애니멀

Animal| 동물들 시간 범위: 크라이오제니안 – 현재, | |

|---|---|

| |

| 과학적 분류 | |

| 도메인: | 진핵생물 |

| 클레이드: | 아모르페아 |

| 클레이드: | 오바조아 |

| (순위 없음): | Opisthokonta |

| (순위 없음): | 홀로조아 |

| (순위 없음): | 필로조아과 |

| 왕국: | 애니멀리아 린네 |

| 세분류 | |

| |

| 동의어 | |

동물은 생물학적 왕국인 애니멀리아에 있는 다세포 진핵생물입니다. 동물은 거의 예외 없이 유기물을 섭취하고 산소를 호흡하며 근세포를 가지고 이동할 수 있으며 성생식을 할 수 있으며 배아 발달 동안 속이 빈 세포 구인 포배에서 성장합니다.

2022년 현재, 약 216만 종의 살아있는 동물이 기술되어 있으며, 그 중 약 105만 종이 곤충이고, 85,000 종 이상이 연체동물이며, 약 65,000 종이 척추동물입니다. 지구상에는 무려 777만 종의 동물이 있는 것으로 추정되고 있습니다. 동물의 몸 길이는 8.5μm(0.00033인치)에서 33.6m(110피트)입니다. 그들은 복잡한 생태와 서로의 환경과 상호 작용을 하며 복잡한 먹이 그물을 형성합니다. 동물에 대한 과학적 연구는 동물학으로 알려져 있고 동물의 행동에 대한 연구는 윤리학으로 알려져 있습니다.

대부분의 살아있는 동물 종들은 구성원들이 양쪽으로 대칭되는 몸통 계획을 가지고 있는 고도로 증식하는 분기군인 침입종 빌레테리아에 속합니다. 현존하는 쌍각류는 기저군인 Xenacoelomorpha를 포함하지만, 대다수는 두 개의 큰 상문에 속합니다: 절지동물, 연체동물, 편충, 환형동물, 선충 등과 같은 문을 포함하는 원시동물과 세 개의 극피동물, 반색동물 및 척색동물을 포함하는 중생동물, 척추동물이 가장 성공적인 아문인 후자. 초기 복합 동물로 해석되는 선캄브리아기의 생명체는 원생대 후기의 에디아카란 생물군에 이미 존재했지만, 원시 스폰지와 다른 추측성 초기 동물의 화석은 일찍이 토니안 시대로 거슬러 올라갑니다. 거의 모든 현대 동물 문은 약 5억 3900만 년 전(Mya)에 시작된 캄브리아기 폭발 때 해양 종으로 화석 기록에서 명확하게 확립되었으며, 대부분의 클래스는 오르도비스기 방사선 485.4 Mya. 6,모든 살아있는 동물들에게 공통적인 유전자 그룹 331개가 확인되었는데, 이들은 크라이오제니아 시대에 650 Mya를 살았던 단일 공통 조상에서 유래했을 수도 있습니다.

역사적으로 아리스토텔레스는 동물을 피가 있는 것과 없는 것으로 나누었습니다. Carl Linnaeus는 1758년에 그의 Systema Naturae로 동물에 대한 최초의 계층적 생물학적 분류를 만들었고, Jean-Baptiste Lamark는 1809년까지 14개의 문으로 확장했습니다. 1874년 에른스트 해켈은 동물계를 다세포 메타조아(현재 애니멀리아와 동의어)와 더 이상 동물로 간주되지 않는 단세포 생물인 원생동물로 나누었습니다. 현대에 동물의 생물학적 분류는 분류군 사이의 진화적 관계를 입증하는 데 효과적인 분자 계통 발생학과 같은 고급 기술에 의존합니다.

인간은 다른 많은 동물 종들을 식용(고기, 달걀, 낙농장 포함), 재료(가죽, 모피, 양모), 애완동물, 운송, 서비스를 위한 일을 하는 동물로 사용합니다. 최초의 길들여진 동물인 개는 사냥, 안보, 전쟁에서 말, 비둘기, 맹금류와 같이 사용되었고, 다른 육상 및 수생 동물들은 스포츠, 트로피 또는 이익을 위해 사냥됩니다. 인간이 아닌 동물은 또한 인류 진화의 중요한 문화적 요소이며, 가장 초기부터 동굴 예술과 토템에 등장했으며 신화, 종교, 예술, 문학, 헤럴드, 정치, 스포츠에 자주 등장합니다.

어원

"동물"이라는 단어는 '숨이나 영혼을 가지고 있다'라는 뜻의 라틴어 애니멀리스에서 왔습니다.[4] 생물학적 정의에는 애니멀리아 왕국의 모든 구성원이 포함됩니다.[5] 구어체에서 동물이라는 용어는 종종 사람이 아닌 동물만을 지칭하기 위해 사용됩니다.[6][7][8][9] 메타조아(metazoa)라는 용어는 고대 그리스어 μ ετα (meta, "나중에"를 의미함)와 ζῷᾰ (zoia, 동물을 의미함)에서 유래했습니다.

특성.

동물들은 다른 생물들과 구별되는 몇 가지 특징들을 가지고 있습니다. 동물은 진핵생물이고 다세포입니다.[12] 스스로 양분을 생산하는 식물이나 조류와 달리 [13]동물은 유기물을 먹고 내부에서 소화하는 종속영양생물입니다.[14][15][16] 아주 적은 예외를 제외하고, 동물들은 호기성 호흡을 합니다.[a][18] 모든 동물은 적어도 생애 주기 동안 운동성이[19] 있지만 해면, 산호, 홍합, 따개비와 같은 일부 동물은 나중에 무균 상태가 됩니다. 배반은 동물 특유의 배아 발달 단계로, 세포가 전문 조직과 기관으로 분화될 수 있도록 합니다.[20]

구조.

모든 동물은 세포로 구성되어 있으며 콜라겐과 탄성 당단백질로 구성된 특징적인 세포외 기질로 둘러싸여 있습니다.[21] 발달하는 동안 동물 세포외 기질은 세포가 이동하고 재구성될 수 있는 비교적 유연한 프레임워크를 형성하여 복잡한 구조의 형성을 가능하게 합니다. 이것은 석회화되어 껍질, 뼈 및 가시와 같은 구조를 형성할 수 있습니다.[22] 대조적으로, 다른 다세포 생물(주로 조류, 식물 및 곰팡이)의 세포는 세포벽에 의해 제자리에 고정되고, 따라서 점진적인 성장에 의해 발달합니다.[23] 동물 세포는 독특하게 단단한 접합부, 틈 접합부, 데스모솜이라고 불리는 세포 접합부를 가지고 있습니다.[24]

특히 해면동물과 플라코조아와 같은 동물의 몸은 거의 예외 없이 조직으로 분화됩니다.[25] 여기에는 운동을 가능하게 하는 근육과 신호를 전달하고 신체를 조정하는 신경 조직이 포함됩니다. 일반적으로 (Ctenophora, Cnidaria 및 편평충에서) 하나의 개구 또는 두 개의 개구(대부분의 이방충에서)가 있는 내부 소화실도 있습니다.[26]

재생산 및 개발

거의 모든 동물들이 어떤 형태의 성적 생식을 이용합니다.[27] 그들은 감수분열에 의해 반수체 생식체를 생산합니다; 더 작은 운동성 생식체는 정자이고 더 큰 운동성이 없는 생식체는 난자입니다.[28] 이들은 융합하여 접합체를 형성하고,[29] 접합체는 유사분열을 통해 속이 빈 구, 포배라고 합니다. 해면동물에서 배반유충은 새로운 장소로 헤엄쳐 가서 해저에 붙어 새로운 해면으로 발달합니다.[30] 대부분의 다른 그룹에서 배반은 더 복잡한 재배열을 겪습니다.[31] 그것은 먼저 소화실과 두 개의 분리된 생식층, 외부 외배엽과 내부 내배엽을 가진 위관을 형성합니다.[32] 대부분의 경우 세 번째 생식층인 중배엽도 이들 사이에서 발생합니다.[33] 그런 다음 이 생식층이 분화하여 조직과 기관을 형성합니다.[34]

성적 생식 중 가까운 친척과 교미하는 반복적인 사례는 일반적으로 유해한 열성 형질의 유병률 증가로 인해 개체군 내에서 근친 우울증으로 이어집니다.[35][36] 동물들은 근친교배를 피하기 위한 수많은 메커니즘을 발전시켜 왔습니다.[37]

어떤 동물들은 무성 생식을 할 수 있고, 이것은 종종 부모의 유전적 복제를 초래합니다. 이것은 파편화, 히드라 및 기타 분생포자에서와 같은 싹; 또는 진딧물에서와 같이 짝짓기 없이 수정란이 생성되는 분만 생성을 통해 발생할 수 있습니다.[38][39]

생태학

동물은 영양 수준과 유기물을 섭취하는 방법에 따라 생태학적 그룹으로 분류됩니다. 이러한 분류에는 육식동물(물고기, 식충, 식충 등의 하위 범주로 더 구분됨), 초식동물(엽식동물, 그라민식동물, 검소동물, 과채동물, 과즙식동물, 알조동물 등으로 하위 범주 분류됨), 잡식동물, 곰팡이, 청소부/퇴적동물,[40] 기생충 등이 포함됩니다.[41] 각 생물군집의 동물들 사이의 상호작용은 그 생태계 내에서 복잡한 먹이 그물을 형성합니다. 육식성 또는 잡식성 종에서 포식은 포식자가 다른 생물인 먹이를 먹고 사는 소비자와 자원의 상호작용입니다.[42] 포식자는 종종 먹이를 먹지 않기 위해 반 포식자의 적응을 진화시킵니다. 서로에게 가해지는 선택적 압력은 포식자와 먹잇감 사이의 진화적 군비 경쟁으로 이어져 다양한 적대적/경쟁적 공진화를 초래합니다.[43][44] 거의 모든 다세포 포식자는 동물입니다.[45] 일부 소비자는 다양한 방법을 사용합니다. 예를 들어, 기생 말벌에서는 유충이 숙주의 살아있는 조직을 먹고 그 과정에서 [46]죽이지만 성충은 주로 꽃에서 꿀을 섭취합니다.[47] 다른 동물들은 매부리바다거북이 주로 해면동물을 먹는 것과 같이 매우 구체적인 섭식 행동을 할 수도 있습니다.[48]

대부분의 동물들은 광합성을 통해 식물과 식물 플랑크톤(생산자라고 통칭)이 생산하는 바이오매스와 바이오 에너지에 의존합니다. 초식동물은 주요 소비자로서 식물의 재료를 직접 먹어 영양소를 소화하고 흡수하는 반면, 영양 수준이 높은 육식동물과 다른 동물들은 초식동물이나 초식동물을 먹은 다른 동물들을 먹어 영양소를 간접적으로 획득합니다. 동물은 탄수화물, 지질, 단백질 및 기타 생체 분자를 산화시켜 동물이 성장하고 기초 대사를 유지하고 운동과 같은 다른 생물학적 과정을 촉진합니다.[49][50][51] 열수분출구와 어두운 해저의 냉수분출구 근처에 사는 일부 저서동물은 고세균과 박테리아에 의해 화학 합성을 통해 생성된 유기물을 섭취합니다.[52]

동물들은 원래 바다에서 진화했습니다. 절지동물의 계통은 육상 식물과 비슷한 시기에 땅을 식민지로 삼았습니다. 아마도 캄브리아기 후기 또는 오르도비스기 초기에 5억 1천만 년에서 4억 7천 백만 년 전 사이였을 것입니다.[53] 엽지느러미 물고기 틱타알릭과 같은 척추동물은 약 3억 7500만 년 전인 데본기 후기에 육지로 이동하기 시작했습니다.[54][55] 동물들은 소금물, 열수 분출구, 담수, 온천, 늪, 숲, 목초지, 사막, 공기 및 기타 동물, 식물, 곰팡이 및 암석의 내부를 포함하여 거의 모든 지구의 서식지와 미세 서식지를 차지합니다.[56] 하지만 동물들은 특별히 열에 강하지는 않습니다. 그들 중 극소수만이 50°C(122°F) 이상의 일정한 온도에서 살아남을 수 있습니다.[57] 극소수의 동물들만이 남극대륙의 가장 극한의 추운 사막에 살고 있습니다.[58]

다양성

크기

흰긴수염고래(Balaenoptera musculus)는 지금까지 살았던 동물 중 가장 큰 동물로, 무게는 190톤까지 나가고 길이는 33.6미터(110피트)까지 나갑니다.[59][60][61] 현존하는 가장 큰 육상 동물은 아프리카 덤불 코끼리(록소돈타 아프리카나)로 몸무게는 최대 12.25톤[59], 길이는 최대 10.67미터(35.0피트)입니다.[59] 지금까지 살았던 가장 큰 육상 동물은 무게가 무려 73톤이나 나갔을 수도 있는 아르젠티노사우루스와 같은 티타노사우루스 용각류 공룡과 39미터에 달했을 수도 있는 슈퍼사우루스였습니다.[62][63] 몇몇 동물들은 미세합니다; 일부 Myxozoa (크니다리아 내의 절대 기생충)는 20 µm 이상으로 자라지 않고, 가장 작은 종들 중 하나 (Myxobolus shekel)는 완전히 자랐을 때 8.5 µm 이하입니다.

주요 문의 수와 서식지

다음 표는 주요 동물 문에 대해 기술된 현존하는 종의 추정 수와 주요 서식지([66]육상, 담수,[67] 해양)[68] 및 자유 생활 또는 기생 생활 방식을 나열합니다.[69] 여기에 표시된 종 추정치는 과학적으로 설명된 수치를 기반으로 합니다. 훨씬 더 큰 추정치는 다양한 예측 방법을 기반으로 계산되었으며, 이는 매우 다양할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 약 25,000-27,000 종의 선충이 기술된 반면, 발표된 선충 종의 총 개체수에 대한 추정치는 10,000-20,000 종, 50,000 종, 천만 종, 그리고 1억 종을 포함합니다.[70] 분류학적 계층 내의 패턴을 사용하여, 아직 설명되지 않은 것들을 포함한 총 동물 종의 수는 2011년에 약 777만 종으로 계산되었습니다.[71][72][b]

| 문 | 예 | 기술종 | 땅 | 바다 | 담수 | 자유생활 | 기생 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 지족류 |  | 1,257,000[66] | 1,000,000 (insects)[74] | >40,000 (말락-) ostraca)[75] | 94,000[67] | 네[68] | >45,000[c][69] |

| 연체동물 |  | 85,000[66] 107,000[76] | 35,000[76] | 60,000[76] | 5,000[67] 12,000[76] | 네[68] | >5,600[69] |

| 초르다타 |  | >70,000[66][77] | 23,000[78] | 13,000[78] | 18,000[67] 9,000[78] | 네. | 40 (메기)[79][69] |

| 플라티헬름 인츠 |  | 29,500[66] | 네[80] | 네[68] | 1,300[67] | 네[68] 3,000–6,500[81] | >40,000[69] 4,000–25,000[81] |

| 네마토다 |  | 25,000[66] | 네(토양)[68] | 4,000[70] | 2,000[67] | 11,000[70] | 14,000[70] |

| 아넬리다 |  | 17,000[66] | 네(토양)[68] | 네[68] | 1,750[67] | 네. | 400[69] |

| 크니다리아 |  | 16,000[66] | 네[68] | 예(소수)[68] | 네[68] | >1,350 (Mixozoa)[69] | |

| 포리페라 |  | 10,800[66] | 네[68] | 200–300[67] | 네. | 네[82] | |

| 에키노데르마타 |  | 7,500[66] | 7,500[66] | 네[68] | |||

| 브라이오조아 |  | 6,000[66] | 네[68] | 60–80[67] | 네. | ||

| 로티페라 |  | 2,000[66] | >400[83] | 2,000[67] | 네. | ||

| 네메르티 |  | 1,350[84][85] | 네. | 네. | 네. | ||

| 타르디그라다 |  | 1,335[66] | 네[86] (moist 공장) | 네. | 네. | 네. | |

진화적 기원

동물들은 에디아카란 생물군처럼 오래 전에, 선캄브리아기 말에, 그리고 아마도 어느 정도 더 일찍 발견됩니다. 이 생명체들이 동물을 포함하고 있는지는 오랫동안 의심되어 왔지만,[87][88][89] 디킨소니아의 화석에서 동물의 지질 콜레스테롤이 발견됨으로써 그들의 본성이 확립되었습니다.[90] 동물들은 저산소 상태에서 태어난 것으로 생각되는데, 이는 그들이 완전히 혐기성 호흡에 의해 살 수 있었지만, 호기성 대사에 특화되면서 그들은 그들의 환경에서 산소에 완전히 의존하게 되었다는 것을 암시합니다.[91]

많은 동물 문은 약 5억 3900만 년 전에 시작된 캄브리아기 폭발 동안 버지스 셰일과 같은 침대에서 화석 기록에 처음 등장합니다.[92] 이 암석에 현존하는 문에는 연체동물, 완족류, 오니코포란, 완족류, 절지동물, 극피동물, 반정족류 등이 포함되며, 포식성 아노말로카리스와 같이 현재는 멸종된 수많은 형태가 있습니다. 그러나 이 사건의 명백한 갑작스러운 것은 이 모든 동물들이 동시에 나타났다는 것을 보여주기 보다는 화석 기록의 산물일 수 있습니다.[93][94][95][96] 이러한 견해는 영국 챈우드 숲에서 발견된 가장 초기의 에디아카란 왕관군(cnidarian, 557–562 mya, 캄브리아기 폭발 전 약 2천만 년)인 오로랄루미나 아텐보로이(Auroralumina attenborouii)의 발견에 의해 뒷받침됩니다. 현대의 분선충처럼 선충으로 작은 먹이를 잡아먹는 가장 초기의 포식자 중 하나로 여겨집니다.[97]

일부 고생물학자들은 동물들이 캄브리아기 폭발보다 훨씬 더 일찍, 아마도 10억년 전에 나타났을 것이라고 제안했습니다.[98] 예를 들어 동물을 대표할 수 있는 초기 화석은 사우스 오스트레일리아의 트레조나 층의 6억 6천 5백만 년 된 암석에 나타납니다. 이 화석들은 아마도 초기 해면동물일 것으로 해석됩니다.[99] 토니안 시대(1gya에서)에 발견된 흔적과 굴과 같은 흔적 화석은 지렁이만큼 크고 복잡한 세모세포 벌레와 같은 동물의 존재를 나타낼 수 있습니다.[100] 그러나 거대한 단세포 원생생물인 그로미아 스페리카(Gromia sphaerica)에 의해 비슷한 흔적이 생성되므로 토니안 흔적 화석은 초기 동물 진화를 나타내지 않을 수 있습니다.[101][102] 비슷한 시기에 스트로마톨라이트라고 불리는 미생물의 층층이 쌓인 매트는 아마도 새로 진화한 동물들의 방목 때문에 다양성이 감소했습니다.[103] 벌레 같은 동물의 굴의 흔적 화석을 닮은 퇴적물이 채워진 튜브와 같은 물체는 북미의 1.2 갸 바위, 호주와 북미의 1.5 갸 바위, 호주의 1.7 갸 바위에서 발견되었습니다. 동물의 기원을 가지고 있다는 그들의 해석은 물 탈출이나 다른 구조물일 수 있기 때문에 논쟁의 여지가 있습니다.[104][105]

-

Ediacaran biota (c. 635–542 mya)의 Dickinsonia costata는 알려진 가장 초기의 동물 종 중 하나입니다.[90]

-

이디아카라 포식자인 오로랄루미나 아텐보로이(Auroralumina attenboroughii)[97]

-

Anomalocaris canadensis는 캄브리아기 폭발에서 나타난 많은 동물 종 중 하나로 약 539mya를 시작하여 버지스 셰일의 화석층에서 발견됩니다.

계통발생학

외부계통발생학

동물들은 단일계통으로 공통된 조상으로부터 유래되었음을 의미합니다. 동물들은 초아노플라겔라타와 자매를 이루며, 초아노조아를 형성합니다.[106] 계통수의 날짜는 대략 몇 백만 년 전에 계통이 얼마나 갈라졌는지를 나타냅니다.[107][108][109][110][111]

Ros-Rocher와 동료들(2021)은 동물의 기원을 단세포 조상으로 추적하여 클라도그램에 나타난 외부 계통 발생을 제공합니다. 관계의 불확실성은 점선으로 표시됩니다.[112]

| Opisthokonta |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1300미아 |

내부 계통발생학

가장 기본적인 동물인 포리페라(Porifera), 크테노포라(Ctenophora), 크니다리아(Cnidaria), 플라코조아(Placozoa)는 양쪽 대칭이 결여된 신체 계획을 가지고 있습니다. 그들의 관계는 여전히 논쟁의 여지가 있습니다; 다른 모든 동물들의 자매 그룹은 신체 계획 발달에 중요한 hox 유전자가 [113]없는 Porifera 또는 Ctenophora일 수 있습니다.[114]

이 유전자들은 플라코조아와[115][116] 고등동물인 빌레테리아에서 발견됩니다.[117][118] 모든 살아있는 동물들에게 공통적인 유전자 집단 6,331개가 확인되었는데, 이들은 선캄브리아기에 6억 5천만 년 전에 살았던 하나의 공통된 조상으로부터 생겨났을지도 모릅니다. 이들 중 25개는 동물에서만 발견되는 새로운 핵심 유전자 그룹이며, 이들 중 8개는 Wnt 및 TGF-베타 신호 전달 경로의 필수 구성 요소에 대한 것으로, 신체의 축 시스템(3차원)에 대한 패턴을 제공함으로써 동물이 다세포화될 수 있게 했을 수 있음, 그리고 또 다른 7개는 발달 조절에 관여하는 호메오도메인 단백질을 포함하는 전사 인자입니다.[119][120]

Giribet과 Edgecombe(2020)는 그들이 동물의 합의된 내부 계통 발생으로 간주하는 것을 제공하여 나무의 기저부(색선)에 있는 구조에 대한 불확실성을 구현합니다.[121]

| 애니멀리아 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 다세포의 |

Kapli와 동료들(2021)의 대체 계통발생학은 Xenacoelamorpha + Ambulacraria에 대한 제남불라크라리아 분기군을 제안합니다. 이것은 Chordata의 자매로 Deuterostomia 내에 있거나, Deuterostomia가 paraphyletic으로 회수되고, 제남불라크라리아는 Chordata + Protostomia로 구성된 제안된 Centroneuralia 분기군의 자매입니다.[122]

비빌라테리아

몇몇 동물 문들은 양쪽 대칭성이 부족합니다. 이것들은 포리페라(바다 해면), 플라코조아(플라코조아), 크니다리아(해파리, 말미잘, 산호를 포함), 크테노포라(콤 젤리)입니다.

해면동물은 다른 동물들과 신체적으로 매우 구별되며, 가장 오래된 동물문을 대표하고 다른 모든 동물들과 자매군을 형성하면서 가장 먼저 갈라진 것으로 오랫동안 여겨졌습니다.[123] 다른 모든 동물들과 형태학적으로 다른 점이 있음에도 불구하고, 유전적 증거는 해면동물이 빗 젤리보다 다른 동물들과 더 밀접한 관련이 있을 수 있다는 것을 암시합니다.[124][125] 해면동물은 대부분의 다른 동물문에서 볼 수 있는 복잡한 조직이 없습니다;[126] 그들의 세포는 분화되어 있지만, 대부분의 경우 다른 모든 동물들과 달리 별개의 조직으로 조직화되지 않습니다.[127] 그들은 일반적으로 기공을 통해 물을 끌어들여 음식과 영양소를 걸러내어 먹이를 먹습니다.[128]

빗자루와 느리다리아는 방사상으로 대칭을 이루며 하나의 구멍이 있는 소화실을 가지고 있어 입과 항문의 역할을 모두 합니다.[129] 두 문의 동물들은 뚜렷한 조직을 가지고 있지만, 이것들은 별개의 기관으로 조직화되어 있지 않습니다.[130] 그들은 외배엽과 내배엽의 두 개의 주요 생식층만을 가지고 있는 이중모세포입니다.[131]

이 작은 플라코조아는 영구적인 소화실과 대칭성이 없습니다. 그들은 표면적으로 아메바를 닮았습니다.[132][133] 그들의 계통발생은 제대로 정의되지 않았으며 활발한 연구가 진행 중입니다.[124][134]

빌라테리아

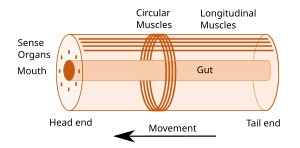

약 29개의 문과 백만 종 이상의 종으로 구성된 나머지 대부분의 동물들은 양쪽으로 대칭되는 몸통 평면을 가진 빌레테리아(Bilateria)라는 분기군을 형성합니다. 빌레테리아는 세 개의 잘 발달된 생식층을 가진 세 개의 삼중 모세포이며, 그들의 조직은 별개의 기관을 형성합니다. 소화실에는 입과 항문의 두 개의 개구부가 있고, 내부 체강, 실롬 또는 가성 실롬이 있습니다. 이 동물들은 머리 끝(앞쪽)과 꼬리 끝(뒤쪽), 등(등쪽) 표면과 배(배쪽) 표면, 왼쪽과 오른쪽 측면을 가지고 있습니다.[135][136]

앞쪽 끝이 있다는 것은 음식, 두족화를 선호하는 것, 감각 기관과 입이 있는 머리의 발달과 같은 신체의 이 부분이 자극을 만난다는 것을 의미합니다. 많은 양악류 동물들은 몸을 수축시키는 원형 근육과 몸을 짧게 하는 반대쪽 종형 근육의 조합을 가지고 있습니다;[136] 이것들은 정수적인 골격을 가진 부드러운 몸을 가진 동물들이 연동 운동에 의해 움직일 수 있게 합니다.[137] 그들은 또한 입에서 항문까지 기본적으로 원통형의 몸을 통해 연장되는 내장을 가지고 있습니다. 많은 쌍각류 문들은 섬모와 함께 헤엄치는 1차 유충을 가지고 있고 감각 세포를 포함하는 정점 기관을 가지고 있습니다. 그러나, 진화의 시간이 지나면서, 이러한 특징들 중 하나 또는 그 이상을 상실한 후손 공간들이 진화해왔습니다. 예를 들어, 성충의 극피동물은 (유충과 달리) 방사상으로 대칭인 반면, 일부 기생 벌레는 극도로 단순화된 신체 구조를 가지고 있습니다.[135][136]

유전학 연구는 빌라테리아 내의 관계에 대한 동물학자들의 이해를 상당히 변화시켰습니다. 대부분은 두 가지 주요 계통인 프로토스톰과 중수소스톰에 속하는 것으로 보입니다.[138] 종종 가장 기초적인 쌍각류는 Xenacoelomorpha이며, 다른 모든 쌍각류는 네프로조아[139][140][141] 아군에 속한다고 제안됩니다. 그러나 이 제안은 다른 연구에서 Xenacoelomorpha가 다른 쌍각류보다 Ambulacraria와 더 밀접한 관련이 있다는 것을 발견하면서 논란이 되었습니다.[122]

프로토스톰과 듀테로스톰

프로토스톰과 듀테로스톰은 여러 가지 방식으로 다릅니다. 발달 초기에, 중생대 배아는 세포 분열 동안 방사상 절단을 겪는 반면, 많은 원생대(Spiralia)는 나선형 절단을 겪습니다.[142] 두 그룹의 동물들은 완전한 소화관을 가지고 있지만, 원생동물에서는 배아 내장의 첫 번째 입구가 입으로 발달하고, 2차적으로 항문이 형성됩니다. 중족체에서는 항문이 먼저 형성되고 입이 2차적으로 발달합니다.[143][144] 대부분의 원형질체는 분열성 발달을 가지고 있는데, 여기서 세포는 단순히 위의 내부를 채워 중배엽을 형성합니다. 중배엽은 중배엽에서 내배엽의 침윤을 통해 장골 주머니에 의해 형성됩니다.[145]

주요 중생대 문은 에키노데르마타(Echinodermata)와 초르다타(Chordata)입니다.[146] 극피동물은 전적으로 해양이며 불가사리, 성게, 해삼을 포함합니다.[147] 척골동물은 척추동물(등뼈를 가진 동물)에 의해 지배되는데,[148] 척추동물은 물고기, 양서류, 파충류, 새, 그리고 포유류로 이루어져 있습니다.[149] 중족충은 또한 Hemichordata(뿔벌레)를 포함합니다.[150][151]

에크디소조아

Ecdysozoa는 털갈이에 의해 성장하는 ecdis의 공유된 특성에서 이름을 따온 프로토스톰입니다.[152] 여기에는 곤충, 거미, 게, 그리고 그들의 친족을 포함하는 가장 큰 동물 문인 아르트로포다가 포함됩니다. 이 모든 것은 반복되는 부분으로 나누어진 몸체를 가지고 있으며, 일반적으로 한 쌍의 부속기를 가지고 있습니다. 두 개의 작은 문인 오니초포라와 타르디그라다는 절지동물의 가까운 동족이며 이러한 특성을 공유합니다. 에크디소조아류에는 선충류나 회충류도 포함되며, 아마도 두 번째로 큰 동물문일 것입니다. 회충은 일반적으로 미세하며, 물이 있는 거의 모든 환경에서 발생하며,[153] 일부는 중요한 기생충입니다.[154] 이들과 관련된 더 작은 문으로는 Nematomorpha 또는 말털벌레와 Kinorhyncha, Priapulida 및 Loricifera가 있습니다. 이 그룹들은 슈도코엘롬이라고 불리는 축소된 실롬을 가지고 있습니다.[155]

스피릴리아

스피랄리아(Spiralia)는 초기 배아에서 나선형 절단에 의해 발달하는 거대한 원생체군입니다.[156] Spiralia의 계통발생은 논쟁의 여지가 있지만, 그것은 큰 분기군인 Lophotrochozoa과 위트리치와 편충을 포함하는 Rouphozoa과 같은 더 작은 문 그룹을 포함합니다. 이 모든 것들은 자매 그룹인 윤각류를 포함하는 그나티페라가 있는 Platytrochozoa로 분류됩니다.[157][158]

Lophotrochozoa는 연체동물, 환형동물, 완족류, 네머티안, 브라이오조아 및 곤충류를 포함합니다.[157][159][160] 기술된 종수로 두 번째로 큰 동물문인 연체동물은 달팽이, 조개, 오징어를 포함하는 반면, 환형동물은 지렁이, 갯지렁이, 거머리와 같은 분절된 벌레입니다. 이 두 그룹은 트로코포어 유충을 공유하기 때문에 오랫동안 가까운 친척으로 여겨졌습니다.[161][162]

분류연혁

고전 시대에 아리스토텔레스는 자신의 관찰을 바탕으로 [e]동물을 피가 있는 것(대략 척추동물)과 없는 것(대략 척추동물)으로 나누었습니다. 그리고 나서 동물들은 (혈액이 있고, 두 다리가 있고, 이성적인 영혼이 있는) 인간에서부터 (혈액이 없고, 네 다리가 있고, 민감한 영혼이 있는) 갑각류와 같은 다른 그룹들을 거쳐 (혈액이 없고, 다리가 없고, 민감한 영혼이 있는) 해면동물과 같은 자연적으로 생성되는 생물들 (혈액이 없고, 다리가 없고, 채소 영혼이 있는)까지의 척도로 배열되었습니다. 아리스토텔레스는 해면체가 그의 체계에서 감각, 식욕, 운동을 가져야 하는 동물인지 아니면 그렇지 않은 식물인지 확신하지 못했습니다. 그는 해면체가 촉각을 감지할 수 있고 바위에서 떼어내려고 하면 수축할 수 있지만 식물처럼 뿌리를 내리고 움직이지 않는다는 것을 알고 있었습니다.[164]

1758년 칼 린네는 그의 자연계(Systema Naturae)에서 최초의 계층적 분류를 만들었습니다.[165] 그의 원래 계획에서, 그 동물들은 베르메스, 곤충, 물고기자리, 양서류, 아베스, 그리고 포유류로 나뉘어진 세 왕국 중 하나였습니다. 그 이후로 마지막 4개의 문은 모두 하나의 문인 초르다타로 편입되었고, 그의 곤충(갑각류와 거미류를 포함)과 버메스는 이름이 바뀌거나 해체되었습니다. 이 과정은 1793년 장 밥티스트 드 라마르크(Jean-Baptiste de Lamark)에 의해 시작되었는데, 그는 베르메스를 혼돈 상태(혼란스러운 혼란 상태)[f]라고 부르며, 그 무리를 세 개의 새로운 문, 즉 벌레, 극피동물, 그리고 용종(산호와 해파리를 포함하는)으로 나누었습니다. 1809년까지 라마르크는 그의 저서 동물학에서 척추동물(포유류, 조류, 파충류, 어류의 4개의 문)과 연체동물을 제외한 9개의 문을 만들었습니다.[163]

1817년, 조르주 쿠비에는 비교 해부학을 사용하여 동물을 4개의 부화("문에 해당하는 다른 신체 계획을 가진 가지"), 즉 척추동물, 연체동물, 관절동물(절지동물과 아넬리드), 유생동물(반추동물)(극피동물, 분추동물)로 분류했습니다.[167] 1828년 발생학자 칼 에른스트 폰 베어, 1857년 동물학자 루이 아가시즈, 1860년 비교 해부학자 리처드 오웬이 네 개로 나뉘었습니다.[168]

1874년 에른스트 헤켈은 동물 왕국을 두 개의 하위 왕국으로 나누었습니다. 6번째 동물문인 해면동물을 포함한 메타조아(다세포동물)와 원생동물(단세포동물)은 5개의 문(coelenterate, 극피동물, 관절동물, 연체동물, 척추동물)을 포함합니다.[169][168] 원생동물은 나중에 전 왕국인 프로티스타로 옮겨졌고, 오직 메타조아족만을 애니멀리아의 동의어로 남겼습니다.[170]

인간의 문화속에서

실용적인 용도

인간은 가축 사육장과 주로 바다에서 야생 종을 사냥하여 많은 다른 동물 종들을 먹이로 이용합니다.[171][172] 많은 종의 해양 물고기는 식용으로 상업적으로 잡힙니다. 더 적은 수의 종들이 상업적으로 양식됩니다.[171][173][174] 인간과 가축은 모든 육상 척추동물의 생물량의 90% 이상을 차지하며, 모든 곤충을 합친 것과 거의 같습니다.[175]

두족류, 갑각류, 이매패류 또는 복족류 연체동물을 포함한 무척추동물은 사냥을 하거나 먹이로 양식됩니다.[176] 닭, 소, 양, 돼지 및 기타 동물은 전 세계에서 고기를 위한 가축으로 사육됩니다.[172][177][178] 양모와 같은 동물 섬유는 직물을 만드는 데 사용되는 반면 동물 사뉴는 래싱 및 바인딩으로 사용되었으며 가죽은 신발 및 기타 품목을 만드는 데 널리 사용됩니다. 동물들은 코트나 모자와 같은 물건들을 만들기 위해 그들의 털을 위해 사냥되고 농사를 지었습니다.[179] 카민(코키닐),[180][181] 쉘락,[182][183] 커메스를 포함한 염료는[184][185] 곤충의 몸에서 만들어졌습니다. 소와 말을 포함한 일하는 동물들은 농사 첫날부터 일과 운송에 사용되었습니다.[186]

초파리 초파리와 같은 동물들은 실험 모델로서 과학에서 중요한 역할을 합니다.[187][188][189][190] 동물들은 18세기에 발견된 이후로 백신을 만드는 데 사용되었습니다.[191] 암 치료제인 트라브렉틴과 같은 일부 의약품은 독소 또는 동물 출처의 다른 분자를 기반으로 합니다.[192]

사람들은 사냥개를 이용하여 동물을 쫓고 되찾는 것을 돕고,[193] 새와 포유류를 잡기 위해 맹금류를 이용한 [194]반면, 끈으로 묶인 가마우지는 물고기를 잡기 위해 이용되었습니다.[195] 독 다트 개구리는 블로우파이프 다트의 끝을 독살하는 데 사용되었습니다.[196][197] 타란튤라, 문어 같은 무척추동물부터 사마귀 같은 곤충,[198] 뱀, 카멜레온 같은 파충류,[199] 카나리아, 잉꼬, 앵무새[200] 같은 새들까지 다양한 동물들이 애완동물로 기릅니다. 하지만, 가장 많이 사육되는 애완동물 종은 포유동물, 즉 개, 고양이, 토끼입니다.[201][202][203] 인간의 동반자로서의 동물의 역할과 자신의 권리를 가진 개체로서의 동물의 존재 사이에는 긴장 관계가 존재합니다.[204] 다양한 육상 및 수생 동물을 사냥하여 사냥합니다.[205]

상징적 용도

동물들은 고대 이집트에서와 같이 역사적이고 라스코의 동굴 벽화에서와 같이 선사시대부터 예술의 대상이었습니다. 주요 동물 그림으로는 알브레히트 뒤러의 1515년작 '코뿔소'와 조지 스텁스의 1762년작 말 초상화 '휘슬재킷'이 있습니다.[206] 곤충, 새, 포유류는 거대한 벌레 영화와 [207]같이 문학과 영화에서 역할을 합니다.[208][209][210]

곤충과[211] 포유류를[212] 포함한 동물들은 신화와 종교에 등장합니다. 일본과 유럽 모두에서 나비는 사람의 영혼을 의인화한 것으로 간주되었고,[211][213][214] 반면에 스카라비틀은 고대 이집트에서 신성시되었습니다.[215] 포유류 중에는 소,[216] 사슴,[212] 말,[217] 사자,[218] 박쥐,[219] 곰,[220] 늑대[221] 등이 신화와 숭배의 대상입니다. 서양과 중국의 황도대의 별자리는 동물을 기반으로 합니다.[222][223]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 헤네기야즈쇼케이는 미토콘드리아 DNA를 가지고 있지 않거나 호기성 호흡을 이용하지 않습니다.[17]

- ^ 분류학에 DNA 바코드를 적용하는 것은 이를 더욱 복잡하게 만듭니다. 2016년 바코드 분석에서는 캐나다에서만 총 100,000종에 가까운 곤충 종을 추정했으며 전 세계 곤충 동물군은 1천만 종을 초과해야 하며, 그 중 거의 200만 종이 담쟁이덩굴(Cecidomyiidae)로 알려진 단일 파리과에 속한다고 추정했습니다.[73]

- ^ 기생체를 포함하지 않습니다.[69]

- ^ 파일 비교:Annelid는 이 일반적인 신체 계획으로 특정 문의 더 구체적이고 상세한 모델을 위해 흰색 배경.svg를 다시 했습니다.

- ^ 그의 동물과 동물의 부분에 관한 역사에서.

- ^ 접두사 unespèce de는 경멸적입니다.[166]

참고문헌

- ^ de Queiroz, Kevin; Cantino, Philip; Gauthier, Jacques, eds. (2020). "Metazoa E. Haeckel 1874 [J. R. Garey and K. M. Halanych], converted clade name". Phylonyms: A Companion to the PhyloCode (1st ed.). CRC Press. p. 1352. doi:10.1201/9780429446276. ISBN 9780429446276. S2CID 242704712.

- ^ Nielsen, Claus (2008). "Six major steps in animal evolution: are we derived sponge larvae?". Evolution & Development. 10 (2): 241–257. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00231.x. PMID 18315817. S2CID 8531859.

- ^ a b c Rothmaler, Werner (1951). "Die Abteilungen und Klassen der Pflanzen". Feddes Repertorium, Journal of Botanical Taxonomy and Geobotany. 54 (2–3): 256–266. doi:10.1002/fedr.19510540208.

- ^ Cresswell, Julia (2010). The Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954793-7.

'having the breath of life', from anima 'air, breath, life'.

- ^ "Animal". The American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. 2006.

- ^ "animal". English Oxford Living Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Boly, Melanie; Seth, Anil K.; Wilke, Melanie; Ingmundson, Paul; Baars, Bernard; Laureys, Steven; Edelman, David; Tsuchiya, Naotsugu (2013). "Consciousness in humans and non-human animals: recent advances and future directions". Frontiers in Psychology. 4: 625. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00625. PMC 3814086. PMID 24198791.

- ^ "The use of non-human animals in research". Royal Society. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ "Nonhuman definition and meaning". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ "Metazoan". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ "Metazoa". Collins. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022. 그리고 추가 메타 (센스 1) 2022년 7월 30일 웨이백 머신에 보관 및 -zoa 2022년 7월 30일 웨이백 머신에 보관.

- ^ Avila, Vernon L. (1995). Biology: Investigating Life on Earth. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 767–. ISBN 978-0-86720-942-6.

- ^ Davidson, Michael W. "Animal Cell Structure". Archived from the original on 20 September 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ "Palaeos:Metazoa". Palaeos. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Bergman, Jennifer. "Heterotrophs". Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ^ Douglas, Angela E.; Raven, John A. (January 2003). "Genomes at the interface between bacteria and organelles". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 358 (1429): 5–17. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1188. PMC 1693093. PMID 12594915.

- ^ Andrew, Scottie (26 February 2020). "Scientists discovered the first animal that doesn't need oxygen to live. It's changing the definition of what an animal can be". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ Mentel, Marek; Martin, William (2010). "Anaerobic animals from an ancient, anoxic ecological niche". BMC Biology. 8: 32. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-32. PMC 2859860. PMID 20370917.

- ^ Saupe, S. G. "Concepts of Biology". Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ^ Minkoff, Eli C. (2008). Barron's EZ-101 Study Keys Series: Biology (2nd, revised ed.). Barron's Educational Series. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7641-3920-8.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Sangwal, Keshra (2007). Additives and crystallization processes: from fundamentals to applications. John Wiley and Sons. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-470-06153-4.

- ^ Becker, Wayne M. (1991). The world of the cell. Benjamin/Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-0870-9.

- ^ Magloire, Kim (2004). Cracking the AP Biology Exam, 2004–2005 Edition. The Princeton Review. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-375-76393-9.

- ^ Starr, Cecie (2007). Biology: Concepts and Applications without Physiology. Cengage Learning. pp. 362, 365. ISBN 978-0-495-38150-1. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Hillmer, Gero; Lehmann, Ulrich (1983). Fossil Invertebrates. Translated by J. Lettau. CUP Archive. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-521-27028-1. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Knobil, Ernst (1998). Encyclopedia of reproduction, Volume 1. Academic Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-12-227020-8.

- ^ Schwartz, Jill (2010). Master the GED 2011. Peterson's. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-7689-2885-3.

- ^ Hamilton, Matthew B. (2009). Population genetics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4051-3277-0.

- ^ Ville, Claude Alvin; Walker, Warren Franklin; Barnes, Robert D. (1984). General zoology. Saunders College Pub. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-03-062451-3.

- ^ Hamilton, William James; Boyd, James Dixon; Mossman, Harland Winfield (1945). Human embryology: (prenatal development of form and function). Williams & Wilkins. p. 330.

- ^ Philips, Joy B. (1975). Development of vertebrate anatomy. Mosby. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-8016-3927-2.

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: a library of universal knowledge, Volume 10. Encyclopedia Americana Corp. 1918. p. 281.

- ^ Romoser, William S.; Stoffolano, J. G. (1998). The science of entomology. WCB McGraw-Hill. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-697-22848-2.

- ^ Charlesworth, D.; Willis, J. H. (2009). "The genetics of inbreeding depression". Nature Reviews Genetics. 10 (11): 783–796. doi:10.1038/nrg2664. PMID 19834483. S2CID 771357.

- ^ Bernstein, H.; Hopf, F. A.; Michod, R. E. (1987). "The molecular basis of the evolution of sex". Advances in Genetics. 24: 323–370. doi:10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60012-7. ISBN 978-0-12-017624-3. PMID 3324702.

- ^ Pusey, Anne; Wolf, Marisa (1996). "Inbreeding avoidance in animals". Trends Ecol. Evol. 11 (5): 201–206. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)10028-8. PMID 21237809.

- ^ Adiyodi, K. G.; Hughes, Roger N.; Adiyodi, Rita G. (July 2002). Reproductive Biology of Invertebrates, Volume 11, Progress in Asexual Reproduction. Wiley. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-471-48968-9.

- ^ Schatz, Phil. "Concepts of Biology: How Animals Reproduce". OpenStax College. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Marchetti, Mauro; Rivas, Victoria (2001). Geomorphology and environmental impact assessment. Taylor & Francis. p. 84. ISBN 978-90-5809-344-8.

- ^ Levy, Charles K. (1973). Elements of Biology. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-390-55627-1.

- ^ Begon, M.; Townsend, C.; Harper, J. (1996). Ecology: Individuals, populations and communities (Third ed.). Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-86542-845-4.

- ^ Allen, Larry Glen; Pondella, Daniel J.; Horn, Michael H. (2006). Ecology of marine fishes: California and adjacent waters. University of California Press. p. 428. ISBN 978-0-520-24653-9.

- ^ Caro, Tim (2005). Antipredator Defenses in Birds and Mammals. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–6 and passim.

- ^ Simpson, Alastair G.B; Roger, Andrew J. (2004). "The real 'kingdoms' of eukaryotes". Current Biology. 14 (17): R693–696. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.038. PMID 15341755. S2CID 207051421.

- ^ Stevens, Alison N. P. (2010). "Predation, Herbivory, and Parasitism". Nature Education Knowledge. 3 (10): 36. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Jervis, M. A.; Kidd, N. A. C. (November 1986). "Host-Feeding Strategies in Hymenopteran Parasitoids". Biological Reviews. 61 (4): 395–434. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1986.tb00660.x. S2CID 84430254.

- ^ Meylan, Anne (22 January 1988). "Spongivory in Hawksbill Turtles: A Diet of Glass". Science. 239 (4838): 393–395. Bibcode:1988Sci...239..393M. doi:10.1126/science.239.4838.393. JSTOR 1700236. PMID 17836872. S2CID 22971831.

- ^ Clutterbuck, Peter (2000). Understanding Science: Upper Primary. Blake Education. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-86509-170-9.

- ^ Gupta, P. K. (1900). Genetics Classical To Modern. Rastogi Publications. p. 26. ISBN 978-81-7133-896-2.

- ^ Garrett, Reginald; Grisham, Charles M. (2010). Biochemistry. Cengage Learning. p. 535. ISBN 978-0-495-10935-8.

- ^ Castro, Peter; Huber, Michael E. (2007). Marine Biology (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-07-722124-9.

- ^ Rota-Stabelli, Omar; Daley, Allison C.; Pisani, Davide (2013). "Molecular Timetrees Reveal a Cambrian Colonization of Land and a New Scenario for Ecdysozoan Evolution". Current Biology. 23 (5): 392–8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.026. PMID 23375891.

- ^ Daeschler, Edward B.; Shubin, Neil H.; Jenkins, Farish A. Jr. (6 April 2006). "A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan". Nature. 440 (7085): 757–763. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..757D. doi:10.1038/nature04639. PMID 16598249.

- ^ Clack, Jennifer A. (21 November 2005). "Getting a Leg Up on Land". Scientific American. 293 (6): 100–7. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293f.100C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1205-100. PMID 16323697.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn; Schwartz, Karlene V.; Dolan, Michael (1999). Diversity of Life: The Illustrated Guide to the Five Kingdoms. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0-7637-0862-7.

- ^ Clarke, Andrew (2014). "The thermal limits to life on Earth" (PDF). International Journal of Astrobiology. 13 (2): 141–154. Bibcode:2014IJAsB..13..141C. doi:10.1017/S1473550413000438. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2019.

- ^ "Land animals". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Enfield, Middlesex : Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ Davies, Ella (20 April 2016). "The longest animal alive may be one you never thought of". BBC Earth. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "Largest mammal". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Christiansen, Per; Fariña, Richard A. (2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs". Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 71–83. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.1650. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132. S2CID 56028251.

- ^ Curtice, Brian (2020). "Society of Vertebrate Paleontology" (PDF). Vertpaleo.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Fiala, Ivan (10 July 2008). "Myxozoa". Tree of Life Web Project. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Kaur, H.; Singh, R. (2011). "Two new species of Myxobolus (Myxozoa: Myxosporea: Bivalvulida) infecting an Indian major carp and a cat fish in wetlands of Punjab, India". Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 35 (2): 169–176. doi:10.1007/s12639-011-0061-4. PMC 3235390. PMID 23024499.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Zhang, Zhi-Qiang (30 August 2013). "Animal biodiversity: An update of classification and diversity in 2013. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013)". Zootaxa. 3703 (1): 5. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.3. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Balian, E. V.; Lévêque, C.; Segers, H.; Martens, K. (2008). Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment. Springer. p. 628. ISBN 978-1-4020-8259-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hogenboom, Melissa. "There are only 35 kinds of animal and most are really weird". BBC Earth. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Poulin, Robert (2007). Evolutionary Ecology of Parasites. Princeton University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-691-12085-0.

- ^ a b c d Felder, Darryl L.; Camp, David K. (2009). Gulf of Mexico Origin, Waters, and Biota: Biodiversity. Texas A&M University Press. p. 1111. ISBN 978-1-60344-269-5.

- ^ "How many species on Earth? About 8.7 million, new estimate says". 24 August 2011. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Mora, Camilo; Tittensor, Derek P.; Adl, Sina; Simpson, Alastair G.B.; Worm, Boris (23 August 2011). Mace, Georgina M. (ed.). "How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?". PLOS Biology. 9 (8): e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. PMC 3160336. PMID 21886479.

- ^ Hebert, Paul D.N.; Ratnasingham, Sujeevan; Zakharov, Evgeny V.; Telfer, Angela C.; Levesque-Beaudin, Valerie; Milton, Megan A.; Pedersen, Stephanie; Jannetta, Paul; deWaard, Jeremy R. (1 August 2016). "Counting animal species with DNA barcodes: Canadian insects". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371 (1702): 20150333. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0333. PMC 4971185. PMID 27481785.

- ^ Stork, Nigel E. (January 2018). "How Many Species of Insects and Other Terrestrial Arthropods Are There on Earth?". Annual Review of Entomology. 63 (1): 31–45. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-020117-043348. PMID 28938083. S2CID 23755007. 스토크는 1m 곤충의 이름이 붙었다고 언급하며, 이보다 훨씬 더 큰 예측치를 내놓았습니다.

- ^ Poore, Hugh F. (2002). "Introduction". Crustacea: Malacostraca. Zoological catalogue of Australia. Vol. 19.2A. CSIRO Publishing. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-643-06901-5.

- ^ a b c d Nicol, David (June 1969). "The Number of Living Species of Molluscs". Systematic Zoology. 18 (2): 251–254. doi:10.2307/2412618. JSTOR 2412618.

- ^ Uetz, P. "A Quarter Century of Reptile and Amphibian Databases". Herpetological Review. 52: 246–255. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b c Reaka-Kudla, Marjorie L.; Wilson, Don E.; Wilson, Edward O. (1996). Biodiversity II: Understanding and Protecting Our Biological Resources. Joseph Henry Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-309-52075-1.

- ^ Burton, Derek; Burton, Margaret (2017). Essential Fish Biology: Diversity, Structure and Function. Oxford University Press. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-19-878555-2.

Trichomycteridae ... includes obligate parasitic fish. Thus 17 genera from 2 subfamilies, Vandelliinae; 4 genera, 9spp. and Stegophilinae; 13 genera, 31 spp. are parasites on gills (Vandelliinae) or skin (stegophilines) of fish.

- ^ Sluys, R. (1999). "Global diversity of land planarians (Platyhelminthes, Tricladida, Terricola): a new indicator-taxon in biodiversity and conservation studies". Biodiversity and Conservation. 8 (12): 1663–1681. doi:10.1023/A:1008994925673. S2CID 38784755.

- ^ a b Pandian, T. J. (2020). Reproduction and Development in Platyhelminthes. CRC Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-1-000-05490-3. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Morand, Serge; Krasnov, Boris R.; Littlewood, D. Timothy J. (2015). Parasite Diversity and Diversification. Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-107-03765-6. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Fontaneto, Diego. "Marine Rotifers An Unexplored World of Richness" (PDF). JMBA Global Marine Environment. pp. 4–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Chernyshev, A. V. (September 2021). "An updated classification of the phylum Nemertea". Invertebrate Zoology. 18 (3): 188–196. doi:10.15298/invertzool.18.3.01. S2CID 239872311. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Hookabe, Natsumi; Kajihara, Hiroshi; Chernyshev, Alexei V.; Jimi, Naoto; Hasegawa, Naohiro; Kohtsuka, Hisanori; Okanishi, Masanori; Tani, Kenichiro; Fujiwara, Yoshihiro; Tsuchida, Shinji; Ueshima, Rei (2022). "Molecular Phylogeny of the Genus Nipponnemertes (Nemertea: Monostilifera: Cratenemertidae) and Descriptions of 10 New Species, With Notes on Small Body Size in a Newly Discovered Clade". Frontiers in Marine Science. 9. doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.906383. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Hickman, Cleveland P.; Keen, Susan L.; Larson, Allan; Eisenhour, David J. (2018). Animal Diversity (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education, New York. ISBN 978-1-260-08427-6.

- ^ Shen, Bing; Dong, Lin; Xiao, Shuhai; Kowalewski, Michał (2008). "The Avalon Explosion: Evolution of Ediacara Morphospace". Science. 319 (5859): 81–84. Bibcode:2008Sci...319...81S. doi:10.1126/science.1150279. PMID 18174439. S2CID 206509488.

- ^ Chen, Zhe; Chen, Xiang; Zhou, Chuanming; Yuan, Xunlai; Xiao, Shuhai (1 June 2018). "Late Ediacaran trackways produced by bilaterian animals with paired appendages". Science Advances. 4 (6): eaao6691. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.6691C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao6691. PMC 5990303. PMID 29881773.

- ^ Schopf, J. William (1999). Evolution!: facts and fallacies. Academic Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-12-628860-5.

- ^ a b Bobrovskiy, Ilya; Hope, Janet M.; Ivantsov, Andrey; Nettersheim, Benjamin J.; Hallmann, Christian; Brocks, Jochen J. (20 September 2018). "Ancient steroids establish the Ediacaran fossil Dickinsonia as one of the earliest animals". Science. 361 (6408): 1246–1249. Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1246B. doi:10.1126/science.aat7228. PMID 30237355.

- ^ Zimorski, Verena; Mentel, Marek; Tielens, Aloysius G. M.; Martin, William F. (2019). "Energy metabolism in anaerobic eukaryotes and Earth's late oxygenation". Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 140: 279–294. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.03.030. PMC 6856725. PMID 30935869.

- ^ "Stratigraphic Chart 2022" (PDF). International Stratigraphic Commission. February 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Maloof, A. C.; Porter, S. M.; Moore, J. L.; Dudas, F. O.; Bowring, S. A.; Higgins, J. A.; Fike, D. A.; Eddy, M. P. (2010). "The earliest Cambrian record of animals and ocean geochemical change". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 122 (11–12): 1731–1774. Bibcode:2010GSAB..122.1731M. doi:10.1130/B30346.1. S2CID 6694681.

- ^ "New Timeline for Appearances of Skeletal Animals in Fossil Record Developed by UCSB Researchers". The Regents of the University of California. 10 November 2010. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Conway-Morris, Simon (2003). "The Cambrian "explosion" of metazoans and molecular biology: would Darwin be satisfied?". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 47 (7–8): 505–515. PMID 14756326. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "The Tree of Life". The Burgess Shale. Royal Ontario Museum. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ a b Dunn, F. S.; Kenchington, C. G.; Parry, L. A.; Clark, J. W.; Kendall, R. S.; Wilby, P. R. (25 July 2022). "A crown-group cnidarian from the Ediacaran of Charnwood Forest, UK". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 6 (8): 1095–1104. doi:10.1038/s41559-022-01807-x. PMC 9349040. PMID 35879540.

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2005). Biology (7th ed.). Pearson, Benjamin Cummings. p. 526. ISBN 978-0-8053-7171-0.

- ^ Maloof, Adam C.; Rose, Catherine V.; Beach, Robert; Samuels, Bradley M.; Calmet, Claire C.; Erwin, Douglas H.; Poirier, Gerald R.; Yao, Nan; Simons, Frederik J. (17 August 2010). "Possible animal-body fossils in pre-Marinoan limestones from South Australia". Nature Geoscience. 3 (9): 653–659. Bibcode:2010NatGe...3..653M. doi:10.1038/ngeo934.

- ^ Seilacher, Adolf; Bose, Pradip K.; Pfluger, Friedrich (2 October 1998). "Triploblastic animals more than 1 billion years ago: trace fossil evidence from india". Science. 282 (5386): 80–83. Bibcode:1998Sci...282...80S. doi:10.1126/science.282.5386.80. PMID 9756480.

- ^ Matz, Mikhail V.; Frank, Tamara M.; Marshall, N. Justin; Widder, Edith A.; Johnsen, Sönke (9 December 2008). "Giant Deep-Sea Protist Produces Bilaterian-like Traces". Current Biology. 18 (23): 1849–54. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.028. PMID 19026540. S2CID 8819675.

- ^ Reilly, Michael (20 November 2008). "Single-celled giant upends early evolution". NBC News. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ Bengtson, S. (2002). "Origins and early evolution of predation" (PDF). In Kowalewski, M.; Kelley, P. H. (eds.). The fossil record of predation. The Paleontological Society Papers. Vol. 8. The Paleontological Society. pp. 289–317. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Seilacher, Adolf (2007). Trace fossil analysis. Berlin: Springer. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-3-540-47226-1. OCLC 191467085.

- ^ Breyer, J. A. (1995). "Possible new evidence for the origin of metazoans prior to 1 Ga: Sediment-filled tubes from the Mesoproterozoic Allamoore Formation, Trans-Pecos Texas". Geology. 23 (3): 269–272. Bibcode:1995Geo....23..269B. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0269:PNEFTO>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Budd, Graham E.; Jensen, Sören (2017). "The origin of the animals and a 'Savannah' hypothesis for early bilaterian evolution". Biological Reviews. 92 (1): 446–473. doi:10.1111/brv.12239. PMID 26588818.

- ^ Peterson, Kevin J.; Cotton, James A.; Gehling, James G.; Pisani, Davide (27 April 2008). "The Ediacaran emergence of bilaterians: congruence between the genetic and the geological fossil records". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1496): 1435–1443. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2233. PMC 2614224. PMID 18192191.

- ^ Parfrey, Laura Wegener; Lahr, Daniel J. G.; Knoll, Andrew H.; Katz, Laura A. (16 August 2011). "Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (33): 13624–13629. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10813624P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110633108. PMC 3158185. PMID 21810989.

- ^ "Raising the Standard in Fossil Calibration". Fossil Calibration Database. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Laumer, Christopher E.; Gruber-Vodicka, Harald; Hadfield, Michael G.; Pearse, Vicki B.; Riesgo, Ana; Marioni, John C.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2018). "Support for a clade of Placozoa and Cnidaria in genes with minimal compositional bias". eLife. 2018, 7: e36278. doi:10.7554/eLife.36278. PMC 6277202. PMID 30373720.

- ^ Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W. (2018). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Ros-Rocher, Núria; Pérez-Posada, Alberto; Leger, Michelle M.; Ruiz-Trillo, Iñaki (2021). "The origin of animals: an ancestral reconstruction of the unicellular-to-multicellular transition". Open Biology. The Royal Society. 11 (2): 200359. doi:10.1098/rsob.200359. ISSN 2046-2441. PMC 8061703. PMID 33622103.

- ^ Kapli, Paschalia; Telford, Maximilian J. (11 December 2020). "Topology-dependent asymmetry in systematic errors affects phylogenetic placement of Ctenophora and Xenacoelomorpha". Science Advances. 6 (10): eabc5162. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.5162K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abc5162. PMC 7732190. PMID 33310849.

- ^ Giribet, Gonzalo (27 September 2016). "Genomics and the animal tree of life: conflicts and future prospects". Zoologica Scripta. 45: 14–21. doi:10.1111/zsc.12215.

- ^ "Evolution and Development" (PDF). Carnegie Institution for Science Department of Embryology. 1 May 2012. p. 38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Dellaporta, Stephen; Holland, Peter; Schierwater, Bernd; Jakob, Wolfgang; Sagasser, Sven; Kuhn, Kerstin (April 2004). "The Trox-2 Hox/ParaHox gene of Trichoplax (Placozoa) marks an epithelial boundary". Development Genes and Evolution. 214 (4): 170–175. doi:10.1007/s00427-004-0390-8. PMID 14997392. S2CID 41288638.

- ^ Peterson, Kevin J.; Eernisse, Douglas J (2001). "Animal phylogeny and the ancestry of bilaterians: Inferences from morphology and 18S rDNA gene sequences". Evolution and Development. 3 (3): 170–205. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.121.1228. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003170.x. PMID 11440251. S2CID 7829548.

- ^ Kraemer-Eis, Andrea; Ferretti, Luca; Schiffer, Philipp; Heger, Peter; Wiehe, Thomas (2016). "A catalogue of Bilaterian-specific genes – their function and expression profiles in early development" (PDF). bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/041806. S2CID 89080338. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2018.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (4 May 2018). "The Very First Animal Appeared Amid an Explosion of DNA". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Paps, Jordi; Holland, Peter W. H. (30 April 2018). "Reconstruction of the ancestral metazoan genome reveals an increase in genomic novelty". Nature Communications. 9 (1730 (2018)): 1730. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.1730P. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04136-5. PMC 5928047. PMID 29712911.

- ^ Giribet, G.; Edgecombe, G.D. (2020). The Invertebrate Tree of Life. Princeton University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-6911-7025-1. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ a b Kapli, Paschalia; Natsidis, Paschalis; Leite, Daniel J.; Fursman, Maximilian; Jeffrie, Nadia; Rahman, Imran A.; Philippe, Hervé; Copley, Richard R.; Telford, Maximilian J. (19 March 2021). "Lack of support for Deuterostomia prompts reinterpretation of the first Bilateria". Science Advances. 7 (12): eabe2741. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2741K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe2741. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7978419. PMID 33741592.

- ^ Bhamrah, H. S.; Juneja, Kavita (2003). An Introduction to Porifera. Anmol Publications. p. 58. ISBN 978-81-261-0675-2.

- ^ a b Schultz, Darrin T.; Haddock, Steven H. D.; Bredeson, Jessen V.; Green, Richard E.; Simakov, Oleg; Rokhsar, Daniel S. (17 May 2023). "Ancient gene linkages support ctenophores as sister to other animals". Nature. 618 (7963): 110–117. Bibcode:2023Natur.618..110S. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05936-6. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 10232365. PMID 37198475. S2CID 258765122.

- ^ Whelan, Nathan V.; Kocot, Kevin M.; Moroz, Tatiana P.; Mukherjee, Krishanu; Williams, Peter; Paulay, Gustav; Moroz, Leonid L.; Halanych, Kenneth M. (9 October 2017). "Ctenophore relationships and their placement as the sister group to all other animals". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1 (11): 1737–1746. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0331-3. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 5664179. PMID 28993654.

- ^ Sumich, James L. (2008). Laboratory and Field Investigations in Marine Life. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7637-5730-4.

- ^ Jessop, Nancy Meyer (1970). Biosphere; a study of life. Prentice-Hall. p. 428.

- ^ Sharma, N. S. (2005). Continuity And Evolution Of Animals. Mittal Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-81-8293-018-6.

- ^ Langstroth, Lovell; Langstroth, Libby (2000). Newberry, Todd (ed.). A Living Bay: The Underwater World of Monterey Bay. University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-520-22149-9.

- ^ Safra, Jacob E. (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 16. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^ Kotpal, R.L. (2012). Modern Text Book of Zoology: Invertebrates. Rastogi Publications. p. 184. ISBN 978-81-7133-903-7.

- ^ Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Holt-Saunders International. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ "Introduction to Placozoa". UCMP Berkeley. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Srivastava, Mansi; Begovic, Emina; Chapman, Jarrod; Putnam, Nicholas H.; Hellsten, Uffe; Kawashima, Takeshi; Kuo, Alan; Mitros, Therese; Salamov, Asaf; Carpenter, Meredith L.; Signorovitch, Ana Y.; Moreno, Maria A.; Kamm, Kai; Grimwood, Jane; Schmutz, Jeremy (1 August 2008). "The Trichoplax genome and the nature of placozoans". Nature. 454 (7207): 955–960. Bibcode:2008Natur.454..955S. doi:10.1038/nature07191. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 18719581. S2CID 4415492.

- ^ a b Minelli, Alessandro (2009). Perspectives in Animal Phylogeny and Evolution. Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-856620-5.

- ^ a b c Brusca, Richard C. (2016). "Introduction to the Bilateria and the Phylum Xenacoelomorpha Triploblasty and Bilateral Symmetry Provide New Avenues for Animal Radiation". Invertebrates (PDF). Sinauer Associates. pp. 345–372. ISBN 978-1-60535-375-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Quillin, K. J. (May 1998). "Ontogenetic scaling of hydrostatic skeletons: geometric, static stress and dynamic stress scaling of the earthworm lumbricus terrestris". Journal of Experimental Biology. 201 (12): 1871–1883. doi:10.1242/jeb.201.12.1871. PMID 9600869. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Telford, Maximilian J. (2008). "Resolving Animal Phylogeny: A Sledgehammer for a Tough Nut?". Developmental Cell. 14 (4): 457–459. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.016. PMID 18410719.

- ^ Philippe, H.; Brinkmann, H.; Copley, R.R.; Moroz, L. L.; Nakano, H.; Poustka, A.J.; Wallberg, A.; Peterson, K. J.; Telford, M.J. (2011). "Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella". Nature. 470 (7333): 255–258. Bibcode:2011Natur.470..255P. doi:10.1038/nature09676. PMC 4025995. PMID 21307940.

- ^ Perseke, M.; Hankeln, T.; Weich, B.; Fritzsch, G.; Stadler, P.F.; Israelsson, O.; Bernhard, D.; Schlegel, M. (August 2007). "The mitochondrial DNA of Xenoturbella bocki: genomic architecture and phylogenetic analysis" (PDF). Theory Biosci. 126 (1): 35–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.177.8060. doi:10.1007/s12064-007-0007-7. PMID 18087755. S2CID 17065867. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Cannon, Johanna T.; Vellutini, Bruno C.; Smith III, Julian.; Ronquist, Frederik; Jondelius, Ulf; Hejnol, Andreas (3 February 2016). "Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa". Nature. 530 (7588): 89–93. Bibcode:2016Natur.530...89C. doi:10.1038/nature16520. PMID 26842059. S2CID 205247296. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Valentine, James W. (July 1997). "Cleavage patterns and the topology of the metazoan tree of life". PNAS. 94 (15): 8001–8005. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.8001V. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.8001. PMC 21545. PMID 9223303.

- ^ Peters, Kenneth E.; Walters, Clifford C.; Moldowan, J. Michael (2005). The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers and isotopes in petroleum systems and Earth history. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 717. ISBN 978-0-521-83762-0.

- ^ Hejnol, A.; Martindale, M.Q. (2009). "The mouth, the anus, and the blastopore – open questions about questionable openings". In Telford, M.J.; Littlewood, D.J. (eds.). Animal Evolution – Genomes, Fossils, and Trees. Oxford University Press. pp. 33–40. ISBN 978-0-19-957030-0. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Safra, Jacob E. (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1; Volume 3. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 767. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^ Hyde, Kenneth (2004). Zoology: An Inside View of Animals. Kendall Hunt. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-7575-0997-1.

- ^ Alcamo, Edward (1998). Biology Coloring Workbook. The Princeton Review. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-679-77884-4.

- ^ Holmes, Thom (2008). The First Vertebrates. Infobase Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8160-5958-4.

- ^ Rice, Stanley A. (2007). Encyclopedia of evolution. Infobase Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8160-5515-9.

- ^ Tobin, Allan J.; Dusheck, Jennie (2005). Asking about life. Cengage Learning. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-534-40653-0.

- ^ Simakov, Oleg; Kawashima, Takeshi; Marlétaz, Ferdinand; Jenkins, Jerry; Koyanagi, Ryo; Mitros, Therese; Hisata, Kanako; Bredeson, Jessen; Shoguchi, Eiichi (26 November 2015). "Hemichordate genomes and deuterostome origins". Nature. 527 (7579): 459–465. Bibcode:2015Natur.527..459S. doi:10.1038/nature16150. PMC 4729200. PMID 26580012.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2005). The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-618-61916-0.

- ^ Prewitt, Nancy L.; Underwood, Larry S.; Surver, William (2003). BioInquiry: making connections in biology. John Wiley. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-471-20228-8.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel, Paul (1998). Parasites in social insects. Princeton University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-691-05924-2.

- ^ Miller, Stephen A.; Harley, John P. (2006). Zoology. McGraw-Hill. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-07-063682-8.

- ^ Shankland, M.; Seaver, E.C. (2000). "Evolution of the bilaterian body plan: What have we learned from annelids?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (9): 4434–4437. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.4434S. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4434. JSTOR 122407. PMC 34316. PMID 10781038.

- ^ a b Struck, Torsten H.; Wey-Fabrizius, Alexandra R.; Golombek, Anja; Hering, Lars; Weigert, Anne; Bleidorn, Christoph; Klebow, Sabrina; Iakovenko, Nataliia; Hausdorf, Bernhard; Petersen, Malte; Kück, Patrick; Herlyn, Holger; Hankeln, Thomas (2014). "Platyzoan Paraphyly Based on Phylogenomic Data Supports a Noncoelomate Ancestry of Spiralia". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (7): 1833–1849. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu143. PMID 24748651.

- ^ Fröbius, Andreas C.; Funch, Peter (April 2017). "Rotiferan Hox genes give new insights into the evolution of metazoan bodyplans". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 9. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8....9F. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00020-w. PMC 5431905. PMID 28377584.

- ^ Hervé, Philippe; Lartillot, Nicolas; Brinkmann, Henner (May 2005). "Multigene Analyses of Bilaterian Animals Corroborate the Monophyly of Ecdysozoa, Lophotrochozoa, and Protostomia". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (5): 1246–1253. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi111. PMID 15703236.

- ^ Speer, Brian R. (2000). "Introduction to the Lophotrochozoa Of molluscs, worms, and lophophores..." UCMP Berkeley. Archived from the original on 16 August 2000. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Giribet, G.; Distel, D.L.; Polz, M.; Sterrer, W.; Wheeler, W.C. (2000). "Triploblastic relationships with emphasis on the acoelomates and the position of Gnathostomulida, Cycliophora, Plathelminthes, and Chaetognatha: a combined approach of 18S rDNA sequences and morphology". Syst Biol. 49 (3): 539–562. doi:10.1080/10635159950127385. PMID 12116426.

- ^ Kim, Chang Bae; Moon, Seung Yeo; Gelder, Stuart R.; Kim, Won (September 1996). "Phylogenetic Relationships of Annelids, Molluscs, and Arthropods Evidenced from Molecules and Morphology". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 43 (3): 207–215. Bibcode:1996JMolE..43..207K. doi:10.1007/PL00006079. PMID 8703086.

- ^ a b Gould, Stephen Jay (2011). The Lying Stones of Marrakech. Harvard University Press. pp. 130–134. ISBN 978-0-674-06167-5.

- ^ Leroi, Armand Marie (2014). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury. pp. 111–119, 270–271. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ^ "Espèce de". Reverso Dictionnnaire. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ De Wit, Hendrik C. D. (1994). Histoire du Développement de la Biologie, Volume III. Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-2-88074-264-5.

- ^ a b Valentine, James W. (2004). On the Origin of Phyla. University of Chicago Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-226-84548-7.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1874). Anthropogenie oder Entwickelungsgeschichte des menschen (in German). W. Engelmann. p. 202.

- ^ Hutchins, Michael (2003). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia (2nd ed.). Gale. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7876-5777-2.

- ^ a b "Fisheries and Aquaculture". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Graphic detail Charts, maps and infographics. Counting chickens". The Economist. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Helfman, Gene S. (2007). Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources. Island Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-59726-760-1.

- ^ "World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture" (PDF). fao.org. FAO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Eggleton, Paul (17 October 2020). "The State of the World's Insects". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1): 61–82. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-050035. ISSN 1543-5938.

- ^ "Shellfish climbs up the popularity ladder". Seafood Business. January 2002. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Breeds of Cattle at Cattle Today". Cattle-today.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ Lukefahr, S. D.; Cheeke, P. R. "Rabbit project development strategies in subsistence farming systems". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "Ancient fabrics, high-tech geotextiles". Natural Fibres. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Cochineal and Carmine". Major colourants and dyestuffs, mainly produced in horticultural systems. FAO. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ "Guidance for Industry: Cochineal Extract and Carmine". FDA. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ "How Shellac Is Manufactured". The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912–1954). 18 December 1937. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Pearnchob, N.; Siepmann, J.; Bodmeier, R. (2003). "Pharmaceutical applications of shellac: moisture-protective and taste-masking coatings and extended-release matrix tablets". Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy. 29 (8): 925–938. doi:10.1081/ddc-120024188. PMID 14570313. S2CID 13150932.

- ^ Barber, E. J. W. (1991). Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton University Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN 978-0-691-00224-8.

- ^ Munro, John H. (2003). "Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Technology, and Organisation". In Jenkins, David (ed.). The Cambridge History of Western Textiles. Cambridge University Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-0-521-34107-3.

- ^ Pond, Wilson G. (2004). Encyclopedia of Animal Science. CRC Press. pp. 248–250. ISBN 978-0-8247-5496-9. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Genetics Research". Animal Health Trust. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Drug Development". Animal Research.info. Archived from the original on 8 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Animal Experimentation". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "EU statistics show decline in animal research numbers". Speaking of Research. 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ "Vaccines and animal cell technology". Animal Cell Technology Industrial Platform. 10 June 2013. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "Medicines by Design". National Institute of Health. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Fergus, Charles (2002). Gun Dog Breeds, A Guide to Spaniels, Retrievers, and Pointing Dogs. The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-618-7.

- ^ "History of Falconry". The Falconry Centre. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ King, Richard J. (2013). The Devil's Cormorant: A Natural History. University of New Hampshire Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-61168-225-0.

- ^ "AmphibiaWeb – Dendrobatidae". AmphibiaWeb. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ^ Heying, H. (2003). "Dendrobatidae". Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 12 February 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "Other bugs". Keeping Insects. 18 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Kaplan, Melissa. "So, you think you want a reptile?". Anapsid.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Pet Birds". PDSA. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Animals in Healthcare Facilities" (PDF). 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ The Humane Society of the United States. "U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics". Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Rabbit Industry profile" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Plous, S. (1993). "The Role of Animals in Human Society". Journal of Social Issues. 49 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb00906.x.

- ^ Hummel, Richard (1994). Hunting and Fishing for Sport: Commerce, Controversy, Popular Culture. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-646-1.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (27 June 2014). "The top 10 animal portraits in art". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Paterson, Jennifer (29 October 2013). "Animals in Film and Media". Oxford Bibliographies. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0044. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Gregersdotter, Katarina; Höglund, Johan; Hållén, Nicklas (2016). Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism. Springer. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-137-49639-3.

- ^ Warren, Bill; Thomas, Bill (2009). Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition. McFarland & Company. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4766-2505-8.

- ^ Crouse, Richard (2008). Son of the 100 Best Movies You've Never Seen. ECW Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-55490-330-6.

- ^ a b Hearn, Lafcadio (1904). Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-21901-1.

- ^ a b "Deer". Trees for Life. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Louis, Chevalier de Jaucourt (Biography) (January 2011). "Butterfly". Encyclopedia of Diderot and d'Alembert. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ 허친스, M, 아서 V. Evans, Roser W. Garrison and Neil Schlager (Eds) (2003) Grzimek의 동물 생명 백과사전, 2판. 3권, 곤충. 게일, 2003.

- ^ Ben-Tor, Daphna (1989). Scarabs, A Reflection of Ancient Egypt. Jerusalem: Israel Museum. p. 8. ISBN 978-965-278-083-6.

- ^ Biswas, Soutik (15 October 2015). "Why the humble cow is India's most polarising animal". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ van Gulik, Robert Hans. Hayagrīva: The Mantrayānic Aspect of Horse-cult in China and Japan. Brill Archive. p. 9.

- ^ Grainger, Richard (24 June 2012). "Lion Depiction across Ancient and Modern Religions". Alert. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ Read, Kay Almere; Gonzalez, Jason J. (2000). Mesoamerican Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 132–134.

- ^ Wunn, Ina (January 2000). "Beginning of Religion". Numen. 47 (4): 417–452. doi:10.1163/156852700511612. S2CID 53595088.

- ^ McCone, Kim R. (1987). "Hund, Wolf, und Krieger bei den Indogermanen". In Meid, W. (ed.). Studien zum indogermanischen Wortschatz. Innsbruck. pp. 101–154.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ Lau, Theodora (2005). The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes. Souvenir Press. pp. 2–8, 30–35, 60–64, 88–94, 118–124, 148–153, 178–184, 208–213, 238–244, 270–278, 306–312, 338–344.

- ^ Tester, S. Jim (1987). A History of Western Astrology. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 31–33 and passim. ISBN 978-0-85115-446-6.

![Dickinsonia costata from the Ediacaran biota (c. 635–542 mya) is one of the earliest animal species known.[90]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fb/DickinsoniaCostata.jpg/320px-DickinsoniaCostata.jpg)

![Auroralumina attenboroughii, an Ediacaran predator (c. 560 mya)[97]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/63/Auroralumina_attenboroughii_reconstruction.jpg/209px-Auroralumina_attenboroughii_reconstruction.jpg)