아연

Zinc | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 아연 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 외모 | 은의 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 표준원자량 Ar°(Zn) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 주기율표의 아연 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 원자 번호 (Z) | 30 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 그룹. | 12조 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 기간 | 4교시 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 블록 | 디블록 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 전자배치 | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 쉘당 전자 수 | 2, 8, 18, 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 물리적 특성 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 단계 STP에서 | 단단한 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 융점 | 692.68K (419.53°C, 787.15°F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 비등점 | 1180K (907°C, 1665°F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 밀도 (근처) | 7.14g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 액체 상태일 때(에) | 6.57g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 핵융합열 | 7.32 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 기화열 | 115 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 몰열용량 | 25.470 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

증기압

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 원자 특성 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 산화상태 | -2, 0, +1, +2 (양광성 산화물) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 전기 음성도 | 폴링 눈금 : 1.65 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 이온화 에너지 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 경험 : 오후 134시 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 122±4pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 오후139 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 육각밀폐(hcp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3850m/s (at) (롤링) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| m 30.2 m/(m K)(25°C ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 116 W/(m K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| N 59.0 N m (20°C ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| -11.4x10cm−63/mol (298K)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 108 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 계수 | 43 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 70 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 327–412 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS cas | 7440-66-6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (기원전 1000년 이전) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (1746) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 에 의해 | Rasaratna Samuccaya (1300) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 원소 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

아연은 화학 원소로 기호는 Zn이고 원자 번호는 30입니다.아연은 실온에서 약간 부서지기 쉬운 금속이며 산화가 제거되면 반짝이는 회색 빛의 외관을 갖습니다.주기율표의 그룹 12(IIB)의 첫 번째 원소입니다.어떤 면에서 아연은 마그네슘과 화학적으로 유사합니다. 두 원소는 오직 하나의 정상적인 산화 상태(+2)를 나타내고, Zn2+ 및 Mg2+ 이온은 비슷한 크기입니다.[note 1]아연은 지구의 지각에서 24번째로 풍부한 원소이며 다섯 개의 안정한 동위 원소를 가지고 있습니다.가장 흔한 아연 광석은 황화 아연 광물인 스팔레라이트(아연 블렌드)입니다.호주, 아시아 및 미국에 가장 큰 가동 가능한 로드가 있습니다.아연은 광석의 거품 부유, 로스팅, 전기(전기)를 이용한 최종 추출 등에 의해 정제됩니다.

아연은 인간,[4][5][6] 동물,[7] 식물[8], 미생물에[9] 필수적인 미량 원소이며 산전 및 산후 발달에 필요합니다.[10]그것은 철 다음으로 인간에게 두 번째로 풍부한 미량 금속이며 모든 효소 등급에서 나타나는 유일한 금속입니다.[8][6]아연은 많은 효소들의 중요한 보조 인자이기 때문에 산호 성장에 필수적인 영양소이기도 합니다.[11]

아연 결핍은 개발도상국의 약 20억 명에게 영향을 미치며 많은 질병과 관련이 있습니다.[12]어린이의 경우 결핍은 성장 지체, 성 성숙 지연, 감염 취약성, 설사를 유발합니다.[10]반응 중심에 아연 원자가 있는 효소는 사람의 알코올 탈수소효소와 같은 생화학 분야에 널리 퍼져 있습니다.[13]과도한 아연의 섭취는 무감각, 무기력, 구리 결핍을 유발할 수 있습니다.특히 극지방 내의 해양 생물군에서 아연의 결핍은 주요 조류 군집의 활력을 손상시켜 복잡한 해양 영양 구조를 불안정하게 하고 결과적으로 생물 다양성에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[14]

구리와 아연의 비율이 다양한 합금인 황동은 일찍이 기원전 3천년경 에게 해 지역과 현재 이라크, 아랍 에미리트 연합국, 칼미키아, 투르크메니스탄, 조지아를 포함한 지역에서 사용되었습니다.기원전 2천년에는 현재 서인도, 우즈베키스탄, 이란, 시리아, 이라크, 이스라엘 등의 지역에서 사용되었습니다.[15][16][17]아연 금속은 고대 로마인들과 그리스인들에게 알려졌지만, 인도에서 12세기까지 대규모로 생산되지 않았습니다.[18]라자스탄의 광산은 아연의 생산이 기원전 6세기로 거슬러 올라간다는 확실한 증거를 제시했습니다.[19]현재까지 순수 아연에 대한 가장 오래된 증거는 9세기 초순에 순수 아연을 만들기 위해 증류 과정을 사용한 라자스탄의 자와르에서 유래합니다.[20]연금술사들은 공기 중에서 아연을 태워 "철학자의 털실" 또는 "흰 눈"이라고 부르는 것을 형성했습니다.

이 원소는 아마도 연금술사 파라켈수스에 의해 독일어 징케(가지, 이빨)의 이름을 따 명명되었을 것입니다.독일의 화학자 Andreas Sigismund Margraf는 1746년에 순수한 금속 아연을 발견한 것으로 알려져 있습니다.루이지 갈바니와 알레산드로 볼타의 연구는 1800년까지 아연의 전기화학적 특성을 밝혀냈습니다.철의 내식 아연 도금(열융아연도금)은 아연의 주요 응용 분야입니다.다른 용도는 전기 배터리, 소형 비구조 주조물 및 황동과 같은 합금에 있습니다.유기 실험실에서는 탄산아연과 글루콘산아연(식용 보조제), 염화아연(탈취제에 들어있는), 피리티온아연(안티비듬 샴푸), 황화아연(발광 도료에 들어있는), 디메틸아연 또는 디에틸아연과 같은 다양한 아연 화합물이 일반적으로 사용됩니다.

특성.

물리적 특성

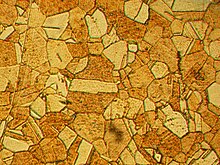

아연은 청백색의 광택이 나는 반자성 금속이지만,[21] 대부분의 상업적 등급의 금속은 무딘 마감을 가지고 있습니다.[22]철보다 밀도가 다소 낮고 육각형의 결정 구조를 가지고 있으며, 왜곡된 형태의 육각형 근접 패킹을 가지고 있으며, 각 원자는 자신의 평면에서 6개의 가장 가까운 이웃을 가지고 있으며(265.9 pm) 290.6 pm의 더 먼 거리에서 6개의 다른 이웃을 가지고 있습니다.[23]금속은 대부분의 온도에서 단단하고 부서지기 쉬우나 100~150°C 사이에서 변형이 가능합니다.[21][22]210°C 이상에서는 금속이 다시 취성을 띠게 되고, 두들김으로써 분쇄할 수 있습니다.[24]아연은 공정한 전기 도체입니다.[21]금속의 경우 아연은 비교적 낮은 용융점(419.5°C)과 끓는점(907°C)을 갖습니다.[25]녹는점은 수은과 카드뮴을 제외한 모든 d-block 금속 중에서 가장 낮습니다. 이러한 이유로 아연, 카드뮴, 수은은 종종 다른 d-block 금속과 같은 전이 금속으로 간주되지 않습니다.[25]

황동을 포함한 많은 합금들이 아연을 포함하고 있습니다.아연과 이진 합금을 형성하는 것으로 오랫동안 알려진 다른 금속은 알루미늄, 안티몬, 비스무트, 금, 철, 납, 수은, 은, 주석, 마그네슘, 코발트, 니켈, 텔루륨, 나트륨입니다.[26]아연과 지르코늄 모두 강자성이 아니지만, 그들의 합금인 ZrZn은

2 35K 이하의 강자성을 나타냅니다.[21]

발생

아연은 지구 지각의 약 75ppm (0.0075%)을 차지하며, 24번째로 풍부한 원소입니다.아연의 일반적인 배경 농도는 대기 중에서 1 μg/m를3 초과하지 않으며 토양 중에서는 300 mg/kg, 식생 중에서는 100 mg/kg, 담수 중에서는 20 μg/L, 해수 중에서는 5 μg/L를 초과하지 않습니다.[27]이 원소는 일반적으로 구리 및 납 광석과 같은 다른 기본 금속과 관련되어 있습니다.[28]아연은 칼코필(chalcophile)인데, 이는 이 원소가 가벼운 칼코겐 산소나 할로겐과 같은 비 칼코겐 전기 음성 원소보다는 황 및 다른 무거운 칼코겐과 함께 광물에서 발견될 가능성이 더 높다는 것을 의미합니다.초기 지구 대기의 환원 조건에서 지각이 굳어지면서 형성된 황화물.[29]황화아연의 일종인 스팔레라이트는 아연을 60~62% 함유하고 있기 때문에 가장 많이 채굴되는 아연 함유 광석입니다.[28]

아연의 다른 원천 광물로는 스미스소나이트(탄산아연), 헤미모파이트(실리케이트아연), 워츠나이트(황화아연), 그리고 때로는 하이드로아연사이트(염산아연)가 있습니다.[30]워자이트를 제외한 다른 모든 광물들은 원시 아연 황화물의 풍화에 의해 형성되었습니다.[29]

확인된 세계 아연 자원은 총 약 19억에서 28억 톤에 달합니다.[31][32]대규모 예금은 호주, 캐나다, 미국에 있으며, 이란에서 가장 많은 예금이 있습니다.[29][33][34]가장 최근의 아연 매장량 추정치(현재의 채굴 및 생산 관행과 관련된 명시된 최소 물리적 기준을 충족)는 2009년에 이루어졌으며, 약 480 Mt으로 계산되었습니다.[35] 반면, 아연 매장량은 경제적인 기반(위치, 등급, 품질)을 기반으로 하는 지리적으로 확인된 광체입니다.ty, and number)을 결정할 때.탐사 및 광산 개발은 지속적인 과정이기 때문에 아연 매장량은 고정된 수치가 아니며 아연 광석 공급의 지속 가능성은 단순히 오늘날의 아연 광산의 광산 수명을 추정하는 것만으로는 판단할 수 없습니다.이 개념은 미국 지질조사국(USGS)의 데이터에 의해 잘 뒷받침되고 있으며, 이는 1990년과 2010년 사이에 정제 아연 생산량이 80% 증가했음에도 불구하고 아연의 예비 수명은 변함이 없음을 보여줍니다.2002년까지 약 3억 4천 6백만 톤이 추출되었으며, 학자들은 약 1억 9천 5백만 톤에서 3억 5백만 톤이 사용되고 있다고 추정했습니다.[36][37][38]

동위 원소

자연에는 아연의 안정 동위 원소가 5개 존재하며, Zn이 가장 풍부한 동위 원소입니다.[39][40]자연에서 발견되는 다른 동위 원소는 Zn(27.73%), Zn(4.04%), Zn(18.45%), Zn(0.61%)[40]입니다.

수십 개의 방사성 동위원소가 특징지어졌습니다.반감기가 243.66일인 65

Zn이 가장 활성이 낮은 방사성동위원소이며, 그 다음으로 반감기가 46.5시간입니다.[39]아연은 10개의 핵 이성질체를 가지고 있고, 그 중 Zn은 가장 긴 반감기를 가지고 있습니다.[39]위첨자 m은 준안정 동위원소를 나타냅니다.준안정 동위원소의 핵은 들뜬 상태에 있으며 감마선 형태의 광자를 방출함으로써 바닥 상태로 돌아갈 것입니다.61

Zn은 3개의 여기 준안정 상태를 가지고 있고 Zn은 2개를 가지고 있습니다.[41]동위 원소 Zn, Zn, Zn 및 Zn은 각각 단 하나의 여기 준안정 상태를 갖습니다.[39]

66보다 질량이 작은 아연의 방사성 동위원소의 가장 일반적인 붕괴 모드는 전자 포획입니다.전자 포획으로 인한 붕괴 생성물은 구리의 동위 원소입니다.[39]

- Zn + e → Cu

66보다 질량수가 높은 아연의 방사성 동위원소의 가장 일반적인 붕괴 모드는 갈륨의 동위원소를 생성하는 베타 붕괴(β−)입니다.[39]

- Zn → Ga + e + +

화합물과 화학

반응성

아연은 [Ar]3d4s의102 전자 배열을 가지며 주기율표의 그룹 12의 멤버.중간 정도의 반응성 금속과 강력한 환원제입니다.[42]순수 금속의 표면은 빠르게 변색되고, 결국 대기 이산화탄소와의 반응에

2의해 염기성 탄산아연의 보호막인 Zn

5(OH)(

6CO)의3 보호막을 형성합니다.[43]

아연은 밝은 청록색 불꽃과 함께 공기 중에서 타며 산화아연의 연기를 내뿜습니다.[44]아연은 산, 알칼리 및 기타 비금속과 쉽게 반응합니다.[45]극도로 순수한 아연은 실온에서 산과 천천히 반응합니다.[44]염산이나 황산과 같은 강한 산은 패시베이션 층을 제거할 수 있고 산과의 반응은 수소 가스를 방출합니다.[44]

아연의 화학은 +2 산화 상태에 의해 지배됩니다.이 산화 상태의 화합물이 형성되면, 외각의 전자가 소실되고, 전자 구성 [Ar]3d를10 갖는 베어 아연 이온이 생성됩니다.[46]수용액 상에서, [Zn(HO

2)]62+

은 주요한 종입니다.[47]285°C 이상의 온도에서 염화아연과 함께 아연의 휘발은 +1 산화 상태의 아연 화합물인 ZnCl의

2

2 형성을 나타냅니다.[44]+1 또는 +2 이외의 산화 양성 상태의 아연 화합물은 알려져 있지 않습니다.[48]계산 결과 산화 상태가 +4인 아연 화합물이 존재하지 않을 가능성이 높습니다.[49]Zn(III)은 강력한 전기 음성 트라이애니언이 존재할 것으로 예측되지만,[50] 이 가능성에 대해서는 다소 의문이 있습니다.[51]그러나 2021년에 또 다른 화합물이11 ZnBeB(CN) 화학식으로 +3의 산화 상태를 갖는다는 더 많은 증거를 가지고 보고되었습니다.12[52]

아연 화학은 후기 1열 전이 금속인 니켈과 구리의 화학과 비슷하지만, 그것은 채워진 d-쉘을 가지고 있고 화합물은 반자성이고 대부분 무색입니다.[53]아연과 마그네슘의 이온 반경은 거의 일치합니다.이 때문에 일부 동등한 염은 동일한 결정 구조를 가지며,[54] 이온 반경이 결정 요소인 다른 환경에서는 아연의 화학적 성질이 마그네슘의 화학적 성질과 많은 공통점을 갖습니다.[44]다른 측면에서, 후기 1열 전이 금속과 유사성이 거의 없습니다.아연은 N- 및 S- 공여체와 더 큰 공유도 및 훨씬 더 안정적인 복합체를 형성하는 경향이 있습니다.[53]아연의 복합체는 5개의 좌표 복합체가 알려져 있지만 대부분 4개 또는 6개의 좌표를 갖습니다.[44]

아연(I) 화합물

아연 화합물은 매우 희귀합니다.[Zn2]2+ 이온은 용융된 ZnCl에2 금속 아연을 용해시켜 노란색의 반자성 유리를 형성하는 것을 수반합니다.[55][Zn2]2+ 코어는 수은(I) 화합물에 존재하는 [Hg2]2+ 양이온과 유사합니다.이온의 반자성은 이량체 구조를 확인해 줍니다.Zn-Zn 결합을 포함하는 첫 번째 아연(I) 화합물, ( η-CME)Zn.

아연(II) 화합물

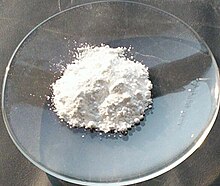

3

2)

2

아연의 이성분 화합물은 대부분의 메탈로이드와 귀금속을 제외한 모든 비금속에 대해 알려져 있습니다.산화물 ZnO는 백색 분말로서 중성 수용액에는 거의 불용성이지만 양성이며, 강한 염기성 용액과 산성 용액 모두에 용해됩니다.[44]다른 칼코게나이드들(ZnS, ZnSe 및 ZnTe)은 전자 및 광학 분야에서 다양한 용도로 사용됩니다.[56]또한, Pnicogenide(ZnN

3

2, ZnP

3

2, ZnAs

3

2 및 ZnSb

3

2),[57][58] 과산화물(ZnO

2), 수소화물(ZnH

2) 및 탄화물(ZnC

2)도 알려져 있습니다.[59]4개의 할로겐화물 중 ZnF는

2 이온성이 가장 높은 반면, 다른 것들(ZnCl

2, ZnBr

2, ZnI

2)은 녹는점이 상대적으로 낮고 공유성이 더 높은 것으로 판단됩니다.[60]

Zn2+

이온을 포함하는 약한 염기성 용액에서, 수산화 Zn(OH)

2은 백색 침전물로서 형성됩니다.더 강한 알칼리 용액에서, 이 수산화물은 아연산염([Zn(OH))42−

[44]을 형성하기 위해 용해됩니다.질산염 Zn(NO3),

2 염소산염 Zn(ClO3),

2 황산 ZnSO

4, 인산 Zn

3(PO4),

2 몰리브데이트 ZnMoO

4, 시안화물 Zn(CN),

2 아르세나이트 Zn(AsO2),

2 아르세나이트 Zn(AsO4)·

28HO

2 및 크로메이트 ZnCrO

4(소수의 착색 아연 화합물 중 하나)는 아연의 다른 일반적인 무기 화합물의 몇 가지 예입니다.[61][62]

유기아연화합물은 아연-탄소 공유 결합을 포함하는 화합물입니다.디에틸아연(Diethylzinc, CH

25)

2Zn은 합성 화학의 시약입니다.이것은 1848년에 아연과 요오드화에틸의 반응으로 처음 보고되었으며, 금속과 탄소 시그마 결합을 포함하는 것으로 알려진 최초의 화합물이었습니다.[63]

아연검정

Cobalticyanide paper (Rinnmann's test for Zn)는 아연의 화학적 지표로 사용될 수 있으며, 물 100ml에 KCo3(CN)6 4g과 KClO3 1g을 용해합니다.종이를 용액에 담근 후 100℃에서 건조합니다.샘플 한 방울을 마른 종이 위에 떨어뜨려 가열합니다.녹색 디스크는 아연의 존재를 나타냅니다.[64]

역사

고대의 용법

고대에 불순한 아연을 사용한 다양한 고립된 예들이 발견되었습니다.아연 광석은 아연과 구리 합금 황동을 별도의 원소로 발견하기 수천 년 전에 제조하는 데 사용되었습니다.기원전 14세기에서 10세기의 유대 황동은 23%의 아연을 함유하고 있습니다.[16]

황동을 생산하는 방법에 대한 지식은 기원전 7세기까지 고대 그리스로 퍼졌지만, 거의 만들어지지 않았습니다.[17]아연이 80~90% 함유된 합금으로 만든 장신구와 납, 철, 안티몬 등 금속류가 나머지를 구성하는 2500년 된 장신구가 발견됐습니다.[28]87.5%의 아연을 함유한 선사시대 조각상이 다키아의 한 고고학 유적지에서 발견되었습니다.[65]

기원전 1세기에 쓴 스트라보의 글(그러나 기원전 4세기 역사가 테오폼푸스의 현재 잃어버린 작품을 인용한다)에는 구리와 섞이면 놋쇠가 되는 "허위 은방울"이 언급되어 있습니다.이것은 황화물 광석을 제련하는 부산물인 소량의 아연을 의미할 수 있습니다.[66]제련용 오븐의 잔재물에 있는 아연은 대개 가치가 없는 것으로 생각되어 버려졌습니다.[67]

황동의 제조는 기원전 30년쯤에 로마인들에게 알려졌습니다.[68]그들은 가루 칼라민 (아연 규산염 또는 탄산염), 숯과 구리를 도가니에서 함께 가열하여 놋쇠를 만들었습니다.[68]결과물인 칼라민 놋쇠는 주조되거나 망치로 모양을 만들어 무기에 사용했습니다.[69]기독교 시대에 로마인들이 때린 몇몇 동전들은 아마도 칼라민 황동으로 만들어졌습니다.[70]

가장 오래된 것으로 알려진 알약은 탄산 아연 하이드로 진사이트와 스미스소나이트로 만들어졌습니다.그 알약들은 눈의 통증에 사용되었고 기원전 140년에 난파된 로마 배 Relitto del Pozino호에서 발견되었습니다.[71][72]

베른 아연정은 대부분 아연으로 이루어진 합금으로 만들어진 로마 갈리아 시대의 봉헌 명판입니다.[73]

서기 300년에서 500년 사이에 쓰여진 것으로 생각되는 차라카 삼히타에는 산화될 때 산화아연으로 생각되는 푸쉬판잔을 생성하는 금속이 언급되어 있습니다.[74][75]인도 우다이푸르 인근 자와르의 아연 광산은 마우리아 시대(c.기원전 322년~기원전 187년)부터 활동했습니다.그러나 금속 아연의 제련은 서기 12세기경에 시작된 것으로 보입니다.[76][77]한 가지 추정치는 이 지역에서 12세기에서 16세기 사이에 약 백만 톤의 금속 아연과 산화 아연을 생산했다는 것입니다.[30]또 다른 추정치는 이 기간 동안 총 60,000톤의 금속 아연 생산량을 제공합니다.[76]서기 약 13세기에 쓰여진 라사라트나 사무카야에는 아연을 함유한 광석의 두 종류가 언급되어 있습니다. 하나는 금속 추출용으로 사용되고 다른 하나는 약용으로 사용됩니다.[77]

초기 연구 및 명명

1374년 경에 쓰여진 의학 용어집에서 아연은 야사다 또는 야사다의 이름으로 힌두교 왕 마다나팔라(다카 왕조의 왕)가 쓴 금속으로 분명히 인식되었습니다.[78]칼라민을 양모와 다른 유기물로 환원하여 불순한 아연을 제련하고 추출하는 것은 인도에서 13세기에 이루어졌습니다.[21][79]중국인들은 17세기까지 그 기술을 배우지 못했습니다.[79]

연금술사들은 공기 중에서 아연 금속을 태우고 응축기에 산화아연을 모았습니다.어떤 연금술사들은 산화아연을 라틴어로 "철학자의 털실"을 뜻하는 lana philosophica라고 불렀고, 반면 다른 이들은 이것이 하얀 눈처럼 보인다고 생각하고 nix album이라고 이름 지었습니다.[80]

그 금속의 이름은 16세기에 스위스 태생의 독일 연금술사인 파라켈수스에 의해 처음 기록되었을 것입니다. 파라켈수스는 그의 책 Liber Mineralium II에서 그 금속을 "진쿰" 또는 "진켄"이라고 언급했습니다.[79][81]이 단어는 아마도 독일의 징크(zinke)에서 유래되었을 것이며, 아마도 "치아 같은, 뾰족한 또는 들쭉날쭉한" (금속 아연 결정체는 바늘 같은 모양을 가지고 있음)을 의미할 것입니다.[82]징크는 또한 주석을 의미하는 독일의 진(zinn)과의 관계 때문에 "주석과 같은"을 암시할 수도 있습니다.[83]또 다른 가능성은 돌을 의미하는 페르시아어 سنگ셍에서 유래했다는 것입니다.그 금속은 또한 인디안 주석, 투타네고, 칼라민, 그리고 스펜서라고도 불렸습니다.[28]

독일의 야금학자 안드레아스 리바비우스는 1596년 포르투갈인들로부터 나포된 화물선에서 말라바르에서 유래한 "칼레이"(말레이어 또는 힌디어로 주석을 뜻하는 단어에서 유래)라고 부르는 것을 받았습니다.[85]Libavius는 아연일 수도 있는 샘플의 특성을 설명했습니다.아연은 17세기와 18세기 초반에 동양에서 유럽으로 정기적으로 수입되었지만,[79] 때로는 매우 비쌌습니다.[note 2]

격리

금속 아연은 서기 1300년까지 인도에서 분리되었습니다.[86][87][88]유럽에서 고립되기 전에, 그것은 서기 1600년경에 인도로부터 수입되었습니다.[89]유럽의 기술 정보를 제공하는 현대의 자료인 Postlewayt의 Universal Dictionary는 1751년 이전에는 아연에 대해 언급하지 않았지만 그 이전에 아연에 대해 연구되었습니다.[77][90]

플랑드르 야금학자이자 연금술사인 P. M. de Respour는 1668년에 산화아연으로부터 금속 아연을 추출했다고 보고했습니다.[30]18세기 초, 에티엔 프랑수아 조프로이는 산화아연이 아연 광석 위에 놓인 철봉 위에 노란색 결정으로 어떻게 응축되는지 설명했습니다.[30]영국에서는 존 레인이 1726년 파산하기 전에 아마도 란도레에서 아연을 제련하는 실험을 했다고 합니다.[91]

1738년 영국에서 윌리엄 챔피언은 수직 레토르트 스타일의 제련소에서 칼라민으로부터 아연을 추출하는 방법에 대한 특허를 냈습니다.[92]그의 기술은 라자스탄의 자와르 아연 광산에서 사용되었던 것과 닮았지만, 그가 동양을 방문했다는 증거는 없습니다.[89]챔피언의 과정은 1851년까지 사용되었습니다.[79]

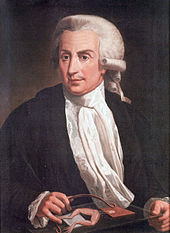

독일의 화학자 안드레아스 마르그라프는 스웨덴의 화학자 안톤 폰 슈바벤이 4년 전에 칼라민으로부터 아연을 증류했음에도 불구하고 보통 서양에서 순수한 금속 아연을 분리한 것으로 인정을 받습니다.[79]그의 1746년 실험에서, Margraf는 금속을 얻기 위해 구리가 없는 밀폐된 그릇에서 칼라민과 숯의 혼합물을 가열했습니다.[93][67]이 절차는 1752년까지 상업적으로 실용화되었습니다.[94]

후반작업

윌리엄 챔피언의 [28]형 존은 1758년 황화아연을 레토르트 공정에서 사용할 수 있는 산화물로 소성하는 공정을 특허 받았습니다.이 이전에는 아연을 생산하는 데 칼라민만 사용할 수 있었습니다.1798년, Johann Christian Rubberg는 최초의 수평 레토르트 제련소를 건설함으로써 제련 공정을 개선했습니다.[95]장 자크 다니엘 도니는 벨기에에서 훨씬 더 많은 아연을 가공하는 다른 종류의 수평 아연 제련소를 지었습니다.[79]이탈리아 의사 루이지 갈바니는 1780년 막 해부한 개구리의 척수와 놋쇠 갈고리가 달린 철제 레일을 연결하면 개구리의 다리가 경련을 일으킨다는 사실을 발견했습니다.[96]그는 신경과 근육이 전기를 만드는 능력을 발견했다고 잘못 생각했고 그 효과를 "동물의 전기"라고 불렀습니다.[97]갈바닉 셀과 아연도금 공정은 모두 루이지 갈바니의 이름을 따서 지어졌고, 그의 발견은 전기 배터리, 아연도금 및 음극 보호를 위한 길을 열었습니다.[97]

갈바니의 친구인 알렉산드로 볼타는 그 효과를 계속 연구했고 1800년에 볼타 파일을 발명했습니다.[96]볼타의 더미는 구리의 한 판과 전해질로 연결된 아연의 한 판으로 단순화된 갈바닉 셀의 스택으로 구성되었습니다.이 유닛들을 직렬로 적층함으로써, 볼타익 파일(또는 "배터리")은 전체적으로 전압이 높아졌고, 이는 단일 셀보다 더 쉽게 사용될 수 있었습니다.전기는 두 금속판 사이의 볼타 전위가 전자를 아연에서 구리로 흐르게 하고 아연을 부식시키기 때문에 생성됩니다.[96]

아연의 비자성적인 특성과 용액에서의 색의 부족은 생화학과 영양에 대한 아연의 중요성을 발견하는 것을 지연시켰습니다.[98]이것은 1940년 혈액에서 이산화탄소를 스크럽하는 효소인 탄산무수화효소가 활성 부위에 아연을 가지고 있는 것으로 밝혀지면서 바뀌었습니다.[98]1955년 소화효소 카르복시펩타이드는 두 번째로 알려진 아연 함유 효소가 되었습니다.[98]

생산.

채광 및 가공

| 순위 | 나라 | 톤즈 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 중국 | 4,210,000 |

| 2 | 페루 | 1,400,000 |

| 3 | 호주. | 1,330,000 |

| 5 | 미국 | 753,000 |

| 4 | 인디아 | 720,000 |

| 6 | 멕시코 | 677,000 |

27°57'17 ″S 016°46'00 ″E/27.95472°S 16.76667°E

27°49'09 ″S 016°36'28 ″E/27.81917°S 16.60778°E

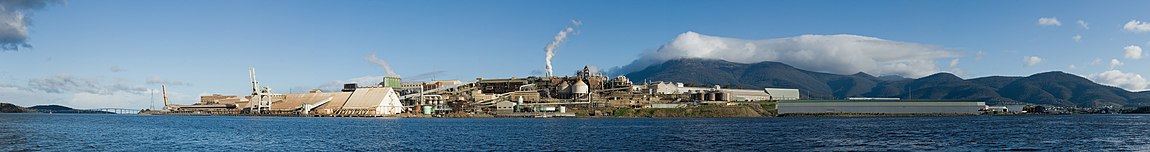

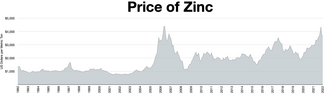

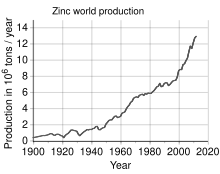

아연은 철, 알루미늄, 구리 다음으로 4번째로 많이 사용되는 금속으로 연간 생산량은 약 1,300만 톤입니다.[31]세계에서 가장 큰 아연 생산업체는 호주의 OZ광물과 벨기에의 유미코어를 합병한 니르스타(Nyrstar)입니다.[100]전 세계 아연의 약 70%는 채굴에서 발생하며, 나머지 30%는 2차 아연의 재활용에서 발생합니다.[101]

상업적으로 순수한 아연은 Special High Grade로 알려져 있으며, 종종 SHG로 약칭되기도 하며 99.995%의 순수도를 가지고 있습니다.[102]

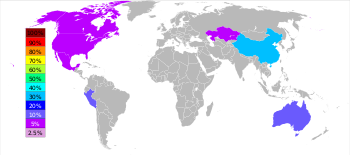

전 세계적으로 신규 아연의 95%는 구리, 납 및 철의 황화물과 스팔라이트(ZnS)가 거의 항상 혼합되어 있는 황화물 광석 퇴적물에서 채굴됩니다.[103]: 6 아연 광산은 중국, 호주, 페루를 주요 지역으로 하여 전 세계에 흩어져 있습니다.중국은 2014년 전 세계 아연 생산량의 38%를 생산했습니다.[31]

아연 금속은 추출 야금법을 사용하여 생산됩니다.[104]: 7 광석을 미세하게 갈은 다음 거품부표를 통해 갠지스(gangue)로부터 광물을 분리하고, 아연 50%, 황 32%, 철 13% 및 SiO

2 5%로 구성된 황화아연 광석 농축물을[104]: 16 얻습니다.[104]: 16

로스팅은 황화아연 농축액을 산화아연으로 바꿉니다.[103]

이산화황은 침출 공정에 필요한 황산의 생산에 사용됩니다.탄산아연, 규산아연 또는 나미비아의 스코르피온 광상과 같은 아연 스피넬 광상을 아연 생산에 사용할 경우, 로스팅을 생략할 수 있습니다.[105]

추가 처리를 위해 두 가지 기본적인 방법이 사용됩니다. 즉, 파이로메탈러지(pyrometalurgy) 또는 전기방사(electrowinning)입니다.파이로메탈러지는 950°C(1,740°F)에서 산화아연과 일산화탄소를 금속으로 환원시켜 아연 증기로 증류하여 온도에서 휘발성이 없는 다른 금속과 분리합니다.[106]아연 증기는 응축기에 모이게 됩니다.[103]아래의 식은 이 과정을 설명합니다.[103]

전기 배선에서 아연은 황산에 의해 광석 농축액에서 침출되고 불순물은 침전됩니다.[107]

마지막으로 아연은 전기 분해에 의해 감소됩니다.[103]

황산은 재생되어 침출 단계로 재활용됩니다.

아연 도금된 공급 원료가 전기 아크로에 공급될 때 아연은 주로 Waelz 공정(2014년 기준 90%)과 같은 여러 공정에 의해 먼지로부터 회수됩니다.[108]

환경영향

아황산 아연 광석을 정제하면 대량의 이산화황과 카드뮴 증기가 생성됩니다.제련소 슬래그 및 기타 잔재물에는 상당한 양의 금속이 포함되어 있습니다.1806년에서 1882년 사이에 약 110만 톤의 금속 아연과 13만 톤의 납이 벨기에의 라 칼라민과 플롬비에르 마을에서 채굴되고 제련되었습니다.[109]과거 채굴 작업의 쓰레기는 아연과 카드뮴을 침출하고, 걸강의 침전물은 사소하지 않은 양의 금속을 포함하고 있습니다.[109]약 2천 년 전, 채굴과 제련에서 나오는 아연의 배출량은 연간 총 1만 톤에 달했습니다.1850년부터 10배 증가한 아연 배출량은 1980년대에 연간 340만 톤으로 정점을 찍고 1990년대에는 270만 톤으로 감소했지만, 2005년 북극 대류권에 대한 연구에서는 아연 배출량이 감소를 반영하지 않는 것으로 나타났습니다.인공 배출과 자연 배출은 20 대 1의 비율로 일어납니다.[8]

공업지역과 광산지역을 흐르는 강의 아연은 20ppm까지 높아질 수 있습니다.[110]효과적인 하수 처리는 이것을 크게 감소시킵니다. 예를 들어, 라인강을 따라 처리하면 아연 수준이 50ppb로 감소합니다.[110]아연의 농도가 2ppm 정도로 낮으면 물고기가 혈액 속에 운반할 수 있는 산소의 양에 악영향을 미칩니다.[111]

아연을 함유한 슬러지를 채굴하거나 정제하거나 수정하는 과정에서 아연으로 오염된 토양은 건조한 토양 1kg당 수 그램의 아연을 함유할 수 있습니다.토양 중 500ppm을 초과하는 아연의 수준은 식물이 철과 망간과 같은 다른 필수 금속을 흡수하는 능력을 방해합니다.일부 토양 샘플에서 아연 수준이 2000ppm에서 180,[110]000ppm(18%)으로 기록되었습니다.

적용들

아연의 주요 용도는 다음을 포함하며, 미국에 대한[114] 비율은 다음과 같습니다.

부식방지 및 배터리

부식 방지제로는 아연이 가장 일반적으로 사용되며,[115] 아연도금(철 또는 강철의 코팅)이 가장 익숙한 형태입니다.2009년 미국에서는 아연 금속의 55%인 893,000톤이 아연도금에 사용되었습니다.[114]

아연은 철이나 강철보다 반응성이 높기 때문에 완전히 부식될 때까지 거의 모든 국소 산화를 유도합니다.[116]산화물과 탄산염(Zn

5(OH)(

6CO

3))

2의 보호 표면층은 아연이 부식됨에 따라 형성됩니다.[117]이러한 보호 기능은 아연 층이 긁힌 후에도 지속되지만 아연이 부식되면서 시간이 지남에 따라 저하됩니다.[117]아연은 전기화학적으로 또는 용융 아연으로 용융 아연도금 또는 분무하여 도포됩니다.아연도금은 체인링크 펜싱, 가드레일, 현수교, 가로등, 금속 지붕, 열교환기, 차체 등에 사용됩니다.[118]

아연의 상대적인 반응성과 산화를 자체로 유도하는 능력은 음극 보호(CP)에서 효율적인 희생 양극으로 만듭니다.예를 들어, 매립 파이프라인의 음극 보호는 아연으로 만들어진 양극을 파이프에 연결함으로써 달성될 수 있습니다.[117]아연은 강철 파이프라인에 전류를 전달하면서 서서히 부식되어 양극(음의 말단)으로 작용합니다.[117][note 3]아연은 바닷물에 노출된 금속을 음극으로 보호하는 데도 사용됩니다.[119]선박의 철제 방향타에 부착된 아연 디스크는 방향타가 손상되지 않은 상태에서 서서히 부식됩니다.[116]마찬가지로, 프로펠러 또는 선박의 용골용 금속 보호 가드에 부착된 아연 플러그는 일시적인 보호를 제공합니다.

아연은 -0.76볼트의 표준전극전위(SEP)로 배터리의 양극재로 사용됩니다. (리튬 배터리의 양극에는 반응성 리튬(SEP -3.04V)이 더 많이 사용됨).분말 아연은 알칼리성 배터리에 이러한 방식으로 사용되며 아연-탄소 배터리의 케이스(음극 역할도 함)는 시트 아연으로 형성됩니다.[120][121]아연은 아연-공기 배터리/연료 전지의 양극 또는 연료로 사용됩니다.[122][123][124]아연-세륨 레독스 흐름 배터리도 아연 기반 음극 반쪽 전지에 의존합니다.[125]

합금

널리 사용되는 아연 합금은 황동으로, 구리는 황동의 종류에 따라 3%에서 45%의 아연과 합금됩니다.[117]황동은 일반적으로 구리보다 연성이 강하고 내식성이 우수합니다.[117]이러한 특성은 통신 장비, 하드웨어, 악기 및 수도 밸브에 유용하게 사용됩니다.[117]

널리 사용되는 다른 아연 합금으로는 니켈 은, 타자기 금속, 연질 및 알루미늄 납땜, 상업용 청동 등이 있습니다.[21]아연은 또한 현대의 파이프 기관에서 파이프의 전통적인 납/주석 합금의 대체재로 사용됩니다.[126]아연 85~88%, 구리 4~10%, 알루미늄 2~8%의 합금은 특정 유형의 기계 베어링에 제한적으로 사용됩니다.아연은 1982년부터 미국 1센트 동전의 주요 금속이었습니다.[127]아연 코어는 구리 동전처럼 보이게 하기 위해 구리의 얇은 층으로 코팅되어 있습니다.1994년에는 33,200톤(36,600 쇼트톤)의 아연이 미국에서 136억 페니를 생산하는 데 사용되었습니다.[128]

아연과 소량의 구리, 알루미늄 및 마그네슘의 합금은 다이캐스팅(die casting) 및 스핀캐스팅(spin casting), 특히 자동차, 전기 및 하드웨어 산업에서 유용합니다.[21]이 합금들은 자막이라는 이름으로 판매되고 있습니다.[129]그 예로는 아연 알루미늄이 있습니다.낮은 융점과 합금의 낮은 점도는 작고 복잡한 모양을 만들 수 있게 해줍니다.작업 온도가 낮으면 주물 제품이 빠르게 냉각되고 조립 시 생산이 빠릅니다.[21][130]Prestal이라는 브랜드로 판매되는 또 다른 합금은 아연 78%, 알루미늄 22%를 함유하고 있으며, 강철만큼 강하지만 플라스틱만큼 가단성이 있다고 보고되고 있습니다.[21][131]이러한 합금의 초가소성으로 인해 세라믹과 시멘트로 만든 다이캐스트를 사용하여 성형할 수 있습니다.[21]

소량의 납을 첨가한 유사한 합금을 시트로 냉간 압연할 수 있습니다.96% 아연과 4% 알루미늄의 합금을 사용하여 낮은 생산 공정에서 사용할 수 있는 스탬핑 다이를 제작할 경우 철 금속 다이가 너무 비쌀 수 있습니다.[132]티타늄 및 구리를 포함하는 아연 합금은 딥 드로잉(deep drawing), 롤 포밍(roll forming) 또는 벤딩(bending)에 의해 형성된 판금을 위한 건축물 정면, 지붕 및 기타 용도에 사용됩니다.[133]무합금 아연은 이러한 제조 공정에 비해 너무 취약합니다.[133]

아연은 밀도가 높고 저렴하고 쉽게 작업할 수 있는 물질로서 납 대체 물질로 사용됩니다.납에 대한 우려에 따라 아연은 낚시에서부터[134] 타이어 밸런스, 플라이휠에 이르기까지 다양한 응용 분야에 대한 가중치로 나타납니다.[135]

카드뮴 아연 텔루라이드(CZT)는 작은 감지 장치의 배열로 나눌 수 있는 반도전성 합금입니다.[136]이 장치들은 집적 회로와 비슷하며 들어오는 감마선 광자의 에너지를 감지할 수 있습니다.[136]흡수 마스크 뒤에 있을 때 CZT 센서 어레이는 광선의 방향을 결정할 수 있습니다.[136]

기타산업용

2009년 미국 전체 아연 생산량의 약 1/4이 아연 화합물에 소비되었습니다.[114] 이들 화합물은 산업적으로 사용되고 있습니다.산화아연은 페인트에서 백색 안료로, 고무 제조에서 열을 분산시키는 촉매제로 널리 사용됩니다.산화아연은 자외선(UV)으로부터 고무 폴리머와 플라스틱을 보호하는 데 사용됩니다.[118]산화아연의 반도체 특성은 바리스터와 복사 제품에 유용하게 사용됩니다.[137]아연-산화아연 사이클은 수소 생산을 위해 아연과 산화아연을 기반으로 하는 2단계 열화학 공정입니다.[138]

염화 아연은 종종 목재에 내화제로[139] 첨가되기도 하고, 때로는 목재 방부제로 첨가되기도 합니다.[140]이것은 다른 화학물질의 제조에 사용됩니다.[139]아연 메틸(Zn(CH3))

2은 다수의 유기 합성에 사용됩니다.[141]황화아연(ZnS)은 시계, X선 및 텔레비전 화면, 야광 페인트 등의 발광 안료에 사용됩니다.[142]ZnS의 결정은 스펙트럼의 중적외선 부분에서 작동하는 레이저에 사용됩니다.[143]황산아연은 염료와 색소의 화학물질입니다.[139]피리티온 아연은 방오 페인트에 사용됩니다.[144]

아연 분말은 모형 로켓에서 추진제로 사용되기도 합니다.[145]아연 70%와 황 분말 30%의 압축 혼합물이 점화되면 격렬한 화학 반응이 발생합니다.[145]이것은 다량의 뜨거운 가스, 열, 빛과 함께 황화아연을 생성합니다.[145]

아연 판금은 지붕, 벽, 조리대의 내구성이 강한 덮개로 사용되며, 마지막은 비스트로스와 굴바에서 흔히 볼 수 있으며, 표면 산화로 인해 청회색 파티나에 사용되고 긁힘에 취약하여 촌스러운 모습으로 알려져 있습니다.[146][147][148][149]

아연의 가장 풍부한 동위 원소인 64

Zn은 중성자 활성화에 매우 취약하여 반감기가 244일이고 강력한 감마선을 생성하는 고방사능 Zn으로 변환됩니다.이 때문에 원자로에서 부식방지제로 사용되는 산화아연은 사용 전에 Zn이 고갈되며, 이를 고갈된 산화아연이라고 합니다.같은 이유로, 아연은 핵무기의 염장 재료로서 제안되어 있습니다 (코발트는 또 다른, 더 잘 알려진 염장 재료입니다).[150]동위원소적으로 농축된 Zn 재킷은 폭발하는 열핵 무기에서 나오는 강력한 고에너지 중성자 플럭스에 의해 조사되어 대량의 Zn을 형성하여 무기 낙진의 방사능을 크게 증가시킵니다.[150]그런 무기는 지금까지 만들어진 적이 없고, 시험된 적도 없으며, 사용된 적도 없는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[150]

65

Zn은 아연을 함유한 합금이 어떻게 마모되는지 또는 생물체에서 아연의 경로와 역할을 연구하기 위한 추적자로 사용됩니다.[151]

아연 디티오카르바메이트 복합체는 농업용 살균제로 사용됩니다. 여기에는 지네브, 메티람, 프로피네브, 지람이 포함됩니다.[152]아연 나프테네이트는 목재 방부제로 사용됩니다.[153]ZDDP 형태의 아연은 엔진 오일의 금속 부품의 마모 방지 첨가제로 사용됩니다.[154]

유기화학

유기아연화학(Organozinc chemistry)은 탄소-아연 결합을 포함하는 화합물의 과학으로, 물리적 특성, 합성 및 화학 반응을 설명합니다.많은 오가노진크 화합물은 상업적으로 중요합니다.[156][157][158][159]중요한 응용 분야는 다음과 같습니다.

- 옥살산에스테르(ROCCOOR)가 알킬할라이드 R'X, 아연 및 염산과 반응하여 α-하이드록시카르복실산에스테르 R'COHCOOR를[160][161] 형성하는 Frankland-Dupa 반응

- 오르가노진크는 그리너드 시약과 반응성이 비슷하지만 친핵성이 훨씬 덜하며 가격이 비싸고 다루기 어렵습니다.오르가노진은 일반적으로 알데하이드와 같은 전기유전자에 친핵성 첨가를 수행하며, 이후 알코올로 환원됩니다.상업적으로 이용 가능한 디오르가노진 화합물은 디메틸아연, 디에틸아연 및 디페닐아연을 포함합니다.Grignard 시약과 마찬가지로, Organozinc는 일반적으로 organobromine precursorganozinc.

아연은 에난티오 선택적 합성을 포함한 유기 합성에서의 촉매 작용에 많은 사용이 있음을 발견하였는데, 이는 귀금속 복합체에 대한 값싸고 쉽게 구할 수 있는 대안입니다.키랄 아연 촉매를 사용하여 얻은 정량적 결과(수율 및 에난티오머 초과)는 팔라듐, 루테늄, 이리듐 등에서 얻은 결과와 유사할 수 있습니다.[162]

식이보조제

대부분의 단일 정제, 처방전 없이 살 수 있는 비타민과 미네랄 보충제에서 아연은 산화아연, 아세트산아연, 글루콘산아연, 또는 아미노산 킬레이트와 같은 형태로 포함됩니다.[163][164]

일반적으로 아연 보충제는 아연 결핍 위험이 높은 경우(저소득 국가 및 중소득 국가 등) 예방 조치로 권장됩니다.[165]황산아연이 일반적으로 사용되는 아연 형태이지만, 시트르산아연, 글루콘산 및 피콜린산염도 유효한 옵션입니다.이 형태들은 산화 아연보다 더 잘 흡수됩니다.[166]

위장염

아연은 개발도상국의 어린이들 사이에서 설사를 치료하는데 저렴하고 효과적인 부분입니다.설사를 하는 동안 아연이 체내에서 고갈되고, 10일에서 14일간의 치료 과정으로 아연을 보충하면 설사 증상의 기간과 심각성을 줄일 수 있고, 3개월 동안은 향후 증상을 예방할 수도 있습니다.[167]위장관염은 아연의 섭취, 아마도 위장관에 있는 이온의 직접적인 항균 작용, 또는 아연의 흡수와 면역 세포로부터의 재방출(모든 과립구는 아연을 분비함) 또는 둘 다에 의해 강하게 약화됩니다.[168][169]

보통감기

아연 보충제(종종 아세트산아연 또는 글루콘산아연 로젠)는 일반적인 감기 치료에 일반적으로 사용되는 식이 보충제의 그룹입니다.[170]아연 보충제를 증상 발생 후 24시간 이내에 75mg/일을 초과하는 용량으로 사용하면 성인의 감기 증상 기간이 약 1일 단축되는 것으로 나타났습니다.[170][171]입으로 아연 보충제를 섭취하는 부작용으로는 나쁜 맛과 메스꺼움이 있습니다.[170][171]아연이 함유된 비강 스프레이의 비강내 사용은 후각의 상실과 관련이 있습니다;[170] 결과적으로, 2009년 6월, 미국 식품의약국(USFDA)은 소비자들에게 비강내 아연의 사용을 중단하라고 경고했습니다.[170]

인간에게 가장 흔한 바이러스성 병원체인 인간 라이노 바이러스는 감기의 주요 원인입니다.[172]아연이 감기 증상의 심각성 및/또는 기간을 감소시키는 가설화된 작용 메커니즘은 코 염증의 억제 및 코 점막에서의 코 바이러스 수용체 결합 및 코 바이러스 복제의 직접적인 억제입니다.[170]체중증가

아연 결핍은 식욕 감퇴로 이어질 수 있습니다.[173]거식증 치료에 아연을 사용하는 것은 1979년부터 권장되어 왔습니다.아연이 거식증의 체중 증가를 개선시켰다는 것이 최소 15개의 임상 실험에서 밝혀졌습니다.1994년 실험은 아연이 거식증 신경증 치료에 있어서 체질량 증가율을 두 배로 증가시킨다는 것을 보여주었습니다.티로신, 트립토판, 티아민과 같은 다른 영양소의 결핍은 이러한 "영양실조에 의한 영양실조" 현상의 원인이 될 수 있습니다.[174]여러 나라에서 아연 보충과 그것이 아동의 성장에 미치는 영향에 관한 33개의 잠재적 개입 실험에 대한 메타분석은 아연 보충만으로도 선형 성장과 체중 증가에 통계적으로 유의한 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타났습니다.존재했을 수도 있는 다른 결함들이 성장 지연에 책임이 없다는 것을 나타내는 것입니다.[175]

다른.

Cochrane 리뷰에 따르면 아연 보충제를 복용하는 사람들은 나이와 관련된 황반변성으로 진행할 가능성이 적을 수 있다고 합니다.[176]아연 보충제는 이전에 영향을 받은 유아들에게 치명적이었던 아연 흡수에 영향을 미치는 유전적 장애인 갑상샘염에 대한 효과적인 치료법입니다.[68]아연 결핍은 주요 우울증(MDD)과 관련이 있으며 아연 보충제가 효과적인 치료법이 될 수 있습니다.[177]아연은 사람들이 잠을 더 잘 수 있도록 도와줄 지도 모릅니다.[6]

국소사용

아연의 국소 제제에는 피부에 사용되는 것이 포함되며, 종종 산화아연의 형태로 사용됩니다.산화아연은 일반적으로 FDA에 의해 안전하고 효과적인[178] 것으로 인식되고 있으며 매우 광안정적인 것으로 여겨집니다.[179]산화아연은 햇볕에 타는 것을 완화하기 위해 자외선 차단제로 제형화된 가장 일반적인 활성 성분 중 하나입니다.[68]기저귀를 갈 때마다 아기의 기저귀 부위(주위)에 얇게 발라 기저귀 발진을 예방할 수 있습니다.[68]

킬레이트 아연은 구취를 방지하기 위해 치약과 구강 세정제에 사용됩니다. 시트르산 아연은 미적분 (타르타르)의 축적을 감소시키는 데 도움을 줍니다.[180][181]

아연 피리티온은 비듬을 예방하기 위해 샴푸에 널리 포함되어 있습니다.[182]

국소 아연은 생식기 헤르페스의 관해를 연장시킬 뿐만 아니라 효과적으로 치료하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[183]

생물학적 역할

아연은 인간과[4][5][6] 다른 동물,[7] 식물과[8] 미생물에 필수적인 미량 원소입니다.[9]아연은 300개 이상의 효소와 1000개 이상의 전사 인자의 기능에 필요하며,[6] 메탈로티오닌에 저장 및 전달됩니다.[184][185]그것은 철 다음으로 인간에게 두 번째로 풍부한 미량 금속이며 모든 효소 등급에서 나타나는 유일한 금속입니다.[8][6]

단백질에서 아연 이온은 종종 아스파르트산, 글루탐산, 시스테인 및 히스티딘의 아미노산 곁사슬에 배위됩니다.단백질 내의 아연 결합(다른 전이 금속의 아연 결합)에 대한 이론적 및 계산적 설명은 어렵습니다.[186]

대략 2-4 그램의 아연이[187] 인체 전체에 분포되어 있습니다.대부분의 아연은 뇌, 근육, 뼈, 신장, 간과 전립선과 눈의 일부에 가장 높은 농도를 가지고 있습니다.[188]정액에는 특히 전립선 기능과 생식 기관 성장의 핵심 요소인 아연이 풍부합니다.[189]

몸의 아연 항상성은 주로 장에 의해 조절됩니다.여기서 ZIP4와 특히 TRPM7은 산후 생존에 필수적인 장내 아연 섭취와 관련이 있었습니다.[190][191]

인간에서 아연의 생물학적 역할은 어디에나 있습니다.[10][5]다양한 유기 리간드와 상호작용하며 RNA와 DNA의 대사, 신호전달, 유전자 발현 등의 역할을 합니다.[10]또한 세포 사멸도 조절합니다.2015년의 검토에 따르면 인간 단백질의 약 10%가 아연을 결합하고 있으며,[192] 수백 개의 아연을 운반하고 운송하는 것 외에도 아라비놉시스 탈리아나 식물의 실리코 연구에서도 2367개의 아연 관련 단백질을 발견했습니다.[8]

In the brain, zinc is stored in specific synaptic vesicles by glutamatergic neurons and can modulate neuronal excitability.[5][6][193] It plays a key role in synaptic plasticity and so in learning.[5][194] Zinc homeostasis also plays a critical role in the functional regulation of the central nervous system.[5][193][6] Dysregulation of zinc homeostasis in the central nervous system that results in excessive synaptic zinc concentrations is believed to induce neurotoxicity through mitochondrial oxidative stress (e.g., by disrupting certain enzymes involved in the electron transport chain, including complex I, complex III, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase), the dysregulation of calcium homeostasis, glutamatergic neuronal excitotoxicity, and interference with intraneuronal signal transduction.[5][195] L- and D-histidine facilitate brain zinc uptake.[196] SLC30A3 is the primary zinc transporter involved in cerebral zinc homeostasis.[5]

Enzymes

Zinc is an efficient Lewis acid, making it a useful catalytic agent in hydroxylation and other enzymatic reactions.[197] The metal also has a flexible coordination geometry, which allows proteins using it to rapidly shift conformations to perform biological reactions.[198] Two examples of zinc-containing enzymes are carbonic anhydrase and carboxypeptidase, which are vital to the processes of carbon dioxide (CO

2) regulation and digestion of proteins, respectively.[199]

In vertebrate blood, carbonic anhydrase converts CO

2 into bicarbonate and the same enzyme transforms the bicarbonate back into CO

2 for exhalation through the lungs.[200] Without this enzyme, this conversion would occur about one million times slower[201] at the normal blood pH of 7 or would require a pH of 10 or more.[202] The non-related β-carbonic anhydrase is required in plants for leaf formation, the synthesis of indole acetic acid (auxin) and alcoholic fermentation.[203]

Carboxypeptidase cleaves peptide linkages during digestion of proteins. A coordinate covalent bond is formed between the terminal peptide and a C=O group attached to zinc, which gives the carbon a positive charge. This helps to create a hydrophobic pocket on the enzyme near the zinc, which attracts the non-polar part of the protein being digested.[199]

Signalling

Zinc has been recognized as a messenger, able to activate signalling pathways. Many of these pathways provide the driving force in aberrant cancer growth. They can be targeted through ZIP transporters.[204]

Other proteins

Zinc serves a purely structural role in zinc fingers, twists and clusters.[205] Zinc fingers form parts of some transcription factors, which are proteins that recognize DNA base sequences during the replication and transcription of DNA. Each of the nine or ten Zn2+

ions in a zinc finger helps maintain the finger's structure by coordinately binding to four amino acids in the transcription factor.[201]

In blood plasma, zinc is bound to and transported by albumin (60%, low-affinity) and transferrin (10%).[187] Because transferrin also transports iron, excessive iron reduces zinc absorption, and vice versa. A similar antagonism exists with copper.[206] The concentration of zinc in blood plasma stays relatively constant regardless of zinc intake.[197] Cells in the salivary gland, prostate, immune system, and intestine use zinc signaling to communicate with other cells.[207]

Zinc may be held in metallothionein reserves within microorganisms or in the intestines or liver of animals.[208] Metallothionein in intestinal cells is capable of adjusting absorption of zinc by 15–40%.[209] However, inadequate or excessive zinc intake can be harmful; excess zinc particularly impairs copper absorption because metallothionein absorbs both metals.[210]

The human dopamine transporter contains a high affinity extracellular zinc binding site which, upon zinc binding, inhibits dopamine reuptake and amplifies amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux in vitro.[211][212][213] The human serotonin transporter and norepinephrine transporter do not contain zinc binding sites.[213] Some EF-hand calcium binding proteins such as S100 or NCS-1 are also able to bind zinc ions.[214]

Nutrition

Dietary recommendations

The U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) updated Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for zinc in 2001. The current EARs for zinc for women and men ages 14 and up is 6.8 and 9.4 mg/day, respectively. The RDAs are 8 and 11 mg/day. RDAs are higher than EARs so as to identify amounts that will cover people with higher than average requirements. RDA for pregnancy is 11 mg/day. RDA for lactation is 12 mg/day. For infants up to 12 months the RDA is 3 mg/day. For children ages 1–13 years the RDA increases with age from 3 to 8 mg/day. As for safety, the IOM sets Tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. In the case of zinc the adult UL is 40 mg/day including both food and supplements combined (lower for children). Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs).[197]

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and Average Requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL are defined the same as in the United States. For people ages 18 and older the PRI calculations are complex, as the EFSA has set higher and higher values as the phytate content of the diet increases. For women, PRIs increase from 7.5 to 12.7 mg/day as phytate intake increases from 300 to 1200 mg/day; for men the range is 9.4 to 16.3 mg/day. These PRIs are higher than the U.S. RDAs.[215] The EFSA reviewed the same safety question and set its UL at 25 mg/day, which is much lower than the U.S. value.[216]

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For zinc labeling purposes 100% of the Daily Value was 15 mg, but on May 27, 2016, it was revised to 11 mg.[217][218] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

Dietary intake

Animal products such as meat, fish, shellfish, fowl, eggs, and dairy contain zinc. The concentration of zinc in plants varies with the level in the soil. With adequate zinc in the soil, the food plants that contain the most zinc are wheat (germ and bran) and various seeds, including sesame, poppy, alfalfa, celery, and mustard.[219] Zinc is also found in beans, nuts, almonds, whole grains, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, and blackcurrant.[220]

Other sources include fortified food and dietary supplements in various forms. A 1998 review concluded that zinc oxide, one of the most common supplements in the United States, and zinc carbonate are nearly insoluble and poorly absorbed in the body.[221] This review cited studies that found lower plasma zinc concentrations in the subjects who consumed zinc oxide and zinc carbonate than in those who took zinc acetate and sulfate salts.[221] For fortification, however, a 2003 review recommended cereals (containing zinc oxide) as a cheap, stable source that is as easily absorbed as the more expensive forms.[222] A 2005 study found that various compounds of zinc, including oxide and sulfate, did not show statistically significant differences in absorption when added as fortificants to maize tortillas.[223]

Deficiency

Nearly two billion people in the developing world are deficient in zinc. Groups at risk include children in developing countries and elderly with chronic illnesses.[12] In children, it causes an increase in infection and diarrhea and contributes to the death of about 800,000 children worldwide per year.[10] The World Health Organization advocates zinc supplementation for severe malnutrition and diarrhea.[224] Zinc supplements help prevent disease and reduce mortality, especially among children with low birth weight or stunted growth.[224] However, zinc supplements should not be administered alone, because many in the developing world have several deficiencies, and zinc interacts with other micronutrients.[225] While zinc deficiency is usually due to insufficient dietary intake, it can be associated with malabsorption, acrodermatitis enteropathica, chronic liver disease, chronic renal disease, sickle cell disease, diabetes, malignancy, and other chronic illnesses.[12]

In the United States, a federal survey of food consumption determined that for women and men over the age of 19, average consumption was 9.7 and 14.2 mg/day, respectively. For women, 17% consumed less than the EAR, for men 11%. The percentages below EAR increased with age.[226] The most recent published update of the survey (NHANES 2013–2014) reported lower averages – 9.3 and 13.2 mg/day – again with intake decreasing with age.[227]

Symptoms of mild zinc deficiency are diverse.[197] Clinical outcomes include depressed growth, diarrhea, impotence and delayed sexual maturation, alopecia, eye and skin lesions, impaired appetite, altered cognition, impaired immune functions, defects in carbohydrate use, and reproductive teratogenesis.[197] Zinc deficiency depresses immunity,[228] but excessive zinc does also.[187]

Despite some concerns,[229] western vegetarians and vegans do not suffer any more from overt zinc deficiency than meat-eaters.[230] Major plant sources of zinc include cooked dried beans, sea vegetables, fortified cereals, soy foods, nuts, peas, and seeds.[229] However, phytates in many whole-grains and fibers may interfere with zinc absorption and marginal zinc intake has poorly understood effects. The zinc chelator phytate, found in seeds and cereal bran, can contribute to zinc malabsorption.[12] Some evidence suggests that more than the US RDA (8 mg/day for adult women; 11 mg/day for adult men) may be needed in those whose diet is high in phytates, such as some vegetarians.[229] The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) guidelines attempt to compensate for this by recommending higher zinc intake when dietary phytate intake is greater.[215] These considerations must be balanced against the paucity of adequate zinc biomarkers, and the most widely used indicator, plasma zinc, has poor sensitivity and specificity.[231]

Soil remediation

Species of Calluna, Erica and Vaccinium can grow in zinc-metalliferous soils, because translocation of toxic ions is prevented by the action of ericoid mycorrhizal fungi.[232]

Agriculture

Zinc deficiency appears to be the most common micronutrient deficiency in crop plants; it is particularly common in high-pH soils.[233] Zinc-deficient soil is cultivated in the cropland of about half of Turkey and India, a third of China, and most of Western Australia. Substantial responses to zinc fertilization have been reported in these areas.[8] Plants that grow in soils that are zinc-deficient are more susceptible to disease. Zinc is added to the soil primarily through the weathering of rocks, but humans have added zinc through fossil fuel combustion, mine waste, phosphate fertilizers, pesticide (zinc phosphide), limestone, manure, sewage sludge, and particles from galvanized surfaces. Excess zinc is toxic to plants, although zinc toxicity is far less widespread.[8]

Precautions

Toxicity

Although zinc is an essential requirement for good health, excess zinc can be harmful. Excessive absorption of zinc suppresses copper and iron absorption.[210] The free zinc ion in solution is highly toxic to plants, invertebrates, and even vertebrate fish.[234] The Free Ion Activity Model is well-established in the literature, and shows that just micromolar amounts of the free ion kills some organisms. A recent example showed 6 micromolar killing 93% of all Daphnia in water.[235]

The free zinc ion is a powerful Lewis acid up to the point of being corrosive. Stomach acid contains hydrochloric acid, in which metallic zinc dissolves readily to give corrosive zinc chloride. Swallowing a post-1982 American one cent piece (97.5% zinc) can cause damage to the stomach lining through the high solubility of the zinc ion in the acidic stomach.[236]

Evidence shows that people taking 100–300 mg of zinc daily may suffer induced copper deficiency. A 2007 trial observed that elderly men taking 80 mg daily were hospitalized for urinary complications more often than those taking a placebo.[237] Levels of 100–300 mg may interfere with the use of copper and iron or adversely affect cholesterol.[210] Zinc in excess of 500 ppm in soil interferes with the plant absorption of other essential metals, such as iron and manganese.[110] A condition called the zinc shakes or "zinc chills" can be induced by inhalation of zinc fumes while brazing or welding galvanized materials.[142] Zinc is a common ingredient of denture cream which may contain between 17 and 38 mg of zinc per gram. Disability and even deaths from excessive use of these products have been claimed.[238]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that zinc damages nerve receptors in the nose, causing anosmia. Reports of anosmia were also observed in the 1930s when zinc preparations were used in a failed attempt to prevent polio infections.[239] On June 16, 2009, the FDA ordered removal of zinc-based intranasal cold products from store shelves. The FDA said the loss of smell can be life-threatening because people with impaired smell cannot detect leaking gas or smoke, and cannot tell if food has spoiled before they eat it.[240]

Recent research suggests that the topical antimicrobial zinc pyrithione is a potent heat shock response inducer that may impair genomic integrity with induction of PARP-dependent energy crisis in cultured human keratinocytes and melanocytes.[241]

Poisoning

In 1982, the US Mint began minting pennies coated in copper but containing primarily zinc. Zinc pennies pose a risk of zinc toxicosis, which can be fatal. One reported case of chronic ingestion of 425 pennies (over 1 kg of zinc) resulted in death due to gastrointestinal bacterial and fungal sepsis. Another patient who ingested 12 grams of zinc showed only lethargy and ataxia (gross lack of coordination of muscle movements).[242] Several other cases have been reported of humans suffering zinc intoxication by the ingestion of zinc coins.[243][244]

Pennies and other small coins are sometimes ingested by dogs, requiring veterinary removal of the foreign objects. The zinc content of some coins can cause zinc toxicity, commonly fatal in dogs through severe hemolytic anemia and liver or kidney damage; vomiting and diarrhea are possible symptoms.[245] Zinc is highly toxic in parrots and poisoning can often be fatal.[246] The consumption of fruit juices stored in galvanized cans has resulted in mass parrot poisonings with zinc.[68]

See also

- List of countries by zinc production

- Spelter

- Wet storage stain

- Zinc alloy electroplating

- Metal fume fever

- Piotr Steinkeller

Notes

- ^ The elements are from different metal groups. See periodic table.

- ^ An East India Company ship carrying a cargo of nearly pure zinc metal from the Orient sank off the coast Sweden in 1745.(Emsley 2001, p. 502)

- ^ Electric current will naturally flow between zinc and steel but in some circumstances inert anodes are used with an external DC source.

Citations

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Zinc". CIAAW. 2007.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ a b Maret, Wolfgang (2013). "Zinc and Human Disease". In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 389–414. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_12. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470098.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Prakash A, Bharti K, Majeed AB (April 2015). "Zinc: indications in brain disorders". Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 29 (2): 131–149. doi:10.1111/fcp.12110. PMID 25659970. S2CID 21141511.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cherasse Y, Urade Y (November 2017). "Dietary Zinc Acts as a Sleep Modulator". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (11): 2334. doi:10.3390/ijms18112334. PMC 5713303. PMID 29113075.

Zinc is the second most abundant trace metal in the human body, and is essential for many biological processes. ... The trace metal zinc is an essential cofactor for more than 300 enzymes and 1000 transcription factors [16]. ... In the central nervous system, zinc is the second most abundant trace metal and is involved in many processes. In addition to its role in enzymatic activity, it also plays a major role in cell signaling and modulation of neuronal activity.

- ^ a b Prasad A. S. (2008). "Zinc in Human Health: Effect of Zinc on Immune Cells". Mol. Med. 14 (5–6): 353–7. doi:10.2119/2008-00033.Prasad. PMC 2277319. PMID 18385818.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Broadley, M. R.; White, P. J.; Hammond, J. P.; Zelko I.; Lux A. (2007). "Zinc in plants". New Phytologist. 173 (4): 677–702. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.01996.x. PMID 17286818.

- ^ a b Zinc's role in microorganisms is particularly reviewed in: Sugarman B (1983). "Zinc and infection". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 5 (1): 137–47. doi:10.1093/clinids/5.1.137. PMID 6338570.

- ^ a b c d e Hambidge, K. M. & Krebs, N. F. (2007). "Zinc deficiency: a special challenge". J. Nutr. 137 (4): 1101–5. doi:10.1093/jn/137.4.1101. PMID 17374687.

- ^ Xiao, Hangfang; Deng, Wenfeng; Wei, Gangjian; Chen, Jiubin; Zheng, Xinqing; Shi, Tuo; Chen, Xuefei; Wang, Chenying; Liu, Xi (October 30, 2020). "A Pilot Study on Zinc Isotopic Compositions in Shallow-Water Coral Skeletons". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 21 (11). Bibcode:2020GGG....2109430X. doi:10.1029/2020GC009430. S2CID 228975484.

- ^ a b c d Prasad, AS (2003). "Zinc deficiency : Has been known of for 40 years but ignored by global health organisations". British Medical Journal. 326 (7386): 409–410. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7386.409. PMC 1125304. PMID 12595353.

- ^ Maret, Wolfgang (2013). "Zinc and the Zinc Proteome". In Banci, Lucia (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. pp. 479–501. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_14. ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. PMID 23595681.

- ^ Anglia, University of East. "Zinc vital to evolution of complex life in polar oceans". phys.org. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ Thornton, C. P. (2007). Of brass and bronze in prehistoric Southwest Asia (PDF). ISBN 978-1-904982-19-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015.

{{cite book}}:website=ignored (help) - ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 1201

- ^ a b Craddock, Paul T. (1978). "The composition of copper alloys used by the Greek, Etruscan and Roman civilizations. The origins and early use of brass". Journal of Archaeological Science. 5 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(78)90015-8.

- ^ "Zinc – Royal Society Of Chemistry". Archived from the original on July 11, 2017.

- ^ "India Was the First to Smelt Zinc by Distillation Process". Infinityfoundation.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Kharakwal, J. S. & Gurjar, L. K. (December 1, 2006). "Zinc and Brass in Archaeological Perspective". Ancient Asia. 1: 139–159. doi:10.5334/aa.06112.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j CRC 2006, p. 4–41

- ^ a b Heiserman 1992, p. 123

- ^ Wells A.F. (1984) Structural Inorganic Chemistry 5th edition p 1277 Oxford Science Publications ISBN 0-19-855370-6

- ^ Scoffern, John (1861). The Useful Metals and Their Alloys. Houlston and Wright. pp. 591–603. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "Zinc Metal Properties". American Galvanizers Association. 2008. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Ingalls, Walter Renton (1902). "Production and Properties of Zinc: A Treatise on the Occurrence and Distribution of Zinc Ore, the Commercial and Technical Conditions Affecting the Production of the Spelter, Its Chemical and Physical Properties and Uses in the Arts, Together with a Historical and Statistical Review of the Industry". The Engineering and Mining Journal: 142–6.

- ^ Rieuwerts, John (2015). The Elements of Environmental Pollution. London and New York: Earthscan Routledge. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-415-85919-6. OCLC 886492996.

- ^ a b c d e Lehto 1968, p. 822

- ^ a b c Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 1202

- ^ a b c d Emsley 2001, p. 502

- ^ a b c d Sai Srujan, A.V (2021). "Mineral Commodity Summaries 2021: Zinc" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ Erickson, R. L. (1973). "Crustal Abundance of Elements, and Mineral Reserves and Resources". U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper (820): 21–25.

- ^ "Country Partnership Strategy—Iran: 2011–12". ECO Trade and development bank. Archived from the original on October 26, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ "IRAN – a growing market with enormous potential". IMRG. July 5, 2010. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Tolcin, A. C. (2009). "Mineral Commodity Summaries 2009: Zinc" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ Gordon, R. B.; Bertram, M.; Graedel, T. E. (2006). "Metal stocks and sustainability". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (5): 1209–14. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.1209G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509498103. PMC 1360560. PMID 16432205.

- ^ Gerst, Michael (2008). "In-Use Stocks of Metals: Status and Implications". Environmental Science and Technology. 42 (19): 7038–45. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.7038G. doi:10.1021/es800420p. PMID 18939524.

- ^ Meylan, Gregoire (2016). "The anthropogenic cycle of zinc: Status quo and perspectives". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 123: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.01.006.

- ^ a b c d e f Alejandro A. Sonzogni (Database Manager), ed. (2008). "Chart of Nuclides". Upton (NY): National Nuclear Data Center, Brookhaven National Laboratory. Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ a b Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S. (2017). "The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 41 (3): 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

- ^ Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), "The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties", Nuclear Physics A, 729: 3–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001

- ^ CRC 2006, pp. 8–29

- ^ Porter, Frank C. (1994). Corrosion Resistance of Zinc and Zinc Alloys. CRC Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8247-9213-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). "Zink". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1034–1041. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- ^ Hinds, John Iredelle Dillard (1908). Inorganic Chemistry: With the Elements of Physical and Theoretical Chemistry (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 506–508.

- ^ Ritchie, Rob (2004). Chemistry (2nd ed.). Letts and Lonsdale. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-84315-438-9.

- ^ Burgess, John (1978). Metal ions in solution. New York: Ellis Horwood. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-470-26293-1.

- ^ Brady, James E.; Humiston, Gerard E.; Heikkinen, Henry (1983). General Chemistry: Principles and Structure (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 671. ISBN 978-0-471-86739-5.

- ^ Kaupp M.; Dolg M.; Stoll H.; Von Schnering H. G. (1994). "Oxidation state +IV in group 12 chemistry. Ab initio study of zinc(IV), cadmium(IV), and mercury(IV) fluorides". Inorganic Chemistry. 33 (10): 2122–2131. doi:10.1021/ic00088a012.

- ^ Samanta, Devleena; Jena, Puru (2012). "Zn in the +III Oxidation State". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 134 (20): 8400–8403. doi:10.1021/ja3029119. PMID 22559713.

- ^ Schlöder, Tobias; et al. (2012). "Can Zinc Really Exist in Its Oxidation State +III?". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 134 (29): 11977–11979. doi:10.1021/ja3052409. PMID 22775535.

- ^ Fang, Hong; Banjade, Huta; Deepika; Jena, Puru (2021). "Realization of the Zn3+ oxidation state". Nanoscale. 13 (33): 14041–14048. doi:10.1039/D1NR02816B. PMID 34477685. S2CID 237400349.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 1206

- ^ CRC 2006, pp. 12–11–12

- ^ Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2008). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 739–741, 843. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ "Zinc Sulfide". American Elements. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Academic American Encyclopedia. Danbury, Connecticut: Grolier Inc. 1994. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-7172-2053-3.

- ^ "Zinc Phosphide". American Elements. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Shulzhenko AA, Ignatyeva IY, Osipov AS, Smirnova TI (2000). "Peculiarities of interaction in the Zn–C system under high pressures and temperatures". Diamond and Related Materials. 9 (2): 129–133. Bibcode:2000DRM.....9..129S. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(99)00231-9.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 1211

- ^ Rasmussen, J. K.; Heilmann, S. M. (1990). "In situ Cyanosilylation of Carbonyl Compounds: O-Trimethylsilyl-4-Methoxymandelonitrile". Organic Syntheses, Collected Volume. 7: 521. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ Perry, D. L. (1995). Handbook of Inorganic Compounds. CRC Press. pp. 448–458. ISBN 978-0-8493-8671-8.

- ^ Frankland, E. (1850). "On the isolation of the organic radicals". Quarterly Journal of the Chemical Society. 2 (3): 263. doi:10.1039/QJ8500200263.

- ^ Lide, David (1998). CRC- Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. CRC press. pp. Section 8 Page 1. ISBN 978-0-8493-0479-8.

- ^ Weeks 1933, p. 20

- ^ Craddock, P. T. (1998). "Zinc in classical antiquity". In Craddock, P.T. (ed.). 2000 years of zinc and brass (rev. ed.). London: British Museum. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-86159-124-4.

- ^ a b Weeks 1933, p. 21

- ^ a b c d e f Emsley 2001, p. 501

- ^ "How is zinc made?". How Products are Made. The Gale Group. 2002. Archived from the original on April 11, 2006. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ^ Chambers 1901, p. 799

- ^ "World's oldest pills treated sore eyes". New Scientist. January 7, 2013. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Giachi, Gianna; Pallecchi, Pasquino; Romualdi, Antonella; Ribechini, Erika; Lucejko, Jeannette Jacqueline; Colombini, Maria Perla; Mariotti Lippi, Marta (2013). "Ingredients of a 2,000-y-old medicine revealed by chemical, mineralogical, and botanical investigations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (4): 1193–1196. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1193G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1216776110. PMC 3557061. PMID 23297212.

- ^ Rehren, Th. (1996). S. Demirci; et al. (eds.). A Roman zinc tablet from Bern, Switzerland: Reconstruction of the Manufacture. Archaeometry 94. The Proceedings of the 29th International Symposium on Archaeometry. pp. 35–45.

- ^ Meulenbeld, G. J. (1999). A History of Indian Medical Literature. Vol. IA. Groningen: Forsten. pp. 130–141. OCLC 165833440.

- ^ Craddock, P. T.; et al. (1998). "Zinc in India". 2000 years of zinc and brass (rev. ed.). London: British Museum. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-86159-124-4.

- ^ a b p. 46, Ancient mining and metallurgy in Rajasthan, S. M. Gandhi, chapter 2 in Crustal Evolution and Metallogeny in the Northwestern Indian Shield: A Festschrift for Asoke Mookherjee, M. Deb, ed., Alpha Science Int'l Ltd., 2000, ISBN 1-84265-001-7.

- ^ a b c Craddock, P. T.; Gurjar L. K.; Hegde K. T. M. (1983). "Zinc production in medieval India". World Archaeology. 15 (2): 211–217. doi:10.1080/00438243.1983.9979899. JSTOR 124653.

- ^ Ray, Prafulla Chandra (1903). A History of Hindu Chemistry from the Earliest Times to the Middle of the Sixteenth Century, A.D.: With Sanskrit Texts, Variants, Translation and Illustrations. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). The Bengal Chemical & Pharmaceutical Works, Ltd. pp. 157–158. (public domain text)

- ^ a b c d e f g Habashi, Fathi. "Discovering the 8th Metal" (PDF). International Zinc Association (IZA). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2008.

- ^ Arny, Henry Vinecome (1917). Principles of Pharmacy (2nd ed.). W. B. Saunders company. p. 483.

- ^ Hoover, Herbert Clark (2003). Georgius Agricola de Re Metallica. Kessinger Publishing. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-7661-3197-2.

- ^ Gerhartz, Wolfgang; et al. (1996). Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (5th ed.). VHC. p. 509. ISBN 978-3-527-20100-6.

- ^ Skeat, W. W (2005). Concise Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Cosimo, Inc. p. 622. ISBN 978-1-59605-092-1.

- ^ Fathi Habashi (1997). Handbook of Extractive Metallurgy. Wiley-VHC. p. 642. ISBN 978-3-527-28792-5.

- ^ Lach, Donald F. (1994). "Technology and the Natural Sciences". Asia in the Making of Europe. University of Chicago Press. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-226-46734-4.

- ^ Vaughan, L Brent (1897). "Zincography". The Junior Encyclopedia Britannica A Reference Library of General Knowledge Volume III P-Z. Chicago: E. G. Melven & Company.

- ^ Castellani, Michael. "Transition Metal Elements" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (2011). Chatopadhyaya, D. P. (ed.). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500. New Delhi: Pearson Longman. p. 86. ISBN 978-81-317-2791-1. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Rhys (1945). "The Zinc Industry in England: the early years up to 1850". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 25: 41–52. doi:10.1179/tns.1945.006.

- ^ Willies, Lynn; Craddock, P. T.; Gurjar, L. J.; Hegde, K. T. M. (1984). "Ancient Lead and Zinc Mining in Rajasthan, India". World Archaeology. 16 (2, Mines and Quarries): 222–233. doi:10.1080/00438243.1984.9979929. JSTOR 124574.

- ^ Roberts, R. O. (1951). "Dr John Lane and the foundation of the non-ferrous metal industry in the Swansea valley". Gower. Gower Society (4): 19.

- ^ Comyns, Alan E. (2007). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Named Processes in Chemical Technology (3rd ed.). CRC Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8493-9163-7.

- ^ Marggraf (1746). "Experiences sur la maniere de tirer le Zinc de sa veritable miniere, c'est à dire, de la pierre calaminaire" [Experiments on a way of extracting zinc from its true mineral; i.e., the stone calamine]. Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et Belles-Lettres de Berlin (in French). 2: 49–57.

- ^ Heiserman 1992, p. 122

- ^ Gray, Leon (2005). Zinc. Marshall Cavendish. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7614-1922-8.

- ^ a b c Warren, Neville G. (2000). Excel Preliminary Physics. Pascal Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-74020-085-1.

- ^ a b "Galvanic Cell". The New International Encyclopaedia. Dodd, Mead and Company. 1903. p. 80.

- ^ a b c Cotton et al. 1999, p. 626

- ^ Jasinski, Stephen M. "Mineral Commodity Summaries 2007: Zinc" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ Attwood, James (February 13, 2006). "Zinifex, Umicore Combine to Form Top Zinc Maker". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017.

- ^ "Zinc Recycling". International Zinc Association. Archived from the original on October 21, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- ^ "Special High Grade Zinc (SHG) 99.995%" (PDF). Nyrstar. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Porter, Frank C. (1991). Zinc Handbook. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8247-8340-2.

- ^ a b c Rosenqvist, Terkel (1922). Principles of Extractive Metallurgy (2nd ed.). Tapir Academic Press. pp. 7, 16, 186. ISBN 978-82-519-1922-7.

- ^ Borg, Gregor; Kärner, Katrin; Buxton, Mike; Armstrong, Richard; van der Merwe, Schalk W. (2003). "Geology of the Skorpion Supergene Zinc Deposit, Southern Namibia". Economic Geology. 98 (4): 749–771. doi:10.2113/98.4.749.

- ^ Bodsworth, Colin (1994). The Extraction and Refining of Metals. CRC Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8493-4433-6.

- ^ Gupta, C. K.; Mukherjee, T. K. (1990). Hydrometallurgy in Extraction Processes. CRC Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8493-6804-2.

- ^ Antrekowitsch, Jürgen; Steinlechner, Stefan; Unger, Alois; Rösler, Gernot; Pichler, Christoph; Rumpold, Rene (2014), "9. Zinc and Residue Recycling", in Worrell, Ernst; Reuter, Markus (eds.), Handbook of Recycling: State-of-the-art for Practitioners, Analysts, and Scientists

- ^ a b Kucha, H.; Martens, A.; Ottenburgs, R.; De Vos, W.; Viaene, W. (1996). "Primary minerals of Zn-Pb mining and metallurgical dumps and their environmental behavior at Plombières, Belgium". Environmental Geology. 27 (1): 1–15. Bibcode:1996EnGeo..27....1K. doi:10.1007/BF00770598. S2CID 129717791.

- ^ a b c d Emsley 2001, p. 504

- ^ Heath, Alan G. (1995). Water pollution and fish physiology. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-87371-632-1.

- ^ "Derwent Estuary – Water Quality Improvement Plan for Heavy Metals". Derwent Estuary Program. June 2007. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2009.

- ^ "The Zinc Works". TChange. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Zinc: World Mine Production (zinc content of concentrate) by Country" (PDF). 2009 Minerals Yearbook: Zinc. Washington, D.C.: United States Geological Survey. February 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2001.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 1203

- ^ a b Stwertka 1998, p. 99

- ^ a b c d e f g Lehto 1968, p. 829

- ^ a b Emsley 2001, p. 503

- ^ Bounoughaz, M.; Salhi, E.; Benzine, K.; Ghali E.; Dalard F. (2003). "A comparative study of the electrochemical behaviour of Algerian zinc and a zinc from a commercial sacrificial anode". Journal of Materials Science. 38 (6): 1139–1145. Bibcode:2003JMatS..38.1139B. doi:10.1023/A:1022824813564. S2CID 135744939.

- ^ Besenhard, Jürgen O. (1999). Handbook of Battery Materials. Wiley-VCH. Bibcode:1999hbm..book.....B. ISBN 978-3-527-29469-5.

- ^ Wiaux, J.-P.; Waefler, J. -P. (1995). "Recycling zinc batteries: an economical challenge in consumer waste management". Journal of Power Sources. 57 (1–2): 61–65. Bibcode:1995JPS....57...61W. doi:10.1016/0378-7753(95)02242-2.

- ^ Culter, T. (1996). "A design guide for rechargeable zinc–air battery technology". Southcon/96. Conference Record. p. 616. doi:10.1109/SOUTHC.1996.535134. ISBN 978-0-7803-3268-3. S2CID 106826667.

- ^ Whartman, Jonathan; Brown, Ian. "Zinc Air Battery-Battery Hybrid for Powering Electric Scooters and Electric Buses" (PDF). The 15th International Electric Vehicle Symposium. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2006. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Cooper, J. F.; Fleming, D.; Hargrove, D.; Koopman, R.; Peterman, K (1995). "A refuelable zinc/air battery for fleet electric vehicle propulsion". NASA Sti/Recon Technical Report N. Society of Automotive Engineers future transportation technology conference and exposition. 96: 11394. Bibcode:1995STIN...9611394C. OSTI 82465.

- ^ Xie, Z.; Liu, Q.; Chang, Z.; Zhang, X. (2013). "The developments and challenges of cerium half-cell in zinc–cerium redox flow battery for energy storage". Electrochimica Acta. 90: 695–704. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2012.12.066.

- ^ Bush, Douglas Earl; Kassel, Richard (2006). The Organ: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 679. ISBN 978-0-415-94174-7.

- ^ "Coin Specifications". United States Mint. Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Jasinski, Stephen M. "Mineral Yearbook 1994: Zinc" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2008. Retrieved November 13, 2008.

- ^ "Diecasting Alloys". Maybrook, NY: Eastern Alloys. Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2009.

- ^ Apelian, D.; Paliwal, M.; Herrschaft, D. C. (1981). "Casting with Zinc Alloys". Journal of Metals. 33 (11): 12–19. Bibcode:1981JOM....33k..12A. doi:10.1007/bf03339527.

- ^ Davies, Geoff (2003). Materials for automobile bodies. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-7506-5692-4.

- ^ Samans, Carl Hubert (1949). Engineering Metals and Their Alloys. Macmillan Co.

- ^ a b Porter, Frank (1994). "Wrought Zinc". Corrosion Resistance of Zinc and Zinc Alloys. CRC Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-8247-9213-8.

- ^ McClane, Albert Jules & Gardner, Keith (1987). The Complete book of fishing: a guide to freshwater, saltwater & big-game fishing. Gallery Books. ISBN 978-0-8317-1565-6. Archived from the original on November 15, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ "Cast flywheel on old Magturbo trainer has been recalled since July 2000". Minoura. Archived from the original on March 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c Katz, Johnathan I. (2002). The Biggest Bangs. Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-19-514570-0.

- ^ Zhang, Xiaoge Gregory (1996). Corrosion and Electrochemistry of Zinc. Springer. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-306-45334-2.

- ^ Weimer, Al (May 17, 2006). "Development of Solar-powered Thermochemical Production of Hydrogen from Water" (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c Heiserman 1992, p. 124

- ^ Blew, Joseph Oscar (1953). "Wood preservatives" (PDF). Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory. hdl:1957/816. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 14, 2012.

- ^ Frankland, Edward (1849). "Notiz über eine neue Reihe organischer Körper, welche Metalle, Phosphor u. s. w. enthalten". Liebig's Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (in German). 71 (2): 213–216. doi:10.1002/jlac.18490710206.

- ^ a b CRC 2006, p. 4-42

- ^ Paschotta, Rüdiger (2008). Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology. Wiley-VCH. p. 798. ISBN 978-3-527-40828-3.

- ^ Konstantinou, I. K.; Albanis, T. A. (2004). "Worldwide occurrence and effects of antifouling paint booster biocides in the aquatic environment: a review". Environment International. 30 (2): 235–248. doi:10.1016/S0160-4120(03)00176-4. PMID 14749112.

- ^ a b c Boudreaux, Kevin A. "Zinc + Sulfur". Angelo State University. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ "Rolled and Titanium Zinc Sheet". Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Things You Should Know About Zinc Countertops". Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Guide to Zinc Countertops: Benefits of Zinc Kitchen Counters". Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Technical Information". Zinc Counters. 2008. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ^ a b c Win, David Tin; Masum, Al (2003). "Weapons of Mass Destruction" (PDF). Assumption University Journal of Technology. Assumption University. 6 (4): 199. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ David E. Newton (1999). Chemical Elements: From Carbon to Krypton. U. X. L. /Gale. ISBN 978-0-7876-2846-8. Archived from the original on July 10, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ Ullmann's Agrochemicals. Wiley-Vch (COR). 2007. pp. 591–592. ISBN 978-3-527-31604-5.

- ^ Walker, J. C. F. (2006). Primary Wood Processing: Principles and Practice. Springer. p. 317. ISBN 978-1-4020-4392-5.

- ^ "ZDDP Engine Oil – The Zinc Factor". Mustang Monthly. Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved September 19, 2009.

- ^ Kim, Jeung Gon; Walsh, Patrick J. (2006). "From Aryl Bromides to Enantioenriched Benzylic Alcohols in a Single Flask: Catalytic Asymmetric Arylation of Aldehydes". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 45 (25): 4175–4178. doi:10.1002/anie.200600741. PMID 16721894.

- ^ Overman, Larry E.; Carpenter, Nancy E. (2005). The Allylic Trihaloacetimidate Rearrangement. Organic Reactions. Vol. 66. pp. 1–107. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or066.01. ISBN 978-0-471-26418-7.

- ^ Rappoport, Zvi; Marek, Ilan (December 17, 2007). The Chemistry of Organozinc Compounds: R-Zn. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-09337-5. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016.

- ^ Knochel, Paul; Jones, Philip (1999). Organozinc reagents: A practical approach. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850121-3. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016.

- ^ Herrmann, Wolfgang A. (January 2002). Synthetic Methods of Organometallic and Inorganic Chemistry: Catalysis. Georg Thieme Verlag. ISBN 978-3-13-103061-0. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016.

- ^ E. Frankland, Ann. 126, 109 (1863)

- ^ E. Frankland, B. F. Duppa, Ann. 135, 25 (1865)

- ^ Łowicki, Daniel; Baś, Sebastian; Mlynarski, Jacek (2015). "Chiral zinc catalysts for asymmetric synthesis". Tetrahedron. 71 (9): 1339–1394. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2014.12.022.

- ^ DiSilvestro, Robert A. (2004). Handbook of Minerals as Nutritional Supplements. CRC Press. pp. 135, 155. ISBN 978-0-8493-1652-4.

- ^ Sanchez, Juliana (February 13, 2013). Zinc Sulphate vs. Zinc Amino Acid Chelate (ZAZO) (Report). USA Government. NCT01791608. Retrieved April 6, 2022 – via U.S. National Library of Medecine.

- ^ Mayo-Wilson, E; Junior, JA; Imdad, A; Dean, S; Chan, XH; Chan, ES; Jaswal, A; Bhutta, ZA (May 15, 2014). "Zinc supplementation for preventing mortality, morbidity, and growth failure in children aged 6 months to 12 years of age". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD009384. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009384.pub2. PMID 24826920.

- ^ Santos HO, Teixeira FJ, Schoenfeld BJ (2019). "Dietary vs. pharmacological doses of zinc: A clinical review". Clin Nutr. 130 (5): 1345–1353. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2019.06.024. PMID 31303527. S2CID 196616666.

- ^ Bhutta ZA, Bird SM, Black RE, Brown KH, Gardner JM, Hidayat A, Khatun F, Martorell R, et al. (2000). "Therapeutic effects of oral zinc in acute and persistent diarrhea in children in developing countries: pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 72 (6): 1516–1522. doi:10.1093/ajcn/72.6.1516. PMID 11101480.

- ^ Aydemir, T. B.; Blanchard, R. K.; Cousins, R. J. (2006). "Zinc supplementation of young men alters metallothionein, zinc transporter, and cytokine gene expression in leukocyte populations". PNAS. 103 (6): 1699–704. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.1699A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510407103. PMC 1413653. PMID 16434472.

- ^ Valko, M.; Morris, H.; Cronin, M. T. D. (2005). "Metals, Toxicity and Oxidative stress" (PDF). Current Medicinal Chemistry. 12 (10): 1161–208. doi:10.2174/0929867053764635. PMID 15892631. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Zinc – Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. February 11, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Science M, Johnstone J, Roth DE, Guyatt G, Loeb M (July 2012). "Zinc for the treatment of the common cold: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". CMAJ. 184 (10): E551-61. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111990. PMC 3394849. PMID 22566526.

- ^ "Common Cold and Runny Nose". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 26, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ Suzuki H, Asakawa A, Li JB, Tsai M, Amitani H, Ohinata K, Komai M, Inui A (2011). "Zinc as an appetite stimulator – the possible role of zinc in the progression of diseases such as cachexia and sarcopenia". Recent Patents on Food, Nutrition & Agriculture. 3 (3): 226–231. doi:10.2174/2212798411103030226. PMID 21846317.

- ^ Shay, Neil F.; Mangian, Heather F. (2000). "Neurobiology of Zinc-Influenced Eating Behavior". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (5): 1493S–1499S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.5.1493S. PMID 10801965.

- ^ Rabinovich D, Smadi Y (2019). "Zinc". StatPearls [Internet]. PMID 31613478.

- ^ Evans JR, Lawrenson JG (2017). "Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7 (9): CD000254. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000254.pub4. PMC 6483465. PMID 28756618.

- ^ Swardfager W, Herrmann N, McIntyre RS, Mazereeuw G, Goldberger K, Cha DS, Schwartz Y, Lanctôt KL (June 2013). "Potential roles of zinc in the pathophysiology and treatment of major depressive disorder". Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37 (5): 911–929. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.03.018. PMID 23567517. S2CID 1725139.

- ^ Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (November 16, 2021). "Questions and Answers: FDA posts deemed final order and proposed order for over-the-counter sunscreen". FDA.

- ^ Chauhan, Ravi; Kumar, Amit; Tripathi, Ramna; Kumar, Akhilesh (2021), Mallakpour, Shadpour; Hussain, Chaudhery Mustansar (eds.), "Advancing of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Cosmetic Applications", Handbook of Consumer Nanoproducts, Singapore: Springer, pp. 1–16, doi:10.1007/978-981-15-6453-6_100-1, ISBN 978-981-15-6453-6, S2CID 245778598, retrieved October 31, 2022

- ^ Roldán, S.; Winkel, E. G.; Herrera, D.; Sanz, M.; Van Winkelhoff, A. J. (2003). "The effects of a new mouthrinse containing chlorhexidine, cetylpyridinium chloride and zinc lactate on the microflora of oral halitosis patients: a dual-centre, double-blind placebo-controlled study". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 30 (5): 427–434. doi:10.1034/j.1600-051X.2003.20004.x. PMID 12716335.

- ^ "Toothpastes". www.ada.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Marks, R.; Pearse, A. D.; Walker, A. P. (1985). "The effects of a shampoo containing zinc pyrithione on the control of dandruff". British Journal of Dermatology. 112 (4): 415–422. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02314.x. PMID 3158327. S2CID 23368244.

- ^ Mahajan, BB; Dhawan, M; Singh, R (January 2013). "Herpes genitalis – Topical zinc sulfate: An alternative therapeutic and modality". Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS. 34 (1): 32–4. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.112867. PMC 3730471. PMID 23919052.

- ^ Cotton et al. 1999, pp. 625–629

- ^ Plum, Laura; Rink, Lothar; Haase, Hajo (2010). "The Essential Toxin: Impact of Zinc on Human Health". Int J Environ Res Public Health. 7 (4): 1342–1365. doi:10.3390/ijerph7041342. PMC 2872358. PMID 20617034.

- ^ Brandt, Erik G.; Hellgren, Mikko; Brinck, Tore; Bergman, Tomas; Edholm, Olle (2009). "Molecular dynamics study of zinc binding to cysteines in a peptide mimic of the alcohol dehydrogenase structural zinc site". Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 11 (6): 975–83. Bibcode:2009PCCP...11..975B. doi:10.1039/b815482a. PMID 19177216.

- ^ a b c Rink, L.; Gabriel P. (2000). "Zinc and the immune system". Proc Nutr Soc. 59 (4): 541–52. doi:10.1017/S0029665100000781. PMID 11115789.

- ^ Wapnir, Raul A. (1990). Protein Nutrition and Mineral Absorption. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-5227-0.

- ^ Berdanier, Carolyn D.; Dwyer, Johanna T.; Feldman, Elaine B. (2007). Handbook of Nutrition and Food. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-9218-4.

- ^ Mittermeier, Lorenz; Gudermann, Thomas; Zakharian, Eleonora; Simmons, David G.; Braun, Vladimir; Chubanov, Masayuki; Hilgendorff, Anne; Recordati, Camilla; Breit, Andreas (February 15, 2019). "TRPM7 is the central gatekeeper of intestinal mineral absorption essential for postnatal survival". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (10): 4706–4715. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.4706M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810633116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6410795. PMID 30770447.

- ^ Kasana, Shakhenabat; Din, Jamila; Maret, Wolfgang (January 2015). "Genetic causes and gene–nutrient interactions in mammalian zinc deficiencies: acrodermatitis enteropathica and transient neonatal zinc deficiency as examples". Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 29: 47–62. doi:10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.10.003. ISSN 1878-3252. PMID 25468189.

- ^ Djoko KY, Ong CL, Walker MJ, McEwan AG (July 2015). "The Role of Copper and Zinc Toxicity in Innate Immune Defense against Bacterial Pathogens". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 290 (31): 18954–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.R115.647099. PMC 4521016. PMID 26055706.

Zn is present in up to 10% of proteins in the human proteome and computational analysis predicted that ~30% of these ~3000 Zn-containing proteins are crucial cellular enzymes, such as hydrolases, ligases, transferases, oxidoreductases, and isomerases (42,43).

- ^ a b Bitanihirwe BK, Cunningham MG (November 2009). "Zinc: the brain's dark horse". Synapse. 63 (11): 1029–1049. doi:10.1002/syn.20683. PMID 19623531. S2CID 206520330.

- ^ Nakashima AS; Dyck RH (2009). "Zinc and cortical plasticity". Brain Res Rev. 59 (2): 347–73. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.10.003. PMID 19026685. S2CID 22507338.

- ^ Tyszka-Czochara M, Grzywacz A, Gdula-Argasińska J, Librowski T, Wiliński B, Opoka W (May 2014). "The role of zinc in the pathogenesis and treatment of central nervous system (CNS) diseases. Implications of zinc homeostasis for proper CNS function" (PDF). Acta Pol. Pharm. 71 (3): 369–377. PMID 25265815. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 29, 2017.

- ^ Yokel, R. A. (2006). "Blood-brain barrier flux of aluminum, manganese, iron and other metals suspected to contribute to metal-induced neurodegeneration". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 10 (2–3): 223–53. doi:10.3233/JAD-2006-102-309. PMID 17119290.

- ^ a b c d e Institute of Medicine (2001). "Zinc". Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. pp. 442–501. doi:10.17226/10026. ISBN 978-0-309-07279-3. PMID 25057538. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017.

- ^ Stipanuk, Martha H. (2006). Biochemical, Physiological & Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition. W. B. Saunders Company. pp. 1043–1067. ISBN 978-0-7216-4452-3.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, pp. 1224–1225

- ^ Kohen, Amnon; Limbach, Hans-Heinrich (2006). Isotope Effects in Chemistry and Biology. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 850. ISBN 978-0-8247-2449-8.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 1225

- ^ Cotton et al. 1999, p. 627

- ^ Gadallah, MA (2000). "Effects of indole-3-acetic acid and zinc on the growth, osmotic potential and soluble carbon and nitrogen components of soybean plants growing under water deficit". Journal of Arid Environments. 44 (4): 451–467. Bibcode:2000JArEn..44..451G. doi:10.1006/jare.1999.0610.

- ^ Ziliotto, Silvia; Ogle, Olivia; Yaylor, Kathryn M. (2018). "Chapter 17. Targeting Zinc(II) Signalling to Prevent Cancer". In Sigel, Astrid; Sigel, Helmut; Freisinger, Eva; Sigel, Roland K. O. (eds.). Metallo-Drugs: Development and Action of Anticancer Agents. pp. 507–529. doi:10.1515/9783110470734-023. ISBN 9783110470734. PMID 29394036.

{{cite book}}:journal=ignored (help) - ^ Cotton et al. 1999, p. 628

- ^ Whitney, Eleanor Noss; Rolfes, Sharon Rady (2005). Understanding Nutrition (10th ed.). Thomson Learning. pp. 447–450. ISBN 978-1-4288-1893-4.

- ^ Hershfinkel, M; Silverman WF; Sekler I (2007). "The Zinc Sensing Receptor, a Link Between Zinc and Cell Signaling". Molecular Medicine. 13 (7–8): 331–336. doi:10.2119/2006-00038.Hershfinkel. PMC 1952663. PMID 17728842.

- ^ Cotton et al. 1999, p. 629

- ^ Blake, Steve (2007). Vitamins and Minerals Demystified. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-07-148901-0.

- ^ a b c Fosmire, G. J. (1990). "Zinc toxicity". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 51 (2): 225–7. doi:10.1093/ajcn/51.2.225. PMID 2407097.

- ^ Krause J (2008). "SPECT and PET of the dopamine transporter in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Expert Rev. Neurother. 8 (4): 611–625. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.4.611. PMID 18416663. S2CID 24589993.

- ^ Sulzer D (2011). "How addictive drugs disrupt presynaptic dopamine neurotransmission". Neuron. 69 (4): 628–649. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.010. PMC 3065181. PMID 21338876.

- ^ a b Scholze P, Nørregaard L, Singer EA, Freissmuth M, Gether U, Sitte HH (2002). "The role of zinc ions in reverse transport mediated by monoamine transporters". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (24): 21505–21513. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112265200. PMID 11940571.