스타틴

Statin| 스타틴 | |

|---|---|

| 약물 클래스 | |

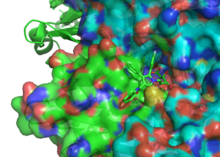

아스페르길루스 테레우스로부터 분리된 화합물인 로바스타틴은 시판된 최초의 스타틴이었다. | |

| 클래스 식별자 | |

| 사용하다 | 고콜레스테롤 |

| ATC 코드 | C10AA |

| 생물학적 표적 | HMG-CoA 환원효소 |

| 임상 데이터 | |

| Drugs.com | 약물 클래스 |

| 외부 링크 | |

| 메쉬 | D019161 |

| Wikidata에서 | |

HMG-CoA 환원효소 억제제로도 알려진 스타틴은 심혈관 질환의 위험이 높은 사람들의 질병과 사망률을 감소시키는 지질 감소 약물의 한 종류이다.그것들은 가장 흔한 콜레스테롤 [1]강하제이다.

콜레스테롤의 저밀도 리포단백질(LDL) 보균자는 지질 가설에 의해 기술된 메커니즘을 통해 아테롬성 동맥경화증과 관상동맥 심장병의 발달에 중요한 역할을 한다.스타틴은 LDL 콜레스테롤을 낮추는 데 효과적이기 때문에 심혈관 질환의 위험이 높은 사람들의 1차 예방뿐만 아니라 심혈관 [2][3][4]질환에 걸린 사람들의 2차 예방에도 널리 사용된다.

스타틴의 부작용은 근육통, 당뇨병 위험 증가, 그리고 간 [5]효소의 비정상적인 혈중 수치를 포함한다.또한 드물지만 심각한 부작용, 특히 근육 [6]손상이 있습니다.그것들은 콜레스테롤 생성에 중추적인 역할을 하는 효소 HMG-CoA 환원효소를 억제합니다.높은 콜레스테롤 수치는 심혈관 [7]질환과 관련이 있다.

스타틴에는 아토르바스타틴, 플루바스타틴, 로바스타틴, 피타바스타틴, 프라바스타틴, 로스바스타틴,[8] 그리고 심바스타틴이 포함된 다양한 형태가 있습니다.스타틴과 에제티미브/심바스타틴과 같은 다른 약물의 조합 제제도 이용할 수 있다.이 클래스는 세계보건기구의 필수 의약품 목록에 있으며,[9] 심바스타틴은 의약품 목록에 포함되어 있습니다.2005년 미국에서 [10]매출액은 187억 달러로 추정되었습니다.가장 많이 팔리는 스타틴은 2003년에 [11]역사상 가장 많이 팔린 약품이 된 리피터로도 알려진 아토르바스타틴이다.제조업체인 화이자는 2008년에 [12]124억 달러의 매출을 기록했다고 보고했습니다.특허 만료로 인해, 2016년에 저렴한 제네릭으로 [13][failed verification]여러 개의 스타틴을[specify] 사용할 수 있게 되었다.

의료 용도

스타틴은 혈중 콜레스테롤 수치를 낮추고 아테롬성 동맥경화와 관련된 질병의 위험을 줄이기 위해 주로 사용되며, 근본적인 위험 인자와 심혈관 질환의 병력에 따라 효과가 달라진다.임상 실무 지침에서는 일반적으로 콜레스테롤을 낮추는 식단과 신체 운동을 통한 생활습관 수정부터 시작할 것을 권고하고 있다.이러한 방법으로 지질강화 목표를 달성할 수 없는 사람들에게 스타틴은 [14][15]도움이 될 수 있다.치료 반응에서 성과 관련된 일부 차이가 [17]설명되었지만,[16] 이 약은 성별에 관계없이 똑같이 잘 듣는 것으로 보인다.

만약 심혈관 질환의 근본적인 병력이 있다면, 그것은 스타틴의 효과에 상당한 영향을 미친다.이는 의약품 사용을 1차 예방과 2차 [18]예방의 광범위한 범주로 분류하는 데 사용될 수 있다.

프라이머리 예방

심혈관 질환의 1차 예방을 위해 미국 예방 서비스 태스크 포스(USPSTF) 2016 가이드라인은 2013 ACC/A CoH 풀링에서 계산한 대로 관상동맥 심장 질환의 위험 인자가 하나 이상 있고 40세에서 75세 사이이며 심장 질환의 위험이 10% 이상인 사람에게 스타틴을 권고한다.ort [18][19][20]알고리즘관상동맥 심장병의 위험 요소에는 혈액 내 지질 수치 이상, 당뇨병, 고혈압, [19]흡연 등이 있었다.그들은 계산된 10년 심혈관 질환 발생 위험이 7.5–10%[19] 이상인 동일한 성인에게 저-중간 용량 스타틴을 선택적으로 사용할 것을 권고했다.70세 이상의 사람들에게서 스타틴은 심혈관 질환의 위험을 줄여주지만 [21]동맥에 콜레스테롤이 많이 막힌 이력이 있는 사람들에게만 해당된다.

대부분의 증거는 스타틴이 콜레스테롤이 높지만 심장병의 병력이 없는 사람들에게 심장병을 예방하는데 효과적이라는 것을 암시한다.2013년 Cochrane 리뷰에서는 [4]위해의 증거 없이 사망 위험 및 기타 좋지 않은 결과가 감소하는 것으로 나타났다.5년 동안 치료를 받은 138명 중 한 명이 사망합니다. 치료를 받은 49명 중 한 명이 심장병을 [10]앓는 경우가 더 적습니다.2011년 검토에서도 유사한 [22]결론에 도달했으며, 2012년 검토에서도 여성과 [23]남성 모두에게 유익성이 발견됐다.2010년 리뷰에서는 심혈관 질환의 병력이 없는 치료는 남성이지만 여성이 아닌 심혈관 질환을 감소시키며,[24] 어느 성에서도 사망에 도움이 되지 않는다고 결론지었다.그 해에 발표된 두 개의 다른 메타 분석에서는, 그 중 하나는 여성으로부터 독점적으로 얻은 데이터를 사용했지만, 1차 [25][26]예방에서는 사망률의 이점이 발견되지 않았다.

국립보건 및 임상 우수 연구소(NICE)는 심혈관 질환에 걸릴 위험이 10%[27] 이상인 성인에게 스타틴 치료를 권장한다.미국심장학회와 미국심장학회의 지침은 LDL 콜레스테롤이 190mg/dL 이하인 성인이나 당뇨병 환자, 40-75세 LDL-C 70–190mg/dl, 또는 10년 간 심장발작 또는 뇌졸중 발병 위험이 7.5% 이상인 사람에게 심혈관 질환의 1차 예방을 위한 스타틴 치료를 권고한다.이 후자 그룹에서 스타틴 할당은 자동적이지 않았지만, 다른 위험 인자와 라이프스타일을 다루는 공유 의사결정을 통해 임상 의사-환자 위험 논의를 한 후에만 수행하도록 권고되었다. 스타틴의 유익성 가능성은 부작용 또는 약물 상호작용의 잠재성과 비교하여 평가되며, 정보에 근거한 패티(patient preference가 도출된다.또한 위험 결정이 불확실한 경우에는 가족력, 관상동맥 칼슘 점수, 발목-상완 지수, 염증 검사(hs-CRP ≤ 2.0mg/L) 등의 요인을 제안하여 위험 결정을 알렸다.사용할 수 있는 추가 요인은 LDL-C 160 160 또는 매우 높은 평생 [28]위험이었다.하지만 스티븐 E와 같은 비평가들.Nissen은 AHA/ACC 가이드라인이 제대로 검증되지 않았으며,[29] 관찰된 리스크가 가이드라인에 의해 예측된 것보다 낮은 모집단을 근거로 하여 위험을 최소 50% 과대평가하고 혜택을 받지 못하는 사람들을 위해 스타틴을 권장하고 있다.유럽심장학회(European Society of Cardiology)와 유럽아테롬성경화학회(European Athermosis Society)는 기본 추정 심혈관 점수와 LDL [30]임계값에 따라 일차 예방을 위해 스타틴 사용을 권장한다.

2차 예방

스타틴은 이미 심혈관 질환이 [31]있는 사람들의 사망률을 낮추는데 효과적이다.기존의 질병은 많은 증상을 보일 수 있다.질병을 정의하는 것은 아테롬성 동맥경화증의 존재에서 이전의 심장마비, 뇌졸중, 안정적이거나 불안정한 협심증,[18] 대동맥류 또는 기타 동맥 허혈성 질환을 포함한다.그것들은 또한 관상동맥 심장 [32]질환에 걸릴 위험이 높은 사람들에게 사용하도록 권장된다.평균적으로 스타틴은 LDL 콜레스테롤을 1.8mmol/L(70mg/dL) 낮출 수 있으며, 이는 심장 질환([33]심장 마비, 돌연사) 발생 횟수가 약 60% 감소하고 장기 치료 후 뇌졸중 위험이 17% 감소하는 것으로 해석된다.고강도 스타틴 [34]요법을 사용하면 더 큰 이점이 관찰된다.그것들은 섬유화합물이나 나이아신보다 트리글리세리드 감소와 HDL 콜레스테롤(좋은 콜레스테롤)[35][36] 상승에 덜 효과가 있습니다.

어떤 연구도 이전 뇌졸중 환자의 인지에 대한 스타틴의 영향을 조사하지 않았다.그러나 혈관 질환자를 포함한 두 개의 대규모 연구(HPS와 PROSPER)에서는 심바스타틴과 프라바스타틴이 [37]인지에 영향을 미치지 않는다고 보고했습니다.

스타틴은 심장 및 혈관 [38]수술의 수술 결과를 개선하기 위해 연구되어 왔다.스타틴 [39]그룹에서 사망률과 심혈관계 부작용은 감소했다.

입원 후 퇴원 시 스타틴 치료를 받는 노인들이 연구되어 왔다.입원 당시 스타틴을 복용하지 않은 심장허혈이 있는 사람은 입원 [40][41]후 2년 후 심각한 심장 이상 증상과 병원 재입원의 위험이 낮다.

비교 효과

직접적인 비교는 존재하지 않지만, 모든 스타틴은 콜레스테롤 [22]감소의 정도나 효능에 관계없이 효과적인 것으로 보인다.심바스타틴과 프라바스타틴은 부작용 [5]발생률이 감소하는 것으로 보인다.

심바스타틴, 프라바스타틴, 아토르바스타틴의 위약효과는 [42]혈액 내 심혈관질환 감소나 지질수치의 차이를 발견하지 못했다.2015년 Cochrane 체계적 검토 업데이트에서는 로수바스타틴이 [43]아토르바스타틴보다 3배 이상 더 강력하다고 보고하였다.

여성

2015년 Cochrane 체계적 검토 결과, 아토르바스타틴은 남성보다 여성에게서 콜레스테롤 강하 효과가 더 높게 나타났다.[43]

아이들.

소아에서 스타틴은 가족성 고콜레스테롤혈증이 [44]있는 사람들의 콜레스테롤 수치를 낮추는데 효과적이다.그러나 그들의 장기적인 안전성은 [44][45]불확실하다.어떤 사람들은 생활습관 변화가 충분하지 않다면 8살에 스타틴을 시작해야 한다고 권고한다.[46]

가족성 고콜레스테롤혈증

스타틴은 가족성 고콜레스테롤혈증을 가진 사람들, 특히 동종결핍증을 [47]가진 사람들에게 LDL 콜레스테롤을 감소시키는데 덜 효과적일 수 있다.이 사람들은 보통 LDL 수용체나 아폴리포단백질 B 유전자에 결함이 있는데,[48] 둘 다 혈액에서 LDL을 제거하는 역할을 한다.스타틴은 가족성 [47]고콜레스테롤혈증에서 가장 중요한 치료제이지만 다른 콜레스테롤 감소 조치가 필요할 [49]수 있다.호모 접합 결핍증을 가진 사람들에게, 비록 높은 용량과 다른 콜레스테롤 감소 약물과 함께 [50]사용되더라도 스타틴은 여전히 도움이 될 수 있다.

조영 유발 신증

2014년 메타 분석 결과 스타틴은 관상동맥조영술/경피적 개입을 받는 사람의 조영 유발 신증 위험을 53% 줄일 수 있는 것으로 나타났다.그 효과는 신장 기능 장애 또는 [51]당뇨병이 있는 사람들에게서 더 강한 것으로 밝혀졌다.

부작용

| 특별한[52] 고려사항이 있는 사용자를 위한 통계 선택 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 조건. | 일반적으로 권장되는 스타틴 | 설명. | |

| 시클로스포린을 복용하는 신장 이식 환자 | 프라바스타틴 또는 플루바스타틴 | 약물 상호작용은 가능하지만, 연구는 이러한 스타틴이 시클로스포린에 [53]대한 노출을 증가시킨다는 것을 보여주지 않았다. | |

| 단백질분해효소 억제제를 복용하는 HIV 양성자 | 아토르바스타틴, 프라바스타틴 또는 플루바스타틴 | 부정적인[54] 상호작용은 다른 선택에서 더 잘 나타난다. | |

| 비스타틴 지질강하제인 젬피브로질을 복용하는 사람 | 아토르바스타틴 | 젬피브로질과 스타틴을 결합하면 횡문근융해증 위험이 증가하며, 그에 따른 신부전[55][56] 위험이 높아집니다. | |

| 항응고제 와파린을 복용하는 사람 | 임의의 상태 | 일부 스타틴은 와파린의 효과를 증가시키기 때문에 스타틴의 사용은 와파린 [57]용량 변경을 요구할 수 있다. | |

가장 중요한 부작용은 근육 문제, 당뇨병 위험 증가, 간 [5][58]손상으로 인한 혈액 내 간 효소 증가이다.5년 이상 치료 스타틴을 복용하면 당뇨병 75건, 출혈성 뇌졸중 7.5건,[31] 근육 손상 5건이 발생한다.이것은 콜레스테롤을 만드는 데 필요한 효소(HMG-CoA 환원효소)를 억제하는 스타틴 때문일 수 있지만, 근육 기능과 [59]당 조절에 중요한10 CoQ 생산과 같은 다른 과정에서도 마찬가지입니다.

다른 가능한 부작용으로는 신경 [60]장애, 췌장 및 간 기능 장애, 그리고 성 기능 장애가 [61]있다.부분적으로 저위험 모집단에서 스타틴의 위해성/유익성 비율이 부작용의 [62][63][64]비율에 크게 의존하기 때문에 그러한 사건이 발생하는 속도는 널리 논의되어 왔다.1차 예방에서 스타틴 임상시험의 코크란 메타 분석에서는 [4]플라시보와 비교하여 스타틴으로 처리된 환자 중 과도한 부작용의 증거가 발견되지 않았다.또 다른 메타 분석에서는 플라시보를 투여받은 사람에 비해 스타틴 치료자의 부작용은 39% 증가했지만 심각한 부작용은 [65]증가하지 않았다.한 연구의 저자는 부작용은 무작위 임상시험보다 임상 [61]실무에서 더 흔하다고 주장했다.체계적 검토에 따르면 임상시험 메타분석 결과 스타틴 사용과 관련된 근육통 비율을 과소평가하는 반면 횡문근융해증의 속도는 여전히 "확실히 낮다"며 임상시험에서 볼 수 있는 것과 유사하다(약 10,000명 당 1-2년).[66]런던에 있는 국립심장폐연구소의 국제순환건강센터의 또 다른 체계적 검토는 사람들이 스타틴에 대해 보고한 부작용의 극히 일부만이 실제로 [67]스타틴에 기인한다고 결론지었다.

인지 효과

다중 체계적 검토와 메타 분석에서는 이용 가능한 증거가 스타틴 사용과 인지 [68][69][70][71][72]감소 사이의 연관성을 뒷받침하지 않는다고 결론지었다.스타틴은 치매, 알츠하이머병의 위험을 줄이고 어떤 [73][needs update]경우에는 인지 장애를 개선시키는 것으로 나타났다.또한 뇌졸중 환자의 선호와 효과 연구에 대한 환자 중심 연구(PROSPER)와[74] 건강 보호 연구(HPS)는 심바스타틴과 프라바스타틴이 혈관 [75]질환의 위험 인자나 병력이 있는 환자에 대한 인지에 영향을 미치지 않았음을 입증했다.

스타틴에 [76]의한 가역적 인지장애에 대한 보고가 있다.미국 식품의약국(FDA)의 스타틴 패키지 삽입물에는 약물(기억 상실, 혼란)[77]에 의한 심각하지 않은 가역적 인지 부작용의 가능성에 대한 경고가 포함되어 있다.

근육들

관찰 연구에서 스타틴을 복용하는 사람들의 10-15%는 근육 문제를 경험한다; 대부분의 경우 근육통은 [6]근육통으로 구성된다.무작위 임상시험에서[66] 볼 수 있는 것보다 훨씬 높은 이 비율은 광범위한 논쟁과 [31][78]토론의 주제가 되어 왔다.

근육과 다른 증상들은 종종 환자들이 스타틴 [79]복용을 중단하게 만든다.이것은 스타틴 불내증으로 알려져 있습니다.최근 무작위 대조 시험(RCT)[80]은 스타틴 불내성 환자에게 동일한 모양의 스타틴 또는 플라시보를 투여하여 이중맹검으로 만들었다. 참가자들은 스타틴 또는 플라시보 중 어느 기간을 복용하고 있는지 알지 못했다.이것은 3번 반복되었기 때문에 랜덤 순서로 6개의 기간이 있었습니다.환자들은 스타틴과 위약과 비슷한 증상에 대해 질문을 받았는데, 이는 스타틴 불내증이 사람들이 스타틴을 복용하고 있다는 것을 아는 것에 달려있다는 것을 보여준다.더 작은 이중맹검 RCT도 비슷한 [81]결과를 얻었다.증상 점수가 표시된 후, 이 두 연구의 참가자 대부분은 스타틴 치료를 재개하려고 했습니다.이러한 연구 결과는 관찰 연구에서 스타틴 증상 비율이 이중맹검 RCT보다 훨씬 더 높은 이유를 설명하는 데 도움이 됩니다.차이는 플라시보 효과의 반대인 노세보 효과에서 비롯된다: 증상은 손상에 [82]대한 예상에 의해 야기된다.

스타틴에 대한 언론 보도는 종종 음성이며, 환자 전단지는 스타틴 치료 중에 드물지만 잠재적으로 심각한 근육 문제가 발생할 수 있다는 것을 환자에게 알려줍니다.이로 인해 위해가 발생할 수 있습니다.노세보 증상은 현실적이고 귀찮으며 치료에 큰 장벽이다.이 때문에 많은 사람들이 심장마비, 뇌졸중, 사망을[84] 줄이기 위해 수많은 대규모 RCT에서 증명된 [83]스타틴을 복용하는 것을 중단한다.

횡문근융해증(근육세포의 파괴)과 스타틴 관련 자가면역근병증과 같은 심각한 근육 문제는 치료 대상자의 [85]0.1% 미만으로 발생한다.횡문근융해증은 결국 생명을 위협하는 신장 손상을 초래할 수 있다.스타틴 유도 횡문근융해증의 위험은 나이가 들수록 증가하고 섬유질과 같은 상호작용하는 약물의 사용, 갑상선 기능 저하증.[86][87]코엔자임 Q10(유비퀴논) 수치는 스타틴 사용 [88]시 감소한다. CoQ10 보충제는 2017년 [89]현재[update] 유효성에 대한 증거가 부족하지만 스타틴 관련 미오파시를 치료하기 위해 가끔 사용된다.SLCO1B1(용질담체 유기 음이온수송체 패밀리 1B1) 유전자는 스타틴 흡수 조절에 관여하는 유기 음이온수송 폴리펩타이드를 코드한다.이 유전자의 공통적인 변이가 2008년에 발견되어 [90]근병증의 위험을 크게 증가시켰다.

1998년부터 2001년까지 스타틴 약물인 아토르바스타틴, 세리바스타틴, 플루바스타틴, 로바스타틴, 프라바스타틴,[91] 심바스타틴으로 치료된 250,000명 이상의 사람들에 대한 기록이 존재한다.횡문근융해증의 발병률은 세리바스타틴이 아닌 스타틴으로 처리된 환자 10,000명당 0.44명이었다.그러나 세리바스타틴을 사용하거나 표준 스타틴(아토르바스타틴, 플루바스타틴, 로바스타틴, 프라바스타틴 또는 심바스타틴)을 섬유산염(페노파이브레이트 또는 젬피브로질) 치료제와 결합할 경우 위험은 10배 이상 높았다.세리바스타틴은 2001년에 [92]제조사에 의해 철수되었다.

일부 연구자들은 플루바스타틴, 로스바스타틴, 프라바스타틴과 같은 친수성 스타틴이 아토르바스타틴, 로바스타틴, 심바스타틴과 같은 친수성 스타틴보다 독성이 덜하다고 제안했지만,[93] 다른 연구들은 연관성을 발견하지 못했다.로바스타틴은 근섬유 [93]손상을 촉진하는 것으로 여겨지는 유전자 아스트로긴-1의 발현을 유도한다.힘줄 파열은 [94]발생하지 않은 것 같습니다.

당뇨병

스타틴 사용과 당뇨병 발병 위험 사이의 관계는 여전히 불분명하고 검토 결과는 [95][96][97][98]엇갈린다.복용량이 많을수록 효과가 크지만 심혈관 질환의 감소가 당뇨병 [99]발병 위험보다 더 크다.폐경 후 여성의 사용은 당뇨병 [100]위험 증가와 관련이 있다.스타틴 사용과 관련된 당뇨병의 위험 증가에 대한 정확한 메커니즘은 [97]불분명하다.그러나 최근의 연구결과는 HMGCoAR의 억제를 주요 [101]메커니즘으로 제시하고 있다.스타틴은 [97]인슐린 호르몬에 반응하여 혈류에서 포도당의 흡수를 감소시키는 것으로 생각됩니다.이것이 일어나는 것으로 생각되는 한 가지 방법은 GLUT1과 [97]같은 세포에 포도당 흡수를 담당하는 특정 단백질의 생산에 필요한 콜레스테롤 합성에 간섭하는 것이다.

암

몇몇 메타분석에서는 암 발병 위험이 증가하지 않았으며 일부 메타분석에서는 발병 [102][103][104][105][106]위험이 감소된 것으로 나타났다.특히 스타틴은 식도암,[107] 대장암,[108] 위암,[109][110] 간세포암,[111] 그리고 어쩌면 전립선암의 위험을 [112][113]줄일 수 있다.그것들은 [114]폐암, [115]신장암,[116] 유방암, 췌장암,[117][118] 방광암의 위험성에 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 보인다.

약물 상호작용

어떤 스타틴도 섬유산염이나 나이아신(지질강하제의 다른 범주)과 결합하면 횡문근융해증의 위험이 10,000명당 [91]거의 6.0명으로 증가한다.간 효소 및 크레아틴 키나아제 모니터링은 특히 고용량 스타틴 또는 스타틴/섬유산 조합에서 신중하며, 근육 경련 또는 신장 기능 [citation needed]저하의 경우 필수이다.

자몽이나 자몽 주스의 섭취는 특정 스타틴의 신진대사를 억제한다.쓴 오렌지도 비슷한 [119]효과가 있을 수 있다.그레이프 프루트 주스(즉 bergamottin과 dihydroxybergamottin)에 Furanocoumarins은 시토 크롬 P450 효소 CYP3A4는 대부분 스타틴(유일한 로바 스타틴의 약한 정도로 하지만, 그것은 중요한 억제제, simvastatin고, atorvastatin)과 몇몇 다른 medications[120](플라보노이드(즉 나린진)의 신진대사 thoug다에 연루되어 있다는 것을 금지한다.ht지책임을 지게 됩니다).이는 스타틴의 수치를 증가시켜 선량 관련 부작용의 위험을 증가시킨다(미오패시/ 횡문근융해증 포함).일부 스타틴 사용자들에게 자몽 주스 섭취를 절대 금지한 것은 [121]논란이 되고 있다.

미국 식품의약국(FDA)은 프로테아제 억제제와 특정 스타틴 약물 간의 상호작용에 관한 처방 정보에 대한 업데이트를 의료 전문가에게 통보했다.단백질분해효소 억제제와 스타틴을 함께 복용하면 스타틴의 혈중 수치를 높이고 근육 손상 위험을 높일 수 있습니다.근막증의 가장 심각한 형태인 횡문근융해증은 [122]신장을 손상시키고 치명적인 신부전으로 이어질 수 있다.

골다공증 및 골절

연구에 따르면 스타틴의 사용은 골다공증과 골절을 예방하거나 골다공증과 [123][124][125][126]골절을 유발할 수 있다.전체 오스트리아 인구의 단면 소급 분석 결과 골다공증에 걸릴 위험은 사용된 [127]선량에 따라 결정된다는 것이 밝혀졌다.

신경 장애

스타틴 섭취는 신경 장애의 [128][129][130][131][132]유병률 증가와 관련이 있다.

작용 메커니즘

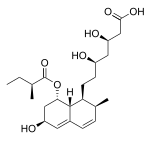

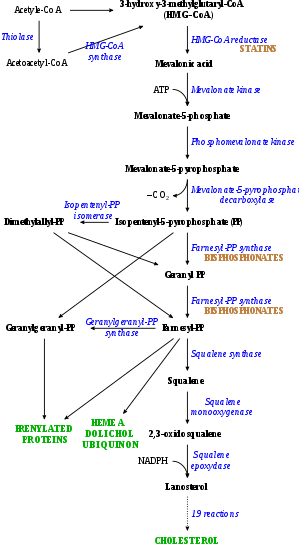

스타틴은 메발론산 경로의 속도 제한 효소인 HMG-CoA 환원효소를 경쟁적으로 억제함으로써 작용한다.스타틴은 분자 수준에서 HMG-CoA와 구조가 유사하기 때문에, 효소의 활성 부위에 맞고 자연 기질(HMG-CoA)과 경쟁할 것입니다.이 경쟁은 HMG-CoA 환원효소가 결국 콜레스테롤을 생성하는 캐스케이드의 다음 분자인 메발론산염을 생산할 수 있는 속도를 감소시킨다.페니실륨과 아스페르길루스 균류에 의해 2차 대사물로 다양한 천연 스타틴이 생성된다.이러한 천연 스타틴은 아마도 [134]생산자와 경쟁하는 박테리아와 곰팡이의 HMG-CoA 환원효소 효소를 억제하는 기능을 할 것입니다.

콜레스테롤 합성 억제

스타틴은 HMG-CoA 환원효소를 억제함으로써 간에서 콜레스테롤을 합성하는 경로를 차단한다.대부분의 순환되는 콜레스테롤이 식단보다는 내부 제조에서 나오기 때문에 이것은 중요하다.간이 콜레스테롤을 더 이상 생산할 수 없게 되면 혈중 콜레스테롤 수치가 떨어지게 됩니다.콜레스테롤 합성은 주로 [135]밤에 일어나는 것으로 보여 효과를 극대화하기 위해 반감기가 짧은 스타틴을 주로 밤에 복용한다.연구는 아침이 [136][137]아닌 밤에 섭취한 단기 작용성 심바스타틴에서 LDL과 총 콜레스테롤 감소가 더 크다는 것을 보여주었지만, 장기 작용성 아토르바스타틴에서는 [138]차이가 없었다.

LDL 흡수량 증가

토끼의 경우 간세포는 간 콜레스테롤의 저하를 감지하고 LDL 수용체를 합성해 콜레스테롤을 [139]순환에서 끌어냄으로써 보상을 모색한다.이것은 막 결합 스테롤 조절 요소 결합 단백질을 분해하는 단백질 분해 효소를 통해 이루어지며, 단백질은 핵으로 이동하고 스테롤 반응 요소에 결합합니다.스테롤 반응 요소는 다양한 다른 단백질, 특히 LDL 수용체의 전사를 증가시킨다.LDL 수용체는 간세포막으로 운반되어 LDL 및 VLDL 입자를 통과시켜 간으로의 흡수를 매개하며, 간에서 콜레스테롤이 담즙염 및 기타 부산물로 재처리됩니다.이것은 혈액에서 순환하는 LDL의 순효과를 감소시킨다.

특정 단백질 프레닐화 감소

스타틴은 HMG CoA 환원효소 경로를 저해함으로써 파르네실 피로인산염 및 게라닐게라닐 피로인산염과 같은 이소프레노이드의 하류 합성을 저해한다.단백질 prenylation의 RhoA(Rho-associated의 단백질과 그에 따른 억제 인산화 효소) 같은 단백질을 위한 수줍음으로, 최소한 부분적으로는, 내피 기능의 개선, 면역 기능의 변조, statins,[140][141][142][143][144][145]의 다른 다면 발현성의 심장 혈관에 이익뿐만 아니라 사실에 포함된다 것은 그거 하나는 l. 다른 약물 수ower LDL은 [146]연구에서 스타틴과 동일한 심혈관 위험 편익을 보여주지 않았으며 스타틴과 [147]함께 암 감소에서 보이는 편익의 일부를 설명할 수도 있다.또한 단백질 프레닐화에 대한 억제 효과는 근육통(미오패시)[148] 및 혈당 상승(당뇨병)[149]을 포함한 스타틴과 관련된 많은 바람직하지 않은 부작용에도 관여할 수 있다.

기타 효과

위에서 설명한 바와 같이 스타틴은 소위 "스타틴의 [143]다원성 효과"를 통해 아테롬성 동맥경화증의 예방에 지질 저하 활성을 넘어서는 작용을 보인다.스타틴의 다방성 효과는 여전히 [150]논란의 여지가 있다.소행성 실험은 스타틴 치료 [151]중 아테로마 퇴행의 직접적인 초음파 증거를 보여주었다.연구자들은 스타틴이 제안된 네 가지 메커니즘(생물의학 연구의 [150]대규모 대상)을 통해 심혈관 질환을 예방한다는 가설을 세운다.

2008년, JUPITER 실험은 높은 콜레스테롤이나 심장병의 병력이 없는 사람들에게 스타틴이 유익하다는 것을 보여주었지만,[152] 염증의 지표인 고감도 C반응단백질(HSCRP) 수치가 높아진 사람들에게만 유익하다는 것을 보여주었다.이 연구는 폴 M이 연구 [153][154][155]설계의 결함으로 인해 비판을 받아왔다. 주피터 실험의 수석 연구원인 Ridker는 이러한 비판에 대해 [156]장황하게 답변했다.

아래의 유전자, 단백질 및 대사물을 클릭하여 각각의 기사와 연결하세요. [§ 1]

- ^ 대화형 경로 맵은 WikiPathways에서 편집할 수 있습니다."Statin_Pathway_WP430".

스타틴의 표적인 HMG-CoA 환원효소는 진핵생물과 고세균이 매우 유사하기 때문에, 스타틴은 고세균의 생합성을 저해함으로써 고세균에 대한 항생제로서도 작용한다.이는 체내 및 [157]체외에서 나타났다.변비 표현형 환자는 장에 메타노제닉 고균이 풍부하기 때문에 과민성 대장증후군 관리를 위한 스타틴 사용이 제안되었으며 실제로 스타틴 사용의 [158][159]숨겨진 이점 중 하나일 수 있다.

이용 가능한 폼

스타틴은 발효 유래와 합성 두 그룹으로 나뉩니다.다음 표에 몇 가지 특정 유형을 나타냅니다.관련된 브랜드명은 국가에 따라 다를 수 있습니다.

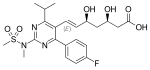

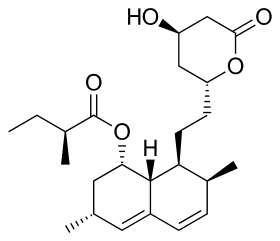

| 스타틴 | 이미지 | 브랜드명 | 파생 | 대사[160] | 반감기 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 아토르바스타틴 | 아르카스, 아토르, 아토리스, 리피토, 토르바스트, 토탈립 | 합성 | CYP3A4 | 14~[161]19시간 | |

| 세리바스타틴 | Baycol, Lipobay (2001년 8월 심각한 횡문근융해증 위험으로 시장에서 철수) | 합성 | 각종 CYP3A 아이소폼[162] | ||

| 플루바스타틴 | Lescol, Lescol XL, Lipaxan, Primesin | 합성 | CYP2C9 | 1 ~[161] 3시간 | |

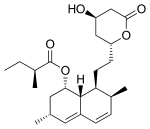

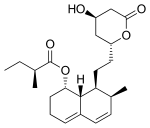

| 로바스타틴 | 알토코르, 알토프레프, 메바코르 | 자연적으로 발생하는 발효유래 화합물.그것은 느타리버섯과 붉은 효모쌀에서 발견된다. | CYP3A4 | 1 ~[161] 3시간 | |

| 메바스타틴 | 콤팩틴 | 붉은 효모 쌀에서 자연적으로 발생하는 화합물 | CYP3A4 | ||

| 피타바스타틴 | 알리프자, 리발로, 리바조, 피타바, 지피타마그 | 합성 | CYP2C9 및 CYP2C8(최소) | ||

| 프라바스타틴 | 아플라틴, 리포스타트, 프라스테롤, 프라바콜, 프라바셀렉트, 사나프라브, 셀렉틴, 셀렉틴, 바스티코르 | 발효유래(세균 Nocardia autotrophica) | 비[163] CYP | 1 ~[161] 3시간 | |

| 로스바스타틴 | 콜카르디올, 콜프리, 크라티브, 크레스토르, 딜리바스, 엑소르타, 콜레로스, 리피도버, 미아스티나, 프로비사코르, 로자스틴, 시메스타트, 스타로스 | 합성 | CYP2C9 및 CYP2C19 | 14~[161]19시간 | |

| 심바스타틴 | 알페우스, 크루스타트, 리페닐, 리펙스, 리포놈, 메디포, 오미스타트, 로심, 세토리린, 심바트릭스, 신콜, 신바트, 신바트, 신바트, 바스트겐, 바스틴, 시포콜, 조코르 | 발효유래(심바스타틴은 아스페르길루스 테레우스 발효물의 합성유래물) | CYP3A4 | 1 ~[161] 3시간 | |

| 아토르바스타틴+암로디핀 | 카듀에, 엔바카르 | 병용요법 : 스타틴 + 칼슘 길항제 | |||

| 아토르바스타틴+페린도프릴+암로디핀 | 트리베람[164][165][166] 주 | 병용요법 : 스타틴 + ACE 억제제 + 칼슘 길항제 | |||

| 로바스타틴 + 나이아신 연장 방출 | 어드바이저, 메바코르 | 병용 요법 | |||

| 로즈바스타틴+에제티미브 | Cholecomb, Delipid Plus, Rosulip, Rosumibe, Viazet[167][168][169][170] | 병용요법 : 스타틴 + 콜레스테롤 흡수 억제제 | |||

| 심바스타틴+에제티미브 | 골토르, 잉기, 스태틱콜, 비토린, 제스탄, 제비스타트 | 병용요법 : 스타틴 + 콜레스테롤 흡수 억제제 | |||

| 심바스타틴 + 나이아신 연장 방출 | 심코라 | 병용 요법 |

LDL 감소 효과는 약제에 따라 다릅니다.세리바스타틴이 가장 강력하며(2001년 8월 심각한 횡문근융해증 위험으로 인해 시장에서 철수) 다음으로 로수바스타틴, 아토르바스타틴, 심바스타틴, 로바스타틴, 로바스타틴, 프라바스타틴, 플루바스타틴 [171]순이다.피타바스타틴의 상대적 효력은 아직 완전히 확립되지 않았지만 예비 연구는 로수바스타틴과 [172]유사한 효력을 나타낸다.

어떤 종류의 스타틴은 자연적으로 발생하며 느타리버섯이나 붉은 효모 쌀과 같은 음식에서 발견될 수 있다.무작위 대조 실험에서는 이러한 식품들이 순환하는 콜레스테롤을 감소시키는 것으로 밝혀졌지만, 실험의 질은 [173]낮은 것으로 판단되었습니다.특허 만료로 인해, 가장[citation needed] 많이 팔리는 브랜드 [174][175][176][177][178][179][180]의약품인 아토르바스타틴을 포함하여 블록버스터 브랜드 스타틴의 대부분은 2012년부터 제네릭으로 제조되었습니다.

| 스태틴 등가 투여량 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDL 감소율 (약) | 아토르바스타틴 | 플루바스타틴 | 로바스타틴 | 프라바스타틴 | 로스바스타틴 | 심바스타틴 |

| 10–20% | – | 20밀리그램 | 10밀리그램 | 10밀리그램 | – | 5밀리그램 |

| 20–30% | – | 40밀리그램 | 20밀리그램 | 20밀리그램 | – | 10밀리그램 |

| 30–40% | 10밀리그램 | 80밀리그램 | 40밀리그램 | 40밀리그램 | 5밀리그램 | 20밀리그램 |

| 40–45% | 20밀리그램 | – | 80밀리그램 | 80밀리그램 | 5~10mg | 40밀리그램 |

| 46–50% | 40밀리그램 | – | – | – | 10 ~ 20 mg | 80 mg* |

| 50–55% | 80밀리그램 | – | – | – | 20밀리그램 | – |

| 56–60% | – | – | – | – | 40밀리그램 | – |

| * 횡문근융해증 위험 증가로 인해 80mg 복용은 더 이상 권장되지 않습니다 | ||||||

| 개시 선량 | ||||||

| 개시 선량 | 10 ~ 20 mg | 20밀리그램 | 10 ~ 20 mg | 40밀리그램 | 10 mg, 갑상선 기능 저하인 경우 5 mg, 65 yo 이상, 아시아인 | 20밀리그램 |

| LDL 감소 목표를 높인 경우 | 40 mg (45 % 이상일 경우 | 25 % 이상일 경우 40 mg | 20 mg (20 % 이상일 경우) | — | LDL > 190 mg/dL일 경우 20 mg (4.87 mmol/L) | 40 mg (45 % 이상일 경우 |

| 최적의 타이밍 | 언제라도요 | 저녁 | 저녁 식사와 함께 | 언제라도요 | 언제라도요 | 저녁 |

[의학적 인용이 필요합니다]

역사

심혈관 질환 발병에서 콜레스테롤의 역할은 20세기 [181]후반에 밝혀졌다.이 지질 가설은 콜레스테롤을 낮춰 심혈관 질환 부담을 줄이려는 시도를 촉발시켰다.치료는 주로 저지방 식단과 클로피브레이트, 콜레스트라민, 니코틴산과 같은 내성이 부족한 약물로 이루어졌다.콜레스테롤 연구원 다니엘 스타인버그는 1984년 관상동맥 1차 예방 시험에서 콜레스테롤 감소가 심장마비와 협심증의 위험을 크게 줄일 수 있다는 것이 입증되었지만 심장내과 의사를 포함한 의사들은 대체로 [182]납득하지 못하고 있다고 쓰고 있다.학계와 제약업계의 과학자들은 콜레스테롤을 더 효과적으로 줄이기 위한 약을 개발하기 시작했다.아세틸-코엔자임 [183]A에서 콜레스테롤을 합성하는 단계에는 여러 가지 잠재적 표적이 있었다.

1971년 제약회사 산쿄에서 일하는 일본인 생화학자 엔도 아키라가 이 문제를 조사하기 시작했다.연구에 따르면 콜레스테롤은 대부분 간에서 HMG-CoA 환원효소와 [11]함께 생성된다.엔도와 그의 팀은 메발론산이 세포벽이나 세포골격의 유지를 위해 유기체가 필요로 하는 많은 물질의 전구체이기 때문에 특정 미생물이 다른 유기체로부터 스스로를 [134]방어하기 위해 효소의 억제제를 생산할 수 있다고 추론했다.이들이 가장 먼저 확인한 인체는 페니실륨 시트리눔 균에 의해 생성된 분자 메바스타틴(ML-236B)이었다.

영국의 한 단체는 페니실륨 브레비콤팩툼에서 같은 화합물을 분리하여 콤팩트틴이라고 이름 짓고 1976년에 [184]그들의 보고서를 발표했다.영국 그룹은 HMG-CoA 환원효소 [medical citation needed]억제에 대한 언급 없이 항진균 성질을 언급하고 있다.메바스타틴은 종양, 근육 악화, 그리고 때로는 실험견의 죽음의 부작용 때문에 시판되지 않았다.수석 과학자이자 후에 Merck & Co.의 CEO인 P. Roy Vagelos는 관심을 가지고 1975년부터 여러 차례 일본을 방문했다.1978년까지 Merck는 1987년 메바코르로 처음 [11]시판된 곰팡이 Aspergillus terreus에서 로바스타틴(메비놀린, MK803)을 분리했다.

1990년대에 공공 캠페인의 결과로, 미국 사람들은 콜레스테롤 수치와 HDL과 LDL 콜레스테롤의 차이점에 익숙해졌고, 다양한 제약회사들은 산쿄와 브리스톨 마이어스 스퀴브에 의해 제조된 프라바스타틴과 같은 그들만의 스타틴을 생산하기 시작했다.1994년 4월, Merck가 후원한 연구, 스칸디나비아의 Simvastatin Survival Study의 결과가 발표되었습니다.연구원들은 후에 머크가 Zocor로 판매한 심바스타틴을 콜레스테롤이 높고 심장병이 있는 4,444명의 환자들을 대상으로 실험했다.5년 후, 연구는 환자들이 콜레스테롤이 35% 감소했고 심장마비로 사망할 확률은 42%[11][185] 감소했다고 결론지었다.1995년에 Zocor와 Mevacor는 둘 다 Merck를 10억 [11]달러 이상 벌어들였습니다.

엔도는 당초의 발견으로부터 이익을 얻지 못했지만, 선구적인 [186]연구로 2006년 일본상, 2008년 래스커·데베이키 임상 의학 연구상을 수상했다.엔도는 또한 2012년 버지니아 주 알렉산드리아에 있는 국립 발명가 명예의 전당에 헌액되었다.마이클 C.콜레스테롤 관련 연구로 노벨상을 받은 브라운과 조셉 골드스타인은 엔도에 대해 "스타틴 치료를 통해 수명을 연장할 수백만 명의 사람들이 아키라 [187]엔도에게 모든 것을 빚지고 있다"고 말했다.

2016년 현재[update], 스타틴의 부작용을 과장하는 잘못된 주장은 대중 [31]건강에 부정적인 영향을 미치면서 널리 언론에 보도되었다.영국 심장 재단이 자금을 지원한 연구의 저자들에 따르면, 2010년대 초 대중 매체에서 스타틴의 효과에 대한 논란이 증폭되어 영국에서 약 20만 명의 사람들이 2016년 중반까지 6개월 동안 스타틴 사용을 중단했다고 한다.그들은 [188]그 결과로 향후 10년 동안 2,000건의 심장마비나 뇌졸중이 더 발생할 수 있다고 추정했다.의도하지 않은 학술적 스타틴 논쟁의 영향은 과학적으로 의심스러운 대체 치료법의 확산이었다.클리블랜드 클리닉의 심장내과 전문의 스티븐 니센은 다음과 같이 말했다. "우리는 환자의 심장과 마음을 위한 싸움에서 웹사이트들에 지고 있습니다.검증되지 않은 치료법을 홍보하고 있습니다.[189]Harriet Hall은 의사 과학적 주장에서 유익성의 과소 진술과 부작용의 과대 진술에 이르는 "상태적 부정주의"의 스펙트럼을 보고 있는데, 이 모든 것은 과학적 [190]증거에 반한다.

로바스타틴(메바코르)은 2001년 [191]12월 미국에서 제네릭 의약품으로 승인되었다.

프라바스타틴(프라바콜)은 2006년 [192]4월 미국에서 제네릭 의약품으로 승인되었다.

Simvastatin(Zocor)은 2006년 [193]6월에 미국에서 제네릭 의약품으로 승인되었다.

아토르바스타틴(Lipitor)은 2011년 [194][195]11월 미국에서 제네릭 의약품으로 승인되었다.

플루바스타틴(Lescol)은 2012년 [196]4월 미국에서 제네릭 의약품으로 승인되었다.

2016년 [197][198]미국에서 피타바스타틴(리발로)과 로수바스타틴(크레스토르)이 제네릭 의약품으로 승인되었습니다.

에제티미브/심바스타틴(Vytorin)과 에제티미브/아토르바스타틴(립트루젯)은 2017년 [199]미국에서 제네릭 의약품으로 승인되었다.

조사.

치매,[200] 폐암,[201][206] 핵 백내장,[202] 고혈압,[203][204] 전립선암과[205] 유방암에서의 스타틴 사용에 대한 임상 연구가 실시되어 왔다.스타틴이 [207]폐렴에 유용하다는 양질의 증거는 없다.이용 가능한 소수의 시험들은 다발성 [208]경화증에서 부가 치료나 단발성 치료로서 스타틴의 사용을 지지하지 않는다.

레퍼런스

- ^ "Cholesterol Drugs". American Heart Association. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Alenghat FJ, Davis AM (26 February 2019). "Management of Blood Cholesterol". JAMA. 321 (8): 800–801. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.0015. PMC 6679800. PMID 30715135.

- ^ National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK) (July 2014). "Lipid Modification: Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and the Modification of Blood Lipids for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). PMID 25340243. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 181.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ a b c Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore TH, Burke M, Davey Smith G, et al. (January 2013). "Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD004816. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5. PMC 6481400. PMID 23440795.

- ^ a b c Naci H, Brugts J, Ades T (July 2013). "Comparative tolerability and harms of individual statins: a study-level network meta-analysis of 246 955 participants from 135 randomized, controlled trials" (PDF). Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 6 (4): 390–99. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000071. PMID 23838105. S2CID 18340552.

- ^ a b Abd TT, Jacobson TA (May 2011). "Statin-induced myopathy: a review and update". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 10 (3): 373–87. doi:10.1517/14740338.2011.540568. PMID 21342078. S2CID 207487287.

- ^ Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, et al. (December 2007). "Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths". Lancet. 370 (9602): 1829–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. PMID 18061058. S2CID 54293528.

- ^ Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Cardiovascular drugs". Martindale: the complete drug reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 1155–434. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ a b Taylor FC, Huffman M, Ebrahim S (December 2013). "Statin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". JAMA. 310 (22): 2451–52. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281348. PMID 24276813.

- ^ a b c d e Simons J (January 2003). "The $10 billion pill". Fortune. 147 (1): 58–62, 66, 68. PMID 12602122.

- ^ "다른 방식으로 작업" 2013년 5월 12일 Wayback Machine, Pwizer 2008 Annual Review, 2009년 4월 23일 페이지 15에서 아카이브.

- ^ LaMattina J. "Patent Expirations Of Crestor And Zetia And The Impact On Other Cholesterol Drugs". Forbes. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ National Cholesterol Education Program (2001). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Executive Summary. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. p. 40. NIH Publication No. 01-3670.

- ^ National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (2010). NICE clinical guideline 67: Lipid modification (PDF). London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. p. 38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2010.

- ^ Fulcher J, O'Connell R, Voysey M, Emberson J, Blackwell L, Mihaylova B, et al. (April 2015). "Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials". Lancet. 385 (9976): 1397–405. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61368-4. hdl:2123/14127. PMID 25579834. S2CID 35330627.

- ^ Cangemi, Roberto; Romiti, Giulio Francesco; Campolongo, Giuseppe; Ruscio, Eleonora; Sciomer, Susanna; Gianfrilli, Daniele; Raparelli, Valeria (March 2017). "Gender related differences in treatment and response to statins in primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention: The never-ending debate". Pharmacological Research. 117: 148–155. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.12.027. PMID 28012963. S2CID 32861954.

- ^ a b c Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. (June 2019). "2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 73 (24): e285–e350. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003. PMID 30423393.

- ^ a b c Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW, García FA, et al. (November 2016). "Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 316 (19): 1997–2007. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.15450. PMID 27838723. S2CID 205075217.

- ^ "ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator". www.cvriskcalculator.com. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' Collaboration (February 2019). "Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials". The Lancet. 393 (10170): 407–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31942-1. PMC 6429627. PMID 30712900.

- ^ a b Tonelli M, Lloyd A, Clement F, Conly J, Husereau D, Hemmelgarn B, et al. (November 2011). "Efficacy of statins for primary prevention in people at low cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis". CMAJ. 183 (16): E1189–202. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101280. PMC 3216447. PMID 21989464.

- ^ Kostis WJ, Cheng JQ, Dobrzynski JM, Cabrera J, Kostis JB (February 2012). "Meta-analysis of statin effects in women versus men". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 59 (6): 572–82. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.067. PMID 22300691.

- ^ Petretta M, Costanzo P, Perrone-Filardi P, Chiariello M (January 2010). "Impact of gender in primary prevention of coronary heart disease with statin therapy: a meta-analysis". International Journal of Cardiology. 138 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.08.001. PMID 18793814.

- ^ Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Erqou S, Sever P, Jukema JW, Ford I, et al. (June 2010). "Statins and all-cause mortality in high-risk primary prevention: a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials involving 65,229 participants". Archives of Internal Medicine. 170 (12): 1024–31. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.182. PMID 20585067.

- ^ Bukkapatnam RN, Gabler NB, Lewis WR (2010). "Statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular mortality in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Preventive Cardiology. 13 (2): 84–90. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7141.2009.00059.x. PMID 20377811.

- ^ "Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification at www.nice.org.uk". Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. (June 2014). "2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 129 (25 Suppl 2): S1–45. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. PMID 24222016.

- ^ Nissen SE (December 2014). "Prevention guidelines: bad process, bad outcome". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (12): 1972–73. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3278. PMID 25285604.

- ^ Reiner Ž, Catapano AL, De Backer G, Graham I, Taskinen MR, Wiklund O, et al. (December 2011). "[ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias]". Revista Espanola de Cardiologia. 64 (12): 1168.e1–1168.e60. doi:10.1016/j.rec.2011.09.015. hdl:2268/205760. PMID 22115524.

- ^ a b c d Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, Armitage J, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. (November 2016). "Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy" (PDF). Lancet (Submitted manuscript). 388 (10059): 2532–61. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5. hdl:10044/1/43661. PMID 27616593. S2CID 4641278.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (March 2010) [May 2008]. "Lipid modification – Cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease – Quick reference guide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka AR (June 2003). "Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 326 (7404): 1423–30. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423. PMC 162260. PMID 12829554.

- ^ Pisaniello AD, Scherer DJ, Kataoka Y, Nicholls SJ (February 2015). "Ongoing challenges for pharmacotherapy for dyslipidemia". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 16 (3): 347–56. doi:10.1517/14656566.2014.986094. PMID 25476544. S2CID 539314.

- ^ Kushner PA, Cobble ME (November 2016). "Hypertriglyceridemia: the importance of identifying patients at risk". Postgraduate Medicine (Review). 128 (8): 848–58. doi:10.1080/00325481.2016.1243005. PMID 27710158. S2CID 45663315.

- ^ Khera AV, Plutzky J (July 2013). "Management of low levels of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol". Circulation (Review). 128 (1): 72–78. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000443. PMC 4231714. PMID 23817482.

- ^ Mijajlović MD, Pavlović A, Brainin M, Heiss WD, Quinn TJ, Ihle-Hansen HB, et al. (December 2017). "Post-stroke dementia – a comprehensive review". BMC Medicine. 15 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0779-7. PMC 5241961. PMID 28095900.

- ^ de Waal BA, Buise MP, van Zundert AA (January 2015). "Perioperative statin therapy in patients at high risk for cardiovascular morbidity undergoing surgery: a review". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 114 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu295. PMID 25186819.

- ^ Antoniou GA, Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Vallabhaneni SR, Brennan JA, Torella F (February 2015). "Meta-analysis of the effects of statins on perioperative outcomes in vascular and endovascular surgery". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 61 (2): 519–32.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2014.10.021. PMID 25498191.

- ^ Sladojevic N, Yu B, Liao JK (December 2017). "ROCK as a therapeutic target for ischemic stroke". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 17 (12): 1167–77. doi:10.1080/14737175.2017.1395700. PMC 6221831. PMID 29057688.

- ^ Li YH, Ueng KC, Jeng JS, Charng MJ, Lin TH, Chien KL, et al. (April 2017). "2017 Taiwan lipid guidelines for high risk patients". Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan Yi Zhi. 116 (4): 217–48. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2016.11.013. PMID 28242176.

- ^ Zhou Z, Rahme E, Pilote L (February 2006). "Are statins created equal? Evidence from randomized trials of pravastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin for cardiovascular disease prevention". American Heart Journal. 151 (2): 273–81. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.04.003. PMID 16442888.

- ^ a b Adams SP, Tsang M, Wright JM (11 March 2015). "Atorvastatin for lowering lipids". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD008226. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008226.pub3. PMC 6464917. PMID 25760954.

- ^ a b Vuorio A, Kuoppala J, Kovanen PT, Humphries SE, Tonstad S, Wiegman A, et al. (November 2019). "Statins for children with familial hypercholesterolemia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006401.pub5. PMC 6836374. PMID 31696945.

- ^ Lamaida N, Capuano E, Pinto L, Capuano E, Capuano R, Capuano V (September 2013). "The safety of statins in children". Acta Paediatrica. 102 (9): 857–62. doi:10.1111/apa.12280. PMID 23631461. S2CID 22846175.

- ^ Braamskamp MJ, Wijburg FA, Wiegman A (April 2012). "Drug therapy of hypercholesterolaemia in children and adolescents". Drugs. 72 (6): 759–72. doi:10.2165/11632810-000000000-00000. PMID 22512364. S2CID 21141894.

- ^ a b Repas TB, Tanner JR (February 2014). "Preventing early cardiovascular death in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 114 (2): 99–108. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2014.023. PMID 24481802.

- ^ Ramasamy I (February 2016). "Update on the molecular biology of dyslipidemias". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 454: 143–85. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2015.10.033. PMID 26546829.

- ^ Rader DJ, Cohen J, Hobbs HH (June 2003). "Monogenic hypercholesterolemia: new insights in pathogenesis and treatment". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 111 (12): 1795–803. doi:10.1172/JCI18925. PMC 161432. PMID 12813012.

- ^ Marais AD, Blom DJ, Firth JC (January 2002). "Statins in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 4 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1007/s11883-002-0058-7. PMID 11772418. S2CID 8075552.

- ^ Liu YH, Liu Y, Duan CY, Tan N, Chen JY, Zhou YL, et al. (March 2015). "Statins for the Prevention of Contrast-Induced Nephropathy After Coronary Angiography/Percutaneous Interventions: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 20 (2): 181–92. doi:10.1177/1074248414549462. PMID 25193735. S2CID 28251228.

- ^ 다음 소스에서 수정된 표이지만 기술적인 설명은 개별 참고 자료를 참조하십시오.

- Consumer Reports; Drug Effectiveness Review Project (March 2013), "Evaluating statin drugs to treat High Cholesterol and Heart Disease: Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF), Best Buy Drugs, Consumer Reports, p. 9, retrieved 27 March 2013

- ^ Asberg A (2003). "Interactions between cyclosporin and lipid-lowering drugs: implications for organ transplant recipients". Drugs. 63 (4): 367–78. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363040-00003. PMID 12558459. S2CID 46971444.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Interactions between certain HIV or hepatitis C drugs and cholesterol-lowering statin drugs can increase the risk of muscle injury". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 유지보수: 부적합한 URL(링크) - ^ Bellosta S, Paoletti R, Corsini A (June 2004). "Safety of statins: focus on clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions". Circulation. 109 (23 Suppl 1): III50–57. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000131519.15067.1f. PMID 15198967.

- ^ Omar MA, Wilson JP (February 2002). "FDA adverse event reports on statin-associated rhabdomyolysis". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (2): 288–95. doi:10.1345/aph.1A289. PMID 11847951. S2CID 43757439.

- ^ Armitage J (November 2007). "The safety of statins in clinical practice". Lancet. 370 (9601): 1781–90. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60716-8. PMID 17559928. S2CID 205948651.

- ^ Bellosta S, Corsini A (November 2012). "Statin drug interactions and related adverse reactions". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 11 (6): 933–46. doi:10.1517/14740338.2012.712959. PMID 22866966. S2CID 6247572.

- ^ Brault M, Ray J, Gomez YH, Mantzoros CS, Daskalopoulou SS (June 2014). "Statin treatment and new-onset diabetes: a review of proposed mechanisms". Metabolism. 63 (6): 735–45. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2014.02.014. PMID 24641882.

- ^ 레러 S, 라인스타인 P.니아신과 결합된 스타틴은 말초 신경 장애의 위험을 줄여준다.Int J 펑트 뉴트리얼 2020년 9월~10월, 1:3 PMID 33330853

- ^ a b Golomb BA, Evans MA (2008). "Statin adverse effects : a review of the literature and evidence for a mitochondrial mechanism". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 8 (6): 373–418. doi:10.2165/0129784-200808060-00004. PMC 2849981. PMID 19159124.

- ^ Kmietowicz Z (March 2014). "New analysis fuels debate on merits of prescribing statins to low risk people". BMJ. 348: g2370. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2370. PMID 24671956. S2CID 46535820.

- ^ Wise J (June 2014). "Open letter raises concerns about NICE guidance on statins". BMJ. 348: g3937. doi:10.1136/bmj.g3937. PMID 24920699. S2CID 42422361.

- ^ Gøtzsche PC (June 2014). "Muscular adverse effects are common with statins". BMJ. 348: g3724. doi:10.1136/bmj.g3724. PMID 24920687. S2CID 206902546.

- ^ Silva MA, Swanson AC, Gandhi PJ, Tataronis GR (January 2006). "Statin-related adverse events: a meta-analysis". Clinical Therapeutics. 28 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.01.005. PMID 16490577.

- ^ a b Mancini GB, Baker S, Bergeron J, Fitchett D, Frohlich J, Genest J, et al. (2011). "Diagnosis, prevention, and management of statin adverse effects and intolerance: proceedings of a Canadian Working Group Consensus Conference". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 27 (5): 635–62. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2011.05.007. PMID 21963058.

- ^ Finegold JA, Manisty CH, Goldacre B, Barron AJ, Francis DP (April 2014). "What proportion of symptomatic side effects in patients taking statins are genuinely caused by the drug? Systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials to aid individual patient choice". European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 21 (4): 464–74. doi:10.1177/2047487314525531. PMID 24623264. S2CID 21064267.

- ^ Swiger KJ, Manalac RJ, Blumenthal RS, Blaha MJ, Martin SS (November 2013). "Statins and cognition: a systematic review and meta-analysis of short- and long-term cognitive effects". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 88 (11): 1213–21. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.07.013. PMID 24095248.

- ^ Mancini GB, Tashakkor AY, Baker S, Bergeron J, Fitchett D, Frohlich J, et al. (December 2013). "Diagnosis, prevention, and management of statin adverse effects and intolerance: Canadian Working Group Consensus update". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 29 (12): 1553–68. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.09.023. PMID 24267801.

- ^ Richardson K, Schoen M, French B, Umscheid CA, Mitchell MD, Arnold SE, et al. (November 2013). "Statins and cognitive function: a systematic review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (10): 688–97. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00007. PMID 24247674. S2CID 207536770.

- ^ Smith DA (May 2014). "ACP Journal Club. Review: statins are not associated with cognitive impairment or dementia in cognitively intact adults". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (10): JC11, JC10. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-160-10-201405200-02011. PMID 24842433. S2CID 1990708.

- ^ Bitzur R (August 2016). "Remembering Statins: Do Statins Have Adverse Cognitive Effects?". Diabetes Care (Review). 39 Suppl 2 (Supplement 2): S253–59. doi:10.2337/dcS15-3022. PMID 27440840.

- ^ Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Erqou S, Sever P, Jukema JW, Ford I, Sattar N (28 June 2010). "Statins and all-cause mortality in high-risk primary prevention: a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials involving 65,229 participants". Archives of Internal Medicine. 170 (12): 1024–31. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.182. PMID 20585067.

- ^ O'Brien EC, Greiner MA, Xian Y, Fonarow GC, Olson DM, Schwamm LH, et al. (13 October 2015). "Clinical Effectiveness of Statin Therapy After Ischemic Stroke: Primary Results From the Statin Therapeutic Area of the Patient-Centered Research Into Outcomes Stroke Patients Prefer and Effectiveness Research (PROSPER) Study". Circulation. 132 (15): 1404–1413. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016183. PMID 26246175. S2CID 11252336.

- ^ Mijajlović MD, Pavlović A, Brainin M, Heiss WD, Quinn TJ, Ihle-Hansen HB, et al. (January 2017). "Post-stroke dementia – a comprehensive review". BMC Medicine. 15 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0779-7. PMC 5241961. PMID 28095900.

- ^ McDonagh J (December 2014). "Statin-related cognitive impairment in the real world: you'll live longer, but you might not like it". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (12): 1889. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5376. PMID 25347692.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 19 January 2016. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Backes JM, Ruisinger JF, Gibson CA, Moriarty PM (January–February 2017). "Statin-associated muscle symptoms-Managing the highly intolerant". Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 11 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2017.01.006. PMID 28391891.

- ^ Yusuf, Salim (September 2016). "Why do people not take life-saving medications? The case of statins". The Lancet. 388 (10048): 943–945. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31532-x. PMID 27598664. S2CID 34832961.

- ^ Herrett, Emily; Williamson, Elizabeth; Brack, Kieran; Beaumont, Danielle; Perkins, Alexander; Thayne, Andrew; Shakur-Still, Haleema; Roberts, Ian; Prowse, Danielle; Goldacre, Ben; van Staa, Tjeerd; MacDonald, Thomas M; Armitage, Jane; Wimborne, Jon; Melrose, Paula; Singh, Jayshireen; Brooks, Lucy; Moore, Michael; Hoffman, Maurice; Smeeth, Liam; StatinWISE Trial Group (24 February 2021). "Statin treatment and muscle symptoms: series of randomised, placebo controlled n-of-1 trials". BMJ. 372: n135. doi:10.1136/bmj.n135. PMC 7903384. PMID 33627334.

- ^ Wood, Frances A.; Howard, James P.; Finegold, Judith A.; Nowbar, Alexandra N.; Thompson, David M.; Arnold, Ahran D.; Rajkumar, Christopher A.; Connolly, Susan; Cegla, Jaimini; Stride, Chris; Sever, Peter; Norton, Christine; Thom, Simon A.M.; Shun-Shin, Matthew J.; Francis, Darrel P. (26 November 2020). "N-of-1 Trial of a Statin, Placebo, or No Treatment to Assess Side Effects". New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (22): 2182–2184. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2031173. PMID 33196154. S2CID 226971988.

- ^ Colloca, Luana; Barsky, Arthur J. (6 February 2020). "Placebo and Nocebo Effects". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (6): 554–561. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1907805. PMID 32023375. S2CID 211046068.

- ^ Nelson, Adam J.; Puri, Rishi; Nissen, Steven E. (August 2020). "Statins in a Distorted Mirror of Media". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 22 (8): 37. doi:10.1007/s11883-020-00853-9. PMID 32557172. S2CID 219730531.

- ^ Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration; Baigent, C; Blackwell, L; Emberson, J; Holland, LE; Reith, C; Bhala, N; Peto, R; Barnes, EH; Keech, A; Simes, J; Collins, R (November 2010). "Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170 000 participants in 26 randomised trials". The Lancet. 376 (9753): 1670–1681. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. PMC 2988224. PMID 21067804.

- ^ Newman CB, Preiss D, Tobert JA, Jacobson TA, Page RL, Goldstein LB, et al. (2019). "Statin Safety and Associated Adverse Events: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 39 (2): e38–e81. doi:10.1161/ATV.0000000000000073. PMID 30580575.

- ^ Rull G, Henderson R (20 January 2015). "Rhabdomyolysis and Other Causes of Myoglobinuria". Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ Mendes P, Robles PG, Mathur S (2014). "Statin-induced rhabdomyolysis: a comprehensive review of case reports". Physiotherapy Canada. 66 (2): 124–32. doi:10.3138/ptc.2012-65. PMC 4006404. PMID 24799748.

- ^ Potgieter M, Pretorius E, Pepper MS (March 2013). "Primary and secondary coenzyme Q10 deficiency: the role of therapeutic supplementation". Nutrition Reviews. 71 (3): 180–88. doi:10.1111/nure.12011. PMID 23452285.

- ^ Tan JT, Barry AR (June 2017). "Coenzyme Q10 supplementation in the management of statin-associated myalgia". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 74 (11): 786–93. doi:10.2146/ajhp160714. PMID 28546301. S2CID 3825396.

- ^ Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, Bowman L, Heath S, Matsuda F, et al. (August 2008). "SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy – a genomewide study". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (8): 789–99. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. PMID 18650507.

- ^ a b Graham DJ, Staffa JA, Shatin D, Andrade SE, Schech SD, La Grenade L, et al. (December 2004). "Incidence of hospitalized rhabdomyolysis in patients treated with lipid-lowering drugs". JAMA. 292 (21): 2585–90. doi:10.1001/jama.292.21.2585. PMID 15572716.

- ^ Backman JT, Filppula AM, Niemi M, Neuvonen PJ (January 2016). "Role of Cytochrome P450 2C8 in Drug Metabolism and Interactions". Pharmacological Reviews (Review). 68 (1): 168–241. doi:10.1124/pr.115.011411. PMID 26721703.

- ^ a b Hanai J, Cao P, Tanksale P, Imamura S, Koshimizu E, Zhao J, et al. (December 2007). "The muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1/MAFbx mediates statin-induced muscle toxicity". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (12): 3940–51. doi:10.1172/JCI32741. PMC 2066198. PMID 17992259.

- ^ Teichtahl AJ, Brady SR, Urquhart DM, Wluka AE, Wang Y, Shaw JE, et al. (February 2016). "Statins and tendinopathy: a systematic review". The Medical Journal of Australia. 204 (3): 115–21.e1. doi:10.5694/mja15.00806. PMID 26866552. S2CID 4652858.

- ^ Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, et al. (February 2010). "Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials". Lancet. 375 (9716): 735–42. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6. PMID 20167359. S2CID 11544414.

- ^ Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, Daeges M, Jeanne TL (November 2016). "Statins for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force". JAMA (Review). 316 (19): 2008–24. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15629. PMID 27838722.

- ^ a b c d Rochlani Y, Kattoor AJ, Pothineni NV, Palagiri RD, Romeo F, Mehta JL (October 2017). "Balancing Primary Prevention and Statin-Induced Diabetes Mellitus Prevention". The American Journal of Cardiology (Review). 120 (7): 1122–28. Bibcode:1981AmJC...48..728H. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.06.054. PMID 28797470.

- ^ He Y, Li X, Gasevic D, Brunt E, McLachlan F, Millenson M, et al. (16 October 2018). "Statins and Multiple Noncardiovascular Outcomes: Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses of Observational Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials". Annals of Internal Medicine. 169 (8): 543–53. doi:10.7326/M18-0808. PMID 30304368. S2CID 52953760.

- ^ Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, Murphy SA, Ho JE, Waters DD, et al. (June 2011). "Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderate-dose statin therapy: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 305 (24): 2556–64. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.860. PMID 21693744.

- ^ Culver AL, Ockene IS, Balasubramanian R, Olendzki BC, Sepavich DM, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. (January 2012). "Statin use and risk of diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women in the Women's Health Initiative". Archives of Internal Medicine. 172 (2): 144–52. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.625. PMID 22231607.

- ^ Carmena R, Betteridge DJ (April 2019). "Diabetogenic Action of Statins: Mechanisms". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 21 (6): 23. doi:10.1007/s11883-019-0780-z. PMID 31037345. S2CID 140506916.

- ^ Jukema JW, Cannon CP, de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG, Trompet S (September 2012). "The controversies of statin therapy: weighing the evidence". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 60 (10): 875–81. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.007. PMID 22902202.

- ^ Rutishauser J (21 November 2011). "Statins in clinical medicine". Swiss Medical Weekly. 141: w13310. doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13310. PMID 22101921.

- ^ Alsheikh-Ali AA, Maddukuri PV, Han H, Karas RH (July 2007). "Effect of the magnitude of lipid lowering on risk of elevated liver enzymes, rhabdomyolysis, and cancer: insights from large randomized statin trials". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 50 (5): 409–18. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.073. PMID 17662392.

- ^ Dale KM, Coleman CI, Henyan NN, Kluger J, White CM (January 2006). "Statins and cancer risk: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 295 (1): 74–80. doi:10.1001/jama.295.1.74. PMID 16391219.

- ^ Alsheikh-Ali AA, Karas RH (March 2009). "The relationship of statins to rhabdomyolysis, malignancy, and hepatic toxicity: evidence from clinical trials". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 11 (2): 100–04. doi:10.1007/s11883-009-0016-8. PMID 19228482. S2CID 42869773.

- ^ Singh S, Singh AG, Singh PP, Murad MH, Iyer PG (June 2013). "Statins are associated with reduced risk of esophageal cancer, particularly in patients with Barrett's esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 11 (6): 620–29. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.036. PMC 3660516. PMID 23357487.

- ^ Liu Y, Tang W, Wang J, Xie L, Li T, He Y, et al. (February 2014). "Association between statin use and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 42 studies". Cancer Causes & Control. 25 (2): 237–49. doi:10.1007/s10552-013-0326-6. PMID 24265089. S2CID 17931279.

- ^ Wu XD, Zeng K, Xue FQ, Chen JH, Chen YQ (October 2013). "Statins are associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 69 (10): 1855–60. doi:10.1007/s00228-013-1547-z. PMID 23748751. S2CID 16584300.

- ^ Singh PP, Singh S (July 2013). "Statins are associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Oncology. 24 (7): 1721–30. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt150. PMID 23599253.

- ^ Pradelli D, Soranna D, Scotti L, Zambon A, Catapano A, Mancia G, et al. (May 2013). "Statins and primary liver cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 22 (3): 229–34. doi:10.1097/cej.0b013e328358761a. PMID 23010949. S2CID 37195287.

- ^ Zhang Y, Zang T (2013). "Association between statin usage and prostate cancer prevention: a refined meta-analysis based on literature from the years 2005–2010". Urologia Internationalis. 90 (3): 259–62. doi:10.1159/000341977. PMID 23052323. S2CID 22078921.

- ^ Bansal D, Undela K, D'Cruz S, Schifano F (2012). "Statin use and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies". PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e46691. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...746691B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046691. PMC 3462187. PMID 23049713.

- ^ Tan M, Song X, Zhang G, Peng A, Li X, Li M, et al. (2013). "Statins and the risk of lung cancer: a meta-analysis". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e57349. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...857349T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057349. PMC 3585354. PMID 23468972.

- ^ Zhang XL, Liu M, Qian J, Zheng JH, Zhang XP, Guo CC, et al. (March 2014). "Statin use and risk of kidney cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized trials". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 77 (3): 458–65. doi:10.1111/bcp.12210. PMC 3952720. PMID 23879311.

- ^ Undela K, Srikanth V, Bansal D (August 2012). "Statin use and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 135 (1): 261–69. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-2154-x. PMID 22806241. S2CID 35249884.

- ^ Cui X, Xie Y, Chen M, Li J, Liao X, Shen J, et al. (July 2012). "Statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis". Cancer Causes & Control. 23 (7): 1099–111. doi:10.1007/s10552-012-9979-9. PMID 22562222. S2CID 13171692.

- ^ Zhang XL, Geng J, Zhang XP, Peng B, Che JP, Yan Y, et al. (April 2013). "Statin use and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis". Cancer Causes & Control. 24 (4): 769–76. doi:10.1007/s10552-013-0159-3. PMID 23361339. S2CID 9030195.

- ^ Katherine Zeratsky, R.D., L.D., Mayo 클리닉: 자몽과 의약품의 간섭에 관한 기사 2017년 5월 1일 접속

- ^ Kane GC, Lipsky JJ (September 2000). "Drug-grapefruit juice interactions". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 75 (9): 933–42. doi:10.4065/75.9.933. PMID 10994829.

- ^ Reamy BV, Stephens MB (July 2007). "The grapefruit-drug interaction debate: role of statins". American Family Physician. 76 (2): 190, 192, author reply 192. PMID 17695563.

- ^ "Statins and HIV or Hepatitis C Drugs: Drug Safety Communication – Interaction Increases Risk of Muscle Injury". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Lin TK, Chou P, Lin CH, Hung YJ, Jong GP (2018). "Long-term effect of statins on the risk of new-onset osteoporosis: A nationwide population-based cohort study". PLOS ONE. 13 (5): e0196713. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1396713L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196713. PMC 5933736. PMID 29723231.

- ^ Wang Z, Li Y, Zhou F, Piao Z, Hao J (May 2016). "Effects of Statins on Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Risk: A PRISMA-compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Medicine (Baltimore). 95 (22): e3042. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000003042. PMC 4900696. PMID 27258488.

- ^ An T, Hao J, Sun S, Li R, Yang M, Cheng G, et al. (January 2017). "Efficacy of statins for osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Osteoporos Int. 28 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1007/s00198-016-3844-8. PMID 27888285. S2CID 4723680.

- ^ Larsson BA, Sundh D, Mellström D, Axelsson KF, Nilsson AG, Lorentzon M (February 2019). "Association Between Cortical Bone Microstructure and Statin Use in Older Women". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 104 (2): 250–257. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-02054. PMID 30423123.

- ^ Leutner M, Matzhold C, Bellach L, Deischinger C, Harreiter J, Thurner S, et al. (September 2019). "Diagnosis of osteoporosis in statin-treated patients is dose-dependent". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 78 (12): annrheumdis–2019–215714. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215714. PMC 6900255. PMID 31558481.

- ^ "BNF is only available in the UK".

- ^ Gaist, D.; Jeppesen, U.; Andersen, M.; Garcia Rodriguez, L. A.; Hallas, J.; Sindrup, S. H. (14 May 2002). "Statins and risk of polyneuropathy: A case-control study". Neurology. 58 (9): 1333–1337. doi:10.1212/wnl.58.9.1333. PMID 12011277. S2CID 14994652.

- ^ Emad, Mohammadreza; Arjmand, Hosein; Farpour, Hamid Reza; Kardeh, Bahareh (25 March 2018). "Lipid-lowering drugs (statins) and peripheral neuropathy". Electronic Physician. 10 (3): 6527–6533. doi:10.19082/6527. PMC 5942574. PMID 29765578.

- ^ Jones, Mark R.; Urits, Ivan; Wolf, John; Corrigan, Devin; Colburn, Luc; Peterson, Emily; Williamson, Amber; Viswanath, Omar (5 May 2020). "Drug-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A Narrative Review". Current Clinical Pharmacology. 15 (1): 38–48. doi:10.2174/1574884714666190121154813. PMC 7365998. PMID 30666914.

- ^ Lehrer, Steven; H. Rheinstein, Peter (9 June 2020). "Statins combined with niacin reduce the risk of peripheral neuropathy". International Journal of Functional Nutrition. 1 (1). doi:10.3892/ijfn.2020.3. PMC 7737454. PMID 33330853.

- ^ Istvan ES, Deisenhofer J (May 2001). "Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase". Science. 292 (5519): 1160–64. Bibcode:2001Sci...292.1160I. doi:10.1126/science.1059344. PMID 11349148. S2CID 37686043.

- ^ a b Endo A (November 1992). "The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors". Journal of Lipid Research. 33 (11): 1569–82. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)41379-3. PMID 1464741.

- ^ Miettinen TA (March 1982). "Diurnal variation of cholesterol precursors squalene and methyl sterols in human plasma lipoproteins". Journal of Lipid Research. 23 (3): 466–73. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)38144-X. PMID 7200504.

- ^ Saito Y, Yoshida S, Nakaya N, Hata Y, Goto Y (July–August 1991). "Comparison between morning and evening doses of simvastatin in hyperlipidemic subjects. A double-blind comparative study". Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis. 11 (4): 816–26. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.11.4.816. PMID 2065035.

- ^ Wallace A, Chinn D, Rubin G (October 2003). "Taking simvastatin in the morning compared with in the evening: randomised controlled trial". BMJ. 327 (7418): 788. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7418.788. PMC 214096. PMID 14525878.

- ^ Cilla DD, Gibson DM, Whitfield LR, Sedman AJ (July 1996). "Pharmacodynamic effects and pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin after administration to normocholesterolemic subjects in the morning and evening". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 36 (7): 604–09. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04224.x. PMID 8844442. S2CID 13586550.

- ^ Ma PT, Gil G, Südhof TC, Bilheimer DW, Goldstein JL, Brown MS (November 1986). "Mevinolin, an inhibitor of cholesterol synthesis, induces mRNA for low density lipoprotein receptor in livers of hamsters and rabbits". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (21): 8370–74. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.8370M. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.21.8370. PMC 386930. PMID 3464957.

- ^ Laufs U, Custodis F, Böhm M (2006). "HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in chronic heart failure: potential mechanisms of benefit and risk". Drugs. 66 (2): 145–54. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666020-00002. PMID 16451090. S2CID 46985044.

- ^ Greenwood J, Steinman L, Zamvil SS (May 2006). "Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 6 (5): 358–70. doi:10.1038/nri1839. PMC 3842637. PMID 16639429.

- ^ Lahera V, Goicoechea M, de Vinuesa SG, Miana M, de las Heras N, Cachofeiro V, et al. (2007). "Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation in atherosclerosis: beneficial effects of statins". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (2): 243–48. doi:10.2174/092986707779313381. PMID 17266583.

- ^ a b Blum A, Shamburek R (April 2009). "The pleiotropic effects of statins on endothelial function, vascular inflammation, immunomodulation and thrombogenesis". Atherosclerosis. 203 (2): 325–30. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.022. PMID 18834985.

- ^ Porter KE, Turner NA (July 2011). "Statins and myocardial remodelling: cell and molecular pathways". Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 13 (e22): e22. doi:10.1017/S1462399411001931. PMID 21718586. S2CID 1975524.

- ^ Sawada N, Liao JK (March 2014). "Rho/Rho-associated coiled-coil forming kinase pathway as therapeutic targets for statins in atherosclerosis". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 20 (8): 1251–67. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5524. PMC 3934442. PMID 23919640.

- ^ "Questions Remain in Cholesterol Research". MedPageToday. 15 August 2014.

- ^ Thurnher M, Nussbaumer O, Gruenbacher G (July 2012). "Novel aspects of mevalonate pathway inhibitors as antitumor agents". Clinical Cancer Research. 18 (13): 3524–31. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0489. PMID 22529099.

- ^ Norata GD, Tibolla G, Catapano AL (October 2014). "Statins and skeletal muscles toxicity: from clinical trials to everyday practice". Pharmacological Research. 88: 107–13. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2014.04.012. PMID 24835295.

- ^ Kowluru A (January 2008). "Protein prenylation in glucose-induced insulin secretion from the pancreatic islet beta cell: a perspective". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 12 (1): 164–73. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00168.x. PMC 3823478. PMID 18053094.

- ^ a b Liao JK, Laufs U (2005). "Pleiotropic Effects of Statins". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 45: 89–118. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095748. PMC 2694580. PMID 15822172.

- ^ Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, et al. (April 2006). "Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial". JAMA. 295 (13): 1556–65. doi:10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002. PMID 16533939.

- ^ Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJ, et al. (November 2008). "Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (21): 2195–207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. PMID 18997196.

- ^ Kones R (December 2010). "Rosuvastatin, inflammation, C-reactive protein, JUPITER, and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease – a perspective". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 4: 383–413. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S10812. PMC 3023269. PMID 21267417.

- ^ Ferdinand KC (February 2011). "Are cardiovascular benefits in statin lipid effects dependent on baseline lipid levels?". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 13 (1): 64–72. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0149-9. PMID 21104458. S2CID 32142669.

- ^ Devaraj S, Siegel D, Jialal I (February 2011). "Statin therapy in metabolic syndrome and hypertension post-JUPITER: what is the value of CRP?". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 13 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0143-2. PMC 3018293. PMID 21046291.

- ^ Ridker, Paul M.; Glynn, Robert J. (November 2010). "The JUPITER Trial: Responding to the Critics". The American Journal of Cardiology. 106 (9): 1351–1356. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.025. PMID 21029837.

- ^ Vögeli B, Shima S, Erb TJ, Wagner T (2019). "Crystal structure of archaeal HMG-CoA reductase: insights into structural changes of the C-terminal helix of the class-I enzyme". FEBS Lett. 593 (5): 543–553. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.13331. PMID 30702149. S2CID 73412833.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Gottlieb K, Wacher V, Sliman J, Pimentel M (2016). "Review article: inhibition of methanogenic archaea by statins as a targeted management strategy for constipation and related disorders". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 43 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1111/apt.13469. PMC 4737270. PMID 26559904.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Lurie-Weinberger MN, Gophna U (2015). "Archaea in and on the Human Body: Health Implications and Future Directions". PLOS Pathog. 11 (6): e1004833. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004833. PMC 4466265. PMID 26066650.

- ^ Bellosta S, Paoletti R, Corsini A (June 2004). "Safety of statins: focus on clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions". Circulation. 109 (23 Suppl 1): III50–07. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000131519.15067.1f. PMID 15198967.

- ^ a b c d e f McKenney JM, Ganz P, Wiggins BS, Saseen JS (2009). "Statins". Clinical Lipidology. Elsevier. pp. 253–280. doi:10.1016/b978-141605469-6.50026-3. ISBN 978-1-4160-5469-6.

The elimination half-life of the statins varies from 1 to 3 hours for lovastatin, simvastatin, pravastatin, and fluvastatin, to 14 to 19 hours for atorvastatin and rosuvastatin (see Table 22-1). The longer the half-life of the statin, the longer the inhibition of reductase and thus a greater reduction in LDL cholesterol. However, the impact of inhibiting cholesterol synthesis persists even with statins that have a relatively short half-life. This is due to their ability to reduce blood levels of lipoproteins, which have a half-life of approximately 2 to 3 days. Because of this, all statins may be dosed once daily. The preferable time of administration is in the evening just before the peak in cholesterol synthesis.

- ^ Boberg M, Angerbauer R, Fey P, Kanhai WK, Karl W, Kern A, et al. (March 1997). "Metabolism of cerivastatin by human liver microsomes in vitro. Characterization of primary metabolic pathways and of cytochrome P450 isozymes involved". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 25 (3): 321–31. PMID 9172950.

- ^ Jacobsen W, Kirchner G, Hallensleben K, Mancinelli L, Deters M, Hackbarth I, et al. (February 1999). "Comparison of cytochrome P-450-dependent metabolism and drug interactions of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors lovastatin and pravastatin in the liver". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 27 (2): 173–79. PMID 9929499.

- ^ "Triveram" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Triveram (2)" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Riclassificazione del medicinale per uso umano "Triveram", ai sensi dell'articolo 8, comma 10, della legge 24 dicembre 1993, n. 537. (Determina n. DG/1422/2019). (19A06231)". GU Serie Generale n.238 (in Italian). 10 October 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Cholecomb" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Cholecomb (2)" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Rosumibe" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Rosumibe (2)" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Shepherd J, Hunninghake DB, Barter P, McKenney JM, Hutchinson HG (March 2003). "Guidelines for lowering lipids to reduce coronary artery disease risk: a comparison of rosuvastatin with atorvastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin for achieving lipid-lowering goals". The American Journal of Cardiology. 91 (5A): 11C–17C, discussion 17C–19C. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00004-3. PMID 12646338.

- ^ Mukhtar RY, Reid J, Reckless JP (February 2005). "Pitavastatin". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 59 (2): 239–52. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00461.x. PMID 1585420. S2CID 221814440.

- ^ Liu J, Zhang J, Shi Y, Grimsgaard S, Alraek T, Fønnebø V (November 2006). "Chinese red yeast rice (Monascus purpureus) for primary hyperlipidemia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Chinese Medicine. 1 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/1749-8546-1-4. PMC 1761143. PMID 17302963.

- ^ Fang J (31 October 2019). "Patent expires today on pharmaceutical superstar Lipitor". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Sandoz launches authorized fluvastatin generic in US". GaBI Online. 31 October 2019. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Teva Announces Final Approval of Lovastatin Tablets". Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. (Press release). 31 October 2019. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "FDA OKs Generic Version of Pravachol". WebMD. 25 April 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Generic Crestor Wins Approval, Dealing a Blow to AstraZeneca". The New York Times. 21 July 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Wilson D (6 March 2011). "Drug Firms Face Billions in Losses as Patents End". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Berenson A (23 June 2006). "Merck Loses Protection for Patent on Zocor". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Goldstein JL, Brown MS (26 March 2015). "A century of cholesterol and coronaries: from plaques to genes to statins". Cell. 161 (1): 161–172. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.036. PMC 4525717. PMID 25815993.

- ^ Steinberg D (2007). The cholesterol wars : the skeptics vs. the preponderance of evidence. Academic Press. pp. 6–9. ISBN 978-0-12-373979-7.

- ^ Endo A (2010). "A historical perspective on the discovery of statins". Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and Biological Sciences. 86 (5): 484–93. Bibcode:2010PJAB...86..484E. doi:10.2183/pjab.86.484. PMC 3108295. PMID 20467214.

- ^ Brown AG, Smale TC, King TJ, Hasenkamp R, Thompson RH (1976). "Crystal and molecular structure of compactin, a new antifungal metabolite from Penicillium brevicompactum". Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1 (11): 1165–70. doi:10.1039/P19760001165. PMID 945291.

- ^ Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group (November 1994). "Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S)". Lancet. 344 (8934): 1383–89. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90566-5. PMID 7968073. S2CID 5965882.

- ^ Lane B (8 May 2012). "National Inventors Hall of Fame Honors 2012 Inductees". Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Landers P (9 January 2006). "How One Scientist Intrigued by Molds Found First Statin". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Boseley S (8 September 2016). "Statins prevent 80,000 heart attacks and strokes a year in UK, study finds". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Husten L (24 July 2017). "Nissen Calls Statin Denialism A Deadly Internet-Driven Cult". CardioBrief. Archived from the original on 19 December 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ Hall H (2017). "Statin Denialism". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 41, no. 3. pp. 40–43. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ "First-Time Generics – December 2001". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "First-Time Generics – April 2006". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "First-Time Generics – June 2006". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ DeNoon DJ (29 November 2011). "FAQ: Generic Lipitor". WebMD. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "First-Time Generic Drug Approvals – November 2011". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "First-Time Generic Drug Approvals – April 2012". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "ANDA (Generic) Drug Approvals in 2016". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 November 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "FDA approves first generic Crestor". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 29 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "CDER 2017 First Generic Drug Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 November 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Wolozin B, Wang SW, Li NC, Lee A, Lee TA, Kazis LE (July 2007). "Simvastatin is associated with a reduced incidence of dementia and Parkinson's disease". BMC Medicine. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-5-20. PMC 1955446. PMID 17640385.

- ^ Khurana V, Bejjanki HR, Caldito G, Owens MW (May 2007). "Statins reduce the risk of lung cancer in humans: a large case-control study of US veterans". Chest. 131 (5): 1282–88. doi:10.1378/chest.06-0931. PMID 17494779.

- ^ Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE, Grady LM (June 2006). "Statin use and incident nuclear cataract". JAMA. 295 (23): 2752–58. doi:10.1001/jama.295.23.2752. PMID 16788130.

- ^ Golomb BA, Dimsdale JE, White HL, Ritchie JB, Criqui MH (April 2008). "Reduction in blood pressure with statins: results from the UCSD Statin Study, a randomized trial". Archives of Internal Medicine. 168 (7): 721–27. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.7.721. PMC 4285458. PMID 18413554.

- ^ Drapala A, Sikora M, Ufnal M (September 2014). "Statins, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and hypertension – a tale of another beneficial effect of statins". Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 15 (3): 250–58. doi:10.1177/1470320314531058. PMID 25037529.

- ^ Mondul AM, Han M, Humphreys EB, Meinhold CL, Walsh PC, Platz EA (April 2011). "Association of statin use with pathological tumor characteristics and prostate cancer recurrence after surgery". The Journal of Urology. 185 (4): 1268–73. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.089. PMC 3584560. PMID 21334020.

- ^ Liu, Binliang; Yi, Zongbi; Guan, Xiuwen; Zeng, Yi-Xin; Ma, Fei (July 2017). "The relationship between statins and breast cancer prognosis varies by statin type and exposure time: a meta-analysis". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 164 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s10549-017-4246-0. PMID 28432513. S2CID 3900946.

- ^ Batais MA, Khan AR, Bin Abdulhak AA (August 2017). "The Use of Statins and Risk of Community-Acquired Pneumonia". Current Infectious Disease Reports. 19 (8): 26. doi:10.1007/s11908-017-0581-x. PMID 28639080. S2CID 20522253.

- ^ Wang, Jin; Xiao, Yousheng; Luo, Man; Luo, Hongye (7 December 2011). "Statins for multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008386. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008386.pub3. PMC 7175839. PMID 22161428.

외부 링크

- "Statins". National Health Service. UK. 3 October 2018.

- Brody JE (16 April 2018). "Weighing the Pros and Cons of Statins". The New York Times.

- "FDA requests removal of strongest warning against using cholesterol-lowering statins during pregnancy; still advises most pregnant patients should stop taking statins". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 30 August 2021.