그리스의 경제

Economy of Greece이 문서는 갱신할 필요가 있습니다.(2018년 8월) |

그리스 농업, 해운, 관광, 그리스 경제의 중요한 부문 | |

| 통화 | 유로(EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| 역년[1] | |

무역 조직 | EU, WTO, OECD, BIS, BSEC[1] |

국가 그룹 | |

| 통계 정보 | |

| 인구. | |

| GDP | |

| GDP 순위 | |

GDP 성장 | |

1인당 GDP | |

1인당 GDP 순위 | |

부문별 GDP | |

노동력 | |

직업별 노동력 | |

| 실업률 | |

평균총급여 | |

순급여의 중위수 | |

주요 산업 | 해운 및 조선업(4일; 2011년),[21][22] 관광, 식품 및 담배 가공, 섬유, 화학, 금속 제품; 광업, 석유[1] |

| 외부의 | |

| 내보내기 | 399억45100만유로 ( |

수출품 |

|

주요 수출 파트너 | |

| Imports(가져오기) | 653억4천100만유로 ( |

수입품 |

|

주요 수입 파트너 | |

| 재정 | |

| 3576억 6500만 유로 ( | |

| - 135억8천900만유로 ( | |

| 수익 | |

| 비용 | |

외환보유고 | |

| 그리스의 경제 |

|---|

|

| 개요 |

| 역사 |

| 관련된 |

그리스의 경제는 명목 국내총생산(GDP)이 연간 [6]2227억 7000만 달러로 세계에서 53번째로 크다.구매력 평가에서 그리스는 연간 [6]3786억 9300만 달러로 세계 54위의 경제대국이다.2020년 현재, 그리스는 27개 회원국으로 [38]구성된 유럽연합에서 16번째로 큰 경제대국이다.국제통화기금(IMF)의 2022년 통계에 따르면 그리스의 1인당 국내총생산(GDP)은 명목가치로 20,940달러, 구매력 [6]평가로 35,596달러다.

그리스는 서비스(80%)와 산업(16%)을 기반으로 한 경제를 가진 선진국으로 2017년 [1]농업 부문은 국민 경제 생산의 4%를 차지할 것으로 추산된다.그리스의 중요한 산업은 관광과 해운업을 포함한다.그리스는 2013년 1800만 명의 외국인 관광객으로 유럽연합에서 7위, 세계에서 [39]16위를 차지했다.그리스 상선은 세계 [40]최대 규모로 2013년 기준으로 그리스 소유 선박이 전 세계 데드웨이트 톤수의 15%를 차지한다.그리스와 아시아 간의 국제 해상 운송에 대한 수요 증가는 해운 산업에 전례 없는 투자를 초래했다.[41]

그리스는 유럽 연합 내에서 중요한 농산물 생산국이다. 그리스는 발칸반도에서 가장 큰 경제를 가지고 있고 중요한 지역 [42][43]투자국이다.그리스는 2013년 [44]알바니아에서 가장 많은 외국인 투자자를 배출했고 불가리아에서 세 번째, 루마니아와 세르비아에서 세 번째, 북마케도니아에서 [45][46][47]가장 중요한 무역 상대국이자 가장 큰 외국인 투자자였다.그리스 통신회사 OTE는 옛 유고슬라비아와 발칸의 일부 [45]국가들에 강력한 투자자가 되었다.

그리스는 선진 [48]고소득 [49]경제국으로 분류되며 경제협력개발기구(OECD)와 흑해경제협력기구(BSEC)의 창립 멤버였다.그 나라는 [50]1981년에 현재의 유럽연합에 가입했다.2001년 그리스는 유로화를 도입하여 [50][51]유로당 340.75 드라크마 환율을 그리스 드라크마로 대체하였다.그리스는 국제통화기금(IMF)과 세계무역기구(WTO) 회원국으로 Ernst & Young의 세계화지수 [52]2011에서 34위를 기록했다.

제2차 세계 대전 (1939-1945)은 그 나라의 경제를 황폐화시켰지만, 1950년부터 1980년까지 이어진 높은 수준의 경제 성장은 그리스 경제의 [53]기적이라고 불려왔다.2000년 이후 그리스는 2003년 5.8%,[54] 2006년 5.7%로 정점을 찍으며 유로존 평균을 웃도는 높은 GDP 성장률을 보였다.그 후의 대불황과 그리스 정부채무위기는, 2008년에 -0.3%, 2009년에 -4.3%, 2010년에 -5.5%, 2011년에 -10.1%, 2012년에 -7.1%, 2013년에 [11][10]-2.5%의 실질 GDP 성장률을 나타내면서, 경제는 급락에 빠졌습니다.2011년 국가 공공부채는 3560억유로(명목 [55]GDP의 172%)에 달했다.그리스는 민간부문과 사상 최대 규모의 채무재조정 협상을 벌여 채권 개인투자자가 [56]1000억 유로를 잃자 2012년 [57]1분기 국가채무 부담을 2800억 유로(GDP의 137%)로 줄였다.그리스는 6년간의 경제 침체 이후 2014년에 실질 GDP 성장률이 0.5%에 달했으나 2015년에 0.2%, 2016년에 [10][11][58][59]0.5% 감소했다.2017년 1.1%, 2018년 1.7%, 2019년 [10][11]1.8%의 완만한 성장률을 보였다.2020년 COVID-19 [6][10][11]대유행으로 인한 세계적인 불황 동안 GDP는 9% 감소했다.하지만 [6][9]2021년 경제는 8.3% 반등했다.

역사

19세기 동안 그리스 경제의 진화는 거의 연구되지 않았다.2006년의 최근의[60] 조사에서는, 농업이 우세한 경제에서 산업의 점진적인 발전과 해운의 한층 더 발전을 조사하고, 1833년에서 1911년 사이의 1인당 GDP 성장률은 다른 서유럽 국가들에 비해 약간 낮았다.(조선업과 같은 중공업을 포함한) 산업 활동은 주로 에르무폴리스와 [61][62]피레아스에서 뚜렷했다.그럼에도 불구하고, 그리스는 경제적 어려움에 직면했고 1826년, 1843년, 1860년, [63]1893년에 대외 차관을 갚지 못했다.

다른 연구들은 생활수준의 비교척도를 제시하면서 경제의 전반적인 동향에 대한 위의 견해를 뒷받침한다.그리스의 1인당 국민소득(구매력 기준)은 1850년 프랑스의 65%, 1890년 56%, [64][65]1938년 62%, 1980년 75%, 2007년 90%, 2008년 96.4%, 2009년 [66][67]97.9%였다.

제2차 세계대전 이후 이 나라의 발전은 그리스의 경제적 [53]기적과 크게 연관되어 있다.이 기간 그리스는 성장률이 일본에 이어 2위, GDP [53]성장률에서는 유럽 1위였다.1960년에서 1973년 사이에 그리스 경제는 평균 7.7% 성장한 반면, EU15는 4.7%,[53] OECD는 4.9%의 성장률을 보였다.이 기간 동안 수출은 연평균 12.6% 증가했다.[53]

장점과 단점

그리스는 2019년 [15]세계 32위로 높은 생활수준과 매우 높은 인간개발지수를 누리고 있다.그러나 최근 심각한 경기 침체로 1인당 GDP는 2009년 EU 평균의 94%에서 2017년부터 [68][69]2019년 사이에 67%로 떨어졌다.같은 기간 1인당 실질 개인소비(AIC)는 EU [68][69]평균의 104%에서 78%로 떨어졌다.

그리스의 주요 산업은 관광, 해운, 공산품, 식품 및 담배 가공, 섬유, 화학, 금속 제품, 광업 및 석유이다.그리스의 GDP 성장률도 평균적으로 1990년대 초부터 EU 평균보다 높았다.그러나 그리스 경제는 높은 실업률, 비효율적인 공공 부문 관료주의, 탈세, 부패, 낮은 글로벌 경쟁력 [70][71]등 여전히 심각한 문제에 직면해 있다.

그리스는 부패인식지수에서 [72]세계 58위, EU 회원국 중 23위를 차지하고 있다.이는 최근 몇 년 동안 꾸준한 개선(위기 이전 순위로의 회귀)을 나타내고 있으며, 특히 2012년 채무위기 절정기에 발생한 최악의 실적과 비교하면 세계 94위, EU [74]내 마지막까지 떨어졌다.그러나 그리스는 여전히 EU의 경제자유지수가 가장 낮고 세계경쟁력지수가 두 번째로 낮아 각각 [75][76]77위와 59위를 기록하고 있다.

그리스는 14년 연속 경제 성장을 한 [77]후 2008년에 경기 침체로 접어들었다.2009년 말까지 그리스 경제는 EU에서 가장 높은 재정적자와 정부 부채 대 GDP 비율에 직면했으며, 몇 번의 상향 조정 끝에 2009년 재정적자는 [78]국내총생산(GDP)의 15.7%로 추산되었다.이와 함께 급속히 증가하는 부채 수준(2009년 GDP의 127.9%)이 차입 비용의 급격한 증가로 이어져 그리스가 글로벌 금융시장에서 사실상 고립되고 심각한 [79]경제위기를 초래했다.

그리스는 글로벌 금융위기 [80]이후 막대한 재정적자를 은폐하려 했다는 비난을 받았다.이 같은 주장은 2009년 10월 선출된 새 PASOK 정부가 2009년 재정적자 전망치를 '6~8%'(이전 신민주주의 정부 추정치)에서 12.7%(나중에 15.7%로 수정)로 대폭 수정한 데 따른 것이다.그러나 개정된 수치의 정확성에 대해서도 의문이 제기되었고, 2012년 2월 그리스 의회는 더 엄격한 [81][82]긴축정책을 정당화하기 위해 적자가 인위적으로 부풀려졌다는 그리스 통계청의 전 의원의 비난에 따라 공식 조사에 찬성표를 던졌다.

| 시대별[54] 평균 GDP 성장률 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961–1970 | 8.44% | ||

| 1971–1980 | 4.70% | ||

| 1981–1990 | 0.70% | ||

| 1991–2000 | 2.36% | ||

| 2001–2007 | 4.11% | ||

| 2008–2011 | −4.8% | ||

| 2012–2015 | −2.52% | ||

그리스 노동인구는 약 500만 명으로 2011년 근로자 1인당 연평균 2032시간의 노동시간으로 멕시코 한국 [83]칠레에 이어 경제협력개발기구(OECD) 국가 중 4위다.그로닝엔 성장 및 개발 센터는 1995년부터 2005년 사이에 그리스가 유럽 국가 중 가장 많은 시간/년 노동력을 가진 나라였으며 그리스인은 연평균 1,900시간, 스페인인은 그 뒤를 이었다(연간 1,800시간/년).[84]

경제위기가 계속되면서 2010년 3월부터 [85]2011년 3월까지 국내 산업생산은 8% 감소했고,[86] 건축활동량은 2010년 73% 감소했다.또한 2010년 2월부터 2011년 [87]2월까지 소매 매출액은 9% 감소했습니다.

2008년과 2013년 사이에 실업률은 2008년 2분기와 3분기의 세대 최저치인 7.2%에서 2013년 6월 최고치인 27.9%로 치솟아 100만 명 이상의 [88][89][90]실업자가 되었다.청년 실업률은 2013년 [91]5월에 64.9%로 최고조에 달했다.실업률은 2022년 [92]3월 전체 실업률이 12.2%, 청년 실업률은 26.4%로 떨어지는 등 최근 몇 년간 꾸준히 개선되고 있다.

유로존 가입

그리스는 2000년 6월 19일 유럽 이사회에 의해 1999년을 기준으로 한 여러 기준(인플레이션율, 재정적자, 공공채무, 장기금리, 환율)에 따라 유럽연합(EU)의 경제통화동맹에 가입했다.2004년 차기 신민주주의 정부에 의해 의뢰된 감사 후, Eurostat는 예산 적자에 대한 통계가 과소 [93]보고되었다고 밝혔다.그러나, 그 후의 모든 수정에도, 적용시의 현행의 Eurostat 회계방식에 의하면, 기준 연도의 예산 적자는 허용 상한(3%)을 넘지 않았기 때문에, 그리스는 여전히 유로존의 가입에 있어서 매우 중요한 조건을 충족하고 있었다(상세한 것은 이하와 같다).

수정된 예산 적자 숫자의 차이는 대부분 새 정부의 일시적인 회계 관행 변경, 즉 군사 물자 [94]수령이 아닌 주문 시 비용을 기록했기 때문이다.그러나 Eurostat에 의한 ESA95 방법론(2000년 이후 적용)의 소급 적용으로 기준 연도(1999년)의 재정적자가 GDP의 3.38%로 증가하여 3% 한도를 넘었다.이는 그리스([95]이탈리아와 같은 다른 유럽 국가들에 대해 비슷한 주장이 제기됨)가 실제로 5개 가입 기준을 모두 충족시키지 못했다는 주장과 그리스가 "확실한" 적자 수치를 통해 유로존에 가입했다는 일반적인 인식을 낳았다.

Greece,[96]의 2005년 OECD보고서에서 명확하게 한다는 새로운 회계 규칙의 재정적 수치에 1997년 99년 영향은 GDP의 0.7에서 1%포인트의 범위, 방법론의 이 소급 변경 1999년,[그리스의]전철 회원 자격의 해에 개정된 적자 3%를 초과하는 책임이 있다고 언급되었다.".이에 따라 그리스 재무장관은 1999년 재정적자가 그리스 적용 당시 현행 ESA79 방법론으로 계산했을 때 소정의 3%를 밑돌고 있다는 점을 명확히 하고 기준을 [97]충족시켰다.

군비에 대한 원래의 회계 관행은 나중에 Eurostat 권고사항에 따라 복원되었고, 이론적으로 ESA95가 계산한 1999년 그리스 예산 적자마저 3% 미만으로 낮췄다(공식 Eurostat 계산은 1999년에 아직 보류 중임).

그리스가 유로존에 가입할 때 미국 은행과 거래한 파생상품과 그리스 등 유로존 국가들이 인위적으로 재정적자를 줄이기 위해 거래한 것에 대한 논란과 혼선을 빚는 경우가 있다.골드만삭스와의 통화스와프는 그리스가 28억 유로의 부채를 "은닉"할 수 있게 해주었지만, 이는 2001년 이후(그리스가 이미 유로존에 가입했던 시점)의 적자액에 영향을 미쳤고 그리스의 유로존 [98]가입과는 관련이 없다.

1999-2009년 법의학 회계사의 연구에 따르면 그리스가 Eurostat에 제출한 데이터는 조작을 나타내는 통계 분포를 가지고 있는 것으로 나타났다. "평균값이 17.74인 그리스는 유로존 회원국 중 벤포드의 법칙에서 가장 큰 편차를 보이며, 벨기에가 17.21로 그 뒤를 이었다.값이 15.[99][100]25인치인 오스트리아.

2010~2018년 정부 채무 위기

이력 채무

그리스는 다른 유럽 국가들과 마찬가지로 19세기에 부채 위기에 직면했고 대공황 기간인 1932년에 비슷한 위기에 직면했다.그러나 일반적으로 20세기에는 세계에서 가장 높은 GDP 성장률(1950년대 초반부터 1970년대 중반까지 25년 동안 일본에 이어 세계 2위)을 보였다.위기 전 세기의 그리스 정부 GDP 대비 부채 평균은 영국,[103] 캐나다 또는 [102][103]프랑스보다 낮았고, 유럽 경제 공동체에 가입할 때까지의 30년 기간(1952-1981) 동안 그리스 정부의 GDP 대비 부채 비율은 평균 19.8%에 불과했다.

| 나라 | 일반 대중 GDP 대비 부채(GDP 대비 %) |

|---|---|

| 영국 | 104.7 |

| 벨기에 | 86.0 |

| 이탈리아 | 76.0 |

| 캐나다 | 71.0 |

| 프랑스. | 62.6 |

| 그리스 | 60.2 |

| 미국 | 47.1 |

| 독일. | 32.1 |

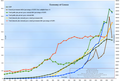

1981년과 1993년 사이에 꾸준히 상승하여 1980년대 중반의 유로존 평균을 넘어섰다(오른쪽 차트 참조).

다음 15년간, 1993년 2007년(즉이 있기도 전에 금융 위기의 2007–2008), 그리스의 정부debt-to-GDP 비율,[103][104]-값보다 낮이탈리아(107%), 벨기에(110%)에 동일한 15년 period,[103]과 comparab 동안 102%평균 대략 변동이 없는(값은 2004년 아테네 올림픽에 의해 영향을 받지 않아) 남아 있었다.그기 위해 르2017년 [105]미국 또는 OECD 평균.

후기에는 연간 재정적자가 GDP의 3%를 웃돌았지만 GDP 대비 부채비율에 미치는 영향은 높은 GDP 성장률로 상쇄되었다.2006년과 2007년의 GDP 대비 부채 가치(약 105%)는 감사 결과 특정 연도에 대해 최대 10% 포인트(2008년과 2009년의 유사한 수정)가 수정되었다.이러한 수정은 부채 수준을 최대 약 10%까지 변경했지만, "그리스가 이전에 부채를 숨기고 있었다"는 일반적인 생각을 낳았다.

채무 위기의 진화

그리스 위기 대침체기의 여러 서구 국가들의 예산 적자 운영하거나 넘GDP.[102]인 그리스의 경우 10%에 도달하기까지 이어지는 혼란이 높은 예산 적자(, 여러 수정 2008년과 2009년에 각각 GDP의 10.2%, 15.1%에 도달할 수 있어 왔었음이 폭로되었다)co.은 유발되었다upledGDP 대비 공공부채 비율이 높다(그때까지[102] GDP의 100%를 약간 웃도는 수치로 몇 년 동안 비교적 안정적이었다).따라서 2009년에 [106]이미 GDP 대비 127%에 달했던 GDP 대비 공적 부채 비율을 제어할 수 없게 된 것으로 보인다.게다가, 유로존의 일원으로서, 그 나라는 근본적으로 자율적인 통화 정책의 유연성이 없었다.마지막으로 그리스 통계에 대한 논란(앞서 언급한 대폭적인 재정적자 수정으로 그리스 공공채무의 산출가치가 약 10% 증가, 즉 2007년까지 GDP 대비 공공채무의 약 100% 증가)이 있었지만, 언론보도의 효과에 대한 논란도 있었다.그 결과 그리스는 2010년 초부터 차입금리를 높인 시장에 의해 "벌"을 받았고, 그리스가 부채를 조달하는 것을 불가능하게 만들었다.

이에 따라 그리스 정부는 2009년 초 3.7%, 2009년 9월 6%였던 적자 전망치를 2009년 [107][108]10월 국내총생산(GDP) 대비 12.7%로 수정하면서 1974년 민주주의 회복 이후 가장 심각한 위기를 맞았다.

앞서 언급한 재정적자 및 채무 수정은 골드만삭스, JP모건체이스 및 기타 많은 은행의 지원을 통해 그리스, 이탈리아 및 기타 많은 유럽 국가의 정부가 [109][110]차입금 일부를 숨길 수 있는 금융상품이 개발되었다는 조사 결과와 관련이 있다.유럽 전역에서 수십 개의 유사한 협정이 체결되었으며, 은행은 관련된 정부의 미래 지급에 대한 대가로 현금을 미리 공급했다. 그 결과, 관련 국가의 부채는 "[110][111][112][113][114][115]장부에서 제외되었다".

슈피겔에 따르면 유럽 정부에 부여된 신용은 스와프로 위장돼 채무로 등록되지 않았다.이는 당시 유로스타트가 금융파생상품 관련 통계를 무시했기 때문이다.독일의 한 파생상품 딜러는 슈피겔에 "마스트리히트 규칙은 스와프를 통해 합법적으로 회피할 수 있다"며 "예전에는 이탈리아가 다른 미국 [115]은행의 도움을 받아 진정한 부채를 감추기 위해 비슷한 수법을 썼다"고 논평했다.이러한 조건들은 그리스와 다른 많은 유럽 정부들이 유럽연합의 적자 목표와 통화 동맹 [116][117][118][119][120][121][122][110][123]지침을 충족시키면서 그들의 분수에 넘치는 지출을 할 수 있게 해주었다.2010년 5월에는 그리스 정부 적자가 다시 수정되어 GDP 대비 가장 높은 13.[124]6%로 추정되었으며, 아이슬란드가 15.7%, 영국이 [125][dubious ]12.6%로 3위를 차지했다.일부 추정에 따르면 [126]공공부채는 2010년 GDP의 120%에 달할 것으로 예측된다.

그 결과 그리스의 국가채무 상환능력에 대한 국제적 신뢰에 위기가 발생하였고, 이는 그리스의 차입금리 상승에 반영되었다(2010년 4월 10년 만기 국채수익률은 7%를 겨우 넘었지만) 많은 부정적인 기사와 맞물려 그리스에 대한 논쟁으로 이어졌다.위기 진화에 있어 국제 뉴스 미디어의 역할).디폴트(높은 차입금리가 시장에 대한 접근을 사실상 금지)를 피하기 위해 2010년 5월 다른 유로존 국가들과 IMF는 그리스에 450억 유로의 긴급 구제차관을 제공하는 '구제 패키지'에 동의했고, 이에 따라 더 많은 자금이 추가되어 총 1100억 [127][128]유로가 되었다.자금을 확보하기 위해 그리스는 재정적자를 [129]억제하기 위해 엄격한 긴축정책을 채택해야 했다.이들의 이행은 유럽위원회, 유럽중앙은행 및 [130][131]IMF에 의해 감시되고 평가된다.

재정위기, 특히 유럽연합과 IMF가 내놓은 긴축정책은 그리스 국민들의 분노를 사고 폭동과 사회 불안으로 이어졌으며, 국제 미디어의 효과에 대한 이론이 있어왔다.다른 사람들은 장기간의 긴축 정책에도 불구하고, 많은 경제학자들에 따르면, 주로 그에 따른 경기 [132][133][134][135][136]침체로 인해 정부 적자가 줄지 않았다고 말한다.

정부가 대규모 민영화 프로그램을 가속화하겠다고 약속함에 [137]따라 공공부문 근로자들은 감원과 임금 삭감에 저항하기 위해 파업에 돌입했다.이민자들은 때때로 극우 [138]극단주의자들에 의해 경제 문제의 희생양으로 취급된다.

2013년 그리스는 선진시장 중 처음으로 다른 금융평가사에 [139][140][141]의해 신흥시장으로 재분류됐다.

2014년 7월까지 긴축정책에 대한 분노와 항의가 여전했으며, 24시간 파업은 국제통화기금, 유럽연합, 유럽중앙은행의 감사원이 10억 유로(약 13억 6천만 달러)의 2차 구제금융 결정을 앞두고 실시한 감사와 맞물려 있었다.7월.[142]

그리스는 2014년 [58][143]2분기에 6년간의 불황에서 벗어났지만 정치적 안정과 채무 지속 가능성 확보는 여전히 과제가 남아 있다.[144]

세 번째 구제금융은 2015년 7월 알렉시스 치프라스의 새로 선출된 좌파 정부와 대립한 후 합의되었다.2017년 6월, 뉴스 보도에 따르면, "압박하는 부채 부담"이 완화되지 않았으며 그리스가 일부 [145]지불을 불이행할 위험이 있다고 한다.국제통화기금(IMF)은 "적절한 시기에" 다시 대출을 받을 수 있어야 한다고 밝혔다.당시 유로존은 그리스에 95억달러, 85억달러의 차입금 및 IMF의 [146]지원으로 가능한 채무구제 가능성의 간략한 세부사항을 부여했다.그리스는 7월 13일 IMF에 2018년 6월까지 이행하기로 약속한 21개의 약속서를 보냈다.여기에는 공공부문 근로계약 상한제, 임시계약 영구계약으로 전환, 사회보장비 [147]지출을 줄이기 위한 연금지급금 재계산이 포함됐다.

그리스의 구제금융은 2018년 [148]8월 20일 성공적으로 끝났다.

구제금융이 채무위기에 미치는 영향

구제금융 프로그램과 관련하여 그리스의 [149][150]GDP가 25% 감소했다.이는 결정적인 영향을 미쳤다.위기의 심각성을 정의하는 핵심 요소인 GDP 대비 부채 비율은 2009년 수준인 127%[151]에서 약 170%로 뛰어오른다.단, GDP의 감소(즉, 같은 부채의 경우) 때문이다.그러한 수준은 [citation needed]지속가능하지 않다고 여겨진다.2013년 보고서에서, IMF는 매우 광범위한 증세와 예산 삭감이 국가의 GDP에 미치는 영향을 과소평가했다고 인정하고 비공식 [152][153][154][150]사과를 발표했다.

COVID-19 대유행

COVID-19 대유행은 그리스 경제의 모든 분야, 특히 관광업에 큰 영향을 미쳤다.그 결과 2020년에는 [6][10][11]GDP가 9% 감소했지만 [6][9]2021년에는 8.3% 반등했다.2021년 6월 유럽위원회는 COVID-19 관련 경제 지원(대출 120억 유로 및 보조금 180억 유로)[155]에 약 300억 유로를 지출하기로 합의했다.

데이터.

다음 표는 1980-2020년의 주요 경제지표이다(IMF 스태프는 2021-2026년 추정).5% 미만의 인플레이션은 [156]녹색이다.

| 연도 | GDP (빌에서).US$PPP) | 1인당 GDP (미화 PPP) | GDP (빌에서).명목상) | 1인당 GDP (공칭 US$) | GDP 성장 (실제) | 인플레이션율 (백분율) | 실업률 (백분율) | 정부채무 (GDP 비율) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 84.2 | 8,790.0 | 56.5 | 5,898.2 | 2.7% | 22.7% | ||

| 1981 | ||||||||

| 1982 | ||||||||

| 1983 | ||||||||

| 1984 | ||||||||

| 1985 | ||||||||

| 1986 | ||||||||

| 1987 | ||||||||

| 1988 | ||||||||

| 1989 | ||||||||

| 1990 | ||||||||

| 1991 | ||||||||

| 1992 | ||||||||

| 1993 | ||||||||

| 1994 | ||||||||

| 1995 | ||||||||

| 1996 | ||||||||

| 1997 | ||||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||

| 2026 |

프라이머리 섹터

농업 및 어업

2010년 목화(183,800톤)과 pistachios의, 그리스는 유럽 연합의 최대 생산국(8천톤)[157]와 두번째 쌀(229,500톤)[157]그리고 올리브의 생산에(147,500톤)[158]3무화과(11,000톤)and[158](는 항공료는 140만톤)[158]와 수박(4만 4000톤)[158]토마토 almonds(578,400의 생산에 올랐다.에 쌓였다)[158]고 produ에서 4번째.담배(2만2천톤)[157]농업은 국가 GDP의[1] 3.8%를 차지하며 노동력의 [1]12.4%를 고용하고 있다.

그리스는 유럽연합 공동농업정책의 주요 수혜국이다.그 나라가 유럽 공동체에 가입함에 따라 농업 인프라의 상당 부분이 업그레이드되었고 농업 생산량이 증가하였다.2000년부터 2007년 사이 그리스의 유기농은 885% 증가해 [159]EU에서 가장 높은 변화율을 보였다.

2007년 그리스는 EU의 [160]지중해 어획량의 19%를 차지해 8만5493t으로 [160]3위를 차지했으며, [160]EU 회원국 중 지중해 어선 수 1위를 차지했다.게다가, 그 나라는 총 어획량에서 87,[160]461톤으로 유럽연합에서 11위를 차지했다.

세컨더리 섹터

산업

2005년부터 2011년까지 그리스는 EU 회원국 중 2005년 수준과 비교하여 산업 생산량이 6%[161] 증가하여 가장 높은 비율을 보였다.유로 통계는 2009년과 [162]2010년 내내 산업 부문이 그리스 재정 위기에 타격을 입었으며, 국내 생산은 5.8%, 산업 생산은 13.[162]4% 감소하였다.현재 그리스는 대리석 생산량에서 이탈리아 스페인에 이어 유럽연합(EU)에서 3위를 차지하고 있다.

1999년부터 2008년까지 그리스의 소매 거래량은 연평균 4.4% 증가(합계 [162]44% 증가), [162]2009년에는 11.3% 감소하였다.2009년에 마이너스 성장이 없었던 부문은 행정 및 서비스 부문으로 2.0%[162]의 근소한 성장률을 보였다.

2009년 그리스의 노동 생산성은 EU [162]평균의 98%였지만 시간당 노동 생산성은 유로존 [162]평균의 74%였다.국내 최대 산업 고용자(2007년)는 제조업(40만7000명),[162] 건설업([162]30만5000명), 광업(1만4000명)[162] 순이었다.

그리스는 중요한 조선 및 선박 정비 산업을 가지고 있다.피레우스 항구 주변의 6개의 조선소는 유럽에서 [163]가장 큰 조선소 중 하나이다.최근 몇 년 동안 그리스는 호화 [164]요트의 건조와 유지보수의 선두주자가 되었다.

HSY-55급 함정, 그리스 조선소에서 그리스 해군을 위해 건조

| ★★★ | . | ★★★ | 산 produ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ★★★ | ★★★ | ★★★ | 치 | ||

| 1 | €450 €897,378,450 | 6 | ★★ | ,323 €140,399,323 | |

| 2 | ★★★ | €€621,788,464 | 7 | ★★★ | €432,559,943 |

| 3 | €€523,821,763 | 8 | €418,527,007 | ||

| 4 | 음료(무알코올) | €€519,888,468 | 9 | 알루미늄 슬래브 | 391,393,930유로 |

| 5 | ★★★ | €,102 €499,789,102 | 10 | 코카콜라 제품 | 388,752,443유로 |

| – | ,279 ( : 20,310,940,279) | ||||

| ★★★ | . | ★★★ | 산 produ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ★★★ | ★★★ | ((€) | |||

| 1 | ,1850,850 | 6 | 438,489,443 | ||

| 2 | 의약품(혼합 또는 혼합되지 않은 제품(기타), p.r.s., n.e.c.) | 670,923,632 | 7 | 맥아제 맥주(무알코올 맥주 제외, 알코올 함유량 0.5% 이하 맥주, 주세) | 405,990,419 |

| 3 | 설탕, 기타 감미료 또는 향미료가 첨가된 물, 즉 청량음료(광물 및 탄산음료 포함) | 561,611,081 | 8 | 지방 함량이 1% 이상 6% 이하인 우유 및 크림, 순 함량 ≤ 2l의 즉시 포장에 함유된 농축되지 않거나 첨가된 설탕 또는 기타 감미료를 함유하지 않음 | 373,780,989 |

| 4 | 열간압연 콘크리트 철근 | ,919,190 | 9 | 담배 또는 담배와 담배 대체물의 혼합물을 포함하는 담배(담배 관세 제외) | 350, 165, 600 |

| 5 | 분쇄, 분말, 블루베인 및 기타 가공되지 않은 치즈(생치즈, 유청치즈 및 커드 제외) | 511,528,250 | 10 | 치즈 퐁듀 및 기타 식품 준비물, N.E.C. | 300,883,207 |

| – | : (17,489,538,838유로) | ||||

| – | 우편번호: 소매판매용 포장; 비포장품 분류 가능 | ||||

★★★

섹터 ( 터)

해운은 [167]고대부터 전통적으로 그리스 경제의 핵심 분야였다.1813년, 그리스 상선은 615척의 [168]배로 구성되었다.총톤수는 15만3580톤으로 3만7526명의 승무원과 5878문의 [168]대포가 동원되었다.1914년에 그 수치는 449,430톤과 1,322척이었다 (이 중 287척이 [169]증기선이었다).

1960년대에 그리스 함대의 규모는 주로 오나시스, 바르디노야니스, 리바노스, 니아르코스의 투자를 [170]통해 거의 두 배로 늘어났다.근대 그리스 해양산업의 기반은 제2차 세계대전 이후 그리스 [170]해운업자들이 1940년대 선박판매법을 통해 미국 정부에 의해 팔린 잉여 선박을 축적할 수 있게 되면서 형성되었다.

유엔 무역 [40]개발 회의에 따르면 그리스는 세계 최대 규모의 상선을 보유하고 있으며, 이는 세계 총 중량 톤수의 15% 이상을 차지한다.그리스 상선의 총 중량 2억4천500만 [40]dwt는 2억2천400만 명으로 2위인 일본과 맞먹는다.게다가 그리스는 유럽연합 전체 dwt의 [171]39.52%를 차지한다.그러나 오늘날의 함대 명단은 1970년대 [167]말 사상 최고치였던 5,000척보다 적다.

그리스는 선박 수로는 중국(5313척) 일본(3991척) [40]독일(3833척)에 이어 세계 4위다.2011-2012년 유럽공동체 선주협회의 보고서에 따르면 그리스 국기는 국제적으로 7번째로 많이 사용되는 반면 [171]EU에서는 2위를 차지하고 있다.

선박의 카테고리로 보면, 그리스 기업은 세계 유조선의[171] 22.6%, 벌크선의 16.1%(dwt)[171]를 보유하고 있다.전 세계 유조선 dwt의 27.45%가 추가로 발주되었으며 [171]벌크선도 12.7%가 [171]발주되었습니다.해운업은 그리스 [172]GDP의 약 6%를 차지하며, 약 160,000명(인력의 [173]4%)이 고용되어 있으며, 그리스 무역 [173]적자의 1/3을 차지한다.2011년 [171]해운 수익은 141억 유로에 달했고, 2000~2010년 그리스 해운은 총 1400억[172] 유로(2009년 공공채무의 절반,[172] 2000-2013년 유럽연합(EU)의 3.5배)에 기여했습니다.2011년 ECSA 보고서에 따르면 [172]약 750개의 그리스 선박회사가 운영되고 있다.

그리스 선주연합(Union of Grais Shipers)의 최신 자료에 따르면 그리스 소유의 원양 함대는 3428척의 선박으로 구성돼 있으며 총 2억4500만t의 데드웨이트를 보유하고 있다.이는 세계 유조선 함대의 23.6%, 건조 벌크 [174]17.2%를 포함한 전 세계 함대의 수송능력의 15.6%에 해당한다.

그리스는 2011년 수출액을 준수출로 환산하면 1770만413만2000달러를 수출해 세계 4위를 차지해 [21]덴마크 독일 한국만 상위권에 올랐다.마찬가지로 그리스에 대한 다른 나라의 해운 서비스를 준수입으로 계산하고 수출입의 차이를 무역수지로 계산하면 2011년 그리스는 70억7천660만5천달러 상당의 수입 해운 서비스를 보유하여 1,07억1천234만2천달러의 [175][176]무역수지 흑자를 내 독일에 이어 2위였다.

| 연도 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006–2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 내보내기: | ||||||||||

| 글로벌[21] 랭킹 | 다섯 번째 | 다섯 번째 | 다섯 번째 | 넷째 | 세 번째 | 다섯 번째 | -b | 다섯 번째 | 여섯 번째 | 넷째 |

| 가치 (백만 달러)[21] | 7,558.995 | 7,560.559 | 7,527.175 | 10,114.736 | 15,402.209 | 16,127.623 | -b | 17,033.714 | 18,559.292 | 17,704.132 |

| 가치(백만유로)[21] | 8,172.559 | 8,432.670 | 7,957.654 | 8,934.660 | 12,382.636 | 12,949.869 | -b | 12,213.786 | 13,976.558 | 12,710.859 |

| 값(%GDP | 5.93 | 5.76 | 5.08 | 5.18 | 6.68 | 6.71 | 없음 | 5.29 | 6.29 | 6.10 |

| Import: | ||||||||||

| 글로벌[175] 랭킹 | 14일 | 13일 | 14일 | -b | 14일 | 16일 | -b | 12번째 | 13일 | 아홉 번째 |

| 가치 (백만 달러)[175] | 3,314.718 | 3,873.791 | 3,757.000 | -b | 5,570.145 | 5,787.234 | -b | 6,653.395 | 7,846.950 | 7,076.605 |

| 가치(백만유로)[175] | 3,583.774 | 4,320.633 | 3,971.863 | -b | 4,478.129 | 4,646.929 | -b | 4,770.724 | 5,909.350 | 5,080.720 |

| 값(%GDP | 2.60 | 2.95 | 2.54 | 없음 | 2.42 | 2.41 | 없음 | 2.06 | 2.66 | 2.44 |

| 무역수지: | ||||||||||

| 글로벌[176] 랭킹 | 첫 번째 | 두 번째 | 첫 번째 | 첫e 번째 | 첫 번째 | 첫 번째 | -b | 두 번째 | 첫 번째 | 두 번째 |

| 가치 (백만 달러)[176] | 4,244.277 | 3,686.768 | 3,770.175 | 10,194.736e | 9,832.064 | 10,340.389 | -b | 10,340.389 | 10,380.319 | 10,712.342 |

| 가치(백만유로)[176] | 4,588.785 | 4,112.037 | 3,985.791 | 8,934.1991e | 7,904.508 | 8,302.940 | -b | 7,443.063 | 8,067.208 | 7,630.140 |

| 값(%GDP | 3.33 | 2.81 | 2.54 | 5.18e | 4.27 | 4.30 | 없음 | 3.22 | 3.63 | 3.66 |

| GDP(백만유로)[177] | 137,930.1 | 146,427.6 | 156,614.3 | 172,431.8 | 185,265.7 | 193,049.7b | 없음 | 231,081.2p | 222,126p.5 | 208,531.7p |

| b 소스 리포트는 시계열의 중단, p 소스 데이터는 잠정적인 것으로 특징지어진다.e 리포트 데이터는 "Imports" 시계열의 관련 중단으로 인해 잘못될 수 있다. | ||||||||||

전기 통신

1949년에서 1980년대 사이에 그리스의 전화 통신은 약자 OTE로 더 잘 알려진 그리스 전기 통신 기구에 의해 국가 독점이었다.1980년대 전화통신의 자유화에도 불구하고 OTE는 여전히 그리스 시장에서 우위를 점하고 있으며 동남유럽에서 [178]가장 큰 통신 회사 중 하나로 부상했다.2011년 이후 이 회사의 주요 주주는 40%의 지분을 보유한 Deutsche Telekom이며, 그리스 정부는 이 회사의 [178]지분 10%를 계속 소유하고 있습니다.OTE는 발칸반도 전역에 Cosmote, 그리스 최대의 이동통신 프로바이더, Cosmote Romania, 알바니아 모바일 커뮤니케이션 [178]등 여러 자회사를 소유하고 있습니다.

그리스에서 활동하는 다른 이동통신 회사로는 윈드헬라스와 보다폰 그리스가 있다.2009년, 국내의 이동 전화 프로바이더의 통계에 근거해 액티브한 휴대 전화 어카운트의 총수는,[179] 2천만개를 넘어, 180%[179]의 침투율을 보이고 있다.게다가,[1] 이 나라에는 574만 5천 개의 활성 유선전화가 있다.

그리스는 최근 몇 년 동안 인터넷 사용에서 유럽연합의 파트너들에 비해 뒤처지는 경향이 있으며, 그 격차는 급속히 좁혀지고 있다.2006년과 2013년 사이에 인터넷 접속 가구의 비율은 각각 23%에서 56%로 두 배 이상 증가했다(EU 평균 49%와 79%[180][181]와 비교).동시에 광대역 연결을 사용하는 가구의 비율은 2006년 4%에서 2013년 55%로 크게 증가했다(EU 평균 30%와 76%[180][181]와 비교).2021년까지 인터넷 접속과 광대역 접속을 가진 그리스 가구의 비율은 각각 [182]85.1%, 85.0%에 달했다.

관광업

현대적 의미의 관광은 1950년 이후 그리스에서 번성하기 시작했지만,[183][184] 고대 관광은 올림픽 [184]경기와 같은 종교 축제나 스포츠 축제와 관련해서도 기록되었다.1950년대 이후 관광업계는 1950년 33,000명에서 1994년 [183]1140만명으로 사상 유례없는 증가세를 보였다.

OECD [185]보고서에 따르면 그리스는 매년 1600만 명 이상의 관광객을 유치하여 2008년 그리스 GDP에 18.2%의 기여도를 보이고 있다.같은 조사에서 그리스에 머무는 동안 평균 관광객 지출은 1,073달러로 그리스가 세계 [185]10위에 올랐습니다.관광업과 직간접적으로 관련된 일자리는 2008년 84만 개로 전체 [185]노동인구의 19%를 차지했다.2009년 그리스는 1,930만 [186]명 이상의 관광객을 맞이했는데,[187] 이는 2008년의 1,770만 명보다 크게 증가한 것이다.

유럽연합 회원국 [188]중 그리스는 2011년 키프로스와 스웨덴 거주자들에게 가장 인기 있는 여행지였다.

관광을 담당하는 부처는 문화관광부이며, 그리스는 그리스의 [185]관광 촉진을 목표로 하는 그리스 국가관광기구도 소유하고 있다.

최근 몇 년 동안 많은 유명 관광 관련 기관들이 그리스 여행지를 최우선 순위에 두고 있다.2009년에는 론리 플래닛이 몬트리올,[189] 두바이와 함께 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 도시인 테살로니키를 선정했고 2011년에는 트레블+레저에서 [190]산토리니 섬을 세계 최고의 섬으로 선정했습니다.이웃한 미코노스 [190]섬은 유럽에서 5번째로 좋은 섬으로 꼽혔습니다.테살로니키는 2014년에 유럽 청년 수도였다.

무역 및 투자

해외투자

공산주의가 몰락한 이후, 그리스는 이웃 발칸 국가들에 많은 투자를 했다.1997년부터 2009년까지 북마케도니아의 외국인 직접투자 자본의 12.11%가 그리스계이며, 이는 4위였다.2009년에만 그리스인들은 3억 8천만 유로를 이 [191]나라에 투자했으며, 그리스 석유와 같은 기업들은 중요한 전략적 투자를 [191]했다.

그리스는 2005년부터[192] 2007년 사이에 불가리아에 13억 8천만 유로를 투자했으며, 많은 중요한 기업(불가리아 포스트뱅크, 불가리아 연합 은행 코카콜라 불가리아 포함)이 그리스 금융 [192]그룹에 의해 소유되고 있습니다.세르비아에서는 250개의 그리스 기업이 총 20억 [193]유로 이상의 투자를 통해 활동하고 있습니다.2016년 루마니아 통계는 그리스의 대(對)로마 투자가 40억유로를 넘어 그리스가 외국인 투자자 [194]중 5, 6위에 랭크된 것을 보여준다.그리스는 공산주의 붕괴 이후 알바니아에 대한 최대 투자국으로 2016년 외국인 투자의 25%가 그리스에서 나오고 있으며, 사업 관계도 매우 견고하고 지속적으로 [195]증가하고 있다.

거래

채무 위기가 시작된 이후 그리스의 무역수지는 2008년 443억 유로에서 2020년 [24][196]181억 5천만 유로로 크게 감소했다.2020년 COVID-19 불황 동안 일시적으로 무역이 감소한 후, 2021년에는 수출과 수입이 각각 [24]29.7%, 33.5% 반등했다.

| 순위 | Imports(가져오기) | 순위 | 내보내기 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 기원. | 가치 | 목적지 | 가치 | ||

| 1 | €7,238.2 | 1 | €2,001.9 | ||

| 2 | €6,918.5 | 2 | €1,821.3 | ||

| 3 | €4,454.0 | 3 | €1,237.0 | ||

| 4 | €3,347.1 | 4 | €1,103.0 | ||

| 5 | €3,098.0 | 5 | €885.4 | ||

| – | €33,330.5 | – | €11,102.0 | ||

| – | 총 | €60,669.9 | – | 총 | €17,334.1 |

| 순위 | Imports(가져오기) | 순위 | 내보내기 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | €22,688.5 | – | €11,377.7 | ||

| – | 총 | €42,045.4 | – | 총 | €22,451.1 |

그리스는 키프로스(18.0%)[198]의 최대 수입국이자 팔라우(82.4%)의 최대 [199]수출국이다.

| Imports(가져오기) | 내보내기 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 순위 | 기원. | 가치 (백만유로) | 가치 (총수의 %) | 순위 | 목적지 | 가치 (백만유로) | 가치 (총수의 %) |

| 1 | 5,967.20132 | 12.6 | 1 | 2,940.25203 | 10.8 | ||

| 2 | 4,381.92656 | 9.2 | 2 | 2,033.77413 | 7.5 | ||

| 3 | 3,668.88622 | 7.7 | 3 | 1,687.03947 | 6.2 | ||

| 4 | 2,674.00587 | 5.6 | 4 | 1,493.75355 | 5.5 | ||

| 5 | 2,278.03883 | 4.8 | 5 | 1,319.28598 | 4.8 | ||

| 6 | 2,198.57126 | 4.6 | 6 | 1,024.73686 | 3.8 | ||

| 7 | 1,978.48460 | 4.2 | 7 | 822.74077 | 3 | ||

| #α | OECD | 23,849.94650 | 50.2 | #α | OECD | 13,276.48107 | 48.8 |

| #β | G7 | 11,933.75417 | 25.1 | #β | G7 | 6,380.86705 | 23.4 |

| #실패하다 | 브릭스 | 8,682.10265 | 18.3 | #실패하다 | 브릭스 | 1,014.17146 | 3.7 |

| #실패하다 | 브릭스 | 8,636.02946 | 18.2 | #실패하다 | 브릭스 | 977.76016 | 3.6 |

| #실패하다 | 석유수출국기구(OPEC) | 8,090.76972 | 17 | #실패하다 | 석유수출국기구(OPEC) | 2,158.60420 | 7.9 |

| #실패하다 | NAFTA | 751.80608 | 1.6 | #실패하다 | NAFTA | 1,215.70257 | 4.5 |

| #a | 21,164.89314 | 44.5 | #a | 11,512.31990 | 42.3 | ||

| #b | 17,794.19344 | 37.4 | #b | 7,234.83595 | 26.6 | ||

| #3 | Africa | 2,787.39502 | 5.9 | #3 | Africa | 1,999.46534 | 7.3 |

| #4 | America | 1,451.15136 | 3.1 | #4 | America | 1,384.04068 | 5.1 |

| #2 | Asia | 14,378.02705 | 30.2 | #2 | Asia | 6,933.51200 | 25.5 |

| #1 | Europe | 28,708.38148 | 60.4 | #1 | Europe | 14,797.20641 | 54.4 |

| #5 | Oceania | 71.70603 | 0.2 | #5 | Oceania | 169.24085 | 0.6 |

| # | World | 47,537.63847 | 100 | # | World | 27,211.06362 | 100 |

| the International Organisations or Country Groups list and ranking presented above (i.e. #greek_letters and/or #latin_letters), is not indicative of the whole picture of Greece's trade; this is instead only an incomplete selection of some major and well known such Organisations and Groups; rounding errors possibly present | |||||||

Transport

As of 2012, Greece had a total of 82 airports,[1] of which 67 were paved and six had runways longer than 3,047 meters.[1] Of these airports, two are classified as "international" by the Hellenic Civil Aviation Authority,[200] but 15 offer international services.[200] Additionally Greece has 9 heliports.[1] Greece does not have a flag carrier, but the country's airline industry is dominated by Aegean Airlines and its subsidiary Olympic Air.

Between 1975 and 2009, Olympic Airways (known after 2003 as Olympic Airlines) was the country's state-owned flag carrier, but financial problems led to its privatization and relaunch as Olympic Air in 2009. Both Aegean Airlines and Olympic Air have won awards for their services; in 2009 and 2011, Aegean Airlines was awarded the "Best regional airline in Europe" award by Skytrax,[201] and also has two gold and one silver awards by the ERA,[201] while Olympic Air holds one silver ERA award for "Airline of the Year"[202] as well as a "Condé Nast Traveller 2011 Readers Choice Awards: Top Domestic Airline" award.[203]

The Greek road network is made up of 116,986 km of roads,[1] of which 1863 km are highways, ranking 24th worldwide, as of 2016.[1] Since the entry of Greece to the European Community (now the European Union), a number of important projects (such as the Egnatia Odos and the Attiki Odos) have been co-funded by the organization, helping to upgrade the country's road network. In 2007, Greece ranked 8th in the European Union in goods transported by road at almost 500 million tons.

Greece's rail network is estimated to be at 2,548 km.[1] Rail transport in Greece is operated by TrainOSE, a current subsidiary of the Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane after the Hellenic Railways Organisation had sold its 100% stake on the operator. Most of the country's network is standard gauge (1,565 km),[1] while the country also has 983 km of narrow gauge.[1] A total of 764 km of rail are electrified.[1] Greece has rail connections with Bulgaria, North Macedonia and Turkey. A total of three suburban railway systems (Proastiakos) are in operation (in Athens, Thessaloniki and Patras), while one metro system, the Athens Metro, is operational in Athens with another, the Thessaloniki Metro, under construction.

According to Eurostat, Greece's largest port by tons of goods transported in 2010 is the port of Aghioi Theodoroi, with 17.38 million tons.[204] The Port of Thessaloniki comes second with 15.8 million tons,[204] followed by the Port of Piraeus, with 13.2 million tons,[204] and the port of Eleusis, with 12.37 million tons.[204] The total number of goods transported through Greece in 2010 amounted to 124.38 million tons,[204] a considerable drop from the 164.3 million tons transported through the country in 2007.[204] Since then, Piraeus has grown to become the Mediterranean's third-largest port thanks to heavy investment by Chinese logistics giant COSCO. In 2013, Piraeus was declared the fastest-growing port in the world.[205]

In 2010 Piraeus handled 513,319 TEUs,[206] followed by Thessaloniki, which handled 273,282 TEUs.[207] In the same year, 83.9 million people passed through Greece's ports,[208] 12.7 million through the port of Paloukia in Salamis,[208] another 12.7 through the port of Perama,[208] 9.5 million through Piraeus[208] and 2.7 million through Igoumenitsa.[208] In 2013, Piraeus handled a record 3.16 million TEUs, the third-largest figure in the Mediterranean, of which 2.52 million were transported through Pier II, owned by COSCO and 644,000 were transported through Pier I, owned by the Greek state.

Energy

Energy production in Greece is dominated by the Public Power Corporation (known mostly by its acronym ΔΕΗ, or in English DEI). In 2009 DEI supplied for 85.6% of all energy demand in Greece,[209] while the number fell to 77.3% in 2010.[209] Almost half (48%) of DEI's power output is generated using lignite, a drop from the 51.6% in 2009.[209] Another 12% comes from Hydroelectric power plants[210] and another 20% from natural gas.[210] Between 2009 and 2010, independent companies' energy production increased by 56%,[209] from 2,709 Gigawatt hour in 2009 to 4,232 GWh in 2010.[209]

In 2008 renewable energy accounted for 8% of the country's total energy consumption,[211] a rise from the 7.2% it accounted for in 2006,[211] but still below the EU average of 10% in 2008.[211] 10% of the country's renewable energy comes from solar power,[159] while most comes from biomass and waste recycling.[159] In line with the European Commission's Directive on Renewable Energy, Greece aims to get 18% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020.[212] In 2013 and for several months, Greece produced more than 20% of its electricity from renewable energy sources and hydroelectric power plants.[213] Greece currently does not have any nuclear power plants in operation, however in 2009 the Academy of Athens suggested that research in the possibility of Greek nuclear power plants begin.[214]

Greece had 10 million barrels of proven oil reserves as of 1 January 2012.[1] Hellenic Petroleum is the country's largest oil company, followed by Motor Oil Hellas. Greece's oil production stands at 1,751 barrels per day (bbl/d), ranked 95th worldwide,[1] while it exports 19,960 bbl/d, ranked 53rd,[1] and imports 355,600 bbl/d, ranked 25th.[1]

In 2011 the Greek government approved the start of oil exploration and drilling in three locations within Greece,[215] with an estimated output of 250 to 300 million barrels over the next 15 to 20 years.[215] The estimated output in euros of the three deposits is €25 billion over a 15-year period,[215] of which €13–€14 billion will enter state coffers.[215] Greece's dispute with Turkey over the Aegean poses substantial obstacles to oil exploration in the Aegean Sea.

In addition to the above, Greece is also to start oil and gas exploration in other locations in the Ionian Sea, as well as the Libyan Sea, within the Greek exclusive economic zone, south of Crete.[216][217] The Ministry of the Environment, Energy and Climate Change announced that there was interest from various countries (including Norway and the United States) in exploration,[217] and the first results regarding the amount of oil and gas in these locations were expected in the summer of 2012.[217] In November 2012, a report published by Deutsche Bank estimated the value of natural gas reserves south of Crete at €427 billion.[218]

A number of oil and gas pipelines are currently under construction or under planning in the country. Such projects include the Interconnector Turkey-Greece-Italy (ITGI) and South Stream gas pipelines.[210]

EuroAsia Interconnector will electrically connect Attica and Crete in Greece with Cyprus and Israel with 2000 MW HVDC undersea power cable.[219][220] EuroAsia Interconnector is specially important for isolated systems, like Cyprus and Crete. Crete is energetically isolated from mainland Greece and Hellenic Republic covers for Crete electricity costs difference of around €300 million per year.[221]

View of a wind farm, Panachaiko mountain

Prinos oil field near Kavala

Taxation and tax evasion

Greece has a tiered tax system based on progressive taxation. Greek law recognizes six categories of taxable income:[222] immovable property, movable property (investment), income from agriculture, business, employment, and income from professional activities. Greece's personal income tax rate, until recently, ranged from 0% for annual incomes below €12,000[222] to 45% for annual incomes over €100,000.[222] Under the new 2010 tax reform, tax exemptions have been abolished.[222]

Also under the new austerity measures and among other changes, the personal income tax-free ceiling has been reduced to €5,000 per annum[223] while further future changes, for example abolition of this ceiling, are already being planned.[224]

Greece's corporate tax dropped from 40% in 2000[222] to 20% in 2010.[222] For 2011 only, corporate tax will be at 24%.[222] Value added tax (VAT) has gone up in 2010 compared to 2009: 23% as opposed to 19%.[222]

The lowest VAT possible is 6.5% (previously 4.5%)[222] for newspapers, periodicals and cultural event tickets, while a tax rate of 13% (from 9%)[222] applies to certain service sector professions. Additionally, both employers and employees have to pay social contribution taxes, which apply at a rate of 16%[222] for white collar jobs and 19.5%[222] for blue collar jobs, and are used for social insurance. In 2017 the VAT tax rate was 24%[225] with minor exceptions, 13% reduced for some basic foodstuffs which will be soon abolished and everything, as it seems, will soon go to 24% in order to fight the phantom of tax evasion.[needs update]

The Ministry of Finance expected tax revenues for 2012 to be €52.7 billion (€23.6 billion in direct taxes and €29.1 billion in indirect taxes),[226] an increase of 5.8% from 2011.[226] In 2012, the government was expected to have considerably higher tax revenues than in 2011 on a number of sectors, primarily housing (an increase of 217.5% from 2011).[226]

Tax evasion

Greece suffers from very high levels of tax evasion. In the last quarter of 2005, tax evasion reached 49%,[227] while in January 2006 it fell to 41.6%.[227] It is worth noting that the newspaper Ethnos which published these figures went bankrupt; it is no longer published and some sources suggest that the information it had published was highly debatable.[228] A study by researchers from the University of Chicago concluded that tax evasion in 2009 by self-employed professionals alone in Greece (accountants, dentists, lawyers, doctors, personal tutors and independent financial advisers) was €28 billion or 31% of the budget deficit that year.[229]

Greece's "shadow economy" was estimated at 24.3% of GDP in 2012, compared with 28.6% for Estonia, 26.5% for Latvia, 21.6% for Italy, 17.1% for Belgium, 14.7% for Sweden, 13.7% for Finland, and 13.5% for Germany, and is certainly related to the fact that the percentage of Greeks that are self-employed is more than double the EU average (2013 est.).[102]

The Tax Justice Network estimated in 2011 that there were over 20 billion euros in Swiss bank accounts held by Greeks.[230] The former Finance Minister of Greece, Evangelos Venizelos, was quoted as saying, "Around 15,000 individuals and companies owe the taxman 37 billion euros".[231] Additionally, the TJN put the number of Greek-owned off-shore companies at over 10,000.[232]

In 2012, Swiss estimates suggested that Greeks had some 20 billion euros in Switzerland of which only one percent had been declared as taxable in Greece.[233] Estimates in 2015 were even more dramatic. They indicated that the amount due to the government of Greece from Greeks' accounts in Swiss banks totaled around 80 billion euros.[234][235]

A mid-2017 report indicated Greeks have been "taxed to the hilt" and many believed that the risk of penalties for tax evasion were less serious than the risk of bankruptcy. One method of evasion is the so-called black market, grey economy or shadow economy: work is done for cash payment which is not declared as income; as well, VAT is not collected and remitted.[236] A January 2017 report[237] by the DiaNEOsis think-tank indicated that unpaid taxes in Greece at the time totaled approximately 95 billion euros, up from 76 billion euros in 2015, much of it was expected to be uncollectable. Another early 2017 study estimated that the loss to the government as a result of tax evasion was between 6% and 9% of the country's GDP, or roughly between 11 billion and 16 billion euros per annum.[238]

The shortfall in the collection of VAT (sales tax) is also significant. In 2014, the government collected 28% less than was owed to it; this shortfall was about double the average for the EU. The uncollected amount that year was about 4.9 billion euros.[239] The DiaNEOsis study estimated that 3.5% of GDP is lost due to VAT fraud, while losses due to smuggling of alcohol, tobacco and petrol amounted to approximately another 0.5% of the country's GDP.[238]

Planned solutions

Following similar actions by the United Kingdom and Germany, the Greek government was in talks with Switzerland in 2011, attempting to force Swiss banks to reveal information on the back accounts of Greek citizens.[240] The Ministry of Finance stated that Greeks with Swiss bank accounts would either be required to pay a tax or reveal information such as the identity of the bank account holder to the Greek internal revenue services.[240] The Greek and Swiss governments were to reach a deal on the matter by the end of 2011.[240]

The solution demanded by Greece still had not been effected as of 2015. That year, estimates indicated that the amount of evaded taxes stored in Swiss banks was around 80 billion euros. By then, however, a tax treaty to address this issue was under serious negotiation between the Greek and Swiss governments.[234][235] An agreement was finally ratified by Switzerland on 1 March 2016 creating a new tax transparency law that would allow for a more effective battle against tax evasion. Starting in 2018, banks in both Greece and Switzerland will exchange information about the bank accounts of citizens of the other country to minimize the possibility of hiding untaxed income.[241]

In 2016 and 2017, the government was encouraging the use of credit cards or debit cards to pay for goods and services in order to reduce cash only payments. By January 2017, taxpayers were only granted tax-allowances or deductions when payments were made electronically, with a "paper trail" of the transactions that the government could easily audit. This was expected to reduce the problem of businesses taking payments but not issuing an invoice;[242] that tactic had been used by various companies to avoid payment of VAT (sales) tax as well as income tax.[243][244]

By 28 July 2017, numerous businesses were required by law to install a point of sale device to enable them to accept payment by credit or debit card. Failure to comply with the electronic payment facility can lead to fines of up to 1,500 euros. The requirement applied to around 400,000 firms or individuals in 85 professions. The greater use of cards was one of the factors that had already achieved significant increases in VAT collection in 2016.[245]

Wealth and standards of living

National and regional GDP

Greece's most economically important regions are Attica, which contributed €87.378 billion to the economy in 2018, and Central Macedonia, which contributed €25.558 billion.[246] The smallest regional economies were those of the North Aegean (€2.549 billion) and Ionian Islands (€3.257 billion).[246]

In terms of GDP per capita, Attica (€23,300) far outranks any other Greek region.[246] The poorest regions in 2018 were the North Aegean (€11,800), Eastern Macedonia and Thrace (€11,900) and Epirus (€12,200).[246] At the national level, GDP per capita in 2018 was €17,200.[246]

| Rank | Region | GDP (€, billions) | Share in EU-27/national GDP (%) | GDP per capita (€) | GDP per capita (PPS) | GDP per capita (€, EU27=100) | GDP per capita (PPS, EU27=100) | GDP per person employed (PPS, EU27=100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attica | 87.378 | 47.3 | 23,300 | 28,000 | 77 | 93 | 99 |

| 2 | Central Macedonia | 25.558 | 13.8 | 13,600 | 16,400 | 45 | 54 | 69 |

| 3 | Thessaly | 9.658 | 5.2 | 13,400 | 16,100 | 44 | 53 | 65 |

| 4 | Crete | 9.386 | 5.1 | 14,800 | 17,800 | 49 | 59 | 68 |

| 5 | Central Greece | 8.767 | 4.7 | 15,800 | 18,900 | 52 | 63 | 81 |

| 6 | Western Greece | 8.322 | 4.5 | 12,700 | 15,200 | 42 | 50 | 65 |

| 7 | Peloponnese | 8.245 | 4.5 | 14,300 | 17,200 | 48 | 57 | 68 |

| 8 | Eastern Macedonia and Thrace | 7.166 | 3.9 | 11,900 | 14,300 | 40 | 48 | 61 |

| 9 | South Aegean | 6.387 | 3.5 | 18,700 | 22,400 | 62 | 74 | 79 |

| 10 | Epirus | 4.077 | 2.2 | 12,200 | 14,700 | 40 | 49 | 63 |

| 11 | Western Macedonia | 3.963 | 2.1 | 14,800 | 17,700 | 49 | 59 | 79 |

| 12 | Ionian Islands | 3.257 | 1.8 | 16,000 | 19,100 | 53 | 63 | 71 |

| 13 | North Aegean | 2.549 | 1.4 | 11,800 | 14,200 | 39 | 47 | 67 |

| – | Greece | 184.714 | 1 | 17,200 | 20,700 | 57 | 69 | 81 |

| – | EU27 | 13,483.857 | 100 | 30,200 | 30,200 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Welfare state

Greece is a welfare state which provides a number of social services such as quasi-universal health care and pensions. In the 2012 budget, expenses for the welfare state (excluding education) stand at an estimated €22.487 billion[226] (€6.577 billion for pensions[226] and €15.910 billion for social security and health care expenses),[226] or 31.9% of the all state expenses.[226]

Largest companies by revenue 2018

According to the 2018 Forbes Global 2000 index, Greece's largest publicly traded companies are:

| Rank | Company | Revenues (€ billion) | Profit (€ billion) | Assets (€ billion) | Market value (€ billion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Piraeus Bank | 3.3 | −0.2 | 81.0 | 1.7 |

| 2 | National Bank of Greece | 2.4 | −0.2 | 77.8 | 3.4 |

| 3 | Alpha Bank | 3.5 | 0.1 | 73.0 | 4.1 |

| 4 | Eurobank Ergasias | 2.2 | 0.1 | 72.1 | 2.6 |

| 5 | Hellenic Petroleum | 9.0 | 0.5 | 8.6 | 2.9 |

| 6 | Bank of Greece | 1.7 | 1.1 | − | 0.4 |

Labour force

Working hours

In 2011, 53.3 percent of employed persons worked more than 40 to 49 hours a week and 24.8 percent worked more than 50 hours a week, totaling up to 78.1 percent of employed persons working 40 or more hours a week.[248] When accounting for varying age groups, the percentage of employees working 40 to 49 hours a week peaked in the 25 to 29 age range.[248] As workers got older, they gradually decreased in percentage working 40 to 49 hours, but increased in working 50+ hours, suggesting a correlation that as employees grow older, they work more hours. Of different occupation groups, skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers and managers were the most likely to work 50+ hours; however, they do not take up a significant portion of the labor force, only 14.3 percent.[249] In 2014, the average number of working hours for Greek employees was 2124 hours, ranking as the third highest among OECD countries and the highest in the Eurozone.[250]

Recent trends in employment indicate that the number of working hours will decrease in the future due to the rise of part-time work. Since 2011, average working hours have decreased.[250] In 1998, Greece passed legislation introducing part-time employment in public services with the goal of reducing unemployment, increasing the total, but decreasing the average number of hours worked per employee.[251] Whether the legislation was successful in increasing public-sector part-time work, labor market trends show that part-time employment has increased from 7.7 percent in 2007 to 11 percent in 2016 of total employment.[252] Both men and women have had the part-time share of employment increase over this period. While women still constitute a majority of part-time workers, recently men have been taking a larger share of part-time employment.[253]

Currency

Between 1832 and 2002 the currency of Greece was the drachma. After signing the Maastricht Treaty, Greece applied to join the eurozone. The two main convergence criteria were a maximum budget deficit of 3% of GDP and a declining public debt if it stood above 60% of GDP. Greece met the criteria as shown in its 1999 annual public account. On 1 January 2001, Greece joined the eurozone, with the adoption of the euro at the fixed exchange rate ₯340.75 to €1. However, in 2001 the euro only existed electronically, so the physical exchange from drachma to euro only took place on 1 January 2002. This was followed by a ten-year period for eligible exchange of drachma to euro, which ended on 1 March 2012.[254]

Prior to the adoption of the euro, 64% of Greek citizens viewed the new currency positively,[255] but in February 2005 this figure fell to 26% and by June 2005 it fell further to 20%.[255] Since 2010 the figure has risen again, and a survey in September 2011 showed that 63% of Greek citizens viewed of the euro positively.[255]

Charts gallery

Greek GDP, Debt and Deficit (Int. 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars)

Greek bank deposits (including repos) since 1998

Poverty rate

As a result of the recession sparked by the public debt crisis, poverty has increased. The rate of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion reached a high of 36% in 2014, before subsiding over the following years to 28.9% in 2020.[13] Those living in extreme poverty rose to 15% in 2015, up from 8.9% in 2011, and a huge increase from 2009 when it was not more than 2.2%.[256] The rate among children 0-17 is 17.6% and for young people 18-29 the rate is 24.4%.[256] With unemployment on the rise, those without jobs are at the highest risk of poverty (70–75%), up from less than 50% in 2011.[256] Those out of work lose their health insurance after two years, further exacerbating the poverty rate. Younger unemployed people tend to rely on the older generations of their families for financial support. However, long-term unemployment has depleted pension funds due to fewer workers making social security contributions, resulting in higher poverty rates in intergenerational households reliant on the reduced pensions received by their retired members. Over the course of the economic crisis, Greeks have endured significant job losses and wage cuts, as well as deep cuts to workers' compensation and welfare benefits. From 2008 to 2013, Greeks became 40% poorer on average, and in 2014 saw their disposable household income drop below 2003 levels.[257]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "CIA World Factbook: Greece, country profile". CIA.

- ^ "World Economic and Financial Surveys World Economic Outlook Database—WEO Groups and Aggregates Information October 2020". Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 13 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database - Changes to the Database". Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 13 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk". Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Group. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Census in Greece: Population Shrinks by 3.5 Percent to 10,432,481". Piraeus: GreekReporter. 30 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2022". Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 19 April 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Quarterly National Accounts (Provisional Data), 1st Quarter 2022". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 7 June 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ "GDP main aggregates and employment estimates for the first quarter of 2022" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 8 June 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Quarterly National Accounts (Provisional Data), 4th Quarter 2021". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 4 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Annual National Accounts (2nd estimate), 2020". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 15 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Real GDP growth rate - volume". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "CONSUMER PRICE INDEX: June 2022, annual inflation 12.1%". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Risk of poverty, 2021". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 27 July 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Income inequality, 2021". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 27 July 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Latest Human Development Index Ranking". Human Development Reports. New York: United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". Human Development Reports. New York: United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "LABOUR FORCE SURVEY: May 2022". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 28 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ "Employment rate by sex, age group 20-64". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 14 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Average annual wages". OECD. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Mean and median income by age and sex - EU-SILC and ECHP surveys". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "ITC Trade Map: List of exporters for Sea Transport, i.e. country ranking in value of exports (services; data code 206; yearly times series)". WTO-ITC. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ Sources on Greek shipping:

- OECD (2010). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Greece 2009. OECD Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-92-64-06083-8.

The Greek shipping industry is well-organised and influential, both domestically and internationally, ... The Hellenic Chamber of Shipping, the world's largest association of ship owners, is the industry's official advisor to the government on all ...

- Christos C. Frangos (2009). Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference: Quantitative and Qualitative Methodologies in the Economic and Administrative Sciences. Christos Frangos. p. 404. ISBN 978-960-98739-0-1.

Finally, the most important Greek industry, shipping, is making huge gains establishing its prowess in the global market, being the biggest in the world, makes Greece a real global player. Shipping, which contributed by 4,5% to the country's ...

- Peter Haggett (2002). Encyclopedia of World Geography: Italy. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1470. ISBN 978-0-7614-7300-8. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

The Greek shipping industry, one of the largest in the world, accounts for more than 30 percent of the income derived from services. It is exempt from government control, unlike other

- Ibpus.com; Int'l Business Publications, USA (2012). Business in Greece for Everyone: Practical Information and Contacts for Success. Int'l Business Publications. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-4387-7220-2.

Greek shipping and List of ports in Greece The shipping industry is a key element of Greek economic activity dating back to ancient times. Today, shipping is one of the country's most important industries. It accounts for 4.5% of ...

- Jill Dubois; Xenia Skoura; Olga Gratsaniti (2003). Greece. Marshall Cavendish. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7614-1499-5.

Greek ships make up 70 percent of the European Union's total merchant fleet. Greece has a large shipbuilding and ship refitting industry. Its six shipyards near Piraeus are among the biggest in Europe. As Greek ships primarily transport ...

- Antōnios M. Antapasēs; Lia I. Athanassiou; Erik Røsæg (2009). Competition and regulation in shipping and shipping related industries. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 273. ISBN 978-90-04-17395-8.

which is a powerful tool of tax policy for the shipping industry in Greece.25 4.

- Tullio Treves; Pineshi (1997). The Law of the Sea: The European Union and Its Member States. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 239–240. ISBN 978-90-411-0326-0.

The Shipping Industry The shipping industry (the transport of persons and goods by sea) constitutes one of the most important factors for the Greek society and economy

- Athanasios A. Pallis (2007). Maritime Transport: The Greek Paradigm. Elsevier. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-7623-1449-2.

Since Greek shipping ranks on top of world shipping business in terms of tonnage and volume, it is of interest to have a closer look at Greek shipping finance.

- OECD (2010). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Greece 2009. OECD Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-92-64-06083-8.

- ^ "Ease of Doing Business in Greece". Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Group. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d "COMMERCIAL TRANSACTIONS OF GREECE : May 2022". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b c "ITC Trade Map Database". WTO-ITC.

- ^ a b "Foreign trade partners of Greece". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "External Debt". Bank of Greece. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ "International Investment Position". Bank of Greece. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ "Government debt down to 95.6% of GDP in euro area" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 21 July 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b c "Fiscal data for the years 2018-2021". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b c "Provision of deficit and debt data for 2021 - first notification" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 22 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "DBRS Morningstar Upgrades the Hellenic Republic to BB (high), Trend Changed to Stable". Frankfurt: DBRS Morningstar. 18 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "Fitch Revises Greece's Outlook to Positive; Affirms at 'BB'". Frankfurt: Fitch Ratings. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Moody's upgrades Greece's rating to Ba3, outlook remains stable". London: Moody's Investors Service. 6 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ "S&P Upgrades Greece Debt Rating To BB+ On Improving Economy". Barron's. New York. 22 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Rating: Greece Credit Rating". CountryEconomy.com. 23 April 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Scope upgrades Greece's long-term credit rating to BB+ and revises the Outlook to Stable". Berlin: Scope Ratings. 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "Gross domestic product at market prices". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 30 July 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2013 Edition" (PDF). Madrid: World Tourism Organization. June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Review of Maritime Transport 2013" (PDF). Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ [1] Archived 8 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Albania Eyes New Markets as Greek Crisis Hits Home". Balkan Insight. 11 July 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

Greece is the Balkan region's largest economy and has been an important investor in Southeast Europe over the past decade.

- ^ Keridis, Dimitris (3 March 2006), Greece and the Balkans: From Stabilization to Growth (lecture), Montreal, QC, CA: Hellenic Studies Unit at Concordia University,

Greece has a larger economy than all the Balkan countries combined. Greece is also an important regional investor

- ^ "Greece was the biggest foreign investor in Albania during 2013". invest-in-albania.org.

- ^ a b Imogen Bell (2002). Central and South-Eastern Europe: 2003. Routledge. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-85743-136-0. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

Greece has become the largest investor into Macedonia (FYRM), while Greek companies such as OTE have also developed strong presences in former Yugoslavia and other Balkan countries.

- ^ Mustafa Aydin; Kostas Ifantis (28 February 2004). Turkish-Greek Relations: The Security Dilemma in the Aegean. Taylor & Francis. pp. 266–267. ISBN 978-0-203-50191-7. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

second largest investor of foreign capital in Albania, and the third largest foreign investor in Bulgaria. Greece is the most important trading partner of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

- ^ Wayne C. Thompson (9 August 2012). Western Europe 2012. Stryker Post. p. 283. ISBN 978-1-61048-898-3. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

Greeks are already among the three largest investors in Bulgaria, Romania and Serbia, and overall Greek investment in the ... Its banking sector represents 16% of banking activities in the region, and Greek banks open a new branch in a Balkan country almost weekly.

- ^ "WEO Groups and Aggregates Information". World Economic Outlook Database. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ "Country and Lending Groups". Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Greece, country profile". European Union. 5 July 2016.

- ^ "Fixed Euro conversion rates". European Central Bank. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ "Singapore takes third spot on Globalization Index 2011". Ernst & Young. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Graham T. Allison; Kalypso Nicolaidis (1997). "The Greek paradox: promise vs. performance". ISBN 9780262510929. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ a b "GDP growth rate". World Development Indicators. Google Public Data Explorer. 12 January 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ "Provision of deficit and debt data for 2014 - second notification" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 21 October 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ "The Greek Debt Restructuring: An Autopsy" (PDF).

- ^ "Euro area government debt up to 92% of GDP". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 22 July 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b Bensasson, Marcus (4 November 2014). "Greece exited recession in second quarter, says EU Commission". Kathimerini. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Eurozone recovery falters as Greece slips back into recession". The Guardian. London. 12 February 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ K. Kostis; S. Petmezas (2006). Η Ανάπτυξη της Ελληνικής οικονομίας τον 19ο αιώνα [Development of the Greek economy in the 19th century]. Athens: Alexandria Publications.

- ^ G. Anastasopoulos (1946). Ιστορία της Ελληνικής Βιομηχανίας 1840–1940 [History of Greek Industry 1840–1940]. Athens: Elliniki Ekdotiki Etairia.

- ^ L.S. Skartsis (2012). Greek Vehicle & Machine Manufacturers 1800 to present: A Pictorial History (eBook). Marathon.

- ^ "A Greek Odyssey: 1821–2201". Ekathimerini.com. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Paul Bairoch, Europe's GNP 1800–1975, Journal of European Economic History, 5, pgs. 273–340 (1976)

- ^ Angus Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy 1820–1992, OECD (1995)

- ^ Eurostat, including updated data since 1980 and data released in April 2008

- ^ "FIELD LISTING:: GDP – PER CAPITA (PPP)". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ a b "GDP per capita in purchasing power standards" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 13 December 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Consumption per capita in purchasing power standards in 2019". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 15 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Premium content". The Economist. 9 December 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Greek taxpayers sense evasion crackdown". Financial Times

- ^ "2021 Corruption Perceptions Index". Berlin: Transparency International. 25 January 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index 2008". Transparency International. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ "2012 Corruption Perceptions Index". Berlin: Transparency International. 5 December 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "2022 Index of Economic Freedom". Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "The Global Competitiveness Report 2019". Geneva: World Economic Forum. 8 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". World Economic Outlook Database. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ "Provision of deficit and debt data for 2012 - second notification" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Charter, David. Storm over bailout of Greece, EU's most ailing economy. Time Online: Brussels, 2010

- ^ Faiola, Anthony (10 February 2010). "'Greece's economic crisis could signal trouble for its neighbors'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Βουλή: "Ναι" στη σύσταση εξεταστικής για το έλλειμμα το 2009" [Parliament: "Yes" to the creation of a committee to investigate the deficit of 2009]. Skai TV. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ "Υπόθεση ΕΛΣΤΑΤ: Για ποινικοποίηση της αλήθειας μίλησε ο Γ. Παπακωνσταντίνου" [ELSTAT case: Criminalization of the truth, says G. Papakonstantinou]. Skai TV. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

According to the referral of the case, 'from the entire collection of evidence, and especially from witnesses, there exists proof in relation to actions deserving of criminal punishment and with persons who held offices in the previous government of Greece' and from most interviews with witnesses it is noted that 'they speak of an artificial and arbitrary swelling of the national deficit in 2009 and for the liability of the -then- Prime Minister, members of the then-government and then-officials of the Ministry of Finance'

- ^ "Average annual hours actually worked per worker" (database). OECD. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Groningen Growth; Development Centre; Pegasus Interactive (6 October 2008). "v4.ethnos.gr – Oι αργίες των Eλλήνων – ειδησεις, κοινωνια, ειδικες δημοσιευσεις". Ethnos.gr. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "The Production Index in Industry recorded a decline of 8.0% in March 2011 compared with March 2010" (PDF). statistics.gr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ^ "Building Activity Survey: January 2011" (PDF). statistics.gr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ^ "The Turnover Index in Retail Trade, excluding automotive fuel, recorded a fall of 9.0% in February 2011 compared with February 2010" (PDF). statistics.gr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ^ "LABOUR FORCE SURVEY: June 2013" (PDF). Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 12 September 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "LABOUR FORCE SURVEY: 2nd quarter 2009" (PDF). National Statistical Service of Greece. 17 September 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "LABOUR FORCE SURVEY: 3rd quarter 2009" (PDF). National Statistical Service of Greece. 17 December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "LABOUR FORCE SURVEY: May 2013" (PDF). Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 8 August 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ "LABOUR FORCE SURVEY: March 2022". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 18 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ "Report by Eurostat on the revision of the Greek government deficit and debt figures". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 22 November 2004. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Simitis, Costas; Stournaras, Yannis (27 April 2012). "Greece did not cause the euro crisis". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ Story, Louise; Thomas Jr, Landon; Schwartz, Nelson D. (14 February 2010). "Wall St. Helped to Mask Debt Fueling Europe's Crisis". The New York Times.

Steil, Benn (21 February 2002). "Enron and Italy: Parallels between Rome's efforts to qualify for euro entry and the financial chicanery in Texas". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011.

Piga, Gustavo (2001). "Derivatives and Public Debt Management" (PDF). International Securities Market Association (ISMA) in cooperation with the Council on Foreign Relations. - ^ OECD Economic Surveys (Greece), Vol. 2005/12, September 2005, p.47. OECD Publishing. 22 September 2005. ISBN 9789264011748. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ "Finmin says fiscal data saga has ended in wake of EU report". 8 December 2004.

- ^ "Goldman bet against Entire European Nations". Washingtons Blog. 16 July 2011.

- ^ Tim Harford (9 September 2011). "Look out for No. 1". Financial Times.

- ^ Rauch, Bernhard; Max, Göttsche; Brähler, Gernot; Engel, Stefan (2011). "Fact and Fiction in EU-Governmental Economic Data". German Economic Review. 12 (3): 244–254. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0475.2011.00542.x. S2CID 155072460.

- ^ Angus Maddison, "Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992", OECD (1995)

- ^ a b c d e "2010-2018 Greek Debt Crisis and Greece's Past: Myths, Popular Notions and Implications". Academia.edu. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "IMF Data Mapper". IMF. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "Greek Debt/GDP: Only 22% In 1980". Economics in Pictures. 1 September 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "Debt-To-GDP Ratio". Investopedia (2018). Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "Eurostat (Government debt data)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Lynn, Matthew (2011). Bust: Greece, the Euro and the Sovereign Debt Crisis. Hobeken, New Jersey: Bloomberg Press. ISBN 978-0-470-97611-1.

- ^ "Greece's Sovereign-Debt Crunch: A Very European Crisis". The Economist. 4 February 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Rehn: No Other State Will Need a Bail-Out". EU Observer. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ a b c "Greece Paid Goldman $300 Million To Help It Hide Its Ballooning Debts". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ LOUISE STORY; LANDON THOMAS Jr; NELSON D. SCHWARTZ (13 February 2010). "Global Business: Wall St. Helped to Mask Debt Fueling Europe's Crisis". The New York Times.

In dozens of deals across the Continent, banks provided cash upfront in return for government payments in the future, with those liabilities then left off the books. Greece, for example, traded away the rights to airport fees and lottery proceeds in years to come.

- ^ Nicholas Dunbar; Elisa Martinuzzi (5 March 2012). "Goldman Secret Greece Loan Shows Two Sinners as Client Unravels". Bloomberg.

Greece actually executed the swap transactions to reduce its debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratio because all member states were required by the Maastricht Treaty to show an improvement in their public finances," Laffan said in an e- mail. "The swaps were one of several techniques that many European governments used to meet the terms of the treaty."

- ^ Edmund Conway Economics (15 February 2010). "Did Goldman Sachs help Britain hide its debts too?". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010.

One of the more intriguing lines from that latter piece says: "Instruments developed by Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and a wide range of other banks enabled politicians to mask additional borrowing in Greece, Italy and possibly elsewhere." So, the obvious question goes, what about the UK? Did Britain hide its debts? Was Goldman Sachs involved? Should we panic?

- ^ Elena Moya (16 February 2010). "Banks that inflated Greek debt should be investigated, EU urges". The Guardian.

"These instruments were not invented by Greece, nor did investment banks discover them just for Greece," said Christophoros Sardelis, who was chief of Greece's debt management agency when the contracts were conducted with Goldman Sachs.Such contracts were also used by other European countries until Eurostat, the EU's statistic agency, stopped accepting them later in the decade. Eurostat has also asked Athens to clarify the contracts.

- ^ a b Beat Balzli (8 February 2010). "Greek Debt Crisis: How Goldman Sachs Helped Greece to Mask its True Debt". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

This credit disguised as a swap didn't show up in the Greek debt statistics. Eurostat's reporting rules don't comprehensively record transactions involving financial derivatives. "The Maastricht rules can be circumvented quite legally through swaps," says a German derivatives dealer. In previous years, Italy used a similar trick to mask its true debt with the help of a different US bank.

- ^ "Greece not alone in exploiting EU accounting flaws". Reuters. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ "Greece is far from the EU's only joker". Newsweek. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "The Euro PIIGS out". Librus Magazine. 22 October 2010. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "'Creative accounting' masks EU budget deficit problems". Sunday Business. 26 June 2005. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "How Europe's governments have enronized their debts". Euromoney. September 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ "How Italy shrank its deficit". Euromoney. 1 December 2001. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Italy faces restructured derivatives hit". Financial Times. 25 June 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Story, Louise; Thomas Jr, Landon; Schwartz, Nelson D. (14 February 2010). "Wall St. Helped To Mask Debt Fueling Europe's Crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Papandreou Faces Bond Rout as Budget Worsens, Workers Strike". Bloomberg. 22 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Staff (19 February 2010). "Britain's Deficit Third Worst in the World, Table". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ Melander, Ingrid; Papchristou, Harry (5 November 2009). "Greek Debt To Reach 120.8 Pct of GDP in '10 – Draft". Reuters. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ "Greece Faces 'Unprecedented' Cuts as $159B Rescue Nears". Bloomberg. 3 May 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Kerin Hope (2 May 2010). "EU Puts Positive Spin on Greek Rescue". Financial Times. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ Newman, Rick (3 November 2011). "Lessons for Congress From the Chaos in Greece". US News. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ "Greece's Austerity Measures". BBC News. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ "Greek Parliament Passes Austerity Measures". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Drew, Kevin (5 December 2011). "Times Topics European Union". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ Kavoussi, Bonnie (24 October 2011). "Greek Austerity: Budget Cuts Deepen Recession, Quicken Reckoning". Huffington Post. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ "Greece: Country's Deficit Will Fall, No New Austerity Needed". Huffington Post. 24 October 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ Granitsas, Alkman; Paris, Costas (6 December 2011). "Greek Politician Expects Recession Will Linger". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ "Greece to see out year in recession". Financial Times. 3 July 2011. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ "Greek public sector workers hold 24-hour strike". BBC News. 9 July 2014.

- ^ "Greek politics: Immigrants as scapegoats". The Economist. 6 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Greece First Developed Market Cut to Emerging at MSCI". Bloomberg. 12 June 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Market Classification". New York: MSCI. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "S&P Dow Jones Indices Announces Country Classification Consultation Results" (PDF). New York: S&P Dow Jones Indices. 30 October 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "State workers in Greece hold strike to protest layoffs". Greek Herald. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ "GDP up by 0.3% in the euro area and by 0.4% in the EU28". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "PM eyes stability, says opposition proposals could undermine debt effort". Kathimerini. 15 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ El-Erian, Mohamed (22 June 2017). "Greek debt: IMF and EU's quick fix isn't enough Mohamed El-Erian". The Guardian.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Greece reiterates pledge to IMF to implement 21 prior actions by June 2018".

- ^ "Greece exits final bailout successfully: ESM". Reuters. 20 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "Tsipras says Greece won't go back to old spending ways (Bloomberg ))". 27 June 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ a b "(Keeptalkinggreece) Marianne: The incredible errors by IMF experts & the wrong multiplier". 22 January 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ "General government gross debt - annual data". Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "IMF 'to admit mistakes' in handling Greek debt crisis and bailout (The Guardian)". 5 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "For hard-hit Greeks, IMF mea culpa comes too late (Reuters)". 6 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "IMF admits disastrous love affair with the euro and apologises for the immolation of Greece (The Telegraph)". 29 July 2016. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "EU endorses massive pandemic relief for recession-hit Greece - ABC News". 17 June 2021.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database: October 2021". IMF. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ a b c "Crops products (excluding fruits and vegetables) (annual data)". Eurostat. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Fruits and vegetables (annual data)". Eurostat. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "Sustainable development in the European Union" (PDF). Eurostat. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Fishery statistics; Data 1995–2008" (PDF). Eurostat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "Industrial turnover – mining, quarrying and manufacturing". Eurostat. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Europe in Figures – Yearbook 2011" (PDF). Eurostat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Jill Dubois; Xenia Skoura; Olga Gratsaniti (2003). Greece. Marshall Cavendish. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7614-1499-5.

Greek ships make up 70 percent of the European Union's total merchant fleet. Greece has a large shipbuilding and ship refitting industry. Its six shipyards near Piraeus are among the biggest in Europe. As Greek ships primarily transport ...

- ^ "Mega yacht owners choose Greece for construction and maintenance, Ilias Bellos Kathimerini".

- ^ "Βιομηχανικά Προϊόντα (PRODCOM) (Παραγωγή και Πωλήσεις)". Hellenic Statistical Authority. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Manufacturing products (PRODCOM) :Production and sales – 2010 – Provisional Data". Hellenic Statistical Authority. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ a b Polemis, Spyros M. "The History of Greek Shipping". greece.org. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

- ^ a b Ιστορία των Ελλήνων – Ο Ελληνισμός υπό Ξένη Κυριαρχία 1453–1821 [History of the Greeks – Hellenism under Foreign Rule 1453–1821]. Vol. 8. Athens: Domi Publishings. pp. 652–653. ISBN 960-8177-93-6.

- ^ "Greek Fleet". 1914. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ a b Engber, Daniel (17 August 2005). "So Many Greek Shipping Magnates ..." Slate. Washington Post/slate.msn.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g "ECSA Annual report 2011–2012" (PDF). European Community Shipowners' Associations. ecsa.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d "ECSA Annual report 2010–2011" (PDF). European Community Shipowners' Association. ecsa.eu.

- ^ a b "Greek shipping is modernized to remain a global leader and expand its contribution to the Greek economy". National Bank of Greece. nbg.gr. 11 May 2006. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ^ "As Greece Struggles with Debt Crisis, Its Shipping Tycoons Still Cut a Profit". Time World. 16 May 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d "ITC Trade Map: List of importers for Sea Transport, i.e. country ranking in value of imports (services; data code 206; yearly times series)". WTO-ITC. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d "ITC Trade Map: List of markets for Sea Transport, i.e. country ranking in value of trade balance (services; data code 206; yearly times series)". WTO-ITC. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ "GDP and main components – Current prices". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 13 April 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ a b c "Company Profile". Athens: OTE. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Δύο φορές ο πληθυσμός μας σε συνδέσεις". Hellenic Tellecommunications Organization (OTE). enet.gr. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Internet access and use in 2011" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 14 December 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Internet access and use in 2013" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 18 December 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Survey on the Use of Information and Communications Technologies by Households and Individuals, 2021". Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 8 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ a b Jafa Jafari (2003). Encyclopedia of tourism. ISBN 9780415308908. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ a b Miltiadis Lytras; Ernesto Damiani; Lily Diaz (30 November 2010). Digital culture and e-tourism. ISBN 9781615208685. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d Tourism in OECD Countries 2008: Trends and Policies. OECD. 2008. ISBN 9789264039674. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Nights spent in tourist accommodation establishments – regional – annual data". Eurostat. 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Tourism" (PDF). Eurostat. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Spain, Italy and France: top destinations for holiday trips abroad of EU27 residents in 2011" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 15 April 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ "Ultimate party cities". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ a b "World's Best Awards – Islands". Travel + Leisure. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Macedonia-Turkey: The Ties That Bind". Balkan Insight. 10 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Greek investments in Bulgaria soar since 2005". Sofia Echo. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Greek investment in Serbia tops 2 billion euros". Kathimerini. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Greek investments in Romania exceed 4.0 bln euros". Athens-Macedonian News Agency. 7 August 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Greqia, e para investitore në Shqipëri me 25% te totalit të investimeve". October 2016.