기독교 신학

Christian theology| 시리즈의 일부 |

| 기독교 |

|---|

| 의 시리즈의 일부 |

| 이력 기독교 신학 |

|---|

|

| |

기독교 신학은 기독교 신앙과 [1]실천의 신학이다.이러한 연구는 주로 기독교 전통뿐만 아니라 구약성서와 신약성서의 본문에 초점을 맞추고 있다.기독교 신학자들은 성경적 해석, 이성적 분석, 주장을 사용한다.신학자는 다음과 같은 다양한 이유로 기독교 신학을 연구할 수 있다.

- 그들이 기독교의 교리를[2] 더 잘 이해할 수 있도록 돕다

- 기독교와 다른 전통을[3] 비교하다

- 반대와 비판으로부터 기독교를 지키다

- 기독교[4] 교회의 개혁을 촉진하다

- 기독교의[5] 전파를 돕다

- 현재의 상황 또는 인식된[6] 요구에 대처하기 위해 기독교 전통의 자원을 이용한다.

기독교 신학은 기독교가 세계적인 종교이긴 하지만, 특히 전근대 유럽에서 기독교 이외의 서구 문화의 많은 부분에 스며들었다.

의 전통

기독교 신학은 기독교 전통의 주요 분파마다 크게 다르다.가톨릭, 정교회, 개신교.각각의 전통은 신학교와 장관 구성에 대한 그들만의 독특한 접근 방식을 가지고 있다.

기독교 신학의 한 분야로서의 체계적 신학은 기독교 신앙과 [7]믿음에 대한 질서 있고 합리적이며 일관성 있는 설명을 형성합니다.체계적 신학은 기독교의 근본적 성서에 바탕을 두고 동시에 역사, 특히 철학적 진화를 통해 기독교 교리의 발전을 조사한다.신학적 사고 체계에 내재된 것은 광범위하게 그리고 특히 적용할 수 있는 방법의 개발이다.기독교의 체계적 신학은 일반적으로 다음을 탐구한다.

- 신(신학상 적절)

- 신의 속성

- 삼위일체 기독교 신봉하는 삼위일체

- 성서 해석학 – 성서 원문의 해석

- 창조

- 의 섭리

- Theodic – 악에 대한 온화한 신의 관용 설명

- ★★★

- 해마티올로지 – 죄에 대한 연구

- 기독교학 – 그리스도의 본질과 인물을 연구하는 학문

- 기흉학 – 성령 연구

- 소테리올로지 – 구원의 연구

- 교회학 – 기독교 교회 연구

- 미솔로지 – 기독교 메시지와 선교에 대한 연구

- 영성과 신비주의

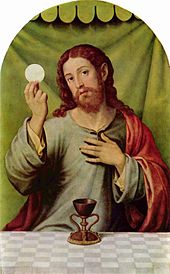

- 성찬 신학

- 종말론 – 인류의 궁극적 운명

- 사후세계

의 계시

계시란 신과의 능동적 또는 수동적 의사소통을 통해 무언가를 드러내거나 드러내거나 드러내는 것으로, 신으로부터 직접 또는 [8]천사와 같은 대리인을 통해 발생할 수 있습니다.그러한 접촉을 경험한 것으로 알려진 사람은 종종[by whom?] 예언자라고 불린다.기독교는 일반적으로 성경을 신성하거나 초자연적으로 드러났거나 영감을 받았다고 생각한다.그러한 계시가 항상 신이나 천사의 존재를 필요로 하는 것은 아니다.예를 들어, 가톨릭 신자들이 내부 장소라고 부르는 개념에서, 초자연적 폭로는 수신자가 듣는 내면의 목소리만을 포함할 수 있다.

토마스 아퀴나스 (1225년-1274년)는 기독교에서 처음 두 가지 유형의 계시, 즉 일반적인 계시와 특별한 [citation needed]계시를 설명했다.

- 생성된 질서의 관찰을 통해 일반적인 폭로가 발생합니다.그러한 관찰은 논리적으로 신의 존재와 신의 속성 중 일부와 같은 중요한 결론으로 이어질 수 있다.일반적인 계시는 또한 기독교 [citation needed]변증론의 한 요소이다.

- 삼위일체나 육신과 같은 특정 세부사항은 성경의 가르침에서 드러났듯이 특별한 계시를 통해서만 추론할 수 있습니다.

영감

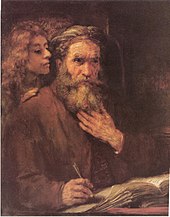

성경에는 저자들이 그들의 메시지에 대해 신성한 영감을 주장하거나 그러한 영감이 다른 사람들에게 미치는 영향을 보고하는 많은 구절이 포함되어 있다.기록된 계시(예: 모세가 돌판에 새겨진 십계명을 받는 것)에 대한 직접적인 설명 외에도, 구약성서의 예언자들은 종종 다음과 같은 구절을 사용하여 계시의 서문을 작성함으로써 그들의 메시지가 신의 기원이었다고 주장했습니다: "그러므로 주를 말한다." (예: 1 Kgs 12:22–241; Chr 17:4; Jer1; 351).3; Ezek 2:4, Zech 7:9 등).베드로의 두 번째 서한은 "성경의 예언은 인간의 의지에 의해 만들어진 것이 아니라, 사람들은 성령에 [9]의해 옮겨지면서 하나님으로부터 말을 받았다"고 주장합니다. 베드로의 두 번째 서한은 또한 바울의 글이 영감을 받았다는 것을 암시합니다.

많은[quantify] 기독교인들은 티모시에게 보낸 바울의 편지에서 "모든 성경은 하나님의 영감으로 주어지고 유익하다"는 증거로 인용하고 있다. 여기서 성 바울은 티모시가 "영원히" (15절)로부터 성경을 알았기 때문에 구약성경을 언급하고 있다.예를 들어, 신학자 C와 같은 다른 사람들은 이 구절을 대신 읽을 수 있는 책을 제공한다. H. Dodd는 다음과 같이 "아마도 렌더링될 것"이라고 제안합니다: "영감받은 모든 성경도 유용하다." 비슷한 번역이 New English Bible, Revision English Bible, New English Standard Version에서 (각주 대용으로) 나타난다.[10]라틴어 벌게이트는 읽을 [11]수 있다.그러나 다른 사람들은 "전통적인" 해석을 옹호한다; 다니엘 B. Wallace는 이 대안을 "아마 최고의 [12]번역은 아닐 것"이라고 말한다.

일부 현대 영어판 성경은 라틴어 어근인 "바람을 불거나 숨을 쉬다"[13]를 가진 영감이라는 단어를 피하면서 "신으로부터 숨을 내쉬다" 또는 "신에 의해 숨을 내쉬다"로 테오뉴스토를 표현한다.

권위

기독교는 일반적으로 성서로 알려진 합의된 책들을 권위적이고 성령의 영감 아래 인간 작가들에 의해 쓰여진 것으로 간주한다.일부 기독교인들은 성경이 전혀 오류가 없고 역사적,[14][15][need quotation to verify][16][17][18][19] 과학적 부분들을 포함하여 모순이 없다고 믿거나 무오류라고 믿는다.

일부 기독교인들은 성경이 스스로를 신성한 영감으로 언급할 수도 없고 또한 잘못되거나 잘못될 수도 있다고 추론한다.성경이 신성한 영감을 받았다면, 영감의 원천은 신성한 것이므로, 만들어지는 것에 실수나 오류의 대상이 되지 않을 것이기 때문이다.그들에게 있어서 신성한 영감, 무질서, 무오류라는 교리는 떼려야 뗄 수 없이 연결되어 있다.성서적 진실성의 개념은 현재의 성서 본문이 완전하고 오류 없이 완전하며 성서 본문의 무결성이 결코 훼손되거나 [14]훼손되지 않았음을 암시함으로써 무적의 더 큰 개념이다.역사학자들은[which?] 성경책들이 [20]쓰여진 지 수백 년이 지난 후에 성경의 무적의 원칙이 채택되었다고[when?] 언급하거나 주장한다.

의

구약성서의 내용은 히브리어 성경과 동일하며, 책의 구분과 순서가 바뀌었지만, 가톨릭 구약성서에는 이단성서로 알려진 추가 텍스트가 포함되어 있다.개신교에서는 구약성경 경전 39권을, 로마 가톨릭과 동방 기독교에서는 46권을 [citation needed]경전으로 인정한다.가톨릭 신자와 개신교 신자 모두 같은 27권의 신약성경 경전을 사용한다.

초기 기독교인들은 히브리 경전을 코이네 그리스어로 번역한 Septuagint를 사용했다.기독교는 이후에 신약성서가 될 다양한 추가 문서들을 지지했다.4세기에 일련의 시노드들, 특히 서기 393년의 하마 시노드는 오늘날 가톨릭 신자들이 사용하는 구약성서의 46권 캐논(및 모두가 사용하는 신약성서의 27권 캐논)과 같은 내용의 목록을 작성했다.확실한 목록은 초기 에큐메니컬 [21]위원회에서 나온 것이 아니다.400년경, 제롬은 로마 주교의 주장으로 초기 시노드의 결정에 따라 성경의 최종 라틴어 판인 벌게이트를 제작했다.이 과정은 신약성서의 규범을 효과적으로 설정하지만, 이 [citation needed]시간 이후에 사용되는 다른 규범 목록의 예는 존재합니다.

16세기 개신교 개혁 기간 동안 일부 개혁가들은 구약성서의 다른 표준 목록을 제안했다.9월경에는 나왔지만 유대교 경전에는 나오지 않았던 본문은 결국 개신교 경전에서는 사라졌다.가톨릭 성경에서는 이 문서들을 신학적 책으로 분류하는 반면, 개신교적 맥락에서는 이 문서들을 '아포크리파라고 부른다.

신학:

기독교에서 신은 우주의 창조자이자 보호자이다.신은 우주의 유일한 궁극적인 힘이지만 그것과는 다르다.성경은 결코 신을 비인간적이라고 말하지 않는다.대신, 그것은 말하고, 보고, 듣고, 행동하고, 사랑하는 그를 개인적인 용어로 지칭한다.신은 의지와 인격을 가지고 있는 것으로 이해되며, 모두 강력하고 신성하며 자애로운 존재이다.그는 성경에서 주로 사람들과 그들의 [22]구원에 관심을 갖는 것으로 묘사되어 있다.

의

★★

많은 개혁 신학자들은 전달 가능한 속성(인간도 가질 수 있는 속성)과 전달 불가능한 속성(신에게만 [23]속하는 속성)을 구별한다.

★★★

기독교[24] 신학에서 신에게 귀속되는 몇 가지 속성은 다음과 같습니다.[citation needed]

- Aseity: "신은 너무 독립적이어서 [25]우리를 필요로 하지 않는다."이는 신이 마치 필요한 것처럼 인간의 손에 의해 섬기지 않는다는 내용의 17장 25절(NIV)에 근거하고 있다.이것은 종종 신의 존재와 자급자족과 관련이 있다.

- 영원신은 시간적 영역 너머에 존재한다.

- 자애로움신은 인간에게 조건과 조건 없이 은총과 선물을 베푸는 것이다.

- 성하-신은 죄로부터 분리되어 있고 부패할 수 없다는 것이다.이사야 6장 3절과 요한계시록 4장 8절에 나오는 "성스러운, 거룩한, 거룩한"의 후렴구를 보면,

- Immanence -신은 초월적이고 성스러우시지만 접근할 수 있고 역동적으로 경험할 수 있습니다.

- 불변성신의 본질은 변하지 않는다.

- 불가항력신이 감정이나 고통을 경험하지 않는다는 것(특히 개방적인 유신론에 의해 논쟁되는 더 논란이 많은 교의).

- 흠잡을 데 없다신은 실수할 수 없다.

- 청순성신은 육체적 구성이 없다.이와 관련된 개념은 예수의 요한복음 4장 24절 "하나님은 영이다"라는 발언에서 파생된 신의 영성입니다.

- 사랑—그 신은 보살핌과 자비이다. 요한복음 4장 16절은 "신은 사랑이다"라고 말한다.

- 미션: 신은 최고의 해방자입니다.전통적으로 신의 선교는 이 목록에 포함되지 않지만, 데이비드 보쉬는 "선교는 주로 교회의 활동이 아니라 신의 [26]속성"이라고 주장해왔다.

- 옴니베네볼런스--신은 전지전능하다.신의 전지전능은 그가 "모든 것이 선하다"고 말한다.

- 전능성-신은 위대하시거나 전능하신 분이다.

- 만능--신은 최고의 존재이며, 어디에나 항상 존재하며, 현실의 모든 지각 또는 모든 것을 수용하는 기반이다.

- 전지과학--신은 최고 또는 모든 것을 알고 있다.

- 일체성:신은 타의 추종을 불허하며, 또한 모든 신성한 속성이 그 자체로 인스턴스화된다는 것(신의 질적 무한함)일신교와 신의 간결함을 참조하십시오.

- Providence -신은 그의 창조물을 흥미와 헌신을 가지고 지켜봐 주신다.신의 섭리는 보통 그의 세계에서의 활동을 언급하지만, 그것은 또한 우주에 대한 그의 배려를 의미하며, 따라서 하나의 속성이다.보통 하느님이 우주의 존재와 자연질서를 지속적으로 지탱하는 것을 가리키는 "일반 섭리"와 인간의 삶에 [27]대한 하느님의 특별한 개입을 의미하는 "특별 섭리" 사이에 구별이 만들어진다.'주권'도 참조하십시오.

- 정의신은 인간 행동의 가장 위대하거나 유일한 척도이다.신의 의는 그의 거룩함, 정의, 또는 그리스도를 통한 그의 구원 활동을 가리킬 수 있다.

- 초월성-신은 물리적 법칙의 자연 영역을 넘어 존재하며 [28]그에 얽매이지 않는다. 그는 또한 일반적이거나 특별한 자기 계시를 떠나 완전히 다른 존재이며 이해할 수 없다.

- 삼위일체 기독교인들에 의해 기독교의 신은 성부, 성자, 성령의 "세뇌 없는" 존재로 이해되며, 그의 "단일성"과 완전히 일치한다. 즉, 자연 안과 저 너머에 있는 하나의 무한한 존재이다.삼위일체 사람은 신의 차원에서도 개인적인 관계를 나타내기 때문에, 그는 우리에 대한 그의 관계와 자신에 대한 그의 관계 모두에서 개인적인 관계입니다.

- 진실성신은 모든 인간이 추구하는 진리이다.그는 흠잡을 데 없이 정직하다.타이터스 1장 2절은 "거짓말을 하지 않는 신"을 말한다.

- 지혜—하나님은 인간의 본성과 세계를 완전히 이해하시고, 그분의 뜻이 하늘과 땅에서 이루어짐을 보시게 될 것이다.로마서 16장 27절은 "유일한 지혜로운 신"에 대해 말한다.

일부 기독교인들은 기독교 이전 시대의 히브리 사람들이 숭배하던 신이 예수를 통해서 그랬던 것처럼 항상 자신을 드러냈다고 믿는다; 그러나 이것은 예수가 태어날 때까지 결코 분명하지 않았다.또한, 주의 천사가 총대주교들에게 신을 드러내면서 말했지만, 어떤 사람들은 항상 신의 영을 통해서만 그들에게 이해를 부여했다고 믿으며, 사람들은 나중에 하나님 자신이 그들을 방문했다는 것을 인지할 수 있었다.

이 믿음은 점차 삼위일체의 현대적 공식으로 발전했는데, 삼위일체는 신은 단일체(야훼)이지만, 신의 단일체에는 삼위일체가 존재하며, 그 의미는 항상 논의되어 왔다.이 신비로운 "트리니티"는 그리스어로는 하이포스테이스(hypostase)로 묘사되고 있고, 영어로는 "사람"으로 묘사되었다.그럼에도 불구하고, 기독교인들은 그들이 오직 하나의 신만을 믿는다고 강조한다.

대부분의 기독교 교회는 유니테리언 일신교 신앙과는 반대로 삼위일체를 가르친다.역사적으로, 대부분의 기독교 교회들은 신의 본성은 미스터리이며, 일반적인 계시를 통해 추론하기 보다는 특별한 계시를 통해 밝혀져야만 하는 것이라고 가르쳐왔다.

기독교 정통주의 전통은 381년에 성문화되어 카파도키아 아버지들의 작업을 통해 완전한 발전에 이른 이 생각을 따른다.그들은 삼위일체라고 불리는 삼위일체(三,一體)로 불리는 신을 "성부", "성자", "동일한 물질"로 묘사되는 성령인 세 명의 "사람"으로 이루어진 것으로 간주한다.그러나 무한대의 신의 실체는 일반적으로 정의되지 않는 것으로 묘사되며, '사람'이라는 단어는 사상의 불완전한 표현이다.

일부 비평가들은 삼자적 신의 개념을 채택하기 때문에 기독교는 삼합교 또는 다신교의 한 형태라고 주장한다.이 개념은 성경에서 예수가 아버지보다 늦게 나타났기 때문에 제2의, 덜하고, 따라서 구별되는 신이 되어야 한다고 주장한 아리우스파의 가르침에서 유래한다.유대인과 이슬람교도들에게 삼위일체로서의 하느님의 개념은 이단적이다.-그것은 다신교와 유사하다고 여겨진다.기독교인들은 일신교가 기독교 신앙의 중심이라고 압도적으로 주장하는데, 이는 삼위일체에 대한 정통 기독교 정의를 제공하는 니케아 신조(다른 것들 중)가 "나는 한 신을 믿는다"로 시작되기 때문이다.

3세기에 테르툴리안은 하느님은 성부와 성자, 그리고 성령으로 존재한다고 주장했는데, 이는 한 [29]물질로 이루어진 세 사람의 존재이다.삼위일체 기독교 신에게 아버지는 성자 하나님(예수가 화신)과 성령, 기독교 신두의 다른 [29]하이포스타즈(사람)와 전혀 별개의 신이 아닙니다.니케아 신조에 따르면, 아들(예수 그리스도)은 "영원히 아버지의 자손"이며, 이는 그들의 신성한 아버지와 아들의 관계가 시간이나 인류 역사 내의 사건에 얽매이지 않는다는 것을 나타낸다.

기독교에서, 삼위일체 교리는 하느님은 세 사람의 상호존재로서 동시에 그리고 영원히 존재하는 존재라고 말한다: 성부, 성자, 그리고 성령.삼위일체 교리는 4세기까지 공식화되지 않았지만, 초기 기독교 이래, 한 사람의 구원은 삼위일체 신의 개념과 매우 밀접하게 연관되어 왔다.그 당시 콘스탄틴 황제는 제1차 니케아 공의회를 소집하여 제국의 모든 주교들이 참석하도록 초대하였다.교황 실베스터 1세는 참석하지 않았지만 그의 특사를 보냈다.의회는 무엇보다도 원래의 니케아 신조를 선포했다.

대부분의 기독교인들에게, 신에 대한 믿음은 삼위일체주의 교리에 담겨 있는데, 삼위일체주의 교리는 신의 세 사람이 함께 하나의 신을 형성한다고 주장한다.삼위일체적 관점은 신이 뜻을 가지고 있고, 신이 신과 인간, 두 가지 뜻을 가지고 있다고 강조하지만, 이들은 결코 충돌하지 않는다.하지만, 이 점은 통일된 신성과 인간성을 지닌 신은 오직 하나라고 주장하는 동양 정교회 기독교인들에 의해 논쟁되고 있다.

삼위일체 기독교 교리는 성부와 아들, 성령의 일체성을 하나의 갓헤드에 세 [30]사람으로서 가르친다.그 교리는 신은 삼인조 신이며, 세 명의 인간으로 존재하거나 그리스어 하이포스타제 [31]안에 존재하지만,[32] 하나의 존재라고 말한다.삼위일체에서의 인격은 영어에서 사용되는 "사람"에 대한 서양의 일반적인 이해와 일치하지 않는다.-그것은 "자유 의지와 의식적인 [33]: 185–186. 활동의 개인적이고 자기 실현된 중심"을 의미하지 않는다.고대인에게 성격은 어떤 의미에서는 개인이었지만 [33]: p.186 항상 공동체 안에 있었다.각 개인은 단지 유사한 성질을 가진 것이 아니라 하나의 동일한 본질 또는 성질을 가진 것으로 이해된다.3세기[34] 초부터 삼위일체 교리는 "하나의 신은 세 사람, 성부, 성자, 성령 [35]안에 존재한다"고 언급되어 왔다.

삼위일체의 믿음인 삼위일체주의는 성공회, 감리교, 루터교, 침례교, 장로교와 같은 개신교 개혁에서 비롯된 다른 저명한 기독교 종파의 표시이다.옥스포드 기독교 교회 사전은 삼위일체를 "기독교 [35]신학의 중심 교의"라고 기술한다.이 교리는 유니테리언스, 일체주의, 모달리즘을 포함하는 논트리너리즘의 입장과 대조된다.소수의 기독교인들은 주로 유니테리언주의라는 제목 아래 비삼위주의 관점을 가지고 있다.

전부는 아니더라도 대부분의 기독교인들은 하느님이 영이며,[John 4:24] 창조되지 않고, 전능하며, 영원한 존재이며, 만물의 창조자이자 지속자이며, 그의 아들 예수 그리스도를 통해 세상의 구원을 행한다고 믿는다.이러한 배경에서, 그리스도와 성령의 신성에 대한 믿음은 [36]삼위일체의 교리로 표현되는데, 삼위일체의 교리는 성부, 성자(로고 예수 그리스도) 그리고 성령의 [1 Jn 5:7]세 개의 구별되고 분리될 수 없는 하이포스타즈(인물)로 존재한다.

삼위일체주의 교리는 대부분의 기독교인들에게 그들의 신앙의 핵심 교리로 여겨진다.논트리니타주의자들은 전형적으로 아버지인 신은 최고이며, 예수는 여전히 신성한 주님과 구세주이지만 신의 아들이며, 성령은 지상에 있는 신의 의지와 유사한 현상이라고 주장한다.성스러운 세 가지는 분리되어 있지만, 성자와 성령은 여전히 성부님으로부터 기원한 것으로 보입니다.

신약성서에는 삼위일체라는 용어가 없고 삼위일체라는 용어가 어디에도 없다.그러나 일부는 신약성서가 "하느님에 [37]대한 삼위일체적 이해를 강요하라"고 성부와 성령을 반복적으로 언급하고 있다고 강조한다.이 교리는 마태복음 28장 19절의 세례식과 같은 신약성서 구절에 사용된 성서 언어에서 발전하여 4세기 말에는 현재의 형태로 널리 보급되었다.

많은 일신교 종교에서 신은 부분적으로 인간 문제에 대한 그의 적극적인 관심 때문에 아버지로서 언급된다. 아버지가 자신에게 의존하는 자녀들에게 관심을 가져주고 아버지로서 그는 인간성, 자녀들에게 최고의 [38]이익을 위해 행동할 것이다.기독교에서 신은 창조자, 양육자, 그리고 그의 [Heb 1:2–5]자녀들을 위한 공급자가 되는 것 외에, 더 문자 그대로의 의미에서 "아버지"라고 불립니다.[Gal 4:1–7] 아버지는 그의 유일한 아들 예수 그리스도와 독특한 관계를 맺고 있다고 하는데, 이것은 독점적이고 친밀한 관계를 암시한다: "아버지 외에는 아무도 아들을 알지 못하고, 아들과 아들이 자신을 [Mt. 11:27]밝히기 위해 선택한 사람 외에는 아무도 아버지를 알지 못한다."

기독교에서 아버지와 인간의 관계는 이전에 볼 수 없었던 의미에서 아이들의 아버지로서, 창조의 창조자, 양육자, 그리고 그의 자녀와 그의 사람들을 위한 공급자로서가 아닙니다.그래서 인간은 일반적으로 신의 자녀로 불리기도 한다.기독교인들에게 아버지와 인간의 관계는 창조주이자 창조된 존재의 관계이며, 그런 점에서 그는 만물의 아버지입니다.신약성경은 이런 의미에서 가족이라는 개념은 어디서든 하나님 아버지로부터 [Eph 3:15]그 이름을 따온 것이며, 따라서 하나님 자신이 가족의 모델이라고 말한다.

그러나 기독교인들이 예수 그리스도를 통해 아버지와 아들의 특별한 관계에 참여자로 만든다고 믿는 더 깊은 법적 의미가 있다.기독교인들은 스스로를 하느님의 [39]양자로 칭한다.

신약성서에서, 하나님 아버지는 예수가 그의 아들이자 [Heb. 1:2–5]후계자라고 믿어지는 성자와 그의 관계에서 특별한 역할을 한다.니케아 신조에 따르면, 아들(예수 그리스도)은 "영원히 아버지의 자손"이며, 이는 그들의 신성한 아버지와 아들의 관계가 시간이나 인류 역사 내의 사건에 얽매이지 않는다는 것을 나타낸다.기독교를 참조해 주세요.성경은 하느님의 창조가 시작될 때 "계시"라고 불리는 그리스도를 말한다.[John 1:1] 창조물 자체가 아니라 삼위일체의 인격에서 평등하다.

동방 정교회 신학에서, 신은 성자와 성령의 "원천" 또는 "원천"이며, 이는 사람의 세 가지에 직관적인 강조를 준다; 그에 비해, 서양 신학은 세 개의 하이포스테스 또는 사람의 "원천"을 직관적인 강조를 주는 신성한 본성에 있는 것으로 설명한다.신의 [citation needed]존재의 일체성까지.

와

기독교학은 기독교 신학에서 주로 예수 그리스도의 자연, 사람, 그리고 행적에 관련된 학문 분야이며, 기독교인들은 하나님의 아들이라고 여긴다.기독교학은 예수님 안에서 인간(인자)과 신(하나님 아들 또는 하나님의 말씀)이 만나는 것과 관련이 있습니다.

주요 고려사항으로는 육신, 예수의 본성과 사람의 관계와 신의 본성과 사람의 관계, 그리고 예수의 구조 작업이 포함됩니다.이와 같이, 기독교학은 일반적으로 예수의 삶의 세부사항이나 가르침보다는 그가 누구인지 또는 무엇인지에 더 관심이 있다.그의 승천 이후 교회가 시작된 이래로 그의 추종자라고 주장하는 사람들에 의해 다양한 관점이 존재해왔고 또 있다.논쟁의 초점은 결국 인간의 본성과 신성한 본성이 한 사람 안에 공존할 수 있는지 여부였다.이 두 성질의 상호 관계에 대한 연구는 대다수의 전통에 대한 관심사 중 하나이다.

예수님에 대한 가르침과 그가 3년간 공직을 수행하면서 이룬 것에 대한 증언들이 신약성경 곳곳에서 발견된다.예수 그리스도의 사람에 대해 코아 성서의 가르침은 예수 그리스도와 영원하고 완전히 하나님(신의)고 완전한 인간의 한 죄 없는 사람에서 같은 time,[40]을 보고예수의 죽음과 부활을 통해 육체 사람이 신하여 구원과 영원한 삶의 약속을 제공된다 화해할 수 있어 요약할 수 있다. 를 통해그의 새 규약예수의 본질에 대한 신학적인 논쟁이 있었지만, 기독교인들은 예수가 신의 화신이며 "진정한 신이자 진정한 인간"이라고 믿는다.예수는 모든 면에서 완전한 인간이 되어 인간의 고통과 유혹을 겪었지만 죄를 짓지 않았다.완전한 신으로서, 그는 죽음을 물리치고 다시 살아났다.성경은 예수가 성령에 의해 잉태되었고 인간 [41]아버지 없이 처녀 어머니 마리아로부터 태어났다고 주장한다.예수님의 사역에 대한 성경에는 기적, 설교, 가르침, 치유, 죽음, 부활이 포함되어 있다.사도 베드로가 1세기 이후 기독교인들 사이에서 유명한 신앙 선언문에서 이렇게 말했습니다. "당신은 살아계신 [Matt 16:16]하나님의 아들 그리스도다.대부분의 기독교인들은 현재 그리스도의 재림을 기다리고 있다. 그들은 그리스도가 남은 메시아적 예언을 이행할 것이라고 믿는다.

그리스도는 그리스어 크리토스(Christos)의 영어 용어로 "기름받은 자"[42]라는 뜻이다.그것은 히브리어의 번역이다 מָשִׁיחַ (Māšîaḥ), usually transliterated into English as Messiah.그 단어는 기독교 성경에 나오는 예수 그리스도에 대한 수많은 언급 때문에 종종 예수의 성으로 오해된다.그 단어는 사실 제목으로 쓰이고, 그래서 그것의 공통적인 역수는 그리스도를 의미하며, 기름부은 예수 또는 메시아 예수를 의미합니다.예수의 추종자들은 예수가 구약성서, 즉 타나크에서 예언한 그리스도, 즉 메시아라고 믿었기 때문에 기독교인으로 알려지게 되었다.

기독교적 논란은 신의 두목의 인물과 그들의 관계에 대해 정점에 이르렀다.기독교학은 제1차 니케아 공의회(325년)부터 제3차 콘스탄티노플 공의회(680년)까지 근본적인 관심사였다.이 기간 동안, 더 넓은 기독교 공동체 내의 다양한 집단의 기독교적 견해는 이단, 그리고 드물게, 그 이후의 종교적 박해로 이어졌다.어떤 경우에, 한 종파의 독특한 기독교학은 그 주된 특징이며, 이러한 경우, 그 종파는 기독교학에 주어진 이름으로 알려져 있는 것이 일반적이다.

아타나시우스와 카파도키아 아버지들의 작업이 영향을 미쳤던 수십 년간의 계속되는 논쟁 끝에 니케아 제1차 공의회에서 내려진 결정과 콘스탄티노플 제1차 공의회에서 재검증되었다.사용된 언어는 유일신이 세 사람(성부, 성자, 성령)에 존재한다는 것이었다. 특히 성자는 성부와 호모우시오스라는 것이 확인되었다.니케아 공의회의 신조는 예수의 완전한 신성과 완전한 인간성에 대해 진술했고, 따라서 어떻게 정확히 신과 인간이 그리스도의 사람 안에서 함께 모이는지에 대한 토론의 길을 준비했다.

니케아는 예수가 완전히 신성하고 또한 인간이라고 주장했다.한 사람이 어떻게 신과 인간이 될 수 있는지, 그리고 그 한 사람 안에서 신과 인간이 어떻게 관련되어 있는지를 명확히 하지 못했다.이것은 4세기와 5세기 기독교 시대의 기독교학적 논쟁으로 이어졌다.

칼케도니아 신조는 모든 기독교적 논쟁을 끝내지는 않았지만, 사용된 용어들을 명확히 했고 다른 모든 기독교에 대한 참고점이 되었다.기독교의 주요 분파인 가톨릭, 동방 정교회, 성공회, 루터교, 개혁은 칼케도니아 기독교의 공식화를 지지하고 있으며, 시리아 정교회, 아시리아 교회, 콥트 정교회, 에티오피아 정교회, 아르메니아 사도주의 등 동방 기독교의 많은 분파는 이를 거부한다.

의

같은 신

성경에 따르면, 삼위일체의 두 번째 사람은 첫 번째 사람(아버지로서의 하나님)과의 영원한 관계 때문에 하나님의 아들이라고 합니다.그는 (삼위일체론자들에 의해) 성부와 성령과 동등하다고 여겨진다.그는 모두 신이고 모두 인간이다. 그의 신성한 본성에 대해서는 신의 아들이지만, 그의 인간 본성에 대해서는 [Rom 1:3–4][43]다윗의 혈통이다.예수의 자기 해석의 핵심은 독특한[22] 의미에서 자녀와 부모 사이의 관계인 그의 "성스러운 의식"이었다.그의 지상에서의 사명은 기독교인들이 영생의 [Jn 17:3]정수라고 믿는 하나님을 그들의 아버지로 알 수 있게 하는 것이었음이 증명되었다.

아들 신은 기독교 신학에서 삼위일체의 두 번째 인물이다.삼위일체 교리는 나사렛의 예수를 본질적으로 통일된 성자 하나님으로 식별하지만, 성부와 성령 하나님(삼위일체 제1인자와 제3인자)에 관해서는 실제로 구별된다.성자 신은 창조 전이나 종말 후에 성부(그리고 성령)와 함께 영원하다(종말론 참조).그래서 예수는 항상 '하나님 아들'이었지만, 육신을 통해 '하나님의 아들'이 되기 전까지는 드러나지 않았다."신의 아들"은 그의 인간성에 관심을 끌지만, "신의 아들"은 화신 이전의 존재를 포함한 그의 신성을 더 일반적으로 지칭한다.그래서 기독교 신학에서 예수는 항상 [44]아들이신 하나님이었다. 비록 그가 화신을 통해 하나님의 아들이 되기 전까지는 그렇게 드러나지 않았다.

"하나님 아들"이라는 정확한 구절은 신약성서에 없다.나중에 이 표현의 신학적인 사용은 예수의 신성을 암시하는 것으로 이해되는 신약성서의 언급에 대한 표준적인 해석으로 다가온 것을 반영하지만, 그가 아버지라고 불렀던 신의 그것과 그의 인물의 구별을 반영합니다.이와 같이, 제목은 기독교적 논쟁보다는 삼위일체 교리의 발전과 더 관련이 있다.신약성서에서 예수가 '하나님의 아들'이라는 칭호를 받는 곳은 40곳이 넘지만 학자들은 이를 동등한 표현으로 여기지 않는다."아들 하나님"은 반삼위일체론자들에 의해 거부당하는데, 그들은 그리스도에 대한 가장 일반적인 용어의 반전을 교리적인 변태로 보고 삼위일체론 쪽으로 기울고 있다.

마태오는 예수를 인용하여 이렇게 말합니다. "평화 중재자들은 복이 있다. 그들은 하나님의 아들이라 불릴 것이다(5장 9절).복음서는 예수님이 신의 아들이라는 것에 대한 많은 논쟁을 독특한 방식으로 기록하고 있다.그러나 사도행전 책과 신약성서의 편지에는 예수가 하나님의 아들이며, 메시아이며, 신에 의해 임명된 사람이라고 믿었던 최초의 기독교인들의 초기 가르침이 기록되어 있다.이것은 많은 곳에서 명백하지만, 히브리어 책의 첫 부분은 권위자로서 히브리 성경의 경전을 인용하면서 신중하고 지속적인 논쟁으로 이 문제를 다루고 있다.예를 들어 저자는 이스라엘 하나님이 예수께 말씀하신 시편 45장 6절을 인용한다.

- 히브리어 1:8아들에 대해 그는 말한다. "하나님, 당신의 왕좌는 영원할 것입니다."

히브리인들이 예수를 신성한 아버지의 정확한 묘사라고 묘사한 저자는 골로스의 한 구절과 유사하다.

- 9 안에서 은 육체적 "

요한의 복음서는 예수와 하늘 아버지와의 관계에 대해 상세히 언급하고 있다.그것은 또한 예수님에 대한 신성의 두 가지 유명한 속성들을 포함하고 있다.

예수님을 하나님이라고 부르는 가장 직접적인 언급은 다양한 글에서 찾을 수 있다.

종교에서 이후의 삼위일체적 진술에 대한 성경적 근거는 마태복음 28에서 발견된 조기 세례식이다.

- 신??

도큐티즘은 예수가 완전히 신성하다고 가르쳤고, 그의 신체는 환상일 뿐이었다.매우 이른 시기에 다양한 기독교 집단이 생겨났고, 특히 서기 2세기에 번성했던 영지주의 종파들은 기독교 신학을 갖는 경향이 있었다.유교적 가르침은 세인트루이스에 의해 공격당했다. 안티오키아의 이그나티우스(2세기 초)는 요한의 서한에 표적이 된 것으로 보인다(연대는 논쟁의 대상이 되지만 전통주의 학자들 사이에서는 1세기 후반부터 비판적인 학자들 사이에서는 2세기 후반까지 다양하다).

니케아 평의회는 삼위일체 교리의 일부로서 니케아 신조를 확인하면서, 그리스도에 있는 모든 인간성을 완전히 배제하는 신학을 거부했다.즉, 삼위일체의 두 번째 인물이 예수님으로 화신되어 완전한 인간으로 변했다는 것이다.

- ★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★?

기독교 역사의 초기 세기들 또한 예수가 평범한 인간이었다고 주장하는 다른 쪽 끝에 집단이 있었다.입양주의자들은 예수가 완전한 인간으로 태어났고, 그가 살아온 삶 때문에 침례자 요한에게 세례를[45] 주었을 때 하나님의 아들로 입양되었다고 가르쳤다.에비온파라고 알려진 또 다른 집단은 예수가 신이 아니라 히브리 성경에 약속된 인간 모시아크 예언자라고 가르쳤다.

이러한 견해들 중 일부는 신의 일체성에 대한 그들의 주장에서 유니테리언즘으로 묘사될 수 있다.신의 머리를 이해하는 방법에 직접적인 영향을 미친 이러한 견해들은 니케아 평의회에 의해 이단으로 선언되었다.기독교의 나머지 고대 역사를 통틀어, 그리스도의 신성을 부정하는 기독교는 교회의 삶에 큰 영향을 미치지 않았다.

- 일게일일일일일일일일일일?

-

- ★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★?

아리아니즘은 예수가 신성하다고 단언했지만, 그럼에도 불구하고 예수는 창조된 존재이며(존재하지 않았던 시절이 있음) 그러므로 아버지 하나님보다 덜 신성하다고 가르쳤다.이 문제는 1요타로 요약된다; 아리안교는 호모우시아를 가르쳤다 - 예수의 신성이 호모우시아가 아니라 아버지 신의 신성과 유사하다는 믿음 - 예수의 신성이 아버지 신의 신성과 동일하다는 믿음.아리우스의 반대자들은 추가적으로 예수의 신성이 아버지 신의 신과 다르다는 믿음을 아리아니즘이라는 용어에 포함시켰다.

아리아니즘은 니케아 평의회에 의해 비난받았지만, 제국의 북부와 서부 지방에서는 여전히 인기를 끌었고, 6세기까지 서유럽의 다수 견해로 남아있었다.사실, 콘스탄티누스의 임종 세례에 대한 기독교 전설에도 기록된 역사에서 아리안이었던 주교가 포함되어 있다.

현대 시대에, 많은 종파들이 삼위일체의 니케아 교리를 거부해 왔는데, 여기에는 기독교도와 야훼의 [46]증인들도 포함된다.

- ★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★?

니케아 평의회에 이은 기독교학적 논쟁은 삼위일체 교리를 지지하는 한편, 그리스도의 인격 속에서 인간과 신의 상호작용을 이해하려고 했다.라오디케아의 아폴로나리스 (310–390)는 예수님에서 신성한 요소가 인간의 누스를 대신한다고 가르쳤다.그러나 이것은 예수의 진정한 인간성을 부정하는 것으로 보여졌고, 그 견해는 제1차 콘스탄티노플 공의회에서 비난받았다.

그 후, 콘스탄티노플의 네스토리우스 (386–451)는 예수를 효과적으로 두 사람 (하나의 신과 한 사람의 인간)으로 분리하는 관점을 시작했다. 이 결합의 메커니즘은 하이포스타시스라고 알려져 있으며 하이포스타시스(hypostasis)와 대조된다.네스토리우스의 신학은 제1차 에페소스 평의회(431년)에서 이단으로 간주되었다.바바이 대왕의 글에서 볼 수 있듯이, 동방 교회의 기독교학은 칼케돈의 기독교와 매우 유사하지만, 많은 정통 기독교인들은 이 그룹을 네스토리우스주의의 영속이라고 생각한다; 현대 동양의 아시리아 교회는 이 용어의 수용을 암시하는 것처럼 이 용어를 피했다.네스토리우스의 모든 신학

다양한 형태의 일신론은 그리스도가 오직 하나의 본성을 가지고 있다고 가르쳤다: 신이 용해되었거나(에우티키아니즘), 또는 신이 그리스도의 인격에서 인간과 하나의 본성으로 결합되었다(미아피시즘).주목할 만한 단물리학 신학자들은 에우티케스였다.451년 칼케돈 평의회에서 단성론은 이단으로 거부되었는데, 그것은 예수 그리스도가 한 사람 안에 두 가지 본성(신성과 인간)이 결합되어 있고, 정적인 결합(칼케돈 신조 참조)이)을 가지고 있다고 단언했다.에우티키아교는 칼케돈교도와 미아피교도에 의해 망각되는 반면, 칼케돈교 공식에 반대한 미아피교파는 동양정교회로서 지속되어 왔다.

신학자들이 칼케도니아 정의와 단성파 사이의 타협점을 찾는 것을 계속하면서, 그리스도의 완전한 인간성을 부분적으로 거부하는 다른 기독교학이 발달했다.단신론은 예수님의 한 사람 안에 두 가지 본성이 있다고 가르쳤지만, 오직 신의 뜻일 뿐이다.이와 밀접한 관련이 있는 것이 모노엘리테와 같은 교리를 고수하면서도 용어가 다른 단성론이다.이러한 입장은 제3차 콘스탄티노플 평의회 (제6차 에큐메니컬 평의회, 680–681)에 의해 이단으로 선언되었다.

★★★

'화신'은 기독교의 갓헤드에 나오는 두 번째 사람이 성모 마리아의 뱃속에서 기적적으로 잉태되었을 때 '육체가 되었다'는 믿음이다.잉카네이트라는 단어는 "살로 만들다" 또는 "살로 만들다"를 뜻하는 라틴어(in=in 또는 into, caronis=carnis)에서 유래했다.화신은 신약성서에 대한 이해를 바탕으로 한 정통(니케인) 기독교의 기본 신학적 가르침입니다.그 화신은 삼합회 신의 창조되지 않은 제2의 하이포스타시스인 예수가 인간의 몸과 자연을 떠맡고 인간과 신이 되었다는 믿음을 나타낸다.성경에서 가장 분명한 가르침은 요한복음 1장 14절에 있습니다. "그리고 말씀이 육체가 되어 [47]우리 사이에 거하게 되었습니다."

전통적으로 정의되는 육신에서, 아들의 신성한 본성은 "진정한 신이자 진정한 인간"인 예수 그리스도와 결합되었지만 인간의 본성과[48] 섞이지 않았다.화신은 매년 크리스마스에 기념되고 기념되며, 또한 "화신의 신비의 다른 측면"은 크리스마스와 [49]성명에서 기념됩니다.

이것은 대부분의 기독교인들이 가지고 있는 전통적인 믿음의 중심이다.이 주제에 대한 대안적 견해(히브리인에 따른 에피온파 및 복음 참조)는 수세기에 걸쳐 제안되어 왔지만(아래 참조) 주류 기독교 단체들에 의해 모두 거절당했다.

최근 수십 년 동안, "단일성"으로 알려진 대안 교리는 다양한 오순절 단체들 사이에서 지지되어 왔지만, 기독교의 나머지 단체들에 의해 거부되었다.

초기 기독교 시대에는 기독교인들 사이에 그리스도의 화신의 본질에 대해 상당한 의견 차이가 있었다.모든 기독교인들이 예수가 정말로 하나님의 아들이라고 믿는 동안, 그의 아들들의 정확한 성격은 신약성서에 언급된 "아버지", "아들", "성령"의 정확한 관계와 함께 논쟁되었다.예수는 분명히 "아들"이었지만, 이것은 정확히 무엇을 의미했을까요?이 주제에 대한 논쟁은 특히 기독교의 첫 4세기 동안 가장 격렬했는데, 유대인 기독교인, 영지교인, 알렉산드라 장로회 아리우스의 추종자, 그리고 성 베드로 신봉자들을 포함했다. 아타나시우스 대왕, 그 중에서도.

결국, 기독교 교회는 성자의 가르침을 받아들였다.아타나시우스와 그의 동맹자들은 그리스도가 삼위일체의 영원한 제2인자의 화신이었고, 그는 완전한 신이자 동시에 완전한 인간이었다.모든 다른 믿음은 이단으로 정의되었다.여기에는 예수가 육체가 아닌 인간의 모습을 하고 있는 신성한 존재라고 말하는 도케티즘, 그리스도가 창조된 존재라고 주장하는 아리아니즘, 그리고 하나님의 아들과 인간인 예수가 같은 몸을 공유하지만 두 개의 별개의 본질을 유지한다고 주장하는 네스토리우스주의가 포함되었다.특정 현대 오순절 교회들이 갖고 있는 일체성 믿음은 대부분의 주류 기독교 단체들에 의해 이단으로 여겨진다.

가장 널리 받아들여진 초기 기독교 교회는 325년 제1차 니케아 평의회, 431년 에페소스 평의회, 451년 칼케돈 평의회에서 화신과 예수의 본성에 대한 정의를 내렸습니다.이 평의회들은 예수가 완전한 하나님이라고 선언했습니다: 아버지로부터 태어났지만 창조된 것은 아닙니다.그리고 성모 마리아로부터 그의 육체와 인간의 본성을 빼앗은 완전한 인간입니다.이 두 가지 본성은, 인간과 신으로,[50] 예수 그리스도의 한 인격으로 극성적으로 결합되었다.

체계적 신학사상 속의 속죄와 화신 사이의 연결은 복잡하다.대체, 만족 또는 크리스투스 빅터와 같은 전통적인 속죄 모델들 안에서, 그리스도는 십자가의 희생이 효과적이고 인간의 죄가 "제거"되거나 "정복"되려면 신이어야 합니다.그의 작품 "삼위일체"와 "신의 왕국"에서 위르겐 몰트만은 그가 "운수"라고 부르는 것과 "필요한" 화신을 구별했습니다.후자는 육신을 소테리컬하게 강조한다: 신의 아들이 인간이 되어 우리의 죄로부터 우리를 구할 수 있었다.반면 전자는 '화신'을 '인류 속에 살고 싶다'는 신의 사랑의 성취라고 말한다.

몰트만은 "필요"의 화신을 말하는 것은 그리스도의 삶에 불공평한 행동을 하는 것이라고 느끼기 때문에 "우연한" 화신을 선호합니다.몰트만의 연구는 다른 체계적 신학자들과 함께 해방 기독교학의 길을 열어준다.

간단히 말해서, 이 교리는 두 가지 본성, 하나는 인간이고 하나는 신이며, 하나는 그리스도의 한 사람 안에 결합되어 있다고 말한다.평의회는 또한 인간과 신이라는 각각의 본성은 구별되고 완전하다고 가르쳤다.이 관점은 때때로 그것을 거부한 사람들에 의해 Dyophysite (두 가지 본성은 두 가지이다.

하이포스타틱 유니언(hypostatic union)은 기독교 신학에서 주류 기독교학에서 예수 그리스도에서 인간성과 신성의 결합을 설명하기 위해 사용되는 기술 용어이다.두 가지 본성의 교리에 대한 간단한 정의는 다음과 같다: "예수 그리스도는 아들과 동일하며, 인간과 [51]신이라는 두 가지 본성의 한 사람이고 하나의 하이포스타시스이다."

에페소스의 제1차 평의회는 이 교리를 인정했고, 그리스도의 인간성과 신성은 로고스의 자연과 하이포스타시스에 따라 하나로 만들어졌다고 말하면서, 그 중요성을 확인했습니다.

제1차 니케아 평의회는 아버지와 아들이 같은 물질이며 영원한 존재라고 선언했다.이 믿음은 니케아 신조에 표현되었다.

라오디케아의 아폴로나리스는 [52]육신을 이해하기 위해 하이포스타시스라는 용어를 처음으로 사용했다.아폴로나리스는 그리스도에서 신과 인간의 결합은 하나의 본질이며 하나의 본질인 하나의 하이포스타시스를 가지고 있다고 묘사했다.

Mopsuestia의 네스토리안 테오도르는 그리스도에 두 개의 천성(인간과 신)과 두 개의 하이포스테이스(인물 또는 인간)[53]가 공존한다고 주장하면서 반대 방향으로 갔다.

칼케도니아 신조는 테오도르에게 육신에는 두 가지 성질이 있다는 것에 동의했다.그러나 칼케돈 평의회는 또한 삼위일체적 정의인 아폴로리나리우스와 같이 본성이 아닌 인물을 나타내는 것과 같이 하이포스타시스를 사용해야 한다고 주장했다.

그래서 평의회는 그리스도에는 두 가지 성질이 있다고 선언했습니다.각각의 성질은 자신의 성질을 유지하며 하나의 생존과 하나의 개인으로 [54]뭉쳤습니다.

한 인간의은 "한 결합이라는 대체 용어로도 됩니다.

칼케도니아 신조를 거부한 오리엔탈 정교회는 유일신교로 알려져 있었는데, 왜냐하면 그들은 화신인 아들을 하나의 본성을 가진 것으로 특징짓는 정의만을 받아들이기 때문이다.칼케도니아의 공식은 네스토리우스 [55]기독교학에서 파생되었고 이와 유사하다고 여겨졌다.반대로, 칼케돈교 신자들은 동양정교를 에우티키아 일신교로 보는 경향이 있었다.그러나, 현대 에큐메니컬 대화에서 동양 정교회는 에우티케스의 교리를 결코 믿지 않았고, 그들은 항상 그리스도의 인간성이 우리 자신의 것과 일치한다고 단언했고, 따라서 그들은 그들 자신을 지칭하기 위해 "미아피사이트"라는 용어를 선호했다(키릴 기독교에 대한 언급)."mia physis tou theou logou sesarkomene").

최근 동방정교와 동방정교회의 지도자들은 통일을 위해 노력하기 위해 공동성명에 서명했다.

기독교적

- 의 죄 일

기독교의 정설은 예수가 완전한 인간이었다고 주장하지만, 히브리인들에게 보내는 서한은 예수가 '성스럽고 악하지 않았다'(7:26)고 말한다.예수 그리스도의 죄 없는 것에 대한 질문은 겉으로 보이는 역설에 초점을 맞추고 있다.완전한 인간이 된다는 것은 아담의 몰락에 참여할 것을 요구하는 것인가, 아니면 창세기 2-3에 따르면 예수가 멸망하기 전에 아담과 이브가 그랬던 것처럼 "불굴의" 상태로 존재할 수 있는가?

- 의

복음주의 작가 도날드 맥클레오드는 예수 그리스도의 죄 없는 본성은 두 가지 요소를 수반한다고 주장한다."첫째, 그리스도는 진짜 [56]죄로부터 자유로워졌다."복음서를 공부하는 것은 예수가 죄의 용서를 빌거나 죄를 고백하는 것에 대한 언급이 없다.그 주장은 예수가 죄를 짓지 않았고, 죄를 입증할 수 없었다는 것이다. 그는 악행이 없었다.실제로 요한복음 8장 46절에서 "너희들 중에 내 죄를 증명할 수 있는 사람이 있느냐"고 물었다고 한다.둘째, 그는 태생적 죄(원죄 또는 태생적 죄)[56]로부터 자유로웠다.

- 의

복음서에 나타난 그리스도의 유혹은 그가 유혹당했음을 확증한다.사실, 그 유혹은 진정성이 있었고 인간이 보통 [57]경험하는 것보다 더 강렬했다.그는 인간의 모든 약점을 경험했다.예수는 배고픔과 갈증, 고통과 친구들의 사랑을 통해 유혹을 받았다.그러므로 인간의 약점은 [58]유혹을 일으킬 수 있다.그럼에도 불구하고, 맥레오드는 "그리스도가 우리와 같지 않았던 중요한 존경 중 하나는 그리스도가 자신의 [58]내부에 있는 어떤 것에도 유혹되지 않았다는 것이다."라고 지적한다.

그리스도가 맞닥뜨린 유혹은 그의 인격과 신의 아들로서의 정체성에 초점을 맞췄다.McLeod는 "예수는 그의 아들로서 유혹을 받을 수 있다"고 쓰고 있다.황야에서의 유혹과 겟세마네에서의 유혹은 이 유혹의 장을 예시한다.사원의 꼭대기에서 몸을 던짐으로써 자신의 아들임을 확인하는 사인을 하는 유혹에 대해 맥레오드는 "표시는 자신을 위한 것이었다: '진짜 문제는 내 아들이다'라고 말하는 것처럼 안심을 구하는 유혹이다.나는 그것이 분명해질 때까지 다른 모든 것, 그리고 더 이상의 모든 봉사를 잊어야 한다.'[59] 맥리드는 이 투쟁을 "그는 인간이 되었고, 외모뿐만 [59]아니라 현실을 받아들여야 한다."라고 화신의 맥락에 두고 있다.

- 의

그리스도의 신성과 인간 본성의 속성(Communicatio idiomatum)의 교감은 칼케도니아 신학에 따르면 그것들이 다른 것을 무시하지 않고 함께 존재한다는 것을 의미한다.즉, 둘 다 한 사람 안에 보존되고 공존한다.그리스도는 신과 인류의 모든 재산을 가지고 있었다.신은 신이 되는 것을 멈추고 인간이 되지 않았다.그리스도는 반은 신이고 반은 인간이 아니었다.그 두 가지 성질은 새로운 제3의 자연으로 섞이지 않았다.독립적이긴 했지만, 그들은 완전히 일치하여 행동했고, 한 천성이 행동하면 다른 천성도 행동했다.이러한 성질은 혼합, 병합, 주입 또는 치환되지 않았습니다.하나는 다른 것으로 변환되지 않았다.그들은 여전히 뚜렷이 구별되었다.

- 탄생

마태복음과 누가복음에서는 예수 그리스도의 처녀출생을 암시한다.어떤 사람들은 이제 대부분의 기독교 종파가 주장하는 이 "독트린"을 무시하거나 심지어 반대한다.이 섹션에서는 처녀 출산에 대한 믿음과 불신을 둘러싼 기독교적 이슈를 살펴봅니다.

비처녀 출산은 일종의 입양주의를 필요로 하는 것 같다.이것은 인간의 개념과 탄생이 예수를 신성하게 만드는 데 필요한 다른 메커니즘과 함께 완전한 인간 예수를 낳는 것처럼 보이기 때문이다.

비처녀 출산은 예수의 완전한 인간성을 지탱하는 것처럼 보일 것이다.William Barclay: "처녀 출산의 가장 큰 문제는 예수가 모든 남자들과 확실히 차별화된다는 것입니다; 그것은 우리에게 불완전한 [60]화신을 남깁니다."

바르트는 처녀 출생을 "성자의 [61]화신의 신비를 동반하고 나타낸다"는 신성한 징조로 말한다.

Donald[62] McLeod는 처녀 출산의 기독교학적 의미를 다음과 같이 제시한다.

- 구원을 인간의 주도적인 행동이라기보다 신의 초자연적인 행동으로 강조합니다.

- 입양주의(정상 출산 시 사실상 필요)를 회피합니다.

- 특히 그리스도가 아담(원죄)의 죄 밖에 있는 것과 관련하여 그리스도의 무죄를 강화합니다.

삼위일체 신의 세 사람이 비교적으로 더 큰지, 동등한지, 작은지에 대한 논의는 초기 기독교학의 많은 다른 분야와 마찬가지로 논쟁의 주제였다.아테네의 아테나고라스 (133–190년)의 글에서 우리는 매우 발달된 삼위일체주의 [63][64]교리를 발견한다.스펙트럼의 한쪽 끝에는 삼위일체의 세 사람이 그들의 차이와 구별을 지우는 것과 같다고 말하는 교리인 모듈리즘이 있었다.스펙트럼의 다른 한쪽 끝에는 삼위일체론뿐만 아니라 급진적인 종속주의 관점이 있었다.이 관점은 후자는 그리스도의 신과 성령에 대한 예수의 권위에 대한 창조주의 아버지의 우선권을 강조했다.니케아 평의회 기간 동안 로마와 알렉산드리아의 모달리즘 주교들은 아타나시우스와 정치적으로 제휴한 반면, 콘스탄티노플(니코메디아), 안티오키아, 예루살렘의 주교들은 아리오스와 아타나시우스 사이의 중간 지점으로 종속주의자들의 편을 들었다.

에 대한

위르겐 몰트만과 발터 캐스퍼와 같은 신학자들은 기독교를 인류학 또는 우주학으로 특징지었다.이들은 각각 '아래로부터의 기독교학'과 '위로부터의 기독교학'이라고도 불린다.인류학적 기독교학은 예수의 인간으로부터 시작되어 그의 삶과 사역으로부터 그가 신성하다는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지 향해 일한다. 반면, 우주론적 기독교학은 반대 방향으로 작용한다.영원한 로고스에서 출발하여 그의 인간성을 향한 우주론적 그리스도론이 작용한다.신학자들은 보통 한쪽에서 시작하고 그들의 선택은 필연적으로 그들의 결과적인 기독교학을 색칠한다.출발점으로, 이러한 옵션은 "다양하지만 상호 보완적인" 접근방식을 나타내며, 각각 고유한 어려움을 야기합니다.'위로부터'와 '아래로부터'는 둘 다 그리스도의 두 가지 본성, 즉 인간과 신의 본성을 받아들여야 한다.빛이 물결이나 입자로 인식될 수 있는 것처럼 예수는 신성과 인간성의 관점에서 생각되어야 한다."또는"은 말할 수 없지만 "둘 다"[65]와 "둘 다"는 말할 필요가 있습니다.

- Cosmological approaches우주론적 접근

위로부터의 기독교는 삼위일체의 제2의 인물인 로고스에서 출발하여 그의 영속성, 창조의 대리인, 그리고 그의 경제적 아들들을 확립한다.예수와 신과의 통합은 신성한 로고가 인간의 본성을 띠는 것처럼 화신에 의해 확립된다.이 접근법은 초기 교회(예: 세인트 폴과 세인트 폴)에서 흔히 볼 수 있었습니다.복음서에 나오는 요한.예수에 대한 완전한 인간성의 귀속은 두 성질이 서로 그들의 속성을 공유한다고 진술함으로써 해결된다.[66]

- Anthropological approaches인류학적 접근

아래로부터의 기독교는 예수가 기존의 로고가 아닌 새로운 인류를 대표하는 존재로서 출발한다.예수님은 우리가 종교적 경험에서 열망하는 모범적인 삶을 살고 있다.이러한 형태의 기독교학은 신비주의에 속하며, 그 뿌리의 일부는 6세기 동양의 기독교 신비주의의 출현으로 거슬러 올라가지만, 서양에서는 11세기와 14세기 사이에 번성했다.최근 신학자인 볼프하트 판넨버그는 부활한 예수가 [67]"신에게 가까이 사는 인간의 운명에 대한 종말론적 성취"라고 주장한다.

기독교 신앙은 본질적으로 정치적인데 부활한 주님으로서 예수에 대한 충성은 모든 지상의 통치와 권위를 상대적이기 때문이다.예수는 바울의 서한에서만 230번 이상 "주님"으로 불리며, 따라서 바오로 서한에서 믿음의 주된 고백이다.게다가, N.T. 라이트는 이 바울의 고백이 구원의 복음의 핵심이라고 주장한다.이 접근법의 아킬레스건은 현시대와 미래의 신의 지배 사이의 종말론적 긴장감의 상실이다.이것은 종종 제국 기독교학에서와 같이 국가가 그리스도의 권위를 함께 선택할 때 발생할 수 있다.현대 정치 기독교는 제국주의 [68]이데올로기를 극복하려고 한다.

의 업적

- 의

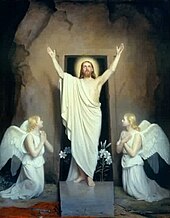

부활은 아마도 예수 그리스도의 삶에서 가장 논란이 많은 측면일 것이다.기독교는 특정 역사에 대한 반응으로서와 고백의 [69]반응으로서 모두 기독교학의 이 점에 의존한다.일부 기독교인들은 그가 부활했기 때문에 세계의 미래가 영원히 바뀌었다고 주장한다.대부분의 기독교인들은 예수의 부활이 하나님과의 화해(고린도전 5장 18절), 죽음의 파괴(고린도전 15장 26절), 예수 그리스도의 추종자들에게 죄의 용서를 가져다 준다고 믿는다.

예수가 죽고 묻힌 후, 신약성서에는 예수가 신체 형태로 다른 사람들에게 나타났다고 쓰여 있다.일부 회의론자들은 그의 외모가 마음이나 정신적으로 추종자들에 의해서만 인식되었다고 말한다.복음서에는 제자들이 예수의 부활한 몸을 목격했다고 믿었고 그것이 신앙의 시초로 이어졌다고 쓰여 있다.그들은 예수가 죽은 후 박해를 두려워하며 숨었다.그들은 예수를 본 후 엄청난 위험에도 불구하고 예수 그리스도의 메시지를 대담하게 선포했다.그들은 회개, 세례, 순종(마태복음 28:19-20)을 통해 신과 화해하라는 예수의 명령을 따랐다.

- 예언자, 사제, 왕으로서의 직책

인류의 중재자인 예수 그리스도는 예언자, 사제, 왕의 세 직책을 수행한다.초기 교회의 에우세비우스는 이 세 가지 분류를 만들어 냈는데, 종교개혁 기간 동안 그것은 학문의 루터교와 존 칼빈과[70] 존 웨슬리의 [71]기독교학에서 실질적인 역할을 했다.

기흉학은 성령을 연구하는 학문이다.프네우마(Pneuma)는 그리스어로 "숨"을 의미하며, 비물질적인 존재나 영향을 은유적으로 묘사한다.기독교 신학에서 기흉학은 성령의 연구를 말한다.기독교에서 성령(또는 성령)은 신의 영이다.삼위일체 기독교의 주류 신앙 안에서 그는 삼위일체의 제3의 인물이다.성령의 일부로서 성령은 성부와 성자와 동등하다.성령의 기독교 신학은 삼위일체 신학의 마지막 부분이었다.

삼위일체 기독교에서 성령은 삼위일체의 세 사람 중 한 명이다.이와 같이 성령은 개인적인 것이고, 신의 일부로서, 그는 완전히 하나님이며,[72][73][74] 하나님의 아버지이자 아들이신 하느님과 동등하고 영원합니다.그는 니케아 [73]신조에 기술된 대로 아버지(또는 아버지와 아들)로부터 발전한다는 점에서 아버지와 아들과 다르다.그의 신성함은 성령에 대한 모독을 용서할 수 없다고 선언하는 신약성경 복음서에[75][76][77] 반영되어 있다.

이 영어 단어는 두 개의 그리스어 단어인 theneμα (pneuma, spirit)와 γγςςς (로고스, 가르침)에서 유래했다.폐렴학은 보통 성령의 인물에 대한 연구와 성령의 업적을 포함한다.후자의 범주는 보통 새로운 탄생, 영적인 선물, 영적 세례, 신성화, 예언자들의 영감, 그리고 성 삼위일체의 내재성에 대한 기독교의 가르침을 포함할 것이다.기독교 종파마다 신학적인 접근법이 다르다.

기독교인들은 성령이 사람들을 예수님에 대한 믿음으로 인도하고 기독교 생활방식을 살 수 있는 능력을 준다고 믿는다.성령님은 모든 기독교인의 몸 안에 계시고, 각각의 몸은 그의 사원이 [1 Cor 3:16]된다.예수는 성령을[Jn 14:26] 그리스어에서 유래한 라틴어로 파라클레투스라고 묘사했다.그 단어는 '컴포터', '상담사', '선생님', '변호사',[78] '진실을 인도하는' 등으로 다양하게 번역된다.한 사람의 삶에서 성령의 행동은 성령의 열매로 알려진 긍정적인 결과를 낳는다고 믿어진다.성령은 아직도 죄의 영향을 경험하는 기독교인들이 스스로는 결코 할 수 없는 일들을 할 수 있게 해줍니다.이러한 영적 재능은 성령에 의해 "잠금 해제"된 선천적인 능력이 아니라, 악마를 쫓아내는 능력이나 단순한 대담한 말과 같은 완전히 새로운 능력입니다.성령의 영향을 통해, 사람은 그 또는 그녀 주변의 세상을 더 명확하게 볼 수 있고, 그나 그녀의 몸과 마음을 이전의 능력을 초과하는 방식으로 사용할 수 있습니다.주어질 수 있는 선물 목록에는 예언, 혀, 치유, 지식의 카리스마 있는 선물이 포함됩니다.기독교인들은 이러한 선물들이 신약 시대에만 주어졌다고 믿는다.기독교인들은 사역, 교육, 기부, 리더십, 그리고 [Rom 12:6–8]자비를 포함한 특정한 "영적 선물"이 오늘날에도 여전히 유효하다는 것에 거의 동의한다.성령의 경험은 때때로 기름부음 받는 것으로 언급된다.

부활 후 그리스도는 제자들에게 "성령과 함께 세례를 받고"[Ac 1:4–8] 이 사건으로 힘을 받을 것이라고 말했는데, 이 약속은 Acts의 두 번째 장에 기술되어 있다.첫 번째 오순절에, 예수의 제자들이 예루살렘에 모였는데, 그때 강한 바람이 들리고 그들의 머리 위로 불길이 나타났다.여러 언어를 구사하는 군중은 제자들이 말하는 것을 들었고, 그들 각자는 그들의 모국어로 말하는 것을 들었다.

성령은 기독교인이나 교회의 삶에서 특정한 신성한 기능을 수행하는 것으로 믿어진다.여기에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

- 죄의 유죄판결.성령은 구원받지 못한 사람에게 그들의 행위의 죄와 [79]하나님 앞에 죄인으로서의 도덕적 지위를 확신시키기 위해 행동한다.

- 개종시키다.성령의 작용은 그 사람을 기독교 [80]신앙으로 인도하는 데 필수적인 부분으로 여겨진다.그 새로운 신자는 "영혼의 재탄생"[81]이다.

- 기독교인의 삶을 가능하게 하는 것.성령은 개개인의 신자들에게 깃들어 정의롭고 성실한 [80]삶을 살 수 있도록 해준다고 믿어진다.

- 중재자 또는 Paraclete로서 중재자, 지지자 또는 옹호자로서의 역할을 하는 사람, 특히 재판 시에.

- 성경에 대한 영감과 해석.성령은 성경의 집필에 영감을 주고 기독교와 교회에 그것을 [82]해석한다.

성령 또한 예수 그리스도의 생애에서 특히 활동적이라고 믿어져서, 예수 그리스도가 지상에서의 일을 완수할 수 있게 해줍니다.성령의 특별한 행동에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

- 그의 출생 원인.예수 탄생에 대한 복음서에 따르면, "그의 화신적 존재의 시작"은 성령 [83][84]덕분이었다.

- 세례식 [80]때 기름을 바르고.

- 그의 사명을 강화했다.예수님의 세례에 따른 사역(복음서에서 성령이 비둘기처럼 그분에게 강림하는 것으로 묘사)은 [80]성령의 권력과 지시에 따라 행해진다.

- 정령의 열매

기독교인들은 "영령의 열매"가 성령의 작용에 의해 기독교에서 생겨난 고결한 특성으로 이루어져 있다고 믿는다.갈라디아서 5장 22절~23절에 열거된 사람들입니다. "그러나 성령의 열매는 사랑, 기쁨, 평화, 인내, 친절, 선함, 성실, 온화,[85] 자제입니다."로마 가톨릭 교회는 이 목록에 관대함, 겸손함, 그리고 [86]순결을 더한다.

- 정령의 선물

기독교인들은 성령이 기독교인들에게 '선물'을 준다고 믿는다.이 선물들은 [80]기독교인 개개인에게 주어진 특정한 능력들로 구성되어 있다.그들은 종종 그리스어로 선물인 카리스마로 알려져 있는데, 카리스마라는 용어는 여기서 유래한다.신약성경은 초자연적인 것에서부터 특정한 부름과 관련된 것에서부터 어느 정도 모든 기독교인들에게 기대되는 것까지 세 가지의 다른 선물 목록을 제공한다.대부분은 이 리스트가 완전하지 않다고 생각하고 있으며, 다른 리스트는 독자적인 리스트를 작성했습니다.성 암브로스는 세례 때 신도에게 쏟아지는 성령의 일곱 가지 선물에 대해 썼다: 1. 지혜의 영; 2.이해의 정신; 3.상담의 정신 4.힘의 정신; 5.지식의 정령 6. 경건함의 정령; 7.[87] 성스러운 두려움의 정령.

성령과 관련하여 기독교인들 사이에 가장 큰 불일치가 존재하는 것은 이러한 선물들, 특히 초자연적인 선물들(때로는 카리스마적인 선물이라고 불린다)의 본질과 발생에 관한 것입니다.

한 가지 견해는 초자연적인 선물은 사도 시대를 위한 특별한 선물이었고, 그 당시 교회의 독특한 조건 때문에 주어졌고,[88] 현재는 극히 드물게 주어졌다는 것이다.이것은[74] 가톨릭 교회와 다른 많은 주류 기독교 단체들의 견해이다.주로 오순절 교파와 카리스마 운동이 지지하는 또 다른 견해는 초자연적인 선물이 없는 것은 성령의 무시와 교회의 그의 업적 때문이라는 것이다.몬타니스트와 같은 일부 소그룹들은 초자연적인 재능을 실천했지만 19세기 [88]후반 오순절 운동이 성장하기 전까지는 드물었다.

초자연적인 선물들의 관련성을 믿는 사람들은 때때로 기독교인들이 그 선물들을 받기 위해 경험해야 하는 성령의 세례나 성령의 충만함에 대해 말한다.많은 교회들은 성령의 세례는 개종과 동일하며, 모든 기독교인들은 정의상 성령으로 [88]세례를 받는다고 주장한다.

우주론:작성된 것

하나님이 말씀하셨습니다. 빛이 있으라. 빛이 있었다.하나님께서는 빛을 보셨으니, 그것은 선하시며, 빛과 어둠을 나누셨다.신은 빛을 낮이라 부르시고 어둠을 밤이라 부르셨다.그리고 저녁과 아침이 첫날이었다.제네시스 1: 3-5

구약성서와 신약성서의 다양한 저자들은 우주론에 대한 그들의 통찰력을 일목요연하게 제공한다.우주는 창세기 1세의 성경에서 가장 잘 알려져 있고 가장 완전한 설명으로 신의 명령에 의해 창조되었습니다.

세계

그러나 이 넓은 이해 안에서 이 교리를 정확히 어떻게 해석해야 하는지에 대한 많은 견해가 있다.

- 일부 기독교인들, 특히 청년과 구 지구 창조론자들은 창세기를 창조의 정확하고 문자 그대로의 설명으로 해석한다.

- Others may understand these to be, instead, spiritual insights more vaguely defined.

It is a tenet of Christian faith (Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant) that God is the creator of all things from nothing, and has made human beings in the Image of God, who by direct inference is also the source of the human soul. In Chalcedonian Christology, Jesus is the Word of God, which was in the beginning and, thus, is uncreated, and hence is God, and consequently identical with the Creator of the world ex nihilo.

Roman Catholicism uses the phrase special creation to refer to the doctrine of immediate or special creation of each human soul. In 2004, the International Theological Commission, then under the presidency of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, published a paper in which it accepts the current scientific accounts of the history of the universe commencing in the Big Bang about 15 billion years ago and of the evolution of all life on earth including humans from the micro organisms commencing about 4 billion years ago.[89] The Roman Catholic Church allows for both a literal and allegorical interpretation of Genesis, so as to allow for the possibility of Creation by means of an evolutionary process over great spans of time, otherwise known as theistic evolution.[dubious ] It believes that the creation of the world is a work of God through the Logos, the Word (idea, intelligence, reason and logic):

- "In the beginning was the Word...and the Word was God...all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made."

The New Testament claims that God created everything by the eternal Word, Jesus Christ his beloved Son. In him

- "all things were created, in heaven and on earth.. . all things were created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together."[90]

Anthropology: Humanity

Christian anthropology is the study of humanity, especially as it relates to the divine. This theological anthropology refers to the study of the human ("anthropology") as it relates to God. It differs from the social science of anthropology, which primarily deals with the comparative study of the physical and social characteristics of humanity across times and places.

One aspect studies the innate nature or constitution of the human, known as the nature of mankind. It is concerned with the relationship between notions such as body, soul and spirit which together form a person, based on their descriptions in the Bible. There are three traditional views of the human constitution– trichotomism, dichotomism and monism (in the sense of anthropology).[91]

Components

- Soul

The semantic domain of Biblical soul is based on the Hebrew word nepes, which presumably means "breath" or "breathing being".[92] This word never means an immortal soul[93] or an incorporeal part of the human being[94] that can survive death of the body as the spirit of dead.[95] This word usually designates the person as a whole[96] or its physical life. In the Septuagint nepes is mostly translated as psyche (ψυχή) and, exceptionally, in the Book of Joshua as empneon (ἔμπνεον), that is "breathing being".[97]

The New Testament follows the terminology of the Septuagint, and thus uses the word psyche with the Hebrew semantic domain and not the Greek,[98] that is an invisible power (or ever more, for Platonists, immortal and immaterial) that gives life and motion to the body and is responsible for its attributes.

In Patristic thought, towards the end of the 2nd century psyche was understood in more a Greek than a Hebrew way, and it was contrasted with the body. In the 3rd century, with the influence of Origen, there was the establishing of the doctrine of the inherent immortality of the soul and its divine nature.[99] Origen also taught the transmigration of the souls and their preexistence, but these views were officially rejected in 553 in the Fifth Ecumenical Council. Inherent immortality of the soul was accepted among western and eastern theologians throughout the middle ages, and after the Reformation, as evidenced by the Westminster Confession.

- Spirit

The spirit (Hebrew ruach, Greek πνεῦμα, pneuma, which can also mean "breath") is likewise an immaterial component. It is often used interchangeably with "soul", psyche, although trichotomists believe that the spirit is distinct from the soul.

- "When Paul speaks of the pneuma of man he does not mean some higher principle within him or some special intellectual or spiritual faculty of his, but simply his self, and the only questions is whether the self is regarded in some particular aspect when it is called pneuma. In the first place, it apparently is regarded in the same way as when it is called psyche– viz. as the self that lives in man's attitude, in the orientation of his will."[100]

- Body, Flesh

The body (Greek σῶμα soma) is the corporeal or physical aspect of a human being. Christians have traditionally believed that the body will be resurrected at the end of the age.

Flesh (Greek σάρξ, sarx) is usually considered synonymous with "body", referring to the corporeal aspect of a human being. The apostle Paul contrasts flesh and spirit in Romans 7–8.

Origin of humanity

The Bible teaches in the book of Genesis the humans were created by God. Some Christians believe that this must have involved a miraculous creative act, while others are comfortable with the idea that God worked through the evolutionary process.

The book of Genesis also teaches that human beings, male and female, were created in the image of God. The exact meaning of this has been debated throughout church history.

Death and afterlife

Christian anthropology has implications for beliefs about death and the afterlife. The Christian church has traditionally taught that the soul of each individual separates from the body at death, to be reunited at the resurrection. This is closely related to the doctrine of the immortality of the soul. For example, the Westminster Confession (chapter XXXII) states:

- "The bodies of men, after death, return to dust, and see corruption: but their souls, which neither die nor sleep, having an immortal subsistence, immediately return to God who gave them"

- Intermediate state

The question then arises: where exactly does the disembodied soul "go" at death? Theologians refer to this subject as the intermediate state. The Old Testament speaks of a place called sheol where the spirits of the dead reside. In the New Testament, hades, the classical Greek realm of the dead, takes the place of sheol. In particular, Jesus teaches in Luke 16:19–31 (Lazarus and Dives) that hades consists of two separate "sections", one for the righteous and one for the unrighteous. His teaching is consistent with intertestamental Jewish thought on the subject.[101]

Fully developed Christian theology goes a step further; on the basis of such texts as Luke 23:43 and Philippians 1:23, it has traditionally been taught that the souls of the dead are received immediately either into heaven or hell, where they will experience a foretaste of their eternal destiny prior to the resurrection. (Roman Catholicism teaches a third possible location, Purgatory, though this is denied by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox.)

- "the souls of the righteous, being then made perfect in holiness, are received into the highest heavens, where they behold the face of God, in light and glory, waiting for the full redemption of their bodies. And the souls of the wicked are cast into hell, where they remain in torments and utter darkness, reserved to the judgment of the great day." (Westminster Confession)

Some Christian groups which stress a monistic anthropology deny that the soul can exist consciously apart from the body. For example, the Seventh-day Adventist Church teaches that the intermediate state is an unconscious sleep; this teaching is informally known as "soul sleep".

- Final state

In Christian belief, both the righteous and the unrighteous will be resurrected at the last judgment. The righteous will receive incorruptible, immortal bodies (1 Corinthians 15), while the unrighteous will be sent to hell. Traditionally, Christians have believed that hell will be a place of eternal physical and psychological punishment. In the last two centuries, annihilationism has become popular.

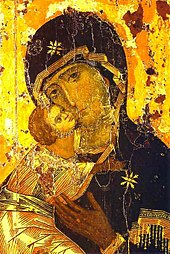

Mariology

The study of the Blessed Virgin Mary, doctrines about her, and how she relates to the Church, Christ, and the individual Christian is called Mariology. Examples of Mariology include the study of and doctrines regarding her Perpetual Virginity, her Motherhood of God (and by extension her Motherhood/Intercession for all Christians), her Immaculate Conception, and her Assumption into heaven. Catholic Mariology is the Marian study specifically in the context of the Catholic Church.

Angelology

Most descriptions of angels in the Bible describe them in military terms. For example, in terms such as encampment (Gen.32:1–2), command structure (Ps.91:11–12; Matt.13:41; Rev.7:2), and combat (Jdg.5:20; Job 19:12; Rev.12:7).

Its specific hierarchy differs slightly from the Hierarchy of Angels as it surrounds more military services, whereas the Hierarchy of angels is a division of angels into non-military services to God.

Members of the heavenly host

Cherubim are depicted as accompanying God's chariot-throne (Ps.80:1). Exodus 25:18–22 refers to two Cherub statues placed on top of the Ark of the Covenant, the two cherubim are usually interpreted as guarding the throne of God. Other guard-like duties include being posted in locations such as the gates of Eden (Gen.3:24). Cherubim were mythological winged bulls or other beasts that were part of ancient Near Eastern traditions.[102]

This angelic designation might be given to angels of various ranks. An example would be Raphael who is ranked variously as a Seraph, Cherub, and Archangel .[103] This is usually a result of conflicting schemes of hierarchies of angels.

It is not known how many angels there are but one figure given in Revelation 5:11 for the number of "many angels in a circle around the throne, as well as the living creatures and the elders" was "ten thousand times ten thousand", which would be 100 million.

Demonology: Fallen angels

In most of Christianity, a fallen angel is an angel who has been exiled or banished from Heaven. Often such banishment is a punishment for disobeying or rebelling against God (see War in Heaven). The best-known fallen angel is Lucifer. Lucifer is a name frequently given to Satan in Christian belief. This usage stems from a particular interpretation, as a reference to a fallen angel, of a passage in the Bible (Isaiah 14:3–20) that speaks of someone who is given the name of "Day Star" or "Morning Star" (in Latin, Lucifer) as fallen from heaven. The Greek etymological synonym of Lucifer, Φωσφόρος (Phosphoros, "light-bearer").[104][105] is used of the morning star in 2 Peter 1:19 and elsewhere with no reference to Satan. But Satan is called Lucifer in many writings later than the Bible, notably in Milton's Paradise Lost (7.131–134, among others), because, according to Milton, Satan was "brighter once amidst the host of Angels, than that star the stars among."

Allegedly, fallen angels are those which have committed one of the seven deadly sins. Therefore, are banished from heaven and suffer in hell for all eternity. Demons from hell would punish the fallen angel by ripping out their wings as a sign of insignificance and low rank. [106]

Heaven

Christianity has taught Heaven as a place of eternal life, in that it is a shared plane to be attained by all the elect (rather than an abstract experience related to individual concepts of the ideal). The Christian Church has been divided over how people gain this eternal life. From the 16th to the late 19th century, Christendom was divided between the Catholic view, the Eastern Orthodox view, the Coptic view, the Jacobite view, the Abyssinian view and Protestant views. See also Christian denominations.

Heaven is the English name for a transcendental realm wherein human beings who have transcended human living live in an afterlife. in the Bible and in English, the term "heaven" may refer to the physical heavens, the sky or the seemingly endless expanse of the universe beyond, the traditional literal meaning of the term in English.

Christianity maintains that entry into Heaven awaits such time as, "When the form of this world has passed away." (*JPII) One view expressed in the Bible is that on the day Christ returns the righteous dead are resurrected first, and then those who are alive and judged righteous will be brought up to join them, to be taken to heaven. (I Thess 4:13–18)

Two related and often confused concepts of heaven in Christianity are better described as the "resurrection of the body", which is exclusively of biblical origin, as contrasted with the "immortality of the soul", which is also evident in the Greek tradition. In the first concept, the soul does not enter heaven until the last judgement or the "end of time" when it (along with the body) is resurrected and judged. In the second concept, the soul goes to a heaven on another plane such as the intermediate state immediately after death. These two concepts are generally combined in the doctrine of the double judgement where the soul is judged once at death and goes to a temporary heaven, while awaiting a second and final physical judgement at the end of the world.(*" JPII, also see eschatology, afterlife)

One popular medieval view of Heaven was that it existed as a physical place above the clouds and that God and the Angels were physically above, watching over man. Heaven as a physical place survived in the concept that it was located far out into space, and that the stars were "lights shining through from heaven".

Many of today's biblical scholars, such as N. T. Wright, in tracing the concept of Heaven back to its Jewish roots, see Earth and Heaven as overlapping or interlocking. Heaven is known as God's space, his dimension, and is not a place that can be reached by human technology. This belief states that Heaven is where God lives and reigns whilst being active and working alongside people on Earth. One day when God restores all things, Heaven and Earth will be forever combined into the New Heavens and New Earth of the World to Come.

Religions that teach about heaven differ on how (and if) one gets into it, typically in the afterlife. In most, entrance to Heaven is conditional on having lived a "good life" (within the terms of the spiritual system). A notable exception to this is the 'sola fide' belief of many mainstream Protestants, which teaches that one does not have to live a perfectly "good life," but that one must accept Jesus Christ as one's saviour, and then Jesus Christ will assume the guilt of one's sins; believers are believed to be forgiven regardless of any good or bad "works" one has participated in.[107]

Many religions state that those who do not go to heaven will go to a place "without the presence of God", Hell, which is eternal (see annihilationism). Some religions believe that other afterlives exist in addition to Heaven and Hell, such as Purgatory. One belief, universalism, believes that everyone will go to Heaven eventually, no matter what they have done or believed on earth. Some forms of Christianity believe Hell to be the termination of the soul.

Various saints have had visions of heaven (2 Corinthians 12:2–4). The Eastern Orthodox concept of life in heaven is described in one of the prayers for the dead: "...a place of light, a place of green pasture, a place of repose, whence all sickness, sorrow and sighing are fled away."[108]

The Church bases its belief in Heaven on some main biblical passages in the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures (Old and New Testaments) and collected church wisdom. Heaven is the Realm of the Blessed Trinity, the angels[109] and the saints.[110]

The essential joy of heaven is called the beatific vision, which is derived from the vision of God's essence. The soul rests perfectly in God, and does not, or cannot desire anything else than God. After the Last Judgment, when the soul is reunited with its body, the body participates in the happiness of the soul. It becomes incorruptible, glorious and perfect. Any physical defects the body may have laboured under are erased. Heaven is also known as paradise in some cases. The Great Gulf separates heaven from hell.

Upon dying, each soul goes to what is called "the particular judgement" where its own afterlife is decided (i.e. Heaven after Purgatory, straight to Heaven, or Hell.) This is different from "the general judgement" also known as "the Last judgement" which will occur when Christ returns to judge all the living and the dead.

The term Heaven (which differs from "The Kingdom of Heaven" see note below) is applied by the biblical authors to the realm in which God currently resides. Eternal life, by contrast, occurs in a renewed, unspoilt and perfect creation, which can be termed Heaven since God will choose to dwell there permanently with his people, as seen in Revelation 21:3. There will no longer be any separation between God and man. The believers themselves will exist in incorruptible, resurrected and new bodies; there will be no sickness, no death and no tears. Some teach that death itself is not a natural part of life, but was allowed to happen after Adam and Eve disobeyed God (see original sin) so that mankind would not live forever in a state of sin and thus a state of separation from God.

Many evangelicals understand this future life to be divided into two distinct periods: first, the Millennial Reign of Christ (the one thousand years) on this earth, referred to in Revelation 20:1–10; secondly, the New Heavens and New Earth, referred to in Revelation 21 and 22. This millennialism (or chiliasm) is a revival of a strong tradition in the Early Church[111] that was dismissed by Saint Augustine of Hippo and the Roman Catholic Church after him.

Not only will the believers spend eternity with God, they will also spend it with each other. John's vision recorded in Revelation describes a New Jerusalem which comes from Heaven to the New Earth, which is seen to be a symbolic reference to the people of God living in community with one another. 'Heaven' will be the place where life will be lived to the full, in the way that the designer planned, each believer 'loving the Lord their God with all their heart and with all their soul and with all their mind' and 'loving their neighbour as themselves' (adapted from Matthew 22:37–38, the Great Commandment)—a place of great joy, without the negative aspects of earthly life. See also World to Come.

- Purgatory

Purgatory is the condition or temporary punishment[30] in which, it is believed, the souls of those who die in a state of grace are made ready for Heaven. This is a theological idea that has ancient roots and is well-attested in early Christian literature, while the poetic conception of purgatory as a geographically situated place is largely the creation of medieval Christian piety and imagination.[30]

The notion of purgatory is associated particularly with the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church (in the Eastern sui juris churches or rites it is a doctrine, though often without using the name "Purgatory"); Anglicans of the Anglo-Catholic tradition generally also hold to the belief. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, believed in an intermediate state between death and the final judgment and in the possibility of "continuing to grow in holiness there."[112][113] The Eastern Orthodox Churches believe in the possibility of a change of situation for the souls of the dead through the prayers of the living and the offering of the Divine Liturgy,[114] and many Eastern Orthodox, especially among ascetics, hope and pray for a general apocatastasis.[115] A similar belief in at least the possibility of a final salvation for all is held by Mormonism.[116] Judaism also believes in the possibility of after-death purification[117] and may even use the word "purgatory" to present its understanding of the meaning of Gehenna.[118] However, the concept of soul "purification" may be explicitly denied in these other faith traditions.

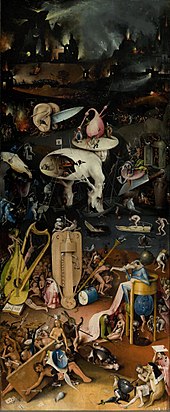

Hell

Hell in Christian beliefs, is a place or a state in which the souls of the unsaved will suffer the consequences of sin. The Christian doctrine of Hell derives from the teaching of the New Testament, where Hell is typically described using the Greek words Gehenna or Tartarus. Unlike Hades, Sheol, or Purgatory it is eternal, and those damned to Hell are without hope. In the New Testament, it is described as the place or state of punishment after death or last judgment for those who have rejected Jesus.[119] In many classical and popular depictions it is also the abode of Satan and of Demons.[120]

Hell is generally defined as the eternal fate of unrepentant sinners after this life.[121] Hell's character is inferred from biblical teaching, which has often been understood literally.[121] Souls are said to pass into Hell by God's irrevocable judgment, either immediately after death (particular judgment) or in the general judgment.[121] Modern theologians generally describe Hell as the logical consequence of the soul using its free will to reject the will of God.[121] It is considered compatible with God's justice and mercy because God will not interfere with the soul's free choice.[121]

Only in the King James Version of the bible is the word "Hell" used to translate certain words, such as sheol (Hebrew) and both hades and Gehenna(Greek). All other translations reserve Hell only for use when Gehenna is mentioned. It is generally agreed that both sheol and hades do not typically refer to the place of eternal punishment, but to the underworld or temporary abode of the dead.[122]

Traditionally, the majority of Protestants have held that Hell will be a place of unending conscious torment, both physical and spiritual,[123] although some recent writers (such as C. S. Lewis[124] and J.P. Moreland[125]) have cast Hell in terms of "eternal separation" from God. Certain biblical texts have led some theologians to the conclusion that punishment in Hell, though eternal and irrevocable, will be proportional to the deeds of each soul (e.g. Matthew 10:15, Luke 12:46–48).[126]

Another area of debate is the fate of the unevangelized (i.e. those who have never had an opportunity to hear the Christian gospel), those who die in infancy, and the mentally disabled. Some Protestants agree with Augustine that people in these categories will be damned to Hell for original sin, while others believe that God will make an exception in these cases.[123]

A "significant minority" believe in the doctrine of conditional immortality,[127] which teaches that those sent to Hell will not experience eternal conscious punishment, but instead will be extinguished or annihilated after a period of "limited conscious punishment".[128] Prominent evangelical theologians who have adopted conditionalist beliefs include John Wenham, Edward Fudge, Clark Pinnock and John Stott (although the latter has described himself as an "agnostic" on the issue of annihilationism).[123] Conditionalists typically reject the traditional concept of the immortality of the soul.

Some Protestants (such as George MacDonald, Karl Randall, Keith DeRose and Thomas Talbott), also, however, in a minority, believe that after serving their sentence in Gehenna, all souls are reconciled to God and admitted to heaven, or ways are found at the time of death of drawing all souls to repentance so that no "hellish" suffering is experienced. This view is often called Christian universalism—its conservative branch is more specifically called 'Biblical or Trinitarian Universalism'—and is not to be confused with Unitarian Universalism. See universal reconciliation, apocatastasis and the problem of Hell.

Theodicy: Allowance of evil

Theodicy can be said to be defense of God's goodness and omnipotence in view of the existence of evil. Specifically, Theodicy is a specific branch of theology and philosophy which attempts to reconcile belief in God with the perceived existence of evil.[129] As such, theodicy can be said to attempt to justify the behaviour of God (at least insofar as God allows evil).

Responses to the problem of evil have sometimes been classified as defenses or theodicies. However, authors disagree on the exact definitions.[130][131][132] Generally, a defense attempts to show that there is no logical incompatibility between the existence of evil and the existence of God. A defense need not argue that this is a probable or plausible explanation, only that the defense is logically possible. A defense attempts to answer the logical problem of evil.

A theodicy, on the other hand, is a more ambitious attempt to provide a plausible justification for the existence of evil. A theodicy attempts to answer the evidential problem of evil.[131] Richard Swinburne maintains that it does not make sense to assume there are greater goods, unless we know what they are, i.e., we have a successful theodicy.[133]

As an example, some authors see arguments including demons or the fall of man as not logically impossible but not very plausible considering our knowledge about the world. Thus they are seen as defenses but not good theodicies.[131] C. S. Lewis writes in his book The Problem of Pain:

We can, perhaps, conceive of a world in which God corrected the results of this abuse of free will by His creatures at every moment: so that a wooden beam became soft as grass when it was used as a weapon, and the air refused to obey me if I attempted to set up in it the sound waves that carry lies or insults. But such a world would be one in which wrong actions were impossible, and in which, therefore, freedom of the will would be void; nay, if the principle were carried out to its logical conclusion, evil thoughts would be impossible, for the cerebral matter which we use in thinking would refuse its task when we attempted to frame them.[134]

Another possible answer is that the world is corrupted due to the sin of mankind. Some answer that because of sin, the world has fallen from the grace of God, and is not perfect. Therefore, evils and imperfections persist because the world is fallen.[citation needed] William A. Dembski argues that the effects of Adam's sin recorded in the Book of Genesis were 'back-dated' by God, and hence applied to the earlier history of the universe.[135]

Evil is sometimes seen as a test or trial for humans. Irenaeus of Lyons and more recently John Hick have argued that evil and suffering are necessary for spiritual growth. This is often combined with the free will argument by arguing that such spiritual growth requires free will decisions. A problem with this is that many evils do not seem to cause any kind of spiritual growth, or even permit it, as when a child is abused from birth and becomes, seemingly inevitably, a brutal adult.

The problem of evil is often phrased in the form: Why do bad things happen to good people?. Christianity teach that all people are inherently sinful due to the fall of man and original sin; for example, Calvinist theology follows a doctrine called federal headship, which argues that the first man, Adam, was the legal representative of the entire human race. A counterargument to the basic version of this principle is that an omniscient God would have predicted this, when he created the world, and an omnipotent God could have prevented it.

The Book of Isaiah clearly claims that God is the source of at least some natural disasters, but Isaiah doesn't attempt to explain the motivation behind the creation of evil.[136] In contrast, the Book of Job is one of the most widely known formulations of the problem of evil in Western thought. In it, Satan challenges God regarding his servant Job, claiming that Job only serves God for the blessings and protection that he receives from him. God allows Satan to plague Job and his family in a number of ways, with the limitation that Satan may not take Job's life (but his children are killed). Job discusses this with three friends and questions God regarding his suffering which he finds to be unjust. God responds in a speech and then more than restores Job's prior health, wealth, and gives him new children.

Bart D. Ehrman argues that different parts of the Bible give different answers. One example is evil as punishment for sin or as a consequence of sin. Ehrman writes that this seems to be based on some notion of free will although this argument is never explicitly mentioned in the Bible. Another argument is that suffering ultimately achieves a greater good, possibly for persons other than the sufferer, that would not have been possible otherwise. The Book of Job offers two different answers: suffering is a test, and you will be rewarded later for passing it; another that God in his might chooses not to reveal his reasons. Ecclesiastes sees suffering as beyond human abilities to comprehend. Apocalyptic parts, including the New Testament, see suffering as due to cosmic evil forces, that God for mysterious reasons has given power over the world, but which will soon be defeated and things will be set right.[137]

Hamartiology: Sin

The Greek word in the New Testament that is translated in English as "sin" is hamartia, which literally means missing the target. 1 John 3:4 states: "Everyone who sins breaks the law; in fact, sin is lawlessness". Jesus clarified the law by defining its foundation: "Jesus replied: 'Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.' This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: 'Love your neighbor as yourself.' All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments." (Matthew 22:36–40)

Hamartiology (Greek: ἁμαρτία, hamartia, "missing the mark," "sin," + -λογια, -logia, "sayings" or "discourse") is the branch of Christian theology, more specifically, systematic theology, which is the study of sin with a view to articulating a doctrine of it.

Substantial branches of hamartiological understanding subscribe to the doctrine of original sin, which was taught by the Apostle Paul in Romans 5:12–19 and popularized by Saint Augustine. He taught that all the descendants of Adam and Eve are guilty of Adam's sin without their own personal choice.[138]

In contrast, Pelagius argued that humans enter life as essentially tabulae rasae. The fall that occurred when Adam and Eve disobeyed God was held by his group to have affected humankind only minimally. But few theologians continue to hold this hamartiological viewpoint.

A third branch of thinking takes an intermediate position, arguing that after the fall of Adam and Eve, humans are born impacted by sin such that they have very decided tendencies toward sinning (which by personal choice all accountable humans but Jesus soon choose to indulge).

The degree to which a Christian believes humanity is impacted by either a literal or metaphorical "fall" determines their understanding of related theological concepts like salvation, justification, and sanctification.

Christian views on sin are mostly understood as legal infraction or contract violation, and so salvation tends to be viewed in legal terms, similar to Jewish thinking.

Sin

In religion, sin is the concept of acts that violate a rule of God. The term sin may also refer to the state of having committed such a violation. Commonly, the moral code of conduct is decreed by a divine entity, i.e. Divine law.

Sin is often used to mean an action that is prohibited or considered wrong; in some religions (notably some sects of Christianity), sin can refer not only to physical actions taken, but also to thoughts and internalized motivations and feelings. Colloquially, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, shameful, harmful, or alienating might be termed "sinful".

An elementary concept of "sin" regards such acts and elements of Earthly living that one cannot take with them into transcendental living. Food, for example is not of transcendental living and therefore its excessive savoring is considered a sin. A more developed concept of "sin" deals with a distinction between sins of death (mortal sin) and the sins of human living (venial sin). In that context, mortal sins are said to have the dire consequence of mortal penalty, while sins of living (food, casual or informal sexuality, play, inebriation) may be regarded as essential spice for transcendental living, even though these may be destructive in the context of human living (obesity, infidelity).

Common ideas surrounding sin in various religions include:

- Punishment for sins, from other people, from God either in life or in afterlife, or from the Universe in general.

- The question of whether an act must be intentional to be sinful.

- The idea that one's conscience should produce guilt for a conscious act of sin.

- A scheme for determining the seriousness of the sin.

- Repentance from (expressing regret for and determining not to commit) sin, and atonement (repayment) for past deeds.

- The possibility of forgiveness of sins, often through communication with a deity or intermediary; in Christianity often referred to as salvation. Crime and justice are related secular concepts.

In Western Christianity, "sin is lawlessness" (1 John 3:4) and so salvation tends to be understood in legal terms, similar to Jewish law. Sin alienates the sinner from God. It has damaged, and completely severed, the relationship of humanity to God. That relationship can only be restored through acceptance of Jesus Christ and his death on the cross as a sacrifice for mankind's sin (see Salvation and Substitutionary atonement).

In Eastern Christianity, sin is viewed in terms of its effects on relationships, both among people and between people and God. Sin is seen as the refusal to follow God's plan, and the desire to be like God and thus in direct opposition to him (see the account of Adam and Eve in the Book of Genesis). To sin is to want control of one's destiny in opposition to the will of God, to do some rigid beliefs.

In the Russian variant of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, sin sometimes is regarded as any mistake made by people in their life. From this point of view every person is sinful because every person makes mistakes during his life. When person accuses others in sins he always must remember that he is also sinner and so he must have mercy for others remembering that God is also merciful to him and to all humanity.

Fall of man

The fall of man or simply the fall refers in Christian doctrine to the transition of the first humans from a state of innocent obedience to God, to a state of guilty disobedience to God. In the Book of Genesis chapter 2, Adam and Eve live at first with God in a paradise, but are then deceived or tempted by the serpent to eat fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, which had been forbidden to them by God. After doing so they become ashamed of their nakedness, and God consequently expelled them from paradise. The fall is not mentioned by name in the Bible, but the story of disobedience and expulsion is recounted in both Testaments in different ways. The Fall can refer to the wider theological inferences for all humankind as a consequence of Eve and Adam's original sin. Examples include the teachings of Paul in Romans 5:12–19 and 1 Cor. 15:21–22.

Some Christian denominations believe the fall corrupted the entire natural world, including human nature, causing people to be born into original sin, a state from which they cannot attain eternal life without the gracious intervention of God. Protestants hold that Jesus' death was a "ransom" by which humanity was offered freedom from the sin acquired at the fall. In other religions, such as Judaism, Islam, and Gnosticism, the term "the fall" is not recognized and varying interpretations of the Eden narrative are presented.

Christianity interprets the fall in a number of ways. Traditional Christian theology accepts the teaching of St Paul in his letter to the Romans[139][better source needed] "For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God" and of St John's Gospel that "God so loved the world that he sent his only son (Jesus Christ) that whoever believes in him should not perish, but have everlasting life".[John 3:16][better source needed]

The doctrine of original sin, as articulated by Augustine of Hippo's interpretation of Paul of Tarsus, provides that the fall caused a fundamental change in human nature, so that all descendants of Adam are born in sin, and can only be redeemed by divine grace. Sacrifice was the only means by which humanity could be redeemed after the fall. Jesus, who was without sin, died on the cross as the ultimate redemption for the sin of humankind.

Original sin

Thus, the moment Adam and Eve ate the fruit from the tree—which God had commanded them not to do—sinful death was born; it was an act of disobedience, thinking they could become like gods, that was the sin. Since Adam was the head of the human race, he is held responsible for the evil that took place, for which reason the fall of man is referred to as the "sin of Adam". This sin caused Adam and his descendants to lose unrestricted access to God Himself. The years of life were limited. "Wherefore, as by one man sin entered into the world, and death by sin; and so death passed upon all men, for that all have sinned" (Romans 5:12). In Christian theology, the death of Jesus on the cross is the atonement to the sin of Adam. "For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive." (1 Corinthians 15:22). As a result of that act of Christ, all who put their trust in Christ alone now have unrestricted access to God through prayer and in presence.

Original sin, which Eastern Christians usually refer to as ancestral sin,[140] is, according to a doctrine proposed in Christian theology, humanity's state of sin resulting from the fall of man.[141] This condition has been characterized in many ways, ranging from something as insignificant as a slight deficiency, or a tendency toward sin yet without collective guilt, referred to as a "sin nature," to something as drastic as total depravity or automatic guilt by all humans through collective guilt.[142]

Those who uphold the doctrine look to the teaching of Paul the Apostle in Romans 5:12–21 and 1 Corinthians 15:22 for its scriptural base,[35] and see it as perhaps implied in Old Testament passages such as Psalm 51:5 and Psalm 58:3.

The Apostolic Fathers and the Apologists mostly dealt with topics other than original sin.[35] The doctrine of original sin was first developed in 2nd-century Bishop of Lyon Irenaeus's struggle against Gnosticism.[35] The Greek Fathers emphasized the cosmic dimension of the fall, namely that since Adam human beings are born into a fallen world, but held fast to belief that man, though fallen, is free.[35] It was in the West that precise definition of the doctrine arose.[35] Augustine of Hippo taught that original sin was both an act of foolishness (insipientia) and of pride and disobedience to the God of Adam and Eve. He thought it was a most subtle job to discern what came first: self-centeredness or failure in seeing truth.[143] The sin would not have taken place, if satan hadn't sown into their senses "the root of evil" (radix Mali).[144] The sin of Adam and Eve wounded their nature, affecting human intelligence and will, as well as affections and desires, including sexual desire. The consequences of the fall were transmitted to their descendants in the form of concupiscence, which is a metaphysical term, and not a psychological one. Thomas Aquinas explained Augustine's doctrine pointing out that the libido (concupiscence), which makes the original sin pass from parents to children, is not a libido actualis, i.e. sexual lust, but libido habitualis, i.e. a wound of the whole of human nature.[145] Augustine insisted that concupiscence was not a being but bad quality, the privation of good or a wound.[146] The bishop of Hippo admitted that sexual concupiscence (libido) might have been present in the perfect human nature in the paradise, and that only later it had become disobedient to human will as a result of the first couple's disobedience to God's will in the original sin.[147] The original sin have made humanity a massa damnata[35] (mass of perdition, condemned crowd). In Augustine's view (termed "Realism"), all of humanity was really present in Adam when he sinned, and therefore all have sinned. Original sin, according to Augustine, consists of the guilt of Adam which all humans inherit. As sinners, humans are utterly depraved in nature, lack the freedom to do good, and cannot respond to the will of God without divine grace. Grace is irresistible, results in conversion, and leads to perseverance.[148]

Augustine's formulation of original sin was popular among Protestant reformers, such as Martin Luther and John Calvin, and also, within Roman Catholicism, in the Jansenist movement, but this movement was declared heretical by the Catholic Church.[149] There are wide-ranging disagreements among Christian groups as to the exact understanding of the doctrine about a state of sinfulness or absence of holiness affecting all humans, even children, with some Christian groups denying it altogether.

The notion of original sin as interpreted by Augustine of Hippo was affirmed by the Protestant Reformer John Calvin. Calvin believed that humans inherit Adamic guilt and are in a state of sin from the moment of conception. This inherently sinful nature (the basis for the Calvinistic doctrine of "total depravity") results in a complete alienation from God and the total inability of humans to achieve reconciliation with God based on their own abilities. Not only do individuals inherit a sinful nature due to Adam's fall, but since he was the federal head and representative of the human race, all whom he represented inherit the guilt of his sin by imputation.

- New Testament

The scriptural basis for the doctrine is found in two New Testament books by Paul the Apostle, Romans 5:12–21 and 1 Corinthians 15:22, in which he identifies Adam as the one man through whom death came into the world.[35] [150]

Total depravity

Total depravity (also called absolute inability and total corruption) is a theological doctrine that derives from the Augustinian concept of original sin. It is the teaching that, as a consequence of the fall of man, every person born into the world is enslaved to the service of sin and, apart from the efficacious or prevenient grace of God, is utterly unable to choose to follow God or choose to accept salvation as it is freely offered.

It is also advocated to various degrees by many Protestant confessions of faith and catechisms, including those of Lutheranism,[151] Arminianism,[152] and Calvinism.[153]

Total depravity is the fallen state of man as a result of original sin. The doctrine of total depravity asserts that people are by nature not inclined or even able to love God wholly with heart, mind, and strength, but rather all are inclined by nature to serve their own will and desires and to reject the rule of God. Even religion and philanthropy are wicked to God to the extent that these originate from a human imagination, passion, and will and are not done to the glory of God. Therefore, in Reformed theology, if God is to save anyone He must predestine, call, elect individuals to salvation since fallen man does not want to, indeed is incapable of choosing God.[154]

Total depravity does not mean, however, that people are as evil as possible. Rather, it means that even the good which a person may intend is faulty in its premise, false in its motive, and weak in its implementation; and there is no mere refinement of natural capacities that can correct this condition. Thus, even acts of generosity and altruism are in fact egoist acts in disguise. All good, consequently, is derived from God alone, and in no way through man.[155]

Comparison among Protestants

This table summarizes three Protestant beliefs on depravity.

| Topic | Calvinism | Lutheranism | Arminianism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depravity and human will | For Calvin, in Total Depravity[156] humanity possesses "free will,"[157] but it is in bondage to sin,[158] until it is "transformed."[159] | For Luther, in Total Depravity[160][161] humanity possesses free-will/free choice in regard to "goods and possessions," but regarding "salvation or damnation" people are in bondage either to God or Satan."[162] | For Arminius, in Depravity[163] humanity possesses freedom from necessity, but not "freedom from sin" unless enabled by "prevenient grace."[164] |

Soteriology: Salvation

Christian soteriology is the branch of Christian theology that deals with one's salvation.[165] It is derived from the Greek sōtērion (salvation) (from sōtēr savior, preserver) + English -logy.[166]

Atonement is a doctrine that describes how human beings can be reconciled to God. In Christian theology the atonement refers to the forgiving or pardoning of one's sin through the death of Jesus Christ by crucifixion, which made possible the reconciliation between God and creation. Within Christianity there are three main theories for how such atonement might work: the ransom theory, the satisfaction theory and the moral influence theory. Christian soteriology is unlike and not to be confused with collective salvation.

Traditional focus

Christian soteriology traditionally focuses on how God ends the separation people have from him due to sin by reconciling them with himself. (Rom. 5:10–11). Many Christians believe they receive the forgiveness of sins (Acts 2:38), life (Rom. 8:11), and salvation (1 Thess. 5:9) bought by Jesus through his innocent suffering, death, and resurrection from the dead three days later (Matt. 28).

Christ's death, resurrection, ascension, and sending of the Holy Spirit, is called The Paschal Mystery. Christ's human birth is called the Incarnation. Either or both are considered in different versions of soteriology.

While not neglecting the Paschal Mystery, many Christians believe salvation is brought through the Incarnation itself, in which God took on human nature so that humans could partake in the divine nature (2 Peter 1.4). As St. Athanasius put it, God became human so that we might become divine (St. Athanasius, De inc. 54, 3: PG 25, 192B.). This grace in Christ (1 Cor. 1:4) is received as a gift of God that cannot be merited by works done prior to one's conversion to Christianity (Eph. 2:8–9), which is brought about by hearing God's Word (Rom. 10:17) and harkening to it. This involves accepting Jesus Christ as the personal saviour and Lord over one's life.

Distinct schools

Protestant teaching, originating with Martin Luther, teaches that salvation is received by grace alone and that one's sole necessary response to this grace is faith alone. Older Christian teaching, as found in Catholic and Orthodox theology, is that salvation is received by grace alone, but that one's necessary response to this grace comprises both faith and works (James 2:24, 26; Rom 2:6–7; Gal 5:6).

Catholic soteriology

Human beings exists because God wanted to share His life with them. In this sense, every human being is God's child. In a fuller sense, to come to salvation is to be reconciled to God through Christ and to be united with His divine Essence via Theosis in the beatific vision of the Godhead. The graces of Christ's passion, death, and resurrection are found in the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church.

Comparison among Protestants

| Protestant beliefs about salvation | |||

| This table summarizes the classical views of three Protestant beliefs about salvation.[167] | |||

| Topic | Calvinism | Lutheranism | Arminianism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human will | Total depravity:[160] Humanity possesses "free will",[168] but it is in bondage to sin,[169] until it is "transformed".[170] | Original Sin:[160] Humanity possesses free will in regard to "goods and possessions", but is sinful by nature and unable to contribute to its own salvation.[171][172][173] | Total depravity: Humanity possesses freedom from necessity, but not "freedom from sin” unless enabled by "prevenient grace".[174] |

| Election | Unconditional election. | Unconditional election.[160][175] | Conditional election in view of foreseen faith or unbelief.[176] |

| Justification and atonement | Justification by faith alone. Various views regarding the extent of the atonement.[177] | Justification for all men,[178] completed at Christ's death and effective through faith alone.[179][180][181][182] | Justification made possible for all through Christ's death, but only completed upon choosing faith in Jesus.[183] |

| Conversion | Monergistic,[184] through the means of grace, irresistible. | Monergistic,[185][186] through the means of grace, resistible.[187] | Synergistic, resistible due to the common grace of free will.[188][189] |