러시아-우크라이나 전쟁

Russo-Ukrainian War| 러시아-우크라이나 전쟁 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 구소련 영토 분쟁의 일부 | |||||||||

왼쪽 위에서 시계 방향: 2022년 하르키우 침공 당시 우크라이나 탱크, 2022년 침공 당시 러시아 군용 차량, 돈바스 전쟁 당시 러시아 지원군, 마리우폴 포위전 당시 러시아 폭격, 크림 침공 당시 러시아 군인, 키이우에 대한 러시아 미사일 공격으로 민간인 사망 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| 제공처: 2022년 이후 우크라이나에 원조를 제공하는 국가는 우크라이나에 대한 군사 원조를 참조하십시오. | 제공처: 자세한 내용은 러시아 군수품 공급업체를 참조하십시오. | ||||||||

| 지휘관 및 지도자 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 힘 | |||||||||

| 분쟁의 주요 지점에 관련된 강점과 단위에 대한 자세한 내용은 다음을 참조하십시오. | |||||||||

| 인명 및 손실 | |||||||||

| 보고서는 매우 다양하지만 최소 수만 개입니다.[3][4] 자세한 내용은 러시아-우크라이나 전쟁의 사상자를 참조하십시오. | |||||||||

러시아-우크라이나 전쟁은[c] 2014년 2월에 시작된 러시아와 우크라이나 간의 지속적인 국제 분쟁입니다.[d] 우크라이나의 존엄혁명 이후 러시아는 우크라이나로부터 크림반도를 합병하고 돈바스 전쟁에서 우크라이나군과 싸우는 친러시아 분리주의자들을 지원했습니다. 처음 8년간의 분쟁에는 해군 사건, 사이버 전쟁, 정치적 긴장 고조도 포함되었습니다. 2022년 2월, 러시아는 우크라이나에 대한 전면적인 침공을 시작했고, 우크라이나의 더 많은 지역을 점령하기 시작했습니다.

2014년 초, 유로마이단 시위는 존엄 혁명과 우크라이나의 친러시아 대통령 빅토르 야누코비치의 축출로 이어졌습니다. 얼마 지나지 않아 우크라이나 동부와 남부에서 친러시아 소요사태가 발생했고, 표시가 없는 러시아군이 크림반도를 점령했습니다. 러시아는 논란이 심한 주민투표를 거쳐 곧 크림반도를 합병했습니다. 2014년 4월, 러시아의 지원을 받는 무장 세력이 우크라이나 동부 돈바스 지역의 마을을 점령하고 도네츠크 인민 공화국(DPR)과 루한스크 인민 공화국(LPR)을 독립 국가로 선포하면서 돈바스 전쟁이 시작되었습니다. 분리주의자들은 러시아로부터 상당하지만 은밀한 지원을 받았고, 분리주의자들이 장악한 지역을 완전히 탈환하려는 우크라이나의 시도는 실패했습니다. 비록 러시아가 개입을 부인했지만, 러시아 군대는 전투에 참여했습니다. 2015년 2월, 러시아와 우크라이나는 분쟁을 끝내기 위해 민스크 II 협정에 서명했지만, 그 후 몇 년 동안 완전히 이행되지 않았습니다. 돈바스 전쟁은 우크라이나와 러시아 및 분리주의 세력 간의 폭력적이지만 정적인 갈등으로 정착되었으며, 많은 짧은 휴전이 있었지만 지속적인 평화는 없었고 영토 통제의 변화도 거의 없었습니다.

2021년부터 러시아는 이웃 벨라루스 내를 포함하여 우크라이나와의 국경 근처에 대규모 군대를 구축했습니다. 러시아 관리들은 우크라이나 공격 계획을 거듭 부인했습니다. 블라디미르 푸틴 러시아 대통령은 부정적인 견해를 표명하고 우크라이나의 존재권을 부인했습니다. 그는 나토의 확대를 비판하고 우크라이나의 군사동맹 가입을 금지할 것을 요구했습니다. 러시아는 DPR과 LPR을 독립 국가로 인정했습니다. 2022년 2월 24일, 푸틴은 러시아가 우크라이나를 점령할 계획이 없다고 주장하면서 우크라이나를 "비무장화하고 비하하는" 특별 군사 작전을 발표했습니다. 뒤이어 일어난 러시아의 침공은 국제적으로 비난을 받았습니다. 많은 국가들이 러시아에 대한 제재를 가하고 기존의 제재를 늘렸습니다. 격렬한 저항에 직면한 러시아는 4월 초 키이우 시도를 포기했습니다. 8월부터 우크라이나군은 북동쪽과 남쪽의 영토를 탈환하기 시작했습니다. 9월 말, 러시아는 부분적으로 점령된 4개 지역의 합병을 선언했고, 이는 국제적으로 비난을 받았습니다. 러시아는 돈바스에서 결정적인 공세를 펼치며 겨울을 보냈습니다. 2023년 봄, 러시아는 또 다른 우크라이나의 반격을 앞두고 진지를 파고들었지만, 중요한 입지를 확보하지 못했습니다. 전쟁으로 인해 난민 위기가 발생하고 수만 명이 사망했습니다.

배경

독립 우크라이나와 오렌지 혁명

1991년 소련(USSR)이 해체된 후 우크라이나와 러시아는 긴밀한 관계를 유지했습니다. 1994년 우크라이나는 핵무기 비확산 조약에 비 핵무기 보유국으로 가입하기로 합의했습니다.[5] 우크라이나에 있던 구소련의 핵무기들이 제거되고 해체되었습니다.[6] 그 대가로 러시아, 영국, 미국은 부다페스트 안보보장각서를 통해 우크라이나의 영토적 통합성과 정치적 독립성을 지키기로 합의했습니다.[7][8] 1999년, 러시아는 유럽 안보 헌장의 서명국 중 하나였으며, 이 헌장은 "각 참가국이 진화함에 따라 동맹 조약을 포함한 안보 협정을 자유롭게 선택하거나 변경할 수 있는 고유한 권리를 재확인"했습니다.[9] 소련이 해체된 후 몇 년 동안, 몇몇 동구권 국가들은 1993년 러시아 헌법 위기, 압하지야 전쟁 (1992-1993), 제1차 체첸 전쟁 (1994-1996)과 같은 러시아와 관련된 지역 안보 위협에 부분적으로 대응하여 NATO에 가입했습니다. 푸틴 대통령은 서방 강대국들이 동유럽 국가들이 가입하지 못하게 하겠다는 약속을 어겼다고 주장했습니다.[10][11]

2004년 우크라이나 대통령 선거는 논란이 있었습니다. 선거 운동 중에 야당 후보인 빅토르 유셴코는 TCDD 다이옥신에 중독되었습니다;[12][13] 그는 나중에 러시아가 연루되었다고 비난했습니다.[14] 지난 11월 선거 참관인들의 투표 조작 의혹에도 불구하고 빅토르 야누코비치 총리가 당선자로 선언됐습니다.[15] 오렌지 혁명으로 알려진 두 달 동안, 대규모 평화 시위가 성공적으로 결과에 도전했습니다. 우크라이나 대법원이 광범위한 선거부정으로 1차 결과를 무효화한 뒤 2차 재선거가 치러져 유셴코 대통령, 율리아 티모셴코 총리가 집권하고 야누코비치 총리가 반대 입장에 놓였습니다.[16] 오렌지 혁명은 종종 다른 21세기 초의 시위 운동, 특히 색 혁명으로 알려진 구소련 내에서 함께 분류됩니다. 앤서니 코데스만에 따르면 러시아 군 장교들은 이러한 색상 혁명을 미국과 유럽 국가들이 이웃 국가들을 불안정하게 하고 러시아의 국가 안보를 약화시키려는 시도로 간주했습니다.[17] 블라디미르 푸틴 러시아 대통령은 2011-2013년 러시아 시위 주최자들이 유셴코의 전 고문이었다고 비난하고 시위를 오렌지 혁명을 러시아로 이전하려는 시도라고 설명했습니다.[18] 이 기간 동안 푸틴을 지지하는 집회는 "반 오렌지 시위"라고 불렸습니다.[19]

2008년 부쿠레슈티 정상회담에서 우크라이나와 조지아는 NATO 가입을 모색했습니다. 나토 회원국들의 반응은 엇갈렸습니다. 서유럽 국가들은 러시아를 적대시하지 않기 위해 우크라이나와 조지아에 회원국 행동계획(MAP)을 제공하는 것에 반대했고, 조지 W. 부시 미국 대통령은 이들의 가입을 추진했습니다.[20] 나토는 궁극적으로 우크라이나와 조지아 지도 제공을 거부했지만, "이들 국가는 언젠가 나토의 회원국이 될 것"이라는 데 동의하는 성명도 발표했습니다. 푸틴 대통령은 그루지야와 우크라이나의 북대서양조약기구(NATO·나토) 가입을 강력히 반대했습니다.[21] 2022년 1월까지 우크라이나의 NATO 가입 가능성은 아직 멀었습니다.[22]

2009년, 야누코비치는 2010년 우크라이나 대통령 선거에 다시 출마할 의사를 밝혔고,[23] 이후 승리했습니다.[24] 2013년 11월, 야누코비치가 갑자기 EU-우크라이나 연합 협정에 서명하지 않고 대신 러시아와 유라시아 경제 연합과의 긴밀한 관계를 선택한 것에 대한 반응으로 대규모 친유럽 연합(EU) 시위가 발생했습니다. 2013년 2월 22일 우크라이나 의회는 우크라이나와 EU의 협정을 최종 타결하는 것을 압도적으로 승인했습니다.[25] 이후 러시아는 제재를 위협하며 우크라이나에 이 협정을 거부하라고 압박했습니다. 세르게이 글라지예프 크렘린궁 고문은 협정이 체결되면 러시아는 우크라이나의 국가 지위를 보장할 수 없다고 말했습니다.[26][27]

유로마이단, 존엄혁명, 친러시아 소요사태

2014년 2월 21일, 유로마이단 운동의 일환으로 수개월간의 시위가 있은 후, 야누코비치와 의회 야당 지도자들은 조기 선거를 위한 합의서에 서명했습니다. 다음 날, 야누코비치는 대통령으로서의 권한을 박탈하는 탄핵 투표를 앞두고 수도에서 도망쳤습니다.[28][29][30][31] 2월 23일, 라다(우크라이나 의회)는 러시아어를 공용어로 만든 2012년 법을 폐지하는 법안을 채택했습니다.[32] 이 법안은 제정되지 않았지만,[33] 러시아계 주민들이 임박한 위험에 처해 있다는 러시아 언론의 주장으로 인해 [34]이 제안은 러시아어를 사용하는 우크라이나 지역에서 부정적인 반응을 불러일으켰습니다.[35]

2월 27일 임시 정부가 수립되었고 조기 대통령 선거가 예정되어 있었습니다. 다음 날 러시아에서 야누코비치는 다시 부상했고, 기자회견에서 러시아가 크림반도에서 군사작전을 시작할 때 우크라이나 대통령 권한대행으로 남아 있다고 선언했습니다. 러시아어를 사용하는 우크라이나 동부 지역의 지도자들은 야누코비치에 대한 지속적인 충성을 [29][36]선언하여 2014년 우크라이나의 친러시아 소요 사태를 촉발시켰습니다.

크림 반도의 러시아 군사 기지

크림 전쟁이 시작될 당시 러시아는 흑해함대 소속 [35]약 1만 2천 명의 군 병력을 크림 반도의 세바스토폴, 카차, 흐바르디스케, 심페로폴 라이온, 사리치 등 여러 곳에 배치했습니다. 2005년 러시아와 우크라이나 사이에 얄타 근처의 사리흐 곶 등대와 다른 많은 등대들의 통제권을 놓고 분쟁이 일어났습니다.[37][38] 러시아의 주둔은 우크라이나와의 기지 및 교통 협정에 의해 허용되었습니다. 이 협정에 따라 크림반도의 러시아군은 최대 2만 5천 명으로 제한되었습니다. 러시아는 우크라이나의 주권을 존중하고, 자국의 입법을 존중하며, 자국의 내정에 간섭하지 않으며, 국제 국경을 넘을 때 '군민증'을 보여줘야 했습니다.[39] 분쟁 초기에, 협정의 관대한 병력 제한으로 인해 러시아는 안보 문제를 해결한다는 명분 아래 크림 반도에서 군사력을 크게 강화하고 특수 부대와 다른 필수 능력을 배치할 수 있었습니다.[35]

1997년 체결된 소련 흑해함대 분할에 관한 원래 조약에 따르면 러시아는 2017년까지 크림에 군사 기지를 두는 것이 허용되었으며, 그 후 크림 자치 공화국과 세바스토폴에서 흑해함대의 일부를 포함한 모든 군 부대를 철수시킵니다. 2010년 4월 21일 빅토르 야누코비치 전 우크라이나 대통령은 2009년 러시아를 해결하기 위해 러시아와 새로운 협정인 하르키우 조약을 체결했습니다.우크라이나 가스 분쟁. 이 협정은 러시아의 크림 반도 체류 기간을 2042년까지 연장하여 갱신할 수 있는 옵션을 제공했습니다.[40]

합법성 및 선전포고

현재 진행 중인 러시아-우크라이나 전쟁에서 공식적인 선전포고는 나오지 않았습니다. 푸틴은 2022년 러시아의 우크라이나 침공을 발표했을 때 공식적인 선전포고를 옆으로 치며 "특별 군사 작전"을 시작하겠다고 주장했습니다.[41] 그러나 이 성명은 우크라이나 정부의[42] 선전포고로 간주되었으며 많은 국제 뉴스 소식통에 의해 그렇게 보도되었습니다.[43][44] 우크라이나 의회는 우크라이나에서의 군사 행동과 관련하여 러시아를 "테러 국가"로 언급하고 있지만,[45] 이를 대신하여 공식적인 선전포고를 발표하지는 않았습니다.

러시아의 우크라이나 침공은 국제법(유엔 헌장 포함)을 위반했습니다.[53][54][55][56] 이 침입은 국제 형법과[57] 우크라이나와 러시아를 포함한 일부 국가의 국내 형법에 따라 침략 범죄라고 불리기도 하지만 이러한 법률에 따른 기소에 절차적 장애물이 존재합니다.[58][59]

역사

러시아의 크림 반도 합병 (2014)

2014년 2월 말 러시아가 크림반도를 점령하기 시작하면서 러시아-우크라이나 전쟁이 시작되었습니다.[60][61][62][63] 2월 22일과 23일, 야누코비치 축출 직후 상대적인 권력 공백 [64]속에서 러시아군과 특수부대가 크림반도 국경 근처로 이동했습니다.[62] 2월 27일 휘장이 없는 러시아군이 크림반도를 점령하기 시작했습니다.[65][66] 러시아는 그 군인들이 그들의 것이라고 일관되게 부인했고, 대신 그들이 지역 "자위대" 부대라고 주장했습니다. 이들은 크림 의회와 정부 건물을 압수했으며 검문소를 설치해 이동을 제한하고 우크라이나 나머지 지역과 크림 반도를 차단했습니다.[67][68][69][70] 이후 며칠 동안 러시아 특수부대는 공항과 통신센터를 점령하고 [71]남부 해군기지와 같은 우크라이나 군사기지를 봉쇄했습니다. 러시아의 사이버 공격으로 우크라이나 정부와 관련된 웹사이트, 뉴스 미디어, 소셜 미디어가 폐쇄되었습니다. 사이버 공격은 또한 러시아가 우크라이나 관리들과 의회 의원들의 휴대전화에 접근할 수 있게 하여 통신을 더욱 방해했습니다.[72] 3월 1일, 러시아 의회는 크림 반도에서 군대 사용을 승인했습니다.[71]

러시아 특수부대가 크림 의회를 점거하는 동안 크림 정부를 해임하고 친러시아 악소노프 정부를 설치한 뒤 크림의 지위를 묻는 주민투표를 발표했습니다. 국민투표는 러시아의 점령하에 실시되었으며 러시아가 설치한 당국에 따르면 결과는 러시아의 가입에 찬성했습니다. 2014년 3월 18일 크림 반도를 합병했습니다. 뒤이어 러시아군이 크림반도에 있는 우크라이나군 기지를 점령하고 그들의 병력을 붙잡았습니다. 3월 24일, 우크라이나는 남은 병력에게 철수 명령을 내렸고, 3월 30일까지 모든 우크라이나군은 반도를 떠났습니다.

4월 15일 우크라이나 의회는 크림반도를 러시아가 일시적으로 점령한 영토로 선포했습니다.[73] 합병 이후 러시아 정부는 한반도를 군사화하고 핵 위협을 가했습니다.[74] 푸틴 대통령은 크림반도에 러시아군 기동부대가 창설될 것이라고 말했습니다.[75] 지난 11월 나토는 러시아가 크림반도에 핵무기를 배치하고 있는 것으로 믿는다고 밝혔습니다.[76] 크림 반도 합병 이후 일부 NATO 회원국들은 우크라이나군을 위한 훈련을 제공하기 시작했습니다.[77]

돈바스 전쟁 (2014–2015)

친러 소요 사태

2014년 2월 말부터 우크라이나 동부 및 남부 지역의 주요 도시에서 친러시아 및 반정부 단체의 시위가 열렸습니다.[78] 우크라이나 남부와 동부 전역에서 첫 시위가 벌어진 것은 우크라이나 새 정부에 대한 불만을 표출한 것이 대부분이었습니다.[78][79] 이 단계에서 러시아의 개입은 시위에 대한 지지의 목소리를 내는 데 국한되었습니다.[79][80] 그러나 러시아는 이를 악용하여 우크라이나에 대한 정치 군사적 협력 캠페인을 시작했습니다.[79][81] 푸틴은 돈바스를 "신 러시아"(Novorosiya)의 일부로 묘사하고 어떻게 이 지역이 우크라이나의 일부가 되었는지에 대해 어리둥절함을 표현하면서 분리주의자들에게 합법성을 주었습니다.[82]

러시아는 3월 말에도 우크라이나 동부 국경 근처에서 병력을 계속 모집하여 4월까지 30-40,000명의 병력에 도달했습니다.[83][35] 그 배치는 확대를 위협하고 우크라이나의 대응을 방해하기 위해 사용되었습니다.[35] 이 위협으로 인해 우크라이나는 분쟁 지역 대신 국경으로 병력을 돌릴 수밖에 없었습니다.[35]

우크라이나 당국은 지난 3월 초 친러시아 시위를 진압하고 현지 분리주의 지도자들을 체포했습니다. 그 지도자들은 러시아 보안 서비스와 관련이 있고 러시아 사업에 관심이 있는 사람들로 대체되었습니다.[84] 2014년 4월까지 러시아 시민들은 체첸과 코사크 전사들을 포함한 러시아의 자원봉사자들과 물자들의 지원을 받아 분리주의 운동을 장악했습니다.[85][86][87][88] 도네츠크 인민공화국(DPR)의 이고르 기르킨 사령관에 따르면, 4월에 이러한 지원이 없었다면, 하르키우와 오데사에서 그랬던 것처럼, 이 운동은 사라졌을 것이라고 합니다.[89] 분리주의 단체들은 지난 5월 우크라이나나 다른 어떤 유엔 회원국도 이를 인정하지 않은 [90][91][92]채 분쟁 중인 국민투표를 실시했습니다.[90]

무력 충돌

2014년 4월, 우크라이나 동부에서 러시아의 지원을 받는 분리주의자들과 우크라이나 간의 무력 충돌이 시작되었습니다. 4월 12일 50명의 친러시아 무장세력이 슬로비안스크와 크라마토르스크 마을을 점령했습니다.[93] 중무장한 남성들은 전 GRU 대령 이고르 기르킨('스트렐코프')[93][94]의 지휘를 받는 러시아군 "자원봉사자"들이었습니다. 그들은 러시아가 점령한 크림반도에서 보내졌으며 휘장을 착용하지 않았습니다.[93] 거킨은 이 행동이 돈바스 전쟁을 촉발했다고 말했습니다. 그는 "나는 전쟁의 방아쇠를 당긴 사람입니다. 우리 부대가 국경을 넘지 않았다면 모든 것이 흐지부지되었을 것입니다."[95][96]

이에 대응하여 4월 15일, 우크라이나 임시 정부는 반테러 작전(ATO)을 시작했지만, 우크라이나군은 준비가 제대로 되어 있지 않았고, 위치도 좋지 않아 작전은 순식간에 중단되었습니다.[97] 4월 말까지 우크라이나는 도네츠크와 루한스크 지방에 대한 통제권을 잃었다고 발표했습니다. 러시아군의 침공 가능성에 대비해 전면적인 전투 경계 태세에 돌입했으며, 러시아군에 징집을 재개했다고 주장했습니다.[98] 5월 동안 우크라이나 캠페인은 우크라이나의 국가 동원이 완료되면 결정적인 공세를 위해 군대를 배치하기 위해 ATO 구역 주변의 핵심 위치를 확보함으로써 분리주의자들을 억제하는 데 중점을 두었습니다.

지난 5월 분리주의자들과 우크라이나 정부의 갈등이 고조되면서 러시아는 허위 정보 전술, 비정규 전투기, 정규 러시아군, 재래식 군사 지원을 결합한 '하이브리드 접근법'을 구사하기 시작했습니다.[99][100][101] 제1차 도네츠크 공항 전투는 우크라이나 대통령 선거 이후에 벌어졌습니다. 그것은 갈등의 전환점을 의미했습니다; 그것은 분리주의자들과 우크라이나 정부 사이의 많은 수의 러시아 "자원봉사자들"이 관련된 첫 번째 전투였습니다.[102][103]: 15 우크라이나에 따르면 2014년 여름 분쟁이 한창일 때 러시아 준군사조직은 전투원의 15%에서 80%를 차지했습니다.[87] 6월부터 러시아는 무기, 갑옷, 그리고 군수품을 가지고 흘렸습니다.

2014년 7월 17일, 러시아군이 여객기인 말레이시아 항공 17편이 우크라이나 동부 상공을 비행하던 중 격추했습니다.[104] 교전이 계속되면서 분쟁지역에서 조사와 시신 수습이 시작됐습니다.[105][106][107]

7월 말까지 우크라이나군은 두 도시 사이의 보급로를 차단하고 도네츠크를 고립시키고 러시아-우크라이나 국경의 통제권을 회복하려고 시도했습니다. 7월 28일까지 사부르-모일라의 전략적 고지는 중요한 철도 중심지인 데발체브 마을과 함께 우크라이나의 통제하에 놓였습니다.[108] 우크라이나군의 이러한 작전 성공은 DPR과 LPR 주 정부의 존재를 위협했고, 러시아는 7월 중순부터 자국 영토에서 우크라이나군을 겨냥한 국경 간 포격을 가했습니다.[109]

2014년 8월 러시아 침공

'노보로시야'를 기치로 뭉친 분리주의자들에게 군사적 패배와 좌절이 잇따르자,[110][111] 러시아는 2014년 8월 중순 국경을 넘어 이른바 '인도주의적 트럭 호송대'를 파견했습니다. 우크라이나는 이번 조치를 "직접적인 침략"이라고 불렀습니다.[112] 우크라이나 국가안보국방위원회는 11월에 거의 매일 호송대가 도착하고 있으며(11월 30일에는 최대 9대의 호송대가 도착했다), 그들의 내용물은 주로 무기와 탄약이라고 보고했습니다. 스트렐코프는 8월 초, 군대에서 "휴가"를 받은 것으로 추정되는 러시아 군인들이 돈바스에 도착하기 시작했다고 주장했습니다.[113]

2014년 8월까지 우크라이나의 "반테러 작전"은 친러시아적인 통제하에 있던 영토를 축소하고 국경에 접근했습니다.[114] 이고르 기르킨은 러시아의 군사 개입을 촉구하며, 그의 비정규 군대의 전투 미숙과 지역 주민들의 모집 어려움이 좌절을 야기했다고 말했습니다. 그는 "블라디미르 푸틴 대통령이 개인적으로 신러시아라고 명명한 영토에서 이 전쟁에서 지면 크렘린의 권력과 개인적으로 대통령의 권력이 위협받을 것입니다."라고 말했습니다.[115]

상황이 악화되자 러시아는 하이브리드 방식을 포기하고 2014년 8월 25일부터 재래식 침공을 시작했습니다.[114][116] 다음날 러시아 국방부는 이 군인들이 "우연히" 국경을 넘었다고 말했습니다.[117][118][119] 니콜라이 미트로킨(Nikolai Mitrokhin)의 추정에 따르면 일로바이스크 전투 중인 2014년 8월 중순까지 20,000~25,000명의 군대가 분리주의 측 돈바스에서 전투를 벌이고 있었고, 40~45%만이 "지역"이었습니다.[120]

2014년 8월 24일, 암브로시프카는 250대의 기갑 차량과 포병 조각의 지원을 [121]받는 러시아 낙하산 부대에 의해 점령되었습니다.[122] 같은 날 페트로 포로셴코 우크라이나 대통령은 이 작전을 우크라이나의 "2014년 애국 전쟁"이자 외부 침략에 대한 전쟁이라고 언급했습니다.[123][124] 8월 25일, 아조프해 연안의 노보아조프스크 근처에서 러시아 군용 차량 기둥이 우크라이나로 건너간 것으로 보고되었습니다. 우크라이나가 점령한 마리우폴을 향해 몇 주 동안 친러시아 세력이 존재하지 않았던 지역으로 향했던 것으로 보입니다.[125][126][127][128][129][130] 러시아군은 노보아조프스크를 점령했고,[131] 러시아군은 마을 내에 주소가 등록되지 않은 우크라이나인들을 추방하기 시작했습니다.[132] 친우크라이나 반전 시위가 마리우폴에서 열렸습니다.[132][133] 유엔 안전보장이사회는 긴급회의를 소집했습니다.[134]

프스코프에 본부를 둔 제76방위공습사단은 지난 8월 우크라이나 영토에 진입해 루한스크 인근에서 교전을 벌여 80명이 사망한 것으로 알려졌습니다. 우크라이나 국방부는 루한스크 인근에서 부대 장갑차 2대를 압수했으며, 다른 지역에서 탱크 3대와 장갑차 2대를 파괴했다고 보고했습니다.[135][136] 러시아 정부는 교전이 일어나지 않았다고 부인했지만,[136] 8월 18일, 제76회는 러시아 국방부 장관 세르게이 쇼이구로부터 "성공적인 군사 임무 완수"와 "용기와 영웅성"으로 러시아 최고의 상 중 하나인 수보로프 훈장을 받았습니다.[136]

러시아 상원의장과 러시아 국영 TV 채널은 러시아 군인들이 우크라이나에 입국한 사실을 인정하면서도 그들을 "자원봉사자"라고 지칭했습니다.[137] 러시아의 야당 신문인 노바야 가제타의 기자는 러시아 군 지도부가 2014년 초여름 우크라이나에서 군인들에게 사표를 내고 전투를 벌인 뒤 군인들에게 우크라이나 진입을 명령하기 시작했다고 전했습니다.[138] 러시아 야당 의원 레프 슐로스버그도 비슷한 성명을 냈지만, 그는 자국 출신 전투원들이 DPR과 LPR의 부대로 위장한 "정규 러시아군"이라고 말했습니다.[139]

2014년 9월 초, 러시아 국영 TV 채널은 우크라이나에서 사망한 러시아 군인들의 장례식에 대해 보도했지만, 그들을 "러시아 세계"를 위해 싸우는 "자원봉사자"라고 묘사했습니다. 발렌티나 마트비옌코 유나이티드 러시아 최고 정치인도 "우리의 이란"에서 싸우는 "자원봉사자"들을 칭찬했습니다.[137] 러시아 국영 TV는 처음으로 우크라이나에서 전투 중 사망한 군인의 장례식을 보여주었습니다.[140]

마리우폴 공세와 제1차 민스크 휴전

9월 3일 포로셴코 대통령은 푸틴 대통령과 "영구적 휴전" 합의에 도달했다고 말했습니다.[141] 러시아는 이를 부인하면서 분쟁 당사자가 아니라고 부인하면서 "그들은 분쟁을 어떻게 해결할 것인지에 대해 논의했을 뿐"이라고 덧붙였습니다.[142][143] 그러자 포로셴코는 암송했습니다.[144][145] 9월 5일 안드레이 켈린 러시아 OSCE 상임대표는 친러시아 분리주의자들이 마리우폴을 "해방시킬 것"이 당연하다고 말했습니다. 우크라이나군은 이 지역에서 러시아 정보조직이 포착됐다고 밝혔습니다. 켈린은 '저쪽에 자원봉사자들이 있을지도 모른다'고 말했습니다.[146] 2014년 9월 4일, 나토의 한 장교는 수천 명의 정규 러시아군이 우크라이나에서 활동하고 있다고 말했습니다.[147]

2014년 9월 5일, 민스크 의정서 휴전 협정은 우크라이나와 도네츠크와 루한스크 오블라스트의 분리주의 통제 지역 사이에 경계선을 그었습니다.

2014년말 및 민스크 II 협약

11월 7일과 12일, 북대서양조약기구(NATO) 관리들은 32대의 탱크, 16대의 대포, 30대의 트럭이 러시아로 들어오는 것을 인용하여 러시아의 주둔을 재확인했습니다.[148] 미국 장군 필립 M. Bridlove는 "러시아 탱크, 러시아 포병, 러시아 방공 시스템 및 러시아 전투 부대"가 목격되었다고 말했습니다.[76][149] 나토는 우크라이나에서 러시아의 탱크, 포병 조각 및 기타 중무장 장비가 증가하는 것을 목격했으며 모스크바에 군대를 철수할 것을 재차 촉구했습니다.[150] 시카고 국제문제협의회는 2014년 중반 고급 군사 시스템의 대규모 유입 이후 러시아 분리주의자들이 우크라이나군에 비해 기술적 이점을 누렸다고 밝혔습니다. 효과적인 대공 무기("Buk", MANPADS)는 우크라이나의 공습을 억제하고 러시아 드론은 정보를 제공했습니다. 그리고 러시아 보안 통신 시스템은 우크라이나 통신 정보를 방해했습니다. 러시아 측은 우크라이나에 부족한 전자전 시스템을 사용했습니다. 분쟁 연구 센터는 러시아 분리주의자들의 기술적 이점에 대해 비슷한 결론을 내렸습니다.[151] 11월 12일 유엔 안전보장이사회 회의에서 영국 대표는 러시아가 OSCE 관측 임무의 능력을 의도적으로 제한하고 있다고 비난하면서 관측자들이 2킬로미터의 국경에서만 감시할 수 있도록 허용되었고, 그들의 능력을 확장하기 위해 배치된 드론이 끼이거나 격추되었다고 지적했습니다.[152][non-primary source needed]

2015년 1월, 도네츠크, 루한스크, 마리우폴은 3개의 전선을 대표했습니다.[154] 포로셴코는 1월 21일 2,000명 이상의 러시아군, 200대의 탱크, 무장 인력 수송선이 국경을 넘었다는 보고가 있는 가운데 위험한 상황이 고조되었다고 설명했습니다. 그는 자신의 걱정 때문에 세계경제포럼 방문을 줄여서 발표했습니다.[155]

2015년 2월 15일, 민스크 II로 알려진 분쟁을 종식시키기 위한 새로운 조치들이 합의되었습니다.[156] 2월 18일, 우크라이나군은 2022년까지 돈바스 전쟁의 마지막 고강도 전투에서 데바틀세브에서 철수했습니다. 2015년 9월 유엔 인권 사무소는 분쟁으로 인해 8,000명의 사상자가 발생했다고 추정했습니다.[157]

갈등선 안정화 (2015~2021)

민스크 협정 이후, 전쟁은 영토 통제에 거의 변화가 없는 합의된 연락선을 중심으로 정적인 참호전으로 정착했습니다. 그 분쟁은 포병 결투, 특수부대 작전, 참호전으로 특징지어졌습니다. 적대 행위는 상당 기간 동안 멈추지 않았고, 반복적인 휴전 시도에도 불구하고 낮은 수준으로 계속되었습니다. 데발체브 함락 이후 몇 달 동안 접촉선을 따라 사소한 교전이 계속되었지만 영토 변화는 일어나지 않았습니다. 양측은 참호, 벙커, 터널의 네트워크를 구축하여 분쟁을 정적인 참호전으로 변화시킴으로써 자신들의 위치를 강화하기 시작했습니다.[158][159] 상대적으로 정적인 분쟁은 일부에서는 "동결"이라는 꼬리표를 붙였지만,[160] 러시아는 싸움이 멈추지 않았기 때문에 결코 이를 달성하지 못했습니다.[161][162] 2014년과 2022년 사이에 29건의 휴전이 있었고, 각각 무기한 효력을 유지하기로 합의했습니다. 그러나 그 중 어느 것도 2주 이상 지속되지 않았습니다.[163]

미국과 국제 관리들은 데발체브 지역을 포함한 우크라이나 동부 지역에서 러시아군의 적극적인 주둔을 계속 보고했습니다.[164] 2015년 러시아 분리주의 세력은 약 36,000명(우크라이나인 34,000명과 비교)으로 추정되며, 이 중 8,500~10,000명이 러시아 군인이었습니다. 또한 약 1,000명의 GRU 병력이 이 지역에서 활동하고 있었습니다.[165] 또 다른 2015년 추정에 따르면 우크라이나군은 러시아군보다 40,000~20,000명 더 많습니다.[166] 2017년에는 평균적으로 3일마다 한 명의 우크라이나 군인이 전투 중 사망했으며,[167] 이 지역에서 약 6,000명의 러시아군과 40,000명의 분리주의 군대가 사망한 것으로 추정됩니다.[168][169]

러시아 현지 언론에서 사망자와 부상자 사례가 거론됐습니다.[170] 돈바스의 모집은 베테랑 및 준군사 조직을 통해 공개적으로 수행되었습니다. 그러한 조직의 리더인 블라디미르 예피모프는 그 과정이 우랄 지역에서 어떻게 작동하는지 설명했습니다. 이 단체는 주로 육군 참전용사를 모집했지만, 군 경험이 있는 경찰관, 소방관 등도 모집했습니다. 한 명의 자원봉사자가 장비를 갖추는 데 드는 비용은 350,000루블(약 6500달러)에 월급은 60,000~240,000루블로 추산되었습니다.[171] 신병들은 분쟁 지역에 도착한 후에야 무기를 받았습니다. 러시아군은 적십자 요원으로 위장해 이동하는 경우가 많았습니다.[172][173][174][175] 모스크바 주재 러시아 적십자 대표 이고르 트뤼노프는 이들 호송대가 인도적 지원 전달을 복잡하게 한다며 비난했습니다.[176] 러시아는 OSCE가 두 개의 국경을 넘어 임무를 확장하는 것을 거부했습니다.[177]

자원봉사자들은 러시아의 용병법을 피하기 위한 "인도적 도움 제공"에 그들의 참여가 제한되었다고 주장하는 문서를 발행받았습니다. 러시아의 용병 금지법은 용병을 "러시아 연방의 이익에 반하는 목적을 가지고 [전투에 참가하는] 사람으로 정의했습니다.[171]

2016년 8월, 우크라이나 정보국인 SBU는 2014년 세르게이 글라지예프(러시아 대통령 고문), 콘스탄틴 자툴린(Konstantin Zatulin) 및 다른 사람들이 우크라이나 동부에서 친러시아 활동가들에 대한 비밀 자금 지원에 대해 논의한 전화 가로채기를 발표했습니다. 행정부 건물의 [178]점거와 분쟁을 촉발한 다른 행동들 일찍이 2014년 2월, 글라지예프는 여러 친러 정당들에게 지방 행정청을 인수하는 방법, 이후에 무엇을 해야 하는지, 요구 사항을 공식화하는 방법에 대해 직접 지시하고 "우리 부하를 보내는 것"을 포함한 러시아의 지원을 약속했습니다.[179][180][181]

2018년 케르치 해협 사건

러시아는 2014년 케르치 해협을 사실상 장악했습니다. 2017년 우크라이나는 해협 사용과 관련하여 중재 법원에 항소했습니다. 2018년까지 러시아는 해협 위에 다리를 건설하여 통과할 수 있는 선박의 크기를 제한하고 새로운 규제를 부과했으며 반복적으로 우크라이나 선박을 억류했습니다.[182] 2018년 11월 25일, 오데사에서 마리우폴로 가던 우크라이나 보트 3척이 러시아 군함에 나포되었고, 우크라이나 선원 24명이 억류되었습니다.[183][184] 하루 뒤인 2018년 11월 26일, 우크라이나 의회는 우크라이나 해안 지역과 러시아 국경 지역을 따라 계엄령을 부과하는 것을 압도적으로 지지했습니다.[185]

2019–2020

2019년 분쟁으로 110명 이상의 우크라이나 군인이 사망했습니다.[186] 2019년 5월, 새로 선출된 볼로디미르 젤렌스키 우크라이나 대통령은 돈바스에서 전쟁을 끝내겠다고 약속하며 취임했습니다.[186] 2019년 12월, 우크라이나와 친러시아 분리주의자들은 전쟁 포로 교환을 시작했습니다. 2019년 12월 29일 약 200명의 죄수들이 교환되었습니다.[187][188][189][190] 우크라이나 당국에 따르면 2020년 우크라이나 군인 50명이 사망했습니다.[191] 러시아는 2019년부터 2021년까지 우크라이나인에게 러시아 내부 여권 65만 장 이상을 발급했습니다.[192][193]

러시아의 우크라이나 주변 군사력 증강 (2021-2022)

2021년 3월부터 4월까지 러시아는 국경 근처에서 대규모 군사력 증강을 시작했으며, 2021년 10월부터 2022년 2월까지 러시아와 벨라루스에서 두 번째 군사력 증강을 시작했습니다.[194] 러시아 정부는 우크라이나를 공격할 계획이 없다고 거듭 부인했습니다.[195][196]

2021년 12월 초, 러시아의 부인에 이어 미국은 국경 근처에서 러시아군과 장비를 보여주는 위성 사진을 포함한 러시아 침공 계획에 대한 정보를 공개했습니다.[197] 정보당국은 살해되거나 무력화될 주요 장소와 개인들의 러시아 명단을 보고했습니다.[198] 미국은 침공 계획을 정확하게 예측한 여러 보고서를 발표했습니다.[198]

러시아의 비난과 요구

침공 이전 몇 달 동안 러시아 관리들은 우크라이나가 긴장과 러시아 공포증을 조장하고 러시아어 사용자들을 억압하고 있다고 비난했습니다. 그들은 우크라이나, NATO 및 기타 EU 국가들에게 여러 가지 안보 요구를 했습니다. 2021년 12월 9일 푸틴은 "러시아 공포증은 대량학살을 향한 첫 걸음"이라고 말했습니다.[199][200] 푸틴의 주장은 국제사회에서 기각됐고,[201] 러시아의 대량학살 주장은 근거 없는 것으로 기각됐습니다.[202][203][204] 2월 21일 [205]연설에서 푸틴은 우크라이나 국가의 합법성에 의문을 제기하면서 "우크라이나는 진정한 국가 전통을 가진 적이 없다"는 부정확한 주장을 반복했습니다.[206] 그는 블라디미르 레닌이 푸틴이 러시아 땅이라고 말한 것에서 별도의 소련 공화국을 떼어내 우크라이나를 만들었고, 니키타 흐루쇼프가 1954년 "어떤 이유로 크림반도를 러시아로부터 빼앗아 우크라이나에 주었다"고 잘못 진술했습니다.[207]

푸틴은 우크라이나 사회와 정부가 신나치즘에 지배당했다고 거짓 주장하며 2차 세계대전 당시 독일이 점령한 우크라이나에서 협력한 역사를 환기시키고 [208][209]유대인이 아닌 러시아 기독교인을 나치 독일의 진정한 희생자로 몰아세운 반유대주의 음모론을 되풀이했습니다.[210][201] 우크라이나에는 네오 나치와 연계된 아조프 대대와 우파 부문을 포함한 극우 변방이 있습니다.[211][209] 분석가들은 푸틴의 수사가 매우 과장되었다고 묘사했습니다.[212][208] 유대인인 Zelenskyy는 그의 할아버지가 나치에 맞서 싸우던 소련 군대에서 복무했다고 말했습니다;[213] 그의 가족 중 세 명이 홀로코스트에서 사망했습니다.[212]

러시아는 우크라이나의 나토 가입을 금지하고 동유럽 회원국에서의 모든 나토 활동을 중단하는 조약을 요구했습니다.[215] 이러한 요구는 거부되었습니다.[216] 우크라이나가 나토에 가입하는 것을 막기 위한 조약은 동맹의 "개방" 정책과 자결 원칙에 어긋날 것이지만, 나토는 우크라이나의 가입 요청에 응하기 위한 노력을 전혀 하지 않았습니다.[217] 옌스 스톨텐베르크 나토 사무총장은 우크라이나의 가입 여부에 대해 "러시아는 발언권이 없다"며 "러시아는 이웃 국가들을 통제하려고 노력할 세력권을 설정할 권리가 없다"고 답했습니다.[218] NATO는 러시아가 우크라이나 국경에서 군대를 철수하는 한 러시아와의 통신을 개선하고 미사일 배치와 군사 훈련에 대해 논의하겠다고 제안했지만 러시아는 철수하지 않았습니다.[219]

완전침략의 서막

돈바스 전투는 2022년 2월 17일부터 크게 확대되었습니다.[220] 우크라이나와 친러시아 분리주의자들은 각각 상대방을 공격했다고 비난했습니다.[221][222] 돈바스에서 러시아 주도 무장세력의 포격이 급격히 증가했는데, 우크라이나와 그 지지자들은 이를 우크라이나군을 자극하거나 침공 명분을 만들기 위한 것으로 여겼습니다.[223][224][225] 2월 18일, 도네츠크와 루한스크 인민 공화국은 각각의 수도에서 민간인들의 긴급 대피를 의무화할 것을 명령했지만,[226][227][228] 관측통들은 완전 대피에는 몇 달이 걸릴 것이라고 언급했습니다.[229] 러시아 정부는 러시아 국영 언론이 우크라이나군이 러시아를 공격하는 모습을 보여주기 위해 거의 시간 단위로 조작된 영상(허위 깃발)을 홍보하는 등 허위 정보 캠페인을 강화했습니다.[230] 많은 허위 정보 영상들은 아마추어 수준이었고, 돈바스에서 주장된 공격, 폭발, 대피는 러시아에 의해 행해졌다는 증거가 나왔습니다.[230][231][232]

2월 21일 22:35 (UTC+3),[233] 푸틴은 러시아 정부가 도네츠크와 루한스크 인민 공화국을 외교적으로 인정할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[234] 같은 날 저녁, 푸틴은 러시아가 "평화 유지 임무"라고 부르는 돈바스에 러시아 군대를 배치하라고 지시했습니다.[235][236] 2월 22일, 연방평의회는 만장일치로 푸틴에게 러시아 밖에서 군사력을 사용할 것을 승인했습니다.[237] 이에 젤렌스키는 군대 예비군의 징병을 명령했습니다.[238] 다음 날 우크라이나 의회는 30일간의 전국 비상사태를 선포하고 모든 예비군 동원을 명령했습니다.[239][240][241] 러시아는 키이우 주재 대사관을 철수하기 시작했습니다.

2월 23일 밤 [243]젤렌스키는 러시아어로 연설을 하며 러시아 시민들에게 전쟁을 막아달라고 호소했습니다.[244][245] 그는 신나치에 대한 러시아의 주장을 거부하고 돈바스를 공격할 의도가 없다고 말했습니다.[246] 드미트리 페스코프 크렘린궁 대변인은 23일 도네츠크와 루한스크의 분리주의 지도자들이 푸틴 대통령에게 우크라이나 포격으로 민간인 사망자가 발생했다며 군사 지원을 호소하는 서한을 보냈다고 밝혔습니다.[247]

러시아의 우크라이나 침공 (2022년~현재)

러시아의 우크라이나 침공은 2022년 2월 24일 아침 [248]푸틴 대통령이 우크라이나를 "비무장화하고 비핵화"하기 위한 "특별 군사 작전"을 발표하면서 시작되었습니다.[249][250] 몇 분 후, 미사일과 공습이 키이우를 포함한 우크라이나 전역을 강타했고, 곧이어 여러 전선을 따라 대규모 지상 침공이 이루어졌습니다. 젤렌스키는 18세에서 60세 사이의 모든 남성 우크라이나 시민들에게 계엄령과 총동원령을 선포했습니다.[253][254]

러시아군의 공격은 처음에는 벨라루스에서 키이우로 향하는 북부 전선, 크림반도에서 남쪽 전선, 루한스크와 도네츠크에서 하르키우로 향하는 남동부 전선에서 시작되었습니다. 북부 전선에서는 키이우를 둘러싼 큰 손실과 우크라이나의 강력한 저항 속에서 러시아의 진격은 3월에 정체되었고, 4월에는 군대가 후퇴했습니다. 4월 8일, 러시아는 알렉산드르 드보르니코프 장군의 지휘 아래 우크라이나 남부와 동부에 군대를 배치했고, 북부에서 철수한 일부 부대는 돈바스로 재배치되었습니다.[257] 4월 19일, 러시아는 하르키우에서 도네츠크와 루한스크에 이르는 500km(300mi) 길이의 전선을 다시 공격했습니다.[258] 5월 13일, 우크라이나의 반격으로 하르키우 인근의 러시아군이 후퇴했습니다. 5월 20일까지 마리우폴은 아조프탈 제철소를 장기간 포위한 후 러시아군에게 함락되었습니다.[259][260] 러시아군은 최전방에서 멀리 떨어진 군과 민간 목표물을 계속 폭격했습니다.[261][262] 이 전쟁은 1990년대 유고슬라비아 전쟁 이후 유럽 내에서 가장 큰 난민 및 인도주의적 위기를 야기했습니다.[263][264] 유엔은 이 전쟁을 제2차 세계 대전 이후 가장 빠르게 증가하는 위기라고 설명했습니다.[265] 침공 첫 주에 유엔은 100만 명 이상의 난민이 우크라이나를 떠났다고 보고했습니다. 이는 이후 9월 24일까지 7,405,590명 이상으로 증가했으며, 이는 일부 난민의 귀환으로 인해 8백만 명 이상이 감소한 것입니다.[266][267]

우크라이나군은 8월에는 남부에서, 9월에는 북동부에서 반격을 가했습니다. 9월 30일, 러시아는 침공 기간 동안 부분적으로 정복했던 우크라이나의 4개의 오블라스를 합병했습니다.[268] 이 합병은 일반적으로 세계 국가들에 의해 인정되지 않고 비난받았습니다.[269] 푸틴이 군사 훈련을 받은 30만 명의 시민들과 징병 대상이 될 수 있는 잠재적으로 약 2,500만 명의 러시아인들로부터 징병을 시작할 것이라고 발표한 후, 해외로 나가는 편도 항공권은 거의 또는 완전히 매진되었습니다.[270][271] 9월에는 북동부의 우크라이나군 공세로 하르키우주 대부분을 탈환하는 데 성공했습니다. 남부의 반격 과정에서 우크라이나는 11월에 케르손 시를 탈환했고 러시아군은 드네프르 강 동쪽 기슭으로 철수했습니다.[citation needed]

그 침략은 침략 전쟁으로 국제적으로 비난 받았습니다.[272][273] 유엔총회 결의안은 러시아군의 전면 철수를 요구했고, 국제사법재판소는 러시아에 군사작전 중단을 명령했고, 유럽평의회는 러시아를 추방했습니다. 많은 국가들이 새로운 제재를 가했고, 이것은 러시아와 세계의 경제에 영향을 미쳤고,[274] 우크라이나에 인도주의적이고 군사적인 원조를 제공했습니다.[275] 2022년 9월, 푸틴은 징병에 저항하는 모든 사람을 10년 징역형으로[276] 처벌하는 법에 서명하여 징병을 탈출하는 러시아인들에게 망명을 허용하는 국제적인 추진을 이끌어냈습니다.[277]

2023년 8월 현재 러시아의 우크라이나 침공 기간 동안 사망하거나 부상한 러시아와 우크라이나 군인의 수는 거의 50만 명입니다.[278] 러시아의 우크라이나 침공 당시 1만 명 이상의 민간인이 사망했습니다.[279] 미국의 기밀 해제 정보 평가에 따르면 2023년 12월 현재 러시아는 침공 전 지상군을 구성하는 36만 명의 병력 중 31만 5천 명, 탱크 3,500대 중 2,200대를 잃었습니다.[280]

인권침해

전쟁 중에 인권 침해와 잔학 범죄가 동시에 발생했습니다. 2014년부터 2021년까지 3,000명 이상의 민간인 사상자가 발생했으며 대부분은 2014년과 2015년에 발생했습니다.[281] 분쟁 지역 주민들의 이동권이 침해되었습니다.[282] 갈등이 시작된 첫 해에 양측은 자의적인 구금을 실행했습니다. 정부가 소유한 지역에서는 2016년 이후 감소한 반면, 분리주의자가 소유한 지역에서는 계속 감소했습니다.[283] 양측이 저지른 학대에 대한 조사는 거의 진전이 없었습니다.[284][285]

2022년 러시아의 우크라이나 침공이 시작된 이래 러시아 당국과 군은 민간인 표적에 대한 고의적인 공격,[286][287] 민간인 학살, 여성과 어린이에 대한 고문과 강간,[288][289] 인구 밀집 지역에서의 무차별적인 공격 등의 형태로 여러 차례 전쟁 범죄를 저질렀습니다. 러시아가 키이우 북쪽 지역에서 철수한 뒤 러시아군의 압도적인 전쟁범죄 증거가 발견됐습니다. 특히 부차 마을에서는 고문, 토막내기, 강간, 약탈, 고의적인 민간인 살해 등 러시아군이 자행한 민간인 학살 증거가 등장했습니다.[290][291][292] 우크라이나 주재 유엔 인권 감시단(OHCHR)은 부차에서 최소 73명의 민간인이 살해되었다고 기록했습니다. 대부분은 남성이지만, 여성과 어린이들입니다.[293] 러시아군이 철수한 후 키이우 지역에서 1,200여 구의 민간인 시신이 발견되었고, 이들 중 일부는 즉결 처형되었습니다. 러시아가 점령한 마리우폴을 중심으로 어린이를 포함한 수천 명의 민간인을 러시아로 강제 추방한 사례와 [294][295]강간, 성폭행, 집단 성폭행,[296] 러시아군에 의한 우크라이나 민간인 고의 살해 등 성폭력 사건이 잇따랐습니다.[297] 또한 러시아는 우크라이나 의료 인프라를 체계적으로 공격했으며, 세계보건기구는 2023년 12월 21일 현재 1,422건의 공격을 보고했습니다.[298]

우크라이나군은 러시아군에 비해 규모는 훨씬 작지만 수감자 학대 등 각종 전쟁범죄를 저지른 혐의도 받고 있습니다.[299][300]

관련 이슈

스필오버

이 구간은 확장이 필요합니다. 추가해서 도와주시면 됩니다. (2023년 11월) |

2023년 9월 19일, CNN은 우크라이나 특수작전군이 9월 8일 하르툼 근처에서 바그너의 지원을 받는 RSF에 대한 일련의 드론 공격과 지상 작전의 배후에 있을 가능성이 있다고 보도했습니다.[301] 키릴로 부디노프 우크라이나 국방부 정보국장은 22일 인터뷰에서 수단 분쟁에 우크라이나가 개입한 사실을 부인할 수도, 확인할 수도 [302]없지만 우크라이나는 전 세계 어느 곳에서나 러시아 전범을 처벌할 것이라고 말했습니다.[303]

2023년 9월과 10월에는 북대서양조약기구(NATO·나토) 회원국인 루마니아에서 우크라이나와의 국경 부근에서 러시아 드론 공격의 잔해로 추정되는 파편이 잇따라 발견됐다는 보도가 나왔습니다.[304][305]

가스 분쟁

2014년까지 우크라이나는 유럽으로 판매되는 러시아 천연가스의 주요 수송로였으며, 이로 인해 우크라이나는 연간 약 30억 달러의 수송료를 벌어들여 우크라이나에서 가장 수익성이 좋은 수출 서비스가 되었습니다.[306] 러시아가 우크라이나를 우회하는 노르트스트림 파이프라인을 가동한 이후 가스 수송량은 꾸준히 감소했습니다.[306] 2014년 2월 러시아-우크라이나 전쟁이 시작된 이후 가스 분야까지 심각한 긴장이 확대되었습니다.[307][308] 이후 돈바스 지역에서 전쟁이 발발하면서 우크라이나의 러시아산 가스 수입 의존도를 줄이기 위한 방안으로 계획됐던 유지브스카 가스전의 우크라이나 자체 셰일가스 매장량 개발 프로젝트가 중단됐습니다.[309] 결국 귄터 외팅어 EU 에너지 담당 집행위원을 불러 우크라이나에 대한 공급과 EU로의 운송을 확보하는 거래를 중개했습니다.[310]

2014년 5월, 우크라이나 이바노-프랑키브스크 주 우렌고이-포마리-우호로드 송유관의 일부가 폭발로 파손되었습니다. 우크라이나 관리들은 러시아 테러리스트들을 비난했습니다.[311] 러시아가 대금 미지급을 이유로 우크라이나 고객에 대한 가스 공급을 제한한 지 하루 만인 2014년 6월 17일 폴타바주에서 송유관의 또 다른 구간이 폭발했습니다. 아르세 아바코프 우크라이나 내무장관은 다음날 폭발이 폭탄에 의한 것이라고 말했습니다.[312]

2015년 러시아 국영 언론은 러시아가 2018년 이후 우크라이나를 통해 유럽에 공급하는 가스 공급을 완전히 포기할 계획이라고 보도했습니다.[313][314] 러시아 국영 에너지 대기업 가스프롬은 이미 우크라이나 전역을 통과하는 가스량을 크게 줄였으며, 통과 다각화 파이프라인(터키 스트림, 노르트 스트림 등)을 통해 수준을 더 낮추겠다는 의사를 밝혔습니다.[315] 가스프롬과 우크라이나는 2019년 말 러시아 가스를 유럽으로 운송하는 5년 계약에 합의했습니다.[316][317]

2020년 러시아에서 튀르키예로 연결되는 TurkStream 천연가스 파이프라인은 우크라이나와 트랜스발칸 파이프라인 시스템을 통한 운송을 전환함으로써 동남유럽의 지역 가스 흐름을 변화시켰습니다.

2021년 5월, 바이든 행정부는 러시아의 Nord Stream 2 가스 파이프라인 배후에 있는 회사에 대한 트럼프의 CAATSA 제재를 독일에 면제했습니다.[320][321] 젤렌스키 우크라이나 대통령은 조 바이든 대통령의 결정에 "놀랍다"며 "실망스럽다"고 말했습니다.[322] 2021년 7월, 미국은 우크라이나가 이 송유관을 둘러싼 독일과의 합의를 비난하지 말 것을 촉구했습니다.[323][324]

2021년 7월, 바이든과 앙겔라 메르켈 독일 총리는 러시아가 노드 스트림을 "정치적 무기"로 사용할 경우 미국이 제재를 촉발할 수 있다는 합의를 체결했습니다. 이 거래는 폴란드와 우크라이나가 러시아 가스 공급이 차단되는 것을 막기 위한 것이었습니다. 우크라이나는 2024년까지 녹색 기술에 대해 5천만 달러를 대출받고 독일은 가스 수송료 손실을 보상하기 위해 우크라이나의 녹색 에너지 전환을 촉진하기 위해 10억 달러 규모의 기금을 조성할 예정입니다. 러시아 정부가 동의할 경우 우크라이나를 경유하는 러시아 가스 운송 계약은 2034년까지 연장됩니다.[325][326][327]

2021년 8월 젤렌스키는 러시아와 독일 사이의 노드 스트림 2 천연가스 파이프라인이 "우크라이나뿐만 아니라 유럽 전체를 위한 위험한 무기"라고 경고했습니다.[328][329] 2021년 9월, 우크라이나의 나프토가즈 CEO 유리 비트렌코는 러시아가 천연가스를 "지정학적 무기"로 사용하고 있다고 비난했습니다.[330] 비트렌코 대변인은 "미국과 독일의 공동성명은 크렘린궁이 가스를 무기로 사용한다면 적절한 대응이 있을 것이라고 말했습니다. 우리는 지금 노드 스트림 2의 운영사인 가즈프롬의 100% 자회사에 대한 제재 부과를 기다리고 있습니다."[331]

잡종전

러시아-우크라이나 분쟁에는 비전통적인 수단을 사용하는 하이브리드 전쟁의 요소도 포함되어 있습니다. 러시아는 2015년 12월 우크라이나 전력망 공격 성공, 2016년 12월 전력망 최초 사이버 공격 성공,[332] 2017년 6월 미국이 알려진 사이버 공격 중 최대 규모라고 주장한 대량 해커 공급망 공격 등 작전에 사이버 전쟁을 활용해 왔습니다.[333] 이에 대한 보복으로 우크라이나 작전에는 2016년 10월 우크라이나에서 크림반도를 점령하고 돈바스의 분리주의 불안을 조장하려는 러시아 계획과 관련하여 2,337개의 이메일을 공개한 수르코프 누출 사건이 포함되었습니다.[334] 우크라이나에 대한 러시아의 정보 전쟁은 러시아가 벌이고 있는 하이브리드 전쟁의 또 다른 전선이었습니다.

지역당, 공산당, 진보사회당, 러시아정교회 사이에 우크라이나에 있는 러시아의 다섯 번째 칼럼도 존재한다고 주장했습니다.[335][336][337]

러시아의 선전전과 허위 정보 제공

전쟁 중에 거짓 이야기가 대중의 분노를 불러일으키기 위해 사용되었습니다. 2014년 4월, 러시아 뉴스 채널인 러시아-1과 NTV는 한 채널과 다른 채널에서 한 남성이 파시스트 우크라이나 갱단의 공격을 받았다고 말하는 모습을 보여주었고, 다른 채널에서는 우익 반러시아 급진주의자들의 훈련에 자금을 지원하고 있다고 말했습니다.[339][340] 세 번째 부분은 그 남자를 신나치 외과의사로 묘사했습니다.[341] 2014년 5월, 러시아-1은 2012년 러시아의 북캅카스 작전 영상을 이용하여 우크라이나의 만행에 대한 이야기를 방송했습니다.[342] 같은 달, 러시아 뉴스 네트워크인 라이프는 도네츠크 국제공항을 막 재탈환한 우크라이나군의 희생자로서 시리아에서 부상당한 어린이의 사진을 2013년에 발표했습니다.[343]

2014년 6월, 몇몇 러시아 국영 뉴스 매체는 우크라이나가 이라크에서 미국에 의해 사용되는 2004년 영상을 사용하여 백린을 사용하고 있다고 보도했습니다.[342] 2014년 7월, 채널 1 러시아는 슬로비안스크의 가상 광장에서 러시아어를 구사하는 3세 소년이 우크라이나 민족주의자들에게 십자가에 못 박혔다는 한 여성의 인터뷰를 방송했는데, 이는 거짓으로 드러났습니다.[344][345][340][342]

2022년 러시아 국영 언론은 우크라이나 동부에서 러시아계로 가득 찬 대량 학살과 집단 무덤에 대한 이야기를 전했습니다. 2014년 격렬한 전투로 지역 영안실의 전기가 차단되면서 루한스크 외곽의 한 세트의 무덤이 파였습니다. 국제앰네스티는 2014년 러시아의 수백 구의 시신으로 채워진 집단 무덤에 대한 주장을 조사했으며 대신 양측이 사법 외 처형을 당한 사건을 발견했습니다.[346][347][348] 러시아 검열 기관인 로스콤나조르는 러시아 언론에 러시아 국가 정보원의 정보만 사용하거나 벌금과 블록에 처해질 것을 명령했으며,[349] 언론과 학교에 전쟁을 "특별 군사 작전"으로 묘사할 것을 명령했습니다.[350] 2022년 3월 4일, 푸틴은 러시아군과 그 작전에 대한 "가짜 뉴스"를 발행하는 사람들에게 최대 15년의 징역형을 도입하는 법안에 서명하여 [351]일부 언론이 우크라이나에 대한 보도를 중단하도록 이끌었습니다.[352] 러시아 야당 정치인 알렉세이 나발니는 러시아 관영매체에 나오는 "거짓말의 괴물"은 상상할 수 없는 일이라고 말했습니다. 그리고 불행하게도, 대체 정보에 접근할 수 없는 사람들을 위한 그것의 설득력도 마찬가지입니다."[353] 그는 트위터를 통해 러시아 국영 언론 인사들 사이의 "전쟁꾼"들은 "전범으로 취급되어야 한다"고 말했습니다. 편집장부터 토크쇼 진행자, 뉴스 편집자에 이르기까지 지금은 제재를 받고 언젠가는 재판을 받아야 합니다."[354]

푸틴 대통령과 러시아 언론은 우크라이나 정부가 젤렌스키 대통령이 유대인임에도 불구하고 러시아의 보호가 필요한 러시아계 민족을 박해하는 신나치주의에 의해 주도되고 있다고 설명했습니다.[355][356][347] 저널리스트 나탈리아 안토노바에 따르면, "러시아의 오늘날 침략 전쟁은 2차 세계 대전에서 나치 독일을 멈추기 위해 죽은 수백만 명의 러시아 군인들의 유산의 직접적인 지속으로 선전에 의해 변형되었습니다."[357] 우크라이나가 러시아가 시작한 나치즘 미화 반대에 관한 총회 결의안 채택을 거부한 것은, 그 중 가장 최근의 것은 나치즘, 신나치즘 및 동시대의 인종차별을 조장하는 기타 관행을 미화 반대하는 총회 결의안 A/C.3/76/L.57/Rev.1입니다. 인종 차별, 외국인 혐오 및 관련 불내증은 우크라이나를 친나치 국가로 제시하는 역할을 하며 실제로 러시아의 주장의 근거를 형성할 가능성이 높으며, 결의안 채택을 거부한 유일한 다른 국가는 미국입니다.[358][359] ECOSOC의 미국 부대표는 이러한 결의안을 "나치 미화를 중단한다는 냉소적인 가장을 사용하여 이웃 국가를 비하하는 러시아의 허위 정보 캠페인을 합법화하고 현대 유럽 역사의 많은 부분에 대한 왜곡된 소련의 서술을 촉진하려는 얄팍한 시도"라고 설명합니다.[360]

러시아 안전보장이사회 부의장이자 전 러시아 대통령인 드미트리 메드베데프는 "우크라이나는 국가가 아니라 인위적으로 영토를 수집했다"며 우크라이나어는 "언어가 아니라 러시아어의 "몽골 방언"이라고 공개적으로 썼습니다.[361] 메드베데프는 또한 우크라이나가 어떤 형태로든 존재해서는 안되며 러시아는 우크라이나의 어떤 독립 국가와도 계속 전쟁을 벌일 것이라고 말했습니다.[362] 게다가 메드베데프는 2023년 7월에 2023년 우크라이나의 반격이 성공했다면 러시아는 핵무기를 사용해야 했을 것이라고 주장했습니다.[363] 메드베데프에 따르면, "우크라이나의 존재는 우크라이나인들에게 치명적으로 위험하며, 그들은 거대한 공동 상태에서의 삶이 죽음보다 낫다는 것을 이해할 것입니다. 그들의 죽음과 사랑하는 사람들의 죽음. 그리고 우크라이나인들이 이것을 빨리 깨달을수록 더 좋습니다."[364] 2024년 2월 22일 메드베데프는 러시아군이 우크라이나로 더 진출하여 남부 도시 오데사를 점령하고 우크라이나 수도 키이우로 다시 진출할 것이라고 주장하면서 러시아의 미래 계획을 설명하고 "우리는 어디에서 멈추어야 합니까? 모르겠어요."[365] 메드베데프는 우크라이나와 미국 언론에 의해 "러시아의 급진주의자(러시아 파시스트)"로 묘사되어 왔습니다.[366]

소셜 미디어에서 만화 시바 이누 개가 일반적으로 확인한 러시아 허위 정보에 맞서 싸울 것이라고 다짐하는 느슨한 온라인 똥 게시자의 간부인 NAFO(북대서양 펠라 조직)는 2022년 6월 이후 러시아 외교관 미하일 울랴노프와의 트위터 다툼으로 악명을 떨쳤습니다.[367]

2024년 2월, 푸틴은 러시아-우크라이나 전쟁이 "내란의 요소"를 가지고 있으며 "러시아 국민이 재결합할 것"이라고 주장했고, 우크라이나 정교회(러시아 정교회의 분파)는 "러시아 국민이 재결합할 것"이라고 주장했습니다. 그것은 주로 러시아의 우크라이나 침공을 지지하고 공개적으로 우크라이나에 대한 군사적 승리를 기도하는 것을 의무화하고 있습니다. "우리의 영혼을 하나로 모으십시오."[368][369][370] 그럼에도 불구하고 우크라이나의 공식 정부 웹사이트에는 우크라이나인과 러시아인이 "하나의 국가"가 아니며 우크라이나인은 독립된 국가라고 명시되어 있습니다.[371] 2022년 4월 《레이팅》이 실시한 여론 조사에 따르면, 대다수의 우크라이나인(91%)은 "러시아인과 우크라이나인은 한 민족"이라는 주장을 지지하지 않는 것으로 나타났습니다.[372]

러시아-북대서양 조약 기구 관계

푸틴은 우크라이나 침공을 정당화하는 연설에서 우크라이나 내부에 나토 군사 인프라가 구축되고 있으며 러시아에 위협이 되고 있다고 거짓 주장했습니다.[373] 세르게이 라브로프 러시아 외무장관은 이번 분쟁을 나토가 시작한 대리전으로 규정했습니다.[374] 그는 "우리는 나토와 전쟁을 벌이고 있다고 생각하지 않는다"고 말했습니다. 불행히도 나토는 러시아와 전쟁을 벌이고 있다고 믿고 있습니다."[375] 나토는 러시아와 전쟁을 벌이고 있는 것이 아니라 "유엔 헌장에 명시된 우크라이나의 자위권"을 회원국들이 지지한다는 공식 방침입니다.[376] 러시아가 크림반도를 합병할 때까지 NATO와 러시아는 협력했습니다.[376] 리언 패네타 전 CIA 국장은 ABC 방송에 미국이 러시아와의 대리전에 '의심의 여지 없이' 관여하고 있다고 말했습니다.[377]

발트해와 흑해 상공을 비행하는 러시아 군용기는 종종 자신의 위치를 표시하지 않거나 항공 교통 관제사와 통신하지 않아 민간 항공기에 잠재적인 위험을 초래합니다. 북대서양조약기구(NATO·나토) 항공기들은 동맹 영공 근처에서 이 항공기들을 추적하고 요격하기 위해 여러 차례 분주 요격된 러시아 항공기는 나토 영공에 진입한 적이 없으며, 안전하고 일상적인 방식으로 요격이 이뤄졌습니다.[378]

리액션

러시아의 크림 반도 합병에 대한 반응

우크라이나의 대응

올렉산드르 투르치노프 우크라이나 임시 대통령은 크림 반도의 크림 의회 건물과 다른 정부 사무실들을 압수하는 것을 지지함으로써 러시아가 "분쟁을 유발했다"고 비난했습니다. 그는 러시아의 군사 행동을 2008년 러시아-조지아 전쟁과 비교했는데, 당시 러시아군은 조지아 공화국의 일부를 점령했고, 압하지야와 남오세티야의 분리된 거주지가 러시아의 지원을 받는 행정부의 통제 하에 세워졌습니다. 그는 푸틴 대통령에게 크림반도에서 러시아군을 철수할 것을 요구하고 우크라이나가 "영토를 보존할 것"이며 "독립을 수호할 것"이라고 말했습니다.[380] 3월 1일, 그는 "군사적 개입은 전쟁의 시작이자 우크라이나와 러시아 사이의 어떤 관계의 끝이 될 것"이라고 경고했습니다.[381] 3월 1일, 올렉산드르 투르치노프 대통령 권한대행은 우크라이나군을 전면 경계 태세와 전투 준비 태세에 돌입시켰습니다.[382]

임시 점령지 및 IDP부는 2014년 러시아의 군사 개입으로 영향을 받은 도네츠크, 루한스크 및 크림 반도의 점령 지역을 관리하기 위해 2016년 4월 20일 우크라이나 정부에 의해 설립되었습니다.[383]

나토와 미국의 군사적 대응

2014년 3월 4일, 미국은 우크라이나에 10억 달러의 원조를 약속했습니다.[384] 러시아의 행동은 역사적으로 인근 국가들, 특히 발트해와 몰도바의 영향권 안에서 긴장을 높였습니다. 모두 러시아어를 사용하는 인구가 많으며, 러시아군은 분리된 몰도바 영토인 트란스니스트리아에 주둔하고 있습니다.[385] 일부는 방어 능력을 높이는 데 자원을 쏟았고,[386] 많은 이들은 최근 몇 년간 가입한 미국과 북대서양조약기구(NATO)의 지원 확대를 요청했습니다.[385][386] 이 분쟁은 소련과 맞서기 위해 창설되었지만 최근 몇 년 동안 "원정 임무"에 더 많은 자원을 할애한 NATO를 "활성화"했습니다.[387]

미국은 2010년대에 러시아와의 분쟁에서 외교적 지원 외에도 우크라이나에 15억 달러의 군사 지원을 제공했습니다.[388] 2018년 미국 하원은 미군의 우크라이나 주방위군 아조프 대대 훈련을 차단하는 조항을 통과시켰습니다. 예년에는 2014년부터 2017년 사이 미국 하원이 아조프 지원을 금지하는 개정안을 통과시켰지만, 국방부의 압력으로 개정안이 조용히 해제됐습니다.[389][390][391]

금융시장

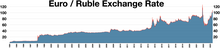

크림 반도의 긴장 고조에 대한 초기 반응이 러시아와 유럽 증시를 폭락시켰습니다.[392] 이 개입으로 스위스 프랑은 달러 대비 2년 만에, 유로 대비 1년 만에 최고치를 기록했습니다. 유로와 미국 달러 모두 상승했고 호주 달러도 상승했습니다.[393] 러시아 증시는 10% 이상 하락했고 러시아 루블화는 미국 달러와 유로에 대해 사상 최저치를 기록했습니다.[394][395][396] 러시아 중앙은행은 통화 안정화를 위해 금리를 인상하고 120억[clarification needed] 달러에 달하는 외환 시장에 개입했습니다.[393] 밀과 곡물 가격이 상승했으며 우크라이나는 두 작물의 주요 수출국입니다.[397]

이후 2014년 3월 크림반도 합병에 대한 금융시장의 반응은 놀라울 정도로 부드러웠으며, 크림반도에서 실시된 국민투표 직후 글로벌 금융시장이 상승했는데, 이는 앞서 러시아 침공 이후 제재가 이미 가격을 매겼다는 설명입니다.[398] 다른 관측통들은 2014년 3월 17일 월요일 EU와 미국의 대러시아 제재 발표 이후 글로벌 금융시장의 긍정적인 반응이 이러한 제재가 러시아에 타격을 주기에는 너무 약하다는 것을 드러냈다고 간주했습니다.[399] 2014년 8월 초, 독일 DAX는 독일의 13번째로 큰 무역 상대국인 러시아가 제재에 보복할 것이라는 우려로 인해 올해 6% 하락했고, 6월 이후 11% 하락했습니다.[400]

돈바스 전쟁에 대한 반응

우크라이나 여론

국제공화연구소는 2014년 9월 12일부터 25일까지 러시아가 합병한 크림반도를 제외한 우크라이나 국민을 대상으로 여론조사를 실시했습니다.[401] 조사 대상자의 89%는 2014년 러시아의 우크라이나 군사 개입에 반대했습니다. 지역별로 살펴보면 동부 우크라이나(드니프로페트롭스크주 포함)에서 조사된 사람들의 78%가 개입에 반대했으며, 남부 우크라이나 89%, 중부 우크라이나 93%, 서부 우크라이나 99%가 개입에 반대했습니다.[401] 모국어별로 보면 러시아어 사용자의 79%, 우크라이나어 사용자의 95%가 개입에 반대했습니다. 조사 대상자의 80%가 단일 국가로 유지되어야 한다고 답했습니다.[401]

2015년 1월 16일부터 22일까지 독일 최대 시장 조사 기관인 GfK의 우크라이나 지사가 러시아에 합병된 크림 지역의 크림 국민을 대상으로 한 여론 조사를 실시했습니다. 조사 결과에 따르면 "조사 대상자의 82%는 크림반도의 러시아 편입을 전적으로 지지한다고 답했고, 또 다른 11%는 부분적인 지지를 표명했습니다. 반대 의견을 낸 사람은 4%에 불과했습니다."[402][403][404]

레바다와 키이우 국제 사회학 연구소가 2020년 9월부터 10월까지 실시한 공동 여론 조사에 따르면 DPR/LPR이 통제하는 이탈 지역에서는 응답자의 절반이 조금 넘는 사람들이 (어느 정도의 자치적 지위가 있든 없든) 러시아에 합류하기를 원했고, 10분의 1도 안 되는 사람들이 독립을 원했고, 12%는 우크라이나로의 재통합을 원했습니다. 이는 키이우가 장악하고 있는 돈바스의 응답자들과 대조적으로 대다수가 분리주의 지역을 우크라이나로 반환해야 한다고 생각했습니다. 2022년 1월 레바다의 결과에 따르면, 이탈 지역에 있는 사람들 중 약 70%가 자신의 영토가 러시아 연방의 일부가 되어야 한다고 답했습니다.[406]

러시아 여론

레바다 센터의 2014년 8월 조사에 따르면 조사 대상 러시아인의 13%만이 우크라이나와의 공개 전쟁에서 러시아 정부를 지지할 것이라고 합니다.[407] 우크라이나 전쟁에 반대하는 거리 시위가 러시아에서 일어났습니다. 주목할 만한 시위는 3월에[408][409] 처음 발생했고 대규모 시위는 2014년 9월 21일 일요일 모스크바 시내에서 "경찰의 엄중한 감독 하에" 평화 행진으로 "수만 명"이 우크라이나 전쟁에 항의하면서 9월에 발생했습니다.[410]

러시아의 우크라이나 침공에 대한 대응

우크라이나 여론

러시아의 우크라이나 침공 일주일 후인 2022년 3월, 우크라이나에 거주하는 러시아계의 82%를 포함한 우크라이나인의 98%가 크림 반도와 분리주의자가 지배하는 돈바스 지역을 포함하지 않은 애쉬크로프트 경의 여론조사에 따르면 우크라이나의 어느 지역도 러시아의 정당한 부분이라고 생각하지 않는다고 답했습니다. 우크라이나인의 97%는 블라디미르 푸틴 러시아 대통령에 대해 비호감이라고 답했고, 94%는 러시아군에 대해 비호감이라고 답했습니다.[411]

2021년 말 우크라이나인의 75%가 일반 러시아인에 대해 긍정적인 태도를 가지고 있다고 답했고, 2022년 5월 우크라이나인의 82%가 일반 러시아인에 대해 부정적인 태도를 가지고 있다고 답했습니다.[412]

러시아 여론

러시아의 "불친절한 나라 목록"에 있는 나라들. 이 목록에는 러시아의 우크라이나 침공에 대해 제재를 가한 국가들이 포함되어 있습니다.[413]

2022년 4월 레바다 센터의 조사에 따르면 조사 대상 러시아인의 약 74%가 우크라이나에서의 "특별 군사 작전"을 지지한다고 보고했으며, 이는 2014년 이후 러시아 여론이 상당히 변화했음을 시사합니다.[414] 일부 소식통에 따르면, 많은 러시아인들이 "특별 군사 작전"을 지지하는 이유는 선전 및 허위 정보와 관련이 있다고 합니다.[415][416] 또한 일부 응답자는 부정적인 결과를 우려하여 여론 조사 기관의 질문에 대답하고 싶지 않다고 제안되었습니다.[417][418] 지난 3월 말 레바다 센터가 러시아에서 실시한 여론조사 결과 다음과 같은 결론이 나왔습니다. 응답자들은 왜 군사작전이 벌어지고 있다고 보느냐는 질문에 우크라이나 내 러시아계 또는 러시아어 사용자인 민간인을 보호하고 방어하기 위한 것(43%), 러시아에 대한 공격을 막기 위한 것(25%), 민족주의자를 제거하고 우크라이나를 '비방화'하기 위한 것(21%), 우크라이나나 돈바스 지역을 러시아에 편입하기 위한 것(3%)이라고 답했습니다."[419]여론조사에 따르면[419] 러시아 대통령의 지지율은 침공 전날 71%에서 2023년 3월 82%로 상승했습니다.[420]

크렘린궁의 분석에 따르면 전쟁에 대한 대중의 지지는 광범위하지만 깊지 않으며 대부분의 러시아인들은 푸틴이 승리라고 부르는 것은 무엇이든 받아들일 것이라고 결론지었습니다. 2023년 9월 VTs 대표IOM 국영 여론조사기관 발레리 표도로프는 인터뷰에서 러시아인의 10~15%만이 전쟁을 적극 지지하고 있다며 "대부분의 러시아인들은 키이우나 오데사 정복을 요구하지 않고 있다"고 말했습니다.

2023년 인권 센터 "기념관"의 위원장인 올레그 오를로프는 블라디미르 푸틴 정권의 러시아가 파시즘으로 전락했으며 군대가 "대량살해"를 저지르고 있다고 주장했습니다.[422][423]

미국

2022년 4월 28일, 조 바이든 미국 대통령은 우크라이나에 무기를 제공하기 위한 200억 달러를 포함하여 우크라이나를 지원하기 위한 330억 달러를 추가로 의회에 요청했습니다.[424] 5월 5일, 우크라이나의 데니스 슈미할 총리는 우크라이나가 2월 24일 러시아의 침공이 시작된 이후 서방 국가들로부터 120억 달러 상당의 무기와 재정 지원을 받았다고 발표했습니다.[425] 2022년 5월 21일, 미국은 우크라이나에 400억 달러의 새로운 군사 및 인도주의적 해외 원조를 제공하는 법안을 통과시켰으며, 이는 역사적으로 큰 자금 약속을 의미했습니다.[426][427] 2022년 8월, 러시아의 전쟁 노력에 대응하기 위한 미국의 국방비 지출은 아프가니스탄에서 처음 5년 동안의 전쟁 비용을 초과했습니다. 워싱턴포스트는 우크라이나 전쟁 전선에 전달된 미국의 새로운 무기들은 더 많은 사상자가 발생하는 보다 긴밀한 전투 시나리오를 시사한다고 보도했습니다.[428] 미국은 증가된 무기 수송량과 기록적인 30억 달러의 군사 원조 패키지로 "우크라이나의 지속적인 힘"을 구축할 것을 기대하고 있습니다.[428]

2022년 4월 22일 티모시 D 교수. 스나이더는 뉴욕 타임즈 매거진에 "우리는 파시즘 부활의 중심적인 예, 즉 러시아 연방의 푸틴 정권을 간과하는 경향이 있었습니다"라는 기사를 실었습니다.[429] 더 넓은 정권에 대해 스나이더는 "[유명한] 러시아 파시스트들은 전쟁 중에 이를 포함한 대중 매체에 접근할 수 있습니다. 러시아 엘리트들의 구성원들은, 무엇보다도 푸틴 자신에게 점점 더 파시즘 개념에 의존하고 있습니다"라고 말하며, "푸틴이 우크라이나 전쟁을 정당화한 것은 기독교적 파시즘의 형태를 나타냅니다."라고 말합니다.[429]

러시아 군수품 공급업체

수개월에 걸쳐 많은 양의 중화기와 군수품을 지출한 후, 러시아 연방은 이란으로부터 전투용 드론, 군수품을 약탈하고 다량의 포병을, 벨라루스로부터 탱크와 다른 기갑 차량을 인도받았습니다. 북한의 포탄과 이란의 탄도미사일을 교환할 계획이었던 것으로 알려졌습니다.[430][431][432][433][434]

미국은 중국이 첨단 무기에 필요한 기술을 러시아에 제공했다고 비난했는데, 중국은 이를 부인했습니다. 미국은 우크라이나에서 전투 중인 러시아 용병 부대에 위성사진을 제공한 중국 기업을 제재했습니다.[435]

2023년 3월, 서방 국가들은 2022년 걸프 국가가 러시아에 158대의 드론을 수출했다는 의혹이 제기되는 가운데, 군사적 용도를 가진 러시아에 대한 상품의 재수출을 중단하라고 아랍에미리트를 압박했습니다.[436] 2023년 5월, 미국은 남아프리카 공화국이 비밀 해군 작전으로 러시아에 무기를 공급했다고 비난했는데,[437] 이는 남아프리카 공화국 대통령 시릴 라마포사가 부인한 주장입니다.[438]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ a b 도네츠크 인민 공화국과 루한스크 인민 공화국은 2014년 5월 우크라이나로부터 독립을 선언한 러시아의 지배를 받는 괴뢰 국가였습니다. 2022년에 그들은 서로, 러시아, 시리아 그리고 북한 그리고 일부 부분적으로 인정된 다른 국가들로부터 국제적인 인정을 받았습니다. 2022년 9월 30일 러시아는 공식적으로 두 기업을 합병했다고 선언했습니다.

- ^ 점령이 시작된 날짜와 관련하여 "일부 모순과 내재된 문제"가 있습니다.[439] 우크라이나 정부와 유럽 인권 재판소는 러시아가 2014년 2월 27일부터 크림반도를 통제했다고 주장하고 있으며,[440] 이 때 러시아 특수부대가 자국의 정치 기관을 장악했습니다.[441] 러시아 정부는 이후 2월 27일을 "특별 작전군의 날"로 제정했습니다.[65] 2015년 우크라이나 의회는 러시아 훈장 "크림 반도 반환을 위하여"에 새겨진 날짜를 [442]인용하여 2014년 2월 20일을 "러시아에 의한 크림 반도와 세바스토폴 임시 점령의 시작"으로 공식 지정했습니다.[443] 그날 블라디미르 콘스탄티노프 당시 크림 최고위원장은 이 지역이 러시아에 합류할 준비가 돼 있을 것이라고 말했습니다.[444] 2018년 세르게이 라브로프 러시아 외무장관은 메달에 대한 더 이른 "시작 날짜"는 "기술적인 오해" 때문이라고 주장했습니다.[445] 푸틴 대통령은 합병에 관한 러시아 영화에서 2014년 2월 22~23일 밤샘 긴급회의 후 크림반도를 러시아에 "복원"하는 작전을 지시했다고 밝혔습니다.[439][446]

- ^ 러시아어: российско-украинская война, 로마자: 로시스코-우크레인스카야 보이나, 우크라이나어: російсько-українська війна, 로마자: 로시스코-우크레인스카 비아이나.

- ^ 많은 국가들이 전쟁에서 호전적이 되는 것 외에 우크라이나에 다양한 수준의 지원을 제공했으며 벨라루스는 2022년 침공에 대해 러시아군에게 영토 접근을 제공했습니다.

참고문헌

- ^ Rainsford, Sarah (6 September 2023). "Ukraine war: Romania reveals Russian drone parts hit its territory". Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ "Maps: Tracking the Russian Invasion of Ukraine". The New York Times. 14 February 2022. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ "'Terrible toll': Russia's invasion of Ukraine in numbers". Euractiv. 14 February 2023. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Hussain, Murtaza (9 March 2023). "The War in Ukraine Is Just Getting Started". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Budjeryn, Mariana (21 May 2021). "Revisiting Ukraine's Nuclear Past Will Not Help Secure Its Future". Lawfare. Archived from the original on 13 January 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Budjeryn, Mariana. "Issue Brief #3: The Breach: Ukraine's Territorial Integrity and the Budapest Memorandum" (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Vasylenko, Volodymyr (15 December 2009). "On assurances without guarantees in a 'shelved document'". The Day. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Harahan, Joseph P. (2014). "With Courage and Persistence: Eliminating and Securing Weapons of Mass Destruction with the Nunn-Luger Cooperative Threat Reduction Programs" (PDF). DTRA History Series. Defense Threat Reduction Agency. ASIN B01LYEJ56H. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Istanbul Document 1999". Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 19 November 1999. Archived from the original on 1 June 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Wiegrefe, Klaus (15 February 2022). "NATO's Eastward Expansion: Is Vladimir Putin Right?". Der Spiegel. ISSN 2195-1349. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Hall, Gavin E. L. (14 February 2022). "Ukraine: the history behind Russia's claim that Nato promised not to expand to the east". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Leung, Rebecca (11 February 2009). "Yushchenko: 'Live And Carry On'". CBS News. CBS. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Study: Dioxin that poisoned Yushchenko made in lab". Kyiv Post. London: Businessgroup. Associated Press. 5 August 2009. ISSN 1563-6429. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ "Yushchenko to Russia: Hand over witnesses". Kyiv Post. Businessgroup. 28 October 2009. ISSN 1563-6429. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ "The Supreme Court findings" (in Ukrainian). Supreme Court of Ukraine. 3 December 2004. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ "Ukraine-Independent Ukraine". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 January 2008. Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- ^ Cordesman, Anthony H. (28 May 2014). "Russia and the 'Color Revolution'". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "Putin calls 'color revolutions' an instrument of destabilization". Kyiv Post. Interfax Ukraine. 15 December 2011. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Антиоранжевый митинг проходит на Поклонной горе [Anti-orange rally takes place on Poklonnaya Hill] (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 4 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Brown, Colin (3 April 2008). "EU allies unite against Bush over Nato membership for Georgia and Ukraine". The Independent. p. 24.

- ^ Evans, Michael (5 April 2008). "President tells summit he wants security and friendship". The Times. p. 46.

President Putin, in a bravura performance before the world's media at the end of the Nato summit, warned President Bush and other alliance leaders that their plan to expand eastwards to Ukraine and Georgia 'didn't contribute to trust and predictability in our relations'.

- ^ Wong, Edward; Jakes, Lara (13 January 2022). "NATO Won't Let Ukraine Join Soon. Here's Why". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Yanukovych tops list of presidential candidates in Ukraine – poll". Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- ^ Harding, Luke (8 February 2010). "Yanukovych set to become president as observers say Ukraine election was fair". The Guardian. Kyiv. ISSN 1756-3224. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Parliament passes statement on Ukraine's aspirations for European integration". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Dinan, Desmond; Nugent, Neil (eds.). The European Union in Crisis. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 3, 274.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (22 September 2013). "Ukraine's EU trade deal will be catastrophic, says Russia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ "Rada removes Yanukovych from office, schedules new elections for May 25". Interfax-Ukraine. 24 February 2014. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Ukraine President Yanukovich impeached". Al Jazeera. 22 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Sindelar, Daisy (23 February 2014). "Was Yanukovych's Ouster Constitutional?". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Feffer, John (14 March 2014). "Who Are These 'People,' Anyway?". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (24 February 2014). "Western nations scramble to contain fallout from Ukraine crisis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ На отмену закона о региональных языках на Украине наложат вето [The abolition of the law on regional languages in Ukraine will be vetoed] (in Russian). Lenta.ru. 1 March 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Ayres, Sabra (28 February 2014). "Is it too late for Kyiv to woo Russian-speaking Ukraine?". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Kofman, Michael (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-9617-3. OCLC 990544142. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

By March 26, the annexation was essentially complete, and Russia began returning seized military hardware to Ukraine.

- ^ Polityuk, Pavel; Robinson, Matt (22 February 2014). Roche, Andrew (ed.). "Ukraine parliament removes Yanukovich, who flees Kyiv in 'coup'". Reuters. Gabriela Baczynska, Marcin Goettig, Peter Graff, Giles Elgood. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ "Yanukovich poshel po stopam Yushchenko – sudy opyat' otbirayut mayaki u rossiyskikh voyennykh" Янукович пошел по стопам Ющенко – суды опять отбирают маяки у российских военных [Yanukovych followed in Yushchenko's footsteps – courts again take away beacons from Russian military]. DELO (in Russian). 11 August 2011. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ Stephen, Chris (16 January 2006). "Russian anger as Ukraine seizes lighthouse". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Kimball, Spencer (11 March 2014). "Bound by treaty: Russia, Ukraine, and Crimea". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Янукович віддав крим російському флоту ще на 25 років. Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ Pullen, R.; Frost, C. (3 March 2022). "Putin's Ukraine invasion – do declarations of war still exist?". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine's envoy says Russia 'declared war'". The Economic Times. Associated Press. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ "'No other option': Excerpts of Putin's speech declaring war". Al Jazeera. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Sheftalovic, Zoya (24 February 2022). "Battles flare across Ukraine after Putin declares war Battles flare as Putin declares war". Politico Europe. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Verkhovna Rada recognized Russia as a terrorist state". ukrinform.net. 15 April 2022. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Wuerth, Ingrid (22 February 2022). "International Law and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine". Lawfare. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Bellinger III, John B. (28 February 2022). "How Russia's Invasion of Ukraine Violates International Law". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Hannum, Hurst. "International law says Putin's war against Ukraine is illegal. Does that matter?". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Neal, Jeff (2 March 2022). "The Ukraine conflict and international law". Harvard Law Today. Interviewees: Blum, Gabriella & Modirzadeh, Naz. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Weiner, Allen S. (24 February 2022). "Stanford's Allen Weiner on the Russian Invasion of Ukraine". Stanford Law School Blogs. Q&A with Driscoll, Sharon. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Dworkin, Anthony (25 February 2022). "International law and the invasion of Ukraine". European Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Wilmhurst, Elizabeth (24 February 2022). "Ukraine: Debunking Russia's legal justifications". Chatham House. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ 여러 참조에 기인함:[46]

- ^ Ranjan, Prabhash; Anil, Achyuth (1 March 2022). "Debunking Russia's international law justifications". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Troconis, Jesus Eduardo (24 February 2022). "Rusia está fuera de la ley internacional". Cambio16. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Gross, Judah Ari (27 February 2022). "Israeli legal experts condemn Ukraine invasion, say it's illegal under international law". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ McIntyre, Juliette; Guilfoyle, Douglas; Paige, Tamsin Phillipa (24 February 2022). "Is international law powerless against Russian aggression in Ukraine? No, but it's complicated". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Dannenbaum, Tom (10 March 2022). "Mechanisms for Criminal Prosecution of Russia's Aggression Against Ukraine". Just Security. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Colangelo, Anthony J. (4 March 2022). "Putin can be prosecuted for crimes of aggression – but likely not any time soon". The Hill. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ *"Ukraine v. Russia (re Crimea) (decision)". European Court of Human Rights. January 2021. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

The Ukrainian Government maintains that the Russian Federation has from 27 February 2014 exercised effective control over the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol ... There was sufficient evidence that during the relevant period the respondent State [Russia] had exercised effective control over Crimea.

- Sasse, Gwendolyn (2023). Russia's War Against Ukraine. Wiley & Sons. p. 2004.

Russia's war against Ukraine began with the annexation of Crimea on 27 February 2014. On that day, Russian special forces without any uniform insignia appeared in Crimea, quickly taking control of strategic, military and political institutions.

- Käihkö, Ilmari (2023). Slava Ukraini!: Strategy and the Spirit of Ukrainian Resistance 2014–2023. Helsinki University Press. p. 72.

If asked when the war began, many Ukrainians believe it was when the unmarked Russian 'little green men' occupied Crimea on February 27, 2014, or February 20, the date given on the official Russian campaign medal 'For the Return of Crimea'.

- Sasse, Gwendolyn (2023). Russia's War Against Ukraine. Wiley & Sons. p. 2004.

- ^ Cathcart, Will (25 April 2014). "Putin's Crimean Medal of Honor, Forged Before the War Even Began". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ a b "The Russian Invasion of the Crimean Peninsula 2014–2015" (PDF). Johns Hopkins University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "10 facts you should know about russian military aggression against Ukraine". Ukraine government. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ 크림 반도와 우크라이나 동부에서 러시아의 작전에서 얻은 교훈 2022년 2월 17일 Wayback Machine에서 보관됨, 페이지 19, RAND Corporation이 2017년에 출판함. "우크라이나 정부는 야누코비치의 축출 이후 과도기에 있었습니다. 결과적으로 발사 시 러시아 작전에 반응하지 않았습니다. 러시아의 과제는 키이우에서 일어난 것과 같은 일반적으로 봉기에 뒤따르는 혼란과 혼란으로 인해 비교적 쉽게 이루어졌습니다. 모스크바는 크림반도의 긴장과 불확실성, 우크라이나 임시정부의 미숙함을 이용했습니다. 우크라이나 지도부 간의 논의에 대한 회의록은 많은 불안과 불확실성, 그리고 고조를 우려한 행동을 취하지 않으려는 태도를 보여줍니다."

- ^ a b DeBenedictis, Kent (2022). Russian 'Hybrid Warfare' and the Annexation of Crimea. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 140.

During the night of 26-27 February, Russian special forces without insignia departed Sevastopol ... They arrived at the Crimean Rada and Council of Ministers buildings in Simferopol, disarmed the security and took control of the buildings ... Putin later signed a decree designating 27 February as Special Operations Forces Day in Russia.

- ^ "Armed men seize two airports in Ukraine's Crimea, Russia denies involvement". Yahoo News. 28 February 2014. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Birnbaum, Michael (15 March 2015). "Putin Details Crimea Takeover Before First Anniversary". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ Mackinnon, Mark (26 February 2014). "Globe in Ukraine: Russian-backed fighters restrict access to Crimean city". Toronto: The Globe & Mail. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ "Russia flexes military muscle as tensions rise in Ukraine's Crimea". CNN. 26 February 2014. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

A CNN team in the area encountered more than one pro-Russian militia checkpoint on the road from Sevastopol to Simferopol.

- ^ "Checkpoints put at all entrances to Sevastopol". Kyiv Post. 26 February 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

Checkpoints were put up at all entrances to Sevastopol last night and the borders to the city are guarded by groups of people, police units, and traffic police.

- ^ a b "Russian parliament approves use of armed forces in Crimea". Deutsche Welle. 26 February 2014. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Jen Weedon, FireEye (2015). "Beyond 'Cyber War': Russia's Use of Strategic Cyber Espionage and Information Operations in Ukraine". In Geers, Kenneth (ed.). Cyber War in Perspective: Russian Aggression against Ukraine. Tallinn: NATO CCD COE Publications. ISBN 978-9949-9544-5-2. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Ukraine Parliament declares Crimea temporarily occupied territory". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ ""Russia Threatens Nuclear Strikes Over Crimea"". The Diplomat. 11 July 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Putin: Russia to set up military force in Crimea". ITV. 19 August 2014. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Ukraine crisis: Russian troops crossed border, Nato says". BBC News. 12 November 2014. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Doorstep statement". Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

NATO Allies have provided training to Ukrainian forces since 2014. In particular, the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada, have conducted significant training in Ukraine since the illegal annexation of Crimea, but also some EU NATO members have been part of these efforts.

- ^ a b Platonova, Daria (2022). The Donbas Conflict in Ukraine : elites, protest, and partition. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-1-003-21371-0. OCLC 1249709944.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ a b c Kofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF) (Report). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. pp. 33–34. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (20 April 2016). "The Donbas in 2014: Explaining Civil Conflict Perhaps, but not Civil War". Europe-Asia Studies. 68 (4): 631–652. doi:10.1080/09668136.2016.1176994. ISSN 0966-8136. S2CID 148334453.

- ^ Karber, Phillip A. (29 September 2015). "Lessons Learned" from the Russo-Ukrainian War (Report). The Potomac Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Freedman, Lawrence (2 November 2014). "Ukraine and the Art of Limited War". Survival. 56 (6): 13. doi:10.1080/00396338.2014.985432. ISSN 0039-6338. S2CID 154981360.

- ^ "Russia's buildup near Ukraine may reach 40,000 troops: U.S. sources". Reuters. 28 March 2014. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Kofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF) (Report). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. p. 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Kofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF) (Report). Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. pp. 43–44. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ "Strelkov/Girkin Demoted, Transnistrian Siloviki Strengthened in 'Donetsk People's Republic'". Jamestown. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Pushing locals aside, Russians take top rebel posts in east Ukraine". Reuters. 27 July 2014. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ Matsuzato, Kimitaka (22 March 2017). "The Donbass War: Outbreak and Deadlock". Demokratizatsiya. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 25 (2): 175–202. ISBN 978-1-4008-8731-6. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (20 April 2016). "The Donbas in 2014: Explaining Civil Conflict Perhaps, but not Civil War". Europe-Asia Studies. 68 (4): 647–648. doi:10.1080/09668136.2016.1176994. ISSN 0966-8136. S2CID 148334453.

- ^ a b "Rebels appeal to join Russia after east Ukraine referendum". Reuters. 12 May 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Ukraine rebels hold referendums in Donetsk and Luhansk". BBC News. 11 May 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Rebels declare victory in East Ukraine vote on self-rule". Reuters. 11 May 2014. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Arel, Dominique; Driscoll, Jesse, eds. (2023). Ukraine's Unnamed War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 138–140.

- ^ Wynnyckyj, Mychailo (2019). Ukraine's Maidan, Russia's War: A Chronicle and Analysis of the Revolution of Dignity. Columbia University Press. pp. 151–153.

- ^ "Russia's Igor Strelkov: I Am Responsible for War in Eastern Ukraine". The Moscow Times. 21 November 2014. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ "Should Putin fear the man who 'pulled the trigger of war' in Ukraine?". Reuters. 26 November 2014. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ Holcomb, Franklin (2017). The Kremlin's Irregular Army (PDF). Institute for the Study of War. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ "Ukraine reinstates conscription as crisis deepens". BBC News. 2 May 2017. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Kofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF) (Report). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. p. 69. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Fedorov, Yury E. (2019). "Russia's 'Hybrid' Aggression Against Ukraine". Routledge Handbook of Russian Security. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-18122-8. Archived from the original on 23 January 2024. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Karber, Phillip A. (29 September 2015). "Lessons Learned" from the Russo-Ukrainian War (Report). The Potomac Foundation. p. 34. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Kofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF) (Report). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. p. 43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Loshkariov, Ivan D.; Sushentsov, Andrey A. (2 January 2016). "Radicalization of Russians in Ukraine: from 'accidental' diaspora to rebel movement". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. Informa UK Limited. 16 (1): 71–90. doi:10.1080/14683857.2016.1149349. ISSN 1468-3857. S2CID 147321629.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew; Clark, Nicola (9 September 2014). "Malaysian Jet Over Ukraine Was Downed by 'High-Energy Objects,' Dutch Investigators Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Raw: Crews begin moving bodies at jet crash site". USA Today. Associated Press. 19 July 2014. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ^ Miller, Nick (19 July 2014). "MH17: 'Unknown groups' use body bags". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ^ Grytsenko, Oksana. "MH17: armed rebels fuel chaos as rotting corpses pile up on the roadside". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ^ "ATO forces take over Debaltseve, Shakhtarsk, Torez, Lutuhyne, fighting for Pervomaisk and Snizhne underway – ATO press center". Interfax-Ukraine News Agency. 28 July 2014. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Sutyagin, Igor (March 2015). "Russian Forces in Ukraine" (PDF). Royal United Services Institute. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Here's Why Putin Calling Eastern Ukraine 'Novorossiya' Is Important". The Huffington Post. 18 April 2014. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M. (17 April 2014). "Away From Show of Diplomacy in Geneva, Putin Puts on a Show of His Own". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Luhn, Alec; Roberts, Dan (23 August 2014). "Ukraine condemns 'direct invasion' as Russian aid convoy crosses border". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Dolgov, Anna (21 November 2014). "Russia's Igor Strelkov: I Am Responsible for War in Eastern Ukraine". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ a b Kofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF) (Report). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. p. 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Nemtsova, Anna (25 July 2014). "Putin's Number One Gunman in Ukraine Warns Him of Possible Defeat". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2018). The road to unfreedom : Russia, Europe, America (1st ed.). New York: Tim Duggan Books. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-525-57446-0. OCLC 1029484935.

- ^ "Captured Russian troops 'in Ukraine by accident'". BBC News. 26 August 2014. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (26 August 2014). "Russia admits its soldiers have been caught in Ukraine". The Guardian. Kyiv. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Freedman, Lawrence (2 November 2014). "Ukraine and the Art of Limited War". Survival. 56 (6): 35. doi:10.1080/00396338.2014.985432. ISSN 0039-6338. S2CID 154981360.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (20 April 2016). "The Donbas in 2014: Explaining Civil Conflict Perhaps, but not Civil War". Europe-Asia Studies. 68 (4): 649. doi:10.1080/09668136.2016.1176994. ISSN 0966-8136. S2CID 148334453.

- ^ "Herashchenko kazhe, shcho Rosiya napala na Ukrayinu shche 24 serpnya" Геращенко каже, що Росія напала на Україну ще 24 серпня [Gerashchenko says that Russia attacked Ukraine on August 24]. Ukrinform (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "V Amvrosiyevku voshli rossiyskiye voyska bez znakov otlichiya" В Амвросиевку вошли российские войска без знаков отличия [Russian troops entered Amvrosievka without insignia]. Liga Novosti (in Russian). 24 August 2014. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Poroshenko: ATO Is Ukraine's Patriotic War". Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

President Petro Poroshenko considers the government's anti-terrorist operation (ATO) against separatists as Ukraine's patriotic war.

- ^ Gearin, Mary (24 August 2014). "Ukrainian POWs marched at bayonet-point through city". ABC (Australia). Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Heintz, Jim (25 August 2014). "Ukraine: Russian Tank Column Enters Southeast". ABC News. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: 'Column from Russia' crosses border". BBC News. 25 August 2014. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Nelson, Soraya Sarhaddi (26 August 2014). "Russian Separatists Open New Front in Southern Ukraine". National Public Radio (NPR). Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew. "Ukraine Says Russian Forces Lead Major New Offensive in East". CNBC. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014.

Tanks, artillery and infantry have crossed from Russia into an unbreached part of eastern Ukraine in recent days, attacking Ukrainian forces and causing panic and wholesale retreat not only in this small border town but a wide swath of territory, in what Ukrainian and Western military officials are calling a stealth invasion.

- ^ Tsevtkova, Maria (26 August 2014). "'Men in green' raise suspicions of east Ukrainian villagers". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

Unidentified, heavily-armed strangers with Russian accents have appeared in an eastern Ukrainian village, arousing residents' suspicions despite Moscow's denials that its troops have deliberately infiltrated the frontier.

- ^ Lowe, Christian; Tsvetkova, Maria (26 August 2014). "In Ukraine, an armoured column appears out of nowhere". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Gowen, Annie; Gearan, Anne (28 August 2014). "Russian armored columns said to capture key Ukrainian towns". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ a b "NATO: 1000 rosyjskich żołnierzy działa na Ukrainie. A Rosja znów: Nie przekraczaliśmy granicy [NA ŻYWO]". gazeta.pl (in Polish). 28 August 2014. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "BBC:Ukraine crisis: 'Thousands of Russians' fighting in east, August 28". BBC News. 28 August 2014. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "U.S. says Russia has 'outright lied' about Ukraine". USA Today. 28 August 2014. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Syly ATO aktyvno nastupayutʹ. Terorysty-naymantsi nesutʹ chymali vtraty" Сили АТО активно наступають. Терористи-найманці несуть чималі втрати [ATO forces are actively advancing. Mercenary terrorists suffer heavy losses]. Міністерство оборони України (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Sanderson, Bill (21 September 2014). "Leaked transcripts reveal Putin's secret Ukraine attack – New York Post". The New York Post. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ a b Morgan, Martin (5 September 2014). "Russia 'will react' to EU sanctions". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ Alfred, Charlotte (6 September 2014). "Russian Journalist: 'Convincing Evidence' Moscow Sent Fighters To Ukraine". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ Warketin, Alexander (29 August 2014). "Disowned and forgotten: Russian soldiers in Ukraine". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ "Russian TV shows funeral of soldier killed 'on leave' in Ukraine". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 5 September 2014. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ В Кремле и Киеве разъяснили заявление о прекращении огня в Донбассе (in Russian). Interfax. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Putin hopes for peace deal by Friday". BBC News. 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Kremlin denies that Poroshenko and Putin agreed on ceasefire". Kyiv Post. 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil (3 September 2014). "Putin Lays Out Proposal to End Ukraine Conflict". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Walker, Shaun; Luhn, Alec; Willsher, Kim (3 September 2014). "Vladimir Putin drafts peace plan for eastern Ukraine". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Russian ambassador anticipates 'liberation' of Mariupol in Ukraine". CNN. 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Croft, Adrian (4 September 2014). Faulconbridge, Guy (ed.). "Russia has 'several thousand' combat troops in Ukraine: NATO officer". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "Russia Sends Dozens Of Tanks Into Ukraine". Sky News. 7 November 2014. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ "Lithuania's statement at the UN Security Council briefing on Ukraine". Permanent Mission of the Republic of Lithuania to UN in New York. 13 November 2014. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "NATO sees increase of Russian tanks and artillery in Ukraine". Ukraine Today. 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Giles, Keir (6 February 2015). "Ukraine crisis: Russia tests new weapons". BBC. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ "Ukraine — Security Council, 7311th meeting" (PDF). United Nations. 12 November 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ "Pro-Russian rebels officially labelled terrorists by Ukraine government". CBC News. 27 January 2015. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Miller, Michael Weiss (26 January 2015). "Putin Is Winning the Ukraine War on Three Fronts". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Lacqua, Francine (21 January 2015). "Ukraine Talks Start as Poroshenko Warns of an Escalation". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Leaders agree peace roadmap". BBC News. 12 February 2015. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "UN News – Close to 8,000 people killed in eastern Ukraine, says UN human rights report". UN News Service Section. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "Go Inside the Frozen Trenches of Eastern Ukraine". Time. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Brown, Daniel. "Here's what it's like inside the bunkers Ukrainian troops are living in every day". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Tsvetkova, Maria (21 July 2015). "Ceasefire brings limited respite for east Ukrainians". Euronews. Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ Kofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF) (Report). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. pp. 52–54. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Whitmore, Brian (26 July 2016). "The Daily Vertical: Ukraine's Forgotten War (Transcript)". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ Місяць тиші на Донбасі. Що відбувається на фронті [The longest truce in Donbas. Does it really exist]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 7 September 2020. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ Bender, Jeremy (11 February 2015). "US Army commander for Europe: Russian troops are currently fighting on Ukraine's front lines". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Preserving Ukraine's Independence, Resisting Russian Aggression: What the United States and NATO Must Do" (PDF). Chicago Council on Global Affairs. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ Peter, Laurence (6 February 2015). "Ukraine 'can't stop Russian armour'". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ 커트 볼커: 2022년 2월 24일 폴리티코 웨이백 머신에 보관된 전체 녹취록(2017년 11월 27일)

- ^ "Kyiv says there are about 6,000 Russian soldiers, 40,000 separatists in Donbas". Kyiv Post. 11 September 2017. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ Miller, Christopher (30 January 2017). "Anxious Ukraine Risks Escalation In 'Creeping Offensive'". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Luhn, Alec (19 January 2015). "They were never there: Russia's silence for families of troops killed in Ukraine". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ a b Quinn, Allison (25 June 2015). "Russia trolls world by saying it can not stop its citizens from fighting in Ukraine". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ Rupert, James (5 January 2015). "How Russians Are Sent to Fight in Ukraine". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ "Head of Sverdlovsk special forces veterans union: 'I help to send volunteers to war in Ukraine'". Kyiv Post. 26 December 2014. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ Kozakov, Ilya (24 December 2014). Глава фонда свердловских ветеранов спецназа: 'Я помогаю добровольцам отправиться воевать на Украину' [Head of spetsnaz veteran fund in Sverdlovsk: 'I'm helping volunteers go to the war in Ukraine']. E1.ru. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ "Russians Used Humanitarian Convoys to Send Militants into Ukraine, Russian Organizer Says". The Interpreter Magazine. 26 December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ "Red Cross Official Says Moscow Used 'Humanitarian' Convoys to Ship Arms to Militants in Ukraine". The Interpreter Magazine. 28 December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ Theise, Eugen (24 June 2015). "OSCE caught in the crossfire of the Ukraine propaganda war". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ Беседы 'Сергея Глазьева' о Крыме и беспорядках на востоке Украины. Расшифровка — Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ Whitmore, Brian (26 August 2016). "Podcast: The Tale Of The Tape". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Uapositon (29 August 2016). "English translation of audio evidence of Putin's Adviser Glazyev and other Russian politicians involvement in war in Ukraine". Uaposition. Focus on Ukraine. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Umland, Andreas (25 November 2016). "Glazyev Tapes: What Moscow's interference in Ukraine means for the Minsk Agreements". Raam op Rusland (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ Larter, David B.; Bodner, Matthew (28 November 2018). "The Sea of Azov won't become the new South China Sea (and Russia knows it)". Defense News. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Russia-Ukraine sea clash in 300 words". BBC News. 30 November 2018. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "The Kerch Strait incident". International Institute for Strategic Studies. December 2018. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Kiev declares martial law after Russian seizure of Ukrainian ships in Black Sea". The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Two Ukrainian Soldiers Killed Over Bloody Weekend In Donbas". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 3 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Betz, Bradford (29 December 2019). "Ukraine, pro-Russian separatists swap prisoners in step to end 5-year war". Fox News. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "Ukraine and pro-Russian separatists exchange prisoners". BBC News. 29 December 2019. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "France's Macron, Germany's Merkel welcome prisoner swap in Ukraine". Reuters. 29 December 2019. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ Ukraine government and separatists begin prisoners swap. Al Jazeera English. 29 December 2019. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Ukraine conflict: Moscow could 'defend' Russia-backed rebels". BBC News. 9 April 2021. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "Kremlin defends Russian military buildup on Ukraine border". The Guardian. 9 April 2021. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ "Zelenskiy: Russian passports in Donbass are a step towards 'annexation'". Reuters. 20 May 2021. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Schogol, Jeff (22 February 2022). "Here's what those mysterious white 'Z' markings on Russian military equipment may mean". Task & Purpose. North Equity. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

[B]ottom line is the 'Z' markings (and others like it) are a deconfliction measure to help prevent fratricide, or friendly fire incidents.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (24 February 2022). "Russia's attack on Ukraine came after months of denials it would attack". The Washington Post. Photograph by Evgeniy Maloletka (Associated Press). Nash Holdings. ISSN 0190-8286. OCLC 2269358. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

On Sunday ... 'There is no invasion. There is no such plans,' Antonov said.

- ^ "Putin attacked Ukraine after insisting for months there was no plan to do so. Now he says there's no plan to take over". CBS News. Kharkiv: CBS (published 22 February 2022). 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Harris, Shane; Sonne, Paul (3 December 2021). "Russia planning massive military offensive against Ukraine involving 175,000 troops, U.S. intelligence warns". The Washington Post. Nash Holdings. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

[U].S. intelligence has found the Kremlin is planning a multi-frontal offensive as soon as early next year involving up to 175,000 troops ... .