간섭 입자 결함

Defective interfering particle결함 간섭성 바이러스로도 알려진 결함 간섭성 입자(DIPs)는 복제 결함 또는 비상동성 [2][3]재조합으로 인해 입자 게놈의 중요한 부분이 손실된 자발적으로 생성된 바이러스 돌연변이입니다.유전자 RNA 조각의 직접 결속을 수반하는 비복제 메커니즘도 [4][5]제안되었지만, 이들의 형성 메커니즘은 바이러스 게놈 복제 중 템플릿 전환의 결과로 추정된다.DIP는 부모 바이러스로부터 유도되어 관련지어지며,[6] 그 결함에 의해 바이러스의 적어도 1개의 필수 유전자가 상실 또는 심각한 손상을 입었기 때문에 비감염성이 되었을 경우에는 DIP로 분류된다.DIP는 보통 여전히 숙주 세포에 침투할 수 있지만, 손실 [7][8]요인을 제공하기 위해 세포와 공동 감염시키기 위해 완전히 기능하는 또 다른 바이러스 입자('도움자' 바이러스)가 필요합니다.

DIP는 1950년대 폰 매그너스와 슐레진저에 의해 처음 관찰되었으며 둘 다 인플루엔자 [9]바이러스와 함께 연구되었다.그러나 DIP에 대한 직접적인 증거는 전자 현미경에서[10] 소포성 구내염 바이러스의 '덩어리' 입자의 존재를 발견한 Hackett에 의해서만 발견되었고 DIPs 용어의 공식화는 1970년에 Huang과 [11]Baltimore에 의해 이루어졌다.DIP는 폴리오바이러스, 사스 코로나바이러스, 홍역, 알파바이러스, 호흡합성세포바이러스 및 인플루엔자 [12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19]바이러스를 포함한 임상 및 실험실 환경에서 DNA 및 RNA 바이러스의 거의 모든 클래스에서 발생할 수 있습니다.

탈당하다

DIP는 실험실에서 실험 조건 하에서 재현될 수 있는 자연 발생 현상으로, 실험용으로 합성될 수도 있습니다.그것들은 오류가 발생하기 쉬운 바이러스 복제에 의해 자발적으로 생성되며, 특히 사용된 효소(복제효소 또는 RNA 의존성 RNA 중합효소)로 인해 DNA 바이러스보다 RNA 바이러스에 널리 퍼져있다.[6][20]DI 게놈은 일반적으로 바이러스 중합효소에 의한 인식에 필요한 흰개미 염기서열과 그들의 게놈을 새로운 입자로 포장하기 위한 염기서열을 유지하지만 [21][22]그 외에는 거의 유지하지 않는다.게놈 삭제 이벤트의 크기는 크게 다를 수 있으며, 광견병 바이러스에서 파생된 DIP에서 6.1kb의 [23]삭제가 나타나는 예도 있습니다.다른 예로, 여러 개의 DI-DNA 식물 바이러스 게놈의 크기는 원래 게놈 크기의 10분의 1에서 2분의 [24]1까지 다양했습니다.

방해다

공감염 중 경쟁적 억제를 통해 부모 바이러스의[6] 기능에 영향을 미치는 입자는 간섭하는 것으로 간주됩니다.즉, 불량 바이러스와 비불량 바이러스가 동시에 복제되지만, 불량 입자가 증가하면 비불량 바이러스의 복제량이 감소한다.간섭의 정도는 게놈 내 결함의 유형과 크기에 따라 달라지며, 게놈 데이터의 대량 삭제는 결함이 있는 [21]게놈의 신속한 복제를 가능하게 합니다.사스-CoV-2는 게놈의 90%를 제거한 합성 DIP가 바이러스보다 [25]3배 빠르게 복제된다.숙주 세포의 동시 감염 동안, 감염성 [21]입자보다 더 많은 바이러스 인자가 비감염성 DIP를 생성하기 위해 사용되는 임계 비율에 도달할 것이다.또한 결함이 있는 입자와 결함이 있는 게놈은 숙주의 선천적 면역 반응을 자극하는 것으로 입증되었으며 바이러스 감염 중 그들의 존재는 항바이러스 [12]반응의 강도와 관련이 있다.그러나 SARS-CoV-2와 같은 일부 바이러스에서는 입자의 간섭에 의한 경쟁 억제 효과가 바이러스 매개 선천성 면역 반응 및 치료 [26]효과를 내는 염증을 감소시킨다.

이 간섭적인 성질은 바이러스 [27][28]치료 연구에 점점 더 중요해지고 있다.특수성 때문에 DIP는 감염 부위가 대상이 될 것으로 생각됩니다.한 예로, 과학자들은 DIP를 사용하여 "보호 바이러스"를 만들어 냈는데, 이것은 더 이상 [29]치명적이지 않은 지점까지 간섭 반응을 유도함으로써 생쥐의 인플루엔자 A 감염의 병원성을 약화시켰다.SARS-CoV-2의 경우, 2020년에 최초의 합성 DIP가 만들어졌으며, 간섭 효과는 병원 형성을 줄이고 햄스터를 심각한 [30]질병으로부터 보호하는 치료적 간섭 입자(TIP)를 생성하기 위해 사용되었다.

병인 발생

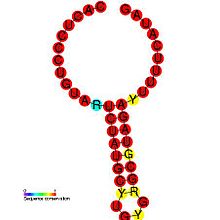

DIP는 특정 바이러스의 병원 형성에 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 나타났다.한 연구는 병원체와 그 결함 있는 변종 사이의 관계를 보여주며, DI 생산의 조절이 바이러스가 어떻게 자신의 감염 복제를 감쇠시키고, 바이러스 부하를 감소시키며, 따라서 숙주가 [31]너무 빨리 죽는 것을 방지함으로써 기생충 효율을 향상시키는지 보여준다.이것에 의해, 바이러스가 새로운 호스트를 확산시켜 감염시키는 시간도 길어집니다.DIP 생성은 바이러스 내에서 조절된다: Coronavirus SL-II cis-acting 복제 요소(이미지 참조)는 소 코로나 바이러스의 DIP 생성 매개에 관여하는 고차 유전체 구조이며, 다른 코로나 바이러스 그룹에서 [1]명백한 호몰로그가 검출된다.1970년 [32]앨리스 황과 데이비드 볼티모어의 작품에서 좀 더 심도 있는 소개를 찾을 수 있다.

결함이 있는 RNA 게놈의 종류

- 삭제는 템플릿의 fragment를 건너뛰는 경우입니다.토마토 반점 시들한 바이러스와 플럭 하우스 [33][22]바이러스에서 이러한 유형의 탈선 사례가 발견될 수 있다.

- 스냅백 이탈은 복제 효소가 한 가닥의 일부를 전사한 후 이 새 가닥을 템플릿으로 사용하는 것입니다.그 결과 머리핀이 생길 수 있습니다.수포성 구내염 [34]바이러스에서 스냅백 결손이 관찰되었습니다.

- 팬핸들 이탈은 중합효소가 부분적으로 만들어진 가닥을 운반한 후 다시 5' 끝을 전사하여 팬핸들 모양을 형성하는 것입니다.팬핸들 변종은 인플루엔자 [35]바이러스에서 발견됩니다.

- 복합 결손이란 삭제와 스냅백 결손이 동시에 발생하는 경우를 말합니다.

- 모자이크 또는 복합 DI 게놈으로, 다양한 영역이 같은 도우미 바이러스 게놈에서 나왔지만 순서가 잘못되었을 수 있습니다.다른 도우미 게놈 세그먼트에서 나왔을 수도 있고 숙주 RNA 세그먼트를 포함할 수도 있습니다.복제가 발생할 [3]수도 있습니다.

조사.

바이러스학자들은 숙주 세포의 감염에 대한 간섭과 DI 게놈이 면역자극 [3]항바이러스제로 어떻게 작용할 수 있는지에 대해 더 많은 것을 배우기 위해 연구를 수행해왔다.또 다른 연구 부문은 DIP를 항바이러스 치료 간섭 입자(TIPs)[36]로 엔지니어링하는 개념을 [37]최근까지 순전히 이론적인 개념으로 추구하고 있습니다.2014년 기사는 선천적인 항바이러스 면역 반응(즉, 간섭체)[38]을 유도하여 인플루엔자 바이러스에 대한 DIP의 면역 자극 효과를 테스트하기 위한 임상 전 작업을 기술하고 있다.후속 연구는 HIV와 SARS-CoV-2에 [25][26]대한[39] TIPs의 임상 전 효능을 테스트했다. 또한 DI-RNA는 처음으로 Partitiviridae 계열의 바이러스를 통한 곰팡이 감염을 돕는 것으로 밝혀져 더 많은 학제 간 [20]작업을 위한 여지가 생겼다.

ViReMa 및 DI-tector와[41] 같은[40] 몇 가지 툴은 차세대 염기서열 데이터의 결함 바이러스 게놈을 검출하는 데 도움이 되며, 랜덤 삭제 라이브러리 염기서열 분석(RanDeL-Seq)[42]과 같은 높은 처리량 접근방식을 통해 DI 입자 증식에 필요한 바이러스 유전 요소를 합리적으로 매핑할 수 있습니다.

레퍼런스

- ^ a b Raman S, Bouma P, Williams GD, Brian DA (June 2003). "Stem-loop III in the 5' untranslated region is a cis-acting element in bovine coronavirus defective interfering RNA replication". Journal of Virology. 77 (12): 6720–6730. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.12.6720-6730.2003. PMC 156170. PMID 12767992.

- ^ White KA, Morris TJ (January 1994). "Nonhomologous RNA recombination in tombusviruses: generation and evolution of defective interfering RNAs by stepwise deletions". Journal of Virology. 68 (1): 14–24. doi:10.1128/JVI.68.1.14-24.1994. PMC 236259. PMID 8254723.

- ^ Pathak KB, Nagy PD (December 2009). "Defective Interfering RNAs: Foes of Viruses and Friends of Virologists". Viruses. 1 (3): 895–919. doi:10.3390/v1030895. PMC 3185524. PMID 21994575.

- ^ Gmyl AP, Belousov EV, Maslova SV, Khitrina EV, Chetverin AB, Agol VI (November 1999). "Nonreplicative RNA recombination in poliovirus". Journal of Virology. 73 (11): 8958–8965. doi:10.1128/JVI.73.11.8958-8965.1999. PMC 112927. PMID 10516001.

- ^ a b c Pathak KB, Nagy PD (December 2009). "Defective Interfering RNAs: Foes of Viruses and Friends of Virologists". Viruses. 1 (3): 895–919. doi:10.3390/v1030895. PMC 3185524. PMID 21994575.

- ^ Makino S, Shieh CK, Soe LH, Baker SC, Lai MM (October 1988). "Primary structure and translation of a defective interfering RNA of murine coronavirus". Virology. 166 (2): 550–560. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(88)90526-0. PMC 7131284. PMID 2845661.

- ^ Palmer SR, Soulsby L, Torgerson P, Brown DW, eds. (2011). Oxford Textbook of Zoonoses: Biology, Clinical Practice, and Public Health Control. OUP Oxford. pp. 399–400. doi:10.1093/med/9780198570028.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-857002-8.

- ^ Gard S, Von Magnus P, Svedmyr A, Birch-Andersen A (October 1952). "Studies on the sedimentation of influenza virus". Archiv für die Gesamte Virusforschung. 4 (5): 591–611. doi:10.1007/BF01242026. PMID 14953289. S2CID 21838623.

- ^ Hackett AJ (September 1964). "A possible morphologic basis for the autointerference phenomenon in vesicular stomatitis virus". Virology. 24 (1): 51–59. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(64)90147-3. PMID 14208902.

- ^ Huang AS, Baltimore D (April 1970). "Defective viral particles and viral disease processes". Nature. 226 (5243): 325–327. Bibcode:1970Natur.226..325H. doi:10.1038/226325a0. PMID 5439728. S2CID 4184206.

- ^ a b Sun Y, Jain D, Koziol-White CJ, Genoyer E, Gilbert M, Tapia K, et al. (September 2015). "Immunostimulatory Defective Viral Genomes from Respiratory Syncytial Virus Promote a Strong Innate Antiviral Response during Infection in Mice and Humans". PLOS Pathogens. 11 (9): e1005122. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005122. PMC 4559413. PMID 26336095.

- ^ Dimmock NJ, Dove BK, Scott PD, Meng B, Taylor I, Cheung L, et al. (2012). "Cloned defective interfering influenza virus protects ferrets from pandemic 2009 influenza A virus and allows protective immunity to be established". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e49394. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...749394D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049394. PMC 3521014. PMID 23251341.

- ^ Saira K, Lin X, DePasse JV, Halpin R, Twaddle A, Stockwell T, et al. (July 2013). "Sequence analysis of in vivo defective interfering-like RNA of influenza A H1N1 pandemic virus". Journal of Virology. 87 (14): 8064–8074. doi:10.1128/JVI.00240-13. PMC 3700204. PMID 23678180.

- ^ Petterson E, Guo TC, Evensen Ø, Mikalsen AB (November 2016). "Experimental piscine alphavirus RNA recombination in vivo yields both viable virus and defective viral RNA". Scientific Reports. 6: 36317. Bibcode:2016NatSR...636317P. doi:10.1038/srep36317. PMC 5090867. PMID 27805034.

- ^ Cattaneo R, Schmid A, Eschle D, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Billeter MA (October 1988). "Biased hypermutation and other genetic changes in defective measles viruses in human brain infections". Cell. 55 (2): 255–265. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90048-7. PMC 7126660. PMID 3167982.

- ^ Makino S, Yokomori K, Lai MM (December 1990). "Analysis of efficiently packaged defective interfering RNAs of murine coronavirus: localization of a possible RNA-packaging signal". Journal of Virology. 64 (12): 6045–6053. doi:10.1128/JVI.64.12.6045-6053.1990. PMC 248778. PMID 2243386.

- ^ Lundquist RE, Sullivan M, Maizel JV (November 1979). "Characterization of a new isolate of poliovirus defective interfering particles". Cell. 18 (3): 759–769. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(79)90129-6. PMID 229964. S2CID 35964939.

- ^ Stauffer Thompson KA, Rempala GA, Yin J (April 2009). "Multiple-hit inhibition of infection by defective interfering particles". The Journal of General Virology. 90 (Pt 4): 888–899. doi:10.1099/vir.0.005249-0. PMC 2889439. PMID 19264636.

- ^ a b Chiba S, Lin YH, Kondo H, Kanematsu S, Suzuki N (February 2013). "Effects of defective interfering RNA on symptom induction by, and replication of, a novel partitivirus from a phytopathogenic fungus, Rosellinia necatrix". Journal of Virology. 87 (4): 2330–2341. doi:10.1128/JVI.02835-12. PMC 3571465. PMID 23236074.

- ^ a b c Dimmock NJ, Easton AJ, Leppard KN, eds. (2015). "Innate and intrinsic immunity". Introduction to Modern Virology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 201–217. ISBN 978-1-119-09453-1.

- ^ a b Resende R, de Haan P, van de Vossen E, de Avila AC, Goldbach R, Peters D (October 1992). "Defective interfering L RNA segments of tomato spotted wilt virus retain both virus genome termini and have extensive internal deletions". The Journal of General Virology. 73 (10): 2509–2516. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-73-10-2509. PMID 1402797.

- ^ Conzelmann KK, Cox JH, Thiel HJ (October 1991). "An L (polymerase)-deficient rabies virus defective interfering particle RNA is replicated and transcribed by heterologous helper virus L proteins". Virology. 184 (2): 655–663. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(91)90435-e. PMID 1887588.

- ^ Patil BL, Dasgupta I (2006). "Defective Interfering Dnas of Plant Viruses". Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 25 (1): 47–64. doi:10.1080/07352680500391295. S2CID 85790514.

- ^ a b c Yao, Shun; Narayanan, Anoop; Majowicz, Sydney; Jose, Joyce; Archetti, Marco (2020-11-23). "A Synthetic Defective Interfering SARS-CoV-2": 2020.11.22.393587. doi:10.1101/2020.11.22.393587v1.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ a b Chaturvedi S, Vasen G, Pablo M, Chen X, Beutler N, Kumar A, et al. (December 2021). "Identification of a therapeutic interfering particle-A single-dose SARS-CoV-2 antiviral intervention with a high barrier to resistance". Cell. 184 (25): 6022–6036.e18. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.11.004. PMC 8577993. PMID 34838159.

- ^ Weinberger LS, Schaffer DV, Arkin AP (September 2003). "Theoretical design of a gene therapy to prevent AIDS but not human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection". Journal of Virology. 77 (18): 10028–10036. doi:10.1128/jvi.77.18.10028-10036.2003. PMC 224590. PMID 12941913.

- ^ Thompson KA, Yin J (September 2010). "Population dynamics of an RNA virus and its defective interfering particles in passage cultures". Virology Journal. 7: 257. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-7-257. PMC 2955718. PMID 20920247.

- ^ Easton AJ, Scott PD, Edworthy NL, Meng B, Marriott AC, Dimmock NJ (March 2011). "A novel broad-spectrum treatment for respiratory virus infections: influenza-based defective interfering virus provides protection against pneumovirus infection in vivo" (PDF). Vaccine. 29 (15): 2777–2784. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.102. PMID 21320545.

- ^ Villanueva MT (December 2021). "Interfering viral-like particles inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 21 (1): d41573–021–00205-5. doi:10.1038/d41573-021-00205-5. PMID 34873320. S2CID 244935707.

- ^ Lukhovitskaya NI, Thaduri S, Garushyants SK, Torrance L, Savenkov EI (June 2013). "Deciphering the mechanism of defective interfering RNA (DI RNA) biogenesis reveals that a viral protein and the DI RNA act antagonistically in virus infection". Journal of Virology. 87 (11): 6091–6103. doi:10.1128/JVI.03322-12. PMC 3648117. PMID 23514891.

- ^ Huang AS, Baltimore D (April 1970). "Defective viral particles and viral disease processes". Nature. 226 (5243): 325–327. Bibcode:1970Natur.226..325H. doi:10.1038/226325a0. PMID 5439728. S2CID 4184206.

- ^ Jaworski E, Routh A (May 2017). "Parallel ClickSeq and Nanopore sequencing elucidates the rapid evolution of defective-interfering RNAs in Flock House virus". PLOS Pathogens. 13 (5): e1006365. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006365. PMC 5435362. PMID 28475646.

- ^ Schubert M, Lazzarini RA (February 1981). "Structure and origin of a snapback defective interfering particle RNA of vesicular stomatitis virus". Journal of Virology. 37 (2): 661–672. doi:10.1128/JVI.37.2.661-672.1981. PMC 171054. PMID 6261012.

- ^ Fodor E, Pritlove DC, Brownlee GG (June 1994). "The influenza virus panhandle is involved in the initiation of transcription". Journal of Virology. 68 (6): 4092–4096. doi:10.1128/JVI.68.6.4092-4096.1994. PMC 236924. PMID 8189550.

- ^ Metzger VT, Lloyd-Smith JO, Weinberger LS (March 2011). "Autonomous targeting of infectious superspreaders using engineered transmissible therapies". PLOS Computational Biology. 7 (3): e1002015. Bibcode:2011PLSCB...7E2015M. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002015. PMC 3060167. PMID 21483468.

- ^ Gladstone Institutes. "A New Class of Antiviral Therapy Could Treat COVID-19". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- ^ Dimmock NJ, Easton AJ (May 2014). "Defective interfering influenza virus RNAs: time to reevaluate their clinical potential as broad-spectrum antivirals?". Journal of Virology. 88 (10): 5217–5227. doi:10.1128/JVI.03193-13. PMC 4019098. PMID 24574404.

- ^ Tanner EJ, Jung SY, Glazier J, Thompson C, Zhou Y, Martin B, Son HI, Riley JL, Weinberger LS (2019-10-30). "Discovery and Engineering of a Therapeutic Interfering Particle (TIP): a combination self-renewing antiviral". doi:10.1101/820456. S2CID 208600143.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ Routh A, Johnson JE (January 2014). "Discovery of functional genomic motifs in viruses with ViReMa-a Virus Recombination Mapper-for analysis of next-generation sequencing data". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (2): e11. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt916. PMC 3902915. PMID 24137010.

- ^ Beauclair G, Mura M, Combredet C, Tangy F, Jouvenet N, Komarova AV (October 2018). "DI-tector: defective interfering viral genomes' detector for next-generation sequencing data". RNA. 24 (10): 1285–1296. doi:10.1261/rna.066910.118. PMC 6140465. PMID 30012569.

- ^ Notton T, Glazier JJ, Saykally VR, Thompson CE, Weinberger LS (January 2021). "RanDeL-Seq: a High-Throughput Method to Map Viral cis- and trans-Acting Elements". mBio. 12 (1): e01724–20. doi:10.1128/mBio.01724-20. PMC 7845639. PMID 33468683.