이란 혁명

Iranian Revolution| 이란 혁명 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 이란과 냉전의 헌법 제정 시도의 일부 | |||

테헤란 칼리지 브리지에서의 대규모 시위 | |||

| 날짜. | 1978년 1월 7일 ~ 1979년 2월 11일 (1년 1개월 4일) | ||

| 위치 | |||

| 원인 | |||

| 목표들 | 팔라비 왕조 전복 | ||

| 방법들 | |||

| 결과 | |||

| 내란 당사자 | |||

| 주요 수치 | |||

| |||

| 사상자 및 손실 | |||

| 이란 혁명의 사상자를 보다 | |||

| 이란의 역사 |

|---|

|

| 타임라인 |

는 샤 모하마드 레자 팔라비에 팔라비 왕조 전복, 그의 governm을 바꾸는 일에 사건들의 이란 혁명(페르시아:انقلاب ایران, romanized:Enqelâb-e Irân, 발음[ʔiːɾɒːnʔeɴɢeˌlɒːbe]), 또한 이슬람 혁명(페르시아:انقلاب اسلامی, romanized:Enqelâb-e Eslâmī)[3]로 알려져 있었다.멤머는이슬람 공화국이 [4]반정부 세력의 지도자인 아야톨라 루홀라 호메이니의 통치하에 있었다.혁명은 다양한 좌파 및 이슬람 [5]단체들의 지지를 받았다.

1953년 이란 쿠데타 이후 팔라비는 미국 및 서방세계와 동맹을 맺고 독재 군주로서 더욱 확고하게 통치했다.그는 26년 [6][7]동안 권력을 유지하기 위해 미국의 지원에 크게 의존했다.이것은[vague] 1963년 백인 혁명과 1964년 아야톨라 호메이니의 체포와 추방으로 이어졌다.호메이니와 샤 사이의 엄청난 긴장 속에서, 시위는 1977년 10월에 시작되었고, 세속적인 요소와 종교적 [8][9][10]요소를 모두 포함한 시민 저항 운동으로 발전했다.1978년 혁명의 [11][12]도화선으로 여겨졌던 렉스 시네마가 불에 타면서 시위가 급속히 격화됐고 그해 8월부터 12월까지 파업과 시위로 나라가 마비됐다.

1979년 1월 16일, 샤는 마지막 페르시아 군주로서 이란을 떠나[13] 섭정 위원회와 야당에 기반을 둔 총리였던 샤푸르 바흐티아르에게 임무를 맡겼다.아야톨라 호메이니는 [6][14]이란 정부의 초청을 받아 테헤란으로 돌아와 수천 명의 [15]이란인들의 인사를 받았다.왕실의 통치는 2월 11일 게릴라들과 반군들이 무장 거리 싸움에서 샤에 충성하는 군대를 제압하고 호메이니를 공식 권좌에 [16][17]앉히면서 무너졌다.이란은 국민투표를 통해[18] 1979년 4월 1일 이슬람 공화국이 되고 1979년 12월 호메이니가 최고 지도자가 된 신민주 공화국 헌법을[8][9][19][20] 제정하고 승인했다.

그 혁명은 [21]전 세계에 걸쳐 일어난 놀라움으로서는 이례적이었다.이것은[22]는 상대적인 번영을 겪고 있는 나라에 일어났습니다;[6][20] 빠른 속도로 심오한 변화를 생산했다;[23] 엄청나게 인기가 있었다; 많은 이란인들의 미국 망명 허용이 결과적으로;[24]과 친 서구는 편지를 대신했다 혁명(전쟁의 패배가 금융 위기 농민 반란, 또는 불만을 품은 군사)의 관습적인 원인의 많은이 부족했다.authoritaria cular[25]권위주의와[6] 전체주의 [27]사이에 걸쳐 있는 반서방 신권정치의 개념에 기초한 반(反)서방 군주제[6][19][20][26].이들 외에도 혁명은 지역 전체의 시아파 부활과 중동에서 [28]지배적인 아랍 수니파의 패권 근절을 추구했다.

배경(1891~1977)

혁명과 그 포퓰리즘, 민족주의, 그리고 나중에는 시아파 이슬람의 특징을 발전시킨 이유는 다음과 같습니다.

- 제국주의에 대한 반발

- 1953년 이란 쿠데타

- 1973년 석유 수입의 횡재로 인한 기대치의 상승

- 지나치게 야심찬 경제 프로그램

- 1977-1978년 짧고 급격한 경제위축에 대한 분노[Note 1]

- 이전 정권의 다른 단점들.

샤의 정권은 당시 [33][35]사회 일부 계층에 의해 억압적이고 잔인하며 [33][34]부패하고 사치스러운 정권으로 여겨졌다.또한 경제 병목현상, 부족,[36] 인플레이션을 초래한 몇 가지 기본적인 기능 장애로 인해 어려움을 겪었습니다.샤는 이란 문화에 영향을 미치고 있는 비이슬람 서방 권력(즉, 미국)[37][38]에 신세를 진 것으로 많은 사람들에 의해 인식되었다.동시에, 샤에 대한 지지도는 [39]10년 초 OPEC 석유 가격 인상에 대한 샤의 지지의 결과로 서방 정치인들과 언론들 사이에서 시들해졌을 수 있다.카터 대통령이 인권침해를 저지른 국가들은 미국의 무기나 원조를 박탈당할 것이라는 인권정책을 제정했을 때, 이는 일부 이란인들에게 정부에 의한 탄압이 [40]진정되기를 바라며 공개 서한과 탄원서를 게시할 용기를 주었다.

모하마드 레자 샤 팔라비의 왕정을 이슬람과 호메이니로 대체한 혁명은 부분적으로 시아파 버전의 이슬람 부흥이 확산된 데 기인한다.그것은 서구화에 저항했고 아야톨라 호메이니가 시아파 이맘 후세인 이븐 알리의 전철을 밟는 것으로 보았고, 샤는 후세인 독재자 야지드 [41]1세의 역할을 맡았다.또 다른 요인으로는 호메이니의 이슬람 운동을 샤의 통치 기간 동안 과소평가한 것, 마르크스주의자와 이슬람[42][43][44] 사회주의자에 비해 사소한 위협으로 여겼던 것, 그리고 호메이니주의자들이 [45]소외될 수 있다고 여겼던 정부의 세속주의 반대자들에 의한 것이 있다.

담배 시위(1891)

19세기 말 시아파 성직자(울라마)는 이란 사회에 큰 영향을 미쳤다.성직자들은 1891년 담배 시위로 군주제에 반대하는 강력한 정치세력임을 처음 보여주었다.1890년 3월 20일 이란의 오랜 군주 나시르 알딘 샤는 영국 소령 G.F.에게 양보를 허락했다.50년간 [46]담배의 생산, 판매, 수출을 독점해 온 Talbot.그 당시 페르시아 담배 산업은 200,000명 이상의 사람들을 고용했기 때문에, 양허는 수입이 많은 [47]담배 사업에 주로 의존하는 페르시아 농부들과 바자르들에게 큰 타격을 주었다.이에 대한 보이콧과 시위는 미르자 하산 시라지의 파트와(사법령)[48]로 인해 광범위하고 광범위했다.2년 만에 Nasir al-Din Shah는 대중 운동을 멈출 힘이 없음을 깨닫고 [49]양보를 취소했다.

담배 시위는 샤와 외국의 이익에 대한 이란의 첫 번째 중대한 저항으로 국민의 힘과 그들 [46]사이의 울라마의 영향력을 드러냈다.

페르시아 헌법 혁명(1905년-1911년)

증가하는 불만은 1905-1911년의 헌법 혁명까지 계속되었다.혁명은 의회, 국민협의회의 설립, 그리고 첫 번째 헌법의 승인으로 이어졌다.비록 헌법 혁명은 카자르 정권의 독재 정권을 약화시키는 데는 성공했지만, 강력한 대안 정부를 제공하는 데는 실패했다.그러므로, 새로운 의회가 설립된 후 수십 년 동안, 많은 중요한 사건들이 일어났다.이러한 사건들 중 많은 것들이 입헌주의자들과 페르시아의 샤들 사이의 투쟁의 연속이라고 볼 수 있는데, 이들 중 다수는 의회에 대항하는 외세의 지원을 받았다.

레자 샤(1921~1935)

헌법혁명 이후 조성된 불안과 혼란은 1921년 2월 쿠데타로 권력을 잡은 페르시아의 엘리트 코사크 여단 사령관 레자 칸의 부상으로 이어졌다.그는 1925년 마지막 카자르 샤인 아흐메드 샤를 퇴위시키고 국회에서 군주로 지명되면서 입헌군주제를 확립했고 이후 팔라비 왕조의 창시자인 레자 샤로 알려지게 되었다.

그의 통치 기간 동안 광범위한 사회, 경제, 정치 개혁이 도입되었고, 그 중 많은 것들이 이란 혁명의 환경을 제공할 대중의 불만을 야기시켰다.특히 논란이 된 것은 이슬람 율법을 서양 율법으로 대체하고 이슬람 전통의상 금지, 성별 분리, 니캅으로 [50]여성의 얼굴을 가리는 행위였다.경찰은 그의 공공 히잡 금지에 저항하는 여성들을 강제 퇴거시키고 갈기갈기 찢었다.

1935년에는 고하르샤드 모스크의 [51][52][53]반란으로 수십 명이 사망하고 수백 명이 부상했다.한편, 레자 샤의 초기 부흥기에, 압둘 카림 하에리 야즈디는 쿰 신학교를 설립하고, 신학부에 중요한 변화를 일으켰다.그러나 그를 따르는 다른 종교 지도자들과 마찬가지로 그는 정치적 이슈에 관여하는 것을 피했다.따라서 레자 샤 통치 기간 동안 성직자들에 의해 조직된 광범위한 반정부 시도는 없었다.하지만 미래의 아야톨라 호메이니가 셰이크 압둘 카림 하에리의 [54]제자였다.

Mosaddegh and The Englo-Iranian Oil Company(1951-1952)

1901년부터 영국 석유회사인 앵글로-페르시아 석유회사(1931년 앵글로-이란 석유회사로 개명)가 이란 석유의 판매와 생산을 독점하게 되었다.그것은 세계에서 [55]가장 수익성이 높은 영국 사업이었다.대부분의 이란인들은 가난하게 살았고, 반면 이란 석유로 창출되는 부는 영국을 세계 정상으로 유지하는 데 결정적인 역할을 했다.1951년 모하마드 모사데그 이란 총리는 이란에서 회사를 몰아내고 석유 매장량을 되찾고 이란을 외세로부터 해방시키겠다고 약속했다.

1952년 모사데흐는 영국-이란 석유회사를 국유화하고 국민적 영웅이 되었다.그러나 영국인들은 격분하여 그가 도둑질을 했다고 비난했다.영국은 세계법원과 유엔에 처벌을 요구했지만 실패했고, 페르시아만에 군함을 보냈고, 마침내 압도적인 금수 조치를 내렸다.Mosaddegh는 그에 대한 영국의 캠페인에 동요하지 않았다.프랑크푸르트 노이 프레세라는 한 유럽 신문은 모사데그가 "영국에게 조금이라도 양보하느니 차라리 페르시아 기름에 튀기겠다"고 보도했다.영국은 무력 침공을 고려했지만 윈스턴 처칠 영국 총리는 해리 S. 미국 대통령의 군사적 지원을 거부당하자 쿠데타를 결심했다. 모사데흐와 같은 민족주의 운동에 동조하고 영국-이란 석유회사를 운영하는 사람들과 같은 구식 제국주의자들에 대해서는 경멸밖에 하지 않았던 트루먼.그러나 모사데흐는 처칠의 계획을 알고 1952년 10월 영국 대사관을 폐쇄하라고 명령하여 모든 영국 외교관과 요원을 출국시켰다.

비록 영국이 트루먼 대통령에 의해 미국의 지원을 요청했으나, 드와이트 D의 당선은 거절당했다. 1952년 11월 미국 대통령으로서 아이젠하워는 분쟁에 대한 미국의 입장을 바꿨다.1953년 1월 20일, 미국 국무장관 존 포스터 덜레스와 그의 형 앨런 덜레스 CIA 국장은 모사데흐에 대항할 준비가 되어 있다고 영국 외무장관에게 말했다.그들의 눈에는 미국과 결정적으로 동맹을 맺지 않은 어떤 나라도 잠재적인 적이었다.이란은 막대한 석유 부와 소련과의 긴 국경, 그리고 민족주의 수상을 가지고 있었다.공산주의에 빠져 제2의 중국(마오쩌둥 내전에서 승리한 후)이 될 것이라는 전망은 덜레스 형제를 공포에 떨게 했다.아약스 작전은 이란의 유일한 민주 정부가 [56]축출된 작전이다.

이란 쿠데타 (1953년)

1941년, 영국과 소련 연합군의 침공으로 나치 독일에 우호적이라고 여겨졌던 레자 샤가 물러나고 그의 아들인 모하마드 레자 팔라비가 왕위에 올랐다.1953년 민주적으로 선출된 모하마드 모사데흐 총리에 의해 이란 석유 산업이 국유화되면서 미영 양국은 이란 석유에 대한 매우 효과적인 금수 조치를 취했고, 은밀히 의회를 불안정하게 만들고 그들의 동맹인 팔라비에게 통제권을 돌려주는 것을 도왔다.미국 중앙정보국(CIA)이 조직한 '아약스 작전'은 영국 MI6의 지원을 받아 모사데흐를 축출하기 위한 군사 쿠데타를 계획했다.샤는 8월 15일 쿠데타 시도가 실패하자 이탈리아로 도망쳤으나 8월 [57]19일 두 번째 시도 끝에 돌아왔다.

팔라비는 두 정권이 이란의 강력한 북쪽 이웃 국가인 소련의 확대에 반대한다는 점을 공유하면서 미국 정부와 긴밀한 관계를 유지했다.그의 아버지처럼, 샤의 정부는 독재정권, 현대화와 서구화에 초점을 맞추고 있으며, 이란 헌법에 있는 종교적이고 민주적인 조치들을[citation needed] 무시한 것으로 알려져 있다.좌파 및 이슬람 단체들은 사바크 비밀경찰에 의한 이란 헌법 위반, 정치적 부패, 정치적 탄압, 고문, 살인을 이유로 그의 정부를 공격했다.

백인 혁명(1963년-1978년)

백인 혁명은 1963년 샤 모하마드 레자 팔라비에 의해 시작된 이란의 광범위한 개혁으로 1978년까지 지속되었다.Mohammad Reza Shah의 개혁 프로그램은 특히 전통적인 시스템을 지지하는 계층을 약화시키기 위해 만들어졌다.그것은 토지 개혁, 토지 개혁 자금 조달을 위한 일부 국영 공장의 판매, 여성의 선거권 부여, 산림과 목장의 국유화, 문맹퇴치 단체의 구성, 산업 [58]종사자들을 위한 이익 공유 계획의 제도로 구성되었다.

샤는 백인혁명을 서구화를 [59]향한 한 걸음이라고 선전했고, 그것은 팔라비 왕조를 합법화하는 방법이었다.백인 혁명을 일으킨 이유 중 하나는 샤가 지주들의 영향력을 없애고 농민과 노동자 [60][61]계층 사이에 새로운 지지 기반을 만들고 싶어했기 때문이다.따라서, 이란의 백인 혁명은 위에서부터 개혁을 도입하고 전통적인 권력 패턴을 보존하려는 시도였다.백인 혁명의 본질인 토지 개혁을 통해 샤는 시골의 농민들과 동맹을 맺고 도시의 귀족들과 관계를 끊기를 희망했다.

그러나 샤가 예상하지 못했던 것은, 백색 혁명이 샤가 피하려고 했던 많은 문제들을 야기하는 데 도움을 준 새로운 사회적 긴장을 초래했다는 것이다.샤의 개혁은 과거 샤의 군주제에 가장 큰 도전을 제기했던 두 계급, 즉 지식층과 도시 노동자 계층을 합친 규모를 4배 이상 늘렸다.샤에 대한 그들의 분노는 정당, 전문 협회, 노동조합, 독립 신문과 같이 과거에 자신들을 대표했던 조직들이 없어지면서 더욱 커졌다.토지 개혁은 농민들을 정부와 연합시키는 대신, 많은 수의 독립 농민들과 땅 없는 노동자들을 왕에 대한 충성심 없이 느슨한 정치적 대포가 되게 했다.많은 대중들은 점점 부패하는 정부에 분개했다; 대중의 운명에 더 관심이 있는 것으로 보여진 성직자들에 대한 그들의 충성심은 일관되거나 증가했다.에반드 에이브러햄이 지적한 것처럼: "백인혁명은 붉은 혁명을 선점하기 위해 고안되었다.대신 이슬람 [62]혁명의 발판을 마련했다.백인 혁명의 경제적 '낙수' 전략도 뜻대로 되지 않았다.이론적으로, 엘리트에게 흘러들어간 오일머니는 일자리와 공장을 만들고, 결국 돈을 분배하는 데 사용되어야 했지만, 그 대신에 부는 정상에 갇혀 [63]극소수의 손에 집중되는 경향이 있었다.

아야톨라 호메이니의 봉기와 망명(1963년-현재)

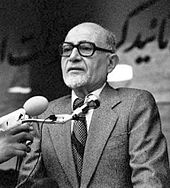

혁명 이후의 지도자--시아파 성직자 아야톨라 루홀라 호메이니는 1963년 샤와 그의 백인 혁명에 대한 반대를 이끌면서 처음으로 정치적으로 두각을 나타냈습니다.호메이니는 1963년 샤를 [64]"이란에서 이슬람을 파괴하는 길로 접어들었다"고 선언한 후 체포됐다.반정부 [65]소식통에 따르면 경찰의 총격으로 1만5천명이 숨지는 등 이란 전역에서 3일간 대규모 폭동이 이어졌다.그러나 반혁명 소식통들은 32명만이 [66]사망했을 것으로 추측했다.

호메이니는 가택연금 8개월 만에 풀려났으며 이란이 이스라엘과의 긴밀한 협력과 이란 내 미국 정부 인사들에 대한 항복, 즉 외교적 면책특권의 확대를 비난하며 소동을 계속했다.1964년 11월 호메이니는 다시 체포되어 이라크 나자프(주로 이라크 나자프)에서 15년 동안 망명 생활을 했다.

이란 혁명의 이념

"불만을 품은 고요함,"[67]의 잠정적인 시기에 시작되는 이란의 상생과 1979년 혁명 사상을 형성할 서구화의 진전으로 국왕의 세속적인 통치의 기본은 생각을 약화시킬:Gharbzadegi—that 서부 문화의 잘랄 Al-e-Ahmad의 방식은 전염병이나 중독으로;[68]알리 시작했다.Shariat나는 억압적인 식민주의, 신식민지주의,[69] 자본주의로부터 제3세계의 진정한 해방자로서의 이슬람에 대한 비전과 모테자 모타하리의 시아파 신앙에 대한 대중화된 재탄생은 모두 퍼졌고 청취자, 독자 그리고 [68]지지자들을 얻었다.

가장 중요한 것은, 호메이니가 부정과 폭정에 대한 반란, 특히 순교는 시아파의 일부이며,[70] 이슬람교도들은 혁명 구호인 "동도 서도 이슬람 공화국도 아니다!"에 영감을 준 자유 자본주의와 공산주의의 영향을 거부해야 한다고 설교했다는 점이다.

호메이니 대통령은 공공의 시각에서 벗어나 이슬람교도들이 주도적인 이슬람 법학자나 [71]법학자들에 의한 통치나 감독이라는 형태로 "보호를 필요로 하는" 정부로서의 velayat-e faqih (법학자의 보호) 이데올로기를 발전시켰다.이러한 [Note 2]규칙은 이슬람에서 궁극적으로 "기도와 단식보다 더 필요한" 것이었는데, 이는 전통적인 샤리아 법으로부터의 이탈로부터 이슬람을 보호하고 그렇게 함으로써 가난, 부당함, 그리고 외국 [72]비신앙자들에 의한 이슬람 땅의 "벼락치기"를 제거할 것이기 때문이다.

이슬람 법학자의 집권을 이 생각이 그의 책 이슬람 정부, 모스크의 설교를 통해, 그리고 학생들 야당 네트워크 사이에서(talabeh), ex-students(Morteza Motahhari, 모하마드 Beheshti, Mohammad-Javad Bahonar, 악바르 하셰미 라프산자니, 모하마드 Mofatteh 같은 수 있는 성직자들), Khomeini[73][74]에 의해 카세트 연설을 밀반입 유포되었다. 그리고 트래드이란 [73]내 전문 사업가(바자리)들.

반대 단체 및 단체

다른 야당 단체로는 메흐디 바자르간이 이끄는 이란 개혁주의 이슬람 자유 운동과 보다 세속적인 국민 전선 등 입헌주의 자유주의자들이었다.그들은 도시 중산층에 기반을 두고 있었고, 샤가 신정체제로 [76]대체하기 보다는 1906년의 이란 헌법을 준수하기를 원했지만, 호메이니의 [77]군대의 결속력과 조직력은 부족했다.

주로 이란의 투데당과 페다이안 게릴라[Note 3] 등 공산주의 단체들은 정부의 탄압으로 상당히 약화되었다.그럼에도 불구하고 게릴라들은 1979년[79] 2월 마지막 전복에서 "정권의 쿠데타"[80]를 실현하는 데 중요한 역할을 했다.가장 강력한 게릴라 단체인 인민 무자헤딘은 좌파 이슬람교도였고 반동적인 성직자들의 영향력에 반대했다.

몇몇 중요한 성직자들은 호메이니의 선례를 따르지 않았다.인기 있는 아야톨라 마흐무드 탈레반은 좌파를 지지한 반면, 이란에서 가장 나이가 많고 영향력 있는 아야톨라 모하마드 카젬 샤리아트마다리는 처음에는 정치에 초연했다가 민주 혁명을 [81]지지했다.

호메이니가 그를 후원하는 한편 국민들 가운데 사무 규칙, whic의 factions[84]—particularly 그의 계획으로 있을 것 구체적인 내용을 피하는(불필요한'atheistic 마르크스 주의자들의를 제외하고)[8][82]은 샤의 정부(부패와 불평등한 소득과 개발)[8][83]의 사회 경제적인 문제에 초점을 두이 반대를 결합하는 일했다.h을 가장 믿서방 제국주의자들의 [Note 4][85]선전 캠페인의 결과로 이란 사람들은 편견을 갖게 되었다.

포스트샤 시대에는 그의 신권정치와 충돌하고 그의 운동에 의해 억압된 일부 혁명가들이 [83]속임수를 호소했지만, 그 사이 반샤의 단결은 [86]유지되었다.

1970–1977

1970년대의 몇몇 사건들이 1979년 혁명의 발판을 마련했다.

1971년 페르세폴리스에서 열린 페르시아 제국의 2500년 기념행사는 사치 때문에 비난을 받았다."이슬람이 금지한 음주를 외국인들이 즐겼기 때문에 이란인들은 축제에서 제외되었을 뿐만 아니라 일부는 [87]굶주리고 있었습니다."5년 뒤 샤는 이란 태양력의 첫 해를 이슬람 히즈리에서 사이러스 대왕의 왕위 계승으로 바꿔 경건한 이란 이슬람교도들을 화나게 했다.[88]

1970년대의 석유 붐은 수만 명의 비인기 외국인 숙련 노동자들의 존재와 함께 인플레이션, 폐기물, 그리고 [89]빈부격차를 가속화시켰다.많은 이란인들은 또한 샤의 가족이 석유로 창출된 수입의 가장 큰 수혜자라는 사실과 국가 소득과 가족 소득 사이의 경계가 모호하다는 사실에 분노했다.1976년까지 샤는 석유 수입으로 10억 달러 이상을 축적했고, 63명의 왕자와 공주를 포함한 그의 가족은 50억 달러에서 200억 달러를 축적했으며, 가족 재단은 약 30억 [90]달러를 통제했다.1977년 중반까지 인플레이션과 싸우기 위한 경제적 긴축 조치는 건설업에 종사하는 도시에 정착하는 수천 명의 가난하고 비숙련 남성 이주자들에게 불균형적으로 영향을 미쳤다.문화적으로나 종교적으로 [91]보수적이었던 많은 이들이 혁명 시위대와 "군인"[92]의 핵심을 형성했다.

모든 이란인들은 새로운 정당인 제즈브-에 라스타히즈 당에 가입하고 회비를 내야 했다. 다른 모든 정당들은 [93]금지되었다.그 정당은 높은 가격으로 상인들을 결산하고 투옥하는 포퓰리즘적인 "반익" 캠페인을 통해 인플레이션에 맞서려는 시도는 [94]암시장을 부채질하면서 상인들을 분노시키고 정치화시켰다.

1977년 샤는 새 미국 대통령 지미 카터의 정치적 권리의 중요성에 대한 "정중한 상기"에 대해 일부 죄수들을 사면하고 적십자사가 감옥을 방문하도록 허용함으로써 대응했다.1977년까지 자유주의 야당은 조직을 결성하고 [95]정부를 비난하는 공개 서한을 발행했다.이러한 배경에서 1977년 10월 테헤란의 독일-이란 문화 협회가 새롭게 부활한 이란 작가 협회와 독일 괴테에 의해 조직된 일련의 문학 낭독회를 개최했을 때 정권에 대한 사회적 불만과 정치적 항의의 공개적인 첫 번째 중요한 징후가 나타났다.인스티튜니트.이 "텐 나이트" (Dah Shab)에서 이란의 가장 저명한 시인 및 작가 57명이 수천 명의 청취자들에게 그들의 작품을 읽어주었다.그들은 검열의 종식을 요구하며 [96]표현의 자유를 주장했다.

또한 1977년에는 인기 있고 영향력 있는 이슬람 이론가 알리 샤리아티가 불가사의한 상황에서 사망했다.이는 둘 다 그를 사바크의 손에 의해 순교자로 간주한 그의 추종자들을 화나게 했고, 호메이니의 잠재적인 혁명적 경쟁자를 제거했다.마침내, 10월에 호메이니의 아들 모스타파가 심장마비로 사망했고, 그의 죽음도 SABAK의 탓으로 돌렸습니다.이후 테헤란에서 열린 모스타파 추도식은 호메이니를 다시 [97][98]주목받게 했다.

아웃브레이크

1977년에는 샤의 정치적 자유화 정책이 진행 중이었다.샤의 세속적인 반대자들은 정부를 [99][100]비난하기 위해 비밀리에 만나기 시작했다.좌파 지식인 사이드 솔탄푸르가 이끄는 이란 작가협회는 테헤란의 괴테 연구소에서 반정부 시를 [99]낭독했다.알리 샤리아티가 영국에서 사망한 직후, 야당은 [14][99]샤가 자신을 살해했다고 비난하면서 또 다른 공개 시위로 이어졌다.

일련의 사건은 루홀라 호메이니의 장남이자 수석 보좌관인 모스타파 호메이니의 사망으로 시작되었다.그는 1977년 10월 23일 자정 이라크 나자프에서 의문스럽게 사망했다.많은 사람들이 그의 죽음이 SABAK에 [101]의한 것이라고 믿었지만, SAVAK와 이라크 정부는 심장마비를 사인으로 선언했다.호메이니는 사건 이후 침묵을 지켰고, 이란에서는 이 소식이 퍼지면서 [102][103]여러 도시에서 항의와 애도 행사가 이어졌다.모스타파의 애도에는 호메이니의 정치적 자격증, 왕정에 대한 지속적인 반대와 그들의 망명에 의해 정치적 캐스팅이 주어졌다.의식의 이러한 차원은 가족의 [19]종교적 자격을 넘어선다.

혁명이 다가오고 있다(1978년)

항의 시작(1월)

1978년 1월 7일, "이란과 붉은색과 검은색 식민지화"라는 제목의 기사가 전국 일간지 에텔라트 신문에 실렸다.정부 요원이 가명으로 작성한 이 보고서는 호메이니를 "영국 요원"이자 "미친 인도 시인"으로 비난하며 이란을 신식민지주의자와 [6][14]공산주의자들에게 팔아넘기려는 음모를 꾸몄다.

기사가 나자마자 호메이니에 대한 모욕에 분노한 쿰시의 종교 신학생들이 경찰과 충돌했다.정부에 따르면 이 충돌로 2명이 사망했으며, 야당에 따르면 70명이 사망하고 500명 이상이 부상했다.마찬가지로,[6][14][100][104][105][106] 서로 다른 출처의 사상자 수치에 불일치가 있다.

야당의 통합(2~3월)

시아파의 관습에 따르면, 제사는 사람이 죽은 [107]지 40일 후에 행해진다.호메이니(순교자의 피가 이슬람의 나무에 물을 주어야 한다고 선언한)[100]에 고무된 급진주의자들은 학생들의 죽음을 추모하기 위해 모스크와 온건파 성직자들을 압박했고,[108] 이 기회를 시위를 일으키는데 이용했다.수년간 종교행사를 수행하는데 사용되어 온 모스크와 바자회의 비공식 네트워크는 점점 더 협력적인 시위 [19][107][109][110]조직으로 통합되었다.

쿰 충돌 40일 만인 2월 18일, 여러 도시에서 시위가 일어났다.[111]가장 큰 폭동은 타브리즈에서 일어났는데, 이 곳은 대규모 폭동으로 전락했다."서양"과 영화관, 술집, 국유 은행, 경찰서와 같은 정부 상징물들이 [107]불탔다.이란 제국군 부대가 질서 회복을 위해 이 도시에 배치됐으며, 정부에 따르면 사망자 수는 [112]6명인 반면 호메이니는 수백 명이 "전투했다"[9][99][100][113]고 주장했다.

40일 뒤인 3월 29일 [107]테헤란을 포함한 최소 55개 도시에서 시위가 조직됐다.점점 더 예측 가능한 양상으로, 주요 [107][114]도시에서 치명적인 폭동이 일어났고, 40일 후인 5월 10일에 다시 일어났다.이로 인해 군 특공대원들이 아야톨라 샤리아트마다리의 집에 총격을 가해 그의 제자 중 한 명이 사망한 사건이 발생했다.샤리아트마다리는 즉시 "헌법 정부"에 대한 지지를 선언하고 1906년 [9][100][107]헌법 정책으로 복귀했다.

정부의 대응

샤는 시위에 완전히 놀랐고,[9][20][6] 설상가상으로 위기 상황에서 종종 우유부단해졌습니다. 사실상 그가 내릴 모든 주요 결정은 그의 정부에 역효과를 초래했고 혁명가들을 [6]더욱 자극했습니다.

[107][108][109][114]그는 Majlis에 완전한 민주 선거 1979년에 열릴 것이라고 약속했다 그 샤 자유화의 그의 계획에보다는still-nascent 반대 운동에 대한 무력 사용을 계속 협상하기:, 검열 완화되어 있는 결의안이 왕실 내의 비리를 줄이기 위해 징집되었다로 결정했다. 정부는;[109]과시위대는 군사법원이 아닌 민간법원에서 재판을 받았고, 빠르게 [111][114]풀려났다.

이란 보안군은 1963년 [112]이후 폭동 진압 훈련이나 장비를 받지 못했다.그 결과, 경찰력은 시위를 통제할 수 없었고, 그래서 군대가 자주 [114]배치되었다.군인들은 치명적인 무력을 사용하지 말라고 지시받았지만, 경험이 없는 군인들은 과도하게 반응하여 반대파를 겁주지 않고 폭력을 부추기고 [112]국왕으로부터 공식적인 비난을 받은 사례도 있었다.미국의 카터 행정부도 이란에 [100][115]대한 비살상 최루탄과 고무탄 판매를 거부했다.

지난 2월 타브리즈 폭동이 일어나자 샤는 야당에 대한 양보로 시내 모든 SAVAK 관리들을 해고했고, 곧 대중이 [9][20][114]비난한 공무원들과 정부 관리들을 해고하기 시작했다.첫 번째 국가적 양보를 통해 그는 강경파인 네마톨라 나시리 SABAK 총장을 보다 온건한 나세르 모가담 [6][114]장군으로 교체했다.정부는 또한 샤리아트마다리와 같은 온건파 종교 지도자들과 협상을 벌이며 그의 [14]집에 대한 급습에 대해 사과했다.

초여름(6월)

여름까지 시위는 정체되어 4개월 동안 꾸준히 진행되었으며, 시위가 더 큰 이스파한과 더 작은 테헤란을 제외한 각 주요 도시에서 약 1만 명의 참가자들이 40일마다 시위를 벌였다.이는 [116]이란에 있는 1500만 명 이상의 성인 중 소수에 해당한다.

호메이니의 희망에 반하여 샤리아트마다리는 6월 17일 애도 시위를 하루 [107]동안 실시할 것을 요구했다.비록 긴장은 여전했지만, 샤의 정책은 효과가 있어 아무제가가 "위기는 끝났다"[117]고 선언하게 만들었다.이란에서의 이러한 사건들과 이후의 사건들은 1947년 [118]CIA가 설립된 이래 미국이 경험한 가장 중요한 전략적 놀라움 중 하나로 자주 언급된다.

정부의 규제 완화의 신호탄으로 카림 산자비, 샤푸르 바흐티아르, 다리우시 포우하르 등 세 명의 세속주의 야당 지도자는 이란 [9][100][109]헌법에 따라 통치할 것을 요구하는 공개 서한을 샤에게 보낼 수 있었다.

시위 재개(8~9월)

자파르 샤리프 에마미 총리 임명 (8월 11일)

8월까지 시위는 "가동"[119]되었고 시위대의 수는 수십만 [116]명으로 급증했다.아무제가르 정부는 인플레이션을 억제하기 위해 지출을 줄이고 사업을 축소했다.그러나 이러한 감축으로 인해 특히 노동자 계층 지역에 사는 젊고, 숙련되지 않은 남성 근로자들의 정리해고가 급증했다.1978년 여름, 노동자 계층은 대규모 [113]거리 시위에 동참했다.게다가 이슬람의 성스러운 달인 라마단이어서 많은 사람들에게 [107]신앙심이 높아졌습니다.

주요 도시에서는 시위가 계속 확대됐고 이스파한에서는 아야톨라 잘랄루딘 [120][107]타헤리의 석방을 위해 시위대가 투쟁하던 치명적인 폭동이 일어났다.8월 11일 서구의 문화와 정부 건물의 상징이 불에 탔고 미국인 노동자를 태운 버스가 [107][109]폭격을 당하면서 도시에 계엄령이 선포되었다.시위를 막지 못하자 아무제가르 총리는 사의를 표명했다.

샤는 점점 더 자신이 상황을 통제하지 못하고 있다고 느꼈고 [9][100]완전한 유화책을 통해 상황을 되찾기를 희망했다.그는 자파르 샤리프 에마미를 베테랑 총리로 임명하기로 결정했다.에마미는 이전 총리 [6][14]재임 기간 동안 부패했다는 평판이 있었지만 성직자들과의 가족 관계 때문에 발탁되었다.

샤프의 지도 아래 샤리프-에마미는 "야당의 [14]요구를 들어주기도 전에 수용하는" 정책을 효과적으로 시작했다.정부는 라스타히즈당을 폐지하고, 모든 정당을 합법화하고 정치범을 석방하며, 표현의 자유를 증가시키고, SAVAK의 권한을 축소하고, 34명의 [109]지휘관을 해임하고, 카지노와 나이트클럽을 폐쇄하고, 제국 달력을 폐지했다.정부는 또한 부패한 정부와 왕족들을 기소하기 시작했다.샤리프-에마미는 향후 [109]선거를 조직하기 위해 아야톨라 샤리아트마다리, 카림 산자비 국민전선 지도자와 협상에 들어갔다.검열이 사실상 중단되었고, 신문들은 종종 샤에 대해 비판적이고 부정적인 시위에 대해 대대적으로 보도하기 시작했다.Majlis (의회)는 [6]또한 정부에 대한 결의안을 발표하기 시작했다.

시네마 렉스 파이어 (8월 19일)

8월 19일 남서부 아바단에서는 방화범 4명이 시네마 렉스 영화관의 문을 막고 불을 질렀다.2001년 [121]미국에서 9.11 테러가 일어나기 전 역사상 가장 큰 테러 공격으로 극장 안에서 422명이 불에 타 사망했다.호메이니는 즉시 샤와 사바크가 불을 지른 것을 비난했고,[9][100][122] 널리 퍼진 혁명 분위기 때문에 대중들은 자신들이 관련이 없다는 정부의 주장에도 불구하고 샤가 불을 지른 것을 비난했습니다.수만 명의 사람들이 거리로 나와 "샤를 불태워라!" "샤가 죄인이다!"[111]라고 외쳤다.

혁명 이후, 많은 사람들은 이슬람 무장세력이 [121][123][124][125][126][127]불을 질렀다고 주장했다.이슬람 공화국 정부가 경찰관을 처형한 후, 유일한 생존 방화범이라고 주장하는 한 남자가 불을 [128]질렀다고 주장했다.수사를 방해하기 위해 재판장들의 사임을 강요한 후, 새 정부는 마침내 그가 혁명적인 [123][128]대의를 위한 궁극적인 희생으로 스스로 그것을 했다고 주장했음에도 불구하고 "샤의 명령에 불을 지른 것"으로 호세인 탈라크자데를 처형했다.

계엄령 선포와 잘레 광장 학살(9월 4일)

9월 4일은 라마단 월말을 기념하는 휴일인 이드 알 피트르를 기념했다.20만 명에서 50만 명의 [107]사람들이 참석한 야외 기도 허가서가 교부되었다.대신 성직자들은 군중들에게 테헤란 중심부를 통과하는 대규모 행진을 지시했고, 보도에 따르면 샤는 불안하고 [107]혼란스러운 채 헬리콥터에서 행진을 지켜보았다.며칠 후, 훨씬 더 큰 시위가 벌어졌고, 처음으로 시위자들은 호메이니의 귀환과 이슬람 공화국 [107]설립을 요구했다.

9월 8일 자정, 샤는 테헤란과 전국의 11개 주요 도시에 계엄령을 선포했다.모든 거리 시위는 금지되었고 야간 통행금지가 설정되었다.테헤란의 계엄사령관은 [9][6][14][99][100][113][121]반대파에 대한 엄한 것으로 알려진 골람 알리 오비시 장군이었다.그러나 샤는 계엄령이 해제되면 자유화를 계속할 것임을 분명히 했다.그는 시위자들이 [100][108][109]거리로 나가는 것을 피하기를 바라며 샤리프-에마미의 시민 정부를 유지했습니다.

그러나 5000명의 시위대는 시위대에 저항하거나 선언문을 듣지 못해 거리로 뛰쳐나와 잘레 [9][19][100]광장에서 군인들과 대치했다.경고사격으로 군중을 해산시키지 못한 후, 군인들은 군중을 향해 직접 발포하여 [107]64명이 사망했고, 오비시 장군은 30명의 군인들이 주변 [9][14][20][100][107][110][122]건물에서 무장 저격수에 의해 사망했다고 주장했다.야당이 블랙 프라이데이라고 부르는 이날 하루 동안 추가 충돌로 인해 야당의 사망자는 [6][113]89명으로 늘어났다.

블랙 프라이데이에 대한 반응

이번 사망은 파키스탄을 충격에 빠트렸고 샤와 야당의 화해 시도에 타격을 입혔다.호메이니는 즉각 "4000명의 무고한 시위대가 시온주의자들에 의해 학살당했다"고 선언했고 이는 정부와의 더 이상의 타협을 거부할 빌미를 제공했다.

샤 자신은 블랙 프라이데이의 사건에 공포를 느꼈고, 비록 이것이 그가 [6][107][112]총격에 책임이 있다는 대중의 인식을 거의 흔들지 않았지만, 그 사건을 신랄하게 비난했다.계엄령이 공식적으로 발효된 가운데, 정부는 시위나 파업을 [109]더 이상 중단하지 않고 시위 지도자들과 협상을 계속하기로 결정했다.이에 따라 [114]군인들의 심각한 개입 없이 시위 집회가 자주 열렸다.

전국 파업(9~11월)

9월 9일에는 테헤란의 주요 정유소 근로자 700명이 파업을 벌였고, 9월 11일에는 다른 5개 도시의 정유소에서도 같은 일이 일어났다.9월 13일 테헤란의 중앙정부 직원들이 동시에 [6][14][99]파업을 시작했다.

10월 하순에는 전국적으로 총파업이 선포되었고, 석유 산업과 인쇄 [19][99]매체에서 가장 큰 피해를 입힌 거의 모든 주요 산업의 근로자들이 직장을 그만두었다.주요 산업 전반에 특별한 "파업 위원회"가 설치되어 활동을 [120]조직하고 조정하였다.

샤는 [109]파업자들을 단속하려는 것이 아니라, 그들에게 후한 임금 인상을 주었으며, 정부 관저에 사는 파업자들은 그들의 [9][6][109]집에 머물도록 허락했다.11월 초까지, 샤 정부의 많은 중요한 관료들은 파업자들을 업무에 [9][6][99][100]복귀시키기 위한 샤의 강제 조치를 요구하고 있었다.

호메이니 프랑스로 이동(11월)

호메이니와 야당의 접촉을 끊고자 샤는 호메이니를 나자프로부터 추방하도록 이라크 정부를 압박했다.호메이니는 이라크를 떠나 프랑스 파리 인근 마을인 노플레샤토에 있는 이란 망명자들이 구입한 집으로 이사했다.샤는 호메이니가 나자프 사원으로부터 고립되고 시위 운동으로부터 고립되기를 바랐다.대신, 그 계획은 역효과를 낳았다.호메이니의 지지자들은 이라크보다 뛰어난 전화와 우편 연결을 가지고 있어 이란에 그의 [14][100][114]설교 테이프와 녹취록으로 넘쳐났다.

샤에게 더 안 좋은 것은 서방 언론, 특히 영국 방송(BBC)이 즉시 호메이니를 [14][129]스포트라이트로 등장시켰다는 점이다.호메이니는 자신을 권력을 추구하지 않고 대신 그의 사람들을 "압박"으로부터 해방시키려는 "동양의 신비주의자"로 묘사하면서 서양에서 빠르게 유명해졌다.보통 그러한 주장에 비판적인 많은 서방 언론 매체들은 호메이니의 가장 강력한 [14][100]도구 중 하나가 되었다.

게다가, 언론의 보도는 아야톨라 샤리아트마다리와 아야톨라 탈레가니 [107][109][114]같은 온건파 성직자들의 영향력을 잠식했다.BBC는 나중에 성명을 발표하면서 샤에게 "비판적인" 기질을 가졌다고 인정했고, BBC의 방송이 "[6]인구의 집단적 인식을 바꾸는데 도움이 되었다"고 말했다.

11월에는 카림 산자비 국가전선의 비종교적인 지도자가 호메이니를 만나기 위해 파리로 날아갔다.그곳에서 두 사람은 "이슬람적이고 민주적인" 헌법 초안을 위한 협정에 서명했다.그것은 성직자들과 세속적인 [6][107]야당들 사이에 이제 공식적인 동맹이 되었음을 암시했다.민주적인 파사드를 만드는 것을 돕기 위해 호메이니는 서구화된 인물들(사데 큐트자데, 에브라힘 야즈디 등)을 야당의 공적인 대변인으로 앉혔고, 신권정치를 [6]만들겠다는 그의 의도에 대해서는 언론에 말하지 않았다.

테헤란 대학 시위(11월 5일)

거리 시위는 군부의 거의 반응 없이 계속되었다; 10월 말, 정부 관계자들은 테헤란 대학을 학생 [109][114]시위대에게 사실상 양도했다.설상가상으로, 야당은 점점 더 무기로 무장하고, 군인들을 향해 총을 쏘고,[20][100] 나라를 불안정하게 만들기 위해 은행과 정부 건물을 공격했다.

11월 5일, 테헤란 대학의 시위는 무장한 [120][19][109][114]군인들과 싸움이 일어난 후 치명적이 되었다.몇 시간 만에 테헤란은 전면적인 폭동을 일으켰다.영화관, 백화점, 정부 및 경찰 건물과 같은 서양 상징물 블록들이 잇따라 압수, 약탈, 불태워졌다.테헤란 주재 영국 대사관도 일부 불에 타 파괴됐고 미국 대사관도 같은 운명을 맞을 뻔했다.이 사건은 외국 관측통들에게 "테헤란이 [9][100][114][130]불탄 날"로 알려지게 되었다.

폭도들의 대부분은 테헤란 남부의 모스크에 의해 조직된 어린 10대 소년들이었고, 그들의 물라들에 의해 서양과 세속적인 [19][114][130]상징들을 공격하고 파괴하도록 격려받았다.군과 경찰은 자신들의 명령에 혼란스러워하고 폭력을 일으키지 말라는 샤의 압력으로 사실상 포기했고 [100][114][130][131]개입하지 않았다.

군사정권 임명(11월 6일)

거리의 상황이 걷잡을 수 없이 악화되자, 이 나라 내에서 유명하고 평판이 좋은 많은 사람들이 샤에게 다가가 혼란을 [6][20][100][114]막아달라고 간청하기 시작했다.

11월 6일 샤프는 샤리프 에마미를 총리직에서 해임하고 대신 [6][130]군사정부를 임명하기로 결정했다.샤는 상황에 [9][100][130]대한 온화한 접근법 때문에 골람-레자 아즈하리 장군을 총리로 선택했다.그가 선택한 내각은 이름뿐인 군사 내각이었고 주로 민간 [130]지도자로 구성되었다.

같은 날 샤는 이란 TV에서 연설을 [6][14][131]했다.그는 이전에 [109]그가 부르기를 고집했던 더 거창한 샤한샤(왕들의 왕) 대신에 자신을 파데샤(주왕)라고 불렀다.그는 연설에서 "나는 당신의 혁명의 목소리를 들었다...이 혁명은 이란의 왕인 내가 지지하지 않을 수 없다"[109][132]고 말했다.그는 자신의 통치 기간 동안 저지른 실수에 대해 사과하고 부패가 [114][131]더 이상 존재하지 않도록 하겠다고 약속했다.그는 민주주의를 실현하기 위해 야당과 협력하기 시작할 것이며 연립정부를 [9][114][131]구성할 것이라고 말했다.사실상 샤는 군사정부(임시 과도정부라고 표현)가 전면적인 [109]탄압을 실시하지 못하도록 억제할 의도였다.

혁명가들이 샤로부터 나약함을 감지하고 "피냄새"[114][132]를 풍기면서 연설은 역효과를 낳았다.호메이니는 샤와의 화해가 없을 것이라고 발표했고 모든 이란인들에게 그를 [114][132]타도할 것을 요구했다.

군 당국은 이란의 주요 산유지인 후제스탄주에 계엄령을 선포하고 석유시설에 병력을 배치했다.해군 병력은 석유 [9][100][130]산업에서도 파업 방해자로 쓰였다.거리 행진은 감소했고 석유 생산량은 다시 증가하기 시작해 혁명 이전의 수준에 [100][130]거의 도달했다.반정부 세력에 대한 상징적인 타격으로 파리 호메이니를 방문했던 카림 산자비는 [109]이란으로 돌아오자마자 체포됐다.

그러나 정부는 여전히 유화정책과 [6][14][114][131]협상정책을 지속했다.샤는 아미르 압바스-호베이다 전 총리와 네마톨라 나시리 [6][14][114]전 사바크 대표를 포함한 100명의 자국 정부 관리들을 부패 혐의로 체포할 것을 명령했다.

무하람 시위(12월 초)

호메이니는 군사정부를 비난하고 시위를 [107][133]계속할 것을 요구했다.그와 시위 주최자들은 이슬람교의 신성한 달인 무하람 기간 동안 일련의 점증하는 시위를 계획했으며, 타수아와 아슈라의 날에 대규모 시위로 절정을 이뤘습니다. 아슈라는 세 번째 시아파 이슬람교도 이맘 [107]후세인 이븐 알리의 순교를 기념하는 날이다.

군 당국이 거리 시위를 금지하고 통행금지를 연장하는 동안, 샤는 잠재적인 [109]폭력에 대한 깊은 불안감에 직면했다.

1978년 12월 2일, 무하람 시위가 시작되었다.이슬람의 달로 이름 붙여진 무하람 시위는 인상적으로 거대하고 중추적이었다.200만 명이[134] 넘는 시위대(대부분은 테헤란 남부 사원에서 온 물라들에 의해 개종된 10대들)가 거리로 뛰쳐나와 샤하드 광장을 가득 메웠다.시위대는 야간 통행금지를 무시하고 종종 옥상으로 올라가 "알라우-악바르" ('신은 위대하다')를 외치며 밖으로 나갔다.한 목격자에 따르면, 거리에서의 많은 충돌은 심각하기보다는 장난기 있는 분위기였고,[114] 보안군은 반대파에 대해 "키드 글러브"를 사용했다고 한다.그럼에도 불구하고, 정부는 적어도 12명의 야당이 [133]사망했다고 보고했다.

시위대는 샤 모하마드 레자 팔라비가 권좌에서 물러나고 아야톨라 루홀라 호메이니가 망명지에서 복귀할 것을 요구했다.시위는 믿을 수 없을 정도로 빠르게 증가하여 첫 주에 6백만에서 9백만 명에 달했다.인구의 약 5%가 무하람 시위로 거리로 나왔다.무하람의 달 시작과 끝 모두, 시위는 성공했고, 샤는 그 [134]달 말에 권좌에서 물러났다.

혁명이 성공하자 아야톨라 호메이니는 이란으로 돌아와 종교와 정치의 영원한 지도자로 거듭났다.호메이니는 1930년대 [135]그의 스승인 유명한 학자 야즈디 하리가 사망한 이후 유명세를 타면서 수년간 샤의 야당 지도자였다.망명 생활 중에도 호메이니 씨는 이란과 관련이 있었다.그는 이란 국경 밖의 시위를 지지하면서 "자유와 제국주의의 결속으로부터의 해방"이 [135]임박했다고 선언했다.

타스아·아슈라 행진(12월 10일~11일)

타수아와 아슈라(12월 10일과 11일)의 날이 다가옴에 따라 샤는 치명적인 대결을 막기 위해 후퇴하기 시작했다.아야톨라 샤리아트마다리와의 협상에서 샤는 120명의 정치범과 카림 산자비의 석방을 명령했고, 12월 8일 거리 시위의 금지를 철회했다.행진자들에게 허가증이 발급되었고, 군대는 행렬의 길에서 제거되었다.이에 따라 샤리아트마다리는 시위 [109]기간 동안 폭력사태가 발생하지 않도록 하겠다고 약속했다.

타수아와 아슈라 시절인 1978년 12월 10일과 11일에는 600만에서 900만 명의 반샤 시위대가 이란 전역을 행진했다.한 역사학자에 따르면, "과장이라고 해서 할인하더라도,[136] 이 수치는 역사상 가장 큰 규모의 시위 사건일 수도 있다."이 행진은 아야톨라 탈레반과 카림 산자비 국민전선 지도자에 의해 주도되었으며, 이는 세속적이고 종교적인 반대파의 "통합"을 상징한다.물라와 바자회는 사실상 집회를 감시했고 폭력을 시도했던 시위자들은 [107]제지당했다.

이틀간 10%가 넘는 국민이 반(反) 샤흐 시위를 벌였으며, 이는 이전의 어떤 혁명보다도 높은 비율일 가능성이 있다.프랑스, 러시아, 루마니아 혁명이 1%의 [24]인구를 포함하는 것은 드문 일이다.

혁명(1978년 후반-1979년)

이란 사회 대부분은 다가오는 혁명에 대해 행복감에 빠져 있었다.세속적이고 좌파적인 정치인들은 호메이니가 그들이 지지하는 모든 [6]입장과는 정반대라는 사실을 무시한 채 그 여파로 권력을 잡기를 희망하며 이 운동에 뛰어들었다.호메이니가 자유주의자가 아니라는 것이 세속적인 이란인들에게 점점 더 분명해지는 반면, 그는 유명 인사로 널리 인식되었고, 결국 권력은 세속적인 [6][114]집단에게 넘어갈 것이다.

군의 사기저하(1978년 12월)

군 지도부는 우유부단함 때문에 점점 더 마비되었고 일반 병사들은 자신들의 무기를 사용하는 것이 금지되어 있는 동안 시위대에 맞서야 했고,[112] 만약 그들이 무기를 사용한다면 샤에 의해 비난 받았다.호메이니는 점점 더 군인들에게 [111][100]야당에 귀순할 것을 요구했다.혁명가들은 탈영병들에게 꽃과 민간 의복을 주면서 잔류병들에게는 보복하겠다고 위협했다.

12월 11일, 테헤란의 라비잔 막사에서 12명의 장교가 자국군에 의해 사살되었다.더 이상의 반란이 두려워서 많은 병사들이 [112]병영으로 돌려보내졌다.마슈하드(이란에서 두 번째로 큰 도시)는 시위대에게 버림받았고, 많은 지방 도시들에서 시위자들이 효과적으로 [107]통제되었다.

야당과 미국 및 내부 협상(1978년 12월 말)

카터 행정부는 [137]군주제에 대한 지속적인 지원에 대한 논쟁에 점점 더 몰두하게 되었다.11월에 윌리엄 설리번 대사는 카터에게 전보를[137] 보냈다.이 전보는 사실상 샤가 시위에서 살아남지 못할 것이며 미국은 샤의 정부에 대한 지지를 철회하고 군주를 설득하여 퇴위시키는 것을 고려해야 한다는 그의 믿음을 선언했다.미국은 친서방군 장교, 중산층 전문가, 온건파 성직자들로 구성된 연합군을 결성하는 데 도움을 줄 것이며, 호메이니는 간디 같은 정신적 [137]지도자로 취임할 것이다.

이 전보는 미국 내각에서 활발한 논쟁을 불러일으켰으며, 즈비그니예프 브레진스키 [137]국가안보보좌관과 같은 일부 인사들은 이를 전면 거부했다.사이러스 밴스 국무장관은 군사 [107]진압을 거부했다. 그와 그의 지지자들은 호메이니와 그의 [115][137]집단의 "온건하고 진보적인" 의도를 믿었다.

친호메이니 진영과의 접촉이 활발해졌다.혁명가들의 반응을 바탕으로, 일부 미국 관리들(특히 설리번 대사)은 호메이니가 진정으로 민주주의를 [6]만들려 한다고 느꼈다.역사학자 압바스 밀라니에 따르면, 이는 미국이 호메이니의 [6][138][139]권력 상승을 효과적으로 돕는 결과를 낳았다.

샤는 민간인이자 야당의 일원인 새 총리를 찾기 시작했다.12월 28일, 그는 또 다른 주요 국민 전선 인물인 샤푸르 바흐티아르와 협정을 맺었다.바흐티아르는 총리로 임명될 것이고, 샤와 그의 가족은 이 나라를 떠날 것이다.그의 왕실의 의무는 섭정위원회에 의해 수행될 것이며, 그가 떠난 지 3개월 후에 이란이 군주제로 남을 것인지 공화국이 될 것인지를 결정하는 국민투표가 제출될 것이다.샤의 적수였던 바흐티아르는 [14]민주주의보다는 강경한 종교 통치를 시행하려는 호메이니의 의도를 점점 더 잘 알고 있기 때문에 정부에 합류할 동기를 부여하게 되었다.카림 산자비는 즉시 바흐티아르를 국민전선에서 추방했고, 바흐티아르는 호메이니에 의해 비난받았다. 호메이니는 그의 정부를 받아들이는 것이 "거짓 [6][140]신에 대한 복종"과 같다고 선언했다.

샤가 떠난다(1979년 1월)

샤는 바흐티아르가 설립되기를 바라며 그의 출발을 계속 미루었다.그 결과 이란 국민들에게 바흐티아르는 샤의 마지막 총리로 비쳐져 그의 지지를 [107]약화시켰다.

나토 부사령관 로버트 하이어가 이란에 [6]입성했다.친(親)샤 군사 쿠데타 가능성은 여전했지만, 하이어는 바흐티아르의 과도정부에 [6][100][107][141]합의하기 위해 군 지도자들을 만나 그들과 호메이니 동맹들 사이에 회담을 설정했다.설리번 대사는 이에 동의하지 않고, 호메이니의 반대 [107][141]세력과 직접 협력하도록 하우저에게 압력을 넣으려 했다.그럼에도 불구하고, Huyser는 승리했고 군대와 야당과 함께 계속 일했다.그는 2월 [107][141]3일에 이란을 떠났다.샤는 후이저의 사명에 개인적으로 분노했고, 미국은 더 이상 그의 권력을 [100]원하지 않는다고 느꼈다.

1979년 1월 16일 아침, 바흐티아르는 공식적으로 총리로 임명되었다.같은 날, 눈물을 흘린 샤와 그의 가족은 이집트로 망명하기 위해 이란을 떠나 다시는 [6]돌아오지 않았다.

바흐티아르의 총리직과 호메이니의 복귀(1979년 1월~2월)

샤의 퇴임 소식이 알려지자 전국 곳곳에서는 기쁨의 광경이 펼쳐졌다.수백만 명의 사람들이 거리로 쏟아져 나왔고,[107][142] 사실상 남아있는 군주제의 모든 표지판은 군중들에 의해 허물어졌다.바흐티아르는 SAVAK를 해산하고 남은 정치범들을 모두 석방했다.그는 군부에 대규모 시위를 허용하라고 명령했고, 자유 선거를 약속했으며, 혁명가들을 "국민 통합"[140][143]의 정부로 초대했다.

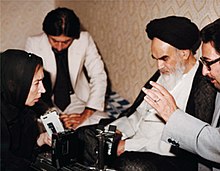

바흐티아르는 "우리는 곧 아야톨라 호메이니를 고향으로 맞이할 영광을 갖게 될 것"[140]이라고 선언하면서 신성한 도시 콤에 바티칸과 같은 국가를 만들려는 의도로 호메이니를 이란으로 다시 초대했다.1979년 2월 1일 호메이니는 에어프랑스 보잉 [144]747기를 타고 테헤란으로 돌아왔다.수백만 명의 이란인들이 그를 공항에서 데려온 차가 열렬한 환영 [145]인파에 압도된 후 그는 헬리콥터를 타야 했다.

호메이니는 이제 논란의 여지가 없는 [4][146]혁명의 지도자였을 뿐만 아니라, 일부에서 반신반의 인물이 되어 비행기에서 내려오면서 '호메이니, 오 이맘, 우리는 당신에게 경의를 표합니다. 당신에게 평화가 있기를 빕니다'라고 외치며 환영했다.[147]군중들은 이제 "이슬람, 이슬람, 호메이니, 우리는 당신을 따를 것이다," 그리고 심지어 "[148]왕을 위한 호메이니"를 외치는 것으로 알려졌다.오랜 망명 생활을 마치고 귀국한 소감을 묻는 기자의 질문에 호메이니는 "아무것도 아니다"라고 답했다.

호메이니 대통령은 이날 바흐티아르 정부에 대한 거부 의사를 분명히 했다.나는 정부를 임명하고, 나는 이 나라를 지지하는 정부를 임명한다."[140]2월 5일은 Refah 학교 남쪽 이란에서 그의 본부에서 그는 일각에서 자신의 총리로 야당 지도자 메흐디 Bazargan(그 religious-nationalist 자유 운동에서, 국민 전선과 제휴)신설되고 종교 의무로서 Bazargan에게 순종하기 이란인들에게 명하신 대로 임시 혁명 정부는 선언했다.[120][14][107][140]

내가 성스러운 법 집행자로부터 받은 후견인이라 할지라도, 나는 이로써 바자간을 통치자로 선포한다. 내가 그를 임명했으니, 그는 복종해야 한다.국민은 그에게 복종해야 한다.이것은 평범한 정부가 아니다.그것은 샤리아에 기반을 둔 정부이다.이 정부에 반대하는 것은 이슬람의 샤리아에 반대하는 것을 의미합니다.신의 정부에 대한 반란은 신에 대한 반란이다.신에 대한 반란은 [149][150]신성모독이다.

화가 난 바흐티아르는 자신의 연설을 했다.그는 합법적인 지도자임을 재확인하며 다음과 같이 선언했다.

이란은 하나의 정부를 가지고 있다.나나 당신이나 다른 이란인에게 이 이상은 참을 수 없습니다.이슬람교도로서 지하드가 이슬람교도 한 명이 다른 이슬람교도에게 대항하는 것을 가리킨다는 것을 들어본 적이 없다.나는 아야톨라 호메이니에게 임시 정부를 구성하도록 허락하지 않을 것이다.살다 보면 단호히 거절해야 할 때가 온다.나는 이슬람 공화국에 관한 책을 본 적이 없고, 그 문제에 관한 다른 사람도 본 적이 없다.아야톨라를 둘러싼 몇몇 사람들은 폭력적인 독수리 같다...성직자들은 쿰에 가서 그들 주변에 벽을 쌓고 그들만의 [140]바티칸을 만들어야 한다.

무장 전투와 군주제 붕괴(1979년 2월)

두 경쟁 정부 사이의 긴장이 급속히 고조되었다.그의 지지를 보여주기 위해 호메이니 대통령은 시위대가 전국 거리를 점거할 것을 요구했다.그는 또한 미국 관리들에게 바흐티아르에 [6]대한 지지를 철회할 것을 경고하는 서한을 보냈다.바흐티아르는 호메이니로 망명하면서 점점 고립되어 갔다.군대는 지도력이 완전히 마비된 채 무너지고 있었고, 바흐티아르를 지지해야 할지 아니면 스스로 행동해야 할지 확신이 없었고, 일반 병사들은 사기가 떨어졌거나 [107][112]탈영했다.

2월 9일, 도산 타페 공군기지에서 친 호메이니 공군 기술자들의 반란이 일어났다.친샤 불멸의 근위대가 반군을 체포하려 하자 무장 전투가 벌어졌다.곧 많은 군중이 거리로 나와 바리케이드를 쌓고 반군을 지지했고 이슬람-마르크스주의 게릴라들은 그들의 무기를 들고 [107]지원에 동참했다.

무장 반군들은 무기 공장을 공격하여 5만 자루의 기관총을 탈취하여 전투에 참여한 민간인들에게 배포했다.반군은 테헤란 전역의 경찰서와 군 기지를 습격하기 시작했다.이 도시의 계엄사령관인 메흐디 라히미는 민간인 [131]사상자가 발생할 것을 우려하여 3만 명의 충성스런 불멸의 경비대를 동원하지 않기로 결정했다.

비이슬람 임시정부의 마지막 붕괴는 2월 11일 오후 2시 최고군사위원회가 "현재의 정치적 분쟁에서 중립적"이라고 선언했을 때 일어났다.더 이상의 무질서와 [151][152]유혈사태를 막기 위해"모든 군 병력은 그들의 기지로 돌아가라는 명령을 받았고, 사실상 호메이니에게 [112]국가 전체의 통제권을 넘겨주었다.혁명가들은 팔라비 왕조의 정부 청사, TV, 라디오 방송국, 궁전을 장악하여 이란 왕정의 종말을 알렸다.바흐티아르는 총탄을 맞고 궁전을 탈출해 변장을 하고 이란을 탈출했다.그는 1991년 파리에서 이슬람 공화국 요원에게 암살당했다.

이 시기는 이란에서는 매년 2월 1일부터 11일까지 '파쥬르의 [153]10년'으로 기념되고 있다.이슬람 혁명의 승전 기념일은 국가가 후원하는 시위가 [154][155]있는 국경일이다.

사상자

일부 정보원 (순교재단의 연구원 Emadeddin Baghi와 같은)은 혁명 [156][Note 5]기간인 1978-79년에 2,781명의 시위대와 혁명가들이 사망했다고 주장한다.호메이니는 훨씬 더 많은 숫자에 대해 보고했다; 그는 "샤의 [157][158][159]정권에 의해 6만 명의 남자, 여자, 아이들이 순교했다"고 말했다.이 60,000명의 숫자와 관련하여, 군사 역사학자 스펜서 C. 터커는 "코메이니 정권이 선전을 목적으로 혁명의 사망자 수를 크게 과장했다"[160]고 지적한다.터커는 이란 혁명(1978년 1월부터 1979년 2월까지) 중 사망한 것으로 추정되는 것에 대한 역사학자들의 합의가 532명에서 2781명 [160]사이라고 설명한다.역사학자 에르반드 아브라함안에 따르면 혁명이 통합되면서 혁명법원에 의해 처형된 숫자는 혁명을 [162]막으려는 왕당 정부에 의해 살해된 숫자보다 많았다.[161]터커의 추산에 따르면 1980년부터 1985년까지 25,000명에서 40,000명의 이란인이 체포되었고 15,000명의 이란인이 재판을 받았으며 8,000명에서 9,500명의 [160]이란인이 처형되었다.

이란 혁명의 노래

혁명과 가장 밀접한 관련이 있는 노래는 이슬람 혁명 기간 중, 그리고 팔라비 [163]왕조에 반대하여 작곡된 서사시 발라드이다.혁명이 통합되기 전에, 이러한 구호는 다양한 정치적 지지자들에 의해 만들어졌고, 종종 지하와 홈 스튜디오의 카세트 테이프에 녹음되었다.학교에서, 이 노래들은 Fajr [164]Decidents의 축하의 일부로 학생들이 불렀다."이란 이란" 또는 "알라 알라" 구호는 유명한 혁명 [165]노래입니다.

여성의 역할

이란 혁명은 젠더형 혁명이었다; 새 정권의 수사학의 대부분은 이란 [166]사회에서 여성의 지위에 초점이 맞춰졌다.미사여구를 넘어 수천 명의 여성들이 [167]혁명에 대거 동원됐고,[168] 남성들과 함께 다양한 그룹의 여성들이 적극적으로 참여했다.여성들은 투표를 통해 참여했을 뿐만 아니라 행진, 시위, [169]구호를 외치며 혁명에 기여했다.여성들은 도움을 요청하고 도움이 필요한 사람들을 위해 집을 열어주는 의사들을 포함하여 부상자들을 돌보는 일에 관여했다.여성들은 종종 살해, 고문, 체포 또는 부상을 당했고 일부는 게릴라 활동에 참여했으며 대부분은 비폭력적인 [170]방법으로 기여했다.많은 여성들이 혁명에 직접 관여하는 것뿐만 아니라 남성과 다른 비정치적인 여성들을 동원하는 데 있어서도 중요한 역할을 했다.많은 여성들이 아이들을 안고 시위를 벌였고,[170] 그들의 존재는 필요하면 총을 쏘라는 명령을 받은 군인들을 무장 해제시키는 주요 이유 중 하나였다.

여성 참여에 대한 호메이니의 미사여구

아야톨라 호메이니 씨는 "여러분들은 여러분이 이 운동의 선두에 있다는 것을 증명했습니다.당신은 우리의 이슬람 운동에 큰 몫을 하고 있습니다.우리나라의 미래는 여러분의 [171]지원에 달려 있습니다.그는 히잡의 이미지를 혁명의 상징으로 언급하며 "존경받는 여성들이 국왕 정권에 대한 혐오감을 표현하기 위해 겸손한 복장을 하고 시위하는 나라- 그런 나라가 [172]승리할 것이다"라고 말했다.그는 또 "최근 시위에는 각계각층의 여성들이 참여했다"며 "우리는 이것을 '거리의 주민'이라고 부르고 있다"고 말했다.여성은 독립과 자유를 위한 [173]투쟁에서 남성과 나란히 싸웠다.호메이니는 여성들에게 여러 도시에서 반샤 시위에 참여할 것을 호소했다.게다가 여성들은 나중에 이슬람 공화국과 새로운 [169]헌법에 찬성표를 던지려는 호메이니의 충동에 응했다.여성들은 혁명에 매우 중추적이어서 여성들이 단체 방청객으로 오는 것을 금지하자는 최고 지원군의 제안에 대해 호메이니는 "나는 이 여성들과 함께 샤를 내쫓았다. 그들이 [172]오는 데는 아무런 문제가 없다"고 말했다.

혁명 후, 호메이니 씨는 남성들을 동원한 여성들을 칭찬하면서, 이 운동의 성공의 많은 부분을 여성들에게 돌렸다. "여러분들은 여러분이 운동의 선봉장이라는 것을 증명했고, 남성들은 여러분들로부터 영감을 얻고, 이란의 남성들은 존경받는 여성들로부터 교훈을 얻었다.당신은 [171]그 운동의 선두에 서 있습니다.

호메이니와 그의 동료 지도자들은 여성 인권 문제를 둘러싸고 춤을 추었고 오히려 여성들에게 시위에 참여하도록 독려하고 반샤 [174]정서를 부추기는 등 여성들을 동원하는 데 수사력을 집중했다는 주장이 있다.

여성의 참여율 변동

혁명에 대한 여성의 공헌과 이러한 공헌의 배후에 있는 의도는 복잡하고 층이 있다.여성들이 혁명의 일부가 된 동기는 복잡하고 종교적, 정치적, 경제적[175] 이유들 사이에서 다양했으며 여성들은 다양한 계급과 [176]배경에서 참여하였다.노동자 계층과 [170]농촌 출신 여성들뿐만 아니라 세속, 도시, 전문 가정의 많은 서양 교육 받은 중상류 여성들도 참여했습니다.피다이얀 칼크처럼 다양한 그룹이 있었고, 무자헤딘은 샤의 [170]정권에 대항하는 혁명 기간 동안 게릴라 부대로 기능했다.이슬람공화국의 정치적 지위에서 때로는 수렴하고 때로는 이탈하는 다양한 의제를 가진 다른 여성 그룹도 있었다.예를 들어 팔라비 왕조 때부터 존재했던 조직적인 페미니즘은 샤가 이슬람주의자들을 [172]달래기 위해 여성 문제에 대한 각료직을 사임한 후 혁명 운동에 동참했다.이란 여성단체 회원들은 혁명을 지지하기 위해 행진을 벌였고 정부와 연계된 여성들도 샤의 [174]정권에 등을 돌리는 것이 중요했다.하지만, 후에 여성복에 대한 혁명의 입장과 여성복에 대한 여성운동가들의 입장 사이에 약간의 긴장감이 있었고 그들은 [175]반대 행사에서 불편함을 느끼기 시작했다.

어떤 사람들은 이러한 정치화와 여성 동원이 새 정권이 그들을 대중과 정치 영역에서 몰아내는 것을 어렵게 만들었다고 주장한다.혁명은 (대부분의 시위와 [177]투표를 통해) 이란 여성들의 정치에 대한 전례 없는 개방으로 이어졌고, 일부 저자들은 이것이 이란 여성들의 정치 참여와 공공 [169]영역에서의 역할에 지속적인 영향을 미쳤다고 주장한다.일부 여성들은 마르지 하디치와 같은 새 정권의 지도자들의 내부 모임에 속해 있기도 했다.여성의 정치화 외에도 혁명 기간 동안 여성들이 정치에 참여하도록 강요한 특별한 상황들이 있었다.예를 들어, "계엄령과 통금 시간, 가게와 직장 폐쇄의 조합, 가을과 겨울의 추위는 종종 가정 내에 정치적 논의의 [178]중심이 되는 결과를 초래했다."여성들은 남성들과 함께 뉴스와 언론, 정치적 토론에 참여하며 "혁명은 [178]남녀노소를 불문하고 누구에게나 관심 있는 유일한 주제였다"고 말했다.1978년과 1979년 동안 여성 가정에서는 대인관계 소식과 일화를 주고받는 모임이 많았다.이러한 개인 계정들은 많은 [170]사람들에 의해 공식적인 뉴스 보도가 신뢰받지 못했던 시대에 가치가 있었다.

활동가, 종교인, 정권에 불만을 품은 여성들은 반샤 우산 아래 단결할 수 있었다.그러나 "여성들은 혁명에 동참하는 이유로 단결되지 않은 만큼 혁명과 그 결과에 대한 그들의 의견도 단결되지 않았다"[179]는 점에 주목해야 한다.이러한 동원과 높은 여성 참여율에도 불구하고, 그들은 여전히 남성들에게 독점적인 지도적 지위에서 유지되었다; 여성들은 [174]혁명의 엘리트 계층이라기 보다는 평민의 일부라고 여겨진다.

여성의 참여에 관한 학술 문헌

혁명에 [169]관한 여성의 개별적인 이야기를 탐구하는 학술 문헌이 있지만, 대부분의 학술적 작품은 혁명 중 이란 여성의 역할보다는 혁명이 여성에 미치는 영향에 초점을 맞추고 있다.스콜라 Guity Nashat을 강조 이 혁명을 무시한 측면,"비록 그 사건들이 2월 11일 혁명에 이르기에 여성들의 참여의 성공에 도움이 되었습니다, 대부분의 연구 참여하거나 자신들의 기여에 대한 이유를 다루지 않았다."[180]자넷 바우어는 여성들의 일상 생활을 검사하는 필요성을 주장하고 있다., 그들의 생활 조건과 혁명의 사회 정치적인 사건에 대한 그들의 참여를 이해하기 위해 다른 그룹과의 관계.그는 또 혁명 직전 사회생활과 계급 차이를 형성한 문화 이념 사회 물질적 요인을 연구해 이란 여성의 사회 의식이 어떻게 발전했는지, 그리고 그것이 어떻게 그들을 대중의 [170]시위에 참여하게 했는지 이해할 필요가 있다고 설명한다.Caroline M. Brooks는 여성들이 Majlis가 아닌 시위를 통해 그들의 우려를 표현하도록 내버려졌다고 주장한다.따라서, 이것은 "운동가 여성들에게 위험한 협상 위치"를 만들어냈다. 왜냐하면 그들은 지성을 통해 그들의 입장을 주장하기 보다는 "거리에서 숫자로 무장하고 무력으로 [174]격퇴"할 수 있었기 때문이다.

학술 문헌에는 여성을 동원한 이유에 대한 몇 가지 논쟁이 있는 이해들이 있다.어떤 이들은 여성의 미시적 행동이 종교적, 정치적 이데올로기를 통해 이해될 수 있다고 주장하는 반면,[170] 다른 이들은 사실 연구해야 할 정보, 상징, 맥락의 조작의 효과라고 주장한다.

여파

1979년 초부터 1982년 또는 1983년까지 이란은 "혁명적 위기 모드"[181]에 있었다.전제군주제가 [182]전복된 후 경제와 정부기구가 붕괴되고 군과 보안군은 혼란에 빠졌다.그러나 1982년까지 호메이니와 그의 지지자들은 경쟁 분파를 분쇄하고 지역 반란을 진압하고 권력을 공고히 했다.

동시에, 위기와 해결의 두 가지 사건은 이란 인질 사태, 사담 후세인의 이라크 침공, 그리고 아볼라산 바니사드르 [181][183]대통령직이었다.

호메이니의 권력 강화

혁명가들 간의 갈등

일부 관찰자들은 그의 핵심 지지자들을 제외한 연합군의 멤버들 호메이니 영적 지도자의 통치자에게도 이상이 되기 위한 것 생각"로고anti-dictatorial 진정한 대중들의 모든anti-Shah 폭넓은 연대에 기반을 두고 곧 이슬람 원리 주의자 power-grab로 탈바꿈시켰다 어떻게 시작했다,"[185] 믿는다.[186]호메이니는 70대 중반으로 공직에 오른 적이 없고 이란을 떠난 지 10년이 넘었으며 질문자들에게 "종교 고위 인사들은 [184]통치를 원하지 않는다"고 말했다.그러나 이맘의 중심적 역할을 누구도 부인할 수 없었고, 다른 파벌들은 너무 작아서 실질적인 영향을 미칠 수 없었다.

또 다른 견해는 호메이니가 "이데올로기적, 정치적, [187]조직적 패권을 압도적"이었고, 비신화 단체들은 대중의 지지를 [Note 6]받는 호메이니의 운동에 심각하게 도전한 적이 없다는 것이다.호메이니에 반대하는 이란인들은 이란 [189]정부를 전복시키려는 외국 주도의 '제5의 칼럼니스트'라고 주장해 왔다.

혁명조직의 호메이니와 그의 추종자들은 메흐디 바자르간의 이란 임시정부 등 임시동맹국을[191] 이용해 자신이 이끄는[190] 이슬람공화국을 [192]위한 호메이니의 벨라야트-에 파키흐 디자인을 실행했다.

혁명의 조직

| 시리즈의 일부 이슬람주의 |

|---|

| |

| 정치 시리즈의 일부 |

| 공화주의 |

|---|

| |

The most important bodies of the revolution were the Revolutionary Council, the Revolutionary Guards, Revolutionary Tribunals, Islamic Republican Party, and Revolutionary Committees (komitehs).[193]

While the moderate Bazargan and his government (temporarily) reassured the middle class, it became apparent they did not have power over the "Khomeinist" revolutionary bodies, particularly the Revolutionary Council (the "real power" in the revolutionary state),[194][195] and later the Islamic Republican Party. Inevitably, the overlapping authority of the Revolutionary Council (which had the power to pass laws) and Bazargan's government was a source of conflict,[196] despite the fact that both had been approved by and/or put in place by Khomeini.

This conflict lasted only a few months however. The provisional government fell shortly after American Embassy officials were taken hostage on 4 November 1979. Bazargan's resignation was received by Khomeini without complaint, saying "Mr. Bazargan ... was a little tired and preferred to stay on the sidelines for a while." Khomeini later described his appointment of Bazargan as a "mistake."[197]

The Revolutionary Guard, or Pasdaran-e Enqelab, was established by Khomeini on 5 May 1979, as a counterweight both to the armed groups of the left, and to the Shah's military. The guard eventually grew into "a full-scale" military force,[198] becoming "the strongest institution of the revolution."[199]

Serving under the Pasdaran were/are the Baseej-e Mostaz'afin, ("Oppressed Mobilization")[200] volunteers in everything from earthquake emergency management to attacking opposition demonstrators and newspaper offices.[201] The Islamic Republican Party[202] then fought to establish a theocratic government by velayat-e faqih.

Thousands of komiteh or Revolutionary Committees[203] served as "the eyes and ears" of the new rule and are credited by critics with "many arbitrary arrests, executions and confiscations of property".[204]

Also enforcing the will of the government were the Hezbollahi (the Party of God), "strong-arm thugs" who attacked demonstrators and offices of newspapers critical of Khomeini.[205]

Two major political groups that formed after the fall of the Shah that clashed with and were eventually suppressed by pro-Khomeini groups, were the moderate religious Muslim People's Republican Party (MPRP) which was associated with Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari, and the secular leftist National Democratic Front (NDF).

1979 ethnic uprisings

Following the events of the revolution, Marxist guerrillas and federalist parties revolted in some regions comprising Khuzistan, Kurdistan and Gonbad-e Qabus, which resulted in fighting between them and revolutionary forces. These revolts began in April 1979 and lasted between several months to over a year, depending on the region.

Establishment of Islamic republic government

Referendum of 12 Farvardin

On 30 and 31 March (Farvardin 10, 11) a referendum was held over whether to replace the monarchy with an "Islamic republic". Khomeini called for a massive turnout[206] and only the National Democratic Front, Fadayan, and several Kurdish parties opposed the vote.[206] The results showed that 98.2% had voted in favor of the Islamic Republic.[206]

Writing of the constitution

In June 1979 the Freedom Movement released its draft constitution for the Islamic Republic that it had been working on since Khomeini was in exile. It included a Guardian Council to veto un-Islamic legislation, but had no guardian jurist ruler.[207] Leftists found the draft too conservative and in need of major changes but Khomeini declared it 'correct'.[208] To approve the new constitution and prevent leftist alterations, a relatively small seventy-three-member Assembly of Experts for Constitution was elected that summer. Critics complained that "vote-rigging, violence against undesirable candidates and the dissemination of false information" was used to "produce an assembly overwhelmingly dominated by clergy, all took active roles during the revolution and loyal to Khomeini."[209]

Khomeini (and the assembly) now rejected the constitution – its correctness notwithstanding – and Khomeini declared that the new government should be based "100% on Islam."[210]

In addition to the president, the new constitution included a more powerful post of guardian jurist ruler intended for Khomeini,[211] with control of the military and security services, and power to appoint several top government and judicial officials. It increased the power and number of clerics on the Council of Guardians and gave it control over elections[212] as well as laws passed by the legislature.

The new constitution was also approved overwhelmingly by the December 1979 constitutional referendum, but with more opposition[Note 7] and smaller turnout.[213]

Hostage crisis

In late October 1979, the exiled and dying Shah was admitted into the United States for cancer treatment. In Iran there was an immediate outcry, and both Khomeini and leftist groups demanded the Shah's return to Iran for trial and execution. On 4 November 1979 youthful Islamists, calling themselves Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, invaded the US embassy compound in Tehran and seized its staff. Revolutionaries were angry because of how the Shah had left Iran which spawned rumors of another U.S.–backed coup in Iran that would re-install him. The occupation was also intended as leverage to demand the return of the Shah to stand trial in exchange for the hostages, and depose Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan, who they believed was plotting to normalize relations with the U.S. The students held 52 American diplomats hostage for 444 days, which played a role in helping to pass the constitution, suppressing moderates, and otherwise radicalising the revolution.[214]

Holding the hostages was very popular and continued even after the death of the Shah. As Khomeini explained to his future President Banisadr, "This action has many benefits. ... This has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people's vote without difficulty ..."[215]

With great publicity the students released documents from the American embassy, which they labeled a "den of spies",[216] showing that moderate Iranian leaders had met with U.S. officials (and didn't release similar evidence of high-ranking Islamists having done the same).[217] Among the casualties of the hostage crisis was Prime Minister Bazargan and his government, who resigned in November unable to enforce the government's order to release the hostages.[218]

The prestige of Khomeini and the hostage taking was further enhanced with the failure of a hostage rescue attempt, widely credited to divine intervention.[219]

The hostage crisis ended with the signing of the Algiers Accords in Algeria on 19 January 1981. The hostages were formally released to United States custody the following day, just minutes after Ronald Reagan was sworn in as the new American president.

Suppression of opposition

In early March 1979, Khomeini announced, "do not use this term, 'democratic.' That is the Western style," giving pro-democracy liberals (and later leftists) a taste of disappointments to come.[206] In succession the National Democratic Front was banned in August 1979, the provisional government was disempowered in November, the Muslim People's Republican Party was banned in January 1980, the People's Mujahedin of Iran guerrillas came under attack in February 1980, a purge of universities started in March 1980, and the liberal Islamist President Abolhassan Banisadr was impeached in June 1981.[220]

After the revolution, human rights groups estimated the number of casualties suffered by protesters and prisoners of the new system to be several thousand. The first to be executed were members of the old system – senior generals, followed by over 200 senior civilian officials[221] – as punishment and to eliminate the danger of a coup d'état. Brief trials lacking defense attorneys, juries, transparency or the opportunity for the accused to defend themselves[222] were held by revolutionary judges such as Sadegh Khalkhali, the Sharia judge. By January 1980 "at least 582 persons had been executed."[223] Among those executed was Amir Abbas Hoveida, former Prime Minister of Iran.[224]

Between January 1980 and June 1981, when Bani-Sadr was impeached, at least 900 executions took place,[225] for everything from drug and sexual offenses to "corruption on earth", from plotting counter-revolution and spying for Israel to membership in opposition groups.[226] In the ensuing 12 months Amnesty International documented 2,946 executions, with several thousand more killed in the next two years according to the anti-government guerilla People's Mujahedin of Iran.[227]

Closing of non-Islamist newspapers

In mid-August 1979, shortly after the election of the constitution-writing assembly, several dozen newspapers and magazines opposing Khomeini's idea of theocratic rule by jurists were shut down.[228][229][230] When protests were organized by the National Democratic Front (NDF), Khomeini angrily denounced them saying, "we thought we were dealing with human beings. It is evident we are not."[231]

... After each revolution several thousand of these corrupt elements are executed in public and burnt and the story is over. They are not allowed to publish newspapers.[231]

Hundreds were injured by "rocks, clubs, chains and iron bars" when Hezbollahi attacked the protesters,[229] and shortly after, a warrant was issued for the arrest of the NDF's leader.[232]

Muslim People's Republican Party

In December the moderate Islamic party Muslim People's Republican Party (MPRP) and its spiritual leader Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari had become a rallying point for Iranians who wanted democracy not theocracy.[233] Riots broke out in Shariatmadari's Azeri home region with members of the MPRP and Shariatmadari's followers seizing the Tabriz television station and using it to "broadcast demands and grievances." The regime reacted quickly, sending Revolutionary Guards to retake the TV station, mediators to defuse complaints and activists to stage a massive pro-Khomeini counter-demonstration.[234] The party was suppressed,[233] and in 1982 Shariatmadari was "demoted" from the rank of Grand Ayatollah and many of his clerical followers were purged.[235]

Islamist left

In January 1980, Abolhassan Banisadr was elected president of Iran. Though an adviser to Khomeini, he was a leftist who clashed with another ally of Khomeini, the theocratic Islamic Republic Party (IRP) – the controlling power in the new parliament.[236]

At the same time, erstwhile revolutionary allies of Khomeini – the Islamist modernist guerrilla group People's Mujahedin of Iran (or MEK) – were being suppressed by Khomeini's forces. Khomeini attacked the MEK, referring to them as monafeqin (hypocrites) and kafer (unbelievers).[237] Hezbollahi people attacked meeting places, bookstores, and newsstands of Mujahideen and other leftists,[238] driving them underground. Universities were closed to purge them of opponents of theocratic rule as a part of the "Cultural Revolution", and 20,000 teachers and nearly 8,000 military officers deemed too westernized were dismissed.[239]

By mid-1981 matters came to a head. An attempt by Khomeini to forge a reconciliation between Banisadr and IRP leaders had failed,[240] and now it was Banisadr who was the rallying point "for all doubters and dissidents" of the theocracy, including the MEK.[241]

When leaders of the National Front called for a demonstration in June 1981 in favor of Banisadr, Khomeini threatened its leaders with the death penalty for apostasy "if they did not repent".[242] Leaders of the Freedom Movement of Iran were compelled to make and publicly broadcast apologies for supporting the Front's appeal.[242] Those attending the rally were menaced by Hezbollahi and Revolutionary Guards and intimidated into silence.[243]

On 28 June 1981, a bombing of the office of the IRP killed around 70 high-ranking officials, cabinet members and members of parliament, including Mohammad Beheshti, the secretary-general of the party and head of the Islamic Republic's judicial system. The government arrested thousands, and there were hundreds of executions against the MEK and its followers.[244] Despite these and other assassinations[202] the hoped-for mass uprising and armed struggle against the Khomeiniists was crushed.

In May 1979, the Furqan Group (Guruh-i Furqan) assassinated an important lieutenant of Khomeini, Morteza Motahhari.[245]

International impact

Internationally, the initial impact of the revolution was immense. In the non-Muslim world, it changed the image of Islam, generating much interest in Islam—both sympathetic[246] and hostile[247]—and even speculation that the revolution might change "the world balance of power more than any political event since Hitler's conquest of Europe."[248]

The Islamic Republic positioned itself as a revolutionary beacon under the slogan "neither East nor West, only Islamic Republic ("Na Sharq, Na Gharb, Faqat Jumhuri-e Islami," i.e. neither Soviet nor American / West European models), and called for the overthrow of capitalism, American influence, and social injustice in the Middle East and the rest of the world. Revolutionary leaders in Iran gave and sought support from non-Muslim activists such as the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, IRA in Ireland and anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, insofar as favoring leftist revolutionaries over Islamist, but ideologically different and strategically harmful causes, such as the neighboring Afghan Mujahideen.[249] The revolution itself was supported by the Palestine Liberation Organization.[250] In terms of future relevance, the conflicts that originated from the Iranian Revolution continued to define geo-politics for the last three decades, continuing to do so today.[251]

Persian Gulf and the Iran–Iraq War

Supporters of the revolution both within and outside of Iran began calling for the overthrow of monarchies in the region and for them to be replaced by Islamic republics. This alarmed many of Iran's neighbours, particularly Kuwait, Iraq and Saudi Arabia as well as Western nations dependent on Middle Eastern oil for their energy needs.

In September 1980, Iraq took advantage of the febrile situation and invaded Iran. At the centre of Iraq's objectives was the annexation of the East Bank of the Shaat Al-Arab waterway that makes up part of the border between the two nations and which had been the site of numerous border skirmishes between the two countries going back to the late 1960s. The president of Iraq, Saddam Hussein, also wanted to annex the Iranian province of Khuzestan, substantially populated by Iranian Arabs. There was also concern that a Shia-centric revolution in Iran may stimulate a similar uprising in Iraq, where the country's Sunni minority ruled over the Shia majority.

Hussein was confident that with Iraq's armed forces being well-equipped with new technology and with high morale would enjoy a decisive strategic advantage against an Iranian military that had recently had much of its command officers purged following the Revolution. Iran was also struggling to find replacement parts for much of its US- and British-supplied equipment. Hussein believed that victory would therefore come swiftly.

However Iran was "galvanized"[252] by the invasion and the populace of Iran rallied behind their new government in an effort to repel the invaders. After some early successes, the Iraqi invasion stalled and was then repelled and by 1982, Iran had recaptured almost all of its territories. In June 1982, with Iraqi forces all but expelled from Iranian territory, the Iraqi government offered a ceasefire. This was rejected by Khomeini, who declared that the only condition for peace was that "the regime in Baghdad must fall and must be replaced by an Islamic republic".[253]

The war would continue for another six years during which time countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and other Gulf states provided financial assistance to Iraq in an effort to prevent an Iranian victory, even though their relations with Iraq were often hostile - Kuwait itself was invaded by Iraq two years after the peace agreement between Iraq and Iran was signed.

Like the hostage crisis, the war served in part as an opportunity for the government to strengthen revolutionary ardour and revolutionary groups;[citation needed] the Revolutionary Guard and committees at the expense of its remaining allies-turned-opponents, such as the MEK.[254][255] While enormously costly and destructive, the war "rejuvenate[d] the drive for national unity and Islamic revolution" and "inhibited fractious debate and dispute" in Iran.[256]

Foreign relations

The Islamic Republic of Iran experienced difficult relations with some Western countries, especially the United States and the Eastern Bloc nations led by the Soviet Union. Iran was under constant US unilateral sanctions, which were tightened under the presidency of Bill Clinton. Britain suspended all diplomatic relations with Iran and did not re-open their embassy in Tehran until 1988.[257] Relations with the USSR became strained as well after the Soviet government condemned Khomeini's repression of certain minorities after the Revolution.[258]

For Israel, relations dates back to the Shah until relations were cut on 18 February 1979 when Iran adopted its anti-Zionist stance. The former embassy in Tehran was handed over to the PLO and allied itself with several anti-Israeli Islamist militant groups since.[259]

After the U.S. sanctions were tightened and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation and the People's Republic of China became the main principal allies for Iran.[260] Relations between the two countries became improved after Vladimir Putin took office in 2000 and increasingly warmer in recent years following an international backlash over the annexation of Crimea in 2014 which led to sanctions by the Western powers. Russia had sought Iran on expanding arms trade over the past three decades especially with the cooperation with the Assad government during the Syrian civil war.[261][262] Iran also began its economic cooperation with China that includes “political, strategic and economic” components between the two nations.[263][264][265][266][267]

In the Muslim world

In the Muslim world, particularly in its early years, the revolution inspired enormous enthusiasm and redoubled opposition to western imperialism, intervention and influence. Islamist insurgents rose in Saudi Arabia (1979), Egypt (1981), Syria (1982), and Lebanon (1983).[268]

In Pakistan, it has been noted that the "press was largely favorable towards the new government"; the Islamist parties were even more enthusiastic; while the ruler, General Zia-ul-Haq, himself on an Islamization drive since he took power in 1977, talked of "simultaneous triumph of Islamic ideology in both our countries" and that "Khomeini is a symbol of Islamic insurgence." Some American analysts noted that, at this point, Khomeini's influence and prestige in Pakistan was greater than Zia-ul-Haq's himself.[269] After Khomeini claimed that Americans were behind the 1979 Grand Mosque seizure, student protesters from the Quaid-e-Azam University in Islamabad attacked the US embassy, setting it on fire and taking hostages. While the crisis was quickly defused by the Pakistan military, the next day, before some 120 Pakistani army officers stationed in Iran on the road to hajj, Khomeini said "it is a cause of joy that… all Pakistan has risen against the United States" and the struggle is not that of the US and Iran but "the entire world of disbelief and the world of Islam". According to journalist Yaroslav Trofimov, "the Pakistani officers, many of whom had graduated from Western military academies, seemed swayed by the ayatollah’s intoxicating words."[270]

Ultimately only the Lebanese Islamists succeeded. The Islamic revolutionary government itself is credited with helping establish Hezbollah in Lebanon[271] and the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq.

On the other side of the ledger, at least one observer argues that despite great effort and expense the only countries outside Iran the revolution had a "measure of lasting influence" on are Lebanon and Iraq.[272] Others claim the devastating Iran–Iraq War "mortally wounded ... the ideal of spreading the Islamic revolution,"[183] or that the Islamic Republic's pursuit of an ideological rather than a "nationalist, pragmatic" foreign policy has weakened Iran's "place as a great regional power".[273]

Domestic impact

Views differ on the impact of the revolution.[Note 8] For some it was "the most significant, hopeful and profound event in the entirety of contemporary Islamic history,"[275] while other Iranians believe that the revolution was a time when "for a few years we all lost our minds",[276] and which "promised us heaven, but... created a hell on earth."[277]

Internally, Iran has had some success in recent years in the broadening of education and health care for the poor, and particularly governmental promotion of Islam, and the elimination of secularism and American influence in government. Criticisms have been raised with regards to political freedom, governmental honesty and efficiency, economic equality and self-sufficiency, or even popular religious devotion.[278][279] Opinion polls and observers report widespread dissatisfaction, including a "rift" between the revolutionary generation and younger Iranians who find it "impossible to understand what their parents were so passionate about."[280] To honor the 40th anniversary of revolution around 50,000 prisoners were forgiven by order Ali Khamenei to receive "Islamic clemency".[281][282][283] Many religious minorities such as Christians, Baháʼís, Jews and Zoroastrians have left since the Islamic Revolution of 1979.[284][285]

Human development

Literacy has continued to increase under the Islamic Republic.[286][287] By 2002, illiteracy rates dropped by more than half.[288][289] Maternal and infant mortality rates have also been cut significantly.[290] Population growth was first encouraged, but discouraged after 1988.[291] Overall, Iran's Human development Index rating has climbed significantly from 0.569 in 1980 to 0.732 in 2002, on a par with neighbouring Turkey.[292][293] In the latest HDI, however, Iran has since fallen 8 ranks below Turkey.[294]

Politics and government

Iran has elected governmental bodies at the national, provincial, and local levels. Although these bodies are subordinate to theocracy – which has veto power over who can run for parliament (or Islamic Consultative Assembly) and whether its bills can become law – they have more power than equivalent organs in the Shah's government.

Iran's Sunni minority (about 8%) has seen some unrest.[295] Five of the 290 parliamentary seats are allocated to their communities.[296]

The members of the Baháʼí Faith have been declared heretical and subversive.[297] While persecution occurred before the Revolution since then more than 200 Baháʼís have been executed or presumed killed, and many more have been imprisoned, deprived of jobs, pensions, businesses, and educational opportunities. Baháʼí holy places have been confiscated, vandalized, or destroyed. More recently, Baháʼís in Iran have been deprived of education and work. Several thousand young Baháʼís between the ages of 17 and 24 have been expelled from universities.

Whether the Islamic Republic has brought more or less severe political repression is disputed. Grumbling once done about the tyranny and corruption of the Shah and his court is now directed against "the Mullahs."[298] Fear of SAVAK has been replaced by fear of Revolutionary Guards, and other religious revolutionary enforcers.[205] Violations of human rights by the theocratic government is said to be worse than during the monarchy,[299] and in any case extremely grave.[300] Reports of torture, imprisonment of dissidents, and the murder of prominent critics have been made by human rights groups. Censorship is handled by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, without whose official permission, "no books or magazines are published, no audiotapes are distributed, no movies are shown and no cultural organization is established. Men and women are not allowed to dance or swim with each other."[301]

Women

Throughout the beginning of the 20th century and prior to the revolution, many women leaders emerged and demanded basic social rights for women.[302] During the reign of Reza Shah, the government mandated the removal of the veil and promoted the education of young girls.[302] However, the push-back of the Shii clerics made progress difficult, and the government had to contain its promotion of basic women's rights to the norms of the patriarchal social hierarchy in order to accommodate the clerics.[302] After the abdication of Reza Shah in 1941, the discipline of the government decreased, and women were able to further exercise their rights, including the ability to wear the veil if they wanted.[302] More organization of women's groups occurred in the 1960s and 70s, and they used the government's modernization to define and advocate for women's issues.[302] During these decades, women became active in formerly male domains such as the parliament, the cabinet, armed forces, legal professions, and fields of science and technology.[302] Additionally, women achieved the right to vote in 1963.[302] Many of these achievements and rights that Iranian women had gained in the decades leading up to the revolution were reversed by the Islamic Revolution.[302]

The revolutionary government rewrote laws in an attempt to force women to leave the workforce by promoting the early retirement of female government employees, the closing of childcare centers, enforcing full Islamic cover in offices and public places, as well as preventing women from studying in 140 fields in higher education.[302] Women fought back against these changes, and as activist and writer Mahnaz Afkhami writes, "The regime succeeded in putting women back in the veil in public places, but not in resocializing them into fundamentalist norms."[302] After the revolution, women often had to work hard to support their families as the post-revolutionary economy suffered.[302] Women also asserted themselves in the arts, literature, education, and politics.[302]

Women – especially those from traditional backgrounds – participated on a large scale in demonstrations leading up to the revolution.[303] They were encouraged by Ayatollah Khomeini to join him in overthrowing the Pahlavi dynasty.[176] However, most of these women expected the revolution to lead to an increase in their rights and opportunities rather than the restrictions that actually occurred.[176] The policy enacted by the revolutionary government and its attempts to limit the rights of women were challenged by the mobilization and politicization of women that occurred during and after the revolution.[176] Women's resistance included remaining in the work force in large numbers and challenging Islamic dress by showing hair under their head scarves.[176] The Iranian government has had to reconsider and change aspects of its policies towards women because of their resistance to laws that restrict their rights.[176]

Since the revolution, university enrollment and the number of women in the civil service and higher education has risen.[Note 9] and several women have been elected to the Iranian parliament.

Homosexuality

Homosexuality has a long history in pre-modern Iran. Sextus Empiricus asserts in his Outlines of Scepticism (written circa C.E. 200) that the laws of the Parthian Empire were tolerant towards homosexual behaviour, and Persian men were known to "indulge in intercourse with males." (1:152)[305] These ancient practices continued into the Islamic period of Iran, with one scholar noting how "...homosexuality and homoerotic expressions were tolerated in numerous public places, from monasteries and seminaries to taverns, military camps, bathhouses and coffee houses. In the early Safavid era (1501-1723), male houses of prostitution (amard khaneh) were legally recognized and paid taxes."[306]: 157 It was during the late Qajar period that following modernization the society was heteronormalized.[307] During the reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a faux same-sex wedding occurred between two young men with ties to the royal court, which became a source of shame and outrage for some citizens and was utilized by Islamists as further evidence of the "immoral" monarchy. This also tied the monarchy to the West, which had begun to be regarded in reactionary Islamic discourse as immoral due to "...female nudity and open adult male homosexuality.".[306]: 161

When Ruhollah Khomeini came to power in 1979, he called for homosexuals to be "exterminated",[308] and one of his first political actions was to institute imprisonment, corporal punishment, and the death penalty for any sexual acts outside traditional Islamic heterosexual marriage. In a 1979 interview with The New York Times, a journalist asked Khomeini to justify the state-sanctioned shootings of homosexuals. In reply Khomeini compared them as well as other adulterers to gangrene, thieves, and murderers.[309]

Iran is currently one of the world's only jurisdictions to actively execute gay men.[310][311][312] Amnesty International reports that approximately 5,000 gays have been executed in Iran since the revolution, including two gay men executed in 2014, both hanged for engaging in consensual homosexual relations.[313]

Economy

Iran's post-revolutionary economy has a significant state-owned or parastatal sector, including businesses owned by the Revolutionary Guards and Bonyad foundations.[314][315]

Since the revolution Iran's GDP (PPP) has grown from $114 billion in 1980 to $858 billion in 2010.[316] GDP per capita (PPP) has grown from $4,295 in 1980 to $11,396 in 2010.[316]

Since the revolution Iran's GDP (Nominal) has grown from $90.392 billion in 1979 to $385.874 in 2015.[317] GDP per capita (nominal) has grown from $2290 in 1979 to $5470 in 2016.[318] Real GNI per capita in 2011 constant international dollars decreased after the revolution and during the Iran-Iraq war from $7762 in 1979 to $3699 at the end of the war in 1989. After three decades of reconstruction and growth since then, it has not yet reached its 1979 level and has only recovered to $6751 in 2016.[319] Data on GNI per capita in PPP terms is only available since 1990 globally. In PPP terms, GNI per capita has increased from Int. $11,425 in 1990 to Int. $18,544 in 2016. But most of this increase can be attributed to the rise in oil prices in the 2000s.[320]

The value of Iran's currency declined precipitously after the revolution. Whereas on 15 March 1978, 71.46 rials equaled one U.S. dollar, in January 2018, 44,650 rials amounted to one dollar.[321]

The economy has become slightly more diversified since the revolution, with 80% of Iranian GDP dependent on oil and gas as of 2010,[322] comparing to above 90% at the end of the Pahlavi period.[citation needed] The Islamic Republic lags some countries in transparency and ease of doing business according to international surveys. Transparency International ranked Iran 136th out of 175 countries in transparency (i.e. lack of corruption) for its 2014 index;[314] and the IRI was ranked 130th out of the 189 countries surveyed in the World Bank 2015 Doing Business Report.[323]

Islamic political culture

It is said that there were attempts to incorporate modern political and social concepts into Islamic canon since 1950. The attempt was a reaction to the secular political discourse namely Marxism, liberalism and nationalism. Following the death of Ayatollah Boroujerdi, some of the scholars like Murtaza Mutahhari, Muhammad Beheshti and Mahmoud Taleghani found new opportunity to change conditions. Before them, Boroujerdi was considered a conservative Marja. They tried to reform conditions after the death of the ayatollah. They presented their arguments by rendering lectures in 1960 and 1963 in Tehran. The result of the lectures was the book "An inquiry into principles of Mar'jaiyat". Some of the major issues highlighted were the government in Islam, the need for the clergy's independent financial organization, Islam as a way of life, advising and guiding youth and necessity of being community. Allameh Tabatabei refers to velayat as a political philosophy for Shia and velayat faqih for Shia community. There are also other attempts to formulate a new attitude of Islam such as the publication of three volumes of Maktab Tashayyo. Also some believe that it is indispensable to revive the religious gathered in Hoseyniyeh-e-Ershad.[324]

Gallery

Current Iranian leader, Ali Khamenei in a Revolutionary protest in Mashhad.

Removal of Shah's statue by the people in University of Tehran.

Khomeini at Mehrabad Airport.

People accompanying Khomeini from Mehrabad to Behesht Zahra.

Depictions in US media

- Argo, starring Ben Affleck, a film on the US government rescuing Americans in Iranian hostage crisis.

- Persepolis is an autobiographical series of comics by Marjane Satrapi first published in 2000 that depicts the author's childhood in Iran during and after the Islamic Revolution. The 2007 animated film Persepolis is based upon on it.

- Septembers of Shiraz is a movie about an Iranian Jewish family. After creating a prosperous life in Iran, they may be forced to abandon everything as a revolution looms on the horizon. It is based on the 2007 novel The Septembers of Shiraz by Dalia Sofer.

See also

- Revolution-related topics

- 1979 energy crisis

- Background and causes of the Iranian Revolution

- Civil resistance

- Fajr decade

- Guadeloupe conference

- History of Iran

- History of political Islam in Iran

- History of the Islamic Republic of Iran

- Iran hostage crisis

- Jimmy Carter's engagement with Khomeini

- Organizations of the Iranian Revolution

- Ruhollah Khomeini

- Russian Revolution

- Related conflicts

- General

Notes

- ^ According to Kurzman, scholars writing on the revolution who have mentioned this include:

- ^ See: Velayat-e faqih (book by Khomeini)#Importance of Islamic Government

- ^ Marxist guerrillas groups were the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (OIPFG) and the breakaway Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (IPFG), and some minor groups.[78]

- ^ See: Hokumat-e Islami : Velayat-e faqih (book by Khomeini)#Why Islamic Government has not been established

- ^ Researcher Emad al-Din Baghi at the Martyrs Foundation (Bonyad Shahid) counted 2,781 protesters killed in 1978–79, a total of 3,164 killed between 1963 and 1979.

- ^ For example, Islamic Republic Party and allied forces controlled approximately 80% of the seats on the Assembly of Experts of Constitution.[188] An impressive margin even allowing for electoral manipulation

- ^ opposition included some clerics, including Ayatollah Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari, and by secularists such as the National Front who urged a boycott

- ^ example: "Secular Iranian writers of the early 1980s, most of whom supported the revolution, lamented the course it eventually took."[274]

- ^ It reached 66% in 2003.[304]

References

Citations

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan (2004). "IRAN ii. IRANIAN HISTORY (2) Islamic period (page 6)". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume XIII/3: Iran II. Iranian history–Iran V. Peoples of Iran. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 243–246. ISBN 978-0-933273-89-4.

Fear of the shah and his regime had disappeared, and anti-government and pro-Khomeini demonstrations escalated, with the soldiers refusing to shoot the offenders, who went on a rampage, burning cinemas and destroying banks and some government buildings.

- ^ Chalcraft, John (2016). "The Iranian Revolution of 1979". Popular Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. p. 445. ISBN 978-1107007505.

(...) thirty-seven days by a caretaker regime, which collapsed on 11 February when guerillas and rebel troops overwhelmed troops loyal to the shah in armed street fighting.

- ^ * "Islamic Revolution History of Iran." Iran Chamber Society. Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- Brumberg, Daniel. [2004] 2009. "Islamic Revolution of Iran." MSN Encarta. Archived on 31 October 2009.

- Khorrami, Mohammad Mehdi. 1998. "The Islamic Revolution." Vis à Vis Beyond the Veil. Internews. Archived from the original Archived 27 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine on 27 February 2009.

- "Revolution." The Iranian. 2006. from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Iran." Jubilee Campaign. Archived from the original on 6 August 2006.

- Hoveyda, Fereydoon. The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution. ISBN 0-275-97858-3.

- ^ a b Gölz (2017), p. 229.

- ^ Goodarzi, Jubin M. (8 February 2013). "Syria and Iran: Alliance Cooperation in a Changing Regional Environment" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Milani, Abbas (22 May 2012). The Shah. ISBN 9780230340381.

- ^ Sylvan, David; Majeski, Stephen (2009). U.S. foreign policy in perspective: clients, enemies and empire. London. p. 121. doi:10.4324/9780203799451. ISBN 978-0-415-70134-1. OCLC 259970287.

- ^ a b c d Abrahamian (1982), p. 479.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Afkhami, Gholam-Reza (12 January 2009). The Life and Times of the Shah. ISBN 9780520942165.

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand. 2009. "Mass Protests in the Islamic Revolution, 1977–79." Pp. 162–78 in Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present, edited by A. Roberts and T. G. Ash. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Mottahedeh, Roy. 2004. The Mantle of the Prophet: Religion and Politics in Iran. p. 375.

- ^ "The Iranian Revolution". fsmitha.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016.

- ^ Kabalan, Marwan J. (2020). "Iran-Iraq-Syria". In Mansour, Imad; Thompson, William R. (eds.). Shocks and Rivalries in the Middle East and North Africa. Georgetown University Press. p. 113.

After more than a year of civil strife and street protests, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left Iran for exile in January 1979.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Milani, Abbas (2008). Eminent Persians. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0907-0.

- ^ "1979: Exiled Ayatollah Khomeini returns to Iran." BBC: On This Day. 2007. Archived 24 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Graham (1980), p. 228.

- ^ Kurzman (2004), p. 111.

- ^ "Islamic Republic Iran." Britannica Student Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 March 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kurzman (2004).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Amuzegar (1991), p. 253

- ^ Amuzegar (1991), pp. 4, 9–12.

- ^ Arjomand (1988), p. 191.

- ^ Amuzegar (1991), p. 10.

- ^ a b Kurzman (2004), p. 121.

- ^ Amanat 2017, p. 897.

- ^ International Journal of Middle East Studies 19, 1987, p. 261

- ^ Özbudun, Ergun (2011). "Authoritarian Regimes". In Badie, Bertrand; Berg-Schlosser, Dirk; Morlino, Leonardo (eds.). International Encyclopedia of Political Science. SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 109. ISBN 978-1452266497.

Another interesting borderline case between authoritarianism and totalitarianism is Iran, where an almost totalitarian interpretation of a religious ideology is combined with elements of limited pluralism. Under the Islamist regime, Islam has been transformed into a political ideology with a totalitarian bent, and the limited pluralism is allowed only among political groups loyal to the Islamic revolution.

- ^ Nasr, Vali (2006). "The Battle for the Middle East". THE SHIA REVIVAL:How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32968-1.

- ^ Sick, All Fall Down, p. 187

- ^ Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Harvard University Press, 1980, p. 189

- ^ Keddie, N. R. (1983). "Iranian Revolutions in Comparative Perspective". American Historical Review. 88 (3): 589. doi:10.2307/1864588. JSTOR 1864588.

- ^ Bakhash (1984), p. 13.

- ^ a b Harney (1998), pp. 37, 47, 67, 128, 155, 167.

- ^ Abrahamian (1982), p. 437.

- ^ Mackey (1996), pp. 236, 260.

- ^ Graham (1980), pp. 19, 96.

- ^ Brumberg (2001), p. [page needed].

- ^ Shirley (1997), p. 207.

- ^ Cooper, Andrew Scott. 2011. The Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle East. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 1439155178.

- ^ Keddie (2003), p. 214.

- ^ Taheri (1985), p. 238.

- ^ Moin (2000), p. 178.

- ^ Hoveyda, Fereydoun (2003). The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian mythology and Islamic revolution. Praeger. p. 22. ISBN 0-275-97858-3.

- ^ Abrahamian (1982), pp. 533–534.

- ^ Schirazi (1997), pp. 293–34.

- ^ a b Keddie, Nikki. 1966. Religion and Rebellion in Iran: The Tobacco Protest of 1891–92. Frank Cass. p. 38.

- ^ Moaddel, Mansoor (1992). "Shi'i Political Discourse and Class Mobilization in the Tobacco Movement of 1890–1892". Sociological Forum. 7 (3): 459. doi:10.1007/BF01117556. JSTOR 684660. S2CID 145696393.

- ^ Lambton, Ann (1987). Qajar Persia. University of Texas Press, p. 248

- ^ Mottahedeh, Roy. 2000. The Mantle of the Prophet: Religion and Politics in Iran. Oneworld. p. 218.

- ^ Mackey (1996), p. 184.

- ^ Bakhash (1984), p. 22.

- ^ Taheri (1985), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Rajaee, Farhang (1983). Islamic Values and World View: Khomeyni on Man, the State and International Politics (PDF). American Values Projected Abroad. Vol. 13. Lanham: University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-3578-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009.

- ^ Rajaee, Farhang (2010). Islamism and Modernism: The Changing Discourse in Iran. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292774360.

- ^ "BP and Iran: The Forgotten History". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ All the Shah's Men

- ^ Dehghan, Saeed Kamali; Norton-Taylor, Richard (19 August 2013). "CIA admits role in 1953 Iranian coup". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Arjomand (1988), pp. 72–73.

- ^ "Iran: The White Revolution". Time Magazine. 11 February 1966. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Siavoshi, Sussan (1990). Liberal Nationalism in Iran: The failure of a movement. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8133-7413-0.

- ^ Bayar, Assef (1994). "Historiography, class, and Iranian workers". In Lockman, Zachary (ed.). Workers and Working Classes in the Middle East: Struggles, Histories, Historiographies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7914-1665-5.

- ^ Abrahamian (2008), p. 143.

- ^ Abrahamian (2008), p. 140.

- ^ Nehzat by Ruhani vol. 1, p. 195, quoted in Moin (2000), p. 75

- ^ Khomeini & Algar (1981), p. 17.

- ^ "Emad Baghi: English". emadbaghi.com. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Graham (1980), p. 69.

- ^ a b Mackey (1996), pp. 215, 264–265.

- ^ Keddie (2003), pp. 201–207.

- ^ Wright, Robin (2000) "The Last Great Revolution Turmoil and Transformation in Iran" Archived 23 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

- ^ Dabashi, Theology of Discontent (1993), pp. 419, 443

- ^ Khomeini & Algar (1981), pp. 52, 54, 80.

- ^ a b Taheri (1985), p. 196.

- ^ "Mixtape: Cassetternet Radiolab". WNYC Studios. 12 November 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Curtis, John; Sandmann, Ina Sarikhani; Stanley, Tim (2021). Epic Iran: 5000 years of culture. V & A Publications. p. 281 (fig. 17). ISBN 978-1851779291.

- ^ Abrahamian (1982), pp. 502–503.

- ^ Kurzman (2004), pp. 144–145.

- ^ Burns, Gene (1996). "Ideology, Culture, and Ambiguity: The Revolutionary Process in Iran". Theory and Society. 25 (3): 349–388. doi:10.1007/BF00158262. JSTOR 658050. S2CID 144151974.

- ^ Kurzman (2004), pp. 145–146.

- ^ Abrahamian (1982), p. 495.

- ^ Fischer, Michael M.J. (2003). Iran: from religious dispute to revolution. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0299184742.

- ^ Mackey (1996), p. 276.

- ^ a b Abrahamian (1993), p. 30.

- ^ Abrahamian (1982), pp. 478–479.

- ^ Khomeini & Algar (1981), p. 34.

- ^ Keddie (2003), p. 240.

- ^ Wright, Robin (2000). The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil And Transformation in Iran. Alfred A. Knopf: Distributed by Random House. p. 220. ISBN 0-375-40639-5.

- ^ Abrahamian (1982), p. 444.

- ^ Graham (1980), p. 94.

- ^ Gelvin, James L. (2008). The Modern Middle East Second Edition. Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 285.

- ^ Moin (2000), p. 163.

- ^ Graham (1980), p. 226.

- ^ Moin (2000), p. 174.

- ^ Graham (1980), p. 96.

- ^ Abrahamian (1982), pp. 501–503.

- ^ Gölz, Olmo. "Dah Šab – Zehn Literaturabende in Teheran 1977: Der Kampf um das Monopol literarischer Legitimität." Die Welt des Islams 55, Nr. 1 (2015): 83–111.

- ^ Moin (2000), pp. 184–185.

- ^ Taheri (1985), pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ritter, Daniel (May 2010). "Why the Iranian Revolution Was Non-Violent". Archived from the original on 12 October 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requiresjournal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Pahlavi, Farah (2004). An Enduring Love: My Life with the Shah. New York, NY: Hyperion Books. ISBN 140135209-X.

- ^ Siddiqui, Abdar Rahman Koya with an introduction by Iqbal, ed. (2009). Imam Khomeini life, thought and legacy : essays from an Islamic movement perspective. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Book Trust. p. 41. ISBN 9789675062254. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015.

- ^ Harmon, Daniel E. (2004). Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. New York: Infobase Pub. p. 47. ISBN 9781438106564.

- ^ Brumberg (2001), p. 92.