조현병

Schizophrenia| 조현병 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 조현병 진단을 받은 사람이 수놓은 천 | |

| 발음 | |

| 전문 | 정신과 |

| 증상 | 환각(보통 목소리를 듣는다), 망상, 사회적 고립, 감정이 무뎌지고 혼란스러운 사고[2][3] |

| 합병증 | 자살, 심장병, 생활습관병[4] |

| 통상적인 발병 | 16세~30세[3] |

| 지속 | 만성적인[3] |

| 원인들 | 환경 및 유전적 요인[5] |

| 위험요소 | 가족력, 청소년기의 대마초 사용, 임신 중의 문제, 어린 시절의 역경, 늦겨울이나 이른 봄에 태어난 것, 나이 많은 아버지, 도시에서[5][6] 태어나거나 자란 것 |

| 진단방법 | 관찰된 행동, 보고된 경험, 당사자와[7] 친숙한 타인의 보고에 근거합니다. |

| 감별진단 | 물질사용장애, 헌팅턴병, 기분장애(양극성장애, 주요우울장애), 자폐,[8] 경계선성격장애,[9] 조현병장애, 조현병성격장애, 조현병성격장애, 반사회성격장애, 정신병적 우울, 불안, 파괴적 기분조절장애 |

| 관리 | 상담, 생활기술교육[2][5] |

| 약 | 항정신병약[5] |

| 예후 | 기대수명[10][11] 20~28년 단축 |

| 빈도수. | 전 세계 인구의 ~0.32%(300명 중 1명)가 영향을 받습니다.[12] |

| 데스 | ~17,000 (2015)[13] |

조현병은 정신병의 지속적이거나 반복적인 증상을 특징으로 하는 정신 질환입니다[14].[5]주요 증상으로는 환각(일반적으로 목소리가 들림), 망상, 체계적이지 못한 사고 등이 있습니다.[7]다른 증상으로는 사회적 금단현상, 납작한 영향 등이 있습니다.[5]증상은 일반적으로 점진적으로 발전하고, 젊은 성인기에 시작되며, 많은 경우 해결됩니다.[3][7]객관적인 진단 테스트는 없습니다; 진단은 관찰된 행동, 보고된 경험을 포함하는 정신 의학적 이력, 그리고 그 사람에게 익숙한 다른 사람들의 보고에 근거합니다.[7]조현병 진단을 위해서는 최소 6개월 이상(DSM-5에 따라) 또는 1개월 이상(ICD-11에 따라) 설명된 증상이 있어야 합니다.[7][15]조현병을 앓고 있는 많은 사람들은 다른 정신 질환, 특히 물질 사용 장애, 우울증, 불안 장애, 강박 장애 등을 가지고 있습니다.[7]

약 0.3%에서 0.7%의 사람들이 일생 동안 조현병 진단을 받습니다.[16]2017년에는 약 110만 건, 2022년에는 전 세계적으로 총 2400만 건의 신규 사례가 발생했습니다.[2][17]수컷이 암컷보다 더 자주 영향을 받고 평균적으로 더 일찍 발병합니다.[2]조현병의 원인에는 유전적 요인과 환경적 요인이 포함될 수 있습니다.[5]유전적 요인은 흔하고 드문 다양한 유전적 변이를 포함합니다.[18]가능한 환경적 요인으로는 도시에서의 양육, 어린 시절의 역경, 청소년기의 대마초 사용, 감염, 어머니나 아버지의 나이, 임신 중 영양 부족 등이 있습니다.[5][19]

조현병 진단을 받은 사람의 절반 정도는 장기적으로 상당한 호전을 보이고 더 이상의 재발은 없을 것이며, 이 중 적은 비율은 완전히 회복될 것입니다.[7][20]나머지 절반은 평생 장애를 갖게 됩니다.[21]심한 경우에는 병원에 입원할 수도 있습니다.[20]장기 실업, 빈곤, 노숙, 착취, 피해와 같은 사회적 문제는 일반적으로 조현병과 관련이 있습니다.[22][23]조현병 환자는 일반인과 비교해 자살률이 높고(전체 약 5%) 신체 건강 문제가 [24][25]많아 평균 수명이 20[10]~28세 감소하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[11]2015년에는 약 17,000명의 사망자가 조현병과 관련이 있습니다.[13]

치료의 주축은 상담, 직업훈련, 사회복귀와 함께 항정신병 약물치료입니다.[5]최대 3분의 1의 사람들이 초기 항정신병 약물에 반응하지 않으며, 이 경우 클로자핀이 사용될 수 있습니다.[26]15개의 항정신병 약물에 대한 네트워크 비교 메타분석에서 클로자핀은 다른 모든 약물보다 상당히 효과적이었지만 클로자핀의 다중모드 작용이 더 많은 부작용을 일으킬 수 있습니다.[27]의사가 자기나 타인에게 위해를 끼칠 우려가 있다고 판단되는 상황에서는 단기 비자발적 입원을 할 수 있습니다.[28]장기 입원은 심각한 정신분열증을 가진 소수의 사람들에게 사용됩니다.[29]지원 서비스가 제한적이거나 이용할 수 없는 일부 국가에서는 장기 입원이 더 일반적입니다.[30]

징후 및 증상

정신분열증은 인식, 생각, 기분, 행동에 있어서 상당한 변화를 특징으로 하는 정신 질환입니다.[31]증상은 긍정적, 부정적, 인지적 증상으로 설명됩니다.[3][32]조현병의 긍정적인 증상은 어떤 정신병에 대해서도 동일하며 때로는 정신병적인 증상이라고도 합니다.이것들은 다양한 정신 상태에 존재할 수 있고 종종 일시적이어서 조현병의 초기 진단에 문제가 있습니다.나중에 조현병 진단을 받은 사람에게서 처음으로 언급된 정신병을 FEP(First-Episode Psychosis)라고 합니다.[33][34]

양성증상

긍정적인 증상은 평소에는 경험하지 못했지만 조현병에서 정신병적인 증상이 나타나는 동안 사람들에게 나타나는 증상입니다.그것들은 망상, 환각, 그리고 일반적으로 정신병의 징후로 여겨지는 흐트러진 생각과 말을 포함합니다.[33]환각은 조현병[35] 환자의 80%의 일생 중 어느 시점에서 발생하며, 가장 흔히 청각(가장 자주 듣는 목소리)을 수반하지만, 때로는 다른 감각, 시각, 후각, 촉각을 수반할 수 있습니다.[36]여러 감각을 포함하는 환각의 빈도는 한 감각만을 포함하는 환각의 두 배입니다.[35]그것들은 또한 전형적으로 망상 주제의 내용과 관련이 있습니다.[37]망상은 본질적으로 기이하거나 박해적입니다.다른 사람처럼 느끼는 것과 같은 자기 경험의 왜곡은 또한 사람의 마음 속에 생각이 삽입되고 있다고 믿는 것과 같은 것, 때로는 수동성 현상이라고 불리는 것도 일반적입니다.[38]사고 장애는 사고를 막는 것과 체계적이지 못한 말을 포함할 수 있습니다.[3]긍정적인 증상은 일반적으로 약물에[5] 잘 반응하고 질병의 경과에 따라 감소하는데, 아마도 도파민 활동의 나이와 관련된 감소와 관련이 있을 것입니다.[7]

부정적인 경우

부정적인 증상은 정상적인 감정 반응이나 다른 사고 과정의 결핍입니다.부정적인 증상의 다섯 가지 영역은 무딘 효과 – 납작한 표정을 보이거나 감정이 거의 없는 것; 알로지아 – 말의 빈곤; 무장애 – 즐거움을 느끼지 못하는 것; 사회성 – 관계를 형성하려는 욕구의 부족, 그리고 혐오 – 동기와 무관심의 부족입니다.[39][40]폐기와 무장애는 보상 처리의 장애로 인한 동기적 결함으로 여겨집니다.[41][42]보상은 동기부여의 주요 동인이며 이것은 대부분 도파민에 의해 매개됩니다.[42]부정적인 증상은 다차원적이며, 무관심 또는 동기 부족, 표현 감소의 두 가지 하위 영역으로 분류되었습니다.[39][43]무관심은 혐오, 무장애, 그리고 사회적 금단현상을 포함합니다; 감소된 표현은 무뚝뚝한 감정과 고독감을 포함합니다.[44]때때로 감소된 표현은 언어적인 것과 비언어적인 것으로 취급됩니다.[45]

무관심은 가장 자주 발견되는 부정적인 증상의 약 50%를 차지하며 기능적인 결과와 그에 따른 삶의 질에 영향을 미칩니다.무관심은 목표 지향적 행동을 포함한 기억과 계획에 영향을 미치는 방해 받는 인지 처리와 관련이 있습니다.[46]두 하위 영역은 별도의 치료 방법이 필요함을 시사했습니다.[47]우울증과 불안감이 줄어든 것과 관련된 고통의 결핍은 또 다른 주목할 만한 부정적인 증상입니다.[48]조현병에 내재된 부정적인 증상을 일차적 증상이라고 하며, 항정신병, 약물 사용 장애, 사회적 박탈 등의 부작용을 이차적인 부정적인 증상이라고 하며, 이는 종종 구별됩니다.[49]부정적인 증상은 약물에 대한 반응이 적고 치료가 가장 어렵습니다.[47]그러나 제대로 평가하면 이차적인 부정적인 증상은 치료가 가능합니다.[43]

부정적인 증상의 존재를 구체적으로 평가하고 증상의 심각도를 측정하기 위한 척도, 그리고 그 변화는 모든 유형의 증상을 다루는 PANNS와 같은 이전 척도부터 도입되었습니다.[47]이러한 척도는 CAINS(Crystal Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms)와 BNSS(Brief Negative Symptoms Scale)를 2세대 척도라고도 합니다.[47][48][50]도입 10년 후인 2020년, BNSS의 사용에 대한 문화 간 연구에서 5개 도메인 구조에 대한 유효하고 신뢰할 수 있는 심리측정학적 증거를 발견했습니다.BNSS는 5개의 인식된 영역의 음성 증상의 유무와 심각도 및 감소된 정상 고통의 추가 항목을 모두 평가할 수 있습니다.심리사회적, 약리학적 개입의 실험에서 부정적인 증상의 변화를 측정하는 데 사용되어 왔습니다.[48]

인지증상

조현병 환자의 약 70%가 인지 결손을 가지고 있는 것으로 추정되며, 이는 초기 발병과 말기 발병에서 가장 두드러집니다.[51][52]이러한 증상은 종종 병이 발병하기 훨씬 전에 발생하며, 소아기나 초기 청소년기에 나타날 수 있습니다.[53][54]그것들은 핵심적인 특징이지만 긍정적인 증상과 부정적인 증상과 마찬가지로 핵심적인 증상으로 간주되지 않습니다.[55][56]그러나, 그들의 존재와 기능 장애의 정도는 핵심 증상의 제시보다 더 나은 기능 지표로 간주됩니다.[53]인지 결손은 첫 회 정신병에서 악화되다가 다시 기저로 돌아오고, 병이 진행되는 동안에도 상당히 안정적으로 유지됩니다.[57][58]

인지력의 결핍은 조현병에서 부정적인 심리사회적 결과를 초래하는 것으로 보이며, 아이큐가 100에서 70–85로 감소할 수 있는 것과 동일하다고 주장됩니다.[59][60]인지 결손은 신경 인지(비사회적) 또는 사회적 인지의 것일 수 있습니다.[51]신경인지(neurocognition)는 정보를 받고 기억하는 능력으로 언어적 유창성, 기억력, 추론력, 문제 해결력, 처리 속도, 청각 및 시각적 인식을 포함합니다.[58]언어적 기억력과 주의력이 가장 큰 영향을 받는 것으로 나타났습니다.[60][61]언어적 기억 장애는 의미 처리(단어와 관련된 의미)의 감소된 수준과 관련이 있습니다.[62]기억력의 또 다른 장애는 기억력의 장애는 기억력 장애입니다.[63]조현병에서 지속적으로 발견되는 시각적 인식의 장애는 시각적 후방 마스킹입니다.[58]시각적 처리 장애는 복잡한 시각적 환상을 인지하지 못하는 것을 포함합니다.[64]사회적 인식은 사회 세계에서 자기와 다른 사람들을 이해하고 해석하는 데 필요한 정신적인 작용과 관련이 있습니다.[58][51]이는 또한 동반된 장애이며, 종종 얼굴 감정 인식이 어렵다는 것을 발견합니다.[65][66]얼굴 인식은 일반적인 사회적 상호작용에 매우 중요합니다.[67]인지 장애는 일반적으로 항정신병약에 반응하지 않으며, 이를 개선하기 위해 사용되는 다양한 개입이 있습니다. 인지 치료 요법은 특히 도움이 됩니다.[56]

정신분열증에서 종종 발견되는 신경학적인 부드러운 증상과 미세 운동의 상실은 FEP의 효과적인 치료로 해결될 수 있습니다.[15][68]

시작

발병은 일반적으로 10대 후반에서 30대 초반 사이에 발생하며, 20대 초중반에는 남성에서, 20대 후반에는 여성에서 가장 많이 발생합니다.[3][7][15]17세 이전의 발병은 조기발병으로 알려져 [69]있으며, 13세 이전의 발병은 때때로 발생할 수 있는 것처럼 소아 정신분열증 또는 매우 조기발병으로 알려져 있습니다.[7][70]40세에서 60세 사이에 발병할 수 있으며, 후기발병 조현병으로 알려져 있습니다.[51]조현병으로 구분하기 어려울 수 있는 60세 이상의 발병은 매우 늦은 발병형 조현병 유사 정신병으로 알려져 있습니다.[51]늦게 발병한 여성들은 영향을 받는 비율이 더 높다는 것을 보여주었습니다; 그들은 덜 심각한 증상을 가지고 있고 더 적은 양의 항정신병약을 필요로 합니다.[51]남성의 조기 발병 경향은 나중에 여성의 폐경 후 발달의 증가에 의해 균형을 이루는 것으로 보입니다.폐경 전에 생성된 에스트로겐은 도파민 수용체를 감쇠시키는 효과가 있지만 유전자 과부하로 인해 보호 기능이 무시될 수 있습니다.[71]조현병을 앓고 있는 노인들의 수가 극적으로 증가했습니다.[72]

발병은 갑자기 일어날 수도 있고 여러 징후와 증상이 천천히 그리고 점진적으로 발달한 후에 일어날 수도 있습니다.[7]정신분열증을 가진 사람들의 최대 75%가 전단계를 거칩니다.[73]프로드롬 단계의 음성 및 인지 증상은 FEP(첫 번째 에피소드 정신병)보다 수개월, 최대 5년까지 선행할 수 있습니다.[57][74]FEP와 치료로부터의 기간은 기능적 결과의 요인으로 간주되는 치료되지 않은 정신병(DUP)의 기간으로 알려져 있습니다.전단계는 정신병 발병의 고위험군 단계입니다.[58]첫 회 정신병으로의 진행이 불가피하지 않기 때문에, 위험한 정신 상태에 있는 대체 용어가 종종 선호됩니다.[58]어린 나이의 인지 기능 장애는 젊은 사람의 일상적인 인지 발달에 영향을 미칩니다.[75]발육 단계에서의 인식과 조기 개입은 교육 및 사회 발전에 대한 관련 장애를 최소화할 것이며 많은 연구의 초점이 되어 왔습니다.[57][74]

위험요소

조현병은 정확한 경계나 단일 원인이 없는 신경 발달 장애로 설명되며, 취약성 요인과 관련된 유전자-환경 상호작용으로 인해 발생하는 것으로 생각됩니다.[5][76][77]임신부터 성인에 이르기까지 다양하고 다양한 모욕이 수반될 수 있기 때문에 이러한 위험 요소들의 상호 작용은 복잡합니다.[77]환경적 요인들이 상호작용하지 않는 유전적 성향은 정신분열증을 발생시키지 않을 것입니다.[77][78]유전적인 요소는 태교 전 뇌 발달이 방해받고, 환경적인 영향이 산후 뇌 발달에 영향을 준다는 것을 의미합니다.[79]유전적으로 민감한 어린이들이 환경적 위험 요소의 영향에 더 취약하다는 증거가 있습니다.[79]

유전의

조현병의 유전성 추정치는 70%에서 80% 사이이며, 이는 조현병 위험의 개인차의 70%에서 80%가 유전과 관련이 있음을 의미합니다.[18][80]이러한 추정치는 유전적인 영향과 환경적인 영향을 분리하는 것이 어렵기 때문에 다양하며, 그 정확성에 의문이 제기되었습니다.[81][82]조현병 발병의 가장 큰 위험 요인은 질병과 1급 관계를 갖는 것입니다. (위험도는 6.5%입니다.) 조현병 환자의 일란성 쌍둥이의 40% 이상도 영향을 받습니다.[83]한 부모가 영향을 받는 경우 위험은 약 13%이고 두 부모가 모두 영향을 받는 경우 위험은 거의 50%[80]입니다.그러나 DSM-5는 조현병을 앓고 있는 대부분의 사람들이 정신병의 가족력이 없다는 것을 나타냅니다.[7]조현병의 후보 유전자 연구의 결과는 일반적으로 일관된 연관성을 찾지 못했고,[84] 유전체 전반의 연관성 연구에 의해 확인된 유전적 위치는 질병의 변화의 작은 부분만을 설명합니다.[85]

많은 유전자들이 작은 효과와 알려지지 않은 전염과 발현을 가진 조현병에 관련된 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[18][86][87]이러한 효과 크기를 다유성 위험 점수로 합하면 조현병에 대한 책임의 최소 7%를 설명할 수 있습니다.[88]조현병 환자의 약 5%는 희귀 복사 수 변이(CNV)에 적어도 부분적으로 기인하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 이러한 구조적 변이는 22q11.2(디조지 증후군) 및 17q12(17q12 마이크로삭제 증후군)의 삭제, 16p11.2(가장 자주 발견됨) 및 del을 포함하는 알려진 게놈 장애와 관련이 있습니다.15q11.2 (번사이드-버틀러 증후군)[89]에서 에션스.이러한 CNV 중 일부는 조현병 발생 위험을 20배까지 증가시키며, 자폐증과 지적 장애를 동반하는 경우가 많습니다.[89]

CRHR1과 CRHBP 유전자는 자살 행동의 심각성과 관련이 있습니다.이 유전자들은 HPA 축의 조절에 필요한 스트레스 반응 단백질을 코드화하고, 그들의 상호작용은 이 축에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.스트레스에 대한 반응은 부정적 피드백 메커니즘, 항상성, 그리고 변화된 행동으로 이어지는 감정의 조절을 방해할 가능성이 있는 HPA 축의 기능에 지속적인 변화를 일으킬 수 있습니다.[78]

조현병 환자들의 출산율이 낮다는 점에서 조현병이 유전적으로 어떻게 영향을 받을 수 있느냐는 문제는 역설적입니다.조현병의 위험을 높이는 유전자 변이가 생식 건강에 부정적인 영향을 미치기 때문에 선택될 것으로 예상됩니다.조현병 위험과 관련된 대립유전자가 영향을 받지 않은 사람들에게 건강상의 이점을 준다는 것을 포함한 많은 가능성 있는 설명들이 제안되었습니다.[90][91]일부 증거는 이 아이디어를 지지하지 않지만,[82] 다른 증거는 각각 적은 양을 기여하는 다수의 대립유전자가 지속될 수 있다고 제안합니다.[92]

메타분석 결과 조현병에서 산화적 DNA 손상이 크게 증가한 것으로 나타났습니다.[93]

환경의

환경적인 요인들은 각각 나중에 조현병을 일으킬 수 있는 약간의 위험과 관련이 있으며, 산소 결핍, 감염, 산전 모성 스트레스, 산전 발달 중 어머니의 영양실조 등이 있습니다.[94]위험은 모성 비만, 산화 스트레스 증가, 도파민과 세로토닌 경로의 잘못된 조절과 관련이 있습니다.[95]산모의 스트레스와 감염 모두 소염성 사이토카인의 증가를 통해 태아의 신경 발달을 변화시키는 것으로 입증되었습니다.[96]겨울이나 봄에 태어나는 것과 관련된 약간의 위험이 있는데 아마도 비타민 D 결핍이나[97] 태교 바이러스 감염 때문일 것입니다.[83]임신 중이나 출생 시 즈음에 발생하는 다른 감염들은 Toxoplasma gondii와 Clamydia에 의한 감염을 포함합니다.[98]위험성이 높아지면 약 5~8% 정도 됩니다.[99]어린 시절 뇌의 바이러스 감염은 성인기 정신분열증의 위험과도 연관이 있습니다.[100]

아동기 트라우마로 분류되는 부정적인 아동기 경험(ACE)은 괴롭힘이나 학대에서 부모의 죽음에 이르기까지 다양합니다.[101]어린 시절의 많은 불리한 경험들은 유독한 스트레스를 유발하고 정신병의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있습니다.[101][102][103]ACE를 포함한 만성 외상은 신경계 전반에 걸쳐 지속적인 염증 조절 장애를 촉진할 수 있습니다.[104]이러한 면역체계의 변화를 통해 조기 스트레스가 조현병의 발병에 기여할 수 있다는 것이 제시되고 있습니다.[104]정신분열증은 ACE와 성인 정신건강 결과 사이의 연결고리로부터 이익을 얻는 마지막 진단이었습니다.[105]

아동기나 성인기에 도시 환경에서 생활하는 것은 약물 복용, 인종, 사회적 집단의 크기 등을 고려한 [24][106]후에도 조현병 위험을 2배까지 증가시키는 것으로 지속적으로 밝혀졌습니다.[107]도시 환경과 오염 사이의 가능한 관계가 조현병의 높은 위험의 원인으로 제시되고 있습니다.[108]다른 위험요소로는 사회적 고립, 사회적 역경과 인종차별과 관련된 이민, 가족의 기능장애, 실업, 열악한 주거환경 등이 있습니다.[83][109]40세 이상의 아버지나 20세 미만의 부모를 둔 것도 정신분열증과 관련이 있습니다.[5][110]

물질사용

조현병 환자의 절반 정도가 술, 담배, 대마초 등 오락용 약물을 과도하게 사용하고 있습니다.[111][112]암페타민이나 코카인과 같은 자극제의 사용은 정신분열증과 매우 유사하게 나타나는 일시적인 자극제 정신병으로 이어질 수 있습니다.드물게, 알코올 사용은 유사한 알코올 관련 정신병을 초래할 수도 있습니다.[83][113]약물은 또한 우울증, 불안, 지루함, 외로움을 다루기 위해 조현병을 앓고 있는 사람들에 의해 대처 방법으로 사용될 수도 있습니다.[111][114]대마초와 담배의 사용은 인지 결손의 발달과 관련이 없으며, 때로는 이들의 사용이 이러한 증상을 개선시키는 역관계가 발견되기도 합니다.[56]그러나 물질 사용 장애는 자살 위험 증가와 치료에 대한 반응이 좋지 않은 것과 관련이 있습니다.[115][116]

대마초 사용은 조현병의 발병에 기여하는 요인이 될 수 있으며, 이미 위험에 처한 사람들에게 잠재적으로 질병의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있습니다.[117][118][119]증가된 위험은 개인 안에 특정한 유전자의 존재를 요구할 수도 있습니다.[19]그 사용은 비율을 두 배로 증가시키는 것과 관련이 있습니다.[120]

원인들

조현병의 원인은 밝혀지지 않았고, 변화된 뇌 기능과 조현병 사이의 연관성을 설명하기 위해 많은 모델들이 제시되었습니다.[24]조현병의 지배적인 모델은 신경발달장애의 모델이며, 증상이 뚜렷해지기 전에 일어나는 근본적인 변화는 유전자와 환경 사이의 상호작용에서 발생하는 것으로 보입니다.[121]광범위한 연구가 이 모델을 뒷받침합니다.[73]임신과 출산 중 산모의 감염, 영양실조, 합병증은 조현병 발병의 위험인자로 알려져 있으며, 보통 특정 신경 발달 단계와 겹치는 시기인 18세에서 25세 사이에 나타납니다.[122]유전자-환경 상호작용은 감각 및 인지 기능에 영향을 미치는 신경 회로의 결손으로 이어집니다.[73]

제안된 일반적인 도파민과 글루타메이트 모델은 상호 배타적인 것이 아닙니다; 각각은 조현병의 신경생물학에서 역할을 하는 것으로 보입니다.[123]가장 일반적으로 제시된 모델은 정신분열증의 도파민 가설이었는데, 정신분열증은 도파민 신경세포의 오발성에 대한 정신의 잘못된 해석 때문이라고 합니다.[124]이것은 망상과 환각 증상과 직접적인 관련이 있습니다.[125][126][127]비정상적인 도파민 신호 전달은 도파민 수용체에 영향을 미치는 약물의 유용성과 급성 정신병 동안 도파민 수치가 증가한다는 관찰에 근거하여 조현병에 연루되었습니다.[128][129]배측 전전두엽 피질에서 D1 수용체의 감소도 작업 기억력의 결손의 원인이 될 수 있습니다.[130][131]

정신분열증의 글루타메이트 가설은 시상과 피질 사이의 연결에 영향을 미치는 신경 진동과 글루타머테릭 신경 전달 사이의 변화를 연결합니다.[132]연구에 따르면 글루타메이트 수용체인 NMDA 수용체와 펜시클리딘과 케타민과 같은 글루타메이트 차단 약물의 감소된 표현은 조현병과 관련된 증상과 인지 문제를 모방할 수 있다고 합니다.[132][133][134]사후 연구는 뇌 형태 측정의 이상뿐만 아니라 [135]이러한 뉴런의 부분 집합이 GAD67(GAD1)을 발현하지 못한다는 것을 지속적으로 발견합니다.조현병에서 비정상적인 인터뉴런의 하위 집합은 작업 기억 작업 중에 필요한 신경 앙상블의 동기화를 담당합니다.이것들은 30에서 80헤르츠 사이의 주파수를 가진 감마파로 생성된 신경 진동을 제공합니다.조현병에서는 작업 기억 작업과 감마파가 모두 손상되어 비정상적인 인터네론 기능을 반영할 수 있습니다.[135][136][137][138]신경 발달에 방해가 될 수 있는 중요한 과정은 성상세포의 형성인 성상세포입니다.성상세포는 신경회로의 형성과 유지에 중요한 역할을 하며, 이러한 역할의 붕괴는 조현병을 포함한 다양한 신경 발달 장애를 초래할 수 있다고 생각됩니다.[139]더 깊은 피질 층에 있는 성상세포의 감소된 숫자가 성상세포의 글루타메이트 수송체인 EAAT2의 감소된 표현과 관련이 있다는 증거가 제시됩니다; 글루타메이트 가설을 지지합니다.[139]

정신분열증은 계획, 억제, 작업 기억력과 같은 실행 기능의 결손이 만연해 있습니다.이러한 기능들은 분리 가능하지만, 조현병에서의 그들의 역기능은 작업 기억에 목표와 관련된 정보를 표현하는 능력의 근본적인 결함을 반영하고 이것을 사용하여 인지와 행동을 지시할 수 있습니다.[140][141]이러한 장애는 많은 신경 영상학적 이상과 관련이 있습니다.예를 들어, 기능적 신경 영상 연구는 작업 기억 작업에 대한 제어에 비해 일정 수준의 성능을 달성하기 위해 배측 전전두엽 피질이 더 큰 정도로 활성화되는 신경 처리 효율 감소의 증거를 보고합니다.이러한 이상은 피라미드 세포 밀도의 증가와 수지상 척추 밀도의 감소로 입증되는 감소된 신경질의 일관된 사후 발견과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.이러한 세포 및 기능적 이상은 작업 기억 작업의 결손과 관련하여 감소된 회색 물질 부피를 발견하는 구조 신경 영상 연구에도 반영될 수 있습니다.[142]

긍정적인 증상들은 상부측두엽의 피질적 엷어지는 것과 관련이 있습니다.[143]부정적인 증상의 심각성은 전두엽 피질의 좌측 내측 궤도의 두께 감소와 관련이 있습니다.[144]전통적으로 쾌락을 경험하는 능력의 감소로 정의되는 무헤도니아는 조현병에서 자주 보고됩니다.그러나 많은 증거들은 정신분열증에서 쾌락적 반응이 온전하며,[145] 무장애라고 보고된 것은 보상과 관련된 다른 과정에서의 기능장애의 반영이라고 시사합니다.[146]전반적으로, 보상 예측의 실패는 정상적인 쾌락적 반응에도 불구하고 보상을 얻기 위해 필요한 인지와 행동의 생성에 장애를 초래할 것으로 생각됩니다.[147]

또 다른 이론은 비정상적인 뇌의 측면화를 정신분열증을 가진 사람들에게 훨씬 더 흔한 왼손잡이의 발달과 연결시킵니다.[148]이러한 반구 비대칭의 비정상적인 발달은 조현병에서 두드러집니다.[149]연구들은 그 연관성이 측면화와 조현병 사이의 유전적 연관성을 반영할 수 있는 진실하고 입증 가능한 효과라고 결론 내렸습니다.[148][150]

베이지안 뇌 기능 모델은 세포 기능의 이상을 증상과 연결하기 위해 사용되었습니다.[151][152]환각과 망상 모두 사전 기대의 부적절한 부호화를 반영하는 것으로 제안되어, 기대가 감각 지각과 신념 형성에 과도한 영향을 미치게 합니다.예측 코딩을 매개하는 승인된 회로 모델에서, 감소된 NMDA 수용체 활성화는 이론적으로 망상과 환각의 긍정적인 증상을 초래할 수 있습니다.[153][154][155]

진단.

기준

조현병은 미국정신의학협회가 발간하는 정신질환 진단 및 통계 매뉴얼(DSM)이나 세계보건기구(WHO)가 발간하는 국제질병통계분류(ICD)의 기준에 따라 진단됩니다.이러한 기준은 당사자가 스스로 보고한 경험과 보고된 행동의 이상을 이용한 후 정신과적 평가를 거칩니다.정신 상태 검사는 평가의 중요한 부분입니다.[156]양성 및 음성 증상의 심각도를 평가하기 위한 확립된 도구는 PANSS(Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale)입니다.[157]이는 부정적 증상과 관련된 단점이 있는 것으로 보이며, 다른 척도인 CAINS(Crystal Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms)와 BNSS(Brief Negative Symptoms Scale)가 도입되었습니다.[47]2013년에 발표된 DSM-5는 증상의 8가지 차원을 요약하는 증상 차원의 심각도 평가 척도를 제공합니다.[55]

DSM-5는 조현병 진단을 받으려면 최소 6개월 동안 사회적 또는 직업적 기능에 중대한 영향을 미치면서 한 달 동안 두 가지 진단 기준을 충족해야 한다고 밝혔습니다.그 증상들 중 하나는 망상, 환각, 혹은 체계적이지 못한 말일 필요가 있습니다.두 번째 증상은 부정적인 증상 중 하나일 수도 있고, 심하게 체계적이지 않거나 무력한 행동일 수도 있습니다.[7]조현병 진단에 필요한 6개월 전까지 조현병 진단을 달리할 수 있습니다.[7]

호주에서 진단 가이드라인은 정상적인 기능에 영향을 줄 수 있을 정도로 증상이 심한 6개월 이상입니다.[158]영국에서 진단은 대부분의 시간 동안 한 달 동안 증상을 보이는 것을 기준으로 하며, 일상 생활을 하고 공부하거나 수행하는 능력에 상당한 영향을 미치는 증상과 다른 유사한 조건은 배제됩니다.[159]

ICD 기준은 일반적으로 유럽 국가에서 사용되며, DSM 기준은 주로 미국과 캐나다에서 사용되며, 연구 연구에서 널리 사용되고 있습니다.실제로는 두 제도 간의 합의가 높은 편입니다.[160]조현병에 대한 ICD-11 기준에 대한 현재의 제안은 증상으로 자기장애를 추가할 것을 권고하고 있습니다.[38]

두 진단 시스템 간의 해결되지 않은 주요 차이점은 기능 저하 결과의 DSM 요구 사항입니다.세계보건기구 ICD는 조현병을 앓고 있는 모든 사람들이 기능적 결함을 가지고 있는 것은 아니라고 주장합니다. 따라서 이들이 진단에 구체적인 것은 아니라고 합니다.[55]

동반성

조현병을 앓고 있는 많은 사람들은 공황장애, 강박장애 또는 약물 사용 장애와 같은 하나 이상의 다른 정신 질환을 가지고 있을 수 있습니다.이것들은 치료가 필요한 별개의 질환들입니다.[7]정신분열증, 물질사용장애, 반사회적 인격장애는 모두 폭력의 위험을 증가시킵니다.[161]동반성 물질 사용 장애는 자살의 위험을 증가시키기도 합니다.[115]

수면장애는 종종 조현병과 함께 발생하며, 재발의 초기 징후일 수 있습니다.[162]수면장애는 흐트러진 사고와 같은 긍정적인 증상과 연관되어 있으며, 피질 가소성과 인지에 악영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[162]수면장애에서는 기억의 통합이 방해를 받습니다.[163]그것들은 질병의 심각성, 좋지 않은 예후, 그리고 낮은 삶의 질과 관련이 있습니다.[164][165]수면 시작과 유지 불면증은 치료를 받았는지 안 받았는지에 관계없이 일반적인 증상입니다.[164]유전적 변이는 생체 리듬, 도파민 및 히스타민 대사, 신호 전달과 관련된 이러한 조건과 관련이 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[166]

조현병은 또한 제2형 당뇨병, 자가면역질환, 심혈관질환을 포함한 많은 신체적 동반질환과 관련이 있습니다.이들과 조현병의 연관성은 부분적으로 약물(예: 항정신병약제로 인한 이상지질혈증), 환경적 요인(예: 흡연율 증가로 인한 합병증), 또는 질병 자체와 관련이 있을 수 있습니다(예: 조현병).제2형 당뇨병과 일부 심혈관 질환은 유전적으로 연관되어 있다고 생각됩니다.이러한 신체적 동반질환은 장애를 가진 사람들의 기대수명 감소에 기여합니다.[167]

감별진단

정신분열증 진단을 하기 위해서는 정신분열증의 다른 가능한 원인들이 배제되어야 합니다.[168]: 858 한 달 미만 지속되는 정신병적 증상은 짧은 정신병적 장애 또는 조현병적 장애로 진단될 수 있습니다.정신병은 DSM-5 범주로 기타 특정 조현병 스펙트럼 및 기타 정신병적 장애에 표시됩니다.정신분열증은 정신병적 증상과 함께 기분장애의 증상이 실질적으로 나타나는 경우 진단됩니다.일반적인 의학적 상태나 물질로 인해 발생하는 정신병을 이차 정신병이라고 합니다.[7]

정신병적 증상은 조울증,[8] 경계선 인격 장애,[9] 약물 중독, 약물 유발 정신병, 그리고 다수의 약물 금단 증후군을 포함한 여러 가지 다른 증상에서 나타날 수 있습니다.망상장애에서는 비기묘한 망상이, 사회불안장애에서는 사회적 위축, 회피적 성격장애, 정신분열성 인격장애 등도 있습니다.조현병 인격장애는 조현병과 비슷하면서도 심하지 않은 증상을 갖고 있습니다.[7]조현병은 강박장애(OCD)와 함께 우연히 설명될 수 있는 것보다 훨씬 더 자주 발생하지만, 강박장애(OCD)에서 발생하는 강박장애와 조현병 망상을 구분하기는 어려울 수 있습니다.[169]외상 후 스트레스 장애의 증상과 상당한 중복이 있을 수 있습니다.[170]

대사 장애, 전신 감염, 매독, HIV 관련 신경 인지 장애, 간질, 변연계성 뇌염, 뇌병변과 같은 정신병적 조현병 유사 증상을 거의 일으키지 않을 수 있는 의학적 질병을 배제하기 위해 더 일반적인 의학 및 신경학적 검사가 필요할 수 있습니다.뇌졸중, 다발성 경화증, 갑상샘기능항진증, 갑상샘기능저하증, 알츠하이머병, 헌팅턴병, 전측두엽성 치매, 루이체성 치매 등의 치매도 조현병과 유사한 정신병적 증상과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.[171]정신착란은 시각적 환각, 급성 발병 및 의식의 변동 수준으로 구별될 수 있으며 근본적인 의학적 질환을 나타내는 것을 배제할 필요가 있을 수 있습니다.특별한 의학적 적응증이 있거나 항정신병 약물로 인한 부작용이 있을 수 있는 경우가 아니라면 재발을 위해 일반적으로 조사를 반복하지 않습니다.[172]아이들에게서 환각은 전형적인 어린 시절의 환상과 분리되어야 합니다.[7]소아 정신분열증과 자폐증을 구분하는 것은 어렵습니다.[70]

예방

조현병은 나중에 발병할 수 있는 확실한 지표가 없어 예방이 어렵습니다.[173]2011년 현재 조현병의 전구병기에서 환자를 치료하는 것이 이익이 되는지 여부는 불분명합니다.[needs update][174]: 43 정신병 초기 개입 프로그램의 시행 증가와 근본적인 경험적 증거 사이에는 차이가 있습니다.[174]: 44

2009년 현재 1기 정신병 환자에 대한 조기 개입이 단기적인 결과를 향상시킬 수 있다는 증거가 일부 있지만, 5년 후에는 이러한 조치로 인한 혜택이 거의 없습니다.[needs update][24]인지행동치료는 1년[175] 후 고위험군의 정신병 위험을 줄일 수 있으며 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)에 의해 이 그룹에서 권장됩니다.[31]다른 예방책은 대마초, 코카인, 그리고 암페타민을 포함하여, 그 병의 발생과 관련된 약들을 피하는 것입니다.[83]

제1화 정신병 후 항정신병약이 처방되고, 관해 후 재발을 피하기 위해 예방적 유지 사용이 계속됩니다.그러나 일부 사람들은 한 번의 에피소드 후에 회복하고 항정신병약의 장기적인 사용이 필요하지 않을 것으로 인식되지만 이 그룹을 식별할 수 있는 방법은 없습니다.[176]

관리

조현병의 주된 치료법은 종종 심리사회적 개입과 사회적 지원과 함께 항정신병 약물의 사용입니다.[24][177]드롭인 센터를 포함한 지역사회 지원 서비스, 지역사회 정신건강팀 구성원의 방문, 취업 지원,[178] 지원 단체 등이 일반적입니다.정신병적 증상의 시작부터 치료를 받기까지의 시간 – 치료받지 않은 정신병(DUP)의 기간 – 은 단기적으로나 장기적으로 결과가 좋지 않은 것과 관련이 있습니다.[179]

자발적이거나 비자발적으로 병원에 입원하는 것은 환자가 심각한 증상을 겪고 있다고 생각하는 의사와 법원에 의해 부과될 수 있습니다.영국에서는 1950년대 항정신병약의 등장과 함께 정신병원이라고 불리는 대형 정신병원들이 문을 닫기 시작했고, 장기 입원이 회복에 미치는 부정적인 영향을 인식했습니다.[22]이러한 과정을 탈제도화라고 하며, 이러한 변화를 뒷받침하기 위해 지역사회 및 지원 서비스가 개발되었습니다.다른 많은 나라들도 60년대부터 미국을 따라갔습니다.[180]아직도 퇴원할 만큼 나아지지 않은 소규모 집단이 남아 있습니다.[22][29]필요한 지원과 사회적 서비스가 부족한 일부 국가에서는 장기 입원이 더 일반적입니다.[30]

약

정신분열증의 첫번째 치료법은 항정신병약입니다.현재 전형적인 항정신병이라고 불리는 1세대 항정신병약은 D2 수용체를 차단하는 도파민 길항제로 도파민의 신경전달에 영향을 미칩니다.나중에 가져온 것들, 비정형 항정신병 약물로 알려진 2세대 항정신병 약물은 또 다른 신경 전달 물질인 세로토닌에도 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.항정신병약은 사용 후 몇 시간 안에 불안 증상을 줄일 수 있지만, 다른 증상의 경우에는 효과가 완전히 나타나기까지 며칠 또는 몇 주가 걸릴 수 있습니다.[33][181]그들은 부정적이고 인지적인 증상에 거의 영향을 미치지 않는데, 이것은 추가적인 심리 치료와 약물에 의해 도움을 받을 수 있습니다.[182]사람마다 반응과 내성이 다르기 때문에 모두에게 1차 치료에 적합한 항정신병약은 없습니다.[183]약물치료를 중단하는 것은 12개월 동안 증상이 없는 완전한 회복을 한 번의 정신병적 증상 후에 고려될 수 있습니다.반복적인 재발은 장기적인 전망을 악화시키고 2회 이후 재발할 위험이 크며, 대개 장기적인 치료가 권장됩니다.[184][185]

조현병 환자의 절반 정도는 항정신병 약물에 호의적으로 반응하고, 기능의 회복도 좋습니다.[186]하지만, 긍정적인 증상은 3분의 1까지 지속됩니다.약효가 없는 다른 항정신병 약물을 6주에 걸쳐 두 번 시험한 후 치료 저항성 조현병(TRS)으로 분류되며 클로자핀이 제공됩니다.[187][26]클로자핀은 4% 미만의 사람들에게 무과립구증(백혈구 수 감소)의 잠재적인 심각한 부작용을 가지고 있지만 이 그룹의 약 절반에 도움이 됩니다.[24][83][188]

조현병 환자의 약 30~50%가 질병에 걸렸다는 사실을 인정하지 않거나 권장 치료법을 준수하지 않습니다.[189]정기적인 약물 복용을 원치 않거나 할 수 없는 사람들을 위해서는 경구 약물보다 더 큰 정도로 재발 위험을 줄이는 [190]항정신병 약물의 장기 작용 주사를 사용할 수 있습니다.[191]심리사회적 개입과 함께 사용하면 치료에 대한 장기적인 순응도를 향상시킬 수 있습니다.[192]

역효과

박하증을 포함한 추체외 증상은 다양한 정도로 시판되는 모든 항정신병과 관련이 있습니다.[193]: 566 2세대 항정신병 약물이 전형적인 항정신병 약물에 비해 추체외로 증상이 감소했다는 증거는 거의 없습니다.[193]: 566 지각 운동 장애는 항정신병 약물의 장기간 사용으로 인해 발생할 수 있으며, 수개월 또는 수년간 사용한 후에 발생합니다.[194]항정신병성 클로자핀은 혈전색전증(폐색전증 포함), 심근염, 심근병증과도 관련이 있습니다.

심리사회적 개입

가족 요법,[195] 집단 요법, 인지 교정 요법(CRT),[196] 인지 행동 요법(CBT), 그리고 메타 인지 훈련과 같은 정신 분열증 치료에 여러 종류의 심리 사회적 개입이 유용할 수 있습니다.[197][198]항정신병 약물의 부작용으로 종종 필요한 기술 훈련, 약물 사용에 대한 도움, 체중 관리도 제공됩니다.[199]미국에서는 첫 회 정신병에 대한 개입을 조정된 특수 치료(CSC)라고 알려진 전반적인 접근 방식으로 통합했으며 교육에 대한 지원도 포함하고 있습니다.[33]영국에서는 모든 단계에 걸친 진료가 권장되는 치료 지침의 많은 부분을 다루는 유사한 접근 방식입니다.[31]재발을 줄이고 병원에 머무는 횟수를 줄이는 것이 목적입니다.[195]

교육, 취업, 주거 등에 대한 다른 지원 서비스가 제공되는 것이 보통입니다.병원에 입원해 있다가 퇴원하는 중증 조현병 환자의 경우 병원 환경에서 벗어나 지역사회에서 지원을 제공하기 위해 통합적으로 서비스를 제공하는 경우가 많습니다.의약품 관리, 주거, 재정 외에도 쇼핑, 대중교통 이용 등 일상적인 일에 대한 지원이 이루어지고 있습니다.이 접근 방식은 적극적인 지역사회 치료(ACT)로 알려져 있으며 증상, 사회적 기능 및 삶의 질에서 긍정적인 결과를 얻는 것으로 나타났습니다.[200][201]또 다른 보다 강력한 접근 방식은 집중 치료 관리(ICM)로 알려져 있습니다. ICM은 ACT보다 한 단계 더 발전한 단계이며, 소규모 사례 부하(20명 미만)에서 고강도 지원을 강조합니다.이 방법은 지역사회에서 장기요양을 제공하는 것입니다.연구들은 ICM이 사회적 기능을 포함한 많은 관련 결과들을 개선시킨다는 것을 보여줍니다.[202]

일부 연구에서는 CBT가 증상을 줄이거나 재발을 방지하는 데 효과가 있다는 증거가 거의 없습니다.[203][204]그러나, 다른 연구들은 CBT가 (약물과 함께 사용될 때) 전반적인 정신병적 증상을 개선한다는 것을 발견했고, 캐나다에서 권장되었지만, 사회적 기능, 재발, 또는 삶의 질에 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 보여졌습니다.[205]영국에서는 조현병 치료에 부가요법으로 권장되고 있습니다.[181][204]미술치료는 일부 사람들에게 부정적인 증상을 개선하는 것으로 보여지고 영국 NICE에 의해 권장됩니다.[181]이러한 접근법은 잘 연구되지 않았다는 비판을 받고 있으며,[206][207] 예를 들어 호주 지침에서는 예술 치료가 권장되지 않습니다.[208]정신분열증을 개인적으로 경험한 사람들이 서로에게 도움을 주는 동료 지원은 혜택이 불분명합니다.[209]

다른.

유산소 운동을 포함한 운동은 긍정적인 증상과 부정적인 증상, 인지, 작업 기억력을 향상시키고 삶의 질을 향상시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[210][211]또한 운동은 조현병 환자들의 해마 부피를 증가시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.해마 부피의 감소는 질병의 발생과 관련된 요인 중 하나입니다.[210]하지만, 신체 활동에 대한 동기를 높이고 참여를 유지해야 하는 문제는 여전히 남아 있습니다.[212]감독 세션이 권장됩니다.[211]영국에서는 건강한 식사 조언이 운동 프로그램과 함께 제공됩니다.[213]

부적절한 식단은 종종 정신분열증에서 발견되며 엽산과 비타민 D를 포함한 비타민 결핍은 정신분열증의 발병과 심장병을 포함한 조기 사망의 위험 요소와 관련이 있습니다.[214][215]정신분열증을 가진 사람들은 모든 정신 질환 중에서 최악의 식이요법을 가지고 있을 것입니다.엽산과 비타민 D의 수치가 낮아진 것은 첫 번째 에피소드 정신병에서 현저하게 낮아진 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[214]엽산 보충제를 사용하는 것이 좋습니다.[216]아연 결핍도 지적되었습니다.[217]비타민 B12 또한 종종 부족하고 이것은 더 나쁜 증상과 연관이 있습니다.B 비타민의 보충은 증상을 상당히 개선시키고, 인지 결손의 일부를 역전시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[214]또한 장내 미생물 무리에서 주목할 만한 기능 장애가 생균제 사용으로 인해 이익을 얻을 수 있다고 제안됩니다.[217]

예후

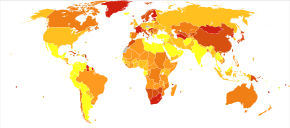

| 무자료 ≤ 185 185–197 197–207 207–218 218–229 229–240 | 240–251 251–262 262–273 273–284 284–295 ≥ 295 |

정신분열증은 엄청난 인적, 경제적 비용을 수반합니다.[5]이것은 기대수명을 20살에서[10] 28살 사이로 줄여줍니다.[11]이것은 주로 심장병,[218] 당뇨병,[11] 비만, 빈약한 식단, 좌식 생활, 흡연과의 연관성 때문이며, 자살률의 증가는 덜한 역할을 합니다.[10][219]항정신병 약물의 부작용 또한 위험을 증가시킬 수 있습니다.[10]

조현병 환자의 거의 40%가 심혈관 질환의 합병증으로 사망하는데, 이는 점점 더 연관되어 있는 것으로 보입니다.[215]갑작스러운 심장 사망의 근본적인 요인은 브루가다 증후군일 수 있습니다 – 조현병과 관련된 것과 겹치는 BRS 돌연변이는 칼슘 채널 돌연변이입니다.[215]BRS는 특정 항정신병 약물과 항우울제로부터 약물로 유도될 수도 있습니다.[215]원발성 다지증, 즉 과다한 체액 섭취는 만성 정신 분열증을 가진 사람들에게 비교적 흔하게 발생합니다.[220][221]이것은 생명을 위협할 수 있는 저나트륨혈증으로 이어질 수 있습니다.항정신병약은 구강건조증을 유발할 수 있지만, 이 질환의 원인이 될 수 있는 몇 가지 다른 요인들이 있습니다; 이것은 평균 수명을 13퍼센트 줄일 수 있을지도 모릅니다.[221]조현병 사망률을 높이는 데 장애가 되는 것은 빈곤, 다른 질병의 증상, 스트레스, 낙인 그리고 약물 부작용을 간과하는 것입니다.[222]

조현병은 장애의 주요 원인입니다.2016년에는 12번째로 장애 상태로 분류되었습니다.[223]조현병 환자의 약 75%가 재발과 함께 지속적인 장애를 가지고 있습니다.[224]어떤 사람들은 완전히 회복되고 어떤 사람들은 사회에서 잘 기능합니다.[225]조현병 환자들은 대부분 지역사회의 지원을 받으며 독립적으로 생활합니다.[24]약 85%가 실업자입니다.[5]정신분열증의 첫 번째 증상을 가진 사람의 경우 장기적으로 좋은 결과가 31%, 중간 결과가 42%, 그리고 31%[226]에서 좋지 않은 결과가 나타납니다.수컷이 암컷보다 더 자주 영향을 받고 더 나쁜 결과를 가져옵니다.[227]정신분열증의 결과가[228] 선진국보다 개발도상국에서 더 잘 나타난다는 연구 결과들이 의문시되고 있습니다.[229]장기실업, 빈곤, 노숙, 착취, 낙인찍기, 피해와 같은 사회적 문제는 공통적인 결과이며, 사회적 배제로 이어집니다.[22][23]

조현병과 관련된 평균 자살률은 5%에서 6%로 추정되며, 대부분 발병 후 또는 첫 병원 입원 기간에 발생합니다.[15][25]적어도 한 번 이상 자살을 시도하는 경우가 몇 배(20~40%)에 이릅니다.[7][97]남성 성, 우울증, 높은 아이큐,[230] 심한 흡연, 약물 [231]사용 등 다양한 위험 요소가 있습니다.[115]반복적인 재발은 자살 행동의 위험 증가와 관련이 있습니다.[176]클로자핀의 사용은 자살과 공격의 위험을 줄일 수 있습니다.[232]

조현병과 담배 흡연 사이의 강한 연관성이 세계적인 연구에서 밝혀졌습니다.[233][234]흡연은 조현병 진단을 받은 사람들에게서 특히 높은데, 일반 인구의 20%에 비해 80~90%가 일반 흡연자인 것으로 추정됩니다.[234]담배를 피우는 사람들은 담배를 많이 피우는 경향이 있고, 니코틴 함량이 높은 담배를 추가로 피웁니다.[37]이것이 증상을 개선하기 위한 것이라는 의견도 있습니다.[235]정신분열증을 가진 사람들 사이에서 대마초를 사용하는 것 또한 흔한 일입니다.[115]

정신분열증은 치매의 위험을 증가시킵니다.[236]

폭력.

조현병을 앓고 있는 대부분의 사람들은 공격적이지 않고, 가해자보다는 폭력의 피해자일 가능성이 높습니다.[7]조현병을 앓고 있는 사람들은 더 광범위한 사회적 배제 역학의 일부로서 폭력적인 범죄에 의해 착취되고 희생됩니다.[22][23]정신분열증 진단을 받은 사람들은 또한 높은 비율로 강제 약물 주입, 격리, 그리고 구속을 당합니다.[28][29]

정신분열증을 가진 사람들에 의한 폭력의 위험은 작습니다.위험이 높은 부분군이 있습니다.[161]이러한 위험은 일반적으로 물질 사용 장애와 같은 동반 질환, 특히 알코올이나 반사회적 인격 장애와 관련이 있습니다.[161]물질 사용 장애는 강하게 연관되어 있고, 다른 위험 요소들은 인지 및 사회적 인지의 결손과 연관되어 있는데, 여기에는 안면 인식과 정신 장애 이론에 부분적으로 포함되어 있습니다.[237][238]인지 기능, 의사 결정 및 얼굴 인식의 불량은 폭력과 같은 부적절한 반응을 초래할 수 있는 상황에 대해 잘못된 판단을 내리는 데 기여할 수 있습니다.[239]이와 관련된 위험 요소들은 또한 반사회적 인격 장애에도 존재하며, 동반 장애로 존재할 경우 폭력의 위험이 크게 증가합니다.[240][241]

역학

2017년에 세계질병부담연구는 110만 명의 새로운 환자가 발생했다고 추정했습니다.[needs update][17] 2022년 세계보건기구(WHO)는 전 세계적으로 총 2,400만 명의 환자가 발생했다고 보고했습니다.[2]조현병은 사람들의 삶의 어떤 시점에서 약 0.3-0.7%에게 영향을 미칩니다.[16][11]분쟁 지역에서는 이 수치가 4.0~6.5%[242]까지 올라갈 수 있습니다.여성보다 남성에서 1.4배 더 자주 발생하며, 일반적으로 남성에서 먼저 발생합니다.[83]

전세계적으로 조현병은 가장 흔한 정신병입니다.[52]조현병의 빈도는 전 세계,[7] 국가 내,[243] 지역 및 인근 수준에서 다양합니다.[244] 시간이 지남에 따라, 지리적 위치에 따라, 성별에 따라 연구 간 유병률의 차이는 5배에 달합니다.[5]

조현병은 전세계 장애의 약 1%를[needs update][83] 유발하고 2015년에는 17,000명의 사망자를 냈습니다.[13]

2000년 WHO는 10만 명당 연령 표준 유병률이 아프리카 343명에서 일본과 오세아니아 544명까지, 여성은 아프리카 378명에서 동남유럽 527명까지 다양하다는 것을 발견했습니다.[needs update][245]

역사

개념전개요

조현병과 유사한 증후군에 대한 기록은 19세기 이전의 기록에서는 드문 편입니다; 가장 초기의 사례 보고는 1797년과 1809년이었습니다.[246]조기 치매를 의미하는 치매 praecox는 1886년 독일 정신과 의사 하인리히 슐레가 사용했고, 1891년 아놀드 픽이 헤브프레니아 사례 보고서에서 사용했습니다.1893년 에밀 크레플린은 이 용어를 사용하여 치매 프레콕스와 조울증(현재 조울증이라고 함)[10]이라는 두 가지 정신 사이의 구분을 지었습니다.그 장애가 퇴행성 치매가 아니라는 것이 명백해졌을 때, 그것은 1908년 Eugen Bleuler에 의해 조현병으로 이름이 바뀌었습니다.[247]

조현병이라는 단어는 '마음의 분열'로 번역되며, 그리스어 schizein에서 현대 라틴어입니다. (고대 그리스어: σχίζειν, litted) 갈라짐)과 phr ē, (고대 그리스어: φρήν, 불이 켜짐. '마음')그것의 사용은 성격, 사고, 기억, 인식 사이의 기능 분리를 묘사하기 위한 것이었습니다.[247]

20세기 초 정신과 의사 커트 슈나이더는 조현병의 정신병적 증상을 환각과 망상의 두 그룹으로 분류했습니다.환각은 청각에만 국한된 것으로 나열되었고 망상에는 사고 장애가 포함되어 있었습니다.이것들은 일급이라 불리는 중요한 증상으로 보여졌습니다.가장 흔한 1순위 증상은 사고 장애에 속하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[page needed][249][page needed][250]2013년 1순위 증상은 DSM-5 기준에서 제외되었습니다.[251] 조현병 진단에는 유용하지 않을 수 있지만, 감별 진단에는 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[252]

정신분열증의 하위 유형 - 편집증, 조직화되지 않은, 카타토닉, 미분화, 잔류로 분류됨 - DSM-5 (2013) 또는 ICD-11에 의해 분리된 상태로 더 이상 인식되지 않습니다.[253][254][255]

진단폭

1960년대 이전에는, 비폭력적인 소규모 범죄자들과 여성들이 정신분열증 진단을 받기도 했는데, 후자는 가부장제 안에서 아내와 어머니로서 그들의 의무를 수행하지 않는 것에 대해 나쁜 것으로 분류했습니다.[256]1960년대 중후반, 흑인 남성들은 "적대적이고 공격적"으로 분류되어 훨씬 더 높은 비율로 조현병 진단을 받았고, 그들의 시민권과 블랙 파워 행동주의는 망상으로 분류되었습니다.[256][257]

1970년대 초 미국에서 조현병 진단 모델은 광범위하고 임상적으로 DSM II를 사용하여 진단되었으며, ICD-9 기준을 사용한 유럽보다 미국에서 훨씬 더 많이 진단되었습니다.미국 모델은 정신 질환을 앓고 있는 사람들을 명확하게 구분하지 못했다는 비판을 받았습니다.1980년에 DSM III가 출판되었고 임상 기반 조직검사 사회적 모델에서 이유 기반 의료 모델로의 초점 전환을 보여주었습니다.[258]DSM IV는 증거 기반 의료 모델에 대한 관심을 높였습니다.[259]

역사적 취급

1930년대에 발작(경련)이나 혼수상태를 유발하는 여러 가지 충격요법이 조현병 치료에 사용되었습니다.[260]인슐린 쇼크는 혼수상태를 유도하기 위해 다량의 인슐린을 주입하는 것을 수반했고, 이것은 결과적으로 저혈당과 경련을 일으켰습니다.[260][261]발작을 유발하기 위한 전기의 사용은 1938년까지 전기 경련 치료법(ECT)으로 사용되었습니다.[262]

미국에서는 1930년대부터 1970년대까지, 프랑스에서는 1980년대까지 시행된, 엽전술과 전두엽 수술을 포함한 정신과 수술은 인권 침해로 인식되고 있습니다.[263][264]1950년대 중반에 최초의 전형적인 항정신병약인 클로프로마진이 소개되었고,[265] 1970년대에 최초의 전형적인 항정신병약인 클로자핀이 소개되었습니다.[266]

정치적 학대

1960년대부터 1989년까지 소련과 동구권의 정신과 의사들은 "나중에 증상이 나타날 것이라는 가정"에 근거하여 정신병의 징후 없이 [267][268]정신분열증이 부진한 수천 명의 사람들을 진단했습니다.[269]이제는 신뢰를 잃게 된 이 진단은 정치적 반체제 인사들을 가두는 편리한 방법을 제공했습니다.[270]

사회와 문화

미국의 경우, 정신분열증의 연간 비용 - 직접 비용 (외래, 입원, 약물, 장기 치료)과 비의료 비용 (법 집행, 직장 생산성 감소, 실업)을 포함한 - 627억 달러로 추정되었습니다.[271][a]영국에서는 2016년 비용이 연간 118억 파운드로 책정되었으며, 이 수치의 3분의 1이 병원, 사회 관리 및 치료 비용에 직접적으로 기인합니다.[5]

낙인

2002년에 일본에서 조현병의 용어는 세이신 분레츠 精神分裂病(seishin-bunretesu-byo, litt. '마음이 분열되는 병')에서 도고시쵸쇼(togo-shitcho-shop, litt.)로 변경되었습니다. '통합 – dys 규제 신드롬')을 통해 낙인을 줄일 수 있습니다."통합 장애"로도 해석되는 이 새로운 이름은 조직검사 사회모델에서 영감을 얻었습니다.[275]비슷한 변화가 2012년 한국에서도 동조 장애로 이루어졌습니다.[276]

문화묘사

'뷰티풀 마인드'라는 책은 정신분열증 진단을 받고 노벨 경제학상을 받은 존 포브스 내쉬의 삶을 기록한 책입니다.이 책은 같은 이름의 영화로 만들어졌습니다; 이전의 다큐멘터리 영화는 '찬란한 광기'였습니다.

1964년에 정신분열증 진단을 받은 세 명의 남성이 각각 예수 그리스도라고 망상적인 믿음을 가지고 있다는 사례 연구가 입실란티의 세 명의 그리스도로 출판되었습니다. 세 명의 그리스도라는 제목의 영화가 2020년에 개봉되었습니다.[277][278]

언론 보도는 조현병과 폭력 사이의 연관성에 대한 대중의 인식을 강화합니다;[279] 영화에서, 조현병을 가진 사람들은 다른 사람들에게 위험한 존재로 묘사될 가능성이 매우 높습니다.[280]영국의 보고 조건 지침과 수상 캠페인에서는 2013년 이후 부정적인 보고가 감소하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[281]

연구방향

2015년 코크란 리뷰는 조현병의 긍정적인 증상, 특히 청각 언어 환각(AVHs)을 치료하기 위한 뇌 자극 기술의 혜택에 대한 명확하지 않은 증거를 발견했습니다.[282]대부분의 연구는 경두개 직류 자극(tDCM)과 반복적인 경두개 자기 자극(rTMS)에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다.[283]심뇌 자극을 위한 집속 초음파 기반 기술은 AVH 치료에 대한 통찰력을 제공할 수 있습니다.[283]

조현병 진단과 치료에 도움을 줄 잠재적 바이오마커 연구는 2020년 현재 활발한 연구 분야입니다.가능한 바이오마커에는 염증,[96] 신경영상,[284] 뇌유래 신경영양인자(BDNF),[285] 언어 분석 등이 포함됩니다.C-반응성 단백질과 같은 일부 마커는 일부 정신 질환에 관련된 염증 수치를 감지하는 데 유용하지만 장애 특이적이지는 않습니다.다른 염증성 사이토카인들은 항정신병 치료 후 정상화되는 첫 회 정신병과 급성 재발에서 증가하는 것으로 발견되며, 이들은 상태표지자로 간주될 수 있습니다.[286]조현병에서 수면 스핀들의 결손은 손상된 시상피질 회로의 표지 및 기억 장애의 메커니즘으로 작용할 수 있습니다.[163]마이크로RNA는 초기 신경세포 발달에 매우 큰 영향을 미치며, 그들의 파괴는 여러 CNS 장애와 관련이 있습니다; 순환하는 마이크로RNA는 혈액과 뇌척수액과 같은 체액에서 발견되며, 그 수준의 변화는 뇌 조직의 특정한 영역에서의 마이크로RNA 수준의 변화와 관련이 있는 것으로 보입니다.이 연구들은 cimiRNA가 조현병을 포함한 많은 질병에서 초기에 정확한 바이오마커가 될 가능성이 있음을 시사합니다.[287][288]

해설서

참고문헌

- ^ Jones D (2003) [1917]. Roach P, Hartmann J, Setter J (eds.). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8.

- ^ a b c d e "Schizophrenia Fact sheet". World Health Organization. 10 January 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Schizophrenia". Health topics. US National Institute of Mental Health. April 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "Medicinal treatment of psychosis/schizophrenia". Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB (July 2016). "Schizophrenia". The Lancet. 388 (10039): 86–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6. PMC 4940219. PMID 26777917.

- ^ Gruebner O, Rapp MA, Adli M, et al. (February 2017). "Cities and mental health". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 114 (8): 121–127. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121. PMC 5374256. PMID 28302261.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 99–105. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ a b Ferri FF (2010). "Chapter S". Ferri's differential diagnosis: a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-07699-9.

- ^ a b Paris J (December 2018). "Differential Diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 41 (4): 575–582. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2018.07.001. PMID 30447725. S2CID 53951650.

- ^ a b c d e f Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB (2014). "Excess early mortality in schizophrenia". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 10: 425–448. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153657. PMID 24313570.

- ^ a b c d e "Schizophrenia". Statistics. US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). 22 April 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Schizophrenia Fact Sheet and Information". World Health Organization.

- ^ a b c Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ "ICD-11: 6A20 Schizophrenia". World Health Organization. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ferri FF (2019). Ferri's clinical advisor 2019: 5 books in 1. Elsevier. pp. 1225–1226. ISBN 9780323530422.

- ^ a b Javitt DC (June 2014). "Balancing therapeutic safety and efficacy to improve clinical and economic outcomes in schizophrenia: a clinical overview". The American Journal of Managed Care. 20 (8 Suppl): S160-165. PMID 25180705.

- ^ a b James SL, Abate D (November 2018). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". The Lancet. 392 (10159): 1789–1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. PMC 6227754. PMID 30496104.

- ^ a b c van de Leemput J, Hess JL, Glatt SJ, Tsuang MT (2016). "Genetics of Schizophrenia: Historical Insights and Prevailing Evidence". Advances in Genetics. 96: 99–141. doi:10.1016/bs.adgen.2016.08.001. PMID 27968732.

- ^ a b Parakh P, Basu D (August 2013). "Cannabis and psychosis: have we found the missing links?". Asian Journal of Psychiatry (Review). 6 (4): 281–287. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2013.03.012. PMID 23810133.

Cannabis acts as a component cause of psychosis, that is, it increases the risk of psychosis in people with certain genetic or environmental vulnerabilities, though by itself, it is neither a sufficient nor a necessary cause of psychosis.

- ^ a b Vita A, Barlati S (May 2018). "Recovery from schizophrenia: is it possible?". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 31 (3): 246–255. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000407. PMID 29474266. S2CID 35299996.

- ^ Lawrence RE, First MB, Lieberman JA (2015). "Chapter 48: Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses". In Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA, First MB, Riba MB (eds.). Psychiatry (fourth ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 798, 816, 819. doi:10.1002/9781118753378.ch48. ISBN 978-1-118-84547-9.

- ^ a b c d e Killaspy H (September 2014). "Contemporary mental health rehabilitation". East Asian Archives of Psychiatry. 24 (3): 89–94. PMID 25316799.

- ^ a b c Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, et al. (17 October 2018). "Global Epidemiology and Burden of Schizophrenia: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 44 (6): 1195–1203. doi:10.1093/schbul/sby058. PMC 6192504. PMID 29762765.

- ^ a b c d e f g van Os J, Kapur S (August 2009). "Schizophrenia" (PDF). Lancet. 374 (9690): 635–645. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. PMID 19700006. S2CID 208792724. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ a b Hor K, Taylor M (November 2010). "Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (4 Suppl): 81–90. doi:10.1177/1359786810385490. PMC 2951591. PMID 20923923.

- ^ a b Siskind D, Siskind V, Kisely S (November 2017). "Clozapine Response Rates among People with Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Data from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 62 (11): 772–777. doi:10.1177/0706743717718167. PMC 5697625. PMID 28655284.

- ^ Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". The Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- ^ a b Becker T, Kilian R (2006). "Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across western Europe: what can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care?". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 113 (429): 9–16. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00711.x. PMID 16445476. S2CID 34615961.

- ^ a b c Capdevielle D, Boulenger JP, Villebrun D, Ritchie K (September 2009). "Durées d'hospitalisation des patients souffrant de schizophrénie: implication des systèmes de soin et conséquences médicoéconomiques" [Schizophrenic patients' length of stay: mental health care implication and medicoeconomic consequences]. L'Encéphale (in French). 35 (4): 394–399. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2008.11.005. PMID 19748377.

- ^ a b Narayan KK, Kumar DS (January 2012). "Disability in a Group of Long-stay Patients with Schizophrenia: Experience from a Mental Hospital". Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 34 (1): 70–75. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.96164. PMC 3361848. PMID 22661812.

- ^ a b c "Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). March 2014. pp. 4–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Stępnicki P, Kondej M, Kaczor AA (20 August 2018). "Current Concepts and Treatments of Schizophrenia". Molecules. 23 (8): 2087. doi:10.3390/molecules23082087. PMC 6222385. PMID 30127324.

- ^ a b c d "RAISE Questions and Answers". US National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Marshall M (September 2005). "Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review". Archives of General Psychiatry. 62 (9): 975–983. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975. PMID 16143729.

- ^ a b Montagnese M, Leptourgos P, Fernyhough C, et al. (January 2021). "A Review of Multimodal Hallucinations: Categorization, Assessment, Theoretical Perspectives, and Clinical Recommendations". Schizophr Bull. 47 (1): 237–248. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbaa101. PMC 7825001. PMID 32772114.

- ^ Császár N, Kapócs G, Bókkon I (27 May 2019). "A possible key role of vision in the development of schizophrenia". Reviews in the Neurosciences. 30 (4): 359–379. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2018-0022. PMID 30244235. S2CID 52813070.

- ^ a b American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 299–304. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6.

- ^ a b Heinz A, Voss M, Lawrie SM, et al. (September 2016). "Shall we really say goodbye to first rank symptoms?". European Psychiatry. 37: 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.04.010. PMID 27429167. S2CID 13761854.

- ^ a b Adida M, Azorin JM, Belzeaux R, Fakra E (December 2015). "[Negative Symptoms: Clinical and Psychometric Aspects]". L'Encephale. 41 (6 Suppl 1): 6S15–17. doi:10.1016/S0013-7006(16)30004-5. PMID 26776385.

- ^ Mach C, Dollfus S (April 2016). "[Scale for Assessing Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review]". L'Encephale. 42 (2): 165–171. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2015.12.020. PMID 26923997.

- ^ Waltz JA, Gold JM (2016). "Motivational Deficits in Schizophrenia and the Representation of Expected Value". Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 27: 375–410. doi:10.1007/7854_2015_385. ISBN 978-3-319-26933-7. PMC 4792780. PMID 26370946.

- ^ a b Husain M, Roiser JP (August 2018). "Neuroscience of apathy and anhedonia: a transdiagnostic approach". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 19 (8): 470–484. doi:10.1038/s41583-018-0029-9. PMID 29946157. S2CID 49428707.

- ^ a b Galderisi S, Mucci A, Buchanan RW, Arango C (August 2018). "Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new developments and unanswered research questions". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (8): 664–677. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30050-6. PMID 29602739. S2CID 4483198.

- ^ Klaus F, Dorsaz O, Kaiser S (19 September 2018). "[Negative symptoms in schizophrenia – overview and practical implications]". Revue médicale suisse. 14 (619): 1660–1664. doi:10.53738/REVMED.2018.14.619.1660. PMID 30230774. S2CID 246764656.

- ^ Batinic B (June 2019). "Cognitive Models of Positive and Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia and Implications for Treatment". Psychiatria Danubina. 31 (Suppl 2): 181–184. PMID 31158119.

- ^ Bortolon C, Macgregor A, Capdevielle D, Raffard S (September 2018). "Apathy in schizophrenia: A review of neuropsychological and neuroanatomical studies". Neuropsychologia. 118 (Pt B): 22–33. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.09.033. PMID 28966139. S2CID 13411386.

- ^ a b c d e Marder SR, Kirkpatrick B (May 2014). "Defining and measuring negative symptoms of schizophrenia in clinical trials". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 24 (5): 737–743. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.10.016. PMID 24275698. S2CID 5172022.

- ^ a b c Tatsumi K, Kirkpatrick B, Strauss GP, Opler M (April 2020). "The brief negative symptom scale in translation: A review of psychometric properties and beyond". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 33: 36–44. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.01.018. PMID 32081498. S2CID 211141678.

- ^ Klaus F, Kaiser S, Kirschner M (June 2018). "[Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia – an Overview]". Therapeutische Umschau. 75 (1): 51–56. doi:10.1024/0040-5930/a000966. PMID 29909762. S2CID 196502392.

- ^ Wójciak P, Rybakowski J (30 April 2018). "Clinical picture, pathogenesis and psychometric assessment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia". Psychiatria Polska. 52 (2): 185–197. doi:10.12740/PP/70610. PMID 29975360.

- ^ a b c d e f Murante T, Cohen CI (January 2017). "Cognitive Functioning in Older Adults With Schizophrenia". Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing). 15 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20160032. PMC 6519630. PMID 31975837.

- ^ a b Kar SK, Jain M (July 2016). "Current understandings about cognition and the neurobiological correlates in schizophrenia". Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice. 7 (3): 412–418. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.176185. PMC 4898111. PMID 27365960.

- ^ a b Bozikas VP, Andreou C (February 2011). "Longitudinal studies of cognition in first episode psychosis: a systematic review of the literature". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 45 (2): 93–108. doi:10.3109/00048674.2010.541418. PMID 21320033. S2CID 26135485.

- ^ Shah JN, Qureshi SU, Jawaid A, Schulz PE (June 2012). "Is there evidence for late cognitive decline in chronic schizophrenia?". The Psychiatric Quarterly. 83 (2): 127–144. doi:10.1007/s11126-011-9189-8. PMID 21863346. S2CID 10970088.

- ^ a b c Biedermann F, Fleischhacker WW (August 2016). "Psychotic disorders in DSM-5 and ICD-11". CNS Spectrums. 21 (4): 349–354. doi:10.1017/S1092852916000316. PMID 27418328. S2CID 24728447.

- ^ a b c Vidailhet P (September 2013). "[First-episode psychosis, cognitive difficulties and remediation]". L'Encéphale (in French). 39 (Suppl 2): S83-92. doi:10.1016/S0013-7006(13)70101-5. PMID 24084427.

- ^ a b c Hashimoto K (5 July 2019). "Recent Advances in the Early Intervention in Schizophrenia: Future Direction from Preclinical Findings". Current Psychiatry Reports. 21 (8): 75. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1063-7. PMID 31278495. S2CID 195814019.

- ^ a b c d e f Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J (June 2019). "Nonsocial and social cognition in schizophrenia: current evidence and future directions". World Psychiatry. 18 (2): 146–161. doi:10.1002/wps.20624. PMC 6502429. PMID 31059632.

- ^ Javitt DC, Sweet RA (September 2015). "Auditory dysfunction in schizophrenia: integrating clinical and basic features". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 16 (9): 535–550. doi:10.1038/nrn4002. PMC 4692466. PMID 26289573.

- ^ a b Megreya AM (2016). "Face perception in schizophrenia: a specific deficit". Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 21 (1): 60–72. doi:10.1080/13546805.2015.1133407. PMID 26816133. S2CID 26125559.

- ^ Eack SM (July 2012). "Cognitive remediation: a new generation of psychosocial interventions for people with schizophrenia". Social Work. 57 (3): 235–246. doi:10.1093/sw/sws008. PMC 3683242. PMID 23252315.

- ^ Pomarol-Clotet E, Oh M, Laws KR, McKenna PJ (February 2008). "Semantic priming in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 192 (2): 92–97. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032102. hdl:2299/2735. PMID 18245021.

- ^ Goldberg TE, Keefe RS, Goldman RS, Robinson DG, Harvey PD (April 2010). "Circumstances under which practice does not make perfect: a review of the practice effect literature in schizophrenia and its relevance to clinical treatment studies". Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (5): 1053–1062. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.211. PMC 3055399. PMID 20090669.

- ^ King DJ, Hodgekins J, Chouinard PA, Chouinard VA, Sperandio I (June 2017). "A review of abnormalities in the perception of visual illusions in schizophrenia". Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 24 (3): 734–751. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1168-5. PMC 5486866. PMID 27730532.

- ^ Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ (September 2010). "Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (5): 1009–1019. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn192. PMC 2930336. PMID 19329561.

- ^ Le Gall E, Iakimova G (December 2018). "[Social cognition in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder: Points of convergence and functional differences]". L'Encéphale. 44 (6): 523–537. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2018.03.004. PMID 30122298. S2CID 150099236.

- ^ Grill-Spector K, Weiner KS, Kay K, Gomez J (September 2017). "The Functional Neuroanatomy of Human Face Perception". Annual Review of Vision Science. 3: 167–196. doi:10.1146/annurev-vision-102016-061214. PMC 6345578. PMID 28715955.

- ^ Fountoulakis KN, Panagiotidis P, Kimiskidis V, Nimatoudis I, Gonda X (February 2019). "Neurological soft signs in familial and sporadic schizophrenia". Psychiatry Research. 272: 222–229. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.105. PMID 30590276. S2CID 56476015.

- ^ Bourgou Gaha S, Halayem Dhouib S, Amado I, Bouden A (June 2015). "[Neurological soft signs in early onset schizophrenia]". L'Encephale. 41 (3): 209–214. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2014.01.005. PMID 24854724.

- ^ a b Da Fonseca D, Fourneret P (December 2018). "[Very early onset schizophrenia]". L'Encephale. 44 (6S): S8–S11. doi:10.1016/S0013-7006(19)30071-5. PMID 30935493. S2CID 150798223.

- ^ Häfner H (2019). "From Onset and Prodromal Stage to a Life-Long Course of Schizophrenia and Its Symptom Dimensions: How Sex, Age, and Other Risk Factors Influence Incidence and Course of Illness". Psychiatry Journal. 2019: 9804836. doi:10.1155/2019/9804836. PMC 6500669. PMID 31139639.

- ^ Cohen CI, Freeman K, Ghoneim D, et al. (March 2018). "Advances in the Conceptualization and Study of Schizophrenia in Later Life". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 41 (1): 39–53. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.10.004. PMID 29412847.

- ^ a b c George M, Maheshwari S, Chandran S, Manohar JS, Sathyanarayana Rao TS (October 2017). "Understanding the schizophrenia prodrome". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 59 (4): 505–509. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_464_17 (inactive 1 August 2023). PMC 5806335. PMID 29497198.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 메인 : 2023년 8월 기준 DOI 비활성화 (링크) - ^ a b Conroy S, Francis M, Hulvershorn LA (March 2018). "Identifying and treating the prodromal phases of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia". Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry. 5 (1): 113–128. doi:10.1007/s40501-018-0138-0. PMC 6196741. PMID 30364516.

- ^ Lecardeur L, Meunier-Cussac S, Dollfus S (May 2013). "[Cognitive deficits in first episode psychosis patients and people at risk for psychosis: from diagnosis to treatment]". L'Encephale. 39 (Suppl 1): S64-71. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2012.10.011. PMID 23528322.

- ^ Mullin AP, Gokhale A, Moreno-De-Luca A, Sanyal S, Waddington JL, Faundez V (December 2013). "Neurodevelopmental disorders: mechanisms and boundary definitions from genomes, interactomes and proteomes". Transl Psychiatry. 3 (12): e329. doi:10.1038/tp.2013.108. PMC 4030327. PMID 24301647.

- ^ a b c Davis J, Eyre H, Jacka FN, et al. (June 2016). "A review of vulnerability and risks for schizophrenia: Beyond the two hit hypothesis". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 65: 185–194. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.017. PMC 4876729. PMID 27073049.

- ^ a b Perkovic MN, Erjavec GN, Strac DS, et al. (March 2017). "Theranostic biomarkers for schizophrenia". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (4): 733. doi:10.3390/ijms18040733. PMC 5412319. PMID 28358316.

- ^ a b Suvisaari J (2010). "[Risk factors of schizophrenia]". Duodecim (in Finnish). 126 (8): 869–876. PMID 20597333.

- ^ a b Combs DR, Mueser KT, Gutierrez MM (2011). "Chapter 8: Schizophrenia: Etiological considerations". In Hersen M, Beidel DC (eds.). Adult psychopathology and diagnosis (6th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-13884-7.

- ^ O'Donovan MC, Williams NM, Owen MJ (October 2003). "Recent advances in the genetics of schizophrenia". Human Molecular Genetics. 12 Spec No 2: R125–133. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg302. PMID 12952866.

- ^ a b Torrey EF, Yolken RH (August 2019). "Schizophrenia as a pseudogenetic disease: A call for more gene-environmental studies". Psychiatry Research. 278: 146–150. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.006. PMID 31200193. S2CID 173991937.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Picchioni MM, Murray RM (July 2007). "Schizophrenia". BMJ. 335 (7610): 91–95. doi:10.1136/bmj.39227.616447.BE. PMC 1914490. PMID 17626963.

- ^ Farrell MS, Werge T, Sklar P, et al. (May 2015). "Evaluating historical candidate genes for schizophrenia". Molecular Psychiatry. 20 (5): 555–562. doi:10.1038/mp.2015.16. PMC 4414705. PMID 25754081.

- ^ Schulz SC, Green MF, Nelson KJ (2016). Schizophrenia and Psychotic Spectrum Disorders. Oxford University Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 9780199378067.

- ^ Schork AJ, Wang Y, Thompson WK, Dale AM, Andreassen OA (February 2016). "New statistical approaches exploit the polygenic architecture of schizophrenia—implications for the underlying neurobiology". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 36: 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2015.10.008. PMC 5380793. PMID 26555806.

- ^ Coelewij L, Curtis D (2018). "Mini-review: Update on the genetics of schizophrenia". Annals of Human Genetics. 82 (5): 239–243. doi:10.1111/ahg.12259. ISSN 0003-4800. PMID 29923609. S2CID 49311660.

- ^ Kendler KS (March 2016). "The Schizophrenia Polygenic Risk Score: To What Does It Predispose in Adolescence?". JAMA Psychiatry. 73 (3): 193–194. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2964. PMID 26817666.

- ^ a b Lowther C, Costain G, Baribeau DA, Bassett AS (September 2017). "Genomic Disorders in Psychiatry—What Does the Clinician Need to Know?". Current Psychiatry Reports. 19 (11): 82. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0831-5. PMID 28929285. S2CID 4776174.

- ^ Bundy H, Stahl D, MacCabe JH (February 2011). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of the fertility of patients with schizophrenia and their unaffected relatives: Fertility in schizophrenia". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 123 (2): 98–106. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01623.x. PMID 20958271. S2CID 45179016.

- ^ van Dongen J, Boomsma DI (March 2013). "The evolutionary paradox and the missing heritability of schizophrenia". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 162 (2): 122–136. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.32135. PMID 23355297. S2CID 9648115.

- ^ Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB (2 July 2016). "Schizophrenia". Lancet. 388 (10039): 86–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6. PMC 4940219. PMID 26777917.

- ^ Goh XX, Tang PY, Tee SF (July 2021). "8-Hydroxy-2'-Deoxyguanosine and Reactive Oxygen Species as Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Mental Illnesses: A Meta-Analysis". Psychiatry Investig (Meta-analysis). 18 (7): 603–618. doi:10.30773/pi.2020.0417. PMC 8328836. PMID 34340273.

- ^ Stilo SA, Murray RM (14 September 2019). "Non-Genetic Factors in Schizophrenia". Current Psychiatry Reports. 21 (10): 100. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3. PMC 6745031. PMID 31522306.

- ^ Cirulli F, Musillo C, Berry A (5 February 2020). "Maternal Obesity as a Risk Factor for Brain Development and Mental Health in the Offspring". Neuroscience. 447: 122–135. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.01.023. hdl:11573/1387747. PMID 32032668. S2CID 211029692.

- ^ a b Upthegrove R, Khandaker GM (2020). "Cytokines, Oxidative Stress and Cellular Markers of Inflammation in Schizophrenia" (PDF). Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 44: 49–66. doi:10.1007/7854_2018_88. ISBN 978-3-030-39140-9. PMID 31115797. S2CID 162169817.

- ^ a b Chiang M, Natarajan R, Fan X (February 2016). "Vitamin D in schizophrenia: a clinical review". Evidence-Based Mental Health. 19 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1136/eb-2015-102117. PMID 26767392. S2CID 206926835.

- ^ Arias I, Sorlozano A, Villegas E, et al. (April 2012). "Infectious agents associated with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Research. 136 (1–3): 128–136. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.026. PMID 22104141. S2CID 2687441.

- ^ Yolken R (June 2004). "Viruses and schizophrenia: a focus on herpes simplex virus". Herpes. 11 (Suppl 2): 83A–88A. PMID 15319094.

- ^ Khandaker GM (August 2012). "Childhood infection and adult schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of population-based studies". Schizophr. Res. 139 (1–3): 161–168. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.05.023. PMC 3485564. PMID 22704639.

- ^ a b Pearce J, Murray C, Larkin W (July 2019). "Childhood adversity and trauma:experiences of professionals trained to routinely enquire about childhood adversity". Heliyon. 5 (7): e01900. Bibcode:2019Heliy...501900P. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01900. PMC 6658729. PMID 31372522.

- ^ Dvir Y, Denietolis B, Frazier JA (October 2013). "Childhood trauma and psychosis". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 22 (4): 629–641. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2013.04.006. PMID 24012077. S2CID 40053289.

- ^ Misiak B, Krefft M, Bielawski T, Moustafa AA, Sąsiadek MM, Frydecka D (April 2017). "Toward a unified theory of childhood trauma and psychosis: A comprehensive review of epidemiological, clinical, neuropsychological and biological findings". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 75: 393–406. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.015. PMID 28216171. S2CID 21614845.

- ^ a b Nettis MA, Pariante CM, Mondelli V (2020). "Early-Life Adversity, Systemic Inflammation and Comorbid Physical and Psychiatric Illnesses of Adult Life". Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 44: 207–225. doi:10.1007/7854_2019_89. ISBN 978-3-030-39140-9. PMID 30895531. S2CID 84842249.

- ^ Guloksuz S, van Os J (January 2018). "The slow death of the concept of schizophrenia and the painful birth of the psychosis spectrum". Psychological Medicine. 48 (2): 229–244. doi:10.1017/S0033291717001775. PMID 28689498.

- ^ Costa E, Silva JA, Steffen RE (November 2019). "Urban environment and psychiatric disorders: a review of the neuroscience and biology". Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 100S: 153940. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2019.07.004. PMID 31610855. S2CID 204704312.

- ^ van Os J (April 2004). "Does the urban environment cause psychosis?". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 184 (4): 287–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.4.287. PMID 15056569.

- ^ Attademo L, Bernardini F, Garinella R, Compton MT (March 2017). "Environmental pollution and risk of psychotic disorders: A review of the science to date". Schizophrenia Research. 181: 55–59. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.003. PMID 27720315. S2CID 25505446.

- ^ Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E, Kahn RS (March 2007). "Migration and schizophrenia". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 20 (2): 111–115. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f68e. PMID 17278906. S2CID 21391349.

- ^ Sharma R, Agarwal A, Rohra VK, et al. (April 2015). "Effects of increased paternal age on sperm quality, reproductive outcome and associated epigenetic risks to offspring". Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 13: 35. doi:10.1186/s12958-015-0028-x. PMC 4455614. PMID 25928123.

- ^ a b Gregg L, Barrowclough C, Haddock G (May 2007). "Reasons for increased substance use in psychosis". Clinical Psychology Review. 27 (4): 494–510. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.004. PMID 17240501.

- ^ Sagud M, Mihaljević-Peles A, Mück-Seler D, et al. (September 2009). "Smoking and schizophrenia". Psychiatria Danubina. 21 (3): 371–375. PMID 19794359.

- ^ Larson M (30 March 2006). "Alcohol-Related Psychosis". EMedicine. Archived from the original on 9 November 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2006.

- ^ Leweke FM, Koethe D (June 2008). "Cannabis and psychiatric disorders: it is not only addiction". Addiction Biology. 13 (2): 264–75. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00106.x. PMID 18482435. S2CID 205400285.

- ^ a b c d Khokhar JY, Henricks AM, Sullivan ED, Green AI (2018). "Unique Effects of Clozapine: A Pharmacological Perspective". Apprentices to Genius: A tribute to Solomon H. Snyder. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 82. pp. 137–162. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2017.09.009. ISBN 978-0128140871. PMC 7197512. PMID 29413518.

- ^ Bighelli I, Rodolico A, García-Mieres H, et al. (November 2021). "Psychosocial and psychological interventions for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet Psychiatry. 8 (11): 969–980. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00243-1. PMID 34653393. S2CID 239003358.

- ^ Patel S, Khan S, M S, Hamid P (July 2020). "The Association Between Cannabis Use and Schizophrenia: Causative or Curative? A Systematic Review". Cureus. 12 (7): e9309. doi:10.7759/cureus.9309. PMC 7442038. PMID 32839678.

- ^ Hasan A, von Keller R, Friemel CM, Hall W, Schneider M, Koethe D, Leweke FM, Strube W, Hoch E (June 2020). "Cannabis use and psychosis: a review of reviews". Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 270 (4): 403–412. doi:10.1007/s00406-019-01068-z. PMID 31563981. S2CID 203567900.

- ^ "Causes — Schizophrenia". UK National Health Service. 11 November 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Ortiz-Medina MB, Perea M, Torales J, et al. (November 2018). "Cannabis consumption and psychosis or schizophrenia development". The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 64 (7): 690–704. doi:10.1177/0020764018801690. PMID 30442059. S2CID 53563635.

- ^ Hayes D, Kyriakopoulos M (August 2018). "Dilemmas in the treatment of early-onset first-episode psychosis". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 8 (8): 231–239. doi:10.1177/2045125318765725. PMC 6058451. PMID 30065814.

- ^ Cannon TD (December 2015). "How Schizophrenia Develops: Cognitive and Brain Mechanisms Underlying Onset of Psychosis". Trends Cogn Sci. 19 (12): 744–756. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.09.009. PMC 4673025. PMID 26493362.

- ^ Correll CU, Schooler NR (2020). "Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Review and Clinical Guide for Recognition, Assessment, and Treatment". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 16: 519–534. doi:10.2147/NDT.S225643. PMC 7041437. PMID 32110026.

- ^ Howes OD (1 January 2017). "The Role of Genes, Stress, and Dopamine in the Development of Schizophrenia". Biological Psychiatry. 81 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.07.014. PMC 5675052. PMID 27720198.

- ^ Broyd A, Balzan RP, Woodward TS, Allen P (June 2017). "Dopamine, cognitive biases and assessment of certainty: A neurocognitive model of delusions". Clinical Psychology Review. 54: 96–106. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.006. PMID 28448827.

- ^ Howes OD, Murray RM (May 2014). "Schizophrenia: an integrated sociodevelopmental-cognitive model". Lancet. 383 (9929): 1677–1687. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62036-X. PMC 4127444. PMID 24315522.

- ^ Grace AA (August 2016). "Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 17 (8): 524–532. doi:10.1038/nrn.2016.57. PMC 5166560. PMID 27256556.

- ^ Fusar-Poli P, Meyer-Lindenberg A (January 2013). "Striatal presynaptic dopamine in schizophrenia, part II: meta-analysis of [(18)F/(11)C]-DOPA PET studies". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 39 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbr180. PMC 3523905. PMID 22282454.

- ^ Howes OD, Kambeitz J, Kim E, et al. (August 2012). "The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment". Archives of General Psychiatry. 69 (8): 776–786. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.169. PMC 3730746. PMID 22474070.

- ^ Arnsten AF, Girgis RR, Gray DL, Mailman RB (January 2017). "Novel Dopamine Therapeutics for Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia". Biological Psychiatry. 81 (1): 67–77. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.028. PMC 4949134. PMID 26946382.

- ^ Maia TV, Frank MJ (January 2017). "An Integrative Perspective on the Role of Dopamine in Schizophrenia". Biological Psychiatry. 81 (1): 52–66. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.021. PMC 5486232. PMID 27452791.

- ^ a b Pratt J, Dawson N, Morris BJ, et al. (February 2017). "Thalamo-cortical communication, glutamatergic neurotransmission and neural oscillations: A unique window into the origins of ScZ?" (PDF). Schizophrenia Research. 180: 4–12. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.013. PMID 27317361. S2CID 205075178.

- ^ Catts VS, Lai YL, Weickert CS, Weickert TW, Catts SV (April 2016). "A quantitative review of the post-mortem evidence for decreased cortical N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor expression levels in schizophrenia: How can we link molecular abnormalities to mismatch negativity deficits?". Biological Psychology. 116: 57–67. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.10.013. PMID 26549579.

- ^ Michie PT, Malmierca MS, Harms L, Todd J (April 2016). "The neurobiology of MMN and implications for schizophrenia". Biological Psychology. 116: 90–97. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.01.011. PMID 26826620. S2CID 41179430.

- ^ a b Marín O (January 2012). "Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 13 (2): 107–120. doi:10.1038/nrn3155. PMID 22251963. S2CID 205507186.

- ^ Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW (April 2005). "Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 6 (4): 312–324. doi:10.1038/nrn1648. PMID 15803162. S2CID 3335493.

- ^ Senkowski D, Gallinat J (June 2015). "Dysfunctional prefrontal gamma-band oscillations reflect working memory and other cognitive deficits in schizophrenia". Biological Psychiatry. 77 (12): 1010–1019. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.02.034. PMID 25847179. S2CID 206104940.

Several studies that investigated perceptual processes found impaired GBR in ScZ patients over sensory areas, such as the auditory and visual cortex. Moreover, studies examining steady-state auditory-evoked potentials showed deficits in the gen- eration of oscillations in the gamma band.

- ^ Reilly TJ, Nottage JF, Studerus E, et al. (July 2018). "Gamma band oscillations in the early phase of psychosis: A systematic review". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 90: 381–399. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.006. PMID 29656029. S2CID 4891072.

Decreased gamma power in response to a task was a relatively consistent finding, with 5 out of 6 studies reported reduced evoked or induced power.

- ^ a b Sloan SA, Barres BA (August 2014). "Mechanisms of astrocyte development and their contributions to neurodevelopmental disorders". Curr Opin Neurobiol. 27: 75–81. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2014.03.005. PMC 4433289. PMID 24694749.

- ^ Lesh TA, Niendam TA, Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS (January 2011). "Cognitive control deficits in schizophrenia: mechanisms and meaning". Neuropsychopharmacology. 36 (1): 316–338. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.156. PMC 3052853. PMID 20844478.

- ^ Barch DM, Ceaser A (January 2012). "Cognition in schizophrenia: core psychological and neural mechanisms". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 16 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.015. PMC 3860986. PMID 22169777.

- ^ Eisenberg DP, Berman KF (January 2010). "Executive function, neural circuitry, and genetic mechanisms in schizophrenia". Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (1): 258–277. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.111. PMC 2794926. PMID 19693005.

- ^ Walton E, Hibar DP, van Erp TG, et al. (May 2017). "Positive symptoms associate with cortical thinning in the superior temporal gyrus via the ENIGMA Schizophrenia consortium". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 135 (5): 439–447. doi:10.1111/acps.12718. PMC 5399182. PMID 28369804.

- ^ Walton E, Hibar DP, van Erp TG, et al. (Karolinska Schizophrenia Project Consortium (KaSP)) (January 2018). "Prefrontal cortical thinning links to negative symptoms in schizophrenia via the ENIGMA consortium". Psychological Medicine. 48 (1): 82–94. doi:10.1017/S0033291717001283. PMC 5826665. PMID 28545597.

- ^ Cohen AS, Minor KS (January 2010). "Emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia revisited: meta-analysis of laboratory studies". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (1): 143–150. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn061. PMC 2800132. PMID 18562345.

- ^ Strauss GP, Gold JM (April 2012). "A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 169 (4): 364–373. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030447. PMC 3732829. PMID 22407079.

- ^ Young J, Anticevic A, Barch D (2018). "Cognitive and Motivational Neuroscience of Psychotic Disorders". In Charney D, Buxbaum J, Sklar P, Nestler E (eds.). Charney & Nestler's Neurobiology of Mental Illness (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 215, 217. ISBN 9780190681425.

Several recent reviews (e.g., Cohen and Minor, 2010) have found that individuals with schizophrenia show relatively intact self-reported emotional responses to affect-eliciting stimuli as well as other indicators of intact response(215)...Taken together, the literature increasingly suggests that there may be a deficit in putatively DA-mediated reward learning and/ or reward prediction functions in schizophrenia. Such findings suggest that impairment in striatal reward prediction mechanisms may influence "wanting" in schizophrenia in a way that reduces the ability of individuals with schizophrenia to use anticipated rewards to drive motivated behavior.(217)

- ^ a b Wiberg A, Ng M, Al Omran Y, et al. (1 October 2019). "Handedness, language areas and neuropsychiatric diseases: insights from brain imaging and genetics". Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 142 (10): 2938–2947. doi:10.1093/brain/awz257. PMC 6763735. PMID 31504236.

- ^ Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Kennedy H, Van Essen DC, Christen Y (2016). "Intra- and Inter-hemispheric Connectivity Supporting Hemispheric Specialization". Micro-, Meso- and Macro-Connectomics of the Brain. Research and Perspectives in Neurosciences. pp. 129–146. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-27777-6_9. ISBN 978-3-319-27776-9. PMID 28590670. S2CID 147813648.

- ^ Ocklenburg S, Güntürkün O, Hugdahl K, Hirnstein M (December 2015). "Laterality and mental disorders in the postgenomic age—A closer look at schizophrenia and language lateralization". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 59: 100–110. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.08.019. PMID 26598216. S2CID 15983622.

- ^ Friston KJ, Stephan KE, Montague R, Dolan RJ (July 2014). "Computational psychiatry: the brain as a phantastic organ". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 1 (2): 148–158. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70275-5. PMID 26360579. S2CID 15504512.

- ^ Griffin JD, Fletcher PC (May 2017). "Predictive Processing, Source Monitoring, and Psychosis". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 13: 265–289. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045145. PMC 5424073. PMID 28375719.

- ^ Fletcher PC, Frith CD (January 2009). "Perceiving is believing: a Bayesian approach to explaining the positive symptoms of schizophrenia" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 10 (1): 48–58. doi:10.1038/nrn2536. PMID 19050712. S2CID 6219485.

- ^ Corlett PR, Taylor JR, Wang XJ, Fletcher PC, Krystal JH (November 2010). "Toward a neurobiology of delusions". Progress in Neurobiology. 92 (3): 345–369. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.06.007. PMC 3676875. PMID 20558235.

- ^ Bastos AM, Usrey WM, Adams RA, et al. (21 November 2012). "Canonical microcircuits for predictive coding". Neuron. 76 (4): 695–711. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.038. PMC 3777738. PMID 23177956.

- ^ Soltan M, Girguis J (8 May 2017). "How to approach the mental state examination". BMJ. 357: j1821. doi:10.1136/sbmj.j1821. PMID 31055448. S2CID 145820368. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Lindenmayer JP (1 December 2017). "Are Shorter Versions of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Doable? A Critical Review". Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 14 (11–12): 73–76. PMC 5788254. PMID 29410940.

- ^ "Diagnosis of schizophrenia". Australian Department of Health. 10 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Schizophrenia – Diagnosis". UK National Health Service. 23 October 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ Jakobsen KD, Frederiksen JN, Hansen T, et al. (2005). "Reliability of clinical ICD-10 schizophrenia diagnoses". Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 59 (3): 209–212. doi:10.1080/08039480510027698. PMID 16195122. S2CID 24590483.

- ^ a b c Richard-Devantoy S, Olie JP, Gourevitch R (December 2009). "[Risk of homicide and major mental disorders: a critical review]". L'Encephale. 35 (6): 521–530. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2008.10.009. PMID 20004282.

- ^ a b Staedt J, Hauser M, Gudlowski Y, Stoppe G (February 2010). "Sleep disorders in schizophrenia". Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie. 78 (2): 70–80. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1109967. PMID 20066610. S2CID 260137215.

- ^ a b Pocivavsek A, Rowland LM (13 January 2018). "Basic Neuroscience Illuminates Causal Relationship Between Sleep and Memory: Translating to Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 44 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbx151. PMC 5768044. PMID 29136236.

- ^ a b Monti JM, BaHammam AS, Pandi-Perumal SR, et al. (3 June 2013). "Sleep and circadian rhythm dysregulation in schizophrenia". Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 43: 209–216. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.12.021. PMID 23318689. S2CID 19626589.

- ^ Faulkner SM, Bee PE, Meyer N, Dijk DJ, Drake RJ (August 2019). "Light therapies to improve sleep in intrinsic circadian rhythm sleep disorders and neuro-psychiatric illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 46: 108–123. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2019.04.012. PMID 31108433.

- ^ Assimakopoulos K, Karaivazoglou K, Skokou M, et al. (24 March 2018). "Genetic Variations Associated with Sleep Disorders in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review". Medicines. 5 (2): 27. doi:10.3390/medicines5020027. PMC 6023503. PMID 29587340.

- ^ Dieset I, Andreassen O, Haukvik U (2016). "Somatic Comorbidity in Schizophrenia: Some Possible Biological Mechanisms Across the Life Span". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 42 (6): 1316–1319. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbw028. PMC 5049521. PMID 27033328.

- ^ Schrimpf LA, Aggarwal A, Lauriello J (June 2018). "Psychosis". Continuum (Minneap Minn). 24 (3): 845–860. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000602. PMID 29851881. S2CID 243933980.

- ^ Bottas A (15 April 2009). "Comorbidity: Schizophrenia With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Psychiatric Times. 26 (4). Archived from the original on 3 April 2013.

- ^ OConghaile A, DeLisi LE (May 2015). "Distinguishing schizophrenia from posttraumatic stress disorder with psychosis". Curr Opin Psychiatry. 28 (3): 249–255. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000158. PMID 25785709. S2CID 12523516.

- ^ Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH (2012). "Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice". In Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J (eds.). Bradley's neurology in clinical practice. Vol. 1 (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 92–111. ISBN 978-1-4377-0434-1.

- ^ Leucht S, Bauer S, Siafis S, Hamza T, Wu H, Schneider-Thoma J, Salanti G, Davis JM (November 2021). "Examination of Dosing of Antipsychotic Drugs for Relapse Prevention in Patients With Stable Schizophrenia: A Meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry. 78 (11): 1238–1248. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2130. PMC 8374744. PMID 34406325.

- ^ Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGorry P (May 2007). "The empirical status of the ultra high-risk (prodromal) research paradigm". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 33 (3): 661–664. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm031. PMC 2526144. PMID 17470445.

- ^ a b Marshall M, Rathbone J (June 2011). "Early intervention for psychosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD004718. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004718.pub3. PMC 4163966. PMID 21678345.

- ^ Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, Morrison AP, Kendall T (January 2013). "Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 346: f185. doi:10.1136/bmj.f185. PMC 3548617. PMID 23335473.

- ^ a b Taylor M, Jauhar S (September 2019). "Are we getting any better at staying better? The long view on relapse and recovery in first episode nonaffective psychosis and schizophrenia". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 9: 204512531987003. doi:10.1177/2045125319870033. PMC 6732843. PMID 31523418.

- ^ Weiden PJ (July 2016). "Beyond Psychopharmacology: Emerging Psychosocial Interventions for Core Symptoms of Schizophrenia". Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing). 14 (3): 315–327. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20160014. PMC 6526802. PMID 31975812.

- ^ McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, Wolfe R, Pascaris A (March 2007). "Cognitive training for supported employment: 2–3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (3): 437–441. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.3.437. PMID 17329468.

- ^ Souaiby L, Gaillard R, Krebs MO (August 2016). "[Duration of untreated psychosis: A state-of-the-art review and critical analysis]". Encephale. 42 (4): 361–366. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2015.09.007. PMID 27161262.

- ^ Fuller Torrey E (June 2015). "Deinstitutionalization and the rise of violence". CNS Spectrums. 20 (3): 207–214. doi:10.1017/S1092852914000753. PMID 25683467.

- ^ a b c "Schizophrenia – Treatment". UK National Health Service. 23 October 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Ortiz-Orendain J, Covarrubias-Castillo SA, Vazquez-Alvarez AO, Castiello-de Obeso S, Arias Quiñones GE, Seegers M, Colunga-Lozano LE (December 2019). "Modafinil for people with schizophrenia or related disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD008661. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008661.pub2. PMC 6906203. PMID 31828767.

- ^ Lally J, MacCabe JH (June 2015). "Antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: a review". British Medical Bulletin. 114 (1): 169–179. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldv017. PMID 25957394.

- ^ Keks N, Schwartz D, Hope J (October 2019). "Stopping and switching antipsychotic drugs". Australian Prescriber. 42 (5): 152–157. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2019.052. PMC 6787301. PMID 31631928.

- ^ Harrow M, Jobe TH (September 2013). "Does long-term treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotic medications facilitate recovery?". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 39 (5): 962–5. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbt034. PMC 3756791. PMID 23512950.

- ^ Elkis H, Buckley PF (June 2016). "Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 39 (2): 239–65. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.01.006. PMID 27216902.

- ^ Gillespie AL, Samanaite R, Mill J, Egerton A, MacCabe JH (13 January 2017). "Is treatment-resistant schizophrenia categorically distinct from treatment-responsive schizophrenia? a systematic review". BMC Psychiatry. 17 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-1177-y. PMC 5237235. PMID 28086761.

- ^ Essali A, Al-Haj Haasan N, Li C, Rathbone J (January 2009). "Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (1): CD000059. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000059.pub2. PMC 7065592. PMID 19160174.

- ^ Baier M (August 2010). "Insight in schizophrenia: a review". Current Psychiatry Reports. 12 (4): 356–361. doi:10.1007/s11920-010-0125-7. PMID 20526897. S2CID 29323212.

- ^ Peters L, Krogmann A, von Hardenberg L, et al. (19 November 2019). "Long-Acting Injections in Schizophrenia: a 3-Year Update on Randomized Controlled Trials Published January 2016 – March 2019". Current Psychiatry Reports. 21 (12): 124. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1114-0. PMID 31745659. S2CID 208144438.

- ^ Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, et al. (June 2012). "Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 379 (9831): 2063–2071. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60239-6. PMID 22560607. S2CID 2018124.

- ^ McEvoy JP (2006). "Risks versus benefits of different types of long-acting injectable antipsychotics". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (Suppl 5): 15–18. PMID 16822092.

- ^ a b Chow CL, Kadouh NK, Bostwick JR, VandenBerg AM (June 2020). "Akathisia and Newer Second-Generation Antipsychotic Drugs: A Review of Current Evidence". Pharmacotherapy. 40 (6): 565–574. doi:10.1002/phar.2404. hdl:2027.42/155998. PMID 32342999. S2CID 216596357.

- ^ Carbon M, Kane JM, Leucht S, Correll CU (October 2018). "Tardive dyskinesia risk with first- and second-generation antipsychotics in comparative randomized controlled trials: a meta-analysis". World Psychiatry. 17 (3): 330–340. doi:10.1002/wps.20579. PMC 6127753. PMID 30192088.

- ^ a b Pharoah F, Mari J, Rathbone J, Wong W (December 2010). Pharoah F (ed.). "Family intervention for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD000088. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000088.pub2. PMC 4204509. PMID 21154340.

- ^ Bellani M, Ricciardi C, Rossetti MG, Zovetti N, Perlini C, Brambilla P (September 2019). "Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: the earlier the better?". Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 29: e57. doi:10.1017/S2045796019000532. PMC 8061237. PMID 31556864.

- ^ Philipp R, Kriston L, Lanio J, et al. (2019). "Effectiveness of metacognitive interventions for mental disorders in adults-A systematic review and meta-analysis (METACOG)". Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 26 (2): 227–240. doi:10.1002/cpp.2345. PMID 30456821. S2CID 53872643.

- ^ Rouy M, Saliou P, Nalborczyk L, Pereira M, Roux P, Faivre N (July 2021). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of metacognitive abilities in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders" (PDF). Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 126: 329–337. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.03.017. PMID 33757817. S2CID 232288918.

- ^ Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, et al. (January 2010). "The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (1): 48–70. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp115. PMC 2800143. PMID 19955389.

- ^ Bond GR, Drake RE (June 2015). "The critical ingredients of assertive community treatment". World Psychiatry. 14 (2): 240–242. doi:10.1002/wps.20234. PMC 4471983. PMID 26043344.

- ^ Smeerdijk M (2017). "[Using resource groups in assertive community treatment; literature review and recommendation]". Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie. 59 (8): 466–473. PMID 28880347.

- ^ Dieterich M (6 January 2017). "Intensive case management for severe mental illness". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD007906. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007906.pub3. PMC 6472672. PMID 28067944.

- ^ Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Radua J, et al. (January 2014). "Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential bias". The British Journal of Psychiatry (Review). 204 (1): 20–29. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116285. PMID 24385461.

- ^ a b Jones C, Hacker D, Meaden A, et al. (November 2018). "Cognitive behavioural therapy plus standard care versus standard care plus other psychosocial treatments for people with schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (6): CD008712. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008712.pub3. PMC 6516879. PMID 30480760.

- ^ Health Quality, Ontario (2018). "Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Psychosis: A Health Technology Assessment". Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series. 18 (5): 1–141. PMC 6235075. PMID 30443277.

- ^ Ruddy R, Milnes D (October 2005). "Art therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003728. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003728.pub2. PMID 16235338. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011.

- ^ Ruddy RA, Dent-Brown K (January 2007). "Drama therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005378. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005378.pub2. PMID 17253555. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011.

- ^ Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, et al. (May 2016). "Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 50 (5): 410–472. doi:10.1177/0004867416641195. PMID 27106681. S2CID 6536743.

- ^ Chien WT, Clifton AV, Zhao S, Lui S (4 April 2019). "Peer support for people with schizophrenia or other serious mental illness". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (6): CD010880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010880.pub2. PMC 6448529. PMID 30946482.

- ^ a b Girdler SJ, Confino JE, Woesner ME (15 February 2019). "Exercise as a Treatment for Schizophrenia: A Review". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 49 (1): 56–69. PMC 6386427. PMID 30858639.

- ^ a b Firth J (1 May 2017). "Aerobic Exercise Improves Cognitive Functioning in People With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 43 (3): 546–556. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbw115. PMC 5464163. PMID 27521348.

- ^ Tréhout M, Dollfus S (December 2018). "[Physical activity in patients with schizophrenia: From neurobiology to clinical benefits]". L'Encéphale. 44 (6): 538–547. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2018.05.005. PMID 29983176. S2CID 150334210.