μ- opio이드 수용체

μ-opioid receptor

μ-오피오이드 수용체(MOR)는 엔케팔린 및 베타-엔도르핀에 대해서는 높은 친화도를 갖지만 다이노르핀에 대해서는 낮은 친화도를 갖는 오피오이드 수용체의 한 종류입니다. 그들은 μ(mu)-오피오이드 펩티드(MOP) 수용체라고도 합니다. 원형의 μ-오피오이드 수용체 작용제는 모르핀으로, 아편의 주요 정신 활성 알칼로이드이며 수용체 이름이 지어졌으며, mu는 원래 그리스어로 화합물의 이름과 같은 모르페우스의 첫 글자입니다. Gi 알파 소단위체를 활성화시켜 아데닐산 사이클라제 활성을 억제하여 cAMP 수치를 낮추는 억제성 G-단백질 결합 수용체입니다.

구조.

비활성 μ-오피오이드 수용체의 구조는 길항제인 β-FNA와[6] 알비모판으로 결정되었습니다.[7] DAMGO,[8] β-엔돌핀,[9] 펜타닐 및 모르핀을 포함한 작용제와 함께 활성 상태의 많은 구조도 이용할 수 있습니다.[10] 작용제 BU72가 있는 구조는 분해능이 가장 높지만 [11]실험적인 인공물일 수 있는 설명되지 않은 특징을 포함합니다.[12][13] 이러한 많은 증거는 기능적 선택성을 가진 새로운 종류의 오피오이드의 구조 기반 설계를 가능하게 했습니다.[14]

스플라이스 변형

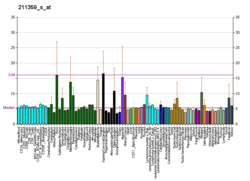

μ-opioid 수용체의 세 가지 변이체가 잘 특성화되어 있지만 역전사 중합효소 연쇄 반응은 인간에서 최대 10개의 총 스플라이스 변이체를 확인했습니다.[15][16][17]

| μ1 | μ1 오피오이드 수용체에 대해서는 다른 변이체보다 더 많이 알려져 있습니다. |

| μ2 | TRIMU 5는 μ 수용체의2 선택적 작용제입니다.[18] |

| μ3 | μ3 변형은 2003년에 처음 기술되었습니다.[19] 알칼로이드를 아편계에 반응하지만 아편계 펩타이드는 반응하지 않습니다.[20] |

위치

세포 유형에 따라 시냅스 전 또는 시냅스 후에 존재할 수 있습니다.

μ-opioid 수용체는 대부분 관주위 회색 영역과 척수의 표재성 등뿔(특히 Rolando의 젤라틴)에 시냅스 전으로 존재합니다. 그들이 위치한 다른 영역에는 외이도의 핵뿐만 아니라 후각구의 외부 신경총층, 핵은 대뇌 피질의 여러 층에 축적되고 편도체의 일부 핵에 축적됩니다.

일부 MOR은 장관에서도 발견됩니다. 이러한 수용체의 활성화는 α 작용제의 주요 부작용인 변비를 유발하는 연동 작용을 억제합니다.[21]

활성화

MOR은 GABA의 시냅스 전 방출의 억제를 통해 신경 흥분성의 급성 변화를 매개할 수 있습니다. MOR의 활성화는 작용제에 따라 수지상 척추에 다른 영향을 미치며 μ-수용체에서의 기능적 선택성의 예가 될 수 있습니다.[22] 이 두 가지 별개의 메커니즘의 생리학적 및 병리학적 역할은 아직 명확히 밝혀지지 않았습니다. 아마도 둘 다 오피오이드 중독과 오피오이드로 인한 인지 결손에 관여할 수 있습니다.

모르핀과 같은 작용제에 의한 μ-opioid 수용체의 활성화는 진통, 진정, 혈압의 약간 감소, 가려움, 메스꺼움, 행복감, 호흡 저하, 미오증(수축성 동공), 장 운동 저하를 유발하며, 종종 변비를 유발합니다. 진통, 진정, 행복감, 가려움증 및 호흡 감소와 같은 이러한 영향 중 일부는 내성이 발달함에 따라 지속적으로 사용하면 감소하는 경향이 있습니다. 미오시스와 감소된 장 운동성은 지속되는 경향이 있으며, 이러한 효과에 대한 내성은 거의 발생하지 않습니다.

표준 MOR1 아이소폼은 모르핀 유도성 진통을 담당하는 반면, 대체 접합된 MOR1D 아이소폼은 모르핀 유도성 가려움증에 필요합니다.[23]

비활성화

다른 G 단백질 결합 수용체와 마찬가지로 μ-opioid 수용체에 의한 신호 전달은 여러 가지 다른 메커니즘을 통해 종결되며, 이는 만성적인 사용으로 인해 상향 조절되어 빠른 타키필락시스로 이어집니다.[24] MOR의 가장 중요한 조절 단백질은 베타 1과 베타 2의 β-arrestin parestin과 [25][26][27]RGS 단백질 RGS4, RGS9-2, RGS14, RGSZ2입니다.[28][29]

오피오이드를 장기간 또는 고용량으로 사용하면 추가적인 내성 기전이 개입될 수도 있습니다. 여기에는 MOR 유전자 발현의 하향 조절이 포함되므로 β-arrestin 또는 RGS 단백질에 의해 유도되는 더 단기적인 탈감작과 달리 세포 표면에 존재하는 수용체의 수는 실제로 감소합니다.[30][31][32] 오피오이드 사용에 대한 또 다른 장기적인 적응은 오피오이드 반대 효과를 발휘할 수 있는 글루타메이트 및 뇌의 기타 경로의 상향 조절일 수 있으므로 MOR 활성화에 관계없이 다운스트림 경로를 변경하여 오피오이드 약물의 효과를 감소시킵니다.[33][34]

허용치와 과다복용

치명적인 오피오이드 과다복용은 일반적으로 서맥 호흡, 저산소 혈증 및 심박출량 감소(혈관 확장으로 인해 저혈압이 발생하고 서맥은 심박출량 감소에 더욱 기여함)로 인해 발생합니다.[35][36][37] 오피오이드가 에탄올, 벤조디아제핀, 바르비투레이트 또는 기타 중추 억제제와 결합될 때 강화 효과가 발생하여 의식을 급격히 잃고 치명적인 과다 복용의 위험이 증가할 수 있습니다.[35][36]

호흡기 우울증에 대한 상당한 내성은 빠르게 발달하고 내성이 있는 사람은 더 많은 용량을 견딜 수 있습니다.[38] 그러나 호흡성 우울증에 대한 내성은 금단 기간 동안 빠르게 소실되어 일주일 이내에 완전히 역전될 수 있습니다. 오피오이드 중단 후 내성이 사라진 후 이전 용량으로 돌아온 사람들에게 많은 과다복용이 발생합니다. 이는 오피오이드 중독으로 의학적 치료를 받는 중독자들이 특히 재발에 취약할 수 있기 때문에 방출될 때 과다 복용의 큰 위험에 빠집니다.

덜 일반적으로, 대량의 과다복용은 혈관 확장과 서맥으로 인한 순환 붕괴를 유발하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[39]

오피오이드 과다복용은 오피오이드 길항제 사용을 통해 빠르게 역전될 수 있는데, 날록손이 가장 널리 사용되는 예입니다.[35] 오피오이드 길항제는 µ-오피오이드 수용체에 경쟁적으로 결합하고 오피오이드 길항제를 대체함으로써 작용합니다. 날록손의 추가 투여가 필요할 수 있으며 활력징후를 모니터링하여 저산소성 뇌손상을 예방하기 위한 지원적인 관리가 필요합니다.

Tramadol과 tapentadol은 SNRI로서의 이중 효과와 관련된 추가적인 위험을 가지고 있으며 세로토닌 증후군과 발작을 일으킬 수 있습니다. 이러한 위험에도 불구하고 이러한 약물이 모르핀에 비해 호흡 저하의 위험이 낮다는 것을 시사하는 증거가 있습니다.[40]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ a b c GRCh38: 앙상블 릴리즈 89: ENSG00000112038 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ a b c GRCm38: 앙상블 릴리즈 89: ENSMUSG000000766 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Zhorov BS, Ananthanarayanan VS (March 2000). "Homology models of mu-opioid receptor with organic and inorganic cations at conserved aspartates in the second and third transmembrane domains". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 375 (1): 31–49. doi:10.1006/abbi.1999.1529. PMID 10683246.

- ^ Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, et al. (March 2012). "Crystal structure of the µ-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist". Nature. 485 (7398): 321–326. Bibcode:2012Natur.485..321M. doi:10.1038/nature10954. PMC 3523197. PMID 22437502.

- ^ Robertson MJ, Papasergi-Scott MM, He F, Seven AB, Meyerowitz JG, Panova O, et al. (December 2022). "Structure determination of inactive-state GPCRs with a universal nanobody". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 29 (12): 1188–1195. doi:10.1038/s41594-022-00859-8. PMID 36396979.

- ^ Koehl A, Hu H, Maeda S, Zhang Y, Qu Q, Paggi JM, et al. (June 2018). "Structure of the µ-opioid receptor-Gi protein complex". Nature. 558 (7711): 547–552. Bibcode:2018Natur.558..547K. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0219-7. PMC 6317904. PMID 29899455.

- ^ Wang Y, Zhuang Y, DiBerto JF, Zhou XE, Schmitz GP, Yuan Q, et al. (January 2023). "Structures of the entire human opioid receptor family". Cell. 186 (2): 413–427.e17. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.026. PMID 36638794. S2CID 255750597.

- ^ Zhuang Y, Wang Y, He B, He X, Zhou XE, Guo S, et al. (November 2022). "Molecular recognition of morphine and fentanyl by the human μ-opioid receptor". Cell. 185 (23): 4361–4375.e19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.041. PMID 36368306. S2CID 253426623.

- ^ Huang W, Manglik A, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Laeremans T, Feinberg EN, Sanborn AL, et al. (August 2015). "Structural insights into µ-opioid receptor activation". Nature. 524 (7565): 315–321. Bibcode:2015Natur.524..315H. doi:10.1038/nature14886. PMC 4639397. PMID 26245379.

- ^ Zou R, Wang X, Li S, Chan HS, Vogel H, Yuan S (2022). "The role of metal ions in G protein‐coupled receptor signalling and drug discovery". WIREs Computational Molecular Science. 12 (2): e1565. doi:10.1002/wcms.1565. ISSN 1759-0876. S2CID 237649760.

- ^ Munro TA (October 2023). "Reanalysis of a μ opioid receptor crystal structure reveals a covalent adduct with BU72". BMC Biology. 21 (1): 213. doi:10.1186/s12915-023-01689-w. PMC 10566028. PMID 37817141.

- ^ Faouzi A, Wang H, Zaidi SA, DiBerto JF, Che T, Qu Q, et al. (January 2023). "Structure-based design of bitopic ligands for the µ-opioid receptor". Nature. 613 (7945): 767–774. Bibcode:2023Natur.613..767F. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05588-y. PMC 10328120. PMID 36450356.

- ^ Dortch-Carnes J, Russell K (January 2007). "Morphine-stimulated nitric oxide release in rabbit aqueous humor". Experimental Eye Research. 84 (1): 185–190. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2006.09.014. PMC 1766947. PMID 17094965.

- ^ Pan L, Xu J, Yu R, Xu MM, Pan YX, Pasternak GW (2005). "Identification and characterization of six new alternatively spliced variants of the human mu opioid receptor gene, Oprm". Neuroscience. 133 (1): 209–220. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.033. PMID 15893644. S2CID 22410194.

- ^ Xu J, Lu Z, Narayan A, Le Rouzic VP, Xu M, Hunkele A, et al. (April 2017). "Alternatively spliced mu opioid receptor C termini impact the diverse actions of morphine". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 127 (4): 1561–1573. doi:10.1172/JCI88760. PMC 5373896. PMID 28319053.

- ^ Eisenberg RM (April 1994). "TRIMU-5, a mu 2-opioid receptor agonist, stimulates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 47 (4): 943–946. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(94)90300-X. PMID 8029266. S2CID 54354971.

- ^ Cadet P, Mantione KJ, Stefano GB (May 2003). "Molecular identification and functional expression of mu 3, a novel alternatively spliced variant of the human mu opiate receptor gene". Journal of Immunology. 170 (10): 5118–5123. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5118. PMID 12734358.

- ^ Stefano GB (June 2004). "Endogenous morphine: a role in wellness medicine". Medical Science Monitor. 10 (6): ED5. PMID 15173675.

- ^ Chen W, Chung HH, Cheng JT (March 2012). "Opiate-induced constipation related to activation of small intestine opioid μ2-receptors". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (12): 1391–1396. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1391. PMC 3319967. PMID 22493554.

- ^ Liao D, Lin H, Law PY, Loh HH (February 2005). "Mu-opioid receptors modulate the stability of dendritic spines". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (5): 1725–1730. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.1725L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406797102. JSTOR 3374498. PMC 545084. PMID 15659552.

- ^ Liu XY, Liu ZC, Sun YG, Ross M, Kim S, Tsai FF, et al. (October 2011). "Unidirectional cross-activation of GRPR by MOR1D uncouples itch and analgesia induced by opioids". Cell. 147 (2): 447–458. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.043. PMC 3197217. PMID 22000021.*요약 위치:

- ^ Martini L, Whistler JL (October 2007). "The role of mu opioid receptor desensitization and endocytosis in morphine tolerance and dependence". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 17 (5): 556–564. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2007.10.004. PMID 18068348. S2CID 29491629.

- ^ Zuo Z (September 2005). "The role of opioid receptor internalization and beta-arrestins in the development of opioid tolerance". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 101 (3): 728–734. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000160588.32007.AD. PMID 16115983.

- ^ Marie N, Aguila B, Allouche S (November 2006). "Tracking the opioid receptors on the way of desensitization". Cellular Signalling. 18 (11): 1815–1833. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.03.015. PMID 16750901.

- ^ DuPen A, Shen D, Ersek M (September 2007). "Mechanisms of opioid-induced tolerance and hyperalgesia". Pain Management Nursing. 8 (3): 113–121. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2007.02.004. PMID 17723928.

- ^ Garzón J, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Sánchez-Blázquez P (May 2005). "Morphine alters the selective association between mu-opioid receptors and specific RGS proteins in mouse periaqueductal gray matter". Neuropharmacology. 48 (6): 853–868. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.004. PMID 15829256. S2CID 23797166.

- ^ Hooks SB, Martemyanov K, Zachariou V (January 2008). "A role of RGS proteins in drug addiction". Biochemical Pharmacology. 75 (1): 76–84. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.045. PMID 17880927.

- ^ Sirohi S, Dighe SV, Walker EA, Yoburn BC (November 2008). "The analgesic efficacy of fentanyl: relationship to tolerance and mu-opioid receptor regulation". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 91 (1): 115–120. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2008.06.019. PMC 2597555. PMID 18640146.

- ^ Lopez-Gimenez JF, Vilaró MT, Milligan G (November 2008). "Morphine desensitization, internalization, and down-regulation of the mu opioid receptor is facilitated by serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptor coactivation". Molecular Pharmacology. 74 (5): 1278–1291. doi:10.1124/mol.108.048272. PMID 18703670. S2CID 6310244.

- ^ Kraus J (June 2009). "Regulation of mu-opioid receptors by cytokines". Frontiers in Bioscience. 1 (1): 164–170. doi:10.2741/e16. PMID 19482692.

- ^ García-Fuster MJ, Ramos-Miguel A, Rivero G, La Harpe R, Meana JJ, García-Sevilla JA (November 2008). "Regulation of the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways in the prefrontal cortex of short- and long-term human opiate abusers". Neuroscience. 157 (1): 105–119. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.002. PMID 18834930. S2CID 9022097.

- ^ Ueda H, Ueda M (June 2009). "Mechanisms underlying morphine analgesic tolerance and dependence". Frontiers in Bioscience. 14 (14): 5260–5272. doi:10.2741/3596. PMID 19482614.

- ^ a b c Blok (2017). "Opioid toxicity" (PDF). Clinical Key. Elsevier.

- ^ a b Hughes CG, McGrane S, Pandharipande PP (2012). "Sedation in the intensive care setting". Clinical Pharmacology. 4 (53): 53–63. doi:10.2147/CPAA.S26582. PMC 3508653. PMID 23204873.

- ^ Shanazari AA, Aslani Z, Ramshini E, Alaei H (2011). "Acute and chronic effects of morphine on cardiovascular system and the baroreflexes sensitivity during severe increase in blood pressure in rats". ARYA Atherosclerosis. 7 (3): 111–117. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(88)90399-1. PMC 3347855. PMID 22577457.

- ^ Algera MH, Olofsen E, Moss L, Dobbins RL, Niesters M, van Velzen M, et al. (March 2021). "Tolerance to Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression in Chronic High-Dose Opioid Users: A Model-Based Comparison With Opioid-Naïve Individuals". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 109 (3): 637–645. doi:10.1002/cpt.2027. PMC 7983936. PMID 32865832.

- ^ Krantz MJ, Palmer RB, Haigney MC (January 2021). "Cardiovascular Complications of Opioid Use: JACC State-of-the-Art Review". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 77 (2): 205–223. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.002. PMID 33446314. S2CID 231613932.

- ^ Houmes RJ, Voets MA, Verkaaik A, Erdmann W, Lachmann B (April 1992). "Efficacy and safety of tramadol versus morphine for moderate and severe postoperative pain with special regard to respiratory depression". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 74 (4): 510–514. doi:10.1213/00000539-199204000-00007. PMID 1554117. S2CID 24530179.