낙태

Abortion| 낙태 | |

|---|---|

| 기타이름 | 유도유산, 임신중절 |

| 전문 | 산부인과 |

| ICD-10-PCS | 10A0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 779.6 |

| MeSH | D000028 |

| 메드라인플러스 | 007382 |

| e메디신 | 252560 |

낙태는 배아나 태아를 제거하거나 추방하여 임신을 종료하는 것입니다.[nb 1] 유산 또는 '자발적 낙태'는 모든 임신의 약 30~40%에서 발생합니다.[2][3] 임신을 끝내기 위해 의도적인 조치를 취할 때, 그것은 유도 낙태, 혹은 덜 빈번한 "유도 유산"이라고 불립니다. 수정되지 않은 낙태라는 단어는 일반적으로 낙태를 유도하는 것을 말합니다.[4][5] 여성들이 낙태를 하는 가장 흔한 이유는 출산 시기와 가족 규모를 제한하기 위해서입니다.[6][7][8] 보고된 다른 이유로는 모성 건강, 아이를 살 여유가 없는 것, 가정 폭력, 부양 부족, 너무 어리다고 느끼는 것, 교육을 이수하거나 경력을 쌓기를 희망하는 것, 강간이나 근친상간의 결과로 임신한 아이를 기를 수 없거나 기꺼이 키울 수 없는 것 등이 있습니다.[6][8][9]

산업화된 사회에서 합법적으로 행해질 때, 유도 낙태는 의학에서 가장 안전한 절차 중 하나입니다.[10]: 1 [11] 미국의 경우 출산 후보다 유도 낙태 후 산모 사망 위험이 14배나 낮은 것으로 나타났습니다.[12] 안전하지 않은 낙태(필요한 기술이 부족하거나 자원이 부족한 환경에서 수행되는 낙태)는 특히 개발도상국에서 산모 사망의 5-13%를 차지합니다.[13] 그러나 자체 관리하는 약물 낙태는 임신 초기 내내 효과가 높고 안전합니다.[14][15][16] 공중 보건 데이터는 안전한 낙태를 합법적이고 접근 가능하게 만드는 것이 산모의 사망을 감소시킨다는 것을 보여줍니다.[17][18]

현대적인 방법은 낙태를 위해 약물이나 수술을 사용합니다.[19] 프로스타글란딘과 병용하는 약제 마이페프리스톤은 임신 1, 2기에 수술만큼 안전하고 효과적인 것으로 보입니다.[19][20] 가장 일반적인 수술 기법은 자궁경부를 확장하고 흡입 장치를 사용하는 것입니다.[21] 피임약이나 자궁 내 장치와 같은 산아제한은 낙태 직후에 사용할 수 있습니다.[20] 원하는 여성에게 합법적이고 안전하게 시술할 때, 유도 낙태는 장기적인 정신적 또는 신체적 문제의 위험을 증가시키지 않습니다.[22] 이와는 대조적으로, 비숙련자, 위험한 장비 또는 비위생적인 시설에서 수행되는 안전하지 않은 낙태는 매년 22,000명에서 44,000명 사이의 사망과 690만 명의 병원 입원을 야기합니다.[23] 세계보건기구는 "낙태 후 관리를 포함한 합법적이고 안전하며 포괄적인 낙태 치료에 대한 접근은 가능한 한 높은 수준의 성 및 생식 건강을 달성하는 데 필수적"이라고 말합니다.[24] 역사적으로, 낙태는 한약재, 날카로운 도구, 힘을 주는 마사지 또는 다른 전통적인 방법을 사용하여 시도되었습니다.[25]

전 세계에서 매년 약 7천 3백만 건의 낙태가 행해지고 있으며,[26] 약 45%가 안전하지 않게 행해지고 있습니다.[27] 2003년과 2008년 사이에 낙태율은 거의 변하지 않았으며,[28] 그 전에는 가족 계획과 출산 통제에 대한 접근성이 증가함에 따라 적어도 20년 동안 감소했습니다.[29] 2018년[update] 기준 전 세계 여성의 37%가 이성에 대한 제한 없이 합법적인 낙태에 접근했습니다.[30] 낙태를 허용하는 국가들은 임신중절이 얼마나 늦게 허용되는지에 대한 제한이 다릅니다.[31] 낙태율은 낙태를 제한하는 국가와 광범위하게 허용하는 국가 간에 유사하지만, 이는 부분적으로 낙태를 제한하는 국가가 의도하지 않은 임신율이 더 높은 경향이 있기 때문입니다.[32]

전 세계적으로 1973년 이후 낙태에 대한 법적 접근이 증가하는 경향이 널리 퍼졌지만,[33] 도덕적, 종교적, 윤리적, 법적 문제에 대해서는 여전히 논쟁이 있습니다.[34][35] 낙태를 반대하는 사람들은 종종 배아나 태아가 생명권을 가진 사람이라고 주장하며, 따라서 이를 살인과 동일시합니다.[36][37] 그것의 합법성을 지지하는 사람들은 종종 그것이 여성의 재생산권이라고 주장합니다.[38] 다른 사람들은 공중 보건 조치로서 합법적이고 접근 가능한 낙태를 선호합니다.[39] 낙태법과 시술에 대한 견해는 전 세계적으로 다릅니다. 일부 국가에서는 낙태가 합법적이고 여성들은 낙태에 대한 선택권이 있습니다.[40] 일부 지역에서는 강간, 태아 결함, 빈곤, 여성의 건강에 대한 위험 또는 근친상간과 같은 특정한 경우에만 낙태가 합법적입니다.[41]

종류들

유도된

전 세계적으로 매년 약 2억 5백만 건의 임신이 발생합니다. 3분의 1 이상은 의도하지 않은 낙태이며, 5분의 1 정도는 낙태를 유도합니다.[28][42] 대부분의 낙태는 의도하지 않은 임신에서 비롯됩니다.[43][44] 영국에서는 낙태의 1~2%가 태아의 유전적인 문제 때문에 이뤄지고 있습니다.[22] 임신은 여러 가지 방법으로 의도적으로 중단될 수 있습니다. 선택되는 방식은 종종 임신이 진행됨에 따라 크기가 증가하는 배아 또는 태아의 임신 연령에 따라 달라집니다.[45][46]

합법성, 지역적 이용 가능성, 의사나 여성의 개인적 선호도 등으로 인해 특정 시술을 선택할 수 있습니다. 유도 낙태를 조달하는 이유는 일반적으로 치료적이거나 선택적인 것으로 특징지어집니다. 낙태는 임신한 여성의 생명을 구하기 위해, 여성의 신체적 또는 정신적 건강에 해를 끼치는 것을 방지하기 위해, 아이가 사망 또는 질병의 가능성이 상당히 증가할 것이라는 징후가 있는 임신을 종료하기 위해, 또는 선택적으로 그 위험을 줄이기 위해 수행될 때 의학적으로 치료적 낙태라고 불립니다. 다태임신과 관련된 건강상의 위험을 줄이기 위한 태아의 수.[47][48] 낙태는 비의료적인 이유로 여성의 요청에 의해 이루어지는 경우에 선택적 또는 자발적 낙태라고 합니다.[48] '선택적 수술'은 일반적으로 의학적으로 필요하든 필요하지 않든 예정된 모든 수술을 의미하기 때문에 선택적이라는 용어를 두고 혼란이 발생하기도 합니다.[49]

자발적

유산은 자연유산이라고도 하며 임신 24주 전에 의도치 않게 태아나 태아를 추방하는 것입니다.[50] 임신 37주 전에 끝나는 임신은 "조산" 또는 "조산"입니다.[51] 태아가 생존 후 자궁에서 사망하거나 분만 중에 사망할 때 보통 "사산"이라고 합니다.[52] 조산과 사산은 일반적으로 유산으로 간주되지 않지만 이러한 용어의 사용이 겹치는 경우가 있습니다.[53]

미국과 중국의 임산부를 대상으로 한 연구에 따르면 배아의 40%에서 60% 사이가 출생으로 진행되지 않는 것으로 나타났습니다.[54][55][56] 유산의 대부분은 여성이 임신했다는 것을 알기 전에 발생하며,[48] 많은 임신은 의료 종사자가 배아를 발견하기 전에 자발적으로 중단됩니다.[57] 알려진 임신의 15%에서 30% 사이는 임신한 여성의 나이와 건강에 따라 임상적으로 명백한 유산으로 끝납니다.[58] 이러한 자연유산의 80%는 임신 초기에 발생합니다.[59]

임신 초기 자발적 낙태의 가장 흔한 원인은 배아나 태아의 염색체 이상으로,[48][60] 샘플링된 임신 초기 손실의 최소 50%를 차지합니다.[61] 다른 원인으로는 혈관질환(루푸스 등), 당뇨병, 기타 호르몬 문제, 감염, 자궁 이상 등이 있습니다.[60] 모성 연령의 증가와 이전의 자발적 낙태의 여성의 병력은 자발적 낙태의 더 큰 위험과 관련된 두 가지 주요 요인입니다.[61] 자발적인 낙태는 우발적인 외상에 의해서도 발생할 수 있습니다; 유산을 일으키기 위한 의도적인 외상이나 스트레스는 유도된 낙태 또는 페티사이드로 간주됩니다.[62]

방법들

의료의

의료 낙태는 낙태 약물에 의해 유발되는 것입니다. 1970년대에 프로스타글란딘 유사체와 1980년대에 항프로게스토겐 미페프리스톤(RU-486이라고도 함)을 이용할 수 있게 되면서 의료적 낙태는 낙태의 대안적인 방법이 되었습니다.[20][19][63][64]

가장 일반적인 임신 초기 의료 낙태 요법은 임신 10주(70일)까지의 미소프로스톨(또는 때로는 다른 프로스타글란딘 유사체, 게메프로스트)과 조합된 미페프리스톤,[65][66] 임신 7주까지의 프로스타글란딘 유사체와 조합된 메토트렉세이트 또는 프로스타글란딘 유사체 단독을 사용합니다.[19] Mifepristone-misoprostol 조합 요법은 Methotrexate-misoprostol 조합 요법보다 더 빨리 작용하고 임신 후기에 더 효과적이며, 조합 요법은 특히 임신 후기에 misoprostol 단독 요법보다 더 효과적입니다.[63][67] 임신 70일 전에 시행할 때는 마이페프리스톤과 24시간에서 48시간 사이에 볼에 미소프로스톨이 포함된 의료용 낙태 요법이 효과적입니다.[66][65]

임신 7주까지의 초기 낙태에서는 특히 임상 실습에 흡인된 조직에 대한 상세한 검사가 포함되지 않은 경우 미페프리스톤-미소프로스톨 병용 요법을 사용하는 의료적 낙태가 수술적 낙태(진공 흡인)보다 더 효과적인 것으로 간주됩니다.[68] 미페프리스톤을 사용한 초기 의료 낙태 요법과 24-48시간 후 협측 또는 질 미소프로스톨은 임신 9주까지 98% 효과가 있으며, 9주에서 10주의 효능은 [65][69]94%로 약간 감소합니다. 의료적 낙태가 실패할 경우 수술적 낙태를 통해 시술을 완료해야 합니다.[70]

조기 [71][72]의료 낙태는 영국,[73][74] 프랑스,[75] 스위스, 미국, 북유럽 국가에서 임신 9주 전 낙태의 대부분을 차지합니다.[76]

프로스타글란딘 유사체와 함께 미페프리스톤을 사용하는 의료 낙태 요법은 대부분의 유럽, 중국, 인도의 캐나다에서 임신 2기 낙태에 사용되는 가장 일반적인 방법이며,[64] 미국은 임신 2기 낙태의 96%가 확장 및 후송에 의해 수술적으로 수행되는 것과 대조적입니다.[77]

2020년 코크란 체계적 검토(Cochrane Systematic Review)는 여성에게 조기 의료 낙태 시술의 두 번째 단계를 완료하기 위해 집으로 가져갈 약물을 제공하는 것이 효과적인 낙태를 초래한다고 결론지었습니다.[78] 자가 투여 의료 낙태가 의료 낙태를 관리하는 데 도움이 되는 의료 전문가가 있는 제공자가 투여하는 의료 낙태만큼 안전한지 여부를 결정하기 위해서는 추가 연구가 필요합니다.[78] 여성이 안전하게 낙태 약물을 자가 투여할 수 있도록 허용하는 것은 낙태에 대한 접근성을 향상시킬 가능성이 있습니다.[78] 다른 연구 격차가 확인된 것은 스스로 낙태를 위해 약을 집으로 가져가기로 선택한 여성들을 가장 잘 지원하는 방법입니다.[78]

외과

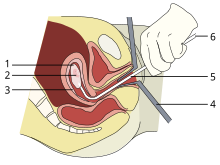

1:양수낭

2:배아

3:자궁안감

4:스펙큘러

5: 보케트

6: 흡입 펌프 부착

임신 15주까지는 흡입-흡인 또는 진공흡인이 유도 낙태의 가장 일반적인 수술 방법입니다.[79] 수동진공흡인법(MVA)은 수동주사기를 이용하여 흡입에 의해 태아나 배아, 태반, 막을 제거하는 방법으로 구성되어 있으며, 전기진공흡인법(EVA)은 전동펌프를 이용하고 있습니다. 이 두 가지 기술은 모두 임신 초기에 사용할 수 있습니다. MVA는 14주까지 사용할 수 있지만 미국에서는 더 일찍 사용하는 경우가 많습니다. EVA는 나중에 사용할 수 있습니다.[77]

"미니 흡입" 및 "생리 추출"이라고도 하는 MVA 또는 EVA는 자궁경부 확장이 필요하지 않을 수 있는 임신 초기에 사용할 수 있습니다. 확장 및 큐티지(D&C)는 자궁경부(확장)를 열고 흡입기나 날카로운 기구를 통해 조직(큐티지)을 제거하는 것을 말합니다. D&C는 악성 가능성이 있는 자궁 내막 검사, 이상 출혈 조사, 낙태 등 다양한 이유로 시행되는 표준 부인과 시술입니다. 세계보건기구는 흡입 흡인이 불가능한 경우에만 날카로운 큐벳을 사용할 것을 권장합니다.[80]

12~16주 후에 사용하는 확장 및 배출(D&E)은 수술기구와 흡입을 이용하여 자궁경부를 열고 자궁을 비우는 것으로 구성되어 있습니다. D&E는 질적으로 수행되며 절개가 필요하지 않습니다. 온전한 확장 및 추출(D&X)은 온전한 태아를 제거하면 수술 안전성이 향상되거나 다른 이유로 18주에서 20주 후에 사용되는 변형된 D&E를 말합니다.[81]

낙태는 또한 히스테리 절제술이나 육즙 자궁 절제술에 의해 수술적으로 시행될 수도 있습니다. 히스테리절제술 낙태는 제왕절개와 비슷한 시술로 전신마취 상태에서 시행됩니다. 제왕절개보다 작은 절개가 필요하며 임신 후기에 사용할 수 있습니다. 자궁육부 자궁절제술은 임신한 상태에서 자궁 전체를 절제하는 것을 말합니다. 히스테리 절제술과 자궁 절제술은 D&E나 유도 낙태보다 훨씬 더 높은 산모의 이환율과 사망률과 관련이 있습니다.[82]

일반적으로 첫 번째 삼분기 시술은 국소 마취를 사용하여 수행할 수 있는 반면, 두 번째 삼분기 방법은 깊은 진정 또는 전신 마취가 필요할 수 있습니다.[83][84][85]

노동유인낙태

확장 및 적출에 필요한 의료 기술이 부족한 곳이나, 시술자가 선호하는 경우, 먼저 진통을 유도한 후 필요한 경우 태아 사망을 유도함으로써 낙태를 유도할 수 있습니다.[86] 이것은 때때로 "유도 유산"이라고 불립니다. 이 절차는 임신 13주부터 임신 3개월까지 수행할 수 있습니다. 미국에서는 매우 드문 일이지만, 스웨덴을 비롯한 인근 국가에서는 임신 2기 내내 발생한 낙태의 80% 이상이 노동으로 인한 낙태입니다.[87]

노동으로 인한 낙태와 확장 및 추출 방법을 비교한 제한된 데이터만 사용할 수 있습니다.[87] D&E와 달리 18주 후 노동으로 인한 낙태는 짧은 태아 생존의 발생으로 인해 복잡해질 수 있으며, 이는 법적으로 산아로 특징지어질 수 있습니다. 이런 이유로 미국에서는 노동으로 인한 낙태가 법적으로 위험합니다.[87][88]

기타방법

역사적으로, 낙태 특성을 가지고 있다고 알려진 많은 약초들이 민간 의학에 사용되었습니다. 이 중에는 탄시, 페니로얄, 블랙 코호쉬, 그리고 지금은 멸종된 실피움이 있습니다.[89]: 44–47, 62–63, 154–155, 230–231

1978년 콜로라도에서 한 여성이 페니로얄 오일을 복용하여 임신을 종료하려고 시도했을 때 사망하고 또 다른 여성이 장기 손상을 입었습니다.[90] 약초를 낙태 환자로 무분별하게 사용하면 다발성 장기 부전과 같은 심각한 심지어 치명적인 부작용을 일으킬 수 [91]있기 때문에 의사들은 그러한 사용을 권장하지 않습니다.

복부에 외상을 입혀서 낙태를 시도하기도 합니다. 힘의 정도가 심할 경우 유산을 유도하는 데 반드시 성공하지 못한 채 심각한 내상을 일으킬 수 있습니다.[92] 동남아에는 강제 복부 마사지를 통해 낙태를 시도하는 고대 전통이 있습니다.[93] 캄보디아 앙코르와트 사원을 장식하는 기초 부조 중 하나는 저승으로 보내진 여성에게 그러한 낙태를 행하는 악마를 묘사하고 있습니다.[93]

보고된 안전하지 않은 자가 유발 낙태 방법에는 미소프로스톨의 오용, 뜨개질 바늘과 옷걸이와 같은 비수술적 도구를 자궁에 삽입하는 방법 등이 있습니다. 임신을 종료하는 이러한 방법들과 다른 방법들을 "유도 유산"이라고 부를 수 있습니다. 이러한 방법은 외과적 낙태가 합법적이고 이용 가능한 국가에서는 거의 사용되지 않습니다.[94]

안전.

낙태의 건강상 위험은 주로 시술이 안전하게 이루어지는지, 안전하지 않게 이루어지는지에 달려 있습니다. 세계보건기구(WHO)는 안전하지 않은 낙태를 숙련되지 않은 개인, 위험한 장비 또는 비위생적인 시설에서 행하는 낙태로 정의합니다.[95] 선진국에서 행해지는 합법적인 낙태는 의학에서 가장 안전한 절차 중 하나입니다.[10][96] 2012년 기준 미국에서 낙태는 여성이 출산보다 약 14배 안전한 것으로 추정되었습니다.[12] CDC는 2019년 미국의 임신 관련 사망률을 산아 10만 명당 17.2명의 산모 사망률을 기록한 반면,[97] 미국의 낙태 사망률은 10만 건당 0.43명으로 추정했습니다.[11][98][99] 영국에서는 왕립산부인과의사회와 산부인과 의사회의 지침에 "여성은 임신을 지속하는 것보다 일반적으로 낙태가 더 안전하다는 것을 조언받아야 한다"고 명시하고 있습니다.[100] 전 세계적으로 평균적으로 낙태는 임신을 임신 기간까지 하는 것보다 더 안전합니다. 2007년의 한 연구는 "전 세계적으로 모든 임신의 26%가 유도 낙태에 의해 종료되는 반면, "부적절하게 수행된 [낙태] 시술로 인한 사망은 전 세계적으로 산모 사망의 13%를 차지한다"[101]고 보고했습니다. 2000년 인도네시아에서 200만 건의 임신이 낙태로 끝났고, 450만 건의 임신이 임신 기간으로 옮겨졌으며, 산모 사망의 14-16%가 낙태로 인한 것으로 추정되었습니다.[102]

2000년부터 2009년까지 미국에서 낙태는 성형수술보다 사망률이 낮았고 마라톤을 뛰는 것보다 낮거나 비슷했으며 승용차로 760마일(1,220km)을 이동하는 것과 거의 맞먹었습니다.[11] 낙태 서비스를 신청한 지 5년 만에 낙태를 거부당한 뒤 출산한 여성들이 임신 1기나 2기 낙태를 한 여성들보다 더 나쁜 건강 상태를 보고했습니다.[103] 낙태와 관련된 사망률의 위험은 임신 연령에 따라 증가하지만 출산에 비해서는 낮은 수준을 유지하고 있습니다.[104] 외래 낙태는 임신 64일부터 70일까지 63일 전과 마찬가지로 안전합니다.[105]

임신 10주까지의 임신 초기 임신 초기 임신 중절에서 미페프리스톤과 미소프로스톨의 복합요법을 사용한 의료용 낙태와 수술용 낙태(진공흡인)는 안전성과 유효성 측면에서 거의 차이가 없습니다.[68] 프로스타글란딘 유사체 미소프로스톨 단독을 이용한 의료적 낙태는 미페프리스톤과 미소프로스톨 병용요법이나 외과적 낙태에 비해 효과가 떨어지고 통증이 심합니다.[106][107]

임신 1기의 진공흡인술은 수술적 낙태의 가장 안전한 방법으로 1차 진료실, 낙태 클리닉, 병원에서 시행할 수 있습니다. 드물게 발생하는 합병증은 자궁 천공, 골반 감염, 그리고 대피를 위한 2차 시술이 필요한 임신 유지물을 포함할 수 있습니다.[108] 미국에서 낙태 관련 사망자의 3분의 1을 감염이 차지하고 있습니다.[109] 초임기 진공흡인낙태 합병증 발생률은 병원, 외과센터, 사무실 등에서 시술하든 유사합니다.[110] 예방 항생제(독시사이클린이나 메트로니다졸 등)는 일반적으로 낙태 시술 전에 투여되는데,[111] 이는 수술 후 자궁 감염의 위험을 상당히 감소시키는 것으로 여겨지기 때문입니다.[83][112] 그러나 항생제는 낙태약과 함께 일상적으로 투여되지는 않습니다.[113] 낙태 시술을 의사가 하느냐, 중간 단계의 시술자가 하느냐에 따라 시술에 실패하는 비율은 크게 달라지지 않는 것으로 보입니다.[114]

임신 2기 낙태 후 합병증은 임신 1기 낙태 후 합병증과 비슷하고 선택한 방법에 따라 다소 다릅니다.[115] 임신 중절로 인한 사망 위험은 임신 9주 전에 백만 분의 일에서 만 분의 일까지 임신 21주 이상에 거의 만 분의 일까지(지난 생리 기간에서 측정) 출산으로 인한 사망 위험의 약 절반에 육박합니다.[116][117] (낙태를 유도하든 유산을 치료하든) 이전에 수술로 자궁을 제거한 것은 미래의 임신에서 조산의 위험이 약간 증가하는 것과 상관관계가 있는 것으로 보입니다. 이를 뒷받침하는 연구들은 낙태나 유산과 관련이 없는 요인들을 통제하지 못했고, 따라서 여러 가능성이 제시되었지만 이 상관관계의 원인은 밝혀지지 않았습니다.[118][119]

낙태의 위험성으로 알려진 일부는 주로 낙태 반대 단체들에 의해 촉진되지만 [120][121]과학적인 뒷받침은 부족합니다.[120] 예를 들어, 유도 낙태와 유방암 사이의 연관성에 대한 질문은 광범위하게 조사되었습니다. 주요 의료 및 과학 기관(WHO, National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, OBGYN Royal College of OBGYN, American Congress of OBGYN)은 낙태가 유방암을 유발하지 않는다는 결론을 내렸습니다.[122]

과거에는 불법조차도 자동적으로 낙태가 안전하지 않다는 것을 의미하지 않았습니다. 역사학자 린다 고든(Linda Gordon)은 미국을 언급하며 "사실 이 나라에서 불법 낙태는 인상적인 안전 기록을 가지고 있습니다."[123]: 25 라고 말합니다. 리키 솔링거에 의하면

낙태와 공공정책에 대한 광범위한 사람들에 의해 공표된 관련 신화는 합법화되기 전에 낙태주의자들은 더럽고 위험한 뒷골목 도살자였다는 것입니다. [T]그의 역사적 증거는 그러한 주장을 뒷받침하지 않습니다.[124]: 4

저자 제롬 베이츠와 에드워드 자와드스키는 20세기 초 미국 동부에서 13,844건의 낙태를 치명적인 결과 없이 성공적으로 마쳤다고 자부한 불법 낙태 시술자의 사례를 묘사합니다.[125]: 59 1870년대 뉴욕시에서 유명한 낙태 시술자이자 조산사인 Madame Restell (Anna Trow Lohman)은 10만 명이[126] 넘는 환자들 중에서 아주 적은 수의 여성을 잃은 것으로 보입니다. 이는 당시의 출산 사망률보다 낮은 사망률입니다. 1936년 저명한 산부인과 교수 프레드릭 J. 타우시그는 미국에서 불법의 세월 동안 사망률이 증가한 원인은

지난 50년 동안 이 사고의 실제적이고 비례적인 빈도는, 첫째, 도구적으로 유도된 낙태의 수가 증가했기 때문에, 둘째, 조산사가 처리하는 낙태에 비해 의사가 처리하는 낙태의 비례적인 증가 때문에, 그리고 셋째, 자궁을 비울 때 손가락 대신 기구를 사용하는 일반적인 경향으로 말입니다.[127]: 223

정신건강

현재의 증거로는 원치 않는 임신이 예상되는 것 외에는 대부분의 낙태와 정신 건강 문제[22][128] 사이에 어떠한 관계도 발견되지 않습니다.[129] 미국 심리학 협회의 보고서는 여성의 첫 번째 낙태가 임신 1기에 시행될 때 정신 건강에 위협이 되지 않는다는 결론을 내렸습니다. 그러한 여성들은 원치 않는 임신을 임신한 여성들보다 정신 건강 문제를 가질 가능성이 더 적습니다. 여성의 두 번째 이상의 낙태의 정신 건강 결과는 덜 확실합니다.[129][130] 일부 오래된 리뷰는 낙태가 심리적 문제의 위험 증가와 관련이 있다고 결론지었지만,[131] 이후 의학 문헌을 검토한 결과 적절한 대조군을 사용하지 않은 것으로 나타났습니다.[128] 대조군을 사용했을 때 낙태를 받는 것은 나쁜 심리적 결과와 관련이 없습니다.[128] 하지만 낙태에 대한 접근이 거부된 낙태를 원하는 여성들은 거부 이후 불안감이 커지고 있습니다.[128]

비록 일부 연구들이 태아 이상 때문에 임신 초기 이후 낙태를 선택하는 여성들에게 부정적인 정신 건강 결과를 보여주지만,[132] 이것을 결정적으로 보여주기 위해서는 더 엄격한 연구가 필요할 것입니다.[133] 낙태로 인한 부정적인 심리적 영향으로 제안된 일부는 낙태 반대 옹호자들에 의해 "낙태 후 증후군"이라고 불리는 별도의 질환으로 언급되었지만, 미국에서는 이를 의학이나 심리학 전문가들이 인정하지 않고 있습니다.[134]

2020년 미국 여성을 대상으로 한 장기 연구에 따르면 여성의 약 99%가 낙태 후 5년 후 올바른 결정을 내렸다고 느낀 것으로 나타났습니다. 슬픔이나 죄책감을 느끼는 여성이 거의 없는 가운데 안도감이 주된 감정이었습니다. 사회적 낙인은 수년 후 부정적인 감정과 후회를 예측하는 주요 요인이었습니다.[135]

안전하지 못한 낙태

낙태를 원하는 여성들은 특히 그것이 법적으로 제한될 때 안전하지 않은 방법을 사용할 수 있습니다. 적절한 의료 훈련이나 시설 없이 스스로 유도한 낙태를 시도하거나 사람의 도움을 받을 수 있습니다. 이로 인해 불완전 낙태, 패혈증, 출혈, 내장기관 손상 등 심각한 합병증이 발생할 수 있습니다.[136]

안전하지 않은 낙태는 전 세계 여성들의 부상과 사망의 주요 원인입니다. 데이터는 부정확하지만, 안전하지 않은 낙태가 매년 약 2천만 건 시행되고 있으며, 97%가 개발도상국에서 이루어지고 있는 것으로 추정됩니다.[10] 안전하지 않은 낙태는 수백만 명의 부상자를 초래한다고 여겨집니다.[10][137] 사망 추정치는 방법론에 따라 다르며 지난 10년 동안 37,000에서 70,000 사이였습니다.[10][138][139] 안전하지 않은 낙태로 인한 사망은 전체 산모 사망의 약 13%를 차지합니다.[140] 세계보건기구는 1990년대 이래로 사망률이 떨어졌다고 믿고 있습니다.[141] 안전하지 않은 낙태의 수를 줄이기 위해, 공중 보건 단체들은 일반적으로 낙태의 합법화, 의료인의 훈련, 그리고 생식-보건 서비스에 대한 접근 보장을 강조하는 것을 지지해 왔습니다.[142]

낙태가 안전하게 이루어지는지 여부는 낙태의 법적 지위가 가장 큰 요인입니다. 낙태 제한법이 있는 나라들은 낙태가 합법적이고 이용 가능한 나라들에 비해 안전하지 않은 낙태율이 높고 전반적인 낙태율도 비슷합니다.[138][28] 예를 들어, 1996년 남아프리카 공화국의 낙태 합법화는 낙태 관련 합병증의 빈도에 즉각적인 긍정적인 영향을 미쳤으며,[143] 낙태 관련 사망률은 90%[144] 이상 감소했습니다. 루마니아와 네팔과 같은 다른 나라들이 낙태법을 자유화한 후에도 비슷한 산모 사망률 감소가 관찰되었습니다.[145] 2011년의 한 연구는 미국에서, 일부 주 차원의 낙태 금지법들이 그 주에서의 낮은 낙태율과 상관관계가 있다고 결론지었습니다.[146] 그러나 이번 분석에서는 낙태를 하기 위한 그러한 법이 없는 다른 주로의 여행은 고려하지 않았습니다.[147] 게다가, 효과적인 피임법에 대한 접근의 부족은 안전하지 못한 낙태의 원인이 됩니다. 전 세계적으로 현대적인 가족 계획과 산모 건강 서비스를 쉽게 이용할 수 있다면 안전하지 않은 낙태의 발생률이 최대 75%(연간 2천만에서 5백만) 감소할 수 있을 것으로 추정되었습니다.[148] 이러한 낙태율은 유산, '유도유산', '월경조절', '미니낙태', '월경조절/월경조절' 등으로 다양하게 보고될 수 있어 측정이 어려울 수 있습니다.[149][150]

세계 여성의 40%는 임신 제한 범위 내에서 치료적 낙태와 선택적 낙태에 접근할 수 있는 반면,[31] 추가적으로 35%는 특정 신체적, 정신적 또는 사회경제적 기준을 충족할 경우 합법적 낙태에 접근할 수 있습니다.[41] 산모의 사망률은 안전한 낙태로 인한 경우는 거의 없지만, 안전하지 않은 낙태는 연간 7만 명의 사망자와 500만 명의 장애를 초래합니다.[138] 안전하지 않은 낙태의 합병증은 전 세계적으로 산모 사망률의 약 8분의 1을 차지하지만,[151] 이는 지역에 따라 다릅니다.[152] 안전하지 않은 낙태로 인한 2차 불임은 약 2,400만 명의 여성에게 영향을 미칩니다.[153] 안전하지 않은 낙태 비율은 1995년과 2008년 사이 44%에서 49%로 증가했습니다.[28] 안전하지 않은 낙태의 결과를 해결하기 위해 건강 교육, 가족 계획 접근, 낙태 중 및 낙태 후 건강 관리의 개선이 제안되었습니다.[154]

인시퀀스

일반적으로 사용되는 낙태의 발생률을 측정하는 두 가지 방법이 있습니다.

- 낙태율 – 15세에서 44세 사이의 여성 1,000명당 연간 낙태 횟수;[155] 일부 출처는 15-49세 범위를 사용합니다.

- 낙태율 – 알려진 임신 100건 중 낙태 횟수; 임신에는 산아, 낙태, 유산이 포함됩니다.

낙태가 불법이거나 사회적 낙인이 짙게 찍혀 있는 많은 곳에서 낙태에 대한 의학적 보도는 신뢰할 수 없습니다.[156] 이 때문에 표준오차와 관련된 확실성을 판단하지 않고 낙태 발생률을 추정해야 합니다.[28] 전 세계적으로 낙태 시술 건수는 2000년대 초반에 안정적으로 유지되고 있는 것으로 보이며, 2003년에는 4,160만 건, 2008년에는 4,380만 건이 시술되었습니다.[28] 전 세계적으로 낙태율은 여성 1000명당 28명이었지만 선진국은 여성 1000명당 24명, 개발도상국은 여성 1000명당 29명이었습니다.[28] 같은 2012년 연구에 따르면, 2008년에 알려진 임신의 추정된 낙태 비율은 전 세계적으로 21%였으며, 선진국은 26%, 개발도상국은 20%[28]였습니다.

평균적으로 낙태 제한법이 있는 국가와 낙태에 대한 접근이 더 자유로운 국가에서 낙태 발생률은 유사합니다.[157] 낙태 제한법은 안전하지 않게 시행되는 낙태 비율의 증가와 관련이 있습니다.[31][158][157] 개발도상국의 안전하지 않은 낙태율은 부분적으로 현대 피임약에 대한 접근 부족에 기인합니다. Guttmacher Institute에 따르면 피임약에 대한 접근을 제공하면 전 세계적으로 매년 약 1,450만 건의 안전하지 않은 낙태와 38,000건의 안전하지 않은 낙태로 인한 사망이 줄어들 것입니다.[159]

합법적이고 유도된 낙태의 비율은 전 세계적으로 매우 다양합니다. Guttmacher Institute의 직원들의 보고에 따르면, 2008년에 완전한 통계를 가진 국가들에서는 연간 여성 1000명당 7명(독일과 스위스)에서 연간 여성 1000명당 30명(에스토니아)까지 다양했습니다. 유도 낙태로 끝난 임신의 비율은 같은 그룹에서 약 10%(이스라엘, 네덜란드, 스위스)에서 30%(에스토니아)까지 다양했지만 통계가 불완전한 것으로 간주된 헝가리와 루마니아에서는 36%까지 높을 수 있습니다.[160][161]

2002년 미국의 한 연구는 낙태를 한 여성의 절반 정도가 임신 당시 피임의 한 형태를 사용하고 있었다고 결론지었습니다. 콘돔을 사용하는 사람의 절반과 피임약을 사용하는 사람의 4분의 3이 일관되지 않은 사용을 보고했으며 콘돔을 사용하는 사람의 42%가 미끄러지거나 부서져 고장이 났다고 보고했습니다.[162] Guttmacher Institute는 소수 여성들이 "의도하지 않은 임신의 비율이 훨씬 더 높기 때문에" 미국의 대부분의 낙태는 소수 여성들에 의해 얻어집니다"라고 추정했습니다.[163] 카이저 가족 재단의 2022년 분석에 따르면, 미시시피주 인구의 44%, 텍사스주 인구의 59%, 루이지애나주 인구의 42%(주 보건부), 앨라배마주 인구의 35%가 낙태를 받는 사람들의 80%, 74%, 72%, 70%가 유색인종으로 구성되어 있습니다.[164]

낙태율은 또한 여성이 생식 기간 동안 낙태한 평균 횟수로 표현될 수 있으며, 이를 총 낙태율(TAR)이라고 합니다.[165]

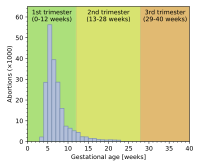

임신연령 및 방법

임신 단계와 실천 방법에 따라 낙태율이 달라집니다. 2003년 질병통제예방센터(CDC)는 미국에서 보고된 합법적인 유도 낙태의 26%가 임신 6주 미만에서, 18%는 7주, 15%는 8주, 18%는 9주에서 10주, 10%는 11주에서 12주, 6%는 13주에서 15주, 16~20주에 4%, 21주 이상에 1%입니다. 이 중 91%는 'cure'(suction-흡인, 확장 및 경화, 확장 및 대피), 8%는 '의료'(미페프리스톤), >1%는 'intra 자궁 주입'(saline 또는 프로스타글란딘), 1%는 '기타'(히스테리절제술 및 자궁절제술 포함)에 의해 수행된 것으로 분류되었습니다. CDC에 따르면 데이터 수집의 어려움으로 인해 데이터는 잠정적인 것으로 봐야 하며 20주 이상 보고된 일부 태아 사망은 유도 낙태와 동일한 절차로 죽은 태아의 제거가 이루어지면 낙태로 잘못 분류되는 자연사일 수 있습니다.[8]

Guttmacher Institute는 2000년 동안 미국에서 2,200개의 온전한 확장 및 추출 절차가 있었다고 추정했습니다. 이는 그 해에 수행된 전체 낙태 수의 <0.2%>를 차지합니다.[167] 이와 유사하게 2006년 잉글랜드와 웨일즈에서는 종료의 89%가 12주 이하에서, 9%는 13주에서 19주 사이에서, 2%는 20주 이상에서 발생했습니다. 보고된 것 중 64%는 진공흡인, 6%는 D&E, 30%는 의료용이었습니다.[168] 중국, 인도, 베트남 등 개발도상국에서는 선진국보다 임신 2기 낙태가 더 많습니다.[169]

임신 후기(20주 후)에 낙태를 해야 하는 의학적 이유와 비의학적 이유가 있습니다. 2008년부터 2010년까지 캘리포니아 샌프란시스코 대학에서 440명 이상의 여성들이 낙태 치료를 받는 데 지연을 겪는 이유에 대해 질문을 받았습니다. 이 연구는 20주 후에 낙태를 얻은 사람의 거의 절반이 임신 후기까지 임신을 의심하지 않는다는 것을 발견했습니다.[170] 이번 연구에서 발견된 낙태 시술의 다른 장벽으로는 낙태 시술을 어디서 받을 수 있는지에 대한 정보 부족, 교통편의 어려움, 보험 적용 부족, 낙태 시술에 대한 비용 지불 불가 등이 있었습니다.[170]

임신 후기에 낙태를 추구하는 의학적 이유로는 태아 이상과 임신한 사람에게 건강상의 위험이 있습니다.[171] 빠르면 임신 10주 만에 다운증후군이나 낭포성 섬유증을 진단할 수 있는 진단 검사도 있지만, 구조적 태아 이상은 임신이 훨씬 늦게 발견되는 경우가 많습니다.[170] 구조적 태아 이상의 비율은 치명적인데, 이는 태아가 출생 전 또는 직후에 거의 틀림없이 사망할 것이라는 것을 의미합니다.[170] 임신 후기에는 조기 중증 자간전증, 긴급한 치료가 필요한 새로 진단된 암, 양막낭(PPROM)의 조기 파열과 함께 종종 발생하는 자궁 내 감염(코리오양막염)과 같은 생명을 위협하는 상태도 발생할 수 있습니다.[170] 태아가 생존하기 전에 이와 같은 심각한 의학적 상태가 발생한 경우, 임신한 사람은 자신의 건강을 지키기 위해 낙태를 추구할 수 있습니다.[170]

동기

개인적인

여성이 낙태하는 이유는 전 세계적으로 다양하고 다양합니다.[8][6][7] 그 이유들 중 일부는 아이를 살 여유가 없는 것, 가정 폭력, 지원 부족, 그들이 너무 어리다고 느끼는 것, 그리고 교육을 이수하거나 경력을 쌓기를 바라는 것을 포함할 수 있습니다.[9] 강간이나 근친상간의 결과로 임신한 아이를 키울 수 없거나 기꺼이 키울 수 없는 것 등이 추가적인 이유입니다.[6][172]

사회적

사회적 압력의 결과로 일부 낙태가 이루어집니다.[173] 여기에는 특정 성별 또는 인종의 자녀에 대한 선호, 미혼 또는 초기 모성에 대한 불만족, 장애인에 대한 낙인, 가족에 대한 경제적 지원 부족, 피임 방법에 대한 접근 부족 또는 거부 또는 인구 통제를 위한 노력(중국의 한 자녀 정책과 같은)이 포함될 수 있습니다. 이러한 요인들은 때때로 강제 낙태나 성 선택적 낙태로 이어질 수 있습니다.[174] 남자 아이들을 선호하는 문화에서, 일부 여성들은 성 선택적 낙태를 하는데, 이것은 이전의 여성 유아 살해 관행을 부분적으로 대체했습니다.[174]

산모와 태아 건강

27개국 중 3개국 여성의 약 3분의 1과 이 27개국 중 7개국 여성의 약 7%가 주요 원인으로 꼽힌 모성 건강도 추가적인 요인입니다.[8][6]

미국 연방 대법원은 로 대 웨이드와 도 대 볼턴의 판결에서 "태아의 삶에 대한 국가의 관심은 태아가 어머니와 독립적으로 생존할 수 있는 시점으로 정의되는 생존 가능성의 시점에서만 강제력을 갖게 된다고 판결했습니다. 생존가능성의 시점 이후에도 국가는 임신부의 생명이나 건강보다 태아의 생명을 선호할 수 없습니다. 프라이버시권에 따라 의사는 '모체의 생명이나 건강의 보존을 위한 의학적 판단'을 자유롭게 이용할 수 있어야 합니다. 법원은 로를 결정한 같은 날 볼턴 목사에 대해서도 결정했는데, 볼턴 목사는 "의학적 판단은 신체적, 정서적, 심리적, 가족 및 여성의 나이 등 환자의 안녕과 관련된 모든 요소에 비추어 행사될 수 있습니다. 이 모든 요소는 건강과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다. 이를 통해 주치의는 최선의 의학적 판단을 내리는 데 필요한 병실을 사용할 수 있습니다."[175]: 1200–1201

TV 연예인인 셰리 핑크빈이 임신 5개월 차에 탈리도마이드에 노출되었다는 사실을 발견한 후 미국에서 여론이 바뀌었습니다. 미국에서 합법적인 낙태를 할 수 없었기 때문에, 그녀는 스웨덴으로 여행을 갔습니다. 1962년부터 1965년까지 독일 홍역의 발병으로 15,000명의 아기들이 심각한 선천적 장애를 갖게 되었습니다. 1967년 미국의사협회는 낙태법의 자유화를 공개적으로 지지했습니다. 1965년 국민여론조사센터 여론조사에 따르면 산모의 생명이 위험할 때 낙태를 지지하는 비율은 73%, 선천적 장애가 있을 때는 57%, 강간이나 근친상간으로 인한 임신은 59%로 나타났습니다.[176]

암

이 섹션을 업데이트해야 합니다. (2022년 9월) |

임신 중 암 발생률은 0.02~1%로 산모의 암은 산모의 생명을 보호하기 위해 낙태를 고려하거나 치료 중 태아에게 발생할 수 있는 잠재적인 손상에 대한 반응으로 이어지는 경우가 많습니다. 이것은 특히 자궁경부암에 해당되는데, 가장 흔한 유형은 임신 2,000-13,000건 중 1건에서 발생하며, 이 경우 치료 시작은 "태아 생명의 보존과 공존할 수 없습니다. (신보조 화학요법을 선택하지 않는 한)" 매우 초기 단계의 자궁경부암(I 및 IIa)은 근치적 자궁절제술 및 골반 림프절 박리술, 방사선 치료 또는 둘 다로 치료될 수 있으며, 후기 단계는 방사선 치료로 치료됩니다. 화학 요법을 동시에 사용할 수 있습니다. 임신 중 유방암의 치료에는 태아에 대한 고려도 수반되는데, 이는 임신 후기가 출산 후 추적 방사선 치료를 시행할 수 없는 한 수정된 근치적 유방 절제술을 선호하기 때문입니다.[177]

단일 화학 요법 약물에 노출되면 태아에 대한 기형 유발 효과의 7.5-17% 위험이 발생하는 것으로 추정되며 여러 약물 치료의 위험이 더 높습니다. 40Gy 이상의 방사선으로 치료하면 대개 자연유산이 됩니다. 임신 초기, 특히 발달 8~15주 동안 훨씬 더 낮은 용량에 노출되면 지적 장애나 소두증을 유발할 수 있으며, 이 단계 또는 이후 단계에서 노출되면 자궁 내 성장과 출생 체중이 감소할 수 있습니다. 0.005–0.025 Gy 이상에 노출되면 IQ가 용량에 따라 감소합니다.[177] 복부 차폐로 방사선 피폭량을 크게 줄일 수 있는 것은 조사 부위가 태아와 얼마나 멀리 떨어져 있느냐에 따라 가능합니다.[178][179]

출산 과정 자체도 산모를 위험에 빠뜨릴 수 있습니다. Li et al. 에 따르면, "[v]질 전달은 림프혈관 채널로 종양 세포의 파종, 출혈, 자궁경부 열상 및 에피시오토미 부위에 악성 세포의 이식을 초래할 수 있는 반면, 복부 전달은 비수술적 치료의 개시를 지연시킬 수 있습니다."[180]

역사와 종교

고대부터 낙태는 한약재가 유산자의 역할을 하거나, 무력을 사용하여 날카로운 도구를 사용하거나, 다른 전통적인 약재의 방법을 사용하여 행해졌습니다.[25] 낙태는 오랜 역사를 가지고 있으며 고대 중국,[182] 고대 인도,[183] 고대 이집트, 에버스 파피루스(기원전 1550년),c. 후베날 시대의 로마 제국(c.서기 200년)과 같이 다양한 문명으로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있습니다.[25] 낙태에 대한 가장 초기의 예술적 표현 중 하나는 앙코르 와트(1150)c.의 베이스 부조입니다. 힌두교와 불교 문화에서 사후 심판을 나타내는 일련의 프리즈에서 발견되며, 복부 낙태의 기술을 묘사합니다.[93]

유대교(창세기 2:7)에서 태아는 여성의 바깥에 안전하게 있고, 생존할 수 있으며, 첫 호흡을 할 때까지 인간의 영혼을 가진 것으로 간주되지 않습니다.[184][185][186] 태아는 자궁에 있는 동안 인간의 생명이 아닌 여성의 귀중한 재산으로 여겨집니다(출애굽기 21:22–23). 유대교는 사람들이 결실을 맺고 아이를 가짐으로써 증식하도록 장려하는 반면, 낙태는 허용되며 임신한 여성의 생명이 위험할 때 필요하다고 여겨집니다.[187][188] 인간의 삶은 임신에서 시작된다는 데 동의하지 않는 유대교를 포함한 몇몇 종교들은 종교의 자유를 이유로 낙태의 합법성을 지지합니다.[189] 이슬람교에서 낙태는 전통적으로 이슬람교도들이 영혼이 태아 안으로 들어간다고 믿는 시점까지 허용되는데,[25] 여러 신학자들은 임신 후 40일, 임신 후 120일, 또는 임신 후 120일까지라고 생각합니다.[190] 중동과 북아프리카와 같은 이슬람 신앙이 높은 지역에서는 낙태가 크게 제한되거나 금지됩니다.[191]

일부 의학자들과 낙태 반대자들은 히포크라테스 선서가 고대 그리스의 의사들이 낙태하는 것을 금지한다고 제안했습니다.[25] 다른 학자들은 이 해석에 동의하지 않으며 [25]히포크라테스 코퍼스의 의학 문헌은 선서 바로 옆에 낙태 기술에 대한 설명을 포함하고 있다고 말합니다.[192] 서기 43년에 의사 스크라이보니우스 라거스는 히포크라테스 선서가 에페소스의 소라누스와 마찬가지로 낙태를 금지한다고 썼지만, 당시 모든 의사들이 낙태를 엄격하게 준수하지는 않았습니다. 소라누스의 1세기 또는 2세기 CE 작업인 Gynaecology에 따르면, 의료 종사자들 중 한 당사자는 히포크라테스 선서에서 요구하는 모든 낙태를 금지했고, 그가 속한 다른 당사자는 어머니의 건강을 위해서만 낙태를 기꺼이 규정했습니다.[193][194] 정치학 (350 BCE)에서 아리스토텔레스는 유아 살해를 인구 통제의 수단으로 비난했습니다. 그는 이러한 경우에 낙태를 선호했는데,[195][196] "감동과 생명이 발달하기 전에 그것에 대해 실행되어야 한다. 합법적인 낙태와 불법적인 낙태 사이의 경계는 감각이 있고 살아 있다는 사실로 표시될 것이기 때문이다."[197]

가톨릭교회에서는 임신중절이 피임이나 구강성교, 임신중절보다 향락을 목적으로 한 결혼에서 성교 등의 행위에 비해 얼마나 심각한 낙태인지에 대한 의견이 분분했습니다.[198]: 155–167 가톨릭 교회는 19세기가 되어서야 낙태에 대한 강력한 반대를 시작했습니다.[25][189] 일찍이 ~100년경에 디다케는 낙태가 죄악이라고 가르쳤습니다.[199] 몇몇 역사학자들은 19세기 이전에는 대부분의 가톨릭 작가들이 임신을 촉진하거나 유혹하기 전에 임신을 중단하는 것을 낙태로 간주하지 않았다고 주장합니다.[200][201][202] 이 저자들 중에는 세인트루이스와 같은 교회의 의사들이 있었습니다. 아우구스티누스, 성 아우구스티누스 토마스 아퀴나스와 세인트. 알폰수스 리구오리. 1588년, 교황 식스토 5세 r.(1585–1590)는 교황 비오 9세 (그의 1869 황소 사도 세디스) 이전에 임신의 단계에 상관없이 모든 낙태를 살인으로 규정하고 낙태를 비난하는 교회 정책을 도입한 유일한 교황이었습니다.[203][198]: 362–364 [89]: 157–158 식스토 5세의 선언은 1591년 교황 그레고리오 14세에 의해 번복되었습니다.[204] 1917년의 교회법 재수정에서 사도 세디스는 어머니에 대한 파문을 배제한 판독 가능성을 제거하기 위해 부분적으로 강화되었습니다.[205] 교회의 가르침을 성문화한 요약본인 가톨릭교회 교리문답서에 나오는 발언들은 임신한 순간부터 낙태를 살인으로 간주하고 합법적인 낙태를 중단할 것을 촉구합니다.[206]

일부 제한된 범위에서 낙태 권리를 지지하는 교단에는 연합 감리교, 성공회, 미국 복음주의 루터교 및 미국 장로교가 있습니다.[207] 2014년 미국의 낙태 환자에 대한 Guttmacher 조사에 따르면 많은 사람들이 종교적 소속을 보고했습니다: 24%가 가톨릭 신자인 반면 30%는 개신교 신자였습니다.[208] 1995년 조사에 따르면 가톨릭 여성들은 일반인들만큼 임신을 중단할 가능성이 높고, 개신교인들은 임신을 중단할 가능성이 적으며, 복음주의 기독교인들은 임신을 중단할 가능성이 가장 적다고 합니다.[8][6] 2019년 퓨 리서치 센터 연구에 따르면 백인 복음주의자 35%[209]를 제외하고 대부분의 기독교 교단은 미국에서 낙태를 합법화한 로 대 웨이드(Roe v. Wade)를 뒤집는 것에 반대했습니다.

낙태는 상당히 일반적인 관행이었고, [211][212]19세기까지 항상 불법이거나 논란이 있었던 것은 아닙니다.[213][214] 1648년 에드워드 코크로 거슬러 올라가는 초기 영국 관습법을 포함한 관습법에 따르면,[215] 낙태는 일반적으로 임신을 촉진하기 전([216][217][218]태아 후 14-26주 또는 4개월에서 6개월 사이), 그리고 여성의 재량에 따라 허용되었습니다;[189] 이것이 범죄인지를 결정하는 것은 임신을 촉진한 후에 낙태가 이루어졌는지 여부였습니다.[215] 유럽과 북미에서는 17세기부터 낙태 기술이 발전했는데, 대부분의 의료계에서 성적 문제에 대한 보수주의가 낙태 기술의 광범위한 확장을 막았습니다.[25][219][220] 일부 의사 외에 다른 의료 종사자들도 그들의 서비스를 광고했고, 그들은 미국과 영국에서 때때로 [221]리텔리즘이라고 불리는 이 관행이 금지되었던 19세기까지 널리 규제되지 않았습니다.[25][nb 2]

가장 유명하고 결과적인 미국인 호라티오 스토러 중 한 명인 19세기 의사들은 도덕적 근거뿐만 아니라 인종차별주의자와 여성 혐오주의자에 대한 낙태 금지법을 주장했습니다.[222][223][224][225] 교회 단체들은 또한 낙태 반대 운동에 큰 영향을 미쳤고,[25][213][223] 종교 단체들은 20세기 이래로 더욱 그러했습니다.[222] 초기 낙태금지법 중에는 의사나 낙태 시술자만 처벌하는 경우도 있었고,[189] 여성은 스스로 유도한 낙태로 형사재판을 받을 수 있는 반면,[215] 일반적으로 기소되는 경우는 거의 없었습니다.[213] 미국에서는 1930년경 출산에 비해 낙태 절차가 점진적으로 개선되면서 낙태가 더 안전해 질 때까지 낙태가 출산보다 더 위험하다는 주장도 나왔습니다.[nb 3] 다른 사람들은 19세기 초기 낙태는 조산사들이 주로 일하는 위생적인 조건에서 비교적 안전했다고 주장합니다.[226][227][228] 몇몇 학자들은 개선된 의료 절차에도 불구하고, 1930년대부터 1970년대까지의 기간 동안 조직적인 범죄에 의한 낙태 제공자들에 대한 통제가 증가하면서 낙태 금지법의 더 많은 열정적인 시행이 있었다고 주장합니다.[nb 4]

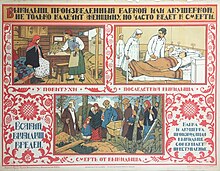

1920년 소련 러시아는 레닌이 어떤 여성도 강제로 출산하지 말라고 주장한 후 낙태를 합법화한 첫 번째 국가가 되었습니다.[229][230] 아이슬란드(1935)와 스웨덴(1938)은 낙태의 특정한 또는 모든 형태를 합법화하기 위해 이를 따를 것입니다.[231] 나치 독일(1935)에서는 "유전적으로 아픈" 사람들에게 낙태를 허용하는 법이 있었고, 독일 주식을 고려하는 여성들은 낙태하는 것이 특별히 금지되었습니다.[232] 20세기 후반부터 더 많은 국가에서 낙태가 합법화되었습니다.[25] 일본에서 낙태는 1948년 '우생보호법'에 의해 처음으로 합법화되었는데, 이는 '후천적' 인간의 출생을 막기 위한 것이었습니다. 2022년[update] 현재, 일본의 지속적인 가부장적 문화와 여성의 사회적 역할에 대한 전통적인 관점 때문에, 낙태를 원하는 여성들은 보통 그들의 파트너로부터 서면 허가를 받아야 합니다.[233][234]

사회와 문화

낙태 논쟁

유도 낙태는 오랫동안 상당한 논쟁의 대상이 되어 왔습니다. 낙태를 둘러싼 윤리적, 도덕적, 철학적, 생물학적, 종교적, 법적 문제는 가치체계와 관련이 있습니다. 낙태에 대한 의견은 태아의 권리, 정부의 권위, 그리고 여성의 권리에 관한 것일 수 있습니다.

공개 토론과 비공개 토론 모두에서 낙태 접근에 찬성하거나 반대하는 주장은 유도 낙태의 도덕적 허용성 또는 낙태를 허용하거나 제한하는 법의 정당성에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다.[235] 세계의사협회 '치료적 낙태에 관한 선언'은 "엄마의 이익과 태어나지 않은 아이의 이익이 충돌하는 상황은 딜레마를 야기하며 임신을 고의적으로 종료해야 하는지에 대한 의문을 제기한다"[236]고 지적했습니다. 특히 낙태법과 관련된 낙태 논쟁은 종종 이 두 가지 입장 중 하나를 옹호하는 단체들에 의해 주도됩니다. 완전한 금지를 포함하여 낙태에 대한 더 큰 법적 제한을 찬성하는 집단들은 대부분 스스로를 "친생명"이라고 표현하는 반면, 그러한 법적 제한에 반대하는 집단들은 스스로를 "친선택"이라고 표현합니다.[237]

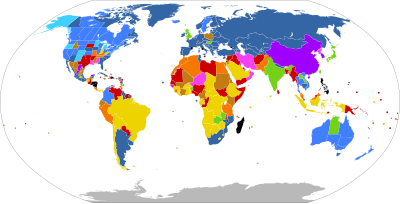

현대 낙태법

| 요청 시 법적: | |

| 임신제한 없음 | |

| 처음 17주 이후의 임신 제한 | |

| 처음 17주 동안의 임신 제한 | |

| 임신한계 불분명 | |

| 법적으로 다음의 경우에 한함: | |

| 여성의 생명, 건강*, 강간*, 태아 장애* 또는 사회경제적 요인에 대한 위험 | |

| 여성의 생명, 건강*, 강간 또는 태아 손상에 대한 위험 | |

| 여성의 생명, 건강* 또는 태아 손상에 대한 위험 | |

| 여성의 생명에 대한 위험*, 건강에 대한 위험*, 강간* | |

| 여성의 생명이나 건강에 대한 위험 | |

| 여성의 생명에 대한 위험 | |

| 예외없이 불법임 | |

| 정보 없음 | |

| * 해당 범주의 일부 국가 또는 영토에는 적용되지 않음 | |

낙태와 관련된 현행 법률은 다양합니다. 종교적, 도덕적, 문화적 요인이 전 세계적으로 낙태법에 계속 영향을 미치고 있습니다. 생명권, 자유권, 사람의 담보권, 생식건강권 등이 낙태죄 존부의 근거가 되는 인권의 주요 쟁점입니다.

낙태가 합법적인 지역에서는 여성이 합법적인 낙태(여성의 동의 없이 행해지는 낙태는 피티사이드로 간주됨)를 얻기 전에 종종 특정 요건을 충족해야 합니다. 이러한 요구 사항은 일반적으로 태아의 나이에 따라 달라지는데, 종종 합법성의 창을 규제하기 위해 삼박자 기반 시스템을 사용하거나 미국에서처럼 태아의 생존 가능성에 대한 의사의 평가에 따라 결정됩니다. 일부 관할 구역에서는 시술 전 대기 기간을 요구하거나 태아 발달 정보 배포를 규정하거나 미성년자인 딸이 낙태를 요청할 경우 부모에게 연락하도록 하고 있습니다.[238] 그 밖의 관할구역에서는 여성이 태아를 낙태하기 전에 태아의 아버지의 동의를 받아야 할 것을 요구할 수 있고, 낙태 제공자들이 여성들에게 시술의 건강상 위험에 대해 알려주고, 때로는 의학 문헌에 의해 뒷받침되지 않는 "risks"을 포함하며, 여러 의료 당국이 낙태가 의학적 또는 사회적으로 필요하다는 것을 증명합니다. 비상 상황에서는 많은 제한이 면제됩니다. 한[239] 자녀 정책을 종료하고 현재 두 자녀 정책을 시행하고 있는 [240][241]중국은 인구 통제 전략의 일환으로 때때로 의무적인 낙태를 포함시켰습니다.[242]

다른 지역에서는 낙태를 거의 전면적으로 금지하고 있습니다. 이것들의 전부는 아니지만 많은 것들이 다양한 상황에서 합법적인 낙태를 허용합니다. 이러한 상황은 관할권에 따라 다르지만, 임신이 강간이나 근친상간의 결과인지, 태아의 발달이 손상되었는지, 여성의 신체적 또는 정신적 행복이 위험에 처했는지, 또는 사회경제적 고려로 출산을 어렵게 하는지 등이 포함될 수 있습니다.[41] 니카라과처럼 낙태가 전면 금지된 나라들에서 의료 당국은 임신으로 인한 산모 사망은 물론 다른 산부인과 응급 상황을 치료할 경우 의사들의 기소 우려로 사망하는 등 직간접적으로 산모 사망이 증가한 것으로 기록했습니다.[243][244] 방글라데시와 같이 명목상 낙태를 금지하는 일부 국가들은 월경위생을 가장하여 낙태를 시술하는 진료소를 지원할 수도 있습니다.[245] 이것은 전통 의학의 용어이기도 합니다.[246] 낙태가 불법이거나 심한 사회적 낙인이 찍혀 있는 곳에서는 임산부가 의료 관광에 종사하고 임신을 종료할 수 있는 국가로 여행할 수 있습니다.[247] 여행할 수단이 없는 여성들은 불법 낙태 제공자들에게 의존하거나 스스로 낙태를 시도할 수 있습니다.[248]

Women on Waves라는 단체는 1999년부터 의학적 낙태에 대한 교육을 제공하고 있습니다. NGO는 운송 컨테이너 안에 이동식 진료소를 만들었고, 그런 다음 임대된 배를 타고 낙태 제한법이 있는 국가로 이동합니다. 네덜란드에 등록된 선박이기 때문에 네덜란드 법은 선박이 공해에 있을 때 우선 적용됩니다. 이 단체는 항구에 있는 동안 무료 워크숍과 교육을 제공하고, 공해에서는 의료진이 합법적으로 낙태 약물을 처방하고 상담할 수 있습니다.[249][250][251]

성선택적 낙태

초음파 검사와 양수 검사를 통해 부모는 출산 전에 성을 결정할 수 있습니다. 이 기술의 발전은 성 선택적 낙태, 즉 성에 따라 태아를 종료시키는 결과로 이어졌습니다. 여성 태아의 선택적 종결은 가장 일반적입니다.

성 선택적 낙태는 일부 국가에서 남녀 아이들의 출산율 사이에 눈에 띄는 차이에 부분적으로 책임이 있습니다. 아시아의 많은 지역에서 남자 아이들에 대한 선호도가 보고되고 있으며, 대만, 한국, 인도, 중국에서 여성 출생을 제한하기 위해 사용되는 낙태가 보고되었습니다.[252] 문제의 국가가 공식적으로 성 선택적 낙태나 심지어 성 선별을 금지했을 수도 있음에도 불구하고, 이러한 남성과 여성의 표준 출산율과의 편차는 발생합니다.[253][254][255][256] 중국에서는 1979년 제정된 한 자녀 정책으로 인해 남성 자녀에 대한 역사적 선호 현상이 악화되었습니다.[257]

많은 나라들이 성 선택적 낙태의 발생을 줄이기 위한 입법 조치를 취했습니다. 1994년 국제 인구 개발 회의에서 180개 이상의 주에서 "여자 아이에 대한 모든 형태의 차별과 아들 선호의 근본 원인"을 제거하기로 합의했으며,[258] 2011년 PACE 결의안에 의해 비난을 받은 조건도 있습니다.[259] 세계보건기구(WHO)와 유니세프(UNICEF)는 다른 유엔 기관들과 함께 성 선택적 낙태를 줄이기 위해 낙태에 대한 접근을 제한하는 조치가 의도하지 않은 부정적인 결과를 초래한다는 것을 발견했는데, 이는 주로 여성들이 안전하지 않은, 불법적인 낙태를 추구하거나 강요받을 수 있다는 사실에서 비롯됩니다.[258] 반면에, 성 불평등을 줄이기 위한 조치는 부정적인 결과를 수반하지 않으면서 그러한 낙태의 유병률을 줄일 수 있습니다.[258][260]

낙태반대폭력

낙태 제공자와 이들 시설은 살인, 살인미수, 납치, 스토킹, 폭행, 방화, 폭파 등 다양한 형태의 폭력을 당했습니다. 낙태 반대 폭력은 정부와 학자들에 의해 테러로 분류됩니다.[261][262] 미국과 캐나다에서는 1977년 이후 200건 이상의 폭탄 테러/총기와 수백 건의 폭행을 포함하여 8,000건 이상의 폭력, 무단 침입 및 사망 위협 사건이 제공업체에 의해 기록되었습니다.[263] 낙태 반대자들의 대다수는 폭력적인 행위에 관여하지 않았습니다.

미국에서는 낙태 시술 의사 데이비드 건(1993), 존 브리튼(1994), 바넷 슬레피안(1998), 조지 틸러(2009) 등 4명이 살해됐습니다. 또한 미국과 호주에서는 제임스 배럿, 섀넌 로니, 리앤 니콜스, 로버트 샌더슨과 같은 접수원과 경비원을 포함한 낙태 클리닉의 다른 직원들도 살해되었습니다. 미국과 캐나다에서도 상처(예: Garson Romalis)와 살인 미수 사건이 발생했습니다. 낙태 제공자에 대한 수백 건의 폭격, 방화, 산성 공격, 침입, 공공 기물 파손 사건이 발생했습니다.[264][265] 낙태 반대 폭력의 주목할 만한 가해자로는 에릭 로버트 루돌프, 스콧 로더, 셸리 섀넌, 폴 제닝스 힐 등이 있습니다.[266]

낙태가 합법적인 일부 국가에서는 낙태에 대한 접근을 법적으로 보호하고 있습니다. 이러한 법은 일반적으로 낙태 클리닉을 방해, 파괴, 피켓팅 및 기타 행동으로부터 보호하거나 위협과 괴롭힘으로부터 여성과 그러한 시설의 직원을 보호하려고 합니다.

물리적 폭력보다 훨씬 더 흔한 것은 심리적 압박입니다. 2003년, Chris Danze는 오스틴에 있는 Planned Parenthood 시설의 건설을 막기 위해 텍사스 전역에서 낙태 반대 단체들을 조직했습니다. 이 단체들은 공사 관계자들의 신상정보를 온라인에 공개하고 하루 최대 1200통의 전화를 보내 교회에 연락했습니다.[267] 일부 시위자들은 여성들이 진료소에 들어가는 것을 카메라에 녹화합니다.[267]

비인간적인 예

자연유산은 다양한 동물에서 발생합니다. 예를 들어, 양의 경우 문을 통해 몰려들거나 개에게 쫓기는 것과 같은 스트레스나 신체적인 힘으로 인해 발생할 수 있습니다.[268] 소의 경우, 낙태는 브루셀라증이나 캄필로박터와 같은 전염성 질병에 의해 발생할 수 있지만, 종종 백신 접종으로 통제될 수 있습니다.[269] 솔잎을 먹으면 소의 낙태도 유도할 수 있습니다.[270][271] 빗자루풀, 스컹크 양배추, 독 헴록, 나무 담배를 포함한 여러 식물은 소와[272]: 45–46 양과 염소에서 태아 기형과 낙태를 유발하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[272]: 77–80 말의 경우, 태아가 치명적인 백색 증후군(생식기성 장신경절증)을 가지고 있으면 낙태되거나 재흡수될 수 있습니다. 지배적인 백색 유전자(WW)에 대해 동형접합을 하는 망아지 배아도 출생 전에 낙태되거나 재흡수되는 것으로 이론화되어 있습니다.[273] 많은 상어와 가오리 종에서 스트레스로 인한 낙태가 포획 시 자주 발생합니다.[274]

바이러스 감염은 개의 낙태를 유발할 수 있습니다.[275] 고양이는 호르몬 불균형을 포함한 많은 이유로 자연유산을 경험할 수 있습니다. 임신한 고양이, 특히 트랩 중성자 복귀 프로그램에서 원치 않는 고양이가 태어나지 않도록 임신한 고양이를 대상으로 낙태와 스파잉을 병행합니다.[276][277][278] 암컷 설치류는 브루스 효과라고 알려진 임신에 책임이 없는 수컷의 냄새에 노출되면 임신을 종료할 수 있습니다.[279]

동물 사육의 맥락에서 동물에게도 낙태가 유도될 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 부적절하게 교미된 암말, 또는 암말이 임신한 것을 인지하지 못한 소유자가 구입한 암말에서 낙태가 유도될 수 있습니다.[280] 야생에서의 빈도는 의문시되고 있지만,[281][282][283] 말과 얼룩말에서 페티사이드가 발생할 수 있는 것은 임신한 암말의 수컷 괴롭힘이나 강제 교배 때문입니다.[284] 수컷 회색랑구르 원숭이들은 수컷을 차지한 후 암컷을 공격하여 유산을 일으킬 수도 있습니다.[285]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 산부인과(OB/GYN) 교재, 사전 및 기타 출처에 명시된 정의 목록은 낙태의 정의를 참조하십시오. 낙태에 대한 정의는 출처마다 다르며, 낙태를 정의하는 데 사용되는 언어는 과학적 지식뿐만 아니라 사회적, 정치적 의견을 반영하는 경우가 많습니다.[1]

- ^ 미국에서는 1820년대에 시작된 낙태와 관련된 최초의 법이 실제 또는 인지된 위험으로부터 여성을 보호하기 위해 만들어졌고, 더 제한적인 법은 제공자에게만 불이익을 주었습니다. 1859년까지 33개 주 중 21개 주에서 낙태는 범죄가 되지 않았고, 낙태 이전에 대한 처벌은 더 낮았지만, 낙태는 금지되었습니다. 이는 1860년대부터 반이민적, 반카톨릭적 정서의 영향을 받아 변했습니다.[189]

- ^ 1930년까지 미국의 의료 절차는 출산과 낙태 모두 개선되었지만 동등하지는 않았으며 임신 초기에 유도된 낙태는 출산보다 안전해졌습니다. 1973년 로 대 웨이드(Roe v. Wade)는 임신 초기의 낙태가 출산보다 안전하다는 것을 인정했습니다. 출처는 다음을 참조하십시오.

- "The 1970s". Time Communication 1940–1989: Retrospective. Time. 1989.

Blackmun was also swayed by the fact that most abortion prohibitions were enacted in the 19th century when the procedure was more dangerous than now.

- Will GF (1990). Suddenly: The American Idea Abroad and at Home, 1986–1990. Free Press. p. 312. ISBN 0-02-934435-2.

- Lewis J, Shimabukuro JO (28 January 2001). "Abortion Law Development: A Brief Overview". Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Schultz DA (2002). Encyclopedia of American Law. Infobase Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 0-8160-4329-9. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015.

- Lahey JN (24 September 2009). "Birthing a Nation: Fertility Control Access and the 19th Century Demographic Transition" (PDF; preliminary version). Colloquium. Pomona College. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2012.

- "The 1970s". Time Communication 1940–1989: Retrospective. Time. 1989.

- ^ 출처는 다음을 참조하십시오.

- 제임스 도너, 곤경에 처한 여성들: 미국에서의 낙태에 관한 진실, 모나크 북스, 1959.

- 앤 오클리, 잡힌 자궁, 바질 블랙웰, 1984, 91쪽.

- 리키 솔린저, 낙태론자: 법에 반대하는 여자, 자유언론, 1994, pp. xi, 5, 16–17, 157–175.

- 레슬리 J. 레이건, 낙태가 범죄였을 때: 미국의 여성, 의학, 그리고 법, 1867–1973, 캘리포니아 대학 출판, 1997.

- 맥스 에반스, 밀리 부인: Silver City에서 Kitchikan, University of New Mexico Press, 2002, pp. 209–218, 230, 267–286, 305

참고문헌

- ^ Kulczycki A. "Abortion". Oxford Bibliographies. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ The Johns Hopkins Manual of Gynecology and Obstetrics (4 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012. pp. 438–439. ISBN 9781451148015. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ "How many people are affected by or at risk for pregnancy loss or miscarriage?". www.nichd.nih.gov. 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Home : Oxford English Dictionary". www.oed.com. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ "Abortion (noun)". Oxford Living Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

[mass noun] The deliberate termination of a human pregnancy, most often performed during the first 28 weeks of pregnancy

- ^ a b c d e f Bankole A, Singh S, Haas T (1998). "Reasons Why Women Have Induced Abortions: Evidence from 27 Countries". International Family Planning Perspectives. 24 (3): 117–127, 152. doi:10.2307/3038208. JSTOR 3038208. Archived from the original on 17 January 2006.

Worldwide, the most commonly reported reason women cite for having an abortion is to postpone or stop childbearing. The second most common reason—socioeconomic concerns—includes disruption of education or employment; lack of support from the father; desire to provide schooling for existing children; and poverty, unemployment or inability to afford additional children. In addition, relationship problems with a husband or partner and a woman's perception that she is too young constitute other important categories of reasons. Women's characteristics are associated with their reasons for having an abortion: With few exceptions, older women and married women are the most likely to identify limiting childbearing as their main reason for abortion. - Conclusions - Reasons women give for why they seek abortion are often far more complex than simply not intending to become pregnant; the decision to have an abortion is usually motivated by more than one factor.

- ^ a b Chae, Sophia; Desai, Sheila; Crowell, Marjorie; Sedgh, Gilda (1 October 2017). "Reasons why women have induced abortions: a synthesis of findings from 14 countries". Contraception. 96 (4): 233–241. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2017.06.014. PMC 5957082. PMID 28694165.

In most countries, the most frequently cited reasons for having an abortion were socioeconomic concerns or limiting childbearing. With some exceptions, little variation existed in the reasons given by women's sociodemographic characteristics. Data from three countries where multiple reasons could be reported in the survey showed that women often have more than one reason for having an abortion.

- ^ a b c d e f "The limitations of U.S. statistics on abortion". Issues in Brief. New York: The Guttmacher Institute. 1997. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012.

- ^ a b Stotland NL (July 2019). "Update on Reproductive Rights and Women's Mental Health". The Medical Clinics of North America. 103 (4): 751–766. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2019.02.006. PMID 31078205. S2CID 153307516.

- ^ a b c d e Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S, Romero M, Ganatra B, Okonofua FE, Shah IH (25 November 2006). "Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic". Lancet. 368 (9550): 1908–1919. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6. PMID 17126724. S2CID 6188636.

- ^ a b c Raymond EG, Grossman D, Weaver MA, Toti S, Winikoff B (November 2014). "Mortality of induced abortion, other outpatient surgical procedures and common activities in the United States". Contraception. 90 (5): 476–479. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.012. PMID 25152259.

Results: The abortion-related mortality rate in 2000-2009 in the United States was 0.7 per 100,000 abortions. Studies in approximately the same years found mortality rates of 0.8-1.7 deaths per 100,000 plastic surgery procedures, 0-1.7 deaths per 100,000 dental procedures, 0.6-1.2 deaths per 100,000 marathons run and at least 4 deaths among 100,000 cyclists in a large annual bicycling event. The traffic fatality rate per 758 vehicle miles traveled by passenger cars in the United States in 2007-2011 was about equal to the abortion-related mortality rate. Conclusions: The safety of induced abortion as practiced in the United States for the past decade met or exceeded expectations for outpatient surgical procedures and compared favorably to that of two common nonmedical voluntary activities.

- ^ a b Raymond EG, Grimes DA (February 2012). "The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 119 (2 Pt 1): 215–219. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823fe923. PMID 22270271. S2CID 25534071.

Conclusion: Legal induced abortion is markedly safer than childbirth. The risk of death associated with childbirth is approximately 14 times higher than that with abortion. Similarly, the overall morbidity associated with childbirth exceeds that with abortion.

- ^ "Preventing unsafe abortion". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ "Self-management Recommendation 50: Self-management of medical abortion in whole or in part at gestational ages < 12 weeks (3.6.2) - Abortion care guideline". WHO Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research. 19 November 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Moseson H, Jayaweera R, Raifman S, Keefe-Oates B, Filippa S, Motana R, et al. (October 2020). "Self-managed medication abortion outcomes: results from a prospective pilot study". Reproductive Health. 17 (1): 164. doi:10.1186/s12978-020-01016-4. PMC 7588945. PMID 33109230.

- ^ Moseson H, Jayaweera R, Egwuatu I, Grosso B, Kristianingrum IA, Nmezi S, et al. (January 2022). "Effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion with accompaniment support in Argentina and Nigeria (SAFE): a prospective, observational cohort study and non-inferiority analysis with historical controls". The Lancet. Global Health. 10 (1): e105–e113. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00461-7. PMC 9359894. PMID 34801131.

- ^ Faúndes A, Shah IH (October 2015). "Evidence supporting broader access to safe legal abortion". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. World Report on Women's Health 2015: The unfinished agenda of women's reproductive health. 131 (Suppl 1): S56–S59. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.03.018. PMID 26433508.

A strong body of accumulated evidence shows that the simple means to drastically reduce unsafe abortion-related maternal deaths and morbidity is to make abortion legal and institutional termination of pregnancy broadly accessible. [...] [C]riminalization of abortion only increases mortality and morbidity without decreasing the incidence of induced abortion, and that decriminalization rapidly reduces abortion-related mortality and does not increase abortion rates.

- ^ Latt, Su Mon; Milner, Allison; Kavanagh, Anne (January 2019). "Abortion laws reform may reduce maternal mortality: an ecological study in 162 countries". BMC Women's Health. 19 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0705-y. PMC 6321671. PMID 30611257.

- ^ a b c d Zhang J, Zhou K, Shan D, Luo X (May 2022). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (5): CD002855. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub5. PMC 9128719. PMID 35608608.

- ^ a b c Kapp N, Whyte P, Tang J, Jackson E, Brahmi D (September 2013). "A review of evidence for safe abortion care". Contraception. 88 (3): 350–363. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.027. PMID 23261233.

- ^ "Abortion – Women's Health Issues". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ a b c Lohr PA, Fjerstad M, Desilva U, Lyus R (2014). "Abortion". BMJ. 348: f7553. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7553. S2CID 220108457.

- ^ "Induced Abortion Worldwide Guttmacher Institute". Guttmacher.org. 1 March 2018. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "Abortion". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD, Joffe C (2009). "1. Abortion and medicine: A sociopolitical history" (PDF). Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy (1st ed.). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-1293-5. OL 15895486W. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012.

- ^ "Abortion". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ "Worldwide, an estimated 25 million unsafe abortions occur each year". World Health Organization. 28 September 2017. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sedgh G, Singh S, Shah IH, Ahman E, Henshaw SK, Bankole A (February 2012). "Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008" (PDF). Lancet. 379 (9816): 625–632. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61786-8. PMID 22264435. S2CID 27378192. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2012.

Because few of the abortion estimates were based on studies of random samples of women, and because we did not use a model-based approach to estimate abortion incidence, it was not possible to compute confidence intervals based on standard errors around the estimates. Drawing on the information available on the accuracy and precision of abortion estimates that were used to develop the subregional, regional, and worldwide rates, we computed intervals of certainty around these rates (webappendix). We computed wider intervals for unsafe abortion rates than for safe abortion rates. The basis for these intervals included published and unpublished assessments of abortion reporting in countries with liberal laws, recently published studies of national unsafe abortion, and high and low estimates of the numbers of unsafe abortion developed by WHO.

- ^ Sedgh G, Henshaw SK, Singh S, Bankole A, Drescher J (September 2007). "Legal abortion worldwide: incidence and recent trends". International Family Planning Perspectives. 33 (3): 106–116. doi:10.1363/3310607. PMID 17938093. Archived from the original on 19 August 2009.

- ^ "Induced Abortion Worldwide". Guttmacher Institute. 1 March 2018. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

Of the world's 1.64 billion women of reproductive age, 6% live where abortion is banned outright, and 37% live where it is allowed without restriction as to reason. Most women live in countries with laws that fall between these two extremes.

- ^ a b c Culwell KR, Vekemans M, de Silva U, Hurwitz M, Crane BB (July 2010). "Critical gaps in universal access to reproductive health: contraception and prevention of unsafe abortion". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 110 (Suppl): S13–S16. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.04.003. PMID 20451196. S2CID 40586023.

- ^ "Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion Worldwide". Guttmacher Institute. 28 May 2020. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

Abortion is sought and needed even in settings where it is restricted—that is, in countries where it is prohibited altogether or is allowed only to save the women's life or to preserve her physical or mental health. Unintended pregnancy rates are highest in countries that restrict abortion access and lowest in countries where abortion is broadly legal. As a result, abortion rates are similar in countries where abortion is restricted and those where the procedure is broadly legal (i.e., where it is available on request or on socioeconomic grounds).

- ^ Staff, F. P. (24 June 2022). "Roe Abolition Makes U.S. a Global Outlier". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ Paola A, Walker R, LaCivita L (2010). Nixon F (ed.). Medical ethics and humanities. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-7637-6063-2. OL 13764930W. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

- ^ Johnstone MJ (2009). "Bioethics a nursing perspective". Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses Journal (5th ed.). Sydney, NSW: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. 3 (4): 24–30. ISBN 978-0-7295-7873-8. PMID 2129925. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

Although abortion has been legal in many countries for several decades now, its moral permissibilities continues to be the subject of heated public debate.

- ^ Driscoll M (18 October 2013). "What do 55 million people have in common?". Fox News. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Hansen D (18 March 2014). "Abortion: Murder, or Medical Procedure?". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Sifris RN (2013). Reproductive freedom, torture and international human rights: challenging the masculinisation of torture. Hoboken, NJ: Taylor & Francis. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-135-11522-7. OCLC 869373168. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015.

- ^ Åhman, Elisabeth (2007). Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003 (5th ed.). World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-159612-1. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ 파비올라 산체스, 메간 야네츠키, 멕시코 낙태 비범죄화, 시술 접근성 확대 중남미 추세 확대, 2023년 9월 6일 AP통신

- ^ a b c Boland R, Katzive L (September 2008). "Developments in laws on induced abortion: 1998-2007". International Family Planning Perspectives. 34 (3): 110–120. doi:10.1363/3411008. PMID 18957353. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011.

- ^ Cheng L (1 November 2008). "Surgical versus medical methods for second-trimester induced abortion". The WHO Reproductive Health Library. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ Bankole A, Singh S, Haas T (1998). "Reasons Why Women Have Induced Abortions: Evidence from 27 Countries". International Family Planning Perspectives. 24 (3): 117–27, 152. doi:10.2307/3038208. JSTOR 3038208. Archived from the original on 17 January 2006.

- ^ Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM (September 2005). "Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantitative and qualitative perspectives" (PDF). Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 37 (3): 110–118. doi:10.1111/j.1931-2393.2005.tb00045.x. PMID 16150658. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2006.

- ^ Stubblefield PG (2002). "10. Family Planning". In Berek JS (ed.). Novak's Gynecology (13 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-3262-8.

- ^ Bartlett LA, Berg CJ, Shulman HB, Zane SB, Green CA, Whitehead S, Atrash HK (2004). "Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 103 (4): 729–737. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000116260.81570.60. PMID 15051566. S2CID 42597014.

- ^ Roche NE (28 September 2004). "Therapeutic Abortion". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 14 December 2004. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, Halvorson LM, Hoffman BL, Bradshaw KD, Cunningham FG, eds. (2008). "6. First-Trimester Abortion". Williams Gynecology (1 ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-147257-9.

- ^ Janiak, Elizabeth; Goldberg, Alisa B. (1 February 2016). "Eliminating the phrase 'elective abortion': why language matters". Contraception. 93 (2): 89–92. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.10.008. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 26480889. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Churchill Livingstone medical dictionary. Edinburgh New York: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. 2008. ISBN 978-0-443-10412-1.

The preferred term for unintentional loss of the product of conception prior to 24 weeks' gestation is miscarriage.

- ^ AnnasGJ, Elias S (2007). "51. Legal and Ethical Issues in Obstetric Practice". In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL (eds.). Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. p. 669. ISBN 978-0-443-06930-7.

A preterm birth is defined as one that occurs before the completion of 37 menstrual weeks of gestation, regardless of birth weight.

- ^ Stillbirth. Concise Medical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0199557141. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015.

birth of a fetus that shows no evidence of life (heartbeat, respiration, or independent movement) at any time later than 24 weeks after conception

- ^ "7 FAM 1470 Documenting Stillbirth (Fetal Death)". United States Department of State. 18 February 2011. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Annas GJ, Elias S (2007). "24. Pregnancy loss". In Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL (eds.). Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-06930-7.

- ^ Jarvis GE (7 June 2017). "Early embryo mortality in natural human reproduction: What the data say [version 2; peer review: 2 approved, 1 approved with reservations]". f1000research.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ Jarvis GE (26 August 2016). "Estimating limits for natural human embryo mortality [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]". f1000research.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Katz VL (2007). "16. Spontaneous and Recurrent Abortion – Etiology, Diagnosis, Treatment". In Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM (eds.). Katz: Comprehensive Gynecology (5 th ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-02951-3.

- ^ Stovall TG (2002). "17. Early Pregnancy Loss and Ectopic Pregnancy". In Berek JS (ed.). Novak's Gynecology (13 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-3262-8.

- ^ Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Casey BM, Sheffield JS, eds. (2014). Williams Obstetrics (24th ed.). McGraw Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-179893-8.

- ^ a b Stöppler MS. Shiel Jr WC (ed.). "Miscarriage (Spontaneous Abortion)". MedicineNet.com. WebMD. Archived from the original on 29 August 2004. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ a b Jauniaux E, Kaminopetros P, El-Rafaey H (1999). "Early pregnancy loss". In Whittle MJ, Rodeck CH (eds.). Fetal medicine: basic science and clinical practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 837. ISBN 978-0-443-05357-3. OCLC 42792567.[영구적 데드링크]

- ^ "Fetal Homicide Laws". National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ a b Creinin MD, Gemzell-Danielsson K (2009). "Medical abortion in early pregnancy". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD (eds.). Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 111–134. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ a b Kapp N, von Hertzen H (2009). "Medical methods to induce abortion in the second trimester". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD (eds.). Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 178–192. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ a b c Chen MJ, Creinin MD (July 2015). "Mifepristone With Buccal Misoprostol for Medical Abortion: A Systematic Review". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 126 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000897. PMID 26241251. S2CID 20800109. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ a b Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (8 February 2019). "Mifeprex (mifepristone) Information". FDA. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Wildschut H, Both MI, Medema S, Thomee E, Wildhagen MF, Kapp N (January 2011). "Medical methods for mid-trimester termination of pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (1): CD005216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005216.pub2. PMC 8557267. PMID 21249669.

- ^ a b WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2006). Frequently asked clinical questions about medical abortion (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 92-4-159484-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Fjerstad M, Sivin I, Lichtenberg ES, Trussell J, Cleland K, Cullins V (September 2009). "Effectiveness of medical abortion with mifepristone and buccal misoprostol through 59 gestational days". Contraception. 80 (3): 282–286. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.03.010. PMC 3766037. PMID 19698822. 2001년부터 2006년 3월까지 미국의 Planned Parenthood 클리닉에서 이전에 사용한 요법(mifepristone 200 mg, 이후 24-48시간 후 질 미소프로스톨 800 mcg)은 임신 63일 동안 98.5%의 효과가 있었고, 임신율은 약 0.5%였습니다. 그리고 문제성 출혈, 지속적인 임신낭, 임상의의 판단 또는 여성의 요청을 포함한 다양한 이유로 자궁 밖으로 배출되는 여성의 1%가 추가로 발생합니다. 2006년 4월부터 현재 미국의 Planned Parenthood 클리닉에서 사용하고 있는 이 요법(mifepristone 200 mg, 24-48시간 후 buccal misoprostol 800 mcg)은 임신 59일 동안 98% 효과가 있습니다.

- ^ Holmquist S, Gilliam M (2008). "Induced abortion". In Gibbs RS, Karlan BY, Haney AF, Nygaard I (eds.). Danforth's obstetrics and gynecology (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 586–603. ISBN 978-0-7817-6937-2.

- ^ "Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2010" (PDF). London: Department of Health, United Kingdom. 24 May 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ "Abortion statistics, year ending 31 December 2010" (PDF). Edinburgh: ISD, NHS Scotland. 31 May 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Vilain A, Mouquet MC (22 June 2011). "Voluntary terminations of pregnancies in 2008 and 2009" (PDF). Paris: DREES, Ministry of Health, France. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ "Abortions in Switzerland 2010". Neuchâtel: Office of Federal Statistics, Switzerland. 5 July 2011. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Jones RK, Witwer E, Jerman J (2019). Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2017 (Report). Guttmacher Institute. doi:10.1363/2019.30760.

- ^ Gissler M, Heino A (21 February 2011). "Induced abortions in the Nordic countries 2009" (PDF). Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ a b Meckstroth K, Paul M (2009). "First-trimester aspiration abortion". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD (eds.). Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 135–156. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ a b c d Gambir K, Kim C, Necastro KA, Ganatra B, Ngo TD (March 2020). "Self-administered versus provider-administered medical abortion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (3): CD013181. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013181.pub2. PMC 7062143. PMID 32150279.

- ^ Healthwise (2004). "Manual and vacuum aspiration for abortion". WebMD. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ World Health Organization (2017). "Dilatation and curettage". Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Guide for Midwives and Doctors. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154587-7. OCLC 181845530. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ Hammond C, Chasen S (2009). Dilation and evacuation. In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES Borgatta L Grimes DA Stubblefield P Creinin (eds)Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 178–192. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ "ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 135: Second-trimester abortion". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 121 (6): 1394–1406. June 2013. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000431056.79334.cc. PMID 23812485. S2CID 205384119.

- ^ a b Templeton A, Grimes DA (December 2011). "Clinical practice. A request for abortion". The New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (23): 2198–2204. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1103639. PMID 22150038.

- ^ Allen RH, Singh R (June 2018). "Society of Family Planning clinical guidelines pain control in surgical abortion part 1 - local anesthesia and minimal sedation". Contraception. 97 (6): 471–477. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.014. PMID 29407363. S2CID 3777869. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Cansino C, Denny C, Carlisle AS, Stubblefield P (December 2021). "Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: Pain control in surgical abortion part 2 - Moderate sedation, deep sedation, and general anesthesia". Contraception. 104 (6): 583–592. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2021.08.007. PMID 34425082. S2CID 237279946. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Borgatta, Lynn (December 2014). "Labor Induction Termination of Pregnancy". Global Library of Women's Medicine. GLOWM.10444. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10444. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Borgatta, Lynn; Kapp, Nathalie (July 2011). "Clinical guidelines. Labor induction abortion in the second trimester". Contraception. 84 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.005. PMID 21664506. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

10. What is the effect of feticide on labor induction abortion outcome? Deliberately causing demise of the fetus before labor induction abortion is performed primarily to avoid transient fetal survival after expulsion; this approach may be for the comfort of both the woman and the staff, to avoid futile resuscitation efforts. Some providers allege that feticide also facilitates delivery, although little data support this claim. Transient fetal survival is very unlikely after intraamniotic installation of saline or urea, which are directly feticidal. Transient survival with misoprostol for labor induction abortion at greater than 18 weeks ranges from 0% to 50% and has been observed in up to 13% of abortions performed with high-dose oxytocin. Factors associated with a higher likelihood of transient fetal survival with labor induction abortion include increasing gestational age, decreasing abortion interval and the use of nonfeticidal inductive agents such as the PGE1 analogues.

- ^ 2015 Clinical Policy Guidelines (PDF). National Abortion Federation. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

Policy Statement: Medical induction abortion is a safe and effective method for termination of pregnancies beyond the first trimester when performed by trained clinicians in medical offices, freestanding clinics, ambulatory surgery centers, and hospitals. Feticidal agents may be particularly important when issues of viability arise.

- ^ a b Riddle, John M (1997). Eve's herbs: a history of contraception and abortion in the West. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-27024-4. OCLC 36126503.

- ^ Sullivan JB, Rumack BH, Thomas H, Peterson RG, Bryson P (December 1979). "Pennyroyal oil poisoning and hepatotoxicity". JAMA. 242 (26): 2873–2874. doi:10.1001/jama.1979.03300260043027. PMID 513258. S2CID 26198529.

- ^ Ciganda C, Laborde A (2003). "Herbal infusions used for induced abortion". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 41 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1081/CLT-120021104. PMID 12807304. S2CID 44851492.

- ^ Smith JP (1998). "Risky choices: the dangers of teens using self-induced abortion attempts". Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 12 (3): 147–151. doi:10.1016/S0891-5245(98)90245-0. PMID 9652283.

- ^ a b c d Potts M, Graff M, Taing J (October 2007). "Thousand-year-old depictions of massage abortion". The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 33 (4): 233–234. doi:10.1783/147118907782101904. PMID 17925100.

- ^ Thapa SR, Rimal D, Preston J (September 2006). "Self induction of abortion with instrumentation". Australian Family Physician. 35 (9): 697–698. PMID 16969439. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009.

- ^ "The Prevention and Management of Unsafe Abortion" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 1992. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ Grimes DA, Creinin MD (April 2004). "Induced abortion: an overview for internists". Annals of Internal Medicine. 140 (8): 620–626. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00009. PMID 15096333.

- ^ Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Mayes N, Johnston E, et al. (May 2019). "Vital Signs: Pregnancy-Related Deaths, United States, 2011-2015, and Strategies for Prevention, 13 States, 2013-2017". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (18): 423–429. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6818e1. PMC 6542194. PMID 31071074.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences Engineering; Health Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Board on Population Health Public Health Practice; Committee on Reproductive Health Services: Assessing the Safety Quality of Abortion Care in the U.S (2018). Read "The Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the United States" at NAP.edu. doi:10.17226/24950. ISBN 978-0-309-46818-3. PMID 29897702. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ Kortsmit, Katherine (2022). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2020". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 71 (10): 1–27. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7110a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 9707346. PMID 36417304.

The national case-fatality rate for legal induced abortion for 2013–2019 was 0.43 deaths related to legal induced abortions per 100,000 reported legal abortions. This case-fatality rate was lower than the rates for the previous 5-year periods.

- ^ Donnelly L (26 February 2011). "Abortion is Safer than Having a Baby, Doctors Say". The Telegraph.

- ^ Dixon-Mueller R, Germain A (January 2007). "Fertility regulation and reproductive health in the Millennium Development Goals: the search for a perfect indicator". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (1): 45–51. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.068056. PMC 1716248. PMID 16571693.

- ^ "Abortion in Indonesia" (PDF). Guttmacher Institute. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Ralph LJ, Schwarz EB, Grossman D, Foster DG (August 2019). "Self-reported Physical Health of Women Who Did and Did Not Terminate Pregnancy After Seeking Abortion Services: A Cohort Study". Annals of Internal Medicine. 171 (4): 238–247. doi:10.7326/M18-1666. PMID 31181576. S2CID 184482546.

- ^ Raymond EG, Grimes DA (February 2012). "The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 119 (2 Pt 1): 215–219. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823fe923. PMID 22270271. S2CID 25534071.

- ^ Abbas D, Chong E, Raymond EG (September 2015). "Outpatient medical abortion is safe and effective through 70 days gestation". Contraception. 92 (3): 197–199. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.06.018. PMID 26118638.

- ^ Grossman D (3 September 2004). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion: RHL commentary". Reproductive Health Library. Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Chien P, Thomson M (15 December 2006). "Medical versus surgical methods for first trimester termination of pregnancy: RHL commentary". Reproductive Health Library. Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 17 May 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ Westfall JM, Sophocles A, Burggraf H, Ellis S (1998). "Manual vacuum aspiration for first-trimester abortion". Archives of Family Medicine. 7 (6): 559–562. doi:10.1001/archfami.7.6.559. PMID 9821831. Archived from the original on 5 April 2005.

- ^ Dempsey A (December 2012). "Serious infection associated with induced abortion in the United States". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 55 (4): 888–892. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e31826fd8f8. PMID 23090457.

- ^ White K, Carroll E, Grossman D (November 2015). "Complications from first-trimester aspiration abortion: a systematic review of the literature". Contraception. 92 (5): 422–438. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.07.013. PMID 26238336.

- ^ "ACOG practice bulletin No. 104: antibiotic prophylaxis for gynecologic procedures". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 113 (5): 1180–1189. May 2009. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a6d011. PMID 19384149.

- ^ Sawaya GF, Grady D, Kerlikowske K, Grimes DA (May 1996). "Antibiotics at the time of induced abortion: the case for universal prophylaxis based on a meta-analysis". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 87 (5 Pt 2): 884–890. PMID 8677129.

- ^ Achilles SL, Reeves MF (April 2011). "Prevention of infection after induced abortion: release date October 2010: SFP guideline 20102". Contraception. 83 (4): 295–309. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.11.006. PMID 21397086.

- ^ Barnard S, Kim C, Park MH, Ngo TD (July 2015). "Doctors or mid-level providers for abortion" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (7): CD011242. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011242.pub2. PMC 9188302. PMID 26214844. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ Lerma K, Shaw KA (December 2017). "Update on second trimester medical abortion". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 29 (6): 413–418. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000409. PMID 28922193. S2CID 12459747.

Second trimester surgical abortion is well tolerated and increasingly expeditious

- ^ Steinauer J, Jackson A, Grossman D, et al. (Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology) (June 2013). "Second-trimester abortion. Practice Bulletin No. 135". American College of Obstetrics & Gynecology - Practice Bulletins. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

The mortality rate associated with abortion is low (0.6 per 100,000 legal, induced abortions), and the risk of death associated with childbirth is approximately 14 times higher than that with abortion. Abortion-related mortality increases with each week of gestation, with a rate of 0.1 per 100,000 procedures at 8 weeks of gestation or less, and 8.9 per 100,000 procedures at 21 weeks of gestation or greater.

- ^ Bartlett LA, Berg CJ, Shulman HB, Zane SB, Green CA, Whitehead S, Atrash HK (April 2004). "Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 103 (4): 729–737. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000116260.81570.60. PMID 15051566. S2CID 42597014.

The risk factor that continues to be most strongly associated with mortality from legal abortion is gestational age at the time of the abortion

- ^ Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V (May 2016). "Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis" (PDF). American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 214 (5): 572–591. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.044. PMID 26743506. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

Prior surgical uterine evacuation for either I-TOP[induced termination of pregnancy] or SAB[spontaneous abortion, - also known as miscarriage] is an independent risk factor for PTB[pre-term birth]. These data warrant caution in the use of surgical uterine evacuation and should encourage safer surgical techniques as well as medical methods.

- ^ Averbach SH, Seidman D, Steinauer J, Darney P (January 2017). "Re: Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 216 (1): 87. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.08.038. PMID 27596618. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ a b Jasen P (October 2005). "Breast cancer and the politics of abortion in the United States". Medical History. 49 (4): 423–444. doi:10.1017/S0025727300009145. PMC 1251638. PMID 16562329.

- ^ Schneider AP, Zainer CM, Kubat CK, Mullen NK, Windisch AK (August 2014). "The breast cancer epidemic: 10 facts". The Linacre Quarterly. Catholic Medical Association. 81 (3): 244–277. doi:10.1179/2050854914Y.0000000027. PMC 4135458. PMID 25249706.

an association between [induced abortion] and breast cancer has been found by numerous Western and non-Western researchers from around the world. This is especially true in more recent reports that allow for a sufficient breast cancer latency period since an adoption of a Western life style in sexual and reproductive behavior.

- ^ 낙태와 유방암에 대한 주요 의료기관의 입장문은 다음과 같습니다.

- 세계보건기구:

- 국립 암 연구소:

- 미국 암 협회:

- 왕립 산부인과 의사 대학:

- 미국 산부인과 학회:

- ^ Gordon L (2002). The Moral Property of Women. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02764-7.

- ^ Solinger R (1998). "Introduction". In Solinger R (ed.). Abortion Wars: A Half Century of Struggle, 1950–2000. University of California Press. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-520-20952-7.

- ^ Bates JE, Zawadzki ES (1964). Criminal Abortion: A Study in Medical Sociology. Charles C. Thomas. ISBN 978-0-398-00109-4.

- ^ Keller A (1981). Scandalous Lady: The Life and Times of Madame Restell. Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-689-11213-3.

- ^ Taussig FJ (1936). Abortion Spontaneous and Induced: Medical and Social Aspects. C.V. Mosby.

- ^ a b c d Horvath S, Schreiber CA (September 2017). "Unintended Pregnancy, Induced Abortion, and Mental Health". Current Psychiatry Reports. 19 (11): 77. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0832-4. PMID 28905259. S2CID 4769393.

- ^ a b "APA Task Force Finds Single Abortion Not a Threat to Women's Mental Health" (Press release). American Psychological Association. 12 August 2008. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ "Report of the APA Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion" (PDF). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 13 August 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2010.

- ^ Coleman PK (September 2011). "Abortion and mental health: quantitative synthesis and analysis of research published 1995-2009". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 199 (3): 180–186. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.077230. PMID 21881096.

- ^ "Mental Health and Abortion". American Psychological Association. 2008. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Steinberg JR (2011). "Later abortions and mental health: psychological experiences of women having later abortions--a critical review of research". Women's Health Issues. 21 (3 Suppl): S44–S48. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.002. PMID 21530839.

- ^ Kelly K (February 2014). "The spread of 'Post Abortion Syndrome' as social diagnosis". Social Science & Medicine. 102: 18–25. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.030. PMID 24565137.

- ^ Rocca CH, Samari G, Foster DG, Gould H, Kimport K (March 2020). "Emotions and decision rightness over five years following an abortion: An examination of decision difficulty and abortion stigma". Social Science & Medicine. 248: 112704. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112704. PMID 31941577.

- ^ Okonofua F (November 2006). "Abortion and maternal mortality in the developing world" (PDF). Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 28 (11): 974–979. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32307-6. PMID 17169222. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2012.

- ^ Haddad LB, Nour NM (2009). "Unsafe abortion: unnecessary maternal mortality". Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2 (2): 122–126. PMC 2709326. PMID 19609407.

- ^ a b c Shah I, Ahman E (December 2009). "Unsafe abortion: global and regional incidence, trends, consequences, and challenges" (PDF). Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 31 (12): 1149–1158. doi:10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34376-6. PMID 20085681. S2CID 35742951. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–2128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Speroff L, Darney PD (2010). A clinical guide for contraception (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-60831-610-6.

- ^ World Health Organisation (2011). Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008 (PDF) (6th ed.). World Health Organisation. p. 27. ISBN 978-92-4-150111-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2014.

- ^ Berer M (2000). "Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 78 (5): 580–592. PMC 2560758. PMID 10859852.

- ^ Jewkes R, Rees H, Dickson K, Brown H, Levin J (March 2005). "The impact of age on the epidemiology of incomplete abortions in South Africa after legislative change". BJOG. 112 (3): 355–359. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00422.x. PMID 15713153. S2CID 41663939.

- ^ Bateman C (December 2007). "Maternal mortalities 90% down as legal TOPs more than triple". South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 97 (12): 1238–1242. PMID 18264602. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017.

- ^ Conti JA, Brant AR, Shumaker HD, Reeves MF (December 2016). "Update on abortion policy". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 28 (6): 517–521. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000324. PMID 27805969. S2CID 26052790.

- ^ New MJ (15 February 2011). "Analyzing the Effect of Anti-Abortion U.S. State Legislation in the Post-Casey Era". State Politics & Policy Quarterly. 11 (1): 28–47. doi:10.1177/1532440010387397. S2CID 53314166.

- ^ Medoff MH, Dennis C (21 July 2014). "Another Critical Review of New's Reanalysis of the Impact of Antiabortion Legislation". State Politics & Policy Quarterly. 14 (3): 269–76. doi:10.1177/1532440014535476. S2CID 155464018.

- ^ "Facts on Investing in Family Planning and Maternal and Newborn Health" (PDF). Guttmacher Institute. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S, Romero M, Ganatra B, Okonofua FE, Shah IH (November 2006). "Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic". Lancet. 368 (9550): 1908–1919. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6. PMID 17126724. S2CID 6188636. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ Nations MK, Misago C, Fonseca W, Correia LL, Campbell OM (June 1997). "Women's hidden transcripts about abortion in Brazil". Social Science & Medicine. 44 (12): 1833–1845. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00293-6. PMID 9194245.

- ^ Maclean G (2005). "XI. Dimension, Dynamics and Diversity: A 3D Approach to Appraising Global Maternal and Neonatal Health Initiatives". In Balin RE (ed.). Trends in Midwifery Research. Nova Publishers. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-1-59454-477-4. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015.

- ^ Salter C, Johnson HB, Hengen N (1997). "Care for Postabortion Complications: Saving Women's Lives". Population Reports. Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. 25 (1). Archived from the original on 7 December 2009.

- ^ "Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ UNICEF; UNFPA; WHO; World Bank (2010). "Packages of interventions: Family planning, safe abortion care, maternal, newborn and child health". Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "Facts on Induced Abortion Worldwide" (PDF). World Health Organization. January 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Sedgh G, Henshaw S, Singh S, Ahman E, Shah IH (October 2007). "Induced abortion: estimated rates and trends worldwide". Lancet. 370 (9595): 1338–1345. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.4197. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61575-X. PMID 17933648. S2CID 28458527.

- ^ a b Rosenthal E (12 October 2007). "Legal or Not, Abortion Rates Compare". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ Shah I, Ahman E (December 2009). "Unsafe abortion: global and regional incidence, trends, consequences, and challenges". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 31 (12): 1149–1158. doi:10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34376-6. PMID 20085681. S2CID 35742951.

However, a woman's chance of having an abortion is similar whether she lives in a developed or a developing region: in 2003 the rates were 26 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44 in developed areas and 29 per 1,000 in developing areas. The main difference is in safety, with abortion being safe and easily accessible in developed countries and generally restricted and unsafe in most developing countries.

- ^ "Facts on Investing in Family Planning and Maternal and Newborn Health" (PDF). Guttmacher Institute. November 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Sedgh G, Singh S, Henshaw SK, Bankole A (September 2011). "Legal abortion worldwide in 2008: levels and recent trends". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 43 (3): 188–198. doi:10.1363/4318811. PMID 21884387. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012.

- ^ "Populație". Romanian Statistical Yearbook (PDF). National Institute of Statistics. 15 May 2011. p. 62. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Jones RK, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK (2002). "Contraceptive use among U.S. women having abortions in 2000-2001" (PDF). Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 34 (6): 294–303. doi:10.2307/3097748. JSTOR 3097748. PMID 12558092. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2006.

- ^ Cohen SA (2008). "Abortion and Women of Color: The Bigger Picture". Guttmacher Policy Review. 11 (3). Archived from the original on 15 September 2008.

- ^ Pettus EW, Willingham L (1 February 2022). "Minority women most affected if abortion is banned, limited". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Kortsmit, et al. (2021). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2019". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 70 (9): 1–29. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7009a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 8654281. PMID 34818321.

- ^ Strauss LT, Gamble SB, Parker WY, Cook DA, Zane SB, Hamdan S (November 2006). "Abortion surveillance--United States, 2003". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries. 55 (11): 1–32. PMID 17119534. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017.

- ^ Finer LB, Henshaw SK (2003). "Abortion incidence and services in the United States in 2000". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 35 (1): 6–15. doi:10.1363/3500603. PMID 12602752. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016.

- ^ Department of Health (2007). "Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2006". Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ Cheng L (1 November 2008). "Surgical versus medical methods for second-trimester induced abortion: RHL commentary". The WHO Reproductive Health Library. Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009. 주석:

Lohr PA, Hayes JL, Gemzell-Danielsson K (January 2008). "Surgical versus medical methods for second trimester induced abortion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD006714. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006714.pub2. PMID 18254113. S2CID 205184764. - ^ a b c d e f "Abortions Later in Pregnancy". KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). 5 December 2019.

- ^ Vaughn, Lewis (2023). Bioethics: Principles, Issues, and Cases (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-19-760902-6.

- ^ Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM (September 2005). "Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantitative and qualitative perspectives". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 37 (3): 110–118. doi:10.1111/j.1931-2393.2005.tb00045.x. PMID 16150658. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012.