심혈관질환

Cardiovascular disease| 심혈관질환 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 섬유증(노란색)과 아밀로이드증(갈색)이 있는 심장의 마이크로그래프.모바트의 얼룩. | |

| 전문 | 심장학 |

| 증상 | 가슴통증, 호흡곤란 |

| 합병증 | 심정지 |

| 평상시 시작 | 나이든[1] 어른들 |

| 종류들 | 관상동맥질환, 뇌졸중, 심부전, 고혈압성 심장질환, 류머티즘성 심장질환, 심근병증[2][3] |

| 예방 | 건강한 식습관, 운동, 담배 연기 회피, 제한된 알코올 섭취[2] |

| 치료 | 고혈압, 고혈지질, 당뇨병[2] 치료 |

| 죽음 | 1790만 / 32%(2015년)[4] |

심혈관 질환(CVD)은 심장이나 혈관이 관련된 질병의 일종이다.[2]CVD에는 협심증, 심근경색(일반적으로 심장마비로 알려져 있음)과 같은 관상동맥질환(CAD)이 포함된다.[2]다른 CVD로는 뇌졸중, 심부전, 고혈압 심장질환, 류머티즘 심장질환, 심근병증, 비정상적인 심장박동, 선천성 심장질환, 발판성 심장질환, 카드염, 대동맥동맥류, 말초동맥질환, 혈전증, 정맥혈전증 등이 있다.[2][3]

근본적인 메커니즘은 질병에 따라 다르다.[2]식이 요인은 CVD 사망의 53%와 관련이 있는 것으로 추정된다.[5]관상동맥질환, 뇌졸중, 말초동맥질환은 동맥경화증을 수반한다.[2]이것은 고혈압, 흡연, 당뇨병, 운동부족, 비만, 고혈중 콜레스테롤, 식습관 불량, 과도한 알코올 섭취,[2] 수면 부족 등이 원인일 수 있다.[6][7]고혈압은 CVD 사망의 약 13%를 차지하고 있으며 담배는 9%, 당뇨병 6%, 운동부족 6%, 비만 5%를 차지하고 있는 것으로 추정된다.[2]류머티즘 심장병은 치료되지 않은 줄무늬 목구멍을 따를 수 있다.[2]

CVD의 최대 90%를 예방할 수 있을 것으로 추정된다.[8][9]CVD의 예방에는 건강한 식습관, 운동, 담배 연기 회피 및 알코올 섭취 제한 등을 통해 위험 요인을 개선하는 것이 포함된다.[2]고혈압, 지질, 당뇨병 등 위험요인을 치료하는 것도 이롭다.[2]인후염이 있는 사람들을 항생제로 치료하면 류머티즘 심장병의 위험을 줄일 수 있다.[10][needs update]그렇지 않으면 건강한 사람들에게 아스피린을 사용하는 것은 분명치 않은 이득이다.[11][12]

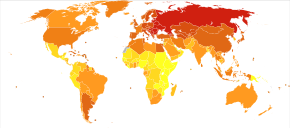

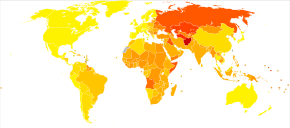

심혈관질환은 아프리카를 제외한 전 세계적으로 사망원인 1위다.[2]CVD를 합치면, 1990년의 1,230만 명(25.8%)에 비해 2015년에는 1,790만 명(32.1%)이 사망하였다.[4][3]CVD로 인한 사망은 특정 연령대에 더 흔하고 개발도상국 대부분에서 증가하고 있는 반면, 1970년대 이후 대부분의 선진국에서는 감소하고 있다.[13][14]관상동맥 질환과 뇌졸중은 남성 CVD 사망의 80%, 여성 CVD 사망의 75%를 차지한다.[2]대부분의 심혈관 질환은 노인에게 영향을 미친다.미국은 20~40세 인구의 11%가 CVD를 보유하고 있으며, 40~60세 37%, 60~80세 71%, 80세 이상 85%가 CVD를 보유하고 있다.[1]선진국에서는 관상동맥질환으로 인한 평균 사망연령이 80세 전후인 반면 개발도상국에서는 68세 전후다.[13]질병의 진단은 일반적으로 여성에 비해 남성에게서 7년에서 10년 일찍 일어난다.[2]: 48

종류들

혈관과 관련된 심혈관 질환이 많다.그것들은 혈관 질환으로 알려져 있다.[citation needed]

- 관상동맥질환(관상동맥질환, 허혈성심장질환이라고도 한다)

- 말초동맥질환 – 팔과 다리에 혈액을 공급하는 혈관질환

- 뇌혈관질환 – 뇌에 혈액을 공급하는 혈관질환(뇌졸중 포함)

- 신장동맥협착증

- 대동맥류

심장과 관련된 심혈관 질환도 많다.

- 심근병증 – 심장근육 질환

- 고혈압성 심장질환 – 고혈압 또는 고혈압에 이차적인 심장질환

- 심부전 - 심장이 조직의 대사 요건을 충족시키기 위해 충분한 혈액을 조직에 공급하지 못해 발생하는 임상 증후군

- 폐심장질환 – 심장 우측에 호흡기 질환이 있는 경우

- 심장 부정맥 – 심장 박동의 이상

- 염증성 심장병

- 발판성 심장병

- 선천성 심장 질환 – 태어날 때 존재하는 심장 구조 기형

- 류머티즘 심장병 – A군 연쇄상구균 감염에 의한 류머티즘 열로 인한 심장 근육과 판막 손상.

위험요소

심장질환의 위험요인은 연령, 성별, 담배 사용, 신체부활, 과도한 알코올 섭취, 건강하지 못한 식단, 비만, 유전적 성향 및 심혈관질환 가족력, 혈압 상승(고혈압), 혈당 상승(당뇨병), 혈당 상승(고혈압), 혈당 상승(고혈압), 혈중 콜레스테롤 상승(고지질혈증), 진단되지 않음 등 여러 가지가 있다.셀리악병, 정신사회적인 요인, 가난과 낮은 교육 상태, 대기오염과 수면부족.[16][17][18][2][19]각 위험 요인의 개별 기여도는 지역 사회 또는 민족 그룹에 따라 다르지만, 이러한 위험 요인의 전체적인 기여는 매우 일관적이다.[20]나이, 성별 또는 가족력/유전적 성향과 같은 이러한 위험 요인 중 일부는 불변하지만, 많은 중요한 심혈관 위험 요인은 라이프스타일 변화, 사회 변화, 약물 치료(예: 고혈압, 고지혈증, 당뇨병 예방)에 의해 수정할 수 있다.[21]비만이 있는 사람들은 관상동맥의 아테롬성 동맥경화증의 위험을 증가시킨다.[22]

유전학

부모의 심혈관계 질환은 발병 위험이 최대 3배[23] 증가하며 유전학은 심혈관 질환의 중요한 위험 요인이다.유전적 심혈관 질환은 단일 변종(멘델리아어) 또는 다세대적 영향의 결과로 발생할 수 있다.[24]이러한 질환은 드물지만 하나의 질병을 유발하는 DNA 변형으로 추적할 수 있는 유전성 심혈관질환은 40개가 넘는다.[24]대부분의 흔한 심혈관 질환은 멘델리아인이 아니며 각각 작은 효과와 연관된 수백, 수천 가지의 유전적 변형(단일 뉴클레오티드 다형성증이라고 알려져 있음)에 기인 것이다.[25][26]

나이

나이는 심혈관 질환이나 심장 질환을 발병하는 데 가장 중요한 위험 인자로, 10년 마다 위험의 약 3배가 된다.[27]관상동맥 지방 줄무늬는 청소년기에 형성되기 시작할 수 있다.[28]관상동맥심장질환으로 사망하는 사람의 82%가 65세 이상으로 추정된다.[29]동시에 뇌졸중 위험은 55세 이후 10년마다 두 배로 증가한다.[30]

나이가 들면 심혈관/심장질환의 위험이 높아지는 이유를 설명하기 위해 복수의 설명이 제안된다.그 중 하나는 혈청 콜레스테롤 수치와 관련이 있다.[31]대부분의 인구에서 혈청 총콜레스테롤 수치는 나이가 들수록 증가한다.남성의 경우, 이 증가는 45세에서 50세 전후로 낮아진다.여성의 경우 60~65세까지 급격한 증가세가 이어지고 있다.[31]

노화는 혈관벽의 기계적, 구조적 성질의 변화와도 관련이 있는데, 이는 동맥 탄력성의 상실과 동맥 적합성의 저하로 이어져 관상동맥질환을 초래할 수 있다.[32]

섹스

남성들은 폐경 전 여성들보다 심장병의 위험이 더 크다.[27][33]일단 폐경이 지나고 나면, 세계보건기구와 유엔의 더 최근의 자료들이 이를 반박하고 있지만, 여성의 위험은 남성의 위험과[33] 비슷하다는 주장이 제기되었다.[27]여성이 당뇨병에 걸리면 당뇨병에 걸린 남성보다 심장병에 걸릴 확률이 높다.[34]

관상동맥 심장질환은 중년 남성이 여성보다 2~5배 더 흔하다.[31]세계보건기구의 연구에서 성은 관상동맥 심장병 사망률의 성비 변동의 약 40%에 기여한다.[35]또 다른 연구는 성 차이가 심혈관 질환과[31] 관련된 위험의 거의 절반을 설명한다는 유사한 결과를 보고한다. 심혈관 질환의 성 차이에 대한 제안된 설명 중 하나는 호르몬 차이다.[31]여성들 사이에서는 에스트로겐이 성호르몬이 지배적이다.에스트로겐은 포도당 대사와 지혈계에 보호 효과를 줄 수 있으며 내피 세포 기능을 향상시키는데 직접적인 영향을 줄 수 있다.[31]폐경 후 에스트로겐의 생산량은 감소하고, 이것은 LDL과 총콜레스테롤 수치를 증가시키면서 HDL 콜레스테롤 수치를 감소시킴으로써 여성 지질대사를 보다 무신론적인 형태로 변화시킬 수 있다.[31]

남녀 간에는 체중, 키, 체지방 분포, 심박수, 뇌졸중 볼륨, 동맥 순응 등의 차이가 있다.[32]바로 고령자의 경우 연령과 관련된 큰 동맥의 융통성과 경직성이 남성보다 여성들 사이에서 더 두드러진다.[32]이것은 폐경기에 독립적인 여성의 작은 신체 크기와 동맥 치수에 의해 야기될 수 있다.[32]

담배

담배는 흡연 담배의 주요 형태다.[2]담배 사용에 따른 건강에 대한 위험은 직접 담배를 소비하는 것뿐만 아니라 간접흡연에 노출되는 것에서도 발생한다.[2]심혈관 질환의 약 10%는 흡연에 기인한다.[2] 그러나 30세까지 담배를 끊는 사람들은 흡연하지 않는 사람들만큼 거의 사망위험이 낮다.[36]

물리적 비활동

불충분한 신체 활동(주당 5 x 30분 이하의 보통 활동 또는 3 x 20분 미만의 활발한 활동으로 정의됨)은 현재 전 세계적으로 사망률의 네 번째 주요 위험 요인이다.[2]2008년에는 15세 이상 성인의 31.3%(남성 28.2%, 여성 34.4%)가 신체활동이 미흡한 것으로 나타났다.[2]허혈성 심장질환과 당뇨병의 위험은 매주 150분 정도의 적당한 신체활동(또는 이에 준하는 것)에 참여하는 성인의 경우 거의 3분의 1로 줄어든다.[37]또한, 신체 활동은 체중 감소를 돕고 혈당 조절, 혈압, 지질 프로필, 인슐린 민감도를 향상시킨다.이러한 영향은 적어도 부분적으로 심혈관 편익을 설명할 수 있다.[2]

다이어트

비록 이 모든 연관성이 원인을 나타내는지 여부는 논쟁의 여지가 있지만 포화지방, 트랜스지방, 소금, 과일, 야채, 생선의 낮은 섭취는 심혈관계 위험과 관련이 있다.세계보건기구는 전세계적으로 약 170만 명의 사망자를 과일과 채소 섭취가 적은 탓으로 돌리고 있다.[2]지방과 당분이 많은 가공식품과 같은 고에너지 식품을 자주 섭취하면 비만을 촉진하고 심혈관 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다.[2]식이 소금의 섭취량은 또한 혈압 수치와 전반적인 심혈관 위험을 결정하는 중요한 요인이 될 수 있다.[2]최소한 2년 동안 포화지방 섭취를 줄이면 심혈관 질환의 위험이 줄어든다는 적당한 품질의 증거가 있다.[38]트랜스지방 섭취가 많으면 혈중 지질이나 순환 염증 표지에 악영향을 미치고,[39] 식단에서 트랜스지방 제거가 널리 주장되어 왔다.[40][41]2018년 세계보건기구는 트랜스 지방이 연간 50만 명 이상의 사망의 원인이라고 추정했다.[41]설탕 섭취량이 많아지면 혈압이 높아지고 지질이 좋지 않다는 증거가 있으며,[42] 당분 섭취도 당뇨병의 숙성 위험을 증가시킨다.[43]가공육을 많이 섭취하는 것은 심혈관 질환의 위험 증가와 관련이 있는데, 부분적으로 식이 염분 섭취 증가로 인한 것일 수 있다.[18]

알코올

알코올 소비와 심혈관 질환의 관계는 복잡하며, 알코올 소비량에 따라 달라질 수 있다.[44]높은 수준의 음주와 심혈관 질환 사이에는 직접적인 관계가 있다.[2]과음 에피소드가 없는 낮은 수준의 음주는 심혈관 질환의 위험 감소와 관련이 있을 수 있지만,[45] 적당한 알코올 소비와 뇌졸중으로부터 보호 사이의 연관성은 무관심하다는 증거가 있다.[46]인구 수준에서는 음주의 건강 위험이 잠재적 편익을 초과한다.[2][47]

셀리악병

치료되지 않은 셀리악병은 많은 종류의 심혈관 질환의 발달을 유발할 수 있으며, 대부분은 글루텐이 없는 식이요법과 장 치유를 통해 개선되거나 해결된다.그러나 셀리악성 질환에 대한 인식과 진단이 지연되면 돌이킬 수 없는 심장 손상을 초래할 수 있다.[19]

잠

수면 부족은 양이나 질 면에서 성인과 청소년 모두에게 심혈관 위험을 증가시키는 것으로 기록되어 있다.권고안은 유아들은 일반적으로 하루에 12시간 이상 잠을 자야 하며, 청소년들은 적어도 8시간에서 9시간, 그리고 성인은 7시간 또는 8시간 이상 잠을 자야 한다고 제시한다.성인 미국인의 약 3분의 1은 권장 수면시간인 7시간보다 낮으며, 10대를 대상으로 한 연구에서 학습된 사람들 중 2.2%만이 충분한 수면을 취했으며, 이들 중 많은 사람들은 양질의 수면을 취하지 못했다.연구에 따르면 하룻밤에 7시간 미만의 수면을 취하는 짧은 수면자들은 심혈관 질환의 위험이 10~30% 더 높은 것으로 나타났다.[6][48]

수면 장애 호흡 장애와 불면증 같은 수면 장애도 심혈관 질환 위험이 더 높은 것과 관련이 있다.[49]약 5천만에서 7천만 명의 미국인들이 불면증, 수면 무호흡증 또는 다른 만성 수면 장애로 고통 받고 있다.

게다가 수면 연구는 인종과 계급의 차이를 보여준다.짧은 수면과 나쁜 수면은 백인보다 소수민족에서 더 자주 보고되는 경향이 있다.아프리카계 미국인들은 짧은 수면을 백인보다 5배 더 자주 경험하고 있으며, 아마도 사회적 환경적 요인 때문일 것이라고 보고한다.불우 이웃에 사는 흑인 아이들과 아이들은 백인 아이들보다 수면 무호흡증의 비율이 훨씬 높다.[7]

사회경제적 불이익

심혈관계 질환은 고소득 국가보다 저소득 및 중산층 국가에 더 큰 영향을 미친다.[50]중저소득 국가에서는 심혈관 질환의 사회 패턴에 대한 정보가 상대적으로 적지만 고소득 국가에서는 저소득과 낮은 교육 지위가 일관되게 심혈관 질환의 위험성과 연관되어 있다.[50][51]사회-경제적 불평등을 증가시킨 정책들은 인과관계를 암시하는 심혈관 질환의[50] 후속적인 사회-경제적 차이와 연관되어 있다.정신사회적 요인, 환경적 노출, 건강 행동, 의료 접근 및 품질은 심혈관 질환의 사회 경제적 차이에 기여한다.[52]건강의 사회결정요인위원회는 심혈관질환과 비커뮤니케이션성 질환의 불평등을 해소하기 위해 권력, 재산, 교육, 주택, 환경요인, 영양, 건강관리의 보다 균등한 분배가 필요하다고 권고했다.[53]

대기 오염

미립자 물질은 심혈관 질환에 대한 장단기 노출 효과로 연구되어 왔다.현재 CVD 위험을 결정하기 위해 구배율을 사용하는 지름 2.5마이크로미터(PM2.5) 미만의 공기 중 입자가 주요 초점이다.전반적으로 장기 PM 노출은 아테롬성 동맥경화와 염증 발생률을 증가시켰다.단기 노출(2시간)에 대해서는 PM2.5 25μg/m마다3 CVD 사망 위험이 48%씩 증가했다.[54]또한 불과 5일의 노출 후 PM2.5 10.5μg/m마다3 수축기(2.8mmHg)와 이완기(2.7mmHg) 혈압 상승이 일어났다.[54]다른2.5 연구들은 PM이 불규칙한 심장 박동, 감소된 심박수 변동성, 그리고 가장 두드러진 심부전을 포함시켰다.[54][55]PM은2.5 경동맥이 두꺼워지고 급성심근경색 위험이 증가하는 것과도 관련이 있다.[54][55]

심혈관계 위험도 평가

기존의 심혈관 질환이나 심장마비나 뇌졸중과 같은 이전의 심혈관 질환은 미래 심혈관 질환의 가장 강력한 예측 변수다.[56]나이, 성별, 흡연, 혈압, 지질과 당뇨병은 심혈관 질환이 있는 것으로 알려져 있지 않은 사람들에게 미래의 심혈관 질환의 중요한 예측 변수다.[57]이러한 조치들, 그리고 때로는 다른 조치들을 복합 위험 점수로 결합하여 개인의 향후 심혈관 질환 위험을 추정할 수 있다.[56]각각의 장점이 논의되기는 하지만 수많은 위험 점수가 존재한다.[58]다른 진단 테스트와 바이오마커는 여전히 평가 중이지만, 현재 이러한 테스트는 일상적 사용을 뒷받침할 명확한 증거가 부족하다.They include family history, coronary artery calcification score, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), ankle–brachial pressure index, lipoprotein subclasses and particle concentration, lipoprotein(a), apolipoproteins A-I and B, fibrinogen, white blood cell count, homocysteine, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), and m신장 기능이 있는 [59][60]아커들높은 혈중 인은 또한 위험 증가와 관련이 있다.[61]

우울증 및 외상성 스트레스

정신 건강 문제, 특히 우울증과 외상성 스트레스가 심혈관 질환과 연관되어 있다는 증거가 있다.정신건강문제는 흡연, 식생활 불량, 좌식생활 등 심혈관질환의 위험요인과 관련이 있는 것으로 알려져 있지만, 이러한 요인만으로는 우울증, 스트레스, 불안감에서 나타나는 심혈관질환의 위험 증가가 설명되지 않는다.[62]게다가 외상 후 스트레스 장애는 우울증과 다른 공변량을 조절한 후에도 사고 관상동맥 심장 질환의 위험 증가와 독립적으로 연관되어 있다.[63]

직업적 노출

일과 심혈관 질환의 관계에 대해서는 거의 알려져 있지 않지만, 특정 독소, 극도의 더위와 추위, 담배 연기 노출, 스트레스와 우울증과 같은 정신 건강 우려 사이에 연관성이 확립되어 있다.[64]

비화학위험인자

2015년 SBU 보고서에서 비화학 요인을 조사한 결과 다음과 같은 연관성이 발견되었다.[65]

- 정신적으로 스트레스를 많이 받는 일, 그들의 근무 상황에 대한 통제력 부족, 즉 노력-효과-불균형을[65] 가지고.

- 직장에서 낮은 사회적 지원을 경험하거나, 부정을 경험하거나, 개인의 발전을 위한 기회가 불충분하거나, 고용 불안을[65] 경험하는 사람

- 야간 근무를 하는 사람들, 또는 장시간[65] 근무한 사람들

- 소음에[65] 노출된 사람들

특히 뇌졸중의 위험도 전리방사선에 노출되어 증가했다.[65]고혈압은 직업적 부담을 경험하고 교대근무를 하는 사람들에게서 더 자주 발병한다.[65]위험에 처한 여성과 남성의 차이는 작지만 남성은 직장 생활 중 여성보다 두 배나 더 자주 심장마비나 뇌졸중으로 고통받고 사망할 위험이 있다.[65]

화학적 위험인자

2017년 SBU 보고서는 실리카 분진, 엔진 배기 가스 또는 용접 가스에 대한 작업장 노출이 심장병과 관련이 있다는 증거를 발견했다.[66]비소, 벤조피렌, 납, 다이너마이트, 탄소 이설피드, 일산화탄소, 금속 작업 유체 및 담배 연기에 대한 직업상 피폭에 대한 연관성도 존재한다.[66]황산염 펄핑 공정을 사용할 때 알루미늄의 전해질 생산이나 용지의 생산과 관련된 작업은 심장병과 관련이 있다.[66]또한 심장 질환과 TCDD(다이옥신)를 함유한 페녹시산이나 석면 등 특정 작업 환경에서 더 이상 허용되지 않는 화합물에 대한 노출 사이에 연관성이 발견되었다.[66]

실리카 분진이나 석면에 대한 작업장 노출은 폐심장질환과도 관련이 있다.납에 대한 작업장 노출, 탄소 이설화, TCDD를 함유한 페녹시아시드는 물론 알루미늄이 전해질적으로 생산되는 환경에서 작업하는 것이 뇌졸중과 관련이 있다는 증거가 있다.[66]

체성 돌연변이

2017년 현재 혈액 세포에서 백혈병과 관련된 특정 돌연변이가 심혈관 질환의 위험도 증가시킬 수 있다는 증거가 제시되고 있다.인간의 유전 데이터를 살펴보는 몇몇 대규모 연구 프로젝트에서는 이러한 돌연변이의 존재, 즉 집단 조혈증으로 알려진 상태와 심혈관 질환 관련 사건 및 사망률 사이에 강력한 연관성을 발견했다.[67]

방사선요법

암에 대한 방사선 치료는 유방암 치료에서 관찰된 바와 같이 심장병과 사망의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다.[68]치료용 방사선은 이후의 심장마비나 뇌졸중의 위험을 정상 속도의 1.5배에서 4배 증가시킨다.[69]그 증가는 선량 강도, 부피 및 위치에 따라 선량에 따라 달라진다.

심혈관 질환에 대한 방사선 치료로 인한 부작용은 방사선 유도 심장 질환 또는 방사선 유도 혈관 질환으로 불린다.[70]증상은 용량에 의존하며 심근병증, 심근섬유증, 판막심장질환, 관상동맥질환, 심장부정맥, 말초동맥질환 등이 있다.방사선에 의한 섬유화, 혈관 세포 손상 및 산화 스트레스는 이러한 부작용과 다른 늦은 부작용을 초래할 수 있다.[70]

병리학

심혈관질환의 주요 전구체인 아테롬성 동맥경화증이 어린 시절부터 시작된다는 연구결과가 나왔다.청소년 아테롬성 동맥경화의 병리학적 결정요인 연구는 7~9세 청소년의 모든 대동맥과 오른쪽 관상동맥의 절반 이상에 근접한 병변이 나타난다는 것을 보여주었다.[72]

비만과 당뇨병은 만성 신장질환과 고콜로스테롤라혈증의 역사처럼 심혈관질환과 연관되어 있다.[73][74]실제로 심혈관질환은 당뇨 합병증 중 가장 생명을 위협하는 질환으로 당뇨병 환자는 비당뇨병보다 심혈관 관련 원인으로 사망할 확률이 2~4배 높다.[75][76][77]

선별

심전도 검사(휴식 중 또는 운동 중)는 위험성이 낮은 증상 없는 환자에게는 권장하지 않는다.[78]여기에는 위험요인이 없는 젊은 층이 포함된다.[79]고위험군에서 심전도 검사를 위한 증거는 결론에 이르지 못한다.[80]추가적으로 심장 초음파 검사, 심근관류 영상 검사, 심장 스트레스 테스트는 증상이 없는 위험성이 낮은 사람들에게는 권장되지 않는다.[81]일부 바이오마커는 미래 심혈관 질환의 위험을 예측하는 데 전통적인 심혈관 위험 인자를 추가할 수 있지만, 일부 바이오마커의 가치는 의심스럽다.[82][83]발목-브래치알지수(ABI), 고감도 C-반응 단백질(hsCRP), 관상동맥 칼슘 등도 2018년 현재 증상이 없는 사람에게 효과가 불분명하다.[84]

NIH는 심장질환이나 지방질 질환의 가족력이 있는 경우 2세부터 시작하는 어린이들에게 지방질 검사를 권고하고 있다.[85]조기 테스트가 다이어트와 운동과 같은 위험에 처한 사람들의 생활습관 요인을 개선하기를 바란다.[86]

1차 예방 개입에 대한 선별과 선택은 전통적으로 다양한 점수를 사용하여 절대 위험을 통해 수행되었다(ex).프레이밍햄 또는 레이놀즈 위험 점수).[87]이러한 계층화는 라이프스타일 개입(일반적으로 더 낮은 위험과 중간 위험)을 받는 사람들을 약물(더 높은 위험)에서 분리시켰다.이용 가능한 위험점수의 수와 다양성은 배가됐지만, 2016년 검토에 따른 효능은 외부 유효성 검증이나 영향 분석이 미흡해 불분명했다.[88]위험 계층화 모델은 종종 모집단 그룹에 대한 민감도가 부족하며 중간 위험 그룹과 낮은 위험 그룹 사이에서 많은 수의 부정적인 사건을 설명하지 않는다.[87]이에 따라 향후 예방적 심사는 대규모 위험도 평가보다는 각 개입의 무작위 재판 결과에 따라 예방적용 쪽으로 전환되는 것으로 보인다.

예방

확립된 위험요인을 피하면 심혈관질환의 90%까지 예방할 수 있다.[8][89]현재 시행되고 있는 심혈관 질환 예방 대책은 다음과 같다.

- 지중해식, 채식주의자, 채식주의자, 채식주의자 또는 다른 식물성 식단과 같은 건강한 식단을 유지하는 것.[90][91][92][93]

- 포화 지방을 건강한 선택으로 대체:임상 실험 결과, 포화 지방을 다불포화 식물성 오일로 대체하면 CVD가 30% 감소하는 것으로 나타났다.사전 관찰 연구에 따르면 많은 모집단에서 포화지방의 낮은 섭취와 다불포화지방 및 일불포화지방의 높은 섭취가 CVD의 낮은 섭취율과 관련이 있다는 것을 알 수 있다.[94]

- 만약 과체중이거나 비만이면 체지방을 줄인다.[95]체중 감량의 효과는 식생활 변화와 구별하기 어려운 경우가 많고, 체중 감량 식단에 대한 증거도 제한적이다.[96]심각한 비만을 가진 사람들의 관찰 연구에서 비만 수술 후 체중 감량은 심혈관 위험의 46% 감소와 관련이 있다.[97]

- 알코올 섭취를 권장하는 일일 한도로 제한하라;[90] 알코올 음료를 적당히 섭취하는 사람들은 심혈관 질환의 위험이 25~30% 낮다.[98][99]그러나 유전적으로 술을 적게 섭취하는 경향이 있는 사람들은 심혈관 질환의[100] 발병률이 낮아서 알코올 자체가 보호가 되지 않을 수도 있다는 것을 암시한다.과도한 알코올 섭취는 심혈관 질환의[101][99] 위험을 증가시키고 알코올 섭취는 섭취 다음날 심혈관 질환의 위험 증가와 관련이 있다.[99]

- 비 HDL 콜레스테롤을 감소시킨다.[102][103]스타틴 치료는 심혈관 사망률을 약 31%[104] 감소시킨다.

- 담배를 끊고 간접흡연을 피한다.[90]흡연을 중단하면 위험이 약 35%[105] 감소한다.

- 주당 최소 150분(2시간 30분)의 적당한 운동.[106][107]

- 혈압이 상승할 경우 혈압을 낮추십시오.혈압이 10mmHg 감소하면 위험성이 [108]약 20% 감소한다.혈압을 낮추는 것은 정상 혈압 범위에서도 효과가 있는 것으로 보인다.[109][110][111]

- 정신적 사회적 스트레스를 줄인다.[112]이 조치는 정신사회적 개입을 구성하는 것의 정의를 부정확하게 함으로써 복잡할 수 있다.[113]정신적 스트레스로 인한 심근 허혈은 이전 심장질환을 앓고 있는 사람들의 심장질환 위험 증가와 관련이 있다.[114]심한 감정적 육체적 스트레스는 어떤 사람들에게는 타코츠보 증후군으로 알려진 심장 기능 장애의 한 형태로 이어진다.[115]그러나 스트레스는 고혈압에서 비교적 작은 역할을 한다.[116]구체적인 이완 요법은 분명치 않은 이점이 있다.[117][118]

- 수면이 부족하면 고혈압의 위험도 높아진다.성인들은 약 7~9시간의 수면이 필요하다.수면무호흡증은 또한 호흡을 멈추게 하여 심장질환의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있는 당신의 몸에 스트레스를 줄 수 있기 때문에 주요한 위험이다.[119][120]

대부분의 지침은 예방 전략을 결합할 것을 권고한다.둘 이상의 심혈관 위험 인자를 감소시키는 것을 목표로 하는 개입이 혈압, 체질량 지수, 허리 둘레에 유익한 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 일부 증거가 있다. 그러나 증거는 제한적이었고 저자들은 심혈관 질환과 사망률에 미치는 영향에 대해 확고한 결론을 도출할 수 없었다.[121]

단순히 심혈관 질환 위험 점수를 사람들에게 제공하는 것만으로도 심혈관 질환 위험 인자를 평상시 진료에 비해 소량 줄일 수 있다는 추가 증거가 있다.[122]그러나 이러한 점수를 제공하는 것이 심혈관 질환에 영향을 미치는지에 대해서는 약간의 불확실성이 있었다.치주염에 걸린 사람의 치과진료가 심혈관질환 위험에 영향을 미치는지 여부는 불분명하다.[123]

다이어트

과일과 채소를 많이 섭취하면 심혈관 질환과 사망 위험이 줄어든다.[124]

2021년 검토 결과, 플랜트 기반 다이어트는 건강한 플랜트 기반 다이어트를 소비할 경우 CVD에 대한 위험 감소를 제공할 수 있다는 사실이 밝혀졌다.건강에 좋지 않은 식물성 식단은 고기를 포함한 일반 식단에 비해 이점을 제공하지 못한다.[91]유사한 메타분석과 체계적 검토에서도 식습관을 조사해 "동물 사료와 건강하지 못한 식물 식품이 적은 식이요법이 CVD 예방에 도움이 된다"[92]는 결과가 나왔다.2018년 관찰 연구의 메타 분석은 "대부분의 국가에서 채식주의 식단은 잡식성 식단에 비해 더 유리한 심장-메타볼릭 프로파일과 연관되어 있다"고 결론지었다.[93]

지중해식 식단이 심혈관 결과를 향상시킬 수 있다는 증거가 있다.[125]또한 지중해식 식단이 저지방 식단보다 심혈관 위험 인자에 대한 장기적인 변화(예: 낮은 콜레스테롤 수치와 혈압)를 가져오는 데 더 효과적일 수 있다는 증거도 있다.[126]

DASH 다이어트(너트, 생선, 과일, 야채가 많고 단것, 붉은 고기, 지방이 적음)는 혈압을 낮추고,[127] 총량 및 저밀도 지단백질[128] 콜레스테롤을 낮추고, 대사증후군을 개선하는 것으로 나타났으나,[129] 장기적인 이점에 대해서는 의문이 제기되었다.[130]높은 섬유질 식단은 심혈관 질환의 낮은 위험과 관련이 있다.[131]

세계적으로 식이요법 가이드라인은 포화지방 감소를 권고하고 있으며 [132]심혈관질환에서 식이지방의 역할이 복잡하고 논란이 있지만 식단에서 포화지방을 불포화지방으로 대체하는 것이 건전한 의학적 조언이라는 오랜 공감대가 형성돼 있다.[133]총 지방 섭취량은 심혈관 위험과 관련이 없는 것으로 밝혀졌다.[134][135]2020년 체계적인 검토 결과 최소 2년 동안 포화지방 섭취를 줄인 것이 심혈관 질환의 감소를 유발한다는 중간 정도의 품질 증거를 발견했다.[136]그러나 2015년 관찰 연구의 메타분석은 포화지방 섭취와 심혈관 질환 사이에 설득력 있는 연관성을 찾지 못했다.[137]포화지방의 대용으로 사용되는 것의 변동은 발견의 일부 차이를 설명할 수 있다.[133]다불포화 지방으로 대체하는 것의 이점은 가장 큰 것으로 보이는 반면,[138] 포화 지방을 탄수화물로 대체하는 것은 유익한 효과를 거두지 못하는 것으로 보인다.[138]다이어트 트랜스 지방산이 높은 심혈관 disease,[139]이 되는 것으로이며 2015년에 식품 의약품 안전청(FDA)이 'no 더 오래부분적으로oils(PHOs)수소를 첨가한 산업적으로 생산된 트랜스 지방산(IP-TFA)의 주요 음식 원료 자격을 갖춘 전문가들 사이에서 의견 일치를 것으로 연관되어 있다., are는 일반적으로 인간의 식품에 어떤 용도로도 안전하다고 인정된다.'[140]심혈관 위험을 개선하기 위해 첨가된 오메가-3 지방산(지질 생선의 다포화지방의 일종)의 식이요법 보충에 관한 상반된 증거가 있다.[141][142]

혈압이 높거나 정상인 사람에게 저염식을 권하는 이점이 명확하지 않다.[143]심부전이 있는 사람들은, 한 가지 연구가 배제된 후, 나머지 실험들은 이익을 얻는 경향을 보여준다.[144][145]식이 소금의 또 다른 리뷰는 높은 식이 소금의 섭취가 혈압을 증가시키고 고혈압을 악화시킨다는 강력한 증거가 있으며, 혈압 상승의 결과로 심혈관 질환의 발생 횟수를 증가시킨다는 결론을 내렸다.[146][147]높은 소금 섭취가 심혈관 사망률을 증가시킨다는 적당한 증거가 발견되었고, 전반적인 사망률, 뇌졸중, 좌심실 비대증 증가의 일부 증거가 발견되었다.[146]

간헐적 단식

전반적으로 현재의 과학적 증거 체계는 간헐적 단식이 심혈관 질환을 예방할 수 있을지 불확실하다.[148]간헐적인 단식은 사람들이 규칙적인 식습관보다 더 많은 체중을 감량하는 데 도움이 될 수 있지만, 에너지 제한 식단과 다르지 않았다.[148]

약물

혈압약은 연령, [149]심혈관계 위험의 기준치 [150]또는 혈압에 관계없이 위험에 처한 사람들의 심혈관 질환을 감소시킨다.[108][151]일반적으로 사용되는 약물 요법은 모든 주요 심혈관 질환의 위험을 줄이는데 유사한 효능을 가지고 있지만, 특정 결과를 예방하는 약들 사이에는 차이가 있을 수 있다.[152]혈압의 큰 감소는 더 큰 위험을 감소시킨다.[152] 그리고 대부분의 고혈압을 가진 사람들은 혈압의 적절한 감소를 이루기 위해 두 가지 이상의 약을 필요로 한다.[153]약물에 대한 집착은 종종 좋지 않으며 휴대 전화 문자 메시지 전달이 중독성을 향상시키기 위해 시도되어 왔지만, 그것이 심혈관 질환의 2차 예방을 변화시킨다는 충분한 증거가 없다.[154]

스타틴은 심혈관 질환 이력이 있는 사람들에게서 심혈관 질환을 예방하는데 효과적이다.[155]여성보다 남성이 사건 발생률이 높기 때문에 사건 감소는 여성보다 남성이 더 쉽게 볼 수 있다.[155]위험에 처해 있지만 심혈관 질환의 이력이 없는 사람들(1차 예방)에서 스타틴은 사망 위험과 사망 및 비치사 심혈관 질환의 결합을 감소시킨다.[156]그러나 그 이익은 적다.[157]미국의 가이드라인은 향후 10년간 심혈관 질환의 위험이 12% 이상인 사람에게 스타틴을 권고한다.[158]Niacin, 섬유산염, CETP 억제제들은 HDL 콜레스테롤을 증가시키지만 이미 스타틴을 복용하고 있는 사람들의 심혈관 질환의 위험에는 영향을 미치지 않는다.[159]섬유종은 심혈관 질환과 관상동맥 질환의 위험을 낮춘다. 그러나 그들이 모든 원인 사망률을 감소시킨다는 증거는 없다.[160]

비록 증거가 확실하지는 않지만, 당뇨병 치료제는 제2형 당뇨병에 걸린 사람들의 심혈관 위험을 줄일 수 있다.[161]2009년 27,049명의 참가자와 2,370개의 주요 혈관 이벤트를 포함한 메타분석 결과, 평균 추적기간 4.4년에 걸쳐 보다 집중적인 포도당이 감소하면서 심혈관 질환의 상대적 위험 감소율은 15%였으나 주요 저혈당증의 위험성은 증가했다.[162]

아스피린은 심혈관 질환과 관련하여 심각한 출혈의 위험이 거의 같기 때문에 심장 질환의 위험이 낮은 사람들에게만 미미한 편익인 것으로 밝혀졌다.[163]70세 이상 고령자를 포함하여 매우 위험성이 낮은 사람에게는 권장하지 않는다.[164][165]미국 예방 서비스 대책 위원회는 55세 이하의 여성과 45세 이하의 남성에게 예방에 아스피린을 사용하지 말라고 권고하지만, 일부 개인에게는 권장한다.[166]

좌심장질환이나 저산소성 폐질환이 있는 폐고혈압을 가진 사람에게 혈관활성제를 사용하면 위해와 불필요한 비용이 발생할 수 있다.[167]

관상동맥 심장질환 2차 예방을 위한 항생제

항생제는 관상동맥질환 환자들이 심장마비와 뇌졸중의 위험을 줄이는데 도움을 줄 수 있다.[168]그러나 최근의 증거는 관상동맥 심장질환의 2차 예방을 위한 항생제가 사망률 증가와 뇌졸중 발생으로 해롭다는 것을 시사한다.[168]그래서 현재 2차 관상동맥심장질환을 예방하기 위해 항생제 사용이 지원되지 않는다.

신체활동

심장마비에 따른 운동 기반 심장 재활은 심혈관 질환으로 인한 사망 위험을 줄이고 입원을 줄인다.[169]심혈관 위험은 증가했지만 심혈관 질환의 역사는 없는 사람들에게 운동 훈련의 이점에 대한 높은 수준의 연구는 거의 없었다.[170]

체계적 리뷰는 비활동이 전 세계 관상동맥심장질환으로 인한 질병 부담의 6%를 차지한다고 추정했다.[171]저자들은 만약 신체적인 비활동성이 제거되었다면 2008년 유럽에서 12만1천명의 관상동맥 심장병으로 인한 사망자를 피할 수 있었을 것이라고 추정했다.제한된 수의 연구에서 나온 낮은 품질의 증거는 요가가 혈압과 콜레스테롤에 이로운 영향을 미친다는 것을 보여준다.[172]잠정적인 증거는 집에 기반을 둔 연습 프로그램이 연습 고수도를 향상시키는데 더 효율적일 수 있다는 것을 암시한다.[173]

건강보조식품

건강한 식단이 유익하지만 항산화제 보충제(비타민E, 비타민C 등)나 비타민의 효과가 심혈관 질환으로부터 보호되지 않아 어떤 경우에는 해를 끼칠 수 있다.[174][175][176][177]미네랄 보충제 또한 유용하지 않은 것으로 밝혀졌다.[178]비타민 B3의 일종인 나이아신은 고위험군에서 심혈관 질환의 위험이 다소 감소하는 예외일 수 있다.[179][180]마그네슘 보충제는 용량 의존적인 방식으로 고혈압을 낮춘다.[181]마그네슘 치료는 긴 QT 증후군을 가진 토르사이드 데 포인트와 관련된 심실 부정맥과 디옥신 중독에 의한 부정맥에 걸린 사람들의 치료에도 권장된다.[182]오메가-3 지방산 보충제를 뒷받침할 증거가 없다.[183]

관리

심혈관 질환은 주로 식이요법과 생활습관 개입에 초점을 맞춘 초기 치료로 치료가 가능하다.[2]인플루엔자는 심장마비와 뇌졸중을 일으킬 가능성이 더 높기 때문에 인플루엔자 예방접종은 심장병 환자의 심혈관 질환과 사망의 가능성을 감소시킬 수 있다.[184]

적절한 CVD 관리를 위해서는 MI 및 뇌졸중 사례에 집중해야 하며, 특히 저소득 또는 중간 소득 수준을 가진 개발도상국의 경우 모든 개입의 비용 효율성을 염두에 두어야 한다.[87]MI에 대해서는 아스피린, 아테놀, 스트렙토키나아제, 조직 플라시미노겐 활성제를 사용한 전략이 저소득 및 중간소득 지역의 품질조정 수명년(QALY)에 비교되었다.아스피린과 아테놀롤에 대한 단일 QALY 비용은 25달러 미만, 스트렙토키나아제는 약 680달러, t-PA는 16,000달러였다.[185]동일한 지역에서 2차 CVD 예방을 위해 함께 사용되는 아스피린, ACE 억제제, 베타 차단제 및 스타틴은 단일 QALY 비용이 350달러로 나타났다.[185]

혈압 목표를 140 ~ 160/90 ~ 100 mmHg로 낮춘 경우 사망률 및 심각한 이상 사건 측면에서 추가적인 편익은 없을 것이다.[186]

역학

심혈관 질환은 전 세계적으로, 그리고 아프리카를 제외한 모든 지역에서 사망의 주요 원인이다.[2]2008년에는 전 세계 사망자의 30%가 심혈관 질환에 기인했다.심혈관 질환으로 인한 사망은 전 세계 심혈관 질환으로 인한 사망의 80% 이상이 해당 국가에서 발생하기 때문에 저소득 국가 및 중산층 국가에서도 더 높다.또한 2030년까지 매년 2300만명이 넘는 사람들이 심혈관 질환으로 사망할 것으로 추산된다.

세계 인구의 20%에 불과하지만 전 세계 심혈관 질환 부담의 60%가 남아시아 아대륙에서 발생할 것으로 추산된다.이것은 유전적 성향과 환경적 요인의 조합에 부차적인 것일 수 있다.인도심장협회와 같은 단체들은 이 문제에 대한 경각심을 높이기 위해 세계심장연맹과 협력하고 있다.[187]

리서치

심혈관 질환이 역사 이전부터 존재했다는 증거가 있으며 [188]심혈관 질환에 대한 연구는 적어도 18세기부터 시작되었다.[189]모든 형태의 심혈관 질환의 원인, 예방 및/또는 치료는 생명 의학 연구의 활발한 분야로 남아 있으며, 매주 수백 개의 과학 연구가 발표되고 있다.

최근의 연구 분야에는 염증과 아테롬성[190] 동맥경화증의 연관성, 새로운 치료적 개입의 가능성,[191] 그리고 관상동맥 심장병의 유전성 등이 포함되어 있다.[192]

참조

- ^ a b Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. (January 2013). "Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association". Circulation. 127 (1): e6–e245. doi:10.1161/cir.0b013e31828124ad. PMC 5408511. PMID 23239837.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Shanthi M, Pekka P, Norrving B (2011). Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control (PDF). World Health Organization in collaboration with the World Heart Federation and the World Stroke Organization. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-92-4-156437-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-17.

- ^ a b c Naghavi M, Wang H, Lozano R, Davis A, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. (GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ a b Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Petersen, Kristina S.; Kris-Etherton, Penny M. (2021-11-28). "Diet quality assessment and the relationship between diet quality and cardiovascular disease risk". Nutrients. 13 (12): 4305. doi:10.3390/nu13124305. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 8706326. PMID 34959857.

- ^ a b Jackson CL, Redline S, Emmons KM (March 2015). "Sleep as a potential fundamental contributor to disparities in cardiovascular health". Annual Review of Public Health. 36 (1): 417–40. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122838. PMC 4736723. PMID 25785893.

- ^ a b Wang R, Dong Y, Weng J, Kontos EZ, Chervin RD, Rosen CL, et al. (January 2017). "Associations among Neighborhood, Race, and Sleep Apnea Severity in Children. A Six-City Analysis". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 14 (1): 76–84. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201609-662OC. PMC 5291481. PMID 27768852.

- ^ a b McGill HC, McMahan CA, Gidding SS (March 2008). "Preventing heart disease in the 21st century: implications of the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) study". Circulation. 117 (9): 1216–27. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717033. PMID 18316498.

- ^ O'Donnell MJ, Chin SL, Rangarajan S, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, et al. (August 2016). "Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): a case-control study". Lancet. 388 (10046): 761–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30506-2. PMID 27431356. S2CID 39752176.

- ^ Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB (November 2013). "Antibiotics for sore throat". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD000023. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000023.pub4. PMC 6457983. PMID 24190439.

- ^ Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Gurung T, Freeman K, Johnson S, Ngianga-Bakwin K, et al. (2013). "Aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: a systematic review of the balance of evidence from reviews of randomized trials". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e81970. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...881970S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081970. PMC 3855368. PMID 24339983.

- ^ Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Gurung T, Freeman K, Johnson S, Kandala NB, et al. (September 2013). "Aspirin for prophylactic use in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: a systematic review and overview of reviews". Health Technology Assessment. 17 (43): 1–253. doi:10.3310/hta17430. PMC 4781046. PMID 24074752.

- ^ a b Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (2010). "Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease". In Fuster V, Kelly BB (eds.). Promoting cardiovascular health in the developing world : a critical challenge to achieve global health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-14774-3. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Roth GA, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJ, Naghavi M (April 2014). "Temporal trends in ischemic heart disease mortality in 21 world regions, 1980 to 2010: the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study". Circulation. 129 (14): 1483–92. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.004042. PMC 4181359. PMID 24573352.

- ^ a b "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-11-11. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

- ^ Fuster V, Kelly BB, eds. (2010). Promoting Cardiovascular Health in the Developing World: A Critical Challenge to Achieve Global Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-14774-3.

- ^ Finks SW, Airee A, Chow SL, Macaulay TE, Moranville MP, Rogers KC, Trujillo TC (April 2012). "Key articles of dietary interventions that influence cardiovascular mortality". Pharmacotherapy. 32 (4): e54-87. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.2011.01087.x. PMID 22392596. S2CID 36437057.

- ^ a b Micha R, Michas G, Mozaffarian D (December 2012). "Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes--an updated review of the evidence". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 14 (6): 515–24. doi:10.1007/s11883-012-0282-8. PMC 3483430. PMID 23001745.

- ^ a b Ciaccio EJ, Lewis SK, Biviano AB, Iyer V, Garan H, Green PH (August 2017). "Cardiovascular involvement in celiac disease". World Journal of Cardiology (Review). 9 (8): 652–666. doi:10.4330/wjc.v9.i8.652. PMC 5583538. PMID 28932354.

- ^ Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. (2004). "Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study". Lancet. 364 (9438): 937–52. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. hdl:10983/21615. PMID 15364185. S2CID 30811593.

- ^ McPhee S (2012). Current medical diagnosis & treatment. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 430. ISBN 978-0-07-176372-1.

- ^ Eckel RH (November 1997). "Obesity and heart disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee, American Heart Association". Circulation. 96 (9): 3248–50. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.96.9.3248. PMID 9386201.

- ^ Kathiresan S, Srivastava D (March 2012). "Genetics of human cardiovascular disease". Cell. 148 (6): 1242–57. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.001. PMC 3319439. PMID 22424232.

- ^ a b Semsarian, Christopher; Ingles, Jodie; Ross, Samantha Barratt; Dunwoodie, Sally L.; Bagnall, Richard D.; Kovacic, Jason C. (2021-05-25). "Precision Medicine in Cardiovascular Disease: Genetics and Impact on Phenotypes: JACC Focus Seminar 1/5". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 77 (20): 2517–2530. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.071. ISSN 0735-1097. PMID 34016265. S2CID 235073575.

- ^ Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, Hall LM, Willenborg C, Kanoni S, et al. (October 2015). "A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease". Nature Genetics. 47 (10): 1121–1130. doi:10.1038/ng.3396. PMC 4589895. PMID 26343387.

- ^ MacRae CA, Vasan RS (June 2016). "The Future of Genetics and Genomics: Closing the Phenotype Gap in Precision Medicine". Circulation. 133 (25): 2634–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022547. PMC 6188655. PMID 27324359.

- ^ a b c Finegold JA, Asaria P, Francis DP (September 2013). "Mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, region, and age: statistics from World Health Organisation and United Nations". International Journal of Cardiology. 168 (2): 934–45. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.046. PMC 3819990. PMID 23218570.

- ^ D'Adamo E, Guardamagna O, Chiarelli F, Bartuli A, Liccardo D, Ferrari F, Nobili V (2015). "Atherogenic dyslipidemia and cardiovascular risk factors in obese children". International Journal of Endocrinology. 2015: 912047. doi:10.1155/2015/912047. PMC 4309297. PMID 25663838.

- ^ "심장마비의 위험성을 이해하십시오."미국 심장 협회http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartAttack/UnderstandYourRiskofHeartAttack/Understand-Your-Risk-of-Heart-Attack_UCM_002040_Article.jsp#

- ^ 맥케이, 멘사, 멘디스 등심장병과 뇌졸중의 지도책.세계보건기구.2004년 1월.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jousilahti P, Vartiainen E, Tuomilehto J, Puska P (March 1999). "Sex, age, cardiovascular risk factors, and coronary heart disease: a prospective follow-up study of 14 786 middle-aged men and women in Finland". Circulation. 99 (9): 1165–72. doi:10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1165. PMID 10069784.

- ^ a b c d Jani B, Rajkumar C (June 2006). "Ageing and vascular ageing". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 82 (968): 357–62. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2005.036053. PMC 2563742. PMID 16754702.

- ^ a b "Risk factors". Archived from the original on 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Diabetes raises women's risk of heart disease more than for men". NPR.org. May 22, 2014. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ 잭슨 R, 챔블스 L, 히긴스 M, 쿠울라스마 K, 빈버그 L, 윌리엄스 D(WHO MONICA Project, ARIC Study)46개 공동체의 등가성 심장병 사망률과 위험 요인의 성 차이: 생태학적 분석.심근경색 위험요소1999; 7:43–54.

- ^ Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I (June 2004). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors". BMJ. 328 (7455): 1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. PMC 437139. PMID 15213107.

- ^ World Health Organization; UNAIDS (2007). Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. World Health Organization. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-92-4-154726-0. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016.

- ^ Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS (August 2020). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (8): CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3. PMC 8092457. PMID 32827219.

- ^ Booker CS, Mann JI (July 2008). "Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular health: translation of the evidence base". Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases. 18 (6): 448–56. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2008.02.005. PMID 18468872.

- ^ Remig V, Franklin B, Margolis S, Kostas G, Nece T, Street JC (April 2010). "Trans fats in America: a review of their use, consumption, health implications, and regulation". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 110 (4): 585–92. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.12.024. hdl:2097/6377. PMID 20338284.

- ^ a b "WHO plan to eliminate industrially-produced trans-fatty acids from global food supply". World Health Organization. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Te Morenga LA, Howatson AJ, Jones RM, Mann J (July 2014). "Dietary sugars and cardiometabolic risk: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of the effects on blood pressure and lipids". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 100 (1): 65–79. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.081521. PMID 24808490.

- ^ "윌리 로제트 2002"

- ^ Bell S, Daskalopoulou M, Rapsomaniki E, George J, Britton A, Bobak M, et al. (March 2017). "Association between clinically recorded alcohol consumption and initial presentation of 12 cardiovascular diseases: population based cohort study using linked health records". BMJ. 356: j909. doi:10.1136/bmj.j909. PMC 5594422. PMID 28331015.

- ^ Mukamal KJ, Chen CM, Rao SR, Breslow RA (March 2010). "Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular mortality among U.S. adults, 1987 to 2002". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 55 (13): 1328–35. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.056. PMC 3865979. PMID 20338493.

- ^ Millwood IY, Walters RG, Mei XW, Guo Y, Yang L, Bian Z, et al. (May 2019). "Conventional and genetic evidence on alcohol and vascular disease aetiology: a prospective study of 500 000 men and women in China". Lancet. 393 (10183): 1831–1842. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31772-0. PMC 6497989. PMID 30955975.

- ^ World Health Organization (2011). Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-156415-1. Archived from the original on 2016-05-07.

- ^ Cespedes Feliciano EM, Quante M, Rifas-Shiman SL, Redline S, Oken E, Taveras EM (July 2018). "Objective Sleep Characteristics and Cardiometabolic Health in Young Adolescents". Pediatrics. 142 (1): e20174085. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-4085. PMC 6260972. PMID 29907703. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ St-Onge MP, Grandner MA, Brown D, Conroy MB, Jean-Louis G, Coons M, Bhatt DL (November 2016). "Sleep Duration and Quality: Impact on Lifestyle Behaviors and Cardiometabolic Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation (Review). 134 (18): e367–e386. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000444. PMC 5567876. PMID 27647451.

- ^ a b c Di Cesare M, Khang YH, Asaria P, Blakely T, Cowan MJ, Farzadfar F, et al. (February 2013). "Inequalities in non-communicable diseases and effective responses". Lancet. 381 (9866): 585–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61851-0. hdl:10906/80012. PMID 23410608. S2CID 41892834.

- ^ Mackenbach JP, Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Groenhof F (July 2000). "Socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular disease mortality; an international study". European Heart Journal. 21 (14): 1141–51. doi:10.1053/euhj.1999.1990. PMID 10924297.

- ^ Clark AM, DesMeules M, Luo W, Duncan AS, Wielgosz A (November 2009). "Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: risks and implications for care". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 6 (11): 712–22. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2009.163. PMID 19770848. S2CID 21835944.

- ^ World Health Organization (2008). Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health : Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report. World Health Organization. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-92-4-156370-3. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01.

- ^ a b c d Franchini M, Mannucci PM (March 2012). "Air pollution and cardiovascular disease". Thrombosis Research. 129 (3): 230–4. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2011.10.030. PMID 22113148.

- ^ a b Sun Q, Hong X, Wold LE (June 2010). "Cardiovascular effects of ambient particulate air pollution exposure". Circulation. 121 (25): 2755–65. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.893461. PMC 2924678. PMID 20585020.

- ^ a b Tunstall-Pedoe H (March 2011). "Cardiovascular Risk and Risk Scores: ASSIGN, Framingham, QRISK and others: how to choose". Heart. 97 (6): 442–4. doi:10.1136/hrt.2010.214858. PMID 21339319. S2CID 6420111.

- ^ World Health Organization (2007). Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Guidelines for Assessment and Management of Cardiovascular Risk. World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154717-8. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06.

- ^ van Staa TP, Gulliford M, Ng ES, Goldacre B, Smeeth L (2014). "Prediction of cardiovascular risk using Framingham, ASSIGN and QRISK2: how well do they predict individual rather than population risk?". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e106455. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j6455V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106455. PMC 4182667. PMID 25271417.

- ^ Hlatky MA, Greenland P, Arnett DK, Ballantyne CM, Criqui MH, Elkind MS, et al. (May 2009). "Criteria for evaluation of novel markers of cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association". Circulation. 119 (17): 2408–16. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192278. PMC 2956982. PMID 19364974.

- ^ Eckel RH, Cornier MA (August 2014). "Update on the NCEP ATP-III emerging cardiometabolic risk factors". BMC Medicine. 12 (1): 115. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-12-115. PMC 4283079. PMID 25154373.

- ^ Bai W, Li J, Liu J (October 2016). "Serum phosphorus, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the general population: A meta-analysis". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 461: 76–82. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2016.07.020. PMID 27475981.

- ^ Cohen BE, Edmondson D, Kronish IM (November 2015). "State of the Art Review: Depression, Stress, Anxiety, and Cardiovascular Disease". American Journal of Hypertension. 28 (11): 1295–302. doi:10.1093/ajh/hpv047. PMC 4612342. PMID 25911639.

- ^ Edmondson D, Kronish IM, Shaffer JA, Falzon L, Burg MM (November 2013). "Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk for coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review". American Heart Journal. 166 (5): 806–14. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.031. PMC 3815706. PMID 24176435.

- ^ "CDC - NIOSH Program Portfolio : Cancer, Reproductive, and Cardiovascular Diseases : Program Description". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) (2015-08-26). "Occupational Exposures and Cardiovascular Disease". www.sbu.se. Archived from the original on 2017-06-14. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ^ a b c d e Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). "Occupational health and safety – chemical exposure". www.sbu.se. Archived from the original on 2017-06-06. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ^ Jan M, Ebert BL, Jaiswal S (January 2017). "Clonal hematopoiesis". Seminars in Hematology. 54 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2016.10.002. PMC 8045769. PMID 28088988.

- ^ Taylor CW, Nisbet A, McGale P, Darby SC (December 2007). "Cardiac exposures in breast cancer radiotherapy: 1950s-1990s". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 69 (5): 1484–95. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.034. PMID 18035211.

- ^ Weintraub NL, Jones WK, Manka D (March 2010). "Understanding radiation-induced vascular disease". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 55 (12): 1237–1239. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.053. PMC 3807611. PMID 20298931.

- ^ a b Klee NS, McCarthy CG, Martinez-Quinones P, Webb RC (November 2017). "Out of the frying pan and into the fire: damage-associated molecular patterns and cardiovascular toxicity following cancer therapy". Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease. 11 (11): 297–317. doi:10.1177/1753944717729141. PMC 5933669. PMID 28911261.

- ^ Bertazzo S, Gentleman E, Cloyd KL, Chester AH, Yacoub MH, Stevens MM (June 2013). "Nano-analytical electron microscopy reveals fundamental insights into human cardiovascular tissue calcification". Nature Materials. 12 (6): 576–83. Bibcode:2013NatMa..12..576B. doi:10.1038/nmat3627. PMC 5833942. PMID 23603848.

- ^ Vanhecke TE, Miller WM, Franklin BA, Weber JE, McCullough PA (October 2006). "Awareness, knowledge, and perception of heart disease among adolescents". European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. 13 (5): 718–23. doi:10.1097/01.hjr.0000214611.91490.5e. PMID 17001210. S2CID 36312234.

- ^ Highlander P, Shaw GP (February 2010). "Current pharmacotherapeutic concepts for the treatment of cardiovascular disease in diabetics". Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease. 4 (1): 43–54. doi:10.1177/1753944709354305. PMID 19965897. S2CID 23913203.

- ^ NPS Medicinewise (1 March 2011). "NPS Prescribing Practice Review 53: Managing lipids". Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Kvan E, Pettersen KI, Sandvik L, Reikvam A (October 2007). "High mortality in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction: cardiovascular co-morbidities contribute most to the high risk". International Journal of Cardiology. 121 (2): 184–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.003. PMID 17184858.

- ^ Norhammar A, Malmberg K, Diderholm E, Lagerqvist B, Lindahl B, Rydén L, Wallentin L (February 2004). "Diabetes mellitus: the major risk factor in unstable coronary artery disease even after consideration of the extent of coronary artery disease and benefits of revascularization". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 43 (4): 585–91. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.050. PMID 14975468.

- ^ DECODE, European Diabetes Epidemiology Group (August 1999). "Glucose tolerance and mortality: comparison of WHO and American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria. The DECODE study group. European Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Diabetes Epidemiology: Collaborative analysis Of Diagnostic criteria in Europe". Lancet. 354 (9179): 617–21. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)12131-1. PMID 10466661. S2CID 54227479.

- ^ Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, et al. (June 2018). "Screening for Cardiovascular Disease Risk With Electrocardiography: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 319 (22): 2308–2314. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.6848. PMID 29896632.

- ^ Maron BJ, Friedman RA, Kligfield P, Levine BD, Viskin S, Chaitman BR, et al. (October 2014). "Assessment of the 12-lead ECG as a screening test for detection of cardiovascular disease in healthy general populations of young people (12-25 Years of Age): a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology". Circulation. 130 (15): 1303–34. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000025. PMID 25223981.

- ^ Moyer VA (October 2012). "Screening for coronary heart disease with electrocardiography: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (7): 512–8. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00514. PMID 22847227.

- ^ Chou R (March 2015). "Cardiac screening with electrocardiography, stress echocardiography, or myocardial perfusion imaging: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (6): 438–47. doi:10.7326/M14-1225. PMID 25775317.

- ^ Wang TJ, Gona P, Larson MG, Tofler GH, Levy D, Newton-Cheh C, et al. (December 2006). "Multiple biomarkers for the prediction of first major cardiovascular events and death". The New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (25): 2631–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055373. PMID 17182988. S2CID 196411135.

- ^ Spence JD (November 2006). "Technology Insight: ultrasound measurement of carotid plaque--patient management, genetic research, and therapy evaluation". Nature Clinical Practice. Neurology. 2 (11): 611–9. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0324. PMID 17057748. S2CID 26077254.

- ^ Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, et al. (July 2018). "Risk Assessment for Cardiovascular Disease With Nontraditional Risk Factors: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 320 (3): 272–280. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8359. PMID 29998297.

- ^ Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health Risk Reduction in Children Adolescents (December 2011). "Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report". Pediatrics. 128 (Supplement 5): S213-56. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2107C. PMC 4536582. PMID 22084329.

- ^ Saenger AK (August 2012). "Universal lipid screening in children and adolescents: a baby step toward primordial prevention?". Clinical Chemistry. 58 (8): 1179–81. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2012.182287. PMID 22510399.

- ^ a b c Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Braunwald E (2014). Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicine (Tenth ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-4557-5133-4. OCLC 890409638.

- ^ Damen JA, Hooft L, Schuit E, Debray TP, Collins GS, Tzoulaki I, et al. (May 2016). "Prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk in the general population: systematic review". BMJ. 353: i2416. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2416. PMC 4868251. PMID 27184143.

- ^ McNeal CJ, Dajani T, Wilson D, Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Dickerson JB, Ory M (January 2010). "Hypercholesterolemia in youth: opportunities and obstacles to prevent premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 12 (1): 20–8. doi:10.1007/s11883-009-0072-0. PMID 20425267. S2CID 37833889.

- ^ a b c "Heart Attack—Prevention". NHS Direct. 28 November 2019.

- ^ a b Quek, Jingxuan; Lim, Grace; Lim, Wen Hui; Ng, Cheng Han; So, Wei Zheng; Toh, Jonathan; Pan, Xin Hui; Chin, Yip Han; Muthiah, Mark D.; Chan, Siew Pang; Foo, Roger S. Y. (2021-11-05). "The Association of Plant-Based Diet With Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Prospect Cohort Studies". Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 8: 756810. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.756810. ISSN 2297-055X. PMC 8604150. PMID 34805312.

- ^ a b Gan, Zuo Hua; Cheong, Huey Chiat; Tu, Yu-Kang; Kuo, Po-Hsiu (2021-11-05). "Association between Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies". Nutrients. 13 (11): 3952. doi:10.3390/nu13113952. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 8624676. PMID 34836208.

- ^ a b Benatar, Jocelyne R.; Stewart, Ralph A. H. (2018). "Cardiometabolic risk factors in vegans; A meta-analysis of observational studies". PLOS ONE. 13 (12): e0209086. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1309086B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0209086. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6301673. PMID 30571724.

- ^ 프랭크 색스, 앨리스 H. 리히텐슈타인, 제이슨 H.Y.우, 로렌스 J. 애플, 마크 A.크레저, 페니 크리스 에더튼, 마이클 밀러, 에릭 B림, 로렌스 L. 루델, 제니퍼 G. 로빈슨, 닐 J. 스톤, 린다 V.밴 혼: 식이 지방과 심혈관 질환: 미국 심장 협회의 대통령 자문, 2017년 6월 15일, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510Circulation. 2017;e1–e23, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510

- ^ McTigue KM, Hess R, Ziouras J (September 2006). "Obesity in older adults: a systematic review of the evidence for diagnosis and treatment". Obesity. 14 (9): 1485–97. doi:10.1038/oby.2006.171. PMID 17030958. S2CID 45241607.

- ^ Semlitsch T, Krenn C, Jeitler K, Berghold A, Horvath K, Siebenhofer A (February 2021). "Long-term effects of weight-reducing diets in people with hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (2): CD008274. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008274.pub4. PMC 8093137. PMID 33555049.

- ^ Kwok CS, Pradhan A, Khan MA, Anderson SG, Keavney BD, Myint PK, et al. (April 2014). "Bariatric surgery and its impact on cardiovascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Cardiology. 173 (1): 20–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.02.026. hdl:2164/3181. PMID 24636546.

- ^ Ronksley PE, Brien SE, Turner BJ, Mukamal KJ, Ghali WA (February 2011). "Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 342: d671. doi:10.1136/bmj.d671. PMC 3043109. PMID 21343207.

- ^ a b c Mostofsky E, Chahal HS, Mukamal KJ, Rimm EB, Mittleman MA (March 2016). "Alcohol and Immediate Risk of Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis". Circulation. 133 (10): 979–87. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019743. PMC 4783255. PMID 26936862.

- ^ Holmes MV, Dale CE, Zuccolo L, Silverwood RJ, Guo Y, Ye Z, et al. (July 2014). "Association between alcohol and cardiovascular disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data". BMJ. 349: g4164. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4164. PMC 4091648. PMID 25011450.

- ^ Klatsky AL (May 2009). "Alcohol and cardiovascular diseases". Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy. 7 (5): 499–506. doi:10.1586/erc.09.22. PMID 19419257. S2CID 23782870.

- ^ McMahan CA, Gidding SS, Malcom GT, Tracy RE, Strong JP, McGill HC (October 2006). "Pathobiological determinants of atherosclerosis in youth risk scores are associated with early and advanced atherosclerosis". Pediatrics. 118 (4): 1447–55. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0970. PMID 17015535. S2CID 37741456.

- ^ Raitakari OT, Rönnemaa T, Järvisalo MJ, Kaitosaari T, Volanen I, Kallio K, et al. (December 2005). "Endothelial function in healthy 11-year-old children after dietary intervention with onset in infancy: the Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project for children (STRIP)". Circulation. 112 (24): 3786–94. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583195. PMID 16330680.

- ^ Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, Daeges M, Jeanne TL (November 2016). "Statins for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force". JAMA. 316 (19): 2008–2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15629. PMID 27838722.

- ^ Critchley J, Capewell S (2004-01-01). Critchley JA (ed.). "Smoking cessation for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003041. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003041.pub2. PMID 14974003. (회수됨, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003041.pub3 참조)

- ^ "Chapter 4: Active Adults". health.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-03-13.

- ^ "Physical activity guidelines for adults". NHS Choices. 2018-04-26. Archived from the original on 2017-02-19.

- ^ a b Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T, Emberson J, et al. (March 2016). "Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 387 (10022): 957–967. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8. PMID 26724178.

- ^ "Many more people could benefit from blood pressure-lowering medication". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "expert reaction to study looking at pharmacological blood pressure lowering for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease across different levels of blood pressure Science Media Centre". Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ 아들러 A, Agodoa L, Algra A, Asselbergs FW베케트 NS, 베르 주는 E,(알.(도 될까, 2021년까지)."Pharmacological 혈압 심장 혈관 질환의 예방하기 위해 혈압의 다른 분야를 낮추는 것:개별participant-level 데이터 메타 분석".Lancet.397명(10285):1625–1636. doi:10.1016(21)00590-0.PMC8102467.PMID 33933205.CC하의 4.0이 받은 이용 가능합니다.

- ^ Linden W, Stossel C, Maurice J (April 1996). "Psychosocial interventions for patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 156 (7): 745–52. doi:10.1001/archinte.1996.00440070065008. PMID 8615707. S2CID 45312858.

- ^ Thompson DR, Ski CF (December 2013). "Psychosocial interventions in cardiovascular disease--what are they?" (PDF). European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 20 (6): 916–7. doi:10.1177/2047487313494031. PMID 24169589. S2CID 35497445.

- ^ Wei J, Rooks C, Ramadan R, Shah AJ, Bremner JD, Quyyumi AA, et al. (July 2014). "Meta-analysis of mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia and subsequent cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease". The American Journal of Cardiology. 114 (2): 187–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.022. PMC 4126399. PMID 24856319.

- ^ Pelliccia F, Greco C, Vitale C, Rosano G, Gaudio C, Kaski JC (August 2014). "Takotsubo syndrome (stress cardiomyopathy): an intriguing clinical condition in search of its identity". The American Journal of Medicine. 127 (8): 699–704. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.004. PMID 24754972.

- ^ Marshall IJ, Wolfe CD, McKevitt C (July 2012). "Lay perspectives on hypertension and drug adherence: systematic review of qualitative research". BMJ. 345: e3953. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3953. PMC 3392078. PMID 22777025.

- ^ Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, Campbell F, Beyer FR, Cook JV, et al. (February 2006). "Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Hypertension. 24 (2): 215–33. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000199800.72563.26. PMID 16508562. S2CID 9125890.

- ^ Abbott RA, Whear R, Rodgers LR, Bethel A, Thompson Coon J, Kuyken W, et al. (May 2014). "Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness based cognitive therapy in vascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 76 (5): 341–51. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.02.012. PMID 24745774.

- ^ 미국 국립 의학 도서관(2021년 3월 24일).심장병 예방.MedlinePlus.https://medlineplus.gov/howtopreventheartdisease.html.

- ^ 미국 보건 및 휴먼 서비스부.심혈관 질환.국가보완 및 통합 건강 센터.https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/cardiovascular-disease.

- ^ Uthman OA, Hartley L, Rees K, Taylor F, Ebrahim S, Clarke A (August 2015). "Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in low- and middle-income countries" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD011163. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011163.pub2. PMC 6999125. PMID 26272648.

- ^ Karmali KN, Persell SD, Perel P, Lloyd-Jones DM, Berendsen MA, Huffman MD (March 2017). "Risk scoring for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (6): CD006887. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006887.pub4. PMC 6464686. PMID 28290160.

- ^ Liu W, Cao Y, Dong L, Zhu Y, Wu Y, Lv Z, et al. (December 2019). "Periodontal therapy for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in people with periodontitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (4): CD009197. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009197.pub4. PMC 6953391. PMID 31887786.

- ^ Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, Zhu M, Zhao G, Bao W, Hu FB (July 2014). "Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". BMJ. 349: g4490. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4490. PMC 4115152. PMID 25073782.

- ^ Walker C, Reamy BV (April 2009). "Diets for cardiovascular disease prevention: what is the evidence?". American Family Physician. 79 (7): 571–8. PMID 19378874.

- ^ Nordmann AJ, Suter-Zimmermann K, Bucher HC, Shai I, Tuttle KR, Estruch R, Briel M (September 2011). "Meta-analysis comparing Mediterranean to low-fat diets for modification of cardiovascular risk factors". The American Journal of Medicine. 124 (9): 841–51.e2. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.024. PMID 21854893. Archived from the original on 2013-12-20.

- ^ Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al. (January 2001). "Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. PMID 11136953.

- ^ Obarzanek E, Sacks FM, Vollmer WM, Bray GA, Miller ER, Lin PH, et al. (July 2001). "Effects on blood lipids of a blood pressure-lowering diet: the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Trial". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 74 (1): 80–9. doi:10.1093/ajcn/74.1.80. PMID 11451721.

- ^ Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi T, Azizi F (December 2005). "Beneficial effects of a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension eating plan on features of the metabolic syndrome". Diabetes Care. 28 (12): 2823–31. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.12.2823. PMID 16306540.

- ^ Logan AG (March 2007). "DASH Diet: time for a critical appraisal?". American Journal of Hypertension. 20 (3): 223–4. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.10.006. PMID 17324730.

- ^ Hajishafiee M, Saneei P, Benisi-Kohansal S, Esmaillzadeh A (July 2016). "Cereal Fibre Intake and Risk of Mortality From All Causes, CVD, Cancer and Inflammatory Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies". The British Journal of Nutrition. 116 (2): 343–52. doi:10.1017/S0007114516001938. PMID 27193606.

- ^ Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Leelarthaepin B, Majchrzak-Hong SF, Faurot KR, Suchindran CM, et al. (February 2013). "Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis". BMJ. 346: e8707. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8707. PMC 4688426. PMID 23386268.

- ^ a b Lichtenstein AH (November 2019). "Dietary Fat and Cardiovascular Disease: Ebb and Flow Over the Last Half Century". Advances in Nutrition. 10 (Suppl_4): S332–S339. doi:10.1093/advances/nmz024. PMC 6855944. PMID 31728492.

- ^ "Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition Report of an expert consultation". World Health Organization. WHO/FAO. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ Willett WC (July 2012). "Dietary fats and coronary heart disease". Journal of Internal Medicine. 272 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02553.x. PMID 22583051. S2CID 43493760.

- ^ Hooper, Lee; Martin, Nicole; Jimoh, Oluseyi F.; Kirk, Christian; Foster, Eve; Abdelhamid, Asmaa S. (21 August 2020). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (8): CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8092457. PMID 32827219.

- ^ de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, Cozma AI, Ha V, Kishibe T, et al. (August 2015). "Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". BMJ. 351 (h3978): h3978. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3978. PMC 4532752. PMID 26268692.

- ^ a b Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JH, Appel LJ, Creager MA, Kris-Etherton PM, et al. (July 2017). "Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 136 (3): e1–e23. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510. PMID 28620111. S2CID 367602.

- ^ Chowdhury R, Warnakula S, Kunutsor S, Crowe F, Ward HA, Johnson L, et al. (March 2014). "Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (6): 398–406. doi:10.7326/M13-1788. PMID 24723079. S2CID 52013596.

- ^ Food Drug Administration, HHS (May 2018). "Final Determination Regarding Partially Hydrogenated Oils. Notification; declaratory order; extension of compliance date". Federal Register. 83 (98): 23358–9. PMID 30019869.

- ^ Abdelhamid AS, Brown TJ, Brainard JS, Biswas P, Thorpe GC, Moore HJ, et al. (February 2020). "Omega-3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (3): CD003177. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003177.pub5. PMC 7049091. PMID 32114706.

- ^ Aung T, Halsey J, Kromhout D, Gerstein HC, Marchioli R, Tavazzi L, et al. (March 2018). "Associations of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplement Use With Cardiovascular Disease Risks: Meta-analysis of 10 Trials Involving 77 917 Individuals". JAMA Cardiology. 3 (3): 225–234. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.5205. PMC 5885893. PMID 29387889.

- ^ Adler AJ, Taylor F, Martin N, Gottlieb S, Taylor RS, Ebrahim S (December 2014). "Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD009217. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009217.pub3. PMC 6483405. PMID 25519688.

- ^ He FJ, MacGregor GA (July 2011). "Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: meta-analysis of outcome trials" (PDF). Lancet. 378 (9789): 380–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61174-4. PMID 21803192. S2CID 43795786. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-20. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- ^ Paterna S, Gaspare P, Fasullo S, Sarullo FM, Di Pasquale P (February 2008). "Normal-sodium diet compared with low-sodium diet in compensated congestive heart failure: is sodium an old enemy or a new friend?". Clinical Science. 114 (3): 221–30. doi:10.1042/CS20070193. PMID 17688420. S2CID 2248777.

- ^ a b Bochud M, Marques-Vidal P, Burnier M, Paccaud F (2012). "Dietary Salt Intake and Cardiovascular Disease: Summarizing the Evidence". Public Health Reviews. 33 (2): 530–52. doi:10.1007/BF03391649. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21.

- ^ Cook NR, Cutler JA, Obarzanek E, Buring JE, Rexrode KM, Kumanyika SK, et al. (April 2007). "Long term effects of dietary sodium reduction on cardiovascular disease outcomes: observational follow-up of the trials of hypertension prevention (TOHP)". BMJ. 334 (7599): 885–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.39147.604896.55. PMC 1857760. PMID 17449506.

- ^ a b Allaf M, Elghazaly H, Mohamed OG, Fareen MF, Zaman S, Salmasi AM, et al. (Cochrane Heart Group) (January 2021). "Intermittent fasting for the prevention of cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (3): CD013496. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013496.pub2. PMC 8092432. PMID 33512717.

- ^ Turnbull F, Neal B, Ninomiya T, Algert C, Arima H, Barzi F, et al. (May 2008). "Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomised trials". BMJ. 336 (7653): 1121–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.39548.738368.BE. PMC 2386598. PMID 18480116.

- ^ Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration (August 2014). "Blood pressure-lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of individual patient data". Lancet. 384 (9943): 591–598. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61212-5. PMID 25131978. S2CID 19951800.

- ^ Czernichow S, Zanchetti A, Turnbull F, Barzi F, Ninomiya T, Kengne AP, et al. (January 2011). "The effects of blood pressure reduction and of different blood pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events according to baseline blood pressure: meta-analysis of randomized trials". Journal of Hypertension. 29 (1): 4–16. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834000be. PMID 20881867. S2CID 10374187.

- ^ a b Turnbull F (November 2003). "Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trials". Lancet (Submitted manuscript). 362 (9395): 1527–35. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14739-3. PMID 14615107. S2CID 10730075.

- ^ Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, Williams KA, Sanchez E (April 2014). "An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". Hypertension. 63 (4): 878–85. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000003. PMID 24243703.

- ^ Adler AJ, Martin N, Mariani J, Tajer CD, Owolabi OO, Free C, et al. (Cochrane Heart Group) (April 2017). "Mobile phone text messaging to improve medication adherence in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (4): CD011851. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011851.pub2. PMC 6478182. PMID 28455948.

- ^ a b Gutierrez J, Ramirez G, Rundek T, Sacco RL (June 2012). "Statin therapy in the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events: a sex-based meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 172 (12): 909–19. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2145. PMID 22732744.

- ^ Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore TH, Burke M, Davey Smith G, et al. (January 2013). "Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD004816. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5. PMC 6481400. PMID 23440795.

- ^ "Statins in primary cardiovascular prevention?". Prescrire International. 27 (195): 183. July–August 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ Downs JR, O'Malley PG (August 2015). "Management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular disease risk reduction: synopsis of the 2014 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense clinical practice guideline". Annals of Internal Medicine. 163 (4): 291–7. doi:10.7326/m15-0840. PMID 26099117.

- ^ Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis DP (July 2014). "Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients". BMJ. 349: g4379. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4379. PMC 4103514. PMID 25038074.

- ^ Jakob T, Nordmann AJ, Schandelmaier S, Ferreira-González I, Briel M, et al. (Cochrane Heart Group) (November 2016). "Fibrates for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (3): CD009753. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009753.pub2. PMC 6464497. PMID 27849333.

- ^ Holman RR, Sourij H, Califf RM (June 2014). "Cardiovascular outcome trials of glucose-lowering drugs or strategies in type 2 diabetes". Lancet. 383 (9933): 2008–17. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60794-7. PMID 24910232. S2CID 5064731.

- ^ Turnbull FM, Abraira C, Anderson RJ, Byington RP, Chalmers JP, Duckworth WC, et al. (November 2009). "Intensive glucose control and macrovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes". Diabetologia. 52 (11): 2288–98. doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1470-0. PMID 19655124.

- ^ Berger JS, Lala A, Krantz MJ, Baker GS, Hiatt WR (July 2011). "Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients without clinical cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials". American Heart Journal. 162 (1): 115–24.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.04.006. PMID 21742097.

- ^ "Final Recommendation Statement Aspirin for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Preventive Medication". March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. (March 2019). "2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 74 (10): e177–e232. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010. PMC 7685565. PMID 30894318.

- ^ US Preventive Services Task Force (March 2009). "Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 150 (6): 396–404. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00008. PMID 19293072.

- ^ American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society (September 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American College of Chest Physicians and American Thoracic Society, archived from the original on 3 November 2013, retrieved 6 January 2013

- ^ a b Sethi NJ, Safi S, Korang SK, Hróbjartsson A, Skoog M, Gluud C, Jakobsen JC, et al. (Cochrane Heart Group) (February 2021). "Antibiotics for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (5): CD003610. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003610.pub4. PMC 8094925. PMID 33704780.

- ^ Dibben, Grace; Faulkner, James; Oldridge, Neil; Rees, Karen; Thompson, David R.; Zwisler, Ann-Dorthe; Taylor, Rod S. (6 November 2021). "Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (11): CD001800. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8571912. PMID 34741536.

- ^ Seron P, Lanas F, Pardo Hernandez H, Bonfill Cosp X (August 2014). "Exercise for people with high cardiovascular risk". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD009387. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009387.pub2. PMC 6669260. PMID 25120097.

- ^ Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT (July 2012). "Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy". Lancet. 380 (9838): 219–29. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. PMC 3645500. PMID 22818936.

- ^ Hartley L, Dyakova M, Holmes J, Clarke A, Lee MS, Ernst E, Rees K (May 2014). "Yoga for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD010072. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010072.pub2. PMID 24825181.

- ^ Ashworth NL, Chad KE, Harrison EL, Reeder BA, Marshall SC (January 2005). "Home versus center based physical activity programs in older adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004017. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004017.pub2. PMC 6464851. PMID 15674925.

- ^ Al-Khudairy L, Flowers N, Wheelhouse R, Ghannam O, Hartley L, Stranges S, Rees K (March 2017). "Vitamin C supplementation for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (3): CD011114. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011114.pub2. PMC 6464316. PMID 28301692.

- ^ Bhupathiraju SN, Tucker KL (August 2011). "Coronary heart disease prevention: nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 412 (17–18): 1493–514. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2011.04.038. PMC 5945285. PMID 21575619.

- ^ Myung SK, Ju W, Cho B, Oh SW, Park SM, Koo BK, Park BJ (January 2013). "Efficacy of vitamin and antioxidant supplements in prevention of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMJ. 346: f10. doi:10.1136/bmj.f10. PMC 3548618. PMID 23335472.

- ^ Kim J, Choi J, Kwon SY, McEvoy JW, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS, et al. (July 2018). "Association of Multivitamin and Mineral Supplementation and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 11 (7): e004224. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004224. PMID 29991644. S2CID 51615818.

- ^ Fortmann SP, Burda BU, Senger CA, Lin JS, Whitlock EP (December 2013). "Vitamin and mineral supplements in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: An updated systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (12): 824–34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-12-201312170-00729. PMID 24217421.

- ^ Bruckert E, Labreuche J, Amarenco P (June 2010). "Meta-analysis of the effect of nicotinic acid alone or in combination on cardiovascular events and atherosclerosis". Atherosclerosis. 210 (2): 353–61. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.12.023. PMID 20079494.

- ^ Lavigne PM, Karas RH (January 2013). "The current state of niacin in cardiovascular disease prevention: a systematic review and meta-regression". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 61 (4): 440–446. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.030. PMID 23265337.

- ^ Jee SH, Miller ER, Guallar E, Singh VK, Appel LJ, Klag MJ (August 2002). "The effect of magnesium supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". American Journal of Hypertension. 15 (8): 691–6. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(02)02964-3. PMID 12160191.

- ^ Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, Buxton AE, Chaitman B, Fromer M, et al. (September 2006). "ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society". Circulation. 114 (10): e385-484. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.178233. PMID 16935995.

- ^ Kwak SM, Myung SK, Lee YJ, Seo HG (May 2012). "Efficacy of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid) in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials". Archives of Internal Medicine. 172 (9): 686–94. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.262. PMID 22493407.

- ^ Clar C, Oseni Z, Flowers N, Keshtkar-Jahromi M, Rees K (May 2015). "Influenza vaccines for preventing cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (5): CD005050. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005050.pub3. PMC 8511741. PMID 25940444. S2CID 205176857.

- ^ a b Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF (2018). Braunwald's Heart Disease E-Book: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 15. ISBN 9780323555937.

- ^ Saiz LC, Gorricho J, Garjón J, Celaya MC, Erviti J, Leache L (September 2020). "Blood pressure targets for the treatment of people with hypertension and cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (9): CD010315. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010315.pub4. PMC 8094921. PMID 32905623.

- ^ Roo S. "Cardiac Disease Among South Asians: A Silent Epidemic". Indian Heart Association. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2018-12-31.

- ^ Thompson RC, Allam AH, Lombardi GP, Wann LS, Sutherland ML, Sutherland JD, et al. (April 2013). "Atherosclerosis across 4000 years of human history: the Horus study of four ancient populations". Lancet. 381 (9873): 1211–22. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60598-x. PMID 23489753. S2CID 16928278.

- ^ Alberti FB (2013-05-01). "John Hunter's Heart". The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 95 (5): 168–69. doi:10.1308/003588413X13643054409261. ISSN 1473-6357.

- ^ Ruparelia N, Chai JT, Fisher EA, Choudhury RP (March 2017). "Inflammatory processes in cardiovascular disease: a route to targeted therapies". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 14 (3): 133–144. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2016.185. PMC 5525550. PMID 27905474.

- ^ Tang WH, Hazen SL (January 2017). "Atherosclerosis in 2016: Advances in new therapeutic targets for atherosclerosis". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 14 (2): 71–72. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2016.216. PMC 5880294. PMID 28094270.

- ^ Swerdlow DI, Humphries SE (February 2017). "Genetics of CHD in 2016: Common and rare genetic variants and risk of CHD". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 14 (2): 73–74. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2016.209. PMID 28054577. S2CID 13738641.