팔로인디아인

Paleo-Indians| 글리토돈 사냥꾼 하인리히 하더(1858–1935), C.1920.  리토 민족이나 팔레오인도 인들은 아메리카 대륙의 가장 초기 알려진 정착민들이다.이 시기의 이름은 "리틱 날염" 석기들이 출현한 데서 유래되었다. |

플레이스토세 후기의 마지막 빙하 에피소드 동안 아메리카 대륙에 들어온 최초의 민족은 팔레오인디아인, 즉 팔레오인디아인 또는 팔레오 아메리카인이었다.접두사 "paleo-"는 그리스 형용사 palaios(παλαις)에서 따온 것으로, "구" 또는 "고전"을 의미한다."팔레오-인도인"이라는 용어는 특히 서반구의 석판기에 적용되며 "팔레오-인도인"이라는 용어와 구별된다.[1]

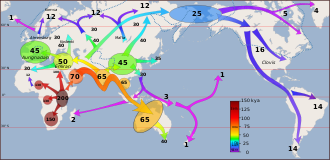

전통적인 이론들은 큰 동물 사냥꾼들이 북아시아에서 육교(베링아)를 통해 베링 해협을 건너 아메리카 대륙으로 들어갔다는 것을 암시한다.이 다리는 기원전 45,000년에서 12,000년까지 존재했다.[2]소규모의 고립된 수렵채집가들은 알래스카까지 큰 초식동물 무리들과 함께 이주했다.c. 16,500 – c. 13,500 BCE (c.18,500 – c. 15,500 BP)로부터, 북미의 태평양 해안과 계곡을 따라 얼음 없는 복도가 개발되었다.[3]이로 인해 인간이 뒤따르는 동물들은 대륙의 내륙으로 남쪽으로 이주할 수 있게 되었다.사람들은 걸어서 가거나 해안선을 따라 배를 이용했다.미국인들의 정확한 날짜와 경로는 현재 진행중인 논쟁의 대상으로 남아있다.[4]적어도 두 개의 형태학적으로 다른 팔레오-인도 인종이 1만년 전에 멕시코의 서로 다른 지리적 지역에 공존하고 있었다.[5]

석기, 특히 발사체 지점과 스크래퍼는 아메리카 대륙에서 가장 초기의 인간 활동의 주요한 증거다.고고학자들과 인류학자들은 문화적 시기를 분류하기 위해 살아남은 조작된 석판 조각 도구를 사용한다.[6]과학적인 증거는 토착 미국인과 동부 시베리아 인구를 연결한다.아메리카 대륙의 원주민들은 DNA와 같은 분자 데이터에서 나타난 언어적 요인, 혈액형의 분포, 유전적 구성 등에 의해 시베리아 인구와 연결되어 왔다.[7]적어도 두 번의 분리된 이주에 대한 증거가 있다.[8]기원전 8000년에서 7000년 사이에 기후가 안정되어 인구의 증가와 석판 기술의 발달로 이어져 보다 좌식적인 생활방식을 갖게 되었다.

아메리카로의 이주

연구원들은 팔레오-인디언이 아메리카 대륙으로 이동하는 정확한 날짜와 경로를 포함하여, 아메리카 대륙으로 이동하는 구체적인 사항에 대해 연구하고 토론하고 있다.[10]전통적인 이론은 이 초기 이주민들이 1만 7천년 전에 동부 시베리아와 현재의 알래스카 사이의 베링아로 이주했다고 주장한다.[11] 그 당시, 이 빙하는 해수면을 현저히 낮췄다.[12]이 사람들은 로랑티드와 코르딜레란 빙판 사이에 펼쳐져 있는 얼음 없는 복도를 따라 지금은 간결한 플리스토센 메가파우나를 따라다닌 것으로 여겨진다.[13]대안적인 제안 시나리오는 태평양 연안에서 남미로 도보로 이동하거나 보트를 이용하거나 도보로 이동하는 것을 포함한다.[14]후자의 증거는 그 후 마지막 빙하 기간이 끝난 후 100미터 이상의 해수면 상승에 의해 가려졌을 것이다.[15]

고고학자들은 팔레오-인도인들이 4만년에서 16,500년 전 사이에 베링기아에서 이주했다고 주장한다.[16][17][18]이 시간 범위는 실질적인 논쟁의 원천으로 남아 있다.전통적인 추정에 따르면 인간은 15,000년에서 20,000년 전 사이의 어느 시점에 북미에 도달했다.[19][20][21][22]현재까지 달성된 몇 개의 합의 영역은 중앙아시아에서 유래한 것으로, 마지막 빙하 기간 말기에 아메리카 대륙이 널리 거주하고 있거나, 더 구체적으로 말하면 현재까지의 약 16,000–13,000년 전에 후기 빙하 최대치로 알려져 있다.[11][23]그러나 유럽으로부터의 이주를 포함한, 팔레오인디안의 기원에 대한 대안 이론이 존재한다.[24]

주기화

알래스카(동부 베링기아)의 유적지는 팔레오인도인들의 초기 증거가 발견된 곳이며,[25][26][27] 북부 브리티시 컬럼비아, 서부 알버타, 유콘의 올드 크로 플랫 지역의 고고학적 유적들이 그 뒤를 잇고 있다.[28]팔레오인도인들은 결국 아메리카 전역에서 번성할 것이다.[29]이 민족들은 넓은 지리적 지역에 걸쳐 분포되어 있었고, 따라서 생활방식의 지역적 편차가 있었다.그러나, 모든 개별 집단은 공통적인 스타일의 석기 제작을 공유하여, 박치기 스타일과 진행 상황을 식별할 수 있게 하였다.[27]이 초기 Paleo-Indian 시대의 석판 감소 도구 어댑테이션은 대가족의 약 20-60명으로 구성된 높은 이동성 대역에 의해 활용된 아메리카 전역에서 발견되었다.[30][31]1년 중 몇 달 동안은 음식이 풍부했을 것이다.호수와 강에는 많은 종의 물고기, 새, 그리고 수생 포유류가 살고 있었다.견과류, 딸기류, 식용 뿌리는 숲과 습지에서 발견될 수 있었다.가을은 식료품을 보관해야 하고 겨울 준비를 위해 옷을 만들어야 하기 때문에 바쁜 시기였을 것이다.겨울 동안, 해안 어업 단체들은 신선한 음식과 털을 사냥하고 가두기 위해 내륙으로 이동했다.[32]

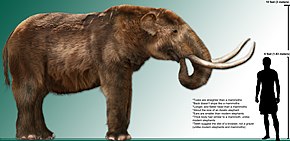

늦은 빙하기 기후 변화는 식물 집단과 동물의 개체수를 변화시켰다.[33]선호하는 자원이 고갈되고 새로운 물자가 모색됨에 따라 집단이 이곳저곳으로 이동했다.[29]작은 띠들은 봄과 여름 동안 사냥과 채집을 이용했고, 가을과 겨울을 위해 작은 직계 가족 집단으로 침입했다.가족 그룹은 3-6일마다 이동하며, 아마도 연간 360km(220mi)까지 이동했을 것이다.[34][35]성공적인 사냥으로 인해 다이어트는 종종 지속되고 단백질이 풍부했다.의복은 은신처 건설에도 사용되었던 다양한 동물 가죽으로 만들어졌다.[36]초기 및 중간 인디언 시대의 상당 기간 동안 내륙의 악단은 주로 지금은 간결한 메가파우나 사냥을 통해 존속된 것으로 생각된다.[29]대형 플리스토세 포유류는 거대한 비버, 스텝지드, 사향소, 마스토돈, 울리 매머드, 고대 순록(조기 순록)이었다.[37]

기원전 11,500년경 (기원전 13,500 BP)c.에 나타난 클로비스 문화는 의심할 여지 없이 생존을 위해 메가파우나에만 의존하지는 않았다.[38][39]대신 소형 지상 게임, 수생동물, 다양한 식물군을 포함하는 혼합 포획 전략을 채택했다.[40]팔레오-인디언 그룹은 효율적인 사냥꾼이었고 다양한 도구들을 가지고 다녔다.여기에는 도축 및 은신처리에 사용되는 마이크로 블레이드뿐만 아니라 고효율의 분쇄식 창 포인트가 포함되었다.[41]많은 출처에서 만들어진 발사체 지점과 해머스톤은 교환되거나 새로운 장소로 옮겨진다.[42]석기는 노스다코타와 노스웨스트 영토에서 몬타나주와 와이오밍으로 거래되거나 남겨졌다.[43]브리티시 컬럼비아 내륙에서 캘리포니아 해안까지 교역로도 발견되었다.[43]

대륙의 북반부를 뒤덮었던 빙하가 점차 녹기 시작하여 약 17,500–14,500년 전에 점령할 새로운 땅이 드러났다.[33]이와 동시에, 큰 포유동물들 사이의 세계적인 멸종이 시작되었다.북아메리카에서, 낙타들과 말들은 결국 사라졌고, 후자는 스페인 사람들이 CE 15세기 말에 그 말을 다시 소개할 때까지 대륙에 다시 나타나지 않았다.[44]4월 멸종사건이 일어났을 때, 후기 팔레오-인도인들은 다른 생존수단에 더 의존했을 것이다.[45]

기원전 10,500 – 9,500 BP(c. 12,500 – c. 11,500 BP)부터 대평원의 넓은 범위의 큰 사냥감을 찾는 사람들은 들소(미국 들소의 이른 사촌)라는 하나의 동물 종에 집중하기 시작했다.[46]이러한 들소 중심의 사냥 전통 중 가장 일찍 알려진 것은 폴섬 전통이다.폴섬 사람들은 매년 같은 샘과 더 높은 지대의 다른 선호 지역으로 돌아가면서 거의 모든 해 동안 작은 가족 집단으로 여행을 했다.[47]그곳에서 그들은 아마도 임시 거처를 마련하거나 석기를 만들거나 수리하거나 고기를 가공한 후 이동하면서 며칠 동안 야영을 할 것이다.[46]팔레오-인도인들은 수가 많지 않았고 인구 밀도는 상당히 낮았다.[48]

분류

팔레오-인도인들은 일반적으로 석판 감소 또는 석판 중심 "스타일"과 지역 적응에 의해 분류된다.[27][49]다른 창 포인트와 마찬가지로 리틱 기술도 박리된 창 포인트가 총칭하여 발사 포인트라고 부른다.이 발사체들은 "flute"라고 불리는 긴 홈을 가진 조각난 돌로 만들어진다.창 점들은 보통 점의 양쪽에서 한 조각씩 깎아서 만들어지곤 했다.[50]그리고 나서 그 점은 나무나 뼈로 된 창에 묶였다.빙하기가 짧게는 17–13Ka BP, 길게는 25–27Ka BP 정도로 끝나면서 환경이 바뀌면서,[51] 많은 동물들이 새로운 식량원을 이용하기 위해 육지로 이주했다.들소, 매머드, 마스토돈과 같은 이러한 동물들을 따르는 인간들은 그래서 빅게임 사냥꾼이라는 이름을 얻었다.[52]그 시기의 태평양 연안 단체들은 어업으로 생계를 유지하는데 가장 중요한 원천으로 의존했을 것이다.[53]

고고학자들은 북아메리카에서 가장 초기 인류의 정착지가 현재의 팔레오-인디언 시대(최후 빙하 최대 2만년 전 이전)의 출현 전 수천년 전이었다는 증거를 종합하고 있다.[54]증거에 따르면 사람들은 기원전 3만년 전 베링기아라고 불리는 빙하가 없는 지역에 북부 유콘만큼 동쪽에 살고 있었다.[55][56]최근까지 북아메리카에 처음 도착한 팔레오인도인들은 클로비스 문화에 속한다고 일반적으로 여겨졌다.이 고고학적 단계는 뉴멕시코 주의 클로비스 시의 이름을 따서 명명되었는데, 1936년 블랙워터 드로 현장에서 독특한 클로비스 지점이 발견되었는데, 그 곳에서 플레이스토세 동물의 뼈와 직접 관련되었다.[57]

아메리카 대륙 전역의 일련의 고고학적 유적지로부터 나온 최근 자료는 클로비스('팔레오-인도인')의 시간 범위를 재조사해야 한다는 것을 시사한다.특정 사이트에서 쿠퍼의 페리 근처 Idaho,[58]선인장 힐에 Virginia,[59]Meadowcroft Rockshelter에 Pennsylvania,[60]베어 Spirit마운틴에 웨스트 Virginia,[61]카타마르카:아르헨티나 북부의 도시. 그리고 살타에서 Argentina,[62]Pilauco과 몬테 베르드에 Chile,[63][64]더 최고에 남 Carolina,[65]과 면적 50,340㎢Mexico[66][67]에 있는 가까운 시일을 불러 일으켰다.S에는 광범한Paleo-Indian occupat.이온. 일부 사이트는 빙하가 없는 회랑의 이동 시간대를 상당히 앞지르기 때문에 걸어서 또는 보트로 횡단되는 추가적인 해안 이동 경로가 있음을 시사한다.[68]지질학적 증거는 태평양 연안 항로가 2만 3천년 전과 1만 6천년 이후 육로 여행에 개방되었음을 시사한다.[69]

남아메리카

남아메리카의 몬테 베르데 유적지는 그곳의 인구가 아마도 영토였고 일년 중 대부분 동안 그들의 강 유역에 거주했음을 나타낸다.반면에, 다른 남미 그룹들은 이동성이 뛰어나 마스토돈이나 거대한 나무늘보 같은 큰 게임 동물을 사냥했다.그들은 고전적인 분리형 발사체 점 기술을 사용했다.

주요 예로는 초원, 사바나 평원, 패기 있는 숲의 엘 조보 지점(베네수엘라), 물고기 꼬리 또는 마갈라네 지점(대륙의 다양한 지역, 그러나 주로 남반부), 파이잔 지점(페루와 에콰도르)과 관련된 개체군(페루와 에콰도르)이 있다.[70]

이 사이트들의 날짜는 14,000 BP(베네수엘라 타이마-타이마)에서 c. 10,000 BP까지이다.[71]엘 조보 발사체 지점은 베네수엘라 만에서 높은 산과 계곡에 이르기까지 베네수엘라 북서부에 대부분 분포했다.그들을 이용하는 인구는 일정한 제한 지역 내에 머물러 있는 것 같은 수렵채집자였다.[72][73]엘 조보 포인트는 아마도 14,200 – c. 12,980 BP로 거슬러 올라가는 가장 이른 지점이었을 것이고 그것들은 큰 포유류 사냥에 사용되었다.[74]이와는 대조적으로, 물고기 꼬리는 c. 11,000 B에 해당한다.파타고니아의 P.는 훨씬 더 넓은 지리적 분포를 가지고 있었지만, 대부분 대륙의 중부와 남부에 있었다.[75][76]

고고유전학

원주민 아메린디아 유전학과 가장 흔히 연관된 하플로그룹 Q-M3.[78] Y-DNA는 (mtDNA)와 마찬가지로 Y염색체의 대다수가 특이하고 감수분열 시 재결합하지 않는다는 점에서 다른 핵염색체들과 다르다.이를 통해 돌연변이의 역사적 패턴을 쉽게 연구할 수 있다.[79]이 패턴은 원주민들이 두 가지 매우 독특한 유전적 에피소드를 경험했다는 것을 보여준다: 첫째는 아메리카 대륙의 초기 인구와 둘째는 유럽의 아메리카 식민지화와 같은 것이다.[80]전자는 오늘날 토착 아메리카 인구에 존재하는 유전자 라인의 수와 건국성 하플라타입의 결정인자다.[81][unreliable source?]

아메리카 대륙의 인간 정착은 베링해안선으로부터 단계별로 발생했으며, 베링아에서는 건국 인구를 위한 초기 경유지가 이루어졌다.[82][83][84][85]남미에 특화된 Y 계통의 미세 위성 다양성과 분포는 이 지역의 초기 식민지화 이후 특정 아메린디아 인종이 고립되어 있음을 보여준다.[86]그러나 나 드네, 이누이트, 토착 알래스카 인구는 다양한 mtDNA 돌연변이를 가진 다른 원주민 아메린디아인들과 구별되는 하플로그룹 Q(Y-DNA) 돌연변이를 보인다.[87][88][89]이것은 북아메리카와 그린랜드의 북쪽 극단으로 이주한 초기 이주자들이 나중에 이주한 인구에서 유래했음을 시사한다.[90]

고대로의 전환

아메리카 대륙의 고대 시대는 따뜻하고 더 건조한 기후와 마지막 메가파우나의 소멸을 특징으로 하는 변화하는 환경을 보았다.[91]이 시기에 대부분의 인구 집단은 여전히 이동성이 높은 수렵채집자였지만, 이제는 개별 집단이 현지에서 이용할 수 있는 자원에 초점을 맞추기 시작했다.따라서 시간이 흐르면서 남서쪽, 북극, 빈곤, 달튼, 플라노 전통과 같은 지역 일반화의 양상이 증가하고 있다.이러한 지역 적응은 사냥과 채집 의존도가 낮으며, 작은 게임, 생선, 계절에 따라 야생 채소, 수확한 식물 음식의 혼합 경제로 표준이 될 것이다.[35][92]많은 그룹들이 큰 사냥감을 계속 사냥했지만 그들의 사냥 전통은 더욱 다양해지고 육류 조달 방법은 더욱 정교해졌다.[33]고대의 매장지 내에 유물과 자료의 배치로 일부 집단의 지위에 따른 사회적 차별화가 나타났다.[93]

참고 항목

- 애덤스 카운티 팰리노-인디안 구 – (해리학 현장)

- 알링턴 스프링스 맨 – (인간 잔해)

- 블랙워터 그리기 – (양식 현장)

- 보락스 호수 현장 – (양식지)

- 불여인 – (인간 잔해)

- 칼리코 초기 남성 사이트 – (양식 사이트)

- Caverna da Pedra Pintada – (수색 현장)

- 코디 콤플렉스 – (문화그룹)

- 쿠에바 데 라스 마노스 – (케이브 그림)

- 이스트 포크 사이트 – (양식 사이트)

- 포트록 동굴 – (양식지)

- Hiscock 사이트 – (육상 사이트)

- 켄뉴윅 맨 – (인간 잔해)

- 레안데르탈인 부인 – (인간 잔해)

- Lehner 매머드 킬 사이트 – (수색 사이트)

- 린덴마이어 사이트 – (수색 사이트)

- 루지아 우먼 – (인간 잔해)

- Marmes Rockshelter – (Archeological 사이트)

- 마스토돈 주 유적지 – (수학 유적지)

- 미라동굴 – (양식지)

- Naia – (인간 잔해)

- 페이즐리 동굴 – (양식지)

- 페뇨녀 – (인간 잔해)

- 포스트 패턴 – (아카이아 문화)

- 산다이귀토 복합체 – (양식지)

- 산디아 맨 동굴 – (양식지)

- 상행선강유적지 – (양식유적지)

- Witt 사이트 – (양식 사이트)

- X̲yytem – (양식 현장)

- 쿼드 사이트 – (양식 사이트)

참조

- ^ 구석기시대란 특히 250만년 전 동반구의 플리스토세 말기 사이의 시기를 가리킨다.그것은 신세계 고고학에서 사용되지 않는다.

- ^ Liz Sonneborn (January 2007). Chronology of American Indian History. Infobase Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8160-6770-1. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "먼저 미국인들20,000-Year Layover – 제니퍼 Viegas, 디스커버리 뉴스 Endured".102012년 10월에 원래에서 Archived.Retrieved 2009년 11월 18일.고고학적 증거, 실제로는 사람들이 신세계에 베링 육교를 떠나 4만 여년 전지만, 북미에 급속한 팽창에 대해서 15,000년 전에, 얼음이 말 그대로 2페이지 Archived 3월 13일 2012년은 승객을 머신에 망가져야 일어나지 않기 시작했다 인식하고 있다.

- ^ H. Trawick Ward; R. P. Stephen Davis (1999). Time before history: the archaeology of North Carolina. UNC Press Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8078-4780-0. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "10,000-year-old skeleton challenges theory of how humans arrived in Americas". The Independent. 7 January 2020.

- ^ "Method and Theory in American Archaeology". Gordon Willey and Philip Phillips. University of Chicago. 1958. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ Patricia J. Ash; David J. Robinson (2011). The Emergence of Humans: An Exploration of the Evolutionary Timeline. John Wiley & Sons. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-119-96424-7.

- ^ Pitblado, B. L. (2011-03-12). "A Tale of Two Migrations: Reconciling Recent Biological and Archaeological Evidence for the Pleistocene Peopling of the Americas". Journal of Archaeological Research. 19 (4): 327–375. doi:10.1007/s10814-011-9049-y. S2CID 144261387.

- ^ Burenhult, Göran (2000). Die ersten Menschen. Weltbild Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8289-0741-6.

- ^ Phillip M. White (2006). American Indian chronology: chronologies of the American mosaic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-313-33820-5. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man - A Genetic Odyssey (Digitised online by Google books). Random House. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-8129-7146-0. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ Fitzhugh, Drs. William; Goddard, Ives; Ousley, Steve; Owsley, Doug; Stanford, Dennis. "Paleoamerican". Smithsonian Institution Anthropology Outreach Office. Archived from the original on 2009-01-05. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Fladmark, K. R. (Jan 1979). "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity. 44 (1): 55–69. doi:10.2307/279189. JSTOR 279189.

- ^ "68 Responses to "Sea will rise 'to levels of last Ice Age'"". Center for Climate Systems Research, Columbia University. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Introduction". Government of Canada. Parks Canada. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-04-24. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

Canada's oldest known home is a cave in Yukon occupied not 12,000 years ago as at U.S. sites, but at least 20,000 years ago

- ^ "Pleistocene Archaeology of the Old Crow Flats". Vuntut National Park of Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-10-22. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

However, despite the lack of this conclusive and widespread evidence, there are suggestions of human occupation in the northern Yukon about 24,000 years ago, and hints of the presence of humans in the Old Crow Basin as far back as about 40,000 years ago.

- ^ "Journey of mankind". Bradshaw Foundation. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Spencer Wells (2006). Deep Ancestry: Inside the Genographic Project. National Geographic Books. pp. 222–. ISBN 978-0-7922-6215-2. OCLC 1031966951.

- ^ John H. Relethford (17 January 2017). 50 Great Myths of Human Evolution: Understanding Misconceptions about Our Origins. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 192–. ISBN 978-0-470-67391-1. OCLC 1238190784.

- ^ H. James Birx, ed. (10 June 2010). 21st Century Anthropology: A Reference Handbook. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4522-6630-5. OCLC 1102541304.

- ^ John E Kicza; Rebecca Horn (3 November 2016). Resilient Cultures: America's Native Peoples Confront European Colonialization 1500-1800 (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-50987-7.

- ^ Bonatto, SL; Salzano, FM (1997). "A single and early migration for the peopling of the Americas supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". PNAS. 94 (5): 1866–71. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.1866B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1866. PMC 20009. PMID 9050871.

- ^ Neves, W. A.; Powell, J. F.; Prous, A.; Ozolins, E. G.; Blum, M. (1999). "Lapa vermelha IV Hominid 1: morphological affinities of the earliest known American". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 22 (4): 461. doi:10.1590/S1415-47571999000400001.

- ^ Bruce Elliott Johansen; Barry Pritzker (2008). Encyclopedia of American Indian history. ABC-CLIO. pp. 451–. ISBN 978-1-85109-817-0. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Period 1 (10,000 to 8,000 years ago)". Learners Portal Breton University. 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- ^ a b c Wm. Jack Hranicky; Wm Jack Hranicky Rpa (17 June 2010). North American Projectile Points - Revised. AuthorHouse. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-4520-2632-9. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Norman Herz; Ervan G. Garrison (1998). Geological methods for archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-509024-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Barry Lewis; Robert Jurmain; Lynn Kilgore (10 December 2008). Understanding Humans: Introduction to Physical Anthropology and Archaeology. Cengage Learning. pp. 342–348. ISBN 978-0-495-60474-7. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ David J. Wishart (2004). Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. U of Nebraska Press. p. 589. ISBN 978-0-8032-4787-1. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Rickey Butch Walker (December 2008). Warrior Mountains Indian Heritage - Teacher's Edition. Heart of Dixie Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-934610-27-5. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Dawn Elaine Bastian; Judy K. Mitchell (2004). Handbook of Native American mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-85109-533-9. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Pielou, E.C. (1991). After the Ice Age : The Return of Life to Glaciated North America (Digitised online by Google books). University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-66812-3. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ David R. Starbuck (31 May 2006). The archeology of New Hampshire: exploring 10,000 years in the Granite State. UPNE. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-58465-562-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b Fiedel, Stuart J (1992). Prehistory of the Americas (Digitised online by Google books). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42544-5. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ "Alabama Archaeology: Prehistoric Alabama". University of Alabama Press. 1999. Archived from the original on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ Breitburg, Emanual; John B. Broster; Arthur L. Reesman; Richard G. Strearns (1996). "Coats-Hines Site: Tennessee's First Paleoindian Mastodon Association" (PDF). Current Research in the Pleistocene. 13: 6–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ Catherine Anne Cavanaugh; Michael Payne; Donald Grant Wetherell (2006). Alberta formed, Alberta transformed. University of Alberta. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-55238-194-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ McMenamin, M. A. S. (2011). "A recycled small Cumberland-Barnes Palaeoindian biface projectile point from southeastern Connecticut". Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. 72 (2): 70–73.

- ^ Scott C. Zeman (2002). Chronology of the American West: from 23,000 B.C.E. through the twentieth century. ABC-CLIO. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-57607-207-3. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ William C. Sturtevant (21 February 1985). Handbook of North American Indians. Government Printing Office. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-16-004580-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Emory Dean Keoke; Kay Marie Porterfield (January 2005). Trade, Transportation, and Warfare. Infobase Publishing. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-8160-5395-7. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b Brantingham, P. Jeffrey; Kuhn, Steven L.; Kerry, Kristopher W. (2004). The Early Upper Paleolithic beyond Western Europe. University of California Press. pp. 41–66. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ "A brief history of the horse in America: Horse phylogeny and evolution". Ben Singer. Canadian Geographic. 2005. Archived from the original on 2014-08-19. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ Anderson, David G; Sassaman, Kenneth E (1996). The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast (Digitised online by Google books). University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0835-3. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ a b Mann, Charles C. (2006-10-10). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus (Digitised online by Google books). Random House of Canada. ISBN 978-1-4000-3205-1. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Folsom Traditions". University of Manitoba, Archaeological Society. 1998. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ "Beginnings to 1500 C.E". Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. Archived from the original on 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Vance T. Holliday (1997). Paleoindian geoarchaeology of the southern High Plains. University of Texas Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-292-73114-1. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Adovasio, J. M., J.M. (2002). The First Americans: In Pursuit of Archaeology's Greatest Mystery. with Jake Page. New York: Random House. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-375-50552-2.

- ^ Wolfgang H. Berger; Elizabeth Noble Shor (25 April 2009). Ocean: reflections on a century of exploration. University of California Press. p. 397. ISBN 978-0-520-24778-9. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ McHugh, Tom; Hobson, Victoria (1979). The Time of the Buffalo. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-8105-9. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ deFrance, Susan D.; Keefer, David K.; Richardson, James B.; Alvarez, Adan U. (2010). "Late Paleo-Indian Coastal Foragers: Specialized Extractive". Latin American Antiquity. 12 (4): 413–426. doi:10.2307/972087. JSTOR 972087. S2CID 163802845.

- ^ "Alberta History pre 1800 - Jasper Alberta". Jasper Alberta. 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ 브래들리, B.와 스탠포드 D. "북대서양 빙상지대 복도: 신대륙으로 가는 팔레오일식 경로 가능성"2004년 세계 고고학 34.

- ^ 라우버, 패트리샤누가 제일 처음 왔니?선사시대 미국인에 대한 새로운 단서.워싱턴 D.C.:내셔널 지오그래픽 소사이어티, 2003.

- ^ "National Park Service Southeastern Archaeological Center: The Paleoindian Period". Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Wade, Lizzie (2019-08-29). "First people in the Americas came by sea, ancient tools unearthed by Idaho river suggest". Science AAAS. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ "Science News Online: Early New World Settlers Rise in East". Science News. 2000. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Meadowcroft Rockshelter". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Author Discovers Ceremonial Site". Archaeology Site Article listing. Herald Mall Media. Archived from the original on 2018-11-09. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ "Encontraron la evidencia humana más antigua de Argentina".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: 타이틀로 보관된 사본(링크) - ^ "Monte Verde Archaeological Site - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "CNN.com: Man in Americas Earlier Than Thought". 2004-11-18. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Ignacio Villarreal (2010-08-25). "Mexican Archaeologists Extract 10,000 Year-Old Skeleton from Flooded Cave in Quintana Roo". Artdaily.com. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ^ "Skull in Underwater Cave May Be Earliest Trace of First Americans - NatGeo News Watch". Blogs.nationalgeographic.com. 2011-02-18. Archived from the original on 2011-02-26. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ^ "Does skull prove that the first Americans came from Europe?". The University of Texas at Austin - Web Central. Archived from the original on 2004-03-02. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Jordan, David K (2009). "Prehistoric Beringia". University of California-San Diego. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ TOM D. DILLEHAY, The Late Pleistocene Cultures of South America.진화 인류학, 1999

- ^ Cummings, Vicki; Jordan, Peter; Zvelebil, Marek (2014). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers. OUP Oxford. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-19-102526-6.

- ^ Hosé R. Oliver, Taima-tima와 북남미 사람들의 시사점.2016-04-25년 Wayback Machine에 보관 bradshawfoundation.com

- ^ 올리버, J.R., 알렉산더, C.S. (2003)Ocupaciones humanas del Plesitoceno 터미널 in el Occidente de 베네수엘라.마구아레1783-246

- ^ Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William (2008). Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer Science. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-387-75228-0.

- ^ Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William (2008). Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer Science. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-387-75228-0.

- ^ Dillehay, Thomas D. (2008). The Settlement of the Americas. Basic Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-7867-2543-4.

- ^ Balanovsky, Oleg; Gurianov, Vladimir; Zaporozhchenko, Valery; et al. (February 2017). "Phylogeography of human Y-chromosome haplogroup Q3-L275 from an academic/citizen science collaboration". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17 (S1): 18. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0870-2. PMC 5333174. PMID 28251872.

- ^ "Y-Chromosome Evidence for Differing Ancient Demographic Histories in the Americas" (PDF). University College London 73:524–539. 2003. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ^ Orgel L (2004). "Prebiotic chemistry and the origin of the RNA world" (PDF). Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 39 (2): 99–123. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.537.7679. doi:10.1080/10409230490460765. PMID 15217990. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ^ Wendy Tymchuk, ed. (2008). "Learn about Y-DNA Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. Archived from the original (Verbal tutorial possible) on 2010-06-22. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ Wendy Tymchuk, ed. (2008). "Learn about Y-DNA Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. Archived from the original (Verbal tutorial possible) on 2010-04-21. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ Alice Roberts (2010). The Incredible Human Journey. A&C Black. pp. 101–03. ISBN 978-1-4088-1091-0.

- ^ "First Americans Endured 20,000-Year Layover - Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News". Archived from the original on 2012-10-10. Retrieved 2009-11-18. 2페이지 Wayback Machine에 2012-03-13 보관

- ^ "Pause Is Seen in a Continent's Peopling". The New York Times. 13 Mar 2014.

- ^ Than, Ker (2008). "New World Settlers Took 20,000-Year Pit Stop". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ^ "Summary of knowledge on the subclades of Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ^ Ruhlen M (November 1998). "The origin of the Na-Dene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (23): 13994–6. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9513994R. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13994. PMC 25007. PMID 9811914.

- ^ Zegura SL, Karafet TM, Zhivotovsky LA, Hammer MF (January 2004). "High-resolution SNPs and microsatellite haplotypes point to a single, recent entry of Native American Y chromosomes into the Americas". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (1): 164–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh009. PMID 14595095.

- ^ Saillard, Juliette; Forster, Peter; Lynnerup, Niels; Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen; Nørby, Søren (2000). "mtDNA Variation among Greenland Eskimos. The Edge of the Beringian Expansion". Laboratory of Biological Anthropology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, University of Hamburg, Hamburg. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ^ Torroni, A.; Schurr, T. G.; Yang, C. C.; Szathmary, E.; Williams, R. C.; Schanfield, M. S.; Troup, G. A.; Knowler, W. C.; Lawrence, D. N.; Weiss, K. M.; Wallace, D. C. (January 1992). "Native American Mitochondrial DNA Analysis Indicates That the Amerind and the Nadene Populations Were Founded by Two Independent Migrations". Center for Genetics and Molecular Medicine and Departments of Biochemistry and Anthropology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Genetics Society of America. 1992. Vol 130, 153-162. 130 (1): 153–162. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ^ Douglas Ian Campbell; Patrick Michael Whittle (2017). Resurrecting Extinct Species: Ethics and Authenticity. Springer. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-3-319-69578-5.

- ^ Stuart B. Schwartz, Frank Salomon (1999-12-28). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas (Digitised online by Google books). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63075-7. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Imbrie, J; K.P.Imbrie (1979). Ice Ages: Solving the Mystery. Short Hills NJ: Enslow Publishers. ISBN 978-0-226-66811-6.

추가 읽기

- Jablonski, Nina G (2002). The First Americans: The Pleistocene Colonization of the New World. California Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-0-940228-49-8.

- Peter Charles Hoffer (2006). The Brave New World: A History of Early America. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8483-2.

- Meltzer, David J (2009). First peoples in a new world: colonizing ice age America. University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 978-0-520-25052-9.

외부 링크

| 위키미디어 커먼즈에는 리틱 시기와 관련된 미디어가 있다. |