대장암

Colorectal cancer| 대장암 | |

|---|---|

| 기타이름 | 대장암, 직장암, 장암 |

| |

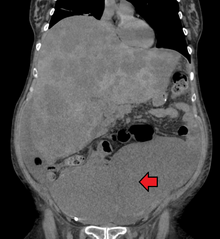

| 두 개의 대장 종양의 위치 및 모양 | |

| 전문 | 소화기내과 일반외과 종양학 |

| 증상 | 대변의 피, 배변의 변화, 의도치 않은 체중 감소, 구토, 피로감[1] |

| 원인들 | 노령, 생활 습관 요인 및 유전적 장애[2][3] |

| 위험요소 | 다이어트, 비만, 흡연, 신체활동 부족, 알코올 사용[2][4] |

| 진단방법 | 구불결장내시경 또는 대장내시경[1] 중 조직생검 |

| 예방 | 45세부터 75세까지의 심사 |

| 치료 | 수술, 방사선치료, 화학요법, 표적치료[5] |

| 예후 | 5년 생존율 65%(미국)[6] |

| 빈도수. | 940만 (2015)[7] |

| 죽음 | 551,000 (2018)[8] |

대장암(CRC)은 대장이나 직장(대장의 일부)에서 발생하는 암으로 대장암, 대장암, 직장암이라고도 합니다.[5] 증상과 징후로는 대변의 피, 배변 변화, 체중 감소, 피로감 등이 있을 수 있습니다.[9] 대부분의 대장암은 고령과 생활습관 요인에 의한 것으로, 기저 유전적 장애로 인한 경우는 소수에 불과합니다.[2][3] 위험 요소에는 식이, 비만, 흡연 및 신체 활동 부족이 포함됩니다.[2] 위험도를 높이는 식이 요인으로는 붉은 고기, 가공육, 알코올 등이 있습니다.[2][4] 또 다른 위험 요소는 염증성 장질환으로 크론병과 궤양성 대장염이 있습니다.[2] 대장암을 유발할 수 있는 유전성 질환으로는 가족성 선종성 용종증, 유전성 비용종성 대장암 등이 있지만 이들은 5% 미만입니다.[2][3] 일반적으로 양성 종양으로 시작하며, 종종 용종의 형태로 시간이 지남에 따라 암이 됩니다.[2]

구불결장경 검사 또는 대장 내시경 검사 시 대장의 검체를 채취하여 대장암을 진단할 수 있습니다.[1] 그런 다음 질병이 퍼졌는지 여부를 확인하기 위한 의료 영상 촬영이 수행됩니다.[5] 검진은 대장암으로 인한 사망을 예방하고 감소시키는 데 효과적입니다.[10] 45세부터 75세까지는 여러 가지 방법 중 하나로 검진을 받는 것이 좋습니다. 50세부터 권장되다가 대장암 발생량이 증가하여 45세로 변경되었습니다.[10][11] 대장 내시경 검사 중 작은 용종이 발견되면 제거할 수 있습니다.[2] 큰 용종이나 종양이 발견되면 조직검사를 통해 암 여부를 확인할 수 있습니다. 아스피린을 비롯한 비스테로이드성 소염제는 용종 절제 시 통증 발생 위험을 줄여줍니다.[2][12] 그러나 부작용 때문에 일반적인 사용은 권장되지 않습니다.[13]

대장암에 사용되는 치료법에는 수술, 방사선 치료, 화학요법 및 표적 치료의 일부 조합이 포함될 수 있습니다.[5] 대장 벽 안에 갇혀 있는 암은 수술로 치료가 가능한 반면, 광범위하게 퍼진 암은 보통 치료가 불가능하며, 관리는 삶의 질과 증상을 개선하는 데 중점을 두고 있습니다.[5] 2014년 미국의 5년 생존율은 약 65%였습니다.[6] 개인의 생존 가능성은 암이 얼마나 진행되었는지, 수술로 모든 암을 제거할 수 있는지, 그리고 개인의 전반적인 건강에 달려 있습니다.[1] 전 세계적으로 대장암은 전체 환자의 약 10%를 차지하는 세 번째로 흔한 암입니다.[14] 2018년에는 109만 명의 신규 환자와 55만 1천 명의 사망자가 발생했습니다.[8] 65% 이상의 사례가 발견되는 선진국에서 더 흔합니다.[2] 남성보다 여성에게 덜 흔합니다.[2]

징후 및 증상

대장암의 징후와 증상은 대장 내 종양의 위치, 체내 다른 곳으로 전이되었는지 여부(전이)에 따라 달라집니다. 전형적인 경고 징후는 변비 악화, 대변의 피, 대변의 질(두께) 저하, 식욕 감퇴, 체중 감소, 메스꺼움이나 구토 등입니다.[15] 대장암 환자의 약 50%는 아무런 증상을 보고하지 않습니다.[16]

직장 출혈이나 빈혈은 50세 이상에서 위험도가 높은 증상입니다.[17] 일반적으로 체중 감소와 배변 습관의 변화는 직장 출혈과 관련이 있는지 여부에만 관심이 있습니다.[17][18]

원인

대장암 환자의 75~95%는 유전적 위험이 거의 없거나 전혀 없는 사람에게서 발생합니다.[19][20] 위험 요소에는 고령, 남성 성별,[20] 지방, 설탕, 알코올, 붉은 고기, 가공육, 비만, 흡연 및 신체 운동 부족이 포함됩니다.[19][21] MD 앤더슨 암센터가 개발한 직장암 생존계산기도 인종을 위험요인으로 보고 있지만, 이로 인해 임상 의사결정의 불평등이 발생할 수 있는지에 대해서는 형평성 문제가 제기되고 있습니다.[22][23] 약 10%의 사례가 불충분한 활동과 관련이 있습니다.[24] 알코올로 인한 위험은 하루에 한 잔 이상일 때 증가하는 것으로 보입니다.[25] 하루에 5잔의 물을 마시는 것은 대장암과 선종성 용종의 위험 감소와 관련이 있습니다.[26] Streptococcus gallolyticus는 대장암과 관련이 있습니다.[27] Streptococcus bovis/Streptoccus equinus complex의 일부 균주는 매일 수백만 명이 섭취하므로 안전할 수 있습니다.[28] Streptococcus bovis/gallolyticus 균혈증이 있는 사람의 25~80%에서 대장 종양이 동반됩니다.[29] Streptococcus bovis/gallolyticus의 혈청 유병률은 고위험군에서 기저 장 병변의 조기 예측을 위한 후보 실용적인 마커로 간주됩니다.[29] Streptococcus bovis/gallolyticus 항원에 대한 항체 또는 혈류 내 항원 자체의 존재가 대장 내 발암에 대한 표지자로 작용할 수 있다고 제안되었습니다.[29]

병원성 대장균은 유전독성 대사물질인 콜리박틴을 생성해 대장암 발생 위험을 높일 수 있습니다.[30]

염증성 장질환

염증성 장질환(궤양성 대장염, 크론병)이 있는 사람은 대장암에 걸릴 위험이 높아집니다.[31][32] 질병이 오래 걸릴수록 위험이 증가하고, 염증의 심각성이 더 심해질 수 있습니다.[33] 이러한 고위험군에서는 아스피린으로 예방하는 것과 정기적인 대장 내시경을 병행하는 것이 좋습니다.[34] 이 고위험군의 내시경 감시는 조기 진단을 통해 대장암의 발생을 감소시키고 대장암으로 사망할 가능성도 감소시킬 수 있습니다.[34] 염증성 장질환을 앓고 있는 사람들은 매년 대장암 환자의 2% 미만을 차지합니다.[33] 크론병 환자의 경우 10년이 지나면 2%, 20년이 지나면 8%, 30년이 지나면 18%가 대장암에 걸립니다.[33] 궤양성 대장염이 있는 사람의 경우 약 16%에서 30년 동안 대장의 암 전구 또는 암이 발생합니다.[33]

유전학

1급 친척(부모, 형제자매 등) 2명 이상의 가족력이 있는 사람은 질병 발생 위험이 2~3배 더 크며, 이 그룹은 전체 사례의 약 20%를 차지합니다. 많은 유전자 증후군들은 또한 더 높은 대장암 발병률과 관련이 있습니다. 이 중 가장 흔한 것은 대장암 환자의 약 3%에 존재하는 유전성 비다형성 대장암(HNPCC, 또는 린치 증후군)입니다.[20] 대장암과 강하게 연관되어 있는 다른 증후군으로는 가드너 증후군과 가족성 선종성 용종증(FAP)이 있습니다.[35] 이러한 증후군을 가진 사람들의 경우 거의 항상 암이 발생하며 암 발생의 1%를 차지합니다.[36] FAP가 있는 사람은 악성화 위험이 높아 예방적으로 전 직장 절제술이 권장될 수 있습니다. 대장 절제술은 직장이 남아 있으면 직장암 위험이 높기 때문에 예방 조치로 충분하지 않을 수 있습니다.[37] 대장에 영향을 미치는 가장 흔한 용종증 증후군은 CRC의 25-40% [38]위험과 관련이 있는 톱니모양 용종증 증후군입니다.[39]

유전자 쌍(POLE 및 POLD1)의 돌연변이는 가족성 대장암과 관련이 있습니다.[40]

대장암으로 인한 대부분의 사망은 전이성 질환과 관련이 있습니다. 대장암 1(MACC1)과 관련된 전이성 질환, 전이 가능성에 기여하는 것으로 보이는 유전자가 분리됐습니다.[41] 간세포 성장인자 발현에 영향을 미치는 전사인자입니다. 이 유전자는 세포 배양에서 대장암 세포의 증식, 침입 및 산란, 쥐의 종양 성장 및 전이와 관련이 있습니다. MACC1은 암 개입의 잠재적인 표적이 될 수 있지만, 이 가능성은 임상 연구를 통해 확인할 필요가 있습니다.[42]

종양 억제 프로모터의 비정상적인 DNA 메틸화와 같은 후성유전적 요인이 대장암 발병에 작용합니다.[43]

아슈케나지 유대인은 APC 유전자의 돌연변이가 더 흔해 선종에 이어 대장암에 걸릴 위험률이 6% 더 높습니다.[44]

병인

대장암은 위장관의 대장이나 직장을 둘러싸고 있는 상피세포에서 발생하는 질환으로, 신호전달 활성을 증가시키는 Wnt 신호전달 경로의 유전적 변이로 인해 발생하는 경우가 가장 많습니다.[45] Wnt 신호전달 경로는 일반적으로 이 라이닝을 유지하는 것을 포함하여 이 세포들의 정상적인 기능에 중요한 역할을 합니다. 돌연변이는 유전되거나 후천적으로 발생할 수 있으며, 대부분은 장 crypt 줄기세포에서 발생합니다.[46][47][48] 모든 대장암에서 가장 흔한 돌연변이 유전자는 APC 단백질을 생산하는 APC 유전자입니다.[45] APC 단백질은 β-catenin 단백질의 축적을 막습니다. APC가 없으면 β-catenin이 높은 수준으로 축적되어 핵 내로 전위(이동)되어 DNA와 결합하고 원발암 유전자의 전사를 활성화합니다. 이 유전자들은 보통 줄기세포 재생과 분화에 중요하지만, 높은 수준으로 부적절하게 발현되면 암을 유발할 수 있습니다.[45] 대부분의 대장암에서 APC가 변이되는 반면, 일부 암은 자체 분해를 차단하는 β-catenin(CTNNB1)의 변이로 인해 β-catenin이 증가하거나 AXIN1, AXIN2, TCF7L2, NKD1 등 APC와 유사한 기능을 가진 다른 유전자에 변이가 있습니다.[49]

Wnt 신호 전달 경로의 결함을 넘어 세포가 암이 되려면 다른 돌연변이가 발생해야 합니다. TP53 유전자에 의해 생성된 p53 단백질은 정상적으로 세포 분열을 감시하고 Wnt 경로 결함이 있는 경우 프로그램된 사멸을 유도합니다. 결국 세포주는 TP53 유전자의 돌연변이를 획득하고 조직을 양성 상피종양에서 침습성 상피세포암으로 변형시킵니다. 가끔 p53을 암호화하는 유전자는 돌연변이가 되지 않지만 BAX라는 이름의 다른 보호 단백질은 돌연변이가 됩니다.[49]

대장암에서 일반적으로 비활성화되는 프로그램된 세포 사멸을 담당하는 다른 단백질은 TGF-β 및 DCC(대장암에서 삭제됨)입니다. TGF-β는 적어도 대장암의 절반에서 비활성화 돌연변이를 가지고 있습니다. 때때로 TGF-β는 비활성화되지 않지만 SMAD라는 다운스트림 단백질은 비활성화됩니다.[49] DCC는 일반적으로 대장암에서 염색체의 결손된 부분을 가지고 있습니다.[50]

전체 인간 유전자의 약 70%가 대장암에서 발현되며, 대장암에서 다른 형태의 암에 비해 발현이 증가한 비율은 1%를 조금 넘습니다.[51] 일부 유전자는 종양 유전자입니다: 대장암에서 과발현됩니다. 예를 들어, 보통 성장 인자에 반응하여 세포가 분열하도록 자극하는 KRAS, RAF, PI3K 단백질을 암호화하는 유전자는 세포 증식의 과활성화를 초래하는 돌연변이를 획득할 수 있습니다. 돌연변이의 시간 순서가 중요할 때가 있습니다. 이전 APC 돌연변이가 발생한 경우, 1차 KRAS 돌연변이는 자가 제한 과형성 또는 경계선 병변보다는 암으로 진행하는 경우가 많습니다.[52] 종양 억제제인 PTEN은 보통 PI3K를 억제하지만, 때때로 돌연변이가 되어 비활성화될 수 있습니다.[49]

종합적인 유전체 규모 분석 결과 대장암은 과돌연변이와 비과돌연변이 종양 유형으로 분류될 수 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.[53] 상기 유전자에 대해 설명된 발암성 및 불활성화 돌연변이 외에, 비-과돌연변이 샘플은 또한 돌연변이 CTNNB1, FAM123B, SOX9, ATM 및 ARID1A를 포함합니다. 과돌연변이 종양은 ACVR2A, TGFBR2, MSH3, MSH6, SLC9A9, TCF7L2 및 BRAF의 돌연변이 형태를 나타냅니다. 두 종양 유형에 걸쳐 이들 유전자의 공통된 주제는 Wnt 및 TGF-β 신호 전달 경로에 관여한다는 것이며, 이는 대장암의 중심 역할인 MYC의 활성을 증가시킵니다.[53]

불일치 복구(MMR) 결핍 종양은 비교적 많은 양의 폴리뉴클레오티드 탠덤 반복을 특징으로 합니다.[54] 이는 MMR 단백질의 결핍으로 인한 것으로, 일반적으로 후성유전학적 침묵과 유전적 돌연변이(예: 린치 증후군)에 의해 발생합니다.[55] 대장암 종양의 15~18%는 MMR 결핍을 가지고 있으며, 3%는 린치 증후군으로 발병합니다.[56] 불일치 복구 시스템의 역할은 세포 내 유전 물질의 무결성(즉, 오류 검출 및 수정)을 보호하는 것입니다.[55] 결과적으로 MMR 단백질이 결핍되면 유전적 손상을 감지하고 복구하지 못해 암을 유발하는 돌연변이가 추가로 발생하고 대장암이 진행될 수 있습니다.[55]

폴립토 암 진행 순서는 대장암 발병의 고전적인 모델입니다.[57] 이 선종-암종 서열에서 정상적인 상피세포는 진행성 유전자 돌연변이 과정에 의해 선종과 같은 이형성 세포로 진행한 후 암종으로 진행합니다.[59] 용종에서 CRC 서열의 중심에는 유전자 돌연변이, 후성유전학적 변화 및 국소 염증 변화가 있습니다.[57] 폴리포 CRC 서열은 특정 분자 변화가 다양한 암 아형으로 어떻게 이어지는지를 설명하기 위한 기본 프레임워크로 사용될 수 있습니다.[57]

현장결함

"현장 암화"라는 용어는 1953년에 암이 발생하기 쉬운 (당시에는 거의 알려지지 않은 과정에 의해) 사전 조건화된 상피의 영역 또는 "현장"을 설명하기 위해 처음 사용되었습니다.[60] 이후 새로운 암이 발생할 가능성이 높은 악성 전 또는 종양 전 조직을 설명하기 위해 "현장 암화", "현장 발암", "현장 결함", "현장 효과"라는 용어가 사용되었습니다.[61]

현장 결함은 대장암으로 진행하는 데 중요합니다.[62][63]

그러나 루빈이 지적한 바와 같이, "암 연구의 대부분은 생체 내에서 잘 정의된 종양 또는 시험관 내에서 별개의 종양성 초점에 대해 수행되었습니다. 그러나 돌연변이 표현형 인간 대장 종양에서 발견되는 체세포 돌연변이의 80% 이상이 말단 클론 확장이 시작되기 전에 발생한다는 증거가 있습니다."[64][65] 유사하게, Vogelstein [66]등은 종양에서 확인된 체세포 돌연변이의 절반 이상이 (현장 결함에서) 종양 전 단계에서, 겉보기에 정상적인 세포의 성장 동안 발생했다고 지적했습니다. 마찬가지로 종양에 존재하는 후성유전학적 변화는 종양 전 필드 결함에서 발생했을 수 있습니다.[67]

현장 효과에 대한 확장된 관점은 종양 전 세포의 분자 및 병리학적 변화뿐만 아니라 종양 시작에서 사망까지의 종양 진화에 대한 외인성 환경 요인 및 국소 미세 환경의 분자 변화의 영향을 포괄하는 "생리학적 현장 효과"라고 불립니다.[68]

후성유전학

후성유전학적 변화는 유전적(돌연변이) 변화보다 대장암에서 훨씬 더 자주 발생합니다. Vogelstein [66]등에 의해 기술된 바와 같이, 대장의 평균적인 암은 1 또는 2개의 종양 유전자 돌연변이와 1 내지 5개의 종양 억제자 돌연변이(함께 "운전자 돌연변이"로 지정됨)만을 가지며, 약 60개의 추가적인 "탑승자" 돌연변이가 있습니다. 종양 유전자 및 종양 억제 유전자는 잘 연구되어 있으며 병리학(Pathogenesis)에서 위에 설명되어 있습니다.[69][70]

miRNA 발현의 후성유전학적 변화 외에도 유전자 발현 수준을 변화시키는 암의 다른 일반적인 후성유전학적 변화 유형에는 단백질을 암호화하는 유전자의 CpG 섬의 직접적인 과메틸화 또는 저메틸화, 그리고 유전자 발현에 영향을 미치는 히스톤 및 염색체 구조의 변화가 포함됩니다.[71] 한 예로 단백질 코딩 유전자의 147개의 과메틸화와 27개의 저메틸화가 대장암과 빈번하게 연관되어 있었습니다. 과메틸화된 유전자 중 10개는 대장암의 100%에서 과메틸화되었고, 다른 많은 유전자들은 대장암의 50% 이상에서 과메틸화되었습니다.[72] 또한 miRNA의 과메틸화 11건과 저메틸화 96건도 대장암과 연관이 있었습니다.[72] 정상적인 노화의 정상적인 결과로 비정상적인(이상) 메틸화가 일어나며 나이가 들수록 대장암 위험이 높아집니다.[73] 이 나이와 관련된 메틸화의 원인과 계기는 알려져 있지 않습니다.[73][74] 나이와 관련된 메틸화 변화를 보이는 유전자의 약 절반은 대장암 발병에 관여하는 것으로 밝혀진 동일한 유전자입니다.[73] 이러한 연구 결과는 나이가 대장암 발병 위험 증가와 관련이 있는 이유를 제시할 수 있습니다.[73]

DNA 복구 효소 발현의 후성유전학적 감소는 암의 유전적 및 후성유전학적 불안정성 특성으로 이어질 가능성이 있습니다.[75][76][67] 발암 및 신생물 기사에서 요약된 바와 같이, 일반적으로 산발적인 암의 경우 DNA 복구의 결핍은 DNA 복구 유전자의 돌연변이로 인한 경우도 있지만, DNA 복구 유전자의 발현을 감소시키거나 침묵시키는 후생유전적 변화로 인한 경우가 훨씬 더 많습니다.[77]

대장암 발병과 관련된 후성유전학적 변화는 화학요법에 대한 사람의 반응에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[78]

게놈 후성유전체학

대장암의 공통 분자 아형(CMS) 분류는 2015년에 처음 도입되었습니다. 지금까지 CMS 분류는 명확한 생물학적 해석 가능성과 향후 임상 계층화 및 아형 기반 표적 개입의 기초가 되는 CRC에 대해 사용할 수 있는 가장 강력한 분류 시스템으로 간주되었습니다.[79]

대장암의 새로운 에피게놈 기반 분류(EpiC)는 CRC를 가진 사람들에게 4가지 인핸서 아형을 도입하는 2021년에 제안되었습니다. 6개의 히스톤 마크를 사용하는 염색질 상태는 EpiC 아형을 식별하는 것이 특징입니다. 이전에 소개된 합의 분자 하위 유형(CMS) 및 EpiC를 기반으로 한 조합형 치료 접근법은 현재의 치료 전략을 크게 향상시킬 수 있습니다.[80]

진단.

대장암 진단은 병변의 위치에 따라 일반적으로 대장 내시경 또는 구불결장경 검사 중 종양 발생 가능성이 의심되는 대장 부위를 샘플링하여 수행합니다.[20] 조직 검체의 현미경 검사로 확인됩니다.[citation needed]

의료영상

CT 촬영에서 대장암이 처음 발견되기도 합니다.[81]

전이 여부는 흉부, 복부 및 골반의 CT 스캔에 의해 결정됩니다.[20] 특정한 경우에는 PET 및 MRI와 같은 다른 잠재적 영상 검사를 사용할 수 있습니다.[20] MRI는 종양의 국소 단계를 결정하고 최적의 수술 접근 방식을 계획하는 데 특히 유용합니다.[81]

완전한 반응을 얻는 환자를 식별하기 위해 신보조 화학 방사선 치료 완료 후 MRI도 수행합니다. MRI와 내시경 모두에서 완전한 반응을 보이는 환자는 수술적 절제가 필요하지 않을 수 있으며 불필요한 수술적 이환율과 합병증을 피할 수 있습니다.[82] 직장암의 비수술적 치료를 위해 선택된 환자는 주기적인 MRI 검사를 받고 신체 검사를 받은 후 내시경 시술을 통해 소수의 환자에게서 발생할 수 있는 종양의 재성장을 감지해야 합니다. 국소 재발이 발생하면 주기적인 추적 관찰을 통해 인양 수술로 아직 크기가 작고 완치가 가능할 때 발견할 수 있습니다. 또한, MRI 종양 퇴행 등급은 환자의 장기 생존 결과와 상관 관계가 있는 화학 방사선 치료 후에 할당될 수 있습니다.[83]

조직병리학

종양의 조직병리학적 특성은 조직검사 또는 수술에서 채취한 조직의 분석으로부터 보고됩니다. 병리학 보고서에는 종양 세포와 종양이 건강한 조직으로 침입하는 방법, 마지막으로 종양이 완전히 제거된 것처럼 보이는 경우 등 종양 조직의 현미경적 특성에 대한 설명이 포함되어 있습니다. 대장암의 가장 흔한 형태는 선암으로 전체 대장암의 95%[85]에서 98%[86] 사이를 구성합니다. 다른 더 희귀한 유형에는 림프종, 선편평 및 편평 세포암이 포함됩니다. 일부 하위 유형은 더 공격적입니다.[87] 불확실한 경우에는 면역 조직 화학이 사용될 수 있습니다.[88]

스테이징

암의 병기 설정은 방사선학적 소견과 병리학적 소견 모두를 기반으로 합니다. 대부분의 다른 형태의 암과 마찬가지로 종양 병기 설정은 초기 종양이 얼마나 퍼졌는지, 림프절과 더 먼 기관에서 전이가 있는지를 고려하는 TNM 시스템을 기반으로 합니다.[20] AJCC 8판은 2018년에 출판되었습니다.[89]

예방

대장암 환자의 절반 정도는 생활습관 요인에 의한 것으로 추정됐고, 전체 환자의 4분의 1 정도는 예방이 가능합니다.[90] 감시를 늘리고, 신체 활동을 하고, 섬유질이 많은 식단을 섭취하고, 흡연과 알코올 섭취를 줄이면 위험이 줄어듭니다.[91][92]

라이프스타일

강력한 증거가 있는 생활습관 위험요인으로는 운동부족, 흡연, 음주, 비만 등이 있습니다.[93][94][95] 충분한 운동과 건강한 식생활을 병행하여 정상 체중을 유지함으로써 대장암 발생 위험을 줄일 수 있습니다.[96]

현재의 연구는 지속적으로 더 많은 붉은 고기와 가공육을 섭취하는 것을 질병의 더 높은 위험과 연결시킵니다.[97] 1970년대를 기점으로 대장암을 예방하기 위한 식이요법 권고에는 통곡물, 과일, 채소 섭취를 늘리고, 붉은 고기와 가공육 섭취를 줄이는 것이 포함되는 경우가 많았습니다. 이것은 동물 연구와 후향적 관찰 연구를 기반으로 했습니다. 그러나 대규모 전향적 연구는 중요한 보호 효과를 입증하는 데 실패했으며 암의 여러 원인과 식이와 건강 사이의 상관 관계 연구의 복잡성 때문에 특정 식이 개입이 중요한 보호 효과를 가질지 여부는 불확실합니다.[98]: 432–433 [99]: 125–126 2018년 국립 암 연구소는 "지방과 고기가 적고 섬유질, 과일, 채소가 많은 식단이 CRC의 위험을 임상적으로 중요한 정도로 감소시킨다는 믿을 만한 증거는 없다"고 말했습니다.[93][100]

세계 암 연구 기금에 따르면 술을 마시는 것과 가공육을 먹는 것은 대장암의 위험을 증가시킨다고 합니다.[101]

2014년 세계보건기구 암 보고서는 식이섬유가 대장암 예방에 도움이 될 수 있다는 가설이 세워졌지만, 당시 대부분의 연구는 아직 상관관계를 연구하지 않았다고 지적했습니다.[99] 그러나 2019년 리뷰에서는 식이섬유와 통곡물의 이점에 대한 증거를 발견했습니다.[102] 세계암연구기금은 2017년 기준 대장암 예방을 위한 섬유질의 이점을 "가능성이 있다"고 평가했습니다.[103] 2022년 우산 리뷰에 따르면 해당 협회에 대해 "확신할 만한 증거"가 있다고 합니다.[104]

더 높은 신체 활동을 권장합니다.[21][105] 신체 운동은 대장의 약간의 감소와 관련이 있지만 직장암 위험은 관련이 없습니다.[106][107] 높은 수준의 신체활동은 대장암 위험을 약 21%[108] 감소시킵니다. 오랫동안 규칙적으로 앉아 있는 것은 대장암으로 인한 사망률이 높아지는 것과 관련이 있습니다. 규칙적인 운동은 위험을 부정하는 것이 아니라 오히려 낮춥니다.[109]

의약품 및 보충제

아스피린과 셀레콕시브는 고위험군의 대장암 위험을 감소시키는 것으로 보입니다.[110][111] 아스피린은 대장암 예방을 위해 50~60세, 출혈 위험이 증가하지 않고 심혈관 질환 위험이 있는 사람에게 권장됩니다.[112] 평균 위험이 있는 사람에게는 권장되지 않습니다.[113]

칼슘 보충에 대한 잠정적인 증거는 있지만 권고를 하기에는 충분하지 않습니다.[114] 비타민 D 섭취와 혈액 수치는 대장암 위험을 낮추는 것과 관련이 있습니다.[115][116]

스크리닝

대장암의 80% 이상이 선종성 용종에서 발생하기 때문에 이 암에 대한 검진은 조기 발견과 예방 모두에 효과적입니다.[20][117] 검진을 통한 대장암 증례의 진단은 증상이 있는 증례의 진단 2-3년 전에 발생하는 경향이 있습니다.[20] 발견된 모든 용종은 대장 내시경이나 구불결장경 검사를 통해 제거할 수 있으므로 암으로 전환되는 것을 방지할 수 있습니다. 검진은 대장암 사망률을 60%[118]까지 줄일 수 있는 가능성이 있습니다.

3가지 주요 선별검사는 대장내시경, 분변잠혈검사, 유연구불결장경검사입니다. 세 가지 중 42%의 암이 발견되는 대장 우측을 가려낼 수 없는 것은 구불결장경 검사뿐입니다.[119] 그러나 유연한 구불결장경 검사는 어떤 원인에 의한 사망 위험을 줄이는 가장 좋은 증거입니다.[120]

대변의 분변잠혈검사(FOBT)는 일반적으로 2년마다 권장되며 과이악 기반 또는 면역화학적일 수 있습니다.[20] 비정상적인 FOBT 결과가 발견되면, 참가자들은 일반적으로 추적 대장 내시경 검사를 받기 위해 의뢰됩니다. FOBT 검사는 1-2년에 한 번 시행하면 대장암 사망률이 16% 감소하고 검진에 참여한 사람 중 대장암 사망률은 23%까지 감소할 수 있지만 모든 원인에 의한 사망률을 감소시키는 것은 입증되지 않았습니다.[121] 면역화학적 검사는 정확하며 검사 전 식이요법이나 약물요법을 변경할 필요가 없습니다.[122] 그러나 영국의 연구에 따르면 이러한 면역화학적 검사의 경우 장암 환자의 절반 이상을 놓칠 수 있는 지점에 추가 조사의 문턱이 설정되어 있습니다. 이 연구는 NHS 영국의 장암 검진 프로그램이 (차단 수준 이상인지 또는 이하인지만 알 수 있는 것이 아니라) 대변의 정확한 혈액 농도를 제공하는 이 검사의 능력을 더 잘 활용할 수 있음을 시사합니다.[123][124]

다른 옵션으로는 가상 대장 내시경 검사 및 대변 DNA 스크리닝 테스트(FIT-DNA)가 있습니다. CT 스캔을 통한 가상 대장내시경 검사는 암과 큰 선종을 발견하기 위한 표준 대장내시경 검사만큼 효과적으로 보이지만 방사선 피폭과 관련된 비용이 많이 들고 표준 대장내시경 검사만큼 감지된 비정상적인 성장을 제거할 수 없습니다.[20] 대변 DNA 스크리닝 테스트는 대장암 및 전암 병변과 관련된 바이오마커를 찾으며, 여기에는 변경된 DNA 및 혈액 헤모글로빈이 포함됩니다. 대장 내시경 검사에서 양성 결과가 나와야 합니다. FIT-DNA는 FIT보다 더 많은 거짓 양성을 가지고 있으므로 더 많은 부작용을 초래합니다.[10] 3년의 검진 간격이 정확한지는 2016년 기준으로 추가 연구가 필요합니다.[10]

추천 사항

미국에서는 일반적으로 50세에서 75세 사이에서 검진을 권장합니다.[10][125] 미국 암 협회는 45세부터 시작할 것을 권장합니다.[126] 76세에서 85세 사이의 사람들은 심사 결정을 개별화해야 합니다.[10] 고위험자의 경우 일반적으로 40세 정도에 검사가 시작됩니다.[20][127]

2년마다 대변을 이용한 검사, 2년마다 대변 면역화학 검사와 함께 10년마다 구불결장경 검사, 10년마다 대장 내시경 검사 등 여러 가지 검진 방법이 권장됩니다.[125] 이 두 가지 방법 중 어느 것이 더 나은지는 불분명합니다.[128] 대장 내시경 검사는 대장의 첫 번째 부분에서 더 많은 암을 발견할 수 있지만 더 많은 비용과 더 많은 합병증과 관련이 있습니다.[128] 정상적인 결과와 함께 양질의 대장 내시경 검사를 받은 평균 위험이 있는 사람들의 경우, 미국 소화기 학회는 대장 내시경 검사 후 10년 동안 어떤 종류의 검진도 권장하지 않습니다.[129][130] 75세 이상이거나 기대수명이 10년 미만인 분들은 심사를 권장하지 않습니다.[131] 1000명 중 1명이 혜택을 받기 위해서는 심사 후 약 10년이 소요됩니다.[132] USPSTF는 심사를 위한 7가지 잠재적인 전략을 나열하고 있는데, 가장 중요한 것은 이러한 전략 중 적어도 하나가 적절하게 사용된다는 것입니다.[10]

캐나다에서는 정상위험군인 50~75세 중 2년마다 대변면역화학검사나 FOBT를, 10년마다 구불결장경검사를 권고하고 있습니다.[133] 대장내시경 검사는 덜 선호합니다.[133]

일부 국가에서는 일반적으로 50세에서 60세 사이에 시작하는 특정 연령대의 모든 성인에게 FOBT 검사를 제공하는 국가 대장 검진 프로그램이 있습니다. 조직적인 심사를 받는 국가의 예로는 영국,[134] 호주,[135] 네덜란드,[136] 홍콩, 대만이 있습니다.[137]

영국의 장암 검진 프로그램은 60세에서 74세 사이의 사람들에게 2년마다 대변 면역화학 검사(FIT)를 권고함으로써 경고 신호를 찾는 것을 목표로 합니다. FIT는 대변에서 혈액을 측정하며, 특정 기준치 이상의 수치를 가진 사람은 장 조직에서 암의 징후를 검사받을 수 있습니다. 암 발생 가능성이 있는 성장은 제거됩니다.[138][124]

치료

대장암의 치료는 완치나 완화를 목표로 할 수 있습니다. 어떤 목표를 채택할지는 종양의 단계뿐만 아니라, 그 사람의 건강과 선호도를 포함한 다양한 요소들에 달려 있습니다.[139] 다학제 팀에서의 평가는 환자가 수술에 적합한지 여부를 결정하는 중요한 부분입니다.[140] 대장암이 조기에 걸리면 수술이 완치될 수 있습니다. 그러나 나중에 (전이가 있는) 발견되면 가능성이 낮고 치료는 종양으로 인한 증상을 완화하고 가능한 한 환자를 편안하게 유지하기 위해 완화를 지향하는 경우가 많습니다.[20]

수술.

초기에는 대장 내시경 검사 중에 내시경 점막 절제술이나 내시경 점막하 박리술 등 여러 방법 중 하나를 이용하여 대장암을 제거할 수 있습니다.[5] 림프절 전이 가능성이 낮고 종양의 크기와 위치가 일괄 절제가 가능한 경우 내시경 절제가 가능합니다.[141] 국소 암 환자의 경우 선호되는 치료법은 적절한 여백을 가진 완전한 외과적 제거이며 완치를 시도합니다. 선택하는 절차는 부분 대장 절제술(또는 직장 병변에 대한 직장 절제술)로, 배액 림프절의 제거를 용이하게 하기 위해 결장 또는 직장의 영향을 받은 부분을 메조콜론 및 혈액 공급의 일부와 함께 제거합니다. 이는 개인과 관련된 요인 및 병변 요인에 따라 개복술 또는 복강경을 통해 수행할 수 있습니다.[20] 그런 다음 대장을 다시 연결하거나 사람이 대장 절제술을 받을 수 있습니다.[5]

간이나 폐에 전이가 거의 없는 경우, 이것들도 제거될 수 있습니다. 암을 제거하기 전에 암을 축소하기 위해 수술 전에 화학 요법을 사용할 수 있습니다. 대장암의 가장 흔한 재발 부위는 간과 폐입니다.[20] 복막암종증 세포 감소 수술의 경우 때때로 HIPEC와 함께 암을 제거하기 위해 사용될 수 있습니다.[142]

화학요법

대장암과 직장암 모두 특정한 경우에 수술 외에 항암치료를 사용하기도 합니다. 대장암과 직장암 관리에 항암치료를 추가할지는 질병의 병기에 따라 결정됩니다.[143]

1기 대장암에서는 항암치료가 제공되지 않으며 수술이 결정적인 치료법입니다. II기 대장암에서 화학요법의 역할은 논쟁의 여지가 있으며, T4 종양, 미분화 종양, 혈관 및 신경주위 침윤 또는 부적절한 림프절 샘플링과 같은 위험 요소가 확인되지 않는 한 일반적으로 제공되지 않습니다.[144] 또한 불일치 복구 유전자의 이상을 가지고 있는 사람들은 항암 치료의 혜택을 받지 못하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다. III기 및 IV기 대장암의 경우 화학요법은 치료의 필수적인 부분입니다.[20]

암이 림프절이나 먼 장기로 전이된 경우, 각각 3기, 4기 대장암의 경우와 마찬가지로 화학요법제인 플루오로우라실, 카페시타빈, 옥살리플라틴을 첨가하면 기대수명이 늘어납니다. 림프절에 암이 포함되어 있지 않다면 항암치료의 이점은 논란의 여지가 있습니다. 암이 광범위하게 전이되거나 절제할 수 없는 경우 치료는 완화됩니다. 일반적으로 이 환경에서는 다양한 화학 요법 약물이 사용될 수 있습니다.[20] 이 질환에 대한 화학 요법 약물에는 capecitabine, fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin 및 UFT가 포함될 수 있습니다.[145] 약제는 카페시타빈과 플루오로우라실이 서로 교환 가능하며, 카페시타빈은 경구용 약제, 플루오로우라실은 정맥용 약제입니다. CRC에 사용되는 일부 특정 요법은 CAPOX, FOLFOX, FOLFOXIRI 및 FOLFIRI입니다.[146] 베바시주맙과 같은 항혈관신생제는 1차 치료에서 추가되는 경우가 많습니다.[citation needed] 두 번째 라인 환경에서 사용되는 또 다른 종류의 약물은 표피 성장 인자 수용체 억제제이며, 이 중 FDA 승인을 받은 세 가지 약물은 아프리벡트, 세툭시맙 및 파니투맙입니다.[147][148]

저기 직장암에 대한 접근법의 가장 큰 차이점은 방사선 치료의 통합입니다. 종종 외과적 절제가 가능하도록 신보조적인 방식으로 화학 요법과 함께 사용되어 궁극적으로 대장 절제술이 필요하지 않습니다. 그러나 낮은 누운 종양에서는 불가능할 수 있으며, 이 경우 영구적인 대장 절제술이 필요할 수 있습니다. 4기 직장암은 4기 대장암과 유사하게 치료됩니다.

복막암종증으로 인한 4기 대장암은 HIPEC를 사용하여 세포 환원 수술과 결합하여 치료할 수 있습니다.[149][150][151] 또한 T4 대장암은 향후 재발을 피하기 위해 HIPEC로 치료할 수 있습니다.[152]

방사선치료

방사선과 화학 요법의 조합이 직장암에 유용할 수 있지만,[20] 치료가 필요한 일부 사람들에게 화학 방사선 요법은 급성 치료 관련 독성을 증가시킬 수 있으며, 국소 재발과 관련이 적지만 방사선 요법 단독에 비해 생존율을 향상시키는 것으로 나타나지 않았습니다.[142] 대장암에서 방사선 치료의 사용은 방사선에 대한 장의 민감성으로 인해 일상적이지 않습니다.[153] 방사선 치료는 화학요법과 마찬가지로 직장암의 임상 T3 및 T4 단계에 대한 신보조제로 사용될 수 있습니다.[154] 이로 인해 종양의 크기를 줄이거나 단계를 낮추어 수술적 절제를 준비하고 국소 재발률도 감소시킵니다.[154] 국소 진행성 직장암의 경우 신보조화학요법이 표준 치료법이 되었습니다.[155] 또한 CRC 환자의 10~15%에서 발생하는 CRC 폐 전이에 대한 효과적인 치료법으로 수술이 불가능한 경우 방사선 치료가 제시되고 있습니다.[156]

면역요법

면역관문억제제를 사용한 면역요법은 불일치 복구결핍과 미세위성 불안정성이 있는 대장암의 한 종류에 유용한 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[157][158][159] Pembrolizumab은 MMR이 부족하고 일반적인 치료에 실패한 진행성 CRC 종양에 대해 승인되었습니다.[160] 그러나 호전되는 대부분의 사람들은 몇 달 또는 몇 년 후에도 여전히 악화됩니다.[158]

한편, 2022년 6월에 The New England Journal of Medicine에 발표된 전향적 2상 연구에서, 12명의 dMMR (dimined match repair) 단계 II 또는 III 직장 선암종 환자에게 항-항-제인 dostarlimab을 투여했습니다.PD-1 단일클론항체를 3주마다 6개월간 투여합니다 12개월(범위, 6~25개월)의 중간 추적 후, 12명의 환자 모두 MRI, 18F-플루오로데옥시글루코스-양전자 방출 단층 촬영, 내시경 평가, 디지털 직장 검사 또는 조직 검사에서 종양의 증거 없이 완전한 임상 반응을 보였습니다. 게다가, 시험에서 화학 방사선 치료나 수술이 필요한 환자는 없었고, 3등급 이상의 부작용을 보고한 환자도 없었습니다. 그러나 이 연구 결과는 유망하지만 연구 규모가 작고 장기적인 결과에 대한 불확실성이 있습니다.[161]

완화의료

완화의료는 진행성 대장암이 있거나 증상이 현저한 사람이라면 누구나 권장합니다.[162][163]

완화 의료의 참여는 증상, 불안감을 개선하고 병원에 입원하는 것을 방지함으로써 환자와 가족 모두의 삶의 질을 향상시키는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[164]

난치성 대장암 환자에서 완화의료는 암의 증상이나 합병증을 완화하지만 기저암을 치료하려는 시도는 하지 않는 시술로 구성되어 삶의 질을 향상시킬 수 있습니다. 수술 옵션에는 암 조직의 일부를 비치료적으로 제거하거나 장의 일부를 우회하거나 스텐트를 배치하는 것이 포함될 수 있습니다. 이러한 시술은 증상을 개선하고 종양으로 인한 출혈, 복통, 장폐색 등의 합병증을 줄이는 것으로 고려할 수 있습니다.[165] 대증적 치료의 비수술적 방법에는 통증 치료제뿐만 아니라 종양 크기를 줄이기 위한 방사선 치료가 포함됩니다.[166]

후속조치

미국 국립 종합 암 네트워크와 미국 임상 종양학회는 대장암 추적에 대한 지침을 제공합니다.[167][168] 2년간은 3개월에서 6개월, 5년간은 6개월 간격으로 병력과 신체검사가 권장됩니다. 암배아항원 혈중수치 측정은 동일한 시기를 따르지만, T2 이상 병변이 있는 사람에게만 권고됩니다. 흉부, 복부, 골반 CT 스캔은 재발 위험이 높은 사람(예: 분화도가 낮은 종양 또는 정맥 또는 림프 침범이 있는 사람)과 치료 수술 후보자(치료 목적)의 경우 처음 3년 동안 매년 고려할 수 있습니다. 대장내시경 검사는 초기 병기 중에 방해 종괴로 인해 시행할 수 없는 경우를 제외하고 1년 후에 시행할 수 있으며, 이 경우 3개월에서 6개월 후에 시행해야 합니다. 융모성 용종, 1센티미터 이상의 용종 또는 고등급 이형성이 발견되면 3년 후, 5년마다 반복될 수 있습니다. 그 외 이상에 대해서는 1년 후 대장내시경을 반복할 수 있습니다.[143]

일상적인 PET 또는 초음파 검사, 흉부 X선, 완전한 혈구 수 또는 간 기능 검사는 권장되지 않습니다.[167][168]

전이가 없는 대장암을 치료하기 위해 치료적 수술이나 보조 요법(또는 둘 다)을 받은 사람들의 경우, 강도 높은 감시와 면밀한 추적 관찰이 추가적인 생존 혜택을 제공하지 못하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[169]

운동

앞으로 암 생존자에게 2차 치료로 운동을 권장할 수도 있습니다. 역학 연구에서 운동은 대장암 특유의 사망률과 모든 원인에 의한 사망률을 감소시킬 수 있습니다. 이익을 관찰하는 데 필요한 특정 운동량에 대한 결과가 상충되었습니다. 이러한 차이는 종양 생물학과 바이오마커의 발현의 차이를 반영할 수 있습니다. Wnt 신호전달 경로에 관여하는 CTNNB1 발현(β-catenin)이 부족한 종양을 가진 사람들은 대장암 사망률 감소를 관찰하기 위해 운동의 척도인 MET(Metabolic Equivalent) 시간이 주당 18시간 이상 필요했습니다. 운동이 생존에 어떻게 도움이 되는지에 대한 메커니즘은 면역 감시 및 염증 경로에 관여할 수 있습니다. 임상 연구에서, 1차 치료를 마친 후 2주간의 적당한 운동을 한 II-III기 대장암 환자들에게서 친염증 반응이 발견되었습니다. 산화적 균형은 관찰되는 또 다른 이점의 가능한 메커니즘일 수 있습니다. 1차 치료 후 2주간 적당한 운동을 한 사람들의 소변에서 8-oxo-dG의 현저한 감소가 발견되었습니다. 다른 가능한 메커니즘은 대사 호르몬과 성 스테로이드 호르몬을 포함할 수 있지만 이러한 경로는 다른 유형의 암에 관련될 수 있습니다.[170][171]

또 다른 잠재적 바이오마커는 p27일 수 있습니다. p27을 발현하고 주당 18 MET 시간 이상을 수행하는 종양이 있는 생존자는 주당 18 MET 시간 미만인 생존자에 비해 대장암 사망률 생존율이 감소한 것으로 나타났습니다. 운동을 한 p27 발현이 없는 생존자들은 더 나쁜 결과를 보였습니다. PI3K/AKT/mTOR 경로의 구성적 활성화는 p27의 손실을 설명할 수 있으며 과도한 에너지 균형은 p27을 상향 조절하여 암세포가 분열하는 것을 막을 수 있습니다.[171]

신체 활동은 비 진행성 대장암 환자에게 이점을 제공합니다. 단기간에 유산소 체력, 암 관련 피로도, 건강 관련 삶의 질 향상이 보고되었습니다.[172] 하지만 불안이나 우울증과 같은 질병 관련 정신건강 수준에서는 이러한 개선이 관찰되지 않았습니다.[172]

예후

600개 미만의 유전자가 대장암의 결과와 관련이 있습니다.[51] 여기에는 높은 발현이 나쁜 결과와 관련된 불리한 유전자, 예를 들어 열 충격 70 kDa 단백질 1(HSPA1A) 및 높은 발현이 더 나은 생존과 관련된 유리한 유전자, 예를 들어 추정 RNA 결합 단백질 3(RBM3)이 포함됩니다.[51] 예후는 또한 pre-mRNA 스플라이싱 장치의 불량한 충실도와 관련이 있으며, 따라서 많은 수의 이탈 대체 스플라이싱과 관련이 있습니다.[173]

재발률

수술이 성공한 사람의 5년 평균 재발률은 1기 암의 경우 5%, 2기 암의 경우 12%, 3기 암의 경우 33%입니다. 그러나 위험 인자의 수에 따라 II 단계에서는 9-22%, III 단계에서는 17-44%입니다.[174]

생존율

유럽에서는 대장암의 5년 생존율이 60% 미만입니다. 선진국에서는 이 병에 걸린 사람의 약 3분의 1이 이 병으로 사망합니다.[20]

생존은 발견 및 관련된 암의 종류와 직접적인 관련이 있지만 증상이 있는 암은 일반적으로 상당히 진행되어 있기 때문에 전반적으로 좋지 않습니다. 조기 발견의 생존율은 말기 암의 약 5배입니다. 점막근층(TNM 병기 Tis, N0, M0)을 뚫지 않은 종양을 가진 사람은 5년 생존율이 100%인 반면, T1(점막하층 내) 또는 T2(근층 내)의 침습성 암을 가진 사람은 평균 5년 생존율이 약 90%입니다. 더 침습적인 종양을 가지고 있지만 노드 관련이 없는 사람들(T3-4, N0, M0)은 평균 5년 생존율이 약 70%입니다. 양성 영역 림프절을 가진 사람들(어떤 T, N1-3, M0)은 평균 5년 생존율이 약 40%인 반면, 원격 전이를 가진 사람들(어떤 T, 어떤 N, M1)은 예후가 나쁘며 5년 생존율은 <5%에서 31%입니다.[175][176][177][178][179] 예후는 사람의 체력 수준, 전이 범위 및 종양 등급을 포함한 다양한 요인에 따라 달라집니다.[citation needed]

생존하는 사람들에게 미치는 대장암의 영향은 크게 다르지만 종종 질병과 치료의 신체적, 심리적 결과에 적응할 필요가 있습니다.[180] 예를 들어, 1차 치료가 끝난 후에 요실금, 성기능 장애,[181][182] 기공 관리[183] 문제, 암[184] 재발에 대한 두려움을 경험하는 사람들이 흔합니다.

2021년에 발표된 질적 체계적인 리뷰는 대장암을 포함하거나 그 이상의 생활에 대한 적응에 영향을 미치는 세 가지 주요 요인이 있음을 강조했습니다: 지지 메커니즘, 치료의 후기 효과의 심각성 및 심리사회적 적응. 따라서 사람들이 치료 후 생활에 더 잘 적응할 수 있도록 적절한 지원을 제공받는 것이 중요합니다.[185]

역학

전 세계적으로 매년[20] 100만 명 이상의 사람들이 대장암에 걸려 1990년 49만 명에서 2010년 현재 약 71만 5천 명이 사망하고 있습니다.[186]

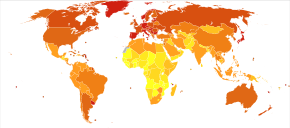

2012년[update] 기준 여성에서 두 번째로 흔한 암의 원인(진단의 9.2%)이며, 남성에서 세 번째로 흔한 원인(10.0%)[14]: 16 이며, 폐암, 위암, 간암 다음으로 네 번째로 흔한 암 사망 원인입니다.[187] 개발도상국보다 선진국에서 더 흔합니다.[188] 전 세계 발병률은 10배로 다양하며 호주, 뉴질랜드, 유럽 및 미국에서 가장 높은 발병률을 보이고 아프리카 및 중남부 아시아에서 가장 낮은 발병률을 보이고 있습니다.[189]

미국

2022년 미국의 대장암 발병률은 약 151,000명으로 예상되었으며, 여기에는 106,000명 이상의 새로운 대장암 환자(남성 54,000명, 여성 52,000명)와 약 45,000명의 새로운 직장암 환자가 포함됩니다.[190] 1980년대 이후 대장암 발병률이 감소하면서 주로 검진 개선으로 인해 50세 이상 성인에서 2014년부터 2018년까지 연평균 약 2%씩 감소했습니다.[190] 하지만 25세에서 50세 사이의 사람들에게서 대장암 발병률이 증가했습니다. 2023년 초 미국암학회(ACS)는 2019년 진단(대장암)의 20%가 55세 미만 환자에서 발생했으며, 이는 1995년의 약 2배 수준이며, 50세 미만에서는 진행성 질환 비율이 매년 약 3%씩 증가했다고 보고했습니다. 2023년에는 50세 미만에서 19,550명의 진단과 3,750명의 사망자가 발생할 것으로 예측했습니다.[191] 대장암은 또한 흑인 사회에 불균형적으로 영향을 미치는데, 흑인 사회는 그 비율이 미국의 모든 인종/민족 집단 중에서 가장 높습니다. 아프리카계 미국인은 대부분의 다른 그룹보다 대장암에 걸릴 확률이 약 20%, 사망할 확률이 약 40% 높습니다. 미국 흑인들은 종종 암 예방, 발견, 치료, 생존에 더 큰 장애물을 경험하는데, 여기에는 복잡하고 암과의 명백한 연관성을 넘어서는 체계적인 인종적 차이가 포함됩니다.

영국

영국에서는 연간 약 41,000명이 대장암에 걸려 네 번째로 흔한 유형입니다.[192]

호주.

호주에서 남성 19명 중 1명과 여성 28명 중 1명은 75세 이전에 대장암이 발병하고, 남성 10명 중 1명과 여성 15명 중 1명은 85세 이전에 발병하게 됩니다.[193]

파푸아뉴기니

파푸아뉴기니와 솔로몬제도를 포함한 다른 태평양 섬나라들과 같은 개발도상국에서 대장암은 사람들 사이에서 매우 희귀한 암으로 폐암, 위암, 간암, 유방암에 비해 흔하지 않습니다. 매년 최소 10만 명 중 8명이 대장암에 걸릴 가능성이 가장 높은 것으로 추정되는데, 이는 여성 10만 명 중 24명이 대장암인 폐암이나 유방암과는 다릅니다.[194]

역사

프톨레마이오스 시대에 다클레 오아시스에 살았던 고대 이집트 미라에서 직장암 진단을 받았습니다.[195]

사회와 문화

조사.

예비 시험관내 증거는 유산균(예: 유산균, 연쇄상구균 또는 락토코커스)이 항산화 활성, 면역 조절, 프로그램된 세포 사멸 촉진, 항증식 효과, 그리고 암세포의 후성유전학적 변형.[196]

대장암과 장암의 마우스 모델이 개발되어 연구에 활용되고 있습니다.[197][198][199]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ a b c d "General Information About Colon Cancer". NCI. May 12, 2014. Archived from the original on July 4, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bosman FT (2014). "Chapter 5.5: Colorectal Cancer". In Stewart BW, Wild CP (eds.). World Cancer Report. the International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. pp. 392–402. ISBN 978-92-832-0443-5.

- ^ a b c "Colorectal Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)". National Cancer Institute. February 27, 2014. Archived from the original on July 5, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ a b Theodoratou E, Timofeeva M, Li X, Meng X, Ioannidis JP (August 2017). "Nature, Nurture, and Cancer Risks: Genetic and Nutritional Contributions to Cancer". Annual Review of Nutrition (Review). 37: 293–320. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-051004. PMC 6143166. PMID 28826375.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. May 12, 2014. Archived from the original on July 5, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Colon and Rectum Cancer". NCI. Archived from the original on June 24, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ^ Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (November 2018). "Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 68 (6): 394–424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492. PMID 30207593. S2CID 52188256.

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer Signs and Symptoms Signs of Colorectal Cancer". www.cancer.org. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW, García FA, et al. (June 2016). "Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 315 (23): 2564–2575. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5989. PMID 27304597.

- ^ "First Colonoscopies Now Recommended at Age 45". ThedaCare. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Thorat MA, Cuzick J (December 2013). "Role of aspirin in cancer prevention". Current Oncology Reports. 15 (6): 533–540. doi:10.1007/s11912-013-0351-3. PMID 24114189. S2CID 40187047.

- ^ "Routine aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer: recommendation statement". American Family Physician. 76 (1): 109–113. July 2007. PMID 17668849. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Forman D, Ferlay J (2014). "Chapter 1.1: The global and regional burden of cancer". In Stewart BW, Wild CP (eds.). World Cancer Report. the International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. pp. 16–53. ISBN 978-92-832-0443-5.

- ^ Alpers DH, Kalloo AN, Kaplowitz N, Owyang C, Powell DW (2008). Yamada T (ed.). Principles of clinical gastroenterology. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 381. ISBN 978-1-4051-6910-3. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015.

- ^ Juul JS, Hornung N, Andersen B, Laurberg S, Olesen F, Vedsted P (August 2018). "The value of using the faecal immunochemical test in general practice on patients presenting with non-alarm symptoms of colorectal cancer". British Journal of Cancer. 119 (4): 471–479. doi:10.1038/s41416-018-0178-7. PMC 6133998. PMID 30065255.

- ^ a b Astin M, Griffin T, Neal RD, Rose P, Hamilton W (May 2011). "The diagnostic value of symptoms for colorectal cancer in primary care: a systematic review". The British Journal of General Practice. 61 (586): e231–e243. doi:10.3399/bjgp11X572427. PMC 3080228. PMID 21619747.

- ^ Adelstein BA, Macaskill P, Chan SF, Katelaris PH, Irwig L (May 2011). "Most bowel cancer symptoms do not indicate colorectal cancer and polyps: a systematic review". BMC Gastroenterology. 11: 65. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-11-65. PMC 3120795. PMID 21624112.

- ^ a b Watson AJ, Collins PD (2011). "Colon cancer: a civilization disorder". Digestive Diseases. 29 (2): 222–228. doi:10.1159/000323926. PMID 21734388. S2CID 7640363.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, Lynch HT, Minsky B, Nordlinger B, Starling N (March 2010). "Colorectal cancer". Lancet. 375 (9719): 1030–1047. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60353-4. PMID 20304247. S2CID 25299272.

- ^ a b "Colorectal Cancer 2011 Report: Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Colorectal Cancer" (PDF). World Cancer Research Fund & American Institute for Cancer Research. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 9, 2016.

- ^ Vyas, Darshali A.; Eisenstein, Leo G.; Jones, David S. (August 27, 2020). Malina, Debra (ed.). "Hidden in Plain Sight — Reconsidering the Use of Race Correction in Clinical Algorithms". New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (9): 874–882. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2004740. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 32853499. S2CID 221359557.

- ^ Bowles, Tawnya L.; Hu, Chung-Yuan; You, Nancy Y.; Skibber, John M.; Rodriguez-Bigas, Miguel A.; Chang, George J. (May 2013). "An Individualized Conditional Survival Calculator for Patients with Rectal Cancer". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 56 (5): 551–559. doi:10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827bd287. ISSN 0012-3706. PMC 3673550. PMID 23575393.

- ^ Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT (July 2012). "Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy". Lancet. 380 (9838): 219–229. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. PMC 3645500. PMID 22818936.

- ^ Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, Rota M, Scotti L, Islami F, et al. (September 2011). "Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies". Annals of Oncology. 22 (9): 1958–1972. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq653. PMID 21307158.

- ^ Valtin H (November 2002). ""Drink at least eight glasses of water a day." Really? Is there scientific evidence for "8 x 8"?". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 283 (5): R993–1004. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00365.2002. PMID 12376390. S2CID 2256436.

- ^ Boleij A, van Gelder MM, Swinkels DW, Tjalsma H (November 2011). "Clinical Importance of Streptococcus gallolyticus infection among colorectal cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 53 (9): 870–878. doi:10.1093/cid/cir609. PMID 21960713.

- ^ Jans C, Meile L, Lacroix C, Stevens MJ (July 2015). "Genomics, evolution, and molecular epidemiology of the Streptococcus bovis/Streptococcus equinus complex (SBSEC)". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 33: 419–436. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2014.09.017. PMID 25233845.

- ^ a b c Abdulamir AS, Hafidh RR, Abu Bakar F (January 2011). "The association of Streptococcus bovis/gallolyticus with colorectal tumors: the nature and the underlying mechanisms of its etiological role". Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 30 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-30-11. PMC 3032743. PMID 21247505.

이 기사는 CC BY 2.0 라이센스로 제공되는 Ahmed S Abdulamir, Rand R Hafidh 및 Fatimah Abu Bakar의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

이 기사는 CC BY 2.0 라이센스로 제공되는 Ahmed S Abdulamir, Rand R Hafidh 및 Fatimah Abu Bakar의 텍스트를 통합합니다. - ^ Arthur JC (June 2020). "Microbiota and colorectal cancer: colibactin makes its mark". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 17 (6): 317–318. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-0303-y. PMID 32317778. S2CID 216033220.

- ^ Jawad N, Direkze N, Leedham SJ (2011). "Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colon Cancer". Inflammation and Gastrointestinal Cancers. Recent Results in Cancer Research. Vol. 185. pp. 99–115. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-03503-6_6. ISBN 978-3-642-03502-9. PMID 21822822.

- ^ Hu T, Li LF, Shen J, Zhang L, Cho CH (2015). "Chronic inflammation and colorectal cancer: the role of vascular endothelial growth factor". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 21 (21): 2960–2967. doi:10.2174/1381612821666150514104244. PMID 26004415.

- ^ a b c d Triantafillidis JK, Nasioulas G, Kosmidis PA (July 2009). "Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, risk factors, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention strategies". Anticancer Research. 29 (7): 2727–2737. PMID 19596953.

- ^ a b Bye WA, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, Jairath V, East JE (September 2017). "Strategies for detecting colon cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (9): CD000279. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000279.pub4. PMC 6483622. PMID 28922695.

- ^ Juhn E, Khachemoune A (2010). "Gardner syndrome: skin manifestations, differential diagnosis and management". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 11 (2): 117–122. doi:10.2165/11311180-000000000-00000. PMID 20141232. S2CID 36836169.

- ^ Half E, Bercovich D, Rozen P (October 2009). "Familial adenomatous polyposis". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 4: 22. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-4-22. PMC 2772987. PMID 19822006.

- ^ Möslein G, Pistorius S, Saeger HD, Schackert HK (March 2003). "Preventive surgery for colon cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome". Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 388 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1007/s00423-003-0364-8. PMID 12690475. S2CID 21385340.

- ^ Mankaney G, Rouphael C, Burke CA (April 2020). "Serrated Polyposis Syndrome". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 18 (4): 777–779. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.09.006. PMID 31520728.

- ^ Fan C, Younis A, Bookhout CE, Crockett SD (March 2018). "Management of Serrated Polyps of the Colon". Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 16 (1): 182–202. doi:10.1007/s11938-018-0176-0. PMC 6284520. PMID 29445907.

- ^ Bourdais R, Rousseau B, Pujals A, Boussion H, Joly C, Guillemin A, et al. (May 2017). "Polymerase proofreading domain mutations: New opportunities for immunotherapy in hypermutated colorectal cancer beyond MMR deficiency". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 113: 242–248. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.03.027. PMID 28427513.

- ^ Stein U, Walther W, Arlt F, Schwabe H, Smith J, Fichtner I, et al. (January 2009). "MACC1, a newly identified key regulator of HGF-MET signaling, predicts colon cancer metastasis". Nature Medicine. 15 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1038/nm.1889. PMID 19098908. S2CID 8854895.

- ^ 고형암의 새로운 표적인 Stein U (2013) MACC1. 전문가 의견 대상

- ^ Schuebel KE, Chen W, Cope L, Glöckner SC, Suzuki H, Yi JM, et al. (September 2007). "Comparing the DNA hypermethylome with gene mutations in human colorectal cancer". PLOS Genetics. 3 (9): 1709–1723. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030157. PMC 1988850. PMID 17892325.

- ^ "What is the relationship between Ashkenazi Jews and colorectal cancer?". WebMD. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c Tabibzadeh, Alireza; Tameshkel, Fahimeh Safarnezhad; Moradi, Yousef; Soltani, Saber; Moradi-Lakeh, Maziar; Ashrafi, G. Hossein; Motamed, Nima; Zamani, Farhad; Motevalian, Seyed Abbas; Panahi, Mahshid; Esghaei, Maryam; Ajdarkosh, Hossein; Mousavi-Jarrahi, Alireza; Niya, Mohammad Hadi Karbalaie (October 30, 2020). "Signal transduction pathway mutations in gastrointestinal (GI) cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 18713. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1018713T. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-73770-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7599243. PMID 33127962.

- ^ Ionov Y, Peinado MA, Malkhosyan S, Shibata D, Perucho M (June 1993). "Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis". Nature. 363 (6429): 558–561. Bibcode:1993Natur.363..558I. doi:10.1038/363558a0. PMID 8505985. S2CID 4254940.

- ^ Chakravarthi S, Krishnan B, Madhavan M (1999). "Apoptosis and expression of p53 in colorectal neoplasms". Indian J. Med. Res. 86 (7): 95–102.

- ^ Abdul Khalek FJ, Gallicano GI, Mishra L (November 2010). "Colon cancer stem cells". Gastrointestinal Cancer Research (Suppl 1): S16–S23. PMC 3047031. PMID 21472043.

- ^ a b c d Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM (December 2009). "Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (25): 2449–2460. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804588. PMC 2843693. PMID 20018966.

- ^ Mehlen P, Fearon ER (August 2004). "Role of the dependence receptor DCC in colorectal cancer pathogenesis". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 22 (16): 3420–3428. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.02.019. PMID 15310786.

- ^ a b c Uhlen M, Zhang C, Lee S, Sjöstedt E, Fagerberg L, Bidkhori G, et al. (August 2017). "A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome". Science. 357 (6352): eaan2507. doi:10.1126/science.aan2507. PMID 28818916.

- ^ Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW (August 2004). "Cancer genes and the pathways they control". Nature Medicine. 10 (8): 789–799. doi:10.1038/nm1087. PMID 15286780. S2CID 205383514.

- ^ a b c Muzny DM, Bainbridge MN, Chang K, Dinh HH, Drummond JA, Fowler G, et al. (Cancer Genome Atlas Network) (July 2012). "Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer". Nature. 487 (7407): 330–337. Bibcode:2012Natur.487..330T. doi:10.1038/nature11252. PMC 3401966. PMID 22810696.

- ^ Gatalica Z, Vranic S, Xiu J, Swensen J, Reddy S (July 2016). "High microsatellite instability (MSI-H) colorectal carcinoma: a brief review of predictive biomarkers in the era of personalized medicine". Familial Cancer. 15 (3): 405–412. doi:10.1007/s10689-016-9884-6. PMC 4901118. PMID 26875156.

- ^ a b c Ryan E, Sheahan K, Creavin B, Mohan HM, Winter DC (August 2017). "The current value of determining the mismatch repair status of colorectal cancer: A rationale for routine testing". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 116: 38–57. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.05.006. PMID 28693799.

- ^ Hissong E, Crowe EP, Yantiss RK, Chen YT (November 2018). "Assessing colorectal cancer mismatch repair status in the modern era: a survey of current practices and re-evaluation of the role of microsatellite instability testing". Modern Pathology. 31 (11): 1756–1766. doi:10.1038/s41379-018-0094-7. PMID 29955148.

- ^ a b c Grady WM, Markowitz SD (March 2015). "The molecular pathogenesis of colorectal cancer and its potential application to colorectal cancer screening". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 60 (3): 762–772. doi:10.1007/s10620-014-3444-4. PMC 4779895. PMID 25492499.

- ^ Leslie, A.; Carey, F. A.; Pratt, N. R.; Steele, R. J. C. (July 2002). "The colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence". The British Journal of Surgery. 89 (7): 845–860. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02120.x. ISSN 0007-1323. PMID 12081733. S2CID 36456541.

- ^ Nguyen, Long H.; Goel, Ajay; Chung, Daniel C. (January 2020). "Pathways of Colorectal Carcinogenesis". Gastroenterology. 158 (2): 291–302. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.059. ISSN 0016-5085. PMC 6981255. PMID 31622622.

- ^ Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W (September 1953). "Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin". Cancer. 6 (5): 963–968. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<963::AID-CNCR2820060515>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 13094644. S2CID 6736946.

- ^ Giovannucci E, Ogino S (September 2005). "DNA methylation, field effects, and colorectal cancer". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 97 (18): 1317–1319. doi:10.1093/jnci/dji305. PMID 16174847.

- ^ Bernstein C, Bernstein H, Payne CM, Dvorak K, Garewal H (February 2008). "Field defects in progression to gastrointestinal tract cancers". Cancer Letters. 260 (1–2): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2007.11.027. PMC 2744582. PMID 18164807.

- ^ Nguyen H, Loustaunau C, Facista A, Ramsey L, Hassounah N, Taylor H, et al. (July 2010). "Deficient Pms2, ERCC1, Ku86, CcOI in field defects during progression to colon cancer". Journal of Visualized Experiments (41): 1931. doi:10.3791/1931. PMC 3149991. PMID 20689513. 28분 비디오

- ^ Rubin H (March 2011). "Fields and field cancerization: the preneoplastic origins of cancer: asymptomatic hyperplastic fields are precursors of neoplasia, and their progression to tumors can be tracked by saturation density in culture". BioEssays. 33 (3): 224–231. doi:10.1002/bies.201000067. PMID 21254148. S2CID 44981539.

- ^ Tsao JL, Yatabe Y, Salovaara R, Järvinen HJ, Mecklin JP, Aaltonen LA, et al. (February 2000). "Genetic reconstruction of individual colorectal tumor histories". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (3): 1236–1241. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.1236T. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.3.1236. PMC 15581. PMID 10655514.

- ^ a b Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Kinzler KW (March 2013). "Cancer genome landscapes". Science. 339 (6127): 1546–1558. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1546V. doi:10.1126/science.1235122. PMC 3749880. PMID 23539594.

- ^ a b Bernstein C, Nfonsam V, Prasad AR, Bernstein H (March 2013). "Epigenetic field defects in progression to cancer". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 5 (3): 43–49. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v5.i3.43. PMC 3648662. PMID 23671730.

- ^ Lochhead P, Chan AT, Nishihara R, Fuchs CS, Beck AH, Giovannucci E, Ogino S (January 2015). "Etiologic field effect: reappraisal of the field effect concept in cancer predisposition and progression". Modern Pathology. 28 (1): 14–29. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2014.81. PMC 4265316. PMID 24925058.

- ^ Wilbur B, ed. (2009). The World of the Cell (7th ed.). San Francisco, C.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ 킴볼의 생물학 페이지. 2017년 12월 31일 Wayback Machine "Oncogenes"에서 아카이브됨 자유 전문

- ^ Kanwal R, Gupta S (April 2012). "Epigenetic modifications in cancer". Clinical Genetics. 81 (4): 303–311. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01809.x. PMC 3590802. PMID 22082348.

- ^ a b Schnekenburger M, Diederich M (March 2012). "Epigenetics Offer New Horizons for Colorectal Cancer Prevention". Current Colorectal Cancer Reports. 8 (1): 66–81. doi:10.1007/s11888-011-0116-z. PMC 3277709. PMID 22389639.

- ^ a b c d Lao VV, Grady WM (October 2011). "Epigenetics and colorectal cancer". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 8 (12): 686–700. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2011.173. PMC 3391545. PMID 22009203.

- ^ Klutstein M, Nejman D, Greenfield R, Cedar H (June 2016). "DNA Methylation in Cancer and Aging". Cancer Research. 76 (12): 3446–3450. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3278. PMID 27256564.

- ^ Jacinto FV, Esteller M (July 2007). "Mutator pathways unleashed by epigenetic silencing in human cancer". Mutagenesis. 22 (4): 247–253. doi:10.1093/mutage/gem009. PMID 17412712.

- ^ Lahtz C, Pfeifer GP (February 2011). "Epigenetic changes of DNA repair genes in cancer". Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 3 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjq053. PMC 3030973. PMID 21278452.

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Coppedè F, Lopomo A, Spisni R, Migliore L (January 2014). "Genetic and epigenetic biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of colorectal cancer". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (4): 943–956. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i4.943. PMC 3921546. PMID 24574767.

- ^ Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reyniès A, Schlicker A, Soneson C, et al. (November 2015). "The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer". Nature Medicine. 21 (11): 1350–1356. doi:10.1038/nm.3967. PMC 4636487. PMID 26457759.

- ^ Orouji E, Raman AT, Singh AK, Sorokin A, Arslan E, Ghosh AK, et al. (May 2021). "Chromatin state dynamics confers specific therapeutic strategies in enhancer subtypes of colorectal cancer". Gut. 71 (5): 938–949. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322835. PMC 8745382. PMID 34059508. S2CID 235269540.

- ^ a b "Colorectal Cancer". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Awiwi, MO; Kaur, H; Ernst, R; Rauch, GM; Morani, AC; Stanietzky, N; Palmquist, SM; Salem, UI (2023). "Restaging MRI of Rectal Adenocarcinoma after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy: Imaging Findings and Potential Pitfalls". Radiographics. 43 (4): e220135. doi:10.1148/rg.220135. PMID 36927125. S2CID 257583845.

- ^ Awiwi, MO; Kaur, H; Ernst, R; Rauch, GM; Morani, AC; Stanietzky, N; Palmquist, SM; Salem, UI (April 2023). "Restaging MRI of Rectal Adenocarcinoma after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy: Imaging Findings and Potential Pitfalls". Radiographics. 43 (4): e220135. doi:10.1148/rg.220135. PMID 36927125. S2CID 257583845.

- ^ Kang H, O'Connell JB, Leonardi MJ, Maggard MA, McGory ML, Ko CY (February 2007). "Rare tumors of the colon and rectum: a national review". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 22 (2): 183–189. doi:10.1007/s00384-006-0145-2. PMID 16845516. S2CID 34693873.

- ^ "Colon, Rectosigmoid, and Rectum Equivalent Terms and Definitions C180-C189, C199, C209, (Excludes lymphoma and leukemia M9590 – M9992 and Kaposi sarcoma M9140) – Colon Solid Tumor Rules 2018. July 2019 Update" (PDF). National Cancer Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Colorectal cancer types". Cancer Treatment Centers of America. October 4, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Di Como JA, Mahendraraj K, Lau CS, Chamberlain RS (October 2015). "Adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon and rectum: a population based clinical outcomes study involving 578 patients from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result (SEER) database (1973–2010)". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 221 (4): 56. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.08.044.

- ^ Whiteside G, Munglani R (September 1998). "TUNEL, Hoechst and immunohistochemistry triple-labelling: an improved method for detection of apoptosis in tissue sections--an update". Brain Research. Brain Research Protocols. 3 (1): 52–53. doi:10.1016/s1385-299x(98)00020-8. PMID 9767106.

- ^ "TNM staging of colorectal carcinoma (AJCC 8th edition)". www.pathologyoutlines.com. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Parkin DM, Boyd L, Walker LC (December 2011). "16. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010". British Journal of Cancer. 105 (S2): S77–S81. doi:10.1038/bjc.2011.489. PMC 3252065. PMID 22158327.

- ^ Searke D (2006). Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 809. ISBN 978-0199747979. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015.

- ^ Rennert G (2007). Cancer Prevention. Springer. p. 179. ISBN 978-3540376965. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015.

- ^ a b "Colorectal Cancer Prevention Overview". National Cancer Institute. March 1, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "Cancer prevention". World Health Organization. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^ Chaplin A, Rodriguez RM, Segura-Sampedro JJ, Ochogavía-Seguí A, Romaguera D, Barceló-Coblijn G (October 2022). "Insights behind the Relationship between Colorectal Cancer and Obesity: Is Visceral Adipose Tissue the Missing Link?". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (21): 13128. doi:10.3390/ijms232113128. PMC 9655590. PMID 36361914.

- ^ Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K (August 2016). "Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (8): 794–798. doi:10.1056/nejmsr1606602. PMC 6754861. PMID 27557308.

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer – Risk Factors and Prevention". June 25, 2012.

- ^ Willett WC (2014). "Diet, nutrition, and cancer: where next for public health?". In Stewart BW, Wild CP (eds.). World Cancer Report. the International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. pp. 432–435. ISBN 978-92-832-0443-5.

- ^ a b Willett WC, Key T, Romieu I (2014). "Chapter 2.6: Diet, obesity, and physical activity". In Stewart BW, Wild CP (eds.). World Cancer Report. the International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. pp. 124–133. ISBN 978-92-832-0443-5.

Several large prospective cohort studies of dietary fibre and colon cancer risk have not supported an association, although an inverse relation was seen in the large European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study and a recent meta-analysis. The variation in findings from prospective studies needs to be better understood; dietary fibre is complex and heterogeneous, and the relation with colorectal cancer could differ by dietary source. (p. 127)

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer Prevention Description of Evidence". National Cancer Institute. March 1, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "Colorectal cancer".

- ^ Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Te Morenga L (February 2019). "Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses". Lancet. 393 (10170): 434–445. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9. PMID 30638909. S2CID 58632705.

- ^ Song M, Chan AT (January 2019). "Environmental Factors, Gut Microbiota, and Colorectal Cancer Prevention". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 17 (2): 275–289. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.012. PMC 6314893. PMID 30031175.

Despite the longstanding hypothesis that a high-fiber diet may protect against colorectal cancer... epidemiologic studies associating dietary fiber intake with subsequent risk of colorectal cancer have yielded inconsistent results... Nonetheless, based on existing evidence, the most recent expert report from the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research in 2017 concludes that there is probable evidence

- ^ Jabbari M, Pourmoradian S, Eini-Zinab H, Mosharkesh E, Hosseini Balam F, Yaghmaei Y, et al. (November 2022). "Levels of evidence for the association between different food groups/items consumption and the risk of various cancer sites: an umbrella review". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 73 (7): 861–874. doi:10.1080/09637486.2022.2103523. PMID 35920747. S2CID 251280745.

- ^ Pérez-Cueto FJ, Verbeke W (April 2012). "Consumer implications of the WCRF's permanent update on colorectal cancer". Meat Science. 90 (4): 977–978. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.11.032. PMID 22196090.

- ^ Harriss DJ, Atkinson G, Batterham A, George K, Cable NT, Reilly T, et al. (September 2009). "Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk (2): a systematic review and meta-analysis of associations with leisure-time physical activity". Colorectal Disease. 11 (7): 689–701. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01767.x. PMID 19207713. S2CID 8026021.

- ^ Robsahm TE, Aagnes B, Hjartåker A, Langseth H, Bray FI, Larsen IK (November 2013). "Body mass index, physical activity, and colorectal cancer by anatomical subsites: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 22 (6): 492–505. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328360f434. PMID 23591454. S2CID 24764995.

- ^ Kyu HH, Bachman VF, Alexander LT, Mumford JE, Afshin A, Estep K, et al. (August 2016). "Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". BMJ. 354: i3857. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3857. PMC 4979358. PMID 27510511.

- ^ Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, Alter DA (January 2015). "Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (2): 123–132. doi:10.7326/M14-1651. PMID 25599350. S2CID 7256176.

- ^ Cooper K, Squires H, Carroll C, Papaioannou D, Booth A, Logan RF, et al. (June 2010). "Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer: systematic review and economic evaluation". Health Technology Assessment. 14 (32): 1–206. doi:10.3310/hta14320. PMID 20594533.

- ^ Emilsson L, Holme Ø, Bretthauer M, Cook NR, Buring JE, Løberg M, et al. (January 2017). "Systematic review with meta-analysis: the comparative effectiveness of aspirin vs. screening for colorectal cancer prevention". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 45 (2): 193–204. doi:10.1111/apt.13857. PMID 27859394.

- ^ Bibbins-Domingo K (June 2016). "Aspirin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Colorectal Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (12): 836–845. doi:10.7326/M16-0577. PMID 27064677.

- ^ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. "Aspirin or Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for the Primary Prevention of Colorectal Cancer". United States Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016.

2010/2011

- ^ Weingarten MA, Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J (January 2008). "Dietary calcium supplementation for preventing colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (1): CD003548. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003548.pub4. PMC 8719254. PMID 18254022.

- ^ Ma Y, Zhang P, Wang F, Yang J, Liu Z, Qin H (October 2011). "Association between vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (28): 3775–3782. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7566. PMID 21876081.

- ^ Yin L, Grandi N, Raum E, Haug U, Arndt V, Brenner H (2011). "Meta-analysis: Serum vitamin D and colorectal adenoma risk". Preventive Medicine. 53 (1–2): 10–16. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.05.013. PMID 21672549.

- ^ "What Can I Do to Reduce My Risk of Colorectal Cancer?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 2, 2014. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ a b He J, Efron JE (2011). "Screening for colorectal cancer". Advances in Surgery. 45: 31–44. doi:10.1016/j.yasu.2011.03.006. hdl:2328/11906. PMID 21954677.

- ^ Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A (March 2012). "Trends in colorectal cancer incidence rates in the United States by tumor location and stage, 1992-2008". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 21 (3): 411–416. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1020. PMID 22219318.

- ^ Swartz AW, Eberth JM, Josey MJ, Strayer SM (October 2017). "Reanalysis of All-Cause Mortality in the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2016 Evidence Report on Colorectal Cancer Screening". Annals of Internal Medicine. 167 (8): 602–603. doi:10.7326/M17-0859. PMC 5823607. PMID 28828493.

- ^ Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, Towler B, Irwig L (June 2008). "Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 103 (6): 1541–1549. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01875.x. PMID 18479499. S2CID 26338156.

- ^ Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA (February 2014). "Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (3): 171. doi:10.7326/M13-1484. PMC 4189821. PMID 24658694.

- ^ "New pathways could improve bowel cancer screening". NIHR Evidence. September 13, 2021. doi:10.3310/alert_47581. S2CID 239113610. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Li SJ, Sharples LD, Benton SC, Blyuss O, Mathews C, Sasieni P, Duffy SW (September 2021). "Faecal immunochemical testing in bowel cancer screening: Estimating outcomes for different diagnostic policies". Journal of Medical Screening. 28 (3): 277–285. doi:10.1177/0969141320980501. PMC 8366184. PMID 33342370.

- ^ a b Qaseem A, Crandall CJ, Mustafa RA, Hicks LA, Wilt TJ, Forciea MA, et al. (November 2019). "Screening for Colorectal Cancer in Asymptomatic Average-Risk Adults: A Guidance Statement From the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 171 (9): 643–654. doi:10.7326/M19-0642. PMC 8152103. PMID 31683290.

- ^ Wolf AM, Fontham ET, Church TR, Flowers CR, Guerra CE, LaMonte SJ, et al. (July 2018). "Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 68 (4): 250–281. doi:10.3322/caac.21457. PMID 29846947.

- ^ "Screening for Colorectal Cancer". U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2008. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M (April 2014). "Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies". BMJ. 348 (apr09 1): g2467. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2467. PMC 3980789. PMID 24922745.

- ^ "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF). Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. American Gastroenterological Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, Bond J, Burt R, Ferrucci J, et al. (February 2003). "Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence". Gastroenterology. 124 (2): 544–560. doi:10.1053/gast.2003.50044. PMID 12557158. S2CID 29354772.

- ^ Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Hopkins RH, Humphrey LL, Levine J, Sweet DE, Shekelle P (March 2012). "Screening for colorectal cancer: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 156 (5): 378–386. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00010. PMID 22393133.

- ^ Tang V, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Lee SJ (April 2015). "Time to benefit for colorectal cancer screening: survival meta-analysis of flexible sigmoidoscopy trials". BMJ. 350: h1662. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1662. PMC 4399600. PMID 25881903.

- ^ a b Bacchus CM, Dunfield L, Gorber SC, Holmes NM, Birtwhistle R, Dickinson JA, Lewin G, Singh H, Klarenbach S, Mai V, Tonelli M (March 2016). "Recommendations on screening for colorectal cancer in primary care". CMAJ. 188 (5): 340–348. doi:10.1503/cmaj.151125. PMC 4786388. PMID 26903355.

- ^ "NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme". cancerscreening.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014.

- ^ "Home – Bowel Cancer Australia". bowelcanceraustralia.org. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Bevolkingsonderzoek darmkanker". rivm.nl. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014.

- ^ Tepus M, Yau TO (July 2020). "Non-Invasive Colorectal Cancer Screening: An Overview". Gastrointestinal Tumors. 7 (3): 62–73. doi:10.1159/000507701. PMC 7445682. PMID 32903904.

- ^ "New pathways could improve bowel cancer screening". NIHR Evidence. September 13, 2021. doi:10.3310/alert_47581. S2CID 239113610.

- ^ Stein A, Atanackovic D, Bokemeyer C (September 2011). "Current standards and new trends in the primary treatment of colorectal cancer". European Journal of Cancer. 47 (Suppl 3): S312–S314. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70183-6. PMID 21943995.

- ^ Chiorean EG, Nandakumar G, Fadelu T, Temin S, Alarcon-Rozas AE, Bejarano S, et al. (March 2020). "Treatment of Patients With Late-Stage Colorectal Cancer: ASCO Resource-Stratified Guideline". JCO Global Oncology. 6 (6): 414–438. doi:10.1200/JGO.19.00367. PMC 7124947. PMID 32150483.

- ^ Yamashita, Ken; Oka, Shiro; Tanaka, Shinji; et al. (March 1, 2019). "Long-term prognosis after treatment for T1 carcinoma of laterally spreading tumors: a multicenter retrospective study". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 34 (3): 481–490. doi:10.1007/s00384-018-3203-7. ISSN 1432-1262. PMID 30607579. S2CID 57427824.

- ^ a b McCarthy K, Pearson K, Fulton R, Hewitt J, et al. (Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group) (December 2012). "Pre-operative chemoradiation for non-metastatic locally advanced rectal cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD008368. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008368.pub2. PMID 23235660.

- ^ a b "Colorectal (Colon) Cancer". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ Böckelman C, Engelmann BE, Kaprio T, Hansen TF, Glimelius B (January 2015). "Risk of recurrence in patients with colon cancer stage II and III: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature". Acta Oncologica. 54 (1): 5–16. doi:10.3109/0284186x.2014.975839. PMID 25430983.

- ^ "Chemotherapy of metastatic colorectal cancer". Prescrire International. 19 (109): 219–224. October 2010. PMID 21180382.

- ^ Fakih MG (June 2015). "Metastatic colorectal cancer: current state and future directions". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 33 (16): 1809–1824. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7633. PMID 25918280.

- ^ Shaib W, Mahajan R, El-Rayes B (September 2013). "Markers of resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer". Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 4 (3): 308–318. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2013.029. PMC 3712296. PMID 23997942.

- ^ Yau TO (October 2019). "Precision treatment in colorectal cancer: Now and the future". JGH Open. 3 (5): 361–369. doi:10.1002/jgh3.12153. PMC 6788378. PMID 31633039.

- ^ Sugarbaker PH, Van der Speeten K (February 2016). "Surgical technology and pharmacology of hyperthermic perioperative chemotherapy". Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 7 (1): 29–44. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.105. PMC 4754302. PMID 26941982.

- ^ Segura-Sampedro JJ, Morales-Soriano R (August 2020). "Prophylactic HIPEC with oxaliplatin might be of benefit in T4 and perforated colon cancer: another possible interpretation of the COLOPEC results". Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas. 112 (8): 666. doi:10.17235/reed.2020.6755/2019. PMID 32686435.

- ^ Esquivel J, Sticca R, Sugarbaker P, Levine E, Yan TD, Alexander R, et al. (January 2007). "Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of peritoneal surface malignancies of colonic origin: a consensus statement. Society of Surgical Oncology". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 14 (1): 128–133. doi:10.1245/s10434-006-9185-7. PMID 17072675. S2CID 21282326.

- ^ Arjona-Sánchez A, Espinosa-Redondo E, Gutiérrez-Calvo A, Segura-Sampedro JJ, Pérez-Viejo E, Concepción-Martín V, et al. (April 2023). "Efficacy and Safety of Intraoperative Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Colon Cancer: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA Surgery. 158 (7): 683–691. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2023.0662. PMC 10134040. PMID 37099280.

- ^ DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA (2008). DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1258–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7207-5.

- ^ a b Feeney G, Sehgal R, Sheehan M, Hogan A, Regan M, Joyce M, Kerin M (September 2019). "Neoadjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer management". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 25 (33): 4850–4869. doi:10.3748/wjg.v25.i33.4850. PMC 6737323. PMID 31543678.

- ^ Li Y, Wang J, Ma X, Tan L, Yan Y, Xue C, et al. (2016). "A Review of Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer". International Journal of Biological Sciences. 12 (8): 1022–1031. doi:10.7150/ijbs.15438. PMC 4971740. PMID 27489505.

- ^ Cao C, Wang D, Tian DH, Wilson-Smith A, Huang J, Rimner A (December 2019). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of stereotactic body radiation therapy for colorectal pulmonary metastases". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 11 (12): 5187–5198. doi:10.21037/jtd.2019.12.12. PMC 6988072. PMID 32030236.

- ^ Boland PM, Ma WW (May 2017). "Immunotherapy for Colorectal Cancer". Cancers. 9 (5): 50. doi:10.3390/cancers9050050. PMC 5447960. PMID 28492495.

- ^ a b Syn NL, Teng MW, Mok TS, Soo RA (December 2017). "De-novo and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint targeting". The Lancet. Oncology. 18 (12): e731–e741. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30607-1. PMID 29208439.

- ^ Borras, DM, Verbandt, S, Ausserhofer, M, et al. (November 2023). "Single cell dynamics of tumor specificity vs bystander activity in CD8+ T cells define the diverse immune landscapes in colorectal cancer". Cell. Discovery. 9 (114): 114. doi:10.1038/s41421-023-00605-4. PMID 37968259.

- ^ "FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. February 9, 2019.

- ^ Cercek A, Lumish M, Sinopoli J, Weiss J, Shia J, Lamendola-Essel M, El Dika IH, Segal N, Shcherba M, Sugarman R, Stadler Z, Yaeger R, Smith JJ, Rousseau B, Argiles G, Patel M, Desai A, Saltz LB, Widmar M, Iyer K, Zhang J, Gianino N, Crane C, Romesser PB, Pappou EP, Paty P, Garcia-Aguilar J, Gonen M, Gollub M, Weiser MR, Schalper KA, Diaz LA Jr (June 2022). "PD-1 Blockade in Mismatch Repair–Deficient, Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 386 (25): 2363–2376. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2201445. PMC 9492301. PMID 35660797. S2CID 249395846.

- ^ "Palliative or Supportive Care". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ "ASCO Provisional Clinical Opinion: The Integration of Palliative Care into Standard Oncology Care". ASCO. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Higginson IJ, Evans CJ (September–October 2010). "What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families?". Cancer Journal. 16 (5): 423–435. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181f684e5. PMID 20890138. S2CID 39881122.

- ^ Wasserberg N, Kaufman HS (December 2007). "Palliation of colorectal cancer". Surgical Oncology. 16 (4): 299–310. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2007.08.008. PMID 17913495.

- ^ Amersi F, Stamos MJ, Ko CY (July 2004). "Palliative care for colorectal cancer". Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America. 13 (3): 467–477. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2004.03.002. PMID 15236729.

- ^ a b "National Comprehensive Cancer Network" (PDF). nccn.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Desch CE, Benson AB, Somerfield MR, Flynn PJ, Krause C, Loprinzi CL, et al. (November 2005). "Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (33): 8512–8519. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. PMID 16260687.

- ^ Jeffery M, Hickey BE, Hider PN (September 2019). "Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (9): CD002200. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002200.pub4. PMC 6726414. PMID 31483854.

- ^ Betof AS, Dewhirst MW, Jones LW (March 2013). "Effects and potential mechanisms of exercise training on cancer progression: a translational perspective". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 30 (Suppl): S75–S87. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2012.05.001. PMC 3638811. PMID 22610066.

- ^ a b Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM (June 2012). "Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 104 (11): 815–840. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs207. PMC 3465697. PMID 22570317.

- ^ a b McGettigan M, Cardwell CR, Cantwell MM, Tully MA (May 2020). "Physical activity interventions for disease-related physical and mental health during and following treatment in people with non-advanced colorectal cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (5): CD012864. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012864.pub2. PMC 7196359. PMID 32361988.

- ^ Strømme JM, Johannessen B, Skotheim RI (2023). "Deviating alternative splicing as a molecular subtype of microsatellite stable colorectal cancer". JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics. 7: e2200159. doi:10.1200/CCI.22.00159. PMID 36821799.

- ^ Osterman E, Glimelius B (September 2018). "Recurrence Risk After Up-to-Date Colon Cancer Staging, Surgery, and Pathology: Analysis of the Entire Swedish Population". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 61 (9): 1016–1025. doi:10.1097/dcr.0000000000001158. PMID 30086050. S2CID 51934598.

- ^ Zacharakis M, Xynos ID, Lazaris A, Smaro T, Kosmas C, Dokou A, et al. (February 2010). "Predictors of survival in stage IV metastatic colorectal cancer". Anticancer Research. 30 (2): 653–660. PMID 20332485.

- ^ Agabegi ED, Agabegi SS (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7153-5.

- ^ Hong Y (June 30, 2020). "Clinical study of colorectal cancer operation: Survival analysis". Korean Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020. 16 (1): 3–8. doi:10.14216/kjco.20002. PMC 9942716. PMID 36945303.

- ^ "Five-Year Survival Rates". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ Xu Z, Becerra AZ, Fleming FJ, Aquina CT, Dolan JG, Monson JR, et al. (October 2019). "Treatments for Stage IV Colon Cancer and Overall Survival". The Journal of Surgical Research. 242: 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2019.04.034. PMID 31071604. S2CID 149443256.

- ^ Drageset S, Lindstrøm TC, Underlid K (April 2016). ""I just have to move on": Women's coping experiences and reflections following their first year after primary breast cancer surgery". European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 21: 205–211. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2015.10.005. PMID 26521054.

- ^ Restivo A, Zorcolo L, D'Alia G, Cocco F, Cossu A, Scintu F, Casula G (February 2016). "Risk of complications and long-term functional alterations after local excision of rectal tumors with transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM)". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 31 (2): 257–266. doi:10.1007/s00384-015-2371-y. PMID 26298182. S2CID 29087556.

- ^ Bregendahl S, Emmertsen KJ, Lindegaard JC, Laurberg S (January 2015). "Urinary and sexual dysfunction in women after resection with and without preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a population-based cross-sectional study". Colorectal Disease. 17 (1): 26–37. doi:10.1111/codi.12758. PMID 25156386. S2CID 42069306.

- ^ Ramirez M, McMullen C, Grant M, Altschuler A, Hornbrook MC, Krouse RS (December 2009). "Figuring out sex in a reconfigured body: experiences of female colorectal cancer survivors with ostomies". Women & Health. 49 (8): 608–624. doi:10.1080/03630240903496093. PMC 2836795. PMID 20183104.

- ^ Steele N, Haigh R, Knowles G, Mackean M (September 2007). "Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) testing in colorectal cancer follow up: what do patients think?". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 83 (983): 612–614. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2007.059634. PMC 2600007. PMID 17823231.

- ^ McGeechan GJ, Byrnes K, Campbell M, Carthy N, Eberhardt J, Paton W, et al. (January 2021). "A systematic review and qualitative synthesis of the experience of living with colorectal cancer as a chronic illness". Psychology & Health. 37 (3): 350–374. doi:10.1080/08870446.2020.1867137. PMID 33499649. S2CID 231771176.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–2128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253.

- ^ WHO (February 2010). "Cancer". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ Merika E, Saif MW, Katz A, Syrigos K, Syrigos C, Morse M (2010). "Review. Colon cancer vaccines: an update". In Vivo. 24 (5): 607–628. PMID 20952724.

- ^ Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM (2010). "Colorectal Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2008 – Summary". Archived from the original on October 17, 2012.; "GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10". Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Archived from the original on May 8, 2011.

- ^ a b "Colorectal cancer: Statistics". Cancer.net, American Society of Clinical Oncology. February 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ Katella K. "Colorectal Cancer: What Millennials and Gen Zers Need to Know". YaleMedicine.

- ^ "Bowel cancer About bowel cancer Cancer Research UK". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ^ Cancer in Australia: an Overview, 2014. Cancer series No 90. Cat. No. CAN 88. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2014. ISBN 978-1-74249-677-1.

- ^ Cancer in Papua New Guinea: an Overview, 2016. Cancer series No. 176. Cat. No. CAN 88. Papua New Guinea Department of Health. 2016.

- ^ Rehemtulla A (December 2010). "Dinosaurs and ancient civilizations: reflections on the treatment of cancer". Neoplasia. 12 (12): 957–968. doi:10.1593/neo.101588. PMC 3003131. PMID 21170260.

- ^ Zhong L, Zhang X, Covasa M (June 2014). "Emerging roles of lactic acid bacteria in protection against colorectal cancer". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (24): 7878–7886. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7878. PMC 4069315. PMID 24976724.

- ^ Golovko D, Kedrin D, Yilmaz ÖH, Roper J (2015). "Colorectal cancer models for novel drug discovery". Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 10 (11): 1217–1229. doi:10.1517/17460441.2015.1079618. PMC 4872297. PMID 26295972.

- ^ Oh BY, Hong HK, Lee WY, Cho YB (February 2017). "Animal models of colorectal cancer with liver metastasis". Cancer Letters. 387: 114–120. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.048. PMID 26850374.

- ^ Evans JP, Sutton PA, Winiarski BK, Fenwick SW, Malik HZ, Vimalachandran D, et al. (February 2016). "From mice to men: Murine models of colorectal cancer for use in translational research". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 98: 94–105. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.10.009. PMID 26558688.

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer Atlas". Archived from the original on January 13, 2016.