메타미졸

Metamizole | |

| |

| 임상자료 | |

|---|---|

| 상호 | Novalgin[2], Algocalmin,[1] Angin 등 |

| 기타이름 | 디피론 (BAN, USAN, Sulpyrine (JAN)) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 국제 약품명 |

| 임신 카테고리 | |

| 의 경로 행정부. | 구강, IM, IV, 직장 |

| ATC코드 | |

| 법적지위 | |

| 법적지위 | |

| 약동학적 자료 | |

| 생체이용률 | 100% (활성 대사산물)[11] |

| 단백질결합 | 48~58% (활성 대사산물)[11] |

| 신진대사 | 간[11] |

| 제거 반감기 | 14분(모 화합물; 비경구);[4] 대사물: 2-4시간[11] |

| 배설 | 소변(96%, IV; 85%, 구강), 대변(4%, IV).[4] |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 |

|

| 펍켐 CID | |

| 드럭뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니아이 | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| CHEMBL | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA) | |

| ECHA 인포카드 | 100.000.631 |

| 화학물질 및 물리적 데이터 | |

| 공식 | C13H17N3O4S |

| 어금니 질량 | 311.36 g·mol−1 |

| 3D 모델(Jsmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

메타미졸 또는 디피론으로 알려진 약물은 진통제, 경련 완화제 및 해열제입니다. 가장 일반적으로 경구 또는 정맥 주사로 투여됩니다.[12][11][13] 암피론 술폰산염 계열 의약품에 속하며 1922년 특허를 받았습니다. 메타미졸은 다양한 상호로 판매되고 있습니다.[14][3] 독일에서 "노발진"이라는 브랜드로 처음 의학적으로 사용되었습니다.[15]

메타미졸은 많은 국가에서 처방전 없이 구입할 수 있지만 1970년대부터 일부 국가에서는 무과립구증을 포함한 심각한 부작용과 관련된 연구로 인해 금지되었습니다.[16] 다른 연구에 따르면 다른 진통제보다 안전한 약물이라고 합니다.[17][18] 메타미졸은 사용 가능한 많은 국가에서 인기가 있습니다.[19]

의료용

주로 수술 중 통증, 급성 손상, 결장, 암성 통증, 기타 급성/만성 형태의 통증 및 다른 약제에 반응하지 않는 고열에 사용됩니다.[4]

특수인구

비록 동물 연구들이 선천적 결함의 위험을 최소한으로 보여준다는 점에서 안심할 수 있지만, 임신에 있어서 그것의 사용은 권장되지 않습니다. 노인과 간 또는 신장에 장애가 있는 사람들에게 사용하는 것이 권장되지만, 이러한 그룹의 사람들이 치료를 받아야 한다면 대개 용량을 낮추고 주의를 기울이는 것이 좋습니다. 수유 중에는 모유로 배설되기 때문에 사용하는 것이 좋습니다.[4]

역기능

메타미졸은 혈액 관련 독성(혈액이상증)의 가능성이 있지만 비스테로이드성 항염증제(NSAIDs)에 비해 신장, 심혈관, 위장 독성을 덜 유발합니다.[11] NSAIDs와 마찬가지로 특히 천식이 있는 환자에서 기관지 경련이나 아나필락시스를 유발할 수 있습니다.[13]

심각한 부작용으로는 무과립구증, 무플라스틱 빈혈, 과민 반응(아나필락시스 및 기관지 경련과 같은), 독성 표피 괴사증이 있으며, 화학적으로 술폰아미드와 관련이 있기 때문에 포르피리아의 급성 공격을 유발할 수 있습니다.[3][11][13] 무과립구증의 상대적 위험은 해당 비율에 대한 추정 국가에 따라 크게 차이가 나는 것으로 보이며 위험에 대한 의견은 크게 갈립니다.[3][20][21] 유전학은 메타미졸 감수성에 중요한 역할을 할 수 있습니다.[22] 일부 개체군은 다른 개체군보다 메타미졸 유도 무과립구증으로 고통받기 쉽다고 제안됩니다. 예를 들어, 메타미졸 관련 무과립구증은 스페인 사람들과 대조적으로 영국 인구에서 더 빈번한 부작용인 것으로 보입니다.[23] 유럽의약품청의 평가 보고서는 "비과립구증을 유발할 가능성은 연구 대상 인구의 유전적 특성과 관련이 있을 수 있다"[24]고 언급했습니다.

2015년 메타 분석에 따르면, "병원 환경에서 단기간 사용할 수 있는" 증거에 대해 메타미졸은 널리 사용되는 다른 진통제와 비교했을 때 안전한 선택인 것처럼 보이지만, 분석된 "보고서의 전반적인 품질이 좋지 않아 결과가 제한되었다"고 결론지었습니다.[25]

2016년의 체계적인 검토 결과 메타미졸은 상부 위장관 출혈의 상대적 위험을 1.4배에서 2.7배까지 크게 증가시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[26] 이 약의 제조업체 중 한 곳의 연구에 따르면 치료 첫 주 동안 무과립구증의 위험은 백만 분의 1.1이었고 디클로페낙의 경우 백만 분의 5.9였습니다.

금기사항

사용된 제제의 메타미졸 또는 부형제(예: 락토오스)에 대한 이전의 과민성(무과립구증 또는 아나필락시스), 급성 포르피리아, 손상된 조혈(화학요법제 치료로 인한), 임신 3분기(신생아에서 부작용의 가능성), 수유, 체중이 16 kg 미만인 어린이, 아스피린 유발 천식 병력 및 진통제에 대한 기타 과민 반응.[4]

2018년 유럽의약품청(EMA)은 메타미졸의 안전성을 검토한 결과 일반인에게 일반적으로 안전하다고 결론 내렸습니다. 그러나 임신 3기나 모유 수유 중에는 태아나 영아에게 신장 장애나 동맥관의 위험이 있어 사용하지 말 것을 권고했습니다.[9]

| 약물(들) | 교호작용/상호작용에 대한 이론적 잠재력에 대한 이유 |

|---|---|

| 시클로스포린 | 시클로스포린의 혈청 수치가 감소했습니다.[4] |

| 클로르프로마진 | 부가적인 저체온증(저체온)이 발생할 수 있습니다.[4] |

| 히드록시에틸 전분 | 급성 신부전. 증거는 적지만 동시 투여를 권장하지 않습니다.[27] |

| 메토트렉세이트 | 혈액학적(혈액) 독성에 대한 추가 위험.[4] 좀 더 구체적으로 골수형성증.[27] |

경구용 항응고제(혈액 희석제), 리튬, 캡토프릴, 트리암테렌 및 항고혈압제도 메타미졸과 상호작용할 수 있습니다. 다른 피라졸론은 이러한 물질과 상호작용하지 않는 것으로 알려져 있기 때문입니다.

과다 복용

과량 복용 시 상당히 안전한 것으로 여겨지지만, 이러한 경우에는 일반적으로 흡수를 제한하고 배설을 가속화하는 조치(예: 혈액투석)와 함께 보조적인 조치가 권장됩니다.[4]

물리화학

메타미졸은 설폰산이며 칼슘, 나트륨 및 마그네슘 염 형태로 제공됩니다.[3] 나트륨 염 모노하이드레이트 형태는 백색/거의 결정질인 분말로 빛이 있는 곳에서는 불안정하고 물과 에탄올에는 매우 용해되지만 디클로로메탄에는 거의 용해되지 않습니다.[28] 3791

약리학

뇌와 척수 프로스타글란딘(염증, 통증, 발열에 관여하는 지방과 같은 분자) 합성을 억제하는 것이 관여할 수 있다고 여겨지지만, 그 정확한 작용 메커니즘은 알려져 있지 않습니다.[13] 2000년대에 연구원들은 메타미졸이 전구약물이라는 또 다른 메커니즘을 밝혀냈습니다. 메타미졸 자체는 활성 물질인 다른 화학 물질로 분해됩니다. 그 결과 칸나비노이드 및 NSAID 아라키돈산 접합체 쌍, 특히 아라키도노일-4-메틸아미노안티피린(ARA-4-MAA) 및 아라키도노일-4-아미노안티피린(ARA-4-AA)이 생성됩니다.[17][29] 이 작용 메커니즘은 파라세타몰 및 활성 아라키돈산 대사산물 AM404와 비교되었습니다. CB1 수용체 역작용제 AM-251은 디피론의 이화작용 반응과 열 진통을 감소시킬 수 있었습니다.[30] 또 다른 연구에서는 CB2 역작용제 AM-630에[31] 의해 항진증 효과가 역전되는 것을 발견했습니다. 프로스타글란딘, 특히 프로스타글란딘 E2에 의해 유발되는 열을 억제하는 것처럼 보이지만 [32]메타미졸은 대사산물에 의해 치료 효과를 생성하는 것으로 보입니다. 특히 N-메틸-4-아미노안티피린(MAA) 및 4-아미노안티피린(AA)은 FAAH 효소를 통해 형성되어 아라키도노일-4-메틸아미노안티피린(ARA-4-MAA) 및 아라키도노일-4-아미노안티피린(ARA-4-AA)을 생성하는 것을 특징으로 하는 방법.[4]

| 대사물 | 머리글자 | 생물학적으로 활성화? | 약동학적 성질 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAA | 네. | 생체 이용률은 ≈ 90%입니다. 혈장 단백질 결합: 58%. 최초(구강) 용량의 3±1%로 소변으로 배출됨 | |

| AA | 네. | 생체 이용률은 ≈ 22.5%입니다. 혈장 단백질 결합: 48%. 최초(구강) 용량의 6±3%로 소변으로 배출됨 | |

| FAA | 아니요. | 혈장 단백질 결합: 18%. 최초 경구 투여량의 23±4%로 소변 내 배설량 | |

| 아 | 아니요. | 혈장 단백질 결합: 14%. 최초 경구 투여량의 26±8%로 소변 내 배설량 |

역사

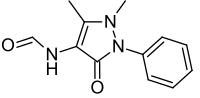

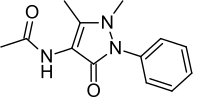

루트비히 크노르는 페닐히드라진의 발견을 포함한 퓨린과 당에 관한 연구로 노벨상을 수상한 에밀 피셔의 학생이었습니다.[1][33] 1880년대에 크노르는 페닐히드라진으로부터 키닌 유도체를 만들려고 시도하다가, 대신 피라졸 유도체를 만들었고, 메틸화 후에 그는 안티피린이라고도 불리는 페나존을 만들었는데, 이것은 현대의 모든 해열진통제의 '어머니'라고 불렸습니다.[1][34]: 26–27 그 약의 판매는 폭발적으로 증가했고, 1890년대에 루시우스 & Co.(현재의 사노피인 ho스트 AG의 전신) 티어파벤파브릭 마이스터의 화학자들은 안티피린보다 3배 더 활성이 높은 피라미드론이라는 또 다른 유도체를 만들었습니다.

1893년, 안티피린의 유도체인 아미노피린이 ho스트의 프리드리히 스톨즈에 의해 만들어졌습니다. 그러나 나중에 ho스트의 화학자들은 1913년에 도입된 멜루브린(안티피린아미노메탄술폰산나트륨)이라는 유도체를 만들었고, 마침내 1920년에 메타미졸이 합성되었습니다. 메타미졸은 멜루브린의 메틸 유도체이며 또한 피라미드의 더 용해성이 높은 전구약물입니다.[1][34]: 26–27 메타미졸은 1922년 독일에서 "노발진"으로 처음 시판되었습니다.[1][18]

사회와 문화

법적지위

메타미졸 가용성 세계지도(Dipyron) 제한된 제한이 있는 장외 제품입니다. 사용 가능하지만 처방의 필요성에 대한 데이터는 없습니다. 처방 전용으로 사용에 상당히 제한이 있습니다. 처방 전용이며 사용에 광범위한 제한이 있습니다. 사람이 사용하는 것이 금지되어 있습니다. 여전히 수의학 사례에서 사용할 수 있습니다. 데이터가 없습니다. |

메타미졸은 몇몇 국가에서 금지되어 있으며, 다른 국가에서는 처방전에 의해 사용할 수 있으며(때로는 강한 경고가 있고, 때로는 그렇지 않은 경우도 있습니다), 다른 국가에서는 처방전에 의해 사용할 수 있습니다.[36][37][38] 예를 들어 스웨덴(1974년), 미국(1977년),[39] 인도(2013년, 2014년 금지 해제)에서 승인이 철회되었습니다.[40][41][42]

메타미졸은 미국에서 금지되어 있지만, 마이애미의 히스패닉계의 28%가 메타미졸을 보유하고 있으며,[43] 샌디에이고의 히스패닉계의 38%가 일부 사용을 보고한 것으로 소규모 조사에서 보고되었습니다.[44]

미국에서 말에 디피론을 무단으로 판매하고 사용하는 일이 있었습니다. FDA는 안전성에 대한 시험 데이터를 검토한 후 말의 발열 치료를 위해 승인했습니다.[8]

오피오이드 사태 속에서 메타미졸의 법적 지위가 옥시코돈 소비와 관계가 있다는 연구 결과가 나와 이들 약물의 사용이 역의 상관관계가 있음을 보여줍니다. 그것의 사용은 특히 메타미졸의 제한적이고 통제된 사용에서 오피오이드의 중독 위험을 조정할 때 유용할 수 있습니다.[45] 2019년 이스라엘 컨퍼런스에서도 승인된 상태를 오피오이드 의존성에 대한 예방책으로 정당화했으며 메타미졸은 신장 장애 환자에게 대부분의 진통제보다 안전합니다.[46]

메타미졸은 브라질 상파울루에서 가장 많이 판매되는 의약품으로 2016년 488톤을 차지했습니다.[47] 다른 나라와 비교하여 이러한 대조적인 소비를 감안할 때, 2001년 브라질 보건 규제 기관(ANVISA)은 안전성 평가를 위한 국제 패널을 소집했고, 그 결과 혜택이 위험을 상당히 능가하고, 제한을 부과하면 인구에게 상당한 부정적인 결과를 초래할 것이라는 결론을 내렸습니다.[48][21] 라틴 아메리카에서도 전반적으로 높은 인기를 얻고 있습니다. 2022년 브라질에서만 2억 1,500만 회분 이상이 투여되었습니다.[49]

불가리아 의약품 소파마는 2014년 기준으로 10년 넘게 불가리아에서 가장 많이 팔리는 진통제인 아날진(Angin)이라는 브랜드로 생산하고 있습니다.[50]

독일에서 이 약은 가장 일반적으로 처방되는 진통제입니다.[45]

2012년 인도네시아에서는 두통이 사용량의 70%를 차지하고 있습니다.[51]

2018년, 스페인에서 몇몇 영국인들이 사망한 후 스페인의 조사관들은 Nolotil(스페인에서 메타미졸로 알려져 있음)을 조사했습니다. 이러한 사망의 가능한 요인은 무과립구증(백혈구 수 감소)을 유발할 수 있는 메타미졸의 부작용일 수 있습니다.[52]

브랜드명

메타미졸은 국제적인 비영리 명칭이며, 시판되는 국가에서는 많은 브랜드 이름으로 제공됩니다.[2]

루마니아에서 메타미졸은 Zentiva가 Algocalmin으로 시판한 오리지널 의약품으로 500 mg 즉시 출시 정제로 구입할 수 있습니다. 용매 2ml에 메타미졸 나트륨 1g을 녹인 주사제로도 사용할 수 있습니다.

이스라엘에서는 테바에서 제조한 "옵탈긴"(히브리어: אופטלגין)이라는 브랜드로 판매되고 있습니다.

대한민국(설피린)과 일본에서는 설피린과 설피린으로 알려져 있습니다. (スルピリン)[53][54]

아진

아진(러시아어: а нальгин)은 옛 소련 약전에서 사용된 총칭으로 슬라브 국가에서 계속 사용되고 있습니다. 러시아의 한 회사는 2011년에 그 이름을 그들의 상표로 주장하려고 시도했지만 실패했습니다.[56][57] 불가리아에서는 2004년 Sopharma가 Angin을 상표로 등록하는 데 성공했습니다.[58]

진통제는 인도 약리학에서 사용되는 일반적인 용어이기도 합니다.[59]

참고문헌

- ^ a b c d e f Brune K (December 1997). "The early history of non-opioid analgesics". Acute Pain. 1: 33–40. doi:10.1016/S1366-0071(97)80033-2.

- ^ a b "Metamizole Annex I - List of nationally authorised medicinal products" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2018-06-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-05. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ a b c d e Martindale W, Sweetman SC, eds. (2009). Martindale: The complete drug reference (36th ed.). London; Chicago: Pharmaceuticale Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Fachinformation (Zusammenfassung der Merkmale des Arzneimittels) Novaminsulfon injekt 1000 mg Lichtenstein Novaminsulfon injekt 2500 mg Lichtenstein" (PDF). Winthrop Arzneimittel GmbH (in German). Zinteva Pharm GmbH. February 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Notice of Amendment: Addition of Metamizole (Dipyrone) to the Prescription Drug List (PDL)". Government of Canada. 2022-07-18. Archived from the original on 2022-08-30. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ "Recent NZ Gazette Notices Relating to Classification". medsafe.govt.nz. 2020-03-06. Archived from the original on 2023-04-29. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ "Minutes of the 63rd meeting of the Medicines Classification Committee - 10 Oct 2019". medsafe.govt.nz. 2019-12-04. Archived from the original on 2023-06-10. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ a b FDA's Center for Veterinary Medicine (November 26, 2019). "Zimeta (dipyrone injection) - Veterinarians". FDA. Archived from the original on 2022-01-17. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ a b European Medicines Agency (2018-09-17). "Metamizole containing medicinal products - EMA recommends aligning doses of metamizole medicines and their use during pregnancy and breastfeeding". European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original on 2023-02-01. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- CHMP (2018-12-13). "Metamizole - Assessment report" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (published 2019-03-28). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-05. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- "Metamizole Annex II - Scientific conclusions" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2019-03-28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-05. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- "Metamizole - Annex III - Amendments to relevant sections of the Product Information" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2018-06-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-05. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "Risikoinformationen - Metamizol (Novalgin, Berlosin, Novaminsulfon, etc.): BfArM weist auf richtige Indikationsstellung und Beachtung von Vorsichtsmaßnahmen und Warnhinweisen hin" [Risk information - Metamizol (Novalgin, Berlosin, Novaminsulfon, etc.): BfArM points out the correct indication and compliance with precautionary measures and warnings]. Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (Federal Institute for Pharmaceuticals and Medical Products). 2009-05-28. Archived from the original on 2023-05-18. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jage J, Laufenberg-Feldmann R, Heid F (April 2008). "[Medikamente zur postoperativen Schmerztherapie: Bewährtes und Neues. Teil 1: Nichtopioide]" [Drugs for postoperative analgesia: routine and new aspects. Part 1: non-opioids]. Der Anaesthesist (in German). 57 (4): 382–390. doi:10.1007/s00101-008-1326-x. PMID 18351305. S2CID 32814418.

- ^ "Fachinformation (Zusammenfassung der Merkmale des Arzneimittels) Novaminsulfon injekt 1000 mg Lichtenstein Novaminsulfon injekt 2500 mg Lichtenstein" (PDF). Winthrop Arzneimittel GmbH (in German). Zinteva Pharm GmbH. February 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d Brack A, Rittner HL, Schäfer M (March 2004). "Nichtopioidanalgetika zur perioperativen Schmerztherapie" [Non-opioid analgesics for perioperative pain therapy. Risks and rational basis for use]. Der Anaesthesist (in German). 53 (3): 263–280. doi:10.1007/s00101-003-0641-5. PMID 15021958. S2CID 8829564.

- ^ "Metamizole Annex I - List of nationally authorised medicinal products" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2018-06-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-05. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 530. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2005). Consolidated List of Products Whose Consumption and/or Sale Have Been Banned, Withdrawn, Severely Restricted of Not Approved by Governments (PDF) (12th ed.). New York: United Nations. pp. 171–5. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ a b Lutz M (November 2019). "Metamizole (Dipyrone) and the Liver: A Review of the Literature". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 59 (11): 1433–1442. doi:10.1002/jcph.1512. PMID 31433499.

- ^ a b c Nikolova I, Tencheva J, Voinikov J, Petkova V, Benbasat N, Danchev N (2014). "Metamizole: A Review Profile of a Well-Known "Forgotten" Drug. Part I: Pharmaceutical and Nonclinical Profile". Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 26 (6): 3329–3337. doi:10.5504/BBEQ.2012.0089. ISSN 1310-2818. S2CID 56205439.

- ^ Sznejder, Henry; Amand, Caroline; Stewart, Andrew; Salazar, Ricardo; Scala, Wanessa Alessandra Ruiz (2022). "Real world evidence of the use of metamizole (dipyrone) by the Brazilian population. A retrospective cohort with over 380,000 patients". Einstein (São Paulo). Sociedade Beneficente Israelita Brasileira Hospital Albert Einstein. 20. doi:10.31744/einstein_journal/2022ao6353. ISSN 1679-4508.

- ^ Pogatzki-Zahn E, Chandrasena C, Schug SA (October 2014). "Nonopioid analgesics for postoperative pain management". Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 27 (5): 513–519. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000113. PMID 25102238. S2CID 31337982.

- ^ a b Reis SL, Batista AP, Assumpção J, Ramos ER, Colacite J, Souza LF (2022-10-09). "A bibliographic analysis on the use of Dipyrone and Agranulocytosis". Research, Society and Development. 11 (13): e369111335570. doi:10.33448/rsd-v11i13.35570. S2CID 252870061. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ García-Martín E, Esguevillas G, Blanca-López N, García-Menaya J, Blanca M, Amo G, et al. (September 2015). "Genetic determinants of metamizole metabolism modify the risk of developing anaphylaxis". Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 25 (9): 462–464. doi:10.1097/FPC.0000000000000157. PMID 26111152.

- ^ Mérida Rodrigo L, Faus Felipe V, Poveda Gómez F, García Alegría J (April 2009). "[Agranulocytosis from metamizole: a potential problem for the British population]". Revista Clinica Espanola. 209 (4): 176–179. doi:10.1016/s0014-2565(09)71310-4. PMID 19457324.

- ^ Assessment report: metamizole-containing medicinal products (PDF) (Report). European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). 13 December 2018. EMA/143912/2019.

- ^ Kötter, Thomas; da Costa, Bruno R.; Fässler, Margrit; Blozik, Eva; Linde, Klaus; Jüni, Peter; Reichenbach, Stephan; Scherer, Martin (13 April 2015). "Metamizole-Associated Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. Public Library of Science (PLoS). 10 (4): e0122918. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122918. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ^ Andrade S, Bartels DB, Lange R, Sandford L, Gurwitz J (October 2016). "Safety of metamizole: a systematic review of the literature". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 41 (5): 459–477. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12422. PMID 27422768. S2CID 24538147.

- ^ a b Aronson JK, ed. (2015). Meyler's side effects of drugs: the international encyclopedia of adverse drug reactions and interactions. Vol. 4 (16th ed.). Amsterdam Boston Heidelberg: Elsevier. pp. 859–862. ISBN 978-0-444-53716-4. OCLC 927102885.

- ^ "Metamizole". European pharmacopoeia (English 8.1 ed.). Council Of Europe: European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare. 2013. p. 3791. ISBN 978-92-871-7527-4.

- ^ Jasiecka A, Maślanka T, Jaroszewski JJ (2014). "Pharmacological characteristics of metamizole". Polish Journal of Veterinary Sciences. 17 (1): 207–214. doi:10.2478/pjvs-2014-0030. PMID 24724493.

- ^ Crunfli F, Vilela FC, Giusti-Paiva A (March 2015). "Cannabinoid CB1 receptors mediate the effects of dipyrone". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 42 (3): 246–255. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12347. PMID 25430877. S2CID 13598808.

- ^ Gonçalves Dos Santos G, Vieira WF, Vendramini PH, Bassani da Silva B, Fernandes Magalhães S, Tambeli CH, Parada CA (May 2020). "Dipyrone is locally hydrolyzed to 4-methylaminoantipyrine and its antihyperalgesic effect depends on CB2 and kappa-opioid receptors activation". European Journal of Pharmacology. 874: 173005. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173005. PMID 32057719. S2CID 211112059.

- ^ Malvar D, Aguiar FA, Vaz A, Assis DC, de Melo MC, Jabor VA, et al. (August 2014). "Dipyrone metabolite 4-MAA induces hypothermia and inhibits PGE2 -dependent and -independent fever while 4-AA only blocks PGE2 -dependent fever". British Journal of Pharmacology. 171 (15): 3666–3679. doi:10.1111/bph.12717. PMC 4128064. PMID 24712707.

- ^ "Emil Fischer – Biographical". Nobel Committee.

- ^ a b c Raviña Rubira E (2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.

- ^ "New and Nonofficial Remedies: Melubrine". JAMA. 61 (11): 869. 1913.

- ^ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2005). Consolidated List of Products Whose Consumption and/or Sale Have Been Banned, Withdrawn, Severely Restricted of Not Approved by Governments (PDF) (12th ed.). New York: United Nations. pp. 171–5. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ 유엔 사무국의 경제 사회부 통합 제품 목록 14호(2005년 1월 ~ 2008년 10월): 의약품 국제연합 – 뉴욕, 2009

- ^ Rogosch T, Sinning C, Podlewski A, Watzer B, Schlosburg J, Lichtman AH, et al. (January 2012). "Novel bioactive metabolites of dipyrone (metamizol)". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 20 (1): 101–107. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.11.028. PMC 3248997. PMID 22172309.

- ^ Gardner S (1977-06-07). Drug products containing dipyrone - Withdrawal of Approval of New Drug Applications (Report). Vol. 42. Federal Register (published 1977-06-17). pp. 30893–4. ISSN 0097-6326. Archived from the original on 2020-09-29. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

This notice withdraws approval of the new drug applications (NDA's) for drug products containing dipyrone. The drug products have been used to reduce fever, but they are not shown to be safe for use. On the basis of new evidence, not contained in the applications or not available until after the applications were approved, evaluated together with the evidence available when the applications were approved, the Commissioner of Food and Drugs finds that such drugs have not been shown to be safe for use upon the basis of which the applications were approved. (...) approval of the NDA's providing for the drug products named above, and all amendments and supplements applying thereto, is withdrawn effective June 27,1977. Shipment in interstate commerce of the above-listed products or of any identical, related, or similar product, not the subject of an approved NDA, will then be unlawful.

- ^ Bhaumik S (July 2013). "India's health ministry bans pioglitazone, metamizole, and flupentixol-melitracen". BMJ. 347: f4366. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4366. PMID 23833116. S2CID 45107003.

- ^ "Govt lifts ban on painkiller Analgin". Business Standard India. 19 March 2014.

- ^ Panda AK (2014-02-13). Drugs Rules - G.S.R. 86(E) 13.02.2014 Revoke GSR378(E) Reg. Suspension of Analgin (PDF) (Report). New Delhi: The Gazette of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-08-11. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ Garcia S, Canoniero M, Lopes G, Soriano AO (September 2006). "Metamizole use among Hispanics in Miami: report of a survey conducted in a primary care setting". Southern Medical Journal. 99 (9): 924–926. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000233020.68212.8f. PMID 17004525. S2CID 41638378.

- ^ Taylor L, Abarca S, Henry B, Friedman L (September 2001). "Use of Neo-melubrina, a banned antipyretic drug, in San Diego, California: a survey of patients and providers". The Western Journal of Medicine. 175 (3): 159–163. doi:10.1136/ewjm.175.3.159. PMC 1071527. PMID 11527837.

- ^ a b Preissner S, Siramshetty VB, Dunkel M, Steinborn P, Luft FC, Preissner R (2019). "Pain-Prescription Differences - An Analysis of 500,000 Discharge Summaries". Current Drug Research Reviews. 11 (1): 58–66. doi:10.2174/1874473711666180911091846. PMID 30207223. S2CID 52192130.

- ^ Dinavitser N (January 2020). "Dipyrone – a Good Medication with a Bad Reputation". Journal of Medical Toxicology. Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel: American College of Medical Toxicology. 16 (1): 75–86. doi:10.1007/s13181-019-00743-w. PMC 6942089. PMID 31721040.

ACMT/IST 2019 American-Israeli Medical Toxicology Conference

- ^ Aragão RB, Semensatto D, Calixto LA, Labuto G (2020). "Pharmaceutical market, environmental public policies and water quality: the case of the São Paulo Metropolitan Region, Brazil". Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 36 (11): e00192319. doi:10.1590/0102-311x00192319. ISSN 1678-4464. PMID 33237204. S2CID 227168554.

- ^ Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) (24 July 2001). Painel Internacional de Avaliação da Segurança da Dipirona [International Panel for the Evaluation of Dipyrone Safety] (PDF) (Report) (in Portuguese). Brasília. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-21.

- ^ Biernath A (2023-08-17). "Dipirona: por que é vendida no Brasil, mas proibida nos EUA e em parte da Europa?". BBC News Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-09-21.

- ^ Petkova V, Valchanova V, Ibrahim A, Nikolova I, Benbasat N, Dimitrov M (March 2014). "Marketing approaches for OTC analgesics in Bulgaria". Biotechnology, Biotechnological Equipment. 28 (2): 360–365. doi:10.1080/13102818.2014.911477. PMC 4433822. PMID 26019521.

- ^ Kurniawati M, Ikawati Z, Raharjo B (2012). "The evaluation of metamizole use in some places of pharmacy service in Cilacap county". Jurnal Manajemen Dan Pelayanan Farmasi (Journal of Management and Pharmacy Practice) (in Indonesian). 2 (1): 50–55.

- ^ "Exclusive: southern spain hospitals in british expat hotspot issue warning for 'lethal' painkiller nolotil". 23 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Kim CH (2004-08-26). "해열진통제 '설피린' 국내사용 논란" [Controversy over domestic use of antipyretic analgesic Sulpyrin]. 경기신문 [kgnews] (in Korean). Archived from the original on 2023-08-14. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Regulatory Science Society of Japan (2022). The Japanese Pharmacopoeia (PDF) (18th English ed.). Yakuji Nippo-sha. p. 1760. ISBN 978-4840815895. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-01-20. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ Ministry of Health of the USSR (1968). Государственная Фармакопея Союза Советских Социалистических Республик [State Pharmacopoeia of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics] (in Russian) (10th ed.). Moscow: Медицина [Medicine]. p. 94.

- ^ Ovchinnikov R (2011-12-22). "Анальгин хотят отпустить в одни руки" [Analgin want to let go in one hand]. Известия (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2023-08-12.

- ^ "Pavel Sadovsky comments on trademarks registering for RIA Novosti - Insights". EPAM Law. 2012-02-22. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ "Sopharma wins TM battle over analgesic drug Analgin". FFBH. 2004-08-05. Archived from the original on 2023-08-14. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2007). Indian Pharmacopeia (PDF). Vol. 2. Ghaziabad, India: Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission. p. 117. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-28. Retrieved 2023-08-13.