". Milk & Dairy Products. FAO's Animal Production and Health Division. 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Ramet. Camel milk and cheese making. Archived from the original on 2012-06-24.

- ^ "Fresh from your local drome'dairy'?". Food and Agriculture Organization. 6 July 2001. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012.

- ^ Ramet. Methods of processing camel milk into cheese. Archived from the original on 2012-06-24.

- ^ Young, Philippa. "In Mongolian the Word 'Gobi' Means 'Desert'". Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

As evening approaches we are offered camel meat boats, dumplings stuffed with a finely chopped mixture of meat and vegetables, followed by camel milk tea and finally, warm fresh camel's milk to aid digestion and help us sleep.

- ^ "Netherlands' 'crazy' camel farmer". BBC. 5 November 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ "Al Ain Dairy launches camel-milk ice cream". The National. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- ^ Tariq, M., Rabia, R., Jamil, A., Sakhwat, A., A., Aadil, A. 및 Muhammad S., 2010.파키스탄의 낙타(카멜루스 드로메다리우스) 고기의 미네랄과 영양 조성물.저널-파키스탄 화학회, 제33권(6)

- ^ "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ a b c Yagil. Camels Products Other Than Milk. Archived from the original on 2011-02-20.

- ^ Madame Guinaudeau (2003). Traditional Moroccan Cooking: Recipes from Fez. London: Serif. ISBN 978-1-897959-43-5.

- ^ Aleme, A., D., 2013.에티오피아 일부 지역의 귀중한 영양 공급원으로서의 낙타 고기의 리뷰.농업과학공학기술연구.제1권, 제4호, 2013년 12월, PP: 40~43.에서 온라인으로 입수할 수 있습니다.

- ^ Rubenstein, Dustin (23 July 2010). "How to Cook Camel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

He cut the pieces very small and cooked them for a long time. I decided to try something a bit different the following night and cut the pieces a bit bigger and cooked them for less time, as I like my meat rarer than he does. This was a bad idea. It seems that the more you cook camel, the more tender it becomes. So we had what amounted to two pounds or more of rubber for dinner that night.

- ^ Arthur, Rick (4 January 2012). "The Instant Expert: camels, the ships of the desert". The National. UAE: Abu Dhabi Media.

As the meat can be dry, however, the Abu Dhabi Officer's Club, for one, serves camel burger with beef or lamb fat mixed in, improving texture and taste.

- ^ Jasra, Abdel Wahid; Isani, G. B.; Camel Applied Research and Development Network (2000). Socio-economics of camel herders in Pakistan. The Camel Applied Research and Development Network. p. 164. Archived from the original on 2016-06-10.

- ^ 낙타 고기 먹을 사람? 혹 하나, 두 개?2017-01-26 Wayback Machine에서 보관수호자, 입소문

- ^ a b Sherwood, Andy (17 September 2012). "Camel burgers in Abu Dhabi". Time Out Abu Dhabi. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Webster, George (9 February 2010). "Dubai diners flock to eat new 'camel burger'". CNN World. CNN. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Bin Saeed, Abdulaziz A.; Al-Hamdan, Nasser A.; Fontaine, Robert E. (2005). "Plague from eating raw camel liver". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (9): 1456–7. doi:10.3201/eid1109.050081. PMC 3310619. PMID 16229781.

- ^ McBride, Louise (14 June 2010). "SA hits world camel meat supply hump". Stock Journal. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Burin, Margaret (7 August 2015). "Australians urged to develop taste for camel meat". ABC News. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Bazckowski, Halina (22 March 2020). "The beasts that beat the drought: Camels sought after for meat, milk and cheese". ABC News. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Book 1, Number 0184". Purification (Kitab al-Taharah). Partial Translation of Sunan Abu-Dawud, Book 1. Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

Narrated Al-Bara' ibn Azib: The Messenger of Allah (peace_be_upon_him) was asked about performing ablution after eating the flesh of the camel. He replied: Perform ablution, after eating it. He was asked about performing ablution after eating meat. He replied: Do not perform ablution after eating it. He was asked about saying prayer in places where the camels lie down. He replied: Do not offer prayer in places where the camels lie down. These are the places of Satan. He was asked about saying prayer in the sheepfolds. He replied: You may offer prayer in such places; these are the places of blessing.

- ^ Williams, John Alden (1994). The Word of Islam. University of Texas Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-292-79076-6. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ 캄포, 후안 에두아르도(2009).이슬람 백과사전.인포베이스 출판사, 페이지 128

- ^ Heinemann, Moshe (2013-08-20). "Cholov Yisroel: Does a Neshama Good". Kashrus Kurrents. Star-K. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ http://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/9912#v=41 Wayback Machine에서 2015-02-07 아카이브 완료

- ^ 선사시대 사우디아라비아 낙타 조각, BBC, 2021년 9월 15일

- ^ a b c Dolby, Karen (10 August 2010). You Must Remember This: Easy Tricks & Proven Tips to Never Forget Anything, Ever Again. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 170. ISBN 9780307716255.

- ^ Abokor, Axmed Cali (1987). The Camel in Somali Oral Tradition. Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 7, 10–11. ISBN 9789171062697.

- ^ "Drought threatening Somali nomads, UN humanitarian office says". UN News Centre. 14 November 2003. Archived from the original on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

A four-year drought is threatening the lives of Somali nomads, and those of the camel herds on which they depend for transportation and milk

- ^ 파라, K.O;Nyariki, D.M.;응구기, R.K.;' 누어'란, I.M.;Guliye, A.Y(2004년)."그 소말리아와 낙타:생태학, 관리와 경제".Anthropologist.6(1):45–55. doi:10.1080/09720073.2004.11890828.S2CID 4980638.소말리아 목축민들이 낙타가 사회 안에서는...그 낙타는 소말리아 사회에서 지방 경제의 중추적인 역할과 문화 담당하는 세상의 어떤 다른 지역 사회다.유엔 식량 농업 기구(FAO, 1979년)의 추산에 의하면, 약 15만 단봉 낙타는 세계 평야 text 버전에 있다.2013-01-02 Wayback Machine에 보관

- ^ "Feral camel". Northern Territory government. 17 August 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Pople, A. R.; McLeod, S. R. (2010). "Demography of feral camels in central Australia and its relevance to population control". The Rangeland Journal. 32: 11. doi:10.1071/RJ09053.

- ^ Saalfeld, W.K.; Edwards, GP (2008). "Ecology of feral camels in Australia" (PDF). Managing the impacts of feral camels in Australia: a new way of doing business. Alice Springs: Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre. ISBN 978-1-74158-094-5. ISSN 1832-6684. Archived from the original (DKCRC Report 47) on 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2011-12-25.

- ^ Tsai, Vivian (14 September 2012). "Australia Culls 100,000 Feral Camels To Limit Environmental Damage, Many More Will Be Killed". U.S. Edition. International Business Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ "Bactrian Camel" (PDF). Denver Zoo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Hare, J. (2008). "Camelus ferus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T63543A12689285. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T63543A12689285.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

일반 참고 자료 및 인용 참고 자료

- 낙타와 낙타 우유.유엔 식량농업기구가 발표한 보고서(1982)

- Ramet, J. P. (2011). The technology of making cheese from camel milk (Camelus dromedarius). FAO Animal Production and Health Paper. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-103154-4. ISSN 0254-6019. OCLC 476039542. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Vannithone, S.; Davidson, A. (1999). "Camel". The Oxford companion to food. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-19-211579-9.

- Wilson, R.T. (1984). The camel. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-77512-1.

- Yagil, R. (1982). Camels and Camel Milk. FAO Animal Production and Health Paper. Vol. 26. Rome: Food And Agriculture Organization Of The United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-101169-0. ISSN 0254-6019.

추가 정보

- Gilchrist, W. (1851). A Practical Treatise on the Treatment of the Diseases of the Elephant, Camel & Horned Cattle: with instructions for improving their efficiency; also, a description of the medicines used in the treatment of their diseases; and a general outline of their anatomy. Calcutta, India: Military Orphan Press.