갑각류

Crustacean| 갑각류 시간 범위: Ma D N Cambrian ~현재 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 그리고 위에서 아래로:그랩스그랩스(게), 호마루스 가마루스(랍스터), 프로캄바루스클라크이(가재), 리마타 암보이넨시스(새우), 유피아수퍼바(크릴), 헤밀레피스토스 레아무리(나무집), 칼라노이드아(요새우), 레파스 아나테라(바나클라클라) | |

| 과학적 분류 | |

| 왕국: | 애니멀리아 |

| 문: | 절지동물 |

| Clade: | 범쿠라스타케아목 |

| 하위문: | 갑각류 |

| 포함된 그룹 | |

| 분류학적으로 포함되지만 전통적으로 제외된 분류군 | |

갑각류(Crustacea /krˈstesteɪ)/)는 크고 다양한 절지동물 분류군을 형성하며, 여기에는 십각류, 종자새우,[1] 분지동물, 어금니, 크릴류, 레미페데스, 등각류, 등각류, 등각류, 요각류, 양각류, 사마귀새우 등이 포함된다.갑각류 그룹은 맨디불라타 군락 아래의 아문처럼 취급될 수 있다.이제 육각류는 갑각류 집단 깊숙이 생겨났고, 완성된 집단은 범각류 [2]집단이라고 불린다.일부 갑각류(리미디아,[3] 두족류, 분지동물)는 다른 갑각류보다 곤충과 다른 육각류와 더 밀접하게 관련되어 있다.

67,000종이 기술되어 있으며 크기는 0.1mm(0.004인치)의 스티고탄툴루스 스톡키에서 최대 3.8m(12.5피트)의 다리 넓이와 20kg(44파운드)의 질량을 가진 일본 거미 게에 이르기까지 다양하다.다른 절지동물들처럼, 갑각류도 외골격을 가지고 있는데, 그들은 그것을 성장시키기 위해 털을 깎는다.곤충, 다지동물, 골지동물 등 절지동물의 다른 집단과 구별되는 것은 편생(양분된) 사지를 소유하고 있으며, 가지족동물과 요족동물의 나우플리우스 단계와 같은 애벌레 형태이다.

대부분의 갑각류는 자유롭게 사는 수생 동물이지만, 일부는 육생 동물이고, 일부는 기생 동물이고, 일부는 세실 동물이다.이 집단은 캄브리아기까지 거슬러 올라가는 광범위한 화석 기록을 가지고 있다.매년 790만 톤 이상의 갑각류가 어업이나 양식업에서 인간의 [4]소비를 위해 생산되고 있으며, 그 대부분은 새우와 새우이다.크릴과 요각류는 널리 잡히지는 않지만, 지구상에서 가장 큰 바이오매스를 가진 동물일 수 있으며 먹이사슬의 중요한 부분을 형성하고 있습니다.갑각류에 대한 과학적 연구는 발암학으로 알려져 있고, 발암학에서 일하는 과학자는 발암학자이다.

구조.

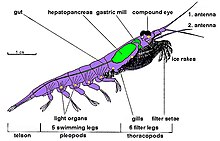

갑각류의 몸은 세 부분으로 구성되어 있는데, 세 개의 영역으로 분류된다: 두부 [5]또는 머리, 송골 또는 흉부,[6] 그리고 늑골 또는 [7]복부.머리와 흉곽은 하나의 큰 [9]갑옷으로 덮인 머리 흉곽을 [8]형성하기 위해 함께 결합될 수 있다.갑각류의 몸은 단단한 외골격에 의해 보호되며, 이는 동물이 자라기 위해 털을 깎아야 한다.각 소마이트 주변의 껍데기는 등골, 복부 흉골, 외측 늑막으로 나눌 수 있다.외골격의 다양한 부분이 함께 [10]: 289 결합될 수 있습니다.

각 소마이트 또는 신체 세그먼트는 한 쌍의 부속물을 가질 수 있습니다: 머리 부분에는 두 쌍의 더듬이, 하악골과 [5]상악골이 포함됩니다. 흉부 세그먼트는 다리를 가지고 있으며, 이는 송골동물(걷는 다리)과 상악골(먹이는 다리)[6]로 특화될 수 있습니다.복부는 복부를 [7]이루고 항문을 지탱하는 텔슨으로 끝나며, 종종 꼬리 [11]부채꼴을 형성하기 위해 요각류에 의해 옆구리가 형성된다.다른 갑각류 동물에 있는 부속물의 수와 다양성은 이 그룹의 [12]성공에 부분적으로 책임이 있을 수 있습니다.

갑각류 부속물은 일반적으로 두 부분으로 나뉘어져 있다는 것을 의미하며, 이것은 두 번째 더듬이를 포함하지만, 첫 번째 더듬이는 포함하지 않습니다. 단일한 더듬이는 말라코스트라카강에서 예외적으로 더듬이가 일반적으로 짝짓기이거나 심지어 [13][14]삼엽성일 수도 있습니다.혼수 상태가 갑각류에서 진화한 파생 상태인지, 아니면 다른 모든 집단에서 사지의 두 번째 가지를 잃었는지는 불분명하다.예를 들어, 삼엽충은 또한 혼수성 [15]맹장을 가지고 있었다.

본체강은 개방된 순환계이며,[16] 여기서 등 근처에 위치한 심장에 의해 혈액이 혈액으로 보내집니다.말라코스트라카는 산소를 운반하는 색소로 헤모시아닌을 가지고 있으며, 요각류, 배척류, 따개비류 및 분지동물은 헤모글로빈을 [17]가지고 있다.소화관은 종종 음식을 분쇄하기 위한 전어 같은 "가스트릭 밀"과 음식을 흡수하는 한 쌍의 소화샘을 가지고 있는 직선 튜브로 구성되어 있습니다; 이 구조는 나선형으로 [18]되어 있습니다.신장의 기능을 하는 구조물은 더듬이 근처에 있습니다.뇌는 더듬이에 가까운 신경절의 형태로 존재하며,[19] 주요 신경절의 집합은 내장 아래에서 발견됩니다.

많은 십각동물에서, 첫 번째 (때로는 두 번째) 쌍은 정자 전달을 위해 수컷에 특화되어 있다.많은 육생 갑각류들은 계절에 따라 짝짓기를 하고 알을 방출하기 위해 바다로 돌아간다.우드리스와 같은 다른 동물들은 비록 습한 환경이지만 땅 위에 알을 낳는다.대부분의 십각류에서 암컷은 자유롭게 헤엄치는 [20]유충으로 부화할 때까지 알을 보관한다.

생태학

대부분의 갑각류는 해양 또는 담수 환경에서 살지만, 육지 게, 육지 소라게, 그리고 우들레와 같은 몇몇 집단은 육지에서의 생활에 적응했다.해양 갑각류는 곤충이 [21][22]육지에 있는 것처럼 바다 어디에나 있다.비록 몇몇 분류학적 단위가 기생하고 숙주에 붙어 살지만, 대부분의 갑각류들은 또한 독립적으로 움직이며 움직인다. 그리고 성인 따오기는 "갈치류 이"라고 불릴 수 있는 "시모토아 엑시구아"와 같이 살고, 그들은 첫번째로 머리에 붙어 산다.e기판이며 독립적으로 이동할 수 없습니다.몇몇 브런치우란들은 염도의 급격한 변화를 견딜 수 있고 또한 숙주를 해양에서 해양이 아닌 [23]: 672 종으로 바꿀 수 있다.크릴은 남극 동물 [24]: 64 군집의 먹이사슬의 가장 중요한 부분이자 가장 아래층이다.일부 갑각류는 중국 미튼 게, 에리오헤이어 시넨시스,[25] 아시아 해안 게, 헤미그라프수스 샹귀네우스 [26]같은 중요한 침입종이다.

라이프 사이클

짝짓기 방식

대부분의 갑각류는 성별이 분리되어 성적으로 번식한다.사실, 최근의 연구는 어떻게 수컷 갑각류인지 설명해준다.캘리포니아는 암컷에게 효모를 먹이는 대신 해조류를 먹이는 것을 선호하며, 식생활 차이에 따라 짝짓기를 할 암컷을 결정합니다.[27] 작은 숫자들은 따개비, 레미페데스,[28] 그리고 세팔로카리다를 포함한 암수동체이다.[29]어떤 사람들은 심지어 그들의 [29]삶의 과정에서 성별을 바꿀 수도 있다.처녀생식은 또한 갑각류 사이에 널리 퍼져 있는데,[27] 수컷에 의한 수정 없이 암컷에 의해 실행 가능한 난자가 생산된다.이것은 많은 분지동물, 일부 배척동물, 일부 등각동물, 그리고 마모크렙스 가재 같은 특정 "고위" 갑각류에서 발생합니다.

계란

많은 갑각류 집단에서 수정란은 단순히 물기둥으로 방출되는 반면, 다른 그룹은 알을 부화할 준비가 될 때까지 알을 붙잡기 위한 많은 메커니즘을 개발했습니다.대부분의 십각류는 흉부에 붙어 있는 알을 가지고 다니는 반면, 과충류, 노트라칸류, 아노스트라칸류, 그리고 많은 등각류는 등각류와 흉부 사지에서 [27]알주머니를 형성한다.암컷 브란치우라는 외부 가시나무에 알을 담지 않고 돌이나 다른 [30]: 788 물체에 열을 지어 붙인다.대부분의 렙토스트라칸과 크릴은 가슴 다리 사이에 알을 가지고 다닌다; 어떤 요각류는 특별한 얇은 벽의 주머니 속에 알을 가지고 다니는 반면, 다른 요각류는 길고 엉킨 [27]끈으로 함께 붙어 있다.

유충

갑각류는 많은 애벌레 형태를 보이는데, 그 중 가장 빠르고 특징적인 것은 나우플리우스이다.이것은 세 쌍의 부속물이 있는데, 모두 어린 동물의 머리에서 나온 것이고, 한 쌍의 나비눈이 있습니다.대부분의 집단에서, 조에아(zoea[31])를 포함한 추가적인 유충 단계가 있다.이 이름은 박물학자들이 그것이 별개의 종이라고 [32]믿었을 때 붙여졌다.그것은 나우플리우스 단계를 따르고 애벌레 이후의 단계보다 앞선다.유충은 두부 부속물을 사용하는 나우플리와 수영에 복부 부속물을 사용하는 메가로파와 달리 흉부 부속물을 사용하여 헤엄친다.그것은 종종 등딱지에 뾰족한 부분이 있는데, 이것은 이 작은 유기체들이 방향성 [33]수영을 유지하는데 도움을 줄 수 있습니다.많은 십각류에서, 그들의 빠른 발달로 인해, 조아는 첫 번째 유충 단계이다.어떤 경우에, 동물 단계는 균사 단계로 이어지며, 또 다른 경우에는 갑각류 그룹에 따라 메가로파 단계로 이어진다.

분류 및 계통발생

"크루스타시안"이라는 이름은 피에르 벨롱과 기욤 론델레를 포함한 동물들을 묘사하기 위한 초기 작품에서 유래했지만, 그의 "아프테라"에 [34]갑각류를 포함시킨 칼 린네를 포함한 몇몇 후대의 작가들에 의해 사용되지 않았다."크루스타체아"라는 이름을 사용한 최초의 명명학적으로 유효한 작품은 [35]1772년 Morten Thrane Brünnich의 Zoologié Fundamenta였다. 하지만 그는 첼리케도 [34]그 그룹에 포함시켰다.

갑각류 아문은 거의 67,000개의 [36]종으로 구성되어 있으며, 이것은 단지 다음과 같이 생각됩니다.대부분의 종이 아직 [37]발견되지 않았기 때문에 총수의 1/10에서 1/100이 남아 있다.대부분의 갑각류는 몸집이 작지만, 형태에 큰 차이가 있어 세계에서 가장 큰 절지동물인 일본 거미게와 가장 작은 길이 100마이크로미터(0.004인치)[38]의 스티고탄툴루스 스톡키를 [39]모두 포함합니다.다양한 형태의 갑각류에도 불구하고, 갑각류는 나우플리우스라고 알려진 특별한 애벌레 형태에 의해 결합됩니다.

갑각류와 다른 분류군의 정확한 관계는 2012년 4월[update] 현재 완전히 해결되지 않았다.형태학에 기초한 연구는 갑각류와 헥사포다류가 자매 집단이라는 범각류 [40]가설을 이끌었다.DNA 염기서열을 사용한 보다 최근의 연구는 갑각류가 더 큰 범각류 [41][42]분류군 안에 포진된 채 측계통임을 시사한다.

갑각류의 분류는 상당히 다양했지만 마틴과[43] 데이비스가 사용한 시스템은 이전의 연구들을 대부분 대체한다.미스타코카리다와 브랜치우라는 맥실로포다의 일부로 취급되며, 때때로 그들만의 분류로 취급된다.일반적으로 6개의 클래스가 인식됩니다.

다음 분지도는 헥사포다 [44]분류와 관련하여 측문 갑각류의 현존하는 여러 그룹 간의 업데이트된 관계를 보여준다.

| 범쿠라스타케아목 |

| 갑각류 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

이 도표에 따르면 육각류는 갑각류 나무 깊은 곳에 있으며, 육각류는 올리고스트라칸보다 다청류에 확실히 가깝다.

화석 기록

갑각류는 풍부하고 광범위한 화석 기록을 가지고 있는데, 이것은 중세 캄브리아기 버제스 [45][46]셰일의 카나데스피스와 스나티카리스와 같은 동물에서 시작된다.대부분의 주요 갑각류 그룹은 캄브리아기가 끝나기 전에 화석 기록에 나타난다. 즉, 분지오파다, 맥실로포다, 말라코스트라카이다. 그렇지 않으면 오르도비스기에 [47]시작되었을 캄브리아기 동물이 진정한 배척동물인지에 대해서는 논란이 있다.나중에 나타나는 유일한 분류는 화석 기록이 없는 세팔로카리다와 테즈누소카리스 골디치 화석에서 처음 기술되었지만,[49] 석탄기에나 나타나는 레미피디아이다.[48]대부분의 초기 갑각류들은 희귀하지만 화석 갑각류들은 [45]석탄기 이후부터 풍부해진다.

말라코스트라카 내에서는 크릴 [50]화석은 알려져 있지 않지만, 호프로카리다와 필로포다 모두 현재 멸종된 중요한 그룹뿐만 아니라 현존하는 구성원도 포함하고 있다(호프로카리다: 사마귀 새우가 존재하는 반면, 아이스크로넥티다;[51] 필로포다: 카나디다: 카나디다: 렙토크라카[46]).Cumacea와 Isopoda는 모두 최초의 [52][53]진정한 사마귀 [54]새우와 마찬가지로 석탄기로부터 알려져 있다.십이지장에서는 트라이아스기에 [55][56]새우와 폴리셸리드가,[57][58] 쥐라기에는 새우와 게가 등장한다.화석 굴인 오피오모르파는 유령 새우에 기인하는 반면, 화석 굴인 캄보리그마는 가재에 기인한다.누라의 페름기-트라이아스기 퇴적물은 유령 새우의 것으로 여겨지는 가장 오래된 (페름기: 로디언) 하천 굴을 보존하고 있다.Axiidea, Gebiidea) 및 가재(데카포다:아스타시어(Astacidea,[59] Parastacidea).

하지만, 갑각류의 거대한 방사선은 백악기, 특히 게에서 발생했고, 그들의 주요 포식자인 뼈 있는 [58]물고기의 적응 방사선에 의해 움직였을지도 모른다.최초의 진짜 바닷가재는 [60]백악기에도 나타난다.

인간의 소비

많은 갑각류가 인간에 의해 소비되고 있으며, 2007년에 거의 1,700,000톤이 생산되었다; 이 생산물의 대부분은 게, 바닷가재, 새우, 가재, 그리고 [61]새우와 같은 십각류 갑각류 동물이다.소비용으로 잡힌 갑각류 중 60% 이상이 새우와 새우이며, 80% 가까이가 아시아에서 생산되고 있으며, 중국만 [61]세계 전체의 거의 절반을 생산하고 있다.부패하지 않은 갑각류들은 널리 소비되지 않고 있으며,[62] 지구상에서 가장 훌륭한 생물체 중 하나를 가진 크릴새우 11만8천톤의 크릴새우만이 [61]잡히고 있다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Calman, William Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 552.

- ^ Rota-Stabelli, Omar; Kayal, Ehsan; Gleeson, Dianne; et al. (2010). "Ecdysozoan Mitogenomics: Evidence for a Common Origin of the Legged Invertebrates, the Panarthropoda". Genome Biology and Evolution. 2: 425–440. doi:10.1093/gbe/evq030. PMC 2998192. PMID 20624745.

- ^ Koenemann, Stefan; Jenner, Ronald A.; Hoenemann, Mario; et al. (2010-03-01). "Arthropod phylogeny revisited, with a focus on crustacean relationships". Arthropod Structure & Development. 39 (2–3): 88–110. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2009.10.003. ISSN 1467-8039. PMID 19854296.

- ^ "The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018 - Meeting the sustainable development goals" (PDF). fao.org. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2018.

- ^ a b "Cephalon". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ a b "Thorax". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ a b "Abdomen". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Cephalothorax". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Carapace". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ P. J. Hayward; J. S. Ryland (1995). Handbook of the marine fauna of north-west Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854055-7. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Telson". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Elizabeth Pennisi (July 4, 1997). "Crab legs and lobster claws". Science. 277 (5322): 36. doi:10.1126/science.277.5322.36. S2CID 83148200.

- ^ "Antennule". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Crustaceamorpha: appendages". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ N. C. Hughes (February 2003). "Trilobite tagmosis and body patterning from morphological and developmental perspectives". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43 (1): 185–206. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.185. PMID 21680423.

- ^ Akira Sakurai. "Closed and Open Circulatory System". Georgia State University. Archived from the original on 2016-09-17. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Klaus Urich (1994). "Respiratory pigments". Comparative Animal Biochemistry. Springer. pp. 249–287. ISBN 978-3-540-57420-0.

- ^ H. J. Ceccaldi. Anatomy and physiology of digestive tract of Crustaceans Decapods reared in aquaculture (PDF). Advances in Tropical Aquaculture. Tahiti Feb. 20 – March 4, 1989. AQUACOP, IFREMER. Actes de Colloque 9. pp. 243–259.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ Ghiselin, Michael T. (2005). "Crustacean". Encarta. Microsoft.

- ^ Burkenroad, M. D. (1963). "The evolution of the Eucarida (Crustacea, Eumalacostraca), in relation to the fossil record". Tulane Studies in Geology. 2 (1): 1–17.

- ^ "Crabs, lobsters, prawns and other crustaceans". Australian Museum. January 5, 2010. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Benthic animals". Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2014-05-11. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Alan P. Covich; James H. Thorp (1991). "Crustacea: Introduction and Peracarida". In James H. Thorp; Alan P. Covich (eds.). Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates (1st ed.). Academic Press. pp. 665–722. ISBN 978-0-12-690645-5. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Virtue, P. D.; Nichols, P. D.; Nicols, S. (1997). "Dietary-related mechanisms of survival in Euphasia superba: biochemical changes during long term starvation and bacteria as a possible source of nutrition.". In Bruno Battaglia; Valencia, José; Walton, D. W. H. (eds.). Antarctic communities: species, structure, and survival. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48033-8. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Gollasch, Stephan (October 30, 2006). "Eriocheir sinensis" (PDF). Global Invasive Species Database. Invasive Species Specialist Group. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ John J. McDermott (1999). "The western Pacific brachyuran Hemigrapsus sanguineus (Grapsidae) in its new habitat along the Atlantic coast of the United States: feeding, cheliped morphology and growth". In Schram, Frederick R.; Klein, J. C. von Vaupel (eds.). Crustaceans and the biodiversity crisis: Proceedings of the Fourth International Crustacean Congress, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, July 20–24, 1998. Koninklijke Brill. pp. 425–444. ISBN 978-90-04-11387-9. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ a b c d "Crustacean (arthropod)". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ G. L. Pesce. "Remipedia Yager, 1981".

- ^ a b D. E. Aiken; V. Tunnicliffe; C. T. Shih; L. D. Delorme. "Crustacean". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Alan P. Covich; James H. Thorp (2001). "Introduction to the Subphylum Crustacea". In James H. Thorp; Alan P. Covich (eds.). Ecology and classification of North American freshwater invertebrates (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 777–798. ISBN 978-0-12-690647-9. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Zoea". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (가입 또는 참여기관 회원가입 필요)

- ^ Calman, William Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 356.

- ^ W. F. R. Weldon (July 1889). "Note on the function of the spines of the Crustacean zoœa" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 1 (2): 169–172. doi:10.1017/S0025315400057994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17.

- ^ a b Lipke B. Holthuis (1991). "Introduction". Marine Lobsters of the World. FAO Species Catalogue, Volume 13. Food and Agriculture Organization. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-92-5-103027-1.

- ^ M. T. Brünnich (1772). Zoologiæ fundamenta prælectionibus academicis accomodata. Grunde i Dyrelaeren (in Latin and Danish). Copenhagen & Leipzig: Fridericus Christianus Pelt. pp. 1–254.

- ^ Zhi-Qiang Zhang (2011). Z.-Q. Zhang (ed.). "Animal biodiversity: an outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness - Phylum Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848" (PDF). Zootaxa. 4138: 99–103.

- ^ "Crustaceans — bugs of the sea". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Japanese Spider Crabs Arrive at Aquarium". Oregon Coast Aquarium. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Craig R. McClain; Alison G. Boyer (June 22, 2009). "Biodiversity and body size are linked across metazoans". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1665): 2209–2215. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0245. PMC 2677615. PMID 19324730.

- ^ J. Zrzavý; P. Štys (May 1997). "The basic body plan of arthropods: insights from evolutionary morphology and developmental biology". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 10 (3): 353–367. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1997.10030353.x. S2CID 84906139.

- ^ Jerome C. Regier; Jeffrey W. Shultz; Andreas Zwick; April Hussey; Bernard Ball; Regina Wetzer; Joel W. Martin; Clifford W. Cunningham (February 25, 2010). "Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences". Nature. 463 (7284): 1079–1083. Bibcode:2010Natur.463.1079R. doi:10.1038/nature08742. PMID 20147900. S2CID 4427443.

- ^ Björn M. von Reumont; Ronald A. Jenner; Matthew A. Wills; Emiliano Dell'Ampio; Günther Pass; Ingo Ebersberger; Benjamin Meyer; Stefan Koenemann; Thomas M. Iliffe; Alexandros Stamatakis; Oliver Niehuis; Karen Meusemann; Bernhard Misof (March 2012). "Pancrustacean phylogeny in the light of new phylogenomic data: support for Remipedia as the possible sister group of Hexapoda". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (3): 1031–1045. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr270. PMID 22049065.

- ^ Joel W. Martin; George E. Davis (2001). An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea (PDF). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. pp. 1–132.

- ^ Schwentner M, Combosch DJ, Nelson JP, Giribet G (2017). "A Phylogenomic Solution to the Origin of Insects by Resolving Crustacean-Hexapod Relationships". Current Biology. 27 (12): 1818–1824.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.040. PMID 28602656.

- ^ a b "Fossil Record". Fossil Groups: Crustacea. University of Bristol. Archived from the original on 2016-09-07. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ a b Briggs, Derek (January 23, 1978). "The morphology, mode of life, and affinities of Canadaspis perfecta (Crustacea: Phyllocarida), Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 281 (984): 439–487. Bibcode:1978RSPTB.281..439B. doi:10.1098/rstb.1978.0005.

- ^ Olney, Matthew. "Ostracods". An insight into micropalaeontology. University College, London. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Hessler, R. R. (1984). "Cephalocarida: living fossil without a fossil record". In N. Eldredge; S. M. Stanley (eds.). Living Fossils. New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-3-540-90957-6.

- ^ Koenemann, Stefan; Schram, Frederick R.; Hönemann, Mario; Iliffe, Thomas M. (12 April 2007). "Phylogenetic analysis of Remipedia (Crustacea)". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 7 (1): 33–51. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2006.07.001.

- ^ "Antarctic Prehistory". Australian Antarctic Division. July 29, 2008. Archived from the original on September 30, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ Jenner, Ronald A.; Hof, Cees H. J.; Schram, Frederick R. (1998). "Palaeo- and archaeostomatopods (Hoplocarida: Crustacea) from the Bear Gulch Limestone, Mississippian (Namurian), of central Montana". Contributions to Zoology. 67 (3): 155–186. doi:10.1163/18759866-06703001.

- ^ Schram, Frederick; Hof, Cees H. J.; Mapes, Royal H. & Snowdon, Polly (2003). "Paleozoic cumaceans (Crustacea, Malacostraca, Peracarida) from North America". Contributions to Zoology. 72 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1163/18759866-07201001.

- ^ Schram, Frederick R. (August 28, 1970). "Isopod from the Pennsylvanian of Illinois". Science. 169 (3948): 854–855. Bibcode:1970Sci...169..854S. doi:10.1126/science.169.3948.854. PMID 5432581. S2CID 31851291.

- ^ Hof, Cees H. J. (1998). "Fossil stomatopods (Crustacea: Malacostraca) and their phylogenetic impact". Journal of Natural History. 32 (10 & 11): 1567–1576. doi:10.1080/00222939800771101.

- ^ Crean, Robert P. D. (November 14, 2004). "Dendrobranchiata". Order Decapoda. University of Bristol. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ Karasawa, Hiroaki; Takahashi, Fumio; Doi, Eiji; Ishida, Hideo (2003). "First notice of the family Coleiidae Van Straelen (Crustacea: Decapoda: Eryonoides) from the upper Triassic of Japan". Paleontological Research. 7 (4): 357–362. doi:10.2517/prpsj.7.357. S2CID 129330859.

- ^ Chace, Fenner A. Jr.; Manning, Raymond B. (1972). "Two new caridean shrimps, one representing a new family, from marine pools on Ascension Island (Crustacea: Decapoda: Natantia)". Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 131 (131): 1–18. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.131. S2CID 53067015.

- ^ a b Wägele, J. W. (December 1989). "On the influence of fishes on the evolution of benthic crustaceans". Zeitschrift für Zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung. 27 (4): 297–309. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1989.tb00352.x.

- ^ Baucon, A.; Ronchi, A.; Felletti, F.; Neto de Carvalho, C. (2014). "Evolution of Crustaceans at the edge of the end-Permian crisis: ichnonetwork analysis of the fluvial succession of Nurra (Permian-Triassic, Sardinia, Italy)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 410: 74. Bibcode:2014PPP...410...74B. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.05.034. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Tshudy, Dale; Donaldson, W. Steven; Collom, Christopher; et al. (2005). "Hoploparia albertaensis, a new species of clawed lobster (Nephropidae) from the Late Coniacean, shallow-marine Bad Heart Formation of northwestern Alberta, Canada". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (5): 961–968. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079[0961:HAANSO]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 131067067.

- ^ a b c "FIGIS: Global Production Statistics 1950–2007". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Nicol, Steven; Endo, Yoshinari (1997). Krill Fisheries of the World. Fisheries Technical Paper. Vol. 367. Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 978-92-5-104012-6.

원천

Powers, M., Hill, G., Weaver, R. 및 Goymann, W. (2020년)해양 요각류인 Tigriopus Californicus의 붉은 카로티노이드 착색에 대한 짝 선택 실험.윤리학, 126(3), 344~352.https://doi.org/10.1111/eth.12976

외부 링크

Wikisource 텍스트:

Wikisource 텍스트:- "Encyclopedia Americana - Wikipedia". Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 8. 1920.

- Clark, Hubert Lyman; Ingersoll, Ernest (1905). "Crustacea". New International Encyclopedia. Vol. 5.

- 갑각류 생물에 관한 온라인 자료인 Crustacea.net

- 갑각류:로스앤젤레스 카운티 자연사 박물관

- 갑각류:트리 오브 라이프 웹 프로젝트

- 갑각류 학회

- 자연사 컬렉션: 갑각류:에든버러 대학교

- 싱가포르 해안의 갑각류(크루스타키아)

- 갑각류(조개, 바닷가재, 새우, 새우, 따개비) 웨이백 머신에 2012년 1월 11일 보관: 생물다양성 탐색기