헬레니즘 시대

Hellenistic period| 그리스의 역사 |

|---|

|

| |

헬레니즘 시대는 기원전 31년[1] 악티움 전투와 이듬해 [2]프톨레마이오스 이집트 정복으로 나타나듯이 기원전 323년 알렉산더 대왕의 죽음과 로마 제국의 출현 사이의 지중해 역사 기간을 포함한다.헬레니즘 시대 이전의 그리스 기간은 고전 그리스로 알려져 있고, 그 이후의 기간은 로마 그리스로 알려져 있다.고대 그리스어 헬라스(Hellas, Hellas)는 원래 그리스에서 널리 알려진 이름으로, 헬레니즘이라는 단어에서 [3]유래되었다."헬레니즘"은 "헬레니즘"과 구별되는데, "헬레니즘"은 첫 번째가 고대 그리스의 직접적인 영향 아래 있는 모든 영토를 아우르는 반면, 후자는 그리스 자체를 지칭한다는 것이다.대신, "헬레니즘"이라는 용어는 알렉산더 대왕의 정복 이후 그리스 문화, 이 경우 동양에서 영향을 받은 것을 말한다.

헬레니즘 시대에 그리스의 문화적 영향력과 힘은 지중해 세계와 서아시아의 대부분, 심지어 인도 아대륙의 일부에서 지배적이었고, 예술, 점성술, 탐험, 문학, 건축, 음악, m의 번영과 발전을 경험했다.아테마틱스, 철학.그럼에도 불구하고, 그것은 종종 그리스 고전 시대의 계몽과 비교하여, 때로는 퇴폐나 [4]퇴폐의 과도기로 여겨진다.헬레니즘 시대는 뉴 코미디, 알렉산드리아의 시, 셉투아긴트와 스토이즘, 에피쿠아니즘, 피로니즘의 철학의 발흥을 보았다.그리스 과학은 수학자 유클리드와 수학자 아르키메데스의 연구에 의해 발전되었다.종교 영역은 그리스-이집트 세라피스와 같은 새로운 신들, 아티스와 사이벨레와 같은 동양의 신들, 박트리아와 북서 인도의 헬레니즘 문화와 불교 사이의 융합으로 확장되었다.

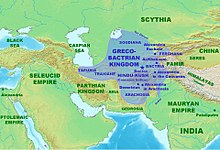

기원전 330년 알렉산더 대왕의 아케메네스 제국 침략과 그 직후 붕괴 이후 헬레니즘 왕국은 남서아시아(세레우코스 제국, 페르가몬 왕국), 북동아프리카(프톨레마이오스 왕국), 남아시아(그렉코액트리아 왕국), 인도-그리스 왕국(그레스코브리아 왕국)에 세워졌다.헬레니즘 시대는 아시아와 [6]아프리카에 그리스 도시와 왕국을 세운 그리스 식민지의[5] 새로운 물결로 특징지어졌다.이것은 그리스 문화와 언어를 현대 인도까지 아우르는 이러한 새로운 영역으로 수출하는 결과를 가져왔다.이 새로운 왕국은 또한 토착 문화의 영향을 받았고, 유익하고, 필요하거나, 편리한 지역의 관행을 채택했다.따라서 헬레니즘 문화는 고대 그리스 세계와 서아시아,[7] 북동아프리카, 서남아시아의 융합을 상징한다.이 혼합물은 코이네 그리스어로 알려진 일반적인 아티케에 기반을 둔 그리스 사투리를 만들어냈고, 이것은 헬레니즘 세계 전체에서 링귀아 프랑카가 되었다.

학자들과 역사학자들은 어떤 사건이 헬레니즘 시대의 종말을 알리는지에 대해 의견이 분분하다.헬레니즘 시대는 기원전 31년 악티움 전투에서 프톨레마이오스 왕국이 마지막으로 패배하고 기원전 146년 로마가 그리스 심장부를 정복하는 것으로 끝나거나 심지어 기원전 [8][9]330년 로마 제국의 수도 콘스탄티누스 대제가 수도를 콘스탄티노폴리스로 옮기면서 끝날 것으로 보인다.Angelos Chaniotis는 그리스인들을 [10]로마 제국에 완전히 통합시킨 138년 하드리아누스의 죽음으로 헬레니즘 시대를 마감하고, 기원전 321년부터 서기 256년까지의 범위가 [11]주어질 수 있다.

어원학

이 단어는 "헬레니스트" + "ic"[citation needed]처럼 고대 그리스어 λistḗḗhell (헬레니스트는 "그리스어를 사용하는 사람")에서 유래했다.

헬레니즘 시대의 개념은 19세기 개념이며 고대 그리스에는 존재하지 않았다.비록 단어 형태나 의미, 예를 들어 그리스 문명 숭배자(고대 그리스어:Ἑλληνιστής, Hellēnistēs)에 관련된 고대 times,[12]했던 이후로 요한 드로이젠 19세기 중반에 그의 고전적인 일 Geschichte 데 Hellenismus(헬레니즘의 역사)에서, 때 그리고 그리스 집단 기간을 정의하고자 하는 용어는 헬레니즘 시대를 만들어 낸 증명되고 있다.ure알렉산더의 [13]정복 이후 그리스가 아닌 세계에 퍼져나갔습니다.드로이센 이후, 헬레니즘과 같은 관련 용어들은 다양한 맥락에서 널리 사용되었습니다; 주목할 만한 사용법은 매튜 아놀드의 문화와 무정부에서 헬레니즘이 [14]헤브라주의와 대조되게 사용되었습니다.

그리스 문화의 확산이 그 용어가 암시하는 일반화된 현상이 아니었기 때문에 헬레니즘 용어의 주요 문제는 그것의 편리성에 있다.정복된 세계의 일부 지역은 다른 지역보다 그리스의 영향을 더 많이 받았다.헬레니즘이라는 용어는 또한 그들이 정착한 지역에서는 그리스인들이 다수를 차지했지만, 많은 경우, 그리스 정착민들은 실제로 원주민들 사이에서 소수였다는 것을 암시한다.그리스 인구와 원주민 인구가 항상 섞였던 것은 아니다; 그리스인들이 이주하여 그들만의 문화를 가져왔지만, 상호작용이 항상 [citation needed]일어난 것은 아니다.

원천

몇 개의 파편들이 존재하지만, 알렉산더의 죽음 이후 100년까지 거슬러 올라가는 완전한 역사 작품은 남아 있지 않다.주요 헬레니즘 역사학자 카르디아의 히에로니무스(알렉산드로스, 안티고노스 1세 등 후계자 밑에서 활동한), 사모스의 두리스, 필라르코스의 작품들은 모두 [15]유실된다.헬레니즘 시대에 가장 오래되고 가장 신뢰할 수 있는 자료는 기원전 168년까지 아카이아 동맹의 정치인이었던 메가로폴리스의 폴리비우스입니다.[15]그의 역사는 결국 기원전 220년에서 167년까지 40권의 책으로 늘어났다.

폴리비우스 이후의 가장 중요한 자료는 디오도로스 시쿨루스로 그는 기원전 60년에서 30년 사이에 그의 비블리오테카 역사서를 썼고 히에로니무스와 같은 중요한 초기 자료들을 복제했지만, 그의 헬레니즘 시대에 대한 설명은 입소스 전투 (기원전 301년) 이후 끊어진다.또 다른 중요한 자료인 플루타르코스의 c.평행생활은 개인의 성격과 도덕성에 대한 문제에 더 몰두하고 있지만, 중요한 헬레니즘 인물들의 역사를 요약하고 있다.알렉산드리아의 아피안 (기원후 1세기 후반–165년 이전)은 일부 헬레니즘 [citation needed]왕국에 대한 정보를 포함한 로마 제국의 역사를 썼다.

다른 자료들은 폼페이우스 트로구스의 역사 필립카이의 저스틴의 (2세기) 대명사와 콘스탄티노플의 포토오스 1세의 알렉산더 이후의 아리아 사건 요약을 포함한다.덜 보충적인 자료로는 Curtius Rufus, Pausanias, Pliny, 그리고 Suda라는 비잔틴 백과사전이 있다.철학 분야에서는, 디오게네스 라에르티우스의 삶과 저명한 철학자들의 의견이 주요 출처이다; 키케로의 De Natura Deorum과 같은 작품들 또한 헬레니즘 시대의 [citation needed]철학 학파에 대한 더 자세한 내용을 제공한다.

배경

고대 그리스는 전통적으로 맹렬하게 독립적인 도시국가들의 까다로운 집합체였다.펠로폰네소스 전쟁 (기원전 431–404년) 이후, 그리스는 스파르타의 패권 하에 놓였고, 스파르타는 탁월했지만 전능하지는 않았다.스파르타의 패권은 레옥트라 전투(기원전 371년) 이후 테반의 패권에 의해 계승되었지만, 만티네이아 전투(기원전 362년) 이후 그리스는 어느 국가도 우위를 차지할 수 없을 정도로 약해졌다.필리포스 2세 치하에서 마케도니아의 지배가 시작된 것은 이러한 배경에서였다.마케도니아는 그리스 세계의 변방에 위치해 있었고, 왕실은 그리스 혈통을 주장했지만, 마케도니아인들은 나머지 그리스인들에게 반 야만적인 존재로 무시당했다.그러나, 마케도니아는 대부분의 그리스 국가들에 비해 넓은 지역을 통제하고 상대적으로 강력한 중앙집권 정부를 가지고 있었다.

필립 2세는 마케도니아 영토를 확장하기 위해 모든 기회를 잡은 강하고 확장론적인 왕이었다.기원전 352년에 그는 테살리아와 마그네시아를 합병했다.기원전 338년, 필리포스는 10년간의 혼란 끝에 카이로네이아 전투에서 테반과 아테네 연합군을 물리쳤다.그 여파로 필립은 코린트 동맹을 결성하여 그리스의 대부분을 사실상 직접 지배하에 두었다.그는 동맹의 헤게몬으로 선출되었고 페르시아의 아케메네스 제국에 대항하는 캠페인이 계획되었다.그러나 기원전 336년, 이 캠페인이 초기 단계에 있을 때, 그는 [4]암살당했다.

아버지의 뒤를 이어 알렉산더는 페르시아 전쟁을 직접 지휘했다.10년간의 캠페인 기간 동안 알렉산더는 페르시아 왕 다리우스 3세를 전복시키며 페르시아 제국 전체를 정복했다.정복된 땅에는 소아시아, 아시리아, 레반트, 이집트, 메소포타미아, 미디어, 페르시아, 그리고 오늘날의 아프가니스탄, 파키스탄, 중앙아시아의 스텝들이 포함되었습니다.그러나 수년간의 끊임없는 캠페인은 그들에게 피해를 입혔고 알렉산더는 기원전 323년에 죽었다.

그가 죽은 후, 알렉산더가 정복한 거대한 영토들은 서쪽의 로마와 동쪽의 파르티아가 부상할 때까지 다음 2, 3세기 동안 그리스의 강력한 영향의 대상이 되었다.그리스와 레반타인 문화가 혼합되면서, 혼합된 헬레니즘 문화의 발전이 시작되었고 그리스 문화의 주요 중심에서 고립되어도 지속되었다.

알렉산더의 정복 이후와 디아도키 통치 기간 동안 마케도니아 제국을 가로지르는 변화들 중 일부는 그리스의 영향 없이 일어났을 것이라고 주장할 수 있다.피터 그린이 언급했듯이, 정복의 많은 요소들이 헬레니즘 시대라는 용어로 합쳐졌다.이집트와 소아시아와 메소포타미아 지역을 포함한 알렉산더의 침략군에 의해 정복된 특정 지역들은 기꺼이 정복에 넘어갔고 알렉산더를 [16]정복자라기보다는 해방자로 여겼다.

게다가 정복된 지역의 대부분은 알렉산더의 장군이자 후계자인 디아도치 가문이 계속 통치할 것이다.처음에는 제국 전체가 그들 사이에 분할되었지만, 몇몇 영토들은 비교적 빨리 상실되거나 명목상 마케도니아 통치 하에 남아있었다.200년이 지난 후, 로마에 의해 프톨레마이오스식 이집트를 정복하기 전까지, 훨씬 축소되고 다소 타락한 국가들만 [9]남아있었다.

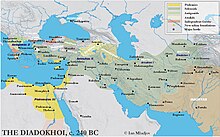

디아도치

알렉산더 대왕이 사망했을 때(기원전 323년 6월 10일), 그는 사트라프라고 불리는 많은 본질적으로 자율적인 영토로 구성된 무질서한 제국을 남겼다.선택된 후계자가 없다면 누가 마케도니아의 왕이 되어야 하는지에 대한 그의 장군들 사이에 즉각적인 논쟁이 있었다.이 장군들은 디아도키(그리스어: δάχχχχι di di, "후계자"라는 뜻의 디아도호이)로 알려지게 되었다.

멜레아거와 보병은 알렉산더의 이복형제 필립 아리다우스의 출마를 지지했고, 기병 지휘관 페르디카스는 알렉산더의 아이가 록사나에 의해 태어날 때까지 기다리는 것을 지지했다.보병이 바빌로니아의 궁전을 급습한 후 타협안이 마련되었다 – 아리다에우스 (필립 3세)는 왕이 되어야 했고 록사나의 아이가 남자 아이라고 가정하면 그와 함께 통치해야 했다.페르디카스 자신은 제국의 섭정(에피멜레트)이 되었고, 멜레아거는 그의 부관이 되었다.그러나 곧 페르디카스는 멜리거와 다른 보병 지도자들을 살해하고 완전한 [17]통제권을 장악했다.페르디카스를 지지했던 장군들은 바빌로니아 분할에서 제국의 여러 지역의 사트랩이 됨으로써 보상을 받았지만, 아리아누스의 기록처럼, "모든 사람들이 그를 의심하고 있었고,[18] 그는 그들을 의심하고 있었다"는 이유로 페르디카스의 입지는 흔들렸다.

디아도키 전쟁은 페르디카스가 알렉산더의 여동생 클레오파트라와 결혼할 계획을 세우고 안티고노스 1세 모노프탈무스의 소아시아에서의 리더십에 의문을 제기하기 시작하면서 시작되었다.안티고노스는 그리스로 도망쳤고, 안티파테르와 크레이터로스와 함께 아나톨리아를 침공했다.반란군은 트라키아의 사트라프인 리시마코스와 이집트의 사트라프인 프톨레마이오스의 지원을 받았다.비록 카파도키아의 사트라프인 에우메네스가 소아시아의 반란군을 물리쳤지만, 페르디카스 자신은 이집트를 c.침공하는 동안 페이톤, 셀레우코스, 그리고 안티게네스(아마도 [19]프톨레마이오스의 도움으로)에 의해 살해되었다.프톨레마이오스는 페르디카스의 살인자들과 타협하여 페이톤과 아리히데오스를 그의 자리에 섭정하게 만들었지만, 곧 이것들은 트리파라디소스 조약에서 안티파이터와 새로운 합의에 이르렀다.안티파테르는 제국의 섭정이 되었고, 두 왕은 마케도니아로 옮겨졌다.안티고노스는 소아시아를, 프톨레마이오스는 이집트를, 리시마코스는 트라키아를, 셀레우코스 1세는 바빌론을 지배했다.

제2차 디아도치 전쟁은 기원전 319년 안티파테르가 죽은 후 시작되었다.안티파테르는 자신의 아들 카산데르를 넘겨주면서 폴리페르촌을 그의 후계자로 선언하였다.카산데르는 폴리페르콘(에우메네스가 합류)에 맞서 반란을 일으켰고 안티고노스, 리시마코스, 프톨레마이오스의 지원을 받았다.기원전 317년, 카산데르는 마케도니아를 침공하여, 올림피아스를 사형선고하고 소년왕 알렉산더 4세와 그의 어머니를 붙잡았다.아시아에서, 에우메네스는 수년간의 전투 끝에 그의 부하들에게 배신당했고 안티고노스에게 넘겨졌고 안티고누스는 그를 처형했다.

제3차 디아도키 전쟁은 안티고누스의 힘과 야망 때문에 일어났다.그는 마치 자신이 왕인 것처럼 새트랩을 제거하고 임명하기 시작했고 엑바타나, 페르세폴리스, 수사의 왕실의 보물도 약탈해 2만5000탈렌트를 [20]챙겼다.셀레우코스는 이집트로 도망쳐야 했고 안티고노스는 곧 프톨레마이오스, 리시마코스, 카산데르와 전쟁을 하게 되었다.그는 페니키아를 침공하여 티레를 포위하고 가자 지구를 습격하여 함대를 건설하기 시작했다.프톨레마이오스는 시리아를 침공하여 기원전 312년 가자 전투에서 안티고노스의 아들 데메트리우스 폴리오케테스를 물리쳤고, 셀레우코스는 바빌로니아와 동부 사트라피들을 장악할 수 있었다.기원전 310년, 카산데르는 젊은 알렉산더 4세와 그의 어머니 록사나를 살해했고, 수 세기 동안 마케도니아를 지배했던 아르게이드 왕조는 끝이 났다.

안티고노스는 그의 아들 데메트리오스를 그리스에 대한 지배권을 되찾기 위해 보냈다.기원전 307년 그는 아테네를 점령하고 카산데르의 총독인 팔레론의 드미트리우스를 추방하고 도시를 다시 해방시켰다.데메트리우스는 이제 살라미스 전투에서 그의 함대를 물리치고 키프로스를 장악하면서 프톨레마이오스에게 관심을 돌렸다.이 승리의 여파로 안티고노스는 왕(바실레오스) 칭호를 가져다가 그의 아들 데메트리우스 폴리오케테스에게 수여했고, 나머지 디아도키 가문도 곧 [21]그 뒤를 따랐다.데메트리우스는 기원전 302년 로도스를 포위하고 그리스 대부분을 정복함으로써 카산드로스의 마케도니아에 대항하는 동맹을 결성함으로써 그의 원정을 계속했다.

전쟁의 결정적 교전은 리시마코스가 서부 아나톨리아의 대부분을 침략하고 점령했을 때 이루어졌지만, 곧 프리기아의 입소스 근처에서 안티고노스와 데메트리오스에 의해 고립되었다.셀레우코스는 리시마코스를 구하기 위해 제시간에 도착했고 기원전 301년 입소스 전투에서 안티고노스를 완전히 패배시켰다.셀레우코스의 전쟁 코끼리들은 결정적으로 판명되었고, 안티고노스는 죽임을 당했고, 데메트리오스는 그리스에서 반항적인 아테네를 탈환함으로써 그의 통치의 잔재를 보존하려고 그리스로 도망쳤다.한편, 리시마코스는 이오니아를, 셀레우코스는 킬리키아를, 프톨레마이오스는 키프로스를 점령했다.

그러나 기원전 298년 카산드로스가 죽은 후, 여전히 상당한 충성스러운 군대와 함대를 유지하던 데메트리우스는 마케도니아를 침공하여 마케도니아 왕좌를 장악하고 테살리아와 그리스 중부 대부분을 정복했다.[22]그는 기원전 288년 트라키아의 리시마코스와 에피루스의 피로스가 마케도니아를 두 전선으로 침공했을 때 패배했고, 빠르게 왕국을 스스로 분할했다.데메트리오스는 용병들과 함께 그리스 중부로 도망쳤고 그리스와 북부 펠로폰네소스에서 지지를 모으기 시작했다.그들이 그에게 등을 돌린 후, 그는 다시 아테네를 포위했지만, 그 후 아테네와 프톨레마이오스와 조약을 맺어 소아시아로 건너가 리시마코스의 소유지였던 이오니아에 있는 리시마코스와 전쟁을 벌일 수 있도록 허락했고, 그의 아들 안티고노스 고나타스는 그리스에 남겨졌다.초기 성공 이후, 그는 기원전 285년 셀레우코스에게 항복할 것을 강요당했고 나중에 [23]포로로 잡혔다가 죽었다.자신을 위해 마케도니아와 테살리아를 점령했던 리시마코스는 셀레우코스가 소아시아에 있는 그의 영토를 침략했을 때 전쟁에 내몰렸고, 기원전 281년 사르디스 근처의 코루페디움 전투에서 패배하여 죽었다.그 후 셀레우코스는 트라키아와 마케도니아에 있는 리시마코스의 유럽 영토를 정복하려 했으나, 셀레우코스 궁전으로 피신하여 마케도니아의 왕으로 칭송받았던 프톨레마이오스 케라우누스("벼락")에게 암살당했다.프톨레마이오스는 기원전 279년 마케도니아가 갈리아에 의해 침략당했을 때 죽었고, 그의 머리는 창에 박혀서, 그 나라는 무정부 상태에 빠졌다.안티고노스 2세 고나타스는 277년 여름 트라키아를 침공하여 18,000명의 갈리아 대군을 물리쳤다.그는 빠르게 마케도니아의 왕으로 환영받았고 35년 [24]동안 통치했다.

이 시점에서 헬레니즘 시대의 주요 세력은 데메트리우스의 아들 안티고노스 2세 고나타스의 마케도니아, 프톨레마이오스 1세의 프톨레마이오스 왕국, 셀레우코스의 아들 안티코스 1세 소테르의 셀레우코스 제국이었다.

남유럽

에피루스 왕국

에피루스는 몰로시안 아이아키대 왕조에 의해 지배된 발칸 반도 서부의 그리스 왕국이었다.에피루스는 필리포스 2세와 알렉산더의 통치 기간 동안 마케도니아의 동맹이었다.

281년 피로스(별명 "독수리"로 불림)는 타렌툼을 돕기 위해 이탈리아 남부를 침공했다.피로스는 헤라클레아 전투와 아스쿨룸 전투에서 로마인들을 물리쳤다.승리를 거뒀지만, 그는 큰 손실로 인해 후퇴할 수밖에 없었고, 그래서 "피릭 승리"라는 용어가 붙었다.피로스는 남쪽으로 방향을 틀어 시칠리아를 침공했지만 성공하지 못하고 이탈리아로 돌아갔다.베네벤툼 전투(기원전 275년) 이후 피로스는 모든 이탈리아 영토를 잃고 에피루스로 떠났다.

피로스는 기원전 275년 마케도니아와 전쟁을 벌여 안티고노스 2세 고나타를 폐위시키고 272년까지 마케도니아와 테살리아를 잠시 통치했다.그 후 그는 그리스 남부를 침공했고, 기원전 272년 아르고스와의 전투에서 전사했다.피루스가 죽은 후에도 에피루스는 작은 힘으로 남아있었다.기원전 233년 아이아시드 왕실은 폐위되었고 에피로테 동맹이라고 불리는 연방 국가가 수립되었다.이 동맹은 제3차 마케도니아 전쟁 (기원전 171–168년)에 로마에 의해 정복되었다.

마케도니아 왕국

시티움의 제노의 제자인 안티고노스 2세는 그리스에서 마케도니아를 방어하고 마케도니아의 힘을 강화하는데 대부분의 시간을 보냈다. 처음에는 크레모니데아 전쟁에서 아테네인들을 상대로, 그 다음에는 시콘의 아라투스 아카이아 동맹에 맞서서.안티고니드 정권 하에서는 마케도니아는 종종 자금이 부족했고, 판개움 광산은 필립 2세 정권 때처럼 더 이상 생산성이 없었고, 알렉산더의 캠페인으로 얻은 재산은 소진되었고, 시골 지역은 갈리아 [25]침략으로 약탈당했다.마케도니아 인구의 상당수도 알렉산드로스에 의해 해외로 이주했거나 새로운 동부의 그리스 도시로 이주하는 것을 선택했다.인구의 3분의 2가 이민을 갔고, 마케도니아 군대는 필립 [26]2세 치하보다 훨씬 적은 25,000명의 징집병만 의존할 수 있었다.

안티고노스 2세는 기원전 239년에 죽을 때까지 통치했다.그의 아들 데메트리오스 2세는 곧 기원전 229년에 죽었고, 아이(필립 5세)를 왕으로 남겼고, 안티고누스 도슨 장군은 섭정이었다.도손은 스파르타 왕 클레오메네스 3세와의 전쟁에서 마케도니아를 승리로 이끌었고 스파르타를 점령했다.

기원전 221년 도손이 사망했을 때 권력을 잡은 필리포스 5세는 그리스를 통합하고 "서쪽에 떠오르는 구름"에 맞서 독립을 지킬 재능과 기회를 가진 마지막 마케도니아 통치자, 즉 로마의 계속 증가하는 권력이었다.그는 "헬라스의 달링"으로 알려져 있었다.그의 후원 아래, 나우팍토스 조약 (기원전 217년)은 마케도니아와 그리스 리그 사이의 가장 최근의 전쟁을 종식시켰고, 이 시기에 그는 아테네, 로도스, 페르가뭄을 제외한 그리스 전역을 지배했다.

기원전 215년 필리포스는 일리리아를 주시하며 로마의 적 카르타고의 한니발과 동맹을 맺었고, 이로 인해 아카이아 동맹, 로도스, 페르가뭄과 동맹을 맺었다.제1차 마케도니아 전쟁은 기원전 212년에 발발하여 기원전 205년에 결론 없이 끝났다.필리포스는 에게 해의 지배권을 위해 페르가뭄과 로도스와 전쟁을 계속했고 아티카를 침략함으로써 그리스에 대한 로마의 불개입 요구를 무시했다.기원전 198년, 제2차 마케도니아 전쟁 중에 필리포스는 로마의 프로콘술 티투스 쿤티우스 플라미니누스에 의해 시노세팔레에서 결정적으로 패배했고 마케도니아는 그리스의 모든 영토를 잃었다.남부 그리스는 명목상의 자치권을 유지했지만, 지금은 완전히 로마의 세력권에 편입되었다.안티고니드 마케도니아의 종말은 필리포스 5세의 아들 페르세우스가 제3차 마케도니아 전쟁 (기원전 171–168년)에서 로마에 패배하고 포로로 잡혔을 때 찾아왔다.

그리스의 나머지 지역

헬레니즘 기간 동안 그리스어를 사용하는 세계 내에서 그리스 고유의 중요성은 급격히 떨어졌다.헬레니즘 문화의 가장 큰 중심은 각각 프톨레마이오스 이집트와 셀레우코스 시리아의 수도였던 알렉산드리아와 안티오키아였다.알렉산더의 정복은 그리스 세계의 지평을 크게 넓혔고, 기원전 5세기와 4세기를 기록한 도시들 사이의 끝없는 갈등을 하찮고 하찮게 보이게 만들었다.그것은 특히 젊고 야심찬 사람들이 동부의 새로운 그리스 제국으로 꾸준히 이주하도록 이끌었다.많은 그리스인들은 알렉산드리아, 안티오키아, 그리고 알렉산더의 후세에 세워진 다른 많은 헬레니즘 도시들로, 현대 아프가니스탄과 파키스탄처럼 멀리 이주했다.

독립 도시 국가들은 헬레니즘 왕국들과 경쟁할 수 없었고, 보통 그들 중 한 나라에게 보호를 받는 대가로 헬레니즘 통치자들에게 명예를 주면서 동맹을 맺도록 강요당했다.한 예로 아테네가 있는데, 아테네는 라미아 전쟁 (기원전 323–322년)에서 안티파이터에 의해 결정적으로 패배했고 피레아스 항구에는 보수 과두정치를 [27]지지하는 마케도니아 군대가 주둔하고 있었다.데메트리오스 폴리오케테스가 기원전 307년 아테네를 점령하고 민주주의를 회복한 후, 아테네 사람들은 아고라에 그와 그의 아버지 안티고노스를 금으로 만든 조각상을 세우고 그들에게 왕의 칭호를 부여함으로써 그들을 기렸다.아테네는 나중에 프톨레마이오스의 이집트와 동맹을 맺고 마케도니아의 통치를 물리쳤고, 결국 프톨레마이오스의 왕들을 위한 종교 숭배 단체를 설립했고, 프톨레마이오스에 대한 그의 도움을 기리기 위해 도시의 필레 중 하나를 명명했다.프톨레마이오스의 돈과 그들의 노력을 뒷받침하는 함대에도 불구하고, 아테네와 스파르타는 크레모니데아 전쟁 (기원전 267–261년) 동안 안티고노스 2세에게 패배했다.아테네는 마케도니아 군대에 의해 점령되었고 마케도니아 관리들에 의해 운영되었다.

스파르타는 독립을 유지했지만, 펠로폰네소스에서 더 이상 주요 군사 강국이 아니었다.스파르타의 왕 클레오메네스 3세 (기원전 235–222년)는 군 복무를 할 수 있는 위축된 스파르타 시민의 규모를 늘리고 스파르타의 권력을 회복하기 위해 보수적인 에포르에 맞서 군사 쿠데타를 일으켰고 급진적인 사회 및 토지 개혁을 추진했다.스파르타의 패권 도전은 셀라시아 전투(기원전 222년)에서 아카이아 동맹과 마케도니아의 힘에 의해 좌절되었다.

아이톨리아 동맹(est.기원전 370년), 아카이아 동맹(est.기원전 280년), 보이오티아 동맹, 북부 동맹(비잔티움, 칼케돈, 헤라클라 폰티카, 티움),[28] 그리고 키클레이데스의 네시오틱 동맹과 같은 다른 도시 국가들은 자기 방어 차원에서 연합 국가를 형성했다.이들 연방은 외교 정책과 군사 문제를 통제하는 중앙 정부와 관련되었고, 대부분의 지방 통치를 도시 국가들에게 맡겼다.아카이아 동맹과 같은 국가에서는, 이것은 또한 다른 민족 집단들이 동등한 권리를 가진 연방에 가입하는 것을 포함했다. 이 경우에는 비아카이아인들이다.[29]아케아 동맹은 마케도니아인들을 펠로폰네소스로부터 몰아내고 코린트를 해방시킬 수 있었고, 코린트는 정식으로 동맹에 가입했다.

헬레니즘 왕국의 지배로부터 완전한 독립을 유지한 몇 안 되는 도시 국가 중 하나는 로도스였다.해적들로부터 무역 함대를 보호하는 숙련된 해군과 동쪽에서 에게해로 가는 항로를 포괄하는 이상적인 전략적 거점으로 로도스는 헬레니즘 시대에 번영했다.이곳은 문화와 상업의 중심지가 되었고, 동전이 널리 유통되었고, 철학 학교들이 지중해에서 최고 중의 하나가 되었다.데메트리우스 폴리오케테스 (기원전 305–304년)의 포위 속에 1년 동안 버텨낸 후, 로디아인들은 그들의 승리를 기념하기 위해 로도스의 거상을 지었다.그들은 세심하게 중립적인 자세를 유지하고 주요 헬레니즘 [30]왕국들 사이의 힘의 균형을 보존하는 행동을 함으로써 강력한 해군의 유지로 독립을 유지했다.

처음에 로데스는 프톨레마이오스 왕국과 매우 밀접한 관계를 가지고 있었다.로데스는 나중에 셀레우코스 왕조에 대항하는 로마의 동맹이 되었고, 로마-세레우코스 전쟁 (기원전 192년-188년)에서의 그들의 역할로 카리아에 있는 영토를 받았다.로마는 결국 로도스를 공격하고 섬을 로마의 속주로 합병했다.

발칸 반도

서부 발칸 해안에는 달마태 왕국과 아르디아이 왕국과 같은 다양한 일리리아 부족과 왕국이 살고 있었으며, 테우타 여왕(기원전 231-227년 재위) 치하에서 해적 행위를 자주 했다.더 내륙에는 일리리아 파이오니아 왕국과 아그리아네 부족이 있었다.아드리아 해 연안의 일리리아인들은 헬레니즘의 영향과 영향을 받았고 일부 부족들은 일리리아에 있는 그리스 식민지와 가깝기 때문에 그리스어를 채택했다[31][32][33].Illyrians 고대 그리스인들(그Illyrian형 헬멧, 원래 그리스의 타입과 같은)과 또한 그들의 shields[34]과 그들의 전쟁에 belts[35](단 한줄도 발견되었다 고대의 지배는 장식을 채택했다, 기원전 3세기 현대 Selce ePoshtme,의 지배를 필립 V메이스 아래에서 시간에 있는 의 부분에서 데이트를 했고 무기와 갑옷들이 수입된 것입니다.don[36]cm이다.

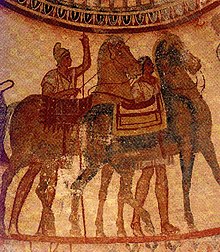

오드리시안 왕국은 강력한 오드리시안 부족의 왕 아래 트라키아 부족의 연합체였다.트라키아의 여러 지역은 마케도니아의 필리포스 2세, 알렉산더 대왕, 리시마코스, 프톨레마이오스 2세, 그리고 필리포스 5세 통치하에 있었지만 종종 그들 자신의 왕들에 의해 통치되었다.트라키아인들과 아그리아인들은 알렉산더에 의해 펠타스트와 경기병으로 널리 사용되었고,[37] 그의 군대의 약 5분의 1을 구성했다.디아도치는 또한 트라키아 용병들을 그들의 군대에 사용했고 그들은 식민지 개척자로도 사용되었다.오드리안인들은 그리스어를 행정과[38] 귀족의 언어로 사용했다.귀족들은 또한 복장, 장식, 군사 장비에서 그리스 패션을 채택하여 다른 [39]부족에까지 그것을 전파했다.트라키아의 왕들은 [40]헬레니즘화된 최초의 왕들 중 하나였다.

기원전 278년 이후 오드리시아인들은 코몬토리우스와 카바루스 왕에 의해 지배된 켈트 왕국 티리스에서 강력한 경쟁자를 가지고 있었지만, 기원전 212년에 그들의 적을 정복하고 그들의 수도를 파괴했다.

서부 지중해

남부 이탈리아 (Magna Graecia)와 남동부 시칠리아는 기원전 8세기에 그리스에 의해 식민지화 되었다.기원전 4세기에 그리스의 주요 도시이자 패권자는 시라쿠사였다.헬레니즘 기간 동안 시칠리아의 주요 인물은 기원전 317년 용병으로 도시를 점령한 시라쿠사의 아가토클레스 (기원전 361–289년)였다.아가토클레스는 시칠리아에 있는 대부분의 그리스 도시들로 그의 권력을 확장했고, 카르타고인들과 오랜 전쟁을 치렀고, 기원전 310년에 튀니지를 침공하여 그곳에서 카르타고 군대를 물리쳤다.유럽군이 그 지역을 침공한 것은 이번이 처음이었다.이 전쟁 후에 그는 시칠리아 남동부의 대부분을 지배했고 동부의 [41]헬레니즘 왕들을 모방하여 스스로 왕으로 선포했다.아가토클레스는 브루티아인과 로마인에 맞서 타렌툼을 방어하기 위해 이탈리아(기원전 300년)c.를 침공했지만 성공하지 못했다.

로마 이전의 갈리아에 살던 그리스인들은 대부분 프랑스 프로방스 지중해 연안에 한정되어 있었다.이 지역의 첫 번째 그리스 식민지는 마살리아로 기원전 4세기까지 6,000명의 주민이 사는 지중해의 가장 큰 무역 항구 중 하나가 되었다.마살리아는 또한 니스와 아그데와 같은 그리스의 해안 도시들을 지배한 지역 패권자이기도 했다.마살리아에서 주조된 동전은 리구로-셀틱 갈리아의 모든 지역에서 발견되었다.켈트 동전은 그리스 [43]문양의 영향을 받았고, 그리스 문자는 다양한 켈트 동전, 특히 [44]남프랑스의 동전들에서 찾아볼 수 있다.마살리아에서 온 무역업자들은 프랑스 내륙 깊숙이 듀랑스 강, 론 강, 갈리아 강, 스위스, 부르고뉴로 육로 무역로를 개설했다.헬레니즘 시대에는 그리스 알파벳이 마살리아(기원전 3세기, 2세기)에서 남쪽 갈리아로 전파되었고 스트라보에 따르면, 마살리아는 또한 켈트가 그리스어를 [45]배우러 갔던 교육의 중심지였다.로마의 충실한 동맹이었던 마살리아는 기원전 49년 폼페이우스 편을 들어 시저의 군대에 점령될 때까지 독립을 유지했다.

Emporion(현대 Empúries), 원래 이오니아와마 살리 아에서 Archaic-period 이주민들에 의해 샌트 마르티의 마을 부근에서 BC6세기에 설립된 그 도시(는 L'Escala, 스페인 카탈로니아 지역의 일부를 구성하는 해외 섬에 있)[46]5번째 세기 BC들 안에 이베리아 본토에 새로운 도시(neapolis)로 태웠다 d'Empúries.[47]엠포리온은 그리스 식민지 주민과 이베리아 원주민의 혼합 인구를 포함했고, 리비와 스트라보는 그들이 다른 지역에 살았다고 주장했지만, 이 두 집단은 [48]결국 통합되었다.이 도시는 이베리아의 지배적인 무역 중심지이자 헬레니즘 문명의 중심지가 되었고, 결국 제2차 포에니 전쟁 [49](기원전 218-201년) 동안 카르타고 제국에 맞서 로마 공화국의 편을 들었습니다.그러나, 엠포리온은 기원전 195년경에 히스파니아 시테리오르의 로마 속주가 설립되면서 정치적 독립을 잃었고 기원전 1세기에 이르러서는 [50][51]문화적으로 완전히 로마화가 되었다.

헬레니즘 근동

아시아와 이집트의 헬레니즘 국가들은 상비군 용병들과 그리스-마케도니아 [52]정착민들의 작은 핵심으로 뒷받침된 그리스-마케도니아 통치자들과 통치자들의 점령 엘리트들에 의해 운영되었다.그리스로부터의 이민의 촉진은 이 시스템의 확립에 있어서 중요했다.헬레니즘의 군주들은 왕국을 왕실 재산으로 운영했고, 무거운 세금 수입의 대부분은 어떤 종류의 혁명으로부터 그들의 통치를 보존한 군대와 준군사부대로 들어갔다.마케도니아와 헬레니즘의 군주들은 특권 있는 귀족의 동반자 또는 친구(헤타이로이, 필로이)[53]와 함께 전장에서 그들의 군대를 이끌 것으로 기대되었다.군주는 또한 사람들의 자선적인 후원자 역할을 할 것으로 기대되었다; 이 공공 자선 사업은 프로젝트를 세우고 선물을 나눠주지만 또한 그리스 문화와 종교를 홍보하는 것을 의미할 수 있다.

프톨레마이오스 왕국

알렉산더 대왕의 장군들과 대리인 역할을 했던 7명의 경호원 중 한 명인 체질병 프톨레마이오스는 기원전 323년 알렉산더가 죽은 후 이집트의 사트라프로 임명되었다.기원전 305년, 그는 로도스 공성전에서 로디아인들을 돕는 그의 역할로 나중에 "소터"로 알려진 프톨레마이오스 1세를 자칭했다.프톨레마이오스는 이집트 상부에 프톨레마이오스 헤르미우 같은 새로운 도시를 건설했고 그의 참전용사들을 이집트 전역에, 특히 파이염 지역에 정착시켰다.그리스 문화와 무역의 중심지인 알렉산드리아는 그의 수도가 되었다.이집트의 첫 항구 도시로서, 이집트는 지중해의 주요 곡물 수출국이 되었다.

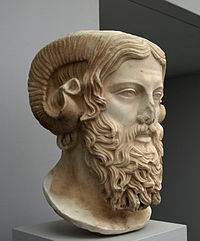

이집트인들은 프톨레마이아가 독립한 이집트의 파라오의 후계자로 인정되었지만, 프톨레마이아는 섭섭하게 받아들였다.프톨레마이오스 왕가는 그들의 형제자매와 결혼하는 것, 이집트 양식과 복장으로 공공 기념물에 그들 자신을 묘사하는 것, 이집트 종교 생활에 참여하는 것과 같은 이집트 파라오의 전통을 계승했다.프톨레마이오스의 지배자 컬트는 프톨레마이오스를 신으로 묘사했고 프톨레마이오스를 위한 신전이 왕국 곳곳에 세워졌다.프톨레마이오스 1세는 심지어 새로운 신 세라피스를 창조했는데, 세라피스는 두 이집트 신들의 결합이었다.아피스와 오시리스, 그리스 신들의 속성.프톨레마이오스 행정은 고대 이집트의 관료제처럼 고도로 중앙집권화되어 관세, 소비세, 벌금, 세금 등을 통해 가능한 한 많은 수입을 인구로부터 끌어내는 데 초점을 맞췄다.모든 계급의 하급 관리들, 세금 농부들, 점원들, 그리고 감독자들이 이것을 가능하게 했다.이집트 시골은 이러한 왕실 관료제도에 [54]의해 직접 관리되었다.키프로스와 키레네와 같은 외부 영토는 왕실에 의해 임명된 군 지휘관인 스트래티고이에 의해 운영되었다.

프톨레마이오스 2세 치하에서 칼리마코스, 로도스의 아폴로니우스, 테오크리토스, 그리고 알렉산드리아 플레이아드를 포함한 많은 다른 시인들이 이 도시를 헬레니즘 문학의 중심지로 만들었다.프톨레마이오스 자신은 도서관, 과학 연구, 그리고 도서관 구내에 살고 있는 개별 학자들을 후원하고 싶어했다.그와 그의 후계자들은 또한 콜레-시리아 지역을 두고 시리아 전쟁이라고 알려진 셀레우키드와 일련의 전쟁을 벌였다.프톨레마이오스 4세는 팔랑가이트로 훈련된 이집트 원주민들을 이용하여 셀레우코스 족에 대항한 라피아 (기원전 217년)의 대전에서 승리했다.그러나 이 이집트 병사들은 반란을 일으켜 결국 기원전 205년에서 186/185년 사이에 테바이드 지역에 이탈한 이집트 국가를 세워 프톨레마이오스 국가를 [55]심각하게 약화시켰다.

프톨레마이오스의 가족은 기원전 30년의 로마 정복 때까지 이집트를 통치했다.왕조의 모든 남성 통치자들은 프톨레마이오스라는 이름을 얻었다.그들 남편의 자매였던 프톨레마이오스 여왕들은 보통 클레오파트라, 아르시노에 또는 베레니케로 불렸다.이 왕가의 가장 유명한 멤버는 율리우스 카이사르와 폼페이, 그리고 후에 옥타비아누스와 마크 안토니우스 사이의 로마 정치 싸움에서 그녀의 역할로 알려진 마지막 여왕 클레오파트라 7세였다.비록 헬레니즘 문화가 이슬람 정복 때까지 로마와 비잔틴 시대 내내 이집트에서 계속 번성했지만, 로마에 의한 정복에서의 그녀의 자살은 이집트의 프톨레마이오스 통치의 종말을 알렸다.

셀레우코스 제국

알렉산더의 제국의 분할에 이어 셀레우코스 1세 니카토르는 바빌로니아를 받았다.그곳에서 그는 알렉산더의 동쪽 영토 근처를 포함하도록 확장한 새로운 [56][57][58][59]제국을 만들었다.그 권력의 절정기에는 중앙 아나톨리아, 레반트, 메소포타미아, 페르시아, 오늘날의 투르크메니스탄, 파미르, 그리고 파키스탄의 일부를 포함했다.그것은 5천만에서 6천만 [60]명으로 추정되는 다양한 인구를 포함했다.그러나 안티오코스 c.1세 (기원전 324/323–261년) 치하에서, 다루기 힘든 제국은 이미 영토를 빼앗기기 시작하고 있었다.페르가뭄은 에우메네스 1세 휘하에서 그를 상대로 보낸 셀레우코스 군대를 물리쳤다.카파도키아, 비티니아, 폰투스 왕국은 이 시기까지 모두 실질적으로 독립되어 있었다.프톨레마이오스처럼 안티오코스 1세는 그의 아버지 셀레우코스 1세를 신격화하면서 왕조적인 종교 집단을 세웠다.공식적으로 아폴로의 후손이라고 알려진 셀레우코스는 자신의 사제들과 매달 제사를 지냈다.제국의 침식은 셀레우코스 2세 치하에서 계속되었는데, 셀레우코스 2세는 그의 형제 안티오쿠스 히에락스와 내전을 벌여야 했고 박트리아, 소그디아나, 파르티아가 이탈하는 것을 막을 수 없었다.히에락스는 셀레우코스 아나톨리아의 대부분을 자신을 위해 분할했지만, 갈라티아 동맹들과 함께 현재 왕위를 주장하는 페르가몬의 아탈로스 1세에게 패배했다.

광대한 셀레우코스 제국은 이집트와 마찬가지로 대부분 그리스-마케도니아 [59][61][62][63]정치 엘리트들에 의해 지배되었다.지배적인 엘리트를 형성한 도시의 그리스 인구는 그리스로부터의 [59][61]이민으로 강화되었다.이 도시들에는 안티오키아, 시리아 테트라폴리스의 다른 도시들, 셀레우키아(바빌론 북쪽), 유프라테스 강의 두라 유로포스와 같은 새롭게 설립된 식민지가 포함되었다.이 도시들은 의회, 의회, 선출된 치안 판사와 같은 전통적인 그리스 도시 국가 기관들을 유지했지만, 이것은 그들이 항상 왕실 셀레우코스 관리들에 의해 통제되었기 때문에 겉모습이었다.이 도시들 외에도 셀레우코스인들이 그들의 통치를 강화하기 위해 제국 전역에 심은 셀레우코스 수비대(코리아), 군사 식민지(카토이키아이), 그리스 마을(코마이)도 많이 있었다.이 '그레코-마케도니아' 인구(지역 여성과 결혼한 정착민들의 아들들도 포함)는 안티오코스 3세의 통치 기간 동안 (총 셀레우코스 군대 80,000명 중) 35,000명으로 구성된 집단을 구성할 수 있었다.나머지 군대는 원주민 [64]군대로 구성되었다.안티오코스 3세는 셀레우코스 1세가 죽은 이후 제국의 모든 잃어버린 지방을 되찾기 위해 여러 번의 활발한 캠페인을 벌였다.라피아에서 프톨레마이오스 4세의 군대에 패한 후, 안티오코스 3세는 박트리아, 파르티아, 아리아나, 소그디아나, 게드로시아, 드란지아나를 포함한 극동 이탈 지역 (기원전 212-205년)을 정복하기 위해 동쪽으로 긴 원정을 이끌었다.그는 성공적이었고, 이 지방들의 대부분을 적어도 명목상의 속국으로 돌려보내고 그들의 [65]통치자들로부터 공물을 받았다.프톨레마이오스 4세 (기원전 204년)가 죽은 후, 안티오코스는 이집트의 약점을 이용하여 5차 시리아 전쟁 (기원전 [66]202년-195년)에서 콜레-시리아를 정복했다.이후 그는 아시아에서 페르가메네 영토로 영향력을 확대하기 시작했고 유럽으로 건너가 헬레스폰트 강 리시마키아를 요새화했지만, 마그네시아 전투(기원전 190년)에서 결정적인 패배로 아나톨리아와 그리스로의 확장은 갑자기 중단되었다.전쟁을 끝낸 아파메아 조약에서 안티오코스는 황소자리 서쪽 아나톨리아에 있는 그의 모든 영토를 잃었고 15,000탈렌트의 [67]거액을 배상해야 했다.

기원전 2세기 중반 파르티아 미트리다테스 1세 치하의 파르티아인들에게 제국의 동쪽 지역 대부분이 정복되었지만, 셀레우코스 왕들은 아르메니아 왕 티그라네스 대왕의 침략과 로마 장군 폼페이의 최후까지 시리아로부터 잔당 국가를 계속 통치했다.

아탈리드 페르가뭄

| 외부 비디오 | |

|---|---|

| |

리시마코스가 죽은 후, 그의 장교 중 한 명인 필레타에루스는 기원전 282년 9,000탈렌트의 리시마코스의 전쟁 자금과 함께 페르가뭄 시를 장악하고 셀레우코스 1세에게 충성하며 사실상의 독립을 선언했다.그의 후손인 아탈로스 1세는 갈라디아 침략자들을 물리치고 스스로를 독립 왕이라고 선언했다.아탈로스 1세 (기원전 241–197년)는 1차 및 2차 마케도니아 전쟁 동안 마케도니아의 필리포스 5세에 대항하는 로마의 강력한 동맹자였다.기원전 190년 셀레우코스 왕조에 대항한 그의 지원으로, 에우메네스 2세는 소아시아의 모든 이전의 셀레우코스 왕국을 보상받았다.플루타르코스에 따르면 에우메네스 2세는 20만 권의 책을 가진 알렉산드리아 도서관에[69] 버금가는 것으로 알려진 페르가몬 도서관을 설립함으로써 페르가몬을 문화와 과학의 중심지로 만들었다.그것은 독서실과 그림 컬렉션을 포함하고 있었다.에우메네스 2세는 또한 도시의 아크로폴리스에 기가토마치를 묘사한 프리즈로 페르가뭄 제단을 건설했다.퍼가멈은 양피지(퍼가메나) 생산의 중심지이기도 했다.아탈루스는 왕위 계승 위기를 피하기 위해 기원전 133년[70] 아탈루스 3세가 로마 공화국에 왕국을 물려줄 때까지 페르가몬을 통치했다.

갈라티아

갈라티아에 정착한 켈트족은 기원전 270년 레오타리오스와 레온노리오스의 지도 아래 트라키아를 통해 왔다.그들은 '코끼리 전투'에서 셀레우코스 1세에게 패배했지만, 여전히 중앙 아나톨리아에 켈트족의 영토를 세울 수 있었다.갈라디아인들은 전사로써 존경받았고 후임 국가들의 군대에서 용병으로 널리 사용되었다.그들은 계속해서 비티니아와 페르가몬과 같은 인접 왕국을 공격하여 공물을 약탈하고 빼앗았다.이것은 그들이 페르가몬 (기원전 241–197년)의 통치자 아탈루스를 물리치려 했던 셀레우코스 왕 안티오쿠스 히에락스의 편을 들면서 끝이 났다.아탈루스는 갈리아인들을 심하게 물리쳤고 갈라티아에 국한되게 했다.죽어가는 갈리아(페르가몬에 전시된 유명한 조각상)의 주제는 고귀한 적에 대한 그리스인들의 승리를 나타내는 한 세대에 걸쳐 헬레니즘 미술에서 가장 인기 있는 것으로 남아 있었다.기원전 2세기 초에 갈라디아인들은 소아시아에 대한 종주권을 되찾으려는 마지막 셀레우코스 왕 안티오코스 대왕의 동맹이 되었다.기원전 189년, 로마는 그나이우스 만리우스 벌소를 갈라디아에 대한 원정에 보냈다.갈라티아는 기원전 189년부터 지역 통치자들을 통해 로마에 의해 지배되었다.

페르가몬과 로마에 패한 후 갈라디아인들은 서서히 헬레니즘화되었고 역사학자[71] 저스틴에 의해 갈로-그라에치(Gallo-Graeci)로 불렸으며 디오도로스 시쿨루스의 저서 '헬로-노갈라타이(Hellnnogala tai)'에 "지옥"으로 불렸다.

비티니아

비티니아인들은 북서 아나톨리아에 살았던 트라키아 민족이다.알렉산더가 비티니아를 정복한 후, 비티니아 지역은 알렉산더 대왕의 장군인 칼라스를 물리치고 비티니아의 독립을 유지한 원주민 왕 바스의 통치 아래 놓였다.그의 아들인 비티니아의 지포에테스 1세는 리시마코스와 셀레우코스 1세에 대해 이러한 자치권을 유지했고 기원전 297년에 왕(바실레오스) 칭호를 받았다.그의 아들이자 후계자인 니코메데스 1세는 니코메디아를 세웠는데, 니코메디아는 곧 큰 번영을 이루었고, 그의 오랜 c.통치 기간(기원전 278년–기원전 255년) 동안 비티니아 왕국은 아나톨리아의 작은 군주국들 사이에서 상당한 위치를 차지했습니다.니코메데스는 또한 용병으로 켈트 갈라티아인들을 아나톨리아로 초대했고, 그들은 나중에 그의 아들 프루시아스 1세에게 등을 돌렸고, 그들은 전투에서 그들을 물리쳤다.그들의 마지막 왕 니코메데스 4세는 폰토스의 미트리다테스 6세에 대항할 수 없었고, 로마 원로원에 의해 왕좌에 복귀한 후, 로마 공화국에 그의 왕국을 유언으로 물려주었다(기원전 74년).

카파도키아

폰투스와 토러스 산맥 사이에 위치한 산악 지역인 카파도키아는 페르시아 왕조에 의해 통치되었다.아리아라테스 1세 (기원전 332년–322년)는 페르시아의 지배하에 있던 카파도키아의 사트라프였고 알렉산더의 정복 후에도 그는 그 자리를 유지했다.알렉산더가 죽은 후 그는 에우메네스에게 패배하고 기원전 322년에 십자가에 못 박혔지만, 그의 아들인 아리아라테스 2세는 왕위를 되찾고 전쟁 중인 디아도키에 맞서 자치권을 유지하는데 성공했다.

기원전 255년, 아리아라테스 3세는 왕의 칭호를 얻었고 셀레우코스 왕국의 동맹으로 남아있던 안티오코스 2세의 딸 스트라토니케와 결혼했다.아리아라테스 4세 치하에서, 카파도키아는 로마와 관계를 맺게 되었는데, 처음에는 안티오코스 대왕의 대의를 옹호하는 적이었고, 그 다음에는 마케도니아의 페르세우스에 대항하는 동맹으로, 그리고 마침내 셀레우코스와의 전쟁에서였다.아리아라테스 5세는 또한 페르가몬 왕좌의 주장자인 아리스토니쿠스와 로마와 전쟁을 벌였고, 그들의 군대는 기원전 130년에 전멸했다.이 패배로 폰토스는 왕국을 침략하고 정복할 수 있었다.

폰토스 왕국

폰토스 왕국은 흑해 남쪽 해안에 있던 헬레니즘 왕국이었다.그것은 기원전 291년 미트리다테스 1세에 의해 설립되었고 기원전 63년 로마 공화국에 의해 정복될 때까지 지속되었다.페르시아 아케메네스 제국의 후예인 왕조에 의해 통치되었음에도 불구하고 흑해와 그 주변 왕국에 대한 그리스 도시들의 영향으로 헬레니즘화 되었다.폰토스 문화는 그리스와 이란의 요소들이 혼합되어 있었고, 왕국의 가장 헬레니즘화된 부분은 해안에 있었고, 트라페주스와 시노페와 같은 그리스 식민지가 거주했고, 후자는 왕국의 수도가 되었다.경구적 증거 또한 내부에서의 광범위한 헬레니즘적 영향을 보여준다.미트리다테스 2세의 통치 기간 동안, 폰토스는 왕가의 결혼을 통해 셀레우코스인들과 동맹을 맺었다.미트리다테스 6세 유파토르 시대에는 아나톨리아어들이 계속 사용되었지만 그리스어가 왕국의 공용어였다.

이 왕국은 콜키스, 카파도키아, 파플라고니아, 비티니아, 소아르메니아, 보스포란 왕국, 타우릭 체르소네소스의 그리스 식민지 그리고 잠시 동안 아시아의 로마 속주를 정복한 미트리다테스 6세 치하에서 가장 큰 규모로 성장했다.페르시아와 그리스가 혼혈인 미트리다테스는 자신을 "미트리다테스 유파토르 디오니소스 [73]왕"으로 칭하는 로마의 '바르바리안'에 대항하는 그리스인들의 수호자이자 "위대한 해방자"라고 자신을 표현했다.미트리다테스는 또한 알렉산더의 아나톨 헤어스타일로 자신을 묘사했고 마케도니아 왕들이 후손이라고 주장한 헤라클레스의 상징성을 사용했다.미트리다트 전쟁에서 로마와 오랜 투쟁 끝에 폰토스는 패배했다; 폰토스의 동쪽 절반은 의뢰왕국으로 살아남은 반면, 폰토스의 일부는 비티니아 속주로 로마 공화국에 통합되었다.

아르메니아

오르온티드 아르메니아는 페르시아 정복 이후 공식적으로 알렉산더 대왕의 제국에 넘어갔다.알렉산더는 아르메니아를 통치하기 위해 미트라네스라는 오론티드를 임명했다.아르메니아는 나중에 셀레우코스 제국의 속국이 되었지만, 상당한 자치권을 유지하며 토착 통치자들을 유지했습니다.기원전 212년 말에 이 나라는 코마게네 또는 소르메니아를 포함한 대아르메니아와 아르메니아 소펜 두 왕국으로 나뉘었다.그 왕국들은 셀레우코스 지배로부터 너무 독립되어 안티오코스 3세가 통치하는 동안 그들과 전쟁을 벌였고 그들의 통치자들을 교체했다.

기원전 190년 마그네시아 전투에서 셀레우시스가 패배한 후, 소펜과 대아르메니아의 왕들은 반란을 일으켜 독립을 선언했고, 아르탁시아스는 기원전 188년 아르메니아 아르탁시아드 왕조의 첫 번째 왕이 되었다.아르탁시아드 통치 기간 동안 아르메니아는 헬레니즘화 시기를 거쳤다.화폐학적 증거는 그리스의 예술 양식과 그리스어의 사용을 보여준다.몇몇 동전들은 아르메니아 왕들을 "필레네"라고 묘사한다.티그라네스 대왕(기원전 95-55년)의 통치 기간 동안 아르메니아 왕국은 시리아 테트라폴리스 전체를 포함한 많은 그리스 도시들을 포함하면서 가장 큰 범위에 도달했다.티그라네스 대왕의 부인 클레오파트라는 수사 암피크라테스나 역사학자 스셉시스의 메트로도루스 같은 그리스인들을 아르메니아 궁전으로 초대했고, 플루타르코스에 따르면,[74] 로마 장군 루쿨루스가 아르메니아 수도 티그라노케르타를 점령했을 때, 그는 티그라네스를 위해 연극을 하기 위해 도착한 그리스 배우들을 발견했다.티그라네스의 후계자인 아르타바스데스 2세는 그리스 비극을 직접 작곡하기도 했다.

파르티아

파르티아는 후에 알렉산더의 제국에 전해진 아케메네스 제국의 북동부 이란 사트라피였다.셀레우코스 왕조 하에서 파르티아는 니카노르와 필립과 같은 다양한 그리스 사트라프들에 의해 통치되었다.기원전 247년, 안티오코스 2세 테오스가 죽은 후, 파르티아에 있는 셀레우코스 통치자 안드라고라스는 그의 독립을 선언하고 왕실의 다이아뎀을 쓰고 왕위를 주장하는 모습을 보여주는 동전을 주조하기 시작했다.그는 기원전 238년까지 파르니 부족의 지도자 아르사케스가 파르티아를 정복하고 안드라고라스를 죽이고 아르사키아 왕조를 출범시킬 때까지 통치했다.안티오코스 3세는 기원전 209년 아르사케스 2세로부터 아르사키드가 지배하던 영토를 되찾았다.아르사케스 2세는 평화를 위해 소송을 했고 셀레우코스 왕조의 신하가 되었다.프라아테스 c.1세 (기원전 176–171년)가 되어서야 아르사키드들은 다시 [75]그들의 독립을 주장하기 시작했다.

파르티아의 미트리다테스 1세의 통치 기간 동안, 아르사키드의 지배는 헤라트(기원전 167년), 바빌로니아(기원전 144년), 미디어(기원전 141년), 페르시아(기원전 139년), 시리아의 많은 지역(기원전 110년대)으로 확장되었다.셀레우코스-파르티아 전쟁은 셀레우코스 왕조가 안티오코스 7세 시데테스(기원전 138–129년 재위) 통치하에 메소포타미아를 침공하면서 계속되었지만, 그는 결국 파르티아 반격에 의해 사망했다.셀레우코스 왕조가 몰락한 후, 파르티아인들은 로마-파르티아 전쟁 (기원전 66년–기원후 217년)에서 이웃한 로마와 자주 싸웠다.파르티아 제국에도 헬레니즘의 흔적이 많이 남아 있었다.파르티아인들은 그리스어뿐만 아니라 그들 자신의 파르티아어(그리스어보다 적지만)를 행정 언어로 사용했고, 또한 그리스 드라크마를 화폐로 사용했다.그들은 그리스 연극을 즐겼고 그리스 예술은 파르티아 미술에 영향을 미쳤다.파르티아인들은 이란의 신들과 혼합된 그리스 신들을 계속 숭배했다.그들의 통치자들은 헬레니즘 왕들의 방식으로 통치자 숭배단을 설립했고 종종 헬레니즘 왕족의 칭호를 사용했다.

이란에 대한 헬레니즘의 영향은 범위 면에서 중요했지만 깊이와 내구성은 아니었다. 근동과 달리 이란-조로아스터교 사상과 이상은 이란 본토에서 영감의 주요 원천으로 남아 있었고 파르티아와 사산 왕조 [76]말기에 곧 부활했다.

나바테아 왕국

나바테아 왕국은 시나이 반도와 아라비아 반도 사이에 위치한 아랍 국가였다.수도는 향로의 중요한 무역도시인 페트라였다.나바테아인들은 안티고노스의 공격에 저항했고 셀레우코스인들과 싸우는 동안 하스모네아인들의 동맹이었지만, 후에 헤롯 대왕과 싸웠다.나바테인의 헬레니즘화는 주변 지역에 비해 상대적으로 늦게 일어났다.나바테아의 물질 문화는 기원전 [77]1세기 아레타스 3세 필헬레네의 통치 때까지 그리스의 영향을 전혀 받지 않았다.아레타스는 다마스쿠스를 점령하고 페트라 수영장 단지와 정원을 헬레니즘 스타일로 지었다.나바테인들은 원래 돌덩어리나 기둥과 같은 상징적 형태로 그들의 전통적인 신들을 숭배했지만, 헬레니즘 시대에는 그들의 신들을 그리스 신들과 동일시하고 그리스 [78]조각의 영향을 받은 비유적인 형태로 묘사하기 시작했다.나바테아 미술은 그리스의 영향을 보여주며 디오니스의 [79]장면을 묘사한 그림들이 발견되었다.그들은 또한 그리스어를 아람어, 아랍어와 함께 상업 언어로 서서히 채택했다.

유대

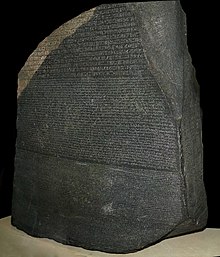

헬레니즘 기간 동안, 유다는 셀레우코스 제국과 프톨레마이오스 이집트 사이의 국경 지역이 되었고, 따라서 종종 시리아 전쟁의 최전방이었고,[80] 이러한 분쟁 동안 여러 차례 주인이 바뀌었다.헬레니즘 왕국에서, 유다는 헬레니즘의 신하로서 이스라엘 대제사장의 세습 직위에 의해 통치되었다.이 시기는 또한 헬레니즘 유대교의 발흥을 보였는데, 이 유대교는 알렉산드리아와 안티오키아의 유대인 디아스포라에서 처음 발전했고, 그 후 유대까지 확산되었다.이 문화적 혼합주의의 주요 문학적 산물은 히브리어, 성서 아람어에서 코이네 그리스어로 히브리어 성경을 9월 번역한 것이다.이 번역본을 만든 이유는 많은 알렉산드리아 유대인들이 히브리어와 [81]아람어를 구사할 수 있는 능력을 잃었기 때문인 것으로 보인다.

기원전 301년과 219년 사이에 프톨레마이아가 비교적 평화롭게 유대를 통치했고, 유대인들은 종종 프톨레마이오스 행정과 군대에서 일하는 것을 발견했고, 이것은 헬레니즘화된 유대인 엘리트 계층(예: 토바이어드)의 상승을 이끌었다.안티오코스 3세의 전쟁은 그 지역을 셀레우코스 제국으로 만들었다; 예루살렘은 기원전 198년에 그의 지배 하에 놓였고 신전은 수리되었고 돈과 [82]공물을 제공받았다.안티오코스 4세 에피파네스는 기원전 169년 이집트를 침공하는 동안 유대에서의 소요가 있은 후 예루살렘을 약탈하고 신전을 약탈했다.안티오코스는 유대인들의 주요 종교 의식과 전통을 금지했다.그는 그 지역을 헬레니즘화하고 그의 제국을 통일하려고 시도했을지도 모르며 이에 대한 유대인들의 저항은 결국 폭력의 격화로 이어졌다.어쨌든, 친유대파와 반유대파 사이의 긴장은 유다 마카베오스의 기원전 174-135년의 마카베아 반란으로 이어졌다.

현대적 해석은 이 시기를 [83][84]유대교의 헬레니즘화된 형태와 정통적인 형태 사이의 내전으로 본다.이 반란으로부터 하스모니아 왕조로 알려진 독립적인 유대 왕국이 형성되었고, 하스모니아 왕조는 기원전 165년부터 기원전 63년까지 지속되었다.하스모네 왕조는 결국 로마 내전과 동시에 내전으로 붕괴되었다.마지막 하스모네의 통치자 안티고노스 2세 마타티아스는 기원전 37년에 헤롯에게 붙잡혀 처형되었다.원래 그리스의 지배권에 대한 반란이었지만, 하스모네 왕국과 그에 이은 헤롯 왕국은 점차 헬레니즘화 되었다.기원전 37년부터 기원전 4년까지, 헤롯 대왕은 로마 원로원에 의해 임명된 유대-로마 왕으로 통치했다.그는 이 신전을 상당히 확장하여 세계에서 가장 큰 종교 건축물 중 하나로 만들었다.확대된 신전과 다른 헤로데식 건축양식은 상당한 헬레니즘 건축의 영향을 보여준다.그의 아들인 헤롯 아르켈라우스는 기원전 4년부터 그가 로마 유대의 형성을 위해 폐위된 서기 6년까지 통치했다.

그리스-박트리아인

그리스의 박트리아 왕국은 셀레우코스 제국의 분리독립으로 시작되었는데, 제국의 크기 때문에 중앙 통제로부터 상당한 자유를 얻었다.기원전 255년에서 246년 사이, 박트리아, 소그디아나, 마르기아나(오늘날 아프가니스탄의 대부분)의 주지사는 이 과정을 논리적으로 극단적으로 진행했고 스스로를 왕이라고 선언했다.디오도토스의 아들인 디오도토스 2세는 기원전 230년 소그디아나의 사트라프일 가능성이 있는 에우티데모스에 의해 전복되었고, 에우티데모스는 그의 왕조를 세웠다.기원전 210년, 그리스-박트리아 왕국은 안티오코스 3세가 이끄는 셀레우코스 제국에 의해 침략당했다.전장에서 승리하는 동안 안티오코스는 현상유지에 이점이 있다는 것을 깨닫고(아마도 박트리아가 시리아로부터 통치될 수 없다는 것을 느꼈을 것이다) 그의 딸 중 하나를 에우티데모스의 아들에게 시집보내 그리스-박트리아 왕조를 합법화한 것으로 보인다.곧이어 그리스-박트리아 왕국이 확장되어, 아마도 파르티아 왕 아르사케스 2세가 안티오코스에게 패배한 것을 이용했을 것이다.

스트라보에 따르면 그리스-박트리아인들은 실크로드 교역로를 통해 중국과 접촉한 것으로 보인다(Strabo, 11.11.1).인도의 자료들은 또한 불교 승려들과 그리스인들 사이의 종교적인 접촉을 유지하고 있으며, 일부 그리스-박트리아인들은 불교로 개종했다.에우티데모스의 아들이자 후계자인 데메트리오스는 마우리아 제국이 멸망한 후 기원전 180년 인도 북서부를 침공했다; 마우리아인들은 아마도 박트리아인(그리고 셀레우코스)의 동맹이었을 것이다.침략의 정확한 정당성은 아직 불분명하지만, 기원전 175년경 그리스인들은 북서부 인도의 일부를 지배했다.이 시기는 그리스-박트리아 역사의 난독화의 시작이기도 하다.데메트리오스는 기원전 180년경에 사망했을 가능성이 있다; 화폐학적 증거는 그 직후에 몇몇 다른 왕들이 존재했음을 암시한다.이 시점에서 그리스-박트리아 왕국은 몇 년 동안 여러 개의 반독립 지역으로 갈라졌고 종종 그들끼리 전쟁을 벌였을 가능성이 있다.헬리오클레스는 박트리아를 기원전 130년까지 지배한 마지막 그리스인이었는데, 박트리아는 중앙아시아 부족의 침략(스키티아와 유에지)으로 인해 권력이 무너졌다.하지만, 그리스의 도시 문명은 왕국이 멸망한 후에도 박트리아에서 지속된 것으로 보이며, 그리스 통치를 대체한 부족들에게 헬레니즘적인 영향을 끼쳤다.그 후 쿠샨 제국은 계속해서 그리스어를 화폐에 사용하였고 그리스인들은 계속해서 제국에서 영향력을 행사하였다.

인도-그리스 왕국이 그리스-박트리아 왕국으로부터 분리되면서 더 고립된 지위가 생겨났고, 따라서 인도-그리스 왕국의 세부 사항은 박트리아보다 훨씬 더 모호해졌다.인도의 왕으로 추정되는 많은 사람들은 그들의 이름이 새겨진 동전 때문에 알려져 있다.고고학적 발견과 부족한 역사적 기록과 함께 화폐학적 증거들은 동서양의 융합이 인도-그리스 [citation needed]왕국에서 최고조에 달했음을 암시한다.

데메트리오스가 죽은 후, 인도의 박트리아 왕들 사이의 내전으로 아폴로도토스 1세(기원전 180년/175년)는 박트리아로부터 통치하지 않은 최초의 적절한 인도-그리스 왕으로 독립할 수 있었다.그의 많은 동전들이 인도에서 발견되었고, 그는 간다라뿐만 아니라 펀자브 서부에서 통치한 것으로 보인다.아폴로도토스 1세는 박트리아 왕 안티마코스 [86]1세의 아들인 안티마코스 2세에 의해 계승되거나 함께 통치되었다.기원전 155년(또는 165년)에 그는 가장 성공적인 인도-그리스 왕 메난데르 1세에 의해 계승된 것으로 보인다.메난더는 불교로 개종했고, 이 종교의 열렬한 후원자였던 것으로 보인다; 그는 일부 불교 문헌에서 '밀린다'로 기억된다.그는 또한 펀자브까지 왕국을 더 동쪽으로 확장했지만, 이러한 정복은 [citation needed]다소 일시적인 것이었다.

메난데르(c.기원전 130년)의 죽음 이후, 왕국은 분열된 것으로 보이며, 여러 '킹'들이 다른 지역에서 동시에 목격되었다.이것은 불가피하게 그리스의 지위를 약화시켰고, 영토는 점차 상실된 것으로 보인다.기원전 70년경, 아라코시아와 파로파미사대의 서쪽 지역은 박트리아 왕국의 종말에 책임이 있는 부족들에 의해 부족들의 침략으로 상실되었다.결과적으로 생긴 인도-스키티아 왕국은 남아 있는 인도-그리스 왕국을 점차 동쪽으로 밀어낸 것으로 보인다.인도-그리스 왕국은 서기 10년 경까지 서부 펀자브에 남아있던 것으로 보이며, 그 때 인도-스키티아인들에 [citation needed]의해 마침내 멸망했다.스트라토 3세는 디오도토스 왕조의 마지막 왕위이자 독립 헬레니즘 왕으로 서기 [89][90]10년 그의 죽음을 통치했다.

쿠샨 제국은 인도-그리크를 정복한 후 그리스-불교, 그리스어, 그리스 문자, 그리스 화폐, 예술 양식을 이어받았다.그리스인들은 몇 세대에 걸쳐 인도의 문화 세계에서 중요한 부분을 계속 차지하고 있었다.부처의 묘사는 그리스 문화의 영향을 받은 것으로 보인다: 간다라 시대의 부처 묘사는 종종 헤라클레스의 [91]보호를 받는 부처의 모습을 보여준다.

인도 문학에서 몇 가지 언급은 야바나족이나 그리스인의 지식을 칭찬한다.마하바라타족은 그들을 "모든 것을 아는 야바나"라고 칭찬한다. 예를 들어, "오왕 야바나들은 모든 것을 알고 있다; 수라스인들은 특히 그렇다.mleccha는 일반적으로 비마나라고 불리는 비행 기계와 같은 그들 자신의 [92]공상의 창조물과 결합되어 있다.수학자 바라하미히라의 "브리햇 삼히타"는 이렇게 말한다: "그리스인들은 비록 불순하지만, 그들은 과학 훈련을 받았고 그곳에서 다른 사람들보다 뛰어났기 때문에 존경받아야 한다..."[93]

다른 국가와 헬레니즘의 영향

헬레니즘 문화는 헬레니즘 시대에 세계의 영향력이 최고조에 달했다.헬레니즘 또는 적어도 필헬레니즘은 헬레니즘 왕국의 국경의 대부분의 지역에 도달했다.비록 이 지역들 중 일부는 그리스인이나 심지어 그리스어를 하는 엘리트들에 의해 통치되지 않았지만, 어떤 헬레니즘적 영향들은 이 지역들의 역사적 기록과 물질 문화에서 볼 수 있다.다른 지역은 이 시기 이전에 그리스 식민지와 접촉했고, 단순히 헬레니즘화와 혼합의 지속적인 과정을 보았다.

헬레니즘 시대 이전에는 크림반도와 타만반도의 해안에 그리스 식민지가 세워졌다.보스포란 왕국은 스파르타 왕조 (기원전 438–110)의 지배하에 있는 마에오티아인, 트라키아인, 크림 스키타이인, 그리고 치메리아인과 같은 그리스 도시 국가들과 지역 부족민들로 이루어진 다민족 왕국이었다.스파르타시드는 판티카파이움 출신의 헬레니즘화된 트라키아 가문이다.보스포라인들은 폰토스-카스피 스텝의 스키타이인들과 오랫동안 무역 접촉을 유지했고, 헬레니즘의 영향은 스키타이 네아폴리스와 같은 크림 반도의 스키타이 정착지에서 볼 수 있다.파에리사데스 5세 치하의 보스포라 왕국에 대한 스키타이인들의 압력은 기원전 107년에 보호를 위해 폰토스 왕 미트라다테스 6세 치하의 최종적인 봉신으로 이어졌다.그것은 나중에 로마의 속국이 되었다.중앙아시아의 스텝에 있는 다른 스키타이인들은 박트리아의 그리스인들을 통해 헬레니즘 문화와 접촉했다.많은 스키타이 엘리트들이 그리스 제품을 구입했고 일부 스키타이 예술은 그리스의 영향을 보여준다.적어도 일부 스키타이인들은 헬레니즘화된 것으로 보인다. 왜냐하면 우리는 스키타이 왕국의 엘리트들 사이의 그리스 방식 채택에 대한 갈등을 알고 있기 때문이다.이 헬레니즘화된 스키타이인들은 "젊은 스키타이인들"[95]로 알려져 있었다.Callipidae로 알려진 폰틱 올비아 주변의 민족들은 혼합되고 헬레니즘화된 그리스-스키티아인들이었다.[96]

The Greek colonies on the west coast of the Black sea, such as Istros, Tomi and Callatis traded with the Thracian Getae who occupied modern-day Dobruja. From the 6th century BC on, the multiethnic people in this region gradually intermixed with each other, creating a Greco-Getic populace.[97] Numismatic evidence shows that Hellenic influence penetrated further inland. Getae in Wallachia and Moldavia coined Getic tetradrachms, Getic imitations of Macedonian coinage.[98]

The ancient Georgian kingdoms had trade relations with the Greek city-states on the Black Sea coast such as Poti and Sukhumi. The kingdom of Colchis, which later became a Roman client state, received Hellenistic influences from the Black Sea Greek colonies.

In Arabia, Bahrain, which was referred to by the Greeks as Tylos, the centre of pearl trading, when Nearchus came to discover it serving under Alexander the Great.[99] The Greek admiral Nearchus is believed to have been the first of Alexander's commanders to visit these islands. It is not known whether Bahrain was part of the Seleucid Empire, although the archaeological site at Qalat Al Bahrain has been proposed as a Seleucid base in the Persian Gulf.[100] Alexander had planned to settle the eastern shores of the Persian Gulf with Greek colonists, and although it is not clear that this happened on the scale he envisaged, Tylos was very much part of the Hellenised world: the language of the upper classes was Greek (although Aramaic was in everyday use), while Zeus was worshipped in the form of the Arabian sun-god Shams.[101] Tylos even became the site of Greek athletic contests.[102]

Carthage was a Phoenician colony on the coast of Tunisia. Carthaginian culture came into contact with the Greeks through Punic colonies in Sicily and through their widespread Mediterranean trade network. While the Carthaginians retained their Punic culture and language, they did adopt some Hellenistic ways, one of the most prominent of which was their military practices. The core of Carthage's military was the Greek-style phalanx formed by citizen hoplite spearmen who had been conscripted into service, though their armies also included large numbers of mercenaries. After their defeat in the First Punic War, Carthage hired a Spartan mercenary captain, Xanthippus of Carthage, to reform their military forces. Xanthippus reformed the Carthaginian military along Macedonian army lines.

By the 2nd century BC, the kingdom of Numidia also began to see Hellenistic culture influence its art and architecture. The Numidian royal monument at Chemtou is one example of Numidian Hellenized architecture. Reliefs on the monument also show the Numidians had adopted Greco-Macedonian type armor and shields for their soldiers.[103]

Ptolemaic Egypt was the center of Hellenistic influence in Africa and Greek colonies also thrived in the region of Cyrene, Libya. The kingdom of Meroë was in constant contact with Ptolemaic Egypt and Hellenistic influences can be seen in their art and archaeology. There was a temple to Serapis, the Greco-Egyptian god.

Rise of Rome

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Widespread Roman interference in the Greek world was probably inevitable given the general manner of the ascendancy of the Roman Republic. This Roman-Greek interaction began as a consequence of the Greek city-states located along the coast of southern Italy. Rome had come to dominate the Italian peninsula, and desired the submission of the Greek cities to its rule. Although they initially resisted, allying themselves with Pyrrhus of Epirus, and defeating the Romans at several battles, the Greek cities were unable to maintain this position and were absorbed by the Roman republic. Shortly afterwards, Rome became involved in Sicily, fighting against the Carthaginians in the First Punic War. The result was the complete conquest of Sicily, including its previously powerful Greek cities, by the Romans.

Roman entanglement in the Balkans began when Illyrian piratical raids on Roman merchants led to invasions of Illyria (the First and, Second Illyrian Wars). Tension between Macedon and Rome increased when the young king of Macedon, Philip V, harbored one of the chief pirates, Demetrius of Pharos[104] (a former client of Rome). As a result, in an attempt to reduce Roman influence in the Balkans, Philip allied himself with Carthage after Hannibal had dealt the Romans a massive defeat at the Battle of Cannae (216 BC) during the Second Punic War. Forcing the Romans to fight on another front when they were at a nadir of manpower gained Philip the lasting enmity of the Romans—the only real result from the somewhat insubstantial First Macedonian War (215–202 BC).

Once the Second Punic War had been resolved, and the Romans had begun to regather their strength, they looked to re-assert their influence in the Balkans, and to curb the expansion of Philip. A pretext for war was provided by Philip's refusal to end his war with Attalid Pergamum and Rhodes, both Roman allies.[105] The Romans, also allied with the Aetolian League of Greek city-states (which resented Philip's power), thus declared war on Macedon in 200 BC, starting the Second Macedonian War. This ended with a decisive Roman victory at the Battle of Cynoscephalae (197 BC). Like most Roman peace treaties of the period, the resultant 'Peace of Flaminius' was designed utterly to crush the power of the defeated party; a massive indemnity was levied, Philip's fleet was surrendered to Rome, and Macedon was effectively returned to its ancient boundaries, losing influence over the city-states of southern Greece, and land in Thrace and Asia Minor. The result was the end of Macedon as a major power in the Mediterranean.

As a result of the confusion in Greece at the end of the Second Macedonian War, the Seleucid Empire also became entangled with the Romans. The Seleucid Antiochus III had allied with Philip V of Macedon in 203 BC, agreeing that they should jointly conquer the lands of the boy-king of Egypt, Ptolemy V. After defeating Ptolemy in the Fifth Syrian War, Antiochus concentrated on occupying the Ptolemaic possessions in Asia Minor. However, this brought Antiochus into conflict with Rhodes and Pergamum, two important Roman allies, and began a 'cold war' between Rome and Antiochus (not helped by the presence of Hannibal at the Seleucid court).[4] Meanwhile, in mainland Greece, the Aetolian League, which had sided with Rome against Macedon, now grew to resent the Roman presence in Greece. This presented Antiochus III with a pretext to invade Greece and 'liberate' it from Roman influence, thus starting the Roman-Syrian War (192–188 BC). In 191 BC, the Romans under Manius Acilius Glabrio routed him at Thermopylae and obliged him to withdraw to Asia. During the course of this war Roman troops moved into Asia for the first time, where they defeated Antiochus again at the Battle of Magnesia (190 BC). A crippling treaty was imposed on Antiochus, with Seleucid possessions in Asia Minor removed and given to Rhodes and Pergamum, the size of the Seleucid navy reduced, and a massive war indemnity invoked.

Thus, in less than twenty years, Rome had destroyed the power of one of the successor states, crippled another, and firmly entrenched its influence over Greece. This was primarily a result of the over-ambition of the Macedonian kings, and their unintended provocation of Rome, though Rome was quick to exploit the situation. In another twenty years, the Macedonian kingdom was no more. Seeking to re-assert Macedonian power and Greek independence, Philip V's son Perseus incurred the wrath of the Romans, resulting in the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC). Victorious, the Romans abolished the Macedonian kingdom, replacing it with four puppet republics; these lasted a further twenty years before Macedon was formally annexed as a Roman province (146 BC) after yet another rebellion under Andriscus. Rome now demanded that the Achaean League, the last stronghold of Greek independence, be dissolved. The Achaeans refused and declared war on Rome. Most of the Greek cities rallied to the Achaeans' side, even slaves were freed to fight for Greek independence. The Roman consul Lucius Mummius advanced from Macedonia and defeated the Greeks at Corinth, which was razed to the ground. In 146 BC, the Greek peninsula, though not the islands, became a Roman protectorate. Roman taxes were imposed, except in Athens and Sparta, and all the cities had to accept rule by Rome's local allies.

The Attalid dynasty of Pergamum lasted little longer; a Roman ally until the end, its final king Attalus III died in 133 BC without an heir, and taking the alliance to its natural conclusion, willed Pergamum to the Roman Republic.[106] The final Greek resistance came in 88 BC, when King Mithridates of Pontus rebelled against Rome, captured Roman held Anatolia, and massacred up to 100,000 Romans and Roman allies across Asia Minor. Many Greek cities, including Athens, overthrew their Roman puppet rulers and joined him in the Mithridatic wars. When he was driven out of Greece by the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the latter laid siege to Athens and razed the city. Mithridates was finally defeated by Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) in 65 BC. Further ruin was brought to Greece by the Roman civil wars, which were partly fought in Greece. Finally, in 27 BC, Augustus directly annexed Greece to the new Roman Empire as the province of Achaea. The struggles with Rome had left Greece depopulated and demoralised. Nevertheless, Roman rule at least brought an end to warfare, and cities such as Athens, Corinth, Thessaloniki and Patras soon recovered their prosperity.

Contrarily, having so firmly entrenched themselves into Greek affairs, the Romans now completely ignored the rapidly disintegrating Seleucid empire (perhaps because it posed no threat); and left the Ptolemaic kingdom to decline quietly, while acting as a protector of sorts, in as much as to stop other powers taking Egypt over (including the famous line-in-the-sand incident when the Seleucid Antiochus IV Epiphanes tried to invade Egypt).[4] Eventually, instability in the near east resulting from the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Seleucid Empire caused the Roman proconsul Pompey the Great to abolish the Seleucid rump state, absorbing much of Syria into the Roman Republic.[106] Famously, the end of Ptolemaic Egypt came as the final act in the republican civil war between the Roman triumvirs Mark Anthony and Augustus Caesar. After the defeat of Anthony and his lover, the last Ptolemaic monarch, Cleopatra VII, at the Battle of Actium, Augustus invaded Egypt and took it as his own personal fiefdom.[106] He thereby completed both the destruction of the Hellenistic kingdoms and the Roman Republic, and ended (in hindsight) the Hellenistic era.

Culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

In some fields Hellenistic culture thrived, particularly in its preservation of the past. The states of the Hellenistic period were deeply fixated with the past and its seemingly lost glories.[108] The preservation of many classical and archaic works of art and literature (including the works of the three great classical tragedians, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides) are due to the efforts of the Hellenistic Greeks. The museum and library of Alexandria was the center of this conservationist activity. With the support of royal stipends, Alexandrian scholars collected, translated, copied, classified, and critiqued every book they could find. Most of the great literary figures of the Hellenistic period studied at Alexandria and conducted research there. They were scholar poets, writing not only poetry but treatises on Homer and other archaic and classical Greek literature.[109]

Athens retained its position as the most prestigious seat of higher education, especially in the domains of philosophy and rhetoric, with considerable libraries and philosophical schools.[110] Alexandria had the monumental museum (a research center) and Library of Alexandria which was estimated to have had 700,000 volumes.[110] The city of Pergamon also had a large library and became a major center of book production.[110] The island of Rhodes had a library and also boasted a famous finishing school for politics and diplomacy. Libraries were also present in Antioch, Pella, and Kos. Cicero was educated in Athens and Mark Antony in Rhodes.[110] Antioch was founded as a metropolis and center of Greek learning which retained its status into the era of Christianity.[110] Seleucia replaced Babylon as the metropolis of the lower Tigris.

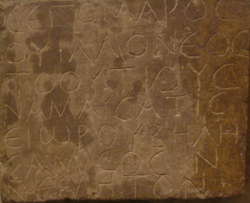

The spread of Greek culture and language throughout the Near East and Asia owed much to the development of newly founded cities and deliberate colonization policies by the successor states, which in turn was necessary for maintaining their military forces. Settlements such as Ai-Khanoum, on trade routes, allowed Greek culture to mix and spread. The language of Philip II's and Alexander's court and army (which was made up of various Greek and non-Greek speaking peoples) was a version of Attic Greek, and over time this language developed into Koine, the lingua franca of the successor states.

The identification of local gods with similar Greek deities, a practice termed 'Interpretatio graeca', stimulated the building of Greek-style temples, and Greek culture in the cities meant that buildings such as gymnasia and theaters became common. Many cities maintained nominal autonomy while under the rule of the local king or satrap, and often had Greek-style institutions. Greek dedications, statues, architecture, and inscriptions have all been found. However, local cultures were not replaced, and mostly went on as before, but now with a new Greco-Macedonian or otherwise Hellenized elite. An example that shows the spread of Greek theater is Plutarch's story of the death of Crassus, in which his head was taken to the Parthian court and used as a prop in a performance of The Bacchae. Theaters have also been found: for example, in Ai-Khanoum on the edge of Bactria, the theater has 35 rows – larger than the theater in Babylon.

The spread of Greek influence and language is also shown through ancient Greek coinage. Portraits became more realistic, and the obverse of the coin was often used to display a propagandistic image, commemorating an event or displaying the image of a favored god. The use of Greek-style portraits and Greek language continued under the Roman, Parthian, and Kushan empires, even as the use of Greek was in decline.

Hellenization and acculturation

The concept of Hellenization, meaning the adoption of Greek culture in non-Greek regions, has long been controversial. Undoubtedly Greek influence did spread through the Hellenistic realms, but to what extent, and whether this was a deliberate policy or mere cultural diffusion, have been hotly debated.

It seems likely that Alexander himself pursued policies which led to Hellenization, such as the foundations of new cities and Greek colonies. While it may have been a deliberate attempt to spread Greek culture (or as Arrian says, "to civilise the natives"), it is more likely that it was a series of pragmatic measures designed to aid in the rule of his enormous empire.[20] Cities and colonies were centers of administrative control and Macedonian power in a newly conquered region. Alexander also seems to have attempted to create a mixed Greco-Persian elite class as shown by the Susa weddings and his adoption of some forms of Persian dress and court culture. He also brought Persian and other non-Greek peoples into his military and even the elite cavalry units of the companion cavalry. Again, it is probably better to see these policies as a pragmatic response to the demands of ruling a large empire[20] than to any idealized attempt to bringing Greek culture to the 'barbarians'. This approach was bitterly resented by the Macedonians and discarded by most of the Diadochi after Alexander's death. These policies can also be interpreted as the result of Alexander's possible megalomania[112] during his later years.

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, the influx of Greek colonists into the new realms continued to spread Greek culture into Asia. The founding of new cities and military colonies continued to be a major part of the Successors' struggle for control of any particular region, and these continued to be centers of cultural diffusion. The spread of Greek culture under the Successors seems mostly to have occurred with the spreading of Greeks themselves, rather than as an active policy.

Throughout the Hellenistic world, these Greco-Macedonian colonists considered themselves by and large superior to the native "barbarians" and excluded most non-Greeks from the upper echelons of courtly and government life. Most of the native population was not Hellenized, had little access to Greek culture and often found themselves discriminated against by their Hellenic overlords.[113] Gymnasiums and their Greek education, for example, were for Greeks only. Greek cities and colonies may have exported Greek art and architecture as far as the Indus, but these were mostly enclaves of Greek culture for the transplanted Greek elite. The degree of influence that Greek culture had throughout the Hellenistic kingdoms was therefore highly localized and based mostly on a few great cities like Alexandria and Antioch. Some natives did learn Greek and adopt Greek ways, but this was mostly limited to a few local elites who were allowed to retain their posts by the Diadochi and also to a small number of mid-level administrators who acted as intermediaries between the Greek speaking upper class and their subjects. In the Seleucid Empire, for example, this group amounted to only 2.5 percent of the official class.[114]

Hellenistic art nevertheless had a considerable influence on the cultures that had been affected by the Hellenistic expansion. As far as the Indian subcontinent, Hellenistic influence on Indian art was broad and far-reaching, and had effects for several centuries following the forays of Alexander the Great.

Despite their initial reluctance, the Successors seem to have later deliberately naturalized themselves to their different regions, presumably in order to help maintain control of the population.[115] In the Ptolemaic kingdom, we find some Egyptianized Greeks by the 2nd century onwards. In the Indo-Greek kingdom we find kings who were converts to Buddhism (e.g., Menander). The Greeks in the regions therefore gradually become 'localized', adopting local customs as appropriate. In this way, hybrid 'Hellenistic' cultures naturally emerged, at least among the upper echelons of society.

The trends of Hellenization were therefore accompanied by Greeks adopting native ways over time, but this was widely varied by place and by social class. The farther away from the Mediterranean and the lower in social status, the more likely that a colonist was to adopt local ways, while the Greco-Macedonian elites and royal families usually remained thoroughly Greek and viewed most non-Greeks with disdain. It was not until Cleopatra VII that a Ptolemaic ruler bothered to learn the Egyptian language of their subjects.

Religion

In the Hellenistic period, there was much continuity in Greek religion: the Greek gods continued to be worshiped, and the same rites were practiced as before. However the socio-political changes brought on by the conquest of the Persian empire and Greek emigration abroad meant that change also came to religious practices. This varied greatly by location. Athens, Sparta and most cities in the Greek mainland did not see much religious change or new gods (with the exception of the Egyptian Isis in Athens),[116] while the multi-ethnic Alexandria had a very varied group of gods and religious practices, including Egyptian, Jewish and Greek. Greek emigres brought their Greek religion everywhere they went, even as far as India and Afghanistan. Non-Greeks also had more freedom to travel and trade throughout the Mediterranean and in this period we can see Egyptian gods such as Serapis, and the Syrian gods Atargatis and Hadad, as well as a Jewish synagogue, all coexisting on the island of Delos alongside classical Greek deities.[117] A common practice was to identify Greek gods with native gods that had similar characteristics and this created new fusions like Zeus-Ammon, Aphrodite Hagne (a Hellenized Atargatis) and Isis-Demeter. Greek emigres faced individual religious choices they had not faced on their home cities, where the gods they worshiped were dictated by tradition.

Hellenistic monarchies were closely associated with the religious life of the kingdoms they ruled. This had already been a feature of Macedonian kingship, which had priestly duties.[118] Hellenistic kings adopted patron deities as protectors of their house and sometimes claimed descent from them. The Seleucids for example took on Apollo as patron, the Antigonids had Herakles, and the Ptolemies claimed Dionysus among others.[119]

The worship of dynastic ruler cults was also a feature of this period, most notably in Egypt, where the Ptolemies adopted earlier Pharaonic practice, and established themselves as god-kings. These cults were usually associated with a specific temple in honor of the ruler such as the Ptolemaieia at Alexandria and had their own festivals and theatrical performances. The setting up of ruler cults was more based on the systematized honors offered to the kings (sacrifice, proskynesis, statues, altars, hymns) which put them on par with the gods (isotheism) than on actual belief of their divine nature. According to Peter Green, these cults did not produce genuine belief of the divinity of rulers among the Greeks and Macedonians.[120] The worship of Alexander was also popular, as in the long lived cult at Erythrae and of course, at Alexandria, where his tomb was located.

The Hellenistic age also saw a rise in the disillusionment with traditional religion.[121] The rise of philosophy and the sciences had removed the gods from many of their traditional domains such as their role in the movement of the heavenly bodies and natural disasters. The Sophists proclaimed the centrality of humanity and agnosticism; the belief in Euhemerism (the view that the gods were simply ancient kings and heroes), became popular. The popular philosopher Epicurus promoted a view of disinterested gods living far away from the human realm in metakosmia. The apotheosis of rulers also brought the idea of divinity down to earth. While there does seem to have been a substantial decline in religiosity, this was mostly reserved for the educated classes.[122]

Magic was practiced widely, and this, too, was a continuation from earlier times. Throughout the Hellenistic world, people would consult oracles, and use charms and figurines to deter misfortune or to cast spells. Also developed in this era was the complex system of astrology, which sought to determine a person's character and future in the movements of the sun, moon, and planets. Astrology was widely associated with the cult of Tyche (luck, fortune), which grew in popularity during this period.

Literature

The Hellenistic period saw the rise of New Comedy, the only few surviving representative texts being those of Menander (born 342/341 BC). Only one play, Dyskolos, survives in its entirety. The plots of this new Hellenistic comedy of manners were more domestic and formulaic, stereotypical low born characters such as slaves became more important, the language was colloquial and major motifs included escapism, marriage, romance and luck (Tyche).[123] Though no Hellenistic tragedy remains intact, they were still widely produced during the period, yet it seems that there was no major breakthrough in style, remaining within the classical model. The Supplementum Hellenisticum, a modern collection of extant fragments, contains the fragments of 150 authors.[124]

Hellenistic poets now sought patronage from kings, and wrote works in their honor. The scholars at the libraries in Alexandria and Pergamon focused on the collection, cataloging, and literary criticism of classical Athenian works and ancient Greek myths. The poet-critic Callimachus, a staunch elitist, wrote hymns equating Ptolemy II to Zeus and Apollo. He promoted short poetic forms such as the epigram, epyllion and the iambic and attacked epic as base and common ("big book, big evil" was his doctrine).[125] He also wrote a massive catalog of the holdings of the library of Alexandria, the famous Pinakes. Callimachus was extremely influential in his time and also for the development of Augustan poetry. Another poet, Apollonius of Rhodes, attempted to revive the epic for the Hellenistic world with his Argonautica. He had been a student of Callimachus and later became chief librarian (prostates) of the library of Alexandria. Apollonius and Callimachus spent much of their careers feuding with each other. Pastoral poetry also thrived during the Hellenistic era, Theocritus was a major poet who popularized the genre.

This period also saw the rise of the ancient Greek novel, such as Daphnis and Chloe and the Ephesian Tale.

Around 240 BC Livius Andronicus, a Greek slave from southern Italy, translated Homer's Odyssey into Latin. Greek literature would have a dominant effect on the development of the Latin literature of the Romans. The poetry of Virgil, Horace and Ovid were all based on Hellenistic styles.

Philosophy

During the Hellenistic period, many different schools of thought developed, and these schools of Hellenistic philosophy had a significant influence on the Greek and Roman ruling elite.

Athens, with its multiple philosophical schools, continued to remain the center of philosophical thought. However, Athens had now lost her political freedom, and Hellenistic philosophy is a reflection of this new difficult period. In this political climate, Hellenistic philosophers went in search of goals such as ataraxia (un-disturbedness), autarky (self-sufficiency), and apatheia (freedom from suffering), which would allow them to wrest well-being or eudaimonia out of the most difficult turns of fortune. This occupation with the inner life, with personal inner liberty and with the pursuit of eudaimonia is what all Hellenistic philosophical schools have in common.[126]

The Epicureans and the Cynics eschewed public offices and civic service, which amounted to a rejection of the polis itself, the defining institution of the Greek world. Epicurus promoted atomism and an asceticism based on freedom from pain as its ultimate goal. The Cyrenaics and Epicureans embraced hedonism, arguing that pleasure was the only true good. Cynics such as Diogenes of Sinope rejected all material possessions and social conventions (nomos) as unnatural and useless. Stoicism, founded by Zeno of Citium, taught that virtue was sufficient for eudaimonia as it would allow one to live in accordance with Nature or Logos. The philosophical schools of Aristotle (the Peripatetics of the Lyceum) and Plato (Platonism at the Academy) also remained influential. Against these dogmatic schools of philosophy the Pyrrhonist school embraced philosophical skepticism, and, starting with Arcesilaus, Plato's Academy also embraced skepticism in the form of Academic Skepticism.

The spread of Christianity throughout the Roman world, followed by the spread of Islam, ushered in the end of Hellenistic philosophy and the beginnings of Medieval philosophy (often forcefully, as under Justinian I), which was dominated by the three Abrahamic traditions: Jewish philosophy, Christian philosophy, and early Islamic philosophy. In spite of this shift, Hellenistic philosophy continued to influence these three religious traditions and the Renaissance thought which followed them.

Sciences

Hellenistic culture produced seats of learning throughout the Mediterranean. Hellenistic science differed from Greek science in at least two ways: first, it benefited from the cross-fertilization of Greek ideas with those that had developed in the larger Hellenistic world; secondly, to some extent, it was supported by royal patrons in the kingdoms founded by Alexander's successors. Especially important to Hellenistic science was the city of Alexandria in Egypt, which became a major center of scientific research in the 3rd century BC. Hellenistic scholars frequently employed the principles developed in earlier Greek thought: the application of mathematics and deliberate empirical research, in their scientific investigations.[128][129]

Hellenistic Geometers such as Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC), Apollonius of Perga (c. 262 – c. 190 BC), and Euclid (c. 325–265 BC), whose Elements became the most important textbook in Western mathematics until the 19th century AD, built upon the work of the mathematicians of the Classical age, such as Theodorus, Archytas, Theaetetus, Eudoxus, and the so-called Pythagoreans. Euclid developed proofs for the Pythagorean Theorem, for the infinitude of primes, and worked on the five Platonic solids.[130] Eratosthenes measured the Earth's circumference with remarkable accuracy.[131] He was also the first to calculate the tilt of the Earth's axis (again with remarkable accuracy). Additionally, he may have accurately calculated the distance from the Earth to the Sun and invented the leap day.[132] Known as the "Father of Geography", Eratosthenes also created the first map of the world incorporating parallels and meridians, based on the available geographical knowledge of the era.

Astronomers like Hipparchus (c. 190 – c. 120 BC) built upon the measurements of the Babylonian astronomers before him, to measure the precession of the Earth. Pliny reports that Hipparchus produced the first systematic star catalog after he observed a new star (it is uncertain whether this was a nova or a comet) and wished to preserve astronomical record of the stars, so that other new stars could be discovered.[135] It has recently been claimed that a celestial globe based on Hipparchus' star catalog sits atop the broad shoulders of a large 2nd-century Roman statue known as the Farnese Atlas.[136] Another astronomer, Aristarchos of Samos, developed a heliocentric system.

The level of Hellenistic achievement in astronomy and engineering is impressively shown by the Antikythera mechanism (150–100 BC). It is a 37-gear mechanical computer which computed the motions of the Sun and Moon, including lunar and solar eclipses predicted on the basis of astronomical periods believed to have been learned from the Babylonians.[137] Devices of this sort are not found again until the 10th century, when a simpler eight-geared luni-solar calculator incorporated into an astrolabe was described by the Persian scholar, Al-Biruni.[138][failed verification] Similarly complex devices were also developed by other Muslim engineers and astronomers during the Middle Ages.[137][failed verification]

Medicine, which was dominated by the Hippocratic tradition, saw new advances under Praxagoras of Kos, who theorized that blood traveled through the veins. Herophilos (335–280 BC) was the first to base his conclusions on dissection of the human body and animal vivisection, and to provide accurate descriptions of the nervous system, liver and other key organs. Influenced by Philinus of Cos (fl. 250 BC), a student of Herophilos, a new medical sect emerged, the Empiric school, which was based on strict observation and rejected unseen causes of the Dogmatic school.

Bolos of Mendes made developments in alchemy and Theophrastus was known for his work in plant classification. Crateuas wrote a compendium on botanic pharmacy. The library of Alexandria included a zoo for research and Hellenistic zoologists include Archelaos, Leonidas of Byzantion, Apollodoros of Alexandria and Bion of Soloi.

Ctesibius wrote the first treatises on the science of compressed air and its uses in pumps (and even in a kind of cannon). This, in combination with his work on the elasticity of air On pneumatics, earned him the title of "father of pneumatics.

Hero of Alexandria, a Greek mathematician and engineer, who is often considered to be the greatest experimenter of antiquity,[139] described[140] the construction of the aeolipile (a version of which is known as Hero's engine) which was a rocket-like reaction engine and the first-recorded steam engine. It was described almost two millennia before the industrial revolution.

Technological developments from the Hellenistic period include cogged gears, pulleys, the screw, Archimedes' screw, the steam engine, the screw press, glassblowing, hollow bronze casting, surveying instruments, an odometer, the pantograph, the water clock, the watermill, a water organ, and the Piston pump.[141]

The interpretation of Hellenistic science varies widely. At one extreme is the view of the English classical scholar Cornford, who believed that "all the most important and original work was done in the three centuries from 600 to 300 BC".[142] At the other is the view of the Italian physicist and mathematician Lucio Russo, who claims that scientific method was actually born in the 3rd century BC, to be forgotten during the Roman period and only revived in the Renaissance.[143]

Military science

Hellenistic warfare was a continuation of the military developments of Iphicrates and Philip II of Macedon, particularly his use of the Macedonian phalanx, a dense formation of pikemen, in conjunction with heavy companion cavalry. Armies of the Hellenistic period differed from those of the classical period in being largely made up of professional soldiers and also in their greater specialization and technical proficiency in siege warfare. Hellenistic armies were significantly larger than those of classical Greece relying increasingly on Greek mercenaries (misthophoroi; men-for-pay) and also on non-Greek soldiery such as Thracians, Galatians, Egyptians and Iranians. Some ethnic groups were known for their martial skill in a particular mode of combat and were highly sought after, including Tarantine cavalry, Cretan archers, Rhodian slingers and Thracian peltasts. This period also saw the adoption of new weapons and troop types such as Thureophoroi and the Thorakitai who used the oval Thureos shield and fought with javelins and the machaira sword. The use of heavily armored cataphracts and also horse archers was adopted by the Seleucids, Greco-Bactrians, Armenians and Pontus. The use of war elephants also became common. Seleucus received Indian war elephants from the Mauryan empire, and used them to good effect at the battle of Ipsus. He kept a core of 500 of them at Apameia. The Ptolemies used the smaller African elephant.

Hellenistic military equipment was generally characterized by an increase in size. Hellenistic-era warships grew from the trireme to include more banks of oars and larger numbers of rowers and soldiers as in the Quadrireme and Quinquereme. The Ptolemaic Tessarakonteres was the largest ship constructed in Antiquity. New siege engines were developed during this period. An unknown engineer developed the torsion-spring catapult (c. 360 BC) and Dionysios of Alexandria designed a repeating ballista, the Polybolos. Preserved examples of ball projectiles range from 4.4 to 78 kg (9.7 to 172.0 lb).[144] Demetrius Poliorcetes was notorious for the large siege engines employed in his campaigns, especially during the 12-month siege of Rhodes when he had Epimachos of Athens build a massive 160 ton siege tower named Helepolis, filled with artillery.

Art

The term Hellenistic is a modern invention; the Hellenistic World not only included a huge area covering the whole of the Aegean, rather than the Classical Greece focused on the Poleis of Athens and Sparta, but also a huge time range. In artistic terms this means that there is huge variety which is often put under the heading of "Hellenistic Art" for convenience.

Hellenistic art saw a turn from the idealistic, perfected, calm and composed figures of classical Greek art to a style dominated by realism and the depiction of emotion (pathos) and character (ethos). The motif of deceptively realistic naturalism in art (aletheia) is reflected in stories such as that of the painter Zeuxis, who was said to have painted grapes that seemed so real that birds came and pecked at them.[145] The female nude also became more popular as epitomized by the Aphrodite of Cnidos of Praxiteles and art in general became more erotic (e.g., Leda and the Swan and Scopa's Pothos). The dominant ideals of Hellenistic art were those of sensuality and passion.[146]

People of all ages and social statuses were depicted in the art of the Hellenistic age. Artists such as Peiraikos chose mundane and lower class subjects for his paintings. According to Pliny, "He painted barbers' shops, cobblers' stalls, asses, eatables and similar subjects, earning for himself the name of rhyparographos [painter of dirt/low things]. In these subjects he could give consummate pleasure, selling them for more than other artists received for their large pictures" (Natural History, Book XXXV.112). Even barbarians, such as the Galatians, were depicted in heroic form, prefiguring the artistic theme of the noble savage. The image of Alexander the Great was also an important artistic theme, and all of the diadochi had themselves depicted imitating Alexander's youthful look. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to the Hellenistic period, including Laocoön and his Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace.

Developments in painting included experiments in chiaroscuro by Zeuxis and the development of landscape painting and still life painting.[147] Greek temples built during the Hellenistic period were generally larger than classical ones, such as the temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the temple of Artemis at Sardis, and the temple of Apollo at Didyma (rebuilt by Seleucus in 300 BC). The royal palace (basileion) also came into its own during the Hellenistic period, the first extant example being the massive 4th-century villa of Cassander at Vergina.

This period also saw the first written works of art history in the histories of Duris of Samos and Xenocrates of Athens, a sculptor and a historian of sculpture and painting.

There has been a trend in writing the history of this period to depict Hellenistic art as a decadent style, following the Golden Age of Classical Athens. Pliny the Elder, after having described the sculpture of the classical period, says: Cessavit deinde ars ("then art disappeared").[148] The 18th century terms Baroque and Rococo have sometimes been applied to the art of this complex and individual period. The renewal of the historiographical approach as well as some recent discoveries, such as the tombs of Vergina, allow a better appreciation of this period's artistic richness.

Influence on Christianity

Alexander's conquests helped the spread of Christianity (from: Greek Χρῑστῐᾱνισμός). One of Alexander's generals, Seleucus I Nicator who controlled most of Asia Minor, Syria, Mesopotamia, and the Iranian Plateau after Alexander's death, founded Antioch, which is known as the cradle of Christianity, since the name "Christian" for Jesus' followers first emerged there. The New Testament of the Bible (from: Koine Greek τὰ βιβλία, tà biblía, "the books") was written in Koine Greek.[149]

Hellenistic period and modern culture

The focus on the Hellenistic period over the course of the 19th century by scholars and historians has led to an issue common to the study of historical periods; historians see the period of focus as a mirror of the period in which they are living. Many 19th-century scholars contended that the Hellenistic period represented a cultural decline from the brilliance of classical Greece. Though this comparison is now seen as unfair and meaningless, it has been noted that even commentators of the time saw the end of a cultural era which could not be matched again.[150] This may be inextricably linked with the nature of government. It has been noted by Herodotus that after the establishment of the Athenian democracy:

the Athenians found themselves suddenly a great power. Not just in one field, but in everything they set their minds to ... As subjects of a tyrant, what had they accomplished? ...Held down like slaves they had shirked and slacked; once they had won their freedom, not a citizen but he could feel like he was labouring for himself[151]

Thus, with the decline of the Greek polis, and the establishment of monarchical states, the environment and social freedom in which to excel may have been reduced.[152] A parallel can be drawn with the productivity of the city states of Italy during the Renaissance, and their subsequent decline under autocratic rulers.[citation needed]

However, William Woodthorpe Tarn, between World War I and World War II and the heyday of the League of Nations, focused on the issues of racial and cultural confrontation and the nature of colonial rule. Michael Rostovtzeff, who fled the Russian Revolution, concentrated predominantly on the rise of the capitalist bourgeoisie in areas of Greek rule. Arnaldo Momigliano, an Italian Jew who wrote before and after the Second World War, studied the problem of mutual understanding between races in the conquered areas. Moses Hadas portrayed an optimistic picture of synthesis of culture from the perspective of the 1950s, while Frank William Walbank in the 1960s and 1970s had a materialistic approach to the Hellenistic period, focusing mainly on class relations. Recently, however, papyrologist C. Préaux has concentrated predominantly on the economic system, interactions between kings and cities, and provides a generally pessimistic view on the period. Peter Green, on the other hand, writes from the point of view of late-20th-century liberalism, his focus being on individualism, the breakdown of convention, experiments, and a postmodern disillusionment with all institutions and political processes.[16]

See also

References

- ^ Art of the Hellenistic Age and the Hellenistic Tradition. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013. Archived here.

- ^ Hellenistic Age. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013. Archived here.

- ^ "Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age". www.penfield.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-08.

- ^ a b c d Green, Peter (2008). Alexander The Great and the Hellenistic Age. London: Orion. ISBN 978-0-7538-2413-9.

- ^ Professor Gerhard Rempel, Hellenistic Civilization (Western New England College) Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ulrich Wilcken, Griechische Geschichte im Rahmen der Altertumsgeschichte.

- ^ Green, p. xvii.

- ^ "Hellenistic Age". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ a b Green, P (2008). Alexander The Great and the Hellenistic Age. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-7538-2413-9.

- ^ Chaniotis, Angelos (2018). Age of Conquests: The Greek World from Alexander to Hadrian. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 4.

- ^ Anderson, Terence J.; Twining, William (2015). "Law and archaeology: Modified Wigmorean Analysis". In Chapman, Robert; Wylie, Alison (eds.). Material Evidence: Learning from Archaeological Practice. Abingdon, UK; New York, NY: Routledge. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-317-57622-8. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Ἑλληνιστής. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Chaniotis, Angelos (2011). Greek History: Hellenistic. Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-980507-5.

- ^ Arnold, Matthew (1869). "Chapter IV". Culture and Anarchy. Smith, Elder & Co. p. 143. Arnold, Matthew; Garnett, Jane (editor) (2006). "Chapter IV". Culture and Anarchy. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-280511-9.

{{cite book}}:first2=has generic name (help) - ^ a b F.W. Walbank et al. THE CAMBRIDGE ANCIENT HISTORY, SECOND EDITION, VOLUME VII, PART I: The Hellenistic World, p. 1.

- ^ a b Green, Peter (2007). The Hellenistic Age (A Short History). New York: Modern Library Chronicles.

- ^ Green, Peter (1990); Alexander to Actium, the historical evolution of the Hellenistic age. University of California Press. pp. 7-8.

- ^ Green, p. 9.

- ^ Green, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Green, p. 21.

- ^ Green, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Green, p. 126.

- ^ Green, p. 129.

- ^ Green, p. 134.

- ^ Green, p. 199

- ^ Bugh, Glenn R. (editor). The Cambridge Companion to the Hellenistic World, 2007. p. 35

- ^ Green, Peter; Alexander to Actium, the historical evolution of the Hellenistic age, p. 11.

- ^ McGing, BC. The Foreign Policy of Mithridates VI Eupator, King of Pontus, p. 17.

- ^ Green, p. 139.

- ^ Berthold, Richard M., Rhodes in the Hellenistic Age, Cornell University Press, 1984, p. 12.

- ^ Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, Jennifer Tolbert Roberts, and Sarah B. Pomeroy. A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture. Oxford University Press p. 255

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 6: The Fourth Century BC by D. M. Lewis (Editor), John Boardman (Editor), Simon Hornblower (Editor), M. Ostwald (Editor), ISBN 0-521-23348-8, 1994, p. 423, "Through contact with their Greek neighbors some Illyrian tribe became bilingual (Strabo Vii.7.8.Diglottoi) in particular the Bylliones and the Taulantian tribes close to Epidamnus"

- ^ Dalmatia: research in the Roman province 1970–2001 : papers in honour of J.J by David Davison, Vincent L. Gaffney, J. J. Wilkes, Emilio Marin, 2006, p. 21, "...completely Hellenised town..."

- ^ The Illyrians: history and culture, History and Culture Series, The Illyrians: History and Culture, Aleksandar Stipčević, ISBN 0-8155-5052-9, 1977, p. 174

- ^ The Illyrians (The Peoples of Europe) by John Wilkes, 1996, pp. 233, 236. "The Illyrians liked decorated belt-buckles or clasps (see figure 29). Some of gold and silver with openwork designs of stylised birds have a similar distribution to the Mramorac bracelets and may also have been produced under Greek influence."

- ^ Carte de la Macédoine et du monde égéen vers 200 av. J.-C.

- ^ Webber, Christopher; Odyrsian arms equipment and tactics.

- ^ The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace: Orpheus Unmasked (Oxford Monographs on Classical Archaeology) by Z. H. Archibald, 1998, ISBN 0-19-815047-4, p. 3

- ^ The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace: Orpheus Unmasked (Oxford Monographs on Classical Archaeology) by Z. H. Archibald, 1998, ISBN 0-19-815047-4, p. 5

- ^ The Peloponnesian War: A Military Study (Warfare and History) by J. F. Lazenby,2003, p. 224, "... number of strongholds, and he made himself useful fighting 'the Thracians without a king' on behalf of the more Hellenized Thracian kings and their Greek neighbours (Nepos, Alc. ...

- ^ Walbank et al. (2008), p. 394.

- ^ Delamarre, Xavier. Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise. Editions Errance, Paris, 2008, p. 299

- ^ Boardman, John (1993), The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity, Princeton University Press, p. 308.

- ^ Celtic Inscriptions on Gaulish and British Coins by Beale Poste p. 135

- ^ Momigliano, Arnaldo. Alien Wisdom: The Limits of Hellenization, pp. 54-55.

- ^ Tang, Birgit (2005), Delos, Carthage, Ampurias: the Housing of Three Mediterranean Trading Centres, Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider (Accademia di Danimarca), pp. 15–16, ISBN 8882653056

- ^ Lapunzina, Alejandro (2005), Architecture of Spain, London: Greenwoood Press, ISBN 0-313-31963-4, pp. 69-71.

- ^ Tang, Birgit (2005), Delos, Carthage, Ampurias: the Housing of Three Mediterranean Trading Centres, Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider (Accademia di Danimarca), pp. 17–18, ISBN 8882653056

- ^ Lapunzina, Alejandro (2005), Architecture of Spain, London: Greenwoood Press, ISBN 0-313-31963-4, p. 70.

- ^ Lapunzina, Alejandro (2005), Architecture of Spain, London: Greenwoood Press, ISBN 0-313-31963-4, pp. 70-71.

- ^ Tang, Birgit (2005), Delos, Carthage, Ampurias: the Housing of Three Mediterranean Trading Centres, Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider (Accademia di Danimarca), pp. 16–17, ISBN 8882653056

- ^ Green, p. 187

- ^ Green, p. 190

- ^ Green, p. 193.

- ^ Green, p. 291.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth Raymond (2006). Provincial reactions to Roman imperialism: the aftermath of the Jewish revolt, A.D. 66-70, Parts 66-70. University of California, Berkeley. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-542-82473-9.

... and the Greeks, or at least the Greco-Macedonian Seleucid Empire, replace the Persians as the Easterners.

- ^ Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (London, England) (1993). The Journal of Hellenic studies, Volumes 113-114. Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies. p. 211.

The Seleucid kingdom has traditionally been regarded as basically a Greco-Macedonian state and its rulers thought of as successors to Alexander.