파슈툰스

Pashtunsپښتانه | |

|---|---|

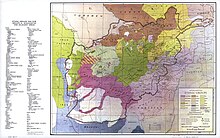

아프가니스탄 남부의 파슈툰 부족 및 종교인 수 | |

| 총인구 | |

| c. 4천9백만 | |

| 인구가 많은 지역 | |

| 40,097,131 (2023)[1] | |

| 18,831,361 (2023)[2] | |

| 3,200,000 (2018)[3][4] | |

| 169,000 (2022)[5] | |

| 538,000 (2021)[6] | |

| 100,000 (2009)[7] | |

| 32,400 (2017)[8] | |

| 31,700 (2021)[9] | |

| 19,800 (2015)[10] | |

| 12,662 (2021)[11] | |

| 언어들 | |

| 파슈토 서로 다른 방언: 와네치 주, 중부 파슈토 주, 남부 파슈토 주, 북부 파슈토[12] 주 | |

| 종교 | |

| 과반수: 수니파 이슬람교 소수자: 시아파 이슬람,[13] 수피즘,[14][15]힌두교와[16] 시크교[17] | |

| 관련 민족 | |

| 그 밖의 이란계 민족 | |

Pashtuns (/ˈpʌʃˌtʊn/, /ˈpɑːʃˌtʊn/, /ˈpæʃˌtuːn/; Pashto: پښتانه, romanized: Pəx̌tānə́;[18] Pashto pronunciation:[pəxˈtɑːna]), also known as Pakhtuns,[19] or Pathans,[a] are a nomadic,[23][24][25]pastoral,[26][27]Eastern Iranic ethnic group[19] primarily residing in northwestern Pakistan and southern and eastern Afghanistan.[28][29] 이 용어의 의미가 아프가니스탄의 모든 민족 구성원들의 대명사가 [35]된 이후인 1970년대까지 그들은 역사적으로 아프가니스탄[b] 사람들이라고도 불렸습니다.[35][36]

파슈툰족은 파슈토어를 사용하며, 파슈토어는 이란어족의 동부 이란어파에 속합니다. 또한 다리어는 아프가니스탄에서 파슈툰족의 제2언어로 [37][38]사용되며 파키스탄과 인도에서는 힌디어-우르두어와 다른 지역 언어를 제2언어로 사용합니다.[39][40][41][42]

파슈툰 부족과 씨족은 350~400개로 추정되며 다양한 기원설을 가지고 있습니다.[43][44][45] 전 세계적으로 파슈툰족의 총 인구는 약 4,900만 명으로 추정되지만,[46] 1979년 이후 아프가니스탄에서 공식적인 인구 조사가 없었기 때문에 이 수치는 논란이 되고 있습니다.[47] 그들은 파키스탄에서 두 번째로 큰 민족이며 아프가니스탄에서 가장 큰 민족 중 하나이며,[48] 전체 파키스탄 인구의 약 18.24%, 전체 아프가니스탄 인구의 약 47%를 구성합니다.[49][50][51] 인도에는 북부 로힐칸드 지역은 물론 델리, 뭄바이 등 인도 주요 도시에 파슈툰 디아스포라의 중요하고 역사적인 공동체가 존재합니다.[52][53]

지리적 분포

| 에 관한 시리즈의 일부 |

| 파슈툰스 |

|---|

| 제국과 왕조 |

아프가니스탄과 파키스탄

파슈툰은 아무 강 남쪽과 인더스 강 서쪽의 넓은 지역에 걸쳐 펼쳐져 있습니다. 그들은 아프가니스탄과 파키스탄 전역에서 발견될 수 있습니다.[28] 파슈툰족이 다수를 차지하는 대도시로는 잘랄라바드, 칸다하르, 바누, 데라 이스마일 칸, 고스트, 코하트, 라슈카르 가, 마르단, 밍고라, 페샤와르, 퀘타 등이 있습니다. 파슈툰스는 또한 아보타바드, 파라, 가즈니, 헤라트, 이슬라마바드, 카불, 카라치, 쿤두즈, 라호르, 마자르이샤리프, 물탄, 라왈핀디, m왈리, 애톡 등 여러 도시에 살고 있습니다.

파키스탄의 금융 수도인 카라치 시는 카불과 페샤와르보다 더 큰 세계에서 가장 큰 도시 공동체인 파슈툰스의 본거지입니다.[54] 마찬가지로, 이 나라의 정치 수도인 이슬라마바드는 파슈토어 사용자 공동체에 속한 도시 인구의 20% 이상을 차지하는 파슈툰스의 주요 도시 중심지 역할도 하고 있습니다.

인도

인도의 파슈툰족은 흔히 파슈툰족(파슈툰족을 뜻하는 힌두스타니어)으로 불리며, 그들과 아대륙의 다른 민족들에 의해 널리 알려집니다.[55][56][57][58] 일부 인도인들은 인도 아대륙에서 무슬림 정복 중 현지 여성과 결혼하여 인도에 정착한 파슈툰족 병사들의 후손이라고 주장합니다.[59] 인도가 분열된 후 많은 파타인들이 인도 공화국에서 살기를 선택했고, 럭나우 대학의 교수인 칸 모하마드 아티프는 "인도의 파타인 인구는 아프가니스탄 인구의 두 배"라고 추정합니다.[60]

역사적으로, 파슈툰은 식민지 인도에서 영국의 라지 이전과 동안 인도의 다양한 도시에 정착했습니다. 봄베이(현재 뭄바이라고 불리는), 파루카바드, 델리, 캘커타, 사하라푸르, 로힐칸드, 자이푸르, 방갈로르 등이 여기에 포함됩니다.[52][61][53] 정착민들은 현재의 아프가니스탄과 파키스탄(1947년 이전의 영국령 인도)의 파슈툰족의 후손입니다. 인도의 일부 지역에서는 카불리왈라라고 불리기도 합니다.[62]

인도에는 중요한 파슈툰 디아스포라 공동체가 존재합니다.[63][59] 2011년 현재 인도의 파슈토어 사용자는 21,677명에 불과하지만, 인도의 민족 또는 조상 파슈툰 인구의 추정치는 3,200,000명에서[3][4][64] 11,482,000명으로[65] 아프가니스탄 인구(약 3,000만 명)의 두 배에 이릅니다.[66]

우타르 프라데시의 로힐칸드 지역은 파슈툰 조상의 로힐라 공동체의 이름을 따서 지어졌습니다. 이 지역은 파슈툰 왕조인 람푸르 왕가의 통치를 받게 되었습니다.[67] 그들은 또한 파슈툰 혈통을 가진 인구가 각각 백만 명이 넘는 중부 인도의 마하라슈트라 주와 동부 인도의 서벵골 주에 살고 있습니다;[68] 봄베이와 캘커타는 모두 식민지 시대 동안 아프가니스탄에서 온 파슈툰 이민자들의 주요 위치였습니다.[69] 라자스탄의 자이푸르와 카르나타카의 방갈로르에도 각각 10만 명 이상의 인구가 살고 있습니다.[68] 봄베이(현재 뭄바이로 불리는)와 캘커타(Calcuta)는 모두 파슈툰 인구가 100만 명이 넘는 반면 자이푸르(Jaipur)와 방갈로르(Bangalor)는 약 10만 명으로 추정됩니다. 방갈로르에 있는 파슈툰족에는 아버지가 가즈니에서 방갈로르에 정착한 칸 남매 페로스, 산제이, 아크바르 칸이 있습니다.[70]

19세기 영국이 카리브해, 남아프리카 등지에서 일하기 위해 영국령 인도에서 온 농민들을 계약종으로 받아들였을 때, 제국을 잃고 실업자와 안절부절못하던 로히야들은 트리니다드, 수리남, 가이아나, 피지까지 먼 곳으로 보내졌습니다. 사탕수수 밭에서 다른 인디언들과 함께 일하고 육체노동을 하는 것입니다.[71] 이 이민자들 중 많은 사람들이 그곳에 머물며 그들만의 독특한 공동체를 형성했습니다. 그들 중 일부는 다른 남아시아 무슬림 민족과 동화되어 더 큰 인도 공동체와 함께 공동의 인도 무슬림 공동체를 형성하여 독특한 유산을 잃었습니다. 일부 파슈툰들은 같은 시대에 호주까지 여행했습니다.[72]

오늘날 파슈툰족은 인도의 길이와 폭에 걸쳐 존재하는 다양하게 흩어져 있는 공동체의 집합체이며, 가장 많은 인구가 주로 인도 북부와 중부의 평야에 정착합니다.[73][74][75] 1947년 인도의 분할 이후, 그들 중 많은 사람들이 파키스탄으로 이주했습니다.[73] 인도 파슈툰족의 대다수는 우르두어를 사용하는 공동체로,[76] 여러 세대에 걸쳐 지역 사회에 동화되었습니다.[76] 파슈툰은 인도의 다양한 분야, 특히 정치, 엔터테인먼트 산업 및 스포츠에 영향을 미치고 기여했습니다.[75]

이란

파슈툰은 또한 이란의 동부와 북부 지역에서 더 적은 숫자로 발견됩니다.[77] 1600년대 중반의 기록은 사파비드 이란의 호라산 주에 사는 두라니 파슈툰스를 보고합니다.[78] 이란의 길지 파슈툰족의 짧은 통치 이후, 나데르 샤는 칸다하르의 마지막 독립적인 길지 통치자인 후세인 호탁을 물리쳤습니다. 나데르 샤는 아프가니스탄 남부의 두라니족 지배권을 확보하기 위해 후세인 호탁과 다수의 질지 파슈툰족을 이란 북부의 마잔다란 주로 추방했습니다. 한때 거대했던 이 유배 사회의 잔재들은 동화되기는 했지만 여전히 파슈툰계를 주장하고 있습니다.[79] 18세기 초 몇 년 동안 이란 코라산의 두라니 파슈툰족의 수는 크게 증가했습니다.[80] 나중에 이 지역은 두라니 제국 자체의 일부가 되었습니다. 아프가니스탄의 두 번째 두라니 왕 티무르 샤 두라니는 마슈하드에서 태어났습니다.[81] 동부의 두라니 통치와 동시에 아프샤리드 통치 기간 동안 아제르바이잔의 2인자였던 아자드 칸 아프간 민족은 짧은 기간 동안 이란과 아제르바이잔의 서부 지역에서 권력을 잡았습니다.[82] 1988년 표본 조사에 따르면, 이란 호라산주 남부 지역의 전체 아프가니스탄 난민의 75%가 두라니 파슈툰스였습니다.[83]

기타지역

인도인과 파키스탄인 파슈툰족은 해당 국가의 영연방/영연방 연계를 활용해 왔으며, 1960년대경부터 주로 영국, 캐나다, 호주뿐만 아니라 다른 영연방 국가(및 미국)에서도 현대적인 공동체가 설립되었습니다. 일부 파슈툰족은 아라비아 반도와 같은 중동에도 정착했습니다. 예를 들어, 1976년에서 1981년 사이에 약 30만 명의 파슈툰족이 페르시아만 국가로 이주했으며, 이는 파키스탄 이민자의 35%를 차지합니다.[84] 파키스탄과 아프가니스탄의 전 세계 디아스포라에는 파슈툰스가 포함되어 있습니다.

어원

고대 역사 참고 자료: 파슈툰

기원전 1500년에서 1200년 사이의 베다 산스크리트 찬송가 텍스트인 리그베다의 일곱 번째 만다라에는 다사라냐에서 수다와 싸웠던 부족 중 하나인 팍타스(Pakthás)라는 부족이 언급되어 있습니다.[85][86]

पक्थास 족, 발라나 족, 알리나 족, 시바스 족, 비사닌 족이 모였습니다. 그러나 트르투스는 전리품과 영웅들의 전쟁에 대한 사랑을 통해 아리아의 동지가 와서 그들을 이끌었습니다.

— Rigveda, Book 7, Hymn 18, Verse 7

하인리히 짐머(Heinrich Zimmer)는 기원전 430년 헤로도토스(Pactyans)가 언급한 부족과 그들을 연결합니다.[87][88][89]

다른 인도인들은 인도의 북쪽에 있는 카스파티루스[κα σπα τύρῳ] 마을과 팩티크[πα κτυϊκῇ] 국가 근처에 살고 있습니다. 이들은 박트리아인들처럼 살고 있습니다. 그들은 모든 인도인들 중에서 가장 호전적이고, 그들은 금을 얻기 위해 보내집니다. 이 지역들은 모래 때문에 모든 것이 황폐하기 때문입니다.

— Herodotus, The Histories, Book III, Chapter 102, Section 1

이 팩티아인들은 일찍이 기원전 1천년, 오늘날 아프가니스탄의 아케메네스 아라코시아 사트라피의 동쪽 국경에서 살았습니다.[90] 헤로도토스는 아파리타이(ἀ πα ρύτα ι)로 알려진 부족에 대해서도 언급합니다. Thomas Holdich는 그들을 아프리카 부족과 연결시켰습니다.[92][93][94]

사타기대, 간다리, 다디개, 아파리태(ἀ πα ρύτα ι)가 백칠십 달란트를 합하여 지급하였는데, 이 지방이 일곱 번째 지방이었습니다.

— Herodotus, The Histories, Book III, Chapter 91, Section 4

요제프 마르쿠르트는 파슈툰족을 프톨레마이오스 150년에 인용된 파르시 ē타이(πα ρσιῆτα ι), 파르시오이(π άρσιοι)와 같은 이름과 연결시켰습니다.

"이 나라의 북쪽 지역에는 볼리타이족이 살고 있고, 서쪽 지역에는 파르시오이(π άρσιοι)에 사는 아리스토필로이족이 살고 있습니다. 남부 지역은 ē ρσιῆτ타이(암보타이), 동부 지역은 암보타이(암보타이)가 거주하고 있습니다. 파로파니사다이 지방에 있는 마을과 마을은 다음과 같습니다. 파르시아나 자르자우아/바르자우라 아르토아르타 바보라나 카피사 니판다입니다."

— Ptolemy, 150 CE, 6.18.3-4

그리스 지리학자 스트라보(기원전 43년에서 서기 23년 사이)는 스키타이 부족인 파시아니(πα σια νοί)에 대해 언급하고 있는데, 이는 파슈토어가 스키타이어와 매우 유사한 동이란어라는 점을 감안할 때 파슈툰족과도 동일시됩니다.

"대부분의 스키타이인들은...각각의 부족들은 고유한 이름을 가지고 있습니다. 모두 또는 그 중 가장 큰 부분은 유목민입니다. 가장 잘 알려진 부족들은 이악사르테스의 반대편에 있는 나라에서 온 박트리아나족, 아시족, 파시아니족, 토차리족, 사카룰리족을 빼앗은 부족들입니다."

— Strabo, The Geography, Book XI, Chapter 8, Section 2

이것은 프톨레마이오스의 파르시오이(π άρσιοι)를 다른 형태로 렌더링한 것으로 여겨집니다. 조니 쳉은 프톨레마이오스의 파시오이(π άρσιοι)와 스트라보의 파시아니(πα σια νοί)에 대해 반성하면서 다음과 같이 말합니다. "두 형태 모두 ι에 대한 υ의 약간의 음성 대체를 보여주며, 파시아노이에서 r의 손실은 이전의 아시아노이의 인내심 때문입니다. 따라서 그들은 오늘날의 파슈툰족의 (언어적) 조상으로 가장 유력한 후보입니다."[103]

중간 역사 참조: 아프간

18세기 현대 아프가니스탄이 등장하기 전까지 중세 시대에 파슈툰족은 종종 "아프간"이라고 불렸습니다.[104] 수많은 저명한 학자들이 지지하는 어원론적 견해는 아프가니스탄이라는 이름이 분명히 산스크리트어 ś 바칸, 즉 힌두교 쿠시의 고대 주민들에게 사용되었던 이름이었던 아리안의 아사케노이에서 유래했다는 것입니다. ś 바칸은 문자 그대로 "말꾼", "말 사육사" 또는 "카발리멘"을 의미합니다 ("말"을 뜻하는 산스크리트어와 아베스탄어에서 온 ś 바 또는 아스파). 이 견해는 Christian Lassen,[107] J. W. McCrindle,[108] M. V. de Saint Martin,[109] 그리고 E와 같은 학자들에 의해 주장되었습니다. 리클러스,[110][111][112][113][114][115]

아프간(Abgân)이라는 이름에 대한 가장 초기의 언급은 서기 3세기 동안 사산 제국의 샤푸르 1세에 의한 것입니다. 4세기에 특정 민족을 지칭하는 "아프간/아프간"(αβ γα να νο)이라는 단어가 북부 아프가니스탄에서 발견된 박트리아 문서에 언급되어 있습니다.

"브레다그 와타난에서 온 오르무즈드 부누칸에게... ...의 인사와 경의를 표합니다." "아프간 족장 헤프탈의 소탕(?)" "투카리스탄과 가르키스탄의 재판관입니다." 게다가, "당신에게서 편지가 왔습니다." 그래서 저는 제 건강과 관련하여 선생님께서 어떻게 저에게 ''를 쓰셨는지 들었습니다. 저는 건강한 상태로 도착했고, (그리고) (이후에 (?) '라는 메시지가 당신에게 전송되었다고 들었습니다 : ... 농사를 돌보시되 명령이 내려지셨습니다. 당신은 곡식을 넘겨준 다음 시민 상점에 요청해야 합니다. 저는 주문하지 않을 것이기 때문에...나는 내가 직접 명령하고 겨울을 존중하여 사람들을 당신에게 보내고 농사를 돌봅니다, 오르무즈드 부누칸에게, 인사합니다."

— the Bactrian documents, 4th century

"아프간 사람들의 일족인 [당신](플)이 나에게 이렇게 말했기 때문입니다.그리고 부인하지 말았어야 했습니까? 아프간[119] 사람들이 말들을 빼앗았습니다."

— the Bactrian documents, 4th century, Sims-Williams 2007b, pp. 90-91

"아프간에 입찰하기 위해... 게다가 그들은 아프간인들 때문에 [전쟁]누(?)에 처해 있기 때문에 [당신은] 낫 카라간에게 벌을 부과해야 합니다 ... 와르누의 영주... 아프간인..."

— the Bactrian documents, 4th century, Sims-Williams 2007b, pp. 90-91

아프가니스탄이라는 이름은 나중에 서기 6세기에 인도 천문학자 바라하 미히라가 브리하트 삼히타에서 "아바가 ṇ"[अवगाण]의 형태로 기록됩니다.

"이것은 촐라 사람들, 아프간 사람들(아바가 ṇ), 백인 훈족, 중국인들에게 불리할 것입니다."

— Varāha Mihira, 6th century CE, chapt. 11, verse 61

아프가니스탄이라는 단어는 982년 ḥ 우두드 알 ʿ 알람에도 등장했는데, 여기서 아마도 아프가니스탄의 가르데즈 근처에 위치한 사울이라는 마을을 언급하고 있습니다.

"산 위의 쾌적한 마을 살. 살아있는 아프간 사람들"[123]이라고 말했습니다.

같은 책은 또한 닌하르(낭가르하르)의 한 왕에 대해서도 이야기하고 있는데, 그 왕은 무슬림, 아프가니스탄 그리고 힌두교의 부인들을 가지고 있었습니다.[124] 11세기에 아프간인들은 오늘날 파키스탄의 인더스강 서쪽 부족 지역에서 반란을 일으킨 아프간인들의 집단을 묘사한 알비루니의 타리크울 힌드("인더스의 역사")에 언급되어 있습니다.[123][125]

가즈나비드 연대기 작자 알 웃비는 그의 타리크이 야미니에서 자야팔라가 패배한 후 많은 아프간인과 킬지인(아마도 현대의 길지인)이 사북티긴의 군대에 입대했다고 기록했습니다.[126] 알 우트비는 또한 아프간인들과 질지들이 마흐무드 가즈나비의 군대에 속해 토카리스탄으로 원정을 보냈으며, 마흐무드 가즈나비는 아불파즐 베하키에 의해서도 확인된 바와 같이 반대하는 아프간인들의 무리를 공격하고 처벌했다고 말했습니다.[127] 아프간인들도 구리드 왕국(1148–1215)에 등록되었다고 기록되어 있습니다.[128] 1290년 킬지 왕조가 시작될 때까지 아프간인들은 북부 인도에서 잘 알려져 있었습니다.

이븐 바투타는 킬지 왕조 시대에 이어 아프가니스탄을 방문했을 때도 아프간인들에 대한 글을 썼습니다.

"우리는 이전에 광활한 마을이었던 카불로 여행을 떠났고, 그 곳은 현재 아프간인들이 점령하고 있습니다. 그들은 산과 오물을 품고 있고 상당한 힘을 가지고 있으며, 대부분 도로 공사를 하고 있습니다. 그들의 주요 산은 쿠 술레이만이라고 불립니다. 예언자 술레이만[솔로몬]이 이 산에 올라 어둠으로 뒤덮인 인도를 내다보다가 그곳에 들어가지 못하고 돌아왔다고 합니다."[129]

— Ibn Battuta, 1333

16세기 무슬림 역사가 페리슈타는 아대륙의 무슬림 통치 역사에 대해 다음과 같이 썼습니다.

따라서 그는 가족 및 여러 아랍 가신들과 함께 물탄과 페샤와르 사이에 위치한 술라이만 산맥으로 은퇴하고 마호메트즘의 산신도가 된 아프가니스탄 족장 중 한 명과 결혼하여 딸을 낳았습니다. 이 결혼으로 인해 많은 아이들이 태어났고, 그 중에는 역사적으로 유명한 두 아들이 있었습니다. 한 사람은 로디이고, 다른 한 사람은 수르이고, 그들은 나중에 각각 오늘날까지도 그들의 이름을 가진 지파의 우두머리가 되었습니다. 나는 <무틀라울안와르>에서, 존경할 만한 작가가 쓴 작품으로, 데칸에 있는 칸데쉬 마을인 부르한푸르에서 조달한 것으로, 아프간 사람들은 바로의 종족의 콥트교도들이며, 예언자 모세가 홍해에서 압도당한 이교도들을 능가할 때에, 많은 콥트교도들이 유대인 신앙으로 개종했습니다. 그러나 다른 사람들은 고집이 세고 자기 의지가 강해 진정한 신앙을 받아들이기를 거부하고 조국을 떠나 인도로 와서 결국 술리마니 산맥에 정착했고, 그곳에서 아프간 사람들의 이름을 얻었습니다.[33]

역사와 기원

파슈툰족의 민족 발생은 불분명합니다. 역사학자들과 파슈툰족 사이에는 많은 상충되는 이론들이 있습니다. 현대 학자들은 파슈툰이 모두 같은 기원을 가지고 있는 것은 아니라고 생각합니다. 오늘날의 파슈툰족의 초기 조상들은 동부 이란 고원에 퍼져 있는 오래된 이란 부족에 속했을 수도 있습니다.[130][131][29] 역사학자들은 또한 기원전 2세기에서 1천년 사이에 팍타스(Pakthas, 팩션)라고 불리는 다양한 고대 민족에 대한 언급을 접했습니다.[132][133]

모한 랄(Mohan Lal)은 1846년에 "아프간의 기원은 너무 모호하여, 심지어 가장 오래되고 영리한 부족들 중에서도, 그 누구도 이 점에 대해 만족스러운 정보를 줄 수 없습니다."라고 말했습니다.[134] 다른 사람들은 파슈툰족의 단일 기원은 가능성이 없으며 오히려 부족 연합이라고 제안했습니다.

"파슈툰족과 아프간인의 기원을 찾는 것은 아마존의 기원을 탐구하는 것과 같습니다. 한 가지 구체적인 시작이 있습니까? 그리고 파슈툰족은 원래 아프간인과 동일합니까? 비록 오늘날 파슈툰인들은 그들만의 언어와 문화를 가진 분명한 민족 집단을 구성하고 있지만, 현대의 모든 파슈툰인들이 같은 민족적 기원을 가지고 있다는 증거는 전혀 없습니다. 사실 그럴 가능성은 매우 낮습니다."[123]

— Vogelsang, 2002

언어적 기원

파슈토어는 일반적으로 이란 동부의 언어로 분류됩니다.[135][136][137] 문자 언어와 특징을 공유하고 있는데, 문자 언어는 멸종된 박트리아어에 가장 가까운 언어이지만 [138]소그드어뿐만 아니라 흐와레즈미안어, 슈흐니어, 상레치어, 호타니어 사카어와도 특징을 공유합니다.[139]

일각에서는 파슈토어가 바다흐샨 지역에서 유래했을 가능성이 있으며, 코타니어와 유사한 사카어와 관련이 있다고 주장합니다.[140] 사실 주요 언어학자 게오르그 모르겐스티어른은 파슈토어를 사카어 방언으로 묘사했고 다른 많은 언어들도 파슈토어와 다른 사카어들 사이의 유사성을 관찰했으며, 이는 원래 파슈토어 사용자들이 사카어 집단이었을 수도 있음을 시사합니다.[141][142] 게다가 또다른 스키타이계 언어인 파슈토어와 오세티안어, 그들의 어휘에서 청이 부족한[143] 다른 동부 이란 언어들을 공유하는 것은 파슈토어와 오세티안어 사이의 공통적인 동족 손실을 시사하며, 그는 당시 옥수스어 북쪽에서 사용되었을 가능성이 있는 재구성된 옛 파슈토어에 가까운 문서화되지 않은 사카 방언으로 설명합니다.[144] 그러나 다른 이들은 올드 아베스탄과 친밀도를 감안할 때 훨씬 더 오래된 이란인 조상을 제시했습니다.[145]

다양한 원산지

한 학파에 따르면, 파슈툰인들은 페르시아인, 그리스인, 터키인, 아랍인, 박트리아인, 스키타이인, 타르타르인, 훈족(헤프탈리트인), 몽골인, 몽골인, 몽골인, 무굴인, 그리고 이 파슈툰인들이 살고 있는 지역을 건너온 모든 사람들을 포함한 다양한 민족의 후손이라고 합니다. 게다가 그들은 또한, 아마도 가장 놀라운 것은, 이스라엘 혈통입니다.[146][147]

일부 파슈툰 부족들은 아랍계의 후손이라고 주장하고 있으며, 일부는 사이이데스라고 주장하고 있습니다.[148]

한 역사적 기록은 파슈툰족을 고대 이집트의 과거로 추정할 수 있는 것과 연결하고 있지만, 이를 뒷받침하는 증거가 부족합니다.[149]

아프가니스탄 문화에 대해 광범위하게 글을 쓴 헨리 월터 벨류(Henry Walter Bellew)는 일부 사람들이 방가시 파슈툰족이 이스마일 사마니(Ismail Samani)와 연결되어 있다고 주장한다고 언급했습니다.[150]

그리스어 기원

Firasat et al. 2007에 따르면, 파슈툰족의 일부가 그리스인의 후손일 수도 있지만, 그들은 또한 그리스 혈통이 크세르크세스 1세가 데려온 그리스 노예들로부터 왔을 수도 있음을 시사합니다.[151]

파슈툰족의 그리스 혈통은 동족 집단을 기준으로 추적할 수도 있습니다. 그리고 Hoplogroup J2는 셈족의 인구이며, 이 Hoplogroup은 그리스인과 파슈툰족의 6.5%와 이스라엘인 인구의 55.6%에서 발견됩니다.[152]

최근 여러 기관과 연구소의 학자들이 파슈툰에 대한 유전자 연구를 많이 진행하고 있습니다. 파키스탄 파슈툰스의 그리스 유산을 조사했습니다. 이 연구에서는 알렉산더의 군사의 후손인 파슈툰족, 칼라시족, 부루쇼족을 고려했습니다.[153]

헨리 발터 벨류(Henry Walter Bellew, 1834–1892)는 파슈툰족이 그리스와 인도 라즈푸트의 뿌리를 혼합했을 가능성이 있다고 생각했습니다.[154][155]

알렉산더의 짧은 점령 이후, 셀레우코스 제국의 후계국은 기원전 305년까지 파슈툰족에게 영향력을 확대했고, 그들은 동맹 조약의 일환으로 인도 마우리아 제국에게 지배권을 포기했습니다.[156]

페샤와르와 칸다하르의 몇몇 집단들은 알렉산더 대왕과 함께 도착한 그리스인들의 후손이라고 믿고 있습니다.[157]

헤프탈라이트 기원

어떤 기록에 따르면, 질지 부족은 칼라인들과 연결되어 있다고 합니다.[158] 알콰리즈미에 이어 요제프 마크워트는 할라족이 헤프탈리트 연합의 잔재라고 주장했습니다.[159] 비록 그들이 튀르크계 가오주 출신이라는[160] 견해가 "현재 가장 두드러진 것 같다"고 할지라도,[159] 헤프탈리트인은 인도-이란인이었을지도 모릅니다.[161] 할라족은 원래 튀르크어를 사용하는 민족이었고 중세 시대에는 이란 파슈토어를 사용하는 부족들과 연합했을 수도 있습니다.[162]

그러나, 언어학자 심스-윌리엄스에 따르면, 역사학자 5세에 따르면,[163] 고고학 문서들은 칼라지족이 헤프탈리트족의 계승자였다는 주장을 뒷받침하지 않습니다. 미노르스키, 칼라지족은 "아마도 헤프탈리트족과 정치적으로만 연관되었을 것입니다."[164]

게오르크 모르겐스티어네에 따르면, 두라니 제국이 1747년에 형성되기 전에 "압달리"로 알려진 두라니 부족은 [165]헤프탈리트와 관련이 있을 수 있다고 합니다.[166] 아이독디 쿠르바노프는 헤프탈리트 연합이 붕괴된 후에 다른 지역 집단에 동화되었을 가능성이 있다고 제안하는 이 견해를 지지합니다.[167]

<캠브리지 히스토리 오브 이란> 3권 1호에 따르면 아프가니스탄의 질지 부족은 헤프탈리트의 후손입니다.[168]

인류학과 구전

이스라엘 민족으로부터의 파슈툰 혈통론

일부 인류학자들은 파슈툰 부족들의 구전에 신뢰를 보냅니다. 예를 들어, 이슬람 백과사전에 따르면 파슈툰계의 이스라엘 민족 혈통론은 17세기 무굴 황제 제항기르 치세에 칸-에-제한 로디의 역사를 집대성한 니마트 알라 알-하라위로 거슬러 올라갑니다.[169] 13세기 Tabaqat-i Nasiri는 서기 8세기 말 아프가니스탄의 고르 지역에 이민자 바니 이스라엘의 정착에 대해 논의하며, 고르에 유대인의 비문에 의해 입증되었습니다. 역사학자 안드레 윙크는 이 이야기가 "페르시아-아프간 연대기에서 끈질기게 주장되는 일부 아프간 부족의 유대인 기원에 대한 놀라운 이론의 단서를 담고 있을 수 있다"고 제안합니다.[170] 바니 이스라엘에 대한 이러한 언급은 이스라엘의 12개 지파가 분산되었을 때 다른 히브리 지파 중에서도 요셉 지파가 아프가니스탄 지역에 정착했다는 파슈툰스의 일반적인 견해에 동의합니다.[171] 이 구전은 파슈툰 부족 사이에 널리 퍼져 있습니다. 집단이 기독교와 이슬람교로 개종한 후 십여 개의 잃어버린 부족에서 내려온 수세기 동안 많은 전설이 있습니다. 그래서 파슈토의 부족명 유수프자이는 "요셉의 아들"로 번역됩니다. 비슷한 이야기가 14세기 이븐 바투타와 16세기 페리슈타를 포함한 많은 역사가들에 의해 전해집니다.[33] 그러나 이름의 유사성은 이슬람교를 통해 아랍어의 존재에서도 찾을 수 있습니다.[172]

파슈툰족이 이스라엘 자손이라는 믿음에서 한 가지 상충되는 문제는 십여 개의 잃어버린 부족이 아시리아의 통치자에 의해 추방되었다는 것이고, 마그잔-에-아프가니는 그들이 통치자에 의해 동쪽으로 아프가니스탄으로 가는 것을 허락받았다고 말합니다. 이런 불일치는 페르시아가 수십 년 전에 아시리아를 정복했던 메데스와 칼데아 바빌로니아 제국을 정복하면서 고대 아시리아 제국의 땅을 손에 넣었다는 사실로 설명할 수 있습니다. 그러나 고대의 어떤 저자도 이스라엘 민족이 더 동쪽으로 이동했다는 사실을 언급하지 않고 있거나, 십여 개의 잃어버린 부족을 언급한 고대 성서 외의 문헌도 전혀 없습니다.[173]

일부 아프가니스탄 역사학자들은 파슈툰이 고대 이스라엘 민족과 관련이 있다고 주장했습니다. 모한 랄은 다음과 같은 글을 쓴 마운트투아트 엘핀스톤의 말을 인용했습니다.

"아프간 역사가들은, 고레와 아라비아의 이스라엘 자손들이, 하나님의 일치와 그들의 종교적 믿음의 순수성에 대한 지식을 보존하고, 고레의 아프간인들이 예언자들 중 마지막이자 가장 위대한 사람(무함마드)의 등장에, 그들의 아라비아 형제들의 초대에 귀를 기울였다고 이야기합니다." 그 족장은 카울레드...우리가 모든 무례한 나라들이 그들의 고대에 유리한 설명을 받는 쉬운 방법을 생각한다면, 나는 우리가 아프간인의 후손을 유대인의 후손으로, 트로이인의 후손으로, 아일랜드인의 후손을 마일스인이나 브라만의 후손으로 분류하는 것이 두렵습니다."[174]

— Mountstuart Elphinstone, 1841

이 이론은 역사적 증거에 의해 입증되지 않았다는 비판을 받아 왔습니다.[172] 자만 스타니자이(Zaman Stanizai)는 이 이론을 비판합니다.[172]

"파슈툰족이 이스라엘의 잃어버린 부족의 후손이라는 '신화된' 오해는 14세기 인도에서 대중화된 조작입니다. 논리적 불일치와 역사적 부조화로 가득 차 있으며, 유전체 분석을 통해 과학적으로 밝혀진 불가역적 DNA 염기서열 분석을 통해 뒷받침된 인도-이란 파슈툰스의 기원에 대한 결정적 증거와 극명한 대조를 이루는 주장입니다."

— [172]

유전학 연구에 따르면 파슈툰스는 유대인보다 더 큰 R1a1a*-M198 모달 할로 그룹을 가지고 있습니다.[175]

"우리의 연구는 아프가니스탄 출신의 파탄들과 파키스탄 출신의 파탄들 사이의 유전적 유사성을 보여주는데, 이 둘은 하플로그룹 R1a1a*-M198 (>50%)의 우세와 동일한 모달 하플로타입의 공유를 특징으로 합니다...그리스인들과 유대인들이 파토스인들에게 조상으로 제안되었지만, 그들의 유전적 기원은 여전히 모호합니다...전체적으로 아슈케나지 유대인은 하플로그룹 R1a1a-M198에 대해 15.3%의 빈도를 보입니다."

— "Afghanistan from a Y-chromosome perspective", European Journal of Human Genetics

근세

그들의 현대 과거는 델리 술탄국(칼지와 로디 왕조), 호탁 왕조, 두라니 제국까지 거슬러 올라갑니다. 호타크의 통치자들은 사파비족에게 반란을 일으켰고 1722년부터 1729년까지 페르시아의 많은 지역을 장악했습니다.[176] 그 뒤를 이어 나데르 샤 치하의 전 고위 군 사령관이자 현재 아프가니스탄, 파키스탄, 카슈미르, 인도 펀자브는 물론 이란의 코히스탄과 코라산 지방까지 대부분을 차지하는 두라니 제국의 창시자인 아흐마드 샤 두라니가 정복되었습니다.[177] 슈자 샤 두라니가 다스리던 19세기 전반 두라니 왕조가 쇠락한 뒤 바라크자이 왕조가 제국을 장악했습니다. 구체적으로 모하메드 자는 1826년경부터 1973년 자히르 샤의 통치가 끝날 때까지 아프가니스탄의 군주제를 유지했습니다.

19세기의 소위 "위대한 게임" 동안, 영국과 러시아 제국 간의 경쟁은 아프가니스탄의 파슈툰족에게 외국의 지배에 저항하고 어느 정도의 자치권을 유지하는 데 유용했습니다 (말라칸드 포위전 참조). 그러나 압두르 라만 칸 (1880–1901)의 통치 기간 동안 파슈툰 지역은 정치적으로 두란트 선에 의해 나뉘었습니다. 국경의 결과로 파키스탄 서부가 될 지역은 영국령 인도 내에 속했습니다.

20세기에, 아슈파클라 칸,[178][179] 압둘 사마드 칸 아차크자이, 아말 카탁, 바차 칸, 그리고 그의 아들 왈리 칸(모두 쿠다이 키드마트가르의 일원들)을 포함하여, 많은 정치적으로 활동적인 파슈툰 지도자들이 인도의 독립을 지지했습니다. 그리고 모한다스 간디의 비폭력적인 저항 방법에서 영감을 얻었습니다.[180][181] 많은 파슈툰족들은 또한 이슬람 동맹에서 무함마드 알리 진나의 가까운 동료였던 유수프 카탁과 압두르 랍 니슈타르를 포함하여 비폭력 저항을 통해 독립적인 파키스탄을 위해 싸우기 위해 일했습니다.[182] 아프가니스탄의 파슈툰족은 제3차 영-아프간 전쟁 이후 아마눌라 칸의 통치 기간 동안 영국의 정치적 개입으로부터 완전히 독립했습니다. 1950년대에 이르러 파슈투니스탄에 대한 대중적인 요구가 아프가니스탄과 파키스탄의 새로운 주에서 들리기 시작했습니다. 이것은 두 나라 사이의 나쁜 관계로 이어졌습니다. 아프간 군주제는 1973년 다우드 칸 대통령이 파슈툰 민족주의 의제로 사촌 자히르 샤로부터 아프간을 장악하면서 막을 내렸고, 이는 이웃 국가들의 대리전의 문을 열었습니다. 1978년 4월, 다우드 칸은 하피줄라 아민이 기획한 유혈 쿠데타로 가족, 친척들과 함께 암살당했습니다. 이웃 파키스탄에 망명중인 아프간 무자헤딘 사령관들은 아프가니스탄 민주 공화국을 상대로 게릴라전을 모집하기 시작했습니다 - 이 정부는 또한 하피줄라 아민, 누르 무하마드 타라키, 모하마드 아슬람 바탄자르 장군, 샤나와즈 타나이, 모하마드 굴랍조이 외에도 여러 명이 있습니다. 1979년, 소련은 증가하는 반란을 물리치기 위해 남쪽 이웃 아프가니스탄에 개입했습니다. 아프간 무자헤딘은 미국, 사우디아라비아, 중국 등이 자금을 지원했으며 압둘 라술 사야프, 굴부딘 헥마티야르, 잘랄루딘 하카니, 모하마드 나비 모하마디, 모하마드 유누스 칼리스 등 파슈툰족 지휘관도 일부 포함됐습니다. 그 사이 수백만 명의 파슈툰족이 파키스탄과 이란에서 아프가니스탄 디아스포라에 합류했고, 거기서 수만 명이 유럽, 북미, 오세아니아 및 세계 다른 지역으로 이동했습니다.[183] 아프가니스탄 정부와 군부는 1992년 4월 모하마드 나지불라의 아프가니스탄 공화국이 붕괴될 때까지 파슈툰족을 지배적으로 유지했습니다.[184]

압둘 라힘 와르다크, 압둘 살람 아지미, 안와룰-하크 아하디, 아미르자이 상인, 굴람 파루크 와르다크, 하미드 카르자이, 모하마드 이샤크 알로코, 오마르 자킬왈, 셰르 모하마드 카리미, 잘메이 라소울, 유세프 파슈툰 등 아프가니스탄 이슬람 공화국의 많은 고위 공무원들이 파슈툰 사람들이었습니다. 아프가니스탄의 현 주지사 목록에도 파슈툰족이 많이 포함되어 있습니다. 물라 야쿱은 국방장관 대행, 시라주딘 하카니는 내무장관 대행, 아미르 칸 무타치는 외무장관 대행, 굴 아하 이샤크자이는 재무장관 대행, 하산 아크훈트는 총리 대행을 맡고 있습니다. 다른 많은 장관들도 파슈툰족입니다.

자히르 샤 국왕이 대표로 있던 아프간 왕실을 모하마드자이스라고 칭합니다. 다른 유명한 파슈툰들로는 17세기 시인인 쿠샬 칸 카탁과 라만 바바, 그리고 동시대의 아프가니스탄 우주비행사 압둘 아하드 모흐만, 전 미국 대사 잘메이 칼릴자드, 그리고 아슈라프 가니 등이 있습니다.

파키스탄과 인도의 많은 파슈툰인들은 주로 파슈토를 버리고 우르두어, 펀자브어, 힌드코어와 같은 언어를 사용하여 비파슈툰 문화를 채택했습니다.[185] 여기에는 굴람 모하마드(1947년부터 1951년까지 초대 재무장관, 1951년부터 1955년까지 제3대 파키스탄 총독),[186][187][188][189][190] 제2대 파키스탄 대통령이었던 아유브 칸, 제3대 인도 대통령이었던 자키르 후세인, 파키스탄 핵무기 프로그램의 아버지 압둘 카디르 칸 등이 포함됩니다.

파키스탄의 각 정당의 대통령인 아스판디르 왈리 칸, 마흐무드 칸 아착자이, 시라줄 하크, 아프타브 아흐마드 셰르파오와 같은 더 많은 사람들이 고위 정부 직책을 맡았습니다. 다른 사람들은 스포츠(예: 임란 칸, 만수르 알리 칸 파타우디, 유니스 칸, 샤히드 아프리디, 이르판 파탄, 자한기르 칸, 얀셰르 칸, 하심 칸, 라시드 칸, 샤힌 아프리디, 나셈 샤, 미스바 울 하크, 무지브 우르 라흐만, 모하마드 와심)와 문학(예: 가니 칸, 함자 신와리, 카비르)에서 유명해졌습니다. 2014년 최연소 노벨 평화상 수상자가 된 말랄라 유사프자이(Malala Yousafzai)는 파키스탄 파슈툰족입니다.

인도의 많은 발리우드 영화 스타들은 파슈툰 혈통을 가지고 있습니다; 가장 주목할 만한 스타들 중 일부는 Aamir Khan, Shahruk Khan, Salman Khan, Feroz Khan, Madhubala, Kader Khan, Saif Ali Khan, Saha Ali Khan, Sara Ali Khan, 그리고 Zarine Khan입니다.[191][192] 게다가, 인도의 전 대통령 중 한 명인 자키르 후세인은 아프리디 부족에 속했습니다.[193][194][195] 전 알제리 주재 인도 대사이자 인디라 간디의 고문인 모하마드 유누스는 파슈툰 출신으로 전설적인 바차 칸과 관련이 있습니다.[196][197][198][199]

1990년대 후반에 파슈툰스는 집권 정권의 주요 민족 집단이었습니다. 아프가니스탄 이슬람 토후국(탈레반 정권).[200][201][failed verification] 탈레반에 맞서 싸우던 북부동맹에도 파슈툰족이 다수 포함됐습니다. 그들 중에는 압둘라 압둘라, 압둘 카디르와 그의 형제 압둘 하크, 압둘 라술 사야프, 아사둘라 칼리드, 하미드 카르자이, 굴 아그하 셰르자이가 있었습니다. 탈레반 정권은 2001년 말 미국 주도의 아프가니스탄 전쟁 중 축출돼 카르자이 행정부로 교체됐습니다.[202] 이어 가니 행정부와 탈레반(아프가니스탄 이슬람 토후국)의 아프가니스탄 재점령이 잇따랐습니다.

아프가니스탄에서의 오랜 전쟁으로 인해 파슈툰스는 특출난 전사로 명성을 얻었습니다.[203] 일부 활동가들과 지식인들은 파슈툰 지식주의와 전쟁 전 문화를 재건하기 위해 노력하고 있습니다.[204]

유전학

아프가니스탄에서 온 파슈툰의 대부분은 R1a에 속하며, 빈도는 50~65%[205]입니다. 서브클레이드 R1a-Z2125는 40%[206]의 주파수에서 발생합니다. 이 하위 분류군은 주로 타지크족, 투르크멘족, 우즈베키스탄인 그리고 코카서스와 이란의 일부 개체군에서 발견됩니다.[207] 하플로그룹 G-M201은 아프가니스탄 파슈툰스에서 9%에 달하며 아프가니스탄 남부에서 파슈툰스에서 두 번째로 자주 발생하는 하플로그룹입니다.[205][208] 하플로그룹 L과 하플로그룹 J2는 전체 빈도 6%[205]에서 발생합니다. 아프가니스탄의 4개 민족에 대한 미토콘드리아 DNA 분석에 따르면, 아프가니스탄 파슈툰족 중 mtDNA의 대부분은 서유라시아 계통에 속하며, 남아시아 또는 동아시아의 개체군보다는 서유라시아 및 중앙아시아 개체군과 더 큰 친화력을 공유합니다. 하플로그룹 분석에 따르면 아프가니스탄의 파슈툰족과 타직족은 조상의 유산을 공유하고 있습니다. 연구된 민족 중에서 파슈툰족이 가장 큰 mtDNA 다양성을 가지고 있습니다.[209] 파키스탄 파슈툰족 중 가장 빈번한 하플로그룹은 28-50%의 비율로 발견되는 하플로그룹 R입니다. 하플로그룹 J2는 연구에 따라 9%에서 24%, 하플로그룹 E는 4%에서 13%의 빈도로 발견되었습니다. 하플로그룹 L은 8%의 비율로 발생합니다. 특정 파키스탄 파슈툰 그룹은 높은 수준의 R1b를 나타냅니다.[210][211] 전체적인 파슈툰족은 유전적으로 다양하며, 파슈툰족은 하나의 유전적 집단이 아닙니다. 서로 다른 파슈툰 그룹은 서로 다른 유전적 배경을 나타내어 상당한 이질성을 초래합니다.[212]

정의들

누가 정확히 파슈툰인의 자격을 갖추었는지에 대해 파슈툰인들의 가장 두드러진 견해는 다음과 같습니다.[213]

- 파슈토를 모국어로 사용하는 사람들. 파슈토어는 파슈툰족 사이에서 "민족 정체성의 주요 지표 중 하나"입니다.[214]

- 파슈툰왈리의 코드를 준수합니다.[213][215] 문화적 정의에 따라 파슈툰은 파슈툰왈리 코드를 준수해야 합니다.[216]

- 파슈툰족은 파슈툰족 아버지를 둔 사람만 파슈툰족이어야 한다는 파슈툰왈리의 중요한 정통 율법에 근거하여 부계 혈통을 통해 파슈툰족에 속합니다. 이 정의는 언어에 덜 중점을 둡니다.[217]

부족

복잡한 부족 체계는 파슈툰족의 중요한 제도입니다.[219] 부족 체계는 여러 수준의 조직을 가지고 있습니다: 그들이 속한 부족은 사르바니 부족, 베타니 부족, 가르하슈티 부족, 카를라니 부족의 네 개의 '더 큰' 부족 그룹입니다.[220] 그런 다음 부족은 khels라고 불리는 친족 그룹으로 나뉘며, 이 그룹은 다시 더 작은 그룹(플라리나 또는 플라가니)으로 나뉘며, 각각은 kahols라고 불리는 몇 개의 확장된 가족으로 구성됩니다.[221]

Durrani and Ghilji Pashtuns

두라니스족과 길지족은 파슈툰족의 가장 큰 두 집단이며, 아프가니스탄 파슈툰족의 약 3분의 2가 이 연합에 속해 있습니다.[222] 두라니 부족은 더 도시적이고 정치적으로 성공한 반면, 길지족은 더 많고, 더 시골적이며, 더 강경하다고 알려져 있습니다. 18세기에, 그 단체들은 때때로 협력했고 다른 때에는 서로 싸웠습니다. 두라니스는 1978년 사우르 혁명이 일어나기 전까지 현대 아프가니스탄을 계속 통치했습니다.[223]

두라니 연맹의 통치는 토지 소유권의 상호 부족 구조와 더 관련이 있는 반면, 질지족 간의 동맹은 더 강합니다.[222]

언어

파슈토어는 대부분의 파슈툰족의 모국어입니다.[224][225][226] 이 언어는 아프가니스탄의 두 개의 국가 언어 중 하나입니다.[227][228] 파키스탄에서는 두 번째로 많이 사용되는 언어이지만 [229]교육 시스템에서 공식적으로 무시되는 경우가 많습니다.[230][231][232][233][234][235] 이것은 학생들이 다른 언어로 가르치는 것을 완전히 이해할 능력이 없기 때문에 [236][237]파슈툰스의 경제 발전에 악영향을 미친다고 비판 받아 왔습니다.[238] 로버트 니콜스(Robert Nichols)의 발언:[239]

이슬람과 우르두어를 통한 통합을 도모하는 민족주의적 환경에서 파슈토어 교재를 집필하는 정치는 독특한 효과를 나타냈습니다. 20세기의 박툰, 특히 반영적이고 친박툰 민족주의자인 압둘 가파르 칸에 대한 교훈은 없었습니다. 19세기와 20세기 아프가니스탄의 파슈툰 국가 건설자들에 대한 교훈은 없었습니다. 파슈토어의 종교적이거나 역사적인 자료를 샘플링한 것은 거의 또는 전혀 없었습니다.

— Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors, Chapter 8, page 278

파슈토어는 이란 동부 언어로 분류되지만,[240] 현저하게 많은 수의 단어들이 파슈토어 고유어입니다.[241][242] 동사와 관련된 파슈토 형태론은 다른 이란어에 비해 복잡합니다.[243] 이와 관련하여 맥켄지는 다음과 같이 말합니다.[244]

파슈토의 고대 구조를 현대 이란어의 선두적인 언어인 페르시아어의 훨씬 단순화된 형태와 비교하면, 우리는 파슈토가 아이슬란드어가 영어와 같은 관계에 있는 '2촌'과 이웃을 상징한다는 것을 알 수 있습니다.

— David Neil MacKenzie

파슈토어는 많은 수의 방언을 가지고 있는데, 일반적으로 북부, 남부, 중부 그룹으로 나뉘며, 타리노어 또는 와 ṇ에티어도 별개의 그룹으로 분류됩니다. 엘펜베인은 다음과 같이 언급합니다. "변증법의 차이는 주로 음운론과 어휘에 있습니다. 형태와 구문은 와네치를 제외하고는 상당히 균일합니다."[248] 이브라힘 칸은 ښ 문자에 대해 다음과 같은 분류를 제공합니다: /ç+/의 음가를 갖는 북부 서부 방언(예: 길자이족이 사용함), /x/의 음가를 갖는 북동부 방언(유사프자이족 등이 사용함), /x/의 음가를 갖는 남부 서부 방언(압달리스어 등이 사용함), /ʂ어/를 갖는 남동부 방언(카카르어 등이 사용함). 그는 카를라 ṇ 부족이 사용하는 중앙 방언이 북부 /x/와 남부 /ʃ/의 구별로도 나눌 수 있음을 설명하지만, 또한 이러한 중앙 방언은 모음 이동이 있어 구별된다고 제공합니다. 예를 들어 /ɑ/알레프로 대표되는 비중앙 방언은 바니시 방언으로 /ɔː/가 됩니다.

최초의 파슈토 알파벳은 16세기에 피르 로샨에 의해 개발되었습니다.[250] 1958년 카불에서 열린 아프가니스탄과 파키스탄의 파슈툰 학자들과 작가들의 회의는 현재의 파슈토 알파벳을 표준화했습니다.[251]

문화

파슈툰 문화는 파슈툰왈리, 이슬람교, 파슈토어에 대한 이해를 기반으로 합니다. 카불 방언은 현재의 파슈토 알파벳을 표준화하는 데 사용됩니다.[251] 시는 또한 파슈툰 문화의 중요한 부분이며 수세기 동안 이어져 왔습니다.[252] 기원전 330년 알렉산더가 페르시아 제국을 패배시킨 것으로 거슬러 올라가는 이슬람 이전의 전통은 아마도 전통 춤의 형태로 살아남았고, 문학 양식과 음악은 페르시아 전통의 영향과 지역화된 변형과 해석과 융합된 지역 악기를 반영합니다. 다른 이슬람교도들처럼, 파슈툰족도 이슬람의 휴일을 기념합니다. 파키스탄에 살고 있는 파슈툰족과는 반대로, 아프가니스탄의 노루즈는 모든 아프가니스탄 민족들에게 아프가니스탄의 새해로 기념되고 있습니다.

지르가

또 다른 중요한 파슈툰 기관은 선출된 원로들의 로야 지르가(파슈토: لويه جرګه) 또는 '대의원회'입니다. 부족 생활에서 대부분의 결정은 지르가(파슈토: جرګه)의 구성원들에 의해 내려지는데, 지르가는 대체로 평등주의적인 파슈툰족이 실행 가능한 통치 기구로 기꺼이 인정하는 주요 권한 기관이었습니다.

종교

이슬람 이전에 조로아스터교,[255] 불교, 힌두교와 같은 파슈툰에 의해 행해진 다양한 다른 믿음들이 있었습니다.[256]

파슈툰족의 압도적 다수는 수니파 이슬람교를 고수하며 하나피 사상파에 속해 있습니다. 카이버 파크툰크화와 파크티아에는 작은 시아파 공동체가 존재합니다. 시아파는 투리족에 속하지만 방가쉬족은 약 50%의 시아파와 나머지 수니파로 주로 파라치나르, 쿠람, 한구, 코하트, 오락자이 등지에서 발견됩니다.[257]

수피 활동의 유산은 노래와 춤에서 분명히 알 수 있듯이 일부 파슈툰 지역, 특히 카이버 파크툰크화에서 발견될 수 있습니다. 많은 파슈툰족들은 유명한 울레마, 이슬람 학자들인데, 코란의 타파세를 나퀴브 부트 타파세르로, 타프세르 울 아자메인, 타프세르 나퀴비, 누르 우트 타파세르 등을 포함한 500권 이상의 책을 저술한 마울라나 아자마, 노블 코란의 번역을 도운 무함마드 무흐신 칸 등이 있습니다. Sahih Al-Bukhari와 다른 많은 책들이 영어로 쓰여졌습니다.[258] 많은 파슈툰인들은 자신들의 정체성이 파슈툰 문화와 역사와 직접적으로 연결되지 않는 탈레반과 국제 테러에 연루되는 것으로부터 되찾기를 원합니다.[259]

특히 인도의 분할 이후와 탈레반의 부상 이후에 많은 힌두교인과 시크교도 파슈툰크들이 카이버 파크툰크화에서 이주했기 때문에, 비무슬림에 대한 정보는 거의 없습니다.[260][261]

또한 인도로 이주한 힌두 파슈툰족, 때로는 쉰 칼라이족이라고도 알려져 있습니다.[262][263] '푸른 피부의'(파슈툰 여성들의 얼굴 문신 색을 일컫는 말)라는 뜻의 쉰 칼라이(Sheen Khalai)로 알려진 작은 파슈툰 힌두 공동체는 분할 후 인도 라자스탄의 운니아라(Unniara)로 이주했습니다.[264] 1947년 이전에는 영국령 인도령 발루치스탄 지방의 퀘타, 로랄라이, 메이크터 지역에 거주했습니다.[265][264][266] 그들은 주로 파슈툰 카카르 부족의 일원입니다. 오늘날, 그들은 계속해서 파슈토어를 사용하고 아탄 춤을 통해 파슈툰 문화를 기념합니다.[265][264]

또한 티라, 오라크자이, 쿠람, 말라칸드, 스와트에는 소수의 파슈툰 시크교도들이 있습니다. 카이버 파크툰크화에서 계속되는 반란으로 인해 일부 파슈툰 시크교도들은 페샤와르와 난카나 사히브와 같은 도시에 정착하기 위해 조상의 마을에서 내부적으로 쫓겨났습니다.[267][268][269]

파슈토 문학과 시

파슈툰족의 대다수는 이란어족에 [271]속하며 최대 6천만 명이 사용하는 파슈토어를 모국어로 사용합니다.[272][273] 파슈토 아랍어 문자로 쓰이며, 남부 "파슈토"와 북부 "푸흐토"의 두 가지 주요 방언으로 나뉩니다. 이 언어는 고대에 기원을 두고 있으며 아베스탄어와 박트리아어와 같은 멸종된 언어와 유사성을 지니고 있습니다.[274] 슈흐니어, 와키어와 같은 파미르어족과 오세틱어족이 가장 가까운 현대 친척으로 알려져 있습니다.[275] 파슈토어는 페르시아어와 베다어 산스크리트어와 같은 이웃 언어에서 어휘를 차용한 고대의 유산을 가지고 있을 수 있습니다. 현대 대출은 주로 영어에서 나옵니다.[276]

가장 이른 것은 셰이크 말리의 스와트 정복에 관한 것입니다.[277] 피르 로샨은 무굴족과 싸우면서 파슈토 책을 많이 쓴 것으로 추정됩니다. 압둘 하이 하비비(Abdul Hai Habibi)와 같은 파슈툰 학자들은 가장 초기의 파슈토 작업이 아미르 크르 수리(Amir Kror Suri)로 거슬러 올라간다고 믿고 있으며, 파타 카자나(Pata Khazana)에서 발견된 글을 증거로 사용하고 있습니다. 아미르 폴라드 수리의 아들인 아미르 크로르 수리는 아프가니스탄의 고르 지역 출신의 8세기 민중 영웅이자 왕이었습니다.[278][279] 그러나 이는 강력한 증거 부족으로 인해 여러 유럽 전문가들에 의해 논란이 되고 있습니다.

시의 출현은 파슈토를 근대로 이행시키는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 파슈토 문학은 20세기에 파슈토 가잘스를 발전시킨 아미르 함자 신와리의 시와 함께 중요한 명성을 얻었습니다.[280] 1919년 대중매체의 확장이 진행되는 동안 마흐무드 타르지는 세라즈 알 아크바르(Seraj-al-Akhbar)를 발행하여 아프가니스탄 최초의 파슈토 신문이 되었습니다. 1977년, 칸 로샨 칸은 타와리크-에-하피즈 레흐마트카니를 썼는데, 그 안에는 가계도와 파슈툰 부족 이름이 들어 있습니다. 압둘 가니 칸, 아프잘 칸 카탁, 아흐마드 샤 두라니, 아즈말 카탁, 굴람 무하마드 타르지, 함자 신와리, 하니프 박타쉬, 쿠샬 칸 카탁, 나조 토키, 파레샨 카탁, 라만 바바, 슈자 샤 두라니, 티무르 샤 두라니 등이 대표적인 시인입니다.[281][282]

미디어와 예술

파슈토 미디어는 지난 10년 동안 확장되었으며, 여러 파슈토 TV 채널을 이용할 수 있게 되었습니다. 인기 있는 것 중 두 가지는 파키스탄에 기반을 둔 AVT 카이버와 파슈토 원입니다. 전 세계의 파슈툰들, 특히 아랍 국가들은 오락 목적으로, 그리고 그들의 모국에 대한 최신 뉴스를 얻기 위해 이것들을 시청합니다.[283] 다른 것들은 아프가니스탄에 기반을 둔 샴샤드 TV, 라디오 텔레비전 아프가니스탄, TOLOnews, 그리고 Bagh-e-Simsim이라고 불리는 특별한 어린이 쇼가 있는 Lemar TV입니다. 파슈토 프로그램을 제공하는 국제 뉴스 소스로는 BBC 파슈토와 미국의 소리가 있습니다.

페샤와르에 본사를 둔 제작자들은 1970년대부터 파슈토어 영화를 만들었습니다.

파슈툰 공연자들은 춤, 검술, 그리고 다른 신체적인 위업을 포함한 다양한 신체적인 표현의 열렬한 참가자로 남아있습니다. 아마도 가장 일반적인 예술적 표현의 형태는 다양한 형태의 파슈툰 춤에서 볼 수 있을 것입니다. 가장 눈에 띄는 춤 중 하나는 고대의 뿌리를 가지고 있는 아탄입니다. 엄격한 운동인 아탄은 음악가들이 돌(드럼), 타블라스(퍼커션), 루밥(활을 찬 현악기), 툴라(목제 플루트)를 포함한 다양한 고유 악기들을 연주하면서 행해집니다. 빠른 원형의 움직임으로, 무용수들은 수피 빙글빙글 도는 더비시와 비슷하게, 아무도 춤추지 않을 때까지 공연을 합니다. 수많은 다른 춤들은 특히 파키스탄에서 온 다양한 부족들과 관련이 있는데, 그 중에는 하타크 왈 아탄르(카타크 부족의 이름에서 따온 것), 마수드 왈 아탄르(현대에는 장전된 소총의 저글링을 수반함), 와지로 아탄르(Waziro Atanrh) 등이 있습니다. 브라호니로 알려진 카탁 왈 아탄르의 하위 유형은 최대 3개의 검을 사용하는 것으로 엄청난 기술이 필요합니다. 젊은 여성들과 소녀들은 종종 악기인 Tumbal (Dayereh)과의 결혼식에서 즐거움을 줍니다.[284]

스포츠

아프가니스탄 크리켓 대표팀과 파키스탄 크리켓 대표팀 모두 파슈툰 선수들을 보유하고 있습니다.[285] 파슈툰족의 가장 인기 있는 스포츠 중 하나는 18세기 초 영국인의 도착과 함께 남아시아에 소개된 크리켓입니다. Many Pashtuns have become prominent international cricketers, including Imran Khan, Shahid Afridi, Majid Khan, Misbah-ul-Haq, Younis Khan,[286] Umar Gul,[287] Junaid Khan,[288] Fakhar Zaman,[289] Mohammad Rizwan,[290] Usman Shinwari, Naseem Shah, Shaheen Afridi, Iftikhar Ahmed, Mohammad Wasim and Yasir Shah.[291] 호주 크리켓 선수 파와드 아흐메드(Fawad Ahmed)는 파키스탄 출신의 파슈툰 출신으로 호주 대표팀에서 뛰었습니다.[292]

마카(Makha)는 카이버 파크툰크화의 전통적인 양궁 스포츠로, 원위 끝에 받침 접시 모양의 금속판이 있는 긴 화살(게샤이)과 긴 활을 가지고 경기를 합니다.[293] 아프가니스탄에서 일부 파슈툰인들은 여전히 고대의 부즈카시 스포츠에 참가하는데, 말 타는 사람들은 염소나 송아지 사체를 골 서클에 놓으려고 시도합니다.[294][295][296]

여성들.

파슈툰 여성들은 수수한 옷차림 때문에 겸손하고 명예롭다고 알려져 있습니다.[297][298] 파슈툰 여성들의 삶은 매우 보수적인 농촌 지역에 사는 사람들부터 도심에서 발견되는 사람들까지 다양합니다.[299] 마을 단위에서는 여성 마을 지도자를 "카랴다르"라고 부릅니다. 그녀의 임무는 여성의 의식을 목격하고, 여성들을 종교 축제에 참가시키고, 여성 사망자들을 매장하기 위한 준비를 하고, 사망한 여성들을 위한 봉사를 수행하는 것을 포함할 수 있습니다. 그녀는 또한 자신의 가족을 위해 결혼을 주선하고 남성과 여성의 갈등을 중재합니다.[300] 비록 많은 파슈툰족 여성들이 부족과 문맹으로 남아 있지만, 일부 여성들은 대학을 마치고 정규 직업 세계에 합류했습니다.[299]

수십 년에 걸친 전쟁과 탈레반의 부상은 이슬람 율법의 엄격한 해석으로 인해 많은 권리가 축소되면서 파슈툰 여성들에게 상당한 어려움을 야기했습니다. 아프가니스탄 여성 난민들의 어려운 삶은 1985년 6월 내셔널 지오그래픽 잡지의 표지에 묘사된 상징적인 아프가니스탄 소녀(샤르밧 굴라)와 함께 상당한 악명을 얻었습니다.[301]

파슈툰 여성들을 위한 현대 사회 개혁은 아프가니스탄의 소라야 타르지 여왕이 여성들의 삶과 가족 내에서의 그들의 위치를 향상시키기 위해 빠른 개혁을 한 20세기 초에 시작되었습니다. 그녀는 아프가니스탄의 통치자 명단에 등장한 유일한 여성이었습니다. 아프가니스탄과 이슬람교도 여성 운동가 중 최초이자 가장 강력한 인물 중 한 명으로 인정받고 있습니다. 여성을 위한 사회 개혁에 대한 그녀의 옹호는 시위로 이어졌고 1929년 아마눌라 왕의 통치의 궁극적인 종말에 기여했습니다.[302] 페미니스트 지도자 미나 케슈와르 카말이 여성 인권 운동을 벌이고 1977년 아프가니스탄 여성 혁명 협회(RAWA)를 설립하면서 민권은 1970년대에도 중요한 문제로 남아 있었습니다.

요즘 파슈툰족 여성들은 은둔생활을 하는 전통적인 주부들부터 남성과 동등함을 추구하거나 성취한 도시 노동자들까지 다양합니다.[299] 그러나 많은 사회적 장애물로 인해 문해율은 남성보다 상당히 낮습니다.[304] 여성에 대한 학대는 파키스탄과 아프가니스탄의 정부 관리뿐만 아니라 보수적인 종교 단체와 씨름하고 있는 여성 인권 단체에 의해 존재하고 있으며 점점 더 많은 도전을 받고 있습니다. 1992년 책에 따르면, "강력한 인내의 윤리는 전통적인 파슈툰 여성들이 그들의 삶에서 그들이 인정하는 고통을 완화하는 능력을 심각하게 제한합니다."[305]

현상에 더욱 도전한 비다 사마드자이는 2003년 미스 아프가니스탄으로 선정되었는데, 이 업적은 여성의 개인적 권리를 지지하는 사람들과 반전통주의자와 비이슬람주의자로 보는 사람들의 지지가 혼합되어 이루어졌습니다. 일부는 아프가니스탄과 파키스탄에서 정치적 지위를 얻었습니다.[306] 많은 파슈툰 여성들이 TV 진행자, 기자, 배우로 발견됩니다.[61] 1942년, 인도의 마릴린 먼로인 마드후발라(뭄타즈 제한)가 발리우드 영화계에 진출했습니다.[191] 1970년대와 1980년대의 발리우드 블록버스터에는 구자라트의 역사적인 파탄 공동체인 왕실 바비 왕조의 혈통을 따온 파르빈 바비가 출연했습니다.[307] 자리네 칸과 같은 다른 인도 여배우들과 모델들은 그 산업에서 계속 일하고 있습니다.[192] 1980년대 동안 많은 파슈툰 여성들이 아프가니스탄 공산 정권의 군대에서 복무했습니다. Khatol Mohammadzai는 아프가니스탄 내전 동안 낙하산 부대에서 복무했으며 나중에 아프간 육군 준장으로 승진했습니다.[308] Nigar Johar는 파키스탄 육군의 3성 장군이며, 또 다른 Pashtun 여성은 파키스탄 공군의 전투기 조종사가 되었습니다.[309] 파슈툰족 여성들은 종종 그들의 법적인 권리가 남편이나 남자 친척들에게 유리하게 축소됩니다. 예를 들어, 파키스탄에서 여성은 공식적으로 투표할 수 있지만, 일부는 남성에 의해 투표함에 접근하지 못하게 되었습니다.[310]

주목할 만한 사람들

설명주

- 참고: 외국의 파슈툰 인구 통계(표기가 없는 인구 포함)는 다양한 인구 조사, UN, CIA의 World Factbook 및 Ethnologue에서 도출되었습니다.

참고문헌

- ^ "South Asia :: Pakistan – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "Afghanistan". 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b Ali, Arshad (15 February 2018). "Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan's great granddaughter seeks citizenship for 'Phastoons' in India". Daily News and Analysis. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

Interacting with mediapersons on Wednesday, Yasmin, the president of All India Pakhtoon Jirga-e-Hind, said that there were 32 lakh Phastoons in the country who were living and working in India but were yet to get citizenship.

- ^ a b "Frontier Gandhi's granddaughter urges Centre to grant citizenship to Pathans". The News International. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Southern Pashto: Iran (2022)". Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ 아프간계 미국인 20만명 중 42%=8만4000명, 파키스탄계 미국인 36만3699명 중 15%=54,554명. 미국 내 아프가니스탄 및 파키스탄 파슈툰 총 = 538,554명입니다.

- ^ Maclean, William (10 June 2009). "Support for Taliban dives among British Pashtuns". Reuters. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Southern Pashto: Tajikistan (2017)". Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ "Knowledge of languages by age and gender: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions". Census Profile, 2021 Census. Statistics Canada Statistique Canada. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Perepis.ru". perepis2002.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "Language used at home". profile.id.com.au. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Khan, Ibrahim (7 September 2021). "Tarīno and Karlāṇi dialects". Pashto. 50 (661). ISSN 0555-8158.

- ^ 부족별로 아프가니스탄 부족을 이기려는 미국의 계획은 위험합니다, 토마스 L. 맥클래치 신문사 토마스 L. 날, 맥클래치 신문사. 2010년 2월 4일.

- ^ Azami, Dawood (23 February 2011). "Sufism returns to Afghanistan after years of repression". BBC News. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Afghanistan - Sufis". Country Studies. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ Haidar, Suhasini (3 February 2018). "Tattooed 'blue-skinned' Hindu Pushtuns look back at their roots". The Hindu. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "Pakhtun Sikhs keeping their culture alive". Dawn. 7 July 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ David, Anne Boyle (1 January 2014). Descriptive Grammar of Pashto and its Dialects. De Gruyter Mouton. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-61451-231-8.

- ^ a b Minahan, James B. (30 August 2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598846607 – via Google Books.

- ^ James William Spain (1963). The Pathan Borderland. Mouton. p. 40. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

The most familiar name in the west is Pathan, a Hindi term adopted by the British, which is usually applied only to the people living east of the Durand.

- ^ Pathan. World English Dictionary. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

Pathan (pəˈtɑːn) — n a member of the Pashto-speaking people of Afghanistan, Western Pakistan, and elsewhere, most of whom are Muslim in religion [C17: from Hindi]

- ^ von Fürer-Haimendorf, Christoph (1985). Tribal populations and cultures of the Indian subcontinent. Handbuch der Orientalistik/2,7. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 126. ISBN 90-04-07120-2. OCLC 240120731. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ Lindisfarne, Nancy; Tapper, Nancy (23 May 1991). Bartered Brides: Politics, Gender and Marriage in an Afghan Tribal Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-521-38158-1.

As for the Pashtun nomads, passing the length of the region, they maintain a complex chain of transactions involving goods and information. Most important, each nomad household has a series of 'friends' in Uzbek, Aymak and Hazara villages along the route, usually debtors who take cash advances, animals and wool from them, to be redeemed in local produce and fodder over a number of years. Nomads regard these friendships as important interest-bearing investments akin to the lands some of them own in the same villages; recently villagers have sometimes withheld their dues, but relations between the participants are cordial, in spite of latent tensions and backbiting.

- ^ Rubin, Barnett R. (1 January 2002). The Fragmentation of Afghanistan: State Formation and Collapse in the International System. Yale University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-300-09519-7.

In some parts of Afghanistan, Pashtun nomads favored by the state often clashed with non- Pashtun (especially Hazara) peasants. Much of their pasture was granted to them by the state after being expropriated from conquered non-Pashtun communities. The nomads appear to have lost these pastures as the Hazaras gained autonomy in the recent war.___Nomads depend on peasants for their staple food, grain, while peasants rely on nomads for animal products, trade goods, credit, and information...Nomads are also ideally situated for smuggling. For some Baluch and Pashtun nomads, as well as settled tribes in border areas, smuggling has been a source of more income than agriculture or pastoralism. Seaso- nal migration patterns of nomads have been disrupted by war and state formation throughout history, and the Afghan-Soviet war was no exception.

- ^ Baiza, Yahia (21 August 2013). Education in Afghanistan: Developments, Influences and Legacies Since 1901. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-134-12082-6.

A typical issue that continues to disturb social order in Afghanistan even at the present time (2012) concerns the Pashtun nomads and grazing lands. Throughout the period 1929 78, governments supported the desire of the Pashtun nomads to take their cattle to graze in Hazara regions. Kishtmand writes that when Daoud visited Hazaristan in the 1950s. where the majority of the population are Hazaras, the local people com- plained about Pashtun nomads bringing their cattle to their grazing lands and destroying their harvest and land. Daoud responded that it was the right of the Pashtuns to do so and that the land belonged to them (Kishtmand 2002: 106).

- ^ Clunan, Anne; Trinkunas, Harold A. (10 May 2010). Ungoverned Spaces: Alternatives to State Authority in an Era of Softened Sovereignty. Stanford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8047-7012-5.

In 1846, the British sought to segregate settled areas on the frontier from the pastoral Pashtun communities found in the surrounding hills." British au- thorities made no attempt "to advance into the highlands, or even to secure the main passages through the mountains such as the Khyber Pass."2" In addition, the Close Border Policy tried to contract services from more resistant hill tribes in an attempt to co-opt them. In exchange for their cooperation, the tribes would receive a stipend for their services.

- ^ Banuazizi, Ali; Weiner, Myron (1 August 1988). The State, Religion, and Ethnic Politics: Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Syracuse University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8156-2448-6.

The Hazaras, who rebelled and fought an extended war against the Afghan government, were stripped of their control over the Hindu Kush pastures and the pastures were given to the Pashtun pastoralists. This had a devastating impact on the Hazara's society and economy. These pastures had been held in common by the vari- ous regional Hazara groups and so had provided important bases for large "tribal" affiliations to be maintained. With the loss of their sum- mer pastures the units of practical Hazara affiliation declined. Also, Hazara leaders were killed or deported, and their lands were confis- cated. These activities of the Afghan government, carried on as a deliberate policy, sometimes exacerbated by other outrages effected by the Pashtun pastoralists, emasculated the Hazaras.

- ^ a b Dan Caldwell (17 February 2011). Vortex of Conflict: U.S. Policy Toward Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iraq. Stanford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8047-7666-0.

A majority of Pashtuns live south of the Hindu Kush (the 500-mile mountain range that covers northwestern Pakistan to central and eastern Pakistan) and with some Persian speaking ethnic groups.

- ^ a b "Pashtun". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ Sims-Williams, Nicholas. "Bactrian Documents from Northern Afghanistan. Vol II: Letters and Buddhist". Khalili Collections: 19.

- ^ "Afghan and Afghanistan". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "History of Afghanistan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah (Firishta). "History of the Mohamedan Power in India". Persian Literature in Translation. Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Glossary". British Library. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ a b Huang, Guiyou (30 December 2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Asian American Literature [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-56720-736-1.

In Afghanistan, up until the 1970s, the common reference to Afghan meant Pashtun. . . . The term Afghan as an inclusive term for all ethnic groups was an effort begun by the "modernizing" King Amanullah (1909-1921). . . .

- ^ Tyler, John A. (10 October 2021). Afghanistan Graveyard of Empires: Why the Most Powerful Armies of Their Time Found Only Defeat or Shame in This Land Of Endless Wars. Aries Consolidated LLC. ISBN 978-1-387-68356-7.

The largest ethnic group in Afghanistan is that of Pashtuns, who were historically known as the Afghans. The term Afghan is now intended to indicate people of other ethnic groups as well.

- ^ Bodetti, Austin (11 July 2019). "What will happen to Afghanistan's national languages?". The New Arab.

- ^ Chiovenda, Andrea (12 November 2019). Crafting Masculine Selves: Culture, War, and Psychodynamics in Afghanistan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-007355-8.

Niamatullah knew Persian very well, as all the educated Pashtuns generally do in Afghanistan

- ^ "Hindu Society and English Rule". The Westminster Review. The Leonard Scott Publishing Company. 108 (213–214): 154. 1877.

Hindustani had arisen as a lingua franca from the intercourse of the Persian-speaking Pathans with the Hindi-speaking Hindus.

- ^ Hakala, Walter N. (2012). "Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan's Cultures" (PDF). National Geographic. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

In the 1980s and '90s, at least three million Afghans--mostly Pashtun--fled to Pakistan, where a substantial number spent several years being exposed to Hindi- and Urdu-language media, especially Bollywood films and songs, and being educated in Urdu-language schools, both of which contributed to the decline of Dari, even among urban Pashtuns.

- ^ Krishnamurthy, Rajeshwari (28 June 2013). "Kabul Diary: Discovering the Indian connection". Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

Most Afghans in Kabul understand and/or speak Hindi, thanks to the popularity of Indian cinema in the country.

- ^ Green, Nile (2017). Afghanistan's Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban. University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-520-29413-4.

Many of the communities of ethnic Pashtuns (known as Pathans in India) that had emerged in India over the previous centuries lived peaceably among their Hindu neighbors. Most of these Indo-Afghans lost the ability to speak Pashto and instead spoke Hindi and Punjabi.

- ^ Romano, Amy (2003). A Historical Atlas of Afghanistan. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 0-8239-3863-8. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ Syed Saleem Shahzad (20 October 2006). "Profiles of Pakistan's Seven Tribal Agencies". Jamestown. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ "Who Are the Pashtun People of Afghanistan and Pakistan?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Lewis, Paul M. (2009). "Pashto, Northern". SIL International. Dallas, TX: Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Ethnic population: 49,529,000 possibly total Pashto in all countries.

- ^ "Hybrid Census to Generate Spatially-disaggregated Population Estimate". United Nations world data form. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Pakistan - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2022. (2022년판 보관)

- ^ "South Asia :: Pakistan — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "What Languages Are Spoken In Pakistan?". World atlas. 30 July 2019.

- ^ a b Canfield, Robert L.; Rasuly-Paleczek, Gabriele (4 October 2010). Ethnicity, Authority and Power in Central Asia: New Games Great and Small. Routledge. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-136-92750-8.

By the late-eighteenth century perhaps 100,000 "Afghan" or "Puthan" migrants had established several generations of political control and economic consolidation within numerous Rohilkhand communities

- ^ a b "Pakhtoons in Kashmir". The Hindu. 20 July 1954. Archived from the original on 9 December 2004. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

Over a lakh Pakhtoons living in Jammu and Kashmir as nomad tribesmen without any nationality became Indian subjects on July 17. Batches of them received certificates to this effect from the Kashmir Prime Minister, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, at village Gutligabh, 17 miles from Srinagar.

- ^ Siddiqui, Niloufer A. (2022). Under the Gun. Cambridge University Press. p. 186. ISBN 9781009242523.

- ^ "Pashtun". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

Pashtun, also spelled Pushtun or Pakhtun, Hindustani Pathan, Persian Afghan, Pashto-speaking people residing primarily in the region that lies between the Hindu Kush in northeastern Afghanistan and the northern stretch of the Indus River in Pakistan.

- ^ George Morton-Jack (24 February 2015). The Indian Army on the Western Front South Asia Edition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-107-11765-5.

'Pathan', an Urdu and a Hindi term, was usually used by the British when speaking in English. They preferred it to 'Pashtun', 'Pashtoon', 'Pakhtun' or 'Pukhtun', all Pashtu versions of the same word, which the frontier tribesmen would have used when speaking of themselves in their own Pashtu dialects.

- ^ "Memons, Khojas, Cheliyas, Moplahs ... How Well Do You Know Them?". Islamic Voice. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ "Pathan". Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ a b "Study of the Pathan Communities in Four States of India". Khyber.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint : 잘못된 URL (링크) - ^ Alavi, Shams Ur Rehman (11 December 2008). "Indian Pathans to broker peace in Afghanistan". Hindustan Times.

- ^ a b Haleem, Safia (24 July 2007). "Study of the Pathan Communities in Four States of India". Khyber.org. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint : 잘못된 URL (링크) - ^ "The 'Kabuliwala' Afghans of Kolkata". BBC News. 23 May 2015.

- ^ "Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues – 2001". Census of India. 2001. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Ravik (15 February 2018). "Frontier Gandhi's granddaughter urges Centre to grant citizenship to Pathans". The Indian Express. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Pashtun in India". Joshua Project.

- ^ Alavi, Shams Ur Rehman (11 December 2008). "Indian Pathans to broker peace in Afghanistan". Hindustan Times.

Pathans are now scattered across the country, and have pockets of influence in parts of UP, Bihar and other states. They have also shone in several fields, especially Bollywood and sports. The three most famous Indian Pathans are Dilip Kumar, Shah Rukh Khan and Irfan Pathan. "The population of Pathans in India is twice their population in Afghanistan and though we no longer have ties (with that country), we have a common ancestry and feel it's our duty to help put an end to this menace," Atif added. Academicians, social activists, writers and religious scholars are part of the initiative. The All India Muslim Majlis, All India Minorities Federation and several other organisations have joined the call for peace and are making preparations for the jirga.

- ^ Frey, James (16 September 2020). The Indian Rebellion, 1857–1859: A Short History with Documents. Hackett Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-62466-905-7.

- ^ a b "Pashtun, Pathan in India". Joshua Project.

- ^ Finnigan, Christopher (29 October 2018). ""The Kabuliwala represents a dilemma between the state and migratory history of the world" – Shah Mahmoud Hanifi". London School of Economics.

- ^ "Bollywood actor Firoz Khan dies at 70". Dawn. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ "Afghans of Guyana". Wahid Momand. Afghanland.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ "Northern Pashtuns in Australia". Joshua Project.

- ^ a b Jasim Khan (27 December 2015). Being Salman. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 34, 35, 37, 38–. ISBN 978-81-8475-094-2.

Superstar Salman Khan is a Pashtun from the Akuzai clan...One has to travel roughly forty-five kilometres from Mingora towards Peshawar to reach the nondescript town of Malakand. This is the place where the forebears of Salman Khan once lived. They belonged to the Akuzai clan of the Pashtun tribe...

- ^ Swarup, Shubhangi (27 January 2011). "The Kingdom of Khan". Open. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ a b Alavi, Shams Ur Rehman (11 December 2008). "Indian Pathans to broker peace in Afghanistan". Hindustan Times.

Pathans are now scattered across the country, and have pockets of influence in parts of UP, Bihar and other states. They have also shone in several fields, especially Bollywood and sports. The three most famous Indian Pathans are Dilip Kumar, Shah Rukh Khan and Irfan Pathan. "The population of Pathans in India is twice their population in Afghanistan and though we no longer have ties (with that country), we have a common ancestry and feel it's our duty to help put an end to this menace", Atif added. Academicians, social activists, writers and religious scholars are part of the initiative. The All India Muslim Majlis, All India Minorities Federation and several other organisations have joined the call for peace and are making preparations for the jirga.

- ^ a b Nile Green (2017). Afghanistan's Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban. Univ of California Press. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-520-29413-4.

- ^ Windfuhr, Gernot (13 May 2013). Iranian Languages. Routledge. pp. 703–731. ISBN 978-1-135-79704-1.

- ^ "DORRĀNĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "ḠILZĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

Nāder Shah also defeated the last independent Ḡalzay ruler of Qandahār, Shah Ḥosayn Hotak, Shah Maḥmūd's brother in 1150/1738. Shah Ḥosayn and large numbers of the Ḡalzī were deported to Mazandarān (Marvī, pp. 543-52; Lockhart, 1938, pp. 115-20). The remnants of this once sizable exiled community, although assimilated, continue to claim Ḡalzī Pashtun descent.

- ^ "DORRĀNĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

raided in Khorasan, and "in the course of a very few years greatly increased in numbers"

- ^ Dalrymple, William; Anand, Anita (2017). Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-8885-8.

- ^ "ĀZĀD KHAN AFḠĀN". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "DORRĀNĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

According to a sample survey in 1988, nearly 75 percent of all Afghan refugees in the southern part of Persian Khorasan were Dorrānī, that is, about 280,000 people (Papoli-Yazdi, p. 62).

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (2002). Pakistan: nationalism without a nation?. Zed Books. p. 27. ISBN 1-84277-117-5. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ p. 2 D. R. 반다르카르의 "고대 인도 문화의 일부 측면"

- ^ "Rig Veda: Rig-Veda, Book 7: HYMN XVIII. Indra". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ 맥도넬, 에이에이, 키스, 에이비 1912. 이름과 주제에 대한 베다 인덱스.

- ^ 현재 아프가니스탄과 파키스탄에 있는 팩션 영토를 보여주는 메디안 제국의 지도...링크

- ^ "Herodotus, The Histories, Book 3, chapter 102, section 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "The History of Herodotus Chapter 7, Written 440 B.C.E, Translated by George Rawlinson". Piney.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ^ "The History of Herodotus Book 3, Chapter 91, Verse 4; Written 440 B.C.E, Translated by G. C. Macaulay". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ "Herodotus, The Histories, Book 3, chapter 91, section 4". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2007). History of Pakistan: Pakistan through ages. Sang-e Meel Publications. p. 77. ISBN 978-969-35-2020-0.

- ^ Holdich, Thomas (12 March 2019). The Gates of India, Being an Historical Narrative. Creative Media Partners, LLC. pp. 28, 31. ISBN 978-0-530-94119-6.

- ^ Ptolemy; Humbach, Helmut; Ziegler, Susanne (1998). Geography, book 6 : Middle East, Central and North Asia, China. Part 1. Text and English/German translations (in Greek). Reichert. p. 224. ISBN 978-3-89500-061-4.

- ^ Marquart, Joseph. Untersuchungen zur geschichte von Eran II (1905) (in German). p. 177.

- ^ "Strabo, Geography, BOOK XI., CHAPTER VIII., section 2". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1 January 1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 91. ISBN 9788172110284.

According to Strabo (c. 54 B.C., A.D. 24), who refers to the authority of Apollodorus of Artemia [sic], the Greeks of Bactria became masters of Ariana, a vague term roughly indicating the eastern districts of the Persian empire, and of India.

- ^ Sinor, Denis, ed. (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 117. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243049. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.

All contemporary historians, archeologists and linguists are agreed that since the Scythian and Sarmatian tribes were of the Iranian linguistic group...

- ^ a b Humbach, Helmut; Faiss, Klaus (2012). Herodotus's Scythians and Ptolemy's Central Asia: Semasiological and Onomasiological Studies. Reichert Verlag. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-89500-887-0.

- ^ Alikuzai, Hamid Wahed (October 2013). A Concise History of Afghanistan in 25 Volumes. Trafford Publishing. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-4907-1441-7.

- ^ Cheung, Johnny. "Cheung2017-On the Origin of the Terms "Afghan" & "Pashtun" (Again) - Gnoli Memorial Volume.pdf". p. 39.

- ^ Morano, Enrico; Provasi, Elio; Rossi, Adriano Valerio (2017). "On the Origin of Terms Afghan and Pashtun". Studia Philologica Iranica: Gherardo Gnoli Memorial Volume. Scienze e lettere. p. 39. ISBN 978-88-6687-115-6.

- ^ "Pashtun people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

Pashtun...bore the exclusive name of Afghan before that name came to denote any native of the present land area of Afghanistan.

- ^ * "아프간이라는 이름은 분명히 아리안의 아사케노이인 아스바칸에서 유래되었습니다..." (메가스테네스와 아리안, 180쪽) 참고 항목: 알렉산더의 인도 침공, p 38; JW 맥크린들).

- "아프간이라는 이름조차도 아리안은 아스바카야나에서 유래한 것으로, 그들의 유명한 품종의 말을 다루는 것에서 이 제목을 파생했을 것입니다."(참조: 해외 인도 사상과 문화의 각인, p 124, Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan).

- cf: "그들의 이름(아프간)은 산스크리트어, 아스바어, 또는 말인 아스바카어에서 유래된 "카발리에"라는 의미이며, 그들의 나라는 오늘날과 같이 고대에 우수한 말 품종으로 주목받았을 것이라는 것을 보여줍니다. 아스바카(Asvaka)는 카불 강 북쪽에 정착한 중요한 부족으로, 알렉산더(Alexander)의 팔에 대한 용감한 저항을 제공했지만 효과적이지 못했습니다(참조: 스코틀랜드 지리 잡지, 1999, p 275, Royal Scottish Geographic Society).

- "아프간인은 그리스인의 아사카니입니다; 이 단어는 '말꾼'을 의미하는 산스크리트어 아슈바카입니다"(참조: Sva, 1915, p 113, Christopher Molesworth Birdwood).

- Cf: "이 이름은 기병의 의미로 산스크리트어 아스바카를 나타내며, 이것은 알렉산더 원정의 역사가들의 아사카니 또는 아사카니에서 거의 수정되지 않은 것으로 나타납니다." (홉슨-잡슨: 구어체 앵글로-인디안 단어와 어구, 그리고 일종의 용어인 어원학 용어집..Henry Yule, AD Burnell).

- ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1977) [1952]. Ancient India (Reprinted ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. p. 99. ISBN 978-8-12080-436-4.

- ^ Indische Alterthumskunde, Vol I, fn 6; 또한 Vol II, p 129 등.

- ^ "아프간이라는 이름은 분명히 아리안의 아사케노이인 아스바칸에서 유래되었습니다..." (메가스테네스와 아리안, 180쪽) 참고 항목: 알렉산더의 인도 침공, p 38; J. W. 맥크린들).

- ^ Etude Surla Geog Grecque & c, pp 39-47, M. V. de Saint Martin.

- ^ 지구와 그 거주자들, 1891, p 83, 엘리제 리클루스 - 지리학.

- ^ "아프간이라는 이름조차도 아리안은 아스바카야나에서 유래한 것으로, 그들의 유명한 품종의 말을 다루는 것에서 이 제목을 파생했을 것입니다."(참조: 해외에서의 인도 사상과 문화의 각인, p 124, Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan).

- ^ cf: "그들의 이름(아프간)은 산스크리트어, 아스바어, 또는 말인 아스바카어에서 유래된 "카발리에"라는 의미이며, 그들의 나라는 오늘날과 같이 고대에 우수한 말 품종으로 주목받았을 것이라는 것을 보여줍니다. 아스바카(Asvaka)는 카불 강 북쪽에 정착한 중요한 부족으로, 알렉산더(Alexander)의 팔에 대한 용감한 저항을 제공했지만 효과적이지 못했습니다(참조: 스코틀랜드 지리 잡지, 1999, p 275, Royal Scottish Geographic Society).

- ^ "아프간인들은 그리스인들의 아사카니입니다; 이 단어는 '말꾼'을 의미하는 산스크리트어 아슈바카입니다"(참조: 스바, 1915, p 113, 크리스토퍼 몰스워스 버드우드).

- ^ Cf: "이 이름은 기병의 의미로 산스크리트어 아스바카를 나타내며, 이것은 알렉산더 원정의 역사가들의 아사카니 또는 아사카니에서 거의 수정되지 않은 것으로 나타납니다." (홉슨-잡슨: 구어체 앵글로-인디안 단어와 어구, 그리고 일종의 용어인 어원학 용어집..Henry Yule, AD Burnell).

- ^ Asvaka = 아프가니스탄에 대한 더 이상의 참고 문헌 참조: 수치 연대기, 1893, p 100, Royal Numismic Society (Great Britain); Awq, 1983, p 5, 조르지오 베르셀린; Der Islam, 1960, p 58, Carl Heinrich Becker, Maymūn ibn al-Qāsim Tabarann ī; 인도 역사 저널: Golden Jubily Volume, 1973, p 470, 인도 트리반드럼 (도시), 케랄라 대학. 역사학과; 인종 및 언어적 제휴와 관련된 고대 인도의 문학사, 1970, p 17, 찬드라 차크라베르티; 스틸더포르투지시셴리리리크 임 20 자흐훈트, p 124, 윈프리드 크로이첸. 참고: Works, 1865, p 164, H. H. 윌슨 박사; 지구와 그 주민들, 1891, p 83; Chants populares des Afghans, 1880, pclxiv, James Darmesteter; Nouvellegeie universelle v. 9, 1884, p.59, Elize Reclus; Alexander the Great, 2004, p.318, Lewis Vance Cummings (생략 및 자서전); Nouveau 사전 설문지 de géographie universelle content 1o Lagéographie 체격 ... 2o La .., 1879, Louis Rouseslet, Louis Vivien de Saint-Martin; Pauranika Personages의 민족적 해석, 1971, p 34, Chandra Chakraberty; Revue Internationale, 1803, p 803; 인도 역사 저널: Golden Jubily Volume, 1973, p 470, Trivandrum, 인도(도시). 케랄라 대학교. 역사학과; 에든버러 대학 출판부, 1969, 113쪽, 에든버러 대학; 시제젠원, 1930, 68쪽, 시제지추반. Cf 또한: 중세 인도의 고급 역사, 1983, p 31, J. L. 메타 박사; 아시아 관계, 1948, p 301, 아시아 관계 기구("미국 내 배포: 뉴욕 태평양 관계 연구소"); 스코틀랜드 지리 잡지, 1892, p 275, 왕립 스코틀랜드 지리 학회 - 지리; 고대 및 중세 인도의 지리학 사전, 1971, p 87, Nundo Lal Dey; Milind Pa ṅ 회의 Nag Sen, 1996, p 64, P. K. Kaul - 사회과학; 델리 술탄국, 1959, p 30, 아시르바디 랄 스리바스타바; 인도 역사 저널, 1965, p 354, 알라하바드 현대 인도 역사학과, 트라반코레 대학교 - 인도; 메모아레스 술레 콘테레 옥시덴탈레스, 1858, p 313, fn 3, 스타니슬라스 줄리엔 쉬안장 - 불교.

- ^ Noelle-Karimi, Christine; Conrad J. Schetter; Reinhard Schlagintweit (2002). Afghanistan -a country without a state?. University of Michigan, United States: IKO. p. 18. ISBN 3-88939-628-3. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

The earliest mention of the name 'Afghan' (Abgan) is to be found in a Sasanid inscription from the 3rd century, and it appears in India in the form of 'Avagana'...

- ^ Balogh, Dániel (12 March 2020). Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia: Sources for their Origin and History. Barkhuis. p. 144. ISBN 978-94-93194-01-4.

[ To Ormuzd Bunukan , ... greetings and homage from ... ) , Pithe ( sot ] ang ( ? ) of Parpaz ( under ) [ the glorious ) yabghu of [ Heph ] thal , the chief ... of the Afghans

- ^ Sims-Williams, Nicholas (2000). Bactrian documents from northern Afghanistan. Oxford: The Nour Foundation in association with Azimuth Editions and Oxford University Press. ISBN 1-874780-92-7.

- ^ 박트리아의 작은 왕국

- ^ "Sanskritdictionary.com: Definition of avagāṇa". sanskritdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ "Afghan". Ch. M. Kieffer. Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition. 15 December 1983. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ a b Varāhamihira; Bhat, M. Ramakrishna (1981). Bṛhat Saṁhitā of Varāhamihira: with english translation, exhaustive notes and literary comments. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 143. ISBN 978-81-208-0098-4.

- ^ a b c d Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 18. ISBN 0-631-19841-5. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Minorsky, V. V.; Bosworth, C. E. (31 January 2015). Hudud al-'Alam 'The Regions of the World' - A Persian Geography 372 A.H. (982 AD). Gibb Memorial Trust. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-909724-75-4.

Ninhar, a place of which the king makes a show of Islam, and has many wives, (namely) over thirty Muslim, Afghan, and Hindu (wives).

- ^ 펀자브와 북서 변경 지방의 부족과 주조에 관한 용어집 3권, H.A. Rose, Denzil Ibbetson Sir Atlantic Publishers & Distributors 출판사, 1997, 211페이지, ISBN 81-85297-70-3, ISBN 978-81-85297-70-5

- ^ "AMEER NASIR-OOD-DEEN SUBOOKTUGEEN". Ferishta, History of the Rise of Mohammedan Power in India, Volume 1: Section 15. Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

The Afghans and Khiljis who resided among the mountains having taken the oath of allegiance to Subooktugeen, many of them were enlisted in his army, after which he returned in triumph to Ghizny.

- ^ R. Khanam, 중동 및 중앙아시아 백과사전 민족지 : P-Z, 3권 - 18페이지

- ^ Houtsma, M. Th. (1993). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. BRILL. pp. 150–51. ISBN 90-04-09796-1. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ Ibn Battuta (2004). Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354 (reprint, illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 0-415-34473-5. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ "Old Iranian Online". University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ "Pashtun people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

...though most scholars believe it more likely that they arose from an intermingling of ancient Aryans from the north or west with subsequent invaders.

- ^ Nath, Samir (2002). Dictionary of Vedanta. Sarup & Sons. p. 273. ISBN 81-7890-056-4. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ "7". The History of Herodotus. Translated by George Rawlinson. The History Files. 4 February 1998 [original written 440 BC]. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2006.

{{cite book}}: CS1 메인트: 기타(링크) - ^ Lal, Mohan (1846). Life of the Amir Dost Mohammed Khan; of Kabul. Vol. 1. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 3. ISBN 0-7787-9335-4. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ "Encolypedia Iranica, AFGHANISTAN vi. Paṣ̌tō".

(69) Paṣ̌tō undoubtedly belongs to the Northeastern Iranic branch. It shares with Munǰī the change of *δ > l, but this tendency extends also to Sogdian

- ^ Comrie, Bernard (2009). The World's Major Languages.

Pashto belongs to the North-Eastern group within the Iranian Languages

- ^ Afghanistan volume 28. Historical Society of Afghanistan. 1975.

Pashto originally belonged to the north - eastern branch of the Iranic languages

- ^ Waghmar, Burzine; Frye, Richard N. (2001). "Bactrian History and Language: An Overview". Journal of the K. R. Cama Oriental Institute. 64: 40–48.

- ^ "Encolypedia Iranica, AFGHANISTAN vi. Paṣ̌tō".

It shares with Munǰī the change of *δ > l, but this tendency extends also to Sogdian. The Waṇ. dialect shares with Munǰī the change of -t- > -y-/0. If we want to assume that this agreement points to some special connection, and not to a secondary, parallel development, we should have to admit that one branch of pre-Paṣ̌tō had already, before the splitting off of Waṇ., retained some special connection with Munǰī, an assumption unsupported by any other facts. Apart from l <*δ the only agreement between Paṣ̌tō and Munǰī appears to be Pṣ̌t. zə; Munǰī zo/a "I." Note also Pṣ̌t. l but Munǰī x̌ < θ (Pṣ̌t. plan "wide", cal(w)or "four", but Munǰī paҳəy, čfūr, Yidḡa čšīr < *čəҳfūr). Paṣ̌tō has dr-, wr- < *θr-, *fr- like Khotanese Saka (see above 23). An isolated, but important, agreement with Sangl. is the remarkable change of *rs/z > Pṣ̌t. ҳt/ǧd; Sangl. ṣ̌t/ẓ̌d (obəҳta "juniper;" Sangl. wəṣ̌t; (w)ūǧd "long;" vəẓ̌dük) (see above 25). But we find similar development also in Shugh. ambaҳc, vūγ̌j. The most plausible explanation seems to be that *rs (with unvoiced r) became *ṣ̌s and, with differentiation *ṣ̌c, and *rz, through *ẓ̌z > ẓ̌j (from which Shugh. ҳc, γ̌j). Pṣ̌t. and Sangl. then shared a further differentiation into ṣ̌t, ẓ̌d ( > Pṣ̌t. ҳt, ğd).

- ^ "Encolypedia Iranica, AFGHANISTAN vi. Paṣ̌tō".

It is, however, possible that the original home of Paṣ̌tō may have been in Badaḵšān, somewhere between Munǰī and Sangl. and Shugh., with some contact with a Saka dialect akin to Khotanese.

- ^ Indo-Iranica. Kolkata, India: Iran Society. 1946. pp. 173–174.

... and their language is most closely related to on the one hand with Saka on the other with Munji-Yidgha

- ^ Bečka, Jiří (1969). A Study in Pashto Stress. Academia. p. 32.

Pashto in its origin, is probably a Saka dialect.

- ^ Cheung, Jonny (2007). Etymological Dictionary of the Iranian Verb. (Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series).

- ^ Cheung, Jonny (2007). Etymological dictionary of the Iranian verb. (Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series).

- ^ "Enyclopedia Iranica, AFGHANISTAN vi. Paṣ̌tō".

But it seems that the Old Iranic ancestor dialect of Paṣ̌tō must have been close to that of the Gathas.

- ^ Acheson, Ben (30 June 2023). The Pashtun Tribes in Afghanistan: Wolves Among Men. Pen and Sword Military. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-3990-6924-3.

Given the range of raiders and residents that the area has seen over the centuries, it is easy to see why today's Pashtuns could be descended from Persians, Greeks, Turks, Bactrians, Scythians, Tartars, Huns, Mongols, Moghuls or anyone else who has crossed the region over the years.__More unexpected are the alleged Pashtun ties to Israel (Israelites).

- ^ "Who Are the Pashtun People of Afghanistan and Pakistan?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

Many scholars believe that the Pashtun people are descended from several ancestral groups. Likely the foundational population were of eastern Iranian (Persian) origin and brought the Indo-European language east with them. They probably mixed with other peoples, including possibly the Hephthalites or White Huns, 'Arabs', Mughals, and others who passed through the area.

- ^ 캐롤, 올라프. 1984. 파탄족: 기원전 500년-서기 1957년 (옥스퍼드 인 아시아 역사 재인쇄)." 옥스퍼드 대학 출판부.

- ^ Barmazid. "Theory of Coptic origin of Pashtuns".

- ^ Bellew, Henry Walter (8 March 1891). An Inquiry Into the Ethnography of Afghanistan Prepared for and Presented to the 9th International Congress of Orientalists (London, Sept. 1891). p. 105.

By Some, the Bangash ancestor, Ismail, is connected with the Sultan Ismail, founder of the Saimani dynasty, which succeddeded to that of the Suffari (founded by Yacub Bin Leith or Lais) 875 A.D.

- ^ Firasat, Sadaf; Khaliq, Shagufta; Mohyuddin, Aisha; Papaioannou, Myrto; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Underhill, Peter A; Ayub, Qasim (January 2007). "Y-chromosomal evidence for a limited Greek contribution to the Pathan population of Pakistan". European Journal of Human Genetics. 15 (1): 121–126. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201726. PMC 2588664. PMID 17047675.

- ^ Huang, De-Shuang; Bevilacqua, Vitoantonio; Figueroa, Juan Carlos; Premaratne, Prashan (20 July 2013). Intelligent Computing Theories: 9th International Conference, ICIC 2013, Nanning, China, July 28-31, 2013, Proceedings. Springer. p. 409. ISBN 978-3-642-39479-9.

The Haplogroup J2 is from the Semitic population as well as the population shar- ing the common African ancestor. This Haplogroup was found 6.5 % in both the Greek and Pashtun population while 55.6% in the Israel population. The Israel popu- lation however did not result in exact match for haplotype of the 9 or 7 markers tested. Very few exact matches were found only with the 5 markers test. However the 7 marker test had many exact matches from the Greek population.

- ^ Huang, De-Shuang; Bevilacqua, Vitoantonio; Figueroa, Juan Carlos; Premaratne, Prashan (20 July 2013). Intelligent Computing Theories: 9th International Conference, ICIC 2013, Nanning, China, July 28-31, 2013, Proceedings. Springer. p. 403. ISBN 978-3-642-39479-9.

A number of genetic studies of the Pashtuns have been conducted recently by researchers of various universities and research groups. The Greek ancestry of the Pashtuns of Pakistan has been investigated in [1]. In this study, the claim of the three populations of the region, i.e. the Pashtuns, the Kalash and the Burusho, to have des- cended from the soldiers of Alexander, has been considered.

- ^ Quddus, Syed Abdul (1987). The Pathans. Ferozsons. p. 28.

Grierson finds a form Paithan in use in the East Gangetic Valley to denote a Muslim Rajput. Bellew, one of the greatest authorities on Pathans, notes that several characteristics are common to both the Rajputs and the Afghans and suggests that Sarban, one of the ancestors of the Afghans, was a corruption of the word Suryabans (solar race) from which many Rajputs claim descent. The great Muslim historian Masudi writes that Qandahar was a separate kingdom with a non- Muslim ruler and states that it is a country of Rajputs. It would be pertinent to mention here that at the time of Masudi most of the Afghans were concentrated in Qandahar and adjacent areas and had not expanded to the north. Therefore, it is highly significant that Masudi should call Qandahar a Rajput country.

- ^ Ahmad, Khaled (31 August 2009). "Pathans and Hindu Rajputs". Khyber. Archived from the original on 20 June 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

In a nutshell, Bellew's thesis is that all Afghan tribal names can be traced to Greek and Rajput names, which posits the further possibility of a great Greek mixing with the ancient border tribes of India.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint : 잘못된 URL (링크) - ^ Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul – The Name". Strabo (64 BC – 24 AD). American International School of Kabul. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Alexander took these away from the Aryans and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.

- ^ Mansoor A, Mazhar K, Khaliq S, et al. (April 2004). "Investigation of the Greek ancestry of populations from northern Pakistan". Hum Genet. 114 (5): 484–90. doi:10.1007/s00439-004-1094-x. PMID 14986106. S2CID 5715518.

- ^ Minorsky, V. "The Khalaj West of the Oxus". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 10 (2): 417–437. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00087607. S2CID 162589866. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011.

The fact is that the important Ghilzai tribe occupies now the region round Ghazni, where the Khalaj used to live and that historical data all point, to the transformation of the Turkish Khalaj into Afghan Ghilzai.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint : 잘못된 URL (링크) - ^ a b "ḵ 알라 지 트라이브" - 이란어 백과사전, 2010년 12월 15일 (피에르 오버링)

- ^ de la Vaissière 2003, pp. 119–137. 2003 (

- ^ Rezakhani 2017, p. 135 CITEREFRezakhani ( "헤프탈리트인들이 원래 튀르크계 출신이었고 나중에야 박트리아인을 행정 언어로 채택했다는 주장이 현재 가장 두드러진 것으로 보입니다(de la Vaissière 2007: 122).

- ^ Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

- ^ Bonasli, Sonel (2016). "The Khalaj and their language". Endangered Turkic Languages II A. Aralık: 273–275.

- ^ Minorsky, V. "The Khalaj West of the Oxus [excerpts from "The Turkish Dialect of the Khalaj", Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol 10, No 2, pp 417–437]". Khyber.ORG. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint : 잘못된 URL (링크) - ^ Runion, Meredith L. (24 April 2017). The History of Afghanistan, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610697781.

- ^ Morgenstierne, Georg (1979). "The Linguistic Stratification of Afghanistan". Afghan Studies. 2: 23–33.

- ^ Kurbano, Aydogdy. "THE HEPHTHALITES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS" (PDF). Department of History and Cultural Studies of the Free University, Berlin (PhD Thesis): 242. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

The Hephthalites may also have participated in the origin of the Afghans. The Afghan tribe Abdal is one of the big tribes that has lived there for centuries. Renaming the Abdals to Durrani occurred in 1747, when descendants from the Sadozai branch Zirak of this tribe, Ahmad-khan Abdali, became the shah of Afghanistan. In 1747 the tribe changed its name to "Durrani" when Ahmad khan became the first king of Afghanistan and accepted the title "Dur-i-Duran" (the pearl of pearls, from Arabian: "durr" – pearl).

- ^ Fisher, William Bayne; Yarshater, Ehsan (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- ^ Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (1987). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. Vol. 2. BRILL. p. 150. ISBN 90-04-08265-4. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ Wink, Andre (2002). Al-Hind: the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th–11th Centuries Vol 1. Brill. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0391041738. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Oreck, Alden. "The Virtual Jewish History Tour, Afghanistan". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d Stanizai, Zaman (9 October 2020). Are Pashtuns the Lost Tribe of Israel?. doi:10.33774/coe-2020-vntk7-v4. S2CID 234658271.

- ^ McCarthy, Rory (17 January 2010). "Pashtun clue to lost tribes of Israel". The Observer.

- ^ 아미르 도스트 모하메드 칸의 삶; 카불의 1권. Mohan Lal(1846) 지음, pg.5

- ^ Lacau, Harlette; Gayden, Tenzin; Regueiro, Maria; Chennakrishnaiah, Shilpa; Bukhari, Areej; Underhill, Peter A.; Garcia-Bertrand, Ralph L.; Herrera, Rene J. (October 2012). "Afghanistan from a Y-chromosome perspective". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (10): 1063–1070. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.59. PMC 3449065. PMID 22510847.

- ^ Edward G. Browne, M.A., M.B. "A Literary History of Persia, Volume 4: Modern Times (1500–1924), Chapter IV. An Outline Of The History Of Persia During The Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722–1922)". London: Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: 다중 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Louis Dupree, Nancy Hatch Dupree; et al. "Last Afghan empire". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ Thakurta, R.N. Guha (1978). The Contemporary, Volume 22. National Galvanizing Pvt. Limited.

- ^ Rajesh, K. Guru. Sarfarosh: A Naadi Exposition of the Lives of Indian Revolutionaries. Notion Press. p. 524. ISBN 9789352061730.

Ashfaqullah's father, Shafeequlla Khan, was a member of a Pathan military family.

- ^ "Abdul Ghaffar Khan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ "Abdul Ghaffar Khan". I Love India. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ "Mohammad Yousaf Khan Khattak". Pakpost.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ "Young Afghan refugees and asylum seekers in the UK". UN university. 18 June 2018.

- ^ Ahady, Anwar-ul-Haq (1995). "The Decline of the Pashtuns in Afghanistan". Asian Survey. 35 (7): 621–634. doi:10.2307/2645419. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645419.

- ^ Hakala, Walter N. (2012). "Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan's Cultures" (PDF). National Geographic. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

In the 1980s and '90s, at least three million Afghans--mostly Pashtun--fled to Pakistan, where a substantial number spent several years being exposed to Hindustani-language media, especially Bollywood films and songs, and being educated in Urdu-language schools, both of which contributed to the decline of Dari, even among urban Pashtuns.

- ^ Rahi, Arwin (25 February 2020). "Why Afghanistan should leave Pakistani Pashtuns alone". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Malik Ghulam Muhammad - Governor-General of Pakistan". Pakistan Herald. 23 July 2017. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Ex Gov.Gen. Ghulam Muhammad's 54th death anniversary today". Samaa TV. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ Sheikh, Majid (22 October 2017). "The history of Lahore's Kakayzais". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Kumarasingham, H. (2016). "Bureaucratic Statism". Constitution-making in Asia: Decolonisation and State-Building in the Aftermath of the British Empire (1 ed.). U.S.: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-24509-4.

- ^ a b Devasher, Tilak (15 September 2022). The Pashtuns: A Contested History. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-93-94407-64-0.

The Pashtuns have made a vital contribution in diverse spheres of life: all rulers of Afghanistan since 1747, except for a nine-month interlude in 1929 and between 1992 and 1996, have been Pashtuns. In Pakistan, Ayub Khan, a Tarin Pashtun, as also Gen. Yahya Khan and Ghulam Ishaq Khan, became presidents; in India, Zakir Hussain, an Afridi Pashtun, became president. Muhammed Yusuf Khan (Dilip Kumar) and Mumtaz Jahan (Madhubala) were great Bollywood actors; Mansoor Ali Khan (Tiger Pataudi) led the Indian cricket team;

- ^ a b Dalal, Mangal (8 January 2010). "When men were men". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

She's a Pathan girl who speaks Hindi and Urdu well and was spectacular in the screen test. It was pure luck.

- ^ Sharma, Vishwamitra (2007). Famous Indians of the 21st century. Pustak Mahal. p. 60. ISBN 978-81-223-0829-7. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Fārūqī, Z̤iāʼulḥasan (1999). Dr. Zakir Hussain, quest for truth (by Ziāʼulḥasan Fārūqī). APH Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 81-7648-056-8.

- ^ Johri, P.K (1999). Educational thought. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. p. 267. ISBN 81-261-2175-0.

- ^ "To Islamabad and the Frontier". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 26 May 2003. Archived from the original on 3 July 2003. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

Ruled now by parties of the religious right, the Frontier province emerges soon after one proceeds westwards from Islamabad. I was lucky to find Ajmal Khan Khattak in his humble home in Akora Khattak, beyond the Indus. Once Badshah Khan's young lieutenant, Mr. Khattak spent years with him in Afghanistan and offered a host of memories. And I was able to meet Badshah Khan's surviving children, Wali Khan, the famous political figure of the NWFP, and his half-sister, Mehr Taj, whose husband Yahya Jan, a schoolmaster who became a Minister in the Frontier, was the brother of the late Mohammed Yunus, who had made India his home.

- ^ Darbari, Raj (1983). Commonwealth and Nehru. Vision Books. p. 28. ISBN 81-261-2175-0.

- ^ The Pathan unarmed: opposition & memory in the North West Frontier (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). James Currey.

He was visiting his cousin Mohammed Yunus, a Pathan who had chosen to move to Delhi at Partition and become a well-known figure in the Congress regime.

- ^ Encyclopædia of Muslim Biography. A.P.H. Pub. Corp.

Mohammad Yunus is belong to a rich and distinguished Pathan family and son of Haji Ghulam Samdani (1827–1926).

- ^ Watkins, Andrew (17 August 2022). "One Year Later: Taliban Reprise Repressive Rule, but Struggle to Build a State". United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Cruickshank, Dan. "Afghanistan: At the Crossroads of Ancient Civilisations". BBC. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ "Afghan Government 2009" (PDF). scis.org. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2011.

- ^ "Leaving Afghanistan's 'Bagarm Airfield' Was a Grave Military Mistake: Trump". Khaama Press. 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "Redeeming the Pashtun, the ultimate warriors". Macleans.ca. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Lacau, Harlette; Gayden, Tenzin; Reguerio, Maria; Underhill, Peter (October 2012). "Afghanistan from a Y-chromosome perspective". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (October 2012): 1063–70. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.59. PMC 3449065. PMID 22510847.

- ^ Nagy, Péter L.; Olasz, Judit; Neparáczki, Endre; Rouse, Nicholas; Kapuria, Karan; Cano, Samantha; Chen, Huijie; Di Cristofaro, Julie; Runfeldt, Goran; Ekomasova, Natalia; Maróti, Zoltán; Jeney, János; Litvinov, Sergey; Dzhaubermezov, Murat; Gabidullina, Lilya; Szentirmay, Zoltán; Szabados, György; Zgonjanin, Dragana; Chiaroni, Jacques; Behar, Doron M.; Khusnutdinova, Elza; Underhill, Peter A.; Kásler, Miklós (January 2021). "Determination of the phylogenetic origins of the Árpád Dynasty based on Y chromosome sequencing of Béla the Third". European Journal of Human Genetics. 29 (1): 164–172. doi:10.1038/s41431-020-0683-z. PMC 7809292. PMID 32636469.

- ^ Underhill, Peter A.; Poznik, G. David; Rootsi, Siiri; Järve, Mari; Lin, Alice A.; Wang, Jianbin; Passarelli, Ben; Kanbar, Jad; Myres, Natalie M.; King, Roy J.; Di Cristofaro, Julie; Sahakyan, Hovhannes; Behar, Doron M.; Kushniarevich, Alena; Šarac, Jelena; Šaric, Tena; Rudan, Pavao; Pathak, Ajai Kumar; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Grugni, Viola; Semino, Ornella; Yepiskoposyan, Levon; Bahmanimehr, Ardeshir; Farjadian, Shirin; Balanovsky, Oleg; Khusnutdinova, Elza K.; Herrera, Rene J.; Chiaroni, Jacques; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Quake, Stephen R.; Kivisild, Toomas; Villems, Richard (January 2015). "The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a". European Journal of Human Genetics. 23 (1): 124–131. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.50. PMC 4266736. PMID 24667786.

- ^ Di Cristofaro, Julie; Pennarun, Erwan; Mazières, Stéphane; Myres, Natalie M.; Lin, Alice A.; Temori, Shah Aga; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Witzel, Michael; King, Roy J.; Underhill, Peter A.; Villems, Richard; Chiaroni, Jacques (2013). "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e76748. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876748D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076748. PMC 3799995. PMID 24204668.