조세피난처

Tax haven| 시리즈의 일부 |

| 과세 |

|---|

|

| 재정 정책의 일면 |

조세피난처는 외국인 투자자들에게 매우 낮은 "유효한"[a][1][2][3][4][5] 세율을 가진 국가이다.전통적인 정의에 따르면 조세피난처는 재정적인 [b][6]비밀도 제공한다.그러나, 높은 수준의 비밀 유지율을 가지고 있지만, 특히 미국과 독일이 금융 비밀 지수([c]FSI) 순위에서 차지하는 세율은 높은 나라도 일부 조세 피난처 목록에 포함될 수 있지만, 보편적으로 조세 피난처로 간주되지는 않는다.이와는 대조적으로, 비밀 수준이 낮지만 "유효한" 과세율이 낮은 국가, 특히 FSI 순위에서 아일랜드는 대부분의 조세 피난처 [9]목록에 나타난다.효과적인 세율에 대한 합의는 학자들이 "세금 피난처"와 "해외 금융 센터"라는 용어가 거의 [10]동의어라는 것을 주목하게 만들었다.

전통적인 조세피난처는 저지와 같이 세율이 0% 정도 개방되어 있지만, 그 결과 양국간 조세조약이 제한적으로 체결되었다.현대 법인세 피난처는 0이 아닌 '헤드라인' 세율과 OECD 준수 수준이 높아 양국 조세조약의 큰 네트워크가 형성돼 있다.그러나, 베이스 침식과 이익 이동(BEPS) 툴에 의해서, 기업은, 피난처 뿐만이 아니라, 조세 조약이 체결되고 있는 모든 나라에서도, 거의 제로(0)에 가까운 「유효한」세율을 달성할 수 있습니다.이 세율은 조세 피난처 리스트에 올라 있습니다.현대 연구에 따르면 조세피난처 상위 10곳에는 네덜란드 싱가포르 아일랜드 영국 등 기업 중심의 피신처가 포함되며 룩셈부르크 홍콩 케이맨 제도 버뮤다 영국 버진아일랜드 스위스는 전통적인 조세피난처와 주요 법인세피난처로 분류된다.법인세피난처는 흔히 전통적인 [11][12][13]조세피난처에 대한 "수용소" 역할을 한다.

조세피난처를 사용하면 조세피난처가 아닌 국가에서는 세수가 손실된다.회피되는 세금의 § 재무규모 추정치는 다양하지만,[14][15][16][17] 가장 신뢰할 수 있는 세금은 연간 1,000억~2,500억 달러의 범위를 가진다.또 조세피난처에 있는 자본은 과세표준에서 영구적으로 이탈할 수 있다.조세피난처에 보유된 자본의 추정치도 다양하다.가장 신뢰할 수 있는 추정치는 미화 7~10조 달러(글로벌 [18]자산의 최대 10%)이다.전통적인 조세피난처와 법인세피난처의 폐해는 특히 개발도상국에서 두드러져 왔는데,[19][20][21] 개발도상국에서는 인프라 건설을 위해 세수가 필요하다.

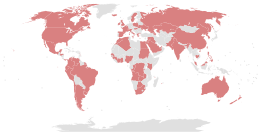

15퍼센트 [d]이상의 국가가 조세피난처로 [4][9]분류되기도 한다.조세피난처는 대부분 성공적이고 잘 관리된 경제국이며, 피신처가 된 것이 [24][25]번영을 가져왔다.석유와 가스 수출국을 제외한 상위 1015개국의 1인당 GDP는 조세피난처다.(BEPS의 흐름에 의해) 1인당 GDP가 부풀어 오르기 때문에, 피난처는 과잉 레버리지(국제 자본이 GDP 대비 인위적인 채무 가격을 잘못 책정하는) 경향이 있다.이는 국제 자본 흐름이 재조정될 때 심각한 신용 주기 및/또는 부동산/은행 위기를 초래할 수 있다.아일랜드의 Celtic Tiger와 2009-13년의 후속 금융 위기가 [26]그 예입니다.저지도 [27]마찬가지야.조사에 따르면 ①미국은 최대 수혜국이며, 미국 기업들의 조세피난처 사용은 미국 재무부 [28]수입을 극대화했다.

조세피난처(OECD 등)와의 전쟁에 대한 역사적 초점IMF 프로젝트)는, 공통의 기준, 투명성,[29] 데이터 공유에 근거하고 있었습니다.세금 [30][19][16]손실의 대부분을 BEPS 도구가 책임지고 있는 OECD에 준거한 법인세 피난처의 증가는 이러한 접근법에 [31][32]대한 비판으로 이어졌다.미국과 유럽연합의 많은 회원국과 같은 고세 관할권은 2017-18년 OECD BEPS 프로젝트에서 탈퇴하여 반(反) BEPS 조세 제도를 도입하였다(예: 2017년 미국 감세 및 고용법("TC–JA Gilt")).하이브리드 "영토" 세금 체계, 제안된 EU 디지털 서비스 세금 제도 및 EU 공통 통합 법인세 기반.[31]

정의들

맥락

조세피난처를 구성하는 것에 대한 구체적인 정의에 대해서는 확립된 합의가 없다.는 조세 정의 네트워크 2018,[33]에 미국 정부 책임 Office,[34]에 의해 미국 의회 연구 Service,[35]에 의하여 유럽 Parliament,[36]이 2017년 조사와 학계를 대표하는 resea에서 2015년 조사에서 2008년 조사의 것과 같은 비정부 기구들부터 이 결론입니다.세금 h의 rchers아벤스[37]

그러나 조세피난처라는 명칭이 양국 조세조약에 따라 개발 및 무역을 모색하는 국가에 영향을 미치기 때문에 이 문제는 중요하다.아일랜드는 2016년 주요 20개국(G20) 브라질에 의해 블랙리스트에 올랐을 때 양국 [38][39]교역은 감소했다.

학술적 비양적(1994~2016)

조세피난처에 [40]관한 첫 번째 중요한 논문 중 하나는 제임스 R.의 1994년 하인스-라이스 논문이다. 하인스 [41]주니어2017년 [43]말에도 조세피난처 [42]조사에 관한 논문 중 가장 많이 인용된 논문이며, 조세피난처 [42]조사에 관한 저자로는 하인즈가 가장 많이 인용한 논문이다.조세피난처에 대한 통찰을 제공할 뿐 아니라 조세피난처가 되는 나라들의 다양성이 너무 커서 세부적인 정의가 부적절하다는 견해를 보였다.하인스는 조세피난처가 유별나게 낮은 세율을 가진 나라 집단이라고만 언급했다.하인스는 2009년 Dammika [4]Dharmapala와의 논문에서 이 접근법을 재확인했다.

2008년 12월 다르마팔라는 OECD 프로세스가 조세피난처 정의에 은행 비밀주의를 포함시킬 필요성을 상당 부분 배제했으며, 현재는 "최초 그리고 무엇보다도 낮은 법인세율 또는 제로"[37]이며, 이것이 [1][2][3]조세피난처에 대한 일반적인 "금융사전" 정의가 되었다고 썼다.

Hines는 2016년에 ① 조세피난처 거버넌스 인센티브에 대한 연구를 포함시키기 위해 그의 정의를 수정했다. 이는 학술 [10][40][44]용어집에서도 널리 받아들여지고 있다.

조세피난처는 일반적으로 외국인 투자자들에게 낮은 세율을 부과하거나 제로 세율을 부과하는 작고 잘 관리된 주들이다.

--

OECD-IMF (1998–2018)

1998년 4월 OECD는 조세피난처를 '3/4'[45][46] 기준을 충족한다는 정의를 내놓았다.그것은 그들의 "유해한 세금 경쟁:새로운 글로벌 이슈" 이니셔티브.[47]OECD가 조세피난처 [22]목록을 처음 발표한 2000년까지 OECD 회원국은 모두 OECD의 새로운 조세 목적 투명성 및 정보 교환에 관한 글로벌 포럼에 참여한 것으로 간주되어 기준 ii와 기준 ii를 충족하지 못했다.OECD는 35개 회원국 중 조세피난처에 등재된 적이 없어 아일랜드 [48]룩셈부르크 네덜란드 스위스를 조세피난처로 규정하기도 한다.

2017년에는 트리니다드토바고만이 1998년 OECD의 정의를 충족시켰기 때문에 [49][50][51]그 정의는 평판이 나빠졌다.

②2001년 [29]미국의 새 부시 행정부의 반대에 따라 제4기준이 철회됐고 2002년 OECD 보고서에서는 3가지 기준 [9]중 2가지로 정의됐다.

1998년 OECD 정의는 "OECD 조세피난처"[52]에 의해 가장 자주 언급된다.때, 2017년에, 해당 매개 변수, 뒷면은 흙 속 트리니다드 & 하지만 그 정의;토바고를 조세 피난처로, 제한된 이후 주로 조세 피난처에 2015년 미국 의회 조사국 조사를 포함해 조세 피난처 academics,[37][44][53]에서, 및 Hines' 수 있도록 할인된 가질 자격을 잃어버린 신뢰성( 앞서 언급한). 저 세율 피난처(예: 첫 번째 기준이 적용되는 경우) OECD 법인을 개선하여 OECD 정의를 회피한다(따라서 두 번째와 세 번째 기준은 [35]적용되지 않는다).

따라서 OECD 이니셔티브가 조세회피 활동에 미치는 영향은 (의심할 여지 없이 제한적이긴 하지만) 증거는 제시하지 않는다.따라서 조세피난처 기업 이용에 큰 영향을 미칠 것으로는 기대할 수 없다.

--

2000년 4월 금융안정포럼(FSF)은 관련 개념의 오프쇼어 파이낸셜센터(OFC)[54]를 정의해 2000년 6월 IMF가 채택해 46개 [55]OFC 목록을 작성했다.FSF-IMF의 정의는 BEPS 도구의 피난처가 제공하는 것과 BEPS 도구로부터의 회계 흐름이 "비례에 어긋나" 따라서 피난처의 경제 통계를 왜곡한다는 하인스의 관찰에 초점을 맞췄다.FSF-IMF 목록은 1994년에 [9]하인즈가 너무 작다고 여겼던 네덜란드와 같은 새로운 법인세 피난처를 포착했다.2007년 4월 IMF는 보다 정량적인 접근법을 사용하여 22개 주요 OFC [56]목록을 작성했으며, 2018년에는 전체 [30]흐름의 85%를 처리하는 8개 주요 OFC를 열거했다.2010년경부터 세무학계는 OFC와 조세피난처를 동의어로 [10][57][58]간주했다.

학술 양적(2010~2018)

2010년 10월 하인스는 52개 조세피난처 목록을 발표했는데, 그는 이를 기업의 투자 [23]흐름을 분석하여 양적으로 확장하였다.하인스의 최대 피난처는 법인세 피난처가 지배하고 있었다.Dharmapala는 2014년에 BEPS [59]툴로부터의 글로벌 조세 피난 활동의 대부분을 차지했다고 지적했다.Hines 2010 목록은 세계 10대 조세 피난처를 최초로 추산한 것이며, 그 중 저지와 영국령 버진아일랜드 두 곳만이 OECD의 2000년 명단에 올랐다.

2017년 7월 암스테르담 대학의 CORPNET 그룹은 조세피난처에 대한 정의를 무시하고 Orbis 데이터베이스에서 9,800만 개의 글로벌 기업 연결을 분석하는 순수 정량적 접근법에 초점을 맞췄다.CORPNET의 상위 5개 컨짓 OFC와 상위 5개 싱크 OFC 목록은 Hines 2010년 목록의 상위 10개 피신처 중 9개와 일치하며, 2009-12년에야 세법을 바꾼 영국에서만 차이를 보였다.[60]CORPNET의 Conduit와 Sink OFCs 연구는 조세피난처에 대한 이해를 두 가지 [61][62]분류로 나눈다.

- 24 싱크 OFC: 경제시스템에서 불균형한 가치가 사라지는 국가(예: 전통적인 조세피난처)

- 5 관로 OFC: 가치의 불균형이 OFC(현대 법인세 피난처 등) 쪽으로 이동하는 국가.

2018년 6월 세무학자인 가브리엘 주크만(et alia)은 조세피난처에 대한 정의도 무시한 채 Hines와 Dharmapala가 [63]지적한 기업의 "이익 이동"(BEPS)과 "기업 수익성 향상"을 추정하는 연구를 발표했다.주크먼은 CORPNET 연구가 구글, 페이스북, 애플이 [64]오르비스에 등장하지 않기 때문에 아일랜드, 케이맨 제도 등 미국 기술기업과 연계된 피난처가 부족하다고 지적했다.그럼에도 불구하고, 주크만이 선정한 2018년 10대 안식처 리스트는 하인즈 2010년 10대 안식처 중 9곳과 일치하지만, 아일랜드는 세계 최대의 [65]안식처이다.이들 리스트(Hines 2010, CORPNET 2017, Zucman 2018)는 순수 양적 접근 방식을 채택한 것으로 최대 법인세 피난처에 대해 확고한 공감대를 보였다.

관련 정의

조세정의네트워크는 2009년 10월 조세피난처 학술목록에는 없지만 투명성 문제가 있는 OECD 준거국에 관한 과제를 강조하기 위해 금융비밀지수(FSI)와 비밀관할권을 [33]도입했다.FSI는 세율이나 BEPS 흐름을 계산에서 평가하지 않지만, 특히 미국과 독일을 주요 "비밀 관할권"[66][67][68]으로 나열할 때 금융 [c]매체에서 조세 피난처 정의로 잘못 해석되는 경우가 많다.하지만 조세피난처 유형도 비밀유지권에 속한다.

그룹화

조세피난처는 다양하고 다양하지만 조세학계는 조세피난처의 발전 [69][70][71][72]이력에 대해 논의할 때 조세피난처의 세 가지 주요 "그룹화"를 인식하기도 한다.

§ 역사에서 논의되었듯이, 최초의 조세 피난처 허브는 1920년대 중반에 만들어진 취리히-주그-리히텐슈타인 삼각지대로,[69] 이후 1929년에 룩셈부르크에 합류했다.프라이버시와 비밀은 유럽 조세피난처의 중요한 측면으로 확립되었다.그러나 현대 유럽 조세피난처에는 네덜란드 아일랜드 [e]등 OECD의 투명성이 높은 기업 중심의 조세피난처도 포함된다.유럽의 조세피난처는 조세피난처로 가는 글로벌 흐름의 중요한 부분으로 작용하며, 5대 글로벌 컨짓 OFC 중 3개가 유럽(네덜란드, 스위스, 아일랜드)[61]이다.유럽 관련 조세피난처는 네덜란드, 아일랜드, 스위스, 룩셈부르크 등 4개 조세피난처 상위 10개국에 포함된다.

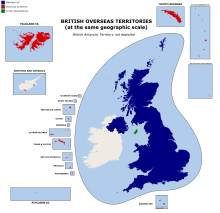

조세피난처 중 상당수는 영국의 옛 또는 현재 종속국이며 여전히 같은 핵심 법률 [70]구조를 사용하고 있다.§ 10대 조세피난처 목록에는 카리브해 조세피난처(버뮤다, 버진아일랜드, 케이맨 제도 등), 채널 제도 조세피난처(저지 등), 아시아 조세피난처(싱가포르, 홍콩 등) 등 6곳이 있다.①역사에서 논의한 바와 같이, 영국은 1929년에 최초의 "비거주 기업"을 설립하여 [69][70]제2차 세계대전 후 유럽 달러 역외 금융 센터 시장을 주도하였다.2009-2012년 법인세법 개정 이후 영국은 주요 법인 중심 조세 [60]피난처로 다시 부상했습니다.5개의 주요 글로벌 컨짓 OFC 중 2개가 이 그룹(영국 및 싱가포르 [61]등)에 속해 있습니다.

2009년 11월, 전 영국 은행 직원이자 바하마 은행 감독관이었던 마이클 풋은 3개의 영국 왕실 종속국(건시, 맨 섬 및 저지)과 6개의 해외 영토(앵구야, 버뮤다, 영국령 버진 아일랜드, 케이맨 제도, 지브롤터, 터키 제도)에 대한 통합 보고서를 발표했다.역외 금융 센터로서의 portunity와 과제"를 HM [73][74]재무부에 제공합니다.

①역사에서 논의한 바와 같이, 이들 조세피난처는 대부분 1960년대 후반으로 거슬러 올라가며,[69] 이들 그룹의 구조와 서비스를 효과적으로 모방하고 있다.조세피난처 대부분은 OECD 회원국이 아니거나 대영제국과 관련된 조세피난처의 경우 OECD 고위회원이 핵심이 [69][71]아니다.일부는 조세피난처를 억제하기 위한 OECD의 다양한 이니셔티브(예: 바누아투와 사모아)[69]에서 차질을 빚었다.그러나 대만(아시아 PAC)과 모리셔스(아프리카)와 같은 다른 국가들은 지난 수십 [71]년 동안 물질적으로 성장했다.대만은 [75]비밀주의에 초점을 맞춘 "아시아의 스위스"로 묘사되어 왔다.신흥시장 관련 조세피난처는 5대 글로벌 컨짓트 OFC나 상위 10대 조세피난처 리스트에 포함되지 않았지만 대만과 모리셔스 모두 상위 10대 글로벌 싱크 OFC에 [61]랭크되어 있습니다.

리스트

의 종류

조세피난처 목록은 크게 세 가지 유형이 작성되었습니다.[35]

- 정부,:이 목록과 정치적 질적,[76]회원들으며 대체로 학문적 연구에 의해 무시된다(또는 각 다른),다 OECD나 EU의 국가 혹은 § 톱 10세금[37][53]OECD는 2017년 목록, 트리니다드 &에;[49]를 유럽 연합이의 2017년 list,[77]도 17개 국가들 한 나라 토바곴다 목록 결코 질적.ns.[78][79]

- 비정부, 질적: 이것들은 다양한 속성(예를 들어 피난처에서 이용할 수 있는 조세 구조의 유형)에 근거한 주관적인 점수 시스템을 따릅니다.가장 잘 알려진 것은 옥스팜의 법인세 피난처 [80][81]목록과 금융비밀 지수(FSI는 특정 조세 피난처의 목록이 아닙니다)입니다.[c]

- 접근법에 수 잘 알려진 것은 다음과 같습니다.을 사용하다

- 세율 – Hines-Rice 1994 목록 [41]및 Dharmapala와 같은 유효 세율에 초점을 맞춘다.Hines 2009 [4]list. (Hines와 Dharmapala는 이 리스트의 랭킹을 회피했다.)

- 연결 – Orbis 연결(CORPNET의 2017 Conduit 및 Sink OFCs 등) 또는 ITEP 연결 2017 [82]목록과 같은 자회사 연결에 초점을 맞춥니다.

- Quantum – 이익 이동에 초점을 맞춥니다. BEPS 흐름은 Zucman과 같습니다.Törslöv-Wier 2018 목록,[63][83] FDI 흐름은 James Hines 2010 [23]목록 또는 Products like the ITEP Profits 2017 [f][82]목록과 같다.

연구는 또한 대리 지표를 강조하며, 그 중 가장 두드러진 두 가지 지표는 다음과 같다.

- 미국의 조세 역전 – 조세 피난처의 "센스 체크"는 개인 또는 기업이 미국 법인세율이 높은 것을 법적으로 피하기 위해 낮은 조세 관할권에 재입안하는지 여부이며, 또한 다국적 기업이 아일랜드와 같은 영토 조세 제도에 기반을 둔다는 이점 때문입니다.1983년 이후 미국 법인세 환급액 상위 3개소는 다음과 같습니다.아일랜드(#1), 버뮤다(#2), 영국(#[84]3)

- 1인당 GDP 표– 조세피난처의 또 다른 '센스 체크'는 IP 기반의 BEPS 툴과 채무 기반의 BEPS 툴로부터의 GDP 데이터의 왜곡입니다.비석유 및 가스 국가(예: 카타르, 노르웨이)와 마이크로 관할권을 제외하고, 결과적으로 1인당 GDP가 가장 높은 국가는 룩셈부르크(1위), 싱가포르(2위), 아일랜드(3위)를 필두로 하는 조세 피난처이다.

조세피난처 상위 10개

조세피난처를 식별하는 양적 기법이 2010년 이후 상승함에 따라 가장 큰 조세피난처 목록이 보다 안정적으로 작성되었다.다르마팔라는 기업의 BEPS 흐름이 조세피난처 활동을 지배하고 있기 때문에 이들 대부분은 법인세피난처라고 지적했다.[59]가브리엘 주크먼의 2018년 6월 연구에서 상위 10개 조세피난처 중 9개가 2010년 이후 다른 두 가지 양적 연구 중 상위 10개 목록에 올랐다.상위 5개 컨짓 OFC 중 4개가 대표되지만, 영국은 2009-2012년에 [60]세법을 변경했을 뿐이다.저지는 Hines 2010 목록에만 표시되지만 상위 5개의 Sink OFC가 모두 표시됩니다.

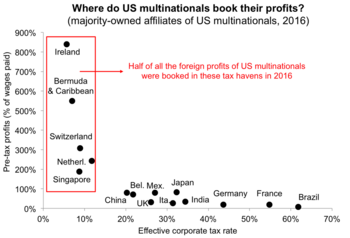

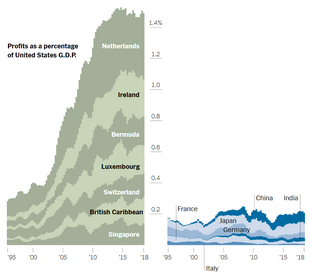

이 조사에서는, BEPS 툴의 최대 유저인 Apple, Google, 및 [85][86][87]Facebook의 주요 지역 거점인 아일랜드와 싱가포르의 성장을 포착하고 있습니다.2015년 1분기에 애플은 역사상 가장 큰 규모의 BEPS 조치를 완료했으며, 당시 노벨상 수상자인 경제학자 폴 크루그먼은 이를 "레프레칸 경제학"이라고 불렀다.2018년 9월, NBER는 TCJA 송환 세금 데이터를 사용하여 주요 조세 피난처를 "아일랜드, 룩셈부르크, 네덜란드, 스위스, 싱가포르, 버뮤다 및 카리브해 피난처"[88][89]로 열거했다.

| ' ' ' | [23] | ITEP 2017 [f] [82] | [63] |

|---|---|---|---|

| ★★ | 익익 | ||

| ★★ | |||

| 1 | 의 경우*★ | 네덜란드* | ★★★★★★ |

| 2 | 제도 | 아일란드* | 케이맨 제도* & 브리티시 버진아일랜드* |

| 3 | 아일란드* | 버뮤다* | 가가★★★* |

| 4 | 스스 swit★★* | 의 경우*★ | 위위★★* |

| 5 | 버뮤다* | 제도 | 덜덜★ ★★★★* ★ |

| 6 | 홍콩★ | 스스 swit★★* | lux lux★ ★ |

| 7 | 싱가포르*)★ | ||

| 8 | 네덜란드* | II | 콩콩* |

| 9 | 싱가포르*)★ | 홍콩★ | 버뮤다* |

| 10 | 버진아일랜드 | 버진아일랜드 | '('으로 표기) 안식처 ) 2개의 안식처 포함) |

(*) 3개 모두 상위 10개 조세피난처로 표시되며, 아일랜드, 싱가포르, 스위스, 네덜란드(Conduit OFCs), 케이맨 제도, 영국령 버진 아일랜드, 룩셈부르크, 홍콩, 버뮤다(Cs 싱크대) 등 9개 주요 조세피난처가 이 기준을 충족합니다.

()) CORPNET의 2017년 조사에서 5개의 Conduit OFC(아일랜드, 싱가포르, 스위스, 네덜란드, 영국) 중 하나로 표시되기도 한다.

()) CORPNET의 2017년 조사에서도 상위 5개의 싱크 OFC(영국령 버진아일랜드, 룩셈부르크, 홍콩, 저지, 버뮤다)로 나타난다.

(δ) OECD 2000년 35개 조세피난처 중 최초이자 최대 규모(OECD 목록에는 [22][49]2017년까지 트리니다드&토바고만 포함)로 지정됐다.

따라서 세계 최대의 조세피난처에 대한 학계의 가장 강력한 합의는 다음과 같습니다.아일랜드, 싱가포르, 스위스 및 네덜란드(주요 OFC 도관), 케이맨 제도, 영국령 버진 아일랜드, 룩셈부르크, 홍콩 및 버뮤다(주요 OFC 도관)는 여전히 변화 중이다.

이들 10개 주요 피난처 중 영국과 네덜란드를 제외한 모든 곳이 1994년 원래 하인스-라이스 목록에 포함되었다.영국은 1994년 조세피난처가 아니었고 하인즈는 1994년 네덜란드의 실효세율을 20% 이상으로 추정했다.(아일랜드는 실효세율이 4%로 가장 낮다고 확인)다음 중 4개:아일랜드, 싱가포르, 스위스(Conduit OFC 5대 중 3대), 홍콩(Sink OFC 5대)은 Hines-Rice 1994 목록의 7대 조세피난처 서브카테고리에 포함되어 조세피난처 [41]축소에는 진전이 없음을 보여준다.

대리 지표에 관해서는 캐나다를 제외한 이 목록에는 1982년 이후 두 개 이상의 미국 세금 역전 혜택을 받은 7개 국가가 모두 포함되어 있다([84]여기를 참조).게다가 이들 주요 조세피난처 중 6곳은 1인당 GDP 상위 15위 안에 들며, 나머지 4곳 중 3곳인 카리브해 지역은 IMF-세계은행 1인당 GDP 표에 포함되지 않았다.

2018년 6월 세계 경제 데이터에 대한 BEPS 흐름의 영향에 관한 IMF 공동 보고서에서는 이들 중 8개(스위스, 영국 제외)가 세계 [30]주요 조세피난처로 꼽혔다.

조세피난처 상위 20개

조세피난처에 대한 비정부, 정량적 연구의 가장 긴 목록은 암스테르담 대학 CORPNET 2017년 7월 컨짓트 및 싱크 OFCs 연구로 29개(5개 컨짓트 OFCs 및 25개 싱크 OFCs)이다.다음은 다른 주요 목록과 일치하는 가장 큰 20개(5개의 Conduit OFC와 15개의 Sink OFC)입니다.

(*) Hines 2010, ITEP 2017, Zucman 2018 (위)의 3가지 양적목록에서 ① Top 10 조세피난처로 표시되며, 이들 9개 조세피난처는 모두 아래와 같다.

(♣) James Hines 2010 52개 조세 피난처 목록에 표시되며, 아래 20개 위치 중 17개가 James Hines 2010 목록에 있습니다.

(δ) OECD 2000년 35개 조세피난처(OECD 목록에는 2017년까지 트리니다드 토바고만 포함) 중 가장 큰 규모로 확인되었으며, 아래 4곳만이 OECD [22]목록에 올랐다.

(↕) 유럽연합(EU)의 17개 조세피난처 중 [77]첫 번째 2017년 목록에 표시됨. 아래는 EU 2017년 목록에 있는 한 곳뿐입니다.

주권 는 다음과 같습니다.

- *♣대규모 법인세 피난처이며, 일부 세무 학계에서는 가장 [15][83][89][90]큰 기업으로서 IP 기반 BEPS 도구(예: 이중 아일랜드)의 선두 기업이지만 부채 기반 BEPS 도구도 있습니다.[84][91]

- *♣아시아의 주요 법인세 피난처(대부분의 미국 기술 기업을 위한 APAC 본사)이자 아시아 싱크 OFC, 홍콩 및 [92]대만의 핵심 통로입니다.

- *♣델란드 – 주요 법인세 [11]피난처이자 IP 기반 BEPS 도구(예: Dutch Sandwich)를 통한 최대 규모의 Conduit OFC. 부채 기반 BEPS [93][94]도구의 전통적인 선두 업체입니다.

- 영국 – 2009–12년 세법 개편 후 법인세 피난처 증가; 24개의 싱크 OFC 중 17개가 영국의 현재 또는 이전 종속국이다(싱크 OFC [12][84]표 참조).

또는 :

- *♣스위스 – 주요 전통적인 조세 피난처(또는 Sink OFC)와 주요 법인세 피난처(또는 Conduit OFC) 모두 Jersey의 주요 Sink OFC와 밀접하게[citation needed] 연계되어 있습니다.

- *♣룩셈부르크 – 세계에서 가장 큰 싱크 OFC 중 하나(많은 법인세 피난처, 특히 아일랜드와 [95]네덜란드의 종착역).

- *♣홍콩 – "아시아의 룩셈부르크"이며, 거의 룩셈부르크만큼 큰 OFC를 보유하고 있으며, APAC의 최대 법인세 피난처인 싱가포르와 연결되어 있습니다.

소버린(사실상 포함)은 주로 전통적인 조세피난처로 특징지어지지만 세율은 0이 아니다.

- ♣사이프러스 금융위기 때 키프로스 금융시스템이 붕괴될 뻔했지만 [80]10위권 안에 다시 이름을 올렸다.

- 대만 – APAC의 주요 전통적인 조세 피난처. Tax Justice Network에 의해 "아시아의 스위스"[75]로 표현되었습니다.

- ♣신종 – EU [96][97]내 신흥 조세피난처로서 [98][99]언론의 광범위한 정밀조사의 대상이 되고 있다.

매우 전통적인 조세 피난처(즉, 명시적인 0% 세율)인 주권국 또는 하위국가는 다음을 포함한다(반대 표의 전체 목록).

- ♣아직도 주요 전통적인 조세 피난처인 ♣ Jersey(영국 [72]종속국); CORPNET 연구는 Conduit OFC Switz와의 매우 강력한 연관성(예: 스위스는 전통적인 조세 피난처로서 저지에 점점 더 의존하고 있음);[27] 재정 안정성의 문제를 확인하였다.

- (♣ CORPNET 연구(여기에 기재)가 아닌 완전성을 위해 포함된 "세금 [100]피난처"인 인간(영국 종속국)의 Isle).

- 현재 영국의 해외 영토는 반대쪽 표를 참조해 주십시오.여기서 24개의 싱크 OFC 중 17개는 현재 또는 과거 영국의 종속국입니다.

- ♣프리셔스 – SE 아시아(특히 인도)와 아프리카 경제의 주요 조세 피난처가 되어 현재 종합 [106][107]8위에 올라 있다.

- 퀴라소 – 네덜란드 의존도는 옥스팜 조세피난처 리스트 8위, OFC 싱크 12위에 올랐고 최근 EU의 그레이리스트가 [108]됐다.

- ♣ δLiechtenstein – 매우 전통적인 유럽 조세 피난처로 오랫동안 확립되어 있으며 세계 10대 싱크 [109]OFC의 바로 바깥에 있습니다.

- ♣ δBahama – 전통적인 조세 피난처로서 기능하는 것(제12위 Sink OFC)과 기업 피난처 중 ITEP 수익 리스트(그림 4, 16페이지)[82]에서 8위, FSI에서 세 번째로 높은 기밀성 점수.

- ♣samoa↕samoa – 전통적인 조세피난처(Sink OFC 14위)로, FSI에서 가장 높은 기밀성 점수 중 하나로 꼽히던 곳이지만,[110] 그 이후 어느 정도 감소했습니다.

2010년 이후의 조세피난처에 대한 연구는 양적 분석(등급 매겨짐)에 초점을 맞추고 있으며, 조세피난처가 법인세 회피가 아닌 개별 조세회피에 사용되기 때문에 데이터가 제한된 매우 작은 조세피난처를 무시하는 경향이 있다.마지막으로 신뢰할 수 있는 광범위한 조세피난처 리스트는 제임스 하인즈 2010년 52개 조세피난처 리스트다.아래에 나타나 있지만, 2017년 7월 Conduit and Sink OFCs 연구에서 확인된 영국, 대만, 퀴라소 등 2010년 안식처로 간주되지 않은 안식처를 포함하기 위해 55개까지 확대되었다.James Hines 2010 목록은 원래 35개의 OECD 조세피난처 [22]중 34개를 포함하고 있으며, ① Top 10 조세피난처 및 ② Top 20 조세피난처와 비교해 볼 때 OECD의 과정은 작은 피난처의 준수에 초점을 맞추고 있음을 보여준다.

- 안도라II

- 2

- 바부다II

- 아루바II

- 바레인↕바레인

- 바베이도스↕바베이도스

- 버진아일랜드

- 제도

- 제도

- 에 없음[]

- 도미니카

- 그레나다 ↕ δ gren

- 건세이 3세

- 섬 »

- 룩스

- 마카오↕

- 제도↕마셜 제도↕마셜 제도

- 몬세라토

- Nauru‡Δ나우루Ⅱ

- Netherlands† &, AntillesΔ네덜란드&, 안틸레스 밑의

- NiueΔNiUEII

- Panama↕Δ파나마↕오브랜드

- Samoa‡↕Δ사모아↕사모아

- 샌 Marino산마리노

- Seychelles‡Δ세이셸 2세

- Singapore†싱가포르 singapore

- 세인트 키츠와 NevisΔ세인트키츠 네비스II

- 세인트 Lucia↕Δ세인트루시아δ 스톤 ↕

- 세인트 Martin세인트마틴

- 세인트 빈센트와 그 Grenadines‡Δ세인트빈센트 그레나딘 2세.

- Switzerland†스위스 swit

- 하인스가 아닌 날에[Taiwan‡]리스트에 없음 하인스 list[대만★].

- TongaΔ동아 tong

- 오스만 투르크족과 CaicosΔ터키어 및 카이코스II

- [ Kingdom이(가) 목록에

- 바누아투 van van van van van van

()) CORPNET이 2017년에 선정한 5개의 컨짓 중 하나로, 위 목록은 5개의 컨짓 중 5개를 포함합니다.

()) CORPNET에 의해 2017년에 가장 큰 24개의 싱크 중 하나로 확인되었으며, 위 목록에는 24개 중 23개가 포함되어 있습니다(Guyana 누락).

(↕) 유럽연합(EU)의 첫 번째 2017년 조세피난처 17개 중 8개.[77]

(δ) OECD 2000년 35개 조세피난처(OECD 목록에는 2017년까지 트리니다드&토바고만 포함) 중 첫 번째이자 가장 큰 것으로 확인되었으며, 위 목록에는 35개(미국령 버진아일랜드 실종)[22] 중 34개가 포함되어 있다.

인 경우

엔티티: " 국 u u u 。

- 델라웨어(미국)는 강력한 비밀유지법과 자유로운 통합체제를 가진 독특한 "육지" 전문 피난처이다. 단, 연방세와 주세가 적용된다(see 역사 [111]참조).

- 푸에르토리코(미국)는 미국의 [112]법인세 피난처인 '양도'에 가까웠지만 2017년 감세 및 고용법에 의해 대부분 [113]삭제됐다.

금융비밀성 목록(예: 금융비밀성 지수)에는 포함되지만 법인세 피난처나 전통적인 조세 피난처 목록에는 포함되지 않는 주요 주권 국가는 다음과 같다.

- 미국 – 금융비밀지수에 따르면 비밀주의로 유명한 (미국을 조세피난처로 참조); 일부 [66]목록에 "논란스러운" 모습이 나타난다.

- 독일 – 미국과 마찬가지로 독일은 금융비밀지수에[114] 따라 조세비밀리스트에 포함될 수 있습니다.

조세피난처 연구의 주요 학계 지도자들, 즉 제임스 R.의 조세피난처 목록에 미국과 독일 어느 나라도 나타나지 않았다. 하인스 주니어, 다미카 다르마팔라, 가브리엘 주크만.외국 기업이 조세피난처의 [84]기본 특징인 미국이나 독일에 세금을 돌려준 사례는 알려진 바 없다.

- 레바논 베이루트는 이전에 중동에서 유일한 조세 피난처로 명성을 떨쳤다.그러나 1966년 [115]인트라 뱅크 붕괴 이후 레바논의 정치적 군사적 악화는 레바논을 조세피난처로 사용하는 외국인을 단념시켰다.

- 라이베리아는 선박 등록 산업이 번창했다.1990년대와 2000년대 초반의 일련의 폭력적이고 유혈이 낭자한 내전은 그 나라에 대한 신뢰를 심각하게 손상시켰다.선박 등록 사업이 아직 계속되고 있는 것은, 그 초기의 성공에 대한 반증이기도 하고, 미국 뉴욕으로 국내 선박 등록부를 옮겼다는 반증이기도 하다.

- 탕헤르 국제지구는 1945년 스페인의 실효통치가 끝나 1956년 모로코와 정식으로 재결합할 때까지 조세피난처로서 잠시 존재했다.

- 일부 태평양 섬들은 조세피난처였지만 1990년대 후반 블랙리스트의 위협으로 규제와 투명성을 요구하는 OECD의 요구에 의해 축소되었다.2008년 5월 바누아투 금융청장은 바누아투가 법을 개혁하고 조세피난처가 되는 것을 중단할 것이라고 말했다."우리는 오랫동안 이 오명과 연관되어 왔고, 이제는 조세 [116][117]피난처에서 벗어나는 것을 목표로 하고 있습니다."

스케일

★★★

조세피난처의 재정 규모를 추정하는 것은 조세피난처 고유의 투명성 [31]결여로 인해 복잡하다.아일랜드, 룩셈부르크 및 네덜란드와 같은 OECD 투명성 요건을 준수하는 국가에서도 대체 비밀유지 도구를 제공한다(예: 신탁, QIAIF 및 ULL).[118]예를 들어, EU 집행위원회가 애플의 아일랜드 세율이 0.005%라는 것을 발견했을 때, 그들은 애플이 1990년대 [119]초부터 아일랜드의 공공 계정 신청을 피하기 위해 아일랜드 ULL을 사용했다는 것을 알게 되었다.

또 조세피난처로 인한 연간 세금 손실액(수천억달러로 추정)과 조세피난처에 있는 자본금(수조달러로 [118]추정)을 중심으로 한 수치 사이에 혼선이 빚어질 수 있다.

2019년 3월[update] 현재 재무규모를 추정하기 위한 가장 신뢰할 수 있는 방법은 다음과 같다.[118]

제1의 방법('은행 데이터')의 조잡한 파생상품인 NGO에 의해 만들어진 다른 많은 '구제물'이 있으며, 글로벌 뱅킹 및 금융 종합 데이터로부터 잘못된 해석과 결론을 얻어 잘못된 [118][120]추정치를 산출한다는 비판을 종종 받고 있다.

오프쇼어 가격: 재방문(2012~2014년)

재정 효과에 대한 주목할 만한 연구는 2012-2014년에 McKinsey & Company 수석 이코노미스트 James S가 재방문한 오프쇼어 가격입니다. Henry.[121][122][123] Henry는 Tax Justice Network(TJN; 조세정의 네트워크)의 연구를 수행했으며, 분석의 일환으로 다양한 조직의 [118][31]과거 재무 추정 기록을 연대순으로 작성했습니다.

Henry는 주로 다양한 규제 소스의 글로벌 뱅킹 데이터를 사용하여 [122][123]다음을 추정했습니다.

- 21조~32조달러(글로벌 자산의 20% 이상)의 글로벌 자산은 80개 이상의 오프쇼어 시큐러티 [124]관할구역에 사실상 비과세 투자되고 있다.

- 상기의 이유로 연간 1,900억~2,550억달러의 세수가 손실됩니다.

- USD 7.3 ~ 9.3조 달러는 데이터를 이용할 수 있는 139개 "저소득에서 중간소득까지" 국가의 개인에 의해 대표된다.

- 이 수치에는 "금융 자산"만 포함되며 부동산, 귀금속 등의 자산은 포함되지 않습니다.

헨리의 신뢰성과 이 분석의 깊이는 보고서가 국제적인 관심을 [121][125][126]끌었다는 것을 의미했다.TJN은 글로벌 불평등과 개발도상국 [127]수익 손실의 관점에서 분석의 결과에 대한 또 다른 보고서로 그의 보고서를 보완했다.이 보고서는 Jersey Finance(Jersey Finance)(Jersey의 금융 서비스 부문 로비 그룹)가 자금을 지원하고 두 명의 미국 학자인 Richard Morriss와 Andrew [120]Gordon이 작성한 2013년 보고서에 의해 비판받았다.2014년, TJN은 이러한 [128][129]비판에 대응한 보고서를 발표했다.

숨겨진 부국 (2015)

2015년 프랑스의 조세경제학자 가브리엘 주크만은 조세피난처에 있어 보고되지 않은 부국의 순대외자산 포지션의 양을 산출하기 위해 전 세계 국민계정 자료를 이용한 숨겨진 부를 발간했다.주크만은 세계 가계의 금융자산 중 약 8~10%인 7조6000억 달러가 조세피난처에 [18][20][130][31]있다고 추정했다.

Zucman은 2015년 저서에 이어 조세피난처 기업 사용에 초점을 맞춘 몇몇 공동저자 논문인 The Missing Profits of Nations (2016–2018)[14][15]와 The Excritant Tax Privilege (2018)[88][89]를 발표했는데, 이 논문은 기업들이 연간 2,500억 달러의 세금을 회피하고 있음을 보여준다.Zucman은 이들 중 거의 절반이 미국 [131]기업이며,[132] 2004년 이후 미국 기업들이 해외 현금 예금을 미화 1~2조 달러에 축적한 원동력이라는 것을 보여주었다.주크만 분석(et alia)에 따르면 글로벌 GDP 수치는 다국적 BEPS [133][31]흐름에 의해 실질적으로 왜곡된 것으로 나타났다.

주크만과 공동저자가 2022년에 실시한 연구에 따르면 다국적 기업의 수익의 36%가 조세피난처로 [134]옮겨지고 있다.만약 이익이 국내 재원으로 재분배된다면, "국내 이익은 고세 유럽연합 국가에서는 약 20%, 미국에서는 10%, 개발도상국에서는 약 5% 증가할 것이고,[134] 조세피난처에서는 55% 감소할 것이다."

OECD/IMF (2007년)

2007년 OECD는 해외에 보유된 자본이 미화 5조~7조 달러에 달하며,[135] 이는 관리 대상 글로벌 총 투자의 약 6~8%를 차지한다고 추정했다.2017년 OECD BEPS 프로젝트의 일환으로 조세피난처형 [16][31]관할권을 통해 수행된 BEPS 활동을 통해 과세를 피할 수 있는 기업 이익은 미화 1,000억 달러에서 2400억 달러에 이를 것으로 추산했다.

2018년이면 IMF의 계간지 재정 &, 개발, 국제 통화 기금과 세금 학자들이라는 제목의 사이에 공동 연구,"면사포 피어싱"을 출판했다는 추정 경의 US$ 12조에서 세계적인 기업 투자 전 세계였다"단지 기업 투자 상상"구조화를 방지하기 법인세 과세했으며, 집중에서 8개의 주요 locati.ons.[30]같은 팀은 2019년 글로벌 외국인 직접투자(FDI)의 높은 비율을 '유령'으로 추정하고 조세피난처에 빈 기업 껍데기가 선진국과 신흥시장, 개발도상국의 세금 징수를 저해한다는 연구결과를 추가로 발표했다.[19]그 연구는 아일랜드를 지목했고 아일랜드 외국인 직접투자의 3분의 2 이상이 "유령"[136][137]이라고 추정했다.

인센티브

★★

몇몇 연구논문에 따르면 제임스 R. 하인스 주니어는 조세피난처가 전형적으로 작지만 잘 관리되고 있으며 조세피난처가 되면 상당한 [24][25]번영을 가져왔다는 것을 보여주었다.2009년 하인즈와 다르마팔라는 국가의 약 15%가 조세피난처라고 제안했지만,[4] 왜 더 많은 나라들이 조세피난처가 되지 않았는지 의아해 했다.

오늘날 세계에는 약 40개의 주요 조세피난처가 있지만 조세피난처가 되기 위한 상당한 규모의 경제적 이익은 왜 더 이상 존재하지 않는지에 대한 의문을 제기한다.

--

하인즈와 다르마팔라는 조세피난처가 되려는 작은 나라들에게 통치가 주요 이슈라고 결론지었다.외국 기업과 투자자들의 신뢰를 받는 강력한 지배구조와 법률을 가진 나라만이 조세피난처가 [4]될 것이다.조세피난처 연구의 주요 학술 리더인 하인스와 다르마팔라는 조세피난처 연구의 재정적 이익에 대해 긍정적인 견해를 갖고 있어 조세 정의를 옹호하는 비정부기구(예: 조세 [138][139][140]정의 네트워크)와 격렬한 갈등을 빚고 있다.

1인당 GDP

조세피난처는 1인당 국내총생산(GDP) 순위가 높다.왜냐하면 [30][141]조세피난처의 경제통계가 BEPS 흐름에 의해 인위적으로 부풀려지지만 조세피난처에서는 과세되지 않기 때문이다.특히 기업 중심의 조세피난처는 BEPS의 가장 큰 흐름으로 석유 및 가스 국가를 제외한 상위 10~15개국의 대부분을 차지하고 있다(아래 표 참조).조세피난처에 대한 연구는 중요한 [56]조세피난처 지표로서 중요한 천연자원이 없을 때 1인당 GDP 점수가 높다는 것을 시사한다.FSF-IMF의 오프쇼어 금융센터 정의의 핵심은 금융 BEPS 흐름이 토착 경제 [56]규모에 비례하지 않는 국가이다.애플의 2015년 1분기 아일랜드에서의 "레프론 경제학" BEPS 거래는 극적인 사례였다. 이로 인해 아일랜드는 2017년 2월 GDP와 GNI 지표를 포기하고 새로운 지표, 수정된 국민총소득(GNI)을 채택했다.

GDP의 인위적인 인플레이션은 저가의 외국 자본(피난처 부채 대 GDP 측정 기준 사용)을 끌어들여 더 강력한 경제 [25]성장 단계를 초래할 수 있다.그러나 레버리지의 증가는 특히 GDP의 인위적인 성격이 외국인 [26][142]투자자들에게 노출되는 더 심각한 신용 사이클로 이어진다.

| 국제통화기금 (2017) 1인당 GDP [아쉬움직임] | 세계은행 (2016년)1인당 GDP [아쉬움직임] [아쉬움직임] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

★★★★★★★

★★★

2018년 조세회피처 이코노미스트 가브리엘 주크만은 대부분의 법인세 분쟁이 고세 관할권과 저세 관할권 [145]간에 발생하는 것이 아니라 고세 관할권 간에 발생하는 것임을 보여주었다.아일랜드 룩셈부르크 네덜란드 등 주요 피신처와의 분쟁은 사실상 [63][146]드문 것으로 나타났다.

우리는 현재의 국제세제도에서 조세피난처로 이동하는 이익에 대항하기 위한 인센티브를 고세국의 세무당국이 가지고 있지 않다는 것을 이론적으로나 경험적으로 보여준다.그들은 대신 다른 고세 국가에서 예치된 이익을 재배치하는 데 집행력을 집중하여 사실상 서로의 수익을 가로채고 있다.이 정책 실패는 고세 국가에 관련된 높은 비용에도 불구하고 수익이 저세 국가로 계속 이동하는 것을 설명할 수 있다.

--

이점

의

조세피난처에 대한 연구 중 논란이 되는 부분은 조세피난처가 고과세 국가의 조세제도에 대한 인식된 문제를 해결함으로써 실제로 세계 경제 성장을 촉진한다는 제안이다(예를 들어 위의 "세계적" 조세제도에 대한 논의).조세 피난처 연구에 Hines,[148]Dharmapala,[37]과 others,[149]언급합니다 증거는, 특정 사례에서, 조세 피난처 동쪽으로 움직이기 시작 경제 성장을 촉진하였고, 국내 활동에 세금 인상에,지만 국제 조달 가능한 자본이나 inc.에 더 낮은 세금을 유익한 하이브리드 세제를 지원할 수 있는 등과 같은 중요한 학문적 지도자들,ome:

조세피난처가 조세피난처에 미치는 영향은 명확하지 않지만, 조세피난처를 이용할 수 있다는 것은 인근 고세국의 경제활동을 자극하는 것으로 보인다.

--

조세피난처는 다른 나라들 간의 세금 경쟁의 성격을 바꿔서, 조세피난처를 통해 거래가 이루어지는 모바일 국제 투자자들에게 효과적으로 완화되는 높은 국내 세율을 유지할 수 있게 해줄 가능성이 매우 가능성이 높다.[..] 사실 조세피난처 근처에 있는 국가들은 멀리 있는 국가들보다 더 빠른 실질소득 증가를 보여왔는데, 이는 부분적으로 금융 흐름과 그 시장 효과의 결과일 수 있다.

--

조세피난처와 밀접한 관련이 있는 오프쇼어 파이낸셜 센터 조사에 관한 가장 인용된 논문("OFC")[150]은 OFC가 인근 고세 또는 원천경제에 대해 긍정적인 측면과 부정적인 측면을 지적하고 OFC를 [151]약간 선호했다.

결론: 양자간 샘플과 다자간 샘플을 모두 사용하여 성공적인 오프쇼어 금융센터는 탈세 및 자금세탁을 촉진하기 때문에 소스 국가의 나쁜 행동을 조장한다는 것을 경험적으로 알 수 있다.보다 좋은 것을 시퀀스. [...] 우리는 잠정적으로 OFC가 "심볼"로 더 잘 특징지어진다고 결론짓는다.

--

그러나 조세피난처에 관한 중요한 논문에서 조세피난처를 정상적인 조세제도의 관할구역에 기생하는 존재로 규정하고 있는 [152]슬렘로드와 윌슨의 연구 등 다른 저명한 조세학자들이 이러한 견해를 강하게 반박하고 있다.게다가 조세 정의 운동 단체들은 하인즈나 다른 사람들에 대해서도 이러한 [139][140]견해에 대해 똑같이 비판적이었다.2018년 6월 IMF의 조사에 따르면 조세피난처에서 고과세국으로의 외국인 직접투자(FDI)의 대부분은 실제로는 고과세 [30]국가에서 비롯되었으며, 예를 들어 영국에 대한 가장 큰 직접투자원은 영국이지만 조세피난처를 [153]통해 투자된 것으로 나타났다.

기업 과세가 경제성장에 미치는 영향과 법인세를 부과해야 하는지 여부에 대한 광범위한 경제이론의 경계가 모호해지기 쉽다.주크만과 같은 조세피난처를 조사한 다른 연구자들은 조세피난처의 부당성을 강조하고 그 효과가 [154]사회 발전을 위한 소득 손실이라고 본다.그것은 [155]양측 지지자들이 있는 여전히 논쟁의 여지가 있는 분야이다.

미국 세금 영수증

1994년 [149]하인스-라이스지의 조사 결과는 조세피난처로부터의 낮은 외국 세율이 궁극적으로 미국의 세금 [41]징수를 강화한다는 것이었다.하인스는 조세피난처를 이용해 외국세를 내지 않은 결과, 미국 다국적 기업들은 미국의 조세부채를 줄일 수 있는 외국 세액공제를 쌓는 것을 피했다는 것을 보여주었다.하인스는 여러 차례 이 같은 사실을 밝혀냈으며 ① 2010년 조세피난처에 관한 중요한 논문에서 미국의 다국적 기업들이 조세피난처와 BEPS 도구를 이용해 일본의 일본 투자에 대해 어떻게 세금을 회피했는지를 보여주면서 이는 [28]기업 차원의 다른 실증연구에서도 확인되고 있다고 지적했다.Hines의 관찰 및 OECD시도에 아일랜드의 BEPS제정 tools,[h][29]는지 그 이유는 세금 회피의 구글, 페이스북, 그리고 사과맛 같은 아일랜드 BEPS제정 도구로 기업들이 일반에게 공개에도 불구하고, 작은 미국에 의해 시행된를 억제하는데 미국의 대북 적대 정책을 조세 피난처에 대한 1996년"check-the-box"[g]규칙을 포함한 미국 정책 영향을 끼칠 것이다.는 멈추m.[149]

외국세율이 낮아지면 외국세에 대한 공제액이 줄어들고 미국의 최종 세금 징수액이 증가한다(Hines and Rice, 1994).[41]Dyreng and Lindsey(2009)[28]는 특정 조세피난처에 외국계 계열사를 둔 미국 기업들이 유사한 미국 대기업들보다 낮은 외국세와 높은 미국 세금을 낸다는 증거를 제시한다.

--

2018년 6월부터 9월까지의 조사에서는, 미국의 다국적 기업이 조세 피난처와 BEPS [131][132][133]툴의 최대 글로벌 유저인 것을 확인했습니다.

미국의 다국적기업들은 지배적인 외국기업 규정을 지켜온 다른 나라의 다국적기업들보다 조세피난처를[i] 더 많이 이용한다.조세피난처에 예치된 외국 이익의 비율이 미국만큼 높은 OECD 국가는 없다.[...] 이는 조세피난처로 전환된 전 세계 이익의 절반이 미국 다국적 기업에 의해 이전되고 있음을 시사한다.반면 EU 국가에는 약 25%, OECD 나머지 국가에는 10%, 개발도상국에는 15%가 발생한다(Törslöv et al., 2018).

--

2019년, Council on Foreign Relations(외교위원회)와 같은 비학술단체는 조세피난처를 미국 기업이 사용하는 규모를 파악했다.

미국 기업들이 해외에서 벌어들인 수익의 절반 이상이 여전히 소수의 저세금 피난처에만 예약되어 있는데, 물론 그곳에서는 고객, 근로자, 그리고 대부분의 사업을 용이하게 하는 납세자들이 실제로 살고 있지 않다.다국적 기업은 버뮤다의 법인세율 제로(0)를 이용하여 아일랜드를 통해 글로벌 매출을 라우팅하고 네덜란드 자회사에 로열티를 지불한 다음 수입을 버뮤다 자회사로 돌릴 수 있습니다.

--

조세 정의 단체들은 하인스의 연구를 미국이 높은 세금 국가들과 세금 경쟁을 벌이는 것으로 해석했다.2017년 TCJA는 미국 재무부가 미국 이외의 수입에서 BEPS 도구를 사용하여 축적한 1조 달러 이상의 해외 이익에 대해 15.5%의 송환세를 부과할 수 있게 됨으로써 이러한 견해를 뒷받침하는 것으로 보인다.만약 이러한 미국 다국적 기업들이 그들이 벌어들인 나라들에서 이러한 비미국 이익에 대해 세금을 냈다면, 미국 세금에 대한 추가 부담은 거의 없었을 것이다.주크먼과 라이트(2018년)의 연구에 따르면 TCJA 송환 혜택의 대부분은 미국 [88][j]재무부가 아닌 미국 다국적 기업의 주주들에게 돌아간 것으로 추정됐다.

조세피난처를 연구하는 학자들은 미국 기업이 조세피난처를 이용하는 것을 지지하는 것은 미국과 다른 고세율 경제협력개발기구(OECD) 국가들 간의 정치적 타협으로 미국의 "세계적" 조세제도의 [157][158]단점을 보완하기 위한 것이라고 보고 있다.하인스 장관은 조세피난처에 대한 미국의 다국적 수요를 없애기 위해 대부분의 다른 국가들이 사용하는 "영토" 세금 체계로의 전환을 지지했다.2016년 하인스는 독일 조세학자들과 함께 독일 다국적 기업들이 조세피난처를 거의 이용하지 않는다는 것을 보여주었다. 왜냐하면 그들의 조세제도는 "영토" 시스템이기 때문에 조세피난처에 [159]대한 필요성을 없애기 때문이다.

하인스의 연구는 경제자문위원회(CEA)가 2017년 TCJA 법안의 초안을 작성하고 하이브리드 '영토' 조세제도로의 [160][161]이행을 주창하면서 인용했다.

★★★

개인과 기업이 조세피난처에 [53][162]어떻게 관여하는지와 관련하여 주목할 만한 개념들이 많이 있다.

상태

조세피난처에 관한 몇몇 저명한 저자들은 조세피난처로부터 운영되는 전문 서비스 회사들의 법적, 조세 및 기타 요건이 상충되는 국가의 [72][163]요구보다 더 높은 우선순위가 주어지는 그들의 역외 금융 산업에 의해 그들을 "포착된 국가"라고 묘사하고 있다.이 용어는 안티구아,[165] 세이셸,[166] 저지 [167]등 소규모 [164]조세피난처에 특히 사용된다.그러나 "포착된 국가"라는 용어는 더 크고 더 확립된 OECD와 EU의 역외 금융 센터나 조세 [168][169][170]피난처에도 사용되어 왔다.로넨 팔란은 조세피난처가 '무역센터'로 출발한 곳에서도 결국 이들 국가의 법을 [171]작성한 강력한 외국 금융 및 법률회사들에 의해 붙잡힐 수 있다고 지적했다.구체적인 예로는 2016년 아마존사의 프로젝트 골드크레스트 세금 구조를 공개하는 것을 들 수 있다.이는 룩셈부르크주가 2년 이상 아마존과 긴밀히 협력하여 글로벌 세금을 [172][173]회피하는 것을 도와준 것을 보여준다.네덜란드 정부가 더치샌드위치 BEPS 툴을 만들어 법인세 회피 조항을 없앤 것도 그 예다.네덜란드 로펌은 이를 미국 기업에 판매했다.

2003년 5월 ABN Amro Holding NV의 전 벤처캐피털 임원이었던 Joop Wijn이 그의 미국 방문에 대해 보도할 때까지 머지않아 그는 수십 명의 미국 세무 변호사, 회계사 및 법인 이사에게 새로운 네덜란드 조세 정책을 제안할 것입니다.2005년 7월, 그는 세무 컨설턴트의 비판에 대응하기 위해 미국 기업의 탈세를 막기 위한 조항을 폐지하기로 결심한다.

--

우대 판결

우선세법(PTR)은 예를 들어 도시 재생을 장려하기 위한 세금 인센티브와 같은 좋은 이유로 관할구역에 의해 사용될 수 있다.그러나 PTR은 전통적인 [53]조세피난처에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 조세제도의 측면을 제공하기 위해 사용될 수도 있다.예를 들어, 영국 시민들이 그들의 자산에 대해 세금을 전액 내는 반면, 영국에 합법적으로 거주하는 외국 시민들은 그들이 영국 밖에 남겨져 있는 한, 그들의 글로벌 자산에 세금을 내지 않는다. 따라서, 외국인 거주자들에게 영국은 전통적인 조세 [176]피난처와 비슷한 방식으로 행동한다.일부 세무학자는 PTR이 전통적인 조세피난처와의 차이를 [53][177]"다른 무엇보다 중요한 문제"로 만든다고 말한다.OECD는 1998년에 시작된 PTRs의 조사를, 1998년에 시작된 장기 프로젝트의 중요한 부분으로 삼았다. OECD는 2019년까지 255개 이상의 PTRs를 [178]조사했다.2014년 Lux Leaks 공개는 룩셈부르크 당국이 PriceWaterhouseCoopers의 기업 고객에게 발행한 PTR 548장을 공개했습니다.EU 집행위원회가 2016년 애플에 사상 최대 규모의 과징금 130억 달러를 부과했을 때, 그들은 애플이 1991년과 [119][179]2007년에 "우대 세금 판결"을 받았다고 주장했다.

반전

법인은 세금역전을 통해 법률 본사를 고세 주택 관할구역에서 조세피난처로 이전할 수 있다.'나체세 역전'이란 기업이 새 사업장에서 영업활동을 거의 하지 않았던 곳이다.최초의 세금 역전 사건은 1983년 [180][181]맥더모트 인터네셔널에서 파나마에 대한 '나체 역전'이었다.미 의회는 2004년 [181]미국 일자리 창출법에 IRS 규정 7874를 도입함으로써 미국 기업에 대한 '나체 반전'을 사실상 금지했다.'합병세 역전'은 기업이 새로운 장소에 [181]'실질적인 사업 존재'를 가진 법인과 합병함으로써 7874를 극복하는 것이다.실질적인 사업 존재에 대한 요구는 미국 기업들이 더 큰 조세 피난처, 특히 OECD 조세 피난처와 EU 조세 피난처로 전환될 수 있다는 것을 의미했다.2016년 미 재무부의 규제 강화와 2017년 TCJA 미국 세제 개혁으로 미국 기업이 조세 [181]피난처로 전환하는 세제 혜택이 축소됐다.

기업이 조세피난처에 세금을 역전하는 경우에도 미이체 이익은 새로운 [181]조세피난처로 옮겨야 한다.이를 기저 침식 및 이익 이동([59]BEPS) 기술이라고 합니다.Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich와 같은 주목할 만한 BEPS 도구는 2004년부터 [182]2017년까지 버뮤다(예: 애플의 버뮤다 블랙홀)와 같은 조세 피난처에 미화 1~2조 달러의 해외 현금 보유고를 쌓기 위해 미국 기업에 의해 사용되었다.§ Financial scale에서 논의한 바와 같이, 2017년에는 BEPS 툴이 세금으로 인한 연간 기업 이익에서 미화 1,000억~2,000억 달러를 차폐한 것으로 OECD는 추정했으며, 2018년에는 연간 2,500억 달러에 가까웠다고 추정했다.이는 2012-2016년 OECD BEPS 프로젝트에도 불구하고 이루어졌다.2015년에 애플은 자사의 IP 중 3,000억 달러를 아일랜드로 이전하면서 사상 최대 규모의 BEPS 거래를 실행했는데, 이를 하이브리드 세금 역전이라고 합니다.

가장 큰 BEPS 도구는 지적재산권(IP) 회계를 사용하여 국가 간에 수익을 이전하는 도구입니다.한 관할구역의 비용을 다른 관할구역의 이익과 비교하여 청구하는 기업의 개념(즉, 이전가격)은 잘 이해되고 수용된다.그러나 IP를 통해 기업은 비용을 대폭 '재평가'할 수 있습니다.예를 들어, 주요 소프트웨어를 개발하려면 급여와 오버헤드가 10억 달러에 달할 수 있습니다.IP 어카운팅에서는 소프트웨어의 법적 소유권을 조세피난처로 이전할 수 있습니다.이것에 의해, 1,000억달러의 가치를 재평가할 수 있습니다.이것에 의해, 소프트웨어의 글로벌 이익에 대해서 청구되는 새로운 가격이 됩니다.이로 인해 전 세계 이익이 조세피난처로 다시 이동하게 됩니다.IP는 "선도적인 법인세 [183][184]회피 수단"으로 묘사되어 왔다.

카리브해나 채널 아일랜드와 같은 전통적인 조세피난처는 개인과 기업에게 비과세 성질을 분명히 하는 경우가 많다.그러나 이 때문에 다른 고세 관할권과 완전한 양자 조세협약을 맺을 수 없다.대신 조세피난처(예: 조세피난처에 대한 양도세 원천징수)의 사용을 피하기 위해 조세조약이 제한되고 제한된다.이 문제를 해결하기 위해 다른 조세피난처들은 0이 아닌 높은 법인세율을 유지하면서도 복잡하고 기밀성이 높은 BEPS 도구와 PTR을 제공하여 법인세율을 0에 가깝게 만듭니다.이러한 세금은 모두 IP법의 주요 관할구역에서 두드러집니다(그림 참조).이러한 「법인세 피난처」(또는 「Conduit OFC」)는, BEPS 툴/PTR를 사용하는 기업에 「실질적인 존재」를 요구함으로써, 한층 더 신뢰도를 높입니다.이것은 고용세라고 불리며, 약 2~3%의 수익에 손해를 줄 수 있습니다.그러나, 이러한 이니셔티브에 의해, 법인세 피난처는 완전한 양자 조세 조약의 대규모 네트워크를 유지할 수 있게 되어, 피난처에 근거지를 둔 기업은, 글로벌한 미이체 이익을 피난처로 되돌릴 수 있게 됩니다(상기와 같이, Sink OFCs).이들 '법인세 피난처'는 조세피난처와의 관련성을 강하게 부인하고 높은 수준의 준수와 투명성을 유지하고 있으며, 이들 중 다수는 OECD 또는 EU 회원국이기도 하다.조세피난처 상위 10곳 중 상당수가 법인세피난처다.

2017년 암스테르담 대학의 CORPNET 연구 그룹은 9,800만 개 이상의 글로벌 기업 커넥션에 대한 다년간의 빅데이터 분석 결과를 발표했습니다.CORPNET은 조세피난처에 대한 사전 정의나 법적 또는 조세구조 개념을 무시하고 양적 접근법을 채택하였다.CORPNET의 결과에 따르면 조세피난처에 대한 이해는 기업이 미이체자금을 송금하는 전통적인 조세피난처인 싱크 OFC와 고과세 관할구역에서 싱크 OFC로 분류된다.CORPNET의 상위 5개 컨짓 OFC와 상위 5개 싱크 OFC는 양적인 접근법만을 따르고 있지만, 다른 학계 top 상위 10개 조세피난처와 밀접하게 일치합니다.CORPNET의 Conduit OFCs에는 네덜란드, 영국, 스위스, 아일랜드 [61][62][186]등 OECD 및/또는 EU 조세피난처로 간주되는 여러 주요 관할권이 포함되어 있습니다.Conduit OFCs는 현대의 "법인세 피난처"와, Sink OFCs는 "전통적인 조세 피난처"와 밀접한 관련이 있습니다.

포장지 ★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★

조세피난처는 기업 구조뿐만 아니라 특수목적차량(SPV) 또는 특수목적회사(SPC)[72]로도 알려진 자산을 보유하기 위한 비과세(또는 "세금중립") 법적 포장지도 제공합니다.이러한 SPV 및 SPC는 세금, 관세 및 부가세가 면제될 뿐만 아니라 규제 요건 및 특정 부문의 [72]은행 요건에 맞게 조정됩니다.예를 들어 제110조 SPV는 세계 증권화 시장의 [186]주요 포장지다.이 SPV는 지방세 기반을 해칠 수 있기 때문에 대형 금융센터에서는 허용되지 않지만 은행이 증권화에서 필요로 하는 파산 원점 요건을 지원하기 위해 제공되는 고아 구조를 포함한다.케이맨 제도 SPC는 지적재산권(IP) 자산, 암호화 화폐 자산, 탄소 신용 자산 등의 자산 클래스를 수용할 수 있어 자산 관리자들이 사용하는 구조이며, 경쟁 제품으로는 아일랜드 QIAIF와 룩셈부르크의 [187]SICAV가 있다.

및 있는 것은 다음과 같습니다.

★★★★★★★★★(2008)

2008년 독일 연방 정보국은 리히텐슈타인 은행인 LGT Treuhand의 전 IT 데이터 아카이브 담당자 Heinrich Kieber에게 1,250개의 [188]고객 계좌 상세 목록을 위해 420만 유로를 지불했습니다.불법 [189]탈세 혐의에 대한 조사와 체포가 이어졌다.독일 당국은 미국 국세청과 데이터를 공유했으며, 영국 HMRC는 동일한 [190]데이터에 대해 10만 GBP €를 지불했다.다른 정부들, 특히 덴마크와 스웨덴은 그것이 도난당한 재산으로 간주되는 정보에 대한 지불을 거부했다; 리히텐슈타인 당국은 독일 당국을 [191]스파이 혐의로 고발했다.

Virgin 유출)

2013년 4월, ICIJ(International Consortium of Investigative Journals)는 ICIJ에 익명으로 유출된 250만 건의 조세 피난처 고객 파일을 검색 가능한 260기가바이트 데이터베이스를 공개하고 58개국 [192][193]112명의 언론인과 함께 분석했습니다.대부분의 고객은 중국 본토, 홍콩, 대만, 러시아 연방 및 옛 소련 공화국 출신이며, 영국령 버진아일랜드가 중국 고객들에게 가장 중요한 조세 피난처로, 키프로스가 러시아 [194]고객들에게 중요한 조세 피난처로 지목되었다.프랑수아 올랑드의 선거운동 매니저인 장 자크 오귀에, 몽골 재무장관 바야르트 상가자브, 아제르바이잔 대통령, 러시아 부총리의 부인, 캐나다 정치인 앤서니 [195]머천트 등 다양한 유명 인사들이 유출됐다.

누수)

2014년 11월 ICIJ(International Consortium of Investigative Journalists)는 룩셈부르크의 PricewaterhouseCoopers에게 2002년부터 2010년까지 제공한 룩셈부르크의 기밀 개인 세금 판결에 관한 28,000개의 문서를 공개했다.이번 ICIJ 조사에서는 룩셈부르크에 본사를 둔 340개 이상의 다국적 기업에 대해 548건의 세금 판결이 나왔다.LuxLeaks 부부의 공개는 룩셈부르크와 다른 지역의 법인세 회피 계획에 대한 국제적인 관심과 의견을 끌었다.이 스캔들은 다국적 기업에 [196][197]유리한 세금 덤핑과 조세 회피 제도를 규제하기 위한 조치의 시행에 기여하였다.

누수(

2015년 2월 프랑스 신문 Le Monde는 스위스 자회사인 HSBC Private Bank(Suisse)를 통해 영국 다국적 은행 HSBC의 지식과 장려로 운영되는 탈세 계획에 관한 3.3기가바이트 이상의 기밀 고객 데이터를 제공받았다.이 정보원은 프랑스 컴퓨터 분석가 에르베 팔치아니로 제네바에 있는 HSBC에 10만 명 이상의 고객과 2만 개의 오프쇼어 기업이 보유한 계좌에 대한 데이터를 제공했다.이 공개는 스위스 은행 역사상 가장 큰 유출로 불리고 있다.르몽드는 가디언, 쥐드도이체 차이퉁,[198][199] ICIJ 등 47개 언론사에 소속된 154명의 기자들을 불러 이 자료를 취재했다.

페이퍼(

2015년에는 214,488개 이상의 해외 법인에 대한 재무 및 변호사-클라이언트 정보를 상세하게 기술한 총 260만 테라바이트의 문서가 Suddeutsche Zeungs(Zuungz)의 독일 언론인 Bastian Obermayer에게 이례적으로 유출되었습니다.SZ는 ICIJ와 80개국 107개 언론사 기자들과 함께 전례 없는 규모의 자료를 분석했다.1년 이상의 분석 끝에 2016년 4월 3일 첫 뉴스가 발표되었습니다.이 문서는 데이비드 캐머런 영국 총리와 지그문두르 다비드 군라우손 [200]아이슬란드 총리를 포함한 전 세계 유명 인사들의 이름을 올렸다.

페이퍼(

2017년에는 19개 조세피난처를 망라한 해외 마법서클 로펌 애플비의 개인 및 주요 기업 고객 활동 모두 1340만 테라바이트의 문서가 수트도이체차이퉁(SZ)의 독일 기자 프레데리크 오버마이어와 바스티안 오버마이어에게 유출됐다.2015년의 파나마 페이퍼스와 마찬가지로, SZ는 ICIJ 및 100개 이상의 미디어 조직과 협력하여 문서를 처리했습니다.여기에는 애플, AIG, 찰스 왕세자, 엘리자베스 2세 여왕, 후안 마누엘 산토스 콜롬비아 대통령, 윌버 로스 당시 미국 상무장관 등 12만 명 이상의 이름과 기업의 이름이 적혀 있다.이는 1.4테라바이트로 [201]역사상 가장 큰 데이터 유출로 2016년 파나마 페이퍼스에 버금가는 규모입니다.

2021) Pandora 페20 (2021)

2021년 10월 ICIJ(International Consortium of Investigative Journalists)는 유출된 문서와 2.9 테라바이트의 데이터가 포함된 1,190만 건을 기록했습니다.이 유출은 100명 이상의 억만장자, 유명인사, 재계 지도자들뿐만 아니라 현재와 전직 대통령, 총리, 국가원수들을 포함한 35명의 세계 지도자들의 해외 비밀 계좌가 폭로되었다.

★★

할 수

- 하고 데이터 및 공유를 .조세피난처 내에서 운영되는 실체에 대한 가시성을 촉진하는 조치(데이터 및 정보 공유 포함).

- 이니셔티브에 하기 위해 .OECD와 EU가 투명성 이니셔티브와 함께 조세피난처에 의한 협력을 장려하기 위해 사용하는 강압적인 도구입니다.

- 으로 한 및.조세피난처와 관련하여 구체적으로 식별된 문제를 대상으로 하는 일련의 입법 및/또는 규제 조치.

- 를 폐지하는 .조세피난처 이용 인센티브를 없애기 위해 고세관할구역이 세제개편을 실시하는 경우.

★★★★

FATCA

2010년 의회는 은행, 주식중개업자, 헤지펀드, 연기금, 보험회사, 신탁 등 광범위한 외국 금융기관(FFI)이 미국 국세청(IRS)에 직접 보고하도록 하는 외국계정세법(FATCA)을 통과시켰다.FATCA는 2014년 1월부터 FFI가 미국 각 클라이언트의 이름과 주소, 연간 최대 계좌 잔액 및 [202]미국인이 소유한 계정의 총 대변과 대변에 대한 연례 보고서를 IRS에 제공하도록 요구하고 있습니다.또한 FATCA는 증권거래소에 상장되지 않은 외국기업이나 미국 지분의 10%를 보유한 외국파트너십은 미국 소유자의 이름과 세금 식별번호(TIN)를 국세청에 보고해야 합니다.또한 FATCA는 해외 금융자산을 50,000달러 이상 보유한 미국 시민권자와 그린카드 소지자는 [203]2010 회계연도부터 1040 세금신고서를 제출해야 합니다.

OECD CRS

2014년 OECD는 FACTA에 따라 전 세계 수준의 세금 및 금융 정보 자동 교환을 위한 정보 표준인 Common Reporting Standard(FACTA가 데이터를 처리하기 위해 이미 필요함)를 적용했다.2017년 1월 1일부터 CRS에 참여하는 국가는 호주, 바하마, 바레인, 브라질, 브루나이 다루살람, 캐나다, 칠레, 중국, 쿡 제도, 홍콩, 인도네시아, 이스라엘, 일본, 쿠웨이트, 레바논, 마카오, 말레이시아, 모리셔스, 모나코, 뉴질랜드, 파나마, 사우디아라비아, 파나마, 브라질이다.아테스, 우루과이.[204]

2009년 4월 2일 런던 G20 정상회의에서 G20 국가들은 조세피난처에 대한 블랙리스트를 정의하기로 합의했다.이 블랙리스트는 '국제적으로 합의된 조세기준'[205]에 따라 4단계 시스템에 따라 세분화된다.2009년 4월 2일 현재 목록은 OECD [206]웹사이트에서 볼 수 있다.4개의 계층은 다음과 같습니다.

- 이 기준을 실질적으로 시행한 국가(중국은 제외하지만 홍콩과 마카오를 제외한다)

- 아직 완전히 구현되지 않은 조세 피난처(몬세라트, 나우루, 니우에, 파나마, 바누아투 포함)

- 표준(과테말라, 코스타리카 및 우루과이 포함)에 전념하고 있지만 아직 완전히 구현되지 않은 금융 센터.

- 표표 、 빈빈빈빈빈 ( 빈빈빈빈빈 )

하위 계층의 국가들은 처음에는 '비협력 조세 피난처'로 분류되었다.우루과이는 처음에 비협조적인 것으로 분류되었다.하지만, 항소심에서 OECD는 조세 투명성 규정을 충족시켰다고 말했고, 따라서 그것을 앞당겼다.필리핀은 블랙리스트에서 삭제하기 위한 조치를 취했고, 말레이시아의 나집 라작 총리는 말레이시아가 하위권에 [207]속하지 말아야 한다고 일찍이 제안했었다.

2009년 4월 OECD는 수석 엔젤 구리아를 통해 코스타리카, 말레이시아, 필리핀, 우루과이가 "OECD [208]기준에 따른 정보 교환을 전면 약속"한 후 블랙리스트에서 삭제되었다고 발표했다.니콜라 사르코지 전 프랑스 대통령이 중국과 별도로 홍콩과 마카오를 포함하라고 요구했음에도 불구하고,[205] 그것들은 아직 독립적으로 포함되지 않았지만 나중에 추가될 것으로 예상된다.

이 단속에 대한 정부의 대응은 [209]보편적이지는 않지만 대체로 지지를 보내고 있다.룩셈부르크의 장 클로드 융커 총리는 G20이 [210]반대하는 순수 조세피난처와 구별할 수 없는 통합 인프라를 제공하는 미국의 여러 주를 포함하지 않은 것에 대해 "신뢰성이 없다"고 비판했다.2012년 현재 89개국이 OECD의 [211]화이트리스트에 등재될 만큼 충분한 개혁을 시행하고 있다.국제투명성기구에 따르면 부패가 가장 적은 나라의 절반은 [212]조세피난처였다.

연합

2017년 12월 EU 집행위원회는 준거와 협력을 장려하기 위해 다음과 같은 '블랙리스트'를 채택했다.아메리칸사모아, 바레인, 바베이도스, 그레나다, 괌, 한국, 마카오, 마셜 제도, 몽골, 나미비아, 팔라우, 파나마, 세인트루시아, 사모아, 트리니다드 토바고, 튀니지, 아랍에미리트.[77]또한, 위원회는 EU와의 협력을 이미 약속하고 조세 투명성과 [213]협력에 관한 규칙을 변경하기로 한 47개 관할구역의 "그릴리스트"를 배출했다.EU의 17개 조세피난처 중 오직 한 곳, 즉 사모아가 상위 20개 조세피난처에 있었다.EU의 리스트에는 OECD나 EU의 관할권, 혹은 상위 10개 [78][79][214][215]조세피난처는 포함되지 않았다.몇 주 후 2018년 1월, EU 세무 집행관 피에르 모스코비치는 아일랜드와 네덜란드를 "세금 블랙홀"[216][217]이라고 불렀다.불과 몇 개월 후 EU는 블랙리스트를 더 [218]줄였고, 2018년 11월까지 5개 국가만 포함되었습니다.미국령 사모아, 괌, 사모아, 트리니다드 & 토바고 및 미국령 버진아일랜드.[219]그러나 2019년 3월까지 EU 블랙리스트는 10대 조세피난처인 버뮤다, 5대 싱크 OFC [220]등 15개 지역으로 확대됐다.

2019년 3월 27일 유럽의회는 룩셈부르크, 몰타, 아일랜드, 네덜란드, 키프로스를 "세금 피난처의 특성을 보이고 공격적인 조세 [221][222]계획을 촉진한다"고 비유한 새로운 보고서를 수용하는 것에 대해 찬성 505표, 반대 63표로 찬성표를 던졌다.그러나 이 투표에도 불구하고 EU 집행위원회는 이들 EU 관할권을 블랙리스트에 [223]포함시킬 의무가 없다.

2000년대 초반부터 포르투갈은 정부에 의해 조세피난처로 간주되는 특정 국가 목록을 채택하고 있으며, 이 목록과 관련된 일련의 포르투갈 거주 납세자에 대한 조세 처벌이다.그럼에도 불구하고, 그 목록은 경제적 관점에서 객관적이거나 합리적이지 않다는 비판을 받아왔다[224].

★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★」

인버전

미국 기업이 카리브해 조세피난처(버뮤다, 케이맨 제도 등)에 세금을 남발하는 것을 막기 위해 미 의회는 2004년 미국 일자리 창출법을 통과시키면서 IRS 코드에 규정 7874를 추가했다.이 법률은 효과적이었지만, 훨씬 더 큰 합병세 역전을 방지하기 위해 2014-2016년 미국 재무부의 추가 규제가 요구되었고, 이는 아일랜드에서 제안된 2016년 화이자-앨러건의 유효 블록으로 절정에 달했다.이러한 변화 이후, 더 이상의 중요한 미국의 세금 반역은 없었다.

BEPS ® BEPS

2012년 G20 Los Cabos 정상회의에서 OECD는 기업의 기반 침식과 이익 이동(BEPS) 활동을 퇴치하는 프로젝트를 수행하기로 합의했다.2015년 G20 안탈리아 정상회의에서 경제협력개발기구(OECD)의 국내 및 양국 조세조약 조항을 통해 이행되도록 설계된 '15개 행동'이 합의됐다.OECD BEPS Multilateral Instrument(MLI)는 2016년 11월 24일에 채택되어 78개 이상의 국가에서 서명되었으며, 2018년 7월에 발효되었다.MLI는 국가별 보고서(CbCr)를 포함한 제안된 이니셔티브 중 몇 가지를 '물타기'하고 여러 OECD 및 EU 조세피난처를 이용했던 몇 가지 옵트아웃을 제공했다는 비판을 받아왔다.미국은 MLI에 서명하지 않았다.

더블

Double Irish는 역사상 가장 큰 BEPS 도구였으며, 2015년까지 미국 세금으로 인한 기업 이익의 대부분이 1,000억 달러 이상을 보호하게 되었습니다.EU 집행위원회가 불법 하이브리드-더블 아일랜드 구조물을 사용했다는 이유로 130억 유로의 벌금을 부과했을 때, 그들의 보고서는 애플이 적어도 1991년 [225]이전부터 이 구조물을 사용해왔다고 지적했다.워싱턴의 몇몇 상·의회 조사에서는 2000년 이후 더블 아이리쉬에 대한 대중의 지식을 인용했다.그러나 2015년에 아일랜드가 최종적으로 이 구조물을 폐쇄하도록 강요한 것은 미국이 아니라 [226]EU 집행위원회였다. 그리고 기존 사용자들은 2020년까지 대체 약정을 찾을 수 있었다. 그 중 두 가지(예: 싱글 몰트 약정)는 이미 [227][228]운영되고 있었다.OECD MLI(위)에 대한 미국의 입장과 마찬가지로 조세피난처 최대 사용자이자 수혜국인 미국이 아무런 조치를 취하지 않은 것이 원인이다.그러나 일부 논객들은 2017 TCJA까지 미국 법인세법의 근본적인 개혁이 [229]이를 바꿀 수 있다고 지적한다.

★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★」

★★★

2007년부터 2010년까지 아일랜드에 대한 세금 환입이 22차례나 줄어들자 영국은 법인세법을 [230]전면 개혁하기로 결정했다.2009년부터 2012년까지 영국은 헤드라인 법인세율을 28%에서 20%로 낮추고(결국 19%로), 영국의 법인세 코드를 '세계세제'에서 '영토세제'로 변경했으며, 저세 특허 [230]상자를 포함한 새로운 IP 기반 BEPS 도구를 만들었습니다.2014년 월스트리트저널은 "미국의 세금 역전 거래에서 이제 영국이 승자"[231]라고 보도했다.2015년 발표에서 HMRC는 2007년부터 2010년까지의 영국의 미해결 전환 중 많은 부분이 세제 개혁의 결과로 영국으로 돌아갔음을 보여주었다(나머지 대부분은 후속 거래에 들어갔고 [232]샤이어를 포함하여 돌아올 수 없었다).

★★★

미국은 2017년 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017(TCJA; 감세 및 고용법)의 통과로 영국과 거의 유사한 개혁에 따라 미국 법인세율을 35%에서 21%로 낮추고, 미국 법인세 코드를 "세계적 조세 시스템"에서 FDi와 같은 하이브리드 "영토세 시스템"으로 변경하며, 새로운 IP 기반의 BEPS 툴(FDi)을 만들었다.BEAT [233][234]세금과 같은 기타 BEPS 방지 도구.TCJA를 옹호하면서 대통령 경제자문위원회(CEA)는 학자인 제임스 R.의 작업에 크게 의존했다. 미국 기업의 조세피난처 이용과 TCJA에 [43]대한 미국 기업의 대응 가능성에 대해 하인스 주니어.TCJA 이후, 화이자는 아일랜드의 Alergan plc와 2016년 번복했을 때 예상했던 것과 매우 유사한 글로벌 종합 세율을 이끌어 왔다.

는 다국적 하기 위한 1월 1일, 는 " 2.0명명했다.보도자료에서 OECD는 그들의 제안이 중국, 브라질, 인도뿐만 아니라 미국도 지지한다고 발표했다.새로운 제안에는 제품의 가치가 창출되는 곳(현재와 같이)보다는 제품이 소비되는 곳의 이익에 대한 과세를 중심으로 한 보다 근본적인 법인세 개혁이 포함되어 있다.EU는 이 개념을 오랫동안 지지해 왔지만 미국은 전통적으로 이를 저지해왔다.그러나 2017년 TCJA가 통과됨에 따라 조세피난처 중 여전히 세계 최대 이용자인 미국 기업의 조세피난처 사용에 대한 미국 정부의 시각은 달라졌다고 여겨진다.이 새로운 OECD 이니셔티브에 대응하여 EU, 특히 프랑스는 OECD BEPS 2.0 이니셔티브가 2020년까지 결론에 도달할 수 있도록 하기 위해 "디지털 세금" 제안을 철회했다.

★★★

인 단계

고대 그리스에서는 저과세 지역이 기록되지만 조세학계는 조세피난처라고 알려진 것을 현대 [69][70]현상으로 파악하고 그 발전 과정에서 다음과 같은 단계에 주목한다.

- 19세기 뉴저지와 델라웨어 회사입니다.1880년대에 뉴저지는 재정난에 빠졌고, 리언 애벗 주지사는 뉴욕의 변호사 딜이 "기존 기업" (비거주 기업 아님)을 포함한 기업 구조를 설립하기 위한 보다 진보적인 체제를 만드는 계획을 지지했다.델라웨어는 1898년 일반법인에 따라 뉴욕의 다른 변호사들로부터 로비를 받아왔다.남해 버블의 결과로 앵글로색슨계에서의 제한적인 법인화 체제 때문에 뉴저지주와 델라웨어주는 성공적이었고, 명시적으로 조세 피난처(예: 미국 연방세 및 주세 적용)는 아니지만, 많은 미래 조세 피난처들은 그들의 "자유적" 법인화 [69]체제를 모방할 것이다.

- 제1차 세계 대전 이후.조세 피난처의 현대적 개념은 [69][235]제1차 세계 대전 직후 불확실한 시점에 나타난 것으로 일반적으로 받아들여지고 있다. 버뮤다는 1935년 새로 설립된 코니어스 딜 & 피어먼의 [236]법률 제정에 기초해 최초의 조세 피난처라고 주장하기도 한다.그러나 대부분의 세무학자들은 취리히-주그-리히텐슈타인 삼각지대를 1920년대 [69][237]중반에 만들어진 최초의 조세 피난처 허브로 꼽는다.리히텐슈타인의 1924년 민법은 악명 높은 안스탈트 회사 차량을 만들어 냈고 취리히와 주그는 Aktiengesellschaft/Societe Anonyme와 다른 황동 판 회사를 [69]개발했습니다.세무학자인 Ronen Palan은 조세피난처의 세 가지 주요 그룹 중 이 기간에 출현한 두 그룹을 지목했습니다.

- 대영제국에 기반을 둔 조세 피난처입니다.1929년 이집트 Delta Land and Investment Co.의 법정 사건. 영국의 Ltd. V. Todd는 "비거주 법인"을 설립하고 영국에서 사업 활동이 없는 영국 등록 회사는 영국의 과세 의무가 없음을 인정했습니다.조세학자인 솔 피치오토는 이러한 "비거주" 기업의 설립은 "어떤 의미에서 영국을 조세 피난처로 만든 허점"이라고 지적했다.이 판결은 버뮤다, 바베이도스, 케이맨 [53][70]제도를 포함한 대영제국에 적용되었다.

- 유럽에 기반을 둔 조세 피난처취리히-주그-리히텐슈타인 삼각지대가 확장되어 1929년 룩셈부르크가 비과세 지주회사를 [69]설립하면서 합류했다.그러나 1934년 세계적인 불황에 대한 반작용으로 1934년 스위스 은행법은 스위스 형법에 [53]은행 비밀주의를 포함시켰다.비밀과 사생활은 [70]다른 조세피난처와 비교하여 유럽에 기반을 둔 조세피난처들의 중요하고 독특한 부분이 될 것이다.

- 제2차 세계대전 후 오프쇼어 금융 센터.제2차 세계대전 후 시행된 환율 통제는 유로달러 시장의 창출과 오프쇼어 파이낸셜 센터(OFC)[56]의 증가로 이어졌다.이들 OFC의 대부분은 케이맨과 버뮤다를 포함한 제1차 세계대전 이후의 전통적인 조세 피난처였지만 홍콩과 싱가포르와 같은 새로운 중심지가 [56]생겨났다.이러한 OFC의 글로벌 금융 센터로서의 런던의 위치는 1957년 영국 은행이 영국에 소재하지 않은 대출자와 차입자를 대신하여 실행한 거래는 비록 거래가 규제 또는 세금 목적으로 영국에서 이루어졌다고 공식적으로 간주되지 않는다고 판결했을 때 확보되었다.런던에서 [53][70][238]일어난 것으로만 기록되었습니다.OFC의 증가는 계속되어 2008년까지 케이맨 제도는 세계에서 4번째로 큰 금융 중심지가 되고 싱가포르와 홍콩은 주요 지역 금융 [53]중심지가 된다.2010년까지 세무학자들은 OFC를 조세피난처와 동의어로 간주할 것이며 대부분의 서비스가 세금과 [10][72]관련이 있다고 생각할 것이다.

- 신흥 경제에 기반을 둔 조세 피난처.OFC의 급격한 증가와 함께 1960년대 후반부터 새로운 조세피난처가 개발 도상국 및 신흥 시장에 등장하기 시작했고, 이는 팔란의 세 번째 그룹이 되었다.최초의 태평양 조세 피난처는 호주의 자치 외부 영토인 노퍽 섬(1966년)이었다.이어 바누아투(1970-71년), 나우루(1972년), 쿡 제도(1981년), 통가(1984년), 사모아(1988년), 마셜 제도(1990년), 나우루(1994년)[69]가 뒤를 이었다.이들 모든 피난처는 비거주기업, 스위스식 은행비밀보호법, 신탁회사, 해상보험법, 선박 및 항공기 리스 편의법, 혜택 등 성공한 대영제국과 유럽의 조세피난처를 모델로 한 친숙한 법령을 도입했다.새로운 온라인 서비스(도박, 포르노 등)[53][71]에 대한 법적 규제

- 기업 중심의 조세 피난처.1981년 미국 국세청은 미국 납세자의 조세피난처 사용에 관한 고든 보고서를 발간하여 미국 [239]기업의 조세피난처 사용을 강조하였다.1983년, 미국 법인 McDermott International은 [181]파나마에 대한 최초의 세금 반입을 실행했다.EU 집행위원회는 애플이 1991년부터 악명 높은 더블 아일랜드 BEPS 도구를 사용하기 시작했음을 보여주었다.미국 세무학자 제임스 R. 하인스 주니어는 1994년 미국 기업들이 아일랜드와 [41]같은 OECD 조세피난처에서 약 4%의 효과적인 세율을 달성하고 있음을 보여주었다.2004년 미 의회가 IRS 규정 7874의 도입으로 카리브해 조세피난처에 대한 미국 기업들의 '나체 세금반전'을 중단하자 OECD [181]조세피난처로 이전하는 미국 기업의 '합병반전'이 훨씬 더 크게 일어났다.OECD에 준거하고 투명하지만 전통적인 [71][72]조세피난처와 유사한 순세율을 달성할 수 있는 복잡한 기초 침식과 이익 이동(BEPS) 도구를 제공하는 새로운 종류의 법인세가 등장했다.조세피난처를 억제하기 위한 OECD의 이니셔티브는 주로 팔란의 제3의 신흥경제 기반 조세피난처에 영향을 미치지만 기업 중심의 조세피난처는 대영제국의 조세피난처와 유럽 기반 조세피난처, 네덜란드, 싱가포르, 아일랜드, 영국을 포함한 최대 규모의 OFC에서 나왔다.심지어 룩셈부르크, 홍콩, 카리브해(케이맨, 버뮤다, 영국령 버진아일랜드), 스위스 [72]같은 전통적인 조세피난처도 개혁했다.이들의 BEPS 활동 규모는 Hines의 2010년 목록, Conduit and Sink OFC 2017 목록, Zucman의 2018년 목록 등 2010년부터 이 10개 국가 그룹이 학계 조세 피난처 목록을 지배할 것임을 의미한다.

주목할 만한 사건

- 1929년, 영국 법원은 이집트 델타 랜드 앤 인베스트먼트사의 판결을 내렸습니다. Ltd. V. Todd. 영국에서 영업활동을 하지 않는 영국 등록 회사는 영국 과세의 의무가 없습니다.솔 피치오토는 이러한 "비거주" 기업의 설립은 "어떤 의미에서 영국을 조세 피난처로 만든 구멍"이라고 지적했다.이 판결은 버뮤다, 바베이도스, 케이맨 [53]제도를 포함한 대영제국에 적용되었다.

- 1934년 세계적인 불황에 대한 반작용으로 1934년 스위스 은행법은 스위스 형법에 은행 비밀주의를 포함시켰다.법률은 "직업상 비밀에 관한 절대적인 침묵"(스위스 은행 계좌)을 요구했다."Absolute"는 스위스를 포함한 모든 정부로부터 보호를 의미합니다.스위스 은행의 영업비밀에 대한 조사나 조사까지 [53]형사범죄로 규정했다.

- 1981년 미국 재무부와 법무장관은 다음과 같이 부여된다.조세피난처와 미국 납세자에 의한 그 사용: 리처드 A의 개요.Gordon의 국세청 국제조세특별변호사.Gordon Report는 아일랜드와 같은 새로운 [239]유형의 법인세 피난처를 식별한다.

- 1983. 맥더모트 인터내셔널이 텍사스에서 파나마 [180][181]조세피난처로 이전함에 따라 처음으로 공식적으로 미국 법인세 역전 사실을 인정했다.

- 1994년 제임스 R. 하인스 주니어는 7대 조세피난처를 포함한 41개 조세피난처에 대한 첫 학술 목록을 작성하면서 중요한 하인스-라이스 논문을 발행하고 있다.하인스-라이스 신문은 이익 이동이라는 용어를 사용했으며, 많은 조세피난처들이 헤드라인 세율은 높지만 실효 세율은 훨씬 낮았다.하인즈는 미국이 조세피난처의 [41]주요 사용자라는 것을 보여준다.

- 2000. OECD는 3개의 OECD 기준 중 2개를 충족한 35개의 조세피난처를 처음으로 공식 발표했다.기존 35개 회원국 중 EU-28개 회원국 중 조세피난처에 [22]등재된 나라는 없다.2008년까지 오직 트리니다드 토바고만이 조세 [49]피난처가 되기 위한 OECD 기준을 충족시켰다.학계에서는 "OECD 조세피난처"와 "EU 조세피난처"라는 용어를 사용하기 시작한다.

- 2000. FSF-IMF는 질적 [55]기준을 사용하여 42~46개의 OFC 목록을 사용하여 오프쇼어 파이낸셜 센터(OFC)를 정의하고 있으며, 2007년에 IMF는 22개의 [56]OFC의 개정된 양적 기반 목록을 작성했으며, 2018년에는 8개의 주요 OFC의 [30]85%를 담당하는 양적 기반 목록을 작성했다.2010년까지 세무학계는 OFC와 조세피난처를 [10]동의어로 간주한다.

- 2004. 미국 의회는 2004년 미국 일자리 창출법(AJCA)을 IRS 섹션 7874와 함께 통과시켜 미국 기업이 카리브해 [181]조세피난처에 대한 나체 반입을 사실상 종식시켰다.

- 2009년 조세정의네트워크는 조세피난처 학술목록에는 없지만 투명성에 문제가 있는 OECD 준거국가에 관한 문제를 강조하기 위해 금융비밀지수(FSI)와 비밀관할권을 [33]도입했다.

- 2010년 제임스 R. 하인스 주니어는 52개의 조세피난처 목록을 발표했는데, 과거 조세피난처 목록과는 달리 기업의 투자 [23]흐름을 분석하여 양적으로 규모를 조정했다.Hines 2010 목록은 세계 10대 조세 피난처를 최초로 추산한 것이며, 그 중 저지와 영국령 버진아일랜드 두 곳만이 OECD의 2000년 명단에 올랐다.[23]

- 2015. Medtronic은 아일랜드에서 Covidien plc와의 합병으로 사상 최대 규모의 세금 반전을 완료하고, Apple Inc.는 역사상 최대 규모의 하이브리드 세금 반전을 완료하며, 2016년까지 미국 재무부는 반전의 규칙을 강화하여 Pfizer를 유발합니다.1,600억 달러 규모의 Alergan [181]plc와의 합병을 중단하다

- 2017. 암스테르담 대학의 CORPNET 그룹은 순수하게 정량적인 접근방식을 사용하여 OFC에 대한 이해를 Conduit OFC와 Sink OFC로 나눕니다.CORPNET은 상위 5개의 Conduit OFC 목록과 상위 5개의 Sink OFC 목록 중 상위 10개 안식처 목록에만 일치합니다. 2009~[60][61]2012년

- 2017. EU 집행위원회는 2017년 블랙리스트에 17개국, 2017년 그레이리스트에 [77]47개국을 포함한 조세피난처 공식 리스트를 작성하지만, 이전 2010년 OECD 목록과 마찬가지로 OECD 국가나 EU-28개 국가 중 조세피난처 [78][79]상위 10개국에는 포함되지 않는다.

- 2018. 세무학자인 Gabriel Zucman(et alia)은 기업의 "이익 이동"(BEPS)이 연간 2,500억 달러 이상을 [14][63]세금으로부터 보호하고 있다고 추정합니다.주크만의 2018년 10대 안식처 리스트는 하인즈 2010년 10대 안식처 중 9곳과 일치하지만 아일랜드는 세계 최대 [65]안식처다.애호박사는 미국 기업들이 전체 이익의 거의 절반을 [88][89][131][132]이전하고 있다는 것을 보여준다.

- 2019년 유럽 의회는 EU 집행위원회 조세피난처 목록에 포함되어야 할 5개의 "EU 조세피난처"[k][221][240][241]를 선정하여 찬성 505표, 반대 63표로 보고서를 승인한다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

추가 정보

학술 논문

다음은 미국 연방준비은행 세인트루이스에서 경제논문의 IDEA/RePEC 데이터베이스에서 가장 많이 인용된 조세피난처에 관한 논문이다. 루이스.[42]

조세피난처에 [40]대한 가장 중요한 연구로 EU 집행위원회 2017 요약본에 의해 ())라고 표시된 논문들이 인용되었다.

| 순위 | 종이. | 저널 | 볼륨 발행 페이지 | 작성자 | 연도 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1‡ | 재정적 천국:해외 조세피난처 및 미국 기업[41] | 분기별 경제 저널 | 109 (1) 149-182 | 제임스 하인스, 에릭 라이스 | 1994 |

| 2‡ | 조세피난처[242] 운영에 대한 수요 | 공공 경제 저널 | 90 (3) 513-531 | 미히르 데사이, C F 폴리, 제임스 하인스 | 2006 |

| 3‡ | 조세피난처가 [4]되는 나라는 어디인가요? | 공공 경제 저널 | 93 (9-10) 1058-1068 | 다미카 다르마팔라, 제임스 하인스 | 2009 |

| 4‡ | 사라진 국가:유럽과 미국은 순채무국인가, 아니면 [10]순채권국인가? | 분기별 경제 저널 | 128 (3) 1321-1364 | 가브리엘 주크먼 | 2013 |

| 5‡ | 조세피난처와의[152] 조세경쟁 | 공공 경제 저널 | 93 (11-12) 1261-1270 | 조엘 슬렘로드, 존 D.윌슨 | 2006 |

| 6 | 조세피난처에 [37]의해 어떤 문제와 기회가 만들어집니까? | 옥스퍼드 경제 정책 리뷰 | 24 (4) 661-679 | 다미카 다르마팔라, 제임스 하인스 | 2008 |

| 7 | 조세피난처에 대한 찬사:국제 조세[149] 계획 | 유럽 경제 리뷰 | 54 (1) 82-95 | 칭홍, 마이클 스마트 | 2010 |

| 8‡ | 은행 비밀 유지 종료:G20 조세피난처 단속 평가 | 미국 경제 저널 | 6 (1) 65-91 | 닐스 요하네센, 가브리엘 주크만 | 2014 |

| 9‡ | 국경을 넘나드는 세금:부와 기업의[18] 이익 추적 | 경제 전망 저널 | 28 (4) 121-148 | 가브리엘 주크먼 | 2014 |

| 10‡ | 보물군도[23] | 경제 전망 저널 | 24 (4) 103-26 | 제임스 하인스 | 2010 |

주요 도서

(Google Scholar 인용문 300개 이상 포함)

- Sol Piccolo (1992). International Business Taxation (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0899307770.

- Raymond W. Baker (2005). Capitalism's Achilles' Heel: Dirty Money, and How to Renew the Free-Market System. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0471644880.

- Ronen Palan; Richard Murphy; Christian Chavagneux (2009). Tax Havens: How Globalization Really Works. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7612-9.

- Nicholas Shaxson (2011). Treasure Islands: Uncovering the Damage of Offshore Banking and Tax Havens. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-10501-0.

- Jane G. Gravelle (2015). Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion (PDF). Congressional Research Service. ISBN 978-1482527681.: 6

- Gabriel Zucman (2016). The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226422640.

각종 기사

- Foremny, D. 및 Von Hagen, J. (2012).CEPR 토론서 9154, C.E.P.R. "위기에 처한 재정 연방주의"토론 용지

- Henry, James S. (October 2003). The Blood Bankers: Tales from the Global Underground Economy. New York, NY: Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 978-1-56858-254-2.

- Morriss, Andrew P. (2010). Offshore Financial Centers and Regulatory Competition. Washington: The AEI Press. ISBN 978-0-8447-4324-0.

- Scevola, Carlo; Sneiderova, Karina (January 2010). Offshore Jurisdictions Guide. Geneva, Switzerland: CS&P Fiduciaire. ISBN 978-1-60594-433-3.

- 국제탐구기자 컨소시엄으로부터:

- "새로운 은행 유출은 부자들이 조세피난처의 허점을 얼마나 악용하고 있는지를 보여준다" (2014-07-08)

- "Hidden in Plain Sight: 뉴욕 저스트 어나더 아일랜드 헤이븐" (2014-07-03)

- "태양과 그림자: 섬의 천국이 돈의 천국이 된 경위(2014-06-09)

- 유출된 기록으로 중국 엘리트 해외 보유 현황(2014-01-21)

- 비밀 "해외의 글로벌 영향 노출 파일"(2013-04-03)

- Alan Rusbridger (2016년 10월 27일)."파나마: 숨겨진 수조 권" (1/2부), 뉴욕 서평

메모들

- ^ 많은 기업 중심의 조세피난처는 명목세율(네덜란드 25%, 영국 19%, 싱가포르 17%, 아일랜드 12.5%)이 높지만 실효세율을 0에 가깝게 하기 위해 과세소득에서 항목을 충분히 제외하는 세제를 유지하고 있다.

- ^ 2000년 이후 OECD-IMF-FATF는 은행 비밀주의를 줄이고 투명성을 높이기 위한 이니셔티브로, 현대 학계는 비밀주의 구성요소가 중복되는 것으로 간주한다.의 정의를 참조해 주세요.

- ^ a b c FSI는 종종 "세금 피난처"의 등급으로 잘못 인용되지만, FSI는 현대의 양적 조세 피난처 목록과 같은 조세 회피 또는 BEPS 흐름을 수량화하지 않습니다. FSI는 비밀 유지 지표의 질적 점수이며, 가장 일반적인 비밀 유지 도구인 무한 책임 회사, 신탁 및 다양한 특수 목적을 채점하지 않습니다.차량(예: 아일랜드 QIAIF 및 L–Q)IAIF) - 아일랜드나 영국 [7][8]등 주요 조세피난처에 공적계좌를 제출할 필요가 있는 것은 거의 없습니다.

- ^ 2018년 9월 현재 주권국가 목록은 206개이므로 15%는 30개 조세피난처에 불과합니다.OECD의 2000년 목록에는 35개 [22]조세피난처가 있습니다.James Hines 2010 목록에는 52개 조세피난처가 [23]있습니다.2017년 Conduit and Sink OFCs 연구 목록에는 29개 주가 있습니다.

- ^ 아일랜드도 대영제국과 관련된 조세피난처와 연결되어 있는데, 아일랜드의 관습법 체계와 법인세 제도는 영국으로부터 파생된 것이며, 그 후 유럽 대륙으로부터 파생된 것이다.

- ^ a b ITEP 리스트는 Fortune 500대 기업만을 대상으로 하고 있습니다.글로벌 조사에서 도출된 조세회피처 리스트와의 강한 상관관계는 미국 다국적 기업이 글로벌 조세회피의 가장 지배적인 원천이며 조세회피처 사용자임을 강조하고 있습니다.

- ^ 1996년 이전, 미국은 다른 고소득 국가들과 마찬가지로, 이익 이동에 도움이 되는 일부 외국 소득(로열티나 이자 등)에 즉시 세금을 부과하도록 고안된 "통제된 외국 기업" 조항이라고 알려진 반회피 규정을 가지고 있었다.1996년 IRS는 미국 다국적기업이 외국법인을 기업이 아닌 조세 목적상 무시된 법인으로 취급하는 것을 선택함으로써 이러한 규칙 중 일부를 피할 수 있도록 하는 규정을 발표했다.이 조치는 "체크박스"라고 불리는데, 이는 IRS 양식 8832에서 실행되어야 하고, 미국 이외의 수익에 아일랜드 BEPS 도구를 사용하는 것이 미국 다국적 기업들이 미국을 떠나는 것을 막기 위한 타협이었기 때문이다(10페이지).[88]

- ^ 미국은 2016년 11월 24일 OECD BEPS 다자간 기구(MLI)의 서명을 거부했다.

- ^ 이 신문은 조세피난처를 아일랜드, 룩셈부르크, 네덜란드, 스위스, 싱가포르, 버뮤다, 카리브해 등 6페이지로 열거하고 있다.

- ^ Zucman과 Wright의 분석은 미국 다국적 기업이 최종적으로 35%의 이율을 지불할 것이라고 가정했다(예를 들어 그들은 미래의 어느 단계에서 해외 현금을 본국으로 송환할 것이다). 만약 그들이 해외 현금을 미국 밖에 영구히 둘 것이라고 가정한다면, 미국 재무부는 그렇게 할 것이다.

- ^ 유럽의회 표결은 EU의 조세피난처(블랙리스트 또는 그레이리스트)에 이들 EU 조세피난처를 공식적으로 포함시키는 EU 집행위원회에 대해 구속력이 없다. 구속력을 가지려면 모든 [223]회원국의 만장일치 표결이어야 한다.

레퍼런스

- ^ a b "Financial Times Lexicon: Definition of tax haven". Financial Times. June 2018. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

A country with little or no taxation that offers foreign individuals or corporations residency so that they can avoid tax at home.

- ^ a b "Tax haven definition and meaning Collins English Dictionary". Collins Dictionary. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

A tax haven is a country or place which has a low rate of tax so that people choose to live there or register companies there in order to avoid paying higher tax in their own countries.

- ^ a b "Tax haven definition and meaning Cambridge English Dictionary". Cambridge English Dictionary. 2018. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

a place where people pay less tax than they would pay if they lived in their own country

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dhammika Dharmapala; James R. Hines Jr. (2009). "Which countries become tax havens?" (PDF). Journal of Public Economics. 93 (9–10): 1058–1068. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.07.005. S2CID 16653726. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

The 'tax havens' are locations with very low tax rates and other tax attributes designed to appeal to foreign investors.

- ^ a b James R. Hines Jr.; Anna Gumpert; Monika Schnitzer (2016). "Multinational Firms and Tax Havens". The Review of Economics and Statistics. 98 (4): 713–727. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00591. S2CID 54649623. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

Tax havens are typically small, well-governed states that impose low or zero tax rates on foreign investors.

- ^ Shaxson, Nicholas (9 January 2011). "Explainer: what is a tax haven?". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ "New report: is Apple paying less than 1% tax in the EU?". Tax Justice Network. 28 June 2018. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

The use of private 'unlimited liability company' (ULC) status, which exempts companies from filing financial reports publicly. The fact that Apple, Google and many others continue to keep their Irish financial information secret is due to a failure by the Irish government to implement the 2013 EU Accounting Directive, which would require full public financial statements, until 2017, and even then retaining an exemption from financial reporting for certain holding companies until 2022

- ^ "Ireland's playing games in the last chance saloon of tax justice". Richard Murphy. 4 July 2018. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

Local subsidiaries of multinationals must always be required to file their accounts on public record, which is not the case at present. Ireland is not just a tax haven at present, it is also a corporate secrecy jurisdiction.

- ^ a b c d Laurens Booijink; Francis Weyzig (July 2007). "Identifying Tax Havens and Offshore Finance Centres" (PDF). Tax Justice Network and Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

Various attempts have been made to identify and list tax havens and offshore finance centres (OFCs). This Briefing Paper aims to compare these lists and clarify the criteria used in preparing them.

- ^ a b c d e f Gabriel Zucman (August 2013). "The Missing Wealth of Nations: Are Europe and The U.S. Net Debtors or Net Creditors?" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 128 (3): 1321–1364. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.371.3828. doi:10.1093/qje/qjt012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

Tax havens are low-tax jurisdictions that offer businesses and individuals opportunities for tax avoidance' (Hines, 2008). In this paper, I will use the expression 'tax haven' and 'offshore financial center' interchangeably (the list of tax havens considered by Dharmapala and Hines (2009) is identical to the list of offshore financial centers considered by the Financial Stability Forum (IMF, 2000), barring minor exceptions)

- ^ a b "Netherlands and UK are biggest channels for corporate tax avoidance". The Guardian. 25 July 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Is the U.K. Already the Kind of Tax Haven It Claims It Won't Be?". Bloomberg News. 31 July 2017. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Tax Havens Can Be Surprisingly Close to Home". Bloomberg View. 11 April 2017. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ a b c "Zucman:Corporations Push Profits Into Corporate Tax Havens as Countries Struggle in Pursuit, Gabrial Zucman Study Says". Wall Street Journal. 10 June 2018. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

Such profit shifting leads to a total annual revenue loss of $250 billion globally

- ^ a b c Gabriel Zucman (April 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations" (PDF). p. 68. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ a b c "BEPS Project Background Brief" (PDF). OECD. January 2017. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

With a conservatively estimated annual revenue loss of USD 100 to 240 billion, the stakes are high for governments around the world. The impact of BEPS on developing countries, as a percentage of tax revenues, is estimated to be even higher than in developed countries.

- ^ "Tax havens cost governments $200 billion a year. It's time to change the way global tax works". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Gabriel Zucman (August 2014). "Taxing across Borders: Tracking Personal Wealth and Corporate Profits". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 28 (4): 121–48. doi:10.1257/jep.28.4.121.

- ^ a b c Jannick Damgaard; Thomas Elkjaer; Niels Johannesen (September 2019). "The Rise of Phantom Investments". Finance & Development IMF Quarterly. 56 (3).

- ^ a b Gabriel Zucman (8 November 2017). "The desperate inequality behind global tax dodging". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

The equivalent of 10% of global GDP is held offshore by rich individuals in the form of bank deposits, equities, bonds and mutual fund shares, most of the time in the name of faceless shell corporations, foundations and trusts.

- ^ "Every cent lost to tax havens could be used to strengthen our health and social systems". openDemocracy. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Towards Global Tax Co-operation" (PDF). OECD. April 2000. p. 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

TAX HAVENS: 1.Andorra 2.Anguilla 3.Antigua and Barbuda 4.Aruba 5.Bahamas 6.Bahrain 7.Barbados 8.Belize 9.British Virgin Islands 10.Cook Islands 11.Dominica 12.Gibraltar 13.Grenada 14.Guernsey 15.Isle of Man 16.Jersey 17.Liberia 18.Liechtenstein 19.Maldives 20.Marshall Islands 21.Monaco 22.Montserrat 23.Nauru 24.Net Antilles 25.Niue 26.Panama 27.Samoa 28.Seychelles 29.St. Lucia 30.St. Kitts & Nevis 31.St. Vincent and the Grenadines 32.Tonga 33.Turks & Caicos 34.U.S. Virgin Islands 35.Vanuatu

- ^ a b c d e f g h i James R. Hines Jr. (2010). "Treasure Islands". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 4 (24): 103–125.

Table 1: 52 Tax Havens

- ^ a b c James R. Hines Jr. (2007). "Tax Havens" (PDF). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

Tax havens are low-tax jurisdictions that offer businesses and individuals opportunities for tax avoidance. They attract disproportionate shares of world foreign direct investment, and, largely as a consequence, their economies have grown much more rapidly than the world as a whole over the past 25 years.

- ^ a b c James R. Hines Jr. (2005). "Do Tax Havens Flourish" (PDF). Tax Policy and the Economy. 19: 65–99. doi:10.1086/tpe.19.20061896. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

ABSTRACT: Per capita real GDP in tax haven countries grew at an average annual rate of 3.3 percent between 1982 and 1999, which compares favorably to the world average of 1.4 percent.

- ^ a b Heike Joebges (January 2017). "CRISIS RECOVERY IN A COUNTRY WITH A HIGH PRESENCE OF FOREIGN-OWNED COMPANIES: The Case of Ireland" (PDF). IMK Macroeconomic Policy Institute, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ a b Oliver Bullough (8 December 2015). "The fall of Jersey: how a tax haven goes bust". The Guardian.

Jersey bet its future on finance but since 2007 it has fallen on hard times and is heading for bankruptcy. Is the island's perilous present Britain's bleak future?

- ^ a b c Scott Dyreng; Bradley P. Lindsey (12 October 2009). "Using Financial Accounting Data to Examine the Effect of Foreign Operations Located in Tax Havens and Other Countries on US Multinational Firms' Tax Rates". Journal of Accounting Research. 47 (5): 1283–1316. doi:10.1111/j.1475-679X.2009.00346.x.

Finally, we find that US firms with operations in some tax haven countries have higher federal tax rates on foreign income than other firms. This result suggests that in some cases, tax haven operations may increase US tax collections at the expense of foreign country tax collections.

- ^ a b c James K. Jackson (11 March 2010). "The OECD Initiative on Tax Havens" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

As a result of the Bush Administration’s efforts, the OECD backed away from its efforts to target “harmful tax practices” and shifted the scope of its efforts to improving exchanges of tax information between member countries.

- ^ a b c d e f g Damgaard, Jannick; Elkjaer, Thomas; Johannesen, Niels (June 2018). "Piercing the Veil of Tax Havens". Finance & Development, IMF Quarterly. 55 (2). Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

The eight major pass-through economies—the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Hong Kong SAR, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Ireland, and Singapore—host more than 85 percent of the world’s investment in special purpose entities, which are often set up for tax reasons.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicholas Shaxson (September 2019). "Tackling Tax Havens". Finance & Development IMF Quarterly. 56 (3).

- ^ Alex Cobham (11 September 2017). "New UN tax handbook: Lower-income countries vs OECD BEPS failure". Tax Justice Network. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "Tax Havens". Tax Justice Network. 2018.

There is no generally agreed definition of what a tax haven is.

- ^ "INTERNATIONAL TAXATION: Large U.S. Corporations and Federal Contractors with Subsidiaries in Jurisdictions Listed as Tax Havens or Financial Privacy Jurisdictions" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. 18 December 2008. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

Table 1: Jurisdictions Listed as Tax Havens or Financial Privacy Jurisdictions and the Sources of Those Jurisdictions

- ^ a b c Jane Gravelle (15 January 2015). "Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion". Congressional Research Service, Cornell University. p. 4.

Table 1. Countries Listed on Various Tax Haven Lists

- ^ "Understanding the rationale for compiling 'tax haven' lists" (PDF). European Parliamentary Research Service. December 2017. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

There is no single definition of a tax haven, although there are a number of commonalities in the various concepts used

- ^ a b c d e f g Dhammika Dharmapala (December 2008). "What Problems and Opportunities are Created by Tax Havens?". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 24 (4): 3. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

Although tax havens have attracted widespread interest (and a considerable amount of opprobrium) in recent years, there is no standard definition of what this term means. Typically, the term is applied to countries and territories that offer favorable tax regimes for foreign investors.

- ^ "Blacklisted by Brazil, Dublin funds find new ways to invest". Reuters. 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ "Tax haven blacklisting in Latin America". Tax Justice Network. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ a b c Vincent Bouvatier; Gunther Capelle-Blancard; Anne-Laure Delatte (July 2017). "Banks in Tax Havens: First Evidence based on Country-by-Country Reporting" (PDF). EU Commission. p. 50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

Figure D: Tax Haven Literature Review: A Typology

- ^ a b c d e f g h James R. Hines Jr.; Eric Rice (February 1994). "FISCAL PARADISE: FOREIGN TAX HAVENS AND AMERICAN BUSINESS" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics (Harvard/MIT). 9 (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

We identify 41 countries and regions as tax havens for the purposes of U. S. businesses. Together the seven tax havens with populations greater than one million (Hong Kong, Ireland, Liberia, Lebanon, Panama, Singapore, and Switzerland) account for 80 percent of total tax haven population and 89 percent of tax haven GDP.

- ^ a b c d "IDEAS/RePEc Database". Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

Tax Havens by Most Cited

- ^ a b "TAX CUTS AND JOBS ACT OF 2017 Corporate Tax Reform and Wages: Theory and Evidence" (PDF). whitehouse.gov. 17 October 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2018 – via National Archives.

[In the Whitehouse advocating for the TCJA] Applying Hines and Rice’s (1994) findings to a statutory corporate rate reduction of 15 percentage points (from 35 to 20 percent) suggests that reduced profit shifting would result in more than $140 billion of repatriated profit based on 2016 numbers.

- ^ a b Sébastien Laffitte; Farid Toubal (July 2018). "Firms, Trade and Profit Shifting: Evidence from Aggregate Data" (PDF). CESifo Economic Studies: 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

Concerning the characterization of tax havens, we follow the definition proposed by Hines and Rice (1994) which has been recently used by Dharmapala and Hines (2009).

- ^ "COUNTERING OFFSHORE TAX EVASION" (PDF). OECD. September 2009. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ "Tax Haven Criteria". Oecd.org. 26 February 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Harmful Tax Competition: An Emerging Global Issue" (PDF). OECD. 9 April 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Francis Weyzig (2013). "Tax treaty shopping: structural determinants of FDI routed through the Netherlands" (PDF). International Tax and Public Finance. 20 (6): 910–937. doi:10.1007/s10797-012-9250-z. S2CID 45082557. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

The four OECD member countries Luxembourg, Ireland, Belgium, and Switzerland, which can also be regarded as tax havens for multinationals because of their special tax regimes.

- ^ a b c d Vanessa Houlder (September 2017). "Trinidad & Tobago left as the last blacklisted tax haven". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

Alex Cobham of the Tax Justice Network said: It's disheartening to see the OECD fall back into the old pattern of creating 'tax haven' blacklists on the basis of criteria that are so weak as to be near enough meaningless, and then declaring success when the list is empty.”

- ^ "Activists and experts ridicule OECD's tax havens 'blacklist' as a farce". Humanosphere. 30 June 2017. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

One of the criteria, for example, is that a country must be at least “largely compliant” with the Exchange Of Information on Request standard, a bilateral country-to-country information exchange. According to Turner, this standard is outdated and has been proven to not really work.

- ^ "Oxfam disputes opaque OECD failing just one tax haven on transparency". Oxfam. 30 June 2017. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "What Makes a Country a Tax Haven? An Assessment of International Standards Shows Why Ireland Is Not a Tax Haven" (PDF). Department of Finance (Ireland)/Economic and Social Research Institute Review. September 2013. p. 403. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

Ireland does not meet any of the OECD criteria for being a tax haven but because of its 12.5 per cent corporation tax rate and the open nature of the Irish economy, Ireland has on a few occasions been labeled a tax haven.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ronen Palan (1 October 2009). "History of Tax Havens". History and Policy. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

The OECD is clearly ill-equipped to deal with tax havens, not least as many of its members, including the UK, Switzerland, Ireland and the Benelux countries are themselves considered tax havens

- ^ "Report from the Working Group on Offshore Centres" (PDF). Financial Stability Forum. 5 April 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Offshore Financial Centers: IMF Background Paper". International Monetary Fund. 23 June 2000. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Ahmed Zoromé (1 April 2007). "Concept of Offshore Financial Centers: In Search of an Operational Definition" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

IMF Working Paper 07/87

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requiresjournal=(help) - ^ Ronen Palan (4 April 2012). "Tax Havens and Offshore Financial Centres" (PDF). University of Birmingham. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

Some experts see no difference between tax havens and OFCs and employ the terms interchangeably.

- ^ Ronen Palan; Richard Murphy (2010). Tax Havens and Offshore Financial Centres. Cornell Studies in Money. Cornell University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780801476129. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

Yet today it is difficult to distinguish between the activities of tax havens and OFCs.

- ^ a b c Dhammika Dharmapala (2014). "What Do We Know About Base Erosion and Profit Shifting? A Review of the Empirical Literature". University of Chicago. p. 1. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

It focuses particularly on the dominant approach within the economics literature on income shifting, which dates back to Hines and Rice (1994) and which we refer to as the “Hines-Rice” approach.

- ^ a b c d William McBride (14 October 2014). "Tax Reform in the UK Reversed the Tide of Corporate Tax Inversions". Tax Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Javier Garcia-Bernardo; Jan Fichtner; Frank W. Takes; Eelke M. Heemskerk (24 July 2017). "Uncovering Offshore Financial Centers: Conduits and Sinks in the Global Corporate Ownership Network". Nature. 7 (6246): 6246. arXiv:1703.03016. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.6246G. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06322-9. PMC 5524793. PMID 28740120.

- ^ a b "The countries which are conduits for the biggest tax havens". RTE News. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Torslov; Ludvig Wier (June 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations". National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Papers. p. 31. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

Appendix Table 2: Tax Havens

- ^ Gabriel Zucman (April 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Papers. p. 35. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Ireland is the world's biggest corporate 'tax haven', say academics". Irish Times. 13 June 2018. Archived from the original on 24 August 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

New Gabriel Zucman study claims State shelters more multinational profits than the entire Caribbean

- ^ a b Jesse Drucker (27 January 2016). "The World's Favorite New Tax Haven Is the United States". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Wood, Robert W. (27 January 2016). "The World's Next Top Tax Haven Is...America". Forbes. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Swanson, Ana (5 April 2016). "How the U.S. became one of the world's biggest tax havens". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ronen Palan (1 October 2009). "History of Tax Havens". History & Policy. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sol Piccolo (1992). International Business Taxation (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0899307770. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Jason Sharman (2006). "The Struggle for Global Tax Regulation". Havens in a Storm: The Struggle for Global Tax Regulation. Cornell University Press. p. 224. ISBN 9780801445040. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt7z6jm.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nicholas Shaxson (2011). Treasure Islands: Uncovering the Damage of Offshore Banking and Tax Havens. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-10501-0.

- ^ Sir Michael Foot (October 2009). Final report of the independent Review of British offshore financial centres (PDF) (Report). HM Treasury. ISBN 9781845325923. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Nick Mathiason (13 September 2009). "Britain 'may be forced to bail out tax havens'". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ a b Nicholas Shaxson (10 February 2016). "Taiwan, the un-noticed Asian tax haven?". Tax Justice Network. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Andres Knobel (27 July 2018). "Blacklist, whitewashed: How the OECD bent its rules to help tax haven USA". Tax Justice Network. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

We’ve criticised for years the farcical nature of ‘tax haven’ blacklists, whether EU or OECD ones. They all turn out to be politicised, misleading and ineffective

- ^ a b c d e Rochelle Toplensky (5 December 2017). "EU puts 17 countries on blacklist". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

The 17 countries on the European list are American Samoa, Bahrain, Barbados, Grenada, Guam, South Korea, Macau, the Marshall Islands, Mongolia, Namibia, Palau, Panama, St Lucia, Samoa, Trinidad & Tobago, Tunisia and the UAE

- ^ a b c "Outbreak of 'so whatery' over EU tax haven blacklist". Irish Times. 7 December 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

It was certainly an improvement on the list recently published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which featured only one name – Trinidad & Tobago – but campaigners believe the European Union has much more to do if it is to prove it is serious about addressing tax havens.

- ^ a b c "EU puts 17 countries on tax haven blacklist". Financial Times. 8 December 2017. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

EU members were not screened but Oxfam said that if the criteria were applied to publicly available information the list should feature 35 countries including EU members Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Malta

- ^ a b "Tax Battles: the dangerous global race to the bottom on corporate tax". Oxfam. December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ "TAX BATTLES The dangerous global Race to the Bottom on Corporate Tax" (PDF). Oxfam. December 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d Richard Phillips; Matt Gardner; Alexandria Robins; Michelle Surka (2017). "Offshore Shell Games 2017" (PDF). Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Amount of Tax Haven Connections (Figure 1, Page 11), Amount of Tax Haven Profits (Figure 4, Page 16)

- ^ a b "Zucman:Corporations Push Profits Into Corporate Tax Havens as Countries Struggle in Pursuit, Gabrial Zucman Study Says". Wall Street Journal. 10 June 2018. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

The new research draws on data from countries such as Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands that hadn’t previously been collected.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zachary Mider (1 March 2017). "Tracking the tax runaways". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ "Tech giants eating up Dublin's office market". Irish Times. 18 April 2018. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "Google's new APAC headquarters in Singapore is a blend of office building and tech campus". CNBC. November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "Facebook's Singapore APAC Headquarters". The Independent. October 2015. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Wright (September 2018). "The Exorbitant Tax Privilege" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research: 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requiresjournal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f "Half of U.S. foreign profits booked in tax havens, especially Ireland: NBER paper". The Japan Times. 10 September 2018. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

“Ireland solidifies its position as the #1 tax haven,” Zucman said on Twitter. “U.S. firms book more profits in Ireland than in China, Japan, Germany, France & Mexico combined. Irish tax rate: 5.7%.”

- ^ "Ireland is the world's biggest corporate 'tax haven', say academics". Irish Times. 13 June 2018. Archived from the original on 24 August 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

Study claims State shelters more multinational profits than the entire Caribbean

- ^ "Ireland: Where Profits Pile Up, Helping Multinationals Keep Taxes Low". Bloomberg News. October 2013. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Multinationals channel more money through "hubs" in Singapore, Switzerland than ever before, Tax Office says". Sydney Morning Herald. 5 February 2015. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Google's 'Dutch Sandwich' Shielded 16 Billion Euros From Tax". Bloomberg. 2 January 2018. Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Bermuda? Guess again. Turns out Holland is the tax haven of choice for US companies". The Correspondent. 30 June 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Markle, Kevin S.; Shackelford, Douglas A. (June 2009). "Do Multinationals or Domestic Firms Face higher Effective Tax Rates?". National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w15091.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requiresjournal=(help) - ^ "Scientists have found a way of showing how Malta is a global top ten tax haven". Malta Today. 31 July 2017. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ Borg, Jacob (29 July 2017). "'Malta is main EU tax haven' - study". Times Malta. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ "Malta is a target for Italian mafia, Russia loan sharks, damning probe says". Times of Malta. 20 May 2017. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ Grech, Herman (25 May 2017). "Is Malta really Europe's 'pirate base' for tax?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ "The Isle of Man is failing at being a tax haven". Tax Research UK. 2 August 2017. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Top tax haven got more investment in 2013 than India and Brazil: U.N". Reuters. 28 January 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Guardian US interactive team (21 January 2014). "China's princelings storing riches in Caribbean offshore haven". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Dan Nakaso: U.S. tax shelter appears secure; San Jose Mercury News, 25 Dec. 2012, pp. 1, 5

- ^ William Brittain-Catlin (2005): Offshore – The Dark Side of the Global Economy; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005.

- ^ "Defend Gibraltar? Better condemn it as a dodgy tax haven". The Guardian. 9 April 2017. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ "Deloitte promotes Mauritius as tax haven to avoid big payouts to poor African nations". The Guardian. 3 November 2013.

- ^ "Rise of tax haven Mauritius comes at the expense of rest of Africa". Irish Times. 7 November 2017. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "EU RELEASES TAX HAVEN BLACKLIST; NETHERLANDS NOT ON IT". NL.com. 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Liechtenstein: The mysterious tax heaven that's losing the trust of the super-rich". The Independent U.K. 8 March 2018. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "SAMOA: Ranked No.1 as world's most secretive tax haven, potential for more investors". Pacific Guardians. 15 February 2015. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Leslie Wayne (2012): How Delaware Thrives as a Corporate Tax Haven Archived 12 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine; The New York Times, 30 Jun. 2012.

- ^ Reuven S. Avi-Yonah (2012): Statement to Congress; University of Michigan School of Law, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Congress, 20 Sep. 2012.

- ^ "Puerto Rico Governor: GOP tax bill is 'serious setback' for the island". CNN. 20 September 2017. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ Fischer, Konrad (25 October 2016). "A German Tax Haven". Handelsblatt Global. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Lebanon: Election Under Fire". Time Magazine. 17 May 1976. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ Klan, Anthony (6 May 2008). "Vanuatu to ditch tax haven". The Australian. Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2008.