네안데르탈인

Neanderthal| 네안데르탈인 시간적 범위: Middle to Late Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| 네안데르탈인의 뼈대를 대략적으로 재구성한 것입니다. 흉골을 포함한 중앙 갈비뼈와 골반의 일부는 현생 인류의 것입니다. | |

| 과학 분류 | |

| 도메인: | 진핵생물 |

| 왕국: | 애니멀리아 |

| 문: | 코데아타 |

| 클래스: | 포유류 |

| 주문: | 영장류 |

| 하위 주문: | Haplorhini |

| 인프라오더: | 시미이포르메스 |

| 가족: | 호미니과 |

| 하위 그룹: | 호미니내 |

| 부족: | 호미니니 |

| 속: | 호모 |

| 종: | †H. 네안데르탈렌시스 |

| 이항명 | |

| †호모네안데르탈렌시스 왕, 1864년 | |

| |

| 유럽(파란색), 서남아시아(주황색), 우즈베키스탄(녹색) 및 알타이 산맥(자외선)에서 알려진 네안데르탈인 범위 | |

| 동의어[6] | |

| 호모

팔레오안트로푸스 프로탄트로푸스

| |

Neanderthals (/niˈændərˌtɑːl, neɪ-, -ˌθɑːl/ nee-AN-də(r)-TAHL, nay-, - THAHL;[7] Homo neanderthalensis or H. sapiens neanderthalensis) are an extinct group of archaic humans (generally regarded as a distinct species, though some regard it as a subspecies of Homo sapiens) who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago.[8][9][10][11] 네안데르탈인 1형 표본은 1856년 오늘날 독일의 네안데르 계곡에서 발견되었습니다.

네안데르탈인의 계통이 언제 현대 인류의 계통과 갈라졌는지는 명확하지 않습니다. 연구는 31만 5천[12] 년 전부터 80만 년 이상 전까지 다양한 시기를 만들어냈습니다.[13] 네안데르탈인이 조상 H. 하이델베르겐시스로부터 갈라진 연대도 불분명합니다. 가장 오래된 잠재적인 네안데르탈인의 뼈는 43만년 전으로 거슬러 올라가지만, 그 분류는 아직 불확실합니다.[14] 네안데르탈인은 특히 13만년 전 이후의 수많은 화석에서 알려져 있습니다.[15]

네안데르탈인이 멸종한 이유에 대해서는 논쟁의 여지가 있습니다.[16][17] 그들의 멸종에 대한 이론에는 작은 인구 규모와 근친 교배, 경쟁적 대체,[18] 현대 인간과의 교배 및 동화,[19] 기후,[20][21][22] 질병 [23][24]또는 이러한 요인의 조합과 같은 인구 통계학적 요인이 포함됩니다.[22]

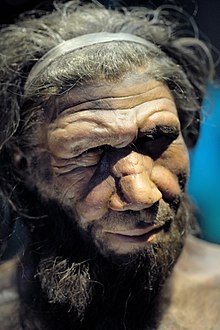

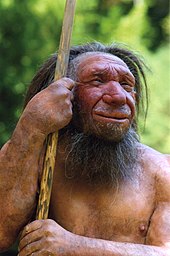

20세기 초의 많은 기간 동안, 유럽의 연구자들은 네안데르탈인을 원시적이고, 우둔하고, 야만적이라고 묘사했습니다. 그 이후 과학계에서 이들에 대한 지식과 인식이 확연히 달라졌지만, 아직 진화하지 못한 동굴인 원형의 이미지는 대중문화에 만연해 있습니다.[25][26] 사실, 네안데르탈인의 기술은 꽤 정교했습니다. It includes the Mousterian stone-tool industry[27][28] as well as the abilities to create fire,[29][30] build cave hearths[31][32] (to cook food, keep warm, defend themselves from animals, placing it at the centre of their homes),[33] make adhesive birch bark tar,[34] craft at least simple clothes similar to blankets and ponchos,[35] weave,[36] go seafaring through the Mediterranean,[37][38] 약용식물을 사용하고,[39][40][41] 중상을 치료하고,[42] 음식을 보관하며,[43] 로스팅, 삶기,[44] 흡연 등 다양한 조리법을 사용합니다.[45] 네안데르탈인은 주로 발굽이 달린 포유류뿐만 아니라 [46]메가파우나 식물,[25][47][48][49][50] 작은 포유류, 새, 수생 및 해양 자원 등 다양한 먹이를 섭취했습니다.[51] 비록 그들이 최상위 포식자였을지 모르지만, 그들은 여전히 동굴 사자, 동굴 하이에나, 그리고 다른 큰 포식자들과 경쟁했습니다.[52] 상징적인 사고와 구석기 시대 예술의 많은 예들은 네안데르탈인에게 결정적으로[53] 귀속되지 않았습니다. 즉, 새의 발톱과 깃털로 만든 장식품,[54][55] 조개껍질,[56] 결정체와 화석을 포함한 특이한 물체들의 수집품,[57] 판각,[58] 음악 제작(디브제 베이브 플루트로 표현되었을 가능성도 있음),[59] 스페인의 동굴 벽화는 65,000년 전으로 거슬러[60] 올라갑니다.[61][62] 종교적 신념에 대한 일부 주장이 제기되었습니다.[63] 네안데르탈인은 언어의 복잡성은 알려져 있지 않지만, 아마도 말로 표현할 수 있었을 것입니다.[64][65]

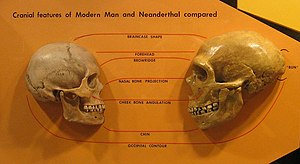

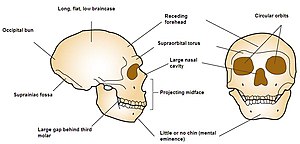

네안데르탈인은 현대 인류에 비해 체격이 더 건장하고 팔다리가 비례적으로 짧았습니다. 연구자들은 이러한 특징들을 종종 추운 기후에서 열을 보존하기 위한 적응으로 설명하지만, 또한 네안데르탈인이 종종 거주했던 더 따뜻하고 숲이 우거진 풍경에서 전력질주를 위한 적응이었을 수도 있습니다.[66] 그들은 전문적인 체지방 저장과[67] 따뜻한 공기에[68] 대한 코 확대와 같은 감기에 특화된 적응을 했습니다 (비록 코는 유전적 드리프트로[69] 인해 발생했을 수 있습니다). 평균적인 네안데르탈인 남성의 키는 약 165cm (5피트 5인치), 여성의 키는 153cm (5피트 0인치)로 산업화 이전의 현대 유럽인들과 비슷했습니다.[70] 네안데르탈인 남녀의 뇌 케이스는 평균 약 1,600 cm3(98 cuin), 1,300 cm3(79 cuin)로 [71][72][73]현대 인류 평균(각각 1,260 cm3(77 cuin), 1,130 cm3(69 cuin)보다 상당히 컸습니다.[74] 네안데르탈인의 두개골은 더 길쭉했고 뇌는 더 작은 두정엽과[75][76][77] 소뇌를 가지고 있었지만,[78][79] 더 큰 측두엽과 후두엽 및 오비탈인 전두엽 영역을 가지고 있었습니다.[80][81]

네안데르탈인의 총 개체수는 낮은 상태를 유지하여 약한 유해 유전자 변이체를[82] 증식시키고 효과적인 장거리 네트워크를 배제했습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 지역 문화와 지역 사회 간의 정기적인 의사 소통의 증거가 있습니다.[83][84] 그들은 동굴을 자주 드나들었고 계절적으로 동굴 사이를 이동했을 수 있습니다.[85] 네안데르탈인은 외상률이 높은 고스트레스 환경에서 살았고, 약 80%가 40세 이전에 사망했습니다.[86]

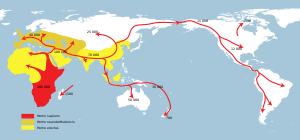

2010년 네안데르탈인 게놈 프로젝트의 초안 보고서는 네안데르탈인과 현생 인류 사이의 이종교배에 대한 증거를 제시했습니다.[87][88][89] 아마도 316,000년에서 219,000년 전에 발생했을 가능성이 있지만,[90] 10만년 전과 65,000년 전에 다시 발생했을 가능성이 더 높습니다.[91] 네안데르탈인은 또한 시베리아에서 고대 인류의 다른 집단인 데니소반과 교배한 것으로 보입니다.[92][93] 유라시아인, 오스트레일리아 원주민, 멜라네시아인, 아메리카 원주민 및 북아프리카인의 게놈의 약 1-4%가 네안데르탈인 조상인 반면, 사하라 이남 아프리카의 대부분의 거주자는 약 0.3%의 네안데르탈인 유전자를 가지고 있으며 초기 사피엔스에서 네안데르탈인으로의 유전자 흐름 및/또는 최근 유라시아인이 아프리카로 이주한 흔적을 보존합니다. 총 20% 정도의 네안데르탈인 유전자 변이가 현대인에게 생존합니다.[94] 비록 네안데르탈인으로부터 물려받은 많은 유전자 변이체들이 해롭고 선택되었을 수 있지만,[82] 네안데르탈인의 침입은 현대 인간 면역 체계에 영향을 미친 것으로 보이며,[95][96][97][98] 또한 여러 다른 생물학적 기능과 구조에 관련되어 있지만,[99] 많은 부분이 비암호화 DNA인 것으로 보입니다.[100]

분류법

어원

네안데르탈인은 최초로 확인된 표본이 발견된 네안데르 계곡의 이름을 따서 지어졌습니다. 이 계곡의 이름은 네안데르탈인이었고 이 종은 1901년 철자법이 개혁되기 전까지 독일어로 네안데르탈인이었습니다.[b] 이 종의 철자 네안데르탈인은 과학 출판물에서도 가끔 볼 수 있지만, 학명 H. neanderthalensis는 우선 순위 원칙에 따라 항상 철자가 붙여집니다. 독일어로 된 이 종의 토착어 이름은 항상 네안데르탈인("네안데르탈인")이지만, 네안데르탈인은 항상 계곡을 나타냅니다.[c] 계곡 자체는 17세기 후반 독일 신학자이자 찬송가 작가인 요아힘 네안데르의 이름을 따서 지어졌는데, 그는 이 지역을 자주 방문했습니다.[101] 그의 이름은 '새로운 사람'을 의미하며, 독일 성 노이만의 학식 있는 그리스화입니다.

네안데르탈인은 /t/( /ni ˈæ nd ə rt ɑː l/에서와 같이) 또는 마찰음 /θ /( /ni ˈæ nd ə rt θɔː l/에서와 같이)의 표준 영어 발음을 사용하여 발음할 수 있습니다.

유형 표본인 네안데르탈인 1은 인류학 문헌에서 "네안데르탈인 두개골" 또는 "네안데르탈인 두개골"로 알려져 있었고, 두개골을 기반으로 재구성된 개체는 때때로 "네안데르탈인"으로 불렸습니다.[107] 호모 네안데르탈렌시스("Homo neanderthalensis")라는 이항명은 아일랜드 지질학자 윌리엄 킹(William King)이 1863년 제33회 영국 과학 협회에 보낸 논문에서 처음 제안했습니다.[108][109][110] 그러나 1864년, 그는 네안데르탈인의 뇌 사례를 침팬지의 뇌 사례와 비교하고 그들이 "도덕적이고 [신학적인[d]] 개념을 가질 수 없다"고 주장하면서 네안데르탈인과 현생 인류를 다른 속으로 분류할 것을 권고했습니다.[111]

연구이력

최초의 네안데르탈인 유적인 엥기스 2 (두개)는 1829년 벨기에 그로츠 엥기스에서 네덜란드인/벨기에 선사학자 필리프-찰스 슈메링에 의해 발견되었습니다. 그는 이 "저조하게 개발된" 인간의 유해들이 멸종된 동물 종들의 공존하는 유해들과 동시에 그리고 같은 원인들에 의해 매장되었을 것이라고 결론지었습니다.[112] 1848년, 포브스 채석장의 지브롤터 1호는 에드먼드 헨리 레네 플린트 장관에 의해 지브롤터 과학 학회에 제출되었지만, 현대 인간의 두개골로 여겨졌습니다.[113] 1856년, 지역 학교 교사 요한 칼 풀로트는 네안데르탈인 계곡의 클라인 펠트호퍼 그로트(Kleine Feldhofer Grotte)의 뼈를 현생 인류와 구별되는 것으로 [e]인식하고 1857년 독일 인류학자 헤르만 샤프하우젠(Hermann Schaffhausen)에게 연구를 의뢰했습니다. 두개골, 넓적다리뼈, 오른팔, 왼쪽 상완골과 척골, 왼쪽 장골(엉덩이뼈), 오른쪽 어깨뼈 일부, 갈비뼈 조각으로 구성되어 있었습니다.[111][114] 찰스 다윈(Charles Darwin)의 종의 기원(Origin of Species)에 이어 풀롯(Fullrott)과 샤프하우젠(Shaffhausen)은 뼈가 고대 현대 인간 형태를 나타낸다고 주장했습니다.[26][111][115][116] 사회 다윈주의자인 샤프하우젠(Shaffhausen)은 인간이 야만에서 문명화로 선형적으로 진행되었다고 믿었고, 따라서 네안데르탈인은 야만적인 동굴 거주자라고 결론 내렸습니다.[26] 풀로트와 샤프하우젠은 단 하나의 발견만을 근거로 새로운 종을 정의하는 것에 반대하는 다작하는 병리학자 루돌프 비르초우의 반대에 부딪혔습니다. 1872년, Virchow는 네안데르탈인의 특성을 구식 대신 노쇠, 질병 및 기형의 증거로 잘못 해석하여 [117]세기 말까지 네안데르탈인의 연구를 지연시켰습니다.[26][115]

20세기 초까지 수많은 다른 네안데르탈인의 발견이 이루어졌고, H. neanderthalensis는 합법적인 종으로 확립되었습니다. 가장 영향력 있는 표본은 프랑스 라 샤펠오생트의 라 샤펠오생트 1 ("The Old Man")입니다. 프랑스 고생물학자 마르셀린 불레(Marcellin Boule)는 고생물학을 과학으로 정립한 최초의 논문 중 표본에 대해 자세히 설명하면서 여러 출판물을 저술했지만, 그를 구부정하고 유인원처럼 생겼으며 현생 인류와 원격으로 관련된 것으로만 재구성했습니다. 네안데르탈인보다 현생 인류와 훨씬 더 유사한 것으로 보이는 1912년 필트다운 인간의 '발견'(거짓말)은 원시 인류의 서로 다른 여러 갈래가 존재한다는 증거로 사용되었으며, 부울의 H. 네안데르탈인에 대한 먼 친척이자 진화의 막다른 골목으로 재구성하는 것을 뒷받침했습니다.[26][118][119][120] 그는 네안데르탈인의 대중적인 이미지를 야만적이고, 구부정하고, 몽둥이를 휘두르는 원초적인 존재로 만들었습니다. 이 이미지는 수십 년 동안 재현되었고, 1911년 J.-H. Rosny a î네의 The Quest for Fire와 1927년 H. G. Wells의 The Grisly Folk와 같은 SF 작품에서 대중화되었습니다. 1911년 스코틀랜드 인류학자 아서 키스(Arthur Keith)는 라 샤펠-오-세인트 1을 현대 인류의 즉각적인 전조로 재구성하고, 불 옆에 앉아 도구를 제작하고, 목걸이를 착용하고, 보다 인간적인 자세를 취했습니다. 그러나 이는 많은 과학적 공감대를 이끌어내지 못했고, 키스는 이후 1915년 논문을 포기했습니다.[26][115][121]

세기 중반에 이르러 필트다운 맨이 거짓말로 노출된 것과 라 샤펠-오-세인트 1(삶의 굴곡을 초래한 골관절염)에 대한 재검토 및 새로운 발견을 바탕으로 과학계는 네안데르탈인에 대한 이해를 재검토하기 시작했습니다. 네안데르탈인의 행동, 지능, 문화와 같은 아이디어들이 논의되고 있었고, 그것들에 대한 더 인간적인 이미지가 나타났습니다. 1939년, 미국의 인류학자 칼튼 쿤은 네안데르탈인이 현대의 비즈니스 정장과 모자를 쓰고 재건하여, 그들이 현재까지 살아남았다면, 현대의 인간들과 어느 정도 구별이 되지 않을 것이라고 강조했습니다. 윌리엄 골딩의 1955년 소설 상속자들은 네안데르탈인을 훨씬 더 감정적이고 문명화된 모습으로 묘사합니다.[25][26][120] 그러나 불의 이미지는 1960년대까지 작품에 계속 영향을 미쳤습니다. 오늘날 네안데르탈인의 재건은 종종 매우 인간적입니다.[115][120]

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — | (Ar. 라미두스) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(백만년전) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

네안데르탈인과 초기 현생 인류 사이의 교잡은 1890년 영국 인류학자 토마스 헉슬리([123]Thomas Huxley), 1907년 덴마크 민족학자 한스 페더 스텐스비([124]Hans Peder Steensby), 1962년 쿤([122]Koon) 등에 의해 일찍부터 제안되었습니다.[125] 2000년대 초반에 잡종으로 추정되는 표본들이 발견되었습니다: Lagar Velho 1과[126][127][128][129] Muierii 1.[130] 그러나 유사한 해부학은 이종교배가 아닌 유사한 환경에 적응함으로써 발생했을 수도 있습니다.[100] 네안데르탈인의 혼합물은 2010년에 최초의 네안데르탈인 게놈 서열의 지도와 함께 현대 개체군에 존재하는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[87] 이것은 크로아티아 빈디자 동굴에 있는 3개의 표본을 기반으로 한 것으로, 거의 4%의 오래된 DNA를 포함하고 있습니다(게놈의 거의 완전한 시퀀싱을 가능하게 함). 그러나 샘플의 보존으로 인해 믿을 수 없을 정도로 높은 돌연변이율을 기반으로 200자(베이스 쌍)당 약 1개의 오류가 발생했습니다. 2012년 영국계 미국인 유전학자 그레이엄 쿱(Graham Coup)은 그 대신 다른 고대 인류 종이 현대 인류와 교배했다는 증거를 발견했다고 가설을 세웠는데, 이는 2013년 시베리아 데니소바 동굴의 발가락 뼈에 보존된 고품질 네안데르탈인 유전체의 염기서열 분석으로 입증되었습니다.[100]

분류

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 고대 단백체 [131]및 유전체를 현대 종의 것과 비교한 2019년 계통발생학 |

네안데르탈인은 인간인 호모속에 속하는 호미노이드이며 일반적으로 H. neanderthalens라는 별개의 종으로 분류되지만 때로는 호모 사피엔스 네안데르탈인으로 현대 인간의 아종으로 분류되기도 합니다. 이것은 현대 인간을 H. sapiens sapiens로 분류해야 합니다.[132]

논란의 상당 부분은 '종'이라는 용어의 모호함에서 비롯되는데, 일반적으로 유전적으로 고립된 두 개체군을 구별하는 데 사용되지만, 현생 인류와 네안데르탈인의 혼혈이 발생한 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[132][133] 그러나 현대 인간에서 네안데르탈인 유래의 patrilineal Y-chromosome과 matrilineal mitrobinal DNA(mtDNA)의 부재는 네안데르탈인 X 염색체 DNA의 과소 표현과 함께 일부 잡종 교배의 생식력 감소 또는 빈번한 불임을 의미할 수 있으며,[89][134][135][136] 이는 그룹 간의 부분적인 생물학적 생식 장벽을 나타냅니다. 따라서 종의 구별.[89] 2014년 유전학자 스반테 패보(Svante Päbo)는 이러한 "분류학적 전쟁"을 해결할 수 없는 것으로 묘사하면서 "이 사건을 완벽하게 설명하는 종의 정의가 없기 때문"이라고 논란을 요약했습니다.[132]

네안데르탈인은 현생 인류보다는 데니소바인과 더 밀접한 관계가 있었을 것으로 생각됩니다. 마찬가지로, 네안데르탈인과 데니소반인은 핵 DNA(nDNA)를 기반으로 현대 인간보다 더 최근의 공통 조상(LCA)을 공유합니다. 그러나 네안데르탈인과 현생 인류는 보다 최근의 미토콘드리아 LCA(mtDNA를 연구하여 관찰 가능)와 Y 염색체 LCA를 공유합니다.[137] 이것은 아마도 네안데르탈인/데니소반인의 분열 이후에 일어난 이종교배 사건 때문일 것입니다. 여기에는 알려지지 않은 고대 인간에서 데니소바인으로 유입되는 내성 [92][93][131][138][139]또는 아프리카에서 네안데르탈인으로 유입된 초기의 미확인 현대 인간의 물결이 포함됩니다.[137][140][141] 스페인의 시마 데 로스 휴에소스(Sima de los Hueos)에서 온 ~43만년 된 초기 네안데르탈인 계통의 고대 인류의 mtDNA가 다른 네안데르탈인이나 현생 인류의 mtDNA와 더 밀접한 관련이 있다는 사실이 후자의 가설을 지지하는 증거로 인용되었습니다.[137][14][140]

진화

H. hidelbergensis는 유럽, 아시아 및 아프리카에서 각각 개체군이 고립되기 전에 네안데르탈인, 데니소반 및 현생 인류의 마지막 공통 조상이라고 주로 생각됩니다.[143] H. hidelbergensis와 네안데르탈인의 분류학적 구분은 대부분 300년에서 243,000년 전 사이의 유럽의 해양 동위원소 단계 8 동안의 화석 격차에 기반을 두고 있습니다. 관례적으로 "네안데르탈인"은 이 격차 이후의 화석입니다.[12][25][142] 스페인에 있는 43만 년 전의 시마 데 로스 휴에소스 유적지에서 나온 고대 인류의 DNA는 데니소반인보다 네안데르탈인과 더 밀접한 관련이 있음을 보여주며, 이는 네안데르탈인과 데니소반인 사이의 분열이 이 시기 이전에 이루어져야 함을 보여줍니다.[14][144][145] 400,000년 된 아뢰에라 3호 두개골은 네안데르탈인의 초기 구성원일 수도 있습니다.[146] 중기 플라이스토세 동안 서유럽과 아프리카 사이의 유전자 흐름이 이탈리아 세프라노와 세르비아 시체보 협곡의 일부 중기 플라이스토세 유럽 호미닌 표본에서 네안데르탈인의 특성을 가렸을 가능성이 있습니다.[14] 화석 기록은 13만년 전 이후부터 훨씬 더 완성된 것이며,[147] 이 시기의 표본은 알려진 네안데르탈인의 골격의 대부분을 차지합니다.[148][149] 이탈리아의 Visogliano 지역과 Fontana Ranuccio 지역의 치아 유적은 네안데르탈인의 치아 특징이 중기 플라이스토세 기간 동안 약 450년에서 43만년 전에 진화했음을 나타냅니다.[150]

네안데르탈인/인류 분열에 따른 네안데르탈인의 진화와 관련된 두 가지 주요 가설은 2단계와 강착입니다. 2단계는 살레 빙하와 같은 단일한 주요 환경 사건으로 인해 유럽 H. 하이델베르겐시스가 신체 크기와 견고성이 급격히 증가하고 머리가 길어졌으며(1단계) 두개골 해부학에 다른 변화가 발생했다고 주장합니다(2단계).[128] 하지만 네안데르탈인 해부학이 전적으로 추운 날씨에 적응해서 움직인 것은 아닐 수도 있습니다.[66] 강착에 따르면 네안데르탈인은 초기 네안데르탈인 이전(MIS 12, 엘스터 빙하화), 초기 네안데르탈인 센수라토(MIS 11–9, 홀슈타인 간빙), 초기 네안데르탈인(MIS 7–5, 살레 빙하화-에미안), 고전적 네안데르탈인 센수 스트릭토(MIS 4–3, 뷔름 빙하화).[142]

네안데르탈인/인류의 분열에 대한 수많은 날짜가 제시되었습니다. 약 25만년 전의 연대는 "H. helmei"를 마지막 공통 조상(LCA)으로 인용하고 있으며, 이 분열은 레발루아의 석기 제작 기술과 관련이 있습니다. 약 40만년 전의 연대는 H. hidelbergensis를 LCA로 사용합니다. 60만년 전의 추정치는 "H. rodhesiensis"가 현대 인류 계통과 네안데르탈인/H. hidelbergensis 계통으로 분리된 LCA였을 것으로 추정합니다.[151] 80만년 전에는 H. anteceus가 LCA로 존재했지만, 이 모델의 다른 변형은 그 날짜를 100만년 전으로 되돌릴 것입니다.[14][151] 그러나 H. antecessor enamel proteomes에 대한 2020년 분석에 따르면 H. antecessor는 관련이 있지만 직접 조상은 아닙니다.[152] DNA 연구는 538–315,[12] 553–321,[153] 565–503,[154] 654–475,[151] 690–550,[155] 765–550,[14][92] 741–317,[156] 800–520,000년 전에 이루어진 네안데르탈인/인류 발산 시기에 대한 다양한 결과를 산출했습니다.[157][13]

네안데르탈인과 데니소반인은 현생 인류보다 서로 더 밀접한 관계가 있는데, 이는 네안데르탈인/데니소반 분열이 현생 인류와 분열된 후에 발생했다는 것을 의미합니다.[14][92][138][158] 염기쌍(bp)당 연간 1 × 10−9 또는 0.5 × 10의−9 돌연변이율을 가정했을 때, 네안데르탈인/데니소반 분열은 각각 236–190,000년 또는 473–381,000년 전에 발생했습니다.[92] 29년마다 새로운 세대와 함께 세대당 1.1 × 10을−8 사용하면 74만 4천 년 전의 시간입니다. 연간 5 × 10−10 뉴클레오티드 부위를 사용하면 61만 6천 년 전입니다. 후자의 연대를 사용하면 호미닌이 유럽 전역에 퍼져 있을 때 이미 분열이 일어났고, 독특한 네안데르탈인의 특징은 600-500,000년 전에 진화하기 시작했을 것입니다.[138] 갈라지기 전에 아프리카에서 유럽으로 이주한 네안데르탈인/데니소반인(또는 "네안데르소반인")은 이미 존재했던 정체불명의 "초고대인" 인간 종과 교배한 것으로 보입니다. 이 초고대인들은 약 1.9 mya의 아프리카에서 이주한 초기의 후손입니다.[159]

유전적 증거에 따르면 데니소반에서 분리된 후 네안데르탈인은 마지막 빙하기 동안 아프리카 밖으로 현생 인류가 확장되기 전에 현생 인류로 이어지는 계통에서 유전자 흐름(유전체의 약 3%)을 경험했으며, 이 이종교배는 약 200-300,000년 전에 이루어졌다고 합니다.[141]

인구통계

범위

에미안 간빙기(13만년 전) 이전에 살았던 네안데르탈인 이전과 초기는 잘 알려지지 않았으며 대부분 서유럽 지역에서 왔습니다. 13만년 전부터 화석 기록의 질은 서·중·동·지중해 유럽은 [15]물론 서남아시아, 중앙아시아, 북아시아에서 시베리아 남부의 알타이 산맥까지 기록된 고전적인 네안데르탈인과 함께 극적으로 증가합니다. 반면, 네안데르탈인 이전과 초기의 네안데르탈인들은 프랑스, 스페인, 이탈리아만을 지속적으로 점령한 것으로 보이지만, 일부는 이 "핵심 지역"을 벗어나 동쪽으로 임시 정착지를 형성한 것으로 보입니다(비록 유럽을 떠나지는 않았지만). 그럼에도 불구하고 프랑스 남서부는 네안데르탈인 이전, 초기, 그리고 고전적인 네안데르탈인의 유적 밀도가 가장 높습니다.[160] 네안데르탈인은 유럽 대륙이 초기 인류에 의해 산발적으로 점령되었을 뿐이기 때문에 유럽을 영구적으로 점령한 최초의 인류 종이었습니다.[161]

가장 남쪽에서 발견된 것은 레반트의 슈크바 동굴에서 기록되었습니다;[162] 북아프리카 제벨 이르후드와[163] 하우아 프테아의[164] 네안데르탈인에 대한 보고는 H. 사피엔스로 재확인되었습니다. 그들의 존재는 시베리아 85°E 데니소바 동굴에 기록되어 있습니다; 두개골인 동남쪽 중국 마바 맨은 네안데르탈인과 몇 가지 물리적 특성을 공유하지만, 이것은 네안데르탈인이 태평양으로 범위를 확장하기보다는 수렴 진화의 결과일 수 있습니다.[165] 일반적으로 최북단은 55°N으로 알려져 있으며, 50~53°N 사이의 명확한 지점이 알려져 있습니다. 그러나 빙하의 발달로 대부분의 인간 유해가 파괴되기 때문에 이를 평가하기는 어렵습니다. 고생물학자 트린 켈버그 닐슨은 남스칸디나비아의 점령에 대한 증거가 부족한 것은 (적어도 에미안의 간빙기 동안) 전자의 설명과 이 지역에 대한 연구 부족 때문이라고 주장했습니다.[166][167] 중기 구석기시대 유물은 러시아 평원에서 최대 60°N까지 발견되었지만,[168][169][170] 이는 현생 인류에 의한 것일 가능성이 더 높습니다.[171] 2017년 한 연구는 북아메리카에 있는 13만년 된 캘리포니아의 Cerutti Mastodon 유적지에 Homo가 존재했다고 주장했지만,[172] 이것은 대체로 믿을 수 없는 것으로 여겨집니다.[173][174][175]

지난 빙하기의 급변하는 기후(Dansgaard–Oeschger 사건)가 네안데르탈인에게 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지는 알려지지 않았는데, 온난화 기간은 더 유리한 온도를 생성하지만 숲의 성장을 촉진하고 거대 동물원을 저지하는 반면 추운 기간은 그 반대를 생성하기 때문입니다.[176] 그러나 네안데르탈인은 숲이 우거진 풍경을 선호했을 수도 있습니다.[66] 연평균 기온이 온화한 안정적인 환경이 가장 적합한 네안데르탈인 서식지였을 수 있습니다.[177] 개체수는 바다 동위원소 단계 8과 6(각각 300,000년과 191,000년 전 살레 빙하기)와 같이 추운 시기에 정점에 도달했을 수 있습니다. 빙하가 최대로 이동하는 동안 특정 피난처에 거주하는 영구 동토층 지역을 피하기 위해 얼음이 각각 후퇴하고 성장함에 따라 그들의 범위가 확장되고 수축될 수 있습니다.[176] 2021년 이스라엘 인류학자 이스라엘 헤르슈코비츠와 동료들은 네안데르탈인과 더 고대 H. 에렉투스 특성이 혼합된 140~120,000년 된 이스라엘 네셔 람라 유적이 빙하기 이후 유럽을 식민지로 만든 그러한 원천 개체군 중 하나라고 제안했습니다.[178]

인구.

현생 인류와 마찬가지로 네안데르탈인은 약 3,000~12,000명의 유효인구(자녀를 낳거나 낳을 수 있는 사람의 수)를 가진 매우 적은 인구의 후손일 것입니다. 하지만 네안데르탈인은 자연선택의 효과가 떨어져 약한 유해 유전자를 증식시키면서 이처럼 매우 낮은 개체수를 유지했습니다.[82][179] 다양한 연구에서 mtDNA 분석을 사용하여 약 1,000~5,000마리,[179] 5,000~9,000마리가 일정하게 유지되거나 [180]3,000~25,000마리가 5만 2,000년 전까지 꾸준히 증가하다가 멸종될 때까지 감소하는 [176]등 다양한 유효 개체군을 산출합니다.[84] 고고학적 증거에 따르면 네안데르탈인/현대 인류 전환기 동안 서유럽에서 현대 인류의 인구가 10배 증가했으며,[181] 네안데르탈인은 출산율 감소, 유아 사망률 증가 또는 둘의 조합으로 인해 인구학적으로 불리했을 수 있습니다.[182] 더 높은 수만[138] 명의 총 인구를 제공하는 추정치는 논쟁의 여지가 있습니다.[179] 지속적으로 낮은 인구는 "보세루피아 덫"의 맥락에서 설명될 수 있습니다: 인구의 운반 능력은 얻을 수 있는 식량의 양에 의해 제한되고, 이는 결국 기술에 의해 제한됩니다. 혁신은 인구와 함께 증가하지만, 인구가 너무 적으면 혁신이 매우 빠르게 일어나지 않고 인구는 낮게 유지됩니다. 이는 네안데르탈인의 리튬 기술이 약 15만년간 정체된 것과 일치합니다.[176]

206명의 네안데르탈인 표본에서, 다른 연령 인구 통계와 비교하여 젊고 성숙한 성인의 풍부함에 기초하여, 그들 중 약 80%가 40세가 되기 전에 사망했습니다. 이 높은 사망률은 아마도 그들의 높은 스트레스 환경 때문이었을 것입니다.[86] 그러나 네안데르탈인과 동시대 현대 인류의 피라미드도 동일했을 것으로 추정되고 있습니다.[176] 네안데르탈인의 유아 사망률은 유라시아 북부에서 약 43%로 매우 높은 것으로 추정되었습니다.[183]

해부학

빌드

네안데르탈인은 전형적인 현생 인류보다 더 튼튼하고 튼튼한 체구를 가졌고,[70] 더 넓고 통 모양의 갈비뼈 우리; 더 넓은 골반;[25][184] 그리고 비례적으로 더 짧은 팔뚝과 앞다리를 가지고 있었습니다.[66][185]

남성 14명과 여성 7명의 네안데르탈인 장골 45개를 기준으로 평균 신장은 남성 164~168cm(5피트 5인치에서 5피트 6인치), 여성 152~156cm(5피트 0인치에서 5피트 1인치)였습니다.[70] 비교하자면, 상부 구석기시대 인류의 평균 신장은 각각 176.2 cm (5 ft 9.4 in)와 162.9 cm (5 ft 4.1 in)이지만, 이는 21명의 수컷과 15명의 암컷을 기준으로 시기가 끝날 무렵보다 10 cm (4 in) 감소한 것이며,[186] 1900년의 평균 신장은 163 cm (5 ft 4 in)와 152.7 cm (5 ft 0 in)였습니다. 제각기[187] 화석 기록에 따르면 성인 네안데르탈인의 키는 약 147.5cm에서 177cm(4피트 10인치에서 5피트 10인치)로 다양했지만 일부는 훨씬 더 컸을 수 있습니다(발자국 길이 기준으로는 73.8cm에서 184.8cm, 발자국 너비 기준으로는 65.8cm에서 189.3cm).[188] 네안데르탈인의 경우, 26개 표본의 표본에서 평균 77.6kg(171lb)의 수컷과 66.4kg(146lb)의 암컷이 발견되었습니다.[189] 76kg(168lb)을 사용하여 네안데르탈인 남성의 체질량 지수는 26.9–28.2로 계산되었으며, 이는 현대 인간의 과체중과 관련이 있습니다. 이는 매우 견고한 빌드를 나타냅니다.[70] 지방과 체열 생산을 저장하는 것과 관련된 네안데르탈인 LEPR 유전자는 털북숭이매머드의 유전자와 유사하며, 추운 기후에 적응했을 가능성이 높습니다.[67]

네안데르탈인의 목 척추뼈는 (대부분의) 현생 인류의 목뼈보다 앞에서 뒤로 그리고 가로로 더 두껍기 때문에 안정성을 가져왔고, 아마도 다른 머리 모양과 크기를 수용할 수 있습니다.[190] 갈비뼈가 있는 네안데르탈인의 흉곽은 현대 인류와 크기가 비슷했지만, 더 길고 곧은 갈비뼈는 넓어진 중저흉부와 더 강한 호흡과 같았을 것이며, 이는 횡격막이 더 크고 폐활량이 더 클 수 있음을 나타냅니다.[184][191][192] Kebara 2의 폐활량은 9.04 L(2.39 US gal)로 추정되었는데, 이는 남성의 경우 6 L(1.6 US gal), 여성의 경우 4.7 L(1.2 US gal)의 평균 폐활량과 비교됩니다. 네안데르탈인의 가슴도 더 뚜렷했습니다(앞에서 뒤로, 또는 앞에서 뒤로 확장됨). 천골(골반이 척추와 연결되는 곳)은 더 수직으로 기울어져 있었고, 골반에 대해 더 낮게 배치되어 척추가 덜 구부러지고(경락을 덜 나타냄), 어느 정도 접히는(침입되기 위해) 원인이 되었습니다. 현대 인구에서 이 상태는 인구의 일부에만 영향을 미치며 요추 천골이라고 알려져 있습니다.[193] 척추에 대한 이러한 수정은 측면(중측) 굴곡을 향상시켜 더 넓은 하부 흉곽을 더 잘 지원합니다. 일부 사람들은 이 특징이 모든 호모에게, 심지어 열대성으로 적응된 호모 에르고스타터 또는 에렉투스에게 정상적일 것이라고 주장하며, 대부분의 현대 인류에서 더 좁은 흉곽의 상태는 독특한 특징입니다.[184]

신체 비율은 일반적으로 추운 기후에서[194] 발달한 인간 개체군과 유사하기 때문에 "과북극"으로 언급됩니다. 네안데르탈인의 체구는 현대 인간의[195] 이누이트와 시베리아 유픽의 체구와 가장 유사하며 팔다리가 짧아지면 체온이 더 많이 유지됩니다.[185][194][196] 그럼에도 불구하고, 이베리아와 같은 더 온대 기후의 네안데르탈인은 여전히 "과극"의 체격을 유지하고 있습니다.[197] 2019년 영국 인류학자 존 스튜어트(John Stewart)와 동료들은 네안데르탈인이 더 차가운 매머드 스텝보다 더 따뜻한 숲이 우거진 지역을 선호한다는 증거와 DNA 분석으로 인해 현대 인간보다 빠르게 변하는 근육 섬유의 비율이 더 높다는 것을 보여주기 때문에 대신 스프린트에 적응했다고 제안했습니다. 그는 지구력을 지향하는 현대 인간의 체격과는 반대로 전력 질주에 적응한 것으로 그들의 신체 비율과 더 큰 근육량을 설명했는데,[66] 끈기 사냥은 사냥꾼이 열이 소진될 정도로 먹이를 사냥할 수 있는 더운 기후에서만 효과적일 수 있기 때문입니다. 그들은 발뒤꿈치 뼈가 길어 [198]지구력 달리기 능력이 떨어졌고, 팔다리가 짧아지면 팔다리의 순간 팔이 줄어 손목과 발목의 순회전력이 높아져 더 빠른 가속도가 발생했을 것입니다.[66] 1981년, 미국 고생물학자 에릭 트린카우스(Erik Trinkaus)는 이 대체 설명에 주목했지만, 가능성이 낮다고 생각했습니다.[185][199]

얼굴

네안데르탈인은 턱이 덜 발달했고, 이마가 경사진 상태였으며, 코가 더 길고 더 넓었습니다. 네안데르탈인의 두개골은 일반적으로 대부분의 현생 인류보다 더 길쭉하지만 더 넓고 덜 구형이며, 비록 그것을 가지고 있는 현생 인류의 범위 내에 있지만, 두개골의 뒤쪽에 있는 돌기인 후두부 빵,[200] 즉 "치뇽"과 훨씬 더 유사한 특징을 가지고 있습니다. 두개골 기저부와 측두골이 두개골 앞쪽으로 점점 더 높게 배치되고, 두개골 캡이 평평하기 때문에 발생합니다.[201]

네안데르탈인의 얼굴은 중안면 예후가 특징인데, 여기서 접합부 아치는 현대 인간에 비해 후방에 위치하고, 상악골과 비강골은 더 전방에 위치합니다.[202] 네안데르탈인의 안구는 현대 인류의 안구보다 큽니다. 한 연구는 네안데르탈인이 신피질과 사회성 발달을 희생시키면서 시각 능력을 향상시켰기 때문이라고 제안했습니다.[203] 하지만, 이 연구는 안구의 크기가 네안데르탈인이나 현생 인류의 인지 능력에 대한 어떤 증거도 제시하지 못한다는 결론을 내린 다른 연구자들에 의해 거부되었습니다.[204]

예상되는 네안데르탈인 코와 부비동은 일반적으로 폐로 들어갈 때 공기가 따뜻해지고 습기가 유지되는 것으로 설명되었습니다("비강 방사체" 가설).[205] 만약 그들의 코가 더 넓었다면, 그것은 추위에 적응한 생물들의 일반적으로 좁아진 모양과 다르고, 대신 유전적 표류에 의해 발생했을 것입니다. 또한 넓게 재건된 부비동은 크기가 엄청나게 크지 않아 현대 인류의 부비동에 버금가는 크기입니다. 그러나 부비동 크기가 냉기를 호흡하는 데 중요한 요소가 아니라면 실제 기능은 불분명하기 때문에 이러한 코를 진화시키기 위한 진화 압력의 좋은 지표가 아닐 수 있습니다.[206] 또한, 네안데르탈인 코의 컴퓨터 재구성과 예측된 연조직 패턴은 현대 북극 사람들의 코와 일부 유사성을 보여주며, 잠재적으로 두 개체군의 코가 차갑고 건조한 공기를 마시기 위해 수렴적으로 진화했음을 의미합니다.[68]

네안데르탈인은 다소 큰 턱을 가지고 있는데, 한때 네안데르탈인의 앞니를 심하게 착용한 것으로 입증된 큰 무는 힘에 대한 반응으로 인용되기도 했지만("앞니 하중" 가설), 현대 인류에서도 비슷한 착용 추세가 나타나고 있습니다. 또한 턱의 큰 치아에 맞게 진화하여 마모와 마모에 더 잘 견딜 수 있었고,[205][207] 뒷니에 비해 앞니의 마모가 증가한 것은 아마도 반복적인 사용에서 비롯된 것일 것입니다. 네안데르탈인 치과용 착용 패턴은 현대 이누이트의 착용 패턴과 가장 유사합니다.[205] 앞니는 크고 삽 모양이며, 현생인류에 비해 과육(치핵)이 커져서 어금니가 더 커지는 상태인 타우로돈티즘의 빈도가 유난히 높았습니다. 타우로돈티즘은 한때 기계적 이점을 제공하거나 반복적인 사용에서 비롯된 네안데르탈인의 구별되는 특징이라고 생각되었지만, 단순히 유전적 표류의 산물일 가능성이 더 높았습니다.[208] 네안데르탈인과 현생인류의 무는 힘은 현재 현생인류의 수컷과 암컷에서 각각 약 285 N(64 lbf)과 255 N(57 lbf)으로 [205]거의 비슷한 것으로 생각됩니다.[209]

뇌

네안데르탈인의 뇌 케이스는 평균적으로 남성의 경우 1,640 cm3 (100 cuin), 여성의 경우 1,460 cm3 (89 cuin)로 [72][73]현존하는 인간의 모든 그룹의 평균보다 상당히 큽니다.[74] 예를 들어, 현대 유럽 남성은 평균 1,362 cm3 (83.1 cuin), 여성은 1,201 cm3 (73.3 cuin)입니다.[210] 19만 년 전부터 25,000년 전까지 28개의 현생 인류 표본의 평균은 성별을 제외하고 약 1,478 cm3(90.2 cuin)였으며, 현생 인류의 뇌 크기는 상부 구석기 시대 이후 감소한 것으로 추정됩니다.[211] 가장 큰 네안데르탈인의 뇌인 아무드 1은 인류에서 기록된 가장 큰 것 중 하나인 1,736 cm3 (105.9 cuin)로 계산되었습니다.[73] 네안데르탈인과 인간 유아 모두 약 400 cm3 (24 cuin)입니다.[212]

후방에서 볼 때, 네안데르탈인의 뇌 케이스는 해부학적으로 현대인의 뇌 케이스보다 낮고, 더 넓고, 더 둥글게 보입니다. 이 특징적인 모양은 "앙봄베"(폭탄과 같은)라고 불리며, 네안데르탈인의 독특한 모습으로, 다른 모든 인류 종(대부분의 현생 인류 포함)은 일반적으로 좁고 비교적 직립한 두개골 금고를 뒤에서 볼 때 가지고 있습니다.[213][214][215][216] 네안데르탈인의 뇌는 상대적으로 더 작은 두정엽과[80] 더 큰 소뇌를 특징으로 했을 것입니다.[80][217] 또한 네안데르탈인의 뇌는 후두엽이 더 크며(네안데르탈인의 두개골 해부학에서 후두엽 번의 고전적인 발생과 두개골의 더 큰 폭과 관련이 있음), 이는 호모 사피엔스에 비해 뇌-내부 영역의 비례성에 있어서 내부적인 차이를 의미합니다. 화석 두개골로 얻은 외부 측정치와 일치합니다.[203][218] 그들의 뇌는 또한 더 큰 측두엽 극,[217] 더 넓은 전두엽 피질의 궤도,[219] 그리고 더 큰 후각 구근을 가지고 [220]있어서 언어 이해와 감정(시간적 기능), 의사 결정(전두엽 피질의 궤도), 그리고 후각(전두엽 피질)과의 연관성에 있어서 잠재적인 차이를 시사합니다. 그들의 뇌는 또한 다른 뇌의 성장과 발달 속도를 보여줍니다.[221] 이러한 차이는 약간은 있지만 자연스러운 선택에서 볼 수 있었을 것이며 사회적 행동, 기술 혁신 및 예술적 산출물과 같은 것에서 물질적 기록의 차이의 기초가 되고 설명할 수 있습니다.[18][222]

머리카락과 피부색

최근 현대 유럽인들의 밝은 피부는 아마도 청동기 시대까지 특별히 번식하지 않았다고 주장되었지만,[223] 햇빛의 부족은 아마도 네안데르탈인의 더 밝은 피부의 증식으로 이어졌을 것입니다.[224] 유전적으로 BNC2는 밝은 피부색과 관련이 있는 네안데르탈인에 존재했지만 현대 인구에서 영국 바이오뱅크의 어두운 피부색과 관련이 있는 BNC2의 두 번째 변형도 존재했습니다.[223] 남동부 유럽에서 온 세 마리의 네안데르탈인 여성의 DNA 분석 결과, 그들은 갈색 눈, 어두운 피부색, 갈색 머리를 가졌고, 한 마리는 붉은 머리를 가졌다는 것을 알 수 있습니다.[225][226]

현대 인간에서 피부와 머리카락 색은 MC1R 유전자에 의해 암호화되는 파오멜라닌(빨간색 색소)에 대한 유멜라닌(검은색 색소)의 비율을 증가시키는 멜라닌 세포 자극 호르몬에 의해 조절됩니다. 기능 상실을 유발하고 밝은 피부와 머리카락 색과 관련이 있는 유전자의 현대인의 알려진 5가지 변종과 창백한 피부와 붉은 머리카락과 관련이 있을 수 있는 네안데르탈인의 다른 알려지지 않은 변종(R307G 변종)이 있습니다. R307G 변종은 이탈리아 몬티 레시니와 스페인 쿠에바 델 시드론의 네안데르탈인에서 확인되었습니다.[227] 그러나 현대 인간과 마찬가지로 빨간색은 다른 많은 염기서열 분석된 네안데르탈인에게는 존재하지 않기 때문에 아마도 그리 흔한 머리카락 색은 아니었을 것입니다.[223]

대사

최대 자연 수명과 성인기, 폐경기 및 임신 시기는 현대 인간과 매우 유사했을 가능성이 높습니다.[176] 그러나 치아와 치아 법랑질의 성장 속도를 [228][229]바탕으로 나이 바이오마커에 의해 뒷받침되지는 않지만 네안데르탈인이 현대 인간보다 더 빨리 성숙했다는 가설이 세워졌습니다.[86] 성숙도의 주요 차이는 목의 아틀라스 뼈와 네안데르탈인에서 현대인보다 약 2년 늦게 융합된 중간 흉추이지만, 이는 성장 속도보다는 해부학적인 차이에서 비롯된 것일 가능성이 높습니다.[230][231]

일반적으로 네안데르탈인 열량 요구량에 대한 모델은 현대 인간의 섭취량보다 상당히 높은 섭취량을 보고하는데, 이는 일반적으로 네안데르탈인이 더 높은 근육량으로 인해 더 높은 기초 대사율(BMR)을 가지고 있다고 가정하기 때문입니다. 추위에 맞서 더 빠른 성장 속도와 더 큰 체온 생산;[232][233][234] 먹이를 찾는 동안 더 많은 일일 이동 거리로 인해 더 높은 일일 신체 활동 수준(PAL).[233][234] 그러나, 높은 BMR과 PAL을 사용하여, 미국 고고학자 Bryan Hockett은 임신한 네안데르탈인이 하루에 5,500 칼로리를 소비했을 것이고, 이것은 큰 사냥감 고기에 크게 의존해야 했을 것이라고 추정했습니다; 그러한 식단은 수많은 결핍이나 영양소 중독을 일으켰을 것입니다. 그래서 그는 이것들이 근거가 부족한 가정이라고 결론 내렸습니다.[234]

네안데르탈인은 겨울에 낮 시간이 줄어든 지역에 살고, 큰 사냥감(매복 전술을 강화하기 위해 일반적으로 밤에 사냥하는 포식자)을 사냥하고, 큰 눈과 시각적 처리 신경 중심을 가지고 있기 때문에 대낮보다는 어두운 조명 조건에서 더 활동했을 수 있습니다. 유전적으로 색맹은 일반적으로 북위도 개체군과 상관관계가 있으며 크로아티아 빈디자 동굴의 네안데르탈인은 색맹에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 옵신 유전자를 일부 대체했습니다. 그러나 이러한 대체의 기능적 의미는 결정적이지 않습니다.[235] ASB1 및 EXOC6 근처의 네안데르탈인 유래 대립유전자는 저녁 사람, 기면증 및 낮 낮잠과 관련이 있습니다.[223]

병리학

네안데르탈인은 높은 비율의 외상 손상을 입었는데, 표본의 약 79-94%가 치유된 주요 외상의 증거를 보여주었으며, 그 중 37-52%는 심각한 부상을 입었고, 13-19%는 성인이 되기 전에 부상을 입었습니다.[236] 한 극단적인 예는 샤니다르 1인데, 샤니다르 1은 청소년기에 뼈가 부러진 후 불유합, 왼쪽 쇄골의 골수염(뼈 감염), 비정상적인 걸음걸이, 왼쪽 눈의 시력 문제, 그리고[237] 난청(아마도 수영하는 사람의 귀)으로 인해 오른쪽 팔이 절단된 징후를 보입니다.[238] 1995년, 트린카우스는 약 80%가 자신들의 부상에 굴복하여 40세가 되기 전에 사망했다고 추정했고, 따라서 네안데르탈인이 위험한 사냥 전략("rodeo rider" 가설)을 사용했다고 이론을 세웠습니다.[86] 그러나 두개골 외상의 비율은 네안데르탈인과 중기 구석기 시대 현생 인류 사이에 크게 다르지 않습니다(네안데르탈인이 더 높은 사망 위험을 가졌던 것으로 보이지만),[239] 상부 구석기 시대 현생 인류와 40세 이후에 사망한 네안데르탈인의 표본은 거의 없습니다.[182] 그리고 그들 사이에는 전반적으로 유사한 부상 패턴이 있습니다. 2012년 트린카우스(Trinkaus)는 네안데르탈인이 대인 폭력과 같은 현대 인간과 같은 방식으로 스스로 부상을 입었다고 결론 내렸습니다.[240] 네안데르탈인 표본 124개를 조사한 2016년 연구에서는 높은 외상률이 대신 동물 공격에 의한 것이라고 주장했으며, 표본의 약 36%가 곰 공격, 21%의 큰 고양이 공격, 17%의 늑대 공격(총 92건의 양성 사례, 74%)의 희생자인 것으로 나타났습니다. 하이에나가 공격한 사례는 없었지만, 하이에나는 적어도 기회주의적으로 네안데르탈인을 공격했을 것입니다.[241] 이러한 극심한 포식은 아마도 먹이와 동굴 공간을 둘러싼 경쟁으로 인한 일반적인 대립과 이러한 육식동물을 사냥하는 네안데르탈인에서 비롯되었을 것입니다.[241]

낮은 개체군은 낮은 유전적 다양성과 아마도 근친 교배를 유발하여 개체군의 유해한 돌연변이(근친 우울증)를 걸러내는 능력을 감소시켰습니다. 그러나 이것이 네안데르탈인의 유전적 부담에 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지, 따라서 이것이 현대 인간보다 더 높은 출생 결함률을 야기했는지는 알려지지 않았습니다.[242] 그러나 시드론 동굴의 13명의 주민들은 근친상간이나 열성 장애로 인해 17개의 다른 선천적 결함을 집단적으로 나타냈다고 알려져 있습니다.[243] 라 샤펠-오-세인트 1은 고령(60대 또는 70대)으로 인해 바스트럽병, 척추, 골관절염의 징후가 있었습니다.[244] 약 30세 또는 40세에 사망했을 가능성이 있는 샤니다르 1은 운동을 제한할 수 있는 퇴행성 질환인 확산 특발성 골격성 과조영증(DISH)의 가장 오래된 사례로 진단되었으며, 이는 정확하다면 나이가 많은 네안데르탈인의 발병률이 적당히 높다는 것을 나타냅니다.[245]

네안데르탈인은 여러 전염병과 기생충에 감염되었습니다. 현대인들은 질병을 그들에게 옮겼을 가능성이 있습니다; 한 가지 가능한 후보는 위 박테리아 헬리코박터 파일로리입니다.[246] 현대의 인유두종 바이러스 변종 16A는 네안데르탈인의 내습으로 인해 발생할 수 있습니다.[247] 스페인 쿠에바 델 시드론의 한 네안데르탈인은 위장 엔테로시토존 비네누시 감염의 증거를 보여줍니다.[248] 프랑스 라 페라시 1호의 다리뼈에는 골을 감싸는 조직의 염증인 주위염과 일치하는 병변이 있는데, 이는 주로 흉부 감염이나 폐암에 의해 발생하는 비후성 골관절염의 결과일 가능성이 있습니다.[249] 일부 개체군이 일반적으로 충치를 유발하는 음식을 대량으로 섭취했음에도 불구하고 네안데르탈인은 현대 인간보다 충치율이 낮았는데, 이는 충치를 유발하는 구강 박테리아, 즉 Streptococcus mutans가 부족함을 나타낼 수 있습니다.[250]

프랑스 페레에 사는 25만년 된 네안데르탈인 어린이 두 명이 호미닌의 납에 노출된 최초의 사례를 보여줍니다. 그들은 오염된 음식이나 물을 먹거나 마시거나 화재로 인한 납으로 된 연기를 마셔 두 가지 다른 경우에 노출되었습니다. 현장에서 25km(16mi) 이내에 두 개의 납 광산이 있습니다.[251]

문화

사회구조

군역동학

네안데르탈인은 동시대의 현생 인류보다 더 드문드문 분포된 집단에서 살았을 가능성이 높지만,[176] 집단의 크기는 평균 10~30개체로 추정되며, 이는 현생 수렵 채집인들과 유사합니다.[31] 네안데르탈인 그룹 구성에 대한 신뢰할 수 있는 증거는 스페인의 쿠에바 델 시드론과 프랑스 르 로젤의 발자국에서 나왔습니다.[188] 전자는 성인 7명, 청소년 3명, 청소년 2명, 유아 1명입니다.[252] 반면, 후자는 발자국 크기에 따라 청소년과 청소년이 90%[188]를 차지하는 10~13명의 구성원 그룹을 보여줍니다.

2018년 분석된 네안데르탈인 어린이의 치아는 현대 수렵 채집인과 유사하게 2.5년 후에 젖을 뗀 것으로 나타났으며, 봄에 태어났으며, 이는 출생 주기가 환경 주기와 일치하는 현대 인간 및 기타 포유류와 일치합니다.[251] 성장 둔화와 같은 낮은 연령의 높은 스트레스로 인한 다양한 질병으로 인해 나타나는 영국 고고학자 폴 페티트(Paul Pettit)는 성별의 아이들이 이유 후 바로 일을 할 수 있다고 가정했습니다.[183] 트린카우스(Trinkaus)는 청소년기에 도달하면 크고 위험한 사냥에 참여할 것으로 예상했을 수 있다고 말했습니다.[86] 그러나 뼈 외상은 현대 이누이트와 비슷하며, 이는 네안데르탈인과 동시대 현대 인류 사이의 유사한 어린 시절을 암시할 수 있습니다.[253] 게다가, 그러한 발육 부진은 혹독한 겨울과 낮은 식량 자원으로 인해 발생했을 수도 있습니다.[251]

3명 이하의 증거를 보여주는 사이트는 핵가족 또는 특수 작업 그룹(사냥 파티 등)을 위한 임시 캠핑장을 대표했을 수 있습니다.[31] 밴드는 계절에 따라 특정 동굴 사이를 이동하여 특정 음식과 같은 계절성 물질의 잔해로 표시되고 세대를 거쳐 동일한 위치로 돌아갔을 가능성이 높습니다. 일부 사이트는 100년 이상 사용되었을 수 있습니다.[254] 동굴곰은 동굴 공간을 놓고 네안데르탈인과 크게 경쟁했을 수 있으며,[255] 50,000년 전 이후로 동굴곰 개체수가 감소하고 있습니다(비록 네안데르탈인이 죽은 지 훨씬 후에 멸종되었습니다).[256][257] 네안데르탈인은 또한 입구가 남쪽을 향해 있는 동굴을 선호했습니다.[258] 네안데르탈인은 일반적으로 동굴 거주자로 간주되지만 '홈 베이스'는 동굴이지만 레반트의 동시 거주 동굴 시스템 근처의 노천 정착지는 이 지역의 동굴과 노천 기지 사이의 이동성을 나타낼 수 있습니다. 장기적인 노천 정착지에 대한 증거는 이스라엘의 '아인카시시'[259][260]와 우크라이나의 몰도바 1세로부터 알려져 있습니다. 비록 네안데르탈인은 평원과 고원을 포함한 다양한 환경에 거주할 수 있는 능력이 있었던 것으로 보이지만, 노천 네안데르탈인 유적지는 일반적으로 거주 공간이 아닌 도축 및 도살장으로 사용된 것으로 해석됩니다.[85]

2022년, 러시아 시베리아 남부 알타이 산맥의 차가르스카야 동굴에서 처음으로 알려진 네안데르탈인 가족(성인 6명, 어린이 5명)의 유해가 발굴되었습니다. 아버지, 딸, 그리고 사촌으로 보이는 가족이 함께 죽었을 가능성이 높습니다. 아마도 기아 때문일 것입니다.[261][262]

그룹간 관계

캐나다 민족 고고학자인 브라이언 헤이든(Brian Hayden)은 근친 교배를 피하여 약 450-500마리의 개체로 구성된 자생 개체군을 계산했는데, 이는 이러한 밴드가 8-53개의 다른 밴드와 상호 작용하도록 요구하지만, 낮은 개체군 밀도를 고려할 때 더 큰 추정치일 수 있습니다.[31] 스페인 쿠에바 델 시드론의 네안데르탈인의 mtDNA를 분석한 결과, 세 명의 성인 남성은 같은 모계 계통에 속하는 반면, 세 명의 성인 여성은 다른 계통에 속하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 이것은 한 여성이 파트너와 함께 살기 위해 자신의 그룹에서 이사한 부계 거주지를 암시합니다.[263] 하지만 러시아 데니소바 동굴에서 발견된 네안데르탈인의 DNA는 네안데르탈인이 근친 교배 계수를 가졌다는 것을 보여줍니다. 1⁄8(그녀의 부모는 평범한 어머니, 이중 1촌, 삼촌과 조카, 이모와 조카, 또는 할아버지와 손녀, 또는 할머니와 손자를 둔 이복 형제였습니다.) 그리고 쿠에바 델 시드론의 거주자들은 몇 가지 결함을 보이는데, 이는 근친상간이나 열성 장애로 인해 발생했을 수 있습니다.

대부분의 네안데르탈인 유물이 주요 정착지에서 5km(3.1mi) 밖에 떨어지지 않은 곳에서 나온 것임을 고려했을 때, 헤이든은 이 밴드들이 매우 자주 상호작용할 가능성이 낮다고 생각했고,[31] 네안데르탈인의 뇌와 그들의 작은 그룹 크기와 인구 밀도에 대한 지도는 그들이 그룹 간 상호작용과 무역을 위한 능력이 감소했음을 나타낼 수 있다고 생각했습니다.[203] 그러나 정착지에서 몇 개의 네안데르탈인 유물은 20, 30, 100 및 300km(12.5, 18.5, 60 및 185마일) 떨어진 곳에서 발생했을 수 있습니다. 이를 바탕으로 헤이든은 또한 거시적 밴드가 형성되어 호주 서부 사막의 저밀도 수렵 채집 사회와 매우 유사한 기능을 한다고 추측했습니다. 매크로 밴드는 총 13,000 km2(5,000 sq mi)를 포함하며, 각 밴드는 1,200–2,800 km2(460–1,080 sq mi)를 차지하며 짝짓기 네트워크를 위해 또는 희박한 시간과 적에 대처하기 위해 강력한 동맹을 유지합니다.[31] 마찬가지로, 영국의 인류학자 에일루네드 피어스와 키프로스의 고고학자 테오도라 무시우는 네안데르탈인이 800명 이상의 사람들을 포함하는 지리적으로 광범위한 민족 언어 부족을 형성할 수 있었다고 추측했습니다. 현대 수렵채집인들의 흑요석 이동 거리와 부족 규모에서 볼 수 있는 추세와 비교하여 출처에서 최대 300km(190mi)까지 흑요석의 이동을 기반으로 합니다. 그러나 그들의 모델에 따르면 네안데르탈인은 아마도 인구가 현저히 적기 때문에 현대 인간만큼 장거리 네트워크를 유지하는 데 효율적이지 않았을 것입니다.[264] Hayden은 프랑스 La Ferrassie에 있는 6명 또는 7명의 사람들의 명백한 공동묘지에 주목했는데, 이것은 현대 인류에서, 독특한 사회적 정체성을 유지하고 일부 자원, 무역, 제조 등을 통제하는 기업 집단의 증거로 일반적으로 사용됩니다. 라 페라시는 또한 플라이스토세 유럽에서 가장 부유한 동물 이동 경로 중 하나에 위치해 있습니다.[31]

유전자 분석 결과 최소 3개 이상의 별개의 지리적 그룹이 존재하는 것으로 나타났습니다.서유럽, 지중해 연안, 캅카스 동쪽 등 이들 지역 사이에 약간의 이동이 있습니다.[84] 에미안 이후의 서유럽 무스터 암석은 크게 세 가지 거시적 영역으로 분류할 수 있습니다. 남서쪽의 쿨리아 전통의 무스테리안, 북동쪽의 미코퀴엔, 그리고 전자 둘 사이에 쌍면 도구(MBT)가 있는 무스테리안. MBT는 실제로 두 개의 다른 문화의 상호 작용과 융합을 나타낼 수 있습니다.[83] 남부 네안데르탈인은 돌출된 턱이 적고 어금니 뒤의 간격이 짧으며 수직으로 더 높은 턱뼈와 같은 북부 대응물과 지역 해부학적 차이를 보입니다.[265] 이 모든 것은 대신 네안데르탈인 공동체가 한 지역 내에서 이웃 공동체와 정기적으로 상호 작용했음을 시사하지만, 그 이후에는 그렇게 자주는 아닙니다.[83]

그럼에도 불구하고 장기간에 걸쳐 대규모 대륙간 이동의 증거가 있습니다. 코카서스[139] 산맥의 메즈마이스카야 동굴과 시베리아 알타이 산맥의[90] 데니소바 동굴의 초기 표본은 서유럽에서 발견된 것과 유전적으로 다른 반면, 이 동굴의 후기 표본은 같은 위치에서 발견된 초기 표본보다 서유럽 네안데르탈인 표본과 더 유사한 유전적 프로필을 가지고 있습니다. 시간이 지남에 따라 장거리 이주와 인구 대체를 제안합니다.[90][139] 마찬가지로, 또한 알타이 산맥에 있는 차가르스카야 동굴과 올라드니코프 동굴의 유물과 DNA는 데니소바 동굴에서 더 오래된 네안데르탈인의 유물과 DNA보다 약 3,000-4,000km(1,900-2,500mi) 떨어진 동유럽 네안데르탈인 유적지의 것과 유사하며, 이는 시베리아로의 두 가지 뚜렷한 이주 사건을 시사합니다.[266] 네안데르탈인은 MIS 4(71~57,000년 전) 동안 개체수가 크게 감소한 것으로 보입니다. 그리고 미코키아 전통의 분포는 중부 유럽과 코카서스가 프루트 강과 드니에스터 강을 따라 흩어진 동부 프랑스나 헝가리(미코키아 전통의 변두리)의 피난처에서 온 공동체들에 의해 다시 인구화되었음을 나타낼 수 있습니다.[267]

그룹 간 갈등의 증거도 있습니다. 프랑스 라 로슈 피에로의 한 해골은 깊은 칼날 상처로 인해 두개골 위에 치유된 골절을 보였고,[268] 이라크 샤니다르 동굴의 또 다른 해골은 발사체 무기 부상의 특징인 갈비뼈 병변을 가진 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[269]

사회계층

때때로 그들은 도전적인 큰 게임의 사냥꾼이었고 소규모 집단에서 살았기 때문에 현대 수렵-채집 사회에서 볼 수 있는 성적인 분업이 없었다고 제안됩니다. 즉, 남성이 여성과 함께 사냥하고 아이들이 먹이를 찾는 대신, 남성, 여성, 아이들이 모두 사냥에 참여해야 했습니다. 그러나 현대 수렵-채집인들의 경우 육류 의존도가 높을수록 분업이 높아집니다.[31] 게다가, 네안데르탈인 남성과 여성의 치아 착용 패턴은 그들이 보통 물건을 운반할 때 치아를 사용했음을 시사하지만, 남성은 윗니에 더 많이 착용하고 여성은 아랫니에 더 많이 착용하여 작업에서 약간의 문화적 차이를 시사합니다.[270]

일부 네안데르탈인은 표범 가죽이나 랩터 깃털과 같은 장식 옷이나 보석을 착용하여 그룹에서 높아진 위상을 보여주었다고 주장되고 있습니다. 헤이든은 발견된 네안데르탈인의 무덤의 수가 적은 것은 일부 현대 수렵채집가들의 경우와 마찬가지로 고위직 구성원들만이 정교한 매장을 받을 수 있기 때문이라고 추정했습니다.[31] 트링카우스는 노인 네안데르탈인들이 높은 사망률을 감안할 때 오랫동안 특별한 매장 의식을 치렀다고 제안했습니다.[86] 대신에, 더 많은 네안데르탈인들이 매장을 받았을 수도 있지만, 무덤은 곰들에 의해 침윤되고 파괴되었습니다.[271] 알려진 모든 무덤의 3분의 1이 넘는 4세 미만의 네안데르탈인의 무덤 20개가 발견되었다는 점을 감안할 때, 사망한 어린이들은 다른 연령 인구 통계보다 매장 기간 동안 더 많은 보살핌을 받았을 수 있습니다.[253]

몇몇 자연 암석 보호소에서 회수된 네안데르탈인의 해골을 보면서, 트린카우스는 네안데르탈인이 여러 차례 외상과 관련된 부상을 입은 것으로 기록되었지만, 그들 중 누구도 다리에 움직임을 약화시킬 정도로 심각한 외상을 입지 않았다고 말했습니다. 그는 네안데르탈인 문화에서 가치 있는 것은 집단에 음식을 제공하는 것에서 비롯된다고 제안했습니다. 쇠약해지는 부상은 이러한 가치를 제거하고 거의 즉각적인 죽음을 초래할 것이며, 동굴에서 동굴로 이동하는 동안 집단을 따라가지 못한 사람들은 남겨졌습니다.[86] 그러나 매우 쇠약한 부상을 입은 사람들이 몇 년 동안 간호를 받고 지역 사회 내에서 가장 취약한 사람들을 돌보는 예는 H. hidelbergensis로 더 거슬러 올라갑니다.[42][253] 특히 높은 외상률을 감안할 때, 그러한 이타적인 전략이 오랫동안 종으로서 생존을 보장했을 가능성이 있습니다.[42]

음식.

사냥과 채집

네안데르탈인은 한때 청소부로 간주되었지만 지금은 최상위 포식자로 간주됩니다.[272][273] 1980년, 저지(Jersey)의 라 코테 데 브렐레이드(La Cotte de St Brelade)에 있는 매머드 두개골 더미 두 개가 매머드 드라이브 사냥의 증거라는 가설이 세워졌지만, 이는 논쟁의 여지가 있습니다.[274][275] 숲이 우거진 환경에서 사는 네안데르탈인은 매복 사냥꾼이었을 가능성이 높으며, 짧은 속도로 그들의 목표물인 최상급 성체에게 접근하여 공격하고, 가까운 곳에서 창을 들이밀었습니다.[66][276] 어린 동물이나 상처를 입은 동물은 덫, 발사체 또는 추적을 사용하여 사냥했을 수 있습니다.[276] 몇몇 사이트는 네안데르탈인이 대규모의 무차별적인 사냥으로 동물 무리 전체를 도살한 다음 처리할 사체를 신중하게 선택했다는 증거를 보여줍니다.[277] 그럼에도 불구하고, 그들은 다양한 서식지에 적응할 수 있었습니다.[51][275] 그들은 주로 주변에 풍부한 것을 먹은 것으로 보이며,[53] 스텝 지역(일반적으로 지중해 밖)은 큰 사냥감, 숲에서 사는 지역에서 다양한 식물과 작은 동물을 섭취하는 고기를 거의 전적으로 먹고 삽니다. 그리고 수변 공동체는 수생 자원을 모으고 있지만, 동남 이베리아 반도와 같은 더 남쪽의 온대 지역에서도 큰 사냥감은 여전히 네안데르탈인의 식단에서 두드러지게 나타났습니다.[278] 대조적으로 현대 인류는 더 복잡한 음식 추출 전략을 사용하고 일반적으로 더 다양한 식단을 가진 것으로 보입니다.[279] 그럼에도 불구하고, 네안데르탈인은 특히 살코기를 주로 먹는 겨울에 영양소 결핍과 단백질 중독을 예방하기 위해 여전히 충분히 다양한 식단을 먹어야 했을 것입니다. 살코기가 제공하지 않는 다른 필수 영양소의 함량이 높은 음식은 지방이 풍부한 뇌,[42] 탄수화물이 풍부하고 풍부한 지하 저장 기관(뿌리와 괴경 포함)[280] 또는 현대 이누이트와 같은 초식 먹이 항목의 위 내용물과 같은 식단의 필수 구성 요소였을 것입니다.[281]

For meat, they appear to have fed predominantly on hoofed mammals,[282] namely red deer and reindeer as these two were the most abundant game,[46][283] but also on other Pleistocene megafauna such as chamois,[284] ibex,[285] wild boar,[284] steppe wisent,[286] aurochs,[284] woolly mammoth,[287] straight-tusked elephant,[288] woolly rhinoceros,[289] wild horse,[283] and so on.[25][47][290] 동면 안팎에서 직접 동굴과 불곰을 사냥하고 도살했다는 증거가 있습니다.[291] 크로아티아 빈디자 동굴의 네안데르탈인 뼈 콜라겐을 분석한 결과 거의 모든 단백질이 동물성 고기에서 유래한 것으로 나타났습니다.[47] 몇몇 동굴들은 토끼와 거북이들이 규칙적으로 소비된다는 증거를 보여줍니다. 지브롤터 유적지에는 메추라기, 콘크레이크, 우들라크, 볏 종달새 등 143종의 다양한 조류 종들이 남아 있습니다.[51] 까마귀와 독수리와 같은 청소하는 새들이 흔히 이용되었습니다.[292] 네안데르탈인들은 이베리아, 이탈리아, 펠로폰네소스 반도의 해양 자원을 이용해 조개류를 파도타기하거나 잠수한 [51][293][294]곳도 15만년 전 스페인 쿠에바 바욘딜로에서 현생 인류의 어업 기록과 비슷했습니다.[295] 지브롤터의 뱅가드 동굴에서 주민들은 지중해의 물개, 짧은 부리의 큰돌고래, 큰돌고래, 대서양 참다랑어, 도미, 보라색 성게를 먹었고 포르투갈의 Gruta da Figueira Brava에서는 조개, 게, 물고기의 대규모 수확의 증거가 있습니다.[51][296][297] 송어, 처브, 장어의 경우 이탈리아 그로테 디 카스텔시비타,[294] 처브와 유럽산 농어의 경우 프랑스 아브리 뒤 마라스, 프랑스 페레,[298] 흑해 연어의 경우 러시아 쿠다로 동굴에서 민물낚시의 증거가 발견되었습니다.[299]

식용 식물과 버섯 유적은 여러 동굴에서 기록되어 있습니다.[49] 치석을 기반으로 한 스페인 쿠에바 델 시드론 출신의 네안데르탈인은 버섯, 잣, 이끼로 고기가 없는 식단을 했을 가능성이 높으며, 이는 그들이 숲 수렵꾼임을 나타냅니다.[248] 이스라엘 아무드 동굴의 잔해는 무화과, 야자수 열매, 그리고 다양한 곡물과 식용 풀로 이루어진 식단을 나타냅니다.[50] 다리 관절에 생긴 몇 개의 뼈 외상은 습관적인 쪼그려 앉는 것을 암시할 수 있는데, 이 경우 음식을 수집하는 동안 이루어졌을 가능성이 높습니다.[300] 벨기에 Grote de Spy의 치석은 주민들이 양털코뿔소와 무플론 양을 포함한 고기를 많이 먹는 동시에 정기적으로 버섯을 먹었다는 것을 나타냅니다.[248] 50,000년 전에 만들어진 스페인 엘 솔트의 네안데르탈인 분변 물질(가장 오래된 인간의 분변 물질로 기록됨)은 주로 고기를 먹지만 식물의 상당한 성분을 가지고 있습니다.[301] 요리된 식물 음식(주로 콩류와 도토리)의 증거는 이스라엘의 케바라 동굴 유적지에서 발견되었으며, 거주자들은 봄과 가을에 식물을 모으고 가을을 제외한 모든 계절에 사냥을 할 수 있지만, 동굴은 늦여름에서 초가을에 버려졌을 가능성이 있습니다.[40] 이라크 샤니다르 동굴에서 네안데르탈인은 다양한 수확기를 가진 식물을 수집했는데, 이는 특정 식물을 수확하기 위해 이 지역으로 돌아올 예정이며, 육류와 식물 모두에 대해 복잡한 식량 수집 행동을 가지고 있음을 나타냅니다.[48]

음식 준비

네안데르탈인은 아마도 로스팅과 같은 광범위한 요리 기술을 사용할 수 있으며 수프, 스튜 또는 동물성 육수를 데우거나 끓일 수 있었을 것입니다.[44] 정착지에 동물 뼈 조각이 풍부하다는 것은 이미 기아로 죽은 동물로부터 채취한 끓는 골수에서 지방을 만드는 것을 나타낼 수 있습니다. 이러한 방법은 지방 소비를 상당히 증가시켰을 것이며, 이는 저탄수화물 및 고단백 섭취를 가진 지역 사회의 주요 영양 요구 사항이었습니다.[44][302] 네안데르탈인의 치아 크기는 10만 년 전 이후 감소 추세를 보였는데, 이는 요리에 대한 의존도가 증가했거나 음식을 부드럽게 했을 기술인 삶기의 도래를 나타낼 수 있습니다.[303]

스페인 쿠에바 델 시드론에서 네안데르탈인은 음식을 요리하고 훈제했을 가능성이 높으며,[45] 야로와 카모마일과 같은 특정 식물을 향료로 사용했을 수도 있습니다.[44][39] 지브롤터의 고럼 동굴에서 네안데르탈인은 잣에 접근하기 위해 솔방울을 굽고 있었을지도 모릅니다.[51]

프랑스의 Grotte du Lazaret에서는 가을 사냥철에 붉은 사슴 총 23마리, 아이벡스 6마리, 오로크 3마리, 노루 1마리가 사냥된 것으로 보이는데, 이 시기에는 강한 수컷과 암컷 사슴 무리들이 함께 모여 발정을 합니다. 사체 전체를 동굴로 운반한 뒤 도살한 것으로 보입니다. 이것은 부패하기 전에 섭취하기에 너무 많은 양의 음식이기 때문에, 이 네안데르탈인들은 겨울이 시작되기 전에 그것을 치료하고 보존했을 가능성이 있습니다. 16만 년 전에, 그것은 음식 저장의 가장 오래된 잠재적 증거입니다.[43] 일반적인 먹잇감(즉, 매머드)으로부터 일반적으로 수집될 수 있는 많은 양의 고기와 지방은 또한 음식 저장 능력을 나타낼 수 있습니다.[304] 조개류의 경우, 조개류가 매우 빨리 상하기 때문에 네안데르탈인은 수집 후 곧 그것을 먹고, 요리하거나, 어떤 식으로든 보존해야 했습니다. 스페인 쿠에바 데 로스 아비오네스(Cueva de los Aviones)에서 조류인 야니아 루벤스(Jania rubens)와 관련된 식용 조류의 잔해는 일부 현대 수렵 채집 협회와 마찬가지로 채집된 조개를 물에 적신 조류에 넣어 소비할 때까지 살아 있고 신선하게 유지한다는 것을 나타낼 수 있습니다.[305]

경쟁.

거대한 빙하기 포식자들과의 경쟁은 다소 높았습니다. 동굴 사자는 말, 큰 사슴 및 야생 소를 목표로 했을 가능성이 높으며 표범은 주로 순록과 노루를 목표로 했으며, 이는 네안데르탈인의 식단과 크게 겹쳤습니다. 네안데르탈인은 그런 사나운 포식자들로부터 살인을 저지하기 위해 소리를 지르거나 팔을 흔들거나 돌을 던지는 집단 시위를 벌이거나 재빨리 고기를 모아 살인을 포기했을 수도 있습니다. 그러나 벨기에의 그로테 드 스파이에서 당시 주요 포식자였던 늑대, 동굴 사자, 동굴 곰의 유해는 네안데르탈인이 어느 정도 경쟁자를 사냥했음을 나타냅니다.[52]

네안데르탈인과 동굴 하이에나는 틈새 차별화를 예시했고, 서로 경쟁하는 것을 적극적으로 피했을 수 있습니다. 비록 그들은 모두 사슴, 말, 그리고 소와 같은 생물 집단을 주로 목표로 삼았지만, 네안데르탈인은 주로 전자와 동굴 하이에나를 사냥했습니다. 또한, 네안데르탈인 동굴의 동물 유해는 그들이 원시 개체를 사냥하는 것을 선호하는 반면, 동굴 하이에나는 더 약하거나 어린 먹이를 사냥하고, 동굴 하이에나 동굴은 육식동물의 유해가 더 풍부하다는 것을 나타냅니다.[46] 그럼에도 불구하고 동굴 하이에나가 네안데르탈인 야영지에서 음식과 남은 음식을 훔치고 죽은 네안데르탈인 시체를 치웠다는 증거가 있습니다.[306]

식인 풍습

네안데르탈인이 그들의 범위에 걸쳐 식인 풍습을 실행한 몇 가지 사례가 있습니다.[308][309] 첫 번째 사례는 1899년 크로아티아의 크라피나 유적지에서 나왔고,[120] 다른 사례들은 스페인의 쿠에바 델 시드론과[265] 자파라라, 그리고 프랑스의 그로트 드 물라-게르시,[310] 레스 프라델, 그리고 라 퀴나에서 발견되었습니다. 벨기에 그로츠 데 고예에 있는 식인종 네안데르탈인 5명의 경우, 상지가 관절이 부러지고, 하지가 박리되어 박살이 나고(골수를 뽑아낼 가능성이 있음), 흉강이 헐리고 턱이 절단되었다는 증거가 있습니다. 도살자들이 도구를 다시 만지기 위해 일부 뼈를 사용했다는 증거도 있습니다. Grots de Goyet의 네안데르탈인 고기 가공은 그들이 말과 순록을 가공했던 방식과 비슷합니다.[308][309] 프랑스 마릴락 르 프랑에 있는 네안데르탈인의 약 35%는 도살의 명백한 징후를 보이고 있으며, 소화된 치아가 존재한다는 것은 시체가 버려진 채 청소부, 하이에나에 의해 먹혔다는 것을 나타냅니다.[311]

이러한 식인주의적 성향은 의식적인 배변, 매장 전 배변(청소기나 악취 방지), 전쟁 행위 또는 단순히 음식을 위한 것으로 설명되었습니다. 적은 수의 사례와 동물보다 식인종에게 보이는 절단 자국의 수가 더 많기 때문에(경험이 없음을 나타낸다) 식인종은 아마도 그리 흔한 관행이 아니었을 것이며, 기록된 인류 역사에서 일부 경우처럼 식량이 극도로 부족한 시기에만 이루어졌을 수 있습니다.[309]

예술.

개인 장식품

네안데르탈인은 황토 안료인 황토를 사용했습니다. 오크레는 네안데르탈인 유적지에서 60년에서 45,000년 전에 잘 기록되어 있으며, 가장 초기의 예는 네덜란드 마스트리흐트-벨베데레에서 250-200,000년 전으로 거슬러 올라갑니다(H. sapiens의 오크레 기록과 유사한 시간대).[312] 바디 페인트로 기능했을 것으로 추정되며, 프랑스 페흐 드 라제(Pech de l'Azé)의 색소를 분석한 결과 부드러운 물질(가죽이나 사람의 피부 등)에 적용된 것으로 나타났습니다.[313] 그러나 현대의 사냥꾼들은 바디 페인트 외에도 약용, 가죽 태닝용, 식품 방부제, 방충제 등으로 황토를 사용하기 때문에 네안데르탈인의 장식용 페인트로 사용하는 것은 사변적입니다.[312] 황토 안료를 혼합하는 데 사용된 것으로 보이는 용기는 루마니아 페 ș테라 시아레이에서 발견되었으며, 이는 오로지 미적인 목적으로 황토가 변형되었음을 나타낼 수 있습니다.

네안데르탈인은 독특한 모양의 물건들을 모았고, 이탈리아 그로타 디 푸마네(Grotta di Fumane)에서 100km(62mi) 이상 떨어진 곳에서 약 47,500년 전에 발견된 붉은 색으로 칠해진 아스파 마진가타(Aspa marginata) 바다 달팽이 껍질과 같이, 그것들을 펜던트(pendant)로 수정했을 것으로 추정됩니다.[315] 스페인 쿠에바 데 로스 아비오네스에서 생산된, 붉은 색소와 노란 색소와 관련된, 거친 꼬막, 글라이시메리스, 그리고 스폰딜루스 게데로푸스에 속하는 엄보를 통해 구멍을 뚫은, 그리고 후자는 헤마타이트와 황철석의 적색에서 흑색의 혼합물이고, 스페인 쿠에바 안톤의 괴타이트와 헤마타이트의 오렌지 혼합물의 흔적이 있는 왕 가리비 껍질입니다. 후자의 발견자들은 자연적으로 선명한 내부 색상과 일치하도록 외관에 안료를 적용했다고 주장합니다.[56][305] 1949년부터 1963년까지 프랑스의 그로트 뒤 렌에서 발굴된 샤텔페로니안 구슬은 동물의 이빨, 조개껍질, 상아 등으로 만들어졌지만 연대는 불확실하고 샤텔페로니안 유물은 실제로 현생 인류에 의해 제작되어 단순히 네안데르탈인의 유해와 함께 재증착되었을 수 있습니다.[316][317][318][319]

지브롤터 고생물학자인 클라이브(Clive)와 제랄딘 핀레이슨(Geraldine Finlayson)은 네안데르탈인이 다양한 새 부위, 특히 검은 깃털을 예술적 매개체로 사용했다고 제안했습니다.[320] 2012년, Finlaysons와 동료들은 유라시아 전역의 1,699개 지역을 조사했고, 일반적으로 어떤 인간 종에서도 소비되지 않는 랩터와 코비드(corvid)가 과도하게 표현되었고, 살집이 있는 몸통 대신 날개 뼈만 처리되는 것을 보여준다고 주장했습니다. 따라서 개인 장식품으로 사용하기 위해 특히 큰 비행 깃털이 깃털을 뽑았다는 증거입니다. 그들은 구체적으로 중기 구석기 유적지의 시네레우스 독수리, 붉은부리칼새, 황조롱이, 작은황조롱이, 고산칼새, 룩, 잭도, 흰꼬리수리 등에 주목했습니다.[321] 네안데르탈인이 변형의 증거를 제시했다고 주장하는 다른 새들은 황금 독수리, 바위 비둘기, 일반 까마귀, 수염 독수리입니다.[322] 새 뼈 보석에 대한 최초의 주장은 크로아티아 크라피나 근처의 한 현금에서 발견된 13만년 된 흰 꼬리 독수리 발톱으로, 2015년 목걸이였을 것으로 추측됩니다.[323][324] 유사한 39,000년 된 스페인 제국 독수리 탈론 목걸이가 2019년 스페인의 코바 포라다에서 보고되었지만 논쟁의 여지가 있는 샤텔페로니안 층에서 보고되었습니다.[325] 2017년, 43-38,000년 전의 우크라이나 자스칼나야 VI 암석 보호소에서 17개의 절개 장식 까마귀 뼈가 보고되었습니다. 노치들은 서로 어느 정도 등거리에 있기 때문에, 단순한 도살로 설명될 수 없는 최초의 변형된 새 뼈이며, 이에 대한 설계 의도의 주장은 직접적인 증거에 기초합니다.[54]

1975년에 발견된 소위 '라 로슈코타드의 가면'은 32년, 40년 또는 75,000년 전에[326] 구멍을 통해 뼈가 밀어낸, 주로 납작한 부싯돌 조각으로, 뼈가 눈을 나타내며, 얼굴의 상반부와 닮았다고 알려져 왔습니다.[327][328] 얼굴을 나타내는 것인지, 아니면 예술에 해당하는지가 다투어집니다.[329] 1988년, 미국 고고학자 알렉산더 마샤크(Alexander Marshack)는 프랑스 그로트 드 로르투스(Grote de L'Hortus)의 네안데르탈인이 복원된 표범의 두개골, 팔랑지 및 꼬리 척추를 근거로 표범 가죽을 개인 장식품으로 착용했다고 추측했습니다.[31][330]

추상화

2014년 현재, 유럽과 중동의 27개의 다른 저-중 구석기 유적에서 63개의 판각이 보고되었으며, 그 중 20개는 11개 유적의 부싯돌 피질에, 7개는 7개 유적의 슬래브에, 36개는 13개 유적의 조약돌에 있습니다. 이것들이 상징적인 의도로 만들어졌는지 아닌지에 대해서는 논란이 되고 있습니다.[58] 2012년 지브롤터 고럼 동굴 바닥에 깊게 긁힌 자국이 발견됐는데, 발견자들은 이를 네안데르탈인의 추상 미술로 해석해 왔습니다.[331][332] 흠집도 곰이 만들었을 수 있습니다.[271] 2021년 독일 아인혼회흘레 동굴 입구에서 약 5만 1천 년 전의 것으로 추정되는 5개의 새겨진 오프셋 쉐브론이 서로 위로 쌓여 있는 아일랜드 엘크팔랑스가 발견되었습니다.[333]

2018년 스페인 라 파시에가, 몰트라비에소, 도냐 트리니다드의 동굴 벽에 있는 일부 붉은 페인트로 칠해진 점, 원반, 선, 손 스텐실은 서유럽에 현생 인류가 도착하기 최소 2만 년 전인 66,000년 전보다 더 오래된 것으로 추정됩니다. 이것은 네안데르탈인의 저자임을 나타낼 것이고, 프랑스 레 메르베일레스와 스페인 쿠에바 델 카스티요와 같은 다른 서유럽 지역에서도 기록된 유사한 도상학이 잠재적으로 네안데르탈인의 기원을 가질 수 있습니다.[61][62][334] 그러나 이 스페인 동굴들의 연대, 따라서 네안데르탈인의 것으로 추정되는 것에 대해서는 논란이 되고 있습니다.[60]

네안데르탈인은 실제 기능적 목적이나 사용으로 인한 손상의 징후 없이 결정이나 화석과 같은 다양한 특이한 물체를 수집한 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 이 물건들이 단순히 미적 특성 때문에 선택된 것인지, 아니면 어떤 상징적 의미가 그것들에 적용된 것인지는 불분명합니다. 이러한 품목은 주로 석영 결정이지만 세루사이트, 철 황철석, 석회석 및 갈레나와 같은 다른 광물도 있습니다. 헝가리 타타에서 나온 십자가가 새겨진 매머드 이빨과 누뮬라이트 화석 껍질, 프랑스 라 페라시의 무덤에서 파낸 18개의 컵스톤이 있는 대형 슬래브, 붉은 황토로 코팅된 루마니아 페 ș테라 시아레이의 지오데 등 몇몇 연구 결과들은 변형된 것을 특징으로 합니다. 프랑스 네안데르탈인 유적지에서도 많은 화석 껍질이 알려져 있는데, 예를 들면 콤베 그레날의 린코넬리드와 타라브라툴리나, 그로트 데 카날레트의 벨렘나이트 부리, 그로트 드 엘 하이네의 폴립, 라 곤테리 불루네의 성게, 린코넬라 등이 있습니다. 그로트 뒤 렌의 논쟁적인 샤텔페로니안 층에서 나온 깃털 별과 벨렘나이트 부리.[57]

음악

곰의 긴 뼈로 만들어진 네안데르탈인의 뼈 피리 조각은 1920년대 슬로베니아 포토치카 지할카와 1985년 헝가리 이스타를로스-카 ő이-바를랑과 슬로베니아 모크리슈카자마에서 보고되었지만, 이것들은 현재 현대 인간의 활동에 기인합니다. 1995년에 발견된 슬로베니아 출신의 43,000년된 디브제 베이브 플루트는 일부 연구자들에 의해 네안데르탈인의 것으로 여겨져 왔으며, 캐나다의 음악학자 로버트 핑크는 원래 플루트의 음계가 디아토닉 또는 펜타토닉이라고 말했습니다.[339] 그러나 이 날짜는 현대 인류의 유럽 이민과도 겹치는데, 이것은 네안데르탈인에 의해 제조되지 않았을 가능성도 있다는 것을 의미합니다.[340] 2015년 동물학자 카주스 디드리히는 피리가 전혀 아니며, 윙윙거리는 소리에서 비롯된 절단 자국이 부족해 구멍을 청소하는 하이에나에 의해 만들어졌다고 주장했지만,[338] 2018년 슬로베니아 고고학자 마티야 튀르크와 동료들은 이 구멍이 치아에 의해 만들어졌을 가능성은 매우 낮다고 반박했습니다. 뼈 피리에 항상 상처 자국이 있는 것은 아닙니다.[59]

기술

분명히 15만 년 동안 네안데르탈인의 리튬 기술 혁신이 정체되었음에도 불구하고,[176] 네안데르탈인의 기술이 이전에 생각했던 것보다 더 정교했다는 증거가 있습니다.[64] 그러나 잠재적으로 쇠약해지는 부상의 빈도가 높기 때문에 매우 복잡한 기술이 출현하는 것을 막을 수 있었을 것입니다. 왜냐하면 큰 부상은 초보자를 효과적으로 가르치는 전문가의 능력을 방해했을 것이기 때문입니다.[236]

석기

네안데르탈인은 석기를 만들었고, 무스테리아 산업과 연관이 있습니다.[27] 무스테리안은 또한 일찍이 31만 5천년 전에[341] 북아프리카 H. 사피엔스와 관련이 있으며, 약 47-37,000년 전에 중국 북부에서 진지타이나 통티안동과 같은 동굴에서 발견되었습니다.[342] 그것은 약 30만년 전에 아쿨레아의 이전 산업(H. erectus가 발명한 약 1.8 mya)에서 직접 발전한 Levallois 기법으로 진화했습니다. Levallois는 플레이크 모양과 크기를 쉽게 조절할 수 있도록 했고, 배우기 어렵고 직관적이지 않은 과정으로 Levallois 기법은 순수하게 관찰 학습을 통해 배운 것이 아니라 세대에게 직접 가르쳤을 수도 있습니다.[28]

프랑스 남서부의 샤렌티아 산업의 퀴나 및 라 페라시 아형, 대서양 및 북서부 유럽 해안을 따라 아슐레 전통의 무스테리아 아형 A 및 B와 같은 무스테리아 산업의 뚜렷한 지역적 변형이 있습니다.[343] 중부 및 동유럽의 미코퀴엔 산업과 시베리아 알타이 산맥의 관련 시비랴치카 변종,[266] 서유럽의 덴티큘라 무스테리안 산업, 자그로스 산맥 주변의 라클루어 산업, 스페인 칸타브리아와 피레네 산맥 양쪽의 플레이크 클리버 산업. 20세기 중반, 프랑스 고고학자 프랑수아 보르데스는 미국 고고학자 루이스 빈포드를 상대로 이 다양성을 설명하기 위한 논쟁을 벌였으며("보르데스-빈포드 논쟁"), 보르데스는 이것들이 독특한 민족 전통을 나타내고 빈포드는 다양한 환경(본질적으로 형태 대 기능)에 의해 발생했다고 주장했습니다.[343] 후자의 정서는 현대 인간에 비해 창의성의 정도가 낮다는 것을 나타내며, 새로운 기술을 만들기보다는 동일한 도구를 다른 환경에 적용합니다.[53] 프랑스의 Grotte du Renne에는 연속적인 점유 순서가 잘 기록되어 있으며, 석판 전통은 Levallois–Charentian, Discoid–Denticulate (43,300 ±929년 - 40,900 ±719년 전), Levallois Mousterian (40,200 ±1,500년 - 38,400년 ±1,300년 전), Châtelperronian (40,930 ±393년 - 33,670년 ±450년 전)으로 나눌 수 있습니다.[344]

네안데르탈인이 장거리 무기를 가지고 있었는지에 대해서는 약간의 논쟁이 있습니다.[345][346] 시리아 움멜틀렐에서 온 아프리카 야생 엉덩이의 목에 난 상처는 무거운 레발루아 지점의 창에 의한 것으로 보이며,[347] 네안데르탈인에서 습관적인 투척과 일치하는 뼈 외상이 보고되었습니다.[345][346] 프랑스 Abri du Maras의 일부 창 끝은 너무 약해서 찌르는 창으로 사용되지 않았을 수 있으며, 이는 그들이 다트로 사용되었음을 시사합니다.[298]

유기공구

프랑스 중부와 스페인 북부의 샤텔페로니안은 무스테리아인과 구별되는 산업이며, 네안데르탈인이 이주한 현대 인류로부터 도구 제작 기술을 차용(또는 문화화 과정에 의해)하고 뼈 도구와 장식품을 만드는 문화를 나타낸다는 가설이 논란이 되고 있습니다. 이 틀에서, 그 제작자들은 네안데르탈인 무스테리아인과 현대 인류 오리냐키아인 사이의 과도기적인 문화였을 것입니다.[348][349][350][351][352] 반대 의견은 샤텔페로니안이 현대 인간에 의해 제조되었다는 것입니다.[353] Mousterian/Chattelperronian과 유사한 갑작스러운 전환은 50,000년 전 La Quina-Neronian 전환과 같이 블레이드 및 미세석과 같은 현대 인간과 일반적으로 관련된 기술을 특징으로 하는 자연적 혁신을 나타낼 수도 있습니다. 다른 모호한 과도기 문화로는 이탈리아 울루치아 산업과 [354]발칸반도 젤레티아 산업이 있습니다.[355]

이민 전에 네안데르탈인의 뼈 도구에 대한 유일한 증거는 동물의 갈비뼈(ribisoir)인데, 이는 동물을 더 유연하게 만들거나 방수하기 위해 가죽에 문질러집니다. 그러나 이것은 현대 인류가 예상보다 일찍 이민을 오는 증거가 될 수도 있습니다. 2013년, 프랑스의 페흐-드-라제와 인근 아브리 페이로니에서 51,400년에서 41,100년 된 두 마리의 사슴 갈비뼈 부스러기가 보고되었습니다.[350][100][100] 2020년에 아브리 페이로니(Abri Peyrony)에서 오록스(aurox) 또는 들소 갈비로 만든 5개의 리쏘어(lissoir)가 추가로 보고되었으며, 하나는 약 51,400년 전으로, 다른 하나는 47,700~41,100년 전으로 거슬러 올라갑니다. 이는 해당 기술이 이 지역에서 오랫동안 사용되었음을 나타냅니다. 순록 유적이 가장 풍부했기 때문에, 덜 풍부한 소 갈비를 사용하는 것은 소 갈비에 대한 특정한 선호를 나타낼 수 있습니다. 잠재적인 리수어는 독일 그로스 그로트 (매머드로 만들어진)와 프랑스 그로트 데 카날레트 (붉은 사슴)에서도 보고되었습니다.[356]

이탈리아의 10개 해안 지역(즉, Grotta del Cavallo와 Grotta dei Moscerini)과 그리스의 칼라마키아 동굴에 있는 네안데르탈인은 매끄러운 조개 껍질을 사용하여 긁힌 조각들을 만들었고, 아마도 그것들을 나무 손잡이로 대충 만든 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 아마 조개가 가장 튼튼한 껍질을 가지고 있기 때문에 그들은 이 조개 종을 선택했을 것입니다. Grotta dei Moscerini에서는 조개껍질의 약 24%가 해저에서 산 채로 채집되었는데, 이는 네안데르탈인들이 조개껍질을 채취하기 위해 얕은 물로 걷거나 잠수해야 한다는 것을 의미합니다. 네안데르탈인은 캄파니아 화산 호에 있는 이탈리아의 Grotta di Santa Lucia에서 다공성 화산 부석을 채취했는데, 이는 아마도 현생 인류의 경우 점과 바늘을 연마하는 데 사용되었을 것입니다. 가격은 조개 도구와 관련이 있습니다.[294]

프랑스 Abri du Maras에서는 꼬인 섬유와 네안데르탈인과 관련된 3겹의 속박-섬유 조각이 끈과 끈을 생산한다는 것을 보여주지만, 이 기술을 만드는 데 사용된 물질(동물의 털, 가죽, 솔기 또는 식물의 섬유와 같은)은 생분해성이고 보존 상태가 매우 좋지 않기 때문에 이 기술이 얼마나 널리 퍼졌는지는 불분명합니다. 이 기술은 그물, 용기, 포장, 바구니, 운반 장치, 넥타이, 끈, 마구, 옷, 신발, 침대, 침구, 매트, 바닥재, 지붕재, 벽, 올가미 등의 제작을 가능하게 하는 적어도 직조와 매듭에 대한 기본 지식을 나타낼 수 있었고, 하프닝에 중요했을 것입니다. 어로와 해로 52-41,000년 전의 코드 조각은 섬유 기술의 가장 오래된 직접적인 증거이지만, 쿠에바 안톤의 115,000년 된 구멍 뚫린 조개 목걸이가 가장 오래된 간접적인 증거입니다.[36][298] 2020년, 영국 고고학자 레베카 와그 사익스(Rebecca Wragg Sykes)는 발견의 진위에 대해 신중한 지지를 표명했지만, 끈이 너무 약해서 제한된 기능을 가졌을 것이라고 지적했습니다. 하나의 가능성은 작은 물체를 부착하거나 끈으로 묶기 위한 나사산입니다.[357]

고고학 기록에 따르면 네안데르탈인은 동물 가죽과 자작나무 껍질을 일반적으로 사용했으며, 두 가지 모두 화석화가 잘 되지 않기 때문에 상황적 증거에 기반을 두고 있지만 요리 용기를 만드는 데 사용했을 수도 있습니다.[303] 이스라엘 케바라 동굴의 네안데르탈인이 박차를 가한 거북이의 등껍질을 용기로 사용했을 가능성이 있습니다.[358]

이탈리아의 Poggetti Vecchi 유적지에서, 그들이 사냥꾼과 채집인 사회에서 흔한 도구인 땅을 파는 막대기를 만들기 위해 나무 가지를 가공하기 위해 불을 사용했다는 증거가 있습니다.[359]

화재 및 시공

많은 무스터교 유적지들은 화재의 증거를 가지고 있으며, 일부는 장기간 동안 화재를 일으킬 수 있었는지, 아니면 단순히 자연적으로 발생하는 산불을 제거할 수 있었는지는 불분명합니다. 불을 지피는 능력에 대한 간접적인 증거로는 프랑스 북서부의 후기 무스테리아 (50,000년 전쯤)에서 나온 수십 개의 분기점에 있는 황철석 잔여물과 후기 네안데르탈인이 수집한 이산화망간이 있는데, 이는 나무의 연소 온도를 낮출 수 있다는 것을 나타낼 수 있습니다.[29][30][360] 그들은 또한 포장, 도살, 난로 및 목재 보관과 같은 특정 활동을 위한 구역을 설정할 수 있었습니다. 많은 네안데르탈인 유적지들은 정착지를 포기한 후 곰의 침투와 같이 수만 년 동안 자연적으로 지역이 황폐화되었기 때문에 그러한 활동에 대한 증거가 부족합니다.[271]

여러 동굴에서 난로의 증거가 포착되었습니다. 네안데르탈인들은 난로를 만들 때 단 한 개의 난로를 위한 적절한 환기 장치가 부족하면 몇 분 안에 동굴을 사람이 살 수 없게 만들 수 있기 때문에 공기 순환을 고려했을 가능성이 높습니다. 스페인의 아브릭 로마니 바위 보호소는 8개의 균일한 간격의 난로가 암벽에 기대어 늘어서 있으며, 한 사람은 불 양쪽에서 자고 있습니다.[31][32] 벽에 난로가 늘어서 있는 스페인 쿠에바 데 볼로모르에서는 연기가 천장으로 흘러나와 동굴 밖으로 이어졌습니다. 프랑스의 Grotte du Lazaret에서는 내부 동굴 온도가 외부 온도보다 높기 때문에 겨울 동안 연기가 자연적으로 환기되었을 것입니다. 마찬가지로 동굴에도 겨울에만 사람이 살 가능성이 높습니다.[32]

1990년 프랑스 그로트 드 브루니켈 내 입구에서 300m(980ft) 이상 떨어진 큰 방에서 깨진 석순 조각으로 만들어진 폭이 수 미터에 달하는 176,000년 된 두 개의 고리 구조물이 발견되었습니다. 하나의 고리는 6.7 m × 4.5 m (22 ft × 15 ft)이며 석순 조각은 평균 길이가 34.4 cm (13.5 in)이고, 다른 하나는 평균 길이가 29.5 cm (11.6 in)인 2.2 m × 2.1 m (7.2 ft × 6.9 ft)입니다. 총 112m (367피트) 또는 2.2t (2.4단톤) 상당의 석순 조각을 위한 4개의 다른 석순 조각도 있었습니다. 불과 탄 뼈가 사용되었다는 증거도 인간의 활동을 암시합니다. 네안데르탈인으로 구성된 팀이 이 구조물을 건설하는 데 필요했을 것으로 보이지만, 이 챔버의 실제 목적은 불확실합니다. 동굴 깊은 곳에 복잡한 구조물을 짓는 것은 고고학 기록상 전례가 없는 일이며, 정교한 조명과 건축 기술, 지하 환경에 대한 탁월한 친숙함을 나타냅니다.[361]

44,000년 된 몰도바 I 노천 유적지인 우크라이나는 여러 네안데르탈인이 장기간 거주할 목적으로 매머드 뼈로 만든 7m × 10m (23ft × 33ft) 크기의 고리 모양 주거지의 증거를 보여줍니다. 난로와 취사장, 부싯돌 작업장 등이 있었던 것으로 보이며, 목공 흔적이 남아 있습니다. 러시아 평원의 상부 구석기 시대 현생 인류도 매머드 뼈로 주택 구조물을 만든 것으로 추정됩니다.[85]

자작나무

네안데르탈인은 자작나무의 껍질을 이용하여 접착력이 있는 자작나무 껍질 타르를 만들었습니다.[362] 오랫동안 자작나무 껍질 타르는 복잡한 조리법을 따라야 하고, 따라서 복잡한 인지 능력과 문화적 전달을 보여준다고 믿어져 왔습니다. 그러나 2019년의 한 연구는 평평하고 경사진 바위와 같은 매끄러운 수직 표면 옆에서 자작나무 껍질을 태우는 것으로 간단히 만들 수 있다는 것을 보여주었습니다.[34] 따라서 타르 제조에는 문화적 과정 자체가 필요하지 않습니다. 그러나 쾨니히사우에(독일)에서 네안데르탈인은 이런 지상 방식으로 타르를 만드는 것이 아니라 기술적으로 더 까다로운 지하 생산 방식을 채택했습니다. 이것은 그들의 기술 중 일부가 문화적 과정에 의해 전달되었다는 우리의 최고의 지표 중 하나입니다.[363]

옷이요.

네안데르탈인은 잠자는 동안 현대 인간과 비슷한 온도 범위에서 생존할 수 있었을 것입니다. 개방 및 풍속 5.4 km/h (3.4 mph) 또는 밀폐된 공간에서 발가벗은 상태에서 27–28 °C (81–82 °F). Eemian 간빙기에는 평균적으로 7월에는 17.4 °C (63.3 °F), 1월에는 1 °C (34 °F)로 낮았고, 가장 추운 날에는 -30 °C (-22 °F)로 떨어졌습니다. 덴마크의 물리학자 Bent Sørensen은 네안데르탈인이 피부로 가는 공기 흐름을 막을 수 있는 맞춤형 옷을 필요로 한다고 가정했습니다. 특히 장시간 여행(사냥 여행 등)을 하는 동안에는 발을 완전히 감싸는 맞춤형 신발이 필요했을 수도 있습니다.[364]

그럼에도 불구하고 현대 인류가 사용했을 것으로 추정되는 뼈 바느질 바늘과 꿰매는 송곳니와 달리, 옷을 유행시키는 데 사용될 수 있었던 유일한 알려진 네안데르탈인 도구는 담요나 판초와 비슷한 제품을 만들 수 있었던 히드 스크래퍼입니다. 그리고 그들이 맞는 옷을 만들 수 있다는 직접적인 증거는 없습니다.[35][365] 네안데르탈인의 맞춤법에 대한 간접적인 증거로는 직조 능력을 나타낼 수 있는 끈 제조 능력과 [298]오렌지 색소의 존재를 근거로 송곳, 구멍 뚫는 염색 가죽으로 사용되었을 것으로 추측되는 스페인 쿠에바 데 로스 아비오네스의 자연적으로 뾰족한 말 중족골이 있습니다.[305] 어떤 경우든 네안데르탈인은 몸의 대부분을 가려야 했을 것이고, 동시대 인류는 80~90%[365][366]를 가졌을 것입니다.

인류/네안데르탈인 혼혈은 중동에서 발생한 것으로 알려져 있고, 네안데르탈인의 대응물에서 내려온 현생 들쥐 종이 없기 때문에(몸 이는 옷을 입은 개체에서만 서식한다), 더 더운 기후의 네안데르탈인(또는 인간)이 옷을 입지 않았거나, 네안데르탈인이 고도로 전문화되었을 가능성이 있습니다.[366]

시퍼링

그리스 섬에 있는 중기 구석기 시대 석기 유적은 이오니아 해에서 네안데르탈인에 의한 초기 항해가 200-150,000년 전으로 거슬러 올라간다는 것을 나타냅니다. 크레타섬에서 가장 오래된 석기 유물은 130~107,000년 전, 세팔로니아는 125,000년 전, 자킨토스는 110~35,000년 전으로 거슬러 올라갑니다. 이러한 공예품의 제작자들은 단순한 갈대 배를 이용하여 하루 동안 왕복 횡단을 했을 가능성이 높습니다.[37] 그러한 유적이 있는 다른 지중해 섬들로는 사르데냐, 멜로스, 알로니소스,[38] 낙소스가 있으며(낙소스는 육지와 연결되었을 수 있지만),[367] 그들은 지브롤터 해협을 건넜을 가능성이 있습니다.[38] 만약 이 해석이 맞다면, 네안데르탈인이 보트를 설계하고 개방된 바다를 항해하는 능력은 그들의 진보된 인지적이고 기술적인 능력을 말해줄 것입니다.[38][367]

약

그들의 위험한 사냥과 치유에 대한 광범위한 해골 증거를 고려할 때, 네안데르탈인은 잦은 외상을 입거나 회복하는 삶을 살았던 것으로 보입니다. 많은 뼈에 잘 치유된 골절은 부목의 설정을 나타냅니다. 심각한 머리와 갈비뼈 외상을 입은 사람은 동물의 피부로 만든 붕대와 같은 주요 상처를 입히는 방식을 가지고 있었다고 말합니다. 대체로, 그들은 심각한 감염을 피한 것으로 보이며, 그러한 상처의 장기 치료가 양호함을 나타냅니다.[42]

그들의 약용 식물에 대한 지식은 현대 인류의 지식과 맞먹었습니다.[42] 스페인 쿠에바 델 시드론의 한 개인은 아스피린의 유효 성분인 살리실산이 함유된 포플러를 사용하여 치아 농양을 약으로 복용한 것으로 보이며 항생제를 생산하는 페니실리움 크리소게눔의 흔적도 있었습니다.[248] 그들은 또한 야로와 카모마일을 사용했을 수도 있고, 독을 나타낼 수 있으므로 억제 작용을 해야 하는 그들의 쓴맛은 그것이 의도적인 행동이었을 가능성이 높다는 것을 의미합니다.[39] 이스라엘의 케바라 동굴에서, 일반적인 포도 덩굴, 페르시아 터펜타인 나무의 피스타치오, 에르빌 씨와 참나무 도토리를 포함하여, 역사적으로 약효로 사용되었던 식물 유적이 발견되었습니다.[40]

언어

언어의 복잡성 정도는 확립하기 어렵지만, 네안데르탈인이 기술적, 문화적 복잡성을 어느 정도 달성하고 인간과 교배했다는 점을 고려할 때, 그들이 적어도 현대 인간에 필적할 정도로 꽤 명확했다고 보는 것이 합리적입니다. 가혹한 환경에서 살아남기 위해서는 다소 복잡한 언어(구문법을 사용할 수도 있음)가 필요했으며, 네안데르탈인은 위치, 사냥 및 채집, 도구 제작 기술과 같은 주제에 대해 의사 소통해야 했습니다.[64][368][369] 현대 인간의 FOXP2 유전자는 언어 및 언어 발달과 관련이 있습니다. FOXP2는 네안데르탈인에 [370]존재했지만 유전자의 현대 인간 변종은 존재하지 않았습니다.[371] 신경학적으로, 네안데르탈인은 문장의 공식화와 언어 이해력을 작동시키는 브로카의 영역이 확장되었지만, 언어의 신경 기질에 영향을 미치는 것으로 추정되는 48개의 유전자 그룹 중 11개는 네안데르탈인과 현대 인간 사이에 다른 메틸화 패턴을 가졌습니다. 이것은 현대 인간이 언어를 표현하는 능력이 네안데르탈인보다 더 강하다는 것을 나타낼 수 있습니다.[372]

1971년 인지과학자 필립 리버만(Philip Lieberman)은 네안데르탈인의 성대를 재구성하려고 시도했고, 입의 크기가 크고 인두강의 크기가 작기 때문에 신생아의 것과 비슷하고 광범위한 말소리를 낼 수 없다는 결론을 내렸습니다(그의 재구성에 따르면). 따라서 입 안에 혀 전체를 맞추기 위해 후두가 하강할 필요가 없습니다. 그는 그들이 해부학적으로 /a/, /i/, /u/, /ɔ/, /g/, /k/ 소리를 낼 수 없었기 때문에 명확한 말을 할 수 있는 능력이 부족했다고 주장했습니다. 그러나 후두가 없다고 해서 반드시 모음의 용량이 줄어드는 것은 아닙니다.[376] 1983년 케바라 2에서 인간의 언어 생산에 사용되는 네안데르탈인의 히오이드 뼈가 발견되었는데, 이것은 네안데르탈인이 언어를 할 수 있었다는 것을 암시합니다. 또한 조상인 Shimad de los Hueos 호미닌은 인간과 같은 히오이드와 귀뼈를 가지고 있었는데, 이것은 현대 인간 성악 장치의 초기 진화를 암시할 수 있습니다. 그러나 효이드는 성대 해부학에 대한 통찰력을 확실하게 제공하지 않습니다.[65] 후속 연구에서는 네안데르탈인의 성악 장치를 현대 인간의 성악 레퍼토리와 유사한 것으로 재구성합니다.[377] 2015년에 Lieberman은 네안데르탈인이 구문론적 언어를 구사할 수 있다고 가정했지만, 그럼에도 불구하고 어떤 인간의 방언도 습득할 수 없습니다.[378]

행동적 근대성이 최근의 독특한 현대적 인간의 혁신인지, 아니면 네안데르탈인도 그것을 소유하고 있는지 논의됩니다.[55][369][379][380]

종교

장례식

비록 네안데르탈인이 그들의 죽음을 묻긴 했지만, 화석 유해의[53] 풍부함을 설명할 수 있는 최소한 가끔은 그 행동이 사후 삶에 대한 종교적인 믿음을 나타내지 않습니다. 왜냐하면 그것은 큰 감정이나[381] 청소 방지와 같은 비 상징적인 동기도 가질 수 있기 때문입니다.[382]

알려진 네안데르탈인의 매장 수에 대한 추정치는 36개에서 60개에 이릅니다.[383][384][385][386] 가장 오래된 것으로 확인된 매장은 약 70,000년 이전에는 발생하지 않는 것으로 보입니다.[387] 기록된 네안데르탈인 매장의 수가 적다는 것은 그 활동이 특별히 흔하지 않았다는 것을 의미합니다. 네안데르탈인 문화의 비인간적인 환경은 대부분 단순하고 얕은 무덤과 구덩이로 구성되었습니다.[388] 프랑스의 라 페라시나 이라크의 샤니다르와 같은 유적지들은 발견된 사람들의 수 때문에 네안데르탈인 문화의 빈소나 묘지의 존재를 암시할 수 있습니다.[388]

네안데르탈인의 장례식에 대한 논쟁은 1908년 프랑스 남서부의 한 동굴에 있는 작은 인공 구멍에서 라 샤펠-오-생트 1호가 발견된 이후 활발하게 진행되고 있으며, 이는 상징적인 방식으로 매장된 것으로 매우 논란이 되고 있습니다.[389][390][391] 이라크 샤니다르 동굴의 또 다른 무덤은 침적 당시 꽃이 피었을 수도 있는 여러 꽃의 꽃가루(야로우, 세기, 돼지풀, 포도 히아신스, 조인트 소나무 및 홀리호크)와 관련이 있습니다.[392] 그 식물들의 약효는 미국 고고학자 랄프 솔레키가 묻힌 남자가 어떤 지도자, 치유자, 또는 무당이었다고 주장하게 했고, "꽃과 네안데르탈인의 연관성은 그가 '영혼'을 가졌다는 것을 나타내는 우리의 인간성에 대한 지식에 완전히 새로운 차원을 추가합니다."[393] 하지만, 이 꽃가루는 이 남성이 죽은 후 작은 설치류에 의해 침전되었을 가능성도 있습니다.[394]

특히 어린이와 유아의 무덤은 공예품과 뼈와 같은 무덤용품과 관련이 있습니다. 프랑스 라 페라시 출신 신생아의 무덤은 부싯돌 3개가 긁힌 채 발견됐고, 시리아 데데리예 출신 신생아는 가슴에 삼각형 부싯돌을 얹은 채 발견됐습니다. 이스라엘의 아무드 동굴에서 태어난 10개월 된 아이는 붉은 사슴 하악골과 관련이 있었고, 다른 동물의 유해가 현재 파편으로 줄어든 것을 감안할 때 일부러 그곳에 놓였을 가능성이 높습니다. 우즈베키스탄의 Teshik-Tash 1은 아이벡스 뿔의 원과 관련이 있었고, 석회암 슬라브는 머리를 지지했다고 주장했습니다.[253] 우크라이나 크림반도 키익코바의 한 어린이는 부싯돌 조각에 의도적인 조각이 새겨져 있어서 엄청난 기술이 필요했을 것입니다.[58] 그럼에도 불구하고 이들은 중대물의 중요성과 가치가 불분명하기 때문에 논란의 여지가 있는 상징적 의미의 증거가 됩니다.[253]

컬트

한때 일부 유럽 동굴에 있는 동굴곰의 뼈, 특히 두개골이 특정한 순서로 배열되어 있다는 주장이 있었는데, 이는 곰을 죽인 후 의식적으로 뼈를 배열한 고대 곰 숭배를 나타냅니다. 이것은 현대 인간 북극 수렵·채집가들의 곰 관련 의식과 일치할 것이지만, 그 배열의 주장된 특수성은 또한 자연적인 원인에 의해 충분히 설명될 수 있고,[63][381] 곰 숭배의 존재가 토테미즘이 최초의 종교라는 생각과 일치하기 때문에 편견이 도입될 수 있고, 증거의 부당한 추정을 초래합니다.[395]

또한 한 때 네안데르탈인이 다른 네안데르탈인을 사냥하고 죽이고 식인했으며 두개골을 어떤 의식의 초점으로 사용했다고 생각되었습니다.[309] 1962년, 이탈리아 고생물학자 알베르토 블랑은 이탈리아 그로타 과타리의 두개골이 머리에 빠르게 부딪혀 의식적인 살인을 나타내는 증거와 뇌에 접근하기 위한 정확하고 의도적인 절개의 증거를 가지고 있다고 믿었습니다. 그는 말레이시아와 보르네오의 헤드헌터 희생자들과 [396]비교하며 두개골 숭배의 증거로 제시했습니다.[381] 하지만 지금은 동굴 해녀를 파낸 결과로 생각됩니다.[397] 네안데르탈인이 식인 풍습을 실행한 것으로 알려져 있지만, 의식적인 반항을 암시하는 증거는 거의 없습니다.[308]

2019년 지브롤터 고생물학자 스튜어트(Stewart), 제랄딘(Geraldine), 클라이브 핀레이슨(Clive Finlayson)과 스페인 고고학자 프란시스코 구즈만(Francisco Guzmann)은 황금 독수리가 네안데르탈인에게 상징적인 가치가 있다고 추측했습니다. 금독수리 뼈가 다른 새의 뼈에 비해 눈에 띄게 높은 수정 증거 비율을 가지고 있다고 보고했기 때문에 일부 현대 인간 사회에서 예시되었습니다. 그리고 나서 그들은 황금 독수리가 힘의 상징이었던 "태양 새의 컬"을 제안했습니다.[55][322] 크로아티아의 크라피나에서 나온 마모와 심지어 끈의 잔재에서 나온 증거가 있는데, 이것은 랩터 탈론이 개인 장식품으로 착용되었음을 시사합니다.[398]

이종교배

현대인과의 교배

최초의 네안데르탈인 게놈 서열은 2010년에 발표되었으며, 네안데르탈인과 초기 현생 인류 사이의 이종교배를 강하게 나타냈습니다.[87][400][401][402] 연구된 모든 현대 개체군의 게놈에는 네안데르탈인 DNA가 포함되어 있습니다.[87][89][403][404][405] 이 비율에 대한 다양한 추정치가 존재하는데, 예를 들어 현대 유라시아인의 경우 1-4%[87] 또는 3.4-7.9%,[406] 현대 유럽인의 경우 1.8-2.4%, 현대 동아시아인의 경우 2.3-2.6%입니다.[407] 농업 이전의 유럽인들은 현대 동아시아인들과 비슷하거나 약간 더 높은 [405]비율을 가졌던 것으로 보이며, 전자에서는 네안데르탈인의 침입 이전에 갈라졌던 집단과의 희석으로 인해 그 숫자가 감소했을 수 있습니다.[100] 일반적으로, 연구들은 사하라 사막 이남의 아프리카인들에게서 유의미한 수준의 네안데르탈인 DNA를 발견하지 못했다고 보고했지만, 2020년의 한 연구는 5개의 아프리카 표본 집단의 게놈에서 0.3-0.5%를 발견했는데, 아마도 유라시아인들이 아프리카인들과 역 이주하고 교배한 결과일 것입니다. 더 큰 아프리카 밖 이주 이전에 호모 사피엔스의 분산체에서 인간 대 네안데르탈인의 유전자 흐름뿐만 아니라 유럽과 아시아 인구에 대해 더 동등한 네안데르탈인 DNA 비율을 보여주었습니다.[405] 오늘날의 모든 개체군에서 네안데르탈인 DNA의 이러한 낮은 비율은 이종교배가 오늘날의 유전자 풀에 기여하지 않은 현대 인간의 다른 개체군에서 더 흔하지 않은 경우가 아니라면 드물게 과거 이종교배를 나타냅니다.[408][100] 유전된 네안데르탈인 유전체 중 현대 유럽인은 25%, 현대 동아시아인은 32%가 바이러스 면역과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.[409] 전체적으로 네안데르탈인 게놈의 약 20%가 현대 인간 유전자 풀에서 살아남은 것으로 보입니다.[94]

그러나, 네안데르탈인은 적은 개체수와 그로 인한 자연 선택의 효과 감소로 인해 여러 약한 유해 돌연변이를 축적하고, 훨씬 더 많은 현대 인류에게 소개되어 서서히 선택되고 있습니다. 초기 교잡 인구는 현대 인류에 비해 체력이 최대 94% 감소했을 수 있습니다. 이 조치로 인해 네안데르탈인의 체력이 상당히 향상되었을 수 있습니다.[82] 튀르키예의 고대 유전자에 초점을 맞춘 2017년 연구에서는 실리아병, 말라리아 중증도 및 코스텔로 증후군과의 연관성을 발견했습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 일부 유전자는 현대 동아시아인들이 환경에 적응하는 것을 도왔을 수 있습니다; 붉은 머리와 자외선 민감성과 약한 관련이 있을 수 있는 MC1R 유전자의 추정적인 네안데르탈인 Val92Met 변이체는 주로 유럽인이 아닌 동아시아인에게서 발견됩니다.[412][413] 면역계와 관련된 일부 유전자는 OAS1,[414] STAT2,[415] TLR6,[96] TLR1, TLR10 [416]및 면역 반응과 관련된 여러 유전자와 같이 이동에 영향을 미쳤을 수 있습니다.[95][f] 또한, 네안데르탈인 유전자는 뇌의 구조와 기능,[g] 케라틴 필라멘트, 당 대사, 근육 수축, 체지방 분포, 에나멜 두께 및 난모세포 감수분열에도 관련이 있습니다.[99] 그럼에도 불구하고 생존한 침입의 대부분은 생물학적 기능이 거의 없는 비코딩("정크") DNA인 것으로 보입니다.[100]

X-염색체에는 상염색체에 비해 네브데르탈인 조상이 상당히 적습니다. 이것은 현대 인간과의 혼혈이 성에 치우쳐 있다는 것을 암시했고, 주로 현대 인간 암컷과 네안데르탈인 수컷 사이의 교미의 결과였습니다. 다른 저자들은 이것이 네안데탈 대립유전자에 대한 부정적인 선택 때문일 수 있다고 제안했지만 이 두 제안은 상호 배타적이지 않습니다.[141] 2023년 연구에 따르면 X-염색체에 대한 네안데르탈인 조상의 낮은 수준은 혼합물 사건의 성별 편향에 의해 가장 잘 설명된다는 것이 확인되었으며, 이 저자는 또한 고대 유전자에 대한 부정적인 선택에 대한 증거를 발견했습니다.[418]

네안데르탈인 mtDNA는 (엄마에서 아이로 전해지는) 현대 인간에게는 없습니다.[136][155][419] 이것은 주로 네안데르탈인 수컷과 현대 인간 암컷 사이에 이종교배가 일어났다는 증거입니다.[420] 스반테 패보(Svante Päbo)에 따르면, 현생 인류가 네안데르탈인보다 사회적으로 지배적이었다는 것은 분명하지 않으며, 이것이 왜 이종교배가 네안데르탈인 수컷과 현생 인류 암컷 사이에서 주로 발생했는지를 설명할 수 있습니다.[421] 또한, 비록 네안데르탈인 여성과 현생 인간 남성이 교배했더라도, 이들을 임신한 여성이 아들만 낳는다면, 네안데르탈인 mtDNA 계통은 멸종되었을 수 있습니다.[421]

현대 인류의 네안데르탈인 유래 Y-염색체가 부족하기 때문에(아버지에서 아들로 전해짐), 현대 인구에 조상을 기여한 잡종은 주로 여성이거나, 네안데르탈인 Y-염색체가 H. 사피엔스와 맞지 않아 멸종되었다고 주장되기도 했습니다.[100][422]

연결 불균형 매핑에 따르면 현대 인간 게놈에 마지막으로 유입된 네안데르탈인 유전자는 86-37,000년 전에 발생했지만 아마도 65-47,000년 전에 발생했을 것입니다.[423] 오늘날의 인간 게놈에 기여한 네안데르탈인의 유전자는 유럽 전체가 아닌 근동의 이종교배에서 비롯되었다고 생각됩니다. 그러나 이종교배는 여전히 현대 게놈에 기여하지 못하고 발생했습니다.[100] 약 40,000년 된 현생 인류 Oase 2는 2015년에 6-9%(포인트 추정치 7.3%)의 네안데르탈인 DNA를 가지고 있는 것으로 밝혀졌으며, 이는 4-6세대 이전의 네안데르탈인 조상을 나타냈지만, 이 잡종 집단은 후기 유럽인의 게놈에 실질적인 기여를 하지 못한 것으로 보입니다.[410] 2016년 데니소바 동굴에서 발견된 네안데르탈인의 DNA는 10만년 전에 이종교배를 했다는 증거를 밝혀냈고, 레반트와 같은 곳에서 H. sapiens의 초기 분산과 이종교배가 빠르면 12만년 전에 발생했을 수 있습니다.[91] 아프리카 밖에서 가장 오래된 H. sapiens 유적은 194-177,000년 전에 Misliya 동굴에서, Skhul and Qafzeh 120-90,000년 전에 발견되었습니다.[424] 카프제 인류는 타분 동굴 근처에서 네안데르탈인과 거의 같은 시기에 살았습니다.[425] 독일 Hollenstein-Stadel의 네안데르탈인은 더 최근의 네안데르탈인에 비해 mtDNA가 매우 다양한데, 아마도 316,000년에서 219,000년 전 사이에 인간 mtDNA가 침입했기 때문이거나 단순히 유전적으로 분리되었기 때문일 수 있습니다.[90] 어쨌든, 이 최초의 이종교배 사건들은 현대 인간 게놈에 어떤 흔적도 남기지 않았습니다.[426]

이종교배 모델을 반대하는 사람들은 유전적 유사성이 이종교배 대신 공통 조상의 잔해일 뿐이라고 주장하지만,[427] 이것은 사하라 사막 이남의 아프리카인들이 왜 네안데르탈인 DNA를 가지고 있지 않은지를 설명하지 못하기 때문에 가능성이 낮습니다.[401]

2023년 12월, 과학자들은 네안데르탈인과 데니소반인으로부터 현생 인류가 물려받은 유전자가 생물학적으로 현생 인류의 일상에 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 보고했습니다.[428]

데니소바인과의 교배

nDNA는 네안데르탈인과 데니소반이 현생 인류보다 서로 더 밀접한 관련이 있음을 확인했지만, 네안데르탈인과 현생 인류는 데니소반과 일부 알려지지 않은 인류 종 사이의 교배 때문에 더 최근의 모계에서 전염된 mtDNA 공통 조상을 공유합니다. mtDNA를 바라보는 스페인 북부 시마 데 로스 휴에소스의 40만 년 된 네안데르탈인과 비슷한 인간들은 네안데르탈인보다 데니소반인과 더 밀접한 관련이 있습니다. 비슷한 시기의 유라시아에 있는 여러 네안데르탈인과 유사한 화석들은 종종 H. hidelbergensis로 분류되는데, 그 중 일부는 데니소반과 교배했을 수 있는 초기 인류의 유물 개체군일 수 있습니다.[430] 이것은 또한 약 270,000년 전에 다른 네안데르탈인(시마 데 로스 휴에소스 제외)으로부터 갈라진 mtDNA를 가진 약 124,000년 전의 독일 네안데르탈인 표본을 설명하는 데 사용되지만, 유전체 DNA는 150,000년 전에 갈라진 것을 나타냅니다.[90]

데니소바 동굴에서 데니소바의 게놈을 시퀀싱한 결과 게놈의 17%가 네안데르탈인에서 유래한 것으로 나타났습니다.[93] 이 네안데르탈인 DNA는 크로아티아 빈디자 동굴이나 코카서스 메즈마이스카야 동굴의 네안데르탈인보다 같은 동굴의 12만 년 된 네안데르탈인 뼈와 더 유사해 이종교배가 국지적임을 시사했습니다.[92]

90,000년 된 데니소바 11세의 경우, 그녀의 아버지는 이 지역의 더 최근 거주자들과 관련된 데니소바인이고, 그녀의 어머니는 크로아티아의 빈디자 동굴에서 더 최근 유럽의 네안데르탈인과 관련된 네안데르탈인인인 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 데니소반의 뼈가 얼마나 적은지를 감안할 때, 1세대 잡종의 발견은 이 종들 사이에 이종교배가 매우 흔했다는 것을 나타내며, 유라시아를 가로지르는 네안데르탈인의 이동은 12만년 전 이후 언젠가 발생했을 가능성이 높습니다.[431]

절멸

전이

네안데르탈인의 멸종은 더 광범위한 후기 플라이스토세 거대 동물 멸종 사건의 일부였습니다.[432] 그들의 멸종 원인이 무엇이든 간에, 네안데르탈인은 41,000년에서 39,000년 전에 유럽 전역에서 현대 인류의 상부 구석기 시대 오리냐기 시대 석기 기술로 거의 완전히 대체되었음을 나타냅니다.[8][9][11][433] 네안데르탈인은 BP 44,200에서 BP 40,600 사이에 북서유럽에서 사라졌습니다.[434] 그러나 이베리아 네안데르탈인은 약 35,000년 전까지 지속된 것으로 추정되며, 이는 과도기 석류 집합체의 연대 범위에서 알 수 있습니다.—샤텔페로니안, 울루지안, 원시 오리냐키안, 초기 오리냐키안. 후자의 두 가지는 현대 인간에 기인하지만, 전자의 두 가지는 저자가 확인되지 않았으며, 잠재적으로 네안데르탈인/현대 인간의 동거 및 문화적 전파의 산물입니다. 게다가, 에브로 강 남쪽에 있는 오리냐키아인의 출현은 약 37,500년 전으로 거슬러 올라가는데, 이것은 에브로 강이 현대 인류의 이민을 막고 따라서 네안데르탈인의 지속성을 연장시키는 지리적 장벽을 제시했다는 "에브로 프론티어" 가설을 촉발시켰습니다.[435][436] 그러나 이베리아 전환기의 연대는 스페인 쿠에바 바욘딜로에서 43,000-40,800년 전으로 논쟁 중입니다.[437][438][439][440] 샤텔페로니안은 약 42,500년에서 41,600년 전에 이베리아 북동부에서 나타납니다.[435]

지브롤터에 있는 일부 네안데르탈인은 이보다 훨씬 나중에 자프라야(3만년 전)[441]나 고럼 동굴(2만8천년 전)[442]과 같이 직접적인 연대가 아닌 모호한 인공물을 기반으로 했기 때문에 정확하지 않을 수 있습니다.[11] 네안데르탈인이 우랄 산맥의[169] 극지방 피난처에서 살아남았다는 주장은 현대 인류가 아직 유럽의 북부 지역을 식민지로 삼지 않았을 수도 있는 시기에 북부 시베리아 바이조바야 유적지에서 34,000년 전으로 거슬러 올라가는 무스터 석기에 의해 느슨하게 지지됩니다.[171] 그러나 4만년 전의 것으로 추정되는 인근 마몬토바야 쿠리아 유적지에서 현대인의 유해가 알려졌습니다.[443] 메즈마이스카야 동굴의 네안데르탈인 유적의 간접 연대 측정은 약 30,000년 전의 연대를 보고했지만, 직접 연대 측정은 대신 39,700 ± 1,100년 전을 산출했으며, 이는 유럽의 나머지 지역에서 나타나는 추세와 더 일치합니다.[10]

상부 구석기 시대의 현대 인류가 유럽으로 이주한 가장 초기의 징후는 4만 8천 년 전에 시작된 발칸 보후니인 산업으로, 레반틴 에미란 산업에서 유래했을 가능성이 높으며,[355] 유럽의 가장 초기의 뼈는 불가리아,[444] 이탈리아,[445] 영국에서 약 45~43,000년 전으로 거슬러 올라갑니다.[446] 이 현대 인류의 물결은 네안데르탈인을 대체했습니다.[8] 그러나 네안데르탈인과 H. 사피엔스는 훨씬 더 오랜 접촉 역사를 가지고 있습니다. DNA 증거에 따르면 H. sapiens는 빠르면 120-100,000년 전에 네안데르탈인과 접촉하여 혼합물을 만들었습니다. 네안데르탈인의 것으로 추정되는 그리스 아피디마 동굴의 21만년 된 두개골 파편을 2019년 재분석한 결과, 현생인류의 것으로 결론내렸으며, 동굴에서 나온 17만년 전의 네안데르탈인 두개골은 H. 사피엔스가 약 4만년 전으로 돌아가기 전까지 네안데르탈인으로 대체되었음을 나타냅니다.[447] 이 식별은 2020년 연구에 의해 반박되었습니다.[448] 고고학적 증거에 따르면 네안데르탈인은 약 10만 년 전부터 약 60~50,000년 전까지 근동에서 현생 인류를 이주시켰다고 합니다.[100]

원인

현생인류

역사적으로 현대 인류의 기술은 더 효율적인 무기와 생존 전략으로 네안데르탈인의 기술보다 훨씬 뛰어나다고 여겨졌고, 네안데르탈인은 단순히 경쟁할 수 없어서 멸종되었습니다.[19]

네안데르탈인/현대인의 내향성의 발견은 오늘날 모든 인간의 유전적 구성이 전 세계에 흩어져 있는 여러 다른 인간 집단 간의 복잡한 유전적 접촉의 결과라는 다중 영역 가설의 부활을 야기했습니다. 이 모델에 의해, 네안데르탈인과 다른 최근의 고대 인류들은 단순히 현대 인간 게놈에 동화되었습니다. 즉, 그들은 효과적으로 멸종으로 번식했습니다.[19] 현생 인류는 약 3,000년에서 5,000년 동안 유럽에서 네안데르탈인과 공존했습니다.[449]

기후 변화

그들의 궁극적인 멸종은 극심한 계절성의 시기인 하인리히 사건 4와 일치합니다. 나중에 하인리히 사건은 또한 유럽의 인구가 붕괴되었을 때 거대한 문화적 전환과 관련이 있습니다.[20][21] 이 기후 변화는 이전의 콜드 스파이크와 같은 네안데르탈인의 여러 지역에서 개체수가 감소했을 수 있지만, 이 지역들은 대신 이주한 인간들에 의해 개체수가 다시 증가하여 네안데르탈인의 멸종으로 이어졌습니다.[450] 남부 이베리아에서는 H4 기간 동안 네안데르탈인의 개체수가 감소하고 아르테미시아가 지배하는 사막 스텝의 증식이 관련되었다는 증거가 있습니다.[451]

그들의 낮은 인구는 생존율이나 출산율의 작은 감소가 빠르게 멸종으로 이어질 수 있는 환경 변화에 취약하게 만들기 때문에 기후 변화가 주요 동인이라고 제안되었습니다.[452] 하지만, 네안데르탈인과 그들의 조상들은 수십만 년의 유럽 거주 기간 동안 몇 차례의 빙하기를 겪으며 살아남았습니다.[279] 또한 약 40,000년 전, 네안데르탈인의 개체수가 이미 다른 요인들에 의해 감소하고 있었을 수도 있지만, 이탈리아의 캄파니아 이그님브라이트 분화로 인해 1년 동안 2-4 °C (3.6–7.2 °F)의 냉각이 발생하고 몇 년 동안 산성비가 추가로 발생했기 때문에 최종적인 소멸을 초래했을 수도 있다고 제안됩니다.[22][453]

질병

현생 인류는 아프리카 질병을 네안데르탈인에게 도입하여 멸종에 기여했을 수 있습니다. 면역력 부족은 이미 낮은 인구로 인해 네안데르탈인 인구에게 잠재적으로 치명적이었고, 낮은 유전적 다양성은 더 적은 수의 네안데르탈인이 이러한 새로운 질병에 자연적으로 면역력을 갖게 할 수도 있었습니다("차분적 병원체 내성" 가설). 그러나 현대 인간과 비교하여 네안데르탈인은 적응 면역계와 관련된 12개의 주요 조직적합성 복합체(MHC) 유전자에 대해 유사하거나 더 높은 유전적 다양성을 나타내어 이 모델에 의문을 제기했습니다.[24]

낮은 인구와 근친상간 우울증은 부적응적 출생 결함을 야기했을 수 있으며, 이는 그들의 감소(돌연변이 용해)에 기여했을 수 있습니다.[243]

20세기 후반 뉴기니에서 식인 풍습으로 인해 포레 사람들은 전염성 해면상 뇌병증, 특히 뇌 조직에서 발견되는 프리온을 섭취하여 전염되는 매우 치명적인 질병인 쿠루에 의해 사망했습니다. 그러나 PRNP 유전자의 129개 변이체를 가진 개인은 자연적으로 프리온에 면역성이 있었습니다. 이 유전자를 연구한 결과 129 변종이 모든 현대 인류에게 널리 퍼져 있다는 발견으로 이어졌는데, 이는 인류 선사 시대의 어느 시점에서 광범위한 식인 풍습을 나타낼 수 있습니다. 네안데르탈인은 어느 정도 식인 풍습을 행했고 현대 인류와 공존했던 것으로 알려져 있기 때문에, 영국의 고생물학자 사이먼 언더다운은 현대 인류가 쿠루와 유사한 해면병을 네안데르탈인에게 옮겼다고 추측했고, 129개의 변종이 네안데르탈인에게는 없었던 것으로 보이기 때문에, 그것은 그들을 빠르게 죽였습니다.[23][454]

대중문화에서

네안데르탈인은 문학, 시각 미디어, 코미디 등 대중문화에서 등장했습니다. "동굴인"의 원형은 종종 네안데르탈인을 조롱하고 동물의 본능에 의해 움직이는 원시적이고, 촉수가 있고, 너클을 끌며, 몽둥이를 휘두르고, 괴성을 지르며, 비사회적인 캐릭터로 묘사합니다. "네안데르탈인"은 모욕으로 사용될 수도 있습니다.[25]

문학에서 그들은 H. G. 웰스의 '그리슬리 포크'나 엘리자베스 마샬 토마스의 '애니멀 와이프'처럼 때때로 야만적이거나 괴물 같은 것으로 묘사되지만, 윌리엄 골딩의 '상속자들', 비에른 쿠르텐의 '호랑이의 춤', 장 M.처럼 때로는 문명화되지만 낯선 문화로 묘사됩니다. 아우엘의 동굴곰 클랜과 그녀의 지구의 아이들 시리즈.[26]

참고 항목

- 데니소반 – 아시아 고대 인류

- 초기 인류의 이동

- 초기 유럽 현생 인류 – 유럽에서 해부학적으로 가장 초기의 현생 인류 페이지에

- 호모 플로레시엔시스 – 인도네시아 플로레스에서 온 고대 인류

- 호모 루조넨시스 – 필리핀 루조넨시스에서 온 고대 인류

- 호모날레디 – 남아프리카 고대 인류 종

- 휴먼 타임라인

각주

- ^ 석회암을 채굴한 후 1900년까지 동굴이 파여 사라졌습니다. 1997년 고고학자 랄프 슈미츠와 위르겐 티센에 의해 재발견되었습니다.[101]

- ^ 독일어 철자 탈("valley")은 1901년까지 사용되었지만 그 이후로 탈이었습니다. (독일어 명사는 영어 dale와 동음임) 독일어 /t/ 음소는 15세기에서 19세기 사이에 자주 쓰였지만, 1901년에 Tal이라는 철자가 표준화되었고, 계곡에 대한 독일어 이름 네안데르탈인과 종에 대한 네안데르탈인의 오래된 철자는 모두 h가 없는 철자로 바뀌었습니다.[102][103]

- ^ 메트만의 "네안데르 계곡"에는 네안데르탈인 박물관(독일어로는 네안데르탈인 박물관이 필요하지만), 네안데르탈인 역(반호프 네안데르탈인), 그리고 관광객들을 위한 몇 가지 희귀한 행사와 같은 구식 철자를 사용하는 지역적인 특이한 점이 있습니다. 이를 넘어 종을 참조할 때 사용하는 것이 도시 컨벤션입니다.[103]

- ^ 왕은 오타를 내고 "신학적"이라고 말했습니다.

- ^ 이 뼈들은 빌헬름 베커쇼프와 프리드리히 빌헬름 피에퍼의 연구원들에 의해 발견되었습니다. 처음에 노동자들은 뼈를 잔해로 던졌지만, 베커쇼프는 뼈를 보관하라고 말했습니다. 피에퍼는 풀로트에게 동굴로 올라와 뼈를 조사해달라고 요청했는데, 베커쇼프와 피에퍼는 이 뼈가 동굴 곰의 것이라고 믿었습니다.[101]

- ^ OAS1과[414] STAT2는[415] 둘 다 바이러스 주입(인터페론)과 싸우는 것과 관련이 있으며, 나열된 톨 유사 수용체([416]TLR)는 세포가 박테리아, 곰팡이 또는 기생 병원체를 식별할 수 있도록 합니다. 아프리카 기원은 또한 더 강한 염증 반응과 상관관계가 있습니다.[95]

- ^ 더 높은 수준의 네안데르탈인 유래 유전자는 네안데르탈인의 것과 유사한 후두골 및 두정골 형태뿐만 아니라 시각 피질 및 두정골 내 황반(시각 처리와 관련된)의 변형과 관련이 있습니다.[417]

- ^ 호모 플로레시엔시스는 알려지지 않은 조상들의 알려지지 않은 위치에서 시작되어 인도네시아의 외딴 지역에 도달했습니다. 호모 에렉투스는 아프리카에서 서아시아로, 그리고 동아시아와 인도네시아로 퍼졌습니다; 유럽에서의 존재는 불확실하지만, 그것은 스페인에서 발견된 호모 에렉투스를 낳았습니다. 호모 하이델베르겐시스는 알 수 없는 위치에 있는 호모 에렉투스에서 유래하여 아프리카, 아시아 남부 및 유럽 전역에 흩어져 있습니다(다른 과학자들은 화석을 하이델베르겐시스라고 해석하며 여기서는 후기 에렉투스라고 합니다). 현생 인류는 아프리카에서 서아시아로, 그리고 유럽과 남아시아로 퍼져나갔고, 결국 호주와 아메리카에 도달했습니다. 오른쪽에는 네안데르탈인과 데니소반인 외에 고대 아프리카 기원의 세 번째 유전자 흐름이 표시되어 있습니다.[429] 이 차트에는 네안데르탈인/데니소반인 공통 조상에 대한 초고대(Electus 1.9 mya에서 갈라짐) 침입이 없습니다.[159]

참고문헌

- ^ a b Haeckel, E. (1895). Systematische Phylogenie: Wirbelthiere (in German). G. Reimer. p. 601.

- ^ Schwalbe, G. (1906). Studien zur Vorgeschichte des Menschen [Studies on the pre-history of man] (in German). Stuttgart, E. Nägele. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.61918. hdl:2027/uc1.b4298459.

- ^ Klaatsch, H. (1909). "Preuves que l'Homo Mousteriensis Hauseri appartient au type de Neandertal" [Evidence that Homo Mousteriensis Hauseri belongs to the Neanderthal type]. L'Homme Préhistorique (in French). 7: 10–16.

- ^ Romeo, L. (1979). Ecce Homo!: a lexicon of man. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 92. ISBN 978-90-272-2006-6.

- ^ a b c d e McCown, T.; Keith, A. (1939). The stone age of Mount Carmel. The fossil human remains from the Levalloisso-Mousterian. Vol. 2. Clarenden Press.

- ^ Szalay, F. S.; Delson, E. (2013). Evolutionary history of the Primates. Academic Press. p. 508. ISBN 978-1-4832-8925-0.

- ^ Wells, J. (2008). Longman pronunciation dictionary (3rd ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b c Higham, T.; Douka, K.; Wood, R.; Ramsey, C. B.; Brock, F.; Basell, L.; Camps, M.; Arrizabalaga, A.; Baena, J.; Barroso-Ruíz, C.; C. Bergman; C. Boitard; P. Boscato; M. Caparrós; N.J. Conard; C. Draily; A. Froment; B. Galván; P. Gambassini; A. Garcia-Moreno; S. Grimaldi; P. Haesaerts; B. Holt; M.-J. Iriarte-Chiapusso; A. Jelinek; J.F. Jordá Pardo; J.-M. Maíllo-Fernández; A. Marom; J. Maroto; M. Menéndez; L. Metz; E. Morin; A. Moroni; F. Negrino; E. Panagopoulou; M. Peresani; S. Pirson; M. de la Rasilla; J. Riel-Salvatore; A. Ronchitelli; D. Santamaria; P. Semal; L. Slimak; J. Soler; N. Soler; A. Villaluenga; R. Pinhasi; R. Jacobi; et al. (2014). "The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance". Nature. 512 (7514): 306–309. Bibcode:2014Natur.512..306H. doi:10.1038/nature13621. hdl:1885/75138. PMID 25143113. S2CID 205239973.

We show that the Mousterian [the Neanderthal tool-making tradition] ended by 41,030–39,260 calibrated years BP (at 95.4% probability) across Europe. We also demonstrate that succeeding 'transitional' archaeological industries, one of which has been linked with Neanderthals (Châtelperronian), end at a similar time.

- ^ a b Higham, T. (2011). "European Middle and Upper Palaeolithic radiocarbon dates are often older than they look: problems with previous dates and some remedies". Antiquity. 85 (327): 235–249. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00067570. S2CID 163207571.

Few events of European prehistory are more important than the transition from ancient to modern humans about 40,000 years ago, a period that unfortunately lies near the limit of radiocarbon dating. This paper shows that as many as 70 per cent of the oldest radiocarbon dates in the literature may be too young, due to contamination by modern carbon.

- ^ a b Pinhasi, R.; Higham, T. F. G.; Golovanova, L. V.; Doronichev, V. B. (2011). "Revised age of late Neanderthal occupation and the end of the Middle Palaeolithic in the northern Caucasus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (21): 8611–8616. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.8611P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018938108. PMC 3102382. PMID 21555570.

The direct date of the fossil (39,700±1,100 14C BP) is in good agreement with the probability distribution function, indicating at a high level of probability that Neanderthals did not survive at Mezmaiskaya Cave after 39 kya cal BP. [...] This challenges previous claims for late Neanderthal survival in the northern Caucasus. [...] Our results confirm the lack of reliably dated Neanderthal fossils younger than ≈40 kya cal BP in any other region of Western Eurasia, including the Caucasus.

- ^ a b c Galván, B.; Hernández, C. M.; Mallol, C.; Mercier, N.; Sistiaga, A.; Soler, V. (2014). "New evidence of early Neanderthal disappearance in the Iberian Peninsula". Journal of Human Evolution. 75: 16–27. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.06.002. PMID 25016565.

- ^ a b c Stringer, C. (2012). "The status of Homo heidelbergensis (Schoetensack 1908)". Evolutionary Anthropology. 21 (3): 101–107. doi:10.1002/evan.21311. PMID 22718477. S2CID 205826399.

- ^ a b Gómez-Robles, A. (2019). "Dental evolutionary rates and its implications for the Neanderthal–modern human divergence". Science Advances. 5 (5): eaaw1268. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.1268G. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw1268. PMC 6520022. PMID 31106274.

- ^ a b c d e f g Meyer, M.; Arsuaga, J.; de Filippo, C.; Nagel, S. (2016). "Nuclear DNA sequences from the Middle Pleistocene Sima de los Huesos hominins". Nature. 531 (7595): 504–507. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..504M. doi:10.1038/nature17405. PMID 26976447. S2CID 4467094.

- ^ a b Klein, R. G. (1983). "What Do We Know About Neanderthals and Cro-Magnon Man?". Anthropology. 52 (3): 386–392. JSTOR 41210959.

- ^ Vaesen, Krist; Dusseldorp, Gerrit L.; Brandt, Mark J. (2021). "An emerging consensus in palaeoanthropology: Demography was the main factor responsible for the disappearance of Neanderthals". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 4925. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.4925V. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-84410-7. PMC 7921565. PMID 33649483.

- ^ Vaesen, Krist; Dusseldorp, Gerrit L.; Brandt, Mark J. (2021). "Author correction: 'An Emerging Consensus in Palaeoanthropology: Demography Was the Main Factor Responsible for the Disappearance of Neanderthals'". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 8450. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.8450V. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-88189-5. PMC 8044239. PMID 33850254. S2CID 233232999.

- ^ a b Wynn, Thomas; Overmann, Karenleigh A; Coolidge, Frederick L (2016). "The false dichotomy: A refutation of the Neandertal indistinguishability claim". Journal of Anthropological Sciences. 94 (94): 201–221. doi:10.4436/jass.94022 (inactive March 6, 2024). PMID 26708102. S2CID 15817439.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 메인트: DOI 2024년 3월 기준 비활성화 (링크) - ^ a b c Villa, P.; Roebroeks, W. (2014). "Neandertal demise: an archaeological analysis of the modern human superiority complex". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e96424. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...996424V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096424. PMC 4005592. PMID 24789039.

- ^ a b Bradtmöller, M.; Pastoors, A.; Weninger, B.; Weninger, G. (2012). "The repeated replacement model – Rapid climate change and population dynamics in Late Pleistocene Europe". Quaternary International. 247: 38–49. Bibcode:2012QuInt.247...38B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2010.10.015.

- ^ a b Wolf, D.; Kolb, T.; Alcaraz-Castaño, M.; Heinrich, S. (2018). "Climate deteriorations and Neanderthal demise in interior Iberia". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 7048. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.7048W. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25343-6. PMC 5935692. PMID 29728579.

- ^ a b c Black, B. A.; Neely, R. R.; Manga, M. (2015). "Campanian Ignimbrite volcanism, climate, and the final decline of the Neanderthals" (PDF). Geology. 43 (5): 411–414. Bibcode:2015Geo....43..411B. doi:10.1130/G36514.1. OSTI 1512181. S2CID 128647846.

- ^ a b Underdown, S. (2008). "A potential role for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies in Neanderthal extinction". Medical Hypotheses. 71 (1): 4–7. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2007.12.014. PMID 18280671.

- ^ a b Sullivan, A. P.; de Manuel, M.; Marques-Bonet, T.; Perry, G. H. (2017). "An evolutionary medicine perspective on Neandertal extinction" (PDF). Journal of Human Evolution. 108: 62–71. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.03.004. PMID 28622932. S2CID 4592682.

- ^ a b c d e f g Papagianni & Morse 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Drell, J. R. R. (2000). "Neanderthals: a history of interpretation". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 19 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1111/1468-0092.00096. S2CID 54616107.

- ^ a b Shaw, I.; Jameson, R., eds. (1999). A dictionary of archaeology. Blackwell. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-631-17423-3.

- ^ a b Lycett, S. J.; von Cramon-Taubadel, N. (2013). "A 3D morphometric analysis of surface geometry in Levallois cores: patterns of stability and variability across regions and their implications". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (3): 1508–1517. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40.1508L. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.11.005.

- ^ a b Sorensen, A. C.; Claud, E.; Soressi, M. (2018). "Neandertal fire-making technology inferred from microwear analysis". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 10065. Bibcode:2018NatSR...810065S. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28342-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6053370. PMID 30026576.

- ^ a b Brittingham, A.; Hren, M. T.; Hartman, G.; Wilkinson, K. N.; Mallol, C.; Gasparyan, B.; Adler, D. S. (2019). "Geochemical evidence for the control of fire by Middle Palaeolithic hominins". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 15368. Bibcode:2019NatSR...915368B. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-51433-0. PMC 6814844. PMID 31653870.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hayden, B. (2012). "Neandertal social structure?". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 31 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.2011.00376.x.

- ^ a b c Kedar, Y.; Barkai, R. (2019). "The significance of air circulation and hearth location at Paleolithic cave sites". Open Quaternary. 5 (1): 4. doi:10.5334/oq.52.

- ^ Angelucci, Diego E.; Nabais, Mariana; Zilhão, João (2023). "Formation processes, fire use, and patterns of human occupation across the Middle Palaeolithic (MIS 5a-5b) of Gruta da Oliveira (Almonda karst system, Torres Novas, Portugal)". PLOS ONE. 18 (10): e0292075. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1892075A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0292075. PMC 10566745. PMID 37819902.

- ^ a b Schmidt, P.; Blessing, M.; Rageot, M.; Iovita, R.; Pfleging, J.; Nickel, K. G.; Righetti, L.; Tennie, C. (2019). "Birch tar production does not prove Neanderthal behavioral complexity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (36): 17707–17711. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11617707S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1911137116. PMC 6731756. PMID 31427508.

- ^ a b Hoffecker, J. F. (2009). "The spread of modern humans in Europe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16040–16045. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616040H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903446106. PMC 2752585. PMID 19571003.

- ^ a b Hardy, B. L.; Moncel, M.-H.; Kerfant, C.; et al. (2020). "Direct evidence of Neanderthal fibre technology and its cognitive and behavioral implications". Scientific Reports. 10 (4889): 4889. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.4889H. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61839-w. PMC 7145842. PMID 32273518.

- ^ a b Ferentinos, G.; Gkioni, M.; Geraga, M.; Papatheodorou, G. (2012). "Early seafaring activity in the southern Ionian Islands, Mediterranean Sea". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (7): 2167–2176. Bibcode:2011JQS....26..553S. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.01.032.

- ^ a b c d Strasser, T. F.; Runnels, C.; Wegmann, K. W.; Panagopoulou, E. (2011). "Dating Palaeolithic sites in southwestern Crete, Greece". Journal of Quaternary Science. 26 (5): 553–560. Bibcode:2011JQS....26..553S. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.01.032.

- ^ a b c Buckley, S.; Hardy, K.; Huffman, M. (2013). "Neanderthal self-medication in context". Antiquity. 87 (337): 873–878. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00049528. S2CID 160563162.

- ^ a b c Lev, E.; Kislev, M. E.; Bar-Yosef, O. (2005). "Mousterian vegetal food in Kebara Cave, Mt. Carmel". Journal of Archaeological Science. 32 (3): 475–484. Bibcode:2005JArSc..32..475L. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2004.11.006.

- ^ Power, R. C.; Salazar-García, D. C.; Rubini, M.; Darlas, A.; Harvati, K.; Walker, M.; Hublin, J.; Henry, A. G. (2018). "Dental calculus indicates widespread plant use within the stable Neanderthal dietary niche". Journal of Human Evolution. 119: 27–41. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.02.009. hdl:10550/65536. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 29685752. S2CID 13831823.

- ^ a b c d e f Spikins, P.; Needham, A.; Wright, B. (2019). "Living to fight another day: The ecological and evolutionary significance of Neanderthal healthcare". Quaternary Science Reviews. 217: 98–118. Bibcode:2019QSRv..217...98S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.08.011.

- ^ a b c Valensi, P.; Michel, V.; et al. (2013). "New data on human behavior from a 160,000 year old Acheulean occupation level at Lazaret cave, south-east France: An archaeozoological approach". Quaternary International. 316: 123–139. Bibcode:2013QuInt.316..123V. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.10.034.

- ^ a b c d Krief, S.; Daujeard, C.; Moncel, M.; Lamon, N.; Reynolds, V. (2015). "Flavouring food: the contribution of chimpanzee behaviour to the understanding of Neanderthal calculus composition and plant use in Neanderthal diets". Antiquity. 89 (344): 464–471. doi:10.15184/aqy.2014.7. S2CID 86646905.

- ^ a b Hardy, K.; Buckley, S.; Collins, M. J.; Estalrrich, A. (2012). "Neanderthal medics? Evidence for food, cooking, and medicinal plants entrapped in dental calculus". The Science of Nature. 99 (8): 617–626. Bibcode:2012NW.....99..617H. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0942-0. PMID 22806252. S2CID 10925552.

- ^ a b c d Dusseldorp, G. L. (2013). "Neanderthals and Cave Hyenas: Co-existence, Competition or Conflict?" (PDF). In Clark, J. L.; Speth, J. D. (eds.). Zooarchaeology and Modern Human Origins. Vertebrate paleobiology and paleoanthropology. Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. pp. 191–208. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6766-9_12. ISBN 978-94-007-6765-2.

- ^ a b c Richards, M. P.; Pettitt, P. B.; Trinkaus, E.; Smith, F. H.; Paunović, M.; Karavanić, I. (2000). "Neanderthal diet at Vindija and Neanderthal predation: The evidence from stable isotopes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (13): 7663–7666. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.7663R. doi:10.1073/pnas.120178997. JSTOR 122870. PMC 16602. PMID 10852955.

- ^ a b Henry, A. G.; Brooks, A. S.; Piperno, D. R. (2011). "Microfossils in calculus demonstrate consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets (Shanidar III, Iraq; Spy I and II, Belgium)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (2): 486–491. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108..486H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016868108. PMC 3021051. PMID 21187393.

- ^ a b Shipley, G. P.; Kindscher, K. (2016). "Evidence for the paleoethnobotany of the Neanderthal: a review of the literature". Scientifica. 2016: 1–12. doi:10.1155/2016/8927654. PMC 5098096. PMID 27843675.

- ^ a b Madella, M.; Jones, M. K.; Goldberg, P.; Goren, Y.; Hovers, E. (2002). "The Exploitation of plant resources by Neanderthals in Amud Cave (Israel): the evidence from phytolith studies". Journal of Archaeological Science. 29 (7): 703–719. Bibcode:2002JArSc..29..703M. doi:10.1006/jasc.2001.0743. S2CID 43217031.

- ^ a b c d e f 브라운 2011.

- ^ a b Shipman 2015, pp. 120-143.

- ^ a b c d 2015년을 모두 망쳤어요.

- ^ a b d’Errico, F.; Tsvelykh, A. (2017). "A decorated raven bone from the Zaskalnaya VI (Kolosovskaya) Neanderthal site, Crimea". PLOS ONE. 12 (3): e0173435. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1273435M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173435. PMC 5371307. PMID 28355292.

- ^ a b c 2019년 마무리.

- ^ a b Hoffman, D. L.; Angelucci, D. E.; Villaverde, V.; Zapata, Z.; Zilhão, J. (2018). "Symbolic use of marine shells and mineral pigments by Iberian Neandertals 115,000 years ago". Science Advances. 4 (2): eaar5255. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.5255H. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aar5255. PMC 5833998. PMID 29507889.

- ^ a b c Moncel, M.-H.; Chiotti, L.; Gaillard, C.; Onoratini, G.; Pleurdeau, D. (2012). "Non utilitarian objects in the Palaeolithic: emergence of the sense of precious?". Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia. 401: 25–27. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2012.05.004.

- ^ a b c Majkić, A.; d’Errico, F.; Stepanchuk, V. (2018). "Assessing the significance of Palaeolithic engraved cortexes. A case study from the Mousterian site of Kiik-Koba, Crimea". PLOS ONE. 13 (5): e0195049. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1395049M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195049. PMC 5931501. PMID 29718916.

- ^ a b Turk, M.; Turk, I.; Dimkaroski, L. (2018). "The Mousterian musical instrument from the Divje Babe I Cave (Slovenia): arguments on the material evidence for Neanderthal musical behaviour". L'Anthropologie. 122 (4): 1–28. doi:10.1016/j.anthro.2018.10.001. S2CID 133682741. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Aubert, M.; Brumm, A.; Huntley, J. (2018). "Early dates for 'Neanderthal cave art' may be wrong". Journal of Human Evolution. 125: 215–217. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.08.004. PMID 30173883. S2CID 52145541.

- ^ a b Pike, A. W.; Hoffmann, D. L.; Pettitt, P. B.; García-Diez, M.; Zilhão, J. (2017). "Dating Palaeolithic cave art: Why U–Th is the way to go" (PDF). Quaternary International. 432: 41–49. Bibcode:2017QuInt.432...41P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.12.013. S2CID 130629624.

- ^ a b Hoffmann, D. L.; Standish, C. D.; García-Diez, M.; Pettitt, P. B.; Milton, J. A.; Zilhão, J.; Alcolea-González, J. J.; Cantalejo-Duarte, P.; Collado, H.; de Balbín, R.; Lorblanchet, M.; Ramos-Muñoz, J.; Weniger, G.-C.; Pike, A. W. G. (2018). "U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberian cave art". Science. 359 (6378): 912–915. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..912H. doi:10.1126/science.aap7778. hdl:10498/21578. PMID 29472483.

- ^ a b Wunn, I. (2000). "Beginning of religion". Numen. 47 (4): 417–452. doi:10.1163/156852700511612.

- ^ a b c Dediu, D.; Levinson, S. C. (2018). "Neanderthal language revisited: not only us". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 21: 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.01.001. hdl:21.11116/0000-0000-1667-4. S2CID 54391128.

- ^ a b D’Anastasio, R.; Wroe, S.; Tuniz, C.; Mancini, L.; Cesana, D. T. (2013). "Micro-biomechanics of the Kebara 2 hyoid and its implications for speech in Neanderthals". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e82261. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...882261D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082261. PMC 3867335. PMID 24367509.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stewart, J.R.; García-Rodríguez, O.; Knul, M.V.; Sewell, L.; Montgomery, H.; Thomas, M.G.; Diekmann, Y. (2019). "Palaeoecological and genetic evidence for Neanderthal power locomotion as an adaptation to a woodland environment". Quaternary Science Reviews. 217: 310–315. Bibcode:2019QSRv..217..310S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.023. S2CID 133980969.

- ^ a b Kislev, M.; Barkai, R. (2018). "Neanderthal and woolly mammoth molecular resemblance". Human Biology. 90 (2): 115–128. doi:10.13110/humanbiology.90.2.03. PMID 33951886. S2CID 106401104.

- ^ a b de Azevedo, S.; González, M. F.; Cintas, C.; et al. (2017). "Nasal airflow simulations suggest convergent adaptation in Neanderthals and modern humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (47): 12442–12447. Bibcode:2017PNAS..11412442D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1703790114. PMC 5703271. PMID 29087302.

- ^ Rae, T. C.; Koppe, T.; Stringer, C. B. (2011). "The Neanderthal face is not cold adapted". Journal of Human Evolution. 60 (2): 234–239. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.10.003. PMID 21183202.