타밀나두 주

Tamil Nadu타밀나두 주 | |

|---|---|

| 어원: 타밀 주 | |

| 닉네임: "사원의 땅" | |

| 좌우명: 바이마이 ē 벨룸 (진실만이 승리) | |

| 애국가: "타밀 타이 발투" (마더 타밀어에 대한 초청) | |

인도 타밀나두의 위치 | |

| 좌표: 11°N 79°E / 11°N 79°E/ | |

| 나라 | |

| 지역 | 남인도 |

| 그전에 | 마드라스 주 |

| 형성 | 1956년 11월 1일 |

| 자본의 그리고 가장 큰 도시 | 첸나이 |

| 가장 큰 지하철 | 첸나이 수도권 |

| 구 | 38(5부) |

| 정부 | |

| • 몸 | 타밀나두 주 정부 |

| • 주지사 | R. N. 라비 |

| • 주임장관 | M. K. 스탈린 (DMK) |

| 주 의회 | 유니캐머럴 |

| • 조립 | 타밀나두 입법의회 (234석) |

| 국민의회 | 인도 의회 |

| • 라지야 사바 | 18석 |

| • 록 사바 | 39석 |

| 고등법원 | 마드라스 고등법원 |

| 지역 | |

| • 합계 | 130,058 km2 (50,216 sq mi) |

| • 랭크 | 10일 |

| 치수 | |

| • 길이 | 1,076 km (669 mi) |

| 승진 | 189 m (620 ft) |

| 최고고도 | 2,636 m (8,648 ft) |

| 최하고도 | 0m(0ft) |

| 인구. (2011)[1] | |

| • 합계 | 72,147,030 |

| • 랭크 | 6일 |

| • 밀도 | 554.7/km2 (1,437/sq mi) |

| • 어반 | 48.4% |

| • 시골 | 51.6% |

| 어원 | |

| 언어 | |

| • 오피셜 | 타밀어[2] |

| • 추가관계자 | 영어[2] |

| • 공식대본 | 타밀 문자 |

| GDP | |

| • 합계(2022~23년) | ₹23.65 라크 크로어 (3천억 달러) |

| • 랭크 | 두번째 |

| • 인당 | |

| 시간대 | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 코드 | IN-TN |

| 차량등록 | TN |

| HDI (2021) | |

| 문해력 (2011) | |

| 성비 (2011) | 996♀/1000 ♂ (3rd) |

| 웹사이트 | tn |

| 타밀나두의 상징 | |

| |

| 송 | "Tamil Thai Valthu" (마더 타밀어에 대한 초청) |

| 새 | 에메랄드 도브 |

| 나비 | 타밀 요먼 |

| 플라워 | 글로리오사 릴리 |

| 과일 | 잭프루트 |

| 포유류 | Nilgiri Tahr |

| 나무 | 아시안 팜 |

| 주 고속도로 표시 | |

| |

| 타밀나두 주의 고속도로 TN SH1 - TN SH223 | |

| 인도의 주 상징 목록 | |

Tamil Nadu (/ˌtæmɪl ˈnɑːduː/; 타밀어:[ˈ 타미 ɻ ˈ나 ːɽɯ], abr.TN)은 인도 최남단에 위치한 주이다. 면적으로는 10번째로 크고 인구로는 6번째로 많은 타밀나두 주는 타밀족의 고향으로, 가장 오래 존속한 고전 언어 중 하나이며 공용어 역할을 하고 있습니다. 수도이자 가장 큰 도시는 첸나이입니다.

인도 반도의 남동쪽 해안에 위치한 타밀나두는 서쪽으로는 웨스턴 가츠와 데칸 고원, 북쪽으로는 이스트 가츠, 동쪽으로는 벵골 만을 끼고 있는 동부 해안 평원, 남동쪽으로는 만나르 만과 팔크 해협, 반도의 남쪽 곶에 위치한 라카디브 해, 카베리 강이 주를 양분하고 있습니다. 정치적으로 타밀나두는 인도 케랄라주, 카르나타카주, 안드라프라데시주와 연합 영토인 푸두체리주에 속하며 팜반섬에서 스리랑카 북부 주와 국제 해상 국경을 공유합니다.

고고학적 증거에 따르면 타밀나두는 400년 이상 거주했으며 5,500년 이상의 지속적인 문화 역사를 가지고 있습니다. 역사적으로, 타밀라캄 지역은 타밀어를 사용하는 드라비다인들이 거주했고, 상암 시대의 체라스, 촐라, 판디야스의 삼두정치, 팔라바스 (3-9세기), 그리고 나중에 비자야나가라 제국 (14-17세기)과 같은 여러 정권에 의해 지배되었습니다. 유럽의 식민지화는 17세기에 무역항을 설립하면서 시작되었고, 1947년 인도 독립 이전 2세기 동안 영국은 마드라스 대통령직으로 남인도의 많은 부분을 지배했습니다. 독립 후 이 지역은 인도 공화국의 마드라스 주가 되었고 1956년 언어적으로 주들이 현재의 모습으로 다시 그려지면서 더 재편되었습니다. 1969년에 타밀나두라는 이름으로 개명되었습니다. 따라서 문화, 요리 및 건축은 수년 동안 여러 가지 영향을 받았으며 다양하게 발전했습니다.

타밀나두는 인도에서 가장 도시화된 주로서 ₹ 23.65 라크 크로어 (3천억 달러)의 주 국내총생산 (GSDP)을 자랑하며 인도의 28개 주 중에서 두 번째로 큰 경제를 자랑합니다. ₹ 275,583명(3,500달러)으로 국내에서 9번째로 높은 1인당 GSDP를 보유하고 있으며, 인간 개발 지수에서 11위를 차지하고 있습니다. 타밀나두는 또한 가장 산업화된 주 중 하나이며, 제조업 부문이 주의 GDP의 거의 3분의 1을 차지합니다. 다양한 문화와 건축, 긴 해안선, 숲과 산이 있는 타밀나두는 많은 고대 유물, 역사적 건물, 종교 유적지, 해변, 언덕 역, 요새 등의 본거지입니다. 이 주의 관광산업이 있는 폭포와 4개의 세계문화유산을 보유하고 있으며, 이는 인도의 주들 중에서 가장 큰 것입니다. 산림은 지리적 면적의 17.4%를 차지하는 22,643km2(8,743sqmi)의 면적을 차지하며, 보호 구역은 3,305km2(1,276sqmi)의 면적을 차지하며, 3개의 생물권 보호 구역, 맹그로브 숲, 5개의 국립 공원, 18개의 야생 동물 보호 구역 및 17개의 조류 보호 구역으로 구성됩니다. Kollywood라는 별명을 가진 타밀 영화 산업은 타밀의 대중 문화에서 영향력 있는 역할을 하고 있습니다.

어원

이름은 "땅"을 의미하는 나두와 "타밀의 땅"을 의미하는 타밀어에서 유래되었습니다. 타밀어라는 단어의 기원과 정확한 어원은 여러 이론들이 증명하고 있어 불분명합니다.[5]

역사

선사시대 (기원전 5세기 이전)

고고학적 증거는 이 지역이 4억년 전에 호미니드들이 거주하고 있었다는 것을 보여줍니다.[6][7] 인도 고고학조사국(ASI)이 아디차날루르에서 수습한 유물은 3천800여 년 전부터 계속된 역사를 보여주고 있습니다.[8] 기원전 1500년에서 2000년 사이의 인더스 문자가 있는 신석기 시대의 셀트는 하라판어의 사용을 나타냅니다.[9][10] 키즈하디에서 발굴된 것은 인도-갠지스 평원의 도시화 시기인 기원전 6세기로 거슬러 올라가는 거대한 도시 정착지를 밝혀냈습니다.[11] 아디차날루르에서 발견된 더 많은 비문들은 기원전 5세기경의 초보적인 문자인 타밀 브라흐미를 사용합니다.[12] 키엘라디에서 발견된 항아리 조각들은 인더스 계곡 문자와 나중에 사용된 타밀 브라흐미 문자 사이의 전환인 문자를 나타냅니다.[13]

상암기(기원전 5세기~기원전 3세기)

상암시대는 기원전 500년부터 서기 300년까지 약 8세기 동안 지속되었으며, 이 시기의 주요 역사적 원천은 상암문학에서 비롯되었습니다.[14][15] 고대 타밀라캄은 군주제 국가인 체라스, 촐라, 판디아스의 삼두정치에 의해 통치되었습니다.[16] 체라스족은 타밀캄의 서부 지역을, 판디아족은 남부 지역을, 촐라족은 카베리 삼각주에 근거지를 두고 있었습니다. 벤드하르라고 불리는 왕들은 벨리르 족장들이 이끄는 벨랄라(농민)의 몇몇 부족들을 지배했습니다.[17] 통치자들은 베다 종교, 불교 및 자이나교를 포함한 여러 종교를 후원했으며, 가장 오래된 작품은 타밀 문법 책인 톨카피얌(Tolkāpiyam)입니다.[18][19]

그 왕국들은 북쪽과 로마의 다른 왕국들과 외교적, 무역적으로 중요한 접촉을 했습니다.[20] 로마와 한족으로부터의 무역의 많은 부분은 진주와 비단과 함께 향신료가 가장 귀중한 상품인 무지리스와 코르카이를 포함한 항구를 통해 촉진되었습니다.[21][22] 기원후 300년부터 고대 타밀 왕국의 봉건제였을 가능성이 있는 전사들로 구성된 벨랄라르 공동체의 것으로 추정되는 타밀캄의 칼라브라스인들.[23] 칼라브라 시대는 타밀 역사의 "어두운 시기"라고 불리며, 일반적으로 문헌에 언급된 내용과 시대가 끝난 후 수세기가 지난 비문에서 이에 대한 정보가 유추됩니다.[24] 쌍둥이 타밀 서사시 실라파티카람과 마니메칼라이는 그 시대에 쓰여졌습니다.[25] 발루바르의 타밀 고전 티루쿠랄은 같은 시기에 만들어진 것으로 추정됩니다.[26][27]

중세 시대 (4~13세기)

서기 7세기 경, 박티 운동 기간 동안 사이비즘과 바이슈나비즘이 부활하기 전에 불교와 자이나비즘을 옹호했던 판디아족과 촐라족에 의해 칼라브라족이 전복되었습니다.[28] 비록 그들은 이전에 존재했지만, 그 시기는 칸치푸람을 수도로 하여 남인도의 일부 지역을 통치했던 마헨드라바르만 1세 치하에서 6세기에 팔라바족이 부상했습니다.[29] 팔라바는 팔라바로 거슬러 올라가는 사원 입구에 있는 화려한 탑인 거대한 고푸람의 기원과 함께 건축을 후원한 것으로 유명합니다. 그들은 마하발리푸람에 바위를 깎아 만든 기념물들과 칸치푸람에 있는 사원들을 세웠습니다.[30] 팔라바스는 그들의 통치 기간 내내 촐라족, 판디아족과 지속적인 갈등을 겪었습니다. 판디야족은 서기 6세기 말에 카둔곤에 의해 부활했고, 우라이유르에서 촐라족이 무명 상태에 빠지면서, 타밀 국가는 팔라바족과 판디야족으로 나뉘었습니다.[31] 팔라바족은 서기 9세기에 마침내 아디티야 1세에게 패배했습니다.[32]

촐라족은 비자얄라야 촐라 아래 9세기에 지배적인 왕국이 되었고, 그는 이후의 통치자들에 의해 더욱 확장되어 탄자부르를 촐라의 새로운 수도로 세웠습니다. 11세기에 라자라자 1세는 인도 남부 전역과 현재의 스리랑카, 몰디브 일부를 정복하고 인도양 전역에서 촐라의 영향력을 증가시키면서 촐라 제국을 확장했습니다.[33][34] Rajaraja는 타밀 국가를 개별 행정 단위로 개편하는 것을 포함한 행정 개혁을 가져왔습니다.[35] 그의 아들 라젠드라 촐라 1세 아래에서 촐라 제국은 절정에 이르렀고 북쪽의 벵골까지 뻗어 있었고 인도양을 가로질러 뻗어 있었습니다.[36] 촐라족은 드라비다 양식으로 많은 사원을 세웠는데, 가장 눈에 띄는 것은 탄자부르에 있는 브리하디스바라 사원으로 라자 라자와 라젠드라가 지은 간가이콘다 촐라푸람이 지은 시대의 가장 중요한 사원 중 하나입니다.[37]

13세기 초에 마라바르만 순다라 1세의 통치하에 판디아 가문이 다시 최고 통치자가 되었습니다.[38] 그들은 그들의 수도 마두라이에서 통치했고 다른 해양 제국들과 무역 관계를 넓혔습니다.[39] 13세기 동안 마르코 폴로는 판디야스를 현존하는 가장 부유한 제국으로 언급했습니다. 판디아스는 또한 마두라이에 있는 미낙시 암만 사원을 포함한 많은 사원들을 지었습니다.[40]

비자야나가르와 나약 시대 (서기 14-17세기)

13세기와 14세기에는 델리 술탄국의 공격이 반복되었습니다.[41] 비자야나가라 왕국은 서기 1336년에 세워졌습니다.[42] 비자야나가라 제국은 결국 1370년까지 타밀 국가 전체를 정복했고 1565년 데칸 술탄 연합에 의해 탈리코타 전투에서 패배할 때까지 거의 두 세기 동안 통치했습니다.[43][44] 나중에 비자야나가라 제국의 군정이었던 나약족은 마두라이의 나약족과 탄자부르의 나약족이 가장 두드러진 지역을 장악했습니다.[45][46] 그들은 팔라야카라르 제도를 도입했고, 마두라이의 미낙시 사원을 포함한 타밀나두의 유명한 사원들 중 일부를 재건했습니다.[47]

이후의 분쟁과 유럽의 식민지화 (17세기~20세기)

18세기에 무굴 제국은 카르나틱의 나와브를 통해 이 지역을 통치했고, 아르콧은 마두라이 나약족을 물리쳤습니다.[48] 마라족은 트리치노폴리 공방전(1751-1752) 이후 여러 차례 공격해 나와브족을 물리쳤습니다.[49][50][51] 이것은 단명한 탄자부르 마라타 왕국으로 이어졌습니다.[52]

유럽인들은 16세기부터 동부 해안을 따라 무역 센터를 설립하기 시작했습니다. 포르투갈인들은 1522년에 도착했고 오늘날 마드라스의 밀라포레 근처에 상토메라는 이름의 항구를 건설했습니다.[53] 1609년, 네덜란드인들은 풀리카트에 정착지를 세웠고 덴마크인들은 타란감바디에 정착지를 세웠습니다.[54][55] 1639년 8월 20일, 영국 동인도 회사의 프란치스코 데이는 비자야나거 황제 페다 벤카타 라야를 만나 코로만델 해안의 토지에 대한 무역 활동에 대한 보조금을 받았습니다.[56][57][58] 1년 후, 회사는 포트 세인트를 지었습니다. 조지, 이 지역에서 영국령 라지의 핵이 된 인도 최초의 주요 영국인 정착지.[59][60] 1693년 프랑스는 퐁디체리에 무역소를 설립했습니다. 영국과 프랑스는 무역을 확장하기 위해 경쟁했고, 이것은 7년 전쟁의 일부로 완디워시 전투로 이어졌습니다.[61] 영국은 1749년 엑사-라-샤펠 조약을 통해 지배권을 되찾았고, 1759년 프랑스의 포위 공격에 저항했습니다.[62][63] 카르나틱의 나왑족은 북부의 영국 동인도 회사에 영토의 상당 부분을 양도하고 남부에서 세수 징수권을 부여하여 폴리가르 전쟁으로 알려진 팔라이야카라족과 지속적인 분쟁을 일으켰습니다. 풀리 테바르는 초기 적수 중 한 명으로, 후에 시바간가이의 라니 벨루 나치야르와 판칼라쿠리치의 카타봄만이 폴리가르 전쟁의 첫 번째 시리즈에 참여했습니다.[64][65] 마루투 형제는 카타봄만의 형제인 오오마이투라이와 함께 제2차 폴리가르 전쟁에서 영국과 싸운 데헤런 친나말라이, 케랄라 바르마 파자시 라자와 연합을 결성했습니다.[66] 18세기 후반, 마이소르 왕국은 이 지역의 일부를 점령하고 영국과 지속적인 전투를 벌였으며, 이는 네 번의 앵글로-마이소르 전쟁으로 끝이 났습니다.[67]

18세기까지 영국은 대부분의 지역을 정복하고 마드라스를 수도로 하는 마드라스 대통령제를 확립했습니다.[68] 1799년 제4차 영미소르 전쟁에서 마이소르가 패배하고 1801년 제2차 폴리가르 전쟁에서 영국이 승리한 후, 영국은 인도 남부 대부분을 나중에 마드라스 대통령제로 알려진 곳으로 통합했습니다.[69] 1806년 7월 10일, 벨로르 요새에서 인도 세포이가 영국 동인도 회사를 상대로 벌인 대규모 반란의 첫 사례인 벨로르 반란이 일어났습니다.[70][71] 1857년 인도 반란 이후, 영국 왕실이 회사로부터 통치권을 넘겨받은 후 영국 왕실이 형성되었습니다.[72]

여름 몬순의 실패와 료트와리 제도의 행정적 결함은 마드라스 대통령제에서 두 가지 심각한 기근, 즉 1876-78년의 대기근과 수백만 명의 사망자를 낸 1896-97년의 인도 기근, 그리고 많은 타밀인들이 보세 노동자로서 결국 현재의 타밀 디아스포라를 형성하는 다른 영국 국가들로 이주했습니다.[73] 인도독립운동은 1884년 12월 마드라스에서 열린 신학계대회 이후 신학계학회 회원들이 전파한 사상을 바탕으로 20세기 초 인도국민회의가 결성되면서 탄력을 받게 되었습니다.[74][75] 타밀 나두는 V.O. 치담바람 필라이, 수브라마니야 시바, 바라티야르를 포함한 다양한 독립운동 기여자들의 근거지였습니다.[76] 타밀족은 수바스 찬드라 보스가 설립한 인도 국민군(INA)의 구성원들 중 상당한 비율을 차지했습니다.[77]

독립 이후 (1947년 ~ 현재)

1947년 인도 독립 이후, 마드라스 대통령직은 마드라스 주가 되었고, 현재의 타밀 나두와 안드라 프라데시, 카르나타카, 케랄라의 일부로 구성됩니다. 안드라주는 1953년에 주에서 분리되었고 1956년에 언어적으로 주들이 현재의 형태로 다시 그려지면서 주는 더 재편되었습니다.[78][79] 1969년 1월 14일, 마드라스 주는 "타밀 나라"라는 뜻의 타밀 나두로 개칭되었습니다.[80][81] 1965년 힌디어의 부과와 의사소통 수단으로서 영어를 계속하는 것을 지지하는 선동이 일어났고, 결국 영어는 힌디어와 함께 인도의 공식 언어로 남게 되었습니다.[82] 독립 후 타밀나두의 경제는 민간 부문의 참여, 대외 무역, 해외 직접 투자에 대한 정부의 엄격한 통제를 받으며 사회주의 체제에 순응했습니다. 인도 독립 직후 수십 년 동안 변동을 겪은 타밀나두의 경제는 개혁 지향적인 경제 정책으로 인해 1970년대부터 지속적으로 전국 평균 성장률을 상회했습니다.[83] 2000년대에 이 주는 미국에서 가장 도시화되고 생활 수준이 높은 주 중 하나가 되었습니다.[84]

환경

지리

타밀나두 주의 면적은 130,058 km2 (50,216 sq mi)이며 인도에서 10번째로 큰 주이다.[84] 인도 반도의 남동쪽 해안에 위치하고 있으며, 서쪽으로는 웨스턴 가츠와 데칸 고원, 북쪽으로는 이스트 가츠, 동쪽으로는 벵골 만에 인접한 동부 해안 평야, 남동쪽으로는 마나르 만과 팔크 해협이 있습니다. 반도 남쪽 [85]곶에 있는 라카디브 해 정치적으로 타밀나두는 인도 케랄라주, 카르나타카주, 안드라프라데시주와 연합 영토인 푸두체리주에 속하며 팜반섬에서 스리랑카 북부 주와 국제 해상 국경을 공유합니다. Palk 해협과 Rama's Bridge로 알려진 낮은 모래톱과 섬들의 사슬이 이 지역을 동남쪽 해안에 위치한 스리랑카로부터 분리시킵니다.[86][87] 인도 본토의 최남단은 인도양과 벵골만, 아라비아해가 만나는 칸야쿠마리에 있습니다.[88]

웨스턴 가츠는 닐기리 언덕의 도다베타(Doddabetta)에서 가장 높은 봉우리를 가진 서쪽 경계를 따라 남쪽으로 달립니다.[89][90] 이스턴 가츠는 동부 해안을 따라 벵골 만과 평행하게 달리고 그 사이의 육지 지대는 코로만델 지역을 형성합니다.[91] 카베리 강이 교차하는 불연속적인 산맥입니다.[92] 두 산맥은 케랄라주 북부와 카르나타카주와 타밀나두주 경계를 따라 거의 초승달로 이어지는 닐기리 산맥에서 만나며, 타밀나두주와 안드라프라데시주 경계의 서쪽 부분에 있는 이스턴 가츠의 상대적으로 낮은 언덕까지 확장됩니다.[93]

데칸 고원은 산맥과 고원 경사가 서쪽에서 동쪽으로 완만하게 이어져 서가츠에서 발생하여 동쪽으로 흐르는 주요 강이 생성되는 높은 지역입니다.[94][95][96]

타밀나두는 1,076 km(669 mi)의 해안선을 가지고 있으며 구자라트 다음으로 이 나라에서 두 번째로 긴 해안선입니다.[97] 만나르 만과 락샤드위프 섬에 위치한 산호초가 있습니다.[98] 2004년 인도양 쓰나미로 인해 타밀나두의 해안선이 영구적으로 변경되었습니다.[99]

지질학

타밀나두는 대부분 지진 위험이 낮은 지역에 속하며, 낮은 지역에서 중간 정도의 위험 지역에 속합니다. 2002년 인도 표준국(BIS) 지도에 따르면, 타밀나두는 2구역과 3구역에 속합니다.[100] 데칸의 화산 현무암층은 백악기 말 무렵에 발생한 6,700만 년에서 6,600만 년 전 사이의 거대한 데칸 트랩 화산 폭발로 인해 깔렸습니다.[101] 여러 해 동안 지속된 화산 활동에 의해 층이 형성되었고 화산이 멸종되었을 때, 그들은 표처럼 위에 일반적으로 광대한 평평한 지역을 가진 고지대 지역을 남겼습니다.[102] 타밀나두의 주요 토양은 붉은 양토, 라테라이트, 검은색, 충적층 및 식염수입니다. 철 함량이 더 높은 붉은 토양은 주 및 모든 내륙 지역의 더 큰 부분을 차지합니다. 검은 흙은 서부 타밀나두와 남부 해안의 일부에서 발견됩니다. 충적토는 비옥한 카베리 삼각주 지역에서 발견되며, 주머니에서 발견되는 라테라이트 토양과 증발량이 많은 해안 전역의 염수성 토양.[103]

기후.

이 지역은 열대성 기후이며 강우를 몬순에 의존합니다.[104] 타밀나두는 북동, 북서, 서쪽, 남쪽, 높은 강우량, 높은 고도의 구릉지, 카베리 삼각주의 7개 농경 기후 지역으로 나뉩니다.[105] 열대성 습하고 건조한 기후가 서가츠 동쪽의 반건조한 비 그림자를 제외한 대부분의 내륙 반도 지역에 우세합니다. 겨울과 초여름은 평균 기온이 18 °C (64 °F) 이상인 긴 건조 기간이고 여름은 50 °C (122 °F)를 초과하는 매우 덥고 우기는 6 월에서 9 월까지 지속되며 연간 강우량은 750 ~ 1,500 mm (30 ~ 59 인치)입니다. 9월에 건조한 북동 몬순이 시작되면 인도의 대부분의 강수량은 타밀나두에 떨어져 다른 주들은 상대적으로 건조합니다.[106] 더운 반건조 기후는 주 남부와 남부 중부 내륙을 포함하는 웨스턴 가츠 동부 지역에 우세하고 연간 400~750 밀리미터(15.7~29.5 인치)의 강우량을 가지며, 더운 여름과 건조한 겨울은 20~24 °C(68~75 °F)의 기온을 보입니다. 3월과 5월 사이의 달은 덥고 건조하며, 월평균 기온은 32°C (90°F) 정도이며, 강수량은 320mm (13인치)입니다. 인공 관개가 없으면 이 지역은 농업에 적합하지 않습니다.[107]

6월부터 9월까지의 남서 계절풍은 이 지역 강우량의 대부분을 차지합니다. 남서 몬순의 아라비아 해 분지는 케랄라에서 서쪽 가츠 지방을 강타하고 콘칸 해안을 따라 북쪽으로 이동하며 주의 서쪽 지역에 강수량을 기록합니다. 높은 웨스턴 갓은 바람이 데칸 고원에 도달하는 것을 막으므로 바람이 없는 지역(바람이 없는 지역)에는 비가 거의 내리지 않습니다.[108][109] 남서 몬순의 벵골 만 분지는 인도 북동쪽으로 향하면서 벵골 만과 코라만델 해안에서 수분을 채취하여 육지의 형태 때문에 남서 몬순으로부터 많은 강우를 받지 못합니다. 북부 타밀나두는 대부분의 비를 북동 몬순에서 내립니다.[110] 북동 몬순은 지표면 고기압계가 가장 강한 11월부터 3월 초까지 발생합니다.[111] 북인도양 열대성 저기압은 벵골만과 아라비아해에서 연중 발생하며 파괴적인 바람과 폭우를 몰고 옵니다.[112][113] 이 주의 연간 강우량은 약 945mm(37.2인치)이며, 이 중 48%는 북동 몬순, 52%는 남서 몬순을 통과합니다. 이 주의 수자원은 전국적으로 3%에 불과하며 수자원을 충전하기 위해 전적으로 비에 의존하고 있으며 몬순 실패는 심각한 물 부족과 심각한 가뭄으로 이어집니다.[114][115]

동식물군

숲은 지리적 면적의 17.4%를 차지하는 22,643km2(8,743sq mi)의 면적을 차지합니다.[116] 타밀나두에는 다양한 기후와 지리 때문에 다양한 식물과 동물이 있습니다. 낙엽성 숲은 웨스턴 가츠를 따라 발견되며, 내륙에는 열대 건조림과 관목 지대가 일반적입니다. 남부 웨스턴 가츠에는 사우스 웨스턴 가츠 산지 열대 우림이라고 불리는 높은 고도에 위치한 열대 우림이 있습니다.[117] 웨스턴 가츠는 세계에서 8개의 가장 뜨거운 생물 다양성 핫스팟 중 하나이며 유네스코 세계 문화 유산입니다.[118] 타밀나두가 원산지인 야생생물은 약 2,000여 종, 안지오스프 5640여 종(약용식물 1,559종, 고유종 533종, 재배식물 야생친척 260여 종, 적색목록 230여 종), 선충류, 지의류, 균류, 해조류 및 박테리아를 제외한 64종(토종 4종, 도입종 60종 포함)[119]과 184종의 선충류. 일반적인 식물 종은 주 나무: 팔미라 야자, 유칼립투스, 고무, 신초나, 뭉친 대나무(Bambusa arundinacea), 커먼 티크(common teak), 아노게이수스 라티폴리아(Anogeissus latifolia), 인도 월계수, 성장 및 인도 라버눔(Indian laburnum), 아르디시아(Ardisia) 및 솔라나과(Solanaceae)와 같은 꽃이 피는 나무를 포함합니다. 희귀하고 독특한 식물 생명에는 콤브레툼 오발리폴리움, 에본(디오스피로스 닐라그리카), 하베나리아 라리플로라(난초), 알소필라(Alsophila), 임파티엔스 엘레강스(Impatiens elegans), 라눈쿨루스 레니포르미스(Ranunculus reniformis) 및 왕 양치류가 포함됩니다.[120]

타밀나두의 중요한 생태 지역은 닐기리 언덕에 있는 닐기리 생물권 보호 구역, 아가스티야 말라-카다몸 언덕에 있는 아가시야말라 생물권 보호 구역, 만나르 산호초입니다.[121] 만나르 생물권 보호구역은 바다, 섬, 산호초, 염습지, 맹그로브 등 인접한 해안선의 면적이 10,500km2(4,100sqmi)에 달합니다. 돌고래, 듀공, 고래, 해삼 등 멸종위기에 처한 수생종의 서식지입니다.[122][123] 타테카드, 카달룬디, 베단탕갈, 랑가나티투, 쿠마라콤, 닐라파투, 풀리캣을 포함한 조류 보호 구역에는 수많은 철새와 지역 새들이 살고 있습니다.[124][125]

보호 구역의 면적은 3,305km2(1,276sqmi)로, 지리적 면적의 2.54%와 주의 기록된 산림 면적 22,643km2(8,743sqmi)의 15%를 구성합니다.[116] 무두말라이 국립공원은 1940년에 설립되었고 남인도 최초의 현대 야생동물 보호구역이었습니다. 보호 구역은 인도 정부의 환경 및 산림부와 타밀 나두 산림부에 의해 관리됩니다. 피차바람은 북쪽의 벨라 강어귀와 남쪽의 콜레룬 강어귀에 망그로브 숲이 걸쳐 있는 여러 섬으로 구성되어 있습니다. 피차바람 맹그로브 숲은 45km2(17sq mi)에 달하는 인도에서 가장 큰 맹그로브 숲 중 하나이며 경제적으로 중요한 조개, 물고기 및 이주 조류의 희귀한 품종의 존재를 지원합니다.[126][127] 주에는 307.84 km2 (118.86 sq mi)에 달하는 5개의 국립공원이 있습니다.아나말라이, 무두말라이, 무쿠르티, 만나르 만, 해양 국립공원, 첸나이 내 도시 국립공원인 Guindy.[128] 타밀나두에는 18개의 야생동물 보호구역이 있습니다.[128][129] 타밀 나두는 인도에서 멸종 위기에 처한 벵골 호랑이와 인도 코끼리가 가장 많이 서식하는 곳 중 하나입니다.[130][131] 프로젝트 코끼리에 따라 타밀 나두에는 아가시야말라이, 아나말라이, 코임바토레, 닐기리스, 스리빌리푸투르 등 5개의 코끼리 보호구역이 선포되어 있습니다.[128] 타밀 나두는 프로젝트 호랑이에 참여하고 있으며 아나말라이, 칼라카드문단투라이, 무두말라이, 사샤망갈람, 메가말라이 등 5개의 호랑이 보호구역을 선포했습니다.[128][132][133] 타밀나두에는 17개의 새 보호구역이 선포되어 있습니다.[128][134][135]

탄자부르 지역의 티루비다이마루두르에 보존 구역이 하나 있습니다. 인도 중앙 동물원 당국이 인정한 동물원은 두 곳으로, 모두 첸나이에 위치한 아리냐르 안나 동물원과 마드라스 악어 은행 신탁이 있습니다.[136] 주에는 코임바토레의 코임바토레 동물원, 벨로레의 아미르티 동물원, 살렘의 쿠룸팜파티 야생동물원, 예르카우드의 예르카우드 사슴공원, 티루치라팔리의 무콤부 사슴공원, 닐기리스의 오오티 사슴공원과 같은 지역 행정 기관이 운영하는 다른 소규모 동물원이 있습니다.[128] 코임바토레 지역의 아마라바티, 다르마푸리 지역의 호게나칼, 살렘 지역의 쿠룸바파티, 첸나이의 마드라스 악어 은행 신탁, 티루반나말라이 지역의 사누르에 위치한 악어 농장은 다섯 곳입니다.[128] 이 지역에서 발견된 멸종위기종으로는 회색거대다람쥐,[137] 회색 가느다란 로리스,[138] 나무늘보, 닐기리타흐르,[139][140] 닐기리랑구르,[141] 사자꼬리마카크,[142] 인도표범 등이 있습니다.[143]

| 애니멀 | 새 | 나비 | 나무 | 과일 | 플라워 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nilgiri tahr (Nilgiritragus hylocrius) | 에메랄드 비둘기 (Chalcopaps indica) | 타밀 여만 (시로크로아타이스) | 팔미라야자 (Borassus flabellifer) | 잭프루트 (Artocarpus heterophyllus) | 글로리 백합 (글로리오사 슈퍼바) |

행정과 정치

행정부.

| 제목 | 이름. |

|---|---|

| 주지사 | R. N. 라비[146] |

| 주임장관 | M. K. 스탈린[147] |

| 대법원장 | S. V. Gangapurwala[148] |

첸나이는 주의 주도이며 주 행정부, 입법부, 사법부 수장을 맡고 있습니다.[149] 주 정부의 행정은 다양한 사무국 부서를 통해 기능합니다. 주에는 43개의 부서가 있으며 부서에는 다양한 사업과 이사회를 관리할 수 있는 추가 하위 부서가 있습니다.[150] 주는 38개의 구역으로 나뉘며, 각 구역은 타밀 나두 정부에 의해 구역에 임명된 인도 행정 서비스(IAS)의 관리인 지구 수집가에 의해 관리됩니다. 세입 관리를 위해 이 지역은 세입 부서 책임자(RDO)가 관리하는 87개의 세입 부서로 더 세분화되며, 이 부서는 타힐다르스가 관리하는 310개의 토크로 구성됩니다.[151] 토크는 17,680개의 수익 마을로 구성된 피르카스(Firkas)라고 불리는 1349개의 수익 블록으로 나뉩니다.[151] 지방 행정은 마을 행정관(VAO)에 의해 관리되는 15개의 지방 자치 단체, 121개의 지방 자치 단체 및 528개의 마을 판차야트와 385개의 판차야트 조합 및 12,618개의 마을 판차야트로 구성됩니다.[152][151][153] 1688년에 설립된 그레이터 첸나이 법인은 세계에서 두 번째로 오래되었고 타밀 나두는 마을 판차야트를 새로운 행정 단위로 설립한 최초의 주였습니다.[154][152]

입법부

인도 헌법에 따라 주지사는 주의 법정 수장이며 사실상의 행정 권한을 가진 최고 장관을 임명합니다.[155] 1861년 인도 의회법은 4~8명의 위원으로 마드라스 대통령 입법회를 설치하였으나 단순한 자문기구에 불과하였고 1892년에는 20명, 1909년에는 50명으로 증원되었습니다.[156][157] 마드라스 입법회는 1921년 인도 정부법(1919)에 의해 3년의 임기로 설립되었으며, 132명의 의원으로 구성되었으며, 그 중 34명이 주지사에 의해 지명되고 나머지는 선출되었습니다.[158] 1935년 인도 정부법은 1937년 7월 54~56명의 의원으로 구성된 새로운 입법회를 만들면서 양원제 입법회를 설립했습니다.[158] 마드라스 주의 첫 번째 입법부는 1952년 선거 이후 1952년 3월 1일에 구성되었습니다. 1956년 재조직 후 의석수는 206석이었고, 1962년에는 234석으로 더 늘었습니다.[158] 1986년 타밀나두 입법회(폐지)법에 의해 입법회가 폐지되면서 주 정부는 단원제 입법회로 이동했습니다.[159] 타밀 나두 입법회는 포트 세인트에 있습니다. 첸나이의 조지.[160] 주 정부는 39명을 록 사바에, 18명을 인도 의회의 라지야 사바에 선출합니다.[161]

법질서

마드라스 고등법원은 1862년 6월 26일에 설립되었으며 주의 모든 민형사 법원을 통제하는 주의 최고 사법 기관입니다.[162] 대법원장이 위원장을 맡고 있으며 2004년부터 마두라이에 벤치를 두고 있습니다.[163] 1859년 마드라스 주 경찰로 설립된 타밀나두 경찰은 타밀나두 주 정부 내무부 산하에서 운영되며 주 내 법과 질서를 유지하는 역할을 합니다.[164] 2023년[update] 현재 경찰국장이 이끄는 1.32 라크 이상의 경찰 인력으로 구성되어 있습니다.[165][166] 여성은 경찰력의 17.6%를 형성하고 있으며, 222개의 여성 특별 경찰서를 통해 여성에 대한 폭력을 구체적으로 처리하고 있습니다.[167][168][169] 2023년[update] 현재 주에는 철도 47개, 교통 경찰서 243개 등 전국에서 가장 높은 1854개 경찰서가 있습니다.[167][170] 각 지역의 교통 관리는 각 지방 행정부 산하 교통 경찰이 담당합니다.[171] 이 주는 2018년 범죄율이 라크당 2.2명으로 여성에게 가장 안전한 주 중 하나로 지속적으로 선정되고 있습니다.[172]

정치

인도의 선거는 1950년에 설립된 독립 기구인 인도 선거 위원회에 의해 실시됩니다.[173] 타밀나두의 정치는 1960년대까지 전국 정당들에 의해 지배되었고 그 이후로 지역 정당들이 지배해 왔습니다. 마드라스 대통령 시절 정의당과 스와라지당은 양대 정당이었습니다.[174] 1920년대와 1930년대 사이에 테아가로야 체티와 E.V. 라마스와미(흔히 페리야르로 알려져 있음)가 주도한 자기 존중 운동이 마드라스 대통령제에서 등장했고 정의당의 결성을 이끌었습니다.[175] 정의당은 결국 1937년 선거에서 인도 국민회의에 패배했고 차크라바르티 라자고팔라차리는 마드라스 대통령직의 수석 장관이 되었습니다.[174] 1944년, 페리야르는 정의당을 사회적 조직으로 변화시켰고, 당명을 드라비다르 카즈하감(Dravidar Kazhagam)으로 바꾸고, 선거 정치에서 물러났습니다.[176] 독립 후 인도국민회의는 자와할랄 네루의 사망 이후 당을 이끌고 랄 바하두르 샤스트리 총리와 인디라 간디 총리의 선출을 보장한 K. 카마라즈의 지도 아래 1950~60년대 타밀나두 정치 현장을 장악했습니다.[177][178] 페리야르의 추종자인 C. N. Annadurai는 1949년 Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK)을 결성했습니다.[179]

타밀나두의 반(反)힌드 선동은 1967년 타밀나두의 첫 정부를 구성한 드라비다 정당의 발흥으로 이어졌습니다.[180] 1972년 DMK의 분열로 M. G. Ramachandran이 이끄는 전인도 안나 드라비다 문네트라 카즈하감(AIADMK)이 결성되었습니다.[181] 드라비다 정당들은 타밀나두 선거 정치를 계속 지배하고 있으며, 국가 정당들은 일반적으로 드라비다 주요 정당인 AIADMK와 DMK의 하위 파트너로 협력하고 있습니다.[182] M. Karunanidhi는 Annadurai와 J. J. Jayalithaa가 M. G. Ramachandran에 이어 AIADMK의 지도자로 성공한 후 DMK의 지도자가 되었습니다.[183][177] 카루나니디와 자야랄리타는 1980년대부터 2010년대 초까지 주 정치를 장악했으며, 32년 넘게 장관직을 겸임했습니다.[177]

독립 후 첫 인도 총독이었던 C. 라자고팔라차리는 타밀나두 출신입니다. 이 주는 세 명의 인도 대통령, 즉 사르베팔리 라다크리쉬난 [184]R. 벤카타라만과 APJ 압둘 칼람.[185][186]

인구통계

| 연도 | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 19,252,630 | — |

| 1911 | 20,902,616 | +8.6% |

| 1921 | 21,628,518 | +3.5% |

| 1931 | 23,472,099 | +8.5% |

| 1941 | 26,267,507 | +11.9% |

| 1951 | 30,119,047 | +14.7% |

| 1961 | 33,686,953 | +11.8% |

| 1971 | 41,199,168 | +22.3% |

| 1981 | 48,408,077 | +17.5% |

| 1991 | 55,858,946 | +15.4% |

| 2001 | 62,405,679 | +11.7% |

| 2011 | 72,147,030 | +15.6% |

| 출처:인도의[187] 인구 조사 | ||

2011년 인구 조사에 따르면 타밀나두의 인구는 7.21크로어이며 인도에서 7번째로 인구가 많은 주이다.[1] 인구는 2023년에 7.68크로어가 될 것으로 예상되며 2036년에는 7.8크로어로 증가할 것으로 예상됩니다.[188] 타밀 나두는 도시 지역에 거주하는 인구의 48.4% 이상을 가진 나라에서 가장 도시화된 주 중 하나입니다.[84] 2011년 인구 조사에 따르면 성비는 남성 1000명당 996명의 여성으로 전국 평균인 943명보다 높았습니다.[189] 출생 시 성비는 2015-16년 제4차 전국가족건강조사(NFHS)에서 954명으로 기록되었으며, 2019-21년 제5차 NFHS에서는 878명으로 더욱 감소하여 주 중 3위를 차지했습니다.[190] 2011년 인구 조사에 따르면 문해율은 80.1%로 전국 평균 73%[191]보다 높았습니다. 문해율은 2017년 통계위원회 조사에 따르면 82.9%로 추정되었습니다.[192] 2011년[update] 기준으로 6세 이하 아동은 약 2,317만 가구입니다.[193] 총 1,440만 명(20%)이 예정된 카스트(SC)에 속했고, 80만 명(1.1%)이 예정된 부족(ST)에 속했습니다.[194]

2017년[update] 기준으로 이 주는 인구 유지에 필요한 것보다 낮은 1.6명의 여성이 태어나 인도에서 가장 낮은 출산율을 기록했습니다.[195] 2021년[update] 기준 인간개발지수(HDI)는 0.686으로 인도(0.633)보다 높지만 중위권을 기록했습니다.[196] 2019년[update] 기준 출생 시 기대 수명은 74세로 인도 주 중 가장 높았습니다.[197] 2023년 다차원 빈곤 지수에 따르면 2.2%의 사람들이 빈곤선 아래에 살고 있으며, 이는 인도 주 중 가장 낮은 것 중 하나입니다.[198]

도시와 마을

첸나이의 수도는 860만 명 이상의 주민이 거주하는 주에서 가장 인구가 많은 도시 집적지이며 코임바토레, 마두라이, 티루치라팔리, 티루푸르가 각각 그 뒤를 이었습니다.[199]

| 순위 | 이름. | 구 | 팝. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

첸나이  코임바토레 | 1 | 첸나이 | 첸나이 | 8,696,010 |  마두라이  티루치라팔리 | ||||

| 2 | 코임바토레 | 코임바토레 | 2,151,466 | ||||||

| 3 | 마두라이 | 마두라이 | 1,462,420 | ||||||

| 4 | 티루치라팔리 | 티루치라팔리 | 1,021,717 | ||||||

| 5 | 티루푸르 | 티루푸르 | 962,982 | ||||||

| 6 | 살렘 | 살렘 | 919,150 | ||||||

| 7 | 에로데 | 에로데 | 521,776 | ||||||

| 8 | 벨로레 | 벨로레 | 504,079 | ||||||

| 9 | Tirunelveli | Tirunelveli | 498,984 | ||||||

| 10 | 투두쿠디 | 투두쿠디 | 410,760 | ||||||

종교와 민족

이 주는 다양한 민족 종교 공동체의 본거지입니다.[201][202] 2011년 인구 조사에 따르면 힌두교는 87% 이상의 신자를 가진 주요 종교입니다. 기독교인은 6.1%로 주에서 가장 큰 종교적 소수자이며, 이슬람교가 5.9%[200]로 그 뒤를 이었습니다. Tamils form majority of the population with minorities including Telugus,[203] Marwaris,[204] Gujaratis,[205] Parsis,[206] Sindhis,[207] Odias,[208] Kannadigas,[209] Anglo-Indians,[210] Bengalis,[211] Punjabis,[212] and Malayalees.[213] 주에는 또한 상당한 외국인 인구가 있습니다.[214][215] 2011년[update] 기준, 주에는 349만 명의 이민자가 있습니다.[216]

언어

타밀어는 타밀나두어의 공용어이며, 영어는 추가 공용어 역할을 합니다.[2] 타밀어는 가장 오래된 언어 중 하나이며 인도의 고전적인 언어로 처음 인정받았습니다.[218] 2011년 인구 조사에 따르면 타밀어는 주 인구의 88.4%가 제1언어로 사용하고 있으며, 텔루구어(5.87%), 칸나다어(1.58%), 우르두어(1.75%), 말레이알람어(1%) 및 기타 언어(1.53%)[217]가 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 북부 타밀나두의 마드라스 바샤이, 서부 타밀나두의 콩구 타밀 등 여러 지역에서 다양한 타밀어가 사용되고 있습니다. 마두라이 주변의 마두라이 타밀어와 남동부 타밀나두의 넬라이 타밀어.[219][220] 오늘날 타밀나두어의 타밀어는 산스크리트어와 영어와 같은 다른 언어의 외래어를 자유롭게 사용하지만 드라비다어는 드라비다어의 일부이며 드라비다어 원어의 많은 특징을 보존하고 있습니다.[221][222] 한국어,[223] 일본어,[224] 프랑스어,[225] 만다린 중국어,[226] 독일어[227] 및 스페인어는 주에 있는 외국인 주재원이 사용합니다.[225]

LGBT 권리

타밀나두의 LGBT 권리는 인도에서 가장 진보적입니다.[228][229] 2008년, 타밀 나두는 트랜스젠더 복지 위원회를 설립했고, 트랜스젠더들이 정부 병원에서 무료로 성전환 수술을 받을 수 있는 트랜스젠더 복지 정책을 처음으로 도입했습니다.[230] 첸나이 레인보우 프라이드는 2009년부터 매년 첸나이에서 개최되고 있습니다.[231] 2021년 타밀 나두는 마드라스 고등법원의 지시에 따라 전환 치료를 금지하고 성관계 유아에 대한 성 선택적 수술을 강제한 최초의 인도 주가 되었습니다.[232][233][234] 2019년 마드라스 고등법원은 1955년 힌두교 결혼법에 따른 "신부"라는 용어에 트랜스 여성이 포함되어 있으므로 남성과 트랜스젠더 여성 간의 결혼을 합법화한다고 판결했습니다.[235]

문화유산

옷

타밀 여성들은 전통적으로 길이가 5야드(4.6m)에서 9야드(8.2m)에 이르는 다양한 드레이프와 폭이 2피트(0.61m)에서 4피트(1.2m)에 이르는 옷으로 구성되어 있으며, 인도 철학에 따르면 한쪽 끝은 어깨에 걸치고 미드리프를 제외하고 있습니다. 배꼽은 생명과 창의력의 원천으로 여겨집니다.[236][237] 실라파디카람과 같은 고대 타밀어 시는 여성을 절묘한 옷걸이나 사리로 묘사합니다.[238] 여성들은 결혼과 같은 특별한 날에 색색의 비단 사레를 입습니다.[239] 남자들은 종종 밝은 색 줄무늬로 테두리를 두른 4.5 미터 (15 피트) 길이의 하얀 직사각형 천 조각인 도티를 입습니다. 보통 허리와 다리를 감싸고 허리에 매듭을 짓습니다.[240] 전형적인 바틱 패턴의 화려한 런기는 시골에서 가장 흔한 남성복입니다.[241] 도시 지역 사람들은 일반적으로 맞춤형 옷을 입고 있으며, 웨스턴 드레스가 인기가 있습니다. 서양식 교복은 학교에서 남학생과 여학생 모두 착용합니다. 심지어 시골 지역에서도 말이죠.[241] 칸치푸람 실크 사리는 타밀나두의 칸치푸람 지역에서 만들어지는 실크 사리의 한 종류로, 이 사리들은 남인도의 대부분의 여성들이 신부나 특별한 행사용 사리로 착용합니다. 그것은 2005-2006년 인도 정부에 의해 지리적 표시로 인정받았습니다.[242][243] 코바이 코라 코튼은 코임바토레에서 만들어진 목화 사리의 한 종류입니다.[243][244]

요리.

쌀은 주식이며 타밀 식사의 일부로 삼바, 라삼, 포리얄과 함께 제공됩니다.[245] 코코넛과 향신료는 타밀 요리에 광범위하게 사용됩니다. 이 지역은 쌀, 콩류 및 렌틸콩으로 만든 전통적인 비채식 및 채식 요리를 포함하는 풍부한 요리를 가지고 있으며 향료와 향신료의 혼합으로 달성된 독특한 향과 풍미를 가지고 있습니다.[246][247] 전통적인 식사 방법은 바닥에 앉기, 바나나 잎에 음식을 제공하기,[248] 오른손의 깨끗한 손가락을 사용하여 음식을 입으로 가져가는 것입니다.[249] 식사 후 손가락을 씻습니다; 쉽게 분해되는 바나나 잎은 버려지거나 소의 먹이가 됩니다.[250] 바나나 잎을 먹는 것은 수천 년 된 관습이며 음식에 독특한 맛을 부여하고 건강에 좋다고 여겨집니다.[251] 이들리, 도사, 우타팜, 퐁갈, 파니야람은 타밀나두에서 인기 있는 아침 식사입니다.[252]

문학.

타밀나두는 상암 시대로부터 2500년 이상 거슬러 올라가는 독립적인 문학 전통을 가지고 있습니다.[253] 초기 타밀 문학은 타밀 상감(Tamil Sangams)이라고 알려진 세 개의 연속적인 시적 집합체로 구성되었으며, 그 중 가장 초기의 것은 고대 전통에 따르면 인도의 남쪽 멀리 지금은 사라진 대륙에서 열렸습니다.[254] 여기에는 가장 오래된 문법 논문인 Tholkappiyam과 서사시 Silappatikaram과 Manimekalai가 포함됩니다.[255] 바위 칙령과 영웅석에서 발견된 가장 초기의 비문 기록은 기원전 3세기경으로 거슬러 올라갑니다.[256] [257] 상암시대의 문헌은 대략 연대를 기준으로 하여 두 가지로 분류하여 정리한 것입니다. 파티넨마엘카나쿠는 에우ṭṭ 우토카이와 파투파투와 파티넨킬카나쿠로 구성되어 있습니다. 현존하는 타밀어 문법은 주로 톨카피얌을 기반으로 한 13세기 문법책 ṉṉū에 기반을 두고 있으며, 타밀어 문법은 ḻ웃투, 솔, 포루ḷ, 야푸, ṇ아이 등 다섯 부분으로 구성되어 있습니다. 티루발루바르의 윤리에 관한 책인 티루쿠랄은 타밀 문학의 가장 인기 있는 작품 중 하나입니다.[259]

중세 초기에 알바르스와 나얀마르스가 작곡한 찬송가로 서기 6세기 박티 운동에 이어 바이슈나바와 사이바 문학이 두드러졌습니다.[260][261][262] 그 다음 해에, 타밀 문학은 캄바르에 의해 12세기에 쓰여진 라마바타람을 포함한 주목할 만한 작품들로 다시 번창했습니다.[263] 다양한 침략과 불안정으로 인해 중기에 소강상태를 보이다가 서기 14세기에 타밀 문학이 회복되었고, 주목할 만한 작품은 아루나기리나타르의 티루푸갈(Tirupugal)입니다.[264] 1578년, 포르투갈인들은 '탐비라안 바나캄'이라는 이름의 타밀어 책을 오래된 타밀 문자로 출판하여 타밀어가 인쇄되고 출판된 최초의 인도어가 되었습니다.[265] 마드라스 대학에서 출판한 타밀 렉시콘은 인도어로 출판된 사전 중 최초입니다.[266] 19세기는 타밀 르네상스와 미낙시 순다람 필라이, U.V. 스와미나타 아이어, 라말링가 아디갈, 마라이말라이 아디갈, 바라티다산과 같은 작가들의 글과 시를 탄생시켰습니다.[267][268] 인도 독립 운동 기간 동안, 많은 타밀 시인과 작가들은 민족 정신, 사회적 형평성, 세속주의 사상, 특히 바라티아와 바라티다산을 자극하려고 노력했습니다.[269]

건축

드라비다 건축은 타밀나두의 독특한 암석 건축 양식입니다.[270] 드라비다 건축에서 사원과 필라레드 홀을 둘러싸고 있는 4각형의 울타리 안에 있는 성소, 성문 피라미드 또는 고푸람으로 이어지는 문 앞에 있는 현관 또는 만타파스로 간주되는 사원은 여러 목적으로 사용되며 이러한 사원의 변함없는 동반물입니다. 이 외에도, 남인도 사원에는 보통 칼야니 또는 푸쉬카르니라고 불리는 탱크가 있습니다.[271] 고푸람은 기념비적인 탑으로, 보통 사원 입구에 장식되어 있으며, 드라비다 양식의 코일과 힌두교 사원의 두드러진 특징을 형성합니다.[272] 그 위에는 구불구불한 석재로 사원 단지를 둘러싸고 있는 벽을 통과하는 관문 역할을 하는 칼라삼이 있습니다.[273] 고푸람의 기원은 마하발리푸람과 칸치푸람에 기념물 그룹을 세운 팔라바족으로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있습니다.[30] 촐라족은 나중에 똑같이 확장했고 12세기 판디야 통치에 의해 이 문들은 사원의 외관의 지배적인 특징이 되었습니다.[274][275] 주 문장은 또한 배경에 고푸람의 이미지가 있는 아쇼카의 사자 수도를 특징으로 합니다.[276] 비남은 사원의 가르바그리하 또는 내부 성소 위에 지어진 유사한 구조물이지만, 탄자부르의 브리하디스바라 사원을 포함한 몇 가지 예외를 제외하고는 보통 드라비다 건축의 고푸람보다 작습니다.[277][278]

중세와 이후 영국의 무갈 영향으로 힌두, 이슬람 및 고딕 부흥 양식의 혼합이 증가하여 영국 시대 동안 여러 기관이 이 양식을 따라 독특한 인도-사라식 건축물이 탄생했습니다.[279][280] 20세기 초에 아르데코는 도시 풍경에 등장했습니다.[281] 독립 이후, 건축물은 석회암과 벽돌 건축에서 콘크리트 기둥으로 전환되면서 모더니즘의 상승을 목격했습니다.[282]

예술

타밀 나두는 인도의 음악, 예술, 춤의 주요 중심지입니다.[283] 첸나이는 남인도의 문화 수도라고 불립니다.[284] 상암 시대에 예술 형태는 이얄(시), 이사이(음악), 나다캄(드라마)으로 분류되었습니다.[285] 바라타나탐은 타밀나두에서 유래된 고전적인 춤 형태이며 인도의 가장 오래된 춤 중 하나입니다.[286][287][288] 다른 지역 민속 춤으로는 카라카탐, 카바디, 쿠디야탐, 오일리라탐, 파라이아탐, 푸라바이아탐 등이 있습니다.[289][290][291][292] 타밀나두의 춤, 옷, 조각들은 신체와 모성의 아름다움을 전형적으로 보여줍니다.[293] 코투는 고대의 민속 예술로, 예술가들이 춤과 음악을 동반한 서사시로부터 이야기를 들려줍니다.[294]

고대 타밀 국가는 실라파티카람과 같은 상암 문학에 의해 묘사된 타밀 판니사이라는 고유한 음악 체계를 가지고 있었습니다.[295] 서기 7세기로 거슬러 올라가는 팔라바 비문은 인도 음악의 기보법에 대한 가장 초기의 현존하는 예들 중 하나를 가지고 있습니다.[296] 파라이, 타라이, 야즈, 무라수와 같은 상암 시대로 거슬러 올라가는 이 지역의 전통 악기들이 많이 있습니다.[297][298] 나다스와람은 절과 결혼식에서 사용되는 주요 악기로 북악기의 한 종류인 타빌과 자주 동반되는 갈대 악기입니다.[299] 멜람은 고대 타밀라캄의 마달람과 다른 유사한 타악기들로 이루어진 그룹으로 행사 중에 연주됩니다.[300] 타밀나두의 전통 음악은 카르나틱 음악으로 알려져 있는데, 카르나틱 음악은 Mutuswami Dikshitar와 같은 작곡가들에 의해 리드미컬하고 구조화된 음악을 포함합니다.[301] 다양한 민속 음악의 조합인 Gaana는 주로 북첸나이의 노동자 계급 지역에서 노래됩니다.[302]

주에는 예술 연구에 참여하고 주요 관광 명소인 많은 박물관, 갤러리 및 기타 기관이 있습니다.[303] 18세기 초에 설립된 정부 박물관과 국립 미술관은 이 나라에서 가장 오래된 박물관 중 하나입니다.[304] 포트 세인트 구내에 있는 박물관. 조지는 영국 시대의 물건들을 소장하고 있습니다.[305] 이 박물관은 인도 고고학 조사에 의해 관리되며 1947년 8월 15일 인도 독립 선언 이후 세인트 조지 요새에 최초의 인도 국기가 게양되었습니다.[306]

타밀 나두는 또한 "Kollywood"라는 별명을 가진 타밀 영화 산업의 본거지이며 인도에서 가장 큰 영화 제작 산업 중 하나입니다.[307][308] Kollywood라는 용어는 Kodambakkam과 Hollywood의 합성어입니다.[309] 1916년 타밀어에서 최초의 무성 영화가 제작되었고 최초의 토키는 다국어 영화인 칼리다스(Kalidas)로, 인도 최초의 토키 영화인 알람 아라(Alam Ara) 이후 겨우 7개월 후인 1931년 10월 31일에 개봉되었습니다.[310][311] 코임바토레에 남인도 최초의 영화관을 세운 사미카누 빈센트(Samikannu Vincent)는 영화를 상영하기 위해 마을이나 마을과 가까운 넓은 공터에 텐트를 치는 '텐트 시네마(Tent Cinema)'라는 개념을 도입했습니다. 그 종류의 첫 번째는 "에디슨의 그랜드 시네마메가폰"이라고 불리는 마드라스에서 설립되었습니다.[312][313][314]

축제

퐁갈은 타밀족에 의해 기념되는 주요하고 며칠에 걸친 수확 축제입니다.[315] 타밀 태양력에 따라 타이의 달에 관측되며 보통 1월 14일 또는 15일에 해당합니다.[316] 태양신인 수리아에게 바쳐지며, 축제는 '끓다, 넘치다'라는 뜻의 의례적인 '퐁알'에서 따온 이름으로, 수리아에게 바치는 재규어와 함께 우유에 삶아진 쌀의 새로운 수확으로 준비된 전통 음식을 말합니다.[317][318][319] 마투퐁갈은 소들이 목욕을 하고, 뿔을 연마하고 밝은 색으로 칠할 때, 목 주위에 꽃 화관을 놓고 행렬할 때, 소들을 축하하기 위한 것입니다.[320] 잘리카투는 많은 사람들이 모여드는 기간에 열리는 전통 행사로, 황소 한 마리가 군중 속으로 풀어지고, 황소가 탈출을 시도하는 동안 여러 명의 인간 참가자들이 황소의 등에 있는 큰 혹을 양팔로 잡고 매달리려고 시도합니다.[321]

푸탄두는 타밀 달력에서 1년의 첫 날을 나타내는 타밀 새해로 알려져 있습니다. 축제 날짜는 타밀 달 치티라이의 첫 날로 태양력 힌두 달력의 태양 주기로 설정되며 그레고리력으로 매년 4월 또는 약 14일에 해당합니다.[323] 카르티카이 디팜(Kartika Deepam)은 그레고리안 11월 또는 12월에 해당하는 카르티카 달 보름날에 관찰되는 빛의 축제입니다.[324][325] 타이푸삼은 타이의 보름달 첫 날에 푸삼 별과 일치하는 타밀 축제이며 무루간 영주에게 바칩니다. 카바디 아탐(Kavadi Aattam)은 타이푸삼의 중심부이며 부채 속박을 강조하는 신자들에 의해 행해지는 희생과 제물을 바치는 의식적인 행위입니다.[326][327] Aadi Perukku는 물의 생명을 유지하는 속성에 경의를 표하는 Adi의 타밀 달 18일에 기념되는 타밀 문화 축제입니다. 암만과 아이야나르 신들의 숭배는 타밀나두 전역의 사원에서 한 달 동안 많은 팡파르와 함께 조직됩니다.[300] 판구니 우티람은 판구니 달의 푸르니마(보름달)에 표시되며 다양한 힌두교 신들의 결혼식을 축하합니다.[328]

Tyagaraja Aradhana는 작곡가 Tyagaraja에게 바치는 매년 열리는 음악 축제입니다. 탄자부르 지역의 티루바이야루에는 매년 수천 명의 음악가들이 모입니다.[329] 첸나이일 티루바이야루는 매년 12월 18일부터 25일까지 첸나이에서 열리는 음악 축제입니다.[330] 첸나이 상암은 옛 마을 축제와 예술, 예술가들을 되살리려는 의도로 첸나이에서 매년 열리는 대규모 개방형 타밀 문화 축제입니다.[331] 1927년 마드라스 음악 아카데미에 의해 시작된 마드라스 음악 시즌은 매년 12월 한 달 동안 기념되며 도시 출신 예술가들의 전통 카르나틱 음악 공연이 특징입니다.[332]

경제.

1970년대 개혁 중심의 경제 정책으로 인해 국가 경제는 지속적으로 전국 평균 성장률을 상회했습니다.[333] 2022년 현재 타밀나두의 GSDP는 ₹ 23.65 라크크로어(3천억 달러)로 2004년 ₹ 2.19 라크크로어(270억 달러)에서 크게 성장한 인도 주 중 두 번째로 높습니다. 1인당 NDSP는 ₹ 275,583(3,500달러)입니다. 타밀나두는 인도에서 가장 도시화된 주입니다.[334] 주정부는 빈곤선 아래 인구의 비율이 가장 낮았지만 농촌 실업률은 전국 평균인 28명에 비해 천 명당 47명으로 상당히 높습니다.[198][335] 2020년[update] 기준으로 주에는 38,837개의 공장이 가장 많고 260만 명의 고용 노동력이 있습니다.[336][337]

주정부는 자동차, 소프트웨어 서비스, 하드웨어, 섬유, 의료 및 금융 서비스를 포함한 다양한 부문에 의해 고정된 다양한 산업 기반을 가지고 있습니다.[338][339] 2022년[update] 기준 서비스업이 GSDP의 55%, 제조업이 32%, 농업이 13%[340]를 차지했습니다. 그 주에는 42개의 경제특구가 있습니다.[341] 인도 정부의 보고서에 따르면 타밀나두는 2023년 인도에서 가장 수출 경쟁력이 있는 주이다.[342]

- 서비스

2022년 현재 인도는 ₹ 57,687크로어(72억 달러)의 가치를 가진 인도의 주요 정보기술(IT) 수출국 중 하나입니다. 2000년에 설립된 첸나이의 티델 파크는 아시아에서 처음이자 가장 큰 IT 파크 중 하나였습니다.[345] SEZ의 존재와 정부 정책은 다른 지역에서 외국인 투자와 구직자를 끌어들인 이 부문의 성장에 기여했습니다.[346][347] 2020년대 들어 첸나이는 SaaS의 주요 공급업체가 되었고 "인도의 SaaS 수도"라고 불립니다.[348][349]

주에는 2013년 설립된 코임바토레 증권거래소와 2015년 설립된 마드라스 증권거래소, 거래량 기준으로 인도에서 세 번째로 큰 두 개의 증권거래소가 있습니다.[350][351] 1683년 6월 21일 인도 최초의 유럽식 은행 시스템인 마드라스 은행이 설립되었고, 그 뒤를 이어 힌두스탄 은행(1770년)과 인도 일반 은행(1786년) 등 최초의 상업 은행이 설립되었습니다.[352] 마드라스 은행은 1921년 두 개의 다른 은행들과 합병하여 임페리얼 뱅크 오브 인디아(Imperial Bank of India)를 설립했고 1955년에는 인도에서 가장 큰 은행인 스테이트 뱅크 오브 인디아(State Bank of India)가 되었습니다.[353] 6개 은행을 포함하여 400개 이상의 금융 산업 사업체가 주에 본사를 두고 있습니다.[354][355][356][357] 주 정부는 인도 중앙은행인 인도준비은행의 남부 지역 사무소와 첸나이의 지역 훈련 센터 및 직원 대학을 주최합니다.[358] 주에는 세계 은행의 상설 백 오피스가 있습니다.[359]

- 제조업

제조업은 중앙 정부 소유 기업과는 별도로 국영 산업 기업인 TTDC(Tamil Nadu Industrial Development Corporation)에 의해 다양한 주에서 관리됩니다. 전자 하드웨어는 2023년에 53억 7천만 달러의 생산량을 기록한 주요 제조업으로, 인도 주 중에서는 가장 큽니다.[360][361] 많은 자동차 회사가 주에 제조 기지를 두고 있으며 첸나이의 자동차 산업은 인도 전체 자동차 부품 및 자동차 생산량의 35% 이상을 차지하여 "인도의 디트로이트"라는 별명을 얻었습니다.[362][363][364] 첸나이에 있는 인테그랄 코치 팩토리는 인도 철도를 위한 철도 코치 및 기타 롤링 스톡을 제조합니다.[365]

또 다른 주요 산업은 주 정부가 인도에서 운영 중인 섬유 섬유 공장의 절반 이상을 차지하고 있는 섬유입니다.[366][367] 코임바토레는 면화 생산과 섬유 산업으로 인해 종종 남인도의 맨체스터라고 불립니다.[368] 2022년[update] 현재 티루푸르는 4,800억 달러 규모의 의류를 수출하여 인도에서 전체 섬유 수출의 거의 54%를 차지하고 있으며, 면 니트 수출로 인해 도시는 니트 수도로 알려져 있습니다.[369][370] 2015년[update] 현재 타밀나두의 섬유 산업은 모든 산업에서 총 투자 자본의 17%를 차지합니다.[371] 2021년 현재 인도에서 수출되는 가죽 제품의 40%는 ₹ 9,252크로어(12억 달러)에 해당하는 주에서 제조되고 있습니다. 이 주는 인도의 모터와 펌프 요구량의 3분의 2를 공급하고 있으며, 인정된 지리적 표시인 "Coimbatore Wet Grinder"를 보유한 습식 분쇄기의 가장 큰 수출국 중 하나입니다.[373][374]

아루반카두와 티루치라팔리에는 두 개의 군수공장이 있습니다.[375][376] 첸나이에 본사를 둔 AVANI는 인도군의 사용을 위해 기갑 전투 차량, 주요 전차, 탱크 엔진 및 장갑 의류를 제조합니다.[377]>[378] ISRO, 인도 우주국이 마헨드라기리에서 추진 시설을 운영하고 있습니다.[379]

- 농업

농업은 GSDP에 13%를 기여하며 농촌 지역의 주요 고용 창출원입니다.[340] 2022년[update] 기준으로 이 주는 634만 헥타르가 경작 중입니다.[380][381] 쌀은 주식 곡물로 주는 2021-22년에 790만 톤의 생산량을 가진 가장 큰 생산국 중 하나입니다.[382] 카베리 삼각주 지역은 타밀나두의 밥그릇으로 알려져 있습니다.[383] 비식량 곡물 중 사탕수수는 2021-22년 연간 생산량이 1,610만 톤인 주요 작물입니다.[384] 주(州)[385]는 향신료를 생산하는 주이며, 인도에서 오일 씨, 타피오카, 정향, 꽃을 가장 많이 생산하는 주이다. 주정부는 과일의 6.5%, 채소 생산량의 4.2%를 차지합니다.[386][387] 이 주는 과일 재배 면적의 78% 이상을 차지하는 바나나와 망고의 주요 생산지입니다.[388] 2019년[update] 기준으로 이 주는 천연 고무와 코코넛의 두 번째로 큰 생산국입니다.[389] 차는 독특한 맛의 닐기리 차의 주요 생산지인 힐 스테이션에서 인기 있는 작물입니다.[390][391]

2022년[update] 기준으로 이 주는 연간 208억 개의 생산 규모를 가진 가금류 및 계란의 최대 생산국으로 전국 생산량의 16% 이상에 기여하고 있습니다.[392] 이 주의 어민 인구는 105만 명이며 해안은 3개의 주요 어항, 3개의 중어항 및 363개의 어장 센터로 구성되어 있습니다.[393] 2022년[update] 기준 어업 생산량은 80만 톤으로 인도 전체 어류 생산량의 5%를 차지했습니다.[394] 양식에는 새우, 해초, 홍합, 조개 및 굴 양식이 포함됩니다.[395] "인도 녹색 혁명의 아버지"로 알려진 M. S. 스와미나탄은 타밀나두 출신입니다.[396]

사회 기반 시설

급수

국가는 국토 면적의 4%, 인구의 6% 가까이를 차지하고 있지만 국가 수자원의 3%에 불과하고 1인당 물 가용량은 800m3(28,000cuft)로 전국 평균 2,300m3(81,000cuft)보다 낮습니다.[397] 상태는 수자원을 보충하기 위한 몬순에 의존합니다. 61개의 저수지가 있는 17개의 주요 하천 유역과 24,864만 입방미터(MCM)의 총 지표수 잠재량을 가진 약 41,948개의 탱크가 있으며, 이 중 90%가 관개용으로 사용됩니다. 사용 가능한 지하수 충전은 22,423 MCM입니다.[397] 주요 강으로는 카베리, 바바니, 바이가이, 타미라바라니 등이 있습니다. 대부분의 강이 다른 주에서 발원하기 때문에 주들은 상당한 양의 물을 이웃 주에 의존하고 있으며, 이로 인해 종종 분쟁이 발생했습니다.[398] 주에는 116개의 큰 댐이 있습니다.[399] 강을 제외한 대부분의 물은 주 전역의 41,000개 이상의 탱크와 16.8 라크 유정에 저장된 빗물에서 나옵니다.[380]

상하수도 처리는 첸나이의 첸나이 메트로 상하수도 위원회와 같은 각 지방 행정 기관에서 관리합니다.[400][401] 민주르에 있는 국내 최대의 담수화 공장들은 대체 식수 수단을 제공합니다.[402] 2011년 인구 조사에 따르면 안전한 식수를 이용할 수 있는 가구는 83.4%에 불과하여 전국 평균 85.5%[403]에 미치지 못합니다. 상수원은 또한 환경 오염과 산업의 폐수 배출로 인해 위협을 받고 있습니다.[404]

보건위생

이 주는 99.96% 이상의 사람들이 화장실을 이용할 수 있는 위생 시설 측면에서 선도적인 주 중 하나입니다.[405] 주정부는 견고한 의료 시설을 갖추고 있으며 높은 기대 수명인 74세(6위)와 98.4%의 기관 분만율(2위)과 같은 모든 건강 관련 매개 변수에서 더 높은 순위를 차지하고 있습니다.[197][406] 유엔이 설정하고 2015년까지 달성될 것으로 예상되는 밀레니엄 개발 목표의 인구 통계학적으로 관련된 세 가지 목표 중에서 타밀 나두는 2009년까지 산모 건강의 개선과 유아 사망률 및 어린이 사망률 감소와 관련된 목표를 달성했습니다.[407][408]

주의 의료 인프라에는 정부가 운영하는 병원과 개인 병원이 모두 포함됩니다. 2023년[update] 기준 주에는 404개의 공공 병원, 1,776개의 공공 진료소, 11,030개의 보건소, 481개의 이동식 유닛이 있으며 94,700개 이상의 병상을 수용할 수 있습니다.[409][410] 첸나이 종합병원은 1664년 11월 16일에 설립되었으며 인도의 첫 번째 주요 병원이었습니다.[411] 주 정부는 적격 연령대를 위해 무료 소아마비 백신을 투여합니다.[412] 타밀 나두는 의료 관광의 주요 중심지이며 첸나이는 "인도의 건강 수도"라고 불립니다.[413] 인도를 방문하는 전체 의료 관광객의 40% 이상이 타밀나두에 도착할 정도로 의료 관광은 경제의 중요한 부분을 형성하고 있습니다.[414]

의사소통

타밀나두는 해저 광섬유 케이블로 연결된 인도의 4개 주 중 하나입니다.[415][416][417] 2023년[update] 현재 바르티 에어텔, BSNL, 보다폰 아이디어, 릴라이언스 지오 등 4개 휴대폰 사업자가 4G 및 5G 모바일 서비스를 제공하는 GSM 네트워크를 운영하고 있습니다.[418][419] 유선 및 광대역 서비스는 5개 주요 사업자 및 기타 소규모 지역 사업자가 제공합니다.[419] 타밀나두는 인터넷 사용과 보급률이 높은 주 중 하나입니다.[420] 2018년 주 정부는 초고속 인터넷을 제공하기 위해 주 전역에 55,000km(34,000mi)의 광섬유를 설치할 계획을 발표했습니다.[421]

힘과 에너지

주내의 전력 분배는 첸나이에 본부를 둔 타밀나두 전기 위원회에 의해 이루어집니다.[422] 2023년[update] 기준 하루 평균 소비량은 15,000MW이며, 40%의 전력만 현지에서 생산하고 나머지 60%는 구매를 통해 충족합니다.[423] 2022년[update] 기준으로 이 주는 1인당 가용성이 1588.7Kwh로 4번째로 큰 전력 소비자입니다.[424][425] 2023년[update] 기준으로 주에서는 재생 가능한 자원의 54.6%로 38,248MW의 설치 전력 용량이 세 번째로 높습니다.[426][427] 화력발전은 10,000MW 이상을 보유한 가장 큰 기여자입니다.[426] 타밀나두는 인도 최초의 완전한 토착 원자력 발전소인 칼팍캄과 쿠단쿨람에서 두 개의 가동 중인 원자력 발전소를 보유한 유일한 주입니다. 인도에서 가장 큰 원자력 발전소이며 인도에서 생산되는 전체 원자력 발전의 거의 3분의 1을 생산합니다.[428][429][430] 타밀 나두는 세계에서 가장 큰 육상 풍력 발전소 중 하나인 팔하트 갭과 무판달의 두 지역 중 대부분을 기반으로 8,000MW 이상의 기존 풍력 발전 용량을 보유하고 있습니다.[431]

미디어

신문 발행은 1785년 주간지 마드라스 쿠리어의 창간으로 시작되었습니다.[432] 1795년 주간지 마드라스 가제트와 관보가 그 뒤를 이었습니다.[433][434] 1836년에 설립된 스펙테이터는 인도인이 소유한 최초의 영국 신문이었고 1853년에 최초의 일간 신문이 되었습니다.[435] 최초의 타밀어 신문인 스와데사미트란은 1899년에 창간되었습니다.[436][437] 주에는 타밀어, 영어, 텔루구어 등 다양한 언어로 발행되는 신문과 잡지가 많이 있습니다.[438] 하루에 1개 이상의 라크가 유통되는 주요 일간지로는 힌두교, 디나 탄티, 디나카란, 타임스 오브 인디아, 디나 말라르, 데칸 크로니클 등이 있습니다.[439] 일부 지역에 널리 퍼져 있는 여러 정기 간행물과 지역 신문도 여러 도시의 판본을 가져옵니다.[440]

정부는 1974년에 설립된 첸나이 센터에서 지상파와 위성 텔레비전 채널을 운영하고 있습니다.[441] 1993년 4월 14일 도어다르샨의 타밀어 지역 채널인 DD 포디가이가 출범했습니다.[442] 1993년에 설립된 인도 최대 방송사 중 하나인 썬 네트워크를 포함하여 30개 이상의 민간 위성 텔레비전 네트워크가 있습니다.[443] 케이블 TV 서비스는 주 정부가 전적으로 통제하는 반면 DTH와 IPTV는 다양한 민간 사업자를 통해 이용할 수 있습니다.[444][445] 라디오 방송은 1924년 Madras Presidence Radio Club에 의해 시작되었습니다.[446] 올 인디아 라디오는 1938년에 설립되었습니다.[447] 모든 인도 라디오, 헬로 FM, 수리안 FM, 라디오 미르치, 라디오 시티, BIG FM이 운영하는 많은 AM 및 FM 라디오 방송국이 있습니다.[448][449] 2006년 타밀나두 주 정부는 모든 가정에 무료 텔레비전을 배포하여 텔레비전 서비스의 보급률을 높였습니다.[450][451] 2010년대 초부터 다이렉트 투 홈은 케이블 텔레비전 서비스를 대체하여 점점 인기를 얻고 있습니다.[452] 타밀 텔레비전 시리즈는 오락의 주요 주요 주요 시간원을 형성합니다.[453]

다른이들

소방 서비스는 356개의 운영 소방서를 운영하는 타밀 나두 소방 구조 서비스가 담당합니다.[454] 우편 서비스는 주에서 11,800개 이상의 우체국을 운영하는 인도 우정이 담당합니다.[455] 최초의 우체국은 1786년 6월 1일 포트 세인트에서 설립되었습니다. 1786년 6월 1일 조지.[456]

교통.

도로

타밀나두는 2023년 기준 약 2.71 라크km에 달하는 광범위한 도로망을 보유하고 있으며, 도로 밀도는 1000km당2 2,084.71km(1,295.38마일)로 전국 평균인 1000km당2 1,926.02km(1,196.77마일)보다 높습니다.[457] 주의 고속도로 부서(HD)는 1946년 4월에 설립되었으며 주에서 국도, 주 고속도로, 주요 지방 도로 및 기타 도로의 건설 및 유지 관리를 담당합니다.[458] 120개의 사단으로 11개의 날개를 통해 운행되며 주에서 73,187km(45,476마일)의 고속도로를 유지하고 있습니다.[459][460]

| 유형 | NH | SH | MDR | ODR | OR | 총 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 길이(km) | 6,805 | 12,291 | 12,034 | 42,057 | 197,542 | 271,000 |

주에는 길이 6,805km(4,228mi)의 48개의 국도가 있으며 1971년에 설립된 타밀나두 고속도로 부서의 국가 고속도로 날개는 인도 국가 고속도로청(NHAI)이 규정한 국가 고속도로의 유지 보수를 담당합니다.[461][462] 6,805킬로미터(4,228마일) 길이의 주 고속도로가 있으며, 이 고속도로는 주의 본부, 주요 도시 및 국도를 연결합니다.[463][460] 2020년 현재 32,598대의 버스가 운행되고 있으며, 주 수송대는 20,946대의 버스와 함께 개인 버스 7,596대, 미니 버스 4,056대가 운행되고 있습니다.[464] 1947년 마드라스 대통령직을 운행하는 개인 버스가 국유화되면서 설립된 타밀나두주 교통공사(TNSTC)는 주에서 주요 대중교통 버스 운영업체입니다.[464] 시외버스 노선과 시외버스 노선을 따라 버스를 운행하고 있으며, 장거리 급행 운행을 하는 주급행교통공사(SETC) 등 8개 사업부와 시내 노선을 운영하고 있습니다.첸나이의 메트로폴리탄 교통 공사와 국영 고속 교통 공사.[464][465] 2020년 기준으로 타밀나두에는 3,210만 대의 차량이 등록되어 있습니다.[466]

레일

타밀나두의 철도 네트워크는 인도 철도 남부 철도의 일부를 구성하며, 첸나이에 본사를 두고 첸나이, 티루치라팔리, 마두라이, 살렘의 4개 부서를 두고 있습니다.[467] 2023년 기준으로 주 전체 철도 선로 길이는 5,601km(3,480mi)이며 노선 길이는 3,858km(2,397mi)입니다.[468] 주에는 532개의 기차역이 있으며 첸나이 센트럴, 첸나이 에그모어, 코임바토레 분기점, 마두라이 분기점이 최고의 수익을 올리는 역입니다.[469][470] 또한 인도 철도는 첸나이, 아락코남, 에로데, 로야푸람에 전기 기관차 창고, 에로데, 티루치라팔리, 톤디어펫에 디젤 기관차 창고, 쿠노르에 증기 기관차 창고, 다양한 정비 창고를 보유하고 있습니다.

| 노선길이(km) | 선로 길이(km) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 광궤 | 미터 게이지 | 총 | 광궤 | 미터 게이지 | 총 | ||

| 전동식 | 전기화되지 않음 | 총 | |||||

| 3,476 | 336 | 3,812 | 46 | 3,858 | 5,555 | 46 | 5,601 |

첸나이는 1928년에 설립된 212km(132mi)에 달하는 남부 철도에 의해 운영되는 잘 구축된 교외 철도 네트워크를 가지고 있습니다.[473][474] MRTS(Mass Rapid Transit System)는 1995년 첸나이 해변에서 벨라체리까지 단일 노선으로 운행되는 고가 도시 대중 교통 시스템입니다.[473][475]첸나이 메트로는 2015년에 개통된 첸나이의 고속 환승 철도 시스템으로 2023년에 54.1km(33.6mi)에 걸쳐 운행되는 두 개의 운영 노선으로 구성되어 있습니다.[476]닐기리 산악 철도는 1,000mm입니다.1908년 영국이 건설하고 인도에서 유일한 랙 철도인 닐기리스 지구의 3피트 3+3 ⁄ 8인치) 미터궤 철도.

공기와 우주

이 주의 항공 역사는 1910년 지아코모 당젤리스가 아시아 최초로 동력 비행기를 만들고 아일랜드 그라운드에서 시험 비행을 했을 때 시작되었습니다.[480] 1915년, 타타 에어 메일은 인도에서 민간 항공의 시작을 알리는 카라치와 마드라스 사이의 항공 우편 서비스를 시작했습니다.[481] 1932년 10월 15일 J.R.D. 타타는 항공 우편물을 실은 Puss Moth 항공기를 카라치에서 봄베이의 Juhu Airstrip로 운항했고 비행기는 비행사 Nevill Vintcent에 의해 Madras로 계속 운항되어 첫 번째 예정된 상업 비행을 기념했습니다.[482][483] 타밀나두에는 3개의 국제 공항, 1개의 제한된 국제 공항, 6개의 국내 또는 민간 공항이 있습니다.[484][485]

첸나이 공항은 인도에서 여객 수송으로 네 번째로 붐비는 공항으로 주요 국제 공항이자 주(州)의 주요 관문입니다.[486] 마두라이는 국제선 운항이 제한된 세관 공항인 반면, 코임바토레와 티루치라팔리가 주에 있는 다른 국제공항들입니다.[486] 국내선은 투티코린과 살렘과 같은 특정 공항으로 운항되며, 항공편은 인도 정부의 UDAN 계획에 의해 더 많은 국내 공항으로 도입될 계획입니다.[487] 이 지역은 인도 공군의 남부 공군 사령부의 관할 아래 있습니다. 공군은 술루르 주, 탐바람 주, 탄자부르 주에 세 개의 공군 기지를 운영하고 있습니다.[488] 인도 해군은 아라크코남, 우치풀리, 첸나이에서 공군기지를 운영하고 있습니다.[489][490] 2019년 인도우주연구기구(ISRO)는 투두쿠디 지역의 쿨라세카라파트남 근처에 새로운 로켓 발사대를 설치한다고 발표했습니다.[491]

물.

인도 정부의 항만, 해운, 수로부가 관리하는 첸나이, 엔노어, 투두쿠디 3개의 주요 항구가 있습니다.[492] 나가파티남에는 중간 해상 항구가 있으며, 그 외 16개의 소규모 항구는 고속도로와 타밀나두 정부의 소규모 항구가 관리하고 있습니다.[457] 타밀나두는 첸나이에 주요 기지를 두고 있는 인도 해군의 동부 해군 사령부와 남부 해군 사령부의 일부를 구성하고 있습니다.[493][494]

교육

타밀나두는 인도에서 문맹률이 가장 높은 주 중 하나로, 2017년 국가통계위원회 조사에 따르면 82.9%로 전국 평균 77.7%[192][495]보다 높은 것으로 추정됩니다. 이 주는 학교 등록을 늘리기 위해 K. K. Kamaraj에 의해 대규모로 도입된 점심 식사 계획으로 인해 1960년대 이후 가장 높은 문맹률 성장을 보였습니다.[496][497] 이 계획은 1982년 영양실조를 퇴치하기 위해 '영양 정오 식사 계획'으로 더욱 업그레이드되었습니다.[498][499] 2022년[update] 현재, 주는 95.6%로 전국 평균 79.6%[500]를 훨씬 웃도는 고등교육 등록률을 기록하고 있습니다. Pratham의 초등학교 교육에 대한 분석은 낮은 중도 탈락률을 보여주었지만 다른 특정 주에 비해 교육의 질이 좋지 않았습니다.[501]

2022년[update] 기준으로 주에는 각각 54.71 라크, 28.44 라크 및 56.9 라크 학생을 교육하는 37,211개 이상의 관립 학교, 8,403개의 관립 보조 학교, 12,631개의 사립 학교가 있습니다.[502][503] 정부 지원 학교에는 3,12,683명의 교사가 있으며 80,217명의 교사가 있으며 평균 교사-학생 비율은 1:26.6입니다.[504] 공립학교는 모두 타밀 나두 주 교육 위원회에 소속되어 있는 반면, 사립학교는 타밀 나두 주 중등 교육 위원회, 중앙 중등 교육 위원회 (CBSE) 중 하나에 소속되어 있을 수 있습니다. 인도 학교 자격증 시험 협의회(ICSE) 또는 국립 오픈 스쿨링 협회(NIOS).[505] 학교 교육은 3세 이후부터 유치원 2년 과정으로 시작하여 인도 10+2 계획, 학교 10년, 고등 중등 교육 2년 과정을 따릅니다.[506]

2023년[update] 현재 주에는 공립대학 24개, 사립대학 4개, 예비대학 28개 등 56개 대학이 있습니다.[507] 마드라스 대학교는 1857년에 설립되었으며 인도 최초의 근대 대학 중 하나입니다.[508] 주에는 34개의 정부 대학을 포함하여 510개의 공과 대학이 있습니다.[509][510] 인도 공과대학교 마드라스는 1794년에 설립된 안나 대학교(Anna University) 기디(Guindy)의 최고의 공과대학입니다.[511] 인도 육군 장교 훈련소는 첸나이에 본부를 두고 있습니다.[512] 또한 주에는 496개의 폴리테크닉 기관이 있으며 92개의 정부 대학과 935개의 예술 과학 대학이 있으며 302개의 정부 운영 대학도 포함되어 있습니다.[509][513][514] 마드라스 크리스천 칼리지 (1837), 프레지던트 칼리지 (1840), 파차이야파 칼리지 (1842)는 미국에서 가장 오래된 예술 과학 대학 중 하나입니다.[515]

주에는 전통의학 21개와 현대의학 4개를 포함하여 870개 이상의 의학, 간호 및 치과대학이 있습니다.[516] 마드라스 의과대학은 1835년에 설립되었으며 인도에서 가장 오래된 의과대학 중 하나입니다.[517] 2023년 NIRF(National Institutional Ranking Framework) 순위에 따르면, 주 출신의 26개 대학, 15개 공학, 35개 예술 과학, 8개 경영 및 8개 의과 대학이 국가 100위 안에 들었습니다.[518][519] 2023년[update] 현재 주 정부는 사회적으로 낙후된 사회를 위한 교육 기관에 69%의 유보율을 보유하고 있으며, 이는 인도의 모든 주 중 가장 높은 수치입니다.[520] 주에는 국가적으로 중요한 10개 기관이 있습니다.[521] 타밀나두농업대학, 중앙목화연구소, 사탕수수사육연구소, 산림유전학 및 나무사육연구소(IFGTB), 인도임업연구교육협의회 등의 연구소가 농업 연구에 참여하고 있습니다.[522][523][524]

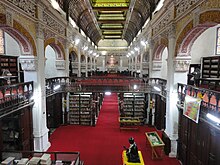

2023년[update] 현재 주에는 4622개의 공공 도서관이 있습니다.[525] 1896년에 설립된 코네마라 공공 도서관은 가장 오래된 도서관 중 하나이며 인도에서 발행되는 모든 신문과 책의 사본을 받는 인도의 4개 국립 기탁 센터 중 하나이며 안나 100주년 도서관은 아시아에서 가장 큰 도서관입니다.[526][527] 주 전역에 걸쳐 많은 연구 기관이 있습니다.[528] 첸나이 도서전은 남인도 도서 판매자 및 출판인 협회(BAPASI)가 주관하는 연례 도서전으로 일반적으로 12월에서 1월에 열립니다.[529]

관광 및 레크리에이션

다양한 문화와 건축, 다양한 지역으로 타밀나두는 강력한 관광 산업을 가지고 있습니다. 1971년 타밀나두 정부는 타밀나두 관광 개발 공사를 설립했는데, 이 공사는 주에서 관광 진흥과 관광 관련 인프라 개발을 담당하는 노드 기관입니다.[530] 관광, 문화 및 종교 기부 부서에서 관리합니다.[531] "타밀 나두를 황홀하게"라는 태그 라인이 관광 프로모션에 채택되었습니다.[532][533] 21세기에 이 주는 국내외 관광객들이 가장 많이 찾는 곳 중 하나였습니다.[533][534] 2020년[update] 현재 타밀나두는 1억 4,070만 명 이상의 관광객이 주를 방문하여 가장 많은 관광객 수를 기록했습니다.[535]

타밀나두는 1,076 킬로미터(669 마일)의 긴 해안선을 가지고 있으며 해안에는 많은 해변이 있습니다.[536] 13 km (8.1 mi)에 이르는 마리나 해변은 세계에서 두 번째로 긴 도시 해변입니다.[537] 이 주는 서부와 동부의 갓으로 둘러싸여 있기 때문에 많은 언덕 역이 있으며, 닐기리 언덕에 위치한 우다가만달람(Ooty)과 팔라니 언덕에 있는 코다이카날이 인기가 있습니다.[538][539][540] 타밀나두에는 바위를 깎아 만든 동굴 사원들이 많이 있고 여러 시기에 걸쳐 지어진 34,000개 이상의 사원들이 있는데, 그 중 일부는 수세기 전에 지어졌습니다.[541][542] 많은 강과 개울이 있는 주에는 쿠르탈람 폭포와 호게나칼 폭포를 포함한 많은 폭포가 있습니다.[543][544] 이 주의 유네스코에 의해 선언된 네 개의 세계 문화 유산은 마하발리푸람의 기념물 그룹,[545] 위대한 살아있는 촐라 사원,[37] 닐기리 산 철도,[546][547] 그리고 닐기리 생물권 보호 구역입니다.[548][549]

스포츠

카바디는 주 경기인 타밀나두 경기인 컨택트 스포츠입니다.[550][551] 프로 카바디 리그는 타밀 탈리아가 주를 대표하는 가장 인기 있는 지역 기반 프랜차이즈 토너먼트입니다.[552][553] 체스는 서기 7세기에 사투랑감으로 시작된 인기있는 보드게임입니다.[554] 첸나이는 전 세계 챔피언 비스와나탄 아난드(Viswanathan Anand)를 포함한 다수의 체스 그랜드 마스터의 본거지이며, 주에서는 2013년 세계 체스 챔피언십과 2022년 제44회 체스 올림피아드를 개최했습니다.[555][556][557][558] 팔랑구지,[559] 우리야디,[560] 길리단다,[561] 다얌과[562] 같은 전통 놀이가 지역 전역에서 열립니다. 잘리카투와 레클라는 황소들이 참여하는 전통적인 스포츠 행사입니다.[563][564] 전통 무술로는 실람바탐,[565] 가타구스티,[566] 아디무라이 등이 있습니다.[567]

크리켓은 그 주에서 가장 인기 있는 스포츠입니다.[568] 1916년에 설립된 M.A. 치담바람 경기장은 인도에서 가장 오래된 크리켓 경기장 중 하나이며 여러 ICC 크리켓 월드컵 동안 경기를 개최했습니다.[569][570][571] 1987년에 설립된 MRF 페이스 재단은 첸나이에 기반을 둔 볼링 아카데미입니다.[572] 첸나이는 가장 성공적인 인도 프리미어 리그(IPL) 크리켓 팀 첸나이 슈퍼 킹즈의 본거지이며 2011년과 2012년 시즌 동안 결승전을 개최했습니다.[573][574] 축구는 또한 인도 슈퍼리그가 주요 클럽 대항전이고 주를 대표하는 첸나이인 FC와 함께 인기가 있습니다.[575][576][577]

첸나이와 코임바토레를 포함한 주요 도시에는 축구와 육상 경기를 주최하고 배구, 농구, 카바디, 탁구를 위한 다목적 실내 시설이 있습니다.[578][579] 첸나이는 1995년 남아시아 경기를 개최했습니다.[580] 타밀 나두 하키 협회는 이 주의 하키 관리 기구이며 첸나이의 라다크리쉬난 시장은 국제 하키 대회, 2005년 남자 챔피언 트로피, 2007년 남자 아시아 컵의 개최지였습니다.[581] 마드라스 보트 클럽(1846년 설립)과 로얄 마드라스 요트 클럽(1911년 설립)은 첸나이에서 요트, 조정, 카누 스포츠를 장려하고 있습니다.[582] 1990년에 시작된 마드라스 모터 레이스 트랙은 인도 최초의 영구 경주 서킷으로 포뮬러 레이싱 이벤트를 개최합니다.[583] 코임바토레는 종종 "인도의 모터스포츠 허브"와 "인도 모터스포츠의 뒷마당"으로 불리며, 포뮬러 3 카테고리 서킷인 카리 모터 스피드웨이를 개최합니다.[584][585] 경주는 Guindy 경주장에서 열리며 주정부에는 코스모폴리탄 클럽, 짐카나 클럽, 코임바토레 골프 클럽 등 3개의 18홀 골프장이 있습니다.[586]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ a b Population and decadal change by residence (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 2. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Tamil Nadu Official Language Act, 1956". Act of 27 December 1956 (PDF). Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly. p. 1.

- ^ a b Gross State Domestic Product (Current Prices) (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Per Capita Net State Domestic Product (Current Prices) (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Zvelebil, Kamil V. (1973). The smile of Murugan: on Tamil literature of South India. Leiden: Brill. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-3-4470-1582-0.

- ^ "Science News : Archaeology – Anthropology : Sharp stones found in India signal surprisingly early toolmaking advances". 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "The Washington Post : Very old, very sophisticated tools found in India. The question is: Who made them?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Skeletons dating back 3,800 years throw light on evolution". The Times of India. 1 January 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ T, Saravanan (22 February 2018). "How a recent archaeological discovery throws light on the history of Tamil script". Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "the eternal harappan script". Open magazine. 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Shekar, Anjana (21 August 2020). "Keezhadi sixth phase: What do the findings so far tell us?". The News Minute. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "A rare inscription". The Hindu. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ "Artifacts unearthed at Keeladi to find a special place in museum". The Hindu. 19 February 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Jesudasan, Dennis S. (20 September 2019). "Keezhadi excavations: Sangam era older than previously thought, finds study". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Dr. Anjali (2017). Social and Cultural History of Ancient India. Lucknow: OnlineGatha—The Endless Tale. pp. 123–136. ISBN 978-93-86352-69-9.

- ^ "Three Crowned Kings of Tamilakam". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education. p. 425. ISBN 978-8-1317-1120-0.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil (1991). "Comments on the Tolkappiyam Theory of Literature". Archiv Orientální. 59: 345–359.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil (1973). The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. Brill. p. 51. ISBN 90-04-03591-5. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "The Edicts of King Ashoka". Colorado State University. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni

- ^ Neelakanta Sastri, K.A. (1955). A History of South India: From Prehistoric Times To the Fall of Vijayanagar. Oxford. pp. 125–127. ISBN 978-0-1956-0686-7.

- ^ "The Medieval Spice Trade and the Diffusion of the Chile". Gastronomica. 7. 26 October 2021.

- ^ Chakrabarty, D.K. (2010). The Geopolitical Orbits of Ancient India: The Geographical Frames of the Ancient Indian Dynasties. Oxford. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-1990-8832-4.

- ^ T.V. Mahalingam (1981). Proceedings of the Second Annual Conference. South Indian History Congress. pp. 28–34.

- ^ S. Sundararajan. Ancient Tamil Country: Its Social and Economic Structure. Navrang, 1991. p. 233.

- ^ Iḷacai Cuppiramaṇiyapiḷḷai Muttucāmi (1994). Tamil Culture as Revealed in Tirukkural. Makkal Ilakkia Publications. p. 137.

- ^ Gopalan, Subramania (1979). The Social Philosophy of Tirukkural. Affiliated East-West Press. p. 53.

- ^ Sastri, K.A. Nilakanta (2002) [1955]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-19-560686-7.

- ^ Francis, Emmanuel (28 October 2021). "Pallavas". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History: 1–4. doi:10.1002/9781119399919.eahaa00499. ISBN 9781119399919. S2CID 240189630.

- ^ a b "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "Pandya dynasty". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Jouveau-Dubreuil, Gabriel (1995). "The Pallavas". Asian Educational Services: 83.

- ^ Biddulph, Charles Hubert (1964). Coins of the Cholas. Numismatic Society of India. p. 34.

- ^ John Man (1999). Atlas of the year 1000. Harvard University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-6745-4187-0.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education. p. 590. ISBN 978-8-1317-1120-0.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2003) [2002]. The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. New Delhi: Penguin Books. pp. 364–365. ISBN 978-0-1430-2989-2.

- ^ a b "Great Living Chola Temples". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Aiyangar, Sakkottai Krishnaswami (1921). South India and her Muhammadan Invaders. Chennai: Oxford University Press. p. 44.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 458. ISBN 9788122411980.

- ^ "Meenakshi Amman Temple". Britannica. 30 November 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot (2001). Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra. Oxford University Press. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-1980-3123-9.

- ^ Gilmartin, David; Lawrence, Bruce B. (2000). Beyond Turk and Hindu: Rethinking Religious Identities in Islamicate South Asia. University Press of Florida. pp. 300–306, 321–322. ISBN 978-0-8130-3099-9.

- ^ Srivastava, Kanhaiya L (1980). The position of Hindus under the Delhi Sultanate, 1206–1526. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 202. ISBN 978-8-1215-0224-5.

- ^ "Rama Raya (1484–1565): élite mobility in a Persianized world". A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761. 2005. pp. 78–104. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521254847.006. ISBN 978-0-5212-5484-7.

- ^ Eugene F. Irschick (1969). Politics and Social Conflict in South India. University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-5200-0596-9.

- ^ Balendu Sekaram, Kandavalli (1975). The Nayaks of Madurai. Hyderabad: Andhra Pradesh Sahithya Akademi. OCLC 4910527.

- ^ Bayly, Susan (2004). Saints, Goddesses and Kings: Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700–1900 (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-52189-103-5.

- ^ Naravane, M.S. (2014). Battles of the Honourable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. pp. 151, 154–158. ISBN 978-8-1313-0034-3.

- ^ Ramaswami, N. S. (1984). Political history of Carnatic under the Nawabs. Abhinav Publications. pp. 43–79. ISBN 978-0-8364-1262-8.

- ^ Tony Jaques (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O. Greenwood. pp. 1034–1035. ISBN 978-0-313-33538-9.

- ^ Subramanian, K. R. (1928). The Maratha Rajas of Tanjore. Madras: K. R. Subramanian. pp. 52–53.

- ^ Bhosle, Pratap Sinh Serfoji Raje (2017). Contributions of Thanjavur Maratha Kings. Notion press. ISBN 978-1-9482-3095-7.

- ^ "Rhythms of the Portuguese presence in the Bay of Bengal". Indian Institute of Asian Studies. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Origin of the Name Madras". Corporation of Madras. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "Danish flavour". Frontline. India. 6 November 2009. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Rao, Velcheru Narayana; Shulman, David; Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1998). Symbols of substance : court and state in Nayaka period Tamilnadu. Oxford : Oxford University Press, Delhi. p. xix, 349 p., [16] p. of plates : ill., maps ; 22 cm. ISBN 0-19-564399-2.

- ^ Thilakavathy, M.; Maya, R. K. (5 June 2019). Facets of Contemporary history. MJP Publisher. p. 583.

- ^ Frykenberg, Robert Eric (26 June 2008). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-1982-6377-7.

- ^ Roberts J. M. (1997). A short history of the world. Helicon publishing Ltd. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-1951-1504-8.

- ^ Wagret, Paul (1977). Nagel's encyclopedia-guide. India, Nepal. Geneva: Nagel Publishers. p. 556. ISBN 978-2-8263-0023-6. OCLC 4202160.

- ^ "Seven Years' War: Battle of Wandiwash". History Net: Where History Comes Alive – World & US History Online. 21 August 2006. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ S., Muthiah (21 November 2010). "Madras Miscellany: When Pondy was wasted". The Hindu. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). A global chronology of conflict. ABC—CLIO. p. 756. ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1.

- ^ "Velu Nachiyar, India's Joan of Arc" (Press release). Government of India. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ Yang, Anand A (2007). "Bandits and Kings:Moral Authority and Resistance in Early Colonial India". The Journal of Asian Studies. 66 (4): 881–896. doi:10.1017/S0021911807001234. JSTOR 20203235.

- ^ Caldwell, Robert (1881). A Political and General History of the District of Tinnevelly, in the Presidency of Madras. Government Press. pp. 195–222.

- ^ Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of Modern India:1707 A.D. to 2000 A.D. Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 94. ISBN 978-8-1269-0085-5.

- ^ "Madras Presidency". Britannica. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Naravane, M. S. (2014). Battles of the Honourable East India Company: Making of the Raj. New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. pp. 172–181. ISBN 978-81-313-0034-3.

- ^ "July, 1806 Vellore". Outlook. 17 July 2006. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Pletcher, Kenneth. "Vellore Mutiny". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Adcock, C.S. (2013). The Limits of Tolerance: Indian Secularism and the Politics of Religious Freedom. Oxford University Press. pp. 23–25. ISBN 978-0-1999-9543-1.

- ^ Kolappan, B. (22 August 2013). "The great famine of Madras and the men who made it". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Sitaramayya, Pattabhi (1935). The History of the Indian National Congress. Working Committee of the Congress.

- ^ Bevir, Mark (2003). "Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress". International Journal of Hindu Studies. University of California. 7 (1–3): 14–18. doi:10.1007/s11407-003-0005-4. S2CID 54542458.

Theosophical Society provided the framework for action within which some of its Indian and British members worked to form the Indian National Congress.

- ^ "Subramania Bharati: The poet and the patriot". The Hindu. 9 December 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "An inspiring saga of the Tamil diaspora's contribution to India's freedom struggle". The Hindu. 7 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Andhra State Act, 1953". Act of 14 September 1953 (PDF). Madras Legislative Assembly. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "States Reorganisation Act, 1956". Act of 14 September 1953 (PDF). Parliament of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Tracing the demand to rename Madras State as Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. 6 July 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Sundari, S. (2007). Migrant women and urban labour market: concepts and case studies. Deep & Deep Publications. p. 105. ISBN 9788176299664. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ V. Shoba (14 August 2011). "Chennai says it in Hindi". The Indian Express. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Krishna, K.L. (September 2004). "Economic Growth in Indian States" (PDF). ICRIER. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Demography of Tamil Nadu (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Patrick, David (1907). Chambers's Concise Gazetteer of the World. W.& R.Chambers. p. 353.

- ^ "Adam's bridge". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Map of Sri Lanka with Palk Strait and Palk Bay" (PDF). UN. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Kanyakumari alias Cape Comorin". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Myers, Norman; Mittermeier, Russell A.; Mittermeier, Cristina G.; Da Fonseca, Gustavo A. B.; Kent, Jennifer (2000). "Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities". Nature. 403 (6772): 853–858. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..853M. doi:10.1038/35002501. PMID 10706275. S2CID 4414279. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ Playne, Somerset; Bond, J. W; Wright, Arnold (2004). Southern India: its history, people, commerce, and industrial resources. Asian Educational Service. p. 417. OCLC 58540809. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Eastern Ghats". Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ DellaSala, Dominick A.; Goldstei, Michael I. (2020). Encyclopedia of the World's Biomes. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-1281-6097-8.

- ^ Eagan, J. S. C (1916). The Nilgiri Guide And Directory. Chennai: S.P.C.K. Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-1494-8220-9.

- ^ Bose, Mihir (1977). Indian Journal of Earth Sciences. Indian Journal of Earth Sciences. p. 21.

- ^ "Eastern Deccan Plateau Moist Forests". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- ^ Dr. Jadoan, Atar Singh (September 2001). Military Geography of South-East Asia. India: Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-8-1261-1008-7.

- ^ "Centre for Coastal Zone Management and Coastal Shelter Belt". Institute for Ocean Management, Anna University Chennai. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Jenkins, Martin (1988). Coral Reefs of the World: Indian Ocean, Red Sea and Gulf. United Nations Environment Programme. p. 84.

- ^ The Indian Ocean Tsunami and its Environmental Impacts (Report). Global Development Research Center. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Amateur Seismic Centre, Pune". Asc-india.org. 30 March 2007. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Chu, Jennifer (11 December 2014). "What really killed the dinosaurs?". MIT. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ "Deccan Plateau". Britannica. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Strategic plan, Tamil Nadu perspective (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 20. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ McKnight, Tom L; Hess, Darrel (2000). "Climate Zones and Types: The Köppen System". Physical Geography: A Landscape Appreciation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 205–211. ISBN 978-0-1302-0263-5.

- ^ "Farmers Guide, introduction". Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "India's heatwave tragedy". BBC News. 17 May 2002. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Caviedes, C. N. (18 September 2001). El Niño in History: Storming Through the Ages (1st ed.). University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-2099-0.

- ^ World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2005.

- ^ "South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 5 January 2005.

- ^ "North East Monsoon". IMD. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Rohli, Robert V.; Vega, Anthony J. (2007). Climatology. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-7637-3828-0.

- ^ Annual frequency of cyclonic disturbances over the Bay of Bengal (BOB), Arabian Sea (AS) and land surface of India (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "The only difference between a hurricane, a cyclone, and a typhoon is the location where the storm occurs". NOAA. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Assessment of Recent Droughts in Tamil Nadu (Report). Water Technology Centre, Indian Agricultural Research Institute. October 1995. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Strategic plan, Tamil Nadu perspective (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 3. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Forest Wildlife resources". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ South Western Ghats montane rain forests (PDF) (Report). Ecological Restoration Alliance. Retrieved 15 April 2006.

- ^ "Western Ghats". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Forests of Tamil Nadu". ENVIS. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Biodiversity, Tamil Nadu Dept. of Forests (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Biosphere Reserves in India (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ Sacratees, J.; Karthigarani, R. (2008). Environment impact assessment. APH Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-8-1313-0407-5.

- ^ "Conservation and Sustainable-use of the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve's Coastal Biodiversity". Global Environment Facility. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Baker, H.R.; Inglis, Chas. M. (1930). The birds of southern India, including Madras, Malabar, Travancore, Cochin, Coorg and Mysore. Chennai: Superintendent, Government Press.

- ^ Grimmett, Richard; Inskipp, Tim (30 November 2005). Birds of Southern India. A&C Black.

- ^ "Pichavaram". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Top 5 Largest Mangrove and Swamp Forest in India". Walk through India. 7 January 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Bio-Diversity and Wild Life in Tamil Nadu". ENVIS. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu's 18th wildlife sanctuary to come up in Erode". The New Indian Express. 21 March 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ Panwar, H. S. (1987). Project Tiger: The reserves, the tigers, and their future. Noyes Publications, Park Ridge, N.J. pp. 110–117. ISBN 978-0-8155-1133-5.

- ^ "Project Elephant Status". Times of India. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ "Eight New Tiger Reserves". Press Release. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Press Information Bureau, Govt. of India. 13 November 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ^ Kumar, B. Aravind (6 February 2021). "Srivilliputhur–Megamalai Tiger Reserve in TN approved". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Migratory birds flock to Vettangudi Sanctuary". The Hindu. 9 November 2004. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Kazhuveli wetland in Tamil Nadu declared bird sanctuary". Indian Express. 7 December 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Guindy Children's Park upgraded to medium zoo". The New Indian Express. 28 July 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Grizzled Squirrel Wildlife Sanctuary". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Singh, M.; Lindburg, D.G.; Udhayan, A.; Kumar, M.A.; Kumara, H.N. (1999). Status survey of slender loris Loris tardigradus lydekkerianus. Oryx. pp. 31–37.

- ^ Kottur, Samad (2012). Daroji-an ecological destination. Drongo. ISBN 978-9-3508-7269-7.

- ^ "Nilgiri tahr population over 3,000: WWF-India". The Hindu. 3 October 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Malviya, M.; Srivastav, A.; Nigam, P.; Tyagi, P.C. (2011). "Indian National Studbook of Nilgiri Langur (Trachypithecus johnii)" (PDF). Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun and Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Singh, M.; Kumar, A.; Kumara, H.N. (2020). "Macaca silenus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T12559A17951402. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12559A17951402.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Stein, A.B.; Athreya, V.; Gerngross, P.; Balme, G.; Henschel, P.; Karanth, U.; Miquelle, D.; Rostro-Garcia, S.; Kamler, J.F.; Laguardia, A.; Khorozyan, I.; Ghoddousi, A. (2020). "Panthera pardus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T15954A163991139. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T15954A163991139.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "State Symbols of India". Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change, Government of India. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Symbols of Tamil Nadu". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "R. N. Ravi is new Governor of Tamil Nadu". The Times of India. 11 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "MK Stalin sworn in as Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ "Justice SV Gangapurwala sworn in as Chief Justice of Madras HC". The News Minute. 28 May 2023. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu". Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "List of Departments". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "Government units, Tamil Nadu". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Local Government". Government of India. p. 1. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Statistical year book of India (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 1. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Town panchayats". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Durga Das Basu (1960). Introduction to the Constitution of India. LexisNexis Butterworths. p. 241,245. ISBN 978-81-8038-559-9.

- ^ "Indian Councils Act". Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Indian Councils Act, 1909". Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "History of state legislature". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Little hope for revival of Tamil Nadu's legislative council". Times of India. 2 August 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "History of fort". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Term of houses". Election Commission of India. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "History of Madras High Court". Madras High Court. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "History of Madras High Court, Madurai bench". Madras High Court. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu Police-history". Tamil Nadu Police. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Tamil Nadu Police-Policy document 2023-24 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. p. 3. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu Police-Organizational structure". Tamil Nadu Police. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ a b Tamil Nadu Police-Policy document 2023-24 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. p. 5. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Rukmini S. (19 August 2015). "Women police personnel face bias, says report". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu, women in police". Women police India. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Police Ranking 2022 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 12. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ The Tamil Nadu Town and Country Planning Act, 1971 (Tamil Nadu Act 35 of 1972) (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Crime in India 2019 - Statistics Volume 1 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Setup of Election Commission of India". Election Commission of India. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Ralhan, O.P. (2002). Encyclopedia of Political Parties. Print House. pp. 180–199. ISBN 978-8-1748-8287-5.

- ^ Irschick, Eugene F. (1969). Political and Social Conflict in South India; The non-Brahmin movement and Tamil Separatism, 1916–1929. University of California Press. OCLC 249254802.

- ^ "75 years of carrying the legacy of Periyar". The Hindu. 26 August 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "Chief Ministers of Tamil Nadu since 1920". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 164. ASIN B003DXXMC4.

- ^ Marican, Y. "Genesis of DMK" (PDF). Asian Studies: 1.

- ^ The Madras Legislative Assembly, 1962-67, A Review (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "A look at the events leading up to the birth of AIADMK". The Hindu. 21 October 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Wyatt, A.K.J. (2002). "New Alignments in South Indian Politics: The 2001 Assembly Elections in Tamil Nadu". Asian Survey. University of California Press. 42 (5): 733–753. doi:10.1525/as.2002.42.5.733. hdl:1983/1811.

- ^ "Jayalalithaa vs Janaki: The last succession battle". The Hindu. 10 February 2017. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Guha, Ramachandra (15 April 2006). "Why Amartya Sen should become the next president of India". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Hazarika, Sanjoy (17 July 1987). "India's Mild New President: Ramaswamy Venkataraman". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Ramana, M. V.; Reddy, C., Rammanohar (2003). Prisoners of the Nuclear Dream. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan. p. 169. ISBN 978-8-1250-2477-4.

- ^ Decadal variation in population 1901-2011, Tamil Nadu (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Population projection report 2011-36 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 56. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Sex Ratio, 2011 census" (Press release). 21 August 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Fifth National Family Health Survey-Update on Child Sex Ratio" (Press release). Government of India. 17 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ State wise literacy rate (Report). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Household Social Consumption on Education in India (PDF) (Report). Government of India. 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Census highlights, 2011 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ SC/ST population in Tamil Nadu 2011 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Population projection report 2011-36 (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 25. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Sub-national HDI – Area Database (Report). Global Data Lab. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Life expectancy 2019 (Report). Global Data Lab. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Multidimensional Poverty Index (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 35. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ a b Urban Agglomerations and Cities having population 1 lakh and above (PDF). Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011 (Report). Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ a b Population by religion community – 2011 (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "The magic of melting pot called Chennai". The Hindu. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "A different mirror". The Hindu. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "'Telugu Speaking People in TN are Not Aliens'". New Indian Express. 18 March 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "From Rajasthan with love". New Indian Express. 6 November 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Go Gujrati this navratri". New Indian Express. 20 October 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "The Parsis of Madras". Madras Musings. XVIII (12). 15 October 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Sindhis to usher in new year with fanfare". The Times of India. 24 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Why Oriyas find Chennai warm and hospitable". The Times of India. 12 May 2012. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Chennai's Kannadigas not complaining". The Times of India. 5 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 June 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "The Anglo-Indians of Chennai". Madras Musings. XX (12). 15 October 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "A slice of Bengal in Chennai". The Times of India. 22 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ B.R., Madhu (16 September 2009). "The Punjabis of Chennai". Madras Musings. XX (12). Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Chennai Malayalee Club leads Onam 2023 celebrations". Media India. 1 September 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "When Madras welcomed them". Deccan Chronicle. 27 August 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Deepavali, the expat edition". New Indian Express. 24 October 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Migration of Labour in the Country" (Press release). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b Census India Catalog (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Tamil language". Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Smirnitskaya, Anna (March 2019). "Diglossia and Tamil varieties in Chennai". Acta Linguistica Petropolitana (3): 318–334. doi:10.30842/alp2306573714317. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Several dialects of Tamil". Inkl. 31 October 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Southworth, Franklin C. (2005). Linguistic archaeology of South Asia. Routledge. p. 129-132. ISBN 978-0-415-33323-8.

- ^ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge University Press. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-521-77111-5.

- ^ Akundi, Sweta (18 October 2018). "K and the city: Why are more and more Chennaiites learning Korean?". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020.

- ^ "Konnichiwa!". The Hindu. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ a b "How many tongues can you speak?". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020.

- ^ Akundi, Sweta (25 October 2018). "How Mandarin has become crucial in Chennai". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Guten Morgen! Chennaiites signing up for German lessons on the rise". The Times of India. 14 May 2018. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020.

- ^ "LGBT community in Tamil Nadu seeks state government's support". Indian Express. 15 December 2013. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Hamid, Zubeda (3 February 2016). "LGBT community in city sees sign of hope". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ The Case of Tamil Nadu Transgender Welfare Board: Insights for Developing Practical Models of Social Protection Programmes for Transgender People in India (Report). United Nations. 27 May 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Menon, Priya (3 July 2021). "A decade of Pride in Chennai". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Muzaffar, Maroosha. "Indian state set to be the first to ban conversion therapy of LGBT+ individuals". Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "1st in India & Asia, and 2nd globally, Tamil Nadu bans sex-selective surgeries for infants". The Print. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu Becomes First State to Ban So‑Called Corrective Surgery on Intersex Babies". The Swaddle. 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Transgenders have marriage rights says Madras High Court". leaflet. 23 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Boulanger, Chantal (1997). Saris: An Illustrated Guide to the Indian Art of Draping. New York: Shakti Press International. ISBN 0-9661496-1-0.

- ^ Lynton, Linda (1995). The Sari. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-8109-4461-9.

- ^ Parthasarathy, R. (1993). The Tale of an Anklet: An Epic of South India – The Cilappatikaram of Ilanko Atikal, Translations from the Asian Classics. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-2310-7849-8.

- ^ C. Monahan, Susanne; Andrew Mirola, William; O. Emerson, Michael (2001). Sociology of Religion. Prentice Hall. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-1302-5380-4.

- ^ "About Dhoti". Britannica. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Clothing in India". Britannica. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Weaving through the threads". The Hindu. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ a b Geographical indications of India (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "31 ethnic Indian products given". Financial Express. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ "Food Balance Sheets and Crops Primary Equivalent". FAO. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ Czarra, Fred (2009). Spices: A Global History. Reaktion Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-8618-9426-7.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (2002). Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-5202-3674-5.

- ^ Molina, A.B.; Roa, V.N.; Van den Bergh, I.; Maghuyop, M.A. (2000). Advancing banana and plantain R & D in Asia and the Pacific. Biodiversity International. p. 84. ISBN 978-9-7191-7513-1.

- ^ Kalman, Bobbie (2009). India: The Culture. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7787-9287-1.

- ^ "Serving on a banana leaf". ISCKON. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "The Benefits of Eating Food on Banana Leaves". India Times. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Achaya, K.T. (1 November 2003). The Story of Our Food. Universities Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-8-1737-1293-7.

- ^ 즈벨빌 1973, p. 12: "...지금까지 타밀어 문자의 발전을 위해 제안된 가장 수용 가능한 시기는 치담바라나타 체티아르 (1907–1967)의 시기인 것 같습니다. 상암 문학 – 기원전 200년에서 기원후 200년; 2. 포스트 상암 문학 – AD 200 – AD 600; 3. 중세 초기 문학 – AD 600년에서 AD 1200년; 4. 후기 중세 문학 – AD 1200년에서 AD 1800년; 5. 근대 이전의 문학 – AD 1800~1900"

- ^ Abraham, S. A. (2003). "Chera, Chola, Pandya: Using Archaeological Evidence to Identify the Tamil Kingdoms of Early Historic South India" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 42 (2): 207. doi:10.1353/asi.2003.0031. hdl:10125/17189. S2CID 153420843. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Ramaswamy, Vijaya (1993). "Women and Farm Work in Tamil Folk Songs". Social Scientist. 21 (9/11): 113–129. doi:10.2307/3520429. JSTOR 3520429.

As early as the Tolkappiyam (which has sections ranging from the 3rd century BCE to the 5th century CE) the eco-types in South India have been classified into

- ^ Maloney, C. (1970). "The Beginnings of Civilization in South India". The Journal of Asian Studies. 29 (3): 603–616. doi:10.2307/2943246. JSTOR 2943246. S2CID 162291987.

- ^ Stein, B. (1977). "Circulation and the Historical Geography of Tamil Country". The Journal of Asian Studies. 37 (1): 7–26. doi:10.2307/2053325. JSTOR 2053325. S2CID 144599197.

- ^ "Five fold grammar of Tamil". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Pillai, M. S. (1994). Tamil literature. New Delhi: Asian Education Service. ISBN 978-8-120-60955-6.

- ^ Pillai, P. Govinda (4 October 2022). "Chapter 11". The Bhakti Movement: Renaissance or Revivalism?. Taylor & Francis. pp. Thirdly, the movement had blossomed first down south or the Tamil country. ISBN 978-1-000-78039-0.

- ^ Padmaja, T. (2002). Temples of Kr̥ṣṇa in South India: History, Art, and Traditions in Tamil nāḍu. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-398-4.

- ^ Nair, Rukmini Bhaya; de Souza, Peter Ronald (2020). Keywords for India: A Conceptual Lexicon for the 21st Century. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-03925-4.

- ^ P S Sundaram (3 May 2002). Kamba Ramayana. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-9-351-18100-2.

- ^ Bergunder, Michael; Frese, Heiko; Schröder, Ulrike (2011). Ritual, Caste, and Religion in Colonial South India. Primus Books. p. 107. ISBN 978-9-380-60721-4.

- ^ Karthik Madhavan (21 June 2010). "Tamil saw its first book in 1578". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Kolappan, B. (22 June 2014). "Delay, howlers in Tamil Lexicon embarrass scholars". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Karen Prechilis (1999). The embodiment of bhakti. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-195-12813-0.

- ^ Arooran, K. Nambi (1980). Tamil Renaissance and the Dravidian Movement, 1905-1944. Koodal.

- ^ "Bharathiyar Who Impressed Bharatidasan". Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies. ISSN 1305-578X. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Harman, William P. (9 October 1992). The sacred marriage of a Hindu goddess. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 6. ISBN 978-8-1208-0810-2.

- ^ Fergusson, James (1997) [1910]. History of Indian and Eastern Architecture (3rd ed.). New Delhi: Low Price Publications. p. 309.

- ^ Ching, Francis D.K.; et al. (2007). A Global History of Architecture. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-4712-6892-5.

- ^ Ching, Francis D.K. (1995). A Visual Dictionary of Architecture. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-4712-8451-2.

- ^ Mitchell, George (1988). The Hindu Temple. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 151–153. ISBN 978-0-2265-3230-1.

- ^ "Gopuram". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ "Which Tamil Nadu temple is the state emblem?". Times of India. 7 November 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ S.R. Balasubrahmanyam (1975), Middle Chola Temples, Thomson Press, pp. 16–29, ISBN 978-9-0602-3607-9