록히드 마틴 F-35 라이트닝 II

Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II| F-35 라이트닝 II | |

|---|---|

| |

| U.S. Air Force F-35A | |

| 역할. | 멀티롤 파이터 |

| 국원 | 미국 |

| 제조사 | 록히드 마틴 |

| 첫 비행 | 2006년 12월 15일;( (F-35A) |

| 소개 | |

| 상황 | 사용중 |

| 주 사용자 | 미국 공군 |

| 제작 | 2006~현재 |

| 제작번호 | 1,000+[4] |

| 에서 개발됨 | 록히드 마틴 X-35 |

록히드 마틴 F-35 라이트닝 II는 공중 우위와 타격 임무를 모두 수행하기 위한 단일 좌석, 단일 엔진, 전천후 스텔스 멀티롤 전투기 계열입니다. 또한 전자전 및 정보, 감시 및 정찰 기능을 제공할 수 있습니다. 록히드 마틴은 주요 파트너인 Northrop Grumman과 BAE Systems와 함께 F-35의 주요 계약업체입니다. 이 항공기에는 기존의 이착륙(CTOL) F-35A, 짧은 이착륙(STOVL) F-35B, 그리고 캐리어 기반(CV/CATOBAR) F-35C의 세 가지 주요 변형이 있습니다.

이 항공기는 록히드 마틴 X-35에서 내려오는데, 2001년에 보잉 X-32를 꺾고 합동 타격 전투기(JSF) 프로그램에서 우승했습니다. 그것의 개발은 주로 미국에 의해 자금이 지원되며, 북대서양 조약 기구(NATO)의 프로그램 파트너 국가들과 영국, 호주, 캐나다, 이탈리아, 노르웨이, 덴마크, 네덜란드 및 이전 튀르키예를 포함한 가까운 미국 동맹국들로부터 추가 자금이 지원됩니다. 다른 여러 국가에서도 항공기를 주문했거나 주문을 고려하고 있습니다. 이 프로그램은 전례 없는 규모, 복잡성, 비용 증가 및 배송 지연으로 인해 비판을 받았습니다.[8][N 1] 아직 개발 및 테스트 중인 항공기를 동시에 생산하는 인수 전략은 고가의 설계 변경 및 개조로 이어졌습니다.[10][11]

F-35는 2006년 처음 비행해 2015년 7월 미 해병대 F-35B와 함께 취역한 데 이어 2016년 8월 미 공군 F-35A, 2019년 2월 미 해군 F-35C와 함께 취역했습니다.[1][2][3] 이 항공기는 이스라엘 공군에 의해 2018년에 처음으로 전투에 사용되었습니다.[12] 미국은 2044년까지 2,456대의 F-35를 구매할 계획이며, 이는 수십 년 동안 미 공군, 해군, 해병대의 승무원 전술 항공의 대부분을 대표할 것입니다. 이 항공기는 NATO와 미국 연합 공군력의 초석이 될 것이며 2070년까지 운영될 계획입니다.[13][14]

발전

프로그램 기원

F-35는 JSF(Joint Strike Fighter) 프로그램의 산물로, 1980년대와 1990년대의 다양한 전투기 프로그램이 결합되었습니다. 1983년부터 1994년까지 운영된 국방고등연구계획국(DARPA)의 첨단 단기이착륙기(ASTOVL) 프로그램이 그 전신이었습니다. ASTOVL은 미국 해병대(USMC)와 영국 해군을 위한 해리어 점프 제트 대체기를 개발하는 것을 목표로 삼았습니다. ASTOVL의 기밀 프로그램 중 하나인 SSF(Supronic STOVL Fighter) 아래, 록히드 스컹크 웍스(Lockheed Skunk Works)는 미 공군(USAF)과 USMC 모두를 위한 스텔스 초음속 STOVL 전투기에 대한 연구를 수행했습니다. 탐색된 핵심 기술은 축 구동식 리프트 팬(SDLF) 시스템이었습니다. 록히드사의 컨셉은 엔진이 하나 달린 카나드 델타 항공기로 무게는 약 24,000파운드(11,000kg)입니다. ASTOVL은 1993년에 CALF(Common Affordable Lightweight Fighter)로 다시 명명되었으며 록히드, 맥도넬 더글러스, 보잉 등이 참여했습니다.[15][16]

1993년 미국 공군의 MRF(Multi-Role Fighter)와 미국 해군(USN)의 A/F-X(Advanced Fighter-Attack) 프로그램이 취소됨에 따라 JAST(Joint Advanced Strike Technology) 프로그램이 등장했습니다. 상대적으로 저렴한 F-16 대체품을 위한 프로그램인 MRF는 냉전 이후 국방 태세가 F-16 함대 사용을 완화하고 F-22 첨단 전술 전투기(ATF) 프로그램으로 인한 예산 압박 증가로 인해 사용 수명이 연장되고 지연되었습니다. A/F-X는 1991년 미국의 A-6 대체용 첨단 전술 항공기(ATA) 프로그램 후속 조치로 시작되었으며, 1991년 기술적 문제와 비용 초과로 인해 A-12 어벤저 II가 취소되었습니다. 같은 해, F-14를 대체하기 위한 미국 공군의 ATF 프로그램의 해군 개발인 NATF (Naval Advanced Tactical Fighter)가 종료되면서, A-X에 추가적인 전투기 능력이 추가되었고, 그 후 A/F-X로 이름이 바뀌었습니다. 예산 압박이 가중되는 가운데, 1993년 9월 국방부(DoD)의 상향식 검토(BUR)는 MRF와 A/F-X의 취소를 발표했으며, 이는 새로운 JAST 프로그램에 적용 가능한 경험을 가져온 것입니다.[16] JAST는 새로운 항공기를 개발하기 위한 것이 아니라 요구 사항을 개발하고 기술을 성숙시키며 첨단 타격전에 대한 개념을 입증하기 위한 것이었습니다.[17]

JAST가 진행됨에 따라 1996년까지 개념 시연기에 대한 필요성이 대두되었으며, 이는 ASTOVL/CALF의 본격적인 비행 시연 단계와 일치할 것입니다. ASTOVL/CALF 개념이 JAST 헌장과 일치하는 것처럼 보였기 때문에, 두 프로그램은 결국 JAST라는 이름으로 1994년 합병되었고, 프로그램은 현재 USAF, USMC, USN에 서비스를 제공하고 있습니다.[17] JAST는 이후 1995년에 합동 타격 전투기(JSF)로 이름이 바뀌었고, 맥도넬 더글러스, 노스럽 그루먼, 록히드 마틴이 STOVL을 제출했습니다.[N 2] 그리고 보잉사. JSF는 결국 해리어, F-16, F/A-18, A-10, F-117 등 미국과 동맹국의 재고에 있는 다수의 다역 및 타격 전투기를 대체할 것으로 예상되었습니다.[18]

국제적인 참여는 영국의 ASTOVL 프로그램 참여를 시작으로 JSF 프로그램의 핵심적인 측면입니다. 공군의 현대화를 요구하는 많은 국제 파트너들이 JSF에 관심이 있었습니다. 영국은 1995년 JAST/JSF의 창립 멤버로 가입하여 JSF 프로그램의 유일한 Tier 1 파트너가 되었습니다. 이탈리아, 네덜란드, 덴마크, 노르웨이, 캐나다, 호주, 튀르크 튀르키예는 개념 시연 단계(CDP)에서 이 프로그램을 진행했으며 이탈리아와 네덜란드는 Tier 2 파트너, 나머지 Tier 3 파트너입니다. 따라서 이 항공기는 국제 파트너와 협력하여 개발되어 수출용으로 사용할 수 있게 되었습니다.[20]

JSF 대회

보잉과 록히드 마틴은 1997년 초 CDP에 선정되었으며, 그들의 컨셉 데모 항공기는 각각 X-32와 X-35로 지정되었습니다. 맥도넬 더글러스 팀은 탈락했고, 노스롭 그루먼과 브리티시 에어로스페이스는 록히드 마틴 팀에 합류했습니다. 각 회사는 기존의 이착륙(CTOL), 항공모함 이착륙(CV), STOVL을 시연하기 위해 두 대의 시제품 항공기를 제작했습니다.[N 3] 록히드 마틴의 설계는 ASTOVL/CALF 프로그램에 따라 수행되는 SDLF 시스템에 대한 작업을 활용할 것입니다. STOVL 작동을 가능하게 한 X-35의 핵심 측면인 SDLF 시스템은 구동축과 터빈을 연결하는 클러치를 결합하여 엔진의 회전 노즐에서 추력을 증가시킴으로써 활성화될 수 있는 전방 중앙 동체의 리프트 팬으로 구성됩니다. Convair Model 200,[N 4] Rockwell XFV-12, Yakovlev Yak-141과 같은 유사한 시스템을 도입한 이전 항공기의 연구도 고려되었습니다.[22][23][24] 반면 보잉의 X-32는 STOVL 운용 시 증강 터보팬을 재구성하는 직접 리프트 시스템을 사용했습니다.

록히드 마틴의 공통점 전략은 STOVL 변종의 SDLF를 연료 탱크로 대체하고, 뒤의 스위블 노즐을 CTOL 변종의 2차원 추력 벡터링 노즐로 대체하는 것이었습니다.[N 5] STOVL 작동은 특허받은 샤프트 구동식 리프트 팬 추진 시스템을 통해 가능합니다.[25] 이를 통해 STOVL 및 CTOL 변형에 대해 동일한 공기역학적 구성이 가능한 반면 CV 변형에는 날개가 확장되어 운반체 복구를 위해 착륙 속도를 줄일 수 있습니다. JAST 합병에 따른 공기역학적 특성과 캐리어 회수 요구사항으로 인해 ASTOVL/CALF의 카나드 델타 설계에 비해 기존 테일에 설계 구성이 정착되었습니다. 특히 기존 테일 구성은 ASTOVL/CALF 카나드 구성에 비해 캐리어 회수 위험이 훨씬 낮습니다. 통신사 호환성을 염두에 두지 않고 설계되었습니다. 이는 이 설계 단계에서 공통성 목표가 중요했기 때문에 세 가지 변형 모두에서 더 큰 공통성을 가능하게 했습니다.[26] Lockheed Martin의 프로토타입은 CTOL을 시연하기 위한 X-35A와 STOVL 시연을 위한 X-35B와 CV 호환성 시연을 위한 더 큰 날개의 X-35C로 구성됩니다.[27]

X-35A는 2000년 10월 24일에 처음 비행하여 아음속 및 초음속 비행 특성, 핸들링, 사거리 및 기동 성능에 대한 비행 테스트를 수행했습니다.[28] 28번의 비행 끝에 STOVL 테스트를 위해 X-35B로 개조되었으며, SDLF, 3베어링 스위블 모듈(3BSM) 및 롤 컨트롤 덕트가 추가되었습니다. X-35B는 안정적인 호버, 수직 착륙 및 500피트(150m) 미만의 짧은 이륙을 통해 SDLF 시스템을 성공적으로 시연할 수 있습니다.[26][29] X-35C는 2000년 12월 16일 처음 비행하여 야전 상륙함 연습 시험을 실시했습니다.[28]

2001년 10월 26일, Lockheed Martin은 수상자로 발표되었고, SDD(System Development and Demonstration) 계약을 받았습니다; Pratt & Whitney는 별도로 JSF용 F135 엔진의 개발 계약을 체결했습니다.[30] 표준 DoD 번호와 일치하지 않는 F-35 지정은 프로그램 관리자인 Mike Hough 소장에 의해 즉석에서 결정되었다고 알려져 있습니다. 이것은 JSF의 F-24 지정을 기대했던 Lockheed Martin에게도 놀라운 일이었습니다.[31]

설계 및 제작

JSF 프로그램이 시스템 개발 및 시연 단계로 넘어가면서, F-35 전투기를 만들기 위해 X-35 시연기 설계가 수정되었습니다. 전방 동체를 5인치(13cm) 늘려 임무용 항공전자를 위한 공간을 마련했고, 수평 스태빌라이저는 균형과 제어를 유지하기 위해 2인치(5.1cm) 뒤로 이동했습니다. 다이버리스 초음속 흡입구는 4면에서 3면 카울 형태로 바뀌었고 30인치(76cm) 뒤로 이동했습니다. 동체 부분은 더 꽉 찼고, 무기 베이를 수용하기 위해 중앙선을 따라 1인치(2.5cm)의 상면이 상승했습니다. X-35 프로토타입의 지정에 따라 세 가지 변형이 F-35A(CTOL), F-35B(STOVL), F-35C(CV)로 지정되었으며 모두 설계 수명이 8,000시간입니다. 원청업체인 Lockheed Martin은 텍사스의 Fort Worth에서 전체적인 시스템 통합 및 최종 조립 및 체크아웃(FACO)을 수행하고 있으며,[N 6] Northrop Grumman과 BAE Systems는 임무 시스템 및 기체용 부품을 공급하고 있습니다.[32][33]

전투기의 시스템을 추가하면 무게가 더 늘어납니다. F-35B가 가장 많이 증가한 것은 2003년 변종 간의 공통성을 위해 무기 베이를 확장하기로 결정한 영향이 컸으며, 총 중량 증가량은 2,200 파운드(1,000 kg)에 달하여 8%가 넘는 것으로 알려졌으며, 이로 인해 모든 STOVL 핵심 성능 매개 변수(KPP) 임계값이 누락되었습니다.[34] 2003년 12월, 중량 증가를 줄이기 위해 STOVL 중량 공격 팀(SWAT)이 구성되었습니다. 변경 사항으로는 얇은 기체 구성원, 더 작은 무기 베이 및 수직 안정기, 롤 포스트 콘센트에 공급되는 추력 감소, 조종석 바로 뒤 날개-메이트 조인트, 전기 요소 및 기체를 재설계하는 것이 있습니다. 또한 흡입구는 더 강력하고 더 큰 질량 흐름 엔진을 수용하도록 수정되었습니다.[35][36] SWAT 노력으로 인한 많은 변화가 공통성을 위해 세 가지 변형 모두에 적용되었습니다. 2004년 9월까지, 이러한 노력들은 F-35B의 무게를 3,000 파운드 (1,400 kg) 이상 줄였고, F-35A와 F-35C는 각각 2,400 파운드 (1,100 kg)와 1,900 파운드 (860 kg)의 무게를 줄였습니다.[26][37] 경량화 작업에는 62억 달러가 소요되었으며 18개월 지연이 발생했습니다.[38]

AA-1로 명명된 첫 번째 F-35A는 2006년 2월 19일 포트워스에서 출시되어 2006년 12월 15일에 첫 비행을 했습니다.[N 7][39] 2006년, F-35는 제2차 세계 대전의 록히드 P-38 라이트닝의 이름을 따서 "라이트닝 II"라는 이름이 붙여졌습니다.[40] 일부 미 공군 조종사들은 대신 이 항공기에 "팬더"라는 별명을 붙였습니다.[41]

항공기의 소프트웨어는 SDD용 6개 릴리스 또는 블록으로 개발되었습니다. 처음 두 블록인 1A와 1B는 초기 조종사 훈련과 다단계 보안을 위해 F-35를 준비했습니다. 블록 2A는 훈련 능력을 향상시켰으며, 2B는 USMC의 초기 운영 능력(IOC)을 위해 계획된 최초의 전투 준비 릴리스였습니다. 블록 3i는 새로운 하드웨어를 갖추면서도 2B의 기능을 유지하고 있으며, USAF의 IOC를 위해 계획되었습니다. SDD용 최종 릴리스인 Block 3F는 전체 비행 범위와 모든 기본 전투 기능을 갖추고 있습니다. 소프트웨어 릴리스와 함께 각 블록에는 비행 및 구조 테스트에서 얻은 항공 전자 하드웨어 업데이트와 항공기 개선도 포함되어 있습니다.[42] "동시성"이라고 알려진 것에서 일부 저속 초기 생산(LRIP) 항공기 로트는 초기 블록 구성으로 제공되며 개발이 완료되면 최종적으로 블록 3F로 업그레이드됩니다.[43] 17,000회의 비행 테스트 시간을 거쳐 2018년 4월 SDD 단계의 최종 비행이 완료되었습니다.[44] F-22와 마찬가지로 F-35는 사이버 공격과 기술 도용 노력뿐만 아니라 공급망의 무결성에 대한 잠재적인 취약성의 표적이 되었습니다.[45][46][47]

테스트 결과, 초기 F-35B 기체는 조기 균열에 취약했고,[N 8] F-35C 고정 장치 후크 설계는 신뢰할 수 없었으며, 연료 탱크는 낙뢰에 너무 취약했으며, 헬멧 디스플레이에 문제가 있었습니다. 소프트웨어는 전례 없는 범위와 복잡성으로 인해 반복적으로 지연되었습니다. 2009년, DoD Joint Estimate Team(JET)은 이 프로그램이 공개 일정보다 30개월 늦었다고 추정했습니다.[48][49] 2011년, 이 프로그램은 "재기준화"되었습니다. 즉, 이 프로그램의 비용과 일정 목표가 변경되어 IOC는 계획된 2010년에서 2015년 7월로 연기되었습니다.[50][51] 테스트, 결함 수정, 생산을 동시에 진행하기로 한 결정은 비효율적이라는 비판을 받았고, 2014년 프랭크 켄달 국방부 인수 장관은 이를 "인수 배임"이라고 불렀습니다.[52] 세 가지 변형은 부품의 25%만을 공유하여 예상되는 공통점인 70%[53]에 훨씬 못 미쳤습니다. 이 프로그램은 계약자에 의한 품질 관리의 단점뿐만 아니라 비용 초과와 총 예상 수명 비용에 대해서도 상당한 비판을 받았습니다.[54][55]

JSF 프로그램은 2001년 SDD가 수상되었을 때 기준 연도인 2002년에 약 2,000억 달러의 인수 비용이 소요될 것으로 예상되었습니다.[56][57] 2005년 초, 정부 책임 사무소(GAO)는 비용과 일정에서 주요 프로그램 위험을 확인했습니다.[58] 비용이 많이 드는 지연은 국방부와 계약자들 사이의 관계를 긴장시켰습니다.[59] 2017년까지 지연 및 비용 초과로 인해 F-35 프로그램의 예상 구매 비용은 4,065억 달러로 증가했으며, 운영 및 유지 관리 비용을 포함한 연간 총 평생 비용(즉, 2070년까지)은 1조 5,000억 달러로 증가했습니다.[60][61][62] LRIP Lot 13에 대한 F-35A의 단가는 7,920만 달러였습니다.[63] 2019년 말부터 2024년 3월까지 공동 시뮬레이션 환경으로의 통합을 포함한 개발 및 운영 시험 및 평가 지연으로 인해 Fort Worth 공장의 실제 생산률은 이미 2020년까지 풀 레이트에 도달했지만, Fort Worth 공장의 풀 레이트는 연간 156대입니다.[64][65]

업그레이드 및 추가 개발

기본적인 공대공 및 타격 능력을 갖춘 최초의 전투 가능한 Block 2B 구성은 2015년 7월 USMC에 의해 준비 완료 선언되었습니다.[1] Block 3F 구성은 2018년 12월에 운영 테스트 및 평가(OT&E)를 시작했으며 2023년 말 완료 후 2024년 3월에 SDD를 완료했습니다.[66] F-35 프로그램은 2021년까지 초기 LRIP 항공기가 기본 블록 3F 표준으로 점진적으로 업그레이드되는 등 지속 및 업그레이드 개발도 진행하고 있습니다.[67]

F-35는 수명 동안 지속적으로 업그레이드 될 것으로 예상됩니다. C2D2(Continuous Capability Development and Delivery)라는 첫 번째 업그레이드 프로그램은 2019년에 시작되었으며 현재 2024년까지 진행될 계획입니다. C2D2의 단기 개발 우선 순위는 블록 4로, 해외 고객 고유의 무기를 포함한 추가 무기를 통합하고, 항공 전자 장치를 새로 고치고, ESM 기능을 개선하며, 원격 작동 비디오 강화 수신기(ROVER) 지원을 추가할 것입니다.[68][69] 또한 C2D2는 신속한 릴리스를 가능하게 하기 위해 민첩한 소프트웨어 개발에 더욱 중점을 둡니다.[70] 2018년, 공군 라이프 사이클 관리 센터(AFLCMC)는 적응형 엔진 전환 프로그램(AETP)에 따라 수행된 연구를 활용하여 F-35에 잠재적으로 적용할 수 있는 보다 강력하고 효율적인 적응형 사이클 엔진을 개발하기 위해 제너럴 일렉트릭(General Electric)과 프랫 & 휘트니(Pratt & Whitney)에 계약을 체결했습니다. 2022년에는, F-35 적응형 엔진 교체(FAER) 프로그램은 2028년까지 적응형 사이클 엔진을 항공기에 통합하기 위해 시작되었습니다.[71][72]

방산업체들은 공식적인 프로그램 계약 외에 F-35에 대한 업그레이드를 제안했습니다. 2013년 Northrop Grumman은 ThNDR(Threat Nullification Defensive Resource)이라는 이름의 지향성 적외선 대응 제품군을 개발했다고 밝혔습니다. 이 대책 시스템은 DAS(Distributed Aperture System) 센서와 동일한 공간을 공유하고 적외선 유도 미사일로부터 보호하는 레이저 미사일 방해 장치 역할을 합니다.[73]

이스라엘은 자체 장비를 포함하여 핵심 항전기에 대한 접근성을 높이기를 원합니다.[74]

2022년 9월, 중국산 합금이 허니웰 펌프에 사용된 것으로 판단되어 F-35 인도가 일시 중단되었습니다.[75]

조달 및 국제 참여

미국은 1,763대의 F-35A를 USAF에, 353대의 F-35B와 67대의 F-35C를 USMC에, 273대의 F-35C를 USN에 조달하기로 계획하고 있습니다. 또한 영국, 이탈리아, 네덜란드, 튀르크 튀르키예 스트랄리아, 노르웨이, 덴마크, 캐나다는 US$4를 지원하기로 합의했습니다.3,750억 개의 개발 비용이 투입되며, 영국은 Tier 1 파트너로서 계획된 개발 비용의 약 10%를 부담합니다.[19] 초기 계획은 미국과 8개 주요 협력국이 2035년까지 3,100대 이상의 F-35를 획득하는 것이었습니다.[77] 국제 참여의 세 단계는 일반적으로 프로그램의 재정적 지분, 국가 기업이 입찰에 공개한 기술 이전 및 하도급 금액, 국가가 생산 항공기를 얻을 수 있는 순서를 반영합니다.[78] 이스라엘과 싱가포르는 프로그램 파트너 국가들과 함께 안보 협력 참여국(SCP)으로 가입했습니다.[79][80][81] 벨기에, 일본, 한국을 포함한 SCP 및 비파트너 국가에 대한 판매는 국방부의 대외 군사 판매 프로그램을 통해 이루어집니다.[7][82] 튀르키예는 2019년 7월 러시아 S-400 지대공 미사일 시스템을 구입한 후 보안 문제로 F-35 프로그램에서 제외되었습니다.

설계.

개요

F-35는 단일 엔진, 초음속, 스텔스 멀티롤 전투기 제품군입니다.[86] 미국에 진출한 두 번째 5세대 전투기이자 첫 번째 작전용 초음속 STOVL 스텔스 전투기인 F-35는 낮은 관측값을 강조합니다. 고도의 상황 인식과 장거리 치사율을 가능하게 하는 첨단 항전 및 센서 융합;[87][88][89] 미 공군은 첨단 센서와 임무 시스템으로 인해 이 항공기를 적의 방공(SEAD) 임무를 억제하기 위한 주요 타격 전투기로 간주합니다.[90]

F-35는 스텔스용 수직 스태빌라이저 2개가 장착된 윙 테일 구성입니다. 비행 제어 표면에는 최첨단 플랩, 플라론,[N 10] 방향타 및 모든 움직임이 있는 수평 꼬리(스태빌레이터)가 포함되며, 최첨단 루트 확장 또는 체인은[91] 입구까지 전진합니다. F-35A와 F-35B의 날개폭이 상대적으로 짧은 것은 미군의 강습상륙함 주차장과 엘리베이터 내부에 장착해야 한다는 요구사항에 의해 결정됩니다. F-35C의 날개폭이 클수록 연료 효율이 높습니다.[92][93] 고정식 디버터리스 초음속 흡입구(DSI)는 부딪힌 압축 표면과 전방으로 쓸어내는 카울을 사용하여 차체의 경계층을 흡입구에서 멀리 떨어뜨려 엔진의 Y 덕트를 형성합니다.[94] 구조적으로, F-35는 F-22로부터 교훈을 얻었습니다. 복합재는 기체 중량의 35%를 차지하며, 대부분은 비스말레이미드 및 복합 에폭시 재료이며, 이후 생산 로트에서는 일부 탄소 나노 튜브 강화 에폭시입니다.[95][96][97] F-35는 대체하는 경량 전투기보다 상당히 무겁고, 가장 가벼운 변형은 29,300파운드(13,300kg)[98]의 빈 무게를 가지고 있습니다.

더 큰 쌍발 엔진 F-22의 최고 속도는 부족하지만 F-35는 F-16, F/A-18 등 4세대 전투기와 경쟁력이 있으며, 특히 F-35의 내부 무기 베이가 외부 상점의 드래그를 제거하기 때문에 무기를 휴대할 때 경쟁력이 있습니다.[99] 모든 변형 모델의 최고 속도는 마하 1.6이며, 전체 내부 페이로드로 달성할 수 있습니다. F135 엔진은 애프터버너에서 초음속 대시와 함께 좋은 아음속 가속력과 에너지를 제공합니다. 대형 스태빌라이저, 리딩 엣지 익스텐션 및 플랩, 캔티드 러더는 50°의 다듬어진 알파로 뛰어난 높은 알파(공격 각도) 특성을 제공합니다. 완화된 안정성과 3중 중복 플라이 바이 와이어 컨트롤은 우수한 핸들링 품질과 이탈 방지 기능을 제공합니다.[100][101] F-35는 F-16의 내부 연료의 두 배 이상을 가지고 있어 전투 반경이 상당히 넓어지고 스텔스 기능을 통해 보다 효율적인 임무 비행 프로파일을 제공합니다.[102]

센서 및 항공 전자 장치

F-35의 임무 시스템은 항공기의 가장 복잡한 측면 중 하나입니다. 항전 및 센서 융합은 조종사의 상황 인식 및 지휘 및 제어 능력을 향상시키고 네트워크 중심 전쟁을 용이하게 하도록 설계되었습니다.[86][103] 주요 센서로는 Northrop Grumman AN/APG-81 능동 전자 스캔 어레이(AESA) 레이더, BAE Systems AN/ASQ-239 Barracuda 전자전 시스템, Northrop Grumman/Raytheon AN/AAQ-37 전자 광학 분산 조리개 시스템(DAS), Lockheed Martin AN/AAQ-40 Electro-Optical Targeting System(EOTS) 및 Northrop Grumman AN/ASQ-242 Communications, Navigation and Identification(CNI) 제품군. F-35는 센서 상호 통신을 통해 지역 전투 공간에 대한 응집력 있는 이미지를 제공하고 서로 간에 가능한 사용 및 조합을 제공하도록 설계되었습니다. 예를 들어 APG-81 레이더는 전자전 시스템의 일부 역할도 합니다.[104]

F-35의 소프트웨어 대부분은 C와 C++ 프로그래밍 언어로 개발되었으며, F-22의 Ada83 코드도 사용되었으며, Block 3F 소프트웨어는 860만 줄의 코드를 가지고 있습니다.[105][106] Green Hills Software Integrity DO-178B 실시간 운영 체제(RTOS)는 ICP(Integrated Core Processor) 상에서 구동되며, 데이터 네트워킹에는 IEEE 1394b 및 파이버 채널 버스가 포함됩니다.[107][108] 소프트웨어 정의 무선 시스템에 대한 함대 소프트웨어 업그레이드를 가능하게 하고 업그레이드 유연성과 경제성을 높이기 위해 항공전자는 실용적인 경우 상용 기성품(COTS) 구성 요소를 사용합니다.[109][110][111] 특히 센서 융합을 위한 미션 시스템 소프트웨어는 프로그램에서 가장 어려운 부분 중 하나였으며 상당한 프로그램 지연을 초래했습니다.[N 11][113][114]

APG-81 레이더는 신속한 빔 민첩성을 위해 전자 스캔을 사용하며 수동 및 능동 공대공 모드, 타격 모드 및 합성 개구 레이더(SAR) 기능을 통합하여 80nmi(150km)를 초과하는 범위에서 다중 표적 추적을 수행합니다. 안테나는 스텔스를 위해 뒤로 기울어져 있습니다.[115] 레이더를 보완하는 것은 AAQ-37 DAS로, 모든 측면의 미사일 발사 경고와 목표 추적을 제공하는 6개의 적외선 센서로 구성되어 있습니다. DAS는 상황 인식 적외선 탐색 트랙(SAIRST) 역할을 하며 조종사에게 헬멧 바이저에 있는 구형 적외선 및 야간 영상을 제공합니다.[116] ASQ-239 Barracuda 전자전 시스템에는 날개와 꼬리의 가장자리에 내장된 10개의 무선 주파수 안테나가 있으며, 모든 측면의 레이더 경보 수신기(RWR)를 지원합니다. 또한 무선 주파수 및 적외선 추적 기능의 센서 융합, 지오로케이션 위협 타겟팅, 미사일에 대한 자기 방어를 위한 다중 스펙트럼 이미지 대책을 제공합니다. 전자전 시스템은 적대적인 레이더를 탐지하고 방해할 수 있습니다.[117] AAQ-40 EOTS는 측면이 낮은 코 밑 창문 뒤에 내부적으로 장착되어 레이저 타겟팅, 전방 적외선(FLIR), 장거리 IRST 기능을 수행합니다.[118] ASQ-242 CNI 제품군은 방향성 다기능 고급 데이터 링크(MADL)를 포함한 6개의 서로 다른 물리적 링크를 사용하여 비밀 CNI 기능을 수행합니다.[119][120] 센서 융합을 통해 무선 주파수 수신기와 적외선 센서의 정보를 결합하여 조종사를 위한 하나의 전술 그림을 형성합니다. 모든 측면의 목표 방향과 식별은 낮은 관찰 가능성을 손상시키지 않고 MADL을 통해 다른 플랫폼으로 공유할 수 있으며, Link 16은 레거시 시스템과의 통신을 위해 존재합니다.[121]

F-35는 처음부터 수명 동안 향상된 프로세서, 센서 및 소프트웨어 향상을 통합하도록 설계되었습니다. 새로운 코어 프로세서와 새로운 조종석 디스플레이가 포함된 테크놀로지 리프레시 3는 15번 구역 항공기를 위해 계획되어 있습니다.[122] Lockheed Martin은 Block 4 구성을 위한 Advanced EOTS를 제공했습니다. 개선된 센서는 최소한의 변경으로 기본 EOTS와 동일한 영역에 적합합니다.[123] 2018년 6월, 록히드 마틴(Lockheed Martin)은 향상된 DAS를 위해 레이시온(Raytheon)을 선택했습니다.[124] 미 공군은 F-35가 센서와 통신 장비를 통해 무인 전투 항공기(UCAV)의 공격을 조정할 수 있는 가능성을 연구했습니다.[125]

AN/APG-85라고 불리는 새로운 레이더가 4 블록 F-35를 위해 계획되어 있습니다.[126] JPO에 따르면 새로운 레이더는 세 가지 주요 F-35 변종과 모두 호환될 것입니다. 그러나 구형 항공기에 새로운 레이더가 장착될지 여부는 불분명합니다.[126]

스텔스와 시그니처

스텔스는 F-35 설계의 핵심 요소이며, 기체의 세심한 형상과 레이더 흡수 물질(RAM)의 사용을 통해 레이더 단면(RCS)을 최소화합니다. RCS를 줄이기 위한 가시적인 조치에는 가장자리 정렬, 피부 패널의 세레이션, 엔진 얼굴 및 터빈의 마스킹이 포함됩니다. 또한, F-35의 DSI는 스플리터 갭이나 블리딩 시스템 대신 압축 범프와 전방 스위핑 카울을 사용하여 경계층을 입구 덕트에서 멀어지게 함으로써 다이버터 캐비티를 제거하고 레이더 시그니처를 더욱 감소시킵니다.[94][127] F-35의 RCS는 특정 주파수와 각도에서 금속제 골프공보다 낮은 것이 특징이며, 일부 조건에서는 F-35가 F-22와 스텔스적으로 비교됩니다.[128][129][130] 유지 보수성을 위해 F-35의 스텔스 설계는 F-22와 같은 이전 스텔스 항공기로부터 교훈을 얻었습니다. F-35의 레이더 흡수 섬유 매트 스킨은 오래된 탑코트보다 내구성이 뛰어나고 유지 보수가 덜 필요합니다.[131] 이 항공기는 또한 적외선 및 시각적 신호를 줄이고 무선 주파수 방사기를 엄격하게 제어하여 탐지를 방지했습니다.[132][133][134] F-35의 스텔스 설계는 주로 고주파 X-밴드 파장에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다.[135] 저주파 레이더는 레일리 산란으로 인해 스텔스 항공기를 탐지할 수 있지만 이러한 레이더는 눈에 띄고 어수선하기 쉬우며 정밀도가 부족합니다.[136][137][138] RCS를 위장하기 위해 항공기는 4개의 루네부르크 렌즈 반사판을 장착할 수 있습니다.[139]

F-35의 소음으로 인해 항공기의 잠재적 기지 근처의 주거 지역과 두 개의 기지 근처의 주민들이 우려했습니다.애리조나주 루크 공군기지와 플로리다주 에글린 공군기지(AFB)는 각각 2008년과 2009년 환경영향 연구를 요청했습니다.[140] 소음 수준은 데시벨로 F-16과 같은 이전 전투기와 비슷했지만 F-35의 음향 파워는 특히 낮은 주파수에서 더 강합니다.[141] 후속 조사와 연구에 따르면 F-35의 소음은 F-16 및 F/A-18E/F와 눈에 띄게 다르지 않은 것으로 나타났지만 일부 관측자에게는 더 큰 저주파 소음이 눈에 띄었습니다.[142][143][144]

콕핏

유리 조종석은 조종사에게 좋은 상황 인식을 주기 위해 설계되었습니다. 메인 디스플레이는 20 x 8인치(50 x 20cm) 파노라마 터치 스크린으로 비행 계기, 관리, CNI 정보 및 통합 주의 및 경고를 보여줍니다. 조종사는 정보 배열을 사용자 정의할 수 있습니다. 메인 디스플레이 아래에는 더 작은 스탠바이 디스플레이가 있습니다.[145] 조종석에는 Adacel이 개발한 음성 인식 시스템이 있습니다.[146] F-35에는 헤드업 디스플레이가 없고, 헬멧 장착 디스플레이 시스템(HMDS)에서 비행 및 전투 정보가 조종사 헬멧의 바이저에 표시됩니다.[147] 원피스 틴티드 캐노피는 전면에 힌지 연결되어 있으며 구조적 강도를 위해 내부 프레임이 있습니다. Martin-Baker US16E 배출 시트는 측면 레일에 장착된 트윈 캐터펄트 시스템에 의해 시작됩니다.[148] 우측 사이드 스틱 및 스로틀 핸즈온 스로틀 앤 스틱 시스템이 있습니다. 생명 유지를 위해 온보드 산소 발생 시스템(OBOGS)은 통합 전원 패키지(IPP)에 의해 장착 및 전원 공급되며, 보조 산소통 및 비상 시 백업 산소 시스템이 있습니다.[149]

비전 시스템즈 인터내셔널[N 12] 헬멧 디스플레이는 F-35의 인간-기계 인터페이스의 핵심 부품입니다. HMDS는 이전 전투기의 대시보드에 장착된 헤드업 디스플레이 대신 헬멧 바이저에 비행 및 전투 정보를 입력하여 조종사가 어느 방향을 향하든 볼 수 있도록 합니다.[150] Distributed Aperture System(분산 조리개 시스템)의 적외선 및 야간 시야 영상을 HMDS에 직접 표시할 수 있으며 조종사가 항공기를 "통관"할 수 있습니다. HMDS는 F-35 조종사가 항공기의 코가 다른 곳을 가리키고 있을 때도 미사일을 목표로 발사할 수 있도록 함으로써 미사일을 찾는 사람들을 시야에서 높은 각도로 막아줍니다.[151][152] 각 헬멧의 가격은 40만 달러입니다.[153] HMDS는 기존 헬멧보다 무게가 많이 나가며, 사출 시 경량 조종사를 위험에 빠뜨릴 수 있다는 우려가 있습니다.[154]

개발 중에 HMDS의 진동, 지터, 야간 시야 및 센서 디스플레이 문제로 인해, 록히드 마틴과 엘빗은 2011년에 AN/AVS-9 야간 시야 고글을 백업으로 기반으로 하는 대체 HMDS에 대한 사양 초안을 발표했으며, 그 해 말에 BAE 시스템이 선택되었습니다.[155][156] 대체 HMDS를 채택하기 위해서는 조종석 재설계가 필요할 것입니다.[157][158] 기본 헬멧의 진보에 따라 대체 HMDS의 개발은 2013년 10월에 중단되었습니다.[159][160] 2016년, 개선된 야간 투시경 카메라, 새로운 액정 디스플레이, 자동 정렬 및 소프트웨어 향상 기능을 갖춘 3세대 헬멧이 LRIP 로트 7과 함께 소개되었습니다.[159]

무장

스텔스 모양을 유지하기 위해 F-35에는 각각 2개의 무기 스테이션이 있는 2개의 내부 무기 베이가 있습니다. 2개의 선외기 무기 스테이션은 각각 F-35B의 경우 최대 2,500파운드(1,100kg) 또는 1,500파운드(680kg)의 무기를 탑재할 수 있으며, 2개의 선외기 스테이션은 공대공 미사일을 탑재할 수 있습니다. 선외기지의 공대지 무기로는 JDAM(Joint Direct Attack Munition), Paveway 계열의 폭탄, JSOW(Joint Stadpose Weapon), 클러스터 군수품(Wind Corrected Munitions Dispensor) 등이 있습니다. 이 기지는 또한 GBU-39 소구경 폭탄 (SDB), GBU-53/B SDB II, SPEAR 3와 같은 여러 개의 소형 탄약을 운반할 수 있습니다. F-35A와 F-35C의 경우 한 기지당 최대 4개의 SDB를 운반할 수 있고, F-35B의 경우 3개의 SDB를 운반할 수 있습니다.[161][162][163] 인보드 스테이션은 AIM-120 AMRAAM과 최종적으로 AIM-260 JATM을 탑재할 수 있습니다. 무기 베이 뒤의 두 칸에는 플레어, 왕겨, 견인된 미끼가 있습니다.[164]

항공기는 스텔스가 필요하지 않은 임무를 위해 6개의 외부 무기 스테이션을 사용할 수 있습니다.[165] 윙팁 파일론은 각각 AIM-9X 또는 AIM-132 ASRAAM을 운반할 수 있으며 레이더 단면을 줄이기 위해 외부로 캔팅됩니다.[166][167] 또한 각 날개에는 5,000파운드(2,300kg)의 선내 스테이션과 2,500파운드(1,100kg)의 중간 스테이션, 또는 F-35B의 경우 1,500파운드(680kg)의 중간 스테이션이 있습니다. 외부 날개 기지는 AGM-158 지대지 미사일(JASSM) 순항 미사일과 같은 무기 베이 내부에 들어가지 않는 대형 공대지 무기를 운반할 수 있습니다. 8개의 AIM-120과 2개의 AIM-9의 공대공 미사일 탑재가 가능하며, 2,000lb(910kg) 폭탄 6개, AIM-120 2개, AIM-9 2개의 구성도 가능합니다.[151][168][169] F-35는 GAU-12/U 이퀄라이저의 보다 가벼운 4배럴 변형인 25mm GAU-22/A 회전식 대포로 무장되어 있습니다.[170] F-35A는 182발을 싣고 왼쪽 날개 뿌리 부근에 내부에 장착되어 있습니다.[citation needed] 이 포는 다른 미군 전투기들이 들고 다니는 20mm 포보다 지상 목표물에 더 효과적입니다.[dubious ][citation needed] 2020년, USAF 보고서는 F-35A의 GAU-22/A에서 "수용할 수 없는" 정확도 문제를 지적했습니다. 이는 총기 장착대의 "오정렬"로 인한 것으로, 균열이 발생하기 쉬웠습니다.[171] 이러한 문제는 2024년까지 해결되었습니다.[172] F-35B와 F-35C는 내부 총이 없고 대신 GAU-22/A와 220발을 실은 Terma A/S 다중 임무 포드(MMP)를 사용할 수 있습니다. 포드는 항공기 중앙선에 장착되어 레이더 단면을 줄일 수 있습니다.[170][173][verification needed] 총 대신 포드는 전자전, 공중 정찰 또는 후방 전술 레이더와 같은 다양한 장비와 목적으로도 사용할 수 있습니다.[174][175] 이 포드는 한때 F-35A 변종에서 총을 괴롭혔던 정확도 문제에 민감하지 않았지만 분명히 문제가 없었습니다.[171][172]

록히드 마틴은 사이드킥이라고 불리는 무기 랙을 개발하고 있습니다. 사이드킥은 내부 선외기 스테이션이 두 개의 AIM-120을 운반할 수 있도록 하여 내부 공대공 탑재체를 현재 블록 4에 제공되는 6개의 미사일로 늘릴 수 있습니다.[176][177] 또한 블록 4에는 F-35B가 내부 선외기 스테이션당 4개의 SDB를 운반할 수 있도록 재배치된 유압 라인과 브래킷이 있습니다. MBDA Meteor의 통합도 계획되어 있습니다.[178][179] USAF와 USN은 내부적으로 AGM-88G AARGM-ER를 F-35A와 F-35C에 통합할 계획입니다.[180] 노르웨이와 호주는 F-35의 해군 타격 미사일(NSM)을 개조하는 데 자금을 지원하고 있습니다. 합동 타격 미사일(JSM)로 지정된 두 개의 미사일은 외부에서 추가로 네 개를 운반할 수 있습니다.[181] B61 핵폭탄의 내부 운반을 통한 핵무기 운반은 2024년 블록 4B에 계획되어 있습니다.[182] 극초음속 미사일과 고체 레이저와 같은 직접 에너지 무기는 모두 현재 미래의 업그레이드로 고려되고 있습니다.[N 13][186] Lockheed Martin은 여러 개의 개별 레이저 모듈을 결합한 스펙트럼 빔을 사용하는 파이버 레이저를 다양한 수준으로 확장할 수 있는 단일 고출력 빔으로 통합하는 것을 연구하고 있습니다.[187]

미 공군은 F-35A가 경쟁 환경에서 근접 항공 지원(CAS) 임무를 수행할 계획입니다; 전용 공격 플랫폼만큼 적합하지 않다는 비판이 있는 가운데, 미 공군 참모총장 마크 웰시는 유도 로켓을 포함한 CAS 종류의 무기에 중점을 두었습니다. 충돌하기 전에 개별 발사체로 산산조각이 나는 파편 로켓, 그리고 더 많은 용량의 포 포드를 위한 더 소형 탄약.[188] 단편적인 로켓 탄두는 각각의 로켓이 "천 발의 폭발"을 만들어내고, 스트래핑 런보다 더 많은 발사체를 제공하기 때문에 대포 포탄보다 더 큰 효과를 만들어냅니다.[189]

엔진

단일 엔진 항공기는 프랫 & 휘트니 F135 로우 바이패스 증강 터보팬에 의해 구동되며, 정격 추력은 군사력에서 28,000파운드(125kN), 애프터버너에서 43,000파운드(191kN)입니다. F-22가 사용하는 프랫 앤 휘트니 F119에서 파생된 F135는 아음속 추력과 연비를 높이기 위해 팬이 더 커지고 바이패스 비율이 높아졌으며 F119와 달리 슈퍼크루즈에 최적화되지 않았습니다.[190] 엔진은 연료 분사기를 두꺼운 곡선 베인에 통합하는 관찰 가능성이 낮은 증강기, 즉 애프터버너를 사용하여 F-35의 스텔스에 기여합니다. 이 베인은 세라믹 레이더 흡수 물질로 덮여 있고 터빈을 가리킵니다. 스텔스 증강기는 개발 초기에 낮은 고도와 빠른 속도에서 압력 맥동, 즉 "삐걱"과 같은 문제가 있었습니다.[191] 낮은 관측 가능한 축대칭 노즐은 후미 가장자리에 톱니 패턴을 만드는 15개의 부분적으로 중첩된 플랩으로 구성되어 있어 레이더 서명을 줄이고 배기 플룸의 적외선 서명을 줄이는 셰이드 와류를 생성합니다.[192] 엔진의 크기가 크기 때문에 미 해군은 해상 물류 지원을 용이하게 하기 위해 진행 중인 보충 시스템을 수정해야 했습니다.[193] F-35의 IPP(Integrated Power Package)는 전력 및 열 관리를 수행하며 환경 제어, 보조 전원 장치, 엔진 시동 및 기타 기능을 단일 시스템으로 통합합니다.[194]

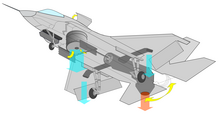

F-35B용 F135-PW-600 변형 모델은 STOVL 작동을 가능하게 하기 위해 SDLF(Shaft-Driven Lift Fan)를 통합합니다. Lockheed Martin이 설계하고 Rolls-Royce가 개발한 SDLF, Rolls-Royce Lift System은 리프트 팬, 드라이브 샤프트, 두 개의 롤 포스트 및 "3개의 베어링 회전 모듈"(3BSM)로 구성됩니다. 노즐에는 평행하지 않은 베이스가 있는 짧은 실린더와 유사한 3개의 베어링이 있습니다. 모터에 의해 톱니 가장자리가 회전하면 노즐이 엔진과 선형에서 수직으로 회전합니다. 추력 벡터링 3BSM 노즐을 사용하면 메인 엔진 배기가 항공기 꼬리에서 아래로 편향될 수 있으며, 가압 연료를 작동 유체로 사용하는 "연료 유압" 액추에이터에 의해 이동됩니다.[195][196][197] 해리어의 페가수스 엔진이 직접적인 엔진 추력을 전적으로 이용해 양력을 올리는 것과는 달리, F-35B의 시스템은 리프트 팬으로 스위블 노즐의 추력을 증가시킵니다. 팬은 클러치와 결합할 때 구동축을 통해 저압 터빈에 의해 구동되며 항공기 전면 근처에 배치되어 3BSM 노즐의 토크에 대응합니다.[198][199][200] 저속 비행 중 롤 제어는 가열되지 않은 엔진 바이패스 공기를 롤 포스트라고 하는 날개 장착 추력 노즐을 통해 전환함으로써 달성됩니다.[201][202]

2000년대에 General Electric/Rolls-Royce F136이 개발되고 있었는데, 원래는 Lot 6 이후의 F-35 엔진이 경쟁적으로 입찰되었습니다. General Electric YF120의 기술을 사용한 F136은 흡입구를 최대한 활용한 질량 흐름 설계로 인해 F135보다 온도 마진이 더 컸다고 합니다.[35][203] F136은 2011년 12월 자금 부족으로 인해 취소되었습니다.[204][205]

F-35는 새로운 위협에 적응하고 추가 기능을 가능하게 하기 위해 수명 주기 동안 추진 업그레이드를 받을 것으로 예상됩니다. 2016년에는 적응형 사이클 엔진을 개발하고 테스트하기 위한 적응형 엔진 전환 프로그램(AETP)이 시작되었으며, 주요 잠재적 응용 분야 중 하나는 F-35의 재진입입니다. 2018년에는 GE와 P&W가 각각 XA100과 XA101로 명명된 45,000lbf(200kN) 추력 등급 시연기 개발 계약을 체결했습니다.[71] P&W는 잠재적인 재도전 외에도 기준선인 F135를 개선할 계획이며, 2017년 P&W는 F135 Growth Option 1.0 및 2.0을 발표했습니다. Growth Option 1.0은 6~10%의 추력 향상과 5~6%의 연료 연소 감소를 제공하는 드롭인 파워 모듈 업그레이드였으며, Growth Option 2.0은 적응형 사이클 XA101이 될 것입니다.[206][207] 2020년에 P&W는 F135 업그레이드 계획을 Growth Options에서 일부 추가 기능과 함께 일련의 엔진 강화 패키지로 변경했으며 XA101은 별도의 클린시트 디자인이 되었습니다. 기능 패키지는 2020년대 중반부터 2년 단위로 통합될 계획입니다.[208]

2020년 12월, GE의 XA100(A100)이 첫 번째 성공적인 주행을 마쳤습니다. 2019년 2월 GE의 상세설계가 완료되었고, 2021년 5월 오하이오주 에반데일에 위치한 GE의 고고도 시험시설에서의 초기시험이 완료되었습니다.[209][210][211] GE는 빠르면 2027년에 A100이 F-35A와 C와 함께 서비스를 시작할 수 있을 것으로 기대하고 있습니다.[212]

유지보수 및 물류

F-35는 이전 스텔스 항공기보다 유지보수가 덜 필요하도록 설계되었습니다. 현장에서 교체할 수 있는 모든 부품의 약 95%가 "깊이 하나"로 되어 있습니다. 즉, 원하는 부품에 도달하기 위해 다른 부품을 제거할 필요가 없습니다. 예를 들어 캐노피를 제거하지 않고도 배출 시트를 교체할 수 있습니다. F-35는 오래된 RAM 코팅보다 내구성이 뛰어나고, 작업하기 쉽고, 경화가 빠르기 때문에 F-22와 같은 오래된 스텔스 항공기에 적용하기 위해 유사한 코팅이 고려되고 있습니다.[131][213][214] F-22의 피부 부식은 갈바닉 부식을 유발하는 피부 간극 필러가 적고 필러가 필요한 기체 피부의 간극이 적으며 배수가 잘되는 F-35를 이끌었습니다.[215] 비행 제어 시스템은 전통적인 유압 시스템이 아닌 전기-정적 액추에이터를 사용합니다. 이러한 컨트롤은 비상 시 리튬 이온 배터리로 작동할 수 있습니다.[216][217] 변종 간의 공통점은 USMC의 첫 항공기 정비 현장 훈련 분대로 이어졌으며, 이는 USAF 레슨을 F-35 작전에 적용했습니다.[218]

F-35는 처음에 ALIS(Autonomic Logistics Information System)라는 컴퓨터화된 유지관리 시스템에 의해 지원되었습니다. 개념적으로 모든 F-35는 모든 유지보수 시설에서 서비스가 가능하며 필요에 따라 모든 부품을 글로벌하게 추적하고 공유할 수 있습니다.[219] 신뢰할 수 없는 진단, 과도한 연결 요구 사항, 보안 취약성 [220]등 수많은 문제로 인해 ALIS는 클라우드 기반 운영 데이터 통합 네트워크(ODIN)로 대체되고 있습니다.[221][222][223] 2020년 9월부터 ODIN 베이스 키트([224]OBK)는 ALIS 소프트웨어뿐만 아니라 ODIN 소프트웨어를 애리조나주의 MCAS(Marine Corps Air Station) 유마(Yuma)에서, 2021년 7월 16일 캘리포니아주의 레무어(Lemoore) 해군 공군기지에서 공격 전투기 편대(VFA) 125와 네바다주 넬리스 공군기지에서 운영하고 있었습니다. 2021년 8월 6일 제422시험평가비행단(TES) 지원. 2022년에는 12개 이상의 OBK 사이트가 ALIS의 SOU-U(Standard Operating Unit Unit) 서버를 대체할 예정입니다.[225] OBK 성능은 ALIS의 두 배입니다.[226][225][224]

운영이력

테스트

최초의 F-35A인 AA-1은 2006년 9월에 엔진을 가동하여 2006년 12월 15일에 첫 비행을 하였습니다.[227] 모든 후속 항공기와 달리 AA-1은 SWAT의 무게 최적화 기능을 갖추고 있지 않았습니다. 결과적으로 추진, 전기 시스템 및 조종석 디스플레이와 같은 후속 항공기에 공통적으로 적용되는 하위 시스템을 주로 테스트했습니다. 이 항공기는 2009년 12월에 비행 테스트에서 퇴역했으며 NAS China Lake에서 실사격 테스트에 사용되었습니다.[228]

최초의 F-35B인 BF-1은 2008년 6월 11일에, 최초의 중량 최적화된 F-35A와 F-35C인 AF-1과 CF-1은 각각 2009년 11월 14일과 2010년 6월 6일에 비행했습니다. F-35B는 2010년 3월 17일에 처음으로 공중을 맴돌았고, 그 다음날 첫 수직 착륙을 했습니다.[229] F-35 통합시험군(ITF)은 에드워즈 공군기지와 해군 공군기지 파투센트 리버에 있는 18대의 항공기로 구성되었습니다. Edwards의 항공기 9대, F-35A 5대, F-35B 3대, F-35C 1대가 F-35A 외피 확장, 비행 하중, 저장고 분리 및 임무 시스템 테스트와 같은 비행 과학 테스트를 수행했습니다. 파툭센트강의 다른 9대의 항공기인 F-35B 5대와 F-35C 4대는 F-35B와 C 포락선 확장과 STOVL과 CV 적합성 테스트를 담당했습니다. 뉴저지주 레이크허스트에 있는 해군 항공전 센터 항공기 부서에서 추가적인 항모 적합성 테스트가 수행되었습니다. 정적 하중과 피로도를 테스트하기 위해 각 변종의 비행하지 않는 항공기 2대가 사용되었습니다.[230] 항공전자와 임무 시스템을 테스트하기 위해 조종석을 복제한 보잉 737-300을 개조한 록히드 마틴 CATBird가 사용되었습니다.[177] F-35의 센서에 대한 현장 테스트는 2009년과 2011년 연습 노던 에지 기간 동안 수행되었으며, 이는 중대한 위험 감소 조치 역할을 했습니다.[231][232]

비행 테스트를 통해 비용이 많이 드는 재설계가 필요하고 지연이 발생하며 여러 대의 항공기 착륙이 발생하는 몇 가지 심각한 결함이 발견되었습니다. 2011년, F-35C는 8번의 착륙 테스트에서 모두 구속 와이어를 잡지 못했고, 2년 후에 재설계된 꼬리 후크가 인도되었습니다.[233][234] 2009년 6월까지, 초기 비행 시험 목표의 많은 부분이 달성되었지만, 그 프로그램은 예정보다 늦었습니다.[235] 소프트웨어와 미션 시스템은 프로그램 지연의 가장 큰 원인 중 하나였으며, 센서 융합은 특히 어려운 것으로 입증되었습니다.[114] 피로도 테스트에서 F-35B는 조기 균열이 여러 번 발생하여 구조를 재설계해야 했습니다.[236] 세 번째 비비행 F-35B는 현재 재설계된 구조물을 테스트하기 위해 계획 중입니다. F-35B와 C는 애프터버너 사용이 길어지면서 열 손상을 입는 수평 꼬리 부분에도 문제가 있었습니다.[N 14][239][240] 초기 비행 통제법은 "날개 낙하"[N 15]에 문제가 있었고 또한 2015년 F-16에 대한 높은 공격 각도 테스트에서 에너지가 부족하다는 것을 보여주는 등 비행기를 부진하게 만들었습니다.[241][242]

F-35B의 해상 시험은 USS 와스프에서 처음 실시되었습니다. 2011년 10월, 두 대의 F-35B가 3주간의 초기 해상 시험인 개발 테스트 I을 수행했습니다.[243] 두 번째 F-35B 해상 시험인 Development Test II는 2013년 8월에 야간 운항을 포함한 시험으로 시작되었으며, 두 대의 항공기가 DAS 영상을 사용하여 19개의 야간 수직 착륙을 완료했습니다.[244][245] 2015년 5월, 6대의 F-35B가 참여한 첫 번째 작전 테스트가 와스프에서 수행되었습니다. 2016년 말 고해주에서의 작전과 관련된 USS 아메리카에 대한 최종 개발 테스트 III가 완료되었습니다.[246] 영국 해군의 F-35는 2018년 10월 HMS Queen Elizabeth호에 처음으로 "롤링" 착륙을 실시했습니다.[247]

재설계된 테일 훅이 도착한 후, F-35C의 항모 기반 개발 테스트 I는 2014년 11월 USS Nimitz에서 시작되었으며 기본적인 주간 항모 운영과 발사 및 복구 처리 절차 수립에 중점을 두었습니다.[248] 야간 작전, 무기 장전, 전력 발사에 초점을 맞춘 개발 시험 II는 2015년 10월에 실시되었습니다. 최종 개발 테스트 III는 2016년 8월에 완료되었으며 비대칭 하중 테스트 및 착륙 자격 및 상호 운용성에 대한 인증 시스템이 포함되었습니다.[249] 2018년 F-35C의 운용 시험이 실시되었고, 그 해 12월 최초의 작전 비행 중대가 비행 안전 이정표를 달성하여 2019년 도입의 길을 열었습니다.[3][250]

F-35의 신뢰성과 가용성은 특히 테스트 초기에 요구 사항에 미치지 못했습니다. ALIS 유지 및 물류 시스템은 과도한 연결 요구 사항과 잘못된 진단으로 어려움을 겪었습니다. 2017년 말, GAO는 F-35 부품을 수리하는 데 필요한 시간이 평균 172일로 "프로그램 목표의 두 배"였으며, 예비 부품 부족으로 인해 준비 상태가 악화되고 있다고 보고했습니다.[251] 2019년에 개별 F-35는 배치된 작전 중 단기간 동안 목표 80% 이상의 임무 수행 가능 비율을 달성했지만 함대 전체의 비율은 목표보다 낮았습니다. 65%라는 함대 가용성 목표도 달성하지 못했지만, 추세는 개선되었습니다. 2024년까지 정렬 불량 문제가 해결될 때까지 F-35A의 내부 총기 정확도는 받아들일 수 없었습니다.[239][252] 2020년 현재 프로그램의 가장 심각한 문제의 수는 절반으로 감소했습니다.[253][254]

SDD의 최종 구성인 Block 3F를 사용한 작동 테스트 및 평가(OT&E)는 2018년 12월에 시작되었지만, 특히 DOD의 JSE(Joint Simulation Environment)와 통합된 기술적 문제로 인해 완료가 지연되었으며,[255] F-35는 2023년 9월에 모든 JSE 시험을 완료했습니다.[65]

미국

트레이닝

F-35A와 F-35B는 2012년 초 기본 비행 훈련을 위해 허가를 받았지만, 당시 시스템 성숙도가 떨어져 안전성과 성능에 대한 우려가 있었습니다.[256][257][258] LRIP(Low Rate Initial Production) 단계 동안, 세 미군 서비스는 비행 시뮬레이터를 사용하여 효과를 테스트하고 문제를 발견하고 설계를 개선하는 전술과 절차를 공동으로 개발했습니다. 2012년 9월 10일, 미국 공군은 F-35A의 운영 효용 평가(OUE)를 시작했는데, 여기에는 물류 지원, 정비, 인력 교육, 조종사 수행 등이 포함됩니다.[259][260]

USMC F-35B 함대 대체 비행대(FRS)는 2012년에 USAF F-35A 훈련 부대와 함께 Eglin AFB에 기반을 두다가 2014년에 MCAS Beaufort로 이동했고 2020년에는 MCAS Miramar에 다른 FRS가 섰습니다.[261][262] USAF F-35A 기초과정은 Eglin AFB와 Luke AFB에서 진행되며, 2013년 1월 Eglin에서 100명의 조종사와 2,100명의 정비사를 동시에 수용할 수 있는 훈련이 시작되었습니다.[263] 또한, F-35A 무기교관 교육과정을 위해 2017년 6월 넬리스 AFB에서 USAF 무기학교 제6무기비행단을 창설하였고, 2022년 6월 F-35A와 함께 제65공격기비행단을 재활성화하여 상대 스텔스기 전술에 대한 훈련을 확대하고 있습니다.[264] USN은 2012년 Eglin AFB에서 VFA-101을 사용하여 F-35C FRS를 구축했지만, 이후 2019년 NAS Lemoore에서 VFA-125에 따라 운영을 이전하고 통합할 예정입니다.[265] F-35C는 2020년에 TOPGUN(Strike Fighter Tactics Instructor) 과정에 도입되었으며 항공기의 추가 기능으로 과정 강의 계획이 크게 개편되었습니다.[266]

미 해병대

2012년 11월 16일, USMC는 MCAS Yuma에서 VMFA-121의 첫 번째 F-35B를 받았습니다.[267] USMC는 2015년 7월 31일 블록 2B 구성에서 F-35B에 대한 초기 작전 능력(IOC)을 선언했으며, 야간 작전, 임무 시스템 및 무기 운반에 일부 제한이 있었습니다.[1][268] USMC F-35B는 2016년 7월 첫 홍기훈련에 참가하여 67가지 종류의 훈련을 실시했습니다.[269] F-35B는 2017년 일본 MCAS 이와쿠니에서 첫 실전배치가 이루어졌고, 2018년 7월 수륙양용돌격함 USS 에식스에서 전투고용이 시작되었으며, 2018년 9월 27일 아프가니스탄에서 탈레반 목표물에 대한 첫 전투공격이 이루어졌습니다.[270]

USMC는 F-35B를 수륙양용 돌격함에 배치하는 것 외에도 전투 공간에 근접하면서 생존성을 높이기 위해 은신처와 은폐가 가능한 엄격한 전진 배치 기지에 분산 배치할 계획입니다. 분산형 STOVL 작전(Distributed STOVL Operations, DSO)으로 알려진 F-35B는 적대적인 미사일 교전 지역 내 동맹 지역의 임시 기지에서 작전을 수행하고 적의 목표 주기인 24~48시간 내에 이동합니다. 이 전략을 통해 F-35B는 작전 요구에 신속하게 대응할 수 있습니다. 이동식 전방 무장 및 급유 지점(M-FARP)은 KC-130 및 MV-22 오스프리 항공기를 수용하여 제트기에 재장전 및 급유를 제공할 뿐만 아니라 이동식 배전 현장의 해상 연결을 위한 연안 지역을 제공합니다. 더 높은 수준의 유지보수를 위해, F-35B는 M-FARP에서 후방 지역의 우호 기지 또는 배로 돌아올 것입니다. F-35B의 배기가스로부터 준비되지 않은 도로를 보호하기 위해 헬리콥터 휴대용 금속 플랭크가 필요합니다. USMC는 더 가벼운 내열 옵션을 연구하고 있습니다.[271] 이러한 작업은 더 큰 규모의 USMC 원정 고도 기지 운영(EABO) 개념의 일부가 되었습니다.[272]

첫 번째 USMC F-35C 비행대대인 VMFA-314는 2021년 7월에 완전 작전 능력을 달성했으며 2022년 1월에 캐리어 에어 윙 9의 일부로 USS 에이브러햄 링컨에 처음 배치되었습니다.[273]

미 공군

블록 3i 구성의 USAF F-35A는 2016년 8월 2일 유타주 힐 공군기지에서 USAF의 제34전투비행단과 IOC를 달성했습니다.[2] F-35A는 2017년 첫 홍기훈련을 실시했습니다; 시스템 성숙도가 향상되었고 항공기는 위협이 높은 환경에서 F-16 공격기 편대를 상대로 15:1의 킬 비율을 기록했습니다.[274] 2019년 4월 15일 UAE의 알다프라 공군기지에 USAF F-35A가 처음 배치되었습니다.[275] 2019년 4월 27일 이라크 북부의 이슬람국가(IS) 터널 네트워크에 대한 공습으로 USAF F-35A가 처음으로 전투에 사용되었습니다.[276]

유럽 기지의 경우 영국의 RAF Lakenheath가 F-35A 2개 중대를 주둔시키는 첫 번째 시설로 선택되었으며, 48대의 항공기가 48 전투비행단의 기존 F-15C와 F-15E 비행단에 추가되었습니다. 2021년 12월 15일 제495전투비행단의 첫 항공기가 도착했습니다.[277][278]

F-35의 운용 비용은 일부 구형 미 공군 전술기보다 높습니다. 2018 회계연도에 F-35A의 비행시간당 비용(CPFH)은 44,000달러로 2019년에는 35,000달러로 감소했습니다.[279] 2015년 A-10의 CPFH는 17,716달러, F-15C는 41,921달러, F-16C는 22,514달러였습니다.[280] 록히드 마틴사는 성과주의 물류 등의 조치를 통해 2025년까지 25,000달러로 줄이기를 희망하고 있습니다.[281]

USN은 2019년 2월 28일 3F 블록에서 F-35C와 함께 작전 수행 상태를 달성했습니다.[3] 2021년 8월 2일, VFA-147의 F-35C와 CMV-22 오스프리는 칼 빈슨호에 탑승한 항공모함 에어윙 2의 일원으로 첫 실전 배치에 착수했습니다.[282]

영국

영국 공군과 영국 해군은 모두 F-35B를 운용하고 있으며, 2010년에 퇴역한 해리어 GR9와 2019년에 퇴역한 토네이도 GR4를 대체했습니다.[283] F-35는 앞으로 30년 동안 영국의 주요 타격기가 될 것입니다. F-35B에 대한 영국 해군의 요구 사항 중 하나는 착륙 시 날개 양력을 사용하여 최대 착륙 중량을 증가시키는 SRVL(Shipbor Rolling and Vertical Landing) 모드였습니다.[284][285] 항공모함 HMS Queen Elizabeth와 HMS Prince of Wales에서 작전을 수행할 때, 영국의 F-35B는 스키 점프를 사용합니다. 이탈리아 해군도 같은 과정을 사용합니다. 영국의 F-35B는 Brimstone 2 미사일을 사용하기 위한 것이 아닙니다.[286] 2013년 7월, 공군 참모총장 스티븐 돌턴 경은 617번 (댐버스터즈) 비행대대가 영국 공군의 첫 F-35 비행대가 될 것이라고 발표했습니다.[287][288] 두 번째 작전 비행대대는 2023년 4월 또는 그 이후에 창설될 플리트 에어 암(Fleet Air Arm)의 809 해군 항공대가 될 것입니다.[289][290]

2013년 4월 12일, 17번 (예비) 시험 평가 비행대 (TES)가 번개 작전 평가 부대로 창설되어 영국 최초로 번개 작전을 수행한 비행대가 되었습니다.[291] 2013년 6월까지 영국 공군은 48대의 F-35 중 3대를 수주했으며, 처음에는 에글린 공군기지에 기지를 두었습니다.[292] 2015년 6월, F-35B는 NAS Patuxent River의 스키점프대에서 첫 발사를 시작했습니다.[293] 2017년 7월 5일, 영국에 기반을 둔 두 번째 RAF 비행대대가 207번 비행대가 될 것이라고 발표되었으며,[294] 2019년 8월 1일 번개 작전 변환 부대로 개편되었습니다.[295] 제617비행단은 2018년 4월 18일 워싱턴 D.C.에서 열린 기념식에서 개조되어, 6월 6일 MCAS 보포트에서 RAF 마햄으로 비행하는 첫 번째 RAF 최전방 비행대대가 되었습니다.[296][297] 2019년 1월 10일, 617 비행대대와 F-35는 전투 준비 완료를 선언했습니다.[298]

2019년 4월, 617편대는 키프로스의 RAF 아크로티리에 배치되었으며, 이는 키프로스 최초의 해외 배치입니다.[299] 2019년 6월 25일, 이라크와 시리아의 이슬람 국가 목표물을 찾는 무장 정찰 비행으로 RAF F-35B의 첫 전투 사용이 시작된 것으로 알려졌습니다.[300] 2019년 10월, 댐버스터즈와 17번 TES F-35가 처음으로 HMS Queen Elizabeth에 탑승했습니다.[301] 617편대는 2020년 1월 22일 RAF 마함을 출발하여 첫 번째 번개와의 붉은 깃발 연습을 시작했습니다.[302] 2022년 11월 현재 26대의 F-35B가 영국에 기반을 두고 있으며(617대, 207대), 추가 3대가 테스트 및 평가 목적으로 미국에 영구적으로 기반을 두고 있습니다([303]17대).

호주.

A35-001로 명명된 호주 최초의 F-35는 2014년에 제작되었으며, 애리조나주 루크 공군 기지의 국제 조종사 훈련 센터(PTC)를 통해 비행 훈련을 제공했습니다.[304] 2017년 3월 3일 아발론 에어쇼에서 처음으로 두 대의 F-35가 호주 대중에게 공개되었습니다.[305] 2021년까지 호주 왕립 공군은 26대의 F-35A를 수용했으며, 미국에서 9대, RAAF 기지 윌리엄타운의 3번 비행대와 2번 작전 전환 부대에서 17대가 운용되었습니다.[304] 41명의 훈련된 RAAF 조종사와 225명의 유지보수를 위한 훈련된 기술자를 보유한 이 함대는 작전에 배치할 준비가 되었다고 선언되었습니다.[306] 당초 호주는 2023년까지 72대의 F-35를 모두 공급받을 것으로 예상됐지만 [305]2월 24일 현재 호주는 63대의 항공기를 공급받았습니다. 최종 9대의 항공기는 2024년에 출시될 예정이며, TR-3 버전이 될 것으로 예상됩니다.[307]

이스라엘

이스라엘 공군(IAF)은 2017년 12월 6일 F-35의 작전 능력을 선언했습니다.[308] 쿠웨이트 신문 알 자리다에 따르면 2018년 7월, 최소 3대의 IAF F-35로 구성된 시험 임무가 이란의 수도 테헤란으로 날아갔다가 텔아비브로 돌아갔습니다. 공개적으로 확인되지 않은 가운데, 지역 지도자들이 이 보고서에 대해 조치를 취했습니다. 이란의 최고 지도자 알리 하메네이는 이 임무에 대해 공군 참모총장과 이란 혁명수비대 사령관을 해고했다고 보도했습니다.[309][310]

2018년 5월 22일, 아미캄 노르킨(Amikam Norkin) IAF 사무총장은 F-35를 두 번의 전투에서 사용했다고 밝혔으며, 이는 F-35의 첫 번째 전투 작전입니다.[12][311] 노르킨은 이 비행기가 "중동 전역"에서 비행했으며, 낮에 베이루트 상공을 비행하는 F-35I의 사진을 보여주었다고 말했습니다.[312] 2019년 7월, 이스라엘은 이란의 미사일 수송에 대한 타격을 확대했습니다. IAF F-35I는 이라크의 이란 목표물을 두 차례 타격한 것으로 알려졌습니다.[313]

2020년 11월, IAF는 8월에 접수된 4대의 항공기 인도 중 유일한 F-35I 테스트베드 항공기의 인도를 발표했는데, 이는 이스라엘이 생산한 무기와 전자 시스템을 나중에 인도받은 F-35에 시험하고 통합하는 데 사용될 것입니다. 이것은 미국이 아닌 공군에 납품된 테스트베드 F-35의 유일한 예입니다.[314][315]

2021년 5월 11일, 8대의 IAF F-35I가 가디언 오브 더 월스 작전의 일환으로 가자 지구 북부의 발사구 50-70개를 포함한 하마스의 로켓 배열의 150개 목표물에 대한 공격에 참여했습니다.[316]

2022년 3월 6일, IDF는 2021년 3월 15일, F-35I가 가자 지구로 무기를 운반하는 이란 무인기 2대를 격추했다고 밝혔습니다.[317] 이것은 F-35에 의해 수행된 첫 번째 작전 격추 및 요격이었습니다. 그들은 또한 이스라엘과 하마스의 전쟁에서 사용되었습니다.[318][319][320]

2023년 11월 2일, IDF는 F-35I를 사용하여 이스라엘-하마스 전쟁 당시 예멘에서 발사된 후티 순항 미사일을 홍해 상공에서 격추했다고 소셜 미디어에 게시했습니다.[321]

이탈리아

2018년 11월 30일, 이탈리아의 F-35A가 초기 작전 능력(IOC)에 도달한 것으로 발표되었습니다. 당시 이탈리아는 10대의 F-35A와 1대의 F-35B를 인도받았으며, 2대의 F-35A와 1대의 F-35B는 훈련을 위해 미국에 주둔하고 있었으며, 나머지 8대의 F-35A는 아멘돌라에 주둔하고 있었습니다.[322]

일본

일본의 F-35A는 2019년 3월 29일 초기 운용능력(IOC)에 도달한 것으로 발표되었습니다. 당시 일본은 미사와 공군기지에 주둔 중이던 F-35A 10대를 인도받았습니다. 일본은 최종적으로 42대의 F-35B를 포함한 총 147대의 F-35를 인수할 계획입니다. 일본의 이즈모급 다목적 구축함을 장착하기 위해 후자의 변종을 사용할 계획입니다.[323][324]

노르웨이

2019년 11월 6일 노르웨이는 계획된 52대의 F-35A 중 15대의 F-35A에 대한 초기 작전 능력(IOC)을 선언했습니다.[325] 2022년 1월 6일 노르웨이의 F-35A는 북대서양조약기구(NATO)의 신속 대응 경보 임무를 위해 F-16을 대체했습니다.[326]

2023년 9월 22일, 노르웨이 왕립 공군의 F-35A 2대가 핀란드 테르보 인근의 고속도로에 착륙하여 처음으로 포장 도로에서 F-35A가 운행할 수 있음을 보여주었습니다. F-35B와 달리 수직으로 착륙할 수 없습니다. 전투기들은 또한 엔진이 작동하면서 연료를 보충했습니다. 노르웨이 왕립 공군 사령관인 롤프 폴랜드 소장은 "전투기는 지상에서 취약하기 때문에 작은 비행장과 현재의 자동차 전용도로를 이용할 수 있어 전쟁에서 우리의 생존 가능성이 높아진다"[327]고 말했습니다.

네덜란드

2021년 12월 27일 네덜란드는 현재까지 F-35A 46대를 수주한 F-35A 24대에 대한 초기 운용 능력(IOC)을 선언했습니다.[328] 2022년 네덜란드는 F-35 6대, 총 52대의 항공기를 추가로 주문할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[329]

변종

F-35는 세 가지 초기 변형으로 설계되었습니다: CTOL 육상 버전인 F-35A, 육상 또는 항공모함에서 사용할 수 있는 STOVL 버전인 F-35B, CATOBAR 항공모함 기반 버전인 F-35C. 그 이후로 이스라엘과 캐나다를 위한 국가별 버전 설계 작업이 있었습니다.

F-35A

F-35A는 미 공군과 다른 공군을 위한 기존의 이착륙(CTOL) 변형입니다. 가장 작고 가벼운 버전이며 모든 변종 중 가장 높은 9g이 가능합니다.

현재 F-35A는 붐과 리셉터클 방식으로 공중급유를 수행하고 있지만 고객이 필요로 하는 경우 프로브 앤 드로그 급유를 위해 항공기를 개조할 수 있습니다.[330][331] 드래그 슈트 포드는 F-35A에 장착할 수 있으며, 노르웨이 왕립 공군이 최초로 채택했습니다.[332]

F-35B

F-35B는 STOVL(short take and vertical landing) 기종입니다. B는 A변종과 비슷한 크기로 A변종 연료량의 약 3분의 1을 희생시켜 축 구동 리프트 팬(SDLF)을 수용합니다.[333][334] 이 제품은 7g으로 제한됩니다. 다른 변종과 달리 F-35B는 착륙 고리가 없습니다. 대신 "STOVL/HOOK" 컨트롤은 정상 비행과 수직 비행 간의 변환을 수행합니다.[335][336] F-35B는 마하 1.6(시속 1,976km)의 성능을 발휘하며 수직 및/또는 단기 이착륙(V/STOL)이 가능합니다.[201]

F-35C

F-35C는 캐터펄트 지원 이륙, 항공모함으로부터의 장벽 구속 복구 작업을 위해 설계된 항공모함 기반 변형입니다. F-35A에 비해 F-35C는 접이식 윙팁 섹션이 있는 더 큰 날개, 저속 제어 개선을 위한 더 큰 제어 표면, 캐리어 구속 착륙의 스트레스를 위한 더 강력한 착륙 기어, 트윈 휠 노즈 기어, 캐리어 구속 케이블과 함께 사용할 수 있는 더 강력한 테일 훅이 특징입니다.[234] 날개 면적이 넓어 착륙 속도를 줄이면서도 사거리와 탑재량을 모두 늘릴 수 있습니다. F-35C는 7.5g으로 제한됩니다.[337]

F-35I "아디르"

F-35I 아디르(Hebrew: Hebrew: אדיר, "대박" 또는 "마이티 원"이라는 뜻)는 이스라엘 특유의 변형된 F-35A입니다. 미국은 처음에는 이스라엘이 센서와 대책을 포함한 자체 전자전 시스템을 통합하는 것을 허용하기 전에 그러한 변화를 허용하지 않았습니다. 메인 컴퓨터에는 추가 시스템을 위한 플러그 앤 플레이 기능이 있습니다. 제안에는 외부 방해 포드와 내부 무기 베이에 새로운 이스라엘 공대공 미사일과 유도 폭탄이 포함됩니다.[340][341] IAF 고위 관계자는 F-35의 스텔스는 30~40년의 사용 수명에도 불구하고 10년 안에 부분적으로 극복될 수 있으며, 따라서 이스라엘이 자체 전자전 시스템을 사용해야 한다고 주장하고 있다고 말했습니다.[342] 이스라엘 항공 우주 산업(IAI)은 2인승 F-35 개념을 고려해 왔습니다. IAI 임원은 "이스라엘뿐만 아니라 다른 공군에서도 2인승에 대한 수요가 알려져 있습니다."라고 말했습니다.[343] IAI는 컨포멀 연료 탱크를 생산할 계획입니다.[344]

이스라엘은 총 75대의 F-35를 주문했으며, 2022년 11월 현재 36대가 이미 인도되었습니다.[345][346]

제안된 변형

CF-35

캐나다 CF-35는 제안된 변형으로 드로그 낙하산의 추가와 F-35B/C 스타일의 연료 주입 탐사선의 포함 가능성을 통해 F-35A와 차이가 있습니다.[332][347] 2012년에는 CF-35가 F-35A와 동일한 붐 급유 시스템을 사용할 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[348] 한 가지 대안은 F-35C의 탐사선 급유와 낮은 착륙 속도를 위해 채택하는 것이었습니다. 그러나 의회 예산 담당관의 보고서는 F-35C의 제한된 성능과 탑재체가 너무 비싸서 지불할 수 없다고 언급했습니다.[349] 2015년 연방 선거 이후 F-35 조달을 취소하겠다는 공약이 포함된 자유당은 [350]새 정부를 구성하고 기존 CF-18 호넷을 대체할 공개 경쟁을 시작했습니다.[351] CF-35 변종은 개발하기에 너무 비싸다고 여겨졌고, 결코 고려되지 않았습니다. 캐나다 정부는 Future Fighter Capability Project에서 다른 수정을 추진하지 않기로 결정하고, 대신 기존 F-35A 변종의 잠재적 조달에 초점을 맞추었습니다.[352]

2022년 3월 28일, 캐나다 정부는 2025년부터 노후화된 CF-18 전투기를 대체하기 위해 록히드 마틴과 88 F-35A[353] 협상을 시작했습니다.[354] 이 항공기는 총 190억 캐나다 달러에 달하는 것으로 알려졌으며, F-35 프로그램 과정에서 770억 캐나다 달러의 수명 주기 비용이 소요될 것으로 추정됩니다.[355][356] 2023년 1월 9일, 캐나다는 공식적으로 88대의 항공기 구매를 확정했으며, 16대의 항공기는 2026년에 최초로 캐나다 왕립 공군에 인도되었고, 2032년에 최종 배치되었습니다.[357][358] CF-35에 대해 확인된 추가적인 특징은 쇼트/아이스 북극 활주로에서의 착륙을 위한 드래그 슈트 포드와 CF-35가 내부적으로 최대 6 x AIM-120D 미사일을 탑재할 수 있는 '사이드킥' 시스템을 포함했습니다(다른 변형에 대한 일반적인 내부 용량 대신).[359]

새로운 수출 변종

2021년 12월, 록히드 마틴이 불특정 외국인 고객을 위해 새로운 변종을 개발하고 있다는 소식이 전해졌습니다. 국방부는 이 작업을 위해 4천9백만 달러의 자금을 공개했습니다.[360]

"F-35D" (개념)

"F-35D"는 2015년 USAF 연구인 "미래 운용 개념"의 일환으로 가상 시나리오를 설명하기 위해 공칭 2035 항공기로 사용되었습니다.[361][362]

연산자

- 이스라엘 공군 – 2023년[update] 7월 기준 39대 인도 (F-35I "Adir")[378] (AS-15)로 지정된 이스라엘 고유의 무기, 전자 장치 및 구조적 업그레이드를 위한 F-35 테스트베드 항공기 1대가 포함됩니다.[379][380] 총 75개가 주문되었습니다.[381]

- 이탈리아 공군 – 2023년[update][382] 4월 기준으로 F-35A 17대, F-35B 3대가 이탈리아 공군에 주문한 F-35A 60대, F-35B 15대를 인도받았습니다.[383][384][385]

- 이탈리아 해군 – 2023년[update] 4월 현재 F-35B 15대 중 3대가 이탈리아 해군에 주문되었습니다.[383][384][385]

- 일본 방공자위대 – 2022년 3월 현재 27대의 F-35A가 운용되고 있으며, F-35A 105대, F-35B 42대 등 총 147대가 운용되고 있습니다.[386][387][388][389]

- 네덜란드 왕립 공군 – 39대의 F-35A가 인도되어 운용되고 있으며, 그 중 8대의 훈련기가 미국 루크 공군기지에 주둔하고 있습니다.[328] 총 52대의 F-35A가 주문되었습니다.[390][391][392]

- 노르웨이 왕립 공군 – 31대의 F-35A가 인도되어 운용 중이며, 2021년[393] 8월 11일 현재 총 52대의 F-35A 중 21대는 노르웨이에, 10대는 미국에 주둔하여 훈련 중입니다.[394] 그들은 드로그 낙하산을 추가함으로써 다른 F-35A와 다릅니다.[395]

- 폴란드 공군 – 2020년 1월 31일에 "기술 리프레시 3" 소프트웨어 업데이트와 드로그 낙하산이 장착된 32대의 F-35A 블록 4 제트기가 주문되었습니다.[396][397] 배송은 2024년에 시작되어 2030년에 끝날 것으로 예상됩니다. 각각 16대씩으로 구성된 2개 비행대대, 총 32대의 추가 F-35 계획이 있습니다.[398]

- 대한민국 공군 – 2022년 1월 현재 F-35A 40대 주문 및 인도 완료,[399][400][401][402][403] 2023년 9월 25대 추가 주문

- 대한민국 해군 – 약 20대의 F-35B가 계획되어 있습니다.[404][405] 아직 한국 의회의 승인을 받지 못했습니다.[406]

- 스위스 공군 – 36 F-35A에서 현재 F-5E/F Tiger II 및 F/A-18C/D Hornet을 교체하라는 명령을 받았습니다. 배송은 2027년에 시작하여 2030년에 완료됩니다.[409][410]

- 영국 공군과 영국 해군(RAF 소유이지만 공동 운용됨) – F-35B 32대는 2021년 11월 항공기 1대를 분실한 후 영국에서 28대를 받았습니다[411][412][413].[303][414][415][416] 나머지 3대는 미국에서 시험과 훈련에 사용됩니다.[417] 2023년까지 42대(FOC 전투기 24대, 훈련기 18대),[418][419] 2021년 기준 총 48대, 총 138대가 발주될 예정으로 2021년 예상치는 60대 또는 80대 수준입니다.[420] 2022년 영국이 F-35B 74대를 인수한다고 발표했는데, 2020년대 중반 138대의 당초 계획을 부활시킬 가능성을 포함해 그 수를 넘어설지에 대한 결정이 내려졌습니다.[421] 2024년 2월 영국은 당초 계획대로 138대의 F-35B 항공기를 조달하겠다는 약속을 재확인하는 신호를 보낸 것으로 보입니다.[422]

- 미 공군 – 계획대로[423][424][425] 302대, F-35 1,372대 제공

- 미 해병대 – 112대의 F-35B/C를 353대의 F-35B와 67대의 F-35C와 함께 인도함[423][426]

- 미국 해군 – F-35C 273대와 함께 30대 인도[423] 예정[426]

잠재적 사업자

- 체코 공군 – 2023년 6월 29일 발표에 따르면 미 국무부는 체코에 최대 56억 2천만 달러 상당의 F-35 항공기, 군수품 및 관련 장비 판매 가능성을 승인했습니다.[427] 체코 정부는 2024년 1월 29일 미국과 F-35A 전투기 24대 구매를 위한 양해각서를 체결했습니다.[428]

- 루마니아 공군 – 루마니아는 F-35 항공기 48대를 2단계로 나누어 구매할 계획입니다.[429] 32대의 F-35 항공기가 참여한 1단계 구매는 루마니아 의회의 승인을 받았으며, 예상 비용은 65억 달러입니다.[430]

주문 및 승인취소

- 중화민국 공군 – 대만이 미국으로부터 F-35 구매를 요청했습니다. 그러나 이는 중국의 비판적인 반응을 우려하여 미국이 거부했습니다. 2009년 3월 대만은 스텔스 기능과 수직 이륙 기능을 갖춘 미국의 5세대 전투기를 다시 구입하려고 했습니다.[citation needed] 그러나 2011년 9월 미국을 방문한 대만 국방부 차관은 대만이 현재 F-16을 개량하느라 바쁜 와중에도 F-35와 같은 차세대 항공기를 계속 조달하려고 한다고 확인했습니다. 이것은 중국으로부터 일반적인 비판적인 반응을 얻었습니다.[431] 대만은 2017년 초 도널드 트럼프 대통령 집권 당시 F-35 구매를 다시 추진해 중국의 비난을 다시 불러일으켰습니다.[432] 2018년 3월 대만은 미국의 무기 조달이 예상됨에 따라 F-35에 대한 관심을 다시 한 번 강조했습니다. F-35B STOVL 변종은 중화인민공화국과 확대되어 제한된 수의 활주로가 폭격된 후 중화민국 공군이 계속 작전을 수행할 수 있도록 하기 때문에 정치적으로 가장 선호되는 것으로 알려졌습니다.[433] 그러나 2018년 4월 미국 정부는 대만군 내 중국 스파이의 우려로 F-35를 대만에 판매하는 것을 꺼리고 있으며, 항공기에 대한 기밀 데이터를 손상시키고 중국 군 관계자에게 접근을 허용할 수 있음이 분명해졌습니다. 2018년 11월 대만 군 수뇌부는 F-16V Viper 항공기를 더 많이 구매하는 쪽으로 F-35 구매를 포기한 것으로 알려졌습니다. 이 결정은 비용과 이전에 제기된 스파이 문제뿐만 아니라 업계 독립성에 대한 우려가 동기가 된 것으로 알려졌습니다.[434]

- 태국 공군 – 8 또는 12대가 F-16A/B 블록 15 ADF를 대체할 계획입니다. 2022년 1월 12일, 태국 내각은 2023 회계연도에 138억 바트로 추정되는 최초 4대의 F-35A에 대한 예산을 승인했습니다.[435][436][437] 2023년 5월 22일, 미국 국방부는 태국의 F-35 전투기 구매 입찰을 거절하고 대신 F-16 블록 70/72 바이퍼와 F-15EX 이글 II 전투기를 제공할 것임을 시사했다고 태국 공군 관계자가 말했습니다.[438]

- 터키 공군 – 30대가 주문되었으며,[439] 최대 100대가 계획되어 있습니다.[440][441] 튀르키예가 러시아로부터 S-400 미사일 시스템을 구매하기로 결정함에 따라 2020년 초까지 계약이 취소되면서 미국은 향후 구매를 금지했습니다. 튀르키예가 발주한 F-35A 30대 중 6대는 2019년 현재 완료(2023년 현재 미국 내 격납고에 보관 중이며, 필요시 미 의회의 2020 회계연도 국방예산 변경에도 불구하고 미 공군으로 이전되지 않음), 그리고 2020년에 두 개가 더 조립 라인에 있었습니다.[445][446] 첫 번째 F-35A 4대는 2018년과[447] 2019년에[448] 터키 조종사 훈련을 위해 루크 공군 기지에 인도되었습니다.[449][450] 2020년 7월 20일, 미국 정부는 당초 튀르키예로 향하던 8대의 F-35A를 압류하고 USAF로 이송하는 것을 공식 승인했으며, 이를 USAF 사양으로 수정하는 계약도 체결했습니다. 미국은 2023년 1월 현재 F-35A 전투기 구매를 위해 튀르키예가 지불한 14억 달러를 환불하지 않고 있습니다. 2024년 2월 1일, 미국은 S-400 문제가 해결되면 튀르키예를 F-35 프로그램에 재도입할 의사를 밝혔습니다.

- 아랍에미리트 공군 – 최대 50대의 F-35를 계획대로 운용할 수 있습니다.[453] 하지만 2021년 1월 27일, 바이든 행정부는 UAE에 대한 F-35 판매를 잠정 중단했습니다.[454] 바이든 행정부는 판매 검토 법안을 보류한 후 2021년 4월 13일 거래를 진행하기로 확정했습니다.[455] 2021년 12월, UAE는 미국의 추가 거래 조건에 동의하지 않아 F-35 구매를 철회했습니다.[456][457]

사고 및 주목할 만한 사건

2014년 6월 23일, Eglin AFB에서 F-35A의 엔진에 불이 났습니다. 조종사는 무사히 탈출했고, 항공기는 5천만 달러로 추정되는 피해를 입었습니다.[458][459] 이 사고로 인해 7월 3일 모든 항공편이 중단되었습니다.[460] 이 함대는 7월 15일 비행 봉투 제한과 함께 비행기로 돌아갔습니다.[461] 2015년 6월, 미국 공군 교육 훈련 사령부(AETC)는 공식 보고서를 발표했는데, 이 보고서는 엔진의 팬 모듈의 3단 로터가 고장으로 인해 팬 케이스와 상부 동체를 절단했기 때문이라고 설명했습니다. Pratt & Whitney는 확장된 "Rub-in"을 적용하여 두 번째 고정자와 세 번째 회전자 일체형 암 씰 사이의 간격을 늘렸고 2016년 초까지 고정자를 미리 고정할 수 있도록 설계를 변경했습니다.[458]

2018년 9월 28일 F-35와 관련된 첫 번째 추락 사고가 발생했습니다. USMC F-35B기가 사우스캐롤라이나주 보퍼트 해병대 비행장 인근에 추락해 조종사가 무사히 탈출했습니다.[462] 이 사고는 연료 튜브의 결함으로 인한 것입니다. 모든 F-35는 10월 11일에 항공기 전체의 튜브 검사가 진행될 때까지 운항이 중단되었습니다.[463] 다음날 대부분의 USAF와 USN F-35는 검사 후 비행 상태로 돌아갔습니다.[464]

2019년 4월 9일, 미사와 공군기지에 부속된 JASDF F-35A가 태평양 상공에서 훈련 임무를 수행하던 중 아오모리현 동쪽에 추락했습니다.[465] 일본은 조사 과정에서 12대의 F-35A를 이륙시켰습니다. 미국과 일본 해군은 실종된 항공기와 조종사를 찾아 물 위에서 추락을 확인한 잔해를 발견했습니다.[465] 조종사의 유해는 6월에 수습되었습니다.[466] 중국이나 러시아가 항공기 인양을 시도할 수도 있다는 추측이 있었지만, 일본 방위성은 양국으로부터 "보고된 활동"이 없었다고 보도했습니다.[467] 조종사는 실종되기 전에 훈련을 중단하겠다는 의사를 무선으로 전달했습니다. 조종사는 최소 15초 전까지 의식과 반응이 있었던 것으로 보이지만, F-35는 조난 신호를 보내지 않았고, 빠른 속도로 하강하면서 조종사는 어떠한 복구 기동도 시도하지 않았습니다. 사고 보고서는 그 원인을 조종사의 공간적 방향감각 상실 때문이라고 설명했습니다.[465]

2020년 5월 19일, 제58전투비행단 소속 USAF F-35A가 에글린 AFB에 착륙하던 중 추락했습니다. 조종사는 탈출했고 안정적인 상태였습니다.[468] 이 사고는 피로로 인한 조종사 오류, 산소 시스템의 설계 문제, 항공기의 더 복잡한 특성이 산만한 문제, 그리고 오작동한 헤드 마운트 디스플레이와 응답하지 않은 비행 제어 시스템이 복합적으로 작용했기 때문입니다.[469]

2020년 9월 29일 캘리포니아 임페리얼 카운티에서 USMC F-35B가 공대공 급유 중 해병대 KC-130과 충돌한 후 추락했습니다. F-35B 조종사는 사출 사고로 부상을 입었고 KC-130은 착륙 장치를 배치하지 않고 들판에 불시착했습니다.[470]

2021년 3월 12일, 애리조나주 해병대 공군기지 유마 인근에서 근접 지원 무기 훈련 야간 비행을 하던 중 F-35B에 탑재된 25mm 포대에서 발사된 포대가 포대를 이탈한 직후 폭발했습니다. 항공기는 3개월 이상 정비를 위해 이륙하지 못했지만 조종사는 다치지 않았습니다.[471]

2021년 11월 17일, 영국 공군 617 편대 F-35B가 지중해에서 일상적인 작전 중 추락했습니다. 조종사는 안전하게 HMS Queen Elizabeth로 복구되었습니다.[414][472][473] 보안에 민감한 모든 장비를 포함한 잔해는 미군과 이탈리아군의 도움으로 대부분 회수되었습니다.[474] 이번 충돌은 흡기부에 남아있던 엔진 블랭킹 플러그가 원인으로 공식적으로 확인됐습니다.[475]

2022년 1월 4일, 대한민국 공군 F-35A가 비행 조종 장치와 엔진을 제외한 모든 시스템이 고장 난 후 벨리 착륙을 했습니다. 조종사는 저고도 비행 중에 일련의 앞머리 소리를 들었고, 다양한 시스템이 작동을 멈췄습니다. 관제탑은 조종사가 탈출할 것을 제안했지만 착륙 장치를 배치하지 않고 무사히 비행기를 착륙시킬 수 있었습니다.[476][477]

2022년 1월 24일, VFA-147을 탑재한 USN F-35C가 칼빈슨호(CVN-70)에 착륙하던 중 경사로 공격을 받아 남중국해에서 배 밖으로 유실되어 승무원 7명이 다쳤습니다. 조종사는 무사히 탈출하여 물에서 건져졌습니다. 2022년 3월 2일, 원격조종차량(ROV)과 심해잠수함 DSCV 피카소의 도움으로 약 12,400피트(3,780m) 깊이에서 항공기를 회수했습니다.[478]

2022년 10월 19일, F-35A가 유타주 힐 공군기지 활주로 북쪽 끝에서 추락했습니다. 조종사는 무사히 탈출하여 다치지 않았습니다. 충돌의 원인은 이전 항공기의 후류 난류로 인한 공기 데이터 시스템의 오류로 인해 기본 비행 조건 데이터 소스와 백업 비행 조건 데이터 소스 간에 여러 번의 급격한 전환이 이루어졌기 때문입니다. 이러한 급격한 전환으로 인해 재설정 값이 축적되었습니다. 부정확한 비행 조건 데이터에 따라 비행 제어법이 작동하고 통제된 비행에서 이탈하는 결과를 초래합니다.[479]

2022년 12월 15일, F-35B는 텍사스의 해군 공군기지 포트워스에서 수직 착륙 실패 중 추락했습니다. 조종사는 땅에 튕겨져 나가 크게 다치지는 않았습니다. 이 항공기는 정부 조종사에 의해 생산 시험 비행 중이었고, 제조사가 아직 미군에 인도하지 않았습니다.[480][481][482]

2023년 9월 17일, 조종사 한 명이 MCAS 보퍼트에서 훈련 비행 중 "미시맵"에 따라 사우스 캐롤라이나 노스 찰스턴 상공에서 F-35B를 이륙했습니다. 조종사가 다치지 않은 동안 전투기는 약 30시간 동안 위치를 찾지 못했습니다.[483][484] 2023년 9월 18일 저녁 전투기의 잔해가 발견되었다는 발표가 있었습니다.[484]

사양(F-35A)

Lockheed Martin의 자료: F-35 사양,[485][486][487][488] Lockheed Martin: F-35 무기,[489] Lockheed Martin: F-35 프로그램 현황,[102] F-35 프로그램 개요,[151] FY2019 Select Acquisition Report(SAR),[337] 운용시험평가국장[490]

일반적 특성

- 승무원: 1명

- 길이: 51.4ft (15.7m)

- 날개폭: 35피트 (11m)

- 높이: 14.4ft (4.4m)

- 날개면적 : 460평방피트 (43m2)

- 종횡비: 2.66

- 공중량 : 29,300lb (13,290kg)

- 총중량: 49,540lb (22,471kg)

- 최대이륙중량 : 65,918파운드 (29,900kg)

- 연료용량 : 18,250 lb (8,278 kg) 내부

- 발전소: 터보팬 연소 후 1 × Pratt & Whitney F135-PW-100, 28,000 lbf (125 kN) 추력 건조, 43,000 lbf (191 kN), 애프터버너 포함

성능

- 최대 속도: 고공에서 마하 1.6

- 해발고도에서 마하 1.06, 700노트(806mph, 1,296km/h)

- 사거리: 1,500 nmi (1,700 mi, 2,800 km)

- 전투거리: 669 nmi(770 mi, 1,239 km) 내부 연료에 대한 차단 임무(공대지)

- 760 nmi(870 mi; 1,410 km), 내부 연료에[492] 대한 공대공 구성

- 서비스 천장: 50,000ft (15,000m)

- g 제한: +9.0

- 날개하중 : 총중량에서 107.7lb/sqft (526kg/m2)

- 추력/중량: 총중량에서 0.87(50% 내부 연료를 탑재한 적재 중량에서 1.07)

무장

- 포 : 1X25mm GAU-22/4통 회전식 대포, 180발[N 16]

- 하드 포인트: 내부 스테이션 4개, 내부 스테이션 5,700파운드(2,600kg), 외부 스테이션 15,000파운드(6,800kg), 총 무기 탑재량 18,000파운드(8,200kg), 다음과 같은 조합을 운반할 수 있는 조항이 있습니다.

- 미사일:

- 공대공 미사일:

- AIM-9X 사이드와인더

- AIM-120 AMRAAM

- AIM-132 ASRAAM

- AIM-260 JATM (통합 예정)[493]

- MBDA Meteor (4블록, F-35B용, 2027년 이전은 아님)[494][178][495]

- 공대지 미사일:

- AGM-88G AARGM-ER (Block 4)

- AGM-158 JASSM[169]

- AGM-179 JAGM

- SPEAR 3 (블록 4, 개발 중, 통합 계약됨)[163][495]

- 스탠드인 공격 무기(SiAW)[496]

- 대함 미사일:

- AGM-158CL LRASM[497](통합)

- 합동 타격 미사일 (통합 진행 중)[498]

- 공대공 미사일:

- 폭탄:

- 미사일:

항전학

- AN/APG-81 또는 AN/APG-85 (Lot 17 이후) AESA 레이더[501][502]

- AN/AAQ-40 전자광학타겟팅 시스템[503]

- AN/AAQ-37 전자광학분산 조리개 시스템[504]

- A/ASQ-239 Barracuda 전자전/전자 대책 시스템[505]

- 다음을 포함하는 AN/ASQ-242 CNI 제품군

변종 간의 차이

| F-35A CTOL | F-35B 스토블 | F-35C CV(캐리어 변형) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 길이 | 51.4 ft (15.7 m) | 51.2 ft (15.6 m) | 51.5 ft (15.7 m) |

| 날개폭 | 35 ft (10.7 m) | 35 ft (10.7 m) | 43 ft (13.1 m) |

| 높이 | 14.4 ft (4.39 m) | 14.3 ft (4.36 m) | 14.7 ft (4.48 m) |

| 날개 면적 | 460평방피트(42.74m2) | 460평방피트(42.74m2) | 668 sq ft (62.06 m2) |

| 공중량 | 28,999 lb (13,154 kg) | 32,472 lb (14,729 kg) | 34,581 lb (15,686 kg) |

| 내부연료 | 18,250 lb (8,278 kg) | 13,500lb (6,123kg) | 19,750 lb (8,958 kg) |

| 무기 탑재체 | 18,000파운드(8,160kg) | 15,000lb (6,800kg) | 18,000파운드(8,160kg) |

| 최대이륙중량 | 70,000파운드(31,800kg)급 | 60,000파운드(27,200kg)급 | 70,000파운드(31,800kg)급 |

| 범위 | >1,200 nmi (2,200 km) | >900nmi (1,700km) | >1,200 nmi (2,200 km) |

| 전투반경 on 내부 연료 | 669 nmi (1,239 km) | 505 nmi (935 km) | 670 nmi (1,241 km) |

| 추력/중량 • 연료 가득 채우기: • 50% 연료: | 0.87 1.07 | 0.90 1.04 | 0.75 0.91 |

| g 한계 | +9.0 | +7.0 | +7.5 |

미디어에서의 등장

참고 항목

관련 개발

- Lockheed Martin X-35 – Joint Strike Fighter 프로그램을 위한 개념 시연기

비슷한 역할, 구성 및 시대를 가진 항공기

- 청두 J-20 – 중국 5세대 전투기

- HAL AMCA – 힌두스탄 항공유한공사가 개발 중인 인도 5세대 전투기

- KAI KF-21 보라매 – 한국과 인도네시아가 개발 중인 첨단 멀티롤 전투기

- Lockheed Martin F-22 랩터 – 미국의 5세대 항공우월 전투기

- 선양 FC-31 – 선양항공이 개발 중인 5세대 제트 전투기

- 수호이 Su-57 – 러시아의 5세대 전투기

- 타이프 카안 – 터키 항공우주산업이 개발 중인 터키 5세대 전투기

- 수호이 Su-75 Checkmate – 수호이가 개발 중인 러시아 단일 엔진 5세대 전투기

관련 목록

메모들

- ^ 2014년까지 이 프로그램은 "예산 대비 1,630억 달러가 초과되었습니다. 그리고 예정보다 7년 늦었습니다."[9]

- ^ 록히드는 1993년 포트워스에서 제너럴 다이내믹스 전투기 사업부를 인수하고 1995년 마틴 마리에타와 합병하여 록히드 마틴을 설립했습니다.

- ^ 위험을 줄이기 위한 개념 시연 항공기였기 때문에 최종 항공기의 내부 구조나 대부분의 하위 시스템을 무기 시스템으로 갖출 필요가 없었습니다.

- ^ F-35 스위블 노즐 디자인은 Convair Model 200이 개척했습니다.[21]

- ^ 추력 벡터링 노즐은 결국 무게를 줄이기 위해 축대칭 저관측 노즐로 대체될 것입니다.

- ^ FACO는 또한 국제 협력을 통한 산업적 이익의 일환으로 일부 파트너 및 수출 고객을 위해 이탈리아 및 일본에서 수행됩니다.

- ^ 이 첫 번째 프로토타입은 SWAT의 무게 최적화가 부족했습니다.

- ^ 초기 F-35B의 사용 수명은 9번 구역 이후의 항공기에서 볼 수 있듯이 개조 전 2,100시간 정도로 낮습니다.

- ^ 튀르키예는 여러 F-35 부품의 유일한 공급업체였으며, 따라서 프로그램은 교체 공급업체를 찾아야 했습니다.

- ^ F-35C는 날개의 접히는 부분에 추가적인 에일론이 있습니다.

- ^ 2014년 마이클 길모어(Michael Gilmore) 운영 테스트 및 평가 책임자는 "소프트웨어 개발, 계약자 실험실의 통합 및 비행 테스트에 대한 성숙한 기능 제공이 계속 예정보다 늦었습니다."라고 말했습니다.[112]

- ^ Rockwell Collins와 Elbit Systems는 합작 투자 회사인 VSI(Vision Systems International)를 설립하고 나중에 Collins Elbit Vision Systems(CEVS)로 이름을 바꾸었습니다.

- ^ 2002년에는 F-35용 고체 레이저 무기가 개발 중이었던 것으로 알려졌습니다.[183][184][185]

- ^ 2011년 말 F-35B와 C의 플러터 테스트에서 수평 꼬리와 꼬리 붐의 "버블링과 물집"이 한 번 관찰되었습니다. 프로그램 사무소에 따르면, 이 문제는 여러 번 복제를 시도했음에도 불구하고 단 한 번 발생했으며, 이후 완화 조치로 개선된 스프레이 온 코팅이 시행되었습니다. 2019년 12월 17일, 국방부 프로그램 사무소는 더 이상의 조치를 취하지 않고 문제를 종결했으며, 대신 기체 뒷면에 위치한 스텔스 코팅과 안테나의 손상 위험을 줄이기 위해 F-35B와 C의 고속 비행에 시간 제한을 가하고 있습니다.[237][238]

- ^ 윙 드롭은 하이그 트랜스소닉 기동 중에 발생할 수 있는 명령되지 않은 롤입니다.

- ^ F-35B와 F-35C에는 220발의 외부 포드에 대포가 있습니다.

참고문헌

- ^ a b c d Drew, James (31 July 2015). "First operational F-35 squadron declared ready for combat". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Insinna, Valerie (2 August 2016). "Air Force Declares F-35A Ready for Combat". Defense News.

- ^ a b c d Eckstein, Megan (28 February 2019). "Navy Declares Initial Operational Capability for F-35C Joint Strike Fighter". USNI News.

- ^ Finnerty, Ryan (19 January 2024). "Lockheed completes assembly of 1,000th F-35". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 18 January 2024. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ "F-35 Global Partnerships". Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Dudley, Richard (5 March 2012). "Program Partners Confirm Support for F-35 Joint Strike Fighter". Defence Update.

- ^ a b Pawlyk, Oriana (28 December 2020). "Key US Ally Declares Its F-35s Ready for Combat". Military.com. 10th paragraph. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Boehm, Eric (26 April 2022). "The $1.7 Trillion F-35 Fighter Jet Program Is About To Get More Expensive". reason.com. Reason. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Drusch, Andrea (16 February 2014). "Fighter plane cost overruns detailed". Politico. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Miller, Kathleen; Capaccio, Tony & Ivory, Danielle (22 February 2013). "Flawed F-35 Too Big to Kill as Lockheed Hooks 45 States". Bloomberg L.P.

- ^ Ciralsky, Adam (16 September 2013). "Will the F-35, the U.S. Military's Flaw-Filled, Years-Overdue Joint Strike Fighter, Ever Actually Fly?". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ a b Ahronheim, Anna (22 May 2018). "IAF Commander: Israel First To Use F-35 Jet In Combat". The Jerusalem Post.

- ^ "US European Command/NATO May Have 450 F-35s by 2030". Aviation Today. 14 June 2021.

- ^ Drew, James (25 March 2016). "Lockheed F-35 service life extended to 2070". FlightGlobal.

- ^ Rich, Stadler (October 1994). "Common Lightweight Fighter" (PDF). Code One Magazine. Lockheed. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2020.

- ^ a b "History (Pre-JAST)". Joint Strike Fighter. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ a b "History (JAST)". Joint Strike Fighter. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ Barrie, Douglas; Norris, Guy & Warwick, Graham (4 April 1995). "Short take-off, low funding". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ a b "The JSF UK Industry Team". Martin Baker Aircraft Company Limited. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006.

- ^ "US, UK sign JAST agreement". Aerospace Daily. New York: McGraw-Hill. 25 November 1995. p. 451.

- ^ Renshaw, Kevin (12 August 2014). "F-35B Lightning II Three-Bearing Swivel Nozzle". Code One Magazine.

- ^ Wilson, George C. (22 January 2002). "The engine that could". Government Executive. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ^ "Propulsion system for a vertical and short takeoff and landing aircraft, United States Patent 5209428". PatentGenius.com. 7 May 1990. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012.

- ^ Gunston, Bill (1997). Yakovlev Aircraft since 1924. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books. p. 16. ISBN 1-55750-978-6.

- ^ Welt, Flying (29 October 2023). "Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II: Top 10 things to know". Flying Welt. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Sheridan, Arthur E.; Burnes, Robert (13 August 2019). "F-35 Program History: From JAST to IOC". American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA): 50. doi:10.2514/5.9781624105678.0001.0076. ISBN 978-1-62410-566-1.

- ^ Bevilaqua, Paul M. (September 2005). "Joint Strike Fighter Dual-Cycle Propulsion System". Journal of Propulsion and Power. 21 (5): 778–783. doi:10.2514/1.15228.

- ^ a b "History (JSF)". Joint Strike Fighter. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ Schreiber, Liev (3 February 2003). "Battle of the X-Planes". NOVA. PBS. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Battle of the X-Planes. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "History (F-35 Acquisition)". Joint Strike Fighter. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Parsch, Andreas (27 April 2006). "Non-Standard DOD Aircraft Designations". Designation Systems.

- ^ Keijsper 2007, pp. 122, 124.

- ^ Hehs, Eric (15 May 2008). "X to F: F-35 Lightning II And Its X-35 Predecessors". Code One Magazine. Lockheed Martin.

- ^ Keijsper 2007, p. 119

- ^ a b Norris, Guy (13 August 2010). "Alternate JSF Engine Thrust Beats Target". Aviation Week.

- ^ Fulghum, David A.; Wall, Robert (19 September 2004). "USAF Plans for Fighters Change". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- ^ Keijsper 2007, 페이지 124,

- ^ Pappalardo, Joe (November 2006). "Weight Watchers: How a team of engineers and a crash diet saved the Joint Strike Fighter". Air & Space Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014.

- ^ Knotts, Keith P. (9 July 2013). "CF-35 Lightning II: Canada's Next Generation Fighter" (PDF). Westdef.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2014.

- ^ "'Lightning II' moniker given to Joint Strike Fighter". U.S. Air Force. 7 June 2006.

- ^ Rogoway, Tyler (17 May 2018). "The Air Force's Elite Weapons School Has Given The F-35 A New Nickname". The War Zone. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018.

- ^ "F-35 Software Development". Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "GAO-06-356: DOD Plans to Enter Production before Testing Demonstrates Acceptable Performance" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. March 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Insinna, Valerie (28 April 2018). "F-35 program office wraps up final developmental flight test". Defense News.

- ^ Haynes, Deborah (15 June 2019). "F-35 jets: Chinese-owned company making parts for top-secret UK-US fighters". Sky News.

- ^ Doffman, Zak (15 June 2019). "U.S. and U.K. F-35 Jets Include 'Core' Circuit Boards From Chinese-Owned Company". Forbes.

- ^ Minnick, Wendell (24 March 2016). "Chinese Businessman Pleads Guilty of Spying on F-35 and F-22". Defense News. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Cox, Bob (1 March 2010). "Internal Pentagon memo predicts that F-35 testing won't be complete until 2016". Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

- ^ Capaccio, Tony (6 January 2010). "Lockheed F-35 Purchases Delayed in Pentagon's Fiscal 2011 Plan". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010.

- ^ Charette, Robert (12 September 2012). "F-35 Program Continues to Struggle with Software". IEEE Spectrum.

- ^ "FY18 DOD Programs F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF)" (PDF). Director, Operational Test and Evaluation. 2018. p. 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2019.

- ^ "Is the F-35 worth it?". 60 Minutes. 16 February 2014. CBS News.

- ^ Tirpak, John (14 March 2016). "All For One and One for All". Air Force.

- ^ Shalal, Andrea (27 April 2015). "U.S. watchdog finds quality violations in Pratt work on F-35 engine". Reuters.

- ^ Barrett, Paul (10 April 2017). "Danger Zone". Bloomberg Businessweek. pp. 50–55.

- ^ Schneider, Greg (27 October 2001). "Lockheed Martin Beats Boeing for Fighter Contract". The Washington Post.

- ^ Dao, James (27 October 2001). "Lockheed Wins $200 Billion Deal for Fighter Jet". The New York Times.

- ^ Merle, Renae (15 March 2005). "GAO Questions Cost Of Joint Strike Fighter". The Washington Post.

- ^ Shalal-Esa, Andrea (17 September 2012). "Pentagon tells Lockheed to shape up on F-35 fighter". Reuters.

- ^ Tirpak, John A. (8 January 2014). "The Cost of Teamwork". Air Force. Arlington, Virginia: Air Force Association. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Capaccio, Anthony (10 July 2017). "F-35 Program Costs Jump to $406.5 Billion in Latest Estimate". Bloomberg.

- ^ Astore, William J. (16 September 2019). "The Pentagon's $1.5 Trillion Addiction to the F-35 Fighter". The Nation. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Tirpak, John (29 October 2019). "Massive $34 Billion F-35 Contract Includes Price Drop as Readiness Improves". Air Force.

- ^ "F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Development Is Nearly Complete, but Deficiencies Found in Testing Need to Be Resolved" (PDF). GAO. June 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ a b Insinna, Valerie (12 March 2024). "Pentagon finally approves F-35 for full rate production after 5-year delay". Breaking Defense.

- ^ Insinna, Valerie (6 December 2019). "After a couple months delay, the F-35 moves into operational tests". Defense News.

- ^ Tirpak, John (25 February 2019). "Keeping the F-35 Ahead of the Bad Guys". Air Force.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin Awarded $1.8 Billion for F-35 Block 4 Development". Defense World. 8 June 2019.

- ^ Tegler, Eric. "International F-35 Customers, Your Airplanes Will Be Delayed". Forbes.

- ^ Zazulia, Nick (19 March 2019). "U.S. Defense Department Plans to Spend $6.6B on F-35 Continuing Development Through 2024". Avionics International.

- ^ a b Trimble, Steven (9 July 2018). "USAF starts work on defining adaptive engine for future fighter". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020.

- ^ "USAF Launches F-35 Advanced Engine Effort". Janes. 31 January 2022.

- ^ Warwick, Graham (12 September 2013). "Northrop Develops Laser Missile Jammer For F-35". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Israel Wants To Put New Equipment Inside The F-35: Exclusive Q&A With Top Officer". 21 September 2021.

- ^ 로이터 직원. (2022년 9월 7일) "펜타곤, 중국산 콘텐츠 확인 위해 F-35기 수용 중단" 예루살렘 포스트. 2022년 10월 28일 회수.

- ^ "Select Acquisition Report: F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program (F-35) as of FY 2020 President's Budget" (PDF). Washington Headquarters Services. 17 April 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "Estimated JSF Air Vehicle Procurement Quantities" (PDF). Joint Strike Fighter. April 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2011.

- ^ "F-35 Lightning: The Joint Strike Fighter Program, 2012". Defense Industry Daily. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013.

- ^ Schnasi, Katherine V. (May 2004). "Joint Strike Fighter Acquisition: Observations on the Supplier Base" (PDF). US General Accounting Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2006.

- ^ "Industry Canada F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Canada's Next Generation Fighter Capability". Government of Canada. 18 November 2002. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ 전투 항공기 월간 2010년 9월 24일.

- ^ Winters, Vice Adm. Mat (9 December 2018). "Head of F-35 Joint Program Office: Stealth fighter enters the new year in midst of a growing phase". Defense News. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ Manson, Katrina; Pitel, Laura (19 June 2018). "US Senate blocks F-35 sales to Turkey". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Liptak, Kevin; Gaouette, Nicole (17 July 2019). "Trump blames Obama as he reluctantly bans F-35 sales to Turkey". CNN. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Host, Pat (1 October 2018). "F-35 chief reaffirms Turkey's status as committed programme partner". Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Capabilities: F-35 Lightning II". Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010.

- ^ Kent, John R.; Geisel, Chris (16 November 2010). "F-35 STOVL supersonic". Lockheed Martin.

- ^ "Open System Architecture (OSA) Secure Processing" (PDF). L3 Technologies. March 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2016.

- ^ Adams, Charlotte (1 September 2003). "JSF: Integrated Avionics Par Excellence". Aviation Today. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Amaani, USAF Tech. Sgt. Lyle (3 April 2009). "Air Force takes combat air acquisitions priorities to Hill". U.S. Air Force. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023.

- ^ 트랜소닉 기동용 AIAA 2007 4433 공격각도에서 F-35의 날개 압력 분포에 대한 CFD 예측

- ^ Ryberg, Eric S. (26 February 2002). "The Influence of Ship Configuration on the Design of the Joint Strike Fighter" (PDF). Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Whittle, Richard (February 2012). "The Ultimate Fighter?". Air & Space/Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ a b Hehs, Eric (15 July 2000). "JSF Diverterless Supersonic Inlet". Code One Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Sloan, Jeff (19 October 2009). "Skinning the F-35 fighter". Composites World. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ "Contract Awarded To Validate Process For JSF". Aerospace Manufacturing and Design. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen (26 May 2011). "Lockheed Martin reveals F-35 to feature nanocomposite structures". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 30 May 2011.

- ^ Nativi, Andy (5 March 2009). "F-35 Air Combat Skills Analyzed". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010.

- ^ Crébas, Frank (May 2018). "F-35 – Out of the Shadows". Combat Aircraft Monthly. Key Publishing. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "Flying The F-35: An Interview With Jon Beesley, F-35 Chief Test Pilot". Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Seligman, Lara (1 March 2016). "Norwegian F-35 Pilot Counters Controversial Dogfighting Report". Defense News. Archived from the original on 26 November 2017.

- ^ a b "F-35 Lightning II Program Status and Fast Facts" (PDF). F-35.ca. Lockheed Martin. 13 March 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2013.

- ^ George, Eric (1 May 2010). "F-35 avionics: an interview with the Joint Strike Fighter's director of mission systems and software". Military & Aerospace Electronics (Interview). Vol. 21, no. 5. PennWell Corporation. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016.

- ^ Sherman, Ron (1 July 2006). "F-35 Electronic Warfare Suite: More Than Self-Protection". Aviation Today. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Robb, John H. (11 February 2001). "Hey C and C++ Can Be Used In Safety Critical Applications Too!". Journal of Cyber Security and Information Systems. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ Warwick, Graham (7 June 2010). "Flight Tests Of Next F-35 Mission-System Block Underway". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Raytheon Selects RACE++ Multicomputers for F-35 Joint Strike Fighter". EmbeddedStar.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ McHale, John (1 February 2010). "F-35 Joint Strike Fighter leverages COTS for avionics systems". Military & Aerospace Electronics. PennWell Corporation. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- ^ Philips, E. H. (5 February 2007). "The Electric Jet". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- ^ Parker, Ian (1 June 2007). "Reducing Risk on the Joint Strike Fighter". Aviation Today. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ Keller, John (16 June 2013). "Tens of thousands of Xilinx FPGAs to be supplied by Lockheed Martin for F-35 Joint Strike Fighter avionics". Intelligent Aerospace. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ FY2013 DOD PROGRAMS F-35 합동타격전투기(JSF)

- ^ Reed, John (23 November 2010). "Schwartz Concerned About F-35A Delays". DoD Buzz. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010.

- ^ a b Lyle, Amaani (6 March 2014). "Program executive officer describes F-35 progress". U.S. Air Force. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023.

- ^ "APG-81 (F-35 Lightning II)". Northrop Grumman Electronic Systems. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ "F-35 Distributed Aperture System (EO DAS)". Northrop Grumman. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Lemons, Greg; Carrington, Karen; Frey, Dr. Thomas; Ledyard, John (24 June 2018). "F-35 Mission Systems Design, Development, and Verification" (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.2018-3519. ISBN 978-1-62410-556-2. S2CID 115841087. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin Missiles and Fire Control: Joint Strike Fighter Electro-Optical Targeting System". Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ "ASQ242 Datasheet" (PDF). Northrop Grumman. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2014.

- ^ "F-35 jet fighters to take integrated avionics to a whole new level". Military & Aerospace Electronics. PennWell Corporation. 1 May 2003.

- ^ "Israel, US Negotiate $450 Million F-35I Avionic Enhancements". Defense Update. 27 July 2012. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012.

- ^ Donald, David (17 June 2019). "F-35 Looks to the Future". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Drew, James (10 September 2015). "Lockheed reveals Advanced EOTS targeting sensor for F-35 Block 4". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020.

- ^ Abbott, Rich (18 June 2018). "Raytheon Picked to Produce F-35 Sensor". Aviation Today. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023.

- ^ Clark, Colin (15 December 2014). "Pawlikowski On Air Force Offset Strategy: F-35s Flying Drone Fleets". Breaking Defense. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023.

- ^ a b Helfrich, Emma (3 January 2023). "F-35 Will Get New Radar Under Massive Upgrade Initiative". The Drive. Archived from the original on 19 January 2024. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Fast History: Lockheed's Diverterless Supersonic Inlet Testbed F-16". Aviation Intel. 22 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013.

- ^ Tirpak, John A. (26 November 2014). "The F-35 on Final Approach". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Clark, Colin (11 March 2015). "Threat Data Biggest Worry For F-35A's IOC; But It 'Will Be On Time'". Breaking Defense. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Clark, Colin (6 June 2014). "Gen. Mike Hostage On The F-35; No Growlers Needed When War Starts". Breaking Defense. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b Butler, Amy (17 May 2010). "New, Classified Stealth Concept Could Affect JSF Maintenance Costs". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021.

- ^ "USAF FY00 activity on the JSF". Director, Operational Test & Evaluation. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.

- ^ "Request for Binding Information Response to the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Defence" (PDF). Lockheed Martin. April 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2012 – via Government.no.

- ^ Capaccio, Tony (4 May 2011). "Lockheed Martin's F-35 Fighter Jet Passes Initial Stealth Hurdle". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015.

- ^ "F-35 – Beyond Stealth". Defense-Update. 14 June 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Ralston, James; Heagy, James; Sullivan, Roger (September 1998). "Environmental/Noise Effects on UHF/VHF UWB SAR" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Plopsky, Guy; Bozzato, Fabrizio (21 August 2014). "The F-35 vs. The VHF Threat". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023.

- ^ Brewer, Jeffrey; Meadows, Shawn (Summer 2006). "Survivability of the Next Strike Fighter". Aircraft Survivability: Susceptibility Reduction. Joint Aircraft Survivability Program Office. p. 23. Archived from the original on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2010 – via Defense Technical Information Center.

- ^ Lockie, Alex (5 May 2017). "This strange mod to the F-35 kills its stealth near Russian defenses – and there's good reason for that". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 25 December 2023.

- ^ Alaimo, Carol Ann (30 November 2008). "Noisy F-35 Still Without A Home". Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Report on Jet Engine Noise Reduction" (PDF). Naval Research Advisory Committee. April 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "F-35 Acoustics Based on Edwards AFB Acoustics, Test". JSF Program Office & Lockheed Martin. April 2009.

- ^ "F-35, F-16 noise difference small, Netherlands study shows". Aviation Week. 31 May 2016.

- ^ Ledbetter, Stewart (31 May 2019). "Wonder no more: F-35 jet noise levels finally confirmed at BTV". NBC News. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023.

- ^ Hensley, Senior Airman James (19 May 2015). "F-35 pilot training begins at Luke". U.S. Air Force. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Schutte, John (10 October 2007). "Researchers fine-tune F-35 pilot-aircraft speech system". U.S. Air Force Materiel Command. Archived from the original on 22 January 2024. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint : bot : 원본 URL 상태 알 수 없음 (링크) - ^ "VSI's Helmet Mounted Display System flies on Joint Strike Fighter". Rockwell Collins. 10 April 2007. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- ^ "Martin-Baker". The JSF UK Industry Team. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ Lowell, Capt. Jonathan (25 August 2019). "Keeping cool over Salt Lake". U.S. Air Force. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Zazulia, Nick (24 August 2018). "F-35: Under the Helmet of the World's Most Advanced Fighter". Avionics International. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Davis, Brigadier General Charles R. (26 September 2006). "F-35 Program Brief" (PDF). U.S. Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2020 – via Joint Strike Fighter.

- ^ "F-35 Distributed Aperture System EO DAS". YouTube. F35JSFVideos. 4 May 2009. Archived from the original on 17 November 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint : bot : 원본 URL 상태 알 수 없음 (링크) - ^ Davenport, Christian (1 April 2015). "Meet the most fascinating part of the F-35: The $400,000 helmet". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ Seligman, Lara (14 October 2015). "F-35's Heavier Helmet Complicates Ejection Risks". Defense News. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin Awards F-35 Contract". Zack's Investment Research. 17 November 2011. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012.

- ^ Warwick, Graham (21 April 2011). "Lockheed Weighs Alternate F-35 Helmet Display". Aviation Week.

- ^ Carey, Bill (15 February 2012). "BAE Drives Dual Approach To Fixing F-35 Helmet Display Issues". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin Selects BAE Systems to Supply F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Helmet Display Solution". BAE Systems. 10 October 2011. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023.

- ^ a b Majumdar, Dave (10 October 2013). "F-35 JPO drops development of BAE alternative helmet". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014.

- ^ Williams, Dan (30 October 2012). "Lockheed Cites Good Reports on Night Flights of F-35 Helmet". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Eshel, Noam (25 August 2010). "Small Diameter Bomb II – GBU-53/B". Defense Update. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "F-35B STOVL Variant". Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Spear Capability 3". MBDA Systems. 9 June 2019. Archived from the original on 11 May 2023.

This new, F-35 Lightning II internal bay compatible, air-to-surface missile

- ^ Keller, John (17 August 2018). "Navy asks BAE Systems to build T-1687/ALE-70(V) electronic warfare (EW) towed decoys for F-35". Military Aerospace Electronics. Archived from the original on 22 January 2024.

- ^ Keijsper 2007, pp. 220, 239.

- ^ Hewson, Robert (4 March 2008). "UK changes JSF configuration for ASRAAM". Jane's. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012.

- ^ Tran, Pierre (22 February 2008). "MBDA Shows Off ASRAAM". Defense News.

- ^ "JSF Suite: BRU-67, BRU-68, LAU-147 – Carriage Systems: Pneumatic Actuated, Single Carriage". ITT.com. 2009.[데드링크]

- ^ a b Digger, Davis (30 October 2007). "JSF Range & Airspace Requirements" (PDF). Headquarters Air Combat Command. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2008 – via Defense Technical Information Center.

- ^ a b "F-35 gun system". General Dynamics Armament and Technical Products. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011."GAU-22/A" (PDF). General Dynamics Armament and Technical Products. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. 2011년 4월 7일 회수.

- ^ a b Capaccio, Tony (30 January 2020). "The Gun On the Air Force's F-35 Has 'Unacceptable' Accuracy". Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ a b Trevithick, Joseph (22 March 2024). "F-35A's Beleaguered 25mm Cannon Is Finally "Effective"". The War Zone. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Keijsper 2007, p. 233.

- ^ Donald, David (11 July 2012). "Terma Highlights F-35 Multi-Mission Pod". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 11 October 2023.

- ^ Bolsøy, Bjørnar (17 September 2009). "F-35 Lightning II status and future prospects". F-16.net. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2009.[unre적으로 신뢰할 수 있는 출처?]

- ^ Everstine, Brian W. (17 June 2019). "Lockheed Looking at Extending the F-35's Range, Weapons Suite". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ a b Lake 2010, pp. 37-45.

- ^ a b Trimble, Stephen (17 September 2010). "MBDA reveals clipped-fin Meteor for F-35". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 21 September 2010.

- ^ Drew, James (25 February 2015). "F-35B Internal Weapons Bay Can't Fit Required Load of Small Diameter Bomb IIs". Inside Defense.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023.

- ^ "Air Force President's Budget FY20". Assistant Secretary of the Air Force, Financial Management and Comptroller.

- ^ "Important cooperative agreement with Lockheed Martin". Kongsberg Defence & Aerospace. 9 June 2009. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012.

- ^ Tirpak, John A. (17 March 2014). "Nuclear Lightning". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014.

- ^ Fulghum, David A. (8 July 2002). "Lasers being developed for F-35 and AC-130". Aviation Week and Space Technology. Archived from the original on 26 June 2004.

- ^ Morris, Jefferson (26 September 2002). "Keeping cool a big challenge for JSF laser, Lockheed Martin says". Aerospace Daily. Archived from the original on 4 June 2004.

- ^ Fulghum, David A. (22 July 2002). "Lasers, HPM weapons near operational status". Aviation Week and Space Technology. Archived from the original on 13 June 2004.

- ^ Norris, Guy (20 May 2013). "High-Speed Strike Weapon To Build On X-51 Flight". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013.

- ^ Drew, James (5 October 2015). "Lockheed considering laser weapon concepts for F-35". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020.

- ^ Parsons, Dan (15 February 2015). "USAF chief keeps sights on close air support mission". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Long Road Ahead For Possible A-10 Follow-On". Aviation Week. 24 March 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about JSF". Joint Strike Fighter. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Warwick, Graham (17 March 2011). "Screech, the F135 and the JSF Engine War". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 21 March 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Katz, Dan (7 July 2017). "The Physics And Techniques Of Infrared Stealth". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (1 October 2012). "US Navy works through F-35C air-ship integration issues". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Chris Wiegand; Bruce A. Bullick; Jeffrey A. Catt; Jeffrey W. Hamstra; Greg P. Walker; Steve Wurth (13 August 2019). "F-35 Air Vehicle Technology Overview". American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA). Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics. 257: 121–160. doi:10.2514/5.9781624105678.0121.0160. ISBN 978-1-62410-566-1.

- ^ "Custom tool to save weeks in F-35B test and evaluation". U.S. Naval Air Systems Command. 6 May 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2024. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Zolfagharifard, Ellie (28 March 2011). "Rolls-Royce's LiftSystem for the Joint Strike Fighter". The Engineer. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ "LiftSystem". Rolls-Royce. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ "Swivel nozzle VJ101D and VJ101E". Vertical Flight Society. 20 June 2009.

- ^ Hirschberg, Mike (1 November 2000). "V/STOL Fighter Programs in Germany: 1956–1975" (PDF). International Powered Lift Conference. p. 50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2012 – via robertcmason.com.

- ^ "How the Harrier hovers". Harrier.org. Archived from the original on 7 July 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- ^ a b Kjelgaard, Chris (21 December 2007). "From Supersonic to Hover: How the F-35 Flies". Space.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023.

- ^ Hutchinson, John. "Going Vertical: Developing a STOVL system" (PDF). Ingenia.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ "GE Rolls-Royce Fighter Engine Team completes study for Netherlands". Rolls-Royce plc. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original on 22 January 2024. Retrieved 23 November 2009.