디펜히드라민

Diphenhydramine | |

| |

| 임상 데이터 | |

|---|---|

| 발음 | /da'f'n'ha'dr'mi'n/ |

| 상호 | 베나드릴, 유니솜, 나이톨, 기타 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| Medline Plus | a682539 |

| 라이선스 데이터 | |

| 임신 카테고리 |

|

| 의존성 책임 | 매우[1] 낮다 |

| 루트 행정부. | 구강, 근육내, 정맥주사, 국소, 직장 |

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 약동학 데이터 | |

| 바이오 어베이러빌리티 | 40~60%[2] |

| 단백질 결합 | 98–99% |

| 대사 | 간(CYP2D6, 기타)[6][7] |

| 반감기 제거 | 범위: 2.4~13.5시간[3][2][4] |

| 배설물 | 소변: 94%[5] 대변: 6 [5]% |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드러그뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니 | |

| 케그 | |

| 체비 | |

| 첸블 | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA ) | |

| ECHA 정보 카드 | 100.000.360 |

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |

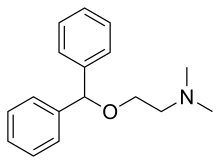

| 공식 | C17H21NO |

| 몰 질량 | 255.361 g/120−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

디펜히드라민(DPH)은 알레르기를 [8]치료하기 위해 주로 사용되는 항히스타민제이다.불면증, 감기 증상, 파킨슨병 떨림, [8]메스꺼움에도 사용할 수 있습니다.입으로 복용하거나 정맥에 주사하거나 근육에 주사하거나 피부에 [8]바릅니다.최대 효과는 일반적으로 투여 후 약 2시간이며, 효과는 최대 [8]7시간까지 지속될 수 있다.

일반적인 부작용으로는 졸음, 협응력 저하, [8]배탈 등이 있다.어린이나 [8][9]노인에게는 사용하지 않는 것이 좋습니다.임신 중 사용 시 명확한 위해 위험은 없지만 모유 수유 중 사용은 [10]권장되지 않습니다.그것은 1세대 H-항히스타민1 및 에탄올아민이며 [8]히스타민의 특정 효과를 차단함으로써 작용한다.디펜히드라민은 또한 항콜린제이며,[11] 결과적으로 권장량보다 높은 용량에서 섬망제로 작용한다.이것은 레크리에이션 사용과 [12]중독의 몇몇 사례로 이어졌다.

디펜히드라민은 George Rieveschl에 의해 처음 만들어졌고 [13][14]1946년에 상업적으로 사용되었다.제네릭 [8]의약품으로 구입할 수 있습니다.그것은 특히 [8]베나드릴이라는 브랜드명으로 판매된다.2017년, 그것은 미국에서 2백만 [15][16]개 이상의 처방으로 241번째로 많이 처방된 약이었다.

의료 용도

디펜히드라민은 알레르기 증상과 가려움증, 일반적인 감기, 불면증, 멀미, 그리고 추체외 [17][18]증상을 포함한 많은 질병을 치료하는데 사용되는 1세대 항히스타민제이다.디펜히드라민은 또한 국소 마취 특성을 가지고 있으며, 리도카인과 [19]같은 일반적인 국소 마취제에 알레르기가 있는 사람들에게 사용되어 왔다.

알레르기

디펜히드라민은 [20]알레르기 치료에 효과적이다.2007년 현재[update], [21]그것은 응급실에서 급성 알레르기 반응에 가장 일반적으로 사용되는 항히스타민제이다.

2007년 시점에서는[update] 이 목적을 위한 사용이 [23]제대로 연구되지 않았지만 주입에 의해 [22]아나필락시스의 에피네프린과 함께 사용되는 경우가 많다.급성 증상이 [20]호전된 후에만 사용을 권장합니다.

크림, 로션, 젤 및 스프레이를 포함한 디펜히드라민의 국소 제제가 제공됩니다.이것들은 가려움을 완화시키고 경구 형태보다 [24]더 적은 전신 효과(예: 졸음)를 일으킬 수 있는 장점이 있다.

운동 장애

디펜히드라민은 항정신병 [25]약물에 의해 유발되는 아카티시아 및 파킨슨병 유사 추체외 증상 치료에 사용된다.또한 1세대 항정신병 약물에 의해 야기되는 안과학적 위기 및 토르티콜리스를 포함한 급성 디스토니아 치료에도 사용된다.

수면.

디펜히드라민은 진정제 특성 때문에 불면증에 대한 처방전 없는 수면 보조제에 널리 사용된다.이 약은 단독으로 또는 타이레놀 PM의 아세트아미노펜(파라세타몰) 또는 애드빌 PM의 이부프로펜과 같은 다른 성분과 조합하여 수면 보조제로 판매되는 여러 제품의 성분입니다.디펜히드라민은 약간의 심리적 [26]의존을 일으킬 수 있다.디펜히드라민은 또한 항불안제로 [27]사용되어 왔다.

디펜히드라민은 또한 장거리 [28]비행에서 자녀들을 잠들게 하거나 진정제를 투여하기 위해 부모들에 의해 처방전에 의해 사용되어 왔다.운항 비상 발생으로 sedating 젊은 승객들 위험에 놓아둔다 이런 비판, 의사들과 항공 산업의 멤버에서 그리고 그들은 그 상황 efficiently,[29]그 약의 부작용, 역설적 반응 특히 기회, 어떤 이에게 개인 bec 수 있기 때문에 반응할 수 없다 부딪혀 왔다.oming 진정제가 아닌 과잉 활성.시애틀 아동병원은 2009년 기사에서 "당신의 편의를 위해 약물을 사용하는 것은 [30]어린이에게 약을 투여하는 것을 지시하는 것이 결코 아니다"라고 주장하면서, 이 사용의 윤리에 대한 문제도 제기되었다.

미국수면의학회(American Academy of Sleep Medicine)의 2017년 임상실천지침은 디펜히드라민 사용이 효과와 증거의 [31]질이 낮다는 이유로 불면증 치료에 사용하지 말 것을 권고했다.

수면에 사용된 디펜히드라민 용량은 12.5~100mg이며, 일반적인 용량은 50mg이다.[32][33][34][35][36]

메스꺼움

디펜히드라민은 또한 구토 방지 성질을 가지고 있어서 현기증과 멀미 [37]시 발생하는 메스꺼움을 치료하는데 유용하다.

특수 모집단

디펜히드라민은 의사의 [8][9][38]진찰을 받지 않는 한 60세 이상이나 6세 미만의 어린이에게는 권장되지 않습니다.이들 집단은 로라타딘, 데슬라타딘, 펙소페나딘,[39] 세티리진, 레보세티리진, 아젤라스틴과 같은 2세대 항히스타민제로 치료해야 한다.강력한 항콜린 작용 효과로 인해 디펜히드라민은 [40][41]노인들에게 피해야 할 약의 목록에 있습니다.

디펜히드라민은 FDA 임신 [42]중 약물 안전 등급 B에 해당한다.그것은 또한 [43]모유에서도 배설된다.가끔 복용하는 디펜히드라민의 저용량은 모유 수유 영아에게 어떠한 부작용도 일으키지 않을 것으로 예상된다.특히 의사 에페드린과 같은 교감 자극 약물과 결합하거나 수유를 확립하기 전에 다량 또는 장기 복용은 아기에게 영향을 미치거나 모유 공급을 감소시킬 수 있다.하루의 마지막 수유 후 취침 시 한 번 복용하면 아기 및 우유 공급에 대한 약물의 유해한 영향을 최소화할 수 있습니다.하지만 항히스타민제는 선호되는 [44]대안이다.

디펜히드라민에 대한 역설적 반응은 특히 어린이들 사이에서 기록되었으며,[45] 이는 진정제 대신 흥분을 일으킬 수 있다.

국소적인 디펜히드라민은 특히 호스피스 환자에게 사용된다.이러한 사용은 지시 없이 이루어지며, 국소 디펜히드라민은 다른 [46]치료법보다 더 효과적인 것으로 연구 결과 나타나지 않기 때문에 메스꺼움 치료제로 사용되어서는 안 된다.

디펜히드라민의 [47]정상 용량으로 인한 임상적으로 명백한 급성 간 손상에 대한 문서화된 사례는 없었다.

부작용

가장 두드러진 부작용은 진정제이다.일반적인 복용량은 혈중 알코올 농도 0.10에 해당하는 운전 장애를 유발하며, 이는 대부분의 음주운전법의 0.[21]08 한계보다 높다.

디펜히드라민은 강력한 항콜린제이며 더 높은 용량에서 잠재적 섬망제이다.이 활동은 입과 목의 건조함, 심박수 증가, 동공 확장, 소변 유지, 변비, 그리고 대량으로 환각이나 섬망의 부작용의 원인이 된다.다른 부작용으로는 운동 장애(운동실조), 홍조된 피부, 적응 부족으로 인한 근점 시야 흐림(순환기피증), 밝은 빛에 대한 비정상적인 민감성(사진공포증), 진정, 집중력 저하, 단기 기억 상실, 시각 장애, 불규칙한 호흡, 어지럼증, 자극성, 피부 가려움증, 혼란이 있다.체온(일반적으로 손과 발), 일시적인 발기부전 및 흥분성, 메스꺼움 치료에 사용될 수 있지만 더 높은 복용량은 [48]구토를 유발할 수 있다.디펜히드라민 과다복용은 때때로 QT [49]연장을 초래할 수 있다.

어떤 사람들은 [50][51]디펜히드라민에 대해 두드러기 형태의 알레르기 반응을 경험한다.

불안감이나 아카티시아와 같은 상태는 디펜히드라민 수치가 증가하면, 특히 레크리에이션 용량과 [45]함께 악화될 수 있습니다.디펜히드라민의 정상 복용량은 다른 1세대 항히스타민제처럼, 또한 안절부절못하는 다리 증후군의 증상을 [52]더 악화시킬 수 있다.디펜히드라민은 간에서 광범위하게 대사되므로 간장애인에게 투여할 때 주의해야 한다.

항콜린제 사용은 노인들의 [53]인지력 저하와 치매 위험 증가와 관련이 있다.

금지 사항

디펜히드라민은 미숙아와 신생아뿐만 아니라 모유 수유 중인 사람들에게도 금지된다.임신 B급 약입니다.디펜히드라민은 알코올과 다른 CNS 억제제에 첨가 효과가 있습니다.모노아민산화효소억제제는 항히스타민제의 항콜린작용을 연장 및 강화한다.[54]

과다 복용

디펜히드라민은 미국에서 [55]가장 흔하게 오용되는 처방전 없이 살 수 있는 약 중 하나이다.과도한 과다 복용의 경우, 제때 치료하지 않으면 급성 디펜히드라민 중독은 심각하고 잠재적으로 치명적인 결과를 초래할 수 있습니다.과다 복용의 증상은 다음과 같습니다.[56]

급성 중독은 치명적일 수 있으며, 2-18시간 내에 심혈관 붕괴와 사망으로 이어질 수 있으며, 일반적으로 증상 및 지원 접근 [39]방식을 사용하여 치료된다.독성의 진단은 병력과 임상 증상에 기초하며, 일반적으로 특정 수준은 [57]유용하지 않습니다.디펜히드라민(클로페닐라민과 유사)이 지연된 정류 칼륨 채널을 차단하고 그 결과 QT 간격을 연장하여 비틀림 데 포인트와 [58]같은 심장 부정맥을 초래할 수 있다는 증거가 여러 개 있습니다.디펜히드라민 독성에 대한 특정 해독제는 알려져 있지 않지만, 항콜린제 증후군은 심각한 섬망이나 빈맥에 [57]대해 피소스티그민으로 치료되었다.벤조디아제핀은 이러한 [59]증상에 걸리기 쉬운 사람들의 정신 질환, 동요, 발작의 가능성을 감소시키기 위해 투여될 수 있다.

상호 작용

알코올은 디펜히드라민으로 [60][61]인한 졸음을 증가시킬 수 있다.

약리학

약역학

| 위치 | Ki(nM) | 종. | 참조 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | ≥3,800 | 인간 | [63][64] |

| NET | 960–2,400 | 인간 | [63][64] |

| DAT | 1,100–2,200 | 인간 | [63][64] |

| 5-HT2A | 260 | 인간 | [64] |

| 5-HT2C | 780 | 인간 | [64] |

| α1B | 1,300 | 인간 | [64] |

| α2A | 2,900 | 인간 | [64] |

| α2B | 1,600 | 인간 | [64] |

| α2C | 2,100 | 인간 | [64] |

| D2. | 20,000 | 쥐. | [65] |

| H1 | 9.6–16 | 인간 | [66][64] |

| H2 | 100,000 이상 | 개의 | [67] |

| H3 | 10,000 이상 | 인간 | [64][68][69] |

| H4 | 10,000 이상 | 인간 | [69] |

| M1 | 80–100 | 인간 | [70][64] |

| M2 | 120–490 | 인간 | [70][64] |

| M3 | 84–229 | 인간 | [70][64] |

| M4 | 53–112 | 인간 | [70][64] |

| M5 | 30–260 | 인간 | [70][64] |

| VGSC | 48,000–86,000 | 쥐. | [71] |

| hERG | 27,100()IC50 | 인간 | [72] |

| 특별히 명기되어 있지 않는 한 값은 K(nMi)입니다.값이 작을수록 약물이 사이트에 강하게 결합됩니다. | |||

디펜히드라민은 전통적으로 길항제라고 알려져 있지만, 주로 히스타민1 H [73]수용체의 역작용제로 작용한다.항히스타민제의 [39]에탄올아민 등급의 구성원이다.히스타민이 모세혈관에 미치는 영향을 역전시킴으로써 알레르기 증상의 강도를 낮출 수 있다.또한 혈액-뇌 장벽을 통과하여 H 수용체를1 중앙에서 [73]역방향으로 괴롭힌다.중추1 H 수용체에 대한 그것의 영향은 졸음을 유발한다.

다른 많은 1세대 항히스타민제와 마찬가지로 디펜히드라민도 강력한 항무스카린제(무스카린성 아세틸콜린 수용체의 경쟁적 길항제)이며, 따라서 높은 용량에서 항콜린성 [74]증후군을 일으킬 수 있다.디펜히드라민의 항파킨슨제로서의 효용은 뇌의 무스카린성 아세틸콜린 수용체에 대한 디펜히드라민의 차단 특성 때문이다.

디펜히드라민은 또한 국소 [71]마취제로서의 작용을 하는 세포 내 나트륨 채널 차단제 역할을 한다.디펜히드라민은 또한 [75]세로토닌의 재흡수를 억제하는 것으로 나타났다.그것은 [76]쥐에서 모르핀에 의해 유도되지만 내인성 오피오이드에 의해 유도되지 않는 진통제의 잠재력이 있는 것으로 나타났다.또한 히스타민 N-메틸전달효소(HNMT)[77][78]의 억제제 역할을 하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.

| 생물학적 표적 | 동작 모드 | 영향 |

|---|---|---|

| H수용체1 | 역작용제 | 알레르기 감소, 진정 |

| mACh 수용체 | 대항마 | 항콜린제; 항파킨슨 |

| 나트륨 채널 | 블로커 | 국소 마취제 |

약동학

디펜히드라민의 경구 생체 가용성은 40%~60% 범위이며,[2] 투여 후 2~3시간 후에 혈장 최대 농도가 발생한다.

신진대사의 주요 경로는 두 개의 연속적인 3차 아민의 탈메틸화이다.생성된 1차 아민은 카르본산으로 [2]더욱 산화된다.디펜히드라민은 시토크롬 P450 효소 CYP2D6, CYP1A2, CYP2C9 및 CYP2C19에 [6]의해 대사된다.

디펜히드라민의 제거 반감기는 완전히 설명되지 않았지만 건강한 [3]성인의 경우 2.4시간에서 9.3시간 사이인 것으로 보인다.1985년 항히스타민 약물동태학 리뷰에서 디펜히드라민 제거 반감기는 5개 연구에 걸쳐 3.4시간에서 9.3시간 사이였고, 중간 제거 반감기는 4.[2]3시간이었다.이후 1990년 연구에 따르면 디펜히드라민 제거 반감기는 어린이 5.4시간, 청소년 9.2시간,[4] 노인 13.5시간이었다.1998년 한 연구에서는 젊은 남성에서 4.1 ± 0.3시간, 노인 남성에서 7.4 ± 3.0시간, 젊은 여성에서 4.4 ± 0.3시간, 그리고 [79]노인 여성에서 4.9 ± 0.6시간의 반감기를 발견했습니다.2018년 어린이와 청소년을 대상으로 한 연구에서 디펜히드라민의 반감기는 8시간에서 [80]9시간이었다.

화학

디펜히드라민은 디페닐메탄 유도체이다.디펜히드라민의 유사물은 항콜린제인 오르페나드린, 진통제인 네포팜 및 항우울제인 토페나신을 포함한다.

체액 검출

디펜히드라민은 혈액, 혈장 또는 [81]혈청에서 정량화될 수 있다.질량분석(GC-MS)에 의한 가스 크로마토그래피를 스크리닝 테스트로서 풀 스캔 모드로 전자 이온화와 함께 사용할 수 있다.정량화에 [81]GC-MS 또는 GC-NDP를 사용할 수 있습니다.경쟁결합 원리에 기초한 면역측정법을 사용한 신속한 소변 약물 검사는 디펜히드라민을 [82]섭취한 사람에 대해 거짓 양성 메타돈 결과를 나타낼 수 있다.정량화는 치료 모니터링, 입원 중인 사람의 중독 진단 확인, 운전 정지 장애의 증거 제공, 사망 [81]조사 지원 등에 사용될 수 있습니다.

역사

디펜히드라민은 1943년 신시내티 [83][84]대학의 전 교수인 조지 리브슐에 의해 발견되었다.1946년, 그것은 미국 [85]FDA에 의해 승인된 최초의 항히스타민제 처방전이 되었다.

1960년대에 디펜히드라민은 신경전달물질 [75]세로토닌의 재흡수를 약하게 억제하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.이 발견은 구조가 비슷하고 부작용이 적은 생존 가능한 항우울제를 찾는 것으로 이어졌고, 결국 선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 [75][86]억제제인 플루옥세틴(Prozac)의 발명으로 이어졌다.유사한 연구가 이전에 항히스타민제인 [87]브롬페닐라민으로부터 최초의 SSRI인 지멜리딘을 합성하는 것으로 이어졌다.

사회와 문화

디펜히드라민은 잠재적으로 심각한 부작용 프로파일과 제한된 행복 효과 때문에 미국에서 남용 가능성이 제한적인 것으로 간주되며, 통제된 물질이 아니다.2002년부터 미국 FDA는 디펜히드라민이 [88]함유된 여러 제품의 사용에 대해 특별한 라벨 부착 경고를 요구해왔다.일부 관할 구역에서 디펜히드라민은 영아 돌연사를 조사하는 동안 수집된 사후 검체에 종종 존재한다. 이 [89][90]약물은 이러한 사건에서 역할을 할 수 있다.

디펜히드라민은 [91]잠비아 공화국에서 금지되고 통제되는 물질 중 하나이며, 여행객들은 이 약을 국내에 반입하지 말 것을 권고받고 있다.몇몇 미국인들이 베나드릴과 [92]디펜히드라민이 함유된 다른 처방전 없이 살 수 있는 약물을 소지한 혐의로 잠비아 마약 집행위원회에 의해 구금되었다.

레크리에이션용

디펜히드라민이 널리 사용되며 일반적으로 가끔 사용하기에 안전한 것으로 간주되지만, 여러 가지 남용 및 중독 사례가 기록되었습니다.[12]그 약은 값싸고 대부분의 나라에서 처방전 없이 팔리기 때문에, 더 인기 있는 불법 약물에 접근하지 못하는 청소년들은 특히 위험에 처해 [93]있다.정신건강에 문제가 있는 사람들, 특히 정신분열증을 앓고 있는 사람들은 항정신병 [94]약물 사용에 의해 야기된 추체외 증상을 치료하기 위해 다량으로 자가 투여되는 약물을 남용하는 경향이 있다.

레크리에이션 사용자들은 [94][95]진정 효과, 가벼운 행복감, 환각을 약물의 바람직한 효과로 보고한다.연구에 따르면 디펜히드라민을 포함한 항무스카린제는 "항우울제와 기분을 좋게 하는 특성이 있을 수 있다"[96]고 한다.진정제 남용 전력이 있는 성인 남성을 대상으로 수행된 연구는 디펜히드라민을 다량 투여한 실험 대상자들이 집중력 저하, 혼란, 떨림, 그리고 흐릿한 [97]시력과 같은 부정적인 효과에도 불구하고 약을 다시 복용하고 싶다고 보고했다는 것을 발견했다.

2020년에는 인터넷 도전 소셜 미디어 플랫폼 TikTok에 의도적으로 염산염의 형태로 과다와 관련된, 베나 드릴 도전 더빙이 불거져도전 참가자 베나 드릴에 결과적인 정신 치료 효과 영화 촬영 목적으로 과다하게 투여하다. 수 있으며, 여러가지 hospitalisations[98]고 적어도에 연루되어 왔다 필요로 한다.e드ath.[99][100]

이름

디펜히드라민은 미국, 캐나다, 남아프리카 [101]공화국에서 McNeil Consumer Healthcare에 의해 Benadryl이라는 상표명으로 판매된다.다른 나라들의 상호로는 디메드롤, 대달론, 나이톨이 있다.또한 일반 의약품으로도 사용할 수 있습니다.

Procter & Gamble은 ZzQuil이라는 브랜드로 디펜히드라민의 처방전을 판매합니다.2014년 이 제품은 연간 매출 1억2천만 달러 이상을 기록했으며 4억1100만 달러 규모의 수면 보조 장치 시장 [102]카테고리에서 29.3%의 점유율을 기록했습니다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Hubbard, John R.; Martin, Peter R. (2001). Substance Abuse in the Mentally and Physically Disabled. CRC Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780824744977.

- ^ a b c d e Paton DM, Webster DR (1985). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of H1-receptor antagonists (the antihistamines)". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 10 (6): 477–97. doi:10.2165/00003088-198510060-00002. PMID 2866055. S2CID 33541001.

- ^ a b AHFS Drug Information. Published by authority of the Board of Directors of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. 1990.

- ^ a b Simons KJ, Watson WT, Martin TJ, Chen XY, Simons FE (July 1990). "Diphenhydramine: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in elderly adults, young adults, and children". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 30 (7): 665–71. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1990.tb01871.x. PMID 2391399. S2CID 25452263.

- ^ a b Garnett WR (February 1986). "Diphenhydramine". American Pharmacy. NS26 (2): 35–40. doi:10.1016/s0095-9561(16)38634-0. PMID 3962845.

- ^ a b Krystal AD (August 2009). "A compendium of placebo-controlled trials of the risks/benefits of pharmacological treatments for insomnia: the empirical basis for U.S. clinical practice". Sleep Med Rev. 13 (4): 265–74. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2008.08.001. PMID 19153052.

- ^ "Showing Diphenhydramine (DB01075)". DrugBank. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 6 September 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ a b Schroeck JL, Ford J, Conway EL, Kurtzhalts KE, Gee ME, Vollmer KA, Mergenhagen KA (November 2016). "Review of Safety and Efficacy of Sleep Medicines in Older Adults". Clinical Therapeutics. 38 (11): 2340–2372. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.09.010. PMID 27751669.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ Ayd, Frank J. (2000). Lexicon of Psychiatry, Neurology, and the Neurosciences. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-7817-2468-5. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b Thomas A, Nallur DG, Jones N, Deslandes PN (January 2009). "Diphenhydramine abuse and detoxification: a brief review and case report". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 23 (1): 101–5. doi:10.1177/0269881107083809. PMID 18308811. S2CID 45490366.

- ^ Dörwald, Florencio Zaragoza (2013). Lead Optimization for Medicinal Chemists: Pharmacokinetic Properties of Functional Groups and Organic Compounds. John Wiley & Sons. p. 225. ISBN 978-3-527-64565-7. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016.

- ^ "Benadryl". Ohio History Central. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride Monograph". Drugs.com. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

- ^ Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freudenreich O (December 2012). "How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient" (PDF). Current Psychiatary. 11 (12): 10–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2013.

- ^ Smith DW, Peterson MR, DeBerard SC (August 1999). "Local anesthesia. Topical application, local infiltration, and field block". Postgraduate Medicine. 106 (2): 57–60, 64–6. doi:10.3810/pgm.1999.08.650. PMID 10456039.

- ^ a b American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ a b Banerji A, Long AA, Camargo CA (2007). "Diphenhydramine versus nonsedating antihistamines for acute allergic reactions: a literature review". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 28 (4): 418–26. doi:10.2500/aap.2007.28.3015. PMID 17883909. S2CID 7596980.

- ^ Young WF (2011). "Chapter 11: Shock". In Humphries RL, Stone CK (eds.). CURRENT Diagnosis and Treatment Emergency Medicine. LANGE CURRENT Series (Seventh ed.). McGraw–Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-170107-5.

- ^ Sheikh A, ten Broek VM, Brown SG, Simons FE (January 2007). "H1-antihistamines for the treatment of anaphylaxis with and without shock". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD006160. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006160.pub2. PMC 6517288. PMID 17253584.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Topical". MedlinePlus. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Aminoff MJ (2012). "Chapter 28. Pharmacologic Management of Parkinsonism & Other Movement Disorders". In Katzung B, Masters S, Trevor A (eds.). Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (12th ed.). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 483–500. ISBN 978-0-07-176401-8.

- ^ Monson K, Schoenstadt A (8 September 2013). "Benadryl Addiction". eMedTV. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014.

- ^ Dinndorf PA, McCabe MA, Friedrich S (August 1998). "Risk of abuse of diphenhydramine in children and adolescents with chronic illnesses". The Journal of Pediatrics. 133 (2): 293–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70240-9. PMID 9709726.

- ^ Crier, Frequent (2 August 2017). "Is it wrong to drug your children so they sleep on a flight?". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Morris, Regan (3 April 2013). "Should parents drug babies on long flights?". BBC News. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Swanson, Wendy S. (25 November 2009). "If It Were My Child: No Benadryl for the Plane". Seattle Children's. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL (February 2017). "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline". J Clin Sleep Med. 13 (2): 307–349. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6470. PMC 5263087. PMID 27998379.

- ^ Vande Griend JP, Anderson SL (2012). "Histamine-1 receptor antagonism for treatment of insomnia". J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 52 (6): e210–9. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2012.12051. PMID 23229983.

- ^ Perry, Paul J. (2007). Psychotropic Drug Handbook. ISBN 9780781762731.

- ^ Lie JD, Tu KN, Shen DD, Wong BM (November 2015). "Pharmacological Treatment of Insomnia". P T. 40 (11): 759–71. PMC 4634348. PMID 26609210.

- ^ Matheson E, Hainer BL (July 2017). "Insomnia: Pharmacologic Therapy". Am Fam Physician. 96 (1): 29–35. PMID 28671376.

- ^ Lippmann S, Yusufzie K, Nawbary MW, Voronovitch L, Matsenko O (2003). "Problems with sleep: what should the doctor do?". Compr Ther. 29 (1): 18–27. doi:10.1007/s12019-003-0003-x. PMID 12701339. S2CID 1508856.

- ^ Flake ZA, Scalley RD, Bailey AG (March 2004). "Practical selection of antiemetics". American Family Physician. 69 (5): 1169–74. PMID 15023018. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Medical Economics (2000). Physicians' Desk Reference for Nonprescription Drugs and Dietary Supplements, 2000 (21st ed.). Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company. ISBN 978-1-56363-341-6.

- ^ a b c Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollmann B (2011). "Chapter 32. Histamine, Bradykinin, and Their Antagonists". In Brunton L (ed.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12e ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 242–245. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ "High risk medications as specified by NCQA's HEDIS Measure: Use of High Risk Medications in the Elderly" (PDF). National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2010.

- ^ "2012 AGS Beers List" (PDF). The American Geriatrics Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Black RA, Hill DA (June 2003). "Over-the-counter medications in pregnancy". American Family Physician. 67 (12): 2517–24. PMID 12825840.

- ^ Spencer JP, Gonzalez LS, Barnhart DJ (July 2001). "Medications in the breast-feeding mother". American Family Physician. 64 (1): 119–26. PMID 11456429.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine". Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). October 2020. PMID 30000938.

- ^ a b de Leon J, Nikoloff DM (February 2008). "Paradoxical excitation on diphenhydramine may be associated with being a CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizer: three case reports". CNS Spectrums. 13 (2): 133–5. doi:10.1017/s109285290001628x. PMID 18227744. S2CID 10856872.

- ^ 그 이유는 다음과 같습니다American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, archived from the original on 1 September 2013, retrieved 1 August 2013.

- Smith TJ, Ritter JK, Poklis JL, Fletcher D, Coyne PJ, Dodson P, Parker G (May 2012). "ABH gel is not absorbed from the skin of normal volunteers". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 43 (5): 961–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.017. PMID 22560361.

- Weschules DJ (December 2005). "Tolerability of the compound ABHR in hospice patients". Journal of Palliative Medicine. 8 (6): 1135–43. doi:10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1135. PMID 16351526.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. PMID 31643789.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Side Effects". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ Aronson, Jeffrey K. (2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Cardiovascular Drugs. Elsevier. p. 623. ISBN 978-0-08-093289-7.

- ^ Heine A (November 1996). "Diphenhydramine: a forgotten allergen?". Contact Dermatitis. 35 (5): 311–2. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02402.x. PMID 9007386. S2CID 32839996.

- ^ Coskey RJ (February 1983). "Contact dermatitis caused by diphenhydramine hydrochloride". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 8 (2): 204–6. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(83)70024-1. PMID 6219138.

- ^ "Restless Legs Syndrome Fact Sheet National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Salahudeen MS, Duffull SB, Nishtala PS (March 2015). "Anticholinergic burden quantified by anticholinergic risk scales and adverse outcomes in older people: a systematic review". BMC Geriatrics. 15 (31): 31. doi:10.1186/s12877-015-0029-9. PMC 4377853. PMID 25879993.

- ^ Sicari, Vincent; Zabbo, Christopher P. (2021), "Diphenhydramine", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30252266, retrieved 27 December 2021

- ^ Huynh DA, Abbas M, Dabaja A (2021). Diphenhydramine Toxicity. PMID 32491510.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine overdose". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013.

- ^ a b Manning B (2012). "Chapter 18. Antihistamines". In Olson K (ed.). Poisoning & Drug Overdose (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-166833-0. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Khalifa M, Drolet B, Daleau P, Lefez C, Gilbert M, Plante S, O'Hara GE, Gleeton O, Hamelin BA, Turgeon J (February 1999). "Block of potassium currents in guinea pig ventricular myocytes and lengthening of cardiac repolarization in man by the histamine H1 receptor antagonist diphenhydramine". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 288 (2): 858–65. PMID 9918600.

- ^ Cole JB, Stellpflug SJ, Gross EA, Smith SW (December 2011). "Wide complex tachycardia in a pediatric diphenhydramine overdose treated with sodium bicarbonate". Pediatric Emergency Care. 27 (12): 1175–7. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823b0e47. PMID 22158278. S2CID 5602304.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine and Alcohol / Food Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ Zimatkin SM, Anichtchik OV (1999). "Alcohol-histamine interactions". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 34 (2): 141–7. doi:10.1093/alcalc/34.2.141. PMID 10344773.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (December 1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". European Journal of Pharmacology. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Krystal AD, Richelson E, Roth T (August 2013). "Review of the histamine system and the clinical effects of H1 antagonists: basis for a new model for understanding the effects of insomnia medications". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 17 (4): 263–72. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2012.08.001. PMID 23357028.

- ^ Tsuchihashi H, Sasaki T, Kojima S, Nagatomo T (1992). "Binding of [3H]haloperidol to dopamine D2 receptors in the rat striatum". J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 44 (11): 911–4. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1992.tb03235.x. PMID 1361536. S2CID 19420332.

- ^ Ghoneim OM, Legere JA, Golbraikh A, Tropsha A, Booth RG (October 2006). "Novel ligands for the human histamine H1 receptor: synthesis, pharmacology, and comparative molecular field analysis studies of 2-dimethylamino-5-(6)-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalenes". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (19): 6640–58. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.05.077. PMID 16782354.

- ^ Gantz I, Schäffer M, DelValle J, Logsdon C, Campbell V, Uhler M, Yamada T (1991). "Molecular cloning of a gene encoding the histamine H2 receptor". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 (2): 429–33. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88..429G. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.2.429. PMC 50824. PMID 1703298.

- ^ Lovenberg TW, Roland BL, Wilson SJ, Jiang X, Pyati J, Huvar A, Jackson MR, Erlander MG (June 1999). "Cloning and functional expression of the human histamine H3 receptor". Molecular Pharmacology. 55 (6): 1101–7. doi:10.1124/mol.55.6.1101. PMID 10347254.

- ^ a b Liu C, Ma X, Jiang X, Wilson SJ, Hofstra CL, Blevitt J, Pyati J, Li X, Chai W, Carruthers N, Lovenberg TW (March 2001). "Cloning and pharmacological characterization of a fourth histamine receptor (H(4)) expressed in bone marrow". Molecular Pharmacology. 59 (3): 420–6. doi:10.1124/mol.59.3.420. PMID 11179434.

- ^ a b c d e Bolden C, Cusack B, Richelson E (February 1992). "Antagonism by antimuscarinic and neuroleptic compounds at the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 260 (2): 576–80. PMID 1346637.

- ^ a b Kim YS, Shin YK, Lee C, Song J (October 2000). "Block of sodium currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons by diphenhydramine". Brain Research. 881 (2): 190–8. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02860-2. PMID 11036158. S2CID 18560451.

- ^ Suessbrich H, Waldegger S, Lang F, Busch AE (April 1996). "Blockade of HERG channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes by the histamine receptor antagonists terfenadine and astemizole". FEBS Letters. 385 (1–2): 77–80. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00355-9. PMID 8641472. S2CID 40355762.

- ^ a b Khilnani G, Khilnani AK (September 2011). "Inverse agonism and its therapeutic significance". Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 43 (5): 492–501. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.84947. PMC 3195115. PMID 22021988.

- ^ Lopez AM (10 May 2010). "Antihistamine Toxicity". Medscape Reference. WebMD LLC. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Domino EF (1999). "History of modern psychopharmacology: a personal view with an emphasis on antidepressants". Psychosomatic Medicine. 61 (5): 591–8. doi:10.1097/00006842-199909000-00002. PMID 10511010.

- ^ Carr KD, Hiller JM, Simon EJ (February 1985). "Diphenhydramine potentiates narcotic but not endogenous opioid analgesia". Neuropeptides. 5 (4–6): 411–4. doi:10.1016/0143-4179(85)90041-1. PMID 2860599. S2CID 45054719.

- ^ Horton JR, Sawada K, Nishibori M, Cheng X (October 2005). "Structural basis for inhibition of histamine N-methyltransferase by diverse drugs". Journal of Molecular Biology. 353 (2): 334–344. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.040. PMC 4021489. PMID 16168438.

- ^ Taylor KM, Snyder SH (May 1972). "Histamine methyltransferase: inhibition and potentiation by antihistamines". Molecular Pharmacology. 8 (3): 300–10. PMID 4402747.

- ^ Scavone JM, Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, Engelhardt N, Shader RI (July 1998). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of diphenhydramine 25 mg in young and elderly volunteers". J Clin Pharmacol. 38 (7): 603–9. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04466.x. PMID 9702844. S2CID 24989721.

- ^ Gelotte CK, Zimmerman BA, Thompson GA (May 2018). "Single-Dose Pharmacokinetic Study of Diphenhydramine HCl in Children and Adolescents". Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 7 (4): 400–407. doi:10.1002/cpdd.391. PMC 5947143. PMID 28967696.

- ^ a b c Pragst F (2007). "Chapter 13: High performance liquid chromatography in forensic toxicological analysis". In Smith RK, Bogusz MJ (eds.). Forensic Science (Handbook of Analytical Separations). Vol. 6 (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. p. 471. ISBN 978-0-444-52214-6.

- ^ Rogers SC, Pruitt CW, Crouch DJ, Caravati EM (September 2010). "Rapid urine drug screens: diphenhydramine and methadone cross-reactivity". Pediatric Emergency Care. 26 (9): 665–6. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181f05443. PMID 20838187. S2CID 31581678.

- ^ Hevesi D (29 September 2007). "George Rieveschl, 91, Allergy Reliever, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 December 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ^ "Benadryl". Ohio History Central. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Ritchie J (24 September 2007). "UC prof, Benadryl inventor dies". Business Courier of Cincinnati. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ^ Awdishn RA, Whitmill M, Coba V, Killu K (October 2008). "Serotonin reuptake inhibition by diphenhydramine and concomitant linezolid use can result in serotonin syndrome". Chest. 134 (4 Meeting abstracts): 4C. doi:10.1378/chest.134.4_MeetingAbstracts.c4002.

- ^ Barondes SH (2003). Better Than Prozac. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-19-515130-5.

- ^ Food and Drug Administration, HHS (December 2002). "Labeling of diphenhydramine-containing drug products for over-the-counter human use. Final rule". Federal Register. 67 (235): 72555–9. PMID 12474879. Archived from the original on 5 November 2008.

- ^ Marinetti L, Lehman L, Casto B, Harshbarger K, Kubiczek P, Davis J (October 2005). "Over-the-counter cold medications-postmortem findings in infants and the relationship to cause of death". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 29 (7): 738–43. doi:10.1093/jat/29.7.738. PMID 16419411.

- ^ Baselt RC (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Biomedical Publications. pp. 489–492. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ^ "List of prohibited and controlled drugs according to chapter 96 of the laws of Zambia". The Drug Enforcement Commission ZAMBIA. Archived from the original (DOC) on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ "Zambia". Country Information > Zambia. Bureau of Consular Affairs, U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Forest E (27 July 2008). "Atypical Drugs of Abuse". Articles & Interviews. Student Doctor Network. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013.

- ^ a b Halpert AG, Olmstead MC, Beninger RJ (January 2002). "Mechanisms and abuse liability of the anti-histamine dimenhydrinate" (PDF). Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 26 (1): 61–7. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00038-0. PMID 11835984. S2CID 46619422.

- ^ Gracious B, Abe N, Sundberg J (December 2010). "The importance of taking a history of over-the-counter medication use: a brief review and case illustration of "PRN" antihistamine dependence in a hospitalized adolescent". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 20 (6): 521–4. doi:10.1089/cap.2010.0031. PMC 3025184. PMID 21186972.

- ^ Dilsaver SC (February 1988). "Antimuscarinic agents as substances of abuse: a review". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 8 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1097/00004714-198802000-00003. PMID 3280616. S2CID 31355546.

- ^ Mumford GK, Silverman K, Griffiths RR (1996). "Reinforcing, subjective, and performance effects of lorazepam and diphenhydramine in humans". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 4 (4): 421–430. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.4.4.421.

- ^ "TikTok Videos Encourage Viewers to Overdose on Benadryl". TikTok Videos Encourage Viewers to Overdose on Benadryl. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Dangerous 'Benadryl Challenge' on Tik Tok may be to blame for the death of Oklahoma teen". KFOR.com Oklahoma City. 28 August 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Teen's Death Prompts Warning on 'Benadryl Challenge'". www.medpagetoday.com. 25 September 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Childrens Benadryl ALLERGY (solution) Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc., McNeil Consumer Healthcare Division". Drugs.com. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Is P&G Preparing to Expand ZzzQuil?". Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

추가 정보

- Björnsdóttir I, Einarson TR, Gudmundsson LS, Einarsdóttir RA (December 2007). "Efficacy of diphenhydramine against cough in humans: a review". Pharmacy World & Science. 29 (6): 577–83. doi:10.1007/s11096-007-9122-2. PMID 17486423. S2CID 8168920.

- Cox D, Ahmed Z, McBride AJ (March 2001). "Diphenhydramine dependence". Addiction. 96 (3): 516–7. PMID 11310441.

- Lieberman JA (2003). "History of the use of antidepressants in primary care" (PDF). Primary Care Companion J. Clinical Psychiatry. 5 (supplement 7): 6–10.

외부 링크

- "Diphenhydramine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.