한글

Hangul| 한글 / / / 글글글 / / / 㐎㐎㐎 한글/조선글 | |

|---|---|

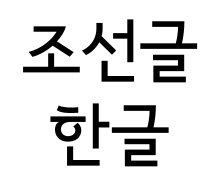

'초송을'과 '한글' | |

| 스크립트 타입 | 기능 |

| 크리에이터 | 조선 세종대왕 |

기간 | 1443 – 현재 |

| 방향 | 한글은 보통 가로로, 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로, 그리고 고전적으로 오른쪽에서 왼쪽으로 씁니다.또한 위에서 아래로, 그리고 오른쪽에서 왼쪽으로 세로로 쓰여 있다. |

인쇄 기준 |

|

| 언어들 | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | 항(286), 한글(한글, 한글)Jamo(자모 서브셋의 경우) |

| 유니코드 | |

유니코드 에일리어스 | 한글 |

|

| 한글 문자 체계 |

|---|

| 한글 |

| 조선걸(북한) |

| 한자 |

| 혼합 스크립트 |

| 점자 |

| 문자 변환 |

|

| 번역 |

|

| 필기 시스템 |

|---|

|

| 아브자드 |

| 아부기다 |

| 알파벳순 |

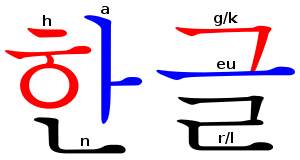

남한에서는 한글, 북한에서는 조선걸로[a] 알려진 한글은 현대 한국어의 [2][3][4]공식 문자 체계이다.다섯 개의 기본 자음은 발음에 사용되는 발음 기관의 형태를 반영하여 음성 특성을 나타내도록 체계적으로 변형되어 있고, 이와 유사하게 모음 글자도 관련 소리에 맞게 체계적으로 변형되어 한글이 특징적인 문자 [5][6][7]체계로 되어 있다.반드시 [6][8]아부기다라고는 할 수 없지만 알파벳과 음절문자의 특징을 조합하여 "음절문자"라고 표현되어 왔다.

한글은 1443년 세종대왕(世宗大王)이 고조선(高朝鮮) 때부터 한글을 쓰기 위한 기본 문자로 사용하던 한자(字字)를 보완(또는 대체)하여 문맹률을 높이기 위해 창제하였다BCE)와 함께 고대 [9][10]중국어의 사용.그 결과, 한글은 처음에 한국의 교육 계층에 의해 비난과 폄하를 받았다.이 문자는 언문(vern門)으로 알려지게 되었고 20세기 [11]중반 한국이 일본으로부터 독립한 후 수십 년 후에야 한글의 원문이 되었다.

현대 한글 맞춤법은 기본 문자 14개와[b] 모음 [c]10개 등 24개를 사용한다.기본 자음 [d]5자, 복합 자음[e] 11자, 복합 모음 [f]11자 등 27개의 복합 자음도 있다.원래 알파벳의 기본 문자 4개는 더 이상 사용되지 않는다: 모음 문자[g] 1개와 자음 문자 [h]3개.한글은 음절 블록으로 알파벳을 2차원으로 배열해서 씁니다.예를 들어 한글의 한글은 한글이 아니라 한글(한글)로 씁니다.그 음절들은 자음 문자로 시작하고, 그 다음에 모음 문자로 시작하고, 잠재적으로 batchim이라고 불리는 또 다른 자음 문자로 시작합니다.모음으로 시작하는 음절의 경우 자음 )(ng)이 무음 자리 표시자 역할을 합니다.단, starts가 문장을 시작하거나 길게 멈춘 후에 starts가 들어갈 때는 성문정지를 표시합니다.

음절은 기본 자음과 시제 자음으로 시작할 수 있지만 복잡한 자음은 아니다.모음은 기본 자음일 수도 있고 복잡 자음일 수도 있고, 두 번째 자음은 기본 자음일 수도 있고, 복잡한 자음일 수도 있고, 제한된 수의 시제 자음일 수도 있습니다.음절의 구성 방법은 모음 기호의 기준선이 수평인지 수직인지에 따라 달라집니다.기준선이 수직인 경우 첫 번째 자음과 모음은 두 번째 자음 위에 표기되지만(있는 경우), 수평 [12]기준선의 경우 모든 성분이 위에서 아래로 개별적으로 표기됩니다.

동아시아의 다른 많은 문자들과 마찬가지로, 한국 문자는 위에서 아래로, 오른쪽에서 왼쪽으로 쓰여졌고, 때때로 여전히 양식적인 목적으로 쓰이고 있다.하지만 한국어는 일본어나 [7]중국어와 달리 일반적으로 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 띄어쓰기를 합니다.이것은 남한과 북한 모두를 포함한 한국 전역의 공식 문자 체계이다.중국 지린(吉林)성 옌볜(延 korean)조선족자치주와 창바이(長白)조선족자치현의 공동 표기 체계다.

이름

공식 명칭

| 한국명(북한) | |

| 조선걸 | |

|---|---|

| 한차 | |

| 개정된 로마자 표기법 | 조선글 |

| 맥쿤-라이샤우어 | 조선걸 |

| IPA | 한국어 발음:[TSO . sso n ]★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★ |

| 한국어 이름(대한민국) | |

| 한글 | |

|---|---|

| 한자 | |

| 개정된 로마자 표기법 | 한글 |

| 맥쿤-라이샤우어 | 한글[13] |

| IPA | 한국어 발음:[하(하)엔]★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★ |

한글은 원래 1443년 [10]세종대왕에 의해 훈민정음이라는 이름이 붙여졌다.훈민정음(훈민정음)은 또한 1446년에 문자의 이면에 있는 논리와 과학을 설명한 문서이다.

한글이라는 이름은 1912년 주시경에 의해 만들어졌다.'위대한'이라는 뜻의 옛말 '한'과 '글'이라는 뜻의 '글'이 합쳐진 이름이다.한이라는 단어는 일반적으로 한국을 지칭할 때 사용되기 때문에 [14]한글을 의미하기도 합니다.다음과 같은 여러 가지 방법으로 로마자로 표기되어 있습니다.

- 한국 정부가 영어 출판물에 사용하고 모든 목적을 위해 권장하는 한글 로마자 개정판의 한글 또는 한글.

- McCune-Reischauer 체계에서 Han'g inl은 많은 영어 사전에서 볼 수 있듯이 영어 단어인 한글로 사용될 때 종종 대문자화되고 발음 없이 표현된다.

- 기술 언어 연구에 권장되는 시스템인 예일 로마자 표기법에서 한쿨.kul.

북한 사람들은 알파벳을 한국의 [15]북한 이름인 조선의 이름을 따서 조선걸이라고 부른다.McCune-Reischauer 시스템의 변형은 로마자 표기에 사용됩니다.

기타 이름

20세기 중반까지 한국의 엘리트들은 한자라는 한자를 사용하는 것을 선호했다.그들은 한자를 진서(眞書)라고 불렀는데, 이는 진정한 글자를 의미합니다.어떤 기록들은 엘리트들이 한글을 '여자의 글씨'라는 뜻의 '암늘'과 '어린이 글씨'라는 뜻의 '아해들'이라고 조롱했지만,[16] 이에 대한 어떠한 문서 증거도 한다.

한글 지지자들은 이것을 올바른 발음을 뜻하는 정음, 국가 문자를 뜻하는 궁문, 그리고 [16]고유 문자를 뜻하는 언문이라고 불렀습니다.

역사

창조.

한국인들은 주로 이두 문자, 향찰 문자, 구결 문자,[17][18][19][20] 각필 문자 등 한글보다 수백 년 앞선 고대 한자를 사용했다.그러나 많은 하층민들은 한글과 중국어를 배우기 어렵고 많은 수의 [21]한자를 사용하기 때문에 문맹이었다.서민의 문맹률을 높이기 위해 조선의 제4대 왕인 세종대왕께서 친히 새로운 글자를 만들어 [3][21][22]반포하셨습니다.세종대왕이 한글을 창제하라고 명했다는 설이 지배적이지만 세종대왕실록과 정인지의 훈민정음 해례 서문 등 당대 기록은 그가 직접 [23]창제했다는 점을 강조하고 있다.

한글은 교육을 거의 받지 않은 사람들이 읽고 쓰는 것을 배울 수 있도록 고안되었다.알파벳에 대한 유명한 속담은 "현자는 아침이 지나기 전에 그들과 친해질 수 있다; 어리석은 사람도 열흘 [24]안에 그것들을 배울 수 있다."이다.

이 프로젝트는 1443년 12월 말 또는 1444년 1월에 완료되었고, 1446년 훈민정음이라는 문서에 기술되어 있으며, 그 후 알파벳 자체의 이름이 [16]붙여졌다.훈민정음의 발행일인 10월 9일은 한국에서 한글날이 되었다.북한의 조선의 날은 1월 15일이다.

1446년에 출판된 훈민정음해례라는 또 다른 문서가 1940년에 발견되었다.이 문서에서는 자음의 디자인은 음양과 모음 [citation needed]조화의 원리에 기초하고 있다고 설명하고 있습니다.

반대

한글은 1440년대에 최만리를 비롯한 한국의 유학자들에 의해 반대에 부딪혔다.그들은 한자가 유일한 적법한 문자 체계라고 믿었다.그들은 또한 한글의 유통을 그들의 [21]지위에 대한 위협으로 보았다.하지만, 한글은 세종대왕의 의도대로 대중문화에 들어갔고, 특히 여성들과 대중소설 [25]작가들에 의해 사용되었다.

연산군은 1504년 왕을 비판하는 문서가 [26]출판된 후 한글의 연구와 출판을 금지하였다.마찬가지로, 중종은 1506년에 [27]한글 연구와 관련된 정부 기관인 언문부를 폐지하였다.

부활

그러나 16세기 후반 가사, 시조시가 번성하면서 한글이 부활했다.17세기에는 한글 소설이 주요 [28]장르가 되었다.하지만 한글의 사용은 맞춤법 표준화가 이루어지지 않아 철자가 상당히 [25]불규칙해졌다.

1796년, 네덜란드 학자 아이작 티칭은 한국어로 쓰여진 책을 서양에 가져온 최초의 사람이 되었다.그가 소장한 책에는 하야시 [29]시헤이의 산고쿠 쓰란 주세쓰가 있다.1785년에 출판된 이 책은 조선왕조와[30] [31]한글을 묘사했다.1832년 영국과 아일랜드의 동양번역기금은 티칭의 프랑스어 [32]번역본을 사후에 출판하는 것을 지원했다.

한국의 민족주의, 갑오개혁주의자들의 추진, 그리고 학교와 [33]문학에서 서양 선교사들의 한글 홍보 덕분에,[26] 한글은 1894년 처음으로 공식 문서에 채택되었다.초등학교 교과서는 1895년에 한글을 사용하기 시작했고 1896년에 창간된 통립신문은 한글과 [34]영자로 인쇄된 최초의 신문이었다.

일제의 개혁과 금지

1910년 한일합방 이후 일본어는 한국의 공용어가 되었다.하지만, 한글은 병합 후에도 여전히 한글을 가르쳤고, 한글은 한자-한글 혼합체로 쓰여져 있었고, 대부분의 어휘 뿌리는 한자로, 문법은 한글로 쓰여 있었다.일본은 조기 한국 문학에 대한 공교육을 금지했고,[35] 이는 어린이들에게 의무화 되었다.

한글의 철자법은 1912년에 부분적으로 표준화되었는데, 이때 모음 아래아(··)가 한자어로 제한되었고, 강조 자음은 ,, ,, ,, and, and, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson, conson음절의 왼쪽, 그러나 [25]이것은 1921년에 떨어졌다.

1930년에 두 번째 식민지 개혁이 일어났다.아래아는 폐지되었다: 강조 자음을 ,, ,, ,, and, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, were, ophon, ophon, were, ophon, ophon, ophon, ophon, were, ophon, ophon, ophon, were,이중 자음 was는 명사 사이에 발생할 때 모음 없이 단독으로 표기되었고, [25]이를 대체하는 주격 was가 모음 뒤에 도입되었다.

1912년 언문( vulgar文)을 대체하기 위해 한글을 만든 언어학자 주시경은 한글연구회(나중에 한글학회로 개명)를 설립했고, 1933년 철자법을 한글 표준화 체계로 개혁했다.주된 변화는 한글을 [25]가능한 한 형태음성학적으로 실용적으로 만드는 것이었다.외국 철자법을 번역하는 시스템이 1940년에 출판되었다.

일제는 1938년 문화 [36]학살 정책의 일환으로 한국어의 학교 출입을 금지했고 [37]1941년에는 모든 한국어 출판물이 금지되었다.

한층 더 개혁하다

확정적인 현대 한글 맞춤법은 광복 직후인 1946년에 출판되었다.북한은 1948년 새 글자를 추가해 완전한 형태음성을 만들려 했고 1953년 이승만은 1921년 식민지 철자법으로 돌아가 철자법을 간소화하려 했지만 불과 몇 [25]년 만에 두 개혁 모두 무산됐다.

북한과 남한 모두 한글 또는 혼합 문자를 공식 문자 체계로 사용해 왔으며, 특히 북한에서 한자의 사용은 계속 줄어들고 있다.

한국에서

1970년대부터 남한에서는 정부의 개입으로 상업문자와 비공식문자가 점차 줄어들기 시작했고, 일부 신문들은 동음이의어 약자 또는 모호성 해명으로만 한자를 사용하고 있다.그러나 현대에 이르기까지의 한국 문서, 역사, 문학, 기록은 주로 한자를 주체로 하여 한문으로 쓰여져 있었으므로, 특히 학계에서 K의 옛 문헌을 해석하고 연구하고자 하는 사람에게는 여전히 중요한 요소이다.오레아, 또는 [38]인문학의 학술적인 글을 읽기를 원하는 모든 사람.

한자에 대한 높은 숙달은 한자어의 어원을 이해하는 데뿐만 아니라 [38]한국어 어휘를 늘리는 데도 유용하다.

북한에서

북한은 1949년 김일성 조선노동당 주석의 지시에 따라 한글을 단독 표기체제로 도입하고 한자 [39]사용을 공식 금지했다.

비한국어

한글을 변형한 규칙을 사용한 체계는 쉬차오터와 앙의진 같은 언어학자들에 의해 시도되었지만, 결국 한자의 사용은 가장 실용적인 해결책이 되었고 대만 [40][41][42]교육부의 승인을 받았다.

서울의 훈민정음학회는 한글 사용을 아시아의 [43]불문어로 확산시키려 했다.2009년 인도네시아 술라웨시 남동부의 바우바우 마을에서 비공식적으로 Cia-Cia [44][45][46][47]언어를 쓰기 위해 채택되었다.

서울을 방문한 많은 인도네시아 CIA 화자들이 한국에서 큰 관심을 끌었고, 그들은 서울 [48]시장 오세훈의 영접을 받았다.그러나 2012년 10월 인도네시아에서 한글을 보급하려는 시도는 결국 [49]실패로 돌아간 것으로 확인됐다.

편지들

한글로 된 글자는 자모( jam letters)현대 알파벳에는 19개의 자음과 21개의 모음(모음)이 있다.그것들은 최세진이 쓴 한자 교과서 훈몽자회에 처음 이름이 붙여졌다.

자음

아래 표는 19개의 자음과 IPA의 각 문자와 발음에 대한 개정된 로마자 표기법을 한국어 알파벳 순서로 나타낸 것입니다(자세한 내용은 한국어 음운학 참조).

| 한글 | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 초기의 | 로마자 표기법 | g | ㅋㅋ | n | d | tt | r | m | b | pp | s | ss | ' [i] | j | JJ | 챠 | k | t | p | h |

| IPA | /k/ | /kcc/ | /n/ | /t/ | /tf/ | /timeout/ | /m/ | /p/ | /pcp/ | /s/ | /sparam/ | 조용한 | /tcp/ | /tt는 / | /tcnm/ | /kcc/ | /tf/ | /pcp/ | /h/ | |

| 최종 | 로마자 표기법 | k | k | n | t | – | l | m | p | – | t | t | 할 수 없다 | t | – | t | k | t | p | t |

| g | ㅋㅋ | n | d | l | m | b | s | ss | 할 수 없다 | j | 챠 | k | t | p | h | |||||

| IPA | /kcc/ | /n/ | /tf/ | – | /timeout/ | /m/ | /pcp/ | – | /tf/ | /timeout/ | /tf/ | – | /tf/ | /kcc/ | /tf/ | /pcp/ | /tf/ | |||

is는 무성음절음절로, 모음으로 시작할 때 자리 표시자로 사용됩니다.아, 아, 아, 아는 절대 음절 표기를 사용하지 않습니다.

자음은 크게 방해음(공기 흐름이 완전히 멈출 때 발생하는 소리) 또는 좁은 개구부(예: 마찰음) 또는 공명음(입, 코 또는 [50]양쪽을 통해 공기가 거의 또는 전혀 방해 없이 흘러나올 때 발생하는 소리)으로 분류된다.아래 표는 한국어 자음을 각각의 범주 및 하위 범주별로 나열한 것입니다.

| 양순골 | 폐포 | 치경구개 | 벨라 | 성문 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 방해물 | 정지(plosive) | 느슨하다 | p (ㅂ) | t (ㄷ) | k (ㄱ) | ||

| 텐션 | p͈ (ㅃ) | t͈ (ㄸ) | k͈ (ㄲ) | ||||

| 흡인된 | pʰ (ㅍ) | t440(표준) | kʰ (ㅋ) | ||||

| 마찰음 | 느슨하다 | s (ㅅ) | h (ㅎ) | ||||

| 텐션 | s͈ (ㅆ) | ||||||

| 파찰하다 | 느슨하다 | t͡ɕ (ㅈ) | |||||

| 텐션 | t͈͡ɕ͈ (ㅉ) | ||||||

| 흡인된 | t͡ɕʰ (ㅊ) | ||||||

| 소노란토 | 비음 | m (ㅁ) | n (ㄴ) | ŋ (ㅇ) | |||

| 액체(측면 근사) | l (ㄹ) | ||||||

모든 한국 장애물은 그 소리를 낼 때 후두가 진동하지 않고 흡인 정도와 긴장 정도에 따라 더욱 구별된다는 점에서 무성하다.긴장된 자음은 성대를 수축시켜서 만들어지고, 강한 흡인음(한글의 아, /p// 등)[50]은 열어서 만들어져요.

한국어 공명자는 목소리를 낸다.

자음 동화

음절 끝 자음의 발음은 다음 글자의 영향을 받을 수 있으며, 그 반대도 마찬가지입니다.다음 표에 이러한 동화 규칙을 설명합니다.수정이 이루어지지 않으면 공백으로 남습니다.

| 전음절 블록의 마지막 글자 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㄱ (k) | ㄲ (k) | ㄴ (n) | ㄷ (t) | ㄹ (l) | ㅁ (m) | ㅂ (p) | ㅅ (t) | ㅆ (t) | ㅇ (ng) | ㅈ (t) | ㅊ (t) | ㅋ (k) | ㅌ (t) | ㅍ (p) | ㅎ (t) | ||

| 후속 음절 블록의 첫 글자 | §(g) | k+k | n+g | t+g | l+g | m+g | b+g | t+g | - | t+g | t+g | t+g | p+g | h+k | |||

| § (n) | ng+n | n+n | l+n | m+n | m+n | t+n | n+t | t+n | t+n | t+n | p+n | h+n | |||||

| §(d) | k+d | n+d | t+t | l+d | m+d | p+d | t+t | t+t | t+t | t+t | k+d | t+t | p+d | h+t | |||

| §(r) | g+n | n+n | l+l | m+n | m+n | - | ng+n | r | |||||||||

| §(m) | g+m | n+m | t+m | l+m | m+m | m+m | t+m | - | ng+m | t+m | t+m | k+d | t+m | p+m | h+m | ||

| § (b) | g+b | p+p | t+b | - | |||||||||||||

| § (s) | ss+s | ||||||||||||||||

| □(표준) | g | kk+h | n | t | r | m | p | s | ss | ng+h | t+ch | t+ch | k+h | t+ch | p+h | h | |

| §(j) | t+ch | ||||||||||||||||

| ((h) | k | kk+h | n+h | t | r/ l+h | m+h | p | t | - | t+ch | t+ch | k | t | p | - | ||

자음 동화는 중간 발성의 결과로 일어난다.or, , 등 모음이나 공명음으로 둘러싸여 있으면 주변 소리의 특성을 띠게 됩니다.플레인 스톱(θ /k/와 같은)은 긴장되지 않는 편안한 성대에서 생성되므로 주변 유성음(진동하는 [50]성대에 의해 생성됨)의 영향을 받기 쉽다.

다음은 단어의 위치에 따라 느슨한 자음( / /p/, / /t/, / /tɕ/, / /k/)이 어떻게 변화하는지를 보여주는 예입니다.굵은 글씨로 된 글자는 음간 음색이 약해지거나 소리가 나는 [50]자음에 비해 느슨한 자음이 부드러워지는 것을 보여준다.

ㅂ

- [밥] – '밥'

- 포이밥 - '밥에 비벼 먹는 것'

ㄷ

- ᄃ [ta] – '모두'

- ① [ mat ]– 'mat'

- [마담] - '아들'

ㅈ

- ☞ [ t͡uk ]– [ tweak ]

- 콩죽

ㄱ

- 【ko】– '공'

- 【세고】– '새로운 공'

자음 and과 also도 약해진다.액체 ,는 초점간 위치에 있을 때 [ɾ]으로 약해진다.예를 들어 단어 (([maɭ], 'word')의 마지막 in는 주어 마커 ㅇ( being가 공명음)에 이어 []]로 바뀌어 [maii]가 된다.

/ / h / 는 매우 약해서 보통 / kw ͡ nt anhajo / [ kw nt nt jo nt anajo ]와 같이 한국어에서는 삭제됩니다.그러나 완전히 삭제되는 대신 다음 소리를 제거하거나 성문 정지 [50]역할을 함으로써 잔해를 남긴다.

첫 번째 장애물의 발음이 풀리지 않아 다른 장애물을 따라갈 때 느슨한 자음이 긴장된다.텐션은 [ip̚k͈u]로 발음되는 [ipkku](입구) /ipku/와 같은 단어에서 볼 수 있습니다.

한글의 자음은 11개의 자음군 중 하나로 결합될 수 있는데, 이 자음은 항상 한 음절 블록의 마지막 위치에 나타난다.They are: ㄳ, ㄵ, ㄶ, ㄺ, ㄻ, ㄼ, ㄽ, ㄾ, ㄿ, ㅀ, and ㅄ.

| 자음 클러스터 조합 (예: [격리] 단, [다른 음절 블록 삽입] - 웁타, an-ja) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 이전 음절 블록의 마지막 글자* | ㄳ (gs) | ㄵ (nj) | ㄶ (nh) | ㄺ (LG) | ㄻ (lm) | ㄼ (파운드) | ㄽ (ls) | ㄾ (l) | ㄿ (lp49) | ㅀ (표준) | ㅄ (ps) | |

| (단독 발음) | g | nj | nh | g | m | b | s | ṭ | p440 | h | p | |

| 후속 블록의 첫 글자** | □(표준) | g+s | n+j | l+h | l+g | l+m | l+b | l+s | l+module | L+P | l+h | p+s |

| §(d) | g+t | nj+d/ nt+ch | n+t | g+d | m+d | b+d | l+t | l+module | p4+d | l+t | p+t | |

자음군 뒤에 by, ,로 시작하는 단어가 붙는 경우, 자음군은 연락이라는 음운학적 현상을 통해 재유사화 됩니다.자음 군집의 첫 번째 자음이 ㄱ, ,, the(정지 자음)인 단어에서는 첫 번째 자음의 자음을 해제하지 않으면 조음이 멈추고 두 번째 자음을 발음할 수 없다.따라서 / / kaps / ('price')와 같은 단어에서는 cannot를 발음할 수 없기 때문에 ap는 [kap̚]로 발음됩니다.두 번째 자음은 보통 앞에 ((으→[으음.si])가 붙으면 다시 살아난다.그 외의 예로는 ( ( / salm / [ sam ] , 'life' 등이 있습니다.최종 자음 군집의 in는 일반적으로 발음이 떨어지지만, 주어 표식 , 뒤에 오면 is가 살아나고 takes이 빈 자음 ㅇ을 대신한다.그래서 이는 [sal.mi]로 발음됩니다.

모음.

아래 표는 한국어 알파벳에서 사용된 21개의 모음과 IPA의 각 문자와 발음에 대한 개정 로마자 표기법(자세한 내용은 한국어 음운학 참조)을 보여줍니다.

| 한글 | ㅏ | ㅐ | ㅑ | ㅒ | ㅓ | ㅔ | ㅕ | ㅖ | ㅗ | ㅘ | ㅙ | ㅚ | ㅛ | ㅜ | ㅝ | ㅞ | ㅟ | ㅠ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅣ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 개정된 로마자 표기법 | a | 아에 | 야 | 야에 | o | e | 여 | 네 | o | 와 | 와에 | oe | 이봐. | u | 우 | 우리가 | wi | 유 | eu | UI/ 이 | i |

| IPA | /a/ | /timeout/ | /ja/ | /jcp/ | /timeout/ | /e/ | /jcp/ | /je/ | /o/ | /wa/ | /wwwww/ | /ö/~[우리] | /jo/ | /u/ | /wwwww/ | /우리/ | /y/~ [sy] | /ju/ | /timeout/ | /dispairi/ | /i/ |

모음은 일반적으로 단모음과 이중모음의 두 가지 범주로 구분됩니다.단음(단음)은 단일 조음 동작(즉, 단음)으로 만들어지며 이중음은 조음 변화를 특징으로 한다.이중모음은 두 가지 구성 요소로 구성되어 있습니다: 글라이드(또는 세미보웰)와 모노폰입니다.정확히 얼마나 많은 모음들이 한국어 단음절로 간주되는지에 대해서는 의견이 분분하다. 가장 큰 모음은 10개이며, 일부 학자들은 8개 또는 [who?]9개를 제안했다.이러한 차이는 두 가지 문제를 드러낸다: 한국어에는 두 개의 앞 원순 모음이 있는지 여부(예: /ö/와 /y/)와 두 번째, 모음 높이에 있어 한국어에는 세 가지 수준의 앞모음이 있는지 여부(예: /e/와 ///가 [51]구별되는지 여부).포만트 자료를 통해 이루어진 실제 음운학 연구에 따르면 현재 표준국어 화자는 모음 and과 [52]in를 발음에서 구별하지 못한다.

알파벳 순서

알파벳의 알파벳 순서는 알파벳의 처음 세 글자를 따서 가나다 순서라고 합니다.한글의 알파벳 순서는 자음과 모음을 섞지 않는다.오히려, 첫째는 연수개 자음, 그 다음은 관음, 순음, 자매음 등입니다.모음은 [53]자음 뒤에 온다.

이력 순서

- ㄱ ㄲ ㅋ ㆁ ㄷ ㄸ ㅌ ㄴ ㅂ ㅃ ㅍ ㅁ ㅈ ㅉ ㅊ ㅅ ㅆ ㆆ ㅎ ㆅ ㅇ ㄹ ㅿ

- ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ ㅗ ㅏ ㅜ ㅓ ㅛ ㅑ ㅠ ㅕ

이것이 현대 알파벳 순서의 기본이다.한국어 시제 자음과 이를 나타내는 이중 글자가 발달하기 전이고, ((null)과 ((ng)이 합쳐지기 전이다.따라서, 북한과 남한 정부가 한글을 전면 사용했을 때, 북한은 알파벳 끝에 새 글자를 배치하고 남한은 비슷한 글자들을 함께 [55][56]묶는 등, 그들은 이 글자들을 다르게 배열했다.

북한 질서

자음의 끝에는 ',' 바로 앞에 ','자를 붙여서 나머지 알파벳의 전통적인 순서를 바꾸지 않도록 합니다.

- ㄱ ㄴ ㄷ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅅ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ ㄲ ㄸ ㅃ ㅆ ㅉ ㅇ

- ㅏ ㅑ ㅓ ㅕ ㅗ ㅛ ㅜ ㅠ ㅡ ㅣ ㅐ ㅒ ㅔ ㅖ ㅚ ㅟ ㅢ ㅘ ㅝ ㅙ ㅞ

옛 이중모음 and과 ,를 포함한 모든 이중모음 and과 raph는 단모음 뒤에 배치되어 최씨의 알파벳 순서를 유지한다.

마지막 글자(침)의 순서는 다음과 같습니다.

- (없음) " " " " " " " " " " " " " 입니다.

(없다는 것은 마지막 문자가 없음을 의미합니다.)

처음과 달리 이 is는 현대어에서는 어미로서만 나타나는 비음 ngng으로 발음된다.두 글자는 첫 번째 순서와 같이 맨 끝에 배치되지만, 결합된 자음은 첫 번째 [55]요소 바로 뒤에 배열됩니다.

남한의 명령

남부 순서에서는 단일 대응 문자 바로 뒤에 이중 문자가 배치됩니다.

현대의 단음모음은 그 형태에 따라 i가 먼저 추가되고, iotized가 추가되고, iotized가 추가된다.w로 시작하는 이중모음은 철자법에 따라 or 또는 plus에 별도의 이중모음이 아닌 제2모음을 더한 순서로 배열된다.

마지막 글자의 순서는 다음과 같습니다.

모든 음절은 받침(또는 무성 ))으로 시작하고 그 뒤에 모음(예: ㅏ + 다 = 다)이 나옵니다.ㄴ, ㄴ 같은 음절에는 받침이 있거나 받침이 없는 군집(받 ()이 있습니다.그러면 두 글자의 조합은 399개, 두 글자 이상의 조합은 10,773개, 한글의 조합은 총 11,172개일 수 있다.[55]

한국 국가 표준 KS X 1026-1에 정의된 고대 한글을 포함한 정렬 순서는 다음과 같습니다.[57]

- Initial consonants: ᄀ, ᄁ, ᅚ, ᄂ, ᄓ, ᄔ, ᄕ, ᄖ, ᅛ, ᅜ, ᅝ, ᄃ, ᄗ, ᄄ, ᅞ, ꥠ, ꥡ, ꥢ, ꥣ, ᄅ, ꥤ, ꥥ, ᄘ, ꥦ, ꥧ, ᄙ, ꥨ, ꥩ, ꥪ, ꥫ, ꥬ, ꥭ, ꥮ, ᄚ, ᄛ, ᄆ, ꥯ, ꥰ, ᄜ, ꥱ, ᄝ, ᄇ, ᄞ, ᄟ, ᄠ, ᄈ, ᄡ, ᄢ, ᄣ, ᄤ, ᄥ, ᄦ, ꥲ, ᄧ, ᄨ, ꥳ, ᄩ, ᄪ, ꥴ, ᄫ, ᄬ, ᄉ, ᄭ, ᄮ, ᄯ, ᄰ, ᄱ, ᄲ, ᄳ, ᄊ, ꥵ, ᄴ, ᄵ, ᄶ, ᄷ, ᄸ, ᄹ, ᄺ, ᄻ, ᄼ, ᄽ, ᄾ, ᄿ, ᅀ, ᄋ, ᅁ, ᅂ, ꥶ, ᅃ, ᅄ, ᅅ, ᅆ, ᅇ, ᅈ, ᅉ, ᅊ, ᅋ, ꥷ, ᅌ, ᄌ, ᅍ, ᄍ, ꥸ, ᅎ, ᅏ, ᅐ, ᅑ, ᄎ, ᅒ, ᅓ,ᅔ, ᅕ, ᄏ, ᄐ, ꥹ, ᄑ, ᅖ, ꥺ, ᅗ, ᄒ, ꥻ, ᅘ, ᅙ, ꥼ, (filler;

U+115F) - 중모음: (필러;

U+1160), ᅡ, ᅶ, ᅷ, ᆣ, ᅢ, ᅣ, ᅸ, ᅹ, ᆤ, ᅤ, ᅥ, ᅺ, ᅻ, ᅼ, ᅦ, ᅧ, ᆥ, ᅽ, ᅾ, ᅨ, ᅩ, ᅪ, ᅫ, ᆦ, ᆧ, ᅿ, ᆀ, ힰ, ᆁ, ᆂ, ힱ, ᆃ, ᅬ, ᅭ, ힲ, ힳ, ᆄ, ᆅ, ힴ, ᆆ, ᆇ, ᆈ, ᅮ, ᆉ, ᆊ, ᅯ, ᆋ, ᅰ, ힵ, ᆌ, ᆍ, ᅱ, ힶ, ᅲ, ᆎ, ힷ, ᆏ, ᆐ, ᆑ, ᆒ, ힸ, ᆓ, ᆔ, ᅳ, ힹ, ힺ, ힻ, ힼ, ᆕ, ᆖ, ᅴ, ᆗ, ᅵ, ᆘ, ᆙ, ힽ, ힾ, ힿ, ퟀ, ᆚ, ퟁ, ퟂ, ᆛ, ퟃ, ᆜ, ퟄ, ᆝ, ᆞ, ퟅ, ᆟ, ퟆ, ᆠ, ᆡ, ᆢ - Final consonants: (none), ᆨ, ᆩ, ᇺ, ᇃ, ᇻ, ᆪ, ᇄ, ᇼ, ᇽ, ᇾ, ᆫ, ᇅ, ᇿ, ᇆ, ퟋ, ᇇ, ᇈ, ᆬ, ퟌ, ᇉ, ᆭ, ᆮ, ᇊ, ퟍ, ퟎ, ᇋ, ퟏ, ퟐ, ퟑ, ퟒ, ퟓ, ퟔ, ᆯ, ᆰ, ퟕ, ᇌ, ퟖ, ᇍ, ᇎ, ᇏ, ᇐ, ퟗ, ᆱ, ᇑ, ᇒ, ퟘ, ᆲ, ퟙ, ᇓ, ퟚ, ᇔ, ᇕ, ᆳ, ᇖ, ᇗ, ퟛ, ᇘ, ᆴ, ᆵ, ᆶ, ᇙ, ퟜ, ퟝ, ᆷ, ᇚ, ퟞ, ퟟ, ᇛ, ퟠ, ᇜ, ퟡ, ᇝ, ᇞ, ᇟ, ퟢ, ᇠ, ᇡ, ᇢ, ᆸ, ퟣ, ᇣ, ퟤ, ퟥ, ퟦ, ᆹ, ퟧ, ퟨ, ퟩ, ᇤ, ᇥ, ᇦ, ᆺ, ᇧ, ᇨ, ᇩ, ퟪ, ᇪ, ퟫ, ᆻ, ퟬ, ퟭ, ퟮ, ퟯ, ퟰ, ퟱ, ퟲ, ᇫ, ퟳ,ퟴ, ᆼ, ᇰ, ᇬ, ᇭ, ퟵ, ᇱ, ᇲ, ᇮ, ᇯ, ퟶ, ᆽ, ퟷ, ퟸ, ퟹ, ᆾ, ᆿ, ᇀ, ᇁ, ᇳ, ퟺ, ퟻ, ᇴ, ᇂ, ᇵ, ᇶ, ᇷ, ᇸ, ᇹ

문자 이름

한글의 문자는 1527년 국어학자 최세진에 의해 명명되었다.한국은 최룡해의 전통적인 이름을 사용하며, 대부분은 문자 + i + eu + 문자 형식을 따른다.최 교수는 비슷한 발음의 한자 문자를 나열해 이 이름들을 설명했다.그러나 한자에서 k, ut, ut이 나오지 않았기 때문에, 최는 문양에 맞지 않는 한자나 and, ot,[58] ot의 원어민 음절인 ye, ot를 사용하여 names, however, ot, ot의 변형된 이름을 붙였다.

원래 최는 훈민정음에 나오는 지, 지, 지, 지, 지, 지, 지, 지, 지, 지, 지, 피, 하이의 불규칙한 한 음절 이름을 붙였는데, 훈민정음에 나오는 마지막 자음으로 사용해서는 안 되기 때문이다.그러나 1933년 모든 자음을 기형으로 하는 새로운 철자법이 제정되면서 명칭이 현재의 형태로 바뀌었다.

북한에서

아래 표는 북한에서 사용되는 한글 자음의 이름을 보여줍니다.북한 알파벳 순으로 배열되어 있고, 북한에서 널리 사용되는 맥쿤-라이샤우어 체계로 로마자로 표기되어 있다.자음은 딱딱하다는 뜻의 enen로 표현됩니다.

| 자음 | ㄱ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅅ | ㅈ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | ㄲ | ㄸ | ㅃ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅉ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 이름. | 기윽 | 니은 | 디읃 | 리을 | 미음 | 비읍 | 시읏 | 지읒 | 치읓 | 키읔 | 티읕 | 피읖 | 히읗 | 된기윽 | 된디읃 | 된비읍 | 된시읏 | 이응 | 된지읒 |

| MCR | 키 | 하지 않다 | 인식되지 않다 | 할 수 없다 | 메모리 | pi6p | 하지 않다 | 하지 않다 | 칩 | ★★ | 하지 않다 | p̣ipp | 하이라이트 | 토인기 | 토엔디. | 토엔비네프 | 하지 않다 | 「그렇게 하고 있지 않다 | 하지 않다 |

북한에서 자음을 가리키는 또 다른 방법은 문자 + ㄴ(-)입니다. 예를 들어, 문자 ㄴ은 gŭ(ㄴ), 문자 ㄴ은 ssŭ(ㄴ)입니다.

한국과 마찬가지로 한글의 모음 이름은 각 모음의 소리와 같다.

한국에서

아래 표는 한국에서 사용되는 한글 자음의 이름을 보여줍니다.한글순으로 배열되어 있으며, 한글 이름은 한국의 공식 로마자 표기 체계인 개정 로마자 표기 체계에서 로마자로 표기되어 있다.자음은 쌍으로 표현되는데 쌍은 쌍으로 표현됩니다.

| 자음 | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 이름(한글) | 기역 | 쌍기역 | 니은 | 디귿 | 쌍디귿 | 리을 | 미음 | 비읍 | 쌍비읍 | 시옷 | 쌍시옷 | 이응 | 지읒 | 쌍지읒 | 치읓 | 키읔 | 티읕 | 피읖 | 히읗 |

| 이름(로밍) | gi-diagnicle(gi-micle) | 쌍기역 | 니은 | 인식하다 | 쌍디굿 | 리을 | 미음 | 바이읍 | 쌍비읍 | si-ot(shi-ot) | 쌍시옷(쌍시옷) | '아이콘' | 지이웃 | 쌍지엇 | 키이웃 | i-euk | i-eut | 빠이읍 | 하이우트 |

스트로크 순서

한글로 된 글자는 callig과 use는 동그라미를 사용하지만, 인쇄된 [59][60]한자는 사용하지 않는다.

표시되지 않는 iotized 모음의 경우, 짧은 스트로크는 단순히 두 배로 늘어납니다.

레터 디자인

| 서예 |

|---|

Scripts typically transcribe languages at the level of morphemes (logographic scripts like Hanja), of syllables (syllabaries like kana), of segments (alphabetic scripts like the Latin script used to write English and many other languages), or, on occasion, of distinctive features. The Korean alphabet incorporates aspects of the latter three, grouping sounds into syllables, using distinct symbols for segments, and in some cases using distinct strokes to indicate distinctive features such as place of articulation (labial, coronal, velar, or glottal) and manner of articulation (plosive, nasal, sibilant, aspiration) for consonants, and iotization (a preceding i-sound), harmonic class and i-mutation for vowels.

For instance, the consonant ㅌ ṭ [tʰ] is composed of three strokes, each one meaningful: the top stroke indicates ㅌ is a plosive, like ㆆ ʔ, ㄱ g, ㄷ d, ㅈ j, which have the same stroke (the last is an affricate, a plosive–fricative sequence); the middle stroke indicates that ㅌ is aspirated, like ㅎ h, ㅋ ḳ, ㅊ ch, which also have this stroke; and the bottom stroke indicates that ㅌ is alveolar, like ㄴ n, ㄷ d, and ㄹ l. (It is said to represent the shape of the tongue when pronouncing coronal consonants, though this is not certain.) Two obsolete consonants, ㆁ and ㅱ, have dual pronunciations, and appear to be composed of two elements corresponding to these two pronunciations: [ŋ]~silence for ㆁ and [m]~[w] for ㅱ.

With vowel letters, a short stroke connected to the main line of the letter indicates that this is one of the vowels that can be iotized; this stroke is then doubled when the vowel is iotized. The position of the stroke indicates which harmonic class the vowel belongs to, light (top or right) or dark (bottom or left). In the modern alphabet, an additional vertical stroke indicates i mutation, deriving ㅐ [ɛ], ㅚ [ø], and ㅟ [y] from ㅏ [a], ㅗ [o], and ㅜ [u]. However, this is not part of the intentional design of the script, but rather a natural development from what were originally diphthongs ending in the vowel ㅣ [i]. Indeed, in many Korean dialects,[citation needed] including the standard dialect of Seoul, some of these may still be diphthongs. For example, in the Seoul dialect, ㅚ may alternatively be pronounced [we̞], and ㅟ [ɥi]. Note: ㅔ [e] as a morpheme is ㅓ combined with ㅣ as a vertical stroke. As a phoneme, its sound is not by i mutation of ㅓ [ʌ].

Beside the letters, the Korean alphabet originally employed diacritic marks to indicate pitch accent. A syllable with a high pitch (거성) was marked with a dot (〮) to the left of it (when writing vertically); a syllable with a rising pitch (상성) was marked with a double dot, like a colon (〯). These are no longer used, as modern Seoul Korean has lost tonality. Vowel length has also been neutralized in Modern Korean[61] and is no longer written.

Consonant design

The consonant letters fall into five homorganic groups, each with a basic shape, and one or more letters derived from this shape by means of additional strokes. In the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye account, the basic shapes iconically represent the articulations the tongue, palate, teeth, and throat take when making these sounds.

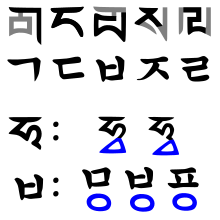

| Simple | Aspirated | Tense | |

|---|---|---|---|

| velar | ㄱ | ㅋ | ㄲ |

| fricatives | ㅅ | ㅆ | |

| palatal | ㅈ | ㅊ | ㅉ |

| coronal | ㄷ | ㅌ | ㄸ |

| bilabial | ㅂ | ㅍ | ㅃ |

- Velar consonants (아음, 牙音a'eum "molar sounds")

- ㄱ g [k], ㅋ ḳ [kʰ]

- Basic shape: ㄱ is a side view of the back of the tongue raised toward the velum (soft palate). (For illustration, access the external link below.) ㅋ is derived from ㄱ with a stroke for the burst of aspiration.

- Sibilant consonants (fricative or palatal) (치음, 齒音chieum "dental sounds"):

- ㅅ s [s], ㅈ j [tɕ], ㅊ ch [tɕʰ]

- Basic shape: ㅅ was originally shaped like a wedge ∧, without the serif on top. It represents a side view of the teeth.[citation needed] The line topping ㅈ represents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The stroke topping ㅊ represents an additional burst of aspiration.

- Coronal consonants (설음, 舌音seoreum "lingual sounds"):

- ㄴ n [n], ㄷ d [t], ㅌ ṭ [tʰ], ㄹ r [ɾ, ɭ]

- Basic shape: ㄴ is a side view of the tip of the tongue raised toward the alveolar ridge (gum ridge). The letters derived from ㄴ are pronounced with the same basic articulation. The line topping ㄷ represents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The middle stroke of ㅌ represents the burst of aspiration. The top of ㄹ represents a flap of the tongue.

- Bilabial consonants (순음, 唇音suneum "labial sounds"):

- ㅁ m [m], ㅂ b [p], ㅍ p̣ [pʰ]

- Basic shape: ㅁ represents the outline of the lips in contact with each other. The top of ㅂ represents the release burst of the b. The top stroke of ㅍ is for the burst of aspiration.

- Dorsal consonants (후음, 喉音hueum "throat sounds"):

- ㅇ '/ng [ŋ], ㅎ h [h]

- Basic shape: ㅇ is an outline of the throat. Originally ㅇ was two letters, a simple circle for silence (null consonant), and a circle topped by a vertical line, ㆁ, for the nasal ng. A now obsolete letter, ㆆ, represented a glottal stop, which is pronounced in the throat and had closure represented by the top line, like ㄱㄷㅈ. Derived from ㆆ is ㅎ, in which the extra stroke represents a burst of aspiration.

Vowel design

Vowel letters are based on three elements:

- A horizontal line representing the flat Earth, the essence of yin.

- A point for the Sun in the heavens, the essence of yang. (This becomes a short stroke when written with a brush.)

- A vertical line for the upright Human, the neutral mediator between the Heaven and Earth.

Short strokes (dots in the earliest documents) were added to these three basic elements to derive the vowel letter:

Simple vowels

- Horizontal letters: these are mid-high back vowels.

- bright ㅗ o

- dark ㅜ u

- dark ㅡ eu (ŭ)

- Vertical letters: these were once low vowels.

- bright ㅏ a

- dark ㅓ eo (ŏ)

- bright ㆍ

- neutral ㅣ i

Compound vowels

The Korean alphabet does not have a letter for w sound. Since an o or u before an a or eo became a [w] sound, and [w] occurred nowhere else, [w] could always be analyzed as a phonemic o or u, and no letter for [w] was needed. However, vowel harmony is observed: dark ㅜ u with dark ㅓ eo for ㅝ wo; bright ㅗ o with bright ㅏ a for ㅘ wa:

- ㅘ wa = ㅗ o + ㅏ a

- ㅝ wo = ㅜ u + ㅓ eo

- ㅙ wae = ㅗ o + ㅐ ae

- ㅞ we = ㅜ u + ㅔ e

The compound vowels ending in ㅣ i were originally diphthongs. However, several have since evolved into pure vowels:

- ㅐ ae = ㅏ a + ㅣ i (pronounced [ɛ])

- ㅔ e = ㅓ eo + ㅣ i (pronounced [e])

- ㅙ wae = ㅘ wa + ㅣ i

- ㅚ oe = ㅗ o + ㅣ i (formerly pronounced [ø], see Korean phonology)

- ㅞ we = ㅝ wo + ㅣ i

- ㅟ wi = ㅜ u + ㅣ i (formerly pronounced [y], see Korean phonology)

- ㅢ ui = ㅡ eu + ㅣ i

Iotized vowels

There is no letter for y. Instead, this sound is indicated by doubling the stroke attached to the baseline of the vowel letter. Of the seven basic vowels, four could be preceded by a y sound, and these four were written as a dot next to a line. (Through the influence of Chinese calligraphy, the dots soon became connected to the line: ㅓㅏㅜㅗ.) A preceding y sound, called iotization, was indicated by doubling this dot: ㅕㅑㅠㅛ yeo, ya, yu, yo. The three vowels that could not be iotized were written with a single stroke: ㅡㆍㅣ eu, (arae a), i.

| Simple | Iotized |

|---|---|

| ㅏ | ㅑ |

| ㅓ | ㅕ |

| ㅗ | ㅛ |

| ㅜ | ㅠ |

| ㅡ | |

| ㅣ |

The simple iotized vowels are:

- ㅑ ya from ㅏ a

- ㅕ yeo from ㅓ eo

- ㅛ yo from ㅗ o

- ㅠ yu from ㅜ u

There are also two iotized diphthongs:

- ㅒ yae from ㅐ ae

- ㅖ ye from ㅔ e

The Korean language of the 15th century had vowel harmony to a greater extent than it does today. Vowels in grammatical morphemes changed according to their environment, falling into groups that "harmonized" with each other. This affected the morphology of the language, and Korean phonology described it in terms of yin and yang: If a root word had yang ('bright') vowels, then most suffixes attached to it also had to have yang vowels; conversely, if the root had yin ('dark') vowels, the suffixes had to be yin as well. There was a third harmonic group called mediating (neutral in Western terminology) that could coexist with either yin or yang vowels.

The Korean neutral vowel was ㅣ i. The yin vowels were ㅡㅜㅓ eu, u, eo; the dots are in the yin directions of down and left. The yang vowels were ㆍㅗㅏ ə, o, a, with the dots in the yang directions of up and right. The Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye states that the shapes of the non-dotted letters ㅡㆍㅣ were chosen to represent the concepts of yin, yang, and mediation: Earth, Heaven, and Human. (The letter ㆍ ə is now obsolete except in the Jeju language.)

The third parameter in designing the vowel letters was choosing ㅡ as the graphic base of ㅜ and ㅗ, and ㅣ as the graphic base of ㅓ and ㅏ. A full understanding of what these horizontal and vertical groups had in common would require knowing the exact sound values these vowels had in the 15th century.

The uncertainty is primarily with the three letters ㆍㅓㅏ. Some linguists reconstruct these as *a, *ɤ, *e, respectively; others as *ə, *e, *a. A third reconstruction is to make them all middle vowels as *ʌ, *ɤ, *a.[62] With the third reconstruction, Middle Korean vowels actually line up in a vowel harmony pattern, albeit with only one front vowel and four middle vowels:

| ㅣ *i | ㅡ *ɯ | ㅜ *u |

| ㅓ *ɤ | ||

| ㆍ *ʌ | ㅗ *o | |

| ㅏ *a |

However, the horizontal letters ㅡㅜㅗ eu, u, o do all appear to have been mid to high back vowels, [*ɯ, *u, *o], and thus to have formed a coherent group phonetically in every reconstruction.

Traditional account

The traditionally accepted account[j][63][unreliable source?] on the design of the letters is that the vowels are derived from various combinations of the following three components: ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ. Here, ㆍ symbolically stands for the (sun in) heaven, ㅡ stands for the (flat) earth, and ㅣ stands for an (upright) human. The original sequence of the Korean vowels, as stated in Hunminjeongeum, listed these three vowels first, followed by various combinations. Thus, the original order of the vowels was: ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ ㅗ ㅏ ㅜ ㅓ ㅛ ㅑ ㅠ ㅕ. Note that two positive vowels (ㅗ ㅏ) including one ㆍ are followed by two negative vowels including one ㆍ, then by two positive vowels each including two of ㆍ, and then by two negative vowels each including two of ㆍ.

The same theory provides the most simple explanation of the shapes of the consonants as an approximation of the shapes of the most representative organ needed to form that sound. The original order of the consonants in Hunminjeong'eum was: ㄱ ㅋ ㆁ ㄷ ㅌ ㄴ ㅂ ㅍ ㅁ ㅈ ㅊ ㅅ ㆆ ㅎ ㅇ ㄹ ㅿ.

- ㄱ representing the [k] sound geometrically describes its tongue back raised.

- ㅋ representing the [kʰ] sound is derived from ㄱ by adding another stroke.

- ㆁ representing the [ŋ] sound may have been derived from ㅇ by addition of a stroke.

- ㄷ representing the [t] sound is derived from ㄴ by adding a stroke.

- ㅌ representing the [tʰ] sound is derived from ㄷ by adding another stroke.

- ㄴ representing the [n] sound geometrically describes a tongue making contact with an upper palate.

- ㅂ representing the [p] sound is derived from ㅁ by adding a stroke.

- ㅍ representing the [pʰ] sound is a variant of ㅂ by adding another stroke.

- ㅁ representing the [m] sound geometrically describes a closed mouth.

- ㅈ representing the [t͡ɕ] sound is derived from ㅅ by adding a stroke.

- ㅊ representing the [t͡ɕʰ] sound is derived from ㅈ by adding another stroke.

- ㅅ representing the [s] sound geometrically describes the sharp teeth.[citation needed]

- ㆆ representing the [ʔ] sound is derived from ㅇ by adding a stroke.

- ㅎ representing the [h] sound is derived from ㆆ by adding another stroke.

- ㅇ representing the absence of a consonant geometrically describes the throat.

- ㄹ representing the [ɾ] and [ɭ] sounds geometrically describes the bending tongue.

- ㅿ representing a weak ㅅ sound describes the sharp teeth, but has a different origin than ㅅ.[clarification needed]

Ledyard's theory of consonant design

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

(Bottom) Derivation of 'Phags-pa w, v, f from variants of the letter [h] (left) plus a subscript [w], and analogous composition of the Korean alphabet w, v, f from variants of the basic letter [p] plus a circle.

Although the Hunminjeong'eum Haerye explains the design of the consonantal letters in terms of articulatory phonetics, as a purely innovative creation, several theories suggest which external sources may have inspired or influenced King Sejong's creation. Professor Gari Ledyard of Columbia University studied possible connections between Hangul and the Mongol 'Phags-pa script of the Yuan dynasty. He, however, also believed that the role of 'Phags-pa script in the creation of the Korean alphabet was quite limited, stating it should not be assumed that Hangul was derived from 'Phags-pa script based on his theory:

It should be clear to any reader that in the total picture, that ['Phags-pa script's] role was quite limited ... Nothing would disturb me more, after this study is published, than to discover in a work on the history of writing a statement like the following: "According to recent investigations, the Korean alphabet was derived from the Mongol's phags-pa script."[64]

Ledyard posits that five of the Korean letters have shapes inspired by 'Phags-pa; a sixth basic letter, the null initial ㅇ, was invented by Sejong. The rest of the letters were derived internally from these six, essentially as described in the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye. However, the five borrowed consonants were not the graphically simplest letters considered basic by the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye, but instead the consonants basic to Chinese phonology: ㄱ, ㄷ, ㅂ, ㅈ, and ㄹ.[citation needed]

The Hunmin Jeong-eum states that King Sejong adapted the 古篆 (gojeon, Gǔ Seal Script) in creating the Korean alphabet. The 古篆 has never been identified. The primary meaning of 古 gǔ is old (Old Seal Script), frustrating philologists because the Korean alphabet bears no functional similarity to Chinese 篆字 zhuànzì seal scripts. However, Ledyard believes 古 gǔ may be a pun on 蒙古 Měnggǔ "Mongol," and that 古篆 is an abbreviation of 蒙古篆字 "Mongol Seal Script," that is, the formal variant of the 'Phags-pa alphabet written to look like the Chinese seal script. There were 'Phags-pa manuscripts in the Korean palace library, including some in the seal-script form, and several of Sejong's ministers knew the script well. If this was the case, Sejong's evasion on the Mongol connection can be understood in light of Korea's relationship with Ming China after the fall of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, and of the literati's contempt for the Mongols.[citation needed]

According to Ledyard, the five borrowed letters were graphically simplified, which allowed for consonant clusters and left room to add a stroke to derive the aspirate plosives, ㅋㅌㅍㅊ. But in contrast to the traditional account, the non-plosives (ㆁ ㄴ ㅁ ㅅ) were derived by removing the top of the basic letters. He points out that while it is easy to derive ㅁ from ㅂ by removing the top, it is not clear how to derive ㅂ from ㅁ in the traditional account, since the shape of ㅂ is not analogous to those of the other plosives.[citation needed]

The explanation of the letter ng also differs from the traditional account. Many Chinese words began with ng, but by King Sejong's day, initial ng was either silent or pronounced [ŋ] in China, and was silent when these words were borrowed into Korean. Also, the expected shape of ng (the short vertical line left by removing the top stroke of ㄱ) would have looked almost identical to the vowel ㅣ [i]. Sejong's solution solved both problems: The vertical stroke left from ㄱ was added to the null symbol ㅇ to create ㆁ (a circle with a vertical line on top), iconically capturing both the pronunciation [ŋ] in the middle or end of a word, and the usual silence at the beginning. (The graphic distinction between null ㅇ and ng ㆁ was eventually lost.)

Another letter composed of two elements to represent two regional pronunciations was ㅱ, which transcribed the Chinese initial 微. This represented either m or w in various Chinese dialects, and was composed of ㅁ [m] plus ㅇ (from 'Phags-pa [w]). In 'Phags-pa, a loop under a letter represented w after vowels, and Ledyard hypothesized that this became the loop at the bottom of ㅱ. In 'Phags-pa the Chinese initial 微 is also transcribed as a compound with w, but in its case the w is placed under an h. Actually, the Chinese consonant series 微非敷 w, v, f is transcribed in 'Phags-pa by the addition of a w under three graphic variants of the letter for h, and the Korean alphabet parallels this convention by adding the w loop to the labial series ㅁㅂㅍ m, b, p, producing now-obsolete ㅱㅸㆄ w, v, f. (Phonetic values in Korean are uncertain, as these consonants were only used to transcribe Chinese.)

As a final piece of evidence, Ledyard notes that most of the borrowed Korean letters were simple geometric shapes, at least originally, but that ㄷd [t] always had a small lip protruding from the upper left corner, just as the 'Phags-pa ꡊd [t] did. This lip can be traced back to the Tibetan letter དd.[citation needed]

There is also the argument that the original theory, which stated the Hangul consonants to have been derived from the shape of the speaker's lips and tongue during the pronunciation of the consonants (initially, at least), slightly strains credulity.[65]

Obsolete letters

Numerous obsolete Korean letters and sequences are no longer used in Korean. Some of these letters were only used to represent the sounds of Chinese rime tables. Some of the Korean sounds represented by these obsolete letters still exist in dialects.

| 13 obsolete consonants (IPA) | Soft consonants | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᄛ | ㅱ | ㅸ | ᄼ | ᄾ | ㅿ | ㆁ | ㅇ | ᅎ | ᅐ | ᅔ | ᅕ | ㆄ | ㆆ | ||

| /l/, /ɾ/, /rʷ/ | /ɱ/, /mʷ/ | /β/, /bʷ/ | /θ/ | /ɕ/ | South Korean: /z/ North Korean: /ɭ/ | initial position: /j/ final position: /ŋ/ | initial position only: /∅/ | /t͡s/ | /t͡ɕ/ | /t͡sʰ/ | /t͡ɕʰ/ | /ɸ/, /fʰ/, /pʷ/ | /ʔ/, /j/ | ||

| Middle Chinese | lh | hm | v | th | x, sch, sz | South Korean: z/z'/zz North Korean: rr/rd/tt | initial position: ye/’eu final position: ng | initial position only: ō/ou | z | j | c | q | fh/ ff | South Korean: '/à North Korean: heu/h'/eu | |

| Identified Chinese Character (Hanzi) | 微(미) /ɱ/ | 非(비) /f/ | 心(심) /s/ | 審(심) /ɕ/ | South Korean: 子 /z/ North Korean: 穰 /ɭ/ | final position: 業 /ŋ/ | initial position: 欲 /∅/ | 精(정) /t͡s/ | 照(조) /t͡ɕ/ | 淸(청) /t͡sʰ/ | 穿(천) /t͡ɕʰ/ | 敷(부) /fʰ/ | 挹(읍) /ʔ/ | ||

| Toneme | falling | mid to falling | mid to falling | mid | mid to falling | dipping/ mid | mid | mid to falling | mid (aspirated) | high (aspirated) | mid to falling (aspirated) | high/mid | |||

| Remark | lenis voiceless dental affricate/ voiced dental affricate | lenis voiceless retroflex affricate/ voiced retroflex affricate | aspirated /t͡s/ | aspirated /t͡ɕ/ | glottal stop | ||||||||||

| Equivalents | Standard Chinese Pinyin: 子 z [tsɨ]; English: z in zoo or zebra; strong z in English zip | identical to the initial position of ng in Cantonese | German pf | "읗" = "euh" in pronunciation | |||||||||||

| 10 obsolete double consonants (IPA) | Hard consonants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㅥ | ᄙ | ㅹ | ᄽ | ᄿ | ᅇ | ᇮ | ᅏ | ᅑ | ㆅ | |

| /ɳ/ | /l̥/ | /pʰ/, /bʱ/ | /z/ | /ʑ/ | /ŋ̊ʷ/ or /ɣ/ | /ŋ̊/ | /d͡z/ | /d͡ʑ/ | /ɦ/ or /ç/, /ɣ̈ʲ/, /ɣ̈/ | |

| Middle Chinese | hn/nn | hl/ll | bh, bhh | sh | zh | hngw/gh or gr | hng | dz, ds | dzh | hh or xh |

| Identified Chinese Character (Hanzi) | 娘(낭) /ɳ/ | 郞(랑) /ɫ/ | 邪(사) /z/ | 禪(선) /ʑ/ | 從(종) /d͡z/ | 牀(상) /d͡ʑ/ | 洪(홍) /ɦ/ | |||

| Remark | aspirated | aspirated | unaspirated fortis voiceless dental affricate | unaspirated fortis voiceless retroflex affricate | guttural | |||||

- 66 obsolete clusters of two consonants: ᇃ, ᄓ /ng/ (like English think), ㅦ /nd/ (as English Monday), ᄖ, ㅧ /ns/ (as English Pennsylvania), ㅨ, ᇉ /tʰ/ (as ㅌ; nt in the language Esperanto), ᄗ /dg/ (similar to ㄲ; equivalent to the word 밖 in Korean), ᇋ /dr/ (like English in drive), ᄘ /ɭ/ (similar to French Belle), ㅪ, ㅬ /lz/ (similar to English lisp but without the vowel), ᇘ, ㅭ /t͡ɬ/ (tl or ll; as in Nahuatl), ᇚ /ṃ/ (mh or mg, mm in English hammer, Middle Korean: pronounced as 목 mog with the ㄱ in the word almost silent), ᇛ, ㅮ, ㅯ (similar to ㅂ in Korean 없다), ㅰ, ᇠ, ᇡ, ㅲ, ᄟ, ㅳ bd (assimilated later into ㄸ), ᇣ, ㅶ bj (assimilated later into ㅉ), ᄨ /bj/ (similar to 비추 in Korean verb 비추다 bit-chu-da but without the vowel), ㅷ, ᄪ, ᇥ /ph/ (pha similar to Korean word 돌입하지 dol ip-haji), ㅺ sk (assimilated later into ㄲ; English: pick), ㅻ sn (assimilated later into nn in English annal), ㅼ sd (initial position; assimilated later into ㄸ), ᄰ, ᄱ sm (assimilated later into nm), ㅽ sb (initial position; similar sound to ㅃ), ᄵ, ㅾ assimilated later into ㅉ), ᄷ, ᄸ, ᄹ /θ/, ᄺ/ɸ/, ᄻ, ᅁ, ᅂ /ð/, ᅃ, ᅄ /v/, ᅅ (assimilated later into ㅿ; English z), ᅆ, ᅈ, ᅉ, ᅊ, ᅋ, ᇬ, ᇭ, ㆂ, ㆃ, ᇯ, ᅍ, ᅒ, ᅓ, ᅖ, ᇵ, ᇶ, ᇷ, ᇸ

- 17 obsolete clusters of three consonants: ᇄ, ㅩ /rgs/ (similar to "rx" in English name Marx), ᇏ, ᇑ /lmg/ (similar to English Pullman), ᇒ, ㅫ, ᇔ, ᇕ, ᇖ, ᇞ, ㅴ, ㅵ, ᄤ, ᄥ, ᄦ, ᄳ, ᄴ

| 1 obsolete vowel (IPA) | Extremely soft vowel |

|---|---|

| ㆍ | |

| /ʌ/ (also commonly found in the Jeju language: /ɒ/, closely similar to vowel:ㅓeo) | |

| Letter name | 아래아 (arae-a) |

| Remarks | formerly the base vowel ㅡ eu in the early development of hangeul when it was considered vowelless, later development into different base vowels for clarification; acts also as a mark that indicates the consonant is pronounced on its own, e.g. s-va-ha → ᄉᆞᄫᅡ 하 |

| Toneme | low |

- 44 obsolete diphthongs and vowel sequences: ᆜ (/j/ or /jɯ/ or /jɤ/, yeu or ehyu); closest similarity to ㅢ, when follow by ㄱ on initial position, pronunciation does not produce any difference: ᄀᆜ /gj/),ᆝ (/jɒ/; closest similarity to ㅛ,ㅑ, ㅠ, ㅕ, when follow by ㄱ on initial position, pronunciation does not produce any difference: ᄀᆝ /gj/), ᆢ(/j/; closest similarity to ㅢ, see former example inᆝ (/j/), ᅷ (/au̯/; Icelandic Á, aw/ow in English allow), ᅸ (/jau̯/; yao or iao; Chinese diphthong iao), ᅹ, ᅺ, ᅻ, ᅼ, ᅽ /ōu/ (紬 ㅊᅽ, ch-ieou; like Chinese: chōu), ᅾ, ᅿ, ᆀ, ᆁ, ᆂ (/w/, wo or wh, hw), ᆃ /ow/ (English window), ㆇ, ㆈ, ᆆ, ᆇ, ㆉ (/jø/; yue), ᆉ /wʌ/ or /oɐ/ (pronounced like u'a, in English suave), ᆊ, ᆋ, ᆌ, ᆍ (wu in English would), ᆎ /juə/ or /yua/ (like Chinese: 元 yuán), ᆏ /ū/ (like Chinese: 軍 jūn), ᆐ, ㆊ /ué/ jujə (ɥe; like Chinese: 瘸 qué), ㆋ jujəj (ɥej; iyye), ᆓ, ㆌ /jü/ or /juj/ (/jy/ or ɥi; yu.i; like German Jürgen), ᆕ, ᆖ (the same as ᆜ in pronunciation, since there is no distinction due to it extreme similarity in pronunciation), ᆗ ɰju (ehyu or eyyu; like English news), ᆘ, ᆙ /ià/ (like Chinese: 墊 diàn), ᆚ, ᆛ, ᆟ, ᆠ (/ʔu/), ㆎ (ʌj; oi or oy, similar to English boy).

In the original Korean alphabet system, double letters were used to represent Chinese voiced (濁音) consonants, which survive in the Shanghainese slack consonants and were not used for Korean words. It was only later that a similar convention was used to represent the modern tense (faucalized) consonants of Korean.

The sibilant (dental) consonants were modified to represent the two series of Chinese sibilants, alveolar and retroflex, a round vs. sharp distinction (analogous to s vs sh) which was never made in Korean, and was even being lost from southern Chinese. The alveolar letters had longer left stems, while retroflexes had longer right stems:

| 5 Place of Articulation (오음, 五音) in Chinese Rime Table | Tenuis 전청 (全淸) | Aspirate 차청 (次淸) | Voiced 전탁 (全濁) | Sonorant 차탁 (次濁) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sibilants 치음 (齒音) | 치두음 (齒頭音) "tooth-head" | ᅎ 精(정) /t͡s/ | ᅔ 淸(청) /t͡sʰ/ | ᅏ 從(종) /d͡z/ | |

| ᄼ 心(심) /s/ | ᄽ 邪(사) /z/ | ||||

| 정치음 (正齒音) "true front-tooth" | ᅐ 照(조) /t͡ɕ/ | ᅕ 穿(천) /t͡ɕʰ/ | ᅑ 牀(상) /d͡ʑ/ | ||

| ᄾ 審(심) /ɕ/ | ᄿ 禪(선) /ʑ/ | ||||

| Coronals 설음 (舌音) | 설상음 (舌上音) "tongue up" | ᅐ 知(지) /ʈ/ | ᅕ 徹(철) /ʈʰ/ | ᅑ 澄(징) /ɖ/ | ㄴ 娘(낭) /ɳ/ |

Most common

- ㆍ ə (in Modern Korean called arae-a 아래아 "lower a"): Presumably pronounced [ʌ], similar to modern ㅓ (eo). It is written as a dot, positioned beneath the consonant. The arae-a is not entirely obsolete, as it can be found in various brand names, and in the Jeju language, where it is pronounced [ɒ]. The ə formed a medial of its own, or was found in the diphthong ㆎ əy, written with the dot under the consonant and ㅣ (i) to its right, in the same fashion as ㅚ or ㅢ.

- ㅿ z (bansiot 반시옷 "half s", banchieum 반치음): An unusual sound, perhaps IPA [ʝ̃] (a nasalized palatal fricative). Modern Korean words previously spelled with ㅿ substitute ㅅ or ㅇ.

- ㆆ ʔ (yeorinhieut 여린히읗 "light hieut" or doenieung 된이응 "strong ieung"): A glottal stop, lighter than ㅎ and harsher than ㅇ.

- ㆁ ŋ (yedieung 옛이응) “old ieung” : The original letter for [ŋ]; now conflated with ㅇ ieung. (With some computer fonts such as Arial Unicode MS, yesieung is shown as a flattened version of ieung, but the correct form is with a long peak, longer than what one would see on a serif version of ieung.)

- ㅸ β (gabyeounbieup 가벼운비읍, sungyeongeumbieup 순경음비읍): IPA [f]. This letter appears to be a digraph of bieup and ieung, but it may be more complicated than that—the circle appears to be only coincidentally similar to ieung. There were three other, less-common letters for sounds in this section of the Chinese rime tables, ㅱ w ([w] or [m]), ㆄ f, and ㅹ ff [v̤]. It operates slightly like a following h in the Latin alphabet (one may think of these letters as bh, mh, ph, and pph respectively). Koreans do not distinguish these sounds now, if they ever did, conflating the fricatives with the corresponding plosives.

Restored letters

To make the Korean alphabet a better morphophonological fit to the Korean language, North Korea introduced six new letters, which were published in the New Orthography for the Korean Language and used officially from 1948 to 1954.

Two obsolete letters were restored: ⟨ㅿ⟩ (리읃), which was used to indicate an alternation in pronunciation between initial /l/ and final /d/; and ⟨ㆆ⟩ (히으), which was only pronounced between vowels. Two modifications of the letter ㄹ were introduced, one which is silent finally, and one which doubled between vowels. A hybrid ㅂ-ㅜ letter was introduced for words that alternated between those two sounds (that is, a /b/, which became /w/ before a vowel). Finally, a vowel ⟨1⟩ was introduced for variable iotation.

Unicode

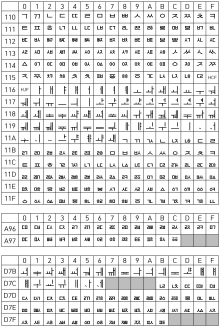

Hangul Jamo (U+1100–U+11FF) and Hangul Compatibility Jamo (U+3130–U+318F) blocks were added to the Unicode Standard in June 1993 with the release of version 1.1. A separate Hangul Syllables block (not shown below due to its length) contains pre-composed syllable block characters, which were first added at the same time, although they were relocated to their present locations in July 1996 with the release of version 2.0.[66]

Hangul Jamo Extended-A (U+A960–U+A97F) and Hangul Jamo Extended-B (U+D7B0–U+D7FF) blocks were added to the Unicode Standard in October 2009 with the release of version 5.2.

| Hangul Jamo[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+110x | ᄀ | ᄁ | ᄂ | ᄃ | ᄄ | ᄅ | ᄆ | ᄇ | ᄈ | ᄉ | ᄊ | ᄋ | ᄌ | ᄍ | ᄎ | ᄏ |

| U+111x | ᄐ | ᄑ | ᄒ | ᄓ | ᄔ | ᄕ | ᄖ | ᄗ | ᄘ | ᄙ | ᄚ | ᄛ | ᄜ | ᄝ | ᄞ | ᄟ |

| U+112x | ᄠ | ᄡ | ᄢ | ᄣ | ᄤ | ᄥ | ᄦ | ᄧ | ᄨ | ᄩ | ᄪ | ᄫ | ᄬ | ᄭ | ᄮ | ᄯ |

| U+113x | ᄰ | ᄱ | ᄲ | ᄳ | ᄴ | ᄵ | ᄶ | ᄷ | ᄸ | ᄹ | ᄺ | ᄻ | ᄼ | ᄽ | ᄾ | ᄿ |

| U+114x | ᅀ | ᅁ | ᅂ | ᅃ | ᅄ | ᅅ | ᅆ | ᅇ | ᅈ | ᅉ | ᅊ | ᅋ | ᅌ | ᅍ | ᅎ | ᅏ |

| U+115x | ᅐ | ᅑ | ᅒ | ᅓ | ᅔ | ᅕ | ᅖ | ᅗ | ᅘ | ᅙ | ᅚ | ᅛ | ᅜ | ᅝ | ᅞ | HC F |

| U+116x | HJ F | ᅡ | ᅢ | ᅣ | ᅤ | ᅥ | ᅦ | ᅧ | ᅨ | ᅩ | ᅪ | ᅫ | ᅬ | ᅭ | ᅮ | ᅯ |

| U+117x | ᅰ | ᅱ | ᅲ | ᅳ | ᅴ | ᅵ | ᅶ | ᅷ | ᅸ | ᅹ | ᅺ | ᅻ | ᅼ | ᅽ | ᅾ | ᅿ |

| U+118x | ᆀ | ᆁ | ᆂ | ᆃ | ᆄ | ᆅ | ᆆ | ᆇ | ᆈ | ᆉ | ᆊ | ᆋ | ᆌ | ᆍ | ᆎ | ᆏ |

| U+119x | ᆐ | ᆑ | ᆒ | ᆓ | ᆔ | ᆕ | ᆖ | ᆗ | ᆘ | ᆙ | ᆚ | ᆛ | ᆜ | ᆝ | ᆞ | ᆟ |

| U+11Ax | ᆠ | ᆡ | ᆢ | ᆣ | ᆤ | ᆥ | ᆦ | ᆧ | ᆨ | ᆩ | ᆪ | ᆫ | ᆬ | ᆭ | ᆮ | ᆯ |

| U+11Bx | ᆰ | ᆱ | ᆲ | ᆳ | ᆴ | ᆵ | ᆶ | ᆷ | ᆸ | ᆹ | ᆺ | ᆻ | ᆼ | ᆽ | ᆾ | ᆿ |

| U+11Cx | ᇀ | ᇁ | ᇂ | ᇃ | ᇄ | ᇅ | ᇆ | ᇇ | ᇈ | ᇉ | ᇊ | ᇋ | ᇌ | ᇍ | ᇎ | ᇏ |

| U+11Dx | ᇐ | ᇑ | ᇒ | ᇓ | ᇔ | ᇕ | ᇖ | ᇗ | ᇘ | ᇙ | ᇚ | ᇛ | ᇜ | ᇝ | ᇞ | ᇟ |

| U+11Ex | ᇠ | ᇡ | ᇢ | ᇣ | ᇤ | ᇥ | ᇦ | ᇧ | ᇨ | ᇩ | ᇪ | ᇫ | ᇬ | ᇭ | ᇮ | ᇯ |

| U+11Fx | ᇰ | ᇱ | ᇲ | ᇳ | ᇴ | ᇵ | ᇶ | ᇷ | ᇸ | ᇹ | ᇺ | ᇻ | ᇼ | ᇽ | ᇾ | ᇿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

| Hangul Jamo Extended-A[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+A96x | ꥠ | ꥡ | ꥢ | ꥣ | ꥤ | ꥥ | ꥦ | ꥧ | ꥨ | ꥩ | ꥪ | ꥫ | ꥬ | ꥭ | ꥮ | ꥯ |

| U+A97x | ꥰ | ꥱ | ꥲ | ꥳ | ꥴ | ꥵ | ꥶ | ꥷ | ꥸ | ꥹ | ꥺ | ꥻ | ꥼ | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Hangul Jamo Extended-B[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+D7Bx | ힰ | ힱ | ힲ | ힳ | ힴ | ힵ | ힶ | ힷ | ힸ | ힹ | ힺ | ힻ | ힼ | ힽ | ힾ | ힿ |

| U+D7Cx | ퟀ | ퟁ | ퟂ | ퟃ | ퟄ | ퟅ | ퟆ | ퟋ | ퟌ | ퟍ | ퟎ | ퟏ | ||||

| U+D7Dx | ퟐ | ퟑ | ퟒ | ퟓ | ퟔ | ퟕ | ퟖ | ퟗ | ퟘ | ퟙ | ퟚ | ퟛ | ퟜ | ퟝ | ퟞ | ퟟ |

| U+D7Ex | ퟠ | ퟡ | ퟢ | ퟣ | ퟤ | ퟥ | ퟦ | ퟧ | ퟨ | ퟩ | ퟪ | ퟫ | ퟬ | ퟭ | ퟮ | ퟯ |

| U+D7Fx | ퟰ | ퟱ | ퟲ | ퟳ | ퟴ | ퟵ | ퟶ | ퟷ | ퟸ | ퟹ | ퟺ | ퟻ | ||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Hangul Compatibility Jamo[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+313x | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄳ | ㄴ | ㄵ | ㄶ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㄺ | ㄻ | ㄼ | ㄽ | ㄾ | ㄿ | |

| U+314x | ㅀ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅄ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | ㅏ |

| U+315x | ㅐ | ㅑ | ㅒ | ㅓ | ㅔ | ㅕ | ㅖ | ㅗ | ㅘ | ㅙ | ㅚ | ㅛ | ㅜ | ㅝ | ㅞ | ㅟ |

| U+316x | ㅠ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅣ | HF | ㅥ | ㅦ | ㅧ | ㅨ | ㅩ | ㅪ | ㅫ | ㅬ | ㅭ | ㅮ | ㅯ |

| U+317x | ㅰ | ㅱ | ㅲ | ㅳ | ㅴ | ㅵ | ㅶ | ㅷ | ㅸ | ㅹ | ㅺ | ㅻ | ㅼ | ㅽ | ㅾ | ㅿ |

| U+318x | ㆀ | ㆁ | ㆂ | ㆃ | ㆄ | ㆅ | ㆆ | ㆇ | ㆈ | ㆉ | ㆊ | ㆋ | ㆌ | ㆍ | ㆎ | |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Parenthesised (U+3200–U+321E) and circled (U+3260–U+327E) Hangul compatibility characters are in the Enclosed CJK Letters and Months block:

| Hangul subset of Enclosed CJK Letters and Months[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+320x | ㈀ | ㈁ | ㈂ | ㈃ | ㈄ | ㈅ | ㈆ | ㈇ | ㈈ | ㈉ | ㈊ | ㈋ | ㈌ | ㈍ | ㈎ | ㈏ |

| U+321x | ㈐ | ㈑ | ㈒ | ㈓ | ㈔ | ㈕ | ㈖ | ㈗ | ㈘ | ㈙ | ㈚ | ㈛ | ㈜ | ㈝ | ㈞ | |

| ... | (U+3220–U+325F omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| U+326x | ㉠ | ㉡ | ㉢ | ㉣ | ㉤ | ㉥ | ㉦ | ㉧ | ㉨ | ㉩ | ㉪ | ㉫ | ㉬ | ㉭ | ㉮ | ㉯ |

| U+327x | ㉰ | ㉱ | ㉲ | ㉳ | ㉴ | ㉵ | ㉶ | ㉷ | ㉸ | ㉹ | ㉺ | ㉻ | ㉼ | ㉽ | ㉾ | |

| ... | (U+3280–U+32FF omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Half-width Hangul compatibility characters (U+FFA0–U+FFDC) are in the Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms block:

| Hangul subset of Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| ... | (U+FF00–U+FF9F omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| U+FFAx | HW HF | ᄀ | ᄁ | ᆪ | ᄂ | ᆬ | ᆭ | ᄃ | ᄄ | ᄅ | ᆰ | ᆱ | ᆲ | ᆳ | ᆴ | ᆵ |

| U+FFBx | ᄚ | ᄆ | ᄇ | ᄈ | ᄡ | ᄉ | ᄊ | ᄋ | ᄌ | ᄍ | ᄎ | ᄏ | ᄐ | ᄑ | ᄒ | |

| U+FFCx | ᅡ | ᅢ | ᅣ | ᅤ | ᅥ | ᅦ | ᅧ | ᅨ | ᅩ | ᅪ | ᅫ | ᅬ | ||||

| U+FFDx | ᅭ | ᅮ | ᅯ | ᅰ | ᅱ | ᅲ | ᅳ | ᅴ | ᅵ | |||||||

| ... | (U+FFE0–U+FFEF omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Korean alphabet in other Unicode blocks:

- Tone marks for Middle Korean[67][68][69] are in the CJK Symbols and Punctuation block: 〮 (

U+302E), 〯 (U+302F) - 11,172 precomposed syllables in the Korean alphabet make up the Hangul Syllables block (

U+AC00–U+D7A3)

Morpho-syllabic blocks

Except for a few grammatical morphemes prior to the twentieth century, no letter stands alone to represent elements of the Korean language. Instead, letters are grouped into syllabic or morphemic blocks of at least two and often three: a consonant or a doubled consonant called the initial (초성, 初聲 choseong syllable onset), a vowel or diphthong called the medial (중성, 中聲 jungseong syllable nucleus), and, optionally, a consonant or consonant cluster at the end of the syllable, called the final (종성, 終聲 jongseong syllable coda). When a syllable has no actual initial consonant, the null initial ㅇ ieung is used as a placeholder. (In the modern Korean alphabet, placeholders are not used for the final position.) Thus, a block contains a minimum of two letters, an initial and a medial. Although the Korean alphabet had historically been organized into syllables, in the modern orthography it is first organized into morphemes, and only secondarily into syllables within those morphemes, with the exception that single-consonant morphemes may not be written alone.

The sets of initial and final consonants are not the same. For instance, ㅇ ng only occurs in final position, while the doubled letters that can occur in final position are limited to ㅆ ss and ㄲ kk.

Not including obsolete letters, 11,172 blocks are possible in the Korean alphabet.[70]

Letter placement within a block

The placement or stacking of letters in the block follows set patterns based on the shape of the medial.

Consonant and vowel sequences such as ㅄ bs, ㅝ wo, or obsolete ㅵ bsd, ㆋ üye are written left to right.

Vowels (medials) are written under the initial consonant, to the right, or wrap around the initial from bottom to right, depending on their shape: If the vowel has a horizontal axis like ㅡ eu, then it is written under the initial; if it has a vertical axis like ㅣ i, then it is written to the right of the initial; and if it combines both orientations, like ㅢ ui, then it wraps around the initial from the bottom to the right:

|

|

|

A final consonant, if present, is always written at the bottom, under the vowel. This is called 받침 batchim "supporting floor":

|

|

| ||||||||||||

A complex final is written left to right:

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

Blocks are always written in phonetic order, initial-medial-final. Therefore:

- Syllables with a horizontal medial are written downward: 읍 eup;

- Syllables with a vertical medial and simple final are written clockwise: 쌍 ssang;

- Syllables with a wrapping medial switch direction (down-right-down): 된 doen;

- Syllables with a complex final are written left to right at the bottom: 밟 balp.

Block shape

Normally the resulting block is written within a square. Some recent fonts (for example Eun,[71] HY깊은샘물M, UnJamo) move towards the European practice of letters whose relative size is fixed, and use whitespace to fill letter positions not used in a particular block, and away from the East Asian tradition of square block characters (方块字). They break one or more of the traditional rules:

- Do not stretch initial consonant vertically, but leave white space below if no lower vowel and/or no final consonant.

- Do not stretch right-hand vowel vertically, but leave white space below if no final consonant. (Often the right-hand vowel extends farther down than the left-hand consonant, like a descender in European typography.)

- Do not stretch final consonant horizontally, but leave white space to its left.

- Do not stretch or pad each block to a fixed width, but allow kerning (variable width) where syllable blocks with no right-hand vowel and no double final consonant can be narrower than blocks that do have a right-hand vowel or double final consonant.

These fonts have been used as design accents on signs or headings, rather than for typesetting large volumes of body text.

Linear Korean

This section may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Korean. (September 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

There was a minor and unsuccessful movement in the early twentieth century to abolish syllabic blocks and write the letters individually and in a row, in the fashion of writing the Latin alphabets, instead of the standard convention of 모아쓰기 (moa-sseugi 'assembled writing'). For example, ㅎㅏㄴㄱㅡㄹ would be written for 한글 (Hangeul).[72] It is called 풀어쓰기 (pureo-sseugi 'unassembled writing').

Avant-garde typographer Ahn Sang-soo made a font for the Hangul Dada exposition that exploded the syllable blocks; but while it strings out the letters horizontally, it retains the distinctive vertical position each letter would normally have within a block, unlike the older linear writing proposals.[73]

Orthography

Until the 20th century, no official orthography of the Korean alphabet had been established. Due to liaison, heavy consonant assimilation, dialectal variants and other reasons, a Korean word can potentially be spelled in multiple ways. Sejong seemed to prefer morphophonemic spelling (representing the underlying root forms) rather than a phonemic one (representing the actual sounds). However, early in its history the Korean alphabet was dominated by phonemic spelling. Over the centuries the orthography became partially morphophonemic, first in nouns and later in verbs. The modern Korean alphabet is as morphophonemic as is practical. The difference between phonetic Romanization, phonemic orthography and morphophonemic orthography can be illustrated with the phrase motaneun sarami:

- Phonetic transcription and translation:

motaneun sarami

[mo.tʰa.nɯn.sa.ɾa.mi]

a person who cannot do it - Phonemic transcription:

모타는사라미

/mo.tʰa.nɯn.sa.la.mi/ - Morphophonemic transcription:

못하는사람이

mot-ha-nɯn-sa.lam-i - Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss:

못–하–는 사람=이 mot-ha-neun saram=i cannot-do-[attributive] person=[subject]

After the Gabo Reform in 1894, the Joseon Dynasty and later the Korean Empire started to write all official documents in the Korean alphabet. Under the government's management, proper usage of the Korean alphabet and Hanja, including orthography, was discussed, until the Korean Empire was annexed by Japan in 1910.

The Government-General of Korea popularised a writing style that mixed Hanja and the Korean alphabet, and was used in the later Joseon dynasty. The government revised the spelling rules in 1912, 1921 and 1930, to be relatively phonemic.[citation needed]

The Hangul Society, founded by Ju Si-gyeong, announced a proposal for a new, strongly morphophonemic orthography in 1933, which became the prototype of the contemporary orthographies in both North and South Korea. After Korea was divided, the North and South revised orthographies separately. The guiding text for orthography of the Korean alphabet is called Hangeul Matchumbeop, whose last South Korean revision was published in 1988 by the Ministry of Education.

Mixed scripts

Since the Late Joseon dynasty period, various Hanja-Hangul mixed systems were used. In these systems, Hanja were used for lexical roots, and the Korean alphabet for grammatical words and inflections, much as kanji and kana are used in Japanese. Hanja have been almost entirely phased out of daily use in North Korea, and in South Korea they are mostly restricted to parenthetical glosses for proper names and for disambiguating homonyms.

Indo-Arabic numerals are mixed in with the Korean alphabet, e.g. 2007년 3월 22일 (22 March 2007).

Latin script and occasionally other scripts may be sprinkled within Korean texts for illustrative purposes, or for unassimilated loanwords. Very occasionally, non-Hangul letters may be mixed into Korean syllabic blocks, as Gㅏ Ga at right.

Readability

Because of syllable clustering, words are shorter on the page than their linear counterparts would be, and the boundaries between syllables are easily visible (which may aid reading, if segmenting words into syllables is more natural for the reader than dividing them into phonemes).[74] Because the component parts of the syllable are relatively simple phonemic characters, the number of strokes per character on average is lower than in Chinese characters. Unlike syllabaries, such as Japanese kana, or Chinese logographs, none of which encode the constituent phonemes within a syllable, the graphic complexity of Korean syllabic blocks varies in direct proportion with the phonemic complexity of the syllable.[75] Like Japanese kana or Chinese characters, and unlike linear alphabets such as those derived from Latin, Korean orthography allows the reader to utilize both the horizontal and vertical visual fields.[76] Since Korean syllables are represented both as collections of phonemes and as unique-looking graphs, they may allow for both visual and aural retrieval of words from the lexicon. Similar syllabic blocks, when written in small size, can be hard to distinguish from, and therefore sometimes confused with, each other. Examples include 홋/훗/흣 (hot/hut/heut), 퀼/퀄 (kwil/kwol), 홍/흥 (hong/heung), and 핥/핣/핢 (halt/halp/halm).

Style

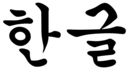

The Korean alphabet may be written either vertically or horizontally. The traditional direction is from top to bottom, right to left. Horizontal writing is also used.[77]

In Hunmin Jeongeum, the Korean alphabet was printed in sans-serif angular lines of even thickness. This style is found in books published before about 1900, and can be found in stone carvings (on statues, for example).[77]

Over the centuries, an ink-brush style of calligraphy developed, employing the same style of lines and angles as traditional Korean calligraphy. This brush style is called gungche (궁체, 宮體), which means Palace Style because the style was mostly developed and used by the maidservants (gungnyeo, 궁녀, 宮女) of the court in Joseon dynasty.

Modern styles that are more suited for printed media were developed in the 20th century. In 1993, new names for both Myeongjo (明朝) and Gothic styles were introduced when Ministry of Culture initiated an effort to standardize typographic terms, and the names Batang (바탕, meaning background) and Dotum (돋움, meaning "stand out") replaced Myeongjo and Gothic respectively. These names are also used in Microsoft Windows.

A sans-serif style with lines of equal width is popular with pencil and pen writing and is often the default typeface of Web browsers. A minor advantage of this style is that it makes it easier to distinguish -eung from -ung even in small or untidy print, as the jongseong ieung (ㅇ) of such fonts usually lacks a serif that could be mistaken for the short vertical line of the letter ㅜ (u).

See also

- Cyrillization of Korean (Kontsevich System)

- Hangul consonant and vowel tables

- Hangul orthography

- Hangul supremacy

- Korean Braille

- Korean language and computers – methods to type the language

- Korean manual alphabet

- Korean mixed script

- Korean phonology

- Korean spelling alphabet

- Myongjo

- Romanization of Korean

Notes

- ^ /ˈhɑːnɡuːl/ HAHN-gool;[1] from Korean 한글, Korean pronunciation: [ha(ː)n.ɡɯl]. Hangul may also be written as Hangeul following South Korea's standard Romanization.

- ^ ㄱ ㄴ ㄷ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅅ ㅇ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ

- ^ ㅏ ㅑ ㅓ ㅕ ㅗ ㅛ ㅜ ㅠ ㅡ ㅣ

- ^ ㄲ ㄸ ㅃ ㅆ ㅉ

- ^ ㄳ ㄵ ㄶ ㄺ ㄻ ㄼ ㄽ ㄾ ㄿ ㅀ ㅄ

- ^ ㅐ ㅒ ㅔ ㅖ ㅘ ㅙ ㅚ ㅝ ㅞ ㅟ ㅢ

- ^ ㆍ

- ^ ㅿ ㆁ ㆆ

- ^ or not written

- ^ The explanation of the origin of the shapes of the letters is provided within a section of Hunminjeongeum itself, 훈민정음 해례본 제자해 (Hunminjeongeum Haeryebon Jajahae or Hunminjeongeum, Chapter: Paraphrases and Examples, Section: Making of Letters), which states: 牙音ㄱ 象舌根閉喉之形. (아음(어금니 소리) ㄱ은 혀뿌리가 목구멍을 막는 모양을 본뜨고), 舌音ㄴ 象舌附上腭之形 ( 설음(혓 소리) ㄴ은 혀(끝)가 윗 잇몸에 붙는 모양을 본뜨고), 脣音ㅁ 象口形. ( 순음(입술소리) ㅁ은 입모양을 본뜨고), 齒音ㅅ 象齒形. ( 치음(잇 소리) ㅅ은 이빨 모양을 본뜨고) 象齒形. 喉音ㅇ. 象喉形 (목구멍 소리ㅇ은 목구멍의 꼴을 본뜬 것이다). ㅋ比ㄱ. 聲出稍 . 故加 . ㄴ而ㄷ. ㄷ而ㅌ. ㅁ而ㅂ. ㅂ而ㅍ. ㅅ而ㅈ. ㅈ而ㅊ. ㅇ而ㅡ. ㅡ而ㅎ. 其因聲加 之義皆同. 而唯 爲異 (ㅋ은ㄱ에 견주어 소리 남이 조금 세므로 획을 더한 것이고, ㄴ에서 ㄷ으로, ㄷ에서 ㅌ으로 함과, ㅁ에서 ㅂ으로 ㅂ에서 ㅍ으로 함과, ㅅ에서 ㅈ으로 ㅈ에서 ㅊ으로 함과, ㅇ에서 ㅡ으로 ㅡ에서 ㅎ으로 함도, 그 소리를 따라 획을 더한 뜻이 같다 . 오직 ㅇ자는 다르다.) 半舌音ㄹ. 半齒音. 亦象舌齒之形而異其體. (반혓소리ㄹ과, 반잇소리 '세모자'는 또한 혀와 이의 꼴을 본뜨되, 그 본을 달리하여 획을 더하는 뜻이 없다.) ...

Citations

- ^ "Hangul". Dictionary by Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ "알고 싶은 한글". 국립국어원. National Institute of Korean Language. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ a b Kim-Renaud 1997, p. 15.

- ^ Cock, Joe (28 June 2016). "A linguist explains why Korean is the best written language". Business Insider. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Sampson 1990, p. 120.

- ^ a b Taylor 1980, p. 67–82.

- ^ a b "How was Hangul invented?". The Economist. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Pae, Hye K. (1 January 2011). "Is Korean a syllabic alphabet or an alphabetic syllabary". Writing Systems Research. 3 (2): 103–115. doi:10.1093/wsr/wsr002. ISSN 1758-6801. S2CID 144290565.

- ^ Kim, Taemin (22 March 2016). "System, learning material, and computer readable medium for executing hangul acquisition method based on phonetics". World Intellectual Property Organization. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Hunminjeongeum Manuscript". Korean Cultural Heritage Administration. 2006. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Fischer, pp. 190, 193.

- ^ "Individual Letters of Hangeul and its Principles". National Institute of Korean Language. 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ McCune & Reischauer 1939, p. 52.

- ^ Lee & Ramsey 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Kim-Renaud 1997, p. 2.

- ^ a b c "Different Names for Hangeul". National Institute of Korean Language. 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Hannas 1997, p. 57.

- ^ Chen, Jiangping (18 January 2016). Multilingual Access and Services for Digital Collections. ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 9781440839559. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Invest Korea Journal. Vol. 23. Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency. 1 January 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

They later devised three different systems for writing Korean with Chinese characters: Hyangchal, Gukyeol and Idu. These systems were similar to those developed later in Japan and were probably used as models by the Japanese.

- ^ "Korea Now". Korea Herald. Vol. 29. 1 July 2000. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ a b c "The Background of the invention of Hangeul". National Institute of Korean Language. The National Academy of the Korean Language. 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Koerner, E. F. K.; Asher, R. E. (28 June 2014). Concise History of the Language Sciences: From the Sumerians to the Cognitivists. Elsevier. p. 54. ISBN 9781483297545. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ "Want to know about Hangeul?". National Institute of Korean Language. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Hunmin Jeongeum Haerye, postface of Jeong Inji, p. 27a, translation from Gari K. Ledyard, The Korean Language Reform of 1446, p. 258

- ^ a b c d e f Pratt, Rutt, Hoare, 1999. Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Routledge.

- ^ a b "4. The providing process of Hangeul". The National Academy of the Korean Language. January 2004. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ "Jeongeumcheong, synonymous with Eonmuncheong (정음청 正音廳, 동의어: 언문청)" (in Korean). Nate / Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ "Korea Britannica article" (in Korean). Enc.daum.net. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ WorldCat, Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu; alternate romaji Sankoku Tsūran Zusetsu

- ^ Cullen, Louis M. (2003). A History of Japan, 1582–1941: Internal and External Worlds, p. 137., p. 137, at Google Books

- ^ Vos, Ken. "Accidental acquisitions: The nineteenth-century Korean collections in the National Museum of Ethnology, Part 1", Archived 2012-06-22 at the Wayback Machine p. 6 (pdf p. 7); Klaproth, Julius. (1832). San kokf tsou ran to sets, ou Aperçu général des trois royaumes, pp. 19 n1., p. 19, at Google Books

- ^ Klaproth, pp. 1–168., p. 1, at Google Books

- ^ Silva, David J. (2008). "Missionary Contributions toward the Revaluation of Han'geul in Late 19th Century Korea". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2008 (192): 57–74. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.527.8160. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2008.035. S2CID 43569773.

- ^ "Korean History". Korea.assembly.go.kr. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ Park, Jung Hwan. 한글, 고종황제 드높이고 주시경 지켜내다 [Hangul, raise the status of Emperor Gojong and protect Ju Si-geong]. news1 (in Korean). Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Hangul 한글". The modern and contemporary history of Hangul (한글의 근·현대사) (in Korean). Daum / Britannica. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

1937년 7월 중일전쟁을 도발한 일본은 한민족 말살정책을 노골적으로 드러내, 1938년 4월에는 조선어과 폐지와 조선어 금지 및 일본어 상용을 강요했다.

- ^ "Under the Media". Lcweb2.loc.gov. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ a b Byon, Andrew Sangpil (2017). Modern Korean Grammar: A Practical Guide. Taylor & Francis. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-1351741293.

- ^ Miyake, Marc Hideo (1998). "Review of Asia's Orthographic Dilemma". Korean Studies. 22: 114–121. ISSN 0145-840X. JSTOR 23719388.

- ^ 洪惟仁 (2010). "閩南語書寫法的理想與現實" [Idealism vs. Reality: Writing Systems for Taiwanese Southern Min] (PDF). 臺灣語文研究 (in Chinese). 5 (1): 89, 101–105.

- ^ 楊允言; 張學謙; 呂美親 (2008). 台語文運動訪談暨史料彙編 [Compilation of Historical Materials and Interviews on the Written Taiwanese Movement] (in Chinese). Taiwan: 國史館. pp. 284–285. ISBN 9789860132946.

- ^ Dong Zhongsi (董忠司), 「台灣閩南語槪論」講授資料彙編, Taiwan Languages and Literature Society

- ^ "Linguistics Scholar Seeks to Globalize Korean Alphabet". Korea Times. 15 October 2008.

- ^ Choe, Sang-Hun (11 September 2009). "South Korea's Latest Export - Its Alphabet - NYTimes.com". The New York Times.

- ^ "Hangeul didn't become Cia Cia's official writing". Korea Times. 6 October 2010.

- ^ Indonesian tribe to use Korean alphabet Archived August 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Si-soo, Park (6 August 2009). "Indonesian Tribe Picks Hangeul as Writing System". Korea Times.

- ^ Kurt Achin (29 January 2010). "Indonesian Tribe Learns to Write with Korean Alphabet". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ^ "Gov't to correct textbook on Cia Cia". Korea Times. 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Kim-Renaud, Young-Key. (2009). Korean : an essential grammar. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-38513-8. OCLC 245598979.

- ^ a b Shin, Jiyoung (15 June 2015). "Vowels and Consonants". In Brown, Lucien; Yeon, Jaehoon (eds.). The Handbook of Korean Linguistics: Brown/The Handbook of Korean Linguistics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781118371008. ISBN 978-1-118-37100-8.

- ^ "한글 맞춤법[시행 2017. 3. 28.] 문화체육관광부 고시 제2017-12호(2017. 3. 28.)" [Hangul Spelling [Enforcement 2017. 3. 28.] Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism Notice No. 2017-12 (2017. 3. 28.)]. ko: 국립국어원, (The National Institute of the Korean Language). 28 March 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "A Quick Guide to Hangul, the Korean Alphabet – Pronunciation and Rules". Mondly Blog. 25 May 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "The Hunmin Chongum Manuscript United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "Korean Language in North and South Korea: The Differences". Day Translations Blog. 1 May 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "The Korean Language: The Key Differences Between North and South". Legal Translations. 16 March 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "An introduction to Korean Standard KS X 1026-1:2007, Hangul processing guide for information interchange" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Letter Names (Hangul 한글) Taekwondo Preschool". www.taekwondopreschool.com. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Korean Alphabet". thinkzone.wlonk.com. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Korean alphabet, pronunciation and language". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Kim-Renaud, Young-Key (2012). Tranter, Nicolas (ed.). The Languages of Japan and Korea. Oxon, UK: Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 9780415462877.

- ^ The Japanese/Korean Vowel Correspondences by Bjarke Frellesvig and John Whitman. Section 3 deals with Middle Korean vowels.

- ^ Korean orthography rules Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Korean language reform of 1446: the origin, background, and Early History of the Korean Alphabet, Gari Keith Ledyard. University of California, 1966, p. 367–368.

- ^ Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, The World's Writing Systems (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 219–220

- ^ Yergeau, F. (1998). "3. Versions of the standards". UTF-8, a transformation format of ISO 10646. doi:10.17487/rfc2279. RFC 2279.

- ^ Ho-Min Sohn (29 March 2001). The Korean Language. Cambridge University Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-521-36943-5.

- ^ Iksop Lee; S. Robert Ramsey (2000). The Korean Language. SUNY Press. pp. 315–. ISBN 978-0-7914-4832-8.

- ^ Ki-Moon Lee; S. Robert Ramsey (3 March 2011). A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge University Press. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-1-139-49448-9.

- ^ Park, ChangHo (2009). Lee, Chungmin; Simpson, Greg B; Kim, Youngjin; Li, Ping (eds.). "Visual processing of Hangul, the Korean script". The Handbook of East Asian Psycholinguistics. III: 379–389. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511596865.030. ISBN 9780511596865 – via Google Books.

- ^ Welch, Craig. "Korean Unicode Fonts". www.wazu.jp.

- ^ Pratt, Keith L.; Rutt, Richard (13 September 1999). Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary – Keith L. Pratt, Richard Rutt, James Hoare – Google Boeken. ISBN 9780700704637. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ Ezer, Oded (9 December 2006). "Hangul Dada, Seoul, Korea". Flickr. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ Taylor 1980, p. 71.

- ^ Taylor 1980, p. 73.

- ^ Taylor 1980, p. 70.

- ^ a b "Koreana Autumn 2007 (English)". Koreana Autumn 2007 (English). Retrieved 13 October 2021.

References

- Chang, Suk-jin (1996). "Scripts and Sounds". Korean. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-55619-728-4. (Volume 4 of the London Oriental and African Language Library).

- "Hangeul Matchumbeop". The Ministry of Education of South Korea. 1988.

- Hannas, W[illia]m C. (1997). Asia's Orthographic Dilemma. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0.

- Kim-Renaud, Young-Key, ed. (1997). The Korean Alphabet: Its History and Structure. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1723-7.

- Lee, Iksop; Ramsey, Samuel Robert (2000). The Korean Language. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-9130-0.

- McCune, G[eorge] M.; Reischauer, E[dwin] O. (1939). "The Romanization of the Korean Language: Based upon Its Phonetic Structure" (PDF). Transactions of the Korea Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. XXIX: 1–55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Sampson, Geoffrey (1990). Writing Systems. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1756-4.

- Silva, David J. (2002). "Western attitudes toward the Korean language: An Overview of Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Mission Literature" (PDF). Korean Studies. 26 (2): 270–286. doi:10.1353/ks.2004.0013. hdl:10106/11257. S2CID 55677193.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (2001). The Korean Language. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36943-5.

- Song, Jae Jung (2005). The Korean Language: Structure, Use and Context. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-39082-5.

- Taylor, Insup (1980). "The Korean writing system: An alphabet? A syllabary? A logography?". In Kolers, P.A.; Wrolstad, M. E.; Bouma, Herman (eds.). Processing of Visual Language. Vol. 2. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0306405761. OCLC 7099393.

External links

- Korean alphabet and pronunciation by Omniglot

- Online Hangul tutorial at Langintro.com

- Hangul table with Audio Slideshow

- Technical information on Hangul and Unicode

- Hangul Sound Keyboard at Kmaru.com

- Learn Hangul at Korean Wiki Project