운동

Exercise

운동은 신체적인 건강과 웰빙을 증진시키거나 유지하는 모든 신체 활동이다.[1]

그것은 성장을 돕고 체력을 향상시키기 위해, 노화를 방지하고, 근육과 심혈관계의 발달, 운동 기술, 체중감량 또는 유지, 건강증진,[2] 또는 단순히 즐거움을 위해 수행된다.많은 개인들이 집단으로 모이고, 교제하며, 정신 건강뿐만 아니라 복지를 증진시킬 수 있는 야외에서 운동을 선택한다.[3][4]

건강상 이익의 관점에서 권장 운동량은 목표, 운동 유형, 연령에 따라 달라진다.적은 양의 운동도 하지 않는 것보다 더 건강하다.[5]

분류

신체 운동은 일반적으로 인체에 미치는 전반적인 영향에 따라 세 가지 유형으로 분류된다.[6]

- 유산소 운동은 큰 근육 그룹을 사용하고 몸이 쉬는 동안보다 더 많은 산소를 사용하도록 하는 모든 신체 활동이다.[6]유산소 운동의 목표는 심혈관 지구력을 높이는 것이다.[7]유산소 운동의 예로는 달리기, 사이클링, 수영, 활발한 걷기, 줄넘기, 조정, 하이킹, 춤추기, 테니스 치기, 지속적인 훈련, 장거리 달리기 등이 있다.[6]

- 근력과 저항력 훈련을 포함하는 혐기성 운동은 근육량을 단단하고 강화하며 증가시킬 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 골밀도, 균형, 조정력을 향상시킬 수 있다.[6]근력 운동의 예로는 팔굽혀펴기, 당기기, 폐, 스쿼트, 벤치 프레스 등이 있다.혐기성 운동은 또한 단기간 근력을 증가시키는 웨이트 트레이닝, 기능 트레이닝, 편심 트레이닝, 인터벌 트레이닝, 스프린트, 고강도 인터벌 트레이닝을 포함한다.[6][8]

- 유연성 운동은 근육을 늘이거나 늘인다.[6]스트레칭과 같은 활동들은 관절의 유연성을 향상시키고 근육을 이완시키는 것을 돕는다.[6]부상 가능성을 줄일 수 있는 동작 범위를 개선하는 게 목표다.[6][9]

신체 운동에는 정확성, 민첩성, 힘, 속도에 초점을 맞춘 훈련도 포함될 수 있다.[10]

운동의 종류는 또한 동적 또는 정적인 것으로 분류될 수 있다.꾸준한 달리기와 같은 '역동적' 운동은 혈류량이 향상되어 운동 중 이완성 혈압이 낮아지는 경향이 있다.반대로 정적 운동(체중 리프팅 등)은 운동 수행 중에 일시적으로나마 수축기압이 크게 상승할 수 있다.[11]

건강 효과

신체운동은 체력유지에 중요하며 건강한 체중유지, 소화기계통 조절, 건강한 골밀도, 근력, 관절운동력 구축 및 유지, 생리적 웰빙 촉진, 수술위험 감소, 면역체계 강화에 기여할 수 있다.일부 연구는 운동이 기대 수명과 전반적인 삶의 질을 증가시킬 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.[12]보통에서 높은 수준의 신체 운동에 참여하는 사람들은 신체적으로 활발하지 않은 개인에 비해 사망률이 낮다.[13]적당한 수준의 운동은 염증 잠재력을 감소시킴으로써 노화를 예방하는 것과 상관되어 왔다.[14]운동으로 얻는 이익의 대부분은 일주일에 약 3500개의 대사 등가물(MET) 분으로 달성되며, 더 높은 수준의 활동에서 수익이 감소한다.[15]예를 들어, 계단을 10분, 진공 청소 15분, 정원 가꾸기 20분, 달리기 20분, 그리고 매일 25분씩 교통을 위해 걷거나 자전거를 타는 것은 일주일에 약 3000 MET분을 함께 달성할 수 있다.[15]신체활동 부족은 전 세계적으로 관상동맥 심장질환으로 인한 질병 부담의 약 6%, 제2형 당뇨병의 7%, 유방암의 10%, 대장암의 10%를 유발한다.[16]전반적으로, 신체적인 비활동은 전세계적으로 9%의 조기 사망률을 유발한다.[16]

| 적응 유형 | 지구력 훈련 효과 | 힘 훈련 효과 | 원천 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 골격근 형태학 및 운동성능적응용 | |||

| 근육비대증 | ↔ | ↑ ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 근력 및 힘 | ↔ ↓ | ↑ ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 근육섬유사이즈 | ↔ ↑ | ↑ ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 묘피릴라 단백질 합성 | ↔ ↑ | ↑ ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 신경근 적응증 | ↔ ↑ | ↑ ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 혐기성 용량 | ↑ | ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 젖산 내성 | ↑ ↑ | ↔ ↑ | [17] |

| 내구성 능력 | ↑ ↑ ↑ | ↔ ↑ | [17] |

| 모세관 성장(혈관신생) | ↑ ↑ | ↔ | [17] |

| 미토콘드리아 생물 발생 | ↑ ↑ | ↔ ↑ | [17] |

| 미토콘드리아 밀도 및 산화 기능 | ↑ ↑ ↑ | ↔ ↑ | [17] |

| 전신 및 대사 적응 | |||

| 골밀도 | ↑ ↑ | ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 염증 표식기 | ↓ ↓ | ↓ | [17] |

| 유연성 | ↑ | ↑ | [17] |

| 자세 | ↔ | ↑ | [17] |

| 일상생활에서의 활동 능력 | ↔ ↑ | ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 기초대사율 | ↑ | ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 체성분 | |||

| 체지방 비율 | ↓ ↓ | ↓ | [17] |

| 희박체질량 | ↔ | ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 포도당 대사 | |||

| 휴면 인슐린 수치 | ↓ | ↓ | [17] |

| 인슐린 민감도 | ↑ ↑ | ↑ ↑ | [17] |

| 포도당 도전에 대한 인슐린 반응 | ↓ ↓ | ↓ ↓ | [17] |

| 심혈관계 적응증 | |||

| 휴식 심박수 | ↓ ↓ | ↔ | [17] |

| 스트로크 볼륨(휴식 및 최대값) | ↑ ↑ | ↔ | [17] |

| 수축기 혈압(휴식) | ↔ ↓ | ↔ | [17] |

| 수축기 혈압(휴식) | ↔ ↓ | ↔ ↓ | [17] |

| 심혈관 위험 프로필 | ↓ ↓ ↓ | ↓ | [17] |

테이블 범례

| |||

피트니스

대부분의 사람들은 신체 활동 수준을 높임으로써 건강을 증진시킬 수 있다.[18]저항력 훈련으로 인한 근육의 크기 증가는 주로 식이요법과 테스토스테론에 의해 결정된다.[19]훈련으로 인한 개선의 이러한 유전적 변화는 엘리트 운동선수들과 더 많은 사람들 사이의 주요한 생리학적 차이들 중 하나이다.[20][21]중년기에 운동을 하면 나중에 신체 능력이 좋아질 수 있다는 증거가 있다.[22]

초기 운동 기술과 발달은 또한 말년의 신체 활동과 성과와도 관련이 있다.일찍부터 운동신경에 능숙한 아이들은 신체적으로 활동적인 경향이 강하기 때문에 운동을 잘 하고 체력수준을 향상시키는 경향이 있다.초기 운동 능력은 어린 시절의 신체 활동과 체력 수준과 긍정적인 상관관계가 있는 반면 운동 능력의 숙련도가 낮으면 좀 더 좌식적인 생활양식이 된다.[23]

수행되는 신체 활동의 종류와 강도는 개인의 건강 수준에 영향을 미칠 수 있다.고강도 인터벌 트레이닝이 낮은 강도 지구력 트레이닝보다 사람의 VO2 최대치를 약간 더 향상시킬 수 있다는 약한 증거가 있다.[24]

심혈관계계통

운동이 심혈관계 시스템에 미치는 이로운 영향은 잘 기록되어 있다.육체적 비활동과 심혈관 질환 사이에는 직접적인 상관관계가 있으며, 육체적 비활동은 관상동맥 질환의 발달을 위한 독립적인 위험인자가 된다.운동량이 적으면 심혈관 질환 사망률이 높아진다.[25][26]

신체 운동에 참여하는 어린이들은 체지방의 손실이 더 크고 심혈관 건강도 증가한다.[27]연구에 따르면 청소년기의 학업 스트레스는 말년에 심혈관 질환의 위험을 증가시키지만, 규칙적인 신체 운동으로 이러한 위험은 크게 감소할 수 있다.[28]주당 약 700–2000 kcal의 에너지 지출에서 수행되는 운동량과 중년 및 노인 남성의 모든 원인 사망률 및 심혈관 질환 사망률 사이에는 용량-반응 관계가 있다.사망률 감소의 가장 큰 잠재력은 적당히 활동적이 되는 좌식민들에게서 나타난다.심장질환이 여성 사망의 주요 원인인 만큼, 노령화 여성의 정기적인 운동은 심혈관 질환의 건강성을 높인다는 연구결과가 나왔다.심혈관 질환 사망률에 대한 신체 활동의 가장 유익한 영향은 중강도의 활동(연령에 따라 최대 산소 흡수량의 40~60%)을 통해 얻을 수 있다.규칙적인 운동을 포함하도록 심근경색 후 행동을 수정하는 사람은 생존율이 향상되었다.앉아서 지내는 사람들은 모든 원인과 심혈관 질환 사망에 대한 가장 높은 위험을 가지고 있다.[29]미국 심장 협회에 따르면, 운동은 심장마비와 뇌졸중을 포함한 심혈관 질환의 위험을 감소시킨다.[26]

면역계

비록 신체 운동과 면역 체계에 대한 수백 개의 연구가 있었지만, 질병과의 연관성에 대한 직접적인 증거는 거의 없다.[30]역학 증거는 적당한 운동이 인간의 면역체계에 유익한 영향을 미친다는 것을 암시한다; 그것은 J곡선으로 모델링된 효과다.적당한 운동은 상부 호흡기 감염(URTI) 발생률이 29% 감소하는 것과 관련이 있지만 마라톤 참가자들의 연구 결과, 그들의 장기간의 고강도 운동이 감염 발생 위험 증가와 관련이 있는 것으로 나타났다.[30]그러나 또 다른 연구는 그 효과를 발견하지 못했다.장기간에 걸친 고강도 운동의 급성 세션으로 인해 면역세포 기능이 손상되고, 일부 연구에서는 운동선수들이 감염될 위험이 더 높다는 것을 밝혀냈다.마라톤 훈련 등 오랜 시간 동안 받는 극심한 스트레스는 림프구 농도를 낮춰 면역체계를 억제할 수 있다는 연구결과가 나왔다.[31]운동선수와 비운동선수들의 면역 체계는 일반적으로 비슷하다.운동선수들은 약간 높은 자연적 킬러 세포수와 세포질 작용이 있을 수 있지만, 이것들은 임상적으로 유의미하지는 않을 것 같다.[30]

비타민 C 보충제는 마라톤 선수들에게서 상부 호흡기 감염의 낮은 발병률과 관련이 있다.[30]

만성질환과 관련이 있는 C-반응 단백질과 같은 염증의 바이오마커는 좌식 개인에 비해 활성 개인에서 감소하며 운동의 긍정적인 효과는 항염증 효과 때문일 수 있다.심장병을 앓고 있는 개인에서 운동 개입은 중요한 심혈관 위험 표시인 피브리노겐과 C-반응 단백질의 혈중 수치를 낮춘다.[32]급성 운동으로 인한 면역 체계의 우울증은 이 항염증 효과의 메커니즘 중 하나일 수 있다.[30]

암

체계적인 리뷰는 신체활동과 암 생존율의 관계를 조사한 45개의 연구를 평가했다.리뷰에 따르면, "[] 신체활동이 전체 원인 감소, 유방암 특이, 대장암 특이 사망률과 관련이 있다는 27개의 관찰 연구에서 일관된 증거가 있었다.현재 다른 암의 생존자에 대한 신체 활동과 사망률 사이의 연관성에 대한 증거가 불충분하다.[33]그 증거는 운동이 불안, 자존감, 정서적 행복과 같은 요소들을 포함하여 암 생존자들의 삶의 질에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 것을 암시한다.[34]적극적인 치료를 받고 있는 암환자의 경우, 운동은 피로와 신체 기능 등 건강 관련 삶의 질에도 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다.[35]이것은 더 높은 강도의 운동으로 더 두드러질 것 같다.[35]

운동은 유방암 생존자들의 암 관련 피로 감소에 기여할 수 있다.[36]비록 그 주제에 대한 제한된 과학적 증거만 있을 뿐이지만, 암세포가 있는 사람들은 육체적인 운동을 하도록 권장된다.[37]다양한 요인들 때문에, 암 캐쉬샤를 가진 몇몇 사람들은 신체 운동을 할 수 있는 제한된 능력을 가지고 있다.[38][39]규정된 운동의 준수는 캐시샤를 가진 개인에게서 낮으며, 이 인구에서 운동의 임상실험은 종종 높은 중퇴율을 겪는다.[38][39]감독하는 고강도 저항성 훈련이 전반적인 삶의 질을 높이는 만큼 유방암 생존자들의 재활에 중요한 부분을 차지해야 한다는 주장까지 나온다.[40]

혈액학적 악성 종양이 있는 성인의 불안과 심각한 부작용에 대한 유산소 운동 효과에 대한 낮은 품질의 증거가 있다.[41]유산소 운동은 사망률, 삶의 질 또는 신체 기능에 거의 또는 전혀 차이가 없을 수 있다.[41]이러한 운동은 약간의 우울증 감소와 피로감 감소로 이어질 수 있다.[41]

신경생물학

신체운동의 신경생물학적 영향은 수없이 많고 뇌구조, 뇌기능, 인지 등에 대한 광범위한 상호관련 영향을 수반한다.[42][43][44][45]인간에 대한 많은 연구 단체는 일관된 유산소 운동(예: 매일 30분)이 특정 인지 기능의 지속적인 개선, 뇌의 유전자 발현에서의 건강한 변화, 그리고 신경 재생성과 행동 가소성의 유익한 형태들을 유발한다는 것을 증명했다. 이러한 장기적 영향들 중 일부는 다음을 포함한다.신경 세포 성장, 신경 활동(예:c-Fos과 BDNF 신호)개선 스트레스 극복, 행동이 향상된 인식 통제 개선 선언적 공간 및 작업 기억, 그리고 뇌 구조와 경로 인식 통제와 기억과 관련된 및 기능적 구조적 개선 증가했다.[42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51]인지에 대한 운동의 영향은 아동과 대학생의 학업성취도 향상, 성인생산성 향상, 노년기의 인지기능 보존, 특정 신경장애의 예방 또는 치료, 전반적인 삶의 질 향상에 중요한 영향을 미친다.[42][52][53][54]

건강한 성인의 경우 유산소 운동은 단 한 번의 운동 후 인지에 대한 일시적인 영향과 몇 달 동안 규칙적인 운동을 한 후 인지에 대한 지속적인 영향을 유발하는 것으로 나타났다.[42][51][55]에어로빅 운동을 정기적으로 하는 사람들(예: 달리기, 조깅, 활발한 걷기, 수영, 사이클링)은 주의력조절, 억제조절, 인지유연성, 작업기억 업데이트 및 용량, 선언 밈과 같은 특정 인지기능을 측정하는 신경정신학적 기능 및 수행시험에서 더 높은 점수를 받는다.공간 메모리 및 정보 처리 속도.[42][46][48][50][51][55]인지에 대한 운동의 일시적 영향은 운동 후 최대 2시간의 기간 동안 대부분의 실행 기능(예: 주의력, 작업 기억력, 인지 유연성, 억제 제어, 문제 해결, 의사결정)과 정보 처리 속도의 개선을 포함한다.[55]

유산소 운동은 긍정적인 영향을 촉진하고 부정적인 영향을 억제하며 급성 심리적 스트레스에 대한 생물학적 반응을 감소시킴으로써 기분과 감정 상태에 대한 장단기적 영향을 유도한다.[55]단기적으로 유산소 운동은 항우울제와 행복감을 동시에 주는 효과가 있는 반면 꾸준한 운동은 기분과 자존감을 전반적으로 향상시킨다.[56][57][58][59][60][61]

규칙적인 유산소 운동은 다양한 중추 신경계 장애와 관련된 증상을 개선하며 이러한 장애의 부속 치료로 사용될 수 있다.주요 우울장애와 주의력 결핍 과잉행동장애에 대한 운동치료 효과의 명확한 증거가 있다.[52][58][62][63][64]미국 신경학아카데미의 경도인지장애 임상실습지침은 임상의가 이 질환을 진단받은 개인에게 정기적인 운동(주 2회)을 권해야 한다는 것을 보여준다.[65]임상적 증거에 대한 검토는 운동을 특정 신경퇴행성 질환, 특히 알츠하이머병과 파킨슨병에 대한 보조요법으로 사용하는 것을 뒷받침한다.[66][67][68][69][70][71]규칙적인 운동은 신경퇴행성 장애의 발생 위험도 낮다는 것과도 관련이 있다.[69][72]많은 임상 전 증거와 새롭게 등장하는 임상 증거들이 약물 중독의 치료와 예방을 위한 부속 치료법으로서의 운동의 사용을 지지한다.[73][74][75][76][77]정기적인 운동도 뇌암에 대한 보조요법으로 제안되었다.[78]우울증

많은 의학 리뷰에 의하면 운동은 인간에게 두드러지고 지속적인 항우울제 효과를 가지고 있으며,[46][58][59][62][79][80] 이는 뇌의 강화된 신호를 통해 매개되는 것으로 여겨지고 있다.[49][62]몇몇 체계적인 리뷰는 우울증 장애 치료에서 육체적 운동의 가능성을 분석했다.우울증에 대한 2013년 코크란 협동의 신체운동 리뷰는 제한된 증거에 근거하여 통제 개입보다 효과적이며 심리학적 또는 항우울제 약물치료에 비견된다고 언급했다.[79]그들의 분석의 코크레인 리뷰가 포함된 3후속 2014년 체계적인 검토에서도 이와 비슷한 결과로 결론이 나:하나는 신체적 운동 항우울제와 겸임 치료(함께 사용된다 즉, 치료)보다 효과가;[62] 다른 두 운동 항우울제 표시했다고 전해진다.알파벳의 F일반적으로 가벼운 우울증과 정신 질환에 대한 부속 치료로서 신체 활동을 포함시킬 것을 권장하고 있다.[58][59]한 체계적인 리뷰는 요가가 산전 우울증의 증상을 완화시키는데 효과적일 수 있다는 점에 주목했다.[81]또 다른 리뷰는 임상시험의 증거가 2-4개월의 우울증 치료제로서 신체 운동의 효과를 뒷받침한다고 주장했다.[46]이러한 혜택은 노년층에서도 주목되어 왔으며, 2019년에 실시한 리뷰에서 운동이 노인의 임상적으로 진단된 우울증에 효과적인 치료법이라는 것을 밝혀냈다.[82]

2016년 7월 메타분석은 신체운동이 통제력에 비해 우울증이 있는 개인의 전반적인 삶의 질을 향상시킨다는 결론을 내렸다.[52][83]

지속적인 유산소 운동 적어도 3도취 약 neurochemicals:anandamide(한endocannabinoid)[84]β-endorphin(는 내재성 진통제)[85]과 phenethylamine 추적이 가능한 아민의 증가된 생합성을 통해 극도로 행복한 과도 상태, 구어체에서는 달리기에서"달리기 선수의 고등"또는 승무원의"노 젓는 사람의 높은"으로 알려져 유도할 수 있다. 그리고 amph에타민 아날로그).[86][87][88]

잠

2012년 검토의 예비 증거는 최대 4개월의 신체 훈련이 40세 이상의 성인의 수면 질을 높일 수 있다는 것을 보여주었다.[89]2010년 한 리뷰는 운동이 일반적으로 대부분의 사람들에게 수면 능력을 향상시켰으며 불면증에 도움이 될 수 있다고 제안했지만, 운동과 수면의 관계에 대한 상세한 결론을 도출하기에는 증거가 불충분하다.[90]2018년 체계적인 검토와 메타분석은 운동이 불면증 환자의 수면 질을 향상시킬 수 있다고 제안했다.[91]

리비도

2013년 한 연구는 운동으로 항우울제 사용과 관련된 성적 흥분 문제가 개선되었다는 것을 발견했다.[92]

효과의 메커니즘

골격근

저항력 훈련과 그에 따른 단백질이 풍부한 식사의 섭취는 근세동맥근단백합성(MPS)을 자극하고 근단백질파괴(MPB)를 억제하여 근육비대증과 근력증진을 촉진한다.[93][94]근육 단백질 합성의 저항력 훈련에 의한 자극rapamycin(mTOR)의 단백질 생합성에 휴대 리보솜에서 mTORC1의 즉각적인 목표(그p70S6 인산화 효소서 번역이 억제 단백질 4EBP1)의 인산화를 통해 이어지는 기계적 목표와 mTORC1의 이후 활성화의 인산화를 통해 발생한다.[93][95]음식 섭취에 따른 근육 단백질 파괴 억제는 주로 혈장 인슐린의 증가를 통해 일어난다.[93][96][97]마찬가지로 β-하이드록시 β-히드록시 β-메틸부티르산 섭취 후 (mTORC1 활성화를 통한) 근육 단백질 합성과 억제된 근육 단백질 분해도 발생하는 것으로 나타났다.[93][96][97][98]

에어로빅 운동은 골격근의 미토콘드리아에서 미토콘드리아 생물 발생과 산화 인산화 능력을 증가시키도록 유도하는데, 이것은 에어로빅 운동이 미하의 지구력 성능을 향상시키는 하나의 메커니즘이다.[99][93][100]이러한 영향은 세포내 AMP의 운동으로 인한 증가를 통해 발생한다.이에 따라 ATP 비율(AMP-activated prote kinase, AMP-activated protector-activator-activator-1α, 미토콘드리아 생물 발생의 마스터 조절기)인 ATC-1α가 활성화된다.[93][100][101]

• PA:인산

• mTOR: 라파마이신의 기계론적 표적

• AMP: 아데노신 단인산염

• ATP: 아데노신 3인산염

• AMPK: AMP 활성 단백질 키나아제

• PGC-1α: 과산화수소 증식기 활성 수용체 감마 활성제-1α

• S6K1: p70S6 키나제

• 4EBP1: 진핵 변환 시작 인자 4E 바인딩 단백질 1

• eIF4E: 진핵 변환 시작 인자 4E

• RPS6: 리보솜 단백질 S6

• eEF2: 진핵연장 인자 2

• RE: 저항 운동, EE: 지구력 운동

• Myo: myofibrillar, Mito: mitochondrial

• AA: 아미노산

• HMB: β-히드록시 β-메틸부티르산

• ↑은 활성화를 나타낸다.

• τ은 억제를 나타낸다.

기타 말초기관

발달된 연구는 운동의 많은 이점이 내분비 기관으로서의 골격근의 역할을 통해 매개된다는 것을 증명했다.즉, 수축근육은 미오킨이라고 알려진 여러 물질을 방출하여 새로운 조직의 성장을 촉진하고, 조직 수리를 촉진하며, 여러 가지 염증성 질환에 걸릴 위험을 감소시킨다.[115]운동은 신체적으로나 정신적으로 많은 건강상의 문제를 일으키는 코티솔의 수치를 감소시킨다.[116]식사 전 지구력 운동은 식사 후 같은 운동보다 혈당을 더 낮춰준다.[117]격렬한 운동(VO2 max의 90~95%)이 적당한 운동(VO2 max의 40~70%)보다 생리학적 심장비대증을 더 많이 유발한다는 증거가 있지만 이것이 전반적인 병적성 및/또는 사망률에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 알 수 없다.[118]에어로빅과 혐기성 운동 모두 심장의 체적(공포성 운동)이나 심근 두께(강도 훈련)를 증가시켜 심장의 기계적 효율을 높이는 작용을 한다.심실벽이 두꺼워지는 심실비대증은 운동 반응으로 발생한다면 일반적으로 유익하고 건강하다.

중추신경계

신체운동이 중추신경계에 미치는 영향은 부분적으로 BDNF, IGF-1, VEGF 등 근육에 의해 혈류로 방출되는 특정 신경퇴행성인자호르몬에 의해 매개된다.[119][120][121][122][123][124]

공중보건대책

지역 사회 전체와 학교 캠페인은 종종 인구의 신체 활동 수준을 높이기 위한 시도로 사용된다.이러한 유형의 프로그램의 효과를 결정하기 위한 연구는 결과가 다양하기 때문에 신중하게 해석될 필요가 있다.[18]걸음걸이, 균형, 조정 및 기능적 작업을 포함하는 것과 같은 노인을 위한 특정 유형의 운동 프로그램이 균형을 개선할 수 있다는 증거가 있다.[125]진보적 저항훈련에 이어 노년층도 신체기능을 향상시켜 대응한다.[126]신체 활동을 촉진하는 간단한 개입은 비용 효율적일 수 있지만, 이 증거는 약하고 연구 사이에 차이가 있다.[127]

환경적 접근법은 유망한 것으로 보인다: 지역사회 캠페인과 함께 계단의 사용을 장려하는 표지판이 운동 수준을 높일 수 있다.[128]예를 들어 콜롬비아 보고타 시는 일요일과 공휴일에 113km(70mi)의 도로를 차단해 시민들이 쉽게 운동을 할 수 있도록 하고 있다.이러한 보행자 구역은 만성 질환을 퇴치하고 건강한 BMI를 유지하기 위한 노력의 일환이다.[129][130]

육체적 운동은 건강관리 비용을 줄이고, 직업의 출석률을 증가시키며, 여성들이 그들의 직업에 쏟는 노력의 양을 증가시킨다고 한다.[131]야외, 특히 교통체증 근처에서 운동을 할 때 대기오염에 추가로 노출되는 것에 대한 우려가 어느 정도 있다.[132]

아이들은 운동과 관련된 부모의 행동을 흉내낼 것이다.따라서 부모들은 신체 활동을 촉진하고 아이들이 스크린 앞에서 보내는 시간을 제한할 수 있다.[133]

과체중이고 신체운동에 참여하는 아이들은 체지방의 감소와 심혈관 건강의 증가를 경험한다.미국 질병관리본부에 따르면, 어린이와 청소년들은 매일 60분 이상의 신체활동을 해야 한다.[134]학교 시스템에서 신체 운동을 실시하고 어린이들이 건강한 생활 방식을 유지하기 위해 장벽을 줄일 수 있는 환경을 확보하는 것이 필수적이다.

유럽위원회 교육문화국장(DG EAC)은 유럽인들이 지나치게 많이 신체활동을 하지 않는다는 연구결과가 나왔듯이, Horizon 2020과 Erasmus+ 프로그램 내에서 건강증진형 신체활동(HEPA) 프로젝트를[135] 위한 프로그램과 기금을 전용했다.자금조달은 EU 전역과 전 세계에서 이 분야에서 활동하는 선수들 간의 협력 증대와 EU와 그 협력국들의 HEPA 홍보, 그리고 유럽 스포츠 위크에 이용할 수 있다.DG EAC는 정기적으로 스포츠와 신체 활동에 관한 유로바로미터를 발행한다.

운동 경향

전 세계적으로 육체적으로 덜 힘든 일로 큰 변화가 있었다.[136]이는 기계화된 교통수단의 이용 증가, 가정 내 노동절약 기술의 보급 확대, 그리고 활발한 여가활동의 감소와 동반되어 왔다.[136]그러나 개인적인 생활 방식의 변화는 운동 부족을 교정할 수 있다.

2015년에 발표된 연구는 신체 운동 개입에 명상을 포함시키면 운동 집착과 자기 효능이 증가하며 심리학적으로도 생리학적으로도 긍정적인 영향을 미친다는 것을 시사한다.[137]

- 운동을 위한 스포츠 활동

스케이트보드는 심혈관 건강에[139][better source needed] 좋다.

운동으로서의 축구

사회문화적 변이

운동하는 동기가 운동 뒤에 있는 것처럼 모든 나라에서 운동하는 것은 다르게 보인다.[3]어떤 나라에서는 사람들이 주로 실내에서 운동하는 반면, 다른 나라에서는 주로 야외에서 운동한다.사람들은 개인적인 즐거움, 건강과 웰빙, 사회적 상호작용, 경쟁 또는 훈련 등을 위해 운동을 할 수 있다.이러한 차이는 잠재적으로 지리적 위치 및 사회적 경향을 포함한 다양한 이유로 인해 기인될 수 있다.

예를 들어, 콜롬비아에서는 시민들이 자국의 야외 환경을 소중히 여기고 축하한다.많은 경우, 그들은 자연과 그들의 공동체를 즐기기 위한 사교 모임으로 야외 활동을 이용한다.콜롬비아 보고타에서는, 사이클 선수, 달리기 선수, 롤러블레이더, 스케이트보드 선수, 그리고 다른 운동선수들이 운동을 하고 그들의 주변을 즐기기 위해 일요일마다 70마일에 이르는 도로가 폐쇄된다.[141]

콜롬비아와 비슷하게, 캄보디아 시민들은 밖에서 사회적으로 운동하는 경향이 있다.이 나라에서는 공중 체육관이 꽤 유명해졌다.이런 야외 체육관에는 공공시설 활용뿐만 아니라 에어로빅과 댄스 세션도 마련돼 대중에게 공개될 예정이다.[142]

스웨덴은 또한 우테겸이라고 불리는 야외 체육관을 개발하기 시작했다.이 체육관은 대중에게 무료이며 종종 아름답고 그림 같은 환경에 놓여진다.사람들은 강에서 수영하고, 보트를 사용하고, 숲을 뛰어다니며 건강을 유지하고 그들 주변의 자연세계를 즐길 것이다.이것은 스웨덴의 지리적 위치 때문에 특히 잘 작동한다.[143]

중국의 일부 지역, 특히 은퇴한 사람들 사이에서 운동하는 것은 사회적으로 근거가 있는 것처럼 보인다.아침에, 네모난 춤은 공원에서 행해진다; 이러한 모임들은 라틴 댄스, 사교 댄스, 탱고 또는 심지어 지터벅을 포함한다.공공장소에서 춤을 추는 것은 사람들이 평소에는 교류하지 않던 사람들과 교류할 수 있게 해주며, 건강과 사회적 이익 모두를 가능하게 한다.[144]

이러한 신체운동의 사회문화적 변화는 서로 다른 지리적 위치와 사회적 기후에 있는 사람들이 어떻게 운동 동기와 방법을 다양하게 가지고 있는지를 보여준다.신체 운동은 건강과 웰빙을 향상시킬 수 있을 뿐만 아니라, 공동체 간의 유대감과 자연미의 감상을 증진시킬 수 있다.[3]

영양과 회복

적절한 영양 섭취는 운동만큼 건강에 중요하다.운동을 할 때, 격렬한 운동에 따른 회복 과정으로 신체에 도움을 주기 위해서는 충분한 미세한 영양분을 공급하면서 신체에 적절한 비율이 되도록 좋은 식단을 갖추는 것이 더욱 중요해진다.[145]

신체운동 참여 후 활동적인 회복이 권장되는 것은 혈액 속 젖산염을 비활동적인 회복보다 더 빨리 제거하기 때문이다.순환에서 젖산염을 제거하면 체온이 쉽게 떨어져 면역체계에 도움이 될 수 있는데, 이는 신체 운동 후 체온이 너무 급격히 떨어지면 개인이 경미한 질병에 취약할 수 있기 때문이다.[146]

운동은 식욕에 영향을 미치지만 식욕을 증가시키는지 감소시키는지 여부는 개인마다 다르며, 운동의 강도와 지속시간에 영향을 받는다.[147]

무리한 운동

무리한 운동이나 과훈련은 격렬한 운동에서 회복하는 몸의 능력을 초과할 때 발생한다.[148]

역사

이 글은 운동을 부정적으로 본 시기와 장소에 대한 정보가 빠져 있다.(2021년 8월) |

운동의 이점은 옛날부터 알려져 있다.기원전 65년으로 거슬러 올라가서, 로마의 정치인이자 변호사인 마르쿠스 시케로는 "혼을 지탱하고 정신을 활기차게 유지하는 것은 운동이다"라고 말했다.[149]운동도 중세 초기에는 북유럽 게르만족의 생존 수단으로 역사적으로 후세에 중시되는 것으로 보였다.[150]

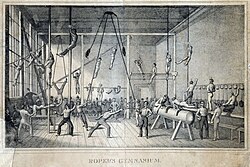

더 최근에, 운동은 19세기에 유익한 힘으로 여겨졌다.1858년 Archibald MacLaren은 옥스퍼드 대학에 체육관을 열고 Frederick Hammersley 소령과 12명의 부사관들을 위한 훈련법을 제정했다.[151]이 식이요법은 1860년 육군 체조 스탭을 결성하여 스포츠를 군생활의 중요한 부분으로 삼았던 영국 육군의 훈련에 동화되었다.[152][153][154]20세기 초에도 몇몇 대중운동 운동이 시작되었다.영국에서 가장 처음이자 가장 중요한 것은 1937년 16만6000명의 회원을 가진 메리 바고트 스택이 1930년 설립한 여성 건강미용연맹([155]Whomen's League of Health and Beauty, Women's League는 1937년 16만6000명의 회원을 가졌다.

신체 건강과 운동(혹은 운동 부족)의 연관성은 1949년에 더욱 확립되어 1953년에 제리 모리스가 이끄는 팀에 의해 보고되었다.[156][157]모리스 박사는 사회적 계급과 직업(버스 지휘자 대 버스 운전사)이 비슷한 남성들은 그들이 받은 운동 수준에 따라 현저하게 심장마비의 비율이 다르다는 점에 주목했다. 버스 운전자들은 앉아서 일하는 직업과 심장병 발병률이 더 높은 반면, 버스 지휘자는 계속해서 움직여야 했고 근친상간도 더 낮았다.심장병의 [157]일종

다른동물

동물에 대한 연구는 에너지 균형을 조절하기 위한 음식 섭취의 변화보다 신체 활동이 더 적응력이 있을 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.[158]

활동 바퀴에 접근할 수 있는 쥐는 자발적인 운동에 참여했고 성인으로 뛰는 경향을 증가시켰다.[159]인공 쥐 선택은 자발적 운동 수준에서 상당한 유전성을 보였으며,[160] "고주동자" 품종은 강화된 유산소 용량,[161] 해마 신경 유전,[162] 골격 근육 형태학을 가지고 있다.[163]

운동 훈련의 효과는 비-매머럴 종에 걸쳐 이질적인 것으로 보인다.예를 들어, 연어의 운동 훈련은 지구력이 약간 향상되는 것을 보여주었고,[164] 황꼬리 호박과 무지개 송어의 강제적인 수영 훈련은 그들의 성장률을 가속시켰고 지속적인 수영에 유리한 근육 형태학을 변화시켰다.[165][166]악어, 악어, 오리는 운동 후에 높은 유산소 능력을 보였다.[167][168][169]지구력 훈련의 효과는 도마뱀의 대부분의 연구에서 발견되지 않았지만,[167][170] 한 연구는 훈련 효과를 보고했다.[171]도마뱀에서 단거리 훈련은 최대 운동능력에 영향을 미치지 않았으며,[171] 몇 주간의 강제적인 러닝머신 운동 후에 과도한 훈련으로 인한 근육 손상이 발생했다.[170]

참고 항목:

참조

- ^ Kylasov A, Gavrov S (2011). Diversity Of Sport: non-destructive evaluation. Paris: UNESCO: Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems. pp. 462–91. ISBN 978-5-89317-227-0.

- ^ "7 great reasons why exercise matters". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Bergstrom, K; Muse, T; Tsai, M; Strangio, S (19 January 2011). "Fitness for Foreigners". Slate Magazine. Slate Magazine. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Deslandes, Andréa; Moraes, Helena; Ferreira, Camila; Veiga, Heloisa; Silveira, Heitor; Mouta, Raphael; Pompeu, Fernando A.M.S.; Coutinho, Evandro Silva Freire; Laks, Jerson (2009). "Exercise and Mental Health: Many Reasons to Move". Neuropsychobiology. 59 (4): 191–198. doi:10.1159/000223730. PMID 19521110. S2CID 14580554.

- ^ "Exercise". UK NHS Live Well. 26 April 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (June 2006). "Your Guide to Physical Activity and Your Heart" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- ^ Wilmore J.; Knuttgen H. (2003). "Aerobic Exercise and Endurance Improving Fitness for Health Benefits". The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 31 (5): 45–51. doi:10.3810/psm.2003.05.367. PMID 20086470. S2CID 2253889.

- ^ De Vos N.; Singh N.; Ross D.; Stavrinos T. (2005). "Optimal Load for Increasing Muscle Power During Explosive Resistance Training in Older Adults". The Journals of Gerontology. 60A (5): 638–47. doi:10.1093/gerona/60.5.638. PMID 15972618.

- ^ O'Connor D.; Crowe M.; Spinks W. (2005). "Effects of static stretching on leg capacity during cycling". Turin. 46 (1): 52–56.

- ^ "What Is Fitness?" (PDF). The CrossFit Journal. October 2002. p. 4. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ de Souza Nery S, Gomides RS, da Silva GV, de Moraes Forjaz CL, Mion D Jr, Tinucci T (1 March 2010). "Intra-Arterial Blood Pressure Response in Hypertensive Subjects during Low- and High-Intensity Resistance Exercise". Clinics. 65 (3): 271–77. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322010000300006. PMC 2845767. PMID 20360917.

- ^ Gremeaux, V; Gayda, M; Lepers, R; Sosner, P; Juneau, M; Nigam, A (December 2012). "Exercise and longevity". Maturitas. 73 (4): 312–17. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.09.012. PMID 23063021.

- ^ Department Of Health And Human Services, United States (1996). "Physical Activity and Health". United States Department of Health. ISBN 978-1-4289-2794-0.

- ^ Woods, Jeffrey A.; Wilund, Kenneth R.; Martin, Stephen A.; Kistler, Brandon M. (29 October 2011). "Exercise, Inflammation and Aging". Aging and Disease. 3 (1): 130–40. PMC 3320801. PMID 22500274.

- ^ a b Kyu, Hmwe H; Bachman, Victoria F; Alexander, Lily T; Mumford, John Everett; Afshin, Ashkan; Estep, Kara; Veerman, J Lennert; Delwiche, Kristen; Iannarone, Marissa L; Moyer, Madeline L; Cercy, Kelly; Vos, Theo; Murray, Christopher J L; Forouzanfar, Mohammad H (9 August 2016). "Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". BMJ. 354: i3857. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3857. PMC 4979358. PMID 27510511.

- ^ a b Lee, I-Min; Shiroma, Eric J; Lobelo, Felipe; Puska, Pekka; Blair, Steven N; Katzmarzyk, Peter T (21 July 2012). "Impact of Physical Inactivity on the World's Major Non-Communicable Diseases". Lancet. 380 (9838): 219–29. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. PMC 3645500. PMID 22818936.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Egan B, Zierath JR (February 2013). "Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation". Cell Metabolism. 17 (2): 162–84. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.012. PMID 23395166.

- ^ a b Neil-Sztramko, Sarah E.; Caldwell, Hilary; Dobbins, Maureen (23 September 2021). "School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD007651. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007651.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8459921. PMID 34555181.

- ^ Hubal MJ, Gordish-Dressman H, Thompson PD, Price TB, Hoffman EP, Angelopoulos TJ, Gordon PM, Moyna NM, Pescatello LS, Visich PS, Zoeller RF, Seip RL, Clarkson PM (June 2005). "Variability in muscle size and strength gain after unilateral resistance training". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 37 (6): 964–72. PMID 15947721.

- ^ Brutsaert TD, Parra EJ (2006). "What makes a champion? Explaining variation in human athletic performance". Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 151 (2–3): 109–23. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2005.12.013. PMID 16448865. S2CID 13711090.

- ^ Geddes, Linda (28 July 2007). "Superhuman". New Scientist. pp. 35–41.

- ^ "Being active combats risk of functional problems".

- ^ Wrotniak, B.H; Epstein, L.H; Dorn, J.M; Jones, K.E; Kondilis, V.A (2006). "The Relationship Between Motor Proficiency and Physical Activity in Children". Pediatrics. 118 (6): e1758-65. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0742. PMID 17142498. S2CID 41653923.

- ^ Milanović, Zoran; Sporiš, Goran; Weston, Matthew (2015). "Effectiveness of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) and Continuous Endurance Training for VO2max Improvements: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials" (PDF). Sports Medicine. 45 (10): 1469–81. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0365-0. PMID 26243014. S2CID 41092016.

- ^ Warburton, Darren E. R.; Nicol, Crystal Whitney; Bredin, Shannon S. D. (14 March 2006). "Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence". CMAJ. 174 (6): 801–809. doi:10.1503/cmaj.051351. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 1402378. PMID 16534088.

- ^ a b "American Heart Association Recommendations for Physical Activity in Adults". American Heart Association. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Julie Lumeng (2006). "Small-group physical education classes result in important health benefits". The Journal of Pediatrics. 148 (3): 418–19. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.02.025. PMID 17243298.

- ^ Ahaneku, Joseph E.; Nwosu, Cosmas M.; Ahaneku, Gladys I. (2000). "Academic Stress and Cardiovascular Health". Academic Medicine. 75 (6): 567–68. doi:10.1097/00001888-200006000-00002. PMID 10875499.

- ^ Fletcher, G.F; Balady, G; Blair, S.N.; Blumenthal, J; Caspersen, C; Chaitman, B; Epstein, S; Froelicher, E.S.S; Froelicher, V.F.; Pina, I.L; Pollock, M.L (1996). "Statement on Exercise: Benefits and Recommendations for Physical Activity Programs for All Americans: A Statement for Health Professionals by the Committee on Exercise and Cardiac Rehabilitation of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association". Circulation. 94 (4): 857–62. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.94.4.857. PMID 8772712.

- ^ a b c d e Gleeson M (August 2007). "Immune function in sport and exercise". J. Appl. Physiol. 103 (2): 693–99. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00008.2007. PMID 17303714. S2CID 18112931.

- ^ Goodman, C. C.; Kapasi, Z.F. (2002). "The effect of exercise on the immune system". Rehabilitation Oncology. 20: 13–15. doi:10.1097/01893697-200220010-00013. S2CID 91074779.

- ^ Swardfager W (2012). "Exercise intervention and inflammatory markers in coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis". Am. Heart J. 163 (4): 666–76. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.12.017. PMID 22520533.

- ^ Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM (2012). "Physical Activity, Biomarkers, and Disease Outcomes in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review". JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 104 (11): 815–40. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs207. PMC 3465697. PMID 22570317.

- ^ Mishra, Shiraz I; Scherer, Roberta W; Geigle, Paula M; Berlanstein, Debra R; Topaloglu, Ozlem; Gotay, Carolyn C; Snyder, Claire (15 August 2012). "Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD007566. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007566.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7387117. PMID 22895961.

- ^ a b Mishra, Shiraz I; Scherer, Roberta W; Snyder, Claire; Geigle, Paula M; Berlanstein, Debra R; Topaloglu, Ozlem (15 August 2012). "Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for people with cancer during active treatment". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD008465. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008465.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7389071. PMID 22895974.

- ^ Meneses-Echávez, José Francisco; González-Jiménez, Emilio; Ramírez-Vélez, Robinson (21 February 2015). "Effects of supervised exercise on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Cancer. 15 (1): 77. doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1069-4. ISSN 1471-2407. PMC 4364505. PMID 25885168.

- ^ Grande AJ, Silva V, Maddocks M (September 2015). "Exercise for cancer cachexia in adults: Executive summary of a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review". Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 6 (3): 208–11. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12055. PMC 4575551. PMID 26401466.

- ^ a b Sadeghi M, Keshavarz-Fathi M, Baracos V, Arends J, Mahmoudi M, Rezaei N (July 2018). "Cancer cachexia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment". Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 127: 91–104. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.05.006. PMID 29891116. S2CID 48363786.

- ^ a b Solheim TS, Laird BJ, Balstad TR, Bye A, Stene G, Baracos V, Strasser F, Griffiths G, Maddocks M, Fallon M, Kaasa S, Fearon K (February 2018). "Cancer cachexia: rationale for the MENAC (Multimodal-Exercise, Nutrition and Anti-inflammatory medication for Cachexia) trial". BMJ Support Palliat Care. 8 (3): 258–265. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001440. PMID 29440149. S2CID 3318359.

- ^ Marques, Vitor (2021), "Resistance Training and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors", 2nd International E-Conference on Cancer Science and Therapy, United Research Forum, doi:10.51219/urforum.2021.vitor-marques, ISBN 978-1-8382915-4-9, S2CID 239519099, retrieved 20 November 2021

- ^ a b c Knips, Linus; Bergenthal, Nils; Streckmann, Fiona; Monsef, Ina; Elter, Thomas; Skoetz, Nicole (31 January 2019). Cochrane Hematological Malignancies Group (ed.). "Aerobic physical exercise for adult patients with hematological malignancies". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (1): CD009075. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009075.pub3. PMC 6354325. PMID 30702150.

- ^ a b c d e Erickson KI, Hillman CH, Kramer AF (August 2015). "Physical activity, brain, and cognition". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 4: 27–32. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.01.005. S2CID 54301951.

- ^ a b Paillard T, Rolland Y, de Souto Barreto P (July 2015). "Protective Effects of Physical Exercise in Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease: A Narrative Review". J Clin Neurol. 11 (3): 212–219. doi:10.3988/jcn.2015.11.3.212. PMC 4507374. PMID 26174783.

Aerobic physical exercise (PE) activates the release of neurotrophic factors and promotes angiogenesis, thereby facilitating neurogenesis and synaptogenesis, which in turn improve memory and cognitive functions. ... Exercise limits the alteration in dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and contributes to optimal functioning of the basal ganglia involved in motor commands and control by adaptive mechanisms involving dopamine and glutamate neurotransmission.

- ^ a b McKee AC, Daneshvar DH, Alvarez VE, Stein TD (January 2014). "The neuropathology of sport". Acta Neuropathol. 127 (1): 29–51. doi:10.1007/s00401-013-1230-6. PMC 4255282. PMID 24366527.

The benefits of regular exercise, physical fitness and sports participation on cardiovascular and brain health are undeniable ... Exercise also enhances psychological health, reduces age-related loss of brain volume, improves cognition, reduces the risk of developing dementia, and impedes neurodegeneration.

- ^ a b Denham J, Marques FZ, O'Brien BJ, Charchar FJ (February 2014). "Exercise: putting action into our epigenome". Sports Med. 44 (2): 189–209. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0114-1. PMID 24163284. S2CID 30210091.

Aerobic physical exercise produces numerous health benefits in the brain. Regular engagement in physical exercise enhances cognitive functioning, increases brain neurotrophic proteins, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and prevents cognitive diseases [76–78]. Recent findings highlight a role for aerobic exercise in modulating chromatin remodelers [21, 79–82]. ... These results were the first to demonstrate that acute and relatively short aerobic exercise modulates epigenetic modifications. The transient epigenetic modifications observed due to chronic running training have also been associated with improved learning and stress-coping strategies, epigenetic changes and increased c-Fos-positive neurons ... Nonetheless, these studies demonstrate the existence of epigenetic changes after acute and chronic exercise and show they are associated with improved cognitive function and elevated markers of neurotrophic factors and neuronal activity (BDNF and c-Fos). ... The aerobic exercise training-induced changes to miRNA profile in the brain seem to be intensity-dependent [164]. These few studies provide a basis for further exploration into potential miRNAs involved in brain and neuronal development and recovery via aerobic exercise.

- ^ a b c d Gomez-Pinilla F, Hillman C (January 2013). "The influence of exercise on cognitive abilities". Comprehensive Physiology. Compr. Physiol. Vol. 3. pp. 403–428. doi:10.1002/cphy.c110063. ISBN 9780470650714. PMC 3951958. PMID 23720292.

- ^ Erickson KI, Leckie RL, Weinstein AM (September 2014). "Physical activity, fitness, and gray matter volume". Neurobiol. Aging. 35 Suppl 2: S20–528. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.034. PMC 4094356. PMID 24952993.

- ^ a b Guiney H, Machado L (February 2013). "Benefits of regular aerobic exercise for executive functioning in healthy populations". Psychon Bull Rev. 20 (1): 73–86. doi:10.3758/s13423-012-0345-4. PMID 23229442. S2CID 24190840.

- ^ a b Erickson KI, Miller DL, Roecklein KA (2012). "The aging hippocampus: interactions between exercise, depression, and BDNF". Neuroscientist. 18 (1): 82–97. doi:10.1177/1073858410397054. PMC 3575139. PMID 21531985.

- ^ a b Buckley J, Cohen JD, Kramer AF, McAuley E, Mullen SP (2014). "Cognitive control in the self-regulation of physical activity and sedentary behavior". Front Hum Neurosci. 8: 747. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00747. PMC 4179677. PMID 25324754.

- ^ a b c Cox EP, O'Dwyer N, Cook R, Vetter M, Cheng HL, Rooney K, O'Connor H (August 2016). "Relationship between physical activity and cognitive function in apparently healthy young to middle-aged adults: A systematic review". J. Sci. Med. Sport. 19 (8): 616–628. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2015.09.003. PMID 26552574.

A range of validated platforms assessed CF across three domains: executive function (12 studies), memory (four studies) and processing speed (seven studies). ... In studies of executive function, five found a significant ES in favour of higher PA, ranging from small to large. Although three of four studies in the memory domain reported a significant benefit of higher PA, there was only one significant ES, which favoured low PA. Only one study examining processing speed had a significant ES, favouring higher PA.

CONCLUSIONS: A limited body of evidence supports a positive effect of PA on CF in young to middle-aged adults. Further research into this relationship at this age stage is warranted. ...

Significant positive effects of PA on cognitive function were found in 12 of the 14 included manuscripts, the relationship being most consistent for executive function, intermediate for memory and weak for processing speed. - ^ a b c Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Richards J, Ward PB, Stubbs B (July 2016). "Exercise improves physical and psychological quality of life in people with depression: A meta-analysis including the evaluation of control group response". Psychiatry Res. 241: 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.054. PMID 27155287. S2CID 4787287.

Exercise has established efficacy as an antidepressant in people with depression. ... Exercise significantly improved physical and psychological domains and overall QoL. ... The lack of improvement among control groups reinforces the role of exercise as a treatment for depression with benefits to QoL.

- ^ Pratali L, Mastorci F, Vitiello N, Sironi A, Gastaldelli A, Gemignani A (November 2014). "Motor Activity in Aging: An Integrated Approach for Better Quality of Life". International Scholarly Research Notices. 2014: 257248. doi:10.1155/2014/257248. PMC 4897547. PMID 27351018.

Research investigating the effects of exercise on older adults has primarily focused on brain structural and functional changes with relation to cognitive improvement. In particular, several cross-sectional and intervention studies have shown a positive association between physical activity and cognition in older persons [86] and an inverse correlation with cognitive decline and dementia [87]. Older adults enrolled in a 6-month aerobic fitness intervention increased brain volume in both gray matter (anterior cingulate cortex, supplementary motor area, posterior middle frontal gyrus, and left superior temporal lobe) and white matter (anterior third of corpus callosum) [88]. In addition, Colcombe and colleagues showed that older adults with higher cardiovascular fitness levels are better at activating attentional resources, including decreased activation of the anterior cingulated cortex. One of the possible mechanisms by which physical activity may benefit cognition is that physical activity maintains brain plasticity, increases brain volume, stimulates neurogenesis and synaptogenesis, and increases neurotrophic factors in different areas of the brain, possibly providing reserve against later cognitive decline and dementia [89, 90].

- ^ Mandolesi, Laura; Polverino, Arianna; Montuori, Simone; Foti, Francesca; Ferraioli, Giampaolo; Sorrentino, Pierpaolo; Sorrentino, Giuseppe (27 April 2018). "Effects of Physical Exercise on Cognitive Functioning and Wellbeing: Biological and Psychological Benefits". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 509. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00509. PMC 5934999. PMID 29755380.

- ^ a b c d Basso JC, Suzuki WA (March 2017). "The Effects of Acute Exercise on Mood, Cognition, Neurophysiology, and Neurochemical Pathways: A Review". Brain Plasticity. 2 (2): 127–152. doi:10.3233/BPL-160040. PMC 5928534. PMID 29765853. Lay summary – Can A Single Exercise Session Benefit Your Brain? (12 June 2017).

A large collection of research in humans has shown that a single bout of exercise alters behavior at the level of affective state and cognitive functioning in several key ways. In terms of affective state, acute exercise decreases negative affect, increases positive affect, and decreases the psychological and physiological response to acute stress [28]. These effects have been reported to persist for up to 24 hours after exercise cessation [28, 29, 53]. In terms of cognitive functioning, acute exercise primarily enhances executive functions dependent on the prefrontal cortex including attention, working memory, problem solving, cognitive flexibility, verbal fluency, decision making, and inhibitory control [9]. These positive changes have been demonstrated to occur with very low to very high exercise intensities [9], with effects lasting for up to two hours after the end of the exercise bout (Fig. 1A) [27]. Moreover, many of these neuropsychological assessments measure several aspects of behavior including both accuracy of performance and speed of processing. McMorris and Hale performed a meta-analysis examining the effects of acute exercise on both accuracy and speed of processing, revealing that speed significantly improved post-exercise, with minimal or no effect on accuracy [17]. These authors concluded that increasing task difficulty or complexity may help to augment the effect of acute exercise on accuracy. ... However, in a comprehensive meta-analysis, Chang and colleagues found that exercise intensities ranging from very light (<50% MHR) to very hard (>93% MHR) have all been reported to improve cognitive functioning [9].

{{cite journal}}:Cite는 사용되지 않는 매개 변수를 사용한다.lay-source=(도움말) - ^ Cunha GS, Ribeiro JL, Oliveira AR (June 2008). "[Levels of beta-endorphin in response to exercise and overtraining]". Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol (in Portuguese). 52 (4): 589–598. doi:10.1590/S0004-27302008000400004. PMID 18604371.

Interestingly, some symptoms of OT are related to beta-endorphin (beta-end(1-31)) effects. Some of its effects, such as analgesia, increasing lactate tolerance, and exercise-induced euphoria, are important for training.

- ^ Boecker H, Sprenger T, Spilker ME, Henriksen G, Koppenhoefer M, Wagner KJ, Valet M, Berthele A, Tolle TR (2008). "The runner's high: opioidergic mechanisms in the human brain". Cereb. Cortex. 18 (11): 2523–2531. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn013. PMID 18296435.

The runner's high describes a euphoric state resulting from long-distance running.

- ^ a b c d Josefsson T, Lindwall M, Archer T (2014). "Physical exercise intervention in depressive disorders: meta-analysis and systematic review". Scand J Med Sci Sports. 24 (2): 259–272. doi:10.1111/sms.12050. PMID 23362828. S2CID 29351791.

- ^ a b c Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Sherrington C, Curtis J, Ward PB (2014). "Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Clin Psychiatry. 75 (9): 964–974. doi:10.4088/JCP.13r08765. PMID 24813261.

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that physical activity reduced depressive symptoms among people with a psychiatric illness. The current meta-analysis differs from previous studies, as it included participants with depressive symptoms with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses (except dysthymia and eating disorders). ... This review provides strong evidence for the antidepressant effect of physical activity; however, the optimal exercise modality, volume, and intensity remain to be determined. ...

Conclusion

Few interventions exist whereby patients can hope to achieve improvements in both psychiatric symptoms and physical health simultaneously without significant risks of adverse effects. Physical activity offers substantial promise for improving outcomes for people living with mental illness, and the inclusion of physical activity and exercise programs within treatment facilities is warranted given the results of this review. - ^ Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW (October 2014). "A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor". J Psychiatr Res. 60C: 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003. PMC 4314337. PMID 25455510.

Consistent evidence indicates that exercise improves cognition and mood, with preliminary evidence suggesting that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may mediate these effects. The aim of the current meta-analysis was to provide an estimate of the strength of the association between exercise and increased BDNF levels in humans across multiple exercise paradigms. We conducted a meta-analysis of 29 studies (N = 1111 participants) examining the effect of exercise on BDNF levels in three exercise paradigms: (1) a single session of exercise, (2) a session of exercise following a program of regular exercise, and (3) resting BDNF levels following a program of regular exercise. Moderators of this effect were also examined. Results demonstrated a moderate effect size for increases in BDNF following a single session of exercise (Hedges' g = 0.46, p < 0.001). Further, regular exercise intensified the effect of a session of exercise on BDNF levels (Hedges' g = 0.59, p = 0.02). Finally, results indicated a small effect of regular exercise on resting BDNF levels (Hedges' g = 0.27, p = 0.005). ... Effect size analysis supports the role of exercise as a strategy for enhancing BDNF activity in humans.

- ^ Lees C, Hopkins J (2013). "Effect of aerobic exercise on cognition, academic achievement, and psychosocial function in children: a systematic review of randomized control trials". Prev Chronic Dis. 10: E174. doi:10.5888/pcd10.130010. PMC 3809922. PMID 24157077.

This omission is relevant, given the evidence that aerobic-based physical activity generates structural changes in the brain, such as neurogenesis, angiogenesis, increased hippocampal volume, and connectivity (12,13). In children, a positive relationship between aerobic fitness, hippocampal volume, and memory has been found (12,13). ... Mental health outcomes included reduced depression and increased self-esteem, although no change was found in anxiety levels (18). ... This systematic review of the literature found that [aerobic physical activity (APA)] is positively associated with cognition, academic achievement, behavior, and psychosocial functioning outcomes. Importantly, Shephard also showed that curriculum time reassigned to APA still results in a measurable, albeit small, improvement in academic performance (24). ... The actual aerobic-based activity does not appear to be a major factor; interventions used many different types of APA and found similar associations. In positive association studies, intensity of the aerobic activity was moderate to vigorous. The amount of time spent in APA varied significantly between studies; however, even as little as 45 minutes per week appeared to have a benefit.

- ^ a b c d Mura G, Moro MF, Patten SB, Carta MG (2014). "Exercise as an add-on strategy for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review". CNS Spectr. 19 (6): 496–508. doi:10.1017/S1092852913000953. PMID 24589012. S2CID 32304140.

Considered overall, the studies included in the present review showed a strong effectiveness of exercise combined with antidepressants. ...

Conclusions

This is the first review to have focused on exercise as an add-on strategy in the treatment of MDD. Our findings corroborate some previous observations that were based on few studies and which were difficult to generalize.41,51,73,92,93 Given the results of the present article, it seems that exercise might be an effective strategy to enhance the antidepressant effect of medication treatments. Moreover, we hypothesize that the main role of exercise on treatment-resistant depression is in inducing neurogenesis by increasing BDNF expression, as was demonstrated by several recent studies. - ^ Den Heijer AE, Groen Y, Tucha L, Fuermaier AB, Koerts J, Lange KW, Thome J, Tucha O (July 2016). "Sweat it out? The effects of physical exercise on cognition and behavior in children and adults with ADHD: a systematic literature review". J. Neural Transm. (Vienna). 124 (Suppl 1): 3–26. doi:10.1007/s00702-016-1593-7. PMC 5281644. PMID 27400928.

- ^ Kamp CF, Sperlich B, Holmberg HC (July 2014). "Exercise reduces the symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and improves social behaviour, motor skills, strength and neuropsychological parameters". Acta Paediatr. 103 (7): 709–14. doi:10.1111/apa.12628. PMID 24612421. S2CID 45881887.

The present review summarises the impact of exercise interventions (1–10 weeks in duration with at least two sessions each week) on parameters related to ADHD in 7-to 13-year-old children. We may conclude that all different types of exercise (here yoga, active games with and without the involvement of balls, walking and athletic training) attenuate the characteristic symptoms of ADHD and improve social behaviour, motor skills, strength and neuropsychological parameters without any undesirable side effects. Available reports do not reveal which type, intensity, duration and frequency of exercise is most effective in this respect and future research focusing on this question with randomised and controlled long-term interventions is warranted.

- ^ Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, Getchius T, Ganguli M, Gloss D, Gronseth GS, Marson D, Pringsheim T, Day GS, Sager M, Stevens J, Rae-Grant A (January 2018). "Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment – Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. Special article. 90 (3): 126–135. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826. PMC 5772157. PMID 29282327. Lay summary – Exercise may improve thinking ability and memory (27 December 2017).

In patients with MCI, exercise training (6 months) is likely to improve cognitive measures and cognitive training may improve cognitive measures. ... Clinicians should recommend regular exercise (Level B). ... Recommendation

For patients diagnosed with MCI, clinicians should recommend regular exercise (twice/week) as part of an overall approach to management (Level B).{{cite journal}}:Cite는 사용되지 않는 매개 변수를 사용한다.lay-date=(도움말) - ^ Farina N, Rusted J, Tabet N (January 2014). "The effect of exercise interventions on cognitive outcome in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review". Int Psychogeriatr. 26 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1017/S1041610213001385. PMID 23962667. S2CID 24936334.

Six RCTs were identified that exclusively considered the effect of exercise in AD patients. Exercise generally had a positive effect on rate of cognitive decline in AD. A meta-analysis found that exercise interventions have a positive effect on global cognitive function, 0.75 (95% CI = 0.32–1.17). ... The most prevalent subtype of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), accounting for up to 65.0% of all dementia cases ... Cognitive decline in AD is attributable at least in part to the buildup of amyloid and tau proteins, which promote neuronal dysfunction and death (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; Karran et al., 2011). Evidence in transgenic mouse models of AD, in which the mice have artificially elevated amyloid load, suggests that exercise programs are able to improve cognitive function (Adlard et al., 2005; Nichol et al., 2007). Adlard and colleagues also determined that the improvement in cognitive performance occurred in conjunction with a reduced amyloid load. Research that includes direct indices of change in such biomarkers will help to determine the mechanisms by which exercise may act on cognition in AD.

- ^ Rao AK, Chou A, Bursley B, Smulofsky J, Jezequel J (January 2014). "Systematic review of the effects of exercise on activities of daily living in people with Alzheimer's disease". Am J Occup Ther. 68 (1): 50–56. doi:10.5014/ajot.2014.009035. PMC 5360200. PMID 24367955.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurological disorder characterized by loss in cognitive function, abnormal behavior, and decreased ability to perform basic activities of daily living [(ADLs)] ... All studies included people with AD who completed an exercise program consisting of aerobic, strength, or balance training or any combination of the three. The length of the exercise programs varied from 12 weeks to 12 months. ... Six studies involving 446 participants tested the effect of exercise on ADL performance ... exercise had a large and significant effect on ADL performance (z = 4.07, p < .0001; average effect size = 0.80). ... These positive effects were apparent with programs ranging in length from 12 wk (Santana-Sosa et al., 2008; Teri et al., 2003) and intermediate length of 16 wk (Roach et al., 2011; Vreugdenhil et al., 2012) to 6 mo (Venturelli et al., 2011) and 12 mo (Rolland et al., 2007). Furthermore, the positive effects of a 3-mo intervention lasted 24 mo (Teri et al., 2003). ... No adverse effects of exercise on ADL performance were noted. ... The study with the largest effect size implemented a walking and aerobic program of only 30 min four times a week (Venturelli et al., 2011).

- ^ Mattson MP (2014). "Interventions that improve body and brain bioenergetics for Parkinson's disease risk reduction and therapy". J Parkinsons Dis. 4 (1): 1–13. doi:10.3233/JPD-130335. PMID 24473219.

- ^ a b Grazina R, Massano J (2013). "Physical exercise and Parkinson's disease: influence on symptoms, disease course and prevention". Rev Neurosci. 24 (2): 139–152. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2012-0087. PMID 23492553. S2CID 33890283.

- ^ van der Kolk NM, King LA (September 2013). "Effects of exercise on mobility in people with Parkinson's disease". Mov. Disord. 28 (11): 1587–1596. doi:10.1002/mds.25658. PMID 24132847. S2CID 22822120.

- ^ Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, Herd CP, Clarke CE, Stowe R, Shah L, Sackley CM, Deane KH, Wheatley K, Ives N (September 2013). "Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson's disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9 (9): CD002817. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002817.pub4. PMC 7120224. PMID 24018704.

- ^ Blondell SJ, Hammersley-Mather R, Veerman JL (May 2014). "Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies". BMC Public Health. 14: 510. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-510. PMC 4064273. PMID 24885250.

Longitudinal observational studies show an association between higher levels of physical activity and a reduced risk of cognitive decline and dementia. A case can be made for a causal interpretation. Future research should use objective measures of physical activity, adjust for the full range of confounders and have adequate follow-up length. Ideally, randomised controlled trials will be conducted. ... On the whole the results do, however, lend support to the notion of a causal relationship between physical activity, cognitive decline and dementia, according to the established criteria for causal inference.

- ^ Carroll ME, Smethells JR (February 2016). "Sex Differences in Behavioral Dyscontrol: Role in Drug Addiction and Novel Treatments". Front. Psychiatry. 6: 175. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00175. PMC 4745113. PMID 26903885.

There is accelerating evidence that physical exercise is a useful treatment for preventing and reducing drug addiction ... In some individuals, exercise has its own rewarding effects, and a behavioral economic interaction may occur, such that physical and social rewards of exercise can substitute for the rewarding effects of drug abuse. ... The value of this form of treatment for drug addiction in laboratory animals and humans is that exercise, if it can substitute for the rewarding effects of drugs, could be self-maintained over an extended period of time. Work to date in [laboratory animals and humans] regarding exercise as a treatment for drug addiction supports this hypothesis. ... However, a RTC study was recently reported by Rawson et al. (226), whereby they used 8 weeks of exercise as a post-residential treatment for METH addiction, showed a significant reduction in use (confirmed by urine screens) in participants who had been using meth 18 days or less a month. ... Animal and human research on physical exercise as a treatment for stimulant addiction indicates that this is one of the most promising treatments on the horizon. [emphasis added]

- ^ Lynch WJ, Peterson AB, Sanchez V, Abel J, Smith MA (September 2013). "Exercise as a novel treatment for drug addiction: a neurobiological and stage-dependent hypothesis". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 37 (8): 1622–1644. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.011. PMC 3788047. PMID 23806439.

- ^ Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–1122. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

Similar to environmental enrichment, studies have found that exercise reduces self-administration and relapse to drugs of abuse (Cosgrove et al., 2002; Zlebnik et al., 2010). There is also some evidence that these preclinical findings translate to human populations, as exercise reduces withdrawal symptoms and relapse in abstinent smokers (Daniel et al., 2006; Prochaska et al., 2008), and one drug recovery program has seen success in participants that train for and compete in a marathon as part of the program (Butler, 2005). ... In humans, the role of dopamine signaling in incentive-sensitization processes has recently been highlighted by the observation of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs. This syndrome is characterized by a medication-induced increase in (or compulsive) engagement in non-drug rewards such as gambling, shopping, or sex (Evans et al., 2006; Aiken, 2007; Lader, 2008).

- ^ Linke SE, Ussher M (2015). "Exercise-based treatments for substance use disorders: evidence, theory, and practicality". Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 41 (1): 7–15. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.976708. PMC 4831948. PMID 25397661.

The limited research conducted suggests that exercise may be an effective adjunctive treatment for SUDs. In contrast to the scarce intervention trials to date, a relative abundance of literature on the theoretical and practical reasons supporting the investigation of this topic has been published. ... numerous theoretical and practical reasons support exercise-based treatments for SUDs, including psychological, behavioral, neurobiological, nearly universal safety profile, and overall positive health effects.

- ^ Zhou Y, Zhao M, Zhou C, Li R (July 2015). "Sex differences in drug addiction and response to exercise intervention: From human to animal studies". Front. Neuroendocrinol. 40: 24–41. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2015.07.001. PMC 4712120. PMID 26182835.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that exercise may serve as a substitute or competition for drug abuse by changing ΔFosB or cFos immunoreactivity in the reward system to protect against later or previous drug use. ... As briefly reviewed above, a large number of human and rodent studies clearly show that there are sex differences in drug addiction and exercise. The sex differences are also found in the effectiveness of exercise on drug addiction prevention and treatment, as well as underlying neurobiological mechanisms. The postulate that exercise serves as an ideal intervention for drug addiction has been widely recognized and used in human and animal rehabilitation. ... In particular, more studies on the neurobiological mechanism of exercise and its roles in preventing and treating drug addiction are needed.

- ^ Cormie P, Nowak AK, Chambers SK, Galvão DA, Newton RU (April 2015). "The potential role of exercise in neuro-oncology". Front. Oncol. 5: 85. doi:10.3389/fonc.2015.00085. PMC 4389372. PMID 25905043.

- ^ a b Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, McMurdo M, Mead GE (September 2013). "Exercise for depression". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9 (9): CD004366. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6. PMID 24026850.

Exercise is moderately more effective than a control intervention for reducing symptoms of depression, but analysis of methodologically robust trials only shows a smaller effect in favour of exercise. When compared to psychological or pharmacological therapies, exercise appears to be no more effective, though this conclusion is based on a few small trials.

- ^ Brené S, Bjørnebekk A, Aberg E, Mathé AA, Olson L, Werme M (2007). "Running is rewarding and antidepressive". Physiol. Behav. 92 (1–2): 136–140. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.015. PMC 2040025. PMID 17561174.

- ^ Gong H, Ni C, Shen X, Wu T, Jiang C (February 2015). "Yoga for prenatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Psychiatry. 15: 14. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0393-1. PMC 4323231. PMID 25652267.

- ^ Miller KJ, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Areerob P, Hennessy D, Mesagno C, Grace F (2020). "Comparative effectiveness of three exercise types to treat clinical depression in older adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Ageing Research Reviews. 58: 100999. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2019.100999. hdl:1959.17/172086. PMID 31837462. S2CID 209179889.

- ^ Chaturvedi, Santosh K.; Chandra, Prabha S.; Issac, Mohan K.; Sudarshan, C. Y. (1 September 1993). "Somatization misattributed to non-pathological vaginal discharge". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 37 (6): 575–579. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(93)90051-G. PMID 8410743.

- ^ Tantimonaco M, Ceci R, Sabatini S, Catani MV, Rossi A, Gasperi V, Maccarrone M (2014). "Physical activity and the endocannabinoid system: an overview". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71 (14): 2681–98. doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1575-6. PMID 24526057. S2CID 14531019.

- ^ Dinas PC, Koutedakis Y, Flouris AD (2011). "Effects of exercise and physical activity on depression". Ir J Med Sci. 180 (2): 319–25. doi:10.1007/s11845-010-0633-9. PMID 21076975. S2CID 40951545.

- ^ Szabo A, Billett E, Turner J (2001). "Phenylethylamine, a possible link to the antidepressant effects of exercise?". Br J Sports Med. 35 (5): 342–43. doi:10.1136/bjsm.35.5.342. PMC 1724404. PMID 11579070.

- ^ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (5): 274–81. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Berry MD (2007). "The potential of trace amines and their receptors for treating neurological and psychiatric diseases". Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2 (1): 3–19. doi:10.2174/157488707779318107. PMID 18473983. S2CID 7127324.

- ^ Yang, PY; Ho, KH; Chen, HC; Chien, MY (2012). "Exercise training improves sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems: A systematic review". Journal of Physiotherapy. 58 (3): 157–63. doi:10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70106-6. PMID 22884182.

- ^ Buman, M.P.; King, A.C. (2010). "Exercise as a Treatment to Enhance Sleep". American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 31 (5): 514. doi:10.1177/1559827610375532. S2CID 73314918.

- ^ Banno, M; Harada, Y; Taniguchi, M; Tobita, R; Tsujimoto, H; Tsujimoto, Y; Kataoka, Y; Noda, A (2018). "Exercise can improve sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PeerJ. 6: e5172. doi:10.7717/peerj.5172. PMC 6045928. PMID 30018855.

- ^ Lorenz, TA; Meston, CM (2013). "Acute Exercise Improves Physical Sexual Arousal in Women Taking Antidepressants". Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 43 (3): 352–361. doi:10.1007/s12160-011-9338-1. PMC 3422071. PMID 22403029.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brook MS, Wilkinson DJ, Phillips BE, Perez-Schindler J, Philp A, Smith K, Atherton PJ (January 2016). "Skeletal muscle homeostasis and plasticity in youth and ageing: impact of nutrition and exercise". Acta Physiologica. 216 (1): 15–41. doi:10.1111/apha.12532. PMC 4843955. PMID 26010896.

- ^ a b c Phillips SM (May 2014). "A brief review of critical processes in exercise-induced muscular hypertrophy". Sports Med. 44 Suppl 1: S71–S77. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0152-3. PMC 4008813. PMID 24791918.

- ^ Brioche T, Pagano AF, Py G, Chopard A (April 2016). "Muscle wasting and aging: Experimental models, fatty infiltrations, and prevention" (PDF). Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 50: 56–87. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2016.04.006. PMID 27106402.

- ^ a b Wilkinson DJ, Hossain T, Hill DS, Phillips BE, Crossland H, Williams J, Loughna P, Churchward-Venne TA, Breen L, Phillips SM, Etheridge T, Rathmacher JA, Smith K, Szewczyk NJ, Atherton PJ (June 2013). "Effects of leucine and its metabolite β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate on human skeletal muscle protein metabolism". J. Physiol. 591 (11): 2911–23. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.253203. PMC 3690694. PMID 23551944.

- ^ a b Wilkinson DJ, Hossain T, Limb MC, Phillips BE, Lund J, Williams JP, Brook MS, Cegielski J, Philp A, Ashcroft S, Rathmacher JA, Szewczyk NJ, Smith K, Atherton PJ (2018). "Impact of the calcium form of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate upon human skeletal muscle protein metabolism". Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 37 (6): 2068–2075. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.09.024. PMC 6295980. PMID 29097038.

Ca-HMB led a significant and rapid (<60 min) peak in plasma HMB concentrations (483.6 ± 14.2 μM, p < 0.0001). This rise in plasma HMB was accompanied by increases in MPS (PA: 0.046 ± 0.004%/h, CaHMB: 0.072 ± 0.004%/h, p < [0.001]) and suppressions in MPB (PA: 7.6 ± 1.2 μmol Phe per leg min−1, Ca-HMB: 5.2 ± 0.8 μmol Phe per leg min−1, p < 0.01). ... During the first 2.5 h period we gathered postabsorptive/fasted measurements, the volunteers then consumed 3.42 g of Ca-HMB (equivalent to 2.74 g of FA-HMB) ... It may seem difficult for one to reconcile that acute provision of CaHMB, in the absence of exogenous nutrition (i.e. EAA's) and following an overnight fast, is still able to elicit a robust, perhaps near maximal stimulation of MPS, i.e. raising the question as to where the additional AA's substrates required for supporting this MPS response are coming from. It would appear that the AA's to support this response are derived from endogenous intracellular/plasma pools and/or protein breakdown (which will increase in fasted periods). ... To conclude, a large single oral dose (~3 g) of Ca-HMB robustly (near maximally) stimulates skeletal muscle anabolism, in the absence of additional nutrient intake; the anabolic effects of Ca-HMB are equivalent to FA-HMB, despite purported differences in bioavailability (Fig. 4).

- ^ Phillips SM (July 2015). "Nutritional supplements in support of resistance exercise to counter age-related sarcopenia". Adv. Nutr. 6 (4): 452–60. doi:10.3945/an.115.008367. PMC 4496741. PMID 26178029.

- ^ Wibom, R.; Hultman, E.; Johansson, M.; Matherei, K.; Constantin-Teodosiu, D.; Schantz, P. G. (1 November 1992). "Adaptation of mitochondrial ATP production in human skeletal muscle to endurance training and detraining". Journal of Applied Physiology. 73 (5): 2004–2010. doi:10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.2004. PMID 1474078.

- ^ a b Boushel R, Lundby C, Qvortrup K, Sahlin K (October 2014). "Mitochondrial plasticity with exercise training and extreme environments". Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 42 (4): 169–74. doi:10.1249/JES.0000000000000025. PMID 25062000. S2CID 39267910.

- ^ Valero T (2014). "Mitochondrial biogenesis: pharmacological approaches". Curr. Pharm. Des. 20 (35): 5507–09. doi:10.2174/138161282035140911142118. hdl:10454/13341. PMID 24606795.

- ^ Lipton JO, Sahin M (October 2014). "The neurology of mTOR". Neuron. 84 (2): 275–91. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.034. PMC 4223653. PMID 25374355.

그림 2: mTOR 신호 경로 - ^ a b Wang, E; Næss, MS; Hoff, J; Albert, TL; Pham, Q; Richardson, RS; Helgerud, J (16 November 2013). "Exercise-training-induced changes in metabolic capacity with age: the role of central cardiovascular plasticity". Age (Dordrecht, Netherlands). 36 (2): 665–76. doi:10.1007/s11357-013-9596-x. PMC 4039249. PMID 24243396.

- ^ Potempa, K; Lopez, M; Braun, LT; Szidon, JP; Fogg, L; Tincknell, T (January 1995). "Physiological outcomes of aerobic exercise training in hemiparetic stroke patients". Stroke: A Journal of Cerebral Circulation. 26 (1): 101–05. doi:10.1161/01.str.26.1.101. PMID 7839377.

- ^ Wilmore, JH; Stanforth, PR; Gagnon, J; Leon, AS; Rao, DC; Skinner, JS; Bouchard, C (July 1996). "Endurance exercise training has a minimal effect on resting heart rate: the HERITAGE Study". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 28 (7): 829–35. doi:10.1097/00005768-199607000-00009. PMID 8832536.

- ^ Carter, JB; Banister, EW; Blaber, AP (2003). "Effect of endurance exercise on autonomic control of heart rate". Sports Medicine. 33 (1): 33–46. doi:10.2165/00007256-200333010-00003. PMID 12477376. S2CID 40393053.

- ^ Chen, Chao-Yin; Dicarlo, Stephen E. (January 1998). "Endurance exercise training-induced resting Bradycardia: A brief review". Sports Medicine, Training and Rehabilitation. 8 (1): 37–77. doi:10.1080/15438629709512518.

- ^ Crewther, BT; Heke, TL; Keogh, JW (February 2013). "The effects of a resistance-training program on strength, body composition and baseline hormones in male athletes training concurrently for rugby union 7's". The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 53 (1): 34–41. PMID 23470909.

- ^ Schoenfeld, BJ (June 2013). "Postexercise hypertrophic adaptations: a reexamination of the hormone hypothesis and its applicability to resistance training program design". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 27 (6): 1720–30. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31828ddd53. PMID 23442269. S2CID 25068522.

- ^ Dalgas, U; Stenager, E; Lund, C; Rasmussen, C; Petersen, T; Sørensen, H; Ingemann-Hansen, T; Overgaard, K (July 2013). "Neural drive increases following resistance training in patients with multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 260 (7): 1822–32. doi:10.1007/s00415-013-6884-4. PMID 23483214. S2CID 848583.

- ^ Staron, RS; Karapondo, DL; Kraemer, WJ; Fry, AC; Gordon, SE; Falkel, JE; Hagerman, FC; Hikida, RS (March 1994). "Skeletal muscle adaptations during early phase of heavy-resistance training in men and women". Journal of Applied Physiology. 76 (3): 1247–55. doi:10.1152/jappl.1994.76.3.1247. PMID 8005869.

- ^ Folland, JP; Williams, AG (2007). "The adaptations to strength training : morphological and neurological contributions to increased strength". Sports Medicine. 37 (2): 145–68. doi:10.2165/00007256-200737020-00004. PMID 17241104. S2CID 9070800.

- ^ Moritani, T; deVries, HA (June 1979). "Neural factors versus hypertrophy in the time course of muscle strength gain". American Journal of Physical Medicine. 58 (3): 115–30. PMID 453338.

- ^ Narici, MV; Roi, GS; Landoni, L; Minetti, AE; Cerretelli, P (1989). "Changes in force, cross-sectional area and neural activation during strength training and detraining of the human quadriceps". European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 59 (4): 310–09. doi:10.1007/bf02388334. PMID 2583179. S2CID 2231992.

- ^ Pedersen, BK (July 2013). "Muscle as a secretory organ". Comprehensive Physiology. 3 (3): 1337–62. doi:10.1002/cphy.c120033. ISBN 978-0-470-65071-4. PMID 23897689.

- ^ Cohen S, Williamson GM (1991). "Stress and infectious disease in humans". Psychological Bulletin. 109 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.109.1.5. PMID 2006229.

- ^ Borer KT, Wuorinen EC, Lukos JR, Denver JW, Porges SW, Burant CF (August 2009). "Two bouts of exercise before meals but not after meals, lower fasting blood glucose". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 41 (8): 1606–14. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31819dfe14. PMID 19568199.

- ^ Wisløff U, Ellingsen Ø, Kemi OJ (July 2009). "High=Intensity Interval Training to Maximize Cardiac Benefit of Exercise Taining?". Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 37 (3): 139–46. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e3181aa65fc. PMID 19550205. S2CID 25057561.

- ^ Paillard T, Rolland Y, de Souto Barreto P (July 2015). "Protective Effects of Physical Exercise in Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease: A Narrative Review". J Clin Neurol. 11 (3): 212–219. doi:10.3988/jcn.2015.11.3.212. PMC 4507374. PMID 26174783.

Aerobic physical exercise (PE) activates the release of neurotrophic factors and promotes angiogenesis, thereby facilitating neurogenesis and synaptogenesis, which in turn improve memory and cognitive functions. ... Exercise limits the alteration in dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and contributes to optimal functioning of the basal ganglia involved in motor commands and control by adaptive mechanisms involving dopamine and glutamate neurotransmission.

- ^ Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW (January 2015). "A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 60: 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003. PMC 4314337. PMID 25455510.

Consistent evidence indicates that exercise improves cognition and mood, with preliminary evidence suggesting that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may mediate these effects. The aim of the current meta-analysis was to provide an estimate of the strength of the association between exercise and increased BDNF levels in humans across multiple exercise paradigms. We conducted a meta-analysis of 29 studies (N = 1111 participants) examining the effect of exercise on BDNF levels in three exercise paradigms: (1) a single session of exercise, (2) a session of exercise following a program of regular exercise, and (3) resting BDNF levels following a program of regular exercise. Moderators of this effect were also examined. Results demonstrated a moderate effect size for increases in BDNF following a single session of exercise (Hedges' g = 0.46, p < 0.001). Further, regular exercise intensified the effect of a session of exercise on BDNF levels (Hedges' g = 0.59, p = 0.02). Finally, results indicated a small effect of regular exercise on resting BDNF levels (Hedges' g = 0.27, p = 0.005). ... Effect size analysis supports the role of exercise as a strategy for enhancing BDNF activity in humans

- ^ Bouchard J, Villeda SA (2015). "Aging and brain rejuvenation as systemic events". J. Neurochem. 132 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1111/jnc.12969. PMC 4301186. PMID 25327899.

From a molecular perspective, elevated systemic levels of circulating growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) in blood elicited by increased exercise have been shown to mediate, in part, enhancements in neurogenesis (Trejo et al. 2001; Fabel et al. 2003).

- ^ Silverman MN, Deuster PA (October 2014). "Biological mechanisms underlying the role of physical fitness in health and resilience". Interface Focus. 4 (5): 20140040. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2014.0040. PMC 4142018. PMID 25285199.

Importantly, physical exercise can improve growth factor signalling directly or indirectly by reducing pro-inflammatory signalling [33]. Exercise-induced increases in brain monoamines (norepinephrine and serotonin) may also contribute to increased expression of hippocampal BDNF [194]. In addition, other growth factors—insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and vascular endothelial growth factor—have been shown to play an important role in BDNF-induced effects on neuroplasticity [33,172,190,192], as well as exerting neuroprotective effects of their own [33,214,215], thereby contributing to the beneficial effects of exercise on brain health.

- ^ Gomez-Pinilla F, Hillman C (January 2013). "The influence of exercise on cognitive abilities". Compr. Physiol. 3 (1): 403–28. doi:10.1002/cphy.c110063. ISBN 978-0-470-65071-4. PMC 3951958. PMID 23720292.

Abundant research in the last decade has shown that exercise is one of the strongest promoters of neurogenesis in the brain of adult rodents (97, 102) and humans (1,61), and this has introduced the possibility that proliferating neurons could contribute to the cognitive enhancement observed with exercise. In addition to BDNF, the actions of IGF-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (54) are considered essential for the angiogenic and neurogenic effects of exercise in the brain. Although the action of exercise on brain angiogenesis has been known for many years (10), it is not until recently that neurovascular adaptations in the hippocampus have been associated with cognitive function (29). Exercise enhances the proliferation of brain endothelial cells throughout the brain (113), hippocampal IGF gene expression (47), and serum levels of both IGF (178) and VEGF (63). IGF-1 and VEGF, apparently produced in the periphery, support exercise induced neurogenesis and angiogenesis, as corroborated by blocking the effects of exercise using antibodies against IGF-1 (47) or VEGF (63).

- ^ Tarumi T, Zhang R (January 2014). "Cerebral hemodynamics of the aging brain: risk of Alzheimer disease and benefit of aerobic exercise". Front Physiol. 5: 6. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00006. PMC 3896879. PMID 24478719.

Exercise-related improvements in brain function and structure may be conferred by the concurrent adaptations in vascular function and structure. Aerobic exercise increases the peripheral levels of growth factors (e.g., BDNF, IFG-1, and VEGF) which cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and stimulate neurogenesis and angiogenesis (Trejo et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2002; Fabel et al., 2003; Lopez-Lopez et al., 2004). Consistent with this, exercise-related enlargement of hippocampus was accompanied by increases in cerebral blood volume and capillary densities (Pereira et al., 2007). Enhanced cerebral perfusion may not only facilitate the delivery of energy substrates, but also lower the risk of vascular-related brain damages, including WMH and silent infarct (Tseng et al., 2013). Furthermore, regular aerobic exercise is associated with lower levels of Aβ deposition in individuals with APOE4 positive (Head et al., 2012), which may also reduce the risk of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and microbleeds (Poels et al., 2010).

- ^ Howe, Tracey E; Rochester, Lynn; Neil, Fiona; Skelton, Dawn A; Ballinger, Claire (9 November 2011). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. CD004963. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004963.pub3. PMID 22071817. S2CID 205176433.

- ^ Liu, Chiung-Ju; Latham, Nancy K. (8 July 2009). "Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD002759. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002759.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4324332. PMID 19588334.

- ^ Gc, V; Wilson, EC; Suhrcke, M; Hardeman, W; Sutton, S; VBI Programme, Team (April 2016). "Are brief interventions to increase physical activity cost-effective? A systematic review". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 50 (7): 408–17. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094655. PMC 4819643. PMID 26438429.

- ^ Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Howze EH, Powell KE, Stone EJ, Rajab MW, Corso P (May 2002). "The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity. A systematic review". Am J Prev Med. 22 (4 Suppl): 73–107. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00434-8. PMID 11985936.

- ^ Durán, Víctor Hugo. "Stopping the rising tide of chronic diseases Everyone's Epidemic". Pan American Health Organization. paho.org. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ Dons, E (2018). "Transport mode choice and body mass index: Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from a European-wide study". Environment International. 119 (119): 109–16. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2018.06.023. hdl:10044/1/61061. PMID 29957352. S2CID 49607716.

- ^ Reed, Jennifer L; Prince, Stephanie A; Cole, Christie A; Fodor, J; Hiremath, Swapnil; Mullen, Kerri-Anne; Tulloch, Heather E; Wright, Erica; Reid, Robert D (19 December 2014). "Workplace physical activity interventions and moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity levels among working-age women: a systematic review protocol". Systematic Reviews. 3 (1): 147. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-147. PMC 4290810. PMID 25526769.

- ^ Laeremans, M (2018). "Black Carbon Reduces the Beneficial Effect of Physical Activity on Lung Function". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 50 (9): 1875–1881. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001632. hdl:10044/1/63478. PMID 29634643. S2CID 207183760.

- ^ Xu, Huilan; Wen, Li Ming; Rissel, Chris (19 March 2015). "Associations of Parental Influences with Physical Activity and Screen Time among Young Children: A Systematic Review". Journal of Obesity. 2015: 546925. doi:10.1155/2015/546925. PMC 4383435. PMID 25874123.

- ^ "Youth Physical Activity Guidelines". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 23 January 2019.

- ^ "Health and Participation". ec.europa.eu. 25 June 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019.

- ^ a b "WHO: Obesity and overweight". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ Kennedy AB, Resnick PB (May 2015). "Mindfulness and Physical Activity". American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 9 (3): 3221–23. doi:10.1177/1559827614564546. S2CID 73116017.

- ^ "Running and jogging - health benefits".

- ^ "5 Reasons Why Skateboarding Is Good Exercise". Longboarding Nation. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Swimming - health benefits".

- ^ Hernández, Javier (24 June 2008). "Car-Free Streets, a Colombian Export, Inspire Debate". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Nicky. "Gyms". Travel Fish. Travel Fish. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Tatlow, Anita. "When in Sweden...making the most of the great outdoors!". Stockholm on a Shoestring. Stockholm on a Shoestring. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Langfitt, Frank. "Beijing's Other Games: Dancing In The Park". NPR.org. National Public Radio. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Kimber N.; Heigenhauser G.; Spriet L.; Dyck D. (2003). "Skeletal muscle fat and carbohydrate metabolism during recovery from glycogen-depleting exercise in humans". The Journal of Physiology. 548 (3): 919–27. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031179. PMC 2342904. PMID 12651914.

- ^ Reilly T, Ekblom B (June 2005). "The use of recovery methods post-exercise". J. Sports Sci. 23 (6): 619–27. doi:10.1080/02640410400021302. PMID 16195010. S2CID 27918213.

- ^ Blundell, J. E.; Gibbons, C.; Caudwell, P.; Finlayson, G.; Hopkins, M. (February 2015). "Appetite control and energy balance: impact of exercise: Appetite control and exercise" (PDF). Obesity Reviews. 16: 67–76. doi:10.1111/obr.12257. PMID 25614205. S2CID 39429480.

- ^ "How to Identify Overtraining Syndrome - 23 Warning Signs". 17 March 2002. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Quotes About Exercise Top 10 List".

- ^ "History of Fitness". www.unm.edu. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ "physical culture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Bogdanovic, Nikolai (19 December 2017). Fit to Fight: A History of the Royal Army Physical Training Corps 1860–2015. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-4728-2421-9.

- ^ Campbell, James D. (16 March 2016). 'The Army Isn't All Work': Physical Culture and the Evolution of the British Army, 1860–1920. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-04453-6.

- ^ Mason, Tony; Riedi, Eliza (4 November 2010). Sport and the Military: The British Armed Forces 1880–1960. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-78897-7.

- ^ "The Fitness League History". The Fitness League. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ Kuper, Simon (11 September 2009). "The man who invented exercise". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ^ a b Morris JN, Heady JA, Raffle PA, Roberts CG, Parks JW (1953). "Coronary heart-disease and physical activity of work". Lancet. 262 (6795): 1053–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(53)90665-5. PMID 13110049.

- ^ Zhu, S.; Eclarinal, J.; Baker, M.S.; Li, G.; Waterland, R.A. (2016). "Developmental programming of energy balance regulation: is physical activity more "programmable" than food intake?". Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 75 (1): 73–77. doi:10.1017/s0029665115004127. PMID 26511431.

- ^ Acosta, W.; Meek, T.H.; Schutz, H.; Dlugosz, E.M.; Vu, K.T.; Garland Jr, T. (2015). "Effects of early-onset voluntary exercise on adult physical activity and associated phenotypes in mice". Physiology & Behavior. 149: 279–86. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.06.020. PMID 26079567.

- ^ Swallow, John G; Carter, Patrick A; Garland, Jr, Theodore (1998). "Artificial selection for increased wheel-running behavior in house mice". Behavior Genetics. 28 (3): 227–37. doi:10.1023/A:1021479331779. PMID 9670598. S2CID 18336243.

- ^ Swallow, John G; Garland, Theodore; Carter, Patrick A; Zhan, Wen-Zhi; Sieck, Gary C (1998). "Effects of voluntary activity and genetic selection on aerobic capacity in house mice (Mus domesticus)". Journal of Applied Physiology. 84 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1152/jappl.1998.84.1.69. PMID 9451619.