인간을

Human| 인간을[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

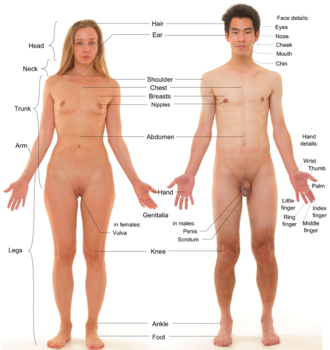

| 성인 남성(왼쪽)과 여성(오른쪽) (태국, 2007) | |

| 과학적 분류 | |

| 도메인: | 진핵생물 |

| 킹덤: | 애니멀리아 |

| 문: | 초르다타 |

| 클래스: | 포유류 |

| 순서: | 영장류 |

| 하위 순서: | 하플로르히니 |

| 인프라오더: | 유사체 |

| 가족: | 호미과 |

| 아과: | 호미니내과 |

| 부족: | 호미니니 |

| 속: | 호모 |

| 종: | H. 사피엔스 |

| 이항명 | |

| 호모 사피엔스 린네, 1758년 | |

| |

| 호모 사피엔스 인구밀도 (2005) | |

인간, 또는 현생 인류 (호모 사피엔스)는 가장 흔하고 널리 퍼져있는 영장류 종입니다.털이 없고, 두 발로 걷는 행동과 높은 지능을 특징으로 하는 유인원인 인간은 큰 두뇌를 가지고 있으며, 이는 인간이 다양한 환경에서 번성하고 적응할 수 있도록 하며, 복잡한 사회와 문명을 발전시킬 수 있도록 하는 더 발전된 인지 능력을 가능하게 합니다.인간은 매우 사회적이고 가족과 친족 관계망에서 정치 국가에 이르기까지 많은 협력적이고 경쟁적인 집단들로 구성된 복잡한 사회 구조 속에서 사는 경향이 있습니다.이와 같이 인간 간의 사회적 상호작용은 사회규범, 언어, 의식 등 매우 다양한 가치관을 형성하고 있으며, 이는 각각 인간사회를 더욱 공고히 하고 있습니다.과학, 기술, 철학, 신화, 종교 및 기타 지식의 틀을 이해하고 영향을 미치려는 욕구는 인류의 발전을 촉진시켜 왔습니다.인간은 또한 인류학, 사회과학, 역사학, 심리학, 의학과 같은 영역을 통해 스스로 공부합니다.

비록 일부 과학자들은 "인간"이라는 용어를 호모 속의 모든 구성원과 동일시하지만, 일반적으로 그것은 일반적으로 현존하는 유일한 구성원인 호모 사피엔스를 가리킵니다.호모 속의 다른 구성원들은 사후에 고대 인류로 알려져 있습니다.해부학적으로 현생 인류는 약 30만년 전 아프리카에서 호모 하이델베르겐시스 또는 유사한 종에서 진화하여 출현했습니다.아프리카 밖으로 이주하면서, 그들은 점차 고대 인류의 지역 개체군을 대체하고 교배했습니다.그들의 역사의 대부분 동안, 인류는 유목민 수렵인 겸 채집인류는인간은 약 16만년에서 6만년 전부터 행동적 근대성을 나타내기 시작했습니다.약 1만 3천 년 전 서남아시아에서 시작된 신석기 혁명으로 농업과 영구적인 인류 정착이 이루어졌습니다.인구가 점점 더 많아지고 밀도가 높아짐에 따라, 공동체 내부와 공동체 간에 통치의 형태가 발달했고, 많은 수의 문명이 흥망성쇠했습니다.2023년 현재[update] 전 세계 인구는 80억 명 이상으로 인류는 지속적으로 증가하고 있습니다.

유전자와 환경은 눈에 보이는 특성, 생리학, 질병 감수성, 정신적 능력, 신체 크기, 수명에 있어 인간의 생물학적 변화에 영향을 미칩니다.인간은 유전적 성향과 신체적 특징과 같은 많은 특성에서 다양하지만, 어떤 두 인간도 최소한 유전적으로 99% 비슷합니다.인간은 성적 이형성을 가지고 있습니다: 일반적으로 남성은 더 큰 신체 힘을 가지고 여성은 더 높은 체지방률을 가지고 있습니다.사춘기가 되면 인간은 2차 성징을 갖게 됩니다.여성들은 보통 12세 정도의 사춘기와 50세 정도의 폐경기 사이에 임신을 할 수 있습니다.

인류는 잡식성으로 다양한 식물과 동물 물질을 섭취할 수 있으며 호모 에렉투스 시대부터 음식을 준비하고 요리하기 위해 불과 다른 형태의 열을 사용해 왔습니다.인간은 음식 없이 8주까지 살 수 있고 물 없이도 며칠 동안 살 수 있습니다.인간은 일반적으로 하루에 평균 7시간에서 9시간 정도 잠을 자는 주행성 동물입니다.출산은 합병증과 사망의 위험이 높은 위험성을 가지고 있습니다.종종, 엄마와 아빠 모두 태어날 때 무력한 아이들을 돌봅니다.

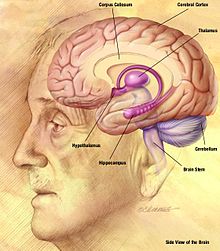

인간은 크고 고도로 발달된 복잡한 전두엽 피질을 가지고 있는데, 이것은 고등 인지와 관련된 뇌의 영역입니다.인간은 고도로 지능이 높고, 기억력이 있으며, 유연한 표정, 자기 인식, 그리고 정신 이론을 가지고 있습니다.인간의 마음은 자기성찰, 사유, 상상력, 자발성, 존재에 대한 견해를 형성할 수 있습니다.이를 통해 복잡한 추론과 후속 세대로의 지식 전달을 통해 기술 발전과 복잡한 도구 개발이 가능해졌습니다.언어, 예술, 무역은 인간의 특징을 정의하는 것입니다.장거리 무역로는 문화적 폭발과 자원 분배로 이어졌을 수 있으며, 이는 인류에게 유사한 다른 종보다 유리한 위치를 제공했습니다.

어원 및 정의

모든 현생 인류는 칼 린네가 1735년에 저술한 시스테마 자연사에서 만든 호모 사피엔스 종으로 분류됩니다.[2]"호모"라는 총칭은 라틴어 호모(homo)에서 18세기에 유래한 것으로, 두 성별의 인간을 가리킵니다.[3][4]인간이라는 단어는 일반적으로 현존하는 유일한 종인 호모 사피엔스를 가리키지만,[5] 일반적으로 인간은 호모 속의 모든 구성원을 가리킬 수 있습니다.[6]"호모 사피엔스"라는 이름은 '현명한 사람' 또는 '지식 있는 사람'을 의미합니다.[7]네안데르탈인이라는 이 속의 멸종된 특정 종들이 별도의 인간 종으로 포함되어야 하는지 아니면 H. 사피엔스의 아종으로 포함되어야 하는지에 대해서는 이견이 있습니다.[5]

인간(Human)[8]은 중세 영어의 외래어로, 궁극적으로는 라틴어 후마누스(humannus)의 형용사형인 호모(homo)에서 유래했습니다.토착 영어 용어 man은 인간 수컷뿐만 아니라 일반적으로 (인류의 동의어) 종을 나타낼 수 있습니다.그것은 또한 어느 한 성별의 개인을 지칭할 수도 있습니다.[9]

동물이라는 단어가 구어적으로 인간의 반의어로 사용되고,[10] 일반적인 생물학적 오해와는 반대로 인간은 동물입니다.[11]사람이라는 단어는 종종 인간과 혼용되지만, 인간성이 모든 인간에게 적용되는지 아니면 모든 지각 있는 존재에게 적용되는지, 그리고 더 나아가 사람성을 잃을 수 있는지에 대한 철학적 논쟁이 존재합니다 (예를 들어 지속적인 식물 상태에 들어가는 것).[12]

진화

인간은 유인원입니다.[13]결국 인간을 탄생시킨 유인원의 계통은 긴팔원숭이(Hylobatidae과)와 오랑우탄(Pongo속), 고릴라(Gorilla속), 그리고 마지막으로 침팬지와 보노보(Pan속)로 나뉘었습니다.인간과 침팬지-보노보 계통 사이의 마지막 분열은 약 800만년 전에서 400만년 전, 중신세 말기에 일어났습니다.[14][15]이 분열 동안, 2번 염색체는 두 개의 다른 염색체의 결합으로 형성되었고, 인간은 다른 유인원의 24개와 비교하여 23쌍의 염색체만을 남겼습니다.[16]침팬지와 보노보로 갈라진 후, 호미닌은 많은 종과 적어도 두 개의 다른 속으로 다양해졌습니다.호모속과 현존하는 유일한 종인 호모 사피엔스를 대표하는 이 혈통들 중 하나를 제외한 모든 것들이 현재 멸종되었습니다.[17]

| 호미노상과 (호미노상과, 유인원) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

호모속은 오스트랄로피테쿠스에서 진화했습니다.[18][19]비록 전환의 화석은 드물지만, 호모의 초기 멤버들은 오스트랄로피테쿠스와 몇 가지 주요 특징들을 공유합니다.[20][21]호모에 대한 가장 초기의 기록은 에티오피아에서 온 280만년 된 LD 350-1 표본이며, 가장 초기의 이름이 붙은 종은 230만년 전에 진화한 호모 하빌리스와 호모 루돌프엔시스입니다.[21]H. ergaster라고 불리는 아프리카 변종 H. ergaster는 2백만 년 전에 진화했고 아프리카를 떠나 유라시아 전역으로 퍼져나간 최초의 고대 인류 종이었습니다.[22]H. 에렉투스는 또한 특징적으로 인간의 신체 계획을 진화시킨 최초의 사람이었습니다.호모 사피엔스는 약 30만년 전 아프리카에 남아있던 H. erctus의 후손인 H. hidelbergensis 또는 H. rodhesiensis로 흔히 지정된 종에서 출현했습니다.[23]H. 사피엔스는 점차 고대 인류의 지역 개체군을 대체하거나 교배하면서 대륙 밖으로 이주했습니다.[24][25][26]인간은 약 16만년에서 7만년 전부터 행동적 근대성을 보이기 시작했습니다.[27][28]

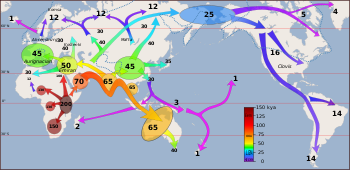

"아프리카 밖으로" 이주는 적어도 두 개의 파도에서 이루어졌는데, 첫 번째는 약 13만년에서 10만년 전, 두 번째는 약 7만년에서 5만년 전에 이루어졌습니다.[29][30]H. sapiens는 모든 대륙과 더 큰 섬들을 식민지로 만들기 시작했고, 125,000년 전 유라시아, [31][32]65,000년 전 오스트레일리아,[33] 15,000년 전 아메리카, 그리고 300년에서 1280년 사이에 하와이, 이스터 섬, 마다가스카르, 그리고 뉴질랜드와 같은 외딴 섬들에 도착했습니다.[34][35]

인류의 진화는 단순한 선형적이거나 분기된 진행이 아니라 관련된 종들 간의 교배를 수반했습니다.[36][37][38]게놈 연구는 실질적으로 갈라진 혈통 사이의 교배가 인류 진화에서 일반적이었다는 것을 보여주었습니다.[39]DNA 증거는 네안데르탈인 기원의 여러 유전자들이 사하라 사막 이남의 모든 개체군들 사이에 존재하며, 네안데르탈인과 데니소반인과 같은 다른 호미닌들은 현재의 사하라 사막 이남의 인간들에게 그들의 게놈의 최대 6%를 기여했을 수 있음을 시사합니다.[36][40][41]

인간의 진화는 인간과 침팬지의 마지막 공통 조상 사이의 분열 이후 일어난 많은 형태적, 발달적, 생리적, 행동적 변화에 의해 특징지어집니다.이러한 적응 중 가장 중요한 것은 털이 없는 것,[42] 의무적인 이족 보행, 뇌 크기 증가 및 성적 이형성 감소입니다.이 모든 변화들 사이의 관계는 계속되는 논쟁의 주제입니다.[43]

역사

선사시대

약 12,000년 전까지, 모든 인간들은 수렵채집꾼으로 살았습니다.[44][45]신석기 혁명(농업의 발명)은 서남아시아에서 처음으로 일어났고 그 후 수 천년에 걸쳐 구세계의 많은 지역으로 퍼졌습니다.[46]그것은 또한 메소아메리카 (약 6,000년 전),[47] 중국,[48][49] 파푸아 뉴기니,[50] 그리고 아프리카의 사헬과 서 사바나 지역에서도 독립적으로 발생했습니다.[51][52][53]

식량 잉여에 대한 접근은 영구적인 인간 정착지의 형성, 동물의 가축화, 그리고 역사상 처음으로 금속 도구의 사용으로 이어졌습니다.농업과 정주 생활은 초기 문명의 출현을 이끌었습니다.[54][55][56]

고대의

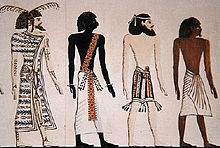

도시 혁명은 기원전 4천년에 도시 국가들, 특히 메소포타미아에 위치한 수메르 도시들의 발전과 함께 일어났습니다.[57]기원전 3000년경에 알려진 가장 초기 형태의 문자인 설형문자가 나타난 것은 이 도시들이었습니다.[58]이 시기에 발전한 다른 주요 문명으로는 고대 이집트와 인더스 계곡 문명이 있습니다.[59]그들은 결국 서로 거래를 했고 바퀴, 쟁기, 돛과 같은 기술을 발명했습니다.[60][61][62][63]천문학과 수학도 발달했고 기자의 대 피라미드가 지어졌습니다.[64][65][66]이 문명들의 쇠퇴를 야기했을 수도 있는 극심한 가뭄이 약 백 년간 지속되었다는 증거가 있으며,[67] 그 여파로 새로운 가뭄들이 나타났습니다.바빌로니아 사람들은 메소포타미아를 지배하게 되었고, 반면에 빈곤점 문화, 미노안, 상 왕조와 [68]같은 다른 사람들은 새로운 지역에서 두각을 나타냈습니다.[69][70][71]

기원전 1200년경 청동기 시대 후기의 붕괴는 많은 문명의 소멸과 그리스 암흑기의 시작을 낳았습니다.[72][73]이 기간 동안 철은 청동을 대체하기 시작했고, 철기 시대로 이어졌습니다.[74]

기원전 5세기에, 역사는 학문으로서 기록되기 시작했고, 이것은 그 당시의 삶에 대한 훨씬 더 명확한 그림을 제공했습니다.[75]기원전 8세기와 6세기 사이에, 유럽은 고대 그리스와 고대 로마가 번성했던 시기인 고전 고대 시대에 접어들었습니다.[76][77]이 무렵 다른 문명들도 두각을 나타냈습니다.마야 문명은 도시를 건설하고 복잡한 달력을 만들기 시작했습니다.[78][79]아프리카에서 악숨 왕국은 쇠퇴하는 쿠시 왕국을 추월했고 인도와 지중해 사이의 무역을 용이하게 했습니다.[80]서아시아에서는 아케메네스 제국의 중앙집권적 통치체제가 후대의 많은 제국의 전신이 되었고,[81] 인도의 굽타 제국과 중국의 한나라는 각각의 지역에서 황금기로 묘사되어 왔습니다.[82][83]

중세의

476년 서로마 제국의 멸망 이후, 유럽은 중세 시대에 접어들었습니다.[84]이 기간 동안 기독교와 교회는 중앙집권적 권위와 교육을 제공할 것입니다.[85]중동에서 이슬람교는 중요한 종교가 되었고 북아프리카로 확장되었습니다.그것은 이슬람 황금기로 이어졌고, 건축의 성과를 고무시켰고, 과학 기술의 오래된 발전의 부활과 독특한 삶의 방식의 형성으로 이어졌습니다.[86][87]영국 왕국, 프랑스 왕국, 신성 로마 제국이 이슬람교도들로부터 성지 지배권을 되찾기 위해 일련의 성전을 선포하면서 기독교와 이슬람 세계는 결국 충돌할 것입니다.[88]

아메리카 대륙에서는 서기 800년경부터 복잡한 미시시피 사회가 생겨났고,[89] 남쪽으로는 아즈텍과 잉카가 지배적인 세력이 되었습니다.[90]몽골 제국은 13세기와 14세기에 유라시아의 많은 부분을 정복했습니다.[91]같은 기간 동안 아프리카의 말리 제국은 세네감비아에서 코트디부아르에 이르는 대륙에서 가장 큰 제국으로 성장했습니다.[92]오세아니아는 남태평양의 많은 섬들에 걸쳐 확장된 투 ʻ 통가 제국의 성장을 보게 될 것입니다.

현대의

유럽과 근동의 초기 근대 시기 (1450–c.1800)는 비잔틴 제국의 최종적인 패배와 오스만 제국의 부상으로 시작되었습니다.[94]한편, 일본은 에도 시대로 접어들었고,[95] 청 왕조는 중국에서[96] 일어났고, 무굴 제국은 인도의 많은 부분을 지배했습니다.[97]유럽은 15세기를 시작으로 르네상스를 [98]겪었고, 새로운 지역의 탐험과 식민지화로 발견의 시대가 시작되었습니다.[99]여기에는 대영제국이 세계 최대의 제국으로[100] 성장하는 것과 아메리카 대륙의 식민지화가 포함됩니다.[101]이 확장은 대서양 노예 무역과[102] 아메리카 원주민들의 대량학살로 이어졌습니다.[103]이 시기는 또한 수학, 역학, 천문학, 생리학의 큰 발전과 함께 과학 혁명을 기념했습니다.[104]

근대 후기(1800-현재)에는 기술 및 산업 혁명이 영상 기술, 운송 및 에너지 개발의 주요 혁신과 같은 발견을 가져왔습니다.[105]미국은 작은 집단의 식민지에서 세계적인 초강대국 중 하나로 가면서 큰 변화를 겪었습니다.[106]나폴레옹 전쟁은 1800년대 초에 유럽을 통해 맹위를 떨쳤고,[107] 스페인은 신세계에서 식민지의 대부분을 잃었고,[108] 반면 유럽인들은 아프리카로 계속 확장하여 50년[109] 이내에 유럽의 지배력이 10%에서 거의 90%로 증가했습니다.[110]

1914년 역사상 가장 치명적인 갈등 중 하나인 제1차 세계대전의 발발로 유럽 국가들 사이의 약한 힘의 균형이 무너졌습니다.[111]1930년대에, 세계적인 경제 위기는 권위주의 정권의 등장과 세계의 거의 모든 나라들이 관련된 2차 세계 대전으로 이어졌습니다.[112]

컨템포러리

1945년 제2차 세계대전이 끝난 후, 소련과 미국의 냉전은 핵무기 경쟁과 우주 경쟁을 포함한 세계적 영향력을 위한 투쟁을 목격했습니다.[113][114]현재의 정보화 시대는 세계가 점점 더 세계화되고 상호 연결되어 가는 것을 보고 있습니다.[115]

서식지 및 개체수

| |

| 세계인구 | 80억 |

|---|---|

| 인구밀도 | 총면적별 16/km2(41/sqmi) 국토별 54/km2(140/제곱미터) |

| 대도시[n2] | Tokyo, Delhi, Shanghai, São Paulo, Mexico City, Cairo, Mumbai, Beijing, Dhaka, Osaka, New York-Newark, Karachi, Buenos Aires, Chongqing, Istanbul, Kolkata, Manila, Lagos, Rio de Janeiro, Tianjin, Kinshasa, Guangzhou, Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, Moscow, Shenzhen, Lahore, Bangalore, Paris, Jakarta, Chennai, Lima, Bogota, Bangkok, London |

초기 인류의 정착지는 물과의 근접성과 생활 방식에 따라 사냥을 위한 동물의 먹이와 농작물을 재배하고 가축을 방목하기 위한 경작지와 같은 다른 천연 자원에 의존했습니다.[119]그러나 현대 인류는 기술, 관개, 도시 계획, 건설, 삼림 벌채, 사막화 등을 통해 서식지를 바꿀 수 있는 큰 능력을 가지고 있습니다.[120]인간의 거주지는 자연 재해, 특히 위험한 장소에 위치하고 건설의 질이 낮은 곳에 위치한 자연 재해에 계속해서 취약합니다.[121]집단화와 의도적인 서식지 변경은 종종 보호를 제공하고, 편안함 또는 물질적인 부를 축적하고, 이용 가능한 식량을 늘리고, 미학을 개선하고, 지식을 증가시키거나 자원을 교환하는 목적으로 행해집니다.[122]

인간은 지구의 많은 극한 환경에 대해 낮거나 좁은 내성을 가지고 있음에도 불구하고 가장 적응력이 뛰어난 종 중 하나입니다.[123]첨단 도구를 통해 인간은 다양한 온도, 습도, 고도까지 견딜 수 있게 되었습니다.[123]결과적으로, 인간은 열대 우림, 건조한 사막, 극도로 추운 북극 지역, 그리고 심하게 오염된 도시를 포함한 세계의 거의 모든 지역에서 발견되는 세계적인 종입니다; 대조적으로, 대부분의 다른 종들은 그들의 제한된 적응력 때문에 몇몇 지리적인 지역에 국한됩니다.[124]그러나 인구 밀도가 지역마다 다르고, 남극과 광대한 바다처럼 넓은 면적의 지표면이 거의 완전히 사람이 살지 않기 때문에 지구 표면에 인구가 균일하게 분포되어 있지 않습니다.[123][125]인간의 대부분(61%)은 아시아에 살고, 나머지는 아메리카(14%), 아프리카(14%), 유럽(11%), 오세아니아(0.5%)[126]에 삽니다.

지난 세기 동안, 인류는 남극대륙, 심해, 그리고 우주와 같은 도전적인 환경을 탐구해왔습니다.[127]이러한 적대적 환경 내에서의 인간 거주는 제한적이고 비용이 많이 들고, 일반적으로 기간이 제한되며, 과학, 군사 또는 산업 탐험으로 제한됩니다.[127]인간은 달을 잠깐 방문한 적이 있고 인간이 만든 로봇 우주선을 통해 다른 천체에 존재감을 느끼게 된 것입니다.[128][129][130]20세기 초반부터 남극에서는 연구소를 통해, 그리고 2000년 이후에는 국제우주정거장에서의 거주를 통해 우주에서 지속적으로 인간의 존재가 있어왔습니다.[131]

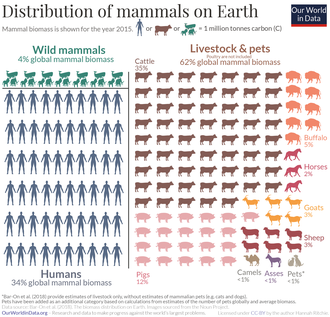

기원전 10,000년경 농업이 출현했을 당시의 인구 추정치는 100만에서 1500만명 사이였습니다.[133][134]서기 4세기에 약 5천만에서 6천만 명의 사람들이 로마 제국의 동쪽과 서쪽을 합친 지역에 살았습니다.[135]기원후 6세기에 처음 기록된 부보닉성 전염병은 인구의 50%를 감소시켰으며, 흑사병으로 유라시아와 북아프리카에서만 7,500만 명에서 2억 명이 사망했습니다.[136]인간의 인구는 1800년에 10억 명에 이른 것으로 믿어지고 있습니다.이후 기하급수적으로 늘어 1930년 20억, 1960년 30억, 1975년 4억, 1987년 5억, 1999년 60억에 달했습니다.[137]2011년[138] 70억명을 돌파했고 2022년 11월 80억명을 돌파했습니다.[139]인류의 선사와 역사는 2백만 년이 넘게 걸렸고 인류의 인구는 10억 명에 이르렀고 70억 명으로 늘어나는데 207년밖에 더 걸리지 않았습니다.[140]2018년 지구상의 모든 인간의 탄소를 합친 바이오매스는 6천만 톤으로 추정되었는데, 이는 가축이 아닌 모든 포유류의 약 10배에 달합니다.[132]

1950년의 7억 5천 1백만 명에서 2018년에는 42억 명(55%)이 도시 지역에 거주했습니다.[141]가장 도시화된 지역은 북미(82%), 중남미(81%), 유럽(74%), 오세아니아(68%) 등이며, 아프리카와 아시아는 전 세계 34억 농촌 인구의 90%에 육박합니다.[141]도시에 사는 인간들의 문제는 다양한 형태의 오염과 범죄,[142] 특히 도심과 교외 빈민가에서의 문제를 포함합니다.인간은 환경에 극적인 영향을 끼쳤습니다.그들은 최상위 포식자이며, 다른 종들이 거의 잡아먹지 않습니다.[143]인류의 인구증가, 산업화, 토지개발, 화석연료의 과잉소비와 연소는 다른 형태의 생명체들의 지속적인 대량 멸종에 크게 기여하는 환경파괴와 오염을 야기시켰습니다.[144][145]

생물학

해부학과 생리학

인간 생리학의 대부분의 측면은 동물 생리학의 대응하는 측면과 밀접하게 상동합니다.인체는 다리, 몸통, 팔, 목, 머리로 구성되어 있습니다.성인 인간의 몸은 약 100조14 개의 세포로 이루어져 있습니다.인간에게 가장 일반적으로 정의되는 신체계는 신경계, 심혈관계, 소화계, 내분비계, 면역계, 장막계, 림프계, 근골격계, 생식계, 호흡기, 비뇨기 등입니다.[146][147]사람의 치아 공식은: 2.1.2.32.1.2.3입니다.인간은 다른 영장류보다 비례적으로 짧은 구개와 훨씬 작은 이빨을 가지고 있습니다.그들은 짧고 비교적 물이 많은 개 이빨을 가진 유일한 영장류입니다.사람들은 독특하게 꽉 찬 치아를 가지고 있는데, 빠진 치아의 틈은 보통 어린 사람들에게서 빠르게 닫힙니다.인간은 점차 세 번째 어금니를 잃어가고 있으며, 일부 사람들은 선천적으로 어금니가 없습니다.[148]

인간은 침팬지와 흔적이 있는 꼬리, 맹장, 유연한 어깨 관절, 잡는 손가락, 엄지손가락을 공유합니다.[149]이족보행증과 뇌의 크기를 제외하고, 인간은 주로 냄새와 청각 그리고 단백질을 소화하는 것에서 침팬지와 다릅니다.[150]인간은 다른 유인원과 비슷한 모낭 밀도를 가지고 있지만, 대부분이 거의 보이지 않을 정도로 짧고 가느다란 털이 주를 이룹니다.[151][152]인간은 땀샘이 부족하고 주로 손바닥과 발바닥에 위치하는 침팬지보다 많은 약 2백만 개의 땀샘이 전신에 퍼져 있습니다.[153]

성인 남성의 세계 평균 신장은 약 171cm인 반면 성인 여성의 세계 평균 신장은 약 159cm인 것으로 추정됩니다.[154]신장의 수축은 어떤 사람들은 중년에 시작할 수 있지만, 극도로 고령인 사람들에게서 전형적인 경향이 있습니다.[155]역사를 통틀어, 인간의 인구는 보편적으로 키가 커졌는데, 아마도 더 나은 영양, 건강 관리, 그리고 생활 조건의 결과일 것입니다.[156]성인 인간의 평균 질량은 여성의 경우 59kg (130파운드)이고 남성의 경우 77kg (170파운드)입니다.[157][158]다른 많은 조건들처럼, 체중과 체형은 유전적 민감성과 환경에 의해 영향을 받고 개인마다 매우 다양합니다.[159][160]

인간은 다른 동물들보다 훨씬 빠르고 정확한 던지기 능력을 가지고 있습니다.[161]인간은 또한 동물계에서 최고의 장거리 달리기 선수들 중 하나이지만, 짧은 거리에서는 느립니다.[162][150]인간의 얇은 체모와 더 생산적인 땀샘은 장거리를 달리는 동안 열에 의한 탈진을 방지하도록 도와줍니다.[163]

유전학

대부분의 동물들처럼, 인간은 이배체와 진핵생물 종입니다.각각의 체세포는 두 세트의 23개 염색체를 가지고 있는데, 각각의 염색체는 한 부모로부터 받은 것입니다; 배우자는 두 부모 세트의 혼합인 한 세트의 염색체만을 가지고 있습니다.23쌍의 염색체 중 22쌍의 염색체와 1쌍의 성염색체가 있습니다.다른 포유류와 마찬가지로 인간도 XY 성 결정 체계를 가지고 있어서 암컷은 XX 성 염색체를, 수컷은 XX 성 염색체를 가지고 있습니다.[164]유전자와 환경은 눈에 보이는 특성, 생리학, 질병 민감성, 정신적 능력에 있어 인간의 생물학적 변화에 영향을 미칩니다.특정 형질에 대한 유전자와 환경의 정확한 영향은 잘 알려져 있지 않습니다.[165][166]

어떤 인간도, 심지어 단일체 쌍둥이조차도 유전적으로 동일하지 않지만,[167] 평균적으로 두 사람은 99.5%-99.9%[168][169]의 유전적 유사성을 가질 것입니다.이것은 그들을 침팬지를 포함한 다른 유인원들보다 더 균질하게 만듭니다.[170][171]다른 많은 종들과 비교했을 때 인간 DNA의 이 작은 변화는 플라이스토세 후기(약 10만년 전) 동안 인간의 개체 수가 소수의 번식 쌍으로 감소한 개체 수 병목 현상을 시사합니다.[172][173]자연 선택의 힘은 지난 15,000년 동안 게놈의 특정 지역이 방향 선택을 보여준다는 증거와 함께 인간 개체수에 계속 작용해 왔습니다.[174]

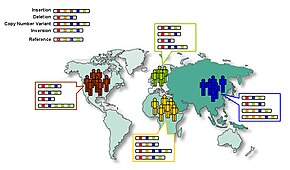

인간 게놈은 2001년에[175] 최초로 염기서열이 밝혀졌고 2020년까지 수십만 개의 게놈이 염기서열이 밝혀졌습니다.[176]2012년 국제 합맵 프로젝트는 11개 모집단의 1,184명의 게놈을 비교하여 160만 개의 단일 뉴클레오티드 다형성을 확인했습니다.[177]아프리카 인구가 가장 많은 수의 개인 유전자 변종을 보유하고 있습니다.아프리카 밖의 인구에서 발견되는 많은 일반적인 변종들이 아프리카 대륙에서도 발견되지만, 여전히 이 지역들, 특히 오세아니아와 아메리카에 사적인 많은 수가 있습니다.[178]2010년까지 인간은 약 22,000개의 유전자를 가지고 있습니다.[179]유전학자들은 어머니에게서만 유전되는 미토콘드리아 DNA를 비교함으로써 모든 현생 인류에서 유전자 표지가 발견되는 마지막 여성 공통 조상, 이른바 미토콘드리아 이브가 9만~20만년 전쯤 살았을 것이라는 결론을 내렸습니다.[180][181][182][183]

생애주기

대부분의 인간의 생식은 성관계를 통한 체내 수정에 의해 이루어지지만 보조생식술을 통해서도 일어날 수 있습니다.[184]평균 임신 기간은 38주이지만 정상 임신은 최대 37일까지 차이가 날 수 있습니다.[185]인간의 배아 발달은 발달의 첫 8주를 포함합니다; 9주가 시작될 때 배아는 태아라고 불립니다.[186]의학적인 이유로 아이가 더 일찍 태어나야 한다면 인간은 조기 진통을 유도하거나 제왕절개 수술을 할 수 있습니다.[187]선진국에서, 유아는 일반적으로 태어날 때 몸무게가 3-4kg (7-9lb)이고 키가 47-53cm (19-21인치)입니다.[188][189]하지만, 저체중아는 개발도상국에서 흔히 볼 수 있으며, 이 지역의 유아 사망률을 높이는 원인이 되고 있습니다.[190]

다른 종들과 비교했을 때, 인간의 출산은 합병증과 사망의 위험이 훨씬 더 높은 위험이 있습니다.[191]태아의 머리 크기는 다른 영장류보다 골반과 더 밀접하게 일치합니다.[192]그 이유가 완전히 이해되지는 않지만,[n 3] 24시간 이상 지속될 수 있는 고통스런 노동에 기여합니다.[194]노동의 성공 가능성은 20세기 동안 부유한 국가들에서 새로운 의료 기술의 등장으로 크게 증가했습니다.이와 대조적으로, 임신과 자연 출산은 선진국보다 산모 사망률이 약 100배나 더 높은 세계의 개발도상국에서 위험한 시련으로 남아 있습니다.[195]

부모의 보살핌이 대부분 어머니에 의해 이루어지는 다른 영장류들과는 달리, 어머니와 아버지는 모두 인간의 자손을 돌봅니다.[196]태어날 때 무력한 인간은 몇 년 동안 성장을 계속하며, 일반적으로 15세에서 17세에 성 성숙에 도달합니다.[197][198][199]인간의 수명은 3단계에서 12단계까지 다양한 단계로 나누어졌습니다.일반적인 단계는 유아기, 아동기, 청소년기, 성인기 및 노년기를 포함합니다.[200]이러한 단계의 길이는 문화와 시대에 따라 다양하지만 청소년기에 비정상적으로 빠른 성장 속도로 대표됩니다.[201]인간 여성은 50세 전후에 폐경이 되고 불임이 됩니다.[202]갱년기는 여성이 노년까지 아이를 계속 낳는 것이 아니라, 더 많은 시간과 자원을 그녀의 기존 자손, 그리고 그들의 아이들에게 더 많은 시간과 자원을 투자하게 함으로써 여성의 전반적인 생식 성공을 증가시킨다고 제안되었습니다.[203][204]

개인의 수명은 유전학과 생활 방식의 선택이라는 두 가지 주요 요소에 달려 있습니다.[205]생물학적/유전적 원인을 포함한 다양한 이유로, 여성이 남성보다 평균 4년 정도 더 오래 삽니다.[206]2018년[update] 기준, 여자 아이가 태어날 때 기대되는 평균 수명은 남자 아이의 70.4세에 비해 74.9세로 추정됩니다.[207][208]인간의 기대 수명에는 지리적으로 상당한 차이가 있으며, 대부분 경제 발전과 관련이 있습니다. 예를 들어, 홍콩의 출생시 기대 수명은 여아 87.6세, 남아 81.8세인 반면, 중앙 아프리카 공화국은 여아 55.0세, 남아 50.6세입니다.[209][210]선진국은 평균연령이 40세 전후로 전반적으로 고령화가 진행되고 있습니다.개발도상국에서, 평균 나이는 15세에서 20세 사이입니다.유럽인 다섯 명 중 한 명이 60세 이상인 반면, 아프리카인 스무 명 중 한 명만이 60세 이상입니다.[211]2012년, 유엔은 전세계적으로 316,600명의 100세 이상 노인들이 살고 있다고 추정했습니다.[212]

| 인간생활단계 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |

| 갓난아기남녀 | 사춘기 이전의 소년 소녀(어린이) | 사춘기 남녀 | 성인남녀 | 노인남녀 |

다이어트

인간은 다양한 식물과 동물 물질을 섭취할 수 있는 잡식성입니다.[213][214]인간 그룹들은 순수하게 채식주의에서 주로 육식주의에 이르기까지 다양한 식단을 채택해왔습니다.어떤 경우에는, 인간의 식사 제한은 결핍 질환을 초래할 수 있지만, 안정적인 인간 집단은 영양적으로 균형 잡힌 음식 공급원을 사용하기 위해 유전자 전문화와 문화적 관습을 통해 많은 식사 패턴에 적응했습니다.[215]인간의 식단은 인간 문화에 현저하게 반영되어 있으며 식품 과학의 발전으로 이어졌습니다.[216]

호모 사피엔스는 약 1만 년 전 농업이 발달하기 전까지 수렵채집법을 유일한 식량 수집 수단으로 사용했습니다.[216]이것은 야생동물을 사냥하고 포획해야 소비할 수 있는 야생동물과 고정식량원(과일, 곡물, 튜버, 버섯, 곤충 유충, 수생 연체동물 등)을 결합하는 것을 포함했습니다.[217]인류는 호모 에렉투스 시대부터 음식을 준비하고 요리하기 위해 불을 사용했다고 제안되어 왔습니다.[218]약 만 년 전, 인류는 농업을 발전시켰고,[219][220][221] 이는 그들의 식단을 크게 변화시켰습니다.이 식습관의 변화는 또한 인간의 생물학을 변화시켰을지도 모릅니다. 낙농업의 확산은 새롭고 풍부한 음식 공급원을 제공하고, 일부 성인들에게 락토오스를 소화시키는 능력의 진화로 이어졌습니다.[222][223]먹는 음식의 종류와 그것들이 준비되는 방법은 시간, 장소, 그리고 문화에 따라 매우 다양했습니다.[224][225]

일반적으로 인간은 저장된 체지방에 따라 음식 없이 8주까지 생존할 수 있습니다.[226]물 없이 생존하는 것은 보통 3-4일로 제한되며, 최대 1주일입니다.[227]2020년에는 매년 900만 명이 직간접적으로 기아와 관련된 원인으로 사망하는 것으로 추정됩니다.[228][229]아동기 영양실조는 또한 흔하고 전 세계적인 질병 부담에 기여합니다.[230]그러나, 세계적인 식량 분배는 균등하지 않고, 일부 사람들 사이의 비만은 급속하게 증가하여, 일부 선진국과 소수 개발도상국에서 건강 문제와 사망률 증가로 이어졌습니다.전 세계적으로 10억 명 이상의 사람들이 비만인 반면,[231] 미국에서는 35%의 사람들이 비만이기 때문에 이것을 "비만 유행병"이라고 부릅니다.[232]비만은 소비되는 칼로리보다 더 많은 칼로리를 소비함으로써 발생하므로, 과도한 체중 증가는 보통 에너지 밀도가 높은 식단에 의해 발생합니다.[231]

생물학적 변이

혈액형, 유전병, 두개골 특징, 얼굴 특징, 장기 체계, 눈의 색, 머리카락의 색과 질감, 키와 체격, 그리고 피부색과 같은 특징들과 함께, 인간의 종에는 생물학적인 다양성이 있습니다.성인 인간의 일반적인 키는 1.4~1.9m(4피트 7인치 및 6피트 3인치) 사이이지만 성별, 민족적 기원, 가족 혈통에 따라 크게 다릅니다.[233][234]신체 크기는 부분적으로 유전자에 의해 결정되며, 식습관, 운동, 수면 패턴과 같은 환경적 요인에 의해서도 상당한 영향을 받습니다.[235]

인구가 다양한 외부 요인에 유전적으로 적응했다는 증거가 있습니다.성인 인간이 젖당을 소화할 수 있게 하는 유전자는 소 사육의 오랜 역사를 가지고 있고 소젖에 더 의존하는 인구에서 높은 빈도로 존재합니다.[236]말라리아에 대한 내성을 증가시킬 수 있는 낫 모양의 세포 빈혈은 말라리아가 유행하는 인구에서 자주 발생합니다.[237][238]오랫동안 거주한 특정 기후를 가진 인구는 추운 지역에서는 키가 작고 땅딸막한 체격을, 더운 지역에서는 키가 크고 날씬하며, 높은 고도에서는 높은 폐활량이나 기타 적응력을 가진 특정한 표현형을 개발하는 경향이 있습니다.[239]일부 개체군은 바다에 사는 생활 방식과 바자우에서의 프리다이빙에 유리한 조건과 같은 매우 특정한 환경 조건에 매우 독특한 적응을 진화시켜 왔습니다.[240]

사람의 머리카락의 색깔은 빨강에서부터 금발, 갈색 그리고 검정까지 다양한데, 이것은 가장 빈번합니다.[241]머리카락 색은 멜라닌의 양에 따라 달라지는데, 나이가 들수록 농도가 옅어지고, 회색 또는 심지어 흰 머리로 이어집니다.피부색은 가장 어두운 갈색에서 가장 밝은 복숭아까지 다양할 수 있고, 심지어 알비니즘의 경우에는 거의 흰색이나 무색입니다.[242]그것은 임상적으로 다양한 경향이 있고 일반적으로 적도 주변의 어두운 피부와 함께 특정한 지리적 지역의 자외선 수준과 상관관계가 있습니다.[243]피부 흑화는 자외선의 태양 복사에 대한 보호로서 진화했을 수도 있습니다.[244]밝은 피부 색소 침착은 햇빛을 필요로 하는 비타민 D의 고갈을 막아줍니다.[245]사람의 피부는 자외선에 노출되는 것에 반응하여 피부를 어둡게(태우는) 할 수 있습니다.[246][247]

인간의 지리적 모집단 간의 편차는 비교적 적으며, 발생하는 변동의 대부분은 개인 수준입니다.[242][248][249]인간의 변화의 많은 부분은 연속적이며, 종종 명확한 경계점이 없습니다.[250][251][252][253]유전자 데이터는 인구 집단을 어떻게 정의하든 간에, 같은 인구 집단에 속한 두 사람은 다른 두 인구 집단에 속한 두 사람만큼 거의 서로 다르다는 것을 보여줍니다.[254][255][256]아프리카, 호주, 그리고 남아시아에서 발견되는 검은 피부의 집단은 서로 밀접한 관련이 없습니다.[257][258]

유전자 연구에 따르면 아프리카 대륙이 원산지인 인류는 유전적으로 가장 다양하며[259] 아프리카로부터 이주 거리가 멀어질수록 유전적 다양성이 감소하는데, 이는 아마도 인류 이주 중 병목 현상의 결과일 것입니다.[260][261]이 비아프리카 개체군들은 고대 개체군과 함께 지역 혼합물로부터 새로운 유전자 입력을 얻었으며 아프리카에서 발견되는 것보다 네안데르탈인과 데니소반인으로부터 훨씬 더 많은 변이를 가지고 있지만 네안데르탈인의 아프리카 개체군에 대한 혼합물은 과소평가될 수 있습니다.[178][262]게다가, 최근의 연구들은 사하라 사막 이남의 아프리카, 특히 서아프리카의 개체군들은 현생 인류보다 앞선 조상의 유전적 변이를 가지고 있으며 대부분의 비아프리카 개체군에서 사라졌다는 것을 발견했습니다.이 조상 중 일부는 네안데르탈인과 현대 인류가 갈라지기 전에 알려지지 않은 고대 호미닌과의 혼합물에서 유래한 것으로 생각됩니다.[263][264]

인간은 남성과 여성으로 나뉘는 것을 의미하는 고노코릭 종입니다.[265][266][267]남성과 여성 사이에 유전적 변이가 가장 큽니다.전 세계 인구에서 동성인의 뉴클레오티드 유전자 변이는 0.1%–0.5%를 넘지 않지만, 남성과 여성의 유전적 차이는 1%에서 2% 사이입니다.수컷은 암컷보다 평균적으로 15% 더 무겁고 15cm 더 큽니다.[268][269]평균적으로 남성은 같은 체중의 여성보다 상체의 힘이 40~50%, 하체의 힘이 20~30% 정도 더 큰데, 이는 근육량이 많고 근육섬유가 크기 때문입니다.[270]여성은 일반적으로 남성보다 체지방률이 높습니다.[271]여성들은 같은 인구의 남성들보다 밝은 피부를 가지고 있습니다; 이것은 임신과 수유 기간 동안 여성들에게 비타민 D가 더 많이 필요하기 때문으로 설명되고 있습니다.[272]여성과 남성 사이에 염색체의 차이가 있기 때문에, 일부 X와 Y 염색체와 관련된 상태와 장애는 남성과 여성 중 한 명에게만 영향을 미칩니다.[273]체중과 볼륨을 허용한 후, 남성의 목소리는 보통 여성의 목소리보다 한 옥타브 더 깊습니다.[274]여성의 수명은 전 세계 거의 모든 인구에서 더 깁니다.[275]사람들 사이에는 성간 질환이 있지만, 이것들은 희귀합니다.[276]

심리학

인간의 중추신경계의 초점인 인간의 뇌는 말초신경계를 조절합니다.호흡과 소화와 같은 "낮은", 비자발적인, 또는 주로 자율적인 활동을 통제하는 것뿐만 아니라, 사고, 추론, 그리고 추상화와 같은 "높은" 질서 기능의 장소이기도 합니다.[277]이러한 인지 과정은 마음을 구성하며, 행동적 결과와 함께 심리학 분야에서 연구됩니다.

인간은 더 높은 인지와 관련된 뇌의 영역인 다른 영장류보다 더 크고 더 발달된 전전두엽 피질을 가지고 있습니다.[278]이것은 인간들이 다른 알려진 종보다 더 똑똑하다고 스스로 선언하게 만들었습니다.[279]인간이 할 수 없는 부분에서 다른 동물들이 감각에 적응하고 탁월하기 때문에 지능을 객관적으로 정의하는 것은 어렵습니다.[280]

엄격하게 독특하지는 않지만, 인간을 다른 동물들과 구별시키는 몇 가지 특징들이 있습니다.[281]인간은 기억력이 있는 유일한 동물이고 "정신적 시간 여행"에 참여할 수 있는 동물일 수도 있습니다.[282]다른 사회적 동물들과 비교해도, 인간은 얼굴 표정에 있어서 이례적으로 높은 유연성을 가지고 있습니다.[283]인간은 감정적인 눈물을 흘리는 유일한 동물로 알려져 있습니다.[284]인간은 거울 실험에서[285] 자기 인식을 할 수 있는 몇 안 되는 동물 중 하나이며 인간이 정신 이론을 가진 유일한 동물인지에 대해서도 논쟁이 있습니다.[286]

잠과 꿈

인간은 일반적으로 주행성입니다.평균 수면 요구량은 성인의 경우 하루에 7시간에서 9시간 사이이고 어린이의 경우 하루에 9시간에서 10시간 사이입니다; 노인들은 보통 6시간에서 7시간 정도 잠을 잡니다.수면 부족이 건강에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있음에도 불구하고, 이보다 더 적은 수면을 취하는 것은 인간들 사이에서 흔한 일입니다.성인 수면시간을 하루 4시간으로 지속적으로 제한하는 것은 기억력 저하, 피로, 공격성, 신체적 불편감을 포함한 생리학적, 정신적 상태의 변화와 상관관계가 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.[287]

잠자는 동안 인간은 감각적인 이미지와 소리를 경험하는 꿈을 꿉니다.꿈은 폰에 의해 자극을 받아 수면 중 렘 단계에서 주로 일어납니다.[288]꿈의 길이는 몇 초에서 30분까지 다양합니다.[289]사람들은 하룻밤에 3~5개의 꿈을 꾸고, 어떤 사람들은 7개까지 꿈을 꾸기도 합니다.[290]꿈을 꾸는 사람들은 렘 단계 중에 깨어나면 그 꿈을 기억할 가능성이 더 높습니다.꿈 속의 사건들은 일반적으로 꿈을 꾸는 사람이 스스로 자각하는 자각몽을 제외하고는 꿈을 꾸는 사람의 통제 밖에 있습니다.[291]꿈은 때때로 창의적인 생각을 하게 하거나 영감을 줄 수 있습니다.[292]

의식과 사상

인간의 의식은, 가장 단순하게도, 내적 또는 외적 존재에 대한 감각 또는 인식입니다.[293]철학자와 과학자들에 의한 수 세기 동안의 분석, 정의, 설명, 논쟁에도 불구하고, 의식은 여전히 혼란스럽고 논란의 여지가 있으며,[294] "한때 우리 삶에서 가장 친숙하고 신비로운 측면"입니다.[295]그 주제에 대해 널리 합의된 유일한 개념은 그것이 존재한다는 직관입니다.[296]정확히 무엇을 연구하고 의식으로 설명해야 하는지에 대해서는 의견이 다릅니다.어떤 철학자들은 의식을 감각적 경험 그 자체인 현상적 의식과 추론이나 직접적인 행동 통제를 위해 사용될 수 있는 접근적 의식으로 나눕니다.[297]그것은 때때로 '마음'과 동의어이기도 하고, 어떤 때는 그것의 한 측면이기도 합니다.역사적으로 그것은 자기성찰, 사적인 생각, 상상력 그리고 자발성과 관련이 있습니다.[298]이제 그것은 종종 어떤 종류의 경험, 인지, 느낌 또는 지각을 포함합니다.그것은 '인식'일 수도 있고, '인식'일 수도 있고, 자기 인식일 수도 있습니다.[299]의식의 수준이나 순서가 다를 수도 있고,[300] 의식의 종류가 다를 수도 있고, 다른 특징을 가진 한 종류일 수도 있습니다.[301]

인지는 사고, 경험, 감각을 통해 지식과 이해를 얻는 과정을 말합니다.[302]인간의 뇌는 감각을 통해 외부세계를 인지하게 되고, 인간 개개인은 자신의 경험에 의해 크게 영향을 받아 주관적인 존재관과 시간의 흐름으로 이어지게 됩니다.[303]사고의 본질은 심리학과 관련 분야의 중심입니다.인지 심리학은 행동의 근본이 되는 정신적 과정인 인지를 연구합니다.[304]주로 수명을 통한 인간의 마음의 발달에 초점을 맞추고 있는 발달 심리학은 사람들이 어떻게 세상 안에서 지각하고 이해하고 행동하게 되는지 그리고 이러한 과정들이 나이가 들면서 어떻게 변하는지를 이해하고자 합니다.[305][306]이것은 지적, 인지적, 신경적, 사회적, 또는 도덕적 발달에 초점을 맞출 수 있습니다.심리학자들은 인간의 상대적인 지능을 평가하고 인구 사이의 분포를 연구하기 위해 지능검사와 지능지수의 개념을 개발했습니다.[307]

동기부여와 감정

인간의 동기는 아직 완전히 이해되지 않았습니다.심리학적 관점에서 매슬로우의 욕구의 위계는 복잡성의 상승 순서로 특정 욕구를 충족시키는 과정으로 정의될 수 있는 잘 정립된 이론입니다.[308]보다 일반적이고 철학적인 관점에서 인간의 동기는 인간 능력의 적용을 요구하는 다양한 목표에 대한 약속 또는 철회로 정의될 수 있습니다.또한 인센티브와 선호도는 모두 요소이며, 인센티브와 선호도 사이의 모든 인지된 관계도 마찬가지입니다.의지력도 포함될 수 있는데, 이 경우 의지력도 하나의 요인이 됩니다.이상적으로, 동기부여와 자발성 둘 다 최적의 방식으로 목표를 선택하고, 노력하고, 실현하는 것을 보장하는데, 이는 아동기부터 시작하여 사회화라고 알려진 과정에서 평생 지속되는 기능입니다.[309]

감정은 생각, 감정, 행동 반응 및 즐거움 또는 불쾌감의 정도와 관련된 다양한 신경 생리학적 변화에 의해 야기되는 신경계와[310][311] 관련된 생물학적 상태입니다.[312][313]그들은 종종 기분, 기질, 성격, 성향, 창의력,[314] 동기와 관련되어 있습니다.감정은 인간의 행동과 학습 능력에 중요한 영향을 미칩니다.[315]극단적이거나 통제되지 않는 감정에 대해 행동하는 것은 사회적 무질서와 범죄로 이어질 수 있으며,[316] 연구에 따르면 범죄자들은 정상보다 낮은 감정 지능을 가지고 있을 수 있습니다.[317]

즐거움, 흥미 또는 만족감과 같이 유쾌하다고 인식되는 감정적 경험은 불안, 슬픔, 분노 및 절망과 같이 불쾌하다고 인식되는 경험과 대조됩니다.[318]행복, 또는 행복한 상태는 인간의 감정 조건입니다.행복의 정의는 일반적인 철학적 주제입니다.어떤 사람들은 그것을 부정적인 영향을 피하면서 긍정적인 감정의 느낌을 경험하는 것으로 정의합니다.[319][320]다른 사람들은 그것을 삶의 만족이나 삶의 질에 대한 평가로 봅니다.[321]최근의 연구는 행복하다는 것은 사람들이 정당하다고 느낄 때 부정적인 감정을 경험하는 것을 포함할 수도 있다는 것을 암시합니다.[322]

섹슈얼리티와 사랑

인간에게 있어 섹슈얼리티는 생물학적, 에로틱, 신체적, 감정적, 사회적, 또는 영적 감정과 행동을 포함합니다.[323][324]시간의 흐름에 따라 역사적 맥락에 따라 달라지는 광의의 용어이기 때문에 정확한 정의가 부족합니다.[324]성에 대한 생물학적, 신체적 측면은 주로 인간의 성 반응 주기를 포함한 인간의 생식 기능에 관한 것입니다.[323][324]성은 또한 삶의 문화적, 정치적, 법적, 철학적, 도덕적, 윤리적, 종교적 측면에 영향을 미치고 영향을 받습니다.[323][324]성욕, 즉 성욕은 성행동의 시작에 존재하는 기본적인 정신 상태입니다.연구에 따르면 남성이 여성보다 성관계를 더 원하고 자주 자위를 한다고 합니다.[325]

인간은 대부분의 인간이 이성애자임에도 불구하고 [326]지속적인 규모의 성적 지향을 따라 어디든 떨어질 수 있습니다.[327][328]동성애적인 행동은 몇몇 다른 동물들에게서 나타나는 반면, 오직 인간과 집에서 기르는 양들만이 동성 관계에 대해 배타적인 선호를 보이는 것으로 지금까지 발견되었습니다.[327]동성애에 매우 관대한 문화는 성적 지향의 비사회적, 생물학적 원인을 뒷받침하는 증거가 대부분입니다.[327] 동성애에 대해 상당히 관대한 문화는 성적 지향의 비율이 현저히 높지 않기 때문입니다.[328][329]신경과학과 유전학의 연구는 인간의 섹슈얼리티의 다른 측면들도 생물학적으로 영향을 받는다는 것을 암시합니다.[330]

사랑은 일반적으로 강한 끌림이나 감정적인 애착의 감정을 말합니다.그것은 비인격적인 것(대상의 사랑, 이상적인 것, 또는 강한 정치적 또는 정신적인 연결)일 수도 있고 대인관계적인 것(인간들 사이의 사랑일 수도 있습니다.[331]도파민을 사랑하면 노르에피네프린, 세로토닌 등의 화학물질이 뇌의 쾌락 중추를 자극해 심장 박동수 증가, 식욕 및 수면 저하, 심한 흥분감 등의 부작용을 초래합니다.[332]

문화

| 가장 널리 쓰이는 언어[333][334] | 영어, 만다린 중국어, 힌디어, 스페인어, 표준 아랍어, 벵골어, 프랑스어, 러시아어, 포르투갈어, 우르두어 |

|---|---|

| 가장 많이 행해지는 종교[334][335] | 기독교, 이슬람교, 힌두교, 불교, 민속 종교, 시크교, 유대교, 무교도 |

인류의 전례 없는 지적 능력은 종의 궁극적인 기술 발전과 그에 따른 생물권 지배의 핵심 요인이었습니다.[336]인간은 멸종된 동족류를 제외하고 일반화 가능한 정보를 가르치고,[337] 복잡한 개념을 생성하고 전달하기 위해 선천적으로 재귀적 매립을 사용하며,[338] 유능한 도구 설계에 필요한 "민속 물리학"에 참여하거나,[339][340] 야생에서 음식을 요리하는 것으로 알려진 유일한 동물입니다.[341]교육과 학습은 인간 사회의 문화적, 민족적 정체성을 보존합니다.[342]대부분 인간에게 독특한 다른 특성과 행동에는 불을 지피는 것,[343] 음소 구조화[344], 그리고 성악 학습이 포함됩니다.[345]

언어

많은 종들이 의사소통을 하지만, 언어는 인간에게 독특하고, 인류를 정의하는 특징이며, 문화적 보편성입니다.[346]다른 동물들의 제한된 시스템과 달리, 인간의 언어는 열려 있습니다 – 제한된 수의 기호를 조합함으로써 무한한 수의 의미를 만들어 낼 수 있습니다.[347][348]인간의 언어는 현재 또는 지역적으로 발생하지는 않지만 대화자의 공유된 상상 속에 존재하는 사물과 사건을 표현하기 위해 단어를 사용하는 변위의 능력도 가지고 있습니다.[148]

언어는 형식에 독립적이라는 점에서 다른 형태의 의사소통과 다릅니다. 같은 의미는 다른 매체를 통해 전달될 수 있고, 음성으로 들을 수 있고, 수화나 글로 시각적으로 전달될 수 있으며, 점자와 같은 촉각적 매체를 통해 전달될 수 있습니다.[349]언어는 인간 사이의 의사소통과 국가, 문화, 민족을 하나로 묶는 정체성의 중심입니다.[350]현재 사용되고 있는 수화를 포함한 약 6천 개의 다른 언어들이 있으며, 수천 개 이상의 멸종된 언어들도 있습니다.[351]

아츠

인간의 예술은 시각, 문학 그리고 공연을 포함한 많은 형태를 취할 수 있습니다.시각 예술은 그림과 조각에서부터 영화, 상호작용 디자인 그리고 건축까지 다양합니다.[352]문학 예술은 산문, 시 그리고 드라마를 포함할 수 있습니다; 반면에 공연 예술은 일반적으로 연극, 음악 그리고 춤을 포함합니다.[353][354]인간은 종종 서로 다른 형태(예를 들어 뮤직비디오)를 결합합니다.[355]예술적인 특징을 가진 것으로 묘사된 다른 개체들은 음식 준비, 비디오 게임 그리고 의학을 포함합니다.[356][357][358]예술은 오락을 제공하고 지식을 전달하는 것뿐만 아니라 정치적 목적으로도 사용됩니다.[359]

예술은 인간의 정의적인 특징이며 창의성과 언어의 관계에 대한 증거가 있습니다.[360]예술의 가장 초기의 증거는 현대 인류가 진화하기 30만년 전에 호모 에렉투스에 의해 만들어진 조개 판화입니다.[361]H. sapiens의 것으로 추정되는 예술품은 적어도 75,000년 전에 존재했으며, 보석과 그림은 남아프리카의 동굴에서 발견되었습니다.[362][363]인간이 왜 예술에 적응했는지에 대해서는 다양한 가설들이 있습니다.이것들은 그들이 문제를 더 잘 해결하도록 허용하고, 다른 인간들을 통제하거나 영향을 미칠 수 있는 수단을 제공하고, 한 사회 내에서 협력과 기여를 장려하거나 잠재적인 짝을 끌어들일 수 있는 가능성을 증가시키는 것을 포함합니다.[364]예술을 통해 발전된 상상력의 사용은 논리와 결합되어 초기 인류에게 진화론적 이점을 주었을지도 모릅니다.[360]

인간이 음악 활동에 참여했다는 증거는 동굴 예술보다 앞서 있으며 지금까지 음악은 거의 모든 알려진 인간 문화에 의해 실행되어 왔습니다.[365]인간의 음악적 능력은 복잡한 사회적 인간 행동을 포함한 다른 능력과 관련이 있는 매우 다양한 음악 장르와 민족 음악이 존재합니다.[365]인간의 뇌는 리듬과 박자에 동기화됨으로써 음악에 반응한다는 것이 밝혀졌는데, 이 과정을 엔트레그먼트라고 합니다.[366]춤은 또한 모든 문화에서[367] 발견되는 인간의 표현의 한 형태이며 초기 인류의 의사소통을 돕는 방법으로 진화했을 수도 있습니다.[368]음악을 듣고 춤을 관찰하는 것은 전두엽 피질의 궤도와 뇌의 다른 즐거움을 감지하는 영역을 자극합니다.[369]

말하기와 달리 읽기와 쓰기는 인간에게 자연스럽게 오는 것이 아니며 가르쳐야 합니다.[370]그럼에도 불구하고, 문학은 단어와 언어의 발명 이전부터 존재해 왔으며, 일부 동굴 내부의 벽에 그려진 30,000년 된 그림들은 일련의 극적인 장면들을 묘사합니다.[371]현존하는 가장 오래된 문학작품 중 하나는 길가메시 서사시로, 약 4,000년 전 고대 바빌로니아의 명판에 처음 새겨져 있습니다.[372]단순히 지식을 전달하는 것을 넘어 이야기를 통한 상상력 소설의 활용과 공유는 인간의 의사소통 능력을 개발하고 짝을 확보할 수 있는 가능성을 높이는 데 도움이 되었을 것입니다.[373]스토리텔링은 청중들에게 도덕적 교훈을 제공하고 협력을 장려하는 방법으로도 사용될 수 있습니다.[371]

도구 및 기술

석기는 적어도 250만년 전에 원시 인류에 의해 사용되었습니다.[375]도구의 사용과 제작은 무엇보다[376] 인간을 정의하는 능력으로 내세웠고 역사적으로 중요한 진화의 단계로 여겨져 왔습니다.[377]이 기술은 약 180만 년 전에 훨씬 더 정교해졌고,[376] 통제된 불의 사용은 약 백만 년 전에 시작되었습니다.[378][379]바퀴 달린 자동차와 바퀴 달린 자동차는 기원전 4천년쯤에 여러 지역에서 동시에 출현했습니다.[61]더 복잡한 도구와 기술의 발달은 땅을 경작하고 동물을 길들일 수 있게 했고, 따라서 신석기 혁명이라고 알려진 농업의 발전에 필수적인 것으로 증명되었습니다.[380]

중국은 종이, 인쇄기, 화약, 나침반 그리고 다른 중요한 발명품들을 개발했습니다.[381]제련의 지속적인 개선은 구리, 청동, 철 그리고 결국 철도, 마천루와 다른 많은 제품에 사용되는 강철의 단조를 가능하게 했습니다.[382]이것은 자동화된 기계의 발명이 인간의 생활 방식에 큰 변화를 가져온 산업 혁명과 동시에 일어났습니다.[383]현대 기술은 기하급수적으로 발전하면서 관찰됩니다.[384] 20세기의 주요 혁신은 다음을 포함합니다: 전기, 페니실린, 반도체, 내연기관, 인터넷, 질소 고정 비료, 비행기, 컴퓨터, 자동차, 피임약, 핵분열, 녹색 혁명, 라디오, 과학 식물 br.파종, 로켓, 에어컨, 텔레비전 그리고 조립 라인.[385]

종교와 영성

종교는 일반적으로 초자연적, 신성한 또는 신성한, 그리고 그러한 믿음과 관련된 관습, 가치관, 제도 및 의식에 관한 믿음 체계로 정의됩니다.어떤 종교들은 도덕률도 가지고 있습니다.최초의 종교의 진화와 역사는 활발한 과학적 연구의 영역이 되었습니다.[386][387][388]인간이 처음 종교를 갖게 된 정확한 시기는 알려지지 않았지만, 연구는 중기 구석기 시대(45-20만년 전) 무렵의 종교적 행동에 대한 믿을 만한 증거를 보여줍니다.[389]인간 사이의 협력을 강제하고 장려하는 역할을 하도록 진화했을지도 모릅니다.[390]

종교를 구성하는 것에 대한 학문적 정의는 인정되지 않습니다.[391]종교는 지구의 지리적, 사회적, 언어적 다양성에 따라 문화와 개인의 관점에 따라 다양한 형태를 취해왔습니다.[391]종교는 사후의 삶에 대한 믿음(흔히 사후세계에 대한 믿음을 포함한다),[392] 삶의 기원,[393] 우주의 본질(종교 우주론)과 그것의 궁극적인 운명(종말론), 그리고 도덕적이거나 부도덕한 것이 무엇인지를 포함할 수 있습니다.[394]모든 종교가 유신론적인 것은 아니지만, 이 질문들에 대한 대답의 공통적인 원천은 신이나 단 하나의 신과 같은 초월적인 신적 존재에 대한 믿음입니다.[395][396]

비록 정확한 종교성의 수준은 측정하기 어려울 수 있지만,[397] 대다수의 사람들은 몇몇 다양한 종교적 또는 영적 믿음을 공언합니다.[398]2015년에는 기독교 신자가 다수였고, 이슬람교도, 힌두교도, 불교도가 뒤를 이었습니다.[399]2015년 기준으로 약 16%, 즉 12억 명에 약간 못 미치는 사람들이 종교적 신념이 없거나 어떤 종교와도 정체성이 없는 사람들을 포함하여 비종교적이었습니다.[400]

과학철학

한 세대에서 다음 세대로 지식을 전달하고 이 정보를 계속 기반으로 도구, 과학 법칙 및 기타 발전을 발전시켜 더욱 발전시킬 수 있는 능력은 인간만의 독특한 측면입니다.[401]이 축적된 지식은 우주가 어떻게 작동하는지에 대한 질문에 답하거나 예측을 하기 위해 테스트 될 수 있으며 인간의 우위를 증진시키는 데 매우 성공적이었습니다.[402]

아리스토텔레스는 최초의 과학자로 묘사되어 왔고,[403] 헬레니즘 시대를 통해 과학적인 사고의 발흥을 앞섰습니다.[404]과학의 다른 초기 발전은 중국의 한 왕조와 이슬람 황금 시대에 이루어졌습니다.[405][86]르네상스 말기에 가까운 과학 혁명은 현대 과학의 출현을 이끌었습니다.[406]

일련의 사건과 영향은 과학을 유사과학과 구별하기 위해 사용되는 관찰과 실험의 과정인 과학적 방법의 발전으로 이어졌습니다.[407]수학에 대한 이해는 인간에게 독특하지만, 다른 종의 동물들은 약간의 숫자 인식을 가지고 있습니다.[408]모든 과학은 세 가지 주요 분야로 나눌 수 있습니다. 형식적인 시스템에 관심이 있는 형식 과학(예: 논리학과 수학), 실용적인 응용에 중점을 둔 응용 과학(예: 공학, 의학), 경험적 관찰에 기반을 두고 자연과학으로 나뉘는 경험 과학(예: 경험적 과학지방 과학(예: 물리학, 화학, 생물학)과 사회 과학(예:[409] 심리학, 경제학, 사회학).

철학은 인간이 자신과 자신이 살고 있는 세계에 대한 근본적인 진리를 이해하고자 하는 학문입니다.[410]철학적 탐구는 인류의 지적 역사 발전에 있어 주요한 특징이었습니다.[411]그것은 확정적인 과학적 지식과 독단적인 종교적 가르침 사이에서 "누구의 땅도 아니다"라고 묘사되어 왔습니다.[412]철학은 종교와 달리 이성과 증거에 의존하지만 과학이 제공하는 경험적 관찰과 실험을 필요로 하지 않습니다.[413]철학의 주요 분야는 형이상학, 인식론, 논리학, 그리고 (윤리학과 미학을 포함하는) 공리학을 포함합니다.[414]

사회의

사회는 인간들 사이의 상호작용으로부터 발생하는 조직과 제도의 체계입니다.인간은 매우 사회적이고 큰 복잡한 사회 집단에서 사는 경향이 있습니다.그들은 수입, 부, 권력, 명성 그리고 다른 요소들에 따라 다른 그룹으로 나뉠 수 있습니다.사회 계층화의 구조와 사회 이동의 정도는 특히 현대 사회와 전통 사회에 따라 다릅니다.[415][unreliable source?]인간 집단은 가족의 규모에서부터 국가에 이르기까지 다양합니다.인간 사회 조직의 첫 번째 형태는 수렵채집 밴드 사회와 닮았다고 생각됩니다.[416][better source needed]

성별

인간사회는 일반적으로 남성적 특성과 여성적 특성을 구분하는 성 정체성과 성 역할을 나타내며 구성원의 성별에 따라 수용 가능한 행동과 태도의 범위를 규정합니다.[417][418]가장 일반적인 분류는 남성과 여성의 성별 이진법입니다.[419]많은 사회들이 제3의 성을 인정하거나 [420]덜 일반적으로 제4 또는 제5의 성을 인정합니다.[421][422]일부 다른 사회에서, 논 바이너리는 남성이나 여성만이 아닌 다양한 성 정체성에 대한 포괄적인 용어로 사용됩니다.[423]

성 역할은 종종 규범, 관행, 복장, 행동, 권리, 의무, 특권, 지위, 권력의 구분과 관련되어 있으며, 오늘날과 과거에 대부분의 사회에서 남성이 여성보다 더 많은 권리와 특권을 누리고 있습니다.[424]사회적 구성체로서 [425]성 역할은 고정되어 있지 않으며 한 사회 내에서 역사적으로 다양합니다.많은 사회에서 지배적인 성 규범에 대한 도전이 재발했습니다.[426][427]초기 인류 사회에서의 성 역할에 대해서는 거의 알려져 있지 않습니다.초기의 현대 인류는 적어도 상부 구석기 시대부터 현대 문화와 비슷한 다양한 성 역할을 했을 것이며, 반면 네안데르탈인은 성적 이형성이 적었고 남성과 여성의 행동 차이가 미미했다는 증거가 있습니다.[428]

친족관계

모든 인간사회는 부모, 자녀 및 다른 후손과의 관계(친족성), 결혼을 통한 관계(친족성)를 바탕으로 사회적 관계의 유형을 구성, 인식, 분류합니다.대부모나 양자녀에게 적용되는 세 번째 유형도 있습니다.이러한 문화적으로 정의된 관계를 친족관계라고 합니다.많은 사회에서 그것은 가장 중요한 사회 조직 원리 중 하나이며 지위와 상속을 전달하는 역할을 합니다.[429]모든 사회는 근친상간 금기의 규칙을 가지고 있는데, 이에 따라 특정한 종류의 친족간의 결혼이 금지되어 있으며, 일부는 특정한 친족간의 결혼을 우대하는 규칙도 가지고 있습니다.[430]

민족성

인간의 민족은 다른 집단과 구분되는 공유된 속성을 바탕으로 함께 하나의 집단으로 동일시하는 사회적 범주입니다.이것들은 거주 지역 내에서 전통, 혈통, 언어, 역사, 사회, 문화, 국가, 종교, 또는 사회적 대우의 공통된 집합이 될 수 있습니다.[431][432]민족성은 비록 둘 다 사회적으로 구성되어 있지만, 신체적 특징에 기초한 인종의 개념과는 별개입니다.[433]특정 인구에 민족성을 할당하는 것은 복잡합니다. 일반적인 민족 지정 내에서도 다양한 하위 그룹이 있을 수 있고, 이러한 민족 그룹의 구성은 집단 및 개인 수준에서 시간이 지남에 따라 변할 수 있기 때문입니다.[170]또한 민족 집단을 구성하는 것에 대해 일반적으로 받아들여지는 정의는 없습니다.[434]민족 집단은 민족 정치 단위의 사회적 정체성과 연대에 강력한 역할을 할 수 있습니다.이것은 19세기와 20세기의 지배적인 형태의 정치조직으로서 국민국가의 부상과 밀접한 관련이 있습니다.[435][436][437]

정부와 정치

농업 인구가 더 크고 더 밀집한 지역사회에 모이면서, 이러한 다양한 집단 간의 상호작용이 증가했습니다.이것은 공동체 내부와 공동체 간의 통치를 발전시키기에 이르렀습니다.[438]만약 그렇게 하는 것이 개인적인 이익을 제공하는 것으로 여겨진다면, 인간은 이전의 강력한 정치적 동맹을 포함하여, 다양한 사회 집단과의 관계를 비교적 쉽게 변화시킬 수 있는 능력을 발전시켜 왔습니다.[439]이러한 인지적 유연성은 개인의 인간이 정치적 이념을 바꿀 수 있게 해주며, 유연성이 높은 사람들은 권위주의적이고 민족주의적인 입장을 지지할 가능성이 적습니다.[440]

정부는 그들이 통치하는 시민들에게 영향을 미치는 법과 정책을 만듭니다.인류 역사를 통틀어 많은 형태의 정부가 있었으며, 각각의 정부는 권력을 얻는 다양한 수단과 인구에 대한 다양한 통제력을 행사할 수 있는 능력을 가지고 있었습니다.[441]2017년 기준으로 전체 국가 정부의 절반 이상이 민주주의 국가이며, 13%는 독재 국가이고 28%는 양쪽의 요소를 포함하고 있습니다.[442]많은 나라들이 국제적인 정치 조직과 동맹을 형성하고 있습니다. 그 중 가장 큰 나라는 193개의 회원국이 있는 유엔입니다.[443]

무역경제학

상품과 서비스의 자발적인 교환인 무역은 인간을 다른 동물과 차별화하는 특성으로 여겨지며 호모 사피엔스에게 다른 인류에 비해 큰 이점을 준 관행으로 꼽혀 왔습니다.[444]증거에 의하면 초기의 H. 사피엔스는 상품과 아이디어를 교환하기 위해 장거리 무역로를 이용했고, 문화적 폭발로 이어졌으며 사냥이 드물었던 반면 현재는 멸종된 네안데르탈인에게는 그러한 무역망이 존재하지 않았다고 합니다.[445][446]초기의 무역은 흑요석과 같은 도구를 만들기 위한 재료를 포함했을 가능성이 높습니다.[447]최초의 진정한 국제 무역로는 로마와 중세 시대를 통한 향신료 무역이었습니다.[448]

초기 인류의 경제는 물물교환 제도 대신 선물을 주는 것에 기반을 두었을 가능성이 더 높았습니다.[449]초기 화폐는 상품으로 구성되어 있었습니다; 가장 오래된 것은 소의 형태이고 가장 널리 사용되는 것은 카오리 껍질이었습니다.[450]화폐는 이후 정부가 발행하는 동전, 종이, 전자 화폐로 발전했습니다.[450]경제학에 대한 인간학은 사회가 어떻게 다른 사람들 사이에 부족한 자원을 분배하는지를 살펴보는 사회과학입니다.[451]인간들 사이의 부의 분배에는 엄청난 불평등이 존재합니다; 가장 부유한 8명의 인간은 모든 인구의 가장 가난한 절반과 같은 금전적 가치가 있습니다.[452]

갈등.

인간은 다른 영장류와 비슷한 비율로 다른 인간에게 폭력을 가하지만, 다른 영장류들 사이에서 영아 살해가 더 흔해지는 등 어른을 죽이는 것을 더 선호합니다.[453]초기 H. 사피엔스의 2%가 살해되어 중세시대에는 12%까지 올랐다가 현대에는 2% 이하로 떨어질 것으로 예측되고 있습니다.[454]폭력에 대한 법적 제도와 강력한 문화적 태도를 가진 사회에서 살인율이 약 0.01%[455]로 인간 인구 사이에 폭력의 차이가 매우 큽니다.

인간이 조직적인 갈등 (즉, 전쟁)을 통해 자신의 종족의 다른 구성원들을 집단으로 살해하려는 의지는 오랫동안 논쟁의 대상이었습니다.한 학파는 전쟁이 경쟁자들을 제거하기 위한 수단으로 진화했고, 항상 타고난 인간의 특성이었다고 주장합니다.또 다른 하나는 전쟁이 비교적 최근의 현상이며, 변화하는 사회적 상황 때문에 나타났다는 것을 암시합니다.[456]아직 정착되지는 않았지만, 현재의 증거는 전쟁과 같은 성향이 약 1만 년 전에, 그리고 많은 곳에서 그것보다 훨씬 더 최근에 흔해졌다는 것을 보여줍니다.[456]전쟁은 인간의 생명에 큰 비용을 끼쳤습니다; 20세기 동안 전쟁의 결과로 1억 6천7백만에서 1억 8천8백만명의 사람들이 사망한 것으로 추정됩니다.[457]전쟁 사상자 데이터는 중세 이전, 특히 세계적인 수치에 대해서는 신뢰성이 떨어집니다.그러나 지난 600년 동안의 어느 시기와 비교해 볼 때, 지난 ~80년(1946년 이후)은 무력 충돌로 인해 전 세계 군과 민간인 사망률이 매우 크게 감소했습니다.

참고 항목

- 인류 진화 화석 목록

- 인류 진화 연표 – 인류 발전의 주요 사건들의 연대순 개요

메모들

참고문헌

- ^ Groves CP (2005). Wilson DE, Reeder DM (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Spamer EE (29 January 1999). "Know Thyself: Responsible Science and the Lectotype of Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences. 149 (1): 109–114. JSTOR 4065043.

- ^ Porkorny (1959). IEW. s.v. "g'hðem" pp. 414–116.

- ^ "Homo". Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House. 23 September 2008. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008.

- ^ a b Barras, Colin (11 January 2016). "We don't know which species should be classed as 'human'". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Definition of human". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Spamer EE (1999). "Know Thyself: Responsible Science and the Lectotype of Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 149: 109–114. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4065043. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ OED. s.v. "human".

- ^ "Man". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

Definition 2: a man belonging to a particular category (as by birth, residence, membership, or occupation) – usually used in combination

- ^ "Thesaurus results for human". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Misconceptions about evolution – Understanding Evolution". University of California, Berkeley. 19 September 2021. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Concept of Personhood". University of Missouri School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Tuttle RH (4 October 2018). "Hominoidea: conceptual history". In Trevathan W, Cartmill M, Dufour D, Larsen C (eds.). International Encyclopedia of Biological Anthropology. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781118584538.ieba0246. ISBN 978-1-118-58442-2. S2CID 240125199. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Goodman M, Tagle DA, Fitch DH, Bailey W, Czelusniak J, Koop BF, et al. (March 1990). "Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of hominoids". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 30 (3): 260–266. Bibcode:1990JMolE..30..260G. doi:10.1007/BF02099995. PMID 2109087. S2CID 2112935.

- ^ Ruvolo M (March 1997). "Molecular phylogeny of the hominoids: inferences from multiple independent DNA sequence data sets". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 14 (3): 248–265. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025761. PMID 9066793.

- ^ MacAndrew A. "Human Chromosome 2 is a fusion of two ancestral chromosomes". Evolution pages. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2006.

- ^ McNulty, Kieran P. (2016). "Hominin Taxonomy and Phylogeny: What's In A Name?". Nature Education Knowledge. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Strait DS (September 2010). "The Evolutionary History of the Australopiths". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 3 (3): 341–352. doi:10.1007/s12052-010-0249-6. ISSN 1936-6434. S2CID 31979188. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Dunsworth HM (September 2010). "Origin of the Genus Homo". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 3 (3): 353–366. doi:10.1007/s12052-010-0247-8. ISSN 1936-6434. S2CID 43116946. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Kimbel WH, Villmoare B (July 2016). "From Australopithecus to Homo: the transition that wasn't". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150248. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0248. PMC 4920303. PMID 27298460. S2CID 20267830.

- ^ a b Villmoare B, Kimbel WH, Seyoum C, Campisano CJ, DiMaggio EN, Rowan J, et al. (March 2015). "Paleoanthropology. Early Homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1352–1355. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1352V. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1343. PMID 25739410.

- ^ Zhu Z, Dennell R, Huang W, Wu Y, Qiu S, Yang S, et al. (July 2018). "Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago". Nature. 559 (7715): 608–612. Bibcode:2018Natur.559..608Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0299-4. PMID 29995848. S2CID 49670311.

- ^ Hublin JJ, Ben-Ncer A, Bailey SE, Freidline SE, Neubauer S, Skinner MM, et al. (June 2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. PMID 28593953. S2CID 256771372. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Out of Africa Revisited". Science (This Week in Science). 308 (5724): 921. 13 May 2005. doi:10.1126/science.308.5724.921g. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 220100436.

- ^ Stringer C (June 2003). "Human evolution: Out of Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6941): 692–693, 695. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..692S. doi:10.1038/423692a. PMID 12802315. S2CID 26693109.

- ^ Johanson D (May 2001). "Origins of Modern Humans: Multiregional or Out of Africa?". actionbioscience. Washington, DC: American Institute of Biological Sciences. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ Marean, Curtis; et al. (2007). "Early human use of marine resources and pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene" (PDF). Nature. 449 (7164): 905–908. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..905M. doi:10.1038/nature06204. PMID 17943129. S2CID 4387442.

- ^ Brooks AS, Yellen JE, Potts R, Behrensmeyer AK, Deino AL, Leslie DE, Ambrose SH, Ferguson JR, d'Errico F, Zipkin AM, Whittaker S, Post J, Veatch EG, Foecke K, Clark JB (2018). "Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age". Science. 360 (6384): 90–94. Bibcode:2018Sci...360...90B. doi:10.1126/science.aao2646. PMID 29545508.

- ^ Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik A, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, et al. (March 2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe". Current Biology. 26 (6): 827–833. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. hdl:2440/114930. PMID 26853362. S2CID 140098861.

- ^ Karmin M, Saag L, Vicente M, Wilson Sayres MA, Järve M, Talas UG, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ Armitage SJ, Jasim SA, Marks AE, Parker AG, Usik VI, Uerpmann HP (January 2011). "The southern route "out of Africa": evidence for an early expansion of modern humans into Arabia". Science. 331 (6016): 453–456. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..453A. doi:10.1126/science.1199113. PMID 21273486. S2CID 20296624. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Rincon P (27 January 2011). "Humans 'left Africa much earlier'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012.

- ^ Clarkson C, Jacobs Z, Marwick B, Fullagar R, Wallis L, Smith M, et al. (July 2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212.

- ^ Lowe DJ (2008). "Polynesian settlement of New Zealand and the impacts of volcanism on early Maori society: an update" (PDF). University of Waikato. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ Appenzeller T (May 2012). "Human migrations: Eastern odyssey". Nature. 485 (7396): 24–26. Bibcode:2012Natur.485...24A. doi:10.1038/485024a. PMID 22552074.

- ^ a b Reich D, Green RE, Kircher M, Krause J, Patterson N, Durand EY, et al. (December 2010). "Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia". Nature. 468 (7327): 1053–1060. Bibcode:2010Natur.468.1053R. doi:10.1038/nature09710. hdl:10230/25596. PMC 4306417. PMID 21179161.

- ^ Hammer MF (May 2013). "Human Hybrids" (PDF). Scientific American. 308 (5): 66–71. Bibcode:2013SciAm.308e..66H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0513-66. PMID 23627222. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2018.

- ^ Yong E (July 2011). "Mosaic humans, the hybrid species". New Scientist. 211 (2823): 34–38. Bibcode:2011NewSc.211...34Y. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(11)61839-3.

- ^ Ackermann RR, Mackay A, Arnold ML (October 2015). "The Hybrid Origin of "Modern" Humans". Evolutionary Biology. 43 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s11692-015-9348-1. S2CID 14329491.

- ^ Noonan JP (May 2010). "Neanderthal genomics and the evolution of modern humans". Genome Research. 20 (5): 547–553. doi:10.1101/gr.076000.108. PMC 2860157. PMID 20439435.

- ^ Abi-Rached L, Jobin MJ, Kulkarni S, McWhinnie A, Dalva K, Gragert L, et al. (October 2011). "The shaping of modern human immune systems by multiregional admixture with archaic humans". Science. 334 (6052): 89–94. Bibcode:2011Sci...334...89A. doi:10.1126/science.1209202. PMC 3677943. PMID 21868630.

- ^ Sandel, Aaron A. (30 July 2013). "Brief communication: Hair density and body mass in mammals and the evolution of human hairlessness". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 152 (1): 145–150. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22333. hdl:2027.42/99654. PMID 23900811. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ Boyd R, Silk JB (2003). How Humans Evolved. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-97854-4.

- ^ Little, Michael A.; Blumler, Mark A. (2015). "Hunter-Gatherers". In Muehlenbein, Michael P. (ed.). Basics in Human Evolution. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 323–335. ISBN 978-0-12-802652-6. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Scarre, Chris (2018). "The world transformed: from foragers and farmers to states and empires". In Scarre, Chris (ed.). The Human Past: World Prehistory and the Development of Human Societies (4th ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 174–197. ISBN 978-0-500-29335-5.

- ^ Colledge S, Conolly J, Dobney K, Manning K, Shennan S (2013). Origins and Spread of Domestic Animals in Southwest Asia and Europe. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. pp. 13–17. ISBN 978-1-61132-324-5. OCLC 855969933. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Scanes CG (January 2018). "The Neolithic Revolution, Animal Domestication, and Early Forms of Animal Agriculture". In Scanes CG, Toukhsati SR (eds.). Animals and Human Society. Elsevier. pp. 103–131. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-805247-1.00006-X. ISBN 978-0-12-805247-1.

- ^ He K, Lu H, Zhang J, Wang C, Huan X (7 June 2017). "Prehistoric evolution of the dualistic structure mixed rice and millet farming in China". The Holocene. 27 (12): 1885–1898. Bibcode:2017Holoc..27.1885H. doi:10.1177/0959683617708455. S2CID 133660098. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Lu H, Zhang J, Liu KB, Wu N, Li Y, Zhou K, et al. (May 2009). "Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (18): 7367–7372. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.7367L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900158106. PMC 2678631. PMID 19383791.

- ^ Denham TP, Haberle SG, Lentfer C, Fullagar R, Field J, Therin M, et al. (July 2003). "Origins of agriculture at Kuk Swamp in the highlands of New Guinea". Science. 301 (5630): 189–193. doi:10.1126/science.1085255. PMID 12817084. S2CID 10644185.

- ^ Scarcelli N, Cubry P, Akakpo R, Thuillet AC, Obidiegwu J, Baco MN, et al. (May 2019). "Yam genomics supports West Africa as a major cradle of crop domestication". Science Advances. 5 (5): eaaw1947. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.1947S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw1947. PMC 6527260. PMID 31114806.

- ^ Winchell F (October 2017). "Evidence for Sorghum Domestication in Fourth Millennium BC Eastern Sudan: Spikelet Morphology from Ceramic Impressions of the Butana Group" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 58 (5): 673–683. doi:10.1086/693898. S2CID 149402650. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Manning K (February 2011). "4500-Year old domesticated pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) from the Tilemsi Valley, Mali: new insights into an alternative cereal domestication pathway". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (2): 312–322. Bibcode:2011JArSc..38..312M. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.09.007.

- ^ Noble TF, Strauss B, Osheim D, Neuschel K, Accamp E (2013). Cengage Advantage Books: Western Civilization: Beyond Boundaries. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-285-66153-7. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ Spielvogel J (1 January 2014). Western Civilization: Volume A: To 1500. Cenpage Learning. ISBN 978-1-285-98299-1. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ Thornton B (2002). Greek Ways: How the Greeks Created Western Civilization. San Francisco: Encounter Books. pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-1-893554-57-3. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Garfinkle SJ, Bang PF, Scheidel W (1 February 2013). Bang PF, Scheidel W (eds.). Ancient Near Eastern City-States. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195188318.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-518831-8. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

{{cite book}}:website=무시됨(도움말) - ^ Woods C (28 February 2020). "The Emergence of Cuneiform Writing". In Hasselbach-Andee R (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages (1st ed.). Wiley. pp. 27–46. doi:10.1002/9781119193814.ch2. ISBN 978-1-119-19329-6. S2CID 216180781.

- ^ Robinson A (October 2015). "Ancient civilization: Cracking the Indus script". Nature. 526 (7574): 499–501. Bibcode:2015Natur.526..499R. doi:10.1038/526499a. PMID 26490603. S2CID 4458743.

- ^ Crawford H (2013). "Trade in the Sumerian world". The Sumerian World. Routledge. pp. 447–461. ISBN 978-1-136-21911-5.

- ^ a b Bodnár M (2018). "Prehistoric innovations: Wheels and wheeled vehicles". Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 69 (2): 271–298. doi:10.1556/072.2018.69.2.3. ISSN 0001-5210. S2CID 115685157. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Pryor FL (1985). "The Invention of the Plow". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 27 (4): 727–743. doi:10.1017/S0010417500011749. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 178600. S2CID 144840498. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Carter R (2012). "19. Watercraft". In Potts DT (ed.). A companion to the archaeology of the ancient Near East. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 347–354. ISBN 978-1-4051-8988-0. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Pedersen O (1993). "Science Before the Greeks". Early physics and astronomy: A historical introduction. CUP Archive. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-40340-5.

- ^ Robson E (2008). Mathematics in ancient Iraq: A social history. Princeton University Press. pp. xxi.

- ^ Edwards JF (2003). "Building the Great Pyramid: Probable Construction Methods Employed at Giza". Technology and Culture. 44 (2): 340–354. doi:10.1353/tech.2003.0063. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 25148110. S2CID 109998651. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Voosen P (August 2018). "New geological age comes under fire". Science. 361 (6402): 537–538. Bibcode:2018Sci...361..537V. doi:10.1126/science.361.6402.537. PMID 30093579. S2CID 51954326.

- ^ Saggs HW (2000). Babylonians. Univ of California Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-520-20222-1.

- ^ Sassaman KE (1 December 2005). "Poverty Point as Structure, Event, Process". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 12 (4): 335–364. doi:10.1007/s10816-005-8460-4. ISSN 1573-7764. S2CID 53393440.

- ^ Lazaridis I, Mittnik A, Patterson N, Mallick S, Rohland N, Pfrengle S, et al. (August 2017). "Genetic origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans". Nature. 548 (7666): 214–218. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..214L. doi:10.1038/nature23310. PMC 5565772. PMID 28783727.

- ^ Keightley DN (1999). "The Shang: China's first historical dynasty". In Loewe M, Shaughnessy EL (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 232–291. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- ^ Kaniewski D, Guiot J, van Campo E (2015). "Drought and societal collapse 3200 years ago in the Eastern Mediterranean: a review". WIREs Climate Change. 6 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1002/wcc.345. S2CID 128460316.

- ^ Drake BL (1 June 2012). "The influence of climatic change on the Late Bronze Age Collapse and the Greek Dark Ages". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (6): 1862–1870. Bibcode:2012JArSc..39.1862D. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.01.029.

- ^ Wells PS (2011). "The Iron Age". In Milisauskas S (ed.). European Prehistory. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 405–460. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-6633-9_11. ISBN 978-1-4419-6633-9.

- ^ Hughes-Warrington M (2018). "Sense and non-sense in Ancient Greek histories". History as Wonder: Beginning with Historiography. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-76315-1.

- ^ Beard M (2 October 2015). "Why ancient Rome matters to the modern world". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Vidergar AB (11 June 2015). "Stanford scholar debunks long-held beliefs about economic growth in ancient Greece". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Inomata T, Triadan D, Vázquez López VA, Fernandez-Diaz JC, Omori T, Méndez Bauer MB, et al. (June 2020). "Monumental architecture at Aguada Fénix and the rise of Maya civilization". Nature. 582 (7813): 530–533. Bibcode:2020Natur.582..530I. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2343-4. PMID 32494009. S2CID 219281856.

- ^ Milbrath S (March 2017). "The Role of Solar Observations in Developing the Preclassic Maya Calendar". Latin American Antiquity. 28 (1): 88–104. doi:10.1017/laq.2016.4. ISSN 1045-6635. S2CID 164417025. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Benoist A, Charbonnier J, Gajda I (2016). "Investigating the eastern edge of the kingdom of Aksum: architecture and pottery from Wakarida". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 46: 25–40. ISSN 0308-8421. JSTOR 45163415. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Farazmand A (1 January 1998). "Administration of the Persian achaemenid world-state empire: implications for modern public administration". International Journal of Public Administration. 21 (1): 25–86. doi:10.1080/01900699808525297. ISSN 0190-0692.

- ^ Ingalls DH (1976). "Kālidāsa and the Attitudes of the Golden Age". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 96 (1): 15–26. doi:10.2307/599886. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 599886. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Xie J (2020). "Pillars of Heaven: The Symbolic Function of Column and Bracket Sets in the Han Dynasty". Architectural History. 63: 1–36. doi:10.1017/arh.2020.1. ISSN 0066-622X. S2CID 229716130. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Marx W, Haunschild R, Bornmann L (2018). "Climate and the Decline and Fall of the Western Roman Empire: A Bibliometric View on an Interdisciplinary Approach to Answer a Most Classic Historical Question". Climate. 6 (4): 90. Bibcode:2018Clim....6...90M. doi:10.3390/cli6040090.

- ^ Brooke JH, Numbers RL, eds. (2011). Science and Religion Around the World. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-532819-6. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ a b Renima A, Tiliouine H, Estes RJ (2016). "The Islamic Golden Age: A Story of the Triumph of the Islamic Civilization". In Tiliouine H, Estes RJ (eds.). The State of Social Progress of Islamic Societies. International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 25–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24774-8_2. ISBN 978-3-319-24774-8.

- ^ Vidal-Nanquet P (1987). The Harper Atlas of World History. Harper & Row Publishers. p. 76.

- ^ Asbridge T (2012). "Introduction: The world of the crusades". The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-770-5.

- ^ Adam King (2002). "Mississippian Period: Overview". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 19 August 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ Conrad G, Demarest AA (1984). Religion and Empire: The Dynamics of Aztec and Inca Expansionism. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-521-31896-3.

- ^ May T (2013). The Mongol Conquests in World History. Reaktion Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-86189-971-2.

- ^ Canós-Donnay S (25 February 2019). "The Empire of Mali". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.266. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Canela SA, Graves MW. "The Tongan Maritime Expansion: A Case in the Evolutionary Ecology of Social Complexity". Asian Perspectives. 37 (2): 135–164.

- ^ Kafadar C (1 January 1994). "Ottomans and Europe". In Brady T, Oberman T, Tracy JD (eds.). Handbook of European History 1400–1600: Late Middle Ages, Renaissance and Reformation. Brill. pp. 589–635. doi:10.1163/9789004391659_019. ISBN 978-90-04-39165-9. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Goree R (19 November 2020). "The Culture of Travel in Edo-Period Japan". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.72. ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Mosca MW (2010). "CHINA'S LAST EMPIRE: The Great Qing". Pacific Affairs. 83. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Suyanta S, Ikhlas S (19 July 2016). "Islamic Education at Mughal Kingdom in India (1526–1857)". Al-Ta Lim Journal. 23 (2): 128–138. doi:10.15548/jt.v23i2.228. ISSN 2355-7893. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Kirkpatrick R (2002). The European Renaissance, 1400–1600. Harlow, England. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-317-88646-4. OCLC 893909816. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 유지 관리: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ Arnold D (2002). The Age of Discovery, 1400–1600 (Second ed.). London. pp. xi. ISBN 978-1-136-47968-7. OCLC 859536800. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 유지 관리: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ Palan R (14 January 2010). "International Financial Centers: The British-Empire, City-States and Commercially Oriented Politics". Theoretical Inquiries in Law. 11 (1). doi:10.2202/1565-3404.1239. ISSN 1565-3404. S2CID 56216309. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Dixon EJ (January 2001). "Human colonization of the Americas: timing, technology and process". Quaternary Science Reviews. 20 (1–3): 277–299. Bibcode:2001QSRv...20..277J. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(00)00116-5.

- ^ Lovejoy PE (1989). "The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on Africa: A Review of the Literature". The Journal of African History. 30 (3): 365–394. doi:10.1017/S0021853700024439. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 182914. S2CID 161321949. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Cave AA (2008). "Genocide in the Americas". In Stone D (ed.). The Historiography of Genocide. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 273–295. doi:10.1057/9780230297784_11. ISBN 978-0-230-29778-4.

- ^ Delisle RG (September 2014). "Can a revolution hide another one? Charles Darwin and the Scientific Revolution". Endeavour. 38 (3–4): 157–158. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2014.10.001. PMID 25457642.

- ^ "Greatest Engineering Achievements of the 20th Century". National Academy of Engineering. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ Herring GC (2008). From colony to superpower : U.S. foreign relations since 1776. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-972343-0. OCLC 299054528. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ O'Rourke KH (March 2006). "The worldwide economic impact of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1793–1815". Journal of Global History. 1 (1): 123–149. doi:10.1017/S1740022806000076. ISSN 1740-0228. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Zimmerman AF (November 1931). "Spain and Its Colonies, 1808–1820". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 11 (4): 439–463. doi:10.2307/2506251. JSTOR 2506251. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ David S (2011). "British History in depth: Slavery and the 'Scramble for Africa'". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Raudzens G (2004). "The Australian Frontier Wars, 1788–1838 (review)". The Journal of Military History. 68 (3): 957–959. doi:10.1353/jmh.2004.0138. ISSN 1543-7795. S2CID 162259092.

- ^ Clark CM (2012). "Polarization of Europe, 1887–1907". The sleepwalkers : how Europe went to war in 1914. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9942-6. OCLC 794136314. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Robert Dahl (1989). Democracy and Its Critics. Yale UP. pp. 239–240. ISBN 0-300-15355-4.

- ^ McDougall WA (May 1985). "Sputnik, the space race, and the Cold War". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 41 (5): 20–25. Bibcode:1985BuAtS..41e..20M. doi:10.1080/00963402.1985.11455962. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^ Plous S (May 1993). "The Nuclear Arms Race: Prisoner's Dilemma or Perceptual Dilemma?". Journal of Peace Research. 30 (2): 163–179. doi:10.1177/0022343393030002004. ISSN 0022-3433. S2CID 5482851. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Sachs JD (April 2017). "Globalization – In the Name of Which Freedom?". Humanistic Management Journal. 1 (2): 237–252. doi:10.1007/s41463-017-0019-5. ISSN 2366-603X. S2CID 133030709. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "World". The World Factbook. CIA. 17 May 2016. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ "World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision" (PDF). United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2017. p. 2&17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "The World's Cities in 2018" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2018.

- ^ Rector RK (2016). The Early River Valley Civilizations (First ed.). New York: Rosen Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4994-6329-3. OCLC 953735302. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "How People Modify the Environment" (PDF). Westerville City School District. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ "Natural disasters and the urban poor" (PDF). World Bank. October 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017.

- ^ Habitat UN (2013). The state of the world's cities 2012 / prosperity of cities. [London]: Routledge. pp. x. ISBN 978-1-135-01559-6. OCLC 889953315. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Piantadosi CA (2003). The biology of human survival : life and death in extreme environments. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-19-974807-5. OCLC 70215878. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ O'Neil D. "Human Biological Adaptability; Overview". Palomar College. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Population distribution and density". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ Bunn SE, Arthington AH (October 2002). "Basic principles and ecological consequences of altered flow regimes for aquatic biodiversity". Environmental Management. 30 (4): 492–507. doi:10.1007/s00267-002-2737-0. hdl:10072/6758. PMID 12481916. S2CID 25834286.

- ^ a b Heim BE (1990–1991). "Exploring the Last Frontiers for Mineral Resources: A Comparison of International Law Regarding the Deep Seabed, Outer Space, and Antarctica". Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law. 23: 819. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Mission to Mars: Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity Rover". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Touchdown! Rosetta's Philae probe lands on comet". European Space Agency. 12 November 2014. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "NEAR-Shoemaker". NASA. Archived from the original on 26 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ Kraft R (11 December 2010). "JSC celebrates ten years of continuous human presence aboard the International Space Station". JSC Features. Johnson Space Center. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ a b Bar-On YM, Phillips R, Milo R (June 2018). "The biomass distribution on Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (25): 6506–6511. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.6506B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115. PMC 6016768. PMID 29784790.

- ^ Tellier LN (2009). Urban world history: an economic and geographical perspective. Presses de l'Université du Québec. p. 26. ISBN 978-2-7605-1588-8. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Thomlinson R (1975). Demographic problems; controversy over population control (2nd ed.). Ecino, CA: Dickenson Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-8221-0166-6.

- ^ Harl KW (1998). "Population estimates of the Roman Empire". Tulane.edu. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Zietz BP, Dunkelberg H (February 2004). "The history of the plague and the research on the causative agent Yersinia pestis". International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 207 (2): 165–178. doi:10.1078/1438-4639-00259. PMC 7128933. PMID 15031959.

- ^ "World's population reaches six billion". BBC News. 5 August 1999. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- ^ United Nations. "World population to reach 8 billion on 15 November 2022". United Nations. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ "Eight billion people, SARS-CoV-2 ancestor and illegal fishing". Nature. 611 (641): 641. 23 November 2022. Bibcode:2022Natur.611..641.. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-03792-4. S2CID 253764233. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ "World Population to Hit Milestone With Birth of 7 Billionth Person". PBS NewsHour. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ a b "68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA). 16 May 2018. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Duhart DT (October 2000). Urban, Suburban, and Rural Victimization, 1993–98 (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ^ Roopnarine PD (March 2014). "Humans are apex predators". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (9): E796. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E.796R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1323645111. PMC 3948303. PMID 24497513.

- ^ Stokstad E (5 May 2019). "Landmark analysis documents the alarming global decline of nature". Science. AAAS. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

For the first time at a global scale, the report has ranked the causes of damage. Topping the list, changes in land use – principally agriculture – that have destroyed habitat. Second, hunting and other kinds of exploitation. These are followed by climate change, pollution, and invasive species, which are being spread by trade and other activities. Climate change will likely overtake the other threats in the next decades, the authors note. Driving these threats are the growing human population, which has doubled since 1970 to 7.6 billion, and consumption. (Per capita of use of materials is up 15% over the past 5 decades.)

- ^ Pimm S, Raven P, Peterson A, Sekercioglu CH, Ehrlich PR (July 2006). "Human impacts on the rates of recent, present, and future bird extinctions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (29): 10941–10946. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10310941P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604181103. PMC 1544153. PMID 16829570.

- ^ Roza G (2007). Inside the human body : using scientific and exponential notation. New York: Rosen Pub. Group's PowerKids Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4042-3362-1. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Human Anatomy". Inner Body. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ a b Collins D (1976). The Human Revolution: From Ape to Artist. Phaidon. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-7148-1676-0.

- ^ Marks JM (2001). Human Biodiversity: Genes, Race, and History. Transaction Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-202-36656-2.

- ^ a b O'Neil D. "Humans". Primates. Palomar College. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "How to be Human: The reason we are so scarily hairy". New Scientist. 2017. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Sandel AA (September 2013). "Brief communication: Hair density and body mass in mammals and the evolution of human hairlessness". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 152 (1): 145–150. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22333. hdl:2027.42/99654. PMID 23900811.

- ^ Kirchweger G (2 February 2001). "The Biology of Skin Color: Black and White". Evolution: Library. PBS. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Roser M, Appel C, Ritchie H (8 October 2013). "Human Height". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Senior Citizens Do Shrink – Just One of the Body Changes of Aging". News. Senior Journal. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Bogin B, Rios L (September 2003). "Rapid morphological change in living humans: implications for modern human origins". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A, Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 136 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00294-5. PMID 14527631.

- ^ "Human weight". Articleworld.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Schlessingerman A (2003). "Mass Of An Adult". The Physics Factbook: An Encyclopedia of Scientific Essays. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ Kushner R (2007). Treatment of the Obese Patient (Contemporary Endocrinology). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-59745-400-1. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ Adams JP, Murphy PG (July 2000). "Obesity in anaesthesia and intensive care". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 85 (1): 91–108. doi:10.1093/bja/85.1.91. PMID 10927998.

- ^ Lombardo MP, Deaner RO (March 2018). "Born to Throw: The Ecological Causes that Shaped the Evolution of Throwing In Humans". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 93 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1086/696721. ISSN 0033-5770. S2CID 90757192.

- ^ Parker-Pope T (27 October 2009). "The Human Body Is Built for Distance". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015.

- ^ John B. "What is the role of sweating glands in balancing body temperature when running a marathon?". Livestrong.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Therman E (1980). Human Chromosomes: Structure, Behavior, Effects. Springer US. pp. 112–124. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-0107-3. ISBN 978-1-4684-0109-7. S2CID 36686283.

- ^ Edwards JH, Dent T, Kahn J (June 1966). "Monozygotic twins of different sex". Journal of Medical Genetics. 3 (2): 117–123. doi:10.1136/jmg.3.2.117. PMC 1012913. PMID 6007033.

- ^ Machin GA (January 1996). "Some causes of genotypic and phenotypic discordance in monozygotic twin pairs". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 61 (3): 216–228. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960122)61:3<216::AID-AJMG5>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 8741866.

- ^ Jonsson H, Magnusdottir E, Eggertsson HP, Stefansson OA, Arnadottir GA, Eiriksson O, et al. (January 2021). "Differences between germline genomes of monozygotic twins". Nature Genetics. 53 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1038/s41588-020-00755-1. PMID 33414551. S2CID 230986741.

- ^ "Genetic – Understanding Human Genetic Variation". Human Genetic Variation. National Institute of Health (NIH). Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

Between any two humans, the amount of genetic variation – biochemical individuality – is about 0.1%.

- ^ Levy S, Sutton G, Ng PC, Feuk L, Halpern AL, Walenz BP, et al. (September 2007). "The diploid genome sequence of an individual human". PLOS Biology. 5 (10): e254. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050254. PMC 1964779. PMID 17803354.

- ^ a b Race, Ethnicity, and Genetics Working Group (October 2005). "The use of racial, ethnic, and ancestral categories in human genetics research". American Journal of Human Genetics. 77 (4): 519–532. doi:10.1086/491747. PMC 1275602. PMID 16175499.

- ^ "Chimps show much greater genetic diversity than humans". Media. University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ Harpending HC, Batzer MA, Gurven M, Jorde LB, Rogers AR, Sherry ST (February 1998). "Genetic traces of ancient demography". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (4): 1961–1967. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.1961H. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.4.1961. PMC 19224. PMID 9465125.

- ^ Jorde LB, Rogers AR, Bamshad M, Watkins WS, Krakowiak P, Sung S, et al. (April 1997). "Microsatellite diversity and the demographic history of modern humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (7): 3100–3103. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.3100J. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.7.3100. PMC 20328. PMID 9096352.

- ^ Wade N (7 March 2007). "Still Evolving, Human Genes Tell New Story". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Pennisi E (February 2001). "The human genome". Science. 291 (5507): 1177–1180. doi:10.1126/science.291.5507.1177. PMID 11233420. S2CID 38355565.

- ^ Rotimi CN, Adeyemo AA (February 2021). "From one human genome to a complex tapestry of ancestry". Nature. 590 (7845): 220–221. Bibcode:2021Natur.590..220R. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00237-2. PMID 33568827. S2CID 231882262.

- ^ Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, et al. (September 2010). "Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations". Nature. 467 (7311): 52–58. Bibcode:2010Natur.467...52T. doi:10.1038/nature09298. PMC 3173859. PMID 20811451.

- ^ a b Bergström A, McCarthy SA, Hui R, Almarri MA, Ayub Q, Danecek P, et al. (March 2020). "Insights into human genetic variation and population history from 929 diverse genomes". Science. 367 (6484): eaay5012. doi:10.1126/science.aay5012. PMC 7115999. PMID 32193295.

Populations in central and southern Africa, the Americas, and Oceania each harbor tens to hundreds of thousands of private, common genetic variants. Most of these variants arose as new mutations rather than through archaic introgression, except in Oceanian populations, where many private variants derive from Denisovan admixture.

- ^ Pertea M, Salzberg SL (2010). "Between a chicken and a grape: estimating the number of human genes". Genome Biology. 11 (5): 206. doi:10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-206. PMC 2898077. PMID 20441615.

- ^ Cann RL, Stoneking M, Wilson AC (1987). "Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution". Nature. 325 (6099): 31–36. Bibcode:1987Natur.325...31C. doi:10.1038/325031a0. PMID 3025745. S2CID 4285418.

- ^ Soares P, Ermini L, Thomson N, Mormina M, Rito T, Röhl A, et al. (June 2009). "Correcting for purifying selection: an improved human mitochondrial molecular clock". American Journal of Human Genetics. 84 (6): 740–759. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.001. PMC 2694979. PMID 19500773.

- ^ "University of Leeds News > Technology > New 'molecular clock' aids dating of human migration history". 20 August 2017. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017.

- ^ Poznik GD, Henn BM, Yee MC, Sliwerska E, Euskirchen GM, Lin AA, et al. (August 2013). "Sequencing Y chromosomes resolves discrepancy in time to common ancestor of males versus females". Science. 341 (6145): 562–565. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..562P. doi:10.1126/science.1237619. PMC 4032117. PMID 23908239.

- ^ Shehan CL (2016). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Family Studies, 4 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-470-65845-1.

- ^ Jukic AM, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, McConnaughey DR, Wilcox AJ (October 2013). "Length of human pregnancy and contributors to its natural variation". Human Reproduction. 28 (10): 2848–2855. doi:10.1093/humrep/det297. PMC 3777570. PMID 23922246.

- ^ Klossner NJ (2005). Introductory Maternity Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-7817-6237-3. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

The fetal stage is from the beginning of the 9th week after fertilization and continues until birth

- ^ World Health Organization (November 2014). "Preterm birth Fact sheet N°363". who.int. Archived from the original on 7 March 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Kiserud T, Benachi A, Hecher K, Perez RG, Carvalho J, Piaggio G, Platt LD (February 2018). "The World Health Organization fetal growth charts: concept, findings, interpretation, and application". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 218 (2S): S619–S629. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.010. PMID 29422204. S2CID 46810955.

- ^ "What is the average baby length? Growth chart by month". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Khor GL (December 2003). "Update on the prevalence of malnutrition among children in Asia". Nepal Medical College Journal. 5 (2): 113–122. PMID 15024783.

- ^ Rosenberg KR (1992). "The evolution of modern human childbirth". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 35 (S15): 89–124. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330350605. ISSN 1096-8644.

- ^ a b Pavličev M, Romero R, Mitteroecker P (January 2020). "Evolution of the human pelvis and obstructed labor: new explanations of an old obstetrical dilemma". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 222 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.043. PMC 9069416. PMID 31251927. S2CID 195761874.

- ^ Barras C (22 December 2016). "The real reasons why childbirth is so painful and dangerous". BBC.

- ^ Kantrowitz B (2 July 2007). "What Kills One Woman Every Minute of Every Day?". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 28 June 2007.

A woman dies in childbirth every minute, most often due to uncontrolled bleeding and infection, with the world's poorest women most vulnerable. The lifetime risk is 1 in 16 in sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 1 in 2,800 in developed countries.

- ^ Rush D (July 2000). "Nutrition and maternal mortality in the developing world". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 72 (1 Suppl): 212S–240S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/72.1.212S. PMID 10871588.

- ^ Laland KN, Brown G (2011). Sense and Nonsense: Evolutionary Perspectives on Human Behaviour. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-958696-7. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Kail RV, Cavanaugh JC (2010). Human Development: A Lifespan View (5th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-495-60037-4. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Schuiling KD, Likis FE (2016). Women's Gynecologic Health. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-284-12501-6. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

The changes that occur during puberty usually happen in an ordered sequence, beginning with thelarche (breast development) at around age 10 or 11, followed by adrenarche (growth of pubic hair due to androgen stimulation), peak height velocity, and finally menarche (the onset of menses), which usually occurs around age 12 or 13.

- ^ Phillips DC (2014). Encyclopedia of Educational Theory and Philosophy. SAGE Publications. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-4833-6475-9. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

On average, the onset of puberty is about 18 months earlier for girls (usually starting around the age of 10 or 11 and lasting until they are 15 to 17) than for boys (who usually begin puberty at about the age of 11 to 12 and complete it by the age of 16 to 17, on average).

- ^ Mintz S (1993). "Life stages". Encyclopedia of American Social History. 3: 7–33.

- ^ Soliman A, De Sanctis V, Elalaily R, Bedair S (November 2014). "Advances in pubertal growth and factors influencing it: Can we increase pubertal growth?". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 18 (Suppl 1): S53-62. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.145075. PMC 4266869. PMID 25538878.

- ^ Walker ML, Herndon JG (September 2008). "Menopause in nonhuman primates?". Biology of Reproduction. 79 (3): 398–406. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.108.068536. PMC 2553520. PMID 18495681.

- ^ Diamond J (1997). Why is Sex Fun? The Evolution of Human Sexuality. New York: Basic Books. pp. 167–170. ISBN 978-0-465-03127-6.

- ^ Peccei JS (2001). "Menopause: Adaptation or epiphenomenon?". Evolutionary Anthropology. 10 (2): 43–57. doi:10.1002/evan.1013. S2CID 1665503.

- ^ Marziali C (7 December 2010). "Reaching Toward the Fountain of Youth". USC Trojan Family Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ Kalben BB (2002). "Why Men Die Younger: Causes of Mortality Differences by Sex". Society of Actuaries. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013.

- ^ "Life expectancy at birth, female (years)". World Bank. 2018. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Life expectancy at birth, male (years)". World Bank. 2018. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Conceição P, et al. (2019). Human Development Report (PDF). ISBN 978-92-1-126439-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

{{cite book}}:work=무시됨(도움말) - ^ "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "The World Factbook". U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2005.

- ^ "Chapter 1: Setting the Scene" (PDF). UNFPA. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ Haenel H (1989). "Phylogenesis and nutrition". Die Nahrung. 33 (9): 867–887. PMID 2697806.