청년국제당

Youth International Party청년국제당 | |

|---|---|

| 지도자 | 노바디(Pigasus는 상징적인 리더로 사용됨) |

| 설립. | 1967년 12월 31일( (이피로서) |

| 본사 | 뉴욕 시 |

| 신문 | 엽스터 타임스 청년국제당 노선 전복 |

| 이데올로기 | 비공식적인 자유주의적 사회주의 무정부 공산주의 녹색 아나키즘 자유연애 |

| 정치적 입장 | 포스트 레프트(비공식) |

| 색상 | 블랙, 그린, 레드 |

| 파티 플래그 | |

| |

흔히 '이피'라고 불리던 청년국제당은 1960년대 후반 자유언론과 반전운동의 미국 청년 중심의 급진적이고 반문화적인 분파였다.1967년 [1][2]12월 31일에 설립되었습니다.1968년 [3]미국 대통령 후보로 돼지(불멸의 돼지)를 전진시키는 등 사회적 현상을 조롱하기 위해 연극적 제스처를 취했다.그들은 매우 연극적이고 반권위적이며 무정부적인 "상징적 정치"[4][5]의 청년 운동으로 묘사되어 왔다.

그들은 거리극장과 정치적 주제의 장난으로 잘 알려져 있었기 때문에, 많은 "구식" 정치 좌파들로부터 무시당하거나 비난을 받았다.ABC 뉴스에 따르면, "이 그룹은 길거리 극장의 장난으로 알려졌으며 한때 '그루초 마르크스주의자'[6]로 불렸다."

배경

이피족은 공식적인 회원 자격이나 위계질서가 없었다.1967년 [7]12월 31일 Abbie와 Anita Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Nancy Kurshan, Paul Krassner가 Hoffmans New York 아파트에서 모임을 갖고 설립하였다.그의 설명에 따르면, 크라스너는 그 이름을 만들었다.언론이 히피(hippie)를 만들었다면 우리 다섯 명이 히피(yppie)를 부화시킬 수는 없었을까.Abbie Hoffman은 썼다.[4][8]

이피족과 관련된 다른 활동가로는 스튜 앨버트, 주디 검보,[9] 에드 [10]샌더스, 로빈 모건,[11] 필 오크스, 로버트 M 등이 있다.Ockene, 윌리엄 쿤스 틀러, 요나 Raskin, 스티브 Conliff, 제롬 Washington,[12]존 싱클레어, 짐 Retherford,[13][14]다나 Beal,[15][16]베티(자리아)Andrew,[17][18]Joanee 자유, 대니 Boyle,[19]벤 Masel,[20][21]톰 Forcade,[22][23]폴 Watson,[24]데이비드 Peel,[25]물결 바늘 그래비, 아롱 Kay,[26][27]Tuli Kupferberg,[28]질 Johnston,[29]데이지는 D.Eadhead,[30][31일]Leatrice Urbanowicz,[32][33]밥 Fass,[34][35]마이어 Vishner,[36][37]앨리스 Torbush,[38][39]펜실베이니아트릭 K. Kropa, Judy Lampe,[40] Steve DeAngelo,[41] Dean Tuckerman,[38] Dennis Peron,[42] Jim Fouratt,[43] Steve Wessing,[21] John Penley,[44] Pete Wagner, Brenton Lengel.[45][46]

반전 시위에서는 이피 국기가 자주 눈에 띄었다.깃발은 검은색 바탕에 가운데에 오각형의 붉은 별이 있고 그 위에 녹색 대마초 잎이 겹쳐져 있었다.익명의 익명의 익명의 이피는 뉴욕타임즈와의 인터뷰에서 "검은색은 무정부 상태를 위한 것이다.빨간 별은 5점짜리 프로그램입니다.이 잎은 환경을 [47]오염시키지 않고 생태적으로 돌멩이질을 하기 위한 마리화나용입니다.이 깃발은 호프만의 책 [48]훔치기에도 언급되어 있다.

애비 호프만과 제리 루빈은 1969년 5개월간의 시카고 7대 음모 재판을 둘러싼 홍보로 인해 가장 유명하고 베스트셀러 작가가 되었다.그들은 둘 다 "이념은 뇌병"이라는 문구를 사용하여 이피족을 규칙에 따라 게임을 한 주류 정당들과 분리시켰다.호프만과 루빈은 1968년 8월 민주당 전당대회에서 범죄 공모와 폭동을 선동한 혐의로 기소된 피고인 7명 중 가장 화려한 인물이었다.호프만과 루빈은 재판을 이피 익살극의 무대로 이용했다.한때 그들은 법복을 [49]입고 법정에 나타났다.

오리진스

이피라는 용어는 1967년 섣달 그믐날에 애비와 아니타 호프만과 함께 크라스너에 의해 발명되었다.Paul Krassner는 2007년 1월 Los Angeles Times 기사에서 다음과 같이 쓰고 있습니다.

히피의 급진화를 나타내는 이름이 필요했습니다.저는 이미 존재했던 현상에 대한 라벨로서 이피를 생각해 냈습니다사이키델릭 히피와 정치 운동가들의 유기적인 연합입니다반전 시위에서 교차수정을 하는 과정에서 우리는 이 나라에서 담배를 피운 죄로 아이들을 감옥에 [50]가두는 것과 지구 반대편에서 네이팜탄으로 그들을 태워 죽이는 것 사이에는 선형적인 연관성이 있다는 것을 깨닫게 되었습니다.

아니타 호프만은 이 단어를 좋아했지만, 뉴욕 타임즈와 다른 "가벼운 타입"들은 이 운동을 진지하게 받아들이기 위해 좀 더 공식적인 이름이 필요하다고 느꼈다.같은 날 밤 그녀는 청년국제당을 창당했다.왜냐하면 청년국제당은 운동을 상징하고 [51]말장난도 잘했기 때문이다.

청년국제당이라는 명칭과 함께, 그 단체는 기쁨의 함성처럼 간단히 이피라고 불렸다.[52]'이피'가 무슨 뜻이죠?Abbie Hoffman은 썼다."에너지 – 즐거움 – 치열함 – 느낌표!"[53]

제1회 기자 회견

야피 부부는 1968년 8월 시카고에서 열린 민주당 전당대회를 5개월 앞둔 3월 17일 뉴욕에서 첫 기자회견을 열었다.주디 콜린스가 기자 [1][54][55]회견에서 노래를 불렀다.시카고 선타임즈는 "Yipes!야피족이 온다!"[50]

신국 개념

| 시리즈의 일부 |

| 사회주의자 미국 |

|---|

이피 "신국" 개념은 대안적이고 반문화적인 기관의 설립을 요구했다: 식품 협동조합; 지하 신문과 지인; 무료 클리닉과 지원 단체; 예술가 집단; 포트래치, "스왑미트"와 무료 상점; 유기농 농업/영농; 해적 라디오, 불법 녹화 및 공중 접근 텔레비전; 무료; 학교 등이피들은 이러한 협력 기관과 급진적인 히피 문화가 기존 시스템을 대체할 때까지 확산될 것이라고 믿었다.이러한 아이디어와 관행의 대부분은 디거스,[56][57] 샌프란시스코 마임 극단, 즐거운 장난꾸러기/데드헤드,[58][59][60] 호그 팜,[61] 레인보우 패밀리,[62] 에살렌 연구소,[63] 평화와 자유당, 화이트 팬더 파티, 팜과 같은 다른 (중복과 혼합) 반문화 단체에서 나왔다.이들 집단과 이피족 사이에는 많은 겹침, 사회적 상호작용, 이종 교배 현상이 있었고, 그래서 비슷한 영향과 [65][66]의도가 있었을 뿐 아니라 크로스오버 [64]멤버쉽도 많았다.

우리는 국민이다.우리는 새로운 국가입니다,"라고 YIP의 New Nation Statement는 히피 운동의 급증에 대해 말했다."우리는 모든 사람이 자신의 삶을 통제하고 서로를 돌봤으면 합니다.삶의 파괴와 이익 [67]축적이 목적인 태도, 제도, 기계를 용납할 수 없다.

목표는 국경 없는 히피 반문화와 그 공동 정신에 뿌리를 둔 분산되고 집단적이며 무정부주의적인 국가였다.Abbie Hoffman은 다음과 같이 썼다.

우리는 정당을 조직하여 Amerika를 이기지 않을 것이다.우리는 마리화나 잎처럼 튼튼한 새로운 국가를 건설함으로써 그것을 [68][69]할 것이다.

"새로운 국가"를 위한 깃발은 가운데에 빨간색 5개의 뾰족한 별이 있는 검은색 배경과 그 위에 녹색 마리화나 잎이 겹쳐진 것으로 구성되었습니다(YIP [70]깃발과 동일).

시카고 역사 박물관은 새로운 국가를 [71]위한 다른 깃발을 보여준다.그것은 마리화나 잎이 아니다.그것은 1달러 지폐 뒷면에 보이는 피라미드의 모든 것을 보는 눈처럼 보이는 아래에 NOW라는 단어를 가지고 있다.

문화와 행동주의

이피들은 종종 로큰롤과 마르크스 형제, 제임스 딘, 레니 브루스와 같은 불손한 대중문화계 인사들에게 경의를 표했다.많은 이피들은 베이비 부머 TV나 팝 레퍼런스가 포함된 별명을 사용했다. (포고는 1970년 지구의 날 포스터에서 처음 사용된 "우리는 적을 만났고 그는 우리다"라는 유명한 슬로건을 만든 것으로 유명하다.)

제시 워커가 Reason 잡지에 쓴 것처럼, 팝 문화에 대한 야피족의 사랑은 구좌파와 신좌파를 차별화하는 한 가지 방법이었다.

40년 전, 이피들은 뉴 레프트의 정치적 급진주의와 반문화의 긴 머리의 풀 흡연 생활 방식을 융합시켰기 때문에 특이해 보였다.오늘날 그러한 조합은 너무 익숙해서 많은 사람들은 시위대와 히피들이 처음에는 서로를 불신했다는 사실조차 깨닫지 못한다.오늘날 이피들에게 가장 궁금한 것은 강경좌파 정치와 대중문화에 대한 깊은 인식을 섞은 방식이다.아비 호프만은 앤디 워홀과 피델 카스트로의 스타일을 결합하고 싶다고 발표했다.제리 루빈은 그의 여자친구뿐만 아니라 "도프, 컬러 TV, 그리고 폭력 혁명"을 위해 Do it!심지어 60년대 후반 좌파로부터 마지못해 존경을 받았던 대중문화의 형태를 찬양할 때 - 로큰롤 - "우리에게 인생/비트를 주고 우리를 자유롭게 해준" 루빈의 음악가 목록에는 제리 리 루이스와 보 디들리와 같은 요란한 오리지널뿐만 아니라 파비안과 프랭키 아발론, 대부분의 상업적 과자들이 록을 남겼다.불충분하다고 경멸받고 있다.한 장에서 루빈은 "백인 이념 좌파"가 자리를 잡으면 "록 댄스는 금기시되고 미니스커트, 할리우드 영화, 만화책은 불법이 될 것"이라고 불평했다.이 모든 것은 카스트로, 마오 주석, 호치민 등 영웅들이었던 자칭 공산주의자로부터 비롯되었다.

이피들이 대중문화를 무비판적으로 삼킨 것은 아니다(호프먼이 TV 밑바닥에 '개소리'라고 적힌 간판을 붙여 놓았다). 그들은 언론의 꿈의 세계를 싸워야 할 [72]또 다른 영역으로 봤기 때문이다.

시위나 퍼레이드에서, 이피들은 종종 사진에 찍히는 것을 막기 위해 페이스 페인트를 칠하거나 화려한 반다나를 착용했다.다른 야피족들은 그들의 은밀한 동료들이 그들의 [73][74][75]장난에 필요한 익명을 허용하며 스포트라이트를 즐겼다.

우드스톡에서 일어난 문화적인 개입 중 하나는 애비 호프먼이 존 싱클레어의 투옥에 반대하는 연설을 하려고 하는 The Who의 공연을 방해하면서 1969년 잠복 중인 마약 담당관에게 두 개의 연장을 제공한 후 징역 10년을 선고받았다.기타 연주자 피트 타운센드는 기타로 호프만을 무대 밖으로 [76]내보냈다.

이피족은 뉴 레프트에서 처음으로 [77]대중매체를 착취한 사람들이다.화려하고 연극적인 이피 액션은 언론 보도를 끌어모으고 사람들이 그들 [78]안에 있는 "억압된" 이피를 표현할 수 있는 무대를 제공하기 위해 만들어졌다.제리 루빈은 "우리는 모든 비이피족이 억압된 이피족이라고 믿는다"고 Do it에서 썼다. "우리는 [78]모든 사람에게서 이피를 끌어내려고 노력한다."

초기 이피 액션

이피들은 [79]유머 감각으로 유명했다.많은 직접적인 행동들은 종종 풍자적이고 정교한 장난이거나 꾸며낸 [80]것이었다.1967년 10월 펜타곤에 대한[81][82] 펜타곤의 공중부양 신청과 루빈, 호프만, 그리고 이 행사에서 회사가 조직한 건물에서의 대규모 시위/모크 공중부양 신청은 두 달 [83]후 설립되었을 때 이피에 대한 기조를 세우는 데 도움을 주었다.

"이피"라는 용어가 만들어지기 직전의 또 다른 유명한 장난은 1967년 8월 24일 뉴욕에서 있었던 게릴라 극장 행사였다.애비 호프만과 미래의 이피족들은 뉴욕 증권거래소 투어에 성공해 관람객 갤러리 발코니에서 아래층 상인들에게 진짜와 가짜 달러를 주먹을 던졌고, 일부는 야유를 퍼부었고, 다른 이들은 가능한 [84]한 빨리 돈을 움켜쥐기 위해 안간힘을 쓰기 시작했다.관람객들은 비슷한 사고를 막기 위해 유리 방벽이 설치될 때까지 갤러리를 폐쇄했다.

뉴욕증권거래소(NYSE) 행사 40주년을 맞아 CNN 머니 에디터 제임스 레드베터는 이 유명한 사건을 다음과 같이 묘사했다.

장난꾸러기들이 난간 너머로 1달러짜리 지폐 한 움큼을 던지기 시작했다.(정확한 지폐 수는 논쟁의 대상이다; 호프만은 나중에 300이라고 썼지만, 다른 사람들은 30, 40개까지만 던져졌다고 말했다.)

아래에 있는 브로커들, 점원들, 그리고 주식 주자들 중 일부는 웃으며 손을 흔들었고, 다른 사람들은 화가 나서 야유를 보내며 주먹을 휘둘렀다.지폐는 경비원들이 건물에서 이 그룹을 제거하기 전에 땅에 떨어질 시간이 거의 없었지만, 뉴스 사진이 찍혔고 증권거래소는 순식간에 상징적인 지위로 미끄러졌다.

일단 밖으로 나오자, 운동가들은 손을 잡고 "자유!어느 순간 호프만은 원 중앙에 서서 미친 듯이 웃으며 5달러 지폐의 가장자리에 불을 붙였지만 뉴욕증권거래소 주자는 그에게서 지폐를 받아 발로 밟으며 말했다. "당신은 역겨워요."

만약 이 장난이 다른 어떤 것도 이루지 못했다면, 그것은 미국에서 가장 이상하고 창의적인 시위자 중 한 명이라는 호프만의 명성을 굳히는 데 도움이 되었다."이피" 운동은 빠르게 미국 반문화의 [85]중요한 부분이 되었다.

1968년 3월 22일 경찰과 충돌이 있었는데, 이피족이 이끄는 많은 반문화 청년들이 "입인"[86][87]을 위해 중앙역으로 내려왔다.그날 밤, '빌리지 보이스'의 돈 맥닐이 "박스 [88][89]협곡에서의 무의미한 대결"이라고 부른 경찰과 격렬한 충돌이 일어났다.한 달 후, 이피스는 센트럴 파크에서 평화롭게 진행되어 2만 명의 [90]인파가 몰린 "입-아웃" 행사를 기획했다.

작가 데이비드 암스트롱은 저서 '트럼펫 투 무기: 미국의 대안 미디어'에서 공연 예술, 게릴라 극장, 정치적 불복종이라는 이피 혼성체가 종종 60년대 미국 좌파/평화 운동의 감성과 직접적으로 충돌했다고 지적합니다.

구조보다는 자발성을 강조한 혁명에 대한 이피들의 비정통적인 접근과 지역 사회 조직보다는 언론 공세는 그들을 주류 문화만큼이나 나머지 좌파들과 거의 대립하게 만들었다.버클리 바브에서 쓴 (제리) 루빈은 "시위에 대해 말할 수 있는 최악의 것은 시위가 지루하다는 것입니다. 평화 운동이 대중 운동으로 성장하지 않은 이유 중 하나는 평화 운동, 즉 그 문학과 그 사건들이 지루하기 때문입니다.혁명적인 [91]콘텐츠를 전달하기 위해서는 좋은 극장이 필요하다.

하원 반미 활동 위원회

하원 반미활동위원회(HUAC)는 1967년 제리 루빈과 애비 호프만을 소환했고, 1968년 민주당 전당대회 이후 다시 소환했다.야피 부부는 언론의 관심을 이용해 이 절차를 조롱했다.루빈은 미국 독립전쟁 군인 복장을 하고 [92]한 회의에 참석자들에게 미국 독립선언서 사본을 나눠주었다.

또 다른 경우, 경찰은 건물 입구에서 호프만을 제지하고 미국 국기를 착용했다는 이유로 그를 체포했다.호프만은 언론을 향해 "조국을 위해 줄 셔츠가 하나밖에 없는 것을 유감스럽게 생각한다"고 조롱했다. 반면 혁명 애국자 네이선 헤일의 마지막 말을 바꾸어 표현했다. 반면 그와 일치하는 베트콩 깃발을 걸치고 있던 루빈은 [93]경찰도 자신을 체포하지 않은 공산주의자들이라고 소리쳤다.

50년대에 가장 효과적인 제재는 테러였다.HUAC의 거의 모든 광고는 '블랙리스트'를 의미했다.그의 누명을 벗을 기회도 없이 증인은 갑자기 친구도 직업도 없는 자신을 발견하곤 했다.그러나 1969년에 HUAC 블랙리스트가 어떻게 SDS 활동가를 공포에 떨게 할 수 있었는지 보는 것은 쉽지 않다.제리 루빈과 같은 목격자들은 미국 기관에 대한 경멸을 공개적으로 자랑해왔다.HUAC로부터의 소환장이 애비 호프만이나 그의 [94]친구들을 스캔들 시킬 것 같지는 않다.

68년 시카고

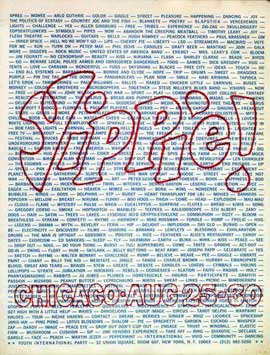

이피 연극은 1968년 시카고에서 열린 민주당 전당대회에서 절정에 달했다.YIP는 반문화의 축하와 [95]국가의 상태에 대한 항의인 6일간의 삶의 축제를 계획했다.이것은 "죽음의 협약"에 대항하기 위한 것이었다.이는 "냄비와 정치를 정치적 잔디에 섞는 운동, 즉 히피와 신좌파 [96]철학을 교차 수정하는 운동"이 될 것이라고 약속했다.대회 전 야피스의 선정적인 발언은 LSD를 시카고의 수도에 넣겠다는 비꼬는 협박을 포함한 연극의 일부였다."해변에서 떡칠 거야!"우리는 황홀경의 정치를 요구한다!포복성 미트볼을 버려라!그리고 항상 '이피'!시카고 – 8월 25-30일' 이피의 요구 리스트 중 첫 번째: "베트남에서의 즉각적인 전쟁 종료."[97][98]

이피 주최측은 유명한 음악가들이 생명의 축제에 참가하여 전국에서 수십만 명에서 수십만 명의 군중을 끌어 모으기를 희망했다.시카고 시는 이 페스티벌에 대한 어떠한 허가도 거부했고 대부분의 음악가들은 이 프로젝트에서 손을 뗐다.공연에 동의한 록 밴드들 중 MC5만 시카고에 와서 연주했고 그들의 세트는 수천 명의 관객과 경찰의 충돌로 인해 부족해졌다.Phil Ochs와 몇몇 다른 싱어송라이터들도 축제 [99]기간 동안 공연을 했다.

민주당 전당대회 기간 동안 열린 생명의 축제와 다른 반전 시위에 대응하여, 시카고 경찰은 시위대와 반복적으로 충돌했고, 수백만 명의 시청자들이 그 행사의 광범위한 TV 방송을 시청했다.8월 28일 저녁, 경찰은 콘래드 힐튼 호텔 앞에서 "전 세계가 지켜보고 있다"[100]는 구호를 외치는 시위자들을 공격했다.이는 [101]'경찰 폭동'이었다고 미국 폭력의 원인과 예방에 관한 전미위원회는 결론지었다.

"경찰 측에서는 경찰 개개인과 많은 경찰들이 군중 분산이나 [101]체포에 필요한 힘을 훨씬 초과하는 폭력 행위를 저질렀다는 결론을 피할 수 없을 만큼 충분히 거친 몽둥이를 휘두르고, 증오의 외침, 불필요한 구타가 있었다."

음모 재판

전대에 이어 8명의 시위자들이 폭동 선동 공모 혐의로 기소되었다.5개월 동안 진행된 그들의 재판은 대대적으로 홍보되었다.시카고 세븐은 애비 호프먼과 제리 루빈을 [102][103][104]포함한 뉴 레프트의 단면을 대표했다.

존 벡맨은 그의 저서 "American Fun: Four Centuries of Joyous Reval"에서 다음과 같이 쓰고 있다.

헤어 신경 쓰지 마세요, 소위 시카고 에잇 (당시 7) 재판은 60년대의 반문화적인 공연이었습니다.게릴라 극장은 그 시대의 시민 분쟁을 결정하기 위해 법정 희극을 응시했다: 운동 대 기성세력.SDS의 리더인 레니 데이비스와 톰 헤이든('포트 휴런 성명'을 쓴 사람), 대학원생 리 와이너와 존 프로인스, 54세의 건장한 기독교 사회주의자 데이비드 델링거, 이피 루빈과 호프먼 등 8명의 피고인은 이견의 세계를 대표하도록 최종 선택된 것으로 보인다."콘스피어, 빌어먹을." 호프만이 농담했다."[105]점심 먹는 것에 대해 의견이 일치하지 않았습니다."

스튜 알버트, 울프 로웬탈, 브래드 폭스, 로빈 파머를 포함한 몇몇 다른 이피들은 이 [106]사건에서 "불기소된 공모자"로 지목된 다른 18명의 활동가들 중 한 명이었다.피고들 중 5명이 처음에는 폭동을 선동하기 위해 주 경계를 넘은 혐의로 유죄 판결을 받았지만, 곧 항소심에서 모든 유죄 판결이 뒤집혔다.피고인 호프만과 루빈은 인기 작가와 연설가가 되어 그들이 등장하는 곳마다 이피의 호전성과 희극을 퍼뜨렸다.예를 들어, 호프만이 머브 그리핀 쇼에 출연했을 때, 그는 미국 국기가 그려진 셔츠를 입었고, CBS는 이 쇼가 [107]방영되었을 때 그의 이미지를 어둡게 만들었다.

이피 운동

청년국제당은 루빈, 호프만, 그리고 다른 창당자들을 넘어 빠르게 퍼져나갔다.YIP는 특히 뉴욕시, 밴쿠버, 워싱턴 DC, 디트로이트, 밀워키, 로스앤젤레스, 투싼, 휴스턴, 오스틴, 콜럼버스, 데이턴, 시카고, 버클리, 샌프란시스코 및 [108]매디슨에 지부를 두고 있습니다.1971년 [109]위스콘신주 매디슨에서 열린 "신국회의"를 시작으로 1970년대까지 YIP 회의가 있었다.

1971년 4월 4일 매디슨 회의 마지막 날, 수백 명의 전경들이 지역 이피들이 행사를 위해 조직한 블록 파티를 해산했고, 결과적으로 [110]이피들과 경찰들 사이에 거리 충돌이 일어났다.

거리 시위

1969년 11월 15일 워싱턴 D.C.에서 열린 반전 시위에서 동부 해안의 이피스는 수천 명의 젊은이들을 이끌고 법무부 [111]청사를 습격했다.

1970년 8월 6일, L.A. 이피스는 디즈니랜드를 침공하여 시청에 신국기를 게양하고 톰 소여의 섬을 점령했다.폭동 진압 경찰이 이피족과 대치하는 동안, 테마 공원은 공원 역사상 두 번째로 일찍 폐쇄되었다.[112]200여 명의 이피족 중 23명이 [113]체포됐다.

밴쿠버 이피스는 1970년 5월 9일 리처드 닉슨의 캄보디아 침공과 켄트주 [114]학생 총격에 항의하기 위해 워싱턴주 블레인에 침입했다.

콜럼버스 이피스는 1972년 5월 11일 닉슨의 북베트남 하이퐁항 [115]광산에 대한 대응으로 그 도시에서 일어난 폭동을 선동한 혐의로 기소되었다.그들은 무죄 판결을 받았다.

YIP는 1971년 5월 초 며칠에 걸쳐 워싱턴 D.C.의 교차로와 다리를 점거함으로써 미국 정부를 폐쇄하려 했던 베트남 전쟁 반대[98] 운동가 연합 회원이었다.노동절 시위는 미국 [116][117]역사상 가장 큰 규모의 대규모 체포를 초래했다.

이피들 사이에서 자주 제기되는 '전국적인' 불만은 뉴욕 중앙 본부 지부가 다른 지부가 존재하지 않는 것처럼 행동하고 의사결정 과정에서 그들을 배제한다는 것이었다.1972년 오하이오에서 열린 YIP 회의에서 이피스는 애비와 제리가 너무 유명하고 부자가 [118]되었기 때문에 당에서 공식 대변인으로 '제외'하는 투표를 했다.

1972년 마이애미 [15][122][123]해변에서 열린 공화·민주당 전당대회에서 이피스와 [119][120][121]지피스가 시위를 벌였다.마이애미 시위 중 일부는 1968년 시카고 시위보다 더 크고 호전적이었다.마이애미 이후, 지피족은 다시 [124]이피족으로 진화했다.

1973년, 이피스는 워터게이트 공모자인 존 미첼의 맨해튼 자택으로 행진했다.

500명의 완고한 이피들이 미첼의 집에서 마지막 행진을 벌였습니다. 워터게이트가 아닌 맨해튼 5번가에 있는 웅장한 아파트 건물이었습니다."마사 미첼을 풀어줘!"라고 그들은 구호를 외쳤다.존, 엿 먹어!미첼 부부가 마침내 창가에 나타나 소동이 무엇인지 확인했을 때, 석공들은 그들의 마지막 "로앤 오더와의 눈 마주침"을 소중히 여겼다.그 순간을 기념하기 위해, 그들은 미첼의 집 [125]문 앞에 거대한 마리화나 관절을 설치했다.

이피스는 1973년 리처드 [126]닉슨 대통령 취임식에서 특히 강한 영향력을 보이며 미국 대통령 [126][127][128]취임식에서 정기적으로 항의했다.1980년 [31][129]디트로이트에서 열린 공화당 전당대회와 1984년 [130][131]댈러스에서 열린 공화당 전당대회에서도 이피스는 99명이 체포됐다.

댈러스, 8월 22일 - 99명의 시위대가 오늘 공화당 전당대회 밖에서 쇼핑객들을 위협하고 페인트를 튀기고 성조기를 불태운 시내를 둘러본 후 체포됐다.청년국제당(Yppies) 소속인 이피스는 댈러스의 [132]무더위 속에 시청의 반사 수영장에 뛰어들어 시내를 누비며 소란을 피웠다.

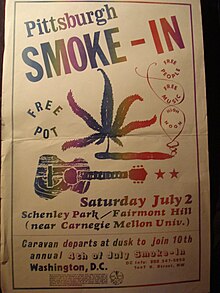

스모크인

이피스는 1970년대와 1980년대에 걸쳐 북미 전역에서 마리화나 "흡연"을 조직했다.1970년 [16][133]7월 4일 워싱턴 D.C.에서 YIP의 첫 번째 흡연자가 25,000명이었다.많은 히피 시위자들이 빌리 그레이엄, 밥 [134]호프와 함께 근처의 "Honor America Day" 축제에 몰려가면서 문화 충돌이 있었다.

1971년 8월 7일, 밴쿠버에서 이피족 흡연자가 경찰의 공격을 받아 캐나다 [135]역사상 가장 유명한 시위 중 하나인 가스타운 폭동이 일어났다.

매년 7월 4일 워싱턴 D.C.에서 열리는 이피 흡연은 반문화 전통이 [41][136][137][138]되었다.

대체 문화

이피들은 그들의 반문화 공동체에 대체 기관을 조직했다.투싼에서, 이피스는 무료 가게를 [139]운영했고, 밴쿠버에서, 이피스는 종종 괴롭힘을 당하는 히피 공동체를 위한 법적 도움을 제공하기 위해 인민방위기금을 설립했습니다. 밀워키에서, 이피스는 이 도시의 첫 번째 식품 [140]협동조합을 출범시키는 것을 도왔습니다.

많은 이피들이 지하 언론에 연루되었다.주요 지하 신문이나 대체 잡지 Yippies 아베 펙(시카고 종자)[141]제프 Shero Nightbyrd(뉴욕의 '쥐 띠'와 '오스틴 태양)[142]폴 Krassner(그 Realist)[1][143]로빈 모건(Ms. 잡지)[144]스티브 Conliff 밥 머서(PurpleBerries, 사워 Grapes[145]고 콜럼버스 프리 프레스)[146]을 포함한 몇몇은 편집인들. (조지아 직선과 노란 색. 핸강 주위 저널,[147] 헨리 바이스본(ULTRA),[148] 제임스 레더포드(The Rag), 메이어 비슈너(LA [36][149][150]위클리), 매튜 랜디 스틴과 스튜 앨버트(버클리 [151][152]일족), 톰 포스케이드(언더그라운드 프레스 신디케이트와 [153]하이타임즈), 가브리엘 [154]샨(대안).뉴욕 이피 코카 크리스탈은 인기 있는 케이블 TV 프로그램인 '춤을 못 추면 혁명을 [155]지킬 수 있다'를 진행했습니다.

이피들은 얼터너티브 음악과 영화에서 활약했다.싱어송라이터 필 옥스와 데이비드 필은 이피들이었다."저는 1968년 초에 이피가 어떤 사람이 될 것인지에 대한 생각을 형성하고 당을 설계하는 것을 도왔습니다,"라고 Ochs는 시카고 8번 [156]재판에서 증언했습니다.

희한하고 전설적인 컬트 영화 메디신 볼 캐러밴(일부 톰 포케이드에 [157]의해 재정 지원됨)은 이피 중퇴자들과 그 [158][159]시대의 다양하고 매혹적이고 역동적인 인물들을 연대기화했다.영화 제목은 나중에 논란이 됐던 "우리는 당신의 딸들을 위해 왔다"[160]로 바뀌었다.

급진적인 음악가들은 보통 이피가 후원하는 행사에서 열광적인 청중들을 발견했고 자주 연주를 제의했다.YIP 계열의 존 싱클레어는 1968년 민주당 전당대회 당시 링컨 파크에서 연주했던 디트로이트의 프로토펑크 밴드 MC5를 [161][162][163]관리했다.1970년 피트 시거는 제리코 비치 [164]파크를 통과하는 고속도로 건설에 반대하는 밴쿠버 이피 집회를 열었다.영향력 있고 상징적인 프로토펑크 밴드인 뉴욕 돌스의 첫 콘서트는 [165]1970년대 다나 빌의 마리화나 체포에 대한 법적 비용을 지불하기 위한 기금을 모으기 위한 이피 자선 행사였다.

청년국제당은 [166][167][168][169][170][171]1979년 인종차별 반대 운동의 미국 지부를 설립했다.인종차별에 반대하는 바위 USA는 나중에 [172][173][174]1983년에 비평가들의 찬사를 받으며, 이피가 조직하고 널리 알려진 레이건 반대 국가 순회공연으로 바뀌었습니다.투어의 잘 알려진 밴드로는 미셸 [175]쇼크, 데드 케네디스,[176] 크루시팩스, MDC,[177] Cause for Alarm, Toxic Reasons, Static Disruptors [178][179]등이 있다.젊은 우피 골드버그가 샌프란시스코 [180]R-A-R 쇼에서 스탠드업 코미디를 선보였다.

밴쿠버 이피 켄 레스터와 데이비드 스패너는 캐나다에서 가장 악명 높은 두 정치 펑크 밴드인 D.O.A.와 더 서브휴먼스의 매니저였다.[181][182][183]뉴욕 이피/하이 타임즈 출판사 톰 포케이드는 1978년 섹스 피스톨스의 미국 [184][185][186]투어 장면을 담은 펑크 록에 관한 최초의 영화 중 하나인 디오아에 자금을 지원했다.

악명 높은 볼티모어 이피 존 워터스는 인터뷰에서 "나는 이피 선동가였고 리틀 리처드처럼 보이고 싶었다"고 주장하면서 유명한 독립 영화 제작자가 되었다.그때는 히피 포주처럼 옷을 입었어요.[187] 펑크가 아직 없어서요."

시스템 장난

이피들은 체제와 그 권위를 조롱했다.1968년 미국 대통령에 돼지(피가수스)를 지명했던 청년국제당은 1976년 '[188][189][190]공식' 후보로 노바디(Nobody)를 대통령으로 선출한 것으로 유명하다.

밴쿠버 이피 베티 "자리아" 앤드류는 1970년 [18]청년 국제당의 시장 후보로 출마했다.그녀의 선거 공약 중 하나는 만유인력의 법칙을 포함한 모든 법을 폐지하여 모두가 약에 [17]취하도록 하는 것이었다.같은 해 버클리 이피 스튜 앨버트는 알라메다 카운티 보안관 선거에 출마해 현직 보안관에 도전해 6만5000표를 [191]얻었다.

1970년 디트로이트 이피스는 시청에 가서 제너럴 모터스 빌딩 폭파 허가를 신청했다.허가가 거부된 후, 이피 부부는 당신이 시스템을 바꾸기 위해 시스템 내에서 일할 수 없다는 것을 보여주는 것이라고 말했다.디트로이트 이피 점프인 잭 [192]플래시는 "이는 합법적인 채널에 대한 나의 마지막 희망을 파괴한다"고 말했다.

로빈 모건, 낸시 커샨, 샤론 크렙스, 주디 검보를 포함한 몇몇 여피족들은 게릴라 극장 페미니스트 단체인 W.I.T.C.H.에서 활동했으며, 이 단체들은 "희생성, 유머, 행동주의"를 결합했다."[193][194]

1970년 11월 7일, 제리 루빈과 런던 이피스는 인기 있는 영국 진행자의 TV 프로그램에 출연했을 때 프로스트 프로그램을 인수했다.이 모든 혼란 속에서, 이피족 한 명이 진행자 데이비드 프로스트의 벌어진 입을 향해 물총을 발사했고, 방송사는 광고 중단을 요구했고, 쇼는 끝이 났다.데일리 미러의 배너 헤드라인: "서리 프리커트"[195]

파이 던지기

정치적 행위로서의 파이 투척은 이피들에 [196]의해 발명되었다.1969년 10월 14일 인디애나주 블루밍턴에서 처음으로 정치적 파이를 던진 것은 전직 지하 신문 편집자이자 제리 루빈의 두잇의 대필자인 짐 레더포드가 전 UC 버클리 총장인 클라크 [197]커의 면전에 크림파이를 던졌을 때였다.레더포드 또한 가장 먼저 체포되었다.다음 파이는 1970년 [198]대통령 직속 외설 및 포르노 위원회 위원에게 못을 박은 톰 포케이드에 의해 던져졌다.1977년 콜럼버스 [199][200]이피 스티브 콘리프 피에 오하이오 주지사 제임스 로즈.

아론 "파이맨" 케이는 가장 유명한 이피 파이 [26][201]던지기 선수가 되었다.Kay의 많은 목표에는 Sen이 포함되어 있었다.다니엘 패트릭 모이니한 [202]뉴욕시장, 아베 빔,[203] 보수운동가 필리스 슐라플리,[204] 워터게이트 강도 프랭크 스터기스,[205] 윌리엄 콜비 전 중앙정보국장, 내셔널 리뷰 발행인/편집인 윌리엄 F. 버클리와 [206]디스코 스튜디오 54의 주인 스티브 [207]루벨입니다

대통령 후보 없음 및 "None of the above"

아마도 이피스의 백조 노래 중 하나는 1976년 Isla Vista 시 자문 위원회에 의해 캘리포니아 주 산타 바바라 카운티에서 실시된 선거 투표용지에 새로운 투표 옵션인 "None of the Of the Over"를 배치하기 위한 획기적인 노력이었을 것이다.이는 이피들의 초기 자유주의적 충동과 이번 선거 대안의 미국 내 첫 사례로, 두 명의 공동 발의자 중 한 명인 매튜 스틴은 "반제도적 이피 업유어스"라고 표현했다.수년 전 스틴은 버클리 부족의 기자로 스튜 앨버트의 이피 운동가였다.이 참신한 발의안은 의회에 의해 만장일치로 채택되어 전국에 파급 효과를 가져왔다.[208]네바다 유권자들은 1986년 주 선거법 개정에서 이 옵션을 승인했다.

1976년, 국가적인 이피들은 Isla Vistans로부터 힌트를 얻어, [188][189][190]70년대 중반 워터게이트 이후의 불안에 스스로 목숨을 끊은 캠페인인 Nobody for President를 지지했다.이피 선거운동 슬로건:[209] "아무도 완벽하지 않다." (한편, 이피 운명의 묘한 반전 속에서 매튜 스틴은 제리 브라운을 대통령으로 선출하기 위한 학생 주도의 선거운동의 재무관이 되었고, 그 해 대통령 선거운동 기간 동안 "대통령을 위한 아무도 없다"와 지미 카터 둘 다와 경쟁했다.)

Isla Vista의 지역 정치, 대통령 선거 운동 및 이피들의 실험적인 조합으로부터, 이 예기치 않은 투표 이니셔티브의 이름과 정신은 빠르게 퍼져나갔다. 즉, 위의 음악 축제, 라디오 및 텔레비전 쇼, 록 밴드, 티셔츠, 버튼, (후일 10년) 수많은 웹사이트 및 기타 관련 소셜 펜 형태로.'대통령을 위한 사람은 없고 위의 사람은 없다'는 '선택권'에 대한 완고한 헌신은 70년대 이후 수그러들지 않고 있으며, 뜻밖에 이피의 유산을 새로운 세기와 다음 [210][211]세대로 가져가면서 성장해왔다.

글쓰기

청년 국제당 내 여성 코커스의 "여성 해방에 관한 해설"은 1970년 시집 "자매결핍은 강력하다"에 수록되었다. 로빈 [193]모건이 편집한 여성 해방 운동 글집.

1971년 6월 Abbie Hoffman과 Al Bell은 선구자 신문 The Youth International Party Line(YPL)을 창간했다.이후 'TAP for Technical American Party' 또는 'Technical Assistance Program'[212]으로 명칭이 변경되었습니다.

밀워키 이피스는 후에 많은 [213]도시에서 그렇게 유명해진 최초의 무정부주의자 지인 스트리트 시트를 발행했다.반독재적 좌파의 국제적 저널인 오픈 로드는 밴쿠버 이피스의 [214][215][216]핵심에 의해 창간되었다.

반공식적인 이피 하우스 오르간인 옙스터 타임즈는 1972년 다나 빌에 의해 창간되어 뉴욕에서 [217][218]출판되었다;[219] 1979년에 이름이 전복으로 바뀌었다.

이피족에서 지피족으로 변신한 탐 포케이드는 1974년 [220]매우 성공적인 하이타임즈 잡지를 창간했다.그래서 많은 엽스터 타임즈 기자들이 하이 타임즈에 글을 쓰곤 했는데, 그것은 종종 팜 [120]팀이라고 불렸습니다.

이피 운동에서 나온 가장 유명한 글은 아비 호프만의 '이 책을 훔치다'로, 이 책은 일반적인 해악을 일으키고 이피 운동의 정신을 담아내는 지침서로 여겨진다.호프만은 또한 이피의 원작이라 불리는 지옥을 위한 혁명의 저자이기도 하다.이 책은 실제 이피들이 없었고, 이 이름은 [221]신화를 만드는 데 사용된 용어일 뿐이라고 주장한다.

Jerry Rubin은 그의 책 Do IT에서 Yipie 운동에 대한 자신의 설명을 발표했습니다. 혁명의 [222]시나리오

이피스가 쓴 이피에 관한 책에는 우드스톡 네이션과 곧 주요 영화가 될 영화 (애비 호프만), 우리는 어디에나 있다 (제리 루빈), 트래싱 (애니타 호프만), 스튜 알버트 (스튜 알버트), 미결 고백 (스튜 알버트), 미결 고백 (스튜 알버트), 등이 있다.그 시대에 관한 다른 책들: 우드스톡 센서스: 60년대 전국 조사(딘 스틸맨과 렉스 와이너),[224] 파나마 모자 산책로(톰 밀러),[225][226] 집으로 가는 길을 찾을 수 없음: 미국, 1945-2000년 돌팔매 시대 (마틴 토르고프), [227]그루브 튜브: 60년대 텔레비전과 청춘의 반란 (애니코 보드로코지),[228] 그리고 켄과 에밀리의 발라드: 또는 반문화에서 온 이야기들 (켄 왓스버거)[108]이다.

1970년대 중반 미네소타 대학 캠퍼스에서 엽스터 타임즈를 배포한 정치 만화가이자 60년대 이후의 이피 운동가 피트 [229]와그너가 쓰고 그린 이 책은 호프만이 "나쁜 [229]취향의 한계에 도달하기 위한 관리"라고 홍보했다.1985년 브레인 트러스트라는 이름의 게릴라 거리극단이 "이피와 같은 신화 제작 전술로 뉴우드와 싸우기 위한 노력"을 회상한다.Brain Trust는 1981년 5월 미니애폴리스에서 열린 와그너와 폴 크라스너 간의 일련의 만남과 인터뷰에 영감을 받아 Krassner가 Dudley Riggs의 Instant Theater [230]Company에서 스탠드업 코미디를 공연했습니다.

1983년, 한 무리의 이피들이 블랙리스트에 오른 뉴스를 발표했습니다. 68년 시카고에서 1984년까지의 비밀사(Beeker Publishing)는 이피 역사의 '전화 번호부 크기의 앤솔로지'(733쪽)로, 대안과 주류 언론의 언론 보도와 많은 개인적인 이야기와 에세이를 포함하고 있다.수많은 사진, 오래된 전단지와 포스터, '지하' 만화, 신문 스크랩, 그리고 다양한 역사적 덧없음을 포함합니다.편집자들은 공식적으로 자신들을 "The New Yppie Book Collective"라고 불렀는데, 여기에는 스티브 콘리프(책의 절반 이상을 쓴), 다나 빌(대장), 그레이스 니콜스, 데이지 데드헤드, 벤 마셀, 앨리스 토르부시, 카렌 워치만, 그리고 [231]카욘이 포함되어 있었다.그것은 아직 인쇄 중이다.

2011년 6월 초연된 밴쿠버 이피 밥 사티의 연극 '이피 인 러브'가 초연되었다.[232][233]

만년

1989년, 간헐적인 우울증을 앓던 애비 호프만은 알코올과 약 150개의 페노바르비탈 [234]알약으로 자살했다.이와는 대조적으로 제리 루빈은 말을 빨리 하는 주식 중개인이 되었고([235]그리고 모든 면에서 꽤 성공적이었다), 후회는 보이지 않았다.1994년에 그는 무단횡단을 [236]하다가 차에 치여 치명상을 입었다.50세가 되었을 때, 루빈은 이전의 많은 반문화적 견해들과 단절되었다; 그는 뉴욕 타임즈와의 인터뷰를 통해 그를 "이피에서 변태적인 여피"라고 묘사했다.인터뷰에서 그는 "내가 되기 전까지는 아무도 정말로 옷을 벗지 않고 '돈 벌어도 괜찮아!'[237]라고 소리 지르지 않았다"고 말했다.

2000년, 에비 호프만의 삶을 소재로 한 할리우드 영화 "Steal This Movie" (그의 책 제목인 "Steal This Book"을 속이다)가 엇갈린 평가를 받았고, 빈센트 도노프리오가 주인공 [238]역할을 맡았다.저명한 영화 평론가 로저 에버트는 이 영화에 [239]긍정적인 평을 내렸으며, 역사적인 사건들을 확실하게 현실화하는 것은 종종 어렵지만, 그는 이 영화가 [239]성공했다고 믿고 있다고 말했다.

영화에서는 로이 로저스와 데일 에반스가 깃발 셔츠를 입고 요들링을 하는 장면이 나온다.호프만은 이 깃발이 전쟁에 반대하는 사람들을 포함한 모든 미국인을 대표한다고 주장했다. 그는 이 깃발을 그들의 배타적 이념 깃발로서 합병하려는 우파의 노력에 저항했다.

빈센트 도노프리오가 그 역할을 하는 흥미로운 임무를 가지고 있는데, 호프만은 대부분의 시간을 오토파일럿으로 보내기 때문이다.그는 카리스마가 있고 극적인 제스처를 본능적으로 파악하고 있지만 일대일로 [239]보면 화가 날 수 있다.

이피족은 2000년대 [240][241][242]초반까지 작은 운동으로 계속되었다.뉴욕 지부는 마리화나를 [134][243][244]합법화하기 위해 수십 년 동안 뉴욕에서 매년 행진을 벌인 것으로 알려져 있다.[16][245] 뉴욕시 이피 다나 빌은 1999년에 글로벌 마리화나 행진을 시작했다.빌은 또한 헤로인 [248][249]중독자들을 치료하기 위해 이보가인을[246][247] 사용하기 위한 운동을 계속했다.또 다른 이피인 A.J. 웨버먼은 밥 딜런의 시를 해체하고 다양한 웹사이트를 통해 그래시 놀의 부랑자들에 대한 추측을 계속했다.베버만은 오랫동안 유대 방위 기구에서 활동해 왔다.

지난 10년간 뉴욕시 이피스는 뉴욕 Lower East [250][44][251]Side의 지속적인 변화에 대한 지역 반신사화 시위에 자주 참여했다.

2008년, A.J. 웨버먼과 WBAI의 인기 라디오 진행자인 동료 설립자인 이피 사이에 매우 공개적인 불화가 있었다.관련 사건들은 특히 전국적인 관심을 [253]끌었던 시카고 폭동에 대한 PBS의 새로운 영화와 겹친 이후 잠깐 동안 언론에 [252]다시 이피들을 불러 일으켰다.행크 아자리아가 애비 호프만, 마크 러팔로가 제리 [254]루빈으로 출연한 이 영화는 새로운 세대의 관심을 끌었다.

이피 박물관 및 카페

2004년, 야피 부부는 국립 에이즈 여단과 함께 뉴욕시의 9 Bleecker Street에 오랫동안[19] 이피 "본사"를 120만 [256]달러에 구입했다.공식 구입 후, 「이피 박물관/카페·기프트 숍」[257][258]으로 개조해, 세계 각국의 반문화·좌파 기념품을 다수 소장하고,[259][260] 야간 라이브 음악을 특집으로 한 독자적인 카페를 제공하고 있다.이 카페는 2011년 여름에 문을 닫았고 같은 해 12월에 지하실을 [261]개조하여 다시 문을 열었다.그 박물관은 [262]뉴욕 대학의 섭정위원회에 의해 인가되었다.

원래 큐레이터의 메시지에 따르면, 이 박물관은 "청년 국제당과 그 모든 오프쇼트의 역사를 보존하기 위해" 설립되었다.이사회: Dana Beal,[263] Aron Kay, David Peel, William Propp, Paul DeRienzo 및 A. J. Weberman.[264]

조지 마르티네즈는 "직업적 위험/민중의 비누상자"[45]로 알려진 이피스의 오픈마이크에서 세미 자주 연설을 했다.

2013년 여름, 이피 카페는 공식적으로 문을 [265][266]닫았다.2014년 초, #9 Bleecker에 있는 이피 빌딩(박물관)은 매각, 폐쇄,[267] 영구적인 청소가 이루어졌으며, 대부분의 기념품과 역사적 자료들은 남아있는 뉴욕 [39]이피들에게 분산되었다.

2017년 현재, #9 Bleecker에 있는 오래된 이피 건물은 "Overthrow"라고 불리는 성공적인 보워리 지역 복싱 클럽으로 완전히 탈바꿈하여 원래의 이피/60년대 혁명적인 장식의 상당 부분을 고의적이고 교묘하게 유지하고 있다.관광객들은 여전히 그것을 [268]보기 위해 들른다.

시카고 7호의 재판

2020년, 넷플릭스는 애런 소킨이 감독한 영화 "The Trial of the Chicago 7"을 개봉했는데, 이 영화에는 이피 멤버 애비 호프만과 제리 [269][270]루빈이 묘사되었다.이 영화는 대부분 긍정적인[271] 평가를 받았고 아카데미 작품상 후보에 올랐다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

- 1968년 민주당 전당대회 시위 활동

- 1971년 노동절 시위

- 미국의 대마초 정당

- 괴상한 장면

- 가스타운 폭동

- 휴먼 비인

- 반전 단체 목록

- 디즈니랜드 리조트 사건 목록

- 평화 운동가 목록

- 미디엄 쿨 – 하스켈 웩슬러의 68년 컨벤션 중 시카고에 대한 획기적인 소설의 시네마 베리테 이야기. 실제 폭동 장면을 배우와 (개선된) 이벤트의 배경으로 사용합니다.

- 대통령 후보 없음

- 위의 항목 중 아무 것도 아니다

- 피가수스

- 1968년 시위

- 사랑의 여름

- 여피라는 용어는 1980년에 만들어졌으며 밥 그린이 쓴 제리 루빈에 관한 1983년 신문 칼럼에 의해 유행되었다. "이피에서 여피로"

- 젠거

레퍼런스

- ^ a b c Paul Krassner (1994). Confessions of a raving, unconfined nut: misadventures in the counter-culture. Simon & Schuster. p. 156. ISBN 9781593765033.

- ^ Neil A. Hamilton, 1960년대 미국 반문화의 동반자 ABC-CLIO, 339페이지, ABC-CLIO, 1997

- ^ David Holloway (2002). "Yippies". St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ a b 애비 호프만, 곧 메이저 영화사가 될 거야, 128페이지Perigee Books, 1980.ISBN 97803995034

- ^ Gitlin, Todd (1993). The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. New York: Bantam Books. pp. 286. ISBN 978-0553372120.

- ^ "1969: Height of the Hippies". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ 루빈, 제리, DO IT! 혁명의 시나리오(81페이지), 사이먼과 슈스터, 1970년.

- ^ Sloman, Larry (August 7, 1998). Steal This Dream: Abbie Hoffman & the Countercultural Revolution in America. Doubleday. ISBN 9780385411622.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (February 2006). "Stew Albert, 66, Who Used Laughter to Protest a War, Dies". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2006.

- ^ Ed Sanders (2011). Fug You: An Informal History of the Peace Eye Bookstore, the Fuck You Press, the Fugs and Counterculture in the Lower East Side. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306818882. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Patricia Bradley (2004). Mass Media and the Shaping of American Feminism, 1963–1975. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604730517. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "Jerome Washington Collection 1979–1988" (PDF). John Jay College of Criminal Justice. John Jay College of Criminal Justice Special Collections of the Lloyd Sealy Library. 1988. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ Robert Sharlet (February 19, 2014). "Jim Retherford, 'the Man in the Red Devil Suit". The Rag Blog. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ James Retherford (June 6, 2018). "Little Big Meshuganah". The Rag Blog. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Oliver, David (June 1977). "INTERVIEW : Dana Beal". High Times. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ a b c Viola, Saira. "Dana Beal Interview". International Times. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Hawthorn, Tom (June 22, 2011). "Yippie for Mayor". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- ^ a b "ZARIA FOR MAYOR (poster)". Past Tense Vancouver. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Amy Starecheski (2016). Ours to Lose: When Squatters Became Homeowners in New York City. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226399942. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ TIMOTHY M. PHELPS (March 20, 1981). "YIPPIE IS SEIZED AFTER A DISPUTE NEAR BOMB SITE". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Elliott, Steve (May 3, 2011). "Remembering Ben Masel: Activist Changed The Cannabis Debate". Toke of the Town. Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ Al Aronowitz. "Tom Forcade, Social Architect". The Blacklisted Journalist. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2002.

- ^ Patrick Anderson (February 27, 1981). High In America: The True Story Behind NORML And The Politics Of Marijuana. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670119905. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ 래리 갬본, 후회 없음, 97쪽, 블랙캣 프레스, 2015.

- ^ Needs, Kris (March 22, 2016). "The tale of David Peel, the dope-smoking hippy who became the King of Punk". TeamRock.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Viola, Saira. "Yippie! Yippie! Pie Aye! Interview with Aron Kay, champion pie thrower, grassroots activist, unrepentant hippie yippie, professional agitator, Jewish world warrior". Gonzo Today. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ Traynor, P. (November 4, 1977). "Come Pie With Me : the Creaming of America" (PDF). Open Road. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ YIPster Times, "Abbie Hoffman: Back to Chicago", 1978년 6월

- ^ Karla Jay (March 3, 2000). Tales of the Lavender Menace : A Memoir of Liberation. Basic Books. p. 231. ISBN 978-0465083664.

- ^ YIPster Times, "Midwest Activism feature May Midwest Midwest" 1977년 12월 2일자

- ^ a b Deadhead, Daisy (January 16, 2008). "I wish someone would phone". Dead Air. Archived from the original on January 25, 2008. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ Rapport, Marc (March 29, 1978). "Student on Ballot with Pie Thrower: she's candidate for lieutenant governor". Daily Kent Stater. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Urbanowicz Removed from State Office Race". Daily Kent Stater. April 5, 1978. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ 데이비드 루이스 스타인, Living the Revolution: 시카고의 이피 가족, 11페이지, 밥스-메릴 회사, 1969년.

- ^ Walker, Jesse (2001). Rebels on the Air: An Alternative History of Radio in America. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0814793817. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Reinholz, Mary. "Yippie and Peace Activist Mayer Vishner Is Dead, Apparently a Suicide". Bedford + Bowery. NYmag. Archived from the original on April 15, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Donadoni, Serena (February 7, 2017). "FILM: Storied Village Activist Mayer Vishner Faces the End in Bracing Doc 'Left on Purpose'". VillageVoice.com. Village Voice. Archived from the original on April 15, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Montgomery, Paul L. (March 18, 1981). "BOMB BURNS TWO DETECTIVES OUTSIDE BUILDING OF YIPPIES". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Moynihan, Colin. "Emptying a Building Long Home to Activists". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Bruce Fessier. "50 years after the Chicago Democratic National Convention, Paul Krassner still hasn't sold out". DesertSun.com. The Desert Sun. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ a b DeAngelo, Steve (2015). The Cannabis Manifesto: A New Paradigm for Wellness. Berkeley, CA, USA: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1583949375. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Pascual, Oscar. "Marijuana Legalization: Seeds Planted Long Ago Finally Flower". SFGate. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ Thomas, Pat (September 22, 2017). "Activist, individualist and entrepreneur Jerry Rubin was the quintessential American". City Arts Magazine. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "Guide to the John Penley Photographs and Papers/Elmer Holmes Bobst Library". New York University. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives (NYU). Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ a b Lennard, Natasha (June 18, 2012). "An Occupier Eyes Congress". Salon. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ^ "Interview With Brenton Lengel". The Fifth Column. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- ^ Reston Jr, James (February 1, 1997). Collision at Home Plate: The Lives of Pete Rose and Bart Giamatti. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803289642. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ 애비 호프만, 73쪽, 이 책을 훔치다.Grove Press, 1971년

- ^ "The Chicago Eight Trial: Selected Contempt Specifications". Famous Trials. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ a b "60s는 LSD를 제외한 상태로 다시 가동됩니다." 2011년 5월 20일 웨이백 머신에서 아카이브되었습니다.폴 크라스너에 의해.2007년 1월 28일로스앤젤레스 타임즈.

- ^ 데이비드 T.델린저, 주디 클라비어, 존 스피처 음모 재판 349쪽입니다밥스-메릴, 1970년ISBN 978-030681882

- ^ 조나 래스킨, 129페이지 '지옥을 위하여'캘리포니아 대학 출판부, 1996.ISBN 978-0520213791

- ^ 애비 호프만, 지옥을 위한 혁명 81페이지다이얼 프레스, 1968.ISBN 978-1560256908

- ^ "The Chicago Eight Trial : Testimony of Judy Collins". Famous Trials. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "NOW with Bill Moyers (transcript dated 11-26-04)". PBS. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2004.

- ^ Julie Stephens (1998). Anti-Disciplinary Protest: Sixties Radicalism and Postmodernism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521629768. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "A People's Hxstory of the Sixties". The Digger Archives. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ 로지 맥기, 그레이트풀 데드 패밀리 앨범의 "토탈 환경 극장", 38-40페이지, 타임 워너 북스 1990, ed.Jerilin Lee Brandelius ISBN 978-0446391672

- ^ 제릴린 리 브랜델리우스, 그레이트풀 데드 패밀리 앨범, 68-69페이지, 타임워너 북스 1990, ed.Jerilin Lee Brandelius ISBN 978-0446391672

- ^ Jesse Jarnow (2016). Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306822551. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Mike Marqusee (2003). Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1583226865. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Michael I. Niman (1997). People of the Rainbow: A Nomadic Utopia. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville. p. 118. ISBN 978-1572337466.

yippies rainbow family.

- ^ 윌리엄 어윈 톰슨, "역사의 끝자락: 문화의 변혁에 대한 추측", 하퍼 앤 로우, 1971년 페이지 27-66페이지.ISBN 978-0686675709

- ^ Klemesrud, Judy (November 11, 1978). "Jerry Rubin's Change of Cause: From Antiwar to 'Me'". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Farrar Straus Giroux, 1968 ISBN 978-0312427597

- ^ Robert Stone, Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties, HarperCollins Publishers, ISBN 978-006095773

- ^ The New Yippie Book Collective (에드), 블랙리스트 뉴스:시카고에서 1984년까지의 비밀 역사, 514쪽.Bleecker Publishing, 1983년.ISBN 978-0912873008

- ^ 애비 호프만, 우드스톡 네이션, 뒷표지빈티지 북스, 1969년

- ^ 존 앤서니 모레타, 히피: 1960년대 역사, 페이지 260McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC. 2017.ISBN 978-0786499496

- ^ Flags of the World – Youth International Party 2012년 2월 10일 Wayback Machine에 보관된 목록

- ^ "Chicago History Museum – Blog » Blog Archive » Yippies in Lincoln Park, 1968". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Walker, Jesse (August 27, 2008). "The Yippie Show". REASON. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ "CHICAGO 10: The Film: The Players: The Yippies". PBS. October 22, 2008. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Shana Alexander (October 25, 1968). "The Loony Humor of the Yippies". LIFE magazine. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Benjamin Shepard (2012). Play, Creativity, and Social Movements: If I Can't Dance, It's Not My Revolution. Routledge. ISBN 9781136829642. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Ghostarchive 및 웨이백 머신에 아카이브: (오디오만 해당) (오디오만)

- ^ 애비 호프만, 곧 메이저 영화사가 될 거야, 페이지 86Perigee Books, 1980.

- ^ a b 제리 루빈, Do It! 86페이지사이먼과 슈스터, 1970년ISBN 978-0671206017

- ^ 조셉 보스킨, 반항적인 웃음: 미국 사람들의 유머, 98페이지.시러큐스 대학 출판부, 1997년

- ^ Craig J. Peariso (February 17, 2015). Radical Theatrics: Put-Ons, Politics, and the Sixties. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295995588. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ "Protest: The Banners of Dissent". TIME. October 27, 1967. p. 9. Archived from the original on January 27, 2008. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ Bloch, Nadine (October 21, 2012). "The Day they Levitated the Pentagon". Waging NonViolence. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ 조나 래스킨, 재미삼아:Abbie Hoffman의 삶과 시대, 117페이지, 캘리포니아 대학 출판부, 1996년

- ^ 곧 메이저 영화가 될 영화:애비 호프만의 자서전, 초판, 페리그리 북스, 1980, 페이지 101.

- ^ Ledbetter, James. "The day the NYSE went Yippie". CNN Money. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2007.

- ^ Susanne E. Shawyer (May 2008). "Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: a Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967–1968". University of Texas, Austin. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ Cottrell, Robert C. (2015). Sex, Drugs, and Rock 'n' Roll: The Rise of America's 1960s Counterculture (Chapter 14: From Hippie to Yippie on the Way to Revolution). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 257–270. ISBN 978-1442246065.

- ^ Gitlin, Todd (1993). The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. New York. pp. 238. ISBN 9780553372120.

- ^ Nat Hentoff (April 21, 2010). "Nat Hentoff on the Police Riot Against Yippies at Grand Central (4 April 1968)". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ 닐 해밀턴, 1960년대 미국 반문화의 동반자 ABC-CLIO, 340페이지, ABC-CLIO, 1997.

- ^ 데이비드 암스트롱, 트럼펫 투 암스: Alternative Media in America, 120-121페이지, 사우스엔드 프레스, 보스턴. 1981년.ISBN 978-0896081932

- ^ Bennett, David Harry (1988). The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History. ISBN 9780807817728. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- ^ Jerry Rubin, Wayback Machine에서 2018년 10월 24일 아카이브된 Yippie 매니페스토.

- ^ GEOGHEGAN, THOMAS (February 24, 1969). "By Any Other Name. Brass Tacks". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^ Patricia Kelly, ed. (2008). 1968: Art and Politics in Chicago. DePaul University Art Museum. ISBN 978-0978907440. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Kayla Schultz (2008). Democracy in America, Yippie! Guerilla Theater and the Reinvigoration of the American Democratic Process During the Cold War. Syracuse University. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ 노먼 메일러, 마이애미, 시카고 공성전 137쪽입니다Signet Books: New American Library, 1968.ISBN 978-0451073105

- ^ a b Stephen Zunes, Jesse Laird (January 2010). "The US Anti-Vietnam War Movement (1964–1973)". International Center on Nonviolent Conflict (ICNC). Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ David Farber (October 17, 1994). Chicago '68. University of Chicago Press. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-0226238012. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ Miller, James (1994). Democracy is in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago. Harvard University Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0674197251.

- ^ a b Max Frankel (1968). The Walker Report, Rights in Conflict: The violent confrontation between demonstrators and police in the parks and streets of Chicago during the week of the Democratic National Convention. Bantam Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-0525191797.

- ^ Goldstein, Sarah (August 12, 2008). "The Mess We Made: An Oral History of the '68 Convention". GQ.com. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ Jon Wiener, Jules Feiffer (August 2006). Conspiracy in the Streets: The Extraordinary Trial of the Chicago Seven. The New Press. ISBN 9781565848337.

- ^ Anorak (December 17, 2013). "The People v The Chicago Seven In Photos: When Yippies Scared The USA". Flashbak. ALUM MEDIA LTD. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ John Beckman (2014). American Fun: Four Centuries of Joyous Revolt. Pantheon Books, New York. ISBN 978-0-307-90818-6. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ 데이비드 T.델린저, 주디 클라비어, 존 스피처, 음모 재판, 601쪽.밥스-메릴, 1970년

- ^ 애비 호프만, 곧 메이저 영화사가 될 거야, 170페이지.Perigee Books, 1980.

- ^ a b Ken Wachsberger (1997). The Ballad of Ken and Emily: or, Tales from the Counterculture. Azenphony Press. ISBN 978-0945531012. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ 새로운 이피 북 컬렉션 블랙리스트 뉴스: 시카고에서 1984년까지의 비밀 역사, 16페이지.Bleecker Publishing, 1983년.

- ^ "이피스는 경찰에게 달걀과 돌을 퍼트렸다"1971년 4월 5일, 록 힐 헤럴드.

- ^ 키프너, 존"눈물 가스는 과격파의 공격을 격퇴한다."뉴욕타임스 1969년 11월 16일

- ^ The New Yippie Book Collective, ed. (1983). Blacklisted News: Secret Histories from Chicago to 1984. Bleecker Publishing. p. 459.

- ^ Thomas, Bryan. "August 6, 1970, the Day the Yippies invaded Disneyland". NightFlight. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ The New Yippie Book Collective, ed. (1983). Blacklisted News: Secret Histories from Chicago to 1984. Bleecker Publishing. p. 457.

- ^ The New Yippie Book Collective, ed. (1983). Blacklisted News: Secret Histories from Chicago to 1984. Bleecker Publishing. p. 403.

- ^ 레스터 프리드먼, 1970년대 미국 영화: 주제와 변주곡, 49쪽, NJ Rutgers University Press, 2007

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (June 17, 1971). "Mayday: The Case for Civil Disobedience". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ "Yippies Exclude Hoffman And Rubin as Spokesmen". New York Times. November 28, 1972. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Steve Conliff (1972). "We are Not McGovernable!: What Cronkite Didn't Tell You about the '72 Democratic Convention". Youth International Party. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Arnett, Andrew. "Hippies, Yippies, Zippies and Beatnicks – A Conversation with Dana Beal". TheStonedSociety.com. The Stoned Society. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Reinholz, Mary. "Yippies vs. Zippies: New Rubin book reveals '70s counterculture feud". TheVillager.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- ^ The New Yippie Book Collective (에드), 블랙리스트 뉴스: 시카고에서 1984년까지의 비밀 역사, 354쪽.Bleecker Publishing, 1983년.

- ^ 2019년 4월 8일 Wayback Machine에 보관된 마리화나 스모크인 컨벤션 홀 밖에서 개최.1972년 7월 10일사라소타 헤럴드 트리부네

- ^ 애비 호프만, 곧 메이저 영화사가 될 거야, 278쪽Perigee Books, 1980.

- ^ James Rosen (May 2008). The Strong Man: John Mitchell and the Secrets of Watergate. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385508643. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ a b CrimethInc, Ex-Workers Collective. "Whoever They Vote For, We Are Ungovernable: A History of Anarchist Counter-Inaugural Protest". CrimethInc. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ Cooperman, Alan (January 21, 1981). "Amid Washington's Pomp, a 'Counter-Inaugural'". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "POSTER: Counter-Inaugural Ball & Protests". AbeBooks.com. Youth International Party. 1981. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Berry, Millard (July 1980). "PHOTO: Yippies for Reagan (Republican National Convention 1980)". Labadie Collection, University of Michigan. Fifth Estate. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ "Yippies protest President Reagan in Dallas 1984". Yippie archives. Youth International Party. August 1984. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ "POSTER: Don't Let Reagan Take You for a Ride!". AbeBooks.com. Youth International Party. 1984. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ "99 ARRESTED IN DALLAS PROTEST". The New York Times. August 23, 1984. Archived from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ The New Yippie Book Collective, ed. (1983). Blacklisted News: Secret Histories from Chicago to 1984. Bleecker Publishing. p. 4.

- ^ a b A. Yippie. "A Brief History of the NYC Cannabis Parade". CannabisParade.org. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ Odam, Jes, "경찰이 이피 음모를 고발한다", Vancouver Sun, 1971년 10월 1일

- ^ Mark Andersen, Mark Jenkins (August 2003). Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation's Capital. Brooklyn, NY, USA: Akashic Books. ISBN 978-1888451443. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Martin Weil, Keith B. Richberg (July 5, 1978). "Demonstration By Yippies Is Mostly Quiet". Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ Harris, Art (July 4, 1979). "Yippies Turn On". Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ Miller, Tom (April 27, 1995). "I Remember Jerry". Tucson Weekly. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ The New Yippie Book Collective, ed. (1983). Blacklisted News: Secret Histories from Chicago to 1984. Bleecker Publishing. p. 656.

- ^ 요나 라스킨, 132페이지 '지옥을 위하여'캘리포니아 대학 출판부, 1996.

- ^ Thorne Webb Dreyer (December 30, 2007). "What Ever Happened To The New Generation?". TheRagBlog. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ Kisseloff, Jeff (January 2007). Generation on Fire: Voices of Protest From The 1960s : An oral history. University Press of Kentucky. p. 64. ISBN 978-0813124162.

- ^ Lorraine Code (2000). Encyclopedia of Feminist Theories. Routledge. p. 350. ISBN 978-0415308854.

- ^ SOUR GRAPS 커버 2015년 11월 15일 OH 콜럼버스 웨이백 머신 유스 인터내셔널 파티에서의 아카이브

- ^ Steve Abbott (April 1, 2012). Ken Wachsberger (ed.). Karl and Groucho's Marxist Dance : Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, Part 2 (Voices from the Underground). Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-1611860313.

- ^ "Georgia Straight Staff 1967-1972". Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ "HOUSTON UNDERGROUND: SPACE CITY!, DIRECT ACTION, AND ULTRA ZINE (1978)". Wild Dog Zine. February 21, 2014. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Ventura, Michael. "Letters at 3AM: He Took the Cat to Texas; this is the final story in the many-storied life of Mayer Vishner". Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- ^ Amateau, Albert (September 26, 2013). "Mayer Vishner, 64, Yippie, antiwar activist, editor". The Villager. Archived from the original on April 15, 2018. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ ^ congress.gov/chronicling 아메리카/마이크로필름 부족의 b c 라이브러리 ^ a b c University of Michigan.gov/archives/underground 신문/마이크로필름 컬렉션

- ^ Joseph, Pat (July 30, 2015). "Sex, Drugs, Revolution: 50 Years On, Barbarians Gather to Recall The Berkeley Barb". California Magazine. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ^ John McMillian (February 17, 2011). Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America. Oxford University Press. pp. 120–126. ISBN 978-0195319927. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ 요나 라스킨, 지옥을 위하여, 캘리포니아 대학 출판부, 1996년 페이지 228.

- ^ "Coca Crystal's Dance Revolution". Unconscious and Irrational. March 21, 2009. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "The Chicago Eight Trial : Testimony of Philip David Ochs". Famous Trials. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ Ouellette, Rick (March 3, 2013). "The Strange, Forgotten Saga of the Medicine Ball Caravan". REEL AND ROCK. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ Greenspun, Roger (August 26, 1971). "Medicine Ball Caravan Bows : Free-Wheeling Bus Is Followed Across U.S." The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Mastropolo, Frank. "Revisiting 'Medicine Ball Caravan,' the 'Woodstock on Wheels'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- ^ IMDb에서 따님을 구하러 왔습니다.

- ^ Julie Burchill, Tony Parsons, "The Boy Looked at Johnny" : 로큰롤의 부고, 명왕성 프레스, 영국, 런던, 1978 ISBN 9780861040308 페이지 19-20

- ^ O'Hagan, Sean (March 3, 2014). "John Sinclair: 'We wanted to kick ass – and raise consciousness'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Tracey, Patrick (March 31, 2000). "Yippie Yi Yay". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ 사티, 밥, "피트 시거를 만난 날", 오이스터 캐처, 메이데이 2014.

- ^ Arthur Kane (2009). I, Doll: Life and Death with the New York Dolls. Chicago Review Press, Chicago, IL. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-55652-941-2. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Alice Torbush, Daisy Deadhead, Rock Against Racistics USA - Tour Dates & Concert Calender, 전복/Yipster Times, 페이지 12-14, 1979년 4월 일러스트: 전복 표지: ROCK ANST RACICSIALICICE, 1979년 4월 8일 보관, 웨이백 머신

- ^ "GRASS ROOTS ACTIVISM, ROCK AGAINST RACISM (1979)". Wild Dog Zine. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ "ANARCHO-PUNKS ORGANIZE FIRST ROCK AGAINST RACISM CONCERT AT UH (1979)". Wild Dog Zine. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Baby Lindy. "Screaming Urge : Impulse Control". Hyped to Death CD archives. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ Webster, Brian. "Rock Against Racism USA". BrianWebster.com. Brian Webster and Associates. Archived from the original on December 18, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ "Rock Against Racism w/NAUSEA, FALSE PROPHETS @ Central Park Bandshell 05.01.88". Signs Of Life NYC. March 31, 2013. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ Ben Nadler (November 29, 2014). Punk in NYC's Lower East Side 1981–1991: Scene History Series, Volume 1. Portland, Oregon, USA: Microcosm Publishing. ISBN 9781621069218. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ L.A. Kauffman (2017). Direct Action: Protest and the Reinvention of American Radicalism. New York: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1784784096. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "POSTER: ROCK AGAINST REAGAN - Clark Park, Detroit". AbeBooks.com. Youth International Party. 1983. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Shocked, Michelle (August 1989). "ANTIHERO : The newest insider at PolyGram, folk singer Michelle Shocked, on working for change through music, on the inside and outside". SPIN archives. Spin. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Liles, Jeff. "Echoes and Reverberations: Dead Kennedys "Rock Against Politics"". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- ^ Dave Dictor (May 22, 2016). MDC: Memoir from a Damaged Civilization: Stories of Punk, Fear, and Redemption. San Francisco: Manic D Press. ISBN 978-1933149998. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "Rock Against Reagan 1983, Washington DC". songkick. July 3, 1983. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Johnathan Kyle Williams (2016). ""Rock against Reagan" : The punk movement, cultural hegemony and Reaganism in the eighties". Scholarworks; University of Northern Iowa. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ "Rock against Reagan with Dead Kennedys, San Francisco, 1983". Utah State University Library digital collections. October 23, 1983. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Beadle, Scott. "Punks and Politicos". Bloodied But Unbowed. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Joe Keithley (April 2004). I, Shithead: A Life in Punk. Vancouver, B.C., Canada: Arsenal Pulp Press. ISBN 978-1551521480. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ *포스터: DOA Rock Against 인종차별 기금 모금, 1979년 10월 13일 thepunkmovie.com에서 Wayback Machine에 보관

- ^ Adrian Boot, Chris Salewicz, 펑크: 음악 혁명의 역사, 104쪽, 펭귄 스튜디오, 1996년.ISBN 978-0140260984

- ^ IMDb의 D.O.A.

- ^ Anthony Haden-Guest (December 8, 2009). The Last Party: Studio 54, Disco, and the Culture of the Night. It Books. ISBN 978-0061723742. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Larocca, Amy. "The Look Book: John Waters, Filmmaker". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Conliff, Steve (Spring 1977). "Everybody needs nobody sometimes" (PDF). Open Road. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 23, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- ^ a b *사진: Nobody For President, Curtis Spangler and Wavy Gravy, 1976년 10월 12일 Wayback Machine에 보관(사진 크레딧: James Stark) HeadCount.org

- ^ a b Wavy Gravy (Winter 1988). "20th Anniversary Rendezvous – Wavy Gravy". WholeEarth.com. Whole Earth Review. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ 스튜 알버트, 대체 스튜 알버트가 누구야? 131쪽레드헨 프레스, 2003.ISBN 978-188996630

- ^ 새로운 이피 북 컬렉션 블랙리스트 뉴스:시카고에서 1984년까지의 비밀 역사, 414페이지.Bleecker Publishing, 1983년.

- ^ a b Robin Morgan, ed. (September 12, 1970). Sisterhood is powerful : an anthology of writings from the women's liberation movement. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0394705392.

- ^ Alice Echols (1989). Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967–1975. University of Minnesota Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0816617876.

feminist yippies.

- ^ 제리 루빈, We Are Everywhere, 248페이지, 하퍼 앤 로우, 1971년 ISBN 978-0060902452

- ^ Laurence Leamer (August 1972). The Paper Revolutionaries: The Rise of the Underground Press. Simon & Schuster. p. 72. ISBN 978-0671211431.

- ^ Barr, Connie (October 15, 1969). "Police arrest one after protestors disrupt Kerr talk". Indiana Daily Student. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Bloomington. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Thomas (December 10, 2000). "Take Sugar, Eggs, Beliefs ... And Aim". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Ghose, Dave. "An Oral History: The pieing of Gov. Jim Rhodes at the Ohio State Fair". Columbus Monthly. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ Shushnick, Irving (December 1977). "Pie Times for Pols". High Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ Biotic Baking Brigade (2004). Pie Any Means Necessary: The Biotic Baking Brigade Cookbook. AK Press, Oakland, CA. p. 15. ISBN 9781902593883. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ *PHOTO : Daniel Patrick Moynihan 상원의원이 Aron Kay에 의해 파이로 히트, 1976년 3월 7일 AP통신 Wayback Machine Photo에서 보관

- ^ Michael Kernan, William Gildea (September 1, 1977). "Two-Pie Tuesday". Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ "PHYLLIS SCHLAFLY ERA OPPOSITION – ARON KAY HOLDING PIE (photo)". AP Images. Associated Press. April 16, 1977. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ "PIE THROWER". AP Images. Associated Press. November 3, 1977. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ The New Yippie Book Collective (에드), 블랙리스트 뉴스: 시카고에서 1984년까지의 비밀 역사 288쪽.Bleecker Publishing, 1983년.

- ^ Bedewi, Jessica. "Entertainment : Step Inside Studio 54: The Wild Nights of 1970's Celebrities, Disco and Debauchery". HeraldWeekly.com. Samyo News. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ "'None Of The Above' Ballot Option In Nevada Upheld By Federal Appeals Court". HuffPost. November 25, 2015. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ 새로운 이피 북 컬렉션 블랙리스트 뉴스:시카고에서 1984년까지의 비밀 역사, 321페이지.Bleecker Publishing, 1983년.

- ^ "Nobody For President". hoaxes.org. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- ^ "Nobody for President 2020". Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Christina Xu. "The Secrets of the Little Pamphlet: Hippies, Hackers, and the Youth International Party Line". Free Range Virtual Library. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Zetteler, Mike (August 28, 1971). "Street Sheet Spreads Yippie Message". Zonyx Report. Milwaukee Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Vancouver Yippie!". Vancouver Anarchist Online Archive. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- ^ "Open Road News Journal". Open Road News Journal. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ Martin, Eryk (2016). "Burn It Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ "Yippies Locked in Struggle to Survive". Reading Eagle. November 7, 1973. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020. 일러스트: Yipster Times 표지, 1975년 6월, 2021년 2월 28일 웨이백 머신에 보관

- ^ Schneider, Daniel B. (May 21, 2000). "F.Y.I." The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ *Overstrow 커버: 1985년 가을 아카이브 2020년 2월 15일 Wayback Machine*** OVAL 커버: Spring 1986 아카이브 2020년 3월 1일 Wayback Machine 크레딧:볼레리움 북스

- ^ Martin A. Lee (2012). Smoke Signals: A Social History of Marijuana – Medical, Recreational and Scientific. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1536620085. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Judith Clavir Albert; Stewart Edward Albert, eds. (1984). The Sixties Papers: Documents of a Rebellious Decade. Connecticut. pp. 402. ISBN 978-0060902452.

- ^ "Rubin, Jerry: Do IT! Scenarios of Revolution". Enotes. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Ed Sanders (January 1970). Shards of God: A novel of the Yippies. Random House. ISBN 978-0394174631.

- ^ "Woodstock Census: The Nationwide Survey of the Sixties Generation". Kirkus Reviews. November 12, 1979. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Tom Miller: Yippie activist Jerry Rubin brought his psychedelic oratory to Arizona". TheRagBlog. January 25, 2010. Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Tom Miller (2017). The Panama Hat Trail. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0816535873.

- ^ Martin Torgoff (2005). Can't Find My Way Home: America in the Great Stoned Age, 1945–2000. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0743230117.

- ^ Aniko Bodroghkozy (February 2001). Groove Tube: Sixties Television and the Youth Rebellion. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822326458.

- ^ a b Pete Wagner (1980). Buy This Book. Minneapolis, MN, USA: Minne HA! HA! Publishing. ISBN 978-0937706008.

- ^ Pete Wagner (1987). Buy This Too. Minneapolis, MN, USA: Minne HA! HA! Publishing. ISBN 978-0937706015.

- ^ New Yippie Book Collective (1983). Blacklisted News: Secret Histories from Chicago, '68, to 1984. Bleecker Publishing. ISBN 9780912873008.

- ^ Hawthorn, Tom. "Yippies in Love: Exploring the Vancouver riot – of 40 years ago". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- ^ 포스터: YIPPIES IN LOVE 아카이브 2021년 2월 25일 밴쿠버 이스트 컬처 센터 로우 웨이백 머신 시어터, 2011년

- ^ King, Wayne (April 9, 1989). "Abbie Hoffman Committed Suicide Using Barbiturates, Autopsy Shows". New York Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ R.C. Baker (September 19, 2017). "Jerry Rubin's Weird Road From Yippie to Yuppie". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ Pace, Eric (November 30, 1994). "Jerry Rubin, 56, Flashy 60's Radical, Dies; 'Yippies' Founder and Chicago 7 Defendant". New York Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ "Jerry Rubin Is 50 (Yes, 50) Years Old". New York Times. July 16, 1988. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ IMDb에서 이 영화 훔치기

- ^ a b c Ebert, Roger (August 25, 2000). "Steal This Movie". RogerEbert.com. Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (April 30, 2001). "Yippie Central". New York Today. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ Archibold, Randal C. (April 15, 2004). "Still Agitating (Forget the Arthritis); Old Yippies Want to Steal Convention, but City Balks". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2004.

- ^ Healy, Patrick; Moynihan, Colin (August 23, 2004). "Yippies Protest Near Bloomberg's Town House". New York Times. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2004.

- ^ Allen, Mike (May 3, 1998). "Pot Smokers' March Is Out of the Park". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Marcelle Clements, The Dog Is Us 및 기타 관찰, Penguin Books, 1987, ISBN 978-0140084450

- ^ Morowitz, Matthew (April 20, 2016). "From Sip-Ins to Smoke-ins ... Marijuana and the Village". OffTheGrid : Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ K.R. Alper; H.S. Lotsof; C.D. Kaplan (2008). "The Ibogaine Medical Subculture". J. Ethnopharmacol. 115 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.034. PMID 18029124.

- ^ Smith, P. "Feature: The Boston Ibogaine Forum -- from Shamanism to Cutting Edge Science". StopTheDrugWar.org. Drug War Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 4, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2009. 빌은 포럼 참가자였습니다.

- ^ Arnett, Andrew. "Dana Beal Wants To Cure Heroin Addiction With Ibogaine". Medium. Orange Beef Press. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ^ Fowlie, Chris. "Dana Beal: Yippie for drug treatment!". ChrisFowlie.com. Archived from the original on September 12, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ^ Ghostarchive 및 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브:

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (June 15, 2008). "East Village Protesters Denounce All Things Gentrified. It's a Tradition". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ^ Rayman, Graham (April 2008). "Yippie Apocalypse in the East Village". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- ^ "CHICAGO 10 : The Film". PBS. October 22, 2008. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ IMDb의 Chicago 10

- ^ Leland, John (May 2003). "Yippies' Answer to Smoke-Filled Rooms". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2003.

- ^ Kolben, Deborah. "Yippies Apply for a Piece of Establishment". New York Sun. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved March 16, 2006.

- ^ Anderson, Lincoln. "Museum will have Abbie's trash, Rubin's road kill". The Villager. Archived from the original on June 24, 2006. Retrieved February 1, 2006.

- ^ "The Yippie Museum". New York Art World. 2007. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- ^ Haught, Lori. "Steal This Coffeehouse : Yippies Revive the 60s Vibe". The Villager. Archived from the original on September 7, 2007. Retrieved November 15, 2006.

- ^ Bleyer, Jennifer (January 20, 2008). "At the Yippie Museum, It's Parrots and Flannel". New York Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2008.

- ^ Sjolin, Sara. "Yippee! The Yippie Museum Cafe Gets Back Its Groove". Local East Village. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ^ "NY Board of Regents – Charter Applications for March 2006". State of New York. September 29, 2006. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (June 11, 2008). "A Yippie Veteran Is in Jail Far From the East Village". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ YippieCafe.com 2021년 2월 28일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브 완료.

- ^ Fitzsimmons, Daniel. "Remembering the Yippies : Counter-cultural haven on Bleecker Street still alive despite legal struggle". NY PRESS. Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (June 9, 2013). "Loan Dispute Threatens a Countercultural Soapbox". New York Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ Peet, Preston. "Requiem for Yippie Stronghold, 9 Bleecker". CelebStoner. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ "About OVERTHROW". OverthrowNYC.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ A. O. Scott. "The Trial of the Chicago 7 Review: They Fought the Law ; Aaron Sorkin and an all-star cast re-enact a real-life '60s courtroom drama with present-day implications". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ Zuckerman, Esther. "How the Ending of Netflix's The Trial of the Chicago 7 Rewrites History". Thrillist. Group Nine Media. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Bailey, Jason (October 18, 2020). "CRITIC'S NOTEBOOK -- The Chicago 7 Trial Onscreen: An Interpretation for Every Era". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

추가 정보

- 이웃집 보고서: 그리니치 빌리지; 이피 가문: Chicago Convention A Recurring Dream 2017년 12월 28일, Wayback Machine New York Times에서 아카이브– 1996년 4월 7일

- 커스터드 파이 던지기 재밌겠다 그것은 예술이기도 하다.2018년 12월 7일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브– Anthony Haden-Guest in The Daily Beast, 2018년 2월 18일.

- 한때 반문화의 유대인 영웅이었던 아론 케이는 2022년 1월 18일 포워드의 존 칼리쉬가 Wayback Machine에서 2022년 1월 30일 보관한 파이를 던졌던 시절을 돌아봅니다.