고혈압

Hypertension| 고혈압 | |

|---|---|

| 기타명 | 동맥고혈압, 고혈압 |

| |

| 동맥 고혈압을 나타내는 자동 팔 혈압계(수축기 혈압 158 mmHg, 이완기 혈압 99 mmHg, 분당 심박수 80회로 나타남) | |

| 전문 | 심장학 |

| 증상 | 없음[1] |

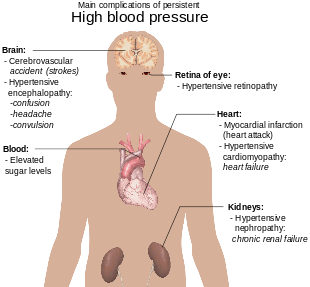

| 합병증 | 관상동맥질환, 뇌졸중, 심부전, 말초동맥질환, 시력저하, 만성신장질환, 치매[2][3][4] |

| 원인들 | 일반적으로 생활 습관과 유전적 요인[5][6] |

| 위험요소 | 수면부족, 과도한 소금, 과도한 체중, 흡연, 음주,[1][5] 대기오염[7] |

| 진단법 | 휴지기 혈압 130/80 or 140/90 mmHg[5][8] |

| 치료 | 라이프스타일 변화, 약물치료[9] |

| 빈도수. | 전[5] 세계적으로 16~37% |

| 사망자 | 940만명 / 18% (2010년)[10] |

| 에 관한 시리즈의 일부 |

| 인체체중 |

|---|

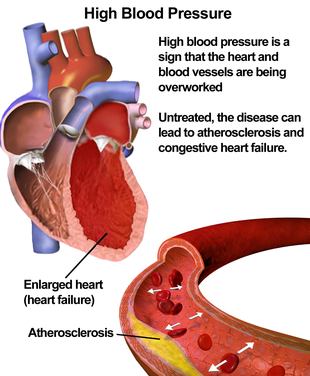

고혈압은 동맥의 혈압이 지속적으로 상승하는 장기적인 의학적 상태입니다.[11] 고혈압은 보통 증상을 일으키지 않습니다.[1] 하지만 뇌졸중, 관상동맥질환, 심부전, 심방세동, 말초동맥질환, 시력저하, 만성신장질환, 치매 등의 주요 위험인자입니다.[2][3][4][12] 고혈압은 전 세계적으로 조기 사망의 주요 원인입니다.[13]

고혈압은 1차(필수) 고혈압 또는 2차 고혈압으로 분류됩니다.[5] 약 90-95%의 경우가 원발성으로, 비특이적인 생활 습관과 유전적 요인에 의한 고혈압으로 정의됩니다.[5][6] 위험을 높이는 생활 습관 요인으로는 식단의 과도한 염분, 과도한 체중, 흡연, 신체적 활동 부족, 알코올 사용 등이 있습니다.[1][5] 나머지 5~10%는 만성 콩팥병, 콩팥동맥이 좁아지거나 내분비계 장애, 피임약 사용 등 명확하게 확인할 수 있는 원인에 의한 고혈압으로 정의되는 이차성 고혈압으로 분류됩니다.[5]

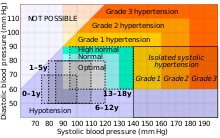

혈압은 수축기(높은 수치) 및 이완기(낮은 수치) 압력의 두 가지 측정값으로 분류됩니다.[1] 대부분의 성인의 경우 정지 상태의 정상 혈압은 수축기 100~130 mm 수은(mmHg), 이완기 60~80 mmHg 범위 내에 있습니다.[8][14] 대부분의 성인의 경우 휴식기 혈압이 130/80 또는 140/90 mmHg 이상인 경우 고혈압이 존재합니다.[5][8] 아이들에게는 다른 번호가 적용됩니다.[15] 24시간 동안의 보행 혈압 모니터링은 사무실 기반 혈압 측정보다 더 정확하게 나타납니다.[5][11] 고혈압은 당뇨병 환자에서 약 2배 정도 발생합니다.[16]

생활습관의 변화와 약물치료는 혈압을 낮추고 건강 합병증의 위험을 낮출 수 있습니다.[9] 생활습관 변화에는 체중 감량, 신체 운동, 염분 섭취 감소, 알코올 섭취 감소, 건강한 식단 등이 있습니다.[5] 생활습관 변화가 충분하지 않으면 혈압약을 사용합니다.[9] 동시에 복용하는 약은 90%의 사람들에게 최대 3가지 약으로 혈압을 조절할 수 있습니다.[5] 약물로 적당히 높은 동맥 혈압(160/100 mmHg 이상으로 정의됨)을 치료하는 것은 기대 수명 향상과 관련이 있습니다.[17] 130/80 mmHg에서 160/100 mmHg 사이의 혈압 치료 효과는 덜 명확하며, 일부 리뷰는 이점을[8][18][19] 발견하고 다른 리뷰는 명확하지 않은 이점을 발견합니다.[20][21][22] 고혈압은 전 세계 인구의 16~37%에 영향을 미칩니다.[5] 2010년 고혈압은 전체 사망자의 17.8%(전 세계적으로 940만 명)의 요인으로 여겨졌습니다.[10]

징후 및 증상

고혈압은 증상이 거의 동반되지 않으며, 보통 건강검진을 통해 본인 확인을 하거나, 관련 없는 문제로 건강관리를 받을 때 확인을 합니다. 고혈압이 있는 일부 사람들은 두통(특히 머리 뒤쪽과 아침)과 현기증, 이명(귀에서 윙윙거리거나 쌕쌕거림), 시력 변화 또는 실신 에피소드를 보고합니다.[23] 그러나 이러한 증상은 고혈압 자체보다는 관련 불안과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.[24]

신체 검사에서 고혈압은 안과 내시경으로 보이는 안저의 변화가 있는 것과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.[25] 고혈압성 망막병증의 전형적인 변화의 심각도는 I등급에서 IV등급이며, I등급과 II등급은 구분이 어려울 수 있습니다.[25] 망막병증의 중증도는 대략 고혈압의 지속 기간이나 중증도와 상관관계가 있습니다.[23]

이차성 고혈압

이차성 고혈압은 특정한 원인에 의한 고혈압으로 특정한 추가적인 징후와 증상이 나타날 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 쿠싱 증후군은 고혈압을 유발할 뿐만 아니라, 자주 트룬 비만,[26] 포도당 불내증, 달 얼굴, 목과 어깨 뒤의 지방 혹(버팔로 혹이라고 함), 보라색 복부 스트레치 마크를 유발합니다.[27] 갑상샘기능항진증은 식욕증가, 빠른 심박수, 불룩해진 눈, 떨림과 함께 체중감소를 일으키는 경우가 많습니다. 신장 동맥 협착(RAS)은 정중선의 왼쪽 또는 오른쪽 또는 양쪽 위치(일방성 RAS)에 국한된 복부 브루트와 관련이 있을 수 있습니다. 대동맥의 협착으로 인해 팔에 비해 하지의 혈압이 저하되거나 대퇴동맥의 맥박이 지연되거나 없어지는 경우가 많습니다. 갈색세포종은 두통, 두근거림, 창백한 외모, 과도한 발한을 동반한 고혈압의 갑작스러운 증상을 유발할 수 있습니다.[27]

고혈압 위기

혈압이 심하게 상승한 경우( 수축기 180 또는 이완기 120 이상)를 고혈압 위기라고 합니다.[28] 고혈압성 위기는 말기 장기 손상의 유무에 따라 고혈압성 응급 또는 고혈압성 응급으로 구분됩니다.[29][30]

고혈압 긴급 상황에서는 혈압 상승으로 인한 장기 손상의 증거가 없습니다. 이러한 경우 경구 약물을 사용하여 24시간에서 48시간에 걸쳐 점진적으로 BP를 낮춥니다.[31]

고혈압 응급 상황에서는 하나 이상의 장기에 직접적인 손상이 있다는 증거가 있습니다.[32][33] 가장 영향을 받는 기관은 뇌, 신장, 심장 및 폐를 포함하며 혼란, 졸음, 흉통 및 호흡 곤란을 포함하는 증상을 유발할 수 있습니다.[31] 고혈압 응급 상황에서 진행 중인 장기 손상을 멈추려면 혈압을 더 빨리 낮춰야 [31]하지만 이 방법에 대한 무작위 대조 시험 증거가 부족합니다.[33]

임신

고혈압은 임신의 약 8-10%에서 발생합니다.[27] 2개의 혈압 측정값이 4시간 간격으로 140/90 mmHg 이상으로 임신 중 고혈압 진단입니다.[34] 임신 중 고혈압은 기존 고혈압, 임신성 고혈압, 또는 자간전증으로 분류할 수 있습니다.[35] 임신 전 만성 고혈압이 있는 여성은 조산, 저체중아 출산, 사산 등의 합병증 위험이 높아집니다.[36] 고혈압이 있고 임신에 합병증이 있었던 여성은 임신에 합병증이 없었던 정상혈압 여성에 비해 심혈관 질환 발생 위험이 3배나 높습니다.[37][38]

자간전증은 임신 후반기와 분만 후 혈압 상승과 소변에 단백질이 존재하는 것을 특징으로 하는 심각한 상태입니다.[27] 임신의 약 5%에서 발생하며 전 세계 모든 산모 사망의 약 16%를 차지합니다.[27] 발육전증은 또한 출생 시 즈음 아기의 사망 위험을 두 배로 증가시킵니다.[27] 보통 자간전증은 증상이 없고 정기적인 검진으로 발견됩니다. 자간전증 증상이 발생하면 두통, 시각장애(흔히 '점멸등'), 구토, 배 위 통증, 붓기 등이 가장 흔합니다. 자간전증은 때때로 생명을 위협하는 상태인 자간전증으로 진행될 수 있는데, 이는 고혈압 응급상황이며 시력저하, 뇌부종, 발작, 신부전, 폐부종, 파종성 혈관내 응고(혈액응고장애)를 포함한 몇 가지 심각한 합병증을 가지고 있습니다.[27][39]

이와 대조적으로 임신성 고혈압은 소변에 단백질이 없는 임신 중 신생성 고혈압으로 정의됩니다.[35]

아이들.

잘 자라지 못하고 발작, 짜증, 에너지 부족, 호흡[40] 곤란 등이 신생아와 어린 영유아의 고혈압과 연관될 수 있습니다. 나이가 많은 영유아의 경우 고혈압은 두통, 설명할 수 없는 과민성, 피로감, 번성 실패, 시야 흐림, 코피, 안면 마비 등을 유발할 수 있습니다.[40][41]

원인들

원발성 고혈압

고혈압은 유전자와 환경 요인의 복잡한 상호 작용에서 비롯됩니다. 혈압에 작은 영향을 미치는 수많은 일반적인 유전자 변이와 혈압에 큰 영향을 미치는 일부 희귀 유전자 변이가 확인되었습니다[42].[43] 또한 유전체 전체 연관 연구(GWAS)에서 혈압과 관련된 35개의 유전적 유전자좌가 확인되었으며, 이 중 12개의 유전적 유전자좌가 새로 발견되었습니다.[44] 확인된 각 새로운 유전자 유전자좌에 대한 Sentinel SNP는 인근의 여러 CpG 부위에서 DNA 메틸화와 연관성을 보여주었습니다. 이 센티넬 SNP는 혈관 평활근 및 신장 기능과 관련된 유전자 내에 위치합니다. DNA 메틸화는 이러한 연관성의 기초가 되는 메커니즘이 이해되지 않더라도 일반적인 유전적 변이를 여러 표현형과 연결시키는 방식으로 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 35개의 센티넬 SNP(알려진 것과 새로운 것)에 대해 이 연구에서 수행된 단일 변이 테스트는 유전자 변이가 단독으로 또는 종합적으로 고혈압과 관련된 임상 표현형의 위험에 기여한다는 것을 보여주었습니다.[44]

관상동맥 절제술: 관상동맥 외전증(coronial artery ectasia, CAE)은 관상동맥이 혈관의 다른 비외전증 부위보다 1.5배 이상으로 확대되는 것이 특징입니다. HTN이 없는 피험자와 비교하여 고혈압(HTN)이 있는 피험자의 CAE의 조정되지 않은 통합 OR은 1.44로 추정되었습니다.[45]

서구적인 식생활과 생활습관이 연관되면 나이가 들면서 혈압이 상승하고, 나중에 고혈압이 될 위험이 큽니다.[46][47] 여러 환경적 요인이 혈압에 영향을 미칩니다. 염분을 많이 섭취하면 염분에 민감한 사람들의 혈압이 높아집니다. 운동 부족과 중심 비만이 개별적인 경우에 역할을 할 수 있습니다. 카페인 섭취,[48] 비타민 D 결핍과[49] 같은 다른 요인들의 가능한 역할은 덜 명확합니다. 비만에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 인슐린 저항성은 X증후군(또는 대사증후군)의 한 구성 요소로 고혈압의 원인이 되기도 합니다.[50]

이러한 노출과 성인 고혈압을 연결하는 메커니즘은 여전히 불분명하지만, 저체중아, 산모 흡연, 모유 수유 부족과 같은 초기 생애의 사건은 성인 필수 고혈압의 위험 요소가 될 수 있습니다.[51] 고혈압 치료를 받지 않은 사람들은 정상 혈압을 가진 사람들에 비해 고혈압 치료를 받지 않은 사람들에서 높은 혈중 요산의 비율이 증가하는 것으로 나타났지만, 고혈압 치료를 받지 않은 사람들은 신장 기능 저하에 대한 인과적인 역할을 하는지 아니면 보조적인 역할을 하는지는 확실하지 않습니다.[52] 평균 혈압은 여름보다 겨울이 더 높을 수 있습니다.[53] 치주 질환은 고혈압과도 연관이 있습니다.[54]

이차성 고혈압

이차성 고혈압은 식별 가능한 원인에서 비롯됩니다. 신장 질환은 고혈압의 가장 흔한 2차 원인입니다.[27] 고혈압은 쿠싱증후군, 갑상샘기능항진증, 갑상샘기능저하증, 말단비대증, Conn증후군 또는 고알도스테론증, 신동맥협착증(죽상경화증 또는 섬유근육이형성증으로 인한 것), 부갑상샘기능항진증, 갈색세포종과 같은 내분비계 질환에 의해서도 발생할 수 있습니다.[27][55] 2차 고혈압의 다른 원인으로는 비만, 수면무호흡증, 임신, 대동맥의 협착, 과음, 과음, 과음, 특정 처방약, 한약, 커피, 코카인, 필로폰 등의 자극제 등이 있습니다.[27][56] 식수를 통한 비소 노출은 혈압 상승과 상관관계가 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.[57][58] 우울증은 고혈압과도 연관이 있었습니다.[59] 외로움도 위험 요소입니다.[60]

2018년 리뷰에 따르면 술을 마시면 남성의 혈압이 상승하는 반면 한 두 잔 이상의 술을 마시면 여성의 위험이 증가하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[61]

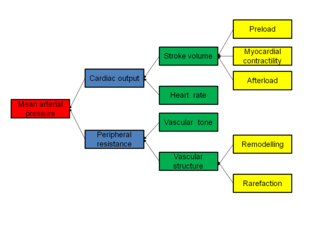

병태생리학

본태성 고혈압이 확립된 대부분의 사람들은 심박출량이 정상인 상태에서 혈류에 대한 저항 증가(총 말초 저항)가 고혈압을 설명합니다.[62] 고혈압 전 또는 '경계성 고혈압'을 가진 일부 젊은 사람들은 높은 심박출량, 높은 심박수 및 정상적인 말초 저항을 가지고 있다는 증거가 있습니다. 이를 초운동 경계성 고혈압이라고 합니다.[63] 이 사람들은 나이가 들면서 심박출량이 떨어지고 말초 저항이 증가하면서 나중에 확립된 필수 고혈압의 전형적인 특징을 갖게 됩니다.[63] 이 패턴이 궁극적으로 고혈압에 걸리는 모든 사람들의 전형적인 것인지에 대해서는 논쟁의 여지가 있습니다.[64] 확립된 고혈압에서 말초 저항이 증가하는 것은 주로 작은 동맥과 동맥의 구조적인 좁아짐에 기인하지만 [65]모세혈관의 수나 밀도의 감소도 기여할 수 있습니다.[66]

동맥 혈관의 혈관 수축이 고혈압에 작용하는지 여부는 명확하지 않습니다.[67] 고혈압은 또한 정맥 복귀를 증가시키고 심장 전부하를 증가시키며 궁극적으로 이완기 기능 장애를 유발할 수 있는 말초 정맥 순응도[68] 감소와 관련이 있습니다.

고혈압이 있는 노인에게서 맥압(수축기 혈압과 이완기 혈압의 차이)이 자주 증가합니다.[69] 이는 수축기압은 비정상적으로 높지만 이완기압은 정상이거나 낮을 수 있으며, 이를 고립성 수축기압 고혈압이라고 합니다.[70] 고혈압이나 수축기 고혈압이 있는 노인의 높은 맥압은 동맥 경직도 증가로 설명되며, 이는 일반적으로 노화를 동반하며 고혈압으로 인해 악화될 수 있습니다.[71]

고혈압에서 말초 저항의 증가를 설명하기 위해 많은 메커니즘이 제안되었습니다. 대부분의 증거는 신장의 염분과 수분 처리 장애(특히 신장 내 레닌-안지오텐신 시스템의 이상)[72] 또는 교감 신경계의 이상을 의미합니다.[73] 이러한 메커니즘은 상호 배타적이지 않으며 대부분의 필수 고혈압 사례에서 둘 다 어느 정도 기여할 가능성이 있습니다. 또한 내피 기능 장애와 혈관 염증도 고혈압에서 말초 저항 증가와 혈관 손상의 원인이 될 수 있다고 제안되었습니다.[74][75] 인터루킨 17은 종양 괴사인자 알파, 인터루킨 1, 인터루킨 6, 인터루킨 8과 같은 고혈압에 관여하는 것으로 생각되는 다른 여러 면역계 화학 신호의 생성을 증가시키는 역할로 관심을 얻었습니다.[76]

식단에 나트륨이 과다하거나 칼륨이 부족하면 세포 내 나트륨이 과다해져 혈관 평활근이 수축돼 혈류가 제한돼 혈압이 높아집니다.[77][78]

진단.

고혈압은 지속적으로 높은 휴식 혈압을 기준으로 진단합니다. 미국 심장 협회(AHA)는 최소 두 번의 개별 건강 관리 방문에 대해 최소 세 번의 휴식 측정을 권장합니다.[79]

영국의 '혈압 UK'는 건강한 혈압은 90/60mmHg에서 120/80mmHg 사이의 수치라고 말합니다.[80]

측정기법

고혈압의 정확한 진단이 이루어지기 위해서는 적절한 혈압 측정 기법을 사용하는 것이 필수적입니다.[81] 혈압을 잘못 측정하면 흔히 볼 수 있고 혈압 수치를 최대 10mmHg까지 바꿀 수 있어 고혈압을 오진하고 오분류할 수 있습니다.[81] 올바른 혈압 측정 기술에는 여러 단계가 포함됩니다. 적절한 혈압 측정을 위해서는 혈압을 측정하는 사람이 최소 5분 동안 조용히 앉아 있어야 하며, 그 다음에는 제대로 맞는 혈압 커프를 맨 위 팔에 적용해야 합니다.[81] 사람은 등을 지지하고 발을 바닥에 평평하게 대고 다리를 꼬지 않은 채로 앉아야 합니다.[81] 혈압을 측정하고 있는 사람은 이 과정에서 말을 하거나 움직이는 것을 피해야 합니다.[81] 측정 중인 팔은 심장 수준의 평평한 표면에 지지되어야 합니다.[81] 정확한 혈압 측정을 위해 의료인이 청진기로 상완동맥을 들으면서 코롯코프 소리를 들을 수 있도록 조용한 방에서 혈압 측정을 해야 합니다.[81][82] 코롯코프 소리를 들으면서 혈압 커프의 공기를 천천히 빼야 합니다(초당 2~3mmHg).[82] 방광은 혈압을 15/10 mmHg까지 상승시킬 수 있으므로 혈압을 측정하기 전에 비워야 합니다.[81] 정확성을 보장하기 위해 1-2분 간격으로 여러 번(최소 2회) 혈압 측정값을 얻어야 합니다.[82] 12~24시간에 걸친 보행 혈압 모니터링이 진단을 확인하는 가장 정확한 방법입니다.[83] 특히 장기 기능이 좋지 않을 때 혈압 수치가 매우 높은 사람은 예외입니다.[84]

24시간 보행 혈압 모니터와 가정용 혈압 기계를 사용할 수 있게 됨에 따라 화이트 코트 고혈압 환자를 잘못 진단하지 않는 것의 중요성이 프로토콜의 변화를 가져왔습니다. 영국에서 현재 모범 사례는 외래 측정을 통해 단일 상승 클리닉 판독을 추적하거나 7일 동안 가정 혈압 모니터링을 수행하는 것입니다.[84] 미국 예방 서비스 태스크 포스는 또한 의료 환경 밖에서 측정할 것을 권장합니다.[83] 노인의 가성 고혈압이나 비압축성 동맥 증후군도 고려가 필요할 수 있습니다. 이 상태는 동맥의 석회화로 인해 동맥 내 혈압 측정이 정상인 상태에서 혈압 커프로 비정상적으로 높은 혈압 수치가 나오기 때문인 것으로 생각됩니다.[85] 기립성 고혈압은 서 있을 때 혈압이 상승하는 것입니다.[86]

기타조사

| 시스템. | 테스트 |

|---|---|

| 신장 | 현미경 소변분석, 소변 내 단백질, BUN, 크레아티닌 |

| 내분비계 | 혈청 나트륨, 칼륨, 칼슘, TSH |

| 대사 | 공복혈당, HDL, LDL, 총콜레스테롤, 중성지방 |

| 다른. | 적혈구용적율, 심전도, 흉부방사선촬영 |

일단 고혈압 진단이 내려지면, 의료 기관은 위험 요소와 다른 증상을 기반으로 근본적인 원인을 파악하려고 시도해야 합니다. 이차성 고혈압은 청소년기 이전의 어린이들에게 더 흔하며, 대부분의 경우 신장 질환에 의해 발생합니다. 일차성 또는 본태성 고혈압은 청소년과 성인에서 더 흔하며 비만, 고혈압 가족력을 포함한 다양한 위험인자를 가지고 있습니다.[93] 2차 고혈압의 가능한 원인을 파악하고, 고혈압이 심장, 눈, 신장에 손상을 입혔는지 여부를 확인하기 위해 실험실 테스트도 수행할 수 있습니다. 당뇨병과 고콜레스테롤 수치에 대한 추가 검사는 심장 질환 발병에 대한 추가적인 위험 요소이며 치료가 필요할 수 있기 때문에 일반적으로 수행됩니다.[6]

고혈압 환자에 대한 초기 평가에는 완전한 병력과 신체 검사가 포함되어야 합니다. 혈청 크레아티닌은 고혈압의 원인 또는 결과일 수 있는 신장 질환의 존재 여부를 평가하기 위해 측정됩니다. 혈청 크레아티닌 단독은 사구체 여과율을 과대평가할 수 있으며 2003 JNC7 지침은 사구체 여과율(eGFR)을 추정하기 위해 MDRD(Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) 공식과 같은 예측 방정식을 사용하는 것을 옹호합니다.[32] eGFR은 또한 신장 기능에 대한 특정 항고혈압 약물의 부작용을 모니터링하는 데 사용할 수 있는 신장 기능의 기본 측정을 제공할 수 있습니다. 또한 소변 샘플의 단백질 검사는 신장 질환의 2차 지표로 사용됩니다. 심전도(EKG/ECG) 검사는 심장이 고혈압으로 인해 스트레스를 받고 있다는 증거를 확인하기 위해 시행합니다. 또한 심장 근육의 비후(좌심실 비대)가 있는지, 또는 심장이 조용한 심장마비와 같은 이전의 사소한 장애를 경험했는지를 보여줄 수 있습니다. 심장의 비대나 손상의 징후를 찾기 위해 흉부 X선 또는 심장 초음파를 수행할 수도 있습니다.[27]

성인구분

| 분류 | 수축기 혈압, mmHg | 그리고/또는 | 이완기 혈압, mmHg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 방법 | 사무실. | 24시간 보행 가능 | 사무실. | 24시간 보행 가능 | |

| 저혈압[94] | <110 | <100 | 또는 | <70 | <60 |

| 미국 심장학회/미국 심장학회 (2017)[95] | |||||

| 보통의 | <120 | <115 | 그리고. | <80 | <75 |

| 고가 | 120–129 | 115–124 | 그리고. | <80 | <75 |

| 고혈압, 1기 | 130–139 | 125–129 | 또는 | 80–89 | 75–79 |

| 고혈압, 2기 | ≥140 | ≥130 | 또는 | ≥90 | ≥80 |

| 유럽고혈압학회 (2023)[96] | |||||

| 최적의 | <120 | — | 그리고. | <80 | — |

| 보통의 | 120–129 | — | 그리고/또는 | 80–84 | — |

| 하이노멀 | 130–139 | — | 그리고/또는 | 85–89 | — |

| 고혈압 1급 | 140–159 | ≥130 | 그리고/또는 | 90–99 | ≥80 |

| 고혈압 2급 | 160–179 | — | 그리고/또는 | 100–109 | — |

| 고혈압, 3급 | ≥180 | — | 그리고/또는 | ≥110 | — |

18세 이상에서 고혈압은 수축기 혈압 또는 이완기 혈압 측정치가 허용 정상치보다 일관되게 높은 것으로 정의됩니다(이는 지침에 따라 129 또는 139 mmHg 수축기 혈압, 89 mmHg 이완기 혈압 이상입니다).[5][8] 측정값이 24시간 보행 또는 가정 모니터링에서 파생된 경우 더 낮은 임계값이 사용됩니다.[95]

아이들.

고혈압은 신생아의 약 0.2~3%에서 발생하지만, 혈압은 건강한 신생아에게서 일상적으로 측정되지 않습니다.[41] 고혈압은 고위험 신생아에게 더 흔합니다. 신생아의 혈압이 정상인지를 판단할 때는 임신 연령, 임신 후 연령, 출생 체중 등 다양한 요인을 고려해야 합니다.[41]

여러 번 방문했을 때 혈압이 상승한 것으로 정의되는 고혈압은 소아 청소년의 1%에서 5%까지 영향을 미치며 건강하지 못한 장기적인 위험과 관련이 있습니다.[97] 아동기에는 나이가 들수록 혈압이 상승하고, 아동기에는 고혈압이 아동의 성별, 나이, 키에 적합한 95분위수 이상의 경우 평균 수축기 또는 이완기 혈압으로 정의됩니다. 그러나 아이를 고혈압으로 분류하기 전에 반복적으로 방문했을 때 고혈압을 확인해야 합니다.[97] 소아 고혈압은 평균 수축기 혈압 또는 이완기 혈압이 90 백분위수 이상이지만 95 백분위수 미만인 것으로 정의되었습니다.[97] 청소년의 경우 성인과 동일한 기준으로 고혈압과 전고혈압을 진단하고 분류할 것을 제안했습니다.[97]

2018년에 발표된 Elbaba M.이 개발한 점수는 의뢰 및 추가 조치의 필요성을 평가하는 가장 간단하고 신뢰할 수 있는 방법 중 하나인 소아 응급 및 외래 진료소에서 고혈압을 자주 경험합니다.[98] 점수는 항목별로 1등급, 2등급, 3등급 10개 항목으로 구성되어 있습니다. 저자는 15점 이하의 중간 점수는 진정한 고혈압과 관련이 없으며 반응성이 있거나 화이트 코트 또는 신뢰할 수 없는 측정일 수 있다고 가정했습니다. 그리고 16점 이상의 점수는 보통 모니터링, 조사 및/또는 치료가 필요한 진정한 고혈압에 대한 경고 알람을 반영합니다.

예방

고혈압이라는 질병 부담의 상당 부분은 고혈압이라는 표시가 없는 사람들이 경험합니다.[99] 따라서 고혈압의 영향을 줄이고 고혈압 치료제의 필요성을 줄이기 위한 인구 전략이 필요합니다. 약물을 시작하기 전에 혈압을 낮추기 위해 생활습관을 바꾸는 것이 좋습니다. 2004년 영국고혈압학회 가이드라인은[100] 2002년[101] 미국 National High BP Education Program이 고혈압의 일차 예방을 위해 제시한 것과 일치하는 생활습관 변화를 제안했습니다.

- 성인의 정상 체중 유지(예: 체질량 지수 20–25 kg/m2)

- 식이 나트륨 섭취량을 100 mmol/일 미만으로 감소(1일 염화나트륨 6g 또는 나트륨 2.4g 미만)

- 규칙적인 유산소 운동(하루 ≥ 30분, 1주일 중 대부분)

- 음주량을 남성은 3단위/일, 여성은 2단위/일로 제한합니다.

- 과일과 채소가 풍부한 식단(예: 하루에 최소 5회 섭취)을 섭취합니다.

- 스트레스 감소[102]

스트레스 관리를 피하거나 배우는 것은 혈압을 조절하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

스트레스를 해소하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 몇 가지 휴식 기술은 다음과 같습니다.

- 묵상

- 온탕

- 요가

- 긴[102] 산책을 하는 것

효과적인 생활습관 수정은 개별 항고혈압제만큼 혈압을 낮출 수 있습니다. 두 가지 이상의 라이프 스타일 수정을 조합하면 훨씬 더 나은 결과를 얻을 수 있습니다.[99] 식이염 섭취를 줄이면 혈압이 낮아진다는 상당한 증거가 있지만, 이것이 사망률과 심혈관 질환의 감소로 이어지는지는 여전히 불확실합니다.[103] 추정 나트륨 섭취 ≥ 6g/day 및 <3g/day 모두 높은 사망 위험 또는 주요 심혈관 질환과 관련이 있지만 높은 나트륨 섭취와 부작용 사이의 연관성은 고혈압이 있는 사람에서만 관찰됩니다. 결과적으로, 무작위 대조 시험의 결과가 없는 경우, 식이 소금 섭취량을 3g/day 이하로 줄이는 것의 현명함에 의문이 제기되었습니다.[103] ESC 지침에 따르면 치주염은 심혈관 건강 상태가 좋지 않은 것과 관련이 있습니다.[105]

고혈압에 대한 일상적인 검사의 가치가 논란이 되고 있습니다.[106][107][108] 2004년 국가고혈압교육프로그램에서 만 3세 이상 어린이는 건강관리 방문[97] 때마다 최소 1회 이상 혈압 측정을 하도록 권고하였고, 국립심폐혈액연구소와 미국소아과학회에서도 비슷한 권고를 하였습니다.[109] 그러나 미국가정의학회는[110] 증상이 없는 소아청소년 고혈압 검진의 유익성과 위해성의 균형을 결정하기에는 이용 가능한 증거가 부족하다는 미국 예방서비스 태스크포스의 견해를 지지합니다.[111][112] 미국 예방 서비스 태스크포스는 사무실 혈압 측정으로 18세 이상 성인의 고혈압 검진을 권고하고 있습니다.[108][113]

관리

2003년 발표된 한 리뷰에 따르면, 혈압을 5 mmHg 감소시키면 뇌졸중 위험이 34%, 허혈성 심장질환이 21% 감소하고, 치매, 심부전, 심혈관질환으로 인한 사망률을 줄일 수 있다고 합니다.[114]

목표혈압

다양한 전문가 그룹이 고혈압 치료를 받을 때 혈압 목표치를 얼마나 낮춰야 하는지에 대한 가이드라인을 만들었습니다. 이러한 그룹은 일반 인구의 경우 140–160 / 90–100 mmHg 범위 미만의 목표를 권장합니다.[14][15][115][116] 코크란 리뷰는 당뇨병이[117] 있는 사람과 이전 심혈관 질환이 있는 사람과 같은 하위 그룹에 유사한 대상을 권장합니다.[118] 또한 Cochrane 리뷰에 따르면 심혈관 위험이 중간에서 높은 노인의 경우 표준 혈압 목표보다 낮은(140/90 mmHg 이하) 달성을 위해 노력하는 이점이 개입과 관련된 위험보다 더 크다는 것을 발견했습니다.[119] 이러한 발견은 다른 모집단에는 적용되지 않을 수 있습니다.[119]

많은 전문가 그룹은 60세에서 80세 사이의 연령대에서 약간 더 높은 목표인 150/90 mmHg를 권장합니다.[14][115][116][120] JNC-8과 미국 의사 대학은 60세 이상의 경우 150/90 mmHg 목표를 권장하지만 [15][121]이 그룹 내 일부 전문가는 이 권장 사항에 동의하지 않습니다.[122] 일부 전문가 그룹은 소변 내 단백질 손실이 있는 당뇨병이나[14] 만성 신장 질환자에서 약간 더 낮은 목표치를 추천하기도 하지만,[123] 다른 전문가 그룹은 일반인과 동일한 목표치를 추천합니다.[15][117] 일부 전문가들은 일부 가이드라인에서 주장하는 것보다 더 집중적인 혈압 강하를 제안하지만,[124] 무엇이 최선의 목표이고 고위험군 개인에 대해 목표가 달라져야 하는지에 대한 문제는 해결되지 않았습니다.[125]

2017년 미국심장학회 가이드라인은 심혈관질환을 경험한 적이 없는 사람 중 10년 이상 심혈관질환 위험이 있는 사람을 대상으로 수축기 혈압이 140mmHg 이상이거나 이완기 BP가 90mmHg 이상인 경우 약물치료를 권장하고 있습니다.[8] 심혈관질환을 경험한 사람이나 10년 이상 심혈관질환 위험이 있는 사람은 수축기 혈압이 130mmHg 이상이거나 이완기 BP가 80mmHg 이상이면 약물치료를 권장합니다.[8]

라이프스타일 수정

고혈압 치료의 첫 번째 라인은 식이 변화, 신체 활동, 체중 감소를 포함한 생활 습관 변화입니다. 이 모든 것들이 과학적 조언에서 권장되었지만,[126] Cochrane 체계적인 검토는 체중 감량 식단이 고혈압 환자의 사망, 장기 합병증 또는 부작용에 미치는 영향에 대한 증거를 찾지 못했습니다.[127] 리뷰 결과 체중과 혈압이 감소한 것으로 나타났습니다.[127] 잠재적인 효과는 단일 약물과 비슷하고 때로는 초과합니다.[14] 고혈압이 약물의 즉각적인 사용을 정당화할 만큼 충분히 높다면, 여전히 약물과 함께 생활습관을 바꾸는 것이 좋습니다.

혈압을 낮추는 것으로 나타난 식이 변화로는 저나트륨 식이요법,[128][129] 우산 리뷰에서 다른 11가지 식이요법에 대해 가장 좋았던 DASH 식이요법(고혈압을 막기 위한 식이요법 접근법),[130][131] 식물성 식이요법 등이 있습니다.[132] 녹차 섭취가 혈압을 낮추는 데 도움이 될 수 있다는 증거는 있지만, 이는 치료제로 권장되기에는 부족합니다.[133] Hibiscus 차 섭취가 수축기 혈압(-4.71 mmHg, 95% CI[-7.87, -1.55]) 및 이완기 혈압(-4.08 mmHg, 95% CI[-6.48, -1.67])[134][135]을 유의하게 감소시킨다는 무작위 배정된 이중맹검 위약 대조 임상시험의 증거가 있습니다. 비트 뿌리즙 섭취도 고혈압인 사람들의 혈압을 상당히 낮춰줍니다.[136][137][138]

식이 칼륨을 늘리면 고혈압 위험을 낮추는 데 잠재적인 이점이 있습니다.[139][140] 2015 식이 지침 자문 위원회(DGAC)는 칼륨이 미국에서 과소 소비되는 부족 영양소 중 하나라고 말했습니다.[141] 그러나 특정 항고혈압제(ACE 억제제 또는 ARB)를 복용하는 사람은 칼륨이 높을 위험이 있으므로 칼륨 보충제 또는 칼륨이 풍부한 소금을 복용해서는 안 됩니다.[142]

혈압을 낮추는 것으로 나타난 신체 운동 요법에는 등각 저항 운동, 유산소 운동, 저항 운동, 장치 유도 호흡이 있습니다.[143]

바이오피드백이나 초월적 명상과 같은 스트레스 감소 기술은 고혈압을 줄이기 위한 다른 치료법의 부가물로 고려될 수 있지만, 그 자체로 심혈관 질환을 예방할 수 있는 증거가 없습니다.[143][144][145] 자가 모니터링 및 약속 알림은 혈압 조절을 개선하기 위한 다른 전략의 사용을 지원할 수 있지만 추가 평가가 필요합니다.[146]

의약품

고혈압 치료를 위해 항고혈압제라고 통칭되는 여러 종류의 약물이 사용 가능합니다.

고혈압 1차 치료제로는 티아지드-이뇨제, 칼슘 채널 차단제, 안지오텐신 전환 효소 억제제(ACE 억제제), 안지오텐신 수용체 차단제(ARBs) 등이 있습니다.[147][15] 이러한 약물은 단독으로 또는 복합적으로 사용될 수 있습니다(ACE 억제제와 ARB는 함께 사용하는 것이 권장되지 않음). 후자의 옵션은 1차 병용 요법에 대한 증거가 충분하지 않지만 [15][148]혈압 값을 치료 전 수준으로 회복시키는 작용을 하는 역조절 메커니즘을 최소화하는 역할을 할 수 있습니다.[149] 대부분의 사람들은 고혈압을 조절하기 위해 하나 이상의 약물을 필요로 합니다.[126] 혈압 조절을 위한 약물은 목표 수준에 도달하지 못할 때 단계별 치료 접근 방식으로 시행해야 합니다.[146] 사망률, 심근경색 또는 뇌졸중에 대한 강력한 증거가 없기 때문에 노인에서 이러한 약물을 철회하는 것은 의료 전문가가 고려할 수 있습니다.[150]

기존에는 아테놀롤과 같은 베타차단제를 고혈압 1차 치료제로 사용했을 때 유익한 효과가 비슷하다고 생각했습니다. 하지만 13개의 시험을 포함한 코크란 리뷰에서 베타 차단제의 효과가 심혈관 질환 예방에 다른 항고혈압제에 비해 떨어지는 것으로 나타났습니다.[151]

고혈압 어린이를 위한 항고혈압제 처방은 근거가 제한적입니다. 위약과 비교하여 단기간에 혈압에 약간의 효과를 나타내는 증거는 제한적입니다. 더 많은 용량을 투여해도 혈압 감소가 더 커지지 않았습니다.[152]

저항성 고혈압

저항성 고혈압은 다른 작용기전과 함께 3가지 이상의 항고혈압제를 동시에 처방받았음에도 불구하고 목표치 이상으로 유지되는 고혈압으로 정의됩니다.[153] 처방받은 약을 지시대로 복용하지 않는 것은 저항성 고혈압의 중요한 원인입니다.[154] 저항성 고혈압은 또한 신경성 고혈압으로 알려진 효과인 자율신경계의 만성적으로 높은 활성도로 인해 발생할 수 있습니다.[155] 이런 상황에서 사람들의 혈압을 낮추기 위한 대안으로 바로 반사를 자극하는 전기 치료법이 연구되고 있습니다.[156]

저항성 고혈압의 일반적인 2차 원인으로는 폐쇄성 수면 무호흡증, 갈색세포종, 신동맥 협착증, 대동맥의 협착증, 원발성 알도스테론증 등이 있습니다.[157] 저항성 고혈압 환자 5명 중 1명꼴로 원발성 알도스테론증이 있는데, 이는 치료가 가능하고 때로는 치료가 가능한 질환입니다.[158]

난치성 고혈압

난치성 고혈압은 장기간 작용하는 티아지드 유사 이뇨제, 칼슘 채널 차단제 및 레닌-안지오텐신 시스템의 차단제를 포함하여 서로 다른 등급의 5개 이상의 항고혈압제에 의해 완화되지 않는 조절되지 않는 상승된 혈압을 특징으로 합니다.[159] 난치성 고혈압을 가진 사람들은 일반적으로 교감신경계 활동이 증가하며, 더 심각한 심혈관 질환과 모든 원인에 의한 사망 위험이 높습니다.[159][160]

비변조

비조절 필수 고혈압은 나트륨 섭취가 안지오텐신 II에 대한 부신 또는 신장 혈관 반응을 조절하지 않는 염에 민감한 고혈압의 한 형태입니다. 이 부분 집합을 가진 개인을 비변조자라고 합니다.[161] 그들은 고혈압 인구의 25-30%를 차지합니다.[162]

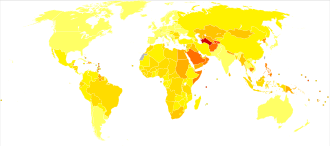

역학

| 무자료 <110 110–220 220–330 330–440 440–550 550–660 | 660–770 770–880 880–990 990–1100 1100–1600 >1600 |

어른들

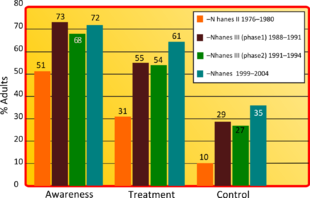

2019년[update] 기준으로 여성 6억 2,600만 명과 남성 6억 5,200만 명을 포함하여 전 세계적으로 30-79세 성인 최소 10억 2,800만 명(세계 인구의 16% 이상)이 고혈압을 앓고 있는 것으로 추정됩니다.[165] 이는 2014년에[166] 비해 약 2억 7천 8백만 명이 증가한 것이며, 같은 연령대의 성인이 전 세계적으로 6억 4천 8백만 명으로 추정되었던 1990년에 비해 거의 두 배가 증가한 것입니다.[165]

고혈압은 남성,[165][166] 사회경제적 지위가 낮은 사람들에게 약간 더 자주 발생하며,[6] 나이가 들수록 더 흔해집니다.[6] 고소득, 중소득 및 저소득 국가에서 흔히 볼 수 있습니다.[166][167] 2004년 고혈압 발병률은 아프리카에서 가장 높았고(남녀 모두 30%), 아메리카에서 가장 낮았습니다(남녀 모두 18%). 국가 수준의 비율은 페루에서 22.8%(남성)와 18.4%(여성)로, 파라과이에서는 61.6%(남성)와 50.9%(여성)로 현저하게 다릅니다.[165] 아프리카의 비율은 2016년에 약 45%였습니다.[168]

유럽에서 고혈압은 2013년[update] 기준 약 30~45%에서 발생합니다.[14] 1995년에는 미국에서 4,300만 명(인구의 24%)이 고혈압을 가지고 있거나 항고혈압제를 복용하고 있는 것으로 추정되었습니다.[169] 2004년까지 이 비율은 29%[170][171]로 증가했으며 2017년에는 32%(7,600만 명의 미국 성인)로 더욱 증가했습니다.[8] 2017년 고혈압에 대한 정의가 변경되면서 미국인의 46%가 영향을 받고 있습니다.[8] 미국의 아프리카계 미국인 성인들은 고혈압 비율이 44%[172]로 세계에서 가장 높습니다. 필리핀계 미국인에게는 더 흔하고 미국계 백인과 멕시코계 미국인에게는 덜 흔합니다.[6][173] 고혈압 비율의 차이는 다요인이며 연구 중입니다.[174]

아이들.

미국에서 지난 20년 동안 어린이와 청소년의 고혈압 발병률이 증가했습니다.[175] 소아 고혈압, 특히 청소년 전 단계에서 성인보다 기저 질환에 더 자주 이차적으로 발생합니다. 신장 질환은 소아 청소년 고혈압의 가장 흔한 2차 원인입니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 일차성 또는 필수성 고혈압이 대부분을 차지합니다.[176]

예후

고혈압은 전 세계적으로 조기 사망의 가장 중요한 예방 가능한 위험 요소입니다.[177] 허혈성 심장질환,[178] 뇌졸중,[27] 말초혈관질환,[179] 심부전, 대동맥류, 미만성 죽상동맥경화증, 만성신장질환, 심방세동, 암, 백혈병, 폐색전증 등 기타 심혈관질환의 위험을 높입니다.[12][27] 고혈압은 인지 장애와 치매의 위험 요소이기도 합니다.[27] 다른 합병증으로는 고혈압성 망막병증, 고혈압성 신병증 등이 있습니다.[32]

역사

측정.

심혈관계에 대한 현대적인 이해는 그의 책 "Demotu cordis"에서 혈액의 순환을 설명한 의사 윌리엄 하비(1578–1657)의 연구에서 시작되었습니다. 영국의 성직자 Stephen Hales는 1733년에 최초로 혈압을 측정했습니다.[180][181] 그러나 임상적 실체로서의 고혈압은 1896년 스키피오네 리바-로치에 의해 커프 기반 혈압계가 발명되면서 독자적으로 등장했습니다.[182] 이를 통해 클리닉에서 수축기 압력을 쉽게 측정할 수 있었습니다. 1905년 니콜라이 코롯코프(Nikolai Korotkoff)는 혈압계 커프가 바람을 뺀 상태에서 청진기로 동맥을 청진할 때 들리는 코롯코프 소리를 설명함으로써 기술을 향상시켰습니다.[181] 이를 통해 수축기 및 이완기 압력을 측정할 수 있었습니다.

신분증

고혈압 위기 환자의 증상과 유사한 증상은 중세 페르시아 의학 문헌에서 "만식증"의 장에서 논의됩니다.[183] 증상은 두통, 머리의 무거움, 움직임의 부진, 전반적인 발적, 몸에 닿는 따뜻함, 두드러지고 팽창되고 긴장된 혈관, 맥박의 충만, 피부의 팽창, 색깔이 있고 조밀한 소변, 식욕부진, 시력저하, 사고력의 장애, 하품, 졸음, 혈관파열 등입니다. 출혈성 뇌졸중도 [184]있고요 포만감 질환은 혈관 내에 혈액이 과도하게 많아진 것으로 추정했습니다.

고혈압을 질병으로 묘사한 것은 1808년 토마스 영, 특히 1836년 리처드 브라이트에게서 비롯되었습니다.[180] 신장 질환의 증거가 없는 사람의 혈압 상승에 대한 최초의 보고는 프레드릭 아크바르 마호메드(Frederick Akbar Mahomed, 1849–1884)에 의해 이루어졌습니다.[185]

1990년대까지 수축기 고혈압은 160mmHg 이상의 수축기 혈압으로 정의되었습니다.[186] 1993년 WHO/ISH 가이드라인은 140 mmHg를 고혈압의 역치로 정의했습니다.[187]

치료

역사적으로 "경맥병"이라고 불리는 것에 대한 치료는 혈액을 적출하거나 거머리를 바르는 것으로 혈액의 양을 줄이는 것으로 구성되었습니다.[180] 이것은 중국의 황조, 코르넬리우스 셀수스, 갈렌, 히포크라테스에 의해 주창되었습니다.[180] 하드펄스 질환의 치료를 위한 치료적 접근은 생활 방식의 변화(분노와 성관계를 멀리함)와 환자를 위한 식이 프로그램(와인, 고기, 패스트리 섭취 피하기, 식사량 줄이기, 저에너지 식단 유지 및 시금치와 식초의 식이 사용)을 포함했습니다.

고혈압에 대한 효과적인 약리학적 치료가 가능해지기 전인 19세기와 20세기에는 세 가지 치료 방식이 사용되었는데, 이는 모두 수많은 부작용과 함께 엄격한 나트륨 제한(예: 쌀밥 식단[180]), 교감신경계의 일부를 수술적으로 절제하는 것), 및 발열 요법(열을 일으키는 물질의 injection, 간접적으로 혈압을 낮추는 것).

고혈압 최초의 화학물질인 티오시아네이트 나트륨은 1900년에 사용되었지만 많은 부작용이 있었고 인기가 없었습니다.[180] 제2차 세계 대전 이후 여러 가지 다른 제제들이 개발되었는데, 그 중 가장 대중적이고 합리적인 효과가 있는 것은 테트라메틸암모늄클로라이드, 헥사메토늄, 히드라진, 레세르핀(약용 식물인 라우볼피아 스펜티나에서 유래)이었습니다. 이 중 어느 것도 잘 견디지 못했습니다.[189][190] 내약성이 뛰어난 최초의 경구용 에이전트의 발견으로 큰 돌파구가 마련되었습니다. 첫 번째는 클로로티아지드로, 최초의 티아지드 이뇨제이며 1958년에 시판된 항생제 설파닐아미드에서 개발되었습니다.[180][191] 이후 베타 차단제, 칼슘 채널 차단제, 안지오텐신 전환효소(ACE) 억제제, 안지오텐신 수용체 차단제, 레닌 억제제 등이 항고혈압제로 개발됐습니다.[188]

사회와 문화

의식.

세계보건기구는 고혈압, 즉 고혈압이 심혈관 사망의 주요 원인이라고 밝혔습니다.[192] 세계고혈압연맹(WHL)은 85개 국가고혈압학회와 연맹의 산하기구로 전 세계 고혈압 인구의 50% 이상이 자신의 상태를 모르고 있다는 사실을 인정했습니다.[192] 이 문제를 해결하기 위해 WHL은 2005년 고혈압에 대한 세계적인 인식 캠페인을 시작했으며 매년 5월 17일을 세계 고혈압의 날(WHD)로 헌정했습니다. 지난 3년 동안 더 많은 국가 사회가 WHD에 참여하고 대중에게 메시지를 전달하기 위해 혁신적인 활동을 하고 있습니다. 2007년, WHL의 47개 회원국으로부터 기록적인 참가가 있었습니다. WHD 주간 동안 이 모든 국가들은 지방 정부, 전문 사회, 비정부 기구 및 민간 산업체와 협력하여 여러 언론 및 공공 집회를 통해 대중의 고혈압 인식을 촉진했습니다. 인터넷과 텔레비전과 같은 대중 매체를 사용하여, 그 메시지는 2억 5천만 명 이상의 사람들에게 도달했습니다. 해마다 기세가 올라감에 따라 WHL은 혈압 상승의 영향을 받는 15억 명으로 추정되는 거의 모든 사람들에게 도달할 수 있다고 확신하고 있습니다.[193]

경제학

고혈압은 미국의 주요 의료 기관을 방문하게 하는 가장 흔한 만성적인 의료 문제입니다. 미국 심장 협회는 2010년 고혈압 직간접 비용을 766억 달러로 추산했습니다.[172] 미국의 경우 고혈압 환자의 80%가 자신의 상태를 인지하고 있으며, 71%는 항고혈압제를 복용하고 있지만, 자신이 고혈압을 적절히 조절하고 있다는 사실을 인지하고 있는 사람은 48%에 불과합니다.[172] 고혈압의 적절한 관리는 고혈압의 진단, 치료 또는 조절의 부적절함으로 인해 방해를 받을 수 있습니다.[194] 의료 제공자는 혈압 목표에 도달하기 위해 여러 약물을 복용하는 것에 대한 저항을 포함하여 혈압 조절을 달성하는 데 많은 장애물에 직면합니다. 사람들은 또한 약 스케줄을 준수하고 생활 방식을 변화시켜야 하는 어려움에 직면합니다. 그럼에도 혈압 목표 달성은 가능하며, 가장 중요한 것은 혈압을 낮추면 심장병과 뇌졸중으로 인한 사망 위험, 다른 쇠약한 상태의 발생, 첨단 의료와 관련된 비용이 크게 감소한다는 것입니다.[195][196]

다른 동물들

고양이의 고혈압은 수축기 혈압이 150 mmHg 이상인 경우를 나타내며, 암로디핀은 일반적인 1차 치료제입니다. 수축기 혈압이 170mmHg 이상인 고양이는 고혈압으로 간주됩니다. 고양이에게 신장 질환이나 망막 박리와 같은 다른 문제가 있는 경우 160mmHg 미만의 혈압도 모니터링해야 할 수 있습니다.[197]

개의 정상 혈압은 품종에 따라 상당히 다를 수 있지만 수축기 혈압이 160mmHg 이상인 경우 특히 대상 장기 손상과 관련이 있는 경우 고혈압이 진단되는 경우가 많습니다.[198] 레닌-안지오텐신 시스템의 억제제와 칼슘 채널 차단제는 종종 개의 고혈압을 치료하는 데 사용되지만 다른 약물은 고혈압을 유발하는 특정 질환에 대해 표시될 수 있습니다.[198]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ a b c d e "High Blood Pressure Fact Sheet". CDC. 19 February 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ a b Lackland DT, Weber MA (May 2015). "Global burden of cardiovascular disease and stroke: hypertension at the core". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 31 (5): 569–571. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.01.009. PMID 25795106.

- ^ a b Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B (2011). Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control (PDF) (1st ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization in collaboration with the World Heart Federation and the World Stroke Organization. p. 38. ISBN 978-92-4-156437-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2014.

- ^ a b Hernandorena I, Duron E, Vidal JS, Hanon O (July 2017). "Treatment options and considerations for hypertensive patients to prevent dementia". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy (Review). 18 (10): 989–1000. doi:10.1080/14656566.2017.1333599. PMID 28532183. S2CID 46601689.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, Caulfield M (August 2015). "Hypertension". Lancet. 386 (9995): 801–812. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61468-9. PMID 25832858. S2CID 208792897.

- ^ a b c d e f Carretero OA, Oparil S (January 2000). "Essential hypertension. Part I: definition and etiology". Circulation. 101 (3): 329–335. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.101.3.329. PMID 10645931.

- ^ Yang BY, Qian Z, Howard SW, Vaughn MG, Fan SJ, Liu KK, Dong GH (April 2018). "Global association between ambient air pollution and blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Environmental Pollution. 235: 576–588. Bibcode:2018EPoll.235..576Y. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.001. PMID 29331891.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA, Williamson JD, Wright JT (June 2018). "2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Hypertension. 71 (6): e13–e115. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065. PMID 29133356.

- ^ a b c "How Is High Blood Pressure Treated?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 10 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ a b Campbell NR, Lackland DT, Lisheng L, Niebylski ML, Nilsson PM, Zhang XH (March 2015). "Using the Global Burden of Disease study to assist development of nation-specific fact sheets to promote prevention and control of hypertension and reduction in dietary salt: a resource from the World Hypertension League". Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 17 (3): 165–167. doi:10.1111/jch.12479. PMC 8031937. PMID 25644474. S2CID 206028313.

- ^ a b Naish J, Court DS (2014). Medical sciences (2 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 562. ISBN 978-0-7020-5249-1.

- ^ a b Lau DH, Nattel S, Kalman JM, Sanders P (August 2017). "Modifiable Risk Factors and Atrial Fibrillation". Circulation (Review). 136 (6): 583–596. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023163. PMID 28784826.

- ^ "Hypertension". World Health Organization. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, et al. (July 2013). "2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)". European Heart Journal. 34 (28): 2159–2219. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. hdl:1854/LU-4127523. PMID 23771844.

- ^ a b c d e f James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT, Narva AS, Ortiz E (February 2014). "2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–520. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PMID 24352797.

- ^ Petrie JR, Guzik TJ, Touyz RM (May 2018). "Diabetes, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Disease: Clinical Insights and Vascular Mechanisms". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 34 (5): 575–584. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.12.005. PMC 5953551. PMID 29459239.

- ^ Musini VM, Tejani AM, Bassett K, Puil L, Wright JM (June 2019). "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults 60 years or older". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD000028. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000028.pub3. PMC 6550717. PMID 31167038.

- ^ Sundström J, Arima H, Jackson R, Turnbull F, Rahimi K, Chalmers J, Woodward M, Neal B (February 2015). "Effects of blood pressure reduction in mild hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (3): 184–191. doi:10.7326/M14-0773. PMID 25531552. S2CID 46553658.

- ^ Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, Bennett A, Neal B, Ninomiya T, Woodward M, MacMahon S, Turnbull F, Hillis GS, Chalmers J, Mant J, Salam A, Rahimi K, Perkovic V, Rodgers A (January 2016). "Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 387 (10017): 435–443. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00805-3. PMID 26559744. S2CID 36805676. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ Diao D, Wright JM, Cundiff DK, Gueyffier F (August 2012). "Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD006742. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006742.pub2. PMC 8985074. PMID 22895954. S2CID 42363250.

- ^ Garrison SR, Kolber MR, Korownyk CS, McCracken RK, Heran BS, Allan GM (August 2017). "Blood pressure targets for hypertension in older adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (8): CD011575. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011575.pub2. PMC 6483478. PMID 28787537.

- ^ Musini VM, Gueyffier F, Puil L, Salzwedel DM, Wright JM (August 2017). "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults aged 18 to 59 years". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (8): CD008276. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008276.pub2. PMC 6483466. PMID 28813123.

- ^ a b Fisher ND, Williams GH (2005). "Hypertensive vascular disease". In Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al. (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1463–1481. ISBN 978-0-07-139140-5.

- ^ Marshall IJ, Wolfe CD, McKevitt C (July 2012). "Lay perspectives on hypertension and drug adherence: systematic review of qualitative research". The BMJ. 345: e3953. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3953. PMC 3392078. PMID 22777025.

- ^ a b Wong TY, Wong T, Mitchell P (February 2007). "The eye in hypertension". Lancet. 369 (9559): 425–435. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60198-6. PMID 17276782. S2CID 28579025.

- ^ "Truncal obesity (Concept Id: C4551560) – MedGen – NCBI". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n O'Brien E, Beevers DG, Lip GY (2007). ABC of hypertension. London: BMJ Books. ISBN 978-1-4051-3061-5.

- ^ "High Blood Pressure – Understanding the Silent Killer". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 21 January 2021.

- ^ Rodriguez MA, Kumar SK, De Caro M (1 April 2010). "Hypertensive crisis". Cardiology in Review. 18 (2): 102–107. doi:10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181c307b7. PMID 20160537. S2CID 34137590.

- ^ "Hypertensive Crisis". heart.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Marik PE, Varon J (June 2007). "Hypertensive crises: challenges and management". Chest. 131 (6): 1949–1962. doi:10.1378/chest.06-2490. PMID 17565029. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ, et al. (Joint National Committee on Prevention, National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee) (December 2003). "Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure". Hypertension. 42 (6): 1206–1252. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. PMID 14656957.

- ^ a b Perez MI, Musini VM (January 2008). "Pharmacological interventions for hypertensive emergencies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 (1): CD003653. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003653.pub3. PMC 6991936. PMID 18254026.

- ^ Harrison's principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. 2011. pp. 55–61. ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6.

- ^ a b "Management of hypertension in pregnant and postpartum women". uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Al Khalaf SY, O'Reilly ÉJ, Barrett PM, B Leite DF, Pawley LC, McCarthy FP, Khashan AS (May 2021). "Impact of Chronic Hypertension and Antihypertensive Treatment on Adverse Perinatal Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of the American Heart Association. 10 (9): e018494. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.018494. PMC 8200761. PMID 33870708.

- ^ "Pregnancy complications increase the risk of heart attacks and stroke in women with high blood pressure". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 21 November 2023. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_60660. S2CID 265356623.

- ^ Al Khalaf S, Chappell LC, Khashan AS, McCarthy FP, O'Reilly ÉJ (July 2023). "Association Between Chronic Hypertension and the Risk of 12 Cardiovascular Diseases Among Parous Women: The Role of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes". Hypertension. 80 (7): 1427–1438. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.20628. PMID 37170819.

- ^ Gibson P (30 July 2009). "Hypertension and Pregnancy". eMedicine Obstetrics and Gynecology. Medscape. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ a b Rodriguez-Cruz E, Ettinger LM (6 April 2010). "Hypertension". eMedicine Pediatrics: Cardiac Disease and Critical Care Medicine. Medscape. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ a b c Dionne JM, Abitbol CL, Flynn JT (January 2012). "Hypertension in infancy: diagnosis, management and outcome". Pediatric Nephrology. 27 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1007/s00467-010-1755-z. PMID 21258818. S2CID 10698052.

- ^ Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, Chasman DI, et al. (September 2011). "Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk". Nature. 478 (7367): 103–109. Bibcode:2011Natur.478..103T. doi:10.1038/nature10405. PMC 3340926. PMID 21909115.

- ^ Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS (February 2001). "Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension". Cell. 104 (4): 545–556. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00241-0. PMID 11239411.

- ^ a b Kato N, Loh M, Takeuchi F, Verweij N, Wang X, Zhang W, et al. (November 2015). "Trans-ancestry genome-wide association study identifies 12 genetic loci influencing blood pressure and implicates a role for DNA methylation". Nature Genetics. 47 (11): 1282–1293. doi:10.1038/ng.3405. PMC 4719169. PMID 26390057.

- ^ Bahremand M, Zereshki E, Matin BK, Rezaei M, Omrani H (2021). "Hypertension and coronary artery ectasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis study". Clinical Hypertension. 27 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/s40885-021-00170-6. PMC 8281588. PMID 34261539.

- ^ Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Larson MG, Kannel WB, D'Agostino RB, Levy D (February 2002). "Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study". JAMA. 287 (8): 1003–1010. doi:10.1001/jama.287.8.1003. PMID 11866648.

- ^ Carrera-Bastos P, Fontes-Villalba M, O'Keefe JH, Lindeberg S, Cordain L (9 March 2011). "The western diet and lifestyle and diseases of civilization". Research Reports in Clinical Cardiology. 2: 15–35. doi:10.2147/RRCC.S16919. S2CID 3231706. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Mesas AE, Leon-Muñoz LM, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Lopez-Garcia E (October 2011). "The effect of coffee on blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in hypertensive individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 94 (4): 1113–1126. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.016667. PMID 21880846.

- ^ Vaidya A, Forman JP (November 2010). "Vitamin D and hypertension: current evidence and future directions". Hypertension. 56 (5): 774–779. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140160. PMID 20937970.

- ^ Sorof J, Daniels S (October 2002). "Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions". Hypertension. 40 (4): 441–447. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000032940.33466.12. PMID 12364344.

- ^ Lawlor DA, Smith GD (May 2005). "Early life determinants of adult blood pressure". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 14 (3): 259–264. doi:10.1097/01.mnh.0000165893.13620.2b. PMID 15821420. S2CID 10646150.

- ^ Gois PH, Souza ER (September 2020). "Pharmacotherapy for hyperuricaemia in hypertensive patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (9): CD008652. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008652.pub4. PMC 8094453. PMID 32877573.

- ^ Fares A (June 2013). "Winter Hypertension: Potential mechanisms". International Journal of Health Sciences. 7 (2): 210–219. doi:10.12816/0006044. PMC 3883610. PMID 24421749.

- ^ Muñoz Aguilera E, Suvan J, Buti J, Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Barbosa Ribeiro A, Orlandi M, et al. (January 2020). Lembo G (ed.). "Periodontitis is associated with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Cardiovascular Research. 116 (1): 28–39. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvz201. PMID 31549149.

- ^ Dluhy RG, Williams GH (1998). "Endocrine hypertension". In Wilson JD, Foster DW, Kronenberg HM (eds.). Williams textbook of endocrinology (9th ed.). Philadelphia; Montreal: W.B. Saunders. pp. 729–749. ISBN 978-0-7216-6152-0.

- ^ Grossman E, Messerli FH (January 2012). "Drug-induced hypertension: an unappreciated cause of secondary hypertension". The American Journal of Medicine. 125 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.05.024. PMID 22195528.

- ^ Jiang J, Liu M, Parvez F, Wang B, Wu F, Eunus M, Bangalore S, Newman JD, Ahmed A, Islam T, Rakibuz-Zaman M, Hasan R, Sarwar G, Levy D, Slavkovich V, Argos M, Scannell Bryan M, Farzan SF, Hayes RB, Graziano JH, Ahsan H, Chen Y (August 2015). "Association between Arsenic Exposure from Drinking Water and Longitudinal Change in Blood Pressure among HEALS Cohort Participants". Environmental Health Perspectives. 123 (8): 806–812. doi:10.1289/ehp.1409004. PMC 4529016. PMID 25816368.

- ^ Abhyankar LN, Jones MR, Guallar E, Navas-Acien A (April 2012). "Arsenic exposure and hypertension: a systematic review". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (4): 494–500. doi:10.1289/ehp.1103988. PMC 3339454. PMID 22138666.

- ^ Meng L, Chen D, Yang Y, Zheng Y, Hui R (May 2012). "Depression increases the risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". Journal of Hypertension. 30 (5): 842–851. doi:10.1097/hjh.0b013e32835080b7. PMID 22343537. S2CID 32187480.

- ^ Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT (October 2010). "Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms". Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 40 (2): 218–227. doi:10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. PMC 3874845. PMID 20652462.

- ^ Roerecke M, Tobe SW, Kaczorowski J, Bacon SL, Vafaei A, Hasan OS, Krishnan RJ, Raifu AO, Rehm J (June 2018). "Sex-Specific Associations Between Alcohol Consumption and Incidence of Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies". Journal of the American Heart Association. 7 (13): e008202. doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.008202. PMC 6064910. PMID 29950485.

- ^ Conway J (April 1984). "Hemodynamic aspects of essential hypertension in humans". Physiological Reviews. 64 (2): 617–660. doi:10.1152/physrev.1984.64.2.617. PMID 6369352.

- ^ a b Palatini P, Julius S (June 2009). "The role of cardiac autonomic function in hypertension and cardiovascular disease". Current Hypertension Reports. 11 (3): 199–205. doi:10.1007/s11906-009-0035-4. PMID 19442329. S2CID 11320300.

- ^ Andersson OK, Lingman M, Himmelmann A, Sivertsson R, Widgren BR (2004). "Prediction of future hypertension by casual blood pressure or invasive hemodynamics? A 30-year follow-up study". Blood Pressure. 13 (6): 350–354. doi:10.1080/08037050410004819. PMID 15771219. S2CID 28992820.

- ^ Folkow B (April 1982). "Physiological aspects of primary hypertension". Physiological Reviews. 62 (2): 347–504. doi:10.1152/physrev.1982.62.2.347. PMID 6461865.

- ^ Struijker Boudier HA, le Noble JL, Messing MW, Huijberts MS, le Noble FA, van Essen H (December 1992). "The microcirculation and hypertension". Journal of Hypertension Supplement. 10 (7): S147–156. doi:10.1097/00004872-199212000-00016. PMID 1291649.

- ^ Schiffrin EL (February 1992). "Reactivity of small blood vessels in hypertension: relation with structural changes. State of the art lecture". Hypertension. 19 (2 Suppl): II1-9. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.19.2_Suppl.II1-a. PMID 1735561.

- ^ Safar ME, London GM (August 1987). "Arterial and venous compliance in sustained essential hypertension". Hypertension. 10 (2): 133–139. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.10.2.133. PMID 3301662.

- ^ Steppan J, Barodka V, Berkowitz DE, Nyhan D (2 August 2011). "Vascular stiffness and increased pulse pressure in the aging cardiovascular system". Cardiology Research and Practice. 2011: 263585. doi:10.4061/2011/263585. PMC 3154449. PMID 21845218.

- ^ Chobanian AV (August 2007). "Clinical practice. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (8): 789–796. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp071137. PMID 17715411. S2CID 42515260.

- ^ Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA (May 2005). "Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 25 (5): 932–943. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000160548.78317.29. PMID 15731494.

- ^ Navar LG (December 2010). "Counterpoint: Activation of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system is the dominant contributor to systemic hypertension". Journal of Applied Physiology. 109 (6): 1998–2000, discussion 2015. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00182.2010a. PMC 3006411. PMID 21148349.

- ^ Esler M, Lambert E, Schlaich M (December 2010). "Point: Chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system is the dominant contributor to systemic hypertension". Journal of Applied Physiology. 109 (6): 1996–1998, discussion 2016. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00182.2010. PMID 20185633. S2CID 7685157.

- ^ Versari D, Daghini E, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Taddei S (June 2009). "Endothelium-dependent contractions and endothelial dysfunction in human hypertension". British Journal of Pharmacology. 157 (4): 527–536. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00240.x. PMC 2707964. PMID 19630832.

- ^ Marchesi C, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL (July 2008). "Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular inflammation". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 29 (7): 367–374. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.003. PMID 18579222.

- ^ Gooch JL, Sharma AC (September 2014). "Targeting the immune system to treat hypertension: where are we?". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 23 (5): 473–479. doi:10.1097/MNH.0000000000000052. PMID 25036747. S2CID 13383731.

- ^ Adrogué HJ, Madias NE (May 2007). "Sodium and potassium in the pathogenesis of hypertension". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (19): 1966–1978. doi:10.1056/NEJMra064486. PMID 17494929. S2CID 22345731.

- ^ Perez V, Chang ET (November 2014). "Sodium-to-potassium ratio and blood pressure, hypertension, and related factors". Advances in Nutrition. 5 (6): 712–741. doi:10.3945/an.114.006783. PMC 4224208. PMID 25398734.

- ^ Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, Ferdinand KC, Ann Forciea M, Frishman WH, Jaigobin C, Kostis JB, Mancia G, Oparil S, Ortiz E, Reisin E, Rich MW, Schocken DD, Weber MA, Wesley DJ, Harrington RA, Bates ER, Bhatt DL, Bridges CR, Eisenberg MJ, Ferrari VA, Fisher JD, Gardner TJ, Gentile F, Gilson MF, Hlatky MA, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Moliterno DJ, Mukherjee D, Rosenson RS, Stein JH, Weitz HH, Wesley DJ (2011). "ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension". Journal of the American Society of Hypertension. 5 (4): 259–352. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2011.06.001. PMID 21771565.

- ^ "Blood Pressure UK". www.bloodpressureuk.org. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Viera AJ (July 2017). "Screening for Hypertension and Lowering Blood Pressure for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Events". The Medical Clinics of North America (Review). 101 (4): 701–712. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2017.03.003. PMID 28577621.

- ^ a b c Vischer AS, Burkard T (2017). "Principles of Blood Pressure Measurement – Current Techniques, Office vs Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurement". Hypertension: From basic research to clinical practice (Review). Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 956. pp. 85–96. doi:10.1007/5584_2016_49. ISBN 978-3-319-44250-1. PMID 27417699.

- ^ a b Siu AL (November 2015). "Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 163 (10): 778–786. doi:10.7326/m15-2223. PMID 26458123.

- ^ a b National Clinical Guidance Centre (August 2011). "7 Diagnosis of Hypertension, 7.5 Link from evidence to recommendations" (PDF). Hypertension (NICE CG 127). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. p. 102. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Franklin SS, Wilkinson IB, McEniery CM (February 2012). "Unusual hypertensive phenotypes: what is their significance?". Hypertension. 59 (2): 173–178. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.182956. PMID 22184330.

- ^ Kario K (June 2009). "Orthostatic hypertension: a measure of blood pressure variation for predicting cardiovascular risk". Circulation Journal. 73 (6): 1002–1007. doi:10.1253/circj.cj-09-0286. PMID 19430163.

- ^ Loscalzo J, Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL (2008). Harrison's principles of internal medicine. McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-147691-1.

- ^ Padwal RS, Hemmelgarn BR, Khan NA, Grover S, McKay DW, Wilson T, Petal (May 2009). "The 2009 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 25 (5): 279–286. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70491-X. PMC 2707176. PMID 19417858.

- ^ Padwal RS, Hemmelgarn BR, Khan NA, Grover S, McAlister FA, McKay DW, et al. (June 2008). "The 2008 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 24 (6): 455–463. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(08)70619-6. PMC 2643189. PMID 18548142.

- ^ Padwal RS, Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA, McKay DW, Grover S, Wilson T, et al. (May 2007). "The 2007 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 23 (7): 529–538. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(07)70797-3. PMC 2650756. PMID 17534459.

- ^ Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA, Grover S, Myers MG, McKay DW, Bolli P, Abbott C, Schiffrin EL, Honos G, Burgess E, Mann K, Wilson T, Penner B, Tremblay G, Milot A, Chockalingam A, Touyz RM, Tobe SW (May 2006). "The 2006 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part I – Blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 22 (7): 573–581. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(06)70279-3. PMC 2560864. PMID 16755312.

- ^ Hemmelgarn BR, McAllister FA, Myers MG, McKay DW, Bolli P, Abbott C, Schiffrin EL, Grover S, Honos G, Lebel M, Mann K, Wilson T, Penner B, Tremblay G, Tobe SW, Feldman RD (June 2005). "The 2005 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 21 (8): 645–656. PMID 16003448.

- ^ Luma GB, Spiotta RT (May 2006). "Hypertension in children and adolescents". American Family Physician. 73 (9): 1558–1568. PMID 16719248.

- ^ Divisón-Garrote JA, Banegas JR, De la Cruz JJ, Escobar-Cervantes C, De la Sierra A, Gorostidi M, Vinyoles E, Abellán-Aleman J, Segura J, Ruilope LM (1 September 2016). "Hypotension based on office and ambulatory monitoring blood pressure. Prevalence and clinical profile among a cohort of 70,997 treated hypertensives". Journal of the American Society of Hypertension: JASH. 10 (9): 714–723. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2016.06.035. ISSN 1878-7436. PMID 27451950.

- ^ a b Whelton PK, Carey RM, Mancia G, Kreutz R, Bundy JD, Williams B (14 September 2022). "Harmonization of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension Blood Pressure/Hypertension Guidelines". European Heart Journal. 43 (35): 3302–3311. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac432. ISSN 0195-668X. PMC 9470378. PMID 36100239.

- ^ Mancia G, Kreutz R, Brunström M, Burnier M, Grassi G, Januszewicz A, Muiesan ML, Tsioufis K, Agabiti-Rosei E, Algharably EA, Azizi M, Benetos A, Borghi C, Hitij JB, Cifkova R (1 December 2023). "2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA)". Journal of Hypertension. 41 (12): 1874–2071. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000003480. ISSN 1473-5598. PMID 37345492.

- ^ a b c d e National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children Adolescents (August 2004). "The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents". Pediatrics. 114 (2 Suppl 4th Report): 555–576. doi:10.1542/peds.114.2.S2.555. hdl:2027/uc1.c095473177. PMID 15286277.

- ^ Elbaba M (2018). "NOVEL HYPERTENSION DIAGNOSTIC SCORE IN CHILDREN". Pediatric Nephrology. 33 (10): 1902–1903 – via 233 SPRING ST, NEW YORK, NY 10013 USA: SPRINGER.

- ^ a b Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ, Davis M, McInnes GT, Potter JF, Sever PS, McG Thom S (March 2004). "Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the fourth working party of the British Hypertension Society, 2004-BHS IV". Journal of Human Hypertension. 18 (3): 139–185. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001683. PMID 14973512.

- ^ Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ, Davis M, McInnes GT, Potter JF, Sever PS, Thom SM, BHS guidelines working party, for the British Hypertension Society (13 March 2004). "British Hypertension Society guidelines for hypertension management 2004 (BHS-IV): summary". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 328 (7440): 634–640. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7440.634. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 381142. PMID 15016698.

- ^ Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, Cutler JA, Havas S, Kotchen TA, Roccella EJ, Stout R, Vallbona C, Winston MC, Karimbakas J (October 2002). "Primary prevention of hypertension: clinical and public health advisory from The National High Blood Pressure Education Program". JAMA. 288 (15): 1882–1888. doi:10.1001/jama.288.15.1882. PMID 12377087. S2CID 11071351.

- ^ a b "Hypertension: Causes, symptoms, and treatments". medicalnewstoday.com. 10 November 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Evidence-based policy for salt reduction is needed". Lancet. 388 (10043): 438. July 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31205-3. PMID 27507743. S2CID 205982690.

- ^ Mente A, O'Donnell M, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Lear S, McQueen M, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Lanas F, Li W, Lu Y, Yi S, Rensheng L, Iqbal R, Mony P, Yusuf R, Yusoff K, Szuba A, Oguz A, Rosengren A, Bahonar A, Yusufali A, Schutte AE, Chifamba J, Mann JF, Anand SS, Teo K, Yusuf S (July 2016). "Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled analysis of data from four studies". Lancet. 388 (10043): 464–475. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30467-6. hdl:10379/16625. PMID 27216139. S2CID 44581906.

The results showed that cardiovascular disease and death are increased with low sodium intake (compared with moderate intake) irrespective of hypertension status, whereas there is a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and death only in individuals with hypertension consuming more than 6 g of sodium per day (representing only 10% of the population studied)

- ^ Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren M, Albus C, Benlian P, Boysen G, Cifkova R, Deaton C, Ebrahim S, Fisher M, Germano G, Hobbs R, Hoes A, Karadeniz S, Mezzani A, Prescott E, Ryden L, Scherer M, Syvänne M, Scholte op Reimer WJ, Vrints C, Wood D, Zamorano JL, Zannad F (July 2012). "European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts)". European Heart Journal. 33 (13): 1635–1701. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092. PMID 22555213.

- ^ Chiolero A, Bovet P, Paradis G (March 2013). "Screening for elevated blood pressure in children and adolescents: a critical appraisal". JAMA Pediatrics. 167 (3): 266–273. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.438. PMID 23303490.

- ^ Daniels SR, Gidding SS (March 2013). "Blood pressure screening in children and adolescents: is the glass half empty or more than half full?". JAMA Pediatrics. 167 (3): 302–304. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.439. PMID 23303514.

- ^ a b Schmidt BM, Durao S, Toews I, Bavuma CM, Hohlfeld A, Nury E, et al. (Cochrane Hypertension Group) (May 2020). "Screening strategies for hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (5): CD013212. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013212.pub2. PMC 7203601. PMID 32378196.

- ^ "Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report". Pediatrics. 128 (Suppl 5): S213–S256. December 2011. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2107C. PMC 4536582. PMID 22084329.

- ^ "Hypertension – Clinical Preventive Service Recommendation". Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Moyer VA (November 2013). "Screening for primary hypertension in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (9): 613–619. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00725. PMID 24097285. S2CID 20193715.

- ^ "Document United States Preventive Services Taskforce". uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, et al. (April 2021). "Screening for Hypertension in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 325 (16): 1650–1656. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4987. PMID 33904861. S2CID 233409679.

- ^ Law M, Wald N, Morris J (2003). "Lowering blood pressure to prevent myocardial infarction and stroke: a new preventive strategy". Health Technology Assessment. 7 (31): 1–94. doi:10.3310/hta7310. PMID 14604498.

- ^ a b Daskalopoulou SS, Rabi DM, Zarnke KB, Dasgupta K, Nerenberg K, Cloutier L, et al. (May 2015). "The 2015 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 31 (5): 549–568. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.02.016. PMID 25936483.

- ^ a b "Hypertension: Recommendations, Guidance and guidelines". NICE. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ a b Arguedas JA, Leiva V, Wright JM (October 2013). "Blood pressure targets for hypertension in people with diabetes mellitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD008277. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008277.pub2. PMID 24170669.

- ^ Saiz LC, Gorricho J, Garjón J, Celaya MC, Erviti J, Leache L (November 2022). "Blood pressure targets for the treatment of people with hypertension and cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (11): CD010315. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010315.pub5. PMC 9673465. PMID 36398903.

- ^ a b Arguedas JA, Leiva V, Wright JM (December 2020). "Blood pressure targets in adults with hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (12): CD004349. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004349.pub3. PMC 8094587. PMID 33332584.

- ^ Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, Humphrey LL, Frost J, Forciea MA (March 2017). "Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older to Higher Versus Lower Blood Pressure Targets: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 166 (6): 430–437. doi:10.7326/M16-1785. PMID 28135725.

- ^ Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, Humphrey LL, Frost J, Forciea MA (March 2017). "Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older to Higher Versus Lower Blood Pressure Targets: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 166 (6): 430–437. doi:10.7326/m16-1785. PMID 28135725.

- ^ Wright JT, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, Ogedegbe G, Dennison Himmelfarb CR (April 2014). "Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (7): 499–503. doi:10.7326/m13-2981. PMID 24424788.

- ^ "KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease" (PDF). Kidney International Supplements. December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2015.

- ^ Brunström M, Carlberg B (January 2016). "Lower blood pressure targets: to whom do they apply?". Lancet. 387 (10017): 405–406. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00816-8. PMID 26559745. S2CID 44282689.

- ^ Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, Rodgers A (June 2016). "Intensive blood pressure lowering – Authors' reply". Lancet. 387 (10035): 2291. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30366-X. PMID 27302266.

- ^ a b Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, Williams KA, Sanchez E (April 2014). "An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". Hypertension. 63 (4): 878–885. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000003. PMC 10280688. PMID 24243703.

- ^ a b Semlitsch T, Krenn C, Jeitler K, Berghold A, Horvath K, Siebenhofer A (February 2021). "Long-term effects of weight-reducing diets in people with hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (2): CD008274. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008274.pub4. PMC 8093137. PMID 33555049.

- ^ He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA (April 2013). "Effect of longer-term modest salt reduction on blood pressure". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 30 (4): CD004937. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004937.pub2. PMID 23633321. S2CID 23522004.

- ^ Huang L, Trieu K, Yoshimura S, Neal B, Woodward M, Campbell NR, et al. (February 2020). "Effect of dose and duration of reduction in dietary sodium on blood pressure levels: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials". The BMJ. 368: m315. doi:10.1136/bmj.m315. PMC 7190039. PMID 32094151.

- ^ Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al. (January 2001). "Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. PMID 11136953.

- ^ Sukhato K, Akksilp K, Dellow A, Vathesatogkit P, Anothaisintawee T (December 2020). "Efficacy of different dietary patterns on lowering of blood pressure level: an umbrella review". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 112 (6): 1584–1598. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqaa252. PMID 33022695.

- ^ Joshi S, Ettinger L, Liebman SE (2020). "Plant-Based Diets and Hypertension". American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 14 (4): 397–405. doi:10.1177/1559827619875411. PMC 7692016. PMID 33281520.

- ^ Xu R, Yang K, Ding J, Chen G (February 2020). "Effect of green tea supplementation on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Medicine. 99 (6): e19047. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019047. PMC 7015560. PMID 32028419.

- ^ Najafpour Boushehri S, Karimbeiki R, Ghasempour S, Ghalishourani SS, Pourmasoumi M, Hadi A, et al. (February 2020). "The efficacy of sour tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) on selected cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Phytotherapy Research. 34 (2): 329–339. doi:10.1002/ptr.6541. PMID 31943427. S2CID 210333560.

- ^ McKay DL, Chen CY, Saltzman E, Blumberg JB (February 2010). "Hibiscus sabdariffa L. tea (tisane) lowers blood pressure in prehypertensive and mildly hypertensive adults". The Journal of Nutrition. 140 (2): 298–303. doi:10.3945/jn.109.115097. PMID 20018807.

- ^ "Beetroot juice lowers high blood pressure, suggests research". British Heart Foundation.

- ^ Siervo M, Lara J, Ogbonmwan I, Mathers JC (June 2013). "Inorganic nitrate and beetroot juice supplementation reduces blood pressure in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Nutrition. 143 (6): 818–826. doi:10.3945/jn.112.170233. PMID 23596162.

- ^ Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Kabir A, Azizi F, Ghasemi A (November 2017). "The Nitrate-Independent Blood Pressure-Lowering Effect of Beetroot Juice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Advances in Nutrition. 8 (6): 830–838. doi:10.3945/an.117.016717. PMC 5683004. PMID 29141968.

- ^ Aburto NJ, Hanson S, Gutierrez H, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP (April 2013). "Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: systematic review and meta-analyses". The BMJ. 346: f1378. doi:10.1136/bmj.f1378. PMC 4816263. PMID 23558164.

- ^ Stone MS, Martyn L, Weaver CM (July 2016). "Potassium Intake, Bioavailability, Hypertension, and Glucose Control". Nutrients. 8 (7): 444. doi:10.3390/nu8070444. PMC 4963920. PMID 27455317.

- ^ "Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee". Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Raebel MA (June 2012). "Hyperkalemia associated with use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers". Cardiovascular Therapeutics. 30 (3): e156–166. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00258.x. PMID 21883995.

- ^ a b Brook RD, Appel LJ, Rubenfire M, Ogedegbe G, Bisognano JD, Elliott WJ, Fuchs FD, Hughes JW, Lackland DT, Staffileno BA, Townsend RR, Rajagopalan S (June 2013). "Beyond medications and diet: alternative approaches to lowering blood pressure: a scientific statement from the american heart association". Hypertension. 61 (6): 1360–1383. doi:10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f. PMID 23608661.

- ^ Nagele E, Jeitler K, Horvath K, Semlitsch T, Posch N, Herrmann KH, Grouven U, Hermanns T, Hemkens LG, Siebenhofer A (October 2014). "Clinical effectiveness of stress-reduction techniques in patients with hypertension: systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Hypertension. 32 (10): 1936–1944, discussion 1944. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000298. PMID 25084308. S2CID 20098894.

- ^ Dickinson HO, Campbell F, Beyer FR, Nicolson DJ, Cook JV, Ford GA, Mason JM (January 2008). "Relaxation therapies for the management of primary hypertension in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004935. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004935.pub2. PMID 18254065.

- ^ a b Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T (March 2010). "Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD005182. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005182.pub4. hdl:10344/9179. PMID 20238338. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ Wright JM, Musini VM, Gill R (April 2018). "First-line drugs for hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (4): CD001841. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub3. PMC 6513559. PMID 29667175.

- ^ Chen JM, Heran BS, Wright JM (October 2009). "Blood pressure lowering efficacy of diuretics as second-line therapy for primary hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD007187. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007187.pub2. PMID 19821398. S2CID 73993182.

- ^ Garjón J, Saiz LC, Azparren A, Gaminde I, Ariz MJ, Erviti J, et al. (Cochrane Hypertension Group) (February 2020). "First-line combination therapy versus first-line monotherapy for primary hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD010316. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010316.pub3. PMC 7002970. PMID 32026465.

- ^ Reeve E, Jordan V, Thompson W, Sawan M, Todd A, Gammie TM, et al. (Cochrane Hypertension Group) (June 2020). "Withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs in older people". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6): CD012572. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012572.pub2. PMC 7387859. PMID 32519776.

- ^ Wiysonge CS, Bradley HA, Volmink J, Mayosi BM, Opie LH (January 2017). "Beta-blockers for hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD002003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub5. PMC 5369873. PMID 28107561.

- ^ Chaturvedi S, Lipszyc DH, Licht C, Craig JC, Parekh R, et al. (Cochrane Hypertension Group) (February 2014). "Pharmacological interventions for hypertension in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD008117. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008117.pub2. PMID 24488616.

- ^ Vongpatanasin W (June 2014). "Resistant hypertension: a review of diagnosis and management" (PDF). JAMA. 311 (21): 2216–2224. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.5180. PMID 24893089. S2CID 28630392. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Santschi V, Chiolero A, Burnier M (November 2009). "Electronic monitors of drug adherence: tools to make rational therapeutic decisions". Journal of Hypertension. 27 (11): 2294–2295, author reply 2295. doi:10.1097/hjh.0b013e328332a501. PMID 20724871.

- ^ Zubcevic J, Waki H, Raizada MK, Paton JF (June 2011). "Autonomic-immune-vascular interaction: an emerging concept for neurogenic hypertension". Hypertension. 57 (6): 1026–1033. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.169748. PMC 3105900. PMID 21536990.

- ^ Wallbach M, Koziolek MJ (September 2018). "Baroreceptors in the carotid and hypertension-systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of baroreflex activation therapy on blood pressure". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 33 (9): 1485–1493. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfx279. PMID 29136223.

- ^ Sarwar MS, Islam MS, Al Baker SM, Hasnat A (May 2013). "Resistant hypertension: underlying causes and treatment". Drug Research. 63 (5): 217–223. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1337930. PMID 23526242. S2CID 8247941.

- ^ Young WF (February 2019). "Diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism: practical clinical perspectives". Journal of Internal Medicine. 285 (2): 126–148. doi:10.1111/joim.12831. PMID 30255616. S2CID 52824356.

- ^ a b Acelajado MC, Hughes ZH, Oparil S, Calhoun DA (March 2019). "Treatment of resistant and refractory hypertension". Circulation Research. 124 (7): 1061–1070. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312156. PMC 6469348. PMID 30920924.

- ^ Dudenbostel T, Siddiqui M, Oparil S, Calhoun DA (June 2016). "Refractory hypertension: A novel phenotype of antihypertensive treatment failure". Hypertension. 67 (6): 1085–1092. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.06587. PMC 5425297. PMID 27091893.

- ^ Williams GH, Hollenberg NK (November 1985). "Non-modulating essential hypertension: a subset particularly responsive to converting enzyme inhibitors". Journal of Hypertension Supplement. 3 (2): S81–S87. PMID 3003304.

- ^ Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL (2005). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.[페이지 필요]

- ^ "Blood Pressure". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, Riley LM, Paciorek CJ, Stevens GA, Gregg EW, Bennett JE, Solomon B, Singleton RK, Sophiea MK, Iurilli ML, Lhoste VP, Cowan MJ, Savin S (11 September 2021). "Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants". The Lancet. 398 (10304): 957–980. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 8446938. PMID 34450083. S2CID 237286310.

- ^ a b c "Raised blood pressure". World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016.

- ^ Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J (2005). "Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data". Lancet (Submitted manuscript). 365 (9455): 217–223. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. PMID 15652604. S2CID 7244386. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ Oyedele D (20 February 2018). "Social divide". D+C, development and cooperation. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, Brown C, Cutler JA, Higgins M, Horan MJ, Labarthe D (March 1995). "Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991". Hypertension. 25 (3): 305–313. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.25.3.305. PMID 7875754. S2CID 23660820.

- ^ a b Burt VL, Cutler JA, Higgins M, Horan MJ, Labarthe D, Whelton P, Brown C, Roccella EJ (July 1995). "Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult US population. Data from the health examination surveys, 1960 to 1991". Hypertension. 26 (1): 60–69. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.26.1.60. PMID 7607734. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012.

- ^ Ostchega Y, Dillon CF, Hughes JP, Carroll M, Yoon S (July 2007). "Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in older U.S. adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988 to 2004". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 55 (7): 1056–1065. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01215.x. PMID 17608879. S2CID 27522876.

- ^ a b c Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, et al. (February 2010). "Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association". Circulation. 121 (7): e46–e215. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. PMID 20019324.

- ^ "Culture-Specific of Health Risk Health Status: Morbidity and Mortality". Stanford. 16 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ Frohlich ED (October 2011). "Epidemiological issues are not simply black and white". Hypertension. 58 (4): 546–547. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.178541. PMID 21911712.

- ^ Falkner B (July 2010). "Hypertension in children and adolescents: epidemiology and natural history". Pediatric Nephrology. 25 (7): 1219–1224. doi:10.1007/s00467-009-1200-3. PMC 2874036. PMID 19421783.

- ^ Luma GB, Spiotta RT (May 2006). "Hypertension in children and adolescents". American Family Physician. 73 (9): 1558–1568. PMID 16719248. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007.

- ^ "Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R (December 2002). "Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies". Lancet. 360 (9349): 1903–1913. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11911-8. PMID 12493255. S2CID 54363452.

- ^ Singer DR, Kite A (June 2008). "Management of hypertension in peripheral arterial disease: does the choice of drugs matter?". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 35 (6): 701–708. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.01.007. PMID 18375152.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Esunge PM (October 1991). "From blood pressure to hypertension: the history of research". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 84 (10): 621. doi:10.1177/014107689108401019. PMC 1295564. PMID 1744849.

- ^ a b Kotchen TA (October 2011). "Historical trends and milestones in hypertension research: a model of the process of translational research". Hypertension. 58 (4): 522–38. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.177766. PMID 21859967.

- ^ Postel-Vinay N, ed. (1996). A century of arterial hypertension 1896–1996. Chichester: Wiley. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-471-96788-0.

- ^ Heydari M, Dalfardi B, Golzari SE, Habibi H, Zarshenas MM (July 2014). "The medieval origins of the concept of hypertension". Heart Views. 15 (3): 96–98. doi:10.4103/1995-705X.144807. PMC 4268622. PMID 25538828.

- ^ Emtiazy M, Choopani R, Khodadoost M, Tansaz M, Dehghan S, Ghahremani Z (2014). "Avicenna's doctrine about arterial hypertension". Acta medico-historica Adriatica. 12 (1): 157–162. PMID 25310615.

- ^ Swales JD, ed. (1995). Manual of hypertension. Oxford: Blackwell Science. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-86542-861-4.

- ^ Wilking SV (16 December 1988). "Determinants of Isolated Systolic Hypertension". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 260 (23): 3451–3455. doi:10.1001/jama.1988.03410230069030. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 3210285.

- ^ "1993 guidelines for the management of mild hypertension: memorandum from a WHO/ISH meeting". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 71 (5): 503–517. 1993. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 2393474. PMID 8261554.

- ^ a b Dustan HP, Roccella EJ, Garrison HH (September 1996). "Controlling hypertension. A research success story". Archives of Internal Medicine. 156 (17): 1926–1935. doi:10.1001/archinte.156.17.1926. PMID 8823146.

- ^ Lyons HH, Hoobler SW (February 1948). "Experiences with tetraethylammonium chloride in hypertension". Journal of the American Medical Association. 136 (9): 608–613. doi:10.1001/jama.1948.02890260016005. PMID 18899127.

- ^ Bakris GL, Frohlich ED (December 1989). "The evolution of antihypertensive therapy: an overview of four decades of experience". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 14 (7): 1595–1608. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(89)90002-8. PMID 2685075.

- ^ Novello FC, Sprague JM (1957). "Benzothiadiazine dioxides as novel diuretics". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79 (8): 2028–2029. doi:10.1021/ja01565a079.

- ^ a b Chockalingam A (May 2007). "Impact of World Hypertension Day". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 23 (7): 517–519. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(07)70795-X. PMC 2650754. PMID 17534457.

- ^ Chockalingam A (June 2008). "World Hypertension Day and global awareness". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 24 (6): 441–444. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(08)70617-2. PMC 2643187. PMID 18548140.

- ^ Alcocer L, Cueto L (June 2008). "Hypertension, a health economics perspective". Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease. 2 (3): 147–155. doi:10.1177/1753944708090572. PMID 19124418. S2CID 31053059.

- ^ Elliott WJ (October 2003). "The economic impact of hypertension". Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 5 (3 Suppl 2): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1524-6175.2003.02463.x. PMC 8099256. PMID 12826765. S2CID 26799038.

- ^ Coca A (2008). "Economic benefits of treating high-risk hypertension with angiotensin II receptor antagonists (blockers)". Clinical Drug Investigation. 28 (4): 211–220. doi:10.2165/00044011-200828040-00002. PMID 18345711. S2CID 8294060.

- ^ Taylor SS, Sparkes AH, Briscoe K, Carter J, Sala SC, Jepson RE, Reynolds BS, Scansen BA (March 2017). "ISFM Consensus Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension in Cats". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 19 (3): 288–303. doi:10.1177/1098612X17693500. PMID 28245741.

- ^ a b Acierno MJ, Brown S, Coleman AE, Jepson RE, Papich M, Stepien RL, Syme HM (November 2018). "ACVIM consensus statement: Guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and management of systemic hypertension in dogs and cats". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 32 (6): 1803–1822. doi:10.1111/jvim.15331. PMC 6271319. PMID 30353952.

추가읽기

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. (February 2014). "2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PMID 24352797.