파라세타몰

Paracetamol | |

| |

| 임상 데이터 | |

|---|---|

| 발음 | 파라세타몰: /ˌpərˈsiːtəmɒl/ 아세트아미노펜: /əˌsːsiətˈmɪnəfɪn/ |

| 상호 | 타이레놀, 파나돌[1] 등 |

| 기타 이름 | N-아세틸-파라-아미노페놀(APAP), 아세트아미노펜(USAN) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| 메드라인플러스 | a681004 |

| 라이센스 데이터 | |

| 임신 카테고리 |

|

| 경로: 행정부. | 구강(입으로), 직장, 정맥(IV) |

| 약물류 | 진통제와 해열제 |

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적 지위 | |

| 법적 지위 | |

| 약동학 데이터 | |

| 생물학적 가용성 | 63–89%[4]: 73 |

| 단백질 결합 | 과다 복용 시 10-25[5]%까지 무시할 수 있는 |

| 신진대사 | 주로 간에서[8] |

| 대사물 | APAP 글루코스, APAP 황산염, APAP GSH, APAP cys, AM404, NAPQI[6] |

| 작용 개시 | 경로별 통증 완화 시작: 구두 – 37분[7] 정맥 주사 – 8분[7] |

| 제거 반감기 | 1.9~2.5시간[5] |

| 배설물 | 소변[5] |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| 펍켐 CID | |

| 펍켐 | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드러그 뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니 | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| CHEMBL | |

| PDB 리간드 | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA) | |

| ECHA 인포카드 | 100.002.870 |

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |

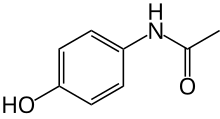

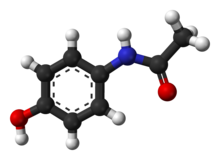

| 공식 | C8H9NO2 |

| 몰 질량 | 151.185 g·mol−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| 밀도 | 1.263g/cm3 |

| 녹는점 | 169°C(336°F) |

| 물에 대한 용해도 | |

| |

| |

| (계속) | |

파라세타몰 (아세트아미노펜[a] 또는 파라-하이드록시아세타닐라이드)은 발열 및 경미한 통증을 치료하는 [12][13][14]데 사용되는 비오피오이드 진통제 및 해열제입니다.처방전 없이 널리 사용되며 일반적인 상표명으로는 타이레놀, 파나돌 등이 있습니다.

표준 용량에서 파라세타몰은 체온을 [13][15][16]약간만 낮춥니다. 그런 [17]점에서 파라세타몰은 이부프로펜보다 낮으며, 발열에 사용하는 이점은 [13][18][19]분명하지 않습니다.파라세타몰은 급성 가벼운 편두통의 통증을 완화시킬 수 있지만 간헐적인 긴장성 [20][21]두통에서는 약간만 완화시킬 수 있습니다.그러나 아스피린/파라세타몰/카페인 조합은 통증이 가벼운 두 가지 조건 모두에 도움이 되며,[22][23] 이들에게 첫 번째 치료법으로 권장됩니다.파라세타몰은 수술 후 통증에는 효과적이지만, 이부프로펜보다 [24]약합니다.파라세타몰/이부프로펜 조합은 효력을 더욱 증가시키며 [24][25]두 약물 단독보다 우수합니다.골관절염에서 제공되는 통증 완화 파라세타몰은 작고 임상적으로 [14][26][27]중요하지 않습니다.요통, 암통, 신경성 통증에 사용하는 것에 대한 찬성하는 [14][28][26][29][30][31]증거는 불충분합니다.

단기적으로 파라세타몰은 [32]지시에 따라 사용할 때 안전하고 효과적입니다.단기 부작용은 드물고 이부프로펜과 [33]유사하지만, 파라세타몰은 일반적으로 비스테로이드 항염증제(NSAID)보다 [34]안전합니다.파라세타몰은 또한 이부프로펜과 [35][36]같은 NSAID를 견딜 수 없는 환자들에게도 종종 사용됩니다.파라세타몰을 만성적으로 섭취하면 헤모글로빈 수치가 저하되어 위장 [37]출혈 가능성이 있으며 간 기능 검사에 이상이 있을 수 있습니다.일부 역학 연구는 파라세타몰을 심혈관, 신장 및 위장 질환과 연관시켰지만, 주로 교란된 편견과 파라세타몰의 [38][39][37][36][40]단기 사용과 관련이 거의 없습니다.파라세타몰은 하루에 [41][42]4그램의 용량으로 고혈압 환자의 수축기 혈압을 약간 증가시킬 수 있습니다.파라세타몰이 이러한 증가의 진정한 원인인지 [41]여부는 불분명하지만, 천식의 빈도 증가와 발달 및 생식 장애는 임신 중 파라세타몰을 장기간 사용하는 여성의 자손에서 관찰됩니다.어떤 연구들은 임신 중의 파라세타몰과 자폐 스펙트럼 장애와 주의력 결핍 과잉 행동 장애 사이의 연관성에 대한 증거가 있다고 제안하지만, 인과 관계를 [43][44]확립하기 위해서는 더 많은 연구가 필요합니다.이것은 임신 중에 그것의 사용을 가능한 한 짧은 [41][45][46]시간 동안 가장 낮은 효과적인 복용량으로 제한하라는 일부 요구를 촉발시켰습니다.

성인에게 권장되는 하루 최대 복용량은 3그램에서 [47][48][26]4그램입니다.높은 용량은 [49]간부전을 포함한 독성을 유발할 수 있습니다.파라세타몰 중독은 서구 세계에서 급성 간부전의 주요 원인이며, 미국, 영국, 호주,[50][51][52] 뉴질랜드에서 약물 과다복용의 대부분을 차지합니다.

파라세타몰은 1878년 하몬 노스롭 모스에 의해 처음 만들어졌으며 아마도 1852년 찰스 프레데릭 게르하르트에 [53][54][55]의해 만들어졌을 것입니다.그것은 미국과 [56]유럽 모두에서 통증과 발열에 가장 흔하게 사용되는 약으로 사용됩니다.그것은 세계보건기구의 필수 [57]의약품 목록에 올라 있습니다.파라세타몰은 타이레놀, 파나돌 등의 [58]상표명을 포함한 제네릭 의약품으로 제공됩니다.2020년, 500만 건 이상의 [59][60]처방과 함께 미국에서 118번째로 가장 많이 처방된 약물이었습니다.

어원

"[61]아세트아미노펜"이라는 단어는 N-아세틸아미노페놀의 단축형이며 1955년 맥닐 연구소에 의해 처음으로 만들어졌습니다.

"paracetamol"[62]이라는 단어는 para-acetyl-amino-phenol의 단축형이며 1956년 [63]프레더릭 스턴즈 & Co에 의해 만들어지고 제조되고 판매되었습니다.

의료 용도

열.

파라세타몰은 열을 내리는 데 선택되는 약입니다.하지만, 특히 [13]성인의 해열 특성에 대한 연구가 부족했습니다.일반 관행에서 파라세타몰과 발열 관리에 대한 가장 최근의 리뷰(2008)는 그 이점이 [13]불분명하다고 주장했습니다.게다가, 일반적인 감기에 사용될 때, 파라세타몰은 코막힘이나 콧물을 완화시킬 수 있지만, 인후염, 메스꺼움, 재채기 또는 기침과 같은 다른 감기 증상은 아닙니다. 하지만, 이러한 데이터는 [64]질이 좋지 않습니다.

중환자 치료를 받는 환자의 경우 파라세타몰은 대조군 개입보다 체온을 0.2–0.3°C만 더 낮췄습니다.[15] 사망률에는 차이가 없었습니다.그것은 [65]뇌졸중을 가진 열성 환자들의 결과를 바꾸지 않았습니다.패혈증에서 파라세타몰 사용에 대한 결과는 모순됩니다. 더 높은 사망률, 더 낮은 사망률, 그리고 사망률의 변화가 [15]모두 보고되었습니다.파라세타몰은 뎅기열 치료에 아무런 이점을 제공하지 않았고 잠재적인 간 [66]손상의 징후인 간 효소 상승률이 더 높았습니다.전반적으로,[19] 입원 환자에게 파라세타몰을 포함한 해열제를 정기적으로 투여하는 것은 지원되지 않습니다.

열이 있는 아이들에게 파라세타몰의 효과는 [67]명확하지 않습니다.파라세타몰은 체온을 낮추는 목적으로만 사용되어서는 안 되지만,[68] 고통스러워하는 것처럼 보이는 열이 있는 아이들에게는 고려될 수 있습니다.발열성 발작을 예방하지 않으며, 그 [68][69]목적으로 사용해서는 안 됩니다.파라세타몰을 표준 용량으로 복용한 후 어린이의 체온이 0.2°C 감소하는 것은 특히 응급 [13]상황에서 의심스러운 가치가 있는 것으로 보입니다.이것에 근거하여, 일부 의사들은 온도를 0.7°[16]C까지 낮출 수 있는 더 높은 선량을 사용하는 것을 지지합니다.메타 분석에 따르면 파라세타몰은 [71]2세 미만의 어린이를 포함한 어린이에서 이부프로펜보다 효과가 덜하며(다른[70] 분석에 따르면 약간 덜 효과적이며) 동등한 [17]안전성을 가지고 있습니다.천식의 악화는 두 [72]약물 모두 비슷한 빈도로 발생합니다.파라세타몰과 이부프로펜을 5세 미만의 어린이에게 동시에 투여하는 것은 권장되지 않지만,[68] 필요한 경우 용량을 번갈아 투여할 수 있습니다.

고통

파라세타몰은 감기, 독감, 염좌,[73] 월경곤란 등으로 인한 통증뿐만 아니라 두통, 근육통, 경미한 관절염 통증, 치통과 같은 가벼운 통증에서 중간 정도의 통증을 완화하는 데 사용됩니다.특히 만성 통증의 치료에 대한 증거가 [14]불충분하기 때문에 급성 경도에서 중등도의 통증에 권장됩니다.

근골격통

골관절염과 요통과 같은 근골격계 질환에서 파라세타몰의 이점은 [14]불확실합니다.

그것은 [14][26]골관절염에서 임상적으로 중요하지 않은 작은 이점만을 제공하는 것으로 보입니다.골관절염의 관리를 위한 미국 류마티스 관절염 대학 재단의 지침은 파라세타몰의 임상 시험에서의 효과 크기가 매우 작았다고 지적하며, 이는 대부분의 개인에게 효과가 [27]없음을 시사합니다.가이드라인은 비스테로이드 항염증제를 용인하지 않는 사람들에게 단기 및 일시적인 사용을 조건부로 권장합니다.정기적으로 복용하는 사람들에게는 간 독성에 대한 [27]모니터링이 필요합니다.근본적으로 손 [74]골관절염에 대해서는 EURA에서 동일한 권고가 발표되었습니다.마찬가지로 무릎 골관절염 치료를 위한 유럽 알고리즘 ES CEO는 파라세타몰의 사용을 단기 구조 진통제로만 [75]제한할 것을 권장합니다.

파라세타몰은 급성 요통에 [14][28]효과가 없습니다.무작위 임상 실험은 만성 또는 근골격 요통에 대한 사용을 평가하지 않았으며, 파라세타몰에 대한 찬성 증거는 [26][29][28]부족합니다.

두통

파라세타몰은 급성 [20]편두통에 효과적입니다. 대조군의 [76]20%에 비해 39%의 사람들이 한 시간에 통증 완화를 경험합니다.아스피린/파라세타몰/카페인 조합 또한 "효과의 강력한 증거를 가지고 있으며 [22]편두통에 대한 첫 번째 치료법으로 사용될 수 있습니다."파라세타몰은 그 자체로 그것들을 [21]자주 가지고 있는 사람들의 발작적인 긴장 두통을 약간 완화시킬 뿐입니다.그러나 아스피린/파라세타몰/카페인 조합은 파라세타몰 단독 및 위약 모두보다 [77]우수하고 긴장 두통의 의미 있는 완화를 제공합니다. 약물을 투여한 지 2시간 후에 파라세타몰 21%, 위약 18%와 비교하여 29%가 통증이 없었습니다.독일, 오스트리아, 스위스의 두통 학회와 독일 신경학회는 이 조합을 긴장성 두통의 자가 치료를 위한 "강조된" 조합으로 추천하며, 파라세타몰/카페인 조합은 "첫 번째 선택의 치료제"이고, 파라세타몰은 "두 [23]번째 선택의 치료제"입니다.

치과 및 기타 수술 후 통증

치과 수술 후의 통증은 다른 종류의 급성 [78]통증에 대한 진통 작용에 대한 신뢰할 수 있는 모델을 제공합니다.이러한 통증의 완화를 위해, 파라세타몰은 [24]이부프로펜보다 낮습니다.비스테로이드성 항염증제(NSAIDs) 이부프로펜, 나프록센 또는 디클로페낙의 전체 치료 용량은 치과 [79]통증에 대해 자주 처방되는 파라세타몰/코데인 조합보다 분명히 더 효과적입니다.파라세타몰과 NSAID 시부프로펜 또는 디클로페낙의 조합은 유망하며, 파라세타몰 또는 NSAID [24][25][80][81]단독보다 더 나은 통증 제어를 제공할 수 있습니다.또한, 파라세타몰/이부프로펜 조합은 파라세타몰/코데인 및 이부프로펜/[25]코데인 조합보다 우수할 수 있습니다.

치과 및 기타 수술을 포함한 일반적인 수술 후 통증의 메타 분석은 파라세타몰/코데인 조합이 파라세타몰 단독보다 더 효과적임을 보여주었습니다. 참가자의 53%에게 상당한 통증 완화를 제공한 반면 위약은 7%[82]만 도움을 주었습니다.

기타통증

파라세타몰은 신생아의 [83][84]절차상 고통을 완화시키는 데 실패합니다.회음부 통증의 경우 산후 파라세타몰은 비스테로이드 항염증제(NSAIDs)[85]보다 덜 효과적인 것으로 보입니다.

파라세타몰을 암 통증과 신경병적 통증에 사용하는 것을 지지하거나 반박하는 연구는 [30][31]부족합니다.응급실에서 [86]급성 통증 조절을 위해 파라세타몰 정맥 주사를 사용하는 것을 지지하는 증거는 제한적입니다.급성 [87]통증의 치료에는 파라세타몰과 카페인의 조합이 파라세타몰 단독보다 우수합니다.

특허관 동맥류

파라세타몰은 특허관 동맥류에서 도관 폐쇄를 돕습니다.이것은 이부프로펜이나 인도메타신만큼 효과적이지만,[88] 이부프로펜보다 위장관 출혈의 빈도가 적습니다.그러나 극도로 낮은 출생 체중과 임신 연령의 유아에게 그것을 사용하는 것은 [88]더 많은 연구가 필요합니다.

부작용

메스꺼움과 복통 같은 위장 부작용이 흔하며, 그 빈도는 [36]이부프로펜과 비슷합니다.위험을 감수하는 행동이 증가할 [89]수 있습니다.미국 식품의약국에 따르면, 이 약은 스티븐스와 같은 희귀하고 치명적인 피부 반응을 일으킬 수 있습니다.Johnson 증후군과 독성 표피 [90]괴사증은 프랑스 약물 감시 데이터베이스의 분석에서 이러한 [91]반응의 명백한 위험성을 나타내지 않았습니다.

골관절염에 대한 임상시험에서 부작용을 보고한 참가자의 수는 파라세타몰과 플라시보를 복용한 참가자와 유사했습니다.그러나, 이 효과의 임상적 중요성은 [39]불확실하지만, 비정상적인 간 기능 검사(간에 약간의 염증이나 손상이 있었다는 것을 의미)는 파라세타몰을 복용한 사람들에게서 거의 4배 이상의 가능성이 있었습니다.무릎 통증에 대한 파라세타몰 치료 13주 후, 참가자의 20%에서 위장관 출혈을 나타내는 헤모글로빈 수치의 감소가 관찰되었으며, 이 비율은 이부프로펜 [37]그룹과 유사했습니다.

통제된 연구의 부재로 인해 파라세타몰의 장기적인 안전성에 대한 대부분의 정보는 [36]관찰 연구에서 나옵니다.이는 파라세타몰 [37][36][40]용량이 증가함에 따라 심혈관(뇌졸중, 심근경색), 위장(궤양, 출혈) 및 신장 부작용뿐만 아니라 사망률이 증가하는 일관된 패턴을 나타냅니다.파라세타몰의 사용은 소화성 [36]궤양의 위험이 1.9배 높은 것과 관련이 있습니다.고용량(하루에 2-3g 이상)으로 정기적으로 복용하는 사람들은 위장 출혈 [41]및 기타 출혈의 위험이 훨씬 높습니다.메타 분석에 따르면 파라세타몰은 신장 손상 위험을 23%,[92] 신장암 위험을 28%[40] 증가시킬 수 있습니다.파라세타몰은 특히 과다복용으로 간에 위험하지만, 이 약물을 과다복용하지 않더라도 비스테로이드성 [35]항염증제 사용자보다 간 이식이 더 자주 필요한 급성 간부전이 발생할 수 있습니다.파라세타몰은 혈압과 [36]심박수를 약간이지만 상당히 증가시킵니다.대부분의 관찰 연구는 만성적으로 사용될 경우, 예상되는 무작위 확인 [42]실험에서 확인된 바와 같이 고혈압 발병 위험을 증가시킬 수 있음을 시사합니다.투여량이 많을수록 위험이 높아집니다.[41]

소아에서 파라세타몰 사용과 천식 사이의 연관성은 [93]논란의 여지가 있습니다.하지만, 가장 최근의 연구는 [94]연관성이 없으며, 파라세타몰 이후 아이들의 천식 악화의 빈도는 자주 사용되는 또 다른 진통제 이부프로펜 [72]이후와 같다는 것을 시사합니다.

임신 중 사용

임신 중 파라세타몰 안전성에 대한 조사가 강화되었습니다.임신 초기 파라세타몰 사용과 부정적인 임신 결과 또는 선천적 결함 사이에는 연관성이 없는 것으로 보입니다.그러나 임신 [41]중 파라세타몰을 장기간 사용하는 여성의 자손에서 천식과 발달 및 생식 장애의 가능성에 대한 징후가 존재합니다.

임신 중에 산모가 파라세타몰을 사용하는 것은 소아 [95][96]천식의 위험 증가와 관련이 있지만 파라세타몰을 사용할 수 있는 모성 감염도 관련이 있으며, 이러한 영향을 분리하는 [41]것은 어렵습니다.파라세타몰(Paracetamol)은 소규모 메타분석에서 자폐 스펙트럼 장애, 주의력 결핍 과잉행동 장애, 과잉행동 증상 및 행동 장애의 20-30% 증가와 관련이 있었으며, 더 큰 인구통계학적 자료를 사용한 메타분석에서는 연관성이 더 낮았습니다.그러나 이것이 인과관계인지 여부는 불분명하며 [41][97][98]결과에 잠재적인 편향이 있었습니다.연구의 많은 수, 일관성, 그리고 견고한 설계가 이러한 신경 발달 [43][44]장애의 위험을 증가시키는 파라세타몰을 선호하는 강력한 증거를 제공한다는 주장도 있습니다.동물 실험에서 파라세타몰은 태아의 테스토스테론 생산을 방해하고, 몇몇 역학 연구는 크립토르키드증과 산모의 파라세타몰 사용을 2주 이상 연관시켰습니다.반면에, 몇몇 연구들은 [41]어떤 연관성도 발견하지 못했습니다.

합의된 권고 사항은 임신 중 파라세타몰의 장기간 사용을 피하고 필요할 때, 가장 낮은 유효 용량과 가장 짧은 [41][45][46]시간 동안만 사용하는 것으로 보입니다.

과다 복용

파라세타몰의 과다복용, 즉 3~[47][48]4그램의 건강한 성인에게 권장되는 파라세타몰의 일일 최대 권장량 이상을 복용하면 잠재적으로 치명적인 간 [99][100]손상을 일으킬 수 있습니다.성인의 과다복용의 대다수가 자살 시도와 관련이 있지만, 많은 경우는 종종 파라세타몰 함유 제품을 [101]장기간에 걸쳐 사용하기 때문에 우발적입니다.

파라세타몰 독성은 서구 세계에서 급성 간부전의 주요 원인이며, 미국, 영국, 호주,[50][102][51][52] 뉴질랜드에서 약물 과다복용의 대부분을 차지합니다.파라세타몰 과다복용은 다른 약리학적 [103]물질의 과다복용보다 미국의 독극물 통제 센터에 더 많은 호출을 초래합니다.FDA에 따르면, 미국에서는 1990년대 동안 "56,000명의 응급실 방문, 26,000명의 입원, 458명의 사망이 아세트아미노펜과 관련된 과다 복용과 관련이 있습니다.이러한 추정치 내에서 의도하지 않은 아세트아미노펜 과다복용은 응급실 방문의 거의 25%, 입원의 10%, [104]사망의 25%를 차지했습니다."

과다복용은 종종 처방 오피오이드의 고용량 레크리에이션 사용과 관련이 있는데, 이 오피오이드는 파라세타몰과 가장 [105]자주 결합되기 때문입니다.알코올을 [106]자주 섭취하면 과다복용 위험이 높아질 수 있습니다.

치료되지 않은 파라세타몰 과다복용은 길고 고통스러운 질병을 초래합니다.파라세타몰 독성의 징후와 증상은 처음에는 없거나 특이적인 증상일 수 있습니다.과다복용의 첫 증상은 일반적으로 섭취 후 몇 시간 후에 시작되며, 급성 간부전이 [107]시작되면서 메스꺼움, 구토, 땀, 통증이 동반됩니다.파라세타몰을 과다 복용한 사람들은 잠들거나 의식을 잃지 않지만 파라세타몰로 자살을 시도하는 대부분의 사람들은 그들이 [108][109]약물에 의해 의식을 잃게 될 것이라고 잘못 믿고 있습니다.

치료는 몸에서 파라세타몰을 제거하고 글루타티온을 [109]보충하는 것을 목표로 합니다.활성탄은 과다복용 후 즉시 병원에 오면 파라세타몰의 흡수를 줄이기 위해 사용될 수 있습니다.해독제인 아세틸시스테인 (N-acetylcysteine 또는 NAC라고도 함)이 글루타티온의 전구체 역할을 하는 동안, 신체가 가능한 간의 손상을 예방하거나 적어도 감소시킬 수 있을 만큼 충분히 재생을 돕습니다; 간의 손상이 심각해지면 종종 [50][110]간 이식이 필요합니다.NAC는 일반적으로 치료 노모그램(위험 요인이 있는 사람들을 위한 것, 그렇지 않은 사람들을 위한 것) 다음에 제공되었지만, 노모그램의 사용은 더 이상 위험 요인의 사용을 뒷받침하는 증거로 권장되지 않습니다.그리고 많은 위험 요소들은 부정확하고 임상 [111][112]실습에서 충분한 확실성으로 결정하기 어렵습니다.파라세타몰의 독성은 퀴논 대사물 NAPQI에 기인하며 NAC는 [109]또한 파라세타몰을 중화시키는데 도움을 줍니다.신부전은 또한 가능한 [106]부작용입니다.

상호 작용

메토클로프라미드와 같은 프로키네틱제는 위 배출을 가속화하고, 파라세타몰 피크 혈장 농도(Cmax)까지 시간(tmax)을 단축하고, C를 증가시킵니다max.프로판테라인과 모르핀과 같은 위 배출을 늦추는 약물은 [113][114]C를 연장하고max 감소시킵니다max.모르핀과의 상호작용은 환자가 파라세타몰의 치료적 농도를 달성하지 못하는 결과를 초래할 수 있습니다. 메토클로프라미드 및 프로판테인과의 상호작용의 임상적 중요성은 불분명합니다.[114]

사이토크롬 유도체가 NAPQI에 대한 파라세타몰 대사의 독성 경로를 향상시킬 수 있다는 의혹이 제기되었습니다(파라세타몰 #파르마코키네틱스 참조).대체로 이러한 의혹들은 [114]확인되지 않았습니다.연구된 유도체 중 파라세타몰 과다복용에서 잠재적으로 간 독성이 증가했다는 증거는 페노바르비탈, 프리미돈, 이소니아지드, 그리고 아마도 성 요한의 [115]가치에 대해 존재합니다.반면 결핵 치료제 이소니아지드는 NAPQI의 형성을 70%[114]까지 감소시킵니다.

라니티딘은 곡선 아래 파라세타몰 면적을 1.6배 증가시켰습니다.AUC 증가는 니자티딘 및 시사프라이드에서도 관찰됩니다.그 효과는 파라세타몰의 [114]글루쿠론화를 억제하는 이 약물들에 의해 설명됩니다.

파라세타몰은 에티닐에스트라디올의 [114]황화를 억제하여 혈장 농도를 22%까지 높입니다.파라세타몰은 와파린 치료 중 INR을 증가시키므로 일주일에 [116][117][118]2g 이하로 제한해야 합니다.

약리학

약역학

파라세타몰은 사이클로옥시제네이스의 억제와 그 대사물인 N-아라키도노일페놀아민(AM404)[119]의 작용이라는 두 가지 메커니즘을 통해 그 효과를 발휘하는 것으로 보입니다.

첫 번째 메커니즘을 약리학적으로 그리고 그 부작용에서 지원하는 파라세타몰은 COX-1 및 COX-2 효소를 억제함으로써 작용하는 고전적인 비스테로이드 항염증제(NSAID)에 가깝고 특히 선택적인 COX-2 [120]억제제와 유사합니다.파라세타몰은 COX-1 및 COX-2 효소의 활성 형태를 감소시킴으로써 프로스타글란딘 합성을 억제합니다.이것은 아라키돈산과 과산화물의 농도가 낮을 때만 발생합니다.이러한 조건에서, COX-2는 파라세타몰의 명백한 COX-2 선택성을 설명하는 사이클로옥시제네이스의 지배적인 형태입니다.염증 상태에서는 과산화물의 농도가 높아 파라세타몰의 감소 효과를 상쇄합니다.따라서 파라세타몰의 항염증 작용은 [119][120]미미합니다.(COX 억제를 통한) 파라세타몰의 항염증 작용은 또한 위출혈과 같은 기존의 NSAID와 관련된 부작용의 부족을 설명하면서, 주로 신체의 말초 영역이 아닌 중추 신경계를 목표로 하는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.

두 번째 메커니즘은 파라세타몰 대사산물 AM404에 중심을 둡니다.이 대사산물은 파라세타몰을 [119][121]복용하는 사람의 뇌척수액과 동물의 뇌에서 검출되었습니다.분명히, 그것은 지방산 아미드 [119]가수분해효소의 작용에 의해 다른 파라세타몰 대사물 4-아미노페놀로부터 뇌에서 형성됩니다.AM404는 칸나비노이드 수용체 CB1 및 CB2의 약한 작용제, 엔도카나비노이드 수송체의 억제제 및 TRPV1 [119]수용체의 강력한 활성화제입니다.이것과 다른 연구는 칸나비노이드 시스템과 TRPV1이 파라세타몰의 [119][122]진통 효과에 중요한 역할을 할 수 있음을 나타냅니다.

2018년에 Suemaru 등은 쥐에서 파라세타몰이 TRPV1 수용체의[123] 활성화에 의해 항경련 효과를 발휘하고 [124]뉴런의 과분극에 의해 신경 흥분성이 감소한다는 것을 발견했습니다.아세트아미노펜의 항경련 효과의 정확한 메커니즘은 명확하지 않습니다.Suemaru et al.에 따르면,[123] 아세트아미노펜과 그의 활성 대사물 AM404는 마우스에서 펜틸렌테트라졸 유도 발작에 대한 용량 의존적 항경련 활성을 보입니다.

약동학

경구 복용 후 파라세타몰은 소장에서 빠르게 흡수되는 반면 위로부터의 흡수는 무시할 수 있습니다.따라서, 흡수 속도는 위를 비우는 것에 달려 있습니다.음식은 위의 비움과 흡수를 늦추지만, 흡수된 총 양은 [125]그대로 유지됩니다.동일한 실험 대상에서 파라세타몰의 최고 혈장 농도는 단식 시 20분 후와 사료 시 90분 후에 도달했습니다.고탄수화물(단백질이나 고지방은 아님) 음식은 파라세타몰 피크 혈장 농도를 4배까지 감소시킵니다.단식 상태에서도 파라세타몰의 흡수 속도는 가변적이며 제형에 따라 다르며, 최대 혈장 농도는 20분에서 1.5시간 [5]후에 도달합니다.

파라세타몰의 생체 이용률은 용량에 따라 다릅니다. 500 mg 용량의 경우 63%에서 1000 mg [5]용량의 경우 89%로 증가합니다.혈장 말단 제거 반감기는 1.9–[5][126]2.5시간이고 분포량은 약 50 L입니다. 단백질 결합은 15–21%[5]에 도달할 수 있는 과다복용 조건을 제외하고 무시할 수 있습니다.파라세타몰의 일반적인 용량 후 혈청의 농도는 보통 30 μg/mL(200 μmol/[127]L) 미만으로 정점에 도달합니다.4시간 후 농도는 보통 10μg/mL(66μmol/L)[127] 미만입니다.

파라세타몰은 주로 간에서 글루쿠론화 및 황화에 의해 대사되고, 생성물은 소변에서 제거됩니다(오른쪽의 방식 참조).약의 2~5%만이 [5]소변에서 변하지 않고 배설됩니다.UGT1A1 및 UGT1A6에 의한 글루쿠론화는 약물 대사의 50-70%를 차지합니다.파라세타몰의 25~35%는 황산효소 SUT1A1,[128] SUT1A3 및 SUT1E1에 의해 황산으로 전환됩니다.

주로 CYP2E1에 의해 시토크롬 P450 효소에 의한 산화의 작은 대사 경로(5~15%)는 NAPQI(N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine)[128]로 알려진 독성 대사산물을 형성합니다.NAPQI는 파라세타몰의 간 독성을 담당합니다.파라세타몰의 일반적인 용량에서 NAPQI는 글루타티온과의 결합에 의해 빠르게 해독됩니다.무독성 공액 APAP-GSH는 담즙에서 흡수되고 소변으로 배설되는 머캅투릭 공액과 시스테인 공액으로 더 분해됩니다.과다복용 시 글루타티온은 형성된 다량의 NAPQI에 의해 고갈되고, NAPQI는 간세포의 미토콘드리아 단백질에 결합하여 산화적 스트레스와 [128]독성을 일으킵니다.

그러나 대사의 또 다른 중요한 방향은 파라세타몰의 1-2%를 탈아세틸화하여 p-아미노페놀을 형성하는 것입니다. p-아미노페놀은 뇌에서 지방산 아미드 가수분해효소에 의해 AM404로 전환됩니다. 이는 파라세타몰의 [126]진통 작용에 부분적으로 책임이 있을 수 있는 화합물입니다.

화학

합성

고전적 방법

파라세타몰의 생산을 위한 고전적인 방법은 마지막 단계로 4-아미노페놀과 아세트산 무수물의 아세틸화를 포함합니다.그들은 4-아미노페놀이 준비되는 방법에 차이가 있습니다.한 가지 방법에서는 페놀을 질산으로 질화하면 4-니트로페놀을 얻을 수 있으며, 이는 라니 니켈을 수소화하여 4-아미노페놀로 환원됩니다.다른 방법으로, 니트로벤젠은 직접적으로 4-아미노페놀을 생성하여 전해로 환원됩니다.또한 4-니트로페놀은 절대 에탄올 또는 아세트산에틸에서 주석(II) 염화물에 의해 선택적으로 환원되어 91%의 4-아미노페놀을 생성할 수 있습니다.

셀란 합성

Celanese에서 개발된 대체 산업 합성은 먼저 플루오린화 수소가 존재하는 상태에서 페놀과 아세트산 무수물을 케톤으로 직접 아실화한 다음, 케톤을 히드록실아민으로 케톡시메로 전환시키고, 마지막으로 산 촉매로 베크만을 파라아세틸아미노페놀 생성물로 재배열하는 것을 포함한다.[129][132]

반응

4-아미노페놀은 파라세타몰의 아미드 가수분해에 의해 얻을 수 있습니다.이 반응은 소변 샘플에서 파라세타몰을 결정하는 데에도 사용됩니다. 염산으로 가수분해한 후, 4-아미노페놀은 암모니아 용액에서 페놀 유도체, 예를 들어 살리실산과 반응하여 [133]공기에 의해 산화되는 인도페놀 염료를 형성합니다.

역사

아세타닐라이드는 진통제와 해열제 특성을 가진 것으로 발견된 최초의 아닐린 유도체 세렌이며, [134]1886년 칸 & 헤프에 의해 Antifebrin이라는 이름으로 의료계에 빠르게 소개되었습니다.그러나 수용할 수 없는 독성 효과 - 가장 우려되는 것은 메트헤모글로빈혈증으로 인한 청색증, 산소를 결합할3+ 수 없는 메트헤모글로빈이라고 불리는 메트헤모글로빈의 증가, 따라서 조직으로의 산소 운반을 감소시키는 것 - 독성이 덜한 아닐린 [135]유도체의 검색을 촉진했습니다.어떤 보고들은 칸과 헵 또는 샤를 게르하르트라고 불리는 프랑스 화학자가 [54][55]1852년에 파라세타몰을 처음 합성했다고 말합니다.

하몬 노스럽 모스는 [136][137]1877년에 얼음 아세트산에 있는 주석과 p-니트로페놀의 환원을 통해 존스 홉킨스 대학에서 파라세타몰을 합성했지만, 임상 약리학자 조셉 폰 메링이 파라세타몰을 [135]인간에게 시도한 것은 1887년이 되어서였습니다.1893년, 폰 메링은 또 다른 아닐린 [138]유도체인 페나세틴과 파라세타몰의 임상 결과에 대한 논문을 발표했습니다.폰 메링은 페나세틴과 달리 파라세타몰은 메트헤모글로빈혈증을 일으키는 경향이 약간 있다고 주장했습니다.파라세타몰은 페나세틴을 선호하여 빠르게 폐기되었습니다.페나세틴의 판매는 바이엘을 선도적인 제약 [139]회사로 설립했습니다.

Von Mering의 주장은 미국의 두 연구팀이 아세타닐라이드와 페나세틴의 [139]대사를 분석하기 전까지 반세기 동안 근본적으로 이의가 없는 상태로 남아 있었습니다.1947년, David Lester와 Leon Greenberg는 파라세타몰이 사람의 혈액에서 아세타닐라이드의 주요 대사물이라는 강력한 증거를 발견했고, 후속 연구에서 그들은 알비노 쥐에게 투여된 많은 양의 파라세타몰이 메트헤모글로빈혈증을 [140]유발하지 않는다고 보고했습니다.1948년에, Bernard Brodie, Julius Axelrod 그리고 Frederick Flinn은 파라세타몰이 인간에서 아세타닐라이드의 주요 대사산물임을 확인했고,[141][142][143] 파라세타몰의 전구체만큼이나 효과적인 진통제라는 것을 확인했습니다.그들은 또한 메트헤모글로빈혈증이 사람에게서 주로 다른 대사산물인 페닐하이드록실아민에 의해 생성된다고 제안했습니다.1949년 브로디와 액셀로드의 후속 논문은 페나세틴이 파라세타몰로 [144]대사된다는 것을 증명했습니다.이것은 파라세타몰의 "[135]재발견"으로 이어졌습니다.

파라세타몰은 1950년 미국에서 파라세타몰, 아스피린, 그리고 [137]카페인의 조합인 트라이아게시크라는 이름으로 처음 판매되었습니다.1951년 혈액 질환 무과립구증에 걸린 세 명의 사용자에 대한 보고는 시장에서 그것을 제거하도록 이끌었고, 그 질병이 [137]연관성이 없다는 것이 명확해질 때까지 몇 년이 걸렸습니다.이듬해인 1952년에 파라세타몰은 처방약으로 [145]미국 시장에 돌아왔습니다.영국에서 파라세타몰의 마케팅은 1956년 스털링-윈트롭사에 의해 파나돌로 시작되었으며, 처방에 의해서만 이용 가능하며, 어린이와 [146][147]궤양이 있는 사람들에게 안전하기 때문에 아스피린보다 더 선호되는 것으로 홍보되었습니다.1963년, 파라세타몰은 영국 약전에 첨가되었고, 그 이후 부작용이 거의 없고 다른 [146][137]약전과 상호작용이 거의 없는 진통제로 인기를 얻었습니다.

파라세타몰의 안전성에 대한 우려 때문에 1970년대까지 널리 받아들여지는 것이 늦었지만, 1980년대에 파라세타몰의 판매량이 영국을 포함한 많은 나라들의 아스피린 판매량을 앞질렀습니다.이것은 진통제 신증과 [135]혈액학적 독성의 원인으로 비난 받는 페나세틴의 상업적 소멸을 동반했습니다.1955년[148](다른 출처에 따르면 1960년)부터[145] 처방전 없이 미국에서 사용할 수 있는 파라세타몰은 일반적인 가정용 [149]약물이 되었습니다.1988년 스털링 윈스롭은 이스트먼 [150]코닥에 인수되어 1994년 스미스 클라인 비첨에게 장외 의약품 권리를 매각했습니다.

2009년 6월, FDA 자문 위원회는 잠재적인 독성 효과로부터 사람들을 보호하는 것을 돕기 위해 미국에서 파라세타몰 사용에 새로운 제한을 둘 것을 권고했습니다.성인 1인 최대 용량은 1000mg에서 650mg으로 감소할 것이며 파라세타몰과 다른 제품의 조합은 금지될 것입니다.위원회 구성원들은 특히 파라세타몰의 당시 최대 용량이 [151]간 기능에 변화를 일으키는 것으로 나타났다는 사실에 대해 우려했습니다.

2011년 1월, FDA는 파라세타몰이 함유된 처방 조합 제품 제조업체에 정제 또는 캡슐 당 325mg 이하로 제한할 것을 요청하고 제조업체에 심각한 간 손상의 잠재적 위험을 경고하기 위해 모든 처방 조합 제품의 라벨을 업데이트하도록 요구하기 시작했다.[152][153][154][155][156]제조업체들은 처방 의약품에 포함된 파라세타몰의 양을 [153][155]용량 단위당 325mg으로 제한하는 데 3년이 걸렸습니다.

2011년 11월, 의약품 및 건강 관리 제품 규제 기관은 [157]어린이를 위한 액체 파라세타몰의 영국 투여를 개정했습니다.

2013년 9월, 라디오 프로그램 디스 아메리칸 라이프의[158] 에피소드인 "유즈 온리 디렉티드"는 파라세타몰 과다복용으로 인한 사망을 강조했습니다.이 보고서에 이어 프로퍼블리카가 "FDA는 오랫동안 아세트아미노펜의 위험성을 보여주는 연구를 알고 있었습니다.Johnson & [159]Johnson의 부서인 McNeil Consumer Healthcare의 Tylenol 제조업체도 마찬가지입니다.는 안전 경고, 용량 제한 및 약물 [160]사용자를 보호하기 위한 기타 조치에 반복적으로 반대해 왔습니다."

코로나19 범유행 당시 과학계 일각에서는 코로나19 증상을 치료하는 효과적인 진통제라는 평가가 나왔지만,[161][162][163][164] 이는 근거가 없는 것으로 드러났습니다.

사회와 문화

명명

파라세타몰은 세계보건기구(WHO)와 다른 많은 국가에서 사용되는 국제적인 비소유권 이름이자 호주[166] 승인[165] 이름입니다. 아세트아미노펜은 캐나다,[166] 베네수엘라[166], 콜롬비아 및 [166][167]이란에서 일반적으로 사용되는 이름입니다.파라세타몰과 아세트아미노펜은 둘 다 화합물의 화학적 이름인 파라-아세틸아미노페놀의 수축입니다.미국에서 조제 약사들이 사용하는 이니셜리즘 APAP는 대체 화학명 [N-]아세틸-파라-아미노페놀에서 [168]유래되었습니다.

사용 가능한 양식

파라세타몰은 구강,[169] 좌약 및 정맥 주사 형태로 사용할 수 있습니다.정맥 파라세타몰은 [170]미국에서 Ofirmev라는 상표명으로 판매되고 있습니다.

일부 제형에서 파라세타몰은 아편산 코데인과 결합되며, 때때로 호주에서 코코다몰(BAN) 및 파나데인으로 지칭됩니다.미국에서는 [171]처방전이 있어야만 이 조합을 사용할 수 있습니다.2018년 2월 1일부터 오스트레일리아에서도 [172]코데인이 함유된 의약품이 처방전 전용이 되었습니다.파라세타몰은 또한 co-dydramol (BAN), 옥시코돈[174] 또는 하이드로코돈으로 지칭되는 [175]디히드로코데인과 [173]같은 다른 오피오이드와 결합됩니다.또 다른 매우 일반적으로 사용되는 진통제 조합은 프로폭시펜 냅실레이트와 [176]결합된 파라세타몰을 포함합니다.파라세타몰, 코데인 및 독실라민 석신산의 조합 또한 [177]사용 가능합니다.

파라세타몰은 때때로 페닐레프린 [178]염산염과 결합됩니다.때때로 아스코르브산,[178][179] 카페인,[180][181] 말레산 [182]클로르페니라민 또는 과이펜신과[183][184][185] 같은 세 번째 활성 성분이 이 조합에 첨가됩니다.

수의학적 이용

캣츠

파라세타몰은 고양이에게 극도로 독성이 강하며 고양이를 해독하는 데 필요한 UGT1A6 효소가 부족합니다.초기 증상은 구토, 침, 혀와 잇몸의 변색을 포함합니다.사람의 과다 복용과 달리 간 손상은 사망의 원인이 되는 경우가 거의 없습니다. 대신, 적혈구에서 메트헤모글로빈 형성과 하인즈 신체의 생산은 혈액에 의한 산소 수송을 억제하여 질식(메트헤모글로빈혈증 및 용혈성 [186]빈혈)을 유발합니다.N-아세틸시스테인으로 독성을 치료하는 것이 좋습니다.[187]

개들

파라세타몰은 [188]개의 근골격계 통증 치료에 아스피린만큼 효과적인 것으로 보고되었습니다.개에 사용이 허가된 파라세타몰-코데인 제품(브랜드명 Pardale-V)[189]은 수의사, 약사 또는 기타 자격을 갖춘 [189]사람의 감독 하에 구입할 수 있습니다.그것은 오직 수의사의 조언과 극도의 [189]주의로 개들에게 투여되어야 합니다.

개의 독성의 주요 효과는 간 손상이며, GI 궤양이 [187][190][191][192]보고되었습니다.N-아세틸시스테인 치료는 파라세타몰 [187][188]섭취 후 2시간 이내에 투여하면 개에게 효과적입니다.

뱀

파라세타몰은 뱀에게 치명적이며 [193][194]괌의 침습적인 갈색 나무 뱀(Boiga unregularis)의 화학적 통제 프로그램으로 제안되었습니다.80mg의 용량이 뱀들이 먹을 치명적인 미끼로 헬리콥터에[195] 의해 흩어진 죽은 쥐들에게 삽입됩니다.

메모들

- ^ 미국, 캐나다, 일본, 그리고 한국에서 흔히 "아세트아미노펜"이라고 불립니다.

레퍼런스

- ^ 국제 의약품 이름

- ^ "Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 14 June 2019. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Regulatory Decision Summary – Acetaminophen Injection". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Working Group of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine (2015). Schug SA, Palmer GM, Scott DA, Halliwell R, Trinca J (eds.). Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence (4th ed.). Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA), Faculty of Pain Medicine (FPM). ISBN 978-0-9873236-7-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Forrest JA, Clements JA, Prescott LF (1982). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of paracetamol". Clin Pharmacokinet. 7 (2): 93–107. doi:10.2165/00003088-198207020-00001. PMID 7039926. S2CID 20946160.

- ^ "Acetaminophen Pathway (therapeutic doses), Pharmacokinetics". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ a b Pickering G, Macian N, Libert F, Cardot JM, Coissard S, Perovitch P, Maury M, Dubray C (September 2014). "Buccal acetaminophen provides fast analgesia: two randomized clinical trials in healthy volunteers". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 8: 1621–1627. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S63476. PMC 4189711. PMID 25302017.

In postoperative conditions for acute pain of mild to moderate intensity, the quickest reported time to onset of analgesia with APAP is 8 minutes9 for the iv route and 37 minutes6 for the oral route.

- ^ "Codapane Forte Paracetamol and codeine phosphate product information" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ Karthikeyan M, Glen RC, Bender A (2005). "General Melting Point Prediction Based on a Diverse Compound Data Set and Artificial Neural Networks". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 45 (3): 581–590. doi:10.1021/ci0500132. PMID 15921448.

- ^ "melting point data for paracetamol". Lxsrv7.oru.edu. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Granberg RA, Rasmuson AC (1999). "Solubility of paracetamol in pure solvents". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 44 (6): 1391–95. doi:10.1021/je990124v.

- ^ Prescott LF (March 2000). "Paracetamol: past, present, and future". American Journal of Therapeutics. 7 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1097/00045391-200007020-00011. PMID 11319582. S2CID 7754908.

- ^ a b c d e f Warwick C (November 2008). "Paracetamol and fever management". J R Soc Promot Health. 128 (6): 320–323. doi:10.1177/1466424008092794. PMID 19058473. S2CID 25702228.

- ^ a b c d e f g Saragiotto BT, Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG (December 2019). "Paracetamol for pain in adults". BMJ. 367: l6693. doi:10.1136/bmj.l6693. PMID 31892511. S2CID 209524643.

- ^ a b c Chiumello D, Gotti M, Vergani G (April 2017). "Paracetamol in fever in critically ill patients-an update". J Crit Care. 38: 245–252. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.10.021. PMID 27992852. S2CID 5815020.

- ^ a b de Martino M, Chiarugi A (December 2015). "Recent Advances in Pediatric Use of Oral Paracetamol in Fever and Pain Management". Pain Ther. 4 (2): 149–68. doi:10.1007/s40122-015-0040-z. PMC 4676765. PMID 26518691.

- ^ a b Pierce CA, Voss B (March 2010). "Efficacy and safety of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in children and adults: a meta-analysis and qualitative review". Ann Pharmacother. 44 (3): 489–506. doi:10.1345/aph.1M332. PMID 20150507. S2CID 44669940.

- ^ Meremikwu M, Oyo-Ita A (2002). "Paracetamol for treating fever in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002 (2): CD003676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003676. PMC 6532671. PMID 12076499.

- ^ a b Ludwig J, McWhinnie H (May 2019). "Antipyretic drugs in patients with fever and infection: literature review". Br J Nurs. 28 (10): 610–618. doi:10.12968/bjon.2019.28.10.610. PMID 31116598. S2CID 162182092.

- ^ a b Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ (January 2015). "The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the american headache society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies". Headache. 55 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1111/head.12499. PMID 25600718. S2CID 25576700.

- ^ a b Stephens G, Derry S, Moore RA (June 2016). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute treatment of episodic tension-type headache in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 (6): CD011889. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011889.pub2. PMC 6457822. PMID 27306653.

- ^ a b Mayans L, Walling A (February 2018). "Acute Migraine Headache: Treatment Strategies". Am Fam Physician. 97 (4): 243–251. PMID 29671521.

- ^ a b Haag G, Diener HC, May A, Meyer C, Morck H, Straube A, Wessely P, Evers S (April 2011). "Self-medication of migraine and tension-type headache: summary of the evidence-based recommendations of the Deutsche Migräne und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (DMKG), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (DGN), the Österreichische Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (ÖKSG) and the Schweizerische Kopfwehgesellschaft (SKG)". J Headache Pain. 12 (2): 201–217. doi:10.1007/s10194-010-0266-4. PMC 3075399. PMID 21181425.

- ^ a b c d Bailey E, Worthington HV, van Wijk A, Yates JM, Coulthard P, Afzal Z (December 2013). "Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12): CD004624. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004624.pub2. PMID 24338830.

- ^ a b c Moore PA, Hersh EV (August 2013). "Combining ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute pain management after third-molar extractions: translating clinical research to dental practice". J Am Dent Assoc. 144 (8): 898–908. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0207. PMID 23904576.

- ^ a b c d e Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Lin CW, Day RO, et al. (March 2015). "Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials". BMJ. 350: h1225. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1225. PMC 4381278. PMID 25828856.

- ^ a b c Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, Callahan L, Copenhaver C, Dodge C, Felson D, Gellar K, Harvey WF, Hawker G, Herzig E, Kwoh CK, Nelson AE, Samuels J, Scanzello C, White D, Wise B, Altman RD, DiRenzo D, Fontanarosa J, Giradi G, Ishimori M, Misra D, Shah AA, Shmagel AK, Thoma LM, Turgunbaev M, Turner AS, Reston J (February 2020). "2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee". Arthritis Care & Research. 72 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1002/acr.24131. hdl:2027.42/153772. PMID 31908149. S2CID 210043648.

- ^ a b c Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA (April 2017). "Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians". Ann Intern Med. 166 (7): 514–530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367. PMID 28192789. S2CID 207538763.

- ^ a b Saragiotto BT, Machado GC, Ferreira ML, Pinheiro MB, Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG (June 2016). "Paracetamol for low back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6 (6): CD012230. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012230. PMC 6353046. PMID 27271789.

- ^ a b Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, McNicol ED, Bell RF, Carr DB, McIntyre M, Wee B (July 2017). "Oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) for cancer pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7 (2): CD012637. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012637.pub2. PMC 6369932. PMID 28700092.

- ^ a b Wiffen PJ, Knaggs R, Derry S, Cole P, Phillips T, Moore RA (December 2016). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without codeine or dihydrocodeine for neuropathic pain in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12 (5): CD012227. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012227.pub2. PMC 6463878. PMID 28027389.

- ^ "Acetaminophen". Health Canada. 11 October 2012. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Southey ER, Soares-Weiser K, Kleijnen J (September 2009). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical safety and tolerability of ibuprofen compared with paracetamol in paediatric pain and fever". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 25 (9): 2207–2222. doi:10.1185/03007990903116255. PMID 19606950. S2CID 31653539. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ "Acetaminophen vs Ibuprofen: Which is better?". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ a b Moore RA, Moore N (July 2016). "Paracetamol and pain: the kiloton problem". European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 23 (4): 187–188. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000952. PMC 6451482. PMID 31156845.

- ^ a b c d e f g Conaghan PG, Arden N, Avouac B, Migliore A, Rizzoli R (April 2019). "Safety of Paracetamol in Osteoarthritis: What Does the Literature Say?". Drugs Aging. 36 (Suppl 1): 7–14. doi:10.1007/s40266-019-00658-9. PMC 6509082. PMID 31073920.

- ^ a b c d Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, Latchem S, Constanti M, Miller P, Doherty M, Zhang W, Birrell F, Porcheret M, Dziedzic K, Bernstein I, Wise E, Conaghan PG (March 2016). "Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies". Ann Rheum Dis. 75 (3): 552–9. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206914. PMC 4789700. PMID 25732175.

- ^ Alchin J, Dhar A, Siddiqui K, Christo PJ (May 2022). "Why paracetamol (acetaminophen) is a suitable first choice for treating mild to moderate acute pain in adults with liver, kidney or cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, or who are older". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 38 (5): 811–825. doi:10.1080/03007995.2022.2049551. PMID 35253560. S2CID 247251679.

- ^ a b Leopoldino AO, Machado GC, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Day R, McLachlan AJ, Hunter DJ, Ferreira ML (February 2019). "Paracetamol versus placebo for knee and hip osteoarthritis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2 (8): CD013273. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013273. PMC 6388567. PMID 30801133.

- ^ a b c Choueiri TK, Je Y, Cho E (January 2014). "Analgesic use and the risk of kidney cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies". Int J Cancer. 134 (2): 384–96. doi:10.1002/ijc.28093. PMC 3815746. PMID 23400756.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j McCrae JC, Morrison EE, MacIntyre IM, Dear JW, Webb DJ (October 2018). "Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol – a review". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 84 (10): 2218–2230. doi:10.1111/bcp.13656. PMC 6138494. PMID 29863746.

- ^ a b MacIntyre IM, Turtle EJ, Farrah TE, Graham C, Dear JW, Webb DJ (February 2022). "Regular Acetaminophen Use and Blood Pressure in People With Hypertension: The PATH-BP Trial". Circulation. 145 (6): 416–423. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056015. PMC 7612370. PMID 35130054.

- ^ a b Bauer AZ, Kriebel D, Herbert MR, Bornehag CG, Swan SH (May 2018). "Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A review". Horm Behav. 101: 125–147. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.01.003. PMID 29341895. S2CID 4822468.

- ^ a b Gou X, Wang Y, Tang Y, Qu Y, Tang J, Shi J, Xiao D, Mu D (March 2019). "Association of maternal prenatal acetaminophen use with the risk of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: A meta-analysis". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 53 (3): 195–206. doi:10.1177/0004867418823276. PMID 30654621. S2CID 58575048.

- ^ a b Toda K (October 2017). "Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?". Scand J Pain. 17: 445–446. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.09.007. PMID 28986045. S2CID 205183310.

- ^ a b Black E, Khor KE, Kennedy D, Chutatape A, Sharma S, Vancaillie T, Demirkol A (November 2019). "Medication Use and Pain Management in Pregnancy: A Critical Review". Pain Pract. 19 (8): 875–899. doi:10.1111/papr.12814. PMID 31242344. S2CID 195694287.

- ^ a b "Paracetamol for adults: painkiller to treat aches, pains and fever". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ a b "What are the recommended maximum daily dosages of acetaminophen in adults and children?". Medscape. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ "Acetaminophen". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Daly FF, Fountain JS, Murray L, Graudins A, Buckley NA (March 2008). "Guidelines for the management of paracetamol poisoning in Australia and New Zealand—explanation and elaboration. A consensus statement from clinical toxicologists consulting to the Australasian poisons information centres". The Medical Journal of Australia. 188 (5): 296–301. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01625.x. PMID 18312195. S2CID 9505802.

- ^ a b Hawkins LC, Edwards JN, Dargan PI (2007). "Impact of restricting paracetamol pack sizes on paracetamol poisoning in the United Kingdom: a review of the literature". Drug Saf. 30 (6): 465–79. doi:10.2165/00002018-200730060-00002. PMID 17536874. S2CID 36435353.

- ^ a b Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, et al. (2005). "Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study". Hepatology. 42 (6): 1364–72. doi:10.1002/hep.20948. PMID 16317692. S2CID 24758491.

- ^ Mangus BC, Miller MG (2005). Pharmacology application in athletic training. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: F.A. Davis. p. 39. ISBN 9780803620278. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ a b Eyers SJ (April 2012). The effect of regular paracetamol on bronchial responsiveness and asthma control in mild to moderate asthma (Ph.D. thesis). University of Otago). Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ a b Roy J (2011). "Paracetamol – the best selling antipyretic analgesic in the world". An introduction to pharmaceutical sciences: production, chemistry, techniques and technology. Oxford: Biohealthcare. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-908818-04-1. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Aghababian RV (22 October 2010). Essentials of emergency medicine. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 814. ISBN 978-1-4496-1846-9. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Hamilton RJ (2013). Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia : 2013 classic shirt-pocket edition (27th ed.). Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 12. ISBN 9781449665869. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Acetaminophen – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Definition of ACETAMINOPHEN". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "Definition of PARACETAMOL". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "A History of Paracetamol, Its Various Uses & How It Affects You". FeverMates. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Li S, Yue J, Dong BR, Yang M, Lin X, Wu T (July 2013). "Acetaminophen (paracetamol) for the common cold in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 (7): CD008800. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008800.pub2. PMC 7389565. PMID 23818046.

- ^ de Ridder IR, den Hertog HM, van Gemert HM, Schreuder AH, Ruitenberg A, Maasland EL, Saxena R, van Tuijl JH, Jansen BP, Van den Berg-Vos RM, Vermeij F, Koudstaal PJ, Kappelle LJ, Algra A, van der Worp HB, Dippel DW (April 2017). "PAIS 2 (Paracetamol [Acetaminophen] in Stroke 2): Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial". Stroke. 48 (4): 977–982. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015957. PMID 28289240.

- ^ Deen J, von Seidlein L (May 2019). "Paracetamol for dengue fever: no benefit and potential harm?". Lancet Glob Health. 7 (5): e552–e553. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30157-3. PMID 31000122.

- ^ Meremikwu M, Oyo-Ita A (2002). "Paracetamol for treating fever in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002 (2): CD003676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003676. PMC 6532671. PMID 12076499.

- ^ a b c "Recommendations. Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management". nice.org.uk. 7 November 2019. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021.

- ^ Hashimoto R, Suto M, Tsuji M, Sasaki H, Takehara K, Ishiguro A, Kubota M (April 2021). "Use of antipyretics for preventing febrile seizure recurrence in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Eur J Pediatr. 180 (4): 987–997. doi:10.1007/s00431-020-03845-8. PMID 33125519.

- ^ Narayan K, Cooper S, Morphet J, Innes K (August 2017). "Effectiveness of paracetamol versus ibuprofen administration in febrile children: A systematic literature review". J Paediatr Child Health. 53 (8): 800–807. doi:10.1111/jpc.13507. PMID 28437025. S2CID 395470.

- ^ Tan E, Braithwaite I, McKinlay CJ, Dalziel SR (October 2020). "Comparison of Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) With Ibuprofen for Treatment of Fever or Pain in Children Younger Than 2 Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Netw Open. 3 (10): e2022398. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22398. PMC 7599455. PMID 33125495.

- ^ a b Sherbash M, Furuya-Kanamori L, Nader JD, Thalib L (March 2020). "Risk of wheezing and asthma exacerbation in children treated with paracetamol versus ibuprofen: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMC Pulm Med. 20 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/s12890-020-1102-5. PMC 7087361. PMID 32293369.

- ^ Bertolini A, Ferrari A, Ottani A, Guerzoni S, Tacchi R, Leone S (2006). "Paracetamol: new vistas of an old drug". CNS Drug Rev. 12 (3–4): 250–75. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00250.x. PMC 6506194. PMID 17227290.

- ^ Kloppenburg M, Kroon FP, Blanco FJ, Doherty M, Dziedzic KS, Greibrokk E, Haugen IK, Herrero-Beaumont G, Jonsson H, Kjeken I, Maheu E, Ramonda R, Ritt MJ, Smeets W, Smolen JS, Stamm TA, Szekanecz Z, Wittoek R, Carmona L (January 2019). "2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis". Ann Rheum Dis. 78 (1): 16–24. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826. PMID 30154087.

- ^ Bruyère O, Honvo G, Veronese N, Arden NK, Branco J, Curtis EM, Al-Daghri NM, Herrero-Beaumont G, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Rannou F, Rizzoli R, Roth R, Uebelhart D, Cooper C, Reginster JY (December 2019). "An updated algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO)". Semin Arthritis Rheum. 49 (3): 337–350. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.04.008. PMID 31126594.

- ^ Derry S, Moore RA (2013). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4 (4): CD008040. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008040.pub3. PMC 4161111. PMID 23633349.

- ^ Diener HC, Gold M, Hagen M (November 2014). "Use of a fixed combination of acetylsalicylic acid, acetaminophen and caffeine compared with acetaminophen alone in episodic tension-type headache: meta-analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover studies". J Headache Pain. 15 (1): 76. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-76. PMC 4256978. PMID 25406671.

- ^ Pergolizzi JV, Magnusson P, LeQuang JA, Gharibo C, Varrassi G (April 2020). "The pharmacological management of dental pain". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 21 (5): 591–601. doi:10.1080/14656566.2020.1718651. PMID 32027199. S2CID 211046298.

- ^ Hersh EV, Moore PA, Grosser T, Polomano RC, Farrar JT, Saraghi M, Juska SA, Mitchell CH, Theken KN (July 2020). "Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Opioids in Postsurgical Dental Pain". J Dent Res. 99 (7): 777–786. doi:10.1177/0022034520914254. PMC 7313348. PMID 32286125.

- ^ Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (June 2013). "Single dose oral ibuprofen plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 (6): CD010210. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010210.pub2. PMC 6485825. PMID 23794268.

- ^ Daniels SE, Atkinson HC, Stanescu I, Frampton C (October 2018). "Analgesic Efficacy of an Acetaminophen/Ibuprofen Fixed-dose Combination in Moderate to Severe Postoperative Dental Pain: A Randomized, Double-blind, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled Trial". Clin Ther. 40 (10): 1765–1776.e5. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.08.019. PMID 30245281.

- ^ Toms L, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (January 2009). "Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine for postoperative pain in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 (1): CD001547. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001547.pub2. PMC 4171965. PMID 19160199.

- ^ Allegaert K (2020). "A Critical Review on the Relevance of Paracetamol for Procedural Pain Management in Neonates". Front Pediatr. 8: 89. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.00089. PMC 7093493. PMID 32257982.

- ^ Ohlsson A, Shah PS (January 2020). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for prevention or treatment of pain in newborns". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD011219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011219.pub4. PMC 6984663. PMID 31985830.

- ^ Wuytack F, Smith V, Cleary BJ (January 2021). "Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (single dose) for perineal pain in the early postpartum period". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1 (1): CD011352. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011352.pub3. PMC 8092572. PMID 33427305.

- ^ Sin B, Wai M, Tatunchak T, Motov SM (May 2016). "The Use of Intravenous Acetaminophen for Acute Pain in the Emergency Department". Academic Emergency Medicine. 23 (5): 543–53. doi:10.1111/acem.12921. PMID 26824905.

- ^ Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (March 2012). Derry S (ed.). "Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD009281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009281.pub2. PMID 22419343. S2CID 205199173.

- ^ a b Jasani B, Mitra S, Shah PS (December 2022). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (12): CD010061. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010061.pub5. PMC 6984659. PMID 36519620.

- ^ Keaveney A, Peters E, Way B (September 2020). "Effects of acetaminophen on risk taking". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 15 (7): 725–732. doi:10.1093/scan/nsaa108. PMC 7511878. PMID 32888031.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns of rare but serious skin reactions with the pain reliever/fever reducer acetaminophen". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 August 2013. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다. - ^ Lebrun-Vignes B, Guy C, Jean-Pastor MJ, Gras-Champel V, Zenut M (February 2018). "Is acetaminophen associated with a risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis? Analysis of the French Pharmacovigilance Database". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 84 (2): 331–338. doi:10.1111/bcp.13445. PMC 5777438. PMID 28963996.

- ^ Kanchanasurakit S, Arsu A, Siriplabpla W, Duangjai A, Saokaew S (March 2020). "Acetaminophen use and risk of renal impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Kidney Res Clin Pract. 39 (1): 81–92. doi:10.23876/j.krcp.19.106. PMC 7105620. PMID 32172553.

- ^ Lourido-Cebreiro T, Salgado FJ, Valdes L, Gonzalez-Barcala FJ (January 2017). "The association between paracetamol and asthma is still under debate". The Journal of Asthma (Review). 54 (1): 32–8. doi:10.1080/02770903.2016.1194431. PMID 27575940. S2CID 107851.

- ^ Cheelo M, Lodge CJ, Dharmage SC, Simpson JA, Matheson M, Heinrich J, et al. (January 2015). "Paracetamol exposure in pregnancy and early childhood and development of childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 100 (1): 81–9. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-303043. PMID 25429049. S2CID 13520462. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Eyers S, Weatherall M, Jefferies S, Beasley R (April 2011). "Paracetamol in pregnancy and the risk of wheezing in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 41 (4): 482–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03691.x. PMID 21338428. S2CID 205275267.

- ^ Fan G, Wang B, Liu C, Li D (2017). "Prenatal paracetamol use and asthma in childhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 45 (6): 528–533. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2016.10.014. PMID 28237129.

- ^ Masarwa R, Levine H, Gorelik E, Reif S, Perlman A, Matok I (August 2018). "Prenatal Exposure to Acetaminophen and Risk for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autistic Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression Analysis of Cohort Studies". Am J Epidemiol. 187 (8): 1817–1827. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy086. PMID 29688261.

- ^ Ji Y, Azuine RE, Zhang Y, Hou W, Hong X, Wang G, Riley A, Pearson C, Zuckerman B, Wang X (February 2020). "Association of Cord Plasma Biomarkers of In Utero Acetaminophen Exposure With Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Childhood". JAMA Psychiatry. 77 (2): 180–189. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3259. PMC 6822099. PMID 31664451.

- ^ "Acetaminophen Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 14 November 2017. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다. - ^ "Using Acetaminophen and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Safely". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 26 February 2018. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다. - ^ Amar PJ, Schiff ER (July 2007). "Acetaminophen safety and hepatotoxicity--where do we go from here?". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 6 (4): 341–355. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.4.341. PMID 17688378. S2CID 20399748.

- ^ Khashab M, Tector AJ, Kwo PY (2007). "Epidemiology of acute liver failure". Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 9 (1): 66–73. doi:10.1007/s11894-008-0023-x. PMID 17335680. S2CID 30068892.

- ^ Lee WM (2004). "Acetaminophen and the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group: lowering the risks of hepatic failure". Hepatology. 40 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1002/hep.20293. PMID 15239078. S2CID 15485538.

- ^ "Prescription Drug Products Containing Acetaminophen: Actions to Reduce Liver Injury from Unintentional Overdose". regulations.gov. US Food and Drug Administration. 14 January 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다. - ^ Yan H (16 January 2014). "FDA: Acetaminophen doses over 325 mg may lead to liver damage". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ a b Lee WM (December 2017). "Acetaminophen (APAP) hepatotoxicity—Isn't it time for APAP to go away?". Journal of Hepatology. 67 (6): 1324–1331. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.005. PMC 5696016. PMID 28734939.

- ^ Rumack B, Matthew H (1975). "Acetaminophen poisoning and toxicity". Pediatrics. 55 (6): 871–876. doi:10.1542/peds.55.6.871. PMID 1134886. S2CID 45739342.

- ^ "Paracetamol". University of Oxford Centre for Suicide Research. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Mehta S (25 August 2012). "Metabolism of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen), Acetanilide and Phenacetin". PharmaXChange.info. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Highlights of Prescribing Information" (PDF). Acetadote. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Paracetamol overdose: new guidance on treatment with intravenous acetylcysteine". Drug Safety Update. September 2012. pp. A1. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012.

- ^ "Treating paracetamol overdose with intravenous acetylcysteine: new guidance". GOV.UK. 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Nimmo J, Heading RC, Tothill P, Prescott LF (March 1973). "Pharmacological modification of gastric emptying: effects of propantheline and metoclopromide on paracetamol absorption". Br Med J. 1 (5853): 587–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5853.587. PMC 1589913. PMID 4694406.

- ^ a b c d e f Toes MJ, Jones AL, Prescott L (2005). "Drug interactions with paracetamol". Am J Ther. 12 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1097/00045391-200501000-00009. PMID 15662293. S2CID 39595470.

- ^ Kalsi SS, Wood DM, Waring WS, Dargan PI (2011). "Does cytochrome P450 liver isoenzyme induction increase the risk of liver toxicity after paracetamol overdose?". Open Access Emerg Med. 3: 69–76. doi:10.2147/OAEM.S24962. PMC 4753969. PMID 27147854.

- ^ Pinson GM, Beall JW, Kyle JA (October 2013). "A review of warfarin dosing with concurrent acetaminophen therapy". J Pharm Pract. 26 (5): 518–21. doi:10.1177/0897190013488802. PMID 23736105. S2CID 31588052.

- ^ Hughes GJ, Patel PN, Saxena N (June 2011). "Effect of acetaminophen on international normalized ratio in patients receiving warfarin therapy". Pharmacotherapy. 31 (6): 591–7. doi:10.1592/phco.31.6.591. PMID 21923443. S2CID 28548170.

- ^ Zhang Q, Bal-dit-Sollier C, Drouet L, Simoneau G, Alvarez JC, Pruvot S, Aubourg R, Berge N, Bergmann JF, Mouly S, Mahé I (March 2011). "Interaction between acetaminophen and warfarin in adults receiving long-term oral anticoagulants: a randomized controlled trial". Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 67 (3): 309–14. doi:10.1007/s00228-010-0975-2. PMID 21191575. S2CID 25988269.

- ^ a b c d e f Ghanem CI, Pérez MJ, Manautou JE, Mottino AD (July 2016). "Acetaminophen from liver to brain: New insights into drug pharmacological action and toxicity". Pharmacological Research. 109: 119–31. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.020. PMC 4912877. PMID 26921661.

- ^ a b Graham GG, Davies MJ, Day RO, Mohamudally A, Scott KF (June 2013). "The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity and recent pharmacological findings". Inflammopharmacology. 21 (3): 201–32. doi:10.1007/s10787-013-0172-x. PMID 23719833. S2CID 11359488.

- ^ Sharma CV, Long JH, Shah S, Rahman J, Perrett D, Ayoub SS, Mehta V (2017). "First evidence of the conversion of paracetamol to AM404 in human cerebrospinal fluid". J Pain Res. 10: 2703–2709. doi:10.2147/JPR.S143500. PMC 5716395. PMID 29238213.

- ^ Ohashi N, Kohno T (2020). "Analgesic Effect of Acetaminophen: A Review of Known and Novel Mechanisms of Action". Front Pharmacol. 11: 580289. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.580289. PMC 7734311. PMID 33328986.

- ^ a b Suemaru K, Yoshikawa M, Aso H, Watanabe M (September 2018). "TRPV1 mediates the anticonvulsant effects of acetaminophen in mice". Epilepsy Research. 145: 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.06.016. PMID 30007240. S2CID 51652230.

- ^ Ray S, Salzer I, Kronschläger MT, Boehm S (April 2019). "The paracetamol metabolite N-acetylp-benzoquinone imine reduces excitability in first- and second-order neurons of the pain pathway through actions on KV7 channels". Pain. 160 (4): 954–964. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001474. PMC 6430418. PMID 30601242.

- ^ Prescott LF (October 1980). "Kinetics and metabolism of paracetamol and phenacetin". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (Suppl 2): 291S–298S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb01812.x. PMC 1430174. PMID 7002186.

- ^ a b Graham GG, Davies MJ, Day RO, Mohamudally A, Scott KF (June 2013). "The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: Therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity, and recent pharmacological findings". Inflammopharmacology. 21 (3): 201–232. doi:10.1007/s10787-013-0172-x. PMID 23719833. S2CID 11359488.

- ^ a b Marx J, Walls R, Hockberger R (2013). Rosen's Emergency Medicine – Concepts and Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455749874.

- ^ a b c McGill MR, Jaeschke H (September 2013). "Metabolism and disposition of acetaminophen: recent advances in relation to hepatotoxicity and diagnosis". Pharm Res. 30 (9): 2174–87. doi:10.1007/s11095-013-1007-6. PMC 3709007. PMID 23462933.

- ^ a b Friderichs E, Christoph T, Buschmann H. "Analgesics and Antipyretics". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_269.pub2.

- ^ "US Patent 2998450". Archived from the original on 14 April 2021.

- ^ Bellamy FD, Ou K (January 1984). "Selective reduction of aromatic nitro compounds with stannous chloride in non acidic and non aqueous medium". Tetrahedron Letters. 25 (8): 839–842. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80041-1.

- ^ 미국 특허 45242117, 데이븐포트 KG, 힐튼 CB, 1985년 6월 18일 발행, Celanese Corporation에 할당된 "N-acyl-hydroxy 방향족 생산 프로세스"

- ^ Novotny PE, Elser RC (1984). "Indophenol method for acetaminophen in serum examined". Clin. Chem. 30 (6): 884–6. doi:10.1093/clinchem/30.6.884. PMID 6723045.

- ^ Cahn A, Hepp P (1886). "Das Antifebrin, ein neues Fiebermittel" [Antifebrin, a new antipyretic]. Centralblatt für klinische Medizin (in German). 7: 561–4. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Bertolini A, Ferrari A, Ottani A, Guerzoni S, Tacchi R, Leone S (2006). "Paracetamol: New vistas of an old drug". CNS Drug Reviews. 12 (3–4): 250–75. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00250.x. PMC 6506194. PMID 17227290.

- ^ Morse HN (1878). "Ueber eine neue Darstellungsmethode der Acetylamidophenole" [On a new method of preparing acetylamidophenol]. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 11 (1): 232–233. doi:10.1002/cber.18780110151. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d Silverman M, Lydecker M, Lee PR (1992). Bad Medicine: The Prescription Drug Industry in the Third World. Stanford University Press. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-0804716697.

- ^ von Mering J (1893). "Beitrage zur Kenntniss der Antipyretica". Ther Monatsch. 7: 577–587.

- ^ a b Sneader W (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 439. ISBN 978-0471899808. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016.

- ^ Lester D, Greenberg LA, Carroll RP (1947). "The metabolic fate of acetanilid and other aniline derivatives: II. Major metabolites of acetanilid appearing in the blood". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 90 (1): 68–75. PMID 20241897. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008.

- ^ Brodie BB, Axelrod J (1948). "The estimation of acetanilide and its metabolic products, aniline, N-acetyl p-aminophenol and p-aminophenol (free and total conjugated) in biological fluids and tissues". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 22–28. PMID 18885610.

- ^ Brodie BB, Axelrod J (1948). "The fate of acetanilide in man" (PDF). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 29–38. PMID 18885611. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2008.

- ^ Flinn FB, Brodie BB (1948). "The effect on the pain threshold of N-acetyl p-aminophenol, a product derived in the body from acetanilide". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 76–77. PMID 18885618.

- ^ Brodie BB, Axelrod J (1949). "The fate of acetophenetidin (phenacetin) in man and methods for the estimation of acetophenitidin and its metabolites in biological material". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 94 (1): 58–67.

- ^ a b Ameer B, Greenblatt DJ (August 1977). "Acetaminophen". Ann Intern Med. 87 (2): 202–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-87-2-202. PMID 329728.

- ^ a b Spooner JB, Harvey JG (1976). "The history and usage of paracetamol". J Int Med Res. 4 (4 Suppl): 1–6. doi:10.1177/14732300760040S403. PMID 799998. S2CID 11289061.

- ^ Landau R, Achilladelis B, Scriabine A (1999). Pharmaceutical Innovation: Revolutionizing Human Health. Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-941901-21-5. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- ^ "Our Story". McNEIL-PPC, Inc. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ "Medication and Drugs". MedicineNet. 1996–2010. Archived from the original on 22 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ "SEC Info – Eastman Kodak Co – '8-K' for 6/30/94". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "FDA May Restrict Acetaminophen". Webmd. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "FDA limits acetaminophen in prescription combination products; requires liver toxicity warnings" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 13 January 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다. - ^ a b "FDA 의약품 안전 커뮤니케이션:처방 아세트아미노펜 제품은 복용량 단위당 325mg으로 제한되며 박스형 경고는 심각한 간부전의 가능성을 강조할 것이다."미국 식품의약국(FDA). 2011년 1월 13일.2011년 1월 18일 원본에서 보관.2011년 1월 13일 검색.이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

- ^ Perrone M (13 January 2011). "FDA orders lowering pain reliever in Vicodin". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ a b Harris G (13 January 2011). "F.D.A. Plans New Limits on Prescription Painkillers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ "FDA limits acetaminophen in prescription combination products; requires liver toxicity warnings". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 January 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다. - ^ "Liquid paracetamol for children: revised UK dosing instructions introduced" (PDF). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 14 November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Use Only as Directed". This American Life. Episode 505. Chicago. 20 September 2013. Public Radio International. WBEZ. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Gerth J, Miller TC (20 September 2013). "Use Only as Directed". ProPublica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Miller TC, Gerth J (20 September 2013). "Dose of Confusion". ProPublica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Orso D, Federici N, Copetti R, Vetrugno L, Bove T (October 2020). "Infodemic and the spread of fake news in the COVID-19-era". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 27 (5): 327–328. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000713. PMC 7202120. PMID 32332201.

- ^ Torjesen I (April 2020). "Covid-19: ibuprofen can be used for symptoms, says UK agency, but reasons for change in advice are unclear". BMJ. 369: m1555. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1555. PMID 32303505.

- ^ Rinott E, Kozer E, Shapira Y, Bar-Haim A, Youngster I (September 2020). "Ibuprofen use and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 26 (9): 1259.e5–1259.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.003. PMC 7289730. PMID 32535147.

- ^ Day M (March 2020). "Covid-19: ibuprofen should not be used for managing symptoms, say doctors and scientists". BMJ. 368: m1086. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1086. PMID 32184201.

- ^ "Section 1 – Chemical Substances". TGA Approved Terminology for Medicines (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government. July 1999. p. 97. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Macintyre P, Rowbotham D, Walker S (26 September 2008). Clinical Pain Management Second Edition: Acute Pain. CRC Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-340-94009-9. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- ^ "International Non-Proprietary Name for Pharmaceutical Preparations (Recommended List #4)" (PDF). WHO Chronicle. 16 (3): 101–111. March 1962. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Gaunt MJ (8 October 2013). "APAP: An Error-Prone Abbreviation". Pharmacy Times. October 2013 Diabetes. 79 (10). Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Acetaminophen". Physicians' Desk Reference (63rd ed.). Montvale, N.J.: Physicians' Desk Reference. 2009. pp. 1915–1916. ISBN 978-1-56363-703-2. OCLC 276871036.

- ^ Nam S. "IV, PO, and PR Acetaminophen: A Quick Comparison". Pharmacy Times. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "Acetaminophen and Codeine (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 29 June 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Codeine information hub". Therapeutic Goods Administration, Australian Government. 10 April 2018. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Dihydrocodeine (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 2 October 2019. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Oxycodone and Acetaminophen (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 11 November 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Hydrocodone and Acetaminophen (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Propoxyphene and Acetaminophen Tablets". Drugs.com. 21 June 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "APOHealth Paracetamol Plus Codeine & Calmative". Drugs.com. 3 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ a b Atkinson HC, Stanescu I, Anderson BJ (2014). "Increased Phenylephrine Plasma Levels with Administration of Acetaminophen". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (12): 1171–1172. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1313942. PMID 24645960.

- ^ "Ascorbic acid/Phenylephrine/Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Phenylephrine/Caffeine/Paracetamol dual relief". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Beechams Decongestant Plus With Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Senyuva H, Ozden T (2002). "Simultaneous High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Determination of Paracetamol, Phenylephrine HCl, and Chlorpheniramine Maleate in Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 40 (2): 97–100. doi:10.1093/chromsci/40.2.97. PMID 11881712.

- ^ Janin A, Monnet J (2014). "Bioavailability of paracetamol, phenylephrine hydrochloride and guaifenesin in a fixed-combination syrup versus an oral reference product". Journal of International Medical Research. 42 (2): 347–359. doi:10.1177/0300060513503762. PMID 24553480.

- ^ "Paracetamol – phenylephrine hydrochloride – guaifenesin". NPS MedicineWise. National Prescribing Service (Australia). Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Phenylephrine/Guaifenesin/Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 12 September 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Allen AL (June 2003). "The diagnosis of acetaminophen toxicosis in a cat". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 44 (6): 509–10. PMC 340185. PMID 12839249.

- ^ a b c Richardson JA (2000). "Management of acetaminophen and ibuprofen toxicoses in dogs and cats" (PDF). Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. 10 (4): 285–291. doi:10.1111/j.1476-4431.2000.tb00013.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2010.

- ^ a b Maddison JE, Page SW, Church D (2002). Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 260–1. ISBN 978-0702025730.

- ^ a b c "Pardale-V Oral Tablets". NOAH Compendium of Data Sheets for Animal Medicines. The National Office of Animal Health (NOAH). 11 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Villar D, Buck WB, Gonzalez JM (June 1998). "Ibuprofen, aspirin and acetaminophen toxicosis and treatment in dogs and cats". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 40 (3): 156–62. PMID 9610496.

- ^ Gwaltney-Brant S, Meadows I (March 2006). "The 10 Most Common Toxicoses in Dogs". Veterinary Medicine: 142–148. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ Dunayer E (2004). "Ibuprofen toxicosis in dogs, cats, and ferrets". Veterinary Medicine: 580–586. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011.

- ^ Johnston J, Savarie P, Primus T, Eisemann J, Hurley J, Kohler D (2002). "Risk assessment of an acetaminophen baiting program for chemical control of brown tree snakes on Guam: evaluation of baits, snake residues, and potential primary and secondary hazards". Environ Sci Technol. 36 (17): 3827–3833. Bibcode:2002EnST...36.3827J. doi:10.1021/es015873n. PMID 12322757.

- ^ Lendon B (7 September 2010). "Tylenol-loaded mice dropped from air to control snakes". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ Richards S (1 May 2012). "It's Raining Mice". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012.