항산화제

Antioxidant

산화방지제는 산화를 억제하는 화합물로, 활성산소를 생산할 수 있는 화학반응과 유기체의 세포를 손상시킬 수 있는 연쇄반응이다.티올이나 아스코르브산(비타민 C)과 같은 산화 방지제는 이러한 반응을 억제하는 작용을 할 수 있다.산화 스트레스 균형을 맞추기 위해 식물과 동물은 글루타티온과 같이 산화방지제가 겹치는 복잡한 시스템을 유지한다.

식이 요법 항산화제는 비타민 A, C, E뿐이다.항산화라는 용어는 합성고무, 플라스틱, 연료의 산화를 막기 위해 제조 중에 첨가되는 공업용 화학 물질이나 식품과 화장품의 방부제로도 쓰인다.[1]

과일과 야채는 항산화 비타민의 풍부한 공급원이며 건강한 식단의 일부가 될 수 있지만, 식물-식품 섭취가 특히 그러한 음식의 항산화 비타민 때문에 건강상의 이점을 저해한다는 명확한 증거는 없다.[2]항산화제로 시판되는 건강보조식품은 인간의 건강을 증진시키거나 질병을 예방하는 효과가 나타나지 않고 있다.[2]일부 연구에 따르면, 베타 카로틴, 비타민 A, 비타민 E의 보충제는 사망률이나[3][4] 암 위험에 긍정적인 영향을 주지 않는다.[5][needs update][6]덧붙여 셀레늄이나 비타민 E로 보충한다고 해서 심혈관 질환의 위험을 줄이지 않는다.[7][8]

건강연구

식생활과의 관계

식단에서 항산화 비타민을 일정 수준 섭취해야 건강을 유지할 수 있지만, 항산화 성분이 풍부한 식품이나 보충제가 질병 예방 활동을 하는지에 대해서는 여전히 상당한 논쟁이 있다.더욱이 그것들이 실제로 유익하다면, 어떤 항산화제가 식단에서 건강을 촉진하는지, 그리고 일반적인 식이요법 섭취 이상의 양이 얼마인지를 알 수 없다.[9][10][11]항산화비타민이 만성질환을 예방할 수 있다는 가설에 이의를 제기하는 저자도 있고,[9][12] 어떤 저자는 그 가설이 입증되지 않고 잘못 해석되었다고 선언한다.[13]시험관내 항산화 성질이 있는 폴리페놀은 소화에 따른 광범위한 신진대사와 효능에 대한 임상증거가 거의 없어 체내 항산화 활성도를 알 수 없다.[14]

상호작용

항산화 성질을 가진 일반 의약품(및 보충제)은 특정 항암제 및 방사선 치료의 효능을 방해할 수 있다.[15]

역효과

상대적으로 강한 환원산은 위장의 철분, 아연 등 식이성 미네랄에 결합해 흡수되지 않도록 해 항염증 효과를 낼 수 있다.[16]식물성 식단이 많은 옥살산, 타닌, 피틱산이 대표적이다.[17]칼슘과 철분 결핍은 고기를 덜 먹고 콩에서 나오는 피틱산을 많이 섭취하며 통곡빵을 무연으로 먹는 개발도상국에서는 드물지 않다.그러나 발아, 담그기, 미생물 발효는 모두 정제되지 않은 시리얼의 피테이트와 폴리페놀 함량을 줄이는 가정 전략이다.Fe, Zn, Ca 흡수량의 증가는 성인 배부른 곡물에서 그들의 토종 피타이트를 함유한 시리얼에 비해 보고되었다.[18]

| 음식 | 환원산존재 |

|---|---|

| 코코아 콩과 초콜릿, 시금치, 순무, 대황[19] | 옥살산 |

| 통곡물, 옥수수, 콩팥[20] | 피르티산 |

| 차, 콩, 양배추[19][21] | 타닌스 |

많은 양의 산화 방지제는 해로운 장기적 영향을 미칠 수 있다.폐암 환자들을 대상으로 한 베타 카로틴과 레티놀 효능 실험(CARET) 연구는 흡연자들이 베타 카로틴과 비타민 A를 함유한 보충제를 투여한 것이 폐암 발생률을 높인다는 사실을 밝혀냈다.[22]이후의 연구는 이러한 부작용들을 확인했다.[23]약 230,000명의 환자의 데이터를 포함한 한 메타 분석에서 β-카로틴, 비타민 A 또는 비타민 E 보충제가 사망률 증가와 관련이 있지만, 비타민 C에서 유의미한 효과를 보지 못했기 때문에 이러한 유해한 영향은 비흡연자들에게도 볼 수 있다.[24]모든 무작위화된 통제 연구를 함께 검사했을 때 건강 위험은 관찰되지 않았지만, 고품질 및 저생물 위험 실험만 별도로 검사했을 때 사망률 증가가 감지되었다.[25]이러한 저생물 실험의 대다수가 노인이나 질병에 걸린 사람들을 다루었기 때문에, 이러한 결과는 일반 대중에게는 적용되지 않을 수도 있다.[26]이러한 메타분석은 후에 같은 저자에 의해 반복되고 확장되어 이전의 결과를 확인하게 되었다.[25]이 두 간행물은 비타민E 보충제가 사망률을 증가시키고 [27]항산화제 보충제가 대장암의 위험을 증가시켰다는 이전의 몇몇 메타분석과 일치한다.[28]베타 카로틴은 또한 폐암을 증가시킬 수 있다.[28][29]전체적으로 항산화제 보충제에 대한 임상시험이 많은 것은 이들 제품이 건강에 아무런 영향을 미치지 않거나 노인이나 취약계층에 사망률을 소폭 증가시킨다는 것을 시사한다.[9][10][24]

생물학에서의 산화적 도전

신진대사의 역설은 지구상의 대부분의 복잡한 생명체는 그 존재를 위해 산소를 필요로 하지만, 산소는 반응성 산소종을 생성하여 살아있는 유기체를 손상시키는 매우 반응성이 높은 원소라는 것이다.[30]결과적으로, 유기체는 DNA, 단백질, 지질 같은 세포 성분의 산화적 손상을 막기 위해 함께 작용하는 항산화 대사물과 효소의 복잡한 네트워크를 포함한다.[31][32]일반적으로 항산화 시스템은 이러한 반응성 종들이 형성되는 것을 막거나 세포의 중요한 요소들을 손상시키기 전에 그것들을 제거한다.[30][31]그러나 활성산소 종은 리독스 신호와 같은 유용한 세포 기능도 가지고 있다.따라서 항산화 시스템의 기능은 산화제를 완전히 제거하는 것이 아니라 산화제를 최적의 수준으로 유지하는 것이다.[33]

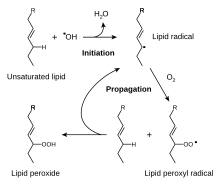

세포에서 생성되는 활성산소 종류로는 과산화수소(HO22), 차아염소산(HClO), 히드록실 래디컬(·OH), 과산화 음이온(O2−) 등의 활성산소가 있다.[34]히드록실 라디칼은 특히 불안정하며 대부분의 생물학적 분자와 비특이적으로 빠르게 반응할 것이다.이 종은 펜톤 반응과 같은 금속으로 만들어진 리독스 반응에서 과산화수소로 생성된다.[35]이러한 산화제는 지질 과산화 같은 화학 연쇄 반응을 일으키거나 DNA나 단백질을 산화시켜 세포를 손상시킬 수 있다.[31]DNA 손상은 DNA 복구 메커니즘에 의해 역전되지 않는다면 돌연변이와 암을 유발할 [36][37]수 있는 반면 단백질 손상은 효소 억제, 변성,[38] 단백질 분해 등을 유발한다.

대사 에너지를 생성하는 과정의 일부로 산소를 사용하면 활성산소가 생성된다.[39]이 과정에서 과산화질소 음이온은 전자전달체인의 여러 단계의 부산물로 생산된다.[40]특히 중요한 것은 고반응성 자유 래디컬이 중간(−Q·)으로 형성되기 때문에 복합 III에서 코엔자임 Q의 감소다.이 불안정한 중간은 전자 전송 체인의 정상적인 일련의 잘 조절된 반응을 통해 이동하는 대신 전자가 산소로 직접 뛰어올라 과산화 음이온을 형성하는 전자 "유출"로 이어질 수 있다.[41]과산화물 또한 복합 I과 같이 감소된 플라보프로테이트의 산화로부터 생성된다.[42]그러나 이러한 효소는 산화제를 생산할 수 있지만 과산화수소를 생성하는 다른 공정들에 대한 전자전달 체인의 상대적 중요성은 불분명하다.[43][44]식물, 해조류, 시아노박테리아에서도 광합성 과정에서 반응성 산소종이 생성되는데,[45] 특히 광도가 높은 조건에서는 더욱 그러하다.[46]이러한 효과는 카로티노이드들이 광진화에 관여하고, 조류와 시아노박테리아에서, 많은 양의 요오드화합물과 셀레늄에 의해 부분적으로 상쇄되는데,[47] 이 항산화물질들은 반응성 산소종의 생성을 막기 위해 광합성 반응 센터의 과도하게 감소된 형태와 반응하는 것을 포함한다.[48][49]

생체 활성 항산화 화합물의 예

항산화제는 물(수분)이나 지질(지질)에 용해되는지에 따라 크게 두 가지로 분류된다.일반적으로 수용성 항산화제는 세포사이토솔과 혈장 내 산화제와 반응하는 반면 지질성 항산화제는 지질 과산화로부터 세포막을 보호한다.[31]이러한 화합물은 체내에서 합성되거나 식단에서 얻을 수 있다.[32]서로 다른 산화 방지제는 체액과 조직에 광범위한 농도에 존재하며, 글루타티온이나 유비퀴논과 같은 일부는 세포 내에 존재하는 반면, 요산과 같은 다른 것들은 더 고르게 분포한다(아래 표 참조).일부 산화방지제는 몇몇 유기체에서만 발견되며 이러한 화합물은 병원균에서 중요할 수 있고 바이러스 요인이 될 수 있다.[50]

이러한 서로 다른 항산화제 사이의 상대적 중요성과 상호작용은 매우 복잡한 질문으로, 다양한 항산화 화합물과 항산화 효소 시스템이 서로에게 시너지 효과와 상호의존적인 효과를 가지고 있다.[51][52]따라서 한 항산화제의 작용은 항산화 시스템의 다른 구성원의 적절한 기능에 따라 달라질 수 있다.[32]한 가지 항산화제에 의해 제공되는 보호의 양은 또한 그것의 농도, 고려되고 있는 특정한 반응성 산소 종에 대한 그것의 반응성, 그리고 그것이 상호작용하는 항산화제의 상태에 따라 달라질 것이다.[32]

일부 화합물은 전이 금속을 킬레이트화하여 세포 내 활성산소의 생성을 촉진시키는 것을 방지함으로써 항산화 방지에 기여한다.특히 중요한 것은 트랜스퍼린이나 페리틴과 같은 철을 결합하는 단백질의 기능인 철을 분리하는 능력이다.[44]셀레늄과 아연은 일반적으로 항산화 미네랄이라고 불리지만, 이러한 화학 원소들은 항산화 작용 자체가 없으며, 대신 항산화 효소의 활동에 필요하다.

| 항산화제 | 용해성 | 인간 혈청 내 μM농도() | 간조직의 농도()μmol/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| 아스코르브산(비타민 C) | 물 | 50–60[53] | 260 (인간)[54] |

| 글루타티온 | 물 | 4[55] | 6,400(인간)[54] |

| 리포산 | 물 | 0.1–0.7[56] | 4–5 (랫드)[57] |

| 요산 | 물 | 200–400[58] | 1600(인간)[54] |

| 카로틴 | 지질 | β-carotene: 0.5–1[59] | 5(인간, 총 카로티노이드)[61] |

| α-토코페롤(비타민 E) | 지질 | 10–40[60] | 50 (인간)[54] |

| 유비쿼시놀(코엔자임 Q) | 지질 | 5[62] | 200 (인간)[63] |

요산

요산은 인간의 혈액에서 단연코 가장 높은 농도 산화 방지제다.우르산(UA)은 크산틴 산화효소에 의해 크산틴에서 생성되는 항산화 옥시퍼린으로, 푸린 신진대사의 중간 산물이다.[64]거의 모든 육지동물에서 요산산화효소는 알란토인에 대한 요산의 산화를 더욱 촉진시키지만 인간과 대부분의 고등 영장류에서는 요산산화효소 유전자가 기능하지 않기 때문에 UA가 더 이상 분해되지 않는다.[65][65][66]이러한 알란토인으로의 요오드 전환이 상실된 진화적 이유는 여전히 적극적인 투기의 화두로 남아 있다.[67][68]요산의 항산화 효과는 연구자들이 이 돌연변이가 초기의 영장류와 인간에게 이롭다고 주장하게 만들었다.[68][69]고고도 적응화에 대한 연구는 요산물이 고고도 저산소증으로 인한 산화 스트레스를 완화시켜 항산화제 역할을 한다는 가설을 뒷받침한다.[70]

요산은 혈액 항산화제[58] 중 가장 높은 농도를 가지고 있으며 인간 혈청 총 항산화 용량의 절반 이상을 제공한다.[71]요산은 과산화물 등 일부 산화물과 반응하지 않고 과산화물,[72] 과산화물, 차아염소산 등에 작용한다는 점에서 항산화 작용도 복합적이다.[64]통풍에 대한 UA의 기여도 상승에 대한 우려는 많은 위험 요소들 중 하나로 간주되어야 한다.[73]그 자체로 볼 때 높은 수준(415–530 μmol/L)에서의 UA 관련 통풍 위험은 연간 0.5%에 불과하며 UA 초과 수준(535+ μmol/L)에서는 연간 4.5%로 증가한다.[74]앞서 언급한 많은 연구들이 정상적인 생리학적 수준 내에서 UA의 항산화 작용을 결정했으며, 일부는 285μmol/L의 높은 수준에서 항산화 활성도를 발견했다.[70][72][75]

비타민 C

아스코르브산 또는 비타민 C는 동물과 식물 모두에서 발견되는 단당 산화 저감(redox) 촉매다.[76]아스코르브산을 만드는 데 필요한 효소 중 하나가 영장류 진화 과정에서 돌연변이에 의해 없어졌기 때문에, 인간은 그것을 그들의 식단에서 얻어야 한다. 그러므로 그것은 식이 비타민이다.[76][77]대부분의 다른 동물들은 그들의 몸에서 이 화합물을 생산할 수 있고 그것을 그들의 식단에서 필요로 하지 않는다.[78]프롤라인 잔류물을 히드록시프로라인으로 산화시켜 프로콜라겐을 콜라겐으로 전환하는데 아스코르브산이 필요하다.[76]다른 세포에서는 글루타티온과의 반응에 의해 감소된 형태로 유지되는데, 이 글루타티온은 이황화 이소머라아제와 글루타독신 단백질에 의해 촉매될 수 있다.[79][80]아스코르브산은 과산화수소 같은 반응성 산소 종을 감소시켜 중화시킬 수 있는 리독스 촉매다.[76][81]아스코르브산은 직접적인 항산화 효과 외에도 식물의 스트레스 저항성에 사용되는 기능인 레독스 효소 아스코르브산 과산화효소의 기질이기도 하다.[82]아스코르브산은 식물의 모든 부분에서 높은 수준으로 존재하며 엽록체에서 20 밀리몰라 농도에 이를 수 있다.[83]

글루타티온

글루타티온느는 대부분의 형태의 유산소 생활에서 발견되는 시스테인 함유 펩타이드다.[84]그것은 식단에 필요하지 않고 대신 그것의 성분인 아미노산의 세포에서 합성된다.[85]글루타티온느는 그것의 시스테인 모이에 있는 티올 그룹이 환원제이고 역방향 산화 및 환원될 수 있기 때문에 항산화 성질을 가지고 있다.세포에서 글루타티온느는 글루타티온 환원효소에 의해 감소된 형태로 유지되며, 글루타티온-아스코르바테 주기의 코르베이트, 글루타티온 과산화효소, 글루타디옥신 등 다른 대사물과 효소 시스템을 감소시키고 산화제와 직접 반응한다.[79]높은 농도와 세포의 리독스 상태를 유지하는 중심 역할 때문에 글루타티온은 가장 중요한 세포 항산화 물질 중 하나이다.[84]어떤 유기체에서 글루타티온느는 액티노미세테스의 미코티올, 어떤 그램 양성 박테리아에서는 바실리티올,[86][87] 키네토플라스틱의 트라이파노티온과 같은 다른 티올에 의해 대체된다.[88][89]

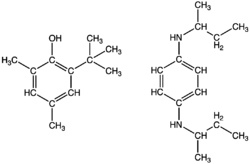

비타민 E

비타민E는 항산화 성질이 있는 지용성 비타민인 토코페롤과 토코트리놀과 관련된 8개 세트의 집합체 이름이다.[90][91]이 중 α-토코페롤은 신체가 이 형태를 우선 흡수하고 대사하는 등 생체이용성이 가장 높아 연구되어 왔다.[92]

α-토코페롤 형태는 지질 용해성 항산화제로서 지질 과산화 연쇄 반응에서 생성된 지질 활성산소와 반응해 산화막으로부터 막을 보호한다고 주장되어 왔다.[90][93]이것은 자유 급진적 매개체를 제거하고 전파 반응이 계속되는 것을 방지한다.이 반응은 산화 α-토코페록실산소를 생성하는데, 이산화기는 코르베이트, 레티놀 또는 유비퀴니놀과 같은 다른 산화방지제에 의해 감소를 통해 활성 감소된 형태로 재생될 수 있다.[94]이는 수용성 항산화제가 아닌 α-토코페롤이 글루타티온느 과산화효소 4(GPX4)-결핍세포를 세포사망으로부터 효율적으로 보호한다는 사실을 보여주는 결과와 맥을 같이한다.[95]GPx4는 생물막 내 지질-하이드로페록시드를 효율적으로 감소시키는 것으로 알려진 유일한 효소다.

그러나 비타민E의 다양한 형태의 역할과 중요성은 현재 불분명하며,[96][97] α-토코페롤의 가장 중요한 기능은 신호 분자로서 이 분자가 항산화 신진대사에 큰 역할을 하지 못한다는 제안까지 나왔다.[98][99]γ토코페롤은 전기영양성 돌연변이체와 반응할 수 있는 핵소포체이고,[92] 토코트리놀은 뉴런의 손상으로부터 보호하는 데 중요할 수 있지만, 다른 형태의 비타민 E의 기능은 훨씬 더 잘 이해되지 않는다.[100]

항산화 활동

효소를 감소시키는 항산화제도 친산소 역할을 할 수 있다.예를 들어 비타민C는 과산화수소 등 산화 물질을 감소시킬 때 항산화 활성이 있지만 [101]펜톤 반응을 통해 활성산소를 생성하는 금속 이온도 감소시킨다.[35][102]

- 2 Fe3+ + Ascorbate → 2 Fe2+ + Detailroascorbate

- 2 Fe2+ + 2 HO22 → 2 Fe3+ + 2 OH, + 2 OH−

항산화제의 항산화 작용과 항산화 작용의 상대적 중요성은 현재 연구의 한 분야지만 폴리펩타이드 산화에 의해 비타민으로서의 효과를 발휘하는 비타민 C는 인체에서 항산화 작용이 대부분인 것으로 보인다.[102]

효소계통

화학 항산화제와 마찬가지로 세포도 항산화 효소의 상호 작용 네트워크에 의해 산화 스트레스로부터 보호된다.[30][31]여기서 산화인산화 등의 공정에 의해 방출되는 과산화수소를 우선 과산화수소로 변환한 후 더 감소시켜 물을 준다.이 해독 경로는 과산화질소가 1단계를 강직하게 한 다음 과산화수소를 제거하는 여러 가지 과산화질소가 있는 다중 효소의 결과물이다.항산화 대사물과 마찬가지로 항산화 방어에 대한 이러한 효소의 기여는 서로 분리되기 힘들 수 있지만 항산화 효소가 하나만 부족한 유전자이전 생쥐의 생성은 유익할 수 있다.[103]

과산화 디퓨타아제, 카탈라아제, 과산화지옥신

과산화분해효소(SOD)는 과산화 음이온이 산소와 과산화수소로 분해되는 것을 촉매로 하는 밀접하게 연관된 효소의 일종이다.[104][105]SOD 효소는 거의 모든 유산소 세포와 세포외 액체에 존재한다.[106]과산화수소 분해효소 효소는 금속 이온 공효소를 함유하고 있는데, 이산화효소에 따라 구리, 아연, 망간 또는 철이 될 수 있다.인간의 경우 구리/진크 SOD는 시토솔에, 망간 SOD는 미토콘드리온에 존재한다.[105]세포외 유체에도 제3의 SOD가 존재하는데, 활성 부지에 구리와 아연을 함유하고 있다.[107]미토콘드리아 이소자임은 이 효소가 부족한 생쥐는 태어나자마자 죽기 때문에 이 세 가지 중에서 생물학적으로 가장 중요한 것 같다.[108]이와는 대조적으로 구리/진크 SOD(Sod1)가 부족한 생쥐는 생존가능하지만 수많은 병리학 및 수명이 단축된 반면(과산화물 관련 기사 참조), 세포외 SOD가 없는 생쥐는 최소한의 결함(과산화물에 민감함)[103][109]을 가지고 있다.식물에서는 시토솔과 미토콘드리아에 SOD 이소자메스가 존재하며, 엽록체에서 발견된 철 SOD는 척추동물과 효모가 없다.[110]

카탈라아제는 과산화수소를 물과 산소로 변환시키는 촉매제로서 철이나 망간의 공동 작용을 이용한다.[111][112]이 단백질은 대부분의 진핵 세포에서 과록시솜에 국부화되어 있다.[113]카탈라아제는 과산화수소가 유일한 기질이지만 탁구 메커니즘을 따르기 때문에 특이한 효소다.여기서, 그것의 공동 계수는 과산화수소의 한 분자에 의해 산화된 다음 결합 산소를 두 번째 기질 분자에 전달함으로써 재생된다.[114]과산화수소 제거에 있어 명백한 중요성에도 불구하고, "아카탈라시아혈증"이라는 카탈라아제의 유전적 결핍을 가진 인간이나, 카탈라아제가 완전히 결핍되도록 유전적으로 조작된 생쥐는 거의 나쁜 영향을 받지 않는다.[115][116]

과산화수소는 과산화수소, 유기 수산화수소 및 과산화수소의 감소를 촉진하는 과산화효소다.[118]대표적인 2-cysteine peroxidoxins, 비정형 2-cysteine peroxidoxins, 1-cysteine peroxidoxins로 구분된다.[119]이들 효소는 활성 부위의 리독스-능동형 시스테인(과산화물 시스테인)이 과산화질소 기질에 의해 황산으로 산화되는 것과 동일한 기본적인 촉매 메커니즘을 공유한다.[120]과산화수소의 이 시스테인 잔류물의 과산화는 이러한 효소를 불활성화시키지만, 이는 황화수소의 작용에 의해 역전될 수 있다.[121]과산화수소는 과산화수소 1이나 2가 부족한 생쥐는 수명이 단축되고 용혈성 빈혈증을 앓고 있는 반면 식물은 과산화수소를 사용해 엽록체에서 발생하는 과산화수소를 제거하기 때문에 항산화 신진대사에 중요한 것으로 보인다.[122][123][124]

티오레독신 및 글루타티온계 시스템

티오레독신 시스템은 12-kDa 단백질 티오레독신과 동반자 티오레독신 환원효소를 함유하고 있다.[125]티오레독신과 관련된 단백질은 모든 서열화된 유기체에 존재한다.아라비도피스탈리아나 같은 식물은 특히 이소성형의 다양성이 크다.[126]티오레독신의 활성 부위는 매우 보존된 CXXC 모티브의 일부로서 활성 디티올 형태(감소)와 산화 이황화 형태 사이에서 순환할 수 있는 두 개의 이웃한 사이스테인으로 구성되어 있다.그것의 활성 상태에서, 티오레독신은 반응성 산소 종을 청소하고 다른 단백질을 감소된 상태로 유지하는 효율적인 감소제 역할을 한다.[127]산화된 후 활성 티오레독신은 티오레독신 환원효소의 작용에 의해 재생되며, NADPH를 전자 공여자로 사용한다.[128]

글루타티온 계통에는 글루타티온, 글루타티온 환원효소, 글루타티온 과산화효소, 글루타티온 S 전이제가 포함된다.[84]이 체계는 동물, 식물, 미생물에서 발견된다.[84][129]글루타티온 과산화효소는 과산화수소와 유기 수산화수소의 분해를 촉진하는 네 가지 셀레늄-코팩터를 함유한 효소다.동물에는 적어도 네 개의 다른 글루타티온 페록시다아제 이소자미가 있다.[130]글루타티온 과산화수소 1은 가장 풍부하고 매우 효율적인 과산화수소 처리제인 반면 글루타티온 과산화수소 4는 지질 수산화물로 가장 활발하다.놀랍게도 글루타티온 과산화효소 1은 이 효소가 부족한 생쥐는 정상적인 수명을 가지지만 유도된 산화 스트레스에 과민반응하기 때문에 불필요한 것이다.[131][132]또한 글루타티온 S 전이체는 지질 과산화물로 높은 활성을 보인다.[133]이러한 효소는 간에서 특히 높은 수치에 있으며 해독 대사에도 도움이 된다.[134]

기술에서의 사용

식품 방부제

이 섹션은 딥 프라이에 대한 정보가 누락되어 있다.(2021년 12월) |

산화 방지제는 식품이 악화되는 것을 막기 위해 식품 첨가물로 사용된다.산소와 햇빛에 노출되는 것이 음식의 산화의 두 가지 주요 요인이기 때문에 음식은 오이와 같이 어두운 곳에 보관하고 용기에 밀봉하거나 심지어 왁스로 코팅하여 보존된다.그러나 산소는 식물의 호흡에도 중요하기 때문에 식물의 물질을 혐기성 상태로 보관하면 불쾌한 맛과 매력없는 색감이 생긴다.[135]결과적으로, 신선한 과일과 야채의 포장은 산소 대기를 8퍼센트까지 포함한다.산화방지제는 박테리아나 진균의 부패와는 달리, 냉동식품이나 냉장식품에서 산화반응이 비교적 빠르게 일어나기 때문에 특히 중요한 종류의 방부제다.[136]These preservatives include natural antioxidants such as ascorbic acid (AA, E300) and tocopherols (E306), as well as synthetic antioxidants such as propyl gallate (PG, E310), tertiary butylhydroquinone (TBHQ), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA, E320) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT, E321).[137][138]

산화의 공격을 받는 가장 흔한 분자는 불포화지방이다; 산화는 그들이 변질되게 만든다.[139]산화지질은 변색되는 경우가 많고 금속성이나 유황성 맛 등 불쾌한 맛이 나는 경우가 많기 때문에 지방이 풍부한 음식에서는 산화를 피하는 것이 중요하다.따라서, 이러한 음식들은 말려서 보존되는 경우가 거의 없고, 대신 흡연, 염장, 발효로 보존된다.심지어 과일과 같은 지방이 적은 식품은 공기 건조 전에 황산 산화 방지제를 뿌린다.산화 작용은 금속으로 촉매되는 경우가 많은데, 그렇기 때문에 버터 같은 지방은 알루미늄 호일에 싸거나 금속 용기에 넣어 두면 절대 안 된다.올리브유와 같은 일부 지방질 식품은 항산화제의 자연 함량에 의해 부분적으로 산화로부터 보호되지만 광옥시화에 민감하게 반응한다.[140]지방성 화장품에 립스틱, 보습제 등 지방성 화장품에도 항산화 방부제가 첨가돼 잡티를 예방한다.[citation needed]

산업용

산화 방지제는 공산품에 자주 첨가된다.산화 방지를 위한 연료와 윤활제, 엔진 불링 잔류물 형성을 유도하는 중합화를 방지하기 위한 가솔린 등에 안정제로 사용하는 것이 일반적이다.[141]2014년 전 세계 천연 및 합성 항산화제 시장은 22억5000만 달러였으며 2020년까지 32억5000만 달러로 성장할 것으로 예측됐다.[142]

항산화 고분자 안정제는 고무, 플라스틱, 접착제 등 폴리머의 열화를 방지하는 데 널리 사용되며, 이 재료의 강도 및 유연성 저하를 초래한다.[143]천연고무와 폴리부타디엔 등 메인 체인에 이중 결합을 함유한 폴리머는 특히 산화·오존 분해에 취약하다.그들은 안티오조나이트에 의해 보호될 수 있다.고체 폴리머 제품은 물질이 분해되고 체인이 깨지면서 노출된 표면에 균열이 생기기 시작한다.균열의 모드는 산소와 오존의 공격에 따라 다르며, 전자는 '미친 포장' 효과를 일으키는 반면, 오존의 공격은 제품의 인장 변형률에 직각으로 정렬된 더 깊은 균열을 발생시킨다.산화와 자외선 저하도 자주 연관되는데, 주로 자외선 복사가 결합 파괴에 의해 활성산소를 생성하기 때문이다.그 후 활성산소는 산소와 반응하여 과산화산소를 생성하는데, 과산화산소는 종종 연쇄반응으로 더 큰 손상을 입힌다.산화되기 쉬운 다른 폴리머로는 폴리프로필렌과 폴리에틸렌이 있다.전자는 모든 반복단위에 2차 탄소 원자가 존재하기 때문에 더 민감하다.이 시점에서 공격이 발생하는 이유는 1차 탄소 원자에 형성된 자유 급진보다 형성된 자유 급진파가 더 안정적이기 때문이다.폴리에틸렌의 산화는 저밀도 폴리에틸렌의 분기점과 같이 체인의 약한 고리에서 발생하는 경향이 있다.[citation needed]

| 연료첨가물 | 구성[144] 요소 | 응용[144] 프로그램 |

|---|---|---|

| AO-22 | N,N'-di-2-부틸-1,4-페닐렌디아민 | 터빈 오일, 변압기 오일, 유압 오일, 왁스 및 그리스 |

| AO-24 | N,N'-di-2-부틸-1,4-페닐렌디아민 | 저온유 |

| AO-29 | 2,6-디-테르트-부틸-4-메틸페놀 | 터빈 오일, 변압기 오일, 유압 오일, 왁스, 그리스 및 가솔린 |

| AO-30 | 2,4-제데틸-6-테르트-부틸페놀 | 제트 연료 및 가솔린(항공 가솔린 포함) |

| AO-31 | 2,4-제데틸-6-테르트-부틸페놀 | 제트 연료 및 가솔린(항공 가솔린 포함) |

| AO-32 | 2,4-제테틸-6-테르트-부틸페놀과 2,6-디-디-테르트-부틸-4-메틸페놀 | 제트 연료 및 가솔린(항공 가솔린 포함) |

| AO-37 | 2,6-디-테르트-부틸페놀 | 제트 연료 및 가솔린, 항공 연료용으로 널리 승인된 |

음식의 수준

항산화 비타민은 야채, 과일, 계란, 콩과류, 견과류에서 발견된다.비타민 A, C, E는 장기간 보관이나 요리에 의해 파괴될 수 있다.[145]이러한 과정은 야채에 함유된 일부 카로티노이드와 같은 항산화제의 생체이용률을 증가시킬 수 있기 때문에 요리와 식품 가공의 효과는 복잡하다.[146]가공식품은 신선식품이나 조리되지 않은 식품보다 항산화비타민이 적게 들어 있는데, 이는 조제식품이 열과 산소에 식품을 노출하기 때문이다.[147]

| 항산화 비타민 | 항산화 비타민이[21][148][149] 많이 함유된 식품 |

|---|---|

| 비타민 C(아스코르브산) | 신선하거나 냉동된 과일 및 야채 |

| 비타민 E(토코페롤, 토코트리놀) | 식물성 기름, 견과류, 씨앗 |

| 카로티노이드(프로비타민 A로서의 카로틴) | 과일, 야채, 계란 |

다른 항산화제는 식단에서 얻어지는 것이 아니라 체내에서 만들어진다.예를 들어 유비퀴놀(coenzyme Q)은 내장에서 잘 흡수되지 않고 메발로네이트 경로를 통해 만들어진다.[63]또 다른 예는 아미노산으로 만들어진 글루타티온이다.어떤 글루타티온이라도 흡수되기 전에 시스틴, 글리신, 글루타민산을 자유롭게 하기 위해 분해되기 때문에, 큰 구강 섭취도 체내 글루타티온의 농도에 거의 영향을 미치지 않는다.[150][151]아세틸시스테인과 같은 많은 양의 황 함유 아미노산이 글루타티온을 증가시킬 수 있지만, 이러한 글루타티온 전구체를 높은 수준으로 먹는 것이 건강한 성인에게 이롭다는 증거는 존재하지 않는다.[152][153]

ORAC의 측정 및 무효화

산화방지제가 집단적으로 다양한 활성산소 종에 대한 반응도가 다른 다양한 화합물 그룹이기 때문에 식품 내 폴리페놀과 카로티노이드 함량을 측정하는 것은 간단한 과정이 아니다.시험관내 식품과학 분석에서 산소급성흡수능력(ORAC)은 한 때 주로 폴리페놀의 존재로부터 온 식품, 주스, 식품첨가물의 항산화 강도를 추정하기 위한 산업 표준이었다.[154][155]앞서 미국 농무부는 2012년 인체 건강과 생물학적으로 무관하다는 이유로 측정과 등급을 철회했는데, 이는 체내 항산화 성질을 가진 폴리페놀에 대한 생리학적 증거가 없는 것을 가리킨다.[156]따라서, 체외 실험에서만 도출된 ORAC 방법은 2010년 현재 더 이상 인간의 식이요법이나 생물학과는 관련이 없는 것으로 간주되지 않는다.[156]

폴리페놀의 존재를 기반으로 한 식품 내 항산화 물질의 대체 체외 측정에는 폴린-시오칼테우 시약과 트로록스 등가 항산화 용량 측정 등이 포함된다.[157]

역사

해양생물의 적응의 일환으로, 지상 식물들은 아스코르브산(비타민 C), 폴리페놀, 토코페롤과 같은 비해양 항산화물질을 생산하기 시작했다.5천만년에서 2억년 전 사이에 혈관 조영 식물의 진화는 광합성의 부산물인 활성 산소 종에 대한 화학적 방어로서 특히 쥬라기 기간 동안 많은 항산화 색소를 개발하는 결과를 낳았다.[158]원래 항산화라는 용어는 특히 산소의 소비를 막는 화학물질을 지칭했다.19세기 후반과 20세기 초반에는 금속 부식 방지, 고무의 불카니화, 내연기관 오염 시 연료의 중합화 등 중요한 산업 공정에서 항산화제의 사용에 대한 광범위한 연구가 집중되었다.[159]

생물학에서 항산화제의 역할에 대한 초기 연구는 산화의 원인인 불포화지방의 산화를 방지하는데 그들의 사용에 초점을 맞췄다.[160]항산화 작용은 지방을 산소가 있는 밀폐 용기에 넣고 산소 소비율을 측정하는 것만으로 간단하게 측정할 수 있었다.그러나 비타민 C와 E를 항산화물질로 식별하여 그 분야에 혁명을 일으키고 생물의 생화학에서 항산화물질의 중요성을 깨닫게 한 것이 바로 비타민 C와 E의 식별이었다.[161][162]항산화 작용의 가능한 메커니즘은 항산화 작용이 있는 물질이 그 자체로 쉽게 산화되는 물질일 가능성이 있다는 것을 인식했을 때 처음 탐구되었다.[163]어떻게 비타민 E가 지질 과산화 과정을 방지하는가에 대한 연구는 산화 반응을 막는 환원제로 항산화제의 식별을 이끌어냈는데, 그들이 세포를 손상시키기 전에 반응하는 산소 종을 청소함으로써 종종 산화 반응을 방지하는 것이다.[164]

참조

- ^ Dabelstein W, Reglitzky A, Schütze A, Reders K (2007). "Automotive Fuels". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_719.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b "Antioxidants: In Depth". NCCIH. November 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud C (2013). "Meta-regression analyses, meta-analyses, and trial sequential analyses of the effects of supplementation with beta-carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E singly or in different combinations on all-cause mortality: do we have evidence for lack of harm?". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e74558. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...874558B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074558. PMC 3765487. PMID 24040282.

- ^ Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Mendiondo MS, Marcum JL, Kryscio RJ (July 2011). "Vitamin E and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis". Current Aging Science. 4 (2): 158–70. doi:10.2174/1874609811104020158. PMC 4030744. PMID 21235492.

- ^ Cortés-Jofré M, Rueda JR, Corsini-Muñoz G, Fonseca-Cortés C, Caraballoso M, Bonfill Cosp X (2012). "Drugs for preventing lung cancer in healthy people". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD002141. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002141.pub2. PMID 23076895.

- ^ Jiang L, Yang KH, Tian JH, Guan QL, Yao N, Cao N, Mi DH, Wu J, Ma B, Yang SH (2010). "Efficacy of antioxidant vitamins and selenium supplement in prostate cancer prevention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Nutrition and Cancer. 62 (6): 719–27. doi:10.1080/01635581.2010.494335. PMID 20661819. S2CID 13611123.

- ^ Rees K, Hartley L, Day C, Flowers N, Clarke A, Stranges S (2013). "Selenium supplementation for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD009671. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009671.pub2. PMC 7433291. PMID 23440843. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ Shekelle PG, Morton SC, Jungvig LK, Udani J, Spar M, Tu W, J Suttorp M, Coulter I, Newberry SJ, Hardy M (April 2004). "Effect of supplemental vitamin E for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 19 (4): 380–9. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30090.x. PMC 1492195. PMID 15061748.

- ^ a b c Stanner SA, Hughes J, Kelly CN, Buttriss J (May 2004). "A review of the epidemiological evidence for the 'antioxidant hypothesis'". Public Health Nutrition. 7 (3): 407–22. doi:10.1079/PHN2003543. PMID 15153272.

- ^ a b Shenkin A (February 2006). "The key role of micronutrients". Clinical Nutrition. 25 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2005.11.006. PMID 16376462.

- ^ Woodside JV, McCall D, McGartland C, Young IS (November 2005). "Micronutrients: dietary intake v. supplement use". The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 64 (4): 543–53. doi:10.1079/PNS2005464. PMID 16313697.

- ^ 음식, 영양, 신체 활동 및 암 예방: 2015년 9월 23일 웨이백머신에 보관된 글로벌 관점.세계 암 연구 기금(2007년)ISBN 978-0-9722522-2-5

- ^ Hail N, Cortes M, Drake EN, Spallholz JE (July 2008). "Cancer chemoprevention: a radical perspective". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 45 (2): 97–110. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.004. PMID 18454943.

- ^ "Flavonoids". Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis. 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ Lemmo W (September 2014). "Potential interactions of prescription and over-the-counter medications having antioxidant capabilities with radiation and chemotherapy". International Journal of Cancer. 137 (11): 2525–33. doi:10.1002/ijc.29208. PMID 25220632. S2CID 205951215.

- ^ Hurrell RF (September 2003). "Influence of vegetable protein sources on trace element and mineral bioavailability". The Journal of Nutrition. 133 (9): 2973S–7S. doi:10.1093/jn/133.9.2973S. PMID 12949395.

- ^ Hunt JR (September 2003). "Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and other trace minerals from vegetarian diets". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 78 (3 Suppl): 633S–639S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/78.3.633S. PMID 12936958.

- ^ Gibson RS, Perlas L, Hotz C (May 2006). "Improving the bioavailability of nutrients in plant foods at the household level". The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 65 (2): 160–8. doi:10.1079/PNS2006489. PMID 16672077.

- ^ a b Mosha TC, Gaga HE, Pace RD, Laswai HS, Mtebe K (June 1995). "Effect of blanching on the content of antinutritional factors in selected vegetables". Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 47 (4): 361–7. doi:10.1007/BF01088275. PMID 8577655. S2CID 1118651.

- ^ Sandberg AS (December 2002). "Bioavailability of minerals in legumes". The British Journal of Nutrition. 88 Suppl 3 (Suppl 3): S281–5. doi:10.1079/BJN/2002718. PMID 12498628.

- ^ a b Beecher GR (October 2003). "Overview of dietary flavonoids: nomenclature, occurrence and intake". The Journal of Nutrition. 133 (10): 3248S–3254S. doi:10.1093/jn/133.10.3248S. PMID 14519822.

- ^ Omenn GS, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, Balmes J, Cullen MR, Glass A, Keogh JP, Meyskens FL, Valanis B, Williams JH, Barnhart S, Cherniack MG, Brodkin CA, Hammar S (November 1996). "Risk factors for lung cancer and for intervention effects in CARET, the Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial" (PDF). Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 88 (21): 1550–9. doi:10.1093/jnci/88.21.1550. PMID 8901853.

- ^ Albanes D (June 1999). "Beta-carotene and lung cancer: a case study". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 69 (6): 1345S–50S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1345S. PMID 10359235.

- ^ a b Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C (February 2007). "Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 297 (8): 842–57. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.842. PMID 17327526.

- ^ a b Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C (14 March 2012). "Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (3): CD007176. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007176.pub2. hdl:10138/136201. PMC 8407395. PMID 22419320.

- ^ 전문가들은 결함이 있는 방법론에 근거한 항산화 비타민 위험을 인용한 연구, 오레곤 주립대학의 뉴스 발표를 사이언스데일리지에 게재했다.2007년 4월 19일 검색됨

- ^ Miller ER, Pastor-Barriuso R, Dalal D, Riemersma RA, Appel LJ, Guallar E (January 2005). "Meta-analysis: high-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality". Annals of Internal Medicine. 142 (1): 37–46. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00110. PMID 15537682.

- ^ a b Bjelakovic G, Nagorni A, Nikolova D, Simonetti RG, Bjelakovic M, Gluud C (July 2006). "Meta-analysis: antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention of colorectal adenoma". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 24 (2): 281–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02970.x. PMID 16842454. S2CID 20452618.

- ^ Cortés-Jofré, Marcela; Rueda, José-Ramón; Asenjo-Lobos, Claudia; Madrid, Eva; Bonfill Cosp, Xavier (4 March 2020). "Drugs for preventing lung cancer in healthy people". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (3): CD002141. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002141.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7059884. PMID 32130738.

- ^ a b c Davies KJ (1995). "Oxidative stress: the paradox of aerobic life". Biochemical Society Symposium. 61: 1–31. doi:10.1042/bss0610001. PMID 8660387.

- ^ a b c d e Sies H (March 1997). "Oxidative stress: oxidants and antioxidants". Experimental Physiology. 82 (2): 291–5. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004024. PMID 9129943. S2CID 20240552.

- ^ a b c d Vertuani S, Angusti A, Manfredini S (2004). "The antioxidants and pro-antioxidants network: an overview". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 10 (14): 1677–94. doi:10.2174/1381612043384655. PMID 15134565.

- ^ Rhee SG (June 2006). "Cell signaling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling". Science. 312 (5782): 1882–3. doi:10.1126/science.1130481. PMID 16809515. S2CID 83598498.

- ^ Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J (2007). "Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 39 (1): 44–84. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. PMID 16978905.

- ^ a b Stohs SJ, Bagchi D (February 1995). "Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions" (PDF). Free Radical Biology & Medicine (Submitted manuscript). 18 (2): 321–36. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.461.6417. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-H. PMID 7744317.

- ^ Nakabeppu Y, Sakumi K, Sakamoto K, Tsuchimoto D, Tsuzuki T, Nakatsu Y (April 2006). "Mutagenesis and carcinogenesis caused by the oxidation of nucleic acids". Biological Chemistry. 387 (4): 373–9. doi:10.1515/BC.2006.050. PMID 16606334. S2CID 20217256.

- ^ Valko M, Izakovic M, Mazur M, Rhodes CJ, Telser J (November 2004). "Role of oxygen radicals in DNA damage and cancer incidence". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 266 (1–2): 37–56. doi:10.1023/B:MCBI.0000049134.69131.89. PMID 15646026. S2CID 207547763.

- ^ Stadtman ER (August 1992). "Protein oxidation and aging". Science. 257 (5074): 1220–4. Bibcode:1992Sci...257.1220S. doi:10.1126/science.1355616. PMID 1355616.

- ^ Raha S, Robinson BH (October 2000). "Mitochondria, oxygen free radicals, disease and ageing". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 25 (10): 502–8. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01674-1. PMID 11050436.

- ^ Lenaz G (2001). "The mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species: mechanisms and implications in human pathology". IUBMB Life. 52 (3–5): 159–64. doi:10.1080/15216540152845957. PMID 11798028. S2CID 45366190.

- ^ Finkel T, Holbrook NJ (November 2000). "Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing". Nature. 408 (6809): 239–47. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..239F. doi:10.1038/35041687. PMID 11089981. S2CID 2502238.

- ^ Hirst J, King MS, Pryde KR (October 2008). "The production of reactive oxygen species by complex I". Biochemical Society Transactions. 36 (Pt 5): 976–80. doi:10.1042/BST0360976. PMID 18793173.

- ^ Seaver LC, Imlay JA (November 2004). "Are respiratory enzymes the primary sources of intracellular hydrogen peroxide?". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (47): 48742–50. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408754200. PMID 15361522.

- ^ a b Imlay JA (2003). "Pathways of oxidative damage". Annual Review of Microbiology. 57: 395–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938. PMID 14527285.

- ^ Demmig-Adams B, Adams WW (December 2002). "Antioxidants in photosynthesis and human nutrition". Science. 298 (5601): 2149–53. Bibcode:2002Sci...298.2149D. doi:10.1126/science.1078002. PMID 12481128. S2CID 27486669.

- ^ Krieger-Liszkay A (January 2005). "Singlet oxygen production in photosynthesis". Journal of Experimental Botany. 56 (411): 337–46. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.327.9651. doi:10.1093/jxb/erh237. PMID 15310815.

- ^ Kupper FC, Carpenter LJ, McFiggans GB, Palmer CJ, Waite TJ, Boneberg E-M, Woitsch S, Weiller M, Abela R, Grolimund D, Potin P, Butler A, Luther GW, Kroneck PMH, Meyer-Klaucke W, Feiters MC (2008). "Iodide accumulation provides kelp with an inorganic antioxidant impacting atmospheric chemistry". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (19): 6954–6958. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.6954K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0709959105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2383960. PMID 18458346.

- ^ Szabó I, Bergantino E, Giacometti GM (July 2005). "Light and oxygenic photosynthesis: energy dissipation as a protection mechanism against photo-oxidation". EMBO Reports. 6 (7): 629–34. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400460. PMC 1369118. PMID 15995679.

- ^ Kerfeld CA (October 2004). "Water-soluble carotenoid proteins of cyanobacteria" (PDF). Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics (Submitted manuscript). 430 (1): 2–9. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.018. PMID 15325905.

- ^ Miller RA, Britigan BE (January 1997). "Role of oxidants in microbial pathophysiology". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 10 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1128/CMR.10.1.1. PMC 172912. PMID 8993856.

- ^ Chaudière J, Ferrari-Iliou R (1999). "Intracellular antioxidants: from chemical to biochemical mechanisms". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 37 (9–10): 949–62. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00090-3. PMID 10541450.

- ^ Sies H (July 1993). "Strategies of antioxidant defense". European Journal of Biochemistry. 215 (2): 213–9. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18025.x. PMID 7688300.

- ^ Khaw KT, Woodhouse P (June 1995). "Interrelation of vitamin C, infection, haemostatic factors, and cardiovascular disease". BMJ. 310 (6994): 1559–63. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6994.1559. PMC 2549940. PMID 7787643.

- ^ a b c d Evelson P, Travacio M, Repetto M, Escobar J, Llesuy S, Lissi EA (April 2001). "Evaluation of total reactive antioxidant potential (TRAP) of tissue homogenates and their cytosols". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 388 (2): 261–6. doi:10.1006/abbi.2001.2292. PMID 11368163.

- ^ Morrison JA, Jacobsen DW, Sprecher DL, Robinson K, Khoury P, Daniels SR (November 1999). "Serum glutathione in adolescent males predicts parental coronary heart disease". Circulation. 100 (22): 2244–7. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.100.22.2244. PMID 10577998.

- ^ Teichert J, Preiss R (November 1992). "HPLC-methods for determination of lipoic acid and its reduced form in human plasma". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology. 30 (11): 511–2. PMID 1490813.

- ^ Akiba S, Matsugo S, Packer L, Konishi T (May 1998). "Assay of protein-bound lipoic acid in tissues by a new enzymatic method". Analytical Biochemistry. 258 (2): 299–304. doi:10.1006/abio.1998.2615. PMID 9570844.

- ^ a b Glantzounis GK, Tsimoyiannis EC, Kappas AM, Galaris DA (2005). "Uric acid and oxidative stress". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 11 (32): 4145–51. doi:10.2174/138161205774913255. PMID 16375736.

- ^ El-Sohemy A, Baylin A, Kabagambe E, Ascherio A, Spiegelman D, Campos H (July 2002). "Individual carotenoid concentrations in adipose tissue and plasma as biomarkers of dietary intake". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 76 (1): 172–9. doi:10.1093/ajcn/76.1.172. PMID 12081831.

- ^ a b Sowell AL, Huff DL, Yeager PR, Caudill SP, Gunter EW (March 1994). "Retinol, alpha-tocopherol, lutein/zeaxanthin, beta-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, alpha-carotene, trans-beta-carotene, and four retinyl esters in serum determined simultaneously by reversed-phase HPLC with multiwavelength detection". Clinical Chemistry. 40 (3): 411–6. doi:10.1093/clinchem/40.3.411. PMID 8131277.

- ^ Stahl W, Schwarz W, Sundquist AR, Sies H (April 1992). "cis-trans isomers of lycopene and beta-carotene in human serum and tissues". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 294 (1): 173–7. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(92)90153-N. PMID 1550343.

- ^ Zita C, Overvad K, Mortensen SA, Sindberg CD, Moesgaard S, Hunter DA (2003). "Serum coenzyme Q10 concentrations in healthy men supplemented with 30 mg or 100 mg coenzyme Q10 for two months in a randomised controlled study". BioFactors. 18 (1–4): 185–93. doi:10.1002/biof.5520180221. PMID 14695934. S2CID 19895215.

- ^ a b Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G (January 2004). "Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1660 (1–2): 171–99. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.012. PMID 14757233.

- ^ a b Enomoto A, Endou H (September 2005). "Roles of organic anion transporters (OATs) and a urate transporter (URAT1) in the pathophysiology of human disease". Clinical and Experimental Nephrology. 9 (3): 195–205. doi:10.1007/s10157-005-0368-5. PMID 16189627. S2CID 6145651.

- ^ a b Wu XW, Lee CC, Muzny DM, Caskey CT (December 1989). "Urate oxidase: primary structure and evolutionary implications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 86 (23): 9412–6. Bibcode:1989PNAS...86.9412W. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.23.9412. PMC 298506. PMID 2594778.

- ^ Wu XW, Muzny DM, Lee CC, Caskey CT (January 1992). "Two independent mutational events in the loss of urate oxidase during hominoid evolution". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 34 (1): 78–84. Bibcode:1992JMolE..34...78W. doi:10.1007/BF00163854. PMID 1556746. S2CID 33424555.

- ^ Álvarez-Lario B, Macarrón-Vicente J (November 2010). "Uric acid and evolution". Rheumatology. 49 (11): 2010–5. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq204. PMID 20627967.

- ^ a b Watanabe S, Kang DH, Feng L, Nakagawa T, Kanellis J, Lan H, Mazzali M, Johnson RJ (September 2002). "Uric acid, hominoid evolution, and the pathogenesis of salt-sensitivity". Hypertension. 40 (3): 355–60. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000028589.66335.AA. PMID 12215479.

- ^ Johnson RJ, Andrews P, Benner SA, Oliver W (2010). "Theodore E. Woodward award. The evolution of obesity: insights from the mid-Miocene". Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 121: 295–305, discussion 305–8. PMC 2917125. PMID 20697570.

- ^ a b Baillie JK, Bates MG, Thompson AA, Waring WS, Partridge RW, Schnopp MF, Simpson A, Gulliver-Sloan F, Maxwell SR, Webb DJ (May 2007). "Endogenous urate production augments plasma antioxidant capacity in healthy lowland subjects exposed to high altitude". Chest. 131 (5): 1473–8. doi:10.1378/chest.06-2235. PMID 17494796.

- ^ Becker BF (June 1993). "Towards the physiological function of uric acid". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 14 (6): 615–31. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(93)90143-I. PMID 8325534.

- ^ a b Sautin YY, Johnson RJ (June 2008). "Uric acid: the oxidant-antioxidant paradox". Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 27 (6): 608–19. doi:10.1080/15257770802138558. PMC 2895915. PMID 18600514.

- ^ Eggebeen AT (September 2007). "Gout: an update". American Family Physician. 76 (6): 801–8. PMID 17910294.

- ^ Campion EW, Glynn RJ, DeLabry LO (March 1987). "Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the Normative Aging Study". The American Journal of Medicine. 82 (3): 421–6. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(87)90441-4. PMID 3826098.

- ^ Nazarewicz RR, Ziolkowski W, Vaccaro PS, Ghafourifar P (December 2007). "Effect of short-term ketogenic diet on redox status of human blood". Rejuvenation Research. 10 (4): 435–40. doi:10.1089/rej.2007.0540. PMID 17663642.

- ^ a b c d "Vitamin C". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 1 July 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Smirnoff N (2001). "L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis". Cofactor Biosynthesis. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 61. pp. 241–66. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(01)61008-2. ISBN 978-0-12-709861-6. PMID 11153268.

- ^ Linster CL, Van Schaftingen E (January 2007). "Vitamin C. Biosynthesis, recycling and degradation in mammals". The FEBS Journal. 274 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05607.x. PMID 17222174. S2CID 21345196.

- ^ a b Meister A (April 1994). "Glutathione-ascorbic acid antioxidant system in animals". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (13): 9397–400. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)36891-6. PMID 8144521.

- ^ Wells WW, Xu DP, Yang YF, Rocque PA (September 1990). "Mammalian thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) and protein disulfide isomerase have dehydroascorbate reductase activity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (26): 15361–4. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)55401-6. PMID 2394726.

- ^ Padayatty SJ, Katz A, Wang Y, Eck P, Kwon O, Lee JH, Chen S, Corpe C, Dutta A, Dutta SK, Levine M (February 2003). "Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation of its role in disease prevention". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 22 (1): 18–35. doi:10.1080/07315724.2003.10719272. PMID 12569111. S2CID 21196776.

- ^ Shigeoka S, Ishikawa T, Tamoi M, Miyagawa Y, Takeda T, Yabuta Y, Yoshimura K (May 2002). "Regulation and function of ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes". Journal of Experimental Botany. 53 (372): 1305–19. doi:10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1305. PMID 11997377.

- ^ Smirnoff N, Wheeler GL (2000). "Ascorbic acid in plants: biosynthesis and function". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 35 (4): 291–314. doi:10.1080/10409230008984166. PMID 11005203. S2CID 85060539.

- ^ a b c d Meister A, Anderson ME (1983). "Glutathione". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 52: 711–60. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. PMID 6137189.

- ^ Meister A (November 1988). "Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 263 (33): 17205–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)77815-6. PMID 3053703.

- ^ Gaballa A, Newton GL, Antelmann H, Parsonage D, Upton H, Rawat M, Claiborne A, Fahey RC, Helmann JD (April 2010). "Biosynthesis and functions of bacillithiol, a major low-molecular-weight thiol in Bacilli". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (14): 6482–6. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.6482G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000928107. PMC 2851989. PMID 20308541.

- ^ Newton GL, Rawat M, La Clair JJ, Jothivasan VK, Budiarto T, Hamilton CJ, Claiborne A, Helmann JD, Fahey RC (September 2009). "Bacillithiol is an antioxidant thiol produced in Bacilli". Nature Chemical Biology. 5 (9): 625–627. doi:10.1038/nchembio.189. PMC 3510479. PMID 19578333.

- ^ Fahey RC (2001). "Novel thiols of prokaryotes". Annual Review of Microbiology. 55: 333–56. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.333. PMID 11544359.

- ^ Fairlamb AH, Cerami A (1992). "Metabolism and functions of trypanothione in the Kinetoplastida". Annual Review of Microbiology. 46: 695–729. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.003403. PMID 1444271.

- ^ a b Herrera E, Barbas C (March 2001). "Vitamin E: action, metabolism and perspectives". Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry. 57 (2): 43–56. doi:10.1007/BF03179812. hdl:10637/720. PMID 11579997. S2CID 7272312.

- ^ Packer L, Weber SU, Rimbach G (February 2001). "Molecular aspects of alpha-tocotrienol antioxidant action and cell signalling". The Journal of Nutrition. 131 (2): 369S–73S. doi:10.1093/jn/131.2.369S. PMID 11160563.

- ^ a b Brigelius-Flohé R, Traber MG (July 1999). "Vitamin E: function and metabolism". FASEB Journal. 13 (10): 1145–55. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.337.5276. doi:10.1096/fasebj.13.10.1145. PMID 10385606. S2CID 7031925.

- ^ Traber MG, Atkinson J (July 2007). "Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 43 (1): 4–15. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.024. PMC 2040110. PMID 17561088.

- ^ Wang X, Quinn PJ (July 1999). "Vitamin E and its function in membranes". Progress in Lipid Research. 38 (4): 309–36. doi:10.1016/S0163-7827(99)00008-9. PMID 10793887.

- ^ Seiler A, Schneider M, Förster H, Roth S, Wirth EK, Culmsee C, Plesnila N, Kremmer E, Rådmark O, Wurst W, Bornkamm GW, Schweizer U, Conrad M (September 2008). "Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent- and AIF-mediated cell death". Cell Metabolism. 8 (3): 237–48. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.005. PMID 18762024.

- ^ Brigelius-Flohé R, Davies KJ (July 2007). "Is vitamin E an antioxidant, a regulator of signal transduction and gene expression, or a 'junk' food? Comments on the two accompanying papers: "Molecular mechanism of alpha-tocopherol action" by A. Azzi and "Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more" by M. Traber and J. Atkinson". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 43 (1): 2–3. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.016. PMID 17561087.

- ^ Atkinson J, Epand RF, Epand RM (March 2008). "Tocopherols and tocotrienols in membranes: a critical review". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 44 (5): 739–64. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.010. PMID 18160049.

- ^ Azzi A (July 2007). "Molecular mechanism of alpha-tocopherol action". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 43 (1): 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.013. PMID 17561089.

- ^ Zingg JM, Azzi A (May 2004). "Non-antioxidant activities of vitamin E". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (9): 1113–33. doi:10.2174/0929867043365332. PMID 15134510. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011.

- ^ Sen CK, Khanna S, Roy S (March 2006). "Tocotrienols: Vitamin E beyond tocopherols". Life Sciences. 78 (18): 2088–98. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.001. PMC 1790869. PMID 16458936.

- ^ Duarte TL, Lunec J (July 2005). "Review: When is an antioxidant not an antioxidant? A review of novel actions and reactions of vitamin C". Free Radical Research. 39 (7): 671–86. doi:10.1080/10715760500104025. PMID 16036346. S2CID 39962659.

- ^ a b Carr A, Frei B (June 1999). "Does vitamin C act as a pro-oxidant under physiological conditions?". FASEB Journal. 13 (9): 1007–24. doi:10.1096/fasebj.13.9.1007. PMID 10336883. S2CID 15426564.

- ^ a b Ho YS, Magnenat JL, Gargano M, Cao J (October 1998). "The nature of antioxidant defense mechanisms: a lesson from transgenic studies". Environmental Health Perspectives. 106 Suppl 5 (Suppl 5): 1219–28. doi:10.2307/3433989. JSTOR 3433989. PMC 1533365. PMID 9788901.

- ^ Zelko IN, Mariani TJ, Folz RJ (August 2002). "Superoxide dismutase multigene family: a comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 33 (3): 337–49. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00905-X. PMID 12126755.

- ^ a b Bannister JV, Bannister WH, Rotilio G (1987). "Aspects of the structure, function, and applications of superoxide dismutase". CRC Critical Reviews in Biochemistry. 22 (2): 111–80. doi:10.3109/10409238709083738. PMID 3315461.

- ^ Johnson F, Giulivi C (2005). "Superoxide dismutases and their impact upon human health". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 26 (4–5): 340–52. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.006. PMID 16099495.

- ^ Nozik-Grayck E, Suliman HB, Piantadosi CA (December 2005). "Extracellular superoxide dismutase". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 37 (12): 2466–71. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2005.06.012. PMID 16087389.

- ^ Melov S, Schneider JA, Day BJ, Hinerfeld D, Coskun P, Mirra SS, Crapo JD, Wallace DC (February 1998). "A novel neurological phenotype in mice lacking mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase". Nature Genetics. 18 (2): 159–63. doi:10.1038/ng0298-159. PMID 9462746. S2CID 20843002.

- ^ Reaume AG, Elliott JL, Hoffman EK, Kowall NW, Ferrante RJ, Siwek DF, Wilcox HM, Flood DG, Beal MF, Brown RH, Scott RW, Snider WD (May 1996). "Motor neurons in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient mice develop normally but exhibit enhanced cell death after axonal injury". Nature Genetics. 13 (1): 43–7. doi:10.1038/ng0596-43. PMID 8673102. S2CID 13070253.

- ^ Van Camp W, Inzé D, Van Montagu M (1997). "The regulation and function of tobacco superoxide dismutases". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 23 (3): 515–20. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00112-3. PMID 9214590.

- ^ Chelikani P, Fita I, Loewen PC (January 2004). "Diversity of structures and properties among catalases" (PDF). Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (Submitted manuscript). 61 (2): 192–208. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-3206-5. hdl:10261/111097. PMID 14745498. S2CID 4411482.

- ^ Zámocký M, Koller F (1999). "Understanding the structure and function of catalases: clues from molecular evolution and in vitro mutagenesis". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 72 (1): 19–66. doi:10.1016/S0079-6107(98)00058-3. PMID 10446501.

- ^ del Río LA, Sandalio LM, Palma JM, Bueno P, Corpas FJ (November 1992). "Metabolism of oxygen radicals in peroxisomes and cellular implications". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 13 (5): 557–80. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(92)90150-F. PMID 1334030.

- ^ Hiner AN, Raven EL, Thorneley RN, García-Cánovas F, Rodríguez-López JN (July 2002). "Mechanisms of compound I formation in heme peroxidases". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 91 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1016/S0162-0134(02)00390-2. PMID 12121759.

- ^ Mueller S, Riedel HD, Stremmel W (December 1997). "Direct evidence for catalase as the predominant H2O2 -removing enzyme in human erythrocytes". Blood. 90 (12): 4973–8. doi:10.1182/blood.V90.12.4973. PMID 9389716.

- ^ Ogata M (February 1991). "Acatalasemia". Human Genetics. 86 (4): 331–40. doi:10.1007/BF00201829. PMID 1999334.

- ^ Parsonage D, Youngblood D, Sarma G, Wood Z, Karplus P, Poole L (2005). "Analysis of the link between enzymatic activity and oligomeric state in AhpC, a bacterial peroxiredoxin". Biochemistry. 44 (31): 10583–92. doi:10.1021/bi050448i. PMC 3832347. PMID 16060667. PDB 1YEX

- ^ Rhee SG, Chae HZ, Kim K (June 2005). "Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 38 (12): 1543–52. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026. PMID 15917183.

- ^ Wood ZA, Schröder E, Robin Harris J, Poole LB (January 2003). "Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 28 (1): 32–40. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(02)00003-8. PMID 12517450.

- ^ Claiborne A, Yeh JI, Mallett TC, Luba J, Crane EJ, Charrier V, Parsonage D (November 1999). "Protein-sulfenic acids: diverse roles for an unlikely player in enzyme catalysis and redox regulation". Biochemistry. 38 (47): 15407–16. doi:10.1021/bi992025k. PMID 10569923.

- ^ Jönsson TJ, Lowther WT (2007). "The peroxiredoxin repair proteins". Peroxiredoxin Systems. Subcellular Biochemistry. Vol. 44. pp. 115–41. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6051-9_6. ISBN 978-1-4020-6050-2. PMC 2391273. PMID 18084892.

- ^ Neumann CA, Krause DS, Carman CV, Das S, Dubey DP, Abraham JL, Bronson RT, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH, Van Etten RA (July 2003). "Essential role for the peroxiredoxin Prdx1 in erythrocyte antioxidant defence and tumour suppression" (PDF). Nature. 424 (6948): 561–5. Bibcode:2003Natur.424..561N. doi:10.1038/nature01819. PMID 12891360. S2CID 3570549.

- ^ Lee TH, Kim SU, Yu SL, Kim SH, Park DS, Moon HB, Dho SH, Kwon KS, Kwon HJ, Han YH, Jeong S, Kang SW, Shin HS, Lee KK, Rhee SG, Yu DY (June 2003). "Peroxiredoxin II is essential for sustaining life span of erythrocytes in mice". Blood. 101 (12): 5033–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-08-2548. PMID 12586629.

- ^ Dietz KJ, Jacob S, Oelze ML, Laxa M, Tognetti V, de Miranda SM, Baier M, Finkemeier I (2006). "The function of peroxiredoxins in plant organelle redox metabolism". Journal of Experimental Botany. 57 (8): 1697–709. doi:10.1093/jxb/erj160. PMID 16606633.

- ^ Nordberg J, Arnér ES (December 2001). "Reactive oxygen species, antioxidants, and the mammalian thioredoxin system". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 31 (11): 1287–312. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00724-9. PMID 11728801.

- ^ Vieira Dos Santos C, Rey P (July 2006). "Plant thioredoxins are key actors in the oxidative stress response". Trends in Plant Science. 11 (7): 329–34. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2006.05.005. PMID 16782394.

- ^ Arnér ES, Holmgren A (October 2000). "Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase". European Journal of Biochemistry. 267 (20): 6102–9. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01701.x. PMID 11012661.

- ^ Mustacich D, Powis G (February 2000). "Thioredoxin reductase". The Biochemical Journal. 346 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3460001. PMC 1220815. PMID 10657232.

- ^ Creissen G, Broadbent P, Stevens R, Wellburn AR, Mullineaux P (May 1996). "Manipulation of glutathione metabolism in transgenic plants". Biochemical Society Transactions. 24 (2): 465–9. doi:10.1042/bst0240465. PMID 8736785.

- ^ Brigelius-Flohé R (November 1999). "Tissue-specific functions of individual glutathione peroxidases". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 27 (9–10): 951–65. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00173-2. PMID 10569628.

- ^ Ho YS, Magnenat JL, Bronson RT, Cao J, Gargano M, Sugawara M, Funk CD (June 1997). "Mice deficient in cellular glutathione peroxidase develop normally and show no increased sensitivity to hyperoxia". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (26): 16644–51. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.26.16644. PMID 9195979.

- ^ de Haan JB, Bladier C, Griffiths P, Kelner M, O'Shea RD, Cheung NS, Bronson RT, Silvestro MJ, Wild S, Zheng SS, Beart PM, Hertzog PJ, Kola I (August 1998). "Mice with a homozygous null mutation for the most abundant glutathione peroxidase, Gpx1, show increased susceptibility to the oxidative stress-inducing agents paraquat and hydrogen peroxide". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (35): 22528–36. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.35.22528. PMID 9712879.

- ^ Sharma R, Yang Y, Sharma A, Awasthi S, Awasthi YC (April 2004). "Antioxidant role of glutathione S-transferases: protection against oxidant toxicity and regulation of stress-mediated apoptosis". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 6 (2): 289–300. doi:10.1089/152308604322899350. PMID 15025930.

- ^ Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR (2005). "Glutathione transferases". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 45: 51–88. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. PMID 15822171.

- ^ Kader AA, Zagory D, Kerbel EL (1989). "Modified atmosphere packaging of fruits and vegetables". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 28 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1080/10408398909527490. PMID 2647417.

- ^ Zallen EM, Hitchcock MJ, Goertz GE (December 1975). "Chilled food systems. Effects of chilled holding on quality of beef loaves". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 67 (6): 552–7. PMID 1184900.

- ^ Iverson F (June 1995). "Phenolic antioxidants: Health Protection Branch studies on butylated hydroxyanisole". Cancer Letters. 93 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1016/0304-3835(95)03787-W. PMID 7600543.

- ^ "E number index". UK food guide. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- ^ Robards K, Kerr AF, Patsalides E (February 1988). "Rancidity and its measurement in edible oils and snack foods. A review". The Analyst. 113 (2): 213–24. Bibcode:1988Ana...113..213R. doi:10.1039/an9881300213. PMID 3288002.

- ^ Del Carlo M, Sacchetti G, Di Mattia C, Compagnone D, Mastrocola D, Liberatore L, Cichelli A (June 2004). "Contribution of the phenolic fraction to the antioxidant activity and oxidative stability of olive oil". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52 (13): 4072–9. doi:10.1021/jf049806z. PMID 15212450.

- ^ Boozer CE, Hammond GS, Hamilton CE, Sen JN (1955). "Air Oxidation of Hydrocarbons.1II. The Stoichiometry and Fate of Inhibitors in Benzene and Chlorobenzene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 77 (12): 3233–7. doi:10.1021/ja01617a026.

- ^ "Global Antioxidants (Natural and Synthetic) Market Poised to Surge From USD 2.25 Billion in 2014 to USD 3.25 Billion by 2020, Growing at 5.5% CAGR". GlobalNewswire, El Segundo, CA. 19 January 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ "Why use Antioxidants?". SpecialChem Adhesives. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ a b "Fuel antioxidants". Innospec Chemicals. Archived from the original on 15 October 2006. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ Rodriguez-Amaya DB (2003). "Food carotenoids: analysis, composition and alterations during storage and processing of foods". Forum of Nutrition. 56: 35–7. PMID 15806788.

- ^ Maiani G, Castón MJ, Catasta G, Toti E, Cambrodón IG, Bysted A, Granado-Lorencio F, Olmedilla-Alonso B, Knuthsen P, Valoti M, Böhm V, Mayer-Miebach E, Behsnilian D, Schlemmer U (September 2009). "Carotenoids: actual knowledge on food sources, intakes, stability and bioavailability and their protective role in humans". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 53 Suppl 2: S194–218. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200800053. hdl:10261/77697. PMID 19035552. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Henry CJ, Heppell N (February 2002). "Nutritional losses and gains during processing: future problems and issues". The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 61 (1): 145–8. doi:10.1079/PNS2001142. PMID 12002789.

- ^ "Antioxidants and Cancer Prevention: Fact Sheet". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ Ortega R (December 2006). "Importance of functional foods in the Mediterranean diet". Public Health Nutrition. 9 (8A): 1136–40. doi:10.1017/S1368980007668530. PMID 17378953.

- ^ Witschi A, Reddy S, Stofer B, Lauterburg BH (1992). "The systemic availability of oral glutathione". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 43 (6): 667–9. doi:10.1007/BF02284971. PMID 1362956. S2CID 27606314.

- ^ Flagg EW, Coates RJ, Eley JW, Jones DP, Gunter EW, Byers TE, Block GS, Greenberg RS (1994). "Dietary glutathione intake in humans and the relationship between intake and plasma total glutathione level". Nutrition and Cancer. 21 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1080/01635589409514302. PMID 8183721.

- ^ Dodd S, Dean O, Copolov DL, Malhi GS, Berk M (December 2008). "N-acetylcysteine for antioxidant therapy: pharmacology and clinical utility". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 8 (12): 1955–62. doi:10.1517/14728220802517901. PMID 18990082. S2CID 74736842.

- ^ van de Poll MC, Dejong CH, Soeters PB (June 2006). "Adequate range for sulfur-containing amino acids and biomarkers for their excess: lessons from enteral and parenteral nutrition". The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (6 Suppl): 1694S–1700S. doi:10.1093/jn/136.6.1694S. PMID 16702341.

- ^ Cao G, Alessio HM, Cutler RG (March 1993). "Oxygen-radical absorbance capacity assay for antioxidants". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 14 (3): 303–11. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(93)90027-R. PMID 8458588.

- ^ Ou B, Hampsch-Woodill M, Prior RL (October 2001). "Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 49 (10): 4619–26. doi:10.1021/jf010586o. PMID 11599998.

- ^ a b "Withdrawn: Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) of Selected Foods, Release 2 (2010)". United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 16 May 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Prior RL, Wu X, Schaich K (May 2005). "Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements" (PDF). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (10): 4290–302. doi:10.1021/jf0502698. PMID 15884874. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ Benzie IF (September 2003). "Evolution of dietary antioxidants". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 136 (1): 113–26. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00368-9. hdl:10397/34754. PMID 14527634.

- ^ Mattill HA (1947). "Antioxidants". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 16: 177–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.16.070147.001141. PMID 20259061.

- ^ German JB (1999). "Food Processing and Lipid Oxidation". Impact of Processing on Food Safety. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 459. pp. 23–50. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4853-9_3. ISBN 978-0-306-46051-7. PMID 10335367.

- ^ Jacob RA (1996). Three eras of vitamin C discovery. Subcellular Biochemistry. Vol. 25. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0325-1_1. ISBN 978-1-4613-7998-0. PMID 8821966.

- ^ Knight JA (1998). "Free radicals: their history and current status in aging and disease". Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science. 28 (6): 331–46. PMID 9846200.

- ^ Moureu C, Dufraisse C (1922). "Sur l'autoxydation: Les antioxygènes". Comptes Rendus des Séances et Mémoires de la Société de Biologie (in French). 86: 321–322.

- ^ Wolf G (March 2005). "The discovery of the antioxidant function of vitamin E: the contribution of Henry A. Mattill". The Journal of Nutrition. 135 (3): 363–6. doi:10.1093/jn/135.3.363. PMID 15735064.

추가 읽기

- 할리웰, 배리, 존 M. C. 거터리지, 생물학 및 의학 분야의 자유 급진주의자 (Oxford University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-19-856869-X

- 레인, 닉, 산소: 세상을 만든 분자 (Oxford University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-19-860783-0

- 포코니, 얀, 넬리 야니슬리바, 마이클 고든, 식품 내 항산화제: 실용화(CRC Press, 2001), ISBN 0-8493-1222-1

외부 링크

위키미디어 커먼스의 항산화 관련 매체

위키미디어 커먼스의 항산화 관련 매체

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{\underset {Oxygen}{O2}}->{\underset {Superoxide}{*O2^{-}}}->[{\ce {Superoxide \atop dismutase}}]{\underset {Hydrogen \atop peroxide}{H2O2}}->[{\ce {Peroxidases \atop catalase}}]{\underset {Water}{H2O}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8feecd26377be56b431d182ea9a398ab6b5d3b7f)