브라흐미 문자

Brahmi script| 브라흐미 브라흐무 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 스크립트 타입 | |

기간 | 적어도 기원전 3세기부터[1] 기원후 5세기까지는 |

| 방향 | 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 |

| 언어들 | 산스크리트어, 팔리어, 프라크리트어, 타밀어, 사카어, 토카리어어 |

| 관련 스크립트 | |

부모 시스템 | |

자시스템 | 다음과 같은 수많은 후속 문자 시스템:

|

자매 제도 | 카로스티 |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | 브라흐(300), 브라흐미 |

| 유니코드 | |

유니코드 에일리어스 | 브라흐미 |

| U+11000 – U+1107f | |

브라흐미 문자의 이론화된 셈어 기원은 보편적으로 [2]동의된 것이 아니다. | |

브라흐미(/brbrːmi/);ISO 브라함(Brahm)은 기원전 [4]3세기에 완전히 발달한 문자로[3] 등장한 고대 남아시아의 문자 체계이다.그 후손인 브라흐미 문자는 오늘날에도 [5][6][7]남아시아와 동남아시아에서 계속 사용되고 있다.

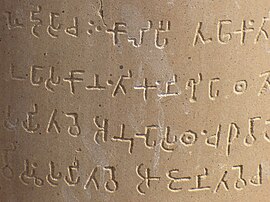

브라흐미는 모음과 자음 기호를 연관짓기 위해 발음을 구분하는 체계를 사용하는 아부기다이다.문자는 마우리아 시대(기원전 3세기)부터 굽타 시대(기원전 4세기) 초반까지 비교적 작은 진화적 변화를 거쳤을 뿐이며, 서기 4세기까지는 문맹이들이 마우리아 [8]비문을 읽고 이해할 수 있었다고 생각된다.그 후 얼마 지나지 않아 브라흐미 원문을 읽을 수 없게 되었다.가장 오래되고 가장 잘 알려진 브라흐미 비문은 기원전 250-232년으로 거슬러 올라가는 인도 중북부 아소카의 암각 칙령이다.브라흐미의 해독은 인도, 특히 캘커타의 [9][10][11][12]아시아 벵골 협회에서 동인도 회사가 통치하던 19세기 초에 유럽 학자들의 관심의 초점이 되었다.브라흐미는 1830년대 [13][14][15][16]학회지에 실린 일련의 학술 기사에서 학회 서기 제임스 프린셉에 의해 해독되었다.그의 비약적인 업적은 크리스찬 라센, 에드윈 노리스, H. H. 윌슨,[17][18][19] 알렉산더 커닝햄 등의 경구적 작품을 바탕으로 만들어졌다.

대부분의 학자들은 브라흐미가 하나 이상의 현대 셈어에서 유래했거나 적어도 영향을 받았다고 말하는 반면, 다른 학자들은 토착 기원이나 훨씬 오래되고 아직 해독되지 않은 하라판 [2][20]문화의 인더스 문자에 대한 연결을 선호한다.브라흐미는 한때 영어로 "핀맨"[21] 문자, 즉 "스틱 피규어" 문자라고 불렸다.가브리엘리아가 관찰한 1880년대 알베르 장 침례테리엔 드 라쿠페리에가 1880년대까지 "라스", "라", "남아오칸", "인도 팔리" 또는 "모리안" (살로몬 1998, 페이지 17)을 포함한 다양한 이름으로 알려져 있었다.아라 수트라.그래서 그 이름은 게오르크 뮐러의 영향력 있는 작품에서 채택되었다. 그러나 변형된 형태인 "브라흐마"[22]가 되었다.5세기의 굽타 문자는 때때로 "후기 브라흐미"라고 불린다.브라흐미 문자는 브라흐미 문자로 분류되는 수많은 지역 변종들로 다양해졌다.남아시아와 동남아시아에서 사용되는 수십 개의 현대 문자는 브라흐미에서 유래하여 세계에서 가장 영향력 있는 문자 전통 [23]중 하나가 되었다.한 조사에 따르면 198개의 스크립트가 최종적으로 [24]그것으로부터 파생된 것으로 나타났다.

브라흐미 문자로 쓰인 기원전 3세기 아소카의 비문 중 브라흐미 숫자로 [25]불리게 된 몇 개의 숫자가 발견되었다.숫자는 덧셈과 곱셈이기 때문에 [25]장소값이 아닙니다.기본적인 숫자 체계가 브라흐미 [25]문자와 관련이 있는지는 알 수 없습니다.그러나 서기 1천년의 후반기에 브라흐미에서 유래한 문자로 쓰인 인도와 동남아시아의 일부 비문은 소수 자릿수 값인 숫자를 포함하고 있으며, 현재 [26]전 세계에서 사용되고 있는 힌두-아랍 숫자 체계에 대한 현존하는 가장 초기의 물질적인 예를 구성한다.그러나 기본적인 숫자 체계는 구술로 증명된 가장 오래된 예가 [27][28][29]점성술에 관한 잃어버린 그리스 작품의 산스크리트 산문 각색에서 기원후 3세기 중반으로 거슬러 올라가기 때문에 더 오래되었다.

★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★」

브라흐미 문자는 힌두교, 자이나교, 불교 등의 고대 인도 문헌과 그들의 중국어 [31][32]번역본에 언급되어 있다.예를 들어, 리피살라 삼다르샤나 파리바르타라는 제목의 랄리타비스타라 수트라(서기 [33]200~300년경)의 10장에는 64개의 리피(스크립트)가 나열되어 있으며, 브라흐미 문자가 그 목록의 선두에 있다.랄리타비스타라 수트라는 미래의 고타마 부처(기원전 500년)인 어린 [34][31]싯다르타가 학교에서 브라만 리피카라와 데바 비다이하의 언어학, 브라흐미 그리고 다른 문자들을 습득했다고 말한다.

판나바나경(기원전 2세기)과 사마바얀가경([35][36]기원전 3세기)과 같은 자이나교의 문헌에서 18개의 고대 문자 목록이 발견된다.이 자이나 문자 목록에는 1번 브라흐미, 4번 카로히가 포함되어 있지만 자바날리야(그리스어일 가능성이 있음)와 불교 목록에 [36]없는 다른 문자 목록도 포함되어 있습니다.

현대의 카로시 문자는 아람 문자에서 파생된 것으로 널리 받아들여지고 있지만, 브라흐미 문자의 기원은 덜 간단하다.살로몬은 1998년에 [5]기존 이론을 검토했고, 포크는 1993년에 [37]개요를 제공했다.

초기 이론들은 이집트 상형문자의 모델에 브라흐미 문자의 그림 문자-아크로포닉 기원을 제안했다.그러나 이러한 생각들은 "순수히 상상력이 풍부하고 추측적"[38]이기 때문에 신뢰를 잃었다.비슷한 생각들이 브라흐미 문자와 인더스 문자를 연결시키려 했지만, 그것들은 증명되지 않았고, 특히 인더스 문자가 아직 [38]해독되지 않았다는 사실로 인해 어려움을 겪고 있다.

주류는 브라흐미가 셈어 문자(보통 아람어)에서 유래했다는 것이다.이것은 알브레히트 베버(1856)와 게오르크 뮐러의 인도 브라흐마 문자의 기원(1895)[39][6]이 출판된 이후 대부분의 스크립트 학자들에 의해 받아들여지고 있다.뮐러의 사상은 특히 영향력이 컸지만, 1895년 이 주제에 대한 그의 오퍼스의 날짜까지, 그는 적어도 다섯 개의 경쟁적인 기원의 이론을 확인할 수 있었다. 하나는 토착 기원을 가정하고 다른 하나는 다양한 셈어 모델에서 [40]그것을 도출했다.

브라흐미 문자의 기원에 대해 가장 논란이 되는 점은 그것이 순수하게 토착적인 발전인지 아니면 인도 밖에서 유래한 문자인지 하는 것이었다.고얄(1979)[41]은 대부분의 원주민 견해 지지자들이 인도 학자들인 반면, 셈족의 기원 이론은 "거의 모든" 서양 학자들에 의해 유지되고 있으며, 살로몬은 논쟁의 양쪽에 [42]"민족주의적 편견"과 "제국주의적 편견"이 있었다는 고얄의 의견에 동의하고 있다.그럼에도 불구하고, 토착 발전의 관점은 뮐러 이전에 쓴 영국 학자들 사이에서 널리 퍼져 있었다: 최초의 토착 기원 지지자들 중 한 명인 알렉산더 커닝햄의 한 구절은, 그의 시대에 토착 기원이 "미지의 서양" 기원에 반하여 영국 학자들을 선호했다는 것을 암시한다.y 대륙 학자들.[40]1877년에 출판된 '커닝햄'은 브라흐미 문자가 무엇보다도 [43]인체에 기초한 그림 원리에서 유래했다고 추측했지만, 1891년에 이르러서는 커닝햄이 문자의 기원을 불확실하게 여겼다고 지적했다.

대부분의 학자들은 브라흐미가 아마 셈어 문자 모델에서 유래했거나 영향을 받았을 것이며, 아람어가 유력한 후보라고 [46]믿고 있다.그러나 직접적인 증거의 부족과 아람어, 카로시어, [47]브라흐미어 사이의 설명할 수 없는 차이 때문에 이 문제는 해결되지 않았다.리처드 살로몬은 [48]브라흐미와 카로슈 문자는 몇 가지 일반적인 특징을 공유하지만, 카로슈 문자와 브라흐미 문자의 차이는 "비슷한 점보다 훨씬 크다"며 "두 문자의 전체적인 차이는 직접적인 선형 발전의 연관성을 희박하게 만든다"고 말한다.

거의 모든 저자들은 기원에 관계없이 인도 문자와 그것에 영향을 미쳤다고 제안된 문자 사이의 차이가 크다는 것을 인정한다.인도의 브라흐미 문자 개발은 문자 형태와 구조 양면에서 광범위했다.또한 베다어 문법에 대한 이론들이 아마도 이러한 발전에 강한 영향을 미쳤을 것이라는 것이 널리 받아들여지고 있다.서양인과 인도인 모두 일부 작가들은 브라흐미가 아소카 통치 기간 동안 짧은 몇 년 만에 발명되어 아소칸 [47]비문에 널리 사용된 셈어 문자에 의해 차용되거나 영감을 받았다고 주장한다.이와는 대조적으로, 일부 저자들은 외국의 [49][50]영향이라는 개념을 거부한다.

Bruce Trigger는 브라흐미가 아람 문자에서 나왔을 가능성이 높지만 광범위한 국지적 발전을 거쳤지만 직접적인 공통 [51]출처에 대한 증거는 없다고 말한다.트리거에 따르면 브라흐미는 적어도 기원전 4, 5세기 스리랑카 및 인도에서 아소카 기둥 이전에 사용되었으며, 카로슈는 고대 [51]시대에 사라지기 전에 남아시아 북서부(현대 아프가니스탄의 동쪽 부분과 파키스탄의 인접 지역)에서만 사용되었다고 한다.살로몬에 따르면 카로슈 문자가 사용된 증거는 주로 불교 기록과 인도-그리스, 인도-스키티아, 인도-파르티아, 쿠샤나 왕조 시대의 기록에서 발견된다.Kharoṭhi는 서기 [48]3세기 경에 일반적으로 사용되지 않게 된 것으로 보인다.

저스티슨과 스티븐스는 브라흐미어와 카로흐어의 고유모음 체계가 셈어 압자드의 문자값 암송을 통해 발전했다고 제안했다.원어 알파벳 학습자는 자음과 표시되지 않은 모음(예: /k//, /k,/, /gə/)을 조합하여 소리를 암송하고, 다른 언어로 차용하는 과정에서 이러한 음절을 기호들의 소리값으로 받아들인다는 것이다.그들은 또한 브라흐미가 북유대인 [52]모델에 기반한다는 생각을 받아들였다.

| ★★★★ | - - 명- - | + 증명서 | 에 |

|---|---|---|---|

| k/kh | |||

| g/gh | ) Semitic 강조(Heth)(Battiprolu) | ||

| c/ch | 덧셈 | ||

| /jh | |||

| /ph | 덧셈 | ||

| communications(비밀번호) | |||

| t/th | |||

| d/dh | 형성 | ||

| h | 백 | ||

| h | 덧셈 |

많은 학자들은 브라흐미의 기원을 셈어 문자 모델, 특히 아람어 [39]문자와 연관짓는다.어떻게 이런 일이 일어났는지에 대한 설명, 특정 셈어 문자, 그리고 연대기는 많은 논쟁의 주제가 되어왔다.뮐러는 막스 베버를 따라 특히 페니키아와 연결시켰고 빌린[53] 날짜를 기원전 8세기 초로 제시했다.셈어족의 덜 눈에 띄는 분파인 남 셈어 문자에 대한 링크도 종종 제안되었지만 그다지 [54]받아들여지지 않았다.마지막으로 브라흐미의 원형이 되는 아람 문자는 인도 아대륙과 지리적으로 가깝고 아람 문자는 아케메네스 제국의 관료 언어였기 때문에 더 선호되는 가설이 되어왔다.하지만, 이 가설은 왜 카로쉬와 브라흐미라는 매우 다른 두 개의 문자가 같은 아람어에서 발전했는지에 대한 미스터리를 설명하지 못한다.가능한 설명은 아소카가 칙령을 위해 황서를 만들었다는 것이지만, 이 [55]추측을 뒷받침할 증거는 없다.

아래 표는 페니키아 문자를 나타내는 첫 번째 열인 셈어 문자의 첫 번째 네 글자와 브라흐미가 가진 유사성을 보여준다.

| ★★ | 이름[56] | ★★★ | ★★★ | 응응 in の | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ★★★ | ★★ | 문자 | |||||||||||||||

| 𐤀 | § [syslog] | 𓃾 | 𐡀 | א | ܐ | 알파 | 𑀅 | ||||||||||

| 𐤁 | 않다 | b [b] | 𓉐 | 𐡁 | ב | ܒ | ββ | 𑀩 | |||||||||

| 𐤂 | g [스위치] | 𓌙 | 𐡂 | ג | ܓ | Γγ | 𑀕 | ||||||||||

| 𐤃 | d [d] | 𓇯 | 𐡃 | ד | ܕ | Δδ | 𑀥 | ||||||||||

1898년 뮐러가 제시한 셈어 가설에 따르면, 가장 오래된 브라흐미 비문은 페니키아 [57][note 1]원형에서 유래했다.살로몬은 뮐러의 주장이 페니키아 원형에 대한 역사적, 지리적, 연대적 근거가 약하다고 말한다.아람어로 된 6개의 마우리아어 비문 등 뮐러의 제안 이후 이루어진 발견들은 페니키아에 대한 뮐러의 제안이 약하다는 것을 암시한다.사실상 카로슈히의 원형이었던 아람어도 브라흐미의 기초였을 가능성이 높다.그러나 고대 인디언들이 왜 두 개의 매우 다른 [55]문자를 개발했는지는 불분명하다.

| ★★★ | 치 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | a | |||

| b [b] | 바 | |||

| g [스위치] | ga | |||

| d [d] | ||||

| h [h], M.L. | ha | |||

| w [w], M.L. | ★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★」 | |||

| z [z] | ! | |||

| § [syslog] | g | |||

| [ [ t ] | THA | |||

| y [j], M.L. | ya | |||

| k [k] | 카 | |||

| l [l] | la | |||

| m [m] | ||||

| n [n] | 나 | |||

| s [s] | a | |||

| ʿ [ ], M.L. | e | |||

| p [p] | » | |||

| ① [s] | ||||

| q [q] | k | |||

| r [r] | 라 | |||

| [ [ ]] ] | a | |||

| t[t] | 타 |

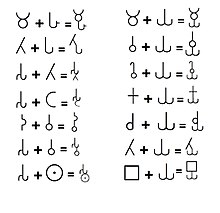

Bühler에 따르면, 브라흐미는 셈어족 언어에서 찾을 수 없는 특정 소리의 기호를 추가했고, 프라크리트어에서는 찾을 수 없는 아람어 소리의 기호를 삭제하거나 용도 변경했다.예를 들어, 아람어는 ,와 같은 프라크리트 치과 정지음 사이에 나타나는 음성 역굴절 특성이 결여되어 있으며, 브라흐미에서 역굴절 자음과 역굴절하지 않는 자음의 기호는 그래픽적으로 매우 유사하며, 마치 둘 다 하나의 원형에서 파생된 것처럼 보인다.(비슷한 후기의 전개에 대해서는, 티베트 문자를 참조해 주세요).아람어는 브라흐미의 자음(kh, th 등)이 없는 반면 브라흐미는 아람어의 자음(q, ,, ),)이 없었고, 이러한 불필요한 자음들은 브라흐미의 자음 중 일부를 채운 것으로 보인다.아람어는 브라흐미크, 아람어는 브라흐미트 등그리고 아람어에 대응하는 강조정지 p가 없었던 곳에서 브라흐미는 대응하는 열망을 위해 두 배로 늘어난 것 같습니다.브라흐미 p와 ph는 그래픽적으로 매우 유사합니다.아람어 p의 같은 소스에서 가져온 것처럼요.Bühler는 다른 흡인 ch, jh, ph, bh 및 dh에 대한 체계적 파생 원리를 보았으며, 이는 문자 오른쪽에 곡선 또는 상향 훅을 추가하는 것을 포함한다(h,[61] h에서 파생되는 것으로 추측됨). 반면 d와 δ(반어 강조 δ와 혼동되지 않음)는 dh 및 δh에서 역형성을 통해 도출되었다.

첨부된 표는 브라흐미 문자와 북 셈어 [62][59]문자 사이의 대응 관계를 나열한 것이다.

뮐러는 페니키아와 브라흐미 둘 다 세 명의 무성 자매어가 있었지만, 알파벳 순서가 없어졌기 때문에, 그들 사이의 대응은 명확하지 않다고 말한다.뮐러는 22개의 북 셈어 문자에 모두 해당하는 브라흐미 파생어를 제안할 수 있었지만, 뮐러 자신이 분명히 인식했듯이, 몇몇은 다른 사람들보다 더 자신만만하다.그는 많은 전임자들이 선호했던 것과 같이 예를 들어 c를 kaph가 아닌 tade rather에 연결하는 것과 같은 지침으로서 발음 일치에 많은 비중을 두는 경향이 있었다.

페니키아에서 유래한 주요 문제들 중 하나는 해당 [55]시기에 페니키아인들과 역사적 접촉에 대한 증거가 부족하다는 것이다.Bühler는 브라흐미 문자의 최초 차용은 그가 주로 비교했던 페니키아 문자의 형태와 동시대인 기원전 800년까지 알려진 가장 오래된 증거보다 상당히 이전으로 거슬러 올라간다고 제안함으로써 이것을 설명했습니다.Bühler는 개발의 [53]이 초기 단계인 압자드 같은 것의 지속 가능성으로 모음 분음 없이 브라흐미 문자를 비공식적으로 쓰는 근현대적 관행을 인용했다.

셈어 가설의 가장 약한 형태는 브라흐미와 카로슈의 발전에 대한 가나데시칸의 문화적 확산 관점과 유사하다.그나데시칸은 아람어를 말하는 페르시아인들에게서 알파벳 소리 표현에 대한 개념을 배웠지만, 문자 시스템의 대부분은 [63]프라크리트의 음운학에 맞춘 새로운 발전이었다.

페르시아의 영향력에 유리한 또 다른 증거는 1925년 프라크리트/산스크리트어 단어 자체가 글을 쓰는 것을 의미하며, 리피는 고대 페르시아어 단어 dipi와 유사하다는 Hultzch의 제안으로,[64][65] 차용 가능성을 시사한다.페르시아 제국에서 가장 가까운 지역에서 온 아소카 칙령 중 몇 개는 디피를 다른 곳에서 리피로 보이는 프라크리트어로 사용하며, 이 지리적 분포는 적어도 뷸러 시대로 거슬러 올라가 페르시아에서 확산되면서 나타난 표준 리피 형태가 이후 변화임을 나타내는 것으로 오랫동안 받아들여져 왔다.세력권페르시안 디피 자체가 엘람인의 [66]차용어라고 생각된다.

그리스-유대어 모델 가설

1993년 출간된 포크의 저서 슈리프트 임 알텐 인디엔은 고대 인도의 [69][70]글쓰기에 관한 연구로 [37]브라흐미의 기원에 관한 섹션이 있다.그것은 그 당시까지의 문헌에 대한 광범위한 리뷰를 특징으로 한다.Falk는 브라흐미의 기본 문자 체계가 Kharoṭh script 문자에서 파생된 것이며, 그 자체가 아람 문자에서 파생된 것이라고 본다.집필 당시 아소카 칙령은 브라흐미에서 가장 오래되고 자신 있게 연대를 알 수 있는 예이며, 그는 그 속에서 "잘못된 언어 양식에서 잘 다듬어진 [71]언어 양식으로의 명백한 발전"을 시간이 지남에 따라 인식하고 있으며, 그는 이 문장이 최근에 [37][72]개발되었음을 나타내는 것으로 받아들이고 있다.포크는 그리스어를 브라흐미의 중요한 원천으로 보는 견해의 주류에서 벗어난다.특히 살로몬은 Falk에 동의하지 않으며, 모음을 나타내는 그리스어와 브라흐미 표기법이 매우 다르다는 증거를 제시한 후 브라흐미가 그리스어의 [73]원형에서 기본 개념까지 도출했는지 의심스럽다고 말한다.또한 살로몬은 "한정적인 의미에서 브라흐미는 카로스티에서 유래했다고 할 수 있지만 실제 문자 형태에 있어서는 두 인도 문자의 차이가 유사점보다 훨씬 크다"[74]고 덧붙였다.

Falk는 또한 [75]그리스 정복과의 연관성을 근거로 Kharoṭī의 기원을 기원전 325년 이전으로 추정했다.살로몬은 포크의 카로시 연대에 대한 주장에 의문을 제기하며 "기껏해야 추측일 뿐 카로시 연대를 위한 확실한 근거가 되기 힘들다"고 쓰고 있다.이 입장에 대한 더 강력한 주장은 우리가 아소카 시대 이전의 대본의 샘플이나 그 발전의 중간 단계에 대한 직접적인 증거를 가지고 있지 않다는 것이다. 하지만 이것은 물론 그러한 초기 형태가 존재하지 않았다는 것을 의미하지는 않는다. 단지, 그들이 존재했다면, 아마도 그들이 m 동안 고용되지 않았기 때문일 것이다.아쇼카 이전의 기념적인 목적.[72]

Bühler와 달리, Falk는 추정 프로토타입을 브라흐미의 개별 캐릭터와 어떻게 매핑했는지에 대한 자세한 내용을 제공하지 않는다.또한 살로몬, 포크는 브라흐미 문자에는 추정된 카로시 문자 소스에는 없는 발음값과 발음이 이상하다는 것을 인정한다.Falk는 [72][76]이전에 인기가 없었던 가설인 그리스 영향 가설을 부활시킴으로써 이러한 이상 현상을 설명하려고 한다.

하르트무트 샤프는 2002년 카로어 및 브라흐어 문자의 리뷰에서 포크의 제안에 대한 살로몬의 질문에 동의하고 "베다어 학자들이 달성한 산스크리트어의 음소 분석 패턴은 그리스 문자보다 브라흐미 문자에 훨씬 더 가깝다"고 말한다.[20]

2018년 현재 해리 포크는 브라흐미가 아소카 당시 그리스어 문자와 북부 카로스티 [77]문자의 장점을 의식적으로 결합해 이성적으로 개발됐다고 단언하며 자신의 견해를 다듬었다."넓고 곧으며 대칭적인 형태"로 그리스식 글자를 선택하였고,[77] 그 편리성을 위해 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 쓰는 것도 채택되었다.한편, 모음에 대한 Kharosti의 처리는 아람어에서 파생된 고유 모음 "a"와 다른 모음 [77]부호를 나타내기 위한 획 추가와 함께 유지되었다.또한, 복잡한 소리를 나타내기 위해 자음을 수직으로 조합하는 새로운 시스템도 [77]개발되었습니다.

기원

인더스 문자와의 연관성과 같은 토착 기원의 가능성은 일부 서양과 인도의 학자들과 작가들에 의해 뒷받침된다.인더스 문자와 유사성이 있다는 이론은 고고학자 존[80] 마샬과 아시리학자 스티븐 [81]랭던과 같은 초기 유럽 학자들에 의해 제안되었다.G. R. 헌터는 그의 저서 "하라파와 모헨조다로의 대본과 그것의 다른 문자와의 연결"(1934)에서 인더스 문자에서 유래한 브라흐미 문자의 어원을 제안했는데, 그의 [82]평가에서 그 일치는 아람 문자보다 상당히 높았다.영국의 고고학자 레이먼드 올친은 브라흐미 문자가 셈어적인 차용어를 가지고 있다는 생각에 반대하는 강력한 주장이 있다고 말했다. 왜냐하면 전체 구조와 개념이 상당히 다르기 때문이다.그는 한때 그 기원이 [83]인더스 문자와 함께 순수하게 토착어였을 수도 있다고 주장했다.그러나, 1995년 후반에 올친과 에르도시는 이 [84]문제를 해결할 증거가 아직 부족하다는 의견을 표명했다.

오늘날 토착 기원 가설은 컴퓨터 과학자 Subhash Kak, 영적인 교사 David Frawley와 Georg Feuerstein, 그리고 사회 인류학자 Jack [85][86][87]Goody와 같은 비전문가들에 의해 더 일반적으로 추진된다.Subhash Kak은 제안된 셈어 [88]기원에 동의하지 않고 대신 셈어 문자의 출현 이전의 인도인과 셈어 세계 간의 상호작용은 역과정을 [89]의미할 수 있다고 말한다.그러나, 이렇게 제시된 연대와 깨지지 않는 문맹의 전통에 대한 개념은 토착 기원을 지지하는 대다수의 학자들에 의해 반대된다.인더스와 브라흐미 사이의 연속성에 대한 증거는 브라흐미와 후기 인더스 문자 사이의 그래픽 유사성에서도 볼 수 있는데, 여기서 가장 흔한 10개의 연결은 브라흐미에서 [90]가장 흔한 10개의 문자 중 하나의 형태와 일치합니다.숫자 사용에 [91]연속성이 있다는 증거도 있다.이러한 연속성에 대한 추가적인 지원은 [92]Das가 수행한 관계에 대한 통계 분석에서 비롯됩니다.살로몬은 인더스 문자의 음성 값을 알지 못한 채 문자 간의 단순한 그래픽 유사성이 연관성에 대한 불충분한 증거라고 여겼다. 그러나 복합어와 분음 변형 패턴의 명백한 유사성은 "흥미롭다"고 말했다.그러나 그는 인더스 [93]문자와 지금까지 해독할 수 없는 인더스 문자의 시간적 차이가 크기 때문에 그것들을 설명하고 평가하는 것은 시기상조라고 느꼈다.

이 생각의 주요 장애물은 기원전 1500년경 인더스 계곡 문명의 붕괴와 기원전 3, 4세기에 처음으로 널리 받아들여진 브라흐미 출현 사이의 천년 반 동안 집필에 대한 증거가 부족하다는 것이다.Iravathan Mahadevan은 인더스 문자로 기원전 1500년의 최신 연대와 기원전 500년경 브라흐미의 가장 오래된 연대를 사용한다고 해도, 천 년이 여전히 둘을 [94]갈라놓고 있다고 주장한다.게다가, 인더스 문자에 대한 인정된 해독은 없기 때문에, 주장된 해독에 근거한 이론을 미약하게 만든다.인더스 문자와 이후 문자 전통 사이의 유망한 연결고리는 남인도 거석문화의 거석 그래피티 기호일 수 있습니다.거석문화는 인더스 기호 목록과 일부 중복될 수 있으며 적어도 서기 3세기까지 브라흐미와 타밀 브라흐미 문자의 출현을 통해 계속 사용되었습니다.이러한 그래피티는 보통 개별적으로 나타나지만, 때때로 두세 명의 그룹으로 발견될 수 있으며 가족, 씨족 또는 종교적 [95]상징으로 생각됩니다.1935년, C. L. 파브리는 마우리아의 펀치 마크 동전에서 발견된 상징들이 인더스 [96]문명의 붕괴에서 살아남은 인더스 문자의 잔재라고 제안했다.타밀-브라흐미의 분파자이자 인더스 문자의 유명한 전문가인 이라바탐 마하데반은 이러한 기미 전통이 인더스 문자와 어느 정도 연관이 있을 수 있다는 생각을 지지해 왔지만, 브라흐미와의 연속성에 대해서는 "전혀"[94] 그 이론을 믿지 않는다고 분명히 말했다.

토착 기원 이론의 또 다른 형태는 살로몬이 이러한 이론들이 본질적으로 [97]완전히 추측적이라고 발견했음에도 불구하고 브라흐미가 니힐로로부터, 셈어 모델이나 인더스 문자로부터 완전히 독립적으로 발명되었다는 것이다.

파니니 (기원전 6세기~4세기)는 산스크리트 문법에 관한 그의 최종 저작인 아슈타디아이에서 대본을 쓰는 것을 뜻하는 인도어인 리피를 언급한다.샤르페에 따르면, 리피와 리비라는 단어는 수메르어 [65][98]두피에서 유래된 고대 페르시아어 두피에서 차용되었다.아소카는 자신의 칙령을 묘사하기 위해 Lip,라는 단어를 사용했는데, 지금은 일반적으로 간단히 "글쓰기" 또는 "설명"으로 번역된다.두 개의 Kharosthi 판의 바위 [note 3]칙령에서 "dipi"로 철자된 "lipi"라는 단어는 고대 페르시아어 원형 딥에서 유래한 것으로 생각되는데, 예를 들어 다리우스 1세가 그의 베히툰 [note 4]비문에 차용과 확산을 [99][100][101][full citation needed]암시하는 것으로 사용되었다.

Scharfe기 때문에 같은 책에서 인도 전통"모든 경우에 문학 문화 유산이 구순애 강조한다."[65]지만 Scharfe은 "대본이 디스크를 인정하면 최상 증거도 없다는 대본이나는 어느 알려진 인도에서, Persian-dominated 북서가 아람 말 사용되었습니다 이외에도, 약 300년 전에 사용되었던 있다고 덧붙였다.위에기원전 3천년에 인더스 계곡과 인근 지역에서 번성했던 인더스 문명의 발굴에 관한 연구.다른 기호들의 수는 음절 문자를 암시하지만, 지금까지 모든 해독 시도는 성공하지 못했다.이 해독되지 않은 문자를 기원전 3세기 이후 유행한 인도 문자와 연결시키려는 일부 인도 학자들의 시도는 완전히 [102]실패입니다.

아소카보다 불과 25년 전에 인도 북동부의 마우리아 궁정에 주재한 그리스 대사 메가스테네스는 성문법도 없고 글도 모르며 모든 것을 [103]기억으로 규제하는 사람들 사이에서 이런 일이 벌어졌다고 말했다.이것은 많은 작가들에 의해 다양하고 논쟁적으로 해석되어 왔다.루도 로처는 메가스테네스의 정보원과 메가스테네스의 [104]해석에 의문을 제기하며 메가스테네스를 신뢰할 수 없다고 거의 완전히 일축했다.팀머는 "메가스테인이 법이 불문율이고 구전이 [105]인도에서 그렇게 중요한 역할을 했다는 사실을 올바르게 관찰했다는 사실에 근거해서" 마우리아인들이 문맹이었다는 오해를 반영하는 것이라고 생각한다.

토착 기원[who?] 이론의 일부 지지자들은 메가스테네스가 한 논평의 신뢰성과 해석에 의문을 제기한다(Geogiica XV.i.53의 Strabo가 인용했다).한 예로, 그 관찰은 "산드라코토스" 왕국(찬드라굽타)의 맥락에서만 적용될 수 있다.그밖에 스트라보(Strab. XV.i.39)에서, 메가 스테 네스 인도의"철학자"카스트(아마 브라만)가 있어야 상습 kings,[106]에"그들이 쓰는 것에 이를 저지른 어떤 유용한"를 제출했지만 이 부분 Megasthenes의 병렬 추출물과 디오도로스 시켈로스Arrian에서 발견된에 나타나지 않음에 주목하고 것으로 알려졌다.[107][108]" asτάξῃsourcesource"(영어 단어 "syntax"의 출처)라는 용어는 특별히 쓰여진 작문이 아닌 일반적인 "작곡" 또는 "편곡"으로 읽힐 수 있기 때문에 원 그리스어에서는 작문 자체의 의미도 완전히 명확하지 않다.메가스테네스와 동시대인인 네아쿠스는 몇 십 년 전 북부 인도에서 글씨를 쓰기 위해 면직물을 사용하는 것에 주목했다.인도학자들은 이것이 Kharoṭh or 또는 아람 문자일 것이라고 다양한 추측을 해왔다.살로몬은 그리스 소식통으로부터의 증거가 단정적이지 않다고 [109]간주한다.Strabo 본인은 인도에서의 문자 사용에 관한 보고서(XV.i.67)와 관련하여 이러한 불일치를 지적하고 있다.

Kenneth Norman(2005)은 브라흐미가 아쇼카의 [110]통치 이전에 오랫동안 고안되었다고 시사한다.

이러한 아쇼칸 이전의 개발에 대한 생각은 매우 최근에 스리랑카 아누라다푸라에서 브라흐마로 보이는 소수의 문자가 새겨진 셰르드가 발견됨으로써 뒷받침되었다.이 셔드들은 탄소 14와 열발광 연대를 통해 아쇼카 이전 시대, 아마도 [111]아쇼카 이전까지 거슬러 올라갑니다.

그는 또한 아소칸 칙령에서 볼 수 있는 변형들이 브라흐미가 마우리아 제국의 [112]재상들 중 하나의 기원을 가지고 있었다면 그렇게 빨리 나타나지 않았을 것이라고 지적한다.그는 브라흐미 문자의 발달 시기를 비문에 나타난 형태로 [112]늦어도 4세기 말 이전으로 추정한다.

잭 구디(1987년)는 고대 인도에는 지식을 구성하고 전달하는 구전 전통과 함께 "아주 오래된 글 문화"가 있었을 것이라고 비슷한 주장을 했다. 왜냐하면 베다 문학은 너무 방대하고, 일관되고, 복잡해서 문자 [113][114]체계 없이 완전히 만들어지고, 정확하게 보존되고, 전파되기 때문이다.

이 점에 대해서는 베다 문학의 양과 질로 볼 때 베다 시대에 브라흐미를 포함한 문자가 없었을 가능성에 대해서는 의견이 분분하다.Falk(1993)는 Goody에 [115]동의하지 않지만, Walter Ong과 John Hartley(2012)는 [116]베다 찬가를 경구적으로 보존하는 것의 어려움에서가 아니라 파니니의 문법이 구성되었을 가능성이 매우 낮다는 점에 동의한다.요하네스 브론호스트(2002)는 베다 찬가의 구두 전달은 충분히 구두로 이루어졌을지도 모르지만 파니니의 문법 발달은 (기원전 [69]4세기 인도 문자의 발달과 일치한다) 문법을 전제로 한다는 중간 입장을 취하고 있다.

이름의 유래

"브라미" (Brahmi)라는 이름의 유래에 대한 여러 가지 다른 설명이 역사에 등장한다.랄리타비스타라 수트라와 같은 일부 불교 경전에는 부처가 [117]어렸을 때 알고 있던 64개의 경전 중 일부로서 브라흐마와 카로시를 열거하고 있다.자이나교의 Vyakhya Pragyapti Sutra, Samvayanga Sutra, Pragyapna Sutra와 같은 자이나교의 여러 경전에는 마하비라가 태어나기 전에 교사들에게 알려진 18개의 필기 대본 목록이 포함되어 있으며, 최초의 것은 Prakr에 있는 밤비이다.브라흐미 문자는 비셰샤 아바샤카와 칼파 수트라라는 두 개의 후기 자이나 수트라에 남아 있는 18개의 문자 목록에서 누락되어 있다.Jain legend recounts that 18 writing scripts were taught by their first Tirthankara Rishabhanatha to his daughter Bambhi (बाम्भी); she emphasized बाम्भी as the main script as she taught others, and therefore the name Brahmi for the script comes after her name.[118]"브라미 문자"라는 표현에 대한 초기의 경구적 증거는 없다.Ashoka himself when he created the first known inscriptions in the new script in the 3rd century BCE, used the expression Dhaṃma Lipi (Prakrit in the Brahmi script: 𑀥𑀁𑀫𑀮𑀺𑀧𑀺, "Inscriptions of the Dharma") but this is not to describe the script of his own Edicts.[119]

6세기에 대한 중국 불교 서적은 그것이 창조된 것이 브라흐마 신이라고 하지만, 모니에-윌리암스,[120][121] 실뱅 레비, 그리고 다른 사람들은 그것이 브라만에 의해 만들어졌기 때문에 그 이름이 지어졌을 가능성이 더 높다고 생각했다.

브라흐미(Brahmi)라는 용어는 인도 문헌에 다른 맥락으로 나타난다.산스크리트어 규칙에 따르면, 그것은 문자 그대로 "브라흐마의" 또는 "브라흐만의 여성 에너지"[122]를 의미하는 여성 단어이다.마하바라타와 같은 다른 문헌에서는 여신, 특히 사라스와티에게는 언어의 여신, 그리고 다른 곳에서는 "브라흐마의 [123]의인화된 샤크티"로 나타난다.

★★★

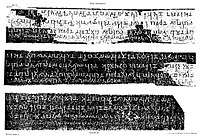

가장 먼저 알려진 브라흐미의 완전한 비문은 기원전 3세기에서 1세기로 거슬러 올라가는 프라크리트,[124] 특히 기원전 250년경 아소카의 칙령이다.프라크릿 기록은 [124]약 1세기경 인도 아대륙에서 발견된 경구 기록보다 우세하다.산스크리트어로 된 최초의 브라흐미 비문은 아요디아, 고순디, 하티바다(둘 다 치토르가르 [125][note 5]근처)에서 발견된 몇 안 되는 것과 같은 기원전 1세기 것이다.고대 비문은 또한 많은 북부와 중부의 인도 유적지에서 발견되었으며, 때때로 남인도에서도 발견되었는데, 이들은 "비문 혼성 산스크리트어"[note 6]라고 불리는 산스크리트어와 프라크리트어를 혼합한 언어이다.이것들은 현대 기술에 의해 기원후 [128][129]1세기에서 4세기 사이의 것으로 추정됩니다.남아 있는 브라흐미 문자 기록은 기둥, 사원 벽, 금속판, 테라코타, 동전, 크리스탈, [130][129]필사본에 새겨진 것으로 발견됩니다.

브라흐미의 기원에 관한 가장 중요한 최근의 발전 중 하나는 스리랑카의 무역 도시 아누라다푸라의 도자기 조각에 새겨진 브라흐미 문자가 발견된 것이다. 이 조각들은 기원전 [131]6세기에서 4세기 초 사이에 만들어진 것이다.1996년 [132]코닝엄 외 연구진은 아누라다푸라 비문의 문자는 브라흐미라고 밝혔지만 아누라다푸라는 드라비다어가 아니라 프라크리트어라고 밝혔다.표본의 역사적 순서는 수세기에 걸친 양식적 정제 수준의 진화를 나타내는 것으로 해석되었고, 그들은 브라흐미 문자가 "수은적 개입"에서 생겨났을 수 있으며 스리랑카의 무역 네트워크의 성장은 이 지역의 [132]첫 등장과 관련이 있다고 결론지었다.살로몬은 1998년 리뷰에서 아누라다푸라 비문은 기원전 4세기 이전의 남아시아에 브라흐미가 존재했다는 설을 뒷받침한다고 밝혔지만,[131] 그 비문이 이후부터 도기공장에 침입한 것이 아니냐는 의구심이 남는다.인도학자 해리 포크는 아소카의 칙령은 브라흐미의 더 오래된 단계를 나타낸다고 주장했지만, 최초의 아누라다푸라 비문의 어떤 고고학적 특징들은 더 늦은 것일 수 있으며,[133] 따라서 이러한 도기 조각들은 기원전 250년 이후부터 존재할 수 있다.

보다 최근인 2013년에 라잔과 야테스크마르는 타밀나두의 포룬탈과 코두마날에서 발굴을 발표했는데, 타밀브라흐미와 프라크리트브라흐미 비문과 파편이 다수 발견되었다.[134]그들의 지층학적 분석은 논알과 숯 샘플의 방사성 탄소 연대와 결합된 것으로, 비문의 맥락이 기원전 [135]6세기에서 아마도 7세기까지 거슬러 올라간다는 것을 보여준다.이것들은 매우 최근에 출판되었기 때문에 아직까지는 문헌에 광범위하게 언급되지 않았다.인도학자 해리 포크는 라잔의 주장이 "특히 잘못된 정보"라고 비판했습니다; 포크는 최초의 비문 중 일부는 브라흐미 문자가 아니라 단지 문자 이전 시대에 [136]남인도에서 수 세기 동안 사용되었던 언어적이지 않은 메가리틱 그래피티 기호로 잘못 해석되었을 뿐이라고 주장합니다.

의 진화(기원전기원전 )

브라흐미 문자의 서체는 마우리아 제국 시대부터 기원전 [138]1세기 말까지 거의 변하지 않았다.이 무렵 인도-스키티아인("북쪽 사트라프")은 인도 북부에 세워진 후 브라흐미 [138]표기 방식에 "혁명적 변화"를 가져왔다.기원전 1세기에는 브라흐미 [138]문자의 모양이 더욱 각지고 세로로 구분된 문자가 균등화되면서 화폐 전설에서 뚜렷하게 나타나 그리스 문자와 시각적으로 더 비슷해졌다.이 새로운 서체에서는, 그 서체는 「신기하고 형식이 좋다」[138]라고 쓰여 있었다.수묵과 필적의 도입은 수묵의 사용으로 인해 각 획의 시작 부분이 두꺼워지는 특징을 가지고 있으며,[138][140] 각 획의 시작 부분에 삼각형 모양의 글씨가 만들어짐으로써 석각의 서체로 재현되었다.이 새로운 문체는 특히 마쓰라어로 된 많은 헌정문, 헌정문,[138] 헌정문 등에서 볼 수 있다.브라흐미 문자의 이 새로운 서예는 다음 [138]반세기의 나머지 대륙에서 채택되었다."새로운 펜 스타일"은 기원후 1세기부터 스크립트의 급속한 진화를 시작하였고,[138] 지역에 따라 변형이 나타나기 시작했다.

★★★★

그리스어와 아람어로 된 몇 개의 비문(20세기에만 발견된) 외에 아소카의 칙령은 브라흐미 문자로 쓰여졌고 때로는 북서쪽의 카로시 문자로 쓰여졌는데, 둘 다 서기 4세기경에 멸종되었고, 아직 발견되어 조사되지 않았다.19세기[145][19]

후기 브라흐미의 6세기 CE 비문은 1785년 찰스 윌킨스에 의해 이미 해독되었는데, 윌킨스는 마우카리 왕 [146]아난타바르만이 쓴 고피카 동굴 비문을 근본적으로 정확하게 번역한 것을 출판했다.윌킨스는 근본적으로 팔라 시대의 대본과 [146]데바나가리의 초기 형태와 같은 후대의 브라흐 문자와의 유사성에 의존한 것으로 보인다.

그러나 초기 브라흐미는 읽을 [146]수 없는 상태로 남아 있었다.1834년 아소카의 알라하바드 기둥에 새겨진 글의 적절한 팩시밀리가 출판되면서 진척이 재개되었는데, 특히 아소카의 칙령과 굽타 제국의 통치자 사무드라굽타의 [142]글들이 포함되어 있다.

고고학자, 언어학자, 동인도 회사의 관리인 제임스 프린셉은 비문을 분석하기 시작했고 통계적 [142]방법에 의존한 초기 브라흐미 문자의 일반적인 특징에 대해 추론했다.1834년 3월에 출판된 이 방법을 통해 그는 비문에서 발견된 문자를 분류할 수 있었고, 발성적인 "굴절"을 가진 자음 문자로 구성된 브라흐미의 구조를 명확히 할 수 있었다.발성 억양 5개 중 4개는 맞췄지만 자음의 가치는 알려지지 않았다.[142]비록 이 통계 방법은 현대적이고 혁신적이었지만, 이 문자의 실제 해독은 몇 년 [147]후 이중언어 비문이 발견될 때까지 기다려야 할 것이다.

같은 해, 1834년, J. 스티븐슨 목사에 의해 카라 동굴 (1세기경)의 중간 초기 브라흐미 문자를 식별하려는 시도가 이루어졌는데, 이는 알라하바드 기둥의 사무드라굽타 비문의 굽타 문자(4세기경)와 유사하지만, 좋은 혼합을 이끌었습니다.ut 1/3) 및 잘못된 추측으로 인해 브라흐미를 [148][142]제대로 해독할 수 없었습니다.

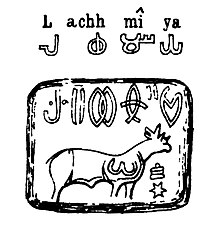

기원전 3세기-2세기의 고대 브라흐미 문자를 해독하기 위한 다음 주요 단계는 1836년 노르웨이 학자 크리스티안 라센에 의해 만들어졌는데, 그는 인도-그리스 왕 아가토클레스의 그리스-브라흐미 동전과 팔리 문자와의 유사점을 사용하여 여러 브라흐미 [19][142][149]문자를 정확하고 안전하게 식별했다.아가토클레스의 이중언어 동전에 대한 일치된 전설은 다음과 같다.

그리스 전설 : βα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δα δ δα δα δα δα δ

브라흐미 전설:라자네 아가투클레사, 아가토클레스 [150]왕

그리고 나서 제임스 프린셉은 브라흐미 [142][151][19][152]문자의 해독을 완료할 수 있었다.라센의 첫 번째 [153]해독을 인정한 후, 프린셉은 인도-그리스 왕 판탈레온의 이중언어 동전을 사용하여 몇 개의 문자를 [149]더 해독했다.James Prinsep then analysed a large number of donatory inscriptions on the reliefs in Sanchi, and noted that most of them ended with the same two Brahmi characters: "𑀤𑀦𑀁".프린셉은 그들이 산스크리트어로 "선물" 또는 "기부"를 의미하는 "다남"을 의미한다고 정확히 추측했고, 이는 알려진 [142][154]글자의 수를 더 늘릴 수 있게 해주었다.싱할라 팔리학자이자 언어학자인 라트나 팔라의 도움으로, 프린셉은 브라흐미 [155][156][157][158]문자의 완전한 해독을 완성했다.1838년 3월에 그가 출판한 일련의 결과에서 Prinsep은 인도 전역에서 발견된 많은 암석 칙령들의 비문을 번역할 수 있었고, 리처드 살로몬에 따르면 완전한 브라흐미 [159][160]문자의 "실질적으로 완벽한" 묘사를 제공할 수 있었다.

아쇼칸의 비문은 인도 전역에서 발견되며, 몇 가지 지역별 변형이 관찰되고 있다.바티프로루 문자는 아소카 치세 몇 십 년 전으로 거슬러 올라가며, 브라흐미 문자의 남쪽 변종에서 발전한 것으로 여겨진다.이 비문에 사용된 언어는 거의 대부분이 불교 유물에 의해 발견되었으며, 일부 비문에서는 칸나다와 텔루구의 고유 이름이 확인되었습니다.23개의 편지가 확인되었습니다.가( are)와 사( are)는 마우리아 브라흐미(,)와 비슷하지만, 바( resemble)와 다(多)는 현대의 칸나다( tel나다)와 텔루구(ug script) 문자와 비슷하다.

타밀브라미는 기원전 3세기까지 남인도, 특히 타밀나두와 케랄라에서 사용되었던 브라흐미 문자의 변형이다.비문은 그들이 같은 시기에 스리랑카 일부에서 사용되었음을 증명한다.20세기에 발견된 약 70개의 남부 브라흐미 비문에 사용된 언어는 프라크리트어로 [78][79]확인되었다.

영어로 볼 때, 스리랑카에서 발견된 브라흐미 문자의 가장 널리 이용 가능한 복제품은 에피그라피아 제일라니카이다; 제1권(1976년)에서는,[161] 많은 비문이 기원전 3세기에서 2세기까지 거슬러 올라간다.

그러나 아소카의 칙령과는 달리, 스리랑카에서 이 초기의 비문의 대부분은 동굴 위에서 발견됩니다.스리랑카 브라흐미 비문의 언어는 대부분 프라크리트어였지만, 안나코다이 [162]문장과 같은 타밀-브라흐미 비문도 발견되었다.브라흐미어로 쓰인 최초의 예는 스리랑카 [132]아누라다푸라에서 볼 수 있다.

와

태국에서 발견된 Khuan Luk Pat 비문은 타밀 브라흐미 문자로 되어 있다.그 연대는 불확실하고 공통 [163][164]시대의 초기 세기로 제안되어 왔다.프레데릭 애셔에 따르면 이집트 쿠세이르 알 카딤과 베레니케에서 도기류에 새겨진 타밀 브라흐미 비문이 발견되었는데, 이는 고대 인도와 홍해 [164]지역 사이에 상거래가 번성했음을 암시한다.추가로 타밀 브라흐미 비문이 오만의 코로리 지역에서 고고학적 유적지 저장 [164]항아리에서 발견되었다.

★★★

브라흐미는 보통 후손의 경우와 같이 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 쓰여진다.그러나 에란에서 발견된 초기 동전에는 아람어처럼 브라흐미가 오른쪽에서 왼쪽으로 새겨져 있다.고대 문자 [165]체계에서는 방향의 불안정성이 상당히 일반적이지만, 필기 방향의 변화에는 몇 가지 다른 예가 알려져 있다.

★★

브라흐미는 각 글자가 자음을 나타낸다는 뜻의 아부기다인 반면, 모음은 단어를 시작할 때를 제외하고 산스크리트어로 마트라라고 불리는 필수 분음 부호로 쓰여진다.모음을 쓰지 않으면 모음 /a/가 이해됩니다.이 "기본 단축 a"는 Kharosth,와 공통되는 특징이지만, 모음에 대한 처리는 다른 점에서는 다르다.

/pr/ 또는 /rv/와 같은 자음 클러스터를 쓸 때 특수 결음 자음을 사용합니다.현대의 데바나가리에서는 가능한 한 접속어의 구성요소가 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 쓰여지는 반면, 브라흐미에서는 글자가 수직으로 아래쪽으로 연결되어 있다.

★★★★★

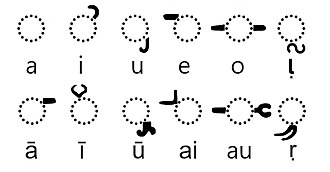

자음 뒤에 오는 모음은 고유하거나 분음 부호에 의해 쓰이지만, 초기 모음에는 전용 문자가 있습니다.아쇼칸 브라흐미에는 세 개의 "원모음"이 있으며, 각각 길이 대비 형태로 발생합니다: /a/, /i/, /u/; 장모음은 단모음의 글자에서 파생됩니다.또한 긴 단대비를 가지지 않는 4개의 "보조" 모음, /e:/, /ai/, /o:/, /au/[166]도 있습니다.단, /ai/의 문자는 /e/에서 파생된 것으로, 원모음의 단대조(역사적으로는 /ai/ 및 /a:i/)와 유사합니다.단, 모음이 없으면 짧은 /a/가 이해되기 때문에 구별되는 모음 분음 부호는 9개뿐입니다./au/의 초기 모음 기호 또한 분음 부호가 있지만, 가장 이른 단계에서 분명히 부족하다.고대 문헌에 따르면 아쇼칸 시대의 문자 목록 시작 부분에 11개 또는 12개의 모음이 열거되어 있으며, 아마 aṃ 또는 [167]aḥ를 추가했을 것이다.브라흐미의 후기 버전은 짧고 긴 ///와 ///의 네 음절 액체를 위한 모음을 추가합니다.중국의 자료들은 이것들이 나중에 나가르주나 혹은 할라 [168]왕의 장관인 샤르바바르만에 의해 발명되었다고 말한다.

모든 자음에 모음이 뒤따르는 브라흐미, 카로슈어의 기본 모음 표기 체계는 프라크리트어에 [169]잘 어울렸지만 브라흐미가 다른 언어에 적응하면서 비라마라는 특별한 표기법이 도입되어 최종 모음의 누락이 알려지게 되었다.또한 Kharoṭh는 초기 모음 표현에 분음 부호로 구별되는 단일 일반 모음 기호가 있고 긴 모음은 구별되지 않는다는 점에서 다르다.

브라흐미의 대조 순서는 산스크리트어 음운론의 전통적인 베다 이론인 식샤에 기반을 둔 대부분의 후예 문자와 동일했던 것으로 추정된다.이것은 초기 모음으로 시작하는 문자 목록(a로 시작)을 시작하고, 바르가스라고 불리는 5개의 음운 관련 그룹에 자음의 하위 집합을 나열하고, 4개의 액체, 3개의 자매음, 그리고 나선형으로 끝납니다.토마스 트라우트만은 브라흐미 문자 계열의 인기의 많은 부분을 이 "훌륭하게 합리적인"[170] 배열 체계에 기인한다.

| k- | g- | c- | j- | 【】 | 【】 | t- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | b- | m- | r- | v- | s- | |||||||||||||||||||

| -a | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 | 𑀴 |

| -아아아아아아아아아아아아아아아아아아악 | 𑀓𑀸 | 𑀔𑀸 | 𑀕𑀸 | 𑀖𑀸 | 𑀗𑀸 | 𑀘𑀸 | 𑀙𑀸 | 𑀚𑀸 | 𑀛𑀸 | 𑀜𑀸 | 𑀝𑀸 | 𑀞𑀸 | 𑀟𑀸 | 𑀠𑀸 | 𑀡𑀸 | 𑀢𑀸 | 𑀣𑀸 | 𑀤𑀸 | 𑀥𑀸 | 𑀦𑀸 | 𑀧𑀸 | 𑀨𑀸 | 𑀩𑀸 | 𑀪𑀸 | 𑀫𑀸 | 𑀬𑀸 | 𑀭𑀸 | 𑀮𑀸 | 𑀯𑀸 | 𑀰𑀸 | 𑀱𑀸 | 𑀲𑀸 | 𑀳𑀸 | 𑀴𑀸 |

| -i | 𑀓𑀺 | 𑀔𑀺 | 𑀕𑀺 | 𑀖𑀺 | 𑀗𑀺 | 𑀘𑀺 | 𑀙𑀺 | 𑀚𑀺 | 𑀛𑀺 | 𑀜𑀺 | 𑀝𑀺 | 𑀞𑀺 | 𑀟𑀺 | 𑀠𑀺 | 𑀡𑀺 | 𑀢𑀺 | 𑀣𑀺 | 𑀤𑀺 | 𑀥𑀺 | 𑀦𑀺 | 𑀧𑀺 | 𑀨𑀺 | 𑀩𑀺 | 𑀪𑀺 | 𑀫𑀺 | 𑀬𑀺 | 𑀭𑀺 | 𑀮𑀺 | 𑀯𑀺 | 𑀰𑀺 | 𑀱𑀺 | 𑀲𑀺 | 𑀳𑀺 | 𑀴𑀺 |

| -cymp-cymp-cymp. | 𑀓𑀻 | 𑀔𑀻 | 𑀕𑀻 | 𑀖𑀻 | 𑀗𑀻 | 𑀘𑀻 | 𑀙𑀻 | 𑀚𑀻 | 𑀛𑀻 | 𑀜𑀻 | 𑀝𑀻 | 𑀞𑀻 | 𑀟𑀻 | 𑀠𑀻 | 𑀡𑀻 | 𑀢𑀻 | 𑀣𑀻 | 𑀤𑀻 | 𑀥𑀻 | 𑀦𑀻 | 𑀧𑀻 | 𑀨𑀻 | 𑀩𑀻 | 𑀪𑀻 | 𑀫𑀻 | 𑀬𑀻 | 𑀭𑀻 | 𑀮𑀻 | 𑀯𑀻 | 𑀰𑀻 | 𑀱𑀻 | 𑀲𑀻 | 𑀳𑀻 | 𑀴𑀻 |

| -u | 𑀓𑀼 | 𑀔𑀼 | 𑀕𑀼 | 𑀖𑀼 | 𑀗𑀼 | 𑀘𑀼 | 𑀙𑀼 | 𑀚𑀼 | 𑀛𑀼 | 𑀜𑀼 | 𑀝𑀼 | 𑀞𑀼 | 𑀟𑀼 | 𑀠𑀼 | 𑀡𑀼 | 𑀢𑀼 | 𑀣𑀼 | 𑀤𑀼 | 𑀥𑀼 | 𑀦𑀼 | 𑀧𑀼 | 𑀨𑀼 | 𑀩𑀼 | 𑀪𑀼 | 𑀫𑀼 | 𑀬𑀼 | 𑀭𑀼 | 𑀮𑀼 | 𑀯𑀼 | 𑀰𑀼 | 𑀱𑀼 | 𑀲𑀼 | 𑀳𑀼 | 𑀴𑀼 |

| 𑀓𑀽 | 𑀔𑀽 | 𑀕𑀽 | 𑀖𑀽 | 𑀗𑀽 | 𑀘𑀽 | 𑀙𑀽 | 𑀚𑀽 | 𑀛𑀽 | 𑀜𑀽 | 𑀝𑀽 | 𑀞𑀽 | 𑀟𑀽 | 𑀠𑀽 | 𑀡 | 𑀢𑀽 | 𑀣𑀽 | 𑀤𑀽 | 𑀥𑀽 | 𑀦𑀽 | 𑀧𑀽 | 𑀨𑀽 | 𑀩𑀽 | 𑀪𑀽 | 𑀫𑀽 | 𑀬𑀽 | 𑀭𑀽 | 𑀮𑀽 | 𑀯𑀽 | 𑀰𑀽 | 𑀱𑀽 | 𑀲𑀽 | 𑀳𑀽 | 𑀴𑀽 | |

| - | 𑀓𑁂 | 𑀔𑁂 | 𑀕𑁂 | 𑀖𑁂 | 𑀗𑁂 | 𑀘𑁂 | 𑀙𑁂 | 𑀚𑁂 | 𑀛𑁂 | 𑀜𑁂 | 𑀝𑁂 | 𑀞𑁂 | 𑀟𑁂 | 𑀠𑁂 | 𑀡 | 𑀢𑁂 | 𑀣𑁂 | 𑀤𑁂 | 𑀥𑁂 | 𑀦𑁂 | 𑀧𑁂 | 𑀨𑁂 | 𑀩𑁂 | 𑀪𑁂 | 𑀫𑁂 | 𑀬𑁂 | 𑀭𑁂 | 𑀮𑁂 | 𑀯𑁂 | 𑀰𑁂 | 𑀱𑁂 | 𑀲𑁂 | 𑀳𑁂 | 𑀴𑁂 |

| -o | 𑀓𑁄 | 𑀔𑁄 | 𑀕𑁄 | 𑀖𑁄 | 𑀗𑁄 | 𑀘𑁄 | 𑀙𑁄 | 𑀚𑁄 | 𑀛𑁄 | 𑀜𑁄 | 𑀝𑁄 | 𑀞𑁄 | 𑀟𑁄 | 𑀠𑁄 | 𑀡 | 𑀢𑁄 | 𑀣𑁄 | 𑀤𑁄 | 𑀥𑁄 | 𑀦𑁄 | 𑀧𑁄 | 𑀨𑁄 | 𑀩𑁄 | 𑀪𑁄 | 𑀫𑁄 | 𑀬𑁄 | 𑀭𑁄 | 𑀮𑁄 | 𑀯𑁄 | 𑀰𑁄 | 𑀱𑁄 | 𑀲𑁄 | 𑀳𑁄 | 𑀴𑁄 |

| - - | 𑀓𑁆 | 𑀔𑁆 | 𑀕𑁆 | 𑀖𑁆 | 𑀗𑁆 | 𑀘𑁆 | 𑀙𑁆 | 𑀚𑁆 | 𑀛𑁆 | 𑀜𑁆 | 𑀝𑁆 | 𑀞𑁆 | 𑀟𑁆 | 𑀠𑁆 | 𑀡𑁆 | 𑀢𑁆 | 𑀣𑁆 | 𑀤𑁆 | 𑀥𑁆 | 𑀦𑁆 | 𑀧𑁆 | 𑀨𑁆 | 𑀩𑁆 | 𑀪𑁆 | 𑀫𑁆 | 𑀬𑁆 | 𑀭𑁆 | 𑀮𑁆 | 𑀯𑁆 | 𑀰𑁆 | 𑀱𑁆 | 𑀲𑁆 | 𑀳𑁆 | 𑀴𑁆 |

구두점

구두점은[172] 아소칸 브라흐미에서 일반적인 규칙이라기보다 예외적인 것으로 인식될 수 있다.예를 들어 기둥 명령어에는 자주 나타나지만 다른 명령어에는 많이 나타나지 않는다. ('기둥 명령어'는 종종 돌기둥에 새겨진 글을 말한다.)각 단어를 따로 쓴다는 생각은 일관되게 사용되지 않았다.

브라흐미 시대 초기에는 구두점의 존재가 잘 드러나지 않는다.각 글자는 단어와 긴 섹션 사이에 간격을 두고 독립적으로 쓰여져 있습니다.

중반에는 시스템이 발달하고 있는 것 같습니다.대시 및 곡선 수평선의 사용법을 확인할 수 있습니다.연꽃 마크가 끝을 나타내는 것 같고, 동그라미 마크가 나타나 마침표를 나타낸다.풀스톱은 여러 가지가 있는 것 같습니다.

말기에는 마침표 시스템이 더 복잡해진다.예를 들어, "/"와 같은 세로로 기울어진 이중 대시에는 구성의 완성을 나타내는 네 가지 형태가 있습니다.후기의 모든 장식적인 표지판에도 불구하고, 표지판들은 비문에 상당히 단순하게 남아 있었다.가능한 이유 중 하나는 글쓰기가 제한되지 않는 반면 판화는 제한되기 때문일 수 있습니다.

Baums는 브라흐미의 [173]컴퓨터 표현에 필요한 7가지 구두점을 식별합니다.

- 싱글(부호) 및 더블(부호) 세로 막대(단다)– 절과 절을 구분합니다.

- 도트(점), 더블 도트(점), 수평선(점) - 짧은 텍스트 단위를 구분합니다.

- 초승달(연꽃) 및 연꽃(연꽃) – 더 큰 텍스트 단위를 구분합니다.

브라흐미 문자의 진화

브라흐미는 일반적으로 세 가지 주요 유형으로 분류되는데, 이는 거의 [174]천년에 걸친 브라흐미 진화의 세 가지 주요 역사적 단계를 나타낸다.

| 브라흐미[175] 문자의 진화 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k- | kh- | g- | 으으- | ②- | c- | 챠 | j- | jh- | ᄂ- | ②- | ②h- | ②- | ②h- | ②- | t- | 이- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | 이- | v- | ②- | ②- | s- | h- | |

| 아쇼카[176] | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 |

| Girnar[177] | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kushan[178] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gujarat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gupta[179] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early Brahmi or "Ashokan Brahmi" (3rd–1st century BCE)

Early "Ashokan" Brahmi (3rd–1st century BCE) is regular and geometric, and organized in a very rational fashion:

Independent vowels

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA | Mātrā | IAST and Sanskrit IPA | Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA | Mātrā | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𑀅 | a /ə/ | 𑀓 | ka /kə/ | 𑀆 | ā /aː/ | 𑀓𑀸 | kā /kaː/ |

| 𑀇 | i /i/ | 𑀓𑀺 | ki /ki/ | 𑀈 | ī /iː/ | 𑀓𑀻 | kī /kiː/ |

| 𑀉 | u /u/ | 𑀓𑀼 | ku /ku/ | 𑀊 | ū /uː/ | 𑀓𑀽 | kū /kuː/ |

| 𑀏 | e /eː/ | 𑀓𑁂 | ke /keː/ | 𑀑 | o /oː/ | 𑀓𑁄 | ko /koː/ |

| 𑀐 | ai /əi/ | 𑀓𑁃 | kai /kəi/ | 𑀒 | au /əu/ | 𑀓𑁅 | kau /kəu/ |

Consonants

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | 𑀓 | ka /k/ | 𑀔 | kha /kʰ/ | 𑀕 | ga /ɡ/ | 𑀖 | gha /ɡʱ/ | 𑀗 | ṅa /ŋ/ | 𑀳 | ha /ɦ/ | ||||

| Palatal | 𑀘 | ca /c/ | 𑀙 | cha /cʰ/ | 𑀚 | ja /ɟ/ | 𑀛 | jha /ɟʱ/ | 𑀜 | ña /ɲ/ | 𑀬 | ya /j/ | 𑀰 | śa /ɕ/ | ||

| Retroflex | 𑀝 | ṭa /ʈ/ | 𑀞 | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | 𑀟 | ḍa /ɖ/ | 𑀠 | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | 𑀡 | ṇa /ɳ/ | 𑀭 | ra /r/ | 𑀱 | ṣa /ʂ/ | ||

| Dental | 𑀢 | ta /t̪/ | 𑀣 | tha /t̪ʰ/ | 𑀤 | da /d̪/ | 𑀥 | dha /d̪ʱ/ | 𑀦 | na /n/ | 𑀮 | la /l/ | 𑀲 | sa /s/ | ||

| Labial | 𑀧 | pa /p/ | 𑀨 | pha /pʰ/ | 𑀩 | ba /b/ | 𑀪 | bha /bʱ/ | 𑀫 | ma /m/ | 𑀯 | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||

The final letter does not fit into the table above; it is 𑀴 ḷa.

Unicode and digitization

Early Ashokan Brahmi was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2010 with the release of version 6.0.

The Unicode block for Brahmi is U+11000–U+1107F. It lies within the Supplementary Multilingual Plane. As of June 2022 there are two non-commercially available fonts that support Brahmi, namely Noto Sans Brahmi commissioned by Google which covers almost all the characters,[180] and Adinatha which only covers Tamil Brahmi.[181] Segoe UI Historic, tied in with Windows 10, also features Brahmi glyphs.[182]

The Sanskrit word for Brahmi, ब्राह्मी (IAST Brāhmī) in the Brahmi script should be rendered as follows: 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻.

| Brahmi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1100x | 𑀀 | 𑀁 | 𑀂 | 𑀃 | 𑀄 | 𑀅 | 𑀆 | 𑀇 | 𑀈 | 𑀉 | 𑀊 | 𑀋 | 𑀌 | 𑀍 | 𑀎 | 𑀏 |

| U+1101x | 𑀐 | 𑀑 | 𑀒 | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 |

| U+1102x | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 |

| U+1103x | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 | 𑀴 | 𑀵 | 𑀶 | 𑀷 | 𑀸 | 𑀹 | 𑀺 | 𑀻 | 𑀼 | 𑀽 | 𑀾 | 𑀿 |

| U+1104x | 𑁀 | 𑁁 | 𑁂 | 𑁃 | 𑁄 | 𑁅 | 𑁆 | 𑁇 | 𑁈 | 𑁉 | 𑁊 | 𑁋 | 𑁌 | 𑁍 | ||

| U+1105x | 𑁒 | 𑁓 | 𑁔 | 𑁕 | 𑁖 | 𑁗 | 𑁘 | 𑁙 | 𑁚 | 𑁛 | 𑁜 | 𑁝 | 𑁞 | 𑁟 | ||

| U+1106x | 𑁠 | 𑁡 | 𑁢 | 𑁣 | 𑁤 | 𑁥 | 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 |

| U+1107x | 𑁰 | 𑁱 | 𑁲 | 𑁳 | 𑁴 | 𑁵 | BNJ | |||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Some famous inscriptions in the Early Brahmi script

The Brahmi script was the medium for some of the most famous inscriptions of ancient India, starting with the Edicts of Ashoka, circa 250 BCE.

Birthplace of the historical Buddha

In a particularly famous Edict, the Rummindei Edict in Lumbini, Nepal, Ashoka describes his visit in the 21st year of his reign, and designates Lumbini as the birthplace of the Buddha. He also, for the first time in historical records, uses the epithet "Sakyamuni" (Sage of the Shakyas), to describe the Buddha.[183]

| Translation (English) | Transliteration (original Brahmi script) | Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

| When King Devanampriya Priyadarsin had been anointed twenty years, he came himself and worshipped (this spot) because the Buddha Shakyamuni was born here. (He) both caused to be made a stone bearing a horse (?) and caused a stone pillar to be set up, (in order to show) that the Blessed One was born here. (He) made the village of Lummini free of taxes, and paying (only) an eighth share (of the produce). — The Rummindei Edict, one of the Minor Pillar Edicts of Ashoka.[183] | 𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀁𑀧𑀺𑀬𑁂𑀦 𑀧𑀺𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺𑀦 𑀮𑀸𑀚𑀺𑀦𑀯𑀻𑀲𑀢𑀺𑀯𑀲𑀸𑀪𑀺𑀲𑀺𑀢𑁂𑀦 — Adapted from transliteration by E. Hultzsch[183] |  The Rummindei pillar edict in Lumbini. |

Heliodorus Pillar inscription

The Heliodorus pillar is a stone column that was erected around 113 BCE in central India[184] in Vidisha near modern Besnagar, by Heliodorus, an ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas in Taxila[185] to the court of the Shunga king Bhagabhadra. Historically, it is one of the earliest known inscriptions related to the Vaishnavism in India.[186][187][188]

| Translation (English) | Transliteration (original Brahmi script) | Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script)[185] |

|---|---|---|

| This Garuda-standard of Vāsudeva, the God of Gods Three immortal precepts (footsteps)... when practiced | 𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀲 𑀯𑀸(𑀲𑀼𑀤𑁂)𑀯𑀲 𑀕𑀭𑀼𑀟𑀥𑁆𑀯𑀚𑁄 𑀅𑀬𑀁 — Adapted from transliterations by E. J. Rapson,[190] Sukthankar,[191] Richard Salomon,[192] and Shane Wallace.[185] |  Heliodorus pillar rubbing (inverted colors). The text is in the Brahmi script of the Sunga period.[192] For a recent photograph. |

Middle Brahmi or "Kushana Brahmi" (1st–3rd centuries CE)

Middle Brahmi or "Kushana Brahmi" was in use from the 1st-3rd centuries CE. It is more rounded than its predecessor, and introduces some significant variations in shapes. Several characters (r̩ and l̩), classified as vowels, were added during the "Middle Brahmi" period between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE, in order to accommodate the transcription of Sanskrit:[193][194]

Independent vowels

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA | Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| a /ə/ | ā /aː/ | ||

| i /i/ | ī /iː/ | ||

| u /u/ | ū /uː/ | ||

| e /eː/ | o /oː/ | ||

| ai /əi/ | au /əu/ | ||

| 𑀋 | ṛ /r̩/ | 𑀌 | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| 𑀍 | l̩ /l̩/ | 𑀎 | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

Consonants

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | ka /k/ | kha /kʰ/ | ga /g/ | gha /ɡʱ/ | ṅa /ŋ/ | ha /ɦ/ | ||||||||||

| Palatal | ca /c/ | cha /cʰ/ | ja /ɟ/ | jha /ɟʱ/ | ña /ɲ/ | ya /j/ | śa /ɕ/ | |||||||||

| Retroflex | ṭa /ʈ/ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | ḍa /ɖ/ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | ṇa /ɳ/ | ra /r/ | ṣa /ʂ/ | |||||||||

| Dental | ta /t̪/ | tha /t̪ʰ/ | da /d̪/ | dha /d̪ʱ/ | na /n/ | la /l/ | sa /s/ | |||||||||

| Labial | pa /p/ | pha /pʰ/ | ba /b/ | bha /bʱ/ | ma /m/ | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||||||||

Examples

Inscribed Kushan statue of Western Satraps King Chastana, with inscription "Shastana" in Middle Brahmi script of the Kushan period (

Ṣa-sta-na).[196]

Ṣa-sta-na).[196]

Here, sta is the conjunct consonant of sa

is the conjunct consonant of sa and ta

and ta , vertically combined. Circa 100 CE.

, vertically combined. Circa 100 CE. The rulers of the Western Satraps were called Mahākhatapa ("Great Satrap") in their Brahmi script inscriptions, as here in a dedicatory inscription by Prime Minister Ayama in the name of his ruler Nahapana, Manmodi Caves, circa 100 CE.[197]

Nasik Cave inscription No.10. of Nahapana, Cave No.10.

Late Brahmi or "Gupta Brahmi" (4th–6th centuries CE)

Independent vowels

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA | Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| a /ə/ | ā /aː/ | ||

| i /i/ | ī /iː/ | ||

| u /u/ | ū /uː/ | ||

| e /eː/ | o /oː/ | ||

| ai /əi/ | au /əu/ | ||

| 𑀋 | ṛ /r̩/ | 𑀌 | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| 𑀍 | l̩ /l̩/ | 𑀎 | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

Consonants

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | ka /k/ | kha /kʰ/ | ga /g/ | gha /ɡʱ/ | ṅa /ŋ/ | ha /ɦ/ | ||||||||||

| Palatal | ca /c/ | cha /cʰ/ | ja /ɟ/ | jha /ɟʱ/ | ña /ɲ/ | ya /j/ | śa /ɕ/ | |||||||||

| Retroflex | ṭa /ʈ/ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | ḍa /ɖ/ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | ṇa /ɳ/ | ra /r/ | ṣa /ʂ/ | |||||||||

| Dental | ta /t̪/ | tha /t̪ʰ/ | da /d̪/ | dha /d̪ʱ/ | na /n/ | la /l/ | sa /s/ | |||||||||

| Labial | pa /p/ | pha /pʰ/ | ba /b/ | bha /bʱ/ | ma /m/ | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||||||||

Examples

Gupta script on stone Kanheri Caves, one of the earliest descendants of Brahmi

The Gopika Cave Inscription of Anantavarman, in the Sanskrit language and using the Gupta script. Barabar Caves, Bihar, or 6th century CE.

Coin of Alchon Huns ruler Mihirakula. Obv: Bust of king, with legend in Gupta script (

)

)

,[200] (Ja)yatu Mihirakula ("Let there be victory to Mihirakula").[201][202][203]

,[200] (Ja)yatu Mihirakula ("Let there be victory to Mihirakula").[201][202][203]

Descendants

Over the course of a millennium, Brahmi developed into numerous regional scripts. Over time, these regional scripts became associated with the local languages. A Northern Brahmi gave rise to the Gupta script during the Gupta Empire, sometimes also called "Late Brahmi" (used during the 5th century), which in turn diversified into a number of cursives during the Middle Ages, including the Siddhaṃ script (6th century) and Śāradā script (9th century).

Southern Brahmi gave rise to the Grantha alphabet (6th century), the Vatteluttu alphabet (8th century), and due to the contact of Hinduism with Southeast Asia during the early centuries CE, also gave rise to the Baybayin in the Philippines, the Javanese script in Indonesia, the Khmer alphabet in Cambodia, and the Old Mon script in Burma.

Also in the Brahmic family of scripts are several Central Asian scripts such as Tibetan, Tocharian (also called slanting Brahmi), and the one used to write the Saka language.

The Brahmi script also evolved into the Nagari script which in turn evolved into Devanagari and Nandinagari. Both were used to write Sanskrit, until the latter was merged into the former. The resulting script is widely adopted across India to write Sanskrit, Marathi, Hindi and its dialects, and Konkani.

The arrangement of Brahmi was adopted as the modern order of Japanese kana, though the letters themselves are unrelated.[204]

| k- | kh- | g- | gh- | ṅ- | c- | ch- | j- | jh- | ñ- | ṭ- | ṭh- | ḍ- | ḍh- | ṇ- | t- | th- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | l- | v- | ś- | ṣ- | s- | h- | |

| Brahmi | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 |

| Gupta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Devanagari | क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य | र | ल | व | श | ष | स | ह |

Possible tangential relationships

Some authors have theorized that some of the basic letters of hangul may have been influenced by the 'Phags-pa script of the Mongol Empire, itself a derivative of the Tibetan alphabet, a Brahmi script (see Origin of Hangul).[206][207] However, one of the authors, Gari Ledyard, on whose work much of this theorized connection rests, cautions against giving 'Phags-pa much credit in the development of Hangul:

I have devoted much space and discussion to the role of the Mongol ʼPhags-pa alphabet in the origin of the Korean alphabet, but it should be clear to any reader that in the total picture, that role was quite limited. [...] The origin of the Korean alphabet is, in fact, not a simple matter at all. Those who say it is "based" in ʼPhags-pa are partly right; those who say it is "based" on abstract drawings of articulatory organs are partly right. ... Nothing would disturb me more, after this study is published, than to discover in a work on the history of writing a statement like the following: "According to recent investigations, the Korean alphabet was derived from the Mongol ʼPhags-pa script" ... ʼPhags-pa contributed none of the things that make this script perhaps the most remarkable in the world.[208]

See also

Notes

- ^ Aramaic is written from right to left, as are several early examples of Brahmi.[58][page needed] For example, Brahmi and Aramaic g (𑀕 and 𐡂) and Brahmi and Aramaic t (𑀢 and 𐡕) are nearly identical, as are several other pairs. Bühler also perceived a pattern of derivation in which certain characters were turned upside down, as with 'pe 𐡐 and 𑀧 pa, which he attributed to a stylistic preference against top-heavy characters.

- ^ Bühler notes that other authors derive

(cha) from qoph. "M.L." indicates that the letter was used as a mater lectionis in some phase of Phoenician or Aramaic. The matres lectionis functioned as occasional vowel markers to indicate medial and final vowels in the otherwise consonant-only script. Aleph 𐤀 and particularly ʿayin 𐤏 only developed this function in later phases of Phoenician and related scripts, though 𐤀 also sometimes functioned to mark an initial prosthetic (or prothetic) vowel from a very early period.[60]

(cha) from qoph. "M.L." indicates that the letter was used as a mater lectionis in some phase of Phoenician or Aramaic. The matres lectionis functioned as occasional vowel markers to indicate medial and final vowels in the otherwise consonant-only script. Aleph 𐤀 and particularly ʿayin 𐤏 only developed this function in later phases of Phoenician and related scripts, though 𐤀 also sometimes functioned to mark an initial prosthetic (or prothetic) vowel from a very early period.[60] - ^ For example, according to Hultzsch, the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi (or at Mansehra) reads: (Ayam) Dhrama-dipi Devanapriyasa Raño likhapitu ("This Dharma-Edict was written by King Devanampriya" Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka (in Sanskrit) (New ed.). p. 51. This appears in the reading of Hultzsch's original rubbing of the Kharoshthi inscription of the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi (here attached, which reads "Di"

rather than "Li"

rather than "Li"  ).

). - ^ For example Column IV, Line 89

- ^ More numerous inscribed Sanskrit records in Brahmi have been found near Mathura and elsewhere, but these are from the 1st century CE onwards.[126]

- ^ The archeological sites near the northern Indian city of Mathura has been one of the largest source of such ancient inscriptions. Andhau (Gujarat) and Nasik (Maharashtra) are other important sources of Brahmi inscriptions from the 1st century CE.[127]

References

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 17. "Until the late nineteenth century, the script of the Aśokan (non-Kharosthi) inscriptions and its immediate derivatives was referred to by various names such as 'lath' or 'Lat', 'Southern Aśokan', 'Indian Pali', 'Mauryan', and so on. The application to it of the name Brahmi [sc. lipi], which stands at the head of the Buddhist and Jaina script lists, was first suggested by T[errien] de Lacouperie, who noted that in the Chinese Buddhist encyclopedia Fa yiian chu lin the scripts whose names corresponded to the Brahmi and Kharosthi of the Lalitavistara are described as written from left to right and from right to left, respectively. He therefore suggested that the name Brahmi should refer to the left-to-right 'Indo-Pali' script of the Aśokan pillar inscriptions, and Kharosthi to the right-to-left 'Bactro-Pali' script of the rock inscriptions from the northwest."

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 17. "... the Brahmi script appeared in the third century B.C. as a fully developed pan-Indian national script (sometimes used as a second script even within the proper territory of Kharosthi in the north-west) and continued to play this role throughout history, becoming the parent of all of the modern Indic scripts both within India and beyond. Thus, with the exceptions of the Indus script in the protohistoric period, of Kharosthi in the northwest in the ancient period, and of the Perso–Arabic and European scripts in the medieval and modern periods, respectively, the history of writing in India is virtually synonymous with the history of the Brahmi script and its derivatives."

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, pp. 19–30.

- ^ a b Salomon, Richard (1995). "On The Origin Of The Early Indian Scripts: A Review Article". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670. Archived from the original on 2019-05-22. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Brahmi". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1999.

Among the many descendants of Brāhmī are Devanāgarī (used for Sanskrit, Hindi and other Indian languages), the Bengali and Gujarati scripts and those of the Dravidian languages

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2017). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- ^ Lahiri, Nayanjot (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. pp. 14, 15. ISBN 978-0-674-05777-7.

Facsimiles of the objects and writings unearthed—from pillars in North India to rocks in Orissa and Gujarat—found their way to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The meetings and publications of the Society provided an unusually fertile environment for innovative speculation, with scholars constantly exchanging notes on, for instance, how they had deciphered the Brahmi letters of various epigraphs from Samudragupta’s Allahabad pillar inscription, to the Karle cave inscriptions. The Eureka moment came in 1837 when James Prinsep, a brilliant secretary of the Asiatic Society, building on earlier pools of epigraphic knowledge, very quickly uncovered the key to the extinct Mauryan Brahmi script. Prinsep unlocked Ashoka; his deciphering of the script made it possible to read the inscriptions.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. pp. 11, 178–179. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8.

The nineteenth century saw considerable advances in what came to be called Indology, the study of India by non-Indians using methods of investigation developed by European scholars in the nineteenth century. In India the use of modern techniques to 'rediscover' the past came into practice. Among these was the decipherment of the brahmi script, largely by James Prinsep. Many inscriptions pertaining to the early past were written in brahmi, but knowledge of how to read the script had been lost. Since inscriptions form the annals of Indian history, this decipherment was a major advance that led to the gradual unfolding of the past from sources other than religious and literary texts. [p. 11] ... Until about a hundred years ago in India, Ashoka was merely one of the many kings mentioned in the Mauryan dynastic list included in the Puranas. Elsewhere in the Buddhist tradition he was referred to as a chakravartin, ..., a universal monarch but this tradition had become extinct in India after the decline of Buddhism. However, in 1837, James Prinsep deciphered an inscription written in the earliest Indian script since the Harappan, brahmi. There were many inscriptions in which the King referred to himself as Devanampiya Piyadassi (the beloved of the gods, Piyadassi). The name did not tally with any mentioned in the dynastic lists, although it was mentioned in the Buddhist chronicles of Sri Lanka. Slowly the clues were put together but the final confirmation came in 1915, with the discovery of yet another version of the edicts in which the King calls himself Devanampiya Ashoka. [pp. 178–179]

- ^ Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015). The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE – 200 CE. Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-521-84697-4.

Like William Jones, Prinsep was also an important figure within the Asiatic Society and is best known for deciphering early Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts. He was something of a polymath, undertaking research into chemistry, meteorology, Indian scriptures, numismatics, archaeology and mineral resources, while fulfilling the role of Assay Master of the East India Company mint in East Bengal (Kolkatta). It was his interest in coins and inscriptions that made him such an important figure in the history of South Asian archaeology, utilising inscribed Indo-Greek coins to decipher Kharosthi and pursuing earlier scholarly work to decipher Brahmi. This work was key to understanding a large part of the Early Historical period in South Asia ...

- ^ Kopf, David (2021). British Orientalism and the Bengal Renaissance: The Dynamics of Indian Modernization 1773–1835. Univ of California Press. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0-520-36163-8.

In 1837, four years after Wilson's departure, James Prinsep, then Secretary of the Asiatic Society, unravelled the mystery of the Brahmi script and thus was able to read the edicts of the great Emperor Asoka. The rediscovery of Buddhist India was the last great achievement of the British orientalists. The later discoveries would be made by Continental Orientalists or by Indians themselves.

- ^ Verma, Anjali (2018). Women and Society in Early Medieval India: Re-interpreting Epigraphs. London: Routledge. pp. 27ff. ISBN 978-0-429-82642-9.

In 1836, James Prinsep published a long series of facsimiles of ancient inscriptions, and this series continued in volumes of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The credit for decipherment of the Brahmi script goes to James Prinsep and thereafter Georg Buhler prepared complete and scientific tables of Brahmi and Khrosthi scripts.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2016). A History of India. London: Routledge. pp. 39ff. ISBN 978-1-317-24212-3.

Ashoka’s reign of more than three decades is the first fairly well-documented period of Indian history. Ashoka left us a series of great inscriptions (major rock edicts, minor rock edicts, pillar edicts) which are among the most important records of India’s past. Ever since they were discovered and deciphered by the British scholar James Prinsep in the 1830s, several generations of Indologists and historians have studied these inscriptions with great care.

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley A. (2009). A New History of India. Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-19-533756-3.

James Prinsep, an amateur epigraphist who worked in the British mint in Calcutta, first deciphered the Brāhmi script.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Pratik (2020). Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 48ff. ISBN 978-1-4214-3874-0.

Prinsep, the Orientalist scholar, as the secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (1832–39), oversaw one of the most productive periods of numismatic and epigraphic study in nineteenth-century India. Between 1833 and 1838, Prinsep published a series of papers based on Indo-Greek coins and his deciphering of Brahmi and Kharoshthi scripts.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 204–205. "Prinsep came to India in 1819 as assistant to the assay master of the Calcutta Mint and remained until 1838, when he returned to England for reasons of health. During this period Prinsep made a long series of discoveries in the fields of epigraphy and numismatics as well as in the natural sciences and technical fields. But he is best known for his breakthroughs in the decipherment of the Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts. ... Although Prinsep's final decipherment was ultimately to rely on paleographic and contextual rather than statistical methods, it is still no less a tribute to his genius that he should have thought to apply such modern techniques to his problem."

- ^ Sircar, D. C. (2017) [1965]. Indian Epigraphy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 11ff. ISBN 978-81-208-4103-1.

The work of the reconstruction of the early period of Indian history was inaugurated by European scholars in the 18th century. Later on, Indians also became interested in the subject. The credit for the decipherment of early Indian inscriptions, written in the Brahmi and Kharosthi alphabets, which paved the way for epigraphical and historical studies in India, is due to scholars like Prinsep, Lassen, Norris and Cunningham.

- ^ a b c d Garg, Sanjay (2017). "Charles Masson: A footloose antiquarian in Afghanistan and the building up of numismatic collections in museums in India and England". In Himanshu Prabha Ray (ed.). Buddhism and Gandhara: An Archaeology of Museum Collections. Taylor & Francis. pp. 181ff. ISBN 978-1-351-25274-4.

- ^ a b Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). "Kharosti and Brahmi". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 122 (2): 391–393. doi:10.2307/3087634. JSTOR 3087634.

- ^ Keay 2000, p. 129–131.

- ^ Falk 1993, p. 106.

- ^ Rajgor 2007.

- ^ Trautmann 2006, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Plofker 2009, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Plofker 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Plofker 2009, p. 47. "A firm upper bound for the date of this invention is attested by a Sanskrit text of the mid-third century CE, the Yavana-jātaka or 'Greek horoscopy' of one Sphujidhvaja, which is a versified form of a translated Greek work on astrology. Some numbers in this text appear in concrete number format."

- ^ Hayashi 2003, p. 119.

- ^ Plofker 2007, pp. 396–397.

- ^ Chhabra, B. Ch. (1970). Sugh Terracotta with Brahmi Barakhadi: appears in the Bulletin National Museum No. 2. New Delhi: National Museum.

- ^ a b Georg Bühler (1898). On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet. K.J. Trübner. pp. 6, 14–15, 23, 29., Quote: "(...) a passage of the Lalitavistara which describes the first visit of Prince Siddhartha, the future Buddha, to the writing school..." (page 6); "In the account of Prince Siddhartha's first visit to the writing school, extracted by Professor Terrien de la Couperie from the Chinese translation of the Lalitavistara of 308 AD, there occurs besides the mention of the sixty-four alphabets, known also from the printed Sanskrit text, the utterance of the Master Visvamitra[.]"

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 8–10 with footnotes

- ^ L. A. Waddell (1914). "The So-Called "Mahapadana" Suttanta and the Date of the Pali Canon". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 46 (3): 661–680. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00047055. S2CID 162074807. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ Nado, Lopon (1982). "The Development of Language in Bhutan". The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 5 (2): 95.

Under different teachers, such as the Brahmin Lipikara and Deva Vidyasinha, he mastered Indian philology and scripts. According to Lalitavistara, there were as many as sixty-four scripts in India.

- ^ Tsung-i, Jao (1964). "Chinese Sources on Brāhmī and Kharoṣṭhī". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 45 (1/4): 39–47. JSTOR 41682442.

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Falk 1993, pp. 109–167.

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, pp. 19–20

- ^ a b Salomon 1996, p. 378.

- ^ a b Bühler 1898, p. 2.

- ^ Goyal, S. R. (1979). S. P. Gupta; K. S. Ramachandran (eds.). The Origin of Brahmi Script., cited after Salomon (1998).

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 19, fn. 42: "there is no doubt some truth in Goyal's comment that some of their views have been affected by 'nationalist bias' and 'imperialist bias,' respectively."

- ^ Cunningham, Alexander (1877). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Vol. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing. p. 54.

- ^ Allchin, F. R.; Erdosy, George (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2.

- ^ Waddell, L. A. (1914). "Besnagar Pillar Inscription B Re-Interpreted". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. 46 (4): 1031–1037. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00047523. S2CID 163470608.

- ^ "Brahmi". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1999.

Brāhmī, writing system ancestral to all Indian scripts except Kharoṣṭhī. Of Aramaic derivation or inspiration, it can be traced to the 8th or 7th century BC, when it may have been introduced to Indian merchants by people of Semitic origin. ... a coin of the 4th century BC, discovered in Madhya Pradesh, is inscribed with Brāhmī characters running from right to left.

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, pp. 18–24.

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, pp. 23, 46–54

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 19–21 with footnotes.

- ^ Annette Wilke & Oliver Moebus 2011, p. 194 with footnote 421.

- ^ a b Trigger, Bruce G. (2004). "Writing Systems: a case study in cultural evolution". In Houston, Stephen D. (ed.). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Justeson, J. S.; Stephens, L. D. (1993). "The evolution of syllabaries from alphabets". Die Sprache. 35: 2–46.

- ^ a b Bühler 1898, p. 84–91.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c Salomon 1998, p. 28.

- ^ After Fischer, Steven R. (2001). A History of Writing. London: Reaction Books. p. 126.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 59,68,71,75.

- ^ Salomon 1996.

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, p. 25.

- ^ Andersen, F. I.; Freedman, D. N. (1992). "Aleph as a vowel in Old Aramaic". Studies in Hebrew and Aramaic Orthography. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. pp. 79–90.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 76–77.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 82–83.

- ^ Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. (2009), The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, John Wiley and Sons Ltd., pp. 173–174

- ^ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Vol. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Scharfe, Hartmut (2002), Education in Ancient India, Handbook of Oriental Studies, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers, pp. 10–12

- ^ Tavernier, Jan (2007). "The Case of Elamite Tep-/Tip- and Akkadian Tuppu". Iran. 45: 57–69. doi:10.1080/05786967.2007.11864718. S2CID 191052711. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ Bopearachchi, Osmund (1993). "On the so-called earliest representation of Ganesa". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 3 (2): 436. doi:10.3406/topoi.1993.1479.

- ^ Osmund Bopearachchi, 2016, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence

- ^ a b "Falk goes too far. It is fair to expect that we believe that Vedic memorisation – though without parallel in any other human society – has been able to preserve very long texts for many centuries without losing a syllable. ... However, the oral composition of a work as complex as Pāṇini's grammar is not only without parallel in other human cultures, it is without parallel in India itself. ... It just will not do to state that our difficulty in conceiving any such thing is our problem." Bronkhorst, Johannes (2002). "Literacy and Rationality in Ancient India". Asiatische Studien/Études Asiatiques. 56 (4): 803–804, 797–831.

- ^ Falk 1993.

- ^ Annette Wilke & Oliver Moebus 2011, p. 194, footnote 421.

- ^ a b c Salomon, Richard (1995). "Review: On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–278. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 22.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 23.

- ^ Falk 1993, pp. 104.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 19–24.

- ^ a b c d Falk, Harry (2018). "The Creation and Spread of Scripts in Ancient India". Literacy in Ancient Everyday Life: 43–66 (online 57–58). doi:10.1515/9783110594065-004. ISBN 9783110594065. S2CID 134470331.

- ^ a b Iravatham Mahadevan (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy. Harvard University Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies. pp. 91–94. ISBN 978-0-674-01227-1.; Iravatham Mahadevan (1970). Tamil-Brahmi Inscriptions. State Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamil Nadu. pp. 1–12.

- ^ a b Bertold Spuler (1975). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Brill Academic. p. 44. ISBN 90-04-04190-7.

- ^ John Marshall (1931). Mohenjo-daro and the Indus civilization: being an official account of archaeological excavations at Mohenjo-Daro carried out by the government of India between the years 1922 and 1927. Asian Educational Services. p. 423. ISBN 978-81-206-1179-5.

Langdon also suggested that the Brahmi script was derived from the Indus writing, ...

- ^ Senarat Paranavitana; Leelananda Prematilleka; Johanna Engelberta van Lohuizen-De Leeuw (1978). Studies in South Asian Culture: Senarat Paranavitana Commemoration Volume. Brill Academic. p. 119. ISBN 90-04-05455-3.

- ^ Hunter, G. R. (1934), The Script of Harappa and Mohenjodaro and Its Connection with Other Scripts, Studies in the history of culture, London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner

- ^ Goody, Jack (1987), The Interface Between the Written and the Oral, Cambridge University Press, pp. 301–302 (note 4)

- ^ Allchin, F. Raymond; Erdosy, George (1995), The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States, Cambridge University Press, p. 336

- ^ Georg Feuerstein; Subhash Kak; David Frawley (2005). The Search of the Cradle of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-81-208-2037-1.

- ^ Goody, Jack (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. pp. 301 footnote 4. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6.

In recent years, I have been leaning towards the view that the Brahmi script had an independent Indian evolution, probably emerging from the breakdown of the old Harappan script in the first half of the second millennium BC.

- ^ Kak, Subhash (1994), "The evolution of early writing in India" (PDF), Indian Journal of History of Science, 28: 375–388

- ^ Kak, S. (2005). "Akhenaten, Surya, and the Rigveda". In Govind Chandra Pande (ed.), The Golden Chain, CRC, 2005.

- ^ Kak, S. (1988). "A frequency analysis of the Indus script". Cryptologia 12: 129–143.

- ^ Kak, S. (1990). "Indus and Brahmi – further connections". Cryptologia 14: 169–183

- ^ Das, S.; Ahuja, A.; Natarajan, B.; Panigrahi, B. K. (2009). "Multi-objective optimization of Kullback-Leibler divergence between Indus and Brahmi writing". World Congress on Nature & Biologically Inspired Computing 2009. NaBIC 2009.1282 – 1286. ISBN 978-1-4244-5053-4

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Khan, Omar. "Mahadevan Interview: Full Text". Harappa. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2006), "Inscribed pots, emerging identities", in Patrick Olivelle (ed.), Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE, Oxford University Press, pp. 121–122

- ^ Fábri, C. L. (1935). "The Punch-Marked Coins: A Survival of the Indus Civilization". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 67 (2): 307–318. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00086482. JSTOR 25201111. S2CID 162603638.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 135.

- ^ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Vol. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii.

- ^ Sharma, R. S. (2006). India's Ancient Past. Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780199087860.

- ^ "The word dipi appears in the Old Persian inscription of Darius I at Behistan (Column IV. 39) having the meaning inscription or 'written document'." Proceedings – Indian History Congress. 2007. p. 90.

- ^ Scharfe, Hartmut (2002), Education in Ancient India, Handbook of Oriental Studies, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers, p. 9

- ^ Strabo (1903). Hamilton, H. C.; Falconer, W. (eds.). Geography. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 15.1.53.

- ^ Rocher 2014.

- ^ Timmer 1930, p. 245.

- ^ Strabo (1903). Hamilton, H. C.; Falconer, W. (eds.). Geography. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 15.1.39.

- ^ Sterling, Gregory E. (1992). Historiography and Self-Definition: Josephos, Luke–Acts, and Apologetic Historiography. Brill. p. 95.

- ^ McCrindle, J. W. (1877). Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian. London: Trübner and Co. pp. 40, 209. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 11.

- ^ Oskar von Hinüber (1989). Der Beginn der Schrift und frühe Schriftlichkeit in Indien. Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur. pp. 241–245. ISBN 9783515056274. OCLC 22195130.

- ^ Kenneth Roy Norman (2005). Buddhist Forum Volume V: Philological Approach to Buddhism. Routledge. pp. 67, 56–57, 65–73. ISBN 978-1-135-75154-8.

- ^ a b Norman, Kenneth R. "The Development of Writing in India and its Effect upon the Pāli Canon". Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Südasiens [Vienna Journal of South Asian Studies], vol. 36, 1992, pp. 239–249. JSTOR 24010823. Accessed 11 May 2020.

- ^ Jack Goody (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. pp. 110–124. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6.

- ^ Goody, Jack (2010). Myth, Ritual and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–47, 65–81. ISBN 978-1-139-49303-1.

- ^ Annette Wilke & Oliver Moebus 2011, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Ong, Walter J.; Hartley, John (2012). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Routledge. pp. 64–69. ISBN 978-0-415-53837-4.

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, pp. 8–9

- ^ Nagrajji, Acharya Shri (2003). Āgama Aura Tripiṭaka, Eka Anuśilana: Language and literature. New Delhi: Concept Publishing. pp. 223–224.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 351. ISBN 9788131711200.

- ^ Levi, Silvain (1906), "The Kharostra Country and the Kharostri Writing", The Indian Antiquary, XXXV: 9

- ^ Monier Monier-Williams (1970). Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass (Reprint of Oxford Claredon). p. xxvi with footnotes. ISBN 978-5-458-25035-1.

- ^ Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (2004). Sanskrit English Dictionary (Practical Hand Book). Asian Educational Services. p. 200. ISBN 978-81-206-1779-7.

- ^ Monier Monier Willians (1899), Brahmi, Oxford University Press, page 742

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, pp. 72–81.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 81–84.

- ^ a b Salomon 1996, p. 377.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 122–123, 129–131, 262–307.

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c Coningham, R.A.E.; Allchin, F.R.; Batt, C.M.; Lucy, D. (22 December 2008). "Passage to India? Anuradhapura and the Early Use of the Brahmi Script". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 6 (1): 73. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001608. S2CID 161465267.

- ^ Falk, H. (2014). "Owner's graffiti on pottery from Tissamaharama", in Zeitchriftfür Archäeologie Aussereuropäischer Kulturen. 6. pp.45–47.

- ^ Rajan prefers the term "Prakrit-Brahmi" to distinguish Prakrit-language Brahmi inscriptions.

- ^ Rajan, K.; Yatheeskumar, V.P. (2013). "New evidences on scientific dates for Brāhmī Script as revealed from Porunthal and Kodumanal Excavations" (PDF). Prāgdhārā. 21–22: 280–295. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Falk, H. (2014), p.46, with footnote 2

- ^ Buddhist art of Mathurā, Ramesh Chandra Sharma, Agam, 1984 Page 26

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Verma, Thakur Prasad (1971). The Palaeography Of Brahmi Script. pp. 82–85.

- ^ Sharma, Ramesh Chandra (1984). Buddhist art of Mathurā. Agam. p. 26. ISBN 9780391031401.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 204–208 Equally impressive was Prinsep's arrangement, presented in plate V of JASB 3, of the unknown alphabet, wherein he gave each of the consonantal characters, whose phonetic values were still entirely unknown, with its "five principal inflections", that is, the vowel diacritics. Not only is this table almost perfectly correct in its arrangement, but the phonetic value of the vowels is correctly identified in four out of five cases (plus anusvard); only the vowel sign for i was incorrectly interpreted as o.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Salomon 1998, pp. 204–208

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol V 1836. p. 723.

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1838.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 204–206.

- ^ a b c Salomon 1998, pp. 206–207

- ^ Daniels, Peter T. (1996), "Methods of Decipherment", in Peter T. Daniels, William Bright (ed.), The World's Writing Systems, Oxford University Press, pp. 141–159, 151, ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7,

Brahmi: The Brahmi script of Ashokan India (SECTION 30) is another that was deciphered largely on the basis of familiar language and familiar related script—but it was made possible largely because of the industry of young James Prinsep (1799-1840), who inventoried the characters found on the immense pillars left by Ashoka and arranged them in a pattern like that used for teaching the Ethiopian abugida (FIGURE 12). Apparently, there had never been a tradition of laying out the full set of aksharas thus—or anyone, Prinsep said, with a better knowledge of Sanskrit than he had had could have read the inscriptions straight away, instead of after discovering a very minor virtual bilingual a few years later. (p. 151)

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1834. pp. 495–499.

- ^ a b Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 1/ by Alexander Cunningham. 1. Government central Press. 1871. p. XII.

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol V 1836. p. 723.

- ^ Asiatic Society of Bengal (1837). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Oxford University.

- ^ More details about Buddhist monuments at Sanchi Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, Archaeological Survey of India, 1989.

- ^ Extract of Prinsep's communication about Lassen's decipherment in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol V 1836. 1836. pp. 723–724.

- ^ Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 1/ by Alexander Cunningham. 1. Government central Press. 1871. p. XI.

- ^ Keay, John (2011). To cherish and conserve the early years of the archaeological survey of India. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 30–31.

- ^ Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 1/ by Alexander Cunningham. 1. Government central Press. 1871. p. XIII.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 207.

- ^ Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor, Charles Allen, Little, Brown Book Group Limited, 2012

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1838. pp. 219–285.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 208.

- ^ Epigraphia Zeylanica: 1904–1912, Volume 1. Government of Sri Lanka, 1976. http://www.royalasiaticsociety.lk/inscriptions/?q=node/12 Archived 2016-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Raghupathy, Ponnambalam (1987). Early settlements in Jaffna, an archaeological survey. Madras: Raghupathy.

- ^ P Shanmugam (2009). Hermann Kulke; et al. (eds.). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 208. ISBN 978-981-230-937-2.

- ^ a b c Frederick Asher (2018). Matthew Adam Cobb (ed.). The Indian Ocean Trade in Antiquity: Political, Cultural and Economic Impacts. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-138-73826-3.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Salomon 1996, pp. 373–4.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 32.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 33.

- ^ Daniels, Peter T. (2008), "Writing systems of major and minor languages", Language in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 287

- ^ Trautmann 2006, p. 62–64.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Manika (1981). Mālwa in Post-Maurya Period: A Critical Study with Special Emphasis on Numismatic Evidences. Punthi Pustak. p. 100.

- ^ Ram Sharma, Brāhmī Script: Development in North-Western India and Central Asia, 2002

- ^ Stefan Baums (2006). "Towards a computer encoding for Brahmi". In Gail, A.J.; Mevissen, G.J.R.; Saloman, R. (eds.). Script and Image: Papers on Art and Epigraphy. New Delhi: Shri Jainendra Press. pp. 111–143.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 43. ISBN 9788131711200.

- ^ Evolutionary chart, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 7, 1838 [1]

- ^ Inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka

- ^ Inscriptions of Western Satrap Rudradaman I on the rock at Girnar circa 150 CE

- ^ Kushan Empire inscriptions circa 150-250 CE.

- ^ Gupta Empire inscription of the Allahabad Pillar by Samudragupta circa 350 CE.

- ^ Google Noto Fonts – Download Noto Sans Brahmi zip file

- ^ Adinatha font announcement

- ^ Script and Font Support in Windows – Windows 10 Archived 2016-08-13 at the Wayback Machine, MSDN Go Global Developer Center.

- ^ a b c Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 164–165.

- ^ Avari, Burjor (2016). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from c. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 9781317236733.

- ^ a b c Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries Shane Wallace, 2016, p.222-223

- ^ Osmund Bopearachchi, 2016, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence

- ^ Burjor Avari (2016). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from C. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. Routledge. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-1-317-23673-3.

- ^ Romila Thapar (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. pp. 216–217. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8.

- ^ Archaeological Survey of India, Annual report 1908–1909 p.129

- ^ Rapson, E. J. (1914). Ancient India. p. 157.

- ^ Sukthankar, Vishnu Sitaram, V. S. Sukthankar Memorial Edition, Vol. II: Analecta, Bombay: Karnatak Publishing House 1945 p.266

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, pp. 265–267

- ^ Brahmi Unicode (PDF). pp. 4–6.

- ^ James Prinsep table of vowels

- ^ Seaby's Coin and Medal Bulletin: July 1980. Seaby Publications Ltd. 1980. p. 219.

- ^ "The three letters give us a complete name, which I read as Ṣastana (vide facsimile and cast). Dr. Vogel read it as Mastana but that is incorrect for Ma was always written with a circular or triangular knob below with two slanting lines joining the knob" in Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society. The Society. 1920.

- ^ Burgess, Jas (1883). Archaeological Survey Of Western India. p. 103.

- ^ a b Das Buch der Schrift: Enthaltend die Schriftzeichen und Alphabete aller ... (in German). K. k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. 1880. p. 126.

- ^ a b "Gupta Unicode" (PDF).

- ^ The "h" (

) is an early variant of the Gupta script

) is an early variant of the Gupta script - ^ Verma, Thakur Prasad (2018). The Imperial Maukharis: History of Imperial Maukharis of Kanauj and Harshavardhana (in Hindi). Notion Press. p. 264. ISBN 9781643248813.

- ^ Sircar, D. C. (2008). Studies in Indian Coins. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 376. ISBN 9788120829732.

- ^ Tandon, Pankaj (2013). Notes on the Evolution of Alchon Coins Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society, No. 216, Summer 2013. Oriental Numismatic Society. pp. 24–34. also Coinindia Alchon Coins (for an exact description of this coin type)

- ^ Smith, Janet S. (Shibamoto) (1996). "Japanese Writing". In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 209–17. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- ^ Evolutionary chart, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 7, 1838 [2]

- ^ Ledyard 1994, p. 336–349.

- ^ Daniels, Peter T. (Spring 2000). "On Writing Syllables: Three Episodes of Script Transfer" (PDF). Studies in the Linguistic Sciences. 30 (1): 73–86.

- ^ Gari Keith Ledyard (1966). The Korean language reform of 1446: the origin, background, and early history of the Korean alphabet, University of California, pp. 367–368, 370, 376.

Bibliography

- Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

- Bühler, Georg (1898). On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet. Strassburg K.J. Trübner.

- Deraniyagala, Siran (2004). The Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective. Department of Archaeological Survey, Government of Sri Lanka. ISBN 978-955-9159-00-1.

- Falk, Harry (1993). Schrift im alten Indien: ein Forschungsbericht mit Anmerkungen (in German). Gunter Narr Verlag.

- Gérard Fussman, Les premiers systèmes d'écriture en Inde, in Annuaire du Collège de France 1988–1989 (in French)

- Hayashi, Takao (2003), "Indian Mathematics", in Grattan-Guinness, Ivor (ed.), Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences, vol. 1, pp. 118–130, Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 976 pages, ISBN 978-0-8018-7396-6.

- Oscar von Hinüber, Der Beginn der Schrift und frühe Schriftlichkeit in Indien, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1990 (in German)

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3797-5.

- Ledyard, Gari (1994). The Korean Language Reform of 1446: The Origin, Background, and Early History of the Korean Alphabet. University Microfilms.

- Masica, Colin (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Norman, Kenneth R. (1992). "The Development of Writing in India and its Effect upon the Pāli Canon". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens / Vienna Journal of South Asian Studies. 36 (Proceedings of the VIIIth World Sanskrit Conference Vienna): 239–249.

- Patel, Purushottam G.; Pandey, Pramod; Rajgor, Dilip (2007). The Indic Scripts: Palaeographic and Linguistic Perspectives. D.K. Printworld. ISBN 978-81-246-0406-9.

- Plofker, K. (2007), "Mathematics of India", in Katz, Victor J. (ed.), The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 685 pages, pp 385–514, pp. 385–514, ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- Plofker, Kim (2009), Mathematics in India: 500 BCE–1800 CE, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6.

- Rocher, Ludo (2014). Studies in Hindu Law and Dharmaśāstra. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-78308-315-2.

- Salomon, Richard (1996). "Brahmi and Kharoshthi". In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- Salomon, Richard (1995). "On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- Trautmann, Thomas (2006). Languages and Nations: The Dravidian Proof in Colonial Madras. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24455-9.

- Timmer, Barbara Catharina Jacoba (1930). Megasthenes en de Indische maatschappij. H.J. Paris.

Further reading

- Buswell Jr., Robert E.; Lopez Jr., David S., eds. (2017). "Brāhmī". The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691157863.

- Hitch, Douglas A. (1989). "BRĀHMĪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 4. pp. 432–433.

- Matthews, P. H. (2014). "Brahmi". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Linguistics (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967512-8.

- Red. (2017). "Brahmi-Schrift". Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens Online (in German). Brill Online.

External links

- "Brahmi Home". brahmi.sourceforge.net. of the Indian Institute of Science

- "Ancient Scripts: Brahmi". www.ancientscripts.com.

- "Brahmi Texts Virtual Vinodh". www.virtualvinodh.com.

- Indoskript 2.0, a paleographic database of Brahmi and Kharosthi

![Early/Middle Brahmi legend on the coinage of Chastana: RAJNO MAHAKSHATRAPASA GHSAMOTIKAPUTRASA CHASHTANASA "Of the Rajah, the Great Satrap, son of Ghsamotika, Chashtana". 1st–2nd century CE.[195]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/ba/Coinage_of_Chastana_with_reverse_Brahmi_legend.jpg/200px-Coinage_of_Chastana_with_reverse_Brahmi_legend.jpg)