독일.

Germany독일 연방 공화국 독일 연방 공화국 (독일어) | |

|---|---|

| 국가:다스 리더 도이첸[a] ("독일인의 노래") | |

| 자본의 그리고 가장 큰 도시 | 베를린[b] 52°31'N 13°23'E / 52.517°N 13.383°E |

| 공용어 | 독일의[c] |

| 성명서 | 독일의 |

| 정부 | 연방 의회 공화국[4] |

• 사장님 | 프랑크 발터 슈타인마이어 |

• 재상 | 올라프 숄츠 |

| 입법부 | 연방[d] 참사원 |

| 지역 | |

• 합계 | 357,600 km2 (138,100 sq mi)[5] (63번째) |

• 물(%) | 1.27[6] |

| 인구. | |

• 2023년 3분기 추정치 | |

• 밀도 | 236/km2 (611.2/sq mi) (58th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023년 견적 |

• 합계 | |

• 인당 | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023년 견적 |

• 합계 | |

• 인당 | |

| 지니 (2022) | 저급의 |

| HDI (2021) | 매우 높음(9일) |

| 통화 | 유로(유로)(유로) |

| 시간대 | UTC+1(CET) |

• 여름(DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| 날짜 형식 |

|

| 주행측 | 맞다 |

| 호출부호 | +49 |

| ISO 3166 코드 | DE |

| 인터넷 TLD | .데 |

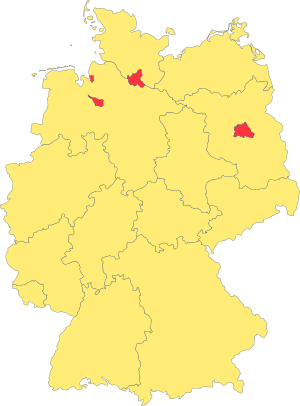

공식적으로 독일 연방 공화국인 [e]독일은 중앙 유럽의 서쪽 지역에 있는 나라입니다.[f] 이 나라는 러시아 다음으로 유럽에서 두 번째로 인구가 많은 나라이며,[g] 유럽 연합에서 가장 인구가 많은 회원국입니다. 독일은 북쪽으로는 발트해와 북해, 남쪽으로는 알프스 산맥 사이에 위치하고 있습니다. 16개의 구성국은 총 인구가 8천 4백만 명이 넘고, 357,600 km2 (138,100 평방 마일)의 면적을 가지고 있으며, 북쪽으로는 덴마크, 동쪽으로는 폴란드와 체코, 남쪽으로는 오스트리아와 스위스, 그리고 서쪽으로는 프랑스, 룩셈부르크, 벨기에, 네덜란드와 국경을 접하고 있습니다. 독일의 수도이자 가장 인구가 많은 도시는 베를린이며 주요 금융 중심지는 프랑크푸르트입니다.

오늘날 독일에 정착한 것은 후기 구석기 시대부터 시작되었으며, 주로 켈트족을 중심으로 신석기 시대부터 다양한 부족이 거주했습니다. 다양한 게르만 부족들이 고전적인 고대부터 현대 독일의 북부 지역에 거주해 왔습니다. 게르마니아라는 이름의 지역은 서기 100년 이전에 기록되었습니다. 962년 독일 왕국은 신성 로마 제국의 대부분을 형성했습니다. 16세기 동안 북부 독일 지역은 종교 개혁의 중심지가 되었습니다. 나폴레옹 전쟁과 1806년 신성 로마 제국의 해체에 이어 1815년 독일 연방이 형성되었습니다.

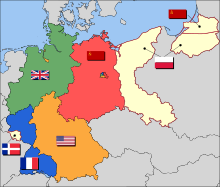

1866년 8월 18일 북독일 연방 조약에 의해 프로이센이 주도하는 북독일 연방이 성립되면서 독일의 근대 국민국가로의 공식적인 통일이 시작되었습니다. 제1차 세계 대전과 1918-19년 독일 혁명 이후, 제국은 반대통령제 바이마르 공화국으로 바뀌었습니다. 1933년 나치의 권력 장악으로 전체주의 독재정권 수립, 제2차 세계대전, 홀로코스트가 발생했습니다. 제2차 세계 대전이 유럽에서 끝나고 연합군의 점령 기간이 된 1949년, 독일 전체는 제한된 주권을 가진 두 개의 분리된 정치로 조직되었습니다: 일반적으로 서독으로 알려진 독일 연방 공화국과 동독으로 알려진 독일 민주 공화국, 베를린은 사법 4강의 지위를 계속 유지했습니다. 독일연방공화국은 유럽경제공동체와 유럽연합의 창립회원국이었고, 독일민주공화국은 공산주의 동구권 국가이자 바르샤바 조약의 회원국이었습니다. 동독의 공산주의 주도 정부가 무너진 후, 독일의 통일은 1990년 10월 3일에 구 동독 국가들이 독일 연방 공화국에 가입하는 것을 보았습니다.

독일은 강한 경제력을 가진 강대국으로 묘사되어 왔습니다; 그것은 유럽에서 가장 큰 경제를 가지고 있습니다. 산업, 과학, 기술 분야의 세계적인 강국으로서 세계 3위의 수출국이자 수입국입니다. 선진국으로서 사회 보장, 보편적 의료 시스템, 등록금 없는 대학 교육을 제공합니다. 독일은 유엔, 유럽연합, NATO, 유럽평의회, G7, G20, OECD의 회원국입니다. 유네스코 세계문화유산 중 세 번째로 많은 수를 보유하고 있습니다.

어원

Germany라는 영어 단어는 줄리어스 시저가 라인 강 동쪽의 사람들을 위해 그것을 채택한 후 사용된 라틴 게르마니아에서 유래되었습니다.[12] 독일어 용어 Deutschland, 원래 diutisciu land ('독일 땅')는 Deutsch (cf)에서 유래되었습니다. 네덜란드어)는 고대 독일어 '국민의'(diot 또는 diota 'people'에서 유래)의 후손으로, 원래 일반인의 언어를 라틴어와 그 로망스 후손과 구별하기 위해 사용되었습니다. 이것은 차례로 고대 게르만어의 *þiudiskaz '국민의' (라틴어로 된 형태인 Theodiscus도 참조)에서 내려오는데, 인도유럽어의 *tewéh ₂ - '국민'의 후손인 *þeudo에서 유래했습니다.

역사

인류 이전의 조상들인 1,100만년 전에 독일에 존재했던 다누비우스 구겐모시는 두 다리로 걸었던 가장 초기의 조상들 중 하나로 이론화되어 있습니다.[14] 고대 인류는 적어도 60만년 전에 독일에 존재했습니다.[15] 현대인이 아닌 인류 최초의 화석(네안데르탈인)이 네안데르 계곡에서 발견되었습니다.[16] 지금까지 발견된 것 중 가장 오래된 악기인 42,000년 된 플루트,[17] 40,000년 된 라이온 맨,[18] 35,000년 된 홀 펠스의 비너스를 포함하여 현대 인간에 대한 유사한 날짜의 증거가 스와비안 주라에서 발견되었습니다.[19] 유럽 청동기 시대에 만들어진 네브라 하늘 원반은 독일 유적지에 귀속되어 왔습니다.[20]

게르만 부족, 로마 변경지역, 프랑크 왕국

게르만 민족은 북유럽 청동기 시대, 초기 철기 시대, 또는 야스토프 문화에서 유래한 것으로 생각됩니다.[21][22] 남부 스칸디나비아와 북부 독일에서 남쪽, 동쪽, 서쪽으로 뻗어 켈트족, 이란족, 발트족, 슬라브족과 접촉했습니다.[23]

아우구스투스 치하에서 로마 제국은 게르만족이 거주하는 땅을 침략하기 시작하여 라인강과 엘베강 사이에 짧은 수명의 로마 속주 게르마니아를 만들었습니다. 서기 9년, 세 개의 로마 군단이 테우토부르크 숲 전투에서 아르미니우스에게 패배했습니다.[24] 이 전투의 결과는 게르마니아를 정복하려는 로마인들의 야망을 만류했고, 따라서 유럽 역사상 가장 중요한 사건 중 하나로 여겨집니다.[25] 서기 100년, 타키투스가 게르마니아를 썼을 때, 게르만 부족들은 라인강과 다뉴브강(라임스 게르마니쿠스)을 따라 정착했고, 현대 독일의 대부분을 차지했습니다. 그러나 바덴뷔르템베르크, 바이에른 남부, 헤센 남부, 라인란트 서부는 로마 속주로 편입되었습니다.[26][27][28]

260년경, 게르만 민족은 로마의 지배를 받는 땅으로 침입했습니다.[29] 375년 훈족의 침공 이후, 그리고 395년부터 로마가 쇠퇴하면서, 게르만 부족들은 더 남서쪽으로 이동했습니다: 프랑크족은 프랑크 왕국을 세우고 동쪽으로 밀어 작센과 바이에른을 정복했고, 오늘날 독일 동부의 지역들은 서슬라브 부족들이 살고 있었습니다.[26]

동프랑크와 신성로마제국

샤를마뉴는 800년에 카롤링거 제국을 세웠고, 843년에 분열되었습니다.[30] 동쪽의 후계 왕국인 동프랑크 왕국은 서쪽의 라인 강에서 동쪽의 엘베 강까지 그리고 북해에서 알프스까지 뻗어 있었습니다.[30] 그 후 신성 로마 제국이 등장했습니다. 오토니아의 통치자들 (919–1024)은 몇몇 주요 공국들을 통합했습니다.[31] 996년 그레고리오 5세는 그의 사촌 오토 3세에 의해 임명된 첫 번째 독일 교황이 되었고, 그는 곧 신성 로마 황제로 즉위했습니다. 신성 로마 제국은 이탈리아 북부와 부르고뉴를 살리아 황제 (1024–1125) 아래에서 흡수했지만 황제들은 투자 논쟁으로 권력을 잃었습니다.[32]

호엔슈타우펜 황제 (1138–1254) 치하에서 독일 제후들은 남쪽과 동쪽으로 독일의 정착을 장려했습니다 (Ostsiedlung).[33] 주로 북독일의 도시들인 한자 동맹의 회원들은 무역의 확대에 번영을 누렸습니다.[34] 인구는 1315년 대기근을 시작으로 1348~1350년 흑사병이 발생하면서 감소했습니다.[35] 1356년에 발행된 황금 황소는 제국의 헌법 구조를 제공하고 7명의 왕자 선출자에 의한 황제 선출을 성문화했습니다.[36]

요하네스 구텐베르크는 유럽에 이동식 인쇄를 도입하여 지식의 민주화를 위한 기초를 마련했습니다.[37] 1517년, 마르틴 루터는 종교개혁을 선동했고 성경의 번역은 언어의 표준화를 시작했습니다; 1555년 아우크스부르크 평화는 "복음주의" (루터교)를 용인했지만, 또한 왕자의 믿음은 그의 신하들의 믿음 (cuius regio, eius regio)이라고 선언했습니다.[38] 쾰른 전쟁부터 30년 전쟁 (1618–1648)까지 종교 갈등은 독일 땅을 황폐화시키고 인구를 상당히 줄였습니다.[39][40]

베스트팔렌 조약으로 제국의 영지들 사이의 종교 전쟁이 종식되었고,[39] 그들의 대부분은 독일어를 사용하는 통치자들은 가톨릭, 루터교 또는 칼뱅교를 공식 종교로 선택할 수 있었습니다.[41] 일련의 제국 개혁(약 1495–1555)에 의해 시작된 법 제도는 상당한 지방 자치와 더 강력한 제국 의회를 제공했습니다.[42] 합스부르크 왕가는 1438년부터 1740년 샤를 6세가 사망할 때까지 황위를 유지했습니다. 오스트리아 왕위 계승 전쟁과 엑스트라 샤펠 조약에 이어 샤를 6세의 딸 마리아 테레사가 그녀의 남편 프란치스코 1세가 황제가 되었을 때 황후 부부로 통치했습니다.[43][44]

1740년부터 오스트리아 합스부르크 군주제와 프로이센 왕국 사이의 이원론이 독일 역사를 지배했습니다. 1772년, 1793년, 1795년 프로이센과 오스트리아는 러시아 제국과 함께 폴란드 분할에 합의했습니다.[45][46] 프랑스 혁명 전쟁, 나폴레옹 시대 및 그 후의 제국 의회의 최종 회의 기간 동안, 대부분의 자유 제국 도시들은 왕조 영토에 의해 합병되었습니다; 교회 영토는 세속화되고 합병되었습니다. 1806년 제국은 해체되었고, 나폴레옹 전쟁 동안 프랑스, 러시아, 프로이센, 합스부르크 왕가(오스트리아)는 독일 국가들의 패권을 놓고 경쟁했습니다.[47]

독일 연방과 제국

나폴레옹의 몰락 이후, 비엔나 회의는 39개의 주권 국가들로 이루어진 느슨한 연맹인 독일 연방을 설립했습니다. 오스트리아의 황제가 상임 대통령으로 임명된 것은 프로이센의 영향력이 커지는 것에 대한 의회의 거부를 반영한 것이었습니다. 복원 정치 내의 의견 불일치는 부분적으로 자유주의 운동의 부상으로 이어졌고, 오스트리아 정치가 클레멘스 폰 메테르니히에 의한 새로운 억압 조치가 뒤따랐습니다.[48][49] 관세동맹인 졸베라인은 경제적 통합을 더욱 촉진시켰습니다.[50] 유럽의 혁명운동에 비추어 볼 때, 지식인들과 평민들은 독일의 문제를 제기하면서 1848년의 혁명을 독일의 주에서 시작했습니다. 프로이센의 프리드리히 빌헬름 4세는 황제의 직함을 제안받았지만, 권력을 잃었고, 그는 왕관과 제안된 헌법을 거부하여 운동에 일시적인 차질을 빚었습니다.[51]

윌리엄 1세는 1862년 오토 폰 비스마르크를 프로이센의 대통령으로 임명했습니다. 비스마르크는 1864년 덴마크와 전쟁을 성공적으로 마무리했습니다. 1866년 오스트리아-프로이센 전쟁에서 프로이센의 결정적인 승리로 그는 오스트리아를 제외한 북독일 연방을 만들 수 있었습니다. 프랑스가 프로이센 전쟁에서 패배한 후, 독일 제후들은 1871년 독일 제국의 건국을 선포했습니다. 프로이센은 새로운 제국의 지배적인 구성국이었고, 프로이센의 왕은 카이저로 통치했고, 베를린은 수도가 되었습니다.[52][53]

독일 통일 이후 그룬더자이트 시기에 독일의 수상으로서 비스마르크의 외교 정책은 동맹을 맺고 전쟁을 피함으로써 강대국으로서의 독일의 위치를 확보했습니다.[53] 그러나 빌헬름 2세 치하에서 독일은 제국주의적인 길을 걷게 되면서 주변국들과 마찰을 빚게 되었습니다.[54] 오스트리아-헝가리의 다국적 영역과 이중 동맹이 형성되었고, 1882년의 삼중 동맹에는 이탈리아가 포함되었습니다. 영국, 프랑스, 러시아는 또한 합스부르크가 발칸 반도에서 러시아의 이익에 간섭하거나 독일이 프랑스에 간섭하는 것을 막기 위해 동맹을 체결했습니다.[55] 1884년 베를린 회의에서 독일은 독일령 동아프리카, 독일령 서남아프리카, 토골란트, 카메룬 등 여러 식민지를 주장했습니다.[56] 이후 독일은 식민지 제국을 더욱 확장하여 태평양과 중국에 대한 보유를 포함시켰습니다.[57] 1904년부터 1907년까지 남아프리카 공화국(현재의 나미비아)의 식민지 정부는 봉기에 대한 처벌로 현지 헤로족과 나마쿠아족을 섬멸하는 행위를 수행했습니다.[58][59] 이것은 20세기 최초의 대량 학살이었습니다.[59]

1914년 6월 28일 오스트리아의 왕세자 암살 사건은 오스트리아-헝가리가 세르비아를 공격하고 제1차 세계대전을 촉발할 수 있는 구실을 제공했습니다. 약 200만 명의 독일 군인이 사망한 4년간의 전쟁 끝에,[60] 일반 휴전으로 그 전쟁은 끝이 났습니다. 독일 혁명(1918년 11월)에 빌헬름 2세와 제후들이 퇴위하면서 독일은 연방 공화국으로 선포되었습니다. 독일의 새 지도부는 1919년 베르사유 조약에 서명하여 연합군의 패배를 받아들였습니다. 역사학자들은 아돌프 히틀러의 부상에 영향력을 행사한 조약을 독일인들은 굴욕적이라고 여겼습니다.[61] 독일은 유럽 영토의 약 13%를 잃었고 아프리카와 태평양의 식민지 소유권을 모두 양도했습니다.[62]

바이마르 공화국과 나치 독일

1919년 8월 11일 프리드리히 에버트 대통령은 민주적인 바이마르 헌법에 서명했습니다.[63] 이어진 권력 투쟁에서 공산주의자들은 바이에른에서 권력을 잡았지만, 다른 곳의 보수적인 요소들은 카프 푸츠치에서 공화국을 전복하려고 시도했습니다. 주요 산업 중심지에서의 거리 싸움, 벨기에와 프랑스 군대의 루르 점령, 초인플레이션 기간이 뒤따랐습니다. 1924년 채무 재조정 계획과 새로운 화폐의 창출은 예술 혁신과 자유주의적 문화 생활의 시대인 황금 20대를 시작하게 했습니다.[64][65][66]

세계적인 대공황은 1929년 독일을 강타했습니다. 하인리히 브뤼닝 총리 정부는 1932년까지 거의 30%의 실업률을 야기한 재정 긴축과 디플레이션 정책을 추구했습니다.[67] 1932년 특별선거 이후 아돌프 히틀러가 이끄는 나치당은 라이히스탁에서 가장 큰 정당이 되었고 1933년 1월 30일 힌덴부르크는 히틀러를 독일 총리로 임명했습니다.[68] 라이히스탁 화재 이후 기본적인 시민권을 폐지하는 법령이 만들어졌고 최초의 나치 강제 수용소가 문을 열었습니다.[69][70] 1933년 3월 23일, 허용법은 히틀러에게 헌법을 무시하고 무제한 입법권을 부여했고 [71]나치 독일의 시작을 알렸습니다. 그의 정부는 중앙집권적인 전체주의 국가를 세우고 국제연맹에서 탈퇴했으며 국가의 재무장을 극적으로 늘렸습니다.[72] 정부가 지원하는 경제 재생 프로그램은 공공 사업에 중점을 두었는데, 그 중 가장 유명한 것은 아우토반(Autoban)이었습니다.[73]

1935년, 이 정권은 베르사유 조약에서 탈퇴하고 유대인과 다른 소수 민족을 대상으로 한 뉘른베르크 법을 도입했습니다.[74] 독일은 또한 1935년에 자르랜드의 지배권을 다시 획득했고,[75] 1936년에 라인란트를 재군사화했으며, 1938년에 오스트리아를 합병했으며, 1938년에 뮌헨 협정으로 수데텐란트를 합병했으며, 1939년 3월에 체코슬로바키아를 점령한 협정을 위반했습니다.[76] 크리스털나흐트(깨진 유리의 밤)는 유대교 회당의 불태움, 유대인 사업의 파괴, 유대인들의 대량 체포를 보았습니다.[77]

1939년 8월, 히틀러 정부는 동유럽을 독일과 소련의 영향권으로 나눈 몰로토프-리벤트롭 조약을 협상했습니다.[78] 1939년 9월 1일, 독일은 폴란드를 침공하여 제2차 세계 대전이 유럽에서 시작되었고,[79] 영국과 프랑스는 9월 3일 독일에 선전포고를 했습니다.[80] 1940년 봄, 독일은 덴마크와 노르웨이, 네덜란드, 벨기에, 룩셈부르크, 프랑스를 정복했고, 프랑스 정부는 휴전 협정에 서명해야 했습니다. 영국은 같은 해 영국 전투에서 독일의 공습을 격퇴했습니다. 1941년 독일군은 유고슬라비아, 그리스, 소련을 침공했습니다. 1942년까지 독일과 그 동맹국들은 유럽 대륙과 북아프리카 대부분을 지배했지만 스탈린그라드 전투에서의 소련의 승리, 연합군의 북아프리카 정복, 1943년 이탈리아 침공 이후 독일군은 반복적인 군사적 패배를 겪었습니다. 1944년, 소련은 동유럽으로 밀고 들어갔고, 서방 동맹국들은 독일의 최종적인 반격에도 불구하고 프랑스에 상륙하여 독일로 들어갔습니다. 1945년 5월 8일 독일은 베를린 전투에서 히틀러가 자살한 후 항복 문서에 서명하여 유럽과[79][81] 나치 독일에서 제2차 세계 대전이 종식되었습니다. 전쟁이 끝난 후 살아남은 나치 관리들은 뉘른베르크 재판에서 전쟁 범죄로 재판을 받았습니다.[82][83]

나중에 홀로코스트라고 알려지게 된 이 사건에서 독일 정부는 소수자들을 유럽 전역의 강제 수용소와 죽음의 수용소에 감금하는 것을 포함하여 박해했습니다. 정권은 조직적으로 600만 명의 유대인, 최소 13만 명의 로마인, 275,000명의 장애인, 수천 명의 여호와의 증인, 수천 명의 동성애자, 수십만 명의 정치적, 종교적 반대자들을 살해했습니다.[84] 독일 점령 국가의 나치 정책으로 폴란드인 270만 명,[85] 우크라이나인 130만 명, 벨라루스인 100만 명, 소련인 350만 명이 사망했습니다.[86][82] 독일군의 사상자는 530만 명으로 추정되고 있으며,[87] 약 90만 명의 독일 민간인이 사망했습니다.[88] 약 1,200만 명의 독일 민족이 동유럽 전역에서 추방되었고, 독일은 전쟁 전 영토의 약 4분의 1을 잃었습니다.[89]

동서독

나치 독일이 항복한 후, 연합국은 독일 국가를 폐지하고 베를린과 독일의 남은 영토를 4개의 점령 구역으로 분할했습니다. 1949년 5월 23일, 프랑스, 영국, 미국의 지배를 받던 서부 지역들이 합병되어 독일 연방 공화국(독일어: 1949년 10월 7일 소비에트 연방은 독일 민주 공화국(GDR)이 되었습니다. 도이치 데모크라시슈 공화국; DDR). 그들은 비공식적으로 서독과 동독으로 알려졌습니다.[91] 동독은 동베를린을 수도로 선택했고, 서독은 본을 임시 수도로 선택해 2국가 해법이 일시적이라는 입장을 강조했습니다.[92]

서독은 "사회적 시장 경제"를 가진 연방 의회 공화국으로 설립되었습니다. 1948년부터 서독은 미국 마셜 플랜에 따라 재건 지원의 주요 수혜국이 되었습니다.[93] 콘라트 아데나워는 1949년 독일의 초대 연방 수상으로 선출되었습니다. 이 나라는 1950년대 초부터 장기적인 경제 성장(Wirtschaftswunder)을 누렸습니다.[94] 서독은 1955년 NATO에 가입하여 유럽 경제 공동체의 창립 회원국이었습니다.[95] 1957년 1월 1일, 자르랜드는 서독에 합류했습니다.[96]

동독은 점령군과 바르샤바 조약을 통해 소련의 정치적, 군사적 통제하에 있던 동구권 국가였습니다. 비록 동독이 민주주의 국가임을 주장했지만, 정치적 권력은 거대한 비밀 조직인 스타시의 지원을 받는 공산주의 지배하의 독일 사회통합당의 지도자들(Politbüro)에 의해서만 행사되었습니다.[97] 동독의 선전이 GDR의 사회 프로그램의 혜택과 서독 침공의 위협에 기반을 둔 반면, 많은 시민들은 자유와 번영을 위해 서방을 찾았습니다.[98] 1961년에 지어진 베를린 장벽은 동독 시민들이 서독으로 탈출하는 것을 막았고, 냉전의 상징이 되었습니다.[99]

1960년대 후반 빌리 브란트 총리의 오스트폴리틱은 동독과 서독 간의 긴장을 완화시켰습니다.[100] 1989년 헝가리는 철의 장막을 해체하고 오스트리아와의 국경을 개방하기로 결정하여 수천 명의 동독인들이 헝가리와 오스트리아를 거쳐 서독으로 이주했습니다. 이것은 GDR에 치명적인 영향을 미쳤고, GDR에서는 정기적인 대규모 시위가 점점 더 많은 지지를 받았습니다. 동독의 국가 유지를 돕기 위해 동독 당국은 국경 제한을 완화했지만, 이는 실제로 독일이 완전한 주권을 되찾은 투 플러스 포 조약으로 끝이 난 웬드 개혁 과정의 가속화로 이어졌습니다. 이로 인해 1990년 10월 3일 독일의 통일이 허용되었고, 구 GDR의 5개 주가 다시 설립되었습니다.[101] 1989년 장벽의 붕괴는 공산주의의 붕괴, 소련의 해체, 독일의 통일, 그리고 "전환점"[102]의 상징이 되었습니다.

통일 독일과 유럽 연합

통일 독일은 서독의 확대된 지속으로 간주되어 국제 기구에서 회원국 지위를 유지했습니다.[103] 베를린/본법(1994)에 근거하여 베를린은 다시 독일의 수도가 되었고, 본은 일부 연방 부처를 유지하는 분데스타트(연방 도시)의 독특한 지위를 얻었습니다.[104] 정부의 이전은 1999년에 완료되었고 동독 경제의 현대화는 2019년까지 지속될 예정이었습니다.[105][106]

독일은 통일 이후 1992년 마스트리흐트 조약과 2007년 리스본 조약을 체결하고 [107]유로존을 공동 창설하는 등 유럽연합에서 보다 적극적인 역할을 수행해 왔습니다.[108] 독일은 발칸반도의 안정성을 확보하기 위해 평화유지군을 파견했고, 탈레반 축출 이후 아프가니스탄에 안보를 제공하기 위한 NATO 노력의 일환으로 독일군을 아프가니스탄에 파견했습니다.[109][110]

2005년 선거에서 앙겔라 메르켈은 최초의 여성 총리가 되었습니다. 2009년 독일 정부는 500억 유로 규모의 경기부양책을 승인했습니다.[111] 21세기 초 독일의 주요 정치 프로젝트 중에는 유럽 통합의 진전, 지속 가능한 에너지 공급을 위한 에너지 전환(Energiewende), 균형 예산을 위한 채무 제동, 출산율을 높이기 위한 조치(프로나탈리즘), 독일 경제 전환을 위한 첨단 기술 전략 등이 있습니다. 인더스트리 4.0으로 요약됩니다.[112] 2015년 유럽 이주 위기 동안 이 나라는 100만 명이 넘는 난민과 이민자를 받아들였습니다.[113]

지리

독일은 북쪽으로는 덴마크, 동쪽으로는 폴란드와 체코, 남동쪽으로는 오스트리아, 남서쪽으로는 스위스와 국경을 접하고 있으며,[4] 유럽에서 일곱 번째로 큰 나라입니다. 서쪽에는 프랑스, 룩셈부르크, 벨기에가 위치해 있고 북서쪽에는 네덜란드가 있습니다. 독일은 또한 북해와, 북북동쪽으로는 발트해와 접해있습니다. 독일 영토의 면적은 357,022 km2 (137,847 sq mi)이며, 348,672 km2 (134,623 sq mi)의 땅과 8,350 km2 (3,224 sq mi)의 물로 구성되어 있습니다.

해발고도는 남쪽의 알프스 산맥(최고점: 2,963m 또는 9,721피트)부터 북서쪽의 북해(Nordsee)와 북동쪽의 발트해(Ostsee)까지입니다. 독일 중부의 숲이 우거진 고지대와 독일 북부의 저지대(최저 지점: 노이엔도르프-작센반데 지방 자치제에서 해발[114] 3.54m 또는 11.6피트의 빌스터마르슈)는 라인강, 다뉴브강, 엘베강과 같은 주요 강이 가로지릅니다. 중요한 천연 자원에는 철광석, 석탄, 포타시, 목재, 갈탄, 우라늄, 구리, 천연 가스, 소금 및 니켈이 포함됩니다.[4]

기후.

독일의 대부분은 온대 기후로 북쪽과 서쪽의 해양성에서 동쪽과 남동쪽의 대륙성에 이르기까지 다양합니다. 겨울은 남알프스 산맥의 추위부터 서늘한 날씨까지 다양하고 일반적으로 강수량이 제한되어 흐립니다. 반면 여름은 덥고 건조한 날씨부터 서늘하고 비가 오는 날씨까지 다양합니다. 북부지방은 북해에서 습한 공기를 유입하는 편서풍이 우세해 기온을 낮추고 강수량을 늘리고 있습니다. 반대로, 동남쪽 지역은 더 극심한 온도를 가집니다.[115]

2019년 2월부터 2020년까지 독일의 월평균 기온은 2020년 1월 최저 3.3 °C(37.9 °F)에서 2019년 6월 최고 19.8 °F(67.6 °F)까지 다양했습니다.[116] 월평균 강수량은 2019년 2월과 4월에 제곱미터당 30리터에서 2020년 2월에 제곱미터당 125리터까지 다양했습니다.[117] 월평균 일조 시간은 2019년 11월 45시간에서 2019년 6월 300시간까지 다양했습니다.[118]

생물다양성

독일의 영토는 5개의 육상 생태 지역으로 나눌 수 있습니다. 대서양 혼합림, 발트해 혼합림, 중유럽 혼합림, 서유럽 활엽수림, 알프스 침엽수 및 혼합림.[119] 2016년[update] 기준 독일 국토 면적의 51%가 농업에 전념하고 있으며, 30%는 삼림, 14%는 정착지 또는 기반 시설로 덮여 있습니다.[120]

식물과 동물은 일반적으로 중앙 유럽에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 것들을 포함합니다. 국립산림목록에 따르면, 너도밤나무, 오크나무, 그리고 다른 낙엽성 나무들이 숲의 40%를 조금 넘고, 대략 60%는 침엽수, 특히 가문비나무와 소나무입니다.[121] 양치식물, 꽃, 곰팡이, 이끼의 종류가 많습니다. 야생 동물에는 노루, 멧돼지, 무플론(야생 양의 아종), 여우, 오소리, 토끼, 소수의 유라시아 비버가 포함됩니다.[122] 파란 옥수수 꽃은 한때 독일의 국가 상징이었습니다.[123]

독일의 16개 국립공원은 자스문트 국립공원, 포포메른 라군 지역 국립공원, 뮈리츠 국립공원, 와덴해 국립공원, 하르츠 국립공원, 하이니치 국립공원, 흑림 국립공원, 색슨 스위스 국립공원, 바이에른 삼림 [124]국립공원과 베르흐테스가덴 국립공원 또한 17개의 생물권 보호 구역과 [125]105개의 자연 공원이 있습니다.[126] 독일에는 400개 이상의 동물원과 동물원이 운영되고 있습니다.[127] 1844년에 문을 연 베를린 동물원은 독일에서 가장 오래된 동물원으로, 세계에서 가장 포괄적인 종의 컬렉션을 자랑합니다.[128]

정치

|  |

| 프랑크 발터 슈타인마이어 대통령 (국가대표) | 올라프 숄츠 재상 (정부 수반) |

독일은 연방, 의회, 대표적인 민주 공화국입니다. 연방 입법권은 연방의회(연방의회)와 연방의회(연방의회)로 구성된 의회에 부여되며, 이들은 함께 입법기관을 구성합니다. 연방 하원은 혼합형 비례대표제를 활용한 직접선거를 통해 선출됩니다. 연방 참사원 의원들은 16개 연방 주 정부를 대표하고 임명됩니다.[4] 독일의 정치 체제는 1949년 헌법에 규정된 기본법(Grundgesetz)에 따라 운영됩니다. 개정안은 일반적으로 연방 하원과 연방 하원 모두의 3분의 2 이상의 찬성을 요구합니다. 인간의 존엄성, 삼권분립, 연방 구조, 법치주의를 보장하는 조항에 표현된 헌법의 기본 원칙은 영구적으로 유효합니다.[129]

현재 프랑크 발터 슈타인마이어 대통령은 국가 원수이며 주로 대표적인 책임과 권한을 가지고 투자하고 있습니다. 그는 연방의회 의원들과 동수의 주 대의원들로 구성된 기관인 연방의회에 의해 선출됩니다.[4] 독일 우선 순위에서 두 번째로 높은 관리는 연방의회에 의해 선출되고 매일의 회의를 감독하는 책임이 있는 연방의회 의장(Bundestagspräsident, 연방의회 의장)입니다.[130] 세 번째로 높은 공직자이자 정부 수반은 연방의회에서 가장 많은 의석을 차지한 정당 또는 연립정부에 의해 선출된 후 연방의회 의장이 임명하는 총리입니다.[4] 현재 올라프 숄츠 총리는 정부 수반이며 내각을 통해 행정권을 행사합니다.[4]

1949년 이래로 정당 체제는 기민련과 독일 사회민주당이 장악하고 있습니다. 지금까지 모든 수상은 이 정당들 중 한 정당의 일원이었습니다. 그러나, 더 작은 자유민주당과 90/녹색연합은 연립정부에서도 하급 파트너였습니다. 민주사회당 좌파는 2007년 이후 독일 연방정부의 주요 정당이 되었습니다. 2017년 독일 연방 선거에서 우파 표퓰리즘 독일을 위한 대안은 처음으로 의회에서 대표성을 얻을 만큼 충분한 표를 얻었습니다.[131][132]

구성주

독일은 연방이며 16개의 구성국으로 구성되어 있으며, 이들을 통칭하여 렌더(Länder)라고 합니다.[133] 각 주(Land)는 자체 헌법을 가지고 있으며,[134] 내부 조직과 관련하여 대체로 자율적입니다.[133] 2017년[update] 기준으로 독일은 401개 구(Kreise)로 구성되어 있으며, 294개의 농촌 지역과 107개의 도시 지역으로 구성되어 있습니다.[135]

|

법

독일은 게르만법을 일부 참고하여 로마법을 기반으로 민법 체계를 갖추고 있습니다.[139] 연방헌법재판소(Bundesverfassungsgericht, 연방헌법재판소)는 헌법 문제를 담당하는 독일 대법원으로 사법심사권을 가지고 있습니다.[140] 독일의 대법원 제도는 전문화되어 있습니다: 민사 및 형사 사건의 경우 최고 항소 법원은 연방 사법 재판소이며, 그 외의 사건의 경우 연방 노동 재판소, 연방 사회 재판소, 연방 재정 재판소 및 연방 행정 재판소입니다.[141]

형법과 사법은 각각 Strafgesetzbuch와 Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch에서 국가 차원에서 성문화되어 있습니다. 독일의 형벌체계는 범죄자의 재활과 국민의 보호를 추구합니다.[142] 한 명의 전문 판사 앞에서 재판을 받는 사소한 범죄와 심각한 정치 범죄를 제외하고는 모든 혐의가 일반 판사(Schöffen)가 전문 판사와 나란히 앉아 있는 혼합 재판소 앞에서 재판을 받습니다.[143][144]

독일은 2016년[update] 기준 10만 명당 1.18건의 살인으로 살인율이 낮습니다.[145] 2018년 전체 범죄율은 1992년 이후 최저치로 떨어졌습니다.[146]

독일에서는 2017년부터 동성결혼이 합법화되었으며, 독일에서는 일반적으로 LGBT 권리가 보호됩니다.[147]

대외관계

독일은 227개의[148] 재외공관 네트워크를 보유하고 있으며 190개 이상의 국가와 관계를 유지하고 있습니다.[149] 독일은 NATO, OECD, G7, G20, 세계은행, IMF의 회원국입니다. 창립 이래 유럽 연합에서 영향력 있는 역할을 해왔으며 1990년 이후 프랑스 및 모든 이웃 국가들과 강력한 동맹 관계를 유지하고 있습니다. 독일은 보다 통일된 유럽의 정치, 경제, 안보 기구의 창설을 추진하고 있습니다.[150][151][152] 독일과 미국 정부는 긴밀한 정치적 동맹국입니다.[153] 문화적 유대와 경제적 이해관계는 대서양주의라는 결과를 낳은 두 나라 사이에 유대감을 형성했습니다.[154] 1990년 이후 독일과 러시아는 에너지 개발이 가장 중요한 요소 중 하나가 되는 "전략적 동반자 관계"를 구축하기 위해 협력했습니다. 협력의 결과, 독일은 천연가스와 원유의 대부분을 러시아로부터 수입했습니다.[155][156]

독일의 개발 정책은 외교 정책의 독립적인 영역입니다. 이는 연방 경제협력개발부에 의해 공식화되고 실행 기관에 의해 수행됩니다. 독일 정부는 개발 정책을 국제 사회의 공동 책임으로 보고 있습니다.[157] 2019년에는 미국에 이어 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 원조 공여국이었습니다.[158]

군사의

독일의 군대인 분데스베어(연방방위군)는 히어(육군 및 특수부대), 해병(해군), 루프트바페(공군), Zentraler Sanitätsdienst der Bundeswehr(합동의료서비스), Streitkräftebasis(합동지원서비스), 사이버 및 정보 영역 서비스(사이버 및 정보 영역 서비스) 지부로 구성되어 있습니다. 절대적으로 독일의 군사비 지출은 세계에서 8번째로 높습니다.[159] 2018년 군사비 지출은 495억 달러로 국가 GDP의 약 1.2%로 NATO 목표인 2%[160][161]를 훨씬 밑돌았습니다. 그러나 2022년 러시아의 우크라이나 침공에 대응하여 올라프 숄츠 총리는 2021년 530억 유로의 군사 예산의 거의 두 배에 해당하는 2022년 일회성 1,000억 유로 투입과 함께 독일의 군사 지출을 나토 목표인 2% 이상으로 늘릴 것이라고 발표했습니다.[162][163]

2020년[update] 1월 현재, 연방군의 병력은 184,001명이며, 민간인은 80,947명입니다.[164] 예비역들은 군이 이용할 수 있고, 국방 훈련과 해외 배치에 참여할 수 있습니다.[165] 2011년까지 18세 남성의 경우 의무적으로 군복무를 했지만, 이는 공식적으로 중단되고 자원봉사로 대체되고 있습니다.[166][167] 2001년부터 여성은 제한 없이 모든 서비스 기능을 수행할 수 있습니다.[168] 스톡홀름국제평화연구소에 따르면, 독일은 2014년부터 2018년까지 세계에서 네 번째로 큰 주요 무기 수출국이었습니다.[169]

평시에는 국방부 장관이 분데스베어를 지휘합니다. 국방부에서 수상은 연방군의 총사령관이 됩니다.[170] 독일 헌법에서 연방군의 역할은 방어적인 것으로만 묘사됩니다. 그러나 1994년 연방헌법재판소의 판결 이후, "방위"라는 용어는 독일 국경의 보호뿐만 아니라 위기 대응 및 분쟁 예방, 또는 더 광범위하게 세계 어느 곳에서나 독일의 안보를 지키는 것을 포함하는 것으로 정의되었습니다. 독일군은 2017년 [update]현재 국제평화유지군의 일환으로 약 3,600명의 병력을 외국에 주둔시키고 있으며, 그 중에는 약 1,200명의 대쉬 작전 지원군, 980명의 나토 주도의 아프가니스탄 레졸루트 지원군, 800명의 코소보 지원군이 포함되어 있습니다.[171][172]

경제.

독일은 고도의 숙련된 노동력, 낮은 수준의 부패, 높은 수준의 혁신을 가진 사회적 시장 경제를 가지고 있습니다.[4][174][175] 세계 3위의 수출국이자 3위의 수입국이며,[4] 유럽에서 경제규모가 가장 크고, 명목 GDP로는[176] 세계 3위, PPP로는 세계 5위의 경제규모를 가지고 있습니다.[177] 구매력 기준으로 측정한 1인당 GDP는 EU27 평균의 121%에 달합니다.[178] 서비스업은 전체 GDP의 약 69%, 산업은 31%를 차지하며, 독일은 2017년[update] 기준으로 유럽에서 가장 큰 제조업 부문을 보유하고 있으며, 농업은 1%를 차지하고 있습니다.[4] 유로스타트가 발표한 실업률은 2020년[update] 1월 기준 3.2%로 EU에서 네 번째로 낮습니다.[179]

독일은 4억 5천만 명 이상의 소비자를 대표하는 유럽 단일 시장의 일부입니다.[180] 국제통화기금(IMF)에 따르면 2017년 유로존 경제의 28%를 차지했습니다.[181] 독일은 2002년에 유럽의 공통 통화인 유로를 도입했습니다.[182] 통화 정책은 프랑크푸르트에 본부를 둔 유럽 중앙 은행에 의해 결정됩니다.[183][173]

현대 자동차의 본고장인 독일의 자동차 산업은 세계에서 가장 경쟁력 있고 혁신적인 산업 중 하나로 [184]간주되며 2021년 기준 생산량 기준으로 6위입니다. 독일은 2022년 차량 생산과[185] 판매 모두 세계 2위의 자동차 제조업체인 폭스바겐 그룹의 본거지이며,[186] 2023년 기준으로 3위의 자동차 수출국입니다.[187]

독일의 10대 수출 품목은 차량, 기계, 화학제품, 전자제품, 전기기기, 의약품, 운송장비, 기초금속, 식품, 고무 및 플라스틱입니다.[188]

2023년 매출액으로 측정한 세계 500대 주식시장 상장기업 중 포춘 글로벌 500대 기업 32곳이 독일에 본사를 두고 있습니다.[189] 프랑크푸르트 증권거래소가 운영하는 독일 증시지수 DAX에는 독일에 본사를 둔 30개 주요 기업이 포함돼 있습니다.[190] 잘 알려진 국제 브랜드로는 메르세데스-벤츠, BMW, 폭스바겐, 아우디, 지멘스, 알리안츠, 아디다스, 포르쉐, 보쉬 및 도이치 텔레콤이 있습니다.[191] 베를린은 스타트업 기업들의 중심지이며, 유럽연합 내 벤처캐피털이 자금을 지원하는 기업들의 선도적인 위치가 되었습니다.[192] 독일은 미텔스탠드 모델로 알려진 전문 중소기업의 비중이 큰 것으로 인정받고 있습니다.[193] 이 회사들은 히든 챔피언이라고 불리는 부문에서 세계 시장 리더의 48%를 대표합니다.[194]

연구 개발 노력은 독일 경제에서 필수적인 부분을 형성하며,[195] 2005년 이후 연구 개발 지출에서 4위를 차지했습니다.[196] 2018년 독일은 이공계 연구 논문 발표 수 기준으로 세계 4위를 기록했습니다.[197] 독일의 연구 기관으로는 막스 플랑크 협회, 헬름홀츠 협회, 프라운호퍼 협회와 라이프니츠 협회 등이 있습니다.[198] 독일은 유럽 우주국의 최대 기여국입니다.[199] 독일은 2023년 글로벌 혁신지수 8위를 기록했습니다.[200]

사회 기반 시설

유럽의 중심지인 독일은 유럽 대륙의 교통 중심지입니다.[201] 도로망은 유럽에서 가장 밀도가 높습니다.[202] 고속도로(Autobahn)는 일부 등급의 차량에 대해 일반적으로 연방에서 의무적으로 규정한 속도 제한이 없는 것으로 널리 알려져 있습니다.[203] 인터시티 익스프레스 또는 ICE 열차 네트워크는 300km/h(190mph)의 속도로 독일의 주요 도시 및 인근 국가의 목적지에 서비스를 제공합니다.[204] 독일의 가장 큰 공항은 프랑크푸르트 공항, 뮌헨 공항, 베를린 브란덴부르크 공항입니다.[205] 함부르크 항은 세계에서 가장 큰 20개의 컨테이너 항구 중 하나입니다.[206]

2019년[update] 독일은 세계 7위의 에너지 소비국이었습니다.[207] 모든 원자력 발전소는 2023년에 단계적으로 폐지되었습니다.[208] 40%의 재생 가능한 자원을 사용하여 국가의 전력 수요를 충족시키며, 태양열 및 해상 풍력 분야에서 "초기 선두주자"로 불렸습니다.[209][210] 독일은 파리 협정과 생물 다양성, 낮은 배출 기준, 물 관리를 촉진하는 여러 조약에 전념하고 있습니다.[211][212][213] 미국의 가정 재활용률은 약 65%[214]로 세계에서 가장 높습니다. 이 나라의 1인당 온실가스 배출량은 2018년[update] EU에서 9번째로 많았지만, 이 수치는 하락세를 보이고 있습니다.[215][216] 독일의 에너지 전환(Energiewende)은 에너지 효율과 재생 에너지를 통해 지속 가능한 경제로 나아가는 것으로 인정받고 있습니다.[217][210] 독일은 1990년에서 2015년[218] 사이에 1차 에너지 소비를 11% 줄였고 2030년까지 30%, 2050년까지 50% 줄이겠다는 목표를 세웠습니다.[219]

관광업

국내외 여행과 관광을 합하면 독일 GDP에 1053억 유로 이상을 직접 기여합니다. 간접적인 영향과 유발적인 영향을 포함하여, 그 산업은 420만 개의 일자리를 지원합니다.[220] 2022년 기준으로 독일은 8번째로 방문이 많은 나라입니다.[221] 가장 인기 있는 랜드마크로는 쾰른 대성당, 브란덴부르크문, 라이히스탁, 드레스덴 프라우엔키르체, 노이슈반슈타인 성, 하이델베르크 성, 바르트부르크 성, 상수시 궁전 등이 있습니다.[222] 프라이부르크 근처의 유로파 파크는 유럽에서 두 번째로 인기 있는 테마 파크 리조트입니다.[223]

인구통계

2011년 독일 인구조사에 따르면 인구가 8,020만 [224]명으로 2022년[update] 현재 8,370만 명으로 증가한 [225]독일은 유럽연합에서 가장 인구가 많은 국가이며, 러시아 다음으로 유럽에서 두 번째로 인구가 많은 국가이며,[h] 세계에서 19번째로 인구가 많은 국가입니다. 인구 밀도는 평방 킬로미터당 227명(590명/sqmi)입니다. 여성 1인당 출산율 1.57명(2022년 추산)은 대체율 2.1명보다 낮고, 세계에서 가장 낮은 출산율 중 하나입니다.[4] 1970년대 이후 독일의 사망률은 출생률을 넘어섰습니다. 그러나 독일은 2010년대 초부터 출생률과 이주율이 증가하고 있습니다. 독일은 평균 나이가 47.4세로 세계에서 세 번째로 나이가 많습니다.[4]

조상들이 각자의 지역에서 수세기 동안 살아왔기 때문에 네 개의 상당한 그룹을 민족 소수자라고 부릅니다.[226] 최북단 슐레스비히홀슈타인 주에는 덴마크 소수민족이 살고 있고,[226] 슬라브족인 소르브족은 작센주와 브란덴부르크주의 루사티아 지역에, 로마족과 신티족은 전국에 살고 있으며, 프리지아족은 슐레스비히홀슈타인 서부 해안과 니더작센주 북서부에 집중되어 있습니다.[226]

독일은 미국 다음으로 세계에서 두 번째로 인기 있는 이민지입니다.[227] 2015년 난민 사태 이후 유엔 경제사회부 인구분과는 독일을 전체 2억 4,400만 명의 이주민 중 약 5%인 1,200만 명이 전 세계에서 두 번째로 많은 국제 이주민의 거주지로 선정했습니다.[228] 난민 위기는 상당한 인구 증가를 초래했습니다. 예를 들어, 2022년 러시아의 우크라이나 침공에 따른 우크라이나 이민자의 대규모 유입은 2023년 4월 기준 독일에서 106만 명 이상의 우크라이나 난민이 발생한 것으로 기록되었습니다.[229] 독일은 2019년[update] 기준 인구 중 이주민 비율이 13.1%[230]로 EU 국가 중 7위를 차지하고 있습니다. 2022년에는 전체 인구의 28.7%인 2,380만 명이 이주 배경을 가지고 있었습니다.[231]

독일에는 많은 대도시가 있습니다. 공식적으로 인정된 11개의 광역 지역이 있습니다. 이 나라의 가장 큰 도시는 베를린이고, 가장 큰 도시 지역은 루르입니다.[232]

| 순위 | 이름. | 주 | 팝. | 순위 | 이름. | 주 | 팝. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 베를린 | 베를린 | 3,644,826 | 11 | 브레멘 | 브레멘 | 569,352 | ||

| 2 | 함부르크 | 함부르크 | 1,841,179 | 12 | 드레스덴 | 작센 주 | 554,649 | ||

| 3 | 뮌헨 | 바이에른 주 | 1,471,508 | 13 | 하노버 | 니더작센 주 | 538,068 | ||

| 4 | 쾰른 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 1,085,664 | 14 | 뉘른베르크 | 바이에른 주 | 518,365 | ||

| 5 | 프랑크푸르트 | 헤세 | 753,056 | 15 | 뒤스부르크 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 498,590 | ||

| 6 | 슈투트가르트 | 바덴뷔르템베르크 주 | 634,830 | 16 | 보훔 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 364,628 | ||

| 7 | 뒤셀도르프 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 619,294 | 17 | 부퍼탈 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 354,382 | ||

| 8 | 라이프치히 | 작센 주 | 587,857 | 18 | 빌레펠트 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 333,786 | ||

| 9 | 도르트문트 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 587,010 | 19 | 본 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 327,258 | ||

| 10 | 에센 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 583,109 | 20 | 뮌스터 | 노르트라인베스트팔렌 주 | 314,319 | ||

종교

기독교는 AD 300년에 현대 독일 지역에 도입되었고 8-9세기 샤를마뉴 시대에 완전히 기독교화되었습니다. 16세기 초 마틴 루터에 의해 종교개혁이 시작된 후, 많은 사람들이 가톨릭 교회를 떠나 루터교와 칼뱅교를 중심으로 개신교가 되었습니다.[233]

2011년 인구조사에 따르면, 응답자의 66.8%가 기독교인이라고 밝혔고, 그 중 3.8%가 기독교인이 아니라고 응답했습니다.[234] 31.7%는 자신을 루터교, 개혁교를 아우르는 독일 개신교(루터교, 개혁교, 개혁교를 아우르는) 신도들을 포함해 개신교라고 선언했습니다. 그리고 두 전통의 행정적 또는 고백적 연합)과 자유 교회(Evangelische Freikirchen); 31.2%는 스스로를 로마 가톨릭 신자라고 선언했고, 정교회 신자들은 1.3%를 차지했습니다. 2016년 자료에 따르면 가톨릭교회와 복음주의교회는 각각 인구의 28.5%와 27.5%를 차지했습니다.[235][236] 이슬람교는 이 나라에서 두 번째로 큰 종교입니다.[237]

2011년 인구 조사에서 응답자의 1.9%(152만 명)가 자신의 종교를 이슬람교라고 말했지만, 이 수치는 신뢰할 수 없는 것으로 여겨집니다. 왜냐하면 이 종교를 지지하는 사람들(그리고 유대교와 같은 다른 종교)의 불균형한 숫자가 질문에 대답하지 않을 권리를 이용했을 가능성이 높기 때문입니다.[238] 대부분의 이슬람교도들은 튀르키예 출신의 수니파와 알레비파이지만 시아파와 아마디야스 그리고 다른 교단들은 소수입니다. 다른 종교들은 독일 인구의 1%도 되지 않습니다.[237]

2018년의 한 연구에 따르면 인구의 38%가 어떤 종교 단체나 종파의 구성원이 아니지만 [239]최대 3분의 1이 여전히 종교적이라고 생각할 수 있습니다. 독일의 이르 종교는 국가 무신론 시행 이전에 주로 개신교였던 구 동독과 주요 대도시에서 가장 강합니다.[240][241]

언어들

독일어는 독일에서 공식적이고 주로 사용되는 언어입니다.[242] 유럽 연합의 24개 공식 언어와 실무 언어 중 하나이며, 유럽 위원회의 3개 절차 언어 중 하나입니다.[243] 독일어는 유럽 연합에서 가장 널리 사용되는 모국어로, 약 1억 명의 원어민이 사용합니다.[244]

독일에서 인정되는 소수민족 언어는 덴마크어, 저독일어, 저레니쉬어, 소르비아어, 루마니아어, 북프리시안어, 사틀란드프리시안어이며, 유럽 지역 언어 헌장에 의해 공식적으로 보호됩니다. 가장 많이 사용되는 이민 언어는 터키어, 아랍어, 쿠르드어, 폴란드어, 이탈리아어, 그리스어, 스페인어, 세르보-크로아티아어, 불가리아어 및 기타 발칸 반도 언어이며 러시아어도 사용됩니다. 독일인은 일반적으로 여러 언어를 사용합니다. 독일 시민의 67%는 적어도 한 개의 외국어로 의사 소통할 수 있고 27%는 적어도 두 개의 외국어로 의사 소통할 수 있다고 주장합니다.[242]

교육

독일에서 교육감독에 대한 책임은 주로 개별 주 내에서 조직됩니다. 만 3세에서 6세 사이의 모든 어린이를 대상으로 선택적 유치원 교육이 실시되며, 이후에는 주에 따라 최소 9년 이상 의무적으로 등교해야 합니다. 초등 교육은 보통 4~6년 동안 지속됩니다.[245] 중등 교육은 학생들이 학업 또는 직업 교육을 추구하는지 여부에 따라 트랙으로 나뉩니다.[246] Duale Ausbildung이라고 불리는 견습 제도는 거의 학사 학위에 필적하는 숙련된 자격으로 이어집니다. 직업 훈련을 받는 학생들이 국영 무역 학교뿐만 아니라 기업에서도 배울 수 있습니다.[245] 이 모델은 전 세계적으로 호평을 받고 재현되고 있습니다.[247]

대부분의 독일 대학은 공공기관이며 학생들은 전통적으로 수수료 지불 없이 공부합니다.[248] 대학에 다니기 위한 일반적인 요구 사항은 아비투르입니다. 2014년 OECD 보고서에 따르면, 독일은 세계에서 세 번째로 선도적인 국제 연구 대상국입니다.[249] 독일에 설립된 대학들은 세계에서 가장 오래된 대학들 중 일부를 포함하고 있으며, 하이델베르크 대학교(1386년 설립), 라이프치히 대학교(1409년 설립), 로스토크 대학교(1419년 설립)가 가장 오래된 대학입니다.[250] 1810년 진보적인 교육 개혁가 빌헬름 폰 훔볼트에 의해 설립된 베를린 훔볼트 대학은 많은 서구 대학들의 학문적 모델이 되었습니다.[251][252] 현대 시대에 독일은 11개의 우수 대학을 개발했습니다.

헬스

크랑켄호이저(Krankenhäuser)라고 불리는 독일의 병원 시스템은 중세시대부터 시작되었으며, 오늘날 독일은 1880년대 비스마르크의 사회법제로부터 시작된 세계에서 가장 오래된 보편적 의료 시스템을 가지고 있습니다.[254] 1880년대 이후 개혁과 조항은 균형 잡힌 의료 시스템을 보장했습니다. 인구는 일부 그룹이 민간 의료 보험 계약을 선택할 수 있는 기준과 함께 법령에 의해 제공되는 건강 보험 계획에 의해 보장됩니다. 세계보건기구(WHO)에 따르면 독일의 보건의료체계는 2013년[update] 기준으로 정부가 77%, 민간이 23%를 지원하고 있습니다.[255] 2014년 독일은 GDP의 11.3%를 의료비로 지출했습니다.[256]

WHO에 따르면 독일은 2019년 기대수명이 남성 78.7세, 여성 84.8세로 세계 21위를 기록했으며, 영아 사망률(생아 1000명당 4명)이 매우 낮았습니다. 2019년[update] 주요 사망 원인은 심혈관 질환으로 37%[257]였습니다. 독일의 비만은 점점 더 주요 건강 문제로 언급되고 있습니다. 2014년 연구에 따르면 독일 성인 인구의 52%가 과체중이거나 비만인 것으로 나타났습니다.[258]

문화

독일 국가의 문화는 종교와 세속을 막론하고 유럽의 주요 지적이고 대중적인 흐름에 의해 형성되어 왔으며, 그 과학자, 작가 및 철학자는 서구 사상의 발전에 중요한 역할을 했습니다.[259] BBC의 세계적인 여론조사는 독일이 2013년과 2014년에 세계에서 가장 긍정적인 영향력을 행사한 것으로 인정받고 있다고 밝혔습니다.[260][261]

독일은 옥토버페스트와 크리스마스 관습과 같은 민속 축제 전통으로 잘 알려져 있으며, 여기에는 재림 화환, 크리스마스 페이저트, 크리스마스 트리, 슈톨렌 케이크 및 기타 관행이 포함됩니다.[262][263] 2023년[update] 현재 유네스코는 독일의 52개 유산을 세계문화유산 목록에 등재했습니다.[264] 독일에는 각 주에서 정한 여러 공휴일이 있습니다; 10월 3일은 1990년부터 독일의 국경일이며, 독일 통일의 날(Tag der Deutschen Einheit)로 기념되고 있습니다.[265]

음악

독일 클래식 음악에는 세계에서 가장 잘 알려진 작곡가들의 작품이 포함되어 있습니다. 디테리히 북스테후데, 요한 세바스티안 바흐, 게오르크 프리드리히 헨델은 바로크 시대의 영향력 있는 작곡가들이었습니다. 루트비히 판 베토벤은 고전주의와 낭만주의 시대 사이의 전환에 중요한 인물이었습니다. 카를 마리아 폰 베버, 펠릭스 멘델스존, 로베르트 슈만, 요하네스 브람스는 중요한 낭만주의 작곡가였습니다. 리하르트 바그너는 오페라로 유명했습니다. Richard Strauss는 낭만주의 후기와 근대 초기의 선두적인 작곡가였습니다. 칼하인츠 스톡하우젠과 볼프강 림은 20세기와 21세기 초의 중요한 작곡가들입니다.[266]

2013년 기준으로 독일은 유럽에서 두 번째로 큰 음악 시장이며, 세계에서 네 번째로 큰 음악 시장입니다.[267] 20세기와 21세기의 독일 대중 음악에는 노이 도이치 벨레, 팝, 오스트록, 헤비 메탈/록, 펑크, 팝 록, 인디, 폴크스뮤직(포크 음악), 슐라거 팝, 독일 힙합의 움직임이 포함됩니다. 크래프트워크와 귤드림이 이 장르를 개척하면서 독일 일렉트로닉 음악은 세계적인 영향력을 갖게 되었습니다.[268] 독일의 테크노 및 하우스 음악계의 DJ 및 아티스트(예: Paul van Dyk, Felix Jahn, Paul Kalkbrenner, Robin Schulz 및 스쿠터)가 유명해졌습니다.[269]

미술, 디자인, 건축

독일 화가들은 서양 미술에 영향을 끼쳤습니다. 알브레히트 뒤러, 한스 홀바인 2세, 마티아스 그뤼네발트, 루카스 크라나흐 2세는 르네상스 시대의 중요한 독일 예술가들, 바로크 시대의 요한 침례교 짐머만, 낭만주의의 카스파 다비드 프리드리히와 칼 스피츠베그, 인상주의의 막스 리버만, 초현실주의의 막스 에른스트였습니다. 20세기에 형성된 몇몇 독일 예술 단체들; 다리 (Die Brücke)와 블루 라이더 (Der Blaue Reiter)는 뮌헨과 베를린의 표현주의 발전에 영향을 미쳤습니다. 새로운 객관성은 바이마르 공화국 시기 표현주의에 대응하여 발생했습니다. 제2차 세계대전 이후 독일 미술의 광범위한 경향은 신표현주의와 뉴 라이프치히 학파를 포함합니다.[270]

독일 디자이너들은 현대 제품 디자인의 초기 리더가 되었습니다.[271] 베를린 패션 위크와 패션 무역 박람회 브레드 앤 버터가 1년에 두 번 열립니다.[272]

독일의 건축적 기여는 로마네스크의 선구자였던 카롤링거 양식과 오토네스크 양식을 포함합니다. 브릭 고딕은 독일에서 발전한 독특한 중세 양식입니다. 또한 르네상스와 바로크 미술에서 지역적이고 전형적인 독일 요소들이 발전했습니다 (예: 웨저 르네상스).[270] 독일의 토착 건축물은 종종 목재 골조(Fachwerk) 전통에 의해 확인되며 지역과 목공 양식에 따라 다릅니다.[273] 산업화가 유럽 전역으로 퍼졌을 때, 고전주의와 때때로 그룬더자이트 스타일이라고 불리는 독특한 스타일의 역사주의가 독일에서 발전했습니다. 표현주의 건축은 1910년대에 독일에서 발전했고 아르데코와 다른 현대 양식에 영향을 미쳤습니다. 독일은 초기 모더니즘 운동에서 특히 중요했습니다: 독일은 헤르만 무테시우스에 의해 시작된 베르흐분트의 본거지이고 발터 그로피우스에 의해 설립된 바우하우스 운동의 본거지입니다.[270] 루트비히 미즈 반 데어 로에는 20세기 후반에 세계에서 가장 유명한 건축가 중 한 명이 되었고, 그는 유리 정면 고층 건물을 구상했습니다.[274] 유명한 현대 건축가와 사무실에는 프리츠커상 수상자인 고트프리트 봄과 프라이 오토가 있습니다.[275]

문학과 철학

독일 문학은 중세와 발터 폰 데어 보겔바이데, 볼프람 폰 에셴바흐 등의 작가들의 작품으로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있습니다. 유명한 독일 작가로는 요한 볼프강 폰 괴테, 프리드리히 실러, 고트홀트 에브라임 레싱, 테오도르 폰테인 등이 있습니다. 그림 형제가 펴낸 민담집은 독일 민담을 국제적으로 널리 알렸습니다.[276] 그림인들은 또한 독일어의 지역적인 변형들을 모으고 체계화하여, 그들의 작업을 역사적인 원칙에 기초를 두었습니다; 때때로 그림 사전이라고 불리는 그들의 독일어 사전은 1838년에 시작되었고, 1854년에 첫 번째 책이 출판되었습니다.[277]

20세기의 영향력 있는 작가로는 게르하트 하우프트만, 토마스 만, 헤르만 헤세, 하인리히 뵐, 귄터 그라스 등이 있습니다.[278] 독일 도서 시장은 미국과 중국에 이어 세계에서 세 번째로 큽니다.[279] 프랑크푸르트 도서전은 500년이 넘는 전통을 가진 국제 거래와 무역을 위해 세계에서 가장 중요합니다.[280] 라이프치히 도서전은 유럽에서도 주요한 위치를 유지하고 있습니다.[281]

독일 철학은 역사적으로 중요합니다. 고트프리트 라이프니츠의 합리주의에 대한 공헌, 임마누엘 칸트의 계몽철학, 요한 고틀립 피히테의 고전적 독일 관념론의 확립, 게오르크 빌헬름 프리드리히 헤겔과 프리드리히 빌헬름 요제프 셸링, 아서 쇼펜하우어의 형이상학적 비관론 구성, 카를 마르크스와 프리드리히 엥겔스의 공산주의 이론 구성, 프리드리히 니체의 관점주의 발전, 분석철학의 여명기에 대한 고틀롭 프레게의 공헌, 마틴 하이데거의 연구 존재, 오스왈드 스펭글러의 역사철학, 프랑크푸르트 학파의 발전은 모두 큰 영향을 미쳤습니다.[282]

미디어

독일에서 국제적으로 운영되는 가장 큰 미디어 회사는 Bertelsmann 엔터프라이즈, Axel Springer SE 및 ProSiebenSat.1 Media입니다. 독일의 텔레비전 시장은 약 3,800만 가구로 유럽에서 가장 큽니다.[283] 독일 가정의 약 90%가 케이블 또는 위성 TV를 보유하고 있으며, 다양한 무료 시청이 가능한 공공 및 상업 채널을 보유하고 있습니다.[284] 독일에는 300개 이상의 공영 및 민영 라디오 방송국이 있습니다; 독일의 전국 라디오 네트워크는 독일의 Deutschland 라디오이고 공영 Deutschwell은 외국어로 된 독일의 주요 라디오 및 텔레비전 방송국입니다.[284] 독일의 신문과 잡지 인쇄 시장은 유럽에서 가장 큽니다.[284] 가장 높은 발행부수를 기록한 논문은 Bild, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Die Welt입니다.[284] 가장 큰 잡지로는 ADAC 모터웰과 Der Spiegel이 있습니다.[284] 독일은 전국적으로 3,400만 명 이상의 플레이어가 있는 대규모 비디오 게임 시장을 가지고 있습니다.[285] 게임스컴은 세계에서 가장 큰 게임 대회입니다.[286]

독일 영화는 영화에 주요한 기술적, 예술적 기여를 했습니다. 스클라다노프스키 형제의 첫 번째 작품은 1895년에 관객들에게 공개되었습니다. 포츠담에 있는 유명한 바벨스버그 스튜디오는 1912년에 설립되었고, 따라서 세계 최초의 대규모 영화 스튜디오입니다. 초기 독일 영화는 로베르트 빈과 프리드리히 빌헬름 무르나우와 같은 독일 표현주의자들에게 특히 영향을 미쳤습니다. 프리츠 랭 감독의 메트로폴리스(1927)는 최초의 주요 공상과학 영화로 일컬어집니다. 1945년 이후, 전쟁 직후의 많은 영화들은 Trümmer film (고무 필름)으로 특징지어질 수 있습니다. 동독 영화는 국영 영화 스튜디오 DEFA에 의해 지배되었고, 서독의 지배적인 장르는 Heimat film ("고국 영화")[287]였습니다. 1970년대와 1980년대에 볼커 슐롱도르프, 베르너 헤르조크, 윔 웬더스, 레이너 베르너 파스빈더와 같은 새로운 독일 영화 감독들은 서독 영화를 비평가들의 찬사를 받았습니다.

아카데미 외국어영화상은 1979년 독일의 영화 "틴 드럼" ("Die Blechtrommel"), 2002년 아프리카의 아무데도 (아프리카의 니르겐두), 그리고 2007년 다른 사람들의 삶 ("Das Leben der Anderen")에게 돌아갔습니다. 다양한 독일인들이 다른 영화에서의 연기로 오스카 상을 수상했습니다. 매년 열리는 유럽 영화상 시상식은 격년으로 유럽 영화 아카데미의 본거지인 베를린에서 열립니다. "베를린"으로 알려진 베를린 국제 영화제는 "황금곰"을 수여하며 1951년부터 매년 열리는 세계 유수의 영화제 중 하나입니다. 롤라스는 매년 베를린에서 독일 영화상을 수상합니다.[288]

요리.

독일 요리는 지역에 따라 다르며 종종 이웃 지역은 바이에른 및 스와비아, 스위스 및 오스트리아의 남부 지역을 포함하여 몇 가지 요리 유사점을 공유합니다. 피자, 스시, 중국 음식, 그리스 음식, 인도 요리, 기부 케밥과 같은 국제적인 품종이 인기가 있습니다.

빵은 독일 요리의 중요한 부분을 차지하며 독일 제과점은 약 600가지의 주요 빵과 1,200가지의 페이스트리와 롤(Brotchen)을 생산합니다.[289] 독일 치즈는 유럽에서 생산되는 전체 치즈의 약 22%를 차지합니다.[290] 2012년 독일에서 생산된 모든 육류의 99% 이상이 돼지고기, 닭고기 또는 쇠고기였습니다. 독일인들은 브라트부르스트와 바이스부르스트를 포함한 거의 1,500가지 종류의 유비쿼터스 소시지를 생산합니다.[291]

국민 주류는 맥주입니다.[292] 2013년 독일의 1인당 맥주 소비량은 110리터(24임팔 갤, 29미 갤)로 세계 최고 수준을 유지하고 있습니다.[293] 독일 맥주 순도 규정은 16세기로 거슬러 올라갑니다.[294] 와인은 독일 와인 지역과 가까운 곳에서 인기를 얻었습니다.[295] 2019년 독일은 세계에서 9번째로 큰 와인 생산국이었습니다.[296]

2018 미슐랭 가이드는 독일의 11개 레스토랑에 별 3개를 수여하여 누적 총 300개의 별을 수여했습니다.[297]

스포츠

축구는 독일에서 가장 인기 있는 스포츠입니다. 독일축구협회(Deutscher Fu ß ball-Bund)는 700만 명 이상의 공식 회원을 보유한 단일 스포츠 단체 중 세계 최대 규모이며, 독일 최고 리그인 분데스리가는 전 세계 프로 스포츠 리그 중 두 번째로 높은 평균 관중을 끌어 모았습니다. 독일 남자 축구 국가대표팀은 1954년, 1974년, 1990년, 2014년 FIFA 월드컵,[300] 1972년, 1980년, 1996년 UEFA 유럽선수권,[301] 2017년 FIFA 컨페더레이션스컵에서 우승했습니다.[302]

독일은 세계적으로 선도적인 모터스포츠 국가 중 하나입니다. BMW와 메르세데스와 같은 건설업체는 모터 스포츠 분야에서 유명한 제조업체입니다. 포르쉐는 르망 24시간 경주에서 19번, 아우디는 13번(2017년[update] 기준) 우승했습니다.[303] 운전자 마이클 슈마허(Michael Schumacher)는 7번의 포뮬러 원 세계 운전자 선수권 대회에서 우승하며 그의 경력 동안 많은 자동차 스포츠 기록을 세웠습니다.[304] 세바스찬 베텔은 또한 역대 가장 성공적인 포뮬러 원 드라이버 중 한 명입니다.[305]

독일 선수들은 역사적으로 올림픽에서 성공적인 경쟁자였으며, 독일 통일 이전 동서독 메달을 합하면 역대 올림픽 메달 수에서 3위를 차지했습니다.[306] 1936년 베를린은 가르미슈파르텐키르헨에서 하계 올림픽과 동계 올림픽을 개최했습니다. 뮌헨은 1972년 하계 올림픽을 개최했습니다.[307][308]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 1952년부터 1990년까지, "Das Reid der Deutschen" 전체가 국가였지만, 공식적인 행사에서 3절만 불렀습니다. 1991년부터 3절만 국가였습니다.[1]

- ^ 베를린은 유일한 헌법상의 수도이자 사법부의 소재지이지만, 독일 연방 공화국의 옛 임시 수도인 본은 "연방 도시"(Bundesstadt)라는 특별한 타이틀을 가지고 있으며, 6개 부처의 주요 소재지입니다.[2]

- ^ 덴마크어, 저독일어, 소르비아어, 로마어, 프리시안어는 유럽 지역 언어 또는 소수 언어 헌장에 의해 인정됩니다.[3]

- ^ 연방 참사원은 때때로 독일 입법부의 상부 회의소라고 불립니다. 독일 헌법은 연방의회와 연방의회를 두 개의 별개의 입법기관으로 규정하고 있기 때문에 이는 기술적으로 잘못된 것입니다. 따라서 독일 연방의회는 양원제 의회가 아닌 단원제 입법기관 2개로 구성되어 있습니다.

- ^ 독일어: 도이칠란트, 확연한[ˈd ɔʏt ʃ랜트]ⓘ

- ^ 독일어: 독일 연방 공화국, 발음 [ˈ b ʊ nd ə ʁ epu ˌ bli ː b ˈ d ɔʏ t ʃ 란트]

- ^ 튀르키예 제외

- ^ 튀르키예 제외

참고문헌

- ^ "Repräsentation und Integration" (in German). Bundespräsidialamt. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "The German Federal Government". deutschland.de. 23 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020.

- ^ Gesley, Jenny (26 September 2018). "The Protection of Minority and Regional Languages in Germany". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Germany". World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Flächennutzung".

- ^ "Surface water and surface water change". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Population by nationality and sex (quarterly figures) [Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht (Quartalszahlen)]". www.destatis.de. Destatis – Statistisches Bundesamt. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Germany)". International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income". Eurostat. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2022.

- ^ Mangold, Max, ed. (2005). Duden, Aussprachewörterbuch (in German) (6th ed.). Dudenverlag. pp. 271, 53f. ISBN 978-3-411-04066-7.

- ^ Schulze, Hagen (1998). Germany: A New History. Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-674-80688-7.

- ^ Lloyd, Albert L.; Lühr, Rosemarie; Springer, Otto (1998). Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Althochdeutschen, Band II (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 699–704. ISBN 978-3-525-20768-0. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. (diutisc의 경우) Lloyd, Albert L.; Lühr, Rosemarie; Springer, Otto (1998). Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Althochdeutschen, Band II (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 685–686. ISBN 978-3-525-20768-0. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. (diot의 경우)

- ^ McRae, Mike (6 November 2019). "We Just Found an 11-Million-Year-Old Ancestor That Hints How Humans Began to Walk". ScienceAlert.

- ^ Wagner, G. A; Krbetschek, M; Degering, D; Bahain, J.-J; Shao, Q; Falgueres, C; Voinchet, P; Dolo, J.-M; Garcia, T; Rightmire, G. P (27 August 2010). "Radiometric dating of the type-site for Homo heidelbergensis at Mauer, Germany". PNAS. 107 (46): 19726–19730. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10719726W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012722107. PMC 2993404. PMID 21041630.

- ^ Hendry, Lisa (5 May 2018). "Who were the Neanderthals?". Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Earliest music instruments found". BBC News. 25 May 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Ice Age Lion Man is world's earliest figurative sculpture". The Art Newspaper. 31 January 2013. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015.

- ^ Conard, Nicholas (2009). "A female figurine from the basal Aurignacian of Hohle Fels Cave in southwestern Germany". Nature. 459 (7244): 248–252. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..248C. doi:10.1038/nature07995. PMID 19444215. S2CID 205216692. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "Nebra Sky Disc". UNESCO. 2013. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014.

- ^ Heather, Peter. "Germany: Ancient History". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Germanic Tribes (Teutons)". History Files. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ Claster, Jill N. (1982). Medieval Experience: 300–1400. New York University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8147-1381-5.

- ^ Wells, Peter (2004). The Battle That Stopped Rome: Emperor Augustus, Arminius, and the Slaughter of the Legions in the Teutoburg Forest. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-393-35203-0.

- ^ 머독 2004, 페이지 57.

- ^ a b 풀브룩 1991, 페이지 9-13.

- ^ Modi, J. J. (1916). "The Ancient Germans: Their History, Constitution, Religion, Manners and Customs". The Journal of the Anthropological Society of Bombay. 10 (7): 647.

Raetia (modern Bavaria and the adjoining country)

- ^ Rüger, C. (2004) [1996]. "Germany". In Bowman, Alan K.; Champlin, Edward; Lintott, Andrew (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: X, The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C. – A.D. 69. Vol. 10 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 527–28. ISBN 978-0-521-26430-3. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016.

- ^ Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil (2005). The crisis of empire, A.D. 193–337. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 12. Cambridge University Press. p. 442. ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2.

- ^ a b 풀브룩 1991, 페이지 11.

- ^ Falk, Avner (2018). Franks and Saracens. Routledge. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-429-89969-0.

- ^ McBrien, Richard (2000). Lives of the Popes: The Pontiffs from St. Peter to Benedict XVI. HarperCollins. p. 138.

- ^ 풀브룩 1991, 페이지 19-20.

- ^ 풀브룩 1991, 13-24쪽.

- ^ Nelson, Lynn Harry. The Great Famine (1315–1317) and the Black Death (1346–1351). University of Kansas. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ 풀브룩 1991, 페이지 27.

- ^ Eisenstein, Elizabeth (1980). The printing press as an agent of change. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–43. ISBN 978-0-521-29955-8.

- ^ Cantoni, Davide (2011). "Adopting a New Religion: The Case of Protestantism in 16th Century Germany" (PDF). Barcelona GSE Working Paper Series. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ a b Philpott, Daniel (January 2000). "The Religious Roots of Modern International Relations". World Politics. 52 (2): 206–245. doi:10.1017/S0043887100002604. S2CID 40773221.

- ^ Macfarlane, Alan (1997). The Savage Wars of Peace: England, Japan and the Malthusian Trap. Blackwell. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-631-18117-0.

- ^ 종교개혁이 신성로마제국에 미친 영향에 대한 일반적인 논의는 참조

- ^ Jeroen Duindam; Jill Diana Harries; Caroline Humfress; Hurvitz Nimrod, eds. (2013). Law and Empire: Ideas, Practices, Actors. Brill. p. 113. ISBN 978-90-04-24951-6.

- ^ Hamish Scott; Brendan Simms, eds. (2007). Cultures of Power in Europe during the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-139-46377-5.

- ^ "Maria Theresa, Holy Roman Empress and Queen of Hungary and Bohemia". British Museum. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (1998). A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge. p. 156.

- ^ Batt, Judy; Wolczuk, Kataryna (2002). Region, State and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 153.

- ^ 풀브룩 1991, 페이지 97.

- ^ Nicholas Atkin; Michael Biddiss; Frank Tallett, eds. (2011). The Wiley-Blackwell Dictionary of Modern European History Since 1789. Wiley. pp. 307–308. ISBN 978-1-4443-9072-8.

- ^ Sondhaus, Lawrence (2007). "Austria, Prussia, and the German Confederation: The Defense of Central Europe, 1815–1854". In Talbot C. Imlay; Monica Duffy Toft (eds.). The Fog of Peace and War Planning: Military and Strategic Planning under Uncertainty. Routledge. pp. 50–74. ISBN 978-1-134-21088-6.

- ^ Henderson, W. O. (January 1934). "The Zollverein". History. 19 (73): 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1934.tb01791.x.

- ^ Hewitson, Mark (2010). "'The Old Forms are Breaking Up, ... Our New Germany is Rebuilding Itself': Constitutionalism, Nationalism and the Creation of a German Polity during the Revolutions of 1848–49". The English Historical Review. 125 (516): 1173–1214. doi:10.1093/ehr/ceq276. JSTOR 40963126.

- ^ "Issues Relevant to U.S. Foreign Diplomacy: Unification of German States". US Department of State Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898)". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Mommsen, Wolfgang J. (1990). "Kaiser Wilhelm II and German Politics". Journal of Contemporary History. 25 (2/3): 289–316. doi:10.1177/002200949002500207. JSTOR 260734. S2CID 154177053.

- ^ 풀브룩 1991, 135쪽, 149쪽.

- ^ Black, John, ed. (2005). 100 maps. Sterling Publishing. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-4027-2885-3.

- ^ Farley, Robert (17 October 2014). "How Imperial Germany Lost Asia". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020.

- ^ Olusoga, David; Erichsen, Casper (2010). The Kaiser's Holocaust: Germany's Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-23141-6.

- ^ a b Michael Bazyler (2016). Holocaust, Genocide, and the Law: A Quest for Justice in a Post-Holocaust World. Oxford University Press. pp. 169–70.

- ^ Crossland, David (22 January 2008). "Last German World War I veteran believed to have died". Spiegel Online. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012.

- ^ Boemeke, Manfred F.; Feldman, Gerald D.; Glaser, Elisabeth (1998). Versailles: A Reassessment after 75 Years. Publications of the German Historical Institute. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–20, 203–220, 469–505. ISBN 978-0-521-62132-8.

- ^ "GERMAN TERRITORIAL LOSSES, TREATY OF VERSAILLES, 1919". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ 풀브룩 1991, 페이지 156-160.

- ^ Nicholls, AJ (2016). "1919–1922: Years of Crisis and Uncertainty". Weimar and the Rise of Hitler. Macmillan. pp. 56–70. ISBN 978-1-349-21337-5.

- ^ Costigliola, Frank (1976). "The United States and the Reconstruction of Germany in the 1920s". The Business History Review. 50 (4): 477–502. doi:10.2307/3113137. JSTOR 3113137. S2CID 155602870.

- ^ Kolb, Eberhard (2005). The Weimar Republic. Translated by P. S. Falla; R. J. Park (2nd ed.). Psychology Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-415-34441-8.

- ^ "PROLOGUE: Roots of the Holocaust". The Holocaust Chronicle. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ 풀브룩 1991, 페이지 155-158, 172-177.

- ^ Evans, Richard (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-14-303469-8.

- ^ "Ein Konzentrationslager für politische Gefangene in der Nähe von Dachau". Münchner Neueste Nachrichten (in German). 21 March 1933. Archived from the original on 10 May 2000.

- ^ von Lüpke-Schwarz, Marc (23 March 2013). "The law that 'enabled' Hitler's dictatorship". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Industrie und Wirtschaft" (in German). Deutsches Historisches Museum. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Evans, Richard (2005). The Third Reich in Power. Penguin. pp. 322–326, 329. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3.

- ^ Bradsher, Greg (2010). "The Nuremberg Laws". Prologue. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ 풀브룩 1991, 188-189쪽.

- ^ "Descent into War". National Archives. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "The "Night of Broken Glass"". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ "German-Soviet Pact". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ a b 풀브룩 1991, 페이지 190-195.

- ^ Hiden, John; Lane, Thomas (200). The Baltic and the Outbreak of the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-521-53120-7.

- ^ "World War II: Key Dates". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ a b Kershaw, Ian (1997). Stalinism and Nazism: dictatorships in comparison. Cambridge University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-521-56521-9.

- ^ Overy, Richard (17 February 2011). "Nuremberg: Nazis on Trial". BBC. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011.

- ^ Niewyk, Donald L.; Nicosia, Francis R. (2000). The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. Columbia University Press. pp. 45–52. ISBN 978-0-231-11200-0.

- ^ Polska 1939–1945: Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami. Institute of National Remembrance. 2009. p. 9.

- ^ Maksudov, S (1994). "Soviet Deaths in the Great Patriotic War: A Note". Europe-Asia Studies. 46 (4): 671–680. doi:10.1080/09668139408412190. PMID 12288331.

- ^ Overmans, Rüdiger (2000). Deutsche militärische Verluste im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Oldenbourg. ISBN 978-3-486-56531-7.

- ^ Kershaw, Ian (2011). The End; Germany 1944–45. Allen Lane. p. 279.

- ^ Demshuk, Andrew (2012). The Lost German East. Cambridge University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-107-02073-3. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016.

- ^ Hughes, R. Gerald (2005). "Unfinished Business from Potsdam: Britain, West Germany, and the Oder-Neisse Line, 1945–1962". The International History Review. 27 (2): 259–294. doi:10.1080/07075332.2005.9641060. JSTOR 40109536. S2CID 162858499.

- ^ "Trabant and Beetle: the Two Germanies, 1949–89". History Workshop Journal. 68: 1–2. 2009. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbp009.

- ^ Wise, Michael Z. (1998). Capital dilemma: Germany's search for a new architecture of democracy. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-56898-134-5.

- ^ Carlin, Wendy (1996). "West German growth and institutions (1945–90)". In Crafts, Nicholas; Toniolo, Gianni (eds.). Economic Growth in Europe Since 1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-521-49964-4.

- ^ Bührer, Werner (24 December 2002). "Deutschland in den 50er Jahren: Wirtschaft in beiden deutschen Staaten" [Economy in both German states]. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017.

- ^ Fulbrook, Mary (2014). A History of Germany 1918–2014: The Divided Nation. Wiley. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-118-77613-1.

- ^ "Rearmament and the European Defense Community". Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ Major, Patrick; Osmond, Jonathan (2002). The Workers' and Peasants' State: Communism and Society in East Germany Under Ulbricht 1945–71. Manchester University Press. pp. 22, 41. ISBN 978-0-7190-6289-6.

- ^ Protzman, Ferdinand (22 August 1989). "Westward Tide of East Germans Is a Popular No-Confidence Vote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012.

- ^ "The Berlin Wall". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Williams, Geoffrey (1986). The European Defence Initiative: Europe's Bid for Equality. Springer. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-1-349-07825-7.

- ^ Deshmukh, Marion. "Iconoclash! Political Imagery from the Berlin Wall to German Unification" (PDF). Wende Museum. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "What the Berlin Wall still stands for". CNN Interactive. 8 November 1999. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008.

- ^ "Vertrag zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik über die Herstellung der Einheit Deutschlands (Einigungsvertrag) Art 11 Verträge der Bundesrepublik Deutschland" (in German). Bundesministerium für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Gesetz zur Umsetzung des Beschlusses des Deutschen Bundestages vom 20. Juni 1991 zur Vollendung der Einheit Deutschlands" [Law on the Implementation of the Beschlusses des Deutschen Bundestages vom 20. Juni 1991 zur Vollendung der Einheit Deutschlands] (PDF) (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz. 26 April 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2016.

- ^ "Brennpunkt: Hauptstadt-Umzug". Focus (in German). 12 April 1999. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011.

- ^ Kulish, Nicholas (19 June 2009). "In East Germany, a Decline as Stark as a Wall". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 April 2011.

- ^ Lemke, Christiane (2010). "Germany's EU Policy: The Domestic Discourse". German Studies Review. 33 (3): 503–516. JSTOR 20787989.

- ^ "Eurozone Fast Facts". CNN. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020.

- ^ Dempsey, Judy (31 October 2006). "Germany is planning a Bosnia withdrawal". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012.

- ^ Knight, Ben (13 February 2019). "Germany to extend Afghanistan military mission". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020.

- ^ "Germany agrees on 50-billion-euro stimulus plan". France 24. 6 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011.

- ^ "Government declaration by Angela Merkel" (in German). ARD Tagesschau. 29 January 2014. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015.

- ^ "Migrant crisis: Migration to Europe explained in seven charts". BBC. 28 January 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016.

- ^ "17: Gebiet und geografische Angaben" (PDF). Statistische Jahrbuch Schleswig-Holstein 2019/2020 (in German). Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein: 307. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Germany: Climate". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Average monthly temperature in Germany from February 2019 to February 2020". Statista. February 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Average monthly precipitation in Germany from February 2019 to February 2020". Statista. February 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Average monthly sunshine hours in Germany from February 2019 to February 2020". Statista. February 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Appunn, Kerstine (30 October 2018). "Climate impact of farming, land use (change) and forestry in Germany". Clean Energy Wire. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020.

- ^ "Spruce, pine, beech, oak – the most common tree species". Third National Forest Inventory. Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Bekker, Henk (2005). Adventure Guide Germany. Hunter. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-58843-503-3.

- ^ Marcel Cleene; Marie Claire Lejeune (2002). Compendium of Symbolic and Ritual Plants in Europe: Herbs. Man & Culture. pp. 194–196. ISBN 978-90-77135-04-4. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "National Parks". Federal Agency for Nature Conservation. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Biosphere reserves". Federal Agency for Nature Conservation. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Nature parks". Federal Agency for Nature Conservation. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Zoo Facts". Zoos and Aquariums of America. Archived from the original on 7 October 2003. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ "Der Zoologische Garten Berlin" (in German). Zoo Berlin. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany" (PDF). Deutscher Bundestag. October 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Seiffert, Jeanette (19 September 2013). "Election 2013: The German parliament". DW. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Germany's political parties CDU, CSU, SPD, AfD, FDP, Left party, Greens – what you need to know". DW. 7 June 2019. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020.

- ^ Stone, Jon (24 September 2017). "German elections: Far-right wins MPs for first time in half a century". The Independent. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Germany". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Example for state constitution: "Constitution of the Land of North Rhine-Westphalia"". Landtag (state assembly) of North Rhine-Westphalia. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ "Verwaltungsgliederung in Deutschland am 30 June 2017 – Gebietsstand: 30 June 2017 (2. Quartal)" (XLS) (in German). Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland. July 2017. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Fläche und Bevölkerung". Statistikportal.de (in German). Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ "Fläche und Bevölkerung nach Ländern" (in German). Statistisches Bundesamt und statistische Landesämter. December 2019. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Gross domestic product – at current prices – 1991 to 2015". Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. 5 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016.

- ^ Merryman, John; Pérez-Perdomo, Rogelio (2007). The Civil Law Tradition: An Introduction to the Legal Systems of Europe and Latin America. Stanford University Press. pp. 31–32, 62. ISBN 978-0-8047-5569-6.

- ^ "Federal Constitutional Court". Bundesverfassungsgericht. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Wöhrmann, Gotthard (22 November 2013). "The Federal Constitutional Court: an Introduction". German Law Archive. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "§ 2 Strafvollzugsgesetz" (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Jehle, Jörg-Martin; German Federal Ministry of Justice (2009). Criminal Justice in Germany. Forum-Verlag. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-936999-51-8. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015.

- ^ Casper, Gerhard; Zeisel, Hans [in German] (January 1972). "Lay Judges in the German Criminal Courts". Journal of Legal Studies. 1 (1): 135–191. doi:10.1086/467481. JSTOR 724014. S2CID 144941508.

- ^ "Intentional Homicide Victims". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Germany's crime rate fell to lowest level in decades in 2018". DW. 2 April 2019. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019.

- ^ "STONEWALL GLOBAL WORKPLACE BRIEFINGS 2018 – GERMANY" (PDF). Stonewall. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "The German Missions Abroad". German Federal Foreign Office. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "The Embassies". German Federal Foreign Office. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Declaration by the Franco-German Defence and Security Council". French Embassy UK. 13 May 2004. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014.

- ^ Freed, John (4 April 2008). "The leader of Europe? Answers an ocean apart". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011.

- ^ "Shaping Globalization – Expanding Partner-ships – Sharing Responsibility: A strategy paper by the German Government" (PDF). Die Bundesregierung. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Relations With Germany". US Department of State. 4 November 2019. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020.

- ^ "U.S.-German Economic Relations Factsheet" (PDF). U.S. Embassy in Berlin. May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Volume 10. One Germany in Europe, 1989–2009 Germany and Russia" (PDF). German Institute for International and Security Affairs. 13 March 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Noël, Pierre (May 2009). "A Market Between Us: Reducing the Political Cost of Europe's Dependence on Russian Gas" (PDF). EPRG Working Paper. University of Cambridge Electricity Policy Research Group: 2; 38. EPRG0916. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ "Aims of German development policy". Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. 10 April 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011.

- ^ Green, Andrew (8 August 2019). "Germany, foreign aid, and the elusive 0.7%". Devex. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019.

- ^ Tian, Nan; Fleurant, Aude; Kuimova, Alexandra; Wezeman, Pieter D.; Wezeman, Siemon T. (April 2019). "Trends in World Military Expenditure". SIPRI Fact Sheet. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "White House considers withdrawing 9,500 US soldiers from Germany". International Insider. 8 June 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Germany to increase defence spending". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ "Germany commits €100 billion to defense spending". Deutsche Welle. 27 February 2022.

- ^ Schuetze, Christopher F. (27 February 2022). "Russia's invasion prompts Germany to beef up military funding". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Aktuelle Personalzahlen der Bundeswehr" [Current personnel numbers of the Federal Defence] (in German). Bundeswehr. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Ausblick: Die Bundeswehr der Zukunft" (in German). Bundeswehr. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (22 November 2010). "Germany to abolish compulsory military service". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (16 March 2011). "Marching orders for conscription in Germany, but what will take its place?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013.

- ^ "Frauen in der Bundeswehr" (in German). Bundeswehr. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Wezeman, Pieter D.; Fleurant, Aude; Kuimova, Alexandra; Tian, Nan; Wezeman, Siemon T. (March 2019). "Trends in International Arms Transfers". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Artikel 65a,87,115b" (PDF) (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Einsatzzahlen – die Stärke der deutschen Kontingente" (in German). Bundeswehr. 18 August 2017. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Germany extends unified armed forces mission in Mali". International Insider. 1 June 2020. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ a b Lavery, Scott; Schmid, Davide (2018). Frankfurt as a financial centre after Brexit (PDF) (Report). SPERI Global Political Economy Brief. University of Sheffield. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index 2019". Transparency International. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Schwab, Klaus. "The Global Competitiveness Report 2018" (PDF). p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Deutschland ist wieder Nummer drei der größten Volkswirtschaften". Der Spiegel (in German). 15 February 2024.

- ^ "GDP, PPP (current international $)". World Bank. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "GDP per capita in PPS". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Unemployment statistics". Eurostat. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "The European single market". European Commission. 5 July 2016. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Germany: Spend More At Home". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ Andrews, Edmund L. (1 January 2002). "Germans Say Goodbye to the Mark, a Symbol of Strength and Unity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011.

- ^ "Monetary policy". Bundesbank. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Randall, Chris (10 December 2019). "CAM study reveals: German carmakers are most innovative". Electrive. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Hyundai, Now the No. 3 Carmaker, Takes Aim at Toyota and Volkswagen". Bloomberg. 20 December 2022.

- ^ "Motor vehicle manufacturers: largest companies by sales 2022". Statista. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Harley, Michael (22 May 2023). "China Overtakes Japan As The World's Biggest Exporter Of Passenger Cars". Forbes.

- ^ "Foreign trade". Statistiches Bundesamt. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "Global 500". Fortune. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "DAX". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Brand value of the leading 10 most valuable German brands in 2019". Statista. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Frost, Simon (28 August 2015). "Berlin outranks London in start-up investment". euractiv.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Dakers, Marion (11 May 2017). "Secrets of growth: the power of Germany's Mittelstand". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019.

- ^ Bayley, Caroline (17 August 2017). "Germany's 'hidden champions' of the Mittelstand". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019.

- ^ "Federal Report on Research and Innovation 2014" (PDF). Federal Ministry of Education and Research. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Gross domestic spending on R&D". OECD. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ McCarthy, Niall (13 January 2020). "The countries leading the world in scientific research". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020.

- ^ Boytchev, Hristio (27 March 2019). "An introduction to the complexities of the German research scene". Nature. 567 (7749): S34–S35. Bibcode:2019Natur.567S..34B. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-00910-7. PMID 30918381.

- ^ "Germany invests 3.3 billion euro in European space exploration and becomes ESA's largest contributor". German Aerospace Centre. 28 November 2019. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Dutta, Soumitra; Lanvin, Bruno; Wunsch-Vincent, Sacha; León, Lorena Rivera; World Intellectual Property Organization (6 January 2024). Global Innovation Index 2023. WIPO. doi:10.34667/tind.46596. ISBN 978-92-805-3432-0. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ "Assessment of strategic plans and policy measures on Investment and Maintenance in Transport Infrastructure" (PDF). International Transport Forum. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ "Transport infrastructure at regional level". Eurostat. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Jeremic, Sam (16 September 2013). "Fun, fun, fun on the autobahn". The West Australian. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013.

- ^ "ICE High-Speed Trains". Eurail. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "ADV Monthly Traffic Report 12/2022" (PDF). Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher Verkehrsflughäfen e.V. 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Top World Container Ports". Port of Hamburg. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Germany". US Energy Information Administration. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Paddison, Laura; Schmidt, Nadine; Kappeler, Inke (15 April 2023). "'A new era': Germany quits nuclear power, closing its final three plants". CNN.

- ^ Wettengel, Julian (2 January 2019). "Renewables supplied 40 percent of net public power in Germany in 2018". Clean Energy Wire. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Germany". International Energy Agency. 16 December 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ "Committed to Biodiversity" (PDF). Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Eddy, Melissa (15 November 2019). "Germany Passes Climate-Protection Law to Ensure 2030 Goals". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Legal Country Mapping: Germany" (PDF). WaterLex. 6 July 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Germany is the world's leading nation for recycling". Climate Action. 11 December 2017. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Greenhouse gas emissions per capita in the European Union (EU-28) in 2018, by country". Statista. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy Data Explorer". International Energy Agency. 10 November 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Federal Ministry for the Environment (29 March 2012). Langfristszenarien und Strategien für den Ausbau der erneuerbaren Energien in Deutschland bei Berücksichtigung der Entwicklung in Europa und global [Long-term Scenarios and Strategies for the Development of Renewable Energy in Germany Considering Development in Europe and Globally] (PDF). Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMU). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2015.

- ^ "China and Germany – Working for an Energy Efficient Future". Energiepartnershcaft. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Germany's Energy Efficiency Strategy 2050 (PDF). Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. March 2020.

- ^ "Tourism as a driver of economic growth in Germany" (PDF). Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. November 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "International Tourism – 2023 starts on a strong note with the Middle East recovering 2019 levels in the first quarter" (PDF). World Tourism Barometer. 21 (2). May 2023.

- ^ "Germany's most visited landmarks". DW. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Attendance at the Europa Park Rust theme park from 2009 to 2018 (in millions)". Statista. 19 June 2020. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Zensus 2011: Bevölkerung am 9. Mai 2011" (PDF). Destatis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ "Bevölkerung nach Geschlecht und Staatsangehörigkeit". Destatis. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ a b c "National Minorities in Germany" (PDF). Federal Ministry of the Interior (Germany). May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Webb, Alex (20 May 2014). "Germany Top Migration Land After U.S. in New OECD Ranking". Bloomberg.

- ^ "International Migration Report 2015 – Highlights" (PDF). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Current population". Federal Statistical Office. 20 June 2023.

- ^ "Foreign population". OECD. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Pressemitteilung Nr. 158 vom 20. April 2023". Statistisches Bundesamt. 20 April 2023.

- ^ 인구통계: Wayback Machine에서 2018년 5월 3일 보관된 세계 도시 지역. 2016년 7월 31일 회수.

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). "Germans". One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 287–294. ISBN 0-313-30984-1.

- ^ "Pressekonferenz "Zensus 2011 – Fakten zur Bevölkerung in Deutschland" am 31. Mai 2013 in Berlin" (PDF). Federal Statistical Office of Germany. pp. 9–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017.

- ^ "Official membership statistics of the Roman Catholic Church in Germany 2016" (PDF). Sekretariat der Deutschen Bischofskonferenz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "Official membership statistics of the Evangelical Church in Germany 2016" (PDF). Evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Bevölkerung im regionalen Vergleich nach Religion (ausführlich) -in %-". Zensus 2011 (in German). Federal Statistical Office of Germany. 9 May 2011. p. Zensus 2011 – Page 6. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013.

- ^ "Zensus 2011 – Fakten zur Bevölkerung in Deutschland" am 31. Mai 2013 in Berlin" [2011 Census – Facts about the population of Germany on 31 May 2013 in Berlin] (PDF) (Press release) (in German). Federal Statistical Office of Germany. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ "Religionszugehörigkeiten 2018". Forschungsgruppe Weltanschauungen in Deutschland (in German). 25 July 2019. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019.

- ^ Thompson, Peter (22 September 2012). "Eastern Germany: the most godless place on Earth". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013.

- ^ "Germany". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Special Eurobarometer 243: Europeans and their Languages (Survey)" (PDF). Europa. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

European Commission (2006). "Special Eurobarometer 243: Europeans and their Languages (Executive Summary)" (PDF). Europa. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2011. - ^ "Frequently asked questions on languages in Europe". European Commission. 26 September 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "The German Language". FAZIT Communication GmbH. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Country profile: Germany" (PDF). Library of Congress. April 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Trines, Stefan (8 November 2016). "Education in Germany". World Education News and Reviews. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "A German model goes global". Financial Times. 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Pitman, Tim; Hannah Forsyth (18 March 2014). "Should we follow the German way of free higher education?". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014.

- ^ Bridgestock, Laura (13 November 2014). "The Growing Popularity of International Study in Germany". QS Topuniversities. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016.

- ^ Bertram, Björn. "Rankings: Universität Heidelberg in International Comparison". Universität Heidelberg. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Humboldt University of Berlin". Times Higher Education. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ Kern, Heinrich (2010). "Humboldt's educational ideal and modern academic education" (PDF). 26th Annual Meeting of the Danube Rectors Conference. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Hospital of the Holy Spirit Lübeck". Lübeck + Travemünde. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Health Care Systems in Transition: Germany (PDF). European Observatory on Health Care Systems. 2000. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2011.

- ^ "Germany statistics summary (2002–present)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Health expenditure, total (% of GDP)". World Bank. 1 January 2016. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017.

- ^ "Germany Country Health Profile 2019" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Overweight and obesity – BMI statistics". Eurostat. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "Germany country profile". BBC News. 25 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015.

- ^ "BBC poll: Germany most popular country in the world". BBC News. 23 May 2013. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013.

- ^ "World Service Global Poll: Negative views of Russia on the rise". BBC. 4 June 2014. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014.

- ^ MacGregor, Neil (28 September 2014). "The country with one people and 1,200 sausages". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014.

- ^ "Christmas Traditions in Austria, Germany, Switzerland". German Ways. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "World Heritage Sites in Germany". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ "Artikel 2 EV – Vertrag zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik über die Herstellung der Einheit Deutschlands (Einigungsvertrag – EV k.a.Abk.)" (in German). buzer.de. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ John Kmetz; Ludwig Finscher; Giselher Schubert; Wilhelm Schepping; Philip V. Bohlman (20 January 2001). "Germany, Federal Republic of". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40055.

- ^ "The Recorded Music Industry in Japan" (PDF). Recording Industry Association of Japan. 2013. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Kraftwerk maintain their legacy as electro-pioneers". Deutsche Welle. 8 April 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2013.

- ^ Nye, Sean. "Minimal Understandings: The Berlin Decade, The Minimal Continuum, and Debates on the Legacy of German Techno". Journal of Popular Music Studies. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ a b c David Jenkinson; Günther Binding; Doris Kutschbach; Ulrich Knapp; Howard Caygill; Achim Preiss; Helmut Börsch-Supan; Thomas Kliemann; April Eisman; Klaus Niehr; Jeffrey Chipps Smith; Ulrich Leben; Heidrun Zinnkann; Angelika Steinmetz; Walter Spiegl; G. Reinheckel; Hannelore Müller; Gerhard Bott; Peter Hornsby; Anna Beatriz Chadour; Erika Speel; A. Kenneth Snowman; Brigitte Dinger; Annamaria Giusti; Harald Olbrich; Christian Herchenröder; David Alan Robertson; Dominic R. Stone; Eduard Isphording; Heinrich Dilly (10 December 2018). "Germany, Federal Republic of". Grove Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T031531. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4.

- ^ "Bauhaus: The Single Most Influential School of Design". Gizmodo. 13 June 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014.

- ^ "Berlin as a fashion capital: the improbable rise". Fashion United UK. 12 January 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015.

- ^ Stiewe, Heinrich (2007). Fachwerkhäuser in Deutschland: Konstruktion, Gestalt und Nutzung vom Mittelalter bis heute. Primus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89678-589-3.

- ^ A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Oxford University Press. 2006. p. 880. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- ^ Jodidio, Philip (2008). 100 Contemporary Architects (1 ed.). Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-0091-3.

- ^ Dégh, Linda (1979). "Grimm's Household Tales and its Place in the Household". Western Folklore. 38 (2): 99–101. doi:10.2307/1498562. JSTOR 1498562.

- ^ "History of the Deutsches Wörterbuch". DWB 150th Anniversary Exhibition and Symposium (in German). Humboldt-Universität. 2004. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ Espmark, Kjell (2001). "The Nobel Prize in Literature". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Annual Report" (PDF). International Publishers Association. October 2014. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ Weidhaas, Peter; Gossage, Carolyn; Wright, Wendy A. (2007). A History of the Frankfurt Book Fair. Dundurn Press. pp. 11. ISBN 978-1-55002-744-0.

- ^ Chase, Jefferson (13 March 2015). "Leipzig Book Fair: Cultural sideshow with a serious side". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015.

- ^ Searle, John (1987). "Introduction". The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ "Distribution of TV in Germany (German)". Astra Sat. 19 February 2013. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Germany". Media Landscapes. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Batchelor, James (16 July 2019). "German consumers spent €4.4bn on video games in 2018". GamesIndustry.biz. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ MacDonald, Keza (23 August 2022). "Pushing Buttons: What to expect from the world's biggest games convention". The Guardian.

- ^ Brockmann, Stephen (2010). A Critical History of German Film. Camden House. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-57113-468-4.

- ^ Reimer, Robert; Reimer, Carol (2019). Historical Dictionary of German Cinema. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-5381-1940-2.

- ^ Philpott, Don (2016). The World of Wine and Food: A Guide to Varieties, Tastes, History, and Pairings. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-4422-6804-3.

- ^ "Where does our cheese come from?". Eurostat. 19 January 2019. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Guide to German Hams and Sausages". German Foods North America. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "In-depth look at Germany's national drink – beer". The Times of India. 16 September 2012. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Payne, Samantha (20 November 2014). "Top 10 Heaviest Beer-drinking Countries: Czech Republic and Germany Sink Most Pints". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2015.

- ^ "492 Years of Good Beer: Germans Toast the Anniversary of Their Beer Purity Law". Spiegel Online. 23 April 2008. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008.

- ^ "German Wine Statistics". Wines of Germany, Deutsches Weininstitut. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.