p53

p53p53, 세포 종양 항원 p53(UniProt명), [5]게놈의 수호자, 인단백질 p53, 종양 억제제 p53, 항원 NY-CO-13, 또는 변형 관련 단백질 53(TRP53)으로 알려진 종양 단백질 P53은 TP53 및 TRP53과 같은 다양한 유기체의 상동 유전자에 의해 코드된 단백질의 아이소 형태이다.이 호몰로지는 암 [6]형성을 막는 척추 동물에서 매우 중요합니다.이처럼 p53은 게놈 [7]돌연변이를 막아 안정성을 유지하는 역할을 해 게놈의 수호자로 불린다.따라서[note 1] TP53은 종양 억제 유전자로 [8][9][10][11][12]분류된다.

p53이라는 이름은 1979년 겉으로 보이는 분자량을 설명하면서 붙여진 것으로, SDS-PAGE 분석 결과 53킬로달톤(kDa) 단백질인 것으로 밝혀졌다.그러나 아미노산 잔기의 질량 합계에 기초한 전장 p53 단백질(p53α)의 실제 질량은 43.7kDa에 불과하다.이는 단백질에 프롤린 잔류물이 많아 SDS-PAGE에서의 이행이 느려 실제보다 [13]무거워 보이기 때문이다.인간 TP53 유전자는 전장 단백질 외에 3.5~43.7kDa 크기의 최소 15개의 단백질 아이소폼을 암호화한다.이 모든 p53 단백질은 p53 [6]동소체라고 불린다.TP53 유전자는 인간 암에서 가장 자주 변이되는 유전자(>50%)로, TP53 유전자가 암 형성을 [6]막는 데 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 나타났다.TP53 유전자는 DNA에 결합하는 단백질을 암호화하고 유전자 발현을 조절해 [14]게놈의 돌연변이를 예방한다.

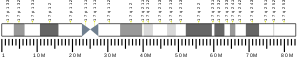

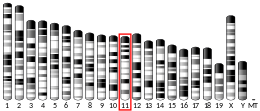

사람의 경우, TP53 유전자는 17번 염색체의 짧은 팔(17p13.1)[8][9][10][11]에 위치한다.이 유전자는 20kb에 달하며, 비코드 엑손 1과 10kb의 매우 긴 첫 번째 인트론을 가지고 있다.코드 배열은 주로 엑손 2, 5, 6, 7, 8에서 높은 보존도를 보이는 5개의 영역을 포함하지만 무척추동물에서 발견되는 배열은 포유동물 [15]TP53과 매우 유사할 뿐이다.TP53 정형어는[16] 완전한 게놈 데이터를 이용할 수 있는 대부분의 포유동물에서 확인되었다.

TP53

사람에게 공통 다형성은 엑손4의 코돈위치72에서 프롤린에 아르기닌 치환을 포함한다.많은 연구들이 이 변이와 암 감수성 사이의 유전적 연관성을 조사해왔다. 그러나 그 결과는 논란의 여지가 있었다.예를 들어, 2009년의 메타 분석에서는 자궁경부암과의 [17]연관성을 보여주지 못했다.2011년 연구에 따르면 TP53 프롤린 돌연변이는 [18]남성의 췌장암 위험에 큰 영향을 미쳤다.아랍 여성을 대상으로 한 연구는 TP53 코돈 72의 프롤린 동형 접합성이 유방암 [19]위험 감소와 관련이 있다는 것을 발견했다.한 연구에 따르면 TP53 코돈 72 다형성, MDM2 SNP309 및 A2164G는 전체적으로 비인두암 감수성과 관련될 수 있으며, MDM2 SNP309가 TP53on 72와 결합하여 [20]비인두암 발병 속도를 높일 수 있다.2011년 연구에 따르면 TP53 코돈 72 다형성은 폐암 [21]위험 증가와 관련이 있는 것으로 나타났다.

2011년 메타 분석에서는 TP53 코돈 72 다형성과 대장암[22] 위험과 자궁내막암 [23]위험 사이에 유의미한 연관성이 발견되지 않았다.브라질 출생 코호트에 대한 2011년 연구에서는 비변성 아르기닌 TP53과 암 [24]가족력이 없는 개인 사이의 연관성을 발견했다.2011년 또 다른 연구에서는 p53 호모 접합(Pro/Pro) 유전자형이 신장 세포암 [25]위험의 유의한 증가와 관련이 있는 것으로 나타났다.

★★★★

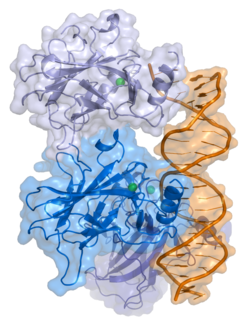

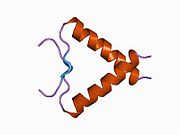

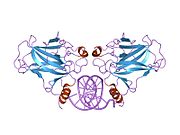

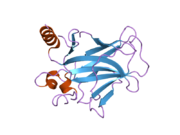

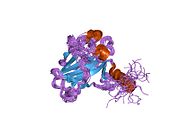

p53에는 7개의 도메인이 있습니다.

- 전사인자를 활성화하는 활성화 도메인 1(AD1)이라고도 하는 산성 N 말단 전사 활성화 도메인(TAD)입니다.N-말단은 두 개의 상보적인 전사 활성화 도메인을 포함하고 있으며, 특히 여러 가지 친아포토시스 [26]유전자의 조절에 관여하는 잔류물 1~42에 큰 도메인이 있고, 잔류물 55~75에 작은 도메인이 있다.

- 아포토시스 활성에 중요한 활성화 도메인 2(AD2) 잔류물 43~63.

- MAPK를 통한 핵 수출에 의한 p53의 아포토시스 활성에 중요한 프롤린 리치 도메인: 잔류물 64~92.

- 중앙 DNA 결합 코어 도메인(DBD)입니다.1개의 아연 원자와 여러 개의 아르기닌 아미노산(잔기 102~292)을 함유한다.이 영역은 p53 공동억제기 LMO3의 [27]바인딩을 담당합니다.

- Nuclear Localization Signaling(NLS) 도메인, 잔류물 316 – 325.

- 호모올리고머화 도메인(OD): 잔류물 307~355.p53 체내 활성에는 사분자화가 필수적이다.

- 중앙 도메인의 DNA 결합 하향 조절에 관여하는 C 말단: 잔류물 356–393.[28]

암에서 p53을 비활성화하는 돌연변이는 보통 DBD에서 발생한다.이러한 돌연변이의 대부분은 표적 DNA 배열에 결합하는 단백질의 능력을 파괴하고, 따라서 이러한 유전자의 전사 활성화를 막는다.따라서 DBD의 돌연변이는 열성 기능 상실 돌연변이입니다.OD이합체에 돌연변이가 있는 p53의 분자와 야생형 p53의 전사가 활성화되지 않도록 한다.따라서, OD 돌연변이는 p53의 기능에 지배적인 부정적인 영향을 미친다.

야생형 p53은 접힌 부위와 구조화되지 않은 [29]부위로 이루어진 불안정한 단백질로 상승작용을 한다.

.

DNA

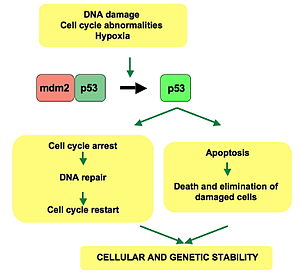

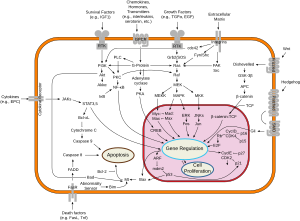

p53은 여러 메커니즘을 통해 세포 주기, 아포토시스 및 게놈 안정성을 통해 조절 또는 진행에 역할을 한다.

- 그것은 DNA가 손상을 입었을 때 DNA 복구 단백질을 활성화시킬 수 있다.따라서,[30] 그것은 노화의 중요한 요소일 수 있다.

- 그것은 DNA 손상 인식에 대한 G1/S 조절 지점에서 세포 주기를 유지함으로써 성장을 멈출 수 있다. 만약 그것이 충분히 오랫동안 세포를 여기 고정시킨다면, DNA 복구 단백질은 손상을 고칠 시간을 갖게 될 것이고 세포는 세포 주기를 계속할 수 있게 될 것이다.

- DNA 손상이 회복 불가능한 것으로 판명되면 아포토시스(즉, 프로그램된 세포사망)를 시작할 수 있다.

- 그것은 짧은 텔로미어에 대한 노화 반응에 필수적이다.

p21 및 기타 수백 개의 하류 유전자를 코드하는 WAF1/CIP1. p21(WAF1)은 G1-S/CDK(CDK4/CDK6, CDK2, 및 CDK1) 복합체(세포 활동 억제 시 G1/S 이행에 중요한 분자)에 결합한다.

p21(WAF1)이 CDK2와 복합되어 있는 경우, 세포는 세포 분열의 다음 단계를 계속할 수 없습니다.돌연변이 p53은 더 이상 효과적인 방법으로 DNA와 결합하지 않으며, 그 결과 p21 단백질은 세포 [31]분열을 위한 "정지 신호"로서 작용하지 못할 것이다.인간 배아줄기세포(hESC) 연구는 일반적으로 G1/S 체크포인트 경로의 기능하지 않는 p53-p21 축을 세포주기 조절 및 DNA 손상 반응(DDR)에 대한 후속 관련성과 함께 설명한다.중요한 것은 p21 mRNA가 hESCs에서 DDR 후에 명확하게 존재하며 상향 조절되지만 p21 단백질은 검출되지 않는다.이 셀 타입에서 p53은 hESC에서 p21 발현을 직접 억제하는 다수의 마이크로RNA(miR-302a, miR-302b, miR-302c 및 miR-302d 등)를 활성화한다.

활성을 하는 사이클린-CDK 에 직접 결합하여 은 또한 더할 수 .p21은 세포 노화와 된 성장 정지를 촉진할 수 있습니다. 그들의 키나아제 활성을 억제하는 사이클린-CDK 복합체에 직접 결합하여 세포 사이클 정지를 일으켜 수복을 가능하게 한다.p21은 또한 분화와 관련된 성장 정지 및 세포 노화와 관련된 보다 영구적인 성장 정지를 중재할 수 있다.단백질의 , 그 단백질을 된다.p21은 p53을 코드하는 것이다.

p53 및 RB1 경로는 p14를 통해 링크됩니다.ARF, 경로가 [32]서로 조절할 수 있는 가능성을 제기합니다.

p53 발현은 자외선에 의해 자극될 수 있으며, 이것은 또한 DNA 손상을 일으킨다.이 경우 p53은 [33][34]태닝을 일으키는 이벤트를 시작할 수 있습니다.

의 수치는 .

인간배아줄기세포(hESC)에서는 p53이 낮은 비활성 [35]수준으로 유지됩니다.이는 p53의 활성화가 hESC의 [36]빠른 분화로 이어지기 때문이다.연구에 따르면 p53의 녹아웃은 분화를 지연시키고 p53의 추가는 자발적인 분화를 일으키며, p53이 어떻게 hESC의 분화를 촉진하고 분화조절자로서 세포주기에서 중요한 역할을 하는지를 보여준다.p53이 hESC에서 안정화 및 활성화되면 p21이 증가하여 보다 긴 G1이 확립됩니다.이는 일반적으로 S상 엔트리의 폐지로 이어져 G1의 셀 사이클을 정지시켜 분화를 일으킨다.그러나 최근 생쥐 배아줄기세포에서의 연구는 P53의 발현이 반드시 [37]분화로 이어지는 것은 아니라는 것을 보여주었다. p53은 또한 miR-34a와 miR-145를 활성화하고, 이는 HESC의 다능성 인자를 억제하여 [35]분화를 더욱 부추긴다.

성체줄기세포의 경우 p53 조절은 성체줄기세포 틈새의 줄기세포를 유지하는 데 중요하다.저산소증과 같은 기계적 신호는 저산소 유도 인자인 HIF-1α와 HIF-2α를 통해 이러한 틈새 세포의 p53 수준에 영향을 미친다.HIF-1α는 p53을 안정시키는 반면 HIF-2α는 p53을 [38]억제한다.p53의 억제는 암 줄기세포 표현형, 유도 만능 줄기세포 및 다른 줄기세포의 역할과 행동(예: 부종 형성)에 중요한 역할을 한다.p53의 수치가 감소된 세포는 정상 [39][40]세포보다 훨씬 더 높은 효율로 줄기세포로 재프로그래밍되는 것으로 나타났다.논문들은 세포주기 정지 및 세포자멸의 부재가 더 많은 세포에게 재프로그래밍의 기회를 준다고 제안한다.p53의 감소는 또한 [41]도롱뇽의 다리에서의 발진 형성의 중요한 측면으로 나타났다. p53 조절은 줄기세포와 분화된 줄기세포 상태, 그리고 줄기세포가 기능하는 것과 [42]암인 것 사이의 장벽으로 작용하는데 매우 중요하다.

위의 세포 및 분자 효과와는 별도로 p53은 혈관신생을 억제함으로써 작용하는 조직 수준의 항암 효과가 있다.종양이 성장함에 따라 새로운 혈관을 모집할 필요가 있으며, p53은 (i) HIF1 및 HIF2와 같은 혈관신생에 영향을 미치는 종양 저산소 조절제와의 간섭, (ii) 혈관신생 촉진 인자의 생성을 억제, (iii) Arres와 같은 혈관신생 억제제의 생산을 직접 증가시킴으로써 이를 억제한다.열 개.[43][44]

백혈병 억제 인자를 조절함으로써 p53은 생쥐에 착상을 용이하게 하고 인간의 번식을 [45]용이하게 하는 것으로 나타났다.

★★★

p53은 DNA 손상(UV, IR 또는 과산화수소 같은 화학 물질에 의해 유발됨), 산화 스트레스,[46] 삼투압 충격, 리보뉴클레오티드 고갈 및 조절 해제된 종양 유전자 발현을 포함하지만 이에 국한되지 않는 무수한 스트레스 인자에 반응하여 활성화된다.이 액티베이션은 두 가지 주요 이벤트로 특징지어집니다.첫째, p53 단백질의 반감기가 급격히 증가하여 스트레스 세포에 p53이 빠르게 축적된다.둘째, 구조변화에 따라 이들 세포에서 p53이 전사조절기로 활성화된다.p53의 활성화를 이끄는 중요한 사건은 p53의 N 말단 도메인의 인산화이다.N 말단 전사 활성화 도메인은 많은 수의 인산화 부위를 포함하며 스트레스 신호를 전달하는 단백질 키나아제들의 주요 표적으로 간주될 수 있다.

p53의 이 전사 활성화 도메인을 목표로 하는 것으로 알려진 단백질 키나아제들은 크게 두 그룹으로 나눌 수 있다.단백질 키나아제 중 첫 번째 그룹은 막 손상, 산화 스트레스, 삼투압 충격, 열충격 등 여러 유형의 스트레스에 반응하는 것으로 알려진 MAPK 패밀리(JNK1-3, ERK1-2, p38 MAPK)에 속한다.유전독성 스트레스에 의해 야기되는 여러 형태의 DNA 손상을 검출하고 반응하는 분자 캐스케이드인 게놈 무결성 체크포인트에 단백질 키나아제 두 번째 그룹(ATR, ATM, CHK1, CHK2, DNA-PK, CAK, TP53RK)이 관련된다.종양유전자는 또한 p14ARF라는 단백질에 의해 매개되는 p53 활성화를 자극한다.

비응력 셀에서는 p53의 연속적인 열화를 통해 p53 레벨을 낮게 유지한다.Mdm2라고 불리는 단백질은 p53에 결합하여, 그것의 작용을 막고 그것을 핵에서 세포로 운반합니다.Mdm2는 또한 유비퀴틴 연결효소로서 작용하여 유비퀴틴을 p53에 공유 결합함으로써 프로테아솜에 의한 분해에 대해 p53을 표시한다.그러나 p53의 유비쿼티화는 가역적이다.p53이 활성화되면 Mdm2도 활성화되어 피드백 루프가 설정됩니다.p53 레벨은 특정 스트레스에 대한 응답으로 진동(또는 반복 펄스)을 나타낼 수 있으며, 이러한 펄스는 셀이 스트레스에서 살아남는지 또는 다이인지를 결정하는 [47]데 중요합니다.

MI-63은 MDM2에 바인드하여 p53의 기능이 [48]억제된 상황에서 p53을 다시 활성화합니다.

유비퀴틴 특이 단백질 효소인 USP7(또는 HAUSP)은 유비퀴틴을 p53에서 분리하여 유비퀴틴 연결효소 경로를 통해 프로테아좀 의존성 분해로부터 보호할 수 있다.이것은 종양 유발 모욕에 반응하여 p53을 안정화시키는 하나의 수단이다.USP42는 또한 p53을 탈유비퀴트화하는 것으로 나타났으며,[49] p53이 스트레스에 반응하는 능력에 필요할 수 있다.

최근의 연구는 HAUSP가 주로 핵에 국한되어 있다는 것을 보여주었지만, 그것의 일부는 세포질과 미토콘드리아에서 발견될 수 있다.HAUSP의 p53에 관한 것입니다. 및 이 증가합니다.HAUSP가 비스트레스 셀의 p53보다 Mdm2에 대한 더 나은 바인딩 파트너인 것으로 나타났습니다.

그러나 USP10은 Mdm2 유비퀴티네이션과 반대로 비압축세포의 세포질에 위치하고 세포질 p53을 탈유비퀴티네이트화하는 것으로 나타났다.DNA 손상에 이어 USP10은 핵으로 이동해 p53 안정성에 기여한다.또한 USP10은 Mdm2와 [50]상호 작용하지 않습니다.

상기 단백질 키나제에 의한 p53의 N말단 인산화 작용은 Mdm2 결합을 방해한다.그런 다음 Pin1과 같은 다른 단백질은 p53으로 모집되어 p53의 배좌 변화를 유도하여 Mdm2 결합을 더욱 방지한다.인산화는 또한 p300과 PCAF와 같은 전사적 공활성제의 결합을 허용하고, p53의 카르복시 말단을 아세틸화함으로써 p53의 DNA 결합 도메인을 노출시켜 특정 유전자를 활성화하거나 억제할 수 있게 한다.Sirt1 및 Sirt7과 같은 탈아세틸화효소는 p53을 탈아세틸화시켜 아포토시스 [51]억제를 초래할 수 있다.일부 종양유전자는 또한 MDM2에 결합하고 활동을 억제하는 단백질의 전사를 자극할 수 있다.

에서의

TP53 유전자가 손상되면 종양 억제가 심각하게 손상된다.TP53 유전자의 기능적 복제 하나만 물려받은 사람들은 성인 초기에 종양에 걸릴 가능성이 높으며, 이는 Li-Fraumeni 증후군으로 알려져 있다.

TP53 유전자는 또한 돌연변이 물질(화학 물질, 방사선 또는 바이러스)에 의해 수정될 수 있으며, 통제되지 않은 세포 분열의 가능성을 증가시킨다.인간 종양의 50% 이상이 TP53 [52]유전자의 돌연변이 또는 결실을 포함한다.p53의 손실은 게놈의 불안정성을 만들고, 가장 자주 유배수성 표현형을 [53]초래한다.

p53의 양을 늘리는 것은 종양의 치료나 확산 방지를 위한 해결책으로 보일 수 있다.그러나 이는 조기 [54]노화를 유발할 수 있기 때문에 사용 가능한 치료 방법은 아닙니다.내인성 정상 p53 기능을 복원하는 것은 어느 정도 가능성이 있습니다.연구는 이 복원이 그 과정에서 다른 세포를 손상시키지 않고 특정 암세포의 퇴행으로 이어질 수 있다는 것을 보여주었다.종양 퇴행이 일어나는 방법은 주로 종양 유형에 따라 달라집니다.예를 들어 림프종에서 내인성 p53 기능의 회복은 세포자멸을 유도하는 반면 세포증식은 정상 수준으로 저하될 수 있다.따라서 p53의 약리학적 재활성화는 실행 가능한 [55][56]암 치료 옵션으로 제시된다.최초의 상업용 유전자 치료제인 겐디신은 2003년 머리와 목의 편평상피암 치료에 대해 중국에서 승인되었다.그것은 조작된 아데노바이러스를 [57]사용하여 p53 유전자의 기능적 복사본을 전달합니다.

특정 병원체들은 또한 TP53 유전자가 발현하는 p53 단백질에 영향을 미칠 수 있다.그러한 예 중 하나인 인간유두종바이러스(HPV)는 p53 단백질에 결합하여 비활성화하는 단백질 E6를 암호화한다.이 메커니즘은 HPV 단백질 E7에 의한 세포 주기 조절기 pRb의 불활성화와 시너지 작용으로 임상적으로 사마귀로 나타나는 반복적인 세포 분열을 가능하게 한다.특정 HPV 유형, 특히 유형 16과 18은 양성 사마귀에서 저경부 이형성증 또는 고경부 이형성증으로 진행될 수 있으며, 이는 암 전 병변의 가역적인 형태이다.수년 동안 지속된 자궁경부 감염은 돌이킬 수 없는 변화를 야기할 수 있으며, 이는 위치암과 결국 침습성 자궁경부암으로 이어질 수 있다.이는 HPV 유전자, 특히 자궁경부암에서 바이러스 DNA의 숙주 [58]게놈으로의 통합에 의해 우선적으로 유지되고 발현되는 두 개의 바이러스 온단백질인 E6와 E7을 코드하는 유전자의 영향에서 비롯된다.

p53 단백질은 건강한 사람의 세포에서 지속적으로 생성되고 분해되어 감쇠된 진동을 일으킵니다(의 이 과정의 확률적 모델 참조).p53 단백질의 분해는 MDM2의 결합과 관련이 있다.부정 피드백 루프에서 MDM2 자체는 p53 단백질에 의해 유도된다.돌연변이 p53 단백질은 종종 MDM2를 유도하지 못해 p53이 매우 높은 수준으로 축적된다.또한 돌연변이 p53 단백질 자체는 정상적인 p53 단백질 농도를 억제할 수 있다.경우에 따라서는 p53의 단일 미센스 돌연변이가 p53의 안정성과 기능을 [60]교란시키는 것으로 나타났다.

인간 유방암 세포의 p53 억제는 CXCR5 케모카인 수용체 유전자 발현을 증가시키고 케모카인 CXCL13에 [61]반응하여 세포 이동을 활성화시키는 것으로 나타났다.

한 연구는 p53과 Myc 단백질이 만성 골수성 백혈병(CML) 세포의 생존에 핵심이었다는 것을 발견했다.약물로 p53과 Myc 단백질을 표적으로 삼은 것은 CML을 [62][63]가진 쥐에게 양성 반응을 보였다.

p53 연53 exper exper of of of of of exper exper exper exper exper exper exper exper exper exper exper exper exper

대부분의 p53 돌연변이는 DNA 염기서열분석에 의해 검출된다.그러나 단일 미스센스 돌연변이는 다소 가벼운 기능적 [60]영향에서 매우 심각한 기능적 영향까지 큰 스펙트럼을 가질 수 있는 것으로 알려져 있다.

TP53 유전자의 돌연변이로 인한 암 표현형의 큰 스펙트럼은 또한 p53 단백질의 다른 동질 형태가 암에 대한 예방을 위한 다른 세포 메커니즘을 가지고 있다는 사실로 뒷받침된다.TP53의 돌연변이는 서로 다른 세포 메커니즘에서 그들의 전반적인 기능을 방지하고, 따라서 암 표현형을 경도에서 심각도로 확장할 수 있다.요철 연구에 따르면 p53 동소형식은 다른 인체 조직에서 다르게 발현되며, 동소형식 내 기능상실 또는 기능상실 돌연변이는 조직 특이적 암을 유발하거나 다른 조직에서 [12][64][65][66]암 줄기세포 잠재력을 제공할 수 있다.TP53 돌연변이는 또한 에너지 대사에 영향을 미치고 유방암 [67]세포의 당분해를 증가시킨다.

p53 단백질의 역학은 길항제 Mdm2와 함께 p53의 농도가 시간 함수로 진동함을 나타낸다.이 "감쇠된" 진동은 임상적으로 기록되고 수학적으로 [69][70]모델링됩니다.또한 수학적 모델은 시스템에 DSB(이중가닥절단) 또는 UV 방사선과 같은 기형물질이 도입되면 p53 농도가 훨씬 더 빠르게 진동한다는 것을 나타냅니다.이는 DNA 손상이 p53 활성화를 유도하는 p53 역학의 현재 이해를 지원하고 모델링한다(자세한 내용은 p53 규제 참조).현재 모델은 또한 p53 동질체의 돌연변이와 p53 진동에 미치는 영향을 모델링하는 데 유용할 수 있으며, 따라서 de novo 조직 특이 약리학적 약물 발견을 촉진할 수 있다.

★★★

p53은 1979년 영국 프린스턴대/UMDNJ(뉴저지 암연구소)와 메모리얼 슬론-케터링 암센터에서 일하는 라이오넬 크로포드, 데이비드 P. 레인, 아놀드 레빈, 로이드 올드 등에 의해 확인되었다.종양의 발생을 유도하는 변종인 SV40 바이러스의 표적으로 존재한다고 가정되어 왔다.생쥐의 TP53 유전자는 1982년 [71]구소련 과학아카데미의 피터 추마코프에 의해 처음 복제됐으며 1983년 모셰 오렌이 데이비드 기볼(Weizmann Institute of Science)[72][73]과 공동으로 독립적으로 복제됐다.인간의 TP53 유전자는 1984년에[8] 복제되었고 [74]전장 복제는 1985년에 이루어졌다.

종양세포 mRNA 정제 후 돌연변이 cDNA를 사용함에 따라 초기에는 종양유전자로 추정되었다.종양 억제 유전자로서의 그것의 역할은 1989년 존스 홉킨스 의과대학의 버트 보겔스타인과 프린스턴 [75][76]대학의 아놀드 레빈에 의해 밝혀졌다.

럿거스 대학의 Waksman Institute의 Warren Maltzman은 TP53이 자외선의 [77]형태로 DNA 손상에 반응한다는 것을 처음으로 증명했다.1991-92년 일련의 간행물에서, 존스 홉킨스 대학의 마이클 카스탄은 TP53이 세포가 DNA [78]손상에 반응하는 것을 돕는 신호 전달 경로의 중요한 부분이라고 보고했다.

1993년,[79] p53은 사이언스지에 의해 올해의 분자로 선정되었다.

Isoforms

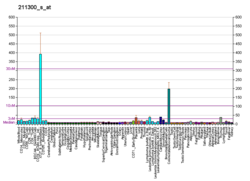

인간 유전자의 95%와 마찬가지로 TP53은 하나 이상의 단백질을 암호화합니다.2005년에 몇 가지 동소형이 발견되었으며, 지금까지 12개의 인간 p53 동소형이 확인되었다(p53α, p53β, p53β, p40p53α, p40p53β, 13133p53α, 160133p53β, p133p53β, 160133p53β, 160160p53β또한 p53 동소형식은 조직의존적으로 발현되며 p53α는 단독으로 [12]발현되지 않는다.

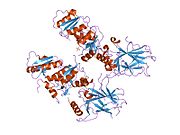

전체 길이 p53 이소폼 단백질은 다른 단백질 도메인으로 세분될 수 있다.N 말단에서 시작하여 먼저 p53 표적 유전자의 서브셋을 유도하기 위해 필요한 아미노 말단 트랜스활성화 도메인(TAD 1, TAD 2)이 있다.이 도메인은 프롤린 리치 도메인(PXXP)에 이어 PXP 모티브가 반복된다(P는 프롤린이고 X는 아미노산일 수 있음).그것은 p53 매개 [80]아포토시스에 특히 필요하다.13133p53β, and 및 δ160p53α, β, ;와 같은 일부 동소체들은 프롤린 리치 도메인이 없으므로 p53의 일부 동소체들은 아포토시스를 매개하지 않고 TP53 [64]유전자의 다양한 역할을 강조한다.그 후 DNA 결합 도메인(DBD)이 있어 단백질이 특이적으로 결합할 수 있다.카르복실 말단 도메인이 단백질을 완성한다.여기에는 핵국재신호(NLS), 핵수출신호(NES) 및 올리고머화 도메인(OD)이 포함된다.NLS와 NES는 p53의 세포하 조절에 책임이 있다.OD를 통해 p53은 사량체를 형성하고 DNA에 결합할 수 있다.이소형식 중에는 일부 도메인이 누락될 수 있지만, 모두 고도로 보존된 DNA 결합 도메인의 대부분을 공유하고 있다.

등형식은 서로 다른 메커니즘으로 형성됩니다.베타와 감마 아이소폼은 인트론 9의 다중 스플라이싱에 의해 생성되며, 이는 다른 C 말단으로 이어진다.또한 인트론 4에서 내부 프로모터를 사용하면 TAD 도메인과 DBD의 일부가 결여된 133 이상 및 160 이하의 이소폼이 된다.또한 코돈 40 또는 160에서의 번역의 대체 개시는 40p53 이상 및 160p53 이하의 [12]등형식을 가진다.

p53 단백질의 등형질 특성으로 인해, 변이된 등형질을 일으키는 TP53 유전자 내의 돌연변이가 TP53 유전자의 단일 돌연변이로 인해 경증에서 중증까지 다양한 암 표현형의 원인 물질임을 보여주는 여러 가지 증거가 있었다(자세한 내용은 p53 돌연변이의 실험 분석 섹션 참조).).

p53은 다음과 상호작용하는 것으로 나타났습니다.

- AIMP2,[81]

- ANKRD2,[82]

- APTX,[83]

- ATM,[84][85][86][87][88]

- ATR,[84][85]

- ATF3,[89][90]

- 아우르카[91]

- BAK1,[92]

- BARD1,[93]

- BLM,[94][95][96][97]

- BRCA1,[93][98][99][100][101]

- BRCA2,[93][102]

- BRCC3,[93]

- BRE,[93]

- CEBPZ,[103]

- CDC14A,[104]

- Cdk1,[105][106]

- CFLAR,[107]

- CHEK1,[94][108][109]

- CCNG1,[110]

- CREBBP,[111][112][113]

- CREB1,[113]

- 사이클린 H,[114]

- CDK7,[114][115]

- DNA-PKS,[85][108][116]

- E4F1,[117][118]

- EFEMP2,[119]

- EIF2AK2,[120]

- ELL,[121]

- EP300,[112][122][123][124]

- ERCC6,[125][126]

- GNL3,[127]

- GPS2,[128]

- GSK3B,[129]

- HSP90AA1,[130][131][132]

- HIF1A,[133][134][135][136]

- HIPK1,[137]

- HIPK2,[138][139]

- HMGB1,[140][141]

- HSPA9,[142]

- 헌팅틴[143]

- ING1,[144][145]

- ING4,[146][147]

- ING5,[146]

- IbBα,[148]

- KPNB1,[130]

- LMO3,[27]

- Mdm2,[111][149][150][151]

- MDM4,[152][153]

- MED1,[154][155]

- MAPK9,[156][157]

- MNAT1,[115]

- NDN,[158]

- NCL,[159]

- 무감각하다[160]

- NF-bB,[161]

- P16,[117][151][162]

- PARC,[163]

- PARP1,[83][164]

- PIAS1,[119][165]

- CDC14B,[104]

- PIN1,[166][167]

- 플래글1,[168]

- PLK3,[169][170]

- PRKRA,[171]

- PHB,[172]

- PML,[149][173][174]

- PSME3,[175]

- PTEN,[150]

- PTK2,[176]

- PTTG1,[177]

- RAD51,[93][178][179]

- RCHY1,[180][181]

- RELA,[161]

- [필요한 건]

- RPA1,[182][183]

- RPL11,[162]

- S100B,[184]

- 스모1,[185][186]

- SMARCA4,[187]

- SMARCB1,[187]

- SMN1,[188]

- STAT3,[161]

- TBP,[189][190]

- TFAP2A,[191]

- TFDP1,[192]

- TIGAR,[193]

- TOP1,[194][195]

- TOP2A,[196]

- TP53BP1,[94][197][198][199][200][201][202]

- TP53BP2,[202][203]

- TOP2B,[196]

- TP53INP1,[204][205]

- TSG101,[206]

- UBE2A,[207]

- UBE2I,[119][185][208][209]

- UBC,[81][175][186][210][211][212][213][214]

- USP7,[215]

- USP10,[50]

- WRN,[97][216]

- WWOX,[217]

- XPB,[125]

- YBX1,[82][218]

- YPEL3,[219]

- YWHAZ,[220]

- Zif268,[221]

- ZNF148,[222]

- SIRT1,[223]

- cirRNA_014511.[224]

참고 항목

- P53의 억제제인 피피트린

메모들

레퍼런스

- ^ a b c GRCh38: 앙상블 릴리즈 89: ENSG00000141510 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ a b c GRCm38: 앙상블 릴리즈 89: ENSMUSG000059552 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Toufektchan E, Toledo F (May 2018). "The Guardian of the Genome Revisited: p53 Downregulates Genes Required for Telomere Maintenance, DNA Repair, and Centromere Structure". Cancers. 10 (5): 135. doi:10.3390/cancers10050135. PMC 5977108. PMID 29734785.

- ^ a b c Surget S, Khoury MP, Bourdon JC (December 2013). "Uncovering the role of p53 splice variants in human malignancy: a clinical perspective". OncoTargets and Therapy. 7: 57–68. doi:10.2147/OTT.S53876. PMC 3872270. PMID 24379683.

- ^ Read AP, Strachan T (1999). "Chapter 18: Cancer Genetics". Human molecular genetics 2. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-33061-5.

- ^ a b c Matlashewski G, Lamb P, Pim D, Peacock J, Crawford L, Benchimol S (December 1984). "Isolation and characterization of a human p53 cDNA clone: expression of the human p53 gene". The EMBO Journal. 3 (13): 3257–62. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02287.x. PMC 557846. PMID 6396087.

- ^ a b Isobe M, Emanuel BS, Givol D, Oren M, Croce CM (1986). "Localization of gene for human p53 tumour antigen to band 17p13". Nature. 320 (6057): 84–5. Bibcode:1986Natur.320...84I. doi:10.1038/320084a0. PMID 3456488. S2CID 4310476.

- ^ a b Kern SE, Kinzler KW, Bruskin A, Jarosz D, Friedman P, Prives C, Vogelstein B (June 1991). "Identification of p53 as a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein". Science. 252 (5013): 1708–11. Bibcode:1991Sci...252.1708K. doi:10.1126/science.2047879. PMID 2047879. S2CID 19647885.

- ^ a b McBride OW, Merry D, Givol D (January 1986). "The gene for human p53 cellular tumor antigen is located on chromosome 17 short arm (17p13)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (1): 130–4. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83..130M. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.1.130. PMC 322805. PMID 3001719.

- ^ a b c d Bourdon JC, Fernandes K, Murray-Zmijewski F, Liu G, Diot A, Xirodimas DP, Saville MK, Lane DP (September 2005). "p53 isoforms can regulate p53 transcriptional activity". Genes & Development. 19 (18): 2122–37. doi:10.1101/gad.1339905. PMC 1221884. PMID 16131611.

- ^ Ziemer MA, Mason A, Carlson DM (September 1982). "Cell-free translations of proline-rich protein mRNAs". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 257 (18): 11176–80. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)33948-6. PMID 7107651.

- ^ Levine AJ, Lane DP, eds. (2010). The p53 family. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-830-0.

- ^ May P, May E (December 1999). "Twenty years of p53 research: structural and functional aspects of the p53 protein". Oncogene. 18 (53): 7621–36. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203285. PMID 10618702.

- ^ "OrthoMaM phylogenetic marker: TP53 coding sequence". Archived from the original on 2018-03-17. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ^ Klug SJ, Ressing M, Koenig J, Abba MC, Agorastos T, Brenna SM, et al. (August 2009). "TP53 codon 72 polymorphism and cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of individual data from 49 studies". The Lancet. Oncology. 10 (8): 772–84. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70187-1. PMID 19625214.

- ^ Sonoyama T, Sakai A, Mita Y, Yasuda Y, Kawamoto H, Yagi T, Yoshioka M, Mimura T, Nakachi K, Ouchida M, Yamamoto K, Shimizu K (2011). "TP53 codon 72 polymorphism is associated with pancreatic cancer risk in males, smokers and drinkers". Molecular Medicine Reports. 4 (3): 489–95. doi:10.3892/mmr.2011.449. PMID 21468597.

- ^ Alawadi S, Ghabreau L, Alsaleh M, Abdulaziz Z, Rafeek M, Akil N, Alkhalaf M (September 2011). "P53 gene polymorphisms and breast cancer risk in Arab women". Medical Oncology. 28 (3): 709–15. doi:10.1007/s12032-010-9505-4. PMID 20443084. S2CID 207372095.

- ^ Yu H, Huang YJ, Liu Z, Wang LE, Li G, Sturgis EM, Johnson DG, Wei Q (September 2011). "Effects of MDM2 promoter polymorphisms and p53 codon 72 polymorphism on risk and age at onset of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck". Molecular Carcinogenesis. 50 (9): 697–706. doi:10.1002/mc.20806. PMC 3142329. PMID 21656578.

- ^ Piao JM, Kim HN, Song HR, Kweon SS, Choi JS, Yun WJ, Kim YC, Oh IJ, Kim KS, Shin MH (September 2011). "p53 codon 72 polymorphism and the risk of lung cancer in a Korean population". Lung Cancer. 73 (3): 264–7. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.12.017. PMID 21316118.

- ^ Wang JJ, Zheng Y, Sun L, Wang L, Yu PB, Dong JH, Zhang L, Xu J, Shi W, Ren YC (November 2011). "TP53 codon 72 polymorphism and colorectal cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis". Molecular Biology Reports. 38 (8): 4847–53. doi:10.1007/s11033-010-0619-8. PMID 21140221. S2CID 11730631.

- ^ Jiang DK, Yao L, Ren WH, Wang WZ, Peng B, Yu L (December 2011). "TP53 Arg72Pro polymorphism and endometrial cancer risk: a meta-analysis". Medical Oncology. 28 (4): 1129–35. doi:10.1007/s12032-010-9597-x. PMID 20552298. S2CID 32990396.

- ^ Thurow HS, Haack R, Hartwig FP, Oliveira IO, Dellagostin OA, Gigante DP, Horta BL, Collares T, Seixas FK (December 2011). "TP53 gene polymorphism: importance to cancer, ethnicity and birth weight in a Brazilian cohort". Journal of Biosciences. 36 (5): 823–31. doi:10.1007/s12038-011-9147-5. PMID 22116280. S2CID 23027087.

- ^ Huang CY, Su CT, Chu JS, Huang SP, Pu YS, Yang HY, Chung CJ, Wu CC, Hsueh YM (December 2011). "The polymorphisms of P53 codon 72 and MDM2 SNP309 and renal cell carcinoma risk in a low arsenic exposure area". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 257 (3): 349–55. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2011.09.018. PMID 21982800.

- ^ Venot C, Maratrat M, Dureuil C, Conseiller E, Bracco L, Debussche L (August 1998). "The requirement for the p53 proline-rich functional domain for mediation of apoptosis is correlated with specific PIG3 gene transactivation and with transcriptional repression". The EMBO Journal. 17 (16): 4668–79. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.16.4668. PMC 1170796. PMID 9707426.

- ^ a b Larsen S, Yokochi T, Isogai E, Nakamura Y, Ozaki T, Nakagawara A (February 2010). "LMO3 interacts with p53 and inhibits its transcriptional activity". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 392 (3): 252–7. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.010. PMID 19995558.

- ^ Harms KL, Chen X (March 2005). "The C terminus of p53 family proteins is a cell fate determinant". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (5): 2014–30. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.5.2014-2030.2005. PMC 549381. PMID 15713654.

- ^ Bell S, Klein C, Müller L, Hansen S, Buchner J (October 2002). "p53 contains large unstructured regions in its native state". Journal of Molecular Biology. 322 (5): 917–27. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00848-3. PMID 12367518.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. Developmental Biology, 10th ed. Sunderland, MA USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers. p. 588.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information (1998). The p53 tumor suppressor protein. Genes and Disease. United States National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- ^ Bates S, Phillips AC, Clark PA, Stott F, Peters G, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH (September 1998). "p14ARF links the tumour suppressors RB and p53". Nature. 395 (6698): 124–5. Bibcode:1998Natur.395..124B. doi:10.1038/25867. PMID 9744267. S2CID 4355786.

- ^ "Genome's guardian gets a tan started". New Scientist. March 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ^ Cui R, Widlund HR, Feige E, Lin JY, Wilensky DL, Igras VE, D'Orazio J, Fung CY, Schanbacher CF, Granter SR, Fisher DE (March 2007). "Central role of p53 in the suntan response and pathologic hyperpigmentation". Cell. 128 (5): 853–64. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.045. PMID 17350573.

- ^ a b Jain AK, Allton K, Iacovino M, Mahen E, Milczarek RJ, Zwaka TP, Kyba M, Barton MC (2012). "p53 regulates cell cycle and microRNAs to promote differentiation of human embryonic stem cells". PLOS Biology. 10 (2): e1001268. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001268. PMC 3289600. PMID 22389628.

- ^ Maimets T, Neganova I, Armstrong L, Lako M (September 2008). "Activation of p53 by nutlin leads to rapid differentiation of human embryonic stem cells". Oncogene. 27 (40): 5277–87. doi:10.1038/onc.2008.166. PMID 18521083.

- ^ ter Huurne M, Peng T, Yi G, van Mierlo G, Marks H, Stunnenberg HG (February 2020). "Critical role for P53 in regulating the cell cycle of ground state embryonic stem cells". Stem Cell Reports. 14 (2): 175–183. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.01.001. PMC 7013234. PMID 32004494.

- ^ Das B, Bayat-Mokhtari R, Tsui M, Lotfi S, Tsuchida R, Felsher DW, Yeger H (August 2012). "HIF-2α suppresses p53 to enhance the stemness and regenerative potential of human embryonic stem cells". Stem Cells. 30 (8): 1685–95. doi:10.1002/stem.1142. PMC 3584519. PMID 22689594.

- ^ Lake BB, Fink J, Klemetsaune L, Fu X, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, Xu Y (May 2012). "Context-dependent enhancement of induced pluripotent stem cell reprogramming by silencing Puma". Stem Cells. 30 (5): 888–97. doi:10.1002/stem.1054. PMC 3531606. PMID 22311782.

- ^ Marión RM, Strati K, Li H, Murga M, Blanco R, Ortega S, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Serrano M, Blasco MA (August 2009). "A p53-mediated DNA damage response limits reprogramming to ensure iPS cell genomic integrity". Nature. 460 (7259): 1149–53. Bibcode:2009Natur.460.1149M. doi:10.1038/nature08287. PMC 3624089. PMID 19668189.

- ^ Yun MH, Gates PB, Brockes JP (October 2013). "Regulation of p53 is critical for vertebrate limb regeneration". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (43): 17392–7. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11017392Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1310519110. PMC 3808590. PMID 24101460.

- ^ Aloni-Grinstein R, Shetzer Y, Kaufman T, Rotter V (August 2014). "p53: the barrier to cancer stem cell formation". FEBS Letters. 588 (16): 2580–9. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.011. PMID 24560790. S2CID 37901173.

- ^ Teodoro JG, Evans SK, Green MR (November 2007). "Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by p53: a new role for the guardian of the genome". Journal of Molecular Medicine (Review). 85 (11): 1175–86. doi:10.1007/s00109-007-0221-2. PMID 17589818. S2CID 10094554.

- ^ Assadian S, El-Assaad W, Wang XQ, Gannon PO, Barrès V, Latour M, Mes-Masson AM, Saad F, Sado Y, Dostie J, Teodoro JG (March 2012). "p53 inhibits angiogenesis by inducing the production of Arresten". Cancer Research. 72 (5): 1270–9. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2348. PMID 22253229.

- ^ Hu W, Feng Z, Teresky AK, Levine AJ (November 2007). "p53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF". Nature. 450 (7170): 721–4. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..721H. doi:10.1038/nature05993. PMID 18046411. S2CID 4357527.

- ^ Han ES, Muller FL, Pérez VI, Qi W, Liang H, Xi L, Fu C, Doyle E, Hickey M, Cornell J, Epstein CJ, Roberts LJ, Van Remmen H, Richardson A (June 2008). "The in vivo gene expression signature of oxidative stress". Physiological Genomics. 34 (1): 112–26. doi:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00239.2007. PMC 2532791. PMID 18445702.

- ^ Purvis, Jeremy E.; Karhohs, Kyle W.; Mock, Caroline; Batchelor, Eric; Loewer, Alexander; Lahav, Galit (2012-06-15). "p53 dynamics control cell fate". Science. 336 (6087): 1440–1444. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1440P. doi:10.1126/science.1218351. ISSN 1095-9203. PMC 4162876. PMID 22700930.

- ^ Canner JA, Sobo M, Ball S, Hutzen B, DeAngelis S, Willis W, Studebaker AW, Ding K, Wang S, Yang D, Lin J (September 2009). "MI-63: a novel small-molecule inhibitor targets MDM2 and induces apoptosis in embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cells with wild-type p53". British Journal of Cancer. 101 (5): 774–81. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605199. PMC 2736841. PMID 19707204.

- ^ Hock AK, Vigneron AM, Carter S, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH (November 2011). "Regulation of p53 stability and function by the deubiquitinating enzyme USP42". The EMBO Journal. 30 (24): 4921–30. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.419. PMC 3243628. PMID 22085928.

- ^ a b Yuan J, Luo K, Zhang L, Cheville JC, Lou Z (February 2010). "USP10 Regulates p53 Localization and Stability by Deubiquitinating p53". Cell. 140 (3): 384–396. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.032. PMID 20096447.

- ^ Vakhrusheva O, Smolka C, Gajawada P, Kostin S, Boettger T, Kubin T, Braun T, Bober E (March 2008). "Sirt7 increases stress resistance of cardiomyocytes and prevents apoptosis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy in mice". Circulation Research. 102 (6): 703–10. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164558. PMID 18239138.

- ^ Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC (July 1991). "p53 mutations in human cancers". Science. 253 (5015): 49–53. Bibcode:1991Sci...253...49H. doi:10.1126/science.1905840. PMID 1905840.

- ^ Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, Baranov E, Hoffman RM, Lowe SW (April 2002). "Dissecting p53 tumor suppressor functions in vivo". Cancer Cell. 1 (3): 289–98. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00047-8. PMID 12086865.

- ^ Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, Lu X, Soron G, Cooper B, Brayton C, Park SH, Thompson T, Karsenty G, Bradley A, Donehower LA (January 2002). "p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes". Nature. 415 (6867): 45–53. Bibcode:2002Natur.415...45T. doi:10.1038/415045a. PMID 11780111. S2CID 749047.

- ^ Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault L, Newman J, Reczek EE, Weissleder R, Jacks T (February 2007). "Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo". Nature. 445 (7128): 661–5. doi:10.1038/nature05541. PMID 17251932. S2CID 4373520.

- ^ Herce HD, Deng W, Helma J, Leonhardt H, Cardoso MC (2013). "Visualization and targeted disruption of protein interactions in living cells". Nature Communications. 4: 2660. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2660H. doi:10.1038/ncomms3660. PMC 3826628. PMID 24154492.

- ^ Pearson S, Jia H, Kandachi K (January 2004). "China approves first gene therapy". Nature Biotechnology. 22 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1038/nbt0104-3. PMC 7097065. PMID 14704685.

- ^ Angeletti PC, Zhang L, Wood C (2008). "The Viral Etiology of AIDS‐Associated Malignancies". The viral etiology of AIDS-associated malignancies. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 56. pp. 509–57. doi:10.1016/S1054-3589(07)56016-3. ISBN 9780123736017. PMC 2149907. PMID 18086422.

- ^ Ribeiro AS, Charlebois DA, Lloyd-Price J (December 2007). "CellLine, a stochastic cell lineage simulator". Bioinformatics. 23 (24): 3409–3411. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm491. PMID 17928303.

- ^ a b Bullock AN, Henckel J, DeDecker BS, Johnson CM, Nikolova PV, Proctor MR, Lane DP, Fersht AR (December 1997). "Thermodynamic stability of wild-type and mutant p53 core domain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (26): 14338–42. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9414338B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.26.14338. PMC 24967. PMID 9405613.

- ^ Mitkin NA, Hook CD, Schwartz AM, Biswas S, Kochetkov DV, Muratova AM, Afanasyeva MA, Kravchenko JE, Bhattacharyya A, Kuprash DV (March 2015). "p53-dependent expression of CXCR5 chemokine receptor in MCF-7 breast cancer cells". Scientific Reports. 5 (5): 9330. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E9330M. doi:10.1038/srep09330. PMC 4365401. PMID 25786345.

- ^ Abraham SA, Hopcroft LE, Carrick E, Drotar ME, Dunn K, Williamson AJ, Korfi K, Baquero P, Park LE, Scott MT, Pellicano F, Pierce A, Copland M, Nourse C, Grimmond SM, Vetrie D, Whetton AD, Holyoake TL (June 2016). "Dual targeting of p53 and c-MYC selectively eliminates leukaemic stem cells". Nature. 534 (7607): 341–6. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..341A. doi:10.1038/nature18288. PMC 4913876. PMID 27281222.

- ^ "Scientists identify drugs to target 'Achilles heel' of Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia cells". myScience. 2016-06-08. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ a b Khoury MP, Bourdon JC (April 2011). "p53 Isoforms: An Intracellular Microprocessor?". Genes & Cancer. 2 (4): 453–65. doi:10.1177/1947601911408893. PMC 3135639. PMID 21779513.

- ^ Avery-Kiejda KA, Morten B, Wong-Brown MW, Mathe A, Scott RJ (March 2014). "The relative mRNA expression of p53 isoforms in breast cancer is associated with clinical features and outcome". Carcinogenesis. 35 (3): 586–96. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgt411. PMID 24336193.

- ^ Arsic N, Gadea G, Lagerqvist EL, Busson M, Cahuzac N, Brock C, Hollande F, Gire V, Pannequin J, Roux P (April 2015). "The p53 isoform Δ133p53β promotes cancer stem cell potential". Stem Cell Reports. 4 (4): 531–40. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.001. PMC 4400643. PMID 25754205.

- ^ Harami-Papp, Hajnalka; Pongor, Lőrinc S.; Munkácsy, Gyöngyi; Horváth, Gergő; Nagy, Ádám M.; Ambrus, Attila; Hauser, Péter; Szabó, András; Tretter, László; Győrffy, Balázs (11 October 2016). "TP53 mutation hits energy metabolism and increases glycolysis in breast cancer". Oncotarget. 7 (41): 67183–67195. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.11594. PMC 5341867. PMID 27582538.

- ^ Geva-Zatorsky N, Rosenfeld N, Itzkovitz S, Milo R, Sigal A, Dekel E, Yarnitzky T, Liron Y, Polak P, Lahav G, Alon U (June 2006). "Oscillations and variability in the p53 system". Molecular Systems Biology. 2: 2006.0033. doi:10.1038/msb4100068. PMC 1681500. PMID 16773083.

- ^ Proctor CJ, Gray DA (August 2008). "Explaining oscillations and variability in the p53-Mdm2 system". BMC Systems Biology. 2 (75): 75. doi:10.1186/1752-0509-2-75. PMC 2553322. PMID 18706112.

- ^ Chong KH, Samarasinghe S, Kulasiri D (December 2013). "Mathematical modelling of p53 basal dynamics and DNA damage response". C-fACS. 259 (20th International Congress on Mathematical Modelling and Simulation): 670–6. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2014.10.010. PMID 25433195.

- ^ Chumakov PM, Iotsova VS, Georgiev GP (1982). "[Isolation of a plasmid clone containing the mRNA sequence for mouse nonviral T-antigen]". Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian). 267 (5): 1272–5. PMID 6295732.

- ^ Oren M, Levine AJ (January 1983). "Molecular cloning of a cDNA specific for the murine p53 cellular tumor antigen". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (1): 56–9. Bibcode:1983PNAS...80...56O. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.1.56. PMC 393308. PMID 6296874.

- ^ Zakut-Houri R, Oren M, Bienz B, Lavie V, Hazum S, Givol D (1983). "A single gene and a pseudogene for the cellular tumour antigen p53". Nature. 306 (5943): 594–7. Bibcode:1983Natur.306..594Z. doi:10.1038/306594a0. PMID 6646235. S2CID 4325094.

- ^ Zakut-Houri R, Bienz-Tadmor B, Givol D, Oren M (May 1985). "Human p53 cellular tumor antigen: cDNA sequence and expression in COS cells". The EMBO Journal. 4 (5): 1251–5. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03768.x. PMC 554332. PMID 4006916.

- ^ Baker SJ, Fearon ER, Nigro JM, Hamilton SR, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, vanTuinen P, Ledbetter DH, Barker DF, Nakamura Y, White R, Vogelstein B (April 1989). "Chromosome 17 deletions and p53 gene mutations in colorectal carcinomas". Science. 244 (4901): 217–21. Bibcode:1989Sci...244..217B. doi:10.1126/science.2649981. PMID 2649981.

- ^ Finlay CA, Hinds PW, Levine AJ (June 1989). "The p53 proto-oncogene can act as a suppressor of transformation". Cell. 57 (7): 1083–93. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(89)90045-7. PMID 2525423.

- ^ Maltzman W, Czyzyk L (September 1984). "UV irradiation stimulates levels of p53 cellular tumor antigen in nontransformed mouse cells". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 4 (9): 1689–94. doi:10.1128/mcb.4.9.1689. PMC 368974. PMID 6092932.

- ^ Kastan MB, Kuerbitz SJ (December 1993). "Control of G1 arrest after DNA damage". Environmental Health Perspectives. 101 (Suppl 5): 55–8. doi:10.2307/3431842. JSTOR 3431842. PMC 1519427. PMID 8013425.

- ^ Koshland DE (December 1993). "Molecule of the year". Science. 262 (5142): 1953. Bibcode:1993Sci...262.1953K. doi:10.1126/science.8266084. PMID 8266084.

- ^ Zhu J, Zhang S, Jiang J, Chen X (December 2000). "Definition of the p53 functional domains necessary for inducing apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (51): 39927–34. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005676200. PMID 10982799.

- ^ a b Han JM, Park BJ, Park SG, Oh YS, Choi SJ, Lee SW, Hwang SK, Chang SH, Cho MH, Kim S (August 2008). "AIMP2/p38, the scaffold for the multi-tRNA synthetase complex, responds to genotoxic stresses via p53". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (32): 11206–11. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511206H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800297105. PMC 2516205. PMID 18695251.

- ^ a b Kojic S, Medeot E, Guccione E, Krmac H, Zara I, Martinelli V, Valle G, Faulkner G (May 2004). "The Ankrd2 protein, a link between the sarcomere and the nucleus in skeletal muscle". Journal of Molecular Biology. 339 (2): 313–25. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.071. PMID 15136035.

- ^ a b Gueven N, Becherel OJ, Kijas AW, Chen P, Howe O, Rudolph JH, Gatti R, Date H, Onodera O, Taucher-Scholz G, Lavin MF (May 2004). "Aprataxin, a novel protein that protects against genotoxic stress". Human Molecular Genetics. 13 (10): 1081–93. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh122. PMID 15044383.

- ^ a b Fabbro M, Savage K, Hobson K, Deans AJ, Powell SN, McArthur GA, Khanna KK (July 2004). "BRCA1-BARD1 complexes are required for p53Ser-15 phosphorylation and a G1/S arrest following ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (30): 31251–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405372200. PMID 15159397.

- ^ a b c Kim ST, Lim DS, Canman CE, Kastan MB (December 1999). "Substrate specificities and identification of putative substrates of ATM kinase family members". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (53): 37538–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.53.37538. PMID 10608806.

- ^ Kang J, Ferguson D, Song H, Bassing C, Eckersdorff M, Alt FW, Xu Y (January 2005). "Functional interaction of H2AX, NBS1, and p53 in ATM-dependent DNA damage responses and tumor suppression". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (2): 661–70. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.2.661-670.2005. PMC 543410. PMID 15632067.

- ^ Khanna KK, Keating KE, Kozlov S, Scott S, Gatei M, Hobson K, Taya Y, Gabrielli B, Chan D, Lees-Miller SP, Lavin MF (December 1998). "ATM associates with and phosphorylates p53: mapping the region of interaction". Nature Genetics. 20 (4): 398–400. doi:10.1038/3882. PMID 9843217. S2CID 23994762.

- ^ Westphal CH, Schmaltz C, Rowan S, Elson A, Fisher DE, Leder P (May 1997). "Genetic interactions between atm and p53 influence cellular proliferation and irradiation-induced cell cycle checkpoints". Cancer Research. 57 (9): 1664–7. PMID 9135004.

- ^ Stelzl U, Worm U, Lalowski M, Haenig C, Brembeck FH, Goehler H, Stroedicke M, Zenkner M, Schoenherr A, Koeppen S, Timm J, Mintzlaff S, Abraham C, Bock N, Kietzmann S, Goedde A, Toksöz E, Droege A, Krobitsch S, Korn B, Birchmeier W, Lehrach H, Wanker EE (September 2005). "A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome". Cell. 122 (6): 957–68. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.029. PMID 16169070.

- ^ Yan C, Wang H, Boyd DD (March 2002). "ATF3 represses 72-kDa type IV collagenase (MMP-2) expression by antagonizing p53-dependent trans-activation of the collagenase promoter". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (13): 10804–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112069200. PMID 11792711.

- ^ Chen SS, Chang PC, Cheng YW, Tang FM, Lin YS (September 2002). "Suppression of the STK15 oncogenic activity requires a transactivation-independent p53 function". The EMBO Journal. 21 (17): 4491–9. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf409. PMC 126178. PMID 12198151.

- ^ Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, Murphy ME, George DL (May 2004). "Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (5): 443–50. doi:10.1038/ncb1123. PMID 15077116. S2CID 43063712.

- ^ a b c d e f Dong Y, Hakimi MA, Chen X, Kumaraswamy E, Cooch NS, Godwin AK, Shiekhattar R (November 2003). "Regulation of BRCC, a holoenzyme complex containing BRCA1 and BRCA2, by a signalosome-like subunit and its role in DNA repair". Molecular Cell. 12 (5): 1087–99. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00424-6. PMID 14636569.

- ^ a b c Sengupta S, Robles AI, Linke SP, Sinogeeva NI, Zhang R, Pedeux R, Ward IM, Celeste A, Nussenzweig A, Chen J, Halazonetis TD, Harris CC (September 2004). "Functional interaction between BLM helicase and 53BP1 in a Chk1-mediated pathway during S-phase arrest". The Journal of Cell Biology. 166 (6): 801–13. doi:10.1083/jcb.200405128. PMC 2172115. PMID 15364958.

- ^ Wang XW, Tseng A, Ellis NA, Spillare EA, Linke SP, Robles AI, Seker H, Yang Q, Hu P, Beresten S, Bemmels NA, Garfield S, Harris CC (August 2001). "Functional interaction of p53 and BLM DNA helicase in apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (35): 32948–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M103298200. PMID 11399766.

- ^ Garkavtsev IV, Kley N, Grigorian IA, Gudkov AV (December 2001). "The Bloom syndrome protein interacts and cooperates with p53 in regulation of transcription and cell growth control". Oncogene. 20 (57): 8276–80. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205120. PMID 11781842.

- ^ a b Yang Q, Zhang R, Wang XW, Spillare EA, Linke SP, Subramanian D, Griffith JD, Li JL, Hickson ID, Shen JC, Loeb LA, Mazur SJ, Appella E, Brosh RM, Karmakar P, Bohr VA, Harris CC (August 2002). "The processing of Holliday junctions by BLM and WRN helicases is regulated by p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (35): 31980–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M204111200. PMID 12080066.

- ^ Abramovitch S, Werner H (2003). "Functional and physical interactions between BRCA1 and p53 in transcriptional regulation of the IGF-IR gene". Hormone and Metabolic Research. 35 (11–12): 758–62. doi:10.1055/s-2004-814154. PMID 14710355.

- ^ Ouchi T, Monteiro AN, August A, Aaronson SA, Hanafusa H (March 1998). "BRCA1 regulates p53-dependent gene expression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (5): 2302–6. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.2302O. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.5.2302. PMC 19327. PMID 9482880.

- ^ Chai YL, Cui J, Shao N, Shyam E, Reddy P, Rao VN (January 1999). "The second BRCT domain of BRCA1 proteins interacts with p53 and stimulates transcription from the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter". Oncogene. 18 (1): 263–8. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202323. PMID 9926942.

- ^ Zhang H, Somasundaram K, Peng Y, Tian H, Zhang H, Bi D, Weber BL, El-Deiry WS (April 1998). "BRCA1 physically associates with p53 and stimulates its transcriptional activity". Oncogene. 16 (13): 1713–21. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201932. PMID 9582019.

- ^ Marmorstein LY, Ouchi T, Aaronson SA (November 1998). "The BRCA2 gene product functionally interacts with p53 and RAD51". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (23): 13869–74. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9513869M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13869. PMC 24938. PMID 9811893.

- ^ Uramoto H, Izumi H, Nagatani G, Ohmori H, Nagasue N, Ise T, Yoshida T, Yasumoto K, Kohno K (April 2003). "Physical interaction of tumour suppressor p53/p73 with CCAAT-binding transcription factor 2 (CTF2) and differential regulation of human high-mobility group 1 (HMG1) gene expression". The Biochemical Journal. 371 (Pt 2): 301–10. doi:10.1042/BJ20021646. PMC 1223307. PMID 12534345.

- ^ a b Li L, Ljungman M, Dixon JE (January 2000). "The human Cdc14 phosphatases interact with and dephosphorylate the tumor suppressor protein p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (4): 2410–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.4.2410. PMID 10644693.

- ^ Luciani MG, Hutchins JR, Zheleva D, Hupp TR (July 2000). "The C-terminal regulatory domain of p53 contains a functional docking site for cyclin A". Journal of Molecular Biology. 300 (3): 503–18. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3830. PMID 10884347.

- ^ Ababneh M, Götz C, Montenarh M (May 2001). "Downregulation of the cdc2/cyclin B protein kinase activity by binding of p53 to p34(cdc2)". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 283 (2): 507–12. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.4792. PMID 11327730.

- ^ Abedini MR, Muller EJ, Brun J, Bergeron R, Gray DA, Tsang BK (June 2008). "Cisplatin induces p53-dependent FLICE-like inhibitory protein ubiquitination in ovarian cancer cells". Cancer Research. 68 (12): 4511–7. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0673. PMID 18559494.

- ^ a b Goudelock DM, Jiang K, Pereira E, Russell B, Sanchez Y (August 2003). "Regulatory interactions between the checkpoint kinase Chk1 and the proteins of the DNA-dependent protein kinase complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (32): 29940–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301765200. PMID 12756247.

- ^ Tian H, Faje AT, Lee SL, Jorgensen TJ (2002). "Radiation-induced phosphorylation of Chk1 at S345 is associated with p53-dependent cell cycle arrest pathways". Neoplasia. 4 (2): 171–80. doi:10.1038/sj.neo.7900219. PMC 1550321. PMID 11896572.

- ^ Zhao L, Samuels T, Winckler S, Korgaonkar C, Tompkins V, Horne MC, Quelle DE (January 2003). "Cyclin G1 has growth inhibitory activity linked to the ARF-Mdm2-p53 and pRb tumor suppressor pathways". Molecular Cancer Research. 1 (3): 195–206. PMID 12556559.

- ^ a b Ito A, Kawaguchi Y, Lai CH, Kovacs JJ, Higashimoto Y, Appella E, Yao TP (November 2002). "MDM2-HDAC1-mediated deacetylation of p53 is required for its degradation". The EMBO Journal. 21 (22): 6236–45. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf616. PMC 137207. PMID 12426395.

- ^ a b Livengood JA, Scoggin KE, Van Orden K, McBryant SJ, Edayathumangalam RS, Laybourn PJ, Nyborg JK (March 2002). "p53 Transcriptional activity is mediated through the SRC1-interacting domain of CBP/p300". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (11): 9054–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108870200. PMID 11782467.

- ^ a b Giebler HA, Lemasson I, Nyborg JK (July 2000). "p53 recruitment of CREB binding protein mediated through phosphorylated CREB: a novel pathway of tumor suppressor regulation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 20 (13): 4849–58. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.13.4849-4858.2000. PMC 85936. PMID 10848610.

- ^ a b Schneider E, Montenarh M, Wagner P (November 1998). "Regulation of CAK kinase activity by p53". Oncogene. 17 (21): 2733–41. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202504. PMID 9840937.

- ^ a b Ko LJ, Shieh SY, Chen X, Jayaraman L, Tamai K, Taya Y, Prives C, Pan ZQ (December 1997). "p53 is phosphorylated by CDK7-cyclin H in a p36MAT1-dependent manner". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 17 (12): 7220–9. doi:10.1128/mcb.17.12.7220. PMC 232579. PMID 9372954.

- ^ Yavuzer U, Smith GC, Bliss T, Werner D, Jackson SP (July 1998). "DNA end-independent activation of DNA-PK mediated via association with the DNA-binding protein C1D". Genes & Development. 12 (14): 2188–99. doi:10.1101/gad.12.14.2188. PMC 317006. PMID 9679063.

- ^ a b Rizos H, Diefenbach E, Badhwar P, Woodruff S, Becker TM, Rooney RJ, Kefford RF (February 2003). "Association of p14ARF with the p120E4F transcriptional repressor enhances cell cycle inhibition". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (7): 4981–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M210978200. PMID 12446718.

- ^ Sandy P, Gostissa M, Fogal V, Cecco LD, Szalay K, Rooney RJ, Schneider C, Del Sal G (January 2000). "p53 is involved in the p120E4F-mediated growth arrest". Oncogene. 19 (2): 188–99. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203250. PMID 10644996.

- ^ a b c Gallagher WM, Argentini M, Sierra V, Bracco L, Debussche L, Conseiller E (June 1999). "MBP1: a novel mutant p53-specific protein partner with oncogenic properties". Oncogene. 18 (24): 3608–16. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202937. PMID 10380882.

- ^ Cuddihy AR, Wong AH, Tam NW, Li S, Koromilas AE (April 1999). "The double-stranded RNA activated protein kinase PKR physically associates with the tumor suppressor p53 protein and phosphorylates human p53 on serine 392 in vitro". Oncogene. 18 (17): 2690–702. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202620. PMID 10348343.

- ^ Shinobu N, Maeda T, Aso T, Ito T, Kondo T, Koike K, Hatakeyama M (June 1999). "Physical interaction and functional antagonism between the RNA polymerase II elongation factor ELL and p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (24): 17003–10. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.24.17003. PMID 10358050.

- ^ Grossman SR, Perez M, Kung AL, Joseph M, Mansur C, Xiao ZX, Kumar S, Howley PM, Livingston DM (October 1998). "p300/MDM2 complexes participate in MDM2-mediated p53 degradation". Molecular Cell. 2 (4): 405–15. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80140-9. PMID 9809062.

- ^ An W, Kim J, Roeder RG (June 2004). "Ordered cooperative functions of PRMT1, p300, and CARM1 in transcriptional activation by p53". Cell. 117 (6): 735–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.009. PMID 15186775.

- ^ Pastorcic M, Das HK (November 2000). "Regulation of transcription of the human presenilin-1 gene by ets transcription factors and the p53 protooncogene". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (45): 34938–45. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005411200. PMID 10942770.

- ^ a b Wang XW, Yeh H, Schaeffer L, Roy R, Moncollin V, Egly JM, Wang Z, Freidberg EC, Evans MK, Taffe BG (June 1995). "p53 modulation of TFIIH-associated nucleotide excision repair activity". Nature Genetics. 10 (2): 188–95. doi:10.1038/ng0695-188. hdl:1765/54884. PMID 7663514. S2CID 38325851.

- ^ Yu A, Fan HY, Liao D, Bailey AD, Weiner AM (May 2000). "Activation of p53 or loss of the Cockayne syndrome group B repair protein causes metaphase fragility of human U1, U2, and 5S genes". Molecular Cell. 5 (5): 801–10. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80320-2. PMID 10882116.

- ^ Tsai RY, McKay RD (December 2002). "A nucleolar mechanism controlling cell proliferation in stem cells and cancer cells". Genes & Development. 16 (23): 2991–3003. doi:10.1101/gad.55671. PMC 187487. PMID 12464630.

- ^ Peng YC, Kuo F, Breiding DE, Wang YF, Mansur CP, Androphy EJ (September 2001). "AMF1 (GPS2) modulates p53 transactivation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 21 (17): 5913–24. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.17.5913-5924.2001. PMC 87310. PMID 11486030.

- ^ Watcharasit P, Bijur GN, Zmijewski JW, Song L, Zmijewska A, Chen X, Johnson GV, Jope RS (June 2002). "Direct, activating interaction between glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and p53 after DNA damage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (12): 7951–5. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.7951W. doi:10.1073/pnas.122062299. PMC 123001. PMID 12048243.

- ^ a b Akakura S, Yoshida M, Yoneda Y, Horinouchi S (May 2001). "A role for Hsc70 in regulating nucleocytoplasmic transport of a temperature-sensitive p53 (p53Val-135)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (18): 14649–57. doi:10.1074/jbc.M100200200. PMID 11297531.

- ^ Wang C, Chen J (January 2003). "Phosphorylation and hsp90 binding mediate heat shock stabilization of p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (3): 2066–71. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206697200. PMID 12427754.

- ^ Peng Y, Chen L, Li C, Lu W, Chen J (November 2001). "Inhibition of MDM2 by hsp90 contributes to mutant p53 stabilization". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (44): 40583–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.M102817200. PMID 11507088.

- ^ Chen D, Li M, Luo J, Gu W (April 2003). "Direct interactions between HIF-1 alpha and Mdm2 modulate p53 function". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (16): 13595–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200694200. PMID 12606552.

- ^ Ravi R, Mookerjee B, Bhujwalla ZM, Sutter CH, Artemov D, Zeng Q, Dillehay LE, Madan A, Semenza GL, Bedi A (January 2000). "Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by p53-induced degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha". Genes & Development. 14 (1): 34–44. doi:10.1101/gad.14.1.34. PMC 316350. PMID 10640274.

- ^ Hansson LO, Friedler A, Freund S, Rudiger S, Fersht AR (August 2002). "Two sequence motifs from HIF-1alpha bind to the DNA-binding site of p53". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (16): 10305–9. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9910305H. doi:10.1073/pnas.122347199. PMC 124909. PMID 12124396.

- ^ An WG, Kanekal M, Simon MC, Maltepe E, Blagosklonny MV, Neckers LM (March 1998). "Stabilization of wild-type p53 by hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha". Nature. 392 (6674): 405–8. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..405A. doi:10.1038/32925. PMID 9537326. S2CID 4423081.

- ^ Kondo S, Lu Y, Debbas M, Lin AW, Sarosi I, Itie A, Wakeham A, Tuan J, Saris C, Elliott G, Ma W, Benchimol S, Lowe SW, Mak TW, Thukral SK (April 2003). "Characterization of cells and gene-targeted mice deficient for the p53-binding kinase homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1 (HIPK1)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (9): 5431–6. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.5431K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0530308100. PMC 154362. PMID 12702766.

- ^ Hofmann TG, Möller A, Sirma H, Zentgraf H, Taya Y, Dröge W, Will H, Schmitz ML (January 2002). "Regulation of p53 activity by its interaction with homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2". Nature Cell Biology. 4 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1038/ncb715. PMID 11740489. S2CID 37789883.

- ^ Kim EJ, Park JS, Um SJ (August 2002). "Identification and characterization of HIPK2 interacting with p73 and modulating functions of the p53 family in vivo". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (35): 32020–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M200153200. PMID 11925430.

- ^ Imamura T, Izumi H, Nagatani G, Ise T, Nomoto M, Iwamoto Y, Kohno K (March 2001). "Interaction with p53 enhances binding of cisplatin-modified DNA by high mobility group 1 protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (10): 7534–40. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008143200. PMID 11106654.

- ^ Dintilhac A, Bernués J (March 2002). "HMGB1 interacts with many apparently unrelated proteins by recognizing short amino acid sequences". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (9): 7021–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108417200. PMID 11748221.

- ^ Wadhwa R, Yaguchi T, Hasan MK, Mitsui Y, Reddel RR, Kaul SC (April 2002). "Hsp70 family member, mot-2/mthsp70/GRP75, binds to the cytoplasmic sequestration domain of the p53 protein". Experimental Cell Research. 274 (2): 246–53. doi:10.1006/excr.2002.5468. PMID 11900485.

- ^ Steffan JS, Kazantsev A, Spasic-Boskovic O, Greenwald M, Zhu YZ, Gohler H, Wanker EE, Bates GP, Housman DE, Thompson LM (June 2000). "The Huntington's disease protein interacts with p53 and CREB-binding protein and represses transcription". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (12): 6763–8. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.6763S. doi:10.1073/pnas.100110097. PMC 18731. PMID 10823891.

- ^ Leung KM, Po LS, Tsang FC, Siu WY, Lau A, Ho HT, Poon RY (September 2002). "The candidate tumor suppressor ING1b can stabilize p53 by disrupting the regulation of p53 by MDM2". Cancer Research. 62 (17): 4890–3. PMID 12208736.

- ^ Garkavtsev I, Grigorian IA, Ossovskaya VS, Chernov MV, Chumakov PM, Gudkov AV (January 1998). "The candidate tumour suppressor p33ING1 cooperates with p53 in cell growth control". Nature. 391 (6664): 295–8. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..295G. doi:10.1038/34675. PMID 9440695. S2CID 4429461.

- ^ a b Shiseki M, Nagashima M, Pedeux RM, Kitahama-Shiseki M, Miura K, Okamura S, Onogi H, Higashimoto Y, Appella E, Yokota J, Harris CC (May 2003). "p29ING4 and p28ING5 bind to p53 and p300, and enhance p53 activity". Cancer Research. 63 (10): 2373–8. PMID 12750254.

- ^ Tsai KW, Tseng HC, Lin WC (October 2008). "Two wobble-splicing events affect ING4 protein subnuclear localization and degradation". Experimental Cell Research. 314 (17): 3130–41. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.08.002. PMID 18775696.

- ^ Chang NS (March 2002). "The non-ankyrin C terminus of Ikappa Balpha physically interacts with p53 in vivo and dissociates in response to apoptotic stress, hypoxia, DNA damage, and transforming growth factor-beta 1-mediated growth suppression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (12): 10323–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106607200. PMID 11799106.

- ^ a b Kurki S, Latonen L, Laiho M (October 2003). "Cellular stress and DNA damage invoke temporally distinct Mdm2, p53 and PML complexes and damage-specific nuclear relocalization". Journal of Cell Science. 116 (Pt 19): 3917–25. doi:10.1242/jcs.00714. PMID 12915590.

- ^ a b Freeman DJ, Li AG, Wei G, Li HH, Kertesz N, Lesche R, Whale AD, Martinez-Diaz H, Rozengurt N, Cardiff RD, Liu X, Wu H (February 2003). "PTEN tumor suppressor regulates p53 protein levels and activity through phosphatase-dependent and -independent mechanisms". Cancer Cell. 3 (2): 117–30. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00021-7. PMID 12620407.

- ^ a b Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG (March 1998). "ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways". Cell. 92 (6): 725–34. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81401-4. PMID 9529249.

- ^ Badciong JC, Haas AL (December 2002). "MdmX is a RING finger ubiquitin ligase capable of synergistically enhancing Mdm2 ubiquitination". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (51): 49668–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M208593200. PMID 12393902.

- ^ Shvarts A, Bazuine M, Dekker P, Ramos YF, Steegenga WT, Merckx G, van Ham RC, van der Houven van Oordt W, van der Eb AJ, Jochemsen AG (July 1997). "Isolation and identification of the human homolog of a new p53-binding protein, Mdmx" (PDF). Genomics. 43 (1): 34–42. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.4775. hdl:2066/142231. PMID 9226370.

- ^ Frade R, Balbo M, Barel M (December 2000). "RB18A, whose gene is localized on chromosome 17q12-q21.1, regulates in vivo p53 transactivating activity". Cancer Research. 60 (23): 6585–9. PMID 11118038.

- ^ Drané P, Barel M, Balbo M, Frade R (December 1997). "Identification of RB18A, a 205 kDa new p53 regulatory protein which shares antigenic and functional properties with p53". Oncogene. 15 (25): 3013–24. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201492. PMID 9444950.

- ^ Hu MC, Qiu WR, Wang YP (November 1997). "JNK1, JNK2 and JNK3 are p53 N-terminal serine 34 kinases". Oncogene. 15 (19): 2277–87. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201401. PMID 9393873.

- ^ Lin Y, Khokhlatchev A, Figeys D, Avruch J (December 2002). "Death-associated protein 4 binds MST1 and augments MST1-induced apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (50): 47991–8001. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202630200. PMID 12384512.

- ^ Taniura H, Matsumoto K, Yoshikawa K (June 1999). "Physical and functional interactions of neuronal growth suppressor necdin with p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (23): 16242–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.23.16242. PMID 10347180.

- ^ Daniely Y, Dimitrova DD, Borowiec JA (August 2002). "Stress-dependent nucleolin mobilization mediated by p53-nucleolin complex formation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (16): 6014–22. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.16.6014-6022.2002. PMC 133981. PMID 12138209.

- ^ Colaluca IN, Tosoni D, Nuciforo P, Senic-Matuglia F, Galimberti V, Viale G, Pece S, Di Fiore PP (January 2008). "NUMB controls p53 tumour suppressor activity". Nature. 451 (7174): 76–80. Bibcode:2008Natur.451...76C. doi:10.1038/nature06412. PMID 18172499. S2CID 4431258.

- ^ a b c Choy MK, Movassagh M, Siggens L, Vujic A, Goddard M, Sánchez A, Perkins N, Figg N, Bennett M, Carroll J, Foo R (June 2010). "High-throughput sequencing identifies STAT3 as the DNA-associated factor for p53-NF-kappaB-complex-dependent gene expression in human heart failure". Genome Medicine. 2 (6): 37. doi:10.1186/gm158. PMC 2905097. PMID 20546595.

- ^ a b Zhang Y, Wolf GW, Bhat K, Jin A, Allio T, Burkhart WA, Xiong Y (December 2003). "Ribosomal protein L11 negatively regulates oncoprotein MDM2 and mediates a p53-dependent ribosomal-stress checkpoint pathway". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (23): 8902–12. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.23.8902-8912.2003. PMC 262682. PMID 14612427.

- ^ Nikolaev AY, Li M, Puskas N, Qin J, Gu W (January 2003). "Parc: a cytoplasmic anchor for p53". Cell. 112 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01255-2. PMID 12526791.

- ^ Malanga M, Pleschke JM, Kleczkowska HE, Althaus FR (May 1998). "Poly(ADP-ribose) binds to specific domains of p53 and alters its DNA binding functions". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (19): 11839–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.19.11839. PMID 9565608.

- ^ Kahyo T, Nishida T, Yasuda H (September 2001). "Involvement of PIAS1 in the sumoylation of tumor suppressor p53". Molecular Cell. 8 (3): 713–8. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00349-5. PMID 11583632.

- ^ Wulf GM, Liou YC, Ryo A, Lee SW, Lu KP (December 2002). "Role of Pin1 in the regulation of p53 stability and p21 transactivation, and cell cycle checkpoints in response to DNA damage". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (50): 47976–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200538200. PMID 12388558.

- ^ Zacchi P, Gostissa M, Uchida T, Salvagno C, Avolio F, Volinia S, Ronai Z, Blandino G, Schneider C, Del Sal G (October 2002). "The prolyl isomerase Pin1 reveals a mechanism to control p53 functions after genotoxic insults". Nature. 419 (6909): 853–7. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..853Z. doi:10.1038/nature01120. PMID 12397362. S2CID 4311658.

- ^ Huang SM, Schönthal AH, Stallcup MR (April 2001). "Enhancement of p53-dependent gene activation by the transcriptional coactivator Zac1". Oncogene. 20 (17): 2134–43. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204298. PMID 11360197.

- ^ Xie S, Wu H, Wang Q, Cogswell JP, Husain I, Conn C, Stambrook P, Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Dai W (November 2001). "Plk3 functionally links DNA damage to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis at least in part via the p53 pathway". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (46): 43305–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106050200. PMID 11551930.

- ^ Bahassi EM, Conn CW, Myer DL, Hennigan RF, McGowan CH, Sanchez Y, Stambrook PJ (September 2002). "Mammalian Polo-like kinase 3 (Plk3) is a multifunctional protein involved in stress response pathways". Oncogene. 21 (43): 6633–40. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205850. PMID 12242661.

- ^ Simons A, Melamed-Bessudo C, Wolkowicz R, Sperling J, Sperling R, Eisenbach L, Rotter V (January 1997). "PACT: cloning and characterization of a cellular p53 binding protein that interacts with Rb". Oncogene. 14 (2): 145–55. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1200825. PMID 9010216.

- ^ Fusaro G, Dasgupta P, Rastogi S, Joshi B, Chellappan S (November 2003). "Prohibitin induces the transcriptional activity of p53 and is exported from the nucleus upon apoptotic signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (48): 47853–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M305171200. PMID 14500729.

- ^ Fogal V, Gostissa M, Sandy P, Zacchi P, Sternsdorf T, Jensen K, Pandolfi PP, Will H, Schneider C, Del Sal G (November 2000). "Regulation of p53 activity in nuclear bodies by a specific PML isoform". The EMBO Journal. 19 (22): 6185–95. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.22.6185. PMC 305840. PMID 11080164.

- ^ Guo A, Salomoni P, Luo J, Shih A, Zhong S, Gu W, Pandolfi PP (October 2000). "The function of PML in p53-dependent apoptosis". Nature Cell Biology. 2 (10): 730–6. doi:10.1038/35036365. PMID 11025664. S2CID 13480833.

- ^ a b Zhang Z, Zhang R (March 2008). "Proteasome activator PA28 gamma regulates p53 by enhancing its MDM2-mediated degradation". The EMBO Journal. 27 (6): 852–64. doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.25. PMC 2265109. PMID 18309296.

- ^ Lim ST, Chen XL, Lim Y, Hanson DA, Vo TT, Howerton K, Larocque N, Fisher SJ, Schlaepfer DD, Ilic D (January 2008). "Nuclear FAK promotes cell proliferation and survival through FERM-enhanced p53 degradation". Molecular Cell. 29 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.031. PMC 2234035. PMID 18206965.

- ^ Bernal JA, Luna R, Espina A, Lázaro I, Ramos-Morales F, Romero F, Arias C, Silva A, Tortolero M, Pintor-Toro JA (October 2002). "Human securin interacts with p53 and modulates p53-mediated transcriptional activity and apoptosis". Nature Genetics. 32 (2): 306–11. doi:10.1038/ng997. PMID 12355087. S2CID 1770399.

- ^ Stürzbecher HW, Donzelmann B, Henning W, Knippschild U, Buchhop S (April 1996). "p53 is linked directly to homologous recombination processes via RAD51/RecA protein interaction". The EMBO Journal. 15 (8): 1992–2002. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00550.x. PMC 450118. PMID 8617246.

- ^ Buchhop S, Gibson MK, Wang XW, Wagner P, Stürzbecher HW, Harris CC (October 1997). "Interaction of p53 with the human Rad51 protein". Nucleic Acids Research. 25 (19): 3868–74. doi:10.1093/nar/25.19.3868. PMC 146972. PMID 9380510.

- ^ Leng RP, Lin Y, Ma W, Wu H, Lemmers B, Chung S, Parant JM, Lozano G, Hakem R, Benchimol S (March 2003). "Pirh2, a p53-induced ubiquitin-protein ligase, promotes p53 degradation". Cell. 112 (6): 779–91. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00193-4. PMID 12654245.

- ^ Sheng Y, Laister RC, Lemak A, Wu B, Tai E, Duan S, Lukin J, Sunnerhagen M, Srisailam S, Karra M, Benchimol S, Arrowsmith CH (December 2008). "Molecular basis of Pirh2-mediated p53 ubiquitylation". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 15 (12): 1334–42. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1521. PMC 4075976. PMID 19043414.

- ^ Romanova LY, Willers H, Blagosklonny MV, Powell SN (December 2004). "The interaction of p53 with replication protein A mediates suppression of homologous recombination". Oncogene. 23 (56): 9025–33. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207982. PMID 15489903.

- ^ Riva F, Zuco V, Vink AA, Supino R, Prosperi E (December 2001). "UV-induced DNA incision and proliferating cell nuclear antigen recruitment to repair sites occur independently of p53-replication protein A interaction in p53 wild type and mutant ovarian carcinoma cells". Carcinogenesis. 22 (12): 1971–8. doi:10.1093/carcin/22.12.1971. PMID 11751427.

- ^ Lin J, Yang Q, Yan Z, Markowitz J, Wilder PT, Carrier F, Weber DJ (August 2004). "Inhibiting S100B restores p53 levels in primary malignant melanoma cancer cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (32): 34071–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405419200. PMID 15178678.

- ^ a b Minty A, Dumont X, Kaghad M, Caput D (November 2000). "Covalent modification of p73alpha by SUMO-1. Two-hybrid screening with p73 identifies novel SUMO-1-interacting proteins and a SUMO-1 interaction motif". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (46): 36316–23. doi:10.1074/jbc.M004293200. PMID 10961991.

- ^ a b Ivanchuk SM, Mondal S, Rutka JT (June 2008). "p14ARF interacts with DAXX: effects on HDM2 and p53". Cell Cycle. 7 (12): 1836–50. doi:10.4161/cc.7.12.6025. PMID 18583933.

- ^ a b Lee D, Kim JW, Seo T, Hwang SG, Choi EJ, Choe J (June 2002). "SWI/SNF complex interacts with tumor suppressor p53 and is necessary for the activation of p53-mediated transcription". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (25): 22330–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111987200. PMID 11950834.

- ^ Young PJ, Day PM, Zhou J, Androphy EJ, Morris GE, Lorson CL (January 2002). "A direct interaction between the survival motor neuron protein and p53 and its relationship to spinal muscular atrophy". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (4): 2852–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108769200. PMID 11704667.

- ^ Seto E, Usheva A, Zambetti GP, Momand J, Horikoshi N, Weinmann R, Levine AJ, Shenk T (December 1992). "Wild-type p53 binds to the TATA-binding protein and represses transcription". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (24): 12028–32. Bibcode:1992PNAS...8912028S. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.24.12028. PMC 50691. PMID 1465435.

- ^ Cvekl A, Kashanchi F, Brady JN, Piatigorsky J (June 1999). "Pax-6 interactions with TATA-box-binding protein and retinoblastoma protein". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 40 (7): 1343–50. PMID 10359315.

- ^ McPherson LA, Loktev AV, Weigel RJ (November 2002). "Tumor suppressor activity of AP2alpha mediated through a direct interaction with p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (47): 45028–33. doi:10.1074/jbc.M208924200. PMID 12226108.

- ^ Sørensen TS, Girling R, Lee CW, Gannon J, Bandara LR, La Thangue NB (October 1996). "Functional interaction between DP-1 and p53". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 16 (10): 5888–95. doi:10.1128/mcb.16.10.5888. PMC 231590. PMID 8816502.

- ^ Green DR, Chipuk JE (July 2006). "p53 and metabolism: Inside the TIGAR". Cell. 126 (1): 30–2. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.032. PMID 16839873.

- ^ Gobert C, Skladanowski A, Larsen AK (August 1999). "The interaction between p53 and DNA topoisomerase I is regulated differently in cells with wild-type and mutant p53". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (18): 10355–60. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9610355G. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.18.10355. PMC 17892. PMID 10468612.

- ^ Mao Y, Mehl IR, Muller MT (February 2002). "Subnuclear distribution of topoisomerase I is linked to ongoing transcription and p53 status". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (3): 1235–40. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.1235M. doi:10.1073/pnas.022631899. PMC 122173. PMID 11805286.

- ^ a b Cowell IG, Okorokov AL, Cutts SA, Padget K, Bell M, Milner J, Austin CA (February 2000). "Human topoisomerase IIalpha and IIbeta interact with the C-terminal region of p53". Experimental Cell Research. 255 (1): 86–94. doi:10.1006/excr.1999.4772. PMID 10666337.

- ^ Derbyshire DJ, Basu BP, Serpell LC, Joo WS, Date T, Iwabuchi K, Doherty AJ (July 2002). "Crystal structure of human 53BP1 BRCT domains bound to p53 tumour suppressor". The EMBO Journal. 21 (14): 3863–72. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf383. PMC 126127. PMID 12110597.

- ^ Ekblad CM, Friedler A, Veprintsev D, Weinberg RL, Itzhaki LS (March 2004). "Comparison of BRCT domains of BRCA1 and 53BP1: a biophysical analysis". Protein Science. 13 (3): 617–25. doi:10.1110/ps.03461404. PMC 2286730. PMID 14978302.

- ^ Lo KW, Kan HM, Chan LN, Xu WG, Wang KP, Wu Z, Sheng M, Zhang M (March 2005). "The 8-kDa dynein light chain binds to p53-binding protein 1 and mediates DNA damage-induced p53 nuclear accumulation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (9): 8172–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M411408200. PMID 15611139.

- ^ Joo WS, Jeffrey PD, Cantor SB, Finnin MS, Livingston DM, Pavletich NP (March 2002). "Structure of the 53BP1 BRCT region bound to p53 and its comparison to the Brca1 BRCT structure". Genes & Development. 16 (5): 583–93. doi:10.1101/gad.959202. PMC 155350. PMID 11877378.

- ^ Derbyshire DJ, Basu BP, Date T, Iwabuchi K, Doherty AJ (October 2002). "Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of the BRCT domains of human 53BP1 bound to the p53 tumour suppressor". Acta Crystallographica D. 58 (Pt 10 Pt 2): 1826–9. doi:10.1107/S0907444902010910. PMID 12351827.

- ^ a b Iwabuchi K, Bartel PL, Li B, Marraccino R, Fields S (June 1994). "Two cellular proteins that bind to wild-type but not mutant p53". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (13): 6098–102. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.6098I. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.13.6098. PMC 44145. PMID 8016121.

- ^ Naumovski L, Cleary ML (July 1996). "The p53-binding protein 53BP2 also interacts with Bc12 and impedes cell cycle progression at G2/M". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 16 (7): 3884–92. doi:10.1128/MCB.16.7.3884. PMC 231385. PMID 8668206.

- ^ Tomasini R, Samir AA, Carrier A, Isnardon D, Cecchinelli B, Soddu S, Malissen B, Dagorn JC, Iovanna JL, Dusetti NJ (September 2003). "TP53INP1s and homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 (HIPK2) are partners in regulating p53 activity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (39): 37722–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301979200. PMID 12851404.

- ^ Okamura S, Arakawa H, Tanaka T, Nakanishi H, Ng CC, Taya Y, Monden M, Nakamura Y (July 2001). "p53DINP1, a p53-inducible gene, regulates p53-dependent apoptosis". Molecular Cell. 8 (1): 85–94. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00284-2. PMID 11511362.

- ^ Li L, Liao J, Ruland J, Mak TW, Cohen SN (February 2001). "A TSG101/MDM2 regulatory loop modulates MDM2 degradation and MDM2/p53 feedback control". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (4): 1619–24. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.1619L. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.4.1619. PMC 29306. PMID 11172000.

- ^ Lyakhovich A, Shekhar MP (April 2003). "Supramolecular complex formation between Rad6 and proteins of the p53 pathway during DNA damage-induced response". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (7): 2463–75. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.7.2463-2475.2003. PMC 150718. PMID 12640129.

- ^ Shen Z, Pardington-Purtymun PE, Comeaux JC, Moyzis RK, Chen DJ (October 1996). "Associations of UBE2I with RAD52, UBL1, p53, and RAD51 proteins in a yeast two-hybrid system". Genomics. 37 (2): 183–6. doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0540. PMID 8921390.

- ^ Bernier-Villamor V, Sampson DA, Matunis MJ, Lima CD (February 2002). "Structural basis for E2-mediated SUMO conjugation revealed by a complex between ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and RanGAP1". Cell. 108 (3): 345–56. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00630-X. PMID 11853669.

- ^ Sehat B, Andersson S, Girnita L, Larsson O (July 2008). "Identification of c-Cbl as a new ligase for insulin-like growth factor-I receptor with distinct roles from Mdm2 in receptor ubiquitination and endocytosis". Cancer Research. 68 (14): 5669–77. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6364. PMID 18632619.

- ^ Song MS, Song SJ, Kim SY, Oh HJ, Lim DS (July 2008). "The tumour suppressor RASSF1A promotes MDM2 self-ubiquitination by disrupting the MDM2-DAXX-HAUSP complex". The EMBO Journal. 27 (13): 1863–74. doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.115. PMC 2486425. PMID 18566590.

- ^ Yang W, Dicker DT, Chen J, El-Deiry WS (March 2008). "CARPs enhance p53 turnover by degrading 14-3-3sigma and stabilizing MDM2". Cell Cycle. 7 (5): 670–82. doi:10.4161/cc.7.5.5701. PMID 18382127.

- ^ Abe Y, Oda-Sato E, Tobiume K, Kawauchi K, Taya Y, Okamoto K, Oren M, Tanaka N (March 2008). "Hedgehog signaling overrides p53-mediated tumor suppression by activating Mdm2". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (12): 4838–43. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.4838A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0712216105. PMC 2290789. PMID 18359851.

- ^ Dohmesen C, Koeppel M, Dobbelstein M (January 2008). "Specific inhibition of Mdm2-mediated neddylation by Tip60". Cell Cycle. 7 (2): 222–31. doi:10.4161/cc.7.2.5185. PMID 18264029.

- ^ Li M, Chen D, Shiloh A, Luo J, Nikolaev AY, Qin J, Gu W (April 2002). "Deubiquitination of p53 by HAUSP is an important pathway for p53 stabilization". Nature. 416 (6881): 648–53. Bibcode:2002Natur.416..648L. doi:10.1038/nature737. PMID 11923872. S2CID 4389394.

- ^ Brosh RM, Karmakar P, Sommers JA, Yang Q, Wang XW, Spillare EA, Harris CC, Bohr VA (September 2001). "p53 Modulates the exonuclease activity of Werner syndrome protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (37): 35093–102. doi:10.1074/jbc.M103332200. PMID 11427532.

- ^ Chang NS, Pratt N, Heath J, Schultz L, Sleve D, Carey GB, Zevotek N (February 2001). "Hyaluronidase induction of a WW domain-containing oxidoreductase that enhances tumor necrosis factor cytotoxicity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (5): 3361–70. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007140200. PMID 11058590.

- ^ Okamoto T, Izumi H, Imamura T, Takano H, Ise T, Uchiumi T, Kuwano M, Kohno K (December 2000). "Direct interaction of p53 with the Y-box binding protein, YB-1: a mechanism for regulation of human gene expression". Oncogene. 19 (54): 6194–202. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204029. PMID 11175333.

- ^ Kelley KD, Miller KR, Todd A, Kelley AR, Tuttle R, Berberich SJ (May 2010). "YPEL3, a p53-regulated gene that induces cellular senescence". Cancer Research. 70 (9): 3566–75. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3219. PMC 2862112. PMID 20388804.

- ^ Waterman MJ, Stavridi ES, Waterman JL, Halazonetis TD (June 1998). "ATM-dependent activation of p53 involves dephosphorylation and association with 14-3-3 proteins". Nature Genetics. 19 (2): 175–8. doi:10.1038/542. PMID 9620776. S2CID 26600934.

- ^ Liu J, Grogan L, Nau MM, Allegra CJ, Chu E, Wright JJ (April 2001). "Physical interaction between p53 and primary response gene Egr-1". International Journal of Oncology. 18 (4): 863–70. doi:10.3892/ijo.18.4.863. PMID 11251186.

- ^ Bai L, Merchant JL (July 2001). "ZBP-89 promotes growth arrest through stabilization of p53". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 21 (14): 4670–83. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.14.4670-4683.2001. PMC 87140. PMID 11416144.

- ^ Yamakuchi M, Lowenstein CJ (March 2009). "MiR-34, SIRT1 and p53: the feedback loop". Cell Cycle. 8 (5): 712–5. doi:10.4161/cc.8.5.7753. PMID 19221490.

- ^ Wang, Yanjie; Zhang, Junhua; Li, Jian; Gui, Rong; Nie, Xinmin; Huang, Rong (14 January 2019). "CircRNA_014511 affects the radiosensitivity of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by binding to miR-29b-2-5p". Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 19 (2): 155–163. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2019.3935. PMC 6535393. PMID 30640591.

외부 링크

- "p53 Knowledgebase". Lane Group at the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology (IMCB), Singapore. Archived from the original on 2006-01-03. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- Li-Fraumeni 증후군에 대한 GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW 엔트리

- 종양단백질 p53 @ OMIM

- p53 기능 회복

- p53 @ 종양학 및 혈액학 유전학과 세포유전학 지도

- TP53 Gene @ GeneCards

- p53 과학 단체가 제공하는 뉴스

- David S. Goodsel l (2002-07-01). "p53 Tumor Suppressor". Molecule of the Month. RCSB Protein Data Bank. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- Thierry Soussi. "p53 Web Site". Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- Living LFS 비영리 Li-Fraumeni Syndrome 환자 지원 조직

- 영국의 George Pantziarka TP53 Trust Li-Fraumeni Syndrome 또는 기타 TP53 관련 장애 환자를 위한 지원 그룹

- IARC TP53 체세포 돌연변이 데이터베이스는 Magali Olivier에 의해 리옹 IARC에서 관리된다.

- PDBe-KB는 PDB for Human P53에서 사용할 수 있는 모든 구조 정보의 개요를 제공합니다.

- DNA 결합에 따른 p53의 과학 애니메이션 구조 변화