인종청소

Ethnic cleansing| 에 관한 시리즈의 일부 |

| 변별력 |

|---|

|

인종 청소는 특정 지역에서 민족적으로 동질적인 지역을 만들기 위한 목적으로 민족적, 인종적 또는 종교적 그룹을 조직적으로 강제로 제거하는 것입니다. 강제퇴거나 인구이송 등의 직접적인 제거와 함께 피해자 집단을 강제로 도피시키고 살인, 강간, 재산파괴 등의 귀환을 방지함으로써 강제이주를 목적으로 하는 간접적인 방법도 포함되어 있습니다.[1][2][3][4][5] 인종 청소의 정의와 혐의는 종종 논쟁의 여지가 있는데, 일부 연구자들과 일부 연구자들은 특정 집단의 지역을 인구 감소시키는 수단으로 강압적인 동화 또는 대량 학살을 제외하고 있습니다.[6][7][8]

비록 학자들이 어떤 사건이 인종 청소를 구성하는지에 대해 동의하지 않지만,[7] 역사를 통틀어 많은 사례가 발생했습니다; 이 용어는 1990년대 유고슬라비아 전쟁 동안 가해자들에 의해 완곡한 표현으로 처음 사용되었습니다. 그 이후로 이 용어는 저널리즘으로 인해 널리 받아들여졌습니다.[9] 연구는 원래 인종 청소 사건에 대한 설명으로 뿌리 깊은 적대감에 초점을 맞추었지만, 보다 최근의 연구는 인종 청소를 "민족 국가의 동질화 경향의 자연스러운 확장"으로 묘사하거나 안보 문제와 민주화 효과를 강조하여 민족 긴장을 기여 요인으로 묘사합니다. 또한 인종 청소의 원인 또는 강화 요인으로서 전쟁의 역할에 대해서도 연구가 집중되어 왔습니다. 그러나 비슷한 전략적 상황에 있는 국가들은 안보 위협으로 인식되는 소수 민족 집단에 매우 다양한 정책을 부과할 수 있습니다.[10]

인종청소는 국제형사법상 법적 정의는 없지만 그 실행방법은 인도에 반한 죄로 간주되고 결과적으로 대량학살협약에 따라 대량학살죄를 구성할 수도 있습니다.[1][11][12]

어원

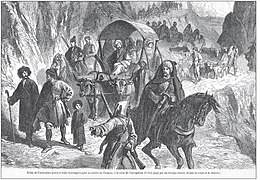

이 용어의 선행어는 그리스어 단어와 rapodismos (ἀνδρα ποδισμ ός; 불)입니다. 기원전 335년 알렉산드로스 대왕의 테베 정복에 수반된 만행을 설명하기 위해 고대 문헌에 사용된 "노예"(en slavement).[16] "치체쿤"이라고도 알려진 서커스 집단 학살은 종종 다양한 역사가들에 의해 19세기 산업 시대 동안 한 국가에 의해 시작된 최초의 대규모 인종 청소 캠페인으로 간주됩니다.[17][18] 1860년대 동안 체르카시인 집단 학살 작전을 감독했던 러시아 제국 장군 니콜라이 예다키모프는 무슬림 체르카시인들을 모국에서 추방하기 위한 "역병"으로 비인간화했습니다. 러시아의 목표는 토지 합병이었고, 예다키모프는 세르비아인들을 강제로 추방한 러시아 군사 작전을 "ochishchenie"(청소)로 지정했습니다.[13]

1900년대 초, 체코인(ochista), 폴란드인(chystiki etniczne), 프랑스인(épuation), 독일인(Säuberung) 사이에서 이 용어의 지역적 변형이 발견되었습니다.[19][page needed] 1913년 발칸 전쟁에 참가한 모든 사람들의 행동을 비난하는 카네기 기금의 보고서에는 민족 집단에 대한 잔혹 행위를 묘사하는 다양한 새로운 용어가 포함되어 있습니다.[20]

제2차 세계 대전 동안 크로아티아 우스타셰는 크로아티아인이 아닌 사람들이 고의로 죽거나 그들의 집에서 뿌리째 뽑힌 군사 행동을 묘사하기 위해 완곡한 표현인 치첸예 테레나("지형을 닦는 것")를 사용했습니다.[21] 우스타셰의 고위 지도자인 빅토르 구티치는 세르비아인들에게 잔혹한 행위를 저지른 것에 대한 완곡한 표현으로 이 용어를 사용한 최초의 크로아티아 민족주의자 중 한 명이었습니다.[22] 이 용어는 나중에 세르비아 체트니크의 내부 비망록에서 1941년에서 1945년 사이에 보스니아인과 크로아티아인에 대해 저지른 여러 보복 학살을 언급하면서 사용되었습니다.[23] 러시아어 문구인 очистка границ(ochistka granits; lit). "국경 정리"(, )는 1930년대 초 소련의 문서에서 22km(14m)에 달하는 바이엘로우시와 우크라이나 SSR의 국경 지대에서 폴란드인들이 강제로 정착한 것을 언급하기 위해 사용되었습니다.[citation needed] 소련의 이러한 인구 이동 과정은 1939-1941년에 훨씬 더 큰 규모로 반복되었으며, 이 과정에는 불충성으로 의심되는 많은 다른 그룹들이 참여했습니다.[24] 홀로코스트 기간 동안 나치 독일은 유럽이 "유대인들로부터 청소"[25]되는 것을 보장하는 정책을 추구했습니다. 나치 총계획서는 독일인들에게 더 많은 생활공간을 제공하기 위한 목적으로 중부와 동유럽의 대부분 슬라브 민족의 대량학살과 인종청소를 요구했습니다.[26]

그 완전한 형태로, 이 용어는 1941년 7월 미하이 안토네스쿠 부총리가 내각 구성원들에게 한 연설에서 루마니아어(순수한 ă)에서 처음으로 등장했습니다. 소련의 침공이 시작된 후,[clarification needed] 그는 이렇게 결론을 내렸습니다: "로마인들이 언제 인종 청소를 할 수 있는 그런 기회를 갖게 될지 모르겠습니다."[27] 1980년대에 소련은 아르메니아인들을 나고르노카라바흐에서 쫓아내기 위한 아제르바이잔의 노력을 묘사하기 위해 문자 그대로 "민족 청소"로 번역되는 "etniceskoye chishcheniye"라는 용어를 사용했습니다.[28][29] 비슷한 시기에 유고슬라비아 언론은 모든 세르비아인들이 코소보를 떠나도록 강요하려는 알바니아 민족주의적 음모라고 주장했습니다. 보스니아 전쟁 (1992-1995) 기간 동안 서방 언론에 의해 널리 대중화되었습니다.

1992년, 독일의 인종 청소에 해당하는 것(독일어: ethnische Sauberung, 발음 [ˈʔɛ tn ɪʃə ˈ츠 ɔɪ̯ b əʁʊŋ]는 완곡하고 부적절한 성격 때문에 Gesellschaft für Deutsche Sprache에 의해 올해의 독일 단어로 선정되었습니다.

정의들

안보리 결의 780호에 따라 제정된 전문가 위원회의 최종 보고서는 인종 청소를 "한 민족 또는 종교 집단이 폭력적이고 공포를 불러일으키는 수단으로 특정 지역에서 다른 민족 또는 종교 집단의 민간인 인구를 제거하기 위해 고안된 목적 있는 정책"이라고 정의했습니다.[31] 이전의 첫 번째 중간 보고서에서, "구 유고슬라비아에서 행해진 정책과 관행을 설명하는 많은 보고서들에 근거하여, '인종청소'가 살인, 고문, 자의적 체포와 구금, 사법 외 처형, 강간과 성폭행에 의해 행해졌다고" 언급했습니다. 게토 지역에서의 민간인 인구의 제한, 강제적인 제거, 민간인 인구의 이동 및 추방, 민간인과 민간인 지역에 대한 고의적인 군사 공격 또는 공격 위협, 재산 파괴의 필요성. 그러한 관행은 반인도적 범죄를 구성하며 특정 전쟁 범죄에 동화될 수 있습니다. 나아가 그러한 행위는 대량학살협약의 의미에도 포함될 수 있습니다."[32]

유엔의 인종 청소에 대한 공식적인 정의는 "다른 민족이나 종교 집단의 주어진 지역에서 사람들을 제거하기 위해 힘이나 위협을 사용함으로써 민족적으로 동질적인 지역을 렌더링하는 것"입니다.[33] 범주로서 인종 청소는 정책의 연속체 또는 스펙트럼을 포함합니다. 앤드류 벨-피알코프의 말을 빌자면, "인종청소는... 쉬운 정의를 거부합니다. 한쪽에서는 강제 이주 및 인구 교환과 사실상 구별할 수 없는 반면 다른 쪽에서는 추방 및 대량 학살과 결합합니다. 그러나 가장 일반적인 수준에서 인종 청소는 특정 지역에서 인구를 추방하는 것으로 이해될 수 있습니다."[34]

테리 마틴(Terry Martin)은 인종 청소를 "특정 영토에서 인종적으로 정의된 인구를 강제로 제거하는 것"이며 "한 쪽 끝에서는 집단 학살과 다른 쪽 끝에서는 비폭력적 압력을 가한 인종 이민 사이의 연속체의 중심 부분을 차지하는 것"이라고 정의했습니다.[24]

제노사이드 워치의 설립자인 그레고리 스탠튼은 이 용어의 증가와 "인종청소"가 법적 정의가 없기 때문에 미디어 사용이 제노사이드로 기소되어야 하는 사건에 대한 관심을 떨어뜨릴 수 있다고 생각합니다.[35][36]

국제법상 범죄로서

인종 청소에 대한 구체적인 범죄를 명시한 국제 조약은 없지만,[37] 넓은 의미의 인종 청소는 국제형사재판소(ICC)와 구 유고슬라비아 국제형사재판소(ICTY)의 법령에 따라 인도에 반하는 범죄로 정의됩니다.[38] 인종 청소에 대한 엄격한 정의에 필수적인 심각한 인권 침해는 반인도적 범죄와 특정 상황에서 대량학살이라는 국제 공법에 속하는 별개의 범죄로 취급됩니다.[39] 제2차 세계대전 후 독일인들이 추방되는 등 법적 구제 없이 인종청소가 이루어진 상황도 있습니다(Preussische Treuhand v. Poland 참조). 티모시 대 워터스(Timothy v. Waters)는 유사한 인종 청소가 미래에 처벌받지 않을 수 있다고 주장합니다.[40]

상호 인종청소

상호 인종 청소는 두 그룹이 자신의 영토 내에서 다른 그룹의 소수 민족 구성원들에게 인종 청소를 저지를 때 발생합니다. 예를 들어 1920년대 그리스-터키 전쟁 이후 튀르키예는 그리스 소수민족을, 그리스는 터키 소수민족을 추방했습니다. 상호 인종 청소가 일어난 다른 예로는 제1차 나고르노-카라바흐 전쟁과[42] 제2차 세계 대전 이후 독일인, 폴란드인, 우크라이나인의 인구 이동이[by whom?] 있습니다.[43]

원인들

마이클 만(Michael Mann)에 따르면 민주주의의 어두운 측면(2004)에서 살인적인 인종 청소는 민주주의의 창조와 밀접한 관련이 있습니다. 그는 살인적인 인종 청소는 시민권을 특정 민족과 연관시키는 민족주의의 부상 때문이라고 주장합니다. 따라서 민주주의는 민족적, 국가적 형태의 배제와 결부되어 있습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 소수 민족은 헌법적 보장을 받는 경향이 있기 때문에 인종 청소를 더 쉽게 저지르는 것은 민주주의 국가가 아닙니다. 살인적인 인종 청소의 가해자일 가능성이 있는 안정적인 권위주의 정권(나치와 공산주의 정권 제외)도 아니고 민주화 과정에 있는 정권들입니다. 민족적 적대감은 민족성이 사회 계층을 무색하게 하는 사회 계층화의 원초적 체계로 나타납니다. 보통 깊이 분열된 사회에서는 계급과 민족 등의 범주가 깊게 얽혀 있는데, 한 민족이 상대방을 억압하거나 착취하는 존재로 비춰질 때 심각한 민족 갈등이 발생할 수 있습니다. 마이클 만(Michael Mann)은 두 민족이 같은 영토에 대한 영유권을 주장하고 위협을 느낄 수 있을 때, 그들의 차이는 심각한 불만과 인종 청소의 위험으로 이어질 수 있다고 주장합니다. 살인적인 인종 청소의 지속은 불안정한 지정학적 환경과 전쟁 상황에서 발생하는 경향이 있습니다. 인종 청소는 높은 수준의 조직을 필요로 하고 일반적으로 국가 또는 다른 권위 있는 권력에 의해 지시되기 때문에 가해자는 일반적으로 인식되는 실패한 국가가 아니라 어느 정도의 일관성과 능력을 가진 국가 권력 또는 기관입니다. 가해자 권력은 민족주의, 국가주의, 폭력의 조합을 선호하는 핵심 선거구의 지지를 받는 경향이 있습니다.[44]

인종 청소는 유럽의 민족주의 시대(19세기와 20세기)에 널리 퍼졌습니다.[45][46] 다민족 유럽인들은 분리와 영토 상실을 막기 위해 소수민족에 대한 인종청소에 참여했습니다.[45] 인종 청소는 국가 간 전쟁 기간 동안 특히 널리 퍼졌습니다.[45]

대량학살

인종 청소는 가장 극단적인 형태가 집단 학살인 폭력의 연속체의 일부로 설명되어 왔습니다. 인종 청소와 집단 학살은 동일한 목표와 방법(예: 강제 이주)을 공유할 수 있지만, 인종 청소는 주어진 영토에서 박해받는 인구를 추방하기 위한 것인 반면, 집단 학살은 집단을 파괴하기 위한 것입니다.[47][48]

일부 학자들은 대량학살을 "살인 인종 청소"의 하위 집합으로 간주합니다.[49] 노먼 나이마크(Norman Naimark)가 쓴 것처럼, 이러한 개념들은 다르지만 "말 그대로 그리고 비유적으로, 민족 청소는 한 민족의 땅을 제거하기 위해 자행되기 때문에 대량 학살로 피를 흘린다"는 것과 관련이 있습니다.[50] 윌리엄 샤바스는 "인종청소는 대량학살이 일어날 것이라는 경고의 표시이기도 합니다. 대량학살은 좌절한 민족청소부의 최후의 수단입니다."[47] 복수의 제노사이드 학자들은 인종청소와 제노사이드를 구분하는 것을 비판하면서, 둘 다 궁극적으로 집단을 파괴하는 결과를 초래하기 때문에 '인종청소'라는 용어를 사용하는 것은 제노사이드 부정의 한 형태라고 주장했습니다.[a][51][35][36]

군사적, 정치적, 경제적 전술로서.

포이베 학살은 제2차 세계 대전 당시와 이후에 주로 유고슬라비아 파르티잔과 OZNA가 율리안 마치 (카르스트 지방과 이스트리아), 크바르네르, 달마티아 등의 이탈리아 영토에서[b] 자행한 대량 학살을 의미합니다.[52][53] 공격 유형은 국가 테러와[52] 이탈리아인에 대한 인종 청소였습니다.[52][53][54][55][56] 푸아베 대학살은 제2차 세계 대전 이후 230,000명에서 350,000명 사이의 이탈리아계 민족(이스트리아계 이탈리아인과 달마티아계 이탈리아인)이 이탈리아로, 그리고 소수는 아메리카, 오스트레일리아, 남아프리카로 탈출하는 것을 의미합니다.[57][58] 전쟁이 끝난 1947년부터 유고슬라비아 당국은 국유화, 수용, 차별적 과세 등 덜 폭력적인 형태의 협박을 가했고,[59] 이로 인해 이민 외에는 선택의 여지가 거의 없었습니다.[60][61][62] 1953년 유고슬라비아에는 36,000명의 선언 이탈리아인이 있었는데, 이는 제2차 세계 대전 이전 이탈리아인 인구의 약 16%에 불과했습니다.[63] 2001년 크로아티아와 2002년 슬로베니아의 인구조사에 따르면, 구 유고슬라비아에 남아있던 이탈리아인은 21,894명(슬로베니아 2,258명, 크로아티아 19,636명)에 달합니다.[64][65] 이스라엘 양치기들은 민족주의와 경제 전쟁의 한 형태로 요르단강 서안 C 지역에서 팔레스타인 양치기들의 체계적인 이동에 참여했습니다.[66][67]

제2차 세계대전 후 1945년 이후 독일 민족이 독일에 강제로 재정착하여 독일인들이 추방된 것과 같이 정치적 해결의 일환으로 강제될 경우, 일종의 인종 청소를 구성하는 강제 인구 운동은 분쟁 후 국가의 장기적인 안정에 기여할 수 있습니다.[70][page needed] 제2차 세계대전 이전 체코슬로바키아와 전쟁 이전 폴란드에서 독일 인구가 많은 일부 사람들이 나치 징고이즘을 장려했지만, 이는 강제적으로 해결된 것처럼 갈등 해결 단계에서 목표 집단이 이동하는 이유에 대해서는 약간의 정당성이 있을 수 있습니다.[70][page needed]

역사학자 노먼 나이마크(Norman Naimark)에 따르면, 인종 청소 과정에서 사원, 책, 기념물, 묘지 및 거리 이름을 포함한 희생자의 물리적 상징이 파괴될 수 있습니다. "인종 청소는 전 국가의 강제 추방뿐만 아니라 그들의 존재에 대한 기억을 근절하는 것을 포함합니다."[71] 많은 경우 인종 청소 의혹을 영속화하는 측과 그 동맹국들은 이 혐의에 대해 격렬하게 이의를 제기해 왔습니다.[clarification needed]

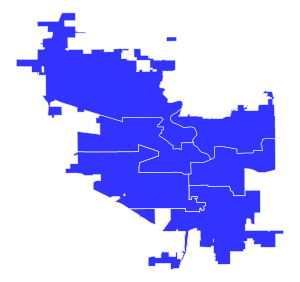

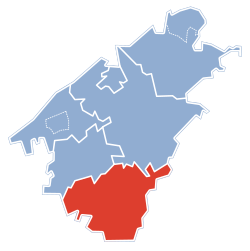

인스턴스

참고 항목

설명주

- ^ "어떻게 극단적인 강요, 정말 폭력 없이 '강제 추방'을 할 수 있었을까요? 정말 추방이 강제될 수 없는 방법입니까? 어떻게 사람들이 저항하지 않을 수 있습니까? 어떻게 한 집단이 어떤 기간 동안 누려온 삶의 방식, 공동체의 파괴를 포함하지 않을 수 있었을까요? 집단을 추방한 사람들이 어떻게 이 파괴를 의도하지 않을 수 있겠습니까? 강제적으로 고국에서 인구를 제거하는 것과 집단의 '파괴'는 어떤 의미에서 다른가요? '청소'와 대량학살의 경계가 비현실적이라면 왜 경찰에 신고하겠습니까?"[51]

- ^ 1947년 평화조약 이후 이탈리아가 유고슬라비아에 연달아 패함

메모들

- ^ a b "Ethnic cleansing". United Nations. United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ Walling, Carrie Booth (2000). "The history and politics of ethnic cleansing". The International Journal of Human Rights. 4 (3–4): 47–66. doi:10.1080/13642980008406892. S2CID 144001685.

Most frequently, however, the aim of ethnic cleansing is to expel the despised ethnic group through either indirect coercion or direct force, and to ensure that return is impossible. Terror is the fundamental method which is used to achieve this end.

Methods of indirect coercion can include: introducing repressive laws and discriminatory measures which are designed to make minority life difficult; the deliberate failure to prevent mob violence against ethnic minorities; using surrogates to inflict violence; the destruction of the physical infrastructure upon which minority life depends; the imprisonment of male members of the ethnic group; threats to rape female members, and threats to kill. If these indirect methods are ineffective, they are often escalated to coerced emigration, where the removal of the ethnic group from the territory is pressured by physical force. This force typically includes physical harassment and the expropriation of property. Deportation is an escalated form of direct coercion because the forcible removal of 'undesirables' from the state's territory is organised, directed and carried out by state agents. The most serious of the direct methods, excluding genocide, is murderous cleansing, which entails the brutal and often public murder of a few or some individuals in order to compel the flight of the remaining members of the group.13 Unlike genocide, when murder is intended to be total and an end in itself, murderous cleansing is used as a tool in an attempt to accomplish the larger aim of expelling survivors from the territory. The process can be made complete by the revokation of the citizenship of those individuals who emigrate or flee. - ^ Schabas, William A. (2003). "'Ethnic Cleansing' and Genocide: Similarities and Distinctions". European Yearbook of Minority Issues Online. 3 (1): 109–128. doi:10.1163/221161104X00075.

The Commission considered techniques of ethnic cleansing to include murder, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, extrajudicial executions, sexual assault, confinement of civilian populations in ghetto areas, forcible removal, displacement and deportation of civilian populations, deliberate military attacks or threats of attacks on civilians and civilian areas, and wanton destruction of property.

- ^ 용어를 과도하게 늘리면 위험을 피할 수 있습니다.인종 청소의 목표는 그 집단이 서식하는 지역에서 영구적으로 제거하는 것입니다...폭력으로 위협하고, 집을 퇴거하고, 대중교통을 조직하고, 원치 않는 사람들의 귀환을 막기 위해 필요한 사람들이 있기 때문에 인종 청소에는 대중적인 차원이 있습니다.인종 청소의 주요 목표는 옥스포드 전후 유럽 역사 핸드북(2012)에서 특정 영토에서 한 집단을 제거하는 것이었습니다. 영국: OUP Oxford.

- ^ Joireman, Sandra Fullerton. Peace, preference, and property : return migration after violent conflict. University of Michigan. p. 49.

Violent conflict changes communities. "Returnees painfully discover that in their period of absence the homeland communities and their identities have undergone transformation, and these ruptures and changes have serious implications for their ability to reclaim a sense of home upon homecoming." The first issue in terms of returning home is usually the restoration of property, specifically the return or rebuilding of homes. People want their property restored, often before they return. But home means more than property, it also refers to the nature of the community. Anthropological literature emphasizes that time and the experience of violence changes people's sense of home and desire to return, and the nature of their communities of origin. To sum up, previous research has identified factors that influence decisions to return: time, trauma, family characteristics and economic opportunities.

- ^ 불루트길 2018, 1136페이지

- ^ a b Garrity, Meghan M (September 27, 2023). ""Ethnic Cleansing": An Analysis of Conceptual and Empirical Ambiguity". Political Science Quarterly. 138 (4): 469–489. doi:10.1093/psquar/qqad082.

- ^ Kirby-McLemore, Jennifer (2021–2022). "Settling the Genocide v. Ethnic Cleansing Debate: Ending Misuse of the Euphemism Ethnic Cleansing". Denver Journal of International Law and Policy. 50: 115.

- ^ Thum 2010, p. 75: way. 완곡한 성격과 가해자들의 언어에서 유래했음에도 불구하고, '민족 청소'는 이제 특정 지역에서 원치 않는 민족을 체계적이고 폭력적으로 제거하는 것을 설명하는 데 널리 받아들여지는 학술 용어입니다.

- ^ Bulutgil, H. Zeynep (2018). "The state of the field and debates on ethnic cleansing". Nationalities Papers. 46 (6): 1136–1145. doi:10.1080/00905992.2018.1457018. S2CID 158519257.

- ^ Jones, Adam (2012). "'Ethnic cleansing' and genocide". Crimes Against Humanity: A Beginner's Guide. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-78074-146-8.

- ^ Schabas, William A. (2003). "'Ethnic Cleansing' and Genocide: Similarities and Distinctions". European Yearbook of Minority Issues Online. 3 (1): 109–128. doi:10.1163/221161104X00075.

'Ethnic cleansing' is probably better described as a popular or journalistic expression, with no recognized legal meaning in a technical sense... 'ethnic cleansing' is equivalent to deportation,' a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions as well as a crime against humanity, and therefore a crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal.

- ^ a b Richmond, Walter (2013). "4: 1864". The Circassian Genocide. New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA: Rutgers University Press. pp. 96, 97. ISBN 978-0-8135-6068-7.

- ^ Levene, Mark (2005). "6: Declining Powers". Genocide in the Age of the Nation-State Volume II: The Rise of the West and the Coming of Genocide. 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010. pp. 299–300. ISBN 1-84511-057-9.

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2011). "Demographic Policy and the Annihilation of the Armenians". The Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15333-9.

The thesis being proposed here is that the Armenian Genocide was not implemented solely as demographic engineering, but also as destruction and annihilation, and that the 5 to 10 percent principle was decisive in achieving this goal. Care was taken so that the number of Armenians deported to Syria, and those who remained behind, would not exceed 5 to 10 percent of the population of the places in which they were found. Such a result could be achieved only through annihilation... According to official Ottoman statistics, it was necessary to reduce the prewar population of 1.3 million Armenians to approximately 200,000.

- ^ Booth Walling, Carrie (2012). "The History and Politics of Ethnic Cleansing". In Booth, Ken (ed.). The Kosovo Tragedy: The Human Rights Dimensions. London: Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-13633-476-4.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013). "3: From War to Genocide". The Circassian Genocide. New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA: Rutgers University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8135-6068-7.

- ^ Levene, Mark (2005). "6: Declining Powers". Genocide in the Age of the Nation-State Volume II: The Rise of the West and the Coming of Genocide. 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010. pp. 298–302. ISBN 1-84511-057-9.

- ^ Ther, Philipp (2004). "The Spell of the Homogeneous Nation State: Structural Factors and Agents of Ethnic Cleansing". In Munz, Rainer; Ohliger, Rainer (eds.). Diasporas and Ethnic Migrants: Germany, Israel and Russia in Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13575-938-4. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Akhund, Nadine (December 31, 2012). "The Two Carnegie Reports: From the Balkan Expedition of 1913 to the Albanian Trip of 1921". Balkanologie. Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires. XIVb (1–2). doi:10.4000/balkanologie.2365. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017 – via balkanologie.revues.org.

- ^ Toal, Gerard; Dahlman, Carl T. (2011). Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-973036-0. Archived from the original on July 6, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ^ West, Richard (1994). Tito and the Rise and Fall of Yugoslavia. New York: Carroll & Graf. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7867-0332-6.

- ^ Becirevic, Edina (2014). Genocide on the River Drina. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-3001-9258-2. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ a b 마틴, 테리 (1998). "소련 민족 청소의 기원" 2019년 7월 24일 웨이백 머신에서 보관. 근대사학회지 70(4), 813–861. pg. 822

- ^ Fulbrooke, Mary (2004). A Concise History of Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-52154-071-1. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Eichholtz, Dietrich (September 2004). "'Generalplan Ost' zur Versklavung osteuropäischer Völker" ['General Plan East' for the enslavement of Eastern European peoples]. Utopie Kreativ (in German). 167: 800–808 – via Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

- ^ Petrovic, Vladimir (2017). Ethnopolitical Temptations Reach Southeastern Europe: Wartime Policy Papers of Vasa Čubrilović and Sabin Manuilă. CEU Press.

- ^ 알렌, 팀, 진 시튼, eds. 갈등의 매체: 전쟁 보도와 민족 폭력의 표상. 제드북스, 1999. p. 152

- ^ Feierstein, Daniel (April 4, 2023). "The Meaning of Concepts: Some Reflections on the Difficulties in Analysing State Crimes". HARM – Journal of Hostility, Aggression, Repression and Malice. 1. doi:10.46586/harm.2023.10453. ISSN 2940-3073.

The concept seems to have been borrowed from the Slavic expression etnicheskoye chishcheniye, first used by Soviet authorities in the 1980s to describe Azeri attempts to expel Armenians from the Nagorno-Karabakh area, and then immediately reappropriated by Serb nationalists to describe their policies in the central region of Yugoslavia.

- ^ Gunkel, Christoph (October 31, 2010). "Ein Jahr, ein (Un-)Wort!" [One year, one (un)word!]. Spiegel Online (in German). Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ^ "Final Report of the Commission of Experts Established Pursuant to United Nations Security Council Resolution 780 (1992)" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. May 27, 1994. p. 33. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

Upon examination of reported information, specific studies and investigations, the Commission confirms its earlier view that 'ethnic cleansing' is a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic or religious group from certain geographic areas. To a large extent, it is carried out in the name of misguided nationalism, historic grievances and a powerful driving sense of revenge. This purpose appears to be the occupation of territory to the exclusion of the purged group or groups. This policy and the practices of warring factions are described separately in the following paragraphs.

제130항. - ^ "Final Report of the Commission of Experts Established Pursuant to United Nations Security Council Resolution 780 (1992)" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. May 27, 1994. p. 33. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2020. 문단 129

- ^ Hayden, Robert M. (1996) "쉰들러의 운명: 대량학살, 인종 청소 및 인구 이동" 2016년 4월 11일 웨이백 머신에서 아카이브. 슬라브 리뷰 55(4), 727-48.

- ^ 앤드류 벨-피알코프, "인종청소의 간략한 역사" 2004년 2월 3일 웨이백 머신에서 보관, 외교 문제 72(3): 110, 1993년 여름. 2006년 5월 20일 회수.

- ^ a b Blum, Rony; Stanton, Gregory H.; Sagi, Shira; Richter, Elihu D. (2007). "'Ethnic cleansing' bleaches the atrocities of genocide". European Journal of Public Health. 18 (2): 204–209. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckm011. PMID 17513346.

- ^ a b 더글러스 싱글테리(2010년 4월), "인종청소와 제노사이드 의도: 사법해석의 실패?", 제노사이드 연구와 예방 5, 1

- ^ Ferdinandusse, Ward (2004). "The Interaction of National and International Approaches in the Repression of International Crimes" (PDF). The European Journal of International Law. 15 (5): 1042, note 7. doi:10.1093/ejil/15.5.1041. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2008.

- ^ "국제형사재판소 로마 규정" 2008년 1월 13일 웨이백 머신에서 보관, 제7조; 구 유고슬라비아 국제형사재판소 업데이트 규정 2009년 8월 6일 웨이백 머신에서 보관, 제5조.

- ^ Shraga, Daphna; Zacklin, Ralph (2004). "The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia". The European Journal of International Law. 15 (3). Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ 티모시 5세. 워터스, "인종 청소의 법적 구성에 관하여" 2018년 11월 6일 웨이백 머신에서 아카이브, 논문 951, 2006, 미시시피 법대. 2006년 12~13년 회수

- ^ Pinxten, Rik; Dikomitis, Lisa (May 1, 2009). When God Comes to Town: Religious Traditions in Urban Contexts. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-920-8. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ Cornell, Svante E. (September 1998). "Religion as a factor in Caucasian conflicts". Civil Wars. 1 (3): 46–64. doi:10.1080/13698249808402381. ISSN 1369-8249.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (July 11, 2004). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10586-5. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ [1]2020년 5월 3일 Wayback Machine에 보관, Mann, Michael (2005), 민주주의의 어두운 면: 인종 청소를 설명합니다. 캠브리지: 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 1장 "논쟁", 1-33쪽.

- ^ a b c Müller-Crepon, Carl; Schvitz, Guy; Cederman, Lars-Erik (2024). ""Right-Peopling" the State: Nationalism, Historical Legacies, and Ethnic Cleansing in Europe, 1886-2020". Journal of Conflict Resolution. doi:10.1177/00220027241227897. ISSN 0022-0027.

- ^ Mylonas, Harris (2013). The Politics of Nation-Building: Making Co-Nationals, Refugees, and Minorities. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139104005. ISBN 978-1-107-02045-0.

- ^ a b Schabas, William (2000). Genocide in International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 199–201. ISBN 9780521787901. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ 인종청소 대 집단학살:

- Lieberman, Benjamin (2010). "'Ethnic cleansing' versus genocide?". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

Explaining the relationship between ethnic cleansing and genocide has caused controversy. Ethnic cleansing shares with genocide the goal of achieving purity but the two can differ in their ultimate aims: ethnic cleansing seeks the forced removal of an undesired group or groups where genocide pursues the group's 'destruction'. Ethnic cleansing and genocide therefore fall along a spectrum of violence against groups with genocide lying on the far end of the spectrum.

- Martin, Terry (1998). "The Origins of Soviet Ethnic Cleansing". The Journal of Modern History. 70 (4): 813–861. doi:10.1086/235168. ISSN 0022-2801. JSTOR 10.1086/235168. S2CID 32917643.

When murder itself becomes the primary goal, it is typically called genocide... Ethnic cleansing is probably best understood as occupying the central part of a continuum between genocide on one end and nonviolent pressured ethnic emigration on the other end. Given this continuum, there will always be ambiguity as to when ethnic cleansing shades into genocide

- Schabas, William A. (2003). "'Ethnic Cleansing' and Genocide: Similarities and Distinctions". European Yearbook of Minority Issues Online. 3 (1): 109–128. doi:10.1163/221161104X00075.

The crime of genocide is aimed at the intentional destruction of an ethnic group. 'Ethnic cleansing' would seem to be targeted at something different, the expulsion of a group with a view to encouraging or at least tolerating its survival elsewhere. Yet ethnic cleansing may well have the effect of rendering the continued existence of a group impossible, thereby effecting its destruction. In other words, forcible deportation may achieve the same result as extermination camps.

- Walling, Carrie Booth (2000). "The history and politics of ethnic cleansing". The International Journal of Human Rights. 4 (3–4): 47–66. doi:10.1080/13642980008406892. S2CID 144001685.

These methods are a part of a wider continuum ranging from genocide at one extreme to emigration under pressure at the other... It is important - politically and legally - to distinguish between genocide and ethnic cleansing. The goal of the former is extermination: the complete annihilation of an ethnic, national or racial group. It contains both a physical element (acts such as murder) and a mental element (those acts are undertaken to destroy, in whole or in part, the said group). Ethnic cleansing involves population expulsions, sometimes accompanied by murder, but its aim is consolidation of power over territory, not the destruction of a complete people.

- Naimark, Norman M. (2002). Fires of Hatred. Harvard University Press. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0-674-00994-3.

A new term was needed because ethnic cleansing and genocide two different activities, and the differences between them are important. As in the case of determining first-degree murder, intentionality is a critical distinction. Genocide is the intentional killing off of part or all of an ethnic, religious, or national group; the murder of a people or peoples (in German, Völkermord) is the objective. The intention of ethnic cleansing is to remove a people and often all traces of them from a concrete territory. The goal, in other words, is to get rid of the "alien" nationality, ethnic, or religious group and to seize control of the territory it had formerly inhabited. At one extreme of its spectrum, ethnic cleansing is closer to forced deportation or what has been called "population transfer"; the idea is to get people to move, and the means are meant to be legal and semi-legal. At the other extreme, however, ethnic cleansing and genocide are distinguishable only by the ultimate intent. Here, both literally and figuratively, ethnic cleansing bleeds into genocide, as mass murder is committed in order to rid the land of a people.

- Hayden, Robert M. (1996). "Schindler's Fate: Genocide, Ethnic Cleansing, and Population Transfers". Slavic Review. 55 (4): 727–748. doi:10.2307/2501233. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2501233. S2CID 232725375.

Hitler wanted the Jews utterly exterminated, not simply driven from particular places. Ethnic cleansing, on the other hand, involves removals rather than extermination and is not exceptional but rather common in particular circumstances.

- Lieberman, Benjamin (2010). "'Ethnic cleansing' versus genocide?". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- ^ Mann, Michael (2005). The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780521538541. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ Naimark, Norman (November 4, 2007). "Theoretical Paper: Ethnic Cleansing". Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Shaw, Martin(2015b), 대량학살이란 무엇인가, Polity Press, ISBN 978-0-7456-8706-3 '청결'과 대량학살.

- ^ a b c Ota Konrád; Boris Barth; Jaromír Mrňka, eds. (2021). Collective Identities and Post-War Violence in Europe, 1944–48. Springer International Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 9783030783860.

- ^ a b Bloxham, Donald; Dirk Moses, Anthony (2011). "Genocide and ethnic cleansing". In Bloxham, Donald; Gerwarth, Robert (eds.). Political Violence in Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 125. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511793271.004. ISBN 9781107005037.

- ^ Silvia Ferreto Clementi. "La pulizia etnica e il manuale Cubrilovic" (in Italian). Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ «.... 지넬로 스카테나르시 델라 프리마 온 데이터 디시에카 비올렌자, 넬 아우투노 델 1943, 시 인트레치아로노 지우스티지알리스모 소마리오 에 트라우소, 파로시스모 나지알리스타, 라이벌 사회성 질병노 디시마멘토 델라 프레센차 이탈리아나 다 쿨라 체에라, 에세 ò 디세레, 라 베네치아 줄리아. Vifunquun motodio e di furia sanguinaria, eun dignnagnessisticolavo, che prevalse inanzituttonel Tratto di pace del 1947, eche sanssunse is sinistri contorni di una "pulizia etnica". 쿨체시 푸 ò 디레토 에체시 소비 ò - 넬 모도피 ù 디세팔레 콘 라 디수마나 페로시아 델레 포이베 - 언아델 바르바리 델 세콜로소.»2007년 2월 10일, 이탈리아 공화국 대통령 조르지오 나폴리타노의 공식 웹사이트로부터, "조르노 델 리코르도" 퀴리날, 로마의 "조르노 델 리코르도" 기념 공식 연설.

- ^ "Il giorno del Ricordo - Croce Rossa Italiana" (in Italian). Archived from the original on January 28, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ "Il Giorno del Ricordo" (in Italian). February 10, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "L'esodo giuliano-dalmata e quegli italiani in fuga che nacquero due volte" (in Italian). February 5, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Pamela Ballinger (April 7, 2009). Genocide: Truth, Memory, and Representation. Duke University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0822392361. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ Tesser, L. (May 14, 2013). Ethnic Cleansing and the European Union – Page 136, Lynn Tesser. Springer. ISBN 9781137308771.

- ^ Ballinger, Pamela (2003). History in Exile: Memory and Identity at the Borders of the Balkans. Princeton University Press. p. 103. ISBN 0691086974.

- ^ Anna C. Bramwell, University of Oxford, UK (1988). Refugees in the Age of Total War. Unwin Hyman. pp. 139, 143. ISBN 9780044451945.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 다중 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ 마타 ž 클레멘치치, 유고슬라비아 해체가 소수자 권리에 미치는 영향: 포스트 유고슬라비아 슬로베니아와 크로아티아의 이탈리아 소수자. 참조 : CS1 maint: 제목(링크)으로 아카이브된 복사본

- ^ "Državni Zavod za Statistiku" (in Croatian). Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- ^ "Popis 2002". Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- ^ Amira, Saad (2021). "The slow violence of Israeli settler-colonialism and the political ecology of ethnic cleansing in the West Bank". Settler Colonial Studies. 11 (4): 512–532. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2021.2007747. S2CID 244736676.

- ^ Graham-Harrison, Emma; Kierszenbaum, Quique (October 21, 2023). "'The most successful land-grab strategy since 1967' as settlers push Bedouins off West Bank territory". The Guardian. Ein Rashash. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023.

- ^ Jones, Adam (2016). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Taylor & Francis. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-1-317-53386-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA: Rutgers University Press. pp. 97, 132. ISBN 978-0-8135-6068-7.

- ^ a b 주트, 토니 (2005). 전후: 1945년 이후 유럽의 역사. 펭귄 프레스.

- ^ Naimark, Norman M. (September 19, 2002). Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Harvard University Press. pp. 209–211. ISBN 978-0-674-00994-3.

참고문헌

- Bell-Fialkoff, Andrew (1993). "A Brief History of Ethnic Cleansing". Foreign Affairs. 72 (3): 110–121. doi:10.2307/20045626. JSTOR 20045626. Archived from the original on February 3, 2004.

- Petrovic, Drazen (1998). "Ethnic Cleansing – An Attempt at Methodology" (PDF). European Journal of International Law. 5 (4): 817.

- Thum, Gregor (2010). "Review: Ethnic Cleansing in Eastern Europe after 1945". Contemporary European History. 19 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1017/S0960777309990257. S2CID 145605508.

- 블라디미르 페트로비치(2007), 에티키자치엔자우레치닌델루(청정의 민족화), 헤리티쿠스 1/2007, 11-36

추가읽기

| 라이브러리 리소스정보 인종청소 |

- Bulutgil, H. Zeynep (2016). The Roots of Ethnic Cleansing in Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-56528-5.

- Dahbour, Omar (2012). "National Rights, Minority Rights, and Ethnic Cleansing". Nationalism and Human Rights: In Theory and Practice in the Middle East, Central Europe, and the Asia-Pacific. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 97–122. ISBN 978-1-137-01202-9.

- Gordon, Neve; Ram, Moriel (2016). "Ethnic cleansing and the formation of settler colonial geographies" (PDF). Political Geography. 53: 20–29. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.01.010.

- Jenne, Erin K. (2016). "The causes and consequences of ethnic cleansing". The Routledge Handbook of Ethnic Conflict. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-72042-5.

- Lieberman, Benjamin (2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3038-5.

- Pegorier, Clotilde (2013). Ethnic Cleansing: A Legal Qualification. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-06783-1.

- Rikhof, Joseph (2022). "Ethnic cleansing and exclusion". Serious International Crimes, Human Rights, and Forced Migration. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-09438-8.

- Ther, Philipp (2014). "The Dark Side of Nation-States: Ethnic Cleansing in Modern Europe". The Dark Side of Nation-States. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78238-303-1.