클로자핀

Clozapine | |

| |

| 임상자료 | |

|---|---|

| 상호 | 클로자릴, 레포넥스, 베르사클로즈[1] 등 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| 메드라인플러스 | a691001 |

| 라이센스 데이터 | |

| 임신 카테고리 |

|

| 의 경로 행정부. | 입으로 근육 주사로 |

| 약품반 | 전형적 항정신병 |

| ATC코드 | |

| 법적지위 | |

| 법적지위 | |

| 약동학적 자료 | |

| 생체이용률 | 60~70% |

| 신진대사 | 간, 여러 CYP 동종효소에 의해 |

| 제거 반감기 | 4~26시간(정상상태에서 mean값 14.2시간) |

| 배설 | 대사 상태 80%: 담도 30%, 신장 50% |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| 펍켐 CID | |

| IUPAR/BPS | |

| 드럭뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니아이 | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| CHEMBL | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA) | |

| ECHA 인포카드 | 100.024.831 |

| 화학물질 및 물리적 데이터 | |

| 공식 | C18H19클N4 |

| 어금니 질량 | 326.83 g·mol−1 |

| 3D 모델(Jsmol) | |

| 융점 | 183 °C (361 °F) |

| 물에 대한 용해도 | 0.1889[5] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

클로자핀은 처음으로 발견된 비정형 항정신병 약물입니다. 다른 항정신병 약물에 대한 반응이 부적절하거나 추체외 부작용으로 다른 약물을 견딜 수 없었던 조현병 진단을 받은 사람들에게 정제나 액상 형태로 주로 사용됩니다. 파킨슨병의 정신병 치료에도 사용됩니다. 미국에서는 조현병이나 정신분열증과 관련된 자살 행위가 반복되는 환자에게도 사용할 수 있도록 허가되어 있습니다.[6] 다른 약물의 효과가 불충분하여 여러 국제 치료 지침에서 사용을 권장하는 경우 금본위제 치료법으로 간주됩니다.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13] 다른 항정신병 약물 치료제에 비해 클로자핀을 시작하고 유지하는 것은 복잡하고 비용이 많이 들고 시간이 많이 소요됩니다.[6][14][15] 치료 저항성 조현병에서 클로자핀의 역할은 Clozaril Collaborative Study Group Study #30에 의해 확립되었습니다. 클로자핀은 정신병증이 오래 지속되고 이미 다른 항정신병약에 부적절한 반응을 보인 환자 그룹에서 클로로프로마진에 비해 현저한 이점을 보였습니다.[16] 다양한 부작용이 있으며 대부분의 선진국에서 강제적인 혈액 모니터링이 필요합니다.[17][18] 심각한 부작용이 있지만 클로자핀은 하나 이상의 다른 항정신병 약물이 부적절한 반응을 보일 때 가장 효과적인 치료법으로 남아 있으며 클로자핀 사용은 모든 원인 사망률, 자살 및 입원 감소를 포함한 여러 개선된 결과와 관련이 있습니다.[19][20][21][22] 네트워크 비교 메타 분석에서 15가지 항정신병 약물 클로자핀은 다른 모든 약물보다 훨씬 더 효과적이었습니다.[23] 환자 만족도에 대한 설문조사는 다른 항정신병약보다 선호도를 보여줍니다.[24]

다른 항정신병약에 비해 치료 첫 18주 동안 무과립구증의 위험이 증가합니다. 1년 후에는 대부분의 다른 항정신병약에서 발견되는 위험보다 감소하기 때문에 다른 두 항정신병약에 반응하지 않고 엄격한 혈액 모니터링을 통해서만 사용할 수 있습니다. 사용되는 정확한 빈도와 혈구 수 임계값은 국가마다 다릅니다.[25][6][17] 클로자핀도 호중구감소증을 유발할 수 있다고 가정되었지만, 이것은 가장 좋은 증거에 의해 뒷받침되지 않습니다.[26] 수십 년 동안 시행되어 온 엄격한 위험 모니터링 및 관리 시스템으로 인해 이러한 합병증으로 인한 사망자는 7700명 중 1명꼴로 매우 드물었습니다.[27] 치료 저항성 조현병에 효과적일 가능성이 있는 유일한 치료법으로 남아 있습니다.[28]

일반적인 부작용으로는 [29]동요, 무월경, 부정맥, 변비, 어지러움, 졸림, 구강건조증, 발기부전, 피로, 갈락토레아, 자궁근종, 고혈당증, 고프로락티나혈증, 과식증, 저혈압, 불면증, 백혈구감소증, 운동장애, 근육경직증, 호중구감소증, 파킨슨증, 자세 저혈압(용량 관련), QT 간격 연장, 발진, 발작, 떨림, 요폐, 구토, 체중 증가.[30] 흔하지 않은 부작용으로는 무과립구증, 혼란, 색전증 및 혈전증, 신경성 악성 증후군이 있습니다.[30] 클로자핀은 일반적으로 지각 운동 장애(TD)와 관련이 없지만 일부 사례 보고서에서는 클로자핀 유발 TD에 대해 설명하고 있으며 이것이 존재할 때 선택 약물로 권장됩니다. 그 외 심각한 위험으로는 발작, 심장의 염증, 높은 혈당 수치, 클로자핀에 의한 위저운동성 증후군으로 인한 변비 등이 있는데, 이는 심하면 장폐색과 사망으로 이어질 수 있으며, 치매로 인한 정신병이 있는 노인의 경우 사망 위험이 증가합니다. 클로자핀의 작용 메커니즘은 완전히 명확하지 않습니다.

그것은 세계 보건 기구의 필수 의약품 목록에 올라 있습니다. 일반 의약품으로 제공됩니다.

역사

클로자핀은 1958년 스위스 제약회사인 Wander AG가 삼환계 항우울제 이미프라민의 화학구조를 바탕으로 합성했습니다.[31][32] 1962년 인간을 대상으로 한 최초의 실험은 실패로 여겨졌습니다. 1965년과 1966년 독일에서의 재판과 1966년 빈에서의 재판은 성공적이었습니다. 1967년 Wander AG는 Sandoz에 인수되었습니다.[31] 1972년 스위스와 오스트리아에서 클로자핀이 레포넥스로 출시되면서 추가 실험이 이루어졌습니다.[31] 2년 후 1975년에 서독과 핀란드에서 출시되었습니다.[31] 비슷한 시기에 미국에서도 초기 검사가 이루어졌습니다.[31] 1975년, 주로 핀란드 남서부에 있는 6개 병원에서 보고된 클로자핀 치료 환자에서 8명의 사망으로 이어진 16건의 무과립구증 사례가 우려로 이어졌습니다.[33] 핀란드 사례를 분석한 결과 모든 무과립구증 사례가 치료 후 첫 18주 이내에 발생했으며 저자들은 이 기간 동안 혈액 모니터링을 제안했습니다.[34] 핀란드의 무과립구증 발병률은 세계 다른 지역보다 20배나 높은 것으로 나타났으며 이는 이 지역의 독특한 유전적 변이 때문일 수 있다는 추측이 있었습니다.[35][36][37] 이 약이 산도즈에 의해 계속 제조되고 유럽에서 사용 가능한 동안 미국에서의 개발은 중단되었습니다.

클로자핀에 대한 관심은 1980년대에도, 특히 치료 저항성 조현병 환자들을 위한 주립 병원의 입원 기간을 며칠이 아닌 몇 년으로 측정하는 경우가 많았기 때문에, 미국에서 조사 역량에 대한 관심이 계속되었습니다.[31] 치료 저항성 조현병에서 클로자핀의 역할은 랜드마크인 Clozaril Collaborative Study Group Study #30에 의해 확립되었습니다. 클로자핀은 장기 정신병 환자 그룹에서 클로로프로마진에 비해 현저한 이점을 보였고 이미 다른 항정신병약에 대해 부적절한 반응을 보였습니다. 여기에는 엄격한 혈액 모니터링과 표준 항정신병 치료보다 우수성을 입증하는 힘이 있는 이중 블라인드 설계가 모두 포함되었습니다. 포함 기준은 이전 항정신병 약물에 최소 3회 이상 반응하지 않은 환자였으며, 그 후 할로페리돌(평균 용량 61 mg +/- 14 mg/d)로 한 번의 블라인드 치료에도 반응하지 않은 환자였습니다. 클로자핀(최대 900mg/d) 또는 클로르프로마진(최대 1800mg/d)의 이중 블라인드 테스트를 위해 무작위로 28개가 추출되었습니다. 클로자핀 환자의 30%가 대조군의 4%에 비해 반응을 보였으며, 입원 평가를 위한 간단한 정신과 등급 척도, 임상 글로벌 인상 척도 및 간호사 관찰 척도가 크게 개선되었으며, 이러한 개선에는 "음성"뿐만 아니라 긍정적인 증상 영역도 포함되었습니다.[16] 이 연구에 따라 미국 식품의약국(FDA)은 1990년에 사용을 승인했습니다. 그러나 FDA는 이러한 위험을 경계하여 무과립구증을 포함한 특정 부작용에 대해 블랙박스 경고를 요구했으며, 혈구 수치를 체계적으로 평가할 수 있도록 환자를 공식적인 추적 시스템에 등록하도록 하는 독특한 조치를 취했습니다.[37][38]

2002년 12월, 클로자핀은 자살 행동의 만성 위험이 있다고 판단되는 조현병 또는 정신분열증 환자의 자살 위험을 감소시키는 것으로 미국에서 승인되었습니다.[39] 2005년 FDA는 혈액 모니터링 빈도 감소를 허용하는 기준을 승인했습니다.[40] 2015년 FDA의 요청에 의해 개별 제조업체인 Patient Registrys가 The Clozapine REMS Registry라는 단일 공유 환자 Registry로 통합되었습니다.[41] 호중구 수치가 낮고 총 백혈구 수를 포함하지 않는 새로운 FDA 모니터링 요구사항의 안전성이 입증되었음에도 불구하고 국제 모니터링은 표준화되지 않았습니다.[42][43][44]

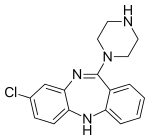

화학

클로자핀은 구조적으로 록사핀과 매우 유사한 디벤조디아제핀(원래 전형적인 항정신병제로 간주됨)입니다. 물에 약간 녹고 아세톤에 녹고 클로로포름에 잘 녹습니다. 물에 대한 용해도는 0.1889mg/L(25°C)입니다.[5] 제조업체인 Novartis는 물에 대한 용해도가 <0.01%(<100mg/L)라고 주장합니다.[45]

임상적 용도

조현병

치료 저항성 정신분열증에서 클로자핀의 역할은 1988년 랜드마크인 멀티센터 이중 맹검[46] 연구에 의해 확립되었습니다. 클로자핀(최대 900mg/d)은 이미 최소 3개의 이전에 부적절한 반응을 보인 장기 정신병 환자 그룹에서 클로자핀(최대 1800mg/d)과 비교하여 현저한 이점을 보였습니다. haloperidol에 대한 이전의 단일 맹검 시험을 포함한 항정신병 약물 (6주 동안 mean 61+/- 14 mg/d). 심각한 부작용이 있지만 클로자핀은 하나 이상의 다른 항정신병 약물이 부적절한 반응을 보일 때 가장 효과적인 치료법으로 남아 있습니다. 클로자핀의 사용은 모든 원인에 의한 사망률, 자살 및 입원률 감소를 포함한 여러 가지 개선된 결과와 관련이 있습니다.[47][19][20] 2013년 15가지 항정신병 약물에 대한 네트워크 비교 메타 분석에서 클로자핀은 다른 모든 약물보다 훨씬 더 효과적인 것으로 나타났습니다.[48] 2021년 영국 연구에서 클로자핀을 복용한 환자의 대부분(응답자의 85% 이상)이 이전 치료법보다 클로자핀을 선호했고, 더 나은 기분을 느꼈고, 계속 복용하기를 원했습니다.[49] 환자 130명을 대상으로 한 2000년 캐나다 조사에서 대다수는 더 나은 만족도, 삶의 질, 치료 순응도, 사고, 기분, 경계심을 보고했습니다.[50][unreliable medical source?]

클로자핀은 다른 항정신병약에 부적절한 반응을 보이거나 추체외로 인한 부작용으로 다른 약물을 견딜 수 없었던 조현병 진단을 받은 사람들에게 주로 사용됩니다. 파킨슨병의 정신병 치료에도 사용됩니다.[51][52] 체계적인 검토와 메타 분석을 통해 뒷받침되는 여러 국제 치료 지침에 의해 다른 약물의 효과가 불충분하고 사용이 권장되는 경우 금본위제 치료법으로 간주됩니다.[7][8][9][10][11][12][53][54] 현재의 모든 지침은 다른 두 가지 항정신병약이 이미 시도된 사람들을 위해 클로자핀을 예약하고 있지만, 클로자핀이 대신 2차 약물로 사용될 수 있다는 증거가 있습니다.[55] 클로자핀 치료는 입원 위험 감소, 약물 중단 위험 감소, 전반적인 증상 감소 및 정신 분열증의 긍정적인 증상 치료에 대한 효과 향상을 포함한 여러 영역에서 개선된 결과를 나타내는 것으로 입증되었습니다.[19][20][21][22] 다양한 부작용에도 불구하고 환자들은 좋은 수준의 만족도를 보고하고 다른 항정신병약에 비해 장기적인 순응도가 좋습니다.[56] 매우 장기적인 추적 연구는 사망률 감소 측면에서 여러 가지 이점을 보여주는데,[47][57] 특히 자살로 인한 사망 감소에 대한 효과가 강하며, 클로자핀은 자살 또는 자살 시도의 위험을 감소시키는 효과가 있는 것으로 알려진 유일한 항정신병제입니다.[58] 클로자핀은 상당한 항응고 효과가 있습니다.[59][60][61][62][63] 클로자핀은 공격성의 개선, 단축된 입원 및 은둔과 같은 제한적인 관행의 감소가 발견된 안전하고 법의학적인 정신 건강 환경에서 널리 사용됩니다.[64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72] 안전한 병원 및 기타 환경에서 클로자핀은 폭력 또는 자해와 관련된 경우 경계선 및 반사회적 인격 장애 치료에도 사용되었습니다.[73][74][59] 경구 치료는 거의 보편적이지만, 보고된 약 100건의 사례 중 약 50%의 환자가 강압적인 개입을 사용하기 전에 경구 약물을 복용하는 것에 동의했지만 간혹 비위 또는 단작용 주사를 사용하여 클로자핀을 시행했습니다.[65][75][67][76][77][78][69][79][68][80] 클로자핀은 또한 80% 이상의 사례에서 성공적으로 카탈로니아를 치료하기 위해 라벨 외로 사용되었습니다.[81]

조울증

일부 치료 지침에서는 체계적인 검토를 바탕으로 클로자핀을 양극성 장애의 제3선 또는 제4선 치료로 권장하고 있습니다.[82][83][84][85] 양극성 장애는 클로자핀의 라벨 외 표시입니다.[citation needed]

중증인격장애

클로자핀은 정서적으로 불안정한 성격 장애에도 사용되며 현재 무작위 대조 시험이 진행 중입니다.[86][87][88][89][74][90][91][73][92] 성격 장애를 치료하기 위해 클로자핀을 사용하는 것은 흔하지 않고 허가를 받지 않습니다.

개시

클로자핀은 일반적으로 병원 환경에서 시작되지만 커뮤니티 시작도 가능합니다.[93][94] 클로자핀을 시작하기 전에 여러 평가를 수행하고 기준선 조사를 수행합니다. 영국과 아일랜드에서는 환자가 처방 기준을 충족한다는 평가가 있어야 합니다. 치료 저항성 조현병, 다른 항정신병약의 추체외로 인한 불내증 또는 파킨슨병의 정신병입니다. 치료 저항력을 확립하는 것은 이전 항정신병 치료의 기간, 용량 및 준수 여부와 적절한 임상적 효과가 없었음을 포함한 약물 이력에 대한 신중한 검토를 포함할 수 있습니다. 진단 검토도 수행할 수 있습니다. 사용 가능한 경우 항정신병 혈장 농도에 대한 검토가 포함될 수 있습니다. 처방전자, 환자, 약국 및 혈액 계수를 수행하는 실험실은 모두 특정 클로자핀 제공업체에 등록되어 있으며, 이 업체는 어떤 원인으로 인한 호중구 감소증의 병력이 없음을 알려주어야 합니다. 클로자핀 공급자들은 클로자핀 관련 호중구감소증이나 무과립구증에 걸린 환자들에 대한 정보를 공유함으로써 클로자핀을 면허증으로 다시 사용할 수 없도록 협력합니다. 클로자핀은 위험 모니터링 기관에서 만족스러운 혈액 결과를 받은 후에만 조제할 수 있으며, 이때 개별 처방전은 개별 환자에게만 발매될 수 있습니다.[95]

기준 검사에는 일반적으로 기준 체중, 허리 둘레 및 BMI, 신장 기능 및 간 기능 평가, 심전도 및 기타 기준 혈액을 포함한 신체 검사를 수행하여 가능한 심근염 모니터링을 용이하게 할 수 있으며, 여기에는 C 반응성 단백질(CRP) 및 트로포닌이 포함될 수 있습니다. 호주와 뉴질랜드에서는 클로자핀 전 심초음파 검사도 흔히 시행합니다.[96] 여러 가지 서비스 프로토콜을 사용할 수 있으며 클로자핀 전 워크업의 범위에 차이가 있습니다. 일부는 공복 지질, HbA1c 및 프로락틴을 포함할 수도 있습니다. 영국 Maudsley Hospital의 Treat service는 또한 MRI 뇌영상, 갑상선 기능 검사, B12, 엽산 및 혈청 칼슘 수치를 포함한 다른 정신병 및 동반 질환의 원인에 대한 여러 조사를 포함한 다양한 조사를 정기적으로 수행합니다. B형 및 C형 간염, HIV 및 매독을 포함하는 혈액 매개 바이러스에 대한 감염 스크리닝 및 항-NMDA, 항-VGKC 및 항-핵 항체 스크리닝에 의한 자가면역 정신병에 대한 스크리닝. 기저 트로포닌, CRP 및 BNP 및 신경성 악성 증후군 CK를 포함하여 심근염과 같은 클로자핀 관련 부작용의 가능성을 모니터링하는 데 사용되는 조사도 수행됩니다.[94]

클로자핀의 용량은 처음에는 적고 몇 주에 걸쳐 점차 증가합니다. 초기 선량은 일반적으로 단계적으로 증가하는 6.5~12.5mg/d 범위에서 반응 평가가 수행되는 일일 250~350mg 범위의 선량에 이르기까지 다양할 수 있습니다.[96] 영국에서는 평균 클로자핀 용량이 450mg/d입니다.[97][98] 그러나 반응은 매우 다양하며 일부 환자는 훨씬 낮은 용량으로 반응하고 그 반대의 경우도 있습니다.

모니터링

초기 선량 적정 단계에서는 일반적으로 다음을 모니터링합니다. 일반적으로 처음에는 매일 맥박, 혈압 및 기립성 저혈압이 문제가 될 수 있으므로 앉거나 서 있을 때 모두 모니터링해야 합니다. 현저한 감소가 있는 경우 선량 증가 속도가 느려질 수 있습니다(온도).[94]

주간 검사는 다음을 포함합니다. 의무적인 전혈 수는 처음 18주 동안 매주 수행됩니다. 정확한 검사와 빈도는 서비스마다 다르지만 일부 서비스에서는 심근염을 나타낼 수 있는 표지자(트로포닌, CRP 및 BNP)에 대한 모니터링도 수행됩니다. 몸무게는 보통 매주 측정됩니다.

그 외의 조사 및 모니터링에는 항상 전체 혈액 수(1년간 야간 및 매월)가 포함됩니다. 체중, 허리둘레, 지질 및 포도당 또는 HbA1c를 모니터링할 수도 있습니다.

클로자핀 반응 및 치료 최적화

다른 항정신병약과 마찬가지로, 그리고 지혜를 받은 것과는 대조적으로 클로자핀에 대한 반응은 일반적으로 개시 직후, 그리고 종종 첫 주 이내에 나타납니다.[99][100] 그렇기는 하지만, 특히 부분적인 응답은 지연될 수 있습니다.[101] 클로자핀에 대한 적절한 시험이 무엇인지는 불확실하지만 권장 사항은 350-400 마이크로그램/L 이상의 혈장 수조 수준에서 적어도 8주 동안 사용해야 한다는 것입니다.[102][103] 개인 간 편차가 상당히 큽니다. 상당수의 환자들이 더 낮거나 훨씬 더 높은 혈장 농도에서 반응하며, 일부 환자들, 특히 젊은 남성 흡연자들은 하루 900 mg의 용량에서도 이러한 혈장 수준에 도달하지 못할 수 있습니다. 그런 다음 허가된 최대치 이상으로 용량을 늘리거나 클로자핀 대사를 억제하는 약물을 추가하는 방법이 있습니다. 불필요한 다약제를 피하는 것이 약물 치료의 일반적인 원칙입니다.

혈액 샘플링 최적화

클로자핀을 위해 절단된 호중구는 호중구 감소증과 무과립구증의 위험을 완화하는 탁월한 능력을 보여주었습니다. 안전에 상당한 여유가 있습니다. 일부 환자는 시작 전후에 한계 호중구 수가 있을 수 있으며 조기 클로자핀 중단의 위험이 있습니다. 호중구 생물학에 대한 지식은 혈액 샘플링 최적화를 가능하게 합니다. 호중구는 G-CSF 생성의 자연적인 주기에 반응하여 일주성 변이를 보이고, 오후에 증가하며, 운동과 흡연 후에 순환에 동원되기도 합니다. 단순히 혈액 샘플링을 이동하는 것은 특히 흑인 집단에서 불필요한 중단을 피할 수 있는 것으로 나타났습니다. 그러나 이것은 일반적인 병원 관행에 방해가 됩니다. 다른 실용적인 단계는 혈액 결과를 몇 시간 안에 그리고 상급자가 언제 이용할 수 있는지 확인하는 것입니다.[66]

클로자핀의 사용 부족

Clozapine is widely recognised as being underused with wide variation in prescribing,[104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111] especially in patients with African heritage.[112][113][114][115][116]

정신과 의사가 처방하는 관행이 사용의 차이와 관련하여 가장 중요한 변수인 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[citation needed] 클로자핀에 대한 정신과 의사들의 태도를 조사한 결과, 많은 사람들이 클로자핀의 사용 경험이 거의 없고, 발생률을 과대평가했으며, 부작용을 두려워했으며, 많은 환자들이 다른 항정신병약보다 클로자핀 복용을 선호하고, 클로자핀 처방을 꺼린다는 사실을 인정하지 않았습니다. 클로자핀으로 치료받은 환자들은 다른 항정신병약으로 치료받은 환자들에 비해 만족도가 낮다고 믿었습니다.[117][118][119] 많은 정신과 의사들의 기대와는 달리, 대부분의 환자들은 혈액 검사와 다른 어려움들이 그들이 인식하는 여러 이점의 가치가 있다고 믿습니다.[49][50] 정신과 의사들은 무과립구증과 같은 심각한 부작용을 두려워하는 반면, 환자들은 과침투에 대해 더 우려합니다.[120] 클로자핀은 더 이상 적극적으로 판매되지 않으며 이것은 또한 클로자핀의 남용에 대한 설명 중 하나일 수 있습니다.[121]

국내외 치료 지침과 환자 자신의 경험에 의해 강력한 증거와 보편적인 지지를 받고 있음에도 불구하고 클로자핀을 사용할 수 있는 대부분의 사람들은 클로자핀을 사용하지 않습니다.[49] 영국의 한 대규모 연구는 클로자핀을 투여받을 수 있는 사람들 중 약 30%가 클로자핀을 투여받고 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.[122] 클로자핀을 시작하는 환자들은 일반적으로 장기간의 지연, 여러 번의 정신병과 고용량 항정신병약제 또는 다약제와 같은 치료에 직면합니다. 이전의 두 가지 항정신병약 대신에 많은 사람들이 효과가 없는 열 가지 이상의 약에 노출되었을 것입니다. 런던 남동부의 4개 병원에서 120명의 환자를 대상으로 한 연구에서 클로자핀이 시작되기 전 평균 9.2회의 항정신병 처방이 있었고 클로자핀 사용의 평균 지연은 5년이었습니다.[123] 근거가 없거나 적극적으로 유해한 것으로 간주되는 치료제는 대신 다중 및 고용량 치료제를 사용합니다.[124]

클로자핀 사용의 인종적 차이

의료 서비스의 일반적인 발견은 소수 집단이 열등한 대우를 받는다는 것입니다. 이것은 미국에서 특히 발견된 것입니다.[125][126][127][128] 미국에서 일반적인 발견은 백인 동료들에 비해 아프리카계 미국인들이 2세대 항정신병 약물을 처방받을 가능성이 낮다는 것입니다. 이는 대안보다 비용이 더 많이 들고 특히 클로자핀의 경우 보훈의료체계에서 비교가 이루어졌을 때와 사회경제적 요인에 대한 차이를 고려했을 때 더욱 분명했습니다.[113][114][129] 클로자핀을 시작할 가능성이 낮을 뿐만 아니라 흑인 환자는 클로자핀을 중단할 가능성이 더 높습니다. 양성 민족성 호중구감소증 때문일 수도 있습니다.

양성 민족성 호중구감소증

호중구의 양성 감소는 모든 민족적 배경의 호중구 감소(BEN)에서 관찰되며, 면역 기능 장애가 없는 호중구 감소 또는 감염에 대한 증가된 책임은 비정상적인 호중구 생산으로 인한 것이 아닙니다. 그러나 순환 세포 감소의 정확한 병인은 아직 알려지지 않았습니다. BEN은 여러 민족과 관련이 있지만 특히 흑인 및 서아프리카 혈통을 가진 민족과 관련이 있습니다.[130] 클로자핀 사용의 어려움은 호중구 수가 백인 집단에 대해 표준화되었다는 것입니다.[131] 상당한 수의 흑인 환자의 경우 표준 호중구 수 임계값은 BEN을 고려하지 않았기 때문에 클로자핀 사용을 허용하지 않았습니다. 2002년부터 영국의 clozapine monitoring service는 혈액학적으로 확인된 BEN 환자에 대해 0.5 × 109/l 더 낮은 기준 범위를 사용하고 있으며, 허용 최소치는 더 낮지만 현재 미국 기준에서 유사한 조정이 가능합니다.[71][43][132] 그러나 낮은 호중구 수가 질병을 반영하지 않음에도 불구하고 상당한 수의 흑인 환자는 자격이 없습니다. 일부 종류의 말라리아로부터 보호하는 Duffy-Null 다형성은 BEN을 예측합니다.[133]

역기능

클로자핀은 심각하고 잠재적으로 치명적인 부작용을 일으킬 수 있습니다. 클로자핀은 (1) 중증 호중구 감소증(저수준의 호중구), (2) 기립성 저혈압(위치를 바꿀 때 저혈압), (3) 발작, (4) 심근염(심장의 염증), 그리고 (5) 치매 관련 정신병 노인에게 사용될 경우 사망의 위험.[4] 발작 임계치를 낮추는 것은 선량과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다. 용량을 천천히 늘리면 발작과 기립성 저혈압의 위험이 감소할 수 있습니다.[134]

일반적인 효과로는 변비, 침 흘림, 야간 침 흘림, 근육 경직, 진정, 떨림, 기립성 저혈압, 고혈당, 체중 증가 등이 있습니다. 지각 장애와 같은 추체외 증상이 발생할 위험은 일반적인 항정신병 약물보다 낮으며, 이는 클로자핀의 항콜린 작용 때문일 수 있습니다. 사람이 다른 항정신병제에서 클로자핀으로 전환한 후 추체외로 증상이 다소 가라앉을 수 있습니다.[134] 클로자핀을 복용하면서 역행성 사정 등 성적인 문제가 보고된 바 있습니다.[4] 드문 부작용으로는 안와부종이 있습니다.[135] 수많은 부작용의 위험에도 불구하고 클로자핀을 계속 복용하면서 많은 부작용을 관리할 수 있습니다.[136]

호중구감소증 및 무과립구증

다른 항정신병약에 비해 클로자핀은 치료 첫 18주 동안 혈액 이상증, 특히 무과립구증의 위험이 증가합니다. 1년 후, 이 위험은 대부분의 항정신병 약물과 관련된 위험으로 감소합니다. 따라서 클로자핀의 사용은 보통 최소한 두 가지 다른 항정신병 약물에 반응하지 않은 사람들을 위한 것이며 엄격한 혈액 모니터링만으로 이루어집니다.[51] 전반적으로 혈액 및 기타 부작용에 대한 우려에도 불구하고 클로자핀 사용은 특히 조현병 환자의 조기 사망의 주요 원인인 자살로 인한 사망률 감소와 관련이 있습니다.[137] 클로자핀 관련 무과립구증 및 호중구감소증의 위험은 엄격한 위험 모니터링 및 관리 시스템의 의무적인 사용을 보장하고 이러한 부작용으로 인한 사망 위험을 7,700명 중 1명 정도로 낮췄습니다.[138] 클로자핀 사용과 특정 혈액 이상증 사이의 연관성은 1970년대 핀란드에서 무과립구증으로 인한 사망자가 8명 발견되었을 때 처음 언급되었습니다.[35] 당시에는 이것이 다른 항정신병약에서도 발견되는 이 부작용의 확립된 비율을 초과하는지 명확하지 않았고, 약물이 완전히 회수되지는 않았지만 사용이 제한되었습니다.[31]

클로자핀 유도성 호중구감소증(CIN)은 사례의 약 3.8%에서, 클로자핀 유도성 무과립구증(CIA)은 0.4%[139]에서 발생합니다. 이것들은 잠재적으로 심각한 부작용이며 무과립구증은 사망을 초래할 수 있습니다. 이러한 위험을 완화하기 위해 클로자핀은 필수 절대 호중구 수(ANC) 모니터링(중성구는 과립구 중 가장 풍부함)에만 사용됩니다. 예를 들어 미국에서는 위험 평가 및 완화 전략(REMS)이 있습니다.[140] 정확한 일정과 혈구 수 역치는 국제적으로[43] 다르고 미국에서 클로자핀을 사용할 수 있는 역치는 영국과 호주에서 현재 사용되는 역치보다 한동안 낮았습니다.[141] 사용된 위험 관리 전략의 효과는 이러한 부작용으로 인한 사망이 7700명의 환자 중 약 1명에서 발생하는 경우가 매우 드물다는 것입니다.[138] 거의 모든 혈액 이상 반응은 치료 후 첫 1년 이내에 발생하고 대부분은 첫 18주 이내에 발생합니다.[139] 1년 치료 후 이러한 위험은 다른 항정신병 약물에서 볼 수 있는 위험의 0.01% 또는 10,000분의 1 정도로 현저하게 감소하며 사망 위험은 여전히 현저하게 낮습니다.[138] 정기적인 혈액 모니터링에서 호중구 수치의 감소가 관찰되면 값에 따라 모니터링이 증가하거나 호중구 수치가 충분히 낮으면 클로자핀을 즉시 중단하고 더 이상 의약품 허가 내에서 사용할 수 없습니다. 클로자핀을 중단하면 거의 항상 호중구 감소가 해결됩니다.[139][138] 그러나 심각한 무과립구증은 자연 감염과 사망을 초래할 수 있지만, 과립구라고 불리는 특정한 종류의 백혈구의 양이 심각하게 감소하는 것입니다. 클로자핀은 약물 유발 무과립구증에 대한 블랙박스 경고를 전달합니다. 신속한 현장 검사는 무과립구증에 대한 모니터링을 단순화할 수 있습니다.[142]

클로자핀 재도전

클로자핀 "재도전"은 클로자핀을 복용하던 중 무과립구증을 경험한 사람이 다시 약을 복용하기 시작하는 것입니다. 호중구 역치가 미국에서 사용되는 것보다 높은 국가에서는 가장 낮은 ANC가 미국보다 차단된 경우 클로자핀을 다시 도입하는 것이 간단한 접근법입니다. 이것은 런던의 한 병원의 대규모 환자 집단에서 입증되었는데, 미국 기준에 따라 클로자핀을 중단한 115명의 환자 중 7명만이 미국의 차단제를 사용했다면 클로자핀을 중단했을 것이라는 사실이 밝혀졌습니다. 이 62명 중 59명은 클로자핀을 무리 없이 계속 사용했고 1명만이 미국 이하의 호중구가 잘려 나갔습니다.[44] 다른 접근법에는 리튬 또는 과립구 집락 자극 인자(G-CSF)를 포함한 호중구 수를 지원하기 위한 다른 약물의 사용이 포함되었습니다. 그러나 재도전 중 무과립구증이 여전히 발생하는 경우 대체 옵션이 제한됩니다.[143][144]

심장독성

클로자핀은 심근염과 심근병증을 거의 일으킬 수 없습니다. 250,000명 이상의 사람들에 대한 클로자핀 노출에 대한 대규모 메타 분석에 따르면 이들은 치료받은 환자 1000명 중 약 7명에서 발생했으며 노출된 환자 10,000명 중 3명과 4명에서 각각 사망했으며 심근염은 치료 후 첫 8주 이내에 거의 독점적으로 발생했지만 심근병증은 훨씬 나중에 발생할 수 있습니다.[145] 질병의 첫 증상은 상기도, 위장관 또는 요로 감염과 관련된 증상을 동반할 수 있는 발열입니다. 일반적으로 C-반응성 단백질(CRP)은 발열과 함께 증가하고 심장 효소인 트로포닌의 상승은 최대 5일 후에 발생합니다. 모니터링 지침은 클로자핀 시작 후 처음 4주 동안 기준선과 매주 CRP와 트로포닌을 확인하고 환자의 질병 징후와 증상을 관찰할 것을 권고합니다.[146] 심부전의 징후는 덜 흔하며 트로포닌의 증가와 함께 발생할 수 있습니다. 최근 환자-대조군 연구에 따르면 클로자핀 용량 적정 속도가 증가함에 따라 클로자핀에 의한 심근염의 위험이 증가하고 연령이 증가하며 발프로산나트륨이 동반됩니다.[147] 대규모 전자건강등록부 연구를 통해 클로자핀 관련 심근염 의심 사례의 90% 가까이가 위양성이라는 사실이 밝혀졌습니다.[148] 클로자핀 유발 심근염 후 재도전이 수행되었으며 이러한 전문가 접근법에 대한 프로토콜이 발표되었습니다.[149] 심근염 후 재도전에 대한 체계적인 검토는 보고된 사례의 60% 이상에서 성공을 보여주었습니다.[150]

위장저운동

인지되지 않고 잠재적으로 생명을 위협할 수 있는 또 다른 효과 스펙트럼은 위장 저운동성으로, 심각한 변비, 대변 충격, 마비성 장폐색, 급성 거대 결장, 허혈 또는 괴사로 나타날 수 있습니다.[151] 방사선 불투과성 표지자를 이용하여 위장 기능을 객관적으로 측정했을 때 클로자핀을 처방받은 사람의 최대 80%에서 대장 저운동이 발생하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[152] Clozapine에 의한 위장관 저운동성은 현재 더 잘 알려진 무과립구증의 부작용보다 사망률이 더 높습니다.[153] 코크란 리뷰는 클로자핀과 다른 항정신병 약물로 인한 위장 저운동에 대한 최선의 치료법에 대한 결정을 안내하는 데 도움이 되는 증거를 거의 발견하지 못했습니다.[154] 장 기능을 모니터링하고 모든 클로자핀 치료를 받은 사람들에게 완하제를 선제적으로 사용하는 것은 대장 통과 시간을 개선하고 심각한 후유증을 줄이는 것으로 나타났습니다.[155]

초침투

클로자핀의 가장 일반적인 부작용 중 하나는 침의 과도한 생성, 즉 과염증입니다(30-80%).[156] 수면이 움직이지 않으면 하루 종일 발생하는 삼킴으로써 침의 정상적인 청소가 불가능하기 때문에 침의 생성은 밤과 아침에 특히 번거롭습니다.[156] 클로자핀은 M1, M2, M 및3 M5 수용체에서 무스카린 길항제인 반면 클로자핀은 M 하위4 집합에서 완전 작용제입니다. M은4 타액선에서 고도로 발현되기 때문에 Magonist4 활성이 과염을 일으키는 것으로 생각됩니다.[157] 클로자핀에 의한 과민반응은 용량과 관련된 현상일 가능성이 높고, 처음 약을 시작할 때 더 심해지는 경향이 있습니다.[156] 용량을 줄이거나 초기 용량 적정을 늦추는 것 외에도 효신,[158] 디펜히드라민과[156] 같은 전신적으로 흡수된 항콜린제와 이프라트로피움 브로마이드와 같은 국소적 항콜린제가 몇 가지 이점을 보여주는 다른 개입이 있습니다.[159] 가벼운 과염은 밤에 베개 위에 수건을 덮고 자는 것으로 관리할 수 있습니다.[159]

중추신경계

CNS side effects include drowsiness, vertigo, headache, tremor, syncope, sleep disturbances, nightmares, restlessness, akinesia, agitation, seizures, rigidity, akathisia, confusion, fatigue, insomnia, hyperkinesia, weakness, lethargy, ataxia, slurred speech, depression, myoclonic jerks, and anxiety. 거의 볼 수 없는 것은 망상, 환각, 섬망, 기억상실, 성욕 증감, 편집증과 과민성, 비정상적인 뇌파, 정신증의 악화, 감각이상, 상태 간질, 강박 증상 등입니다. 다른 항정신병약 클로자핀과 유사하게 신경성 악성 증후군을 유발하는 것은 거의 알려져 있지 않습니다.[160]

요실금

클로자핀은 요실금과 관련이 있지만,[161] 그 모습은 과소 인식될 수 있습니다.[162] 이 부작용은 베타네콜로 수정될 수 있습니다.[163]

인출효과

갑작스러운 금단은 소화불량, 설사, 메스꺼움/통증, 과도한 타액, 과도한 땀 흘림, 불면증, 동요와 같은 콜린성 반동 효과를 유발할 수 있습니다.[164] 갑작스러운 금단은 심각한 운동 장애, 카타토니아, 정신병을 유발할 수도 있습니다.[165] 의사들은 환자와 가족, 간병인들에게 클로자핀의 갑작스러운 금단 증상과 위험성을 인식시킬 것을 권고했습니다. 클로자핀을 중단할 때는 금단 효과의 강도를 줄이기 위해 점진적인 용량 감량이 권장됩니다.[166][167]

체중증가와 당뇨

고혈당 외에도 클로자핀으로 치료받은 환자들은 상당한 체중 증가를 자주 경험합니다.[168] 포도당 대사 장애와 비만은 대사증후군의 구성 요소로 밝혀졌으며 심혈관 질환의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있습니다. 이 데이터는 클로자핀이 다른 비정형 항정신병 약물들보다 대사적으로 나쁜 영향을 미칠 가능성이 더 높다는 것을 암시합니다.[169] 클로자핀 때문에 체중이 증가하는 사람들의 경우 메트포르민을 복용하면 대사증후군의 5가지 구성 요소 중 허리둘레, 공복 포도당, 공복 중성지방의 3가지가 개선될 수 있다고 합니다.[170]

폐렴

국제 부작용 데이터베이스에 따르면 클로자핀 사용은 폐렴의 발병률 및 사망률의 현저한 증가와 관련이 있으며 이는 가장 중요한 부작용 중 하나일 수 있습니다.[171] 염증 해결에 대한 클로자핀 효과의 면역 효과 또는 과염과 관련이 있을 것으로 추측되었지만 이에 대한 메커니즘은 알려져 있지 않습니다.[172][173]

과다 복용

이 구간은 확장이 필요합니다. 추가하여 도움을 드릴 수 있습니다. (2019년 8월) |

과다복용의 증상은 다양할 수 있지만 종종 진정, 혼란, 빈맥, 발작 및 운동실조를 포함합니다. 클로자핀 과다복용으로 인한 사망자가 보고되었지만, 5000 mg 이상의 과다복용이 생존했습니다.[174][175]

약물 상호작용

플루복사민은 클로자핀의 대사를 억제하여 클로자핀의 혈중 농도를 크게 증가시킵니다.[176]

carbamazepine을 clozapine과 동시에 사용할 경우 clozapine의 혈장 수준을 크게 감소시켜 clozapine의 유익한 효과를 감소시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[177][178] 환자는 "카바마제핀이 시작되거나 증가하는 경우 클로자핀의 치료 효과 감소"를 모니터링해야 합니다. carbamazepine을 중단하거나 carbamazepine의 용량을 줄이면 clozapine의 치료 효과를 모니터링해야 합니다. 이 연구는 무과립구증의 위험이 증가하기 때문에 카르바마제핀을 클로자핀과 동시에 사용하지 말 것을 권장합니다.[179]

시프로플록사신은 CYP1A2의 억제제이고 클로자핀은 주요 CYP1A2 기질입니다. 무작위 연구는 시프로플록사신을 동시에 복용하는 피험자의 클로자핀 농도 상승을 보고했습니다.[180] 따라서 클로자핀 처방 정보는 시프로플록사신과 다른 CYP1A2 억제제를 치료에 추가할 때 "클로자핀의 용량을 원래 용량의 3분의 1로 줄인다"고 권장하지만, 시프로플록사신이 치료에서 제거되면 클로자핀을 원래 용량으로 되돌리는 것이 좋습니다.[181]

약리학

약력학

| 단백질 | CZP Ki()nM | NDMC Ki()nM |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 123.7 | 13.9 |

| 5-HT1B | 519 | 406.8 |

| 5-HT1D | 1,356 | 476.2 |

| 5-HT2A | 5.35 | 10.9 |

| 5-HT2B | 8.37 | 2.8 |

| 5-HT2C | 9.44 | 11.9 |

| 5-HT3 | 241 | 272.2 |

| 5-HT5A | 3,857 | 350.6 |

| 5-HT6 | 13.49 | 11.6 |

| 5-HT7 | 17.95 | 60.1 |

| α1A | 1.62 | 104.8 |

| α1B | 7 | 85.2 |

| α2A | 37 | 137.6 |

| α2B | 26.5 | 95.1 |

| α2C | 6 | 117.7 |

| β1 | 5,000 | 6,239 |

| β2 | 1,650 | 4,725 |

| 라1 | 266.25 | 14.3 |

| 라2 | 157 | 101.4 |

| 라3 | 269.08 | 193.5 |

| 라4 | 26.36 | 63.94 |

| 라5 | 255.33 | 283.6 |

| 아1 | 1.13 | 3.4 |

| 아2 | 153 | 345.1 |

| 아3 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 아4 | 665 | 1,028 |

| M1 | 6.17 | 67.6 |

| M2 | 36.67 | 414.5 |

| M3 | 19.25 | 95.7 |

| M4 | 15.33 | 169.9 |

| M5 | 15.5 | 35.4 |

| SERT | 1,624 | 316.6 |

| NET | 3,168 | 493.9 |

| DAT | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 값이 작을수록 약물이 해당 부위에 강하게 결합합니다. 모든 데이터는 복제된 인간 단백질에 대한 것입니다.[182][183] | ||

클로자핀은 도파민 수용체뿐만 아니라 세로토닌과 결합하기 때문에 비정형 항정신병 약물로 분류됩니다.[184] 두 수용체 모두에서 길항제 역할을 합니다.

Clozapine은 세로토닌 수용체의2A 5-HT 아형에서 길항제로, 우울증, 불안 및 조현병과 관련된 부정적인 인지 증상을 개선하는 것으로 추정됩니다.[185][186]

클로자핀과 GABAB 수용체의 직접적인 상호작용도 나타냈습니다.[187] GABAB 수용체가 결핍된 마우스는 세포외 도파민 수치가 증가하고 조현병 동물 모델에서와 동일한 운동 행동 변화를 보입니다.[188] GABAB 수용체 작용제와 양성 알로스테릭 조절제는 이러한 모델의 운동 변화를 감소시킵니다.[189]

클로자핀은 성상세포에서 NMDA 수용체의 글리신 부위에 작용제인 글루타메이트와 D-세린의 방출을 유도하고 [190]성상세포 글루타메이트 수송체의 발현을 감소시킵니다. 이것들은 뉴런을 포함하지 않는 성상세포 세포 배양에도 존재하는 직접적인 효과입니다. 클로자핀은 NMDA 수용체 길항제로 인한 NMDA 수용체 발현 장애를 예방합니다.[191]

약동학

클로자핀은 경구 투여 후 흡수가 거의 완료되지만 1차 통과 대사로 인해 경구 생체 이용률은 60~70%에 불과합니다. 경구 투여 후 농도가 최고조에 이르는 시간은 약 2.5시간이며, 음식물은 클로자핀의 생체 이용률에 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 보입니다. 그러나 음식을 병용 투여하면 흡수 속도가 감소하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[192] 클로자핀의 제거 반감기는 정상 상태 조건(일 복용량에 따라 다름)에서 약 14시간입니다.[medical citation needed]

클로자핀은 시토크롬 P450 시스템을 통해 소변과 대변에서 제거에 적합한 극성 대사산물로 간에서 광범위하게 대사됩니다. 주요 대사산물인 노르클로자핀(desmethyl-clozapine)은 약리학적으로 활성입니다. 시토크롬 P450 동종효소 1A2는 주로 클로자핀 대사를 담당하지만 2C, 2D6, 2E1 및 3A3/4도 역할을 하는 것으로 보입니다. CYP1A2를 유도(예: 담배 연기)하거나 억제(예: 테오필린, 시프로플록사신, 플루복사민)하는 약제는 각각 클로자핀의 대사를 증가시키거나 감소시킬 수 있습니다. 예를 들어 흡연으로 인한 신진대사 유도는 흡연자가 비흡연자에 비해 최대 2배의 클로자핀을 투여해야 동등한 혈장 농도를 얻을 수 있음을 의미합니다.[193]

클로자핀과 노르클로자핀(desmethyl-clozapine) 혈장 수치도 모니터링할 수 있지만 상당한 정도의 변이를 보이고 여성에서 더 높고 나이가 들수록 증가합니다.[194] 클로자핀과 노르클로자핀의 혈장 수준을 모니터링하는 것은 순응도, 대사 상태, 독성 예방 및 용량 최적화 평가에 유용한 것으로 나타났습니다.[193]

| A | 알레목산, 진달래, 진달래 |

| C | Cloment, Clonex, Clopin, Clopine, Cloril, Clorilex, Clozamed, Clozapex, Clozapin, Clozapina, Clozapinum, Clozapyl, Clozaril |

| D | Denzapine, Dicomex |

| E | Elcrit, Excloza |

| F | 파자 클로, 프로이디르 |

| I | 그러길 바랍니다. |

| K | 클로자폴 |

| L | Lanolept, Lapenax, Leponex, Lodux, Lozapine, Lozatric, Luften |

| M | Medazepine, Mezapin |

| N | Nemea, Nirva |

| O | Ozadep, Ozapim |

| R | 굴절, 레프락솔 |

| S | Sanosen, Schizonex, Sensipin, Sequax, Sicozapina, Sizoril, Syclop, Syzopin |

| T | 타닐 |

| U | 우스펜 |

| V | 베르사클로즈 |

| X | 제노팔 |

| Z | 자클로, 자페니아, 자핀, 자포넥스, 자포릴, 지프록, 조핀 |

경제학

필요한 위험 모니터링 및 관리 시스템의 비용에도 불구하고 클로자핀을 사용하는 것은 매우 비용 효율적입니다. 많은 연구에서 다른 항정신병 약물과 비교하여 환자당 연간 수만 달러의 비용을 절감할 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 삶의 질 향상과 관련된 이점을 제시하고 있습니다.[195][196][197] 클로자핀은 일반 의약품으로 제공됩니다.[198]

참고문헌

- ^ a b "Clozapine International Brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c "Clozaril- clozapine tablet". DailyMed. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ a b Hopfinger AJ, Esposito EX, Llinàs A, Glen RC, Goodman JM (January 2009). "Findings of the challenge to predict aqueous solubility". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 49 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1021/ci800436c. PMID 19117422.

- ^ a b c Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (22 September 2023). "Information on Clozapine". FDA.

- ^ a b Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, et al. (July 2012). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 13 (5): 318–378. doi:10.3109/15622975.2012.696143. PMID 22834451. S2CID 20370225.

- ^ a b Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, et al. (January 2010). "The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (1): 71–93. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp116. PMC 2800144. PMID 19955390.

- ^ a b Gaebel W, Weinmann S, Sartorius N, Rutz W, McIntyre JS (September 2005). "Schizophrenia practice guidelines: international survey and comparison". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 187 (3): 248–255. doi:10.1192/bjp.187.3.248. PMID 16135862.

- ^ a b Kuipers E, Yesufu-Udechuku A, Taylor C, Kendall T (February 2014). "Management of psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: summary of updated NICE guidance". BMJ. 348: g1173. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1173. PMID 24523363. S2CID 44282161.

- ^ a b Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, de Bartolomeis A, van Beveren NJ, Birnbaum ML, et al. (March 2017). "Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group Consensus Guidelines on Diagnosis and Terminology". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 174 (3): 216–229. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050503. PMC 6231547. PMID 27919182.

- ^ a b Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, Humberstone V, Jablensky A, Killackey E, et al. (May 2016). "Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 50 (5): 410–472. doi:10.1177/0004867416641195. PMID 27106681.

- ^ Remington G, Addington D, Honer W, Ismail Z, Raedler T, Teehan M (September 2017). "Guidelines for the Pharmacotherapy of Schizophrenia in Adults". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 62 (9): 604–616. doi:10.1177/0706743717720448. PMC 5593252. PMID 28703015.

- ^ Zhang, Mingliang; Owen, R. R.; Pope, S. K.; Smith, G. R. (1996). "Cost-effectiveness of Clozapine Monitoring After the First 6 Months". Archives of General Psychiatry. 53 (10): 954–958. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100104013. PMID 8857873. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Girardin, François R; Poncet, Antoine; Blondon, Marc; Rollason, Victoria; Vernaz, Nathalie; Chalandon, Yves; Dayer, Pierre; Combescure, Christophe (June 2014). "Monitoring white blood cell count in adult patients with schizophrenia who are taking clozapine: a cost-effectiveness analysis". The Lancet Psychiatry. 1 (1): 55–62. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(14)70245-7. ISSN 2215-0366. PMID 26360402.

- ^ a b c Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H (September 1988). "Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine". Archives of General Psychiatry. 45 (9): 789–796. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001. PMID 3046553.

- ^ a b Oloyede, Ebenezer; Taylor, David; MacCabe, James (1 June 2023). "International Variation in Clozapine Hematologic Monitoring—A Call for Action". JAMA Psychiatry. 80 (6): 535–536. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0376. ISSN 2168-622X. PMID 37017962. S2CID 257953116.

- ^ "High risk medicines: clozapine - Care Quality Commission". www.cqc.org.uk. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Masuda T, Misawa F, Takase M, Kane JM, Correll CU (October 2019). "Association With Hospitalization and All-Cause Discontinuation Among Patients With Schizophrenia on Clozapine vs Other Oral Second-Generation Antipsychotics: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies". JAMA Psychiatry. 76 (10): 1052–1062. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1702. PMC 6669790. PMID 31365048.

- ^ a b c "'Last resort' antipsychotic remains the gold standard for treatment-resistant schizophrenia". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). 2 October 2019. doi:10.3310/signal-000826. S2CID 241225484.

- ^ a b Nyakyoma K, Morriss R (2010). "Effectiveness of clozapine use in delaying hospitalization in routine clinical practice: a 2 year observational study". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 43 (2): 67–81. PMID 21052043.

- ^ a b Siskind D, Reddel T, MacCabe JH, Kisely S (June 2019). "The impact of clozapine initiation and cessation on psychiatric hospital admissions and bed days: a mirror image cohort study". Psychopharmacology. 236 (6): 1931–1935. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-5179-6. PMID 30715572. S2CID 59603040.

- ^ Leucht, Stefan; Cipriani, Andrea; Spineli, Loukia; Mavridis, Dimitris; Örey, Deniz; Richter, Franziska; Samara, Myrto; Barbui, Corrado; Engel, Rolf R; Geddes, John R; Kissling, Werner; Stapf, Marko Paul; Lässig, Bettina; Salanti, Georgia; Davis, John M (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". The Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–962. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60733-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- ^ Taylor, D.; Shapland, L.; Laverick, G.; Bond, J.; Munro, J. (December 2000). "Clozapine – a survey of patient perceptions". Psychiatric Bulletin. 24 (12): 450–452. doi:10.1192/pb.24.12.450. ISSN 0955-6036.

- ^ "Clozaril 25 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Myles, N.; Myles, H.; Xia, S.; Large, M.; Kisely, S.; Galletly, C.; Bird, R.; Siskind, D. (21 May 2018). "Meta‐analysis examining the epidemiology of clozapine‐associated neutropenia". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 138 (2): 101–109. doi:10.1111/acps.12898. ISSN 0001-690X. PMID 29786829. S2CID 29157011.

- ^ Li, Xiao-Hong; Zhong, Xiao-Mei; Lu, Li; Zheng, Wei; Wang, Shi-bin; Rao, Wen-wang; Wang, Shuai; Ng, Chee H.; Ungvari, Gabor S.; Wang, Gang; Xiang, Yu-Tao (March 2020). "The prevalence of agranulocytosis and related death in clozapine-treated patients: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies". Psychological Medicine. 50 (4): 583–594. doi:10.1017/S0033291719000369. ISSN 0033-2917. S2CID 75137940.

- ^ Luykx, Jurjen J.; Stam, Noraly; Tanskanen, Antti; Tiihonen, Jari; Taipale, Heidi (September 2020). "In the aftermath of clozapine discontinuation: comparative effectiveness and safety of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia who discontinue clozapine". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 217 (3): 498–505. doi:10.1192/bjp.2019.267. ISSN 0007-1250. PMC 7511905. PMID 31910911.

- ^ "Clozaril 25 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ a b "BNF is only available in the UK". NICE. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Crilly J (March 2007). "The history of clozapine and its emergence in the US market: a review and analysis". History of Psychiatry. 18 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1177/0957154X07070335. PMID 17580753. S2CID 21086497.

- ^ Ellenbroek BA, Cools AR (6 December 2012). Atypical Antipsychotics. Birkhäuser. ISBN 9783034884488 – via Google Books.

- ^ Idänpään-Heikkilä J, Alhava E, Olkinuora M, Palva I (September 1975). "Letter: Clozapine and agranulocytosis". Lancet. 2 (7935): 611. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90206-8. PMID 51442. S2CID 54345964.

- ^ Amsler HA, Teerenhovi L, Barth E, Harjula K, Vuopio P (October 1977). "Agranulocytosis in patients treated with clozapine. A study of the Finnish epidemic". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 56 (4): 241–248. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1977.tb00224.x. PMID 920225. S2CID 24782844.

- ^ a b Griffith RW, Saameli K (October 1975). "Letter: Clozapine and agranulocytosis". Lancet. 2 (7936): 657. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90135-X. PMID 52022. S2CID 53296036.

- ^ Legge SE, Walters JT (March 2019). "Genetics of clozapine-associated neutropenia: recent advances, challenges and future perspective". Pharmacogenomics. 20 (4): 279–290. doi:10.2217/pgs-2018-0188. PMC 6563116. PMID 30767710.

- ^ a b de With SA, Pulit SL, Staal WG, Kahn RS, Ophoff RA (July 2017). "More than 25 years of genetic studies of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis". The Pharmacogenomics Journal. 17 (4): 304–311. doi:10.1038/tpj.2017.6. PMID 28418011. S2CID 5007914.

- ^ Healy D (8 May 2018). The Psychopharmacologists. doi:10.1201/9780203736159. ISBN 9780203736159.

- ^ "Supplemental NDA Approval Letter for Clozaril, NDA 19-758 / S-047" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. 18 December 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Letter to Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ "FDA Modifies REMS Program for Clozapine". www.raps.org. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Sultan RS, Olfson M, Correll CU, Duncan EJ (25 October 2017). "Evaluating the Effect of the Changes in FDA Guidelines for Clozapine Monitoring". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 78 (8): e933–e939. doi:10.4088/jcp.16m11152. PMC 5669833. PMID 28742291.

- ^ a b c Nielsen J, Young C, Ifteni P, Kishimoto T, Xiang YT, Schulte PF, et al. (February 2016). "Worldwide Differences in Regulations of Clozapine Use". CNS Drugs. 30 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0311-1. PMID 26884144. S2CID 23395968.

- ^ a b Oloyede E, Casetta C, Dzahini O, Segev A, Gaughran F, Shergill S, et al. (July 2021). "There Is Life After the UK Clozapine Central Non-Rechallenge Database". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 47 (4): 1088–1098. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbab006. PMC 8266568. PMID 33543755.

- ^ Novartis Pharmaceuticals (April 2006). "Prescribing Information" (PDF). Novartis Pharmaceuticals. p. 36. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- ^ "clozapine (CHEBI:3766)". www.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ a b Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Mehtälä J, Vattulainen P, Correll CU, Tiihonen J (February 2020). "20-year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20)". World Psychiatry. 19 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1002/wps.20699. PMC 6953552. PMID 31922669.

- ^ Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- ^ a b c Taylor D, Shapland L, Laverick G, Bond J, Munro J (December 2000). "Clozapine – a survey of patient perceptions". Psychiatric Bulletin. 24 (12): 450–452. doi:10.1192/pb.24.12.450. ISSN 0955-6036.

- ^ a b Waserman J, Criollo M (May 2000). "Subjective experiences of clozapine treatment by patients with chronic schizophrenia". Psychiatric Services. 51 (5): 666–668. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.51.5.666. PMID 10783189.

- ^ a b "Clozaril 25 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". www.medicines.org.uk. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Great Britain). Parkinson's disease in adults : diagnosis and management : full guideline. OCLC 1105250833.

- ^ Essali A, Al-Haj Haasan N, Li C, Rathbone J, et al. (Cochrane Schizophrenia Group) (January 2009). "Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (1): CD000059. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000059.pub2. PMC 7065592. PMID 19160174.

- ^ Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, Kisely S (November 2016). "Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 209 (5): 385–392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261. PMID 27388573.

- ^ Kahn RS, Winter van Rossum I, Leucht S, McGuire P, Lewis SW, Leboyer M, et al. (October 2018). "Amisulpride and olanzapine followed by open-label treatment with clozapine in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder (OPTiMiSE): a three-phase switching study". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (10): 797–807. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30252-9. PMID 30115598. S2CID 52014623.

- ^ Gaszner P, Makkos Z (May 2004). "Clozapine maintenance therapy in schizophrenia". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 28 (3): 465–469. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.11.011. PMID 15093952. S2CID 36098336.

- ^ Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, Haukka J (August 2009). "11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study)". Lancet. 374 (9690): 620–627. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X. PMID 19595447. S2CID 27282281.

- ^ Taipale H, Lähteenvuo M, Tanskanen A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tiihonen J (January 2021). "Comparative Effectiveness of Antipsychotics for Risk of Attempted or Completed Suicide Among Persons With Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 47 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbaa111. PMC 7824993. PMID 33428766.

- ^ a b Brown D, Larkin F, Sengupta S, Romero-Ureclay JL, Ross CC, Gupta N, et al. (October 2014). "Clozapine: an effective treatment for seriously violent and psychopathic men with antisocial personality disorder in a UK high-security hospital". CNS Spectrums. 19 (5): 391–402. doi:10.1017/S1092852914000157. PMC 4255317. PMID 24698103.

- ^ Krakowski MI, Czobor P, Citrome L, Bark N, Cooper TB (June 2006). "Atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of violent patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (6): 622–629. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.622. PMID 16754835.

- ^ Dalal B, Larkin E, Leese M, Taylor PJ (June 1999). "Clozapine treatment of long-standing schizophrenia and serious violence: a two-year follow-up study of the first 50 patients treated with clozapine in Rampton high security hospital". Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 9 (2): 168–178. doi:10.1002/cbm.304.

- ^ Topiwala A, Fazel S (January 2011). "The pharmacological management of violence in schizophrenia: a structured review". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 11 (1): 53–63. doi:10.1586/ern.10.180. PMID 21158555. S2CID 2190383.

- ^ Frogley C, Taylor D, Dickens G, Picchioni M (October 2012). "A systematic review of the evidence of clozapine's anti-aggressive effects". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (9): 1351–1371. doi:10.1017/S146114571100201X. PMID 22339930.

- ^ Thomson LD (July 2000). "Management of schizophrenia in conditions of high security". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 6 (4): 252–260. doi:10.1192/apt.6.4.252. ISSN 1355-5146.

- ^ a b Silva E, Till A, Adshead G (July 2017). "Ethical dilemmas in psychiatry: When teams disagree". BJPsych Advances. 23 (4): 231–239. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.116.016147.

- ^ a b Silva E, Higgins M, Hammer B, Stephenson P (June 2020). "Clozapine rechallenge and initiation despite neutropenia- a practical, step-by-step guide". BMC Psychiatry. 20 (1): 279. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02592-2. PMC 7275543. PMID 32503471.

- ^ a b Till A, Selwood J, Silva E (February 2019). "The assertive approach to clozapine: nasogastric administration". BJPsych Bulletin. 43 (1): 21–26. doi:10.1192/bjb.2018.61. PMC 6327298. PMID 30223913.

- ^ a b Fisher WA (January 2003). "Elements of successful restraint and seclusion reduction programs and their application in a large, urban, state psychiatric hospital". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 9 (1): 7–15. doi:10.1097/00131746-200301000-00003. PMID 15985912. S2CID 2926142.

- ^ a b Kasinathan J, Mastroianni T (December 2007). "Evaluating the use of enforced clozapine in an Australian forensic psychiatric setting: two cases". BMC Psychiatry. 7 (S1): P13. doi:10.1186/1471-244x-7-s1-p13. ISSN 1471-244X. PMC 3332745.

- ^ Swinton M, Haddock A (January 2000). "Clozapine in Special Hospital: a retrospective case-control study". The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 11 (3): 587–596. doi:10.1080/09585180010006205. ISSN 0958-5184. S2CID 58172685.

- ^ a b Silva E, Higgins M, Hammer B, Stephenson P (1 January 2021). "Clozapine re-challenge and initiation following neutropenia: a review and case series of 14 patients in a high-secure forensic hospital". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 11: 20451253211015070. doi:10.1177/20451253211015070. PMC 8221694. PMID 34221348.

- ^ "Schizophrenia, Violence, Clozapine and Risperidone: a Review". British Journal of Psychiatry. 169 (S31): 21–30. December 1996. doi:10.1192/s0007125000298589. ISSN 0007-1250. S2CID 199026883.

- ^ a b Swinton M (January 2001). "Clozapine in severe borderline personality disorder". The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 12 (3): 580–591. doi:10.1080/09585180110091994. ISSN 0958-5184. S2CID 144701732.

- ^ a b Haw C, Stubbs J (November 2011). "Medication for borderline personality disorder: a survey at a secure hospital". International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 15 (4): 280–285. doi:10.3109/13651501.2011.590211. PMID 22122000. S2CID 43305.

- ^ Henry R, Massey R, Morgan K, Deeks J, Macfarlane H, Holmes N, Silva E (December 2020). "Evaluation of the effectiveness and acceptability of intramuscular clozapine injection: illustrative case series". BJPsych Bulletin. 44 (6): 239–243. doi:10.1192/bjb.2020.6. PMC 7684781. PMID 32081110.

- ^ Casetta C, Oloyede E, Whiskey E, Taylor DM, Gaughran F, Shergill SS, et al. (September 2020). "A retrospective study of intramuscular clozapine prescription for treatment initiation and maintenance in treatment-resistant psychosis" (PDF). The British Journal of Psychiatry. 217 (3): 506–513. doi:10.1192/bjp.2020.115. PMID 32605667. S2CID 220287156.

- ^ Lokshin P, Lerner V, Miodownik C, Dobrusin M, Belmaker RH (October 1999). "Parenteral clozapine: five years of experience". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 19 (5): 479–480. doi:10.1097/00004714-199910000-00018. PMID 10505595.

- ^ Schulte PF, Stienen JJ, Bogers J, Cohen D, van Dijk D, Lionarons WH, et al. (November 2007). "Compulsory treatment with clozapine: a retrospective long-term cohort study". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 30 (6): 539–545. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.09.003. PMID 17928054.

- ^ McLean G, Juckes L (1 December 2001). "Parenteral Clozapine (Clozaril)". Australasian Psychiatry. 9 (4): 371. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1665.2001.0367a.x. ISSN 1039-8562. S2CID 73372315.

- ^ Mossman D, Lehrer DS (December 2000). "Conventional and atypical antipsychotics and the evolving standard of care". Psychiatric Services. 51 (12): 1528–1535. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.51.12.1528. PMID 11097649.

- ^ Pompili M, Lester D, Dominici G, Longo L, Marconi G, Forte A, et al. (May 2013). "Indications for electroconvulsive treatment in schizophrenia: a systematic review". Schizophrenia Research. 146 (1–3): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2022.09.021. PMID 23499244. S2CID 252276294.

- ^ Li XB, Tang YL, Wang CY, de Leon J (May 2015). "Clozapine for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder: a systematic review". Bipolar Disorders. 17 (3): 235–247. doi:10.1111/bdi.12272. PMID 25346322. S2CID 22689570.

- ^ Goodwin GM (June 2009). "Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition--recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 23 (4): 346–388. doi:10.1177/0269881109102919. PMID 19329543. S2CID 27827654.

- ^ Bastiampillai T, Gupta A, Allison S, Chan SK (June 2016). "NICE guidance: why not clozapine for treatment-refractory bipolar disorder?". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 3 (6): 502–503. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30081-5. PMID 27262046.

- ^ Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, et al. (March 2018). "Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder". Bipolar Disorders. 20 (2): 97–170. doi:10.1111/bdi.12609. PMC 5947163. PMID 29536616.

- ^ Gartlehner G, Crotty K, Kennedy S, Edlund MJ, Ali R, Siddiqui M, et al. (October 2021). "Pharmacological Treatments for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". CNS Drugs. 35 (10): 1053–1067. doi:10.26226/morressier.59d4913bd462b8029238a351. PMC 8478737. PMID 34495494.

- ^ Beri A, Boydell J (May 2014). "Clozapine in borderline personality disorder: a review of the evidence". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 26 (2): 139–144. PMID 24812651.

- ^ Frogley C, Anagnostakis K, Mitchell S, Mason F, Taylor D, Dickens G, Picchioni MM (May 2013). "A case series of clozapine for borderline personality disorder". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 25 (2): 125–134. PMID 23638443.

- ^ Dickens GL, Frogley C, Mason F, Anagnostakis K, Picchioni MM (7 October 2016). "Experiences of women in secure care who have been prescribed clozapine for borderline personality disorder". Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 3 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s40479-016-0049-x. PMC 5055694. PMID 27761261.

- ^ Rohde C, Polcwiartek C, Correll CU, Nielsen J (December 2018). "Real-World Effectiveness of Clozapine for Borderline Personality Disorder: Results From a 2-Year Mirror-Image Study". Journal of Personality Disorders. 32 (6): 823–837. doi:10.1521/pedi_2017_31_328. PMID 29120277. S2CID 26203378.

- ^ Stoffers-Winterling J, Storebø OJ, Lieb K (June 2020). "Pharmacotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder: an Update of Published, Unpublished and Ongoing Studies". Current Psychiatry Reports. 22 (8): 37. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-01164-1. PMC 7275094. PMID 32504127.

- ^ "NIHR Funding and Awards Search Website". fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ Flanagan RJ, Lally J, Gee S, Lyon R, Every-Palmer S (October 2020). "Clozapine in the treatment of refractory schizophrenia: a practical guide for healthcare professionals". British Medical Bulletin. 135 (1): 73–89. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldaa024. PMC 7585831. PMID 32885238.

- ^ a b c Beck K, McCutcheon R, Bloomfield MA, Gaughran F, Reis Marques T, MacCabe J, et al. (December 2014). "The practical management of refractory schizophrenia--the Maudsley Treatment REview and Assessment Team service approach". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 130 (6): 427–438. doi:10.1111/acps.12327. PMID 25201058. S2CID 36409113.

- ^ "Clozaril 25 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ a b Taylor D, Barnes TR, Young AH (2019). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry (13th ed.). Hoboken, NJ. ISBN 978-1-119-44260-8. OCLC 1029071684.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ Taylor Shubhra Mace Shameem Mir Robert Kerwin D (January 2000). "A prescription survey of the use of atypical antipsychotics for hospital inpatients in the United Kingdom". International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 4 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1080/13651500052048749. PMID 24927311. S2CID 25337120.

- ^ Sharma A (October 2018). "Maintenance doses for clozapine: past and present". BJPsych Bulletin. 42 (5): 217. doi:10.1192/bjb.2018.64. PMC 6189983. PMID 30345070.

- ^ Suzuki T, Remington G, Arenovich T, Uchida H, Agid O, Graff-Guerrero A, Mamo DC (October 2011). "Time course of improvement with antipsychotic medication in treatment-resistant schizophrenia". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 199 (4): 275–280. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083907. PMID 22187729. S2CID 2382648.

- ^ Kapur S, Arenovich T, Agid O, Zipursky R, Lindborg S, Jones B (May 2005). "Evidence for onset of antipsychotic effects within the first 24 hours of treatment". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (5): 939–946. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.939. PMID 15863796.

- ^ Remington G (2010). "Augmenting Clozapine Response in Treatment-Resistant Schizophreni a". Therapy-Resistant Schizophrenia. Advances in Biological Psychiatry. Vol. 26. Basel: KARGER. pp. 129–151. doi:10.1159/000319813. ISBN 978-3-8055-9511-7.

- ^ Schulte P (2003). "What is an adequate trial with clozapine?: therapeutic drug monitoring and time to response in treatment-refractory schizophrenia". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 42 (7): 607–618. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342070-00001. PMID 12844323. S2CID 25525638.

- ^ Conley RR, Carpenter WT, Tamminga CA (September 1997). "Time to clozapine response in a standardized trial". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 154 (9): 1243–1247. doi:10.1176/ajp.154.9.1243. PMID 9286183.

- ^ Mistry H, Osborn D (July 2011). "Underuse of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 17 (4): 250–255. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.110.008128. ISSN 1355-5146.

- ^ Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, Huang C, Olfson M (February 2014). "Geographic and clinical variation in clozapine use in the United States". Psychiatric Services. 65 (2): 186–192. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201300180. PMID 24233347.

- ^ Downs J, Zinkler M (October 2007). "Clozapine: national review of postcode prescribing". Psychiatric Bulletin. 31 (10): 384–387. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.106.013144. ISSN 0955-6036.

- ^ Purcell H, Lewis S (November 2000). "Postcode prescribing in psychiatry". Psychiatric Bulletin. 24 (11): 420–422. doi:10.1192/pb.24.11.420. ISSN 0955-6036.

- ^ Hayhurst KP, Brown P, Lewis SW (April 2003). "Postcode prescribing for schizophrenia". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 182 (4): 281–283. doi:10.1192/bjp.182.4.281. PMID 12668398.

- ^ Nielsen J, Røge R, Schjerning O, Sørensen HJ, Taylor D (November 2012). "Geographical and temporal variations in clozapine prescription for schizophrenia". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 22 (11): 818–824. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.03.003. PMID 22503785. S2CID 40842497.

- ^ Latimer E, Wynant W, Clark R, Malla A, Moodie E, Tamblyn R, Naidu A (April 2013). "Underprescribing of clozapine and unexplained variation in use across hospitals and regions in the Canadian province of Québec". Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 7 (1): 33–41. doi:10.3371/csrp.lawy.012513. PMID 23367500.

- ^ Whiskey E, Barnard A, Oloyede E, Dzahini O, Taylor DM, Shergill SS (April 2021). "An evaluation of the variation and underuse of clozapine in the United Kingdom" (PDF). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 143 (4): 339–347. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3716864. PMID 33501659. S2CID 235854803.

- ^ Kelly DL, Kreyenbuhl J, Dixon L, Love RC, Medoff D, Conley RR (September 2007). "Clozapine underutilization and discontinuation in African Americans due to leucopenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 33 (5): 1221–1224. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl068. PMC 2632351. PMID 17170061.

- ^ a b Mallinger JB, Fisher SG, Brown T, Lamberti JS (January 2006). "Racial disparities in the use of second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia". Psychiatric Services. 57 (1): 133–136. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.133. PMID 16399976.

- ^ a b Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Valenstein M, Blow FC (October 2003). "Racial disparity in the use of atypical antipsychotic medications among veterans". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (10): 1817–1822. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1817. PMID 14514496.

- ^ Kelly DL, Dixon LB, Kreyenbuhl JA, Medoff D, Lehman AF, Love RC, et al. (September 2006). "Clozapine utilization and outcomes by race in a public mental health system: 1994-2000". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (9): 1404–1411. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0911. PMID 17017827.

- ^ Whiskey E, Olofinjana O, Taylor D (June 2011). "The importance of the recognition of benign ethnic neutropenia in black patients during treatment with clozapine: case reports and database study". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (6): 842–845. doi:10.1177/0269881110364267. PMID 20305043. S2CID 28714732.

- ^ Cirulli G (October 2005). "Clozapine prescribing in adolescent psychiatry: survey of prescribing practice in in-patient units". Psychiatric Bulletin. 29 (10): 377–380. doi:10.1192/pb.29.10.377.

- ^ Nielsen J, Dahm M, Lublin H, Taylor D (July 2010). "Psychiatrists' attitude towards and knowledge of clozapine treatment". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (7): 965–971. doi:10.1177/0269881108100320. PMID 19164499. S2CID 34614417.

- ^ Hodge K, Jespersen S (February 2008). "Side-effects and treatment with clozapine: a comparison between the views of consumers and their clinicians". International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 17 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00506.x. PMID 18211398.

- ^ Angermeyer MC, Löffler W, Müller P, Schulze B, Priebe S (April 2001). "Patients' and relatives' assessment of clozapine treatment". Psychological Medicine. 31 (3): 509–517. doi:10.1017/S0033291701003749. PMID 11305859. S2CID 20487762.

- ^ Kelly D, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan R, Malhotra A (April 2007). "Why Not Clozapine?". Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 1 (1): 92–95. doi:10.3371/csrp.1.1.8.

- ^ Downs J, Zinkler M (October 2007). "Clozapine: national review of postcode prescribing". Psychiatric Bulletin. 31 (10): 384–387. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.106.013144. ISSN 0955-6036.

- ^ Taylor DM, Young C, Paton C (January 2003). "Prior antipsychotic prescribing in patients currently receiving clozapine: a case note review". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (1): 30–34. doi:10.4088/jcp.v64n0107. PMID 12590620.

- ^ Fayek M, Flowers C, Signorelli D, Simpson G (November 2003). "Psychopharmacology: underuse of evidence-based treatments in psychiatry". Psychiatric Services. 54 (11): 1453–4, 1456. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1453. PMID 14600298.

- ^ Pearl R. "Why Health Care Is Different If You're Black, Latino Or Poor". Forbes. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Racism in healthcare: Statistics and examples". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 17 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Bulatao RA, Anderson NB, et al. (National Research Council (US) Panel on Race, Ethnicity, and Health in Later Life) (2004). Stress. National Academies Press (US).

- ^ Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S (October 2019). "Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations". Science. 366 (6464): 447–453. Bibcode:2019Sci...366..447O. doi:10.1126/science.aax2342. PMID 31649194. S2CID 204881868.

- ^ Kelly DL, Dixon LB, Kreyenbuhl JA, Medoff D, Lehman AF, Love RC, et al. (September 2006). "Clozapine utilization and outcomes by race in a public mental health system: 1994-2000". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (9): 1404–1411. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0911. PMID 17017827.

- ^ Atallah-Yunes SA, Ready A, Newburger PE (September 2019). "Benign ethnic neutropenia". Blood Reviews. 37: 100586. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2019.06.003. PMC 6702066. PMID 31255364.

- ^ Haddy TB, Rana SR, Castro O (January 1999). "Benign ethnic neutropenia: what is a normal absolute neutrophil count?". The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 133 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1053/lc.1999.v133.a94931. PMID 10385477.

- ^ Rajagopal S (September 2005). "Clozapine, agranulocytosis, and benign ethnic neutropenia". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 81 (959): 545–546. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.031161. PMC 1743348. PMID 16143678.

- ^ Reich D, Nalls MA, Kao WH, Akylbekova EL, Tandon A, Patterson N, et al. (January 2009). "Reduced neutrophil count in people of African descent is due to a regulatory variant in the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines gene". PLOS Genetics. 5 (1): e1000360. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000360. PMC 2628742. PMID 19180233.

- ^ a b "Clozapine". Pharmacology: MCQs. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013 – via Google Sites.

- ^ Teodoro T, Nogueira V, Aldeias J, Teles Martins M, Salgado J (September 2022). "Clozapine Associated Periorbital Edema in First Episode Psychosis: A Case Report of a Rare Adverse Effect in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 42 (6): 594–596. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001600. PMID 36066404. S2CID 252088054.

- ^ Nielsen J, Correll CU, Manu P, Kane JM (June 2013). "Termination of clozapine treatment due to medical reasons: when is it warranted and how can it be avoided?". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 74 (6): 603–13, quiz 613. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08064. PMID 23842012.

- ^ Vermeulen JM, van Rooijen G, van de Kerkhof MP, Sutterland AL, Correll CU, de Haan L (March 2019). "Clozapine and Long-Term Mortality Risk in Patients With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Studies Lasting 1.1-12.5 Years". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 45 (2): 315–329. doi:10.1093/schbul/sby052. PMC 6403051. PMID 29697804.

- ^ a b c d Li XH, Zhong XM, Lu L, Zheng W, Wang SB, Rao WW, et al. (March 2020). "The prevalence of agranulocytosis and related death in clozapine-treated patients: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies". Psychological Medicine. 50 (4): 583–594. doi:10.1017/S0033291719000369. PMID 30857568. S2CID 75137940.

- ^ a b c Myles N, Myles H, Xia S, Large M, Kisely S, Galletly C, et al. (August 2018). "Meta-analysis examining the epidemiology of clozapine-associated neutropenia". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 138 (2): 101–109. doi:10.1111/acps.12898. PMID 29786829. S2CID 29157011.

- ^ "A Guide for Patients and Caregivers: What You Need to Know About Clozapine and Neutropenia" (PDF). Clozapine REMS. Clozapine REMS Program. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ Whiskey E, Dzahini O, Ramsay R, O'Flynn D, Mijovic A, Gaughran F, et al. (September 2019). "Need to bleed? Clozapine haematological monitoring approaches a time for change". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 34 (5): 264–268. doi:10.1097/yic.0000000000000258. PMID 30882426. S2CID 81977064.

- ^ Kalaria SN, Kelly DL (2019). "Development of point-of-care testing devices to improve clozapine prescribing habits and patient outcomes". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 15: 2365–2370. doi:10.2147/NDT.S216803. PMC 6708436. PMID 31692521.

- ^ Myles N, Myles H, Clark SR, Bird R, Siskind D (October 2017). "Use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to prevent recurrent clozapine-induced neutropenia on drug rechallenge: A systematic review of the literature and clinical recommendations". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 51 (10): 980–989. doi:10.1177/0004867417720516. PMID 28747065.

- ^ Lally J, Malik S, Krivoy A, Whiskey E, Taylor DM, Gaughran FP, et al. (October 2017). "The Use of Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor in Clozapine Rechallenge: A Systematic Review". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 37 (5): 600–604. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000767. PMID 28817489. S2CID 41269943. Archived from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ Siskind D, Sidhu A, Cross J, Chua YT, Myles N, Cohen D, Kisely S (May 2020). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of rates of clozapine-associated myocarditis and cardiomyopathy". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 54 (5): 467–481. doi:10.1177/0004867419898760. PMID 31957459. S2CID 210831575.

- ^ Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, Topliss DJ, McNeil JJ (June 2011). "A new monitoring protocol for clozapine-induced myocarditis based on an analysis of 75 cases and 94 controls". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 45 (6): 458–465. doi:10.3109/00048674.2011.572852. PMID 21524186. S2CID 26627093.

- ^ Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, Topliss DJ, Wolfe R, McNeil JJ (November 2012). "Rapid clozapine dose titration and concomitant sodium valproate increase the risk of myocarditis with clozapine: a case-control study". Schizophrenia Research. 141 (2–3): 173–178. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.018. PMID 23010488. S2CID 25720157.

- ^ Segev A, Iqbal E, McDonagh TA, Casetta C, Oloyede E, Piper S, et al. (December 2021). "Clozapine-induced myocarditis: electronic health register analysis of incidence, timing, clinical markers and diagnostic accuracy". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 219 (6): 644–651. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.58. PMC 8636612. PMID 35048875. S2CID 236297166.

- ^ Griffin JM, Woznica E, Gilotra NA, Nucifora FC (March 2021). "Clozapine-Associated Myocarditis: A Protocol for Monitoring Upon Clozapine Initiation and Recommendations for How to Conduct a Clozapine Rechallenge". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 41 (2): 180–185. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001358. PMID 33587399. S2CID 231926010.

- ^ Richardson N, Greenway SC, Bousman CA (November 2021). "Clozapine-induced myocarditis and patient outcomes after drug rechallenge following myocarditis: A systematic case review". Psychiatry Research. 305: 114247. doi:10.1101/2021.09.03.21263094. PMID 34715441. S2CID 237461869.

- ^ Palmer SE, McLean RM, Ellis PM, Harrison-Woolrych M (May 2008). "Life-threatening clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: an analysis of 102 cases". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69 (5): 759–768. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0509. PMID 18452342.

- ^ Every-Palmer S, Nowitz M, Stanley J, Grant E, Huthwaite M, Dunn H, Ellis PM (March 2016). "Clozapine-treated Patients Have Marked Gastrointestinal Hypomotility, the Probable Basis of Life-threatening Gastrointestinal Complications: A Cross Sectional Study". eBioMedicine. 5: 125–134. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.020. PMC 4816835. PMID 27077119.

- ^ Cohen D, Bogers JP, van Dijk D, Bakker B, Schulte PF (October 2012). "Beyond white blood cell monitoring: screening in the initial phase of clozapine therapy". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 73 (10): 1307–1312. doi:10.4088/JCP.11r06977. PMID 23140648.

- ^ Every-Palmer S, Newton-Howes G, Clarke MJ (January 2017). "Pharmacological treatment for antipsychotic-related constipation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD011128. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011128.pub2. PMC 6465073. PMID 28116777.

- ^ Every-Palmer S, Ellis PM, Nowitz M, Stanley J, Grant E, Huthwaite M, Dunn H (January 2017). "The Porirua Protocol in the Treatment of Clozapine-Induced Gastrointestinal Hypomotility and Constipation: A Pre- and Post-Treatment Study". CNS Drugs. 31 (1): 75–85. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0391-y. PMID 27826741. S2CID 46825178.

- ^ a b c d Syed R, Au K, Cahill C, Duggan L, He Y, Udu V, Xia J (July 2008). Syed R (ed.). "Pharmacological interventions for clozapine-induced hypersalivation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD005579. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005579.pub2. PMC 4160791. PMID 18646130.

- ^ "Treatment of Clozapine-Induced Sialorrhea". Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ Segev A, Evans A, Hodsoll J, Whiskey E, Sheriff RS, Shergill S, MacCabe JH (March 2019). "Hyoscine for clozapine-induced hypersalivation: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over trial". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 34 (2): 101–107. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000251. PMID 30614850. S2CID 58554168.

- ^ a b Bird AM, Smith TL, Walton AE (May 2011). "Current treatment strategies for clozapine-induced sialorrhea". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 45 (5): 667–675. doi:10.1345/aph.1P761. PMID 21540404. S2CID 42222976.

- ^ "ClozarilSide Effects & Drug Interactions". RxList. Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Raja M (July 2011). "Clozapine safety, 35 years later". Current Drug Safety. 6 (3): 164–184. doi:10.2174/157488611797579230. PMID 22122392.

- ^ Barnes TR, Drake MJ, Paton C (January 2012). "Nocturnal enuresis with antipsychotic medication". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 200 (1): 7–9. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095737. PMID 22215862.

- ^ Austin M, Dadlanin N. Clozapine 환자의 난치성 요실금 관리를 위한 Bethanechol과 Aripiprazole. Aust NZJ 정신과 2016년 2월 50일 (2):182. doi: 10.1177/0004867415583878 2015년 4월 28일 Epub PMID 25922356

- ^ Stevenson E, Schembri F, Green DM, Burns JD (August 2013). "Serotonin syndrome associated with clozapine withdrawal". JAMA Neurology. 70 (8): 1054–1055. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.95. PMID 23753931.

- ^ Wadekar M, Syed S (July 2010). "Clozapine-withdrawal catatonia". Psychosomatics. 51 (4): 355–355.e2. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.51.4.355. PMID 20587767.

- ^ Ahmed S, Chengappa KN, Naidu VR, Baker RW, Parepally H, Schooler NR (September 1998). "Clozapine withdrawal-emergent dystonias and dyskinesias: a case series". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 59 (9): 472–477. doi:10.4088/JCP.v59n0906. PMID 9771818.

- ^ Szafrański T, Gmurkowski K (1999). "[Clozapine withdrawal. A review]". Psychiatria Polska. 33 (1): 51–67. PMID 10786215.

- ^ Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, Berisford MA, Goldstein D, Pashdag J, et al. (June 1999). "Novel antipsychotics: comparison of weight gain liabilities". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 60 (6): 358–363. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0602. PMID 10401912.

- ^ Nasrallah HA (January 2008). "Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: insights from receptor-binding profiles". Molecular Psychiatry. 13 (1): 27–35. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002066. PMID 17848919. S2CID 205678886.

- ^ Siskind DJ, Leung J, Russell AW, Wysoczanski D, Kisely S (15 June 2016). Holscher C (ed.). "Metformin for Clozapine Associated Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 11 (6): e0156208. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1156208S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156208. PMC 4909277. PMID 27304831.

- ^ De Leon J, Sanz EJ, De Las Cuevas C (January 2020). "Data From the World Health Organization's Pharmacovigilance Database Supports the Prominent Role of Pneumonia in Mortality Associated With Clozapine Adverse Drug Reactions". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 46 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbz093. PMC 6942151. PMID 31901099.

- ^ Ponsford M, Castle D, Tahir T, Robinson R, Wade W, Steven R, et al. (September 2018). "Clozapine is associated with secondary antibody deficiency". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 214 (2): 83–89. doi:10.1192/bjp.2018.152. PMC 6429246. PMID 30259827.

- ^ Okada M, Fukuyama K, Shiroyama T, Murata M (September 2020). "A Working Hypothesis Regarding Identical Pathomechanisms between Clinical Efficacy and Adverse Reaction of Clozapine via the Activation of Connexin43". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (19): 7019. doi:10.3390/ijms21197019. PMC 7583770. PMID 32987640.

- ^ Keck PE, McElroy SL (2002). "Clinical pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of antimanic and mood-stabilizing medications". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 63 (Suppl 4): 3–11. PMID 11913673.

- ^ Broich K, Heinrich S, Marneros A (July 1998). "Acute clozapine overdose: plasma concentration and outcome". Pharmacopsychiatry. 31 (4): 149–151. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979318. PMID 9754851. S2CID 28623410.

- ^ Sproule BA, Naranjo CA, Brenmer KE, Hassan PC (December 1997). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CNS drug interactions. A critical review of the evidence". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 33 (6): 454–471. doi:10.2165/00003088-199733060-00004. PMID 9435993. S2CID 36883635.

- ^ Tiihonen J, Vartiainen H, Hakola P (January 1995). "Carbamazepine-induced changes in plasma levels of neuroleptics". Pharmacopsychiatry. 28 (1): 26–28. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979584. PMID 7746842. S2CID 260249900.

- ^ Besag FM, Berry D (2006). "Interactions between antiepileptic and antipsychotic drugs". Drug Safety. 29 (2): 95–118. doi:10.2165/00002018-200629020-00001. PMID 16454538. S2CID 45735414.

- ^ Jerling M, Lindström L, Bondesson U, Bertilsson L (August 1994). "Fluvoxamine inhibition and carbamazepine induction of the metabolism of clozapine: evidence from a therapeutic drug monitoring service". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 16 (4): 368–374. doi:10.1097/00007691-199408000-00006. PMID 7974626. S2CID 31325882.

- ^ Raaska K, Neuvonen PJ (November 2000). "Ciprofloxacin increases serum clozapine and N-desmethylclozapine: a study in patients with schizophrenia". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 56 (8): 585–589. doi:10.1007/s002280000192. PMID 11151749. S2CID 20390680.

- ^ 정보 처방. 클로자릴(클로자핀). 동부 하노버, 뉴저지: 노바티스 제약 회사, 2014년 9월.

- ^ a b Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Naheed M, Green B (2001). "Focus on clozapine". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 17 (3): 223–229. doi:10.1185/0300799039117069. PMID 11900316. S2CID 13021800.

- ^ Robinson DS (2007). "CNS Receptor Partial Agonists: A New Approach to Drug Discovery". Primary Psychiatry. 14 (8): 22–24. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- ^ "Clozapine C18H19ClN4". PubChem. U.S. Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ Wu Y, Blichowski M, Daskalakis ZJ, Wu Z, Liu CC, Cortez MA, Snead OC (September 2011). "Evidence that clozapine directly interacts on the GABAB receptor". NeuroReport. 22 (13): 637–641. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e328349739b. PMID 21753741. S2CID 277293.

- ^ Vacher CM, Gassmann M, Desrayaud S, Challet E, Bradaia A, Hoyer D, et al. (May 2006). "Hyperdopaminergia and altered locomotor activity in GABAB1-deficient mice". Journal of Neurochemistry. 97 (4): 979–991. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03806.x. PMID 16606363. S2CID 19780444.

- ^ Wierońska JM, Kusek M, Tokarski K, Wabno J, Froestl W, Pilc A (July 2011). "The GABA B receptor agonist CGP44532 and the positive modulator GS39783 reverse some behavioural changes related to positive syndromes of psychosis in mice". British Journal of Pharmacology. 163 (5): 1034–1047. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01301.x. PMC 3130949. PMID 21371011.

- ^ Tanahashi S, Yamamura S, Nakagawa M, Motomura E, Okada M (March 2012). "Clozapine, but not haloperidol, enhances glial D-serine and L-glutamate release in rat frontal cortex and primary cultured astrocytes". British Journal of Pharmacology. 165 (5): 1543–1555. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01638.x. PMC 3372736. PMID 21880034.

- ^ Xi D, Li YC, Snyder MA, Gao RY, Adelman AE, Zhang W, et al. (May 2011). "Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist ameliorates MK801-induced dysfunction of NMDA receptors via the Akt/GSK-3β pathway in adult rat prefrontal cortex". Neuropsychopharmacology. 36 (6): 1260–1274. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.12. PMC 3079418. PMID 21326193.

- ^ Disanto AR, Golden G (1 August 2009). "Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of clozapine orally disintegrating tablet 12.5 mg: a randomized, open-label, crossover study in healthy male subjects". Clinical Drug Investigation. 29 (8): 539–549. doi:10.2165/00044011-200929080-00004. PMID 19591515. S2CID 45731786.

- ^ a b Rostami-Hodjegan A, Amin AM, Spencer EP, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Flanagan RJ (February 2004). "Influence of dose, cigarette smoking, age, sex, and metabolic activity on plasma clozapine concentrations: a predictive model and nomograms to aid clozapine dose adjustment and to assess compliance in individual patients". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 24 (1): 70–78. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000106221.36344.4d. PMID 14709950. S2CID 31923731.

- ^ Lane HY, Chang YC, Chang WH, Lin SK, Tseng YT, Jann MW (January 1999). "Effects of gender and age on plasma levels of clozapine and its metabolites: analyzed by critical statistics". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 60 (1): 36–40. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0108. PMID 10074876.

- ^ Oh PI, Iskedjian M, Addis A, Lanctôt K, Einarson TR (2001). "Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a cost-utility analysis". The Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 8 (4): 199–206. PMID 11743592.

- ^ Jin H, Tappenden P, MacCabe JH, Robinson S, Byford S (May 2020). "Evaluation of the Cost-effectiveness of Services for Schizophrenia in the UK Across the Entire Care Pathway in a Single Whole-Disease Model". JAMA Network Open. 3 (5): e205888. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5888. PMC 7254180. PMID 32459356.

- ^ Morris S, Hogan T, McGuire A (1998). "The cost-effectiveness of clozapine: a survey of the literature". Clinical Drug Investigation. 15 (2): 137–152. doi:10.2165/00044011-199815020-00007. PMID 18370477. S2CID 33530440.

- ^ "Clozapine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

더보기

- Stahl SM (16 May 2019). The clozapine handbook. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-44746-1. OCLC 1222779588.

- Benkert O, Hippius H. Kompendium der Psychiatrischen Pharmakotherapie (in German) (4th ed.). Springer Verlag.

- Bandelow B, Bleich S, Kropp S. Handbuch Psychopharmaka (in German) (2nd ed.). Hogrefe.

- Dean L (2016). "Clozapine Therapy and CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4 Genotypes". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520368. Bookshelf ID: NBK367795.

외부 링크

- "Clozapine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: 원본 URL 상태 알 수 없음(링크) - "Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) requirements will change on November 15, 2021". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 July 2021.

- "Clozapine REMS Modification Frequently Asked Questions". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 July 2021.