스페인의 경제

Economy of Spain이 문서는 갱신할 필요가 있습니다.할 수 , 이.(2022년 3월) |

| |

| 통화 | 유로(EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| 역년 | |

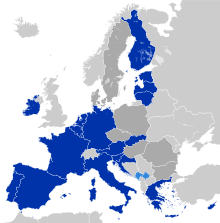

무역 조직 | EU, WTO 및 OECD |

국가 그룹 | |

| 통계 정보 | |

| 인구. | |

| GDP | |

| GDP 순위 | |

GDP 성장 |

|

1인당 GDP | |

1인당 GDP 순위 | |

부문별 GDP | |

노동력 | |

직업별 노동력 |

|

| 실업률 | |

평균총급여 | 2,648유로 / 월 2,800달러 (최소) |

| €2,039 / $2,196 (월급) | |

주요 산업 | [14][15] |

| 외부의 | |

| 내보내기 | |

수출품 | 기계, 자동차, 식료품, 의약품, 의약품, 기타 소비재 |

주요 수출 파트너 | |

| Imports(가져오기) | |

수입품 | 연료, 화학, 반제품, 식품, 소비재, 기계 및 장비, 측정 및 의료 관리 기구 |

주요 수입 파트너 | |

| 재정 | |

| 수익 | GDP의 39.1%(2019년)[17] |

| 비용 | GDP의 41.9%(2019년)[17] |

외환보유고 | |

특별히 명기되어 있지 않는 한, 모든 값은 미국 달러로 표시됩니다. | |

스페인의 경제는 고도로 발달한 사회 시장 [21]경제이다.명목 GDP로는 세계 14위, 유럽에서는 5위다.스페인은 유럽연합(EU)과 유로존, 경제협력개발기구(OECD)와 세계무역기구(WTO) 회원국이다.2019년 스페인은 세계 15위의 수출국이자 14위의 수입국이었다.스페인은 유엔 인간개발지수에서 25위, 세계은행에서 1인당 GDP에서 32위에 올랐다.2005년 이코노미스트지에 따르면, 스페인은 세계에서 10번째로 [22]삶의 질이 높았다.경제 활동의 주요 분야 중 일부는 자동차 산업, 의료 기술, 화학, 조선, 관광, 섬유 산업이다.

2007-2008년의 금융위기 이후, 스페인 경제는 침체기에 빠졌고, 부정적인 거시 경제 실적의 순환으로 접어들었다.EU와 미국의 평균에 비해 스페인 경제는 더 늦게 침체기에 접어들었지만(2008년까지 여전히 성장 중) 더 오래 머물렀다.2000년대의 경제 호황은 역전되어 2012년까지 스페인 노동력의 4분의 1 이상이 실업 상태가 되었다.종합적으로 볼 때, 스페인 [23]GDP는 2009-2013년 동안 거의 9% 감소했다.경제 상황은 2013-2014년까지 개선되기 시작했다.그때까지,[24] 그 나라는 호황기에 축적된 기록적인 무역 적자를 가까스로 만회했다.30년간의 무역수지 [24]적자 끝에 2013년에 무역수지 흑자를 달성했다.2014년과 [25]2015년에는 흑자가 계속 증가했다.

2015년 스페인의 GDP 성장률은 3.2%로 세계 금융위기가 [26]닥치기 직전인 2007년 이후 처음이다.이 성장률은 그 [27]해 EU 경제대국 중 가장 높았다.불과 2년(2014-2015년) 만에 스페인 경제는 2009-2013년 [28]불황으로 손실된 GDP의 85%를 회복했다.이 성공으로 인해 일부 국제 분석가들은 스페인의 현재 회복을 "구조 개혁 [29]노력의 쇼케이스"라고 부르기도 했다.2016년에도 강력한 GDP 성장률이 기록돼 유로존 [30]평균보다 두 배 빠른 성장을 보였다.이런 점에서 스페인 경제는 [31]2017년에도 유로존에서 가장 잘 나가는 주요 경제국으로 남을 것으로 예측됐다.스페인의 실업률은 2013년부터 2017년까지 크게 떨어졌다.실질 실업률은 훨씬 낮은데, 그레이마켓에서 일하는 수백만 명의 사람들이 실업자 또는 비활동자로 간주되지만 여전히 [32]일을 수행하는 것으로 추정되기 때문이다.숨겨진 경제의 추정치는 다양하지만 스페인의 지하경제가 연간 1900억유로(2240억달러)[33] 움직이는 것으로 추정되기 때문에 실질 스페인의 GDP는 약 20% 더 커질 수 있다.고소득 유럽 국가 중 지하경제가 스페인보다 큰 나라는 이탈리아와 그리스뿐이다.따라서 스페인은 공식 수치보다 더 높은 구매력과 더 작은 지니 계수를[34] 가질 수 있다.스페인 정부는 2012년 유럽안정기구(European Stability Mechanism)에 금융위기 [35]때 은행권 구조조정을 공식 요청했다.ESM은 최대 1000억 유로의 지원을 승인했지만, 스페인은 결국 413억 유로의 지원만 받았다.스페인에 대한 ESM 프로그램은 18개월 [36]후 인출된 신용의 전액 상환과 함께 종료되었다.

역사

1986년 스페인이 EEC에 가입했을 때 1인당 GDP는 회원국 [37]평균의 약 72%였다.

1990년대 후반 호세 마리아 아즈나르 전 총리의 보수정권은 1999년 유로화 가입국 자격을 얻는 데 성공했다.

2007년까지 스페인은 자국의 경제 발전과 28개 회원국으로의 확대로 1인당 GDP가 유럽연합 평균의 105%에 달해 이탈리아(103%)보다 약간 앞섰다.1인당 국내총생산(GDP)의 125%를 넘는 주요 EU 집단에 포함된 지역은 바스크 지방, 마드리드,[38] 나바라 등 3곳이다.2008년 독일 신문 디벨트의 계산에 따르면 스페인 경제는 [39]2011년까지 1인당 국민소득에서 독일 같은 나라를 추월할 예정이었고, 2006년 10월에는 실업률이 7.6%로 다른 많은 유럽 국가들에 비해 양호했으며, 특히 1990년대 초반에는 20%를 웃돌았다.과거에 스페인의 경제는 높은 인플레이션을 포함했고 항상 큰 지하 [41]경제를 가지고 있었다.

1997-2007년의 성장 전환은 역사적으로 낮은 금리, 막대한 외국인 투자 비율(그 기간 스페인은 다른 유럽 투자 은행들의 총애를 받았다), 그리고 엄청난 이민 급증으로 촉발된 부동산 거품을 낳았다.2007년에 절정에 달했을 때, 건설은 그 나라 총 국내총생산(GDP)의 15%, 고용의 12%로 확대되었다.이 기간 동안 단기 투기 투자를 포함한 스페인의 자본 유입은 막대한 무역 적자를 지원했다.[37]

부동산 호황의 단점은 가계와 기업 둘 다 개인 부채 수준이 그에 상응하는 상승했다는 것이다; 예비 주택 소유주들이 호가를 맞추려고 애쓰면서, 평균 가계 부채 수준은 10년도 안 되어 세 배가 되었다.이것은 특히 저소득층과 중산층에게 큰 압력을 가했다; 2005년까지 소득 대비 부채의 중앙 비율이 125%로 증가했는데, 이는 주로 지금은 [42]종종 부동산 가치를 초과하는 고가의 호황기 주택담보대출 때문이다.

스페인의 부동산 [43]거품이 글로벌 금융위기로 붕괴된 2008년 초까지 눈에 띄는 진전이 이어졌다.

유럽연합 집행위원회의 예측에 따르면 스페인은 2008년 [44]말까지 세계 2000년대 후반의 경기 침체에 들어갈 것으로 예측되었다.당시 스페인 경제장관은 "스페인이 반세기 만에 가장 심각한 불황을 맞고 있다"[45]고 말한 것으로 전해졌다.스페인 정부는 2009년에 실업률이 16%까지 상승할 것이라고 예측했다.ESADE 경영대학원은 20%[46]를 예측했다.2017년까지 스페인의 1인당 GDP는 유럽연합 [37]평균의 95%로 다시 떨어졌다.

경제 및 금융 위기, 2008-2012

이 섹션은 너무 길어서 쉽게 읽고 탐색할 수 없습니다.(2019년 11월) |

스페인은 2004년 집권여당이 바뀌었을 때 경제성장의 길을 계속 걸어 호세 루이스 로드리게스 사파테로 총리의 첫 임기 동안 스페인 경제의 문제가 분명해졌음에도 불구하고 GDP 성장세가 견조했다.파이낸셜 타임스에 따르면 스페인의 급속히 증가하고 있는 무역 적자, 2008,[47]은"경쟁력의 주요 무역 파트너들에 대한 손실"의 여름과, 또한, 후자의 부분이, 전통적으로 하나를 유럽 파트너 그 당시 특히 이상이 되는 물가률로 국가의 국내 총생산의 10%에 달해 있었다.다지1998년 대비 150%의 집값 상승과 스페인 부동산 붐과 [48]유가 급등과 관련된 가계부채 증가(115%)로 나타났다.

2008년 4월 스페인 정부의 공식 GDP 성장률 전망치는 2.3%였으나 스페인 경제성에 의해 1.6으로 [49]하향 조정되었다.대부분의 독립 예보관의 연구에 따르면 1997-2007년 10년간 GDP 성장률에 3%를 더한 강력한 성장률보다 낮은 [50]0.8%로 떨어졌다.2008년 3분기 동안 국가 GDP는 15년 만에 감소했습니다.2009년 2월 스페인은 다른 유럽 국가들과 함께 공식적으로 경기 [51]침체에 들어간 것으로 확인되었다.

2009년 7월 IMF는 스페인의 2009년 축소를 올해 GDP의 마이너스 4%로 악화시켰다(유럽 평균인 마이너스 4.6%에 근접).2010년에는 스페인 경제가 [52]0.8% 더 위축될 것으로 예측했다.2011년에는 적자가 8.5%로 최고치를 기록했다.2016년 정부의 적자 목표는 약 4%였고, 2017년에는 2.9%로 떨어졌다.유럽위원회는 2016년 3.9%, [53]2017년 2.5%를 요구하고 있다.

부동산 호황과 불황, 2003-2014

2002년 유로화 도입으로 장기금리가 하락하면서 주택담보대출이 2000년에서 2010년 [54]정점으로 4배 이상 급증했다.1997년에 시작된 스페인 부동산 시장의 성장은 가속화되었고 몇 년 안에 부동산 거품으로 발전했고, 주로 지방 정부의 감독 하에 있는 지역 저축 은행인 "카하스"에 의해 자금 조달되고, 역사적으로 낮은 금리와 이민자의 거대한 성장에 의해 공급되었다.이러한 추세를 부채질하면서 스페인 경제는 글로벌 대공황 [55]이전 수개월 동안 EU의 일부 최대 파트너들의 사실상 제로 성장률을 피한 것으로 평가되고 있다.

2005년을 마감하는 5년 동안 스페인 경제는 유럽연합에 [56][57]새로 생긴 일자리의 절반 이상을 창출했다.부동산 붐이 한창일 때 스페인은 독일, 프랑스, 영국을 [54]합친 것보다 더 많은 집을 짓고 있었다.2003년과 2008년 사이에 주택 가격은 신용 [54]폭증에 따라 71%나 급등했다.

2008년에 거품이 꺼지면서 스페인의 대규모 부동산 관련 및 건설 부문이 붕괴되고 대량 해고와 상품 및 서비스에 대한 국내 수요의 붕괴를 초래했다.실업률이 급증했다.

처음에 스페인의 은행과 금융 서비스는 국제 은행들의 초기 위기를 피했다.그러나 경기침체가 깊어지고 부동산 가격이 하락하자 소규모 지역 저축은행인 '카하스'의 부실채권이 늘어나면서 스페인 중앙은행과 정부가 안정·통합 프로그램을 통해 개입해 지역 '카하스'를 인수·통합하고 유럽으로부터 구제금융을 받았다. 2012년 중앙은행은 은행 업무, 특히 "[58][59][60]카하스"를 목표로 했습니다.

2008년의 피크에 이어, 주택 가격은 31%나 급락해,[54] 2014년 후반에 바닥을 쳤다.

유로 부채 위기, 2010-2012

2010년 첫 주에 일부 EU 국가들의 과도한 부채 수준과 보다 일반적으로 유로화의 건전성에 대한 우려가 아일랜드와 그리스에서 포르투갈로, 그리고 스페인에서 덜 확산되었다.

많은 경제학자들은 급격한 긴축 정책과 높은 세금을 결합해 세수 감소로 인한 치솟는 공공부채를 억제하기 위한 일련의 정책을 추천했다.일부 독일 고위 정책 입안자들은 심지어 긴급 구제금융에는 [61]그리스와 같은 EU 원조 수혜자들에 대한 가혹한 처벌이 포함되어야 한다고까지 말했다.스페인 정부 예산은 글로벌 금융위기 직전 수년간 흑자였고 부채는 과도하다고 여겨지지 않았다.

2010년 초 스페인의 국내총생산(GDP) 대비 공공부채 비율은 영국, 프랑스, 독일보다 낮았다.그러나 논평자들은 스페인의 회복이 취약하고 공공부채가 빠르게 증가하고 있으며 어려움에 처한 지방은행들이 대규모 구제금융이 필요할 수 있으며 성장 전망이 좋지 않아 세입이 제한되고 있으며 중앙정부가 지방정부의 지출을 제한하고 있다고 지적했다.1975년 이후 발전해 온 정부 책임 분담 구조 하에서 지출에 대한 많은 책임은 지역에 돌아갔다.중앙 정부는 완강한 지방 [62]정부로부터 인기 없는 지출 삭감에 대한 지지를 얻으려고 노력하는 어려운 입장에 처했다.

2010년 5월 23일, 정부는 [63]1월에 발표된 야심찬 계획을 정리한 추가 긴축 조치를 발표했다.

2011년 9월 현재 스페인 은행은 1,420억 유로의 스페인 국채를 사상 최고 수준으로 보유하고 있습니다.JP모건 [64]체이스에 따르면 2011년 12월 채권 경매는 "대상이 될 가능성이 매우 높다"고 한다.

2012년 2분기까지 스페인 은행들은 규제 당국에 의해 부동산 관련 자산을 비시장 가격으로 보고할 수 있었습니다.그러한 은행에 사들인 투자자들은 알고 있어야 한다.스페인 주택은 몇 [citation needed]년 이상 비어 있으면 토지 장부가격으로 팔 수 없다.

고용위기(2008-현재)

스페인은 1990년대 후반과 2000년대에 걸쳐 큰 개선을 이룬 후 2007년에 약 8%[66]의 저실업률을 달성하고 일부 지역은 완전고용 위기에 놓였다.그 후 스페인은 2008년 10월부터 실업률이 1996년 수준으로 치솟은 심각한 좌절을 겪었다.2007년 10월~2008년 10월 실업률 급상승은 1993년 등 과거 경제위기를 웃돌았다.특히 2008년 10월 스페인은 [67][68]사상 최악의 실업률 상승을 겪었다.비록 스페인의 지하 경제의 규모가 실제 상황을 어느 정도 가리고 있지만, 고용은 스페인 경제의 장기적인 약세였다.2014년까지 구조적 실업률은 18%[69]로 추정되었다.2009년 7월까지, [70]1년 동안 120만 개의 일자리를 줄였다.대형 빌딩과 주택 관련 산업이 실업률 [65]증가에 크게 기여하고 있다.2009년부터 수천 명의 기존 이민자들이 떠나기 시작했지만 일부는 [71]출신국의 열악한 환경 때문에 스페인에서 거주권을 유지했다.전체적으로 2013년 초까지 스페인은 [66]약 27%로 전례 없는 실업률 기록에 도달했다.

2012년 5월에는 보다 유연한 노동시장을 위한 근본적인 노동개혁을 실시하여 기업의 [72]신뢰를 높이기 위해 정리해고를 촉진하였다.

청년 위기

1990년대 초, 스페인은 실업률의 상승을 초래한 더 큰 규모의 유럽 경제 사건의 결과로 경제 위기의 시기를 경험했다.스페인의 많은 청년들은 자신들이 임시 일자리의 순환에 갇혀 있다는 것을 알게 되었고, 이로 인해 임금, 고용 안정성 및 승진 기회를 [73]줄임으로써 노동자의 제2계급을 창출하게 되었다.그 결과, 주로 미혼인 많은 스페인 사람들이 일자리를 찾고 그들의 [74]생활 수준을 높이기 위해 다른 나라로 이민을 갔고,[75] 이는 스페인에서 빈곤선 이하의 삶을 사는 소수의 청소년들만 남겨졌다.스페인은 2000년대에 또 다른 경제 위기를 겪었고, 이는 또한 일자리 안정과 경제적 지위 [76]향상을 위해 이웃 국가로 이주하는 스페인 시민들의 증가를 촉진시켰다.

청년 실업은 여전히 스페인에서 우려되는 문제이며, 청년 기술을 기업에 맞추는 것과 같은 노동 시장 프로그램과 구직 지원을 제안하고 있다.이것은 스페인의 약화된 청년 노동 시장을 개선시킬 것이고, 청년들이 장기 [77]고용을 찾기가 어려워짐에 따라 그들의 학교도 직장을 옮길 것이다.

고용 회복

노동시장 개혁은 연이은 고용 호조 추세에 돌입했다.2014년 2분기까지 스페인 경제는 2008년 [72]이후 처음으로 마이너스 흐름을 반전하고 일자리 창출에 나섰다.1964년 [78]분기별 고용통계가 유지된 이후 일자리 창출 건수가 절대 호조를 보인다는 점을 감안하면 2분기 반전은 갑작스럽고 이례적이었다.노동개혁은 중요한 역할을 한 것 같다.한 가지 증거는 스페인이 이전보다 낮은 GDP 성장률로 일자리를 창출하기 시작했다는 것이다.이전 사이클에서는 성장이 2%에 달했을 때 고용이 증가했고, 이번에는 GDP가 1.2%[69]만 증가한 1년 동안 증가하였다.

예상보다 큰 GDP 성장은 실업률의 추가 하락의 길을 열었다.스페인은 2014년 이후 공식 실업자 수가 매년 꾸준히 감소하고 있다.2016년 동안 스페인의 실업률은 [30]사상 가장 가파른 하락세를 보였다.그해 말까지 스페인은 경기 [30]침체로 잃은 350만 개 이상의 일자리 중 170만 개를 회복했다.2016년 4분기까지 스페인의 실업률은 18.6%로 7년 [79]만에 최저치를 기록했다.2017년 4월 실업수당 신청자가 [80]한 달 동안 사상 최대 감소세를 기록했다.고용창출은 계속 빨라지고 있다.이 점에서 2017년 5월은 2001년 이 기록이 시작된 이래 사회보장제도에 있어서 지금까지 가장 좋은 5월이었고, 그 달 동안 실업수당 청구액은 [81]2009년 6월 이후 최저치로 떨어졌다.

2017년 2분기 실업률은 17%[82]로 2008년 이후 처음으로 400만 명 아래로 떨어졌으며, 분기별 실업률은 사상 최대를 기록했다(1964년 [83]시리즈 시작).2018년에는 실업률이 14.6%로 위기가 [84]시작된 2008년 이후 처음으로 15%를 넘지 못했다.

2017년 현재 노조와 좌파, 중도좌파 정당들은 노동개혁이 [30]고용주에게 너무 치우친다는 이유로 노동개혁을 비난하고 철회하기를 원하고 있다.게다가, 대부분의 신규 계약은 임시 [81]계약입니다.

2019년 페드로 산체스 사회주의 정부는 고용을 촉진하고 지출을 장려하기 위해 최저임금을 22% 인상했다.야당 의원들은 월 858유로에서 1050유로로 인상되면 고용주가 앞서 언급한 [85]인상분을 충당하지 못하기 때문에 120만 명의 근로자들에게 부정적인 영향을 미칠 것이라고 주장했다.

유럽 연합 자금의 삭감

이 섹션은 어떠한 출처도 인용하지 않습니다.(2011년 11월 (이 및 을 확인) |

EEC 가입 이후 스페인의 경제력 강화에 크게 기여해 온 EU로부터의 자본출자는 1990년 이후 다른 나라와의 경제표준화와 EU 확대의 영향으로 크게 감소했다.한편, 유럽 연합 공동 농업 정책(CAP)의 농업 기금은 현재 더 많은 나라에 분산되어 있다.한편, 2004년과 2007년의 유럽연합의 확대에 수반해, 저개발국이 EU에 가입해, 1인당 평균 소득(또는 1인당 GDP)이 저하해, 상대적으로 저개발국이라고 여겨졌던 스페인 지역이 유럽 평균이 되거나 그 이상으로 되어 버렸다.스페인은 [86]차츰 자금을 받는 대신 저개발국가를 위한 자금의 순기여국이 되었다.

경기 회복(2014~2020년)

경기 침체기에 스페인은 수입이 현저하게 감소하고 수출이 증가하여 관광객의 발길이 끊이지 않았다.그 결과, 30년간의 무역 적자를[24] 기록한 후, 2013년에 무역 흑자를 [25]달성해, 2014년과 2015년에 강화되었다.

2015년 스페인의 GDP 성장률은 3.2%로 EU [27]경제대국 중 가장 높았다.불과 2년(2014-2015년) 만에 스페인 경제는 2009-2013년 [28]경기침체로 손실된 GDP의 85%를 회복했고, 일부 국제 분석가들은 스페인의 현재 회복을 "구조 개혁 [29]노력의 쇼케이스"라고 표현했다.

2016년 2분기까지 스페인 경제는 12분기 연속 성장을 기록했으며, 유럽 지역의 [87]나머지 지역을 꾸준히 앞질렀다.스페인 경제는 예상을 뛰어넘어 2016년 유로권 평균의 거의 [88][30]두 배인 3.2%의 성장률을 보이면서 이러한 성장은 계속되었다.경제 회복의 주요 요인 중 하나는 노동 [89]생산성의 극적인 상승으로 촉발된 국제 무역이었다.수출은 내부 평가절하(2008~2016년 임금법안의 반토막), 새로운 시장 개척 및 최근의 완만한 유럽 [88]경제 회복에 힘입어 GDP 대비 약 25%(2008년)에서 33%(2016년)로 급증했다.

스페인 경제는 2017년에도[31] 유로권 주요 경제대국으로 남을 것으로 전망됐으며, 2017년 2분기에는 경제위기 때 손실된 GDP를 모두 회복해 2008년 [89]생산 수준을 처음으로 넘어섰다.

몇 달간의 가격 상승 이후, 2017년까지, 경기침체 동안 임대하던 집주인들은 그들의 부동산을 다시 매매 [90]시장에 내놓기 시작했다.이에 따라 2017년에는 주택판매가 위기 이전(2008) [91]수준으로 회복될 것으로 예상된다.전반적으로, 스페인 부동산 시장은 이번에 임대 부문에서 [90]새로운 호황을 경험하고 있었다.통계원은 2007년 5월에 비해 50개 성 중 48개 성에서 높은 임대료 수준을 기록했으며, 2007년 [90]이후 가장 인구가 많은 10개 성에서 누적 임대료 인플레이션이 5%에서 15% 사이이다.이러한 현상은 바르셀로나나 마드리드 같은 대도시에서 가장 잘 나타나는데,[90] 이 도시들은 관광객들에게 단기 임대한 것으로 인해 평균 가격이 사상 최고치를 경신하고 있다.

데이터.

다음 표는 1980-2020년의 주요 경제지표이다(게다가 2021-2026년의 IMF 추정치를 이탤릭체로 표시).5% 미만의 인플레이션은 [92]녹색이다.

| 연도 | GDP (빌에서).US$PPP) | 1인당 GDP (미화 PPP) | GDP (빌에서).명목상) | 1인당 GDP (공칭 US$) | GDP 성장 (실제) | 인플레이션율 (백분율) | 실업률 (백분율) | 정부채무 (GDP 비율) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 294.4 | 7,819.0 | 230.8 | 6,128.0 | 11.0% | 16.6% | ||

| 1981 | ||||||||

| 1982 | ||||||||

| 1983 | ||||||||

| 1984 | ||||||||

| 1985 | ||||||||

| 1986 | ||||||||

| 1987 | ||||||||

| 1988 | ||||||||

| 1989 | ||||||||

| 1990 | ||||||||

| 1991 | ||||||||

| 1992 | ||||||||

| 1993 | ||||||||

| 1994 | ||||||||

| 1995 | ||||||||

| 1996 | ||||||||

| 1997 | ||||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||

| 2026 |

은행 시스템

스페인의 민간 상업 은행들은 19세기 스페인의 채권국으로서의 역할, 공공 채무를 화폐화하는 능력, 그리고 20세기 초부터 1980년대 후반까지 지속된 국가 승인 과점 협정의 혜택을 받으면서 스페인의 경제 발전에 중심적인 역할을 했다.그 분야의 자유화를 강요했다.스페인 주요 시중은행들이 받은 호의적인 대우와 프랑코 정권 종료 후 스페인 은행(Banco de Espana)과의 긴밀한 관계를 통해 대형 시중은행을 두 개의 대형 은행(산탄데르와 BBVA)으로 재편할 수 있었다는 주장이 제기됐다.국제적 경쟁과 외부 팽창을 위한 민간 기관 Eparing는 한차례 유럽 금융 시장 1992[93]에 이 금융 상업 주의 가운데 상업 은행 부문 이익을 얻고 통합되었습니다, 스페인 감독 당국도의 이익을 내는 저축 은행에 대한 엄청나게 확장 지방 정부 사람들 후원하는 것을 감안했습니다.bec1999-2007년 스페인 경제 호황기에 주택 담보 대출과 부동산 개발 부문에 크게 노출되었다.

Prior to 2010, the Spanish banking system had been credited as one of the most solid of all western banking systems in coping with the ongoing worldwide liquidity crisis, thanks to the country's conservative banking rules and practices. Banks were required to have high capital provisions and to demand various guarantees and securities from intending borrowers. This allowed the banks, particularly the geographically and industrially diversified large banks like BBVA and Santander, to weather the real estate deflation better than expected. Indeed, Spain's large commercial banks have been able to capitalize on their strong position to buy up distressed banking assets elsewhere in Europe and in the United States.[94]

Nevertheless, with the unprecedented crisis of the country's real estate sector, smaller local savings banks ("Cajas"), had been delaying the registering of bad loans, especially those backed by houses and land, to avoid declaring losses. In June 2009 the Spanish government set its banking bailout and reconstruction fund, the Fondo de reestructuración ordenada bancaria (FROB), known in English as Fund for Orderly Bank Restructuring. In the event, State intervention of local savings banks due to default risk was less than feared. On 22 May 2010, the Banco de España took over "CajaSur", as part of a national program to put the country's smaller banks on a firm financial basis.[95] In December 2011, the Spanish central bank, Banco de España (equivalent of the US Federal Reserve), forcibly took over "Caja Mediterraneo", also known as CAM, (a regional savings bank) to prevent its financial collapse.[96][circular reference] The international accounting firm, PriceWaterhouseCooper, estimated an imbalance between CAM's assets and debts of €3,500 million, not counting the industrial corporation. The troubled situation reached its peak with the partial nationalization of Bankia in May 2012. By then it was becoming clear that the mounting real estate losses of the savings banks were undermining confidence in the country's government bonds, thus aggravating a sovereign debt crisis.[97]

In early June 2012, Spain requested European funding of €41 billion[97] "to recapitalize Spanish banks that need it". It was not a sovereign bailout in that the funds were used only for the restructuring of the banking sector a full-fledged bailout for an economy the size of the Spanish would have reached ten or twelve times that amount). In return for the credit line etended by the EMS, there were no tax or macroeconomic conditions.

As of 2017 the cost of restructuring Spain's bankrupt savings banks were estimated to have been €60.7 billion, of which nearly €41.8 billion was put up by the state through the FROB and the rest by the banking sector.[98] The total cost will not be fully understood until those lenders still controlled by the State (Bankia and BMN) are newly privatized.[98] In this regard, by early 2017 the Spanish government was considering a merger of both banks before privatizing the combined bank to recoup an estimated 400 million euros of their bailout costs.[97] During the course of this transformation, most regional savings banks such as the CAM, Catalunya Banc, Banco de Valencia, Novagalicia Banco, Unnim Banc or Cajasur[98] have since been absorbed by the bigger, more international, Spanish banks, which imposed better management practices.

As of 2022, Spanish banks have halved their number of branches to about 20,000 in the decade since the financial crisis and the subsequent international bailout in 2012. The remaining banks have reduced retail opening hours and pushed online banking. A retired urologist with Parkinson's disease gathered more than 600,000 signatures in an online petition "I’m Old, Not an Idiot" asking banks and other institutions to serve all citizens, and not discriminate the oldest and most vulnerable members.[99]

Prices

Due to the lack of own resources, Spain has to import all of its fossil fuels. Besides, until the 2008 crisis, Spain's recent performance had shown an inflationary tendency and an inflationary gap compared to other EMU countries, affecting the country's overall productivity.[100] Moreover, when Spain joined the euro zone, it lost the recourse of resorting to competitive devaluations, risking a permanent and cumulative loss of competitive due to inflation.[101] In a scenario of record oil prices by the mid 2000s this meant much added pressure to the inflation rate. In June 2008 the inflation rate reached a 13-year high at 5.00%.

Then, with the dramatic decrease of oil prices in the second half of 2008 plus the manifest bursting of the real estate bubble, concerns quickly shifted over to the risk of deflation, as Spain recorded in January 2009 its lowest inflation rate in 40 years, followed shortly afterwards, in March 2009 by a negative inflation rate for the first time since the gathering of these statistics started.[102][103] During the 2009−early 2016 period, apart from temporary minor oil shocks, the Spanish economy has generally oscillated between slightly negative to near-zero inflation rates. Analysts reckoned that this was not synonymous with deflation, due to the fact that GDP had been growing since 2014, domestic consumption had rebounded as well and, especially, because core inflation remained slightly positive.[104]

In 2017, moderate inflation between 1-2%, still below the ECB's target, returned as the impact of cheaper fuel prices faded and economic recovery took hold.[31]

Economic strengths

Since the 1990s some Spanish companies have gained multinational status, often expanding their activities in culturally close Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia. Spain is the second biggest foreign investor in Latin America, after the United States. Spanish companies have also expanded into Asia, especially China and India.[105] This early global expansion gave Spanish companies a competitive advantage over some of Spain's competitors and European neighbors. Another contribution to the success of Spanish firms may have to do with booming interest toward Spanish language and culture in Asia and Africa, but also a corporate culture that learned to take risks in unstable markets.

Spanish companies invested in fields like biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, or renewable energy (Iberdrola is the world's largest renewable energy operator[106]), technology companies like Telefónica, Abengoa, Mondragon Corporation, Movistar, Gamesa, Hisdesat, Indra, train manufacturers like CAF and Talgo, global corporations such as the textile company Inditex, petroleum companies like Repsol and infrastructure firms. Six of the ten biggest international construction firms specialising in transport are Spanish, lincluding Ferrovial, Acciona, ACS, OHL and FCC.[107]

Spain is equipped with a solid banking system as well, including two global systemically important banks, Banco Santander and BBVA.

Infrastructure

In the 2012–13 edition of the Global Competitiveness Report Spain was listed 10th in the world in terms of first-class infrastructure. It is the 5th EU country with best infrastructure and ahead of countries like Japan or the United States.[108] In particular, the country is a leader in the field of high-speed rail, having developed the second longest network in the world (only behind China) and leading high-speed projects with Spanish technology around the world.[109][110]

The Spanish infrastructure concession companies, lead 262 transport infrastructure worldwide, representing 36% of the total, according to the latest rankings compiled by the publication Public Works Financing. The top three global occupy Spanish companies: ACS, Global Vía and Abertis, according to the ranking of companies by number of concessions for roads, railways, airports and ports in construction or operation in October 2012. Considering the investment, the first world infrastructure concessionaire is Ferrovial-Cintra, with 72,000 million euros, followed closely by ACS, with 70,200 million. Among the top ten in the world are also the Spanish Sacyr (21,500 million), FCC and Global Vía (with 19,400 million) and OHL (17,870 million).[111]

During 2013 Spanish civil engineering companies signed contracts around the world for a total of 40 billion euros, setting a new record for the national industry.[112]

The port of Valencia in Spain is the busiest seaport in the Mediterranean basin, 5th busiest in Europe and 30th busiest in the world.[113] There are four other Spanish ports in the ranking of the top 125 busiest world seaports (Algeciras, Barcelona, Las Palmas, and Bilbao); as a result, Spain is tied with Japan in the third position of countries leading this ranking.[113]

Exports grow steadily

During the boom years, Spain had built up a trade deficit eventually amounting a record equivalent to 10% of GDP (2007)[24] and the external debt ballooned to the equivalent of 170% of GDP, one of the highest among Western economies.[25] Then, during the economic downturn, Spain reduced significantly imports due to domestic consumption shrinking while – despite the global slowdown – it has been increasing exports and kept attracting growing numbers of tourists. Spanish exports grew by 4.2% in 2013, the highest rate in the European Union. As a result, after three decades of running a trade deficit Spain attained in 2013 a trade surplus.[24] Export growth was driven by capital goods and the automotive sector and the forecast was to reach a surplus equivalent to 2.5% of GDP in 2014.[114] Exports in 2014 were 34% of GDP, up from 24% in 2009.[115] The trade surplus attained in 2013 has been consolidated in 2014 and 2015.[25]

Despite slightly declining exports from fellow EU countries in the same period, Spanish exports continued to grow and in the first half of 2016 the country beat its own record to date exporting goods for 128,041 million euros; from the total, almost 67% were exported to other EU countries.[116] During this same period, from the 70 members of the World Trade Organization (whose combined economies amount to 90% of global GDP), Spain was the country whose exports had grown the most.[117]

In 2016, exports of goods hit historical highs despite a global slowdown in trade, making up for 33% of the total GDP (by comparison, exports represent 12% of GDP in the United States, 18% in Japan, 22% in China or 45% in Germany).[88]

In all, by 2017 foreign sales have been rising every year since 2010, with a degree of unplanned import substitution -a rather unusual feat for Spain when in an expansive phase- which points to structural competitive gains.[31] According to the most recent 2017 data, about 65% of the country's exports go to other EU members.[118]

Sectors of the economy

The Spanish benchmark stock market index is the IBEX 35, which as of 2016 is led by banking (including Banco Santander and BBVA), clothing (Inditex), telecommunications (Telefónica) and energy (Iberdrola).

External trade

Traditionally until 2008, most exports and imports from Spain were held with the countries of the European Union: France, Germany, Italy, UK and Portugal.

In recent years foreign trade has taken refuge outside the European Union. Spain's main customers are Latin America, Asia (Japan, China, India), Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Egypt) and the United States. Principal trading partners in Asia are Japan, China, South Korea, Taiwan. In Africa, countries producing oil (Nigeria, Algeria, Libya) are important partners, as well as Morocco. Latin American countries are very important trading partners, like Argentina, Mexico, Cuba (tourism), Colombia, Brazil, Chile (food products) and Mexico, Venezuela and Argentina (petroleum). [2] Archived 17 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

After the crisis that began in 2008 and the fall of the domestic market, Spain (since 2010) it has turned outwards widely increasing the export supply and export amounts.[119] It has diversified its traditional destinations and has grown significantly in product sales of medium and high technology, including highly competitive markets like the US and Asia. [3] Archived 17 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

| Top trading partners for Spain in 2015[120] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tourism

During the last four decades Spain's foreign tourist industry has grown into the second-biggest in the world. A 2015 survey by the World Economic Forum proclaimed the country's tourism industry as the world's most competitive.[121] The 2017 survey repeated this finding.[122]

By 2018 the country was the second most visited country in the world, overtaking the US and not far behind France.[123] With 83.7 million visitors, the country broke in 2019 its own tourism record for the tenth year in a row.[124]

The size of the business has gone from approximately €40 billion in 2006[14] to about €77 billion in 2016.[125] In 2015 the total value of foreign and domestic tourism came to nearly 5% of the country's GDP and provided employment for about 2 million people.[126]

The headquarters of the World Tourism Organization are located in Madrid.[127]

Automotive industry

The automotive industry is one of the largest employers in the country. In 2015 Spain was the 8th largest automobile producer country in the world and the 2nd largest car manufacturer in Europe after Germany.[128]

By 2016, the automotive industry was generating 8.7 percent of Spain's gross domestic product, employing about nine percent of the manufacturing industry.[128] By 2008 the automobile industry was the 2nd most exported industry[129] while in 2015 about 80% of the total production was for export.[128]

German companies poured €4.8 billion into Spain in 2015, making the country the second-largest destination for German foreign direct investment behind only the U.S. The lion's share of that investment —€4 billion— went to the country's auto industry.[128]

Energy

In 2008, Spanish electricity consumption was an average of 6,523 kWh/person. Spanish electricity usage constituted 88% of the EU15 average (EU15: 7,409 kWh/person), and 73% of the OECD average (8,991 kWh/person).[130]

Spain is one of the world leaders in renewable energies, both as a producer of renewable energy itself and as an exporter of such technology. In 2013 it became the first country ever in the world to have wind power as its main source of energy.[131]

Agribusiness

Agribusiness has been another segment growing aggressively over the last few years. At slightly over 40 billion euros, in 2015 agribusiness exports accounted for 3% of GDP and over 15% of the total Spanish exports.[132]

The boom was shaped during the 2004-2014 period, when Spain's agribusiness exports grew by 95% led by pork, wine and olive oil.[133] By 2012 Spain was by far the biggest producer of olive oil in the world, accounting for 50% of the total production worldwide.[134] By 2013 the country became the world's leading producer of wine;[135] in 2014[136] and 2015[137] Spain was the world's biggest wine exporter. However, poor marketing and low margins remain an issue, as shown by the fact that the main importers of Spanish olive oil and wine (Italy[115] and France,[137] respectively) buy bulk Spanish produce which is then bottled and sold under Italian or French labels, often for a significant markup.[115][136]

Spain is the largest producer and exporter in the EU of citrus fruit (oranges, lemons and small citrus fruits), peaches and apricots.[138] It is also the largest producer and exporter of strawberries in the EU.[139]

Food retail

In 2020, the food distribution sector was dominated by Mercadona (24.5% market share), followed by Carrefour (8.4%), Lidl (6.1%), DIA (5.8), Eroski (4.8), Auchan (3.4%), regional distributors (14.3%) and other (32.7%).[140]

Mining

In 2019, the country was the 7th largest producer of gypsum[141] and the 10th world's largest producer of potash,[142] in addition to being the 15th largest world producer of salt.[143]

Mergers and acquisitions

Between 1985 and 2018 around 23,201 deals have been announced where Spanish companies participated either as the acquirer or the target. These deals cumulate to an overall value of 1,935 bil. USD (1,571.8 bil. EUR). Here is a list of the top 10 deals with Spanish participation:

| Date announced | Acquiror name | Acquiror mid-industry | Acquiror nation | Target name | Target mid-industry | Target nation | Value of transaction ($mil) |

| 10/31/2005 | Telefónica SA | Telecommunications Services | Spain | O2 PLC | Wireless | United Kingdom | 31,659.40 |

| 04/02/2007 | Investor Group | Other Financials | Italy | Endesa SA | Power | Spain | 26,437.77 |

| 05/09/2012 | FROB | Other Financials | Spain | Banco Financiero y de Ahorros | Banks | Spain | 23,785.68 |

| 11/28/2006 | Iberdrola SA | Power | Spain | Scottish Power PLC | Power | United Kingdom | 22,210.00 |

| 02/08/2006 | Airport Dvlp & Invest Ltd | Other Financials | Spain | BAA PLC | Transportation & Infrastructure | United Kingdom | 21,810.57 |

| 03/14/2007 | Imperial Tobacco Overseas Hldg | Other Financials | United Kingdom | Altadis SA | Tobacco | Spain | 17,872.72 |

| 07/23/2004 | Santander Central Hispano SA | Banks | Spain | Abbey National PLC | Banks | United Kingdom | 15,787.49 |

| 07/17/2000 | Vodafone AirTouch PLC | Wireless | United Kingdom | Airtel SA | Other Telecom | Spain | 14,364.85 |

| 12/26/2012 | Banco Financiero y de Ahorros | Banks | Spain | Bankia SA | Banks | Spain | 14,155.31 |

| 04/02/2007 | Enel SpA | Power | Italy | Endesa SA | Power | Spain | 13,469.98 |

See also

References and notes

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "INEbase / Demografía y población /Padrón. Población por municipios /Estadística del Padrón continuo. Últimos datos datos". ine.es. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2022". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "CIA World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "People at risk of poverty or social exclusion". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "Labor force, total - Spain". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "Employment rate by sex, age group 20-64". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ "Unemployment in Spain (in Spanish)". datosmacro.expansion.com. DatosMacro. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "Unemployment in Spain". DatosMacro. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Home". The Global Guru. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Economic report" (PDF). Bank of Spain. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ "Ease of Doing Business in Spain". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Euro area and EU27 government deficit both at 0.6% of GDP" (PDF). ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Simon; Sedghi, Ami (15 April 2011). "How Fitch, Moody's and S&P rate each country's credit rating". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ "Scope affirms Spain's credit ratings at A- with a Stable Outlook". Scope Ratings. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ Official report on Spanish recent Macroeconomics, including tables and graphics (PDF), La Moncloa, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2008, retrieved 13 August 2008

- ^ "The Economist Intelligence Unit's quality-of-life index" (PDF). The Economist. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ "El PIB español sigue sin recuperar el volumen previo a la crisis" (in Spanish). Expansión. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Bolaños, Alejandro (28 February 2014). "España logra en el año 2013 el primer superávit exterior en tres décadas". El País.

- ^ a b c d Bolaños, Alejandro (29 February 2016). "El superávit exterior de la economía española supera el 1,5% del PIB en 2015". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Spanish economy: Spanish economy grew 3.2% in 2015 Economy and Business EL PAÍS English Edition". 29 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Fitch Affirms Spain at 'BBB+'; Outlook Stable". Reuters. 29 January 2016.

- ^ a b "España recupera en sólo 2 años el 85% del PIB perdido durante la crisis" (in Spanish). La Razón. 17 October 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ a b "How Spain became the West's superstar economy". Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Tobias Buck (4 January 2017). "Drop in Spanish jobless total is biggest on record". Financial Times.

- ^ a b c d Tadeo, María (25 May 2017). "Record Exports Give Spanish Recovery Some Tiger Economy Sheen". Bloomberg.

- ^ "La economía sumergida mueve más de cuatro millones de empleos". 25 January 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "España sigue entre los países con más economía sumergida".

- ^ "Spain".

- ^ "Spain European Stability Mechanism". www.esm.europa.eu. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ a b c Pérez, Claudi (18 June 2014). "La renta por habitante española retrocede 16 años en comparación con la UE". El País.

- ^ Login required – Eurostat 2004 GDP figures Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ No camp grows on both Right and Left (PDF), European Foundation Intelligence Digest, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008, retrieved 9 August 2008

- ^ "Spain's Economy: Closing the Gap". OECD Observer. May 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ OECD report for 2006 (PDF), OECD, retrieved 9 August 2008

- ^ Bank of Spain Economic Bulletin 07/2005 (PDF), Bank of Spain, archived from the original (PDFaugest 588) on 19 August 2008

- ^ "Spain (Economy section)", The World Factbook, CIA, 23 April 2009, retrieved 1 May 2009,

GDP growth in 2008 was 1.3%, well below the 3% or higher growth the country enjoyed from 1997 through 2007.

- ^ "Recession to hit Germany, UK and Spain", Financial Times, 10 September 2008, retrieved 11 September 2008

- ^ "Hashtag Spain". Hashtag Spain. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "And worse to come". The Economist. 22 January 2009. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Abellán, L. (30 August 2008), "El tirón de las importaciones eleva el déficit exterior a más del 10% del PIB", El País, Economía (in Spanish), Madrid, retrieved 2 May 2009

- ^ Crawford, Leslie (8 June 2006), "Boomtime Spain waits for the bubble to burst", Financial Times, Europe, Madrid, ISSN 0307-1766

- ^ Europa Press (2008), "La economía española retrocede un 0.2% por primera vez en 15 años", El País, Economía (in Spanish), Madrid (published 31 October 2008)

- ^ Economist Intelligence Unit (28 April 2009), "Spain Economic Data", Country Briefings, The Economist, archived from the original on 20 April 2009, retrieved 2 May 2009

- ^ Day, Paul; Reuters (18 February 2009), "UPDATE 1 – Spain facing long haul as recession confirmed", Forbes, Madrid, archived from the original on 10 June 2009, retrieved 2 May 2009

- ^ "FMI empeora sus pronósticos de la economía española". Finanzas.com. 8 July 2009. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ Casqueiro, Javier (19 July 2016). "Spain's deficit: Spain rejects EU deficit reprisals, insisting economy will grow above 3% this year". El País. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d Tadeo, María; Smyth, Sharon R. (29 November 2016). "Housing Crash Turns Spain's Young into Generation Rent". Bloomberg. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ "OECD figures". OECD. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Tremlett, Giles (26 July 2006). "Economic statistics". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ "Official report on Spanish recent Macroeconomics, including tables and graphics" (PDF). La Moncloa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Minder, Raphael; Kanter, James (28 November 2012). "Spanish Banks Agree to Layoffs and Other Cuts to Receive Rescue Funds in Return". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Giles Tremlett in Madrid (8 June 2012). "The Guardian, Spain's savings banks' 8 June 2012". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Mallet, Victor (21 June 2012). "The bank that broke Spain Financial Times". Financial Times. Ft.com. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ (in English) Merkel Economy Adviser Says Greece Bailout Should Bring Penalty, archived from the original on 19 February 2010, retrieved 15 February 2010

- ^ Ross, Emma (18 March 2010). "Zapatero's Bid to Avoid Greek Fate Hobbled by Regions". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Spain, France Take on Crisis with 8.1 Billion-Euro Debt Sale". Bloomberg.com. December 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Spain's jobless rate soars to 17%", BBC America, Business, BBC News, 24 April 2009, retrieved 2 May 2009

- ^ a b "EPA: Evolución del mercado laboral en España". El País. 28 January 2016.

- ^ Agencias (4 November 2008), "La recesión económica provoca en octubre la mayor subida del paro de la historia", El País, Internacional (in Spanish), Madrid, retrieved 2 May 2009

- ^ "Builders' nightmare", The Economist, Europe, Madrid, 4 December 2008, retrieved 2 May 2009

- ^ a b "Iberian_Dawn". The Economist. 2 August 2014.

- ^ "Two-tier flexibility". The Economist. 9 July 2009.

- ^ González, Sara (1 May 2009), "300.000 inmigrantes han vuelto a su país por culpa del paro", El Periódico de Catalunya, Sociedad (in Spanish), Barcelona: Grupo Zeta, archived from the original on 16 May 2010, retrieved 14 May 2009

- ^ a b "EPA: El paro cae al 24,47% con el primer aumento anual de ocupación desde 2008". 24 July 2014.

- ^ García-Pérez, J. Ignacio; Muñoz-Bullón, Fernando (1 March 2011). "Transitions into Permanent Employment in Spain: An Empirical Analysis for Young Workers". British Journal of Industrial Relations. 49 (1): 103–143. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.597.6996. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2009.00750.x. ISSN 1467-8543. S2CID 154392095.

- ^ Domínguez-Mujica, Josefina; Guerra-Talavera, Raquel; Parreño-Castellano, Juan Manuel (1 December 2014). "Migration at a Time of Global Economic Crisis: The Situation in Spain". International Migration. 52 (6): 113–127. doi:10.1111/imig.12023. ISSN 1468-2435.

- ^ Ayllón, Sara (1 December 2015). "Youth Poverty, Employment, and Leaving the Parental Home in Europe". Review of Income and Wealth. 61 (4): 651–676. doi:10.1111/roiw.12122. ISSN 1475-4991. S2CID 153673821.

- ^ Ahn, Namkee; De La Rica, Sara; Ugidos, Arantza (1 August 1999). "Willingness to Move for Work and Unemployment Duration in Spain" (PDF). Economica. 66 (263): 335–357. doi:10.1111/1468-0335.00174. ISSN 1468-0335.

- ^ Wölfl, Anita (2013). "Improving Employment Prospects for Young Workers in Spain". OECD Economics Department Working Papers. doi:10.1787/5k487n7hg08s-en.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requiresjournal=(help) - ^ "El paro registra una caída récord de 310.400 personas y se crean 402.400 empleos, la mayor cifra en 9 años". 24 July 2014.

- ^ Maria Tadeo (26 January 2017). "Spain Unemployment Falls to Seven-Year Low Amid Budget Talks". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Jobs in Spain: Easter hirings bring record monthly drop in unemployment to Spain". El País. 4 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Working in Spain: Unemployment: Social Security affiliations have best May since 2001". El País. 2 June 2017.

- ^ María Tadeo (27 July 2017). "Spanish Unemployment Falls to Lowest Since Start of 2009". Bloomberg.

- ^ Antonio Maqueda (27 July 2017). "EPA: El paro baja de los cuatro millones por primera vez desde comienzos de 2009". El País (in Spanish).

- ^ Manuel V. Gómez (25 October 2018). "EPA: La tasa de paro baja del 15% por primera vez desde 2008". El País (in Spanish).

- ^ "Spain Takes an Economic Gamble on an Unprecedented Wage Hike". Bloomberg. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "España elige el peor momento para ingresar en el club de los países ricos". Publico.es. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Ampudia, David (25 August 2016). "Spain: Economic growth remains firm in Q2 despite political impasse". FocusEconomics. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Antonio Maqueda (30 January 2017). "GDP growth: Spanish economy outperforms expectations to grow 3.2% in 2016". El País.

- ^ a b Antonio Maqueda (28 July 2017). "EPA: El PIB crece un 0,9% y recupera lo perdido con la crisis". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d Lluís Pellicer; Cristina Delgado (3 July 2017). "Property in Spain: Spain's new real estate boom: the rental market". El País. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Maria Tadeo; Sharon R. Smyth (21 July 2017). "The Spanish Housing Market Is Finally Recovering". Bloomberg.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database: October 2021". IMF. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Pérez, Sofía A. (1997). Banking on Privilege: The Politics of Spanish Financial Reform. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3323-8.

- ^ Spain's largest bank, Banco Santander, took part in the UK government's bail-out of part of the UK banking sector. Charles Smith, article: 'Spain', in Wankel, C. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Business in Today's World, California, USA, 2009.

- ^ Penty, Charles (22 May 2010). "CajaSur, Catholic Church-Owned Lender, Seized by Spain Over Loan Defaults". Bloomberg.

- ^ es:Caja Mediterráneo#2011 Intervención y nacionalización

- ^ a b c Muñoz Montijano, Macarena (15 March 2017). "Spain to Recoup Bailout Funds With Merger of Rescued Banks". Bloomberg.

- ^ a b c de Barrón, Iñigo (11 January 2017). "Spanish bank bailout cost taxpayers €41.8, Audit Court finds". El País.

- ^ Minder, Raphael (25 March 2022). "'I'm Old, Not an Idiot.' One Man's Protest Gets Attention of Spanish Banks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ "Spain's Economy: Closing the Gap". OECD Observer. May 2005. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Balmaseda, Manuel; Sebastian, Miguel (2003). "Spain in the EU: Fifteen Years May Not Be Enough" (ebook). In Royo, Sebastián; Manuel, Paul Christopher (eds.). Spain and Portugal in the European Union: The First Fifteen Years. London: Frank Cass. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-203-49661-9.

- ^ Reuters (13 February 2009), "Spain's Vegara does not expect deflation", Forbes, Madrid, archived from the original on 10 June 2009, retrieved 2 May 2009

- ^ Agencias (15 April 2009), "El IPC de marzo confirma la primera caída de los precios pero frena la deflación", El País, Economía (in Spanish), Madrid, retrieved 2 May 2009

- ^ Guijarro, Raquel Díaz (11 March 2016). "España tiene la inflación más baja de los grandes países del euro". Cinco Días (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "A good bet?", The Economist, Business, Madrid, 30 April 2009, retrieved 14 May 2009

- ^ "Spain's Iberdrola signs investment accord with Gulf group Taqa". Forbes. 25 May 2008. Archived from the original on 7 June 2010.

- ^ "Big in America?", The Economist, Business, Madrid, 8 April 2009, retrieved 14 May 2009

- ^ "Fomento ultima un drástico ajuste de la inversión del 17% en 2013". Cincodias.com. 19 September 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "España, technology for life". Spaintechnology.com. 9 August 2012. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Saudi railway to be built by Spanish-led consortium". Bbc.co.uk. 26 October 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Concesionarias españolas operan el 36% de las infraestructuras mundiales Mis Finanzas en Línea". Misfinanzasenlinea.com. 11 November 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ Jiménez, Miguel (15 February 2014). "Pastor prevé que el AVE del desierto abra la puerta a más obras en Arabia Saudí". El País.

- ^ a b "El puerto de Valencia es el primero de España y el trigésimo del mundo". El País. 23 August 2013.

- ^ "La CE prevé que España tendrá superávit comercial en 2014". Comfia.info. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ a b c "A pressing issue". The Economist. 19 April 2014. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "El récord de exportaciones españolas reduce un 31,4% el déficit comercial". El País (in Spanish). 19 August 2016. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Molina, Carlos (19 September 2016). "España, el país del mundo en el que más suben las exportaciones". Cinco Días (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ Ministerio de Economía Industria y Competitividad (22 August 2017). "Las exportaciones crecen un 10% hasta junio y siguen marcando máximos históricos" (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Spain Business Overview".

- ^ "Spain trade balance, exports, imports by country 2015 WITS Data".

- ^ "Spain has the world's most competitive tourism industry". El País. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ "Country profiles". Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ "List of countries with the highest international tourist numbers". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Spain's 2019 tourist arrivals hit new record high, minister upbeat on trend". Reuters. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "75 million and counting: Spain shattered its own tourism record in 2016". El País. 13 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ ">> Exceptional lifestyle". Invest in Spain. Archived from the original on 18 November 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d Méndez-Barreira, Victor (7 August 2016). "Car Makers Pour Money Into Spain". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ ">> Spain in numbers". Invest in Spain. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Energy in Sweden, Facts and figures, The Swedish Energy Agency, (in Swedish: Energiläget i siffror), Table: Specific electricity production per inhabitant with breakdown by power source (kWh/person), Source: IEA/OECD 2006 T23 Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2007 T25 Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2008 T26 Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2009 T25 Archived 20 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine and 2010 T49 Archived 16 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Spain breezes into record books as wind power becomes main source of energy Spain EL PAÍS English Edition". 15 January 2014.

- ^ "La facturación de las exportaciones agroalimentarias españolas creció un 8,36% el año pasado". abc (in Spanish). 25 April 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "La exportación de la industria alimentaria creció el 5,5% en 2014". El País. 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Spain's bumper olive years come to bitter end". BBC News. 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Spain's wine surplus overflows across globe following year of unusual weather". TheGuardian.com. 19 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Spain becomes world's biggest wine exporter in 2014". the Guardian. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Maté, Vidal (29 February 2016). "Spain tops global wine export table, but is selling product cheap". EL PAÍS English Edition. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Agricultural production - orchards". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "La vida efímera de la fresa". ELMUNDO (in Spanish). 9 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Romera, Javier (23 February 2021). "Mercadona baja precios, pero descarta entrar en una guerra con Lidl y Aldi". El Economista.

- ^ "USGS Gypsum Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Potash Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Salt Production Statistics" (PDF).

External links

Statistical resources

- Banco de España (Spanish Central Bank); features the latest and in depth statistics

- Statistical Institute of Andalusia

- National Institute of Statistics Archived 30 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Statistical Institute of Catalonia

- Statistical Institute of Galicia

- OECD's Spain country Web site and OECD Economic Survey of Spain

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Spain

- Tariffs applied by Spain as provided by ITC's ITC Market Access Map[permanent dead link], an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements

Further reading

- Article: Investing in Spain by Nicholas Vardy – September 2006. A global investor's discussion of Spain's economic boom.

- The Pain in Spain: On May Day, Nearly 1 in 5 are Jobless by Andrés Caca, The Christian Science Monitor, 1 May 2009

- Alternatives to Fiscal Austerity in Spain from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, July 2010

- Starting a Business in Spain Steps to Starting a Limited Company in Spain

- O'Neill, Michael F.; McGettigan, Gerard (2005), "Spanish biotechnology: anyone for PYMEs?", Drug Discovery Today Series News and Comment, London: Elsevier (published 15 August 2005), vol. 10, no. 16, pp. 1078–1081, doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03549-X, ISSN 1359-6446, PMID 16182191

- The Catalan economy in the European context