런던

London런던 | |

|---|---|

| 좌표: 51°30'26 ″ N 0°7′39″W / 51.50722°N 0.12750°W | |

| 주권국 | 영국 |

| 나라 | 잉글랜드 |

| 지역 | 런던(그레이터런던) |

| 의령군 | 그레이터런던 (제정군) 시티 오브 런던 |

| 지방자치구 | 32개의 런던 자치구 그리고 런던시. |

| 로마인이 정착함 | AD 47년;[2] as Londinium |

| 정부 | |

| • 유형 | 행정부시장 및 심의회 |

| • 몸 | 런던 당국 • 사디크 칸 시장 (L) • 런던 의회 |

| • 런던 의회 | 14개 선거구 |

| • 영국 의회 | 73개 선거구 |

| 지역 | |

| • 합계[A] | 606.96 sq mi (1,572.03 km2) |

| • 어반 | 671.0 sq mi (1,737.9 km2) |

| • 메트로 | 3,236 sq mi (8,382 km2) |

| • 시티 오브 런던 | 1.12 sq mi (2.89 km2) |

| • 32개 런던 자치구 (총) | 605.85 sq mi (1,569.14 km2) |

| 승진 | 36피트 (11m) |

| 인구. (2021년 별도) | |

| • 합계[A] | 8,799,800[1] |

| • 밀도 | 14,500/sq mi (5,598/km2) |

| • 어반 (2011)[4] | 9,787,426 |

| • 메트로 (2023)[5] | 14,800,000(런던 대도시권) |

| • 시티 오브 런던 | 8,600[1] |

| 어원 | 런던너 |

| GVA (2021년) | |

| • 합계 | 4,870억 파운드 |

| • 인당 | £55,412 |

| 시간대 | UTC(그리니치 표준시) |

| • 여름(DST) | UTC+1 (영국 여름 시간) |

| 우편번호 영역 | |

| 예산. | 193억 7600만 파운드 250억달러([7]약 25조원) |

| 국제공항 | 런던 내부: 히드로(LHR) 도시(LCY) 런던 외부: 개트윅(LGW) 스탠스테드(STN) 루톤(LTN) 사우스엔드(SEN) |

| 쾌속환승시스템 | 런던 지하철 |

| 경찰 | 메트로폴리탄 (그레이터런던 주) City of London (City of London square mile) |

| 앰뷸런스 | 런던 |

| 불 | 런던 |

| 지오티엘디 | .london |

| 웹사이트 | www |

런던은 영국의 수도이자 가장 큰 도시이며, 인구는 약 880만 명이며,[1] 수도권 기준 서유럽에서 가장 큰 도시이며, 인구는 1,480만 명입니다.[9][note 1] 이 강은 영국 남동쪽 템스 강에 위치해 있으며 북해까지 50마일(80km)의 하구 끝에 있으며 거의 2천년 동안 주요 정착지였습니다.[10] 고대 핵심이자 금융의 중심지인 런던시는 로마인들에 의해 론디니움으로 세워졌으며 중세의 경계를 유지하고 있습니다.[note 2][11] 런던의 서쪽에 있는 웨스트민스터 시는 수세기 동안 국가 정부와 의회를 주최해 왔습니다. 19세기 이래로 "[12]런던"이라는 이름은 역사적으로 미들섹스, 에섹스, 서리, 켄트, 하트퍼드셔 주로 나뉘어진 이 중심부를 둘러싼 대도시를 가리키기도 하는데,[13] 1965년부터 주로 33개 지방 당국과 대런던 당국이 통치하는 [14]대런던으로 구성되어 있습니다.[note 3][15]

세계 주요 글로벌 도시 [16]중 하나로서 런던은 세계 예술, 엔터테인먼트, 패션, 상업 및 금융, 교육, 의료, 미디어, 과학 및 기술, 관광, 교통 및 커뮤니케이션에 강력한 영향력을 행사하고 있습니다.[17][18] 브렉시트 이후 런던 증권거래소에서 주식 상장이 이탈했음에도 불구하고,[19] 런던은 여전히 유럽에서 가장 경제적으로 강력한 도시 중 하나이며,[20] 세계 주요 금융 중심지 중 하나로 남아 있습니다. 유럽에서 가장 큰 고등 교육 기관이 집중되어 [21]있는 이곳은 자연 과학 및 응용 과학 분야의 Imperial College London, 사회 과학 분야의 London School of Economics, 그리고 종합적인 University College London의 본거지입니다.[22][23] 런던은 유럽에서 가장 많은 사람들이 방문하는 도시이고 세계에서 가장 바쁜 도시 공항 시스템을 가지고 있습니다.[24] 런던 지하철은 세계에서 가장 오래된 고속 교통 시스템입니다.[25]

런던의 다양한 문화는 300개 이상의 언어를 포함합니다.[26] 그레이터런던의 2023년 인구는 1,000만[27] 명이 채 되지 않아 영국[29] 인구의 13.4%, 영국 인구의 16% 이상을 [28]차지하며 유럽에서 세 번째로 인구가 많은 도시가 되었습니다. 그레이터 런던 빌딩 지역은 유럽에서 네 번째로 인구가 많은 지역으로, 2011년 인구 조사에서 약 980만 명의 주민이 살고 있습니다.[30][31] 런던 대도시권은 유럽에서 세 번째로 인구가 많은 지역으로, 2016년에 약 1,400만 명이 거주하여 [note 4][32][33]런던에 메가시티의 지위를 부여했습니다.

런던에는 런던의 탑, 큐 가든, 웨스트민스터 궁전, 웨스트민스터 사원, 세인트 마가렛 교회의 결합된 세계 문화 유산, 그리니치 왕립 천문대가 본초 자오선(경도 0°)과 그리니치 표준시를 정의하는 그리니치의 역사적 정착지 등 네 곳이 있습니다.[34] 다른 랜드마크로는 버킹엄 궁전, 런던 아이, 피카딜리 서커스, 세인트 폴 대성당, 타워 브리지, 트라팔가 광장 등이 있습니다. 런던에는 대영 박물관, 국립 갤러리, 자연사 박물관, 테이트 모던, 대영 도서관 및 수많은 웨스트엔드 극장을 포함한 많은 박물관, 갤러리, 도서관 및 문화 행사장이 있습니다.[35] 런던에서 열리는 중요한 스포츠 행사로는 FA컵 결승전, 윔블던 테니스 선수권 대회, 런던 마라톤 등이 있습니다. 2012년, 런던은 세 번의 하계 올림픽을 개최한 첫 번째 도시가 되었습니다.[36]

토노니미

런던은 서기 1세기에 증명된 고대의 이름으로, 보통 라틴어화된 형태의 런던입니다.[37] 이 이름에 대한 현대 과학적 분석은 초기 소스에서 발견된 다양한 형태의 기원을 설명해야 합니다. 라틴어(보통 론디늄), 고대 영어(보통 룬덴), 웨일스어(보통 룬딘). 이러한 다양한 언어에서 소리의 시간에 따른 알려진 발전과 관련하여. 이 이름은 커먼 브라이토닉에서 온 것으로 동의되며, 최근 연구에서는 잃어버린 켈트어 형태의 이름을 *런던존 또는 이와 유사한 것으로 재구성하는 경향이 있습니다. 이것은 라틴어로 Londinium으로 각색되었고 구영어로 차용되었습니다.[38]

1889년까지 "런던"이라는 이름은 공식적으로 런던시에만 적용되었지만, 그 이후로 런던 카운티와 그레이터 런던에도 적용되었습니다.[39]

역사

선사시대

1993년, 복스홀 다리에서 상류의 남쪽 해안에서 청동기 시대 다리의 잔해가 발견되었습니다.[40] 목재 중 두 개는 기원전 1750년에서 1285년 사이의 방사성 탄소였습니다.[40] 2010년, 보홀 다리에서 하류에 있는 템스 강 남쪽 해안에서 기원전 4800년에서 4500년 사이의 거대한 목재 구조물의 기초가 발견되었습니다.[41][42] 두 건축물 모두 템스 강 남쪽 둑에 있는데, 지금은 지하에 있는 에프라 강이 템스 강으로 흘러들어갑니다.[42]

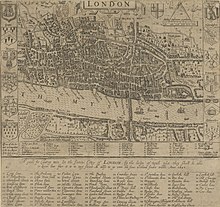

로만 런던

이 지역에 흩어져 있는 브라이토닉 정착지의 증거에도 불구하고, 최초의 주요 정착지는 로마인들에 의해 서기 43년 침공 후 약 4년 [2]후인 서기 47년경에 세워졌습니다.[43] 이것은 서기 61년경 부디카 여왕이 이끄는 이케니 부족이 습격하여 땅에 불태울 때까지만 지속되었습니다.[44]

다음으로 계획된 론디늄의 화신은 번성했고, 콜체스터를 제치고 100년 로마 브리타니아 지방의 주요 도시가 되었습니다. 2세기에 로마 런던의 인구는 약 60,000명이었습니다.[45]

앵글로색슨과 바이킹 시대의 런던

5세기 초 로마의 지배가 무너지면서, 로마 문명은 450년 정도까지 세인트 마틴 인 더 필즈 주변에서 계속되었지만, 성벽으로 둘러싸인 도시 론디니움은 사실상 버려졌습니다.[46] 약 500년부터 룬덴비크로 알려진 앵글로색슨족의 정착지가 옛 로마 도시의 약간 서쪽에서 발달했습니다.[47] 약 680년까지 도시는 다시 주요 항구가 되었지만 대규모 생산에 대한 증거는 거의 없습니다. 820년대부터 반복된 바이킹의 공격은 쇠퇴를 가져왔습니다. 851년과 886년에 성공한 사람들과 994년에 마지막 사람들은 퇴짜를 맞았습니다.[48]

바이킹족은 886년 덴마크 군벌 구스룸과 서색슨족 왕 알프레드 대왕이 공식적으로 합의한 바이킹의 침략에 의해 부과된 정치적, 지리적 통제의 지역으로서 런던에서 체스터까지 대략 경계를 넘어 잉글랜드 동부와 북부 대부분 지역에 덴마크를 적용했습니다. 앵글로색슨 크로니클은 알프레드가 886년에 런던을 근거지로 삼았다고 기록하고 있습니다. 고고학 연구에 따르면 룬덴비크의 포기와 옛 로마 성벽 내의 생명과 무역의 부활이 관련되어 있습니다. 그 후 런던은 약 950년에 극적으로 증가할 때까지 천천히 성장했습니다.[49]

11세기까지 런던은 분명히 영국에서 가장 큰 마을이었습니다. 고백왕 에드워드에 의해 로마네스크 양식으로 재건된 웨스트민스터 사원은 유럽에서 가장 웅장한 교회 중 하나였습니다. 윈체스터는 앵글로색슨 잉글랜드의 수도였지만, 이 때부터 런던은 외국 무역상들의 주요 토론장이자 전쟁 시 방어의 기지가 되었습니다. 프랭크 스탠턴의 견해에 따르면, "그것은 자원을 가지고 있었고, 그것은 국가 수도에 적합한 존엄성과 정치적 자의식을 빠르게 발전시키고 있었습니다."[50]

중세

헤이스팅스 전투에서 승리한 노르망디 공작 윌리엄은 1066년 크리스마스에 새로 완공된 웨스트민스터 사원에서 영국의 왕으로 즉위했습니다.[51] 윌리엄은 주민들을 위협하기 위해 런던의 탑을 세웠는데, 런던의 남동쪽 구석에 돌로 재건된 영국의 많은 탑들 중 첫 번째 탑입니다.[52] 1097년 윌리엄 2세는 같은 이름의 사원 근처에 있는 웨스트민스터 홀을 짓기 시작했습니다. 그것은 새로운 웨스트민스터 궁전의 기초가 되었습니다.[53]

12세기에 지금까지 영국 왕실을 따라다니던 중앙 정부의 기관들은 규모와 정교함이 커졌고 대부분의 목적으로 웨스트민스터에서 점점 더 고정되었습니다. 비록 왕실의 재정이 타워에서 쉬게 되었지만 말입니다. 웨스트민스터시가 진정한 정부의 수도로 발전하는 동안, 그 뚜렷한 이웃인 런던시는 영국의 가장 큰 도시이자 주요 상업 중심지로 남아 있었고, 그 고유의 독특한 행정인 런던 법인 아래 번성했습니다. 1100년에는 약 18,000명이었고 1300년에는 거의 100,000명으로 증가했습니다.[54] 14세기 중반 흑사병으로 런던은 인구의 거의 3분의 1을 잃었습니다.[55] 런던은 1381년 농민 반란의 중심지였습니다.[56]

런던은 1290년 에드워드 1세에 의해 추방되기 전 영국의 유대인 인구의 중심지였습니다. 유대인들에 대한 폭력은 1190년에 일어났는데, 그들이 그의 대관식에 참석한 후에 새로운 왕이 그들의 학살을 명령했다는 소문이 퍼졌습니다.[57] 1264년 시몬 드 몽포르의 반란군은 유대인 500명을 살해하고, 제2차 남작 전쟁을 치렀습니다.[58]

근대 초기

종교개혁은 튜더 시기에 개신교로 점진적인 변화를 가져왔습니다. 런던의 많은 재산이 교회에서 개인 소유로 넘어갔고, 이것은 런던의 무역과 사업을 가속화시켰습니다.[59] 1475년, 한자 동맹은 런던에 스털호프 혹은 스틸야드라고 불리는 영국의 주요 무역 기지(콘토르)를 세웠습니다. 1853년 한자 도시인 뤼벡, 브레멘, 함부르크가 사우스이스턴 철도에 재산을 매각할 때까지 남아있었습니다.[60] 울렌 천은 14세기/15세기 런던에서 염색되지 않고 옷을 벗은 채 로우 컨트리의 인근 해안으로 운송되었습니다.[61]

그러나 영국의 해양기업은 북서유럽의 바다를 넘어서 거의 도달하지 못했습니다. 이탈리아와 지중해로 가는 상업적인 경로는 보통 앤트워프를 거쳐 알프스를 넘었고, 지브롤터 해협을 통과하거나 영국에서 오는 모든 배는 이탈리아나 라구산이 될 가능성이 높았습니다. 1565년 1월에 네덜란드가 영국 선적으로 다시 문을 열면서 상업 활동이 폭발적으로 증가했습니다.[62] 왕실 거래소가 설립되었습니다.[63] 신대륙으로 무역이 확대되면서 중상주의가 성장하고 동인도회사와 같은 독점 무역상이 설립되었습니다. 런던은 영국과 해외에서 이주자들이 도착하면서 북해의 주요 항구가 되었습니다. 인구는 1530년 약 5만명에서 1605년 약 225,000명으로 증가했습니다.[59]

16세기에 윌리엄 셰익스피어와 그의 동시대 사람들은 영국 르네상스 시대에 런던에 살았습니다. 셰익스피어의 글로브 극장은 1599년 사우스워크에 지어졌습니다. 런던에서 무대 공연은 청교도 당국이 1640년대와 1650년대에 극장들을 폐쇄하면서 중단되었습니다.[64] 연극 금지는 1660년 복고 왕정복고 때 해제되었고, 런던에서 가장 오래된 극장인 드루리 레인은 현재 웨스트 엔드 극장 구역에 1663년에 문을 열었습니다.[65]

1603년 튜더 시대가 끝날 무렵, 런던은 여전히 아담했습니다. 1605년 11월 5일 웨스트민스터에서 제임스 1세에 대한 암살 시도가 있었습니다.[66] 1637년 찰스 1세의 정부는 런던 지역의 행정을 개혁하려고 시도했습니다. 이것은 도시공사가 도시 주변 지역을 확장하는 것에 대한 관할권과 행정권을 확장할 것을 요구했습니다. 런던의 자유를 축소하려는 왕실의 시도를 두려워한 나머지, 이러한 추가적인 지역을 관리하는 데 관심이 없거나 권력을 공유해야 하는 도시 길드의 우려로 인해, 도시의 독특한 정부적 지위를 계속 설명하는 회사의 "위대한 거부"가 발생했습니다.[67]

영국 내전에서 대다수의 런던 시민들은 의회의 대의를 지지했습니다. 1642년 왕당파의 초기 진격으로 브렌트포드 전투와 턴햄 그린 전투가 절정에 달한 후, 런던은 통신선으로 알려진 방어벽으로 둘러싸여 있었습니다. 이 라인은 최대 20,000명이 건설했으며 두 달도 안 되어 완공되었습니다.[68] 이 요새들은 1647년 뉴모던군이 런던에 입성했을 때 유일한 시험에 실패했고,[69] 같은 해 의회에 의해 평준화되었습니다.[70]

런던은 17세기 초에 질병에 시달렸고,[71] 1665년에서 1666년 사이에 최대 10만 명, 즉 인구의 5분의 1에 해당하는 사람들이 사망한 대역병이 절정에 달했습니다.[71]

런던 대화재는 1666년 런던의 푸딩 레인에서 발생했고 나무로 된 건물들을 빠르게 휩쓸었습니다.[72] 재건은 10년이 넘게 걸렸고, 폴리매스 로버트 훅이 감독했습니다.[73] 1708년 크리스토퍼 렌의 걸작인 성 바오로 대성당이 완성되었습니다. 조지아 시대 동안 서쪽에 메이페어와 같은 새로운 지구가 형성되었고 템스 강 위의 새로운 다리가 런던 남부의 발전을 장려했습니다. 동쪽으로는 런던항이 하류로 확장되었습니다. 국제 금융 중심지로서의 런던의 발전은 18세기의 많은 기간 동안 성숙해졌습니다.[74]

1762년 조지 3세는 버킹엄 하우스를 인수했고, 그 후 75년 동안 확장되었습니다. 18세기 동안, 런던은 범죄에 시달린다고 전해졌고,[75] 보우 스트리트 러너스는 전문 경찰로서 1750년에 설립되었습니다.[76] 1720~30년대 전염병으로 인해 도시에서 태어난 대부분의 아이들은 다섯 번째 생일이 되기 전에 사망했습니다.[77]

커피 하우스는 아이디어를 토론하는 인기 있는 장소가 되었고, 인쇄술의 성장과 발전은 플리트 스트리트가 영국 언론의 중심이 되면서 뉴스를 널리 이용할 수 있게 되었습니다. 나폴레옹 군대의 암스테르담 침공으로 인해 많은 재정가들이 런던으로 이주했고 1817년 첫 번째 런던 국제 문제가 마련되었습니다. 비슷한 시기에 영국 해군은 잠재적인 경제적 적들에 대한 주요한 억제책으로 작용하면서 세계의 선두적인 전쟁 함대가 되었습니다. 1846년 옥수수법의 폐지는 특히 네덜란드의 경제력을 약화시키기 위한 것이었습니다. 그 후 런던은 암스테르담을 제치고 세계 최고의 금융 중심지가 되었습니다.[78]

근현대 후기

영국의 산업혁명이 시작되면서 도시화의 전례 없는 성장이 이루어졌고, 하이 스트리트(영국의 소매업을 위한 주요 거리)의 수가 급격히 증가했습니다.[79][80] 런던은 약 1831년부터 1925년까지 세계에서 가장 큰 도시였으며, 인구 밀도는 에이커당 802명(헥타르당 325명)이었습니다.[81] 하딩, 하웰앤코와 같이 상품을 판매하는 매장이 늘어나고 있는 것 외에도.—Pall Mall에 위치한 최초의 백화점 중 하나로, 거리에는 수많은 노점상들이 있었습니다.[79] 런던의 과밀한 환경은 콜레라 전염병으로 이어졌고, 1848년에는 14,000명이 목숨을 잃었고, 1866년에는 6,000명이 목숨을 잃었습니다.[82] 증가하는 교통 체증은 세계 최초의 도시 철도 네트워크를 만들었습니다.[83] 메트로폴리탄 작업 위원회는 수도와 일부 주변 카운티의 인프라 확장을 감독했습니다. 1889년 런던 카운티 의회가 수도를 둘러싼 카운티 지역에서 만들어지면서 폐지되었습니다.[84]

20세기 초부터 런던과 영국의 나머지 지역의 하이 스트리트에서 찻집이 발견되었으며, 1894년 피카딜리에서 찻집 체인점의 첫 번째를 연 라이언스(Lyons)가 선두를 달렸습니다.[85] 피카딜리의 기준(Criterion in Piccadilly)과 같은 다방은 참정권 운동 여성들의 인기 있는 만남의 장소가 되었습니다.[86] 1912년에서 1914년 사이 웨스트민스터 사원과 성 바오로 대성당과 같은 역사적인 건물들이 폭격을 당한 참혹한 폭격과 방화 캠페인 동안 도시는 많은 공격의 대상이었습니다.[87]

런던은 제1차 세계 대전에서 독일군에 의해 폭격을 당했고, 제2차 세계 대전 동안 독일 루프트바페의 블리츠와 다른 폭격으로 30,000명 이상의 런던 사람들이 사망했고, 도시 전역의 많은 주택과 다른 건물들이 파괴되었습니다.[88] 1920년 11월 11일 웨스트민스터 사원에 묻힌, 제1차 세계대전 당시 사망한 영국군의 신원 미상의 전사의 무덤.[89] 화이트홀에 위치한 세노타프는 이날 공개됐으며, 매년 11월 11일과 가장 가까운 일요일인 '추모의 일요일'에 열리는 국가추모의 초점입니다.[90]

1948년 하계 올림픽은 원래의 웸블리 경기장에서 열렸고, 런던은 여전히 전쟁에서 회복하고 있었습니다.[91] 1940년대부터, 런던은 주로 자메이카, 인도, 방글라데시, 파키스탄과 같은 영연방 국가들로부터 온 많은 이민자들의 고향이 되었고,[92] 런던을 세계에서 가장 다양한 도시들 중 하나로 만들었습니다. 1951년, 영국의 축제가 사우스 뱅크에서 열렸습니다.[93] 1952년의 대스모그는 1956년 청정대기법으로 이어졌고, 이것은 런던이 악명높았던 "완두콩 수프 안개"를 끝내고 "큰 연기"라는 별명을 얻었습니다.[94]

1960년대 중반에 시작된 런던은 킹스 로드, 첼시, 카나비 스트리트와 관련된 스윙잉 런던 하위 문화로 대표되는 전 세계 청소년 문화의 중심지가 되었습니다.[95] 펑크 시대에 트렌드세터의 역할이 되살아났습니다.[96] 1965년 도시 지역의 성장에 대응하여 런던의 정치적 경계가 확장되었고 새로운 대런던 의회가 만들어졌습니다.[97] 북아일랜드에서의 문제들 동안, 런던은 1973년부터 아일랜드 공화국군의 폭탄 공격을 받았습니다.[98] 이 공격들은 20년 동안 지속되었고, 올드 베일리 폭격을 시작으로 시작되었습니다.[98] 인종적 불평등은 1981년 브릭스턴 폭동에 의해 강조되었습니다.[99]

그레이터 런던의 인구는 제2차 세계 대전 이후 수십 년 동안 감소하여 1939년 860만 명으로 추정되었습니다. 1980년대에는 약 680만 명으로.[100] 런던의 주요 항구는 펠릭스스토웨와 틸버리로 하류로 이동했고, 런던 도크랜드는 카나리아 워프 개발을 포함한 재생의 중심지가 되었습니다. 이것은 1980년대에 런던이 국제 금융 중심지로서의 역할을 증대시킨 데서 비롯되었습니다.[101] 런던 중심부에서 동쪽으로 약 2마일(3.2km) 떨어진 곳에 위치한 템스 장벽은 북해로부터의 조수 해일로부터 런던을 보호하기 위해 1980년대에 완공되었습니다.[102]

그레이터런던 카운슬은 1986년에 폐지되었고, 2000년까지 런던은 중앙 행정부가 없었고, 그레이터런던 당국이 설립되었습니다.[103] 21세기를 맞아 밀레니엄 돔, 런던 아이, 밀레니엄 브릿지가 건설되었습니다.[104] 2005년 7월 6일, 런던은 2012년 하계 올림픽을 세 번 개최한 최초의 도시로 선정되었습니다.[36] 2005년 7월 7일 일련의 테러 공격으로 런던 지하철 3량과 2층 버스가 폭격을 당했습니다.[98]

2008년, 타임지는 뉴욕시와 홍콩과 함께 런던을 나일론콩으로 선정하여 세계에서 가장 영향력 있는 세 개의 글로벌 도시로 선정했습니다.[105] 2015년 1월, 그레이터 런던의 인구는 863만 명으로 1939년 이후 최고치를 기록했습니다.[106] 2016년 브렉시트 국민투표 당시 영국 전체가 유럽연합 탈퇴를 결정했지만 대부분의 런던 선거구는 잔류에 찬성했습니다.[107] 그러나 2020년 초 영국의 EU 탈퇴는 국제 금융 중심지로서 런던의 입지를 약간 약화시켰을 뿐입니다.[108]

2023년 5월 6일, 찰스 3세와 그의 아내 카밀라가 영국과 다른 영연방 왕국의 왕과 여왕으로서 대관식이 런던 웨스트민스터 사원에서 열렸습니다.[109]

행정부.

지방자치단체

런던의 행정부는 도시 전체, 전략적 계층 및 지역 계층의 두 계층으로 구성됩니다. 도시 전체의 행정은 GLA(Greater London Authority)에 의해 조정되고 지방 행정은 33개의 소규모 당국에 의해 수행됩니다.[111] GLA는 집행권을 가진 런던 시장과 시장의 결정을 면밀히 검토하고 매년 시장의 예산 제안을 받아들이거나 거부할 수 있는 런던 의회의 두 가지 선출된 구성 요소로 구성됩니다. GLA는 기능 부서인 TfL(Transport for London)을 통해 런던 교통 시스템의 대부분을 책임지고 있으며, 도시의 경찰 및 소방 서비스를 감독하고 다양한 문제에 대한 런던의 전략적 비전을 수립하는 역할도 맡고 있습니다.[112] GLA의 본부는 뉴햄의 시청입니다. 2016년부터 시장은 주요 서방 수도의 첫 번째 이슬람 시장인 사디크 칸이었습니다.[113] 시장의 법정 계획 전략은 2011년에 가장 최근에 개정된 런던 플랜(London Plan)으로 출판됩니다.[114]

지역 당국은 32개 런던 자치구의 의회와 런던 시공사입니다.[115] 그들은 지역 계획, 학교, 도서관, 여가 및 레크리에이션, 사회 서비스, 지방 도로 및 거부 수집과 같은 대부분의 지역 서비스를 담당합니다.[116] 폐기물 관리와 같은 특정 기능은 공동 배치를 통해 제공됩니다. 2009-2010년 동안 런던 의회와 GLA의 총 세입 지출은 220억 파운드(자치구의 경우 147억 파운드, GLA의 경우 74억 파운드)가 조금 넘었습니다.[117]

런던 소방대는 런던 소방 및 비상 계획 당국이 운영하는 그레이터 런던의 법정 화재 및 구조 서비스입니다. 세계에서 세 번째로 큰 소방 서비스입니다.[118] 전국민 의료 서비스 구급차 서비스는 세계 최대 규모의 현장 무료 응급 구급차 서비스인 LAS(London Ambulance Service) NHS 트러스트(National Health Service)가 제공합니다.[119] 런던 에어 앰뷸런스 자선단체는 필요한 경우 LAS와 연계하여 운영됩니다. 여왕 폐하의 해안 경비대와 왕립 국립 구명보트 기관은 테딩턴 록에서 바다까지 런던 당국의 관할 하에 있는 템스 강에서 운영됩니다.[120]

국민정부

런던은 영국 정부의 소재지입니다. 다우닝가 10번지에 있는 총리 관저뿐만 아니라 많은 정부 부처들은 웨스트민스터 궁전, 특히 화이트홀을 따라 가까이에 위치하고 있습니다.[121] 런던 출신의 의원은 73명이며, 2019년[update] 12월 기준으로 노동당 출신은 49명, 보수당 출신은 21명, 자유민주당 출신은 3명입니다.[122] 런던의 장관직은 1994년에 만들어졌으며 2020년 현재 폴 스컬리가 맡고 있습니다.[123]

치안과 범죄

런던시를 제외한 그레이터 런던의 치안은 시장이 치안 및 범죄 담당 사무소(MOPAC)를 통해 감독하는 메트로폴리탄 경찰("The Met")에 의해 제공됩니다.[124] 메트는 화이트홀에 있는 그레이트 스코틀랜드 야드(Great Scotland Yard)라는 도로에 원래 본사가 위치한 것을 따서 스코틀랜드 야드(Scotland Yard)라고도 불립니다. 런던시에는 자체 경찰인 런던 경찰이 있습니다.[125] 메트 경찰관들이 1863년에 처음 착용한 관리인 헬멧은 "문화 아이콘"과 "영국 법 집행의 상징"으로 불렸습니다.[126] 1929년 메트에 의해 소개된 파란색 경찰 전화 박스(닥터 후에 나오는 타디스의 기초)는 한때 런던과 영국의 지역 도시들에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 광경이었습니다.[127]

영국 교통 경찰은 내셔널 레일, 런던 지하철, 도클랜드 경전철 및 트램링크 서비스의 경찰 서비스를 담당합니다.[128] 국방부 경찰은 일반 대중의 치안에 관여하지 않는 런던의 특수 경찰입니다.[129] 영국 국내 방첩국(MI5)은 템스강 북안의 템스하우스에, 외국 정보국(MI6)은 남안의 SIS빌딩에 본부를 두고 있습니다.[130]

범죄율은 런던의 여러 지역에 걸쳐 매우 다양합니다. 범죄 수치는 전국적으로 지방 자치 단체와 구청 단위로 제공됩니다.[131] 2015년에는 118건의 살인 사건이 발생했는데, 이는 2014년에 비해 25.5% 증가한 수치입니다.[132] 런던에서 기록된 범죄가 증가하고 있으며, 특히 강력한 범죄와 칼부림 및 기타 수단에 의한 살인이 증가하고 있습니다. 2018년 초부터 2018년 4월 중순까지 50건의 살인 사건이 있었습니다. 다른 요인들도 관련되어 있지만, 런던의 경찰에 대한 자금 삭감이 이에 기여했을 것으로 보입니다.[133] 그러나 살인자 수는 2022년에 109명으로 감소했으며 런던의 살인율은 전 세계의 다른 주요 도시보다 훨씬 낮습니다.[134]

지리

범위

그레이터 런던(Greater London)으로도 알려진 런던(London)은 영국의 9개 지역 중 하나이며 도시 대도시 대부분을 아우르는 최상위 하위 구역입니다. 그 중심에 있는 런던시는 한때 전체 정착지를 구성했지만, 도시 면적이 커지면서 런던 법인은 도시와 교외 지역을 통합하려는 시도에 저항했고, 이로 인해 "런던"이 여러 방식으로 정의되게 되었습니다.[135]

Greater London의 40%는 'London'이 우편 주소의 일부를 형성하는 London 포스트 타운에 의해 커버됩니다.[136] 런던 전화 지역 번호(020)는 그레이터 런던과 비슷한 크기로 더 넓은 지역을 대상으로 하지만, 일부 외곽 지역은 제외되고 일부 외곽 지역은 포함됩니다. Greater London 경계는 M25 고속도로에 일정 부분 정렬되어 있습니다.[137]

이제 메트로폴리탄 그린벨트에 의해 더 이상의 도시 확장은 방지되지만, 건축 구역이 경계를 넘어 군데군데 확장되어 별도로 정의된 그레이터런던 도시 구역이 생성됩니다. 이 너머에는 광대한 런던 통근자 벨트가 있습니다.[138] 그레이터런던은 어떤 목적을 위해 이너런던과 아우터런던으로 [139]나뉘고 템스강을 따라 남북으로 나뉘며 비공식적인 중심 런던 지역이 있습니다. 전통적으로 트래팔가 광장과 화이트홀이 만나는 지점 근처의 채링 크로스에 있는 원래의 엘리너 크로스인 런던 공칭 중심부의 좌표는 약 51°30'26 ″ N 00°07'39 ″ W / 51.50722 0W / .50722; -0.12750입니다.

상황

런던 내에서, 런던시와 웨스트민스터시는 모두 도시 지위를 가지고 있고, 런던시와 그레이터런던의 나머지는 모두 중위의 목적을 위한 카운티입니다.[141] 그레이터런던 지역은 미들섹스, 켄트, 서리, 에섹스, 하트퍼드셔의 역사적인 카운티에 속하는 지역을 포함합니다.[142] 영국의 수도, 나중에 영국이라는 런던의 지위는 법령이나 서면으로 부여되거나 확인된 적이 없습니다.[note 5]

수도로서의 지위는 헌법 협약에 의해 확립되었으며, 이는 사실상의 수도로서의 지위가 영국의 미승인 헌법의 일부임을 의미합니다. 영국의 수도는 웨스트민스터 궁전이 12세기와 13세기에 발전하여 왕실의 영구적인 위치가 되었고, 따라서 영국의 정치적인 수도가 되면서 윈체스터에서 런던으로 옮겨졌습니다.[145] 보다 최근에, 그레이터 런던은 영국의 한 지역으로 정의되었고, 이러한 맥락에서 런던이라고 알려져 있습니다.[146]

지형

그레이터런던은 2001년 인구 7,172,036명, 평방마일당 인구밀도 11,760명(4,542/km2)이었던 총 611 평방마일(1,583km2)의 면적을 포함하고 있습니다. 런던 메트로폴리탄 리전(London Metropolitan Region) 또는 런던 메트로폴리탄 집적지(London Metropolitan Agglomeration)로 알려진 확장된 지역의 총 면적은 3,236 평방 마일(8,382km2)이며, 인구는 13,709,000명이고, 인구 밀도는 평방 마일(1,510/km2)당 3,900명입니다.[147]

현대 런던은 템스 강 위에 서 있는데, 그 주요 지리적 특징으로 도시를 남서쪽에서 동쪽으로 가로지르는 항해 가능한 강이 있습니다. 템스 계곡은 의회 언덕, 애딩턴 언덕, 프림로즈 언덕을 포함한 완만한 구불구불한 언덕으로 둘러싸인 범람원입니다. 역사적으로 런던은 템스 강에서 가장 낮은 교점에서 자랐습니다. 템스 강은 한때 넓은 습지대가 있는 훨씬 더 넓고 얕은 강이었습니다. 만조 때, 그것의 해안은 현재 너비의 5배에 이르렀습니다.[148]

빅토리아 시대 이래로 템스 강은 광범위하게 제방을 쌓았고, 현재 런던의 많은 지류들이 지하로 흐르고 있습니다. 템스강은 조수의 강으로 런던은 홍수에 취약합니다.[149] 기후 변화로 인한 고수위의 느리지만 지속적인 상승과 빙하 이후의 반등으로 인한 영국 제도의 느린 '기울기'로 인해 위협은 시간이 지남에 따라 증가했습니다.[150]

기후.

런던은 온화한 해양성 기후(Köppen: Cfb)를 가지고 있습니다. 강우 기록은 적어도 1697년 큐에서 기록이 시작된 이래로 이 도시에 보관되어 왔습니다. 큐에서 한 달 동안 가장 많은 강우량은 1755년 11월에 7.4인치(189mm)이고 가장 적은 강우량은 1788년 12월과 1800년 7월에 모두 0인치(0mm)입니다. 마일 엔드는 1893년 4월에도 0인치(0mm)를 보유하고 있었습니다.[151] 기록상 가장 습한 해는 1903년으로 총 38.1인치(969mm), 가장 건조한 해는 1921년으로 총 12.1인치(308mm)의 강우량을 기록했습니다.[152] 연평균 강수량은 약 600mm에 달하며, 이는 뉴욕시 연간 강수량의 절반에 해당합니다.[153] 상대적으로 적은 연간 강수량에도 불구하고, 런던에는 여전히 연간 1.0mm 기준으로 109.6일의 비가 내리고 있습니다. 하지만 런던은 영국의 기후변화에 취약해 수문학 전문가들 사이에서는 2050년 이전에 런던 가정의 물이 고갈될지 모른다는 우려가 커지고 있습니다.[154]

런던의 극한 기온은 2022년 7월 19일 히드로에서 40.2 °C (104.4 °F), 1981년 12월 13일 노솔트에서 -17.4 °C (0.7 °F)입니다.[155][156] 대기압에 대한 기록은 1692년 이래로 런던에 보관되어 왔습니다. 지금까지 보고된 최고 압력은 2020년 1월 20일의 1,049.8 밀리바(Hg 기준 31.00)입니다.[157]

여름은 대체로 따뜻하고 때로는 덥습니다. 런던의 7월 평균 최고 기온은 23.5 °C (74.3 °F)입니다. 런던은 매년 평균적으로 25 °C (77.0 °F) 이상 31 일, 30.0 °C (86.0 °F) 이상 4.2 일을 경험합니다. 2003년 유럽의 폭염 기간 동안, 장기간의 더위로 인해 수백 명의 더위와 관련된 사망자가 발생했습니다.[158] 1976년 영국에서 32.2 °C (90.0 °F)를 초과하는 보름 연속 발생한 것도 많은 열 관련 사망자를 발생시켰습니다.[159] 1911년 8월 그리니치 기지에서 37.8 °C (100.0 °F) 의 이전 온도는 나중에 비표준으로 간주되었습니다.[160] 가뭄은 특히 여름, 가장 최근인 2018년 여름, 그리고 5월부터 12월까지 평균보다 훨씬 건조한 상태에서 문제가 될 수 있습니다.[161] 그러나 가장 연속적으로 비가 오지 않은 날은 1893년 봄의 73일이었습니다.[162]

겨울은 일반적으로 기온 변화가 거의 없이 시원합니다. 폭설은 드물지만 눈은 보통 겨울에 적어도 한 번씩 내립니다. 봄과 가을은 쾌적할 수 있습니다. 대도시로서 런던은 도시 열섬 효과가 [163]상당하여 런던 중심부가 교외와 외곽보다 5°C(9°F) 더 따뜻합니다.[164]

| 달 | 잰 | 2월 | 마 | 4월 | 그럴지도 모른다 | 준. | 7월 | 8월 | 9월 | 10월 | 11월 | 12월 | 연도 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 높은 °C(°F) 기록 | 17.2 (63.0) | 21.2 (70.2) | 24.5 (76.1) | 29.4 (84.9) | 32.8 (91.0) | 35.6 (96.1) | 40.2 (104.4) | 38.1 (100.6) | 35.0 (95.0) | 29.5 (85.1) | 21.1 (70.0) | 17.4 (63.3) | 40.2 (104.4) |

| 일평균 최대 °C(°F) | 8.4 (47.1) | 9.0 (48.2) | 11.7 (53.1) | 15.0 (59.0) | 18.4 (65.1) | 21.6 (70.9) | 23.9 (75.0) | 23.4 (74.1) | 20.2 (68.4) | 15.8 (60.4) | 11.5 (52.7) | 8.8 (47.8) | 15.7 (60.3) |

| 일평균 °C(°F) | 5.6 (42.1) | 5.8 (42.4) | 7.9 (46.2) | 10.5 (50.9) | 13.7 (56.7) | 16.8 (62.2) | 19.0 (66.2) | 18.7 (65.7) | 15.9 (60.6) | 12.3 (54.1) | 8.4 (47.1) | 5.9 (42.6) | 11.7 (53.1) |

| 평균 일일 최소 °C(°F) | 2.7 (36.9) | 2.7 (36.9) | 4.1 (39.4) | 6.0 (42.8) | 9.1 (48.4) | 12.0 (53.6) | 14.2 (57.6) | 14.1 (57.4) | 11.6 (52.9) | 8.8 (47.8) | 5.3 (41.5) | 3.1 (37.6) | 7.8 (46.0) |

| 최저 °C(°F) 기록 | −16.1 (3.0) | −13.9 (7.0) | −8.9 (16.0) | −5.6 (21.9) | −3.1 (26.4) | −0.6 (30.9) | 3.9 (39.0) | 2.1 (35.8) | 1.4 (34.5) | −5.5 (22.1) | −7.1 (19.2) | −17.4 (0.7) | −17.4 (0.7) |

| 평균 강수량 mm(인치) | 58.8 (2.31) | 45.0 (1.77) | 38.8 (1.53) | 42.3 (1.67) | 45.9 (1.81) | 47.3 (1.86) | 45.8 (1.80) | 52.8 (2.08) | 49.6 (1.95) | 65.1 (2.56) | 66.6 (2.62) | 57.1 (2.25) | 615.0 (24.21) |

| 평균강수량일(≥ 1.0mm) | 11.5 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 10.8 | 111.7 |

| 평균 상대습도(%) | 80 | 77 | 70 | 65 | 67 | 65 | 65 | 69 | 73 | 78 | 81 | 81 | 73 |

| 평균 이슬점 °C(°F) | 3 (37) | 2 (36) | 2 (36) | 4 (39) | 7 (45) | 10 (50) | 12 (54) | 12 (54) | 10 (50) | 9 (48) | 6 (43) | 3 (37) | 7 (44) |

| 월평균 일조시간 | 61.1 | 78.8 | 124.5 | 176.7 | 207.5 | 208.4 | 217.8 | 202.1 | 157.1 | 115.2 | 70.7 | 55.0 | 1,674.8 |

| 가능한 일조율 | 23 | 28 | 31 | 40 | 41 | 41 | 42 | 45 | 40 | 35 | 27 | 21 | 35 |

| 평균자외선지수 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 출처 1: Met Office[165][166][167] Royal Delands 기상 연구소[168][169] | |||||||||||||

| 출처 2: Weather Atlas(햇볕 및 자외선 지수 백분율)[170] CEDA Archive TORO[171][172] 시간 및 날짜[173] 자세한 기후 정보는 런던의 기후를 참조하십시오. | |||||||||||||

- ^ 평균은 히드로 역에서, 극단은 런던 전역의 역에서 취합니다.

지역들

런던의 광대한 도시 지역 내의 장소들은 메이페어, 사우스워크, 웸블리, 화이트채플과 같은 지역 이름을 사용하여 식별됩니다. 이것들은 비공식적인 지정이거나, 스프롤에 의해 흡수된 마을의 이름을 반영하거나, 교구 또는 이전 자치구와 같은 행정 단위로 대체됩니다.[174]

이러한 이름은 전통을 통해 사용되어 왔으며, 각각 고유한 특성을 가지고 있지만 공식적인 경계가 없는 지역을 나타냅니다. 1965년부터 그레이터런던은 고대 런던시 외에 32개의 런던 자치구로 나뉘었습니다.[175] 런던시는 주요 금융 지구이며,[176] 카나리아 워프는 최근 동쪽 도클랜드의 새로운 금융 및 상업 중심지로 발전했습니다.

웨스트엔드는 런던의 주요 엔터테인먼트 및 쇼핑 지역으로 관광객들을 끌어들이고 있습니다.[177] 웨스트 런던은 부동산이 수천만 파운드에 팔릴 수 있는 비싼 주거 지역을 포함합니다.[178] 켄싱턴과 첼시의 부동산 평균 가격은 200만 파운드가 넘으며 런던 중심부 대부분에서 지출액이 비슷하게 높습니다.[179][180]

이스트 엔드는 런던에서 가장 가난한 지역 중 하나일 뿐만 아니라 높은 이민자 인구로 유명한 원래의 런던 항구와 가장 가까운 지역입니다.[181] 주변의 동런던 지역은 런던의 초기 산업 발전의 많은 부분을 목격했고, 현재 런던 리버사이드와 2012년 올림픽과 패럴림픽을 위한 올림픽 공원으로 개발된 로어 리 밸리를 포함한 템스 게이트웨이의 일부로 이 지역 전역의 브라운필드 부지가 재개발되고 있습니다.[181]

건축

런던의 건물들은 너무 다양해서 어떤 특정한 건축 양식으로도 특징지어지지 않습니다. 부분적으로 다양한 나이 때문입니다. 내셔널 갤러리와 같은 많은 그랜드 하우스와 공공 건물은 포틀랜드의 돌로 지어졌습니다. 도시의 일부 지역, 특히 중앙의 바로 서쪽 지역은 흰색 스터코 또는 흰색으로 칠해진 건물로 특징지어집니다. 1666년 화재 이전의 런던 중심부에 몇 개의 건축물이 있는데, 이것들은 몇 개의 흔적이 있는 로마 유적, 런던탑, 그리고 이 도시에 흩어져 있는 튜더 생존자들입니다. 더 멀리는 예를 들어 튜더 기간 햄튼 코트 궁전입니다.[182]

다양한 건축 유산의 일부는 왕립 거래소와 영국 은행과 같은 신고전주의 금융 기관인 크리스토퍼 렌의 17세기 교회에서 20세기 초 올드 베일리 법원과 1960년대 바비컨 에스테이트입니다. 남서쪽 강가에 있는 1939년 배터시 발전소는 지역의 랜드마크이며, 일부 철도 터미널은 빅토리아 시대 건축의 훌륭한 예이며, 특히 세인트루이스입니다. 판크라스와 패딩턴.[183] 런던의 밀도는 다양하며, 중심 지역과 카나리아 워프에서는 고용 밀도가 높고, 런던 내부에서는 주거 밀도가 높으며, 런던 외부에서는 밀도가 낮습니다.

런던 시의 기념비는 인근에서 시작된 런던 대화재를 기념하면서 주변 지역의 풍경을 제공합니다. 파크 레인의 북쪽과 남쪽 끝에 있는 마블 아치(Marble Arch)와 웰링턴 아치(Wellington Arch)는 각각 왕실과 연결되어 있으며 켄싱턴의 앨버트 기념관과 로열 앨버트 홀(Royal Albert Hall)도 마찬가지입니다. 넬슨의 기둥(Nelson's Column)은 런던 중심부의 중심지 중 하나인 트라팔가 광장에 있는 국가 공인 기념물입니다. 오래된 건물들은 주로 벽돌이며, 일반적으로 노란색 런던 주식 벽돌입니다.[184]

밀집 지역에서는 대부분 중·고층 건물을 통해 집중되고 있습니다. 런던의 마천루들인 30개의 세인트 메리 액스("더 거킨"), 42번 타워, 브로드게이트 타워, 원 캐나다 스퀘어 등은 대부분 런던시와 카나리아 워프 두 금융 지구에 있습니다. 성 바오로 대성당과 다른 역사적인 건물들의 보호된 전망을 방해할 수 있는 경우, 특정 장소에서 고층 개발이 제한됩니다.[185] '세인트 폴스 하이츠'로 알려진 이 보호 정책은 1937년부터 런던시에 의해 운영되고 있습니다.[185] 그럼에도 불구하고, 런던 중심부에는 영국과 서유럽에서 가장 높은 건물인 95층의 샤드 런던 다리를 포함한 많은 높은 마천루들이 있습니다.[186]

다른 주목할 만한 현대식 건물로는 메스, 펜처치 스트리트 20번지(워키토키), 사우스워크의 옛 시청, 아트 데코 BBC 방송국, 소머즈 타운/킹스 크로스의 포스트모더니즘 영국 도서관, 제임스 스털링의 제1호 가금류 등이 있습니다. BT 타워는 620피트(189m) 높이에 있으며 상단 근처에 360도 색상의 LED 스크린이 있습니다. 카나리아 워프의 동쪽에 있는 템스 강가에 있는 밀레니엄 돔은 이제 오2 아레나라고 불리는 엔터테인먼트 장소입니다.[187]

자연사

런던 자연사 학회는 런던이 40% 이상의 녹지나 개방된 물을 가진 "세계에서 가장 녹색 도시 중 하나"라고 제안합니다. 그들은 2000종의 꽃이 피는 식물이 그곳에서 자라는 것이 발견되었고, 조수 템즈강이 120종의 물고기를 지탱하고 있다는 것을 나타냅니다.[188] 그들은 런던 중심부에 있는 60종 이상의 새 둥지와 그들의 구성원들이 런던 주변에 47종의 나비, 1173종의 나방, 270종 이상의 거미를 기록했다고 말합니다. 런던의 습지 지역은 많은 물새들의 국가적으로 중요한 개체수를 지원합니다. 런던에는 38개의 특별 과학 관심 지역(SSI)과 2개의 국가 자연 보호 구역, 76개의 지역 자연 보호 구역이 있습니다.[189]

양서류는 테이트 모던(Tate Modern)이 살고 있는 매끄러운 새, 그리고 흔한 개구리, 흔한 두꺼비, 야자수 새, 큰 볏 새를 포함하여 수도에서 흔히 볼 수 있습니다. 반면에, 느림보, 보통 도마뱀, 막대풀 뱀과 애더와 같은 토종 파충류는 대부분 런던 외곽에서만 볼 수 있습니다.[190]

런던의 다른 주민들 중에는 10,000마리의 붉은 여우가 있어서 현재 런던의 평방 마일 당 6마리의 여우가 있습니다. 그레이터런던에서 발견되는 다른 포유류들은 고슴도치, 갈색 쥐, 쥐, 토끼, 땃쥐, 들쥐, 그리고 회색 다람쥐입니다.[191] 에핑 포레스트와 같은 런던 외곽의 야생 지역에서는 붉은여우, 회색다람쥐, 고슴도치 외에도 유럽토끼, 오소리, 들쥐, 둑과 물쥐, 나무쥐, 노란목쥐, 두더지, 땃쥐, 족제비 등 매우 다양한 포유류가 발견됩니다. 죽은 수달 한 마리가 타워 브리지에서 약 1마일 떨어진 와핑의 더 하이웨이에서 발견되었는데, 이것은 수달들이 도시에서 백 년 동안 떨어져 있다가 다시 움직이기 시작했음을 암시합니다.[192] 영국의 18종의 박쥐들 중 10종이 에핑 숲에서 기록되었습니다: 소프라노, 나투시우스 그리고 코먼 피피스트렐, 코먼 녹툴, 세로틴, 바르바셀,[193] 도벤턴, 갈색긴귀, 네터러스 그리고 라이슬러.

붉은 사슴과 휴경지 사슴 무리들이 리치먼드와 부시 파크의 많은 지역을 자유롭게 돌아다닙니다. 숫자가 지속될 수 있도록 하기 위해 매년 11월과 2월에 도태가 일어납니다.[194] 에핑 포레스트는 또한 숲 북쪽의 무리에서 자주 볼 수 있는 휴경 사슴으로도 유명합니다. 흑사병 사슴의 희귀한 개체수는 또한 이든 부아 근처의 사슴 보호구역에서 유지되고 있습니다. 문착사슴은 숲에서도 발견됩니다. 런던 사람들은 도시를 공유하는 새와 여우와 같은 야생 동물에 익숙하지만, 최근에는 도시 사슴이 일반적인 특징이 되기 시작했고, 휴경지 사슴 무리 전체가 런던의 녹지 공간을 이용하기 위해 밤에 주택가로 들어옵니다.[195]

인구통계학

| 출생국 | 인구. | 퍼센트 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5,223,986 | 59.4 | ||

| 영국이 아닌 나라 | 3,575,739 | 40.6 | |

| 322,644 | 3.7 | ||

| 175,991 | 2.0 | ||

| 149,397 | 1.7 | ||

| 138,895 | 1.6 | ||

| 129,774 | 1.5 | ||

| 126,059 | 1.4 | ||

| 117,145 | 1.3 | ||

| 96,566 | 1.1 | ||

| 80,379 | 0.9 | ||

| 77,715 | 0.9 | ||

| 다른이들 | 2,161,174 | 24.6 | |

| 총 | 8,799,725 | 100.0 | |

런던의 지속적인 도시 면적은 그레이터런던을 넘어 2011년 9,787,426명에 달했고,[31] 더 넓은 대도시 지역의 인구는 사용된 정의에 따라 1,200만 명에서 1,400만 명에 달했습니다.[197] 유로스타트에 의하면, 런던은 유럽에서 두 번째로 인구가 많은 대도시 지역이라고 합니다. 1991-2001년 동안 726,000명의 이민자가 그곳에 도착했습니다.[198]

이 지역은 610 평방 마일(1,579km2)에 달하며, 1 평방 마일(5,177/km2)[147] 당 13,410명의 인구 밀도를 제공하여 다른 영국 지역의 10배 이상의 인구 밀도를 제공합니다.[199] 인구 기준으로 런던은 19번째로 큰 도시이며 18번째로 큰 대도시 지역입니다.[200]

2021년 인구 조사에서 런던 내 23.1%의 사회적 임대료, 46.8%의 주택 소유 또는 모기지 또는 대출 및 30%의 개인 임대료가 있습니다.[201] 2021년 인구 조사에서 42.9%가 재택근무를 했고, 20.6%는 차를 몰고 출근했습니다. 교통수단이 가장 많이 감소한 곳은 지하철과 지하철을 이용하는 사람들로 2011년 22.6%에서 2021년 9.6%로 감소했습니다.[202] 런던의 46.7%가 4급 이상의 자격을 가진 인구조사 기관으로 주로 대학 학위를 받았습니다. 16.2%는 자격이 전혀 없었습니다.[203]

연령구조 및 중위연령

런던의 평균 연령은 영국에서 가장 어린 지역 중 하나입니다. 2018년 런던 거주자의 나이는 36.5세로 영국 중위 40.3세보다 어리다고 기록되었습니다.[204]

14세 미만의 어린이는 2018년 아우터 런던 인구의 20.6%, 이너 런던 인구의 18%를 차지했습니다. 15-24세 연령층은 아우터 11.1%, 이너 런던 10.2%, 아우터 런던 25-44세 연령층은 아우터 런던 30.6%, 이너 런던 39.7%, 아우터 런던 45-64세 연령층은 아우터 런던 24%, 이너 런던 20.7%였습니다. 65세 이상은 아우터 런던이 13.6%이지만 이너 런던은 9.3%에 불과합니다.[204]

출생국

2021년 인구 조사에 따르면 런던 인구의 40.6%인 3,575,739명이 외국 태생이며,[205] 1971년 외국 태생 인구가 668,373명이었던 이래로 절대적인 숫자와 약 300만 명의 증가율로 가장 많은 이민자 인구를 가진 도시 중 하나입니다.[206] 전체 인구의 13%가 아시아 태생(32명)이었습니다.전체 외국 출생 인구의 1%, 7.1%가 아프리카 출생(17.5%), 15.5%가 기타 유럽 출생(38.2%), 4.2%가 아메리카와 카리브해에서 태어났습니다(10.3%).[207] 가장 큰 5개의 단일 원산지는 각각 인도, 루마니아, 폴란드, 방글라데시, 파키스탄이었습니다.[207]

2021년 런던에서 태어난 아이들의 약 56.8%가 해외에서 태어난 어머니에게서 태어났습니다.[208] 이러한 경향은 지난 20년 동안 런던에서 2001년 출생한 외국인 산모가 43.3%를 차지한 후 2006년에는 52.5%[208]로 2000년대 중반에 대부분을 차지하게 되었습니다.

2021년 인구 조사에 참여한 외국인 출생 인구의 대부분은 비교적 최근에 도착했습니다. 전체 인구 중 2011년에서 2021년 사이에 도착한 인구는 런던의 16.6%를 차지합니다.[209] 2001년에서 2010년 사이에 도착한 사람은 10.4%, 1991년에서 2001년 사이에는 5.7%, 1990년 이전에는 7.3%[209]입니다.

민족

통계청에 따르면 2021년 인구 조사에 따르면 런던 거주자 8,173,941명 중 53.8%가 백인이었고, 백인 36.8%, 백인 1.8%, 집시/아일랜드 여행자 0.1%, 로마 0.4%, 기타 백인 14.7%가 기타 백인으로 분류되었습니다.[210] 한편, 런던 시민의 22.2%는 아시아계 또는 아시아계 혼혈이었고, 20.8%는 전체 아시아계, 1.4%는 아시아계였습니다. 인도인이 7.5%로 가장 많았고 파키스탄인과 방글라데시인이 각각 3.3%와 3.7%로 뒤를 이었습니다. 중국인이 1.7%, 아랍인이 1.6%를 차지했습니다. 추가적으로 4.6%는 "기타 아시아인"으로 분류되었습니다.[210] 런던 인구의 15.9%가 흑인 또는 흑인 혼혈이었습니다. 13.5%는 완전한 흑인 혈통이었고, 2.4%의 혼혈 유산을 가진 사람들이 포함되었습니다. 흑인 아프리카인들은 런던 인구의 7.9%를 차지했고, 3.9%는 블랙 캐리비안, 1.7%는 "기타 흑인"으로 확인되었습니다. 5.7%는 혼혈이었습니다.[210] 이러한 민족 구조는 1960년대 이후 상당히 변화했습니다. 1961년 추산에 따르면 당시 인구의 2.3%를 차지하는 비백인계 소수민족의 총 인구는 179,109명으로 1991년[213] 1,346,119명과 20.2%, 2021년 4,068,553명과 46.2%로 증가했습니다.[211][212][214] 1971년 추산에 따르면 인구는 6,500,000명으로 전체 인구의 87%를 [215]차지했으며 2021년에는 3,239,281명, 36.8%로 감소했습니다.[214]

2021년 현재 런던 학생의 대다수는 소수 민족 출신입니다. 23.9%는 백인, 14%는 기타 백인, 23.2%는 아시아인, 17.9%는 흑인, 11.3%는 혼혈, 6.3%는 기타, 2.3%는 미분류입니다.[216] 2021년 인구 조사에서 런던의 0세에서 15세까지의 인구 1,695,741명 중 42%가 백인이었고, 이를 다시 30.9%가 백인, 0.5%가 아일랜드인, 10.6%가 기타 백인, 23%가 아시아인, 16.4%가 흑인, 12%가 혼혈, 6.6%가 기타 민족이었습니다.[217]

언어들

2005년 1월, 런던의 민족적, 종교적 다양성에 대한 조사는 런던에서 300개 이상의 언어가 사용되고 50개 이상의 원주민 공동체가 10,000명 이상의 인구를 가지고 있다고 주장했습니다.[218] 2021년 인구 조사에서 78.4%가 영어를 모국어로 사용했습니다.[219] 영어 이외의 가장 큰 5개 언어는 루마니아어, 스페인어, 폴란드어, 벵골어, 포르투갈어였습니다.[219]

종교

2021년 인구조사에 따르면 기독교인(40.66%)이 가장 많았고 무종교(20.7%), 이슬람교도(15%), 무응답(8.5%), 힌두교도(5.15%), 유대인(1.65%), 시크교도(1.64%), 불교도(1.0%), 기타(0.8%)[220][221]가 그 뒤를 이었습니다.

런던은 전통적으로 기독교였으며 특히 런던시에 많은 교회가 있습니다. 시내의 잘 알려진 세인트 폴 대성당과 강 남쪽의 사우스워크 대성당은 성공회 행정 중심지이며,[222] 영국 교회의 수석 주교이자 세계적인 성공회 연합회인 캔터베리 대주교는 런던 람베스 자치구의 람베스 궁전에 주 거주지를 두고 있습니다.[223]

중요한 국가 및 왕실 의식은 세인트 폴 사원과 웨스트민스터 사원 사이에 공유됩니다.[224] 그 사원은 영국과 웨일즈에서 가장 큰 로마 가톨릭 대성당인 근처의 웨스트민스터 대성당과 혼동하지 말아야 합니다.[225] 성공회가 성행하고 있음에도 불구하고 교단 내에서 준수율이 낮은 편입니다. 영국 국교회 통계에 따르면, 성공회 출석률은 길고 꾸준한 감소를 계속하고 있습니다.[226]

주목할 만한 모스크로는 타워 햄릿에 있는 이스트 런던 모스크, 리젠트 공원[227] 가장자리에 있는 런던 중앙 모스크, 아마디야 무슬림 공동체의 바이툴 후투 등이 있습니다. 석유 붐 이후, 중동의 부유한 아랍 이슬람교도들이 런던 서부의 메이페어, 켄싱턴, 나이츠브리지를 기반으로 활동하고 있습니다.[228][229][230] 타워 햄릿과 뉴햄의 동쪽 자치구에는 대규모 벵골 무슬림 공동체가 있습니다.[231]

큰 힌두교 공동체는 해로우와 브렌트의 북서쪽 자치구에서 발견되며, 후자는 2006년[232] 유럽에서 가장 큰 힌두교 사원인 니스덴 사원을 주최했습니다.[233] 런던에는 BAPS 슈리 스와미나라얀 만디르 런던을 포함한 44개의 힌두교 사원이 있습니다. 런던 동부와 서부에는 시크교 공동체가 있으며, 특히 사우스올에는 인도 밖에서 가장 큰 시크교도 인구와 가장 큰 시크교도 사원이 있습니다.[234]

영국 유대인의 대다수는 런던에 살고 있으며, 스탬퍼드 힐, 스탠모어, 골더스 그린, 핀클리, 햄스테드, 헨든, 에드그웨어에 있는 주목할 만한 유대인 공동체가 모두 북런던에 있습니다. 런던 시에 있는 베비스 마크 시나고그는 런던의 역사적인 유대인 공동체에 속해 있습니다. 유럽에서 유일하게 300년 이상 지속적으로 정기적인 예배를 드렸던 유대교 회당입니다. 스탠모어와 캐논 공원 시나고그는 유럽의 모든 정교회 유대교 회당 중 가장 많은 회원을 보유하고 있습니다.[235] 런던 유대인 포럼은 런던 정부의 중요성이 점점 더 커지고 있는 것에 대응하기 위해 2006년에 설립되었습니다.[236]

악센트

콕니는 런던 전역에서 들리는 억양으로, 주로 노동자 계층과 중하위 계층의 런던 사람들이 사용합니다. 그것은 18세기에 그곳에서 유래된 이스트 엔드와 더 넓은 이스트 런던에 주로 기인하지만, 콕니 스타일의 연설은 훨씬 더 오래되었다고 제안됩니다.[238] 코크니의 특징들 중에는 Th-fronting(th를 f로 발음하는 것), 단어 안의 th는 v로 발음하고 H-droping하며, 대부분의 영어 억양과 마찬가지로 코크니 억양은 모음 뒤에 r을 떨어트립니다.[239] 존 캠든 핫튼(John Camden Hotten)은 1859년 그의 은어 사전에서 이스트 엔드의 비용 관리자들을 묘사할 때 콕니가 "유별한 은어의 사용"(콕니 운이 좋은 은어)을 언급합니다. 21세기가 시작된 이래로 콕니 방언의 극단적인 형태는 이스트 엔드 자체의 일부 지역에서 덜 흔하며, 런던의 다른 지역과 교외 지역을 포함한 현대의 거점은 홈 카운티입니다.[240] 이러한 현상은 특히 최근 수십 년 동안 나이 든 이스트엔드 주민들이 많이 유입된 롬포드(런던 하버링 자치구)와 사우스엔드(에식스)와 같은 지역에서 두드러집니다.[241]

하구 영어는 콕니와 수신 발음의 중간 억양입니다.[242] 모든 계층의 사람들이 널리 사용합니다.[243]

다문화 런던 영어(MLE)는 다양한 배경을 가진 젊은 노동자 계층의 다문화 분야에서 점점 더 보편화되고 있는 다문화 학생입니다. 그것은 여러 민족 억양, 특히 아프리카-카리브해와 남아시아 억양이 혼합된 것으로, 콕니의 영향이 큽니다.[244]

수신 발음(RP)은 전통적으로 영국 영어의 표준으로 간주되는 억양입니다.[245] 그것은 런던과 영국 남동부에서 전통적으로 사용되는 표준 연설로 정의되기도 하지만 특정한 지리적 상관관계는 없습니다.[246][247] 주로 상류층과 중상류층의 런던 사람들이 사용합니다.[248]

경제.

2019년 런던의 지역내 총생산은 5,030억 파운드로 영국 GDP의 약 4분의 1을 차지했습니다.[249] 런던에는 5개의 주요 업무 지구가 있습니다: 도시, 웨스트민스터, 카나리아 워프, 캠든 & 이즐링턴, 램베스 & 사우스워크. 그들의 상대적인 중요성에 대한 아이디어를 얻는 한 가지 방법은 사무 공간의 상대적인 양을 보는 것입니다: 그레이터 런던은 2001년에 2,700만 m의2 사무 공간을 가졌고, 그 도시는 800만 m의2 사무 공간으로 가장 많은 공간을 가지고 있습니다. 런던은 세계에서 가장 높은 부동산 가격을 가지고 있습니다.[250]

시티 오브 런던

런던의 금융 산업은 런던시와 카나리아 워프에 기반을 두고 있습니다. 런던은 국제 금융의 가장 중요한 위치로서 세계에서 뛰어난 금융 중심지 중 하나입니다.[251] 런던은 1795년 네덜란드 공화국이 나폴레옹 군대보다 먼저 붕괴된 직후 주요 금융 중심지로 점령했습니다. 이로 인해 암스테르담에 설립된 많은 은행가들(예: Hope, Baring I'm)이 런던으로 이주했습니다. 또한 18세기에 런던의 시장 중심 시스템은 (암스텔담의 은행 중심 시스템과는 반대로) 더 지배적이 되었습니다.[74] 런던 금융 엘리트들은 당시의 가장 정교한 금융 도구를 마스터할 수 있는 유럽 전역의 강력한 유대인 공동체에 의해 강화되었습니다.[78] 이 도시의 경제력은 다양성 덕분입니다.[252][253]

19세기 중반까지 런던은 주요 금융 중심지였으며 세기 말에는 세계 무역의 절반 이상이 영국 통화로 자금을 조달했습니다.[254] 그럼에도 불구하고, 2016년[update] 기준으로 런던은 글로벌 금융 센터 지수(GFCI)에서 세계 1위를 차지하고 있으며,[255] A에서 2위를 차지했습니다.T.[256] Kearney의 2018년 글로벌 도시 지수

런던의 가장 큰 산업은 금융이며, 금융 수출은 영국의 국제수지에 큰 기여를 합니다. 브렉시트 이후 런던 증권거래소에서 주식 상장이 이탈했음에도 불구하고,[19] 런던은 여전히 유럽에서 가장 경제적으로 강력한 도시 중 하나이며,[20] 세계의 주요 금융 중심지 중 하나로 남아 있습니다. BIS에 따르면, BIS는 하루 평균 거래량 5조 1천억 달러의 약 37%를 차지하는 세계에서 가장 큰 통화 거래 센터입니다.[257] 런던 대도시 고용 인구의 85%(320만 명) 이상이 서비스 산업에 종사하고 있습니다. 런던의 경제는 세계적으로 중요한 역할을 했기 때문에 2007-2008년의 금융위기의 영향을 받았습니다. 하지만, 2010년까지 도시는 회복되었고, 새로운 규제 권한을 부여했으며, 잃어버린 기반을 되찾고 런던의 경제적 지배력을 다시 확립했습니다.[258] 런던시는 전문 서비스 본부와 함께 영란은행, 런던 증권거래소, 로이드 오브 런던 보험 시장의 본거지입니다.[259]

영국의 상위 100대 상장 기업(FTSE 100)의 절반 이상과 유럽의 500대 기업 중 100개 이상이 런던 중심부에 본사를 두고 있습니다. FTSE 100 기업의 70% 이상이 런던의 수도권 내에 있으며, Fortune 500 기업의 75%가 런던에 지사를 두고 있습니다.[260] 런던 증권거래소가 의뢰한 1992년 보고서에서, 그의 가족의 제과회사 캐드베리의 회장인 애드리안 캐드베리 경은 전 세계 기업 지배구조 개혁의 기초가 된 모범 사례 강령인 캐드베리 보고서를 제작했습니다.[261]

미디어 및 기술

런던에는 언론사가 집중되어 있으며, 런던에서 두 번째로 경쟁이 치열한 분야가 미디어 유통업입니다.[262] 세계에서 가장 오래된 국영 방송사인 BBC는 중요한 고용주이며, 다른 방송사들도 도시 주변에 본사를 두고 있습니다. 1785년에 설립된 타임즈를 포함한 많은 전국 신문들이 런던에서 편집됩니다. (대부분의 전국 신문이 운영되는) 플리트 스트리트라는 용어는 영국 전국 언론의 상징으로 남아 있습니다. 런던은 세계에서 가장 큰 소매 목적지 중 하나이며, 그 도시는 종종 어느 도시에서나 소매 판매의 상위권에 있거나 그 근처에 있습니다.[263][264] 2017년에는 럭셔리 매장 오픈 1위 도시로 선정되었습니다.[265] 런던항은 매년 4,500만 톤의 화물을 처리하는 영국에서 두 번째로 큰 항구입니다.[266]

많은 기술 회사들이 런던, 특히 실리콘 라운드어바웃으로 알려진 이스트 런던 테크 시티에 기반을 두고 있습니다. 2014년에 그 도시는 geoTLD를 받은 첫 번째 도시 중 하나였습니다.[267] 2014년 2월, 런던은 fDi Intelligence에 의해 2014/15년 리스트에서 미래의 유럽 도시로 선정되었습니다.[268] 제2차 세계대전 당시 앨런 튜링의 근거지였던 블레츨리 공원의 한 박물관은 런던 중심부에서 북쪽으로 40마일(64km) 떨어진 블레츨리에 있으며, 국립 컴퓨터 박물관도 마찬가지입니다.[269]

도시 전역의 소비자에게 에너지를 전달하는 타워, 케이블 및 압력 시스템을 관리하고 운영하는 가스 및 전기 배전 네트워크는 National Grid plc, SGN[270] 및 UK Power Networks에서 관리합니다.[271]

관광업

런던은 세계의 주요 관광지 중 하나이며 2015년에는 6천 5백만 명 이상이 방문하여 세계에서 가장 많이 방문한 도시로 선정되었습니다.[272] 2015년 202억 3천만 달러로 추정되는 방문객 국경 간 지출로 세계 최고의 도시이기도 합니다.[273] 관광업은 런던의 주요 산업 중 하나로 2016년에 70만 명의 정규직 근로자를 고용하고 있으며, 연간 360억 파운드를 경제에 기여하고 있습니다.[274] 이 도시는 영국의 모든 인바운드 방문객 지출의 54%를 차지합니다.[275] 2016년[update] 기준 런던은 트립어드바이저 사용자가 선정한 세계 최고의 도시입니다.[276]

2015년 영국에서 가장 많이 방문한 명소는 모두 런던이었습니다. 가장 많이 방문한 10대 명소는 (장소당 방문 횟수):[277]

- 대영박물관: 6,820,686

- 국립미술관: 5,908,254

- 자연사 박물관(사우스 켄싱턴): 5,284,023

- 사우스뱅크 센터: 5,102,883

- 테이트 모던: 4,712,581

- 빅토리아 앨버트 박물관 (사우스 켄싱턴): 3,432,325

- 과학관: 3,356,212

- 서머셋 하우스: 3,235,104

- 런던탑: 2,785,249

- 국립초상화관 : 2,145,486

2015년 런던의 호텔 객실 수는 138,769개였으며 수년에 걸쳐 증가할 것으로 예상됩니다.[278]

운송

교통은 런던 시장이 관리하는 4대 정책 분야 중 하나이지만,[279] 시장의 재정 통제는 런던으로 들어오는 장거리 철도 네트워크로 확장되지 않습니다. 2007년 런던 시장은 현재 런던 오버그라운드 네트워크를 형성하고 있는 일부 지역 노선에 대한 책임을 맡았으며, 런던 지하철, 트램 및 버스에 대한 기존 책임을 추가했습니다. 대중 교통망은 TfL(Transport for London)에 의해 관리됩니다.[112]

트램과 버스는 물론 런던 지하철을 형성했던 노선들은 1933년 런던 여객 운송 위원회나 런던 교통이 생기면서 통합 운송 시스템의 일부가 되었습니다. Transport for London은 현재 Greater London에서 교통 시스템의 대부분을 담당하는 법정 법인이며, 런던 시장이 임명한 이사회와 위원에 의해 운영됩니다.[280]

항공

런던은 세계에서 가장 바쁜 도시 공역을 가진 주요 국제 항공 운송 중심지입니다.[24] 8개의 공항이 그들의 이름에 런던이라는 단어를 사용하지만 대부분의 교통은 이 중 6개를 통과합니다. 그 외에도 다양한 공항들이 런던에 취항하고 있으며, 주로 일반 항공편을 대상으로 하고 있습니다.

- 런던 서부 힐링던에 위치한 히드로 공항은 수년간 세계에서 국제 교통이 가장 붐비는 공항이었으며, 영국 국적 항공사인 브리티시 에어웨이스의 주요 허브입니다.[281] 2008년 3월에 다섯 번째 터미널이 문을 열었습니다.[282]

- 런던 남쪽 웨스트 서섹스에 있는 개트윅 공항은 영국의 어떤 공항보다 많은 목적지로 가는 항공편을 취급하고 있으며, 승객 수 기준으로 영국 최대의 항공사인 이지젯의 주요 거점입니다.[283]

- 런던 북동쪽에 위치한 스탠스테드 공항은 영국 공항 중 가장 많은 수의 유럽 목적지를 제공하는 항공편을 보유하고 있으며, 국제선 이용객 수 기준 세계 최대 국제 항공사인 라이언에어의 주요 거점입니다.[284]

- 런던 북쪽 베드퍼드셔에 있는 루턴 공항은 몇몇 저가 항공사(특히 이지젯과 위즈 에어)가 단거리 비행에 사용합니다.[285]

- 런던 시티 공항은 런던 동부 뉴햄에 위치한 공항 중 가장 중심적이고 활주로가 가장 짧은 공항으로 비즈니스 여행객들에게 집중되어 있으며, 완전 서비스 단거리 예정 비행과 상당한 비즈니스 제트기 교통량이 혼합되어 있습니다.[286]

- 런던 동쪽에 위치한 사우스엔드 공항(Soutend Airport)은 소규모의 지역 공항으로, 항공사 수는 제한적이지만 증가하고 있습니다.[287] 2017년 런던 공항 중 가장 높은 비율인 사우스엔드의 국제선 승객은 전체의 95% 이상을 차지했습니다.[288]

레일

지중 및 DLR

1863년에 문을 연 런던 지하철은 흔히 지하철이라고 불리는데, 세계에서 가장 오래되고 세 번째로 긴 지하철 시스템입니다.[289][290] 이 시스템은 272개의 역에 서비스를 제공하며, 1890년에 개통된 세계 최초의 지하 전기선인 시티 앤 사우스 런던 철도를 포함한 여러 민간 회사로부터 형성되었습니다.[291]

지하 네트워크에서 매일 400만 번 이상의 여행이 이루어지는데, 매년 10억 번이 넘게 됩니다.[292] 2012년 하계 올림픽 이전에 투입된 65억 파운드(유로 77억)를 포함하여 혼잡을 줄이고 신뢰성을 향상시키기 위한 투자 프로그램이 시도되고 있습니다.[293] 1987년에 개통된 도클랜즈 경전철(DLR)은 도클랜즈, 그리니치, 루이샴을 운행하는 더 작고 가벼운 트램 형식의 차량을 사용하는 두 번째 지역 지하철 시스템입니다.[294]

교외

런던 트래블카드 존에는 368개의 철도역이 있습니다. 특히 런던 남부는 지하철 노선이 적어 철도 집중도가 높습니다. 대부분의 철도 노선은 런던 중심부에서 18개의 터미널 역으로 운행되며, 북쪽의 베드포드와 남쪽의 브라이튼을 연결하는 템즈링크 열차를 제외하고는 루턴 공항과 개트윅 공항을 통해 운행됩니다.[295] 런던에는 승객 수 기준으로 영국에서 가장 붐비는 역인 워터루(Waterloo)가 있으며, 매년 1억 8,400만 명이 넘는 사람들이 (워털루 이스트 역을 포함한) 인터체인지 역 단지를 이용하고 있습니다.[296] 클래펌 정션은 유럽에서 가장 붐비는 철도 인터체인지 중 하나입니다.[297]

더 많은 철도 용량이 필요해짐에 따라 엘리자베스 라인(Crossrail)은 2022년 5월에 개통되었습니다.[298] 런던을 동서로 관통하여 홈 카운티로 들어가는 새로운 철도 노선으로 히드로 공항으로 가는 지점이 있습니다.[299] 이 프로젝트는 150억 파운드의 예상 비용이 들어간 유럽 최대의 건설 프로젝트였습니다.[300]

도시간 및 국제간

런던은 내셔널 레일 네트워크의 중심지이며, 철도 여행의 70%가 런던에서 시작하거나 끝납니다.[301] 킹스크로스역과 유스턴역은 모두 런던에 있는 영국의 두 주요 철도 노선인 이스트코스트 본선과 웨스트코스트 본선의 출발점입니다. 교외 철도 서비스와 마찬가지로 지역 및 도시 간 열차는 도심 주변의 여러 터미널에서 출발하여 런던과 영국의 주요 도시 및 마을 대부분을 직접 연결합니다.[302] 플라잉 스코트맨은 1862년부터 런던과 에딘버러 사이를 운행해온 고속 여객 열차 운행으로, 이 서비스의 이름을 딴 세계적으로 유명한 증기 기관차인 플라잉 스코트맨은 1934년 공식적으로 인증된 시속 100마일(161km/h)에 도달한 최초의 기관차였습니다.[303]

유럽 대륙으로 가는 일부 국제 철도 서비스는 20세기 동안 보트 열차로 운영되었습니다. 1994년에 채널 터널이 개통되면서 런던과 대륙 철도망이 바로 연결되어 유로스타 서비스가 시작될 수 있었습니다. 2007년부터 고속열차가 세인트루이스를 연결하고 있습니다. 릴, 칼레, 파리, 디즈니랜드 파리, 브뤼셀, 암스테르담을 비롯한 유럽 관광지들과 함께하는 판크라스 인터내셔널은 고속 1철도와 채널 터널을 통해 연결됩니다.[304] 켄트와 런던을 연결하는 최초의 국내 고속 열차는 2009년 6월에 시작되었습니다.[305] 런던과 미들랜즈, 노스웨스트잉글랜드, 요크셔를 연결하는 두 번째 고속도로 계획이 있습니다.[306]

버스, 코치 및 트램

런던의 버스 네트워크는 약 9,300대의 차량과 675개 이상의 버스 노선 및 약 19,000개의 버스 정류장으로 24시간 운행됩니다.[307] 2019년에 이 네트워크는 연간 20억 건 이상의 통근 여행을 했습니다.[308] 2010년 이후 매년 평균 12억 파운드의 수익이 발생하고 있습니다.[309] 런던은 세계에서[310] 가장 큰 휠체어 접근이 가능한 네트워크 중 하나이며 2007년 3분기부터 시청각 안내방송이 도입되면서 청각 및 시각 장애인 승객들이 더욱 쉽게 접근할 수 있게 되었습니다.[311]

런던의 코치 허브는 1932년에 문을 연 빅토리아 코치 역입니다. 1970년에 국유화되어 런던 트랜스포트가 매입한 빅토리아 코치 스테이션은 연간 1,400만 명이 넘는 승객을 보유하고 있으며 영국과 유럽 대륙 전역에 서비스를 제공하고 있습니다.[312]

런던에는 트램링크로 알려진 현대식 트램 네트워크가 있습니다. 39개 정류장과 4개 노선을 보유하고 있으며, 2013년에는 2,800만 명을 수송했습니다.[313] 2008년 6월부터 Transport for London은 트램링크를 완전히 소유하고 운영하고 있습니다.[314]

케이블카

런던의 최초이자 지금까지 유일한 케이블카는 2012년 6월에 개장한 런던 케이블카입니다. 케이블카는 템스 강을 건너 그리니치 반도와 도시 동쪽의 로열 도크를 연결합니다. 피크 시간에 각 방향으로 시간당 최대 2,500명의 승객을 태울 수 있습니다.[315]

사이클링

그레이터 런던 지역에서는 약 67만 명의 사람들이 매일 자전거를 이용하는데,[316] 이는 약 880만 명의 전체 인구 중 약 7%가 평균적으로 자전거를 이용한다는 것을 의미합니다.[317] 자전거는 런던을 돌아다니는 점점 더 인기 있는 방법이 되었습니다. 2010년 7월에 자전거 대여 제도가 성공적으로 시작되어 전반적으로 호평을 받았습니다.[318]

항만 및 하천 보트

한때 세계에서 가장 큰 런던항은 2009년 현재 매년 4,500만 톤의 화물을 처리하는 영국에서 두 번째로 큰 항구입니다.[266] 이 화물의 대부분은 그레이터 런던의 경계 밖에 있는 틸버리 항구를 통과합니다.[266]

런던은 템스 클리퍼스로 알려진 템스 강에 강 보트 서비스를 제공하며, 통근 보트와 관광 보트 서비스를 모두 제공합니다.[319] 카나리아 워프, 런던 브리지 시티, 배터시 발전소, 런던 아이(워털루)를 포함한 주요 교각에서는 통근 시간대에 최소 20분 간격으로 서비스가 출발합니다.[320] 매년 250만 명의 승객이 이용하는 울위치 페리는 남북 순환도로를 연결하는 빈번한 서비스입니다.[321]

도로

런던 중심부의 대부분의 여행은 대중교통으로 이루어지지만 교외 지역에서는 자동차 여행이 흔합니다. 내부 순환 도로(도심 주변), 남북 순환 도로(교외 지역), 외부 궤도 고속도로(M25, 대부분의 지역에서 건설 지역 바로 바깥)가 도시를 둘러싸고 있으며, 붐비는 방사형 경로가 교차하고 있지만, 런던 내부로 침투하는 자동차 도로는 거의 없습니다. M25는 길이가 117마일(188km)로 유럽에서 두 번째로 긴 순환도로 고속도로입니다.[322] A1과 M1은 런던과 리즈, 뉴캐슬과 에딘버러를 연결합니다.[323]

오스틴 자동차는 1929년부터 객차(런던 택시)를 만들기 시작했으며, 1948년의 오스틴 FX3, 1958년의 오스틴 FX4, 최근의 모델 TX 등이 있습니다.런던 택시 인터내셔널이 제조한 II 및 TX4. BBC는 "어디에나 있는 검은 택시와 빨간 2층 버스는 모두 런던의 전통에 깊이 새겨져 있는 길고 엉킨 이야기들을 가지고 있습니다"라고 말합니다.[324]

런던은 교통 체증으로 악명이 높습니다; 2009년, 러시아워에서 자동차의 평균 속도는 10.6 mph (17.1 km/h)로 기록되었습니다.[325] 2003년에는 도심의 교통량을 줄이기 위해 혼잡통행료가 도입되었습니다. 몇 가지 예외를 제외하고, 운전자는 런던 중심부의 상당 부분을 포함하는 규정된 구역 내에서 운전하기 위해 비용을 지불해야 합니다.[326] 정의된 구역에 거주하는 운전자는 크게 감소된 시즌 패스를 구입할 수 있습니다.[327] 몇 년 동안, 평일에 런던 중심부로 진입하는 평균 자동차 수는 19만 5천 대에서 12만 5천 대로 줄었습니다.[328]

LTN(Low Traffic Neighbories)은 런던에서 널리 도입되었지만 2023년 교통부는 처음 20년 동안 약 100배의 비용이 발생했으며 시간이 지남에 따라 그 차이가 커지고 있음에도 불구하고 자금 지원을 중단했습니다.[329]

교육

고등교육

런던은 세계적인 고등교육 교육 및 연구의 주요 중심지이며 유럽에서 가장 큰 고등교육 기관이 집중되어 있습니다.[21] QS World University Rankings 2015/16에 따르면, 런던은 세계에서[330] 가장 높은 일류 대학이 밀집해 있으며, 약 11만 명의 유학생 인구가 세계 어느 도시보다 많습니다.[331] 2014년 Pricewaterhouse Coopers 보고서는 런던을 고등교육의 세계적인 수도라고 칭했습니다.[332] 많은 세계적인 교육 기관들이 런던에 기반을 두고 있습니다. 2022년 QS 세계 대학 순위에서 임페리얼 칼리지 런던은 세계 6위, 유니버시티 칼리지 런던(UCL)은 8위, 킹스 칼리지 런던(KCL)은 37위입니다.[333] Imperial College는 2021년 Research Excellence Framework에서 영국 최고의 대학으로 선정될 정도로 모두 정기적으로 높은 순위에 올라 있습니다.[334] 런던 경제대학은 교육과 연구 모두에서 세계 최고의 사회과학 기관으로 묘사되어 왔습니다.[335] 런던 비즈니스 스쿨은 세계 최고의 경영대학원 중 하나로 여겨지고 있으며 2015년에는 파이낸셜 타임즈에 의해 MBA 프로그램이 세계에서 두 번째로 우수한 것으로 평가되었습니다.[336] 이 도시는 또한 세계 10대 공연 예술 학교 (2020년 QS 세계 대학 랭킹[337] 기준) 중 세 곳의 본거지입니다: 왕립 음악 대학 (세계 2위), 왕립 음악 아카데미 (4위), 길드홀 음악 및 연극 학교 (6위).[338]

런던에 학생들이 있고 런던 대학교 월드와이드에 약 48,000명의 학생들이 있는 [339]런던 연방 대학교는 영국에서 가장 큰 접촉 교육 대학입니다.[340] 이 대학에는 시티, 킹스 칼리지 런던, 퀸 메리, 로열 할로웨이, UCL 등 5개의 종합대학과 Birkbeck, Courtauld Institute of Art, Goldsmiths, London Business School, London School of Economics, London School of Healthy & Tropical Medicine, 왕립 음악원, 중앙 스피치 앤 드라마 스쿨, 왕립 수의대 및 동양 및 아프리카 연구 학교.[341]

런던 대학교 체제 밖의 런던의 대학교로는 브루넬 대학교, 임페리얼 칼리지 런던,[note 6] 킹스턴 대학교, 런던 메트로폴리탄 대학교, 이스트 런던 대학교, 웨스트 런던 대학교, 웨스트민스터 대학교, 런던 사우스 뱅크 대학교, 미들섹스 대학교, 그리고 런던 예술대학 (유럽에서 가장 큰 예술, 디자인, 패션, 커뮤니케이션 및 공연 예술 대학).[342] 그 외에도 리젠트 대학교 런던, 리치먼드, 런던의 아메리칸 인터내셔널 대학교, 실러 인터내셔널 대학교 등 3개의 국제 대학이 있습니다.

런던은 바츠와 런던 의과대학 (Queen Mary의 일부), 킹스 칼리지 런던 의과대학 (유럽에서 가장 큰 의과대학), 임페리얼 칼리지 의과대학, UCL 의과대학, 런던 대학교 세인트 조지의 5개 주요 의과대학의 본거지이며 많은 부속 교육 병원이 있습니다. 또한 생명 의학 연구를 위한 주요 센터이며, 영국의 8개 학술 보건 과학 센터 중 3개 기관인 Imperial College Healthcare, King's Health Partners 및 UCL Partners(유럽에서 가장 큰 센터)가 이 도시에 기반을 두고 있습니다.[343] 또한, 이러한 연구 기관에서 많은 생물 의학 및 생명 공학 회사를 분사하는 것은 도시를 중심으로 하며, 가장 눈에 띄는 것은 화이트 시티입니다. 1860년 세인트토머스 병원의 선구적인 간호사 플로렌스 나이팅게일에 의해 설립된 최초의 간호학교는 현재 킹스 칼리지 런던의 일부입니다.[344] 1952년 킹스에서 로잘린드 프랭클린이 이끄는 팀이 DNA의 구조를 확인하는 데 중요한 증거인 51번 사진을 포착했습니다.[345] 런던에는 런던 비즈니스 스쿨, 카스 비즈니스 스쿨(시티 유니버시티 런던의 일부), 헐트 인터내셔널 비즈니스 스쿨, ESCP 유럽, 유럽 비즈니스 스쿨 런던, 임페리얼 칼리지 비즈니스 스쿨, 런던 비즈니스 스쿨, UCL 경영 스쿨 등 수많은 비즈니스 스쿨이 있습니다.

런던은 또한 센트럴 스쿨 오브 발레, 런던 음악 및 드라마틱 아트(LAMDA), 런던 현대 예술 대학(LCCA), 런던 현대 무용 학교, 국립 서커스 예술 센터, 왕립 드라마틱 아트 아카데미(RADA; 총장 케네스 브래너 경) 등 많은 전문 예술 교육 기관의 본거지입니다. Rambert School of Ballet and Contemporary Dance, Royal College of Art, Sylvia Young Theatre School 및 Trinity Laban. 런던 크로이던 자치구에 있는 BRIT 스쿨은 공연 예술과 기술을 위한 교육을 제공합니다.[346]

초중등교육

런던의 대부분의 초등학교와 중등학교와 고등교육 대학은 런던 자치구 또는 기타 국가의 재정 지원에 의해 통제됩니다. 대표적인 예로는 애쉬본 칼리지, 베스날 그린 아카데미, 브램튼 매너 아카데미, 시티 앤 이즐링턴 칼리지, 시티 오브 웨스트민스터 칼리지, 데이비드 게임 칼리지, 일링 등이 있습니다. 해머스미스 앤 웨스트 런던 칼리지, 레이턴 식스 폼 칼리지, 런던 아카데미 오브 엑설런스 칼리지, 타워 햄릿 칼리지, 뉴햄 칼리지 식스 폼 센터. 또한 런던에는 시티 오브 런던 스쿨, 해로우, 세인트 폴 스쿨, 하버다셔스 애스케 소년 스쿨, 유니버시티 칼리지 스쿨, 존 리옹 스쿨, 하이게이트 스쿨, 웨스트민스터 스쿨과 같이 오래되고 유명한 사립 학교와 대학들이 많이 있습니다.

그리니치 왕립 천문대와 학식 있는 학회.

1675년에 설립된 그리니치 왕립 천문대는 항해 목적으로 경도를 계산하는 문제를 해결하기 위해 설립되었습니다. 경도를 푸는 데 있어 이 선구적인 작업은 천문학자 네빌 마스켈라인의 항해 연감에 등장하는데, 이것은 그리니치 자오선을 세계적인 기준점으로 만들었고, 1884년 그리니치를 최고 자오선(경도 0°)으로 국제적으로 채택하는 데 도움이 되었습니다.[347]

런던에 기반을 둔 중요한 과학 학습 학회로는 1660년에 설립된 영국의 국립 과학 아카데미이자 세계에서 가장 오래된 국립 과학 기관인 왕립 학회와 [348]1799년에 설립된 왕립 기관이 있습니다. 1825년부터 왕립 기관 크리스마스 강연은 일반 청중들에게 과학적인 주제를 제시해 왔으며, 강연자로는 항공우주 공학자 프랭크 위틀, 박물학자 데이비드 애튼버러, 진화 생물학자 리처드 도킨스 등이 참여했습니다.[349]

문화

여가 및 오락

여가는 런던 경제의 주요 부분입니다. 2003년의 한 보고서는 영국 전체 여가 경제의 4분의 1을 인구 1000명당 25.6건의 사건으로 런던에[350] 귀속시켰습니다.[351] 이 도시는 세계 4대 패션 수도 중 하나이며, 공식 통계에 따르면 세계에서 세 번째로 바쁜 영화 제작 센터이며, 다른 어떤 도시보다 더 많은 라이브 코미디를 선보이며,[352] 세계 어느 도시보다 가장 많은 극장 관객을 보유하고 있습니다.[353]

런던의 시티 오브 웨스트민스터 내에서 웨스트엔드의 엔터테인먼트 지구는 런던과 세계 영화 시사회가 열리는 레스터 광장과 피카딜리 서커스를 중심으로 거대한 전자 광고가 있습니다.[354] 런던의 극장 구역은 이곳에 있고, 많은 영화관, 술집, 클럽, 식당들과 마찬가지로 (소호에 있는) 차이나타운 구역을 포함하고 있으며, 바로 동쪽에는 전문 상점들을 수용하는 구역인 코벤트 가든이 있습니다. 이 도시는 앤드류 로이드 웨버의 고향으로, 그의 뮤지컬은 20세기 후반부터 웨스트엔드 극장을 지배해 왔습니다.[355] 세계에서 가장 오래 상영된 연극인 아가사 크리스티의 '쥐트랩'은 1952년부터 웨스트엔드에서 공연되어 왔습니다.[356] 로렌스 올리비에의 이름을 딴 로렌스 올리비에 어워드는 매년 런던 극장 협회에서 수여합니다. 영국 왕립발레단, 영국국립발레단, 영국국립오페라단, 영국국립오페라단은 런던에 본부를 두고 있으며, 영국왕립오페라단, 런던 콜리세움, 새들러웰스극장, 로열앨버트홀 등에서 공연하며 전국을 순회하고 있습니다.[357]

Angel에서 북쪽으로 뻗어 있는 Islington의 1 mile (1.6 km) 길이의 Upper Street는 영국의 어떤 거리보다도 많은 술집과 식당을 가지고 있습니다.[358] 유럽에서 가장 번화한 쇼핑 지역은 거의 1마일(1.6km) 길이의 쇼핑 거리인 옥스퍼드 스트리트로, 영국에서 가장 긴 쇼핑 거리입니다. Selfridges 플래그십 스토어를 포함한 수많은 소매업체와 백화점의 본거지입니다.[359] 똑같이 유명한 해롯 백화점이 있는 나이츠브리지는 남서쪽에 위치해 있습니다. 1881년부터 리젠트 스트리트에 플래그십 스토어와 함께 1760년에 문을 연 햄리스는 세계에서 가장 오래된 장난감 가게입니다.[360] 마담 투소 밀랍인형 박물관은 런던의 관광산업이 시작된 1835년 베이커 스트리트에 문을 열었습니다.[361]

런던은 디자이너 John Galliano, Stella McCartney, Manolo Blanik, 그리고 Jimmy Choo의 고향입니다; 그곳의 유명한 예술과 패션 학교들은 런던을 네 개의 국제적인 패션 중심지 중 하나로 만듭니다. 메리 퀀트는 스윙잉 60년대 런던에 있는 킹스 로드 부티크에서 미니스커트를 디자인했습니다.[362] 런던은 인종적으로 다양한 인구로 인해 매우 다양한 요리를 제공합니다. 미식 중심지로는 브릭 레인의 방글라데시 레스토랑과 차이나타운의 중국 레스토랑이 있습니다.[363] 런던 전역에는 인도 요리와 영인도 요리를 제공하는 인도 레스토랑과 마찬가지로 중국 테이크아웃이 있습니다.[364] 1860년경, 런던의 첫 번째 피쉬 앤 칩스 가게가 유대인 이민자인 조셉 말린에 의해 보우에 문을 열었습니다.[324][365] 풀 잉글리시 조식은 빅토리아 시대부터 제공되며, 런던의 많은 카페에서는 하루 종일 풀 잉글리시 조식을 제공합니다.[366] 런던에는 첼시에 있는 Restaurant Gordon Ramsay를 포함하여 5개의 3-Michelin 스타 레스토랑이 있습니다.[367] 런던의 많은 호텔들은 피카딜리에 있는 호텔 카페 로얄의 오스카 와일드 라운지와 같은 전통적인 애프터눈 티 서비스를 제공하며, 예를 들어 에거튼 하우스 호텔에서 제공되는 이상한 나라의 앨리스 테마 애프터눈 티와 같은 테마 티 서비스도 이용할 수 있습니다. 그리고 찰리와 초콜릿 공장은 코벤트 가든에 있는 원 알드위치에서 오후의 차를 주제로 했습니다.[368][369] 이 나라에서 가장 인기 있는 차에 담글 수 있는 비스킷인 초콜릿 소화제는 1925년부터 런던 북서쪽의 할레스덴 공장에서 맥비티에 의해 제조되었습니다.[370]

런던 아이의 불꽃놀이인 비교적 새로운 설날 퍼레이드를 시작으로 매년 다양한 행사가 있습니다; 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 거리 파티인 노팅힐 카니발은 매년 8월 말 은행 휴일에 열립니다. 전통적인 퍼레이드에는 11월의 Lord Mayor's Show, 도시의 거리를 따라 행진하는 행렬과 함께 새로운 Lord Mayor's Show, 그리고 June's Trooping the Color, 영연방과 영국군의 연대들이 왕의 공식 생일을 축하하기 [371]위해 공연하는 공식적인 군사 대회 보이샤키 멜라(Boishakhi Mela)는 영국 방글라데시(Bangladeshi) 공동체가 축하하는 벵골 새해 축제입니다. 이 축제는 유럽에서 가장 큰 야외 아시아 축제입니다. 노팅힐 카니발에 이어 영국에서 두 번째로 큰 거리 축제로 8만 명이 넘는 관광객이 찾고 있습니다.[372] 1862년에 처음 개최된 RHS Chelsea Flower Show (영국 왕립 원예 협회가 운영하는)는 매년 5월에 열립니다.[373]

LGBT 장면

런던에서 현대적 의미로 최초의 게이 바는 1912년 리젠트 스트리트에서 바로 떨어진 헤든 스트리트 9번지 지하에 나이트 클럽으로 설립되어 "성적 자유와 동성 관계의 관용으로 명성을 떨친" 황금 송아지 동굴이었습니다.[374]

런던은 LGBT 관광지였지만, 1967년 영국에서 동성애가 비범죄화된 후 게이 바 문화가 더 눈에 띄었고, 1970년대 초부터 소호(특히 올드 콤프턴 스트리트)는 런던 LGBT 커뮤니티의 중심이 되었습니다.[375] 이전에 아스토리아에 기반을 둔 G-A-Y, 그리고 지금은 Heaven에 기반을 둔 오랜 야간 클럽입니다.[376]

더 넓은 영국의 문화 운동은 LGBT 문화에 영향을 미쳤습니다. 예를 들어, 1970년대 초 영국에서 마크 볼란과 데이비드 보위를 통해 글램 록의 출현은 10대 세대가 양성애자라는 아이디어를 가지고 연주하기 시작하는 것을 보았고, 1973년 런던에서 데뷔한 웨스트 엔드 뮤지컬 록키 호러 쇼는 또한 반문화운동과 성해방운동에 영향을 주었다고 널리 알려져 있습니다.[377] 블리츠 키즈(Boy George 포함)는 코벤트 가든의 블리츠에서 화요일 클럽 나이트를 자주 방문하여 1970년대 후반에 뉴로맨틱 하위 문화 운동을 시작하는 데 도움을 주었습니다.[378] 오늘날, 매년 열리는 런던 프라이드 퍼레이드와 런던 레즈비언과 게이 영화제가 이 도시에서 열립니다.[375]

문학, 영화, 텔레비전

런던은 많은 문학 작품의 배경이 되어 왔습니다. 제프리 초서의 14세기 후반 캔터베리 이야기에 나오는 순례자들은 런던에서 캔터베리로 출발했습니다. 윌리엄 셰익스피어는 그의 삶의 많은 부분을 런던에서 살고 일하며 보냈습니다; 그의 동시대의 벤 존슨도 그곳에 기반을 두었고, 그의 작품 중 일부, 특히 그의 연극 연금술사는 그 도시를 배경으로 했습니다.[379] 다니엘 디포(Daniel Defoe)의 전염병의 해(1722)는 1665년 대역병 사건을 허구화한 것입니다.[379]

런던의 문학 중심지는 전통적으로 언덕이 많은 햄프스테드와 (20세기 초부터) 블룸스버리였습니다. 이 도시와 밀접한 관련이 있는 작가들은 대불꽃 목격담으로 유명한 일기 작가 새뮤얼 페피스, 거리 청소부와 소매치기들로 이루어진 안개가 끼고 눈이 내리고 음울한 런던의 모습을 묘사한 찰스 디킨스, 그리고 초기 빅토리아 시대의 런던에 대한 사람들의 시각에 영향을 미쳤던 버지니아 울프, 20세기의 대표적인 모더니즘 문학 인물 중 한 명으로 여겨집니다.[379] 19세기와 20세기 초의 런던에 대한 나중의 중요한 묘사는 아서 코난 도일의 셜록 홈즈 이야기입니다.[379] 로버트 루이스 스티븐슨은 런던 문학계에 섞여들었고, 1886년에 그는 빅토리안 런던을 배경으로 한 고딕 소설인 지킬 박사와 하이드 씨의 기묘한 사건을 썼습니다.[380] 1898년, H. G. 웰스의 공상과학 소설 "The War of the Worlds"는 화성인들에 의해 침략당한 런던(그리고 영국 남부)을 봅니다.[381] Letitia Elizabeth Landon은 1834년에 런던 계절 달력을 썼습니다. 이 도시의 영향을 받은 현대 작가로는 런던의 전기 작가 피터 애크로이드(Peter Ackroid)와 심리지리학 장르의 글을 쓰는 이안 싱클레어(Iain Sinclair)가 있습니다. 1940년대에 조지 오웰은 런던 이브닝 스탠다드에 "멋진 차 한 잔" (차를 만드는 방법)과 "이상적인 펍" (이상적인 펍)을 포함한 에세이를 썼습니다.[382] 제2차 세계대전으로 런던에서 어린이들이 대피하는 모습은 C. S. 루이스의 첫 번째 나니아 책 "사자, 마녀 그리고 옷장"(1950)에 묘사되어 있습니다. 1925년 크리스마스 이브에 Winnie-the-Pooh는 봉제 장난감 A를 기반으로 한 캐릭터로 런던의 이브닝 뉴스에 데뷔했습니다. A. 밀른은 해롯에서 그의 아들 크리스토퍼 로빈을 위해 샀습니다.[383] 1958년, 작가 마이클 본드는 패딩턴 역에서 발견된 난민인 패딩턴 베어를 만들었습니다. 2014년 영화 《Paddington》에는 칼립소 노래 〈London is the Place for Me〉가 수록되어 있습니다.[384]

런던은 영화 산업에서 중요한 역할을 했습니다. 런던과 국경을 접하는 주요 스튜디오로는 파인우드, 엘트리, 일링, 셰퍼턴, 트위켄햄, 리프슨 등이 있으며, 여기서 제작된 많은 주목할 만한 영화 중 제임스 본드와 해리 포터 시리즈가 있습니다.[385][386] 워킹 타이틀 필름은 런던에 본사를 두고 있습니다. 소호에는 포스트 프로덕션 커뮤니티가 중심이 되고 있으며, 런던에는 프래메스토어와 같은 세계 최대의 시각 효과 회사 6개가 입주해 있습니다.[387] 디지털 퍼포먼스 캡처 스튜디오인 이매진아리움은 앤디 서키스(Andy Serkis)에 의해 설립되었습니다.[388] 런던은 올리버 트위스트(1948), 스크루지(1951), 피터 팬(1953), 백년가닥 달마시안(1961), 마이 페어 레이디(1964), 메리 포핀스(1964), 블로우업(1966), 시계공 오렌지(1971), 롱 굿 프라이데이(1980), 그레이트 마우스 탐정(1986), 노팅 힐(1999), 러브 액츄얼리(2003), V for Vendetta (2005), 스위니 토드: 함대 거리의 악마 이발사(2008)와 왕의 연설(2010). 런던에서 온 주목할만한 배우들과 영화 제작자들은 찰리 채플린, 알프레드 히치콕, 마이클 케인, 줄리 앤드류스, 피터 셀러스, 데이비드 린, 줄리 크리스티, 게리 올드만, 엠마 톰슨, 가이 리치, 크리스토퍼 놀란, 앨런 릭먼, 주드 로, 헬레나 본햄 카터, 이드리스 엘바, 톰 하디, 다니엘 래드클리프, 키이라 나이틀리, 리즈 아메드, 데브 파텔, 다니엘 칼루야, 톰 홀랜드, 다니엘 데이 루이스. 전후 일링 코미디에는 알렉 기네스가 등장했고, 1950년대 해머 호러즈는 크리스토퍼 리가 주연했으며, 마이클 파월의 영화에는 런던을 배경으로 한 초기 슬래셔 피핑 톰(1960)이 포함되었으며, 1970년대 코미디 극단 몬티 파이썬은 코벤트 가든에 영화 편집 스위트룸을 가지고 있었고, 1990년대부터 리처드 커티스의 롬콤에는 휴 그랜트가 등장했습니다. 미국에서 가장 큰 영화관 체인인 Odeon Cinema는 1928년 Oscar Deutsch에 의해 런던에서 설립되었습니다.[389] 영국 아카데미 영화상(BAFTAs)은 1949년부터 런던에서 개최되고 있으며, BAFTA 펠로우십이 아카데미 최고의 영예를 안았습니다.[390] 1957년에 설립된 BFI 런던 영화제는 매년 10월 2주에 걸쳐 열립니다.[391]

런던은 텔레비전 제작의 주요 중심지이며, 텔레비전 센터, ITV 스튜디오, 스카이 캠퍼스 및 분수 스튜디오를 포함한 스튜디오가 있습니다. 후자는 각 포맷이 전 세계로 수출되기 전에 오리지널 탤런트 쇼인 팝 아이돌, 더 엑스 팩터 및 브리튼스 갓 탤런트를 개최했습니다.[392][393] ITV의 프랜차이즈였던 테임즈 텔레비전은 베니 힐과 로완 앳킨슨 (미스터 빈이 테임즈에 의해 처음 상영됨)과 같은 코미디언들을 출연시켰고, 토크백은 사차 바론 코헨이 알리 G로 출연한 다 알리 G 쇼를 제작했습니다.[394] 유명한 텔레비전 연속극인 이스트엔더스를 포함한 많은 텔레비전 쇼들이 런던을 배경으로 하고 있습니다.[395]

박물관, 미술관, 도서관

런던은 많은 박물관, 갤러리, 그리고 다른 기관들의 본거지이며, 그들 중 많은 곳은 무료 입장료를 받고 있고, 연구 역할을 할 뿐만 아니라 주요 관광지입니다. 이것들 중 최초로 설립된 것은 1753년 블룸스버리에 있는 대영 박물관입니다.[396] 원래 고대 유물, 자연사 표본 및 국립 도서관을 포함하고 있던 박물관은 현재 전 세계에서 700만 점의 유물을 보유하고 있습니다. 1824년에는 영국 국립 서양화 컬렉션을 소장하기 위해 국립 미술관이 설립되었습니다. 현재 트라팔가 광장에서 중요한 위치를 차지하고 있습니다.[397]

영국 도서관은 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 도서관이며, 영국의 국립 도서관입니다.[398] LSE의 영국 정치 경제학 도서관, 임페리얼의 압두스 살람 도서관, 킹스의 모언 도서관, 런던 대학교의 상원 하원 도서관 등 대학 도서관뿐만 아니라 웰컴 도서관, 다나 센터 등 많은 연구 도서관이 있습니다.[399]

19세기 후반에 사우스 켄싱턴의 지역은 문화와 과학의 중심지인 "알베르토폴리스"로 개발되었습니다. 빅토리아 앨버트 박물관, 자연사 박물관, 과학 박물관 등 세 개의 주요 국립 박물관이 있습니다. 국립 초상화 미술관은 1856년 영국 역사 속 인물들의 묘사를 소장하기 위해 설립되었습니다. 현재 그 소장품은 세계에서 가장 광범위한 초상화 컬렉션으로 구성되어 있습니다.[400] 영국 미술의 국립 갤러리는 원래 1897년 국립 갤러리의 부속 건물로 설립된 테이트 브리튼에 있습니다. 테이트 갤러리는 이전에 알려진 대로 현대 미술의 주요 중심지가 되었습니다. 2000년, 이 컬렉션은 밀레니엄 다리를 통해 템스 강 북쪽의 보행자들이 접근하는 이전 뱅크사이드 발전소에 있는 새로운 갤러리인 테이트 모던(Tate Modern)으로 이전했습니다.[401]

음악

런던은 세계의 주요 클래식 음악과 대중 음악 수도 중 하나이며 유니버설 뮤직 그룹 인터내셔널과 워너 뮤직 그룹과 같은 주요 음악 회사와 수많은 밴드, 음악가 및 업계 전문가들을 유치하고 있습니다. 이 도시는 또한 바비컨 예술 센터 (런던 심포니 오케스트라와 런던 심포니 코러스의 주요 거점), 사우스뱅크 센터 (런던 필하모닉 오케스트라와 필하모니아 오케스트라), 카도간 홀 (로얄 필하모닉 오케스트라), 로열 앨버트 홀 (프롬스)과 같은 많은 오케스트라와 콘서트 홀의 본거지입니다.[357] 1895년에 처음 열린 8주간의 일상적인 오케스트라 클래식 음악의 여름 시즌인 프롬스는 프롬스의 마지막 밤으로 끝납니다. 런던의 두 주요 오페라 하우스는 왕립 오페라 하우스와 (영국 국립 오페라 극장의 본거지인) 런던 콜리세움입니다.[357] 영국에서 가장 큰 파이프 오르간은 로열 앨버트 홀에 있습니다. 다른 중요한 악기들은 1744년 동요 "오렌지와 레몬"에 등장하는 성 클레멘스 데인스 교회의 종과 같은 성당과 주요 교회에 있습니다.[402] 도시 내에는 여러 개의 음악원이 있습니다. 왕립 음악원, 왕립 음악 대학, 길드홀 음악 및 연극 학교, 트리니티 라반. 1931년에 EMI라는 레코드 레이블이 이 도시에서 설립되었고, 그 해에 회사의 초기 직원인 Alan Blumlein이 스테레오 사운드를 만들었습니다.[403]

런던에는 세계에서 가장 붐비는 실내 공연장인 O 아레나2,[404] 웸블리 아레나 등 록과 팝 콘서트를 위한 수많은 공연장이 있으며, 브릭스턴 아카데미, 해머스미스 아폴로, 셰퍼드 부시 제국 등 중견 공연장도 많이 있습니다.[357] 무선 페스티벌, 러브박스, 하이드 파크의 영국 여름 시간을 포함한 여러 음악 축제가 런던에서 열립니다.[405]

이 도시는 원래의 하드락 카페와 비틀즈가 많은 히트곡을 녹음했던 애비 로드 스튜디오의 본거지입니다. 1960년대, 1970년대 그리고 1980년대에 엘튼 존, 핑크 플로이드, 데이비드 보위, 롤링 스톤스, 킨크스, 퀸, 에릭 클랩튼, 더 후, 클리프 리처드, 레드 제플린, 아이언 메이든, 딥 퍼플, T. 렉스, 경찰, 엘비스 코스텔로, 디어 스트레이츠, 캣 스티븐스, 플리트우드 맥, 큐어, 매드니스, 컬처 클럽, 더스티 스프링필드, 필 콜린스(Phil Collins), 로드 스튜어트(Rod Stewart), 스테이터스 쿠오(Status Quo), 세이드(Sade)는 런던의 거리와 리듬에서 그들의 소리를 이끌어냈습니다.[406][407]

런던은 펑크 음악의 발전에 중요한 역할을 했으며, 섹스 피스톨스, 클래시 그리고 패션 디자이너 비비안 웨스트우드와 같은 인물들이 모두 런던에 기반을 두었습니다.[408][409] Other artists to emerge from the London music scene include George Michael, Kate Bush, Seal, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Bush, the Spice Girls, Jamiroquai, Blur, the Prodigy, Gorillaz, Mumford & Sons, Coldplay, Dido, Amy Winehouse, Adele, Sam Smith, Ed Sheeran, Leona Lewis, Ellie Goulding, Dua Lipa and Florence and the Machine.[410] Gary Numan, Depeche Mode, The Pet Shop Boys, Eurhmics를 포함한 런던 출신의 아티스트들은 신스팝의 발전에 중요한 역할을 했습니다. 후자의 "Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)"는 런던 북부 자택의 다락방에서 녹음되어 홈 레코딩 방식에 대한 트렌드를 예고했습니다.[411] 카리브해의 영향을 받은 런던 출신의 예술가들로는 핫초콜릿, 빌리오션, 소울2 소울, 에디그랜트 등이 있으며 후자는 레게, 소울, 삼바를 록과 팝에 접목시켰습니다.[412] 런던은 또한 도시 음악의 중심지입니다. 특히 영국 차고, 드럼 및 베이스, 덥스텝 및 그림 장르는 도시에서 현지 드럼 및 베이스와 함께 하우스, 힙합 및 레게의 외국 장르에서 진화했습니다. 런던에서 온 도시 활동으로는 스톰지, M.I.A., 제이 션, 리타 오라 등이 있습니다. 음악 방송국 BBC 라디오 1Xtra는 런던과 영국의 나머지 지역에서 지역 도시 현대 음악의 성장을 지원하기 위해 설립되었습니다. 영국 축음기 산업의 연례 대중 음악 시상식인 브릿 어워드가 런던에서 열립니다.[413]

레크리에이션

공원 및 공터

런던시의 2013년 보고서는 런던이 35,000 에이커(14,164 헥타르)의 공공 공원, 삼림 지대 및 정원을 가진 유럽에서 가장 "녹색 도시"라고 말했습니다.[414] 런던 중심 지역에서 가장 큰 공원은 8개의 로열 파크 중 3개, 즉 서쪽의 하이드 파크와 이웃한 켄싱턴 가든, 북쪽의 리젠트 파크입니다.[415] 특히 하이드 파크는 스포츠로 인기가 많고 때로는 야외 콘서트를 개최하기도 합니다. 리젠트 공원에는 세계에서 가장 오래된 과학 동물원인 런던 동물원이 있으며 마담 투소 밀랍인형 박물관 근처에 있습니다.[416] 프림로즈 힐은 도시 스카이라인을 볼 수 있는 인기 있는 장소입니다.[417]

하이드 파크 근처에는 더 작은 로열 파크, 그린 파크, 세인트 제임스 파크가 있습니다.[418] 남동쪽으로는 햄프스테드 히스와 그리니치 공원의 나머지 왕립 공원, 남서쪽으로는 부시 공원과 리치먼드 공원(가장 큰 공원) 등 많은 대형 공원이 도심 외곽에 있습니다. 햄프턴 코트 공원도 로열 파크이지만, 궁전이 포함되어 있기 때문에 8개의 로열 파크와는 달리 역사 왕궁에서 관리합니다.[419]

리치몬드 공원과 가까운 곳에는 세계에서 가장 큰 식물 컬렉션이 있는 큐 가든이 있습니다. 2003년, 그 정원들은 유네스코 세계문화유산 목록에 올랐습니다.[420] 또한 이스트 엔드의 빅토리아 공원과 중앙의 배터시 공원을 포함하여 런던 자치구 의회가 관리하는 공원도 있습니다. 런던 시의 통제를 [421]받는 햄스테드 히스와 에핑 포레스트를 포함하여 비공식적이고 반 자연적인 개방 공간도 있습니다.[422] 햄프스티드 히스는 켄우드 하우스를 포함하고 있는데, 켄우드 하우스는 예전에 위엄 있는 집이었으며 호수가에서 클래식 음악 콘서트가 열리는 여름에 인기 있는 장소입니다.[423] 엡핑 포레스트는 산악자전거, 걷기, 승마, 골프, 낚시, 오리엔티어링 등 다양한 야외 활동의 인기 장소입니다.[421] 영국에서 가장 많은 사람들이 방문하는 테마 파크 중 세 곳인 Staines-upon-Thames 근처의 Sorpe Park, Chessington의 Chessington World of Adventures, 레고랜드 윈저가 런던에서 20마일(32km) 이내에 위치해 있습니다.[424]

걷기

걷기는 런던에서 인기 있는 레크리에이션 활동입니다. 산책로를 제공하는 지역으로는 윔블던 커먼, 에핑 포레스트, 햄프턴 코트 파크, 햄프스테드 히스, 8개의 로열 파크, 운하, 폐철도 선로 등이 있습니다.[425] 최근 운하와 강에 대한 접근성이 향상되었는데, 그 중 약 28마일(45km)이 그레이터 런던(Greater London) 내에 있고, 완들(Wandle) 강을 따라 있는 완들 트레일(Wandle Trail)이 조성된 것을 포함합니다.[426]

녹색 공간을 연결하는 다른 장거리 경로들도 만들어졌는데, 그 중에는 캐피털 링, 그린 체인 워크, 런던 외곽 궤도 경로 ("루프"), 주빌리 워크, 리 밸리 워크, 웨일즈의 공주 다이애나 메모리얼 워크 등이 포함되어 있습니다.[425]

스포츠

런던은 1908년, 1948년, 그리고 2012년에 하계 올림픽을 세 번 개최하여, 근대 올림픽을 세 번 개최한 최초의 도시가 되었습니다.[36] 이 도시는 1934년 대영제국 게임의 개최지이기도 했습니다.[428] 2017년, 런던은 처음으로 세계 육상 선수권 대회를 개최했습니다.[429]

런던에서 가장 인기 있는 스포츠는 축구이며, 2022-23 시즌 프리미어 리그에 7개의 클럽이 있습니다. 아스널, 브렌트포드, 첼시, 크리스탈 팰리스, 풀럼, 토트넘 홋스퍼, 웨스트햄 유나이티드.[430] 런던의 다른 프로 남자 팀들은 AFC 윔블던, 바넷, 브롬리, 찰턴 애슬레틱, 대건햄 & 레드브릿지, 레이튼 오리엔트, 밀월, 퀸즈 파크 레인저스 그리고 서튼 유나이티드 입니다. 런던을 연고로 하는 4개의 팀이 여자 슈퍼리그에 참가하고 있습니다. 아스널, 첼시, 토트넘 그리고 웨스트햄 유나이티드.

두 프리미어십 럭비 유니온 팀은 그레이터런던에 기반을 두고 있습니다. Harlequins 와 Saracens.[431] 릴링 트레일파인더스와 런던 스코티시는 RFU 챔피언십에 참가합니다. 런던 남서부에 위치한 트위크넘 스타디움은 잉글랜드 럭비 유니온 국가대표팀의 홈경기를 개최합니다.[432] 럭비 리그는 영국 북부에서 더 인기가 있지만, 이 스포츠는 런던에 슈퍼 리그에서 뛰는 런던 브롱코스라는 프로 클럽이 있습니다.

런던에서 매년 열리는 가장 유명한 스포츠 대회 중 하나는 1877년부터 윔블던 남서부 교외의 올잉글랜드 클럽에서 열린 윔블던 테니스 챔피언십입니다.[433] 6월 말에서 7월 초에 열리는 이 대회는 세계에서 가장 오래된 테니스 대회이며 가장 권위 있는 대회로 널리 알려져 있습니다.[434][435]

런던에는 영국 크리켓 팀을 개최하는 두 개의 테스트 크리켓 경기장이 있습니다. 로드스(Middlesex C.C.C.의 홈)와 오벌(Oval, Surrey C.C.의 홈). 로드스는 크리켓 월드컵의 네 번의 결승전을 개최했고 크리켓의 고향으로 알려져 있습니다.[436] 골프에서 웬트워스 클럽은 런던의 남서쪽 가장자리에 있는 서리의 버지니아 워터에 위치하고 있으며, 골프에서 가장 오래된 메이저 대회이자 토너먼트인 오픈 챔피언십의 코스 중 하나로 사용되는 런던과 가장 가까운 장소는 켄트의 샌드위치에 있는 로열 세인트 조지입니다.[437] 런던 북부의 알렉산드라 팰리스는 PDC 월드 다트 챔피언십과 마스터스 스누커 대회를 개최합니다. 다른 중요한 연례 행사들은 대규모 참가 런던 마라톤과[438] 옥스퍼드와 캠브리지 사이에 경쟁하는 템스 강 위의 대학 보트 경주입니다.[439]

주목할 만한 사람들

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 런던은 보통 영국에서 왕권에 의해 도시 지위를 부여받는 도시가 아닙니다.

- ^ 참고 항목: 독립 도시 §의 수도

- ^ 대런던 당국은 런던 시장과 런던 의회로 구성되어 있습니다. 런던 시장은 런던시를 운영하는 런던시 공사를 이끄는 런던 시장과 구별됩니다.

- ^ 유럽 통계청(Eurostat)에 따르면, 런던은 EU에서 가장 큰 대도시권을 가지고 있었습니다. Eurostat는 인접한 도심과 주변 통근 지역의 인구의 합을 정의로 사용합니다.

- ^ '정부의 자리'에 대한 콜린스 영어 사전의 정의에 따르면,[143] 영국에는 독자적인 정부가 없기 때문에 런던은 영국의 수도가 아닙니다. '가장 중요한 마을'에 대한 옥스포드 영어 참조 사전의 정의와 다른 많은 당국들에 따르면.[144]

- ^ 임페리얼 칼리지 런던은 1908년에서 2007년 사이에 런던 대학교의 구성 대학이었습니다. 이 기간 동안의 학위는 연방 대학에서 수여했지만, 현재 대학은 자체 학위를 발행합니다.

참고문헌

- ^ a b c "Population and household estimates, England and Wales: Census 2021". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ a b No.1 가금류(ONE 94), 런던 고고학 박물관, 2013. 요크 대학 고고학 데이터 서비스.

- ^ "London weather map". The Met Office. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "2011 Census – Built-up areas". ONS. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ "Major agglomerations of the world". CityPopulation.de. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Fenton, Trevor. "Regional economic activity by gross domestic product, UK: 1998 to 2021". ons.gov.uk.

- ^ "The Greater London Authority Consolidated Budget and Component Budgets for 2021–22" (PDF). London.gov.uk. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Sub-national HDI. "Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org.

- ^ "Major Agglomerations". Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "Roman London". Museum of London. n.d. Archived from the original on 22 March 2008.

- ^ Fowler, Joshua (5 July 2013). "London Government Act: Essex, Kent, Surrey and Middlesex 50 years on". BBC News.

- ^ Mills, AD (2010). Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford University Press. p. 152.

Of course until relatively recent times the name London referred only to the City of London with even Westminster remaining a separate entity. But when the County of London was created in 1888, the name often came to be rather loosely used for this much larger area, which was also sometimes referred to as Greater London from about this date. However, in 1965 Greater London was newly defined as a significantly enlarged area.

- ^ "The baffling map of England's counties". BBC News. 25 April 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ "London Government Act 1963". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ Jones, Bill; Kavanagh, Dennis; Moran, Michael; Norton, Philip (2007). Politics UK. Harlow: Pearson Education. p. 868. ISBN 978-1-4058-2411-8.

- ^ "Global Power City Index 2020". Institute for Urban Strategies – The Mori Memorial Foundation. Retrieved 25 March 2021.; Adewunmi, Bim (10 March 2013). "London: The Everything Capital of the World". The Guardian. London.; "What's The Capital of the World?". More Intelligent Life. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Leading 200 science cities". Nature. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ "The World's Most Influential Cities 2014". Forbes. 14 August 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2021.; Dearden, Lizzie (8 October 2014). "London is 'the most desirable city in the world to work in', study finds". The Independent. London. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ a b Alexandra Muller and Bloomberg News (31 October 2023). "UK's stock market is in a 'doom loop' that's undermining London's status as a global financial capital, investment bank says". Fortune. New York. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ a b "London is Europe's leading economic powerhouse, says new report". London.gov.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Number of international students in London continues to grow" (Press release). Greater London Authority. 20 August 2008. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010.

- ^ "Times Higher Education World University Rankings". 19 September 2018.; "Top Universities: Imperial College London".; "Top Universities: LSE". Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2022". Top Universities. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Revealed: The most crowded skies on the planet". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

London: Our capital's collective airport system is the busiest in the whole world. A total of 170,980,680 passengers.

- ^ "London Underground". Transport for London. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "Languages spoken in the UK population". National Centre for Language. 16 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2008."CILT, the National Centre for Languages". Archived from the original on 13 February 2005. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ "London, UK Metro Area Population 1950-2023". Macrotrends. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Largest EU City. Over 7 million residents in 2001". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ "Focus on London – Population and Migration London DataStore". Greater London Authority. Archived from the original on 16 October 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Demographia World Urban Areas, 15th Annual Edition" (PDF). Demographia. April 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ a b "2011 Census – Built-up areas". nomisweb.co.uk. ONS. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ "Metropolitan Area Populations". Eurostat. 18 June 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "The London Plan (March 2015)". Greater London Authority. 15 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Lists: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- ^ Blackman, Bob (25 January 2008). "West End Must Innovate to Renovate, Says Report". What's on Stage. London. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ a b c "IOC elects London as the Host City of the Games of the XXX Olympiad in 2012" (Press release). International Olympic Committee. 6 July 2005. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2006.

- ^ Mills, Anthony David (2001). A Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780192801067. OCLC 45406491.

- ^ Bynon, Theodora (2016). "London's Name". Transactions of the Philological Society. 114 (3): 281–97. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.12064.

- ^ Mills, David (2001). A Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780192801067. OCLC 45406491.

- ^ a b "First 'London Bridge' in River Thames at Vauxhall". 27 May 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "London's Oldest Prehistoric Structure". BAJR. 3 April 2015. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ a b Milne, Gustav. "London's Oldest Foreshore Structure!". Frog Blog. Thames Discovery Programme. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Perring, Dominic (1991). Roman London. London: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-203-23133-3.

- ^ "British History Timeline - Roman Britain". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ Lancashire, Anne (2002). London Civic Theatre: City Drama and Pageantry from Roman Times to 1558. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-63278-2.

- ^ "The last days of Londinium". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "The early years of Lundenwic". The Museum of London. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008.

- ^ Wheeler, Kip. "Viking Attacks". Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ Vince, Alan (2001). "London". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- ^ Stenton, Frank (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 538–539. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- ^ Ibeji, Mike (17 February 2011). "History – 1066 – King William". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Tinniswood, Adrian. "A History of British Architecture — White Tower". BBC. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- ^ "UK Parliament — Parliament: The building". UK Parliament. 9 November 2007. Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ Schofield, John; Vince, Alan (2003). Medieval Towns: The Archaeology of British Towns in Their European Setting. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8264-6002-8.

- ^ Ibeji, Mike (10 March 2011). "BBC – History – British History in depth: Black Death". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ "Richard II (1367–1400)". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph (1906). "England". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Mundill, Robin R. (2010), "The King's Jews", Continuum, London, pp. 88–99, ISBN 978-1-84725-186-2, LCCN 2010282921, OCLC 466343661, OL 24816680M

- ^ a b Pevsner, Nikolaus (1 January 1962). London – The Cities of London and Westminster. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Penguin Books. p. 48. ASIN B0000CLHU5.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Pounds, Normal J. G. (1973). An Historical Geography of Europe 450 B.C.–A.D. 1330. Cambridge University Press. p. 430. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139163552. ISBN 9781139163552.

- ^ Ramsay, George Daniel (1986). The Queen's Merchants and the Revolt of the Netherlands (The End of the Antwerp Mart, Vol 2). Manchester University Press. pp. 1 & 62–63. ISBN 9780719018497.

- ^ Burgon, John William (1839). The Life and Times of Sir Thomas Gresham, Founder of the Royal Exchange: Including Notices of Many of His Contemporaries. With Illustrations, Volume 2. London: R. Jennings. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-1277223903.

- ^ "From pandemics to puritans: when theatre shut down through history and how it recovered". The Stage.co.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "London's 10 oldest theatres". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Durston, Christopher (1993). James I. London: Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-415-07779-8.

- ^ Doolittle, Ian (2014). "'The Great Refusal': Why Does the City of London Corporation Only Govern the Square Mile?". The London Journal. 39 (1): 21–36. doi:10.1179/0305803413Z.00000000038. S2CID 159791907.

- ^ Flintham, David. "London". Fortified Places. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ 해링턴, 피터 (2003). 영국 남북전쟁 요새 1642–51, 요새 9권, 9, 오스프리 출판사, ISBN 1-84176-604-6 페이지 57

- ^ Flintham, David. "London". Fortified Places. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2021.Razzell, Peter; Razzell, Edward, eds. (1 January 1996). The English Civil War: A contemporary account (v. 1). Wencelaus Hollar (Illustrator), Christopher Hill (Introduction). Caliban Books. ISBN 978-1850660316.Gardiner, Samuel R. (18 December 2016). History of the Great Civil War, 1642-1649. Vol. 3. Forgotten Books (published 16 July 2017). p. 218. ISBN 978-1334658464.

- ^ a b "A List of National Epidemics of Plague in England 1348–1665". Urban Rim. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Pepys, Samuel (2 September 1666) [1893]. Mynors Bright (decipherer); Henry B. Wheatley (eds.). The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Vol. 45: August/September 1666. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22167-3. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013.

- ^ Schofield, John (17 February 2011). "BBC – History – British History in depth: London After the Great Fire". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Amsterdam and London as financial centers in the eighteenth century". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Hell on Earth, or the Town in a Surge (anon., London 1729). Jarndyce Autumn Miscellany 카탈로그, 런던: 2021.

- ^ "PBS – Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street". PBS. 2001. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Harris, Rhian (5 October 2012). "History – The Foundling Hospital". BBC. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ a b Coispeau, Olivier (2016). Finance Masters: A Brief History of International Financial Centers in the Last Millennium. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-310-884-4.

- ^ a b White, Matthew. "The rise of cities in the 18th century". British Library. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Christopher Watson (1993). K.B. Wildey; Wm H. Robinson (eds.). Trends in urbanisation. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Urban Pests. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.522.7409.

- ^ "London: The greatest city". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Brown, Robert W. "London in the Nineteenth Century". University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ "A short history of world metro systems – in pictures". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ Pennybacker, Susan D. (2005). Vision for London, 1889–1914. Routledge. p. 18.

- ^ "Bawden and battenberg: the Lyons teashop lithographs". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "Taking Tea and Talking Politics: The Role of Tearooms". Historic England. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "Suffragettes, violence and militancy". British Library. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Bomb-Damage Maps Reveal London's World War II Devastation". nationalgeographic.com.au. 18 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Buried Among Kings: The Story of the Unknown Warrior". Nam.ac.uk. National Army Museum. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Vaughan-Barratt, Nick (4 November 2009). "Remembrance". BBC Blogs. BBC. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Ronk, Liz (27 July 2013). "LIFE at the 1948 London Olympics". Time. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher; Weinreb, Ben; Keay, Julia; Keay, John (2010). The London Encyclopaedia. Photographs by Matthew Weinreb (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. p. 428. ISBN 9781405049252.

- ^ "1951: King George opens Festival of Britain". BBC. 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Breen, Matt (13 January 2017). "Most Googled: why is London called the 'Big Smoke'?". Time Out London. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Rycroft, Simon (2016). "Mapping Swinging London". Swinging City: A Cultural Geography of London 1950–1974. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 9781317047346.

- ^ Bracken, Gregory B. (2011). Walking Tour London: Sketches of the city's architectural treasures... Journey Through London's Urban Landscapes. Marshall Cavendish International. p. 10. ISBN 9789814435369.

- ^ Webber, Esther (31 March 2016). "The rise and fall of the GLC". BBC Newsmaccess-date=18 June 2017.

- ^ a b c >Godoy, Maria (7 July 2005). "Timeline: London's Explosive History". NPR. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ John, Cindi (5 April 2006). "The legacy of the Brixton riots". BBC. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "London's population hits 8.6m record high". BBC News. 2 February 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Zolfagharifard, Ellie (14 February 2014). "Canary Wharf timeline: from the Thatcher years to Qatari control". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Kendrick, Mary (1988). "The Thames Barrier". Landscape and Urban Planning. 16 (1–2): 57–68. doi:10.1016/0169-2046(88)90034-5.

- ^ "1986: Greater London Council abolished". BBC. 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ Ijeh, Ike (25 June 2010). "Millennium projects: 10 years of good luck". building.co.uk. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ Derudder, Ben; Hoyler, Michael; Taylor, Peter J.; Witlox, Frank, eds. (2015). International Handbook of Globalization and World Cities. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 422. ISBN 9781785360688.

- ^ "Population Growth in London, 1939–2015". London Datastore. Greater London Authority. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015. Alt URL

- ^ Chandler, Mark (24 June 2016). "'Wouldn't you prefer to be President Sadiq?' Thousands call on Sadiq Khan to declare London's independence and join EU". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "London as a Financial Center Since Brexit: Evidence from the 2022 BIS Triennial Survey". Boston University Global Development Policy Center. 16 December 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023.

- ^ "The Coronation Weekend". The Royal Family. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024.

- ^ Vinycomb, John (1909). "The Heraldic Dragon". Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art. Internet Sacred Text Archive. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Who runs London – Find Out Who Runs London and How". London Councils. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ a b "The essential guide to London local government". London Councils. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ "London Elections 2016: Results". BBC News. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ "The London Plan". Greater London Authority. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "London Government Directory – London Borough Councils". London Councils. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "London Government". politics.co.uk. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ "Local Government Financial Statistics England No.21 (2011)" (PDF). 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Who we are". London Fire Brigade. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ "About us". London Ambulance Service NHS Trust. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ "Port of London Act 1968 (as amended)". Port of London Authority. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ "Prime Minister's Office, 10 Downing Street". uk.gov. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Constituencies A-Z – Election 2019". BBC News. 2019. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Minister for London". gov.uk. UK Government. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "MPA: Metropolitan Police Authority". Metropolitan Police Authority. 22 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ "Policing". Greater London Authority. Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ "Just how practical is a traditional Bobby's helmet?". BBC. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Police lose fight to ground Tardis". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "About Us". British Transport Police. 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "Ministry of Defence – Our Purpose". Ministry of Defence Police. 2017. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Andrew, Christopher (2009). The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5. Allen Lane. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-713-99885-6.

- ^ "Recorded Crime: Geographic Breakdown – Metropolitan Police Service". Greater London Authority. 12 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "London murder rate up 14% over the past year". ITV News. 24 January 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Crerar, Pippa; Gayle, Damien (10 April 2018). "Sadiq Khan Holds City Hall Summit on How To Tackle Violent Crime". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Met Police: London homicide figures fall in 2022". BBC. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Beavan, Charles; Bickersteth, Harry (1865). Reports of Cases in Chancery, Argued and Determined in the Rolls Court. Saunders and Benning.

- ^ Stationery Office (1980). The Inner London Letter Post. H.M.S.O. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-10-251580-0.

- ^ "The Essex, Greater London and Hertfordshire (County and London Borough Boundaries) Order". Office of Public Sector Information. 1993. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ "London in its Regional Setting" (PDF). London Assembly. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ London Government Act 1963. Office of Public Sector Information. 1996. ISBN 978-0-16-053895-7. Archived from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- ^ "London — Features — Where is the Centre of London?". BBC. Archived from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ "Lieutenancies Act 1997". OPSI. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ Barlow, I.M. (1991). Metropolitan Government. London: Routledge. p. 346. ISBN 9780415020992.

- ^ Sinclair, J.M. (1994). Collins English dictionary (3rd updated ed.). Glasgow: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0004706788.

- ^ Pearsall, Judy; Trumble, Bill, eds. (2002). The Oxford English Reference Dictionary (2nd, rev ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198606529.

- ^ Schofield, John (June 1999). "When London became a European capital". British Archaeology. Council for British Archaeology (45). ISSN 1357-4442. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- ^ "Government Offices for the English Regions, Fact Files: London". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 January 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- ^ a b "Metropolis: 027 London, World Association of the Major Metropolises" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Sheppard, Francis (2000). London: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-19-285369-1. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ "Flooding". UK Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 15 February 2006. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- ^ ""Sea Levels" – UK Environment Agency". Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ "Weather April". trevorharley.com.

- ^ "Niederschlagsmonatssummen KEW GARDENS 1697–1987". Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Average Annual Precipitation by City in the US – Current Results". currentresults.com. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Saphora Smith (16 May 2022). "London could run out of water in 25 years as cities worldwide face rising risk of drought, report warns". The Independent. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "Minimum Temperatures observed on 13th Dec 1981 at 06Z (SYNOP)/09Z (MIDAS/BUFR) UTC (529 reports)". Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Search Climate Data Online (CDO) National Climatic Data Center (NCDC)". Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (20 January 2020). "London breaks a high-pressure record". BBC News. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ Johnson, H; Kovats, RS; McGregor, G; Stedman, J; Gibbs, M; Walton6, H (1 July 2005). "The impact of the 2003 heat wave on daily mortality in England and Wales and the use of rapid weekly mortality estimates". Eurosurveillance. 10 (7): 15–16. doi:10.2807/esm.10.07.00558-en. PMID 16088043.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 메인트: 숫자 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Taylor, Brian (2002). "1976. The Incredible Heatwave". TheWeatherOutlook. Archived from the original on 12 July 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Monthly Weather Report of the Meteorological Office" (PDF). Wyman and Sons, Ltd. 1911. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "UK Droughts: SPI". UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Philip Eden: Longest drought for 2 years – weatheronline.co.uk". weatheronline.co.uk. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "London's Urban Heat Island: A Summary for Decision Makers" (PDF). Greater London Authority. October 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Eden, Philip (9 June 2004). "Ever Warmer as Temperatures Rival France". London. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "London Heathrow Airport". Met Office. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Station Data". Met Office. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "UK Climate Extremes". Met Office. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Heathrow Airport Extreme Values". KNMI. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ "Heathrow 1981–2010 mean maximum and minimum values". KNMI. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "London, United Kingdom – Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "MIDAS Open: UK daily temperature data, v202007". CEDA Archive. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Maximum temperature date records". TORRO. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Climate & Weather Averages in London, England, United Kingdom". Time and Date. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "London's Boroughs". History Today. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "London boroughs — London Life, GLA". London Government. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ "London as a financial centre". Mayor of London. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008.

- ^ "West End still drawing crowds". BBC News. 22 October 2001. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ Meek, James (17 April 2006). "Super Rich". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ "Information on latest house prices in the Royal Borough". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016.

- ^ Jones, Rupert (8 August 2014). "Average house prices in London jump 19 percent in a year". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ a b Flynn, Emily (6 July 2005). "Tomorrow's East End". Newsweek. New York. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006.

- ^ Summerson, John (1969). Great Palaces (Hampton Court. pp. 12–23). Hamlyn. ISBN 9780600016823.

- ^ "Paddington Station". Great Buildings. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ Lonsdale, Sarah (27 March 2008). "Eco homes: Wooden it be lovely... ?". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ a b "Protected views and tall buildings". City of London.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Take a tour of The Shard's viewing platform". BBC. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ White, Dominic (15 April 2008). "The Lemon Dome That Was Transformed into O2's Concert Crown". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 June 2022.