비정형 항정신병약

Atypical antipsychotic| 비정형 항정신병약 | |

|---|---|

| 마약류 | |

| |

| 동의어 | 제2세대 항정신병, 세로토닌-도파민 길항제 |

| 위키다타에서 | |

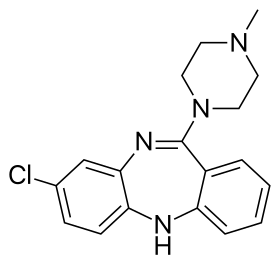

그 비정형 항정신병(미국), 또한 2세대 항정신병고 항 정신 병약의(SDAs)[1][2]한 그룹serotonin–dopamine 길항제(비록 후자는 주로 전형적인 항정신병 예약됩니다 일반적으로 항정신병 약물을 또한 주요한 진정제와 신경 억제성 마취로 알려져 있) 크게 소개하(SGAs).dafte1970년대에는 정신 질환을 치료하곤 했다. 일부 비정형 항정신병 약물들은 정신분열증, 조울증, 자폐증, 그리고 주요 우울증 보조제로서 규제승인(예: 미국의 FDA, 오스트레일리아의 TGA, 영국의 MHRA)을 받았다.

두 세대의 약물 모두 뇌의 도파민 경로에서 수용기를 차단하는 경향이 있다. 비정형은 가장 널리 사용되는 대표적인 항정신병 약물인 할로페리돌보다 불안정 파킨슨병 형태의 움직임, 신체 경직성, 비자발적인 떨림과 같은 환자에게 외사적인 운동조절 장애를 일으킬 가능성이 적다. 그러나 이러한 점에서 비정형 항정신병 약물들 중 극히 일부만이 덜 쓰이고 낮은 잠재력의 1세대 항정신병 약물들보다 우수하다는 것이 입증되었다.[3][4][5]

이들 약물에 대한 경험이 커짐에 따라, 여러 연구에서는 항정신병 약물을 '제1세대'가 아닌 '비정상/2세대'로 광범위하게 특성화하는 효용성에 의문을 제기하고, 각 약제마다 효능과 부작용 프로파일을 가지고 있다는 점에 주목했다. 개별 환자의 니즈를 개별 약물의 특성에 맞추는 뉘앙스적 시각이 더 적절하다는 주장이 제기됐다.[4][3] 비정형 항정신병 약물들은 일반 항정신병 약물보다 안전한 것으로 생각되지만, 여전히 지각 이상증(중증 운동장애), 신경성 악성증후군, 뇌졸중 위험 증가, 갑작스러운 심장사, 혈액 응고, 당뇨병 등 부작용이 심하다. 상당한 체중 증가가 발생할 수 있다. 비평가들은 "1세대와 2세대 항정신병 약물이라는 용어는 이런 구별을 할 가치가 없기 때문에 폐기할 때가 왔다"고 주장해왔다.[6]

의학적 용법

비정형 항정신병 약물들은 일반적으로 정신분열증이나 조울증을 치료하는데 사용된다.[7] 치매, 불안장애, 자폐스펙트럼장애, 강박장애(외부 사용)와 관련된 동요 치료에도 자주 사용된다.[8] 치매의 경우, 다른 치료가 실패한 후, 환자가 자신 및/또는 다른 사람에게 위험할 경우에만 고려해야 한다.[9]

정신분열증

정신분열증의 1차 정신과 치료는 항정신병 약물치료로 약 8~15일 안에 조현병의 양성 증상을 줄일 수 있다.[10] 항정신병 약물들은 단기적으로만 정신분열증의 2차 음성증상을 개선하는 것으로 보이며 전반적으로 음성증상을 악화시킬 수 있다.[11] 전반적으로 비정형 항정신병 약물들이 정신분열증의 부정적인 증상을 치료하는 데 어떤 치료적 효익이 있다는 좋은 증거는 없다.[12]

장기간 치료를 위해 항정신병 약물 사용에 대한 위험과 유익성 평가를 기초로 할 근거는 거의 없다.[13]

특정 환자에게 사용할 항정신병제의 선택은 유익성, 위해성 및 비용에 기초한다.[14] 전형적인 항정신병 약물인지 비정형 항정신병 약물인지 여부는 논쟁의 여지가 있다.[15] 둘 다 저용량에서 보통 용량으로 사용했을 때 동일한 중퇴율과 증상 재발률을 가진다.[16] 나머지 20%[17]에는 환자의 40~50%, 30~40%의 부분적인 반응(세 가지 항정신병 약물 중 6주에서 2주 후 만족스럽게 반응하는 증상의 실패)이 있다. 클로자핀은 특히 단기적으로는 치료 내성 정신분열증의 첫 번째 선택 치료법으로 간주된다. 장기적으로는 부작용의 위험이 선택을 복잡하게 한다.[18] 이에 따라 리스페리돈, 올란자핀, 아리피프라졸 등이 1부 정신질환 치료에 추천됐다.[19][20]

정신분열증 치료의 효능

항정신병 약물들을 1세대와 비정형 범주로 광범위하게 분류하는 효용성은 도전받았다. 개별 약물의 성질을 특정 환자의 필요에 맞추어 보다 뉘앙스를 주는 관점이 바람직하다는 주장이 제기되었다.[3] 비정형(2세대) 항정신병 약물들은 일반 의약품보다 부작용을 줄이면서 정신질환 증상(특히 외사성 증상)을 줄이는데 더 큰 효능을 제공하는 것으로 시판되었지만, 이러한 효과를 보여주는 결과는 종종 건전성이 결여되었고, 비정형적으로 가정하더라도 점점 더 어려움을 겪게 되었다. 처방전이 치솟고 있었다.[21][22] 2005년 미국 정부 기관인 NIMH는 주요 독립 연구(제약사의 자금 지원을 받지 않음)의 다중 사이트 이중 블라인드 연구(CATIE 프로젝트) 결과를 발표했다.[23] 이 연구는 정신분열증 환자 1,493명 중 몇몇 비정형 항정신병 약물들을 나이가 많고 가능성이 중간인 전형적인 항정신병 약물인 페페나진과 비교했다. 연구결과 올란자핀만이 페페나진 단종률(그 효과로 인해 사람들이 복용을 중단한 비율)을 능가하는 것으로 나타났다. 저자들은 정신병학의 감소와 입원률 측면에서 올란자핀의 명백한 우수 효능에 주목했지만 올란자핀은 주요 체중 증가 문제(18개월 평균 9.4lbs), 포도당, 콜레스테롤, 트리글리세리드 증가 등 비교적 심각한 대사 효과와 관련이 있었다.S. 아니 다른 비정형 공부를(risperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone)이 더 좋은 성적을 거두는 방안의 일상적인 perphenazine보다, 비록 더 많은 환자perphen, 그들은, 전형적인 항정신병 perphenazine(는 meta-analysis[3]에 의해 Leucht에서 지원하는(알. TheLancet에 발표되)보다 적은 부작용을 만들어 냈다.azi비정형제 대비 외삽살 효과(8% 대 2%~4%, P=0.002)로 인한 ne. 이 CATIE 연구의 2단계에서는 이러한 연구 결과를 대략적으로 재현했다.[24] 두 가지 유형 간에 준수 여부가 다른 것으로 나타나지 않았다.[25] CATIE와 다른 연구에 대한 전반적인 평가는 많은 연구자들이 전형에 대한 비정형의 첫 번째 처방, 혹은 심지어 두 계층의 구별에 의문을 제기하도록 만들었다.[26][27][28]

'제2세대 항정신병 약물'이라는 용어에 대한 타당성이 없고, 현재 이 범주를 점유하고 있는 약물이 메커니즘, 효능, 부작용 프로파일에서 서로 동일하지 않다는 의견이 제시되었다. [29]

조울증

조울증에서 SGA는 급성 마니아와 혼합된 에피소드를 신속하게 제어하는데 가장 일반적으로 사용되며, 종종 리튬이나 발프로이트와 같은 기분 안정제(이런 경우 작용이 지연되는 경향이 있음)와 함께 사용된다. 가벼운 마니아나 혼합 에피소드일 경우, 무드 스태빌라이저 모노테라피가 먼저 시도될 수 있다.[30] 또한 SGAs는 약물에 따라 급성 조울증이나 예방적 치료와 같은 질환의 다른 측면들을 보조제나 단일요법으로 치료하는데도 사용된다. 퀘티아핀과 올란자핀 모두 조울증 치료 3단계에서 모두 유의미한 효능을 보였다. 루라시돈(무역명 라투다)은 양극성 장애의 급성 우울기에 어느 정도 효능을 보였다.[30][31][32]

주요 우울증

비정신적 주요 우울 장애(MDD)에서 일부 SGA는 부첨가제로서 유의미한 효능을 보였다. 그러한 요인은 다음을 포함한다.[33][34][35][36]

퀘티아핀만이 비정신성 MDD에서 일요법으로 효능을 입증한 반면,[38] 올란자핀/플루옥세틴은 정신질환과 비정신성 MDD 모두에서 효과적인 치료법이다.[39][40]

아리피프라졸, 브렉스피프라졸, 올란자핀, 퀘티아핀이 미국 FDA로부터 MDD에 대한 보조 치료제로 승인받았다.[41][42] 퀘티아핀과 루라시돈은 조울증 때문에 단수로서 승인되었지만 현재 루라시돈은 MDD에 승인되지 않았다.[41]

자폐증

리스페리돈과 아리피프라졸 모두 자폐증에서 자극성으로 FDA 승인을 받았다.[39]

치매알츠하이머병

2007년 5월부터 2008년 4월까지 65세 이상 환자의 비정형 항정신병 약물 사용의 28%를 치매와 알츠하이머가 함께 차지했다.[43] 미국 식품의약국(FDA)은 모든 비정형 항정신병 약물에는 노인 환자의 사망 위험 증가와 관련이 있다는 블랙박스 경고문이 부착될 것을 요구하고 있다.[43] 2005년 FDA는 비정형 항정신병 약물들이 치매에 사용될 때 사망 위험이 증가한다는 권고 경보를 발령했다.[44] 이후 5년간 치매 치료에 비정형 항정신병 약물 사용이 50% 가까이 줄었다.[44]

효능 비교표

| SGA의 상대적 효능 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 일반 약물 이름[33][34][45][4][46] | 정신분열증 | 마니아 | 양극성 유지 관리 | 양극성 우울증 | 주요 우울장애의 부제화 |

| 아미슬프라이드 | +++ | ? | ? | ? | 그러나 (++는 저혈당일 요법으로) |

| 아리피프라졸 | ++ | ++ | ++/+ | -[47] | +++ |

| 아세나핀 | +++ | ++ | ++ | ? (일부 증거는 혼합/혼합 에피소드에서의[48] 우울증 증세를 치료하는 데 효과가 있음을 시사했다.) | ? |

| 블로난세린 | ++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 카리프라진 | +++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 클로자핀 | +++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 일오페리돈 | + | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 루라시돈 | + | ? | ? | +++[47] | ? |

| 멜페론 | +++/++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 올란자핀 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++/++++++++++Fluoxetine과 결합한 경우+++)[47] | ++ |

| 팔리페리돈 | ++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 페로스피론[49] | + | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 쿠에타핀 | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++[47] | ++ |

| 리스페리돈 | +++ | +++ | ++ | -[47] | + |

| 서틴돌 | ++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 지프라시돈 | ++/+ | ++/+ | ? | -[47] | ? |

| 조테핀 | ++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 범례:

| |||||

역효과

보도에 따르면, 다양한 비정형 항정신병 약물들과 관련된 부작용은 다양하며 약물마다 다르다. 일반적으로 비정형 항정신병 약물들은 일반적인 항정신병 약물들에 비해 지각성 이질병의 발생 가능성이 낮다고 널리 알려져 있다. 그러나 지각성 이상증은 일반적으로 항정신병 약물을 장기간(아마도 수십년) 복용한 후에 발병한다. 비교적 짧은 기간 동안 사용되어 온 비정형 항정신병 약물이 지각 이상증 발생률을 낮출지는 확실하지 않다.[30][50]

제안된 다른 부작용들 중 하나는 비정형 항정신병 약물들이 심혈관 질환의 위험을 증가시킨다는 것이다.[51] 카비노프 외 연구진은 심혈관 질환의 증가는 받은 치료법과 무관하게 관찰되며, 그 대신 생활습관이나 식생활 등 여러 가지 다른 요인에 의해 발생한다는 사실을 밝혀냈다.[51]

비정형 항정신병 약물 복용 시 성적 부작용도 보고됐다.[52] 남성 항정신병 약물에서는 성적인 관심을 감소시키고 성적 수행을 손상시키며, 주된 어려움은 사정하지 못하는 것이다.[53] 여성에게는 비정상적인 월경 주기와 불임이 있을 수 있다.[54] 남성과 여성 모두 젖가슴이 커지고 유두에서 액체가 흘러나오는 경우가 있다.[53] 일부 항정신병 약물들에 의해 야기되는 성적 역기능은 프로락틴의 증가의 결과물이다. 설피라이드, 아미술피리드는 물론 리스페르덴, 팔레페리돈(더 작은 범위까지)도 프로락틴의 높은 증가를 유발한다.

2005년 4월 미국 식품의약국(FDA)은 치매 노인 환자 중 비정형 항정신병 약물 복용 위험에 대해 권고와 그에 따른 블랙박스 경고를 발령했다. FDA 권고안은 특히 치매 노인 환자들 사이에서 비정형 항정신병 약물 사용의 감소와 관련이 있었다.[55] 후속 연구 보고서는 치매 환자를 치료하기 위해 재래식 항정신병 약물 및 비정형 항정신병 약물 사용과 관련된 사망위험을 확인했다. 결과적으로, 2008년에 FDA는 고전적인 신경 렙틱스에 대한 블랙박스 경고를 발표했다. 치료 효과에 대한 데이터는 비정형 항정신병 약물에 가장 강하다. 치매 환자의 부작용으로는 사망률 및 뇌혈관 사건 위험 증가뿐 아니라 대사효과, 외사성 증상, 추락, 인지 악화, 심장 부정맥, 폐렴 등이 있다.[56] 기존의 항정신병 약물들은 훨씬 더 큰 안전 위험을 내포할 수 있다. 대체 향정신성 등급(예: 항우울제, 항경련제)의 사용을 뒷받침하는 명확한 효능 증거가 존재하지 않는다.[57]

비정형 항정신병 약물도 무쾌감증을 일으킬 수 있다.[58]

약물유발 강박장애

많은 다른 종류의 약물들은 전에는 증상이 없었던 환자에게 순수한 강박장애를 생성/유도할 수 있다. DSM-5(2013)의 강박장애에 대한 새로운 장에는 이제 약물 유도 강박장애가 구체적으로 포함되어 있다.

올란자핀(Zyprexa)과 같은 비정형 항정신병 약물(제2세대 항정신병 약물)이 환자에게 디노보 OCD를 유도하는 것으로 입증됐다.[59][60][61][62]

지각이상증

모든 비정형 항정신병 약물들은 그들의 패키지 삽입물과 PDR에서 지각 이질병의 가능성에 대해 경고한다. 비정형성 질환을 복용할 때 지각성 이상증의 위험을 진정으로 알 수 있는 것은 불가능한데, 왜냐하면 지각성 이상증은 발병하는 데 수십 년이 걸릴 수 있고 비정형 항정신병 약물들은 모든 장기적 위험을 결정하기 위한 충분한 시간에 걸쳐 검사될 만큼 충분히 오래되지 않았기 때문이다. 비정형물이 지각성 이질병의 위험이 낮은 이유에 대한 한 가지 가설은 일반적인 항정신병 약물보다 훨씬 지용성성이 낮고 D2 수용체와 뇌 조직에서 쉽게 배출되기 때문이다.[63] 대표적인 항정신병 약물들은 D2 수용체에 부착되어 뇌 조직에 축적되어 TD로 이어질 수 있다.[63]

전형적인 항정신병 약물들과 비정형 항정신병 약물들 모두 지각 이질병을 일으킬 수 있다.[64] 한 연구에 따르면, 이 비율은 전형적으로 연간 5.5%인 반면, 비정형 비율은 연 3.9%로 더 낮다고 한다.[64]

신진대사

최근, 신진대사에 대한 우려는 임상의, 환자, FDA에 심각한 관심사가 되고 있다. 2003년, 식품의약품안전청은 비정형 항정신병 약물들을 가진 고혈당증과 당뇨병의 위험에 대한 경고를 포함하도록 모든 비정형 항정신병 약물 제조업체들에게 라벨을 바꾸도록 요구하였다. 또한 모든 비정형은 라벨에 경고를 표시해야 하지만, 일부 증거는 비정형이 체중과 인슐린 민감도에 미치는 영향에서 동일하지 않다는 것을 지적해야 한다.[65] 클루자핀과 올란자핀이 체중증가와 인슐린 민감성 감소에 가장 큰 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타났으며, 리스페리돈과 퀘티아핀이 그 뒤를 잇고 있다는 것이 일반적인 의견이다.[65] 지프라시돈과 아리피프라졸은 체중과 인슐린 저항성에 가장 작은 영향을 미치는 것으로 생각되지만, 이러한 새로운 약물에 대한 임상 경험은 나이든 약물에 비해 그렇게 발달되지 않았다.[65] 이러한 부작용의 메커니즘은 완전히 이해되지는 않지만, 이러한 약물의 여러 가지 약리 작용 사이의 복잡한 상호작용에서 비롯된다고 생각된다. 반면 인슐린 감수성에 대한 그들의 영향 체중(마찬가지로 증가 체중 인슐린 저항할 위험이 있는 알려져 있)에 그들의 영향과 M3recep에 그들의 적대적인 효과의 조합의 결과인 것으로 추정된다 무게에 그에 대한 영향은 주로 H1과 5-HT2C 수용체에 그들의 행동에서 파생된 것으로 생각된다.바위 산그러나 리스페리돈과 그 대사물인 팔레리페리돈, 지프라시돈, 루라시돈, 아리피프라졸, 아세나핀, 일로페리돈과 같은 새로운 약물은 M 수용체에3 임상적으로 미미한 영향을 미치며 인슐린 저항성이 낮은 것으로 보인다. 클로자핀, 올란자핀 및 퀘티아핀(간접적으로 활성대사물, 노르케티아핀을 통해)은 모두 치료 관련 농도에서 M 수용체에3 길항한다.[66]

최근의 증거는 비정형 항정신병 약물들의 대사 효과에서 α1 아드레노셉터와 5-HT2A 수용체의 역할을 시사한다. 그러나 5-HT2A 수용체는 전형적인 항정신병 약물인 이전 항정신병 약물들에 비해 비정형 항정신병 약물들의 치료적 이점에 결정적인 역할을 하는 것으로 여겨진다.[67]

Sernyak과 동료들의 연구는 비정형 항정신병 치료에서 당뇨병의 유병률이 기존 치료법보다 통계적으로 유의하게 높다는 것을 발견했다.[51] 이 연구의 저자들은 카비노프 등이 인과관계라고 제안하는 것은 그 발견이 단지 시간적 연관성을 시사하는 것일 뿐이다.[51] Kabinoff 외 연구진은 다양한 비정형 항정신병 약물 치료 중 인슐린 저항성 위험의 일관성 또는 유의한 차이를 입증하기에 큰 연구의 데이터가 불충분하다고 시사한다.[51]

부작용 비교표

| 비정형 항정신병 약물 부작용 비교 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 일반 이름 | 체중증가 | 대사 효과 | EPS | 높은 프로락틴 | 진정제 | 저혈압 / 직교 | QTc 연장 | 안티에이시 효과 | 기타 부작용 | |||||

| 아미슬프라이드 | + | + | + | ++ | - | - | +++ | - | 발작, 자살 관념 | |||||

| 아리피프라졸 | 0-10%[68] | 0-10%[68] | 10-20%[68] | -[68] | 10-20%[68] | 0-10%[68] | - | - | 발작(0.1~0.3%), 불안, 횡문근융해, 췌장염(<0.1%), 농락증(<1%), 백혈병, 중성미자, 자살이념, 혈관부종(0.1~1%) | |||||

| 아세나핀 | 0-10%[68] | 20%[68] | 0-10%[68] | 0-10%[68] | 10-20%[68] | 0-10%[68] | + | - | 면역과민반응, 혈관부종, 자살이념 | |||||

| 블로난세린 | +/- | - | ++ | + | +/- | - | + | +/- | ||||||

| 클로자핀 | 20-30%[68] | 0-15%[68] | -[68] | -[68] | >30%[68] | 20-30%[68] | + | +++ | 발작(3~5%), 농락증(1.3%), 백혈병, 폐렴, 호흡기 정지, 각도폐쇄 녹내장, 어시노필리아(1%), 혈소판감소증, 스티븐스–존슨 증후군, 심근염, 홍반 다형, 비정상적인 근막염 | |||||

| 일오페리돈 | 0-10%[68] | 0-10%[68] | 0-10%[68] | -[68] | 10-20%[68] | 0-10%[68] | ++ | - | 자살 관념(0.4~1.1%), 싱코프(0.4%) | |||||

| 루라시돈 | -[68] | -[68] | >30%[68] | -[68] | 20-30%[68] | -[68] | + | + | 아그라눌로시증, 발작(<1%), 고농축 혈청 크레아티닌(2~4% | |||||

| 멜페론 | + | + | +/- | - | +/++ | +/++ | ++ | - | 아그라눌로시증, 중성미자, 백혈구증 | |||||

| 올란자핀 | 20-30%[68] | 0-15%[68] | 20-30%[68] | 20-30%[68] | >30%[68] | 0-10%[68] | + | + | 급성 출혈 췌장염, 면역 과민성 반응, 발작(0.9%), 간질증, 자살 관념(0.1~1%) | |||||

| 팔리페리돈 | 0-10%[68] | -[68] | 10-20%[68] | >30%[68] | 20-30%[68] | 0-10%[68] | +/- (7%) | - | 아그라눌로시증, 백혈병, 프리아파스증, 이상증, 고프로락티나혈증, 성기능장애[69] | |||||

| 페로스피론 | ? | ? | >30%[70] | + | + | + | ? | - | 최대 23%[70]의 불면증, CPK 상승[70] 신경성 악성 증후군[70] | |||||

| 쿠에타핀 | 20-30%[68] | 0-15%[68] | 10-20%[68] | -[68] | >30%[68] | 0-10%[68] | ++ | + | 아그라눌로시증, 백혈병, 중성미자(0.3%), 아나필락시스, 발작(0.05~0.5%), 프리아파시즘, 지각이상증(0.1%~5%), 자살이념, 췌장염, 싱코프(0.3~1%) | |||||

| 리무시프라이드[71] | +/- | - | - | -[63] | - | +/- | ? | - | 재생불량성 빈혈의 위험이 있어 시장에서 퇴출되었다. | |||||

| 리스페리돈 | 10-20%[68] | 0-10%[68] | 20-30%[68] | >30%[68] | >30%[68] | 0-10%[68] | + | - | Syncope (1%), pancreatitis, hypothermia, agranulocytosis, leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, hyperprolactinaemia, sexual dysfunction,[69] thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, cerebrovascular incident (<5%), tardive dyskinesia (<5%), priapism, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (<1%), gynecomastia, galactorrhea[72] | |||||

| 서틴돌 | ++ | +/- | - | ++ | - | +++ | +++ | - | - | |||||

| 설피라이드 | + | + | + | +++ | - | +++ | + | - | 황달 | |||||

| 지프라시돈 | 0-10%[68] | 0-10%[68] | 0-10%[68] | -[68] | 20-30%[68] | 0-10%[68] | ++ | - | 싱코페(0.6%), 이상혈증(0.1~2%), 골수 억제, 발작(0.4%), 전치증(0.4%) | |||||

중단

영국 국립공식당은 급성 금단증후군이나 급속한 재발 방지를 위해 항정신병 약물 중단 시 점진적인 금단 조치를 권고하고 있다.[73] 일반적으로 금단 증상으로는 메스꺼움, 구토, 식욕저하 등이 있다.[74] 다른 증상으로는 안절부절못, 땀의 증가, 수면장애 등이 있을 수 있다.[74] 덜 흔하게는 세상이 빙빙 도는 느낌, 무감각한 느낌, 근육통 등이 있을 수 있다.[74] 증상은 일반적으로 짧은 시간이 지나면 해소된다.[74]

항정신병 약물들의 중단이 정신병을 초래할 수 있다는 잠정적인 증거가 있다.[75] 또한 치료 중인 상태가 재발할 수도 있다.[76] 약물치료를 중단했을 때 거의 지각장애가 발생할 수 없다.[74]

약리학

약리역학

비정형 항정신병 약물들은 정신분열증을 효과적으로 치료하기 위해 세로토닌(5-HT), 노레피네프린(α, β), 도파민(D) 수용체와 통합된다.

D2 수용체: 중경로 내 D2 수용체에 대한 고활성 도파민성 활성은 정신분열증(한막, 망상, 편집증)의 양성 증상에 책임이 있다. 항정신병제를 복용한 후 D2 수용체의 길항작용은 전체 뇌에서 일어나 도파민 경로체계 전반에 걸쳐 D2 수용체 길항작용에 의한 다수의 유해한 부작용을 초래한다. 불행히도 D 수용체에2 영향을 미치는 것은 중임벌 경로에서만 가능하지 않다.[77][Stahl AP Explained 1 - 1] 다행히 5-HT2A 수용체 길항작용은 이러한 부작용을 어느 정도 역전시킨다.[Stahl AP Explained 1 - 2] 중간중간 이동 경로에서2 D 도파민성 활성을 감소시키는 것도 무쾌감, 동기부여, 그리고 삶의 경험의 쾌감을 감소시키는 무쾌감 효과를 낳는다. DLPFC와 VMPFC로 가는 중간고사 경로에서, 내생2 D 수용체 도파민 활성은 때때로 조현병에서 낮아서 인지적, 감정적, 그리고 대체로 조현병의 음성 증상을 초래한다. 여기서2 D 수용체 길항작용은 이러한 문제들을 더욱 악화시킨다. 흑연사적 경로에서 D 수용체2 길항작용은 외사적 증세를 일으킨다. 만약 이 반목이 충분히 오래 발생한다면, 비록 항정신병 약물 사용이 중단되더라도, EPS의 증상은 영구적일 수 있다. 결핵균 경로에서 D 수용체2 길항작용은 프로락틴이 상승하게 된다. 프로락틴 수치가 충분히 높아지면 고프로락티나혈증이 발생하여 성기능장애, 체중증가, 뼈의 빠른 제염, 갈락터레아와 아메노레아가 발생할 수 있다.[Stahl AP Explained 1 - 1]

5-HT2A 수용체: 세로토닌이 시냅스 후 5-HT2A 수용체에 방출되면 도파민 뉴런이 억제되어 도파민 방출을 제동하는 역할을 한다.[Stahl AP Explained 1 - 2] 이 브레이크는 도파민 뉴런을 억제하는 5-HT2A 길항제 작용을 통해 교란되어 도파민 분비를 자극한다. 그 결과 도파민은 D2 수용체에서 항정신병 D2 길항작용과 경쟁하여 거기서 길항 결합을 감소시키고 도파민 계통의 여러 경로에서 D 길항작용을2 제거하거나 낮춘다.[Stahl AP Explained 1 - 2] 흑색선 경로에서 EPS를 감소시킨다. 결핵균 경로에서 프로락틴 고도를 감소시키거나 제거한다.[Stahl AP Explained 1 - 3] 5-HT2A 길항작용에 의한 중간중간 경로에서의 도파민 방출은 도파민계의 다른 경로처럼 견고해 보이지 않기 때문에 비정형 항정신병 약물들이 D2 길항작용에 의한 정신분열증의 양성 증상에 대한 유효성의 일부를 여전히 유지하고 있는 이유를 설명한다.[Stahl AP Explained 1 - 3] 5-HT2A 길과 전두엽 피질에서 5-HT2A 길항작용제 입자가 5-HT 수용체를 점유할 때 조현병, 정서적 증상, 인지적 결손 및 이상 증세를 치료하고 감소시킨다.[Stahl AP Explained 1 - 3] 나아가 5-HT2A 수용체 길항작용은 피질 피라미드 세포의 세로토닌적 흥분작용을 차단하여 글루탐산염 방출을 감소시키고, 이는 다시 중음부 경로에서 고활성 도파민성 D2 수용체 활성을 저하시켜 조현병의 양성 증상을 감소시키거나 제거한다.[Stahl AP Explained 1 - 3][78][79]

5-HT1A 수용체 활성화의 일부 효과로는 공격적인 행동/이념 감소,[80] 사회성 증가, 불안 및 우울감 감소 등이 있다.[non-primary source needed] 5-HT2C 활성화는 도파민을 차단하고 노레피네프린 분비를 억제한다. 5-HT2C 수용체 봉쇄는 세로토닌을 증가시켜 뇌내 노레피네프린과 도파민을 방출한다.[77] 그러나 뉴런의 노르에피네프린 재흡수는 지프라시돈과 같은 일부 항정신병 약물들에 의해 급격히 제한된다. 노레피네프린 증가는 혈당 수치인 포도당 수치를 증가시킬 수 있다.[81][82][83] 노레피네프린 증가에 따른 혈당수치 상승은 많은 인간에게 배고픔을 유발하는데, 이것이 노레피네핀이 억제되지 않을 경우 일부 항정신병 약물에서 체중증가가 발생하는 이유다.[84][85][86][87][88] 노레피네프린 억제는 인간의 기분을 안정시킨다.[89] 5-HT6 수용체 길항제들은 인식, 학습, 기억력을 향상시킨다.[90] 5-HT7 수용체는 양극성 조건의 완화에 매우 강력하며 항우울제 효과도 산출한다. 항정신병 약물인 아세나핀,[91] 루라시돈,[92][93] 리스페리돈,[94] 아리피프라졸은[95] 5-HT7 수용체에서 매우 강력하다. H1 수용체에 대한 길항 친화력도 항우울제 효과가 있다. H1 길항작용은 세로토닌과 노르에피네프린 재흡수를 막는다. 히스타민 수치가 증가한 환자들은 세로토닌 수치가 더 낮은 것으로 관찰되었다.[96] 그러나1 H 수용체는 체중 증가와 연관되어 있다. 5-HT1A 수용체에서 부분작용제를 갖는 것은 항정신병 약물에서 체중 증가가 없을 수 있다. 이것은 지프라시돈과 매우 관련이 있지만 QTc 간격이 길어질 위험이 있다.[97][98][99][100] 반면 5-HT3 수용체를 봉쇄하면 QTc 간격이 길어질 위험은 없으나 체중 증가에 대한 위험은 더 커진다.[92] 5-HT3 수용체와의 관계는 클로자핀과 올란자핀에서 볼 수 있는 칼로리 섭취와 포도당을 증가시킨다.[101][102][103] 도파민이 해소되는 또 다른 방법은 D2 수용체와 5-HT1A 수용체 모두에서 작용이 일어나 뇌의 도파민 수치를 정상화하는 것이다. 이것은 할로페리돌과 아리피프라졸에서 발생한다.

든 기쁨과 동기 부여 효과의anhedonic, 손실 D2수용체에서 일부 부품에서는 항정신병(에 불구하고 도파민 자료를 통해mesocortical 경로에서5-HT2A 대립, 것으로 비정형 항정신병), 또는 긍정적인 mood,에 의해 전달되는mesolimbic 경로에서 도파민 부족 혹은 봉쇄에 발생한다.호모od 안정화, 비정형 항정신병 세로토닌 활성에 따른 인지 향상 효과는 비정형 항정신병제의 전반적인 삶의 질에 있어 더 크다. 이는 개인 경험과 비정형 항정신병 약물 사용 간에 가변적인 질문이다.[77]

조건.

억제. 금지: 억제와 반대되는 과정, 생물학적 함수의 켜짐. 릴리스: 적절한 신경전달물질이 시냅스에 결합되어 활성화가 시도되는 시냅스로 방출되도록 한다. 하향 조정 및 상향 조정.

바인딩 프로파일

참고: 달리 명시되지 않는 한 아래 약물은 열거된 수용체에서 길항제/역작용제 역할을 한다.

| 일반 이름[104] | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | 5-HT1A | 5-HT1B | 5-HT2A | 5-HT2C | 5-HT6 | 5-HT7 | α1 | α2 | M1 | M3 | H1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 아미슬프라이드 | - | ++++ | ++++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ++/+ | - | +/- | - | - | - |

| 아리피프라졸 | + | +++(PA) | ++(PA) | + (PA) | ++(PA) | + | +++ | ++(PA) | + | ++(PA) | ++/+ | + | - | - | ++/+ |

| 아세나핀 | +++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++(PA) | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | +++ |

| 블로난세린 | - | ++++ | ++++ | + | - | ? | +++ | + | + | +/- | + (RC) | + (RC) | + | ? | - |

| 브렉스피프라졸 | ++ | ++++(PA) | +++(PA) | ++++ | ++++(PA) | +++ | +++++ | ++(PA) | +++ | ++++ | - | +++ | |||

| 카리프라진 | +++(PA) | ++++(PA) | +++(PA) | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | - | +++ | |||||

| 클로자핀 | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++(PA) | ++/+ | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++++ |

| 일오페리돈 | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | + (PA) | + | +++ | + | ++ | + | ++++ | +++/++ | - | - | +++ |

| 루라시돈 | + | ++++ | ++ | ++ | ++(PA) | ? | ++++ | +/- | ? | ++++ | - | +++/++ | - | - | - |

| 멜페론 | ? | ++ | ++++ | ++ | + (PA) | ? | ++ | + | - | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | - | ++ |

| 올란자핀 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + (PA) | ++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| 팔리페리돈 | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + (PA) | +++/++ | ++++ | + | - | ++++/+++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | +++/++ |

| 쿠에타핀 | + | ++/+ | ++/+ | + | ++/+(PA) | + | + | + | ++ | +++/++ | ++++ | +++/++ | ++ | +++ | ++++ |

| 리스페리돈 | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + (PA) | ++ | ++++ | ++ | - | +++/++ | +++/++ | ++ | - | - | ++ |

| 서틴돌 | ? | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++/+(PA) | ++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++++/+++ | + | - | - | ++/+ |

| 설피라이드 | ? | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 지프라시돈 | +++/++ | +++ | +++ | +++/++ | ++(PA) | ++(PA) | ++++ | ++(PA) | ++ | +++ | +++/++ | ++ | - | - | ++ |

| 조테핀 | +++/++ | +++ | ++++/+++ | +++ | ++(PA) | +++ | ++++ | +++(RC) | ++++ | ++++/+++ | +++ | +++/++ | ++(RC) | ++(RC) | ++++ |

범례:

| 선호도 또는 데이터 없음 | |

| - | 임상적으로 보잘것없는 |

| + | 낮음 |

| ++ | 중간 |

| +++ | 높은 |

| ++++ | 매우 높음 |

| +++++ | 예외적으로 높음 |

| PA | 부분작용제 |

| RC | 복제 랫드 수용체 |

약동학

비정형 항정신병 약물들은 가장 일반적으로 구전으로 투여된다.[53] 항정신병 약물도 주사할 수 있지만 이 방법은 흔하지 않다.[53] 지용성이고 소화관에서 쉽게 흡수되며 혈액뇌장벽과 태반장벽을 쉽게 통과할 수 있다.[53] 일단 뇌에 들어가면 항정신병 약물들은 수용체에 결합하여 시냅스에서 작용한다.[105] 항정신병 약물들은 체내에서 완전히 대사되고 대사물들은 소변으로 배설된다.[106] 이 약들은 반감기가 비교적 길다.[53] 각 약물은 반감기가 다르지만 D2 수용체 점유율은 비정형 항정신병 약물로는 24시간 이내에 떨어져 나가는 반면 일반적인 항정신병 약물에서는 24시간 이상 지속된다.[63] 이것은 약물이 더 빨리 배설되고 더 이상 뇌에서 작용하지 않기 때문에 일반적인 항정신병 약물보다 비정형 항정신병 약물에서 정신질환으로 재발이 더 빨리 일어나는 이유를 설명할 수 있을 것이다.[63] 이러한 약물에 대한 신체적 의존은 매우 드물다.[53] 다만 이 약을 갑자기 끊으면 정신질환 증상, 운동장애, 수면장애 등이 관찰될 수 있다.[53] AAP는 체지방 조직에 저장되어 있다가 서서히 배출되기 때문에 좀처럼 금단 현상이 나타나지 않을 가능성이 있다.[53]

| 이용 가능한 비정형 항정신병 약물들의 약동학 파라미터[107][108][109] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 마약 | 관리[Note 1] 경로 | 반감기(시간1/2 내 t) | 분포량(L/kg 단위의d V) | 단백질 결합 | 배설 | 신진대사에 관여하는 효소 | 생체이용가능성 | 피크 플라즈마 시간(h) | Cmax(ng/mL) |

| 아미슬프라이드 | 구강 | 12 | 5.8 | 16% | 소변(50%), 조류(20%; 70%는 변함없는 약품)[Note 2] | ? | 48% | 두 개의 피크: 1시간 & 3~4시간 후 구강 투여 | 39±3(1시간), 54±4(3-4시간) |

| 아리피프라졸 | 경구, 근육 내(창고 포함) | 75 (활성 대사물의 경우 94) | 4.9 | 99% | 소변(55%), 소변(25%) | CYP2D6 & CYP3A4 | 87%(오랄), 100%(IM) | 3-5 | ? |

| 아세나핀 | 하위 언어 | 24 | 20-25 | 95% | 소변(50%), 조류(40%) | CYP1A2 & UGT1A4 | 35%(하위), <2%(오랄)> | 0.5-1.5 | 4 |

| 블로난세린[110] | 구강 | 10.7(단일 4mg 투여), 12(단일 8mg 투여), 16.2(단일 12mg 투여), 67.9(최신 입찰 투약) | ? | >99.7% | 소변(59%), 배변(30%) | CYP3A4 | 84%(오랄) | <2 | 0.14(단일 4mg 투여), 0.45(단일 8mg 투여), 0.76(단일 12mg 투여), 0.57(입찰 투여) |

| 클로자핀 | 구강 | 8시간(단일 투약), 12시간(매일 투약) | 4.67 | 97% | 소변(50%), 배변(30%) | CYP1A2, CYP3A4, CYP2D6 | 50-60% | 1.5-2.5 | 102-771 |

| 일오페리돈 | 구강 | ? | 1340-2800 | 95% | 소변(45~58%), 배변(20~22%) | CYP2D6 & CYP3A4 | 96% | 2-4 | ? |

| 루라시돈 | 구강 | 18 | 6173 | 99% | 소변 (80%) 소변 (9%) | CYP3A4 | 9-19% | 1-3 | ? |

| 멜페론[111][112] | 구강, 근육내 | 3-4(도덕), 6(IM) | 7–9.9 | 50% | 소변(대사물로서의 70%, 변하지 않는 약물 5~10.4%) | ? | 65%(태블릿), 87%(IM), 54%(도덕 시럽) | 0.5–3 | 75–324 (마약 투약) |

| 올란자핀 | 경구, 근육 내(창고 포함) | 30 | 1000 | 93% | 소변(57%), 배변(30%) | CYP1A2, CYP2D6 | >60% | 6 (오랄) | ? |

| 팔리페리돈 | 경구, 근육 내(창고 포함) | 23 (오랄) | 390-487 | 74% | 소변(80%), 배변(11%) | CYP2D6, CYP3A4 | 28% | 24 (오랄) | ? |

| 페로스피론[70] | 구강 | ? | ? | 92% | 소변(변동되지 않은 약물로 0.4%) | ? | ? | 1.5 | 1.9-5.7 |

| 쿠에타핀 | 구강 | 6 (IR), 7 (XR) | 6-14 | 83% | 소변(73%), 배변(20%) | CYP3A4 | 100% | 1.5(IR), 6(XR) | ? |

| 리스페리돈 | 경구, 근육 내(창고 포함) | 3(전자파)(도덕), 20(PM)(도덕) | 1-2 | 90% 77%(철분) | 소변(70%), 배변(14%) | CYP2D6 | 70% | 3(EM), 17(PM) | ? |

| 서틴돌 | 구강 | 72 (55-90) | 20 | 99.5% | 소변(4%), 조류(46~56%) | CYP2D6 | 74% | 10 | ? |

| 지프라시돈 | 구강, 근육내 | 7 (도덕) | 1.5 | 99% | 소변(66%), 소변(20%) | CYP3A4 & CYP1A2 | 60%(오랄), 100%(IM) | 6-8 | ? |

| 조테핀[113][114] | 구강 | 13.7-15.9 | 10-109 | 97% | 소변(17%) | ? | 7-13% | ? | ? |

| 사용된 두문자어: | |||||||||

| 약물 | 브랜드명 | 클래스 | 차량 | 복용량 | Tmax | t1/2 싱글 | t1/2 복수 | logPc | 참조 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 아리피프라졸라우록실 | 아리스타다 | 비정형적 | 물a | 441-1064mg/4~8주 | 24-35일 | ? | 54~57일 | 7.9–10.0 | |

| 아리피프라졸단수화물 | 아빌리피 마인테나 | 비정형적 | 물a | 300~400mg/4주 | 7일 | ? | 30-47일 | 4.9–5.2 | |

| 브롬페리돌 데카노산염 | 임프로멘 데카노아스 | 전형적 | 참기름 | 40–300mg/4주 | 3-9일 | ? | 21~25일 | 7.9 | [115] |

| 클로펜티졸 데카노산염 | 소르디놀 디포 | 전형적 | 비스콜레오b | 50-600mg/1-4주 | 4-7일 | ? | 19일 | 9.0 | [116] |

| 플루펜티졸 데카노레이트 | 디픽솔 | 전형적 | 비스콜레오b | 10–200 mg/2–4주 | 4-10일 | 8일 | 17일 | 7.2–9.2 | [116][117] |

| 플루페나진데카노산염 | 프로릭신 데카노아테 | 전형적 | 참기름 | 12.5–100 mg/2–5주 | 1-2일 | 1-10일 | 14~100일 | 7.2–9.0 | [118][119][120] |

| 플루페나진 에난산염 | 프로릭신 에난테이트 | 전형적 | 참기름 | 12.5–100 mg/1–4주 | 2-3일 | 4일 | ? | 6.4–7.4 | [119] |

| 플루스피릴렌 | 이맵, 레젯틴 | 전형적 | 물a | 2-12mg/1주 | 1~8일 | 7일 | ? | 5.2–5.8 | [121] |

| 할로페리돌 데카노네이트 | 할돌 데카노아테 | 전형적 | 참기름 | 20–400 mg/2–4주 | 3-9일 | 18-21일 | 7.2–7.9 | [122][123] | |

| 올란자핀파모테 | 자이프렉사 렐프레브 | 비정형적 | 물a | 150–405 mg/2–4주 | 7일 | ? | 30일 | – | |

| 옥시프로테핀 디라노이트 | 메클로핀 | 전형적 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 8.5–8.7 | |

| 팔리페리돈팔미테이트 | 인베가 수스텐나 | 비정형적 | 물a | 39–819 mg/4–12주 | 13~33일 | 25일-115일 | ? | 8.1–10.1 | |

| 페르페나진데카노산염 | 트릴라폰 데카노아트 | 전형적 | 참기름 | 50–200 mg/2–4주 | ? | ? | 27일 | 8.9 | |

| 페르페나진 에난테이트 | 트릴라폰 에난테이트 | 전형적 | 참기름 | 25~200mg/2주 | 2-3일 | ? | 4-7일 | 6.4–7.2 | [124] |

| 피포티아진팔미테이트 | 피포르틸롱구름 | 전형적 | 비스콜레오b | 25-400mg/4주 | 9~10일 | ? | 14-21일 | 8.5–11.6 | [117] |

| 피포티아진 언실렌산염 | 피포르틸 미디엄 | 전형적 | 참기름 | 100–200mg/2주 | ? | ? | ? | 8.4 | |

| 리스페리돈 | 리스페르달 콘스타 | 비정형적 | 마이크로스피어 | 12.5~75mg/2주 | 21일 | ? | 3-6일 | – | |

| 주클루펜티솔 아세테이트 | 클로픽솔 지압효소 | 전형적 | 비스콜레오b | 50–200 mg/1–3일 | 1-2일 | 1-2일 | 4.7–4.9 | ||

| 주클루코펜티졸 데카노산염 | 클로픽솔 디포 | 전형적 | 비스콜레오b | 50–800 mg/2–4주 | 4-9일 | ? | 11-21일 | 7.5–9.0 | |

| 주: 모든 것은 근육내 주입에 의한 것이다. 각주: = 마이크로크리스탈린 또는 나노크리스탈린 수성 서스펜션. b = 저점도의 식물성 오일(특히 중간 체인 트리글리세라이드를 첨가한 분율 코코넛 오일). c = 예측, PubChem and DrugBank에서. 출처: 주: 템플릿을 참조하십시오. | |||||||||

역사

최초의 주요 신경안정제 또는 항정신병 약물인 클로로프로마진(토라진)은 1951년 발견돼 곧바로 임상 실전에 도입됐다. 비정형 항정신병 약물인 클로자핀(클로자릴)이 약물에 의한 아그레망토시스(agranulocytosis)에 대한 우려로 낙마했다. 치료 저항성 정신분열증의 효과와 부작용 감시 시스템 개발 연구에 이어 클로자핀이 생존 가능한 항정신병약으로 재조명됐다. 바커(2003)에 따르면 가장 많이 수용되는 비정형 약물 3종은 클로자핀, 리스페리돈, 올란자핀이다. 하지만, 그는 계속해서 클로자핀은 다른 약물이 실패할 때, 대개 최후의 수단이라고 설명한다. 클로자핀은 아그레망토시스(백혈구 감소)를 유발할 수 있어 환자에 대한 혈액 감시가 필요하다. 치료 내성 정신분열증에 대한 클로자핀의 효과에도 불구하고, 부작용 프로파일이 보다 유리한 에이전트들은 널리 사용되도록 노력되었다. 1990년대에는 2000년대 초반에 이어 올란자핀, 리스페리돈, 퀘티아핀이 도입되었다. 비정형 항정신성 팔리페리돈은 2006년 말 FDA의 승인을 받았다.[citation needed]

비정형 항정신병 약물들은 임상의사들에게 호감을 갖고 있으며, 현재 정신분열증의 일차 치료제로 여겨지고 있으며, 점차 전형적인 항정신병 약물들을 대체하고 있다. 과거에 대부분의 연구자들은 비정형 항정신병 약물의 정의적 특성은 외사 부작용 [125]발생률 감소와 지속적인 프로락틴 상승의 부재라는 데 동의했다.[63]

그 용어는 여전히 부정확할 수 있다. 비정형성(atypicality)의 정의는 외삽성 부작용의 부재를 근거로 하였으나, 비정형 항정신병 약물들이 (일반적인 항정신병 약물보다 적은 정도까지는) 여전히 이러한 효과를 유도할 수 있다는 것이 지금 명확히 이해되고 있다.[126] 최근의 문헌은 특정 약리학적 작용에 더 초점을 맞추고, 에이전트를 "일반적" 또는 "비정상적"으로 분류하는 것에는 덜 초점을 맞추고 있다. 전형적인 항정신병 약물들과 비정형 항정신병 약물들 사이에는 명확한 구분선이 없기 때문에 그 작용에 따른 분류는 어렵다.[63]

보다 최근의 연구는 2세대 항정신병 약물들이 1세대 일반적인 항정신병 약물들보다 우월하다는 개념에 의문을 제기하고 있다. 맨체스터 대학의 연구원들은 삶의 질을 평가하기 위해 여러 가지 매개 변수를 사용하여 전형적인 항정신병 약물들이 비정형 항정신병 약물보다 나쁘지 않다는 것을 발견했다. 이 연구는 영국의 국민건강서비스(NHS)의 자금 지원을 받았다.[127] 각 약물(1세대 또는 2세대)은 바람직한 부작용과 부작용에 대한 고유한 프로파일을 가지고 있기 때문에 신경정신병리학자는 증상 프로파일에 근거하여 구("일반" 또는 1세대) 또는 최신("비정상" 또는 2세대) 항정신병리학적 약물 중 하나를 단독으로 또는 다른 약물과 조합하여 권할 수 있다.e 패턴 및 개별 환자의 부작용 기록.

사회와 문화

2007년 5월과 2008년 4월 사이에 550만 명의 미국인이 비정형 항정신병 약물에 대한 처방전을 최소한 한 개 이상 채웠다.[43] 65세 미만 환자의 경우 정신분열증이나 조울증 치료를 위해 비정형 항정신병제를 처방받은 환자가 71%로 65세 이상 환자의 38%로 줄었다.[43]

규제현황

| 2013년[update] 7월 기준 2세대 항정신병 약물(SGA) 규제 현황 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 일반명 | 미국 FDA 승인 | 캐나다 HPFB 승인[128] | 호주. TGA 승인[129] | 유럽 EMA 승인[130] | 일본. PMDA 승인[131] | 영국 MHRA 승인[132][133][130] | ||||||||

| 아미슬프라이드 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 네 | (일부 회원) | 아니요. | 네 | ||||||||

| 아리피프라졸 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | ||||||||

| 아세나핀 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | ||||||||

| 블로난세린 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 네 | 아니요. | ||||||||

| 카르피프라민 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 네 | 아니요. | ||||||||

| 클로카프라민 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 네 | 아니요. | ||||||||

| 클로자핀 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | ||||||||

| 일오페리돈 | 네 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 거절된 | 아니요. | 아니요. | ||||||||

| 루라시돈 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 아니요. | 네 | ||||||||

| 멜페론 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | ||||||||

| 모사프라민 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 네 | 아니요. | ||||||||

| 올란자핀 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | ||||||||

| 팔리페리돈 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | ||||||||

| 페로스피론 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 네 | 아니요. | ||||||||

| 피마반세린 | 네 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 조사 | 아니요. | (아니오) | ||||||||

| 쿠에타핀 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | ||||||||

| 리무시프라이드 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 인출됨 | 아니요. | 아니요. | ||||||||

| 리스페리돈 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | 네 | ||||||||

| 서틴돌 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 네 | 아니요. | 네 | ||||||||

| 설피라이드 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 네 | 네 | 네 | ||||||||

| 지프라시돈 | 네 | 네 | 네 | (일부 회원) | 아니요. | 네 | ||||||||

| 조테핀 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 네 | 아니요. | ||||||||

메모들

Stahl: AP 설명 1

참조

- ^ Miyake, N; Miyamoto, S; Jarskog, LF (October 2012). "New serotonin/dopamine antagonists for the treatment of schizophrenia: are we making real progress?". Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 6 (3): 122–33. doi:10.3371/CSRP.6.3.4. PMID 23006237.

- ^ Sadock, Benjamin J. (2014). Kaplan & Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. Sadock, Virginia A.,, Ruiz, Pedro (11th ed.). Philadelphia. p. 318. ISBN 978-1-60913-971-1. OCLC 881019573.

- ^ a b c d Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM (January 2009). "Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis". Lancet. 373 (9657): 31–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. PMID 19058842. S2CID 1071537.

- ^ a b c Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- ^ "A roadmap to key pharmacologic principles in using antipsychotics". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 9 (6): 444–54. 2007. doi:10.4088/PCC.v09n0607. PMC 2139919. PMID 18185824.

- ^ Tyrer P, Kendall T (January 2009). "The spurious advance of antipsychotic drug therapy". Lancet. 373 (9657): 4–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61765-1. PMID 19058841. S2CID 19951248.

- ^ "Respiridone". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ Maher AR, Maglione M, Bagley S, Suttorp M, Hu JH, Ewing B, et al. (September 2011). "Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 306 (12): 1359–69. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1360. PMID 21954480.

- ^ American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (April 2012). "American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 60 (4): 616–31. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. PMC 3571677. PMID 22376048.

- ^ "Schizophrenia: Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care" (PDF). Gaskell and the British Psychological Society. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. March 25, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ Aleman A, Lincoln TM, Bruggeman R, Melle I, Arends J, Arango C, Knegtering H (August 2017). "Treatment of negative symptoms: Where do we stand, and where do we go?". Schizophrenia Research. 186: 55–62. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.015. PMID 27293137. S2CID 4907333.

- ^ Fusar-Poli P, Papanastasiou E, Stahl D, Rocchetti M, Carpenter W, Shergill S, McGuire P (July 2015). "Treatments of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: Meta-Analysis of 168 Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 41 (4): 892–9. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu170. PMC 4466178. PMID 25528757.

- ^ Murray RM, Quattrone D, Natesan S, van Os J, Nordentoft M, Howes O, et al. (November 2016). "Should psychiatrists be more cautious about the long-term prophylactic use of antipsychotics?". The British Journal of Psychiatry (Submitted manuscript). 209 (5): 361–365. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.116.182683. PMID 27802977.

- ^ van Os J, Kapur S (August 2009). "Schizophrenia". Lancet. 374 (9690): 635–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. PMID 19700006. S2CID 208792724.

- ^ Kane JM, Correll CU (2010). "Pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 12 (3): 345–57. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.3/jkane. PMC 3085113. PMID 20954430.

- ^ Schultz SH, North SW, Shields CG (June 2007). "Schizophrenia: a review". American Family Physician. 75 (12): 1821–9. PMID 17619525.

- ^ Smith T, Weston C, Lieberman J (August 2010). "Schizophrenia (maintenance treatment)". American Family Physician. 82 (4): 338–9. PMID 20704164.

- ^ Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, Kisely S (November 2016). "Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 209 (5): 385–392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261. PMID 27388573.

- ^ Robinson, Delbert G.; Gallego, Juan A.; John, Majnu; Petrides, Georgios; Hassoun, Youssef; Zhang, Jian-Ping; Lopez, Leonardo; Braga, Raphael J.; Sevy, Serge M.; Addington, Jean; Kellner, Charles H. (2015). "A Randomized Comparison of Aripiprazole and Risperidone for the Acute Treatment of First-Episode Schizophrenia and Related Disorders: 3-Month Outcomes". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 41 (6): 1227–1236. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbv125. ISSN 1745-1701. PMC 4601722. PMID 26338693.

- ^ Gómez-Revuelta, Marcos; Pelayo-Terán, José María; Juncal-Ruiz, María; Vázquez-Bourgon, Javier; Suárez-Pinilla, Paula; Romero-Jiménez, Rodrigo; Setién Suero, Esther; Ayesa-Arriola, Rosa; Crespo-Facorro, Benedicto (April 23, 2020). "Antipsychotic Treatment Effectiveness in First Episode of Psychosis: PAFIP 3-Year Follow-Up Randomized Clinical Trials Comparing Haloperidol, Olanzapine, Risperidone, Aripiprazole, Quetiapine, and Ziprasidone". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 23 (4): 217–229. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyaa004. ISSN 1469-5111. PMC 7177160. PMID 31974576.

- ^ Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, Moloney RM, Stafford RS (February 2011). "Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995-2008". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 20 (2): 177–84. doi:10.1002/pds.2082. PMC 3069498. PMID 21254289.

- ^ Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, Bebbington P (December 2000). "Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis". BMJ. 321 (7273): 1371–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1371. PMC 27538. PMID 11099280.

- ^ Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, et al. (September 2005). "Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (12): 1209–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051688. PMID 16172203.

- ^ Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Davis SM, Rosenheck RA, et al. (April 2006). "Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia following discontinuation of a previous atypical antipsychotic". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (4): 611–22. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.611. PMID 16585435.

- ^ Voruganti LP, Baker LK, Awad AG (March 2008). "New generation antipsychotic drugs and compliance behaviour". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 21 (2): 133–9. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f52851. PMID 18332660. S2CID 34935.

- ^ Paczynski RP, Alexander GC, Chinchilli VM, Kruszewski SP (January 2012). "Quality of evidence in drug compendia supporting off-label use of typical and atypical antipsychotic medications". The International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. 24 (3): 137–46. doi:10.3233/JRS-2012-0567. PMID 22936056.

- ^ Owens DC (2008). "How CATIE brought us back to Kansas: A critical re-evaluation of the concept of atypical antipsychotics and their place in the treatment of schizophrenia". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 14: 17–28. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.107.003970.

- ^ Fischer-Barnicol D, Lanquillon S, Haen E, Zofel P, Koch HJ, Dose M, Klein HE (2008). "Typical and atypical antipsychotics--the misleading dichotomy. Results from the Working Group 'Drugs in Psychiatry' (AGATE)". Neuropsychobiology. 57 (1–2): 80–7. doi:10.1159/000135641. PMID 18515977. S2CID 2669203.

- ^ Whitaker R (2010). Anatomy of an Epidemic. Crown. p. 303. ISBN 978-0307452412.

- ^ a b c Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S (2012). The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines (12th ed.). Informa Healthcare. pp. 12–152, 173–196, 222–235.

- ^ Soreff S, McInnes LA, Ahmed I, Talavera F (August 5, 2013). "Bipolar Affective Disorder Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Post RM, Keck P (July 30, 2013). "Bipolar Disorder in adults: Maintenance treatment". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer Health. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Komossa K, Depping AM, Gaudchau A, Kissling W, Leucht S (December 2010). "Second-generation antipsychotics for major depressive disorder and dysthymia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008121. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008121.pub2. PMID 21154393.

- ^ a b Spielmans GI, Berman MI, Linardatos E, Rosenlicht NZ, Perry A, Tsai AC (2013). "Adjunctive atypical antipsychotic treatment for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of depression, quality of life, and safety outcomes". PLOS Medicine. 10 (3): e1001403. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001403. PMC 3595214. PMID 23554581.

- ^ Nelson JC, Papakostas GI (September 2009). "Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 166 (9): 980–91. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030312. PMID 19687129.

- ^ Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and. "Drug Approvals and Databases - Drug Trials Snapshots: REXULTI for the treatment of major depressive disorder". www.fda.gov. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ Papakostas GI, Fava M, Baer L, Swee MB, Jaeger A, Bobo WV, Shelton RC (December 2015). "Ziprasidone Augmentation of Escitalopram for Major Depressive Disorder: Efficacy Results From a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 172 (12): 1251–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14101251. PMC 4843798. PMID 26085041.

- ^ Maneeton N, Maneeton B, Srisurapanont M, Martin SD (September 2012). "Quetiapine monotherapy in acute phase for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials". BMC Psychiatry. 12: 160. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-160. PMC 3549283. PMID 23017200.

- ^ a b Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DEARKDEX System (Internet) [commited 2013년 10월 10일] 그린우드 빌리지, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- ^ Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, Schatzberg A, Andersen SW, Van Campen LE, et al. (August 2004). "A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 24 (4): 365–73. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000130557.08996.7a. PMID 15232326. S2CID 36295165.

- ^ a b Roberts RJ, Lohano KK, El-Mallakh RS (September 2016). "Antipsychotics as antidepressants". Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 8 (3): 179–88. doi:10.1111/appy.12186. PMID 25963405. S2CID 24264818.

- ^ "U.S. FDA Approves Otsuka and Lundbeck's REXULTI (Brexpiprazole) as Adjunctive Treatment for Adults with Major Depressive Disorder and as a Treatment for Adults with Schizophrenia Discover Otsuka". Otsuka in the U.S. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Cascade E, Kalali AH, Cummings JL (July 2008). "Use of atypical antipsychotics in the elderly". Psychiatry. 5 (7): 28–31. PMC 2695730. PMID 19727265.

- ^ a b Ventimiglia J, Kalali AH, Vahia IV, Jeste DV (November 2010). "An analysis of the intended use of atypical antipsychotics in dementia". Psychiatry. 7 (11): 14–7. PMC 3010964. PMID 21191528.

- ^ Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, Rendell J, Brown R, Stockton S, et al. (October 2011). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 378 (9799): 1306–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8. PMID 21851976. S2CID 25512763.

- ^ Bishara D, Taylor D (2009). "Asenapine monotherapy in the acute treatment of both schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 5: 483–90. doi:10.2147/ndt.s5742. PMC 2762364. PMID 19851515.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor DM, Cornelius V, Smith L, Young AH (December 2014). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of drug treatments for bipolar depression: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 130 (6): 452–69. doi:10.1111/acps.12343. PMID 25283309. S2CID 23324764.

- ^ Szegedi A, Zhao J, van Willigenburg A, Nations KR, Mackle M, Panagides J (June 2011). "Effects of asenapine on depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes: a post hoc analysis of two 3-week clinical trials". BMC Psychiatry. 11: 101. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-101. PMC 3152513. PMID 21689438.

- ^ Kishi T, Iwata N (September 2013). "Efficacy and tolerability of perospirone in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". CNS Drugs. 27 (9): 731–41. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0085-7. PMID 23812802. S2CID 11543666.

- ^ Stroup TS, Marder S, Stein MB (October 23, 2013). "Pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia: Acute and maintenance phase treatment". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Kabinoff GS, Toalson PA, Healey KM, McGuire HC, Hay DP (February 2003). "Metabolic Issues With Atypical Antipsychotics in Primary Care: Dispelling the Myths". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 5 (1): 6–14. doi:10.4088/PCC.v05n0103. PMC 353028. PMID 15156241.

- ^ Uçok A, Gaebel W (February 2008). "Side effects of atypical antipsychotics: a brief overview". World Psychiatry. 7 (1): 58–62. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00154.x. PMC 2327229. PMID 18458771.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McKim W (2007). Antipsychotics in Drugs and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Pharmacology. Upper Saddle River, NJ.: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 241–60.

- ^ McKim W (2007). Psychomotor Stimulants in Drugs and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Pharmacology. Upper Saddle River, NJ.: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 241–60.

- ^ Dorsey ER, Rabbani A, Gallagher SA, Conti RM, Alexander GC (January 2010). "Impact of FDA black box advisory on antipsychotic medication use". Archives of Internal Medicine. 170 (1): 96–103. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.456. PMC 4598075. PMID 20065205.

- ^ Gerhard T, Huybrechts K, Olfson M, Schneeweiss S, Bobo WV, Doraiswamy PM, et al. (July 2014). "Comparative mortality risks of antipsychotic medications in community-dwelling older adults". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 205 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.122499. PMID 23929443.

- ^ Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG (September 2012). "Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: managing safety concerns". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 169 (9): 900–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030342. PMC 3516138. PMID 22952071.

- ^ "Anhedonia: Symptoms, Treatment, and More". Healthline. July 5, 2016.

- ^ Alevizos, Basil; Papageorgiou, Charalambos; Christodoulou, George N. (September 1, 2004). "Obsessive-compulsive symptoms with olanzapine". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 7 (3): 375–377. doi:10.1017/S1461145704004456. ISSN 1461-1457. PMID 15231024.

- ^ Kulkarni, Gajanan; Narayanaswamy, Janardhanan C.; Math, Suresh Bada (January 1, 2012). "Olanzapine induced de-novo obsessive compulsive disorder in a patient with schizophrenia". Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 44 (5): 649–650. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.100406. ISSN 0253-7613. PMC 3480803. PMID 23112432.

- ^ Lykouras, L.; Zervas, I. M.; Gournellis, R.; Malliori, M.; Rabavilas, A. (September 1, 2000). "Olanzapine and obsessive-compulsive symptoms". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 10 (5): 385–387. doi:10.1016/s0924-977x(00)00096-1. ISSN 0924-977X. PMID 10974610. S2CID 276209.

- ^ Schirmbeck, Frederike; Zink, Mathias (March 1, 2012). "Clozapine-Induced Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Critical Review". Current Neuropharmacology. 10 (1): 88–95. doi:10.2174/157015912799362724. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 3286851. PMID 22942882.

- ^ a b c d e f g Seeman P (February 2002). "Atypical antipsychotics: mechanism of action". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 47 (1): 27–38. doi:10.1177/070674370204700106. PMID 11873706.

- ^ a b Correll CU, Schenk EM (March 2008). "Tardive dyskinesia and new antipsychotics". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 21 (2): 151–6. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f53132. PMID 18332662. S2CID 37288246.

- ^ a b c "Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes". Diabetes Care. 27 (2): 596–601. February 2004. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.2.596. PMID 14747245.

- ^ Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). McGraw Hill Professional. pp. 417–455.

- ^ Guenette MD, Giacca A, Hahn M, Teo C, Lam L, Chintoh A, et al. (May 2013). "Atypical antipsychotics and effects of adrenergic and serotonergic receptor binding on insulin secretion in-vivo: an animal model". Schizophrenia Research. 146 (1–3): 162–9. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.023. PMID 23499243. S2CID 43719333.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh "Comparison of Common Side Effects of Second Generation Atypical Antipsychotics". Facts & Comparisons. Wolters Kluwer Health. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ a b Park YW, Kim Y, Lee JH (December 2012). "Antipsychotic-induced sexual dysfunction and its management". The World Journal of Men's Health. 30 (3): 153–9. doi:10.5534/wjmh.2012.30.3.153. PMC 3623530. PMID 23596605.

- ^ a b c d e Onrust SV, McClellan K (2001). "Perospirone". CNS Drugs. 15 (4): 329–37, discussion 338. doi:10.2165/00023210-200115040-00006. PMID 11463136.

- ^ Holm AC, Edsman I, Lundberg T, Odlind B (June 1993). "Tolerability of remoxipride in the long term treatment of schizophrenia. An overview". Drug Safety. 8 (6): 445–56. doi:10.2165/00002018-199308060-00005. PMID 8329149. S2CID 43855244.

- ^ "Risperdal, gynecomastia and galactorrhea in adolescent males". Allnurses.com. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- ^ a b c d e Haddad P, Haddad PM, Dursun S, Deakin B (2004). Adverse Syndromes and Psychiatric Drugs: A Clinical Guide. OUP Oxford. pp. 207–216. ISBN 9780198527480.

- ^ Moncrieff J (July 2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655. S2CID 6267180.

- ^ Sacchetti E, Vita A, Siracusano A, Fleischhacker W (2013). Adherence to Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 85. ISBN 9788847026797.

- ^ a b c d e f Stahl S. Antipsychotics Explained 1 (PDF). University Psychiatry. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Stephen M. Stahl (March 27, 2008). Antipsychotics and Mood Stabilizers: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology . p. 105. ISBN 9780521886642. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Egerton A, Ahmad R, Hirani E, Grasby PM (November 2008). "Modulation of striatal dopamine release by 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor antagonists: [11C]raclopride PET studies in the rat". Psychopharmacology. 200 (4): 487–96. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1226-4. PMID 18597077. S2CID 11800154.

- ^ de Boer SF, Koolhaas JM (December 2005). "5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor agonists and aggression: a pharmacological challenge of the serotonin deficiency hypothesis". European Journal of Pharmacology. 526 (1–3): 125–39. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.065. PMID 16310183.

- ^ "norepinephrine". Cardiosmart.org. December 15, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Veves A, Malik RA (February 1, 2008). Diabetic Neuropathy: Clinical Management. p. 401. ISBN 9781597453110. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "Epinephrine and Norepinephrine". Boundless.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "Cariprazine - Side Effects, Uses, Dosage, Overdose, Pregnancy, Alcohol". RxWiki.com. September 17, 2015. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "INVEGA Side Effects - Schizophrenia Treatment – INVEGA (paliperidone)". Invega.com. May 17, 2016. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "Diabetes Update: Hunger is a Symptom". Diabetesupdate.blogspot.se. August 8, 2007. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "High & Low Blood Sugar". Healthvermont.gov. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "REXULTI (brexpiprazole) Important Safety Information". Rexulti.com. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Stephen M. Stahl (March 27, 2008). Antipsychotics and Mood Stabilizers: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology . p. 172. ISBN 9780521886642. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ King MV, Marsden CA, Fone KC (September 2008). "A role for the 5-HT(1A), 5-HT4 and 5-HT6 receptors in learning and memory". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 29 (9): 482–92. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2008.07.001. PMID 19086256.

- ^ Shahid M, Walker GB, Zorn SH, Wong EH (January 2009). "Asenapine: a novel psychopharmacologic agent with a unique human receptor signature". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 23 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1177/0269881107082944. PMID 18308814. S2CID 206489515.

- ^ a b "Pharmcology Reviews : 200603" (PDF). Accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Ishibashi T, Horisawa T, Tokuda K, Ishiyama T, Ogasa M, Tagashira R, et al. (July 2010). "Pharmacological profile of lurasidone, a novel antipsychotic agent with potent 5-hydroxytryptamine 7 (5-HT7) and 5-HT1A receptor activity". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 334 (1): 171–81. doi:10.1124/jpet.110.167346. PMID 20404009. S2CID 12893717.

- ^ 국립 정신 건강 연구소. PDSD Ki 데이터베이스(인터넷) [2013년 8월 10일자로 지정됨] 채플힐(NC): 노스캐롤라이나 대학교. 1998-2013. 이용 가능 : CS1 maint: 제목으로 보관된 사본(링크)

- ^ Hemmings HC, Egan TD (2013). Pharmacology and Physiology for Anesthesia: Foundations and Clinical . p. 209. ISBN 978-1437716795. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Margaret Jordan Halter (March 12, 2014). Varcarolis' Foundations of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing: A Clinical . p. 61. ISBN 9781455728886. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Tasman A, Kay J, First MB, Lieberman JA, Riba M (March 30, 2015). Psychiatry, 2 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-84547-9.

- ^ "FDA : Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee : Briefing Document for ZELDOX CAPSULES (Ziprasidone HCl)" (PDF). Fda.gov. July 19, 2000. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Wouters W, Tulp MT, Bevan P (May 1988). "Flesinoxan lowers blood pressure and heart rate in cats via 5-HT1A receptors". European Journal of Pharmacology. 149 (3): 213–23. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(88)90651-6. PMID 2842163.

- ^ Horiuchi J, McDowall LM, Dampney RA (November 2008). "Role of 5-HT(1A) receptors in the lower brainstem on the cardiovascular response to dorsomedial hypothalamus activation". Autonomic Neuroscience. 142 (1–2): 71–6. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2008.06.004. PMID 18667366. S2CID 20878941.

- ^ Weber S, Volynets V, Kanuri G, Bergheim I, Bischoff SC (December 2009). "Treatment with the 5-HT3 antagonist tropisetron modulates glucose-induced obesity in mice". International Journal of Obesity. 33 (12): 1339–47. doi:10.1038/ijo.2009.191. PMID 19823183.

- ^ Gobbi G, Janiri L (December 1999). "Clozapine blocks dopamine, 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 responses in the medial prefrontal cortex: an in vivo microiontophoretic study". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 10 (1): 43–9. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(99)00055-3. PMID 10647096. S2CID 24251712.

- ^ Navari RM (January 2014). "Olanzapine for the prevention and treatment of chronic nausea and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting". European Journal of Pharmacology. 722: 180–6. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.08.048. PMID 24157985.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ 컬페퍼, 2007년[verification needed]

- ^ 맥킴, 2007년[verification needed]

- ^ "Medscape Multispecialty – Home page". WebMD. Retrieved November 27, 2013.[전체 인용 필요]

- ^ "Therapeutic Goods Administration – Home page". Department of Health (Australia). Retrieved November 27, 2013.[전체 인용 필요]

- ^ "Daily Med – Home page". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved November 27, 2013.[전체 인용 필요]

- ^ Deeks ED, Keating GM (January 2010). "Blonanserin: a review of its use in the management of schizophrenia". CNS Drugs. 24 (1): 65–84. doi:10.2165/11202620-000000000-00000. PMID 20030420.

- ^ 제품 정보: 은어판(R), 멜페론하이드로클로로이드. Knoll Deutschland GmbH, Ludwigshafen, 1995.

- ^ Borgström L, Larsson H, Molander L (1982). "Pharmacokinetics of parenteral and oral melperone in man". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 23 (2): 173–6. doi:10.1007/BF00545974. PMID 7140807. S2CID 36697288.

- ^ 제품 정보: Nipolept(R), Zotepine. 클링제마 GmbH, 1996년 뮌헨.

- ^ Tanaka O, Kondo T, Otani K, Yasui N, Tokinaga N, Kaneko S (February 1998). "Single oral dose kinetics of zotepine and its relationship to prolactin response and side effects". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 20 (1): 117–9. doi:10.1097/00007691-199802000-00021. PMID 9485566.

- ^ Parent M, Toussaint C, Gilson H (1983). "Long-term treatment of chronic psychotics with bromperidol decanoate: clinical and pharmacokinetic evaluation". Current Therapeutic Research. 34 (1): 1–6.

- ^ a b Jørgensen A, Overø KF (1980). "Clopenthixol and flupenthixol depot preparations in outpatient schizophrenics. III. Serum levels". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 279: 41–54. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb07082.x. PMID 6931472.

- ^ a b Reynolds JE (1993). "Anxiolytic sedatives, hypnotics and neuroleptics.". Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia (30th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 364–623.

- ^ Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW, Davis CM, Richards A, Seidel DR (May 1984). "Future of depot neuroleptic therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic approaches". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 45 (5 Pt 2): 50–9. PMID 6143748.

- ^ a b Curry SH, Whelpton R, de Schepper PJ, Vranckx S, Schiff AA (April 1979). "Kinetics of fluphenazine after fluphenazine dihydrochloride, enanthate and decanoate administration to man". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 7 (4): 325–31. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb00941.x. PMC 1429660. PMID 444352.

- ^ Young D, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW, Garcia N (1984). Explaining the pharmacokinetics of fluphenazine through computer simulations. (Abstract.). 19th Annual Midyear Clinical Meeting of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Dallas, Texas.

- ^ Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ, Schellekens KH, Lenaerts FM, Verbruggen FJ, van Nueten JM, et al. (November 1970). "The pharmacology of fluspirilene (R 6218), a potent, long-acting and injectable neuroleptic drug". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 20 (11): 1689–98. PMID 4992598.

- ^ Beresford R, Ward A (January 1987). "Haloperidol decanoate. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in psychosis". Drugs. 33 (1): 31–49. doi:10.2165/00003495-198733010-00002. PMID 3545764.

- ^ Reyntigens AJ, Heykants JJ, Woestenborghs RJ, Gelders YG, Aerts TJ (1982). "Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol decanoate. A 2-year follow-up". International Pharmacopsychiatry. 17 (4): 238–46. doi:10.1159/000468580. PMID 7185768.

- ^ Larsson M, Axelsson R, Forsman A (1984). "On the pharmacokinetics of perphenazine: a clinical study of perphenazine enanthate and decanoate". Current Therapeutic Research. 36 (6): 1071–88.

- ^ Farah A (2005). "Atypicality of atypical antipsychotics". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 7 (6): 268–74. doi:10.4088/PCC.v07n0602. PMC 1324958. PMID 16498489.

- ^ Weiden PJ (January 2007). "EPS profiles: the atypical antipsychotics are not all the same". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 13 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1097/00131746-200701000-00003. PMID 17242588. S2CID 46319827.

- ^ Jones PB, Barnes TR, Davies L, Dunn G, Lloyd H, Hayhurst KP, et al. (October 2006). "Randomized controlled trial of the effect on Quality of Life of second- vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1)". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (10): 1079–87. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1079. PMID 17015810.

- ^ "Drug Product Database Online Query". Government of Canada, Health Canada, Public Affairs, Consultation and Regions Branch. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Search the TGA website". Australian Government Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ a b "European Medicines Agency: Search". European Medicines Agency. Retrieved February 2, 2018. 검색

- ^ "Search". Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Medicines Information: SPC & PILs". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Guidance: Antipsychotic medicines". Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. August 25, 2005. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

추가 읽기

- Elmorsy E, Smith PA (May 2015). "Bioenergetic disruption of human micro-vascular endothelial cells by antipsychotics" (PDF). Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 460 (3): 857–62. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.03.122. PMID 25824037.

- Simpson GM (September 2005). "Atypical antipsychotics and the burden of disease". The American Journal of Managed Care. 11 (8 Suppl): S235-41. PMID 16180961.

- 새로운 항정신병 약물들은 어린이들에게 위험을 안겨준다(USA Today 2006).

- "NIMH Study to Guide Treatment Choices for Schizophrenia" (Press release). National Institute of Mental Health. September 19, 2005. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

외부 링크

위키미디어 커먼스의 비정형 항정신병 약물 관련 매체

위키미디어 커먼스의 비정형 항정신병 약물 관련 매체