암페타민

Amphetamine | |

| |

| 임상자료 | |

|---|---|

| 발음 | /æmˈfɛtəmiːn/ ( |

| 상명 | 이브케오, 아드데랄,[note 1] 기타 |

| 기타 이름 | α-메틸페네틸아민 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| 메드라인플러스 | a616004 |

| 라이센스 데이터 | |

| 의존성 책임감 있는 | 중간[1] |

| 중독 책임감 있는 | 중간 |

| 경로: 행정 | 의료: 구강, 정맥주사[2] 레크리에이션: 구강, 절연, 직장, 정맥, 근육 내 |

| 마약류 | CNS 흥분제, 식욕부진 |

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적현황 | |

| 법적현황 |

|

| 약동학 데이터 | |

| 생체이용가능성 | 구강: 75~100%[3] |

| 단백질 결합 | 20%[4] |

| 신진대사 | CYP2D6,[5] DBH,[13][14] FMO3[13][15][16] |

| 대사물 | 4-제스록시암페타민, 4-제스록시노레페드린, 4-제스록시페닐아세톤, 벤조산, 히프산, 노레페드린, 페닐라세톤[5][6] |

| 행동 개시 | IR 투약: 30~60분[7] XR 투약: 1.5~2시간[8][9] |

| 제거 반감기 | D-amph: 9~11시간[5][10] L-amph: 11~14시간[5][10] pH 의존성: 7-34시간[11] |

| 작용기간 | IR 투약: 3~6시간[1][8][12] XR 투약: 8-12시간[1][8][12] |

| 배설 | 주로 신장; pH 의존 범위: 1~[5]75% |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| 펍켐 CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드러그뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니 | |

| 케그 | |

| 체비 | |

| 켐벨 | |

| NIAID 화학DB | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.543 |

| 화학 및 물리적 데이터 | |

| 공식 | C9H13N |

| 어금질량 | 135.1987 g·190−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| 치랄리티 | 인종 혼합물[17] |

| 밀도 | 25°C에서[18] .936 g/cm3 |

| 녹는점 | 11.3°C(52.3°F) (예측)[19] |

| 비등점 | 760mmHg에서[20] 203°C(397°F) |

| |

| |

| (iii) | |

암페타민[note 2](Alpha-methylphenethylamine에서 계약)은 주의력 결핍 과잉행동장애(ADHD), 기면증, 비만 치료에 사용되는 중추신경계(CNS) 자극제다.암페타민은 1887년에 발견되었으며 레보암페타민과 덱스트로암페타민이라는 [note 3]두 개의 항정신병제로 존재한다.암페타민은 특정 화학 물질인 레이스 프리 베이스를 적절히 가리키는데, 이것은 순수한 아민 형태에서 두 에나토머의 동일한 부분이다.이 용어는 에반토머의 어떤 조합이나 그것들 중 하나만을 지칭하기 위해 비공식적으로 자주 사용된다.역사적으로 코막힘과 우울증을 치료하는 데 사용되어 왔다.암페타민은 운동능력의 증진제 및 인지력 증진제로도 사용되며, 경쾌하고 쾌락적인 오락성으로도 사용된다.여러 나라에서 처방되는 약으로, 레크리에이션 사용과 관련된 중대한 건강 위험 때문에 암페타민의 무단 점유와 유통이 엄격히 통제되는 경우가 많다.[sources 1]

최초의 암페타민 약품은 다양한 조건을 치료하기 위해 사용된 브랜드인 베네게드린이었다.현재 제약암페타민은 경마암페타민, 아드데랄,[note 4] 덱스트로암페타민 또는 비활성 프로드러그리스덱삼페타민으로 처방되고 있다.암페타민은 뇌에서 모노아민과 흥분성 신경 전달을 증가시키며, 가장 두드러진 효과는 노레피네프린과 도파민 신경전달물질 시스템을 대상으로 한다.[sources 2]

치료용량에서 암페타민은 행복감, 성욕의 변화, 깨어있는 상태의 증가, 인지조절의 향상과 같은 정서적, 인지적 효과를 일으킨다.반응시간 향상, 피로저항성, 근력증진 등 신체적인 효과를 유도한다.암페타민 복용량이 많을 경우 인지 기능이 손상되고 급격한 근육 파괴를 유발할 수 있다.중독은 심한 레크리에이션 암페타민 사용으로 심각한 위험이지만 치료용량에서 장기간 의약품을 사용했을 때 발생할 가능성은 낮다.매우 높은 복용량은 장기간 사용해도 치료용량에서 거의 발생하지 않는 정신질환(예: 망상, 편집증)을 초래할 수 있다.레크리에이션 선량은 일반적으로 규정된 치료선량보다 훨씬 크며 심각한 부작용의 위험이 훨씬 크다.[sources 3]

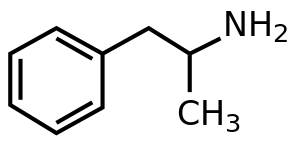

암페타민은 페네틸아민 등급에 속한다.자체 구조 등급인 대체암페타민(대체암페타민)[note 5]의 모화합물로 부프로피온, 캐시논, MDMA, 필로폰 등 눈에 띄는 물질이 포함돼 있기도 하다.페네틸아민 등급의 일원으로서 암페타민은 자연적으로 발생하는 미량 아민 신경계통, 특히 페네틸아민과 N-메틸페네틸아민과도 화학적으로 관련이 있는데, 둘 다 인체 내에서 생성된다.페네틸아민(Penethylamine)은 암페타민의 모성분인 반면, N-메틸페네틸아민(N-methylphenethylamine)[sources 4]은 암페타민(암페타민)의 위치 이성질체로서 메틸군(methyl group)

사용하다

메디컬

암페타민은 주의력결핍과잉행동장애(ADHD), 나팔심증(수면장애), 비만을 치료하는 데 사용되며 특히 우울증과 만성통증의 경우 과거 의학적 적응증에 대해 라벨이 아닌 처방되기도 한다.[1][33][47]일부 동물종에서 충분히 높은 용량으로 장기간 암페타민에 노출되면 도파민 계통이 비정상적으로 발달하거나 신경 손상을 일으키는 것으로 알려져 있지만 ADHD를 앓고 있는 인간에서는 치료용량에서 약물암페타민이 뇌 발달과 신경 성장을 개선하는 것으로 보인다.[48][49][50][51][52]자기공명영상(MRI) 연구 검토 결과, 암페타민으로 장기간 치료하면 ADHD 피험자에서 발견되는 뇌 구조와 기능의 이상이 감소하고 기저 갱년기의 오른쪽 입자핵 등 뇌의 여러 부분에서 기능이 개선되는 것으로 나타났다.[50][51][52]

임상 각성제 연구의 리뷰는 ADHD 치료를 위한 장기 연속 암페타민 사용의 안전성과 효과를 확립했다.[41][53][54]2년간 지속되는 ADHD 치료를 위한 연속 자극제 치료의 무작위 제어 실험은 치료 효과와 안전성을 입증했다.[41][53]2리뷰들 ADHD를 진단하기 위한 장기 지속적인 캐비 아이 자극 요법, 삶과 학문적 성과의 질을 강화하고 결과 relat의 9개 부문을 가로질러 기능 outcomes[노트 6]을 대거 개선 생산 주의력 결핍 과잉 행동 장애(즉, 과민성 주의력 결핍증, 부주의, 충동성)의 핵심 증상을 완화를 위해 효과적이다 지적했다.에 대한 교육지적, 반사회적인 행동, 운전, 비흡연 약물 사용, 비만, 직업, 자존감, 서비스 사용(즉, 학업, 직업, 건강, 재정, 법률 서비스) 및 사회 기능.[41][54]한 리뷰는 평균 4.5 IQ 포인트 증가, 지속적인 주의력 증가, 파괴적 행동과 과잉 행동의 지속적 감소를 발견한 어린이들의 ADHD 암페타민 치료제에 대한 9개월간의 무작위 통제 실험을 강조했다.[53]또 다른 리뷰는 현재까지 시행된 가장 오랜 추적 연구를 바탕으로 유년기에 시작되는 평생 자극제 치료법이 ADHD 증상을 억제하는 데 지속적으로 효과적이며 성인으로서 물질 사용 장애의 발생 위험을 감소시킨다고 지적했다.[41]

ADHD의 현재 모델들은 그것은 어떤 뇌의neurotransmitter 시스템의 기능 장애와 관련된;[55]이 기능 장애는 청반은 prefr까지noradrenergic 전망에서 그mesocorticolimbic 프로젝션에 손상된 도파민 제품 신경 전달과 노르 에피네프린 제품 신경 전달을 포함하는 것을 제안합니다.onta이피질[55]메틸페니데이트나 암페타민 같은 정신안정제는 ADHD 치료에 효과적이다. 왜냐하면 ADHD는 이러한 시스템에서 신경전달물질 활동을 증가시키기 때문이다.[24][55][56]이러한 자극제를 사용하는 사람들의 약 80%는 ADHD 증상의 개선을 본다.[57]ADHD를 앓고 있는 아이들은 흥분제 약을 사용하는 다른 아이들과 가족 구성원들과 더 좋은 관계를 가지며, 학교에서 더 나은 성적을 내고, 덜 산만하고 충동적이며, 주의력이 더 길다.[58][59]약암페타민을 가진 아동, 청소년, 성인의 ADHD 치료에 대한 코크란 리뷰는[note 7] 단기 연구 결과 이러한 약물이 증상의 심각성을 감소시키는 것으로 나타났지만 부작용 때문에 비침습성 의약품에 비해 중단률이 높다고 밝혔다.[61][62]투렛 증후군과 같은 틱장애를 가진 어린이들의 ADHD 치료에 대한 코크란 리뷰는 자극제가 일반적으로 틱을 악화시키지는 않지만, 덱스트로암페타민을 많이 복용하면 일부 개인에서 틱을 악화시킬 수 있다고 밝혔다.[63]

성능 향상

인지성능

2015년에 체계적 검토와 좋은 품질의 임상 메타 분석할 때 낮은(치료)의 복용량에 사용하면, 암페타민 인지 능력을 작업 기억 장기적인 일화 기억, 억제 그리고 관심의 정상적인 건강한 성인들 사이에서 몇몇면들을 포함한 겸손한 아직 모호하지 않은 개선,;[64][65]이 cogn을 생산하는 것을 발견했다.ition-en암페타민의 한싱 효과는 전두엽 피질에서 도파민1 수용체 D와 아드레노셉터 α의2 간접 활성화를 통해 부분적으로 매개되는 것으로 알려져 있다.[24][64]2014년부터 체계적으로 검토한 결과, 암페타민 저선량도 기억력 통합을 향상시켜 정보 회수율 향상으로 이어졌다.[66]암페타민 치료용량은 또한 피질 네트워크 효율을 강화하는데, 이것은 모든 개인의 작업 기억력 향상을 매개하는 효과다.[24][67]암페타민과 다른 ADHD 자극제는 또한 작업 편의성(과제 수행에 대한 동기 부여)을 향상시키고 활력(깨끗함)을 증가시켜 목표 지향적인 행동을 촉진한다.[24][68][69]암페타민과 같은 자극제는 어렵고 지루한 과제에서 성능을 향상시킬 수 있으며 일부 학생들은 공부와 시험 보조 도구로 사용된다.[24][69][70]불법 흥분제 사용에 대한 자체 보고된 연구를 바탕으로 대학생의 5~35%가 오락성 약물이 아닌 학업성취도 향상에 주로 쓰이는 전용 ADHD 흥분제를 사용하고 있다.[71][72][73]그러나 치료 범위를 초과하는 고암페타민 선량은 기억력 및 인지 조절의 다른 측면을 방해할 수 있다.[24][69]

물리적 성능

암페타민은 일부 운동선수들에 의해 지구력 향상과 경계력 향상과 같은 심리적, 운동적 경기력 향상 효과로 사용되지만,[25][37] 대학, 국내, 국제 도핑방지기관에서 규제하는 스포츠 경기에서는 비의료용 암페타민 사용이 금지된다.[74][75]경구 치료용량에서 건강한 사람에게 암페타민은 근육의 근력, 가속도, 혐기성 조건에서의 운동성능, 지구력(즉, 피로발작을 지연시키는 것)을 증가시키는 동시에 반응시간을 향상시키는 것으로 나타났다.[25][76][77]암페타민은 주로 중추신경계 내 도파민의 재흡수 억제와 분비를 통해 지구력과 반응시간을 향상시킨다.[76][77][78]암페타민 및 기타 도파민성 약품도 "안전 스위치"를 오버라이드하여 고정된 수준의 인지된 힘 발휘 시 출력량을 증가시켜 노심 온도 한도를 증가시켜 정상적으로 제한되지 않는 예비 용량에 접근할 수 있도록 한다.[77][79][80]치료용량에서 암페타민의 부작용은 운동능력에 지장을 주지 않지만,[25][76] 훨씬 더 높은 용량에서 암페타민은 빠른 근육파괴나 체온상승과 같은 경기능력에 심각한 손상을 주는 효과를 유발할 수 있다.[26][76]

콘트라인커뮤니케이션

국제화학안전프로그램(IPCS)과 미국 식품의약국(USFDA)에 따르면 암페타민은 약물 남용,[note 9] 심혈관계 질환, 심한 동요 또는 심각한 불안의 이력이 있는 사람들에게서 금지된다.[note 8][33][26][82]또한 동맥경화증(동맥의 경화), 녹내장(안압증가), 갑상선기능항진증(갑상선호르몬의 과잉생성), 또는 중간에서 심각한 고혈압이 있는 개인에게도 억제된다.[33][26][82]이들 기관은 암페타민과 모노아민 산화효소 억제제의 안전한 동시 사용이 기록되어 있지만,[33][26][82] 다른 자극제에 대한 알레르기 반응을 경험했거나 모노아민 산화효소 억제제(MAOI)를 복용하고 있는 사람은 암페타민을 복용해서는 안 된다는 것을 나타낸다.[83][84]이 기관들은 또한 거식증, 조울증, 우울증, 고혈압, 간 또는 신장 질환, 마니아, 정신 질환, 레이노 현상, 발작, 갑상선 문제, 틱스, 투렛 증후군이 있는 사람은 암페타민을 복용하면서 증상을 감시해야 한다고 명시하고 있다.[26][82]인간 연구에서 나온 증거는 치료용 암페타민 사용이 태아나 신생아에게 발달 이상을 일으키지는 않는다는 것을 보여준다(즉, 인간 테라토겐이 아니다), 그러나 암페타민 남용은 태아에게 위험을 준다.[82]암페타민 역시 모유에 들어가는 것으로 나타났기 때문에 IPCS와 미국 식품의약국은 산모들에게 모유를 사용할 때 모유 수유를 피하라고 권고하고 있다.[26][82]USFDA는 가역성 성장 장애의 가능성 때문에 암페타민 약제를 처방한 어린이와 청소년의 키와 몸무게를 모니터링할 것을 권고하고 있다.[note 10][26]

역효과

암페타민의 부작용은 많고 다양하며, 사용된 암페타민의 양은 부작용의 가능성과 심각성을 결정하는 주요 요인이다.[26][37]애더럴, 덱세드린, 그리고 그들의 일반적인 등가물과 같은 암페타민 제품들은 현재 미국 식품의약국으로부터 장기 치료용으로 승인을 받고 있다.[34][26]암페타민의 레크리에이션 사용은 일반적으로 치료 목적으로 사용되는 용량보다 심각한 약물 부작용의 위험이 훨씬 더 크다.[37]

물리적인

심혈관계 부작용으로는 혈관조영반응으로 인한 고혈압이나 저혈압, 레이노우드의 현상(손과 발으로의 혈류 감소), 빈맥(심박수 증가) 등이 있을 수 있다.[26][37][85]남성의 성적 부작용은 발기부전, 잦은 발기부전, 장기 발기부전 등을 포함할 수 있다.[26]위장 부작용으로는 복통, 변비, 설사, 메스꺼움 등이 있을 수 있다.[1][26][86]그 밖에 잠재적인 신체 부작용으로는 식욕 저하, 시야 흐림, 입안 건조, 치아의 과도한 갈림, 코피, 땀 과다, 비염 메디캐멘토사(약물로 인한 코막힘), 발작력 저하, 틱스(운동장애의 일종), 체중 감소 등이 있다.[sources 5]위험한 신체적 부작용은 일반적인 약 복용량에서는 드물다.[37]

암페타민은 중수호흡기중추를 자극하여 더 빠르고 깊은 호흡을 만들어낸다.[37]치료용량을 복용하는 정상인의 경우 이 효과는 대개 눈에 띄지 않지만 이미 호흡이 저하된 상태에서는 분명할 수 있다.[37]암페타민은 또한 배뇨를 조절하는 근육인 비뇨기 방광 괄약근의 수축을 유도하여 배뇨에 어려움을 초래할 수 있다.[37]이 효과는 침대의 습기와 방광 조절의 상실을 치료하는 데 유용할 수 있다.[37]암페타민이 위장에 미치는 영향은 예측할 수 없다.[37]장내 활성도가 높을 경우 암페타민은 위장 운동성(소화계를 통해 내용물이 이동하는 속도)[37]을 감소시킬 수 있지만, 암페타민은 트랙의 매끄러운 근육이 이완되면 운동성을 증가시킬 수 있다.[37]암페타민 또한 약간의 진통 효과가 있으며 오피오이드의 통증 완화 효과를 높일 수 있다.[1][37]

USFDA가 2011년부터 실시한 연구에 따르면 어린이, 청소년 및 성인의 경우 심각한 이상 심혈관 질환(사망, 심장마비, 뇌졸중)과 암페타민 또는 기타 ADHD 자극제의 의료 사용 사이에 연관성이 없다.[sources 6]그러나 암페타민 약은 심혈관 질환을 가진 개인에게 금지된다.[sources 7]

정상적인 치료용량에서 암페타민의 가장 흔한 심리적 부작용으로는 경계력 증가, 불안감, 집중력, 주도력, 자신감과 사교성, 기분 변화(약하게 우울한 기분이 뒤따르는 흥분감), 불면증이나 깨어짐, 피로감 감소 등이 있다.[26][37]덜 흔한 부작용으로는 불안, 성욕의 변화, 거창함, 짜증, 반복적이거나 강박적인 행동, 그리고 안절부절못을 들 수 있다;[sources 8] 이러한 영향은 사용자의 성격과 현재의 정신 상태에 달려 있다.[37]암페타민 정신질환(예: 망상, 편집증)은 헤비유저에서 발생할 수 있다.[26][38][39]비록 매우 드물지만, 이러한 정신병은 장기요법 중 치료용량에서도 발생할 수 있다.[26][39][40]USFDA에 따르면, 자극제가 공격적인 행동이나 적대감을 일으킨다는 "체계적인 증거는 없다"고 한다.[26]

암페타민은 또한 치료용량을 복용하는 사람에게 조건부 장소 선호를 제공하는 것으로 나타났는데,[61][93] 이는 개인이 이전에 암페타민을 사용했던 장소에서 시간을 보내는 것에 대한 선호를 얻게 된다는 것을 의미한다.[93][94]

애

| 중독 및 의존 용어집[94][95][96][97] | |

|---|---|

| |

| 용어 수식어 | |

|---|---|

| |

중독은 심한 레크리에이션 암페타민 사용의 심각한 위험이지만 치료용량에서 장기간 의학적 사용으로 발생할 가능성은 낮다.[41][42][43] 사실, 어린 시절에 시작되는 ADHD에 대한 평생 자극제 치료는 성인으로서 물질 사용 장애가 발생할 위험을 감소시킨다.[41]복측 티그먼트 부위와 측점핵을 연결하는 도파민 경로인 중음부 경로의 병리학적 과활성화는 암페타민 중독의 중심 역할을 한다.[104][105]암페타민 고선량 자가 투여를 자주 하는 개인은 암페타민 중독에 걸릴 위험이 높은데, 이는 고선량에서 만성적으로 사용하면 중독을 위한 '분자 스위치'와 '마스터 컨트롤 단백질'인 악센트 ΔFosB의 수치가 점차 높아지기 때문이다.[95][106][107]일단 핵이 ΔFosB를 충분히 강조하면, 그 표현이 더욱 증가하면서 중독성 있는 행동(즉, 강박적인 약물추구)의 심각성을 증가시키기 시작한다.[106][108]현재 암페타민 중독 치료에 효과적인 약이 없지만, 지속적인 유산소 운동을 꾸준히 하는 것은 그러한 중독이 발생할 위험을 줄이는 것으로 보인다.[109][110]지속적인 유산소 운동은 암페타민 중독에도 효과적인 치료로 보인다;[sources 9] 운동 요법은 임상 치료 결과를 개선하고 중독에 대한 행동 요법과 함께 보조 요법으로 사용될 수 있다.[109][111]

생체분자 메커니즘

과도한 용량에서 암페타민을 만성적으로 사용하면 중상구체투영에서 유전자 발현에 변화를 일으키는데, 이는 전사와 후생유전적 메커니즘을 통해 발생한다.[107][112][113]이러한 변화를 일으키는 가장 중요한 전사 인자는[note 11] 델타 FBJ 머린 골육종 바이러스성 종양 유전체 균질체 동질체 B(ΔFosB), cAMP 반응 요소 결합 단백질(CREB), 핵 인자-카파 B(NF-164B)이다.[107]중독에 ΔFosB 한 가장 중요한 생체 분자의 메커니즘이 D1-type 매체 가시가 있는 뉴런에 중핵 accumbens에ΔFosB overexpression(즉, 유전자 발현의 뚜렷한gene-related에 표현형을 생산하는 비정상적으로 높은 수준)과 sufficient[권은 12]신경 적응할 수 많은, 다량을 규제하고 필요하다.ple beha중독에 관련된 바이오럴 효과([95][106][107]예: 보상 민감화 및 약물 자가 치료 증가)일단 ΔFosB가 충분히 과압되면, ΔFosB 표현이 더 증가하면서 점점 더 심해지는 중독 상태를 유도한다.[95][106]알코올, 카나비노이드, 코카인, 메틸페니데스산, 니코틴, 오피오이드, 펜시클리딘, 프로포폴, 대체암페타민에 중독되었다.[sources 10]

ΔJunD, 전사 인자, G9a, 히스톤 메틸 전달 효소 효소, 그것의 표현으로 ΔFosB과 억제하면 기능에 반대하고 있다.[95][107][117]그 핵 accumbens에 바이러스 벡터와 ΔJunD overexpressing 완전히 그리고 행동의 신경 변화 만성 약물 남용(즉,는 변경 ΔFosB에 의해)에서 보아 온 것 중 많은 차단할 수 있다.[107]마찬가지로,에서accumbal G9a hyperexpression 이어지는 결과는, vario의 ΔFosB과H3K9me2-mediated 억제에 전사한 요인 중에H3K9me2-mediated 억압을 통해 발생한다 마약 use,[출처 11]에 의해ΔFosB-mediated과 행동 신경 가소성의 유도를 막고 있는 히스톤 3리신 잔류물 9dimethylation(H3K9me2)증가했다.우리 ΔFosB trAnscriptional 목표(예:CDK5).[107][117][118]ΔFosB 또한 맛있는 음식., 성, 그리고 운동과 같은 자연 보상에 행동 반응을 조절하는데 중요한 역할을 한다.[108][107][121]두 자연 보상과 중독성 있는 마약과ΔFosB(즉, 그들은 그것을 더 많이 생산하기 위해 뇌를 일으키는)의 표현 실행하면 이러한 보상들의 만성적인 인수에 중독된 비슷한 병적 상태에 빠지게 될 수 있다.[108][107]따라서, ΔFosB 가장 큰 요인 둘 다 암페타민 중독과 과도한 성 접촉이나 암페타민 사용에서 기인하는 강박적인 성적 행동 amphetamine-induced 성적 중독,에 참여하고 있습니다.[108][122][123]이 성적 중독은 일부 환자들은 도파민으로 활성화되는 약물 복용에서도 발생하는 도파민의 불규칙함이다 증후군과 관련되어 있다.[108][121]

amphetamine의 유전자 조절에 미치는 영향과route-dependentdose- 있다.[113]유전자 규칙과 중독에 대한 연구의 대부분의 정맥 암페타민 행정부와 매우 높은 복용량에서 동물에 기초하고 있다.[113]인간 치료적으로 먹고 있고 경구 투여(weight-adjusted)을 해당 사용된 몇몇 연구들은 이러한 변화가, 그들이 일어난다 비교적 경미하고 있습니다.[113]이것은 amphetamine의 의료 사용 유전자 규제에 영향을 주지 않음을 시사한다.[113]

약리학적 치료법

2019년 12월 현재 암페타민 중독에 대한 효과적인 약리 요법이 없다.[update][124][125][126]2015년과 2016년의 검토 결과, TAAR1 선택적 작용제는 심리 자극제 중독 치료제로서 상당한 치료 잠재력을 가지고 있는 것으로 나타났으나,[36][127] 2016년 2월 현재,[update] TAAR1 선택 작용제로서 기능하는 것으로 알려진 화합물은 실험 약물들뿐이다.[36][127]암페타민 중독은 도파민 수용체 활성화 증가와 핵 내 공동 국부화된 NMDA 수용체들을[note 13] 통해 주로 매개되며,[105] 마그네슘 이온은 수용체 칼슘 채널을 차단하여 NMDA 수용체를 억제한다.[105][128]한 리뷰는 동물실험에 근거하여, 병리학적 (중독 유발) 심리 자극제 사용은 뇌전체의 세포내 마그네슘의 수치를 현저하게 감소시킨다고 제안했다.[105]보충 마그네슘[note 14] 치료는 인간에게 암페타민 자가 관리(즉, 자신에게 주어진 복용량)를 감소시키는 것으로 나타났지만 암페타민 중독에 대한 효과적인 단일 치료법은 아니다.[105]

2019년부터 체계적 검토와 메타분석이 암페타민 및 필로폰 중독에 대한 RCT에서 사용된 17가지 약리요법의 효능을 평가한 결과 [125]메틸페니데이트가 암페타민이나 필로폰 자가 투여를 줄일 수 있다는 저강도 증거만 발견됐다.[125]There was low- to moderate-strength evidence of no benefit for most of the other medications used in RCTs, which included antidepressants (bupropion, mirtazapine, sertraline), antipsychotics (aripiprazole), anticonvulsants (topiramate, baclofen, gabapentin), naltrexone, varenicline, citicoline, ondansetron, prometa, riluzole, atomoxetine, dextroam피타민, 모다피닐.[125]

행동 치료

암페타민, 필로폰 또는 코카인 중독에 대한 12가지 심리사회적 개입이 포함된 50가지 재판에 대한 2018년 체계적 검토 및 네트워크 메타분석 결과, 우발적 관리와 지역사회 강화 접근방식을 모두 갖춘 결합치료의 효능(즉, 금주율)과 수용성(즉, 최저)이 가장 높은 것으로 나타났다.중퇴 비율.[129]분석에서 조사된 다른 치료 방법으로는 우발적 관리 또는 공동체 강화 접근법을 이용한 단일 치료법, 인지 행동 치료법, 12단계 프로그램, 비전형 보상 기반 치료법, 심리역학 치료법 및 이와 관련된 기타 결합 치료법이 있다.[129]

덧붙여 육체운동의 신경생물학적 효과에 관한 연구에 의하면 매일의 유산소 운동, 특히 지구력 운동(마라톤 달리기)은 약물 중독의 발달을 방해하고 암페타민 중독에 효과적인 보조 치료(즉, 보충 치료)라고 한다.[sources 9]운동은 특히 정신운동성 중독에 대한 부가적인 치료로 사용될 때 더 나은 치료 결과를 이끌어낸다.[109][111][130]특히 유산소 운동은 정신운동성 자가행정을 감소시키고, 약물추구의 회복(즉, 재발)을 감소시키며, 선조체 내 도파민 수용체2 D(DRD2) 밀도 증가를 유도한다.[108][130]이것은 선조체 DRD2 밀도 저하를 유도하는 병리학적 자극제 사용과는 정반대다.[108]한 리뷰는 운동이 선조체나 보상체계의 다른 부분에서 ΔFosB 또는 c-Fos 면역반응을 변화시킴으로써 약물 중독의 발달을 막을 수도 있다는 점에 주목하였다.[110]

| 신경 재생성의 형태 또는 행동의 가소성 | 보강재 유형 | 원천 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 오파테스 | 정신운동제 | 고지방 또는 설탕 식품 | 성교, 교접 | 체조, 운동 (iii) | 환경 농축 | ||

| ΔFosB 식 핵이 응축D1형MSNs | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [108] |

| 행동적 소성 | |||||||

| 섭취 에스컬레이션 | 네 | 네 | 네 | [108] | |||

| 정신운동제 교차감각 | 네 | 해당되지 않음 | 네 | 네 | 감쇠됨 | 감쇠됨 | [108] |

| 정신운동제 자화자기의 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [108] | |

| 정신운동제 조건부 장소 선호도 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [108] |

| 마약추구행위의 회복 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [108] | ||

| 신경화학적 가소성 | |||||||

| CREB인산화 중앙부에. | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [108] | |

| 감작 도파민 반응 중앙부에. | 아니요. | 네 | 아니요. | 네 | [108] | ||

| 변형된 선조체 도파민 신호 | ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD2 | ↑DRD2 | [108] | |

| 선조체 오피오이드 신호 변경 | 변경 없음 또는 μ-오피오이드 수용체 | μ-오피오이드 수용체 ↑κ-오피오이드 수용체 | μ-오피오이드 수용체 | μ-오피오이드 수용체 | 잔돈 없음 | 잔돈 없음 | [108] |

| 선조체 오피오이드 펩타이드의 변화 | ↑dynorphin 변화 없음: 엥케팔린 | ↑dynorphin | ↓케팔린 | ↑dynorphin | ↑dynorphin | [108] | |

| 메소코르티컬임브 시냅스 가소성 | |||||||

| 핵에 포함된 덴드라이트 수 | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [108] | |||

| 덴드리트 척추 밀도: 핵이 수축하다. | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [108] | |||

의존과 철수

약물 내성은 암페타민 남용(즉, 레크리에이션 암페타민 사용)에서 빠르게 발전하므로, 장기간 복용하는 경우 동일한 효과를 얻기 위해서는 점점 더 많은 양의 약물이 필요하다.[131][132]암페타민과 필로폰을 강제적으로 사용하는 개인에 대한 코크란 탈퇴 검토 결과 "만성중고사용자가 갑자기 암페타민 사용을 중단하면 마지막 투약 후 24시간 이내에 발생하는 시한부 탈퇴 증후군을 신고하는 경우가 많다"[133]고 밝혔다.이 검토에서는 만성 고선량 사용자의 철수 증상이 빈발하여 약 88%의 사례에서 발생하며, 첫 주 동안 현저한 "충돌" 단계가 발생하면서 3~4주 동안 지속된다는 점에 주목하였다.[133]암페타민 금단 증상은 불안, 약물 욕구, 우울한 기분, 피로, 식욕 증진, 운동 증가 또는 감소, 동기부여 부족, 불면증이나 졸림, 자각몽 등이 있을 수 있다.[133]검토 결과 금단증상의 심각성은 개인의 연령 및 의존 정도와 긍정적으로 상관관계가 있는 것으로 나타났다.[133]치료용량에서 암페타민 치료 중단으로 인한 가벼운 금단 증상은 투여량을 테이퍼링하여 피할 수 있다.[1]

과다 복용

암페타민 과다 복용으로 여러 가지 증상이 나타날 수 있지만 적절한 치료로 치명적인 경우는 드물다.[1][82][134]과다 복용 증상의 심각성은 복용량에 따라 증가하고 암페타민에 대한 약물 내성이 감소한다.[37][82]관용적인 개인은 하루에 암페타민 5g을 복용하는 것으로 알려져 있는데, 이는 하루 최대 치료용량의 약 100배에 달한다.[82]중간 정도의 과다복용과 극도로 큰 과다복용의 증상은 아래에 열거되어 있다; 치명적인 암페타민 중독은 보통 경련과 혼수상태도 수반한다.[26][37]2013년 '암페타민 사용 장애'와 관련된 암페타민, 필로폰, 그 밖의 화합물 과다 복용으로 인해 전 세계적으로 3788명이 사망했다(3,425–4,145명, 95% 신뢰).[note 15][135]

| 시스템 | 경미하거나 보통 수준의 과다[26][37][82] 복용 | 심한 과다복용[sources 12] |

|---|---|---|

계통 |

|

|

| ||

| ||

| 비뇨기 |

| |

| 기타 |

독성

설치류나 영장류에서는 암페타민을 충분히 많이 복용하면 도파민성 신경독성이 생기거나 도파민 뉴런이 손상되는데, 도파민 단자 변성, 전달체 및 수용체 기능 저하 등이 특징이다.[137][138]암페타민이 인간에게 직접 신경독성이라는 증거는 없다.[139][140]그러나 다량의 암페타민은 과피증, 반응성 산소종의 과도한 형성, 도파민의 자가산화 증가 등의 결과로 간접적으로 도파민성 신경독성을 유발할 수 있다.[sources 13]고선량 암페타민 노출에 따른 신경독성의 동물모델은 암페타민 유도 신경독성 발달을 위해 과피레시아(심층 체온 ≥ 40 °C) 발생이 필요하다는 것을 나타낸다.[138]40 °C 이상의 뇌 온도 장기 상승은 활성 산소 종의 생성을 촉진하고 세포 단백질 기능을 방해하며 일시적으로 혈액-뇌 장벽 투과성을 증가시킴으로써 실험실 동물의 암페타민 유도 신경독성 개발을 촉진할 가능성이 있다.[138]

정신병

암페타민 과다복용은 망상이나 편집증 같은 다양한 증상을 수반할 수 있는 흥분제 정신착란을 초래할 수 있다.[38][39]암페타민, 덱스트로암페타민, 필로폰 정신질환 치료제에 대한 코크란 리뷰에는 사용자의 약 5~15%가 완전히 회복되지 않는다고 적혀 있다.[38][143]같은 검토에 따르면 항정신병 약물이 급성암페타민 정신질환 증상을 효과적으로 해결하는 것을 보여주는 재판이 적어도 한 차례 있다.[38]정신병은 치료용으로 발생하는 경우가 드물다.[26][39][40]

약물 상호작용

많은 종류의 물질들이 암페타민과 상호작용을 하는 것으로 알려져 있으며, 그 결과 암페타민의 약물 작용이나 신진대사가 변형되거나 상호작용을 하는 물질, 또는 둘 다에 해당된다.[26]암페타민을 대사하는 효소의 억제제(예: CYP2D6, FMO3)는 제거 반감기를 연장시켜 효과가 더 오래 지속된다는 것을 의미한다.[15][26]암페타민은 또한 MAOI와 암페타민 모두 혈장 카테콜아민(즉, 노레피네프린과 도파민)[26]을 증가시키기 때문에 특히 모노아민 산화효소 A 억제제와 상호작용한다. 따라서 두 가지를 동시에 사용하는 것은 위험하다.[26]암페타민은 대부분의 정신 활성 약물의 활동을 조절한다.특히 암페타민은 진정제나 우울제의 효과를 떨어뜨리고 각성제와 항우울제의 효과를 높일 수 있다.[26]암페타민은 혈압과 도파민에 각각 영향을 미치기 때문에 항고혈압과 항정신병 약물의 효과도 줄일 수 있다.[26]아연 보충제는 ADHD 치료에 사용될 때 암페타민의 최소 유효량을 줄일 수 있다.[note 16][148]

일반적으로 식품과 함께 암페타민을 섭취할 때는 유의미한 상호작용이 없지만 위장성분과 소변의 pH는 암페타민의 흡수와 배설에 각각 영향을 미친다.[26]산성 물질은 암페타민의 흡수를 줄이고 소변 배설을 증가시키며 알칼리성 물질은 반대로 작용한다.[26]pH가 흡수에 미치는 효과로 인해 암페타민은 양성자 펌프 억제제2, H항히스타민 등 위산 환원제와도 상호작용을 하여 위장 pH(즉, 산도가 낮아지게 한다)를 증가시킨다.[26]

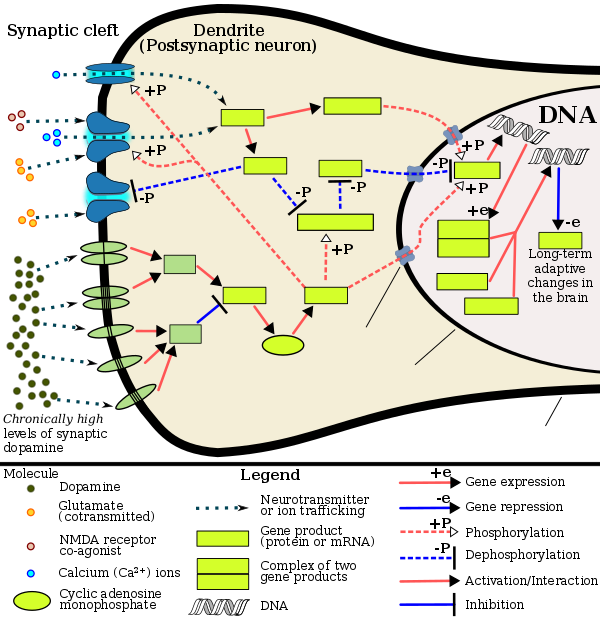

도파민 뉴런의 암페타민 약리역학 |

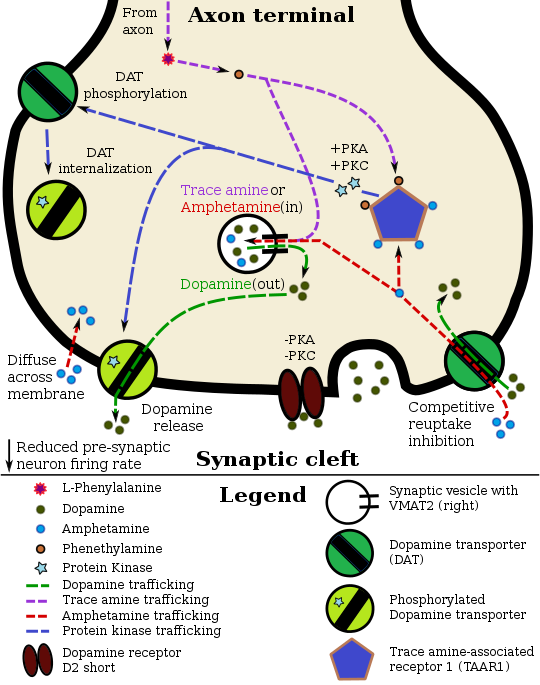

암페타민은 뇌의 보상 및 집행 기능 경로에서 주로 카테콜아민 뉴런에 있는 뉴런으로 모노아민을 뇌에서 뉴런 신호로 사용하는 것을 변경함으로써 행동 효과를 발휘한다.[35][56]보상 회로와 집행 기능에 관여하는 주요 신경전달물질인 도파민과 노레피네프린의 농도는 암페타민이 모노아민 전달체에 미치는 영향 때문에 용량 의존적으로 급격히 증가한다.[35][56][149]암페타민의 강화와 동기부여 만족 촉진 효과는 대부분 중음부 경로에서 도파민 활성이 강화된 데 기인한다.[24]암페타민의 행복과 운동성 자극 효과는 선조체 내 시냅스 도파민과 노르에피네프린 농도를 증가시키는 크기와 속도에 따라 달라진다.[2]

암페타민은 2001년 발견된 G-커플과 G-커플q G단백질커플리셉터s(GPCR)인 미량아민 관련 수용체 1(TAAR1)의 잠재적 완전작용제로 확인돼 뇌 모노아민 조절에 중요하다.[35][155]아데닐 시클라아제 활성화를 통한 생산량 증가와 모노아민 전달 기능을 억제한다.[35][156]모노아민 자가수용체(예: D2 short, presynaptic α2, presynaptic 5-HT1A)는 TAAR1의 반대 효과를 가지며, 이러한 수용체들이 함께 모노아민에 대한 규제 체계를 제공한다.[35][36]특히 암페타민과 트레이스 아민은 TAAR1의 결합 친화력이 높지만 모노아민 오토레셉터는 그렇지 않다.[35][36]영상 연구 결과에 따르면 암페타민과 트레이스 아민에 의한 모노아민 재흡수 억제는 사이트에 따라 다르며 관련된 모노아민 뉴런에서 TAAR1 공동 국소화의 존재에 따라 달라진다.[35]

암페타민은 뉴런 모노아민 전달체 외에도 베시컬 모노아민 전달체, VMAT1, VMAT2뿐만 아니라 SLC1A1, SLC22A3, SLC22A5도 억제한다.[sources 14]SLC1A1은 신경세포에 위치한 글루탐산염 운반체 3(EAT3)이고, SLC22A3는 아스트로사이테스에 존재하는 외부 관계형 모노아민 운반체, SLC22A5는 고선호도 카니틴 운반체다.[sources 14]암페타민은 먹이기 행동, 스트레스, 보상 등에 [4][162]관여하는 신경펩타이드인 코카인과 암페타민 조절 성적표현(CART) 유전자 발현을 강하게 유도해 뉴런 발달과 체외 생존의 관찰 가능한 증가를 유도하는 것으로 알려져 있다.[4][163][164]CART 수용체는 아직 확인되지 않았지만, CART가 고유한i G/Go 결합에 결합한다는 유의미한 증거가 있다.[164][165]암페타민은 또한 매우 높은 용량에서 모노아민 산화를 억제하여 모노아민 및 미량아민 대사량이 감소하고 결과적으로 시냅스 모노아민의 농도가 높아진다.[21][166]인간에서 암페타민이 결합하는 것으로 알려진 시냅스 후 수용체는 5-HT1A 수용체뿐이며, 여기서 암페타민은 미크로폴 친화력이 낮은 작용제 역할을 한다.[167][168]

인간의 amphetamine의 단기 약 효과들의 전체 프로파일은 대부분 dopamine,[35]serotonin,[35]norepinephrine,[35]epinephrine,[149]histamine,[149]CART peptides,[4][162]내인성 opioids,[169][170][171]부신 피질 자극 hormone,[172][173]의 증가 이동 통신 기술 또는 제품 신경 전달을 통해 corticosteroids,는 경우에는 17도출한다.그것과 상호 작용을 통해 이에 영향을 미치2][173]과 glutamate,[153][158].CART, , , , , , , 그리고 다른 생물학적 목표들.[sources 15]암페타민은 또한 7개의 인간탄소 무수효소 효소를 활성화하는데, 그 중 몇 가지는 인간의 뇌에서 발현된다.[174]

덱스트로암페타민은 레보암페타민보다 더 강력한 작용제다.[175]결과적으로 덱스트로암페타민은 레보암페타민보다 약 3~4배 많은 큰 자극을 주지만 레보암페타민은 심혈관계와 말초효과가 약간 더 강하다.[37][175]

도파민

특정 뇌 부위에서는 암페타민이 시냅스 구획에서 도파민 농도를 높인다.[35]암페타민은 뉴런을 통해 또는 뉴런 막에 직접 확산되어 전 시냅스 뉴런으로 들어갈 수 있다.[35]DAT 흡수의 결과, 암페타민은 트랜스포터에서 경쟁적인 재흡수 억제를 생산한다.[35]사전 시냅스 뉴런에 들어가면 암페타민이 활성화되어 단백질 키나제 A(PKA)와 단백질 키나제 C(PKC) 신호를 통해 DAT 인산화를 일으킨다.[35]어느 한 단백질 키나아제에 의한 인산화 작용은 DAT 내분화(비경쟁적 재흡수 억제)를 초래할 수 있지만 PKC 매개 인산화만으로도 DAT를 통한 도파민 수송의 역전을 유도한다(즉, 도파민 유출).[note 16][35][176]암페타민은 또한 세포내 칼슘을 증가시키는 것으로 알려져 있는데, 이것은 확인되지 않은 Ca2+/calmodulin 의존성 단백질 키나아제(CAMK) 의존 경로를 통해 DAT 인산화 작용과 관련된 효과로 도파민 유출을 발생시킨다.[155][153][154]내심 보정 칼륨 채널로 연결된 G 단백질의 직접적인 활성화를 통해 도파민 뉴런의 발화율을 낮춰 초도파민성 상태를 예방한다.[151][152][177]

amphetamine은 도파민의 분자의 시냅스 소포의 시토졸에 VMAT2.[149][150] 의한를 통해 도파민 유출을 통해 자료에서 발생한 다공질 pH기울기의 붕괴를 유도는 시냅스전 수포 모노아민 운송 VMAT2에 VMAT2.[149][150]에 관한 암페타민 섭취,에 Amphetamine 또한 기질.ly,의 시토졸의 도파민e 분자는 사전 시냅스 뉴런에서 에서 역수송을 통해 시냅스 구획으로 방출된다.[35][149][150]

노레피네프린

도파민과 유사하게 암페타민은 용량 의존적으로 에피네프린의 직접적인 전구체인 시냅스 노레피네프린 수치를 증가시킨다.[44][56]뉴런 발현에 근거해mRNA 암페타민은 도파민과 유사하게 노레피네프린에 영향을 미치는 것으로 생각된다.[35][149][176]즉, 암페타민은 인산염, 경쟁적 NET 재흡수 억제, [35][149]로부터의 노레피네프린 방출에서 TAAR1 매개 유출 및 비경쟁적 재흡수 억제를 유도한다.

세로토닌

암페타민은 도파민이나 노르에피네프린과 마찬가지로 세로토닌에 대해서는 유사하지만 뚜렷하지는 않다.[35][56]암페타민은 세로토닌을 통해 세로토닌에 영향을 미치며, 노르에피네프린과 마찬가지로 도파민처럼 암페타민은 인간 5-HT1A 수용체에서 낮은 미세극 친화력을 가지고 있다.[35][149][167][168]

기타 신경전달물질, 펩타이드, 호르몬, 효소

| 효소 | KA()nM | |

|---|---|---|

| hCA4 | 94 | [174] |

| hCA5A을 | 810 | [174][178] |

| hCA5B | 2560 | [174] |

| hCA7 | 910 | [174][178] |

| hCA12 | 640 | [174] |

| hCA13 | 24100 | [174] |

| hCA14 | 9150 | [174] |

인간의 급성 암페타민 투여는 보상체계의 여러 뇌 구조에서 내생성 오피오이드 분비를 증가시킨다.[169][170][171]뇌에서 1차 흥분 신경전달물질인 글루탐산염의 세포외 수치가 암페타민 피폭 이후 선조체에서 증가하는 것으로 나타났다.[153]세포외 글루탐산염의 증가는 도파민 뉴런에 있는 글루탐산염 재흡수 전달체인 EAT3의 암페타민 유도 내장을 통해 발생할 것으로 추정된다.[153][158]암페타민은 또한 마스트 세포에서 히스타민의 선택적 방출을 유도하고, 히스타민성 뉴런으로부터 유출을 유도한다.[149] 급성 암페타민 투여는 또한 시상하부-피티하수체-아드레날린 축을 자극하여 혈장 내 아드레노코스테로이드 호르몬과 코르티코스테로이드 수치를 증가시킬 수 있다.[33][172][173]

12월 2017년에서, 첫번째 공부와 인간의 각성제 탄산 탈수 효소 효소의 상호 작용 평가;11명이 탄산 탈수 효소 꼼꼼히 살펴보았다 효소의[174], 암페타민 강력하게, 그 중 4명은 인간의 뇌에, 낮은 낮은micromolar 활성을 통해nanomolar 표현 7을 활성화시킨다는 것을 발견했다 출판되었다.effects.[174] 사전 임상 연구에 기초하여 뇌탄산 무수화효소 활성화는 인지 강화 효과를 가지고 있지만,[179] 탄산화 무수화효소 억제제의 임상적 사용에 기초하여 다른 조직에서 탄소화 무수화효소 활성화가 녹내장을 악화시키는 것과 같은 부작용과 관련될 수 있다.[179]

암페타민의 경구 생체이용률은 위장 pH에 따라 다양하며,[26] 내장에서 잘 흡수되며, 덱스트로암페타민의 생체이용률은 일반적으로 75%가 넘는다.[3]암페타민은 pK가a 9.9인 약한 염기로,[5] 결과적으로 pH가 기본일 때는 지질 용해성 프리 베이스 형태에 더 많은 약물이 들어가며, 더 많은 약물이 장 상피의 지질 풍부한 세포막을 통해 흡수된다.[5][26]반대로 산성 pH는 약물이 대부분 수용성 계양(소금) 형태로 되어 있고, 적게 흡수된다는 것을 의미한다.[5]혈류에서 순환하는 암페타민의 약 20%는 혈장 단백질과 결합되어 있다.[4]흡수에 이어 암페타민은 체내 대부분의 조직으로 쉽게 분배되며, 뇌척수액과 뇌 조직에서 고농도가 발생한다.[11]

암페타민 에나토머의 반감기는 소변 pH에 따라 다르며 다르다.[5]정상 소변 pH에서 덱스트로암페타민과 레보암페타민의 반감기는 각각 9~11시간, 11~14시간이다.[5]산성이 높은 소변은 엔노머 반감기를 7시간으로 감소시키고,[11] 알칼리성이 높은 소변은 반감기를 34시간까지 증가시킨다.[11]즉시 방출되는 염과 확장 방출된 염은 각각 투여 후 3시간과 7시간 후 혈장 농도에 도달한다.[5]암페타민은 신장을 통해 제거되며, 약물의 30~40%가 정상적인 비뇨기 pH에서 변하지 않고 배설된다.[5]비뇨기 pH가 기본일 때 암페타민은 자유 염기 형태여서 배설량이 적다.[5]소변 pH가 비정상일 때 암페타민의 비뇨기 회복은 소변이 너무 기본인지 산성인지에 따라 각각 1%에서 75%까지 범위가 될 수 있다.[5]경구 투여 후 3시간 이내에 소변에서 암페타민이 나타난다.[11]섭취한 암페타민의 약 90%는 마지막 경구 투여 후 3일 후에 제거된다.[11]

Lisdexamfetamine은 덱스트로암페타민의 약이다.[180][181]위장관에 흡수될 때 암페타민처럼 pH에 민감하지 않다.[181]리스덱삼페타민은 혈류로 흡수된 후 결정되지 않은 아미노펩타아제 효소를 통해 가수분해하여 적혈구에 의해 덱스트로암페타민, 아미노산 L-리신 등으로 완전히 전환된다.[181][180][182]이것은 리스덱삼페타민의 생체활성화에서 속도제한 단계다.[180]리스덱삼페타민의 제거 반감기는 일반적으로 1시간 미만이다.[181][180]리스트덱삼페타민을 덱스트로암페타민으로 변환할 필요가 있기 때문에, 리스트삼페타민 피크가 있는 덱스트로암페타민 수치는 즉시 방출되는 덱스트로암페타민에 대한 등가선량보다 약 1시간 늦었다.[180][182]아마도 적혈구에 의한 속도 제한적인 활성화로 인해, 리스트삼페타민 정맥 투여는 등가선량의 덱스트로암페타민 정맥 투여에 비해 정맥 투여 시간이 크게 지연되고 최고 수치의 감소를 보인다.[180]리스덱삼페타민의 약동학은 경구 투여, 경구 투여, 정맥 투여 여부에 관계없이 유사하다.[180][182]따라서 덱스트로암페타민과는 대조적으로 파렌터럴 사용은 리스덱삼페타민의 주관적 효과를 강화하지 않는다.[180][182]프로드약으로서의 행동과 약동학적 차이 때문에 리스덱삼페타민은 즉각적으로 방출되는 덱스트로암페타민보다 치료 효과 지속시간이 길고 오용 가능성이 줄어든 것을 보여준다.[180][182]

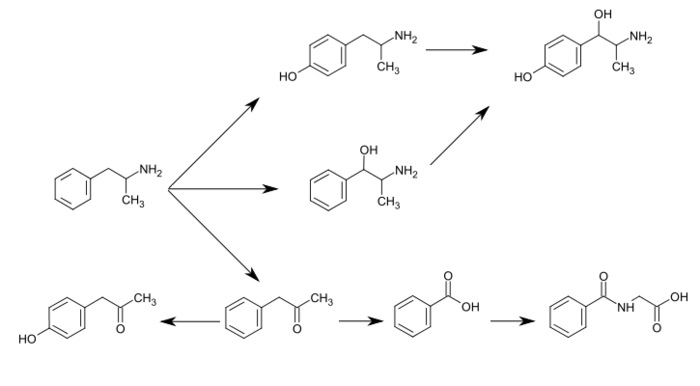

CYP2D6, 도파민 β-히드록실라아제(DBH), 플라빈 함유 모노옥시제 3(FMO3), 부티레이트-CoA 리게아제(XM-ligase), 글리신 N-아킬전달효소(GLYAT)는 암페타민 또는 그 대사물을 사람 내 대사시키는 효소다.[sources 16]암페타민은 4-히드록시암페타민, 4-히드록시노레페드린, 4-히드록시페닐아세톤, 벤조산, 히프산, 노레페드린, 페닐라세톤 등 다양한 배설물 대사 제품을 갖고 있다.[5][6]이들 대사물 중 활성 동조체는 4히드록시암페타민,[183] 4히드록시노레페드린,[184] 노레페드린이다.[185]주요 대사경로는 방향성 파라-수소화, 알리프 알파 및 베타-수소화, N-산소화, N-데알킬화, 탈염 등이 있다.[5][186]인간 내 알려진 대사 경로, 검출 가능한 대사물 및 대사 효소에는 다음이 포함된다.

약리학적 생물학

인간의 메타게놈(즉, 개인과 개인의 몸 안이나 내부에 존재하는 모든 미생물의 유전적 구성)은 개인마다 상당히 다르다.[192][193]이후 microbial과 바이러스 세포들의 인간의 몸에 있는 총 숫자(100조원이 넘는)의 인간 세포 약을 먹는다 개인적인 microbiome 간의 상호 교류를 위해 상당한 가능성이 있습니다,:약물이 인간의 microbiome, microbia에 의해 약물 대사의 구성을 포함한(수조 달러의 수만명)[노트 18][192][194]가 문을.나는 효소 modifying 약물의 약동학 프로필 및 약물의 임상 효능 및 독성 프로필에 영향을 미치는 미생물 약물 대사.[192][193][195]이러한 상호작용을 연구하는 분야를 약리학적 생물학이라고 한다.[192]

암페타민은 대부분의 생체분자 및 기타 경구 투여의 제노바이오틱스(즉, 약물)와 마찬가지로 혈류로 흡수되기 전에 위장형 마이크로바이오타(주로 박테리아)에 의해 난잡한 신진대사를 겪을 것으로 예측된다.[195]인간 내장에서 흔히 발견되는 대장균 변종에서 나온 티라민 산화효소인 암페타민-메타볼라이징 미생물 효소가 2019년 처음 확인됐다.[195]이 효소는 암페타민, 티라민, 페네틸아민 세 화합물에 대해 거의 동일한 결합 친화력으로 대사되는 것으로 밝혀졌다.[195]

관련 내생성 화합물

암페타민은 내생성 미량 아민과 매우 유사한 구조와 기능을 가지고 있는데, 이는 인체와 뇌에서 생성되는 자연적으로 발생하는 신경계수체 분자들이다.[35][44][196]이 집단 중 가장 밀접하게 연관된 화합물은 암페타민의 모성분인 페네틸아민(penethylamine)과 암페타민의 이소머인 N-메틸페네틸아민(즉, 분자식이 동일하다)이다.[35][44][197]인간에서 페네틸아민은 방향족 아미노산 데카르복실라제(AADC) 효소에 의해 L-페닐알라닌에서 직접 생성되는데, 이 효소는 L-DOPA를 도파민으로도 변환시킨다.[44][197]또, N-메틸페네틸아민은 페닐타놀아민 N-메틸전달효소에 의해 페네틸아민으로부터 대사되는데, 이는 노레피네프린을 에피네프린으로 대사시키는 것과 같은 효소다.[44][197]암페타민처럼 페네틸아민과 N-메틸페네틸아민 모두 모노아민 신경전달을 통해 조절한다.[35][196][197] 암페타민과 달리 이 물질은 모두 모노아민 산화효소 B에 의해 분해되어 암페타민보다 반감기가 짧다.[44][197]

화학

인종암페타민 |

페닐-2-니트로펜(오른쪽 컵)

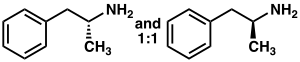

암페타민은 화학식을 가진 포유류 신경전달물질 페네틸아민의 메틸호몰로겐이다. CHN913. 1차 아민에 인접한 탄소 원자는 입체적인 중심이며, 암페타민은 두 개의 에나토머가 혼합된 레이스믹 1:1로 구성되어 있다.[4]이 인종 혼합물은 광학 이소머:[note 19]레보암페타민과 덱스트로암페타민으로 분리될 수 있다.[4]상온에서 암페타민의 순수 프리 베이스는 이동성, 무색, 휘발성 액체로 아민 냄새가 강하며 매캐하고 타는 맛이 특징이다.[20]암페타민 고형염으로는 암페타민 아디페이트,[198] 아스파르타이트,[26] 염산염,[199] 인산염,[200] 사카르타이트,[26] 황산염,[26] 황산염, 황산염 등이 자주 준비된다.[201]덱스트로암페타민 황산염은 가장 흔한 항산화 소금이다.[45]암페타민은 자체 구조계급의 모화합물로 다수의 정신작용 유도체를 포함하고 있다.[13][4]유기화학에서 암페타민은 1,1'-bi-2-나프톨의 입체적 합성에 탁월한 치랄 리간드다.[202]

암페타민 대체 유도체, 즉 '대체 암페타민'은 암페타민을 '백본'으로 함유하고 있는 광범위한 화학물질로,[13][46][203] 특히 암페타민 코어 구조에서 하나 이상의 수소 원자를 대체물로 대체해 형성된 파생 화합물을 이 화학 등급에 포함한다.[13][46][204]암페타민 자체, 필로폰과 같은 자극제, MDMA와 같은 세로토닌 공감제, 에페드린과 같은 해독제 등이 해당된다.[13][46][203]

synthesis합

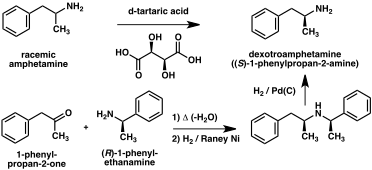

1887년 첫 번째 준비가 보고된 이후 암페타민으로 가는 수많은 합성 루트가 개발되었다.[205][206][207]합법적인 암페타민 합성과 불법적인 암페타민 합성의 가장 일반적인 경로는 Leucart reaction(방법 1)이라고 알려진 비금속 환원법을 사용한다.[45][208]첫 번째 단계에서 페닐아세톤과 폼아미드 사이의 반응은 추가적인 포름산을 사용하거나 포름아미드 자체를 환원제로 하여 N-포름암페타민을 산출한다.그런 다음 염산을 사용하여 이 중간을 가수 분해한 후 유기 용매로 염산을 추출하고 농축하여 증류하여 자유 베이스를 산출한다.그 후 프리 베이스는 유기 용매, 황산이 첨가되고 암페타민이 황산염으로 침전된다.[208][209]

암페타민의 두 에나토머를 분리하기 위해 많은 키랄 해상도가 개발되었다.[206]예를 들어, 인종적 암페타민은 덱스트로암페타민을 생산하기 위해 부분 결정화된 이질성 소금을 형성하기 위해 d-tartaric acid로 처리될 수 있다.[210]치랄 분해능은 광학적으로 순수한 암페타민을 대규모로 획득하는 가장 경제적인 방법으로 남아 있다.[211]또한 암페타민의 항정신성 합성물이 여러 개 개발되었다.한 예에서 광학적으로 순수한 (R)-1-페닐-에타마닌을 페닐아세톤과 응축하여 치랄 쉬프 기지를 산출한다.키 단계에서, 이 중간은 촉매 수소화에 의해 탄소 원자 알파에 대한 치례성의 아미노 그룹으로의 전달에 의해 감소된다.수소화에 의한 벤질리 아민 결합의 갈라짐은 광학적으로 순수한 덱스트로암페타민을 산출한다.[211]

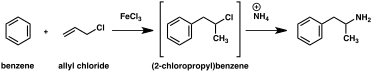

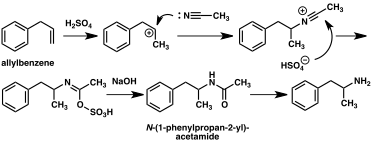

고전적인 유기 반응을 바탕으로 암페타민에 대한 대체 합성 루트가 대거 개발됐다.[206][207]예를 들어, 염화 아릴에 의한 벤젠의 프리델-크래프트 알킬화가 베타 클로로프로필 벤젠을 산출한 후 암모니아와 반응하여 경마암페타민(메소드 2)을 생산하는 것이다.[212]다른 예는 리터 반응(방법 3)을 사용한다.이 경로에서 아릴렌벤젠은 황산에 아세토나이트릴을 반응시켜 유기황산을 산출하고, 유기황산나트륨을 처리하여 아세트아미드 중간을 통해 암페타민을 투여한다.[213][214]세 번째 경로는 에틸 3-옥소부타노산 에틸로 시작되는데, 이 에틸 3-옥소부타노산 에틸에 이어 염화벤질까지 2-메틸-3-페닐-프로파노산으로 전환될 수 있다.이 합성 중량은 호프만이나 커티우스 재배열(방법 4)을 이용하여 암페타민으로 변형할 수 있다.[215]

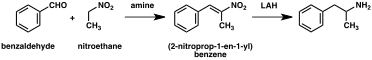

상당수의 암페타민 합성물은 니트로, 이미인, 옥사임 또는 기타 질소를 함유한 기능 그룹의 감소를 특징으로 한다.[207]그러한 예에서 니트로에탄과 함께 벤츠알데히드 응축은 페닐-2-니트로펜을 산출한다.이 중간의 이중 결합 및 니트로 그룹은 촉매 수소화 또는 리튬 알루미늄 하이드라이드 처리(방법 5)를 사용하여 감소한다.[208][216]또 다른 방법은 페닐라세톤이 암모니아와 반응하여 팔라듐 촉매나 리튬 알루미늄 하이드라이드(method 6)를 통해 수소를 사용하여 1차 아민으로 환원되는 이미네 중간 물질을 생성하는 것이다.[208]

| | |

체액 감지

암페타민은 스포츠, 고용, 중독 진단, 포렌식 등을 위한 약물 검사의 일환으로 소변이나 혈액으로 자주 측정된다.[sources 17]암페타민 테스트의 가장 흔한 형태인 면역항암제와 같은 기술은 다수의 동조 약물들과 상호작용을 할 수 있다.[220]암페타민 전용 크로마토그래픽 방법을 채용해 잘못된 양성 결과를 방지한다.[221]처방 암페타민, 처방 암페타민 프로드러그(예: 셀레길린), 레보메트암페타민이 함유된 처방전 의약품,[note 20] 또는 대체 암페타민을 불법으로 획득한 의약품 등 의약품의 출처를 구별하기 위해 치랄 분리 기술을 사용할 수 있다.[221][224][225]벤츠페타민, 클로벤조렉스, 팬프로파존, 펜프로포렉스, 리스덱삼페타민, 메소카브, 필로폰, 태라민, 셀레길린 등 여러 처방약들이 대사물로 암페타민을 생산한다.[2][226][227]이 화합물들은 약물 테스트에서 암페타민에 대한 양성 결과를 산출할 수 있다.[226][227]암페타민은 일반적으로 약 24시간 동안 표준 약물 테스트에 의해서만 검출이 가능하지만, 2-4일 동안 고선량을 검출할 수 있다.[220]

검사의 경우 암페타민 및 필로폰에 대한 효소 곱셈 면역측정법(EMIT) 검사에서 액상 크로마토그래피-탄뎀 질량분석법보다 거짓 양성반응이 더 많이 나올 수 있다는 연구 결과가 나왔다.[224]가스 크로마토그래피-질량분석(GC–MS) 암페타민 및 필로폰의 유도화제(S)-(---------------fluoroacetylprolyl)를 사용하여 소변에서 필로폰을 검출할 수 있다.[221]암페타민 및 필로폰의 GC–MS와 키랄 유도제 모셔의 산성염화제는 덱스트로암페타민과 덱스트로메탐페타민 모두를 소변에서 검출할 수 있다.[221]따라서 후자의 방법은 약물의 다양한 출처를 구별하기 위해 다른 방법을 사용하여 양성반응을 보이는 표본에 사용될 수 있다.[221]

역사, 사회, 문화

| 물질 | 베스트 견적을 내다 | 낮음 견적을 내다 | 높은 견적을 내다 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 암페타민- 활자 흥분제 | 34.16 | 13.42 | 55.24 |

| 대마초 | 192.15 | 165.76 | 234.06 |

| 코카인 | 18.20 | 13.87 | 22.85 |

| 엑스터시 | 20.57 | 8.99 | 32.34 |

| 오파테스 | 19.38 | 13.80 | 26.15 |

| 오피오이드 | 34.26 | 27.01 | 44.54 |

암페타민은 1887년 루마니아 화학자 라즈르 에델레아누에 의해 처음으로 합성되었는데, 그는 그것을 페닐 이소프로필아닌이라고 이름 지었다;[205][229][230] 그 흥분제 효과는 고든 앨리스에 의해 독자적으로 재동기화되었고 동조적인 성질을 가지고 있다고 보고된 1927년까지 알려지지 않았다.[230]암페타민은 1933년 말 스미스, 클라인, 불란서 등이 디콘에스트로 베네드린이라는 상표명으로 흡입기로 판매하기 시작했을 때까지 의학적 용도가 없었다.[27]베네드린 황산염은 3년 뒤 도입돼 기면증, 비만, 저혈압, 성욕저하, 만성통증 등 다양한 질환 치료에 이용됐다.[47][27]제2차 세계 대전 동안, 암페타민과 필로폰은 각성제와 경기력 향상 효과로 연합군과 축군 양군에 의해 광범위하게 사용되었다.[205][231][232]마약의 중독성이 알려지면서 각국 정부는 암페타민 판매를 엄격히 통제하기 시작했다.[205]예를 들어 1970년대 초 미국에서 암페타민은 통제 물질법에 따라 일정 II 통제 물질이 되었다.[233][234]정부의 엄격한 통제에도 불구하고 암페타민은 작가,[235] 음악가,[236] 수학자,[237] 운동선수 등 다양한 배경을 가진 사람들에 의해 합법적이거나 불법적으로 사용되어 왔다.[25]

암페타민은 오늘날에도 은밀한 실험실에서 불법 합성되어 주로 유럽 국가들에서 암페타민 시장에서 판매되고 있다.[238]2018년 유럽연합(EU)[239] 회원국 가운데 15~64세 성인 1190만 명이 평생 한 번 이상 암페타민이나 필로폰을 사용했고,[update] 지난해 170만 명이 모두 사용했다.2012년 동안 EU 회원국 내에서 약 5.9톤의 불법 암페타민이 압수되었다.[240] 같은 기간 EU 내 불법 암페타민의 "시세"는 그램 당 6~38유로였다.[240]유럽 밖에서는 암페타민 불법거래 시장이 필로폰이나 MDMA 시장보다 훨씬 작다.[238]

법적현황

1971년 유엔 향정신성 물질 협약의 결과, 암페타민은 183개 주의 모든 정당에서 조약에 정의된 대로 스케줄 II 통제 물질이 되었다.[28]결과적으로, 그것은 대부분의 국가에서 심하게 규제되고 있다.[241][242]한국과 일본 등 일부 국가는 의료용 암페타민 대체 사용을 금지했다.[243][244]캐나다와 같은 다른 국가들에서 네덜란드가 미국(일정 2세 마약)[26]호주 태국(일정 8)[247](범주 1마취)[248]과 영국(B급 마약)[249]amphetamine은 의학적 치료로 사용이를 허용하는 제한적인 국가 마약 스케줄에 있(목록 나는 마취시키고)[246](나는 마취시키고 일정)[245].[238][29]

의약품

몇몇 현재 판매된 암페타민 제제들의 브랜드 이름 아 드레날리, 아 드레날리 XR, Mydayis,[노트 1]Adzenys ERAdzenys XR-ODT, Dyanavel XR, Evekeo, Evekeo ODT에 판매된다. 그 Evekeo(Evekeo ODT 포함)은 유일한 제품만 라세미 각성제(암페타민 황산으로)이 들어 있는 중 포함 enantiomers을 함유하고 있다.이고그러므로 활동적인 매이티를 단순히 "암페타민"이라고 정확하게 언급할 수 있는 유일한 것이다.[1][33][86]덱스드린과 젠제이지라는 브랜드로 판매되는 덱스트로암페타민은 현재 유일하게 엔안티오퓨어 암페타민 제품이다.덱스트로암페타민의 프로드러브 형태인 리스트삼페타민도 구할 수 있으며, Vyvanse라는 브랜드 이름으로 시판되고 있다.프로드약인 만큼 리스덱삼페타민은 덱스트로암페타민과는 구조적으로 다르며 덱스트로암페타민으로 대사될 때까지 활동이 없다.[34][181]경주용 암페타민의 프리 베이스는 이전에 베네게드린, 시케드린, 소피테드린으로 이용이 가능했다.[2]레보암페타민은 이전에 키드릴로 사용 가능했다.[2]현재 많은 암페타민제약들은 프리베이스의 상대적으로 높은 변동성으로 인해 소금이다.[2][34][45]다만 2015년과 2016년 각각 프리베이스로 구성된 구강정지와 구강해체 태블릿(ODT) 용량 형태가 도입됐다.[86][250][251]현재 일부 브랜드와 해당 상표의 일반 동급 제품들은 아래에 열거되어 있다.

| 브랜드 이름을 붙이다 | 미국 채택된 이름 | (D:L) 비율 | 복용량 형체를 이루다 | 마케팅 시작일 | 미국 소비자 가격 자료 | 원천 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 애더럴 | – | 3:1 (계속) | 태블릿 | 1996 | GoodRx | [2][34] |

| 애더럴 XR | – | 3:1 (계속) | 캡슐을 넣다 | 2001 | GoodRx | [2][34] |

| 마이데이리스 | – | 3:1 (계속) | 캡슐을 넣다 | 2017 | GoodRx | [252][253] |

| 아드제니스 ER | 암페타민 | 3:1 (베이스) | 정지 | 2017 | GoodRx | [254] |

| 애드제니스 XR-ODT | 암페타민 | 3:1 (베이스) | ODT | 2016 | GoodRx | [251][255] |

| 디애나벨 XR | 암페타민 | 3.2:1 (베이스) | 정지 | 2015 | GoodRx | [86][250] |

| 이브케오 | 황산암페타민 암페타민 | 1:1 (계속) | 태블릿 | 2012 | GoodRx | [33][256] |

| 이브케오 ODT | 황산암페타민 암페타민 | 1:1 (계속) | ODT | 2019 | GoodRx | [257] |

| 덱세드린 | 황산페타민 덱스트로암페타민 | 1:0(초기화) | 캡슐을 넣다 | 1976 | GoodRx | [2][34] |

| 제네게디 | 황산페타민 덱스트로암페타민 | 1:0(초기화) | 태블릿 | 2013 | GoodRx | [34][258] |

| 비반스 | 리스덱삼페타민 디메실레이트 | 1:0 (약물) | 캡슐을 넣다 | 2007 | GoodRx | [2][181][259] |

| 태블릿 |

| 약물을 복용하다 | 공식 | 분자질량 [주 21] | 암페타민 베이스 [주 22] | 암페타민 베이스 같은 양으로 | 와의 복용량. 동일본위 내용상의 [주 23] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g/message) | (%) | (30mg 용량) | ||||||||

| 총계 | 밑의 | 총계 | 덱스트로- | 레보- | 덱스트로- | 레보- | ||||

| 황산페타민 덱스트로암페타민[261][262] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 | 270.41 | 73.38% | 73.38% | — | 22.0mg | — | 30.0mg | |

| 황산암페타민 암페타민[263] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 | 270.41 | 73.38% | 36.69% | 36.69% | 11.0mg | 11.0mg | 30.0mg | |

| 애더럴 | 62.57% | 47.49% | 15.08% | 14.2mg | 4.5mg | 35.2mg | ||||

| 25% | 황산페타민[261][262] 덱스트로암페타민 | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 | 270.41 | 73.38% | 73.38% | — | |||

| 25% | 황산암페타민[263] 암페타민 | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 | 270.41 | 73.38% | 36.69% | 36.69% | |||

| 25% | 덱스트로암페타민 사카레이트[264] | (C9H13N)2•C6H10O8 | 480.55 | 270.41 | 56.27% | 56.27% | — | |||

| 25% | 암페타민 아스파라테 단수화물[265] | (C9H13N)•C4H7NO4•H2O | 286.32 | 135.21 | 47.22% | 23.61% | 23.61% | |||

| 리스덱삼페타민 디메실레이트[181] | C15H25N3O•(CH4O3S)2 | 455.49 | 135.21 | 29.68% | 29.68% | — | 8.9mg | — | 74.2mg | |

| 암페타민 베이스 서스펜션[86] | C9H13N | 135.21 | 135.21 | 100% | 76.19% | 23.81% | 22.9mg | 7.1mg | 22.0mg | |

메모들

- ^ a b Mydayis와 같은 Adderall과 다른 혼합 암페타민 소금 제품들은 경주용 암페타민이 아니다. 그들은 동등한 부품 경주 친구와 덱스트로암페타민으로 구성된 혼합물이다.

혼합물에 대한 자세한 내용은 혼합 암페타민 솔트를 참조하고, 현재 시판 중인 암페타민 에나토머의 다양한 혼합물에 대한 자세한 내용은 이 섹션을 참조하십시오. - ^ 동의어와 대체 철자에는 1-페닐프로판-2-아민(IUPAC 이름), α-메틸페네틸아민, 암페타민(국제 비수용성 이름[INN]), β-페닐이소프로필아민, 속도 등이 포함된다.[21][4][22]

- ^ 에반토머는 서로 거울에 비친 이미지로, 구조적으로는 동일하지만 반대 방향의 분자들이다.[23]

레보암페타민과 덱스트로암페타민은 각각 L-암페타민(INN) 또는 D-암페타민(INN)으로도 알려져 있다.[21] - ^ 브랜드명 Adderall은 이 글에 포함된 암페타민 4-소금 혼합물(덱스트로암페타민 황산염 25%, 덱스트로암페타민 사카레이트 25%, 암페타민 황산염 25%, 암페타민 아스파테이트 25%)을 지칭하기 위해 이 글 전반에 걸쳐 사용된다.네 가지 활성 성분 화학물질을 모두 나열한 비수용적 명칭은 지나치게 길다.[34]

- ^ '암페타민'이란 용어도 화학계급을 말하지만, 대체암페타민계급과 달리 '암페타민'계급은 학술문헌에서 표준화된 정의를 가지고 있지 않다.[13][17]이 세분류에 대한 보다 제한적인 정의 중 하나는 암페타민과 필로폰의 경주마 및 에나토머만을 포함한다.[17]세분류에 대한 가장 일반적인 정의는 광범위한 약리학적 및 구조적으로 관련된 화합물을 포함한다.[17]

복수형 사용으로 인해 발생할 수 있는 혼돈으로 인해 본 기사는 경주용 암페타민, 레보암페타민, 덱스트로암페타민 등을 지칭할 때 '암페타민'과 '암페타민'이라는 용어만 사용하고 구조 등급은 '대체 암페타민'이라는 용어를 유보한다. - ^ 장기 지속적 흥분제 치료에서 현저하게 개선된 결과의 비율이 가장 높은 ADHD 관련 결과 영역에는 학업(학업적 결과의 55%) 주행(운전 결과의 100%) 비의료용 약물 사용(중독 관련 결과의 47%) 비만(비만 관련 결과의 65%)이 포함된다.개선), 자존감(자긍심 결과의 50%) 및 사회적 기능(사회적 기능 결과의 67%)이 향상되었다.[54]

장기 자극제 치료로 인한 결과 개선 효과의 가장 큰 크기는 학계(예: 성적 평균, 성취도 시험 점수, 교육 기간, 교육 수준), 자존감(예: 자존감 설문지 평가, 자살 시도 횟수, 자살률)과 사회 기능(예: 자살률)이 포함된 영역에서 발생한다.. 또래 지명 점수, 사회 기술 및 또래, 가족, 연애 관계의 질.[54]

ADHD에 대한 장기 조합 치료(즉, 각성제와 행동요법을 병행하는 치료)는 결과 개선에 대한 효과 크기가 훨씬 더 크며 장기 자극제 치료에만 비해 각 영역 전체에서 결과의 더 큰 비중을 개선한다.[54] - ^ Cochrane 리뷰는 무작위 제어 시험의 고품질의 메타 분석적 체계적 리뷰다.[60]

- ^ USFDA가 지지하는 진술은 제조자의 저작권이 있고 USFDA가 승인한 지식재산권 정보를 규정하는 데서 나온 것이다. USFDA 금지는 반드시 의료행위를 제한하기 위한 것이 아니라 제약회사의 청구권을 제한하기 위한 것이다.[81]

- ^ 한 가지 검토에 따르면, 암페타민은 처방 의사가 매일 약을 픽업하도록 요구하는 등 적절한 약물 통제를 채택할 경우 학대 전력이 있는 개인에게 처방될 수 있다.[2]

- ^ 정상 이하의 키와 체중 증가를 경험하는 개인에서 각성제 치료가 잠시 중단되면 정상 수준으로의 반등이 일어날 것으로 예상된다.[41][53][85]지속적인 각성제 치료 3년 동안 성인 최종 키의 평균 감소량은 2cm이다.[85]

- ^ 전사 인자는 특정 유전자의 발현을 증가시키거나 감소시키는 단백질이다.[114]

- ^ 간단히 말해서, 이 필요하고도 충분한 관계는 핵에 대한 ΔFosB의 과도한 억눌림과 중독과 관련된 행동과 신경 적응은 항상 함께 발생하며 결코 혼자만의 일은 일어나지 않는다는 것을 의미한다.

- ^ NMDA 수용체는 전압에 의존하는 리간드 게이트 이온 채널로 글루탐산염의 동시 결합과 이온 채널을 열기 위한 코아곤스트(D-세린 또는 글리신)가 필요하다.[128]

- ^ 이 검토는 마그네슘 L-아스파테이트와 염화 마그네슘이 중독적인 행동에 상당한 변화를 일으킨다는 것을 보여주었다;[105] 다른 형태의 마그네슘은 언급되지 않았다.

- ^ 95% 신뢰 구간은 실제 사망자 수가 3,425명에서 4,145명 사이에 있을 확률이 95%임을 나타낸다.

- ^ a b 인간 도파민 트랜스포터(hDAT)는 아연 결합 시 도파민 재흡수를 억제하고 암페타민 유도 hDAT 내장을 억제하며 암페타민 유도 도파민 유출을 증폭시키는 고선호성, 세포외, 알로스테릭 Zn2+(zinc 이온) 결합 부위가 있다.[144][145][146][147]인간 세로토닌 트랜스포터와 노레피네프린 트랜스포터는 아연 결합 부위가 들어 있지 않다.[146]

- ^ 4-히드록시암페타민은 시험관내 도파민 베타-히드록시라아제(DBH)에 의해 4-히드록시노레페드린으로 대사되는 것으로 나타났으며 체내에서도 비슷하게 대사되는 것으로 추정된다.[13][187]연구에서 혈청 DBH 농도를 인체에4-hydroxyamphetamine 신진대사에 효과를 측정했습니다 증거는 다른 효소 4-hydroxyamphetamine의 4-hydroxynorephedrine로 변환하는 것이 중재할 수도 있고[187][189] 하지만, 동물 연구로 다른 증거는 이 반응 DBH에 의해 시냅스 vesicl에 촉매 작용이 있음을 의미한다.에스 이내에뇌에 있는 [190][191]노라드레날린 뉴런들

- ^ 해부학적 부위별로 미생물 구성과 미생물 농도에 상당한 변화가 있다.[192][193]어떤 해부학적 부위에서도 가장 높은 농도의 미생물을 포함하고 있는 인간 결장의 액체는 약 1조(10^12)의 박테리아 세포/ml를 포함하고 있다.[192]

- ^ 에반토머는 서로 거울에 비친 이미지로, 구조적으로는 동일하지만 반대 방향의 분자들이다.[23]

- ^ 미국의 일부 OTC 흡입기의 활성 성분은 레베메탐페타민, 레보메탐페타민의 INN, USAN으로 기재되어 있다.[222][223]

- ^ 균일성을 위해 분자 질량은 Lenntech Mole Wealth Calculator를[260] 사용하여 계산되었으며, 발표된 의약품 값의 0.01g/mol 이내였습니다.

- ^ 암페타민 기본 백분율 = 분자 질량base/분자 질량totalAdderall에 대한 암페타민 기본 백분율 = 성분 백분율 / 4의 합계.

- ^ 선량 = (1 / 암페타민 기준 비율) × 스케일링 계수 = (분자 질량total/분자 질량base) × 스케일링 계수.이 열의 값은 30mg의 덱스트로암페타민 황산염으로 조정되었다.이러한 약물들 간의 약리학적 차이(예: 방출, 흡수, 전환, 농도 차이, 항산화제, 반감기 등)로 인해 열거된 값은 등전위 선량으로 간주되지 않아야 한다.

- 이미지 범례

참고 사항

- ^ [2][17][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33]

- ^ [2][10][24][27][33][35][36]

- ^ [10][24][25][26][30][37][38][39][40][41][42][43]

- ^ [44][45][46]

- ^ [1][26][37][85][86][87]

- ^ [88][89][90][91]

- ^ [26][82][88][90]

- ^ [30][26][37][92]

- ^ a b [108][109][110][111][130]

- ^ [106][108][107][115][116]

- ^ [107][118][119][120]

- ^ [22][26][37][134][136]

- ^ [48][138][141][142]

- ^ a b [149][153][157][158][159][160][161]

- ^ [35][149][157][158][162][167]

- ^ a b [5][13][14][15][16][6][187][188]

- ^ [25][217][218][219]

참조

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stahl SM (March 2017). "Amphetamine (D,L)". Prescriber's Guide: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology (6th ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–51. ISBN 9781108228749. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ (June 2013). "Amphetamine, past and present – a pharmacological and clinical perspective". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 27 (6): 479–496. doi:10.1177/0269881113482532. PMC 3666194. PMID 23539642.

The intravenous use of d-amphetamine and other stimulants still pose major safety risks to the individuals indulging in this practice. Some of this intravenous abuse is derived from the diversion of ampoules of d-amphetamine, which are still occasionally prescribed in the UK for the control of severe narcolepsy and other disorders of excessive sedation. ... For these reasons, observations of dependence and abuse of prescription d-amphetamine are rare in clinical practice, and this stimulant can even be prescribed to people with a history of drug abuse provided certain controls, such as daily pick-ups of prescriptions, are put in place (Jasinski and Krishnan, 2009b).

- ^ a b Wishart DS, Djombou Feunang Y, Guo AC, Lo EJ, Marcu A, Grant JR, Sajed T, Johnson D, Li C, Sayeeda Z, Assempour N, Iynkkaran I, Liu Y, Maciejewski A, Gale N, Wilson A, Chin L, Cummings R, Le D, Pon A, Knox C, Wilson M. "Dextroamphetamine DrugBank Online". DrugBank. 5.0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wishart DS, Djombou Feunang Y, Guo AC, Lo EJ, Marcu A, Grant JR, Sajed T, Johnson D, Li C, Sayeeda Z, Assempour N, Iynkkaran I, Liu Y, Maciejewski A, Gale N, Wilson A, Chin L, Cummings R, Le D, Pon A, Knox C, Wilson M. "Amphetamine DrugBank Online". DrugBank. 5.0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc. December 2013. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Santagati NA, Ferrara G, Marrazzo A, Ronsisvalle G (September 2002). "Simultaneous determination of amphetamine and one of its metabolites by HPLC with electrochemical detection". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 30 (2): 247–255. doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00330-8. PMID 12191709.

- ^ "Pharmacology". amphetamine/dextroamphetamine. Medscape. WebMD. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

Onset of action: 30–60 min

- ^ a b c Millichap JG (2010). "Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD". In Millichap JG (ed.). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 112. ISBN 9781441913968.

Table 9.2 Dextroamphetamine formulations of stimulant medication

Dexedrine [Peak:2–3 h] [Duration:5–6 h] ...

Adderall [Peak:2–3 h] [Duration:5–7 h]

Dexedrine spansules [Peak:7–8 h] [Duration:12 h] ...

Adderall XR [Peak:7–8 h] [Duration:12 h]

Vyvanse [Peak:3–4 h] [Duration:12 h] - ^ Brams M, Mao AR, Doyle RL (September 2008). "Onset of efficacy of long-acting psychostimulants in pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Postgraduate Medicine. 120 (3): 69–88. doi:10.3810/pgm.2008.09.1909. PMID 18824827. S2CID 31791162.

- ^ a b c d "Adderall- dextroamphetamine saccharate, amphetamine aspartate, dextroamphetamine sulfate, and amphetamine sulfate tablet". DailyMed. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Metabolism/Pharmacokinetics". Amphetamine. United States National Library of Medicine – Toxicology Data Network. Hazardous Substances Data Bank. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

Duration of effect varies depending on agent and urine pH. Excretion is enhanced in more acidic urine. Half-life is 7 to 34 hours and is, in part, dependent on urine pH (half-life is longer with alkaline urine). ... Amphetamines are distributed into most body tissues with high concentrations occurring in the brain and CSF. Amphetamine appears in the urine within about 3 hours following oral administration. ... Three days after a dose of (+ or -)-amphetamine, human subjects had excreted 91% of the (14)C in the urine

- ^ a b Mignot EJ (October 2012). "A practical guide to the therapy of narcolepsy and hypersomnia syndromes". Neurotherapeutics. 9 (4): 739–752. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0150-9. PMC 3480574. PMID 23065655.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Glennon RA (2013). "Phenylisopropylamine stimulants: amphetamine-related agents". In Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (eds.). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (7th ed.). Philadelphia, USA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 646–648. ISBN 9781609133450.

The simplest unsubstituted phenylisopropylamine, 1-phenyl-2-aminopropane, or amphetamine, serves as a common structural template for hallucinogens and psychostimulants. Amphetamine produces central stimulant, anorectic, and sympathomimetic actions, and it is the prototype member of this class (39). ... The phase 1 metabolism of amphetamine analogs is catalyzed by two systems: cytochrome P450 and flavin monooxygenase. ... Amphetamine can also undergo aromatic hydroxylation to p-hydroxyamphetamine. ... Subsequent oxidation at the benzylic position by DA β-hydroxylase affords p-hydroxynorephedrine. Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

- ^ a b Taylor KB (January 1974). "Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Stereochemical course of the reaction" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 249 (2): 454–458. PMID 4809526. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

Dopamine-β-hydroxylase catalyzed the removal of the pro-R hydrogen atom and the production of 1-norephedrine, (2S,1R)-2-amino-1-hydroxyl-1-phenylpropane, from d-amphetamine.

- ^ a b c Krueger SK, Williams DE (June 2005). "Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 106 (3): 357–387. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001. PMC 1828602. PMID 15922018.

표 5: FMO에 의해 산소가 함유된 N 함유 의약품 및 항생제 - ^ a b Cashman JR, Xiong YN, Xu L, Janowsky A (March 1999). "N-oxygenation of amphetamine and methamphetamine by the human flavin-containing monooxygenase (form 3): role in bioactivation and detoxication". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 288 (3): 1251–1260. PMID 10027866.

- ^ a b c d e Yoshida T (1997). "Chapter 1: Use and Misuse of Amphetamines: An International Overview". In Klee H (ed.). Amphetamine Misuse: International Perspectives on Current Trends. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers. p. 2. ISBN 9789057020810.

Amphetamine, in the singular form, properly applies to the racemate of 2-amino-1-phenylpropane. ... In its broadest context, however, the term [amphetamines] can even embrace a large number of structurally and pharmacologically related substances.

- ^ "Density". Amphetamine. PubChem Compound Database. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. 5 November 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ "Properties: Predicted – EPISuite". Amphetamine. ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Chemical and Physical Properties". Amphetamine. PubChem Compound Database. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ a b c "Compound Summary". Amphetamine. PubChem Compound Database. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. 11 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ a b Greene SL, Kerr F, Braitberg G (October 2008). "Review article: amphetamines and related drugs of abuse". Emergency Medicine Australasia. 20 (5): 391–402. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2008.01114.x. PMID 18973636. S2CID 20755466.

- ^ a b "Enantiomer". IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology. IUPAC Goldbook. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. 2009. doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02069. ISBN 9780967855097. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

One of a pair of molecular entities which are mirror images of each other and non-superposable.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 318, 321. ISBN 9780071481274.

Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in normal subjects and those with ADHD. ... stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks ... through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors. ...

Beyond these general permissive effects, dopamine (acting via D1 receptors) and norepinephrine (acting at several receptors) can, at optimal levels, enhance working memory and aspects of attention. - ^ a b c d e f g Liddle DG, Connor DJ (June 2013). "Nutritional supplements and ergogenic AIDS". Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 40 (2): 487–505. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009. PMID 23668655.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training ...

Physiologic and performance effects

• Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

• Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

• Improved reaction time

• Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

• Increased acceleration

• Increased alertness and attention to task - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an "Adderall XR- dextroamphetamine sulfate, dextroamphetamine saccharate, amphetamine sulfate and amphetamine aspartate capsule, extended release". DailyMed. Shire US Inc. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d Rasmussen N (July 2006). "Making the first anti-depressant: amphetamine in American medicine, 1929–1950". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 61 (3): 288–323. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrj039. PMID 16492800. S2CID 24974454.

However the firm happened to discover the drug, SKF first packaged it as an inhaler so as to exploit the base's volatility and, after sponsoring some trials by East Coast otolaryngological specialists, began to advertise the Benzedrine Inhaler as a decongestant in late 1933.

- ^ a b "Convention on psychotropic substances". United Nations Treaty Collection. United Nations. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ a b Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, Sgambati S, Rotrosen J, Sawtelle R, Utzinger L, Fusillo S (January 2008). "Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 47 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56f1. PMID 18174822.

Stimulant misuse appears to occur both for performance enhancement and their euphorogenic effects, the latter being related to the intrinsic properties of the stimulants (e.g., IR versus ER profile) ...

Although useful in the treatment of ADHD, stimulants are controlled II substances with a history of preclinical and human studies showing potential abuse liability. - ^ a b c Montgomery KA (June 2008). "Sexual desire disorders". Psychiatry. 5 (6): 50–55. PMC 2695750. PMID 19727285.

- ^ "Amphetamine". Medical Subject Headings. United States National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ "Guidelines on the Use of International Nonproprietary Names (INNS) for Pharmaceutical Substances". World Health Organization. 1997. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

In principle, INNs are selected only for the active part of the molecule which is usually the base, acid or alcohol. In some cases, however, the active molecules need to be expanded for various reasons, such as formulation purposes, bioavailability or absorption rate. In 1975 the experts designated for the selection of INN decided to adopt a new policy for naming such molecules. In future, names for different salts or esters of the same active substance should differ only with regard to the inactive moiety of the molecule. ... The latter are called modified INNs (INNMs).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Evekeo- amphetamine sulfate tablet". DailyMed. Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC. 14 August 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "National Drug Code Amphetamine Search Results". National Drug Code Directory. United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". Journal of Neurochemistry. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b c d e Grandy DK, Miller GM, Li JX (February 2016). ""TAARgeting Addiction"-The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution: An Overview of the Plenary Symposium of the 2015 Behavior, Biology and Chemistry Conference". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 159: 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014. PMC 4724540. PMID 26644139.

When considered together with the rapidly growing literature in the field a compelling case emerges in support of developing TAAR1-selective agonists as medications for preventing relapse to psychostimulant abuse.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Westfall DP, Westfall TC (2010). "Miscellaneous Sympathomimetic Agonists". In Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071624428.

- ^ a b c d e Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Ling W (January 2009). Shoptaw SJ, Ali R (ed.). "Treatment for amphetamine psychosis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003026. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003026.pub3. PMC 7004251. PMID 19160215.

A minority of individuals who use amphetamines develop full-blown psychosis requiring care at emergency departments or psychiatric hospitals. In such cases, symptoms of amphetamine psychosis commonly include paranoid and persecutory delusions as well as auditory and visual hallucinations in the presence of extreme agitation. More common (about 18%) is for frequent amphetamine users to report psychotic symptoms that are sub-clinical and that do not require high-intensity intervention ...

About 5–15% of the users who develop an amphetamine psychosis fail to recover completely (Hofmann 1983) ...

Findings from one trial indicate use of antipsychotic medications effectively resolves symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.

psychotic symptoms of individuals with amphetamine psychosis may be due exclusively to heavy use of the drug or heavy use of the drug may exacerbate an underlying vulnerability to schizophrenia. - ^ a b c d e Bramness JG, Gundersen ØH, Guterstam J, Rognli EB, Konstenius M, Løberg EM, Medhus S, Tanum L, Franck J (December 2012). "Amphetamine-induced psychosis—a separate diagnostic entity or primary psychosis triggered in the vulnerable?". BMC Psychiatry. 12: 221. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-221. PMC 3554477. PMID 23216941.

In these studies, amphetamine was given in consecutively higher doses until psychosis was precipitated, often after 100–300 mg of amphetamine ... Secondly, psychosis has been viewed as an adverse event, although rare, in children with ADHD who have been treated with amphetamine

- ^ a b c Greydanus D. "Stimulant Misuse: Strategies to Manage a Growing Problem" (PDF). American College Health Association (Review Article). ACHA Professional Development Program. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Huang YS, Tsai MH (July 2011). "Long-term outcomes with medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: current status of knowledge". CNS Drugs. 25 (7): 539–554. doi:10.2165/11589380-000000000-00000. PMID 21699268. S2CID 3449435.

Several other studies,[97-101] including a meta-analytic review[98] and a retrospective study,[97] suggested that stimulant therapy in childhood is associated with a reduced risk of subsequent substance use, cigarette smoking and alcohol use disorders. ... Recent studies have demonstrated that stimulants, along with the non-stimulants atomoxetine and extended-release guanfacine, are continuously effective for more than 2-year treatment periods with few and tolerable adverse effects. The effectiveness of long-term therapy includes not only the core symptoms of ADHD, but also improved quality of life and academic achievements. The most concerning short-term adverse effects of stimulants, such as elevated blood pressure and heart rate, waned in long-term follow-up studies. ... The current data do not support the potential impact of stimulants on the worsening or development of tics or substance abuse into adulthood. In the longest follow-up study (of more than 10 years), lifetime stimulant treatment for ADHD was effective and protective against the development of adverse psychiatric disorders.

- ^ a b Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE, Holtzman DM (2015). "Chapter 16: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 9780071827706.

Such agents also have important therapeutic uses; cocaine, for example, is used as a local anesthetic (Chapter 2), and amphetamines and methylphenidate are used in low doses to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and in higher doses to treat narcolepsy (Chapter 12). Despite their clinical uses, these drugs are strongly reinforcing, and their long-term use at high doses is linked with potential addiction, especially when they are rapidly administered or when high-potency forms are given.

- ^ a b Kollins SH (May 2008). "A qualitative review of issues arising in the use of psycho-stimulant medications in patients with ADHD and co-morbid substance use disorders". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 24 (5): 1345–1357. doi:10.1185/030079908X280707. PMID 18384709. S2CID 71267668.

When oral formulations of psychostimulants are used at recommended doses and frequencies, they are unlikely to yield effects consistent with abuse potential in patients with ADHD.

- ^ a b c d e f g Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ a b c d "Amphetamine". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Hagel JM, Krizevski R, Marsolais F, Lewinsohn E, Facchini PJ (2012). "Biosynthesis of amphetamine analogs in plants". Trends in Plant Science. 17 (7): 404–412. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.03.004. PMID 22502775.

Substituted amphetamines, which are also called phenylpropylamino alkaloids, are a diverse group of nitrogen-containing compounds that feature a phenethylamine backbone with a methyl group at the α-position relative to the nitrogen (Figure 1). ... Beyond (1R,2S)-ephedrine and (1S,2S)-pseudoephedrine, myriad other substituted amphetamines have important pharmaceutical applications. ... For example, (S)-amphetamine (Figure 4b), a key ingredient in Adderall and Dexedrine, is used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [79]. ...

[Figure 4](b) Examples of synthetic, pharmaceutically important substituted amphetamines. - ^ a b Bett WR (August 1946). "Benzedrine sulphate in clinical medicine; a survey of the literature". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 22 (250): 205–218. doi:10.1136/pgmj.22.250.205. PMC 2478360. PMID 20997404.

- ^ a b Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, Carvalho F, Bastos Mde L (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Archives of Toxicology. 86 (8): 1167–1231. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347. S2CID 2873101.

- ^ Berman S, O'Neill J, Fears S, Bartzokis G, London ED (October 2008). "Abuse of amphetamines and structural abnormalities in the brain". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1141 (1): 195–220. doi:10.1196/annals.1441.031. PMC 2769923. PMID 18991959.

- ^ a b Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K (February 2013). "Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277. PMID 23247506.

- ^ a b Spencer TJ, Brown A, Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N, Lomedico A, Faraone SV, Biederman J (September 2013). "Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 74 (9): 902–917. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08287. PMC 3801446. PMID 24107764.

- ^ a b Frodl T, Skokauskas N (February 2012). "Meta-analysis of structural MRI studies in children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder indicates treatment effects". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 125 (2): 114–126. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01786.x. PMID 22118249. S2CID 25954331.

Basal ganglia regions like the right globus pallidus, the right putamen, and the nucleus caudatus are structurally affected in children with ADHD. These changes and alterations in limbic regions like ACC and amygdala are more pronounced in non-treated populations and seem to diminish over time from child to adulthood. Treatment seems to have positive effects on brain structure.

- ^ a b c d Millichap JG (2010). "Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD". In Millichap JG (ed.). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York, USA: Springer. pp. 121–123, 125–127. ISBN 9781441913968.

Ongoing research has provided answers to many of the parents' concerns, and has confirmed the effectiveness and safety of the long-term use of medication.

- ^ a b c d e Arnold LE, Hodgkins P, Caci H, Kahle J, Young S (February 2015). "Effect of treatment modality on long-term outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review". PLOS ONE. 10 (2): e0116407. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116407. PMC 4340791. PMID 25714373.

The highest proportion of improved outcomes was reported with combination treatment (83% of outcomes). Among significantly improved outcomes, the largest effect sizes were found for combination treatment. The greatest improvements were associated with academic, self-esteem, or social function outcomes.

그림 3: 치료 유형 및 결과 그룹별 치료 혜택 - ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 154–157. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ a b c d e Bidwell LC, McClernon FJ, Kollins SH (August 2011). "Cognitive enhancers for the treatment of ADHD". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 99 (2): 262–274. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.002. PMC 3353150. PMID 21596055.

- ^ Parker J, Wales G, Chalhoub N, Harpin V (September 2013). "The long-term outcomes of interventions for the management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 6: 87–99. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S49114. PMC 3785407. PMID 24082796.

Only one paper53 examining outcomes beyond 36 months met the review criteria. ... There is high level evidence suggesting that pharmacological treatment can have a major beneficial effect on the core symptoms of ADHD (hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity) in approximately 80% of cases compared with placebo controls, in the short term.

- ^ Millichap JG (2010). "Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD". In Millichap JG (ed.). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York, USA: Springer. pp. 111–113. ISBN 9781441913968.

- ^ "Stimulants for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". WebMD. Healthwise. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Scholten RJ, Clarke M, Hetherington J (August 2005). "The Cochrane Collaboration". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 59 (Suppl 1): S147–S149, discussion S195–S196. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602188. PMID 16052183. S2CID 29410060.

- ^ a b Castells X, Blanco-Silvente L, Cunill R (August 2018). "Amphetamines for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (8): CD007813. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007813.pub3. PMC 6513464. PMID 30091808.

- ^ Punja S, Shamseer L, Hartling L, Urichuk L, Vandermeer B, Nikles J, Vohra S (February 2016). "Amphetamines for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD009996. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009996.pub2. PMID 26844979.

- ^ Osland ST, Steeves TD, Pringsheim T (June 2018). "Pharmacological treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with comorbid tic disorders". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (6): CD007990. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007990.pub3. PMC 6513283. PMID 29944175.

- ^ a b Spencer RC, Devilbiss DM, Berridge CW (June 2015). "The Cognition-Enhancing Effects of Psychostimulants Involve Direct Action in the Prefrontal Cortex". Biological Psychiatry. 77 (11): 940–950. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.013. PMC 4377121. PMID 25499957.

The procognitive actions of psychostimulants are only associated with low doses. Surprisingly, despite nearly 80 years of clinical use, the neurobiology of the procognitive actions of psychostimulants has only recently been systematically investigated. Findings from this research unambiguously demonstrate that the cognition-enhancing effects of psychostimulants involve the preferential elevation of catecholamines in the PFC and the subsequent activation of norepinephrine α2 and dopamine D1 receptors. ... This differential modulation of PFC-dependent processes across dose appears to be associated with the differential involvement of noradrenergic α2 versus α1 receptors. Collectively, this evidence indicates that at low, clinically relevant doses, psychostimulants are devoid of the behavioral and neurochemical actions that define this class of drugs and instead act largely as cognitive enhancers (improving PFC-dependent function). ... In particular, in both animals and humans, lower doses maximally improve performance in tests of working memory and response inhibition, whereas maximal suppression of overt behavior and facilitation of attentional processes occurs at higher doses.

- ^ Ilieva IP, Hook CJ, Farah MJ (June 2015). "Prescription Stimulants' Effects on Healthy Inhibitory Control, Working Memory, and Episodic Memory: A Meta-analysis". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 27 (6): 1069–1089. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00776. PMID 25591060. S2CID 15788121.

Specifically, in a set of experiments limited to high-quality designs, we found significant enhancement of several cognitive abilities. ... The results of this meta-analysis ... do confirm the reality of cognitive enhancing effects for normal healthy adults in general, while also indicating that these effects are modest in size.

- ^ Bagot KS, Kaminer Y (April 2014). "Efficacy of stimulants for cognitive enhancement in non-attention deficit hyperactivity disorder youth: a systematic review". Addiction. 109 (4): 547–557. doi:10.1111/add.12460. PMC 4471173. PMID 24749160.

Amphetamine has been shown to improve consolidation of information (0.02 ≥ P ≤ 0.05), leading to improved recall.

- ^ Devous MD, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ (April 2001). "Regional cerebral blood flow response to oral amphetamine challenge in healthy volunteers". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 42 (4): 535–542. PMID 11337538.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 10: Neural and Neuroendocrine Control of the Internal Milieu". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 266. ISBN 9780071481274.

Dopamine acts in the nucleus accumbens to attach motivational significance to stimuli associated with reward.

- ^ a b c Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG (January 2014). "Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacological Reviews. 66 (1): 193–221. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMC 3880463. PMID 24344115.

- ^ Twohey M (26 March 2006). "Pills become an addictive study aid". JS Online. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ Teter CJ, McCabe SE, LaGrange K, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ (October 2006). "Illicit use of specific prescription stimulants among college students: prevalence, motives, and routes of administration". Pharmacotherapy. 26 (10): 1501–1510. doi:10.1592/phco.26.10.1501. PMC 1794223. PMID 16999660.

- ^ Weyandt LL, Oster DR, Marraccini ME, Gudmundsdottir BG, Munro BA, Zavras BM, Kuhar B (September 2014). "Pharmacological interventions for adolescents and adults with ADHD: stimulant and nonstimulant medications and misuse of prescription stimulants". Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 7: 223–249. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S47013. PMC 4164338. PMID 25228824.

misuse of prescription stimulants has become a serious problem on college campuses across the US and has been recently documented in other countries as well. ... Indeed, large numbers of students claim to have engaged in the nonmedical use of prescription stimulants, which is reflected in lifetime prevalence rates of prescription stimulant misuse ranging from 5% to nearly 34% of students.

- ^ Clemow DB, Walker DJ (September 2014). "The potential for misuse and abuse of medications in ADHD: a review". Postgraduate Medicine. 126 (5): 64–81. doi:10.3810/pgm.2014.09.2801. PMID 25295651. S2CID 207580823.

Overall, the data suggest that ADHD medication misuse and diversion are common health care problems for stimulant medications, with the prevalence believed to be approximately 5% to 10% of high school students and 5% to 35% of college students, depending on the study.

- ^ Bracken NM (January 2012). "National Study of Substance Use Trends Among NCAA College Student-Athletes" (PDF). NCAA Publications. National Collegiate Athletic Association. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Docherty JR (June 2008). "Pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (3): 606–622. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124. PMC 2439527. PMID 18500382.

- ^ a b c d Parr JW (July 2011). "Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the athlete: new advances and understanding". Clinics in Sports Medicine. 30 (3): 591–610. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2011.03.007. PMID 21658550.

In 1980, Chandler and Blair47 showed significant increases in knee extension strength, acceleration, anaerobic capacity, time to exhaustion during exercise, pre-exercise and maximum heart rates, and time to exhaustion during maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) testing after administration of 15 mg of dextroamphetamine versus placebo. Most of the information to answer this question has been obtained in the past decade through studies of fatigue rather than an attempt to systematically investigate the effect of ADHD drugs on exercise.

- ^ a b c Roelands B, de Koning J, Foster C, Hettinga F, Meeusen R (May 2013). "Neurophysiological determinants of theoretical concepts and mechanisms involved in pacing". Sports Medicine. 43 (5): 301–311. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0030-4. PMID 23456493. S2CID 30392999.

In high-ambient temperatures, dopaminergic manipulations clearly improve performance. The distribution of the power output reveals that after dopamine reuptake inhibition, subjects are able to maintain a higher power output compared with placebo. ... Dopaminergic drugs appear to override a safety switch and allow athletes to use a reserve capacity that is 'off-limits' in a normal (placebo) situation.

- ^ Parker KL, Lamichhane D, Caetano MS, Narayanan NS (October 2013). "Executive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease and timing deficits". Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 7: 75. doi:10.3389/fnint.2013.00075. PMC 3813949. PMID 24198770.

Manipulations of dopaminergic signaling profoundly influence interval timing, leading to the hypothesis that dopamine influences internal pacemaker, or "clock," activity. For instance, amphetamine, which increases concentrations of dopamine at the synaptic cleft advances the start of responding during interval timing, whereas antagonists of D2 type dopamine receptors typically slow timing;... Depletion of dopamine in healthy volunteers impairs timing, while amphetamine releases synaptic dopamine and speeds up timing.

- ^ Rattray B, Argus C, Martin K, Northey J, Driller M (March 2015). "Is it time to turn our attention toward central mechanisms for post-exertional recovery strategies and performance?". Frontiers in Physiology. 6: 79. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00079. PMC 4362407. PMID 25852568.

Aside from accounting for the reduced performance of mentally fatigued participants, this model rationalizes the reduced RPE and hence improved cycling time trial performance of athletes using a glucose mouthwash (Chambers et al., 2009) and the greater power output during a RPE matched cycling time trial following amphetamine ingestion (Swart, 2009). ... Dopamine stimulating drugs are known to enhance aspects of exercise performance (Roelands et al., 2008)

- ^ Roelands B, De Pauw K, Meeusen R (June 2015). "Neurophysiological effects of exercise in the heat". Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 25 (Suppl 1): 65–78. doi:10.1111/sms.12350. PMID 25943657. S2CID 22782401.

This indicates that subjects did not feel they were producing more power and consequently more heat. The authors concluded that the "safety switch" or the mechanisms existing in the body to prevent harmful effects are overridden by the drug administration (Roelands et al., 2008b). Taken together, these data indicate strong ergogenic effects of an increased DA concentration in the brain, without any change in the perception of effort.

- ^ Kessler S (January 1996). "Drug therapy in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". Southern Medical Journal. 89 (1): 33–38. doi:10.1097/00007611-199601000-00005. PMID 8545689. S2CID 12798818.

statements on package inserts are not intended to limit medical practice. Rather they are intended to limit claims by pharmaceutical companies. ... the FDA asserts explicitly, and the courts have upheld that clinical decisions are to be made by physicians and patients in individual situations.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Heedes G, Ailakis J. "Amphetamine (PIM 934)". INCHEM. International Programme on Chemical Safety. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Feinberg SS (November 2004). "Combining stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review of uses and one possible additional indication". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 65 (11): 1520–1524. doi:10.4088/jcp.v65n1113. PMID 15554766.

- ^ Stewart JW, Deliyannides DA, McGrath PJ (June 2014). "How treatable is refractory depression?". Journal of Affective Disorders. 167: 148–152. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.047. PMID 24972362.

- ^ a b c d Vitiello B (April 2008). "Understanding the risk of using medications for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with respect to physical growth and cardiovascular function". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 17 (2): 459–474. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.010. PMC 2408826. PMID 18295156.

- ^ Ramey JT, Bailen E, Lockey RF (2006). "Rhinitis medicamentosa" (PDF). Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 16 (3): 148–155. PMID 16784007. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

Table 2. Decongestants Causing Rhinitis Medicamentosa

– Nasal decongestants:

– Sympathomimetic:

• Amphetamine - ^ a b "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review Update of Medications used to treat Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children and young adults". United States Food and Drug Administration. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Cooper WO, Habel LA, Sox CM, Chan KA, Arbogast PG, Cheetham TC, Murray KT, Quinn VP, Stein CM, Callahan ST, Fireman BH, Fish FA, Kirshner HS, O'Duffy A, Connell FA, Ray WA (November 2011). "ADHD drugs and serious cardiovascular events in children and young adults". New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (20): 1896–1904. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110212. PMC 4943074. PMID 22043968.

- ^ a b "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review Update of Medications used to treat Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults". United States Food and Drug Administration. 12 December 2011. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Habel LA, Cooper WO, Sox CM, Chan KA, Fireman BH, Arbogast PG, Cheetham TC, Quinn VP, Dublin S, Boudreau DM, Andrade SE, Pawloski PA, Raebel MA, Smith DH, Achacoso N, Uratsu C, Go AS, Sidney S, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Ray WA, Selby JV (December 2011). "ADHD medications and risk of serious cardiovascular events in young and middle-aged adults". JAMA. 306 (24): 2673–2683. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1830. PMC 3350308. PMID 22161946.

- ^ O'Connor PG (February 2012). "Amphetamines". Merck Manual for Health Care Professionals. Merck. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ a b Childs E, de Wit H (May 2009). "Amphetamine-induced place preference in humans". Biological Psychiatry. 65 (10): 900–904. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.016. PMC 2693956. PMID 19111278.

This study demonstrates that humans, like nonhumans, prefer a place associated with amphetamine administration. These findings support the idea that subjective responses to a drug contribute to its ability to establish place conditioning.

- ^ a b Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ a b c d e Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type [nucleus accumbens] neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41. ... Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.

- ^ "Glossary of Terms". Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neuroscience. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Substance-use disorder: A diagnostic term in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) referring to recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Depending on the level of severity, this disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. - ^ a b c Renthal W, Nestler EJ (September 2009). "Chromatin regulation in drug addiction and depression". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 11 (3): 257–268. PMC 2834246. PMID 19877494.

[Psychostimulants] increase cAMP levels in striatum, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and leads to phosphorylation of its targets. This includes the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), the phosphorylation of which induces its association with the histone acetyltransferase, CREB binding protein (CBP) to acetylate histones and facilitate gene activation. This is known to occur on many genes including fosB and c-fos in response to psychostimulant exposure. ΔFosB is also upregulated by chronic psychostimulant treatments, and is known to activate certain genes (eg, cdk5) and repress others (eg, c-fos) where it recruits HDAC1 as a corepressor. ... Chronic exposure to psychostimulants increases glutamatergic [signaling] from the prefrontal cortex to the NAc. Glutamatergic signaling elevates Ca2+ levels in NAc postsynaptic elements where it activates CaMK (calcium/calmodulin protein kinases) signaling, which, in addition to phosphorylating CREB, also phosphorylates HDAC5.

그림 2: 심리 자극에 의한 신호 이벤트 - ^ Broussard JI (January 2012). "Co-transmission of dopamine and glutamate". The Journal of General Physiology. 139 (1): 93–96. doi:10.1085/jgp.201110659. PMC 3250102. PMID 22200950.