CYP2C9

CYP2C9| CYP2C9 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| 식별자 | |||||||||||||

| 별칭 | CYP2C9, CPC9, CYP2C, CYP2C10, CYPIIC9, P450IIC9, 시토크롬 P450 패밀리 2 서브 패밀리 C 멤버 9, 시토크롬 P450 2C9 | ||||||||||||

| 외부 ID | OMIM: 601130 MGI: 1919553 호몰로진: 133566 GeneCard: CYP2C9 | ||||||||||||

| EC 번호 | 1.14.14.51 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| 직교체 | |||||||||||||

| 종 | 인간 | 마우스 | |||||||||||

| 엔트레스 | |||||||||||||

| 앙상블 | |||||||||||||

| 유니프로트 |

| ||||||||||||

| RefSeq(mRNA) | |||||||||||||

| RefSeq(단백질) |

| ||||||||||||

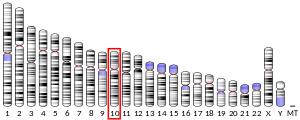

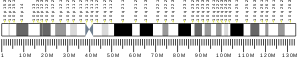

| 위치(UCSC) | Chr 10: 94.94 – 94.99Mb | Cr 19: 39.06 – 39.09Mb | |||||||||||

| PubMed 검색 | [3] | [4] | |||||||||||

| 위키다타 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

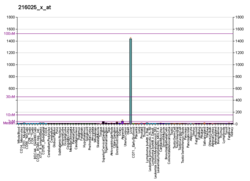

시토크롬 P450 패밀리 2 서브 패밀리 C 멤버 9(약칭 CYP2C9)는 효소 단백질이다. 이 효소는 약물을 포함한 제노바이오틱스와 지방산을 포함한 내생성 화합물의 대사, 산화작용에 의해 관여한다. 인간에서 단백질은 CYP2C9 유전자에 의해 암호화된다.[5][6] 이 유전자는 다형성이 강해 효소에 의한 신진대사의 효율에 영향을 미친다.[7]

함수

CYP2C9는 중요한 사이토크롬 P450 효소로, 이 효소는 산화작용에 의해 유전생물 및 내생성 화합물의 신진대사에 중요한 역할을 한다.[7] CYP2C9는 간 마이크로솜에서 사이토크롬 P450 단백질의 약 18%를 차지한다. 단백질은 주로 간, 십이지장, 소장에서 발현된다.[7] 와파린, 페니토인 등 치료지수가 좁은 약물과 아세노쿠마롤, 톨부타미드, 로사탄, 글리피지드, 일부 비스테로이드성 항염증제 등 일상적으로 처방되는 약물을 포함해 약 100여 가지의 치료제가 CYP2C9에 의해 대사된다. 이와는 대조적으로 알려진 외열 CYP2C9은 세로토닌과 같은 중요한 내생성 화합물을 대사하는 경우가 많으며, 에폭시겐 효소 활동으로 인해 다양한 다불포화 지방산이 이 지방산을 광범위한 생물학적 활성 산물로 변환시킨다.[8][9]

In particular, CYP2C9 metabolizes arachidonic acid to the following eicosatrienoic acid epoxide (EETs) stereoisomer sets: 5R,6S-epoxy-8Z,11Z,14Z-eicosatetrienoic and 5S,6R-epoxy-8Z,11Z,14Z-eicosatetrienoic acids; 11R,12S-epoxy-8Z,11Z,14Z-eicosatetrienoic and 11S,12R-epoxy-5Z,8Z,14Z-eicosatetrienoic acids; and 14R,15S-epoxy-5Z,8Z,11Z-eicosatetrainoic 및 14S,15R-epoxy-5Z,8Z,11Z-eicosatetrainoic acids. It likewise metabolizes docosahexaenoic acid to epoxydocosapentaenoic acids (EDPs; primarily 19,20-epoxy-eicosapentaenoic acid isomers [i.e. 10,11-EDPs]) and eicosapentaenoic acid to epoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (EEQs, primarily 17,18-EEQ and 14,15-EEQ isomers).[10] 동물 모델과 제한된 수의 인간 연구는 고혈압 감소, 심근경색 및 기타 심장에 대한 모욕으로부터 보호, 특정 암의 성장과 전이 촉진, 염증 억제, 혈관 형성 촉진, 그리고 신경 조직에 대한 다양한 작용 보유에 이러한 에폭시드를 포함한다.클러딩 조절 신경호르몬 방출 및 통증 인식 차단(Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid and epoxygenase 참조).[9]

In vitro studies on human and animal cells and tissues and in vivo animal model studies indicate that certain EDPs and EEQs (16,17-EDPs, 19,20-EDPs, 17,18-EEQs have been most often examined) have actions which often oppose those of another product of CYP450 enzymes (e.g. CYP4A1, CYP4A11, CYP4F2, CYP4F3A, and CYP4F3B) viz., 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid(20-HETE), 주로 혈압 조절, 혈관 혈전증, 암 성장 분야에서 활동한다(20-Hydroxyeicosatetraeno acid, epoxyeicosatetraeno acid, epoxydocosapentaeno acid sections 참조). 또한 이러한 연구는 eicosapentaenoic acids와 EEQs가 1) 고혈압과 통증 지각 감소에 있어 EETs보다 더 강력하고, 2) 염증을 억제하는 EETs에 대한 효력보다 더 강력하거나 같으며, 3) 혈관신생, 내피 세포 이동, 내피세포 증식을 억제한다는 점에서 EETs와 정반대의 작용을 한다는 것을 나타낸다.EETs는 각각의 시스템에 자극적인 효과를 가지고 있는 반면, 인간의 유방과 전립선암 세포 라인의 성장과 전이.[11][12][13][14] 오메가-3 지방산이 풍부한 식단의 섭취는 인간뿐만 아니라 동물에서도 EDP와 EEQ의 혈청 및 조직 수준을 극적으로 높이며, 인간에서는 식이성 오메가-3 지방산에 의해 야기되는 다불포화 지방산 대사물의 프로파일에서 단연 가장 두드러진 변화다.[11][14][15]

또한 CYP2C9는 리놀레산을 잠재적으로 매우 독성이 강한 제품인 버놀산(일명 백혈구톡신)과 코로나산(일명 이졸레쿠코톡신)에 대사시킬 수 있다. 이러한 리놀레산 에폭시드는 동물 모델에 다발성 장기 기능 상실과 급성 호흡 곤란을 야기하고 인간에게 이러한 신드롬에 기여할 수 있다.[9]

약리유전체학

CYP2C9 유전자는 다형성이 강하다.[16] 최소 20개의 단일 뉴클레오티드 다형성(SNP)이 효소 활성의 기능적 증거를 가지고 있는 것으로 보고되었다.[16] 실제로, 부작용 약물 반응(ADR)은 종종 유전적 다형성에 대한 CYP2C9 효소 활성의 예상치 못한 변화에서 비롯된다. 특히 와파린과 페니토인과 같은 CYP2C9 기형의 경우 유전적 다형성 또는 약물-약물 상호작용에 의해 대사능력이 저하되면 정상적인 치료용량에서 독성을 유발할 수 있다.[17][18]

CYP2C9*1이라는 라벨은 가장 흔하게 관찰되는 인간 유전자 변형에 PharmVar(PharmVar)에 의해 할당된다.[19] 다른 관련 변형은 PharmVar에 의해 연속된 숫자로 분류되며, 이는 앨러 라벨을 형성하기 위해 별표(별자) 문자 뒤에 쓰여진다.[20][21] 가장 잘 특징지어지는 두 개의 변종 알레르기는 CYP2C9*2 (NM_000771.3:c.430C)T, p이다.Arg144Cys, rs1799853)와 CYP2C9*3(NM_000771.3:c.1075A>C, p. Ile359Leu, rs1057910)[22]은 각각 30%와 80%의 효소 활성 감소를 유발했다.[16]

대사제 표현형

CYP2C9 기질 대사 능력에 기초하여 개인을 그룹별로 분류할 수 있다. 동질성 CYP2C9*1 변종의 운반체(즉, *1/*1 유전자형)는 광범위한 대사물(EM) 또는 일반 대사물로 지정된다.[23] 는 이형의 주에서 가장 CYP2C9*2 또는 CYP2C9*3 alleles의 통신사 중 한가지 alleles(*1/*2, *1/*3)의 지정된 중간 metabolizers이며 그 둘 이 alleles의 사체를, 동형 접합체의.(*2/*3, *2/*2 또는 *3/*3)— 가난한 metabolizers 예(IM)(PM)[24][25]결과적으로 변하지 않은 약의 저에게는, 대사율-그 비율.tabolite -는 PM이 더 높다.

A study of the ability to metabolize warfarin among the carriers of the most well-characterized CYP2C9 genotypes (*1, *2 and *3), expressed as percentage of the mean dose in patients with wild-type alleles (*1/*1), concluded that the mean warfarin maintenance dose was 92% in *1/*2, 74% in *1/*3, 63% in *2/*3, 61% in *2/*2 and 34% in 3/*3.[26]

CYP2C9*3은 아미노산 수열의 Ile359-Leu(I359L) 변화를 반영하며 [27]와파린 이외의 기질에 대한 야생형(CYP2C9*1)에 비해 촉매 활성도가 감소했다.[28] 그것의 보급률은 인종에 따라 다음과 같이 다양하다.

| CYP2C9 다형성 알레르 빈도(%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 아프리카계 미국인 | 블랙아프리카 | 피그미 | 아시아의 | 백인의 | |

| CYP2C9*3 | 2.0 | 0-2.3 | 0 | 1.1-3.6 | 3.3-16.2 |

변형 알레르기의 테스트 패널

2019년 분자병리학 약리유전학협회(PGx) 작업 그룹은 CYP2C9 시험 검사에 변종 알레르기의 최소 패널(1계위)과 변형 알레르기의 확장 패널(2계위)을 포함시킬 것을 권고했다.

PGx 작업 그룹에 의해 Tier 1로 권장되는 CYP2C9 변형 알레르기는 CYP2C9 *2, *3, *5, *6, *8 및 *11을 포함한다. 이 권고안은 CYP2C9 활동 및 기준 물질의 약물 반응 가용성에 대한 기능적 효과와 주요 민족 집단에서 주목할 만한 알레르 주파수에 기초하였다.

계층 2에 CYP2C9*12, *13 및 *15를 포함하려면 다음과 같은 CYP2C9 알레르기가 권장된다.[16]

CYP2C9*13은 exon 2(NM_000771.3:c.269T>C, 페이지 Leu90Pro, rs72558187)의 오식 변종에 의해 정의된다.[16] CYP2C9*13 유병률은 아시아 인구에서 약 1%이지만,[29] 백인에서는 이 변종 유병률이 거의 0이다.[30] 이 변종은 CYP2C9 유전자의 T269C 돌연변이에 의해 발생하며, 이는 제품 효소 단백질에서 프롤라인(L90P)으로 위치-90의 류신을 대체하게 된다. 이 잔류물은 기질 접근 지점 근처에 있으며 L90P 돌연변이는 Diclofenac과 Flurbiprofen과 같이 대사되는 CYP2C9의 친화력을 낮추고 신진대사를 느리게 한다.[29] 그러나 이 변형은 매우 낮은 다민족 부 알레르 주파수와 현재 사용할 수 있는 기준 자료가 부족하기 때문에 PGx 작업 그룹의 Tier 1 권장사항에 포함되지 않는다.[16] 2020년 현재 PharmVar 데이터베이스의 CYP2C9*13에 대한 증거 수준은 증거 수준이 확정적인 Tier 1 주장과 비교하여 제한적이다.[19]

추가 변형

임상적으로 중요한 유전자 변형 알레르기가 모두 PharmVar에 등록된 것은 아니다. 예를 들어, 2017년 연구에서 변종 rs2860905는 일반적인 변종 CYP2C9*2 및 CYP2C9*3보다 와파린 민감도(<4 mg/day)와의 연관성이 더 강한 것으로 나타났다.[31] 알레르 A(전지구 빈도 23%)는 알레르 G(77%)에 비해 와파린 투여량이 감소하는 것과 관련이 있다. 2009년 연구에 따르면 또 다른 변종인 rs4917639는 와파린 민감도에 강한 영향을 미치며, CYP2C9*2와 CYP2C9*3을 하나의 알레르기로 결합한 것과 거의 같다.[32] Rs4917639의 C alle은 전지구적 주파수가 19%이다. CC 또는 CA 유전자형이 있는 환자는 야생형 AA 유전자형이 있는 환자에 비해 와파린 투여량을 줄일 필요가 있을 수 있다.[33] 또 다른 변형인 RS7089580은 전지구적 주파수가 14%인 T알레일이 CYP2C9 유전자 발현 증가와 관련이 있다. RS7089580의 AT 및 TT 유전자형 운송업체는 야생형 AA 유전자형에 비해 CYP2C9 표현 수준을 증가시켰다. rs7089580 T alle에 의한 유전자 발현 증가는 와파린 대사율 증가와 와파린 선량 요건 증가로 이어진다. 2014년에 발표된 연구에서 AT 유전자형은 TT보다 약간 더 높은 발현을 보였지만, 둘 다 AA보다 훨씬 더 높은 발현을 보였다.[34] 또 다른 변종인 rs1934969(2012년과 2014년 연구)는 로사탄 대사 능력에 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타났다. 즉, TT 유전자형 운송업체가 AA 유전자형에 비해 로사탄의 CYP2C9 히드록실화 용량을 증가시켰으며, 그 결과 로사탄의 대사비율이 낮아졌다.[35][36]

CYP2C9 리간즈

CYP2C9의 대부분의 억제제들은 경쟁 억제제들이다. CYP2C9의 비경쟁 억제제로는 니페디핀,[37][38] 페네틸 이소티오시아네이트,[39] 메드록시프로게스테론 아세테이트[40], 6-히드록시플라본이 있다. 6-하이드록시플라본의 비경쟁적 결합 부위는 CYP2C9 효소의 보고된 알로스테리학적 결합 부위로 나타났다.[41]

다음은 CYP2C9의 선택된 기판, 유도체 및 억제제 표이다. 에이전트 클래스가 나열된 경우 클래스 내에 예외가 있을 수 있다.

CYP2C9의 억제제는 다음과 같이 효력별로 분류할 수 있다.

- 혈장 AUC 값이 5배 이상 증가하거나 간극이 80% 이상 감소하는 강함.[42]

- 보통은 혈장 AUC 값이 최소 2배 증가하거나 간극이 50-80%[42] 감소하는 경우.

- 혈장 AUC 값이 1.25배 이상 2배 이하로 증가하거나 간극이 20-50% 감소하는 약함.[42][43]

에폭시겐화효소 활성

CYP2C9는 다양한 롱체인 다불포화지방산을 이중(즉, 알켄) 결합으로 공격하여 신호 분자 역할을 하는 에폭시드 제품을 형성한다. It along with CYP2C8, CYP2C19, CYP2J2, and possibly CYP2S1 are the principle enzymes which metabolizes 1) arachidonic acid to various epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (also termed EETs); 2) linoleic acid to 9,10-epoxy octadecaenoic acids (also termed vernolic acid, linoleic acid 9:10-oxide, or leukotoxin) and 12,13-epoxy-octadecaenoic (also termed coronaic산, 리놀레산 12,13-산화수소 또는 이솔레우코톡신); 3) 다양한 에폭시도코사펜타에노산(EDP라고도 함)에 대한 docosahexaenoic acid (EEQs라고도 함).[9] 동물 모델 연구는 이러한 에폭시드를 조절하는데 관련시킨다: 고혈압, 심근경색 및 기타 심장에 대한 모욕, 다양한 암의 성장, 염증, 혈관 형성 및 통증 인식. 제한된 연구들은 이 에폭시드가 사람에게 유사하게 작용할 수 있다는 것을 암시하지만 증명되지는 않았다.d epoxygenase 페이지).[9] 오메가-3 지방산이 풍부한 식단의 섭취는 오메가-3 지방산의 EDP와 EEQ 대사물의 혈청 및 조직 수준을 극적으로 상승시키기 때문에 동물과 인간에서 그리고 인간에서 일어나는 다불포화 지방산 대사물의 프로파일에서 가장 두드러진 변화다.y 오메가-3 지방산, eicosapentaenoic acids 및 EEQs는 적어도 식이 요법 오메가-3 지방산에 기인하는 유익한 효과의 일부를 담당할 수 있다.[11][14][15]

참고 항목

참조

- ^ Jump up to: a b c GRCh38: 앙상블 릴리스 89: ENSG00000138109 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ Jump up to: a b c GRCm38: 앙상블 릴리스 89: ENSMUSG000067231 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Romkes M, Faletto MB, Blaisdell JA, Raucy JL, Goldstein JA (April 1991). "Cloning and expression of complementary DNAs for multiple members of the human cytochrome P450IIC subfamily". Biochemistry. 30 (13): 3247–55. doi:10.1021/bi00227a012. PMID 2009263.

- ^ Inoue K, Inazawa J, Suzuki Y, Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP, Abe T (September 1994). "Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of chromosomal localization of three human cytochrome P450 2C genes (CYP2C8, 2C9, and 2C10) at 10q24.1". The Japanese Journal of Human Genetics. 39 (3): 337–43. doi:10.1007/BF01874052. PMID 7841444.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "CYP2C9". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. 29 March 2021.

This gene encodes a member of the cytochrome P450 superfamily of enzymes. The cytochrome P450 proteins are monooxygenases which catalyze many reactions involved in drug metabolism and synthesis of cholesterol, steroids and other lipids. This protein localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum and its expression is induced by rifampin. The enzyme is known to metabolize many xenobiotics, including phenytoin, tolbutamide, ibuprofen and S-warfarin. Studies identifying individuals who are poor metabolizers of phenytoin and tolbutamide suggest that this gene is polymorphic. The gene is located within a cluster of cytochrome P450 genes on chromosome 10q24.

이 글은 공개 도메인에 있는 이 출처의 텍스트를 통합한다..

이 글은 공개 도메인에 있는 이 출처의 텍스트를 통합한다.. - ^ Rettie AE, Jones JP (2005). "Clinical and toxicological relevance of CYP2C9: drug-drug interactions and pharmacogenetics". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 45: 477–94. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095821. PMID 15822186.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Spector AA, Kim HY (April 2015). "Cytochrome P450 epoxygenase pathway of polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1851 (4): 356–65. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.07.020. PMC 4314516. PMID 25093613.

- ^ Westphal C, Konkel A, Schunck WH (November 2011). "CYP-eicosanoids--a new link between omega-3 fatty acids and cardiac disease?". Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators. 96 (1–4): 99–108. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2011.09.001. PMID 21945326.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Fleming I (October 2014). "The pharmacology of the cytochrome P450 epoxygenase/soluble epoxide hydrolase axis in the vasculature and cardiovascular disease". Pharmacological Reviews. 66 (4): 1106–40. doi:10.1124/pr.113.007781. PMID 25244930.

- ^ Zhang G, Kodani S, Hammock BD (January 2014). "Stabilized epoxygenated fatty acids regulate inflammation, pain, angiogenesis and cancer". Progress in Lipid Research. 53: 108–23. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2013.11.003. PMC 3914417. PMID 24345640.

- ^ He J, Wang C, Zhu Y, Ai D (May 2016). "Soluble epoxide hydrolase: A potential target for metabolic diseases". Journal of Diabetes. 8 (3): 305–13. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.12358. PMID 26621325.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wagner K, Vito S, Inceoglu B, Hammock BD (October 2014). "The role of long chain fatty acids and their epoxide metabolites in nociceptive signaling". Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators. 113–115: 2–12. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2014.09.001. PMC 4254344. PMID 25240260.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fischer R, Konkel A, Mehling H, Blossey K, Gapelyuk A, Wessel N, et al. (June 2014). "Dietary omega-3 fatty acids modulate the eicosanoid profile in man primarily via the CYP-epoxygenase pathway". Journal of Lipid Research. 55 (6): 1150–64. doi:10.1194/jlr.M047357. PMC 4031946. PMID 24634501.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Pratt VM, Cavallari LH, Del Tredici AL, Hachad H, Ji Y, Moyer AM, et al. (September 2019). "Recommendations for Clinical CYP2C9 Genotyping Allele Selection: A Joint Recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology and College of American Pathologists". The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 21 (5): 746–755. doi:10.1016/j.jmoldx.2019.04.003. PMC 7057225. PMID 31075510.

- ^ García-Martín E, Martínez C, Ladero JM, Agúndez JA (2006). "Interethnic and intraethnic variability of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 polymorphisms in healthy individuals". Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 10 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1007/BF03256440. PMID 16646575. S2CID 25261882.

- ^ Rosemary J, Adithan C (January 2007). "The pharmacogenetics of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19: ethnic variation and clinical significance". Current Clinical Pharmacology. 2 (1): 93–109. doi:10.2174/157488407779422302. PMID 18690857.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "PharmVar Database of CYP2C9".

- ^ Botton MR, Lu X, Zhao G, Repnikova E, Seki Y, Gaedigk A, Schadt EE, Edelmann L, Scott SA (November 2019). "Structural variation at the CYP2C locus: Characterization of deletion and duplication alleles". Human Mutation. 40 (11): e37–e51. doi:10.1002/humu.23855. PMC 6810756. PMID 31260137.

- ^ Botton, Whirl-Carrillo, Tredici, Sangkuhl, Cavallari, Agúndez, Duconge J, Lee, Woodahl, Claudio-Campos, Daly, Klein, Pratt, Scott, Gaedigk (June 2020). "PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2C19". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 109 (2): 352–366. doi:10.1002/cpt.1973. PMC 7769975. PMID 32602114.

- ^ Sullivan-Klose TH, Ghanayem BI, Bell DA, Zhang ZY, Kaminsky LS, Shenfield GM, Miners JO, Birkett DJ, Goldstein JA (August 1996). "The role of the CYP2C9-Leu359 allelic variant in the tolbutamide polymorphism". Pharmacogenetics. 6 (4): 341–9. doi:10.1097/00008571-199608000-00007. PMID 8873220.

- ^ Tornio A, Backman JT (2018). "Cytochrome P450 in Pharmacogenetics: An Update". Pharmacogenetics. Advances in Pharmacology (San Diego, Calif.). 83. pp. 3–32. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2018.04.007. hdl:10138/300396. ISBN 9780128133811. PMID 29801580.

- ^ Caudle KE, Rettie AE, Whirl-Carrillo M, Smith LH, Mintzer S, Lee MT, et al. (November 2014). "Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for CYP2C9 and HLA-B genotypes and phenytoin dosing". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 96 (5): 542–8. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.159. PMC 4206662. PMID 25099164.

- ^ Sychev DA, Shuev GN, Suleymanov SS, Ryzhikova KA, Mirzaev KB, Grishina EA, et al. (2017). "SLCO1B1 gene-polymorphism frequency in Russian and Nanai populations". Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine. 10: 93–99. doi:10.2147/PGPM.S129665. PMC 5386602. PMID 28435307.

- ^ Topić E, Stefanović M, Samardzija M (January 2004). "Association between the CYP2C9 polymorphism and the drug metabolism phenotype". Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 42 (1): 72–8. doi:10.1515/CCLM.2004.014. PMID 15061384. S2CID 22090671.

- ^ CYP2C9 alle 명명법

- ^ Sullivan-Klose TH, Ghanayem BI, Bell DA, Zhang ZY, Kaminsky LS, Shenfield GM, Miners JO, Birkett DJ, Goldstein JA, The role of the CYP2C9-Leu359 allelic variant in the tolbutamide polymorphism, Pharmacogenetics. 1996 Aug; 6(4):341–9

- ^ Jump up to: a b Saikatikorn Y, Lertkiatmongkol P, Assawamakin A, Ruengjitchatchawalya M, Tongsima S (November 2010). "Study of the Structural Pathology Caused by CYP2C9 Polymorphisms towards Flurbiprofen Metabolism Using Molecular Dynamics Simulation.". In Chan JH, Ong YS, Cho SB (eds.). International Conference on Computational Systems-Biology and Bioinformatics. Communications in Computer and Information Science. 115. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 26–35. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-16750-8_3. ISBN 978-3-642-16749-2.

- ^ "rs72558187 allele frequency". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

이 글은 공개 도메인에 있는 이 출처의 텍스트를 통합한다..

이 글은 공개 도메인에 있는 이 출처의 텍스트를 통합한다.. - ^ Claudio-Campos K, Labastida A, Ramos A, Gaedigk A, Renta-Torres J, Padilla D, et al. (2017). "Warfarin Anticoagulation Therapy in Caribbean Hispanics of Puerto Rico: A Candidate Gene Association Study". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 8: 347. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00347. PMC 5461284. PMID 28638342.

- ^ Takeuchi F, McGinnis R, Bourgeois S, Barnes C, Eriksson N, Soranzo N, et al. (March 2009). "A genome-wide association study confirms VKORC1, CYP2C9, and CYP4F2 as principal genetic determinants of warfarin dose". PLOS Genetics. 5 (3): e1000433. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000433. PMC 2652833. PMID 19300499.

- ^ "Clinical Annotation for rs4917639 (CYP2C9); warfarin; (level 2A Dosage)".

- ^ Hernandez W, Aquino-Michaels K, Drozda K, Patel S, Jeong Y, Takahashi H, et al. (June 2015). "Novel single nucleotide polymorphism in CYP2C9 is associated with changes in warfarin clearance and CYP2C9 expression levels in African Americans". Translational Research. 165 (6): 651–7. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2014.11.006. PMC 4433569. PMID 25499099.

- ^ Dorado P, Gallego A, Peñas-LLedó E, Terán E, LLerena A (August 2014). "Relationship between the CYP2C9 IVS8-109A>T polymorphism and high losartan hydroxylation in healthy Ecuadorian volunteers". Pharmacogenomics. 15 (11): 1417–21. doi:10.2217/pgs.14.85. PMID 25303293.

- ^ Hatta FH, Teh LK, Helldén A, Hellgren KE, Roh HK, Salleh MZ, et al. (July 2012). "Search for the molecular basis of ultra-rapid CYP2C9-catalysed metabolism: relationship between SNP IVS8-109A>T and the losartan metabolism phenotype in Swedes". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 68 (7): 1033–42. doi:10.1007/s00228-012-1210-0. PMID 22294058. S2CID 8779233.

- ^ Bourrié M, Meunier V, Berger Y, Fabre G (February 1999). "Role of cytochrome P-4502C9 in irbesartan oxidation by human liver microsomes". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 27 (2): 288–96. PMID 9929518.

- ^ Salsali M, Holt A, Baker GB (February 2004). "Inhibitory effects of the monoamine oxidase inhibitor tranylcypromine on the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and CYP2D6". Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 24 (1): 63–76. doi:10.1023/B:CEMN.0000012725.31108.4a. PMID 15049511. S2CID 22669449.

- ^ Nakajima M, Yoshida R, Shimada N, Yamazaki H, Yokoi T (August 2001). "Inhibition and inactivation of human cytochrome P450 isoforms by phenethyl isothiocyanate". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 29 (8): 1110–3. PMID 11454729.

- ^ Zhang JW, Liu Y, Li W, Hao DC, Yang L (July 2006). "Inhibitory effect of medroxyprogesterone acetate on human liver cytochrome P450 enzymes". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 62 (7): 497–502. doi:10.1007/s00228-006-0128-9. PMID 16645869. S2CID 22333299.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Si D, Wang Y, Zhou YH, Guo Y, Wang J, Zhou H, Li ZS, Fawcett JP (March 2009). "Mechanism of CYP2C9 inhibition by flavones and flavonols". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 37 (3): 629–34. doi:10.1124/dmd.108.023416. PMID 19074529. S2CID 285706.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap Flockhart DA (2007). "Drug Interactions: Cytochrome P450 Drug Interaction Table". Indiana University School of Medicine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "In silico metabolism studies of dietary flavonoids by CYP1A2 and CYP2C9".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t FASS(약물 공식): "Facts for prescribers (Fakta för förskrivare)". Swedish environmental classification of pharmaceuticals (in Swedish).

- ^ Guo Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Chen X, Si D, Zhong D, Fawcett JP, Zhou H (June 2005). "Role of CYP2C9 and its variants (CYP2C9*3 and CYP2C9*13) in the metabolism of lornoxicam in humans". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 33 (6): 749–53. doi:10.1124/dmd.105.003616. PMID 15764711. S2CID 24199800.

- ^ "ketoprofen C16H14O3". PubChem.

- ^ 압둘라 알카탄 & 엠마 알살라멘(2021) 클로피도그렐 치료의 임상적 효과와 안전에 영향을 미치는 상 I 대사 효소와 관련된 유전자의 다형성, 약물대사 & 독성학 전문가 의견, DOI: 10.1080/174255.2021.19.295249

- ^ Bland TM, Haining RL, Tracy TS, Callery PS (October 2005). "CYP2C-catalyzed delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolism: kinetics, pharmacogenetics and interaction with phenytoin". Biochemical Pharmacology. 70 (7): 1096–103. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2005.07.007. PMID 16112652.

- ^ Patton AL, Seely KA, Yarbrough AL, Fantegrossi W, James LP, McCain KR, Fujiwara R, Prather PL, Moran JH, Radominska-Pandya A (April 2018). "Altered metabolism of synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 by human cytochrome P450 2C9 and variants". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 498 (3): 597–602. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.03.028. PMC 6425723. PMID 29522717.

- ^ Stout SM, Cimino NM (February 2014). "Exogenous cannabinoids as substrates, inhibitors, and inducers of human drug metabolizing enzymes: a systematic review". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 46 (1): 86–95. doi:10.3109/03602532.2013.849268. PMID 24160757. S2CID 29133059.

- ^ Miyazawa M, Shindo M, Shimada T (May 2002). "Metabolism of (+)- and (-)-limonenes to respective carveols and perillyl alcohols by CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 in human liver microsomes". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 30 (5): 602–7. doi:10.1124/dmd.30.5.602. PMID 11950794.

- ^ Kosuge K, Jun Y, Watanabe H, Kimura M, Nishimoto M, Ishizaki T, Ohashi K (October 2001). "Effects of CYP3A4 inhibition by diltiazem on pharmacokinetics and dynamics of diazepam in relation to CYP2C19 genotype status". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 29 (10): 1284–9. PMID 11560871.

- ^ Lutz JD, VandenBrink BM, Babu KN, Nelson WL, Kunze KL, Isoherranen N (December 2013). "Stereoselective inhibition of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 by fluoxetine and its metabolite: implications for risk assessment of multiple time-dependent inhibitor systems". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. American Society for Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics (ASPET). 41 (12): 2056–65. doi:10.1124/dmd.113.052639. PMC 3834134. PMID 23785064.

- ^ "Verapamil: Drug information. Lexicomp". UpToDate. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "CANDESARTAN - candesartan tablet". DailyMed. 27 June 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "IRBESARTAN - irbesartan tablet". DailyMed. 4 September 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "EDARBI- azilsartan kamedoxomil tablet". DailyMed. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Kimura Y, Ito H, Ohnishi R, Hatano T (January 2010). "Inhibitory effects of polyphenols on human cytochrome P450 3A4 and 2C9 activity". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 48 (1): 429–35. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2009.10.041. PMID 19883715.

- ^ Pan X, Tan N, Zeng G, Zhang Y, Jia R (October 2005). "Amentoflavone and its derivatives as novel natural inhibitors of human Cathepsin B". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (20): 5819–25. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2005.05.071. PMID 16084098.

- ^ "Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers".

- ^ Jump up to: a b He N, Zhang WQ, Shockley D, Edeki T (February 2002). "Inhibitory effects of H1-antihistamines on CYP2D6- and CYP2C9-mediated drug metabolic reactions in human liver microsomes". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 57 (12): 847–51. doi:10.1007/s00228-001-0399-0. PMID 11936702. S2CID 601644.

- ^ Park JY, Kim KA, Kim SL (November 2003). "Chloramphenicol is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 isoforms CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 in human liver microsomes". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 47 (11): 3464–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.11.3464-3469.2003. PMC 253795. PMID 14576103.

- ^ Robertson P, DeCory HH, Madan A, Parkinson A (June 2000). "In vitro inhibition and induction of human hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes by modafinil". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 28 (6): 664–71. PMID 10820139.

- ^ Yamaori S, Koeda K, Kushihara M, Hada Y, Yamamoto I, Watanabe K (1 January 2012). "Comparison in the in vitro inhibitory effects of major phytocannabinoids and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons contained in marijuana smoke on cytochrome P450 2C9 activity". Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 27 (3): 294–300. doi:10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-11-RG-107. PMID 22166891.

- ^ Briguglio M, Hrelia S, Malaguti M, Serpe L, Canaparo R, Dell'Osso B, et al. (December 2018). "Food Bioactive Compounds and Their Interference in Drug Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Profiles". Pharmaceutics. 10 (4): 277. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics10040277. PMC 6321138. PMID 30558213.

- ^ Huang TY, Yu CP, Hsieh YW, Lin SP, Hou YC (September 2020). "Resveratrol stereoselectively affected (±)warfarin pharmacokinetics and enhanced the anticoagulation effect". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 15910. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1015910H. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-72694-0. PMC 7522226. PMID 32985569.

추가 읽기

- Goldstein JA, de Morais SM (December 1994). "Biochemistry and molecular biology of the human CYP2C subfamily". Pharmacogenetics. 4 (6): 285–99. doi:10.1097/00008571-199412000-00001. PMID 7704034.

- Miners JO, Birkett DJ (June 1998). "Cytochrome P4502C9: an enzyme of major importance in human drug metabolism". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 45 (6): 525–38. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00721.x. PMC 1873650. PMID 9663807.

- Smith G, Stubbins MJ, Harries LW, Wolf CR (December 1998). "Molecular genetics of the human cytochrome P450 monooxygenase superfamily". Xenobiotica. 28 (12): 1129–65. doi:10.1080/004982598238868. PMID 9890157.

- Henderson RF (June 2001). "Species differences in the metabolism of olefins: implications for risk assessment". Chemico-Biological Interactions. 135–136: 53–64. doi:10.1016/S0009-2797(01)00170-3. PMID 11397381.

- Xie HG, Prasad HC, Kim RB, Stein CM (November 2002). "CYP2C9 allelic variants: ethnic distribution and functional significance". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 54 (10): 1257–70. doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00076-5. PMID 12406644.

- Palkimas MP, Skinner HM, Gandhi PJ, Gardner AJ (June 2003). "Polymorphism induced sensitivity to warfarin: a review of the literature". Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis. 15 (3): 205–12. doi:10.1023/B:THRO.0000011376.12309.af. PMID 14739630. S2CID 20497247.

- Daly AK, Aithal GP (August 2003). "Genetic regulation of warfarin metabolism and response". Seminars in Vascular Medicine. 3 (3): 231–8. doi:10.1055/s-2003-44458. PMID 15199455.

외부 링크

| 위키미디어 커먼즈에는 CYP2C9과 관련된 미디어가 있다. |

- PharmGKB: CYP2C9용 PGx 유전자 정보 주석

- SuperCYP: 약물-사이토크롬-상호작용 데이터베이스

- CYP2C9용 PharmVar 데이터베이스

- UCSC 게놈 브라우저의 인간 CYP2C9 유전체 위치 및 CYP2C9 유전자 세부 정보 페이지.