일본의 경제

Economy of Japan | |

| 통화 | 일본 엔(엔, () |

|---|---|

| 4월 1일 ~ 3월 31일 | |

무역 조직 | APEC, WTO, CPTPP, OECD, G-20, G7 등 |

국가 그룹 | |

| 통계 정보 | |

| 인구. | |

| GDP | |

| GDP 순위 | |

GDP 성장 |

|

1인당 GDP | |

1인당 GDP 순위 | |

부문별 GDP | |

성분별 GDP |

|

| - 0.1% (표준)[4] | |

| 33.9 중형(2015년)[10] | |

노동력 | |

직업별 노동력 | |

| 실업률 | |

주요 산업 | |

| 외부의 | |

| 내보내기 | |

수출품 | |

주요 수출 파트너 | |

| Imports(가져오기) | |

수입품 | |

주요 수입 파트너 | |

| 재정 | |

| - 3.5% (GDP 대비) (2017년)[6] | |

| 수익 | 1조714억(2017년 1월)[6] |

| 비용 | 1조8천850억(2017년 1월)[6] |

| 경제 원조 | 기부자: ODA, 103억7천만달러(2016년)[20] |

외환보유고 | |

일본의 경제는 고도로 발달한 자유 시장 [25]경제입니다.명목 GDP 기준으로는 세계 3위,[26][27] 구매력 평가 기준으로는 세계 4위다.한국은 세계에서 두 번째로 [28]큰 선진국이다.일본은 G7과 G20의 회원국이다.세계은행에 따르면, 한국의 1인당 GDP는 40,193달러(2020년)[29]였다.환율 변동으로 일본의 GDP는 달러화로 환산하면 크게 변동한다.이러한 변동을 아틀라스법에 의한 것으로, 1인당 GDP는 약 39,048달러로 추정된다.일본 [30]경제는 일본은행이 실시한 기업심리 조사(Quarterly Tankan)를 통해 예측된다.닛케이225는 시가총액 [31][32]기준으로 세계 5위의 증권거래소인 일본거래소그룹의 우량주 월례보고서를 발표했다.2018년에 일본은 세계 4위의 수입국이자 4위의 [33]수출국이었다.이 나라는 1조 [24]4천억 달러의 가치를 지닌 세계 2위의 외환 보유고를 보유하고 있다.Easy of Do Business Index에서 29위, Global Competitivity [34]Report에서 5위입니다.그것은 경제 복잡도 [35]지수에서 세계 1위를 차지하고 있다.일본은 또한 세계 4위의 소비자 [36]시장이다.

일본은 세계 2위의 자동차 제조국이다.[37]이 나라는 종종 세계에서 가장 혁신적인 국가 중 하나로 꼽히며, 여러 가지 글로벌 특허 출원 척도를 이끌고 있습니다.중국과 [38]한국과의 경쟁이 치열해짐에 따라 현재 일본에서의 제조는 주로 집적회로, 하이브리드 차량, 로봇공학 [39]등 첨단 및 정밀제품에 초점을 맞추고 있다.간사이 지방은 간토 [40][41][42][43]지방 외에 일본 [44]경제의 주요 산업 집적지이자 제조업 중심지이다.일본은 세계 최대 채권국이다.[45][46][47]일본은 통상 연간 무역 흑자를 내고 있으며, 국제 순투자 흑자도 상당하다.일본은 2020년 현재 세계 GDP의 [48][49]8.6%인 12조 달러에 달하는 세계 3위의 금융자산을 보유하고 있다.2017년 현재 Fortune Global 500대 [50]기업 중 51개 기업이 일본에 본사를 두고 있으며,[51] 이는 2013년의 62개에서 감소한 것입니다.그 나라는 총 재산으로 세계에서 세 번째로 크다.

일본의 자산과 재산은 과거 두 부문에서 미국에 이어 2위였다.2015년에는 자산과 [52][53]부의 면에서 중화인민공화국에 뒤졌다.일본은 명목 GDP에서 미국에 이어 세계 2위의 경제대국이었다.2010년에는 [54]중화인민공화국에 의해 가려졌다.

1991년 일본의 자산가격 버블 붕괴는 "잃어버린 10년"으로 알려진 경제 침체의 시기를 이끌었고, 때로는 "잃어버린 20년" 혹은 그 이상으로 연장되었다.1995년부터 2007년까지 GDP는 명목상 [55]5조3천300억 달러에서 4조3천600억 달러로 감소했다.2000년대 초반부터 일본은행은 새로운 [56][57]양적완화 정책을 통해 경제성장을 촉진하기 시작했다.부채 수준은 2007년 글로벌 금융 위기, 2011년 도호쿠 지진과 쓰나미, 후쿠시마 원자력 재해, 2020년부터 COVID-19 대유행으로 계속 증가했다.2021년 현재 일본은 GDP [58][19]대비 약 260%로 선진국에 비해 상당히 높은 수준의 공공부채를 가지고 있으며, 이 부채의 45%는 [58]일본은행이 보유하고 있다.고령화와 인구 감소로 인해 일본 경제는 상당한 과제에 직면해 있으며, 2010년 1억2800만 명으로 정점을 찍고 2022년 [59]현재 1억2550만 명으로 떨어졌다.예측에 따르면 인구는 계속 감소해 21세기 [60][61]중반에는 1억 명 이하로 떨어질 가능성이 있다.

개요

1960년 이후 30년간 경제발전을 거듭하면서 전후 일본의 경제기적이라고 불리는 급속한 경제성장이 일어났다.일본은 1960년대 평균 성장률이 10%, 1970년대 평균 성장률이 5%, 1980년대 평균 4%인 경제산업성의 지도에 의해 1978년부터 2010년까지 중국에 추월당해 세계 2위의 경제대국으로 자리매김할 수 있었다.1990년까지 일본의 1인당 소득은 서구 대부분의 국가와 같거나 앞섰다.

1980년대 후반, 주식과 부동산 가격의 상승은 경제 거품을 만들었다.1990-92년 도쿄 증권거래소가 붕괴하고 1991년 부동산 가격이 최고조에 달하면서 경제 거품이 갑자기 꺼졌다.1990년대 일본의 성장률은 1.5%로 글로벌 성장률에 비해 저조해 잃어버린 10년이라는 용어가 생겨났다.저성장의 10년 후, 그 용어는 잃어버린 20년이 되었다.그럼에도 불구하고 2001년부터 2010년까지 1인당 GDP 성장률은 여전히 유럽과 미국을 [citation needed]앞지르고 있다.

이 저성장률에 따라 일본의 국가채무는 조세 기반이 축소된 고령화 사회에서 상당한 사회복지 지출로 확대되고 있다.폐가의 시나리오는 농촌에서 도시까지 계속 확산되고 있다.

일본은 산지가 많은 화산섬나라로 경제성장과 인구 증가에 대응할 수 있는 천연자원이 부족하기 때문에 원자재나 석유의 수입과 맞바꾸어 엔지니어링·연구·개발 주도의 공산품 등 비교우위를 가진 상품을 수출하고 있다.일본은 자국의 농업 소비 총량에서 유럽연합과 미국에 이어 세계 3대 농산물 수입국이다.도쿄도 중앙도매시장은 유명한 츠키지 어시장을 포함한 일본 최대의 1차 상품 도매시장입니다.표면상으로는 연구 목적의 일본 고래잡이가 국제법상 불법으로 고소되었다.

비록 많은 종류의 광물이 나라 전역에서 채취되었지만, 대부분의 광물 자원은 전후 시대에 수입되어야만 했다.금속을 함유한 광석의 국소 퇴적물은 낮은 등급이기 때문에 처리하기가 어려웠다.1980년대 후반 국토의 70%를 차지했던 거대하고 다양한 산림자원은 광범위하게 활용되지 못했다.지방, 도도부현, 국가 차원의 정치적 결정 때문에 일본은 삼림 자원을 경제적 이익을 위해 이용하지 않기로 결정했다.국내 공급원은 국내 목재 수요의 25-30%만 공급했다.농업과 어업은 가장 잘 개발된 자원이었지만, 수년간의 고된 투자와 노력을 통해서만 가능했다.따라서, 한국은 해외에서 수입된 원재료를 전환하기 위해 제조와 가공 산업을 키웠다.이러한 경제 발전 전략은 필요한 에너지, 교통, 통신 및 기술 노하우를 제공하기 위한 강력한 경제 인프라의 구축을 필요로 했다.

금, 마그네슘, 은의 매장량은 현재의 산업 수요를 충족시키지만, 일본은 현대 산업에 필수적인 많은 광물을 외국 자원에 의존하고 있다.철광석, 구리, 보크사이트, 알루미나는 물론 많은 임산물도 수입해야 한다.

일본은 다른 선진국에 비해 GDP 규모에 비해 수출 수준이 낮은 것이 특징이며, 1970년부터 2018년까지 G7에서 수출 의존도가 가장 낮거나 두 번째로 낮았으며, 수출 의존도가 세계에서 가장 낮은 나라 중 하나였다.1970-2018년 무역의존도가 가장 낮은 경제국 중 하나이기도 하다.

일본은 유난히 낮은 수준의 외국인 투자를 받고 있다.대내 직접투자 재고는 2018년 기준 G7에서 가장 적었고 오스트리아, 폴란드, 스웨덴 등 훨씬 작은 경제국들에 비해 적었다.GDP 대비 대내 직접투자 재고는 세계 최저 수준일 것이다.

일본은 노동 생산성에 있어서 다른 선진국에 뒤처져 있다.1970년부터 2018년까지 일본은 G7에서 [62]항상 노동생산성이 가장 낮았다.2020년에 일본은 OECD 국가 [62]중 노동 생산성이 23위를 차지했다.일본 경제의 특수성은 매우 오래된 기업(신세)으로, 그 중 일부는 1000년 이상 된 것으로, 큰 명성을 누리고 있다.반면 일본에서는 스타트업 문화가 다른 [63]나라만큼 두드러지지 않는다.

역사

일본의 경제사는 가장 많이 연구되고 있는 것 중 하나입니다.첫 번째는 에도의 건국(1603년), 두 번째는 메이지 유신(1868년), 첫 번째 비유럽권력, 세 번째는 제2차 세계대전 패전(1945년) 이후 세계 제2의 경제대국으로 부상한 것이다.

유럽과의 첫 접촉(16세기)

일본은 마르코 폴로가 주로 금으로 된 사원이나 궁전에 대해 기술한 것과 산업시대에 대규모 심층 채굴이 가능하기 전에는 거대한 화산국 특유의 지표 광석이 상대적으로 풍부했기 때문에 귀금속이 풍부한 나라로 여겨졌다.일본은 이 기간 동안 은, 구리, 금의 주요 수출국이 될 예정이었다.

르네상스 일본은 또한 고도의 문화와 강력한 산업화 이전의 기술을 가진 세련된 봉건 사회로 인식되었다.그것은 인구밀도와 도시화 되어 있었다.당시 유럽의 저명한 관찰자들은 일본인들이 "다른 동양 민족들을 능가할 뿐만 아니라 유럽 민족들을 능가한다"고 동의하는 듯 보였다. (Alessandro Valignano, 1584년, "Historia del Principo y Progrreso de la Jesus en Las Indias Orientales."

초기 유럽 관광객들은 일본의 장인정신과 금속세공의 질에 놀랐다.유럽 공통의 천연자원, 특히 철분이 풍부하기 때문이다.

일본에 도착하는 최초의 포르투갈 선박(통상 매년 4척 정도의 소형 선박)의 화물은 거의 모두 중국 상품(비단, 도자기)이었다.일본인들은 그러한 물품의 획득을 매우 기대하고 있었지만, 와코 해적의 습격에 대한 처벌로 중국 천황과의 어떠한 접촉도 금지되어 있었다.포르투갈인(난반이라고 불렸던)이 불을 붙였다.그래서 남방 야만인)은 아시아 무역에서 중개자로 활동할 기회를 찾았다.

에도시대(1603년~1868년)

에도 시대의 시작은 경제적, 종교적 측면에서 유럽 열강과의 활발한 교류가 이루어진 난반 무역 기간의 마지막 수십 년과 일치한다.하세쿠라 쓰네나가가 이끄는 일본 대사관을 미주까지 수송한 500t급 갤런형 배인 산후안바우티스타호 등 일본이 처음으로 원양양양식 군함을 건조해 유럽으로 이어지게 된 것은 에도시대 초반이다.또한 막부는 그 기간 동안 약 350척의 홍도장선, 3개의 돛을 단 무장 무역선을 아시아 지역 내 무역에 위탁하였다.야마다 나가마사와 같은 일본 모험가들은 아시아 전역에서 활동했습니다.

기독교화의 영향을 뿌리뽑기 위해 일본은 사코쿠라는 고립기에 접어들어 경제가 안정되고 완만하게 발전했다.그러나 얼마 지나지 않아 1650년대 내전으로 중국의 주요 도자기 생산 중심지인 징더진(京德hen)이 수십 년 동안 작동하지 않게 되면서 일본 수출 도자기의 생산량이 크게 증가하였다.17세기 후반까지 일본의 도자기 생산은 대부분 규슈에서 수출용이었다.무역은 1740년대에 다시 시작된 중국의 경쟁으로 줄어들다가 19세기 중반 일본의 개국 이후 재개되었다.

에도 시대의 경제 발전에는 도시화, 상품 수송의 증가, 국내외 무역의 현저한 확대, 무역이나 수공업의 보급이 있었다.건설업은 은행업과 상인조합과 함께 번창했다.점차적으로, 한 당국은 농업 생산의 증가와 농촌 수공예의 확산을 감독했다.

18세기 중반까지 에도는 100만 명 이상의 인구가 있었고 오사카와 교토는 각각 40만 명 이상의 인구가 살고 있었다.다른 많은 성곽 마을들도 성장했다.오사카와 교토는 무역과 수공업 생산의 중심지가 되었고, 에도는 식량과 필수 도시 소비재의 공급의 중심지가 되었다.

다이묘가 농민들로부터 쌀의 형태로 세금을 징수했기 때문에 쌀은 경제의 기반이었다.세금은 수확의 40% 정도로 높았다.쌀은 에도의 후다사시 시장에서 팔렸습니다.돈을 마련하기 위해 다이묘는 수확도 되지 않은 쌀을 선물계약으로 팔았다.이 계약들은 현대의 선물 거래와 비슷했다.

일본은 미국의 압력으로 서방세계에 경제를 재개했다.이 기간 동안 일본은 데지마에 있는 네덜란드 무역상을 통해 받은 정보와 서적을 통해 서양의 과학과 기술(랑가쿠, 문자 그대로 네덜란드학)을 점차적으로 연구하였다.연구된 주요 분야로는 지리, 의학, 자연과학, 천문학, 미술, 언어, 전기현상 연구 등 물리과학, 기계과학 등이 있으며, 이는 서양의 기술에서 착안한 일본 시계(와도케이)의 발전으로 대표된다.

전쟁 전 기간(1868년-1945년)

메이지유신 이후 19세기 중반부터 서양의 상업과 영향력까지 개방되어 일본은 두 번의 경제발전을 거쳤다.첫 번째는 1868년에 본격적으로 시작되어 제2차 세계대전까지 이어졌고, 두 번째는 1945년에 시작되어 1980년대 [citation needed]중반까지 계속되었다.

전후 경제 발전은 메이지 정부의 '부국강군정책'에서 시작되었다.메이지 시대(1868-1912) 동안 지도자들은 모든 젊은이들을 위한 새로운 서구식 교육 제도를 시작하고, 수천 명의 학생들을 미국과 유럽에 보냈으며, 일본에서 현대 과학, 수학, 기술, 그리고 외국어를 가르치기 위해 3,000명 이상의 서양인들을 고용했다.정부는 또한 철도를 건설하고, 도로를 개선하고, 국토 개혁 프로그램을 개시하여 나라가 [citation needed]더 발전할 수 있도록 준비하였다.

산업화를 촉진하기 위해, 정부는 민간 기업이 자원을 배분하고 계획을 세우는 것을 도와야 하지만, 민간 부문이 경제 성장을 촉진하는 데 가장 적합하다고 결정했다.정부의 가장 큰 역할은 사업에 좋은 경제적 조건을 제공하는 것을 돕는 것이었다.요컨대 정부는 가이드, 비즈니스는 생산자가 되는 것이었다.메이지 시대 초기에 정부는 기업가들에게 그 가치의 극히 일부에 팔리는 공장과 조선소를 건설했다.이 사업들 중 많은 것들이 빠르게 성장하여 대기업이 되었다.정부는 일련의 친기업 정책을 [citation needed]펴면서 민간기업의 최고 추진자로 부상했다.

1930년대 중반 일본의 명목임금률은 미국(1930년대 중반 환율 기준)보다 '10배' 낮았고, 물가수준은 [citation needed]미국의 약 44%로 추정됐다.

일본의 도시 규모와 산업구조는 도시 전체의 인구와 산업의 [64]대폭적인 변화에도 불구하고 엄격한 규칙성을 유지하고 있다.

전후(1945~1999년)

기업에 대한 정부의 통제와 영향력은 대부분의 다른 [65]나라들보다 광범위하다.입법 조치를 취하는 대신, 그들의 통제는 기업과의 지속적인 협의와 정부의 [65]은행업무에 대한 깊은 개입을 통해 행사된다.

1960년대부터 1980년대까지 전반적인 실질 경제 성장은 매우 컸다. 1960년대 평균 10%, 1970년대 평균 5%, 1980년대 평균 4%였다.그 기간 말, 일본은 [66]고임금 경제로 접어들었다.

1990년대 후반에는 성장이 현저하게 둔화되어 일본의 자산가격 버블 붕괴 후 잃어버린 10년이라고도 불린다.그 결과, 일본은 대규모 공공 사업 프로그램에 자금을 조달하기 위해 막대한 예산 적자(일본 금융 시스템에 수조엔 추가)를 냈다.

1998년까지 일본의 공공사업은 여전히 경기 침체를 끝낼 만큼 수요를 자극하지 못했다.일본 정부는 자포자기한 심정으로 주식과 부동산 시장의 투기과잉을 우려내는 구조개혁에 나섰다.불행하게도 이러한 정책들은 1999년부터 2004년 사이에 일본을 여러 차례 디플레이션으로 이끌었다.일본은행은 인플레이션 기대심리를 높이고 경제성장을 촉진하기 위해 양적완화를 통해 통화공급을 확대했다.당초는 성장을 유도하는 데 실패했지만 결국 인플레이션 기대치에 영향을 미치기 시작했다.2005년 말, 경제는 마침내 지속적인 회복으로 보이는 것을 시작했다.그 해의 GDP 성장률은 2.8%, 연율 4분기 성장률은 5.5%로, [67]같은 기간 미국과 유럽연합의 성장률을 웃돌았다.지금까지의 회복세와는 달리, 내수가 성장의 주된 요인이 되고 있다.

21세기(2000~현재)

오랫동안 제로(0)에 가까운 금리를 유지했지만 양적완화 전략은 물가 디플레이션을 [68]막는데 성공하지 못했다.이로 인해 폴 크루그먼과 같은 일부 경제학자들과 일부 일본 정치인들은 더 높은 인플레이션 [69]기대치를 주창하게 되었다.2006년 7월 제로금리 정책이 종료됐다.2008년에도 일본 중앙은행은 선진국에서 가장 낮은 금리를 유지하고 있었지만, 디플레이션은 해소되지[70] 않고 있어 닛케이 225지수는 약 50%(2007년 6월~2008년 12월)를 웃돌고 있다.그러나 2013년 4월 5일 일본은행은 2년간 일본의 통화 공급량을 2배로 늘려 디플레이션을 해소하기 위해 60조~70조엔의 채권과 증권을 매입한다고 발표했다.닛케이 225지수는 2012년 11월 이후 42%[71] 이상 상승하는 등 전 세계 시장은 정부의 적극적인 정책에 긍정적인 반응을 보이고 있다.이코노미스트는 파산법, 토지 양도법, 세법의 개선이 일본 경제에 도움이 될 것이라고 제안했다.최근 일본은 세계 15개 무역국의 수출시장 1위를 차지하고 있다.

2018년 12월에는 일본과 유럽연합의 자유무역협정이 2019년 2월에 개시되도록 승인되었다.세계 국내총생산(GDP)의 3분의 1에 해당하는 세계 최대 자유무역지대를 만든다.이것에 의해, 일본차의 관세는 10%, 치즈의 관세는 30%, 와인의 관세는 10%, 서비스 시장은 [72]개방되고 있다.

2020년 초 아베 신조(安倍晋三) 총리는 제2차 [74]세계대전 이후 최악의 경제위기를 초래한 점을 들어 COVID-19 [73]대유행 속에 비상사태를 선포했다고 발표했다.일본경제연구센터의 사이토 준은 대유행이 2018년에 [75]저성장을 재개한 일본의 오랜 성장기에 "최후의 타격"을 가했다고 말했다.

일본인의 4분의 1도 안 되는 사람들이 앞으로 수십 [76]년 동안 생활 조건이 개선될 것이라고 예상한다.

2020년 10월 23일, 일본과 영국은 약 152억 파운드의 무역을 촉진하는 첫 번째 자유무역협정에 정식으로 서명했다.대일 수출의 99%에 대해 무관세 무역을 가능하게 한다.[77][78]

2021년 2월 15일 닛케이평균지수는 1991년 [79]11월 이후 최고치인 3만선을 돌파했다.이는 강력한 기업 수익, GDP 데이터 및 COVID-19 [79]백신에 대한 낙관론 때문이다.

2021년 3월 말 소프트뱅크그룹이 사상 최대인 458억8000만 원의 순이익을 올린 것은 전자상거래 업체 쿠팡의 [80]등장에 힘입은 바가 크다.이는 일본 기업의 연간 이익으로는 [80]사상 최대 규모다.

2022년 3월 말 재무성은 국가채무가 정확히 10억1700만엔에 [81]달한다고 발표했다.는 부채 지방 자치 단체와 계약을 포함한 나라의 총 공공 부채:""Japanese 가구 대부분을 일본의 GDP.[81]이코노미스트 고헤이 Iwahara의 거의 250%(9,200명의 억달러)일본인들은 그 부채의 대부분을 GDP수준으로 그런 예외적인 부채만 가능하다고 말했다 1.210 만 억엔을 나타냅니다. 의은행 계좌에 저축한 금액(48%)은 시중은행에 의해 일본 국채를 사는 데 사용된다.그 때문에, 이 채권의 85.7%는 일본 [81]투자가가 보유하고 있다」라고 말했다.그러나 고령화는 [81]저축을 감소시킬 수 있다.

사회 기반 시설

일본은 2018년 세계은행 물류실적지수에서 [82]종합 5위, 인프라 [83]부문에서는 2위를 기록했다.

2005년에는 일본 에너지의 절반, 석탄의 5분의 1, 천연가스의 [84]14%가 석유에서 생산되었다.일본의 원자력 발전은 전력 생산의 4분의 1을 차지했지만 후쿠시마 제1원자력 재해로 인해 일본의 원자력 프로그램을 [85][86]중단하려는 열망이 커졌다.2013년 9월, 일본은 전국 50기의 원자력 발전소를 폐쇄함으로써, 일본은 원자력이 [87]없는 상태가 되었다.그 이후 그 나라는 몇 개의 원자로를 [88]재가동하기로 결정했다.

일본의 도로에 대한 지출은 [89]많은 것으로 여겨져 왔다.포장된 120만 킬로미터의 도로는 주요 [90]교통수단 중 하나이다.일본은 [91]좌측통행입니다.속도, 분할, 접근 제한 유료 도로의 단일 네트워크가 주요 도시를 연결하고 요금 징수 [92]업체에 의해 운영됩니다.신차와 중고차는 저렴하고, 일본 정부는 사람들에게 하이브리드 자동차를 [93]사도록 권장하고 있다.자동차 소유료와 연료세는 에너지 [93]효율을 높이기 위해 사용된다.

철도 수송은 일본의 주요 교통 수단이다.JR 6인승, 긴테쓰 철도, 세이부 철도,[94] 게이오 주식회사 등 수십 개의 일본 철도 회사가 지역 및 지방 여객 운송 시장에서 경쟁하고 있습니다.이러한 기업의 전략은 역 옆에 부동산이나 백화점이 있는 경우가 많고, 많은 주요 역이 [95]역 근처에 주요 백화점이 있다.후쿠오카, 고베, 교토, 나고야, 오사카, 삿포로, 센다이, 도쿄, 요코하마의 도시들은 모두 지하철 시스템을 가지고 있다.250여 대의 고속 신칸센이 주요 [96]도시를 연결합니다.모든 열차는 시간을 엄수하는 것으로 알려져 있으며, 일부 열차 [97]운행에서는 90초의 지연이 고려될 수 있습니다.

일본에는 98명의 승객과 175개의 총 공항이 있으며, 비행은 인기 있는 [98][99]여행 방법입니다.국내 최대 공항인 도쿄 국제공항은 아시아에서 두 번째로 붐비는 [100]공항이다.가장 큰 국제 게이트웨이는 나리타 국제공항(도쿄 지역), 간사이 국제공항(오사카/고베/교토 지역), 주부 국제공항(나고야 지역)[101]이다.일본에서 가장 큰 항구는 나고야항, 요코하마항, 도쿄항, [102]고베항입니다.

일본 에너지의 약 84%가 외국에서 [103][104]수입되고 있다.일본은 세계 최대 액화천연가스 수입국, 2대 석탄 수입국, 3대 석유 [105]수입국이다.일본은 수입 에너지에 대한 의존도가 높기 때문에 자원 [106]다변화를 목표로 하고 있다.일본은 1970년대 오일쇼크 이후 에너지원으로서의 석유의존도를 1973년 77.4%에서 2010년 약 43.7%로 낮추고 천연가스나 원자력에 [107]대한 의존도를 높였다.2019년 9월에는 세계 LNG 시장 활성화와 에너지 [108]공급 안전 강화를 위한 전략으로 세계 액화천연가스 프로젝트에 100억을 투자한다.다른 중요한 에너지원에는 석탄이 있으며, 수력은 일본 최대의 [109][110]재생 에너지원이다.일본의 태양광 시장도 현재 [111]호황을 누리고 있다.등유는 휴대용 난방기, 특히 북쪽에서 가정 [112]난방에 널리 사용된다.많은 택시 회사들이 액화 천연 [113]가스로 그들의 비행대를 운영하고 있다.최근 연비 향상을 위한 성공은 대량 생산된 하이브리드 [93]차량의 도입이었습니다.일본의 경제 부흥에 힘쓰고 있던 아베 신조 수상은 사우디아라비아 및 UAE와 유가 상승에 관한 조약을 체결하여 일본이 그 [114][115]지역에서 안정적으로 인도할 수 있도록 했다.

거시 경제 동향

국제통화기금(IMF)이 추정한 일본의 국내총생산(GDP)의 시장가격 추이를 수백만엔 [116]단위로 나타낸 차트입니다.「 」를[117][118] 참조해 주세요.

| 연도 | 국내 총생산 | 미국 달러 환율 | 물가 지수 (2000=100) | 명목 1인당 GDP (미국 비율) | PPP 1인당 GDP (미국 비율) |

| 1955 | 8,369,500 | ¥360.00 | 10.31 | – | |

| 1960 | 16,009,700 | ¥360.00 | 16.22 | – | |

| 1965 | 32,866,000 | ¥360.00 | 24.95 | – | |

| 1970 | 73,344,900 | ¥360.00 | 38.56 | – | |

| 1975 | 148,327,100 | ¥297.26 | 59.00 | – | |

| 1980 | 240,707,315 | ¥225.82 | 100 | 105.85 | 71.87 |

| 2005 | 502,905,400 | ¥110.01 | 97 | 85.04 | 71.03 |

| 2010 | 477,327,134 | ¥88.54 | 98 | 89.8 | 71.49 |

구매력 평가의 비교를 위해,[119] 2010년 미국 달러는 109파운드로 교환되었다.

GDP 구성

2012년 [120]국내총생산(GDP) 부가가치별 업종.2013년 [121]4월 13일의 환율을 사용하여 환산한다.

| 산업 | 2018년 GDP 부가가치 수십억 | 총 GDP의 % |

|---|---|---|

| 기타 서비스 활동 | 1,238 | 23.5% |

| 제조업 | 947 | 18.0% |

| 부동산 | 697 | 13.2% |

| 도소매업 | 660 | 12.5% |

| 수송 및 통신 | 358 | 6.8% |

| 행정학 | 329 | 6.2% |

| 건설 | 327 | 6.2% |

| 금융 및 보험 | 306 | 5.8% |

| 전기, 가스 및 급수 | 179 | 3.4% |

| 관공서 활동 | 41 | 0.7% |

| 채굴 | 3 | 0.1% |

| 총 | 5,268 | 100% |

주요 지표 개발

다음 표는 1980-2020년의 주요 경제 지표를 보여준다(IMF 스태프는 2020-2026년에 경기부양).2% 미만의 인플레이션은 [122]녹색이다.

| 연도 | GDP (빌에서).미국 PPP) | 1인당 GDP (미국 PPP) | GDP (빌에서).미국 공칭) | 1인당 GDP (미국 공칭) | GDP 성장 (실제) | 인플레이션율 (백분율) | 실업률 (백분율) | 정부채무 (GDP 비율) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1,068.1 | 9,147.0 | 1,127.9 | 9,659.0 | 2.0% | 47.8% | ||

| 1981 | ||||||||

| 1982 | ||||||||

| 1983 | ||||||||

| 1984 | ||||||||

| 1985 | ||||||||

| 1986 | ||||||||

| 1987 | ||||||||

| 1988 | ||||||||

| 1989 | ||||||||

| 1990 | ||||||||

| 1991 | ||||||||

| 1992 | ||||||||

| 1993 | ||||||||

| 1994 | ||||||||

| 1995 | ||||||||

| 1996 | ||||||||

| 1997 | ||||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||

| 2026 |

Sectors of the economy

Agriculture

The Japanese agricultural sector accounts for about 1.1% (2017) of the total country's GDP.[123] Only 12% of Japan's land is suitable for cultivation.[124][125] Due to this lack of arable land, a system of terraces is used to farm in small areas.[126] This results in one of the world's highest levels of crop yields per unit area, with an overall agricultural self-sufficiency rate of about 50% on fewer than 56,000 km2 (14 million acres) cultivated.

Japan's small agricultural sector, however, is also highly subsidized and protected, with government regulations that favor small-scale cultivation instead of large-scale agriculture as practiced in North America.[124] There has been a growing concern about farming as the current farmers are aging with a difficult time finding successors.[127]

Rice accounts for almost all of Japan's cereal production.[128] Japan is the second-largest agricultural product importer in the world.[128] Rice, the most protected crop, is subject to tariffs of 777.7%.[125][129]

Although Japan is usually self-sufficient in rice (except for its use in making rice crackers and processed foods) and wheat, the country must import about 50% of its requirements of other grain and fodder crops and relies on imports for half of its supply of meat.[130][131] Japan imports large quantities of wheat and soybeans.[128] Japan is the 5th largest market for the European Union's agricultural exports.[132][needs update] Over 90% of mandarin oranges in Japan are grown in Japan.[131] Apples are also grown due to restrictions on apple imports.[133]

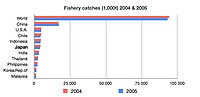

Fishery

Japan ranked fourth in the world in 1996 in tonnage of fish caught.[134] Japan captured 4,074,580 metric tons of fish in 2005, down from 4,987,703 tons in 2000, 9,558,615 tons in 1990, 9,864,422 tons in 1980, 8,520,397 tons in 1970, 5,583,796 tons in 1960 and 2,881,855 tons in 1950.[135] In 2003, the total aquaculture production was predicted at 1,301,437 tonnes.[136] In 2010, Japan's total fisheries production was 4,762,469 fish.[137] Offshore fisheries accounted for an average of 50% of the nation's total fish catches in the late 1980s although they experienced repeated ups and downs during that period.

Coastal fishing by small boats, set nets, or breeding techniques accounts for about one third of the industry's total production, while offshore fishing by medium-sized boats makes up for more than half the total production. Deep-sea fishing from larger vessels makes up the rest. Among the many species of seafood caught are sardines, skipjack tuna, crab, shrimp, salmon, pollock, squid, clams, mackerel, sea bream, sauries, tuna and Japanese amberjack. Freshwater fishing, including salmon, trout and eel hatcheries and fish farms,[138] takes up about 30% of Japan's fishing industry. Among the nearly 300 fish species in the rivers of Japan are native varieties of catfish, chub, herring and goby, as well as such freshwater crustaceans as crabs and crayfish.[139] Marine and freshwater aquaculture is conducted in all 47 prefectures in Japan.[136]

Japan maintains one of the world's largest fishing fleets and accounts for nearly 15% of the global catch,[140] prompting some claims that Japan's fishing is leading to depletion in fish stocks such as tuna.[141] Japan has also sparked controversy by supporting quasi-commercial whaling.[142]

Industry

Japanese manufacturing and industry is very diversified, with a variety of advanced industries that are highly successful. Industry accounts for 30.1% (2017) of the nation's GDP.[123] The country's manufacturing output is the third highest in the world.[143]

Industry is concentrated in several regions, with the Kantō region surrounding Tokyo, (the Keihin industrial region) as well as the Kansai region surrounding Osaka (the Hanshin industrial region) and the Tōkai region surrounding Nagoya (the Chūkyō–Tōkai industrial region) the main industrial centers.[40][41][42][43][44][144] Other industrial centers include the southwestern part of Honshū and northern Shikoku around the Seto Inland Sea (the Setouchi industrial region); and the northern part of Kyūshū (Kitakyūshū). In addition, a long narrow belt of industrial centers called the Taiheiyō Belt is found between Tokyo and Fukuoka, established by particular industries, that have developed as mill towns.

Japan enjoys high technological development in many fields, including consumer electronics, automobile manufacturing, semiconductor manufacturing, optical fibers, optoelectronics, optical media, facsimile and copy machines, and fermentation processes in food and biochemistry. However, many Japanese companies are facing emerging rivals from the United States, South Korea, and China.[145]

Automobile manufacturing

Japan is the third biggest producer of automobiles in the world.[37] Toyota is currently the world's largest car maker, and the Japanese car makers Nissan, Honda, Suzuki, and Mazda also count for some of the largest car makers in the world.[146][147]

Mining and petroleum exploration

Japan's mining production has been minimal, and Japan has very little mining deposits.[148][149] However, massive deposits of rare earths have been found off the coast of Japan.[150] In the 2011 fiscal year, the domestic yield of crude oil was 820 thousand kiloliters, which was 0.4% of Japan's total crude processing volume.[151]

In 2019, Japan was the 2nd largest world producer of iodine,[152] 4th largest worldwide producer of bismuth,[153] the world's 9th largest producer of sulfur[154] and the 10th largest producer of gypsum.[155]

Services

Japan's service sector accounts for 68.7% (2017) of its total economic output.[123] Banking, insurance, real estate, retailing, transportation, and telecommunications are all major industries such as Mitsubishi UFJ, Mizuho, NTT, TEPCO, Nomura, Mitsubishi Estate, ÆON, Mitsui Sumitomo, Softbank, JR East, Seven & I, KDDI and Japan Airlines counting as one of the largest companies in the world.[156][157] Four of the five most circulated newspapers in the world are Japanese newspapers.[158] The Koizumi government set Japan Post, one of the country's largest providers of savings and insurance services for privatization by 2015.[159] The six major keiretsus are the Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, Fuyo, Mitsui, Dai-Ichi Kangyo and Sanwa Groups.[160] Japan is home to 251 companies from the Forbes Global 2000 or 12.55% (as of 2013).[161]

Tourism

In 2012, Japan was the fifth most visited country in Asia and the Pacific, with over 8.3 million tourists.[162] In 2013, due to the weaker yen and easier visa requirements for southwest Asian countries, Japan received a record 11.25 million visitors, which was higher than the government's projected goal of 10 million visitors.[163][164][165] The government hopes to attract 40 million visitors a year by the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.[164] Some of the most popular visited places include the Shinjuku, Ginza, Shibuya and Asakusa areas in Tokyo, and the cities of Osaka, Kobe and Kyoto, as well as Himeji Castle.[166] Hokkaido is also a popular winter destination for visitors with several ski resorts and luxury hotels being built there.[164][167]

Japan's economy is less dependent on international tourism than those of other G7 countries and OECD countries in general; from 1995 to 2014, it was by far the least visited country in the G7 despite being the second largest country in the group,[168] and as of 2013 was one of the least visited countries in the OECD on a per capita basis.[169] In 2013, international tourist receipts was 0.3% of Japan's GDP, while the corresponding figure was 1.3% for the United States and 2.3% for France.[170][171]

Finance

The Tokyo Stock Exchange is the third largest stock exchange in the world by market capitalization, as well as the 2nd largest stock market in Asia, with 2,292 listed companies.[172][173][174] The Nikkei 225 and the TOPIX are the two important stock market indexes of the Tokyo Stock Exchange.[175][176] The Tokyo Stock Exchange and the Osaka Stock Exchange, another major stock exchange in Japan, merged on 1 January 2013, creating one of the world's largest stock exchanges.[174] Other stock exchanges in Japan include the Nagoya Stock Exchange, Fukuoka Stock Exchange and Sapporo Securities Exchange.[177][178]

Labor force

15-24 age (thin line) is Youth unemployment.

The unemployment rate in December 2013 was 3.7%, down 1.5 percentage points from the claimed unemployment rate of 5.2% in June 2009 due to the strong economic recovery.[180][181][182]

In 2008 Japan's labor force consisted of some 66 million workers—40% of whom were women—and was rapidly shrinking.[183] One major long-term concern for the Japanese labor force is its low birthrate.[184] In 2005, the number of deaths in Japan exceeded the number of births, indicating that the decline in population had already started.[185] While one countermeasure for a declining birthrate would be to increase immigration, Japan has struggled to attract potential migrants despite immigration laws being relatively lenient (especially for high-skilled workers) compared to other developed countries.[186] This is also apparent when looking at Japan's work visa programme for "specified skilled worker", which had less than 3,000 applicants, despite an annual goal of attracting 40,000 overseas workers, suggesting Japan faces major challenges in attracting migrants compared to other developed countries regardless of its immigration policies.[187] A Gallup poll found that few potential migrants wished to migrate to Japan compared to other G7 countries, consistent with the country's low migrant inflow.[188][189]

In 1989, the predominantly public sector union confederation, SOHYO (General Council of Trade Unions of Japan), merged with RENGO (Japanese Private Sector Trade Union Confederation) to form the Japanese Trade Union Confederation. Labor union membership is about 12 million.

As of 2019 Japan's unemployment rate was the lowest in the G7.[190] Its employment rate for the working-age population (15-64) was the highest in the G7.[191]

Law and government

Japan ranks 27th of 185 countries in the ease of doing business index 2013.[192]

Japan has one of the smallest tax rates in the developed world.[193] After deductions, the majority of workers are free from personal income taxes. Consumption tax rate is 10%, while corporate tax rates are high, second highest corporate tax rate in the world, at 36.8%.[193][194][195] However, the House of Representatives has passed a bill which will increase the consumption tax to 10% in October 2015.[196] The government has also decided to reduce corporate tax and to phase out automobile tax.[197][198]

In 2016, the IMF encouraged Japan to adopt an income policy that pushes firms to raise employee wages in combination with reforms to tackle the labor market dual tiered employment system to drive higher wages, on top of monetary and fiscal stimulus. Shinzo Abe has encouraged firms to raise wages by at least three percent annually (the inflation target plus average productivity growth).[199][200][201]

Shareholder activism is rare despite the fact that the corporate law gives shareholders strong powers over managers.[202] Under Prime Minister Shinzō Abe, corporate governance reform has been a key initiative to encourage economic growth. In 2012 around 40% of leading Japanese companies had any independent directors while in 2016 most all have begun to appoint independent directors.[199][203]

The government's liabilities include the second largest public debt of any nation with debt of over one quadrillion yen, or 8,535,340,000,000 in USD.[204][205][206] Former Prime Minister Naoto Kan has called the situation 'urgent'.[207]

Japan's central bank has the second largest foreign-exchange reserves after the People's Republic of China, with over one trillion US Dollars in foreign reserves.[208]

Culture

Our expansion could be much bigger and quicker, but we are held back. Nowhere in the world do the [regulatory approvals] take so long. (The process is) old fashioned. — Tony Fernandes, AirAsia chief.[209]

Overview

Nemawashi (根回し), or "consensus building", in Japanese culture is an informal process of quietly laying the foundation for some proposed change or project, by talking to the people concerned, gathering support and feedback, and so forth. It is considered an important element in any major change, before any formal steps are taken, and successful nemawashi enables changes to be carried out with the consent of all sides.

Japanese companies are known for management methods such as "The Toyota Way". Kaizen (改善, Japanese for "improvement") is a Japanese philosophy that focuses on continuous improvement throughout all aspects of life. When applied to the workplace, Kaizen activities continually improve all functions of a business, from manufacturing to management and from the CEO to the assembly line workers.[210] By improving standardized activities and processes, Kaizen aims to eliminate waste (see Lean manufacturing). Kaizen was first implemented in several Japanese businesses during the country's recovery after World War II, including Toyota, and has since spread to businesses throughout the world.[211] Within certain value systems, it is ironic that Japanese workers labor amongst the most hours per day, even though kaizen is supposed to improve all aspects of life. According to the OECD, annual hours worked per employee is below the OECD average and in the middle among G7 countries.[212]

Some companies have powerful enterprise unions and shuntō. The Nenko System or Nenko Joretsu, as it is called in Japan, is the Japanese system of promoting an employee based on his or her proximity to retirement. The advantage of the system is that it allows older employees to achieve a higher salary level before retirement and it usually brings more experience to the executive ranks. The disadvantage of the system is that it does not allow new talent to be combined with experience and those with specialized skills cannot be promoted to the already crowded executive ranks. It also does not guarantee or even attempt to bring the "right person for the right job".

Relationships between government bureaucrats and companies are often close. Amakudari (天下り, amakudari, "descent from heaven") is the institutionalised practice where Japanese senior bureaucrats retire to high-profile positions in the private and public sectors. The practice is increasingly viewed as corrupt and a limitation on efforts to reduce ties between the private sector and the state that prevent economic and political reforms. Lifetime employment (shūshin koyō) and seniority-based career advancement have been common in the Japanese work environment.[193][213] Japan has begun to gradually move away from some of these norms.[214]

Salaryman (サラリーマン, Sararīman, salaried man) refers to someone whose income is salary based; particularly those working for corporations. Its frequent use by Japanese corporations, and its prevalence in Japanese manga and anime has gradually led to its acceptance in English-speaking countries as a noun for a Japanese white-collar businessman. The word can be found in many books and articles pertaining to Japanese culture. Immediately following World War II, becoming a salaryman was viewed as a gateway to a stable, middle-class lifestyle. In modern use, the term carries associations of long working hours, low prestige in the corporate hierarchy, absence of significant sources of income other than salary, wage slavery, and karōshi. The term salaryman refers almost exclusively to males.[citation needed]

An office lady, often abbreviated OL (Japanese: オーエル Ōeru), is a female office worker in Japan who performs generally pink collar tasks such as serving tea and secretarial or clerical work. Like many unmarried Japanese, OLs often live with their parents well into early adulthood. Office ladies are usually full-time permanent staff, although the jobs they do usually have little opportunity for promotion, and there is usually the tacit expectation that they leave their jobs once they get married.[citation needed]

Freeter (フリーター, furītā) is a Japanese expression for people between the age of 15 and 34 who lack full-time employment or are unemployed, excluding homemakers and students. They may also be described as underemployed or freelance workers. These people do not start a career after high school or university but instead usually live as parasite singles with their parents and earn some money with low skilled and low paid jobs. The low income makes it difficult for freeters to start a family, and the lack of qualifications makes it difficult to start a career at a later point in life.[citation needed]

Karōshi (過労死, karōshi), which can be translated quite literally from Japanese as "death from overwork", is occupational sudden death. The major medical causes of karōshi deaths are heart attack and stroke due to stress.[215]

Sōkaiya (総会屋, sōkaiya), (sometimes also translated as corporate bouncers, meeting-men, or corporate blackmailers) are a form of specialized racketeer unique to Japan, and often associated with the yakuza that extort money from or blackmail companies by threatening to publicly humiliate companies and their management, usually in their annual meeting (総会, sōkai). Sarakin (サラ金) is a Japanese term for moneylender, or loan shark. It is a contraction of the Japanese words for salaryman and cash. Around 14 million people, or 10% of the Japanese population, have borrowed from a sarakin. In total, there are about 10,000 firms (down from 30,000 a decade ago); however, the top seven firms make up 70% of the market. The value of outstanding loans totals 100 billion. The biggest sarakin are publicly traded and often allied with big banks.[216]

The first "Western-style" department store in Japan was Mitsukoshi, founded in 1904, which has its root as a kimono store called Echigoya from 1673. When the roots are considered, however, Matsuzakaya has an even longer history, dated from 1611. The kimono store changed to a department store in 1910. In 1924, Matsuzakaya store in Ginza allowed street shoes to be worn indoors, something innovative at the time.[217] These former kimono shop department stores dominated the market in its earlier history. They sold, or rather displayed, luxurious products, which contributed for their sophisticated atmospheres. Another origin of Japanese department store is that from railway company. There have been many private railway operators in the nation, and from the 1920s, they started to build department stores directly linked to their lines' termini. Seibu and Hankyu are the typical examples of this type. From the 1980s onwards, Japanese department stores face fierce competition from supermarkets and convenience stores, gradually losing their presences. Still, depāto are bastions of several aspects of cultural conservatism in the country. Gift certificates for prestigious department stores are frequently given as formal presents in Japan. Department stores in Japan generally offer a wide range of services and can include foreign exchange, travel reservations, ticket sales for local concerts and other events.[citation needed]

Keiretsu

A keiretsu (系列, "system" or "series") is a set of companies with interlocking business relationships and shareholdings. It is a type of business group. The prototypical keiretsu appeared in Japan during the "economic miracle" following World War II. Before Japan's surrender, Japanese industry was controlled by large family-controlled vertical monopolies called zaibatsu. The Allies dismantled the zaibatsu in the late 1940s, but the companies formed from the dismantling of the zaibatsu were reintegrated. The dispersed corporations were re-interlinked through share purchases to form horizontally integrated alliances across many industries. Where possible, keiretsu companies would also supply one another, making the alliances vertically integrated as well. In this period, official government policy promoted the creation of robust trade corporations that could withstand pressures from intensified world trade competition.[218]

The major keiretsu were each centered on one bank, which lent money to the keiretsu's member companies and held equity positions in the companies. Each central bank had great control over the companies in the keiretsu and acted as a monitoring entity and as an emergency bail-out entity. One effect of this structure was to minimize the presence of hostile takeovers in Japan, because no entities could challenge the power of the banks.[citation needed]

There are two types of keiretsu: vertical and horizontal. Vertical keiretsu illustrates the organization and relationships within a company (for example all factors of production of a certain product are connected), while a horizontal keiretsu shows relationships between entities and industries, normally centered on a bank and trading company. Both are complexly woven together and sustain each other.[citation needed]

The Japanese recession in the 1990s had profound effects on the keiretsu. Many of the largest banks were hit hard by bad loan portfolios and forced to merge or go out of business. This had the effect of blurring the lines between the keiretsu: Sumitomo Bank and Mitsui Bank, for instance, became Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation in 2001, while Sanwa Bank (the banker for the Hankyu-Toho Group) became part of Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, now known as MUFG Bank. Additionally, many companies from outside the keiretsu system, such as Sony, began outperforming their counterparts within the system.[citation needed]

Generally, these causes gave rise to a strong notion in the business community that the old keiretsu system was not an effective business model, and led to an overall loosening of keiretsu alliances. While the keiretsu still exist, they are not as centralized or integrated as they were before the 1990s. This, in turn, has led to a growing corporate acquisition industry in Japan, as companies are no longer able to be easily "bailed out" by their banks, as well as rising derivative litigation by more independent shareholders.[citation needed]

Mergers and acquisitions

Japanese companies have been involved in 50,759 deals between 1985 and 2018. This cumulates to a total value of 2,636 bil. USD which translates to 281,469.9 bil. YEN.[219] In the year 1999 there was an all-time high in terms of value of deals with almost 220 bil. USD. The most active year so far was 2017 with over 3,150 deals, but only a total value of 114 bil. USD (see graph "M&A in Japan by number and value").[citation needed]

Here is a list of the most important deals (ranked by value in bil. USD) in Japanese history:[citation needed]

| Date Announced | Acquiror Name | Acquiror Mid Industry | Acquiror State | Target Name | Target Mid Industry | Target State | Value of Transaction ($mil) |

| 13 October 1999 | Sumitomo Bank Ltd | Banks | Japan | Sakura Bank Ltd | Banks | Japan | 45,494.36 |

| 18 February 2005 | Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial Grp | Banks | Japan | UFJ Holdings Inc | Banks | Japan | 41,431.03 |

| 20 August 1999 | Fuji Bank Ltd | Banks | Japan | Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank Ltd | Banks | Japan | 40,096.63 |

| 27 March 1995 | Mitsubishi Bank Ltd | Banks | Japan | Bank of Tokyo Ltd | Banks | Japan | 33,787.73 |

| 18 July 2016 | SoftBank Group Corp | Wireless | Japan | ARM Holdings PLC | Semiconductors | United Kingdom | 31,879.49 |

| 20 August 1999 | Fuji Bank Ltd | Banks | Japan | Industrial Bank of Japan Ltd | Banks | Japan | 30,759.61 |

| 24 August 2004 | Sumitomo Mitsui Finl Grp Inc | Banks | Japan | UFJ Holdings Inc | Banks | Japan | 29,261.48 |

| 28 August 1989 | Mitsui Taiyo Kobe Bank Ltd | Banks | Japan | Taiyo Kobe Bank Ltd | Banks | Japan | 23,016.80 |

| 15 October 2012 | SoftBank Corp | Wireless | Japan | Sprint Nextel Corp | Telecommunications Services | United States | 21,640.00 |

| 20 September 2017 | KK Pangea | Other Financials | Japan | Toshiba Memory Corp | Semiconductors | Japan | 17,930.00 |

Among the top 50 deals by value, 92% of the time the acquiring nation is Japan. Foreign direct investment is playing a much smaller role than national M&A in Japan.

Other economic indicators

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: the indicators are 10 years old and unsupported by citation as well. (February 2019) |

Net international investment position: 266,223 \ billion[221] (1st)[222]

Industrial Production Growth Rate: 7.5% (2010 est.)

Investment (gross fixed): 20.3% of GDP (2010 est.)

Household income or consumption by percentage share:

- Lowest 10%: 4.8%

- Highest 10%: 21.7% (1993)

Agriculture – Products: rice, sugar beets, vegetables, fruit, pork, poultry, dairy products, eggs, fish

Exports – Commodities: machinery and equipment, motor vehicles, semiconductors, chemicals[223]

Imports – Commodities: machinery and equipment, fuels, foodstuffs, chemicals, textiles, raw materials (2001)

Exchange rates:

Japanese Yen per US$1 – 88.67 (2010), 93.57 (2009), 103.58 (2008), 117.99 (2007), 116.18 (2006), 109.69 (2005), 115.93 (2003), 125.39 (2002), 121.53 (2001), 105.16 (January 2000), 113.91 (1999), 130.91 (1998), 120.99 (1997), 108.78 (1996), 94.06 (1995)

Electricity:

- Electricity – consumption: 925.5 billion kWh (2008)

- Electricity – production: 957.9 billion kWh (2008 est.)

- Electricity – exports: 0 kWh (2008)

- Electricity – imports: 0 kWh (2008)

Electricity – Production by source:

- Fossil Fuel: 69.7%

- Hydro: 7.3%

- Nuclear: 22.5%

- Other: 0.5% (2008)

Electricity – Standards:

Oil:

- production: 132,700 bbl/d (21,100 m3/d) (2009) (46th)

- consumption: 4,363,000 bbl/d (693,700 m3/d) (2009) (3rd)

- exports: 380,900 barrels per day (60,560 m3/d) (2008) (64th)

- imports: 5,033,000 barrels per day (800,200 m3/d) (2008) (2nd)

- net imports: 4,620,000 barrels per day (735,000 m3/d) (2008 est.)

- proved reserves: 44,120,000 bbl (7,015,000 m3) (1 January 2010 est.)

See also

- Economic history of Japan

- Economic relations of Japan

- List of exports of Japan

- List of countries by leading trade partners

- List of the largest trading partners of Japan

- List of largest Japanese companies

- Japan External Trade Organization

- Tokugawa coinage

- Tourism in Japan

- Japanese post-war economic miracle

- Japanese asset price bubble

- Machine orders, an economic indicator specific to the Japanese economy

- Quantitative easing

- Loans in Japan

Notes

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Preliminary counts of population of Japan". stat.go.jp. Statistics of Japan. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Bank, World (31 May 2022). "Global Economic Prospects, June 2022" (PDF). openknowledge.worldbank.org. World Bank. p. 26. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "EAST ASIA/SOUTHEAST ASIA :: JAPAN". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) - Japan". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at $3.20 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) - Japan". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at $5.50 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) - Japan". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Income inequality". data.oecd.org. OECD. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Seasonally adjusted series of major items (Labour force, Employed person, Unemployed person, Not in labour force, Unemployment rate)". stat.go.jp. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Employed person by age group". stat.go.jp. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Labor Force by Services". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

Labor Force by Industry and agriculture

{{cite web}}: External link inquote= - ^ "Ease of Doing Business in Japan". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Nakao, Yuka (20 January 2022). "Japan's exports, imports hit record highs in December". Kyodo News. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Japanese Trade and Investment Statistics". jetro.go.jp. Japan External Trade Organization. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ a b Aaron, O'Neill (July 2022). "National debt from 2016 to 2026 in relation to gross domestic product". statista. statista.

National debt from 2017 to 2027

- ^ "Development aid rises again in 2016 but flows to poorest countries dip". OECD. 11 April 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Simon; Sedghi, Ami (15 April 2011). "How Fitch, Moody's and S&P rate each country's credit rating". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ Scope Ratings (6 May 2022). "Scope affirms Japan's A ratings; Outlook revised to Negative". Scope Ratings. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b "HOME > International Policy > Statistics > International Reserves/Foreign Currency Liquidity". Ministry of Finance Japan.

- ^ Lechevalier, Sébastien (2014). The Great Transformation of Japanese Capitalism. Routledge. p. 204. ISBN 9781317974963.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2016 – Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". International Monetary Fund (IMF). Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Kyung Lah (14 February 2011). "Japan: Economy slips to Third in world". CNN.

- ^ "Country statistical profile: Japan". OECD iLibrary. 28 February 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Japan: 2017 Article IV Consultation : Press Release ; Staff Report ; and Statement by the Executive Director for Japan. International Monetary Fund. Asia and Pacific Department. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 2017. ISBN 9781484313497. OCLC 1009601181.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "TANKAN :日本銀行 Bank of Japan". Bank of Japan. Boj.or.jp. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "Monthly Reports - World Federation of Exchanges". WFE.

- ^ "Nikkei Indexes". indexes.nikkei.co.jp.

- ^ "World Trade Statistical Review 2019" (PDF). World Trade Organization. p. 100. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "The Global Competitiveness Report 2018". Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "OEC - Economic Complexity Ranking of Countries (2013-2017)". oec.world. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Household final consumption expenditure (current US$) Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ a b "2013 Production Statistics – First 6 Months". OICA. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ Morris, Ben (12 April 2012). "What does the future hold for Japan's electronics firms?". BBC News. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ "Japan (JPN) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners OEC". OEC - The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ a b Iwadare, Yoshihiko (1 April 2004). "Strengthening the Competitiveness of Local Industries: The Case of an Industrial Cluster Formed by Three Tokai Prefecters" (PDF). Nomura Research Institute. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ a b Kodama, Toshihiro (1 July 2002). "Case study of regional university-industry partnership in practice". Institute for International Studies and Training. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ a b Mori, Junichiro; Kajikawa, Yuya; Sakata, Ichiro (2010). "Evaluating the Impacts of Regional Cluster Policies using Network Analysis" (PDF). International Association for Management of Technology. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ a b Schlunze, Rolf D. "Location and Role of Foreign Firms in Regional Innovation Systems in Japan" (PDF). Ritsumeikan University. p. 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Profile of Osaka/Kansai" (PDF). Japan External Trade Organization Osaka. p. 10. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ "Japan, savings superpower of the world". The Japan Times. 2 September 2018. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Chandler, Marc (19 August 2011). "The yen is a safe haven as Japan is the world's largest creditor". Credit Writedowns. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Obe, Mitsuru (28 May 2013). "Japan World's Largest Creditor Nation for 22nd Straight Year". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ "Allianz Global Wealth Report 2021" (PDF). Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Allianz Global Wealth Report 2015" (PDF). Allianz. 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Global 500 (updated)". Fortune.

- ^ "Global 500 2013". Fortune.

- ^ "Allianz Global Wealth Report 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Global wealth report". Credit Suisse. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "China surges past Japan as No. 2 economy; US next?". News.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ "Japanese GDP, nominal".

- ^ Sean, Ross. "The Diminishing Effects of Japan's Quantitative Easing". Investopedia. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Oh, Sunny. "Here's a lesson from Japan about the threat of a U.S. debt crisis". MarketWatch.

- ^ a b One, Mitsuru. "Nikkei: How the world is embracing Japan style economics". Nikkei.

- ^ "Monthly Report (Population)". Statistics Burea of Japan. 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2019". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Sim, Walter (2019). "Tokyo gets more crowded as Japan hollows out 2019". The Straits Times. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Japan's Productivity Ranks Lowest Among G7 Nations for 50 Straight Years". Nippon.com. 6 January 2022. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022.

- ^ Lufkin, Bryan (12 February 2020). "Why so many of the world's oldest companies are in Japan". BBC. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Mori, Tomoya (2017). "Evolution of the Size and Industrial Structure of Cities in Japan between 1980 and 2010: Constant Churning and Persistent Regularity". Asian Development Review. 34 (2): 86–113. doi:10.1162/adev_a_00096.

- ^ a b Chapra, Muhammad Umer (1993). Islam and Economic Development: A Strategy for Development with Justice and Stability. ISBN 9789694620060.

- ^ Business in context: an introduction to business and its environment by David Needle

- ^ Masake, Hisane. A farewell to zero. Asia Times Online (2 March 2006). Retrieved on 28 December 2006.

- ^ Spiegel, Mark (20 October 2006). "Did Quantitative Easing by the Bank of Japan "Work"?".

- ^ Krugman, Paul. "Saving Japan". web.mit.edu.

- ^ "Economic survey of Japan 2008: Bringing an end to deflation under the new monetary policy framework". 7 April 2008.

- ^ Riley, Charles (4 April 2013). "Bank of Japan takes fight to deflation". CNN.

- ^ "EU-Japan free trade deal cleared for early 2019 start". Reuters. 12 December 2018. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Booker, Brakkton (16 April 2020). "Japan Declares Nationwide State Of Emergency As Coronavirus Spreads". NPR. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Reynolds, Isabel; Nobuhiro, Emi (7 April 2020). "Japan Declares Emergency For Tokyo, Osaka as Hospitals Fill Up". Bloomberg. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Huang, Eustance (7 April 2020). "Japan's economy has been dealt the 'final blow' by the coronavirus pandemic, says analyst". CNBC. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ The Economist, 28 March 2020, page 4.

- ^ "Britain signs first major post-Brexit trade deal with Japan". Reuters. 23 October 2020. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "UK and Japan agree historic free trade agreement". Gov.uk (Government of the United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 11 September 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Nikkei index hits 30,000 for first time in three decades". Nikkei. 15 February 2021. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Softbank just shocked its critics by landing the biggest profit in the history of a Japanese company". CNBC. 12 May 2021. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d Sylvain Saurel (13 May 2022). "Japan Exceeds One Million Billion Yen in Debt — "Whatever It Takes" Has Become the Norm". Medium.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Global Rankings 2018 Logistics Performance Index". lpi.worldbank.org. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Global Rankings 2018 Logistics Performance Index". lpi.worldbank.org. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Chapter 7 Energy Archived 5 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Statistical Handbook of Japan 2007

- ^ Hiroko Tabuchi (13 July 2011). "Japan Premier Wants Shift Away From Nuclear Power". The New York Times.

- ^ Kazuaki Nagata (3 January 2012). "Fukushima meltdowns set nuclear energy debate on its ear". The Japan Times.

- ^ "Japan goes nuclear-free indefinitely". CBC News. 15 September 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ "Nuclear reactor restarts in Japan displacing LNG imports in 2019 - Today in Energy - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (1 March 1997). "Japan's Road to Deep Deficit Is Paved With Public Works". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Chapter 9 Transport Archived 27 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Statistical Handbook of Japan

- ^ "Why Does Japan Drive On The Left?". 2pass. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ All-Japan Road Atlas.

- ^ a b c "Prius No. 1 in Japan sales as green interest grows". USA Today. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ The Association of Japanese Private Railways. 大手民鉄の現況(単体) (PDF) (in Japanese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Nagata, Takeshi; Takahasi, Kentaro (5 November 2013). "Osaka dept stores locked in scrap for survival". The Japan News. Yomiuri Shimbun. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "What is Shinkansen (bullet train)? Most convenient and the fastest train service throughout Japan". JPRail.com. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (28 April 2005). "An obsession with being on time". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Aoki, Mizuho (7 February 2013). "Bubble era's aviation legacy: Too many airports, all ailing". The Japan Times. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Mastny, Lisa (December 2001). "Traveling Light New Paths for International Tourism" (PDF). Worldwatch Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ "Year to date Passenger Traffic". Airports Council International. 8 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ "Narita airport prepares for battle with Asian hubs". The Japan Times. 25 October 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "The JOC Top 50 World Container Ports" (PDF). JOC Group Inc. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ "Nuclear Power in Japan". World Nuclear Association. November 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "Japan's Energy Supply Situation and Basic Policy". FEPC. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "Japan". Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Iwata, Mari (12 November 2013). "Fukushima Watch: Some Power Companies in Black without Nuclear Restarts". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "A lesson in energy diversification". The Japan Times. 1 November 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "Japan to invest $10 billion in global LNG infrastructure projects: minister". Reuters. 26 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ Tsukimori, Osamu; Kebede, Rebekah (15 October 2013). "Japan on gas, coal power building spree to fill nuclear void". Reuters. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "International Energy Statistics". Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Watanabe, Chisaki (31 October 2013). "Kyocera Boosts Solar Sales Goal on Higher Demand in Japan". Bloomberg. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Maeda, Risa (25 October 2013). "Japan kerosene heater sales surge on power worries". Reuters. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "Japan may soon get London-style taxis". The Asahi Shimbun. 11 July 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Suzuki, Takuya (1 May 2013). "Japan, Saudi Arabia agree on security, energy cooperation". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "Abe clinches nuclear technology deal with Abu Dhabi". The Japan Times. 3 May 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "Statistics Bureau Home Page/Chapter 3 National Accounts". Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ "Measuring Worth - Japan". Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ "Yearly Average Currency Exchange Rates Translating foreign currency into U.S. dollars". IRS. 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ Statistics Division of Gifu Prefecture Archived 14 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. (in Japanese) Gifu Prefecture. Accessed 2 November 2007.

- ^ "USD/JPY – U. S. Dollar / Japanese Yen Conversion". Yahoo! Finance. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b c "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b "As Farmers Age, Japan Rethinks Relationship With Food, Fields". PBS. 12 June 2012. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Trip Report – Japan Agricultural Situation". United States Department of Agriculture. 17 August 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ Nagata, Akira; Chen, Bixia (22 May 2012). "Urbanites Help Sustain Japan's Historic Rice Paddy Terraces". Our World. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "How will Japan's farms survive?". The Japan Times. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "Japan – Agriculture". Nations Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "With fewer, bigger plots and fewer part-time farmers, agriculture could compete". The Economist. 13 April 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "Japan Immigration Work Permits and Visas". Skill Clear. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ a b Nagata, Kazuaki (26 February 2008). "Japan needs imports to keep itself fed". The Japan Times. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ "Agricultural trade in 2012: A good story to tell in a difficult year?" (PDF). European Union. January 2013. p. 14. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Wheat, Dan (14 October 2013). "Japan may warm to U.S. apples". Capital Press. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ "World review of fisheries and aquaculture". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Brown, Felicity (2 September 2003). "Fish capture by country". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Japan". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "World fisheries production, by capture and aquaculture, by country (2010)" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Willoughby, Harvey. "Freshwater Fish Culture in Japan". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ Butler, Rhett Ayers (8 August 2007). "List of Freshwater Fishes for Japan". Mongabay. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ "UN tribunal halts Japanese tuna over-fishing". Asia Times. 31 August 1999. Archived from the original on 29 September 2000. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Black, Richard (22 June 2005). "Japanese whaling 'science' rapped". BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ "Manufacturing, value added (current US$) Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Karan, Pradyumna (2010). Japan in the 21st Century: Environment, Economy, and Society. University Press of Kentucky. p. 416. ISBN 978-0813127637.

- ^ Cheng, Roger (9 November 2012). "The era of Japanese consumer electronics giants is dead". CNET. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ "Toyota Again World's Largest Auto Maker". The Wall Street Journal. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ Dawson, Chester (2012). "World Motor Vehicle Production OICA correspondents survey" (PDF). OICA. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "Japan Mining". Library of Congress Country Studies. January 1994. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Overview" (PDF). Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. 2005. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Jamasmie, Cecilia (25 March 2013). "Japan's massive rare earth discovery threatens China's supremacy". Mining.com. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Petroleum Industry in Japan 2013" (PDF). Petroleum Association of Japan. September 2013. p. 71. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "USGS Iodine Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Bismuth Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Sulfur Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Gypsum Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "Fortune Global 500". CNNMoney. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "The World's Biggest Public Companies". Forbes. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "National Newspapers Total Circulation 2011". International Federation of Audit Bureaux of Circulations. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Fujita, Junko (26 October 2013). "Japan govt aims to list Japan Post in three years". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "The Keiretsu of Japan". San José State University.

- ^ Rushe, Dominic. "Chinese banks top Forbes Global 2000 list of world's biggest companies". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Tourism Highlights 2013 Edition" (PDF). World Tourism Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Japan marks new high in tourism". Bangkok Post. 9 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ a b c "Attracting more tourists to Japan". The Japan Times. 6 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ Williams, Carol (11 December 2013). "Record 2013 tourism in Japan despite islands spat, nuclear fallout". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ Schoenberger, Chana R. (3 July 2008). "Japan's 10 Most Popular Tourist Attractions". Forbes. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Takahara, Kanako (8 July 2008). "Boom time for Hokkaido ski resort area". The Japan Times. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "International tourism, number of arrivals - United States, Japan, Germany, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Canada Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ Silver, Nate (18 August 2014). "The Countries Where You're Surrounded By Tourists". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "International tourism, receipts (current US$) Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "GDP (current US$) Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "NYSE Calendar". New York Stock Exchange. 31 January 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "China becomes world's third largest stock market". The Economic Times. 19 June 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Japan approves merger of Tokyo and Osaka exchanges". BBC News. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "The Nikkei 225 Index Performance". Finfacts. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "Tokyo Stock Exchange Tokyo Price Index TOPIX". Bloomberg. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Smith, Simon (22 January 2014). "Horizons introduces leveraged and inverse MSCI Japan ETFs". eftstrategy.com. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "About JSCC History". Japan Securities Clearing Corporation. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ OECD Labour Force Statistics 2020, OECD Labour Force Statistics, OECD, 2020, doi:10.1787/23083387, ISBN 9789264687714

- ^ "雇用情勢は一段と悪化、5月失業率は5年8カ月ぶり高水準(Update3)". Bloomberg. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Fujioka, Toru (29 June 2009). "Japan's Jobless Rate Rises to Five-Year High of 5.2% (Update2)". Bloomberg News. Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Rochan, M (31 January 2014). "Japan's Unemployment Rate Drops to Six-Year Low Amid Rising Inflation". International Business Times. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ "Will Abenomics Ensure Japan's Revival?" (PDF). The New Global. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Traphagan, John (4 August 2014). "Japan's Biggest Challenge (and It's Not China): A Plummeting Population". The National Interest. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Japan population starts to shrink". 22 December 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Oishi, Nana (2012). "The Limits of Immigration Policies: The Challenges of Highly Skilled Migration in Japan". American Behavioral Scientist. 56 (8): 1080–1100. doi:10.1177/0002764212441787. S2CID 154641232.

- ^ "Japan cries 'Help wanted,' but few foreigners heed the call". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Inc, Gallup (8 June 2017). "Number of Potential Migrants Worldwide Tops 700 Million". Gallup.com. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Interactive charts by the OECD". OECD Data. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Interactive charts by the OECD". OECD Data. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Interactive charts by the OECD". OECD Data. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Economy Rankings". Doing Business. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ a b c OECD: Economic survey of Japan 2008 Archived 9 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Temple-West, Patrick; Dixon, Kim (30 March 2012). "US displacing Japan as No 1 for highest corp taxes". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ Isidore, Chris (27 March 2012). "U.S. corporate tax rate: No. 1 in the world". CNNMoney. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ "Update: Lower House passes bills to double consumption tax". The Asahi Shimbun. 26 June 2012. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ "Japan to Phase Out Automobile Tax". NASDAQ. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Overhyped, underappreciated". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "IMF urges Japan to 'reload' Abenomics". Financial Times. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "Japan: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2016 Article IV Mission". www.imf.org. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Nagata, Kazuaki (27 April 2015). "New rules are pushing Japanese corporations to tap more outside directors". The Japan Times Online. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "5. Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Keck, Zachary (10 August 2013). "Japan's Debt About 3 Times Larger Than ASEAN's GDP". The Diplomat. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Einhorn, Bruce (9 August 2013). "Japan Gets to Know a Quadrillion as Debt Hits New High". Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ "Kan warns of Greece-like debt crisis " Japan Today: Japan News and Discussion". Japantoday.com. 11 June 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "Japan's forex reserves up for second straight month". Kuwait News Agency. 6 June 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Mayuko Tani (20 March 2018). "AirAsia had talks with cash-strapped HNA over asset purchases". Nikkei Asian Review.

- ^ Imai, Masaaki (1986). Kaizen: The Key to Japan's Competitive Success. New York, NY: Random House.

- ^ Europe Japan Centre, Kaizen Strategies for Improving Team Performance, Ed. Michael Colenso, London: Pearson Education Limited, 2000

- ^ "Interactive charts by the OECD". OECD Data. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Japan's Economy: Free at last". The Economist. 20 July 2006. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- ^ "Going hybrid". The Economist. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ Asgari, Behrooz; Pickar, Peter; Garay, Victoria (2016). "Karoshi and Karou-jisatsu in Japan: causes, statistics and prevention mechanisms" (PDF). Asia Pacific Business & Economics Perspectives. 4 (2): 49–72.

- ^ Lenders of first resort, The Economist, 22 May 2008

- ^ "松坂屋「ひと・こと・もの」語り". Matsuzakaya.co.jp. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "Japan Again Plans Huge Corporations". The New York Times. 17 July 1954.

- ^ "M&A Statistics by Countries - Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances (IMAA)". Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances (IMAA). Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Current account balance, U.S. dollars, Billions from IMF World Economic Outlook Database, April 2008

- ^ "International Investment Position of Japan (End of 2009)". Ministry of Finance, Japan. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ "「日本売り」なぜ起きない 円安阻むからくりに迫る". Nihon Keizai Shimbun. 8 May 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ "Japanese Business Briefs".