선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor| 선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제 | |

|---|---|

| 약물 클래스 | |

세로토닌, SSRI의 작용 메커니즘에 관여하는 신경전달물질. | |

| 클래스 식별자 | |

| 동의어 | 세로토닌 특이적 재흡수 억제제, 세로토닌 작동성 항우울제[1] |

| 사용하다 | 주요 우울증 장애, 불안 장애 |

| ATC 코드 | N06AB |

| 생물학적 표적 | 세로토닌 트랜스포터 |

| 임상 데이터 | |

| Drugs.com | 약물 클래스 |

| 컨슈머 리포트 | 베스트 바이 드러그 |

| 외부 링크 | |

| 메쉬 | D017367 |

| Wikidata에서 | |

선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제(SSRI)는 주요 우울증, 불안 장애 및 기타 심리적 조건의 치료에 일반적으로 항우울제로 사용되는 약의 한 종류이다.

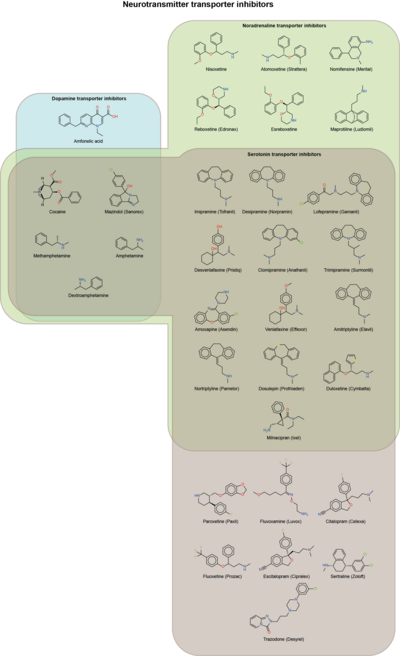

SSRI는 신경전달물질 세로토닌의 시냅스 전 [2]세포로의 재흡수(재흡수)를 제한함으로써 세포외 수준을 증가시킨다.순수 SSRI는 세로토닌 운반체에 강한 친화력을 가지며 노르에피네프린과 도파민 운반체에 대한 친화력은 약하다.

SSRI는 많은 [3]나라에서 가장 널리 처방되는 항우울제이다.경증 또는 중간 정도의 우울증 사례에서 SSRIs의 효능은 논쟁의 여지가 있으며, 특히 청소년 [5][6][7][8]인구에서 부작용에 의해 중요하거나 중요하지 않을 수 있다.

의료 용도

SSRIs의 주요 징후는 주요 우울증 장애이다; 그러나 그들은 종종 사회 불안 장애, 일반화된 불안 장애, 공황 장애, 강박 장애, 섭식 장애, 만성 통증, 그리고 어떤 경우에는 외상 후 스트레스 장애와 같은 불안 장애에 대해 처방된다.그들은 또한 다양한 [9]결과를 가지고 있지만 이인칭 장애를 치료하기 위해 자주 사용된다.

우울증.

항우울제는 영국 국립보건관리연구소(NICE)에 의해 심각한 우울증의 첫 번째 치료법이자 인지치료와 [10]같은 보수적인 조치 이후에도 지속되는 경도에서 중간 정도의 우울증의 치료법으로서 권장된다.그들은 만성적인 건강 문제와 가벼운 [10]우울증을 가진 사람들에게 일상적으로 사용하지 말 것을 권고한다.

우울증의 심각성과 기간에 따라 SSRI의 치료 효과에 대한 논란이 있어왔다.

- 2008년(Kirsch)과 2010년(Fournier)에 발표된 두 개의 메타분석 결과, 경도 및 중간 정도의 우울증에서는 SSRI의 효과가 위약에 비해 작거나 전혀 없는 반면, 매우 심각한 우울증에서는 SSRI의 효과는 "상대적으로 작음"과 "실질적"[6][11] 사이에 있는 것으로 나타났다.2008년 메타 분석은 4가지 새로운 항우울제(SSRIs 파라옥세틴과 플루옥세틴, 비 SSRI 항우울제 네파조돈, 세로토닌과 노르에피네프린 렙타케(SNRI) 베낙신)의 허가 이전에 식품의약국(FDA)에 제출된 35개의 임상시험을 결합했다.저자들은 심각성과 유효성 사이의 관계가 [11]약물 효과의 증가보다는 심각한 우울증 환자의 플라시보 효과 감소에 기인한다고 보았다.일부 연구자들은 이 연구가 [12][13]항우울제의 효과 크기를 과소평가한다는 것을 시사하는 이 연구의 통계적 근거에 의문을 제기했습니다.

- 플루옥세틴과 벤라팍신의 2012년 메타 분석 결과, 기초 우울증 심각도에 관계없이 위약과 관련하여 통계적으로나 임상적으로 유의한 치료 효과가 관찰되었다. 그러나 일부 저자는 제약 산업과의 [14]실질적인 관계를 공개했다.

- 2017년 체계적 검토는 "SSRI 대 위약(placebo)이 우울증 증상에 통계적으로 유의한 영향을 미치는 것으로 보이지만, 이러한 영향의 임상적 의미는 의심스러워 모든 시험이 편향될 위험이 높았다"고 밝혔다.또한 SSRI 대 위약은 심각하거나 심각하지 않은 부작용의 위험을 크게 증가시킨다.우리의 결과는 SSRIs 대 주요 우울증 질환에 대한 위약의 해로운 효과가 잠재적으로 작은 유익한 효과보다 더 큰 것으로 보인다는 것을 보여준다."[8]Fredrik Hieronymus et al.는 이 검토가 부정확하고 오해의 소지가 있다고 비판했지만, 그들은 또한 제약 업계와의 여러 관련성과 연설자료 [15]수령 사실을 폭로했다.

2018년에는 21개 항우울제의 효능과 허용가능성을 비교한 체계적 검토 및 네트워크 메타분석 결과 에스시탈로프람이 가장 [16]효과적인 것으로 나타났다.

아동의 경우,[17] 보이는 편익의 의미에 대한 증거의 질에 대한 우려가 있다.약물을 사용하는 경우 플루옥세틴이 첫 번째 [17]라인으로 나타납니다.

사회 불안 장애

일부 SSRI는 사회적 불안 장애에 효과적이지만, 증상에 대한 효과가 항상 강한 것은 아니며 때때로 심리 치료를 위해 사용이 거부되기도 한다.파록세틴은 사회 불안 장애에 대해 승인된 첫 번째 약물이며, 이 질환에 효과적인 것으로 간주되며, 세르트랄린과 플루복사민도 나중에 승인되었습니다. 에스시탈로프람과 시탈로프람은 허용 가능한 유효성으로 라벨에서 사용되는 반면 플루옥세틴은 이 [18]질환에 대해 효과적이라고 간주되지 않습니다.

외상 후 스트레스 장애

PTSD는 비교적 치료가 어렵고 일반적으로 치료 효과가 높지 않습니다. SSRI도 예외는 아닙니다.그것들은 이 장애에 매우 효과적이지 않고 오직 두 개의 SSRI, 즉 파록세틴과 세르트랄린만이 FDA의 승인을 받았다.Paroxetine은 Sertraline보다 PTSD에 대한 반응과 완화율이 약간 높지만, 두 가지 모두 많은 [citation needed]환자에게 완전히 효과가 있는 것은 아니다.플루옥세틴은 라벨에 붙어있지 않지만, 혼합된 결과를 가지고 있다.; SNRI인 벤라팍신은 라벨에 붙어있지 않지만 다소 효과적인 것으로 여겨진다.플루복사민, 에스시탈로프람, 시탈로프람은 이 질환에서 잘 검사되지 않는다.Paroxetine은 현재 PTSD에 가장 적합한 약으로 남아있지만 효과는 [19]제한적이다.

전신성 불안 장애

SSRI는 교육과 자활활동 등 보수적 조치에 대응하지 못한 일반 불안장애(GAD)의 치료를 위해 국립보건관리 우수연구소(NICE)가 추천한다.GAD는 다양한 이벤트에 대한 과도한 우려가 주된 특징인 일반적인 장애입니다.주요 증상으로는 여러 사건과 문제에 대한 과도한 불안감, 6개월 이상 지속되는 걱정스러운 생각을 통제하기 어려운 것이 있습니다.

항우울제는 [20]GAD의 불안감을 완만하게 또는 완만하게 감소시키며, GAD 치료에 있어 위약보다 우수하다.다른 항우울제의 효능은 비슷하다.[20]

강박장애

캐나다에서 SSRI는 성인 강박장애의 첫 번째 치료제이다.영국에서는 기능장애가 중간 정도에서 심각한 정도일 뿐이며, 경미한 장애가 있는 사람에 대한 2차 치료로서 2019년 초 현재 이 권고안이 [21]검토되고 있다.소아에서 SSRI는 정신의학적 부작용에 [22]대한 면밀한 모니터링을 통해 중간에서 중증의 장애를 가진 사람들의 두 번째 치료법으로 간주될 수 있다.SSRIs, 특히 FDA가 OCD에 대해 승인한 첫 번째 플루복사민은 치료에 효과적이다. SSRIs로 치료받은 환자들은 [23][24]위약으로 치료받은 환자들보다 약 두 배 더 치료에 반응할 가능성이 높다.유효성은 6~24주의 단기 치료 시험과 28~52주의 [25][26][27]중단 시험 모두에서 입증되었다.

공황 장애

파록세틴 CR은 1차 결과 측정에서 위약보다 우수했다.10wk 무작위 대조군에서는 이중맹검 시험 에스시탈로프람이 [28]플라시보보다 효과적이었다.또 다른 SSRI인 플루복사민은 긍정적인 [29]결과를 보였다.그러나 이러한 조건과 수용 가능성에 대한 증거는 명확하지 않다.[30]

섭식 장애

항우울제는 폭식증 [31]치료에서 자가 치료 프로그램의 대안 또는 추가 첫 단계로 권장된다.SSRI(특히 플루옥세틴)는 단기 시험에서 수용성, 내구성 및 증상 감소 효과가 뛰어나기 때문에 다른 항우울제보다 선호된다.장기간의 효능은 여전히 불충분하다.

폭식 [31]장애에도 비슷한 권고 사항이 적용된다.SSRI는 폭식 행동의 단기적인 감소를 제공하지만, 상당한 체중 [32]감소와 관련이 있는 것은 아니다.

임상시험은 거식증 [33]치료에 SSRIs를 사용하는 것에 대해 대부분 부정적인 결과를 낳았다.국립보건 및 임상 우수 연구소[31](National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence)의 치료 지침은 이 장애에서 SSRI를 사용하지 말 것을 권고합니다.미국 정신의학회 사람들은 SSRI가 체중 증가와 관련하여 어떠한 이점도 주지 않지만, 공존하고 있는 우울증, 불안, 강박장애의 [32]치료에 사용될 수 있다고 지적한다.

스트로크 회복

SSRI는 우울증 증상이 있거나 없는 환자를 포함한 뇌졸중 환자의 치료에 오프 라벨로 사용되어 왔다.무작위화된 대조군 임상시험의 2019년 메타 분석에서 의존성, 신경학적 결손, 우울증 및 불안감에 대한 SSRI의 통계적으로 유의한 영향을 발견했지만, 연구는 편향 위험이 높았다.뇌졸중 [34]후 회복을 촉진하기 위해 일상적으로 사용한다는 확실한 증거는 없다.혈전 위험은 SSRI가 혈소판으로의 세로토닌 가용성을 제한하기 때문에 감소한다. 따라서 SSRI와 함께 뇌졸중 회복과 같은 감소된 응고의 이점이 증가한다.

조루

SSRI는 조루 치료에 효과적이다.만성적이고 매일 SSRI를 복용하는 것이 성행위 [35]전에 복용하는 것보다 더 효과적입니다.매일 SSRI를 복용할 때 치료의 효과가 증가하는 것은 SSRI의 치료 효과가 [36]나타나는 데 일반적으로 몇 주가 걸린다는 임상 관찰과 일치한다.성욕 감소에서 무정맥에 이르는 성적 기능 장애는 일반적으로 SSRI를 [37]받는 환자들에게 불응을 초래할 수 있는 상당히 고통스러운 부작용으로 간주된다.그러나 조루증 환자들에게는 이 같은 부작용이 바람직한 효과가 된다.

기타 용도

세르트랄린과 같은 SSRI는 [38]화를 줄이는데 효과가 있는 것으로 밝혀졌다.

부작용

부작용은 이 세분류의 개별 의약품에 따라 다르며 다음을 포함할 수 있다.

성적 기능 장애

SSRI는 무지외반증, 발기부전, 성욕저하, 생식기 저림, 그리고 성적 [44]무쾌감증과 같은 다양한 유형의 성적 기능 장애를 일으킬 수 있습니다.성적인 문제는 SSRI에게 [45]흔하다.초기 시험에서는 (사용자의 자발적 보고에 근거해) 5-15%의 사용자에게서 부작용을 보였지만, 이후 연구에서는 (환자에게 직접 질문한 것에 근거해) 36%에서 98%[46][47][48][49]의 부작용률을 보였다.성기능 저하 또한 사람들이 약을 [50]끊는 가장 흔한 이유 중 하나이다.

어떤 경우에는 SSRI의 [44][51][52]: 14 [48][53]중단 후에도 성적 기능 장애의 증상이 지속될 수 있다.이러한 증상들의 조합은 때때로 Post-SSRI Sexual Disfunction(PSD;[49][46] SSRI 후 성기능 장애)라고 불린다.2019년 6월 11일 유럽 의약품청 약리위험평가위원회는 SSRI 사용과 사용 중단 후 지속적 성기능 장애 사이에 가능한 관계가 있다고 결론 내렸다.위원회는 SSRI와 SNRI의 라벨에 이 가능한 [54][55]위험에 대한 경고를 추가해야 한다고 결론지었다.

SSRI가 성적 부작용을 일으킬 수 있는 메커니즘은 2021년 현재[update] 잘 알려져 있지 않다.가능한 메커니즘의 범위는 (1) 성기능을 포함한 행동을 전체적으로 손상시키는 비특이적 신경학적 효과(예: 진정), (2) 성기능을 매개하는 뇌 시스템에 대한 특정 영향, (3) 성기능을 매개하는 말초 조직 및 장기에 대한 특정 영향, (4) 직접 또는 간접적 영향을 포함한다.성기능을 [56]매개하는 호르몬에 미치는 영향입니다관리 전략에는 발기부전의 경우 실데나필과 같은 PDE5 억제제의 첨가, 성욕저하의 경우 부프로피온으로의 첨가 또는 전환, 전반적인 성기능장애의 경우 [57]네파조돈으로의 전환이 포함된다.

많은 비 SSRI 약물은 성적 부작용과 관련이 없다(예: 부프로피온, 미르타자핀, 티안펩틴, 아고멜라틴, 모클로베미드[58][59][60]).

여러 연구에 따르면 SSRI가 정액 [61]품질에 악영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.

트라조돈(알파 아드레날린 수용체 차단이 있는 항우울제)이 프리아피즘의 악명 높은 원인인 반면, 프리아피즘의 사례는 특정 SSRI(예: 플루옥세틴, 시탈로프람)[62]와 함께 보고되었다.

감성 블링

특정 항우울제는 감정적인 블링(blunting)을 일으킬 수 있으며, 긍정과 부정의 감정의 강도와 무관심, 그리고 [63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71]무욕의 증상으로 특징지어진다.상황에 [72]따라서는 유익하거나 해롭다고 느낄 수 있다.이 부작용은 SSRI와 SNRI와 같은 세로토닌 작동성 항우울제와 특히 관련이 있지만, 부프로피온, 아고멜라틴,[64][70][73][74] 보르티옥세틴과 같은 비정형 항우울제에는 덜할 수 있다.항우울제를 많이 복용할수록 낮은 [64]용량보다 감정적인 블링 현상이 나타날 가능성이 더 높은 것으로 보인다.그것은 복용량을 줄이거나, 약을 중단하거나,[64] 부작용을 일으키는 경향이 덜할 수 있는 다른 항우울제로 바꾸면 감소될 수 있다.

폭력.

연구원 데이비드 힐리와 다른 사람들은 SSRI가 치료와 [75]금단 기간 동안 성인과 어린이 모두에서 폭력적인 행동을 증가시킨다는 결론을 내리고 이용 가능한 데이터를 검토했다.이 견해는 일부 환자 활동가 [76]그룹에서도 공유됩니다.

비전.

급성 협각 녹내장은 SSRI의 가장 흔하고 중요한 안과 부작용으로 종종 [77][78]오진된다.

심장

SSRIs는 CHD에 [79]대한 사전 진단이 없는 사람들의 관상동맥 심장병(CHD) 위험에 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 보인다.대규모 코호트 연구는 임신 [80]첫 3개월 동안 SSRI 사용에 기인하는 심장 기형의 위험이 크게 증가하지 않는 것으로 나타났다.기존에 알려진 심장 질환이 없는 사람들을 대상으로 한 많은 대규모 연구는 SSRI 사용과 [81]관련된 심전도 변화를 보고하지 않았다.QT [82][83][84]연장에 대한 우려로 시탈로프람과 에스시탈로프람의 일일 최대 권장량이 감소하였다.과다복용 시 플루옥세틴은 정맥동 빈맥, 심근경색, 접합부 리듬 및 삼차동 등을 일으키는 것으로 보고되었다.일부 저자들은 [85]SSRI를 복용하고 있는 심각한 기존 심혈관 질환 환자들에게 심전도 모니터링을 제안했다.

출혈

SSRI는 혈소판 유도 [86]지혈에 필수적인 혈소판 세로토닌 수치를 낮추어 비정상적인 출혈의 위험을 직접적으로 증가시킨다.SSRI는 와파린과 같은 항응고제와 [87][88][89][90]아스피린과 같은 항혈소판제와 상호작용합니다.이것은 위장관 출혈과 수술 후 [87]출혈의 위험 증가를 포함한다.두개내 출혈의 상대적인 위험은 증가하지만 절대적인 위험은 매우 낮다.[91]SSRI는 혈소판 기능 [92][93]장애를 일으키는 것으로 알려져 있다.이러한 위험은 간경변이나 [94][95]간부전과 같은 기초 질환의 공존뿐만 아니라 항응고제, 항혈소판제 및 NSAID(비스테로이드성 항염증제)를 복용하는 사람들에게도 더 크다.

골절 위험

종적, 단면적 및 전향적 코호트 연구의 증거는 치료 용량에서의 SSRI 사용과 골밀도 감소, 골절 [96][97][98][99]위험의 증가 사이의 연관성을 시사한다. 이 관계는 보조 비스포네이트 [100]치료에도 지속되는 것으로 보인다.그러나 SSRI와 골절의 관계는 선행시험이 아닌 관측데이터에 근거하고 있기 때문에 현상의 [101]원인이 명확하게 밝혀지지 않았다.또한 SSRI 사용에 따라 골절 유발 추락이 증가하는 것으로 나타나며,[101] 이 약을 사용하는 고령 환자의 추락 위험에 대한 관심이 증가해야 한다는 것을 시사한다.골밀도의 [102]손실은 SSRI를 복용하는 젊은 환자들에게서 발생하지 않는 것으로 보인다.

브룩시즘

SSRI와 SNRI 항우울제는 (흔하지는 않지만) 턱 통증/턱 경련 회복 증후군을 일으킬 수 있다.Buspirone은 SSRI/SNRI 유도 턱 [103][104][105]결림에 대한 브룩시즘 치료에 성공한 것으로 보인다.

중단 증후군

세로토닌 재흡수 억제제는 연장 치료 후에 갑자기 중단되어서는 안 되며, 메스꺼움, 두통, 어지럼증, 오한, 몸살, 공포증, 불면증, 뇌잠 등을 포함할 수 있는 중단 관련 증상을 최소화하기 위해 가능한 한 몇 주에 걸쳐 테이퍼링해야 한다.모든 SSRI에 대해 질적으로 유사한 효과가 [106][107]보고되었지만 파록세틴은 다른 SSRI보다 높은 속도로 중단 관련 증상을 일으킬 수 있다. 플루옥세틴의 반감기가 길고 체내로부터의 클리어런스가 느린 자연 테이퍼링 효과로 인해 중단 효과는 적은 것으로 보인다.SSRI 중단 증상을 최소화하는 한 가지 방법은 환자를 플루옥세틴으로 전환한 다음 플루옥세틴을 [106]테이퍼링 및 중단하는 것입니다.

세로토닌 증후군

세로토닌 증후군은 일반적으로 SSRI를 [108]포함한 두 가지 이상의 세로토닌 작동성 약물의 사용에 의해 발생한다. 세로토닌 증후군은 가벼운 것에서부터 치명적인 것까지 다양하다.경미한 증상으로는 심박수 증가, 발열, 떨림, 땀, 동공 확장, 미오클로누스(간헐적 경련 또는 경련),[109] 과반사 등이 있을 수 있습니다.편두통 트립탄과 함께 우울증에 SSRI 또는 SNRI를 함께 사용하는 것은 세로토닌 [110]증후군의 위험을 증가시키지 않는 것으로 보인다.모노아민산화효소억제제(MAOIs)를 SSRIs와 함께 복용하는 것은 치명적일 수 있는데, 이는 MAOIs가 세로토닌과 다른 신경전달물질을 분해하는 데 필요한 효소인 모노아민산화효소를 교란시키기 때문이다.모노아민 산화효소가 없으면 몸은 과도한 신경전달물질을 제거할 수 없어 위험한 수준까지 축적할 수 있다.세로토닌 신드롬이 올바르게 확인되면 병원 환경에서 회복될 예후는 일반적으로 양호하다.치료는 세로토닌 작동성 약물을 중단하고 보통 벤조디아제핀을 [111]사용하여 교란과 온열증을 관리하기 위한 보조 관리를 제공하는 것으로 구성됩니다.

자살 위험

어린이 및 청소년

단기 무작위 임상시험의 메타 분석 결과 SSRI 사용은 어린이와 [112][113][114]청소년의 자살 행동 위험과 관련이 있는 것으로 밝혀졌다.예를 들어, 2004년 미국 식품의약국(FDA)의 주요 우울증 아동 임상시험 분석 결과, 통계적으로 유의한 "자살 가능 사상과 자살 행동"의 위험이 약 80% 증가했으며, 불안과 적대감은 약 130%[115] 증가했다.FDA에 따르면, 당수의 위험성은 치료 [116][117][118]후 첫 1~2개월 이내에 높아진다.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence(NICE)는 초과 위험을 "치료 초기"[119]에 둡니다.유럽정신의학협회는 치료의 첫 2주에 초과 위험을 배치하고 역학, 예상 코호트, 의료 주장 및 무작위 임상시험 데이터의 조합에 기초하여 보호 효과가 이 초기 기간 이후에 지배한다고 결론짓는다.2014년 코크란 리뷰에 따르면 6개월에서 9개월 사이에 항우울제로 치료받은 아동에서 심리치료로 [118]치료받은 아동에 비해 자살에 대한 관념이 더 높은 것으로 나타났다.

플루옥세틴과 플라시보 치료 중 발생하는 공격성과 적대감을 어린이와 청소년에게 비교한 결과 플루옥세틴 그룹과 플라시보 [120]그룹 사이에 유의미한 차이가 없는 것으로 나타났다.SSRI 처방률이 높을수록 어린이 자살률이 낮아진다는 증거도 있지만, 그 증거가 상관관계가 있기 때문에 그 관계의 본질은 [121]불분명하다.

2004년, 영국의 의약품 및 건강관리 제품 규제청(MHRA)은 플루옥세틴(Prozac)이 우울증을 앓고 있는 어린이에게 유리한 위험-편익 비율을 제공하는 유일한 항우울제라고 판단했지만, 이는 자해와 자살 [122]사상의 위험의 약간의 증가와 관련이 있었다.영국에서는 소아용 SSRI인 세르트랄린(Zoloft)과 플루복사민(Luvox) 2개만 사용이 허가되고 강박장애 치료에만 사용이 허가된다.플루옥세틴은 이 [123]용도로 사용이 허가되지 않았습니다.

어른들

SSRI가 성인의 자살행동의 위험에 영향을 미치는지는 불분명하다.

- 2005년 제약회사 데이터의 메타 분석에서는 SSRI가 자살 위험을 증가시켰다는 증거는 발견되지 않았다. 그러나 중요한 보호 또는 위험 효과를 배제할 [124]수 없었다.

- 2005년 리뷰에서는 SSRI를 위약과 비교하여 그리고 삼환식 항우울제 이외의 치료적 개입에 비해 자살 시도가 증가한다고 관찰되었다.SSRI 대 삼환식 항우울제 [125]간에는 자살 시도의 차이 위험이 검출되지 않았다.

- 한편, 2006년 리뷰는 새로운 SSRI 시대에 항우울제의 광범위한 사용이 전통적으로 기준 자살률이 높은 대부분의 국가에서 자살률의 현저한 감소를 초래한 것으로 보인다고 시사한다.이러한 감소는 특히 남성들에 비해 우울증에 더 많은 도움을 필요로 하는 여성들에게 두드러진다.미국의 대형 샘플에 대한 최근 임상 데이터에서도 [126]항우울제의 자살 방지 효과가 밝혀졌다.

- 무작위 대조 실험의 2006년 메타 분석에 따르면 SSRI는 위약에 비해 자살 발상을 증가시킨다.그러나 관찰 연구는 SSRI가 오래된 항우울제보다 자살 위험을 높이지 않았다는 것을 보여준다.연구원들은 SSRI가 일부 환자에서 자살 위험을 증가시킨다면, 생태학적 연구들이 일반적으로 SSRI 사용이 [127]증가함에 따라 자살률이 감소했다는 것을 발견했기 때문에 추가 사망자의 수는 매우 적다고 말했다.

- 2006년 FDA에 의한 추가적인 메타 분석에서 SSRI의 노화 관련 효과가 발견되었다.25세 미만의 성인들 사이에서, 결과는 자살 행동의 위험이 더 높다는 것을 보여주었다.25세에서 64세 사이의 성인의 경우, 그 효과는 자살 행동에는 중립적인 것으로 보이지만, 25세에서 64세 사이의 성인의 자살 행동에는 보호적일 수 있다.64세 이상 성인의 경우, SSRI는 자살행위의 [112]위험을 줄이는 것으로 보인다.

- 2016년 한 연구는 처방전에 포함된 FDA 블랙박스 자살 경고의 효과를 비판했다.저자들은 [128]경고의 결과로 자살률이 증가할 수 있다고 논의했다.

사망 위험

2017년 메타 분석 결과 SSRI를 포함한 항우울제는 일반 [129]인구의 사망 위험(+33%)과 새로운 심혈관 합병증(+14%)이 유의미하게 증가하는 것과 관련이 있는 것으로 나타났다.반대로, 기존 심혈관 [129]질환이 있는 사람에게는 위험이 크지 않았다.

임신 및 모유 수유

임신 중 SSRI 사용은 다양한 인과관계 증명 정도를 가진 다양한 위험과 관련이 있다.우울증은 음성의 임신 결과와 독립적으로 관련되므로, 항우울제 사용과 특정 부작용 사이의 관찰된 연관성이 원인 관계를 반영하는 정도를 결정하는 것은 일부 경우에 [130]어려웠다.다른 경우, 항우울제 노출에 대한 부작용의 귀속은 상당히 명확해 보인다.

임신 중 SSRI 사용은 약 1.7배의 [131][132]자연유산 위험 증가와 관련이 있다.사용은 또한 [133]조산과도 관련이 있다.

항우울제 노출 임신에서 주요 선천성 기형의 위험성에 대한 체계적인 검토 결과, 주요 기형의 위험과 노출되지 않은 [134]임신과 다르지 않은 심혈관계 선천성 기형의 위험이 약간 증가(3~24%)했다.[135] 다른 연구들은 SSRI 치료를 받지 않는 우울증 산모들 사이에서 심혈관계 선천성 결함의 위험이 증가하는 것을 발견했고, 이는 예를 들어 걱정스러운 산모들이 그들의 유아에 [136]대한 보다 적극적인 검사를 추구할 수 있다는 확인 편견이 있을 가능성을 시사한다.또 다른 연구에서는 심혈관계 선천성 기형의 증가가 없고 SSRI 피폭 [132]임신에서 중대한 기형의 위험이 27% 증가한 것으로 나타났다.

FDA는 2006년 7월 19일 SSRI를 복용하는 수유모들은 반드시 의사와 치료를 논의해야 한다는 성명을 발표했다.그러나 SSRIs의 안전성에 관한 의학 문헌에서는 Sertraline과 Paroxetine과 같은 일부 SSRI가 모유 [137][138][139]수유에 안전한 것으로 판단되었습니다.

신생아 금주 증후군

몇몇 연구는 자궁 내 노출을 가진 유아들 중 다수의 신경, 위장, 자율, 내분비 및/또는 호흡기 증상 증후군인 신생아 금주 증후군을 문서화했다.이러한 신드롬은 단명하지만 장기적인 [140][141]영향이 있는지 여부를 판단하기에 충분한 장기 데이터가 없다.

지속성 폐고혈압

지속성 폐고혈압(PPHN)은 심각하고 생명을 위협하지만 신생아의 출생 직후에 발생하는 매우 드문 폐 질환입니다.PPHN을 가진 신생아는 폐혈관에 높은 압력이 있어 충분한 산소를 혈류로 공급하지 못한다.미국에서는 출생아 1000명당 1~2명꼴로 출생 직후 PPHN이 발병해 집중적인 치료가 필요한 경우가 많다.그것은 상당한 장기 신경학적 [142]결손의 약 25%의 위험과 관련이 있다.2014년 메타 분석 결과 임신 초기 SSRI 피폭과 관련된 지속적인 폐고혈압의 위험이 증가하지 않았으며 임신 후기에 노출과 관련된 위험이 약간 증가했다. "추정 286 - 351명의 여성이 평균 1명의 추가 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페성 페소염신생아의 폐고혈압이 재발한다."[143]2012년에 발표된 검토는 2014년 [144]연구 결과와 매우 유사한 결론에 도달했다.

자손의 신경정신학적 영향

는 2015년 검토 사용할 수 있는 데이터에 따르면 발견한 것은"일부 신호 SSRIs에 출산 전의 노출 ASDs(자폐 범주성 장애의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있는 존재하는)"[145]비록 큰 집단 연구 발표한 2013[146]고 집단 연구를 이용해서 데이터에서 핀란드의 국가 등록의년 1996년과 2010년 및 발행에 2.016을 발견했다SSRI 사용과 [147]자손의 자폐증 사이에 유의미한 연관성은 없다.2016년 핀란드 연구에서도 ADHD와의 연관성은 발견되지 않았지만,[147] 사춘기 초기에 우울증 진단 비율이 증가한 연관성은 발견되었습니다.

과다 복용

SSRIs는 삼환식 항우울제와 같은 전통적인 항우울제와 비교했을 때 과다 복용이 더 안전해 보입니다.이러한 상대적 안전성은 일련의 사례와 처방 [148]건수당 사망에 대한 연구 모두에서 뒷받침된다.그러나 SSRI 중독에 대한 사례 보고는 심각한 독성이 발생할[149] 수 있고 삼환식 [148]항우울제와 비교했을 때 매우 드물지만, 대량 [150]단일 섭취 후에 사망이 보고되고 있다.

SSRIs의 치료 지표가 넓기 때문에, 대부분의 환자들은 적당한 과다 복용 후에 경미하거나 증상이 없을 것이다.SSRI 과다복용 후 가장 일반적으로 보고된 심각한 영향은 세로토닌 증후군이다. 세로토닌 독성은 보통 매우 높은 과다복용이나 여러 가지 약물 [151]섭취와 관련이 있다.보고된 다른 중요한 영향으로는 혼수, 발작, 심장 [148]독성이 있다.

바이폴라 스위치

조울증이 있는 성인과 어린이의 경우 SSRI는 우울증에서 저조증/마니아로 조울증을 일으킬 수 있다.기분 안정제와 함께 복용할 경우 전환 위험은 증가하지 않지만 SSRI를 단발성 요법으로 복용할 경우 전환 위험은 [152][153]평균의 2, 3배가 될 수 있습니다.이러한 변화는 종종 감지하기가 쉽지 않으며 가족 및 정신 건강 전문가의 [154]감시가 필요합니다.이 전환은 이전(하이포) 남성적 증상이 없어도 발생할 수 있으므로 정신과 의사가 예상하지 못할 수 있습니다.

상호 작용

다음 약물은 SSRI를 [155][156]복용하는 사람들에게 세로토닌 증후군을 촉진할 수 있다.

- 라인졸리드

- 모클로베미드, 페넬진, 트라닐시프로민, 셀레길린 및 메틸렌블루를 포함한 모노아민산화효소억제제(MAOI)

- 리튬

- 시부트라민

- MDMA(이스태시)

- 덱스트로메토르판

- 트라마돌

- 5-HTP

- 페티딘/메페리딘

- 세인트 존스 멧돼지

- 요힘베

- 삼환식 항우울제(TCA)

- 세로토닌-노레피네프린 재흡수억제제(SNRI)

- 부스피론

- 트립탄

- 미르타자핀

- 메틸렌 블루

는 실제로 NSAID약물 가족의 진통제 먹을래 물질과 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제의 효율성을 줄이고 위장의 아파 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제 사용으로 야기되는의 증가된 위험이 더 심각하게 만들 것 방해한다.[88][90][157]비스테로이드 약물이 포함됩니다.

- 아스피린

- 이부프로펜(애드빌, 누로펜)

- 나프록센 제제 복용자(Aleve)

잠재성이pharmacokinetic 상호 작용의 다양한 개별 SSRIs과 다른 약들 사이의 숫자를 있다.이들은 대부분 사례는 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제는 능력 특정 P450 cytochromes을 억제하기 위한 것에서 발생한다.[158][159][160]

| 마약 이름 | CYP1A2 | CYP2C9 | CYP2C19 | CYP2D6 | CYP3A4 | CYP2B6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 시탈로프람 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Escitalopram | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| 플루옥세틴 | + | ++ | +/++ | +++ | + | + |

| 플루복사민 | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | + |

| 파록세틴 | + | + | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| 서트랄린 | + | + | +/++ | + | + | + |

범례:

0 – 억제 없음

+ – 가벼운 억제

++ – 중간 정도의 억제

++ – 강력한 억제

CYP2D6 효소는 히드로코돈, 코데인[161] 및 디히드로모르핀의 활성 대사물(각각 히드로모르폰, 모르핀 및 디히드로모르핀)에 대한 신진대사를 전적으로 담당하며, 이들 대사물은 다시 2상 글루쿠론화를 거친다.이러한 오피오이드(그리고 옥시코돈, 트라마돌 및 메타돈)는 선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 [162][163]억제제와의 상호작용 잠재력을 가지고 있다.코데인과 함께 일부 SSRI(파록세틴 및 플루옥세틴)를 사용하면 활성 대사물 모르핀의 혈장 농도가 감소하여 진통 [164][165]효과가 감소할 수 있습니다.

특정 SSRI의 또 다른 중요한 상호작용은 CYP2D6의 잠재적 억제제인 파록세틴과 유방암 치료 및 예방에 일반적으로 사용되는 약제인 타목시펜을 포함한다.타목시펜은 간 시토크롬 P450 효소 시스템, 특히 CYP2D6에 의해 활성 대사물로 대사되는 프로드러그이다.유방암에 걸린 여성들에게서 파록세틴과 타목시펜을 병용하는 것은 가장 [166]오래 사용한 여성들에게서 91%만큼 높은 사망 위험과 관련이 있다.

SSRI 목록

시장에 내놓았다

항우울제

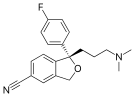

- 시탈로프람(셀렉사)

- Escitalopram (렉사프로)

- 플루옥세틴(프로작)

- 플루복사민(루복사민)

- 파록세틴(Paxil)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

다른이들

- 다폭세틴(프릴리기)

단종

항우울제

시판되지 않음

항우울제

- 알라프로클레이트(GEA-654)

- 센토프로파진

- 세리카민(JO-1017)

- 페목세틴(말렉실, FG-4963)

- Ifoxetine (CGP-15210)

- 오밀록세틴

- 파누라민(WY-26002)

- 피란다민(AY-23713)

- 세프록세틴(S)-노르플루옥세틴)

관련 약물

둘록세틴(심발타), 벤라팍신(에펙소르) 및 데스벤라팍신(프리스티크)은 SNRI로 설명되지만 실제로는 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제(SRI)[167]로 비교적 선택적이다.그들은 노르에피네프린 [167]재흡입에 대한 세로토닌 재흡입을 억제하기 위해 최소 약 10배 이상 선택된다.선택 비율은 venlafaxine의 경우 약 1:30, duloxetine의 경우 1:10, desvenlafaxine의 [167][168]경우 약 1:14입니다.저용량에서 이러한 SNRI는 대부분 SSRI로 작용하며, 고용량에서만 노르에피네프린의 [169][170]재섭취를 현저하게 억제한다.밀나시프란(ixel, Savella)과 그 입체 이성질체 레보밀나시프란(Fetzima)은 세로토닌과 노르에피네프린을 비슷한 정도로 억제하는 유일한 SNRI이며, 둘 다 비율이 1:[167][171]1에 가깝다.

Vilazodone(Viibryd) 및 Vortioxetine(Trintellix)은 세로토닌 수용체의 조절제로서도 작용하며 세로토닌 조절제 및 자극제([172]SMS)[172]로 기술된다.Vilazodone은 5-HT1A1A 수용체 부분작용제이며, Vortioxetine은 5-HT37 수용체 작용제 및 길항제이다.리톡세틴(SL 81–0385)과 루바조돈(YM-992, YM-35995)은 [173][174][175][176]시판되지 않은 유사 의약품이다.이들은 SRI이며 리톡세틴은 5-HT3 수용체[173][174] 길항제이며, 루바조돈은 5-HT2A 수용체 [175][176]길항제이다.

작용 메커니즘

세로토닌 재흡수 억제

뇌에서 메시지는 세포 사이의 작은 간격인 화학적 시냅스를 통해 신경 세포에서 다른 세포로 전달됩니다.정보를 보내는 시냅스 전 세포는 세로토닌을 포함한 신경전달물질을 그 틈으로 방출한다.신경전달물질은 시냅스 후 세포의 표면에 있는 수용체에 의해 인식되며, 이 자극에 의해 신호가 전달된다.이 과정에서 약 10%의 신경 전달 물질이 손실되고, 나머지 90%는 수용체에서 방출되어 모노아민 전달체에 의해 다시 시냅스 전 세포로 흡수됩니다.

SSRI는 세로토닌의 재섭취를 억제한다.그 결과 세로토닌은 시냅스 간격에 평소보다 더 오래 머물러 수용 세포의 수용체를 반복적으로 자극할 수 있다.단기적으로, 이것은 세로토닌이 1차 신경전달물질로 작용하는 시냅스 전체의 신호 전달의 증가로 이어진다.만성 투여 시, 시냅스 후 세로토닌 수용체의 점유 증가는 시냅스 전 뉴런이 더 적은 세로토닌을 합성하고 방출하도록 신호한다.시냅스 내 세로토닌 수치는 떨어졌다가 다시 상승하여 궁극적으로 시냅스 후 세로토닌 [177]수용체의 하향 조절을 초래한다.다른 간접적 영향으로는 노르에피네프린 생산량 증가, 신경 순환 AMP 수치 증가, BDNF 및 CREB와 [178]같은 조절 인자의 수치 증가가 포함될 수 있다.널리 받아들여지고 있는 기분 장애의 생물학에 대한 포괄적인 이론이 없기 때문에, 이러한 변화가 어떻게 SSRIs의 [citation needed]기분 향상과 항불안 효과로 이어지는지에 대한 널리 받아들여지고 있는 이론은 없다.효과가 나타나기까지 몇 주가 걸리는 세로토닌 혈중 수치에 대한 그들의 영향은 그들의 느린 정신의학적 영향에 [179]크게 영향을 미치는 것으로 보인다.

시그마수용체배위자

| 약 | SERT | σ1 | σ2 | § / SERT1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 시탈로프람 | 1.16 | 292–404 | 어거니스트 | 5,410 | 252–348 |

| Escitalopram | 2.5 | 288 | 어거니스트 | ND | ND |

| 플루옥세틴 | 0.81 | 191–240 | 어거니스트 | 16,100 | 296–365 |

| 플루복사민 | 2.2 | 17–36 | 어거니스트 | 8,439 | 7.7–16.4 |

| 파록세틴 | 0.13 | ≥1,893 | ND | 22,870 | ≥14,562 |

| 서트랄린 | 0.29 | 32–57 | 대항마 | 5,297 | 110–197 |

| 값은 K(nM)입니다i.값이 작을수록 더 강하게 약물이 사이트에 결합합니다. | |||||

세로토닌의 재흡수 억제제로서의 작용 외에, 공교롭게도 일부 SSRI는 시그마 [180][181]수용체의 리간드이다.플루복사민은 γ수용체의1 작용제이며, 세르트랄린은 γ수용체의1 길항제이며, 파록세틴은 γ수용체와1 [180][181]유의하게 상호작용하지 않는다.어떤 SSRI도 γ2 수용체에 대해 유의한 친화력을 가지지 않으며, SSRI와 달리 SNRI는 어느 시그마 [180][181]수용체와도 상호작용하지 않는다.플루복사민은 γ1 [180][181]수용체에서 SSRIs의 활성이 단연 가장 강하다.플루복사민의 임상 용량에 의한 γ1 수용체의 높은 점유율은 양전자 방출 단층촬영([180][181]PET) 연구에서 인간의 뇌에서 관찰되었다.플루복사민에 의한 γ수용체의1 작용작용은 [180][181]인지에 유익한 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 생각된다.플루복사민과는 대조적으로, 다른 SSRI의 작용에서 γ1 수용체의 관련성은 [182]SERT에 비해 수용체에 대한 친화력이 매우 낮기 때문에 불확실하고 의심스럽다.

항염증 효과

우울증에 대한 염증과 면역체계의 역할은 광범위하게 연구되어 왔다.이 연관성을 뒷받침하는 증거는 지난 10년간 수많은 연구에서 입증되었다.전국적인 연구와 소규모 코호트 연구의 메타 분석 결과, 제1형 당뇨병, 류마티스 관절염(RA) 또는 간염과 같은 기존 염증 상태와 우울증 위험 증가 사이의 상관관계가 밝혀졌다.데이터는 또한 흑색종과 같은 질병을 치료하는데 소염제를 사용하는 것이 우울증으로 이어질 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.몇몇 메타 분석 연구는 우울증 [183]환자들에게서 프로염증성 사이토카인과 케모카인의 수치가 증가하는 것을 발견했다.이러한 연관성을 통해 과학자들은 항우울제가 면역 체계에 미치는 영향을 조사하게 되었다.

SSRI는 원래 세포외 공간에서 사용 가능한 세로토닌의 수치를 증가시키기 위한 목적으로 발명되었다.하지만, 환자들이 SSRI 치료를 처음 시작할 때부터 효과를 볼 때까지의 지연된 반응은 과학자들이 다른 분자들이 이 [184]약들의 효능에 관여하고 있다고 믿게 만들었다.SSRI의 명백한 항염증 효과를 조사하기 위해 Kohler 등 및 Widdwocha 등 모두 항우울제 처리 후 염증과 관련된 사이토카인 수치가 [185][186]감소하는 메타 분석을 실시했다.네덜란드의 연구자들에 의해 수행된 대규모 코호트 연구는 우울증 장애, 증상, 그리고 염증과 항우울제 사이의 연관성을 조사했다.연구는 SSRI를 복용하는 환자들에게서 염증 효과가 있는 사이토카인 인터류킨(IL)-6의 수치가 약물을 복용하지 않은 [187]환자들에 비해 감소했음을 보여주었다.

SSRIs에 의한 치료에서는 IL-1β, 종양괴사인자(TNF)-α, IL-6, 및 IFN(인터페론)-γ와 같은 염증성 사이토카인의 생산 감소가 나타났으며, 이는 염증 수치의 감소로 이어 면역 [188]반응의 활성화 수치의 감소로 이어졌다.이러한 염증성 사이토카인은 뇌에 존재하는 특수한 대식세포인 미세글리아를 활성화시키는 것으로 나타났다.대식세포는 선천적인 면역 체계에서 숙주 방어를 담당하는 면역 세포의 하위 집합이다.대식세포는 염증 반응을 일으키기 위해 사이토카인과 다른 화학물질을 방출할 수 있다.말초염증은 미세글리아에서 염증 반응을 유발하고 신경염증을 일으킬 수 있다.SSRI는 소염증성 사이토카인 생성을 억제하여 마이크로글리아와 말초 대식세포의 활성화를 감소시킨다.SSRI는 이러한 염증성 사이토카인의 생성을 억제할 뿐만 아니라 IL-10과 같은 항염증성 사이토카인을 상향 조절하는 것으로 나타났다.종합하면, 이것은 전반적인 염증 면역 [188][189]반응을 감소시킨다.

사이토카인 생산에 영향을 미칠 뿐만 아니라 SSRI에 의한 치료가 선천적 면역과 적응적 면역에 관여하는 면역계 세포의 증식과 생존력에 영향을 미친다는 증거가 있다.증거는 SSRI가 적응성 면역에 중요한 세포인 T세포의 증식을 억제하고 염증을 유발할 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.SSRI는 또한 T세포에서 아포토시스, 프로그램된 세포사멸을 유도할 수 있다.SSRIs의 항염증 효과에 대한 작용 메커니즘은 완전히 알려져 있지 않다.그러나 메커니즘에 관여하는 다양한 경로에 대한 증거가 있다.그러한 메커니즘 중 하나는 cAMP의존성 단백질인 단백질인 키나제 A(PKA)의 활성화에 대한 간섭의 결과로 고리형 아데노신 일인산(cAMP)의 수치가 증가하는 것이다.다른 가능한 경로로는 칼슘 이온 채널에 대한 간섭 또는 MAPK 및 노치 신호 [191]경로와 같은[190] 세포 사망 경로를 유도하는 것이 있다.

SSRIs의 항염증 효과는 다발성 경화증, RA, 염증성 장질환, 패혈성 쇼크와 같은 자가면역질환의 치료에 SSRIs의 효과에 대한 연구를 촉진시켰다.이러한 연구는 동물 모델에서 수행되었지만 일관된 면역 조절 효과를 보여주었다.SSRI인 플루옥세틴은 이식편과 [190]숙주병의 동물 모델에서도 효과를 보였다.SSRI는 또한 종양학 치료를 받고 있는 환자들에게 통증 완화제로 성공적으로 사용되어 왔다.이것의 효과는 적어도 부분적으로 SSRIs의 항염증 효과 때문에 가정되었다.[189]

약제유전학

비록 이러한 검사들이 아직 널리 임상적으로 [192]사용될 준비가 되어 있지 않지만, 환자들이 SSRI에 반응할지 혹은 그들의 중단을 야기할 부작용을 가질지를 예측하기 위해 많은 연구들이 유전자 표지를 사용하는 데 전념하고 있다.

TCA와 비교

SSRI는 다른 모노아민 신경전달물질에도 영향을 미치는 초기 항우울제와 달리 세로토닌을 담당하는 재흡수 펌프에만 영향을 미치기 때문에 '선택적'으로 설명되며 결과적으로 SSRI는 부작용이 적다.

SSRIs가 [193]개발되기 전에 가장 일반적으로 사용되는 항우울제 등급이었던 SSRIs와 세환식 항우울제 사이에는 효과 면에서 큰 차이가 없는 것으로 보인다.그러나 SSRI는 독극물 복용량이 높다는 중요한 장점이 있으며, 따라서 자살 수단으로 사용하는 것이 훨씬 더 어렵다.게다가, 그것들은 더 적고 더 가벼운 부작용을 가지고 있다.삼환식 항우울제는 또한 SSRI가 결여한 심각한 심혈관 부작용의 위험도 더 높다.

SSRI는 시냅스 후 신경세포의 고리형 아데노신 일인산(cAMP)과 같은 신호 경로에 작용하여 뇌유래 신경영양인자(BDNF)의 방출로 이어진다.BDNF는 피질 뉴런과 [178]시냅스의 성장과 생존을 강화합니다.

역사

플루옥세틴은 1987년에 도입되어 시판된 최초의 주요 SSRI였다.

논란

FDA가 평가한 항우울제의 결과 발표를 검사한 연구는 좋은 결과를 가진 것이 부정적인 [194]결과를 가진 것보다 훨씬 더 많이 발표될 가능성이 있다고 결론지었다.또한, 항우울제에 대한 185개의 메타 분석을 조사한 결과, 79%가 어떤 식으로든 제약회사에 소속된 저자를 가지고 있었으며 [195]항우울제에 대한 경고 보고를 꺼리는 것으로 나타났다.2022년 포괄적 검토 결과, "우울증이 세로토닌 농도 또는 [196]활성 저하와 관련이 있거나 그에 의해 발생한다는 설득력 있는 증거가 없다"는 사실이 밝혀졌다.

데이비드 힐리는 규제 당국이 항우울제 라벨에 자살 [197]사고를 일으킬 수 있다는 경고를 붙이기 전 수년 동안 경고 표지판을 사용할 수 있었다고 주장해 왔다.이러한 경고가 추가되었을 때, 다른 사람들은 위해의 증거가 설득력이[198][199] 없다고 주장했고, 다른 사람들은 경고가 [200][201]추가된 후에도 계속 그렇게 했다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Barlow DH, durand VM (2009). "Chapter 7: Mood Disorders and Suicide". Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach (Fifth ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 239. ISBN 978-0495095569. OCLC 192055408.

- ^ "Mechanism of Action of Antidepressants" (PDF). Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 36. Summer 2002. S2CID 4937890. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-28.

- ^ Preskorn SH, Ross R, Stanga CY (2004). "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors". In Sheldon H. Preskorn, Hohn P. Feighner, Christina Y. Stanga, Ruth Ross (eds.). Antidepressants: Past, Present and Future. Berlin: Springer. pp. 241–262. ISBN 978-3540430544.

- ^ 오늘의 심리학:우울증과 세로토닌:새로운 리뷰에서 실제로 언급되는 내용

- ^ Kramer P (7 Sep 2011). "In Defense of Antidepressants". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ a b Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J (January 2010). "Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis". JAMA. 303 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1943. PMC 3712503. PMID 20051569.

- ^ Pies R (April 2010). "Antidepressants work, sort of – our system of care does not". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 30 (2): 101–104. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181d52dea. PMID 20520282.

- ^ a b Jakobsen JC, Katakam KK, Schou A, Hellmuth SG, Stallknecht SE, Leth-Møller K, Iversen M, Banke MB, Petersen IJ, Klingenberg SL, Krogh J, Ebert SE, Timm A, Lindschou J, Gluud C (February 2017). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus placebo in patients with major depressive disorder. A systematic review with meta-analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis". BMC Psychiatry. 17 (1): 58. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-1173-2. PMC 5299662. PMID 28178949.

- ^ Medford N, Sierra M, Baker D, David AS (2005). "Understanding and treating depersonalisation disorder". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (2): 92–100. doi:10.1192/apt.11.2.92.

- ^ a b National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (October 2009). "Depression Quick Reference Guide" (PDF). NICE clinical guidelines 90 and 91. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT (February 2008). "Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". PLOS Medicine. 5 (2): e45. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. PMC 2253608. PMID 18303940.

- ^ Horder J, Matthews P, Waldmann R (June 2010). "Placebo, Prozac and PLoS: significant lessons for psychopharmacology". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (10): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/0269881110372544. hdl:2108/54719. PMID 20571143. S2CID 10323933.

- ^ Fountoulakis KN, Möller HJ (August 2010). "Efficacy of antidepressants: a re-analysis and re-interpretation of the Kirsch data". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 14 (3): 405–412. doi:10.1017/S1461145710000957. PMID 20800012.

- ^ Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, Davis JM, Mann JJ (June 2012). "Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine". Archives of General Psychiatry. 69 (6): 572–579. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2044. PMC 3371295. PMID 22393205.

- ^ Hieronymus F, Lisinski A, Näslund J, Eriksson E (2018). "Multiple possible inaccuracies cast doubt on a recent report suggesting selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to be toxic and ineffective". Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 30 (5): 244–250. doi:10.1017/neu.2017.23. PMID 28718394.

- ^ Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, Leucht S, Ruhe HG, Turner EH, Higgins JP, Egger M, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, Imai H, Shinohara K, Tajika A, Ioannidis JP, Geddes JR (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- ^ a b Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Cox GR, Simmons MB, Merry SN (Nov 14, 2012). "Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (9): CD004851. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004851.pub3. hdl:11343/59246. PMC 8786271. PMID 23152227.

- ^ Canton, John; Scott, Kate M; Glue, Paul (2012). "Optimal treatment of social phobia: systematic review and meta-analysis". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 8: 203–215. doi:10.2147/NDT.S23317. ISSN 1176-6328. PMC 3363138. PMID 22665997.

- ^ Alexander, Walter (January 2012). "Pharmacotherapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder In Combat Veterans". Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 37 (1): 32–38. ISSN 1052-1372. PMC 3278188. PMID 22346334.

- ^ a b "www.nice.org.uk" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2013-02-20.

- ^ Katzman, Martin A; Bleau, Pierre; Blier, Pierre; Chokka, Pratap; Kjernisted, Kevin; Van Ameringen, Michael (2014-07-02). "Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders". BMC Psychiatry. 14 (Suppl 1): S1. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-14-S1-S1. ISSN 1471-244X. PMC 4120194. PMID 25081580.

- ^ "Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Core interventions in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder" (PDF). November 2005.

- ^ Arroll B, Elley CR, Fishman T, Goodyear-Smith FA, Kenealy T, Blashki G, et al. (July 2009). Arroll B (ed.). "Antidepressants versus placebo for depression in primary care". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (3): CD007954. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007954. PMID 19588448.

- ^ Busko M (28 February 2008). "Review Finds SSRIs Modestly Effective in Short-Term Treatment of OCD". Medscape. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013.

- ^ Fineberg NA, Brown A, Reghunandanan S, Pampaloni I (2012). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder" (PDF). The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (8): 1173–1191. doi:10.1017/S1461145711001829. PMID 22226028.

- ^ "Sertraline prescribing information" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ^ "Paroxetine prescribing information" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ^ Batelaan, Neeltje M.; Van Balkom, Anton J. L. M.; Stein, Dan J. (2012-04-01). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of panic disorder: an update". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (3): 403–415. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000800. ISSN 1461-1457. PMID 21733234.

- ^ Asnis, G. M.; Hameedi, F. A.; Goddard, A. W.; Potkin, S. G.; Black, D.; Jameel, M.; Desagani, K.; Woods, S. W. (2001-08-05). "Fluvoxamine in the treatment of panic disorder: a multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in outpatients". Psychiatry Research. 103 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00265-7. ISSN 0165-1781. PMID 11472786. S2CID 40412606.

- ^ Bighelli, I.; Castellazzi, M.; Cipriani, A.; Girlanda, F.; Guaiana, G.; Koesters, M.; Turrini, G.; Furukawa, T. A.; Barbui, C. (2018). "Antidepressants for panic disorder in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD010676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010676.pub2. PMC 6494573. PMID 29620793. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- ^ a b c "Eating disorders in over 8s: management" (PDF). Clinical guideline [CG9]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). January 2004.

- ^ a b "Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders". National Guideline Clearinghouse. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25.

- ^ Flament MF, Bissada H, Spettigue W (March 2012). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of eating disorders". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000381. PMID 21414249.

- ^ Legg, Lynn A.; Tilney, Russel; Hsieh, Cheng-Fang; Wu, Simiao; Lundström, Erik; Rudberg, Ann-Sofie; Kutlubaev, Mansur A.; Dennis, Martin; Soleimani, Babak; Barugh, Amanda; Hackett, Maree L. (26 November 2019). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for stroke recovery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009286.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6953348. PMID 31769878.

- ^ Waldinger MD (November 2007). "Premature ejaculation: state of the art". The Urologic Clinics of North America. 34 (4): 591–599, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.08.011. PMID 17983899.

- ^ Machado-Vieira; Baumann; Wheeler-Castillo; Latov; Henter; Salvadore; Zarate (January 2010). "The Timing of Antidepressant Effects: A Comparison of Diverse Pharmacological and Somatic Treatments". Pharmaceuticals. 3 (1): 19–41. doi:10.3390/ph3010019. PMC 3991019. PMID 27713241.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Higgins; Nash; Lynch (September 2010). "Antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: impact, effects, and treatment". Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2: 141–150. doi:10.2147/DHPS.S7634. PMC 3108697. PMID 21701626.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Romero-Martínez Á, Murciano-Martí S, Moya-Albiol L (May 2019). "Is Sertraline a Good Pharmacological Strategy to Control Anger? Results of a Systematic Review". Behavioral Sciences. 9 (5): 57. doi:10.3390/bs9050057. PMC 6562745. PMID 31126061.

- ^ Wu Q, Bencaz AF, Hentz JG, Crowell MD (January 2012). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies". Osteoporosis International. 23 (1): 365–375. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1778-8. PMID 21904950. S2CID 37138272.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Stahl SM, Lonnen AJ (2011). "The Mechanism of Drug-induced Akathsia". CNS Spectrums. PMID 21406165.

- ^ Lane RM (1998). "SSRI-induced extrapyramidal side-effects and akathisia: implications for treatment". Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 12 (2): 192–214. doi:10.1177/026988119801200212. PMID 9694033. S2CID 20944428.

- ^ Koliscak LP, Makela EH (2009). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced akathisia". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 49 (2): e28–36, quiz e37–38. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2009.08083. PMID 19289334.

- ^ Leo RJ (1996). "Movement disorders associated with the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 57 (10): 449–454. doi:10.4088/jcp.v57n1002. PMID 8909330.

- ^ a b Bahrick AS (2008). "Persistence of Sexual Dysfunction Side Effects after Discontinuation of Antidepressant Medications: Emerging Evidence". The Open Psychology Journal. 1: 42–50. doi:10.2174/1874350100801010042.

- ^ Taylor MJ, Rudkin L, Bullemor-Day P, Lubin J, Chukwujekwu C, Hawton K (May 2013). "Strategies for managing sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressant medication". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD003382. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003382.pub3. PMID 23728643.

- ^ a b Bahrick, AS (2006). "Post SSRI sexual dysfunction". American Society for the Advancement of Pharmacotherapy. Tablet 7.3: 2–3.

- ^ Zajecka, J.; Mitchell, S.; Fawcett, J. (1997). "Treatment-emergent changes in sexual function with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as measured with the Rush Sexual Inventory". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 33 (4): 755–760. ISSN 0048-5764. PMID 9493488.

Males and females were found to experience similar rates of treatment emergent sexual dysfunction at 60 percent and 57 percent, respectively.

- ^ a b Reisman Y (October 2017). "Sexual Consequences of Post-SSRI Syndrome". Sexual Medicine Reviews. 5 (4): 429–433. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.05.002. PMID 28642048.

Initial SSRI registration studies found that such side effects were reported by fewer than 10% of patients. When doctors specifically asked about treatment-emergent sexual difficulties, some found that they were present in up to 70% of patients.

- ^ a b Healy, David (2020). "Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction & other enduring sexual dysfunctions". Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 29: e55. doi:10.1017/S2045796019000519. PMC 8061302. PMID 31543091.

Close to 100% of takers of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) have a degree of genital sensory change within 30 min of taking.

- ^ Kennedy SH, Rizvi S (April 2009). "Sexual dysfunction, depression, and the impact of antidepressants". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 29 (2): 157–164. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e31819c76e9. PMID 19512977. S2CID 739831.

- ^ Waldinger MD (2015). "Psychiatric disorders and sexual dysfunction". Neurology of Sexual and Bladder Disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 130. pp. 479–83. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63247-0.00027-4. ISBN 978-0444632470. PMID 26003261.

- ^ "Prozac Highlights of Prescribing Information" (PDF). Eli Lilly and Company. 24 March 2017.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 449. ISBN 978-0890425558.

- ^ Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) (11 June 2019). "New product information wording – Extracts from PRAC recommendations on signals" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. EMA/PRAC/265221/2019.

- ^ "Minutes of PRAC meeting of 13–16 May 2019: Signal of persistent sexual dysfunction after drug withdrawal" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 14 June 2019.

- ^ Gitlin MJ (September 1994). "Psychotropic medications and their effects on sexual function: diagnosis, biology, and treatment approaches". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 55 (9): 406–413. PMID 7929021.

- ^ Balon R (2006). "SSRI-Associated Sexual Dysfunction". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (9): 1504–1509, quiz 1664. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1504. PMID 16946173.

- ^ Serretti A (2009). "Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 29 (3): 259–266. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a5233f. PMID 19440080. S2CID 1663570. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- ^ Clayton AH (2003). "Antidepressant-Associated Sexual Dysfunction: A Potentially Avoidable Therapeutic Challenge". Primary Psychiatry. 10 (1): 55–61. Archived from the original on 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ Kanaly KA, Berman JR (December 2002). "Sexual side effects of SSRI medications: potential treatment strategies for SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunction". Current Women's Health Reports. 2 (6): 409–416. PMID 12429073.

- ^ Koyuncu H, Serefoglu EC, Ozdemir AT, Hellstrom WJ (September 2012). "Deleterious effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment on semen parameters in patients with lifelong premature ejaculation". International Journal of Impotence Research. 24 (5): 171–173. doi:10.1038/ijir.2012.12. PMID 22573230.

- ^ Scherzer, Nikolas D.; Reddy, Amit G.; Le, Tan V.; Chernobylsky, David; Hellstrom, Wayne J.G. (April 2019). "Unintended Consequences: A Review of Pharmacologically-Induced Priapism". Sexual Medicine Reviews. 7 (2): 283–292. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.09.002. PMID 30503727. S2CID 54621798.

- ^ Marazziti D, Mucci F, Tripodi B, Carbone MG, Muscarella A, Falaschi V, Baroni S (April 2019). "Emotional Blunting, Cognitive Impairment, Bone Fractures, and Bleeding as Possible Side Effects of Long-Term Use of SSRIs". Clin Neuropsychiatry. 16 (2): 75–85. PMC 8650205. PMID 34908941.

- ^ a b c d Ma H, Cai M, Wang H (2021). "Emotional Blunting in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder: A Brief Non-systematic Review of Current Research". Front Psychiatry. 12: 792960. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.792960. PMC 8712545. PMID 34970173.

- ^ Barnhart WJ, Makela EH, Latocha MJ (May 2004). "SSRI-induced apathy syndrome: a clinical review". J Psychiatr Pract. 10 (3): 196–199. doi:10.1097/00131746-200405000-00010. PMID 15330228. S2CID 26935586.

- ^ Sansone RA, Sansone LA (October 2010). "SSRI-Induced Indifference". Psychiatry (Edgmont). 7 (10): 14–18. PMC 2989833. PMID 21103140.

- ^ Price J, Cole V, Goodwin GM (September 2009). "Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study". Br J Psychiatry. 195 (3): 211–217. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.051110. PMID 19721109.

- ^ Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, Laredo J (October 2017). "Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: A survey among depressed patients". J Affect Disord. 221: 31–35. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.048. PMID 28628765.

- ^ Read J, Williams J (2018). "Adverse Effects of Antidepressants Reported by a Large International Cohort: Emotional Blunting, Suicidality, and Withdrawal Effects" (PDF). Curr Drug Saf. 13 (3): 176–186. doi:10.2174/1574886313666180605095130. PMID 29866014. S2CID 46934452.

- ^ a b Camino S, Strejilevich SA, Godoy A, Smith J, Szmulewicz A (March 2022). "Are all antidepressants the same? The consumer has a point". Psychol Med: 1–8. doi:10.1017/S0033291722000678. PMID 35346413. S2CID 247777403.

- ^ Garland EJ, Baerg EA (2001). "Amotivational syndrome associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in children and adolescents". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 11 (2): 181–186. doi:10.1089/104454601750284090. PMID 11436958.

- ^ Moncrieff J (October 2015). "Antidepressants: misnamed and misrepresented". World Psychiatry. 14 (3): 302–303. doi:10.1002/wps.20243. PMC 4592647. PMID 26407780.

- ^ Corruble E, de Bodinat C, Belaïdi C, Goodwin GM (November 2013). "Efficacy of agomelatine and escitalopram on depression, subjective sleep and emotional experiences in patients with major depressive disorder: a 24-wk randomized, controlled, double-blind trial". Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 16 (10): 2219–2234. doi:10.1017/S1461145713000679. PMID 23823799.

- ^ Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, Christensen MC (March 2021). "Effectiveness of Vortioxetine on Emotional Blunting in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment". J Affect Disord. 283: 472–479. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.106. PMID 33516560. S2CID 228877905.

- ^ Healy D, Herxheimer A, Menkes DB (September 2006). "Antidepressants and violence: problems at the interface of medicine and law". PLOS Medicine. 3 (9): e372. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030372. PMC 1564177. PMID 16968128.

- ^ Breggin PR, Breggin GR (1995). Talking Back to Prozac. Macmillan Publishers. p. 154. ISBN 978-0312956066.

- ^ Costagliola; Parmeggiani; Semeraro; Sebastiani (December 2008). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a review of its effects on intraocular pressure". Current Neuropharmacology. 6 (4): 293–310. doi:10.2174/157015908787386104. PMC 2701282. PMID 19587851.

- ^ Lochhead, J (September 2015). "SSRI-associated optic neuropathy". Eye (London, England). 29 (9): 1233–1235. doi:10.1038/eye.2015.119. PMC 4565945. PMID 26139049.

- ^ Oh SW, Kim J, Myung SK, Hwang SS, Yoon DH (Mar 20, 2014). "Antidepressant Use and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 78 (4): 727–737. doi:10.1111/bcp.12383. PMC 4239967. PMID 24646010.

- ^ Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, Cohen LS, Holmes LB, Franklin JM, Mogun H, Levin R, Kowal M, Setoguchi S, Hernández-Díaz S (2014). "Antidepressant Use in Pregnancy and the Risk of Cardiac Defects". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (25): 2397–2407. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312828. PMC 4062924. PMID 24941178.

- ^ Goldberg RJ (1998). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: infrequent medical adverse effects". Archives of Family Medicine. 7 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1001/archfami.7.1.78. PMID 9443704.

- ^ FDA (December 2018). "FDA Drug Safety". FDA.

- ^ 시탈로프람과 에스시탈로프람: QT 간격 연장 – 새로운 최대 일일 용량 제한(노인 환자 포함), 금지 사항 및 경고.의약품 및 의료 제품 규제 기관으로부터.문서 날짜:2011년 12월

- ^ "Clinical and ECG Effects of Escitalopram Overdose" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-09-23.

- ^ Pacher P, Ungvari Z, Nanasi PP, Furst S, Kecskemeti V (Jun 1999). "Speculations on difference between tricyclic and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants on their cardiac effects. Is there any?". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (6): 469–480. doi:10.2174/0929867306666220330184544. PMID 10213794. S2CID 28057842.

- ^ Andrade; Sharma (September 2016). "Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Risk of Abnormal Bleeding". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 39 (3): 413–426. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.04.010. PMID 27514297.

- ^ a b Weinrieb RM, Auriacombe M, Lynch KG, Lewis JD (March 2005). "Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and the risk of bleeding". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 4 (2): 337–344. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.2.337. PMID 15794724. S2CID 46551382.

- ^ a b Taylor D, Carol P, Shitij K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0470979693.

- ^ Andrade C, Sandarsh S, Chethan KB, Nagesh KS (December 2010). "Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants and Abnormal Bleeding: A Review for Clinicians and a Reconsideration of Mechanisms". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (12): 1565–1575. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05786blu. PMID 21190637.

- ^ a b de Abajo FJ, García-Rodríguez LA (July 2008). "Risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine therapy: interaction with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and effect of acid-suppressing agents". Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (7): 795–803. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.795. PMID 18606952.

- ^ Hackam DG, Mrkobrada M (2012). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and brain hemorrhage: a meta-analysis". Neurology. 79 (18): 1862–1865. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318271f848. PMID 23077009. S2CID 11941911.

- ^ Serebruany VL (February 2006). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and increased bleeding risk: are we missing something?". The American Journal of Medicine. 119 (2): 113–116. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.044. PMID 16443409.

- ^ Halperin D, Reber G (2007). "Influence of antidepressants on hemostasis". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 9 (1): 47–59. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.1/dhalperin. PMC 3181838. PMID 17506225.

- ^ Andrade C, Sandarsh S, Chethan KB, Nagesh KS (2010). "Serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and abnormal bleeding: a review for clinicians and a reconsideration of mechanisms". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (12): 1565–1575. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05786blu. PMID 21190637.

- ^ de Abajo FJ (2011). "Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on platelet function: mechanisms, clinical outcomes and implications for use in elderly patients". Drugs & Aging. 28 (5): 345–367. doi:10.2165/11589340-000000000-00000. PMID 21542658. S2CID 116561324.

- ^ Eom CS, Lee HK, Ye S, Park SM, Cho KH (May 2012). "Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 27 (5): 1186–1195. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1554. PMID 22258738.

- ^ Bruyère O, Reginster JY (February 2015). "Osteoporosis in patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a focus on fracture outcome". Endocrine. 48 (1): 65–68. doi:10.1007/s12020-014-0357-0. PMID 25091520. S2CID 32286954.

- ^ Hant FN, Bolster MB (April 2016). "Drugs that may harm bone: Mitigating the risk". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 83 (4): 281–288. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.15066. PMID 27055202.

- ^ Fernandes BS, Hodge JM, Pasco JA, Berk M, Williams LJ (January 2016). "Effects of Depression and Serotonergic Antidepressants on Bone: Mechanisms and Implications for the Treatment of Depression". Drugs & Aging. 33 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0323-4. PMID 26547857. S2CID 7648524.

- ^ Nyandege AN, Slattum PW, Harpe SE (April 2015). "Risk of fracture and the concomitant use of bisphosphonates with osteoporosis-inducing medications". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 49 (4): 437–447. doi:10.1177/1060028015569594. PMID 25667198. S2CID 20622369.

- ^ a b Warden SJ, Fuchs RK (October 2016). "Do Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) Cause Fractures?". Current Osteoporosis Reports. 14 (5): 211–218. doi:10.1007/s11914-016-0322-3. PMID 27495351. S2CID 5610316.

- ^ Winterhalder L, Eser P, Widmer J, Villiger PM, Aeberli D (December 2012). "Changes in volumetric BMD of radius and tibia upon antidepressant drug administration in young depressive patients". Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions. 12 (4): 224–229. PMID 23196265.

- ^ Garrett, A. R.; Hawley, J. S. (2018). "SSRI-associated bruxism: A systematic review of published case reports". Neurology. Clinical Practice. 8 (2): 135–141. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000433. ISSN 2163-0402. PMC 5914744. PMID 29708207.

- ^ Prisco, V.; Iannaccone, T.; Di Grezia, G. (2017-04-01). "Use of buspirone in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sleep bruxism". European Psychiatry. Abstract of the 25th European Congress of Psychiatry. 41: S855. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1701. ISSN 0924-9338. S2CID 148816505.

- ^ Albayrak, Yakup; Ekinci, Okan (2011). "Duloxetine-induced nocturnal bruxism resolved by buspirone: case report". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 34 (4): 137–138. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3182227736. ISSN 1537-162X. PMID 21768799.

- ^ a b Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, Rosenbaum JF, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Van Rhoads RS (October 2010). Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (PDF) (third ed.). American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 978-0890423387.[페이지 필요]

- ^ Renoir T (2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant treatment discontinuation syndrome: a review of the clinical evidence and the possible mechanisms involved". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 4: 45. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00045. PMC 3627130. PMID 23596418.

- ^ Volpi-Abadie J, Kaye AM, Kaye AD (2013). "Serotonin syndrome". The Ochsner Journal. 13 (4): 533–540. PMC 3865832. PMID 24358002.

- ^ Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–1120. doi:10.1056/nejmra041867. PMID 15784664. S2CID 37959124.

- ^ Orlova Y, Rizzoli P, Loder E (May 2018). "Association of Coprescription of Triptan Antimigraine Drugs and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor or Selective Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants With Serotonin Syndrome". JAMA Neurology. 75 (5): 566–572. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.5144. PMC 5885255. PMID 29482205.

- ^ Ferri, Fred F. (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1154–1155. ISBN 978-0323448383.

- ^ a b Stone MB, Jones ML (2006-11-17). "Clinical review: relationship between antidepressant drugs and suicidal behavior in adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 11–74. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C (2006-11-17). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 75–140. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ Olfson M, Marcus SC, Shaffer D (August 2006). "Antidepressant drug therapy and suicide in severely depressed children and adults: A case-control study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (8): 865–872. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.865. PMID 16894062.

- ^ Hammad TA (2004-08-16). "Review and evaluation of clinical data. Relationship between psychiatric drugs and pediatric suicidal behavior" (PDF). FDA. pp. 42, 115. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "Antidepressant Use in Children, Adolescents, and Adults". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017.

- ^ "FDA Medication Guide for Antidepressants". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ^ a b Cox GR, Callahan P, Churchill R, Hunot V, Merry SN, Parker AG, Hetrick SE (November 2014). "Psychological therapies versus antidepressant medication, alone and in combination for depression in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (11): CD008324. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008324.pub3. PMC 8556660. PMID 25433518.

- ^ "Overview Depression in adults: recognition and management Guidance NICE". www.nice.org.uk.

- ^ Tauscher-Wisniewski S, Nilsson M, Caldwell C, Plewes J, Allen AJ (October 2007). "Meta-analysis of aggression and/or hostility-related events in children and adolescents treated with fluoxetine compared with placebo". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 17 (5): 713–718. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.0138. PMID 17979590.

- ^ Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ (November 2006). "The relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicide". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (11): 1898–1904. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.11.1898. PMID 17074941. S2CID 2390497.

- ^ "Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants" (PDF). MHRA. 2004-12-01. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents including a summary of available safety and efficacy data". MHRA. 2005-09-29. Archived from the original on 2008-08-02. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D (February 2005). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA's safety review". BMJ. 330 (7488): 385. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.385. PMC 549105. PMID 15718537.

- ^ Fergusson D, Doucette S, Glass KC, Shapiro S, Healy D, Hebert P, Hutton B (February 2005). "Association between suicide attempts and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: systematic review of randomised controlled trials". BMJ. 330 (7488): 396. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.396. PMC 549110. PMID 15718539.

- ^ Rihmer Z, Akiskal H (August 2006). "Do antidepressants t(h)reat(en) depressives? Toward a clinically judicious formulation of the antidepressant-suicidality FDA advisory in light of declining national suicide statistics from many countries". Journal of Affective Disorders. 94 (1–3): 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.003. PMID 16712945.

- ^ Hall WD, Lucke J (2006). "How have the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants affected suicide mortality?". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 40 (11–12): 941–950. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01917.x. PMID 17054562.

- ^ Martínez-Aguayo JC, Arancibia M, Concha S, Madrid E (2016). "Ten years after the FDA black box warning for antidepressant drugs: A critical narrative review". Archives of Clinical Psychiatry. 43 (3): 60–66. doi:10.1590/0101-60830000000086.

- ^ a b Maslej MM, Bolker BM, Russell MJ, Eaton K, Durisko Z, Hollon SD, Swanson GM, Thomson JA, Mulsant BH, Andrews PW (2017). "The Mortality and Myocardial Effects of Antidepressants Are Moderated by Preexisting Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis". Psychother Psychosom. 86 (5): 268–282. doi:10.1159/000477940. PMID 28903117. S2CID 4830115.

- ^ Malm H (December 2012). "Prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and infant outcome". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 34 (6): 607–614. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31826d07ea. PMID 23042258. S2CID 22875385.

- ^ Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M (2006). "Pregnancy outcomes following exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of clinical trials". Reproductive Toxicology. 22 (4): 571–575. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.03.019. PMID 16720091.

- ^ a b Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Hendoiee N, Abdollahi M (2012). "Increasing the risk of spontaneous abortion and major malformations in newborns following use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy: A systematic review and updated meta-analysis". Daru. 20 (1): 75. doi:10.1186/2008-2231-20-75. PMC 3556001. PMID 23351929.

- ^ Eke AC, Saccone G, Berghella V (November 2016). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BJOG. 123 (12): 1900–1907. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14144. PMID 27239775.

- ^ Einarson TR, Kennedy D, Einarson A (2012). "Do findings differ across research design? The case of antidepressant use in pregnancy and malformations". Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology. 19 (2): e334–348. PMID 22946124.

- ^ Riggin L, Frankel Z, Moretti M, Pupco A, Koren G (April 2013). "The fetal safety of fluoxetine: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 35 (4): 362–369. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30965-8. PMID 23660045.

- ^ Koren G, Nordeng HM (February 2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and malformations: case closed?". Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 18 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2012.10.004. PMID 23228547.

- ^ "Breastfeeding Update: SDCBC's quarterly newsletter". Breastfeeding.org. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "Using Antidepressants in Breastfeeding Mothers". kellymom.com. Archived from the original on 2010-09-23. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Gentile S, Rossi A, Bellantuono C (2007). "SSRIs during breastfeeding: spotlight on milk-to-plasma ratio". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 10 (2): 39–51. doi:10.1007/s00737-007-0173-0. PMID 17294355. S2CID 757921.

- ^ Fenger-Grøn J, Thomsen M, Andersen KS, Nielsen RG (September 2011). "Paediatric outcomes following intrauterine exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a systematic review". Danish Medical Bulletin. 58 (9): A4303. PMID 21893008.

- ^ Kieviet N, Dolman KM, Honig A (2013). "The use of psychotropic medication during pregnancy: how about the newborn?". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 9: 1257–1266. doi:10.2147/NDT.S36394. PMC 3770341. PMID 24039427.

- ^ eMedicine 지속성 신생아 폐고혈압

- ^ Grigoriadis S, Vonderporten EH, Mamisashvili L, Tomlinson G, Dennis CL, Koren G, Steiner M, Mousmanis P, Cheung A, Ross LE (2014). "Prenatal exposure to antidepressants and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 348: f6932. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6932. PMC 3898424. PMID 24429387.

- ^ 't Jong GW, Einarson T, Koren G, Einarson A (November 2012). "Antidepressant use in pregnancy and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN): a systematic review". Reproductive Toxicology. 34 (3): 293–297. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.04.015. PMID 22564982.

- ^ Gentile S (August 2015). "Prenatal antidepressant exposure and the risk of autism spectrum disorders in children. Are we looking at the fall of Gods?". Journal of Affective Disorders. 182: 132–137. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.048. PMID 25985383.

- ^ Hviid A, Melbye M, Pasternak B (December 2013). "Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and risk of autism". The New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (25): 2406–2415. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301449. PMID 24350950. S2CID 9064353.

- ^ a b Malm H, Brown AS, Gissler M, Gyllenberg D, Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S, McKeague IW, Weissman M, Wickramaratne P, Artama M, Gingrich JA, Sourander A, et al. (May 2016). "Gestational Exposure to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Offspring Psychiatric Disorders: A National Register-Based Study". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 55 (5): 359–366. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2016.02.013. PMC 4851729. PMID 27126849.

- ^ a b c Isbister GK, Bowe SJ, Dawson A, Whyte IM (2004). "Relative toxicity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in overdose". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 42 (3): 277–285. doi:10.1081/CLT-120037428. PMID 15362595. S2CID 43121327.

- ^ Borys DJ, Setzer SC, Ling LJ, Reisdorf JJ, Day LC, Krenzelok EP (1992). "Acute fluoxetine overdose: a report of 234 cases". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 10 (2): 115–120. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(92)90041-U. PMID 1586402.

- ^ Oström M, Eriksson A, Thorson J, Spigset O (1996). "Fatal overdose with citalopram". Lancet. 348 (9023): 339–340. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64513-8. PMID 8709713. S2CID 5287418.

- ^ Sporer KA (August 1995). "The serotonin syndrome. Implicated drugs, pathophysiology and management". Drug Safety. 13 (2): 94–104. doi:10.2165/00002018-199513020-00004. PMID 7576268. S2CID 19809259.

- ^ Gitlin, Michael J. (2018-12-01). "Antidepressants in bipolar depression: an enduring controversy". International Journal of Bipolar Disorders. 6 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0133-9. ISSN 2194-7511. PMC 6269438. PMID 30506151.

- ^ Viktorin, Alexander; Lichtenstein, Paul; Thase, Michael E.; Larsson, Henrik; Lundholm, Cecilia; Magnusson, Patrik K. E.; Landén, Mikael (2014). "The risk of switch to mania in patients with bipolar disorder during treatment with an antidepressant alone and in combination with a mood stabilizer". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 171 (10): 1067–1073. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111501. ISSN 1535-7228. PMID 24935197. S2CID 25152608.

- ^ Walkup J, Labellarte M (2001). "Complications of SSRI Treatment". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 11 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1089/104454601750143320. PMID 11322738.

- ^ Ener RA, Meglathery SB, Van Decker WA, Gallagher RM (March 2003). "Serotonin syndrome and other serotonergic disorders". Pain Medicine. 4 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03005.x. PMID 12873279.

- ^ Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–1120. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664. S2CID 37959124.

- ^ Warner-Schmidt JL, Vanover KE, Chen EY, Marshall JJ, Greengard P (May 2011). "Antidepressant effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are attenuated by antiinflammatory drugs in mice and humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (22): 9262–9267. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104836108. PMC 3107316. PMID 21518864.

- ^ Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0071624428.

- ^ Ciraulo DA, Shader RI (2011). Ciraulo DA, Shader RI (eds.). Pharmacotherapy of Depression (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 49. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-435-7. ISBN 978-1603274357.

- ^ Jeppesen U, Gram LF, Vistisen K, Loft S, Poulsen HE, Brøsen K (1996). "Dose-dependent inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 by citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetine". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 51 (1): 73–78. doi:10.1007/s002280050163. PMID 8880055. S2CID 19802446.

- ^ Overholser BR, Foster DR (September 2011). "Opioid pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions". The American Journal of Managed Care. 17 (Suppl 11): S276–287. PMID 21999760.

- ^ "Paroxetine hydrochloride – Drug Summary". Physicians' Desk Reference, LLC. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- ^ Smith HS (July 2009). "Opioid metabolism". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 84 (7): 613–624. doi:10.4065/84.7.613. PMC 2704133. PMID 19567715.

- ^ Wiley K, Regan A, McIntyre P (August 2017). "Immunisation and pregnancy – who, what, when and why?". Australian Prescriber. 40 (4): 122–124. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2017.046. PMC 5601969. PMID 28947846.

- ^ Weaver JM (2013). "New FDA black box warning for codeine: how will this affect dentists?". Anesthesia Progress. 60 (2): 35–36. doi:10.2344/0003-3006-60.2.35. PMC 3683877. PMID 23763556.

- ^ Kelly CM, Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Duong-Hua M, Pritchard KI, Austin PC, Paszat LF (February 2010). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and breast cancer mortality in women receiving tamoxifen: a population based cohort study". BMJ. 340: c693. doi:10.1136/bmj.c693. PMC 2817754. PMID 20142325.

- ^ a b c d Shelton RC (2009). "Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors: similarities and differences". Primary Psychiatry. 16 (4): 25.

- ^ Montgomery, Stuart A. (July 2008). "Tolerability of serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants". CNS Spectrums. 13 (7 Suppl 11): 27–33. doi:10.1017/s1092852900028297. ISSN 1092-8529. PMID 18622372. S2CID 24692832.

- ^ Waller DG, Sampson T (2017). Medical Pharmacology and Therapeutics E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-0702071904.

- ^ Kornstein SG, Clayton AH (2010). Women's Mental Health, An Issue of Psychiatric Clinics – E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 389–. ISBN 978-1455700615.

- ^ Bruno A, Morabito P, Spina E, Muscatello MR (2016). "The Role of Levomilnacipran in the Management of Major Depressive Disorder: A Comprehensive Review". Current Neuropharmacology. 14 (2): 191–199. doi:10.2174/1570159x14666151117122458. PMC 4825949. PMID 26572745.

- ^ a b Mandrioli R, Protti M, Mercolini L (2018). "New-Generation, non-SSRI Antidepressants: Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Pharmacological Interactions. Part 1: SNRIs, SMSs, SARIs". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 24 (7): 772–792. doi:10.2174/0929867324666170712165042. PMID 28707591.

- ^ a b Ayd FJ (2000). Lexicon of Psychiatry, Neurology, and the Neurosciences. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 581–. ISBN 978-0781724685.

- ^ a b Progress in Drug Research. Birkhäuser. 2012. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-3034883917.

- ^ a b Moltzen EK, Bang-Andersen B (2006). "Serotonin reuptake inhibitors: the corner stone in treatment of depression for half a century – a medicinal chemistry survey". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (17): 1801–1823. doi:10.2174/156802606778249810. PMID 17017959.

- ^ a b Haddad PM (1999). "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) Past, Present and Future. Edited by S. Clare Standford, R.G. Landes Company". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. Austin, Texas. 15 (6): 471. doi:10.1002/1099-1077(200008)15:6<471::AID-HUP211>3.0.CO;2-4. ISBN 1570596492.

- ^ Goodman LS, Brunton LL, Chabner B, Knollmann BC (2001). Goodman and Gilman's pharmacological basis of therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 459–461. ISBN 978-0071624428.

- ^ a b 콜브, 브라이언, 위쇼 이안.뇌와 행동에 대한 입문뉴욕: Walse Publishers 2006, Print.

- ^ O'Brien FE, O'Connor RM, Clarke G, Dinan TG, Griffin BT, Cryan JF (October 2013). "P-glycoprotein inhibition increases the brain distribution and antidepressant-like activity of escitalopram in rodents". Neuropsychopharmacology. 38 (11): 2209–2219. doi:10.1038/npp.2013.120. PMC 3773671. PMID 23670590.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hindmarch I, Hashimoto K (April 2010). "Cognition and depression: the effects of fluvoxamine, a sigma-1 receptor agonist, reconsidered". Human Psychopharmacology. 25 (3): 193–200. doi:10.1002/hup.1106. PMID 20373470. S2CID 26491662.

- ^ a b c d e f g Albayrak Y, Hashimoto K (2017). "Sigma-1 Receptor Agonists and Their Clinical Implications in Neuropsychiatric Disorders". Sigma Receptors: Their Role in Disease and as Therapeutic Targets. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 964. pp. 153–161. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50174-1_11. ISBN 978-3319501727. PMID 28315270.

- ^ Kishimoto A, Todani A, Miura J, Kitagaki T, Hashimoto K (May 2010). "The opposite effects of fluvoxamine and sertraline in the treatment of psychotic major depression: a case report". Annals of General Psychiatry. 9: 23. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-9-23. PMC 2881105. PMID 20492642.

- ^ Bafna SL, Patel DJ, Mehta JD (August 1972). "Separation of ascorbic acid and 2-keto-L-gulonic acid". Current Neuropharmacology. 61 (8): 1333–1334. doi:10.2174/1570159X14666151208113700. PMC 5050394. PMID 27640518.

- ^ Köhler S, Cierpinsky K, Kronenberg G, Adli M (January 2016). "The serotonergic system in the neurobiology of depression: Relevance for novel antidepressants". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 30 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1177/0269881115609072. PMID 26464458. S2CID 21501578.

- ^ Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Stubbs B, Maes M, Solmi M, Veronese N, de Andrade NQ, Morris G, Fernandes BS, Brunoni AR, Herrmann N, Raison CL, Miller BJ, Lanctôt KL, Carvalho AF (May 2018). "Peripheral Alterations in Cytokine and Chemokine Levels After Antidepressant Drug Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Molecular Neurobiology. 55 (5): 4195–4206. doi:10.1007/s12035-017-0632-1. PMID 28612257. S2CID 4040496.

- ^ Więdłocha M, Marcinowicz P, Krupa R, Janoska-Jaździk M, Janus M, Dębowska W, Mosiołek A, Waszkiewicz N, Szulc A (January 2018). "Effect of antidepressant treatment on peripheral inflammation markers – A meta-analysis". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 80 (Pt C): 217–226. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.04.026. PMID 28445690. S2CID 34659323.

- ^ Vogelzangs N, Duivis HE, Beekman AT, Kluft C, Neuteboom J, Hoogendijk W, Smit JH, de Jonge P, Penninx BW (February 2012). "Association of depressive disorders, depression characteristics and antidepressant medication with inflammation". Translational Psychiatry. 2 (2): e79. doi:10.1038/tp.2012.8. PMC 3309556. PMID 22832816.

- ^ a b Kalkman HO, Feuerbach D (July 2016). "Antidepressant therapies inhibit inflammation and microglial M1-polarization". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 163: 82–93. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.04.001. PMID 27101921.

- ^ a b Nazimek K, Strobel S, Bryniarski P, Kozlowski M, Filipczak-Bryniarska I, Bryniarski K (June 2017). "The role of macrophages in anti-inflammatory activity of antidepressant drugs". Immunobiology. 222 (6): 823–830. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2016.07.001. PMID 27453459.

- ^ a b Gobin V, Van Steendam K, Denys D, Deforce D (May 2014). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a novel class of immunosuppressants". International Immunopharmacology. 20 (1): 148–156. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2014.02.030. PMID 24613205.

- ^ Kang, Peter B.; Draper, Isabelle; Alexander, Matthew S.; Wagner, Richard E.; Pacak, Christina A.; Chahin, Nizar; Berg, Jonathan S.; Finkel, Richard S.; Terada, Naohiro (2019). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors ameliorate MEGF10 myopathy". Human Molecular Genetics. 28 (14): 2365–2377. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddz064. PMC 6606856. PMID 31267131.

- ^ Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, McAlpine DD (2007). "Genetic screening for SSRI drug response among those with major depression: great promise and unseen perils". Depression and Anxiety. 24 (5): 350–357. doi:10.1002/da.20251. PMID 17096399. S2CID 24257390.

- ^ Anderson IM (April 2000). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability". Journal of Affective Disorders. 58 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00092-0. PMID 10760555.

- ^ Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R (January 2008). "Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (3): 252–260. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.486.455. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa065779. PMID 18199864.

- ^ Ebrahim S, Bance S, Athale A, Malachowski C, Ioannidis JP (February 2016). "Meta-analyses with industry involvement are massively published and report no caveats for antidepressants". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 70: 155–163. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.021. PMID 26399904.

- ^ Moncrieff, Joanna; Cooper, Ruth E.; Stockmann, Tom; Amendola, Simone; Hengartner, Michael P.; Horowitz, Mark A. (2022-07-20). "The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence". Molecular Psychiatry: 1–14. doi:10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0. ISSN 1476-5578.

- ^ Healy D, Aldred G (June 2005). "Antidepressant drug use & the risk of suicide". International Review of Psychiatry. 17 (3): 163–172. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.482.5522. doi:10.1080/09540260500071624. PMID 16194787. S2CID 6599566.

- ^ Lapierre YD (September 2003). "Suicidality with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Valid claim?". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 28 (5): 340–347. PMC 193980. PMID 14517577.

- ^ Khan A, Khan S, Kolts R, Brown WA (April 2003). "Suicide rates in clinical trials of SSRIs, other antidepressants, and placebo: analysis of FDA reports". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (4): 790–792. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.790. PMID 12668373. S2CID 20755149.

- ^ Kaizar EE, Greenhouse JB, Seltman H, Kelleher K (2006). "Do antidepressants cause suicidality in children? A Bayesian meta-analysis". Clinical Trials. 3 (2): 73–90, discussion 91–8. doi:10.1191/1740774506cn139oa. PMID 16773951. S2CID 41954145.

- ^ Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Davis J, Mann JJ (June 2012). "Suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant treatment: reanalysis of the randomized placebo-controlled studies of fluoxetine and venlafaxine". Archives of General Psychiatry. 69 (6): 580–587. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2048. PMC 3367101. PMID 22309973.